JAMES GODWIN W. L. THOMAS.

THE FARM-HOUSE KITCHEN.

Vol. ii. page 286.

Title: The Sheepfold and the Common; Or, Within and Without. Vol. 2 (of 2)

Author: Timothy East

Release date: January 27, 2014 [eBook #44769]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Robin Curnow, Julia Neufeld, One

image courtesy of Bridwell Library, Perkins School of

Theology, Southern Methodist University and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE SHEEPFOLD AND THE COMMON.

VOL. II.

"My sheep hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me."—John x. 27.

"Them that are without God judgeth."—1 Cor. v. 19.

BLACKIE AND SON:

GLASGOW, EDINBURGH, AND LONDON.

———

MDCCCLXI.

GLASGOW:

W. G. BLACKIE AND CO., PRINTERS,

VILLAFIELD.

VOL. II.

| Page | |

| Old Rachel, the Blind Woman, | 1 |

| Diversity of Opinion Very Natural, | 18 |

| Union Without Compromise, | 37 |

| The Stage Coach, | 52 |

| A Sabbath in London, | 62 |

| The Sceptic's Visit, | 76 |

| A Renewed Encounter, | 94 |

| The Effect of a Word Spoken in Season, | 108 |

| The Family of the Holmes, | 123 |

| A Misfortune often a Blessing in Disguise, | 134 |

| Christian Experience, | 155 |

| Doubts and Perplexities, | 166 |

| Theatrical Amusements, Part I., | 177 |

| Theatrical Amusements, Part II., | 198 |

| Unitarianism Renounced, | 219 |

| The Path of Truth Forsaken, | 240 |

| The Fruits of Apostasy, | 261 |

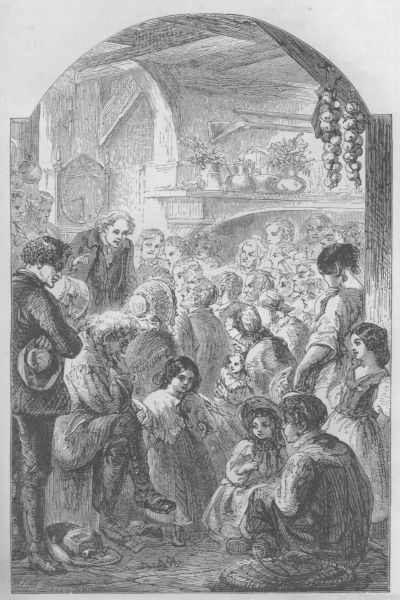

| The Farm-House Kitchen, | 284 |

| A Party at the Elms, | 296 |

| Family Sketches, | 311 |

| Amusements, | 323 |

| The Unhappy Attachment, | 342 |

| A Sequel to the Foregoing, | 365 |

| [vi]The Village Chapel, | 386 |

| Village Characters, | 401 |

| The Pious Cottager, | 422 |

| The Closing Scene of the Young Christian's Career, | 431 |

| The Happy Marriage, | 449 |

| An Old Friendship Revived, | 462 |

| The Wanderer's Return, | 474 |

| A Struggle for Life, | 493 |

| The Sceptic Reclaimed, | 504 |

| The Rector's Death-Bed, | 518 |

| The Rector's Funeral, | 529 |

| The New Rectors, | 540 |

| A Secession at Broadhurst, | 551 |

| A Farewell to Old Friends, | 561 |

| Conclusion, | 575 |

VOL. II.

| Page | |

| The Farm-House Kitchen, | Frontispiece. |

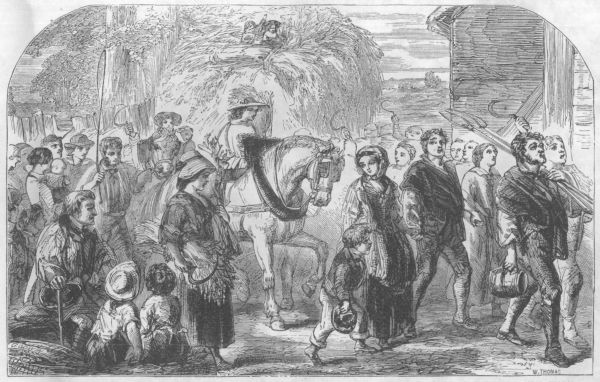

| A Contrast, | Engraved Title. |

| George III. and the Dying Gipsy, | 7 |

| Mistaken Charity—Mr. Sykes's Theory Refuted, | 55 |

| Sabbath Pleasure-Seekers, | 64 |

| The Conspiracy Defeated, | 128 |

| The Mother's Hopes Blasted, | 179 |

| Mr. Beaufoy's Emotion on receiving his Mother's Letter, | 261 |

| Bringing in the Last Load of Corn—The Reapers' Hymn of Praise, | 285 |

| Miss Holmes and Miss Martin taking leave of Mrs. Kent, | 299 |

| First Meeting of Captain Orme and Emma Holmes, | 352 |

| Mr. Swinson assaulted by the Mob, | 396 |

| The Bridal Party welcomed by the Villagers, | 456 |

| The Wanderer's Return, | 480 |

"And so I hear," said Mrs. Stevens to the Rector, when we were spending an evening at his house, "that poor Old Rachel is dead. I really thought she had died long since, as I have not heard anything about her for a long time."

"Yes, Madam," replied Mr. Ingleby, "she is dead, and was buried yesterday; she lies very near some of the finest of my flock."

"She must have lived to a great age, for she was an old woman when I was but a little girl."

"She was, I believe, upwards of ninety, and for several years she lived with some relatives in a state of almost entire seclusion. I had quite lost sight of her, and it was owing to a very casual circumstance that my acquaintance with her was renewed."

"How did you happen again to meet with her?"

"It was in this way. I required some one to weed my garden; and hearing that there was an active clever woman residing at Street, about two miles from the rectory, who was a good hand at such work, I took a walk to find her. On reaching her house I knocked at the door, but received no answer; and just as I was going away, rather disappointed at having made a fruitless journey, a neighbour stepped out of the adjoining cottage, and said, 'If,[2] Sir, you want Mrs. Jones, she has just gone out, but I will go and look for her, if you will perhaps come in here, and rest yourself for a few minutes.' I thanked her, and followed her into the house, where she placed a chair for me, saying, as she left to go in search of Mrs. Jones—'It's no use, Sir, to say nothing to my mother there; she is quite blind, and so deaf, that she can't hear a word which nobody says to her.' The person to whom she pointed sat in an arm-chair, on the opposite side of the fire, wrapped up in flannel, her face nearly concealed by her cap and bonnet, and as motionless as a statue. I sat for a few moments in silence, and then, yielding to a feeling of curiosity, and I would also hope to a better motive, to endeavour to ascertain whether I could impart the soothing influences of religious consolation to the seemingly inanimate object that sat opposite to me, I arose, and placing my lips as near her ear as possible, without touching her, said, audibly and distinctly, 'You are very old.' No reply. This was followed by several common-place questions—such as, 'What is your name?' 'Do you want anything?' 'Are you in any pain?' These and other questions I continued to repeat; but they produced no more effect on her than they would have done on a log. 'Poor thing,' I exclaimed, 'it's no use to try, as she is living out of my reach. The door of access is locked, and the key lost.' I resumed my seat. My anxiety to gain access to her mind increased in proportion to the apparent impossibility of succeeding, and I made another effort. 'Do you ever think about dying?' There was a slight convulsive movement of the hand, but this was no satisfactory proof that she heard my question; however, it showed that the inner spirit was awake, and might possibly be bringing itself to a listening attitude. I then put the all-important question—'Do you know anything about Jesus Christ?' Never shall I forget the effect of this question. Her hands were suddenly raised, her arms extended, and her face glowed with more than human radiance, and, in a tone of transport, she exclaimed, 'What! is that my beloved pastor? It was under your ministry I was brought to know Christ, and feel the preciousness of his[3] love.' This unanticipated exclamation astonished and delighted me, especially when I recognized, by the sound of her voice, Old Rachel. To all my questions relating to her secular condition and wants, she was as insensible as though actually dead. I stood and looked on her with joyous wonder, never having previously known a similar case. I repeated question after question, but had no response, till I asked, 'Is Christ precious to you?' Her reply was prompt and audible: He is precious to my soul—my transport and my trust.' The reply had an electrical effect on my spirit. Marvellous! I never witnessed such a scene as this. I varied my questions again and again; but there was no sign of hearing, or even perceptible motion, though I took hold of her hand. It was as though some angelic spirit kept watch, to prevent any thought relating to earth or time from obtruding itself on her attention, now she was waiting on the verge of the celestial world. One question more, and all intercourse was over. 'Do you long to see Christ?' She instantly replied, 'My soul is in haste to be gone.' Again she relapsed into her statue-like appearance, and in that state continued till the return of her daughter with Mrs. Jones, after transacting my business with whom, I took leave, and walked home, musing on the history of Old Rachel, and resolving that I would soon again pay her a visit."

"I should like," said Mrs. John Roscoe, "to have witnessed this scene, and heard the retiring spirit thus appearing to bear testimony to the more than magic power of the Saviour's name, and of the preciousness of his love."

"And so, Madam, should I," said the Rev. Mr. Guion; "it would have been to me like a voice speaking from another world, in confirmation of the genuineness of our faith, which sees the invisible, and holds conscious intercourse with Him, though we hear him not. I generally find, that a singular ending is closely connected with a singular origin, or a series of eventful occurrences. Can you favour us with some account of her history?"

"Yes, Sir, I can, and it is both interesting and peculiar. I did not know her till she was advanced in age, and had lost her sight;[4] yet, before I knew her, I had often heard her spoken of as an intelligent woman, very fond of books, and remarkable for the neatness and cleanliness of her person, and her regular and punctual attendance at her parish church. When her sight failed her, she was compelled to relinquish the school by which she had gained her livelihood; but she was so much esteemed, that a good allowance was granted by the parish, and this was augmented by weekly subscriptions from some of the members of her church. On passing by her cottage one day, I looked in to see her, though she was not one of my parishioners; but as she had imbibed the Tractarian doctrines of her Rector, and felt a strong repugnance to evangelical truth, I at once perceived that my presence was more disagreeable than pleasing. I therefore withdrew, not intending to repeat my visit until I had prepared her to desire it. I soon hit upon a plan to accomplish this. The old woman had a little favourite grand-daughter in my Sabbath-school, and it occurred to me that I could employ her as the medium of communication; and I commenced operations by giving her and lending her some little books of anecdotes and descriptive stories. After the lapse of several months, I gave her, as a reward for reading to her grandmother, the sketch of the Rev. John Newton's conversion; and this was followed by a tract on regeneration, with which the old woman was so much pleased, that she requested the loan of another on the same subject. No great while after reading this tract she came to hear me preach, and soon became a regular attendant on my ministry; and ere long she sent to say she should be glad if I would call on her. I went; she apologized for her rudeness of manner on my former visit, and excused herself by referring to the influence which superstitious prejudices had acquired over her. From these superstitions she hoped she was now rescued by the attractive power of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

"When it was noised abroad that Rachel, the old blind woman, had left the church, where Tractarian doctrines and ceremonies were the theme of the Rector's ministrations, she received a visit from[5] some of her lady friends, who were very anxious to get her to return, intimating that if she did, they would continue their subscriptions towards her support, otherwise she must not expect to receive any more favours from them. She heard all they chose to say, and thus announced her final decision:—'I have, ladies, attended my parish church for more than fifty years without getting any benefit to my soul, but where I have been only a few Sabbaths I have heard and felt the truth as it is in Jesus, and there I shall continue to go as long as my feeble limbs will carry me. I thank you for all your acts of liberality and kindness to me, but I cannot barter away my freedom, and run the risk of losing my soul. I must live free, though in poverty; and my salvation is now the one thing I value above all price.' She continued for several years both regular and punctual in her attendance on my ministry, but at length was compelled, by increasing infirmities, to give up her house and go to reside with a married daughter. Years rolled on—the grand-daughter had left my school—the cottage where the old woman had resided was occupied by another—she gradually faded from my recollection, and in process of time I had quite forgot her."

"I used," said Mrs. Stevens, "to see her, with her grand-daughter leading her, coming to church and going from it; but she sat in some pew which concealed her from my sight when in the church."

"She was, Madam, one of the most retiring women I ever knew; she had a great objection to be seen, as she knew her conversion and her leaving the ministry of her former Rector had excited a good deal of talk."

"The circumstances attending her conversion to the faith of Christ," observed the Rev. Mr. Guion, "is an evident proof of its genuineness, and of its having been effected by the Holy Spirit; otherwise it would have been impossible for you to have gained her over to the reception of salvation by grace through faith, as she was so self-satisfied with her own Tractarian delusions, and so much under the power of the active agents of the same fatal heresy."

"I must confess that no event in my long pastoral career ever gave[6] me more real pleasure, or excited purer emotions of gratitude to my Divine Master, than being allowed to witness the termination of her course—so unexpected, and so novel."

"I have known," said the Rev. Mr. Guion, "some delivered from their terrors and misgivings, just prior to their departure, who have been in bondage all their life, through fear of death, and then they have felt even a transport of joy in anticipation of the end of their faith, but I have never known a case like this of Old Rachel."

"I recollect," said Mr. Roscoe, "reading in the Times, some years ago, the report of a case bearing a strong resemblance to it in some of its distinctive peculiarities. Mr. M——, of ——-, who had through a very lengthened course distinguished himself by his activity in secular life, and by his practical piety, when drawing near his latter end, appeared quite indifferent, if not positively insensible, to everything bearing a relation to earth, though surrounded by its wealth and honours; but even then he gave unmistakeable signs to his pious relatives, that he was filled with all joy and peace in believing, abounding in hope, through the power of the Holy Ghost."[1]

Mr. Lewellin remarked:—"An intimate friend related to me, some time since, the following circumstances, which belong to the same remarkable order with that of Old Rachel and Mr. M——. He knew a Mr. Griffith, who left Wales when a young man, and settled in London, where he practised as a surgeon for half a century with very considerable success; but feeling the infirmities of age coming on, he disposed of his business and withdrew into private life. From his youth up he had maintained a good report amongst his Christian brethren. He lived for years after he had relinquished his practice, but latterly fell into such a state of apathy that he was unable to recollect his own children, and had even forgotten the English language, which he had spoken for more than fifty years,[7] using, in his Scripture quotations and audible prayers, his native Welsh. He would remain for many hours in succession without appearing to notice any visible object, asking any question, or replying to any observation relating to secular matters. He had withdrawn from the world, living surrounded with invisible realities, the varying aspect of his countenance indicating some active process of thinking and emotion; but when he heard the name of Jesus mentioned, or any allusion to his love in dying for sinners, his eyes would sparkle with peculiar radiance, his hands would clasp together, and he would pour forth expressions of gratitude and joy, which betokened the vital energy of his soul, and the intense interest he felt in anticipation of the grand crisis. On his favourite theme of meditation he evinced no dulness, nor lack of mental energy; he would emerge from his seclusion to hold intelligible intercourse with his Christian brethren, when he heard them give utterance to the joyful sound, and then drew back, without any distinct recognition of their persons, to dwell alone in the pavilion of the Divine presence."[2]

"These are spiritual phenomena," said the Rev. Mr. Roscoe, "which, like the phenomena of nature, are too plain and palpable to be denied, even though it may not be in our power to give all the explanations about the causes of them which our curiosity would like to receive."

"Very true, Sir," said Mr. Ingleby; "but there are certain statements and expressions in the New Testament which throw light enough upon such phenomena to demonstrate that they have their natural causes, and thus they are rescued from the supposition that they are self-originated and self-sustained movements of the human spirit, in some complexed and eccentric condition of existence. Our Lord says to his disciples, 'I am the vine, ye are the branches; he that abideth in me and I in him, the same bringeth forth much fruit' (John xv. 5). The life of the branch depends on its adhesion to the tree which supplies the sap of nourishment. Again, he says, 'I in them' (John xvii. 23). The apostle says, 'I live, yet not I, but Christ liveth in me' (Gal. ii. 20). Again, 'Your life is hid with Christ in God' (Col. iii. 3), denoting its invulnerable security. From the passages which I have now quoted, and there are many others of the same import, we arrive at this conclusion, which is an explanation and a defence of the spiritual phenomenon, that there is an actual, though inexplicable inhabitation of Jesus Christ in the soul of a believer (Rev. iii. 20), sustaining the spiritual life within him, as the vine nourishes the branch which bears its own fruit. And as He has life in himself, he can do this with perfect ease, not only when the believer is in vigorous health, and in the full exercise of all his mental faculties, but when he is labouring under those physical[9] diseases and mental infirmities which, by a slow progression, lead to his decay and death."

The Rev. Mr. Guion observed, "That to deny the existence of such phenomena, and others which bear some affinity to them, simply because they are extraordinary, would be an act of absurdity which no spiritual or even philosophic mind would venture to defend, because the evidence in proof of their actual occurrence is so clear and conclusive. The real question of difficulty to decide is simply this:—Are they supernatural manifestations, or illusions of the imagination? but, in either case, they go off into their own element of mysteriousness, compelling us to believe what we cannot explain. On a supposition that they are real manifestations of Divine power and love, which I fully believe they are, I cannot help thinking that the highly-favoured spirit (Old Rachel, for example), while in such a state of lucid and active unconsciousness, if I may use such an expression, must exist in something like an intermediate position between the material and immaterial world—dying off from one by a very slow progression, and getting meet for the other by a similar process; occasionally stepping back to give unmistakeable signs of the continued possession of the faculties of thought and emotion, and then retreating, as into a citadel standing near the dark frontier of the invisible world, and into which its celestial rays sometimes penetrate."

"In these cases of rare occurrence," said Mr. Roscoe, "it is the soul of the spiritual man retreating from visible and audible fellowship with his pious associates; but biography supplies us with another order of moral phenomena equally inexplicable, yet equally gratifying, tending to confirm the reality of the connection between the visible and invisible world which the Christian revelation so plainly and positively announces. I received, some time ago, the following statement from an elder of a Scotch church, on whose testimony I can place implicit dependence:—'About the month of August, 1838, I went to see my grandfather, a pious old man, ninety-two years of age. I sat by his bedside, and others also were with[10] him. He had been silent and motionless for about five hours, when he opened his eyes, his countenance beaming with joy, and raising his hands he said, I see heaven open, and Jesus Christ at the right hand of God, and the angels of God descending to receive me. These were his last words, and when he had given utterance to them he expired.'"

"This reminds me," said Mr. Lewellin, "of an incident which occurred at Stepney College,[3] not long ago. When Ebenezer Birrel, a student there, was dying, he requested all who were in the room with him to keep silence. He also was silent and motionless. At length he looked and gazed in rapture on some glorious object, which to him alone was visible, exclaiming, as he gazed, 'Beautiful! beautiful!' and in uttering the word 'GLORY!' his head fell and he expired."

"The case of Dr. Gordon, of Hull," said the Rev. Mr. Guion, "differing, as it does in some particulars, from all the specimens we have had of these spiritual phenomena, is, I think, deserving of our special notice. 'He appeared,' says his biographer, 'just as he was expiring, no longer conscious of what took place around him. He gazed upwards, as in wrapt vision. No film overspread his eyes. They beamed with an unwonted lustre, and the whole countenance, losing the aspect of disease and pain, with which we had been so long familiar, glowed with an expression of indescribable rapture. As we watched, in silent wonder and praise, his features, which had become motionless, suddenly yielded for a few seconds to a smile of ecstasy which no pencil could ever depict, and which none who witnessed it can ever forget. And when it passed away, still the whole countenance continued to beam and brighten, as if reflecting the glory on which the soul was gazing. This glorious spectacle continued for about a quarter of an hour, increasing in interest to the last.'"

"I have heard of other cases," remarked Mr. Ingleby, "bearing a strong resemblance to some which have been mentioned; but I have never made much use of them, except as supplementary proofs in confirmation of my own belief in the inseparable connection of[11] the two worlds. They are not absolutely necessary to establish this great fact; yet we must all admit, that such proofs can be supplied, if it should please God to do so; and we know he has done it more than once. Not to dwell on the vision of the apostle Paul, I would just advert to the case of Stephen. When his enemies were gnashing on him with their teeth, expressive of their indignation against him, for accusing them of having betrayed and murdered the Just One—'He, being full of the Holy Ghost, looked up steadfastly into heaven, and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing on the right hand of God' (Acts vii. 55). He saw clearly what the others saw not, and for reporting what he saw he was denounced a blasphemer, and was led out and stoned to death. This case settles two great facts:—First, that God can, when he pleases, unveil to mortal vision the glorious forms and appearances of the invisible world; and secondly, that he has done it."

"I feel unwilling," said the Rev. Mr. Roscoe, "to object to any evidence which tends to confirm our belief in the connection between the visible and invisible world; but I think great caution is necessary in employing such cases as have now been reported in proof of it. What the old Scotchman and the youthful student saw, or thought they saw, may, after all, have been nothing more than the illusions of their own disturbed imagination, left at the closing scene uncontrolled by the immortal spirit itself, while in the act of passing from its material tabernacle, and away from its material senses, into another, a higher, and more congenial economy of existence."

"True, Sir," said Mr. Ingleby; "but then, if we admit that they really are illusions, we must also admit that they are illusive only by a forestalling process; the imagination bringing to the senses, yet bounded by the material economy, objects of vision belonging to another state of existence—framing types of invisible realities—lifting up, in the living temple of humanity, prefigurations of what will be seen when the fulness of time comes for the disembodying of the soul and its glorification. The illusion then relates, not to the UNREALITY of what is seen and felt, but to the unreality of the act[12] of vision, and its consequent excitement and impression, both mental and physical."

"We know," said. Mr. Roscoe, "that God very rarely deviates in his providential administration, from the established laws of his government; but we also know that he does sometimes, and for the purpose of making us know more impressively that he is the Lord, who exercises loving-kindness, judgment, and righteousness in the earth, for in these things he delights. Hence, there have been two translations from earth to heaven, without the intervening infliction of death, but only two, since the fall of man. In reference to the remarkable cases under consideration, there may be some difficulty in deciding whether the persons actually saw what they are reported to have seen, or were imposed on by the mysterious action of their own imagination; but yet I cannot bring my mind to the conclusion, that the visions were positive illusions, and that the happy spirits who saw them, and spake of them, and whose radiant countenances betokened the truthfulness of their testimony, were dying under the spell of self-deception. Such cases, we know, but very rarely occur, and when they do occur they make their appearance quite unexpectedly; but I think they occur often enough, and with such varying peculiarities, as to make us hesitate to pronounce them positive illusions, even if we cannot admit with confidence that they are positive realities."

"At any rate," said Mrs. John Roscoe, "the spell of self-deception, if they were deceived, was soon broken, as in each case death came immediately after they uttered their last joyous exclamation; and then the sublime vision of immortality opened upon them, with all its glorious realities."

The Rev. Mr. Guion here remarked that, "in general, the Lord's people die in hope and with great calmness; and sometimes they rise to confidence, and even to joy, and joy unspeakable. Few, indeed, rise higher than this; but I have known enough, and heard enough, to satisfy me that some do. The case of Dr. Gordon, who uttered no exclamation, is to me a decisive proof of this. He is calm, motionless,[13] wrapped in profound thoughts, when his countenance, which had long been marked by the lines of disease and pain, begins to radiate, till at length its lustre was so clear and bright, attended by an ecstatic smile so ethereal, that the spectators were awe-struck, standing and gazing for the space of a quarter of an hour on this more than human vision. At least, they thought it more than human while they were gazing on it."

"Every effect," said Mr. Ingleby, "must have some adequate cause; and this extraordinary radiation on the countenance of Dr. Gordon was produced either by the action of his own thoughts, or by the intervention of a supernatural power. If produced by his own thoughts, what a hold must his soul have taken of invisible realities when he was dying, to give such a glowing brilliancy to his pallid face! If produced by the intervening action of supernatural power, it was a premature shining forth of the glory to be revealed more fully in the disembodied state. In other words, he did what was done by the impulse of his own conceptions, or God was especially with him in his dying chamber, shedding upon him some effulgent rays of his own glory."

"But to return," said the Rev. Mr. Roscoe, "to the case of Rachel, the old blind woman, which, because it is capable of a more practical bearing, I must confess, interests me more than the splendid case of Dr. Gordon, interesting as it is. But, before I touch on this, will you permit me to ask how long she lived after your unexpected interview with her? and whether there was a recurrence of the astonishing responses to your inquiries?"

"I sat gazing on her," said the Rev. Mr. Ingleby, "some time after I ceased speaking; and before I left her, her countenance had resumed its statue-like appearance of positive insensibility; and every feature was fixed, as though set by the cold hand of death, and there was not a movement of any part of her body, except the breast and the shoulders, from the more powerful action of the lungs. The following week I took a friend with me, in expectation of having another interview with her; but I was disappointed. On entering[14] the cottage, her daughter informed me, that having awoke in the night, and thinking she heard her mother utter some sound, she went with a light to her bedside, when the old woman, after a slight convulsive struggle, raised her hands, and said, 'Dear Saviour, I come to thee,' and died."

"What a splendid transition!" said Mrs. Stevens; "the cottage exchanged for a mansion! What a glorious sequel to all her privations and sufferings! Her happy spirit, long confined in total darkness, is at last liberated, and is now beholding the glory of Christ, and living and moving amidst the celestial beings and sublime grandeur of immortality."

"And yet we are told," said Mr. Roscoe, "that the faith of Christ, which unveils such grand prospects of a future state of existence, is a mere delusion, and that we who indulge them are self-deceived. If we admit this, we must also admit that it is a very remarkable delusion, as it usually comes in its most vivid forms, and with its most attractive influences, just at that period of human existence when all things of earth and of time are vanishing away. At that awful crisis, when the pomp of distinction, the fascination of sensible objects, and the grandeur of wealth, are all losing their hold on us—and nothing is left to man but the shroud, the coffin, and the grave —at that very time the Christian faith opens up a scene of grandeur which no words can adequately describe; and yet the dying man, who feels his departing spirit embracing these revelations as sublime realities, is told by the cold-hearted sceptic that all is a delusion, and he is self-deceived. But he heeds not such random assertions. He moves forward, repeating the soul-inspiring words, 'Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me' (Psal. xxiii. 4)."

"But this case of poor Old Rachel," said the Rev. Mr. Roscoe, "does something more than exhibit the efficacy of the Christian faith, in sustaining the human soul when the dread hour comes—it supplies a proof of the immateriality, and, by a fair inference, of the immortality[15] of the soul itself. We are told, by some sagacious sceptics, that the mind of man, like his body, is material, only that it has passed through a more refined process, and is endowed by nature with certain faculties analogous to the senses; and as they came into existence together at the time of his birth, and live together through life, so they will go out of existence together when they pay the debt of nature, and, at last, perish together. And I must confess that humanity has, in some instances, seemed to give a confirmation to this opinion, as the body and the mind have appeared to wither and decay together, as age and infirmities have come upon them. Hence there has been a loss of memory with the loss of animal vivacity—a loss of intellectual vigour with the loss of physical strength—a loss of imaginative power with the loss of sensitive acuteness—the mind and the body undergoing this reciprocal decay before the change comes which, according to the sceptic's theory, is to end in their extinction. But, then, I have met with another class of cases bearing some analogy to this reciprocal decay, but, at the same time, putting forth indications in confirmation of a reversed issue, as in the history of Old Rachel. In her we see the memory losing the impression of earthly objects, but retaining the impression of heavenly ones. Her intellect lies prostrate and powerless in the presence of sensuous and secular inquiries, but it springs into vigorous activity when spiritual ones are addressed to her. The affections of her heart have died off from the relationships of life; but they are concentrated on the perfection of moral beauty, and cleave to Jesus Christ with an intensity and ardour surpassing that of a youthful passion. Here we have a living exponent, and a confirmation of the truthfulness of the apostolic expression, 'Though our outward man perish, yet the inward man is renewed day by day.' (See John xi. 25, 26)."

"And there is another practical lesson," Mr. Ingleby remarked, "which this case of Old Rachel teaches us, and it is this:—When a man is enlightened by the Spirit, and is brought into fellowship with Jesus Christ, and has felt the power of the world to come, he never outlives his knowledge of these wondrous realities which stand[16] out in bold relief when his remembrance of all other things is blotted out. He may forget the wife of his bosom, and the children who revered and loved him—he may forget his mother tongue, and not recognize the hand which feeds and clothes him—and he may live till almost every sense has become extinct, and the avenues of communication between the imprisoned spirit and the living world are blocked up—but he will never forget by whose blood he has been redeemed—he will never become insensible to the charm of His name or the preciousness of His love—nor will he ever lose sight of the bright and unfading inheritance of which he has received the earnest. Old Rachel was living at ease, conscious of her possessions, even when, in the estimation of others, she was unconscious of her own existence; and indulging the sublimest anticipations of faith and hope, while in the dark cell of her confinement."

"Without giving any opinion," said the Rev. Mr. Roscoe, "as to which of the cases reported this evening is the most remarkable, or presuming to decide, whether they are to be referred to some mysterious action of the imagination, or to a real, yet marvellous manifestation of the Divine presence—leaving each case to stand for your decision on the ground of its own merits—I think we may make a good practical use of the whole of them, as, when we see lights burning, though of varying degrees of brightness, we may avail ourselves of their radiance even if we cannot tell by whom they are enkindled. We believe that the evidence which the Bible supplies, in confirmation of the existence of another world, is sufficiently ample and decisive to satisfy us of its reality; but still it is not so ample and decisive as to preclude the desirableness of some additional evidence. This is often given in the death-chamber of the Christian believer; and not only to him, when dying, but to those who are eye-witnesses of the mode of his departure. When, for example, we see a man of intelligence, of taste, of great sobriety of thinking, and of courteous speech, quite calm on his death-bed, and alternately strongly excited—when we hear him speak of the hope he entertains of a glorious immortality—when we see him rising[17] above hope into full assurance, eager to depart, though surrounded by many of the attractions of earth—when every look, and aspiration, and utterance, beats in harmony with his long-settled expectation of a grand issue to his faith—we may very naturally take his experience, not only as a safe guide, but as a valid testimony to the certainty of what we believe in common. But now suppose, if, in addition to this tranquil state of mind, we should see a bright radiance beaming on the countenance of our dying friend, previously pallid and careworn by disease—and suppose we should see him raise himself up in bed, looking intently, as if seeing some beautiful object concealed from us, and, after a profound silence and stillness of some minutes, we should hear him speak of actually seeing, while in the body, what we believe he will see the moment he is out of the body—would not this tend to strengthen our faith, even though we are unable to decide whether he actually saw, or merely thought he saw, the scenes he described? I think it would; and that even the most dubious on the question of illusion or reality would retire from such a hallowed spectacle, filled with emotions of deep solemnity and joyous delight, similar to what a primitive believer must have felt when looking on the face of Stephen, shining with angelic brilliancy, a visible attestation of the reality of his miraculous vision."

"I think so too," said the Rev. Mr. Guion. "I should like to witness such a sight and hear such an exclamation; and though I will admit that such things may be nothing more than the illusive action of the imagination, yet how comes the imagination, when performing its very last operations, to act with so much power, as to imprint such a visible radiance on a death-struck countenance? I cannot resist the impression that such cases as Old Rachel's and Dr. Gordon's, belonging certainly to a diverse order of spiritual phenomena, are real manifestations of the glory and love of God, and are intended by him, like the translation of Enoch and Elijah, as supplementary evidence to confirm the faith, and animate the hope of his redeemed and beloved children. At any rate, such is the effect they have on me."

"They have the same effect on my mind," said Mr. Ingleby; "especially this case of poor Old Rachel, which will retain its power of impression as long as I exist. I shall never forget the last interview I had with her, nor her death-like appearance when I left her; but when I see her again—and I trust to see her ere long—she will appear in a beauteous form, arrayed in the spotless robe of celestial glory. We know that our latter end is coming, but we know not when it will come, or who of the living will be with us when it does come; nor do we know whether we shall pass away, like Dr. Gordon, while beams of glory are radiating our countenance, or steal out of life like poor Old Rachel, as from under a pile of material ruins; but, for our consolation, we know that our dear Redeemer has promised that He will come to receive us to himself when we depart hence, and that where he is we shall be also, and for ever: 'Wherefore, comfort one another with these words' (1 Thess. iv. 18)."

One morning, while Mrs. Stevens was conversing with Mrs. John Roscoe, a girl who had been attending Mrs. Stevens' Sabbath-school, and who was going into service, called at Fairmount for a Bible which had been awarded to her for her diligence and propriety of behaviour. After expressing her thanks on receiving it, she added, in a very modest tone, "I shall value it for your sake, Ma'am, and I hope I shall love it for its own sake."

"I was very much pleased," said Mrs. John Roscoe, "with the appearance and manners of your young protegé. The reason she gave for loving the Bible is a proof of superior intelligence, and, I should hope, of decided piety."

"Yes, she is an amiable girl, and I hope she is pious. She is a rescue from a godless family. Her parents are very profane persons, and their other children are following their example. I have no doubt of her attachment to the Bible, for she has made herself very conversant with it."

In the evening, when a few friends were assembled, Mrs. John Roscoe mentioned how much pleased she had been with the Sabbath-school girl, and repeated the remark she made on receiving the Bible from Mrs. Stevens.

"For its own sake," said the Rev. Mr. Guion; "that is a substantially good reason for loving the Bible. It is a somewhat singular fact that no book, on any subject or in any language, has so completely divided public belief and sympathy, both on the question of its origin and its practical utility."

"It certainly," Mr. Roscoe replied, "is a very singular, and a very wonderful book: wonderful, if true; more so, if false. If true, we can account for its origin; but how can its origin be accounted for if it be false? If false, it is an invention; and not the invention of one man, but of an organized conspiracy, and a conspiracy of good men, for the Bible is too good a book for bad men to write."

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"I admit that a bad man may write a good book; but to suppose that a number of bad men would conspire to write such a good book as the Bible, is to admit as great a moral impossibility as to imagine that a number of good men would form a confederacy in fraud and duplicity, and then palm off their lying inventions as positive realities. Now, let us look at the case fairly, and I think we may make some logical progress in settling the question of its origin. Here is a Bible, and it consists of two parts—the Old and the New Testament; and we must recollect that the Old Testament would be incomplete without the New, and the New Testament would be incomplete without the Old. Each of these parts consists of different books, or distinct writings, variously designated, occupying the space of nearly 2000 years in the composition of them. If the Bible had been written by any one man in[20] any one age, or if it had been written by contemporary writers living in the same city or country, its integrity might be open to very strong suspicion. But the writers of the Bible lived in different ages and in different countries, spoke different languages, belonged to very different ranks in social life, and most of them were unknown to each other; and yet there is, on all the facts and doctrines, and institutes of these records, an exact concurrence[4] of testimony running through the whole of their writings. Amongst the writers we find legislators, kings, poets, herdsmen, fishermen; one was a publican, and another a tent-maker, who, at one period of his life, denounced as false some of the facts of its record, which, on investigation, he found to be true, and attested the integrity of his new-formed belief by yielding to a martyr's death. And it will be at once perceived by the intelligent reader, that these men were no common-place writers; they moved in no beaten pathway of[21] general knowledge; they are no copyists—they are originals; what they tell us no other men had ever thought of, or, if they had, their thoughts died with them, as they never gave publicity to them. The writers of the Bible appear amongst us as scribes coming from another world, well instructed in the mysteries of a unique faith, admirably adapted to the peculiar exigencies of disordered and perplexed humanity. In addition to the origin of the world and of evil—the mediatorial work and government of the Son of God, the moral character and condition, and responsibilities, and final destiny of the soul of man—and a future economy of existence to last for ever—are the momentous truths which they make known to us, through the media of their multifarious and diversified compositions; of history, prophecy, parable, poetic songs, and plain didactic prose."

Rev. Mr. Roscoe.—"And what is especially deserving of our attention, is the perfect ease and harmony with which they write on these new and sublime discoveries of moral truth, while they all write independently of each other. They admit that they are subordinates, unworthy of the honour of their appointment; yet each one speaks and writes, and without any appearance of dogmatism or ostentation, in the same dignified tone of absolute authority; the voice which speaks and the hand which writes, is human, but what is said or written, comes from some other source."

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"Yes, Sir, I think the correctness of your remark can be demonstrated; at least, it comes as much within the range of demonstration, as any moral or historic truth, or fact, can be brought. The Old Testament is incomplete, and comparatively valueless, without the New; and yet it is written under the obvious impression and belief, that it would be completed; but on what data could its writers base their calculation, that they should have successors who would carry on and perfect what they had begun and advanced through several stages of its progress. Now, I readily believe, that a person of a very acute and comprehensive mind, who has carefully watched and studied the facts and philosophy of history,[22] may, on some special occasions, give some general outline of what will be the state of things within a very near futurity, if he cautiously avoid going into specific and minute details. But the writers of the Old Testament have opened up the roll of a very remote futurity,[5] and have recorded extraordinary events, with their dates and localities, long before their actual occurrence, portraying the likeness of Messiah the Prince, ages before his appearance on earth, and doing it with so much exactness, that it is a perfect resemblance of the wonderful original. How could they have done this, unless they had been guided by a prescient Spirit, to whose eye all the future is as visible as all the past?"

"Foretelling at the same time," said Mrs. John Roscoe, "his tragical death; which no one would have expected as the termination of his benevolent career."

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"It is, I believe, a law in the republic of letters, which no one has attempted to repeal, that all writers shall have the right of giving, if they please, their authorities for what they say; and of letting us know from what source they derive the information which they supply to us. Hence, no one can reasonably object to let the writers of the Bible have the protection of this law, which is of universal application. And what do they say on the question relating to the source of their knowledge? We will take their answer, and then form our own judgment of its integrity from the facts and evidences of the case. "All Scripture is given by inspiration of God:[6] holy men of God spake as they were moved by the Holy Ghost."[7] This is a concise statement of their testimony on this great question; and its integrity is fairly sustained by positive and incidental evidence. We see that they have given proofs of foreknowledge which far surpasses the capabilities of the most acute and comprehensive human mind; while, at the same time, they have made known to us a connected series of moral and[23] spiritual truths, to which no other writers make any allusion, and of which they could have formed no conception, unless they had been under superhuman tuition. What they have done, is its own defence against the imputation of fraud and dishonesty—standing as an imperishable memorial of the love of God to man; and of the fidelity of his servants, in disclaiming the honour of inventing a theory of faith and morals which justly claims a Divine origin. This view of the case, which is their own explanation, settles the question, without requiring us to believe physical impossibilities, or compelling us to reject the unrepealable law of moral evidence."

Mr. Roscoe.—"And we may, I think, very properly regard the great moral power of the Bible as a very telling collateral argument in favour of its Divine origin. You may take any other book, on any other subject, and put it into circulation amongst a mass of people, either semi-barbarians or highly-polished citizens, but it will work no beneficial changes in the general aspect of their moral character. It will leave them, as it finds them. If it finds them, as in India, bowing down and doing homage to stocks and stones, it leaves them worshipping the workmanship of their own hands—still revelling in their cruel and obscene abominations. If it finds them, as in Rome, kissing the crucifix—offering up their adorations and orisons to the Virgin Mary—or visiting the tomb of a real or legendary saint, in expectation of some miraculous healing, it leaves them practising these puerile and senseless exercises. If it finds them, as in Russia, crouching in terror before the great Tyrant, doing his biddings like beasts of burden, it leaves them in this prostrate state of degradation and misery. But put the Bible into circulation amongst the same class of people, and, after a while, you will perceive that it is taking effect upon them. One reads it, and feels its moral power on his conscience and his heart; another reads it, and he is subdued by its authority; others read it and the same result follows: they are drawn together by the attractive power which emanates from it, and become the nucleus of a new order of human beings springing up in the midst of the unchanged natives of the place. They are of the same ancestral[24] origin, and follow the same civil and social avocations and professions; but they are a peculiar people, resembling the primitive believers of the New Testament in intelligence and daring courage. They are new creatures in Christ Jesus; and, in process of time, as they increase in number and consequent activity, they give a new tone and energy to the moral, the political, and the religious sentiments and feelings of an entire community. It is to the Bible that Scotland is indebted for her moral greatness; and England never would have risen to her present eminence had it not been for the old Puritans, who were animated and sustained by the examples, and principles, and spirit of the Bible, in their passive sufferings and active exertions in resisting the encroachments and the cruelties of tyranny and oppression."

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"Your argument, Sir, is a legitimate one, and it is as logical, as it is historically true. The book which effects the changes which are essential to the happiness and well-being of men as individuals, or men living in a community, but which cannot be effected by the wit or eloquence of man, may fairly put in a claim to a higher and a purer origin than mere humanity."

Mr. Stevens.—"Unbelievers, in general, do not trouble themselves to account for the origin of the Bible; they take for granted that it is a book of mysticism and fraud, and at once direct their virulence against it, and hold it up to scorn and contempt."

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"And yet, notwithstanding all these attacks on the Bible, it still lives and commands attention. In the estimation of wise and good men, it takes precedence of all other books: they not only admire, but revere and love it. I have in my parish a good old man who has a large library, and has been a great reader for upwards of twenty years, but now he very rarely reads any book except his Bible. On referring, one day, to his devoted attachment to the Bible, he said—'I feel, when reading it, in the presence of God, and what I read comes with authority and power. The more I read it the more is my attention fixed on another world, and the more intensely do I desire to depart hence. This is a[25] mean and comfortless place of residence when compared with the mansion our Lord is preparing for us in his Father's house.'"

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"Pious people are very fond of the Bible, and their attachment to it increases as they advance in years; their passion for it is often very strong in death."

Mr. Stevens.—"Your remark, Sir, recalls to my remembrance what passed, the other day, in a casual conversation between an intelligent, yet very candid sceptic, and myself. 'There is,' he said, 'one phenomenon connected with the Bible which has long puzzled me to account for; if you can solve it, I shall feel obliged. I have noticed wherever I have been—and I have travelled through Europe and America—I have visited India and some of the islands of the South Seas, and resided for awhile amongst the black population of the West Indies—and whenever I have met with any persons who believe in the truth of the Bible, whether they were refined and intelligent or the reverse, they uniformly evinced for it the same profound reverence and supreme attachment.' 'The solution,' I replied, 'is easily given. They revere it as their statute-book, containing the code of laws which their Divine Legislator has issued to test their obedience to his authority; and they love it, as bringing life and immortality to light; making known to them a Saviour who is able and willing to save them from the wrath to come, and to give them peace of soul as an earnest and a pledge of future and eternal happiness; and they value it for its exceeding great and precious promises, which have a soothing and sustaining influence over their hearts in the times of their sorrows and afflictions.' 'But how is it,' he added, 'that while they cherish such a profound reverence for the Bible, they differ so widely in the interpretation they put on its meaning? How will you account for this rather puzzling fact?' The sudden entrance of several strangers into the room prevented me from making a reply."

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"This difference of interpretation, which sceptics often bring forward as a plausible argument against the Divine origin of the Bible, very frequently perplexes conscientious believers. I recently received a letter from a gentleman who says—'When I[26] think of the sentiments which are held by different bodies of Christians—sentiments which are directly opposed to each other, and which appear to me to admit of no adjustment; and when I recollect that they all profess to derive them from the same source, and are in the habit of appealing to the same authority in support of them—I feel myself approaching a difficulty which I know not how to solve. Is the Bible really such a mysterious book that it is incapable of being understood? Is it an oracle which utters truth and falsehood? If so, it cannot be a safe guide; and if it be not so, how do you account for the very different interpretations which it receives?'"

Mr. Stevens.—"How did you meet the difficulties of the case?"

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"I did not go fully into the question, because I knew, from the cast of his mind, that he would work himself right. I merely stated that conflicting opinions do not, of themselves, possess sufficient weight to set aside any law, or destroy the truth of any proposition which comes attested by its own proper evidence. And to give force to this very obvious truism, I reminded him of our judges, who sometimes give different interpretations of a statute law, without impairing its authority; and of our philosophers, whose different opinions on the primary cause of motion, do not disturb popular belief in the diurnal revolution of our earth. But, after all, we do not differ in our interpretations of the Bible so much as many imagine. It is true there are separate and distinct denominations of Christians, who are regarded by the ignorant and bigoted as the disciples and abettors of very opposite religious creeds; yet if we inquire into the actual state of the case, we shall find that most of them agree in all that is essential and vitally important in the Christian scheme, and that they differ only on what is subordinate, and comparatively unimportant."

Rev. Mr. Roscoe.—"It is supposed by many that this diversity of interpretation which is given to some parts of the Bible would have been prevented if a logical or systematic order had been scrupulously observed. If, for example, the sacred writers had arranged the[27] facts, the doctrines, the precepts, the institutions, the sanctions, the evidences, and the final recompense of the Christian faith, systematically—presenting the whole in a compendious form—there would be, in that case, so much compactness, such symmetrical order—one part of the theory would hang so naturally on another—that it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, for any division of opinion to spring up amongst us on the question of its import or design. We should then think and believe alike. This is what I have heard some speculatists say; but I have no confidence in the integrity of their opinion."[8]

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"The objections against an inspired compendium of Christian doctrine and practice, are, in my judgment, more powerful than the arguments in favour of it. If we had it, we should revere it, and learn it; it would perpetually recur to our recollection in our reflective moments, and by rendering a studious examination of the other parts of the Scripture unnecessary, we should be liable to sink into 'a contented apathy' of spirit, under this conviction, that as we can repeat all, we know all that is necessary for us to know."

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"Archbishop Whately, when alluding to this subject, says, 'that if we had this compendium, both it and the other parts of the Scriptures would be regarded as of Divine authority; but the compendium itself would be looked upon by most as the fused and purified metal; the other, as the mine containing the crude ore. And the compendium itself, being, not like the existing Scriptures, that from which the faith is to be learned, but the very thing to be learned, would come to be regarded by most with an indolent, unthinking veneration, which would exercise little or no influence over them.'"

Mr. Roscoe.—"Universal experience proves, that facility in obtaining a supply to our physical necessities, is not so beneficial to the energy and vigour of the human constitution, as difficulty, which stimulates to labour and invention. Compare, for example, the natives of the South Sea Islands, whose bread-fruit ripens of itself,[29] with the hardy Highlanders of Scotland, who have to toil for their living through frost and snow, as well as sunshine—what a difference in their muscular and masculine conformation and appearance. And the same remark is equally applicable to the mind of man, whose knowledge on any subject, in any department of science, and especially the science of Biblical theology, is accurate and profound, in proportion to the efforts he is obliged to make in its acquisition. A compendium would be the bread-fruit, within reach, and easily plucked. We should, if we had it, become dwarfs in Biblical theology. It is only when our energies are roused by a love of the truth, and stimulated by the difficulties connected with its attainment, that our knowledge in the mystery of Christianity gets perfected, and becomes practically powerful in its influence over the heart and the character."

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"And in addition to the relaxing influence which a compendium would exert over the mind—indisposing it to any labour in searching the Scriptures, except the labour of the memory, and that to a very superficial extent—I have another objection to such a projected scheme, which is this:—I do not think it possible for the Christian faith to be reduced to such a compact, or what you term compendious form, as shall secure amongst its advocates and defenders a perfect unity of belief on all points, without the perpetual exercise of a supernatural agency in the illumination and guidance of the mind, which would amount to something like a plenary inspiration to every believer. Now what can be more logically explicit than the articles of our church; and yet what a very different construction do different men put upon them!"

Mrs. John Roscoe.—"That is true. If I were in a church on a Sabbath morning listening to a Tractarian; if I returned in the afternoon, and heard a Moderate; and if, in the evening, I occupied the same pew, while an Evangelical was doing duty in the pulpit, I should find myself in a modern Babel, witnessing, on a small scale, a new specimen of the confusion of tongues."

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"But this difference of opinion and diversity of[30] interpretation on the same theory of belief, prevails amongst others as well as amongst us. Even amongst unbelievers, who almost deify reason—asserting and maintaining, that it is fully equal to all the exigencies of humanity, without being under any obligation to a Divine inspiration—there is almost an endless diversity of belief and opinion on all questions relating to God, to human responsibility, and the final destiny of man. They are obliged to pass a toleration act to live in peace."

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"I like a toleration act; it is essential to our peace. The period is coming when we shall 'see eye to eye;' but that will be under a dispensation very different to the present; we must now agree to differ, and while contending earnestly for the faith once delivered to the saints, we must live together as brethren."

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"Jesus Christ said to his disciples—'These things I command you, that ye love one another' (John xv. 17); and he says the same things to us. And if we love one another, we shall never vote for a repeal of our toleration act, which admits of some shades of difference in our religious belief and opinions."

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"It was doubted, a few years since, whether even the spiritual members of our various denominations cherished any fraternal esteem and affection for each other—they often acted more like gladiators than brethren; but now they are cultivating a spirit of union and peace."

Mr. Roscoe.—"This change in their spirit and conduct is a very gratifying and auspicious event; but some good men maintain that the entire abolition of the distinctive denominations and their union in one undivided body, would be more conducive to the honour of Christianity, and more favourable to its progressive triumphs."

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"This I conceive to be impracticable during the partial obscurity of the present dispensation; and I must confess that I do not think it advisable. I have no objection to those divisions of opinion which separate us into different denominations, though I deplore the spirit which they sometimes engender. I think that a variation in belief, on some of the minor questions of[31] religion, by keeping our attention awake and active, tends to preserve the more important truths in a purer state; and the action and re-action of one Christian denomination on another, prevents that stagnation of feeling, and that inertness of principle, which an unbroken and undisturbed uniformity admits of."

Mr. Roscoe.—"But, would not the church assume a more imposing aspect, and put forth a more powerful energy, if she could unite all her members in one undivided body, under the immediate authority of one Head, than she does now, broken as she is, into so many subdivisions?"

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"Yes, Sir, if she could preserve her purity uncontaminated; but we ought never to forget, that while the religion we profess is Divine in its origin, and indestructible in its nature, it is human in its forms and administrations. Hence it alternately displays resistless power and exhausted weakness—the sanctity and grandeur of its Author, along with the infirmities and imperfections of the agents to whom it is intrusted—sometimes exciting the profound veneration of the multitude, and at other times their contempt or indifference. And it is this admixture of what is human with what is Divine, that renders it expedient that there should be some exposure to the influence of that re-action of distinctive opinions, and of social attachments, which, by keeping us alive to the purity and extension of our separate communions, tends to promote the purity and extension of the faith which we hold in common."

Mr. Stevens.—"Your opinion exactly accords with my own. Hence, instead of regarding the Established Church, and the various denominations of orthodox Dissenters, as hostile foes, aiming at each other's humiliation and destruction, we should look on them as subjects of the same monarch, each bearing the distinctive insignia of his own order; yet mutually supporting each other without the formality of a visible contact, and, as his sovereign will directs, advancing, each in his own way, the work of reclaiming to a state of allegiance the people who have revolted from his authority."

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"Or, to vary the figure, we may view them as so many servants belonging to the same master, who are employed in cultivating the great moral vineyard, whose reward at last will be in proportion to their fidelity to him, and their affection for each other. If this comparison be just, then, if we cherish a complacent feeling exclusively for those who belong to our own class, and attempt to lord it over our fellow-servants who may belong to another, or treat them discourteously, we dishonour ourselves, and offend against the law of our Lord, who has commanded us to love each other as brethren."

Mr. Roscoe.—"When I consider the fallibility of the human mind—the prejudices of education—the influence of accidental reading and associations—and the extensive prevalence of erroneous opinions, instead of being astonished by the shades of difference which prevail amongst us, I am surprised that we think so nearly alike. We agree on the substantial facts, and doctrines, and institutes, and precepts of revelation, while we differ on some of its forms and ceremonial enactments. But these trifling differences, which do not endanger the safety, nor add to the stability of our faith, ought not to excite jealousy and suspicion, and cause alienation of affection, as though we were avowed enemies. No. When this is the case we give a decisive proof that we do not possess the spirit of the gospel; or, if we possess it, we do not display it, which aggravates rather than extenuates our sin."

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"In the last prayer our Saviour uttered, just before he presented himself the expiatory sacrifice for human guilt, he earnestly entreated that all his disciples, in every future age, might be one, even as he and his Father are one; and he assigns the reason—That the world may know that thou hast sent me. For some ages, the object of that prayer was realized in the harmony which prevailed amongst Christians whose religion was a bond of union more strict and tender than the ties of consanguinity; and with the appellation of brethren they associated all the sentiments of endearment that relation implied. To see men of the most contrary[33] characters and habits—the learned and the rude—the most polished, and the most uncultivated—the inhabitants of countries alienated from each other by institutions the most repugnant, and by contests the most violent—forgetting their ancient animosity, and blending into one mass, at the command of a person whom they had never seen, and who had ceased to be an inhabitant of this world, must have been an astonishing spectacle. Such a sudden assimilation of the most discordant materials; such love issuing from hearts the most selfish, and giving birth to a new race and progeny, could be ascribed to nothing but a Divine interposition; it was an experimental proof of the commencement of that kingdom of God—that celestial economy, by which the powers of the future world are imparted to the present."

Mr. Stevens.—"It must have been a spectacle no less delightful to the eye of the Christian than astonishing to the unbeliever; and had the visible church always exhibited such a spectacle of union and affection, her history would have been the records of her spiritual triumphs, rather than of her persecutions and her miseries. But her bonds of union have been broken asunder, and her love of the brethren has been quenched in the bitter waters of strife. We are the descendants of the holy men who first caught, and first displayed the spirit of the Prince of Peace, but how little do we resemble them! We imbibe the same faith, plead the same promises, claim the same privileges, participate in the same spiritual enjoyments, bear the same distinctive and relative character, and anticipate the same high destiny; but we too often act as though we were released from the obligations which they admitted and discharged; and instead of attempting to convince sceptics and unbelievers of the divinity of our Lord's mission, and the moral efficacy of his death, by our union and our reciprocal affection, we strengthen them in their infidelity by our anti-Christian spirit. Can no remedy be devised to correct this noxious evil, which, like a withering blight, tarnishes the moral lustre of all our distinctive denominations, and does more to embitter the spirit, and extend the triumphs of infidelity, than[34] the most virulent works which issue from her corrupt and hostile press?"

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"Why, Sir, I hope the evil is in some small degree abated by the influence of our public institutions. Those who, a few years since, were envious and jealous of each other, now associate together on the most friendly terms. If the Bible Society has not terminated the contest, it has been the means of concluding a truce between them; and I flatter myself that there will be no renewal of hostilities, even though some of the more bigoted belonging to the different denominations should feel disposed to revive them."

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"I fear, Sir, you are rather too sanguine in your expectations. In the little circle in which we move, in this isolated spot of the religious world, the spirit of fraternal love and union is cherished; but what commotion and strife prevail just now between both the clerical and lay members of our own church!"

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"Yes, Sir, I know it and deplore it. It is the spirit of dry formalism setting itself in array against the spirit of vital Christianity; and the contest will be severe, but the issue is certain—the Word of the Lord will prove more powerful than the traditions of man."

Mr. Stevens.—"I must confess that I am rather sanguine in my calculations of the moral influence of the Bible Society on the best and most active men of our age. Dr. Mason, of New York, says, in the preface to a work which he has published—'Within a few years there has been a manifest relaxation of sectarian rigour among the different denominations in America, so that the spirit of the gospel, in the culture of fraternal charity, has gained a visible and growing ascendency. This happy alteration,' he adds, 'may be attributed, in a great degree, to the influence of missionary and Bible societies.'"

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"And it is so amongst us to some extent. Till the Bible Society arose, and gained a settlement in our land, we had not an inch of neutral ground on which we could assemble, and unite with each other in any religious enterprise; but now we have[35] the province of Goshen assigned us; and the air of that place is so salubrious, the light so clear and brilliant, the atmosphere so temperate and serene, and the harmony of its inhabitants so profound, that we venerate it as the mystic inclosure in which we have an emblematical representation of the celestial inheritance—in which the spirits of the just live in closest union and sweetest concord. May the catholicism of grace and truth wax stronger and stronger, till Ephraim shall not envy Judah, nor Judah vex Ephraim; the strife of sect being overcome and banished by the all-subduing love of God our Saviour!"

Mr. Roscoe.—"And what is it but prejudice, arising from ignorance and misconception, which prevents this cordial union and fraternal attachment? No one, I am conscious, who understands the genius of Christianity, or who has ever felt his bosom glow with supreme love to the Redeemer, can for a single moment presume to recommend disunion amongst the members of the household of faith, though they may occupy different compartments, and commune at separate tables. It is prejudice that kept me aloof from Dissenters, and made me unwilling to associate with them; because I understood that the generality of them rejected the essential doctrines of Christianity; but now my error is corrected, I esteem them as my brethren in Christ; and as I hope to meet them in heaven, and unite with them in the sublime exercises of that holy place, I feel a pleasure in mingling with them on earth."

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"I have lived on terms of intimacy with many who do not belong to the church of which I am a minister, and some of the happiest moments of my life have been spent in social and spiritual intercourse with them. Our conversation, when we have been together, has not turned on the questions on which we differ, but on those on which we agree; and I have often retired from these interviews with my mind relieved from its cares, and both animated and enriched by the interchange of devout sentiment and feeling. And in looking forward to the final consummation, I indulge a hope of partaking of much holy delight in associating with[36] Luther and Calvin, with Fenelon and Claude, with Whitfield and Wesley, with Hall, Foster and Chalmers, and other illustrious men, of the same and other denominations, who have entered into rest. I have lived in stormy times, but I have never increased the fury of the tempest. I have seen the spirit of party raging with desolating violence, and have known some of those, who have borne the image of the heavenly, stand in opposing columns to each other in the field of fierce and angry debate; but I have been enabled, through the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, to hold on my way unconnected with their unhappy hostilities; and now it is with no common feelings of gratitude and delight that I indulge the hope of leaving the church and the world at a period when, if the temple of war is not actually closed, yet our denominations are forming a more correct estimate of each other's relative strength and importance, in the conflict which we have to sustain against the combined powers of superstition and infidelity; and this will necessarily tend to increase our reciprocal esteem and confidence."

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"If, in our intercourse with each other, we always acted on your prudential maxim, of conversing on questions of general agreement, rather than on controversial ones, the spirit of discord would be exorcised from amongst us, and then we might, I think, justly calculate on a more copious measure of the influences of the Spirit poured down from on high, when we should intuitively feel, by a force of evidence too powerful to be withstood, that God is love, and that we never please him more than when we embrace, with cordiality and esteem, all who bear his image, without distinction of sect or party."

Rev. Mr. Roscoe.—"In these sentiments of Christian liberality and charity I now concur most heartily."

The Rev. Mr. Ingleby, on resuming the discussion of the question of union amongst the various denominations of believers in the Divine origin of the faith of Christianity, made the following very pertinent remarks:—"If it were the will of God that the various denominations of Christians should all think and act alike, as the tribes of Israel were required to do under the Levitical dispensation, we should have laws laid down for our guidance with the same minuteness and explicitness as was done for them. But such is not the case. We have certain general principles laid down, and the motives by which all our actions should be governed set before us with clearness and precision, but we have no particular directions as to the external form of church government. We are therefore left free to adopt that ecclesiastical system which, after careful examination, we find most in conformity with the spirit of the New Testament."

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"You mean, Sir, I presume, that we are left free to choose either the Episcopal, or Presbyterian, or Congregational form of church government?"

Rev. Mr. Ingleby.—"Yes, Sir; and though I do not profess to be deeply read in casuistry, yet I believe that very much may be collected from the facts and incidents recorded in Scripture, and from the casual expressions of the sacred writers in favour of each of these forms of church government."

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"And so I think. We are not living under a law laid down with minute exactness, like the ancient tribes of Israel, but have the right of exercising our choice on these matters of church polity, and our choice is determined by preference or expediency, or both. That is, I may deem it expedient to be an Episcopalian in one country, or a Presbyterian in another, or a Congregationalist in a third; and I may, at the same time, most decidedly[38] prefer one of these modes of church government to either of the other, as being, in my opinion, the nearest approach to the teachings of the New Testament. To adopt such a principle as this is, appears to me more in harmony with the spirit of the New Testament dispensation, than putting in a claim for the Divine right of Episcopacy, or Presbyterianism, or Congregationalism; it is an equitable concession to others of the liberty we claim for ourselves; and hence, without being guilty of any degree of inconsistency, we can cultivate Christian fellowship with our brethren of other denominations, without compromising our own principles."

Rev. Mr. Roscoe.—"You will still leave, I presume, as a question open for discussion, the relative conformity of each mode of church government to the New Testament model?"

Rev. Mr. Guion.—"Most certainly; and when discussions go on, untainted by the dogmatism and acrimony of party predilections and antipathies, and are conducted in a liberal and loving spirit, they tend to give solidity to the foundation on which our relative union is based; and show, at the same time, that it can be cemented and perpetuated without any dishonourable compromise."

Mr. Lewellin.—"I was present in a company some time since, when an ingenious Scotchman made out, as he thought, a very strong claim for the superiority of Presbyterianism to the other forms of church government. Episcopacy, he remarked, has the monarchical element too dominant in her constitution—the clergy are everything; in Congregationalism, the democratic element is too dominant—the people are everything; but Presbyterianism unites the two elements, and in about equal proportions the clergy and the people act together—they are a combined power."