Title: Recollections of the War of 1812

Author: William Dunlop

Contributor: A. H. U. Colquhoun

Release date: November 25, 2013 [eBook #44281]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ernest Schaal and The Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

First edition, 250 copies

Second edition, 750 copies

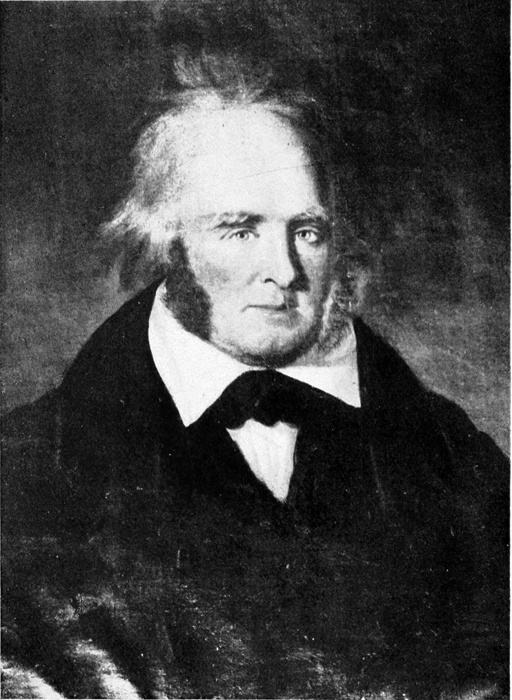

WILLIAM DUNLOP, M.D.

From original painting in the possession of Mrs. Thos. McGaw.

Recollections

of the

War of 1812

By

DR. WM. DUNLOP

With a Biographical Sketch of the Author by

A. H. U. Colquhoun, LL.D.

Deputy Minister of Education, Ontario

SECOND EDITION

TORONTO:

HISTORICAL PUBLISHING CO.

1908.

Entered according to the Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year nineteen hundred and eight, by the Historical Publishing Co., at the Department of Agriculture.

TORONTO:

THE BRYANT PRESS, LIMITED

Sketch of

Dr. William Dunlop

This reprint of an entertaining little narrative of personal experiences in the War of 1812-14 may be appropriately prefaced by a short account of the author. Few of the pioneers of Upper Canada had careers as varied and interesting as that of Dr. William Dunlop, and none possessed a personality quite so striking and original as his. On the Saltfort road, near Goderich, Canada, there is a cairn marking the burial place of two notable worthies of the Huron Tract, and upon it is the following inscription:

Here lies the body of

ROBERT GRAHAM DUNLOP, ESQ.

Commander Royal Navy, M.P.P.

Who after serving his King and country in

every quarter of the globe, dies at Gairbraid,

on the 28th Feby., 1841, in

the 51 year of his age.

Also to the memory of

DR. WILLIAM DUNLOP,

a man of surpassing talent, knowledge,

and benevolence, born in Scotland

in 1792.

He served in the army in Canada and in India

and thereafter distinguished himself

as an author and man of

letters.

He settled in Canada permanently in 1825 and

for more than 20 years was actively

engaged in public and philanthropic

affairs.

Succeeding his brother, Capt. Dunlop, as Member

of the Provincial Parliament and

taking successful interest in

the welfare of Canada,

and died lamented

by many

friends

1848.

The elder of these two brothers, William Dunlop, was born at Greenock, Scotland, in 1792, and became, when a stripling of scarce 21 years of age, a surgeon in the famous 88th, or, Connaught Rangers. Being ordered to Canada, where the war with the United States was in progress, he made his way to the fighting line in the Niagara Peninsula, and there, serving first as surgeon and afterwards as a combatant, he gave indubitable proofs of courage and capacity. When the "appalling intelligence" of the peace concluded by the Treaty of Ghent reached him, Dunlop embarked with his regiment for England, just missing by a few days a share in the glorious action of Waterloo, and was ordered to India. While there his restless activity occupied itself with his medical and military duties, with the congenial task of editing a newspaper, and with numerous tiger hunts. So successful was he as a slayer of tigers that he earned the name of "Tiger" Dunlop, and in his later Canadian days was familiarly known as "The Tiger." An attack of jungle fever drove him back to England on half-pay, and settling in London he lived for a few years what has been called [pg x] a most miscellaneous life. He wrote articles for the magazines. He edited for a time a newspaper called the "British Press," until he quarrelled with the publisher for dismissing contemptuously a political upheaval in France in the following brief "leader": "We perceive that there is a change of ministry in France;—we have heard of no earthquakes in consequence!" He edited a work on medical jurisprudence. He started a Sunday newspaper for Anglo-Indians called "The Telescope," the history of which, declared one of his friends, was a comedy of the drollest kind. He founded a club,—being of convivial tastes and a prince of boon companions,—called The Pig and Whistle. Finally,—and this doubtless led to his returning to Canada,—he became interested, as secretary, or, director, in some industrial concerns, notably a salt works in Cheshire. In London he made the acquaintance of Mr. John Galt, and accompanied him to Canada in 1826. He received from the Canada Company the appointment of Warden of the Forests, and for twenty years was a leading figure in what we now call Western Ontario. [pg xi] If one wishes to know "The Tiger" in this period, he must be sought in the charming pages of the Misses Lizars' book "In the Days of the Canada Company." There, his rollicking humour, his broad sympathies, his eccentric jests are excellently depicted. Dunlop represented Huron in Parliament, where he was a veritable "enfant terrible," speaking his mind in his slap dash way and frequently convulsing the House with merriment. The story of his tossing the coin with his brother to settle which of them should marry Lou McColl, the Highland housekeeper and devoted friend, and the terms of his extraordinary will and testament,—one clause of which (typical of all) leaves some property to a sister "because she is married to a minister whom (God help him) she henpecks",—are famous. Dunlop's literary talents were considerable. He wearied of writing as he did of most things that demanded continuous application. But he had an easy style, much shrewd wit, and undoubted ability. These qualities he displayed in his magazine articles, in his book "The Backwoodsman," and in the "Recollections," which are here reprinted from [pg xii] "The Literary Garland," the Montreal periodical of half a century or more ago. They were penned long after the events concerned had occurred and it may be supposed that he fell into some errors of fact. But as a picture of the manner in which this haphazard war was conducted it is singularly vivid and impressive. The unearthing of manuscripts and official documents about this war will not throw into clearer relief than the following pages do, the desperate circumstances under which a mere handful of French Canadian and Loyalist colonists emerged from their primitive villages and log cabins and with Spartan courage and hardihood drove back the invader again and again and captured large areas of his territory. There are several readable sketches of these campaigns, but none with the freshness and spirit of Dunlop's. In this lies its value and the justification for preserving it. Dunlop retired from Parliament in 1846, and was appointed Superintendent of the Lachine Canal. He died in the village of Lachine in the Autumn of 1848, and his body was conveyed to its resting place at Goderich.

The favourable reception of a small work on this colony has emboldened me again to come before the public in the character of an author, and as it is fifteen years since I last obtruded myself in that capacity, I have at least to boast of the merit assumed to himself by the sailor in his prayer, during a hurricane, "Thou knowest it is seldom that I trouble thee," and I may hope on the same grounds to be listened to.

It is now upwards of thirty-three years since I became acquainted with this country, of which I was eleven years absent. During that time I visited the other quarters of the globe. My design in this work is to shew the almost incredible improvement that has taken place during that period. Notwithstanding all that has been written by tourists, &c., very little indeed is known of the value and capabilities of Canada, as a colony, by the people of Great Britain.

I have not arrived at anything like methodical arrangement further than stating in their chronological order, events and scenes of which I was a witness, with occasional anecdotes of parties therein concerned, so that those who do not approve of such a desultory mode of composition, need not, after this fore-warning, read any further. My intention, in fact, is not exclusively either to instruct or amuse, but, if I possibly can accomplish it, to do a little of both. I wish to give an account of the effect of the changes that have taken place in my day in the colony, on my own feelings, rather than to enter into any philosophical enquiry into their causes; and if in this attempt I should sometimes degenerate into what my late lamented friend, the Ettrick Shepherd, would have denominated havers, I hope you will remember that this is an infirmity to which even Homer (see Horace,) is liable; and if, like hereditary disease, it is a proof of paternity, every author in verse or prose who has written since his day, has ample grounds whereon to found its pretensions to a most ancient and honourable descent.

RECOLLECTIONS OF THE AMERICAN WAR

"My native land, good night."—Byron.

The end of March or the beginning of April, 1813, found me at the Army Depôt in the Isle of Wight. Sir Walter Scott in his Surgeon's Daughter, says that no one who has ever visited that delightful spot can ever forget it, and I fully agree with him, but though perfectly susceptible of the impressions which its numberless beauties leave on the mind, I must confess that the view of a fleet of transports rounding St. Helens to take us to our destination, would have been considered by myself and my comrades, as a pleasanter prospect than all Hampshire could offer to our admiration.

I shall not stay to describe the state of military society in those days at the Army Depôt at Parkhurst barracks and the neighbouring town of Newport. It has been much better done than I could expect to do, by Major Spencer Muggridge, in Blackwood's Magazine; all I can do as a subaltern, is fully to endorse the field officer's statement, and to declare that it is a just, graphic and by no means over-charged description.

[pg 4] I went once, and only once, to the Garrison Mess, in company with two or three officers of my acquaintance, and saw among other novelties of a mess table, one officer shy a leg of mutton at another's head, from one end of the table to the other. This we took as notice to quit; so we made our retreat in good order, and never again returned, or associated with a set of gentlemen who had such a vivacious mode of expressing a difference of opinion.

The fact is, all the worse characters in the army were congregated at the Isle of Wight; men who were afraid to join their regiments from the indifferent estimation they were held in by their brother officers. These stuck to the depôt, and the arrival of a fleet of transports at Spithead or the Mother-bank, was a signal for a general sickness among these worthies. And this was peculiarly the case with those who were bound for Canada, for they knew full well if they could shirk past the month of August, there was no chance of a call on their services until the month of April following. And many scamps took advantage of this. I know one fellow who managed to avoid joining his regiment abroad for no less than three years.

I took my departure from this military paradise for the first time, for this country, in the beginning of August, 1813, in a small, ill-found, undermanned, over-crowded transport, as transports in those days were very apt to be; and after a long, weary, and tempestuous voyage of three months, was landed at Quebec in the beginning [pg 5] of the following November. Next to the tedium of a sea voyage, nothing on earth can be so tiresome as a description of it; the very incidents which a Journal of such a pilgrimage commemorates shew the dreadful state of vacuum and ennui which must have existed in the mind of the patient before such trifles could become of interest sufficient to be thought worthy of notation. A sail in sight,—a bunch of sea-weed floating past the ship,—a log of wood covered with barnacles,—or, better still, one of the numerous tribe of Medusa, with its snake-like feelers and changeable colours—a gull, or a flock of Mother Carey's chickens, paddling in the wake,—are occurrences of sufficient importance to call upon deck all the passengers, even during dinner. Or if they are happy enough to fall in with a shoal of porpoises or dolphins, a flock of flying fish, or a whale blowing and spouting near the ship, such a wonder is quite sufficient to furnish conversation for the happy beholders for the rest of the voyage. For my own part, being familiar with, and also seasoned to, all the wonders of the deep, I make a vow whenever I go on board, that nothing inferior in rank and dignity to a sea-serpent shall ever induce me to mount the companion ladder. On the whole, though it cannot be considered as a very choice bit of reading, I look upon the log-book as by far the best account of a voyage, for it accurately states all that is worthy of note in the fewest possible words. It is the very model of the terse didactic. Who can fail to admire the Caesar-like brevity in [pg 6] an American captain's log: "At noon, light breezes and cloudy weather, wind W.S.W., fell in with a phenomenon—caught a bucket full of it." Under all these circumstances, I think it is highly probable that my readers will readily pardon me for not giving my experience on this subject. I met with no seas "mountains high," as many who have gone down unto the sea in ships have done. Indeed, though I have encountered gales of wind in all the favorite playgrounds of Oeolus—the Bay of Biscay—off the Cape of Good Hope—in the Bay of Bengal—the coast of America, and the Gulph of St. Lawrence, yet I never saw a wave high enough to becalm the main-top sail. So that I must suppose that the original inventor of the phrase was a Cockney, who must have had Garlic hill or Snow hill, or some of the other mountainous regions of the metropolis in his mind's eye when he coined it.

Arrived at Quebec, we reported ourselves, as in duty bound, to the General Commanding, and by his orders we left a subaltern to command the recruits (most of whom, by the way, were mere boys,) and to strengthen the Garrison of Quebec, and the venerable old colonel and myself made all haste to join our regiment up the country. As my worthy old commander was a character, some account of him may not be uninteresting.

Donald McB—— was born in the celebrated winter of 1745-46, while his father, an Invernesshire gentleman, was out with Prince Charles Edward, who, on the unfortunate issue of that campaign for the Jacobite interest, was fain to flee to [pg 7] France, where he joined his royal master, and where, by the Prince's influence, he received a commission in the Scotch Regiment of Guards, and in due time retired with a small pension from the French King, to the town of Dunkirk, where with his family, he remained the rest of his days.

Donald, meanwhile, was left with his kindred in the Highlands, where he grew in all the stinted quantity of grace that is to be found in that barren region, until his seventh year, when he was sent to join his family in Dunkirk. Here he was educated, and as his father's military experience had given him no great love for the profession of arms, he was in due time bound apprentice to his brother-in-law, an eminent surgeon of that town, and might have become a curer instead of inflicter of broken heads, or at least murdered men more scientifically than with the broadsword; but fate ordered it otherwise.

Donald had an objection as strong to the lancet as his father could possibly have to the sword. Had the matter been coolly canvassed, it is hard to say which mode of murder would have obtained the preference, but, always hasty, he did not go philosophically to work, and an accident decided his fate as it has done that of many greater men.

A young nun of great beauty, who had lately taken the veil, had the misfortune to break her leg, and Donald's master, being medical man to the convent, he very reasonably hoped that he would assist in the setting of it—attending upon [pg 8] handsome young nuns might reconcile a man even to being a surgeon of——; but his brother-in-law and the abbess both entered their veto. Piqued at this disappointment, next morning saw him on the tramp, and the next intelligence that was heard of him was that he was serving His Most Christian Majesty in the capacity of a Gentleman Sentinel, (as the Baron of Bradwardine hath it,) in a marching regiment.

This settled the point. His father, seeing that his aversion to the healing art was insuperable, procured a commission in the Regiment de Dillon or Irish Brigade of the French Service.

In this he served for several years, until he had got pretty well up among the lieutenants, and in due time might have figured among the marshals of Napoleon; but the American Revolution breaking out, and it being pretty apparent that France and Great Britain must come into hostile collision, his father, though utterly abhorring the reigning dynasty, could not bear the idea of a son of his fighting against his country and clan, persuaded him to resign his commission in the French Service, and sent him to Scotland with letters of recommendation to some of his kindred and friends, officers in the newly raised Frazer Highlanders (since the 71st,) whom he joined in Greenock in the year 1776, and soon after embarked with them for America in the capacity of a gentleman volunteer, thus beginning the world once more at the age of thirty.

After serving in this regiment till he obtained his ensigncy, he was promoted to be lieutenant [pg 9] and adjutant in the Cavalry of Tarlton's Legion, in which he served and was several times wounded, till the end of the war, when he was disbanded with the rest of his regiment, and placed on half pay. He exchanged into a regiment about to embark for the West Indies, where in seven or eight years, the yellow fever standing his friend by cutting off many of his brother officers, while it passed over him, he in progress of seniority, tontined it up to nearly the head of the lieutenants; the regiment was ordered home in 1790, and after a short time, instead of his company, he received his half-pay as a disbanded lieutenant.

He now, from motives of economy as well as to be near his surviving relatives, retired to Dunkirk; but the approaching revolution soon called him out again, and his promotion, which, though like that of Dugald Dalgetty, it was "dooms slow at first," did come at last. Now after thirty-seven years' hard service in the British Army, (to say nothing of fourteen in the French) in North America, the West Indies, South America, the Cape of Good Hope, Java and India, he found himself a Lieutenant-Colonel of a second battalion serving in Canada. Such is a brief memoir of my old commanding officer. He was a warm-hearted, hot-tempered, jovial, gentlemanly old veteran, who enjoyed the present and never repined at the past; so it may well be imagined that I was in high good luck with such a compagnon de voyage.

Hearing that the American Army, under General Wilkinson, was about to make descent on [pg 10] Canada somewhere about the lower end of Lake Ontario, we were determined to push on with all possible speed.

The roads, however, were declared impracticable, and the only steamboat the Canadas then rejoiced in, though now they must possess nearly one hundred, had sailed that day, and was not expected to return for nearly a week; so it was determined we should try our luck in one of the wretched river craft which in those days enjoyed the carrying trade between Quebec and Montreal. Into the small cabin, therefore of one of these schooners we stowed ourselves. Though the winds were light, we managed to make some way as long as we could take advantage of the flood-tide, and lay by during the ebb; but after this our progress was slow indeed; not entirely from the want of a fair wind, but from the cursed dilatory habits of Frenchmen and their Canadian descendants in all matters connected with business. At every village (and in Lower Canada there is a village at every three leagues along the banks of the St. Lawrence) our captain had or made business—a cask of wine had to be delivered to "le digne Curé" at one place; a box of goods to "M. le Gentilhomme de Magasin" at another; the captain's "parents" lived within a league, and he had not seen them for six weeks,—so off he must go, and no prospect of seeing him any more for that day. The cottage of the cabin boy's mother unluckily lay on the bank of the river, and we must lay to till madame came off with confitures, cabbages and clean shirts for [pg 11] his regalement; then the embracing, and kissing, and bowing, and taking off red night caps to each other, and the telling the news and hearing it, occupied ten times the space that the real business (if any there was) could possibly require. And all this was gone through on their part, as if it was the natural and necessary consequence of a voyage up the River Saint Lawrence. Haste seemed to them quite out of the question; and it is next to impossible to get into a passion and swear at a Frenchman, as you would at a sulky John Bull, or a saucy Yankee, under similar circumstances, for he is utterly unconscious all the time that he is doing anything unworthy; he is so polite, complaisant and good humoured withal, that it is next to impossible to get yourself seriously angry with him. On the fifth day of this tedious voyage, when we had arrived within about fifteen miles of Three Rivers, which is midway between the two cities, we perceived the steamboat passing upwards close under the opposite shore, and we resolved to land, knowing that it was her custom to stop there all night, and proceed in the morning; accordingly we did so, and in a short time were seated in a caleche following at all the speed the roads would admit of—by dint of hard travelling, bribing and coaxing, we managed to get to Three Rivers by moonlight, about one in the morning. So far so good, thought we; but unluckily the moonlight that served us, served the steamboat also, and she had proceeded on her voyage before we came up. As we now, however, had got quite enough [pg 12] of sailing, we determined to proceed by land to Montreal.

The French, I suspect, have always been before us in Colonial policy. An arbitrary government can do things which a free one may not have the nerve to attempt, particularly among a people whose ignorance permits them to see only one side of the question.

The system of land travelling in Lower Canada was better, when we became master of it, than it is now in any part of the North American Continent. At every three leagues there was a "Maison de Poste" kept by a functionary who received his license from government, and denominated a "Maitre de Poste." He was bound by his engagement to find caleches and horses for all travellers, and he made engagements with his neighbors to furnish them when his were employed. These were called "Aides de Poste"; and they received the pay when they performed the duty, deducting a small commission for the Maitre. They were bound to travel when the roads admitted of it, at a rate not less than seven miles an hour, and were not to exceed quarter of an hour in changing horses; and to prevent imposition, in the parlour of each post house, (which was also an inn,) was stuck up a printed paper, giving the distance of each post from the next, and the sum to be charged for each horse and caleche employed, as well as other regulations, with regard to the establishment, which it was necessary for a traveller to know, and any well substantiated charge against these [pg 13] people was sure to call down summary punishment.

The roads not being, as already remarked, in the best order, we did not arrive at Montreal till the end of the second day, when we were congratulated by our more lucky companions who had left Quebec in the steamboat three days later, and arrived at Montreal two days before us; and we were tantalized by a description of all the luxuries of that then little known conveyance, as contrasted with the fatigues and désagréments of our mode of progression. For the last fifty miles of our route there was not to be seen throughout the country a single man fit to carry arms occupied about his farm or workshop; women, children, or men disabled by age or decrepitude were all that were to be met with.

The news had arrived that the long threatened invasion had at last taken place, and every available man was hurrying to meet it. We came up with several regiments of militia on their line of march. They had all a serviceable effective appearance—had been pretty well drilled, and their arms being direct from the tower, were in perfectly good order, nor had they the mobbish appearance that such a levy in any other country would have had. Their capots and trowsers of home-spun stuff, and their blue tuques (night caps) were all of the same cut and color, which gave them an air of uniformity that added much to their military look, for I have always remarked that a body of men's appearance in battalion, depends much less on the fashion of their individual [pg 14] dress and appointments, than on the whole being in strict uniformity.

They marched merrily along to the music of their voyageur songs, and as they perceived our uniform as we came up, they set up the Indian War-whoop, followed by a shout of Vive le Roi along the whole line. Such a body of men in such a temper, and with so perfect a use of their arms as all of them possessed, if posted on such ground as would preclude the possibility of regular troops out-manoeuvering them, (and such positions are not hard to find in Canada,) must have been rather a formidable body to have attacked. Finding that the enemy were between us and our regiment, proceeding to join would have been out of the question. The Colonel therefore requested that we might be attached to the militia on the advance. The Commander-in-Chief finding that the old gentleman had a perfect knowledge of the French language, (not by any means so common an accomplishment in the army in those days as it is now,) gave him command of a large brigade of militia, and, like other men who rise to greatness, his friends and followers shared his good fortune, for a subaltern of our regiment who had come out in another ship and joined us at Montreal, was appointed as his Brigade Major; and I was exalted to the dignity of Principal Medical Officer to his command, and we proceeded to Lachine, the head-quarters of the advance, and where it had been determined to make the stand, in order to cover Montreal, the great commercial [pg 15] emporium of the Canadas, and which, moreover, was the avowed object of the American attack.

Our force here presented rather a motley appearance; besides a small number of the line consisting chiefly of detachments, there was a considerable body of sailors and marines; the former made tolerable Artillery men, and the latter had, I would say, even a more serviceable appearance than an equal body of the line, average it throughout the army.

The fact is that during the war the marines had the best recruits that entered the army. The reason of this, as explained to me by an intelligent non-commissioned officer of that corps, was, that whereas a soldier of the line, returning on furlough to his native village, had barely enough of money to pay his travelling expenses, and support him while there, and even that with a strict attention to economy, the marine, on the other hand, on returning from a three years' cruise, had all the surplus pay and prize money of that period placed in his hands before he started, and this, with his pay going on at the same rate as that of the soldier of the line, enabled him to expend in a much more gentlemanly style of profusion than the other.

The vulgar of all ranks are apt to form their opinions of things rather from their results than the causes of them, and hence they jump to the conclusion that the marine service must be just so much better than that of the line, as the one has so much more money to spend on his return home than the other. And hence, aspiring—or as [pg 16] our quarter master, Tom Sheridan, used to say when recruiting sergeant, perspiring—young heroes, who resolve to gain a field marshal's baton by commencing with a musket, preferred the amphibious path of the jolly to the exclusively terraqueous one of the flat-foot. Besides these and our friends the country militia, there were two corps formed of the gentlemen of Montreal, one of artillery and another of sharp-shooters. I think these were in a perfect state of drill, and in their handsome new uniforms had a most imposing appearance. But if their discipline was commendable, their commissariat was beyond all praise. Long lines of carts were to be seen bearing in casks and hampers of the choicest wines, to say nothing of the venison, turkeys, hams, and all other esculents necessary to recruit their strength under the fatigues of war. With them the Indian found a profitable market for his game, and the fisherman for his fish. There can be little doubt that a gourmand would greatly prefer the comfort of dining with a mess of privates of these distinguished corps to the honour and glory of being half starved (of which he ran no small risk) at the table of the Governor General himself. Such a force opposed to an equal number of regulars, it may be said, was no very hopeful prospect for defending a country. But there are many things which, when taken into consideration, will show that the balance was not so very much against them as at first sight may appear. Men who are fighting for their homes and friends, and almost in sight of their wives and children, have an additional [pg 17] incentive over those who fight for pay and glory. Again, the enemy to attack them had to land from a rapid, a thing which precludes regularity under any circumstances, and they would not be rendered more cool by a heavy fire of artillery while they were yawning and whirling in the current. They must have landed in confusion, and would be attacked before they could form, and should they get over all this, there was a plateau of land in the rear ascended by a high steep bank, which, in tolerable hands, could neither be carried nor turned. Add to all this, that the American regulars, if equal, were not superior to our troops in drill and discipline, the great majority of them having been enlisted for a period too short to form a soldier, under the most favorable circumstances. And much even of that short time had been consumed in long and harassing marches through an unsettled country that could not supply the commissariat, and exposed to fatigue and privation that was rapidly spreading disease among them; dispirited too by recent defeat, with a constantly increasing force hanging on their rear. If they even had forced us at Lachine, they must have done it at an enormous loss. In their advance also towards Montreal, they must have fought every inch of the way, harrassed in front, flank and in rear, and their army so diminished that they could not hold Montreal if they had it. On the whole, therefore,—any reflections on the conduct of General Wilkinson by those great military critics, the editors of American newspapers, to the contrary [pg 18] notwithstanding,—every soldier will admit, that in withdrawing with a comparatively unbroken army to his intrenchment on Salmon River, the American commander did the very wisest thing that under all the circumstances he could have done. What the event of a battle might have been it is now impossible to say, for on this ground it was fated we were to show our devotion to our king and country at a cheaper rate, for the news of the battle of Chrysler's Farm, and the subsequent retreat of the Americans across the river, blighted all our hopes of laurels for this turn.

This was a very brilliant little affair. Colonel Morrison of the 89th Regiment, was sent by General de Rotenburg, with a small corp amounting in all to 820 men, Regulars, Militia and Indians, to watch the motions of the American army, when it broke up from Grenadier Island, near Kingston, and to hang on and harass their rear. This was done so effectually that General Covington was detached with a body at least three times our number to drive them back. Morrison retired till he came to a spot he had selected on his downward march, and there gave them battle. Luckily for us, the first volley we fired killed General Covington, who must have been a brave fine fellow; the officer succeeding him brought his undisciplined levies too near our well-drilled troops before he deployed, and in attempting to do so, got thrown into confusion, thus giving our artillery and gun-boats an opportunity of committing dreadful slaughter [pg 19] among their confused and huddled masses. They rallied, however, again, but were driven off by the bayonet; but all this cost us dear, for we were too much weakened to follow up our victory. They retired therefore in comparative safety to about seven miles above the village of Cornwall, where they crossed the river without loss, save from a body of Highland militia, from Glengarry, who made a sudden attack on their cavalry while embarking, and by firing into the boats by which they were swimming over their horses, made them let go their bridles, and the animals swimming to the shore, were seized upon by Donald, who thus came into action a foot soldier, and went out of it a dragoon, no doubt, like his countryman, sorely "taight wi' ta peast" on his journey home. [A] The enemy then took up a position and fortified a camp, where they remained during the winter, and when preparations were made to drive them out of it in the spring, they suddenly abandoned their position, leaving behind them their stores and baggage, and retreated, followed by our forces, as far as the village of Malone, in the State of New York. Thus ended the "partumeius mons" of the only efficient invasion of Canada during the war. The fact is, the Americans were deceived in all their schemes of conquest in Canada; the disaffected then as now were the loudest in their clamour, and a belief obtained among the Americans that they had only to display their colours to have the whole population flock to them. But the reverse of this was the case. They found themselves in [pg 20] a country so decidedly hostile, that their retreating ranks were thinned by the peasantry firing on them from behind fences and stumps; and it was evident that every man they met was an enemy. The militia at Lachine, after being duly thanked for their services, were sent home, and the regulars went into winter quarters; the sailors and marines to Kingston—and we, having enjoyed our newly acquired dignities for a few days, set off to join our regiment then quartered at Fort Wellington, a clumsy, ill-constructed unflanked redoubt, close to which now stands the large and populous village of Prescott, then consisting of five houses, three of which were unfinished. The journey was a most wretched one. The month of November being far advanced, rain and sleet poured down in torrents—the roads at no season good, were now barely fordable, so that we found it the easiest way to let our waggon go on with our baggage, and walk through the fields, and that too, though at every two hundred yards, or oftener, we had to scramble over a rail fence, six feet high; sometimes we got a lift in a boat, sometimes we were dragged by main force in a waggon through the deep mud, in which it was hard to say whether the peril of upsetting or drowning was the most imminent. Sometimes we marched; but all that could be said of any mode of travel was, that it was but a variety of the disagreeable; so, as there was no glory to be gained in such a service, I was anything but sorry when I learned that I was to halt for some time at a snug, comfortable, [pg 21] warm, cleanly, Dutch farm house, to take charge of the wounded who had suffered in the action of Chrysler's Farm.

[A] The Highlander is no equestrian—he can trot on his feet fifty or sixty miles a day, with much greater ease to himself, and in a shorter space of time, than he could ride the same distance. A gentleman once sent his Highland servant a message on urgent business, and to enable him to execute it sooner, gave him a horse. Donald did not return at the time expected, nor for long after it; at last his master, who was watching anxiously for him, discerned him at a long distance on the road on foot, creeping at a snail's pace, and towing the reluctant quadruped by the bridle. On being objurgated for his tardiness, he replied "he could have been here twa three hours, but he has taight wi' ta peast," i.e. delayed, or impeded by the horse.

Washington Irving is the only describer of your "American Teutonic Race," and this, my debut in the New World, put me down in the midst of that worthy people as unsophisticated as possible. It is refreshing, as his little Lordship of Craigcrook used to say, in this land where every man is a philosopher, and talks of government as if he had been bred at the feet of Machiavel, to meet with a specimen of genuine simplicity, perfectly aware of his own ignorance in matters which in no way concern him. Your Dutchman is the most unchangeable of all human beings, "Caelum non animum mutant, qui trans mare currunt" applies with peculiar force to the Batavian in every clime on the face of the globe. In America, at the Cape of Good Hope, in the congenial marshes of Java, in the West Indies, and at Chinsurhae on the banks of the Ganges, the transmarine Hollander is always the same as in his own native mud of the dams and dykes of Holland,—the same in his house, his dress, his voracious and omniverous appetite, his thrift and his cleanliness.

Among these good, kind, simple people, I spent a month or six weeks very pleasantly. Loyal and warmly attached to the British Crown, they followed our standard in the Revolutionary War, and obtained from government settlements in Canada when driven from their homes on the banks of the Hudson. From what I could learn [pg 22] from them, the Americans had persecuted them and their families with a rancour they displayed to no other race of mankind. When prisoners were taken in action, while the British were treated by them with respect, and even with kindness, the Dutch were deliberately murdered in cold blood. Men without arms in their hands, but suspected of favouring the British cause, were shot before their own doors, or hanged on the apple trees of their own orchards, in presence of their wives and families, who without regard to age or sex, were turned from their homes without remorse or pity. And one old dame told me that she was for six weeks in the woods between Utica and Niagara, unaccompanied by any one but her two infant children, looking for her husband, who she luckily found in the fort of the latter place; at one time she and her poor babes must have perished from hunger, but for some Mohawk Indians, who came up and delivered them, and conducted them to the Fort. The Dutch themselves ascribe this very different treatment of the two races to the fear of the Americans that the British would retaliate in case they were ill used, while the Dutch could not.

This, however, could not have been the case, for had the Americans feared vengeance on the part of the British for the wrongs they inflicted on their countrymen, they must have equally feared that they would not quietly submit to injuries inflicted on men who were their loyal and faithful fellow subjects. I therefore suspect, that, [pg 23] so far as their statements were correct, and they must have been so in the main, for I have the same stories from the Dutch of the Niagara District, who had no communication whatever with their compatriots of Williamsburg, and though we must allow great latitude for exaggeration in a people who were, no doubt, deeply injured, and had been brooding over their wrongs for a period of upwards of thirty years, during all which time their wrath had gathered force as it went, and their stories having no one to contradict them, must have increased with each subsequent narrator, till they had obtained all the credence of time-honoured truth—allowing for all this, but insisting that the stories had a strong foundation in fact, the rigor of their persecution must be attributed to another feeling, and must have, I should think, arisen from this, that the Americans considered that a British subject born within the realm, and fighting for what he believed to be the rights of his country, was only doing what they themselves were doing; whereas, a North American born, whatever his extraction, fighting against what they considered the rights of the people of North America, was a traitor and an apostate, an enemy to the cause of freedom from innate depravity, and therefore, like a noxious animal, was lawfully to be destroyed, "per fas et nefas." However this may be, I found their hatred to the Americans was deep rooted and hearty, and their kindness to us and to our wounded, (for I never trusted them near the American wounded,) in proportion strong and [pg 24] unceasing; my only difficulty with them was to prevent them cramming my patients with all manner of Dutch dainties, for their ideas of practice being Batavian, they affirmed that there was infinitely greater danger from inanition than repletion, and that strength must come from nourishment. "Unless you give de wounded man plenty to eat and drink it is quite certain he can never get through."

Killing with kindness is the commonest cause of death I am aware of, and it is very remiss in the faculty, that it has never yet found a place in the periodical mortuary reports which they publish in great cities in a tabular form—this ought to be amended. Au reste—I was very comfortable, for, while I remained under the hospitable roof of my friend old Cobus, I had an upper room for my sleeping apartment, and the show room of the establishment for my sitting parlor, an honour and preferment which nobody of less rank them an actual line officer of the "riglars" could have presumed to aspire to; to the rest of mankind it was shut and sealed, saving on high days and holidays. This sacred chamber was furnished and decorated in the purest and most classical style of Dutch taste, the whole woodwork, and that included floor, walls and ceiling, were sedulously washed once a week with hot water and soap, vigorously applied with a scrubbing brush. The floor was nicely sanded, and the walls decorated with a tapestry of innumerable home-spun petticoats, evidently never applied to any other (I won't say meaner) purpose, [pg 25] declaring at once the wealth and housewifery of the gude vrow. On the shelf that ran round the whole room, were exhibited the holiday crockery of the establishment, bright and shining, interspersed with pewter spoons, which were easily mistaken for silver from the excessive brightness of their polish. And to conclude the description of my comforts, I had for breakfast and dinner a variety and profusion of meat, fish, eggs, cakes and preserves, that might have satisfied the grenadier company of the Regiment.

On the Saturday morning (for this was the grand cleansing day) I never went forth to visit my hospital without taking my fowling piece in my hand, and made a point of never returning until sunset, as during the intervening period no animal not amphibious could possibly have existed in the domicile; after leaving them I never passed their door on the line of march without passing an hour or two with my old friends, and on such occasions I used to be honoured with the chaste salute of the worthy old dame, which was followed by my going through the same ceremony, to a strapping beauty, her niece, who was "comely to be seen," and in stature rather exceeded myself, though I stand six feet in my stocking soles. An irreverent Irish subaltern of ours impiously likened the decorous and fraternal salute with which I greeted her, to the "slap of a wet brogue against a barn door;" and the angel who in her innocence bestowed that civility on me, was known by my brother officers, who had [pg 26] no platonism in their souls, as "The Doctor's Sylph."

From the end of the first few weeks that I remained here my patients gradually began to diminish,—some died, and these I buried,—some recovered by the remedies employed, or spite of them, and these I forwarded or carried with me to join the Regiment,—and others who from loss of limbs or of the use of them, might be considered as permanently rendered "hors de combat," I sent by easy stages to Montreal General Hospital, thence in the spring to be removed to England as occasion offered, thence to enjoy the honours and emoluments of a Chelsea Pension. The few that remained unfit to be removed I committed to the charge of an Hospital Mate, and proceeded with all convenient speed to join the headquarters of my Regiment.

I joined my regiment at Fort Wellington, and a fine jovial unsophisticated set of "wild tremendous Irishmen" I found my brother officers to be. To do them justice (and I was upwards of four years with them) a more honest-hearted set of fellows never met round a mess table. No private family ever lived in more concord or unanimity than did "Our Mess."

Irishmen though they mostly were, they never quarrelled among themselves. They sometimes fought, to be sure, with strangers, but never in the Regiment, though we rarely went to bed without a respectable quorum of them getting a leetle to the lee side of sobriety.

"Tempora mutantur," says Horace, but I very much doubt if "nos" (that is such as are alive of 'nos') "mutamur in illis." The Army is very different from what it was in my day—sadly changed indeed! It will hardly be believed, but I have dined with officers who, after drinking a few glasses of wine, called for their coffee. If Waterloo was to fight over again, no rational [pg 28] man can suppose that we would gain it after such symptoms of degeneracy. Such lady-like gentlemen would certainly take out vinaigrettes and scream at a charge of the Old Guard, and be horrified at the sight of a set of grim-looking Frenchmen, all grin and gash, whisker and moustache.

I was not, however, allowed to enjoy the festivities of Fort Wellington, such as they were. The enemy being extended along the line of the right bank of the St. Lawrence, and the Lake of the Thousand Islands, it was necessary that we also should extend and occupy points that might enable us to keep up a communication, and maintain a correspondence with our rear. Besides it was considered highly expedient and necessary, that small bodies of the line should be stationed in defensible positions, to form a nucleus, in case of invasion, for the Indians and Militia to rally round and form upon. Accordingly, a garrison had to be maintained in a block-house in the woods of Gananoque, between Brockville and Kingston, and our Grenadier Company being ordered for that service, I was detached to accompany them. A block-house is a most convenient and easily constructed fort in a new country. The lower story is strongly built of stone, and the upper, which overhangs it about eighteen inches, (so that you can fire from above along the wall without being exposed,) is built of logs about a foot square. Both stories are pierced with loop-holes for musquetry, and in the upper are four portholes, to which are fitted four 24-pounder [pg 29] carronades, mounted naval fashion, the whole being surrounded with a strong loop-holed and flanked stoccade, and this makes a very fair protection for an inferior force, against a superior who are unprovided with a battering train, which of course in a few rounds would knock it to splinters.

Except in the expectation of a sudden attack, the officers were permitted to sleep out of the block-house, and a small unfinished house was taken for their residence. The captain and senior lieutenant being, as Bardolph hath it, better accommodated than with wives, we, that is the junior lieutenant and myself, gave up our share of the quarters to them, and established ourselves in what had been a blacksmith's shop, for our winter quarters. In the ante-room to this enviable abode, a jobbing tailor had formed his shop-board, and his rags and shapings proved highly useful in caulking its seams against the wind. By means of a roaring fire kept up on the forge, and a stove in the outer room, we managed to keep ourselves tolerably comfortable during an unusually rigorous winter; and it being on the road side, and a halting station in the woods, we were often visited by friends coming or going, who partook with great goût of our frozen beef—which had to be cut into steaks with a hand-saw. Being on the banks of a fine stream, we never were at loss for ducks, and in the surrounding pine woods the partridges were abundant, and the Indians brought us venison in exchange for rum, so that we had at least a plentiful, [pg 30] if not an elegant table, and we were enabled to pass the winter nights as pleasantly over our ration rum as ever I did in a place with much more splendid "appliances and means to boot."

We passed the remainder of the winter as officers are obliged to do in country quarters. We shot, we lounged, we walked and did all the flirtation that the neighborhood of a mill, a shop, a tavern, with two farm houses within a reasonable forenoon's walk, could afford. We were deprived, however, of the luxury of spitting over a bridge, which Dr. Johnston says is the principal amusement of officers in country quarters, for though we had a bridge close at hand, the stream beneath it was frozen. Early in spring we were relieved by two companies of another Regiment, and having received orders to join, we joined accordingly.

I had the good fortune to be quartered with two companies of my Regiment at the then insignificant village of Cornwall. It is now a flourishing town, and sends a Member to the Provincial Parliament, though it then did not contain more than twenty houses. Here we found ourselves in very agreeable society, composed principally of old officers of the revolutionary war, who had obtained grants of land in this neighbourhood, and had settled down, as we say in this part of the country and its neighbourhood, with their families. An affectation of style, and set entertainments that follow so rapidly the footsteps of wealth, were then and there unknown, and we immediately became on the best possible [pg 31] terms with the highest circles (for these exist in all societies, and the smaller the society, the more distinctly is the circle defined). We walked into their houses as if they had been our own, and no apology was offered, though these were found in such a litter as washing or scrubbing day necessarily implied. The old gentlemen when in town came to Our Mess, and when they had imbibed a sufficient quantity of port, they regaled us with toughish yarns of their military doings during the revolutionary war. And when a tea-drinking party called a sufficient number of the aristocracy together, an extemporaneous dance was got up, a muffled drum and fife furnishing the orchestra.

Towards the end of June our two companies got the route to join headquarters, the Regiment being ordered to the Niagara frontier. But though the troops were relieved, I was not, but ordered to remain till some one should arrive to fill my place, and in the interval between that and my departure a Field Officer, who was sent to command the Militia of the district, arrived.

He was an old acquaintance of mine, and a real good fellow. He had highly distinguished himself during the war, particularly at the storming of Ogdensburg, where he commanded. He was of Highland extraction, and though he had not the misfortune to be born in that country, he had, by means of the instructions of a Celtic moonshee, (as they say in Bengal,) acquired enough of their language to hammer out a translation of a verse or two of the Gaelic Bible, with nearly as [pg 32] much facility as a boy in the first year of the Grammar School would an equal quantity of his Cordery. To all these good gifts he added the advantage of being of the Catholic persuasion, which rendered him the most proper person that could have been selected to take charge of a district the chief part of whose Militia were Highlanders, Catholics, and soldiers, or the sons of soldiers.

I have never met with him since the end of the war, though I might have seen him in Edinburgh at the King's visit; but who could be expected to recognize a respectable Field Officer of Light Infantry, masquerading, disguised for the first time in his life in a kilt, and forming a joint in the tail of the chief of his barbarous clan?

It struck this gentleman that supplies of fresh provisions might be got from the American side, and accordingly he sent emissaries over the river, and the result justified the correctness of his views.

While sitting after dinner one day tete-à-tete with the Colonel, his servant announced that a gentleman wanted to see him. As the word gentleman on this side of the Atlantic conveys no idea of either high birth or high breeding, nor even of a clean shirt, or a whole coat, my friend demanded what kind of a gentleman,—as, like a sensible man as he was, he did not wish to be interrupted in the pleasant occupation of discussing his wine and listening to my agreeable conversation, by a gentleman who possibly might ask him if he wished to buy any eggs, as many [pg 33] species of the genus gentleman on this side of the herring pond might possibly deem a good and sufficient reason for intruding on his privacy. His servant said he believed he must be a kind of Yankee gentleman, for he wore his hat in the parlor, and spit on the carpet. The causa scientiae, as the lawyers say, seemed conclusive to my Commandant, for he was ordered to be admitted, and the Colonel, telling me that he suspected this must be one of his beef customers, requested I would not leave the room, as he wished a witness to the bargain he was about to make.

Accordingly, there entered a tall, good-looking, middle-aged man, dressed in a blue something, that might have been a cross between a surtout and a great coat. He was invited to sit down, and fill his glass, when the following dialogue took place:

Yankee.—I'm Major —— of Vermont State, and I would like to speak to the Colonel in private, I guess, on particular business.

Colonel.—Anything you may have to say to me, Sir, may be said with perfect safety in presence of this gentleman.

Major.—I'm a little in the smuggling line, I reckon.

Colonel.—Aye, and pray what have you smuggled?

Major.—Kettle, (cattle,) I reckon. I heerd that the Colonel wanted some very bad, so I just brought a hundred on 'em across at St. Regis, as fine critters, Colonel, as ever had hair on 'em. [pg 34] So I drove them right up; the Colonel can look at 'em hisself—they are right at the door here.

Colonel.—Well, what price do you ask for them?

Major.—Well, Colonel I expect about the same as other folks gets, I conclude.

Colonel.—That is but reasonable, and you shall have it.

The Commissary of the Post was sent for, and having been previously warned not to be very scrupulous in inspecting the drove, as it was of infinitely more importance to get the army supplied than to obtain them at the very lowest rate per head, he soon returned with a bag of half eagles, and paid the Major the sum demanded. The latter, after carefully counting the coin, returned it into the canvas bag, and opening his coat displayed inside the breast of it, a pocket about the size of a haversack, into which he dropped his treasure, and then deliberately buttoning it up from the bottom to the throat, he filled and drank a glass of wine, to our good healths; adding, "Well, Colonel, I must say you are a leetle the genteelest man to deal with ever I met with, and I'll tell all my friends how handsome you behaved to me; and I'm glad of it for their sakes as well as my own, for jist as I was fixing to start from St. Regis, my friend Colonel —— arrived with three hundred head more. The kettle arnt his'n; they belong to his father, who is our Senator. They do say that it is wrong to supply an innimy, and I think so too; but I don't call that man my innimy who buys [pg 35] what I have to sell, and gives a genteel price for it. We have worse innimies than you Britishers. So I hope the Colonel will behave all the same as well to them as he has done to me; but there was no harm in having the first of the market, you know, Colonel." So with a duck that was intended for a bow, and a knowing grin that seemed to say, "It was just as safe to secure my money before giving you this piece of information," he took his leave and departed, evidently much pleased with the success of his negotiation.

At this time the expense of carrying on the war was enormous. Canada, so far from being able to supply an army and navy with the provisions required, was (as a great many of her effective population were employed in the transport of military and naval stores,) not fit to supply her own wants, and it was essential to secure supplies from wherever they could be got soonest and cheapest. Troops acting on the Niagara frontier, 1,000 miles from the ocean, were fed with flour the produce of England, and pork and beef from Cork, which, with the waste inseparable from a state of war, the expense and accidents to which a long voyage expose them, and the enormous cost of internal conveyance, at least doubled the quantity required, and rendered the price of them at least ten times their original cost. Not only provisions, but every kind of Military and Naval Stores, every bolt of canvas, every rope yarn, as well as the heavier articles of guns, shot, cables, anchors, and all the [pg 36] numerous etceteras for furnishing a large squadron, arming forts, supplying arms for the militia and the line, had to be brought from Montreal to Kingston, a distance of nearly 200 miles, by land in winter, and in summer by flat-bottomed boats, which had to tow up the rapids, and sail up the still parts of the river, (in many places not a mile in breadth, between the British and American shores,) exposed to the shot of the enemy without any protection; for with the small body of troops we had in the country, it was utterly impossible that we could detach a force sufficient to protect the numerous brigades of boats that were daily proceeding up the river, and we must have been utterly undone, had not the ignorance and inertness of the enemy saved us. Had they stationed four field guns, covered by a corps of riflemen, on the banks of the St. Lawrence, they could have cut off our supplies without risking one man. As it was we had only to station a small party at every fifty miles, to be ready to act in case of alarm; but fortunately for us, they rarely or never troubled us. If they had done so with any kind of spirit, we must have abandoned Upper Canada, Kingston and the fleet on Ontario included, and leaving it to its fate, confined ourselves to the defence of such part of the Lower Province as came within the range of our own empire, the sea.

I would do gross injustice to my reader, no less than to myself, were I to quit Cornwall without mentioning a most worthy personage, who, though in a humble station, was one of the [pg 37] best and most original characters I ever met with in my progress through life. This was no other than my worthy hostess, of the principal log hotel, Peggy Bruce. If you could conceive Meg Dodds an Irish instead of a Scotch woman, you would have a lively conception of Peggy. She possessed all the virtues of her prototype, all her culinary talents, all her caprice with guests she did not take a fancy for, and all powers, offensive or defensive, by tongue or broom, as the case in hand rendered the one or the other more expedient.

Peggy was the daughter of a respectable Irish farmer, and had made a runaway match with a handsome young Scotch sergeant. She had accompanied her husband through the various campaigns of the revolutionary war, and at the peace, his regiment being disbanded, they set up a small public house, which, when I knew her as a widow, she still kept. The sign was a long board, decorated by a very formidable likeness of St. Andrew at the one end, and St. Patrick at the other, being the patron saints of the high contracting parties over whose domicile they presided, and the whole surrounded by a splendid wreath of thistles and shamrocks.

Bred in the army, she still retained her old military predeliction, and a scarlet coat was the best recommendation to her good offices. Civilians of whatever rank she deemed an inferior class of the human race, and it would have been a hard task to have convinced her that the Lord [pg 38] Chancellor was equal in dignity or station to a Captain of Dragoons.

It was my luck, (good or bad as the reader may be inclined to determine,) to be a prodigious favourite with the old lady; but even favour with the ladies has its drawbacks and inconveniences, and one of these with me was being dragged to the bedside of every man, woman and child who was taken ill in or about the village. At first I remonstrated against my being appointed physician-extraordinary to the whole parish, with which I was in no way connected; but Peggy found an argument which, as it seemed perfectly satisfactory to herself, had to content me. "What the d—l does the king pay you for, if you are not to attend to his subjects when they require your assistance?"

I once, and only once, outwitted her. She woke me out of a sound sleep a little after midnight, to go and see one of her patients. Having undergone great fatigue the day before, I felt very unwilling to get up. At first I meditated a flat refusal, but I could see with half a glance, that she anticipated my objections, for I saw her eye fix itself on a large ewer of water in the basin stand, and I knew her too well for a moment to suppose that she would hesitate to call in the aid of the pure element to enforce her arguments. So I feigned compliance, but pleaded the impossibility of my getting up, while there was a lady in the room. This appeared only reasonable, so she lit my candle and withdrew to the kitchen fire, while I was at my toilet. Her back was no [pg 39] sooner turned, than I rose, double-locked and bolted the door, and retired again to rest, leaving her to storm in the passage, and ultimately to knock up one of the village doctors, whose skill she was well persuaded was immeasurably inferior to any Army medical man who wore His Majesty's uniform. But though I chuckled at my success at the time, I had to be most wary how I approached her, and many days elapsed before I ventured to come within broom's length of her. At last I appeased her wrath by promising never "in like case to offend," and so obtained her forgiveness, and was once more taken into favour; but Peggy was too old a soldier to be taken in twice, or to trust to the promise of a sleepy man that he would get up. After this, when she required my services, she would listen to no apology on the score of modesty, but placing her lantern on the table, waited patiently till I was dressed, when tucking up her gown through her pocketholes and taking my arm, away we paddled through the mud in company.

After reaching the house of the patient, and after the wife and daughters had been duly scolded for their neglect in not calling her in sooner, we entered into consultation, which like many other medical consultations, generally ended in a difference of opinion. To a military surgeon, much sooner than to any other surgeon, there were certain great leading principles in the healing art, to all impugning of which Peggy was flint and adamant and when these were mooted I much question if she would have succumbed to [pg 40] even the Director General of the Army Medical Board himself.

At the head of her medical dicta was that it was essential to "support the strength." That was to cram the patient with every kind of food that by entreaty or importunity he could be prevailed upon to swallow, (a practice by the way of more learned practitioners than Peggy.) A hot bath with herbs infused in it was another favourite remedy, and on this we were more at one, for the bath would most likely do good, and the herbs no harm. Her concluding act at the breaking up of the consultation was generally to dive into the recesses of a pair of pockets of the size and shape of saddle bags, from which, among other miscellaneous contents, would she fish up a couple of bottles of wine which she deemed might be useful to the patient. After we had finished business I escorted the old lady home, where there was always something comfortable kept warm for supper, which when we had discussed together, with something of a stiffish horn of hot brandy and water, we departed to our respective dormitories.

Peggy, like many of her country, possessed a keen vein of sarcastic humor, which often made her both feared and respected. A Colonel, as good a man, and as brave a soldier as ever drew a sword, but too much of a martinet to be a favourite with the militia of whom he was Inspecting Field Officer, received a command in a division that was then going on actual service. Peggy, who respected his military talents at least [pg 41] as much as she disliked his hauteur, meeting him the day before his departure, addressed him with—"Och! Colonel dear, and are ye going to lave us—sure there will be many a dry eye in the town the day you quit it." When the American Army, under Wilkinson, were coming down the St. Lawrence, a company of Glengarry Militia were placed at Cornwall to watch their movements, and act as might be most expedient. The Captain of the band was named John McDonald, a very good and highly respectable name, but of no earthly use to distinguish a Glengarry man, as there were some hundreds in that part of the world—nor would the prefix of his military rank much mend the matter, as there are probably some score Captain John McDonalds. In this emergency therefore, a soubriquet becomes indispensable. This Captain John had in his youth served in the revolutionary war as a corporal, in the same brigade as Peggy's husband, therefore they were very old friends, and to distinguish him from the clan she named him Captain Corporal John. When it was known that the invading army had abandoned the attempt, and had crossed the river, the men, wisely considering that their services were no longer required in Cornwall, and would be highly useful on their farms, disbanded themselves during the night without the formality of asking leave, so that at morning parade only six appeared on the ground. Such an unheard-of breach of military discipline could not fail to excite the fierce indignation of the worthy veteran; accordingly he [pg 42] vented his wrath in every oath, Gaelic or English, within the range of his vocabulary. Peggy, who witnessed the scene from her window, consoled the incensed commander with "Och! John, dear, don't let the devil get so great a hould of ye as to be blaspheming like a heathen in that fearful way; things are not so bad with you yet, sure you have twice as many men under your command as you had when I knew you first."

Having at last been relieved, I proceeded to join on the Niagara frontier, and therefore marched with a detachment of the Canadian Fencibles to Kingston, where I was joined by a friend of mine, an officer of the 100th, who was bound for the same destination. We accordingly waited on the Deputy Quarter Master General, and stated the necessity of being furnished with land conveyance, as the battle which must decide the campaign, was hourly expected; but that gentleman having newly acquired his dignity, it did not sit easy upon him, and with great hauteur he flatly refused us, and unless we chose to march it, (about 200 miles,) we had no shift but to embark in a batteau loaded with gunpowder, and rowed by a party of De Watteville's regiment. This gentleman, by the bye, afterwards distinguished himself as a naturalist in Sir John Ross' first Polar expedition, and as a most appropriate reward had the honor to stand god-father to a nondescript gull, which bears his name unto this day.

In the batteau, therefore, we deposited ourselves, and with six more in company proceeded on our way, with such speed as a set of rowers, [pg 43] who probably had never had an oar before in their hands, could urge us. The wind though light was ahead; but when we got about six hours distance from Kingston, which perhaps might amount to eighteen or twenty miles, all we could do was to make head-way against it, and as it looked as if there would be more of it, sooner than less, I (who, from my superior nautical experience, having been born and bred in a sea-port town and acquired considerable dexterity both in stealing boats and managing them when stolen, was voted Commodore,) ordered them under the lee of a little rocky island, and carried their dangerous cargo about a hundred yards from where we encamped, that is to say, put the gunpowder at one end of the island and ourselves at the other, hauled up the batteau, lighted fires, and forming a camp of sails and tarpaulins, waited the event. A squall did come down the lake in very handsome style, embellished with a sufficiency of spindrift to make us thankful that we were under the lee of a rock and covered overhead. The squall subsided into a good steady gale, accompanied by a sea that made it utterly impossible that we could have proceeded even if the wind had been as favourable as it was the contrary; we thus had the advantage of enjoying two days of philosophical reflection on a rock in Lake Ontario. On the third it began to moderate, and my comrade and I took one of the empty batteaus with a strong party, and made us directly in shore as we could, and had the good fortune to land about twelve miles [pg 44] above Kingston, determined to make our way on horseback, coute qu'il coute.

Any one who has only seen the roads of Canada in the present day, can form but a very inadequate idea of what they were then between Kingston and Toronto; for a considerable part of the way we were literally up to our saddle-flaps. In those days all the horses along the roads were taken up for Government, and an officer receiving the route gave the proprietor an order for so many horses so many miles, and the nearest Commissary paid it; or he paid it, taking a receipt which, when he showed it to the Commissary at the end of his journey, was refunded. We necessarily took the latter mode, seeing we had no route to show, and therefore paid our way ourselves. The officer who accompanied me being like myself a subaltern, we found we uniformly got the worst horses, as Major A. or Colonel B. or some other "person of worship" was expected, and the best must necessarily be kept for him. It struck me therefore that if "Captain" was a good travelling name, "General" must be a much better; I proposed to my companion that he should have the rank of Major General "for the road only," and I volunteered to act as Aide-de-camp. He liked the plan, but objected that he was too young to look the character, but that as I had a more commanding and dignified presence, I should do General and he Aide-de-camp, and as we were dressed in our surtouts and forage caps, we were well aware that we might easily pass with the uninitiated for any [pg 45] rank we might think proper to assume. Accordingly, when we approached a halt where we were to change horses, he rode briskly forward and began to call lustily about him, as "one having authority," for horses, and pointing to a very active, stout looking pair, peremptorily ordered them to be brought out and saddled; but the man of the house excused himself by saying that he "kept them horses for the sole use of Major B. the Deputy Quarter Master General, and as he had the conducting of the troops on the line of march through which the road lay, and had it in his power to put good jobs in his way, he was not a man whom he could offend on slight grounds."

"D——n Major B!" exclaimed the irreverent and indignant A.D.C. "Would you set his will, or that of fifty like him, against the positive orders of the great General D. who has been sent out by the Duke of Wellington to instruct Sir Gordon Drummond how he is to conduct the campaign? Sir, if by your neglect he is too late for the battle that must soon be fought, you will be answerable for it, and then hanging on your own sign-post is the very mildest punishment you can expect; it is the way we always settled such matters in Spain." To this argument there could be no answer, so the horses were led out just as I came up—my A.D.C. with his hat in his hand holding my stirrup as I mounted. This to those who knew anything about the service would have appeared a little de trop; but to the uninitiated, of whom mine host was one, it only served to inspire [pg 46] him with the higher respect for the great man his horse was about to have the honour to carry.

So far things went on as well as could have been wished; but in turning a corner in a young pine wood about a mile from where we had started, who should we meet full in the face but Major B., (commonly called Beau B.) who was also a captain in my own regiment. After the first salutation he expressed his surprise that the man should have given me his horses. I assured him that I should not have got them, but that he had a much better pair for him. This pacified him, so after a few minutes' conversation, (the A.D.C. and guide keeping a respectful distance,) I told him I had been made a general since I last saw him. He did not see the point of the joke at the time, but on taking leave he took off his hat and bowing till his well brushed and perfumed locks mixed with the hair of his horse's mane, said, loud enough for the guide to hear him, "General D., I have the honor to wish you a very good morning." If there had been any misgivings in the mind of the guide, this could not fail to remove them. Immediately after he rode up to me, and said that if I had no objections he would ride forward, and make such arrangements that there should be no delay in mounting me at the next stage. To this I acceded with the most gracious affability, so he rode on accordingly. His zeal for the service might account for his eagerness, yet I hope I will not be accounted uncharitable when I suspected that the importance, [pg 47] which attaches to the person who is first to communicate an extraordinary piece of news, may have had something to do with all this alacrity. However this may be, it served my purpose, for at every stage not a moment was lost, the news flying like wild fire. I found horses ready at every house, and never was for one moment delayed.

With my friend Beau B. the result was somewhat different, for on arriving at the stage there was nothing for him but our exhausted dog-tired horses to mount, which in the state of the roads would have been utter madness; so he had to wait in a roadside inn, consoling himself with what philosophy he could muster till they were sufficiently recruited with food and rest to continue their journey.

On this journey there occurred a circumstance which, as it is intimately connected with the secret history of the Province, deserves to be related. It will be news to most of my neighbors that the Province of Canada has a secret history of its own, or they may suppose that it may contain some such tit-bits as the secret history of the Court of St. Petersburg in the days of Catharine; but I am sorry to say that our secret history affords nothing so piquante; it only relates to the diplomacy of the Court of St. James, with its effects on the Court of the Chateau St. Louis.

In those days Sir George Prevost filled the vice-regal chair of Her Majesty's dominions in British North America, and a more incompetent [pg 48] Viceroy could hardly have been selected for such trying times. Timid at all times, despairing of his resources, he was afraid to venture anything; and when he did venture, like an unskilful hunter, he spurred his horse spiritedly at the fence, and while the animal rose he suddenly checked him—baulked him in the leap he could have easily cleared, and landed himself in the ditch. Thus he acted at Sackett's Harbour and thus at Plattsburg, where he was in possession of the forts when he ordered the retreat to be sounded, and ran away out of one side of the town while the enemy were equally busy in evacuating it at the other. But to my story. Late on the evening of our first day's journey, and therefore somewhere midway between Kingston and Toronto, we overtook an officer of Sir George Prevost's Staff. He asked us why we were riding so fast? We told him, to be present at the coming battle. He told us we might save ourselves the trouble, as there would be no battle till he was there, and hinted perhaps not then; and strongly recommended that, instead of pushing on through such roads during the night, we should stop at a house he pointed out to us, and where he was going. Thinking, however, that a battle was not always at the option of one party, we determined to push on, while he turned up to a good looking two story white framed house on the lake side of the road. Many years after, the late Mr. Galt was employed to advocate the War Losses in Canada with His Majesty's Government. In one of his conferences with the Colonial Secretary, the latter [pg 49] stated that everything that could be done had been done for the defence of the Province, and that it never had been the intention either of the Imperial or Colonial Government to abandon it. Mr. Galt then placed in his hands a paper purporting to be a copy of a despatch from Sir George Prevost to Sir Gordon Drummond, ordering him to withdraw his forces from the upper part of the Province, and to concentrate them to cover Kingston. The Secretary then, turning to Galt, said rather sternly:

"Sir, you could not have come fairly by this copy of a private despatch?"

Galt calmly replied, "My Lord, however this paper was come by at first, I came honestly enough by it, for it was sent to me with other papers to assist me in advocating the claims of those who have suffered in the war; but I thank your Lordship for admitting that it is a copy of a despatch whether private or public."

His Lordship felt that, in his haste to criminate, he had allowed his diplomacy to be taken by surprise.