Title: The Adventures of a Suburbanite

Author: Ellis Parker Butler

Illustrator: A. B. Phelan

Release date: November 10, 2013 [eBook #44153]

Most recently updated: February 21, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

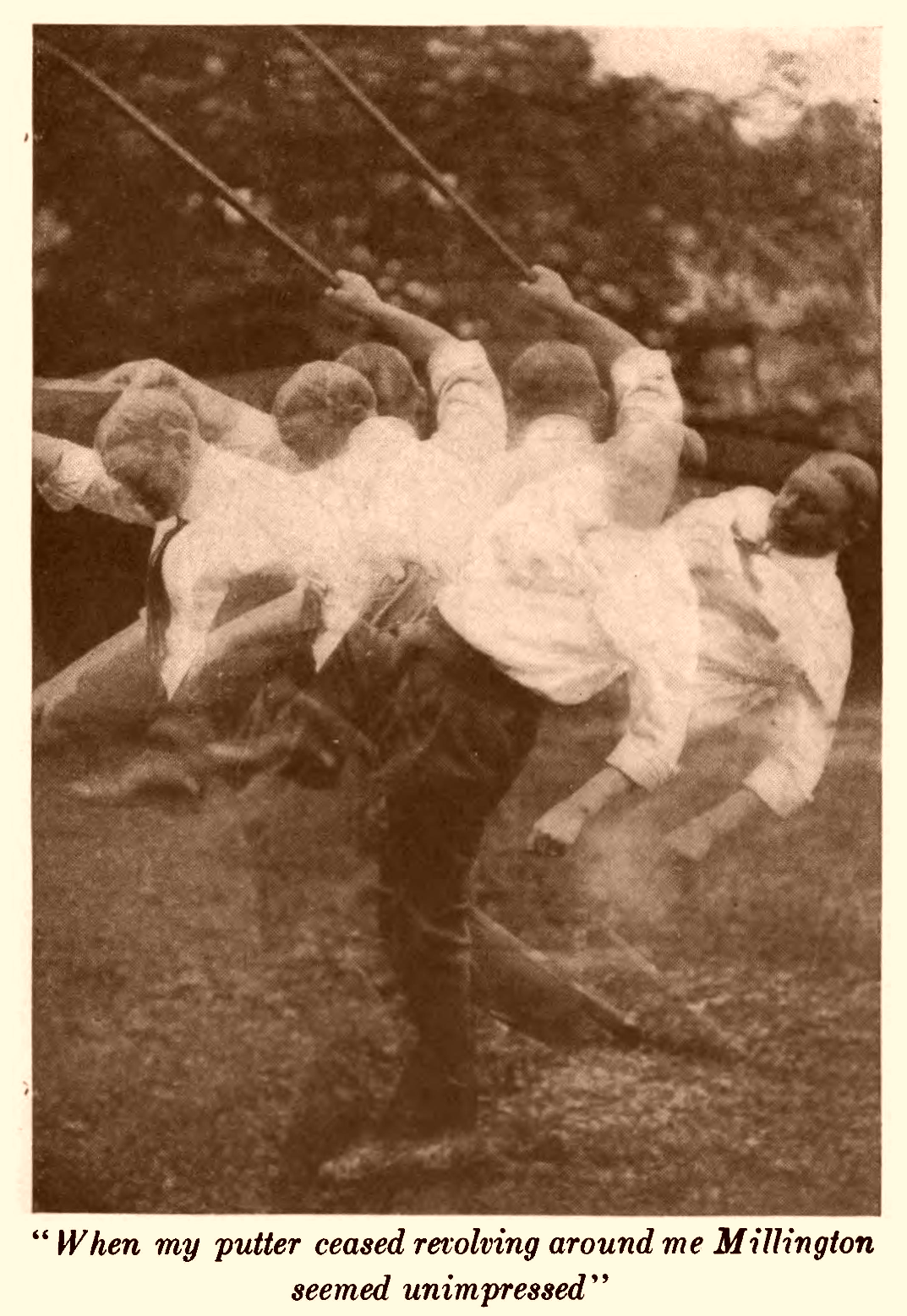

IX. THE ROYAL GAME OR SEVERAL DAYS AFTER THE PIG EPISODE

XI. MY DOMESTICATED AUTOMOBILE

XIII. MILLINGTON'S MOTOR MYSTERY

ISOBEL was born in a flat, and that was no fault of her own; but she was born in a flat, and reared in a flat, and married from a flat, and, for two years after we were married, we lived in a flat; but I am not a born flat-dweller myself, and as soon as possible I proposed that we move to the country. Isobel hesitated, but she hesitated so weakly that on the first of May we had bought the place at Westcote and moved into it.

The very day I moved into my house Millington came over and said he was glad some one had moved in, because the last man that had lived in the house was afraid of automobiles, and would never take a spin with him. He said he hoped I was not afraid; and when I said I was not, he immediately proposed that we take a little spin out to Port Lafayette as soon as I had my furniture straightened around. I thought it was very nice and neighbourly and unusual for a man with an automobile to begin an acquaintance that way; but I did not know Millington's automobile so well then as I grew to know it afterward.

I liked Millington. He was a short, Napoleon-looking man, with bulldog jaws and not very much hair, and I was glad to have him for a neighbour, particularly as my neighbour on the other side was a tall, haughty-looking man. He leaned on the division fence and stared all the while our furniture was being moved in. I spoke to Millington about him, and all Millington said was: “Rolfs? Oh, he's no good! He won't ride in an automobile.”

At first, while we were really getting settled in our house, Isobel was bright and cheerful and seemed to have forgotten flats entirely but on the tenth of May I saw a change coming over her, and when I spoke of it she opened her heart to me.

“John,” she said, “I am afraid I cannot stand it. I shall try to, for your sake, but I do not think I can. I am so lonely! I feel like an atom floating in space.”

“Isobel!” I said kindly but reprovingly. “With the Millingtons on one side and the Rolfs on the other?”

“I know,” she admitted contritely enough; “but you can't understand. Always and always, since I was born, some one has lived overhead, and some one has lived underneath. Sometimes only the janitor lived underneath—”

“Isobel,” I said, “if you will try to explain what you mean—”

“I mean flats,” she said dolefully. “I always lived in a flat, John, and there was always a family above and a family below, and it frightens me to think I am in a house where there is no family above me, and not even a janitor's family below me. It makes me feel naked, or suspended in air, or as if there was no ground under my feet. It makes me gasp!”

“That is nonsense!” I said. “That is the beauty of having a house. We have it all to ourselves. Now, in a flat—”

“We had our flat all to ourselves, John,” she reminded me; “but a flat isn't so unbounded as a house. Just think; there is nothing between us and the top of the sky! Not a single family! It makes me nervous. And there is nothing beneath us!”

“Now, my dear,” I said soothingly, “China is beneath us, and no doubt a very respectable family is keeping house directly below.”

Isobel sighed contentedly.

“I am so glad you thought of that!” she cried. “Now, when I feel lonely, I can imagine I feel the house jar as the Chinese family move their piano, or I can imagine that I hear their phonograph.”

“Very good,” I said; “and if you can imagine all that, why cannot you imagine a family overhead, too? The whole attic is there. Very well; I give up the entire attic to your imagination.”

Then I kissed her and went into the back garden. My opinion is that the man that laid out that back garden was over-sanguine. I am passionately fond of gardening, and believe in back gardens; but at the present price of seed and the present hardness of hoe handles, I think that back garden is too large. This is not a mere flash opinion, either; it is a matter of study. The first day I stuck spade into that garden I had given little thought to its size, but by the time I had spaded all day I began to have a pretty well-defined opinion of gardens and how large they should be, and by the end of the third day of spading I believe I may say I was well equipped to testify as an expert on garden sizes. That was the day the blisters on my hands became raw.

The day after my little conversation with Isobel I returned home from business to find her awaiting me at the gate. She wore a bright smile, and she put her hand through my arm and hopped into step with me.

“John,” she said cheerfully, “the Prawleys moved in to-day.”

“The Prawleys? Who are the Prawleys, and what did they move into?” I asked.

“Why, how do I know who they are, John?” she said. “I suppose we will know all about them soon enough, but you can't expect me to learn all about a family the day they move in. And as for what they moved into, of course there was only one vacant flat.”

“Flat? One vacant flat? What flat?” I asked. I was afraid Isobel was not entirely herself.

“The one above us,” she said, and then as she saw the blank look on my face she said: “The—the—oh, John, don't you understand? The attic!”

“Hum!” I said suspiciously, looking at Isobel; but her face was so bright, and she looked so thoroughly contented that I did not tell her what I thought of this sort of pretending. Too much of it is not good for a person. “Very well,” I said; “I only hope they will not be too noisy.”

“I don't think they will,” said Isobel, smiling. “At least not while you are home.” She helped me off with my light coat, and when we were seated at the table she said: “By the way, Mr. Millington leaned over the fence this afternoon, and said he hoped you would take a little ride to Port Lafayette with him soon. He says his automobile is in almost perfect shape now.”

ISOBEL was brighter at dinner than she had been for some days. She seemed quite contented, now that the imaginary Prawleys had moved into the attic. She said no more about them, and when I had finished my dinner I put on my gardening togs and went out to garden awhile before dark. Blisters are certainly most painful after a day of rest, and I did not work long. I was almost in despair about the garden. Fully half had not been touched, and what I had already done looked ragged and as if it needed doing over again. The more I dug, the more great chunks of sod I found buried in it, and it seemed as if my garden, when I had dug out all the chunks of sod, would be a pit instead of a level. It threatened to be a sunken garden.

“Isobel,” I said angrily, when the sun had set and I was once more sitting in the chair on my veranda, with my hands wrapped in wet handkerchiefs, “you know how passionately fond of gardening I am, and how I longed and pined for a garden for two full years, and you know, therefore, that it takes a great deal of gardening to satisfy me; but I must say that the man who laid out that garden must have been a man of shameful leisure. He laid out a garden twice as large as any garden should be.”

“Then why do you try to work it all?” she asked.

“Oh, work it!” I exclaimed with some irritation. “I can't let half a garden go to weeds! That would look nice, wouldn't it! I'll work it all right! You don't care how I suffer and struggle. You sit here—”

The next evening when I reached home

I did not feel particularly happy. My hands were quite raw, and my back had sharp pains and was stiff, and I spoke gruffly to Millington when he suggested an automobile ride to Port Lafayette for that evening.

“No!” I said shortly. “You ought to know I can't go. I've got to kill myself in that garden!”

But I was resolved Isobel should never see me conquered by a patch of ground, and after dinner I went out with my spade and hoe. When my glance fell on the garden I stopped short. I was very angry.

“Isobel?” I called sharply.

She came tripping around the house and to my side.

“Who did that?” I asked severely. I was in no mood for nonsense.

She looked at the garden. One half of it—not the half I had struggled with, but the other 'half—had been spaded, crushed, ridged, planted, and left in perfect condition. The small cabbage plants had been carefully watered. Not a grain of earth was larger than a pin head. Not a blade of grass stuck up anywhere. Isobel looked at the garden, and then at me.

“I warned him!” she said. “I warned him you would be angry when you came home! I told him you wanted to garden that half of the garden, too, and that you would probably go right up and give him a piece of your mind, but he insisted that he had a right to half the garden, and—”

“Who insisted that he had a right to half my garden?” I demanded.

“Why,” said Isobel, as if surprised at the question, “Mr. Prawley did.”

“Prawley? Prawley? I don't know any Prawley!”

“Don't you know the Prawleys that moved into the flat above us?” said Isobel. “And he is a very nice man, too,” she continued. “He was not at all rude. He merely insisted, in a quiet way, that as he was a tenant and as there was only one back garden, and two families in the house, he was entitled to half the garden.”

She did not give me a chance to speak, but ran on in that vein, while I stood and looked at the garden and, among other things, thought of my blistered hands and my lame back.

“Well and good, Isobel,” I said at length. “I do not wish to have anything to say to the Prawleys, nor do I wish to quarrel with them, and since he demands half the garden you may tell him he is welcome to it. I cannot conceal that in taking half of it away from me he has robbed me of just that much passionate happiness, and you may tell him I do not like the way he gardens, but I will say no more about it!”

“Oh, you dear old John!” said Isobel. “And now you shall not touch that miserable garden with your poor sore hands. You shall just sit on the veranda with me and let me bathe your palms with witch hazel.” Although I assumed an air of sternness in speaking to Isobel of Mr. Prawley I was glad to be able to humour her, for she seemed so much happier after beginning to pretend that the Prawley family occupied the attic of our house. Giving in to these harmless little whims of our wives does much to make life pleasanter for them—and for us—and as long as Mr. Prawley left me my own half of the garden I could not be discontented. One half of that garden was really all a man should attempt to garden, no matter how passionately fond of gardening he might be.

It is fine to be the owner of a bit of soil and to feel the joy of possession, but it is still more delightful to be able to see one's own garden truck springing into life after one has dug and planted and weeded and cultivated with one's own hands. I had no greater desire in life than to devote all my spare time to my garden, but a man must give his health some attention, and Isobel pointed out that if I gardened but one half of the garden I would have time to ride to Port Lafayette with Millington in his automobile now and then, and as Port Lafayette is on the salt water the air would be good for me.

Port Lafayette is about eleven miles from Westcote, and I had often wished to go to Port Lafayette, but Millington is absurdly jealous. Of course, I could have taken Isobel by train in about one half hour, or I could walk it in two or three hours, or drive there in an hour; but I knew that would hurt Millington's feelings. He would take it as an insult to his automobile.

But now I told Isobel that as soon as my garden got into reasonable shape we would go to Port Lafayette with Millington. Isobel told me that my health was more important than radishes, and reasoned that a few weeds in a garden were not a bad thing. Weeds, she said, grow rapidly, while vegetables are modest and retiring things, and she considered that a few weeds in my half of the garden might set a good example to the vegetables.

Mr. Prawley evidently held a different view, for he did not allow a single weed to raise its head in his half of the garden, and I told Isobel, rather sharply, that his idea was the right one, and that I should weed my garden every evening until there was not a weed in it.

“But, John,” she said, “I have never ridden in an automobile, and it would be a great treat for me.”

“No doubt,” I groaned—I was weeding in my garden at the moment—“but, treat or no treat, I am not going to have this half of the garden look like a forest.”

“I know you enjoy it,” she began, but I silenced her.

“I am passionately fond of gardening,” I said, “and I have told you so a million times. Now will you leave me alone to enjoy it, or won't you?”

She went into the house and left me enjoying it alone.

The very next evening, when I looked into my half of the garden, I found it weeded and put into the best of shape, and when I hunted up Isobel, angry indeed at having so much pleasure taken from me, she did not dare look me in the eye.

“Isobel,” I said sharply, “what is the meaning of this?”

“John,” she said meekly, “I am afraid I am to blame. You know Mr. Prawley does not like automobile riding—”

“I know nothing of the kind, Isobel,” I said. “I know I am passionately fond of gardening, and that some one has robbed me of the pleasure I have looked forward to for years: the joy of weeding my own garden on my own land.”

“Mr. Prawley does not like automobile riding,” continued Isobel, “and he came to me this morning and told me his health was so poor that his doctor had told him nothing but gardening could save his life. When he showed the garden to his doctor, the doctor told him he was not getting half enough gardening—that he must garden twice as much. I told Mr. Prawley he could not have your half of the garden, because you were passionately fond of it—”

“True, Isobel!” I said, rubbing my back at the lamest spot.

“But he begged on his knees, saying that while it was only a pleasure for you, it was life and health for him, and when his wife wept, I had not the heart to refuse. He said he would make a fair exchange, and that as he was an anti-vegetarian you could have all the vegetables that grew in your own half, and all that grew in his, too.”

“Isobel,” I said, taking her hand, “this is a great, great disappointment to me. It robs me of a pleasure of which I may say I am passionately fond, but I cannot disown a contract made by my little wife. Mr. Prawley may garden my half of the garden.”

I must admit that the Prawleys were ideal tenants. Not a sound came from his floor of the house. Indeed, I did not see him nor his family at all. But during my days in town he and Isobel seemed to have many conversations, and she was so tender-hearted and easily moved that one by one she let Mr. Prawley take all the outdoor work of which I may rightly claim to be passion—to be exceedingly fond.

Mowing the lawn is one of the things in which I delight. I ardently love pushing the lawn mower, and if, occasionally, I allowed the grass to grow rather long, it was only because I was saving the pleasure of cutting it, as a child saves the icing of its cake for the last sweet bite. I remember remarking, quite in joke, one morning, that the confounded lawn needed mowing again, and that the grass seemed to do nothing but grow, and that I'd probably have to break my back over it when I got home that evening. But when I reached home that evening I suspected that Isobel must have taken my little joke as earnest, for the lawn was nicely mown and the edges trimmed. It seemed, when I questioned Isobel, that Mr. Prawley's doctor was not satisfied with his progress and had assured him that lawn mowing was necessary for his complete recovery. Thus Isobel allowed Mr. Prawley to usurp another of my pleasures.

So, one by one, the outdoor tasks of which I am so passionately fond were wrested from me. I allowed them to go because I thought it necessary to humour Isobel in her pretence that some family occupied a flat above us, and all seemed well; and we were ready to go to Port Lafayette in Mr. Millington's automobile whenever it was ready to take us, when one day in June I happened to notice that our grass was getting unusually long and untidy.

“Isobel,” I said, “I have humoured Mr. Prawley, abandoning to him all the outdoor chores of which I am so passionately fond, but if he is to do this lawn I want him to do it, and not neglect it shamefully. I will not have it looking like this!”

“But, John—” she began.

“I tell you, Isobel,” I said, with rising anger, “I won't have it! I'll stand a good deal, but when I have robbed myself of my greatest pleasure, and then see the other man neglecting it, I rebel. If this goes on I'll forget that Mr. Prawley has bad health. I'll enjoy cutting the lawn myself!”

“John,” said Isobel, throwing her arms about my neck, “you will be so glad! I have good news to tell you! The Prawleys have moved away! Now you can do all your own hoeing and mowing.”

“The Prawleys have moved away?” I gasped.

“Yes,” she said cheerfully, “and now you can garden all the garden, and cut all the lawn and rake all the walks, and weed, and do all the things you are so fond of doing.”

“Isobel,” I said sternly, “if I thought only of myself I would indeed be glad. But I cannot have my little wife fearing the empty flat above her. You must immediately hire another—er—get another family.”

“But I shall not be nervous any more, John,” she said; “and it is a shame to deprive you of the outdoor work.”

I looked out upon the large lawn and the large garden.

“No, Isobel,” I said, “you must take no chances. You may not think you will be nervous, but the feeling may return. If you do not get a family to move in, I shall!”

I rubbed the palms of my hands where the blisters had been, and thought of the middle of my back where the pains and aches had congregated. I was ready to sacrifice my passionate longing for outdoor work once more for Isobel's sake.

“Well,” she said thoughtfully, “I know of an excellent coloured man in Lower Westcote, that we can hire by the day—I mean that we can get to move into the flat—but I can hardly afford, with my present allowance, to pay his wages—that is, I mean—”

“For some time, Isobel,” I said hastily, “I have been thinking your allowance was too small. You must have a—a great many household expenses of which I know nothing.”

“I have,” she said simply.

That evening when I returned from the city I saw that the lawn grass had been cut so closely that it looked as if the lawn had been shaved. Isobel ran to meet me.

“John!” she cried; “John! Who do you think has moved into the flat overhead?”

“Dear me!” I exclaimed. “How should I know?”

“The Prawleys!” she cried. “The Prawleys have moved back again. Are you not glad?”

I concealed my chagrin. I hid the sorrow with which I saw my passionate fondness for outdoor work once more defeated of its object.

“Isobel,” I said, “I wish you would tell Mr. Prawley's doctor to tell Mr. Prawley that it is imperative for Mr. Prawley's best health that Mr. Prawley dig the grass out of the gravel walks to-morrow. Tell him—”

“I told him this evening to do the walks the first thing in the morning,” said Isobel innocently, “and when he has done them I am going to have him help Mary wash the windows.”

NOW that Mr. Prawley is back,” I told Isobel, “we can take that trip to Port Lafayette with Millington,” and it was then Isobel mentioned the advisability of keeping a horse; but Millington and I, not being afraid of automobiles, began to go to Port Lafayette in his automobile. As a rule we began to go every day, and sometimes twice a day, and I must say for Millington's automobile that it was one of the most patient I have ever seen. Patient and willing are the very words. It would start for Port Lafayette as willingly as anything, and go along as patiently as possible. It was a very patient goer. Haste had no charms for it.

Millington used to come over bright and early and say cheerfully, “Well, how would you like to take a little run out to Port Lafayette to-day?” and I would get my cap, and we would go over to his garage and get into the machine. Then Millington would pull a lever or two, and begin to listen for noises indicative of internal disorders. As a rule, they began immediately, but sometimes he would not hear anything that could be called really serious until we reached the corner of the block. Once, I remember, and I shall never forget the date, we went three miles before Millington stopped the car and got out his wrenches and antiseptic bandages and other surgical tools; but usually the noises began inside of the block. Then we would push it home, and postpone the trip for that day, while Millington laboured over the automobile.

“We will get to Port Lafayette yet,” he would say hopefully.

As soon as Isobel mentioned keeping a horse I knew she was beginning to like suburban life, and I was delighted. Having lived all her life in a flat, her mind naturally ran to theatres and roof gardens, rather than to the delights of the suburbs, and her reading still consisted more of department store bargain sales and advertisements of new plays than of seed catalogues and ready mixed paints, as a good suburban wife's reading should; but as soon as she mentioned that it would be nice to have a horse I knew she was at length falling a victim to the allurements of our semi-country existence. In order to add fuel to the flame I took up the suggestion with enthusiasm.

“Isobel,” I said warmly, “that is a splendid idea! A horse is just what we need to add the finishing touch to our happiness! With these splendid, tree-bordered roads—”

“A horse that is not afraid of Mr. Millington's automobile,” interposed Isobel.

“Certainly,” I said, “a horse that you can drive without fear—”

“But not a pokey old thing,” said Isobel.

“By no means,” I agreed; “what we want is a young, fresh horse that can get over the road—”

“And gentle,” said Isobel. “And strong. And he must be a good-looking horse. One with a glossy skin. Reddish brown, with a long tail. I would like a great, big, strong-looking horse, like the Donelleys', but faster, like the Smiths'.”

“Exactly,” I said. “That's the sort of horse I had in mind. And we will get the horse immediately. I shall stay at home tomorrow and select the kind of horse we want, unless Mr. Millington takes me to Port Lafayette—”

“Now, John,” said Isobel, “you must not be too hasty. You must be careful. I think the right way to buy a horse is to shop a little first, and see what people have in stock, and not take the first thing that is offered, the way you do when you buy shirts. You know how hideous some of those last shirts are, and the arms far too long, and we don't want anything like that to happen when you are buying a horse. I have been talking to Mrs. Rolfs, and she says it is mere folly to buy the first horse that is offered. Mrs. Rolfs says it stands to reason that a man who wants to get rid of a horse would be the first man to offer it. As soon as he learned we wanted a horse he would rush to us with the horse, so as not to lose the chance of getting rid of it. And Mrs. Millington says it is worse than foolish to wait until the very last horse is offered and then buy that one, for the man that hung back in that way would undoubtedly be the man that did not particularly care to part with his horse, and would feel that he was doing us a favour, and would ask a perfectly unreasonable price. The thing to do, John, is to buy, as nearly as possible, the middle horse that is offered. If twenty-one horses were offered the thing to do would be to buy the eleventh horse, and in that way we would be sure to get a good horse at a reasonable price.”

I told Isobel that what she said was perfectly logical, and that I would get right to work and frame up an advertisement for the local paper, saying we wanted a horse and would be glad to examine twenty-one of them.

“Now, wait a minute,” she said, when I had started for my desk, “and don't be in too great a hurry. You know the mistake you made in those last socks you bought, by going into the first store you came to, and the very first time you put on those socks they wore full of holes. We don't want a horse that will wear like that. Mrs. Rolfs says we must be very particular what sort of man we buy our horse from. She says it is like suicide to buy a horse from a dealer, because a dealer knows so much more about horses than we do, and is up to so many tricks, that he would have no trouble at all in fooling us, and we would probably get a horse that was worth nothing at all. And Mrs. Millington says it is the greatest mistake in the world to buy a horse from an ordinary suburban commuter. She says commuters know nothing at all about horses and just buy them blindfold, and that, if we buy a horse from a commuter, we are sure to get a worthless horse that the commuter has had foisted upon him and is anxious to get rid of. The person to buy a horse of, John, is a person that knows all about horses, but who is not a dealer.”

“My idea exactly,” I told Isobel, and started for my desk again.

“John, dear,” said Isobel, before I had taken two steps, “why are you always so impetuous? Of course I want a horse, and I would like to have it as soon as possible, but I believe in exercising a little common sense. Where, may I ask, are you going to keep the horse when you have got him?”

Now, this had not occurred to me, but I answered promptly.

“I shall put him out to board,” I said unhesitatingly, and there was really nothing else I could say, for there was no stable on my place. I know plenty of suburbanites who keep horses and have them boarded at the livery stables. But this did not please Isobel.

“You must do nothing of the kind!” said Isobel firmly. “Mrs. Rolfs and Mrs. Millington both say there is nothing worse for a good horse than to put it out to board. Mrs. Rolfs says it is much cheaper to keep your horse in your own bam, and Mrs. Millington says she would have a very low opinion of any man who would trust his horse to a liveryman. She says the horse is man's most faithful servant, and should be treated as such, and that she has not the least doubt that the liveryman would underfeed our horse, and then let it out to hire to some young harum-scarum, who would whip it into a gallop until it got overheated, and then water it when it was so hot the water would sizzle in its stomach, creating steam and giving it a bad case of colic. And Mrs. Rolfs says the liveryman would be pleased with this, rather than sorry, for then he would have to call in the veterinary, who would divide his fee with the liveryman. So, you see, we must keep our horse in our own stable.”

“But, my dear,” I protested, “we have no stable.”

“Then we must build one,” said Isobel with decision. “Mrs. Rolfs, as soon as she heard we were going to keep a horse, lent me a magazine with a picture of a very nice stable, and Mrs. Millington lent me another magazine with some excellent hints on how a modern stable should be arranged, and I think, with all the modern methods of doing things rapidly, we might have our stable all complete in a week, or ten days at the most.”

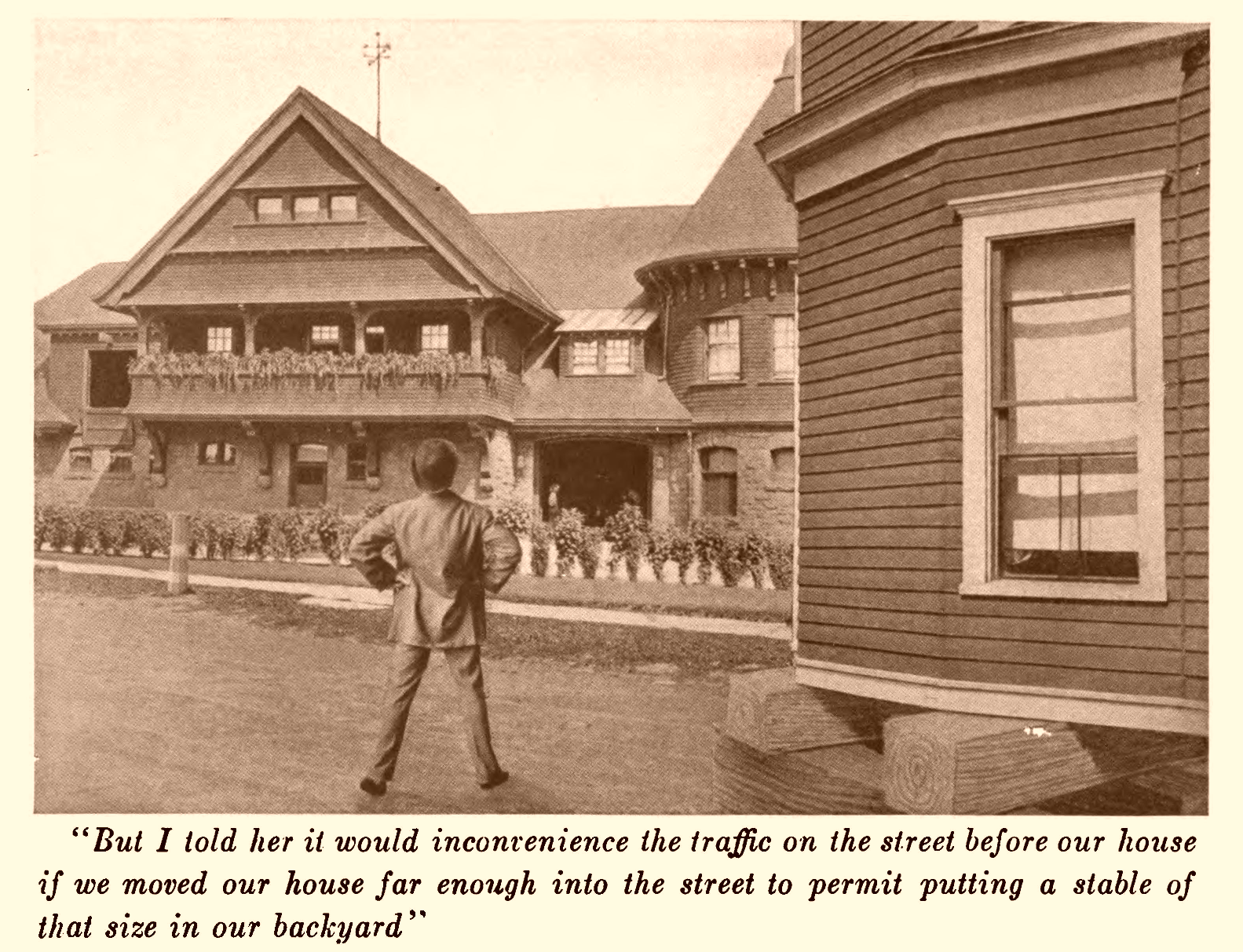

When I looked at Mrs. Rolfs's picture of a stable I felt immediately that it would not suit my purse. I admitted to Isobel that it was a handsome stable, and that the cupola with the weather vane looked very well indeed, and that the idea of having two wings extended from the main building to form a sort of court was a good one; but I told her it would inconvenience the traffic on the street before our house if we moved our house far enough into the street to permit putting a stable of that size in our back-yard. I also told her, as gently as I could, that the style of architecture did not suit our house, for while our house is a plain house, the stable recommended by Mrs. Rolfs was pressed brick and stained shingles, with a slate roof. I also pointed out to Isobel that one horse hardly needed a stable of that size, and that even a very large horse would feel lonely in the main building.

I remarked jocosely that it would be well enough, if we could keep two or three grooms with nothing to do but hunt through the stable, trying to find the horse. If we could afford to do that, it would be a pleasure to awaken in the morning and have one of the grooms come running to us with the light of joy on his face, saying, “What do you think, sir?

“But I told her it would inconvenience the traffic on the street before our house if we moved our house far enough into the street to permit putting a stable of that size in our backyard.”

Isobel smiled in a wan, sad way at this, so I did not say, as I had intended saying if she had received my joke well, that the only horse requiring wings was Pegasus, and that he furnished his own.

Instead, I took up Mrs. Millington's article on the modern stable. It was a masterly article, indeed, and it spoke highly of the gravity stable. No hay forks, no pitching up forage, no elevating feed, no loading of manure from a heap into a wagon. No, indeed! Everything must go down; the natural law of gravitation must do the work. Three stories, with the rear of the stable against the side of the hill. Drive your feed into the top story and unload it. Slide it down into the second story to the horse. Through a trap in the stall the manure falls into a wagon waiting to receive it.

There were other details—electric lights, silver-mounted chains, and other little things—but I did not pay much attention to them. I explained to Isobel that it would be difficult to build a firm, solid hill, large enough to back a three-story stable against, in our backyard. Of course, there were plenty of hills in our part of Long Island that were lying idle and might be had at low cost, but it costs a great deal to move a hill, and all of them were so large they would overlap our property and bury the homes of Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington. This did not greatly impress Isobel, however, and I had to come out firmly and tell her it would be impossible to build a stable three stories high, with two wings, pressed brick, shingle walls, slate roof, and a weather vane, and at the same time erect a nice hill and buy a horse and rig, all with one thousand dollars, which was all the money I could afford to spend.

When I put it that way, and gave her her choice of one thousand dollars' worth of hill, or one thousand dollars' worth of stable, or one thousand dollars' worth of assorted horse, stable, and rig, she chose the last, and only remarked that she would insist on the weather vane and the manure pit. She said that Mrs. Rolfs had taken such an interest, bringing over the magazine, that it was only right to have the weather vane, at least; and that Mrs. Millington had been so interested and kind that the very least we could do was to have the manure pit.

“And another thing,” said Isobel, “Mr. Prawley is going to move out of the flat overhead.”

“Great Cæsar!” I exclaimed. “Is that man quitting again? Isn't he getting enough wages?”

“Wages?” said Isobel. “Nothing has been said about wages. But this Mr. Prawley will not stay if we buy a horse. He says he does not mind gardening your garden and mowing your lawn and taking all your other outdoor exercise for you, but that a horse once reached over the side of the stall and bit him, and he doesn't want to work—to live in a place where horses are liable to bite him at any time without a minute's notice.”

“Tell that fellow,” I said, “that we will get a horse that doesn't bite, or that we will muzzle the horse, or—”

“It would be easier,” said Isobel, “to—to have a Prawley move in who was not afraid of horses. I know of a man in East Westcote, and he has had experience with horses—”

“Very well,” I said. “I suppose you will wish your allowance increased?”

“Yes,” said Isobel, “if the new Mr. Prawley moves into the flat overhead, I will need about five dollars a month more than you have been allowing me.”

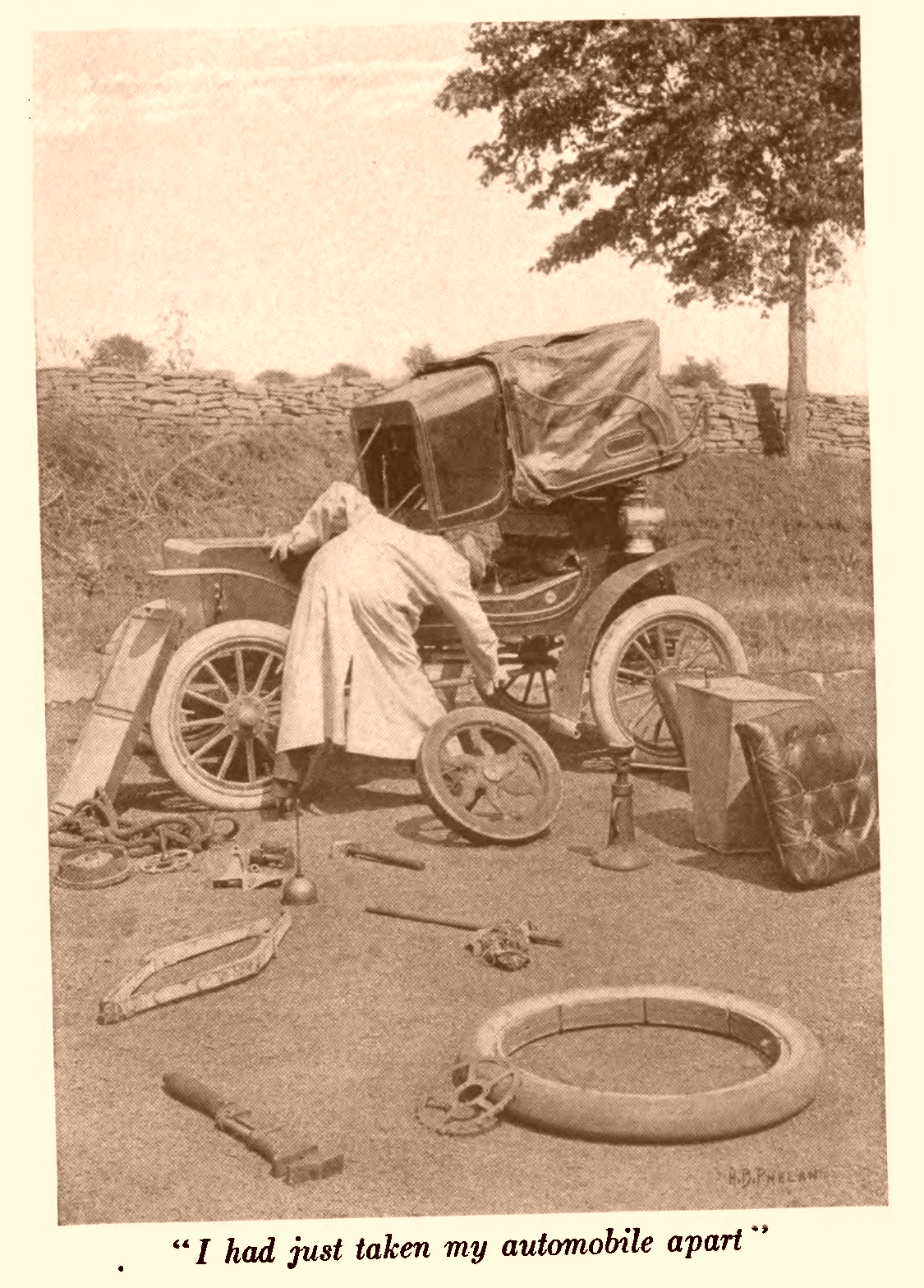

THE next morning I stayed at home to see about getting the stable built in a hurry, but before I had finished breakfast Millington came over and said it was an ideal day for a little spin up to Port Lafayette in his automobile. He said the whole machine was in perfect order and we would dash out to Port Lafayette, have a bath in the salt water, and come spinning back, and he told Isobel and me to get on our hats, and he would have the car before the door in a minute.

Isobel and I hastily finished our coffee and put on our hats and went out to the gate, for, although we were very eager to build the stable, we did not like to offend Millington by refusing his invitation, when he had asked us so often to go to Port Lafayette. In half an hour he arrived at the gate, and we climbed in.

Our usual custom, on these trips to Port Lafayette, was for Millington and me to sit in front, while Isobel and Mrs. Millington sat in the rear. There was a nice little gate in the rear by which they could enter.

You see, Millington's automobile was just a little old. I should not go so far as to say it was the first automobile ever made. It was probably the thirteenth, and Millington was probably the thirteenth owner. I know it had four cylinders, because Millington was constantly remarking that only three were working. Sometimes only one worked, and sometimes that one did not.

When we were all comfortably arranged in our seats, and all snugly tucked in, Millington cranked the machine for half an hour, and then remarked regretfully that this was one of the days none of the cylinders was working, and we got out again.

Mr. Rolfs had come out to see us start, and he helped Millington and me push the automobile back to the Millington garage; and as I walked homeward he said he had heard I was going to buy a horse, and he wanted to give me a little advice.

“Probably you have not given much attention to the subject of deforestation,” he said, “but I have, and it is the great crime of our age.”

I told him I did not see what that had to do with my purchasing a horse, but he said it had everything to do with it.

“When you buy a horse, you have to erect a stable,” he said, “and when you erect a stable, you have to buy lumber, and when you have to buy lumber, you suffer in your purse because the forests have been ruthlessly destroyed. As a friend and neighbour I would not have you go and purchase poor lumber, and with it build a stable that will rot to pieces in a few years. You must buy the best lumber, and that is too expensive to use recklessly. I want to warn you particularly about wire nails. Do not let your builder use them. They loosen in a short time and allow the boards to warp and crack. Personally, if I were building a stable I should have the ends of the boards dovetailed, and instead of nails I should use ash pegs, but I understand you do not wish to go to great expense, so screws will do. Let it be part of your contract that not a nail shall be used in your stable—nothing but screws, and if you can afford brass screws, so much the better. But remember, no nails!”

I thanked Rolfs, and when Millington came over to invite me to take a little run up to Port Lafayette the next morning I told him what Mr. Rolfs had said.

“Now that is just like Rolfs,” he said, “impractical as the day is long. Screws would not do at all. The carpenters would drive the screws with a hammer, and the screws would crack the wood. Take my advice and let it be part of your contract that not a screw is to be used in your stable; nothing but wire nails. But stipulate long wire nails; wire nails so long that they will go clear through and clinch on the other side, and then see that each and every nail is clinched. If you do this you will have no trouble with split lumber and not a board will work loose.”

When I spoke to the builder about the probable cost of the stable, I was sorry I had been so lenient with Isobel, and that I had not put my foot down on the weather vane at once. A weather vane does not add to the comfort of a family horse, and the longer I spoke with the builder the surer I became that what I needed was not a lot of gimcracks, but a plain, simple, story-and-a-half affair, with the chaste architectural lines of a dry-goods box. I mentioned, casually, the hints Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington had given me, but the builder did not seem very enthusiastic about them. He snorted in a peculiar way and then said that if I was going in for that sort of thing I could get better results by having no nails or screws at all. He said I could have holes bored in the boards with a gimlet, and have the stable laced together with rawhide thongs, but that when I got ready to talk business in a sensible way, I could let him know. He said this was his busy day, and that his office was not a lunatic asylum.

I managed to calm him in less than half an hour, and he remained quite docile until I mentioned Isobel and said she hoped he would have the stable ready for the horse within a week. It took me much longer to calm him that time. For a few moments I feared for his reason. But he quieted down.

Then I showed him a plan I had drawn, showing the working of the manure dump, and this had quite a different effect on him. It pleased him immensely, as I could see by his face. I explained how it operated; how throwing a catch allowed one end of the stall floor to drop, while the other end of the stall floor was held in place by hinges, and he said it was certainly a new idea. He asked me whether it was Mr. Rolfs's idea or Mr. Millington's, and when I told him I had worked out the plan myself, he said he had rather thought so.

“It is just such a plan as I should expect a man of your intelligence to work out,” he said.

Then he asked to see my bank-book, and when I had shown him just how much money I had, he said the best way to build the stable was by the day. If it was built by the job, he explained, a builder naturally had to hurry the job, and things were not done as carefully as I wished them done; but if it was done by the day, every hammer stroke would be carefully made, and I could pay every evening for the work done that day.

About the third week of the building operations those careful hammer strokes began to get on my nerves. I never knew hammer strokes so carefully considered and so cautiously delivered. The carpenters were most careful about them, and several times I spoke to the builder and suggested that if shorter nails were used perhaps it would not take so many strokes of the hammer to drive them in. I told him, if he was willing, I was willing to have the rest of the stable done by the job, but he said it had gone too far for that.

There were two men working on my stable—“two souls with but a single thought,” Isobel called them—and they were hard thinkers. The two of them would take hold of a board, one at either end, and hold it in their hands, and look at it, and think. I do not know what they thought about—deforestation, probably—but they would think for ten minutes and then put the board gently to one side and think about another board. They did their thinking, as they did their work, by the day.

We had plenty of time in which to select our horse while our stable was building. My advertisement in the local paper brought a horse to my door the morning after it appeared, and no horse could have suited me quite so well as that one, but I was resolute and firm. I told the man—he was not a dealer nor yet a commuter, and my conversation with him showed me that he knew just enough, and not too much, about horses—that I liked his horse very well indeed, but that I could not purchase it.. At this he seemed downcast, and I did not blame him. He seemed to take my refusal as some sort of personal insult, for the horse was young, large, strong, gentle, and speedy, and the price was right; but every time I began to weaken Isobel said, “John, remember number eleven!” and I refrained from purchasing that horse. I finally sent the man away with warm expressions of my esteem for him as a man, but that did not seem to cheer him much.

An hour later another man brought another horse, and I sent him away also, as was my duty, for he was only number two; but he was hardly gone when horse number one appeared again. I saw at once that I was going to have trouble with that man. He was so sure he had the horse I wanted that he would not go away and stay away. He kept coming back, and each time he went away sadder than before. He was a sad-looking man, anyway, and he would sit in his buggy and talk to me until another horse was driven up, and then he would sigh and drive down to the corner, and sit and look at me reproachfully until the other man drove away again. Then he would drive back and reproach me, with tears in his eyes, for not buying his horse. By lunch time I was almost worn out, and I told Isobel as much when I looked out of the window and saw that handsome horse and his sad driver waiting patiently at my gate. I told her I was tempted to take that horse, Mrs. Rolfs or no Mrs. Rolfs.

“Take that horse?” said Isobel, as if my words surprised her. “Why, of course we are going to take that horse!”

“But, my dear,” I said, “after what you told me about taking the eleventh horse?”

“Certainly,” said Isobel. “What is this but the eleventh horse? It came first, and then another horse came, and then this one came third, and then some other horse came, and then this one came fifth, and so on, and now it is standing there at the gate, the eleventh horse. Certainly we will buy this horse.”

“Isobel,” I said, “we might quite as well have bought it the first time it was driven to our gate as this time.”

“Not at all,” she said; “that would have been an altogether different thing. If we had taken the first horse that was offered we would have regretted it all our lives; but now we can take this horse and feel perfectly safe.”

Bob—that was the name of the horse—fitted into our stable pretty well. He had to bend rather sharply in the middle to get out of his stall, but he was quite limber for a horse of his age and size, so he managed it very well. A stiffer horse might have broken in two or have been permanently bent. The stall was so economically built that a large, long horse like Bob stuck out of it like a long ship in a short dock; he stuck out so far that we had to go around through the carriage room to get on the other side of him. Our new Mr. Prawley did not mind this. He was willing to spend all the time necessary going from one bit of work to another.

There was one advantage in having the stable and everything about it on a small scale—it lessened the depth of the manure pit. The very first night we put Bob in his stall we heard a loud noise in the stable. Isobel suggested that we had overfed Bob, and that he had swelled out and pressed out the sides of the stable, but I thought it more likely that the weather-boarding had slipped loose. I had seen the thoughtful carpenters putting that weather-boarding on the stable. But Isobel and I were both wrong. Bob had merely dropped into the manure pit.

I was glad then that I had chosen a strong horse, for he did not seem to mind the drop in the least. He stood there with his front feet in the basement, as you might say, and with his rear feet upstairs, quite as if that was his usual way of standing. After that he often fell into the manure pit, and he always took it good-naturedly. He got so he expected it, after awhile, and if his stall floor did not drop once a day, he became restless and took no interest in his food. Usually, during the day, Bob and Mr. Prawley dropped into the basement together while Mr. Prawley was currying Bob, but at night, when we heard Bob calling us in the homesick, whinnying tone, and kicking his heels against the side of the stable, we knew what he wanted, and to prevent him kicking the stable to ruins, we—Isobel and I—would go out and drop him into the basement a couple of times. Then he would be satisfied.

There was but one thing we feared: Bob might become so fond of having his forefeet in the basement and his rear feet upstairs, that he would stand no other way, and in course of time his front legs would have to lengthen enough to let his head reach his manger, or his neck would have to stretch. Either would give him the general appearance of a giraffe. While this would be neat for show purposes, it would attract almost too much attention in a family horse. I have no doubt this is the way the giraffe acquired its peculiar construction, but we were able to avoid it, for we awoke one night when Bob made an unaided descent into the manure pit, and when we went to aid him we found he had descended at both ends, on account of the economical hinges used on the drop floor of the stall of our equine palace. Bob showed in every way that he had enjoyed that drop more than any drop he had ever taken, but I drew the line there. I had other things to do more important than conducting a private Coney Island for a horse. If Bob had been a colt I might not have been so stern about it, but I will not pamper a staid old family horse by operating shoot-the-chutes and loop-the-loops for him at two o'clock in the morning.

“Isobel,” I said, “if that horse is to continue in my stable you may tell Mr. Prawley that it is necessary for his health that he sleep in the stable-loft hereafter. It will be good exercise for him to get up at midnight and pull Bob out of the manure pit.”

“This present Mr. Prawley will not do it,” said Isobel. “He has a wife and family at East Westcote, and he—”

“Very well,” I said, “then get another Mr. Prawley!”

Of the new Mr. Prawley it is necessary to speak a few words.

THE new Mr. Prawley (by this time a family, but we still clung to the name Prawley, just as all coloured waiters are called “George”) was a most unusual man.

For a month before we hired him he had been trying to undermine Isobel's faith in the Mr. Prawley from East Westcote. He had called at the house two or three times a week. At first he merely asked for the job of man-of-all-work, as any applicant might have asked for it, but he soon began speaking of our Prawley in the most damaging terms. I believe there was hardly a crime or misdemeanour that he did not lay at the door of our Mr. Prawley, and so insistent was he that Isobel and I had ceased to speak of him as living in our attic.

Isobel decided the two men must be deadly enemies, and that this fellow was set on hounding our Mr. Prawley from pillar to post, like an avenging angel. She concluded that this man must have been frightfully wronged by our Mr. Prawley, and that he had sworn to dog his footsteps to the grave.

But when she let our Mr. Prawley go and hired this new Mr. Prawley, his interest in his predecessor ceased entirely. In place of the eager, longing look his face had worn, he now wore a thin, satisfied look, which I can best describe as that of a hungry jackal licking his chops. Mr. Prawley—his name, he told us, was Duggs, Alonzo Duggs, but we called him Mr. Prawley—was a tall, lean, villanous-looking fellow, with a red, pointed beard, and at times when he leaned on the division fence and looked into Mr. Millington's yard I could see his fingers opening and shutting like the claws of a bird of prey. He seemed to hate Mr. Millington With a deep but hidden hatred, and often, when Mr. Millington was preparing to take Isobel and me to Port Lafayette, Mr. Prawley would stand and grit his teeth in the most unpleasant manner. When I spoke to Mr. Prawley about it he said, “It isn't Mr. Millington. It is the automobile. I hate automobiles!”

For that matter, I was beginning to hate them myself. Many a pleasant ride behind Bob did I have to sacrifice because Millington insisted that we take a little run up to Port Lafayette with him and Mrs. Millington. We would all get into his car, and Millington would pull his cap down tight, and begin to frown and cock his head on one side to hear signs of asthma or heart throbs or whatever the automobile might take a notion to have that day. And off we would go!

I tell you, it was exhilarating. After all there is nothing like motoring. We would roll smoothly down the street, with Millington frowning like a pirate all the way, and then suddenly he would hear the noise he was listening for, and he would stop frowning, and jerk a lever that stopped the car, and hop out with a satisfied expression, and begin to whistle, and open the car in eight places, and take out an assorted hardware store, and adhesive tape, and blankets, and oil cans, and hatchets, and axes, and get to work on the car as happy as a babe; and Mrs. Millington and Isobel and I would walk home.

The sight of an automobile seemed to madden Mr. Prawley, but otherwise he was the meekest of men, and a good example of this was the manner in which he behaved at our Christmas party.

The idea of having a good, old-fashioned Christmas house party for our city friends was Isobel's idea, but the moment she mentioned it I adopted it, and told her we would have Jimmy Dunn out. Jimmy Dunn is one of those rare men that have acquired the suburban-visit habit. Usually when we suburbanites invite a city friend to spend the week-end with us, the city friend balks.

Into his frank eyes comes a furtive, shifty look as he tries to think of an adequate lie to serve as an excuse for not coming, but Jimmy was taken in hand when he was young and flexible, and he has become meek and docile under adversity, as I might say. When any one invites Jimmy to the suburbs he hardly makes a struggle. I suppose it is because of the gradual weakening of his will power.

“Good!” I said. “We will have Jimmy Dunn out over Christmas.”

“Oh! Jimmy Dunn!” scoffed Isobel gently. “Of course we will have Jimmy, but what I mean is to have a lot of people—ten at least—and we must have at least two lovers, because they will look so well in that little alcove room off the parlour, and we can go in and surprise them once in a while. And we will have a Santa Claus, and lots of holly and mistletoe, and a tree with all sorts of foolish presents on it for every one, and—”

“Splendid!” I cried less enthusiastically.

“Now as for the ten—”

“Well,” said Isobel, “we will have Jimmy Dunn—”

“That is what I suggested,” I said meekly. “We will have Jimmy Dunn,” repeated Isobel, “and then we will have—we will have—I wonder who we could get to come out. Mary might come, if she wasn't in Europe.”

“That would make two,” I said cheerfully, “if she wasn't in Europe.” “And we must have a Yule-log!” exclaimed Isobel. “A big, blazing Yule-log, to drink wassail in front of, and to sing carols around.” I told Isobel that, as nearly as I could judge, the fireplaces in our house had not been constructed for big, blazing Yule-logs. I reminded her that when I had spoken to the last owner about having a grate fire he had advised us, with great excitement, not to attempt anything so rash. He had said that if we were careful we might have a gas-log, provided it was a small one and we did not turn on the gas full force, and were sure our insurance was placed in a good, reliable company. He had said that if we were careful about those few things, and kept a pail of water on the roof in case of emergency, we might use a gas-log, provided we extinguished it as soon as we felt any heat coming from it. I had not, at the time, thought of mentioning a Yule-log to him, but I told Isobel now that perhaps we might be able to find a small, gas-burning Yule-log at the gas company's office. Isobel scoffed at the idea. She said we might as well put a hot-water bottle in the grate and try to be merry around that.

“I don't see,” she said, “why people build chimneys in houses if it is going to be dangerous to have a fire in the fireplace.”

“They improve the ventilation, I suppose,” I said, “and then, what would Santa Claus come down if there were no chimneys?”

I frequently drop these half-joking remarks into my conversations with Isobel, and not infrequently she smiles at them in a faraway manner, but this time she jumped at the remark and seized it with both hands.

“John!” she cried, “that is the very, very thing! We will have Santa Claus come down the chimney! And you will be Santa Claus!” I remained calm. Some men would have immediately remembered they had prior engagements for Christmas. Some men would have instantly declared that Santa Claus was an unworthy myth. But not I! I dropped upon my hands and knees and gazed up the chimney. When I withdrew my head, I stood up and grasped Isobel's hand.

“Fine!” I cried with well-simulated enthusiasm. “I'll get an automobile coat from Millington, and sleigh bells and a mask with a long white beard—”

“And a wig with long white hair,” Isobel added joyously.

“And while our guests are all at dinner,” I cried, “I will steal away from the table—”

“John!” exclaimed Isobel. “You can't be Santa Claus! Can't you see that it would never, never do for you to leave the table when your guests were all there? You cannot be Santa Claus, John!”

“Oh, Isobel!”

“No,” she said firmly, “you cannot be Santa Claus. Jimmy Dunn must be Santa Claus!”

We had Jimmy Dunn out the next Sunday and broke it to him as gently as we could, and explained what a lot of fun it would be for him, and how I envied him the chance. For some reason he did not become wildly enthusiastic. Instead he kneeled down, as I had done, and put his head into the fireplace, in his usual slow-going manner, and looked up to where the small oblong of blue sky glowed far, far above him.

When he withdrew his head, he began some maundering talk about, an uncle of his in Baltimore who was far from well, and who was likely to be extremely dead or sick or married about Christmas time, but I had had too much experience with such excuses to pay any attention to him. Isobel and I gathered about him and talked as fast as we could, with merry little laughs, and presently Jimmy seemed more resigned, and said he supposed if he had to be Santa Claus there was no way out of it if he wanted t o keep our friendship. So when he suggested getting an automobile coat to wear, we hailed it as a splendidly original idea, and patted him on the back, and he went away in a rather good humour, particularly when we told him he need not come all the way down from the top of the chimney, but could get into the chimney from the room above the parlour. I told him it would be no trouble at all to take out the iron back of the fireplace, for it was almost falling out, and that we would have a ladder in the chimney for him to come down.

It was Mrs. Rolfs who changed our plans.

As soon as she heard we were going to have a Santa Claus, she brought over a magazine and showed Isobel an article that said Santa Claus was lacking in originality, and that it was much better to have two little girls dressed as snow fairies distribute the presents from the tree, and Mrs. Rolfs said she was willing to lend us her two daughters, if we insisted. So we had to insist.

By the merest oversight, such as might occur in any family excited over the preparations for a Christmas party, Isobel forgot to tell Jimmy Dunn that the plan was changed. She had enough to think of without thinking of that, for she found, at the last moment, that she could not pick up a regularly constituted pair of lovers for the little alcove room, and she had to patch up a temporary pair of lovers by inviting Miss Seiler, depending on Jimmy Dunn to do the best he could as the other half of the pair. Of course Jimmy Dunn does not talk much, and it was apt to be a surprise to him to learn he was scheduled to make love, but Miss Seiler talks enough for two. When Jimmy arrived, about four o'clock Christmas eve, Isobel let him know he was to be a lover, but he was then in the house, and it was too late for him to get away.

Isobel had done nobly in securing guests. Jimmy and Miss Seiler were the only guests from the city, but she had captured some suburbanites. Ten of us made merry at the table—that is, all ten except Jimmy. I was positively ashamed of Jimmy. There we were at the culminating hours of the merry Yule-tide, gathered at the festive board itself, with a bowl of first-rate home-made wassail with ice in it, and Jimmy was expected to smile lovingly, and blush, and all that sort of thing, and what did he do? He sat as mute as a clam, and started uneasily every time a new course appeared. Before dessert arrived he actually arose and asked to be excused.

Now, if you intended making a fool of yourself in a friend's house by impersonating Santa Claus and coming down a chimney in a fur automobile coat, and nonsense like that, you would have sense enough to remember which room upstairs had the chimney that led down into the parlour fireplace, wouldn't you? So I blame Jimmy entirely, and so does Isobel. Jimmy says—of course he had to have some excuse—that we might have told him we had given up the idea of having Santa Claus come down the chimney, and that if we had wanted him to come down any particular chimney we should have put a label on it. “Santa Claus enter here,” I suppose.

Jimmy said he did the best he could; that he knew he did not have much time between the threatened appearance of the dessert and the time he was supposed to issue from the fireplace—and so on! He was quite excited about it. Quite bitter, I may say.

It seems—or so Jimmy says—that, when he left the table, Jimmy went upstairs and got into his automobile coat of fur, and his felt boots, and his mask, and his fur gloves, and his long white hair, and his stocking hat, and that about the time we were sipping coffee he was ready. He says it was no joke to be done up in all those things in an overheated house, and he thought if he got into the chimney he might be in a cool draught, so he poked about until he found a fireplace and backed carefully into it, and pawed with his left foot for the top rung of the ladder. That was about the time we arose from the table with merry laughs, as nearly as Isobel and I can judge.

No one missed Jimmy, except Miss Seiler, and she was so unused to being made love to as Jimmy made love that she thought nothing of a temporary absence. It was not until I took Jimmy's present from the tree and sent one of the Rolfs fairies to hand it to Jimmy that we realized he was not in the parlour, and then Isobel and I both felt hurt to think that Jimmy had selfishly withdrawn from among us when we had gone to all the trouble of getting the other half of a pair of lovers especially on his account. It was not fair to Miss Seiler, and I told Jimmy so the next time I saw him.

When the Rolfs fairy had looked in all the rooms, upstairs and down, and had not found Jimmy, she came back and told Isobel, and that was when Isobel remembered she had forgotten to tell Jimmy we had given up the idea of having a Santa Claus. Isobel looked up the parlour chimney, but he was not there, and then we all started merrily looking up chimneys. We found Santa Claus up the library chimney almost immediately. He was still kicking, but not with much vim—more like a man that is kicking because he has nothing else to do than like a man that enjoys it.

I think we must have been gathering around the Christmas tree to the cheery music of a carol when Santa Claus put his foot on a loose brick in the fireplace and slipped. I claim that if Santa Claus had instantly thrown his body forward he would have been safe enough, but Santa Claus says he did not have time—that he slid down the chimney immediately, as far as his arms would let him. He says that when he caught the edge of the hearth with his hands he did yell; that he yelled as loud as any man could who was wrapped in a fur coat and had his mouth full of white horse-hair whiskers and his face covered by a mask. I say that proves he yelled just as we were singing the carol. He should have yelled a moment sooner, or should have waited half an hour, until the noise in the parlour abated. Santa Claus says he tried to stay there half an hour, but the two bricks he had grasped did not want to wait. They wanted to hurry down the chimney without further delay, and they had their own way about it. So Santa Claus went on down with them.

I tell Santa Claus that even if we were singing carols we would have heard him if he had fallen to the library floor with a bump, and that it was his fault if he did not fall heavily, but he blames the architect. He says that if the chimney had been built large enough he would have done his part and would have fallen hard, but that when he reached the narrow part of the chimney he wedged there. I said that was the fault of wearing an automobile coat that padded him out so he could not fall through an ordinary chimney, and I asked him if he thought any man who meant to fall down chimneys had ever before put on an automobile coat to fall in.

Certainly I, the host, could not be expected to stop the laughter and merriment when I was taking presents from the tree, and bid every one be silent and listen for the muffled tones of a Santa Claus in the library chimney. I do not say Santa Claus did not yell as loudly as he could. Doubtless he did. And I do not say he did not try to get out of the chimney. He says he did, but that with his arms crowded above his head he could do nothing but reach. He says he also kicked, but there was nothing to kick. He says the most fruitless task in the world is to kick when wedged in a chimney with a whole fur automobile coat crowded up under the arms and nothing below to kick but air.

Luckily I was able to send for Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington, whose advice is always valuable, since when I know what they advise I know what not to do. Mr. Rolfs rushed in and was of the opinion that we must get a chisel and chisel a hole in the library wall as near as possible to where Santa Claus was reposing, but when Mr. Millington arrived, breathless, he said this would be simple murder, for as likely as not the chisel would enter between two bricks and perforate Santa Claus beyond repair. Mr. Millington said the thing to do was to get a clothesline and attach it to Santa Claus's feet and pull him down. He said it was logical to pull him downward, because we would then be aided by the law of gravitation. Mr. Rolfs said this was nonsense, and that it would only wedge Santa Claus in the chimney more tightly, and that we would, in all probability, pull him in two, or at least stretch him out so long that he would never be very useful again.

Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington became quite heated in their argument. Mr. Rolfs said that if a rope was to be used it should be used to pull Santa Claus upward, but they compromised by agreeing to cut the clothesline in two, choose up sides, and let one side pull Santa Claus upward, while the other pulled him downward. Then Santa Claus would move in the direction of least resistance. So they got the clothesline, and Mr. Rolfs was about to cut it, when Miss Seiler screamed.

I was doubly glad she screamed just at that juncture, for we had all become so interested in the Rolfs-Millington controversy that we had forgotten how perishable a human being is, and, with two such stubborn men as Rolfs and Millington urging us on, we might have pulled Santa Claus in two while our sporting instincts were aroused by the tug-of-war. That was one reason I was glad Miss Seiler screamed. The other reason was that it showed she was doing her share of representing one half of a pair of lovers. She had done rather poorly up to that time, but she saw that when her lover was about to be pulled asunder was the time to scream, if she was ever going to scream, so she screamed. So we all went upstairs and let the rope down to Santa Claus, and the entire merry Christmas house party pulled, and after we had jerked a few times up came Santa Claus with a sudden bump.

At that moment Miss Seiler screamed again, and when we turned we saw the reason, for the glass door to the little upper porch had opened and Jimmy Dunn was entering the room.

We laid Santa Claus on the floor and let him kick, for he seemed to have acquired the habit, but after awhile he slowed down and only jerked his legs spasmodically. Mr. Millington explained that it was only the reflex action of the muscles, and that probably Santa Claus would kick like that for several months, whenever he lay down. He said if we had followed his advice and pulled downward we would have yanked all the reflex action out of the legs.

As soon as I pulled the mask from his face I recognized Mr. Prawley. Jimmy slipped out of the room and walked all the way to the station, and Miss Seiler stood around, not knowing whether she was to be half of a pair of lovers with Mr. Prawley as the other half, or stop being a lover, or weep because Jimmy had gone. I felt sorry for her, because Mr. Prawley was not a good specimen of a Christmas lover just then. When we stood him on his feet his trousers were still pushed up around his knees, and his fur coat was around his neck. He was so weak we had to hold him up.

“What I want to know,” said Mr. Millington, “is what you were doing in that chimney in my automobile coat?”

“Doing?” said Mr. Prawley. “Why, I'm jolly old Santa Claus. I come down chimneys.”

“Well, my advice to you, Mr. Prawley,” I said, “is to stop it. You don't do it at all right. Don't try it again. I've had enough of this jolly old Santa Claus business. Who told you to do it?”

“The little gentleman with the scared look,” said Mr. Prawley, looking around for Jimmy Dunn. “He isn't here.”

“And what did he give you for doing it?” I asked.

“Nothing!” said Mr. Prawley. “He just—”

“Just what?” I asked when he hesitated. Mr. Prawley drew me to one side and whispered.

“He said I might wear an automobile coat. And I couldn't resist the temptation,” said Mr. Prawley. “I've been hankering to get inside an automobile coat for weeks and weeks, sir. I couldn't resist.”

Of course, I could make nothing of this at the time, so I merely said a few words of good advice, and ordered Mr. Prawley never to try the Santa Claus impersonation again.

“Of course, I'm only an amateur at it,” said Mr. Prawley apologetically, and then he brightened, “but I made good speed as far as I got. I'll bet I broke the world's speed record for jolly old Santa Clauses!”

IN order to relieve the reader's suspense, I may as well say here that Jimmy Dunn did not marry Miss Seiler. It is too bad to have to sacrifice what promised to be a first-class love interest, but the truth is that there is less chance of Jimmy ever marrying Miss Seiler than there seemed likelihood of Isobel and me reaching Port Lafayette in Mr. Millington's automobile.

Usually when we started for Port Lafayette, my wife and Millington's wife would dress for the matinée or church, or wherever they intended going that day, and when Millington heard the knocking sound in his engine and began to get out his tools, they would excuse themselves politely and go and spend the day in the city. They usually returned in time to get into the car and ride back to the garage. But I stuck to Millington. You never can tell when a car of that kind will be ready to start up, and I was really very anxious to go to Port Lafayette. I spent some very delightful days with Millington that way, for when he was mending his car he was always in a charming humour, and as gay and playful as a kitten.

I began to fear that one, if not the only, reason why Mr. Millington was always in such a good humour when his car was in a bad one, was because I had told him that I had heard of a man in Port Lafayette who had a fine farm of White Wyandotte chickens, and that I thought I might buy some for my place. Millington does not believe in Wyandottes. He is all for Orpingtons.

It is remarkable how many wives object to chickens. I do not blame Isobel for not liking chickens, for she was born in a flat, and I am willing to make allowances for her lack of education; but why Mrs. Rolfs and Mrs. Millington should dislike chickens was beyond my comprehension. Both were born in the suburbs, and grew up in a real chickenish atmosphere, and still they do not keep chickens. I must say, however, that Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington are persons of greater intelligence. Almost the first day I moved into the suburb of Westcote, Mr. Rolfs leaned over the division fence and complimented me on my foresight in purchasing such an admirable place on which to raise chickens. He told me that if I needed any advice about chickens he would be glad to supply me with all I wished, just as a neighbourly matter. He seemed to take it as a matter of course that I would arrange for a lot of chickens as soon as I was fairly settled on the place, and in this he was seconded by Mr. Millington.

When Mr. Millington saw Mr. Rolfs talking to me, he came right over and said that, while he hated to boast, he had studied chickens from A to Gizzard, and that when I was ready to get my chickens he could give me some suggestions that would be simply invaluable. We talked the chicken matter over very thoroughly, and I soon saw that they were men of knowledge and deep experience in chicken matters, and when they had decided that I would keep chickens, and what kind of chickens, and where I should build the coop, and what kind of coop I should build, we all shook hands warmly, and I went around front to tell Isobel. I was very enthusiastic about chickens when I went.

After I had interviewed Isobel for three minutes I learned, definitely, that I was not going to keep chickens. There were a great many things Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington had not said about chickens, and those were the very things Isobel told me, and they were all reasons for not having chickens on the place at all. She also threw in an opinion of Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington. It seemed that they were two villains of the most depraved sort, who did not dare keep chickens themselves because they were afraid of their wives, and who were trying to steal a vicarious joy by bossing my chickens when I got them, but that I was not going to get any. Absolutely!

Of course, I always do what Isobel tells me, and when she told me I was not going to have chickens, I obeyed. But I merely told Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington when they came over the next day, that I had been thinking the matter over and that I was doubtful whether the south corner or the north corner would be the best place for the coop. So we three went and looked over the ground again. Both favoured the north corner, so I hung back and seemed undecided and doubtful, and finally, in a week or two, they agreed with me.

I never saw two men so anxious to have a neighbour keep chickens. They were willing to let me have almost everything my own way. It was quite a strain on me, for I had to think of a new objection to their plans every day or so, but I could see the suspense was harder on Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington. Every morning they came and hung over my fence wistfully, and every evening they came over and talked chickens, and on the train to town they spoke freely of the chickens they were going to keep. In a month they were talking of the chickens they were keeping, and bragging about them; and old-seasoned chicken raisers used to hunt them up and sit with them and ask for information on knotty points.

Toward fall Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington were beginning to talk about the large sums of money they were making out of their chickens, and promising settings of their White Orpington and White Wyandotte eggs to the commuters, and they began to be really annoying. They would stand at the fence, hollow-eyed and hungry-looking, staring into my yard, and when I passed they would make slighting remarks about me and the lack of decision in my character. They said sneeringly that they did not believe I would ever get any chickens.

“You, Millington, and you, Rolfs,” I said firmly, “should remember one thing: I am the man who is getting these chickens, and the main thing in raising chickens is to start right. I do not want to go into this thing hastily and then regret it all my life. If you do not like my way, all you have to do is to build coops yourselves and buy chickens and raise them yourselves. Be patient. Every day I am learning more about chickens from your conversations on the train, and when I do get my chickens you will find I have profited by your suggestions.”

Millington and Rolfs had to be satisfied with that, so far as I was concerned, for although I spoke to Isobel frequently on the subject of chickens she had not changed. I silenced Millington by telling him I would have chickens long before he ever succeeded in taking Isobel and me to Port Lafayette in his automobile.

“If that is all you are waiting for,” he said, “we will start to-morrow,” and so we did; but that was all.

Millington and Rolfs, during the winter, worked off some of their surplus chicken energy writing letters to the poultry periodicals. My friends in town began asking me why I did not keep chickens when I lived near to such chicken experts as Rolfs and Millington, by whose experience I could profit; but the worst came one day on the train when Rolfs actually had the assurance to offer me a setting of his White Wyandotte eggs. I blame Rolfs and Millington for acting in this way. No man should brag about chickens he has not; I only bragged about those I meant to get.

By the time spring put forth her tender leaves, Rolfs and Millington were so deep in their imaginary chicken business that they talked nothing else, and all their spare time was spent in my yard, urging me to hurry a little and get the chickens.

“I wish you would hurry a bit in getting those chickens of mine,” Millington would say; “I ought to have at least ten hens sitting by this time.” And then Rolfs would say: “He is right about that. Unless you get my White Wyandottes soon, the chicks will not be hatched out before cold weather. I ought to have the hens on the eggs now.” Occasionally I mentioned chickens in an off-hand way to Isobel, but she had not changed her views.

“Now, Isobel,” I would say, “about chickens—”

At the word “chickens” Isobel would look at me reproachfully, and I would end meekly: “About chickens, as I was saying. Don't you think we could have a pair of broilers to-morrow?”

As a matter of fact, this happened so often that I began to hate the sight of a broiled chicken, and was forced to mention roast chicken once in a while. It was after one of these times that the event happened that stirred all Westcote.

I had reached a point where I dodged Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington when I saw them, in order to avoid their insistent clamour for chickens, when one evening Isobel met me at the door with a smile.

“John!” she cried. “What do you think! Our chicken laid an egg!”

“Chicken?” I asked anxiously. “Did you say chicken?”

“And I am going to give you the egg for dinner,” cried Isobel joyfully. “Just think, John! Our own egg, laid by our own chicken! Do you want it fried, or boiled, or scrambled?”

“Isobel,” I demanded, “what is the meaning of all this?”

“I just could not kill the hen,” Isobel ran on, “after it had been so—so friendly. Could I? I felt as if I would be killing one of the family.”

“People do get to feeling that way about chickens when they keep them,” I said insinuatingly. “Why, Isobel, I have known wives to love chickens so warmly—wives that had never cared a snap for chickens before—wives that hated chickens—and they grew to love chickens so well that as soon as the coop was made—of course it was a nice, clean, airy coop, Isobel—and the dear little fluffy chicks began to peep about—”

Isobel stiffened.

“John,” she said finally “you are not going to keep chickens!”

“Certainly not!” I agreed hastily.

“But of course we can't kill Spotty,” said Isobel. “I call her Spotty because that seems such a perfect name for her. I telephoned for a roaster this morning, because you suggested having a roaster for dinner, John, and when the roaster came it was a live chicken! Imagine!”

“Horrors!” I exclaimed.

“I should think so!” agreed Isobel. “So there was nothing to do but 'phone the grocer to come and get the live roaster, but when I 'phoned, his grandmother was much worse, and the store was closed until she got better—or worse—and I couldn't bear to see the poor thing in the basket with its legs tied all that time, for there is no telling how long an old person like a grandmother will remain in the same condition, so I loosened the roaster in the cellar, and at a quarter past four I heard it cluck. It had laid an egg. I knew that the moment I heard it cluck.”

“Isobel,” I said, “you were born to be the wife of a chicken fancier! You shall eat that egg!”

“No, John,” she said, “you shall eat it. It is our first real egg, laid by our dear little Spotty, and you shall eat it.”

“No, Isobel,” I began, and then, as I saw how determined she was, I compromised. “Let us have the egg scrambled,” I said, “and each of us eat a part.”

“Very well,” said Isobel, “if you will promise not to kill Spotty. We will keep her forever and forever!”

I agreed. Isobel kissed me for that.

After we had eaten the egg—and both Isobel and I agreed that it was really a superior egg—we went down cellar and looked at Spotty. I should say she was a very intelligent-looking hen, but homely. There was nothing flashy about her. She was the kind of hen a man might enter in the Sweepstakes class, and not get a prize, and then enter in the Consolation class and not get a prize, and then enter for the Booby prize and still be outclassed, and then enter in the Plain Old Barnyard Fowl class and not get within ten miles of a prize, and then be taken to the butcher as a Boarding House Broiler, and be refused on account of age, tough looks, and emaciation.