Title: Betty Gordon at Bramble Farm; Or, The Mystery of a Nobody

Author: Alice B. Emerson

Release date: October 8, 2013 [eBook #43907]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| BETTY GORDON AT BRAMBLE FARM |

| BETTY GORDON IN WASHINGTON |

| BETTY GORDON IN THE LAND OF OIL |

| RUTH FIELDING OF THE RED MILL |

| RUTH FIELDING AT BRIARWOOD HALL |

| RUTH FIELDING AT SNOW CAMP |

| RUTH FIELDING AT LIGHTHOUSE POINT |

| RUTH FIELDING AT SILVER RANCH |

| RUTH FIELDING ON CLIFF ISLAND |

| RUTH FIELDING AT SUNRISE FARM |

| RUTH FIELDING AND THE GYPSIES |

| RUTH FIELDING IN MOVING PICTURES |

| RUTH FIELDING DOWN IN DIXIE |

| RUTH FIELDING AT COLLEGE |

| RUTH FIELDING IN THE SADDLE |

| RUTH FIELDING IN THE RED CROSS |

| RUTH FIELDING AT THE WAR FRONT |

| RUTH FIELDING HOMEWARD BOUND |

| RUTH FIELDING DOWN EAST |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"I do wish you'd wear a sunbonnet, Betty," said Mrs. Arnold, glancing up from her ironing board as Betty Gordon came into the kitchen. "You're getting old enough now to think a little about your complexion."

Betty's brown eyes laughed over the rim of the glass of water she had drawn at the sink.

"I can't stand a sunbonnet," she declared vehemently, returning the glass to the nickel holder under the shelf. "I know just how a horse feels with blinders on. You know you wouldn't like it, Mrs. Arnold, if I pulled up half your onion sets in mistake for weeds because I couldn't see what I was doing."

Mrs. Arnold shook her head over the white ruffle she was fluting with nervous, skillful fingers.

"There's no call for you to go grubbing in that onion bed," she said. "I'd like you to have nice[2] hands and not be burnt black as an Indian when your uncle comes. But then, nobody pays any attention to what I say."

There was more truth in this statement than Mrs. Arnold herself suspected. She was one of these patient, anxious women who unconsciously nag every one about them and whose stream of complaint never rises above a constant murmur. Her family were so used to Mrs. Arnold's monotonous fault-finding that they rarely if ever knew what she was complaining about. They did not mean to be disrespectful, but they had fallen into the habit of not listening.

"Uncle Dick won't mind if I'm as black as an Indian," said Betty confidently, spreading out her strong little brown right hand and eyeing it critically. "With all the traveling he's done, I guess he's seen people more tanned than I am. You're sure there wasn't a letter this morning?"

"The young ones said there wasn't," returned Mrs. Arnold, changing her cool iron for a hot one, and testing it by holding it close to her flushed face. "But I don't know that Ted and George would know a letter if they saw it, their heads are so full of fishing."

"I thought Uncle Dick would write again," observed Betty wistfully. "But perhaps there wasn't time. He said he might come any day."

"I don't know what he'll say," worried Mrs.[3] Arnold, her eyes surveying the slender figure leaning against the sink. "Your not being in mourning will certainly seem queer to him. I hope you'll tell him Sally Pettit and I offered to make you black frocks."

Betty smiled, her peculiarly vivid, rich smile.

"Dear Mrs. Arnold!" she said, affection warm in her voice. "Of course I'll tell him. He will understand, and not blame you. And now I'm going to tackle those weeds."

The screen door banged behind her.

Betty Gordon was an orphan, her mother having died in March (it was now June) and her father two years before. The twelve-year-old girl had to her knowledge but one single living relative in the world, her father's brother, Richard Gordon. Betty had never seen this uncle. For years he had traveled about the country, wherever his work called him, sometimes spending months in large cities, sometimes living for weeks in the desert. Mr. Gordon was a promoter of various industrial enterprises and was frequently sent for to investigate new mines, oil wells and other large developments.

"I'd love to travel," thought Betty, pulling at an especially stubborn weed. "I hope Uncle Dick will like me and take me with him wherever he goes. Wouldn't it be just like a fairy story if he should come here and scoop me out of Pineville[4] and take me hundreds of miles away to beautiful and exciting adventures!"

This enchanting prospect so thrilled the energetic young gardener that she sat down comfortably in the middle of the row to dream a little more. While her father lived, Betty's home had been in a small, bustling city where she had gone to school in the winter. The family had always gone to the seashore in the summer; but the only exciting adventure she could recall had been a tedious attack of the measles when she was six years old. Mrs. Gordon, upon her husband's sudden death, had taken her little daughter and come back to Pineville, the only home she had known as a lonely young orphan girl. She had many kind friends in the sleepy country town, and when she died these same friends had taken loving charge of Betty.

The girl's grief for the loss of her mother baffled the villagers who would have known how to deal with sorrow that expressed itself in words or flowed out in tears. Betty's long silences, her desire to be left quite alone in her mother's room, above all her determination not to wear mourning, puzzled them. That she had sustained a great shock no one could doubt. White and miserable, she went about, the shadow of her former gay-hearted self. For the first time in her life she was experiencing a real bereavement.

When Betty's father had died, the girl's grieving was principally for her mother's evident pain. She had always been her mother's confidante and chum, and the bond between them, naturally close, had been strengthened by Mr. Gordon's frequent absences on the road as a salesman. It was Betty and her mother who locked up the house at night, Betty and her mother who discussed household finances and planned to surprise the husband and father. The daughter felt his death keenly, but she could never miss his actual presence as she did that of the mother from whom she had never been separated for one night from the time she was born.

The neighbors took turns staying with the stricken girl in the little brown house that had been home for the two weeks following Mrs. Gordon's death. Then, as Betty seemed to be recovering her natural poise, a discussion of her affairs was instigated. The house had been a rented one and Betty owned practically nothing in the world except the simple articles of furniture that had been her mother's household effects. These Mrs. Arnold stored for her in a vacant loft over a store, and Mrs. Arnold, her mother's closest friend, bore the lonely child off to stay with them till Richard Gordon could be heard from and some arrangement made for the future.

Communication with Mr. Gordon was necessarily[6] slow, since he moved about so frequently, but when the news of his sister-in-law's death reached him, he wrote immediately to Betty, promising to come to Pineville as soon as he could plan his business affairs to release him.

"Betty!" a shrill whisper, apparently in the lilac bushes down by the fence, startled Betty from her day dreams.

"Betty!" came the whisper again.

"Is that you, Ted?" called Betty, standing up and looking expectantly toward the bushes.

"Sh! don't let ma hear you." Ted Arnold parted the lilac bushes sufficiently to show his round, perspiring face. "George and me's going fishing, and we hid the can of worms under the wheelbarrow. Hand 'em to us, will you, Betty? If ma sees us, she'll want something done."

"Did you go to the post-office this morning?" demanded Betty severely.

"Sure I did. There wasn't anything but a postal from pa," came the answer from the bushes. "He's coming home next week, and then it'll be nothing but work in the garden all day long. Hand us the can of worms, like a good sport, won't you?"

"Where did you hide them?" asked Betty absently.

"Under the wheelbarrow, there at the end of[7] the arbor," directed Ted. "Thanks awfully, Betty."

"Where's George?" she asked. "Isn't there another mail at eleven, Ted?"

"Oh, Betty, how you do harp on one subject," complained Ted, poking about in his can of worms with a stick, but keeping carefully out of sight of the kitchen window and the maternal eye. "Hardly anything ever comes in that eleven o'clock mail. Anyway, didn't mother say your uncle would probably come without bothering to write again?"

"I suppose he will," sighed Betty. "Only it seems so long to wait. Where did you say George was?"

Ted answered reluctantly.

"He's in swimming."

"Well I must say! You wait till your father comes home," said Betty ominously.

The boys had been forbidden to go swimming in the treacherous creek hole, and George was where he had no business to be.

"You needn't tell everything you know," muttered Ted uncomfortably, picking up his treasured can and preparing to depart.

"Oh, I won't tell," promised Betty quickly.

She went back to her weeding, and Ted scuffled off to fish.

"Goodness!" Betty pushed the hair from her forehead with a grimy hand. "I do believe this[8] is the warmest day we've had! I'll be glad when I get down to the other end where the arbor makes a little shade."

She had reached the end of the long row and had stood up to rest her back when she saw some one leaning over the white picket fence.

"Probably wants a drink of water," thought Betty, crossing the strip of garden and grass to ask him, after the friendly fashion of Pineville folk. "I've never seen him before."

The stranger was leaning over the fence, staring abstractedly at a border of sweet alyssum which straggled down one side of the sunken brick walk. He was tall and broad-shouldered, and his straw hat pushed slightly back on his head revealed a keen, tanned face and close-cropped iron gray hair. He did not look up as Betty drew near and suddenly she felt shy.

"I—I beg your pardon," she faltered, "were you looking for any particular house?"

The stranger lifted his hat, and a pair of sharp blue eyes smiled pleasantly into Betty's brown ones.

"I was looking, not for a particular house, but for a particular person," admitted the man, gazing at her intently. "I shouldn't wonder if I had found her, too. Can you guess who I am?"

Betty's mind was so full of one subject that[9] it would have been strange indeed if she had failed to guess correctly.

"You're Uncle Dick!" she cried, throwing her arms around his neck and running the risk of spiking herself on the sharp pickets. "Oh, I thought you'd never come!"

Uncle Dick, for it really was Mr. Gordon, hurdled the low fence lightly and stood smiling down on his niece.

"I don't believe in wasting time writing letters," he declared cheerfully, "especially as I seldom know my plans three days ahead. You're the image of your father, child. I should have known you anywhere."

Betty put her hands behind her, suddenly conscious that they could not be very clean.

"I'm afraid I mussed your collar," she apologized contritely. "Mrs. Arnold was hoping you'd write so she could have me all scrubbed up for you;" and here Betty's dimple would flicker out.

Mr. Gordon put an arm about the little figure in the grass-stained rose-colored smock.

"I'd rather find you a garden girl," he announced contentedly. "Isn't there a place where you and I can have a little talk before we go in to see Mrs. Arnold and make our explanations?"

Betty drew him toward the arbor. She knew they would be undisturbed there.

The arbor was rather small and rickety, but at least it was shady. Betty sat down beside her uncle, who braced his feet against the opposite seat to keep his place on the narrow ledge.

"I'm afraid I take up a good deal of room," he said apologetically. "Well, my dear, had you begun to think I was never coming?"

Betty glanced up at him bravely.

"It was pretty long—waiting," she admitted. "But now you're here, Uncle Dick, everything is all right. When can we go away?"

"Aren't you happy here, dear?" asked her uncle, plainly troubled. "I thought from your first letter that Mrs. Arnold was a pretty good kind of friend, and I pictured you as contented as a girl could possibly be after a bitter loss like yours."

He smiled a bit ruefully.

"Maybe I'm not strong on pictures," he added. "I thought of you as a little girl, Betty. Don't know what'll you say, but there's a doll in my grip for you."

Betty laughed musically.

"I've always saved my old doll," she confided, slipping a hand into Uncle Dick's broad fist where it lay clinched on his knee. He was very companionable, was this uncle, and she felt that she already loved him dearly. "But, Uncle Dick, I haven't really played with dolls since we moved from the city. I like outdoor things."

"Well, now, so do I," agreed her uncle. "I can't seem to breathe properly unless I'm outdoors. But about this going away—do you want to leave Pineville, Sister?"

Betty's troubled eyes rested on the little garden hot in the bright sunshine.

"It isn't home any more, without mother," she said slowly. "And—I don't belong, Uncle Dick. Mrs. Arnold is a dear, and I love her and she loves me. But they want to go to California, though they won't talk it before me, 'cause they think I'll feel in the way. Mr. Arnold has a brother on a fruit farm, and he's wild to move out there. As soon as you take me somewhere, they're going to pack up."

"Well, then, we'll have to see that you do belong somewhere," said Mr. Gordon firmly. "Anything else, Sister?"

Betty drew a deep breath.

"It's heavenly to have you to listen to me," she declared. "I want to go! I've never been anywhere,[12] and I feel as though I could go and go and never stop. Daddy was like that. Mother used to say if he hadn't had us to look after he would have been an explorer, but that he had to manage to earn a living and do his traveling as a salesman. Couldn't I learn to be a salesman, a saleswoman, I mean? Lots of girls do travel."

"We'll think it over," answered her uncle diplomatically.

"And then there's another thing," went on Betty, her pent-up thoughts finding relief in speech. "Although Mrs. Arnold was mother's dearest friend, I can't make her understand how mother felt about wearing mourning."

Betty indicated her rose smock.

"Lots of Pineville folks think I don't care about losing my mother," she asserted softly, "because I haven't a single black dress. But mother said mourning was selfish. She wouldn't wear black when daddy died. Black makes other people feel sorry. But I did love mother! And do yet!"

Uncle Dick's keen blue eyes misted and the brave little figure in the bright smock was blurred for a moment.

"I suppose the whole town has been giving you reams of advice," he said irrelevantly. "Well Betty, I can't promise to take you with me—bless me, what would an old bachelor like me do with[13] a young lady like you? But I think I know of a place where you can spend a summer and be neither lonesome nor unhappy. And perhaps in the fall we can make other arrangements."

Betty was disappointed that he did not promise to take her with him at once. But she had been trained not to tease, and she accepted the compromise as pleasantly as it was offered.

"Mrs. Arnold will be disappointed if you don't go round to the front door," she informed her uncle, as he stretched his long legs preparatory to rising from the low seat. "Company always comes to the front door, Uncle Dick."

Mr. Gordon stepped out of the summer house and turned toward the gate.

"We'll walk around and make a proper entry," he declared obligingly. "I meant to, and then as I came up the street I remembered how we used to cut across old Clinton's lot and climb the fence. So I had to come the back way for old times' sake."

Betty's eyes were round with wonder.

"Did you ever live in Pineville?" she asked in astonishment.

"You don't mean to tell me you didn't know that?" Uncle Dick was as surprised as his niece. "Why, they shipped me into this town to read law with old Judge Clay before they found there was no law in me, and your father first met your[14] mother one Sunday when he drove twenty miles from the farm to see me."

Betty was still pondering over this when they reached the Arnold front door and Mrs. Arnold, flustered and delighted, answered Mr. Gordon's knock.

"Sit right down on the front porch where it's cool," she insisted cordially. "I've just put on my dinner, and you'll have time for a good talk. No, Betty, there isn't a thing you can do to help me—you entertain your uncle."

But Betty, who knew that excitement always affected Mrs. Arnold's bump of neatness, determined to set the table, partly to help her hostess and partly, it must be confessed, to make sure that the knives and forks and napkins were in their proper places.

"I'm sure I don't know where those boys can be," scolded the flushed but triumphant mother, as she tested the flaky chicken dumplings and pronounced the dinner "done to a turn." "We'll just sit down without them, and it'll do 'em good," she decided.

Betty ran through the hall to call her uncle. Just as she reached the door two forlorn figures toiled up the porch steps.

"Where's ma?" whispered Ted, for the moment not seeing the stranger and appealing to Betty, who stood in the doorway. "In the kitchen?[15] We thought maybe we could sneak up the front stairs."

Ted was plastered from head to foot with slimy black mud, and George, his younger edition, was draped only in a wet bath towel. Both boys clung to their rough fishing rods, and Ted still carried the dirty tin can that had once held bait.

"I should say," observed Mr. Gordon in his deep voice, "that we had been swimming against orders. Things usually happen in such cases."

"Oh, gee!" sighed Ted despairingly. "Who's that? Company?"

Mrs. Arnold had heard the talk, and she came to the door now, pushing Betty aside gently.

"Well, I must say you're a pretty sight," she told her children. "If your father were at home you know what would happen to you pretty quick. Betty's uncle here, too! Aren't you ashamed of yourselves? I declare, I've a good mind to whip you good. Where are your clothes, George?"

"They—they floated away," mumbled George. "Ted borrowed this towel. It's Mrs. Smith's. Say, ma, we're awful hungry."

"You march upstairs and get cleaned up," said their mother sternly. "We're going to sit down to dinner this minute. Chicken and dumplings. When you come down looking like Christians I'll see about giving you something to eat."

Midway in the delicious dinner Ted and George[16] sidled into the room, very wet and shiny as to hair and conspicuously immaculate as to shirt and collar. Mrs. Arnold relented at the transformation and proceeded to pile two plates high with samples of her culinary skill.

"Betty," said Mr. Gordon suddenly, "is there a garage here where we can hire a car?"

"There isn't a garage in Pineville," answered Betty. "You see we're off the state road where the automobile traffic goes. There are only two or three cars in town, and they're for business. But we can get a horse and buggy, Uncle Dick."

"Guess that's better, after all," said Mr. Gordon contentedly. "I want to talk to you about that plan I spoke of, and we'll stand a better chance of having our talk if we travel behind a horse. I wonder——" his eyes twinkled—"if there's a young man about who would care to earn a quarter by running down to the livery stable and seeing about a horse and buggy for the afternoon?"

Ted and George grinned above their respective dishes of ice-cold rice pudding.

"I'll go," offered Ted.

"I'll go, too," promised George. "Can we drive the rig back to the house?"

Mr. Gordon said they could, and the two boys dispatched their dessert in double quick time. While they went down to the town livery stable,[17] Betty hurried to put on a cool, white frock, but, to Mrs. Arnold's disappointment, she refused to wear a hat.

"The buggy top will be up, so my complexion will be safe," Betty declared merrily, giving Mrs. Arnold a hearty squeeze as that lady followed her downstairs to the porch where Mr. Gordon was waiting.

"What's that? Go without a hat?" he repeated, when Betty consulted him. "I should say so! You're fifty times prettier with those smooth braids than with any hat, I don't care how fine it is. This must be our turnout approaching."

As he guessed, it was their horse and buggy coming toward the house. Ted was driving, assisted by George, and the patient horse was galloping like mad as they urged it on.

"Never knew a boy of that age who could be trusted to drive alone," muttered Mr. Gordon, going down to the gate to meet them.

The boys beamed at him and Betty, sure that they had pleased with their haste. They then watched Betty step in, followed by her uncle, and drive away with something like envy.

"Are you used to driving, Betty?" asked Mr. Gordon, as he chirped lightly to the horse that obediently quickened its lagging pace.

"Why, I've driven some," replied Betty hesitatingly. "But I wouldn't know what to do if[18] he should be frightened at anything. Do you like to drive, Uncle?"

"I'm more used to horseback riding," was the answer. "I hope you'll have a chance to learn that this summer, Betty. I must have you measured for a habit and have it sent up to you from the city. There's no better sport for a man or a woman, to my way of thinking, than can be found in the saddle."

"Where am I going?" asked the girl timidly. "Who'll teach me to ride?"

"Oh, there'll be some one," said her uncle easily. "I never knew a ranch yet where there were not good horsemen. The idea came to me that you might like to spend the summer with Mrs. Peabody, Betty."

"Mrs. Peabody?" repeated Betty, puzzled. "Does she live on a ranch? I'd love to go out West, Uncle Dick."

For a moment Mr. Gordon stared at his niece, a puzzled look in his eyes. Then his face cleared.

"Oh, I see. You've made a natural mistake," he said. "Mrs. Peabody doesn't live out West, Betty, but up-state—about one hundred and fifty miles north of Pineville. I've picked up that word ranch in California. Everything outside the town limits, from a quarter of an acre to a thousand, is called a ranch. I should have said farm."

Betty settled back in the buggy, momentarily disappointed. A farm sounded so tame and—and ordinary.

"The plan came to me while I was sitting out on the porch waiting for dinner," pursued her uncle, unconscious that he had dashed her hopes. "Your father and I had such a happy childhood on a farm that I'm sure he would want you to know something about such a life first-hand. But of course I intend to talk it over with you before writing to Agatha."

"Agatha?" repeated Betty.

"Mrs. Peabody," explained Mr. Gordon. "She[20] and I went to school together. Last year I happened to run across her brother out in the mines. He told me that Agatha had married, rather well, I understood, and was living on a fine, large farm. What did he say they called their place? 'Bramble Farm'—yes, that's it."

"Bramble Farm," echoed Betty. "It sounds like wild roses, doesn't it, Uncle Dick? But suppose Mrs. Peabody doesn't want me to come to live with her?"

"Bless your heart, child, this is no permanent arrangement!" exclaimed her uncle vigorously. "You're my girl, and mighty proud I am to have such a bonny creature claiming kin with me. I've knocked about a good bit, and sometimes the going has been right lonesome."

He seemed to have forgotten the subject of Bramble Farm for the moment, and something in his voice made Betty put out a timid hand and stroke his coat sleeve silently.

"All right, dear," he declared suddenly, throwing off the serious mood with the quick shift that Betty was to learn was characteristic of him. "If your old bachelor uncle had the slightest idea where he would be two weeks from now, he'd take you with him and not let you out of his sight. But I don't know; though I strongly suspect, and it's no place to take a young lady to. However, if we can fix it up with Agatha for you to spend[21] the summer with her, perhaps matters will shape up better in the fall. I'll tell her to get you fattened up a bit; she ought to have plenty of fresh eggs and milk."

Betty made a wry face.

"I don't want to be fat, Uncle Dick," she protested. "I remember a fat girl in school, and she had an awful time. Is Mrs. Peabody old?"

Mr. Gordon laughed.

"That's a delicate question," he admitted. "She's some three or four years younger than I, I believe, and I'm forty-two. Figure it out to suit yourself."

The bay horse had had its own sweet way so far, and now stopped short, the road barred by a wide gate. It turned its head and looked reproachfully at the occupants of the buggy.

"Bless me, I never noticed where we were going," said Mr. Gordon, surprised. "What's this we're in, Betty, a private lane? Where does it lead?"

"Let me open the gate," cried Betty, one foot on the step. "We're in Mr. Bradway's meadow. Uncle Dick. We can keep right on and come out on the turnpike. He doesn't care as long as the gates are kept closed."

"I'll open the gate," said Mr. Gordon decidedly. "Take the reins and drive on through."

Betty obeyed, and Mr. Gordon swung the heavy gate into place again and fastened it.

"Is Mrs. Peabody pretty?" asked Betty, as he took his place beside her and gathered up the lines. "Has she any children?"

The blue eyes surveyed her quizzically.

"A real girl, aren't you?" teased her uncle. "Why, child, I couldn't tell you to save me, whether Agatha is pretty or not. I haven't seen her for years. But she has no children. Her brother, Lem, told me that. She was a pretty girl." Mr. Gordon added reflectively: "I recollect she had long yellow braids and very blue eyes. Yes, she's probably a pretty woman."

To reach the turnpike they had to pass through another barred gate, and then when they did turn into the main road, Mr. Gordon, glancing at his watch, uttered an exclamation.

"Four o'clock," he announced. "Why, it must have been later than I thought when we started. The horse has taken its own sweet time. Look, Betty, is there a place around here where we can get some ice-cream?"

Betty's eyes danced. Like most twelve-year-old girls, she regarded ice-cream as a treat.

"There's a place in Pineville; but let's not go there—the whole town goes to the drug-store in the afternoons," she answered. "Couldn't we go as far as Harburton and stop at the ice-cream[23] parlor? The horse isn't very tired, is it, Uncle Dick?"

"Considering the pace he has been going, I doubt it," responded her uncle. "What's the matter with you and me having a regular lark, Betty? Let's not go back for supper—we'll have it at the hotel. They can put up the horse, and we'll drive back when it's cooler."

Betty was thrilled at the idea of eating supper at the Harburton Hotel; certainly that would be what she called "exciting." But since her mother's death she had learned to think not only for herself but for others.

"Mrs. Arnold would be so worried," she objected, trying to keep the longing out of her voice. "She'd think we'd been struck at the grade crossing. And, Uncle Dick, I don't believe this dress is good enough."

But Mr. Gordon was not accustomed to being balked by objections. He swept Betty's aside with a half-dozen words. They would telephone to Mrs. Arnold. Well, then, if she had no telephone, they would telephone a near neighbor and get her to carry the message. As for the dress—here he glanced contentedly at Betty—he didn't see but that she looked fine enough to attend the King's wedding. She could wash and freshen up a little when they reached the hotel.

Betty's face glowed.

"You're just like Daddy," she said happily. "Mother used to say she never had to worry about anything when he was at home. Mrs. Arnold doesn't either, when her husband's home. Do all husbands do the deciding, Uncle Dick?"

Mr. Gordon submitted, amusedly, that as he was not a husband, he could not give accurate information on that point. But Betty's active mind was turning over something.

"Mrs. Arnold says Mr. Arnold makes the boys stand round," she confided. "I notice they mind him ten times as quick as they do their mother. But they love him more. Do you make people stand round, Uncle Dick?"

Mr. Gordon smiled down into the serious little face tilted to meet his glance.

"I haven't much patience with disobedience, I'm afraid," he replied. "I suppose some of the men I've bossed would consider me a Tartar. Why, Betty? Are you thinking of going on strike against my authority? I don't advise you to try it."

Betty blushed.

"It isn't that," she said hastily. "But—but—well, I have a temper, Uncle Dick. I get so raging mad! If I don't tell you, some one else will, or else you'll see me 'acting up,' as Mrs. Arnold says, before you go. So I thought I'd better tell you."

Mr. Gordon's lips twitched.

"A temper, out of control, is a mighty useless possession," he said solemnly. "But as long as you know you've got a spark of fire in you, Betty, you can watch out for it. Afraid of going on the rampage while you're at Bramble Farm? Is that what's worrying you?"

"Some," confessed his niece, with scarlet cheeks.

"I'll tell you what to do," counseled Mr. Gordon, and his even, rather slow voice soothed Betty inexpressibly. "When you get a 'mad fit,' you fly out to the wood pile and chop kindling as hard as you can. You can't talk and chop wood, and the tongue does most of the mischief when our tempers get the best of us. You'll remember that little trick, won't you?"

Betty promised she would, and, as they were now driving into the thriving county seat of Harburton, she began to point out the few places of interest.

The hotel was opposite the court house, and as they stopped before the curb and Betty saw the porch well filled with men, with here and there a woman in a pretty summer dress, she felt extremely shy. A boy ran up to take their horse and lead it around to the stables for a rub-down and a comfortable supper. Mr. Gordon tucked his niece's hand under his arm and marched unconcernedly up the hotel steps.

"I suppose he's used to hotels," thought Betty, sinking into one of the stuffed red velvet chairs at her uncle's bidding and looking interestedly about her as he went in search of the proprietor. "I wonder if it's fun to live in a hotel all the time instead of a house."

Her uncle came back in a few moments with a pleasant-faced, matronly woman, whom he introduced as the sister of the proprietor. She was to take Betty upstairs and let her make herself neat for supper, which would, so the woman said, be ready in twenty minutes.

"I'll wait for you right here," promised Mr. Gordon, divining in Betty's anxious glance a fear that she would have to search for him on the crowded piazza.

"You drove in, didn't you?" asked Mrs. Holmes, leading the way upstairs and ushering Betty into a pretty, chintz-hung room. "You'll find fresh water in the pitcher, dear. Didn't your father say you were from Pineville?"

Betty, pouring the clear, cool water into the basin, explained that Mr. Gordon was her uncle and said that they had driven over from Pineville that afternoon.

"Well, you want to be careful driving back," cautioned Mrs. Holmes. "The flag man goes off duty at six o'clock, and that crossing lies right[27] in a bad cut. There was a nasty accident there last week."

Betty had read of it in the Pineville Post, and thanked Mrs. Holmes for her warning. When that kind woman had ascertained that Betty needed nothing more, she excused herself and went down to superintend the two waitresses.

Betty managed to smooth her hair nicely with the aid of a convenient sidecomb, and after bathing her face and hands felt quite refreshed and neat again. She found her uncle reading a magazine.

"Well, you look first rate," he greeted her. "I picked this up off the table without glancing at it; it's a fashion magazine. It reminds me, Betty, you'll need some new clothes this summer, eh? You'll have to take Mrs. Arnold when you go shopping. I wouldn't know a bonnet from a pair of gloves."

Betty laughed and slipped her hand into his, and they went toward the dining room. What a dear Uncle Dick was! She had not had many new clothes since her father's death.

The country hotel supper was no better than the average of its kind, but to Betty, to whom any sort of change was "fun," it was delicious. She and Uncle Dick became better acquainted over the simple meal in the pleasant dining room than they could ever have hoped to have been with Mrs. Arnold and the two boys present, and it was not until her dessert was placed before her that Betty remembered her friend.

"Mrs. Arnold will think we're lost!" she exclaimed guiltily. "I meant to telephone! And oh, Uncle Dick, she does hate to keep supper waiting."

Uncle Dick smiled.

"I telephoned the neighbor you told me about," he said reassuringly. "She said she would send one of her children right over with the message. That was while you were upstairs. So I imagine Mrs. Arnold has George and Ted hard at work drying the dishes by this time."

"They don't dry the dishes, 'cause they're boys," explained Betty dimpling. "In Pineville,[29] the men and boys never think of helping with the housework. Mother said once that was one reason she fell in love with daddy—because he came out and helped her to do a pile of dishes one awfully hot Sunday afternoon."

After supper Betty and her uncle walked about Harburton a bit, and Betty glanced into the shop windows. She knew that probably her new dresses, at least the material for them, would be bought here, and she was counting more on the new frocks than even Uncle Dick knew.

When they went back to the hotel it was still light, but the horse was ordered brought around, for they did not want to hurry on the drive home.

"I guess I missed not belonging to any body," she said shyly, after a long silence.

Uncle Dick glanced down at her understandingly.

"I've had that feeling, too," he confessed. "We all need a sense of kinship, I think, Betty. Or a home. I haven't had either for years. Now you and I will make it up to each other, my girl."

The darkness closed in on them, and Uncle Dick got out and lit the two lamps on the dashboard and the little red danger light behind. Once or twice a big automobile came glaring out of the road ahead and swept past them with a roar and a rush, but the easy going horse refused[30] to change its steady trot. But presently, without warning, it stopped.

Uncle Dick slapped the reins smartly, with no result.

"He balks," said Betty apologetically. "I know this horse. The livery stable man says he never balks on the way home, but I suppose he was so good all the afternoon he just has to act up now."

"Balks!" exploded Uncle Dick. "Why, no stable should send out a horse with that habit. Is there any special treatment he favors, Betty?" he added ironically.

Betty considered.

"Whipping him only makes him worse, they say," she answered. "He puts his ears back and kicks. Once he kicked a buggy to pieces. I guess we'll have to get out and coax him, Uncle Dick."

Mr. Gordon snorted, but he climbed down and went to the horse's head.

"You stay where you are, Betty," he commanded. "I'm not going to have you dancing all over this dark road and likely to be run down by a car any minute simply to cater to the whim of a fool horse. You hold the reins and if he once starts don't stop him; I'll catch the step as it goes by."

Betty held the reins tensely and waited. There was no moon, and clouds hid whatever light they[31] might have gained from the stars. It was distinctly eery to be out on the dark road, miles from any house, with no noise save the incessant low hum of the summer insects. Betty shivered slightly.

She could hear her uncle talking in a low tone to the dejected, drooping, stubborn bay horse, and she could see the dim outline of his figure. The rays of the buggy lamps showed her a tiny patch of the wheels and road, but that was every bit she could see.

Up over the slight rise of ground before them shone a glare, followed in a second by the headlights of a large touring car. Abreast of the buggy it stopped.

"Tire trouble?" asked some one with a hint of laughter in the deep strong voice.

"No, head trouble," retorted Mr. Gordon, stepping over to the driver of the car. "Balky horse."

"You don't say!" The motorist seemed surprised and interested. "I'd give you a tow if you were going my way. But, do you know, my son who runs a farm for me has a way of fixing a horse like that. He says it's all mental. Beating 'em is a waste of time. Jim unharnesses a horse that balks with him, leads it on a way and then rolls the wagon up and gears up again. Horse[32] thinks he's starting all over—new trip, you see. What's the word I want?"

"Psychological?" said the sweet, clear voice of Betty promptly.

"Well, I'll be jiggered!" the motorist swept off his cap. "Thank you, whoever you are. That's what I wanted to say. Yes, nowadays they believe in reasoning with a horse. I'll help you unhitch if you say so."

"Let me," pleaded Betty. "Please, Uncle Dick. I know quite a lot about unharnessing. Can't I get out and do one side?"

The motorist was already out of his car, and at her uncle's brief "all right," Betty slipped down and ran to the traces. The stranger observed her curiously.

"Thought you were older," he said genially. "Where did a little tyke like you get hold of such a long word?"

"I read it," replied Betty proudly. "They use it in the Ladies' Aid when they want to raise more money than usual and they hate to ask for it. Mrs. Banker says there's a psychological moment to ask for contributions, and I have to copy the secretary's notes for her."

"I see," said the stranger. "There! Now, Mr. Heady here is free, and we'll lead him up the road a way."

Uncle Dick led the horse, who went willingly[33] enough, and Betty and the kind friend-in-need, as she called him to herself, each took a shaft of the light buggy and pulled it after them. To their surprise, when the horse was again harnessed to the wagon it started at the word "gid-ap," and gave every evidence of a determination to do as all good horses do—whatever they are ordered.

"Guess he's all right," said the motorist, holding out his hand to Mr. Gordon. "Now, don't thank me—only ordinary road courtesy, I assure you. Hope your troubles are over for the night."

The two men exchanged cards, and, lifting his hat to Betty, though he couldn't see her in the buggy, the stranger went back to his car.

"Wasn't he nice?" chattered Betty, as the horse trotted briskly. Uncle Dick grimly resolved to make it pay for the lost time. "We might have been stuck all night."

"Every indication of it," admitted Mr. Gordon. "However, I'm glad to say that I've always found travelers willing to go to any trouble to help. Don't ever leave a person in trouble on the road if you can do one thing to aid him, Betty. I want you to remember that."

Betty promised, a bit sleepily, for the motion and the soft, night air were making her drowsy. She sat up, however, when they came in sight of the winking red and green lights that showed the railroad crossing.

"No gateman, is there?" inquired her uncle. "Well, I'll go ahead and look, and you be ready to drive across when I whistle."

He climbed down and ran forward, and Betty sat quietly, the reins held ready in her hand. In a few moments she heard her signal, a clear, sharp whistle. She spoke to the horse, who moved on at an irritatingly slow pace.

"For goodness sake!" said Betty aloud, "can't you hurry?"

She peered ahead, trying to make out her uncle's figure, but the heavy pine trees that grew on either side of the road threw shadows too deep for anything to be plainly outlined. Betty, nervously on the lookout, scarcely knew when they reached the double track, but she realized her position with a sickening heart thump when the horse stopped suddenly. The bay had chosen the grade crossing as a suitable place to enjoy a second fit of balkiness.

"Uncle Dick!" cried Betty in terror. "Uncle Dick, he's stopped again! Come and help me unhitch!"

No one answered.

Betty had nerves as strong and as much presence of mind as any girl of her age, but a woman grown might consider that she had cause for hysterics if she found herself late at night marooned in the middle of a railroad track with a balky[35] horse and no one near to give her even a word of advice. For a moment Betty rather lost her head and screamed for her uncle. This passed quickly though, and she became calmer. The whip she knew was useless. So was coaxing. There was nothing to do with any certainty of success but to unharness the horse and lead her over. But where was Uncle Dick?

Betty jumped down from the buggy and ran ahead into the darkness, calling.

"Uncle Dick!" shouted Betty. "Uncle Dick, where are you?"

The cheery little hum of the insects filled the silence as soon as her voice died away. There was no other sound. Common sense coming to her aid, Betty reasoned that her uncle would not have gone far from the crossing, and she soon began to retrace her steps, calling at intervals. As she came back to the twinkling red and green lights, she heard a noise that brought her heart into her throat. Some one had groaned!

"He's hurt!" she thought instantly.

The groan was repeated, and, listening carefully, Betty detected that it came from the other side of the road. A few rods away from the flagman's house was a pit that had recently been excavated for some purpose and then abandoned. Betty peered down into this.

"Uncle Dick?" she said softly.

Another deep groan answered her.

Betty ran back to the buggy and managed to twist one of the lamps from the dashboard. She was back in a second, and carefully climbed down into the pit. Sure enough, huddled in a deplorable heap, one foot twisted under him, lay Mr. Gordon.

Betty had had little experience with accidents, but she instinctively took his head in her lap and loosened his collar. He was unconscious, but when she moved him he groaned again heart-breakingly.

"How shall I ever get him up to the road?" wondered Betty, wishing she knew something of first-aid treatment. "If I could drag him up and then go and get the horse and buggy——"

Her pulse gave an astounding leap and her brown eyes dilated. Putting her uncle's head back gently on the gravel, she scrambled to her feet, feeling only that whatever she did she must not waste time in screaming. She had heard the whistle of a train!

The bad, little stubborn horse standing on the track at the mercy of the coming comet! That was Betty's thought as she sped down the road. In the hope that a sense of the danger might have reached the animal's instinct, she gave the bridle a desperate tug when she reached the horse, but it was of no use. Feverishly Betty set to work to unharness the little bay horse.

She was unaccustomed to many of the buckles, and the harness was stiff and unyielding. Working at it in a hurry was very different from the few times she had done it for fun, or with some one to manage all the hard places. She had finished one side when the whistle sounded again. To the girl's overwrought nerves it seemed to be just around the curve. She had no thought of abandoning the animal, however, and she set her teeth and began on the second set of snaps and buckles. These, too, gave way, and with a strong push Betty sent the buggy flying backward free of the tracks, and, seizing the bridle, she led the cause of all the trouble forward and into safety.[38] For the third time the whistle blew warningly, and this time the noise of the train could be plainly heard. But it was nearly a minute before the glare of the headlight showed around the curve.

"Look what didn't hit you, no thanks to you," Betty scolded the horse, as a relief to herself. "I 'most wish I'd left you there; only then we never would get Uncle Dick home."

Poor Betty had now the hardest part of her task before her. She went back and dragged the buggy over the tracks, up to the horse and started the tedious business of harnessing again. She was not sure where all the straps went, but she hoped enough of them would hold together till they could get home. When she had everything as nearly in place as she could get them she climbed down into the pit.

To her surprise, her uncle's eyes were open. He lay gazing at the buggy lamp she had left.

"Uncle Dick," she whispered, "are you hurt? Can you walk? Because you're so big, I can't pull you out very well."

"Why, I can't be hurt," said her uncle slowly in his natural voice. "What's happened? Where are we? Goodness, child, you look like a ghost with a dirty face."

Betty was not concerned with her looks at that moment, and she was so delighted to find her uncle conscious that she did not feel offended at[39] his uncomplimentary remark. In a few words she sketched for him what had happened.

"My dear child!" he ejaculated when she had told him, "have you been through all that? Why, you're the pluckiest little woman I ever heard of! No wonder you look thoroughly done up. All I remember is whistling for you to come ahead and then taking a step that landed me nowhere. In other words, I must have stepped into this pit. I'm not hurt—just a bit dazed."

To prove it, he got to his feet a trifle shakily. Declining Betty's assistance, he managed to scramble out of the pit, up on to the road. His head cleared rapidly, and in a few more moments he declared he felt like himself.

"In with you," he ordered Betty, after a preliminary examination of the harness which, he announced, was "as right as a trivet." "You've done your share for to-night. Go to sleep, if you like, and I'll wake you up in time to hear Mrs. Arnold send Ted out to take the horse around to the livery stable. It wouldn't do for me to do it—I might murder the owner!"

Betty leaned her head against her uncle's broad shoulder, for a minute she thought, and when she woke found herself being helped gently from the buggy.

"You're all right, Betty," soothed Mrs. Arnold's[40] voice in the darkness. "I've worried myself sick! Do you know it's one o'clock?"

Mr. Gordon took the wagon around to the stable, and Betty, with Mrs. Arnold's help, got ready for bed.

Betty was fast asleep almost before the undressing was completed, and she slept until late the next morning. When she came down to the luxury of a special breakfast, she found only Mrs. Arnold in the house.

"Your uncle's gone out to post a letter," that voluble lady informed her. "Both boys have gone fishing again. I'm only waiting for their father to come home and straighten 'em out. Will you have cocoa, dearie?"

Before she had quite finished her breakfast, Mr. Gordon came back from the post-office, and then, as Mrs. Arnold wanted to go over to a neighbor's to borrow a pattern, he sat down opposite Betty.

"You look rested," he commented. "I don't like to think what might have happened last night. However, we'll be optimistic and look ahead. I've written to Mrs. Peabody, dear, and to-morrow I think you and Mrs. Arnold had better go shopping. I'll write you a check this morning. Agatha will want you to come, I know. And to tell you the truth, Betty, I've had a letter that makes me anxious to be off. I want to stay to see[41] you safely started for Bramble Farm, and then I must peg away at this new work. Finished? Then let's go into the sitting room and I'll explain about the check."

The next morning Betty and Mrs. Arnold started for Harburton with what seemed to Betty a small fortune folded in her purse. Mrs. Arnold had shown her how to cash the check at the Pineville Bank, and she was to advise as to material and value of the clothing Betty might select; but the outfit was to represent Betty's choice and was to please her primarily—Uncle Dick had made this very clear.

Betty had learned a good deal about shopping in the last months of her mother's illness, and she did not find it difficult to choose suitable and pretty ginghams for her frocks, a middy blouse or two, some new smocks, and a smart blue sweater. She very sensibly decided that as she was to spend the summer on a farm she did not need elaborate clothes, and she knew, from listening to Mrs. Arnold, that those easiest to iron would probably please Mrs. Peabody most whether she did her own laundry work or had a washerwoman.

When the purchases came home Uncle Dick delighted Betty with his warm approval. For a couple of days the sewing machine whirred from morning to night as the village dressmaker sewed and fitted the new frocks and made the old presentable.[42] Then the letter from Mrs. Peabody arrived.

"I will be very glad to have your niece spend the summer with me," she wrote, in a fine, slanting hand. "The question of board, as you arrange it, is satisfactory. I would not take anything for her, you know, Dick, and for old times' sake would welcome her without compensation, but living is so dreadfully high these days. Joseph has not had good luck lately, and there are so many things against the farmer.... Let me know when to expect Betty and some one will meet her."

The letter rambled on for several pages, complaining rather querulously of hard times and the difficulties under which the writer and her husband managed to "get along."

"Doesn't sound like Agatha, somehow," worried Uncle Dick, a slight frown between his eyes. "She was always a good-natured, happy kind of girl. But most likely she can't write a sunny letter. I know we used to have an aunt whose letters were always referred to as 'calamity howlers.' Yet to meet her you'd think she hadn't a care in the world. Yes, probably Agatha puts her blues into her letters and so doesn't have any left to spill around where she lives."

Several times that day Betty saw him pull the letter from his pocket and re-read it, always with the puzzled lines between his brows. Once he called to her as she was going upstairs.

"Betty," he said rather awkwardly, "I don't know exactly how to put it, but you're going to board with Mrs. Peabody, you know. You'll be independent—not 'beholden,' as the country folk say, to her. I want you to like her and to help her, but, oh, well, I guess I don't know what I am trying to say. Only remember, child, if you don't like Bramble Farm for any good reason, I'll see that you don't have to remain there."

A brand-new little trunk for Betty made its appearance in the front hall of the Arnold house, and two subdued boys—for Mr. Arnold had returned home—helped her carry down her new treasures and, after the clothes were neatly packed, strap and lock the trunk. There was a tiny "over-night" bag, too, fitted with toilet articles and just large enough to hold a nightdress and a dressing gown and slippers. Betty felt very young-ladyish indeed with these traveling accessories.

"I'll order a riding habit for you in the first large city I get to," promised her uncle. "I want you to learn to ride—I wrote Agatha that. She doesn't say anything about saddle horses, but they[44] must have something you can ride. And you'll write to me, my dear, faithfully?"

"Of course," promised Betty, clinging to him, for she had learned to love him dearly even in the short time they had been together. "I'll write to you, Uncle Dick, and I'll do everything you ask me to do. Then, this winter, do let's keep house."

"We will," said Uncle Dick, fervently, "if we have to keep house on the back of a camel in the desert!" At this Betty giggled delightedly.

Betty's train left early in the morning, and her uncle went to the station with her. Mrs. Arnold cried a great deal when she said good-bye, but Betty cheered her up by picturing the long, chatty letters they would write to each other and by assuring her friend that she might yet visit her in California.

Mr. Gordon placed his niece in the care of the conductor and the porter, and the last person Betty saw was this gray-haired uncle running beside the train, waving his hat and smiling at her till her car passed beyond the platform.

"Now," said Betty methodically, "if I think back, I shall cry; so I'll think ahead."

Which she proceeded to do. She pictured Mrs. Peabody as a gray-haired, capable, kindly woman, older than Mrs. Arnold, and perhaps more serene. She might like to be called "Aunt Agatha."[45] Mr. Peabody, she decided, would be short and round, with twinkling blue eyes and perhaps a white stubby beard. He would probably call her "Sis," and would always be studying how to make things about the house comfortable for his wife.

"I hope they have horses and pigs and cows and sheep," mused Betty, the flying landscape slipping past her window unheeded. "And if they have sheep, they'll have a dog. Wouldn't I love to have a dog to take long walks with! And, of course, there will be a flower garden. 'Bramble Farm' sounds like a bed of roses to me."

The idea of roses persisted, and while Betty outwardly was strictly attentive to the things about her, giving up her ticket at the proper time, drinking the cocoa and eating the sandwich the porter brought her (on Uncle Dick's orders she learned) at eleven o'clock, she was in reality busy picturing a white farmhouse set in the center of a rose garden, with a hedge of hollyhocks dividing it from a scarcely less beautiful and orderly vegetable kingdom.

Day dreams, she was soon to learn.

"The next station's yours, Miss," said the porter, breaking in on Betty's reflections. "Any small luggage? No? All right, I'll see that you get off safely."

Betty gathered up her coat and stuffed the magazine she had bought from the train boy, but scarcely glanced at, into her bag. Then she carefully put on her pretty grey silk gloves and tried to see her face in the mirror of the little fitted purse. She wanted to look nice when the Peabodys first saw her.

The train jarred to a standstill.

Betty hurried down the aisle to find the porter waiting for her with his little step. She was the only person to leave the train at Hagar's Corners, and, happening to glance down the line of cars, she saw her trunk, the one solitary piece of baggage, tumbled none too gently to the platform.

The porter with his step swung aboard the train which began to move slowly out. Betty felt unaccountably small and deserted standing there,[47] and as the platform of the last car swept past her, she was conscious of a lump in her throat.

"Hello!" blurted an oddly attractive voice at her shoulder, a boy's voice, shy and brusque but with a sturdy directness that promised strength and honesty.

The blue eyes into which Betty turned to look were honest, too, and the shock of tow-colored hair and the half-embarrassed grin that displayed a set of uneven, white teeth instantly prepossessed the girl in favor of the speaker. There was a splash of brown freckles across the snub nose, and the tanned cheeks and blue overalls told Betty that a country lad stood before her.

"Hello!" she said politely. "You're from Mr. Peabody's, aren't you? Did they send you to meet me?"

"Yes, Mr. Peabody said I was to fetch you," replied the boy. "I knew it was you, 'cause no one else got off the train. If you'll give me your trunk check I'll help the agent put it in the wagon. He locks up and goes off home in a little while."

Betty produced the check and the boy disappeared into the little one-room station. The girl for the first time looked about her. Hagar's Corners, it must be confessed, was not much of a place, if one judged from the station. The station itself was not much more than a shanty,[48] sadly in need of paint and minus the tiny patch of green lawn that often makes the least pretentious railroad station pleasant to the eye. Cinders filled in the road and the ground about the platform. Hitched to a post Betty now saw a thin sorrel horse harnessed to a dilapidated spring wagon with a board laid across it in lieu of a seat. To her astonishment, she saw her trunk lifted into this wagon by the station agent and the boy who had spoken to her.

"Why—why, it doesn't look very comfortable," said Betty to herself. "I wonder if that's the best wagon Mr. Peabody has? But perhaps his good horses are busy, or the carriage is broken or something."

The boy unhitched the sorry nag and drove up to the platform where Betty was waiting. His face flushed under his tan as he jumped down to help her in.

"I'm afraid it isn't nice enough for you," he said, glancing with evident admiration at Betty's frock. "I spread that salt bag on the seat so you wouldn't get rust from the nails in that board on your dress. I'm awfully sorry I haven't a robe to put over your lap."

"Oh, I'm all right," Betty hastened to assure him tactfully. Then, with a desire to put him at his ease, "Where is the town?" she asked.

They had turned from the station straight into[49] a country road, and Betty had not seen a single house.

"Hagar's Corners is just a station," explained the lad. "Mostly milk is shipped from it. All the trading is done at Glenside. There's stores and schools and a good-sized town there. Mr. Peabody had you come to Hagar's Corners 'cause it's half a mile nearer than Glenside. The horse has lost a shoe, and he doesn't want to run up a blacksmith's bill till the foot gets worse than it is."

Betty's brown eyes widened with amazement.

"That horse is limping now," she said severely, "Do you mean to tell me Mr. Peabody will let a horse get a sore foot before he'll pay out a little money to have it shod?"

The boy turned and looked at her with something smoldering in his face that she did not understand. Betty was not used to bitterness.

"Joe Peabody," declared the boy impressively, "would let his own wife go without shoes if he thought she could get through as much work as she can with 'em. Look at my feet!" He thrust out a pair of rough, heavy work shoes, the toes patched abominably, the laces knotted in half a dozen places; Betty noticed that the heel of one was ripped so that the boy's skin showed through. "Let his horse go to save a blacksmith's bill!" repeated the lad contemptuously. "I should think[50] he would! The only thing that counts with Joe Peabody in this world is money!"

Betty's heart sank. To what kind of a home had she come? Her head was beginning to ache, and the glare of the sun on the white, dusty road hurt her eyes. She wished that the wagon had some kind of top, or that the board seat had a back.

"Is it very much further?" she asked wearily.

"I'll bet you're tired," said the boy quickly. "We've a matter of three miles to go yet. The sorrel can't make extra good time even when he has a fair show, but I aim to favor his sore foot if I do get dished out of my dinner."

"I'm so hungry," declared Betty, restored to vivacity at the thought of luncheon. "All I had on the train was a cup of chocolate and a sandwich. Aren't you hungry, too?"

"Considering that all I've had since breakfast at six this morning, is an apple I stole while hunting through the orchard for the turkeys, I'll say I'm starved," admitted the boy. "But I'll have to wait till six to-night, and so will you."

"But I haven't had any lunch!" Betty protested vigorously. "Of course, Mrs. Peabody will let me have something—perhaps they'll wait for me."

The boy pulled on the lines mechanically as the sorrel stumbled.

"If that horse once goes down, he'll die in the road and that'll be the first rest he's known in seven years," he said cryptically. "No, Miss, the Peabodys won't wait for you. They wouldn't wait for their own mother, and that's a fact. Don't I remember seeing the old lady, who was childish the year before she died, crying up in her room because no one had called her to breakfast and she came down too late to get any? Mrs. Peabody puts dinner on the table at twelve sharp, and them as aren't there have to wait till the next meal. Joe Peabody counts it that much food saved, and he's got no intentions of having late-comers gobble it up."

Betty Gordon's straight little chin lifted. Meekness was not one of her characteristics, and her fighting spirit rose to combat with small encouragement.

"My uncle's paying my board, and I intend to eat," she announced firmly. "But maybe I'm upsetting the household by coming so late in the afternoon; only there was no other train till night. I have some chocolate and crackers in my bag—suppose we eat those now?"

"Gee, that will be corking!" the fresh voice of the boy beside her was charged with fervent appreciation. "There's a spring up the road a piece, and we'll stop and get a drink. Chocolate sure will taste good."

Betty was quicker to observe than most girls of her age, her sorrow having taught her to see other people's troubles. As the boy drew rein at the spring and leaped down to bring her a drink from its cool depths, she noticed how thin he was and how red and calloused were his hands.

"Thank you." She smiled, giving back the cup. "That's the coldest water I ever tasted. I'm all cooled off now."

He climbed up beside her again, and the wagon creaked on its journey. As Betty divided the chocolate and crackers, unobtrusively giving her driver the larger portion, she suggested that he might tell her his name.

"I suppose you know I'm Betty Gordon," she said. "You've probably heard Mrs. Peabody say she went to school with my Uncle Dick. Tell me who you are, and then we'll be introduced."

The mouth of the boy twisted curiously, and a sullen look came into the blue eyes.

"You can do without knowing me," he said shortly. "But so long as you'll hear me yelled at from sun-up to sun-down, I might as well make you acquainted with my claims to greatness. I'm the 'poorhouse rat'—now pull your blue skirt away."

"You have no right to talk like that," Betty asserted quietly. "I haven't given you the slightest reason to. And if you are really from the[53] poorhouse, you must be an orphan like me. Can't we be good friends? Besides, I don't know your name even yet."

The boy looked at the sweet girl face and his own cleared.

"I'm a pig!" he muttered with youthful vehemence. "My name's Bob Henderson, Miss. I hadn't any call to flare up like that. But living with the Peabodys doesn't help a fellow when it comes to manners. And I am from the poorhouse. Joe Peabody took me when I was ten years old. I'm thirteen now."

"I'm twelve," said Betty. "Don't call me Miss, it sounds so stiff. I'm Betty. Oh, dear, how dreadfully lame that horse is!"

The poor beast was limping, and in evident pain. Bob Henderson explained that there was nothing they could do except to let him walk slowly and try to keep him on the soft edge of the road.

"He'll have to go five miles to-morrow to Glenside to the blacksmith's," he said moodily. "I'm ashamed to drive a horse through the town in the shape this one's in."

Betty thought indignantly that she would write to the S. P. C. A. They must have agents throughout the country, she knew, and surely it could not be within the law for any farmer to[54] allow his horse to suffer as the sorrel was plainly suffering.

"Is Mr. Peabody poor, Bob?" she ventured timidly. "I'm sure Uncle Dick thought Bramble Farm a fine, large place. He wanted me to learn to ride horseback this summer."

"Have to be on a saw-horse," replied Bob ironically. "You bet Peabody isn't poor! Some say he's worth a hundred thousand if he's worth a penny. But close—say, that man's so close he puts every copper through the wringer. You've come to a sweet place, and no mistake, Betty. I'm kind of sorry to see a girl get caught in the Peabody maw."

"I won't stay 'less I like it," declared Betty quickly. "I'll write to Uncle Dick, and you can come, too, Bob. Why are we turning in here?"

"This," said Bob Henderson pointing with his whip dramatically, "is Bramble Farm."

The wagon was rattling down a narrow lane, for though the horse went at a snail's pace, every bolt and hinge in the wagon was loose and contributed its own measure of noise to their progress. Betty looked about her with interest. On either side of the lane lay rolling fertile fields—in the highest state of cultivation, had she known it. Bramble Farm was famed for its good crops, and whatever people said of its master, the charge of poor farming was never laid at his door. The lane turned abruptly into a neglected driveway, and this led them up to the kitchen door of the farmhouse.

"Never unlocks the front door 'cept for the minister or your funeral," whispered Bob in an aside to Betty, as the kitchen door opened and a tall, thin man came out.

"Took you long enough to get here," he greeted the two young people sourly. "Dinner's been over two hours and more. Hustle that trunk inside, you Bob, and put up the horse. Wapley[56] and Lieson need you to help 'em set tomato plants."

Betty had climbed down and stood helplessly beside the wagon. Mr. Peabody, for she judged the tall, thin man must be the owner of Bramble Farm, though he addressed no word directly to her and Bob was too evidently subdued to attempt any introduction, but swung on his heel and strode off in the direction of the barn. There was nothing for Betty to do but to follow Bob and her trunk into the house.

The kitchen was hot and swarming with flies. There were no screens at the windows, and though the shades were drawn down, the pests easily found their way into the room.

"How do you do, Betty? I hope your trip was pleasant. Dinner's all put away, but it won't be long till supper time. I'm just trying to brush some of the flies out," and to Betty's surprise a thin flaccid hand was thrust into hers. Mrs. Peabody was carrying out her idea of a handshake.

Betty stared in wonder at the lifeless creature who smiled wanly at her. What would Uncle Dick say if he saw Agatha Peabody now? Where were the long yellow braids and the blue eyes he had described? This woman, thin, absolutely colorless in face, voice and manner, dressed in a[57] faded, cheap, blue calico wrapper—was this Uncle Dick's old school friend?

"Perhaps you'd like to go upstairs to your room and lie down a while," Mrs. Peabody was saying. "I'll show you where you're to sleep. How did you leave your uncle, dear?"

Betty answered dully that he was well. Her mind was too taken up with new impressions to know very clearly what was said to her.

"I'm sorry there aren't any screens," apologized her hostess. "But the flies aren't bad on this side of the house, and the mosquitoes only come when there's a marsh wind. You'll find water in the pitcher, and I laid out a clean towel for you. Do you want I should help you unpack your trunk?"

Betty declined the offer with thanks, for she wanted to be alone. She had not noticed Mrs. Peabody's longing glance at the smart little trunk, but later she was to understand that that afternoon she had denied a real heart hunger for handling pretty clothes and the dainty accessories that women love.

When the door had closed on Mrs. Peabody, Betty sat down on the bed to think. She found herself in a long, narrow room with two windows, the sashes propped up with sticks. The floor was bare and scrubbed very clean and the sheets and pillow cases on the narrow iron bed, though of[58] coarse unbleached muslin, were immaculate. Something peculiar about the pillow case made her lean closer to examine it. It was made of flour or salt bags, overcasted finely together!

"'Puts every copper through the wringer.'" The phrase Bob had used came to Betty.

"There's no excuse for such things if he isn't poor," she argued indignantly. "Well, I suppose I'll have to stay a week, anyway. I might as well wash."

A half hour later, the traces of travel removed and her dark frock changed to a pretty pink chambray dress, Betty descended the stairs to begin her acquaintance with Bramble Farm. She wandered through several darkened rooms on the first floor and out into the kitchen without finding Mrs. Peabody. A heavy-set, sullen-faced man was getting a drink from the tin dipper at the sink.

"Want some?" he asked, indicating the pump.

Betty declined, and asked if he knew where Mrs. Peabody was.

"Out in the chicken yard," was the reply. "You the boarder they been talking about?"

"I'm Betty Gordon," said the girl pleasantly.

"Yes, they've been going on for a week about you. Old man's got it all figured out what he'll do with your board. The missis rather thought she ought to have half, but he shut her up mighty[59] quick. Women and money don't hitch up in Peabody's mind."

He laughed coarsely and went out, drawing a plug of tobacco from his hip pocket and taking a tremendous chew from it as he closed the door.

Betty felt a sudden longing for fresh air, and, waiting only for the man to get out of sight, she stepped out on the back porch. A regiment of milk pans were drying in the late afternoon sun and a churn turned up to air showed that Mrs. Peabody made her own butter. Betty was still hungry, and the thought of slices of home-made bread and golden country butter smote her tantalizingly.

"I wonder where the chicken yard is," she thought, going down to the limp gate that swung disconsolately on a rusty hinge.

The Bramble Farm house, she discovered, looking at it critically, was apparently suffering for the minor repairs that make a home attractive. The blinds sagged in several places and in some instances were missing altogether; once white, the paint was now a dirty gray; half the pickets were gone from the garden fence; the lawn was ragged and overgrown with weeds; and the two discouraged-looking flower-beds were choked this early in the season. Betty's weeding habits moved her irresistibly to kneel down and try to free a few of[60] the plants from the mass of tangled creepers that flourished among them.

"Better not let Joe Peabody see you doing that," said Bob Henderson's voice above her bent head. "He hasn't a mite of use for a person who wastes time on flower-beds. If you want to see things in good shape, take a look at the vegetable gardens. The missis has to keep that clear, 'cause after it's once planted, she's supposed to feed us all summer from it."

Betty shook back her hair from a damp forehead.

"For mercy's sake," she demanded with heat, "is there one pleasant, kind thing connected with this place? Who was that awful man I met in the kitchen?"

"Guess it was Lieson, one of the hired men," replied Bob. "He came down to the house to get a drink a few minutes ago. He's all right, Betty, though not much to look at."

"You, Bob!" came a stentorian shout that shot Bob through the gate and in the general direction of the voice with a speed that was little less than astonishing.

Betty stood up, shook the earth from her skirt, and, guided by the shrill cackle of a proud hen, picked her way through a rather cluttered barn-yard till she came to a wire-enclosed space that was the chicken yard. Mrs. Peabody, staggering[61] under the weight of two heavy pails of water, met her at the gate.

"How nice you look!" she said wistfully. "Don't come in here, dear; you might get something on your dress."

"Oh, it washes," returned Betty carelessly. "Do you carry water for the chickens?"

"Twice a day in summer," was the answer. "Before Joe, Mr. Peabody, had water put in the barns, it was an awful job; but he couldn't get a man to help him with the cows unless he had running water at the barn, so this system was new last year. It's a big help."

Silently, and feeling in the way because she could not help, Betty watched the woman fill troughs and drinking vessels for the parched hens that had evidently spent an uncomfortable and dry afternoon in the shadeless yard. Scattering a meager ration of corn, Mrs. Peabody went into the hen house and reappeared presently with a basket filled with eggs.

"They'd lay better if I could get 'em some meat scraps," she confided to Betty as they walked toward the house. "But I dunno—it's so hard to get things done, I've about given up arguing."

She would not let Betty help her with the supper, and was so insistent that she should not touch a dish that Betty yielded, though reluctantly. The heat of the kitchen was intense, for Mrs.[62] Peabody had built a fire of corn cobs in the range. Gas, of course, there was none, and she evidently had not an oil stove or a fireless cooker.

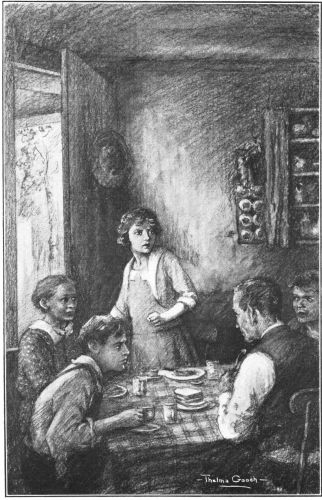

Precisely at six o'clock the men came in.

"They milk after supper, summers," Mrs. Peabody had explained. "The milk stays sweet longer."

Betty watched in round-eyed amazement as Mr. Peabody and the two hired men washed at the sink, with much sputtering and blowing, and combed their hair before a small cracked mirror tacked over the sink. If she had not been very hungry, she was sure the sight would have taken her appetite away. Bob did not come in till they were seated. He had washed outside, he explained, and Betty cherished the idea that perhaps he had acted out of consideration for her.

"What's that?" demanded Mr. Peabody, pointing his fork at a tiny pat of butter before Betty's plate.

There was no other butter on the table, and only a very plain meal of bread, fried potatoes, raspberries and hot tea.

"I—I had a little butter left over from the last churning," faltered Mrs. Peabody. "'Twasn't enough to make even a quarter-pound print, Joe."

"Don't believe it," contradicted her husband. "I told you flat, Agatha, that there was to be no pampering. Betty can eat what we eat, or[63] go without. Take that butter off, do you hear me?"

A sallow flush rose to Mrs. Peabody's thin cheeks, and her lips moved rebelliously. Evidently her husband was practiced at reading her soundless words.

"Board?" he cried belligerently. "What do I care whether she's paying board or not? Don't I have to be the judge of how the house should be run? Food was never higher than 'tis now, and you've got to watch every scrap. You take that butter off and don't let me catch you doing nothin' like that again."

The men were eating stolidly, evidently too used to quarrels to pay any attention to anything but their food. Betty had listened silently, but the bread she ate seemed to choke her. Suddenly she rose to her feet, shaking with rage.

"Take your old butter!" she stormed at the astonished Mr. Peabody. "I wouldn't eat it, if you begged me to. And I won't stay in your house one second longer than it takes to have Uncle Dick send for me—you—you old miserable miser!"

Betty had a confused picture of Mr. Peabody staring at her, his fork arrested half way to his mouth, before she dashed from the kitchen and fled to her room. She flung herself on the bed and burst into tears.

She lay there for a long time, sobbing uncontrollably and more unhappy than she had ever been in her short life. She missed her mother and father intolerably, she longed for the kindness of the good, if querulous, Mrs. Arnold and the comfort of Uncle Dick's tenderness and protection.

"He wouldn't want me to stay here, I know he wouldn't!" she whispered stormily. "He never would have let me come if he had known what kind of a place Bramble Farm is. I'll write to him to-night."

A low whistle came to her. She ran to the window.

"Sh! Got a piece of string?" came a sibilant whisper. Bob Henderson peered up at her from around a lilac bush. "I brought you some bread[65] with raspberries mashed between it. Let down a cord and I'll tie it on."

"I'll come down," said Betty promptly. "Can't we take a walk? It looks awfully pretty up the lane."

"I have to clean two more horses and bed down a sick cow and carry slops to the pigs yet," recited Bob in a matter of fact way, as though these few little duties were commonly performed at the close of his long day. "After that, though, we might go a little way. It won't be dark."

"Well, whistle when you're ready," directed Betty. "I won't come down and run the risk of having to talk to Mr. Peabody. And save me the bread!"

It seemed a long time before Bob whistled, and the gray summer dusk was deepening when Betty ran down to join him. He handed her the bread, wrapped in a bit of clean paper, diffidently.

"I didn't touch it with my hands," he assured her.

Bob's face was shining from a vigorous scrubbing and his hair was plastered tight to his head and still wet. He had so evidently tried to make himself neat and his poor frayed overalls and ridiculous shoes made the task so hopeless that Betty was divided between pity for him and anger at the Peabodys who could treat a member of their household so shabbily.

"I guess you kind of shook the old man up," commented Bob, unconscious of her thoughts. "For half a minute after you slammed the door, he sat there in a daze. Mrs. Peabody wanted to take some supper up to you, but he wouldn't let her. She's deathly afraid of him."

"Did he ever hit her?" asked Betty, horrified.

"No, I don't know that he ever did. He doesn't have to hit her; his talk is worse. They say she used to answer back, but I never heard her open her mouth to argue with him, and I've been here three years."

"Do they pay you well?"

The boy looked at Betty sharply.

"I thought you were kidding," he said frankly. "Poorhouse children don't get paid. We get our board till we're eighteen. We're not supposed to do enough work to cover more'n that. Just the same, I do as much as Wapley or Leison, any day."