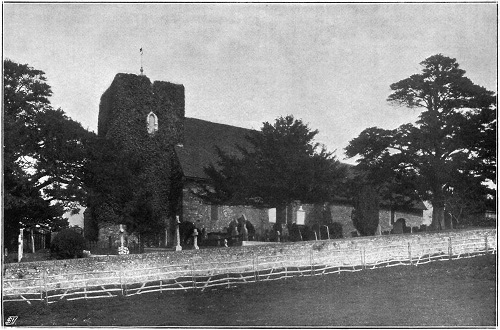

ST. MARTIN'S CHURCH (SOUTH SIDE).

Title: Bell's Cathedrals: The Church of St. Martin, Canterbury

Author: C. F. Routledge

Release date: August 20, 2013 [eBook #43517]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, David Cortesi, David Garcia

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

AN ILLUSTRATED ACCOUNT OF ITS HISTORY AND FABRIC

BY THE

REV. C. F. ROUTLEDGE, M.A., F.S.A.

HON. CANON OF CANTERBURY

LONDON GEORGE BELL & SONS 1898

W. H. WHITE AND CO. LTD.

RIVERSIDE PRESS, EDINBURGH

The associations connected with St. Martin's Church are manifold, and of universal interest. During recent explorations so much fresh matter has been brought to light that it has become almost necessary to re-write the structural description of the building, and to re-consider the date of its foundation. We have endeavoured to lay before our readers a plain summary of the discoveries that have been made, and to elucidate them, as far as possible, from the pages of history—for (in the words of a sound antiquary) "It is every day more true that people want history in guide-books. The tourist is a much better informed person than he used to be, and desires to be still more so."

Charles F. Routledge.

Canterbury, May 1898.

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I.—Introduction | 3 |

| Early Christianity in Britain | 6 |

| Chapter II.—History of the Church | 14 |

| Roman Canterbury | 15 |

| The Saxon Invasion | 21 |

| The Mission of St. Augustine | 24 |

| Baptism of Ethelbert | 31 |

| Bishops of St. Martin's | 34 |

| Chapter III.— | |

| Description of the Church—Exterior | 41 |

| Dedication | 41 |

| Walls | 45 |

| Buttresses | 48 |

| Doorways | 51 |

| Description—Interior | 62 |

| Font | 67 |

| West Wall of Nave | 71 |

| Norman Piscina | 74 |

| Chancel | 76 |

| Chrismatory | 83 |

| Appendix A: List of Rectors | 93 |

| B: Date of Church | 94 |

| C: Eastern Apse, etc. | 99 |

| PAGE | |

| St. Martin's Church (South Side) | Frontispiece |

| East End of Church (Cathedral in Distance) | 2 |

| West Front of Church (Exterior) | 15 |

| Plan of Roman Canterbury | 16 |

| Church in 1840 (Interior) | 39 |

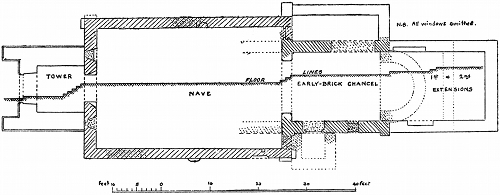

| Plan of Church | 42 |

| S.-E. Angle of Nave (Foundations) | 49 |

| Stukely's Engraving of Church | 50 |

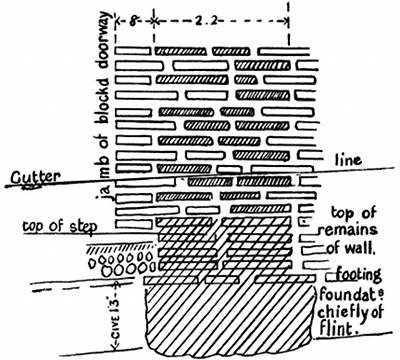

| Foundations (under Panel) | 51 |

| Mrs Parry's Sketch of S.-W. of Chancel | 53 |

| Wall above Adjunct | 55 |

| Saxon Doorway (Interior) | 57 |

| Saxon Doorway (Exterior) | 59 |

| Font | 65 |

| West Wall of Nave | 69 |

| Roman Window | 72 |

| Norman Piscina | 75 |

| Chancel (Photo) | 77 |

| Sedile | 79 |

| Queen Bertha's Tomb | 81 |

| Chrismatory (Shut) | 83 |

| Chrismatory (Open) | 85 |

| St. Martin's (from Old Print) | 91 |

| Tracings of Apse—Appendix C | 99 |

ST. MARTIN'S CHURCH

St. Martin's Church, both from its history and structure occupies a unique position. It is at once the cradle of purely English Christianity, and also a witness of that earlier Christianity which existed in Britain during the period of the Roman occupation. At the recent commemoration of the thirteen-hundredth anniversary of the "coming of St. Augustine," a solemn pilgrimage was made by the Archbishops and Bishops of the Anglican communion to this venerable church as being the one remaining building that could certainly be associated with St. Augustine's preaching; the one spot that without doubt felt his personal presence, whatever we may think of the more or less strong claims put forth on behalf of Ebb's Fleet, Richborough Castle, the ruins of St. Pancras, or the site of Canterbury Cathedral. In a prayer specially written for that occasion occurs the following passage: "We give Thee, O God, hearty thanks that by the preaching of Thy Blessed Servant Augustine, especially in this Holy House in which we are gathered together in Thy Name, Thou didst bring home the truth of the Gospel to our English forefathers, and didst call them out of darkness into Thy marvellous Light."

At the same time, those who were somewhat jealous of the claims of St. Augustine to be considered (as he often is by modern Roman Catholics) "the introducer of Christianity into this island," could point to the fact that, though the ecclesia vetusta of Glastonbury had disappeared, and its later abbey was in ruins, there was here some portion at least of an actual edifice stated by the Venerable Bede to have been [4] "dedicated to the honour of St. Martin, and built of old, while the Romans were still occupying Britain,"—that is, at least 200 years before the advent of the Italian Mission.

Beyond this authentic passage, the proofs of its pre-Augustinian origin can be gathered only from the evidence of archaeological research, upon which we shall enter hereafter: and we must to a great extent depend upon this same evidence for its subsequent history after 597 A.D., though it undoubtedly gave the title of "Bishops of St. Martin's" to some chorepiscopi before the Norman Conquest. The interesting detailed references to individual churches, usually gleaned from ancient Archidiaconal Visitation Registers, are wanting in this case, because the church is, and always has been, exempt from the jurisdiction of the Archdeacon of Canterbury, and we can derive little or no information from the archives at Lambeth, since the Archiepiscopal visitations were, as a rule, merely diocesan and not parochial.

The church is situated on a gently-sloping hill, about a thousand yards due east of the cathedral.

To one looking from the elevated terrace which bounds its churchyard, the panorama is exceedingly picturesque and beautiful. In the distance rises a range of low wooded hills that almost encircle Canterbury, and the conspicuous building of Hales' Place, now the Jesuits' College; while beneath is spread in a hollow the city itself, with its red-tiled roofs interspersed with patches of green, the library and twin towers of St. Augustine's Abbey, and above all the massive cathedral, with "Becket's Crown" in the foreground, and the central "Bell Harry" tower lifting out of the morning's mist its magnificent pinnacles and tracery.

The prospect to Dean Stanley's eye was "one of the most inspiriting that could be found in the world," because of its religious associations, and its reminder that great and lasting good could spring from the smallest beginning. But even in its physical aspect, it is one that, in England at least, can seldom be surpassed; and in olden times the view must have been even more grand and extensive than it is at present, as the church stood in almost solitary grandeur, a permanent brick and stone edifice, above the wooden buildings nestling among thickets of ash—fit emblem of the durability of Divine, as compared with the perishable nature of human, institutions. [5] It must even then have been somewhat of a marvel, on account of the rare mode of its construction, for at that early epoch churches were usually built of hewn oak, and the stone church of St. Ninian's at Whithern is specially mentioned by Bede as having been erected "in a manner unusual among the Britons."

The hill itself, on its northern and eastern sides, is honey-combed with springs, from which down to a late period the city was supplied with water. We can imagine it studded here and there with Roman villas, of which some remains in the shape of tesselated pavements were discovered two or three centuries ago—and crowned possibly by a small Roman encampment; while the church, situated only a few yards off the road to Richborough, would frequently have been seen and admired by soldiers on their march from the sea coast to the great fortress of London, or to the southern stations at Lympne and Dover.

Imagination would picture to itself the reverence felt for so sacred and venerable a spot, yet the fact remains, that up to a recent date the present church was regarded simply as a memorial of the past, a monument erected on the site of the ancient edifice, and reproducing some of its characteristic materials.

Mr Matthew W. Bloxam, for instance, in his preliminary observations to the "Principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture," after giving a sketch of its history and ancient fame, declares that it was rebuilt in the twelfth or thirteenth century, though to all appearance with the materials of the original church. Even Dean Stanley, who cherished for it a fond and enthusiastic love, assures us that, old as the present church is, "it is of far later date than Bertha's Chapel"; while so close an observer of archaeological facts as the late Mr Thomas Wright sweeps away all question as to its traditional continuity by stating boldly that "not a trace of Christianity is found among the innumerable religious and sepulchral monuments of the Roman period in Britain!"

It has been pertinently observed, that "these are conclusions too hastily arrived at; and antiquaries should ever remember that their facts of to-day may receive fresh additions, illustrations, and corrections from the discoveries of to-morrow,"—for since 1880 a series of explorations [6] carried out both above and below ground, and a minute investigation into the character of the existing masonry, have made it more than probable that parts of the original structure mentioned by Bede are still standing, and that the present walls were not only consecrated by the preaching, and actually touched by the hand, of St. Augustine, but may be traced back to a considerably earlier period.

The church has survived its period of apparent disuse after the Roman departure from Britain. It escaped the destructiveness of the Jutes, and the devastation inflicted on Canterbury by the Danish invaders, and has been preserved to us (as we hope to show hereafter) a venerable and genuine relic of Romano-British Christianity. It suffered, indeed, after the Norman Conquest, both from centuries of neglect and also from so-called restoration—becoming at one time what Mr Ruskin would call "an interesting ruin," at another time being plastered and modernised till its ancient features were almost obliterated; but even when enemies were attacking religion from without, and faith grew cold within, the worship of Almighty God was carried on continuously under the shadow of its sacred walls, and on its altar for more than thirteen centuries has been offered the Sacrifice of the Holy Eucharist.

History is silent as to its builder—silent as to the exact date of its foundation. In the simple words of Fuller, "The Light of the Word shone here, but we know not who kindled it."

The mere fact of the existence of such a church involves of necessity the further question as to its immediate origin, whether it be attributed to Roman Christians, or to British converts working under the influence, if not the direct superintendence, of their conquerors. And in discussing this, we must perforce touch lightly the fringe of that well-worn, yet ever-fascinating, inquiry respecting the "earliest introduction of Christianity into Britain"—difficult as it is in ancient traditions and allusions to dissociate fact from fiction, genuine documents from forgeries, history from legend, so eager were the so-called writers of ecclesiastical history to advance their theories, even at the expense of truth.

We may indeed derive some assistance from the fact which we learn from secular historians, that in Apostolic times there was frequent communication between Rome and Britain. [7] After the first conquest of Britain, Roman governors were sent in almost uninterrupted succession, and with them would come, of course, legions and cohorts, perhaps even some of the Prætorian soldiers in whose company the apostle St. Paul lived for a time during the reign of Nero. British chieftains were taken prisoners to Rome, and their sons left there as hostages. Some few Romans, too, such as Seneca, the brother of Gallio, held large possessions in the island. People and places connected with Britain are mentioned by the Roman poets Martial and Juvenal, and by the historian Tacitus. With such constant intercourse as there must have been, stories at least and reports of Christianity would have been brought over to the island as early as the first century, and there were probably individual Christians either among the numerous soldiers quartered here, or among returned captives. We may be doubtful whether at so early an epoch, save perhaps in a few exceptional cases, they formed themselves into regular societies or congregations, and it is not likely that they erected for themselves permanent places of worship. No such antiquity as this can be claimed even for the remains of the Roman church found amid the ruins of Silchester; and church building, as it is generally understood, did not begin at Rome before the fourth century, and it would have taken a few years to spread thence to Gaul, and from Gaul to Britain.

That Christianity did exist in Britain from early times, in a more or less settled form, is no longer a matter of dispute. In the words of Gildas, "Christ, the true Son, offered His rays (i.e. His precepts) to this island, benumbed with icy coldness, and lying far distant from the visible sun. I do not mean from the sun of the temporal firmament, but from the Sun of the highest arch of heaven, existing before all time." Relative to this fact there are a few statements of ancient writers given at dates which are precisely known, during the third century and subsequently: and these statements are familiar to all students, so that they need not be recapitulated at any length. Tertullian (in 208), Origen (in 239), Eusebius (about 320), allude in unmistakable terms to the existence of British Christianity, however rhetorical the passages may appear.

There is, too, the account of the martyrdom of St. Alban, recorded at length in the pages of Bede, which cannot be treated as an idle legend. It took place at Verulam during [8] the persecution under Diocletian and Maximian, somewhere about 303. Although the record does not rest on contemporary evidence, the story was fully believed at Verulam itself as far back as 429 A.D. (i.e. within a hundred and twenty-six years of the traditional date) and is accepted by Constantius in the fifth, as well as by Gildas and Venantius Fortunatus in the sixth, century—while the difficulty of believing in the possibility of a persecution in Britain, which was then under the kindly and tolerant rule of Constantius, seems to us purely imaginary. It is hardly probable that Constantius would have been able to restrain the persecuting zeal of subordinates, in face of the superior authority of Maximian, who is said by Gibbon to have "entertained the most implacable aversion to the name and religion of the Christians." Dean Milman sees no reason for calling in question the historic reality of the event, and suggests that the probable fact of St. Alban being a Roman soldier may have been an additional reason for his not having received the "doubtful protection" of Constantius.

But after this period we come to even surer ground—and from the beginning of the fourth century we find a Christian church fully organised in Britain. At the Council of Arles (in 314) three British bishops were present, whose very names and dioceses are recorded—viz. Eborius of York, Restitutus of London, and Adelphius of Caerleon-on-Usk or Lincoln. British bishops took part in the Councils of Sardica (347) and Ariminium (359), and probably also in the great Council of Nicæan (325). We have also testimony to a regular organisation in the pages of St. Chrysostom, Jerome, Theodoret, etc., ranging from the end of the fourth to the beginning of the fifth century. The conversion of the Southern Picts by Ninian, Bishop of Whithern—the visits of Germanus, Bishop of Auxerre, and Lupus, Bishop of Troyes, to Verulam and elsewhere—the missions of Palladius and Patrick to Ireland—the pilgrimages of British Christians to the Holy Land—and even the fact of the Pelagian heresy being propagated by a Briton—all equally bear witness to the prevalence of Christianity in these early centuries, so that Gildas may not be drawing entirely on his imagination when he describes the Church as "spread over the nation, organised, endowed, having sacred edifices and altars, the three orders of the ministry and monastic institutions, [9] embracing the people of all ranks and classes, and having its own version of the Bible, and its own ritual."

Now, in view of these facts, many writers have not unnaturally endeavoured to trace the introduction of Christianity to some great man, or to some special effort. It seemed so impossible that a complete organisation should have sprung up without a definite founder—and claims have been made on behalf of St. Peter, St. John, Simon Zelotes, and Aristobulus, though without even a shadow of probability to recommend them. Something, indeed, may be urged in favour of the pious belief that St. Paul made his way to this island between his first and second imprisonment. St. Clement of Rome says that he preached "to the extreme boundary of the West"; St. Chrysostom, that from Illyricum "he went to the very ends of the earth"; and Theodoret, that the Apostles, including St. Paul, "brought to all men the laws of the Gospel, and persuaded not only the Romans ... but also the Britons, to receive the laws of the Crucified," while the theory has received the support of Soames, Bishop Burgess, Collier, and other ecclesiastical writers—even Bishop Lightfoot thinking it "not improbable that the western journey of St. Paul included a visit to Gaul," from which an extension of his journey to Britain would not of course be impossible. It is true, too, that (as with the closing years of St. Peter) there is an interval of time after St. Paul's first imprisonment (variously estimated as from four to eight years) which cannot be accounted for; and that the mere fact of silence as to St. Paul having preached in this island need not be unduly pressed, because Britain was at that time an obscure and unimportant province at the extremity of the Roman empire. But the critical historian cannot accept what is, after all, a mere conjecture, unsupported by long tradition or any positive evidence—any more than he can lay stress upon what is only a curious coincidence, between the mention by Martial of Claudia, a British lady in Rome newly married to Pudens—and the salutation of "Claudia and Pudens" in St. Paul's Second Epistle to Timothy, written from Rome. The theory as to this identification, is based on a string of hypotheses, called by Dean Farrar "an elaborate rope of sand." Similar remarks would also apply to the legend that the father of Caractacus, King of the Silures, called Bran the Blessed, was converted to Christianity when captive at [10] Rome (A.D. 51-58) and introduced the Gospel into his native country on his return, though there is a tradition to that effect incorporated into the Welsh Triads, which are probably none of them earlier than the fourteenth century. Tacitus (Ann. xii. 35) only mention the "wife, daughter and brothers" of Caractacus as having surrendered with him, and he would scarcely have omitted the "father," if he had shared their captivity.

There is, indeed, one story which we are very loath to surrender—viz. the story that St. Joseph of Arimathea was sent, with twelve companions, to Britain by the Apostle St. Philip (about 63 A.D.) settled in the Isle of Avalon or Glastonbury, and founded there a monastery, striking his staff into the earth, and making it burst, like Aaron's rod, into leaf, and bloom with the blossom of the Holy Thorn. This legend, indeed, is not actually recorded in writing before William of Malmesbury in the twelfth century, but it may have rested on earlier local tradition. We know that Glastonbury was a Christian sanctuary before the Saxons conquered the district, and Bishop Browne (of Bristol) reminds us that Domesday Book speaks of the "twelve hides (the portions of land said to have been granted to St. Joseph's companions) which never have been taxed," and that at the Council of Basle in 1431 the English Church claimed and received precedence as founded by St. Joseph of Arimathea in Apostolic times. The tradition, too, that the first British Christians erected at Glastonbury a church made of twigs or wattlework (called afterwards the Vetusta Ecclesia, and only destroyed by fire in 1184) has been illustrated, if not confirmed, by recent discoveries at Glastonbury (among the ruins of British houses burned with fire) of baked clay showing the impress of wattlework. There is no known fact connected with the life of St. Joseph of Arimathea that would negative the conclusion that he might have been sent to Britain as a missionary.

Some difficulties would be solved if we could believe the tale about Lucius, a British King, having requested Eleutherius, Bishop of Rome from 171 to 185, to send someone to teach his people Christianity. This legend is recorded by Bede, partly confirmed by Nennius, and accepted by William of Malmesbury. And the name of Lucius has been variously associated with Winchester, Gloucester, Llandaff, St. Peter's [11] Cornhill, St. Martin's Church, St. Mary's Church in Dover Castle, and even the church on the site of Canterbury Cathedral. The story probably owed its origin to a note in Catalogus Pontificum Romanorum, but it does not occur in the earlier catalogue written about 353, and was added to it nearly two hundred years later, with the object apparently of connecting the primitive growth of Christianity in Britain with the See of Rome. Though this ancient story cannot be considered as historical, it is not altogether impossible that it had some foundation in an application from a British prince to receive instruction in Christianity about the end of the second century: and this would give point to the statement of Tertullian (in 208) that "the kingdom and name of Christ were venerated in districts of Britain not yet reached by the Romans."

There is much force in the conclusion arrived at by Bishop Browne, that, "with Gaul so close at hand, its people so near of kin, its government so identical with theirs, the Britons would learn Christianity from, and through, Gaul," to whose church ours should occupy the position of a younger sister. At the same time, this fact must be considered—viz. that the earliest bishops mentioned as having attended the Council of Aries are anterior in point of time to the dated bishops in a great majority of the dioceses of Gaul adjacent to this island, so that we should not too readily abandon the possible belief that there was an independent church in Britain, though we know not when or by whom it was founded.

It only remains in this chapter to mention a few of the traces of British Christianity as supplied by monumental or other evidence well attested. We may believe, with Bede, that over St. Alban's tomb at Verulam, "when the peace of the Christian times returned, a church was built of wonderful workmanship, and worthy of that martyr"; and three churches are spoken of at Caerleon, two of which were dedicated to Julius and Aaron, said to have been martyred in the Diocletian persecution; another at Bangor Iscoed, near Chester; besides one at Candida Casa or Whithern, and the Vetusta Ecclesia at Glastonbury, our own church of St. Martin, and the foundations of that lately discovered in Roman Silchester. This is a fair number, even if we pass over for the time any possible claims to Roman origin on the part of Brixworth, Lyminge, Reculver, and St. Mary's Church in Dover Castle, all of which are ascribed [12] to the Saxon period by Mr J. T. Micklethwaite in his interesting paper read at Canterbury in 1896 before the meeting of the Royal Archæological Institute—though we need not allow that his reasoning is in all cases indisputable.

We possess, too, some sepulchral monuments and inscriptions (not at present very extensive, but probably greatly to be multiplied as fresh excavations and explorations are made) at St. Mary le Wigfred, Lincoln, Caerleon, and Barming, and the Chi-Rho monogram (which was first introduced as a Christian symbol by the Emperor Constantine at the beginning of the fourth century) on various rings, stones, and tesselated pavements, also crosses on pavements at Harpole and Harkstow, and various Christian formulas such as "Vivas in Deo," "In pace," etc.

The dogmatism and incredulity of antiquaries may well be illustrated in the case of Mr T. Wright ("The Celt, the Roman, and the Saxon"). He disbelieves in all traces of Christianity said to be found among monuments of the Roman period; and his scepticism is thorough and comprehensive—more extreme in our opinion than the credulity which he denounces. He allows, indeed, the possibility of there having been some individuals among recruits and merchants and settlers who had embraced the truths of the Gospel, but with a qualification. He thinks the early allusions made by Tertullian, Origen, Jerome, and others are "little better than flourishes of rhetoric." The list of British bishops at the Council of Aries seems to him "extremely suspicious, much like the invention of a later period." He disbelieves the whole account of the Diocletian persecution having extended to Britain, even partially or locally. He doubts the authenticity of the work attributed to Gildas, though his objections have been met and set at rest, for most people, by such competent authorities as Dr Guest and others. But, as an instance of what I cannot but designate as far-fetched scepticism, we may note his explanation of the Christian monogram found on the pavement of a Roman villa at Frampton. He does not question its genuineness, but explains it by surmising that the beautiful villa had probably belonged to some wealthy proprietor, who possessed a taste for literature and philosophy, and with a tolerant spirit, which led him to surround himself with the memorials of all systems, had adopted, among the rest, that which he might learn from some [13] of the imperial coins to be the emblem of Christ—Jesus Christ standing, in his eyes, on the same footing as Pythagoras or Socrates.

Surely we have here a warning against the dogmatism which is often indulged in by archaeological experts, and it may be extended from monuments and remains to legends and traditions, which are often of great weight, even when they cannot be historically proved. It is not unnatural that many people should have become impatient and wearied of such purely negative criticism.

Before coming to the more immediate history of St. Martin's Church, we must say a few words about the Roman occupation of Canterbury, and the events preceding the landing of St. Augustine.

The city is mentioned in the second "iter" of Antonine's Itinerary, under its ancient name of Durovernum or Duroverno, a word supposed to be compounded of dour, "water," and vern, which has been variously interpreted to mean "temple," "marshes," or "alders."

Its position is described as fifty-two miles distant from London, fourteen from Dover, sixteen from Lympne, and twelve from Richborough; and the road from London to each of these last-named places divided itself at this point into three, crossing the ford of the River Stour, so that it would be a natural station for troops on the march.

The Egyptian geographer, Ptolemy, apparently writing about the middle of the second century, gives Durĕnum as one of the three cities of the Cantii; while in the fragmentary map known as the Tabula Peutingerii (called so from Conrad Peutinger, in whose library it was found, and supposed to have been compiled about the time of the Emperor Theodosius the younger) it is put down as "Buroaverus," evidently a corruption of copyists, with the conventional mark usually attached to a city or fortress of considerable size.

Horsley, in his Britannia Romana, suggests that Canterbury was the fortress taken by the seventh legion after Julius Cæsar's second landing; but this is purely conjectural, and founded on the mistaken belief that Cæsar landed at Richborough. Even though the fact is not directly mentioned in the "Notitia Imperii" (enumerating the garrisons of the Empire), it is far from impossible that at some period or other [15] during the first four centuries there were some Roman soldiers quartered for a considerable time at Canterbury. If not wholly or partially surrounded by walls (which is more than probable), the city was at any rate defended by earthworks, and we have evidences of a fortified position held by the Romans immediately above the Whitehall marshes, north-west of the city; and of a stronghold or fort of masonry on the so-called Scotland Hills overlooking the Reed Pond.

Whether much stress be laid on this or not, one fact is absolutely certain, that the extensive Roman foundations discovered by Mr Pilbrow while constructing the deep-drainage system of the city in 1868, the number of Roman tesselated pavements, coins, and other relics found at various periods, and the traces of Roman cemeteries, abundantly prove that Durovernum developed at length into a large and populous place.

Among various discoveries may be enumerated Samian ware, coffins, conduit pipes, rings, bottles, urns, Upchurch pottery, spoons, arrowheads, and skeletons, as well as indications of a [16] large iron foundry; and a long list of gold ornaments includes portions of châtelaines, fibulæ, studs, purses, combs; and (what is especially germane to this history) a purple enamelled Roman brooch of circular shape, and a looped Roman intaglio, found near St. Martin's Church. All these appear to show that the Roman occupation of Canterbury was at once complete and continuous.

Of Roman secular buildings above ground there are indeed no remains, and the ancient city must be traced some eight feet below the present level. But in St. Margaret's and in Sun Street there are undoubted evidences of Roman walls. It is not impossible that, when first occupied, the town of Durovernum was very small, consisting of a citadel surrounded by earth mounds, and that it gradually extended itself afterwards beyond its original limits.

The elegance of some of the enamelled brooches and rings, together with other discoveries, point to a considerable degree of luxury and civilisation. One writer fancied that he detected the remains of raised seats for spectators at a circus or amphitheatre in the so-called Martyr's Field, near the London, Chatham, and Dover Railway Station.

The exact dimensions and extent of the city are open to some doubt. Mr T. Godfrey Faussett fixed the site of the four gates as follows:—(1) Worth Gate, at the end of Castle Street; (2) Riding Gate, on the old road to Dover; (3) North Gate, near the present south-west tower of the Cathedral; and (4) a gate at the Ford, in Beer Cart Lane. Tracing the walls that lie between them, he concluded that the shape of the Roman town was an irregular oval, different from the usual square or rectangle, but accounted for by the low swampy ground that surrounded it, and not unlike the shape of Verulam and Anderida. The city's length, according to his plan, must have been nearly exactly double its breadth—namely 800 yards by 400.

For actual existing buildings that may possibly have been connected with

the Roman occupation, we must have recourse to the churches, which

supply us with traces of early Christianity more rich and numerous than

that of any other town in England. These are to be found in St. Martin's,

St. Pancras, and a church on the site of the present Cathedral. Detailed

investigation of them would bring us to some controversial points, for

[17]

[18]

the discussion of which one must be thoroughly conversant with all the

recent discoveries and explorations that have been made. But we may,

at any rate, state the documentary evidence.

With regard to St. Martin's Church, we have already quoted the statement made by the Venerable Bede.

The same historian also informs us that Augustine, "when the Episcopal See was granted to him in the royal city, recovered therein, supported by the king's assistance, a church which, he was informed, had been built by the ancient work of Roman believers; and consecrated it in the name of our Holy Saviour, God and Lord, Jesus Christ."

He does not mention St. Pancras, but we are indebted for an account of it (evidently based on older traditions) to Thorn, a Benedictine monk of St. Augustine's, in the fourteenth century. "There was not far from the city towards the east, as it were midway between the Church of St. Martin and the walls of the city, a temple or idol-house, where King Ethelbert, according to the rites of his tribe, was wont to pray, and with his nobles to sacrifice to his demons, and not to God—which temple Augustine purged from the pollutions and filth of the Gentiles; and having broken the image which was in it, changed it into a church, and dedicated it in the name of the martyr St. Pancras; and this was the first church dedicated by St. Augustine." St. Pancras, a Roman boy of noble family, was martyred under Diocletian at the age of fourteen, and was regarded as the patron saint of children. Dean Stanley reminds us that the monastery of St. Andrew on the Cœlian Hill, from which St. Augustine came, was built on the very property which had belonged to the family of St. Pancras, so that the name would have been quite familiar to the Roman missionary.

Now, these are the written traditions with regard to the early churches of Canterbury. How far, then, are they confirmed by actual discoveries? A great deal of light has been thrown upon the point within the last few years. In the course of explorations conducted in the Cathedral crypt by Canon Scott Robertson, Dr Sheppard, and myself, there was found at the base of the western wall some masonry of Kentish ragstone covered by a smooth facing of hard plaster, manifestly older than the columns of Prior Ernulf's vaulting shafts, and [19] than Lanfranc's masonry in the upper portion of the wall. We may, therefore, consider it as more than probable that a portion of this wall (which was laid bare to the length of twenty-seven feet) formed part of the original building granted to St. Augustine by King Ethelbert.

The ruins of St. Pancras have also been carefully and minutely investigated, and traces have been found there of both an undoubtedly Roman, and a somewhat later, building. Though Mr J. T. Micklethwaite has satisfied himself that the present foundations can only be assigned to an Early Saxon period, asserting, indeed, that "we have evidence that it was used by St. Augustine himself," his arguments can not yet be accepted as conclusive, and much may be said on the other side.

We may observe an apparent difference in the shapes of these three churches. Of St. Martin's we shall speak at length hereafter, but we may note that, besides the different width of the nave and chancel, there is no sign of an apse at the west end, while indications of an eastern apse are more or less conjectural. In the plan of the original Cathedral, conjecturally drawn by Professor Willis from Edmer's description, and which he supposes was the old Christian church preserved by St. Augustine, the building was a plain parallelogram, with apses at both the east and west ends. The choir was extended into the nave, enclosed by a high breast-wall, and about the middle of the church (on the north and south) were two towers, the tower on the south side containing an altar, and also serving as a porch of entrance. This church was built, according to Edmer, "Romanorum opere," and in imitation of the Church of St. Peter, chief of the apostles, meaning the Vatican Basilica.

In St. Pancras there is a tower, or square porch, at the west end, and two transepts of the same size branching off from the centre of the nave, while the foundations of the chancel walls start farther in than those of the nave wall; and, at the distance of twelve or thirteen feet from the point of junction, can be detected the commencement of an apse. In this church we have discovered no doorways, except the one at the west end through the tower, and the possible indications of one leading into the southern transept, where we may yet see remains of an interesting altar (size, 4 ft. 4 by [20] 2 ft. 2), which, if not the identical one that St. Augustine erected on the site occupied by the idol of Ethelbert, is at any rate a very ancient memorial of it.

It is worthy of remark that these three churches are situated in almost a direct line from east to west, and were all outside the Roman walls, and apart from the Roman cemeteries. The orientation of all of them is nearly perfect.

In treating of the time between the departure of the Romans in 410 and the mission of St. Augustine in 597, we must remember that history is almost silent; only a meagre outline of facts is given us, and these often of a very contradictory character. We must endeavour, however, to give a brief sketch of this intervening period as far as it concerns the south-eastern portion of our island, and of necessity, therefore, includes the fortunes of Canterbury. To account for the comparatively easy conquest of Britain in the middle of the fifth century, we are bidden to remember that the Roman rule, which had at first been of a civilising character, and had fostered commerce and the various arts, had in its latter period degenerated into corruption. Town and country alike were crushed by heavy taxation, aggravated by the arbitrary and ruinous oppression of the tax-gatherers. The population, too, had gradually declined as the estates of landed proprietors grew larger. Moreover, the Roman government had disarmed and enervated the people, and, by crushing all local independence, had crushed all local vigour, so that men forgot how to fight for their country, and constant foreign invasions found them without hope or energy for resistance.

Bishop Stubbs (in his "Constitutional History") remarks on the great contrast between the effects of the Roman occupation in Gaul and Britain. Gaul had so assimilated the cultivation of its masters, that it became more Roman than Italy itself, possessing more flourishing cities and a more active and enlightened church, as well as a Latin language and literature; while Britain, though equally under Roman dominion, had never become Roman. When the legions were removed, any union that may have existed between the two populations absolutely ceased. The Britons forgot the Latin tongue; they had become unaccustomed to the arts of war, and had never learnt the arts of peace, while [21] their clergy lost all sympathy with the growth of religious thought. They could not utilise the public works, or defend the cities of their masters, so that the country became easy to be conquered just in proportion as it was Romanised.

After a continuance of internal dissensions, described by Gildas in high-flown and rhetorical language, the native chiefs were once more troubled by piratical attacks, and by their Irish enemies. It was impossible to resist this combination by the forces of the province itself, and so, imitating that fatal policy of matching barbarian against barbarian, which led to the fall of the Roman Empire, the Britons summoned to their aid a band of English or Jutish warriors, to whom they promised food, clothing, pay, and grants of land. And this application for help was not unnatural, as there was probably in many of the towns a leaven of Teutonic settlers, especially along the "Saxon shore," who had maintained a steady intercourse with their kinsmen that remained behind, and some of whom may have been German war-veterans, pensioned off by successive Roman emperors.

The statement by Mr Green that the "History of England begins in 449 with the landing of Hengist and Horsa in the Isle of Thanet" is principally applicable to the Kingdom of Kent, for the Jutes had been preceded by Angles in the north, who seem to have been for some time in more or less undisputed possession of the country between the mouth of the Humber and the wall of Antoninus; and the eastern shores of the island were to a great extent colonised by kindred tribes.

The leaders in this expedition naturally sent for reinforcements after their first successes, and it is probable that their followers were at the beginning contented with a settlement in the Isle of Thanet, where they would be secure against any possible treachery from the Britons, and would be near the sea, whence their compatriots would bring them aid if necessary—yet they gradually advanced, and their subsequent exploits culminated in the victory of Aylesford, six years after their landing, and the alleged death of the warrior Horsa.

This victory, it is said, was followed in Kent by a dreadful and unsparing massacre. The Jutes, merciless by habit, were provoked by the sullen and treacherous attitude of their victims, [22] and destroyed all the towns which they captured. Some of the wealthier landowners of Kent fled in panic over the sea, but many of the poorer folk took refuge in forests, or escaped to Wales and Cornwall. Famine and pestilence devoured some, others were ruthlessly slaughtered. There was no means of escape, even by seeking shelter within the walls of their churches, since the rage of the English burnt fiercest against the clergy. The priests were slain at the altar, the churches burnt, and the peasants rushed from the flames, only to be cut down by the sword.

The above is the generally accepted theory, but probably in many respects it is an exaggerated account, such as is common in the traditions of conquered nations, and should be accepted with very great hesitation.

A few years after the victory of Aylesford, Richborough, Lympne, and Dover fell permanently into the hands of the invaders.

The Jutes, with whom Kent is more immediately concerned, were the northernmost of the three tribes of the Germanic family. They lived in the marshy forests and along the shores of the extreme peninsula of Denmark, which retains the name of Jutland to the present day. We know little of their early history, but it is probable that the Jutes, the Angles, and the Saxons, although speaking the same language, worshipping the same gods, and using the same laws, had no national or political unity—and the separate expeditions, resulting in the final conquest of Britain, were unconnected with one another, though almost continuous in point of time. It is certain that the invaders to a large extent declined to amalgamate with the people whom they had conquered; nor would they consent to tolerate their existence side by side. A few may have lingered on in servitude round the homesteads of their conquerors, but a large portion of the survivors (as we have said) took refuge in Western Britain.

As to their religion, we know that England for nearly a century and a half was almost entirely a heathen country, represented on a map as a black patch between the Christians of Gaul and the Christian Celts of our island. While the Goths, Vandals, Burgundians, and Franks in other parts of the Roman empire soon became Christians, the English went on worshipping their false gods, such as Woden, Thor, and others, [23] who gave their names to river, homestead, and boundary alike, and even to the days of the week.

And yet their mythology was not so degraded but that it presented in fragments the outlines of Christianity. This was recognised afterwards by Pope Gregory's wise counsel to Augustine not to interfere needlessly with the religious faith of his pagan converts, but allow them to worship the old objects under new names; not to destroy the old temples, but to consecrate them as Christian churches, the reason being that "for hard and rough minds it is impossible to cut away abruptly all old customs, because he who wishes to reach the highest place must ascend by steps and not by jumps." Kemble (in his "Saxons in England") gives an insight into the character of their religion, and accounts for the ultimately rapid spread of Christianity among them by this process of adaptation, and also because the moral demands of the new faith did not seem to the Saxons more onerous than those to which they were previously accustomed. Bede not unnaturally reproaches the Britons for refusing or failing to convert their enemies to the true faith, whereas it had been the habit elsewhere for the Christian priesthood to act as mediators between barbarian invaders and the conquered.

Canterbury seems to have been at once abandoned by the vanquished, because it would have been utterly untenable owing to its position on the main road between the sea-fortresses of Kent and the rest of the kingdom; and it was probably at first unoccupied by the Jutes, so that it remained for many long years uninhabited and desolate. We know that the very name of Durovernum had become forgotten, while the fortresses of the coast still retained their former names without any radical change. This opinion is confirmed by the fact that, while numerous Saxon cemeteries have been found in East Kent—such as at Ash, Kingston, Sarre, etc.—none whatever have been discovered in the district immediately round Canterbury, though the soil has been thoroughly and completely turned over for the purposes of road and drain making, as well as for pits of gravel, sand, and chalk. Moreover, not a single street of our city is on the site of a Roman street, with the partial exception of Watling Street and Beer Cart Lane.

Probably in the early days of the Jutish conquerors [24] Richborough would have been their headquarters, as being conveniently near the coast; and it was not till they had pretty well settled themselves in the country that they fixed on a new capital, to which they gave the name of Cantwarabyrig, "the city of the men of Kent."

The curtain of Christian history is not again lifted over England till the year 597, when, according to the "Anglo-Saxon Chronicle," "Gregory the Pope sent into Britain very many monks, who gospelled God's Word to the English folk." And, connected closely as the mission was with St. Martin's Church, we must enter into it with some detail, though it is an oft-told story, and is familiar even to those who have never visited Canterbury, and know little else of ecclesiastical history.

Gregory had been appointed at an early age "Praetor of the City" by the Emperor Justin II., and had afterwards been sent by Benedict I. and Pelagius II. to Constantinople, where he resided for many years as the representative of the Bishop of Rome. He returned to Rome in 585, and it was near this date that the event occurred which we are now about to narrate. He was at that time about forty-five years old, a monk in the great monastery of St. Andrew on the Cœlian Hill, which he had himself founded; and we may believe that he was remarkable, then as afterwards, for his comprehensive policy, his grasp of great issues, and his minute and careful attention to details in secular as well as religious matters. The vast slave trade prevalent in Europe was to him a special cause of sorrow; and for the purpose of trying to check the evil, to redeem the captives, or to mitigate their sufferings, he was wont to resort to the market-place in Rome whenever a new cargo of slaves arrived from distant countries.

One day, on his visit to the Forum of Trajan, he observed some (traditionally, three) boys with fair complexions, comely faces, and bright flowing hair, exposed for sale. When he saw them, he asked from what region or country they had been brought, and on being told "from the island of Britain, whose inhabitants were of similar appearance," inquired whether these islanders were Christians, or still involved in pagan errors. The answer was, "They are pagans." Then he heaved deep sighs from the bottom of his heart and said: "Alas! that men [25] of such bright countenance should be subject to the author of darkness, and that such grace of outward form should hide minds void of grace within." Being told further, in answer to his question, that they were called Angles, "Rightly so called," said he, "for they have the faces of Angels, and are meet to be fellow-heirs with the angels in heaven. But what is the name of the province from which they were brought?" "Deira" (the land between the Tees and the Humber), said the merchant. "Right again," was the reply, "from wrath (de ira) shall they be rescued, and called to the mercy of Christ." Lastly, on hearing that the king of that province was named Ælla, he exclaimed: "Alleluia! the praise of God the Creator shall be sung in those parts."

Gregory went from the Forum to the Pope (probably Pelagius), and asked him to send to the English nation some minister of the word, by whom the island might be converted to Christ, saying that he himself was prepared to undertake this work with the assistance of the Lord. But though the Pope gave his consent, so great was the love of the Roman people for him, that he was obliged to start from the monastery in the strictest secrecy, accompanied by a few of his comrades. When his departure became known, the people were much excited, and, dividing themselves into three companies, assailed the Pope as he went to church, crying with a terrible voice "What hast thou done? Thou hast offended St. Peter, thou hast destroyed Rome, since thou hast sent Gregory away." The Pope, greatly alarmed, despatched messengers with all possible speed to recall Gregory to Rome. He had already advanced three days along the great northern road when the messengers arrived, and led him back to the city.

Gregory afterwards become abbot of the monastery, and, much against his will, was elected Pope on the death of Pelagius, and consecrated on September 3, 590.

But he never forgot his project for the conversion of England, and in 595 wrote to Candidus, a priest in Gaul, directing him to use part of the Papal patrimony to purchase English youths of the age of seventeen or eighteen years, to be educated in monasteries, no doubt with the intention of sending them afterwards as missionaries to their countrymen.

It was not, however, till the following year that he was able to fulfil the desire of his heart, when he selected as the head of a [26] mission to England Augustine, Prior of St. Andrew's Monastery, and charged him with letters to Vigilius, Bishop of Arles, to the Kings Theodoric and Theodebert, and to their grandmother, Queen Brunehaut or Brunichild. In the course of their journey, however, this missionary band was so terrified by the rumours they heard that they became faint-hearted on the road, and despatched Augustine to Rome to beg that they might be recalled. But Gregory would have no withdrawal, and sent him back again with letters of encouragement to his colleagues. So they went on, crossed the sea from Boulogne, and, either in the autumn of 596 or the early spring of 597, landed in England, somewhere in the Isle of Thanet.

The King of Kent at this time was Ethelbert, who was the most powerful King in England (reckoned by some as the third Bretwalda), and had established his supremacy over the Saxons of Middlesex and Essex, as well as over the English of East Anglia as far north as the Wash: and had driven back the West Saxons when, after an interval of civil feuds, they began again their advance along the Thames, and marched upon London. Ethelbert began to reign in 561. He was believed to be great-grandson of Eric, son of Hengist, a "son of the ash-tree." He had previously, when quite young, been engaged in an encounter with Ceawlin, King of Wessex, and been defeated at Wimbledon. But Ceawlin himself was worsted in 591 by his nephew Cedric at Woodnesbury, in Wiltshire; and Ethelbert had now asserted his supremacy.

Unlike most English kings then, and for a long time afterwards, he had married a foreign wife, Bercta, or Bertha, daughter of Charibert, one of the kings of the Franks in Gaul, reigning in Paris. Bertha was a Christian, and, as Ethelbert was a heathen, it had been expressly stipulated, either by her father, or by her uncle and guardian Chilperic, King of Soissons, that she should enjoy the free exercise of her religion, and keep her faith inviolate.

Bertha is one of the most interesting and romantic characters in English history—our first Christian Queen—possessing apparently much the same influence over Ethelbert as Clotilda had done over Bertha's great ancestor, Clovis, and (though not able to convert him yet) without doubt disposing him [27] favourably towards the new religion. It is variously conjectured that she was born about 555 or 561. We do not know much of her early life, but St. Gregory of Tours, in his contemporary pages, informs us that King Charibert took to wife, Ingoberga, by whom he had a daughter, who afterwards "married a husband in Kent." Charibert was not a man of good character, and being annoyed with his wife Ingoberga, he forsook her, and married Merofledis, the daughter of a certain poor woolmaker in the queen's service. The unfortunate queen was thereupon obliged to fly, and, taking up her abode at Tours, devoted herself to a life of religious seclusion, bringing up her daughter Bertha under the direction of Bishop Gregory, and preparing her thus for the part she afterwards filled in the conversion of England. We may mention here that King Charibert, after the death of Merofledis, proceeded to marry her sister, for which outrage he was solemnly excommunicated by St. Germanus; and, refusing to leave her, "perished, stricken by the just judgment of God." Ingoberga died at the age of seventy, in the year 589.

Bertha was accompanied to England by her chaplain, Liudhard, who was sent with her to preserve her faith. Of Liudhard we know very little that is certain. His name is variously spelt Leotard, Liudhard, or even Liupard. By some he was supposed to be Bishop of Senlis, but his name does not occur in the list of bishops of that see, though it is inserted with a mark of interrogation in Gow's Series Episcoporum. By others he has been entitled Bishop of Soissons, though without any documentary authority. We may probably accept the notion that he was one of the "wandering bishops" who were very numerous at a later period in Gaul. Gocelin calls him the "faithful guardian of the queen." It seems strange that he, who could speak a language akin to that of the English, did not convert some of them previously to the coming of Augustine, who only spoke Latin, and was obliged to converse with them at first through the medium of an interpreter.

However that may be, he was undoubtedly the "harbinger" of Augustine, and had probably endeavoured to stir up his brother prelates of Gaul on behalf of the English, since Pope Gregory, writing at this time to Theodoric and Theodebert, severely condemns the supineness of the Gallic Church, in [28] neglecting to provide for the religious wants of their neighbours, whose "earnest longing for the grace of life had reached his ears."

We may mention here that a coin was found some years ago in the churchyard of St. Martin's, with the inscription, "Lyupardus Eps"—and the Rev. Daniel Haigh (in his notes on the Runic monuments of Kent) says that he has no doubt that this coin belongs to Liudhard, who is called Liphardus in Floras' addition to Bede's Martyro-logia.

Queen Bertha and her chaplain used to worship in the little church of St. Martin, going there daily from Ethelbert's palace, near the site of the present cathedral, through the postern gate of the precincts opposite St. Augustine's gateway. To this circumstance, though by a somewhat fanciful etymology, is attributed its name of Queningate. Owing to long disuse, it is probable that the church had fallen into a state of partial decay, but it was again restored and made suitable for Christian worship—though the Queen, with her chaplain and attendant maidens, may only have used a portion of the ancient building.

But we must now return to Augustine. "On the east of Kent," says Bede, "is the large Isle of Thanet, containing, according to the English way of reckoning, six hundred families, divided from the mainland by the river Wantsum," which at that time was a channel nearly a mile in width, running from Richborough to Reculver, though it has since become a narrow ditch. Here was a small place called Ebbsfleet, still the name of a farmhouse, rising out of Minster Marsh, but, owing to the retreat of the sea, now situated among green fields. There is little to catch the eye in Ebbsfleet itself, which is a mere spit of higher ground, distinguished by its clump of trees, but must then have been a headland, running out into the sea. "Taken as a whole," says Mr Green, "the scene has a wild beauty of its own. To the right, the white curve of Ramsgate Cliffs looks down on the crescent of Pegwell Bay. Far away to the left, across grey marshlands, where smoke-wreaths mark the sites of Richborough and Sandwich, rises the dim cliff-line of Deal." It is unnecessary to enter into the controversy whether Augustine first set foot on English ground here or at Stonar, or beneath the walls of the Roman fortress of Richborough, as apparently stated by Thorn. The whole question is fully discussed in an appendix to the [29] "Mission of St. Augustine," carefully compiled by Canon Mason.

The missionaries had no sooner landed than one or two of their body proceeded to Canterbury, where they duly acquainted King Ethelbert with the fact and object of their arrival. The king gave the messengers a favourable hearing, but bade them remain where they were, saying that he himself would visit them—making, however, this curious stipulation, that they should not hold their first interview under a roof, lest they should practise on him spells and incantations—"though they came," adds Bede, "furnished with Divine and not with magic power."

After some days, the king came to the island, where the interview took place, possibly under a large oak tree close to Cottington Farm, where a Sandbach Cross has been erected by the late Earl Granville as a memorial of the event—and it was at this place that the commemoration of the "Coming of St. Augustine" was held in 1897, by the bishops of both the Anglican and Roman communions. Other traditions name the centre of the island, or the walls of Richborough—but, where-ever it was, the missionaries, on hearing of the king's arrival with his attendant thanes, came to meet him, chanting litanies, with a tall silver cross before them, and a figure of the Saviour painted on an upright board. Besides Augustine himself, who was of great stature, head and shoulders taller than anyone else, were Laurence, afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury, Peter, who became first Abbot of St. Augustine, and nearly forty others.

When the procession stopped, and the chant ceased, Ethelbert courteously bade the missionaries be seated. Then Augustine, through the medium of a Frankish interpreter, having preached to the king the Words of Life and the mercies of the Saviour, was answered by the king in the well known passage:—"Fair indeed are your words and promises, but as they are new to us and of uncertain import, I cannot assent to them so far as to forsake that which I have so long held in common with the whole English nation. But because you have come as strangers from afar into my kingdom, and are desirous to impart to us those things which you believe to be true and most beneficial, we will not do you any harm, but rather receive [30] you in kindly hospitality, and take care to supply you with necessary sustenance. Nor do we forbid you to preach, and win over as many as you can to the faith of your religion."

The king was as good as his word. Before his return to Canterbury, he gave orders that a suitable abode should be prepared for the missionaries near the "Stable Gate," which stood not far from the present church of St. Alphege.

From the Isle of Thanet, Augustine and his companions crossed the ferry to Richborough. Thence they proceeded for about twelve miles almost due west to Canterbury, passing by Ash and Wingham, and then between the villages of Wickham and Ickham, till they came to St. Martin's Hill. There they would catch sight of the little church of St. Martin, which (as they well knew) had been consecrated afresh to the worship of Jesus Christ, and of the city below with its wooden houses dotted about among the ash-groves. As soon as they beheld the city, they walked in procession down the hill, bearing aloft the silver cross and the painted board—and as they passed St. Martin's Church, the choristers, whom Augustine had brought from Gregory's school on the Cœlian Hill, chanted one of Gregory's own litanies, "We beseech Thee, O Lord, in all Thy mercy, let Thy wrath and anger be turned away from this city and from Thy holy house, for we have sinned. Alleluia!"

We can well imagine that the heathen inhabitants of Canterbury must have been struck with astonishment at the unwonted sight, as well as at the swarthy complexions and strange dress of the Roman missionaries. And we may believe that Queen Bertha came forth to meet the band with a feeling of intense joy. Whether Bishop Liudhard was still alive or not, we have no evidence to determine.

Bede tells us that they began at once to imitate the course of life practised in the primitive church, with frequent prayer, watching, and fasting, preaching the word of life to as many as they could, receiving only necessary food from those whom they taught, living themselves conformably to their teaching, being always prepared to suffer, even to die, for the truth which they preached. In St. Martin's Church they met, sang, prayed, celebrated mass, preached, and [31] baptised. And soon the first fruits of their mission began to appear in the conversion and baptism of Ethelbert.

Ethelbert was baptised, according to an early tradition, on the Feast of Pentecost (June 2nd) in the year 597—but where? Of one thing there can be little doubt, that we should certainly expect him to have been baptised in St. Martin's Church. It was here that his queen had worshipped for so many years. It was here that Augustine is distinctly stated by Bede to have baptised—and so it was here (we may conclude with little hesitation) that the baptism of Ethelbert took place—even though we can find no direct statement to that effect earlier than that of John Bromton, writing at the end of the twelfth century, who says that "there (i.e. in St. Martin's) the king was baptised in the name of the Holy Trinity and the faith of the Church."

The rumours of the king's conversion had probably brought a vast multitude of strangers to the city, not only from other parts of Kent, but also from distant quarters. We cannot doubt that, as in the case of the baptism of Clovis, the ceremony was performed with much pomp, to impress the minds of the heathen Saxons. "On that occasion the Church was hung with embroidered tapestry and white curtains: odours of incense like airs of paradise were diffused around, and the building blazed with countless lights."

While Ethelbert remained at the entrance, Queen Bertha, with her attendants, repaired to her customary place of devotion. A portion of the service was performed at the altar, and then Augustine descended to the font, chanting a litany, and preceded by two acolytes with lighted tapers. Then followed prayers for the benediction of the font and the consecration of the water, over which Augustine makes the sign of the Cross three times. Then (according to one variation of the ancient Gallican rite) the two tapers are plunged into the font, and Augustine breathes into it (insufflat) three times, and the Chrism is poured into the font in the form of a Cross, while the water is parted with his hand. Ethelbert at this point is interrogated in the following simple form:—"Dost thou believe in God the Father Almighty? Dost thou too believe in Jesus Christ, His only-begotten Son, our Lord, who was born and suffered! and Dost thou believe in the [32] Holy Ghost, the Holy Church, the remission of sins, and the Resurrection of the flesh?" To each of which questions the king answers, "I believe."

Here follows the actual baptism, after which Ethelbert is signed on the forehead with Chrism in the form of a Cross. Augustine returns to his seat, and another litany is chanted. Had Augustine been at that time a bishop, he would now have administered to the king the Sacrament of Confirmation, but he was not consecrated bishop of the English till a few months afterwards.

It has indeed been objected that the ceremony could not have taken place in St. Martin's Church, because at that time baptism was administered by immersion. This was indeed the general rule, and such expressions as being "let down into the water," "stepping forth from the bath," "coming up from the font," and so on, occur in the writings of Tertullian, Jerome, the Gelasian and Leontine Sacramentaries; and octagonal or circular baptisteries are found in ancient churches, sometimes as much as twenty feet in diameter and five feet deep, erected for this purpose.

On the other hand, this practice was by no means universal, and even as early as the second century affusion was frequently used, with or without immersion. A picture of our Lord's baptism in the baptistery of St. John's at Ravenna (about 450) represents Jesus as standing in the water, and the Baptist pouring water over him from a shell. There is a similar representation in the church of St. Maria in Cosmedin (about 550), and one of earlier date in a fresco from the cemetery of St. Callixtus. On two sarcophagi, mentioned by Ciampinus, representations of a like character are engraved, supposed to be the Baptism of Agilulfus and Theodolinda (about 590), and of Arrichius, second Duke of Beneventum (591). In the latter case a man somewhat advanced in years, kneels to receive baptism, which is administered by affusion only. Both of these are assigned to the same decade as that of King Ethelbert. We may conclude, therefore, that both forms of administering the rite were practised from early times, and it is by no means impossible that Ethelbert was baptised by affusion. It was probably not from the existing font, even though in the seal of N. de Battail, Abbot of St. Augustine's (1224-1252) and in the common seal of St. Augustine's Abbey, the king is [33] represented as standing in a font, resembling in many respects the present one—while the baptism of Rollo, the first Christian Duke of Normandy, is illustrated in an early MS. of the twelfth-century Chronicle of Beuvit de St. More, with Rollo standing (or sitting) naked in a similar tub-like font.

St. Martin's, "a small and mean church," as it is unkindly called by Stukely, after the death of Augustine, Ethelbert, and Bertha, relapses into comparative obscurity, and its history is gathered chiefly from the testimony of architecture. We may, however, mention, as connected with the immediately succeeding period, that there were dug up in the churchyard (besides the Roman ornaments already described) a Saxon or Frankish circular ornament set with garnets, and other things which were of too costly a description to have belonged to any but persons of distinction, with whom they had probably been interred—also three gold looped Merovingian coins, fully described by Mr Roach Smith.

The first historical post-Augustinian record that we find in connection with the church is the well-known charter of 867 (from the Cottonian MSS. Augustus II. 95) granted, when the Kentish Wittenagemot was held at Canterbury, by King Ethelred, and entitled "Grant of a sedes in the place which is called St. Martin's Church, and of a small enclosure pertaining to the same sedes by King Ethelred to his faithful friend Wighelm, priest," endorsed in a contemporary hand, "An sett æt sc'e Martine." In this document Ethelred, King of the West Saxons and Kentishmen, gives and concedes to Wighelm a sedes and tun or enclosure pertaining thereto, of which the boundaries are named, but the Latin is very provincial and obscure. The grant is given to Wighelm for his life, and after his death to his heirs, and the king in strong language lays injunction on his successors "by the faith of St. Martin, confessor of Christ," not to presume to infringe the grant.

Now this charter is one of the most remarkable in the whole series of Anglo-Saxon documents, and confessedly one of the most difficult to comprehend, especially as to the word sedes, which is variously interpreted to refer to the episcopal character of St. Martin's, or to some official appointment in the church, or to a shop, dwelling, or stall for market purposes, in the parish. Whatever be the meaning of many difficult expressions, the charter is important as giving [34] what is probably a complete list of the Canterbury clergy, all of whom attested it.

| Archbishop | Ceolnoth. |

| Abbot | Biarnhelm. |

| Archdeacons | Sigefred, Bearnoth, Herefreth. |

| Priests | Nothheard, Biarnfreth, &c. &c. &c. |

It is also attested by King Ethelred, Duke Eastmund, Abbot Ealhheard, and many others, and is confirmed "in Jesus Christ with the sign of the Holy Cross" in the year 867.

We can hardly doubt that the church suffered some injury at the hands of the Danes, by whom Canterbury was wasted in 851 and again in 1009, though the most serious devastation took place in 1011, when, in the reign of Ethelred the Second, the Danes laid siege to, and captured, the city. On that occasion Archbishop Elphege was seized, bound, and dragged to the Cathedral to see it in flames. He was then carried off, and eventually murdered at Greenwich.

Not very long after this period we discover mention of the suffragan "Bishops of St. Martin's," who were evidently Chorepiscopi, an ancient order of bishops, dating from the third century, who overlooked the country district committed to them, ordaining readers, exorcists and subdeacons, but not (as a rule) deacons and priests, except by express permission of the diocesan bishop. It has been wrongly supposed, without any evidence or tradition, that the bishops of St. Martin's belonged to the great church at Dover, or the Oratory of St. Martin at Romney.

It is said by Battely that the succession of these bishops lasted for the space of nearly four hundred years; but of this there is no proof, and the idea may have sprung from the charter which we have discussed above, while the actual tradition is first mentioned in the "Black Book of the Archdeacons of Canterbury" (probably compiled in the fourteenth or fifteenth century), wherein it is said that "In the time of St. Augustine, first Archbishop of Canterbury, to the time of Archbishop Lanfranc of blessed memory, there was no archdeacon in the city and diocese of Canterbury. But from the time of Archbishop Theodore, who was sixth from St. Augustine, to the time of the aforesaid Lanfranc, there was in the church of St. Martin's, a suburb of Canterbury, a bishop ordained by Theodore, under the authority of Pope Vitalian, who in all [35] the city and diocese of Canterbury undertook duties in the place of the archbishop, conferring holy orders, consecrating churches, and confirming children during his absence." Archbishop Parker speaks of the Bishop of St. Martin's as performing in all things the office of a bishop in the absence of the archbishop, who, for the most part, attended the king's court. "The bishop, himself being a monk, received under obedience the monks of Christ Church, and celebrated in the Metropolitical Church the solemn offices of Divine worship, which being finished he returned to his own place. He and the Prior of Christ Church sat together in synods, both habited alike."

The names of only two bishops are preserved to us—that of Eadsi or Eadsige (1032-38), subsequently Archbishop of Canterbury, who, soon after he had received the pall from the Pope, was afflicted with a loathsome disease which incapacitated him for a time; though he afterwards recovered and administered the see until his death on the fourth day before the Kalends of November in 1050. The other Bishop was Godwin, appointed in 1052 by Archbishop Robert of Jumiéges, who died, according to the Saxon Chronicle, in 1061. The Bishop of St. Martin's was practically merged into the Archdeacon of Canterbury in the time of Lanfranc, who refused to ordain another bishop, saying that "there ought not to be two bishops in one city."

After the Conquest, St. Martin's was partially restored by the Normans, and the interior of the church underwent considerable alteration in the thirteenth century.

The list of the rectors is given in an appendix. They were not persons of any distinction, but from time to time we glean a few interesting details concerning them.

Thus, for instance, in 1321, a dispute arose between Robert de Henney, rector of St. Martin's, and Randolph de Waltham, master of the Free Grammar School of the city of Canterbury, about the rights and privileges of their respective schools. A Special Commission was appointed by the Archbishop, including the chaplain of St. Sepulchre's, the vicar of St. Paul's, the rector of St. Mary de Castro, rector of St. Peter's, and others. The point of dispute was whether in the St. Martin's School (within the church fence or boundary) there should be more than thirteen grammar scholars. The rector was limited to [36] this number for fear of infringing on the privilege of the City Grammar School, though he was entitled to take as many scholars in reading and singing as he pleased. In fact, however, the rector took as many grammar boys as he could get, it being necessary only that when his school was visited by the city schoolmaster or his deputy, the surplus should conceal themselves for the time being. An injunction, however, was granted in the Archbishop's Court to restrain the rector from taking more than his bare thirteen.

This is an extremely interesting record, because it shows that there were two flourishing public schools in Canterbury, probably the most ancient Grammar Schools in England, early in the fourteenth century; and that the pupils paid for their teaching, and learnt other subjects besides grammar.

Thorn, the monk of St. Augustine's, tells us also an amusing story of how John de Bourne, rector of St. Martin's, aided in the escape of one Peter de Dene from St. Augustine's Monastery by placing ladders against the monastery walls. They then rode on horseback together to Bishopsbourne, but Peter was at length recaptured.

In the fourteenth century we find no less than three rectors who were instituted to St. Martin's by the Prior of Christ Church during a vacancy in the see of Canterbury.

We have already mentioned the difficulty of obtaining information concerning the church in the Middle Ages, owing to its being exempt from the jurisdiction of the Archdeacon of Canterbury, and therefore not included in the Archidiaconal Registers, while the Archbishop's Visitations of the diocese were not, as a rule, parochial. By a lucky chance, however, we find some entries in Archbishop Warham's Visitation in 1511, one of which is to the effect that the churchwardens had not furnished accounts for five years, though they had received various monies for keeping graves in order. They were ordered to furnish accounts before the Feast of Purification, under pain of excommunication, &c.

There are many details of interest to be found in the pre-Reformation wills of parishioners, which are preserved in the "Consistory Court." In them we find bequests to the Light of the Holy Cross, the Light of the Blessed Mary, the Light of St. Martin, the Light of St. Christopher, the Light of St. [37] Erasmus, for daily masses before the image of St. Nicholas, to the High Altar, for the purchase of a new Cross, for various ornaments, for paving,—together with tenements, real estate, legacies for the benefit of the poor, and sundry curious personal gifts which wonderfully illustrate the habits and customs of the period. And from an inventory of Parish Church goods in Kent, made in 1552, we find the following entry relating to St. Martin's under the head of "19th July vi., Edward vi.":—

Bartylemewe Barham gent. and Stevyn Goodhewe, churchwardens.

Ffirst, one chalys with the paten of sylver.

Item, one vestment of blewe velvett with a cope to the same.

Item, one vestment of whyte braunchyd damaske with a cope to the same.

Item, one other olde vestment with a cope to the same.

Item, two table clothes.

Item, one long towell, one short towell.

Item, ij corporas with their clothes.

Item, one velvet cushon and one saten cushon.

Item, ij chysts, iiij surplysys.

Item, iij bells and one waggerell bell in the steple. Whereof left in the churche for the mynystracion of dyvyne service: The chalys with the paten of sylver, one cope of blewe velvett, one cope of whyte braunchyd damaske, ij albes, ij table clothes, one long towell, and one short towell, iiij surplysys, the bells in the steple.

For any further particulars concerning the Church after the Reformation we may refer to the meagre account given by William Somner, and the additions made to his history by Nicholas Battely, who states that "St. Martin's claims the priority in the catalogue of Canterbury parish churches upon several titles of antiquity and dignity." He says that he cannot pretend that the present fabric is the same building which was erected in or near the days of King Lucius, or which was repaired and fitted up for Queen Bertha. "But yet it has at this day the appearance of ancientness, not from the wrinkles and ruins of old age, but from the materials (i.e. Roman bricks) used in the repairing or re-edifying of it." He then goes on to make the erroneous statement that "in the porch of this church were buried Queen Bertha, and Liudhard, Bishop of Senlis, and (Thorn saith) King Ethelbert." About [38] ninety years after the time of Battely we come to a description of the church in the pages of Hasted, who, without assigning any reason, ventures on the suggestion that "the Chancel was the whole of the original building of this church or oratory, and was probably built about the year 200: that is, about the middle space of time when the Christians, both Britons and Romans, lived in this island free from all persecutions." Hasted's history is, as a rule, extremely valuable, not only from the style of his writing, but from his extraordinary general accuracy, and the minuteness of his original researches: and we are often at a loss to imagine from what source he could have derived so much information, which at that period was not so accessible as at present.