Title: Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons — Volume 3

Author: John McElroy

Release date: June 1, 2004 [eBook #4259]

Most recently updated: December 27, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

CLOTHING: ITS RAPID DETERIORATION, AND DEVICES TO REPLENISH IT—DESPERATE EFFORTS TO COVER NAKEDNESS—"LITTLE RED CAP" AND HIS LETTER.

SOME FEATURES OF THE MORTALITY—PERCENTAGE OF DEATHS TO THOSE LIVING —AN AVERAGE MEAN ONLY STANDS THE MISERY THREE MONTHS—DESCRIPTION OF THE PRISON AND THE CONDITION OF THE MEN THEREIN, BY A LEADING SCIENTIFIC MAN OF THE SOUTH.

DIFFICULTY OF EXERCISING—EMBARRASSMENTS OF A MORNING WALK—THE RIALTO OF THE PRISON—CURSING THE SOUTHERN CONFEDERACY—THE STORY OF THE BATTLE OF SPOTTSYLVANIA COURTHOUSE.

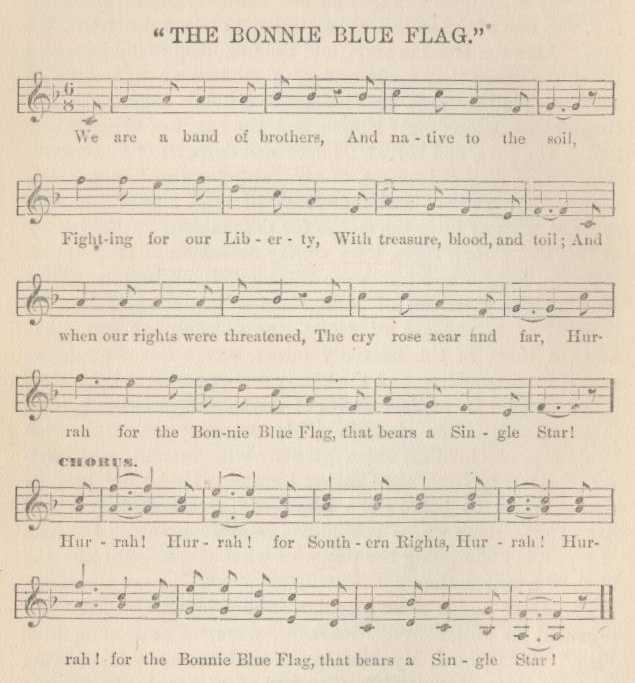

REBEL MUSIC—SINGULAR LACK OF THE CREATIVE POWER AMONG THE SOUTHERNERS —CONTRAST WITH SIMILAR PEOPLE ELSEWHERE—THEIR FAVORITE MUSIC, AND WHERE IT WAS BORROWED FROM—A FIFER WITH ONE TUNE.

AUGUST—NEEDLES STUCK IN PUMPKIN SEEDS—SOME PHENOMENA OF STARVATION —RIOTING IN REMEMBERED LUXURIES.

SURLY BRITON—THE STOLID COURAGE THAT MAKES THE ENGLISH FLAG A BANNER OF TRIUMPH—OUR COMPANY BUGLER, HIS CHARACTERISTICS AND HIS DEATH—URGENT DEMAND FOR MECHANICS—NONE WANT TO GO—TREATMENT OF A REBEL SHOEMAKER —ENLARGEMENT OF THE STOCKADE—IT IS BROKEN BY A STORM —THE WONDERFUL SPRING.

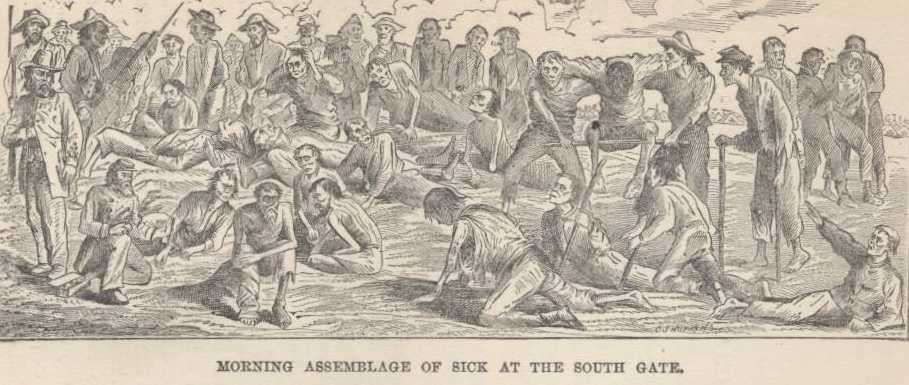

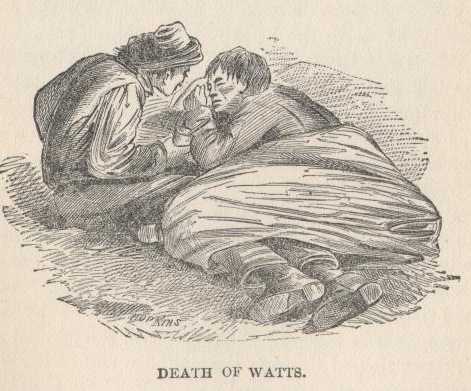

"SICK CALL," AND THE SCENES THAT ACCOMPANIED IT—MUSTERING THE LAME, HALT AND DISEASED AT THE SOUTH GATE—AN UNUSUALLY BAD CASE—GOING OUT TO THE HOSPITAL—ACCOMMODATION AND TREATMENT OF THE PATIENTS THERE—THE HORRIBLE SUFFERING IN THE GANGRENE WARD—BUNGLING AMPUTATIONS BY BLUNDERING PRACTITIONERS—AFFECTION BETWEEN A SAILOR AND HIS WARD —DEATH OF MY COMRADE.

DETERMINATION TO ESCAPE—DIFFERENT PLANS AND THEIR MERITS—I PREFER THE APPALACHICOLA ROUTE—PREPARATIONS FOR DEPARTURE—A HOT DAY—THE FENCE PASSED SUCCESSFULLY PURSUED BY THE HOUNDS—CAUGHT —RETURNED TO THE STOCKADE.

AUGUST—GOOD LUCK IN NOT MEETING CAPTAIN WIRZ—THAT WORTHY'S TREATMENT OF RECAPTURED PRISONERS—SECRET SOCIETIES IN PRISON—SINGULAR MEETING AND ITS RESULT—DISCOVERY AND REMOVAL OF THE OFFICERS AMONG THE ENLISTED MEN.

FOOD—THE MEAGERNESS, INFERIOR QUALITY, AND TERRIBLE SAMENESS —REBEL TESTIMONY ON THE SUBJECT—FUTILITY OF SUCCESSFUL EXPLANATION.

SOLICITUDE AS TO THE FATE OF ATLANTA AND SHERMAN'S ARMY—PAUCITY OF NEWS —HOW WE HEARD THAT ATLANTA HAD FALLEN—ANNOUNCEMENT OF A GENERAL EXCHANGE—WE LEAVE ANDERSONVILLE.

SAVANNAH—DEVICES TO OBTAIN MATERIALS FOR A TENT—THEIR ULTIMATE SUCCESS —RESUMPTION OF TUNNELING—ESCAPING BY WHOLESALE AND BEING RECAPTURED EN MASSE—THE OBSTACLES THAT LAY BETWEEN US AND OUR LINES.

FRANK REVERSTOCK'S ATTEMPT AT ESCAPE—PASSING OFF AS REBEL BOY HE REACHES GRISWOLDVILLE BY RAIL, AND THEN STRIKES ACROSS THE COUNTRY FOR SHERMAN, BUT IS CAUGHT WITHIN TWENTY MILES OF OUR LINES.

SAVANNAH PROVES TO BE A CHANGE FOR THE BETTER—ESCAPE FROM THE BRATS OF GUARDS—COMPARISON BETWEEN WIRZ AND DAVIS—A BRIEF INTERVAL OF GOOD RATIONS—WINDER, THE MAN WITH THE EVIL EYE —THE DISLOYAL WORK OF A SHYSTER.

WHY WE WERE HURRIED OUT OF ANDERSONVILLE—THE OF THE FALL OF ATLANTA —OUR LONGING TO HEAR THE NEWS—ARRIVAL OF SOME FRESH FISH—HOW WE KNEW THEY WERE WESTERN BOYS—DIFFERENCE IN THE APPEARANCE OF THE SOLDIERS OF THE TWO ARMIES.

WHAT CAUSED THE FALL OF ATLANTA—A DISSERTATION UPON AN IMPORTANT PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEM—THE BATTLE OF JONESBORO—WHY IT WAS FOUGHT —HOW SHERMAN DECEIVED HOOD—A DESPERATE BAYONET CHARGE, AND THE ONLY SUCCESSFUL ONE IN THE ATLANTA CAMPAIGN—A GALLANT COLONEL AND HOW HE DIED—THE HEROISM OF SOME ENLISTED MEN—GOING CALMLY INTO CERTAIN DEATH.

A FAIR SACRIFICE—THE STORY OF ONE BOY WHO WILLINGLY GAVE HIS YOUNG LIFE FOR HIS COUNTRY.

WE LEAVE SAVANNAH—MORE HOPES OF EXCHANGE—SCENES AT DEPARTURE —"FLANKERS"—ON THE BACK TRACK TOWARD ANDERSONVILLE—ALARM THEREAT —AT THE PARTING OF TWO WAYS—WE FINALLY BRING UP AT CAMP LAWTON.

OUR NEW QUARTERS AT CAMP LAWTON—BUILDING A HUT—AN EXCEPTIONAL COMMANDANT—HE IS a GOOD MAN, BUT WILL TAKE BRIBES—RATIONS.

THE RAIDERS REAPPEAR ON THE SCENE—THE ATTEMPT TO ASSASSINATE THOSE

WHO WERE CONCERNED IN THE EXECUTION—A COUPLE OF LIVELY FIGHTS, IN

WHICH THE RAIDERS ARE DEFEATED—HOLDING AN ELECTION.

74. The Author's Appearance on Entering Prison

75. His Appearance in July, 1864

76. Little Red Cap

77. "Fresh Fish"

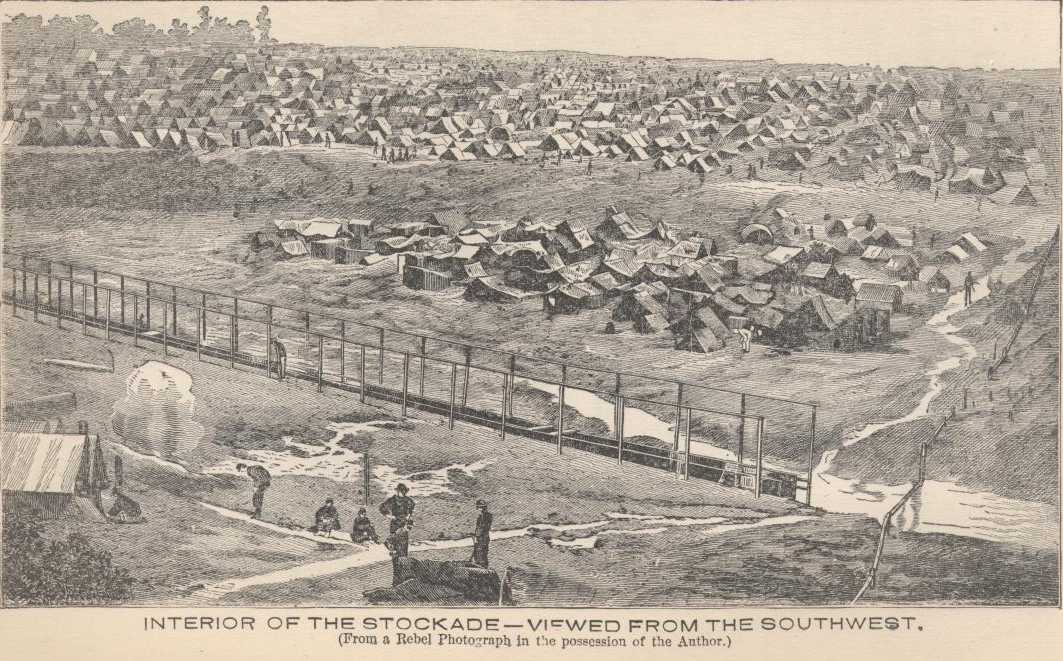

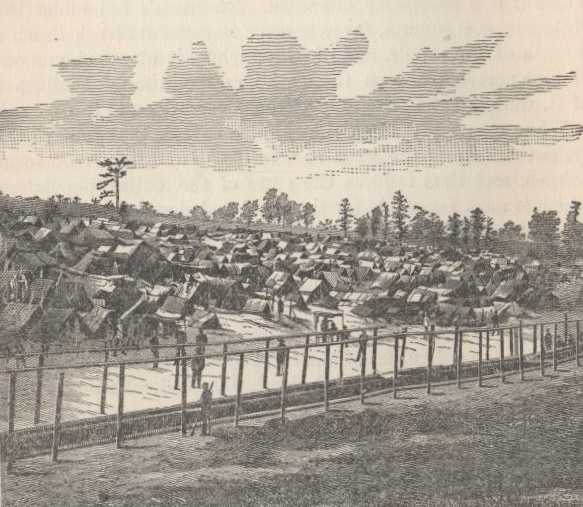

78. Interior of the Stockade, Viewed from the Southwest

79. Burying the Dead

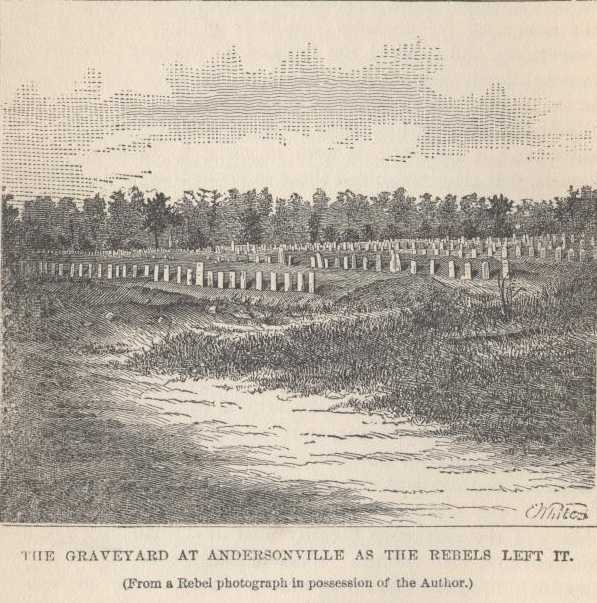

80. The Graveyard at Andersonville, as the Rebels Left It

81. Denouncing the Southern Confederacy

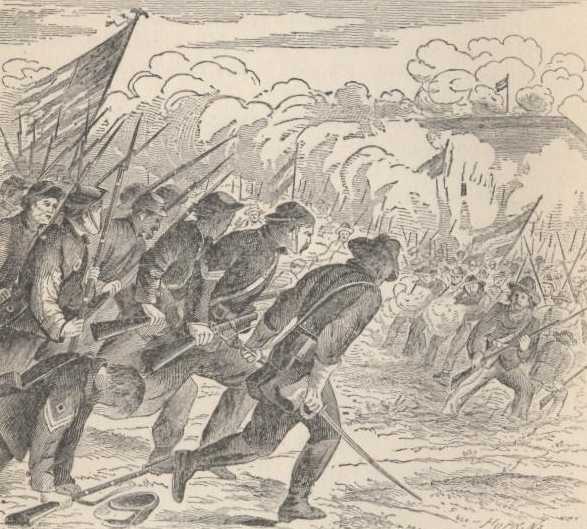

82. The Charge

83. "Flagstaff"

84. Nursing a Sick Comrade

65. A Dream

86. The English Bugler

87. The Break in the Stockade

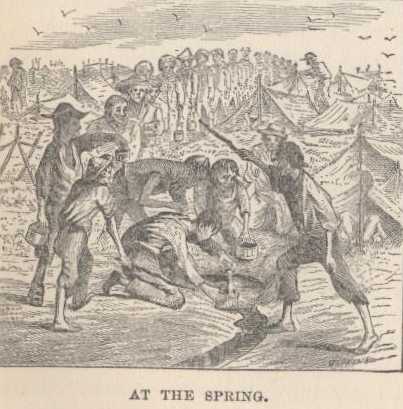

88. At the Spring

89. Morning Assemblage of Sick at the South Gate

91. Old Sailor and Chicken

92. Death of Watts

93. Planning Escape

94. Our Progress was Terribly Slow—Every Step Hurt Fearfully

95. "Come Ashore, There, Quick"

96. He Shrieked Imprecations and Curses

97. The Chain Gang

98. Interior of the Stockade—The Creek at the East Side

99. A Section from the East Side of the Prison Showing the Dead Line

100. "Half-past Eight O'clock, and Atlanta's Gone to H—l!"

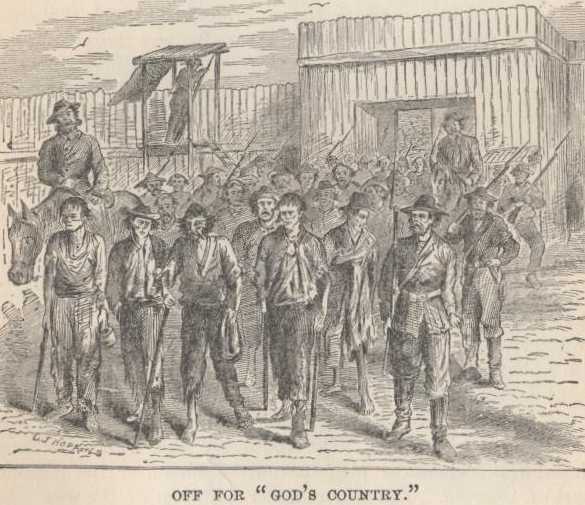

101. Off for "God's Country"

102. Georgian Development of the "Proud Caucasian"

103. It was Very Unpleasant When a Storm Came Up

104. When We Matched Our Intellects Against a Rebel's

107. His New Idea was to have a Heavily Laden Cart Driven Around Inside the Dead Line

108. They Stood Around the Gate and Yelled Derisively

110. "See Heah; You Must Stand Back!"

111. He Bade Them Goodbye

112. "Wha-ah-ye!"

114. One of Ferguson's Cavalry

115. Then the Clear Blue Eyes and Well-remembered Smile

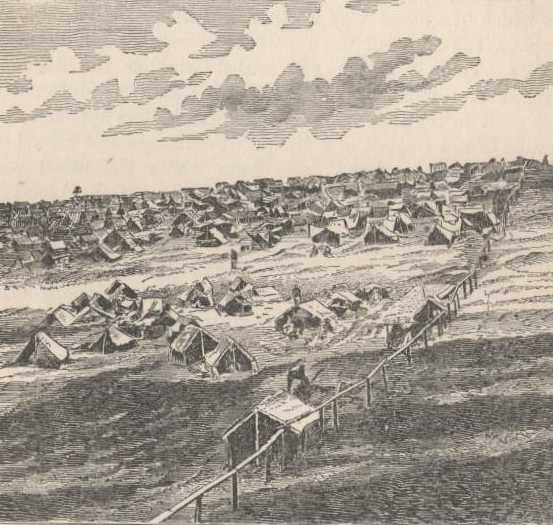

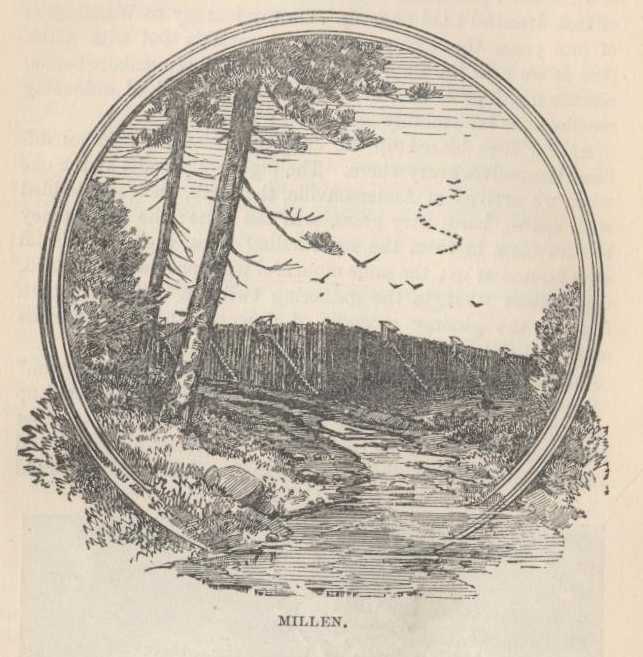

117. Millen

118. A House Builded With Our Own Own Hands

119. Our First Meat

120. A Lucky Find

CLOTHING: ITS RAPID DETERIORATION, AND DEVICES TO REPLENISH IT—DESPERATE EFFORTS TO COVER NAKEDNESS—"LITTLE RED CAP" AND HIS LETTER.

Clothing had now become an object of real solicitude to us older prisoners. The veterans of our crowd—the surviving remnant of those captured at Gettysburg—had been prisoners over a year. The next in seniority—the Chickamauga boys—had been in ten months. The Mine Run fellows were eight months old, and my battalion had had seven months' incarceration. None of us were models of well-dressed gentlemen when captured. Our garments told the whole story of the hard campaigning we had undergone. Now, with months of the wear and tear of prison life, sleeping on the sand, working in tunnels, digging wells, etc., we were tattered and torn to an extent that a second-class tramp would have considered disgraceful.

This is no reflection upon the quality of the clothes furnished by the

Government. We simply reached the limit of the wear of textile fabrics. I

am particular to say this, because I want to contribute my little mite

towards doing justice to a badly abused part of our Army organization

—the Quartermaster's Department. It is fashionable to speak of

"shoddy," and utter some stereotyped sneers about "brown paper shoes," and

"musketo-netting overcoats," when any discussion of the Quartermaster

service is the subject of conversation, but I have no hesitation in asking

the indorsement of my comrades to the statement that we have never found

anywhere else as durable garments as those furnished us by the Government

during our service in the Army. The clothes were not as fine in texture,

nor so stylish in cut as those we wore before or since, but when it came

to wear they could be relied on to the last thread. It was always

marvelous to me that they lasted so well, with the rough usage a soldier

in the field must necessarily give them.

But to return to my subject. I can best illustrate the way our clothes dropped off us, piece by piece, like the petals from the last rose of Summer, by taking my own case as an example: When I entered prison I was clad in the ordinary garb of an enlisted man of the cavalry—stout, comfortable boots, woolen pocks, drawers, pantaloons, with a "reenforcement," or "ready-made patches," as the infantry called them; vest, warm, snug-fitting jacket, under and over shirts, heavy overcoat, and a forage-cap. First my boots fell into cureless ruin, but this was no special hardship, as the weather had become quite warm, and it was more pleasant than otherwise to go barefooted. Then part of the underclothing retired from service. The jacket and vest followed, their end being hastened by having their best portions taken to patch up the pantaloons, which kept giving out at the most embarrassing places. Then the cape of the overcoat was called upon to assist in repairing these continually-recurring breaches in the nether garments. The same insatiate demand finally consumed the whole coat, in a vain attempt to prevent an exposure of person greater than consistent with the usages of society. The pantaloons—or what, by courtesy, I called such, were a monument of careful and ingenious, but hopeless, patching, that should have called forth the admiration of a Florentine artist in mosaic. I have been shown—in later years—many table tops, ornamented in marquetry, inlaid with thousands of little bits of wood, cunningly arranged, and patiently joined together. I always look at them with interest, for I know the work spent upon them: I remember my Andersonville pantaloons.

The clothing upon the upper part of my body had been reduced to the remains of a knit undershirt. It had fallen into so many holes that it looked like the coarse "riddles" through which ashes and gravel are sifted. Wherever these holes were the sun had burned my back, breast and shoulders deeply black. The parts covered by the threads and fragments forming the boundaries of the holes, were still white. When I pulled my alleged shirt off, to wash or to free it from some of its teeming population, my skin showed a fine lace pattern in black and white, that was very interesting to my comrades, and the subject of countless jokes by them.

They used to descant loudly on the chaste elegance of the design, the richness of the tracing, etc., and beg me to furnish them with a copy of it when I got home, for their sisters to work window curtains or tidies by. They were sure that so striking a novelty in patterns would be very acceptable. I would reply to their witticisms in the language of Portia's Prince of Morocco:

Mislike me not for my complexion—

The shadowed livery of the burning sun.

One of the stories told me in my childhood by an old negro nurse, was of a poverty stricken little girl "who slept on the floor and was covered with the door," and she once asked—

"Mamma how do poor folks get along who haven't any door?"

In the same spirit I used to wonder how poor fellows got along who hadn't any shirt.

One common way of keeping up one's clothing was by stealing mealsacks. The meal furnished as rations was brought in in white cotton sacks. Sergeants of detachments were required to return these when the rations were issued the next day. I have before alluded to the general incapacity of the Rebels to deal accurately with even simple numbers. It was never very difficult for a shrewd Sergeant to make nine sacks count as ten. After awhile the Rebels began to see through this sleight of hand manipulation, and to check it. Then the Sergeants resorted to the device of tearing the sacks in two, and turning each half in as a whole one. The cotton cloth gained in this way was used for patching, or, if a boy could succeed in beating the Rebels out of enough of it, he would fabricate himself a shirt or a pair of pantaloons. We obtained all our thread in the same way. A half of a sack, carefully raveled out, would furnish a couple of handfuls of thread. Had it not been for this resource all our sewing and mending would have come to a standstill.

Most of our needles were manufactured by ourselves from bones. A piece of bone, split as near as possible to the required size, was carefully rubbed down upon a brick, and then had an eye laboriously worked through it with a bit of wire or something else available for the purpose. The needles were about the size of ordinary darning needles, and answered the purpose very well.

These devices gave one some conception of the way savages provide for the wants of their lives. Time was with them, as with us, of little importance. It was no loss of time to them, nor to us, to spend a large portion of the waking hours of a week in fabricating a needle out of a bone, where a civilized man could purchase a much better one with the product of three minutes' labor. I do not think any red Indian of the plains exceeded us in the patience with which we worked away at these minutia of life's needs.

Of course the most common source of clothing was the dead, and no body was carried out with any clothing on it that could be of service to the survivors. The Plymouth Pilgrims, who were so well clothed on coming in, and were now dying off very rapidly, furnished many good suits to cover the nakedness of older, prisoners. Most of the prisoners from the Army of the Potomac were well dressed, and as very many died within a month or six weeks after their entrance, they left their clothes in pretty good condition for those who constituted themselves their heirs, administrators and assigns.

For my own part, I had the greatest aversion to wearing dead men's clothes, and could only bring myself to it after I had been a year in prison, and it became a question between doing that and freezing to death.

Every new batch of prisoners was besieged with anxious inquiries on the subject which lay closest to all our hearts:

"What are they doing about exchange!"

Nothing in human experience—save the anxious expectancy of a sail by castaways on a desert island—could equal the intense eagerness with which this question was asked, and the answer awaited. To thousands now hanging on the verge of eternity it meant life or death. Between the first day of July and the first of November over twelve thousand men died, who would doubtless have lived had they been able to reach our lines—"get to God's country," as we expressed it.

The new comers brought little reliable news of contemplated exchange. There was none to bring in the first place, and in the next, soldiers in active service in the field had other things to busy themselves with than reading up the details of the negotiations between the Commissioners of Exchange. They had all heard rumors, however, and by the time they reached Andersonville, they had crystallized these into actual statements of fact. A half hour after they entered the Stockade, a report like this would spread like wildfire:

"An Army of the Potomac man has just come in, who was captured in front of Petersburg. He says that he read in the New York Herald, the day before he was taken, that an exchange had been agreed upon, and that our ships had already started for Savannah to take us home."

Then our hopes would soar up like balloons. We fed ourselves on such stuff

from day to day, and doubtless many lives were greatly prolonged by the

continual encouragement. There was hardly a day when I did not say to

myself that I would much rather die than endure imprisonment another

month, and had I believed that another month would see me still there, I

am pretty certain that I should have ended the matter by crossing the Dead

Line. I was firmly resolved not to die the disgusting, agonizing death

that so many around me were dying.

One of our best purveyors of information was a bright, blue-eyed, fair-haired little drummer boy, as handsome as a girl, well-bred as a lady, and evidently the darling of some refined loving mother. He belonged, I think, to some loyal Virginia regiment, was captured in one of the actions in the Shenandoa Valley, and had been with us in Richmond. We called him "Red Cap," from his wearing a jaunty, gold-laced, crimson cap. Ordinarily, the smaller a drummer boy is the harder he is, but no amount of attrition with rough men could coarse the ingrained refinement of Red Cap's manners. He was between thirteen and fourteen, and it seemed utterly shameful that men, calling themselves soldier should make war on such a tender boy and drag him off to prison.

But no six-footer had a more soldierly heart than little Red Cap, and none were more loyal to the cause. It was a pleasure to hear him tell the story of the fights and movements his regiment had been engaged in. He was a good observer and told his tale with boyish fervor. Shortly after Wirz assumed command he took Red Cap into his office as an Orderly. His bright face and winning manner; fascinated the women visitors at headquarters, and numbers of them tried to adopt him, but with poor success. Like the rest of us, he could see few charms in an existence under the Rebel flag, and turned a deaf ear to their blandishments. He kept his ears open to the conversation of the Rebel officers around him, and frequently secured permission to visit the interior of the Stockade, when he would communicate to us all that he has heard. He received a flattering reception every time he cams in, and no orator ever secured a more attentive audience than would gather around him to listen to what he had to say. He was, beyond a doubt, the best known and most popular person in the prison, and I know all the survivors of his old admirer; share my great interest in him, and my curiosity as to whether he yet lives, and whether his subsequent career has justified the sanguine hopes we all had as to his future. I hope that if he sees this, or any one who knows anything about him, he will communicate with me. There are thousands who will be glad to hear from him.

A most remarkable coincidence occurred in regard to this comrade. Several days after the above had been written, and "set up," but before it had yet appeared in the paper, I received the following letter:

ECKHART MINES,

Alleghany County, Md., March 24.

To the Editor of the BLADE:

Last evening I saw a copy of your paper, in which was a chapter or two of a prison life of a soldier during the late war. I was forcibly struck with the correctness of what he wrote, and the names of several of my old comrades which he quoted: Hill, Limber Jim, etc., etc. I was a drummer boy of Company I, Tenth West Virginia Infantry, and was fifteen years of age a day or two after arriving in Andersonville, which was in the last of February, 1884. Nineteen of my comrades were there with me, and, poor fellows, they are there yet. I have no doubt that I would have remained there, too, had I not been more fortunate.

I do not know who your soldier correspondent is, but assume to say that from the following description he will remember having seen me in Andersonville: I was the little boy that for three or four months officiated as orderly for Captain Wirz. I wore a red cap, and every day could be seen riding Wirz's gray mare, either at headquarters, or about the Stockade. I was acting in this capacity when the six raiders —"Mosby," (proper name Collins) Delaney, Curtis, and—I forget the other names—were executed. I believe that I was the first that conveyed the intelligence to them that Confederate General Winder had approved their sentence. As soon as Wirz received the dispatch to that effect, I ran down to the stocks and told them.

I visited Hill, of Wauseon, Fulton County, O., since the war, and found him hale and hearty. I have not heard from him for a number of years until reading your correspondent's letter last evening. It is the only letter of the series that I have seen, but after reading that one, I feel called upon to certify that I have no doubts of the truthfulness of your correspondent's story. The world will never know or believe the horrors of Andersonville and other prisons in the South. No living, human being, in my judgment, will ever be able to properly paint the horrors of those infernal dens.

I formed the acquaintance of several Ohio soldiers whilst in prison. Among these were O. D. Streeter, of Cleveland, who went to Andersonville about the same time that I did, and escaped, and was the only man that I ever knew that escaped and reached our lines. After an absence of several months he was retaken in one of Sherman's battles before Atlanta, and brought back. I also knew John L. Richards, of Fostoria, Seneca County, O. or Eaglesville, Wood County. Also, a man by the name of Beverly, who was a partner of Charley Aucklebv, of Tennessee. I would like to hear from all of these parties. They all know me.

Mr. Editor, I will close by wishing all my comrades who shared in the sufferings and dangers of Confederate prisons, a long and useful life.

Yours truly,

RANSOM T. POWELL

Speaking of the manner in which the Plymouth Pilgrims were now dying, I am reminded of my theory that the ordinary man's endurance of this prison life did not average over three months. The Plymouth boys arrived in May; the bulk of those who died passed away in July and August. The great increase of prisoners from all sources was in May, June and July. The greatest mortality among these was in August, September and October.

Many came in who had been in good health during their service in the field, but who seemed utterly overwhelmed by the appalling misery they saw on every hand, and giving way to despondency, died in a few days or weeks. I do not mean to include them in the above class, as their sickness was more mental than physical. My idea is that, taking one hundred ordinarily healthful young soldiers from a regiment in active service, and putting them into Andersonville, by the end of the third month at least thirty-three of those weakest and most vulnerable to disease would have succumbed to the exposure, the pollution of ground and air, and the insufficiency of the ration of coarse corn meal. After this the mortality would be somewhat less, say at the end of six months fifty of them would be dead. The remainder would hang on still more tenaciously, and at the end of a year there would be fifteen or twenty still alive. There were sixty-three of my company taken; thirteen lived through. I believe this was about the usual proportion for those who were in as long as we. In all there were forty-five thousand six hundred and thirteen prisoners brought into Andersonville. Of these twelve thousand nine hundred and twelve died there, to say nothing of thousands that died in other prisons in Georgia and the Carolinas, immediately after their removal from Andersonville. One of every three and a-half men upon whom the gates of the Stockade closed never repassed them alive. Twenty-nine per cent. of the boys who so much as set foot in Andersonville died there. Let it be kept in mind all the time, that the average stay of a prisoner there was not four months. The great majority came in after the 1st of May, and left before the middle of September. May 1, 1864, there were ten thousand four hundred and twenty-seven in the Stockade. August 8 there were thirty-three thousand one hundred and fourteen; September 30 all these were dead or gone, except eight thousand two hundred and eighteen, of whom four thousand five hundred and ninety died inside of the next thirty days. The records of the world can shove no parallel to this astounding mortality.

Since the above matter was first published in the BLADE, a friend has sent

me a transcript of the evidence at the Wirz trial, of Professor Joseph

Jones, a Surgeon of high rank in the Rebel Army, and who stood at the head

of the medical profession in Georgia. He visited Andersonville at the

instance of the Surgeon-General of the Confederate States' Army, to make a

study, for the benefit of science, of the phenomena of disease occurring

there. His capacity and opportunities for observation, and for clearly

estimating the value of the facts coming under his notice were, of course,

vastly superior to mine, and as he states the case stronger than I dare

to, for fear of being accused of exaggeration and downright untruth, I

reproduce the major part of his testimony—embodying also his

official report to medical headquarters at Richmond—that my readers

may know how the prison appeared to the eyes of one who, though a bitter

Rebel, was still a humane man and a conscientious observer, striving to

learn the truth:

[Transcript from the printed testimony at the Wirz Trial, pages 618 to 639, inclusive.]

OCTOBER 7, 1885.

Dr. Joseph Jones, for the prosecution:

By the Judge Advocate:

Question. Where do you reside

Answer. In Augusta, Georgia.

Q. Are you a graduate of any medical college?

A. Of the University of Pennsylvania.

Q. How long have you been engaged in the practice of medicine?

A. Eight years.

Q. Has your experience been as a practitioner, or rather as an investigator of medicine as a science?

A. Both.

Q. What position do you hold now?

A. That of Medical Chemist in the Medical College of Georgia, at Augusta.

Q. How long have you held your position in that college?

A. Since 1858.

Q. How were you employed during the Rebellion?

A. I served six months in the early part of it as a private in the ranks, and the rest of the time in the medical department.

Q. Under the direction of whom?

A. Under the direction of Dr. Moore, Surgeon General.

Q. Did you, while acting under his direction, visit Andersonville, professionally?

A. Yes, Sir.

Q. For the purpose of making investigations there?

A. For the purpose of prosecuting investigations ordered by the Surgeon General.

Q. You went there in obedience to a letter of instructions?

A. In obedience to orders which I received.

Q. Did you reduce the results of your investigations to the shape of a report?

A. I was engaged at that work when General Johnston surrendered his army.

(A document being handed to witness.)

Q. Have you examined this extract from your report and compared it with the original?

A. Yes, Sir; I have.

Q. Is it accurate?

A. So far as my examination extended, it is accurate.'

The document just examined by witness was offered in evidence, and is as follows:

Observations upon the diseases of the Federal prisoners, confined to Camp Sumter, Andersonville, in Sumter County, Georgia, instituted with a view to illustrate chiefly the origin and causes of hospital gangrene, the relations of continued and malarial fevers, and the pathology of camp diarrhea and dysentery, by Joseph Jones; Surgeon P. A. C. S., Professor of Medical Chemistry in the Medical College of Georgia, at Augusta, Georgia.

Hearing of the unusual mortality among the Federal prisoners confined at Andersonville; Georgia, in the month of August, 1864, during a visit to Richmond, Va., I expressed to the Surgeon General, S. P. Moore, Confederate States of America, a desire to visit Camp Sumter, with the design of instituting a series of inquiries upon the nature and causes of the prevailing diseases. Smallpox had appeared among the prisoners, and I believed that this would prove an admirable field for the establishment of its characteristic lesions. The condition of Peyer's glands in this disease was considered as worthy of minute investigation. It was believed that a large body of men from the Northern portion of the United States, suddenly transported to a warm Southern climate, and confined upon a small portion of land, would furnish an excellent field for the investigation of the relations of typhus, typhoid, and malarial fevers.

The Surgeon General of the Confederate States of America furnished me with

the following letter of introduction to the Surgeon in charge of the

Confederate States Military Prison at Andersonville, Ga.:

CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA,

SURGEON GENERAL'S OFFICE, RICHMOND, VA.,

August 6, 1864.

SIR:—The field of pathological investigations afforded by the large collection of Federal prisoners in Georgia, is of great extant and importance, and it is believed that results of value to the profession may be obtained by careful investigation of the effects of disease upon the large body of men subjected to a decided change of climate and those circumstances peculiar to prison life. The Surgeon in charge of the hospital for Federal prisoners, together with his assistants, will afford every facility to Surgeon Joseph Jones, in the prosecution of the labors ordered by the Surgeon General. Efficient assistance must be rendered Surgeon Jones by the medical officers, not only in his examinations into the causes and symptoms of the various diseases, but especially in the arduous labors of post mortem examinations.

The medical officers will assist in the performance of such post-mortems as Surgeon Jones may indicate, in order that this great field for pathological investigation may be explored for the benefit of the Medical Department of the Confederate Army.

S. P. MOORE, Surgeon General.

Surgeon ISAIAH H. WHITE,

In charge of Hospital for Federal prisoners, Andersonville, Ga.

In compliance with this letter of the Surgeon General, Isaiah H. White,

Chief Surgeon of the post, and R. R. Stevenson, Surgeon in charge of the

Prison Hospital, afforded the necessary facilities for the prosecution of

my investigations among the sick outside of the Stockade. After the

completion of my labors in the military prison hospital, the following

communication was addressed to Brigadier General John H. Winder, in

consequence of the refusal on the part of the commandant of the interior

of the Confederate States Military Prison to admit me within the Stockade

upon the order of the Surgeon General:

CAMP SUMTER, ANDERSONVILLE GA.,

September 16, 1864.

GENERAL:—I respectfully request the commandant of the post of Andersonville to grant me permission and to furnish the necessary pass to visit the sick and medical officers within the Stockade of the Confederate States Prison. I desire to institute certain inquiries ordered by the Surgeon General. Surgeon Isaiah H. White, Chief Surgeon of the post, and Surgeon R. R. Stevenson, in charge of the Prison Hospital, have afforded me every facility for the prosecution of my labors among the sick outside of the Stockade.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

JOSEPH JONES, Surgeon P. A. C. S.

Brigadier General JOHN H. WINDER,

Commandant, Post Andersonville.

In the absence of General Winder from the post, Captain Winder furnished

the following order:

CAMP SUMTER, ANDERSONVILLE;

September 17, 1864.

CAPTAIN:—You will permit Surgeon Joseph Jones, who has orders from the Surgeon General, to visit the sick within the Stockade that are under medical treatment. Surgeon Jones is ordered to make certain investigations which may prove useful to his profession. By direction of General Winder. Very respectfully, W. S. WINDER, A. A. G.

Captain H. WIRZ, Commanding Prison.

Description of the Confederate States Military Prison Hospital at Andersonville. Number of prisoners, physical condition, food, clothing, habits, moral condition, diseases.

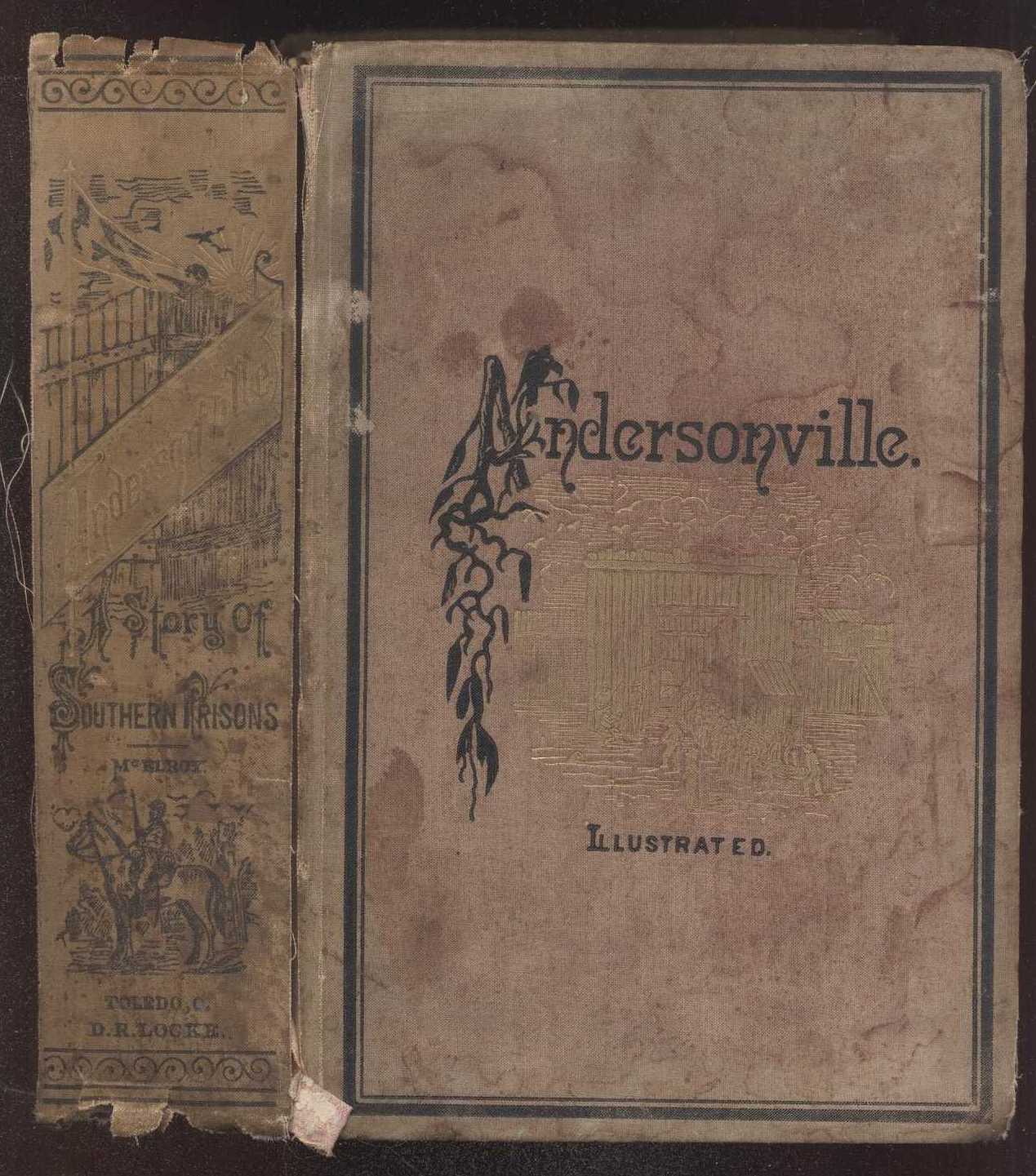

The Confederate Military Prison at Andersonville, Ga., consists of a strong Stockade, twenty feet in height, enclosing twenty-seven acres. The Stockade is formed of strong pine logs, firmly planted in the ground. The main Stockade is surrounded by two other similar rows of pine logs, the middle Stockade being sixteen feet high, and the outer twelve feet. These are intended for offense and defense. If the inner Stockade should at any time be forced by the prisoners, the second forms another line of defense; while in case of an attempt to deliver the prisoners by a force operating upon the exterior, the outer line forms an admirable protection to the Confederate troops, and a most formidable obstacle to cavalry or infantry. The four angles of the outer line are strengthened by earthworks upon commanding eminences, from which the cannon, in case of an outbreak among the prisoners, may sweep the entire enclosure; and it was designed to connect these works by a line of rifle pits, running zig-zag, around the outer Stockade; those rifle pits have never been completed. The ground enclosed by the innermost Stockade lies in the form of a parallelogram, the larger diameter running almost due north and south. This space includes the northern and southern opposing sides of two hills, between which a stream of water runs from west to east. The surface soil of these hills is composed chiefly of sand with varying admixtures of clay and oxide of iron. The clay is sufficiently tenacious to give a considerable degree of consistency to the soil. The internal structure of the hills, as revealed by the deep wells, is similar to that already described. The alternate layers of clay and sand, as well as the oxide of iron, which forms in its various combinations a cement to the sand, allow of extensive tunneling. The prisoners not only constructed numerous dirt huts with balls of clay and sand, taken from the wells which they have excavated all over those hills, but they have also, in some cases, tunneled extensively from these wells. The lower portions of these hills, bordering on the stream, are wet and boggy from the constant oozing of water. The Stockade was built originally to accommodate only ten thousand prisoners, and included at first seventeen acres. Near the close of the month of June the area was enlarged by the addition of ten acres. The ground added was situated on the northern slope of the largest hill.

The average number of square feet of ground to each prisoner in August 1864: 35.7

Within the circumscribed area of the Stockade the Federal prisoners were compelled to perform all the offices of life—cooking, washing, the calls of nature, exercise, and sleeping. During the month of March the prison was less crowded than at any subsequent time, and then the average space of ground to each prisoner was only 98.7 feet, or less than seven square yards. The Federal prisoners were gathered from all parts of the Confederate States east of the Mississippi, and crowded into the confined space, until in the month of June the average number of square feet of ground to each prisoner was only 33.2 or less than four square yards. These figures represent the condition of the Stockade in a better light even than it really was; for a considerable breadth of land along the stream, flowing from west to east between the hills, was low and boggy, and was covered with the excrement of the men, and thus rendered wholly uninhabitable, and in fact useless for every purpose except that of defecation. The pines and other small trees and shrubs, which originally were scattered sparsely over these hills, were in a short time cut down and consumed by the prisoners for firewood, and no shade tree was left in the entire enclosure of the stockade. With their characteristic industry and ingenuity, the Federals constructed for themselves small huts and caves, and attempted to shield themselves from the rain and sun and night damps and dew. But few tents were distributed to the prisoners, and those were in most cases torn and rotten. In the location and arrangement of these tents and huts no order appears to have been followed; in fact, regular streets appear to be out of the question in so crowded an area; especially too, as large bodies of prisoners were from time to time added suddenly without any previous preparations. The irregular arrangement of the huts and imperfect shelters was very unfavorable for the maintenance of a proper system of police.

The police and internal economy of the prison was left almost entirely in

the hands of the prisoners themselves; the duties of the Confederate

soldiers acting as guards being limited to the occupation of the boxes or

lookouts ranged around the stockade at regular intervals, and to the

manning of the batteries at the angles of the prison. Even judicial

matters pertaining to themselves, as the detection and punishment of such

crimes as theft and murder appear to have been in a great measure

abandoned to the prisoners. A striking instance of this occurred in the

month of July, when the Federal prisoners within the Stockade tried,

condemned, and hanged six (6) of their own number, who had been convicted

of stealing and of robbing and murdering their fellow-prisoners. They were

all hung upon the same day, and thousands of the prisoners gathered around

to witness the execution. The Confederate authorities are said not to have

interfered with these proceedings. In this collection of men from all

parts of the world, every phase of human character was represented; the

stronger preyed upon the weaker, and even the sick who were unable to

defend themselves were robbed of their scanty supplies of food and

clothing. Dark stories were afloat, of men, both sick and well, who were

murdered at night, strangled to death by their comrades for scant supplies

of clothing or money. I heard a sick and wounded Federal prisoner accuse

his nurse, a fellow-prisoner of the United States Army, of having

stealthily, during his sleep inoculated his wounded arm with gangrene,

that he might destroy his life and fall heir to his clothing.

....................................

The large number of men confined within the Stockade soon, under a defective system of police, and with imperfect arrangements, covered the surface of the low grounds with excrements. The sinks over the lower portions of the stream were imperfect in their plan and structure, and the excrements were in large measure deposited so near the borders of the stream as not to be washed away, or else accumulated upon the low boggy ground. The volume of water was not sufficient to wash away the feces, and they accumulated in such quantities in the lower portion of the stream as to form a mass of liquid excrement heavy rains caused the water of the stream to rise, and as the arrangements for the passage of the increased amounts of water out of the Stockade were insufficient, the liquid feces overflowed the low grounds and covered them several inches, after the subsidence of the waters. The action of the sun upon this putrefying mass of excrements and fragments of bread and meat and bones excited most rapid fermentation and developed a horrible stench. Improvements were projected for the removal of the filth and for the prevention of its accumulation, but they were only partially and imperfectly carried out. As the forces of the prisoners were reduced by confinement, want of exercise, improper diet, and by scurvy, diarrhea, and dysentery, they were unable to evacuate their bowels within the stream or along its banks, and the excrements were deposited at the very doors of their tents. The vast majority appeared to lose all repulsion to filth, and both sick and well disregarded all the laws of hygiene and personal cleanliness. The accommodations for the sick were imperfect and insufficient. From the organization of the prison, February 24, 1864, to May 22, the sick were treated within the Stockade. In the crowded condition of the Stockade, and with the tents and huts clustered thickly around the hospital, it was impossible to secure proper ventilation or to maintain the necessary police. The Federal prisoners also made frequent forays upon the hospital stores and carried off the food and clothing of the sick. The hospital was, on the 22d of May, removed to its present site without the Stockade, and five acres of ground covered with oaks and pines appropriated to the use of the sick.

The supply of medical officers has been insufficient from the foundation of the prison.

The nurses and attendants upon the sick have been most generally Federal prisoners, who in too many cases appear to have been devoid of moral principle, and who not only neglected their duties, but were also engaged in extensive robbing of the sick.

From the want of proper police and hygienic regulations alone it is not

wonderful that from February 24 to September 21, 1864, nine thousand four

hundred and seventy-nine deaths, nearly one-third the entire number of

prisoners, should have been recorded. I found the Stockade and hospital in

the following condition during my pathological investigations, instituted

in the month of September, 1864:

At the time of my visit to Andersonville a large number of Federal prisoners had been removed to Millen, Savannah; Charleston, and other parts of, the Confederacy, in anticipation of an advance of General Sherman's forces from Atlanta, with the design of liberating their captive brethren; however, about fifteen thousand prisoners remained confined within the limits of the Stockade and Confederate States Military Prison Hospital.

In the Stockade, with the exception of the damp lowlands bordering the small stream, the surface was covered with huts, and small ragged tents and parts of blankets and fragments of oil-cloth, coats, and blankets stretched upon stacks. The tents and huts were not arranged according to any order, and there was in most parts of the enclosure scarcely room for two men to walk abreast between the tents and huts.

If one might judge from the large pieces of corn-bread scattered about in every direction on the ground the prisoners were either very lavishly supplied with this article of diet, or else this kind of food was not relished by them.

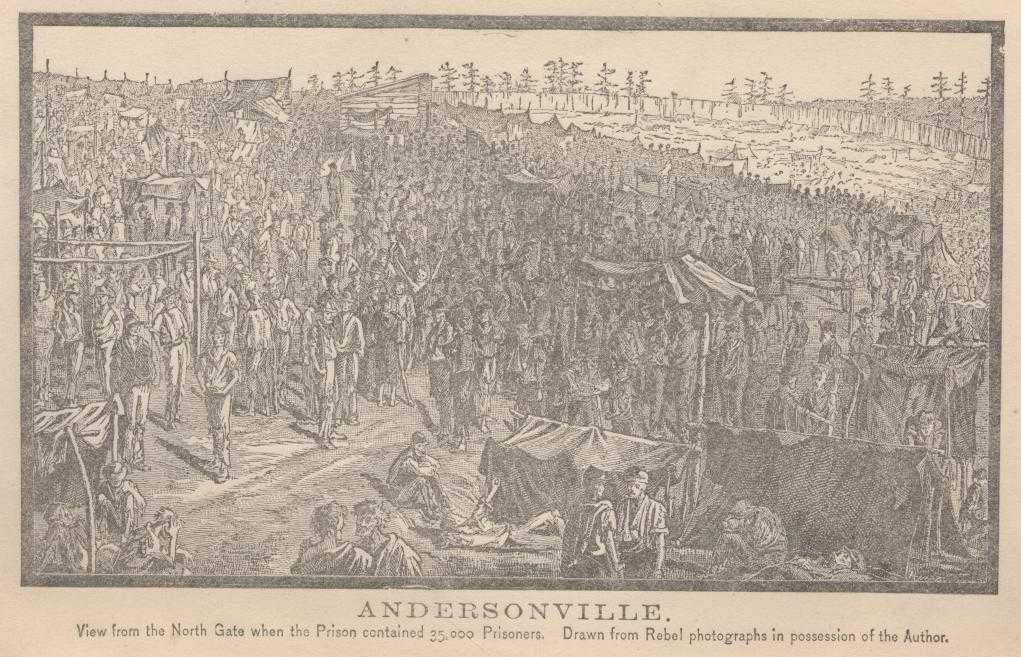

Each day the dead from the Stockade were carried out by their fellow-prisoners and deposited upon the ground under a bush arbor, just outside of the Southwestern Gate. From thence they were carried in carts to the burying ground, one-quarter of a mile northwest, of the Prison. The dead were buried without coffins, side by side, in trenches four feet deep.

The low grounds bordering the stream were covered with human excrements and filth of all kinds, which in many places appeared to be alive with working maggots. An indescribable sickening stench arose from these fermenting masses of human filth.

There were near five thousand seriously ill Federals in the Stockade and Confederate States Military Prison Hospital, and the deaths exceeded one hundred per day, and large numbers of the prisoners who were walking about, and who had not been entered upon the sick reports, were suffering from severe and incurable diarrhea, dysentery, and scurvy. The sick were attended almost entirely by their fellow-prisoners, appointed as nurses, and as they received but little attention, they were compelled to exert themselves at all times to attend to the calls of nature, and hence they retained the power of moving about to within a comparatively short period of the close of life. Owing to the slow progress of the diseases most prevalent, diarrhea, and chronic dysentery, the corpses were as a general rule emaciated.

I visited two thousand sick within the Stockade, lying under some long sheds which had been built at the northern portion for themselves. At this time only one medical officer was in attendance, whereas at least twenty medical officers should have been employed.

Died in the Stockade from its organization, February 24, 186l to

September 2l ....................................................3,254

Died in Hospital during same time ...............................6,225

Total deaths in Hospital and Stockade ...........................9,479

Scurvy, diarrhea, dysentery, and hospital gangrene were the prevailing diseases. I was surprised to find but few cases of malarial fever, and no well-marked cases either of typhus or typhoid fever. The absence of the different forms of malarial fever may be accounted for in the supposition that the artificial atmosphere of the Stockade, crowded densely with human beings and loaded with animal exhalations, was unfavorable to the existence and action of the malarial poison. The absence of typhoid and typhus fevers amongst all the causes which are supposed to generate these diseases, appeared to be due to the fact that the great majority of these prisoners had been in captivity in Virginia, at Belle Island, and in other parts of the Confederacy for months, and even as long as two years, and during this time they had been subjected to the same bad influences, and those who had not had these fevers before either had them during their confinement in Confederate prisons or else their systems, from long exposure, were proof against their action.

The effects of scurvy were manifested on every hand, and in all its various stages, from the muddy, pale complexion, pale gums, feeble, languid muscular motions, lowness of spirits, and fetid breath, to the dusky, dirty, leaden complexion, swollen features, spongy, purple, livid, fungoid, bleeding gums, loose teeth, oedematous limbs, covered with livid vibices, and petechiae spasmodically flexed, painful and hardened extremities, spontaneous hemorrhages from mucous canals, and large, ill-conditioned, spreading ulcers covered with a dark purplish fungus growth. I observed that in some of the cases of scurvy the parotid glands were greatly swollen, and in some instances to such an extent as to preclude entirely the power to articulate. In several cases of dropsy of the abdomen and lower extremities supervening upon scurvy, the patients affirmed that previously to the appearance of the dropsy they had suffered with profuse and obstinate diarrhea, and that when this was checked by a change of diet, from Indian corn-bread baked with the husk, to boiled rice, the dropsy appeared. The severe pains and livid patches were frequently associated with swellings in various parts, and especially in the lower extremities, accompanied with stiffness and contractions of the knee joints and ankles, and often with a brawny feel of the parts, as if lymph had been effused between the integuments and apeneuroses, preventing the motion of the skin over the swollen parts. Many of the prisoners believed that the scurvy was contagious, and I saw men guarding their wells and springs, fearing lest some man suffering with the scurvy might use the water and thus poison them.

I observed also numerous cases of hospital gangrene, and of spreading

scorbutic ulcers, which had supervened upon slight injuries. The scorbutic

ulcers presented a dark, purple fungoid, elevated surface, with livid

swollen edges, and exuded a thin; fetid, sanious fluid, instead of pus.

Many ulcers which originated from the scorbutic condition of the system

appeared to become truly gangrenous, assuming all the characteristics of

hospital gangrene. From the crowded condition, filthy habits, bad diet,

and dejected, depressed condition of the prisoners, their systems had

become so disordered that the smallest abrasion of the skin, from the

rubbing of a shoe, or from the effects of the sun, or from the prick of a

splinter, or from scratching, or a musketo bite, in some cases, took on

rapid and frightful ulceration and gangrene. The long use of salt meat,

ofttimes imperfectly cured, as well as the most total deprivation of

vegetables and fruit, appeared to be the chief causes of the scurvy. I

carefully examined the bakery and the bread furnished the prisoners, and

found that they were supplied almost entirely with corn-bread from which

the husk had not been separated. This husk acted as an irritant to the

alimentary canal, without adding any nutriment to the bread. As far as my

examination extended no fault could be found with the mode in which the

bread was baked; the difficulty lay in the failure to separate the husk

from the corn-meal. I strongly urged the preparation of large quantities

of soup made from the cow and calves' heads with the brains and tongues,

to which a liberal supply of sweet potatos and vegetables might have been

advantageously added. The material existed in abundance for the

preparation of such soup in large quantities with but little additional

expense. Such aliment would have been not only highly nutritious, but it

would also have acted as an efficient remedial agent for the removal of

the scorbutic condition. The sick within the Stockade lay under several

long sheds which were originally built for barracks. These sheds covered

two floors which were open on all sides. The sick lay upon the bare

boards, or upon such ragged blankets as they possessed, without, as far as

I observed, any bedding or even straw.

............................

The haggard, distressed countenances of these miserable, complaining, dejected, living skeletons, crying for medical aid and food, and cursing their Government for its refusal to exchange prisoners, and the ghastly corpses, with their glazed eye balls staring up into vacant space, with the flies swarming down their open and grinning mouths, and over their ragged clothes, infested with numerous lice, as they lay amongst the sick and dying, formed a picture of helpless, hopeless misery which it would be impossible to portray bywords or by the brush. A feeling of disappointment and even resentment on account of the United States Government upon the subject of the exchange of prisoners, appeared to be widespread, and the apparent hopeless nature of the negotiations for some general exchange of prisoners appeared to be a cause of universal regret and deep and injurious despondency. I heard some of the prisoners go so far as to exonerate the Confederate Government from any charge of intentionally subjecting them to a protracted confinement, with its necessary and unavoidable sufferings, in a country cut off from all intercourse with foreign nations, and sorely pressed on all sides, whilst on the other hand they charged their prolonged captivity upon their own Government, which was attempting to make the negro equal to the white man. Some hundred or more of the prisoners had been released from confinement in the Stockade on parole, and filled various offices as clerks, druggists, and carpenters, etc., in the various departments. These men were well clothed, and presented a stout and healthy appearance, and as a general rule they presented a much more robust and healthy appearance than the Confederate troops guarding the prisoners.

The entire grounds are surrounded by a frail board fence, and are strictly guarded by Confederate soldiers, and no prisoner except the paroled attendants is allowed to leave the grounds except by a special permit from the Commandant of the Interior of the Prison.

The patients and attendants, near two thousand in number, are crowded into this confined space and are but poorly supplied with old and ragged tents. Large numbers of them were without any bunks in the tents, and lay upon the ground, oft-times without even a blanket. No beds or straw appeared to have been furnished. The tents extend to within a few yards of the small stream, the eastern portion of which, as we have before said, is used as a privy and is loaded with excrements; and I observed a large pile of corn-bread, bones, and filth of all kinds, thirty feet in diameter and several feet in hight, swarming with myriads of flies, in a vacant space near the pots used for cooking. Millions of flies swarmed over everything, and covered the faces of the sleeping patients, and crawled down their open mouths, and deposited their maggots in the gangrenous wounds of the living, and in the mouths of the dead. Musketos in great numbers also infested the tents, and many of the patients were so stung by these pestiferous insects, that they resembled those suffering from a slight attack of the measles.

The police and hygiene of the hospital were defective in the extreme; the attendants, who appeared in almost every instance to have been selected from the prisoners, seemed to have in many cases but little interest in the welfare of their fellow-captives. The accusation was made that the nurses in many cases robbed the sick of their clothing, money, and rations, and carried on a clandestine trade with the paroled prisoners and Confederate guards without the hospital enclosure, in the clothing, effects of the sick, dying, and dead Federals. They certainly appeared to neglect the comfort and cleanliness of the sick intrusted to their care in a most shameful manner, even after making due allowances for the difficulties of the situation. Many of the sick were literally encrusted with dirt and filth and covered with vermin. When a gangrenous wound needed washing, the limb was thrust out a little from the blanket, or board, or rags upon which the patient was lying, and water poured over it, and all the putrescent matter allowed to soak into the ground floor of the tent. The supply of rags for dressing wounds was said to be very scant, and I saw the most filthy rags which had been applied several times, and imperfectly washed, used in dressing wounds. Where hospital gangrene was prevailing, it was impossible for any wound to escape contagion under these circumstances. The results of the treatment of wounds in the hospital were of the most unsatisfactory character, from this neglect of cleanliness, in the dressings and wounds themselves, as well as from various other causes which will be more fully considered. I saw several gangrenous wounds filled with maggots. I have frequently seen neglected wounds amongst the Confederate soldiers similarly affected; and as far as my experience extends, these worms destroy only the dead tissues and do not injure specially the well parts. I have even heard surgeons affirm that a gangrenous wound which had been thoroughly cleansed by maggots, healed more rapidly than if it had been left to itself. This want of cleanliness on the part of the nurses appeared to be the result of carelessness and inattention, rather than of malignant design, and the whole trouble can be traced to the want of the proper police and sanitary regulations, and to the absence of intelligent organization and division of labor. The abuses were in a large measure due to the almost total absence of system, government, and rigid, but wholesome sanitary regulations. In extenuation of these abuses it was alleged by the medical officers that the Confederate troops were barely sufficient to guard the prisoners, and that it was impossible to obtain any number of experienced nurses from the Confederate forces. In fact the guard appeared to be too small, even for the regulation of the internal hygiene and police of the hospital.

The manner of disposing of the dead was also calculated to depress the

already desponding spirits of these men, many of whom have been confined

for months, and even for nearly two years in Richmond and other places,

and whose strength had been wasted by bad air, bad food, and neglect of

personal cleanliness. The dead-house is merely a frame covered with old

tent cloth and a few bushes, situated in the southwestern corner of the

hospital grounds. When a patient dies, he is simply laid in the narrow

street in front of his tent, until he is removed by Federal negros

detailed to carry off the dead; if a patient dies during the night, he

lies there until the morning, and during the day even the dead were

frequently allowed to remain for hours in these walks. In the dead-house

the corpses lie upon the bare ground, and were in most cases covered with

filth and vermin.

............................

The cooking arrangements are of the most defective character. Five large iron pots similar to those used for boiling sugar cane, appeared to be the only cooking utensils furnished by the hospital for the cooking of nearly two thousand men; and the patients were dependent in great measure upon their own miserable utensils. They were allowed to cook in the tent doors and in the lanes, and this was another source of filth, and another favorable condition for the generation and multiplication of flies and other vermin.

The air of the tents was foul and disagreeable in the extreme, and in fact the entire grounds emitted a most nauseous and disgusting smell. I entered nearly all the tents and carefully examined the cases of interest, and especially the cases of gangrene, upon numerous occasions, during the prosecution of my pathological inquiries at Andersonville, and therefore enjoyed every opportunity to judge correctly of the hygiene and police of the hospital.

There appeared to be almost absolute indifference and neglect on the part of the patients of personal cleanliness; their persons and clothing inmost instances, and especially of those suffering with gangrene and scorbutic ulcers, were filthy in the extreme and covered with vermin. It was too often the case that patients were received from the Stockade in a most deplorable condition. I have seen men brought in from the Stockade in a dying condition, begrimed from head to foot with their own excrements, and so black from smoke and filth that they, resembled negros rather than white men. That this description of the Stockade and hospital has not been overdrawn, will appear from the reports of the surgeons in charge, appended to this report.

.........................

We will examine first the consolidated report of the sick and wounded Federal prisoners. During six months, from the 1st of March to the 31st of August, forty-two thousand six hundred and eighty-six cases of diseases and wounds were reported. No classified record of the sick in the Stockade was kept after the establishment of the hospital without the Prison. This fact, in conjunction with those already presented relating to the insufficiency of medical officers and the extreme illness and even death of many prisoners in the tents in the Stockade, without any medical attention or record beyond the bare number of the dead, demonstrate that these figures, large as they, appear to be, are far below the truth.

As the number of prisoners varied greatly at different periods, the relations between those reported sick and well, as far as those statistics extend, can best be determined by a comparison of the statistics of each month.

During this period of six months no less than five hundred and sixty-five deaths are recorded under the head of 'morbi vanie.' In other words, those men died without having received sufficient medical attention for the determination of even the name of the disease causing death.

During the month of August fifty-three cases and fifty-three deaths are recorded as due to marasmus. Surely this large number of deaths must have been due to some other morbid state than slow wasting. If they were due to improper and insufficient food, they should have been classed accordingly, and if to diarrhea or dysentery or scurvy, the classification should in like manner have been explicit.

We observe a progressive increase of the rate of mortality, from 3.11 per cent. in March to 9.09 per cent. of mean strength, sick and well, in August. The ratio of mortality continued to increase during September, for notwithstanding the removal of one-half of the entire number of prisoners during the early portion of the month, one thousand seven hundred and sixty-seven (1,767) deaths are registered from September 1 to 21, and the largest number of deaths upon any one day occurred during this month, on the 16th, viz. one hundred and nineteen.

The entire number of Federal prisoners confined at Andersonville was about

forty thousand six hundred and eleven; and during the period of near seven

months, from February 24 to September 21, nine thousand four hundred and

seventy-nine (9,479) deaths were recorded; that is, during this period

near one-fourth, or more, exactly one in 4.2, or 13.3 per cent.,

terminated fatally. This increase of mortality was due in great measure to

the accumulation of the sources of disease, as the increase of excrements

and filth of all kinds, and the concentration of noxious effluvia, and

also to the progressive effects of salt diet, crowding, and the hot

climate.

1st. The great mortality among the Federal prisoners confined in the military prison at Andersonville was not referable to climatic causes, or to the nature of the soil and waters.

2d. The chief causes of death were scurvy and its results and bowel affections-chronic and acute diarrhea and dysentery. The bowel affections appear to have been due to the diet, the habits of the patients, the depressed, dejected state of the nervous system and moral and intellectual powers, and to the effluvia arising from the decomposing animal and vegetable filth. The effects of salt meat, and an unvarying diet of cornmeal, with but few vegetables, and imperfect supplies of vinegar and syrup, were manifested in the great prevalence of scurvy. This disease, without doubt, was also influenced to an important extent in its origin and course by the foul animal emanations.

3d. From the sameness of the food and form, the action of the poisonous gases in the densely crowded and filthy Stockade and hospital, the blood was altered in its constitution, even before the manifestation of actual disease. In both the well and the sick the red corpuscles were diminished; and in all diseases uncomplicated with inflammation, the fibrous element was deficient. In cases of ulceration of the mucous membrane of the intestinal canal, the fibrous element of the blood was increased; while in simple diarrhea, uncomplicated with ulceration, it was either diminished or else remained stationary. Heart clots were very common, if not universally present, in cases of ulceration of the intestinal mucous membrane, while in the uncomplicated cases of diarrhea and scurvy, the blood was fluid and did not coagulate readily, and the heart clots and fibrous concretions were almost universally absent. From the watery condition of the blood, there resulted various serous effusions into the pericardium, ventricles of the brain, and into the abdomen. In almost all the cases which I examined after death, even the most emaciated, there was more or less serous effusion into the abdominal cavity. In cases of hospital gangrene of the extremities, and in cases of gangrene of the intestines, heart clots and fibrous coagula were universally present. The presence of those clots in the cases of hospital gangrene, while they were absent in the cases in which there was no inflammatory symptoms, sustains the conclusion that hospital gangrene is a species of inflammation, imperfect and irregular though it may be in its progress, in which the fibrous element and coagulation of the blood are increased, even in those who are suffering from such a condition of the blood, and from such diseases as are naturally accompanied with a decrease in the fibrous constituent.

4th. The fact that hospital Gangrene appeared in the Stockade first, and originated spontaneously without any previous contagion, and occurred sporadically all over the Stockade and prison hospital, was proof positive that this disease will arise whenever the conditions of crowding, filth, foul air, and bad diet are present. The exhalations from the hospital and Stockade appeared to exert their effects to a considerable distance outside of these localities. The origin of hospital gangrene among these prisoners appeared clearly to depend in great measure upon the state of the general system induced by diet, and various external noxious influences. The rapidity of the appearance and action of the gangrene depended upon the powers and state of the constitution, as well as upon the intensity of the poison in the atmosphere, or upon the direct application of poisonous matter to the wounded surface. This was further illustrated by the important fact that hospital gangrene, or a disease resembling it in all essential respects, attacked the intestinal canal of patients laboring under ulceration of the bowels, although there were no local manifestations of gangrene upon the surface of the body. This mode of termination in cases of dysentery was quite common in the foul atmosphere of the Confederate States Military Hospital, in the depressed, depraved condition of the system of these Federal prisoners.

5th. A scorbutic condition of the system appeared to favor the origin of foul ulcers, which frequently took on true hospital gangrene. Scurvy and hospital gangrene frequently existed in the same individual. In such cases, vegetable diet, with vegetable acids, would remove the scorbutic condition without curing the hospital gangrene. From the results of the existing war for the establishment of the independence of the Confederate States, as well as from the published observations of Dr. Trotter, Sir Gilbert Blane, and others of the English navy and army, it is evident that the scorbutic condition of the system, especially in crowded ships and camps, is most favorable to the origin and spread of foul ulcers and hospital gangrene. As in the present case of Andersonville, so also in past times when medical hygiene was almost entirely neglected, those two diseases were almost universally associated in crowded ships. In many cases it was very difficult to decide at first whether the ulcer was a simple result of scurvy or of the action of the prison or hospital gangrene, for there was great similarity in the appearance of the ulcers in the two diseases. So commonly have those two diseases been combined in their origin and action, that the description of scorbutic ulcers, by many authors, evidently includes also many of the prominent characteristics of hospital gangrene. This will be rendered evident by an examination of the observations of Dr. Lind and Sir Gilbert Blane upon scorbutic ulcers.

6th. Gangrenous spots followed by rapid destruction of tissue appeared in some cases where there had been no known wound. Without such well-established facts, it might be assumed that the disease was propagated from one patient to another. In such a filthy and crowded hospital as that of the Confederate States Military Prison at Andersonville, it was impossible to isolate the wounded from the sources of actual contact of the gangrenous matter. The flies swarming over the wounds and over filth of every kind, the filthy, imperfectly washed and scanty supplies of rags, and the limited supply of washing utensils, the same wash-bowl serving for scores of patients, were sources of such constant circulation of the gangrenous matter that the disease might rapidly spread from a single gangrenous wound. The fact already stated, that a form of moist gangrene, resembling hospital gangrene, was quite common in this foul atmosphere, in cases of dysentery, both with and without the existence of the disease upon the entire surface, not only demonstrates the dependence of the disease upon the state of the constitution, but proves in the clearest manner that neither the contact of the poisonous matter of gangrene, nor the direct action of the poisonous atmosphere upon the ulcerated surfaces is necessary to the development of the disease.

7th. In this foul atmosphere amputation did not arrest hospital gangrene; the disease almost invariably returned. Almost every amputation was followed finally by death, either from the effects of gangrene or from the prevailing diarrhea and dysentery. Nitric acid and escharotics generally in this crowded atmosphere, loaded with noxious effluvia, exerted only temporary effects; after their application to the diseased surfaces, the gangrene would frequently return with redoubled energy; and even after the gangrene had been completely removed by local and constitutional treatment, it would frequently return and destroy the patient. As far as my observation extended, very few of the cases of amputation for gangrene recovered. The progress of these cases was frequently very deceptive. I have observed after death the most extensive disorganization of the structures of the stump, when during life there was but little swelling of the part, and the patient was apparently doing well. I endeavored to impress upon the medical officers the view that in this disease treatment was almost useless, without an abundant supply of pure, fresh air, nutritious food, and tonics and stimulants. Such changes, however, as would allow of the isolation of the cases of hospital gangrene appeared to be out of the power of the medical officers.

8th. The gangrenous mass was without true pus, and consisted chiefly of broken-down, disorganized structures. The reaction of the gangrenous matter in certain stages was alkaline.

9th. The best, and in truth the only means of protecting large armies and navies, as well as prisoners, from the ravages of hospital gangrene, is to furnish liberal supplies of well-cured meat, together with fresh beef and vegetables, and to enforce a rigid system of hygiene.

10th. Finally, this gigantic mass of human misery calls loudly for relief, not only for the sake of suffering humanity, but also on account of our own brave soldiers now captives in the hands of the Federal Government. Strict justice to the gallant men of the Confederate Armies, who have been or who may be, so unfortunate as to be compelled to surrender in battle, demands that the Confederate Government should adopt that course which will best secure their health and comfort in captivity; or at least leave their enemies without a shadow of an excuse for any violation of the rules of civilized warfare in the treatment of prisoners.

[End of the Witness's Testimony.]

The variation—from month to month—of the proportion of deaths to the whole number living is singular and interesting. It supports the theory I have advanced above, as the following facts, taken from the official report, will show:

|

In April one in every sixteen died. In May one in every twenty-six died. In June one in every twenty-two died. In July one in every eighteen died. In August one in every eleven died. In September one in every three died. In October one in every two died. In November one in every three died. |

Does the reader fully understand that in September one-third of those in the pen died, that in October one-half of the remainder perished, and in November one-third of those who still survived, died? Let him pause for a moment and read this over carefully again; because its startling magnitude will hardly dawn upon him at first reading. It is true that the fearfully disproportionate mortality of those months was largely due to the fact that it was mostly the sick that remained behind, but even this diminishes but little the frightfulness of the showing. Did any one ever hear of an epidemic so fatal that one-third of those attacked by it in one month died; one-half of the remnant the next month, and one-third of the feeble remainder the next month? If he did, his reading has been much more extensive than mine.

The greatest number of deaths in one day is reported to have occurred on the 23d of August, when one hundred and twenty-seven died, or one man every eleven minutes.

The greatest number of prisoners in the Stockade is stated to have been August 8, when there were thirty-three thousand one hundred and fourteen.

I have always imagined both these statements to be short of the truth,

because my remembrance is that one day in August I counted over two

hundred dead lying in a row. As for the greatest number of prisoners, I

remember quite distinctly standing by the ration wagon during the whole

time of the delivery of rations, to see how many prisoners there really

were inside. That day the One Hundred and Thirty-Third Detachment was

called, and its Sergeant came up and drew rations for a full detachment.

All the other detachments were habitually kept full by replacing those who

died with new comers. As each detachment consisted of two hundred and

seventy men, one hundred and thirty-three detachments would make

thirty-five thousand nine hundred and ten, exclusive of those in the

hospital, and those detailed outside as cooks, clerks, hospital attendants

and various other employments—say from one to two thousand more.

DIFFICULTY OF EXERCISING—EMBARRASSMENTS OF A MORNING WALK—THE RIALTO OF THE PRISON—CURSING THE SOUTHERN CONFEDERACY—THE STORY OF THE BATTLE OF SPOTTSYLVANIA COURTHOUSE.

Certainly, in no other great community, that ever existed upon the face of the globe was there so little daily ebb and flow as in this. Dull as an ordinary Town or City may be; however monotonous, eventless, even stupid the lives of its citizens, there is yet, nevertheless, a flow every day of its life-blood—its population towards its heart, and an ebb of the same, every evening towards its extremities. These recurring tides mingle all classes together and promote the general healthfulness, as the constant motion hither and yon of the ocean's waters purify and sweeten them.

The lack of these helped vastly to make the living mass inside the Stockade a human Dead Sea—or rather a Dying Sea—a putrefying, stinking lake, resolving itself into phosphorescent corruption, like those rotting southern seas, whose seething filth burns in hideous reds, and ghastly greens and yellows.

Being little call for motion of any kind, and no room to exercise whatever wish there might be in that direction, very many succumbed unresistingly to the apathy which was so strongly favored by despondency and the weakness induced by continual hunger, and lying supinely on the hot sand, day in and day out, speedily brought themselves into such a condition as invited the attacks of disease.

It required both determination and effort to take a little walking exercise. The ground was so densely crowded with holes and other devices for shelter that it took one at least ten minutes to pick his way through the narrow and tortuous labyrinth which served as paths for communication between different parts of the Camp. Still further, there was nothing to see anywhere or to form sufficient inducement for any one to make so laborious a journey. One simply encountered at every new step the same unwelcome sights that he had just left; there was a monotony in the misery as in everything else, and consequently the temptation to sit or lie still in one's own quarters became very great.

I used to make it a point to go to some of the remoter parts of the Stockade once every day, simply for exercise. One can gain some idea of the crowd, and the difficulty of making one's way through it, when I say that no point in the prison could be more than fifteen hundred feet from where I staid, and, had the way been clear, I could have walked thither and back in at most a half an hour, yet it usually took me from two to three hours to make one of these journeys.

This daily trip, a few visits to the Creek to wash all over, a few games of chess, attendance upon roll call, drawing rations, cooking and eating the same, "lousing" my fragments of clothes, and doing some little duties for my sick and helpless comrades, constituted the daily routine for myself, as for most of the active youths in the prison.

The Creek was the great meeting point for all inside the Stockade. All able to walk were certain to be there at least once during the day, and we made it a rendezvous, a place to exchange gossip, discuss the latest news, canvass the prospects of exchange, and, most of all, to curse the Rebels. Indeed no conversation ever progressed very far without both speaker and listener taking frequent rests to say bitter things as to the Rebels generally, and Wirz, Winder and Davis in particular.

A conversation between two boys—strangers to each other who came to

the Creek to wash themselves or their clothes, or for some other purpose,

would progress thus:

First Boy—"I belong to the Second Corps,—Hancock's, [the Army of the Potomac boys always mentioned what Corps they belonged to, where the Western boys stated their Regiment.] They got me at Spottsylvania, when they were butting their heads against our breast-works, trying to get even with us for gobbling up Johnson in the morning,"—He stops suddenly and changes tone to say: "I hope to God, that when our folks get Richmond, they will put old Ben Butler in command of it, with orders to limb, skin and jayhawk it worse than he did New Orleans."

Second Boy, (fervently :) "I wish to God he would, and that he'd catch old Jeff., and that grayheaded devil, Winder, and the old Dutch Captain, strip 'em just as we were, put 'em in this pen, with just the rations they are givin' us, and set a guard of plantation niggers over 'em, with orders to blow their whole infernal heads off, if they dared so much as to look at the dead line."

First Boy—(returning to the story of his capture.) "Old Hancock caught the Johnnies that morning the neatest you ever saw anything in your life. After the two armies had murdered each other for four or five days in the Wilderness, by fighting so close together that much of the time you could almost shake hands with the Graybacks, both hauled off a little, and lay and glowered at each other. Each side had lost about twenty thousand men in learning that if it attacked the other it would get mashed fine. So each built a line of works and lay behind them, and tried to nag the other into coming out and attacking. At Spottsylvania our lines and those of the Johnnies weren't twelve hundred yards apart. The ground was clear and clean between them, and any force that attempted to cross it to attack would be cut to pieces, as sure as anything. We laid there three or four days watching each other—just like boys at school, who shake fists and dare each other. At one place the Rebel line ran out towards us like the top of a great letter 'A.' The night of the 11th of May it rained very hard, and then came a fog so thick that you couldn't see the length of a company. Hancock thought he'd take advantage of this. We were all turned out very quietly about four o'clock in the morning. Not a bit of noise was allowed. We even had to take off our canteens and tin cups, that they might not rattle against our bayonets. The ground was so wet that our footsteps couldn't be heard. It was one of those deathly, still movements, when you think your heart is making as much noise as a bass drum.