Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, January 12th, 1895

Author: Various

Editor: F. C. Burnand

Release date: April 7, 2013 [eBook #42478]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Malcolm Farmer, Lesley Halamek and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(By Mr. Punch's own Short Story-teller.)

Introduction.

Not many living men, and even fewer in the ages that are past, have—if I may use the word—sported with greater assiduity and success than I have during a life which is even now little past its middle period. At one time on horseback, at another on the bounding and impulsive elephant; now bestriding the matchless dromedary on his native prairie, now posted on foot in a jungle crowded with golden pheasants in all the native splendour of their plumage; sometimes matching my solitary craft against a host of foxes on the swelling uplands of Leicestershire, sometimes facing the Calydonian boar or the sanguinary panther in their woodland lairs, dealing showers of leaden death from a hundred tubes, or tracking my fearful prey by the lonely light of a wax vesta and despatching it at midnight with my trusty bowie—wherever there were leagues to be walked, risks to be run, or fastnesses to be rushed there not only have I been the first, but (paradoxical as it may appear) there also have I succeeded and have never been successfully followed. My experiences are therefore unique, and it is in the hope that they may to some extent profit a younger generation, less inured, I fear, to hardship and danger than my own, that I now set pen to paper and recount some of the exploits that have made my name famous wherever sport is loved and true sportsmen are revered.

A less modest man might have said more, but one whose deeds speak for him in every quarter of the world may well be content to leave to punier men the ridiculous trumpeting braggadocio that too often makes so-called sportsmen the laughing stock of society. For myself, I can never forget the lesson I learned at an early age from my dear father, himself a shikari of no common order, though to be sure, as he himself would be the first to admit if he were alive, the exploits of the son (I had no brothers) have now thrust the parental performances into the background. Still, it was my father who first inculcated upon my infant mind the daring, the ignorance of fear, the contempt of danger, and the iron endurance which have since made me a household word. Heaven rest the old man! He sleeps his last sleep far away in the Desert of Golden Sand, with no head-stone to mark his resting-place, and neither the roaring of his old enemies the tigers, nor the bellowing of the countless alligators who infest the spot can rouse him any more. Alas! it was trustfulness that destroyed him. He was gored to death by a favourite rhinoceros that he had rescued at a tender age when its mother was killed, and had brought up to know and, as he thought, to love him. But I have always thought myself that the rhinoceros was a treacherous brute, and though I have often been asked to tame one, for presentation to this or that Emperor, I have consistently declined.

Marvellous, however, as my father was in his day for his exploits and his variegated bags of game, he was perhaps even more wonderful for the unswerving accuracy with which he was accustomed to relate his adventures. Far and wide over the steppes of Central Asia, the burning regions of equatorial Africa, the precipitous haunts of the American Grizzly, and the wild retreats of the ferocious Albanian pig—everywhere, in short, where he had set foot or drawn trigger, this peculiarity of his was known and appreciated, and many a respectful sobriquet did it earn for him from the savage tribes amongst whom he spent the best years of his life. In Kashmir he was known as Peili Ton, that is, the man who cannot lie; amongst the swarthy Zambesians the name of Govun Bettîr (the Undefeated and Veracious Man) was a name to conjure with even when in their moments of warlike passion the tribesmen rushed madly through their primeval thickets, shouting their terrible war-cry, "Itzup ures Leeve," that is, "Death to the white-faced robbers."

But what I wished specially to relate about my poor father was the lesson of truthfulness which he inculcated upon me at an early age. He and I (I was then but a lad of twelve) had been hunting the ferocious Pilsener gemsbock through the wild Lagerland in which he makes his home. It happened one morning that we had parted company. To me was assigned the duty of beating through the Bier-Wald, the dense forest which stretches mile upon mile in unbroken gloom to the confines of the Boose-See. The Fates were propitious. Wherever I turned I saw a victim, and one after another I brought down with unerring aim twenty-four (as I thought) of these noble animals, whose horns are now worth a king's ransom, and might, even in those distant days, have rescued a minor German Prince from captivity. Hastening home with my booty loaded upon my back—I was a strong boy for my age, but of course nothing to what I have since become—I met my dear father just as I reached the door of the hut which served us for hunting quarters. Joyously I cast down my burden, and sprang to his side. But my father wore an expression of annoyance, and I soon discovered that the luck had been against him. He had indeed seen ten bocks, but for some reason his aim had lacked its accustomed deadliness, and he had come back empty-handed. I condoled with him in a boy's artless fashion, and proceeded to tell him how fortunate I had been.

"How many have you shot?" he asked me.

"Twenty-four," was my reply.

"Count them," said my father.

I did so, and you may judge of my astonishment when I found that twenty-six had fallen to my gun. I counted again and again. Yes, there were twenty-six of them. With one of my shots I must have brought down three. In the agitation of the moment I had overlooked this. I told my father that I had made a slight mistake, and endeavoured to explain how it had arisen. But my father was inexorable.

"A lie," he said, "is a lie. You said you had shot twenty-four, you have actually killed twenty-six. You must suffer."

Over the rest of the painful scene I draw a veil. The shrieks of my mother, who implored pardon for me on her bended knees, still seem to ring in my ears. Since that time I have always respected not only the strict truth, but also the leather thongs which are in use in the Lagerland for the droves of untameable cattle that roam the prairies. This was my lesson, and I have never, never forgotten it.

A little girl, a charming tiny tot,

I well remember you with many a curl,

Although I recollect you said, "I'm not

A little girl."

We parted. Mid the worry and the whirl

Of life, again, alas! I saw you not.

I kept you in my memory as a pearl

Of winsome childhood. So imagine what

A shock it was this morning to unfurl

My morning paper, there to see you've got

A little girl!

Something to Live for.—The Pall Mall Gazette announced last Friday that "a bevy of head-masters will appear in the pulpit of St. Paul's this month." How many go to a "bevy" we are not aware, though perhaps we might ascertain it from Sir Druriolanus, who could inform us, after several crowded houses, how many go to see the "bevy," and how many combine to make up a "bevy," of ballet beauties in the pantomime; but putting it say at a dozen, the bevy of head-masters in their caps and gowns would find the pulpit of St. Paul's rather a tight fit. Pretty sight though, anyway.

HARLEQUIN HARCOURT, THE SLEEPING BEAUTY, AND THE FINANCIAL FAIRY

PRINCE.

—(See "New Year's Day Dream.")

(Hounds going from Covert to Covert.)

Master Jack (to M.F.H.). "I say, you know, awful nuisance the way these Women follow a Fellow over everything! Makes a Man have to be so beastly careful what he Jumps, don't you know!"

A Tennysonian Fragment from the Popular Pantomime of "Harlequin Harcourt, the Sleeping Beauty, and the Financial Fairy Prince."

["The Revenue Returns," says the Daily News, "for the expired three quarters of the financial year show that a sum of close upon £62,000,000 has been paid into the Exchequer. The Chancellor of the Exchequer's estimated revenue for the whole year was a little over £94,000,000. This is regarded as an indication of the revival of trade, and the promise of a substantial surplus for the next Budget."]

All blessèd boons, though coming late,

To those who wait them issue forth,

For skill in sequel works with fate,

And draws the veil from hidden worth.

He comes, great keeper of our tin,

He is no Tory Hurlo-Thrumbo!

A fairy Prince, with triple chin,

And heavy-footed as poor Jumbo!

He comes, scarce knowing what he seeks,

Though he has heard of Sleeping Beauties.

He hath been dreaming many weeks

Of Income Tax, Stamps, and Death Duties.

He'd charmed the party with his talk

Of Graduation; now grey fear

Knocks at his ribs, his cheek's like chalk,

With thoughts of Revenue for the Year.

More close and close his footsteps wind,

The next year's Budget on his heart.

From Stamps and Liquor will he find

Big plums? Will rich taxpayers "part"?

Here's sleeping Trade! "Lor! what a lark!"

He thinks. "To wake her—were a spree!

A kiss may lift those lashes dark;

She can't resist a buss—from Me!"

A touch, a smack! A boxèd ear.

There came the sound of a smart slap.

The Fairy Prince, with cry of fear,

His hand unto his cheek did clap.

The Sleeping Beauty gave a gape,

A wide-mouthed yawn, a long-drawn stretch.

He rubbed his chins. "This is a jape!

I knew my style the girl would fetch!

"In spite of all that Wilson says,*

I trust those Revenue Returns.

She does revive! Be mine the praise!

By Jove, though, how my left ear burns!

I told 'em that I'd do the trick

With my new fakement, the Death Duties.

Come, Miss, wake up! Revive, dear, quick!

You sleepiest of Sleeping Beauties!"

At last sweet slumbering Trade awoke,

And on her couch her form upreared.

The Prince smiled, rubbed his chins, and spoke.

"Ah, Wilson's prophecy is queered.

He swore that you would not revive,

In his Cassandra-like Review,

But don't sit yawning! Look alive!

Or men will swear I've humbugged you!"

"All right!" said sleepy Trade. "But still

My joints feel somewhat stiff or so.

Say, have you passed that Irish Bill

You schemed—how long was it ago?"

The Chancellor subdued a curse,

Which scarce would serve for a reply,

But dallied with his well-filled purse,

And smiling, put the question by.

* In a pessimistic editorial article, opening the new volume of the Investor's Review.

["The Emperor William is to have the Grand Order of the Imperial Chrysanthemum (the Japanese Garter) to add to his collection, 'in recognition of the services rendered by German officers to Japanese officers in instructing them in military and naval science.'"—Daily Chronicle.]

Oh, the Fatherland, the happy Fatherland,

With fresh happiness will hum,

When their Emperor shall the Order wear

Of the Jap Chry-san-the-mum!

He's "a daisy" now, as the world doth know;

But, oh! won't he be thrice happy,

When he sports the badge of the Golden Flower

Of the cute and grateful Jappy?

If John Chinaman in the little Jap

Has most surely caught a Tartar,

Jap learned to war 'neath the Teuton Star,

So will send him the Jap "Garter."

Bull has given him tips, and has built him ships,

But the Jap don't badge J. B.

No! Peace and War, like most other things,

Are now "made in Ger-ma-ny"!

"Sentiment" for Old-fashioned Play-goers.—"May that confounded 'Woman with a Past,' who monopolises the Present, have no Future!"

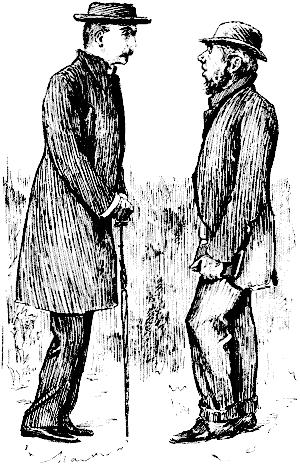

Benevolent Person (recognising an old protégé). "Rogers, I'm sorry to see you in this condition! I understood you had taken the Pledge!"

Rogers. "You're qui' ri', Sir. Only y' see the Water's frozen 't the Main down our Street!"

(An Episode in the Life of A. Briefless, Junior, Esq., Barrister-at-Law, in Three Parts.)

Part I.—The Coming into Possession of the Donkey.

"Yes, Sir," said my excellent and admirable clerk, Portington, "he came here three times, about a month ago. We thought he was mad, so would not let him in. But the third time he left that parcel and that letter. You see, Sir, they are tied together, and as there was a bomb scare on at the time, we did not touch them. That's how it comes, Sir, that you have not had them earlier."

I must confess I was a little annoyed. I frequently absent myself from Pump-Handle Court for days and even weeks together, and then I expect my clerical (I use the adjective in its non-ecclesiastical sense) representative to forward my correspondence.

"It cannot be helped, Portington," I replied; "all I care for are the interests of my clients. If the visitor was one anxious to lay his case before me, I can only trust he has not suffered by my unpremeditated absence."

"I do not think he will have to complain of that, Sir. And as to his case, we don't know whether it is one; none of us like to touch the parcel, lest it should go off."

"You mean with a report—it must get reported," I suggested, with a smile. I allow myself a little frolicsome levity at Yuletide. "Well, where is it?"

"In your room, Sir," and Portington led the way to my special apartment.

I found my chamber tenanted by a miscellaneous collection of articles. Truth to tell I do not use my rooms very frequently, and consequently it has become a sort of a proverb amongst my co-parceners in Pump-Handle Court, à propos of anything of a cumbersome character, "When in doubt, put it into Briefless's cupboard." Not that I really occupy a cupboard; my room (I lay the emphasis on the word) is far more commodious than the largest specimen of those receptacles. Consequently, I was not altogether surprised to find collected together a banjo-case, some curtain rods, a number of framed pictures, and a damaged bicycle. In the centre of the room was an oblong parcel, to which was tied an envelope, doubtless containing an enclosure.

With some slight trepidation—I had no wish to accompany Pump-Handle Court to the skies—I opened the letter. It ran as follows:—

"To A. Briefless, Junior, Esq.—Dear and Honoured Sir,—I have long desired to show you some token of goodwill. I have frequently read your contributions to the leading legal paper of the day (I refer, of course, to the London Charivari), and have been filled with admiration at the clearness of your style and the depth of your knowledge of what may be termed the duplex action of the human heart. As I happen to be Emperor of China I write anonymously. I have been ruined by law and the lawyers. You have never represented me or opposed me. For this I am very, very grateful, and beg you to accept the accompanying present. It is a —— But hush, we are observed."

And at this point the document abruptly terminated. I read the letter to Portington, and asked his opinion upon it. He replied abruptly he "considered the writer a lunatic."

"Well, no, I do not think we can go quite so far as that," I observed. "You see, he seems to have some appreciation of my talents. He may be a trifle eccentric, but I fancy nothing worse."

Encouraged by this belief in the sanity of my semi-anonymous (I use the epithet advisedly, as I take it that the incidental claim to the throne of the Celestial Empire was not urged seriously) correspondent, I opened the package. The brown paper unwound and a picture was revealed to us. It had evidently been painted for many years. The frame (which, in Portington's opinion, was the best portion of the structure) was distinctly old-fashioned. The gilding was tarnished and the woodwork out of repair.

"What is the subject?" I asked, after three or four minutes' close inspection.

"I think, Sir," replied my excellent and admirable clerk, "that it's something to do with a donkey."

Portington was right. On closer investigation the painting revealed itself to be the representation of a cottage in the snow, with some villagers drawing water from a half-frozen pond in the neighbourhood of a rather intelligent donkey, who was watching their proceedings with languid interest.

"Certainly it is a donkey," I exclaimed; "and, to my thinking, a very fine one."

"What shall we do with it, Sir?" asked Portington. "It's no good here; shall I give it to the dustman? He would take it away if we asked him."

For a moment I thought my clerical (I use the adjective in its non-ecclesiastical sense) representative was indulging in jocularity. I found I was in error. Portington was absolutely serious.

"You evidently do not know the value of some of these old frames. Of course I shall take the picture with me to my private residence."

I carried out my intention. The canvas presentment of the donkey and accessories was carefully conveyed in a four-wheeler to Justinian Gardens, where I have rented for some years a very pleasant house. The lady who has honoured me by taking my name, and whom in my more playful humour I sportively term my "better seven-eighths," received me.

"I hope you have brought the music from the Stores," said the lady, after our first greetings. "I suppose that package came from Victoria Street?"

"No, my precious one," I replied; I sometimes use terms of endearment to the members of my domestic circle. "It is a picture given to me by a grateful client."

"Client!" she exclaimed; "and a grateful one! What a find! But why bring it here? Haven't we already more pictures than we want? Why at this moment there's half-a-dozen of extra plates from the Christmas numbers that you would have framed, waiting to be hung."

"But this, my love, is an oil-painting, with what I judge to be a very valuable old-fashioned frame."

By this time my present was revealed.

"Why, it's only the picture of a donkey!" exclaimed my better seven-eighths, with a laugh. "We really don't want that sort of thing in the hall or reception rooms."

"But it is really very fine!" I urged. "Look at the handling of that donkey's ears. And the frame, too, is simply magnificent."

"I don't so much mind the frame. We might take out the picture and put in 'The Arrival of the Boulogne Boat,' the Christmas supplement to the Young Lady's Boudoir, in its stead. And yet it is just as likely as not to spoil it. No, I think we had better put picture and frame in the box-room."

"But my dear," I remonstrated; "this may be a very valuable picture. The head of the donkey is quite remarkable and ——"

"Now do we want portraits of donkeys about the house? The boxroom [pg 17] or the dust-hole is the proper place for them."

"I know you objected to my own likeness—you see the connection with the donkey, dear?" I sometimes make rather humorous remarks during the continuance of the festive season.

"Don't be silly! But this hideous thing should really go into the box-room." And so it went. Perhaps on a future occasion I may trace the further adventures of my grateful client's gift. In my poor judgment they are distinctly interesting and instructive.

She dreamed the doom that Fate pronounces

Against the woman ceased to be,

She dreamed her brain weighed three more ounces,

And was of finer quality.

Her iron nerves all fear derided,

She saw a mouse, but did not run.

With pockets she was well provided,

And she could fire a Maxim gun.

She had abjured each female folly,

Hygienic dress she always wore,

With stern, determined melancholy

The universe she pondered o'er.

Of man in all respects the equal,

At last her heart's desire was hers.

Only, like every other sequel,

Her sequel proved a touch perverse.

She sighed, "My mind with facts is loaded,

No golden vision it retains.

Even Nirvana is exploded,

And, save the Atom, nought remains!

"Each ray of light a mental prism

Must needs determine and arrest.

My life is one long syllogism,

Without a parenthetic jest.

"I who was wont to kneel revering,

In manly chivalry confide,

Am all alone my vessel steering—

And yet I am unsatisfied!

"The gingerbread has lost its gilding

That from afar appeared sublime.

I for eternity am building—

'Twas not amiss to build for time!

"The pilgrimage was long and painful,

Cheerless and cold the heights I win—

About me hangs a shadow baneful

Of that Eternal Feminine.

"Alas, I have not learned my lesson!

I feel a frantic, mad despair.

I'd like to put an evening dress on,

And many roses in my hair!

"My heart desires the old romances,

The fictions dear all facts above,

The flowers, the ices, and the dances,

The days of youth, the days of—Love.

"That giddy whirl, that senseless splendour,

Was dear, although I said it bored,

Agnosticism I'd surrender

Once, once again, to be adored!

"I wished my brain had three more ounces,

For them I bartered happiness;

My heart the new regime denounces,

I wish it had three ounces less!"

She woke. A subtle sense pervaded

Her mind of being someone great;

But very speedily it faded,

Her brain regained its normal state.

She said: "I'd beat them all at college

If I could have those ounces back;

Only—I should not like my knowledge

To make me cleverer than—Jack!"

(Vide "Daily Graphic" passim.)

Odyllic Force! O mystic power divine!

O greater than magician's might!—of course

You know the virtues of this gift of mine,

Odyllic Force!

I can command the vasty deep. I say

Unto the elemental storm—"Be still!"

It may be that the sea will not obey,

But what of that? Deny it if ye may,

Still I command; still, still by night and day

Despite all scorn, I exercise my will

And on the troubled surface of the main

Fresh from my soul, fresh from its limpid source,

I pour my subtle influence—I rain

Odyllic Force.

I say unto the weather—"Be thou fine!"

And straightway, if it be not foul, 'tis fair.

Nay, at my word the very sun will shine

If it should haply chance no clouds are there.

And should the temperature not fall below

The freezing point, until the twenty-first

Frost shall be all unknown, and ice and snow,

And plumbers; and the taps shall freely flow,

Nor shall the leaden pipes presume to show

The shadow of a tendency to burst.

Nay, if the weather be not somewhat cold

It shall be warm. The budding gems of gold,

Should they appear, we shortly may behold,

Flashing amid the prickles of the gorse.

So for the good of man, and beast, and flower

I diligently use my mystic power,

And ever exercise from hour to hour;

Odyllic Force.

Thus do the elements obey my call.

Thus do I influence the Seasons' course

Thus do I exercise for great and small,

The king, the lord, the beggar, one and all,

Odyllic Force.

Lily (from Devonshire, on a visit to her Scotch Cousin Margy in St. Andrews, N.B.). "What a strange thing Fashion is, Margy! Fancy a Game like Golf reaching up as far North as this!"

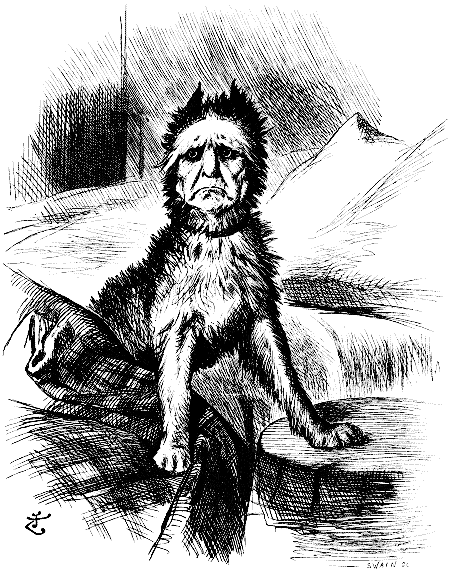

Or, "There's Life in the Old Dog Yet."

["It was my fate, my fortune, about, I think, eighteen years ago to take an active part with regard to other outrages, which first came up in the shape of rumour, but were afterwards well verified, in Bulgaria.... Old as I am, my feelings have not been deadened in regard to matters of such a dreadful description."—Mr. Gladstone's Birthday Speech at Hawarden, December 29, 1894, on the alleged Armenian Atrocities.]

Retirement? Oh, rubbish! Tykes currish or cubbish

May curl up in kennels, or snug up in straw,

But dogs of right mettle to rest will not settle,

While sight's in the eye, and while snap's in the jaw.

A bed in a basket? Mere mongrels may ask it.

A couch and a cushion? They're lap-dog delights.

But pluck and true breeding, such comforts unheeding,

Desert laps and hearth-rugs for frolics and fights.

Retired! How rats chortle! Like "Rab" the immortal

This dog scorns dull rest, and is still "rough on rats."

As always delighting in "plenty o' fechting,"

He pricks up his ears at a whisper of "s-s-scats!"

Aslumber and dreaming? Oh, that is mere seeming,

Curled up tail to muzzle in cosiest sort.

His hairs are a-bristle at whisper or whistle

That gives the least promise of scrimmage or sport.

On rats he's still ruthless! They may think him toothless,

Those red Turkish rodents who once felt his fangs.

Ah! eighteen years earlier his coat was much curlier,

Now white and whispy sparse-scattered it hangs.

But years though they roughen his hide, seem to toughen

The muscles and nerves of this rare sporting tyke.

The rattling old ratter is still game to scatter

A pitful of vermin, of what breed you like.

The Istamboul sort are his favourite sport,

Rabid rodents who raven, red-fanged, in foul hordes,

Turco sewer-bred legions, who earth's fairest regions

Would ravage like Tamerlane's Tartar-swung swords.

Terrors untameable, horrors unnameable,

Mark their maraudings and hang on their track.

Now in fresh numbers they swarm, whilst he slumbers

Who once was the plague of the pestilent pack.

But—Who said—Atrocities? Old animosities

Wake in his spirit and stir in his blood.

Eh? What? Retirement? Nay, not if requirement,

Or prospect of sport, move the old champion's mood.

His heart has not deadened; his old eyes have reddened

With love of the fray and the old righteous wrath.

The varmint old ratter his old foes would scatter.

"Auld Rab" once again will be on the war-path!

"They grew in beauty side by side,

They filled one home with glee"—

Until that evening at dessert

You passed the nuts to me.

Then came the "crack of doom," the twins

No sooner had you seen

Than, "Oh, what fun!" you said, "we'll have

A Bon jour, Philippine!"

"They grew in beauty side by side,

They filled one home with glee"—

Until they found respective graves

Alas! in you and me.

And then to win a gift next morn

We vowed with solemn mien,

Whoe'er should greet the other first

With "Bon jour, Philippine!"

"Bon jour"—I dreamt of it all night,

At dawn recalled it yet,

But clean forgot it whilst I shaved—

At breakfast then we met.

I'd only time, I know, to think

Maid sweeter ne'er was seen,

When you, with laughter-dancing eyes,

Cried, "Bon jour, Philippine!"

And so you won a gift from me,

And chose that I should write

These verses, which I've pondered o'er

For many a sleepless night!

I'll never crack another nut,

When you are there, I mean;

Yet may you greet me often—save

With "Bon jour, Philippine!"

Motto for Modern Managers.—The proper study of (theatre-going) Mankind is—the New Woman.

"OLD AS I AM, MY FEELINGS HAVE NOT BEEN DEADENED IN REGARD TO MATTERS OF SUCH A DREADFUL DESCRIPTION."—Mr. Gladstone's Birthday Speech at Hawarden on the Armenian Atrocities, December 29.

(By an Elderly Victim of Bumbledom.)

["The London Vestries and Boards of Works have not exactly covered themselves with glory in their dealings with the recent snowfall. In very few neighbourhoods was any attempt made on Wednesday to remove the slush, and Nature having taking her course during the night, in the direction of a frost early yesterday morning, the streets in many places were absolutely impassable for wheeled traffic until a liberal layer of sand and gravel had been spread."—Daily Chronicle, January 4.]

Come, gather round me, ratepayers,

So full of fun and glee;

New Bumble's going to play the fool

To please the L. C. C.

They swear that he is able

Improvements for to plan;

I love to hear Progressives say,

"Hush! The New Vestryman!"

Slush! Slush!! Slush!!!

Where is the Vestryman?

Are broom and shovel ready?

What is his brand new plan?

Oh, Slush! Slush! Slush!—

The footways never ran

With a worse slithery slippery slop,

'Neath the Old Vestryman.

When I sit down, impromptu,

All in a soft snow-pie;

Or slide a yard, then come down hard,

I groan, and wonder why.

I blow my blue numb fingers,

I watch a fast-stuck van;

Reform, I cry, seems all my eye.

Where is that Vestryman?

Slush! Slush!! Slush!!!

Why is this, Vestryman?

Is this the outcome shady

Of the Progressive plan?

Oh, Slush! Slush! Slush!

No gravel, sand, or tan!

All slip and slop. I'd like to whop

That blessed Vestryman!!!

Clerk (to Curate). "I'm terrible sorry, Zur, that you be agwaïne to lave us. We've changed ever zo many times since Passen Green died, and always for the wuss!"

[The Flint Town Council has censured the L. & N. W. Railway for dismissing some of its servants for ignorance of the English language.]

Would you tell me, Porter, if the next train is the one for Aberystwyth?

I am really very much obliged for your reply, but as I have not a Cymric dictionary at hand, I am totally unable even to guess at your meaning.

As the man points to the train which is now at the platform, and nods vigorously, I suppose he means me to get in. Still, the fact that it has "Llanrhychwyn" on it makes me a little doubtful whether I shall ever reach Aberystwyth if I enter it.

I am grateful for your attention, Guard, but it was a foot-warmer that I asked for, not the newspaper-boy.

As I have just been hurled down an embankment and find myself sitting much bruised in a shallow pond in a field close to the line, I really fancy that the Welsh-speaking signalman at the adjoining cabin has failed to understand the message wired to him in English from our last stopping station.

I should be glad, Stationmaster, if you would kindly have a telegram sent to my friends saying that I have only four ribs broken.

As you do not appear to understand what I say, and as I suppose there is nobody who knows English in this desolate Welsh valley where the sufferers from the accident are lying, perhaps you will kindly have us all sent back to Shrewsbury as soon as possible.

The man lying next to me, whose arm is hurt, says that the train was not going to Aberystwyth at all. So perhaps it is as well that circumstances have prevented my proceeding further in it.

We should undoubtedly have been much better off if this accident had happened to us in France or Germany, because then we should have been able to secure the services of the railway interpreter.

Thank Heaven! I am back at Chester, where the hotel people do talk English; and in future I shall vote steadily at elections against any party that does not make the total suppression of all so-called "national tongues" within the British Isles a part of its recognised programme.

Mr. Rudolf Lehmann possesses some gifts which peculiarly qualify him to write the volume Smith, Elder & Co. publish, under the title An Artist's Reminiscences. He has passed the age of three-score and ten, and has throughout that period had many opportunities of seeing places, and, more precious, of meeting people. To the study of both he brings keen sight, a good memory, and a genuine, not too obtrusive, sense of humour. Born in Hamburg in 1819, he has sojourned in most of the capitals of Europe, permanently settling down to marriage and life in London. He seems to have known most of the notable personages of the middle and latter half of the century. His wide acquaintance with royalty (some of them mad) would be appalling if it were not mentioned with winning modesty. The volume abounds in good stories, my Baronite particularly delighting in one pertaining to the ceremony of prorogation of parliament by the Queen. Mr. Lehmann was much struck with the spectacle of the old Duke of Wellington carrying the sword of state, Lord Lansdowne bearing the crown, and the Marquis of Winchester with the cap of maintenance set on red velvet cushion. At Lady Granville's the same evening he asked Lord Granville what was the significance of the cap of maintenance. It was one of the few things Lord Granville did not know. "But," he said, "there is Lord Winchester, who carried it this morning. I will go and ask him." The two peers conversed in a whisper, and Lord Granville, returning to his inquiring friend, said, "He does not know either." Mr. Lehmann incidentally mentions that his brother Henry's first success, at the Salon of 1835, was gained by a picture setting forth "Le Départ du Jeune Tobie." At that date Toby had not even arrived to take his place on the volumes in his master's study, and still less, was he M.P. for Barks. It only shows how prophetic is the soul of genius.

(By an Old-fashioned Fellow.)

"Goodwill to man!" the dear old carol saith.

Ah me! Then why so much mean personal pother?

We're credulous of aught that means the scathe

Of a sad sister, or a stumbling brother.

Men are like stout John Bunyan's "Little Faith,"—

Save in believing evil of each other!

There faith indeed is strong; but 'tis a rarity

That such strange Faith is found combined with Charity!

Mem. by a Muser.—Many a spouting member of the "Independent Labour Party" is a "party" who wishes to be independent of labour. Hardie Norsemen, please note!

Party Colourists at work on the Properties.

[The ideal lady's pocket, that shall at once be accessible to its owner and defy the footpad's art, has yet to be invented.—Wears of Tautologus.]

My Julia's chaste and winsome cheer,

Her comely lip, her coral ear,

And eke her knickerbocker gear,—

These be the theme of rhyming folk,

Whereof the skill I here invoke

In malediction of her poke;

In that it passeth human wit

By sleight of hand withal to hit

Upon the pathless track of it.

Though Julia's self therein dispose'

That napkin with the which she blows

For sorry rheum her Greekish nose,

Not if she search with heavy pain

Shall she by taking thought attain

To look upon the thing again;

To him alone of mortal clay

That picketh pokes beside the way

Their deeps are open as the day.

Whenas her alms she would disburse,

In vain she probeth for her purse,

Whereat the beggars shrewdly curse;

Even so their teeth do felons gnash

That lightly lift her ready cash,

Which he that stealeth stealeth trash.

Oft-times she doth full bravely hold

Her breezy reticule of gold

Within her digits' dainty fold;

As certain maids, I well believe,

Do wear th' affections on their sleeve

For any worthless wight to reave.

But though her purse not suffer rape,

Mischance is like in other shape

To put on her a saucy jape;—

If so my lady at the mart

For very joyaunce of her heart

Do purchase her a pasty tart,

Let her not make essay to bring

So beauteous and frail a thing

Within her poke's encompassing;

Lest, sitting down with weary stress,

Unheedful of its buxomness,

She make a right unseemly mess!

Certes a man purblind may see

For these offences needs must be

Some comfortable remedy;

Whoso deviseth such an one,

I trow that his inventiòn

Shall soothly pouch the peerless bun.

Gertrude. "My dear Jessie, what on earth is that Bicycle Suit for?"

Jessie. "Why, to wear, of course."

Gertrude. "But you haven't got a Bicycle!"

Jessie. "No; but I've got a Sewing Machine!"

Perplexed.—You are entirely in error in supposing that the member for Otley, Yorks, has, in accepting a baronetcy, descended from a higher estate. You have been deceived by similarity of sound. The hon. member was not of the same rank as a statesman (who we observe has just repaired to his country seat at Pinley Park, where he will entertain His Serene Highness the Duc de Seidlitz-Poudre) to whom Sir Robert Peel used to allude in the House of Commons as "the noble Baron." In becoming Sir John Barran, Bart., the member for Otley gains a distinct step in the social ladder.

Blind, Deaf, and Dumb.—We are pleased to be able to reassure you. The fact that you have not lately heard or read speeches by Sir William Harcourt is no evidence that the treble disability under which you unhappily labour is increasing. There is a well known case, cited in Littleton upon Coke, where a man was not able to see the Spanish fleet "because it is not yet in sight." For analogous reason you have not lately heard anything of the Chancellor of the Exchequer. He has not been speaking. The fact is, the Squire of Malwood—to use a title by which he is locally known, and in which he most rejoices—was cut out for a rustic recluse. Circumstances have, unwillingly, dragged him into the front of politics, and he has done the duty that lies to his hand. When opportunity can be made he takes his leisure at his lodge in the New Forest, and meditates on the untimely fate of his pre-Plantagenet forbear William Rufus. Nevertheless, we are not without suspicion that Sir William Harcourt shares the peculiarity of Carlyle, of whom you will remember his wife shrewdly remarked that "his love for silence is platonic." If you keep your ears open and your mouth shut, you may probably, before long, hear the familiar voice resounding from a public platform.

A Shakspearean Student.—We had not before heard of the incident. It is, however, quite possible, as you have been informed, that when the Marquis of Salisbury, K.G., heard of the defection of the Earl of Buckinghamshire, who has joined the Liberal forces, the only remark he made was "Off with his head."

Lord Illingworth. My dear Goring, I assure you that a well-tied tie is the first serious step in life.

Lord Goring. My dear Illingworth, five well-made button-holes a day are far more essential. They please women, and women rule society.

Lord Illingworth. I understood you considered women of no importance?

Lord Goring. My dear George, a man's life revolves on curves of intellect. It is on the hard lines of the emotions that a woman's life progresses. Both revolve in cycles of masterpieces. They should revolve on bi-cycles; built, if possible, for two. But I am keeping you?

Lord Illingworth. I wish you were. Nowadays it is only the poor who are kept at the expense of the rich.

Lord Goring. Yes. It is perfectly comic, the number of young men going about the world nowadays who adopt perfect profiles as a useful profession.

Lord Illingworth. Surely that must be the next world? How about the Chiltern Thousands?

Lord Goring. Don't. George. Have you seen Windermere lately? Dear Windermere! I should like to be exactly unlike Windermere.

Lord Illingworth. Poor Windermere! He spends his mornings in doing what is possible, and his evenings in saying what is probable. By the way, do you really understand all I say?

Lord Goring. Yes, when I don't listen attentively.

Lord Illingworth. Reach me the matches, like a good boy—thanks. Now—define these cigarettes—as tobacco.

Lord Goring. My dear George, they are atrocious. And they leave me unsatisfied.

Lord Illingworth. You are a promising disciple of mine. The only use of a disciple is that at the moment of one's triumph he stands behind one's chair and shouts that after all he is immortal.

Lord Goring. You are quite right. It is as well, too, to remember from time to time that nothing that is worth knowing can be learnt.

Lord Illingworth. Certainly, and ugliness is the root of all industry.

Lord Goring. George, your conversation is delightful, but your views are terribly unsound. You are always saying insincere things.

Lord Illingworth. If one tells the truth, one is sure sooner or later to be found out.

Lord Goring. Perhaps. The sky is like a hard hollow sapphire. It is too late to sleep. I shall go down to Covent Garden and look at the roses. Good-night, George! I have had such a pleasant evening!

["The social duty of paying calls, refreshed, as it necessarily is, by frequent cups of tepid tea, is apparently little better than a process of slow poisoning."—Daily Graphic.]

Oh, here's a pretty state of things! Whenever you go calling,

And take this deadly liquor and imbibe it without stint,

You're certainly preparing a catastrophe appalling,

Your mirth is as the little lamb's, unmindful of the mint.

And when your entertainer, who seems so sweetly placid

And quite unlike a criminal, suggests "Another cup?"

She might as well be offering a dose of prussic acid,

And the Public Prosecutor ought to take the matter up!

"The cup that cheers"—that hackneyed phrase is frightfully in error,

If seldom it "inebriates" (it does, the doctors plead),

There lurks within its fatal draught a more efficient terror,

'Twill shortly make a funeral your one and only need!

So since a daily cup or two the thin end of the wedge is,

And since this revelation of our danger has been made,

We all will wear red ribbons and will sign the strictest pledges,

And speedily inaugurate an "Anti-Tea" crusade.

A word to you, Amanda mine. Unless your cruel kindness,

Your efforts to consign me to an early grave, shall cease,

And if you dare, presuming on my long-continued blindness,

To offer me a cup of tea—I'll send for the police!

The Time of Day.—Good, after Newnes to find the style "Bart." The bestowal of the baronetcy quite a Tit-Bit for the Strand. But there is no truth in the report that the event will be followed by the establishment of a new morning paper to be called The Dragon, and edited by Sir George.

The County Council has solved the great Mudford mystery by deciding in favour of Mrs. Arble March, who is in the seventh heaven at being the Seventh Councillor. A wise Legislature had it in contemplation that possibly when the great measure came to be worked, it might not be found to act, however much you pulled the string, and it was accordingly left to the County Council to set on its legs any poor little Parish Council which might have been brought into the world without its full number of members. Thus it came about that Mrs. March got elected. The actual circumstances of her election gave rise to some comment. She was proposed by the Primrose League Ruling Councillor of one adjoining parish, and seconded by the Knight Harbinger of another. Our County Council is a strongly Tory body, and she was easily elected. There was a great outcry against this, as an act of political partisanship. It was. But when it became known that Mrs. Letham Havitt's friends and supporters were all avowed Radicals, popular indignation seemed suddenly to flicker out.

It may be, however, that the indignation only transferred itself to me, for I myself have got, in a most extraordinary and unexpected fashion, into a great hobble. It arose in this way. Having been elected on to the Parish Council at the top of the poll, and having, moreover, been subsequently the recipient of innumerable congratulations from my fellow-parishioners, I not unnaturally—so I still venture to think—desired in some way to show my appreciation of the kind treatment I had received. I accordingly determined to make to every elector a present of coals, and to carry out that intention issued the following circular:—

Ladies and Gentlemen,—For your kindness in electing me at the top of the poll, I can find no terms sufficiently warm to express myself. In commemoration of the great occasion, and as a small thankoffering for my return, I beg your acceptance of the enclosed Coal Ticket, which will entitle you to 2 cwt. of coal from any of the village coal dealers.

I sent this to every elector, high or low, rich or poor. I hardly imagined that the Squire would want coal, but he was a constituent of mine, and he had his ticket. What has been the result of my generosity? This. Whilst almost every coal-ticket has been used, I am denounced right and left in unmeasured terms as an unscrupulous briber. Miss Phill Burtt (who, as might be expected, has been most kind and sympathetic about the whole thing), tells me that even the Squire said it was a very ingenious way of wishing myself Many Happy Returns to the Parish Council. A poor joke, I think, but an undeniably excellent sneer. Black Bob is, as might be expected, much more plain and direct in his denunciation. He says, that if I stand for re-election—in April, 1896!—this ought to be enough to unseat me. A pleasant prospect. I can do nothing. My boats, like my coal, are burnt.

What happened at the Parish Council meeting last night I must leave—till my next.