THE STORY OF SCRAGGLES

GEORGE WHARTON JAMES

Title: The Story of Scraggles

Author: George Wharton James

Illustrator: Sears Gallagher

Release date: March 9, 2013 [eBook #42285]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE STORY OF SCRAGGLES

GEORGE WHARTON JAMES

The Story of Scraggles

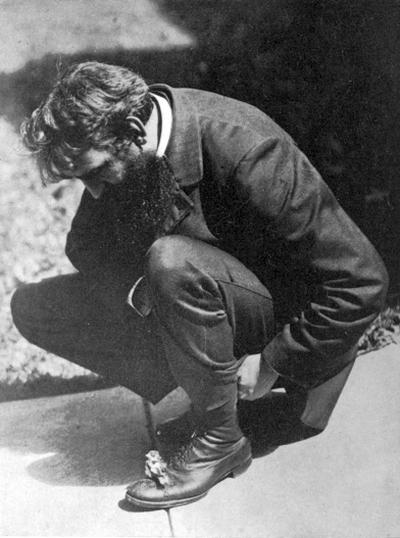

Scraggles and “The ’Fessor.”

Illustrated from Drawings by Sears Gallagher and from Photographs

Boston

Little, Brown, and Company

1906

Copyright, 1906,

By Edith E. Farnsworth.

———

All rights reserved

Published October, 1906

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

Most of our Indians have a tradition that in the days of old animals and man had a common speech. Each was able to understand the other, and thoughts and language were common to all. It was not until man began to regard himself as superior to the animals and think of them as “lower” that this oneness of speech and relationship was lost. Since then envy, jealousy, anger, on one side, and conceit, pride, and contempt on the other have widened the breach, while Love has stood with tearful eyes looking on at the sad and unnatural estrangement.

But in these latter days prophets among the white race have risen up to awaken again within man the desire for brotherhood with the humbler creations of God. Thoreau, John Burroughs, John Muir, Ernest Thompson Seton, W. J. Long, Elizabeth Grinnell, and many others, are showing us our kinship to the birds, buds, bees, blossoms, and beasts. It is with the two thoughts before me of the common speech and understanding existent between the animals and man, and of the kinship that affection shows us does really exist, that I have written the “Story of Scraggles” from her viewpoint, with the confident anticipation that young and old alike will enjoy this truthful record of a sweet and beautiful little life.

While, of course, the thoughts put into Scraggles’ words are mine, the statements of fact are literally true. I have told the story as nearly in accord with the incidents as they actually occurred, as this method of telling the story would permit.

1098 N. Raymond Ave.

Pasadena, California

Feb. 23, 1906

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | How I Came to Live in a House | 1 |

| II. | My First Week In-Doors | 11 |

| III. | My Second Week in the House | 23 |

| IV. | My First Sand Bath | 30 |

| V. | On the Fessor’s Desk and My Hiding-Place | 35 |

| VI. | Preening my Feathers | 43 |

| VII. | Going Out of Doors | 48 |

| VIII. | On Fessor’s Bed | 56 |

| IX. | Going for a Walk | 62 |

| X. | Uncle Herbert’s Visit | 66 |

| XI. | My Illness | 70 |

| XII. | Scraggles’ Last Day | 76 |

| XIII. | How the Story of Scraggles Came to be Written | 81 |

The Story of Scraggles

I was only a little baby song-sparrow, and from the moment I came out of my shell everybody knew there was something the matter with me. I don’t know what it could have been, for my brother and sister were well and strong. Perhaps I was out of the first egg that was laid, and a severe spell of cold had come and partially frozen me; or a storm had shaken the bough in which our nest was, so that I was partly “addled.” Anyhow, no matter what caused it, there was no denying the fact that when I was born I was an ailing little bird, and this made both my father and mother very cross with me. I couldn’t help being so weak, and they might have been kinder to me; but when the other eggs were hatched out and my brother and sister were born, nobody seemed to care for me any more. Of course, my mother gave me something to eat when I cried for it, but the others were so much stronger than I that they pushed me out of the way, and succeeded many a time in getting my share without mother’s knowing anything about it.

I was not active like the others, and when they climbed up to the edge of the nest and stretched out their wings as if they would fly, I felt a dreadful fear come over me. I knew I should fall to the earth if I tried to fly. I don’t know why I felt this, but, do as I would, I could not get rid of the horrible feeling. I tried a number of times to overcome that sickly feeling of fear and dread, but every time I clambered to the nest’s edge I grew dizzy and had to fall back to prevent my pitching headlong forward. My father and mother both scolded me, and taunted me for my cowardice; they urged me to flap my wings more, and again and again showed me how to do it. But my wings were so weak I am sure something was wrong with one of them. And my feathers! I never saw such wretched feathers. In the first place I had no feathers whatever on the under part of my body, and where the feathers did grow they were raggedy and scraggedy and looked for all the world as if they were moth-eaten. So in bird language my father and mother and the others all called me Scraggles, and they treated me as if they felt I was Scraggles—of no use or beauty, and therefore worth “nothing to nobody.”

But in spite of this, I was ill-prepared for the awful fate that came to me one day. My brother and sister had already tried their wings pretty well, and had flown quite a distance, and father and mother were pleased with their progress. Then they came to me and urged me to climb up to the edge of the nest. When I did so, my father came behind me, gave me a sudden push, and over I went. Down, down I fell, through the branches of the tree, fluttering my wings as well as I could, but they would not sustain me. One of them worked so queerly that I went sidewise, and as I struck the ground I rolled over and felt quite dizzy and stunned. When I looked around for my father and mother they were nowhere to be seen. I called aloud, but no answer came, and then I felt so desolate and forlorn that I could have cried. But I thought I had better begin to search for them. So I hopped along to where I saw several birds flying around. All at once I found myself among a number of houses where men and women lived, and I knew there was danger from four-legged creatures they kept, called cats, but, as I saw what seemed to me to be my mother down the street, I hurried along as fast as my weak wing and fluttering heart would let me, until, all at once, I heard quick footsteps behind me. Turning, I saw that it was a large, tall man, with black hair and a black beard, and he walked so quickly that I grew afraid and chirped out to my mother to come and help me. But she paid no attention whatever, and my loud cries arrested the attention of the man. He suddenly stopped, looked at me, and then began to talk to himself. I didn’t understand then what he was saying, but I know I was desperately scared, for my parents had taught me always to keep out of the way of human beings—especially of the little human beings that they called boys and girls. Girls, they said, were not so bad as boys, but it was safest to keep away from all of them. Had I known this big man as I afterwards grew to know him, I shouldn’t have been so scared; but as it was, I tried to get as far away from him as I could. The sidewalk was lined all along with great tall stalks of dandelions and clover, and I tried to push my way through them to where my mother was picking up something to eat on the road. But it was such hard work, and I was so afraid! At last I got through, and then with a cry of joy I hopped as fast as I could to my mother. I felt that surely she would help and protect me, and I was never more surprised and hurt in my life when, without even recognizing me, or saying one single cheep, she flew away so quickly, and so far, that almost immediately I lost sight of her.

What was I to do? For a moment or two my little heart stood still. I was so dreadfully afraid that I couldn’t breathe. Then, before I had recovered, the great tall man, whom I had quite forgotten, came toward me with his quick, decisive strides. I tried to get away from him, and fairly screamed out in my terror; yet it was no use. He was too quick, and I was too weak and helpless, and in less than a minute he had “cornered me” against the trunk of a tree, and I found myself all at once in his strong hand, the fingers of which felt so powerful as they completely surrounded me.

I was too afraid to cry out, and I could only lie still and listen to my heart beat. It went so quick and so hard that I thought I should die; but somehow I was compelled to see that he didn’t hurt me or pinch me, and his voice was all the time talking so softly and gently to me, though it sounded deep and strong like the voice of a storm that once nearly shook me out of our nest. He was carrying me away rapidly, and said something about his wife and “little girlie,” who would surely help him take care of me until I could fly.

Soon we went inside a house. I had never been in such a dark place before, and I was made afraid again, as badly as ever, by two persons, dressed differently from the tall, bearded man, but whose voices were softer and more like a bird’s than his. I heard him tell about seeing me try to reach my mother, and then how she had flown away and deserted me, and he had caught me and brought me home, lest, said he, “some cat should catch the poor little thing and gobble it up.”

That is just how I came to be in a house, and the beginning of my life with human beings,—three of them—a man and two women.

My first week in-doors was very painful and distressing to me. Though my father and mother had never been kind, still they were my father and mother. But now I was all the time with strangers,—great, monstrous, tall human beings, and I was such a tiny little bird! How could I feel at home with them? It scared me just to see them.

Still, scared or not, what was I to do? I had to stay there, for, unlike my home in the nest in the tree, here everything was shut up. The air was warm and close, and it made me feel queer most of the time. It was not fresh and bracing like the out-door air I had been used to. I was shut in,—that was all there was to it; but it took me a long time to learn to make the best of it. For the tall man, now and again, would catch me and put me up onto the window-sill, and I didn’t know that I couldn’t go through the glass. I tried again and again, but always bumped my bill hard against the glass and never got any further. I saw happy little birds outside. They seemed to be strong and well; and how I longed to be with them! I found great pleasure, however, in walking back and forth on the edge of the window sash, and the warm sunshine that shone in upon me was very comforting. When other birds flew near by I used to get very excited, and stretch my legs and neck so hard to see them and get to them, that the “man of the house” would laugh very heartily at me. And then he would call to “Mamma” and “Edith,” and together they would stand and look and laugh at me, while I stretched and chirped and twittered to the birds outside.

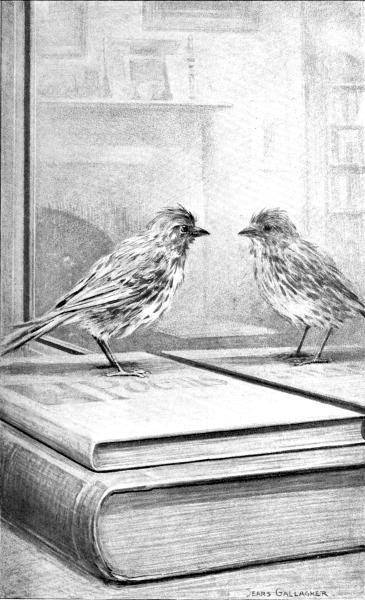

“I saw happy little birds outside.”

Of course, I had not been in the house long before I was a very hungry little bird. I don’t think you know how very hungry so tiny a bird can get. I was desperately hungry. How I was going to be fed I did not know. But I chirped, and cheeped, and called out as loudly as I could, and soon the “Fessor”—as the women called the man[1]—came into the room with a saucer in his hand. In the saucer was some white-looking substance that he called bread and milk. But I didn’t know what to do with it. So to let him know how hungry I was I chirped more, and then opened my mouth wide, and wider still, as baby birds do, hoping that he would find some way of getting the food into me. And he did! Instead of putting it into my throat with his bill—he hadn’t one—as my mother did, he caught me when I wasn’t expecting it, and taking some of the white stuff in his fingers, held it close to me. When I opened my bill to cheep, he pushed it in, and my! how strange it tasted. But it was good. It was sweet, and warm, and nice. So I swallowed it and opened my mouth for more, and he gave me another piece. Then he called to Edith, and she and Mamma came and watched me until, as they said, I was “stuffed as full as an egg.” Two or three times that day he fed me in the same fashion, and I began then to get over my fear of him. He didn’t seem to want to hurt me, and he was very, very gentle with me; and I even began, once or twice, to snuggle down in his hand, for it was so large and warm and comfortable. Then that awful fear came, and I sprang out of his reach and ran to the end of his desk, and when he reached out after me, I wildly leaped off the desk, fell to the floor, and then ran as fast as I could behind the desk in order to be safe.

[1] This was the name given me by a dear little child trying to say Professor, and the name has stuck ever since.

We had several days of this, and I soon found that when he fed me I need not be afraid at all. He never hurt me then. But I never knew when he would hurt. So I thought it best to keep out of his way. He talked very nicely to me, however, I must confess, and I soon learned to like to hear his voice. I felt better when he was in the room, and it was lonesome when he went away, for he shut the door so that I couldn’t go anywhere else.

It was not many days before I knew all about that room. It was a queer room, as compared with rooms I afterwards saw. Mamma and Edith called it Fessor’s “den,” and surely it was a den. There was a desk opposite to one window. On this was a row of books reaching right across, and piles of papers, and pictures, and one thing and another, sometimes on the sides of the desk, and sometimes on the tops of the books. And when the Fessor sat down he would take a little pile of white paper, and a stick with a shining thing at the end that I afterwards learned was a pen, and he would dip it into a bottle full of queer smelling black water and then scratch the wet pen back and forth over the paper, so quickly that it used to make my little head swim to watch him. And the noise! It was simply aggravating beyond words—that is, a tiny bird’s words. How I did hate that pen and that scratching noise! But I’m not going to tell you about that now. I shall have a good deal to tell you about that pen later on.

Well, to go back to the room. By the side of the desk, on the left, was a great tall case full of what the Fessor called books. Every once in a while he would jump up from his seat in a hurry and make one big stride to that case, quickly look over the backs of the books, then seize one, put it on his desk, and begin to turn over the sheets of paper of which it was composed. And his eyes would sparkle and shine sometimes, and at others his brow would wrinkle and his lips pucker up, so that I knew something was going on, whenever he reached for one of those books. The books in front of him he often took out and opened and read from them. Then he would talk to himself and say “Yes!” and “No!” or “I don’t think so!” or “I guess he’s way off,” and then his fingers would grab the pen, dab! it would go into the black water, and over the paper it flew like the dancing shadows that I used to watch sometimes when I was in my nest in the tree.

On one side of the room was a flat thing perched on four legs as high as the desk, called a table. The top of this was covered with more books and papers and photographs. Sometimes Fessor would put me on this table, and I used to go around and explore everything. In one corner of the room was a high pile of boxes, with shelves in them, on which were piled loose papers and more books and things. Such big boxes they were, and so deep, and such piles and piles of things in them! This afterwards became my playhouse and my hiding-place. My! what fun I had in it sometimes, and how glad I was to have it when I found out what a good hiding-place it was.

There were also some Indian baskets in the room, as well as a closet in which were piles of little boxes and a large leather case in which was a thing Fessor called his camera.

Of course, I didn’t find out about all these things at once. I’m just telling you all about them now, so that you will understand, and I shan’t have to tell you again.

The first night I went to nest in the house was a strange experience. Now just look what I’ve said: “Went to nest.” You see a little bird doesn’t think of going to bed, as boys and girls do. She goes to her nest. But there was no nest in Fessor’s den. He was too big to get into one if there had been one, and when it began to grow dark I wondered what would become of me. To be all alone in that dark, dark room would be terrible; and there was no getting to any other birds owing to that shut window. But I needn’t have been afraid. For, just as I was working myself up into a good deal of excitement, Fessor came in, and after giving me some more warm bread and milk,—which made me feel so comfortable and so sleepy,—he said: “And now, little birdie, I’ll have to find a bed for you.” Then I watched him from the desk, where he had placed me, and he got a large Indian basket, and after putting some soft white rags at the bottom, he caught me—though I tried to hop away—and putting me down amongst the rags, he wrapped me up in one of them, and then covered me up as snug and warm as could be. When he went away it was not long before I fell asleep.

Well! he used to do this every night for quite a long time, so that I soon got used to going to bed in the basket, instead of being in my nest, and slept as well as I had ever done before.

It was very strange that he should have hit upon the same name for me in his human talk as my father and mother had in their bird talk, yet it was so. I believe it was the second day after he brought me home that Mamma said to him: “What shall you call your baby bird?” In a moment Fessor replied: “Oh, I’ve already called her Scraggles. She is Scraggles, so she must be called Scraggles.” So, even in man’s speech, I’ve been Scraggles ever since.

Ah, that second week! What a good week it was to me! It changed all my life and made a happy little bird out of me. I lost all my fear of Fessor and Mamma and Edith, and from then on we were the dearest and best of friends. Talk about my father and mother, and my loving them! Even though they were birds, they never showed me the love that this second week taught me was in the hearts of my three human friends. So I want to tell you all about it.

I believe it began that very night Fessor put me in the basket. For, though he was not so gentle as my mother was, somehow I felt that he felt more gentle towards me, and so, though I was still very much afraid of him, I began to get a new feeling in me that seemed to drive some of the fear away.

Then came the pinion nuts. Now, you needn’t laugh! It certainly was those pinion nuts that had a great deal to do with it. As you no doubt know, the pinion is a kind of small pine tree that grows “Out West,” and it has a tiny white nut in it that I have heard Fessor say is “the sweetest nut in existence.” Now I don’t know what “in existence” means, but I do know that the little white nut he gave me was the most delicious morsel I had ever tasted in my life. And how do you think he gave it to me? I think he must have been a mother-bird once, for he did as near like what my own mother used to do as he could. He chewed up the nut until it was all soft and sweet and warm, and then gave me a piece of it. It was so good! oh, so good! and when I cheeped for some more, he put his lips down to me with a large piece of nut all ready for me to eat. Well, at first I didn’t know just what to do. He had such a long black beard, and his moustaches almost covered his lips, that I felt “kind o’ scared,” yet when I looked up into his large dark eyes, they beamed upon me so kindly and gently that I thought I would risk it; so I made a quick dash at the nut, got a bill full, and then drew back.

Fessor laughed at me and said: “You poor, scared little thing!” And he said it so gently that I felt comforted; and so, when he came near to me again with his lips full of nut, I went quite courageously up and pecked away several times.

From that day on I never seemed to be really afraid of him. Sometimes the old fear came back for a little while, and I scampered and hid behind the desk; and at other times, when he tried to pick me up, I would instinctively run from him; and if he followed me too quickly, I would spring from the desk and go fluttering to the floor. But, you see, that was because he didn’t understand I was a little, tiny bird, and had to get used to him by degrees. When he moved quietly and gently I didn’t get scared; but I suppose it takes a big man a long time to learn to move easily and gently as a bird does.

Every night he put me to bed in the Indian basket, wrapping me up as carefully and tenderly as if I were his own baby, all the time telling me in man talk that I needn’t be afraid of him, and that he wouldn’t hurt me for the world.

One day I had quite an exciting experience. I heard Fessor say to Edith: “I’m sure this little birdie ought to have some fresh, out-door air. I’m going to take her out. Come with me and see that she doesn’t get away.” Now I had never thought of such a thing until he suggested it. Of course, I had been uncomfortable in the house, and I wished often that I had had a loving father and mother with a home nest of my own to which I could go, but, since they had so heartlessly deserted me, I had not thought of trying to get away from my kind human friends.

Yet it was wonderfully strange how I felt as soon as I got out-of-doors. A new-old something seemed to come into me, and I’m quite sure that if my wings had been strong enough, I should have flown away regardless of what Fessor had thought or said. I did hop and flutter and try to run into the tall grass, and I tried—oh! how I tried—to fly. But it was all in vain. They were very kind to me, yet would not allow me to run into the grass and hide, as I wanted. I scratched around on the ground a little, and then Fessor snapped his thumb and finger—a thing he often did—and said: “Now, little Scraggles, I think it’s quite time you went in again.”

That was the first time he took me out, but by no means the last. Soon we began to go out every day. He would take me on to the lawn and sit on the steps and watch me as I looked at the grass and the flowers and the wonderful birds flying in the trees. I couldn’t help watching them and trying to imitate them. It was no use, though, for my poor wing would not let me fly.

From now on we went out every day when it was fine, and we grew to understand each other more and more. When Fessor came into the den I used to chirp and tell him how glad I was to see him. Then he would snap his fingers and I would run towards him, and when he put his hand down to the floor, I would jump in, and he would lift me up to the desk. Then, if he had a few minutes to spare, he would chew up pinion nuts for me and let me eat them from his lips; or, if he felt hurried, he would give me three or four and let me eat them myself. I soon grew to enjoy being on his desk. It was so nice to hear him talk! And I think it must have been because he had two or three dictionaries always at hand that I soon grew to understand lots of words. You see, I used to hop about on the dictionaries hour after hour, and eat from them, and often when Fessor opened the pages and pointed with his finger at certain words, he would read them aloud, as he said, to get the different pronunciations; so that, as I looked where he pointed, I soon knew the words pretty well myself.

You see, I was different from other birds. If I had been out of doors all the time with my own father and mother and other birds, I should have known nothing of men and women talk. I should have learned the things that out-door birds learn,—all about the clouds and winds, and bugs and flies and worms and insects, and how to get my own meals. But as it was, I had nothing to do with getting my own food, and so I naturally took to human knowledge in order to occupy my mind and my time.

One day Fessor said to Edith: “I’m going to give Scraggles a sand pile. She ought to have something to take a bath in.” Wasn’t that funny? I didn’t know what he meant. A sand pile, and a bath! But I was soon to learn. In an hour or so he came in with a large box-cover full of sand. He spread out several newspapers on the floor, and then put the sand box on top of them. Well, as soon as I saw the glistening stuff in the sand, I thought it must be something good to eat, and I went and pecked at it so hard that the sand filled up my bill, and got into my eyes and nose so that I was nearly choked. I pecked at it again and got another dose, and I danced and shook my head real hard in order to get the tickling stuff out of my nose and bill. Fessor and Edith stood by looking on, and how they laughed! They laughed, and laughed, and laughed again, for I had to scratch my head all over with my foot to make it feel comfortable after all that sand.

Then Fessor came and said: “Now you wait, Scraggles, and I’ll show you how to take a sand bath.” And he took a handful of the sand and sprinkled it all over me, and as it trickled through my feathers onto my skin, how good it felt! He did this several times, and then all at once I thought I would scratch a place for myself in the sand and then throw the sand with my feet all over my body under my wings. And that was delightful. It was a new sensation, and a good and pleasant one. I felt so fresh and bright afterwards that every day, directly Fessor came into the room after lunch, I was ready for a bath. He nearly always sprinkled the sand over me, and he must have enjoyed it almost as much as I did, for sometimes he stayed with me at the sand pile a full half-hour.

Fessor used to spend an awful lot of time at his desk. The time he wasted there was more than I could ever tell, for he would be hours at a time doing nothing but moving that pen across the paper, making those nasty little dark scratches that in time I learned were called writing. When he came into his den and sat down at the desk I would come to his feet and call, and he would lower his hand for me to jump into, and then he would lift me up on the desk. I generally hunted first for a few pinion nuts, after which I wanted Fessor to play with me. Sometimes he was so busy with his “paper scratching” that he wouldn’t reply when I chirped to him. Then I got right on his paper, and hopped along between the hand that held his blotter and the hand with which he wrote, and there, right under his very nose, and generally on the spot where he wanted to write, would stand and ask him why he didn’t play with me. Sometimes he gently pushed me aside or lifted me out of his way, but generally he smiled at me—and I did love to see him smile—and would let me perch on his fingers or go through some antic or other, such as carrying me around the room on the top of his head, or holding me in his hand and swinging me to and fro as if I were in a nest on a bough swinging hard in a storm. Those were great times.

But sometimes that bothering old pen annoyed me, and I would seize it in my bill as Fessor made it scratch on the paper. As I held on he went on writing, and that used to jerk my head up and down, and, of course, it dragged me right across the paper. But I didn’t intend to let go; I wanted him to stop and talk to me, so back and forth we’d go, he trying to write with me holding onto the pen, and I determined not to let go, my head bobbing up and down to the movements of his writing and my feet slipping over the paper and smearing the ink, until I got too tired to hold on and had to let go.

Now and again he was determined not to let me touch that pen, and then we had a time. He made a barricade of his left hand to protect his writing hand, and tried to keep me away like that, but I showed him how spunky a baby sparrow could be. I pecked at the pen through his fingers, and watched for the least opening, and the moment he gave me a chance, I darted in and seized the pen. Then he tried to shake me off, generally laughing at me, and calling me a queer little birdie all the time, and he even lifted me up while I held on to the pen with my beak, and in that way tried to discourage me from fighting it. But I don’t think he ever knew how I disliked that wretched little stick. Why should it be in Fessor’s hands all the time? I wanted him to take me in his hands and go out for a walk with me, and I didn’t like his spending so much time pushing that pen back and forth.

One day, after we had had a pretty hard fight with the pen, I made a very strange discovery. When Fessor had gone away I saw that the writing on some of the sheets of paper was about me, and I’m going to let you read it. Here is what he wrote:

“Just now I put her on the sash that she might enjoy the sunshine, but the moment I began to write she flew down upon my desk and seized the pen with eager fury. To protect my pen as I write I have barricaded my writing hand with my left hand and the little creature is making desperate and frantic efforts to get inside. Every crevice she attacks, and tries to worm her way in, struggling with invincible determination and occasionally pecking at me, and seizing the end of my finger in her bill and pulling and tugging at it ferociously. Just before I reached this last word she learned how she might outwit me. She sprang upon my writing wrist over the barricade, seized the pen, and held on. Again I put her out. Again she sprang over. This time when I evicted her, she sought to crawl in under my left hand, and now stands, with crest upraised in anger, by my right hand, apparently thinking over a new plan of campaign.

“A pencil attracts her somewhat in the same way, but after a few onslaughts upon the moving pencil she gives it up; but now the battle on the pen has lasted for quite a number of minutes, and though defeated at every turn, she comes back again and again.”

One day I got very cross with Fessor for writing so much, and I determined to hide from him. By this time I knew the “den” pretty well, and I had found, “way back” in the big box in the corner, where the piles of big envelopes and loose papers were, the cutest hiding-place in the world. It was a kind of tiny house formed by the piles of papers and I could just crawl into it through a narrow place, and then I had room to move around easily, and I knew no one could find me. So I slipped off from the desk on this particular day and dodged into the box and hid myself. Fessor didn’t see where I went, and pretty soon he began to wonder where I was, for he looked all around and went and peeked behind the desk and on the book stand and other places where I often “played hide,” but of course he couldn’t find me. I stood as still all the time as a bird knows how, and never let on that I knew he was seeking for me; and so, after a while, he gave up the search.

“The cutest hiding-place in the world.”

And I didn’t let him know where I had my hiding-place. He thought it was in that box, but he never did know. So it was great fun once in a while to slip away and hide, and then when I was hungry suddenly pop out (without his seeing me), run to his feet, chirp and call, and say: “Here’s Scraggles, as hungry as a hunter.” Then he would reach his hand down, lift me up to the desk, and pretend to scold me: “Where have you been, you naughty little bird? I’ve been hunting everywhere for you, and couldn’t find you!” But I wouldn’t let on. I’d just peek at him, first out of one eye and then out of the other, as much as to ask: “Don’t you wish you knew?”

“At first I thought it was another little bird.”

I don’t know what it was that made Fessor laugh so when I tried to “spruce up” and make myself look as pretty as possible. Of course, I know full well that I was not a pretty bird. Perhaps I ought to tell you just exactly how I did look. Now you needn’t laugh and think I don’t know, for I do. I’ve seen myself in the mirror lots of times. Fessor and Edith used to take me and stand me before the glass, and while at first I thought it was another little bird, and I tried to talk to and play with it, I soon learned it was only a picture of myself. So, as I looked at myself quite often, I’ll tell you just how I did appear when I was three months old. My baby bill was gone and I looked more like a full-grown bird, but my feathers were still as scraggedy and raggedy as ever. My body and tail were a mousey-brown, with the wing feathers white and tipped with brown. My neck and breast were partially covered with soft, beautiful down of mouse color, and my head feathers were brown, with just one half-white feather in the centre which looked like a tiny crest. I was the smallest little bird ever seen, I guess,—I mean a sparrow,—and no more like the big, healthy, pert, and bouncing street sparrows than a delicate terrier is like a big bull-dog.

I was going to tell you about the way Fessor laughed when I tried to spruce up and preen my feathers. But I have found on his desk something he wrote, and I shall let you read it for yourselves. He doesn’t tell, though, how he used to sit there and laugh and laugh and laugh, until sometimes I almost thought he’d laugh his head off. And why he should laugh to see a tiny little bird like me make myself look nice, I don’t know. He used to spend time enough himself some days in making himself look neat. He’d put on his dress-suit and his pretty tie, and see that his boots were so finely polished, and all that kind of thing, so why should he laugh so at me?

This is what he wrote:

“Some days she will come and preen her feathers by my side as I write. It is her joy to sit on the very sheet upon which I am engaged, and for five or ten minutes such performances! With first one foot, then the other, she scratches her head with inconceivable rapidity. Then, getting a little oil from her receptacle, she begins to preen; under the left wing, down each feather, occasionally darting her bill like lightning upon some other feather that appears to her to need attention. Such screwing of the neck, twisting of the body, standing on tiptoes to get to the feathers on her body, such stretching to reach the tips! After it is done to her content, she gives herself several little shakes-down all over, quick flutterings and flappings of her wings, and settles down for awhile only to begin again and go through the whole performance once more if something suggests it ought to be done.”

Fessor also thought the way I stretched myself was very funny, though I could see nothing funny in it; so I will let you read what he wrote about that:

“To see her stretch one would think her tiny body was as full of sleep as that of a giant. First, one leg goes sprawling out as far as she can reach, and, with a spasmodic little kick, she brings it back into position, to push out the other. Then each wing in succession is stretched out, and sometimes, whether purposely or not I do not know, she lets the feathers comb through her claw.

“But the most interesting of her ‘stretchings’ comes when I put her on the window-sill and something goes on outside that she becomes interested in and wishes to see. She stretches up her little legs until it appears as if she were on stilts, and then, elongating her neck to more than twice its ordinary length, she veritably appears to be a tall bird with a long neck. Her excitement at such times is intense. She prances and cranes, and looks first out of one eye and then out of the other, hops back and forth, dances up and down, and generally shows a tremendous interest for so small a body.”

Now I must tell you about some of our daily walks. Fessor used to say to me: “Scraggles, you must go out of doors more, and watch the other birds and learn to fly. I want you to fly. How can I turn you loose to be a happy little bird in God’s great free out-of-doors if you don’t learn to fly? Come along now and see how the other birds do it, and then try for yourself.”

Then he would snap his fingers for me and I would come and jump into his hand and he would carry me out of doors where the sparrows and other birds seemed to be having so good a time. Of course, I watched them and was very much interested in them. I used to fairly long to fly as they did, and as they skimmed through the air I would stretch out my legs and wings and try to imitate them with all my might and main. Yet it was no use. My bad wing did not get strong, and it would not hold me up. Then Fessor would put me down on the ground near where a lot of sparrows would be pecking and chattering away on the road, and I felt that he wanted me to make friends with them. So I hopped toward them as fast as I could, and I chirped, and cheeped, and twittered, but, strange to say, never a one of them paid the slightest attention to me. They hardly ever looked at me, and never once said: “How do you do?” As soon as I reached them they flew away and left me to myself. Wasn’t that cruel? It seemed to me it was, but Fessor was always there near by, and would comfort me so sweetly by telling me not to mind; and as he snapped his fingers, I ran back to him, jumped into his hand, and felt comforted as he made me snuggle up to his whiskers, which I soon learned were almost as soft and warm as my mother’s feathers used to be.

Sometimes he would go indoors and tell Mamma that “her efforts were pitiable,” whatever that may mean, and then they would both be so gentle and kind and sweet to me, and talk so soothingly that I felt: “Well, even if I can’t fly, I have dear friends who love me very much and try to make me happy!” and that made me feel much better.

And still, any one would have known that Fessor was once a boy, a real, teasing, mean kind of a boy, for now and again he seemed to delight in teasing me. I must confess I got used to it, and didn’t mind it very much, but at first it distressed me quite a little, and I felt hurt when he just stood there and laughed at me.

One day he had taken me out onto the lawn—as he often did—and I was hopping about, when suddenly he took off his great big, broad-brimmed sombrero and threw it right over me, so that it fell to the ground a few feet beyond me. I was so scared! I saw that black thing skimming over me and thought it was a dreadful something coming to take me and kill me, perhaps; so, though I felt weak all over, I called up all my strength and hopped and fluttered right up to Fessor and jumped for safety upon his foot.

Then he seemed to be ashamed of himself, and said something to Mamma about its being “too bad to tease a poor little Scraggles like that.” So you see, I knew he had done it to tease me. But he picked me up and loved me so sweetly and gave me two pinion nuts which he chewed up for me, so that I couldn’t help forgiving him.

Oh! and I mustn’t forget to tell you about how he used to dig up slugs and worms for me. While I would be hopping about on the lawn he would go to a corner of the lawn and begin to dig. As soon as I saw him digging I didn’t wait to be called, but just hopped over there as fast as I could, and watched. Sometimes he saw the worm or slug or egg sooner than I did, but generally I had seen it and pecked it up before he knew it was there. It was great fun every day to go out and have a feast like that. I believe he enjoyed it as much as I did, and of course it was real good to me, for little birds do like slugs and worms, provided they are not too big for them to swallow. When Fessor would turn up a great, big, long worm and I would try to swallow it, he would laugh at me so funnily. But it was no fun to me, I can assure you, to try to swallow a worm longer than myself. And so I had to go to work with my bill and cut him up into smaller pieces, and that sometimes made me very tired.

Now and again Fessor would take me over to a neighbor’s whom he called “Friar Tuck.”[2] He would say to me in his funny way: “Now, Miss Scraggles, I am the bold and daring Robin Hood. You are a maiden who has fallen into my hands, and you are going to marry me, forsooth. Come along, and we will hie ourselves away to Friar Tuck and bid the jolly priest wed us!” Then snap! would go his fingers. I would run towards him, and he would pick me up, and off we would go.

[2] Note by the Fessor: My neighbor’s name was Tuck, and I meant no disrespect by calling him Friar Tuck.

I don’t think the Tuck family—there were three of them, just as there were three in our house—cared very much for me, though they used to say I was a queer little bird. I didn’t hop around there very much. I generally stayed with Fessor. I felt safer in his hand than anywhere else.

“I used to roost on it a great deal.”

One day when Fessor and Edith and I were out on the lawn, Edith said: “Why don’t you get a bough for Scraggles to roost on?” I don’t know what Fessor replied, but that afternoon Edith brought a bough with quite a number of branches on it, and put it down in the den for me. I used to roost on it a great deal after that, though there were times when I didn’t feel very well that I got more comfort out of a pair of Fessor’s shoes. But that is another story.

As a rule, Fessor was at work at his desk long, dark hours before I was ready to get up in the morning. I would hear him come quietly into the den, so as not to wake Mamma and Edith, and then the clock would strike twice, or three times, and I soon learned that that meant it was a long time before I had to get up. But some mornings he would be quite late, and once or twice he went down to the office (as he called it when he went away to be gone all day) and never saw me at all until night. Well, I didn’t like that at all, so one morning when he was not at the desk when I came from my hiding-place, I went out into the hall in search of him. Not far from the den door I found another doorway, and I went through it into the room. It turned out to be Fessor’s bedroom. He was in bed and fast asleep. That is, I think he must have been asleep by the noise he made, for he slept out loud worse than a humming bee I had once heard. I gave a loud, quick chirp. He didn’t answer, so I called several times, making my voice louder and louder at each call; until at last, with a stretch and a yawn, he threw his arm out of the bed and opened his hand for me to jump in. When he lifted me up on the bed he wanted to know what I meant, such a raggedy, scraggedy little wretch, by coming and waking him up. I didn’t tell him, but I just climbed up over his chest onto his chin and began to peck at his white teeth, and when he tried to catch me I ran and hid in his neck behind his whiskers. Then he bent his head over and held me so lovingly tight, that I was sorry when he let me go. I pecked his neck and he squeezed me between his cheek and his shoulder, and did it several times.

When I jumped onto his chin again I thought I would pinch his lip, so I took tight hold. My, how he did jump! And then when I pinched again, he tried to scare me all into little pieces. What do you think he did? He opened his mouth and filled himself full of air, and then blew me just as hard as he could. I was scared for a moment, but when I saw his dancing, merry, sparkling eyes I knew it was all fun, and I went for his lips again. But he dodged his head so that I couldn’t get at them. He said I pinched too hard, but I don’t believe that, do you? For how could such a tiny little bird hurt so big a man?

Then we had a new game. He stretched out on his back, raised up his knees, and took me and perched me right on top of them. He said I was on a high mountain with a valley behind, and a valley before, and a canyon on each side of me. And then he made an earthquake come. He moved his knees up and down quickly and made me jump. You know I couldn’t fly, but I jumped real hard, and I came rolling and tumbling down the mountain side into Paradise Valley, which was the name he gave to the valley in front. The next time he did it I tumbled off backwards, and that was the Valley of Despair, for he couldn’t reach me, he said, and I had to crawl out myself. What fun it was!

One day when we were playing this game I rolled right off from his knees, off the bed, onto the floor; and I went with such a bump! Then he said I had fallen into the Grand Canyon, and he called out to the Indians to come and catch me and bring me back to him. Of course it was all fun, for he threw his arm out of the bed, snapped his fingers, and gave me his hand, and I was soon nestling snug and warm against his chin and neck. That was such a nice place to be! I used to love to go and catch him in bed, for then I could peck his nose, and ears, and lips, and the white hairs in his beard, and whenever I did that he always snuggled me up close to him and called me his dear, darling little Scraggles.

From all this you can see how dear friends we had already become. So much so, that I was always very lonesome when Fessor had to go away; and several times after he had left the den, and the door downstairs had shut to, I would go out into the hall and call for him, and see if I could find him anywhere. Mamma and Edith were down in the kitchen, so they never heard me; but one day Fessor found out that I was in the habit of looking for him, for he went to the bath-room at the end of the great, long hall in order to refill my saucer with clean water. I had been there once or twice all alone, so I followed him. I had to hop and skip and flutter along pretty quickly, for he was such a big man and had such long legs. He didn’t dream I was so close to him, and when I gave a little chirp as I stood there by his feet, he jumped up and pretty nearly trod on me. “What!” he exclaimed. “What are you doing here? You little, darling rascal!” And then he stooped down and gave me a hand to pick me up and love me.

Ever after that I followed him every chance I got, and he seemed to like it. Even when we went out of doors he let me walk after him. I call it walk, but you know it was not a walk exactly like men and women walk. I had to hop and flutter my wings, and I really don’t know just what word you would use to describe how I travelled along. Fessor said I neither walked, ran, hopped, skipped, jumped, nor flew, and yet my movement was a mixture of all of these. I guess he knows, too; for I heard Uncle Herbert say he was a very learned man, and knew a great deal about many things.

Oh! I haven’t told you yet about Uncle Herbert’s visit. I will tell you that pretty soon.

People used to see us when we were out walking together, and some of them laughed, and others smiled in a queer kind of way with tears in their eyes. But nobody tried to hurt me, for Fessor was there, and he was so big that I knew I was safe every moment when I was with him. How I did enjoy those walks! We went out nearly every day, and he picked out the places where the sun shone, for he said the warm sunshine was good for birdies as well as for men and women.

One day Mamma came up-stairs to the den and said her brother Herbert was coming. Fessor and Edith were both glad, and as Edith called him Uncle Herbert, I always thought of him in the same way. We were all quite excited when he came. Such huggings and kissings and shaking of hands. I could see it from the top of the stairs, and hear what was going on. By and by Edith said to Fessor that he must show Scraggles to Uncle Herbert. So Fessor brought me down in his hand. I don’t think Uncle Herbert cared much for me at first, for he said I was the wretchedest-looking little bald-bellied bird he had ever seen in his life. That made me feel quite bad.

But the next day when they were at dinner Edith lifted me onto the table—a thing that was very seldom allowed, for Mamma didn’t think it was proper for me to run around on the dining-table, either at meal or any other time—and began to play with me. We had lots of fun, and then she lifted me up and wanted to make me perch on the edge of a drinking-glass partially full of water. She did it so quickly that I didn’t have time to get firm hold, and the glass was slippery, too, and what do you think happened? I fell right into that glass, and was half scared to death when my feet touched the cold water. With a quick “cheep” I made a desperate spring, and almost as soon as I was in I was out again. How Edith and Uncle Herbert laughed! Then he said I was a cute little bird.

Well, that night Uncle Herbert and Fessor and Edith and Mamma all went into the room where the piano was, and what a time they had! They sang all together while Fessor played, and then Uncle Herbert sat down and sang some funny songs about darkies and coons and “The Year of Jubilo.” It was too funny for anything. I didn’t know how to laugh as Mamma did, but it did me lots of good to see her. She laughed and laughed until she cried. And I danced and danced to see her so happy, that I grew quite excited and didn’t want to go to bed at all that night. But Fessor made me go. He took me and put me on the bough which I used for my perch, and when I jumped off and began to cheep and call he came in and put me back again; until at last I grew sleepy and dropped off to sleep. But I was very tired next morning. I guess I had laughed and danced too much, and stayed up too late the night before, which is not good for people as well as little birds.

Soon after Uncle Herbert’s visit I was taken quite ill. You see I never was very strong, and every little thing, such as a change in the weather, affected me. Yet when I think about it, it was almost worth while to be sick to feel the tender love Fessor gave me at that time. As soon as he found I couldn’t eat, he went and bought some stuff in a bottle called “bird-food,” and placed it in a saucer on the floor for me. But somehow I could not make up my mind to eat any of it until he came and carried me to the saucer, and there, holding me in his hand, he mixed up some of the food with water and fed it to me. He was so anxious that I should eat that I couldn’t refuse him.

“I couldn’t bear to be anywhere else than right in his hand.”

When he went to write at the desk I did so want to be with him! I couldn’t bear to be anywhere else than right in his hand. Here is a little piece I found on the desk one day which tells just how he used to care for me:

“She is now asleep in my left hand, though it is early afternoon. Crawling in between my fingers, she comfortably arranged herself, perched on one of my bent fingers, (the others covering her), and then, putting her head under her right wing, she quietly dropped off to sleep. Many nights when I am in the study at her bedtime, she has refused to perch on the branches of the bough. She comes to my feet and pleads to be lifted up. As I put down my hand she jumps into it, and as I lift her up and place her in my left hand she nestles down into it as if it were a nest, curves her head under her wing, and goes to sleep. If my fingers are not comfortable to her, she picks at them—sometimes very vigorously—until I put them as she desires.

“The other evening I determined I would not let her go to sleep in my hand, so I made her a cosy nest in the drawer immediately under my right arm. I coaxed her into this by putting two of my fingers into it, upon which she immediately squatted. But something was lacking in the new roosting place or nest. Two fingers were not enough, and for nearly half an hour my daughter and I watched her as she pecked at my fingers and thumb above, seeking to pull them down under her so that she would have a ‘full hand’ to nest on. At length she decided to take the two fingers, so long as with finger and thumb I rubbed her head. Soon her little head swung under her wing, and as soon as she was asleep I withdrew the two under fingers. But this awakened her, and I had to stroke her more before she settled down again. Then, as I wrapped the cloth around and over her, she awakened enough to peep out and learn from me that she was all right, when we left her for the night. She evidently remained contented until morning.”

I also found another little scrap on Fessor’s desk which tells better than I can about how I acted when I was ill. Here it is:

“During the last week she has shown a desire for closeness to me, for petting, handling, caressing, that I never saw in anything alive before. It is pathetic in the extreme. Every moment almost she desires to be near me. There is no seeking concealment, or privacy, or darkness. If I will not take her up in my hand, she nestles on my foot, and for several days I have kept my shoes off to give her the pleasure of feeling the warmth of my foot when I could not spare the time to ‘fuss’ with her on the desk. If I am away, I invariably find her on my return, if she is not eating, roosting on the edge of a pair of extra shoes of mine that always stand in the study.

“When she nestles beside my hand and folds her head under her wing, she loves to have me take the upper part of her head between my finger and thumb and gently rub and caress it, and she makes no effort to remove it, but goes on apparently sleeping as before.”

I wanted to hear his voice and feel the warmth of his hands and those delicious little hugs he gave me when he squeezed me just enough to tell me how much he loved me. And he seemed to understand it all so well,—just how sick a little bird felt. When he took me out of doors he kept me from the cold with his large, loving hands, and yet let the sun shine on me. Twice he made me walk after him, to give me a little healthful exercise; but he would not let me go too far lest I should get too tired.

But I did not get well; and I did so want to be well and strong. I was as happy with my human friends as I could be, and I wanted to live with them a long time. When I heard them say I was a very sick bird it used to put a great fear in my heart that I was going to die, and then I would snuggle up close to Fessor’s hand that he might know I wanted to live.

Here Scraggles’ story as written by herself comes to an end. The Fessor now tells the pathetic remainder of the interesting tale.

It was Thursday, August 3, 1905. We (that is, Scraggles and I) had had a good day together. We went out and I dug worms for her, and she seemed happy and improving in health and appearance. During the day she followed me out to the bath-room and all around several times, and when I went to lie down and read she came and insisted upon my holding her, or allowing her to sit on my hand. When I moved to turn the page she jumped upon my sleeve and hopped up to my shoulder and neck, where she stayed for half an hour or more. This was a new trick, learned only a few days before, and several times she hopped up from my desk, when I put her off the paper as I wrote, and perched quite contentedly on my shoulder or squatted on the back of my neck.

Several times during the day she had begged to be taken up and had fussed around my pencils, and once or twice had fought my pen as I wrote. Placing her on my lap, she snuggled down there contentedly until some movement disturbed her. Once, and the only time I knew her to do it, she tried to fly up from my lap to the desk. When she failed she looked up with such a queer expression that I could not help putting down my hand for her, into which she immediately hopped.

We had had a good two hours together after lunch, when I put her down, and soon she was hopping about the room. After feeding herself she came and perched in her usual place on my foot, but I must have forgotten her for a moment. My brain was much occupied with an important chapter of my book, and jumping up hastily I stepped to the book-case to the left of my desk to consult some volume, and almost as soon as I did so looked around to see where Scraggles was. I looked towards her sand bath and the food saucers, then to her little tree, but she was not to be seen. Then, as I often did, I tilted back my chair to see if she was at my feet, and to my intense distress I saw her there dead, on the bear skin I used as a rug.

There are some griefs that seem puerile. I suppose mine will over this poor, scraggedy, helpless little bird, yet I felt at that moment as I have felt often since, that there are many men I could far better spare than her,—many men with whom two months’ daily association would teach me less than did this little, raggedy, ailing song-sparrow. Her cheerfulness, her courage, her dauntlessness, her self-reliance, her perfect trust and confidence, her evident affection, were all lessons to remain in memory. After she had once given her trust, it never failed. I could handle my books, moving them to and fro over her, placing them anywhere near her, and there was not the slightest evidence of fear; and if anything did alarm her and she could get into my hand and feel its firmness around her, all tremors ceased. With her tiny head protruding from the clenched hand, her bright eyes looking now this way, now that, she watched intently, but without fear, confident in the protecting power of her big friend. And I felt the trust, the confidence reposed in me, the affection, and it drew from me a response totally at variance with the size of the tiny creature.

We buried her where she and I had gone daily, I to dig, she to eat whatever I found that she liked. My daughter lined the little grave appropriately with the beautiful white blossoms known as bird-cages,—lace-like, delicate, and exquisite,—and as we crumbled the earth over her tiny feathered little body, need I be ashamed to confess that tears fell, even as they do now as I write?

The book I was writing when Scraggles came to me was “In and Out of the Old Missions of California.” These interesting buildings were founded by Saint Francis of Assisi, whose love for the birds and lower animals has already become almost a proverb. It was just as I was finishing one of the last chapters of the book that Scraggles’ life went out. Was it not singular that, while dealing with a subject so intimately associated with this great lover of birds, one of these tiny, helpless, feathered sisters should claim my protecting love? There are those who will see in this more than the mere outward facts,—and I shall not be concerned or disturbed if they do.

The writing of the book was so bound up with the short life of Scraggles that, like an inspiration, I felt I must dedicate it to her. In two minutes after the thought came into my mind I had penned the following dedication, which was published and now appears in my book exactly as I wrote it:

TO SCRAGGLES

MY PET SPARROW AND COMPANION

Saint Francis, the founder of the Franciscan order, without whom there would probably have been no missions in California, regarded the birds as his “little brothers and sisters.” Just as I began the actual writing of this book I picked up in the streets a tiny song sparrow, wounded, unable to fly, and that undoubtedly had been thrust out of its nest. In a short time we became close friends and inseparable companions. Hour after hour she sat on my foot, or, better still, perched, with head under her wing, on my left hand, while I wrote with the other. Nothing I did, such as the movement of books, turning of leaves, etc., made her afraid. When I left the room she hopped and fluttered along after me. She died just as the book was receiving its finishing pages. On account of her ragged and unkempt appearance I called her Scraggles; and to her, a tiny morsel of animation, but who had a keen appreciation and reciprocation of a large affection, I dedicate this book.

When I read this to some of my friends they were moved to tears and wanted to know more about Scraggles. As I told the story, others desired to hear it. Then in a lecture on “The Radiant Life” I told it again, and thousands were touched to tears by the simple narrative of the sweet little bird’s beautiful and trustful life.

Fortunately, my familiarity with the camera had made me desire to make some photographs of Scraggles some three weeks before her death. My daughter and I made several, and then a friend came and made two or three others, so that now we feel really blessed in possessing these counterfeit presentments of the little creature.

When our friends saw these photographs they desired copies of them; and when, after the publication of “In and Out of the Old Missions,” strangers began to write both to my publishers and myself for “further particulars about Scraggles,” I felt that I ought to give to others some of the joy and delight and benefit I and mine had in our intercourse with her.

Dear little Scraggles! I little thought when I first saw you struggling to get away from me, as if afraid I might devour you, that we should so soon become such inseparable friends. It was a sudden impulse that led me to pick you up and take you home, and though the loving hearts there welcomed you, they realized better than I did the trouble you would be. But somehow that did not deter us from making you one of us, and you soon recognized the relationship. Our association was short, as men reckon time, but time really has very little to do with life.

So in the short three months you were with me we lived your lifetime together; and though my life is stretching out into further time, and your body is buried, you, dear little Scraggles, still live on with me. I don’t know, and I care less, what the psychologists say about birds having souls, and I am equally indifferent as to what the theologians say of there being a heaven for birds, or birds entering the heaven of human beings. This I do know, that in my own soul, far more real than the demonstrable propositions of life, such as that two and two make four, is the certain assurance that my soul and Scraggles’ will meet when my body and soul are severed.

So sleep, content and serene, dear little Scraggles, in your tiny and flower-embowered resting-place. You know full well in your tiny, but love-filled heart that just so soon as I have met all the human loved ones in the soul-life, I shall seek for you, and seek until I find, for I shall want you even in heaven. My heaven will be incomplete without you. I believe absolutely with Browning, that

So in the life of the future, with understanding and love made sweeter by clearer knowledge, we shall love on; for of all great things that abide forever “the greatest is love.”

Books by George Wharton James

In and Out of the Old Missions of California

An Historical and Pictorial Account of the Francescan Missions. With one hundred forty-two illustrations, including full-page plates, from photographs. 8vo. Cloth. $3.00 net.

The present volume stands as the authority on the old missions of California. Indispensable as a guide-book, and is filled with most valuable material.—San Francisco Argonaut. The author has devoted careful study to the matter of architecture, and to the furniture and decorations of the historic and ancient structures; but, in addition to this, the work is made interesting by the relative matters that have a more human interest.—St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

The Wonders of the Colorado Desert

(Southern California)

With more than three hundred pen and ink sketches from life by Carl Eytel. 8vo. Cloth. $4.00 net.

Mr. James has given the first adequate description of one of the most fascinating regions of this country. The wonderful rivers, lofty mountains, deep canyons, varied life and history of the Colorado Desert in Southern California are vividly set forth, together with an account of a recent hazardous journey made down the overflow of the Colorado River to the mysterious Salton Sea. The pen and ink sketches by the artist are an important feature of this book.

LITTLE, BROWN, & CO., Publishers

254 WASHINGTON STREET, BOSTON

Other Books by George Wharton James

In and Around the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River in Arizona

Illustrated with twenty-three full-page plates and seventy-seven pictures in the text. 8vo. Cloth. Price, $2.50

The volume, crowded with pictures of the marvels and beauties of the Canyon, is of absorbing interest. Dramatic narratives of hairbreadth escapes and thrilling adventures, stories of Indians, their legends and customs, and Mr. James’s own perilous experiences, give a wonderful personal interest in these pages of graphic description of the most stupendous natural wonder on the American Continent.—Philadelphia Public Ledger.

The Indians of the Painted Desert Region

With sixteen full-page pictures and fifty half-page illustrations from photographs. Crown 8vo. Decorated cloth. $2.00 net

“Interesting as a fairy tale and valuable for its accuracy as well” (Literary News), and “a distinct and extremely interesting contribution to topographical and ethnological knowledge” (Buffalo Commercial), is this book by Professor James, in which he vividly describes the Navaho, Hopi, Wallapai, and Havasupai Indians of the Southwest. “The writer has made an intimate personal acquaintance with his subject and has grounded himself in the researches of others,” says the New York Tribune.

LITTLE, BROWN, & CO., Publishers

254 WASHINGTON STREET, BOSTON