The Project Gutenberg eBook, Veronese, by Fr. (François) Crastre,

Translated by Frederic Taber Cooper

MASTERPIECES

IN COLOUR

EDITED BY . .

M. HENRY ROUJON

VERONESE

(1528-1588)

IN THE SAME SERIES

REYNOLDS

VELASQUEZ

GREUZE

TURNER

BOTTICELLI

ROMNEY

REMBRANDT

BELLINI

FRA ANGELICO

ROSSETTI

RAPHAEL

LEIGHTON

HOLMAN HUNT

TITIAN

MILLAIS

LUINI

FRANZ HALS

CARLO DOLCI

GAINSBOROUGH

TINTORETTO

VAN DYCK

DA VINCI

WHISTLER

RUBENS

BOUCHER

| HOLBEIN

BURNE-JONES

LE BRUN

CHARDIN

MILLET

RAEBURN

SARGENT

CONSTABLE

MEMLING

FRAGONARD

DÜRER

LAWRENCE

HOGARTH

WATTEAU

MURILLO

WATTS

INGRES

COROT

DELACROIX

FRA LIPPO LIPPI

PUVIS DE CHAVANNES

MEISSONIER

GEROME

VERONESE

VAN EYCK

|

| MANTEGNA |

IN PREPARATION

PLATE I.—JUPITER DESTROYING THE VICES

(In the Musée du Louvre)

This large composition shows a method rarely employed by

Veronese. The great imaginative artist here tried his hand at

the more vigorous school of painting, and with complete success.

It is especially admired for certain remarkable effects of

foreshortening. This picture, painted for the Ducal Palace, served

as a ceiling decoration in Louis XIVth’s chamber at Versailles,

until it was finally transferred to the Louvre.

[Pg iv]

VERONESE

BY FRANÇOIS CRASTRE

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH

BY FREDERIC TABER COOPER

WITH EIGHT FACSIMILE

REPRODUCTIONS IN COLOUR

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

NEW YORK—PUBLISHERS

[Pg v]

[Pg vi]

COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

THE·PLIMPTON·PRESS

[W·D·O]

NORWOOD·MASS·U·S·A

[Pg vii]

CONTENTS

| Page |

| Introduction | 11 |

| The First Years | 16 |

| The Sojourn in Venice | 27 |

| The Wedding at Cana | 38 |

| Veronese and the Inquisition | 47 |

| The Journey to Rome | 52 |

| The Return to Venice | 53 |

| The Decoration of the Ducal Palace | 57 |

| The Last Years | 65 |

[Pg viii]

[Pg ix]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Plate |

| I. | Jupiter Destroying the Vices | Frontispiece |

| In the Musée du Louvre |

| II. | The Disciples at Emmaus | 14 |

| In the Musée du Louvre |

| III. | The Holy Family | 24 |

| In the Musée du Louvre |

| IV. | The Wedding at Cana | 34 |

| In the Musée du Louvre |

| V. | The Family of Darius | 40 |

| In the National Gallery, London |

| VI. | Calvary | 50 |

| In the Musée du Louvre |

| VII. | The Marriage of St. Catherine | 60 |

| In the Accademia delle Belle Arti, Venice |

| VIII. | The Vision of St. Helena | 70 |

| In the National Gallery, London |

[Pg x]

[Pg 11]

INTRODUCTION

It has been said of Veronese that he was the most

absurd and the most adorable of the great painters.

Paradoxical as it sounds, this judgment is

perfectly true. Absurd, Veronese undoubtedly was,

in his disdain of logic and common sense, in his

complete indifference to historic truth and school traditions,

and in his anachronistic habit of garbing antiq[Pg 12]uity

in modern raiment. “I paint my pictures,” he

said, “without taking these matters into consideration,

and I allow myself the same license which is granted

to poets and to fools.” And it is precisely his riotous

fantasy, his naïve self-confidence, his own peculiar

way of understanding mythology and religion that

have made him the adorable artist whose glory has

been consecrated by the centuries.

PLATE II.—THE DISCIPLES AT EMMAUS

(In the Musée du Louvre)

This biblical scene, as treated by Veronese, in no wise resembles

the same subject as treated by the Primitives or by Rembrandt.

The Venetian Master does not trouble himself about

tradition; for him, this Feast is simply an opportunity for a

beautiful picture, brilliant in colour, and embellished with rich

accessories and architectural drawing.

Thanks to the rare power of his genius, the most

audacious improbabilities vanish beneath the magic

adornments with which he covers them, and it hardly

occurs to one to notice his glaring historical errors or

the superficialities of his pictorial conceptions in the

continual delight inspired by the sense of concentrated

life in his characters, the splendour of his colouring,

the caressing charm of his draperies, the brilliance of

his skies, and the impression of youth and of joy that

radiates from his work. Veronese was neither a

thinker nor an historian, nor a moralist; he was quite

simply a painter, but he was a very great one. If his

preference is for the joyous scenes of life, that is because

life treated him indulgently from his earliest

[Pg 15]

years; if he delights in giving to his pictures a sumptuous

setting, in which silk, brocades and precious vases

abound, it is because he acquired a taste for these

things in that matchless Venice of the sixteenth century,

marvellous treasury of sun-bathed, gaily bedecked

palaces, wherein all the opulence of the East

had been brought together. What these paintings of

Veronese reproduce for us are the thick, rich carpets

of Smyrna, newly unladen from Musselman feluccas,

monkeys imported from tropic islands, greyhounds

brought from Asia, and negro pages purchased on the

Riva dei Schiavoni, the Quay of the Slaves, to bear

the trains of the patrician beauties of Venice. But,

above all, one finds in them Venice herself, Venice

the Glorious, queen of the sea, Venice sated with gold

and lavish of it, sowing her lagunes broadcast with

palaces, and the robes of her women with diamonds.

More truly than Titian or Tintoretto, Veronese is the

chosen painter of the Most Serene Republic. He not

only decorated the ceilings of her palaces and the

walls of her churches: but he took the city of his

adoption as the setting for all his compositions; it is[Pg 16]

at Venice that the Feast at the House of Simon the

Pharisee, the Feast at the House of Levi take place;

it is in Venetian surroundings that Jesus presides over

the Wedding Feast at Cana.

One can understand how the painters of the Venetian

school, nurtured in the dazzling and joyous

light of the sea-born city, transferred to their palette

that vibrant colour with which their artist eyes were

filled; nor is it surprising that Veronese, passionately

enamoured of Venice, achieved, through his wish to

glorify her, that magnificence of colour and of expression

which remains his distinctive mark.

THE FIRST YEARS

Nevertheless, Veronese was not a native of Venice

but of Verona, as is indicated by the surname that

was bestowed upon him during his life and that has

adhered to him ever since. His rightful name was

Paolo Caliari. He was born at Verona in 1528 and

not in 1530, as is asserted by several of his biographers,

notably by Carlo Ridolfi. The correct date is now

verified by the discovery, in San Samuele of Venice,[Pg 17]

Veronese’s parish church, of the register of deaths

wherein the decease of the great painter is entered as

having occurred the 19th of April, 1588, the very day

when he completed his sixtieth year.

Paolo Caliari belonged to a family of artists. His

father, Gabriele Caliari, was a sculptor and enjoyed

some little reputation in his own city. Veronese’s

uncle, Antonio Badile, was a painter, and in such

pictures as are known to be his we find evidence not

only of a good deal of ability, but of a certain facile

grace that justifies the high esteem in which his compatriots

held him.

Veronese’s father, being of a logical turn of mind,

wished, since he himself was a sculptor, to make a sculptor

of his son. Veronese learned to model statuettes

in clay, and, aided by his precocious intelligence, he

acquired a real dexterity in this art, quite remarkable

in one so young.

But this was not his vocation. Frequent visits

to the studio of his uncle Badile had awakened in him

an enthusiasm for painting. He applied himself to

learn to paint with so much zeal and imagination[Pg 18]

that his father made no attempt to check his inclination,

but entrusted him to Badile. The latter was

Veronese’s real teacher, though not the only one, for

young “Paolino” also attended the studio of another

Veronese painter, Giovanni Carotto.

From the outset, Veronese applied himself energetically

to perfecting his skill in line drawing. The

future genial painter of wondrous fantasy yielded himself

without a murmur to the rude but salutary exigencies

of technique. Strange caprice on the part

of an artist who was destined to show so much dexterity

in execution and lavishness in decoration, his

tastes turned towards the most severe and least

imaginative of masters, Albert Durer and Lucas

Van Leyden. It was through copying the engravings

of these illustrious masters that he learned how to draw.

Such lessons always bear their fruit. In this laborious

apprenticeship, Veronese acquired that steadiness

of hand, that firmness of line that was later to

be noted even in his most exuberant paintings,

despite the enormous quantity of canvases that he

produced in the course of his life.[Pg 19]

Even his earliest attempts reveal his abundant

and facile genius; and these first, and one might

almost say immature, works already foreshadow the

great artist. The affectionate patronage of his uncle

Badile greatly facilitated his début. At an age when

young folk have not usually begun to form dreams

of the future, young Caliari had already forced himself

upon the attention of Verona, and the Chapter of

the Church of San Bernardino commissioned him to

paint a Madonna.

He acquitted himself well of this task. The work

proved satisfactory, other orders followed, and the

name of the young artist swiftly spread beyond the

confines of his native city. A short time later,

the cardinal Ercole di Gonzaga decided to decorate the

cathedral at Mantua, recently rebuilt by Giulio

Romano. He sent a summons to Caliari, as well as

to three other Veronese painters who enjoyed a big

reputation: Battista del Moro, Paolo Farinato degli

Uberti, and Brusasorci, who was regarded as the

Titian of Verona. The cardinal instituted a sort of

rivalry between these four artists, and gave them[Pg 20]

orders for four pictures, destined to be competitive.

The subject entrusted to Paolo Caliari was a representation

of the Temptations of St. Anthony. The

young painter applied himself resolutely to the task.

Far from intimidating him, the redoubtable competition

of his three elders served only to excite his

ardour and stimulate his imagination. He painted

the saintly anchorite defending himself against the

blows which the Devil is dealing him with a stick and

repulsing the advances of a woman who has been

raised up from hell itself to tempt him. The cardinal,

delighted with this picture, gave preference to Veronese

over his three competitors.

Veronese lost no time in returning to Verona, but,

however flattering the esteem with which his compatriots

surrounded him might be, he was not long

in finding that the limited scope afforded by his native

city was too narrow for his activity. He had a boyhood

friend, Battista Zelotti, a painter like himself,

and also like himself tormented by dreams of glory.

Together they quitted Verona and betook themselves

to Tiene, in the duchy of Vicenza. Here they had[Pg 21]

the good luck to meet a man of discrimination, in

the person of the paymaster-general Portesco, who

entrusted them with the decoration of his palace.

The two friends apportioned the work between them;

while Zelotti, who had studied at Venice under Titian,

undertook the fresco painting, Veronese decorated the

intervening panels in grisaille, or gray monochrome.

The result of this friendly collaboration was a complete

series of paintings, of great diversity: hunting

scenes, banquets, dances and numerous subjects borrowed

from mythology or from history, the Loves of

Venus and Vulcan, the Heroism of Mucius Scaevola,

the Festival of Cleopatra, and a remarkable Sophonisba.

This work in common was not without profit

to Veronese. Zelotti’s manner closely resembled his

own; they both show the same qualities of colouring

and composition, and the same broad and facile touch.

They collaborated once again on fresco work in

the home of a certain Eni, in the village of Fanzolo,

in the neighbourhood of Trevise. After this they separated,

Zelotti going to Vicenza, whither he had been

summoned, while Caliari betook himself to Venice,[Pg 22]

the Promised Land towards which he was impelled

by his ardent desire for glory.

When he arrived in the Most Serene Republic,

Caliari was not yet twenty-five years old. We have

no reliable document regarding these first years of

his residence there, nor even of the impressions produced

upon him by the opulent and magnificent city.

But these impressions are easy to conceive. To

anyone so sensitive as he to externals, Venice must

have seemed enchanted ground. How could he have

failed to be dazzled, in acquainting himself with that

gorgeous city, enthroned upon the Adriatic, like a

pearl in a casket of velvet? With what joyous eagerness

his colour-enraptured eye must have rested upon

those white marble palaces, moulded and filagreed

in arabesque, those churches paved with precious

mosaics, those quays swarming ceaselessly with a

picturesque and motley crowd of Armenians, Greeks

and Moors, spreading the sun-bathed pavements

with a glittering display of spangled ornaments, turquoise-inlaid

cutlery, and multicoloured fabrics.

PLATE III.—THE HOLY FAMILY

(In the Musée du Louvre)

In this work, one of the most beautiful in the Salon Carré,

Veronese has grouped his figures in a charming manner. Following

his customary formula, he has clothed them in the Venetian

style, but the faces of the Virgin and the Child are remarkable for

their tenderness. It is a matter of regret that time has faded the

colours of this magnificent painting.

If the models that passed in endless procession

[Pg 25]

before his eyes impressed him as magnificent opportunities,

the sight of what other painters had already

wrought from this material aroused his artist soul to

keen enthusiasm. The whole constellation of the

great Venetians had converted the city of the Doges

into an incomparable museum: Giorgione, with his

melancholy compositions, full of vague dreams; Carpaccio,

with his naïve and picturesque reproductions

of Venetian life. Among the living, Sansovino, simultaneously

architect and artist, who built marvellous

palaces and adorned them with graceful frescoes;

Tintoretto, sombre genius whose creative power

largely redeemed the somewhat obscure tints of his

palette; and above them all, Titian, the great Titian,

who at that time was already eighty years of age,

yet still manipulated his brush with the firm hand of

youth.

All these masters Veronese admired indiscriminately,

as was fitting in a young painter who had

never known other models than those of his own

small city. He ran the danger of acquiring mannerisms

and becoming an imitator. By a special grace[Pg 26]

accorded to genius alone, Veronese succeeded in remaining

himself and borrowing nothing either from

his predecessors or his contemporaries. From his

contemplation of the works of the others he gained

only a nobler passion for his art; and he altered nothing

in the personal vision which he already formed

of men and of things.

Vigorous, blessed with good health, jovial by

nature, and much enamoured of the bright and sparkling

side of life, Veronese fashioned his paintings in the

image of his own temperament. His work was always

an exaltation of the joy of living, an apology for those

agreeable externals that render existence pleasant

and easy; fine dwellings, flowers, copious repasts,

women luxuriously apparelled, precious fabrics, horses

and dogs of fine breed. If he wished to paint a Last

Supper, it mattered little to him that legend and history

agree regarding the simplicity and the humble

station of Jesus and his disciples: History and tradition

did not count with him. A repast, whatever

it would be, he could not conceive of, unless around

a sumptuous table, covered with costly vessels, served[Pg 27]

by attendants in picturesque costumes and enlivened

by the antics of buffoons or the harmonies of music.

It was thus that he painted Christ, it was after this

original conception that he worked out his immortal

compositions. Accordingly no one could justly appraise

Veronese, without first setting aside, as he did,

all those historic data which he voluntarily ignored.

THE SOJOURN IN VENICE

There are few painters of whose private life so

little is known as of that of Veronese. The contemporary

documents have disappeared and scarcely

anything more remains than a few of his letters;

and even those are silent as to his day-by-day existence.

All that it is possible to know—and to this

his paintings abundantly bear witness—is that he

was possessed of an agreeable humour, and a pleasing

personality;—worthy gentleman, somewhat quick

of temper and permitting no slight to be put upon

his dignity, still less upon his honour. He was neither

a sycophant nor a courtier, accepting commissions

but never soliciting them. His “disinterestedness,[Pg 28]”

writes Charles Yriarte, “has remained celebrated;

during one entire period of his life, the greater part

of the contracts which he signed with communities

and with convents stipulate barely the value of his

time as a remuneration for his work. This was before

the time when painters were expected to furnish their

colours and their canvases, but demanded only the

price of their toil. Later on, having become, if not

rich—that he never was,—at least celebrated and

independent, he acquired a taste for personal luxury;

he delighted in brilliant fabrics and wore them with

ostentation; he loved horses, dogs, and hunting; he

frequented high society, and brought to it that Italian

open-heartedness which makes the company of the

illustrious a relaxation and a pleasure rather than an

embarrassment or an effort. He won valuable friendships

and was able to retain them until his death.”

Of these friendships, the most efficacious was that

of the Prior of the convent of San Sebastiano, Bernardo

Torlioni, a Veronese by birth, to whom he had

brought letters of introduction. No sooner had young

Caliari arrived in Venice at the beginning of 1555,[Pg 29]

than he presented himself to his venerable compatriot,

who promptly took a fancy to him, and bestirred

himself to serve him. Thanks to Torlioni, Paolo obtained

an order for five pictures, including one large

composition, the Coronation of the Virgin and four

dependent panels. These paintings were destined

to adorn the sacristy of the church of San Sebastiano,

of which Bernardo Torlioni was prior. When the work

was done, the Chapter expressed itself as so well

pleased that it entrusted him with the decoration of

the church itself, including the ceiling. It was here

that Veronese painted his admirable series of episodes

from the History of Esther and Ahasuerus.

The success of this series was so great that the

edifice was placed unconditionally in his hands, and

he was free to follow his fantasy unhampered. Following

a method which was habitual with him, he

enhanced the effect of the large panels painted in

fresco, by means of smaller intervening scenes in

chiaroscuro. Here also one finds him indulging his

hobby for architectural painting, such as always

occupies a large place in his pictures; all around the[Pg 30]

church he painted truncated columns, ornamented

with arabesques and foliage, “with a richness and a

pomp that were already an inseparable feature of his

style.”

In the works of Veronese, the accessories always

play a highly important part; and it is not difficult

to understand the reason. His main object being to

delight the eye, he attributed considerable space to

vases, furniture, armour, fruits, flowers, graceful draperies,

brilliant costumes, mettlesome horses, and more

especially dogs, with which it was his special whim to

embellish his paintings. The dog was his favourite

animal, and even at that epoch its presence was to be

noted in every picture.

When the church, completely decorated, was

opened to the public, there was general rejoicing;

Veronese received the unanimous vote of approval,

from the populace as well as from the artists.

From that day forth, the ability of the young

painter was openly acknowledged, and his fortune

assured. Furthermore, he had arrived in Venice at

a propitious hour. It was the moment when the[Pg 31]

Most Serene Republic, victorious over the seas and

surfeited with wealth, attained the zenith of her glory.

In her opulence Venice chose to employ her treasures

in self-adornment; palaces arose on all sides, the Ducal

Palace itself was redecorated; Sansovino was just

completing the new Government offices. The wealthy

brotherhoods and equally wealthy parishes were seeking

out every painter of repute to decorate their

churches and their convents.

Accordingly, Veronese had arrived at the crucial

moment to satisfy the demands of art. His rivals

were negligible: Salviati, Battista Franco, Lo Schiavone,

Zelotti, Orazio Vocelli the son of Titian, could

none of them hold their own against him. Bordone

was at the court of Francis I. Tintoretto alone, at

the height of his powers, could counterbalance Veronese’s

glory. As to the aged Titian, he was no longer

producing pictures with his old-time fertility; furthermore,

he had already divined the genius of Veronese

and conceived a friendship for him.

And so, throughout thirty-three years, from 1555

to 1588, the masterpieces that were born beneath[Pg 32]

Veronese’s fingers succeeded one another without

interruption. The walls of his adopted city became

overspread with his luminous canvases, eloquent of

the joyousness of Italy, resplendent with the triumphant

beauty of Venice.

Shortly after the decoration of San Sebastiano was

completed, Daniele Barbaro, Patriarch of Aquileia

and wealthy patrician of Venice, had a splendid

residence built him at Masiera by Palladio, a celebrated

architect of the period. Being a man of artistic

taste, he wished to embellish it with paintings and

statues worthy of its imposing architecture. For

the sculpture he summoned Alessandro Vittoria; the

paintings were entrusted to Paolo Veronese.

The patriarch Barbaro was one of his friends, and

accordingly allowed him a free hand, and even left

the choice of subjects to him.

PLATE IV.—THE WEDDING AT CANA

(In the Musée du Louvre)

This immense composition is the most celebrated work by

Veronese. It is considered as one of the masterpieces of all painting.

The greater number of the guests at this feast are portraits

of illustrious characters of the sixteenth century, and the artist has

included himself, along with Tintoretto and Titian, in the group of

musicians in the foreground.

Veronese, who was a prodigiously fertile artist,

left not a single space in Barbaro’s house unoccupied

with colour. Wherever space would not permit of

large compositions, he painted trophies, garlands,

flowers, even statues, possessing all the lustre and

[Pg 35]

relief of marble. Elsewhere he sketched in architectural

fantasies, simulating colonnades and porticoes,

opening upon landscapes borrowed from the

realm of dreams; he conceived imaginary doors,

before which fictitious lacqueys appeared to be standing.

The principal subjects treated by Veronese at Masiera

include Nobility, Honour, Magnificence, Vice, Virtue,

Flora, Pomona, Ceres and Bacchus; then in the ceiling

of the cupola he gathered together all the gods of

Olympus, grouped around Jupiter.

The decorations in the palace at Masiera further

augmented Veronese’s fame. He was now acknowledged

to be the foremost painter of Venice, next to

Titian. Barbaro had been so delighted with his

talents that he determined to do him a service. Standing

well at court, he recommended him to the Signoria.

As a result of this, the latter entrusted him with the

task of redecorating the halls and chambers of the

Doge’s Palace, in conjunction with Tintoretto and

Orazio Titian. Which of the three artists proved

superior it is impossible to decide to-day, because a

fire, occurring in 1576, destroyed their paintings along[Pg 36]

with the palace. But public opinion of that period

gave the palm to Veronese.

It seems as though this verdict must have been

justified, in view of the esteem in which his name

was held.

Shortly afterwards, Sansovino having completed

the construction of the library, the procurators instructed

the architect to arrange with Titian as to a

choice of painters to decorate it in competition. Veronese

was immediately designated, together with

Zelotti, Batista Franco, Giuseppe Salviati, Lo Schiavene

and Il Fratina, who were to divide the twenty-one

ceiling panels between them. Three round compartments

fell to the lot of Veronese, who filled them

with figures representing Music, Geometry with Arithmetic,

and Honour. Under Veronese’s brush these

cold abstractions took on the most charming forms;

they were represented by graceful women, each surrounded

by the attributes of the science which she

symbolized. A recompense was promised by the

procurators to the artist whose paintings should be

adjudged most beautiful. Titian was enthusiastic[Pg 37]

over those of Veronese. Loyal and noble artist that

he was, he himself solicited the votes of the painters

who had taken part in the competition, and thus

Veronese was declared winner by the voice of his own

competitors. The senate offered him a golden chain

which he delighted to wear on solemn occasions.

These great official works did not diminish the number

of his productions for churches, convents, or private

persons of wealth. No other artist affords an example

of similar fecundity.

And what verges upon prodigy is that he never

employed collaborators, as so many other celebrated

painters have done; the only one that he is known to

have had is his brother Benedetto Caliari, whose

artistic aid was limited to painting in the prospective

of the vast architectural designs with which it pleased

Veronese to embellish all his canvases.

The epoch of his most fertile production was between

1562 and 1565; it was also the period in which

he executed his largest and most celebrated paintings,

notably his famous canvas of the Wedding at Cana,

his Feast at the House of the Pharisee, his Feast at[Pg 38]

the House of the Leper, and his Feast at the House

of Simon.

These four pictures are known under the name of

the four Feasts. Two of them belong to France and

hang in the museum of the Louvre, in the room known

by the name of the Salon Carré; these are the Feast

at the House of Simon the Pharisee and the Wedding

at Cana.

THE WEDDING AT CANA

Veronese has treated this subject twice. Accordingly

the picture in the Louvre must not be confounded

with that of the same name in the Brera museum at

Milan. In spite of the value of the latter, it bears

no comparison to the gigantic canvas in the national

museum of France.

PLATE V.—THE FAMILY OF DARIUS

(In the National Gallery, London)

This picturesque painting is one of the most curious of all

Veronese’s works. It was painted in return for the hospitality

which he received from the Pisani family, and all the figures in it

are portraits of members of the household. Another point worthy

of note is the anachronism of the warriors clad in Roman armour

standing before the kneeling women, who are dressed in the manner

of the sixteenth century.

This picture of the Wedding at Cana was painted

by Veronese for the refectory of the convent of San

Giorgio Maggiore, on the island that faces the Riva dei

Schiavoni. It remained there until the time of Napoleon’s

Italian Campaign. Bonaparte, who loved the arts

without understanding them, laid profane hands on the

[Pg 41]

great majority of Italian masterpieces. This painting

by Veronese was one of the number, and found a place

in the Louvre. The treaty of 1815 obliged France

to restore these treasures, but the Austrian commissioners,

appointed to accomplish the restitution, became

alarmed at the difficulties of transportation which

the Wedding at Cana presented. They accordingly

consented to exchange this canvas for a painting by

Le Brun, The Feast at the House of the Pharisee.

Veronese’s masterpiece remained in the Louvre, in

which it is one of the most flawless gems.

The contract drawn up between Veronese and the

Prior of San Giorgio Maggiore for the execution of

this picture has been preserved. The painter bound

himself to deliver it within a year, since the contract

was signed June 6, 1562 and the delivery of the

canvas took place of September 8, 1563. He

was to be furnished with canvas and colours, to be

entitled to take his meals at the convent and receive

a cask of wine as additional recompense. As to

remuneration for his work, it was fixed by mutual agreement

at 324 ducats, which, in the 16th century, cor[Pg 42]responded

to 972 francs in the coin of France. Taking

into consideration the enhanced value of money since

that epoch, these 972 francs would represent to-day

7,000 francs. Such is the price which the greatest

artist of his time received for a masterpiece which

to-day commands the admiration of the entire

world.

Never did Veronese display so much brilliance,

dispense so much imagination as in the Wedding at

Cana; never did he show a greater dexterity in execution;

for, however considerable the dimensions of

the canvas may be, it demanded nothing less than

genius to distribute without clash or disproportion

the hundred and thirty-two personages which compose

it. A painter less thoroughly sure of himself would

have made a sorry mess of this Feast; Veronese has

produced a composition that is admirable for its

balance, in abounding charming details, and unexpected

and picturesque episodes, that do not in the

least detract from the effect of the painting as a

whole.

On this picture, as on so many others from the[Pg 43]

brush of Veronese, one cannot, as has already been

said, pass an equitable judgment, unless one accepts,

without question, the master’s method. Veronese

had no more respect for religious tradition than he

had for mythological legend. To take issue with the

incongruities and anachronisms of the Wedding at

Cana, is voluntarily to debar oneself from discussing

it. If historic exactitude is the one thing that counts

in a painting, then this picture simply does not exist.

But happily painting has no need to justify itself to

history; it is amply sufficient to itself, without borrowing

anything from history, and loses nothing of its

beauty if perchance it does violence to history. And

of this the Wedding at Cana furnishes a most eloquent

proof.

The composition of this famous picture is well

known. Jesus is seated in the middle focus, at the

centre of the table, which is curved on each side in

the form of a horse-shoe. To fill this immense table,

Veronese did not go to the scriptures in search of

personages; he drew them from his surroundings

and from his own imagination.[Pg 44]

The groom, a handsome, black bearded young

man, clad in purple and gold, is no other than Alphonso

d’Avalos, Marquis del Vasto, and the bride is a portrait

of Eleanora of Austria, sister of Charles V., and

Queen of France. On the left, one discovers,

with some surprise, Francis I., Charles V., the Sultan

Achmed II., and Queen Mary of England. Beside

the Sultan is a woman richly robed and holding a

tooth-pick; she is Vittoria Colonna, Marchesa di

Pescara; then, further on are monks, cardinals, and

personal friends of the artist. Standing up, clad in

brocade and holding a cup in his hand, is Veronese’s

brother, Benedetto Caliari. In the centre are a group

of musicians. The octogenarian bending over his

viol, is a portrait of Titian; Bassano is playing the

flute; Tintoretto and Veronese himself draw their

bow across the strings of a ’cello.

The success of the Wedding at Cana was triumphal.

The great painters of Venice, contemporaries of

Veronese, overwhelmed him with proofs of their

admiration; even morose Tintoretto found some extremely

amiable words in which to praise his rival in[Pg 45]

fame, and Titian embraced the happy painter when

he chanced to meet him in the city streets.

These praises were merited; the Wedding at Cana

is quite truly one of the most beautiful masterpieces

in the world’s collection of paintings.

The renown obtained by this admirable work

brought Veronese a host of orders. The various cities

vied with each other to secure him to decorate their

churches or their convents. His first patron, the

Prior Torlioni, ordered a picture from him for the

convent of San Sebastiano, the church of which he

had already decorated. Veronese, by no means ungrateful,

painted for him the Feast at the House of

the Leper, in 1570; three years later he painted for

the dominican monastery of San Giovanni e Paolo the

Feast at the House of Levi, to decorate one side of

the refectory. The monks had only a modest sum

at their disposal and tremblingly offered it to the now

celebrated painter; they naïvely added the donation

of a few casks of wine. Veronese exhibited the most

complete disinterestedness by accepting these humble

offers of the Prior. This was his third Feast.[Pg 46]

The fourth, known under the name of the Feast

at the House of Simon the Pharisee, was executed for

the refectory of the Brotherhood of Servites. It

represents Magdalen on her knees, wiping the feet of

Christ with her hair. This painting now hangs in

the Louvre, opposite the Wedding at Cana. It has

been the property of France for two centuries, and the

history of its acquisition by Louis XIV is curious

enough to be worth the telling. Colbert, having

learned that Spain had negotiated for the purchase

of the Feast at the House of Simon, resolved to go

to any lengths in order to acquire it himself, on behalf

of Louis XIV. The French ambassador to Venice,

Pierre de Bonzi, was charged with the negotiations.

To address himself directly to the Servites was impossible,

since there was a law in the Venetian Republic

forbidding the sale and exportation of any native works

of art. Bonzi pursued the course of informing the

Signoria of his royal master’s wish. The Signoria,

desirous of securing the good will of the great king,

without violating her own laws, purchased with

public funds the picture from the Servites, and straight[Pg 47]way

offered it to Louis XIV, who returned warm thanks

to his “very dear and great friends, allies and confederates,

after having seen this rare and most perfect

original.”

VERONESE AND THE INQUISITION

These four Feasts of Veronese won him a widespread

renown. But there were certain hostile spirits,

uncompromising traditionalists, to whom the fantastic

elements which he introduced into the composition

of his religious pictures were necessarily strongly displeasing.

To introduce dwarfs, buffoons, men at arms

under the influence of liquor, at a feast where Jesus

and his disciples take part,—did not this savour of

irreverence, nay, worse than that, of heresy?

The Feast at the House of Levi the Publican, executed

for the convent of San Giovanni e Paolo, in

which Veronese had given free rein to his imagination,

was denounced to the Holy Office, and on July 18,

1573, the artist was summoned before the tribunal

of the Inquisition.

In the Most Serene Republic this tribunal scarcely[Pg 48]

had the same redoubtable power with which the sombre

fanaticism of Philip II had armed it in Spain. It

was none the less a grave risk to incur its displeasure

at an epoch when the Papacy still held undisputed

sway over the guidance of souls. Consequently this

prosecution caused Veronese serious alarm.

M. Armand Baschet discovered quite recently in

the archives of the Frari, at Venice, the official record

of the trial with all the questions put to him and his

answers.

The judges took special exception to his Feast at

the House of Levi, which seemed to them an outrage

upon religion. Each one of the figures in the picture

was brought up separately for discussion, and the luckless

Veronese was required to make explanation.

What was the significance of that man who was bleeding

at the nose? Why were those two soldiers, on

the steps of the stairway, one of them drinking and

the other eating, clad in German uniform? And, at

a repast where the Saviour figures, what was that

ridiculous buffoon doing with a parroquet on his wrist?

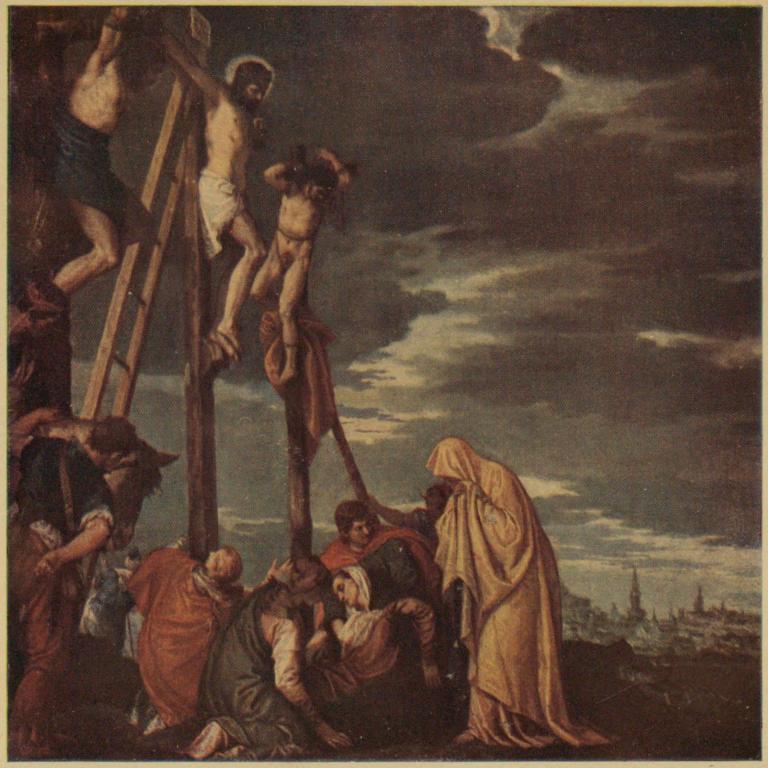

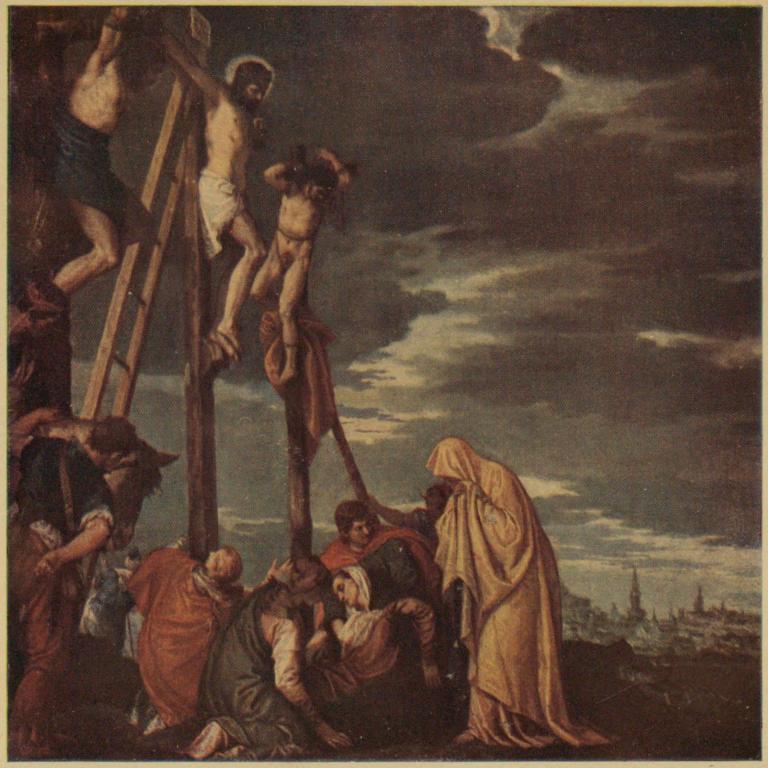

PLATE VI.—CALVARY

(In the Musée du Louvre)

In painting this subject, which so many artists have treated in a

lugubrious tone, Veronese, while preserving the intense sadness

of the scene on Calvary, has none the less succeeded in lavishing

upon it his habitual qualities as a colourist. All the actors in the

divine drama wear gloomy countenances and resplendent robes.

Veronese defended himself as best he could. He

[Pg 51]

assumed a sort of injured innocence and apparently

failed to understand the enormity of the irreverence

with which he was charged. Next, he took shelter

behind the precedent established by the great masters.

He cited Michelangelo and his Last Judgment:

“At Rome, in the Pope’s own chapel, Michelangelo

has represented Our Lord, his Mother, Saint

John, Saint Peter and the Celestial Choir, and he has

represented them all naked, even the Virgin Mary,

and that, too, in diverse attitudes, such as were certainly

not inspired by our greatest of religions.”

Finally, Veronese emphatically denied the charge

of any intentional irreverence toward the Church; he

declared that he had simply permitted himself, perhaps

wrongfully, a certain amount of license such as is

accorded to poets and to fools.

His contrite attitude won him the indulgence of

the Tribunal. But the judges demanded that he should

correct his picture, and he was obliged to remove the

dwarfs and the fools and to modify the attitude of

his men at arms. This is the picture that may be

seen to-day at the Accademia delle Belle Arti, at[Pg 52]

Venice, retouched in accordance with the orders of

the Holy Office.

THE JOURNEY TO ROME

In spite of his keen desire to pay a visit to Rome,

Veronese was kept in Venice by his ceaseless productivity,

and he attained the age of forty without ever

having had the chance of a sight of the Eternal City.

Of all the masterpieces in that home of the Pontiffs,

he knew nothing, excepting of such as he had seen copied

in the form of engravings. The appointment of his

friend and patron as ambassador to the Holy See,

afforded him an opportunity to make the journey so

many times projected and deferred.

No documents exist regarding Veronese’s sojourn

in Rome, but at all events it was fairly brief. Beyond

this, we are reduced to mere conjecture. Furthermore,

there is no extant evidence to sustain the idea that he

practised his art in the Eternal City. If he had

painted any pictures there, some trace of them would

surely have been discovered. It must therefore be

concluded that he contented himself with admiring[Pg 53]

the masterpieces with which his illustrious predecessors,

Raphael and Michelangelo, had enriched the

capital of the Pontiffs.

But his temperament was too peculiar, his manner

too individual, and we may as well acknowledge, his

nature too superficial, to permit of his experiencing

those profound and overwhelming impressions that

radically modify an artistic career.

And for this we ought rather to be thankful than

to complain, since it was only his obstinate insistence

upon remaining himself that saved Veronese from

shipwreck upon the ever threatening reef of imitation.

THE RETURN TO VENICE

From the moment of his return to Venice, Veronese

was besieged from all sides; once again he found himself

enslaved to forced labor by the incessant contracts

demanded of him by his fellow citizens. The scantiness

of documents which we possess regarding his life

does not permit us to name the chronological order

in which he painted his pictures. We shall therefore

gather them into groups for the sake of convenience[Pg 54]

in studying his more important works. Furthermore,

to study one by one, all of his paintings, is not to be

thought of; for this painter was one of the most prolific

producers of which the history of art makes mention.

In every one of his pictures will be found, more

or less accentuated, those qualities of composition, of

picturesqueness, and of colour which together constitute

his glory. Accordingly we shall limit ourselves

to indicating, at the different stages of his career,

those pictures which show most deeply the imprint

of his genius and which also are most closely related

to the life of Venice of which he was, in a certain way,

together with Tintoretto, the official painter. For the

rest the reader may be referred to the complete catalogue

of the works of Veronese given at the close of

this book.

Concerning the private life of the artist we are as

poorly informed as concerning the date of his pictures.

We know only that he married and that he had two

sons, Gabriele and Carletto. When they were old

enough to hold a brush he entrusted them to Bassano,

a Venetian painter whose talent he held in high esteem.[Pg 55]

As regards himself, the documents of the period vaunt

his uprightness, his honesty and his keen sense of

honour. Ridolfi, one of his biographers, who wrote

sixty years after Veronese’s death, and relied upon the

recollections of people who knew him personally,

pictured him as a man of strict principles and settled

habits, and economical almost to the point of avarice.

He cites, as an example of this, that the artist rarely

employed ultramarine, which was very costly at that

time, and thus condemned his works to premature

deterioration.

His fortune, the extent of which we learn from the

fiscal records of Venice, consisted in a few holdings of

real estate at Castelfranco in Trevisano. In 1585

he purchased a small estate at Santa Maria in Porto,

not far from the Pineta of Ravenna. He also possessed

a bank account representing approximately six thousand

sequins. But what was that for a man who was

the most famous and the most fertile artist of his

time?

We have already given examples of his disinterestedness.

Many a time he refused opportunities of[Pg 56]

great wealth. He even declined the offers made

him by Philip II, who tried to lure him to Spain

and would have entrusted him with decorating the

Escurial.

It was about the period of his return to Venice

that Veronese completed his celebrated picture: The

Family of Darius at the Feet of Alexander after the

Battle of Issus, now in the National Gallery at London.

The episode is well known; Darius III., King of

Persia, conquered at Issus by Alexander, sends his

wife and children to beg for clemency from the victor.

Admitted to the conqueror’s tent, the unfortunate

wife perceives a warrior in resplendent garments whom

she takes for Alexander, and throws herself at his feet.

The warrior, however, is only Ephestion, Alexander’s

lieutenant and friend. The wife of Darius apologizes

for her mistake, but Alexander raises her up and says:

“You made no mistake, he also is Alexander.”

Such is the historic theme. But what matters

history to Veronese? Upon this classic subject he has

built the most fantastic, the most improbable, and at

the same time the most fascinating of his compositions.[Pg 57]

The picture was painted for the Pisani family which

had given him hospitality, and every one of the figures

contained in it represents a member of that household.

It is related that, in order to spare his hosts the

necessity of thanking him or the obligation of making

some return, he rolled up his canvas and slipped it

behind his bed in such a way that it would not be

discovered in his room until after his departure.

It is scarcely probable that Veronese could have

painted so large a canvas—fourteen metres by seven—in

the necessarily brief space of a friendly visit,

or that he could have painted in his figures, which are

all of them portraits, without the knowledge of the

Pisani family. But the anecdote is so pretty that it

is pleasant to accept it as true.

It was a direct descendant of the Venetian Procurator,

Count Victor Pisani, who sold the painting

to England in 1857.

THE DECORATION OF THE DUCAL PALACE

In 1577 a violent conflagration destroyed the

greater part of the Ducal Palace. In this disaster[Pg 58]

all the pictures perished with which Tintoretto, Horatio

the son of Titian, and Veronese, had decorated it.

Desiring to restore the palace promptly and give

it a new splendour, the Senate appointed a committee,

authorized to distribute orders among the painters and

decorators of Venice. The competitors were numerous

and eager to secure a chance to collaborate in so

glorious an enterprise; and to this end they paid eager

court to the committee. Veronese alone made no

advances, being unwilling to appear solicitous. This

dignified course was looked upon as excess of pride,

and one day when Jacopo Contanari met him in the

street he reproached him with it. Veronese replied

that it was not his business to seek for honours but to

be deserving of them, and that he had less skill in

soliciting work than in executing it.

PLATE VII.—THE MARRIAGE OF ST. CATHERINE

(In the Accademia delle Belle Arti, Venice)

There is, perhaps, no other religious subject which has so often

stimulated the inspiration of the great Italian painters. Veronese

himself has treated the same scene several times. The painting

here reproduced is considered, in view of the picturesqueness of

its composition, the beauty of the faces, and the brilliance of the

colouring, to be one of the best works of the illustrious artist.

But they could not exclude Veronese, whose fame

had now become universal. Accordingly he was

chosen with Tintoretto, and to them were added

Francisco Bassano and the younger Palma. The

Ducal Palace is therefore a sort of museum of the

works of these masters, and forms the most brilliant

[Pg 61]

collection of paintings relating to the public life and

the glorification of Venice.

Veronese was entrusted with the decoration of the

great central oval of the ceiling, and the lateral panels.

In these he painted the Defence of Scutari, the Taking

of Smyrna, and the Triumph of Venice. This last

named painting is considered by many as Veronese’s

crowning achievement.

Venice is here represented in the form of a superb

and smiling woman, seated upon the clouds, her eyes

raised towards Glory, who offers her a crown. At

her side, Renown celebrates her grandeur; at her feet

are grouped Honour, Liberty, Peace, Juno, and Ceres;

lower down an ethereal structure of admirable daring

and architectural beauty sustains a great assemblage

of gentlemen and ladies richly clad, of cardinals and

bishops, all emulously uniting in the glorification of

Venice. On the ground level standards, trophies,

and cavaliers add the finishing touch to the composition,

and are treated with incomparable vigour and

skill both in chiaroscuro and in perspective.

Although of more modest dimensions, the Taking[Pg 62]

of Smyrna and the Defence of Scutari are in no wise

inferior to the great central composition. In this

same Hall of the Grand Council, Veronese painted

two other great canvases, representing the Military

Expedition of the Doges, Loredan and Mocenigo.

But for that matter there is not a room in the

Palace of the Doges in which Veronese is not represented

by one or more canvases; in the Hall of the

Anticollegio, there is a ceiling painting representing

Venice Enthroned, a work that has unfortunately

deteriorated; in the Hall of the Collegio, a Battle of

Lepanto, a Christ in Glory, Venice and the Doge Venier,

a Faith, a St. Mark, and a ceiling which is considered

as the most beautiful in the whole Palace of the Doges:

Venice Upon the Terrestrial Globe, Between Justice

and Peace. The Hall of the Council of Ten contains,

in the oval ceiling panel: An Old Man resting his Head

on his Hand and A Young Woman. In the Hall of the

“Bussola,” St. Mark crowning the Theological Virtues,

the original of which is at the present time in the

Louvre. Mention should also be made of: The

Triumph of the Doge Venier over the Turks; the[Pg 63]

Return of Contanari, Victor over the Genoese at Chioggia;

the Emperor Frederick at the feet of Alexander

III., and, in the Hall of the Ambassadors, a magnificent

allegory of Venice, personified as a patrician lady

seen from behind, robed in white satin and of marvellous

grace.

Veronese also had a share in the decoration of

another of Venice’s monumental buildings, situated

near the bridge of the Rialto and known by the name

of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi. This building, which

is to-day occupied by the Post Office, formerly served

as warehouse for German business men having commercial

relations with the Republic. These rich

merchants had had the palace adorned by the greatest

painters in Venice. Giorgione and Titian had decorated

its walls not only within, but also on the exterior,

where traces of the paintings can still be seen. Veronese

was entrusted with four compositions, one of which

is an allegory representing Germany receiving the

Imperial Crown. It is believed that the canvas now

in the Museum at Berlin, entitled Jupiter, Fortune and

Germany, once formed part of the decoration of the[Pg 64]

Fondaco dei Tedeschi. It was purchased at Verona

in 1841. Veronese’s celebrity, about the year 1580,

had become world-wide. Every sovereign who prided

himself on his art gallery wished to possess some of

his work. The indefatigable artist endeavoured to

satisfy them all; he even corresponded personally with

several of them. For the Duke of Savoy, he painted

The Queen of Sheba Visiting Solomon; to the Duke

of Mantua, who had honoured him with his friendship,

he sent a Moses Saved from the Waters; to the Emperor

Rudolph II. he gave a Cephale and Procris and

a Poem of Venus. These last two canvases, of which

the German Emperor was very proud, were taken

from him by Gustavus Adolphus, when that triumphant

conqueror passed through Vienna.

Throughout his life, Veronese remained faithful

to the pompous, brilliant, ornamental school of painting.

Not that he was incapable of essaying other

types, but because it was his own preference to paint

ease and luxury on a broad scale. He sometimes had

occasion to handle more vigorous subjects, and in this

he was completely successful, as the magnificent[Pg 65]

painting entitled Jupiter Destroying the Vices abundantly

bears witness.

The surprise experienced in the presence of this

noble work, executed with the energy of a master-hand,

is surpassed only by admiration for the versatility

of a genius which could at will adapt itself to unfamiliar

formulas. This famous painting, proud and virile

in style, was taken from Italy by the victorious Armies

of France, and placed in Versailles in the chamber of

Louis XIV., where for a long period it served as the

ceiling decoration. It was finally removed and now

hangs in the Louvre, in company of other masterpieces

by the same artist.

THE LAST YEARS

The execution of his large official canvases did not

prevent Veronese from responding to all the appeals

which came to him from every side. His unequalled

activity, his prodigious facility made it possible for

him to satisfy these demands. No one knows all the

pictures which he painted for private individuals,

nor all the frescoes with which he adorned certain[Pg 66]

dwellings that have since disappeared. Nevertheless

what a formidable list the works of this painter would

make if the attempt were made to draw up such a list

without omissions! Ridolfi devotes not less than

thirty pages to a simple enumeration of the pictures

which Veronese painted for the neighbouring islands

of Venice, such as Murano and Torcello, for the country

house of the Grimani at Orlago, for that of the Duke

of Tuscany at Artemino, or for the Palace of the Pisani.

To Verona, to Brescia, to Vicenza, to Treviso, to

Padua; to Venice also, to the Frari, to Ognissanti, to

the Umilta, to San Francisco del Orto, to Santa Catarina,

for which he painted his famous Marriage of St.

Catherine, everywhere, in short, where they required

him, he sent marvellous canvases, magic with colour

and with life;—canvases for which to-day museums

vie with each other for their weight in gold.

But Veronese was no longer young; he had entered

well into the fifties; yet nothing in his craftsmanship

betrayed fatigue or waning powers. A genius almost

unique, he went steadily forward and no one could

say of him, in the presence of his latest productions,[Pg 67]

what has so often been said of other illustrious painters:

“That is a work of his old age!” Veronese had the

rare privilege of remaining young to the end.

One day, while following a procession on foot,

Veronese contracted a cold, and after a brief illness he

died. His obsequies took place in the parish church

of San Samuele, April 19, 1588. On that day he

would have completed his sixtieth year.

When we remember that, up to the eve of his death,

Veronese continued to paint with as steady a hand as

at the age of twenty, his death seems premature, and

it is only natural to deplore that this matchless artist

should have failed to obtain the ripe age of Titian.

What masterpieces he might still have painted!

Such as they are, brilliant and luxuriant, his works

remain the most abundant that have ever come from

the palette of any one painter, and Veronese stands

lastingly, in the history of Art, as the most amazing

of all masters, both in colour and in composition.[Pg 68]

PLATE VIII.—THE VISION OF ST. HELENA

(In the National Gallery, London)

This picture has often been attributed to Zelotti, who was a

friend and at one time a collaborator of Veronese. But the composition,

the colouring, the finish of detail, and the sumptuousness

of decoration betray the hand of the immortal author of the Wedding

at Cana.

[Pg 71]

THE WORKS OF PAOLO VERONESE

[Pg 72]

[Pg 73]

THE WORKS OF PAOLO VERONESE

FRANCE

PARIS (MUSEUM OF THE LOUVRE): The Wedding at Cana.—The

Feast at the House of Simon the Pharisee.—Jupiter destroying the Vices.—Portrait

of a Young Woman.—Susannah and the Elders.—The Disciples

at Emmaüs.—The Fainting of Esther.—The Burning of Sodom.—Two

Holy Families.—Calvary.—Jesus Stumbling Beneath the Weight

of the Cross.—St. Mark Crowning the Theological Virtues.—Jesus

Curing Peter’s Mother-in-law.

MONTPELLIER (MUSEUM): The Virgin in the Clouds.—The Marriage

of St. Catherine.—St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata.

RENNES (MUSEUM): Perseus Delivering Andromeda.

LILLE (MUSEUM): Science and Eloquence.—The Martyrdom of St.

George.

ROUEN (MUSEUM): St. Barnabas Curing the Sick.

ENGLAND

LONDON (NATIONAL GALLERY): The Rape of Europa.—The Family

of Darius.—Magdalen at the Feet of the Saviour.—The Vision of St.

Helena.—The Adoration of the Magi.—The Consecration of St. Nicholas.

EDINBURGH (NATIONAL GALLERY): Venus and Adonis.—Mars and

Venus.

DULWICH COLLEGE: A Cardinal pronouncing Benediction.

[Pg 74]

ITALY

VENICE (ACCADEMIA DELLE BELLE ARTI): St. Mark and St. Matthew.—The

Feast at the House of Levi—St. Luke and St. John.—St. Christina

fed by the Angels.—St. Christina thrown into the Lake of Bolsena.—The

Virgin, St. Joseph and several Saints.—The Virgin and St. Dominique.—St.

Christina before the False Gods.—The Annunciation.—The Coronation

of the Virgin.—Isaiah.—Ezechiel.—The Battle of Cursolari.—The

Flagellation of St. Christina.—The Angels of the Passion.—Jesus

and the two Thieves.

VENICE (DUCAL PALACE): The Triumph of Venice.—The Rape of

Europa.—Peace and Justice.

ASOLO (VILLA BARBARO): Fresco Decorations.

ROME (VATICAN): St. Helena.

FLORENCE (UFFIZZI GALLERY): Esther before Ahasuerus.—Portrait

of a Man.—Jesus Crucified.—Prudence, Hope, and Love.—The Annunciation

to the Virgin.—The Martyrdom of St. Justine.—The Martyrdom

of St. Catherine.—The Madonna and the Infant Jesus (Sketch).—Study

for a St. Paul.—Gentleman in a white Robe (Sketch).—Holy Family

with St. Catherine.

FLORENCE (PITTI PALACE): Portrait of Veronese’s Wife.—Portrait of

Daniele Barbaro.—The Baptism of Christ.—Portrait of a Child.—Christ

taking leave of His Mother.

BERGAMO (CARRARA ACADEMY): Reunion in a Garden.—Episode

from the Life of St. Catherine.

TURIN (ROYAL MUSEUM): Magdalen washing the Feet of Christ.—Moses

saved from the Waters.

NAPLES (NATIONAL MUSEUM): The Circumcision.

[Pg 75]

GENOA (DORIA PALACE): Susannah and the Elders.—The same Subject.—Allegorical

Figures.

MODENA (ROYAL GALLERY OF ESTE): St. Peter and St. Paul.—Portrait

of Veronese.—A Captain.

MILAN (BRERA MUSEUM): The Feast at the House of the Pharisee.—The

Adoration of the Magi.—The Last Supper.—The Baptism of Christ.—St.

Gregory and St. Jerome Glorified.—St. Ambrose and St. Augustine

Glorified.—Christ on the Mount of Olives.—St. Anthony, St. Cornelius

and St. Cyprian.

BELGIUM

BRUSSELS (ROYAL MUSEUM): The Adoration of the Magi.—The Holy

Family with St. Theresa and St. Catherine.—Juno lavishing her Treasures

on Venice.

SPAIN

MADRID (MUSEUM OF THE PRADO): Four Portraits of Women of Rank.—Calvary.—The

Woman taken in Adultery.—Magdalen Repentant.—Venus

and Adonis.—Jesus and the Centurion.—The Infant Jesus, St.

Lucia and St. Sebastian.—The Martyrdom of St. Genesius.—Jesus in

the Midst of the Doctors.—Cain wandering with his Family.—The Sacrifice

of Abraham.—The Adoration of the Magi.—Moses saved from the

Waters.—Portrait of a Venetian Woman in Mourning.—Young Man

between Vice and Virtue.—Susannah and the two Elders.

GERMANY

DRESDEN (GALLERY): Christ on the Cross.—Moses saved from the

Waters.—The Rape of Europa.—The Wedding at Cana (reduced size).—Christ

and the two Thieves.—The Good Samaritan.—The Adoration of[Pg 76]

the Magi.—Portraits of Daniele Barbaro (replica).—The Presentation at

the Temple.—Christ cures the Servant of Caharnaum.—Jesus carrying

the Cross.—The Resurrection of Christ.—The Adoration of the Virgin.

BERLIN (MUSEUM): Jupiter, Fortune and Germany.—Mars and Minerva.—Apollo

and Juno.—Jupiter, Juno, Cybile and Neptune.—Christ and the

two Angels.—Four canvases representing Geniuses.—Saturn and Olympe.

MUNICH (PINACOTHEK): Faith and Religion.—The Death of Cleopatra.—Woman

taken in Adultery.—Portrait of a Woman.—Justice and

Prudence.—The Rest in Egypt.—Love holding chained Dogs.—A

Mother and three Children.—Strength and Temperance.—Holy Family.—The

Cure of the Servant of Caharnaum.

AUSTRIA

VIENNA (BELVEDERE): The Rape of Dejanire.—Catherine Cornaro.—Christ

and the Woman taken in Adultery.—Christ and the Samaritan

Woman.—The Adoration of the Magi.—The Marriage of St Catherine.—The

Resurrection.—St. Nicholas.—Quintus Curtius throwing himself

into the Chasm.—Portrait of Marco Antonio Barbaro.—Young Man

caressing a Dog.—Annunciation to the Virgin.—Adam and Eve and their

First-born.—Venus and Adonis.—St. Sebastian.—The Death of Lucrece.—St

John the Baptist—Judith.—Christ entering the House of Zaira.—St.

Catherine and St. Barbara present two Nuns to the Virgin and the Infant

Jesus.

SWEDEN

STOCKHOLM (NATIONAL MUSEUM): The Circumcision.—Magdalen.—A

Holy Family.—A Madonna.

[Pg 77]

RUSSIA

ST. PETERSBURG (HERMITAGE): The Flight into Egypt.—The Adoration

of the Magi.—Holy Family.—Diana and Minerva.—Mars and

Venus.—Portrait of a Man.—Lazarus and the Rich Man.—Christ in

the midst of the Doctors.—The Dead Christ upheld by the Virgin and an

Angel.—The Marriage of St. Catherine.—Various Sketches.

LEUCHTEMBERG GALLERY: The Adoration of the Magi.—The Widow

of the Spanish Ambassador at Venice presenting her Son to Philip II.