A folded piece of paper.

Title: Dave Darrin and the German Submarines

Author: H. Irving Hancock

Release date: December 15, 2012 [eBook #41628]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A folded piece of paper.

Dave Darrin and the German Submarines

OR

Making a Clean-up of the Hun Sea Monsters

By

H. IRVING HANCOCK

Author of “Dave Darrin at Vera Cruz,” “Dave Darrin on

Mediterranean Service,” “Dave Darrin’s South American Cruise,”

“Dave Darrin After the Mine Layers,” etc., etc.

Illustrated

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

Akron, Ohio New York

Made in U. S. A.

Copyright MCMXIX

By THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

CONTENTS

On the prowl at sea. Dan takes the rest cure. Dave springs a new trap for submarines. The enemy’s alarm clock. “Searchlight men, stand ready!” A shell-made geyser. The sea duel. A submarine finish. “Wasted humanity.” Orders by wireless. Shore leave. Mr. Matthews of Chicago. With the British sea-dog.

Chapter II—The Meeting with a Pirate

Dan has forebodings. “’Ware torpedo!” Dan’s “forty winks” end. “All hands to abandon ship!” How the trick worked. A wonderful job. The loiterer at the radio room door. “I’ll keep my eye on you.”

Chapter III—Quick “Doings” over the Shoal

Fisherman’s Shoal. The bubble trail. “Over with the ‘buoy’!” The driver’s job. “Come up, or take a bomb!” Talking with the Pirate. A face seen before. Bechtold does some German lying. Poison vapors. Mystery in a berth. Bechtold’s grab.

Chapter IV—The Trail to Strange News

Fortune is partial to the bold. A hot burn with acid. Saving words from a wreck. Use for a prize crew. Bechtold bluffs. Dave unfolds the coming fate of the prisoner. That ugly word, “spy.” “War breeds savage ideas.”

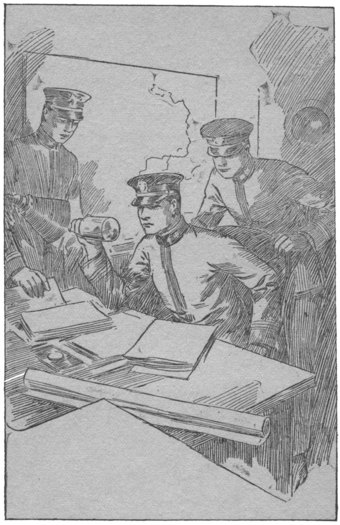

Chapter V—Dave Talks out in Council

The sheet that Dave saved. The drive against the troopships. “Sixty submarines!” Dave has the floor at naval headquarters. “I will stake my soul!” “Darrin, I wish we had you in our navy!” Three big cheers. Danny Grin feels proud.

Chapter VI—The Glowworm of the Sea

Looking for the 117th Division afloat. Dave’s extra nap. The row at the stern. The glow on the sea. The lie passed. Ensign Phelps picks up the mystery. The chart-room conference. The work of a spy. “A traitor on board!”

Chapter VII—Darrin Has a Spy Scare

Dave quizzes the accused. Ferguson’s turn on the rack. The search for evidence. “Have we spies on the ‘Logan’?”

Chapter VIII—The Battle for the Troopship Fleet

On board the troopship fleet. Torpedo talk. “Keep your hair from turning gray before you reach the trenches.” No clues or traces yet. The minute of signals. Vanguard of troopship fleet. Dave swerves for battle. “Let go the depth bomb!”

Chapter IX—When the Enemy Scored

The soldiers feel better. “They can’t hit us.” “They’ve got us!” The start of a panic. Destroyers scurry to save. The biggest submarine fight of all. Big guns roar.

Chapter X—The Hottest Work of All

In Periscope Lane. Shooting of the good old kind. Clean work. Dave Darrin’s lucky time. “Hit is the right word.” Machine guns turn loose. Playing upon the Hun gun-crew. Beatty’s luck changes.

Chapter XI—A Trap and its Prey

Turning turtle. “They’re only Huns.” The fighting storm clears. Listing the survivors. Extent of the American losses. Dan has some questions. Dave plans a ruse. Reardon and the marine. Jordan steps into the trap.

Chapter XII—Dave Hunts a Bigger Fight

Blind man’s buff on the waves. Judged by the goods delivered. Making the best of the unknown. The opening gun. The real fight looms ahead.

Chapter XIII—A Battle Try-out for Souls

The snap-shooting period. Zigzagging for life. A crazy marine waltz. The “Logan” turns special hunter. Dave can’t get ’em all. “Specks” in the sky.

Chapter XIV—Team Work Between Sky and Water

The “blimps” arrive. One of them makes a hit and helps Dave to one. The “Logan’s” guns din out. Through the sea of wreckage. Runkle tells a tale. The accused spy denies. Dan has his “step,” too. How spies are handled in Britain.

Not a word about the “Prince.” Darry is puzzled. “Unmask!” Dalzell grins broadly. Dave thinks he’s dreaming. A warship or a floating dry-goods box?

Chapter XVI—Aboard the Mystery Ship

“Is this a masquerade?” Dan is wrong. Dave in his disguise. “Rubber!” Where did the laugh come in? Real mystery enough. “And the ladies—?” Dave gives it up. Then he doesn’t.

Chapter XVII—The Humorous Adventure

“Abandon ship!” The strangest of war crews. Heinie von Sub moves closer. “Open ports!” The trapper trapped. “Give them a chance.” “Chermany is Chermany.” The whole German story.

Chapter XVIII—Danny Grin Proves His Mettle

The new wheat ship. “Do you begin to see the joke?” Guns at work in the night. The one-sided fight. Cowardly hounds. Dan loads his strategy. A great game. The German brand of treachery. Beating Hun team work with an American single. “Win or sink!”

Chapter XIX—A German View of Submarines

Dan is glad at last. Sparnheim hears a lecture. Then faces an angry woman. “Don’t touch such a beast!” What long life means to a pirate captain. Sparnheim is “insulted.”

Chapter XX—Dan Stalks a Cautious Enemy

Making the enemy guess. Result of Dan’s trick. “He’s going to gun us!” Dan loses men and a gun. “An outrage!” cries the German. “Report.” “Home, James!”

Chapter XXI—The S. O. S. from the “Griswold”

Dave’s best good news. New ships for two. Bad news, it turns out. Runkle is on hand. The chums part company. S. O. S.! The “Griswold” attacked.

Chapter XXII—Dave’s Night of Agony

News of the toughest kind. Flashes from German guns. Dave plans his own attack. “Never again any mercy to a pirate!” “Belle!” Splash!

Chapter XXIII—The Fight to Bring Belle Back

Runkle helps valiantly. The still, white face. The surgeon shakes his head. “She did not suffer.” Darry refuses to wake up. Dan at his chum’s side. The fight for Belle’s life. “’Ware torpedo!”

DAVE DARRIN AND THE GERMAN SUBMARINES

“Anything sighted?” called Lieutenant-Commander Dave Darrin as he stepped briskly from the little chart-room back of the wheel-house and turned his face toward the bridge.

“Nothing, sir, all afternoon,” responded Lieutenant Dan Dalzell from the bridge.

Dave ran lightly up the steps, returning, as he reached the bridge, the salutes of Dalzell, executive officer, and of Ensign Phelps, officer of the deck.

“It’s been a dull afternoon, then?” queried Darrin, his eyes viewing the sea, whose waters rose and fell in gentle swells.

No land was in sight from the bridge of the United States torpedo boat destroyer, “John J. Logan,” which was moving at cruising speed westerly from the coast of Ireland. The course lay through the “Danger Zone” created by the presence of unknown numbers of hidden German submarines.

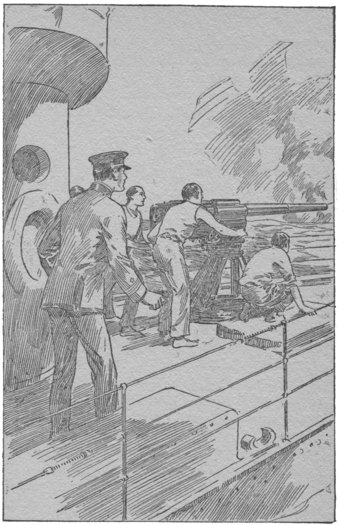

For a winter day the weather had been warm. Forward the two men of the bow watch and the crews of the rapid-fire guns had removed their coats and had left them below.

Though there was neither enemy nor friendly craft in sight, Darrin noted with swift if silent approval that there was no evidence of lax watch. At port and starboard, amidships, there were men on watch, as also at the stern. Members of gun-crews lounged close to their stations, to which additional men could be summoned in a flash. Aft, also, two men stood by the device from which it might be necessary, at any instant, to drop a depth bomb.

Trained down to the last point of condition by constant work, these officers and men of the torpedo boat destroyer made one think of hard, lean hunting dogs, which, in human guise, they really were. Not only had toil brought this about but sleep was something of a luxury aboard the “Logan.” On a cruise these men of Admiral Speare’s fleet of destroyers slept with their clothes on, the same rule applying to the officers.

Dave Darrin had slept in the chart-room for three hours this afternoon, following eighteen hours of duty on deck.

“Any wireless messages worth reading?” was Darrin’s next question.

“None intended for us, sir, and none others of startling nature, sir,” replied Ensign Phelps, handing his superior a loose-leaf note-book. “I think you saw the last one, sir, and since that came in there were none important enough to be filed.”

Dave read the uppermost message, nodded, then handed back the book.

For the next ten minutes Darrin scanned through his glasses, the surface of the sea in all directions.

“I’d like to bag an enemy before supper,” he sighed.

“And I’d like to see you do it,” came heartily from Dan Dalzell.

“Why don’t you turn in for a nap, Dan?” asked Dave, turning to his chum and second in command, whose eyes looked heavy.

“I believe I could,” admitted Dalzell, almost reluctantly. “Mr. Phelps, will you leave word with your relief to have me called just after eight bells?”

Down the steps Dalzell went, to the chart-room, closing the door curtains behind him. It is one of the unwritten rules that, at sea, the commander of a vessel and his executive officer shall not both sleep at the same time.

As for Dave Darrin, he felt that he might be on deck up to midnight, at least. After that he might snatch “forty winks,” leaving orders to be called just before dawn.

Short of sleep always, weighted down with responsibility, young Darrin was happy none the less. First of all, after his wide professional preparation in many quarters of the globe, he was at last actually in the great world war. He was in the very place where big things were being done at sea, and the war had brought him promotion and independent command. What more could so young a naval officer ask, except sufficient contact with the enemy to make life interesting?

An hour passed. Dave and Phelps talked but little, and nothing out of the usual happened, the “Logan” keeping on her course still at cruising speed. But now the sun was well down on the western horizon; the northwesterly wind blew a little harder, though not enough to roughen the surface of the sea noticeably.

“Orderly, there!” called Phelps, quietly from the bridge. “Go to my quarters for my sheepskin coat and bring it here. Do you wish yours, sir?” turning to Darrin.

“I’ll step below and get it,” decided Dave. “I’ll probably be back here with you shortly.”

Going stealthily into the chart-room, Dave took a glance at his chum, now sound asleep in a chair, with a blanket drawn over him. Dave reached for his coat, donned it and buttoned it up, then stepped outside. First of all he moved forward to make a brief but keen inspection of the gun-crews and their pieces; then, to starboard, after which he strolled amidships. For a few minutes he was below to receive the report of the chief engineer, then went aft to inspect the gunners and the watch, returning on the port side to the bridge.

Soon after that the sun sank into the sea, and darkness came rapidly on.

“It’s going to be a fine night, sir,” said Ensign Phelps, as Dave came up on the bridge.

“A fine night for something besides steaming, I hope, Mr. Phelps,” Dave replied, with a smile in which there was something more than mere wistfulness.

“Amen to that!” agreed the young ensign.

“Wind is shifting, sir,” said Mr. Phelps, fifteen minutes later, when darkness had settled down.

“So I observed,” answered the youthful commanding officer. “From nor’west to nor’east. That cloud over to nor’east looks as if it carried a lot of wind.”

Dave took a quick glance at the barometer, but it had not fallen much.

“No storm in sight yet,” said Dave, thoughtfully. “But cloudy.”

“Aye,” nodded Ensign Phelps. “And a black night may aid either us or an enemy.”

“More likely the enemy,” replied Darrin, reflectively. “An observer on a submarine, with the aid of the microphonic or adapted telephonic device, that is now credited with having been perfected, can hear us coming when we’re some distance away.”

“And the same observer can discover our direction as compared with his own position, and can even judge the extent of the distance fairly well,” remarked the ensign.

“True,” Darrin nodded. Then, suddenly, he spoke energetically, as one gripped by a new idea.

“Mr. Phelps, have the word passed to all men on watch to keep a doubly sharp lookout for approaching craft and thus avoid danger of collision. No one carries running lights in these waters. The watch will also be extremely vigilant for submarines.”

Again and again the watch, startled by shadows, of which the sea is ever full at night, called out low-spoken warnings. The officers on the bridge were kept busy investigating these alarms with their night glasses. In fact they frequently were deceived too. Every man’s nerves were on edge; gunners swallowed hard, and with frequency moistened their lips with their tongues. Every man up topside on the “Logan” felt that peril was hovering near. It was not fear; it was perhaps that sixth sense that gives the alarm in moments of unseen danger. So intense was the nervous strain that the creaking of a brace or the sound of a straining plate, as the destroyer rolled, made every man on deck jump.

It was a trying situation and such as brought gray hairs to many a ship’s master in these days of deeds and daring. Better far the rush of a torpedo in their direction than this nerve-racking waiting for something that every man on the destroyer felt was coming.

Lieutenant-Commander Darrin, sensing all this, for the very air was charged with expectancy, frequently steadied the watch with an encouraging word or a sharp, low-spoken command. Dave sympathized with them, for he was in very much the same nervous condition. Of course he could not show it.

“Curtin, we’re in for some work to-night, or else I have an attack of nerves. I feel it,” said Dave without taking his eyes from observation of the sea.

“So do I. Queer how a fellow can sense danger when he neither can hear, see, feel nor smell it,” said Mr. Curtin.

“Submarine hunting is hard on the nerves, but it’s worth while,” returned Dave. “I think that must be what makes life on a destroyer so attractive to us. It is the real sporting game. I—What’s that?”

“Yes, it’s——”

“Sh-h-h!” Dave suddenly stiffened, bringing his glasses quickly to his eyes. “Bow watch there, did you hail?” he demanded in a low, sharp voice.

“Aye, aye, sir,” came the prompt reply, also pitched in a low tone, though full of repressed excitement.

Whatever wind there had been in the cloud Dave had observed to the northeast, had passed. Only the gentlest of breezes blew, though the sky remained overcast, giving an almost ink-black night—a night for dark deeds.

So long did the “Logan” drift that probably every wakeful soul on board felt irritated by the monotony. Suddenly Dave stiffened, bringing his glass quickly to his eyes.

“Sounds and looks like a craft two points off starboard and about half a mile away, sir,” reported the bow watch.

“Aye,” Dave responded. “I see it. Mr. Curtin, pass the word for all hands to quarters.”

Silently officers and men were soon streaming over the decks, on their way to their various stations. Curtin stood with one hand on the engine-room telegraph, awaiting the order for headway.

The three-inch guns were loaded, and also the one-pounders and the machine guns. Two men stood by the darkened searchlight.

“Searchlight men!” Dave called, in a low voice. “You know where we’re looking?”

“Aye, aye, sir.”

“Stand by to put a beam squarely across its conning tower if it proves to be a submarine.”

Again Dave took a long, careful, steady look through his night glass. Secretly he was a-quiver with excitement; outwardly he was wholly calm.

“Throw the beam!” called Dave sharply, a few seconds later. “Gun-crews in line with the enemy, stand by!”

A broad band of light from the searchlight played into the sky, then descended. As the beam reached the water it revealed the tower and deck of a large submarine rolling awash a little more than half a mile away. A muffled cheer rose from some of the members of the watch. The men at the guns were too much occupied to open their mouths.

“Silence in the watch!” Dave commanded, sternly. “Mr. Curtin, half-speed ahead. Bear straight down on the enemy! Ram him if possible! Ram him at all hazards if he is submerging when we reach him,” commanded Lieutenant Commander Darrin.

“Aye, aye,” answered the quartermaster at the wheel.

Like a bloodhound the “Logan” sprang forward.

“Bow guns fire!”

Boom! roared one sharp-tongued three-inch gun. Bang! sounded a one-pounder. The larger shell threw up a column of spray beyond the submarine; the small shell struck the water on the nearer side.

“Full speed ahead, Mr. Curtin. Hold her steady there, quartermaster!”

“Aye, aye, sir.”

The “Logan” was soon racing at more than thirty knots an hour, her nose burrowing into the sea, throwing up great volumes of water.

The enemy submarine had plainly been taken utterly by surprise by the first flash of the “Logan’s” searchlight, for the warning sound that had come across the water had been caused by an oil-burning engine that was supplying power for the recharging of the submarine’s storage batteries.

Such a craft, however, hated and at all times hunted, carries crews trained to swift work. Soon after the “Logan’s” second three-inch gun had fired without registering a hit, a five-inch gun of the submarine was brought into action. Overhead whizzed a shell that just missed the “Logan’s” wireless aerials. A second shot, aimed at the destroyer’s water line, passed hardly more than four feet to starboard.

“Get him!” roared Dave Darrin. “Gunners have their wits about ’em!”

Dan Dalzell took the door curtains with him as he leaped out and ran for the bridge.

The submarine had swung around, and at the same time brought her after gun into action. The submarine swung again bow on. There was no time to dive. She was caught and must fight.

“Torpedo coming, sir!” reported the bow watch, but Darrin had already caught sight, under the searchlight’s glare, of a trail of foam heading straight for the destroyer.

Quick as was the helmsman’s obedience of orders, the “Logan” escaped the torpedo by little more than a hair’s breadth as it rushed on past. Then came a second torpedo. The “Logan,” still driving bow on, save for swerves to avoid torpedoes, escaped the second one by what appeared to breathless watchers to be an even closer margin.

Lieutenant Beatty had taken personal charge of sighting one of the forward guns. He now let fly a shell that tore part of the top of the enemy’s conning tower away.

“That settles him for diving!” cried Darrin, tensely. “Land a shell in the hull and force him to take the dive he doesn’t want!”

Onward came a third rushing torpedo. As the “Logan” swerved to avoid it, a shell from the submarine’s after gun struck and tore away a one-pounder aft on the destroyer, fragments stretching two men on the deck, seriously but not fatally injured. An instant later a shell aimed at the destroyer’s water line forward pierced the hull just below the gun-deck. A fair hit at the water line would have put the “Logan” in a sinking condition, but, owing to the oblique position of the target, the shell, as it struck, glanced off.

“Great work, Mr. Beatty!” shouted Dave hoarsely, as another three-inch shell struck the enemy, this time at the waterline. “Mr. Curtin, half speed ahead!”

As the destroyer began to lose headway and slowly circle the undersea boat, the “Logan’s” crew cheered, this time without rebuke from the bridge. The submarine craft was rapidly filling and sinking.

At a safe distance Darrin watched, for he was humane enough to wish to rescue the German survivors, should there be any. So swift was the sinking of the enemy, however, that there was no time for them to launch and man the collapsible lifeboat that they undoubtedly carried.

Then the seas closed over the hated craft. A few moments later Lieutenant-Commander Darrin gave the order to steam forward slowly, the watch standing by to discover and heave lines to any swimmers there might be afloat. Not a head was seen, however. Three men at the after gun had been observed to jump before the submarine went down, but no trace of them could now be found.

“We’ll never know how many hundreds of decent lives the work of the last minute has saved,” declared Dalzell hoarsely as he reported on the bridge.

“Find out as promptly as possible what damage we have suffered,” Dave ordered. “We were struck several times.”

As Dan saluted and hurried away, Darrin picked up his night glass and once more resumed his scanning of the sea. Lieutenant Curtin had already received orders that the destroyer was to cruise slowly back and forth over and around the spot where the submarine had gone down.

“It seems almost wasted sympathy to try to pick up enemy survivors,” muttered Mr. Curtin rather savagely.

“But it’s humanity just the same,” Darrin returned. “And Americans must practise it.”

“Of course, sir.”

Dalzell, who had summoned the aid of other officers and some of the warrant officers, soon returned.

“Two breaches, one just above water line, and the other below it, sir,” was Dan’s beginning of the report. “I wasn’t aware that a torpedo touched us. If it did, it made a dent, but glanced off without the explosion that a direct hit would have produced. That may account for the dent below the water line. But a shell hit us above water line. Is it possible that a large fragment glanced low enough to make the dent under water? It doesn’t seem possible.”

“Not likely,” smiled Darrin.

“The hole above the water line has been repaired, but men are still working at the one below the line,” Dalzell went on, “and the pumps are working hard. The chief engineer was about to report it to you when I reached him. We have been hit at other points, but no serious damage has been done.”

“We are not in danger of sinking?”

“Doesn’t look like it to me, sir,” Dan replied, “and the chief engineer is of the same opinion.”

“Take the bridge with Mr. Curtin.”

Not more than two minutes was Dave below decks, half of that time with the chief engineer. Then he hurried back, disappearing into the radio room. In a code message he notified destroyer headquarters of the encounter, its result, and the nature of the damage to the “Logan.”

Within five minutes the answer came back through the air:

“Return to repair. Keep alert for enemy craft understood to be more numerous in your waters than usual.”

The order bore the signature of Admiral Speare’s flag-lieutenant.

“Home, James,” smiled Darrin, after reading the order.

So the “Logan” was put about. Dave did not steam fast, for it had been found impossible wholly to stop the hole below water line. Water still came in, though in diminished quantity. Fast speed would be likely to spring the damaged plates.

It was near dawn when land was sighted, and the sun was well up when the “Logan” steamed limpingly into port. Half an hour later American dock authorities had taken charge of the destroyer. Dave waited until he saw his beloved craft in dry dock and the water receding from under her as it was pumped out of the basin in which the “Logan” now lay.

In the meantime Dalzell, who had had two hours’ sleep on the way to port, was busy granting shore leave to such men of the crew as were entitled to have it. More than half of the officers also received leave.

As soon as luncheon had been finished, and after Darrin had conferred with the dock officer, he and Dan went ashore.

“Where shall we go?” asked Dan, when they had left the naval yard behind them.

“Anywhere that fancy takes us,” Darrin answered, “and by dark, of course, to a hotel for as good a shore dinner as war times permit.”

“We’d have a better dinner on board,” laughed Dan, sometimes known in the service as Danny Grin. “These British hotels are all feeling the effects of the enemy’s submarine campaign, and can’t put up a half-way good meal.”

Once in the streets of the port town, the two young American naval officers strolled slowly along. The crowds had a distinctly war-time appearance. Hundreds of British and American jackies and two or three score French naval seamen were to be seen.

“Whoever invented saluting doesn’t have my unqualified gratitude,” grumbled Danny Grin. “My arm is aching now from returning so many salutes.”

“It’s a trifling woe,” Darrin assured him. “Look more sharply, Dan. You missed those two French sailors who saluted you.”

Too good a service man to do a thing like that without regret, Dalzell turned around to discover that the two slighted French sailors were glancing backward. He wheeled completely around, bringing his right hand smartly up to his cap visor and inclining his head forward. Facing forward once more he was just in time to “catch” and return the salutes of three British jackies.

“Quite a bore, isn’t it?” asked a drawling, friendly voice, as the two young officers paused to look in at a shop window’s display.

The young man who had hailed them was attired in a suit and coat of quite distinctly American cut. He was good-looking, agreeable in manner, and possessed of an air of distinction.

“The salute is a matter of discipline, not of opinion,” Dave Darrin answered, pleasantly. “It isn’t as troublesome as it looks.”

“I have sometimes wondered if you didn’t find it tedious,” continued the stranger.

“Sometimes,” Dave admitted, with a nod. “But it shouldn’t be.”

“You are an American, aren’t you?” asked Dalzell.

“Yes. Matthews is my name. I’m over here on what appears to be the foolish mission of trying to buy a lot of fine Irish linen, and that is a commodity which seems to have disappeared from the market.”

Somehow, it didn’t seem quite easy to escape introducing themselves, so Dan performed that office for the naval pair. Darrin would rather not have met strangers in the port that was the destroyer base. Mr. Matthews walked along with them, and presently it developed that he was staying at the hotel where Dave and Dan had decided to dine. So, after an hour’s stroll, the three turned toward the hotel.

“I’ll see you later,” declared Matthews, affably, starting for the elevator on his way to his room.

“Dan,” said Darrin, laying a kindly arm on his chum’s coat-sleeve and speaking in a low voice, “I’d just as soon you wouldn’t introduce us to chance acquaintances.”

“That struck me afterwards,” Dalzell admitted, soberly. “Yet, for once, I do not believe that my bad habit of friendliness with strangers has done any harm. Matthews appears to be all right.”

“I hope he is,” Dave answered.

Later Matthews joined them below.

“It struck me, gentlemen,” he declared, “that my introduction was rather informal. Permit me to offer you my card.”

He tendered to each a bit of pasteboard that neither could very well decline. It was a business card that he had offered, and its legend stated that Matthews was connected with a well-known Chicago dry-goods house.

“But in these times,” smiled their new acquaintance, “an American passport is a better introduction than a mere card.”

Whereupon he produced his passport. After a glance at it the two young naval officers did not see how they could escape offering their own cards, which Matthews gladly accepted and deposited in his own card-case.

He did not intrude, however, but soon moved off, after a cheery word of parting. Dave and Dan went out for another stroll, returning in time for dinner.

Hardly had they seated themselves when Matthews, fresh and smiling, stopped at their table in the dining room.

“I’m afraid you’ll vote me a bore,” he apologized, “but American company is such a treat in this town that I’m going to inquire whether my presence would be distasteful. If not, may I dine with you?”

“Be seated, by all means,” Darrin responded, with as much heartiness as he could summon.

When the soup had been taken away and fish set before them, Matthews asked:

“Don’t you find the patrol work a dreadful bore?”

“It’s often monotonous,” Dave agreed, “but there are some exciting moments that atone for the dulness of many of the hours.”

“And frightfully dangerous work,” Matthews suggested.

“Fighting, I believe, has never been entirely separated from danger,” retorted Dalzell, with a grin.

“Have you sunk anything lately?”

Both naval officers appeared to be too busy with their fish to hear the question.

Matthews looked astonished for only a moment. Then he waited until they were half through with the roast before he inquired:

“How do you like the work of the depth bombs? Are they as useful as it was believed they would be?”

Dave Darrin glanced up quickly. There was no glint of hostility in his eyes. He smiled, and his voice was agreeable as he rejoined:

“Now, I know you will not really expect an answer to that question, Mr. Matthews. The officers and men of the service are under orders not to discuss naval matters with those not in the service.”

“P-p-pardon me, won’t you?” stammered Matthews, a flush appearing under either temple.

“Certainly,” Dave agreed. “Men not in the service do not readily comprehend how necessary it is for Navy men not to discuss their work, especially in war-time.”

Matthews soon changed the subject. After they had gone forth from the dining room he shook hands with them cordially, and took his leave.

“Is he genuine?” asked Dalzell.

“Must be,” Dave replied. “His passport was in form. You know how it is with civilians, Danny-boy. Knowing themselves to be decent and loyal, they cannot understand why service men cannot take them at their own valuation.”

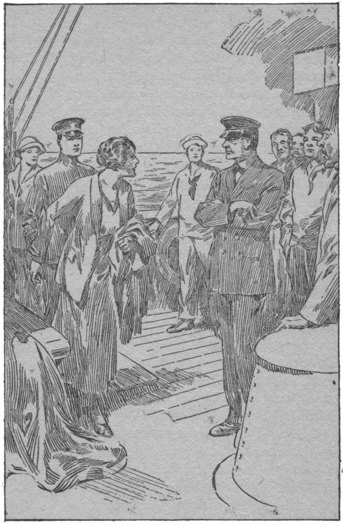

Just as the two were going out for another stroll the double doors flew briskly open to admit a group of more than a dozen British naval officers.

“Hullo, there, Darrin! I say there, Dalzell!”

Surrounded by Britain’s naval officers, our two Americans had to undergo almost an ordeal of handshaking in the lobby.

“But I thought you were far out on the water, Chetwynd,” Dave remarked to one of the officers.

“And so I was, but a bad break in a shaft sent me in,” grumbled the commander of an English destroyer. “Beastly luck! And I was needed out there,” he added, in a whisper, “for the Germans are attempting a big drive underseas. We’ve new information, Darrin, that they’ve more than twice the usual number of submersibles loose in these waters.”

“I’ve been told the same,” Dave nodded, quietly.

“What brought you in?”

“Shell hits, I think they were, though one dent might have been made by a torpedo,” Darrin answered.

“Then you had a fight.”

“A short one.”

“And the German pest?”

“Went to the bottom. I know, for we saw her sink, and her conning tower was so damaged that she couldn’t have kept the water out, once she went under. Besides, we found the surface of the water covered with oil.”

“I’ll wager you did,” agreed Chetwynd, heartily. “You Yankee sailors have sunk dozens of the pests.”

“And hope to sink scores more,” Darrin assured him.

“Oh, you’ll do it,” came the confident answer. “But come on upstairs with us. We’ve a private parlor and a piano, and plan a jolly hour or two.”

From one end of the room, in a lull in the singing, an exasperated English voice rose on the air.

“What I can’t understand,” the speaker cried, “is that the enemy appear to have every facility for getting the latest gossip right out of this port. And they know every time that a liner, a freighter or a warship sails from this port. There is some spy service on shore that communicates with the German submarine commanders.”

“I’d like to catch one of the rascally spies!” Dan uttered to a young English officer.

“What would you do with him?” bantered the other.

“Cook him!” retorted Dan, vengefully. “I don’t know in just what form; probably fricassee him.”

Little did Dalzell dream how soon the answer to the spy problem would come to him.

Thirty-six hours’ work at the dry dock, with changing shifts, put the “Logan” in shape to start seaward again.

Under another black sky, moving into thick weather, the “Logan” swung off at slow speed, with little noise from engines or propellers.

“I feel as if something were going to happen to-night,” said Dalzell, coming to the bridge at midnight after a two-hour nap. A little shudder ran over his body.

“I hope something does,” agreed Darrin, warmly. “But remember—no Jonah forebodings!”

“I—I think it will be something good!” hesitated Dalzell.

“Good or bad, have me called at six bells,” Dave instructed his second in command. “Before that, of course, if anything turns up.”

He went slowly down and entered the chart-room, closing the curtains after him. Taking off his sheepskin coat and hanging it up, Dave dropped into a chair, pulling a pair of blankets over him. Inside of thirty seconds he was sound asleep, dreaming, perhaps, of the night before at the hotel, when he had enjoyed the luxury of removing his clothing and sleeping between sheets.

At three o’clock to the minute a messenger entered and roused him. How Darrin hated to get up! He was horribly sleepy, yet he was on his feet in a twinkling, removing the service blouse that he had worn while sleeping, and dashing cold water in his face. A hurried toilet completed, he drew on and buttoned his blouse, next donned his sheepskin coat and cap, and went out into the dark of the early morning.

“All secure, sir!” reported Dalzell, from the bridge, meaning that reports had come in from all departments of the craft that all was well.

“You had better turn in, Mr. Dalzell,” Dave called, before he began to pace the deck.

“I’m not sleepy, sir,” lied Dalzell, like the brave young gentleman that he was in all critical times. Dan knew that from now until sun-up was the tune that called for utmost vigilance.

Darrin busied himself, as he did frequently every day, by going about the ship, on deck and below deck, on a tour of inspection. This occupied him for nearly an hour. Then he climbed to the bridge.

“Better turn in and get a nap, Danny-boy,” he urged, in an undertone.

“Say!” uttered Danny Grin. “You must know something big is coming off, and you don’t want me to have a hand in it!”

Dave picked up his night glass and began to use it in an effort to help out his subordinate, who stood near him. From time to time Dan also used a glass. A freshening breeze blew in their faces as the boat lounged indolently along on its way. It was drowsy work, yet every officer and man needed to be constantly on the alert.

Despite his denials that he was sleepy, Danny Grin braced himself against a stanchion of the bridge frame and closed his eyes briefly, just before dawn. He wouldn’t have done it had he been the ranking officer on the bridge, but he felt ghastly tired, and Darrin and Ensign Tupper were there and very much awake.

With a start Dan presently came to himself, realizing that he had lost consciousness for a few seconds.

“Oh, it’s all right,” Dan murmured to himself. “Neither Davy nor Tup will know that I’m slipping in half a minute of doze.”

His eyes closing again, despite the roll of the craft, he was soon sound enough asleep to dream fitfully.

And so he stood when the first streaks of dawn appeared astern. It was still dark off over the waters, but the slow-moving destroyer stood vaguely outlined against the eastern streaks in the sky.

Ensign Tupper was observing the compass under the screened binnacle light, and Darrin, glass to his eyes, was peering off to northward when the steady, quick tones of a man of the bow watch reached the bridge:

“’Ware torpedo, coming two points off port bow!”

That seaman’s eyesight was excellent, for the torpedo was still far enough away so that Dave had time to order a sharp swerve to port, and to send a quick signal to the engine room. As the craft turned she fairly jumped forward. The “Logan” was now facing the torpedo’s course, and seemed a bare shade out of its path, but the watchers held their breath during those fractions of a second.

Then it went by, clearing the destroyer amidships by barely two feet. Nothing but the swiftness of Darrin’s orders and the marvelously quick responses from helmsman and engineer had saved the destroyer from being hit.

On Dave’s lips hovered the order to dash forward over the course by which the torpedo had come, which is the usual procedure of destroyer commanders when attacking a submarine.

Instead, as the idea flashed into his head, he ordered the ship stopped.

Danny Grin had come out of his “forty winks” at the hail of the bow watch. Now Dave spoke to him hurriedly. Dalzell fairly leaped down from the bridge, hurrying amidships.

“All hands stand by to abandon ship!” rang the voice of Ensign Tupper, taking his order from Darrin. The alarm to abandon ship was sounded all through the ship.

There was a gasp of consternation, but Dalzell had already met and spoken to three of the junior officers, and these quickly carried the needed word.

The light was yet too faint, and would be for a few minutes, to find such a tantalizingly tiny object as a submarine’s periscope at a distance even of a few hundred yards. Lieutenant-Commander Darrin, therefore, had hit upon a simple trick that he hoped would prove effective. All depended upon the speed with which his ruse could be carried out. Cold perspiration stood out over Darrin as he realized the chances he was taking.

“Bow watch, there! Keep sharp lookout for torpedoes! Half a second might save us!”

Tupper stood with hand on the engine-room telegraph. He already had warned the engineer officer in charge to stand by for quick work.

Dalzell and the officers to whom Darrin had spoken saw to it that nearly all of the men turned out and rushed to the boats. Even the engineer department off watch came tumbling up in their distinctive clothing.

To an onlooker it would have appeared like a real stampede for the boats. Tackle creaked, making a louder noise than usual, but seeming to “stick” as an effort was made to lower loaded boats. The men in boats and at davits were grinning, for their officers had explained the trick.

Dawn’s light streaks had become somewhat more distinct as Dave peered ahead. Mr. Beatty and three men crouched low behind one of the forward guns.

The submarine commander must have rubbed his eyes, for, while he had observed no signs of a hit, he saw the American craft drifting on the water and the crew frantically trying to abandon ship.

Then the thing for which Darrin had hoped and prayed happened. The enemy craft’s conning tower appeared above water four hundred yards away.

“The best shot you ever made in your life, Mr. Beatty!” called Dave in an anxious voice.

The officer behind the gun had been ready all the time. At the first appearance of the conning tower he had drawn the finest sight possible.

The three-inch gun spoke. It seemed ages ere the shell reached its destination.

Then what a cheer ascended as the crew came piling on board from the boats. The conning tower of the submarine had been fairly struck and wrecked.

“Half speed ahead!” commanded Dave’s steady voice, while Dan gave the helmsman his orders. As Tupper sent the signal below the “Logan” gathered headway.

But Darrin had not finished, for on the heels of his first order came the second:

“Open on her with every gun!”

After the wrecking of his conning tower the German commander began to bring his craft to the surface. Perhaps it was his intention to surrender.

“Full speed ahead!” roared Darrin, and Ensign Tupper rang in the signal.

The hull of the submarine was hardly more than awash when five or six shots from the “Logan” struck it at about the same time.

Veering around to the southward the “Logan” prepared to circle the dying enemy. The German craft filled and sank, and Darrin presently gazed overboard at the oil-topped waters through which he was passing.

“A wonderful job! I wonder that you had the nerve to risk it,” muttered Dalzell.

“I don’t know whether it was a wonderful job, or a big fool risk,” Dave almost chattered. “It would have been a fool trick if I had lost the ship by it. I don’t believe that I shall ever try it again.”

“If you hadn’t done just what you did, a second torpedo would have been sent at you,” murmured Dalzell. “You saved the ‘Logan’ and ‘got’ the enemy, if you want to know.”

Grinning, for the responsibility had not been theirs, and the ruse had “worked,” the men of the watch returned to their usual stations, while those off duty returned to their “watch below.” Darrin, however, was shaking an hour later. He had dropped the usual method of defense for once and had tried a trick by which he might have lost his craft. As commander he knew that he had discretionary powers, but at the same time he realized that he had taken a desperate chance.

“Oh, stop that, now!” urged Danny Grin. “If you had steamed straight at the submarine you would have taken even bigger chances of losing the ‘Logan.’ Even had she given up the fight and dived, there wasn’t light enough for you to follow by any trail of bubbles the enemy might have left. The answer, David, little giant, is that the submarine is now at the bottom, and every Hun aboard is now a dead man. In this war the commander who wins victories is the only one who counts.”

Through that day Dave and Dan slept, alternately, only an hour or two at a time. All they sighted were three cargo steamers, two headed toward Liverpool and one returning to “an American port.”

At nine o’clock in the evening Darrin, after another hour’s nap, softly parted the curtains of the chart-room door and peered out. He saw a young sailor standing just back of the open doorway of the radio room. Slight as it was there was a something in the sailor’s attitude of listening that Darrin did not quite like. He stepped out on the deck.

Sighting him, the sailor saluted.

“Jordan!” called Dave, even before his hand reached his visor cap in acknowledgment of the salute.

“Yes, sir!” answered the seaman, coming to attention.

“You belong to this watch?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Your station is with the stern watch?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then what are you doing forward?”

“I left my station, by permission, to go below, sir.”

“Have you been below?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then why are you loitering here?”

Seaman Jordan hesitated, shifted on his feet, glanced down, then hurriedly replied:

“I—I don’t know, sir. I just stopped here a moment. There’s a relief man in my place, sir.”

“Return to your station, Jordan!”

“Aye, aye, sir,” replied the sailor, saluting, wheeling and walking away.

“And I’ll keep my eye on you,” mused Darrin, as he watched the departing sailor. “I may be wrong, but when I first sighted him there was a look on that lad’s face that I didn’t like.”

Even before he reached his station Seaman Jordan was quaking inwardly more apprehensively than is usual with a sailor caught in a slight delinquency.

For several days after that Darrin and the “Logan” cruised back and forth over the area assigned for patrol. During these days nothing much happened out of the usual. Then came a forenoon when Darrin received a wireless message, in code, ordering him to report back at once to the commanding officer of the destroyer patrol.

Mid afternoon found the “Logan” fifteen miles off the port of destination.

“Be on the alert every instant,” was the order Darrin gave out to officers and men. “There have been several sinkings, the last month, in these waters. We are nearing Fisherman’s Shoal, which is believed to be a favorite bit of ground for submarines that hide on the bottom.”

Over Fisherman’s Shoal the water was only about seventy feet in depth—an ideal spot for a lurking, hiding undersea craft.

Five minutes later the bow lookout announced quietly:

“Trail of bubbles ahead, sir.”

Leaving Ensign Phelps on the bridge, Dave and Dan darted down and forward.

A less practised eye might have seen nothing worth noting, but to the two young officers the trail ahead was unmistakable, though Darrin quickly brought up his glass to aid his vision.

“Pass the word for slow speed, Mr. Dalzell,” Dave commanded, quietly. “We want to keep behind that craft for a moment. Pass word to Mr. Briggs to stand by ready to drop a depth bomb.”

Quietly as the orders were given, they were executed with lightning speed. The destroyer began to move more slowly, keeping well behind the bubble trail. At any instant, however, the “Logan” could be expected to leap forward, dropping the depth bomb at just the right moment. Then would come a muffled explosion, and, if the bomb were rightly placed, a broad coating of oil would appear upon the surface.

Dave was now in the very peak of the bow. Watching the bubbly trail he knew that the hidden enemy craft was moving more slowly than the destroyer, and he signalled for bare headway. And now the bubbles were rising as though from a stationary object under the waves.

“Buoy, there!” he ordered, quickly. “Overboard with it.”

Slowly the destroyer moved past the spot, but the weighted, bobbing buoy marked the spot plainly.

“Have a diver ready, Mr. Dalzell,” Dave called. “Make ready to clear away a launch!”

In the matter of effective speed Darrin’s officers and crew had been trained to the last word. Only a few hundred yards did the “Logan” move indolently along, then lay to.

Soon after that the diver and launch were ready. Dave stepped into the launch to take command himself.

“May I go, too, sir?” asked Dan Dalzell, saluting. “I haven’t seen this done before.”

“Clear away a second launch, Mr. Dalzell. The crew will be armed. You will take also a corporal and squad of marines.”

That meant the entire marine force aboard the “Logan.” Dalzell quickly got his force together, while Darrin gave orders to pull back to where the bobbing buoy lay on the water.

“Ready, diver?” called Dave, as the launch backed water and stopped beside the buoy.

“Aye, aye, sir.” The diver’s helmet was fitted into position and the air pump started. The diver signalled that he was ready to go down.

“Men, stand by to help him over the side,” Darrin commanded. “Over he goes!”

Hugging a hammer under one arm the diver took hold of the flexible cable ladder as soon as it had been lowered. Sailors paid out the rope, life line and air pipe as the man in diver’s suit vanished under the water.

Down and down went the diver, a step at a time. The buoy had been placed with such exactness that he did not have to step from the ladder to the sandy bottom. Instead, he stepped on to the deck of a great lurking underseas craft.

He must have grinned, that diver, as he knelt on top of the gray hull and hammered briskly, in the International Code, this message to the Germans inside the submarine shell:

“Come up and surrender, or stay where you are and take a bomb! Which do you want?”

Surely he grinned hard, under his diver’s mask, as he noted the time that elapsed. He knew full well that his hammered message had been heard and understood by the trapped Huns. He could well imagine the panic that the receipt of the message had caused the enemy.

“We’ll send you a bomb, then?” the diver rapped on the hull with his hammer. “I’m going up.”

To this there came instant response. From the inside came the hammered message:

“Don’t bomb! We’ll rise and surrender!”

Chuckling, undoubtedly, the diver signalled and was hoisted to the surface. The instant that his head showed above water the seaman-diver nodded three times toward Darrin. Then he was hauled into the boat, and the launch pulled away from the spot.

“It took the Huns some time to make up their minds?” queried Dave Darrin smilingly, after the diver’s helmet had been removed.

“They didn’t answer until they got the second signal, sir,” replied the diver.

Dalzell’s launch was hovering in the near vicinity, filled with sailors and marines, a rapid-fire one-pounder mounted in the bow.

Both boats were so placed as not to interfere with gun-fire from the “Logan.” Officers and men alike understood that the Huns might attempt treachery after their promise to surrender.

Soon the watchers glimpsed a vague outline rising through the water. The top of a conning tower showed above the water, then the rest of it, and last of all the ugly-looking hull rose until the craft lay fully exposed on the surface of the sea.

The critical moment was now at hand. It would be possible for the submarine to torpedo the destroyer; there was grave danger of the attempt being made even though the vengeful Germans knew that in all probability their own lives would pay the penalty.

The hatch in the tower opened and a young German officer stepped out, waving a white handkerchief. He was followed by several members of the crew. It was evident that the enemy had elected to save their lives, and smiles of grim satisfaction lighted the faces of the watchful American jackies.

“Give way, and lay alongside,” Dave ordered his coxswain, while signalling Dalzell to keep his launch back for the present.

Then Dave addressed the young German officer:

“You understand English?”

“Yes,” came the reply, with a scowl.

“We are coming alongside. Your officers and men will be searched for weapons, then transferred, in detachments, to our launch, and taken aboard our craft.”

The German nodded, addressing a few murmured words to his men, who moved well up forward on the submarine’s slippery deck.

As the launch drew alongside two seamen leaped to the submarine’s deck and held the lines that made the launch fast to it.

Half a dozen armed seamen sprang aboard, with Darrin, who signalled to the second launch to come up on the other side of the German boat.

“Be good enough, sir, to order the rest of your men on deck,” Dave directed, and the German officer shouted the order in his own tongue. More sullen-looking German sailors appeared through the conning tower and lined up forward.

“Did you command here?” Dave demanded of the officer.

“No; my commander is below. I am second in command.”

Dave stepped to the conning tower, bawling down in English:

“All hands on deck. Lively.”

Another human stream answered. Darrin turned to the German officer to ask:

“Are all your crew on deck now?”

Quickly counting, the enemy officer replied:

“Yes; all.”

“And your captain?”

“I do not know why he is not here. I cannot give him orders.”

By this time the marines were aboard from the second launch. Already the first detachment of German sailors, after search, was being transferred to the launch.

“Corporal,” called Darrin, “take four men and go below to find the commander. Watch out for treachery, and shoot fast if you have to.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” returned the corporal, saluting and entering the tower. His men followed him closely.

“I’ve seen the outside of enough of these pests,” said Dave to his chum. “Suppose we go below and see what the inside looks like. The German submarines are different from our own.”

Dalzell nodded and followed, at the same time ordering a couple of stalwart sailors to follow. A boatswain’s mate now remained in command on the submarine deck.

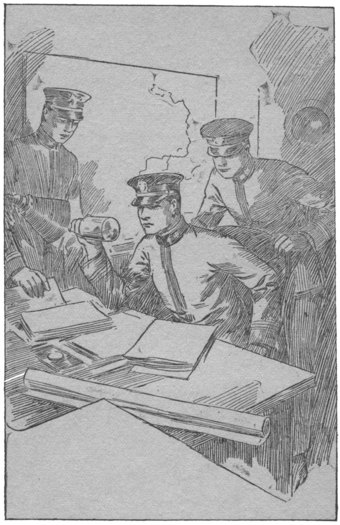

“You get back there!” growled the corporal. Dave reached the lower deck just in time to see the corporal pointing his revolver at a protesting German naval officer.

“Look what he’s been doing, sir,” called the corporal. “Look on the floor, sir.”

On the deck lay a heap of charred papers, still smoking.

Charred papers still smoking.

“If I’d got down a minute earlier, sir, he wouldn’t have had a chance to have that nice little bonfire,” grumbled the corporal.

Dave gave a great start as he took his first look at the face of the German captain.

As for the German, he seemed at least equally disconcerted. Dave Darrin was the first to recover.

“I cannot say that I think your German uniform becoming to a man of your name, Mr. Matthews,” Darrin uttered, in savage banter.

“Matthews?” repeated the German, in a puzzled voice, though he spoke excellent English. “I cannot imagine why you should apply that name to me.”

“It’s your own fault if you can’t,” Darrin retorted. “It’s the name you gave me at the hotel.”

“I’ve never seen you until the present moment,” declared the German, stoutly.

“Surely you have,” Danny Grin broke in. “And how is your firm in Chicago, Mr. Matthews?”

“Chicago?” repeated the German, apparently more puzzled than before.

“If Matthews isn’t your name, and I believe it isn’t,” Darrin continued, “by what name do you prefer to be addressed.”

“I am Ober-Lieutenant von Bechtold,” replied the German.

“Very good, von Bechtold; will you stand back a bit and not bother the corporal?”

Dave bent over to stir the charred, smoking heap of paper with his foot. But the job had been too thoroughly done. Not a scrap of white paper could be found in the heap.

“Of course you do not object to telling me what papers you succeeded in burning,” Darrin bantered.

Ober-Lieutenant von Bechtold smiled.

“You wouldn’t believe me, if I told you, so why tax your credulity?” came his answer.

“Perhaps you didn’t have time to destroy all your records,” Dave went on. “Under the circumstances I know you will pardon me for searching the boat.”

Thrusting aside a curtain, Dave entered a narrow passageway near the stern. Off this passageway were the doors of two sleeping cabins on either side. Dave opened the doors on one side and glanced in. Dan opened one on the other side, but the second door resisted his efforts.

“This locked cabin may contain whatever might be desired to conceal,” Dan hinted.

Turning quickly, Darrin saw that von Bechtold had followed. This the corporal had permitted, but he and a marine private had followed, to keep their eyes on the prisoner.

“If you have the key to this locked door, Captain, it will save us the trouble of smashing the door,” Dave warned. He had followed the usual custom in terming the ober-lieutenant a captain since he had an independent naval command.

“I do not know where the key is,” replied von Bechtold, carelessly. “You may break the door down, if you wish, but you will not be repaid for your trouble.”

“I’ll take the trouble, anyway,” Darrin retorted. “Mr. Dalzell, your shoulder and mine both together.”

As the two young officers squared themselves for the assault on the door a black cloud appeared briefly on von Bechtold’s face. But as Darrin turned, after the first assault, the deep frown was succeeded by a dark smile of mockery.

Bump! bump! At the third assault the lock of the door gave way so that Dave and Dan saved themselves from pitching into the room headfirst.

“Oh, whew!” gasped Danny Grin.

An odor as of peach-stone kernels assailed their nostrils. They thought little of this. It was a sight, rather than the odor, that instantly claimed their attention.

For on the berth, over the coverlid, and fully dressed in civilian attire of good material, lay a man past fifty, stout and with prominent abdomen. He was bald-headed, the fringe of hair at the sides being strongly tinged with gray.

At first glance one might have believed the stranger to be merely asleep, though he would have been a sound sleeper who could slumber on while the door was crashing in. Dave stepped close to the berth.

Dalzell followed, and after them came the submarine’s commander.

“You will go back to the cabin and remain there, Mr. von Bechtold,” Dave directed, without too plain discourtesy. “Corporal, detail one of your men to remain with the prisoner, and see that he doesn’t come back here unless I send for him. Also see to it that he doesn’t do anything else except wait.”

Scowling, von Bechtold withdrew, the marine following at his heels.

As Darrin stepped back into the cabin he saw the stranger lying as they left him.

“Dead!” uttered Dave, bending over the man and looking at him closely. “He lay down for a nap. Look, Dan, how peaceful his expression is. He never had an intimation that it was his last sleep, though this looks like suicide, not accidental death, for the peach-stone odor is that of prussic acid. He has killed himself with a swift poison. Why? Is it that he feared to fall into enemy hands and be quizzed?”

“A civilian, and occupying an officer’s cabin,” Dan murmured. “He must have been of some consequence, to be a passenger on a submarine. He wasn’t a man in the service, or he would have been in uniform.”

“We’ll know something about him, soon, I fancy,” Darrin went on. “Here is a wallet in his coat pocket, also a card case and an envelope well padded with something. Yes,” glancing inside the envelope, “papers. I think we’ll soon solve the secret of this civilian passenger who has met an unplanned death.”

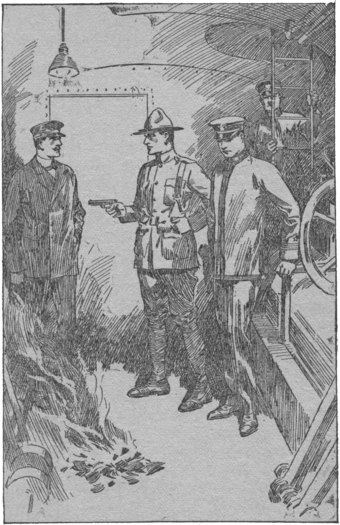

“Here, you! Stop that, or I’ll shoot!” sounded, angrily, the voice of von Bechtold’s guard behind them.

But the German officer, regardless of threats, had dashed past the marine, and was now in the passageway.

“Here, I’ll soon settle you!” cried the marine, wrathfully. But he didn’t, for von Bechtold let a solid fist fly, and the marine, caught unawares, was knocked to the floor.

All in a jiffy von Bechtold reached his objective, the envelope. Snatching it, he made a wild leap back to the cabin, brushing the marine private aside like a feather.

“Grab him!” yelled Dave Darrin, plunging after the German. “Don’t let him do anything to that envelope!”

Fortune has a way of favoring the bold. The corporal and a marine were in the corridor behind Darrin. The ober-lieutenant’s special guard had been hurled aside.

Hearing the outcries, the other two marines in the cabin sprang toward the German officer. One of these von Bechtold tripped and sent sprawling; the other he struck in the chest, pushing him back.

Just an instant later von Bechtold went down on his back, all five of the marines doing their best to get at him in the same second. But the German had had time to knock the lid from a battery cell and to plunge the envelope into the liquid contained in the jar. Then the German was sent to the mat by his assailants.

Darrin, following, his whole thought on the envelope, plunged his right hand down into the fluid, gripping the package that had been snatched from him.

“Sulphuric acid!” he exclaimed, and made a quick dive for a lidded fire bucket that rested in a rack. The old-fashioned name for sulphuric acid is vitriol, and its powers in eating into human flesh are well known. Darrin’s left hand sent the lid of the bucket flying. Hand and envelope were thrust into the water with which, fortunately, the bucket was filled. When sulphuric acid in quantity is added to water heat is generated, but a small quantity of the acid may be washed from the flesh with water to good advantage if done instantly. After a brief washing of the hand Dave drew it out, patting it dry with a handkerchief. Thus the hand, though reddened, was saved from painful injury. The envelope he allowed to remain in the water for some moments.

“Von Bechtold, you are inclined to be a nuisance here,” Darrin said coolly. “I am going to direct these men to take you above.”

“I am helpless,” replied the German, sullenly, from the floor, where he now lay passive, two marines sitting on him ready to renew the struggle if he so desired.

“Take him above, you two men,” Darrin ordered, “and take especial pains to see that he doesn’t try to escape by jumping into the water.”

At this significant remark von Bechtold paled noticeably for a moment. Then his ruddy color came back. He got upon his feet with a resentful air but did not resist the marines who conducted him up to the deck.

Dave now drew out the envelope, which had become well soaked, and took out the enclosure, a single sheet. The writing at the top of the sheet was obliterated. Darrin did not read German fluently, but at the bottom of the sheet he found a few words and phrases that he was able to translate. Their meaning made him gasp.

“Danny-boy,” he murmured to his chum, “I want you to make quick work of transferring the prisoners to the ‘Logan.’ Keep back two of the German engineer crew, and send word to Ensign Phelps to come over on the launch’s next trip with two men of our engine-room force, and to bring along also six seamen and a petty officer. Phelps will take charge of this craft as prize officer.”

The submarine was soon cleared of her officers and crew. Ensign Phelps and his own men came over and took command. Two German engine-room men had been kept back to assist the Americans. On the last trip Darrin and Dalzell returned to the undersea boat and gave the order to Ensign Phelps to proceed on his way to the base port.

As soon as the prize with its captors was under way, Darrin went to the chart-room of the “Logan,” sent for the marine corporal, and ordered that Ober-Lieutenant von Bechtold be brought before him.

As the prisoner was ushered in Dave rose courteously, bowed and pointed to a chair.

“Be seated, if you please. Now, Herr Ober-Lieutenant, your second-in-command and your crew will be taken ashore as ordinary prisoners of war, and turned over to the British military prison authorities. Of course you are aware that your own imprisonment will take place under somewhat different circumstances.”

Von Bechtold, who had accepted the proffered chair, gazed stolidly at this American naval commander, who was several years younger than himself.

“I fear that I do not understand you,” the German replied.

“You soon will, for you speak excellent English,” Darrin returned, with a chilly smile. “Your English does not have exactly the Chicago accent, but it was good enough for your purposes. The Chicagoan speaks with a sort of sub-Bostonese accent, as perhaps you did not know. Your own English has rather the sound of Oxford or Cambridge University in England.”

Opening his eyes wide, and expressing bewilderment, the German begged:

“Will you be good enough to speak more explicitly?”

“Certainly,” Dave assented. “When you are turned over to the British military authorities it will be done with a card showing that you now give the name of von Bechtold——”

“Which is my right name,” interposed the German officer, tartly.

“And the card will also state that, a few days ago, you gave the name of Matthews.”

“Again you use that name of Matthews,” cried von Bechtold, impatiently. “May I ask why?”

“I will make it so clear,” Dave promised him, “that you would understand even though what I am about to say were not true. But it is true. A few days ago you met me at the hotel in port. You met also my executive officer, Mr. Dalzell. You introduced yourself to us as Matthews, claimed to be a buyer for a Chicago dry-goods house, and declared that your mission was to buy linen.”

“Not a word of truth in it,” declared von Bechtold, calmly, with a wave of his hand, as though to brush aside the charge.

“Unfortunately, quite true,” Dave went on, steadily. “You were there under an assumed name and claimed to be an American citizen. You exhibited an American passport; I have heard that your government has a printing office where such documents are turned out. You were there out of uniform. In other words, sir, your conduct on British soil, in civilian dress and under false colors, met with all the requirements of proof that you were there as a spy. It has long been known to the British, and to us, that German spies have abounded in Great Britain and that they obtained a good deal of information that we would rather German submarine commanders did not possess. So, Mr. von-Bechtold-Matthews, it will be my disagreeable duty to hand you over with the charge that you have been serving as a spy. Dalzell and I will be obliged to testify against you. I much fear that a British court-martial will condemn you to be shot.”

“What infamous lie is this that you are threatening to utter against me?” demanded the German officer, leaping to his feet.

“No lie at all, as you know quite well,” Dave went on. “I am sorry to have to bring you to this plight, von Bechtold, but you know that I cannot do otherwise.”

Gazing into the steady eyes of the young American naval officer von Bechtold realized the folly of further acting. Breathing hard, he dropped into a chair.

“It is not a fine thing that you propose to do to me,” he declared. “You do not know, of course, that I have five young children at home, who will need a father.”

“I did not know it,” Dave answered gently. “Yet I feel quite certain that some of the information you have gathered, when ashore in these parts, has resulted in the drowning at sea of a good many men who may have left behind even more than five children.”

“I feel that I am doomed,” shuddered the German, throwing a hand up over his eyes. “My five little children will not see their father again—not even when this war is over.”

“It is too bad,” Dave answered, “but I suppose, Herr Ober-Lieutenant, that it must be classed with the fortune of war. Now, as to the identity of the civilian who lies dead in a berth aboard your late command, it may be that, if you were ready to tell something about the reasons for his presence on board, and why he had in his possession this paper——”

Here Darrin spread out the wet sheet of paper that he had brought from the submarine.

“I can tell you nothing about either the civilian or that paper,” declared von Bechtold, doggedly.

“That is your own affair,” Darrin admitted. “I shall not make any attempt to force you.”

“You had better not!” declared the German, fiercely. “I can die, but I cannot betray my country. Yet have you no heart?—when I tell you about my five little children whom you would deny the privilege of ever seeing their father again?”

“If I were to suppress my report of your activities as a spy,” Darrin continued, “I would be guilty of betraying my country and my country’s allies. It would also be necessary for me to induce my subordinate officer to do the same thing. You will realize the impossibility of our doing such a thing. On the other hand, between now and the time that you are tried by court-martial you will have time to reflect upon whether you wish to try to save yourself from the death sentence by explaining to the British authorities the full meaning of what had been written on this sheet of paper and also the reasons for that civilian being aboard your craft. Then, by throwing yourself on the mercy of the court, you might escape the full penalty meted out to a spy.”

“I shall not do it,” declared von Bechtold, rising and drawing himself to his full height.

“Nor do I believe I could be induced to tell what I knew if I stood in your boots. Orderly!”

To the marine who entered Dave gave the order to summon the guard. Von Bechtold was taken back to the “Logan’s” brig, and locked in for absolutely safe keeping. Darrin went up to the bridge.

“Do you feel sorry for the fellow?” asked Dalzell, when he had heard an account of the interview.

“No more sorry than I do for any man who is down and out,” Dave replied, truthfully. “Now that he is captured and his spy work ended, I believe that ships on these waters will be much safer.”

“He will be just one Hun less, after a firing squad has finished with him,” Dan rejoined.

Dave nodded thoughtfully.

“War breeds savage ideas, doesn’t it?” demanded Danny Grin, with a shrug of his shoulders.

“Not breeds, but brings out,” answered Darrin.

They were nearing the coast now. Destroyers, patrol boats, drifters and mine-sweeping craft sighted the “Logan” and her prize, and the shrill whistles of these hunters of the sea testified to their joy over the capture.

Then the destroyer and her prize entered the port. Darrin brought his craft to anchorage, while the captured submarine was anchored not far away. The German prisoners were taken ashore under guard and turned over to the British authorities.

Ober-Lieutenant von Bechtold, under the charge of being a spy, was marched away under a special guard.

And then Dave made haste to present himself, with the half-destroyed sheet of paper in his pocket, before the flag lieutenant of Vice Admiral Speare.

There was much joy aboard a squadron of six more destroyers, just arrived from Uncle Sam’s country, when, on steaming into port, they heard the news of the capture.

So far as Dave was concerned the document that he had discovered, mutilated as it was, had supplied hints that filled the British Admiralty and the American naval commander with deep apprehension.

Both Darrin and Dalzell were present in the crowded council room on board the vice admiral’s flagship. There were other American naval officers, as well as a few American Army staff officers present. Their faces displayed anxiety.

“It is too bad,” one of the American army staff officers declared, after scanning the damaged sheet under a magnifying glass, “that so much of this is obliterated. Of course, Mr. Darrin, we know that you acted promptly and that you did all in your power, and at considerable risk, to preserve this document. From the disconnected sentences that we can decipher, it would seem that at least sixty of the enemy’s submarines are to concentrate in near-by waters. It is also plain that their mission is to destroy the convoy escort and sink the troopships that are nearing these waters—troopships that convey the entire One Hundred and Seventeenth Division of the United States Army.”

“It would be a frightful disaster, if it came to pass,” boomed the deep tones of a British naval officer.

“It shall not come to pass!” declared an American naval officer.

“Easily said, and I hope as easily done,” replied the British officer. “But you Americans have not yet begun to lose ships loaded with troops. We Britishers have had some sad experiences in that line. Never as yet, though, have we had to face a concentration of sixty enemy submarines!”

“The way it looks to me,” said another American army staff officer, gravely, “is that, while the destroyer escort will surely sink some of the enemy submarines, yet just as surely, with the enemy in such force, will some of our troopships go to the bottom. It is mainly, as I view it, a question of how many troopships we are likely to lose, and how big a loss of soldier life we shall suffer.”

“Sixty submarines!” uttered a British naval officer, savagely. “We haven’t an officer on a destroyer who wouldn’t gladly go to the bottom if he could first have the pleasure of sinking a few of these deep-sea pests!”

“A distressing feature is that we cannot decipher the very part of this document which states where the submarine concentration is expected to strike,” declared a naval staff officer.

“How many British destroyers will be needed to reinforce the available American destroyers?” asked a British officer, apprehensively. “For we have so many uses for our destroyers, on other work, that it is difficult to guess where we are to find destroyers enough to help you Americans.”

This was known, by all present, to be only too true. The British Navy, from super-dreadnoughts to the smallest steam trawlers, was painfully overloaded with work.

“As Mr. Darrin is a destroyer commander with an uncommonly good record to his credit,” said an American naval staff officer, “and as we have not yet heard his opinion, I think we would all like to have his views.”

Dave Darrin glanced at the American naval commander, who sent him an encouraging nod.

“We know, then, gentlemen,” began Dave, “just how many American destroyers are to act as escort to the troopship fleet that is bringing the One Hundred and Seventeenth Division across. We know, also, just how many destroyers under our flag can be taken from patrol duty to safeguard the troopship fleet. We know the length of the sailing line of the troopship fleet; we know the speed of our destroyers. It seems to me that the answer is to be found in these known facts.”

“What is your suggestion as to the plan, then?” asked an officer.

“Gentlemen, in the presence of so many officers of wider experience and greater knowledge, I feel embarrassed to find myself speaking.”

“Go on!” cried several.

Darrin still hesitated.

“First of all, Mr. Darrin, in offering your suggestion, tell us what number of British destroyers you believe that you will need to reinforce the American destroyers that are available for protecting your troopship fleet,” urged one.

Dave still hesitated, though not from shyness. He did some rapid calculating as to the length of the line of troopships sailing in the regular order. Then he figured out how many destroyers could give efficient protection against sixty German submarines.

There was tense silence in the council room. At last Darrin looked up.

“Well,” demanded the insistent British naval staff officer, “how many of our British destroyers do you think, Darrin, are needed to help out your American destroyers?”

Dave turned his face toward the American vice admiral.

“Sir, and gentlemen,” he replied, “if we had three times as many destroyers we could use them. I have an opinion on the subject, but it will sound so childish to you that I should prefer to sit back and let older heads offer suggestions.”

“Darrin,” spoke the flag lieutenant, after a nudge and a whispered word from the vice admiral, “this is no question of age, nor is it wholly a question of experience. Demonstrated ability, ability backed by a record, is entitled to a hearing here. You have done your figuring, and you have reached certain conclusions. How many British destroyers do you believe we shall need to help out the American destroyer fleet that is now available?”

This amounted almost to an order to speak up. Dave reddened perceptibly, opened his mouth as though to speak, closed it again, then cleared his throat and called out steadily:

“Sir, and gentlemen, it is my opinion that the American naval forces available for the work can do all the work! I do not believe that we need an ounce of British help that would be so graciously extended if we asked for it!”

There was a moment’s silence.

“No help needed from us?” demanded the British naval staff officer.

“It would be welcome, sir,” Dave declared, “but you cannot spare the help. Whatever assistance you gave us at this time would weaken your lines of defense or offense at some other point. They are American soldiers who are to be protected, and——”

Here Darrin’s voice failed him for a moment. He felt as though the more than score of pairs of eyes that were regarding him sharply were burning him. He swallowed hard, but returned to the charge and went on, slowly, in words that rapped like machine-gun fire:

“I would stake my soul that the American Navy can safeguard the passage of the One Hundred and Seventeenth Division of the American Army!”

There was a gasp. The words were bold, but, if true, they solved a vexing problem. The spirit of the United States Navy had spoken through Dave Darrin’s lips.

“Darrin,” shouted an American staff officer, bringing a fist down on the table, then springing to his feet, “you’ve answered for us! You’ve given us our chart. I’d trust the best troopship fleet we’ll ever send over the ocean to the guarding care of a dozen young Yankee naval commanders of your stripe.”

In an instant the enthusiasm became infectious. A cheer arose, in which the vice admiral joined. The British naval officer of the booming tones left his seat and went over to grasp Dave’s hand.

“Darrin, I wish we had you in our Navy!” he said, simply.

There was little more left to be agreed upon. It was decided, however, that a combined fleet of British and American patrol boats should be in readiness to swoop down and save lives in case any of the American troopships should be torpedoed.

The council soon broke up. All that was now left to be done was for the vice admiral and his immediate staff to formulate the exact plans for the protection of the One Hundred and Seventeenth Division. Even after the destroyer fleet had turned itself loose on its task, further instructions could be sent in wireless code.

“Gentlemen,” said the vice admiral, rising, “I thank you for your attendance, for your consideration of the problem, and for whatever help you have been able to extend. And I can see no objection,” he added, a twinkle in his eyes, “to your giving three cheers for Lieutenant-Commander Darrin.”

Proud? Not a bit. As the volleys of cheers rang out deafeningly, Dave Darrin felt as though he would enjoy sinking through the deck.

But Danny Grin was there, and he undertook the job of feeling proud for his chum.

Out upon the tossing sea once more. It was a wonder that the “Logan” did not sit much deeper in the water, for she carried a most unusual load of ammunition of every useful kind.

Out upon the sea, and seemingly alone at that. Not a sail was visible to the officers on the taut little destroyer, not a trail of smoke appeared on any part of the horizon. Indeed, the present speed and low fuel consumption aboard the “Logan” allowed only the thinnest wisps of smoke to issue from the raking funnels of the destroyer.

Had Dave needed other destroyer company, for any urgent reason, a signal snapping from his radio aerials would bring one, perhaps two, American destroyers to him within an hour. For some of these bulldog little fighting craft, that were out after the deep-sea pests, were capable of making more than thirty knots an hour.

The “Logan” had been out four days. Though headed westward at this moment, she had not been moving steadily westward, for she was now not more than three hundred and thirty miles west of the coast of Ireland.