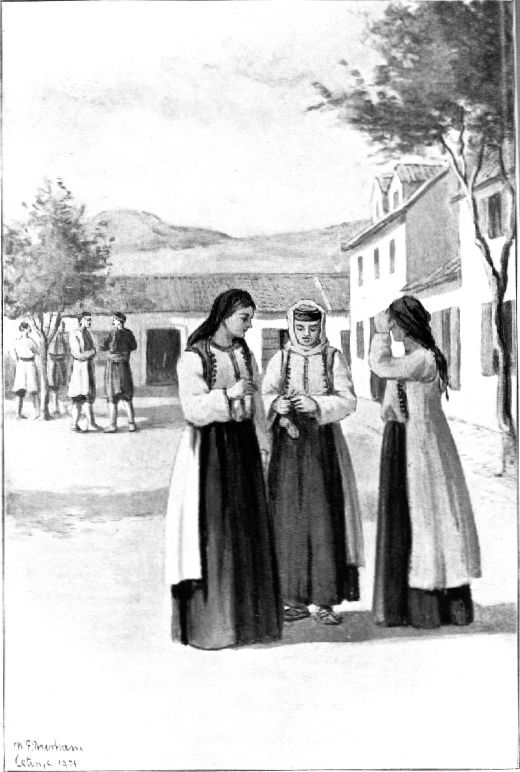

MONTENEGRIN WOMEN, CETINJE.

MONTENEGRIN WOMEN, CETINJE.

Title: Through the Land of the Serb

Author: M. E. Durham

Release date: November 27, 2012 [eBook #41499]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marc D'Hooghe (Images generously made available by the Internet Archive)

| I. | CATTARO—NJEGUSHI—CETINJE |

| II. | PODGORITZA AND RIJEKA |

| III. | OSTROG |

| IV. | NIKSHITJE AND DUKLE |

| V. | OUR LADY AMONG THE ROCKS |

| VI. | ANTIVARI |

| VII. | OF THE NORTH ALBANIAN |

| VIII. | SKODRA |

| IX. | SKODRA TO DULCIGNO |

| X. | BELGRADE |

| XI. | SMEDEREVO—SHABATZ— VALJEVO—UB—OBRENOVATZ |

| XII. | NISH |

| XIII. | PIROT |

| XIV. | EAST SERVIA |

| XV. | THE SHUMADIA AND SOUTH-WEST SERVIA |

| XVI. | KRUSHEVATZ |

MONTENEGRIN WOMEN, CETINJE

CEMETERY NEAR CETINJE

BAKER'S SHOP, RIJEKA—ALBANIAN AND TWO MONTENEGRINS

BULLOCK CART, PODGORITZA

UPPER MONASTERY, OSTROG

RUINS OF ANTIVARI

MOUNTAIN ALBANIANS IN MARKET, PODGORITZA

STREET IN BAZAAR, SKODRA

SKODRA

MOSQUE, SKODRA

SHOP IN BAZAAR, SKODRA

MONTENEGRIN PLOUGH

SERVIAN PEASANTS

TRAVELLING GIPSIES, RIJEKA, MONTENEGRO

SOLDIERS' MONUMENTS

CHURCH, STUDENITZA—WEST DOOR.

CORONATION CHURCH, KRALJEVO

TSAR LAZAR'S CASTLE

CHURCH, KRUSHEVATZ—SIDE WINDOW OF APSE

THE PATRIARCHIA, IPEK (PECH)

PODGORITZA

MAP OF THE LANDS OF THE SERB

In the spelling of proper names the system adopted in the Times Atlas has been followed as nearly as possible. Owing to the absence of Miss Durham in Macedonia, the following pages have not had the advantage of her revision in going through the press.

"What land is this?"

"This is Illyria, lady."

Twelfth Night.

I do not know where the East proper begins, nor does it greatly matter, but it is somewhere on the farther side of the Adriatic, the island-studded coast which the Venetians once held. At any rate, as soon as you leave Trieste you touch the bubbling edge of the ever-simmering Eastern Question, and the unpopularity of the ruling German element is very obvious. "I—do—not—speak—German," said a young officer laboriously, "I am Bocchese"; and as we approached the Bocche he emphasised the fact that he was a Slav returning to a Slav land. Party politics run high even on the steamboat.

We awoke one morning to find the second-class saloon turned into a Herzegovinian camp, piled with gay saddle-bags and rugs upon which squatted, cross-legged, a couple of families in full native costume, and the air was thick with the highly scented tobacco which the whole party smoked incessantly. The friendly steward, a Dalmatian Italian, whispered hastily, "This is a Herzegovinian family, signorin'. Do you like the Herzegovinese?" Rather taken aback, and not knowing what his politics were, I replied, stupidly enough, "I find their costume very interesting," This frivolous remark hurt the steward deeply. "Signorin'," he said very gravely, "these are some of the bravest men in the world. Each one of these that you see would fight till he died." Then in a mysterious undertone, "They cannot live without freedom ... they are leaving their own land ... it has been taken, as you know, by the Austrian.... They are going to Montenegro, to a free country. They have taken with them all their possessions, and they go to find freedom."

I looked at them with a curious sense of pity. Though they knew it not, they were the survivors of an old, old world, the old world which still lingers in out-of-the-way corners, and it was from the twentieth century quite as much as from the Teuton they were endeavouring to flee. All these parti-coloured saddle-bags and little bundles tied up in cotton handkerchiefs represented the worldly goods of three generations, who had left the land of their forebears and were upon a quest as mystical as any conceived by mediæval knight—they were seeking the shrine of Liberty. "Of old sat Freedom on the heights"; let us hope they found her there! I never saw them again.

On the other hand, in a boat with Austrian sympathies, the tale is very different. "I am a Viennese, Fräulein. Imagine what it is to me to have to travel in this dreary place! The people?—they are a rough, discontented set. Very ignorant. Very bad. No, I should not advise you to go to Montenegro—a most mischievous race." "And what about Bosnia and the Herzegovina?" "Oh, you will be quite safe there; we govern that. They are a bad lot, though! But we don't stand any nonsense."

Thus either party seizes upon the stranger and tries to prevent his views being "prejudiced." He seldom has need to complain that he has heard one side only; but there is a Catholic side, an Orthodox side, a Mohammedan side, there are German, Slav, Italian, Turkish, and Albanian sides; and when he has heard them all he feels far less capable of forming an opinion on the Eastern Question than he did before.

Dalmatia has its charms, but tourists swarm there, and the picturesque corners are being rapidly pulled down to provide suitable accommodation for them. Let us pass on, then, nor pause till we have wound our way through that wonderful maze of fiords, the Bocche, and landed on the quay at Cattaro. Cattaro is a tiny, greatly coveted, much-fought-for town. The natural port for Montenegro but the property of Austria, it swelters, breathless, on a strip of shore, with the waters in front of it, and the great wall of the Black Mountain rising sheer up behind. Its "heart's in the Highlands," but the enemy holds it as a garrison town; the Austrian army pervades the neighbourhood, and a big fort, lurking opposite, commands the one road from mountain to coast. Cattaro, after all, is only a half-way house to Montenegro, and this is why Austria lavishes so many troops upon it.

Behind the town starts the rough zigzag track, the celebrated "ladder of Cattaro," which until 1879 was the only path into Montenegro, and is the one the peasants still use. The making of the road was for a long while dreaded by the Montenegrins, who argued that a road that will serve for a cart will also serve for artillery. A tangible, visible gun was their idea of the means by which changes are wrought; but the road that can let in artillery can let in something more subtle, irresistible, and change-working. The road was made, and there is now no barrier to prevent the twentieth century creeping up silently and sweeping over this old-world land almost before its force is recognised. Whether the hardy mountain race which has successfully withstood the gory onslaught of the Turk for five hundred years, will come out unscathed from a bloodless encounter with Western so-called civilisation Time alone can tell.

The road from Cattaro to Cetinje has been so often written of that it is idle to describe it once again, nor can any words do it justice. After some three hours' climbing, we pass the last Austrian black-and-yellow post, and the driver, if he be a son of the mountain, points to the ground and says, "Crnagora!" (Tsernagora). Crnagora, gaunt, grey, drear, a chaos of limestone crags piled one on the other in inextricable confusion, the bare wind-swept bones of a dead world. The first view of the land comes as a shock. The horror of desolation, the endless series of bare mountain tops, the arid wilderness of bare rock majestic in its rugged loneliness, tell with one blow of the sufferings of centuries. The next instant fills one with respect and admiration for the people who have preferred liberty in this wilderness to slavery in fat lands.

Wherever possible, little patches of ground are cultivated, carefully banked up with stones to save the precious soil from being washed away, and up on the mountain sides scrubby oaks dwarfed and twisted by the wind find a foothold among the crags. Most of the men carry revolvers, and the eye soon becomes so much accustomed to weapons that on a return to unarmed lands everyone appears, for a few days, to be rather undressed. The road winds, the red roofs of Njegushi come in sight, and we make our first halt in a Montenegrin town, and rest our weary horses.

We enter the little inn, and our coachman claims his revolver, which is hanging with several others behind the bar, for none are allowed to enter Austria; they are deposited in some house near the frontier and picked up on the way back. George Stanisich, the big landlord, hurries up his womenkind to make ready a meal, looks after the drinks, and converses cheerfully on the topics of the day—preferably on the war, if there happens to be one. "Junastvo" (that is, heroism—"deeds of derring-do") is a subject that occupies a large space in the Montenegrin mind, and no wonder, and every man's ambition is to be considered a "dobar junak" (valiant warrior) and worthy of his forefathers.

Njegushi cannot fail to make a most vivid impression on the mind, for it is the entrance to a world that is new and strange. The little stone-paved room of the inn, hung with portraits of the Prince and the Tsar and Tsaritsa of Russia; the row of loaded revolvers in the bar; the blind minstrel who squats by the door and sings his long monotonous chant while he scrapes upon his one-stringed gusle; and the tall, dignified men in their picturesque garb, all belong to an unknown existence, and the world we have always known is left far below at the foot of the mountain. In Njegushi one feels that one has come a long way from England. It is, in fact, easy to travel much farther without being so far off. Yet the Montenegrin love of liberty and fair play and the Montenegrin sense of honour have made me feel more at home in this far corner of Europe than in any other foreign land.

Njegushi is the Prince's birthplace. His ancestors were some of a number of Herzegovinians who, intolerant of the Turk, emigrated in the fifteenth century. The village they left was called Njegushi, and they gave the same name to their new home. In connection with this I give here a curious tale which I have met with more than once. I repeat it as told; my informants, Servians, believed it firmly, but I can find no confirmation of it.

When these Herzegovinese migrated to Montenegro, a large body of them went yet farther afield and settled in the mountains of Abyssinia, among them a branch of the family of Petrovich of Njegushi, from which is directly descended Menelik, who preserves the title of Negus and is a distant cousin of Prince Nikola of Montenegro, and to this large admixture of Slav blood the Abyssinians owe their fine stature and their high standard of civilisation, as compared with the neighbouring African tribes.

The house of the Prince stands on the left of the road as we leave the town. The road ascends once more; a steep pull up through a bleakness of grey crags; we reach the top of the pass (3350 feet), and turn a corner. "Cetinje!" (Tsetinye), says the driver briefly, and there, in the mountain-locked plain far below, lies the little red-roofed town, a village city, a kindergarten capital, one of the quaintest sights in Europe, so tiny, so entirely wanting in the usual stock properties of a big town and yet so consciously a capital. Two wide streets which run parallel and are joined by various cross streets make up the greater part of it, and it has some 3000 inhabitants. As we enter the town the first building of importance stands up on the left hand, brand-new, a white stone building with a black roof. To any other capital it would not be remarkable either for size or beauty; here it looms large and portentous. It is the biggest building in the town, and it is the Palace of the Austro-Hungarian Legation. Not to be outdone, Russia has just erected an equally magnificent building at the other end of the town, which now lies between representatives of the two rival powers. "Which things are an allegory." Twenty years ago Cetinje was a collection of thatched hovels. To-day, modest as they are, the houses are all solidly built and roofed with tiles. Few more than one storey high, many consisting only of a ground floor, all of them devoid of any attempt at architecture; not a moulding, a cornice, or a porch breaks the general baldness: they are more like a row of toy houses all out of the same box than anything else. The road is very wide, and very white; a row of little clipped trees border it on each side, so clipped that they afford at present about as much shade as telegraph posts, and they all appear to have come out of the same box too. It is all very clean, very neat; not a whiff offends the tenderest nostril, not a cabbage stalk lies in the gutter. It is not merely a toy, but a brand-new one that has not yet been played with.

Cetinje is poor, but dignified and self-respecting. A French or Italian village of the same size clatters, shouts, and screams. Cetinje is never in a hurry, and seldom excited. It contains few important buildings. The only ones of any historic interest are the monastery, the little tower on the hill above it where were formerly stuck the heads of slain Turks, and the old Palace called the Biljardo from the fact that it contained Montenegro's first billiard-table. It now affords quarters for various officials and the Court of Justice. There are no lawyers in Montenegro, and this is said to simplify matters greatly. The Prince is the final Court of Appeal, and reads and considers the petition of any of his subjects that are in difficulties. Such faith have folk in his judgment that Mohammedan subjects of the Sultan have been known to tramp to Crnagora in order to have a quarrel settled by the Gospodar. That he possesses a keen insight into these semi-civilised people and a remarkable power of handling them is evident from the order that is maintained throughout his lands even among the large Mohammedan Albanian population, and it would undoubtedly have been much better for the Balkan peoples had he had larger scope for his administrative powers.

Cetinje's other attractions are the park, the theatre, and the market, where the stranger will have plenty of opportunity of wrestling with the language.

The language is one of the amusements of Montenegro. It is not an easy one. I hunted it about London for months, and it landed me in strange places. The schools and systems that teach all the languages of Europe, Asia, Africa, and America know it not. In the course of my chase I caught a Roumanian, a Hungarian, and an Albanian, but I got no nearer to it. I pursued it to a Balkan Consulate, which proved to consist entirely of Englishmen who knew no word of the tongue, but kindly communicated with a Ministry which consisted, so they said, entirely of very charming men, with whom I should certainly be pleased. The Ministry was puzzled, but wished to give me every encouragement. It had never before had such a run upon its language. It suggested that the most suitable person to instruct me would be an ex-Minister who had come over to attend the funeral of Queen Victoria. The ex-Minister was very polite, but wrote that he was on the point of returning to his native land. He therefore proposed that a certain gallant and dashing officer, attache to the Legation, should be instructed to call and converse with me once a week. "No remuneration, of course," he added, "must be offered to the gallant captain." "But suppose," I said feebly, "the captain doesn't care about the job; it seems a little awkward, doesn't it?" "Oh no," said the Consul, exultant; "when he hears it is by the orders of X., he won't dare refuse." As I am not a character in one of Mr. Anthony Hope's novels, but merely live in a London suburb, I thanked everybody and retired upon a small grammar, dazzled by the fierce light that my inquiries had shed upon the workings of this Balkan State, and wondering if all the others were equally ready to loan out Ministers and attaches to unknown foreigners.

There is a childish simplicity about the conversation of the up-country peasant folk that is quite charming. They are as pleased with a stranger who will talk to them as is a child with a kitten that will run after a string, and, like children, they have no scruples about asking what in a more "grown-up" state of society would be considered indiscreet questions, including even the state of one's inside. The women begin the conversation and retail the details to their lords and masters, who, burning with curiosity, stand aloof with great dignity for a little while, and end by crowding out the women altogether. Neither men nor women have the vaguest idea whence I come nor to what manner of life I am accustomed. When they learn that I have come in a train and a steamboat, their amazement is unbounded. That I come from a far countrie that is full of gold is obvious. "And thou hast come so far to see us? Bravo!" Much patting on the back, and sometimes an affectionate squeeze from an enthusiastic lady, who at once informs the men that I am very thin and very hard. "Bravo! thou art brave. Art married?" "No." Great excitement and much whispering. "Wait, wait," says a woman, and she shouts "Milosh! Milosh!" at the top of her voice. Milosh edges his way through the crowd. He is a tall, sun-tanned thing of about eighteen years, with the eyes of a startled stag. His mother stands on tiptoe and whispers in his ear that this is a chance not to be lightly thrown away. A broad smile spreads over Milosh's face. He looks coy, and twiddles his fingers. "Ask her! ask her!" say the ladies encouragingly. "Ask her!" say the men. Milosh plucks up courage, thumps his chest and blurts out, "Wilt thou have me?" "No, thank you," I say, laughing; and Milosh retires amid the jeers of his friends, but really much relieved. "Milosh, thou art not beautiful enough," say the men; and they suggest one Gavro as being more likely to please. Gavro takes Milosh's place with great alacrity, and the same ceremony is repeated. The crowd enjoys itself vastly, and tries to fit me out with a really handsome specimen. I glance round, and my eye is momentarily caught by a very goodly youth. "No! no! he's mine, he's mine!" cries a woman, who seizes him by the arm, and he is hastily withdrawn from competition amid shouts of laughter. "I have no money," says one youth frankly, "but thou hast perhaps enough." "And he is good and beautiful," say his friends. For they are all cheerfully aware that their faces are their only fortunes. There is a barbaric simplicity and a lack of any attempt at romance about the proposed arrangements which is exquisitely funny, for they are far too honest to pretend that I possess any attractions beyond my supposed wealth. I have often wondered what the crowd would do if I accepted someone temporarily, but have never dared try. Five offers in twenty minutes is about my highest record.

But all these are country amusements. Cetinje is far too civilised a city to indulge in them, and to "see Montenegro" we must wander much farther afield.

Travelling in Montenegro—in fine weather, be it said—is delightful from start to finish. And to Shan, my Albanian driver, whose care, fidelity, and good nature have added greatly to the success of many of my tours, I owe a passing tribute. He is short and dark, a somewhat mixed specimen of his race, and hails from near the borders, where folk are apt to be so mixed that it is hard to tell which is the true type. Careful of his three little horses, and always ready in an emergency, he yet preserves the gay, inconsequent nature of a very young child. His veneer of civilisation causes him to assume for short intervals an appearance of great stiffness and dignity, but it melts suddenly, and his natural spirits bubble through. Thus, at an inn door before foreigners, he is stately, but in the kitchen to which I have been invited to accompany him, he waves his arms wildly and performs a war dance, chaffs the ladies, and makes himself highly agreeable. His tastes are simple and easily satisfied. I have stood him several treats of his own selection, and they usually cost about fourpence. One was an immense liver which was toasted for him in hot wood ashes, and which he consumed along with a whole loaf of bread—whereupon he expressed himself as feeling much better. His generosity is unfailing; at the top of a pass, in a heavy storm of sleet, he offered me the greatcoat he was wearing, and he is always ready to help a distressed wayfarer. One awful evening, when the rain was falling in torrents and it was rapidly growing dark, we were hailed, between Rijeka and Cetinje, by a man in distress. A sheep, his only one, which he was driving up to Cetinje, had fallen, wet and exhausted, by the roadside, and he knew not what to do. Shan was greatly concerned. He explained to me that the man was very poor, the sheep very tired and also that the sheep was a very little one, then he took it in his arms like a baby and arranged it on the box, where it cuddled up against him for warmth, and, through wind, rain, and the blackest night I have ever been out in, he drove three horses abreast, held up an umbrella, nursed the sheep, and sang songs till we arrived safely at our journey's end.

Acting on the principle of "Do as you would be done by," when his pouch is full, he distributes tobacco lavishly along the route with a fine "Damn-the-expense" air which one cannot but admire, and when not a shred remains, he begs it, quite shamelessly, of everyone he meets. When I first made his acquaintance, his appearance puzzled me. Learning that he was an Albanian, I remarked upon the fact to him; he immediately crossed himself hastily. "Yes, an Albanian," he admitted, "but Cattolici, Cattolici," and he added as an extra attraction, "and I came to Montenegro when I was very little." He persists in regarding me as a co-religionist; for the fact that I am neither Orthodox nor Mohammedan is to him quite sufficient proof. His Catholicism is quite original. Unlike most Catholic Albanians, who display a horror of the Orthodox Church, he is most pressing in his attentions to the Orthodox priests, and will never, if he can help it, be left out of a circle of conversation that includes one. One Easter Day I saw him persist in kissing, in Orthodox fashion, the village priest, who having more than enough osculation to go through with his own flock, did his best to dodge him, but was loudly smacked upon the back of the neck. His views upon doctrinal points are mixed, but his simple creed has taught him faith, hope, and charity "which is the greatest of the three."

Withal he is a bit of a buck, and likes to cut a dash in what he considers large towns. He strolls in when I am having dinner and converses with the company at large; he makes me a flowery speech—he is my servant; it is mine to command and his to obey; whatever I order he will carry out with pleasure. When he learns that I shall not require him till to-morrow, he beams all over his sun-tanned face. Then he fidgets and makes pointless remarks. I do not help him. He strolls with elaborate carelessness behind my chair and whispers hurriedly that towns are very expensive, and if I would only advance him a florin or two of his pay—I supply the needful, and later I meet him, a happy man, playing the duke among a crowd of friends, to all of whom he introduces me with great style and elegance. But his dissipations are very mild, though from the swagger he puts on you would think they were bold and bad. I have never seen him the worse for drink, and he is punctuality itself and very honest. Child of the race with about the worst reputation in Europe though he is, I would trust him under most circumstances.

Leaving Cetinje by its only road, we soon reach the top of the pass, and a sudden turn reveals the land beyond. We have come across Europe to the edge of Christianity, and stand on the rocky fortress with the enemy in sight. The white road serpentines down the mountain side, and far below lies the green valley and its tiny village, Dobrsko Selo; on all sides rise the crags wild and majestic; away in the distance gleams the great silver lake of Skodra. Beyond it the blue Albanian mountains, their peaks glittering with snow even in June, show fainter and fainter, and the land of mystery and the unspeakable Turk fades into the sky—a scene so magnificent and so impressive that it is worth all the journey from England just to have looked at it.

We cast loose our third horse, and rattle all the way down to Rijeka, skimming along the mountain side and swinging round the zigzags on a road that it takes barely two hours to descend and quite three to climb up again; for Cetinje lies 1900 feet above the sea, and Rijeka not much more than 200 feet.

Rijeka means a stream, and the town so called is a cluster of most picturesque, half-wooden houses, facing green trees and a ripple of running water and backed by the mountain side—as pretty a place as one need wish to see. The stream's full name is Rijeka Crnoievicheva, the River of Crnoievich, but for everyday use town and river are simply Rijeka. But its full name must not be forgotten, for it keeps alive the fame of Ivan Beg Crnoievich, who ruled in the latter half of the fifteenth century, in the days when Montenegro's worst troubles were beginning. Unable to hold the plains of the Zeta against the Turk, Ivan gathered his men together, burnt his old capital, Zabljak, near the head of the lake, retired into the mountains, and founded Cetinje in 1484. He built a castle above Rijeka as a defence to his new frontier, and swore to hold the Black Mountain against all comers. But he meant his people to grow as a nation worthily, and not to degenerate into a horde of barbarians. He founded the monastery at Cetinje, appointed a bishop and built churches. And—for he was quite abreast of his times—he sent to Venice for type and started a printing press at Rijeka. In spite of the difficulties and dangers that beset the Montenegrins, they printed their first book little more than twenty years later than Caxton printed his at Westminster. Ivan is not dead, but sleeps on the hill above Rijeka, and he will one day awake and lead his people to victory. The printing press was burned by the Turks, and the books which issued from it—fine specimens of the printer's art—are rare.

The stream Rijeka is a very short one. It rises in some curious caverns not much farther up the valley, and flows into the lake of Skodra. The town is built of cranky little houses, half Turkish in style, with open wooden galleries painted green—gimcrack affairs, that look as though they might come down with a run any minute, when filled as they frequently are with a party of heavy men. It has an old-world look, but, as most of the town was burnt by the Turks in 1862, appearances are deceptive. A perfect Bond Street of shops faces the river. Here you can buy at a cheap rate all the necessaries of Montenegrin existence. In the baker's shop the large round flat loaves of bread, very like those dug up at Pompeii, are neatly covered with a white cloth to keep off the flies.

Plenty of tobacco is grown in the neighbourhood. In the autumn the cottages are festooned with the big leaves drying in the sun, and you may see Albanians, sitting on their doorsteps, shredding up the fragrant weed with a sharp knife into long, very fine strips till it looks like a bunch of hair, shearing through a large pile swiftly, with machine—like regularity and precision. Tobacco is a cheap luxury, and I am told Montenegrin tobacco is good. Almost every man in Montenegro smokes from morning till night, generally rolling up the next cigarette before the last is finished.

The town possesses a burgomaster, a post-office, a steamboat office, a Palace, and an inn, which provides a good dinner on market days. It is a clean, prosperous, friendly, and very simple-minded place—I did not realise how simple-minded till I spent an afternoon sitting on the wall by the river, drawing the baker's shop, with some twenty Montenegrins sitting round in a crimson and blue semicircle. It was in the days when I knew nothing of the language, and the Boer War was as yet unfinished. I drew, and my friend talked. A youth in Western garb acted as interpreter. He ascertained whence we had come, and then remarked airily, "Now, I come from Hungary, and I am walking to the Transvaal. This man," pointing out a fine young Montenegrin, "is coming with me!" Stumbling, voluble and excited, in very broken German, he unfolded their crazy plan. They were both brave men and exceedingly rich. "I have two thousand florins, and a hundred more or less makes no difference to him," kept cropping up like the burden of a song. Their families had wept and prayed, but had failed to turn them from their purpose. They were going to walk to the Transvaal. "But you can't," we said. He was hurt. "Of course not all the way," he knew that. They had meant to walk across Albania to Salonika, but the Consul at Skodra had put a stop to this dangerous scheme. Now they were going by sea from Cattaro to Alexandria, and thence, also by sea, to Lorenzo Marques. After this, they should "walk to the Transvaal." "Why don't you walk from Alexandria?" we asked. He answered quite seriously that they had thought of this, but they had been told there was a tribe of Arabs in the centre of Africa even more ferocious than the Albanians, so, though they were of course very brave men, they thought on the whole they preferred the boat. When they arrived, they meant to fight on whichever side appeared likely to win, and then they were going to pick up gold. We thought it our duty to try and dissuade them from their wild-goose chase, but our efforts were treated with scorn. "What can you do? You speak very little German, and your friend nothing but Servian." "No, he doesn't," said the Hungarian indignantly. "He speaks Albanian very well, and I—I know many languages. I speak Servian and Hungarian." The idea that a place existed where no one spoke these well-known tongues was to him most ridiculous, and the Montenegrin, to whom it was imparted, smiled incredulously. We urged the price of living and the cost of Machinery required in gold-mining. The first he did not believe; the second he thought very silly. The gold was there, and he was not such a fool as to require a machine with which to pick it up.

The Montenegrin, who had been bursting with a question for the last quarter of an hour, insisted on its being put. "Could he buy a good revolver in Johannesburg?" He waited anxiously for a reply. "You see," explained the Hungarian, "he must leave his in Montenegro." "But why? It looks a very good one." The Montenegrin patted his weapon lovingly; he only wished he could take it, it would be most useful, but ... in order to reach the boat at Cattaro he must cross Austrian territory, and you are not allowed to carry firearms in Austria! He shook his head dolefully when we said that permission could surely be obtained. "No, this was quite impossible; under no circumstances could it be managed. You don't know what the Austrians are!" said the Hungarian mysteriously. The unknown land, the unknown tongues, the British, the Boers, the rumble-tumble ocean and the perils of the deep were all as nothing beside the difficulty of crossing the one narrow strip of Austrian land. We told him revolvers were plentiful in Johannesburg, and the prospect of finding home comforts cheered him greatly. We parted the best of friends.

From Rijeka the road rises rapidly again, and strikes over the hills, winding through wild and very sparsely inhabited country. The mountain range ends abruptly, and we see the broad plains stretching away below us, with the white town of Podgoritza in the midst of it. The plain is very obviously the bed of the now shrunken lake of Skodra, and the water-worn pebbles are covered with but a thin layer of soil. But both maize and tobacco seem to do well upon it, and every year more land is taken into cultivation. The rough land is covered with wiry turf and low bushes, and swarms with tortoises which graze deliberately by the roadside. The river Moracha has cut itself a deep chasm in the loose soil between us and the town, and tears along in blue-green swirls and eddies. We have to overshoot the town to find the bridge, and we clatter into Podgoritza six or seven hours after leaving Cetinje, according to the weather and the state of the road.

Podgoritza is the biggest town in Montenegro, and has between five and six thousand inhabitants. It is well situated for a trading centre, for it is midway between Cetinje and Nikshitje, and is joined by a good road to Plavnitza, on the lake of Scutari, so is in regular steamboat communication with Skodra and with Antivari via Virbazar. Its position has always given it some importance. As a Turkish garrison town it was a convenient centre from which to invade Montenegro; to the Montenegrin it was part of his birthright—part of the ancient kingdom of Servia—and as such to be wrested from the enemy. It was the brutal massacre of twenty Montenegrins in and near the town in time of peace (October 1874) that decided the Montenegrins to support the Herzegovinian insurrection and declare war. Podgoritza was besieged and taken in October 1876. The walls of the old town were blown to pieces with guns taken from the Turks at Medun, and an entirely new town has since sprung up on the opposite side of the stream Ribnitza. Podgoritza (= "At the Foot of the Mountain"), if you have come straight from the West, is as amusing a place as you need wish to visit. It has not so many show places as Cetinje even, and its charm is quite undefinable. It consists in its varied human crowd, its young barbarians all at play, its ideas that date from the world's well—springs, subtly intermingled with Manchester cottons, lemonade in glass-ball-stoppered bottles, and other blessings of an enlightened present. The currents from the East and the West meet here, the old world and the new; and those to whom the spectacle is of interest, may sit upon the bridge and watch the old order changing.

The Montenegrin town of Podgoritza is clean and bright. The long wide main street of white stone, red-roofed shops with their gay wares, and the large open market square where the weekly bazaar is held, are full of life. Both street and market-place are planted with little trees, acacias and white mulberries; and the bright green foliage, the white road, the red roofs, the green shutters, the variety of costume, make an attractive scene in the blaze of the Southern sun. Across the gold-brown plain rise the blue mountains where lies that invisible line the frontier. The slim minarets of the old Turkish town shoot up and shimmer white on sky and mountain; the river Ribnitza flows between the old town and the new, and over the bridge passes an endless stream of strange folk, the villagers of the plain and the half-wild natives of the Albanian mountains passing from the world of the Middle Ages to a place which feels, however faintly, the forces of the twentieth century. Bullock carts, with two huge wheels and basket-work tops, trail slowly past, groaning and screeching on their ungreased axles. Look well at the carts, for our own forefathers used them in the eleventh century, and they appear in the Harleian MSS.

Everything moves slowly. All day long folk draw water from the stone-topped well on the open space between the old town and the new—draw it slowly and laboriously, for there is no windlass or other labour-saving contrivance, and the water is pulled up in a canvas bag tied to a string. Three or four bagfuls go to one bucket.

In spite of the fact that Podgoritza is the centre of the Anglo-Montenegrin Trading Company and deals in Manchester cottons, the day seems distant when it will lose its other simple habits. I was walking one day down the "High Street" with a friend, when a young Albanian went to call on his tailor. He came out presently with a fine new pair of the tight white trousers that his clan affects. He exhibited them in the middle of the road to two or three friends, and they were all evidently much struck with the make and embroidery. If the garments were so charming "off," what would they be "on"! The whole party hurried across to the shop door of the happy purchaser, and such an alarming unbuckling and untying began to take place that we! discreetly went for a little walk. On our return the transfer had been effected. Two friends were grasping the garment by the front and back, and the wearer was being energetically jigged and shaken into it. This was a tough job, for it was skin-tight. The legs were then hooked-and-eyed up the back, and presently the youth was strutting down the middle of the road stiff-kneed and elegant, with the admiring eyes of Podgoritza upon him, and a ridiculously self-conscious smile.

Wandering gipsy tribes turn up here, too; mysterious roving gangs, their scant possessions, tin pots and tent poles, piled on ponies; their children, often as naked as they were born, perched on top of the load. They have no abiding place; impelled by a primeval instinct, they pass on eternally. Extraordinarily handsome savages some of them are, too. I have seen them on the march—the men in front, three abreast, swinging along like panthers; half stripped, clad in dirty white breeches and cartridges; making up with firearms for deficiency in shirts, and carrying, each man, in addition to his rifle, a long sheath knife and a pistol in his red sash, their matted coal-black locks falling down to their beady, glittering black eyes, which watch you like a cat's, without ever looking you straight in the face. Their white teeth and the brass cases of the cartridges sparkling against their swarthy skins, they passed with their heads held high on their sinewy throats with an air of fierce and sullen independence. Behind follow the boys, women, and children, with all their worldly goods; golden-brown women with scarlet lips and dazzling teeth, their hair hanging in a thick black plait on either side of the face, like that of the ladies of ancient Egypt; holding themselves like queens, and, unlike their lords and masters, smiling very good-naturedly. So entirely do they appear to belong to an unknown, untamed past, that I was astonished when one of them, a splendid girl in tawny orange and crimson, addressed me in fluent Italian outside the Podgoritza inn. "I am a gipsy. Are you Italian?" Italy was her only idea of a foreign land, and England quite unknown to her. She hazarded a guess that it was far off, and imparted the information to a little crowd of Albanian and Montenegrin boys who were hanging around. When the servant of the inn thought the crowd too large, he came out to scatter it. The boys fled precipitately; the girl stood her ground firmly, as one conscious of right, and told him what she thought of him volubly and fiercely, her eyes flashing the while. He retired discomfited, and she informed us superbly, "I told him the ladies wished to speak to me!" Unlike the Montenegrins, she understood at once that we were merely travelling for travelling's sake, and regarded it as perfectly natural. She retired gracefully when she had learnt what she wished to know.

The Montenegrin and Albanian gipsies are mostly Mohammedans, and what is vaguely described as Pagan. They seldom or never, it is said, intermarry with the people among whom they wander, but keep themselves entirely to themselves. One day the old quarter of Podgoritza was agog with a Mohammedan gipsy wedding. From across the river we heard the monotonous rhythmic pulsation of a tambourine, and at intervals the long-drawn Oriental yowl that means music. We strolled down to the bridge and joined the very motley collection of sight-seers. Gay and filthy, they gathered round us, and enjoyed at once the spectacle of two foreigners of unknown origin and the festivity which was going on in the back garden hard by. It could hardly be called a garden, it was the yard of a squalid little hovel backing on the river, and was filled with women in gorgeous raiment walking backwards and forwards in rows that met and swayed apart, singing a long howling chant, while the pom-pom and metallic jingle of the tambourine sounded over the voices with mechanical regularity. Presently all fell aside and left a space, into which leapt a dancing-girl, a mass of white silk gauze with a golden zouave and belt and a dangling coin head-dress. She wreathed her arms gracefully over her head and danced a complicated pas-seul with great aplomb and certainty, her white draperies swirling round her and her gold embroideries flashing in the sunlight. When she ceased, the party withdrew into the dirty little hut, and as we were now the whole attraction to the obviously verminous crowd we withdrew also. The hut was the headquarters of the bridegroom, and this was a preliminary entertainment. Next morning, four carriages dashed into the town at once, bringing the bride and her escort from Skodra in Albania. The horses' heads were decorated with gaily embroidered muslin handkerchiefs, and the bride's carriage was closely curtained and veiled. The amount of men and weapons that poured out of the other vehicles was astounding. When three carriages had unloaded, the bride's carriage drove up close to the entrance of the yard in which the hut stood, and the men made a long tunnel from door to door by holding up white sheets; down this the bride fled safe and invisible, while curiosity devoured the spectators on the bridge. Every window in the hut was already shuttered and barred, and we thought there was no more to be seen.

But our presence had been already noted. A commotion arose among the men at the door of the hovel. A young Montenegrin onlooker came up, pulled together all his foreign vocabulary and stammeringly explained, "They wish you to go into their house." All the men in the crowd were consumed with curiosity about the hidden bride, and obviously envied us the invitation. We hesitated to plunge into the filthy hole. We didn't hesitate long, though. The bride and her friends meant to show off their finery to the foreigners; a dark swagger fellow who would take no denial was sent out to fetch us, and we followed our escort obediently to the cottage door. We paused a half-second on the doorstep; it looked bad inside, but it was too late to go back. A passage was cleft for us immediately, and we found ourselves in a long low room with a mud floor—a noisome, squalid den in which one would not stable an English donkey. There was no light except what came through the small door and the chinks. It was packed with men; their beady, bright eyes and silver weapons glittered, the only sparks of brightness in the gloom.

As my eyes got accustomed to the subdued light, I saw in the corner a huge caldron of chunks of most unpleasant-looking boiled mutton, with floating isles of fat, and my heart sank at the thought that perhaps our invitation included the wedding breakfast. The men guarding the door of the inner apartment parted, and we went in. No man, save the bridegroom, entered here. It was a tiny hole of a room, but its dirty stone walls were ablaze with glittering golden embroideries and it was lighted by oil lamps. The floor was covered with women squatting close together, their brown faces, all unveiled, showing very dark against their gorgeous barbaric costumes. It was a fierce jostle of colours—patches of scarlet, orange, purple and white, mellowed and harmonised by the lavish use of gold over all, coin head-dresses, necklaces, and girdles in reckless profusion. In the light of common day it would doubtless resolve itself into copper-gilt and glass jewels, but by lamplight it was all that could be desired. On a chair, the only one in the room, with her back to the partition wall, so as to be quite invisible to the men in the next room, sat the bride, upright, motionless, rigid like an Eastern idol. Her hands lay in her lap, her clothes were stiff with gold, and she was covered down to the knees with a thick purple and gold veil. There she has to sit without moving all day. She may not even, I am told, feed herself, but what nourishment she is allowed is given her under the veil by one of the other ladies. At her feet, cross-legged on the ground, sat the bridegroom, who I believe had not yet seen her—quite the most decorative bridegroom I ever saw, a good-looking fellow of about five-and-twenty, whose black and white Albanian garments, tight-fitting, showed him off effectively, while the arsenal of fancy weapons in his sash gave him the required touch of savagery. He gazed fixedly at the purple veil, endeavouring vainly to penetrate its mysteries, and, considering the trying circumstances in which he was placed, seemed to be displaying a good deal of fortitude. The air was heavy with scented pastilles, otherwise the human reek must have been unbearable.

Everyone began to talk at once, and it was evident from their nods and smiles that we had done the correct thing in coming. Unfortunately we couldn't understand a word, but we bowed to everyone, repeated our thanks, and tried to express our wonder and admiration. Whether we were intended to stay or not I do not know, but, haunted by a desire to escape with as small a collection of vermin as possible, and also to evade the chunks of mutton in the caldron, we backed our way, bowing, into the outer room after a few minutes, and were politely escorted to the entrance. Judging by the smiles and bows of everyone, our visit gave great satisfaction. After we left, the doors were shut, and there was a long lull, during which the mutton was probably consumed. If so, we escaped only just in time. In the afternoon the tambourines and sing-songs started again, and far into the night the long-drawn yowls of the epithalamium came down the wind.

In spite of the mixed Christian and Mohammedan population, excellent order is maintained. The more I see of the Montenegrin, the more I am struck with his power of keeping order. It is a favourite joke against him that when he asks for a job and is questioned as to his capabilities, he replies that he is prepared to "superintend," and it turns out that he is unable to do anything else. But not even our own policeman can perform the said "superintending" more quietly and efficiently. To the traveller the Mohammedan is very friendly. The attempt of a man to draw or photograph a woman is an insult which is not readily forgiven and may lead to serious consequences, but as long as one conforms to local customs these people are as kindly as one could wish, and not by a long way so black as they have often been painted. As a matter of fact a large proportion of the rows that occur all over the world between different nationalities arise from someone's indiscreet attentions to someone else's girl. And this is why a lady travelling alone almost always has a friendly welcome, for on this point at any rate she is above suspicion.

The Orthodox Montenegrin is equally anxious to make one feel at home. At Easter-tide, when the whole town was greeting each other and giving pink eggs, we were not left out. "Krsti uskrshnio je" ("Christ has risen") is the greeting, to which one must reply, "Truly He has risen," accepting the egg. People go from house to house, and eggs stand ready on the table for the visitors, who kiss the master and mistress of the house three times in the name of the Trinity. Montenegrin kisses—I speak merely as an onlooker—are extremely hearty. It is surprising what a number they get through on such a festival. For four days does the Easter holiday last.

Montenegrins take their holidays quietly. It used to be said of the Englishman that he takes his pleasures sadly. But that was before the evolution of the race culminated in 'Any and 'Arriet. The Montenegrin has not yet reached this pitch of civilisation. I wonder whether he inevitably must, and if so, whether what he will gain will at all compensate for what he must lose. For civilisation, as at present understood, purchases luxuries at the price of physical deterioration. High living is by no means always accompanied by high thinking, and ... the end of it the future must show. When the Montenegrin has learnt what a number of things he cannot possibly do without, let us hope he will be in some way the better. It is certain he will be in many ways the worse.

Things Christian lie on one side of the Ribnitza, and things Mohammedan on the other. The Turkish graveyard lies out beyond the old town, forlorn and melancholy as they mostly are. The burial-ground of the Orthodox is on the Montenegrin side of the town. The dead are borne to the grave in an open coffin, and the waxen face of the corpse is visible. The coffin-lid is carried next in the procession. I was told that this curious custom originated in the fact that sham funerals were used when the Balkan provinces were under Turkish rule as a means of smuggling arms. But I doubt this tale. For the custom used to prevail in Italy, and does still, I believe, in Spain. It is, in all probability, much older than the Turks, and a tradition that dates from the days when burning and not burial was the usual way of disposing of the dead and the body was carried to the funeral pyre upon a bier. The open coffin, the funeral songs, and the commemorative feasts annually held on the graves by many of the South Slavs, the lights and incense burnt upon the graves, and the lighted candles carried in the funeral processions together reproduce, with extraordinary fidelity, the rites and ceremonies of the Romans. And how much older they may be we know not.

I have driven the road many a time since, and I have been again to Ostrog, but I shall never forget that day three years ago when I went there for the first time. It was the only part of that journey about which our advisers said we should find no difficulty; "foreign languages" were spoken, and there would be no trouble about accommodation. We started from Podgoritza early and in high spirits.

The valley of the Zeta is green and well cultivated. It narrows as we ascend it, and an isolated hill crowned with the ruins of a Turkish fortress stands up commandingly in the middle. This is the "bloody" Spuzh of the ballads, the stronghold that guarded the former Turkish frontier. Montenegro at this point was barely fifteen miles across, and Spuzh and Nikshitje gripped it on either hand. From being a border town with an exciting existence Spuzh has subsided into an unimportant village. Danilovgrad, on the other hand, a few miles farther on, a town founded in memory of the late Prince, is full of life, and though a bit rudimentary at present, shows signs of soon becoming large and flourishing. It is possible now to drive right up to the lower monastery of Ostrog by a fine new road, but this did not yet exist on my first visit, and we pulled up at Bogatich—a poverty-stricken collection of huts and a tiny church. A tall, lean, sad-eyed Montenegrin, with his left arm in a sling, came out of the little "han" to greet us, bringing with him a strong whiff of carbolic. They were a melancholy little household. His wife, who brought water for our reeking horses, had had her right arm taken off an inch or two below the elbow, and carried the bucket horribly in the crook of the stump. They cheered up when they heard we wanted a guide to the monastery, and called their daughter from the shed for the purpose.

She came out, a shy, wild-looking thing of about fifteen, barefooted, her knitting in her hands, accepted the job at once, tied our two hand-bags on her back with a bit of cord, and we started up in search of the unknown, armed with a leg of cold mutton, a loaf of black bread, a sketch-book, and a flask of brandy.

It was midday, and almost midsummer; the air was heavy with thunder, and no breath of a breeze stirred as we scrambled up the loose stones. The girl snorted loudly like a pig, to show us the way we should go, and took us, in true Montenegrin fashion, straight up from point to point without heeding the zigzags of the horse-track except where the steepness of the rock compelled her. The way soon became steeper and steeper, in fact a mere rock scramble, and it was abominably hot; and when suddenly our plucky little guide, who had as yet shown no signs of fatigue, gave out all her breath with a long whistle and pointed to the nearest patch of shade, we gladly called a halt. The great advantage of a girl-guide is that she takes you to the right place and you can rest on the way. Little boys as a general rule are vague and inconsequent; they pick up crowds of friends en route, even in the most desolate and apparently uninhabited spots, and you don't generally arrive at your destination. Either they don't know the way, or they conduct you to another spot, for reasons of their own.

We sat with our girl, and made futile attempts to converse with her. It was a wild, lonely spot, and save the rough track worn by generations of pilgrims, as rugged as it was created. Great grey limestone rocks arose around us, with sturdy young trees sprouting in the crannies; a small grey snake wound its way over the sunbaked stones, and a tortoise scrambled about the grass alongside. The valley shimmered in a hot haze far below, and beyond towered the bare crags of the opposite mountains. We seemed a very long way from anywhere. Appearances were however deceptive, as a short scramble brought us to a wall, a gateway, and some buildings. The girl seemed to think we had now arrived, and we imagined that we were about to find the guest-house where French, Italian, and German were spoken. We passed through the gateway on to a long wide shelf on the mountain side, 1900 feet above the sea. Two or three very poor cottages stood at the entrance, and at the farther end a tiny church, crudely painted with a maroon dado of geometrical patterns, and three small houses all apparently shut up and uninhabited. Not a soul was to be seen. The girl went into one of the cottages and fetched a tin pot of cold water, which we all drank greedily, seeing which the cottage woman came out and supplied us with as much as we required, and gave us a bench to sit on. She was mildly concerned at our appearance, for we had sweated all through our shirts, and the girl had left a black hand-print on my back, but she spoke no word of any other language but her own, and speedily retired again to her cottage. We sat on the bench and pondered, feeling very forlorn. If this were Ostrog, as the girl assured us with vigorous nods, it was not worth the roasting scramble. We were miserably disappointed, but decided that, as we had come to see Ostrog, we would see it properly, and that, if there were any inhabitants, they had not finished the midday siesta. We squeezed into a patch of shadow and cut up the mutton and black bread with a pocket-knife; the girl gladly assisted, and ate like a wolf, bolting large chunks with great appetite. There was quite a cheery lot of brandy in the flask, and as we carefully packed up the remains of the meal, in case of a siege, we felt very much better.

Then down the wide white path from the houses came a man, an old, old man in Western garb. He tottered up, and we hailed him in all our known languages; French and Italian failed, but he responded to German, and started at once on his own autobiography. He was an old soldier, he had fought under Karageorgevich. Now he had retired here to end his days. "They" had sent him here, and "they" had made him dig his grave. It was waiting for him on the mountain side. He was very lonely, and had no one to talk to. As soon as we could stem the torrent of his remarks, we asked him about quarters for the night. "Had we an introduction from the Archimandrite at Cetinje?" "No?" Then we had better go back where we had come from, and we had better start at once, if we meant to get to Nikshitje that night. We were appalled. He repeated obstinately, "You must go, and if you take my advice, you will go at once. I can do nothing for you. They," he admitted mysteriously, "cannot bear me. It is useless for me to ask them. They can speak nothing but Servian, and you will not be able to make them understand. They would have to send for me. Moreover, they are asleep." He pointed to "their" house. We asked when "they" were likely to wake up again, and he said it would be in about an hour's time. We doubted his statements, for his air was very malevolent, so as our little maiden was already coiled up on the ground fast asleep, we thought it would be just as well to rest until "they" could be appealed to. The old gentleman "who had no one to talk to" went off and indulged in an animated conversation with the cottage woman, while we dozed under a tree. When we aroused ourselves again, not much rested, we saw the shutters of "their" house were now open, so we marched up to the front door, knocked, and awaited results tremulously.

Nothing happened; we knocked a second time, and fled down the steps. Immediately the door flew open, and there was the Archimandrite of Ostrog himself, in long black gown, crimson sash, and high velvet hat—a little old man whose thin iron-grey locks flowed on his shoulders. He came rushing down the steps and shook us by the hands, saying, "Dobar dan, dobar dan" (good-day), as heartily as though he had been expecting us and we had come at last. We said, "Dobar dan," also, with enthusiasm, and then the conversation came to an abrupt conclusion. He showed us with great ceremony into his sitting-room, and made us sit on the sofa, while he sat opposite on a chair. We felt acutely uncomfortable—not one single word of English, French, German, or Italian did the good man know. We made him understand that we had come from England, which amazed him, and that we had walked from Bogatich. Then we stuck hopelessly and helplessly, while he, undaunted, went on in his native language. It seemed as if our climb to Ostrog had failed, and that flight was all that was left for us. We got up and said "good-bye" politely. Our departure he would by no means permit. "Sjedite, sjedite!" he cried, waving us back to the sofa, and down we sat again, feeling much worse. A Montenegrin about six feet four inches in height, clad in a huge brown overcoat, answered his summoning bell, and presently returned with two glasses of cold water on a brass tray which he offered to us ceremoniously, towering over us and watching us with lofty toleration, as a big dog does a little one. He waited patiently until we had drunk every drop, collected the glasses, and silently retired from the room backwards.

A horrible silence ensued. We took out our watches and showed them to each other, in hopes that the Archimandrite would then understand that our time was really up. But no. A fearful wrestle with the language followed, and lasted till the Big-Dog Montenegrin reappeared, this time with two cups of coffee. We obediently began to consume this, and the Archimandrite, despairing of ever making us understand single-handed, instructed his servant to fetch the gentleman-who-spoke-German. Through him we were at once informed that the Archimandrite offered us hospitality for the night in the house over the way. We were much amazed, and accepted gratefully. With apologies, he then inquired if we were married, and hastened to assure us that there was no disgrace attached to the fact that we were not. We were slightly dismayed when we were told we now had the Archimandrite's gracious permission to visit the shrine, and that we were to start at once.

We were put upon the right track and left to our own devices. We had been up since five, and had only had a scrappy, unhappy doze under the tree, so we told each other we would go to sleep on the first piece of ground that was flat enough. Having zigzagged up some way through the wood, we lay down on a piece of grass, and should have been asleep in a minute had not two natives appeared, an old man and a handsome lad. They seemed much interested and concerned. I merely said it was very hot, and hoped it would be enough for them. Not a bit of it. They started an argument. I said I didn't speak the language, so they shouted to make it clearer, and kept pointing up the path. What they meant I did not know. It was evident, though, that the Handsome Lad did not mean to be trifled with. He squatted alongside of us and shouted in my ear, while the old man sat down and showed signs of staying as long as we did. So we wearily started upwards again, and the Montenegrins, delighted at having made us understand, went their way much pleased with their own cleverness. We dared not rest again, and soon reached the upper monastery of Ostrog, which was so strange and unexpected that the sight of it did away with all thoughts of fatigue at once.

The path ended on a terrace cut in the rock 2500 feet above the sea. The small guest-house stood against the mountain side, and a flight of newly made steps led up through a stone doorway to a series of caverns in the cliff face, cunningly built in and walled up to form tiny rooms, which cling to the rock like swallows' nests. The big natural arch of rock that overshadows them all is grimed with the dead black of smoke, and two great white crosses painted on the cliff mark the shrine. Straight above rises the almost perpendicular wall of bare rock, and far below lies the valley. This is the eagle eyrie that, in 1862, Mirko Petrovich, the Princes father, and twenty-eight men held for eight days against the Turkish army of, it is said, ten thousand men. The Turks tried vainly to shell the tiny stronghold, and even a determined attempt to smoke out the gallant band failed. Mirko and his men, when they had used all their ammunition and had rolled down rocks upon the enemy, succeeded in escaping over the mountains, under cover of night, and reached Rijeka with the loss of one man only. It is a tale which yet brings the light of battle to the eyes of the Montenegrin and sends his fingers to caress the butt of his revolver, and must be heard from Montenegrin lips to be appreciated. A hundred years before, thirty men held this same cavern against an army, and wild as these tales sound, the first glance at the place forces belief. Twice only have the Turks succeeded in occupying it. Once after Mirko and his men left it, and once in 1877, when Suleiman Pasha held it, sent the proud message to Constantinople that he had conquered Montenegro and that it was time to appoint a Turkish governor—and was soon in hot retreat to Spuzh, losing half his men on the way. The lower monastery has, on the other hand, been burnt and rebuilt some ten times.

We sat and stared at the scene of these wild doings. The black, smoke-grimed cavern told of the fierce struggle, and the great white cross of the holy man whose body rests within. Sveti Vasili (St. Basil), a local saint, was, early in the eighteenth century, Metropolitan of the Herzegovina. In his old age he sought refuge in the mountains from Turkish persecution, and passed his last days in this remote cavern cared for and reverenced by the Christian peasants. Shortly after his death they scooped out the rock and formed and dedicated to him the tiny chapel where his body still rests. His shrine is held in the profoundest veneration, and on Trinity Sunday (O.S.) pilgrims flock thither in thousands, tramping on foot from Bosnia, the Herzegovina, from Albania, even from the uttermost corners of the Balkan peninsula—a wonderful and most impressive sight. Not Christians alone but also Mohammedans come to the shrine of St. Vasili of Ostrog, for "four hundred years of apostasy have not obliterated among the Bosnian Mussulmans a sort of superstitious trust in the efficacy of the faith of their fathers," and they come in hopes of help to the shrine of the man who suffered for it. And so also do those strange folk, the Mohammedan Albanians. I have passed the night up there in pilgrimage-time, when the mountain side was a great camp and the greater part of the pilgrims slept by watch fires under the stars; but in spite of the mixed nationalities and the difference of religion, perfect order prevailed, and I saw many acts of friendliness and consideration between folk from very different parts.

The precious relics have always been removed in times of danger, and saved from the fate of those of the Servian St. Sava, which were publicly burned by the Turks. They were, of course, removed during the last war. The coffin is not a weighty one and the soldiers were strong, but it became so heavy as they were carrying it down the valley that they knew not what to do. This they took as a sign from the saint that they should stop. They awaited the Turks, and triumphantly defeated them. At the close of the war the relics were restored to the chapel without any difficulty.

As we sat and looked at the knot of little cliff huts, a figure quite in keeping with them came through the doorway and slowly approached us. A magnificent old giant, with a silver beard and long white locks that flowed upon his shoulders, and showed him to be a priest. A tall black astrachan cap was on his head, and in spite of the heat he wore a heavy cloak of dark blue cloth lined with fur, a long blue tunic, and wide knickerbockers shoved into heavy leather boots at the knee. His high cap and his big cloak gave him great dignity, and he welcomed us with superb stateliness. Then, intimating we were to follow him, he conducted us to his residence. It was a narrow little cave fronted in with planks. Here we had to sit down while he fumbled at what was apparently a small cupboard door. He threw it open, and behold—an oil painting of himself, set in a gorgeous gilt frame that contrasted oddly with its rough surroundings. It was evidently a presentation portrait, and he sat down beaming by the side of it, for us to have every opportunity of admiring the likeness. We spread all our scanty stock of Servian adjectives of approval about recklessly, and the result was that from some mysterious corner he produced a black bottle and a small liqueur glass, opaque with dirt. He held the glass up to the light and looked at it critically; even he realised that it was unclean; then he put in his thumb, which was also encrusted with the grime of ages, and he screwed it round and round. No effect whatever was produced on glass or thumb, for the dirt in both cases was ingrained. For one awful second he contemplated his thumb, and I thought he was going to suck it and make a further effort; but no, he was apparently satisfied, and he filled the glass with a pale spirit, which we hoped was strong enough to kill the germs. We drank his health with a show of enthusiasm which seemed to gratify him, for he patted us both affectionately.

He then showed us up a wooden step ladder to a still tinier cavern, a dim cabin almost filled up by his bed, whose not over white sheets betrayed the unpleasing fact that Ostrog was still subject to nocturnal attacks and much bloodshed. In a glass case on the wall hung his two medals, one Russian, the other Montenegrin, and, next these, three signed and sealed documents in Cyrillic characters. He began reading out place-names in Montenegro, Bosnia, and the Herzegovina, pointing to his medals, and would gladly have "fought all his battles o'er again," if we could but have understood him. His great treasure he displayed last, a large and handsome walking-stick elaborately mounted in gold filigree set with plates engraved with the said names. His admiration for it was unbounded, and he handled it respectfully. The rugged old giant, and his trophies, standing huge in his tiny lair up in the heart of the mountains, the light from the little window falling on his silver hair and beard, the glittering filigree, the dim squalid background, his pride and glee over his treasures, and the royal air with which he showed them, conjured up a whole life-drama in one swift instant. He broke the spell himself by putting the stick carefully back into its case, and, bowing and crossing himself reverently before a little ikon of Our Lady, led the way out to the chapel.

The entrance was a low, narrow, rough-cut slit; he bowed twice and crossed himself, saw that we did the same, then stooped down and went into a small irregular cavern, its rough-hewn walls rudely frescoed with Byzantine figures. It was very dark; one small window, hacked through the cliff face, and the narrow doorway alone lighted it. Upon the rough ikonostasis he pointed out the figure of St. Vasili in bishop's robes. Then slowly and solemnly he began lighting the candles, striking a light with flint and steel. It took him a long time, and his age was betrayed by his tremulous hands and evidently weak sight. When he had finished, and the cavern was a-twinkle with tiny flames, he approached the shrine. Removing the covering, he fumbled with the lock, opened it, and then threw back the lid slowly and respectfully. There lay the embalmed body of the saint; the slipper-clad feet, the embroidered robes, and the gold crucifix on the breast, only, showing. Modern science and ancient faith had combined for perhaps the first and the last time, and the face and hands of the saint were neatly covered with carbolised cotton-wool. I was jolted back into the twentieth century with a rough shock. The sense of smell—perhaps because it is a wild-beast one—brings up its trains of associations more swiftly than any other, and the life of the old world and the life of the modern one leapt up in sharp contrast.

To the old man, on the other hand, the scent was the odour of sanctity. He was filled with awe and reverence, and gazed at the body like one seeing a wondrous vision for the first time. He bent down slowly and kissed the slippered feet, the crucifix on the breast, and the cotton-wool over the face, crossing himself each time. Then, fearful lest we should omit any part of the ceremony, he seized us each in turn by the back of the neck, poked our heads into the coffin and held them down on the right spots. We followed carefully the example he had set, and completed our pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Vasili. He slowly closed and locked the coffin, and rearranged the drapery upon it. Then we debated together as to how an offering was to be made. He, however, helped us out of the difficulty. He took a small metal bowl from the window, placed it reverently upon the coffin and counted some very small coins into it ostentatiously, clink, clink, then turned his back discreetly and began slowly extinguishing the candles. He allowed just sufficient time to carry out the approved ritual, and hurried back eagerly to inspect the bowl. It appeared that we had acted quite correctly on this occasion also. Coming out through the narrow door into the open air again, we prepared to go; but the old man stopped us, pointed upwards, and shouted for someone. The "someone" came, and turned out to be the Handsome and Haughty Lad who had so cruelly chivied us down below. He gazed at us with a superior smile, and in obedience to his orders led us up to a yet higher cavern, where he showed us a spring of very cold clear water. This is highly prized by the pilgrims to the shrine, who all bring bottles or gourds to fetch some away in. The Lad, I think, expected us to do so, and as he had, as he imagined, made us understand by shouting before, he tried the same system again with great violence. We hastily remunerated him for his trouble, in hopes of changing his ideas, and he was sufficiently mollified to shake hands with us. Whereupon we said good-bye, and left him.

Evening was drawing in when we reached the lower monastery, and service had just come to an end in the little church. The Archimandrite, followed by his small congregation, came out as we approached. We were sleepy, dirty, and hungry, and the prospect of another interview in Servian before getting food or rest was almost too much for us. To our dismay, we were again conducted to the Archimandrites sitting-room. Our relief was great when we heard the words, "Vous parlez français, mesdemoiselles?" and we were introduced to a tall man in the long black robes and high cap of the Orthodox ecclesiasts. Singularly beautiful, his long brown hair flowing on his shoulders, he stood there more like a magnificent Leonardo da Vinci than a living human being. He spoke gently and kindly in the oddest broken French, expressing himself in little rudimentary sentences, begging us to be seated and telling us we were very welcome; "for we are Christians," he said simply, "and is not hospitality one of the first of the Christian virtues? I, too, am a guest here to-night. But you who have come so far to see us, it is the least we can do for you. From England," he repeated, "alone, all the way from England to see Montenegro, quelle voyage! véritablement des héros! In Montenegro you are as safe, vous savez, as in your own homes, but the journey—all across Europe, that is another thing!" The Archimandrite, he explained, regretted that our room was so long in being prepared for us. "It is because we have had a pilgrimage here lately and have had to accommodate very many people. Therefore there was no place suitably furnished for you, but they are putting down the carpets, and it will soon be finished." We were horrified, and begged they would not take so much trouble; but he would not hear of it. "Oh, it is a great pleasure to us all to know that in England there is such a good opinion of Montenegro that two ladies will come all alone into our country and trust us; that the English should wish to know us!" I felt like an impostor; it was embarrassing to be given hospitality as the bearer of good-tidings from Great Britain, but to our innocent-minded entertainer the idea seemed quite simple and sufficient. He had nothing but good to say of everyone. For the two small boys who came in with the usual cold water and coffee, he was filled with admiration—their build, their muscular limbs, their honest, open faces. "Montenegrin faces," he said, "ah! but they are beautiful my faithful Montenegrins! It is my life," he went on, "to help these poor people. I have a church, a little, little church, away among the rocks. It is there that I live. If I had known, mesdemoiselles, before, that you were travelling this way, it would have given me great pleasure to show it to you. But I did not know until yesterday"; and he added, with a smile at our astonishment, "Oh yes, in this country, vous savez, one hears of all strangers."

The conversation was broken off by the announcement that our rooms were ready, and we all went over in a solemn little procession to the house over the way, the two ecclesiasts, the four servants and ourselves, and were shown in with many apologies for the poorness of the accommodation. The dear good people were putting the finishing touches when we entered, and had arranged two large rooms most comfortably. The Archimandrite satisfied himself that the water jugs were full, that we had soap, and that the beds were all right. Then both gentlemen shook hands with us and wished us good-night, and withdrew. An anxious quarter of an hour followed, during which we wondered whether we were going to be fed or not, and regretted that we had bestowed the remains of the bread and mutton on the girl; for we had been knocking about since five a.m., and it was now eight p.m. Then there came a most welcome knock at the door, and we were taken to a large dining-room and a good dinner. It was a solemn meal. We were waited on by four men, who came in and out silently, supplied our wants, stood at attention and gazed at us stolidly. The largest was about six feet four and built to match, but extremely tame in spite of his weapons and his I size. I don't think he had the least idea how very small he made us feel.

Early next morning the Archimandrite and our friend were already about, and came to see us breakfast and to beg that we would write our names in the visitors' book. We said all that we could in the way of thanks to our kind entertainer; he murmured a blessing over us, we shook hands, and were soon wandering down the mountain side.

Nikshitje is but two hours' drive from the beginning of the Ostrog track, over a mountain pass and down on to a big plain. Nikshitje, says the Prince, is to be his new capital, and work is going on there actively. That it cannot be the capital yet a while seems pretty certain, for it is a very long way from anywhere, and the foreign Consuls and Ministers, who at present lament their isolation from the world and all its joys at Cetinje, would all cry "Jamais, jamais!" in their best diplomatic French, if called upon to transfer themselves to the heart of the land. It is certainly very beautifully situated; the wall of mountains which encircle the big plain is as fine as any in the country, and it is neither so cold in winter as is Cetinje, nor in summer so hot and close as the low-lying plain of Podgoritza. But until there is a road or a railroad that will connect Nikshitje quickly with the coast, it cannot compete in importance with Cetinje. A line that would connect Servia with Antivari via Nikshitje, join the two Servian peoples, and give Servia a port for export, is so much against Austrian interests, both commercial and political, that Austria will under no conditions permit it to pass through any territory over which she has control. There is no speedier way of drawing truthful political opinions from a mixed company of various nationalities than to design fancy railroads over tender territories. At present no line exists in the Balkan peninsula that runs from north-east to south-west. And in the present disgraceful state of all territory that is under Turkish "government" no new lines through any of the Sultan's property are probable. The love of the Montenegrin for Nikshitje is based partly on sentimental grounds; for the taking of Nikshitje, the biggest Turkish stronghold on their northern frontier, was one of the chief events of the last war. Nikshitje fell in 1877, after a four months' siege conducted by Prince Nikola himself.

That the Prince really intends Nikshitje to be the capital of his country is evident. We have a forecast of its coming splendour in the large and really fine church dedicated to St. Vasili, which stands well placed on a little hill, close by a solid and well-proportioned building, designed with a stern simplicity well in keeping with the Montenegrin spirit. Within, it is lofty and spacious, and the bare stone walls are hung with lists of those who fell in the last war. Russia found the money, and Montenegro the labour. The mouldings and capitals are all cut by Montenegrins, and the engineer that built it is a Montenegrin. Nikshitje has a right to be proud of it. At the foot of the hill on which the new church stands is a tiny little old church, the church of the Montenegrins in Turkish times. In those dark days it was almost completely buried under the earth for safety. Now, with the addition of a fat new tower, it shows itself in the light of day.