Title: The Heart of Pinocchio: New Adventures of the Celebrated Little Puppet

Author: Collodi Nipote

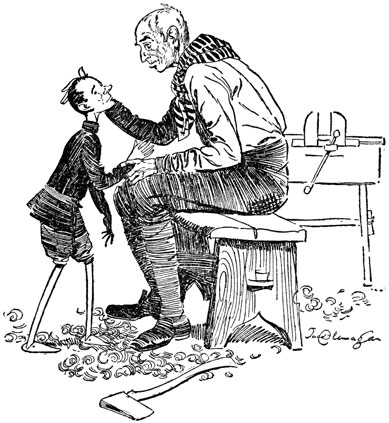

Illustrator: J. R. Flanagan

Translator: Virginia Watson

Release date: November 23, 2012 [eBook #41446]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

The frequent use of ellipses has been retained as printed.

On page 19, "I had better tried" should possibly be "I had better try".

[See p. 147

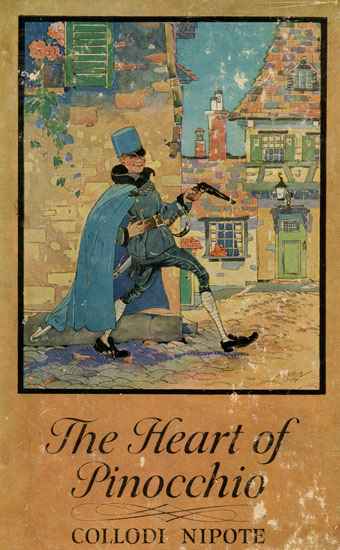

"BUT SMELL THIS" ... AND WHILE HE SPOKE THE RASCAL OF A PINOCCHIO TOOK IN BOTH HIS HANDS THE DISH AND HELD IT CLOSE TO STOLZ'S NOSE

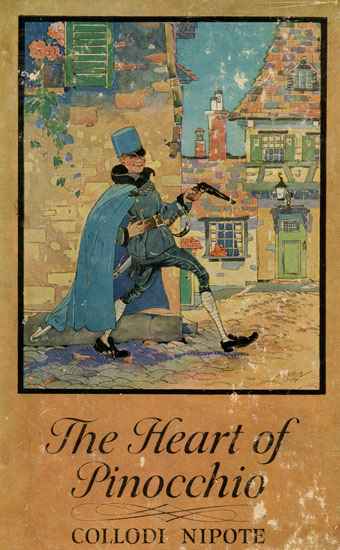

THE HEART OF

PINOCCHIO

New Adventures of the

Celebrated Little Puppet

By

COLLODI NIPOTE

(Paolo Lorenzini)

Adapted from the Italian by

VIRGINIA WATSON

With Drawings by

J. R. Flanagan

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

The Twilight Series

Imaginative Stories and Fairy Tales

Illustrated—Jackets Printed in Colors

The Heart of Pinocchio

Copyright, 1919, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | How Pinocchio Discovered that He Had a Heart and Had Become a Real Boy | 1 |

| II. | How Pinocchio Recognized the Advantages of His Wooden Body | 22 |

| III. | How Pinocchio Sent a Solemn Protest to Francis Joseph to Rectify an Official Bulletin | 33 |

| IV. | How Pinocchio Learned that War Changes Everything—Even the Meaning of Words | 62 |

| V. | In Which Pinocchio Discovers that Sometimes When You Want to Advance You Have to Take a Step Backward | 78 |

| VI. | Wherein We See Pinocchio's Heart | 92 |

| VII. | How Pinocchio Came Face to Face with Our Alpine Troops | 110 |

| VIII. | How Pinocchio Made Two Beasts Sing—Contrary to Nature | 135 |

| IX. | How Pinocchio Complained Because He Was No Longer a Wooden Puppet | 151 |

| X. | Many Deeds and Few Words | 177 |

| XI. | And Now—Finished or Not Finished | 199 |

| "But smell this" ... and while he spoke the rascal of a Pinocchio took in both hands the dish and held it close to Stolz's nose | Frontispiece | |

| "I see the suet-eaters" | Facing page | 36 |

| He saw a rag tied to a pole waving | " | 42 |

| "You beastly little creature, what game are you playing?" | " | 46 |

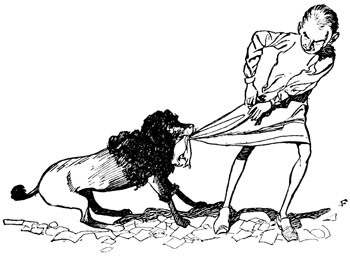

| One day he managed to capture a pig and to drag it along behind him | " | 62 |

| His foot caught Cutemup right in the stomach and knocked him breathless | " | 88 |

| Pinocchio did his best to get on his feet, but couldn't succeed | " | 116 |

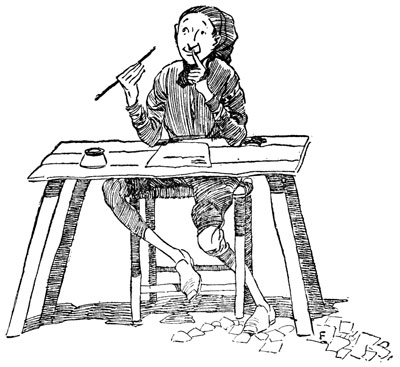

| Ciampanella, the company cook | " | 134 |

Dear Boys and Girls,—Let us hope that none of you has been so unfortunate as to have missed the pleasure of watching sometime or other a puppet show. Probably Punch and Judy is the one you know best, but there are many others with jolly little fellows who dance in and out of all sorts of adventures. So you can imagine Pinocchio, the hero of this book, as one of those lively puppets. And, in case you have never read the earlier book about him, you will want to know something of what happened to him before you meet him in these pages.

One day a poor carpenter, called Master Cherry, began to cut up a piece of wood to make a table-leg of it when, to his utmost amazement, the piece of wood cried out, "Do not strike me so hard!" The frightened carpenter stopped for a moment, and when he began again and struck the wood a blow with his ax the voice cried out once more, "Oh, oh! you have hurt me so!" The carpenter was now so terrified that he was only too glad to turn the piece of wood over to a neighbor, Papa Geppetto, who cut it up into the shape of a boy puppet, painted it, and named it Pinocchio—which means "a piece of pinewood." As soon as he had finished making him, Pinocchio grabbed the old man's wig off his head and started in to play tricks. Papa Geppetto then taught the puppet to walk, and when naughty Pinocchio discovered he could use his legs, he ran away. Then began all kinds of adventures, and Pinocchio was sometimes naughty and selfish, and sometimes kind and considerate, but always funny and jolly.

In this new book Pinocchio's heart has grown through love and consideration for others, so that he becomes a real boy and takes part in the war to help his beautiful country, Italy.

The Translator.

THE HEART OF PINOCCHIO

THE HEART OF

PINOCCHIO

How Pinocchio Discovered That He Had a Heart and Had Become a Real Boy

He yawned, stuck out his tongue and licked the end of his nose, opened his eyes, shut them again, opened them once more and rubbed them vigorously with the back of his hand, jumped up, and then sat down on the sofa, listening intently for several minutes, after which he scratched his noddle solemnly. When Pinocchio scratched his head in this way you could be sure that there was trouble in the air. And so there was. The room was empty, the windows closed, and the door as well; no noise came from the still quiet street; a 2 deep silence filled the air, yet there, right there, close to him, he heard queer sounds like blows—tick-tock ... tick-tock ... tick-tock ... tick-tock.

It sounded like some one who was amusing himself by rapping with his knuckles on a wooden box—tick-tock ... tick-tock ... tick-tock.

"But who is it?" called out the puppet, suddenly, jumping down from the sofa and running to peer into every corner of the room. When he had knocked over the chest, rummaged the wardrobe with the mirror, upset the little table, turned over the chairs, pulled the pictures off the walls, and torn down the window-curtains, he found himself seated on the floor in the middle of the room, dead tired, his face all smeared with dust and spider-webs, his shirt in tatters, his tongue hanging out like a pointer's returning from the hunt. Yet there, close 3 to him, he still heard that strange tick-tock ... tick-tock ... tick-tock ... and it seemed as if those mysterious fingers were rapping even more quickly upon the mysterious wooden box. Pinocchio would have pulled his hair out in desperation if Papa Geppetto hadn't forgotten to make him any. But as the desperation of puppets lasts just about as long as the joy of poor human beings, Pinocchio, laying his right forefinger on the point of his magnificent nose, calmly remarked:

"Let me argue this out. There is no one else in here but me. I am keeping perfectly quiet, not even drawing a long breath, yet the noise keeps up.... Then, since it is not I who am making the noise, some one else must be making it, and as no one outside me is making it, whatever makes it must be inside me."

This seemed reasonable, but Pinocchio, who had not expected he would come to such a conclusion, gave a start, kicked violently, and began to roll around on the ground, yelling as if he would split his throat: "Help! Help!" The thought had suddenly come to him that during the night a mouse had jumped into his mouth and 4 down into his stomach and was searching about in it for some way to get out. But the quieter he kept the noisier grew the tick-tock; in fact, so loud that it seemed to cut off his breath. Fear made him calm.

"Let me argue this out," he said again, laying his forefinger against his nose. "It cannot be a mouse; the movement is too regular, so regular that if I weren't sure that I went to bed without supper I should think I had swallowed Papa Geppetto's watch by mistake.... Hm! If he hadn't told me time and time again that I am only a little puppet without a heart I should almost believe that I had one down inside me, and that this tick-tock were indeed ..."

"Just so!"

"Who said 'Just so'? Who said 'Just so'?" called Pinocchio, looking around in terror. Naturally no one answered him.

"Hm! Did I dream it?" he asked himself. "And even if there is any one who thinks he can frighten me with his 'just so' he will find himself much mistaken. A brave boy does not know what fear is, and I begin to think ...

"'Just so' or not 'just so,' if any one 5 has anything to say to me let him come forward and he will learn what kind of blows I can give."

He turned round and stepped back a few steps. It seemed to him that some one was making a threatening gesture at him. Without hesitating a moment, he rushed forward with his head down, thrashing out blows like a madman. Then he heard a terrible smashing of glass. Pinocchio had hit out at his own image in the wardrobe mirror, which naturally was shattered to bits. There is no need for me to tell you how he felt, because you will have no trouble in picturing it for yourselves. 6

"But how did I come to make such a blunder?" he asked himself, as soon as he had recovered from his surprise. "How did I happen not to recognize myself in the mirror? Am I really so changed...? Can I indeed be changed into a real little boy or am I a puppet as I always was?"

"Just so! Just so! Just so!"

This time there could be no doubt about it. Pinocchio sprang toward the window, opened it, and stuck his head out. There below, a few feet lower down, was a beautiful terrace covered with flowering plants. In the midst of the plants was a stand, and on the stand a magnificent green parrot who just at that moment was scratching under his beak with his claw, and looking around him with one eye open. Down in the street below there was not a soul to be seen.

"Oh, you ugly beast! Was it you who was chattering 'just so, just so, just so'?"

The parrot burst out into a crazy laugh and began to sing in his cracked voice:

"Coccorito wants to know

Who the glass gave such a blow.

Coccorito knows it well

And the master he will tell."

"Hah! Hah! Hah!" And he burst out into another guffaw. Patience, which is the only heritage of donkeys, was certainly not Pinocchio's principal virtue. Moreover, the parrot laughed in such a rude manner that he would have annoyed Jove himself.

"Stop it, idiot!"

"Idiot, idiot, 'yot, 'yot."

"Beast!"

"Beast!"

"Take care ..."

"Take ca-a-a-re."

"I'll give it to you."

"You, you, you."

"Ho! Ho! Ho! Ho!

Who the glass gave such a blow?

Coccorito knows it well

And the master he will tell."

"Will you? I'll make you shut up. Take this, you horrid beast!" 8

There was a large terra-cotta pot with a fine plant of basil in it standing on the window-sill, and the furious Pinocchio seized it in both hands and hurled it down with all his force. Coccorito would have come to a sad ending if the god of parrots had not protected his topknot. The flower-pot grazed the stand and was shattered against the marble parapet, and the pieces, falling down, hit against the large stained-glass window opening on to the terrace and broke it.

Pinocchio, who could hardly believe that he had done so much damage, stood still a moment and gazed stupidly at the pile of broken pieces and at the parrot, who laughed as if he would burst. But when Pinocchio saw a big officer rush angrily over the terrace, with his hair brushed up on his head, a huge mustache beneath his curved nose, and a thick switch in his hand, he was seized with such a fright that he threw over his shoulders the first thing in the way of clothing he could lay his hand on, rushed to the door, opened it with a kick, ran through a small room adjoining, sped down the stairs at breakneck speed, flung open the street door and—Heavens! 9 He felt a violent blow on his stomach and, as if hurled from a catapult, he was thrown into the air and fell down the rest of the steps, his legs out before him. But he didn't stay still when he got to the bottom. He sprang up like a jack-in-the-box, rubbed himself on the injured part, and was off again. He seemed to see some one strolling there in the middle of the street; he thought he heard himself called twice or thrice by a well-known voice, but the fear which was driving him bade him run, and he ran with all the strength he had in his body.

Poor Papa Geppetto! It was indeed he who was strolling in the middle of the street and who, seeing Pinocchio flying out of the house like a madman, wrapped in a flowered chintz curtain, had called to him imploringly.

And so it was—in his hurry Pinocchio had thrown over his shoulders one of the curtains of his room, and if I must tell you 10 all the truth, he was a perfectly comical sight. Soon Pinocchio had a string of people at his heels crying out: "Catch the madman! Give it to the madman!"

Catch him! That was easy to say, but it was no easy matter to grab hold of the rascal. Indeed, his pursuers were soon weary, and Pinocchio might have thought himself safe if a dog hadn't suddenly joined in the game. It was a large jet-black poodle that had come from no one knew where. With a couple of bounds he had caught up with Pinocchio and had seized the curtain in his teeth and was dragging it through the dust. Suddenly he stiffened on his four legs and Pinocchio gave a little whirl and found himself face to face with the animal.

"Ho, ho, ho! What do I see? Oh, Medoro, don't you recognize me? Give me your paw."

Medoro growled and shook the curtain violently, which was still knotted about Pinocchio's waist. It was only then that he noticed the strange covering he had on and burst out laughing.

"Oh, Medoro! What do you really want to do with this rag? I'll give it to you willingly." 11

He had scarcely undone the knots when Medoro made a spring and was off down the street they had come, the curtain in his teeth. The puppet stood there, quite upset. Medoro had given him a lesson. The dog that had been so friendly had turned on him and, after having pulled the miserable old curtain off him, had made off without paying any further attention to his old friend.

"A fine way of doing!" he grumbled. "I'll catch cold running around after that rag. Papa Geppetto won't even thank him.... I had better tried to mend the mirror of the wardrobe or the general's window." 12

The thought of all the troubles he had caused the poor man in so short a time made Pinocchio rather melancholy, and two big tears shone in his bright little eyes. But suddenly he sighed a deep sigh, shrugged his shoulders several times, and with his head high and his hands on his hips, set off again on his way, whistling a popular song.

He had not gone a hundred steps when he stopped suddenly, cocked his ear, listened a moment quietly, and then flung himself into the fields which bordered the street. The wind brought from far off the gay notes of a military band.

There was a huge crowd, but Pinocchio didn't give that a thought, in spite of the fact that he was very tired with his long run. By pushing and poking and kicks in the shins he got up into the front row. Soldiers were passing. At the head was a company of bicycle sharpshooters (bersaglieri), then the band, then the regiment, the Red Cross ambulance, and soldiers, and a long line of sappers. Everybody clapped, threw kisses and flowers, and overwhelmed the bersaglieri with little gifts. The soldiers broke ranks and mingled with the crowd and answered the applause with loud 13 cheers for Italy, the King, and the Army. Some of them marched along in the midst of their families; weeping mothers begged their sons to be careful; the fathers bade them be brave, reminding them of the fighting in '48, '66, '70—the glorious years of our emancipation. The little boys kept close to their fathers, proud to see them armed like the heroes of old legends, and many of the girls besought their sweethearts: "Write to me, won't you? Every day I want you to write to me. If I don't get letters from you I shall think that you are dead and I shall weep so bitterly."

Dead! This word affected Pinocchio so that suddenly he felt his heart beating loudly—that strange tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock which had startled him earlier that morning.

Dead? "Oh! where are they going?" he asked a sprightly old man who was standing near by, shouting, "Hurrah for Italy!" as if he were a boy.

"They are going to the war."

"Are they really off to war? Will they fire only powder from their guns, or real, lead bullets, too?"

"Indeed yes, real bullets, too." 14

"And will they all die?"

"We hope not all of them—but they are going to fight for the honor and greatness of their country, and he who dies for his country may die happy."

Pinocchio did not breathe. He scratched his head solemnly, and with his eyes and mouth made such a face that if the little old man had seen it he would probably have boxed his ears for him. This "die happy" was silly. Death had always frightened him whenever he had come near to it.

"Have you been to war?" Pinocchio asked the little old man, half ironically.

"Can't you see?" and he pointed to a row of medals pinned on his coat.

"And you would go back?"

"Certainly, if they would take me as a volunteer."

This reply brought a strange longing to Pinocchio, all the more that the tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock in the box inside of his body was making so much noise that it rang in his ears. And then the gay notes of the band, the joyous air of the soldiers, the cheers of the crowd, suddenly brought a strange idea into his head. The war, with its cannon, marches on one side, fighting 15 on the other, horses dashing, flags waving in the wind, songs of victory, medals on the breast, prisoners tied together like sausages, war trophies, danced before his eyes in a fantastic dance. The war must be just the place for him, all the more so when he thought that it couldn't be easy to get to it if the little old man who had been there so often couldn't go now.

"I, too, will go to the war with the soldiers," he said, in a low voice, and without wasting a moment he pushed his way between the troops, who, now that they were approaching the station, began to close up the ranks. He found himself by the side of a young blond soldier, who seemed more lonely and sad than the others.

"Will you take me with you?" Pinocchio asked, pulling at his coat.

"Where?"

"To the war."

"You? Are you crazy?"

"No, indeed."

"And you ask me to take you with me?"

"Whom, then, must I ask?"

"There is the guard down there, that one with a blue scarf over his shoulder." 16

When Pinocchio got an idea in his head he had to work it out at any cost. So he repeated his demand to the lieutenant of the guard, who, smiling under his mustache, pointed out the captain inspecting the troops. But the captain could decide nothing without the consent of the battalion commander, who, for his part, would have had to ask the approval of the colonel. He advised Pinocchio to hasten matters by going to the adjutant, who could present his request directly to the general.

They were now in the station. The soldiers took their places in the huge cars, around which crowded their families, friends, and the cheering, curious throng. At the end of the train some first-class carriages were attached into which the orderlies carried the hand-baggage of their higher officers. In front of one compartment reserved for one of these was piled up a regular mountain of small objects—little packages, boxes, rugs, furs, which a cavalry soldier was trying to carry inside. The adjutant, a few feet away, was looking on, trembling with impatience and vexation.

"Quick! Quick! You lazybones! Quick! Quick! Mollica. General Win-the-War 17 will be here in a minute and his things are not yet inside. I'll put you under arrest for a fortnight."

"I respectfully beg the adjutant to observe that I have only two hands for the service of my general and of my country."

"And I beg you to observe that the train is about to start off."

"If the adjutant would order some one to give me a hand ..."

"There isn't any one to be had, confound it!"

Just at that moment Pinocchio advanced resolutely toward the adjutant to put forward his request to be enlisted.

"Mr. Adjutant ... I have come ... to ..."

The adjutant didn't let Pinocchio say another word, but caught hold of him under the chin, squeezed him, shook him gently ... and said:

"Good! I understand ... you want to do something for the army.... Good boy! You are the best kind of a volunteer. Fine! Help Private Mollica to carry in all this stuff and your country will be grateful to you. And you, Mollica, hurry up. I beg you to observe that now you have the four 18 hands you requested for the job. We understand each other, heh?"

Then he was off toward a group of soldiers who were chalking on the door of one of the railway carriages in large letters: "Through Train—Venice—Trieste—Vienna." A big crowd had gathered around, stopping the traffic.

"Ho, boys, who told you to write through train? Next time ask permission from your superior officer.... There will be a little stop before we get there."

"Doesn't matter, sir, as long as we get there."

"Well! You can tell when a train leaves, but not whether it will ever arrive."

"Hurrah for Italy!"

"Good boys! I like that. But rub out what you have written. You are first-class soldiers, you are. We understand each other, heh?" And off he went.

With Pinocchio's aid Private Mollica performed miracles. In a few minutes the general's things were inside, beautifully arranged in the baggage-racks.

"You are a prodigy, boy, I tell you. You have done me a great service and my adjutant will be so pleased that if you will 19 promise to keep guard here a moment I will go to tell him so that he can thank you in the general's name."

"Go along; I'll stay," Pinocchio replied, and took up a position in front of the door that was so soldierly you might have taken him for a distant relative of Napoleon the Great before St. Helena.

But a minute had not gone by and Mollica had not got a hundred steps away when Pinocchio turned as pale as death and trembled so with fright that he almost fell off the step. He had caught sight a short way off of General Win-the-War surrounded by a crowd of officers; and with his marvelous vision had recognized in him Papa Geppetto's furious tenant, whose stained glass he had shattered a few hours before, all on account of saucy Coccorito.

He was lost; there was no possible way of escape! Win-the-War was coming direct to his compartment and the adjutant was guiding him. The crowd in the way divided before him and the soldiers stood stiffly at attention. Even Mollica stood there straight as a ramrod.... Pinocchio gave a leap into the compartment, hoping to escape by the opposite door. 20 But it was not possible to open it.... He heard the sound of the approaching steps, the ring of the spurs.... Pinocchio flung himself down on the floor of the compartment and hid himself, face downward, under one of the seats.

The general, a colonel, and the adjutant got in. A band struck up the national air; thousands of voices cheered the King, Italy, and the Army. The soldiers responded with youthful courage.... You heard a continual medley of good-bys and good wishes, and the quick, sharp repetition of commands. A hundred voices were singing, "Farewell, my dear one, farewell"; a hundred others sang Garibaldi's Hymn.... There was a profound silence in the compartment. Perhaps the superior officers felt the great responsibility of the moment and were moved by it. Pinocchio didn't dare breathe for fear of betraying himself, but in his breast the tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock beat so loudly that he thought it must resound all along the wooden walls of the carriage. The notes of the national air seemed to be quicker ... the cries of the crowd louder ... the locomotive whistled shrilly a 21 desperate good-by ... the train began to move....

"Gentlemen," said the general to his two companions, "let Italy's fate now be fulfilled. To-morrow we shall cross the frontier, for the glory of our King and for the greatness of our country. Long live Italy!"

There was so much emotion in the old soldier's voice that Pinocchio felt as if a rope were strangling his throat. When the train was under way, rumbling noisily along the rails, he burst out crying and discovered that he had a heart just as if he were a real boy!

How Pinocchio Recognized the Advantages of His Wooden Body

"So, Colonel, you understand? This afternoon we shall be at —— (censor); we shall bivouac the troops; to-morrow morning at two we must be on the march. We shall cross the frontier at —— (censor) and we shall descend toward ——. I expect rapid and united advance until we encounter serious opposition. Remind the soldiers of the respect due to property in the conquered lands and to the beaten foes taken prisoners.... I have been told by the commander-in-chief that it has been discovered that there is a host of spies who are working to injure us. I command you to be very severe with spies caught in the act, no matter what their age, race, or social standing. Tell your officers to keep absolutely secret all orders which they receive. If 23 there is the slightest suspicion that an order relating to our advance has reached the ear of a person suspected even in the slightest degree, take him out, stand him with his face to the wall, and give him eight bullets in his back. You understand—without fear of consequences or that you may be mistaken. It would be better than to allow—let us suppose such a case—a whole regiment to be destroyed."

Pinocchio, who had been beginning to enjoy the adventure, the swaying of the train, which, as he lay on his face, tickled his stomach, and the conversation of the general, which greatly interested him, was so terrified at these words that his body felt like goose-flesh. For a moment he thought he would faint. His ears rang loudly and he burst into a sweat. Heigh-ho! The general was not a man to say such things as a joke: "If there is the slightest suspicion that an order relating to our advance 24 has reached the ear of a person suspected even in the slightest degree, take him out, stand him with his face to the wall, and give him eight bullets in his back." It was clear. As clear as it could be! Instead of a single order, Pinocchio had overheard a number ... they would certainly take him for a spy, and most certainly the eight bullets would not be lacking.

"Eight!" he exclaimed to himself as soon as he had managed to grow a little calmer. "Eight! One would be enough for me, and even that would be too much! But I don't want to die with bullets in my back.... I am not a spy at all. Well ... how can I persuade that orang-outang that I am in this compartment and under this seat for no other purpose than to go to war against my country's enemies, and because the authorities certainly wouldn't let me go in a more decent way? And suppose he recognizes me as the one who smashed his stained-glass window that opened out on his terrace, instead of eight bullets, he will order me a couple of dozen.... What a pity! Poor me! Poor Papa Geppetto, what will he say about me? But, to sum it up, I am not a spy, and when any one wants to pretend 25 to be what he is not he must find out the way to show them that he is not what they believe him to be.... The best way, I think, would be to slip off quietly. No one saw me come in here ... all I have to do is to get out without any one's seeing me. It can't be very difficult to do that; I'll just stay quietly until the train gets to its destination, then let these gentlemen step out, and a minute later I'll fade away."

If you could have poked your head under the seat and seen Pinocchio's face at this moment you would have been made happy by his joyful smile. This little bit of reasoning had so quieted his mind that if they had pressed eight muskets against his back to shoot the famous eight bullets into him he would have begun to laugh as if they were doing it only to tickle him.

He stretched himself out slowly, and, lulled by the swaying of the train, was soon overcome by such a tranquil slumber that he couldn't have slept better in his own little bed.

"Poor Pinocchio!" I think I hear you say. "What is going to happen to him now?" Yes, that's the way. It is the usual rule in this world that when a person 26 thinks he can enjoy a moment of blessed repose some misfortune is lying in wait for him. If Pinocchio, instead of letting himself be overcome with sleep, had kept his eyes and ears open while the train was slowing down and the locomotive ahead was puffing noisily he would have heard General Win-the-War let out a yell of pain. Of course, he should have kept it back, but in time of war we pardon certain things, particularly when a general about to make an attack suffers from the torture of rheumatic sciatica, an old trouble of his.

"What's the matter, General?"

"My leg. My pain has come back; it's worse than an Austrian bullet."

"Perhaps you have taken a little cold."

"Perhaps.... It doesn't seem warm here, for a fact, does it, Colonel?"

"No, indeed."

"We are in the mountains and still climbing, and the temperature is going down."

"Gracious me! so it is. They ought ... Major, do me the favor at the next stop to ask if it is possible to heat the compartment. If the rest of you don't like the heat you can just go into the next compartment." 27

"The idea!"

At the next stop, which was not long in coming, the colonel asked permission of his superior officer to go off for an inspection of his men, and the major went off to see about heat for his commanding officer. It was not a hard matter to obtain what he wanted. The general was traveling in an up-to-date carriage, one of those that have under the seats special steam coils which can be connected with the exhaust pipes of the locomotive's boiler, and, by a simple adjustment, begin to send out heat immediately.

The signal for departure had already been given when the major returned joyfully to the compartment.

"Well?"

"The connection is made and we have heat on."

"Or rather we shall have it, because just now ..."

"Excuse me, General, all we have to do is to push that handle where the sign says 'cold' and 'hot' and ..."

The general, who was following the maneuver attentively, uttered an "Oh!" of relief as if the compartment were suddenly 28 transformed into a hothouse, and stretched his legs out comfortably, resting his feet on the opposite seat.

I can't tell you where Pinocchio's thoughts were at this moment. But I can assure you that he was dreaming and that they must have been pleasant dreams, because there was a beautiful smile on his face. But suddenly the expression changed to one strange and painful. Perhaps in his dreams, while he was seated at a table that was spread with the most delicious dainties, he felt himself slipping down, down, and suddenly found himself on a hot gridiron with St. Lawrence in person. It is certain that when he opened his eyes it was impossible to breathe the air beneath the seat, and where his back touched it, it was hot enough to bake a loaf of bread. He started to jump out, but caught sight, right in front of his nose, of the little wheels in the adjutant's spurs. The sight of these brought him back to his real situation.

"But what is the matter?" he said to himself. "Is the axle of the wheel on fire? And can I keep from burning? But if they notice it, too? If no one moves that means that there is no danger ... but, Heavens! 29 it burns! Ouch! I am covered with sweat, but I have got to stand it.... If I get out there will be the eight bullets in my back. Poor me! How much better it would be if I were still nothing but a wooden puppet!"

Well, I can't help him. It's too much for me. It would indeed have been convenient at that moment to be made of wood, for he was in a situation such as no one would wish for any creature of flesh and blood—for me or you, for instance. He had either to stand being steamed on the boiling pipe of the heating apparatus or to give himself up into the hands of the general, who wouldn't delay long the threatened shooting.

Pinocchio was a hero, also a regular martyr, because he stood the torture more than half an hour, turning himself from side to side, moving restlessly, and drawing up his 30 body in one way and another like the aforesaid St. Lawrence of blessed memory, the only difference being that the saint expected to be well cooked on one side and then to turn over and be cooked on the other; while Pinocchio, when he discovered that a certain part of him was about to be cooked in earnest, let out a loud scream and followed it by calls for "Help! help!"

General Win-the-War and the adjutant jumped to their feet like jacks-in-the-box, threw themselves down on the ground, and, without paying any attention to the blow on the heads they gave each other, ran their arms under the seat, and with outstretched hands seized hold of Pinocchio and dragged him out. They nearly tore him in two like a tender chicken, one pulling him on one side and one on the other.

"You wretch!"

"You scoundrel!"

"Who are you?"

"Speak, you miserable creature!"

"General, he is a spy."

"We must question him in German ... he must be an Austrian."

"Wer sind Sie?"

No answer. 31

"What language do you speak, you little beast?"

Poor Pinocchio couldn't even draw a long breath. The general clutched him by the collar with such a military firmness that he turned the color of a ripe cherry. A little more and he would have been strangled to death.

The adjutant saved him by respectfully bidding the general remember that in questioning a prisoner it is necessary to allow him to breathe if you wish an answer.

"Mr. General ... forgive me. I am not a spy. It would be a real crime if you had me shot ... just as soon as we arrive at ... Give me a gun and I will go to war with the troops."

"Oh, you wretch! So you listened to all we said?"

"How could I help it? I was under here when the train started. It was I who helped Private Mollica to put all your stuff inside."

"Even this leather case?"

"Certainly I, I myself."

"Even the despatch-case with the plans! Major, give me your revolver so that I can shoot him like a dog."

"But why do you want to shoot me, Mr. 32 General? I haven't done anything.... I wanted to go to the war to hear the cannon, but I never spied on any one, not even when I went to school.... Can you really take me for a Boche? No, for gracious' sake, no.... Look at my features.... No, no, no, for Heaven's sake! Keep your weapon quiet.... Don't you know who I am?... I am Pinocchio, Papa Geppetto's Pinocchio ... who only this morning broke your stained-glass window...."

At that point the general uttered such a roar that Pinocchio felt his breath leave him. But he saw the officer hand back the pistol to the major and take up from the seat a big leather bag; then he didn't see the bag again, but he felt it several times and with great force exactly on the part of his body which had suffered the most from the heat of the steam coil.... But Pinocchio was saved by his sincerity. General Win-the-War could certainly not have bothered to beat a real spy, but I can tell you that at that moment Pinocchio would have preferred to be still a wooden puppet.

How Pinocchio Sent a Solemn Protest to Francis Joseph to Rectify an Official Bulletin

May had come with her blossoms, but up there a sharp wind was blowing so that it seemed still February. Pinocchio, half naked as he was, shivered like a leaf, and every now and then let out a sneeze which sounded like a bursting shell. At every sneeze Mollica gave him a kick, Corporal Fanfara a box on the ear, and Drummer Stecca a pinch. The only one who didn't abuse him was Bersaglierino, the blond young soldier, more melancholy than his companions, whom he had first accosted in the station when they were setting out. I have told you that Pinocchio trembled with cold, and I will tell you that it was almost a good thing for him to do so; otherwise they would have seen him tremble with 34 fear. If this had happened, his teasing companions would have driven him to despair. Pinocchio was to be pitied. He was at the front, the frontier several miles behind them, and any minute might bring Austrian bullets whistling through the air. The general had spared the youngster from being shot in the back, but he had given orders to put him in the very front line during the advance and to keep him well guarded. In one case the guns of the enemy would do justice to the suspected spy; in the other, Pinocchio would clear himself by his conduct and at the same time would lose his desire for a close view of the enemy.

Private Mollica was furious with him.

"Che-chew! che-chew! che-chew!"

"Plague take you!" Another kick. "Keep still, you little beast! If you let the enemy spot us I'll stick this bayonet in your backbone."

"I can't stand it any longer. I am frozen—che-chew!"

"Stop it!" Another box on the ear. "You are all right. You wanted to be a volunteer; now you see how much fun it is."

"I?"

"Yes, you.... You were the cause of 35 the fine talking-to my general gave me, and you made me lose my place as an orderly where I had a chance to make extra soldi. If you hadn't gone and told him that you had helped me to carry his things and if you hadn't slipped under the seat of that same officer to listen to what he said, I shouldn't have been punished by being sent to the front."

"Are you afraid, then, Mollica?"

"I afraid? But don't you know that if I catch sight of an Austrian I'll eat him?"

"Like the food you took from the general," that rascal of a Pinocchio dared to remark.

There was a chorus of laughs that stopped as if by magic at the sound of a certain roar in the distance and of something whistling through the air and very near.

"There they are!"

"We're in it."

"Where?"

"Where are they?"

Who paid any attention now to Pinocchio? All of them had drawn close to one another and had rushed to the edge of the road, their guns pointed, to examine the distant landscape. The mountain was very 36 steep there and covered with thick vegetation. Down at the bottom, toward the plain, there seemed to be an unexpected rise ... after the steep descent a green stretch through which a river ran like a silver ribbon. Still farther, was a chain of low mountains, almost like a cloud on the edge of the peaceful horizon.

There was the roar of some more shots and the whistling of the shells, and a branch of a tree was splintered and fell.

Pinocchio, alone in the middle of the road, felt a creeping up and down his spine and experienced a trembling in his legs that shook like a palsied man's. The second time he heard a shell whistle he felt that he must find a hole in which to hide himself. He looked about him and caught sight near by of an enormous larch-tree which pointed directly toward the heavens. I don't know how to explain it, but the sight of it took away from Pinocchio the desire to hide himself under the ground and made him wish to climb toward the stars. He gave a spring and shinned up the big trunk in a flash. I bet you a plugged soldo against a lira that you would have done the same.... 37

"I see them! I see them!"

"Who?"

"Whom do you see?"

"Where are they? Where are you that we can't see you?"

"I am up here."

"Bravo! And whom do you see?" Bersaglierino asked.

"I see the suet-eaters."

"Where are they?"

"Down there where there is a kind of slope there is a town hidden among the trees ... up here you can see a roof and the spire of a bell-tower ... you can see people on the roof ... you can see something glisten ... now they are firing."

This time there were several reports, but they seemed to be aiming in another direction, because there was not the usual whistle in the air.

"Whom are they 'strafing'?" Corporal Fanfara asked himself.

"I'll 'strafe' that scoundrel Pinocchio. If you don't come down alive I will bring you down dead with a bullet in the seat of your trousers."

"But listen! Look down there and see whom they're giving it to," cried the enraged 38 Bersaglierino, pointing out a marching column which was hurrying below them.

"Our infantry!"

"Yes, indeed. They will beat us to it. It's a shame."

"Our company ought to start off at a double-quick."

"It must be a half-mile away."

"But the bersaglieri must get there first ... even if there are only the four of us."

"Sure thing."

"Do you hear?"

"Forward, Savoy!"

And, heads lowered and bayonets fixed, they rushed down the slope.

"Ho! boys! Ho! Mol-li-ca! Cor-po-ral!... Oh! They are going off without me! What a mean thing to do! They leave me here at the top of this tree and run off.... But if they think they can play me such a trick they are mistaken.... I am hungry as a wolf, and if I don't get them to feed me, whom can I join? Run, run.... We'll see who gets there first!"

He climbed down the tree, grumbling as he went, tightened the belt of his trousers, drank in several deep breaths of air, and 39 then tore off like an express train behind time.

I will tell you at once, not to keep you in suspense, that the bersaglieri got there the first, the infantry second, and Pinocchio ... a good third. I call it a "good third" merely as a way of expressing it, because when he arrived at the village our soldiers had already passed through it and had advanced some distance beyond, following the Austrians, who had taken to their heels and who were suffering a sharp fire at short range.

The village was so small that it didn't even deserve the name of one. There were ten houses in all besides the church with the bell-tower, and a long shed over which waved the white flag with the red cross. There was a deathlike silence everywhere. On the little square before the church some bodies of Austrian soldiers were lying; among them was that of an officer so ugly that he seemed to have died of fright, but there was a red spot on his back. Pinocchio was terrified at the sight of him, but he had such a longing for his sword, his automatic pistol, his handsome belt, his light-blue cape, and his cap that he persuaded 40 himself it was perfectly silly to be afraid of a dead Austrian, particularly when they weren't afraid of live ones. Without too much reflection, he buckled on the dead man's belt, armed himself with the pistol, wrapped himself in the blue cape, and pressed the cap down on his head. He was good to look at, I can assure you.

The Hapsburg army had never had an officer who could be compared with this puppet who had now become a real boy. Pinocchio was prancing up and down in his new disguise, his sword clanking against the pavement, just like any little lieutenant, when he heard a horrible roar high up overhead, 41 then, a moment later, an explosion which shook the ground! When he lifted up his head to see what had happened he thought he caught sight of some one walking about on the church's bell-tower. He saw a rag tied to a pole waving and, as if in reply to a signal, brumm! another shot that fell closer. Pinocchio, who was suspicious, went into the vestry and, pistol in hand, rushed up the steep little wooden stairs. He got to the top without even making the old worm-eaten stairs squeak. In the space where the bells hung a man in civilian's clothes had his back turned toward him. He was looking off from the balcony, and kept on waving the red cloth. You could see the vast expanse of the plain, and among the green a strange, intermittent flash ... then a puff ... then you heard a roar, followed by a crash, like a moving train rapidly approaching, then a tremendous explosion. The shells never fell as far as the town, but burst all around it, sending up columns of earth and smoke. And off there Pinocchio could see the bersaglieri, the soldiers of his country. The traitor with his signals was directing fire on the Italian troops. 42

Tell me truly, what would you have done if you had been in Pinocchio's place? Would you have fired at the traitor? Yes or no. Well, Pinocchio did the same—cocked his pistol, shut his eyes, pulled the trigger, and pum-pum-pum-pum-pum-pum-pum, seven shots went off. He had expected only one, and was so frightened that he pitched his weapon away and took to his heels, down the steps, without thought of the wretch, who, for his part, did no more signaling, I assure you!

When he had got down to the square Pinocchio rushed across it, and was about to run in the direction where he had seen his bersaglieri fighting, when, passing by the shed where the Red Cross flag waved, he thought he heard the sound of several voices in a lively discussion. He stopped suddenly and very, very quietly approached a big window closed merely by a wire netting. Inside he saw on one side of the large room two rows of beds, in the middle a group of rough-looking soldiers, with waxed mustaches, completely armed, who were busy plotting together. Just at that moment they separated to go to bed. They took off their weapons, hid them under the 43 sheets, and slipped themselves into bed, drawing the covers up to their noses.

"Wunderschön!" ("Fine.")

"When Italian pigs come we make a colossal festival," grunted a Croat and laughed boisterously. "We sick get well, and Italians all croak."

"I'll croak you," muttered Pinocchio, who in a twinkle had understood the deviltry the wretches were planning. He made himself as small as he could, so that the cape dragged on the ground like a petticoat, slunk along the walls of the shed, then rushed off at full speed toward the fields. He was just passing the last house of the village when he found himself unexpectedly surrounded by a score of Austrian soldiers in a half-tipsy condition, so that they took him for their superior officer. He thought himself lost.

"Lieutenant, don't go farther. 'Talians still near and make croak all Croats."

"Croat? I a Croat!"

"'Talians make croak Slovaks, too."

"Oh! Mamma!"

"Ja, ja!"

"Ja, ja!"

Pinocchio had a flash of intuition; he 44 hid his hand under his cape, unsheathed the sword, and, assuming so martial a manner that then and there he could have been taken for a handsome brother of William, he yelled and swore some doggerel which the dolts might think was Hungarian, Dalmatian, or Rumanian, spun 'round and continued on his way to the Italian position. The Austrians followed him, bayonets fixed, convinced that the spirit of Tegetoff had come to life and was leading them to victory. But instead, when they had gone a hundred yards they were showered with bullets and had to fling themselves on the ground in order to escape immediate extermination. Pinocchio saw that he was being shot at more than the others, and didn't know why. All around him the torn-up earth was strewn with plumes.

"I should like to know why they are after me especially, who am not even firing, while they are sparing these monkeys who have followed me and are shooting like mad. Oh! Perhaps it is on account of the uniform of that miserable officer. If that is the case, my dear ones, enough of your sport. 'Oho! I am an Italian. Stop firing, for Heaven's sake, so that I can tell 45 you something important. Oho! Enough, I say!'"

And standing up straight, he hurled the cape and the cap away from him, and with no thought of danger, made for the spot from which came the Italian fire.

Then came the end of the scene. The Croats behind him jumped to their feet like so many jacks-in-the-box, threw their arms about and waved their hands in the air.... From a hedge not far off, a company of bersaglieri came running up and surrounded them, yelling, "Surrender!"

"If one of them moves, stick him like a toad," commanded a lieutenant.

"Don't worry, sir, I'll spit him for your roasting."

"Secure their officer."

"Heh, boys! don't joke ... lower your bayonets. I'm no Austrian officer. I am Pinocchio. Mollica, don't you recognize me?"

"You beastly little creature, what game are you playing? But I'll run you through, all the same."

"What's up now?"

"Lieutenant, Mollica wants to make believe that I am an Austrian lieutenant, because 46 I was the cause of his losing his place as orderly with General Win-the-War, but I am Pinocchio. Do you know me? I am glad. Order these twenty apes, which I have brought all the way here, to be bound, and then if you give me thirty men I will guarantee to catch some others that I have put to bed in the big barracks under the protection of the Red Cross, who pretended they were ill, but who had hidden their guns under the covers to 'croak Italian hogs.'"

"Where are they?"

"I'll tell you now ... then I'll show you up on the tower what a pretty thing I found—a traitor who was making signals to some one far off, and then, boom! there came one of those shells that burst. I meant to let him have one little bullet, but the pistol fired so many at him that I threw everything away...."

"But come on! Come on! Show me the way!"

"Right away, but on one condition—that when I have guided you, you will give me something to eat, because I am so hungry that I could eat that miserable Mollica." 47

"Come on, boy, to the village. Double quick!"

Who would have imagined that his regiment had been fighting continuously for ten hours, leaving some dead on the field and sending not a few wounded to the ambulance? There on the square of the village won by Italy, beneath the shadow of the red, white, and green flag that waved from the summit of the little tower, the brave boys gave vent to unrestrained joy. It was time for rations. In the camp kitchens big pots were steaming, but the soldiers did not crowd around them as usual to fill their canteens. The bersaglieri's attention was held by a sight which put them in good humor, and good humor in war is a rare thing. Pinocchio was eating! He had swallowed three platefuls of soup in five minutes, and as he continued to grunt that he was hungry, they had given him a canteen full to the top and slipped into it a piece of meat that would have been sufficient to satisfy the hunger of four city employees.

"Look out for bones!"

"Are you going to eat them all?" 48

"If he stays with us he'll break the Government."

"Look out, boys, he'll end by bursting."

"Don't you split open with all the Austrians you have eaten, for pork is more indigestible than asses' meat."

"Heh! don't find fault with the food."

"And what kind of meat do you call this?"

"The best beef."

"Lie! I am familiar with animals ... you give beef to the officers; donkey-meat to the soldiers."

"Look out, you Pinocchio, you'll get into trouble with that tongue of yours."

"Then let me eat in peace. You are all staring at me as if I were a Zulu chewing a hen with her feathers on. My tongue can't be dainty both talking and eating."

"Let's murder him."

And then there was a loud burst of laughter from all. Pinocchio was shoveling food into his mouth with both his hands, so that his face was red as a cock's comb and he could scarcely breathe.

They were already as fond of him as if he were their son. His achievements had won for him a certain respect even from the officers whom he amused with his 49 monkeyshines. It had been decided to adopt Pinocchio as the "son of the regiment" and to keep him at the front as a mascot. He was to live with the troops and to wear the uniform of a Boy Scout. The soldiers with common accord had put off his costume to an opportune moment. Do you want to know the reason? The brave boys were afraid to stick Pinocchio into puttees with so many spiral bands because his little thin legs would have frightened people. For the time being they had him put on a pair of short trousers which dragged behind him on the ground, a little cape like a bersagliere's, and a fez with a light-blue tassel so long that it touched his heels. This tassel was Pinocchio's delight, who, in order to look at it, always walked along with his head over his shoulder, and so would keep bumping into first one thing and then another. One day the mischievous Mollica made him run into one of the quarter-master-corps mules, and Pinocchio saluted and asked its pardon. But when he ran into officers, sergeants, corporals, and soldiers, instead of saluting he swore at them all.

It is three days later. General Win-the-War's troops have not advanced. Our bersaglieri 50 are still in camp near ——. It is a sultry, thundering afternoon. Many of the soldiers are sleeping. The Bersaglierino is playing cards with Mollica. Corporal Fanfara is shaving. Stecca is practising on his cornet, trying a variation on a well-known tune. Pinocchio, in the back of the tent, is snoring so loudly that Mollica every now and then hurls a handful of earth at his nose to make him lower his note.

Suddenly the boredom is broken, every one jumps up and runs out to a certain point and crowds around an automobile that has just arrived. Pinocchio wakes up with a start, finds his mouth full of grit, his nose dirty, and hears all the noise about him—has a terrible fright, lets out a yell, and rushes out of the tent. But he is scarcely outside before he feels himself caught up by his legs and whirled around on the ground. He gets up again and is face to face with Bersaglierino, who has not left his post and who laughs loudly at Pinocchio's plight.

"What has happened?"

"The mail has come."

"And you're making all this racket for that? I thought it was the Austrians." 51

"You little coward, you!"

"That's enough, Bersaglierino, if you say that to me again I'll give you such a kick that will change your shape. But why don't you, too, go to see if you have any letters?"

"Who do you think would write me? I am as alone in the world as a dog, just like you, it seems."

"Yes, that's so," replied Pinocchio, swallowing hard, because he had suddenly felt his throat tighten at the thought of Papa Geppetto, from whom he had had no news for many a long day.

"It is a red-letter day for the others. Mollica will have a letter from his father, Fanfara news from his two babies, Stecca kisses from his wife.... I might be killed 52 to-morrow by a bullet in the stomach and they would let me rot in a ditch and that would be the end."

Mollica came back, his arms full of newspapers. His father, a news-dealer in Naples, sent him a copy of every unsold publication, knowing that anything may come in useful in war-times, even old news.

"Heh! Bersaglierino! You want us to play the postman and yet you don't take any trouble to get your scented letter."

"You are joking?"

"No, it's no joke. Here is one really for you, and I congratulate you because if you are engaged she must be at least a countess."

The Bersaglierino took the letter his comrade held out to him and read the address over several times. There was no doubt; it was his name that was written on the scented envelope the color of a blush rose. He turned pale and stood for a moment undecided, then he tore it open and read:

Dear Bersaglierino,—I saw how sad and alone you were at the moment of your departure, so I felt it was my duty as a patriotic Italian girl to write to you. Go and fight for our country; do your duty bravely, and remember that in thought I follow and will follow you every minute. If you return valorously 53 I will meet you and tell you how happy I am; if you fall wounded I will go to your hospital bed to soothe your suffering; if you die for your country my flowers shall lie on your grave and your name will always be written in my heart. Long live Italy!

Your war-godmother,

Fatina.

"Long live Italy!" Bersaglierino shouted like mad. He caught up his hat with its cock plumes and tossed it in the air with all his force, seized Pinocchio who was standing by him, and lifted him up in both his arms, pulled his cap off his head, and then twirled it round on his pate, scratching the poor boy's nose.

"What's got into you? Are you crazy?"

"Am I crazy? I am happy! I am not alone any more, do you understand? I am no longer an unlucky fellow like you with no one belonging to him. But I am fonder of you than ever. Give me a kiss ..." and he pressed such a hearty kiss on his nose that his comrades laughed. But Pinocchio longed to cry. The heart in his body beat a violent tick-tock, tick-tock.

"Have you read what Franz Joe's newspapers say?—'Italian soldiers are brigands who do not respect civilians or the wounded in the hospitals.' That means you, dear 54 Pinocchio, because you shot the traitor on the tower. You can be sure that if the suet-eaters win they will make you pay for the crime."

"Me?"

"Yes, indeed, you! You don't intend to say that I killed him, do you? And you, thank God, are not an enlisted Italian soldier, therefore ..."

"I understand."

The camp was quiet once again; indeed, I might say that tender memories had softened its youthful exuberance. The voices from home were keeping the soldiers silent. It was as if every letter their eyes fell on was speaking to them quietly and they were blessed in listening, their faces shining with happiness. Corporal Fanfara held a sheet of paper on which there was nothing but some strange scrawls. He gazed at it with delight, and while two big tears ran down his cheeks he murmured in his Venetian dialect, "My darling little rascals!" These scrawls of theirs were more welcome to him than the letter from his wife which told of privations, anxiety, and troubles. Private Mollica was acting like a detective, searching through the newspaper pages for his 55 father's dirty finger-marks; and as there was little trouble in finding them he kept repeating every moment, "This was made by my dear old man." Then he kissed the marks so often that his whole mouth was black with printer's ink.

Shortly after every one was writing, some bent over their writing-tablets, some on the back of a good-natured comrade, some stretched out on the ground, some on the edge of a bench, on the staves of a barrel, on a tree-trunk, with pencils, fountain-pens, on post-cards, envelopes, letter-paper spilled out miraculously from portfolios, bags, and canteens. Every one was writing. The Bersaglierino seemed to be composing a poem. He gesticulated, whacked himself on the ear, beat time with his pen that squirted ink in every direction, and every now and then declaimed under his breath certain phrases that were so moving that they made even him weep.

Pinocchio was as silent and gloomy as the hood of a dirty kitchen stove. Squatting at the entrance to the tent, he kept glancing at his companions, and every now and then he would scratch his head so vigorously that he might have been currycombing 56 a donkey. When Pinocchio scratched his head in that way ... Well, now you know that matters were serious, but I tell you they were so serious that he had the courage to interrupt the Bersaglierino in his literary studies.

"Excuse me, but will you do me a favor?"

"What do you want? Keep quiet ... leave me alone ... you make me lose my thread of thought ..."

"So you write with thread, do you? Are you aware that they don't use this any more?"

"Stop your nonsense. Leave me alone, puppet."

"Do me a favor and then ..."

"What is it? Spit it out!"

"Lend me a pencil and a piece of paper."

"You want to write, too?"

"Yes."

"Then you, too, have some one in the world who interests you?"

"Yes ... perhaps."

"A godmother like mine?"

"Hum! No indeed."

"You are serious about wanting to write?" 57

"Yes."

"Here's paper and pencil, then. Do you know how to write?"

"Once I knew how."

"All right. Then let me see it."

"Gladly."

Pinocchio rested his elbows on his knees, chin on his clasped hands, and, biting his pencil, lost himself in profound meditation.

"Excuse me, Bersaglierino."

"Ho! Finished already?"

"No ... that is ... yes, I have finished beginning, but ... I don't know what you put before the beginning."

"Write, 'Dear So-and-so,' or 'My darling, etc., etc.'"

"But you see I can't put either 'dear' or 'my darling.'"

"So you are writing to a creditor?"

"Something like that."

"Heavens! Put his first name, his last name, swear at him, and that's enough."

"Excuse me, Bersaglierino..."

"Oh, are you still there?"

"Yes.... I haven't been able to start the beginning because ..." 58

"Do you or do you not know how to write?"

"Like a lawyer."

"Then?"

"I don't know what his last name is."

"Whose?"

"Franz Joe's."

"Writing to him? You want to write to him? To that miserable Hapsburg?"

The news spread like lightning through the camp. The soldiers passed it from mouth to mouth, laughing like mad: Pinocchio was writing to Emperor Franz Joseph! This was interesting. They must know what the letter said. It would certainly be something to amuse them. So walking quietly, as if they were all eager to take him in the very act, they approached the tent where Pinocchio was composing his missive, not without difficulty. He had not been writing for several minutes and the words seemed so long to put down on paper. He had to keep thinking of the spelling, and the verbs bothered him terribly. When he raised his head to draw a breath of relief before re-reading what he had managed to write, he found himself surrounded by all the regiment. 59

"Oh, you are well brought up, aren't you? Who taught you to stick your noses into other people's business?"

"To whom have you written?"

"To the one I wanted to."

"Let's see the scribbling."

"Look in your mirror and you will see worse lines on your own face."

"We want to read the letter."

"But if you are a pack of illiterates ..."

"Listen, either you will let me see it or 60 I will take you by one ear and the letter with the other hand, and I'll carry you both off to the censor, who will haul you before a court martial that will condemn you to be shot in the back."

"Oh, do you really want to see it, Mollica?"

"You heard what I said."

"On one condition."

"What's that?"

"That you will take charge of it and see that it gets to its address."

"All right. Hand it here, you puppy. Listen to what he writes:

"Mr. Franz Hapsburg,

In his house in Austria,

"You wrote in the papers that the Italian soldiers are rascals because they kill civilians and wounded Ostrians. I want you to know that you are mistaken, because as you know the traitor was killed by a pistol that shot off Ostrian bullets by itself while it was in my hands who am not in the army. That's how our soldiers found the traitor already dead, the traitor who made signals from the church tower, so that the shells fell on the ruins. As for the wounded in the horspital I can asshure you that they were better off than me and you, and that they had guns between their leggs under the sheets. He who tells lies goes to hell and you will certainly go there, but just now I'd like to send you there myself who don't give a hang for you.

"Pinocchio."

I can't describe to you what took place after the letter had been read.

They gave the poor youngster such a feast that they had to put him to bed in a hammock. Before Private Mollica went to sleep he kept repeating: "I have promised to take your letter to Franz Joseph.... You see if I don't send it through all the ranks till it reaches his own hands. On Mollica's honor!... I have promised to take your letter to Franz Joseph!"

How Pinocchio Learned That War Changes Everything—Even the Meaning of Words

The bersaglieri had passed the Isonzo and were intrenched at —— (censor). You certainly know now what the Isonzo is, because war teaches geography better than do teachers in the schools; so I don't intend to explain it to you. Pinocchio had followed his friends, and I assure you no one regretted his coming. When there were orders to carry to the rear or purchases to be made, it was Pinocchio who attended to them. Slender as a lizard and quick as a squirrel, he was out of the trenches without being seen and slipped along the furrows and ditches and the bushes with marvelous dexterity. He had been absolutely forbidden to approach the loopholes, and when they caught him about to disobey he got such boxes on the ears that he had to rub 63 them for half an hour afterward. Mollica, and the Bersaglierino in particular, kept their eyes on him, so that they punished him often.

"I'd like to know why it is you two can stand with your noses against the hole and I mayn't."

"Because of the mosquitoes."

"Who cares for them? I haven't the slightest fear of mosquitoes."

But when he saw them carry off a poor soldier hit in the middle of the forehead and understood that the "mosquitoes" were Austrian bullets, he gained a little wisdom. While the soldiers were suffering from the trench life which restrained their ardent natures, keeping them still and watchful, the rogue of a Pinocchio amused himself with all kinds of jokes. Dirty as he could be, he was always grubbing with his nails in the ground to deepen the trench, to make some new breastwork, to build up an escarp. If they sent him out to find logs of wood to repair the roofs of the dugouts he would come back laden with all sorts of things. Hens and eggs were his favorite booty. One day he managed to capture a pig and to drag it along behind him. But when 64 they got near the trenches the cussed animal began to squeal so horribly that the Austrians opened up a terrific fire on him. For fear of the "mosquitoes" Pinocchio had to let him go, and the pig ran to take refuge among his brothers, the enemy.

That evening it rained cats and dogs. The trench was one slimy pool. The rain dripped everywhere, penetrating, baring the parapets which collapsed, squirting mud and gluing the feet of the soldiers, who, wet to the bone, had to scurry through the wire to carry ammunition to safety and to repair the damage done to the trench. Pinocchio, barelegged, ran back and forth, bemired up to his hair, to give a helping hand to his friends.

"What fun! We seem to be turning into crabs."

"You are a beastly little puppy!"

"Poor Mollica! You really make me sorry for you."

"I make you sorry for me?"

"Certainly. I shouldn't want to be you in all this downpour."

"Why?"

"Because this rain will melt your sugary nature." 65

Mollica, to convince him of the contrary, started to administer one of his usual boxes on the ear, but he slipped and fell, face down, into the mud.

"Are you comfortable, Private Mollica? Tell me were you ever in a softer bed than now?... You look to me like a roll dipped in chocolate.... Bersaglierino, 66 come and see how ugly he is! All chalky up into his hair.... I never saw any one look such an idiot!"

"I wish they would murder you, you beastly little puppy!"

After struggling about in the mud he managed to get to his feet again and had almost caught him, but in one spring Pinocchio was far away. The telephone dugout was a little deeper than the trench and the 67 water was rapidly filling it up. It was already up to the operator's knees. A crowd of soldiers were working hard to stop the flood.

"What are you doing, stupids? Do you think you can bail out this puddle with a cap? You are green. We ought to have big Bertha...."

He didn't get in another word. They took hold of him by his arms and legs and soused him into the dirty water and held him under till he had drunk a cupful. The telephone operator would have liked to see him dead, then and there.

"Hold him under till he is as swollen as a toad. He was calling down misfortune on us, wishing that a shell would fall on us. As if this rain weren't enough (che-chew, che-chew!); we are chilled to the marrow (che-chew!) and are likely to die bravely of cold ... (che-chew!)."

"Enough! Let me go! Help! Bersaglierino! Mollica-a-a!"

"What are you doing to him? Let him go. Shame on you!" yelled Bersaglierino, running up.

"But don't you know that he was wishing a shell would hit us, the little wretch?" 68

"Just as if we hadn't enough troubles now."

"Of course you have enough, and one of your troubles is that you are regular beasts," cried Pinocchio as soon as he could get his breath. "I said I wished for Bertha, the cook in Papa Geppetto's house, to sweep away the water in here, but now I wish I had a broom in my hand to break its handle against your ribs."

"But don't you know that a 'Big Bertha' is a Boche gun that would have blown us into a thousand pieces?"

"So, little devil, do you understand? And now that you have learned your lesson, be off with you."

There was nothing else for poor Pinocchio to do but to spit out the mud still in his mouth and turn on his heel.

"Bersaglierino, I would have believed anything but that words change their meaning in this way. With these idiots you have to pay attention to what you say. They made me swallow so much ditch-water that it will be a miracle if I don't have little fish swimming around in my stomach."

It stopped raining, but as if the Austrians 69 didn't want to give the bersaglieri time to repair the damages caused by the bad weather, they began a furious bombardment of the trench. The "mosquitoes" kept up a terrible singing. Huge projectiles churned up the ground all around, digging out deep holes, raising whirls of earth, throwing off shreds of stone and steel in every direction. One shell had fallen near the telephone and had done great damage. The soldiers couldn't venture any distance from the dugout to aim at the enemy who was firing at them with such accuracy. Mud prevented their movements. They couldn't change their positions because the slippery earth offered no foothold. It was impossible to excavate deep because the earth slid down. It was a critical moment. Several men had been killed, the wounded were moaning bitterly, the dying were groaning.... But the Italian bersaglieri did not lose courage and stood up against the foe, showing a genuine disregard for their lives. Pinocchio longed to cry. He wasn't thinking of the danger to himself, but of the fact that if this devilish fire kept up much longer all his bersaglieri would be killed. Wasn't there anybody to 70 look out for them? What was our artillery doing? Did they really intend to let them all be massacred?

He had scarcely thought this when he heard behind him the thunder of Italian guns. A quarter of an hour later and the Austrians were quite quiet. But the situation hadn't improved. Orders had come from the second line to hold out at all costs because it wouldn't be possible to relieve them until the next evening. An attack in force was expected every minute.

The captain assembled his company and said: "Men, we must stick and be ready for anything. We can't have reinforcements, but to-night they will send us chevaux de frise and barbed wire. But I don't want to be caught like a bird in a net. We have plenty of 'jelly.' If two would volunteer to carry a couple of pounds of it under the entanglements of those gentlemen over yonder we might be able to change our lodgings. They have a fine trench of reinforced concrete with rooms and good beds and bathroom. We'd be better off there than in this mud. What do you say, boys? Is there any one who ..."

They didn't even let him finish. All 71 stepped forward, and, if I am to tell you the truth, Pinocchio, too, but no one noticed him. Mollica and the Bersaglierino were chosen.

It grew dark. Some of them, completely worn out, dozed leaning up against the side of the trench. The Bersaglierino was writing rapidly a letter in pencil. Mollica had pulled out of his knapsack the old newspapers his father had sent him and seemed about to take up his old studies of fingerprints. There were tears in his eyes.

"Heh! Mollica, you look as if you weren't pleased with the duty the captain has given you."

"Well?"

"But you ought to let me go."

"You? But how do you suppose they would let a boy like you carry jelly?"

"Do you think I would eat it all up? I won't say that I mightn't taste it, especially if it is that golden-yellow kind that shivers like a paralytic old man, but I would carry out the order like any one else.... Only, I can't understand how for a little bit of jelly those scoundrels will give up their comfortable trench. It's true that they eat all sorts of miserable kinds of food 72 and that Esau sold his birthright for a mess of pottage, but ..."

"Shut up, you chatterbox! You'll see what will happen. I'll explain to you that 'jelly' in war-time is what we call a mixture of stuff that when put in a pipe under the wire entanglements and set off by a fuse will blow you up sky-high in a thousand pieces, if you don't take to your heels in time."

"And you ... want to go and be blown up?"

"No. I hope to come back safe and sound, and I have still to send your letter to Franz Joey."

Pinocchio was silent and hid himself in a corner without another word. I can't tell you exactly if he had some sad presentiment or if his disillusion resulting from Mollica's technical explanation of "jelly" had put him in a bad humor. There was no doubt about it—war had changed the dictionary. He was still more certain of this when, an hour later, he saw the "Frisian horses" arrive. He was expecting beasts with at least four legs, and instead he saw them drag in front of the trenches a huge roll of iron wound up in an enormous skein of barbed wire. But there was still a 73 greater surprise in store for him. That very night he was to find out that in war-time not only the value of words changes, but that there are some which are canceled from certain persons' vocabulary.

It was night ... and there was nothing to be seen and you couldn't even hear the traditional fly. From the Austrian trench there came a dull regular noise. It seemed as if a lot of pigs were squealing. Instead, it was the Croats who were snoring. No one slept in the Italian trenches. There was a strange coming and going, a fantastic flittering of shadows. There was low talking, commands were passed from mouth to mouth and whispered in the ear—every one was making preparations. Mollica and the Bersaglierino had put steel helmets on their heads and had shields of the same metal on their arms.

"But what are you going to do? You look like the statue of Perseus in the costume of a soldier."

"I would almost rather be in his place and with no more clothes than he has on instead of in this get-up ... but what's there to be done about it? I promised you to take the letter to Franz Joey." 74

A little later Mollica and Bersaglierino left the trench and wriggled along the ground like serpents, carrying with them big metal boxes. The bersaglieri took their places behind the loopholes, their muskets in position, and stood there motionless, anxious, and restless. Pinocchio, too, wanted to see what was happening, and, taking advantage of his guardians' carelessness, slipped out of the trench and squatted down in a big hole which an enemy projectile had hollowed out twenty yards away.

The poor youngster was very sad. The black night, the silence everywhere, the preparations he had watched and could not understand, were the causes of his melancholy.

"But how under the sun did it ever enter Bersaglierino's head to offer himself for this expedition?" he thought. "He might have let some one else go. Not so bad for Mollica. He'll eat up the Austrians like waffles. If any one dares to play a trick on him he'll land him a few good blows and put him where he belongs, but Bersaglierino ... so little and so frail.... If any misfortune happens to him ..."

Some time went by, I can't say how long, 75 but it was quite a little while, because Pinocchio had almost fallen asleep, when the air was shaken by two tremendous explosions. He woke with a start, saw two red flashes shining for an instant on a shower of fragments thrown up to a great height ... then blackness and the fiendish rattling of the machine-guns and crackle of musket fire. Suddenly a long white shaft of light broke the darkness, coming from no one knew where, waving to the right and to the left, and fixing itself on the ground between the two trenches, which were immediately showered by shells.

"And Bersaglierino? And Mollica?" Pinocchio asked himself, anxiously, feeling his throat tighten up.

Suddenly a black shadow was outlined in the gleam of a searchlight that was operated from a distance. It crawled along the ground, moving by starts. They had seen it, too, from the trenches and there were confused cries of, "Come on!" ... "Bravo!" ... "A few more steps!" ... "Stick to it!"

And the figure seemed to gain new strength and to bound like a wild beast. But who was it? Surely the Bersaglierino. 76 The form was small, slender, and very quick. Mollica was large and slow. What had become of him? Between the roar of the explosions and the whistle of the shells there came a shrill cry of anguish. The little shadow slid along, then a leap in the silvery ray, and it was lost in the blackness of the earth torn by the rain of steel.

"Oh, beasts that they are! They have murdered him!" Pinocchio screamed. "Enough! Enough! Wretches! Don't you see that he has ceased to move? Stop shooting.... Give him time to recover.... Perhaps he is wounded."

It seemed that the Austrian fire grew even more murderous.

Pinocchio, beside himself with fury, rushed out of his hiding-place and in a couple of bounds was back in the trench.

"They have wounded Bersaglierino.... He is there ... out there in the No Man's Land.... Help him ... don't let him die so."

They sprang over the top to rescue their wounded comrades, but had scarcely gone a step before they were lost to him.