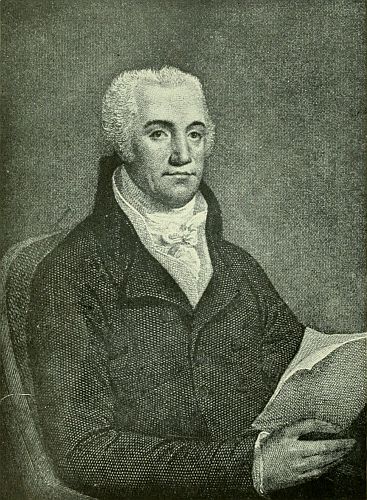

JOEL BARLOW

JOEL BARLOW>FROM AN ENGRAVING BY DURAND AFTER THE PORTRAIT BY ROBERT FULTON

Title: The Friendly Club and Other Portraits

Author: Francis Parsons

Release date: September 30, 2012 [eBook #40898]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The

| ||

Citation of authorities, except so far as they appear in the text, has been considered inappropriate in the case of such informal articles as these. It would be ungracious, however, to omit mention of the writer's indebtedness in connection with the second essay to Mr. Charles Knowles Bolton's "The Elizabeth Whitman Mystery," which is the latest and most comprehensive document on this baffling incident of New England social history.

| PAGE | ||

| I | The Friendly Club | 13 |

| II | The Mystery of the Bell Tavern | 47 |

| III | The Hemans of America | 69 |

| IV | Whom the Gods Love | 83 |

| V | An Eccentric Visitor | 95 |

| VI | Who Was Peter Parley? | 107 |

| VII | A Preacher of the Gospel | 121 |

| VIII | A Friend of Lincoln | 135 |

| IX | Our Battle Laureate | 147 |

| X | The Temple of the Muses | 161 |

| XI | The Friend of Youth | 181 |

| XII | The Christmas Party | 191 |

| XIII | The Fabric of a Dream | 201 |

| XIV | The Quiet Life | 213 |

| Joel Barlow | Frontispiece |

| From the engraving by Durand after the portrait by Robert Fulton | |

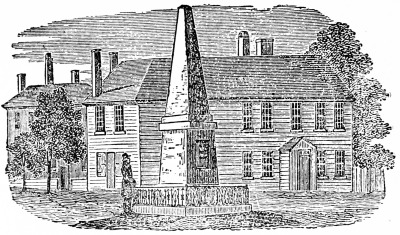

| Lexington Monument and Bell Tavern, Danvers | 64 |

| From Barber's "Massachusetts Historical Collections" | |

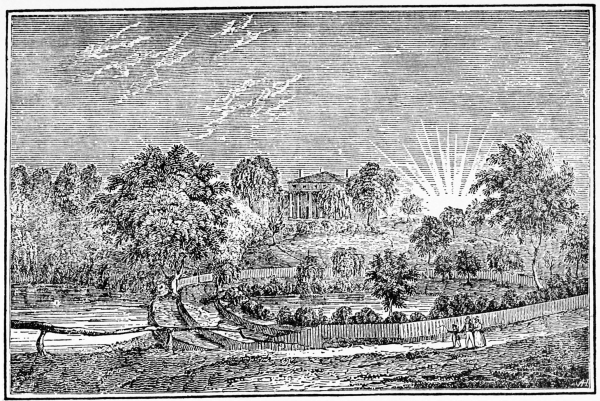

| The Sigourney Mansion | 75 |

| From an old woodcut | |

| Lydia Huntley Sigourney | 78 |

| From a miniature in the Colt Collection by permission of the Wadsworth Atheneum | |

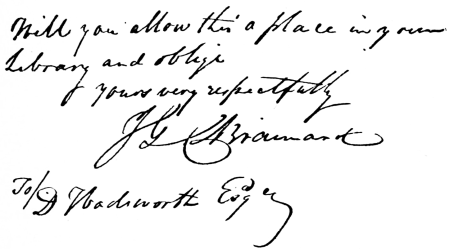

| Inscription to Daniel Wadsworth in J. G. C. Brainard's Hand | 91 |

| Title Page of Brainard's "Occasional Pieces of Poetry" | 92 |

| The Watkinson Library | 166 |

| Drawing by Seth Talcott | |

| Silhouette of Daniel Wadsworth | 170 |

| By permission of The Connecticut Historical Society |

How good this literature was considered in its day is not readily understood by the modern reader, for from the Hudibrastic imitations and heroic couplets of these writers, whose brilliance was dimmed so long ago, the contemporary flavor has long since evaporated. Indeed there is no[16] modern reader in the general sense. It is only the antiquarian, the literary researcher, the casual burrower among the shelves of some old library who now opens these yellow pages and follows for a few moments the stilted lines that seem to him a diluted imitation of Pope, Goldsmith and Butler. Professor Beers of Yale ventures the surmise that he may be the only living man who has read the whole of Joel Barlow's "Columbiad."

Yet in their time this coterie of poets, who gathered in the little Connecticut town after the close of the war for independence, became famous not only in their own land but abroad, and the community where most of them lived and met at their "friendly club"—was it at the Black Horse Tavern or the "Bunch of Grapes"?—shone in reflected glory as the literary center of America. No Boswell was among them to record the sparkling epigrams, the jovial give and take, the profound "political and philosophical" debates of those weekly gatherings. Yet imagination loves to linger on the old friendships, the patriotic aspirations, the common passion for creative art, the wooing of the Muses of an older world, thus dimly shadowed forth against the[17] background of the raw young country just embarking on its mysterious experiment.

Do not doubt that these personages whose individualities are now so effectually concealed behind the veil of their sounding and artificial cantos were real young men who cherished their dreams and their hopes. One can see them gathered around the great wood fire in the low ceiled room redolent of tobacco, blazing hickory and hot Jamaica rum.

Here is Trumbull, the lawyer, the author of "M'Fingal" which everybody has read and which has been published in England and honored with the criticism of the Quarterly and Edinburgh Reviews. He is a little man, rather frail, rather nervous, not without impatience, with a ready wit that sometimes bites deep. Here is Lemuel Hopkins, the physician, whose lank body, long nose and prominent eyes are outward manifestations of his eccentric genius. His presence lends a fillip to the gathering for he is an odd fish and no one can tell what he will do or say next. Threatened all his life with tuberculosis he is nevertheless a man of great muscular strength and during his days as a soldier he used to astonish his comrades by his ability to fire a heavy[18] king's arm, held in one hand at arm's length. In his verses he castigates shams and humbugs of all kinds, whether the nostrums of medical quacks or the irreverent vaporings of General Ethan Allen—

Perhaps Colonel David Humphreys, full of war stories and anecdotes of his intimacy with General Washington, on whose staff he served, is in Hartford for the evening. A well dressed, hearty, sophisticated traveler and man of the world is Colonel Humphreys, who would be recognized at first glance as a soldier, though not as a poet. Nevertheless he is addicted to the writing of verse which is apt to run in the vein of comedy or burlesque when it is not earnestly patriotic. To look at him one would know that he enjoys a good dinner, a good story and a bottle of port.

We may be sure that Joel Barlow is here, the vacillating, visionary Barlow who has tried, or is to try his hand at many pursuits besides epic poetry—the ministry, the law, bookselling, philosophy,[19] journalism and diplomacy—but who is pre-occupied now, as all his life, with his magnum opus, "The Vision of Columbus," later elaborated into "The Columbiad." He is a good looking, if somewhat self-centered young man, a favorite in the days of his New Haven residence with the young ladies of that town. Perhaps it was there that he first met the charming and talented Elizabeth Whitman, the daughter of the Rev. Dr. Elnathan Whitman, sometime pastor of the South Congregational Church in Hartford, who often visited her friend Betty Stiles, the daughter of the president of Yale College. A few of Elizabeth Whitman's letters that have survived—the packet bearing an endorsement in Barlow's handwriting—are evidence that he made her a confidante of his literary schemes and hopes and welcomed her assistance with his great epic. A strong friendship and entire harmony seem to have existed between her and Ruth Baldwin of New Haven, whom Barlow married during the war, and who is said to have "inspired in the poet's breast a remarkable passion, one that survived all the mutations of a most adventurous career, and glowed as fervently at fifty as at twenty-five." For nearly a year the marriage[20] was kept a secret, but parental forgiveness was at last secured and Barlow has now brought his wife to Hartford where he is continuing his legal studies, begun in his college town. But the law will not engross him long. Soon, with his friend Elisha Babcock, he is to start a new journal, "The American Mercury," of which his editorship, like all of Barlow's early enterprises, is to be brief, though the paper is to continue till 1830.

A tall, slender man, Noah Webster by name, a class-mate of Barlow at Yale, though four years his junior, sits near him, relaxing for the moment in the informality of these surroundings his strangely intense powers of mental application, divided just now between the law and the preparation of his "Grammatical Institute." To the "poetical effusions" of his friends he contributes nothing, but he was an intimate of them all and no doubt often attended their gatherings.

Perhaps, now and later, something of the poet's license in the matter of chronology may be granted. Let us assume, then, that young Dr. Mason Cogswell is in town for a day or two, looking over the ground with a view of settling here in the practice of medicine and surgery in[21] which he is now engaged at Stamford, after his training in New York where he served with his brother James at the soldiers' hospital. It is true that the fragments of his diary, which by a fortunate chance were rescued from destruction, do not mention any visit to Hartford as early as this, though his journal does describe a short sojourn here a few years later. Still, his presence is by no means impossible. He is a companionable youth, as popular with the young ladies as Barlow, but with an easier manner, a readier humor. Delighted at this opportunity to sit for an evening at the feet of the older celebrities, he is a welcome guest, for already he has a reputation for versatility and culture and the fact that he was valedictorian of the Yale Class of 1780—and its youngest member—is not forgotten.

Richard Alsop, book-worm, naturalist and linguist, who is beginning to dip into verse, has locked up his book shop for the night and is here. Near him sits a man who is, or is soon to be, his brother-in-law, a tall, dark youth, Theodore Dwight, the brother of the more famous Timothy, whose pastoral duties detain him at Greenfield Hill, but who is sometimes numbered as[22] one of this group. Theodore is now studying law, but he has a flair for writing and makes an occasional adventure into the gazettes.

These more youthful aspirants have their spurs to win. A little later they, with their friend Dr. Elihu Smith, who published the first American poetic anthology, are to get into print in a vein of satirical verse ridiculing the prevalent literary affectation and bombast. After journalistic publication these satires will appear in book form under the title of "The Echo," in the introduction to which the anonymous authors state that the poems "owed their origin to the accidental suggestion of a moment of literary sportiveness." "The Echo" was "Printed at the Porcupine Press by Pasquin Petronius."

That particular sportive moment is still in the future. Now it is sufficient for these younger men to shine in the reflected luster of the established luminaries. These greater lights are worthy indeed of the worship of the lesser stars. Three of them have achieved, or are soon to acquire, an international as well as a national reputation. That "M'Fingal" had provoked discussion in England has been noted. Humphreys's "Address to the Armies of America," written in camp at[23] Peekskill, and dedicated to the Duke de Rochefoucault, was issued with an introductory letter by the poet's friend, the Marquis de Chastellux, in a French translation in Paris, after its publication in England where the Monthly and Critical Reviews gave it a fair amount of praise, though they could not refrain from the statement that the poem was "not a very pleasing one to a good Englishman." Barlow's "Vision of Columbus" was published almost simultaneously in Hartford and London in 1787.

In short these men had attained a genuine intellectual eminence in their generation. They were the cognoscenti of their day. Like most young intellectuals their gospel concerned itself with reform, with the ridicule of shams, with the refusal to accept the popularity of new doctrines as a final test of their value. Trumbull and Barlow, both Yale graduates, had fought with their friend Timothy Dwight their first reform campaign which was an effort to introduce into the somewhat archaic and outworn body of the Yale curriculum the breath of the humanities and of modern thought. Trumbull, according to Moses Coit Tyler, was an example of a "new tone coming into American letters—urbanity,[24] perspective, moderation of emphasis, satire, especially on its more playful side—that of irony."

Their interests were not only literary. They were publicists, political satirists, social philosophers, not without their religious theories. In all these matters their search was for the true standards and as champions of causes and enthusiasts of ideals they exhibited a variation from type in that their warfare was waged, not against the recognized conventions in government, religion and society, but in favor of them. Priding themselves on untrammelled and direct thinking, their reasoning led them to support the established, the orderly, the stable. Temperamentally aristocrats, theoretically republicans—in the broad sense of the term—they were practically federalists. "The Anarchiad," a series of poems they were contributing anonymously about this time to "The New Haven Gazette," dealt satirically with the dangers of national unrest and instability, of selfish aggrandizement and of a fictitious currency. In these verses Hesper addresses "the Sages and Counsellors at Philadelphia" as follows:

And in the same passage occur some lines, attributed to Hopkins, that Daniel Webster may have read:

They ridiculed unsparingly the dangers hidden under the cloak of "Democracy"—dangers imminent and menacing in the days following the end of the war in which most of them had served. In fighting these perils they were sagacious in making use of the means frequently employed by advocates of radicalism—invective, irony and ridicule. For these methods secured, as they naturally would secure if cleverly managed, a wide appeal. Yet the efficiency of such weapons depends very largely upon the occasion. Their potency is contemporary with the events against which they are directed and with the passing years their force weakens. Who reads nowadays the political diatribes of Swift, the tracts of Defoe, or the letters of Junius? Here perhaps is in part an explanation of the great temporary influence of the Hartford Wits, as well as of their complete modern obscuration. The brilliant[26] blade they wielded had a biting edge, but the rust of a century and a half has dulled it.

This general leaning toward the established canons, this impatience with the new doctrines that in the judgment of these men made for disunion and disaster, should be qualified, at least in the religious aspect, in two interesting particulars, each contradictory to the other. Hopkins began adult life as a sceptic but became a defender of the Christian philosophy. Barlow, on the other hand, deserted in later life the orthodox ideals of his youth, never, perhaps, very enthusiastically championed, and during his sojourn in France became a rationalist and free-thinker.

In general, however, the Hartford Wits fought for the established order against the forces of innovation and disintegration and thus when they sat down to unburden their minds of their visions of their country's future greatness, or of their impatience with demagoguery and political short-sightedness, it was natural that their sense of tradition and order should lead their thoughts to seek expression in the verse forms lifted into fame by the masters of an older and greater literature and accepted as the conventional vehicle[27] of poetic expression. Here is another reason, if they must be catalogued, for the forgetfulness of the Hartford Wits. These balanced, formal lines, so expressive of the artificial modes and manners of the subjects of Queen Anne and her successors, are to us prosy, old-fashioned and imitative. Their charm has fled. Can you imagine Miss Amy Lowell reading Hudibras? And we must admit that "M'Fingal," though it has given to literature some still remembered aphorisms, such as—

It is significant that the distinction of the individuals united in the "friendly club" was not confined to their literary activities. In an age sometimes esteemed narrow and limited in its cultural aspects they are refreshing in their versatility. Trumbull was a well-known lawyer and served on the bench for eighteen years, part of his legal training having been pursued in the office[28] of John Adams. It was a strange combination, not unprecedented but nevertheless arresting, of this talent for the law associated with the artistic temperament. For with all his practical attributes Trumbull was essentially an artist. His early poem entitled "An Ode to Sleep," says Tyler, "is a composition resonant of noble and sweet music and making, if one may say so, a nearer approach to genuine poetry than had then [1773] been achieved by any living American except Freneau." And in the following bit of autobiography, quoted by Tyler, may be discerned the self-distrust and depression to which no soul that longs and strives for the beautiful in this imperfect world is entirely a stranger: "Formed with the keenest sensibility and the most extravagantly romantic feelings . . . . I was born the dupe of imagination. My satirical turn was not native. It was produced by the keen spirit of critical observation, operating on disappointed expectation, and revenging itself on real or fancied wrongs."

This is an extraordinary item of self-revelation to come from a man who at various times held office as State's Attorney for Hartford County, member of the General Assembly and Judge of[29] the Superior and Supreme Courts of his State. It may not be an entirely fanciful surmise to attribute a partial cause of the delicate health that followed Trumbull all his long life to the warring elements that strove to unite in his brilliant mentality.

With Dr. Hopkins poetizing was distinctly a by-product. His chief concern was the practice of medicine and in his profession he won a reputation that is not entirely forgotten today by members of the faculty, for he was probably the first American physician to assert that tuberculosis was curable and his success as a specialist in this field was so marked that, says Dr. Walter R. Steiner in a monograph upon him, "patients with this disease came to him for treatment from a great distance—one being recorded to have made the trip all the way from New Orleans." In his treatment he was unique in his day in very largely discarding the use of drugs and relying more upon pure air, good diet and moderate exercise when strength permitted. His theory that fresh air was better for colds than the warm air of houses was revolutionary, but so was almost everything he did—or so it seemed to his contemporaries. At one time he evidently considered[30] that New York City might offer a wider field of practice than the Connecticut capital, for in December, 1789, Trumbull wrote to Oliver Wolcott, "Dr. Hopkins has an itch of running away to New York, but I trust his indolence will prevent him. However if you should catch him in your city, I desire you to take him up or secure him so that we may have him again, for which you shall have sixpence reward and all charges." In spite of his malady he lived till almost fifty-one, dying in April, 1801, the head of the medical profession in Connecticut.

It is to be noted that though Dr. Cogswell was one of the chief contributors to "The Echo" his main business in life was as a surgeon rather than a poet, and he became one of the most skillful surgical practitioners in the country, being the first to introduce into the United States the operation for cataracts and the first to tie the carotid artery. Closely associated with him is the pathetic memory of his daughter Alice who became stone deaf in early childhood and whose infirmity led to the establishment at Hartford of the first school in this country for the education of the deaf. Of this institution Dr. Cogswell was one of the founders and he was a leader in other[31] philanthropic enterprises. He lived till 1830. To the last he wore the knee breeches and silk stockings customary in his youth and which he considered the only proper dress for a gentleman. His death broke the heart of his daughter Alice, to whom he had been a never-failing protection and support, and she died within a fortnight after her father.

In contrast with the activities of their colleagues, the careers of Theodore Dwight and Alsop are associated solely with the product of their pens. Dwight, however, was more of a publicist and editor than a creative literary worker. He had the brains with which nature had endowed his family and his history of the unjustly maligned Hartford Convention is a thoughtful and able piece of work—an original historical document that is illuminating and suggestive. Such distinction as Alsop attained was strictly literary, yet one gets the impression that he worked at writing rather as an amateur than a professional. He was really a student, a scholar, a research worker, and seems to have sought his reward more in the pleasure of following his interests than in the quest of public recognition. Much that he wrote was never published.

There was a great deal in life that Colonel Humphreys enjoyed besides composing verses and a great many activities other than poetry for which he may be remembered. Not the least hint of any paralyzing self-distrust, no subtle questionings as to whether it was all worth while, disturbed his equanimity. And fate rewarded his zest in life by furnishing him with a variety of experiences. They began in the war from which he emerged with a reputation for gallantry and daring and, what was perhaps more valuable, with the firm friendship of George Washington. He participated in the raid into Sag Harbor by Colonel Meigs in '77 and the next year raided the Long Island shore on his own account, burning three enemy ships and getting away without the loss of a man. It was only a freak of the weather that perhaps withheld from him a more glorious exploit for on Christmas night, 1780, he headed a desperate venture that had for its object no less an achievement than the capture of Sir Henry Clinton at his headquarters in New York. The rising of the wintry northwest gale drove the boats of the little group of adventurers away from the intended landing near the foot of Broadway and swept them down through the British[33] shipping in the harbor to Sandy Hook. After Yorktown he was ordered by Washington to carry the captured colors to Congress which in the enthusiasm of the moment voted him a handsome sword.

But this was by the way. Appointed secretary to the commission, consisting of Franklin, John Adams and Jefferson, sent to negotiate treaties of commerce and amity with European nations, he no doubt thoroughly enjoyed his two years in London and Paris. In theory the nobility of Europe may have been anathema to a patriotic[34] citizen of a republic, but practically there were many persons among them whose acquaintance was agreeable to an amiable and gallant gentleman of sensibility like Colonel Humphreys and there was, no doubt, a certain gratification in dedicating one's poems to a duke and in having them reviewed by a marquis who incidentally disclosed the fact that he was an old companion in arms. Also it was pleasant to be elected a fellow of the Royal Society.

On Colonel Humphreys's return he spent some time as a member of the family at Mount Vernon where Washington encouraged him in his project of writing a history of the war which, however, never got any further in print than a memorial of his old general, Putnam. At Mount Vernon he wrote an ode celebrating his great and good friend whose friendship we may reasonably infer constituted one of his chief conversational assets:

It is clear that European life had its attractions for Colonel Humphreys. At all events he returned to it, serving as minister to Portugal and later to Spain whence he imported his famous merino sheep to his acres at Humphreysville, now Seymour. Here, and in the adjoining town of Derby, he projected and to a creditable extent realized, an ideal patriarchal manufacturing and farming community, instructing his operatives and husbandmen in improved industrial methods, in scientific agriculture and stock raising, athletics, poetry and the drama in which one of his productions was actually presented on the stage. At least he accomplished his wish, voiced in his poem "On the Industry of the United States of America"—

Though the friends grouped around the tavern[36] fire are united in two sympathetic qualities—devotion to the Muses and a proud conviction, singularly justified by events, of the destiny of their country—it is manifest that the membership of the little club furnishes only another illustration of the truism that human personality is the most varying thing in the world and that life has different lessons for each of us. The most baffling individuality of them all, the man whose story seems to have been a quest for some mysterious, unattained goal, was Joel Barlow.

In early life everything he attempted went to pieces. His chaplaincy in the army was a tour de force which he dropped as soon as possible. The law proved a mistake almost as soon as begun and his editorship of "The American Mercury" was abandoned after less than a year. Perhaps it was with renewed hope, perhaps it was with something of desperation, that he persuaded himself to embark on an entirely new undertaking and to accept a proposal to journey overseas to procure settlers for the Ohio lands which the Scioto Land Company desired to sell to unsuspecting Frenchmen. It is an established fact that Barlow was unsuspecting himself, but after he had procured the settlers and shipped them off[37] with golden promises the project turned out to be a gigantic fraud. Personal humiliation was added to general discouragement. Yet somehow he survived the mortification. It may be that at this particular time mundane affairs did not seem to be of the utmost importance. He was dwelling somewhat in the clouds, in a vision—the "Vision of Columbus," which he proposed to amplify and republish in a form more fitting the great theme than the first modest edition of the original poem. He was pre-occupied with the millenium he foresaw.

To the present day reader it is of the highest interest to note that the "Vision" foretold the Panama Canal, and that the climax of the poem is a congress of the nations.

Indeed with the break-down of his career as a promoter the tide began to turn. Barlow's friends knew he was innocent of complicity in the land swindle. In Paris he found himself at last in an[38] environment where freedom of thought was encouraged, where the ambitions of a poet were regarded with respect and admiration. He was always an idealist and he caught the contagion in the mental atmosphere of Paris as the revolution came on. Perhaps it seemed to him that his dream of the millenium was coming true. He became a Girondist and a political writer, supporting himself mainly by his pen, with the re-writing of the "Vision" always in the back of his mind. Was this the real Barlow—or was it a phase, a manifestation of a kind of philosophic idealism, fostered by the air of Paris, so favorable to the blossoming of this new flower of liberty and universal human brotherhood which centered on France the minds of all the dreamers of the world?

What did he now think, we wonder, of his dedication of the first edition of his epic, published the year before he sailed for France, to Louis the Sixteenth whom, as one commentator has noted, he soon indirectly assisted in sending to the guillotine? He had gone a long way from the militant conservatism of the brilliant companions of his youth—from the days when he had preached the gospel to American soldiers and[39] had collaborated with Timothy Dwight, at the request of the General Association of the Connecticut Clergy, in getting out an edition of Isaac Watts's metrical versions of the Psalms—to which he had added a few poetical renderings of his own.

For the following years his residence alternated between Paris and London where he found congenial souls among the artists and poets who were members of the Constitutional Society. His "Advice to the Privileged Orders" was attacked by Burke, praised by Fox, proscribed by the British government and translated into French and German. In 1792 he presented to the National Convention of France a treatise on government which was in fact a remarkable state paper, combining profound philosophic theories of government with practical administrative and executive suggestions. As a result he was made a citizen of France—an honor he shared among Americans with only Washington and Hamilton.

Defeat for election as a deputy from Savoy and his repugnance to the excesses of the Revolution appear to have thrown him out of practical politics for a time. And then a strange thing happened. This visionary poet and idealist attempted[40] to retrieve his fortunes in commerce and speculation and actually succeeded. During his consulship at Algiers, from which he anticipated he might never return, he left a letter for his wife in which he stated that his estate might amount to one hundred and twenty thousand dollars if French funds rose to par.

This appointment came to him in a pleasant way. One day in the summer of 1795 he returned from a business trip to the Low Countries to find an old friend waiting for him. Colonel Humphreys, now minister at Lisbon, had arrived at the request of the administration to ask Barlow to accept this mission to Algiers where for a year and a half he was to labor, succeeding in the end in liberating imprisoned countrymen and in effecting a treaty that composed troublesome difficulties.

It must have been an interesting reunion. Humphreys was too much of a cosmopolitan, too generous in spirit, to make Barlow's growing liberalism of thought a personal grievance. Here for the exiled American was first-hand news of the old Connecticut friends—that Trumbull, between ill health and the pressure of public affairs, was neglecting the Muses; that Noah Webster[41] was said to be working on a great lexicon; that Dr. Cogswell had settled in Hartford and married a daughter of Colonel William Ledyard who was killed at Fort Griswold with his own sword in the act of surrender; that a play by Dr. Elihu Smith had been acted at the John Street Theatre in New York; that Timothy Dwight would probably succeed Dr. Stiles as President of Yale—and much besides. Very likely Humphreys confided to his friend his growing interest in Miss Ann Bulkley, an English heiress, whom he had met in Lisbon and who soon afterward was to become his wife, and Barlow no doubt found a sympathetic listener to his great project of enlarging and re-publishing the "Vision."

His return from Algiers found French consols rising with the Napoleonic successes and Barlow lived as became a man of wealth and distinction. Robert Fulton, who made his home with him, painted his portrait in the intervals of experimenting with submarine boats and torpedoes in the Seine and the harbor at Brest. Indeed Barlow had now acquired so strong an influence with the Directory and the French people that his biographer attributes to him the chief part in averting[42] war between France and the United States in the tense days after 1798.

Then followed a return to his own country where he had an ambition to found a national institution for education and the advancement of science. He built a beautiful home, not in New England, be it noted, but near Washington—the "Holland House of America"—and began, but never finished, a history of the United States. He did, however, at last complete "The Columbiad," which was published in Philadelphia in 1807—"the finest specimen of book-making ever produced in America."

Did the great moment hold something of disillusion and disappointment, when, amid the somewhat perfunctory adulation, came the bitter criticism of the Federalists and the expressed conviction of some of his old Yale and Hartford friends that he was an apostate in politics and religion? To him it was clear that they did not understand. How could it be expected that Timothy Dwight, for example, the grandson of Jonathan Edwards, with all of New England's conservatism and provincialism in his blood, could understand? Yet Barlow's ancestral background was the same—but who can fathom the depths[43] of personality, or solve the complexity of motive and aspiration?

Perhaps there were times when the returned wanderer grew homesick for Paris. At last the chance to return to the land that had adopted him came—a chance for notable service in an honorable capacity. War was again in the air and in 1811 Barlow went back to France as minister plenipotentiary, charged with the duty of again averting conflict and negotiating a treaty embodying a settlement of the differences.

In the French capital he took his old house. His old servants came back to him with tears of joy. Old friends gathered about him. It was not easy, however, to clinch the treaty. The Emperor was involved in momentous affairs. The Russian expedition was on foot. The ministers procrastinated. There is an intimation in the record that the poet and political theorist was out-maneuvered in the negotiations by players of a game that had nothing to do with poetry or abstract questions but that concerned itself, persistently and relentlessly, with very definite but not entirely obvious purposes. Yet it does not seem that this inference is conclusively supported by the evidence. However that may be, it was[44] given out that Barlow had secured, and he unquestionably believed that he had secured, an agreement as to the provisions of the proposed treaty. At any rate the Emperor consented to meet the American envoy if he would come to Vilna in West Russia.

So in that dreary winter he set out with a high hope of achieving his greatest service to his country, but what would have happened at Vilna we shall never know, for on Barlow's approach to that town an incredible and stupendous piece of news awaited him. The invincible Grand Army was retreating, apparently in some demoralization. Everything was in confusion. Where the Emperor was, no one knew. Obviously nothing could now be done and the American minister started to return.

Somewhere on those frozen roads the Emperor passed him, racing for Paris to save his dynasty and himself. In the exposure and hardship Barlow fell ill. At the little village of Zarnovich, near Cracow, it became evident that he could travel no further and there, in the midst of that historic cataclysm, he died.

It was a strange ending for one of the old Hartford coterie. In the clairvoyance said sometimes[45] to accompany the supreme moment did he realize that if his great epic might not live forever he had at least given form in his day to a dream of which civilization would never let go? Did any intimation come to him that his "Ode to Hasty Pudding," written off-hand at a Savoyard inn, held more real emotion than all the balanced cadences of his monumental work? No doubt his delirious fancies sometimes went back to the old days. Perhaps he saw once more the faces of his old companions of the friendly club, not clouded now with misunderstanding or disapproval. From beyond the frosted panes came intermittently the confused noises of the great retreat, with all their implications of selfish ambition, human suffering and the continual warfare of the world. Was his belief in the final triumph of the fraternity of mankind shaken by that sinister monotone? It is idle to conjecture, but let us hope that he was comforted by a lingering faith, revived in this hour of his extremity from the days of his youth, that he would soon learn as to the truth of his vision and that he would find as well the answers to the other riddles that had puzzled him all his life.

One of these was called "Charlotte Temple, or a Tale of Truth." In the graveyard of Trinity Church in New York, at the head of Wall Street, is a large stone, flush with the ground, bearing the name of the heroine of this now forgotten story which in its day attained an astonishing popularity. The tale is of a young girl who during the War of the American Revolution eloped from an English school with a British officer who abandoned her in New York where she died soon after the birth of a daughter. The tradition runs that more than a century ago the daughter, grown to womanhood, caused her[50] mother's body to be removed to an English churchyard, but the stone still marks the first resting place and when the writer last saw it two wreaths lay upon it.

In 1797—seven years after the date of the first edition of "Charlotte Temple"—the second of our two novels appeared. It was called "The Coquette" and was written by Mrs. Hannah Foster, the wife of a Brighton, Massachusetts, minister. For many years it was read and re-read throughout the country, the latest edition appearing in 1866. Like "Charlotte Temple" its theme was the tragedy of abandonment. It seems, indeed, that the writer who wished to intrigue the interest of our ancestors of this period was compelled to hang his plot on the judiciously interwoven threads of sentiment and gloom. Perhaps no further proof of this is needed than the example of Charles Brockden Brown's portentous and sinister romances, with their undeniable flashes of genius. But it is well to remember, too, that these were the days when "The Castle of Otranto," "Clarissa Harlowe," and "The Vicar of Wakefield" were all popular, and all exhibited varying phases of the literary vogue of the day. In other words,[51] though the prevailing mode of thought found expression in different forms, the imaginative impulses beneath the various manifestations were the same.

Therefore it is not surprising to find little relief from the tragic note in "The Coquette." It is true that the author endeavors to present the heroine, Eliza Wharton, as a worldly and volatile young woman, but these touches of lightness have lost with the passing years whatever approaches to polite comedy they may have once implied. One must confess that regarded strictly as a piece of fiction the book makes rather hard reading today. But examined with some knowledge of the mystery upon which it is founded, the old novel becomes a genuine human document.

Mrs. Foster was a family connection of Elizabeth Whitman, the original of "Eliza Wharton," and may have known her. Whatever the shortcomings of her portrayal may be, it is clear that the authoress was endeavoring to set forth in her book the character, as she estimated it, of the charming and gifted girl, the tragedy of whose death is still unexplained. It is true that the accuracy of the portrait in all respects may be[52] doubted. For example, the few letters of Elizabeth Whitman that have been preserved are far more spontaneous and delightful than any of Eliza Wharton's epistles which constitute so large a part of the story.

Evidently they are the letters of a different person, as well as a more attractive one, than Mrs. Foster's heroine. Then, too, Mrs. Foster's tale has something of the effect of a tract, of a moral effort. She is driving home an ethical lesson and Eliza is the example to be shunned, whereas modern speculation, grown more tolerant, is apt to question the pre-judgment which guided the novelist's pen. He who today seeks to penetrate the old secret realizes that he is furnished with only half of the evidence. On that incomplete data how can a verdict of condemnation be fairly based? Elizabeth's own story has never been told.

Nevertheless, here, for what it is worth, is Mrs. Foster's notion, adapted to her fictional purposes, of the kind of person the real Elizabeth was, and from this reflection, faint and clouded though it may be, of a genuine and appealing character, the old novel today gathers its greatest interest. For against the somewhat[53] somber background of her New England period this Hartford girl stands forth with a flash of brilliancy and charm. In the midst of a somewhat limited and narrow social life, she was an individualist, an exotic. In contrast with her Puritan environment she seems almost Hellenic—yet one fancies that there is something about her more Gallic than Greek.

She was the eldest of the three daughters of the Rev. Elnathan Whitman, D.D., a Fellow of Yale College, and pastor from 1732 till his death in 1777 of the Second Church in Hartford. It is a singular coincidence that through her mother, born Abigail Stanley, she traced kinship to the Charlotte Stanley who was the original of "Charlotte Temple." Her father was a grandson of that noted divine, Solomon Stoddard of Northampton, who, it will be remembered, was the grandfather of Jonathan Edwards. John Trumbull, the poet and judge, was a cousin and so was Aaron Burr. Besides these, the Pierreponts, the Whitneys, the Ogdens, the Russells, the Wadsworths, were all kin or connected by marriage.

Fairly early in life Elizabeth became engaged to be married to the Rev. Joseph Howe, a Yale[54] graduate, and for a while a tutor at the college, whose chief pastorate was at the New South Church in Boston. During the siege he was compelled to flee from the city and, his health failing, he died at Hartford, probably in 1776.

In that rare volume, "American Poems, Selected and Original," published at Litchfield, 1793, is "An Ode, Addressed to Miss—. By the late Rev. Joseph Howe, of Boston." Its occasion was the departure, by sea, of the young woman to whom it was addressed.

It is possible, indeed probable, that Elizabeth Whitman, who visited occasionally in Boston, inspired these lines, but it appears that on her part this love affair was of only moderate intensity and that her father's death, which occurred in the year following the death of her betrothed, affected her far more than that of the young minister she was to have married.[55] Not long after Mr. Whitman died, while Elizabeth was visiting in New Haven at the home of Dr. Ezra Stiles, President of Yale College, whose daughter Betsy was her intimate friend, her second love affair developed.

The Rev. Joseph Buckminster was also a Yale graduate and tutor, later settling at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in Dr. Stiles's old parish, where his life was spent. He was considered an exceptionally brilliant and promising young man and he seems to have loved and wooed Elizabeth ardently. It appears that she had a deep affection for him, but also an intense dread of the harrowing melancholia from which he at times suffered. There is an intimation, too, as to her own growing doubts of future happiness in the somewhat limited rôle of a New England minister's wife. Would her free and eager spirit find satisfaction in a lifetime of parochial routine? She was discussing her final decision in this matter with her cousin Jeremiah Wadsworth in the arbor of her mother's garden when Buckminster, who did not like Colonel Wadsworth, suddenly appeared and, misunderstanding the situation, went away in great anger.

Are the following lines from a letter of Elizabeth[56] to Joel Barlow, written at Hartford, February 19, 1779, references to this affair?

". . . . to find yourself quite out of Ambition's way, and in the very bosom of content,—this certainly is agreeable, and never more than when one has met with trouble in a busier place. I felt myself no longer afraid when a certain subject was started. I neither trembled nor turned pale, but sat at my ease and felt as if nobody would hurt me. I know you will laugh at me for a pusillanimous creature for being ever so afraid as you have seen me; but I cannot help it. . . .

"As to Mr. Baldwin, if he were at the door, I would not run into the cupboard to avoid him. He may mean well, in writing all to Buckminster and nothing to me; but I do not think it."

After the encounter in the garden Elizabeth wrote Buckminster explaining the matter, and, we may infer, telling him that her decision would have been unfavorable. His reply was the announcement of his approaching marriage, but in spite of this rapid volte face he is said to have cherished Elizabeth's memory during all of his life. Mrs. Dall in her "Romance of the Association" tells the story of his burning the first copy of "The Coquette" he read, which he found on a parishioner's table. "It ought never to have been written," he said, "and shall[57] never be read—at least, not in my parish. Bid the ladies take notice, wherever I find a copy I shall treat it in the same way."

Familiar letters are always a fairly clear indication of character, and it is from these letters of Elizabeth Whitman, printed in part in her little book by Mrs. Dall, that we may obtain our most direct knowledge of her personality. After reading them one closes the book with the conviction that here was a rare and lovely woman. Here is wit, originality, sympathy—one is almost tempted to say a certain tenderness—encouragement, good sense and good advice. The writer obviously had that quality that will forever be wholly captivating to the masculine mind—the ability to enter whole-heartedly into the aspirations and ambitions of a friend, to make them her own, and to supply the comforting assurance and admiration that the male sex so frequently craves and that is so often the spur to high endeavor. There is something very winning about this affectionate sympathy as displayed in these old letters, all, with one exception, written to Joel Barlow at the time when he was striving for accomplishment and recognition as a poet. Yet the writer's[58] praise is not blind or overdone, for she does not hesitate to criticise adversely, though in a most engaging way, some of Barlow's verses that he sends to her for her comment:

"There are so many beauties in your elegies, that it looks like envy or ill-nature to pass them and dwell upon the few faults; but you know that I do not leave them unnoticed or unadmired. If you will have me find fault, I can do it in a few instances with the expression. The sentiments are everywhere beautiful, just and above all criticism. . . . Why are you gloomy? You must not be. Expect everything, hope everything, and do everything to make your circumstances agreeable."

Perhaps Elizabeth did not feel incompetent to assume the rôle of a critic and literary adviser, for she herself had the true artist's desire for self-expression and this found relief in her own poetry which usually took the form of the heroic couplet.

It is inevitable that the reader of these letters should ask himself: Was there anything more than friendship between Barlow and Elizabeth? Doubtless the answer is in the negative. When Elizabeth Whitman first met the poet he was engaged to be married to Ruth Baldwin who always remained one of Elizabeth's closest[59] friends and who through all of Barlow's strange career was his faithful and beloved wife. Yet it is evident that in his correspondent Barlow's wavering and self-centered spirit found a steadying and assuring solace that he could never have forgotten. Is it possible that he knew the secret of the final mystery?

Of love affairs, other than those here indicated, that may have transpired in Elizabeth's experience before the catastrophe, we know little or nothing. No doubt certain emotional adventures occurred as the years passed. She was exceptionally cultivated and entertaining and all accounts agree that she was beautiful, though her exact type of beauty is a matter of speculation, for her portrait which for years after her death hung in her old home was destroyed in 1831, when the house was burned—perhaps with much memoranda which would have given us a clue to her secret.

The following well-rounded sentence from Mrs. Locke's historically inaccurate but emotionally true preface to the edition of 1866 of "The Coquette" is not without its character-illuminating quality. "By her exceeding personal beauty and accomplishments," wrote Mrs.[60] Locke of Elizabeth, of whose personality she seems to have had some reliable evidence, "added to the wealth of her mind, she attracted to her sphere the grave and the gay, the learned and the witty, the worshippers of the beautiful, with those who reverently bend before all inner graces."

For a young woman of the period her life was reasonably varied and her acquaintance extensive. At President Stiles's home, and elsewhere in New Haven, where she often visited, she met many men of distinction. She and Betsy Stiles both spoke French fluently and it is said that Elizabeth was greatly admired by several of the French officers who had known Dr. Stiles at Newport and who called upon him from time to time at New Haven. Certain, it must be confessed rather indefinite, "foreign secretaries" are alleged to have fallen victims to her charms.

There is an intimation that after her father's death she did not always find life at home congenial. This is an inference—though not entirely an inference—that one may readily accept. There was an irony in the fate that placed this vivid creature in a New England parsonage in the last half of the eighteenth century. Paris[61] or Florence in the days of the Renaissance—in such a setting one can visualize her. But, alas! there was little in common between the New England of 1780 and the France or Italy of three hundred years before.

And yet one thing was common—as it is common wherever individuals of the human race abide. When the great passion overwhelmed her and swept her away from all that she had known to a mysterious end, Elizabeth Whitman was no longer a young girl. She was a woman of experience, knowing the ways of her world as well as any one of her day and time. The love that broke down all restraints, that surrendered everything, that threw the world away, was no ordinary affair of the heart. It was, in truth, the irresistible, the incredible, the historic passion. It was of a piece with the substance of which the great dramas of the world are made and against the New England scene it now became the motif of a tragedy.

On a day late in May, 1788, Elizabeth took the stage at Hartford for Boston where she was to visit her friend, Mrs. Henry Hill. No doubt her family knew that something was wrong. They knew, among other things, that she had[62] spent all the preceding night alone in the starlight on the roof of William Lawrence's house on the north side of the old State House square. It was a strange proceeding, but their daughter and sister was, after all, a strange, temperamental creature whose impulses and mental processes they seldom understood and frequently disapproved. Of how much more they were aware we do not know—they must have had their suspicions—but at least they were ignorant of her purpose in her journey. From the moment when she drove away in the stage neither they nor any one of her Hartford friends saw her again—nor did she reach her destination.

On Tuesday, July 29, 1788, the Salem "Mercury" printed the following notice:

"Last Friday, a female stranger died at the Bell Tavern, in Danvers; and on Sunday her remains were decently interred. The circumstances relative to this woman are such as to excite curiosity, and interest our feelings. She was brought to the Bell in a chaise, from Watertown, as she said, by a young man whom she had engaged for that purpose. After she had alighted, and taken a trunk with her into the house, the chaise immediately drove off. She remained at this inn till her death, in expectation of the arrival of her husband, whom she expected to come for her, and appeared anxious at his delay. She was averse to[63] being interrogated concerning herself or connections; and kept much retired to her chamber, employed in needlework, writing, etc. She said, however, that she came from Westfield [Wethersfield?], in Connecticut; that her parents lived in that state; that she had been married only a few months; and that her husband's name was Thomas Walker,—but always carefully concealed her family name. Her linen was all marked E. W. About a fortnight before her death, she was brought to bed of a lifeless child. When those who attended her apprehended her fate, they asked her, whether she did not wish to see her friends. She answered, that she was very desirous of seeing them. It was proposed that she should send for them; to which she objected, hoping in a short time to be able to go to them. From what she said, and from other circumstances, it appeared probable to those who attended her, that she belonged to some country town in Connecticut. Her conversation, her writings, and her manners, bespoke the advantage of a respectable family and good education. Her person was agreeable; her deportment, amiable and engaging; and, though in a state of anxiety, and suspense, she preserved a cheerfulness which seemed to be not the effect of insensibility, but of a firm and patient temper. She was supposed to be about 35 years old. Copies of letters, of her writing, dated at Hartford, Springfield, and other places, were left among her things. This account is given by the family in which she resided; and it is hoped that the publication of it will be a means of ascertaining her friends of her fate."

The hope of the editor of the "Mercury" was realized. This notice, coming to the attention of Mrs. Hill, finally resulted in the identification of the mysterious lady of the Belt Tavern as Elizabeth Whitman.

Monument and Bell Tavern, Danvers.

Monument and Bell Tavern, Danvers.

And that, really, is the whole story. The succinct newspaper statement, with its contemporary note and its effect of reality, furnishes a more effective climax than the phrases of any modern chronicler.

Yet one cannot quite close the record without mention of a few incidents of the last days.

The copies of letters mentioned as found among Elizabeth's belongings evidently escaped her, for,[65] fearful of the outcome of her illness, she burned, as she supposed, all her papers. A poem and part of a letter, both clearly addressed to her lover or husband, though no name was given, escaped her.

"Must I die alone?" she wrote in those final days. "Shall I never see you more? I know that you will come, but you will come too late: This is, I fear, my last ability. Tears fall so, I know not how to write. Why did you leave me in so much distress? But I will not reproach you: All that was dear I left for you: but do not regret it.—May God forgive in both what was amiss:—When I go from hence, I will leave you some way to find me:—if I die, will you come and drop a tear over my grave?"

There is a legend, perhaps apocryphal, that one afternoon she wrote in chalk on the inn door, or on the flagging before it, her initials or other sign, which a small boy rubbed out without her knowledge. That evening, the legend runs, an officer in uniform rode into the town on horseback looking carefully at all the doors and walks, but speaking to no one. Not finding what he evidently sought, he is said to have ridden despondently away.

During all her stay at Danvers, Elizabeth wore a wedding ring and at her request it was buried with her.

As to the identity of the man whom Elizabeth loved there have been many speculations. A cousin of hers, an able man, distinguished in the history of his time, has often been assumed to have been the cause of her tragedy, but it is fair to his memory to say that he denied this assumption vehemently. The late Charles Hoadly, State Librarian of Connecticut, had a theory that the man was a prominent member of the Yale class of 1776, but no evidence for this belief is given. Another supposition is that Elizabeth, against the wishes of her family, had contracted a marriage with a French Romanist who, had he acknowledged this union, would have forfeited his inheritance. Probably Jeremiah Wadsworth, who was her friend and adviser, knew the secret, but if so it perished with him.

Her brother William, who was eight years younger than she, long survived her, dying in Hartford on Christmas Day, 1846, at the age of eighty-six. In the old man, who was one of the last in his city to wear the knee breeches of the preceding century, it would have been difficult to recognize Elizabeth's "little rogue of a brother" whom she frequently commended[67] to Joel Barlow's care while at Yale. Through a slight knowledge of medicine he acquired the title of "Doctor," but he was also admitted to the bar and for some time was Town Clerk, and Clerk of the City Court. In his later years he became something of an antiquary and after the Wadsworth Atheneum was built he found in that castellated home of the humanities, particularly in the library, a grateful refuge from the world, where he was always ready to converse with other visitors upon incidents of days long gone by. One subject, however, was universally accepted as unapproachable. With his son, who died unmarried in Philadelphia in 1875, the line of the Rev. Elnathan Whitman became extinct.

After Elizabeth's death her brother is not known to have mentioned her name outside of the family, but for many years he made an annual pilgrimage to her grave with his sister Abigail. The letter of an old resident tells us that after Elizabeth died the door of her room in the Whitman home was kept locked and nothing disturbed till fire destroyed the building.

We all recall the old story of the Hartford personage who achieved a certain measure of fame by remarking that Mrs. Sigourney's personal obituary poems had added a new terror to death. Dr. Dwight's paper begins with a reference to this same phase of the poetess.

"Whenever any person has died in our country," he says, "during the last score of years, who was of public reputation sufficient to[72] justify it . . . a kind of calm and peaceful confidence has rested in our minds, that, within a brief season, a poetical obituary would appear in the public prints from the well-known pen of Mrs. Sigourney. Indeed so general has been this confidence among the people of Connecticut, that some persons, who, from peculiar modesty or from some other reason, have desired to escape the notice of the great world after death, have been beset by a kind of perpetual fear that she might survive them, and thus, having them at a great disadvantage, might send out their names unto all the earth."

And later on in the essay he mentions the reported story of the man who was unwilling to travel from New Haven to Hartford on the same train with the distinguished Hartford lady lest in case of a railroad accident she might put him into rhyme.

Though it is doubtful if the author of "The Anthology of Spoon River" ever heard of these obituary poems, they form a strange precedent for that original collection of verse. Some of them were gathered by their authoress in a volume entitled "The Man of Uz, and Other Poems," published at Hartford in 1862, where the literary[73] antiquarian may still peruse them. If they originally possessed any poetry it is now extinct, and the only interest remaining is the personal one. To those for whom the older Hartford still has its appeal such names as those of Colonel Samuel Colt, Samuel Tudor, "The Brothers Buell," Harvey Seymour, D. F. Robinson, Judge Thomas S. Williams, Deacon Normand Smith, Governor Joseph Trumbull, and Mary Shipman Deming—to mention only a few—have their memories and possibly their family associations.

Perhaps it is not strange that such a considerable part of Mrs. Sigourney's facile effusions related to the tomb for hers was the age of pensive sentiment. It was the time when the weeping willow was popular in all forms of art, from the tombstone to the mezzotint illustration, when young ladies sang captivatingly, to the harp, of an early death, when funeral sermons were printed, widely circulated and even read, and when everybody was wondering whether they were numbered among the "elect" or—not.

Yet it would be a mistake to give the impression that all the sentiment of the time, or all of Mrs. Sigourney's poetry, partook of gloom. Far[74] from it. Though there was, to be sure, a kind of background of agreeable melancholy, and such alluring titles of her books as "Whisper to a Bride" and "Water Drops" (a plea for temperance) were doubtless not intentionally humorous, Mrs. Sigourney could be playful at times and she invariably painted the immediate scene in colors of the rose. She was, in fact, an idealist. She so far idealized her early surroundings in Norwich, where she was born, that Dr. Dwight, who also knew Norwich in his boyhood, finds difficulty in identifying places and people. She even idealized the Park River, sometimes known in her day, as in ours, by a less euphonious title, alluding to it as "the fair river that girdled the domain [her home on what is now known as Asylum Hill] from which it was protected by a mural parapet." Who other than Mrs. Sigourney could have transformed an ordinary stone wall into a "mural parapet"?

THE SIGOURNEY MANSION

THE SIGOURNEY MANSION

Speaking of the Park River, Mrs. Sigourney,

in the course of describing the pastoral surroundings

of what was then her country home,

confesses that she could never understand why

pigs were unmentionable in polite society—though

we think she herself refrained from[75]

[76]

referring to them by their ordinary term. "Such

treatment," she asserts "is peculiarly ungrateful

in a people who allow this scorned creature

to furnish a large part of their subsistence, to

swell the gains of commerce and to share with

the monarch of ocean the honor of lighting the

evening lamp."

Here are two other references, quoted by Dr. Dwight, to this rural "domain" of which the dwelling house, it will be remembered, is still standing:

"Two fair cows, with coats brushed to a satin sleekness, ruminated at will, and filled large pails with creamy nectar."

And again, the poultry "munificently gave us their eggs, their offspring and themselves."

But even this idealized Sabine farm was not

exempt from the troubles that lie in wait for all

of us, and we must be chivalrous enough to

admit that Mrs. Sigourney bore the sorrows that

came to her with grace and dignity. Soon after

the poetess and her husband took up their residence

here Mr. Sigourney was overtaken by

business troubles, which his wife translates

into "obstructions in the course of mercantile

[77]prosperity," and she cheerfully undertook various

economies, among which was "prolonging

the existence of garments by transmigration."

Later the family moved to a less pretentious

home on High street where the latter part of the

life of Mrs. Sigourney, who survived her husband,

was spent.

Later still this house became a kind of shrine, and a distinguished Yale teacher and poet, whose people, back in his undergraduate days of the sixties, dwelt for a time in the poetess's old home, has told the writer how nice old ladies from the country used to make pilgrimages thither to pluck a spray of lilac from the garden where the poetess was wont to walk and to see the room where she "mused."

The fact is that she appears to have dwelt in a world of the mind that, however real to her, was in reality distinctly artificial, like most of her poetic writings. In these faded verses there now appears to be little real thought, still less real poetry. The only stanzas about which any flavor of poetic eloquence still clings are those entitled "The Return of Napoleon from St. Helena" and "Indian Names." Compare her "Niagara" and "The Indian Summer" with the poems on the same subjects by J. G. C. Brainard,[78] another now almost forgotten Hartford poet of her time, whose early death prevented the flowering of a fame that was just beginning to unfold, and the reader grasps at once the difference between a certain graceful turn of thought and facility of phrase on the one hand, and genuine poetic genius on the other.

LYDIA HUNTLEY SIGOURNEY

LYDIA HUNTLEY SIGOURNEYAnd yet in her day she had a prodigious vogue and the reference to her as "The Hemans of America," while now holding a certain facetious implication, was gravely accepted at the time. Her journey abroad after her husband's death was in its way a sort of mild ovation. She met Queen Victoria and it is significant as well as amusing to find that our Hartford citizeness alluded to the Queen as "a sister woman." Her verses were translated into several languages and she received presents and letters of commendation from the King of Prussia, the Empress of Russia and the Queen of France.

The explanation of her contemporary popularity must lie in the state of mind of the period. In that era "sensibility" was the passport to literary success and Mrs. Sigourney certainly possessed sensibility, if nothing else, to a high degree. Those sentimental, yearly gift books known as "annuals" were a phenomenon of the time, and no "annual" was complete without one or more of her poems. It is time that some qualified person gave to the world a study of this old "annual" literature, so sentimental, so romantic, and so generally languishing. The most delightful appreciation that comes to mind at the moment, of the "annual" as a literary curio is contained in Professor Beers's life of Willis in the American Men of Letters series—or in his essay on Percival in "The Ways of Yale."

There is a certain pathos in the fact that the years have denied this Hartford poetess's gentle claim to immortality, because the impossibility of granting this claim has led the world to neglect two very definite and admirable characteristics she possessed.

One is that she was a remarkably good woman. She carried her Christian precepts into her daily practice in a way that few of us seem to succeed in doing. In spite of a little harmless vanity, everyone who came in contact with her appears to have admired and loved her.

In the social life of the old city she was a

leading and popular figure. Samuel G. Goodrich

in his "Recollections of a Life Time" describing[79]

[80]

Hartford in the second decade of the nineteenth

century says of Mrs. Sigourney, then Miss Huntley:

"Noiselessly and gracefully she glided into

our social circle and ere long was its presiding

genius. . . . Mingling in the gayeties of our

social gatherings and in no respect clouding their

festivity, she led us all toward intellectual pursuits

and amusements. We had even a literary

cotery under her inspiration, its first meetings being

held at Mr. Wadsworth's." Before the writer

lie a half dozen of Mrs. Sigourney's letters written

in her distinct and regular handwriting. They

relate to business matters, to social engagements,

and a few are letters of consolation. Perhaps

they seem a little stilted and formal, but in all

the personal notes there is evident a very genuine

and very charming spirit of sympathy and kindliness.

The other trait that has been largely forgotten is that she was a natural teacher of youth. In her early days in Hartford she conducted a school for girls on singularly successful and somewhat original lines. This she relinquished on her marriage, but for nearly half a century those of her old pupils who lived never failed to meet annually with her in remembrance of their early[81] association. Clearly, she inspired in them all an ardent and lasting affection.

On the writer's desk, among her letters, lies an ancient school copy-book containing the transcript of an address she made to her old scholars August 17, 1822, "on their meeting to form a Charitable and Literary Society." It is characteristic that the greater part of this composition is concerned with affectionate and what now seem rather pathetic sketches of the five young girls of her flock who had died. The address confirms what we know from other sources—that her school was started in 1814, soon after she came from Norwich to Hartford.

The old manuscript abounds in unimpeachable moral aphorisms. One may, perhaps, smile at the carefully balanced phraseology of this: "Some sciences are more attractive to ambition, more congenial with fame, more omnipotent over wealth, but I know of none so closely connected with happiness as the science of doing good." Yet most of us would be better men and women if we applied that maxim in our lives as constantly as did this gentle "lady of old years." In her teaching "the science of doing good" was not a theoretical matter alone. It[82] was directed to practical ends. "During a period of somewhat less than two years and a half," she says, "you completed for the poor 160 garments of different descriptions, many of which were carefully altered and repaired from your own—among them 35 pairs of stockings, knit without sacrifice of time during the afternoon reading and recitation of history. You likewise contributed ten dollars to the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, five dollars to the schools then established among the Cherokees, and distributed religious books to an amount exceeding ten dollars, among the children of poverty and ignorance. . . . Some of you were accustomed to gain time for these extra employments by rising an hour earlier in the morning."

Had Mrs. Sigourney continued her school it is not by any means preposterous to believe that her fame as an educator might have outlasted her reputation in literature, and that she might have shared with Miss Beecher of the old Hartford Female Seminary a certain degree of distinction in connection with the early education of women in this country.

The name of this young man was John Gardiner Calkins Brainard and he was twenty-six years old. Those who inquired about him learned that he was a native of New London and the son of Judge Jeremiah G. Brainard of the Superior Court. In 1815 he had been graduated at Yale—a classmate of that strange genius James Gates Percival, poet, physician, geologist. After studying law in his brother's office he had practiced[86] for a time in Middletown, but it was rumored that his tastes were literary rather than legal, and that the law had not proved very successful.

In spite of his rather uncouth appearance this newcomer soon became a favorite among the young people. He was clever—any one could see that. His frequent witty and amusing sayings gathered an arresting emphasis from their contrast with intervals of quietness and even of apparent depression. Perhaps this hint of an underlying seriousness had its especial charm for the young ladies. Remember that in those days Byron was in fashion. But there was something about this young man that attracted also friends of his own sex. "The first time I ever saw him," says a writer in the "Boston Statesman," quoted by Whittier in his memoir of Brainard, "I met him in a gay and fashionable circle. He was pointed out to me as the poet Brainard—a plain, ordinary looking individual, careless in his dress, and apparently without the least claim to the attention of those who value such advantages(?). But there was no person there so much or so flatteringly attended to. . . . He was evidently the idol, not only of the poetry-loving[87] and gentler sex—but also of the young men who were about him. . . ."

We can picture young Mr. Brainard as one of the leading figures in that "literary cotery," which Goodrich describes and which was presided over by Mrs. Sigourney. It was in a room adjoining Goodrich's at Ripley's Tavern that Brainard soon took up his abode and the two became fast friends.

The discovery was soon made that young Mr. Brainard was by way of being a poet—if, indeed, the fact was not already known. Verses, obviously from his pen, appeared constantly in his newspaper. Indeed some of the paper's readers may have recognized the new editor's hand through their familiarity with the verse he had sometimes written for the "Mirror" before his official connection with that journal. His first contribution to the paper in his new capacity appeared in the issue for February 25, 1822, in which the change of ownership and the new editor were announced. This contribution was in the form of a poem "On the Birthday of Washington."—"Behold the moss'd cornerstone dropp'd from the wall," ran the first line. It was not a great poem, but it sounded a sincere, patriotic[88] note, had a genuine poetic touch and far excelled most newspaper verse of the day.

And so this original young man, with his light brown hair, rather pale face, large eyes and obvious "temperament" began to acquire the character and reputation of a poet. We fancy that this reputation was somewhat limited until on a sudden impulse he wrote "The Fall of Niagara." This piece of blank verse, though now largely forgotten in the lapse of years, had in its time a tremendous vogue. It was copied far and wide, took its place in school readers and for years was declaimed by youthful orators before committees and admiring parents at school exhibitions.

We do not know the exact date of its composition, but it must have been before 1825, for it appeared in the author's first collection of verse published in that year. It was written one raw March evening in an emergency, to make copy for the next morning's paper. Goodrich tells the story. Brainard was half ill with a cold and Goodrich went over with him to the "Mirror" office and started a fire in the Franklin stove, while his companion, miserable and depressed, talked at random, abhorring the compulsion that[89] made writing a necessity and his procrastination that had postponed his work, till the last moment.

"Some time passed," says Goodrich, "in similar talk, when at last Brainard turned suddenly, took up his pen and began to write. I sat apart and left him to his work. Some twenty minutes passed, when, with a radiant smile on his face, he got up, approached the fire, and, taking the candle to light his paper, he read as follows:

"He had hardly done reading when the [printer's] boy came. Brainard handed him the lines—on a small scrap of rather coarse paper—and told him to come again in half an hour. Before this time had elapsed, he had finished, read me the following stanza:

"These lines having been furnished, Brainard left his office and we returned to Miss Lucy's parlor. He seemed utterly unconscious of what he had done. . . . The lines went forth and produced a sensation of delight over the whole country."

It is not too much to say that Niagara brought Brainard fame. To the modern ear inured to free verse its lines may sound perhaps a trifle over sonorous and formal. But it has real poetic eloquence and inspiration. Brainard had never been within less than five hundred miles of the great falls.

The Niagara is the first poem in that collection of the poet's verses published in 1825, alluded to above. Before the writer at the moment lies a copy of this rather rare volume. Goodrich arranged for its publication with Bliss and White of New York and with difficulty persuaded Brainard to do the necessary work of collection and revision. It was the only collection[91] of his verses that was published during the poet's life. Two others were issued after his death—one in 1832, with a memoir by Whittier, and one, with a prefatory sketch by the Rev. Dr. Robbins, in 1842. The copy of the first collection, now on the writer's desk, bears on the fly-leaf this inscription in the author's handwriting:

The thin little book has the title, "Occasional Pieces of Poetry," which is peculiarly appropriate, for most of Brainard's poems were suggested by incidents of daily life that came to his attention. For example, the stage coach from Hartford to New Haven falls through a bridge and two lives are lost—the occurrence prompts him to write the "Lines on a Melancholy Accident;"[92] the visit of Lafayette to this country in 1824 occasions some verses to "the only surviving general of the Revolution;" the death of two persons who were struck by lightning during a religious service in Montville suggests "The Thunder Storm;" the humorous verses entitled "The Captain" result from the genuinely amusing situation that arose in New London harbor when the wreck of the Norwich Methodist meeting house, that had come down the river in a freshet, collided with an anchored schooner.

The fact that the poet took many every-day affairs as the immediate occasion for his versifying accounts for the trivial character of some of his work. On the other hand it illustrates the theory he held of the need of a genuine American literature. Though he read eagerly Byron and Scott, he deprecated in the columns of the "Mirror" the imitation of foreign writers by American men of letters, holding that our own history, traditions and environment gave inspiration enough.

He welcomed the appearance of Cooper with enthusiasm, and a story which ran in the "Mirror" under the title of "Letters from Fort Braddock" and which was largely in the Cooper manner was written by him though published anonymously. Indeed a great part of his work dealt with local matters. "Matchit Moodus" expresses a fantastic legend of the "Moodus noises." "The Black Fox of Salmon River" embodies in verse another grim local tradition. "The Shad Spirit" and "Lines to the Connecticut River" are other similar examples of his use of the folk-lore of the Connecticut valley.

Professor Beers of Yale cites the exquisite little lyric beginning "The dead leaves strew the forest walk," as about the best example of his work. Goodrich says it was written after the departure from Hartford of a young lady from Savannah to whom the poet had been devoted during her visit. Very attractive, too, are the lines on "Indian Summer." The blank verse entitled "The Invalid on the East End of Long Island," has a melancholy note but deserves remembrance. It was there that Brainard spent the few weeks just before the end.

He was too sensitive and unaggressive a soul

both for the law and for the political wrangling

which attended the newspaper controversies of

the day. In the practical life of his country and[93]

[94]

his time, which had small place for artistic

aspiration or expression, he was an anomaly

simply because he was a real poet. To this

situation may be attributed no doubt in large

measure the sense of failure, unquestionably

exaggerated, which he often expressed. "Don't

expect too much of me," he said to Goodrich at

their first meeting, "I never succeeded in anything

yet. I could never draw a mug of cider

without spilling more than half of it."

His frequent depression, however, was not all temperament—it had a physical basis. In the spring of 1827 incipient tuberculosis compelled him to give up his work on the "Mirror," and on September 26, 1828, a month before his thirty-second birthday, he died at his home in New London.

His death called forth the customary poetic obituary from his friend Mrs. Sigourney—one of the best she ever wrote—voicing a sincere and generous appreciation. Whittier, with other poets of the day, added his word of memory and praise. Perhaps a line from Snelling best expresses in a few words the whole story—