Title: From Gretna Green to Land's End: A Literary Journey in England.

Author: Katharine Lee Bates

Release date: September 25, 2012 [eBook #40857]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by sp1nd, JoAnn Greenwood, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

BY KATHARINE COMAN

Copyright, 1907

By Thomas Y. Crowell & Company

Published, October, 1907

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

TO

MY FARING-MATES

KATHARINE COMAN

AND

ANNIE BEECHER SCOVILLE

"Some Shires, Joseph-like, have a better coloured coat than others; and some, with Benjamin, have a more bountiful mess of meat belonging to them. Yet every County hath a child's proportion."

Thomas Fuller.

These summer wanderings through the west of England were undertaken at the request of The Chautauquan, from whose pages the bulk of this material is reprinted. But the chronicle of this recent journey has been supplemented, as the text indicates, by earlier memories.

K. L. B.

FROM ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS

The dominant interest of the northwestern counties is, of course, the Lake District, with its far-famed poetic associations; yet for the student of English history and the lover of Border minstrelsy the upper strip of Cumberland has a strong attraction of its own.

An afternoon run on the Midland brought us from Liverpool to Carlisle. Such are the eccentricities of the English railway system that the "through carriage" into which guard and porter dumped us at Liverpool, a third-class carriage already crowded with one sleeping and one eating family, turned out not to be a through carriage at all; and a new guard, at Hellifield, tore us and our belongings forth and thrust us into an empty first-class, lingering in the doorway until we had produced the inevitable shilling. But the freedom of an empty carriage would have been well worth[2] the honest price of first-class tickets, for as the train sped on from the Ribble into the Eden Valley, with the blue heights of the Pennine range and the long reaches of the Yorkshire moors on our right, and on our left the cloud-caressed summits of Lakeland, we needed all the space there was for our exultant ohs and ahs, not to mention our continual rushing from window to window for the swiftly vanishing views of grey castle and ruined abbey, peel tower and stone sheep-fold, grange and hamlet, and the exquisite, ever-changing panorama of the mist.

Carlisle, "the Border City," a clean, self-respecting, serious town, without beggars, with no superfluous street courtesies, but with effectual aid in need, is the heart of one of the most storied regions of England. The River Drift man and the Cave man seem to have fought the mammoth and the elk and gone their shadowy way untraced in this locality, but the museum in Tullie House contains hammers and axes, found in Cumberland soil, of the Stone Age, and spear-heads and arrow-heads, urns for human ashes, incense cups, food vessels and drinking vessels of the Bronze Age,—mute memorials of life that once was[3] lived so eagerly beneath these same soft, brooding skies.

As for the Romans, they seem here like a race of yesterday. A penny tram took us, in the clear, quiet light of what at home would be the middle of the evening, out to Stanwix, originally, it is believed, an important station in the series of fortresses that guarded the northern boundary of Roman Britain. These frontier lines consisted of a great stone wall, eight feet thick and eighteen feet high, ditched and set with forts and towers, running straight from the Solway to the Tyne, a distance of some seventy-three miles, and a little to the south of this, what is known as the vallum, a fosse with mounds of soil and rock on either side. The local antiquaries, urged on by a committee of Oxford men, have recently discovered a third wall, built of sods, between the two, and excavation and discussion have received a fresh impetus. Was the vallum built by Agricola,—earthworks thrown up by that adventurous general of the first Christian century to secure his conquest? Was the turf wall the erection of the great emperor Hadrian, who visited Britain in the year 120, and was the huge stone rampart constructed,[4] early in the third century, by the Emperor Severus? Or does the stone wall date from Hadrian? Or did he build all three?

While the scholars literally dig for truth, we may sit on the site of this mighty, well-nigh perished bulwark at Stanwix, with what is perhaps the wrinkle left on the landscape by the wall's deep moat dropping, under a screen of hawthorns and wind-silvered poplars, sheer at our feet, and thence we may look out across the Eden, with its dipping gulls and sailing swans, its hurrying swifts and little dancing eddy, to the heights of Carlisle. For the city is built on a natural eminence almost encircled by the Eden and its tributaries, the Petteril and the Caldew. It is a fine view even now, with the level light centred on the red sandstone walls of the grim castle, though factory chimneys push into the upper air, overtopping both the castle and its grave neighbour, the cathedral; but for mass and dignity, for significance, these two are unapproachable: these are Carlisle.

We must not see them yet. We must see a lonely bluff set over with the round clay huts of the Britons, and then, as the Roman legions sweep these like so many mole-hills from their[5] path, we must see in gradual growth a Roman town,—not luxurious, with the tessellated marble pavements and elaborate baths that have left their splendid fragments farther south, but a busy trading-point serving the needs of that frontier line of garrisons which numbered no less than fifteen thousand men. Some few inscribed and sculptured stones, remnants of altars, tombs, and the like, may be seen in the museum, with lamps, dishes, and other specimens of such coarse and simple pottery as was in daily use by common Roman folk when the days and the nights were theirs.

The name Carlisle—and it is said to be the only city of England which bears a purely British name—was originally Caer Lywelydd, British enough in very sooth. This the Romans altered to Lugubalia, and when, in 409, the garrisons of the Wall were recalled for the protection of Rome herself, the Britons of the neighbourhood made it their centre, and it passed into Arthurian tradition as Cardueil. Even the ballads vaguely sing of a time when

But although the Britons sometimes united, under one hero or a succession of heroes, to save the land, now abandoned by the Romans, from the Saxons, they were often at war among themselves, and the headship of their northern confederacy was wrested from Carlisle and transferred to Dumbarton on the Clyde. The kingdom of the Cumbrian Britons, thenceforth known as Strathclyde, fell before the assault of the English kingdom of Northumbria, in which the Christian faith had taken deep root. For though the Britons, in the fourth century of Roman rule, had accepted Christianity, the Angles had come in with their own gods, and a new conversion of the north, effected by missionaries from Iona, took place about the sixth century. Sculptured crosses of this period still remain in Cumberland and Westmoreland, and the Carlisle museum preserves, in Runic letters, a Christian epitaph of "Cimokom, Alh's queen."

is the eloquent record, and from her grave-mound she utters the new hope:[7]

For a moment the mists that have gathered about the shelving rock to which we are looking not merely across the Eden, but across the river of time, divide and reveal the figure of Cuthbert, the great monk of Northumbria, to whom King Egfrith had committed the charge of his newly founded monastery at Caerluel. The Venerable Bede tells how, while the king had gone up into Scotland on a daring expedition against the Picts, in 685, Cuthbert visited the city, whose officials, for his better entertainment, took him to view a Roman fountain of choice workmanship. But he stood beside its carven rim with absent look, leaning on his staff, and murmured: "Perchance even now the conflict is decided." And so it was, to the downfall of Egfrith's power and the confusion of the north. After the ravaging Scots and Picts came the piratical Danes, and, about 875, what was left of Carlisle went up in flame. A rusted sword or two in the museum tells the fierce story of the Danish sack. At the end[8] of the tenth century Cumberland was ceded to Scotland, but was recovered by William Rufus, son of William the Conqueror. Carlisle, the only city added to England since the Norman conquest, was then a heap of ruins; but in 1092, says the "Anglo-Saxon Chronicle," the king "went northward with a great army, and set up the wall of Carluel, and reared the castle."

No longer

but there is still the castle, which even the most precipitate tourist does not fail to visit. We went in one of those wild blusters of wind and rain which are rightly characteristic of this city of tempestuous history, and had to cling to the battlements to keep our footing on the rampart walk. We peeped out through the long slits of the loop-holes, but saw no more formidable enemies than storm-clouds rising from the north. The situation was unfavourable to historic reminiscence, nor did the blatant guide below, who hammered our ears with items of dubious information, help us to a realisation of the castle's robust career. Yet for those who have eyes to read, the stones[9] of these stern towers are a chronicle of ancient reigns and furious wars, dare-devil adventures and piteous tragedy.

The Norman fortress seems to have been reared upon the site of a Roman stronghold, whose walls and conduits are still traceable. After William Rufus came other royal builders, notably Edward I and Richard III. It was in the reign of the first Edward that Carlisle won royal favour by a spirited defence against her Scottish neighbours, the men of Annandale, who, forty thousand strong, marched red-handed across the Border. A Scottish spy within the city set it on fire, but while the men of Carlisle fought the flames, the women scrambled to the walls and, rolling down stones on the assailants and showering them with boiling water, kept them off until an ingenious burgher, venturing out on the platform above the gate, fished up, with a stout hook, the leader of the besiegers and held him high in the air while lances and arrows pierced him through and through. This irregular mode of warfare was too much for the men of Annandale, who marched home in disgust.

During Edward's wars against Wallace[10] he made Carlisle his headquarters. Twice he held Parliaments there, and it was from Carlisle he set forth, a dying king, on his last expedition against the Scots. In four days he had ridden but six miles, and then breath left the exhausted body. His death was kept secret until his son could reach Carlisle, which witnessed, in that eventful July of 1307, a solemn gathering of the barons of England to mourn above the bier of their great war-lord and pay their homage to the ill-starred Edward II. A quarter century later, Lord Dacre, then captain of Carlisle Castle, opened its gates to a royal fugitive from Scotland, Balliol; and Edward III, taking up the cause of the rejected sovereign, made war, from Carlisle as his headquarters, on the Scots. After the Wars of the Roses, Edward IV committed the north of England to the charge of his brother Gloucester, who bore the titles of Lord Warden of the Marches and Captain of Carlisle Castle. Monster though tradition has made him, Richard III seems to have had a sense of beauty, for Richard's Tower still shows mouldings and other ornamental touches unusual in the northern architecture of the period.[11]

But the royal memory which most of all casts a glamour over Carlisle Castle is that of Mary, Queen of Scots. Fleeing from her own subjects, she came to England, in 1568, a self-invited guest. She landed from a fishing-boat at Workington, on the Cumberland coast,—a decisive moment which Wordsworth has crystallised in a sonnet:

Mary was escorted with all courtesy to Cockermouth Castle and thence to Carlisle, where hospitality soon became imprisonment. Her first request of Elizabeth was for clothing, and it was in one of the deep-walled rooms of Queen Mary's Tower, of which only the gateway now remains, that she impatiently[12] looked on while her ladies opened Elizabeth's packet to find—"two torn shifts, two pieces of black velvet, and two pairs of shoes." The parsimony of Queen Bess has a curious echo in the words of Sir Francis Knollys, who, set to keep this disquieting guest under close surveillance, was much concerned when she took to sending to Edinburgh for "coffers of apparell," especially as she did not pay the messengers, so that Elizabeth, after all, was "like to bear the charges" of Mary's vanity. The captive queen was allowed a semblance of freedom in Carlisle. She walked the terrace of the outer ward of the castle, went to service in the cathedral, and sometimes, with her ladies, strolled in the meadows beside the Eden, or watched her gentlemen play a game of football, or even hunted the hare, although her warders were in a fever of anxiety whenever she was on horseback lest she should take it into her wilful, beautiful head to gallop back to Scotland.

But these frowning towers have more terrible records of captivity. Under the old Norman keep are hideous black vaults, with the narrowest of slits for the admission of air and[13] with the walls still showing the rivet-holes of the chains by which the hapless prisoners were so heavily fettered.

Rude devices, supposed to be the pastime of captives, are carved upon the walls of a mural chamber,—a chamber which has special significance for the reader of "Waverley," as here, it is said, Major Macdonald, the original of Fergus MacIvor, was confined. For Carlisle Castle was never more cruel than to the Jacobites of 1745. On November 18 Bonny Prince Charlie, preceded by one hundred Highland pipers, had made triumphal entrance into the surrendered city, through which he passed again, on the 21st of December, in retreat. Carlisle was speedily retaken by the English troops, and its garrison, including Jemmy Dawson of Jacobite song, sent in ignominy to London. Even so the cells of the castle were crammed with prisoners, mainly Scots, who were borne to death in batches. Pinioned in the castle courtyard, seated on black hurdles drawn by white horses,[14] with the executioner, axe in hand, crouching behind, they were drawn, to make a Carlisle holiday, under the gloomy arch of the castle gate, through the thronged and staring street, and along the London road to Harraby Hill, where they suffered, one after another, the barbarous penalty for high treason. The ghastly heads were set up on pikes over the castle gates (yetts), as Scotch balladry well remembers.

But not all the ballads of Carlisle Castle are tragic. Blithe enough is the one that tells how the Lochmaben harper outwitted the warden, who, when the minstrel, mounted on a grey mare, rode up to the castle gate, invited him in to ply his craft.

So he stole into the stable and slipped a halter over the nose of a fine brown stallion belonging to the warden and tied it to the grey mare's tail. Then he turned them loose, and she who had a foal at home would not once let the brown horse bait,

When the loss of the two horses was discovered in the morning, the harper made such ado that the warden paid him three times over for the grey mare.[16]

"And verra gude business," commented our Scotch landlady.

The most famous of the Carlisle Castle ballads relates the rescue of Kinmont Willie, a high-handed cattle-thief of the Border. For between the recognised English and Scottish boundaries lay a strip of so-called Debatable Land, whose settlers, known as the Batables, owed allegiance to neither country, but

This Border was a natural shelter for outlaws, refugees, and "broken men" in general,—reckless fellows who loved the wildness and peril of the life, men of the type depicted in "The Lay of the Last Minstrel."

Although these picturesque plunderers cost the neighbourhood dear, they never failed of sympathy in the hour of doom. The Graemes, for instance, were a large clan who lived by rapine. In 1600, when Elizabeth's government compelled them to give a bond of surety for one another's good behaviour, they numbered more than four hundred fighting men. There was Muckle Willie, and Mickle Willie, and Nimble Willie, and many a Willie more. But the execution of Hughie the Graeme was none the less grievous.

They tried him by a jury of men,

and although his guilt was open, "gude Lord Hume" offered the judge "twenty white owsen" to let him off, and "gude lady Hume" "a peck of white pennies," but it was of no avail, and Hughie went gallantly to his death.

For these Batables had their own code of right and wrong, and were, in their peculiar way, men of honour. There was Hobbie Noble, an English outlaw, who was betrayed by a comrade for English gold, and who, hanged at Carlisle, expressed on the gallows his execration of such conduct.

The seizure of Kinmont Willie was hotly resented, even though his clan, the Armstrongs, who had built themselves strong towers on the Debatable Land, "robbed, spoiled, burned and murdered," as the Warden of the West Marches complained, all along upper Cumberland. The Armstrongs could, at one time, muster out over three thousand horsemen, and Dacres and[19] Howards strove in vain to bring them under control. Yet there was "Border law," too, one of its provisions being that on the appointed days of truce, when the "Lord Wardens of England and Scotland, and Scotland and England" met, each attended by a numerous retinue, at a midway cairn, to hear complaints from either side and administer a rude sort of justice in accordance with "the laws of the Marches," no man present, not even the most notorious freebooter, could be arrested. But William Armstrong of Kinmont was too great a temptation; he had harried Cumberland too long; and a troop of some two hundred English stole after him, as he rode off carelessly along the Liddel bank, when the assemblage broke up, overpowered him, and brought him in bonds to Carlisle.

But this was more than the Scottish warden, Sir Walter Scott of Buccleuch, could bear.

So Buccleuch rode out, one dark night, with a small party of Borderers, and succeeded, aided by one of the gusty storms of [21]the region, in making his way to Carlisle undetected.

The sudden uproar raised by the little band bewildered the garrison, and to Kinmont Willie, heavily ironed in the inner dungeon and expecting death in the morning, came the voices of friends.

But his spirits rose to the occasion, and when Red Rowan,

hoisted Kinmont Willie, whose fetters there was no time to knock off, on his back and carried him up to the breach they had made in the wall, from which they went down by a ladder they had brought with them, the man so narrowly delivered from the noose had his jest ready:

It is high time that we, too, escaped from Carlisle Castle into the open-air delights of the surrounding country. Five miles to the east lies the pleasant village of Wetheral on the Eden. Corby Castle, seat of a branch of the great Howard family, crowns the wooded [23] hill across the river, but we lingered in Wetheral Church for the sake of one who may have been an ancestor of "the fause Sakelde." This stately sleeper is described as Sir Richard Salkeld, "Captain and Keeper of Carlisle," who, at about the time of Henry VII, "in this land was mickle of might." His effigy is sadly battered; both arms are gone, a part of a leg, and the whole body is marred and dinted, with latter-day initials profanely scrawled upon it. But he, lying on the outside, has taken the brunt of abuse and, like a chivalrous lord, protected Dame Jane, his lady, whose alabaster gown still falls in even folds.

We drove eastward ten miles farther, under sun and shower, now by broad meadows where sleek kine, secure at last from cattle-lifters, were tranquilly grazing, now by solemn ranks of Scotch firs and far-reaching parks of smooth-barked, muscular beeches, now through stone-paved hamlets above whose shop-doors we would read the familiar ballad names, Scott, Graham (Graeme), Armstrong, Musgrave, Johnston, Kerr, and wonder how the wild blood of the Border had been tamed to the selling of picture postal cards.[24]

Our goal was Naworth, one of the most romantic of English castles. Its two great towers, as we approached, called imagination back to the days

Naworth is the heart of a luxuriant valley. The position owes its defensive strength to the gorges cut by the Irthing and two tributaries. These three streams, when supplemented by the old moat, made Naworth an island fortress. The seat of the Earls of Carlisle, it was built by Ranulph Dacre in the fourteenth century. Even the present Lady Carlisle, a pronounced Liberal and a vigorous worker in the causes of Temperance and Woman Suffrage, though claiming to be a more thoroughgoing Republican than any of us in the United States, points out with something akin to pride "the stone man" on the Dacre Tower who has upheld the family escutcheon there for a little matter of five hundred years. In the sixteenth century the Dacre lands passed by marriage to the Howards,[25] and "Belted Will," as Sir Walter Scott dubbed Lord William Howard, proved, under Elizabeth and James, an efficient agent of law and order. Two suits of his plate armour still bear witness to the warrior, whom the people called "Bauld Willie," with the same homely directness that named his wife, in recognition of the ample dower she brought him, "Bessie with the braid apron," but his tastes were scholarly and his disposition devout. Lord William's Tower, with its rugged stone walls, its loopholes and battlements, its steep and narrow winding-stair guarded by a massive iron door, its secret passage to the dungeons, is feudal enough in suggestion, yet here may be seen his library with the oak-panelled roof and the great case of tempting old folios, and here his oratory, with its fine wood-carvings, its Flemish altar-piece, and its deep-windowed recess outlooking on a fair expanse of green earth and silver sky.

This castle, with its magnificent baronial hall, its treasures of art and spirit of frank hospitality, was harder to escape from than Carlisle. There was no time to follow the Irthing eastward to the point where, as the Popping Stones tell, Walter Scott offered his[26] warm heart and honest hand to the dark-eyed daughter of a French emigre. But we could not miss Lanercost, the beautiful ruined abbey lying about a mile to the north of Naworth. An Augustine foundation of the twelfth century, it has its memories of Edward I, who visited it with Queen Eleanor in 1180 and came again in broken health, six years later, to spend quietly in King Edward's Tower the last winter of his life. The nave now makes a noble parish church in which windows by William Morris and Burne-Jones glow like jewels. The choir is roofless, but gracious in its ruin, its pavement greened by moss, feathery grasses waving from its lofty arcades, and its walls weathered to all pensive, tender tints. The ancient tombs, most of them bearing the scallop-shells of the Dacres, are rich in sculpture. Into the transept walls are built some square grey stones of the Roman Wall, and a Roman altar forms a part of the clerestory roof. The crypt, too, contains several Roman altars, dedicated to different gods whose figures, after the lapse of two thousand years, are startling in their spirited grace, their energy of life.

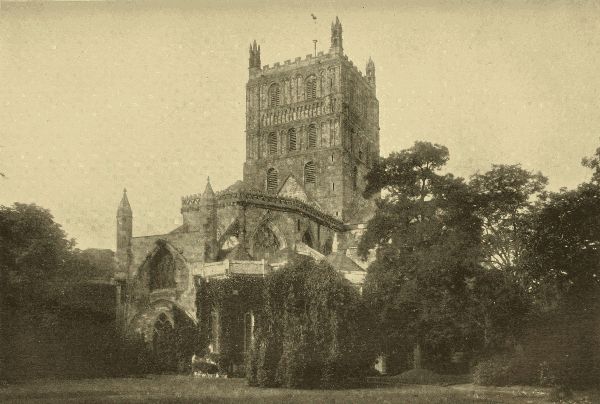

KING EDWARD'S TOWER, LANERCOST ABBEY

KING EDWARD'S TOWER, LANERCOST ABBEY

But Lanercost reminds us that we have all but ignored Carlisle Cathedral, and back we drive, by way of the village of Brampton with its curious old market-hall, to the Border City. After all, we have only followed the custom of the place in slighting the cathedral. Carlisle was ever too busy fighting to pay much heed to formal worship.

The cathedral dates from the time of William Rufus, and still retains two bays of its Norman nave, which suffered from fire in the early part of the thirteenth century. A still more disastrous fire, toward the close of that century, all but destroyed the new choir, which it took the preoccupied citizens one hundred years to rebuild, so that we see to-day Early English arches in combination with Decorated pillars and Late Decorated capitals. These capitals of fresh and piquant designs are an especial feature of the choir, whose prime glory, however, is the great east window with its perfect tracery, although only the upper glass is old. The cathedral has suffered[28] not alone from a series of fires, but from military desecration. Part of its nave was pulled down by the irreverent Roundheads to repair the fortifications, and it was used after Carlisle was retaken from Prince Charlie as a prison for the garrison. Even to-day canny Cumberland shows a grain too much of frugality in pasturing sheep in the cathedral graveyard. Carlisle Cathedral has numbered among its archdeacons Paley of the "Evidences," and among its archdeans Percy of the "Reliques." Among its bridegrooms was Walter Scott, who wedded here his raven-haired lady of the Popping Stones.

One drive more before we seek the Lake Country,—ten miles to the north, this time, across the adventurous Esk, where a fierce wind seemed to carry in it the shout of old slogans and the clash and clang of arms, and across the boundary stream, the Sark, to Gretna Green, where breathless couples used to be married by blacksmith or innkeeper or the first man they met, the furious parents posting after all in vain. Then around by Longtown we drove and back to Carlisle, across the Solway Moss,—reaches of blowing grass in the foreground; dark, broken[29] bogs, where men and women were gathering in the peat, in the middle distance; and beyond, the blue folds of hills on hills. It was already evening, but such was the witchery of the scene, still with something eerie and lawless about it despite an occasional farmhouse with stuffed barns and plump ricks and meadows of unmolested kine, that we would gladly, like the old Borderers whose armorial bearings so frequently included stars and crescents, have spent the night in that Debatable Land, with the moon for our accomplice in moss-trooping.

There are as many "best ways" of making the tour of this enchanted land as there are Lake Country guidebooks, volumes which, at prices varying from ten shillings to "tuppence," are everywhere in evidence. One may journey by rail to Keswick or to Windermere; one may come up from Furness Abbey to Lakeside, passing gradually from the softer scenery to the wilder; or one may enter by way of Penrith and Pooley Bridge, ushered at once into the presence of some of the noblest mountains and perhaps the loveliest lake.

This last was our route, and very satisfactory we found it. Our stay at Penrith had been abbreviated by a municipal councillors' convention which left not a bed for the stranger. We had been forewarned of the religious convention which throngs Keswick the last full week in July, and, indeed, an evangelist bound thither had presented[31] us with tracts as we took our train at Carlisle. But we had not reckoned on finding Penrith in such plethoric condition, and, after an uphill look at the broken red walls of Penrith Castle, which, with Carlisle, Naworth, and Cockermouth, stood for the defence of western England against the Scots, we mounted a motor-bus, of all atrocities, and were banged and clanged along a few miles of fairly level road which transferred us, as we crossed the Eamont, from Cumberland to Westmoreland. The hamlet of Pooley Bridge lies at the lower end of Ullswater, up whose mountain-hemmed reaches of ever-heightening beauty we were borne by The Raven, a leisurely little steamer with a ruddy captain serenely assured that his lake is the queen of all. The evening was cold and gusty,—rougher weather than any we had encountered in our midsummer voyage across the Atlantic,—but, wrapped in our rugs and shedding hairpins down the wind, we could have sailed on forever, so glorious was that sunset vision of great hills almost bending over the riverlike lake that runs on joyously, as from friend to friend, between the guardian ranks.

We lingered for a few days at the head of[32] Ullswater, in Patterdale, and would gladly have lingered longer, if only to watch the play of light and shadow over St. Sunday Crag, Place Fell, Stybarrow Crag, Fairfield, and all that shouldering brotherhood of giants, but we must needs take advantage of the first clear day for the coach-drive to Ambleside, over the Kirkstone Pass,

A week at Ambleside, under Wansfell's "visionary majesties of light," went all too swiftly in the eager exploration of Grasmere and Coniston, Hawkshead, Bowness, Windermere, and those "lofty brethren," the Langdale Pikes, with their famous rock-walled cascade, Dungeon Ghyll. The coach-drive from Ambleside to Keswick carried us, at Dunmailraise, across again from Westmoreland to Cumberland. Helvellyn and Thirlmere dominated the way, but Skiddaw and Derwent Water claimed our allegiance on arrival. What is counted the finest coach-drive in the kingdom, however, the twenty-four-mile circuit from Keswick known as the Buttermere Round, remained to bring us[33] under a final subjection to the silver solitude of Buttermere and Crummock Water and the rugged menace of Honister Crag. The train that hurried us from Keswick to Cockermouth passed along the western shore of pleasant Bassenthwaite Water, but from Workington to Furness Abbey meres and tarns, for all their romantic charm, were forgotten, while, the salt wind on our faces, we looked out, over sand and shingle, on the dim grey vast of ocean.

The Lake Country, it is often said, has no history. The tourist need not go from point to point enquiring

That irregular circle of the Cumberland Hills, varying from some forty to fifty miles in diameter, a compact mass whose mountain lines shut in narrow valleys, each with its own lake, and radiate out from Helvellyn in something like a starfish formation, bears, for all its wildness, the humanised look of land on which many generations of men have lived and died; but the records of that life are scant.[34]

There are several stone-circles, taken to be the remains of British temples, the "mystic Round of Druid frame," notably Long Meg and her Daughters, near Penrith, and the Druid's Circle, just out of Keswick. About the Keswick circle such uncanny influences still linger that no two persons can number the stones alike, nor will your own second count confirm your first. Storm and flood rage against that mysterious shrine, but the wizard blocks cannot be swept away. The Romans, who had stations near Kendal, Penrith, and Ambleside, have left some striking remembrances, notably "that lone Camp on Hardknott's height," and their proud road, still well defined for at least fifteen miles, along the top of High Street ridge. A storied heap of stones awaits the climber at the top of

Here, in 945, the last king of the Cumbrian Britons, Dunmail, was defeated by Edmund of England in the pass between Grasmere and Keswick. Seat Sandal and Steel Fell looked down from either side upon his fall. Edmund raised a cairn above what his Saxon wits supposed was a slain king, but Dunmail[35] is only biding his time. His golden crown was hurled into Grisedale Tarn, high up in the range, where the shoulders of Helvellyn, Seat Sandal, and Fairfield touch, and on the last night of every year these dark warders see a troop of Dunmail's men rise from the tarn, where it is their duty to guard the crown, bearing one more stone to throw down upon the cairn. When the pile is high enough to content the king, who counts each year in his deep grave the crash of another falling stone, he will rise and rule again over Cumberland.

Here history and folk-lore blend. Of pure folk-lore the stranger hears but little. Eden Hall, near Penrith, has a goblet filched from the fairies:

The enchanted rock in the Vale of St. John is celebrated in Scott's "Bridal of Triermain." St. Bees has a triumphant tradition of St. Bega, who, determined to be a nun, ran away from the Irish king, her father, for no better reason than because he meant to marry her to a Norwegian prince, and set sail in a fishing-boat for the Cumberland coast. Her little[36] craft was driven in by the storm to Whitehaven, where she so won upon the sympathies of the Countess of Egremont that this lady besought her lord to give the fugitive land for a convent. It was midsummer, and the graceless husband made answer that he would give as much as the snow should lie upon next morning, but when he awoke and looked out from the castle casement, his demesne for three miles around was white with snow.

Wordsworth's "Song at the Feast of Brougham Castle," "The Horn of Egremont Castle," and "The Somnambulist" relate three legends of the region, of varying degrees of authenticity, and Lord's Island in Derwent Water brings to mind the right noble name of James Radcliffe, third and last Earl of Derwentwater, who declared for his friend and kinsman, the Pretender of 1715. On October sixth the young earl bade his brave girl-wife farewell and rode away to join the rebels, though his favourite dog howled in the courtyard and his dapple-grey started back from the gate. On October fourteenth the cause was lost, and the Earl of Derwentwater was among the seventeen hundred who surrendered at Preston.[37] In the Tower and again on the scaffold his life was offered him if he would acknowledge George I as rightful king and would conform to the Protestant religion, but he said it "would be too dear a purchase." On the evening after his beheading the Northern Lights flamed red over Keswick, so that they are still known in the countryside as Lord Derwentwater's Lights.

The dalesfolk could doubtless tell us more. There may still be dwellers by Windermere who have heard on stormy nights the ghastly shrieks of the Crier of Claife, calling across the lake for a ferry-boat, although it was long ago that a valiant monk from Lady Holm "laid" that troubled spirit, binding it, with book and bell, to refrain from troubling "while ivy is green"; and in the depths of Borrowdale, on a wild dawn, old people may cower deeper in their feather beds to shut out the baying of the phantom hounds that hunt the "barfoot stag" through Watendlath tarn and over the fells down into Borrowdale. There is said to be a local brownie, Hob-Thross by name, sometimes seen, a "body aw ower rough," lying by the fire at midnight. For all his shaggy look, he has so sensitive a spirit[38] that, indefatigable though he is in stealthy household services, the least suggestion of recompense sends him weeping away. He will not even accept his daily dole of milk save on the condition that it be set out for him in a chipped bowl.

But, in the main, the Lake Country keeps its secrets. The names are the telltales, and these speak of Briton and Saxon and the adventurous Viking. Dale, fell, force (waterfall), ghyll (mountain ravine), holm (island), how (mound), scar (cliff-face), are Icelandic words. Mountain names that seem undignified, as Coniston Old Man or Dolly Wagon Pike, are probably mispronunciations of what in the original Celtic or Scandinavian was of grave import. There appears to be a present tendency to substitute for the unintelligible old names plain English terms usually suggested by some peculiarity in the mountain shape, but it is a pity to give up the Celtic Blencathara, Peak of Demons, for Saddleback.

The jubilant throngs who flock to Lakeland every summer concern themselves little with its early history. The English pour into that blessed circuit of hills as into a great playground,[39] coaching, walking, cycling, climbing, boating, keenly alive to the beauty of the scenery and eagerly drinking in the exhilaration of the air. They love to tread the loftiest crests, many of which are crowned with cairns raised by these holiday climbers, each adding his own stone. But it is the shepherd who is in the confidence of the mountains, he who has

Wordsworth first learned to love humanity in the person of the shepherd

Sheep, too, are often seen against the sky-line, and even the cow—that homelike beast who favours you in her innocent rudeness, from the gap of a hawthorn hedge, with that same prolonged, rustic, curious stare that has taxed your modesty in Vermont or Ohio—will forsake the shade of "the honied sycamore" in the valley for summits

There have been fatal accidents upon the more precipitous peaks. Scott and Wordsworth have sung the fate of that "young lover of Nature," Charles Gough, who, one hundred years ago, fell from the Striding Edge of Helvellyn and was watched over in death for no less than three months by his little yellow-haired terrier, there on the lonely banks of Red Tarn, where her persistent barking at last brought shepherds to the body. In the Patterdale churchyard, whose famous great yew is now no more, we noticed a stone commemorating a more recent victim of Helvellyn, a Manchester botanist, who had come summer by summer to climb the mountain, and who, a few years since, on his last essay, a man of seventy-three, had died from exhaustion during the ascent. The brow of Helvellyn, now soft and silvery as a melting dream, now a dark mass banded by broad rainbows, overlooks his grave.

I remember that Nathan's story of the rich man who "had no pity," but took for a guest's dinner the "one little ewe lamb" of his poor neighbour, was read in the Patterdale church that evensong, and it was strange to see how intently those sturdy mountain-lads, their[41] alert-eyed sheep dogs waiting about the door, listened to the parable. Not only does the Scripture imagery—"The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want"—but the phrasing of the prayerbook—"We have erred and strayed from Thy ways like lost sheep"—come with enhanced significance in a pastoral region.

Lakeland in the tourist season is not at its best in point of flowers. The daffodils that in Gowbarrow Park—recently acquired and opened as a national preserve—rejoiced the poet as they danced beside the dancing waves of Ullswater, fade before July, and the patches of ling and heather upon the mountain-sides lack the abundance that purples the Scottish hills, but the delicate harebell nods blithely to the wayfarer from up among the rocks, and the foxglove grows so tall, especially in the higher passes, as to overtop those massive boundaries into which the "wallers" pack away all the loose stone they can.

Birds, too, are not, in midsummer, numerous or varied. Where are Wordsworth's cuckoo and skylark and green linnet? The eagles have been dislodged from their eyries on Eagle Crag. A heavily flapping raven,[42] a congregation of rooks, a few swallows and redbreasts, with perhaps a shy wagtail, may be the only winged wanderers you will salute in an hour's stroll, unless this, as is most likely, has brought you where

There you will be all but sure to see your Atlantic friends, the seagulls, circling slowly within the mountain barriers like prisoners of the air and adding their floating shadows to the reflections in the lake below. For, as Wordsworth notes,—what did Wordsworth fail to note?—the water of these mountain meres is crystal clear and renders back with singular exactitude the "many-coloured images imprest" upon it.

But the life of the Cumbrian hills is the life of grazing flocks, of leaping waterfalls and hidden streams with their "voice of unpretending harmony,"—the life of sun and shadow. Sometimes the sky is of a faint, sweet blue with white clouds wandering in it,—the old Greek myth of Apollo's flocks in violet meadows; sometimes the keenest radiance silvers the upper crest of cumuli that[43] copy in form the massy summits below; sometimes the mellow sunset gold is poured into the valleys as into thirsty cups; but most often curling mists wreathe the mountain-tops and move in plumed procession along their naked sides.

The scenic effects and the joy of climbing are not lost by American tourists, yet these, as a rule, come to the Lake Country in a temper quite unlike that of the English holiday seekers. We come as pilgrims to a Holy Land of Song. We depend perhaps too little upon our own immediate sense of grandeur and beauty, and look perhaps too much to Wordsworth to interpret for us "Nature's old felicities." The Lake Country that has loomed so large in poetry may even disappoint us at the outset. The memory of the Rockies, of our chain of Great Lakes, of Niagara, may disconcert our first impressions of this clump of hills with only four, Scafell Pike, Scafell, Helvellyn, and Skiddaw, exceeding three thousand feet in height; of lakes that range from Windermere, ten miles long and a mile broad, to the reedy little pond of Rydal Water, more conventionally termed "a fairy mere"; of waterfalls that are[44] often chiefly remarkable, even Southey's Lodore, for their lack of water. Scales Tarn, of which Scott wrote,

is seventeen feet deep.

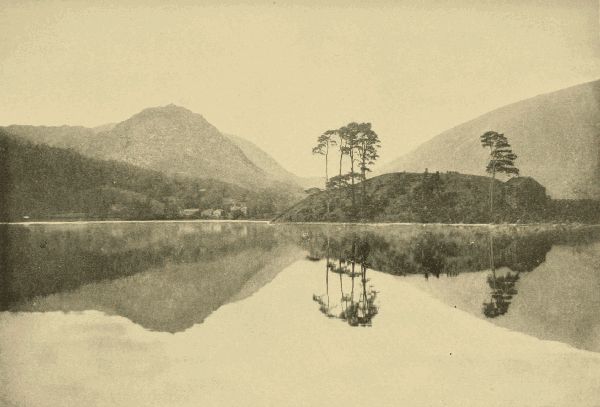

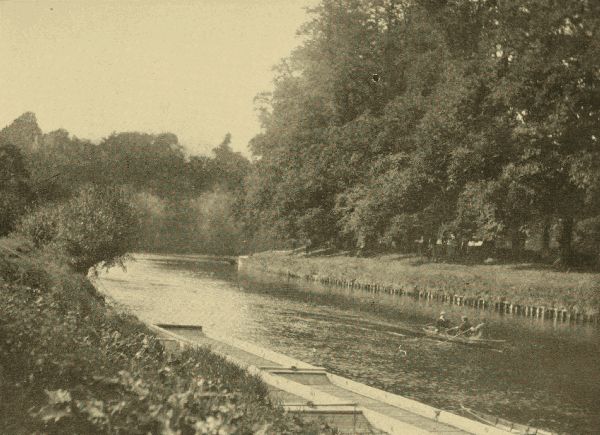

ISLAND IN GRASMERE LAKE

ISLAND IN GRASMERE LAKE

It is all in proportion, all picturesque,—almost in too regular proportion, almost too conspicuously picturesque, as if it had been expressly gotten up for the "tripper." There is nothing of primeval wildness about it. Nature is here the lion tamed, an accredited human playmate. Indeed, one almost feels that here is Nature sitting for her portrait, a self-conscious Nature holding her court of tourists and poets. Yet this is but a fleeting and a shamefaced mood. It takes intimacy to discover the fact of reticence, and those are aliens indeed who think that a single coach-drive, even the boasted "circular tour," has acquainted them with the Lake Country,—yes, though they trudge over the passes (for it is coach etiquette to put the passengers down whenever the road gets steep) Wordsworth in hand. In truth, the great amount [45]of literary association may be to the conscientious "Laker" something of a burden. Skiddaw thrusts forth his notched contour with the insistent question: "What was it Wordsworth said about me?" Ennerdale church and the Pillar Rock tax one's memory of "The Brothers," and every stone sheep-fold calls for a recitation from "Michael." That "cradled nursling of the mountain," the river Duddon, expects one to know by heart the thirty-four sonnets recording how the pedestrian poet

The footpath you follow, the rock you rest upon, the yew you turn to admire, Wishing-Gate and Stepping-Stones admonish you to be ready with your quotation. Even the tiny cascade of Rydal Water—so small as presumably to be put to bed at six o'clock, for it may not be visited after that hour—has been sung by the Grasmere laureate. While your care-free Englishman goes clambering over the golden-mossed rocks and far within the slippery recesses of Dungeon Ghyll, your serious American will sit him down amid the[46] bracken and, tranquilly watched by Lingmoor from across the vale, read "The Idle Shepherd-Boys," and the exquisite description of the scene in Mrs. Humphry Ward's "Fenwick's Career." If he can recall Coleridge's lines about the "sinful sextons' ghosts," so much the better, and if he is of a "thorough" habit of mind, he will have read through Wordsworth's "Excursion" in preparation for this expedition to the Langdales and be annotating the volume on his knee.

There may be something a little naïve in this studious attitude in the presence of natural beauty, but the devotion is sincere. Many a tourist, English and American, comes to the Lake Country to render grateful homage to those starry spirits who have clustered there. Fox Howe, the home of Dr. Arnold and dear to his poet son; The Knoll, home of Harriet Martineau; and the Dove's Nest, for a little while the abode of Mrs. Hemans, are duly pointed out at Ambleside, but not all who linger in that picture-book village and climb the hill to the Church of St. Anne, standing serene with its square, grey, pigeon-peopled tower, know that Faber was a curate[47] there in the youthful years before he "went over to Rome." He lived hard by in what is said to be the oldest house in Ambleside, once a manor-house of distinction,—that long, low stone building with small, deep-set windows and the cheery touches of colour given by the carefully tended flowers about the doors. "A good few" people thought he was not "just bright," our landlady told us, "because he would be walking with his head down, busy at his thoughts," yet Wordsworth said that Faber was the only man he knew who saw more things in Nature than he did in a country ramble. Bowness cherishes recollections of the gay, audacious doings of Professor Wilson (Christopher North), and Troutbeck plumes itself on being the birthplace of Hogarth's father. Keswick, where Shelley once made brief sojourn, holds the poet-dust of Southey and of Frederic Myers, and in Crosthwaite Vicarage may be found a living poet of the Lakes, Canon Rawnsley,—a name to conjure with throughout the district, whose best traditions he fosters and maintains.

Opposite Rydal Mount, at Nab Cottage, dwelt, for the closing years of his clouded life,[48] the darling of the dalesfolk, "Li'le Hartley," first-born son of Coleridge,—that boy "so exquisitely wild" to whom had descended something of his father's genius crossed by the father's frailty. Hartley's demon was not the craving for opium, but for alcohol. After a sore struggle that crippled but did not destroy, he rests in Grasmere churchyard, his stone bearing the inscription, "By Thy Cross and Passion." It was from Nab Cottage that another soul of high endowment, menaced by the opium lust, De Quincey, took a bride, Margaret, a farmer's daughter, who made him the strong and patient wife his peril needed. They dwelt in Dove Cottage at Townend, Grasmere, the hallowed garden-nest where Wordsworth and his wife and his sister Dorothy—that ardent spirit the thought of whom is still "like a flash of light"—had dwelt before. Wordsworth's later homes at Allan Bank, the Grasmere Rectory, and even at Rydal Mount are less precious to memory than this, where he and Coleridge and Dorothy dreamed the great dreams of youth together. Thither came guests who held high converse over frugal fare,—among them Sir Walter Scott, Charles Lamb, "the[49] frolic and the gentle," and that silent poet, the beloved brother John. It was a plain and thrifty life that Dove Cottage knew, with its rustic little rooms and round of household tasks, but thrift took on magic powers in the Lake Country a century ago. Amazing tales are told of the "Wonderful Walker," schoolmaster of Buttermere and curate of Seathwaite, the Pastor of the "Excursion," but his feats of economy might be challenged by the old-time curate of Patterdale, who, on an income of from sixty to ninety dollars a year, lived comfortably, educated his four children, and left them a tidy little fortune. Such queer turns of fate were his that he published his own banns and married his father.

Most of those for whose sake the Lake Country is holy ground lived a contemplative, sequestered life akin to that of the mediæval monks, the scholars and visionaries of a fighting world; but Coniston, on the edge of Lancashire, is the shrine of a warrior saint, Ruskin, whose last earthly home, Brantwood, looks out over Coniston Water, and whose grave in the quiet churchyard, for which Westminster Abbey was refused, is beautifully[50] marked by a symbolically carven cross quarried from the fine greenstone of Coniston Fells. In the Ruskin Museum may be seen many heart-moving memorials of that hero life, all the way from the abstracts of sermons written out for his mother in a laborious childish hand to the purple pall, worked for him by the local Linen Industry he so eagerly founded, and embroidered with his own words: "Unto This Last."

Not in any roll-call of the men of letters who have trodden the Cumbrian Hills should the poet Gray be forgotten. The first known tourist in the Lake Country, he was delighted with Grasmere and Keswick, but Borrowdale, plunged deep amid what the earliest guide-book, that of West in 1774, was to describe as "the most horrid romantic mountains," turned him back in terror.

Yet Wordsworth, for all his illustrious compeers, is still the presiding genius of these opalescent hills and silver meres. It is to him, that plain-faced man who used to go "booing" his verses along these very roads, that multitudes of visitants have owed

It is good for the soul to follow that sane, pure life from its "fair seedtime" on the garden terrace at Cockermouth, where the murmuring Derwent gave

through the boyhood at Hawkshead—that all-angled little huddle of houses near Esthwaite Water—a boyhood whose inner growth is so marvellously portrayed in "The Prelude," on through the long and fruitful manhood of a poet vowed,

to the churchyard beside the Rotha, where Wordsworth and his kin of flesh and spirit keep their "incommunicable sleep."

Fletcher's "Valentinian."

We heard about it first in Ambleside. We were in lodgings half-way up the hill that leads to the serene, forsaken Church of St. Anne. It was there that Faber, fresh from Oxford, had been curate, silently thinking the thoughts that were to send him into the Roman communion, and his young ghost, with the bowed head and the troubled eyes, was one of the friends we had made in the few rainy days of our sojourn. Another was Jock, a magnificent old collie, who accepted homage as his royal due, and would press his great head against the knee of the alien with confident expectation of a caress, lifting in recognition a long, comprehending look of amber eyes. Another friend—though our relations were sometimes[53] strained—was Toby, a piebald pony of piquant disposition. He allowed us to sit in his pony-cart at picturesque spots and read the Lake Poets to him, and to tug him up the hills by his bridle, which he had expert ways of rubbing off, to the joy of passing coach-loads, when our attention was diverted to the landscape. Another was our kindly landlady. She came in with hot tea that Saturday afternoon to cheer up the adventurous member of the party, who had just returned half drowned from a long drive on coachtop for the sake of scenery absolutely blotted out by the downpour. There the "trippers" had sat for hours, huddled under trickling umbrellas, while the conscientious coachman put them off every now and then to clamber down wet banks and gaze at waterfalls, or halted for the due five minutes at a point where nothing was perceptible but the grey slant of the rain to assure them—and the spattered red guidebook confirmed his statement—that this was "the finest view in Westmoreland." So when our landlady began to tell us of the ancient ceremony which the village was to observe that afternoon, the bedrenched one, hugging the bright dot[54] of a fire, grimly implied that the customs and traditions of this sieve-skied island—in five weeks we had had only two rainless days—were nothing to her; but the tea, that moral beverage which enables the English to bear with their climate, wrought its usual reformation.

At half-past five we were standing under our overworked umbrellas on a muddy street corner, waiting for the procession to come by. And presently it came, looking very much as if it had been through a pond to gather the rushes. In front went a brass band, splashing along the puddles to merry music, and then a long train of draggled children, with a few young men and maidens to help on the toddlers, two or three of whom had to be taken up and carried, flowers and all. But soberly and sturdily, in the main, that line of three hundred bonny bairns trotted along through the heavy clay, under the soft rain—little lads in rubber coats and gaiters, some holding their tall bunches of rushes, or elaborate floral designs, upright before them like bayonets, some shouldering them like guns; tired little lassies clasping their "bearings" in their arms like dolls, or[55] dragging them along like kittens. All down the line the small coats and cloaks were not only damp, but greened and mossed and petal-strewn from the resting and rubbing of one another's burdens. These were of divers sorts. Most effective were the slender bundles of rushes,—long, straight rushes gathered that morning from the meres by men who went out in boats for the purpose. These rush-fagots towered up from a distance like green candles, making the line resemble a procession of Catholic fairies. The village, however, took chief pride in the moss-covered standards of various device entwined with rushes and flowers. There were harps of reeds and waterlilies, crosses of ferns and harebells, shepherds' crooks wound with heather, sceptres, shields, anchors, crowns, swords, stars, triangles, hearts, with all manner of nosegays and garlands. Ling and bracken from the hillsides, marigolds from the marsh, spikes of oat and spears of wheat from the harvest-fields, and countless bright-hued blossoms from meadow and dooryard and garden were woven together, with no little taste and skill, in a pretty diversity of patterns.

The bells rang out blithe welcome as the[56] procession neared the steepled Church of St. Mary, where a committee of ladies and gentlemen received the offerings and disposed them, according to their merit, in chancel or aisles. The little bearers were all seated in the front pews, the pews of honour, before we thronging adults, stacking our dripping umbrellas in the porch, might enter. The air was rich with mingled fragrances. Along the chancel rail, in the window-seats, on the pillars, everywhere, were rushes and flowers, the choicest garden-roses whispering with foxglove and daisy and the feathered timothy grass. But sweeter than the blossoms were the faces of the children, glad in their rustic act of worship, well content with their own weariness, no prouder than the smiling angels would have had them be. Only here and there a rosy visage was clouded with disappointment, or twisted ruefully awry in the effort to hold back the tears, for it must needs be that a few devices, on which the childish artists had spent such joyful labour, were assigned by the expert committee to inconspicuous corners. The mere weans behaved surprisingly well, though evensong, a brief and sympathetic service, was punctuated by[57] little sobs, gleeful baby murmurs, and crows of excitement. The vicar told the children, in a few simple words, how, in earlier times, when the church was unpaved, the earth-floor was strewn with sweet-smelling rushes, renewed every summer, and that the rushes and flowers of to-day were brought in memory of the past, and in gratitude for the beauty of their home among the hills and lakes. Then the fresh child voices rang out singing praises to Him who made it all:

They sang, too, their special hymn written for the Ambleside rush-bearers seventy years ago, by the well-beloved vicar of Brathay, the Rev. Owen Lloyd:

One highly important ceremony, to the minds of the children, was yet to come,—the presentation of the gingerbread. As they filed out of the church, twopenny slabs of a peculiarly black and solid substance were given into their eager little hands. The rain had ceased, and we grown-ups all waited in the churchyard, looking down on the issuing file of red tam-o'-shanters, ribboned straw hats, worn grey caps, and, wavering along very low in the line, soft, fair-tinted baby hoods, often cuddled up against some guardian knee. Under the varied headgear ecstatic feasting had begun even in the church porch, though some of the children were too entranced with excitement to find their mouths. One chubby urchin waved his piece of gingerbread in the air, and another laid his on a gravestone and inadvertently sat down on it. A bewildered wee damsel in robin's-egg blue had lost hers in the basket of wild flowers that was slung about her neck. One spud of a boy, roaring as he came, was wiping his eyes with his. In general, however, the rush-bearers were munching with such relish that they did not trouble themselves to remove the tissue paper adhering to the bottom of each cake,[59] but swallowed that as contentedly as the rest. Meanwhile their respective adults were swooping down upon them, dabbing the smear of gingerbread off cheeks and chins, buttoning up little sacques and jackets, and whisking off the most obtrusive patches of half-dried mud. Among these parental regulators was a beaming old woman with a big market-basket on her arm, who brushed and tidied as impartially as if she were grandmother to the whole parish.

Then, again, rang out those gleeful harmonies of which our Puritan bells know nothing. The circle of mountains, faintly flushed with an atoning sunset, looked benignly down on a spectacle familiar to them for hundreds of Christian summer-tides; and if they remembered it still longer ago, as a pagan rite in honour of nature gods, they discreetly kept their knowledge to themselves.

The rushes and flowers brightened the church through the Sunday services, which were well attended by both dalesfolk and visitors. On Monday twelve prizes were awarded, and the bearings were taken away by their respective owners. Then followed "the treat," an afternoon of frolic, with rain only now and then, on a meadow behind St.[60] Mary's. The ice-cream cart, the climbing-pole, swings and games, seemed to hold the full attention of the children, to each of whom was tied a cup; but when the simple supper was brought on to higher ground close by the church, who sat like a gentle mother in the very midst of the merry-make, a jubilant, universal shout, "It's coom! It's coom!" sent all the small feet scampering toward the goodies. To crown it all, the weather obligingly gave opportunity, on the edge of the evening, for fireworks, which even the poor little Wesleyans outside the railing could enjoy.

THE RUSH-BEARING AT GRASMERE

THE RUSH-BEARING AT GRASMERE

The Ambleside rush-bearing takes place on the Saturday before the last Sunday in July. The more famous Grasmere rush-bearing comes on the Saturday next after St. Oswald's Day, August fifth. This year (1906) these two festivals fell just one week apart. The London papers were announcing that it was "brilliant weather in the Lakes," which, in a sense, it was, for the gleams of sunshine between the showers were like opening doors of Paradise; yet we arrived at Grasmere[61] so wet that we paid our sixpences to enter Dove Cottage, a shrine to which we had already made due pilgrimage, and had a cosey half-hour with Mrs. Dixon, well known to the tourist world, before the fireplace whose quiet glow often gladdened the poets and dreamers of its great days gone by.

Our canny old hostess, in the bonnet and shawl which seem to be her official wear, was not disposed this afternoon to talk of the Wordsworths, whom she had served in her girlhood. Her mind was on the rush-bearing for which she had baked the gingerbread forty-three years. There were five hundred squares this time, since, in addition to what would be given to the children, provision must be made for the Sunday afternoon teas throughout Grasmere. The rolling out of the dough had not grown easier with the passing of nearly half a century, and she showed us the swollen muscles of her wrist. Her little granddaughters, their flower erections borne proudly in their arms, were dressed all spick and span for the procession, and stood with her, for their pictures, at the entrance to Dove Cottage.

It was still early, and we strolled over to the tranquil church beside the Rotha. Under[62] the benediction of that grey, embattled tower, in the green churchyard with

sleep Wordsworth, his sister Dorothy, and their kindred, while the names of Hartley Coleridge and Arthur Hugh Clough may be read on stones close by. We brought the poets white heather and heart's ease for our humble share in the rush-bearing.

Grasmere church, with its strange row of rounded arches down the middle of the nave and its curiously raftered roof, still wears the features portrayed in The Excursion:

There were a number of people in the church, but the reverent hush was almost unbroken. Strangers in the green churchyard were moving softly about, reading the inscriptions on stones and brasses, or waiting in the pews, some in the attitude of devotion. In the south aisle leaned against the wall the banner of St. Oswald, a crimson-bordered standard, with the figure of the saint in white and crimson, worked on a golden ground. A short, stout personage, with grey chin-whiskers and a pompous air, presumably the sexton, came in a little after three with a great armful of fresh rushes, and commenced to strew the floor. Soon afterwards the children, with their bearings, had taken their positions, ranged in a long row on the broad churchyard wall, fronting the street, which by this time was crowded with spectators, for the Grasmere rush-bearing is the most noted among the few survivals of what was once, in the northern counties of England, a very general observance. There is an excellent account of it, by an eyewitness, as early as 1789. James Clarke, in his Survey of the Lakes, wrote:[64]

"I happened once to be at Grasmere, at what they call a Rushbearing.... About the latter end of September a number of young women and girls (generally the whole parish) go together to the tops of the hills to gather rushes. These they carry to the church, headed by one of the smartest girls in the company. She who leads the procession is styled the Queen, and carries in her hand a huge garland, and the rest usually have nosegays. The Queen then goes and places her garland upon the pulpit, where it remains till after the next Sunday. The rest then strew their rushes upon the bottom of the pews, and at the church door they are met by a fiddler, who plays before them to the public house, where the evening is spent in all kinds of rustic merriment."

Still more interesting is the record, in Hone's Year Book, by "A Pedestrian." On July 21, 1827, the walking tour of this witness brought him to Grasmere.

"The church door was open, and I discovered that the villagers were strewing the floors with fresh rushes.... During the whole of this day I observed the children busily employed in preparing garlands of such wild flowers as the beautiful valley produces, for the evening procession, which commenced at nine, in the following order: The children, chiefly girls, holding their garlands, paraded through the village, preceded by the Union band. They then entered the church, when the three largest garlands were placed on the altar, and the remaining ones in various parts of the[65] place. In the procession I observed the 'Opium Eater,' Mr. Barber, an opulent gentleman residing in the neighbourhood, Mr. and Mrs. Wordsworth, Miss Wordsworth and Miss Dora Wordsworth. Wordsworth is the chief supporter of these rustic ceremonies. The procession over, the party adjourned to the ballroom, a hayloft at my worthy friend Mr. Bell's (now the Red Lion), where the country lads and lasses tripped it merrily and heavily. They called the amusement dancing. I called it thumping; for he who made the most noise seemed to be esteemed the best dancer; and on the present occasion I think Mr. Pooley, the schoolmaster, bore away the palm. Billy Dawson, the fiddler, boasted to me of having been the officiating minstrel at this ceremony for the last six and forty years.... The dance was kept up to a quarter of twelve, when a livery servant entered and delivered the following verbal message to Billy: 'Master's respects, and will thank you to lend him the fiddle-stick.' Billy took the hint, the Sabbath was at hand, and the pastor of the parish (Sir Richard le Fleming) had adopted this gentle mode of apprising the assembled revellers that they ought to cease their revelry. The servant departed with the fiddle-stick, the chandelier was removed, and when the village clock struck twelve not an individual was to be seen out of doors in the village."

Since then many notices of the Grasmere rush-bearings have been printed, the most illuminating being that of the Rev. Canon[66] Rawnsley, 1890, now included in one of his several collections of Lake Country sketches. He calls attention to the presence, among the bearings, of designs that suggest a Miracle Play connection, as Moses in the bulrushes, the serpent on a pole, and the harps of David and Miriam,—emblems which were all in glowing evidence this past summer. A merry and sympathetic account is given in a ballad of 1864, ascribed to Mr. Edward Button, formerly the Grasmere schoolmaster:

The older hymn of St. Oswald—

is now followed by a hymn from the pen of Canon Rawnsley, whose genial notice, as he passed this August along the churchyard wall of bearings, brought a happy flush to one child-face after another:

The Grasmere rush-bearing, so far as we saw it, was lacking in none of the traditional features, not even the rain. Yet the gently falling showers seemed all unheeded by the line of bright-eyed children, steadfastly propping up on the wall their various tributes. Banners and crosses and crowns were there, and all the customary emblems. Among the several harps was one daintily wrought of marguerites; two little images of Moses reposed in arks woven of flags and grasses; on a moss-covered lattice was traced in lilies: "Consider the lilies of the field." The serpent was made of tough green stems, knotted and twisted together in a long coil about a pole. Geranium, maiden-hair fern, Sweet William, pansies, daisies, dahlias, asters, fuchsias mingled their hues in delicate and intricate devices. Among the decorated perambulators was one all wreathed in heather, with a screen of rushes rising high behind. Its flower-faced baby was all but hidden under a strewing of roses more beautiful than any silken robe, and a wand twined with lilies of the valley swayed unsteadily from his pink fist. Six little maidens in white and green, holding tall stalks of rushes, upheld the rush-bearing[70] sheet—linen spun at Grasmere and woven at Keswick—crossed by blossoming sprays.

The rush-cart, bearing the ribbon-tied bunches of rushes, crowned with leafy oak-boughs and hung with garlands, belonged especially to Lancashire, where it has not yet entirely disappeared; indeed a rush-cart has been seen in recent years taking its way through one of the most squalid quarters of grimy Manchester; but the rush-sheet, on which the precious articles of the parish, silver tankards, teapots, cups, spoons, snuff-boxes, all lent to grace this festival, were arranged, had really gone out until, in this simplified form, it was revived a few years ago at Grasmere by lovers of the past. That the sheet now holds only flowers is due to that same inexorable logic of events which has brought it about that no longer the whole parish with cart-loads of rushes, no longer, even, the strong lads and lasses swinging aloft bunches of rushes and glistening holly boughs, but only little children ranged in cherubic row along the churchyard wall, and crowing babies in their go-carts, bring to St. Oswald the tribute of the summer.[71]

It was from coach-top we caught our farewell glimpse of the charming scene. The village band, playing the Grasmere rush-bearing march—an original tune believed to be at least one hundred and fifty years old—led the way, followed by the gold and crimson banner of the warrior saint. The rush-sheet, borne by the little queen and her maids of honour, came after, and then the throng of one hundred or more children, transforming the street into a garden with the beauty and sweetness of their bearings. As the procession neared the church, the bells pealed out "with all their voices," and we drove off under a sudden pelt of rain, remembering Wordsworth's reference to

Our third rush-bearing we found in Cheshire, on Sunday, August 12. A morning train from Manchester brought us to Macclesfield—keeping the Sabbath with its silk-mills closed, and its steep streets nearly empty—in[72] time for luncheon and a leisurely drive, through occasional gusts of rain, four miles to the east, up and up, into the old Macclesfield Forest. This once wild woodland, infested by savage boars, a lurking-place for outlaws, is now open pasture, grazed over by cows whose milk has helped to make the fame of Cheshire cheese. But Forest Chapel still maintains a rite which flourished when the long since perished trees were sprouts and saplings.

It is a tiny brown church, nested in a hollow of the hills, twelve hundred feet above the sea. In the moss-crowned porch, whose arch was wreathed with flowers and grasses, stood the vicar, as we came up, welcoming the guests of the rush-bearing. For people were panting up the hill in a continuous stream, mill hands from Macclesfield and farmer-folk from all the hamlets round. Perhaps seven or eight hundred were gathered there, hardly one-fourth of whom could find room within the church.

We passed up the walk, thickly strewn with rushes, under that brightly garlanded porch, into a little sanctuary that was a very arbour of greenery and blossom. As we were led up[73] the aisle, our feet sank in a velvety depth of rushes. The air was delicious with fresh, woodsy scents. A cross of lilies rose from the rush-tapestried font. The window-seats were filled with bracken, fern, and goldenrod. The pulpit and reading-desk were curtained with long sprays of bloom held in green bands of woven rushes. The chancel walls were hidden by wind-swayed greens from which shone out, here and there, clustering harebells, cottage roses, and the golden glint of the sunflower. The hanging lamps were gay with asters, larkspur, and gorse. The whole effect was indescribably joyous and rural, frankly suggestive of festivity.

It was early evensong, a three o'clock service. There was to be another at five. After the ritual came the full-voiced singing of a familiar hymn:

So singing, the little congregation filed out into the churchyard, where the greater congregation, unable to gain access, was singing too. It was one of the rare hours of sunshine, all the more blissful for their rarity. The preacher of the day took his stand on a flat tombstone. Little girls were lifted up to seats upon the churchyard wall, and coats were folded and laid across low monuments for the comfort of the old people. A few little boys, on their first emergence into the sunshine, could not resist the temptation to turn an unobtrusive somersault or so over the more distant mounds, but they were promptly beckoned back by their elders and squatted submissively on the turf. The most of the audience stood in decorous quiet. Two generations back, gingerbread stalls and all manner of booths would have been erected about the church, and the rustics, clumping up the steep path in the new boots which every farmer was expected to give his men for the rush-bearing, would have diversified the services by drinking and wrestling.

But altogether still and sacred was the scene on which we looked back as the compulsion of the railway time-table drew us away;[75] the low church tower keeping watch and ward over that green enclosure of God's acre, with the grey memorial crosses and the throng of living worshippers,—a throng that seemed so shadowy, so evanescent, against the long memories of Forest Chapel and the longer memories of those sunlit hills that rejoiced on every side. A yellow rick rose just behind the wall, the straws blowing in the wind as if they wanted to pull away and go to church with the rushes. On the further side of the little temple there towered a giant chestnut, a dome of shining green that seemed to overspread and shelter its Christian neighbour, as if in recognition of some ancient kinship, some divine primeval bond, attested, perhaps, by this very rite of rush-bearing. The enfolding blue of the sky, tender with soft sunshine, hallowed them both.

We all know Liverpool,—but how do we know it? The Landing Stage, hotels whose surprisingly stable floors, broad beds, and fresh foods are grateful to the sea-worn, the inevitable bank, perhaps the shops. Most of us arrive at Liverpool only to hurry out of it,—to Chester, to London, to the Lakes. Seldom do the beguilements of the Head Boots prevail upon the impatient American to visit the birthplaces of its two queerly assorted lions, "Mr. Gladstone and Mrs. 'Emans," of whom the second would surely roar us "as gently as any sucking dove." Yet we might give a passing thought to these as well as to the high-hearted James Martineau and to Hawthorne, our supreme artist in romance, four of whose precious years the country wasted in that "dusky and stifled chamber" of Brunswick Street.[77] And hours must be precious indeed to the visitor who cannot spare even one for the Walker Fine Art Gallery, where hangs Rossetti's great painting of "Dante's Dream,"—the Florentine, his young face yearning with awe and grief, led by compassionate Love to the couch of Beatrice, who lies death-pale amid the flush of poppies.

But the individuality of Liverpool is in its docks,—over six miles of serried basins hollowed out of the bank of the broad Mersey, one of the hardest-worked rivers in the world,—wet docks and dry docks, walled and gated and quayed. From the busiest point of all, the Landing Stage, the mighty ocean liners draw out with their throngs of wearied holiday-makers and their wistful hordes of emigrant home-seekers. And all along the wharves stand merchantmen of infinite variety, laden with iron and salt, with soap and sugar, with earthenware and clay, with timber and tobacco, with coal and grain, with silks and woollens, and, above all, with cotton,—the raw cotton sent in not only from our own southern plantations, but from India and Egypt as well, and the returning cargoes of cloth spun and woven in "the cotton towns"[78] of Lancashire. The life of Liverpool is commerce; it is a city of warehouses and shops. The wide sea-range and the ever-plying ferryboats enable the merchant princes to reside well out of the town. So luxurious is the lot of these merchants deemed to be that Lancashire has set in opposition the terms "a Liverpool gentleman" and "a Manchester man," while one of the ruder cotton towns, Bolton, adds its contribution of "a Bolton chap." This congestion of life in the great port means an extreme of poverty as well as of riches. The poor quarters of Liverpool have been called "the worst slums in Christendom," yet a recent investigation has shown that within a limited area, selected because of its squalor and misery, over five thousand pounds a year goes in drink. The families that herd together by threes and fours in a single dirty cellar, sleeping on straw and shavings, nevertheless have money to spend at "the pub,"—precisely the same flaring, gilded ginshop to-day as when Hawthorne saw and pitied its "sad revellers" half a century ago.

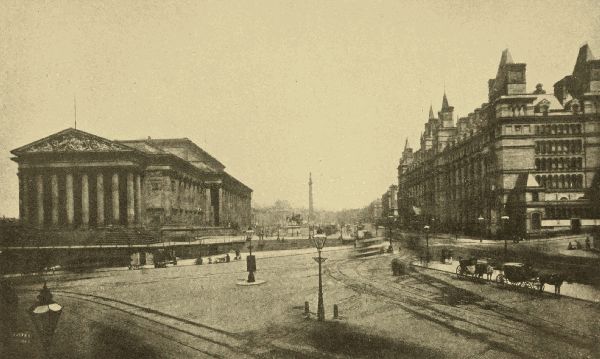

THE QUADRANT, LIVERPOOL

THE QUADRANT, LIVERPOOL

While Liverpool has a sorry pre-eminence for high death-rate and for records of vice and[79] crime, Manchester, "the cinder-heap," may fairly claim to excel in sheer dismalness. The river Irwell, on which it stands, is so black that the Manchester clerks, as the saying goes, run down to it every morning and fill their ink-pots. Not only Manchester, but all the region for ten miles around, is one monster cotton factory. The towns within this sooty ring—tall-chimneyed Bolton; Bury, that has been making cloth since the days of Henry VIII; Middleton on the sable Irk; Rochdale, whose beautiful river is forced to toil not for cotton only, but for flannels and fustians and friezes; bustling Oldham; Ashton-under-Lyme, with its whirr of more than three million spindles; Staley Bridge on the Tame; Stockport in Cheshire; Salford, which practically makes one town with Manchester; and Manchester itself—all stand on a deep coal-field. The miners may be seen, of a Sunday afternoon, lounging at the street corners, or engaged in their favourite sport of flying carrier pigeons, as if the element of air had a peculiar attraction for these human gnomes. If the doves that they fly are white, it is by some special grace, for smut lies thick on wall and ledge, on the monotonous ranks of "workingmen's[80] homes," on the costly public buildings, on the elaborate groups of statuary. One's heart aches for the sculptor whose dream is hardly made pure in marble before it becomes dingy and debased.

Beyond the borders of this magic coal-field, above which some dark enchantment binds all humanity in an intertwisted coil of spinning, weaving, bleaching, printing, buying, selling cotton, are various outlying collieries upon which other manufacturing towns are built,—Warrington, which at the time of our Revolution supplied the Royal Navy with half its sail-cloth; Wigan, whose tradition goes back to King Arthur, but whose renown is derived from its seam of cannel coal; calico Chorley; Preston, of warlike history and still the centre of determined strikes; and plenty more.