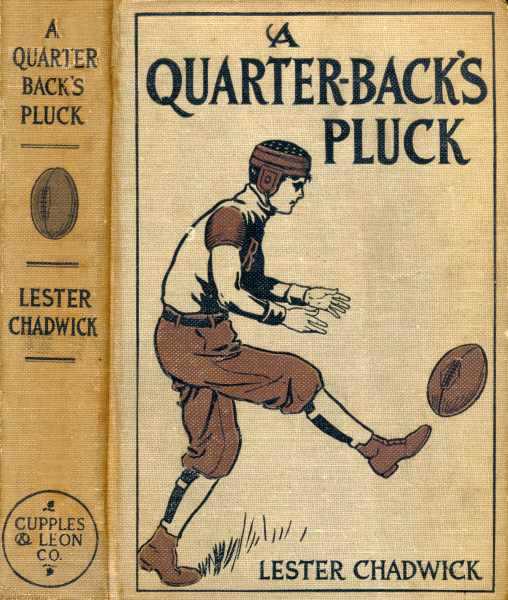

Title: A Quarter-Back's Pluck: A Story of College Football

Author: Lester Chadwick

Release date: September 5, 2012 [eBook #40668]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A Story of College Football

BY

AUTHOR OF “THE RIVAL PITCHERS,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

BOOKS BY LESTER CHADWICK

THE COLLEGE SPORTS SERIES

12mo. Illustrated

THE RIVAL PITCHERS

A Story of College Baseball

A QUARTER-BACK’S PLUCK

A Story of College Football

(Other volumes in preparation)

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY NEW YORK

Copyright, 1910, by

Cupples & Leon Company

A Quarter-Back’s Pluck

Printed in U. S. A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Moving Day | 1 |

| II | Langridge Has a Tumble | 10 |

| III | Phil Gets Bad News | 20 |

| IV | Football Practice | 31 |

| V | A Clash | 43 |

| VI | Professor Tines Objects | 52 |

| VII | The First Line-up | 61 |

| VIII | Langridge and Gerhart Plot | 70 |

| IX | Some Girls | 77 |

| X | A Bottle of Liniment | 91 |

| XI | In Which Some One Becomes a Victim | 100 |

| XII | The First Game | 106 |

| XIII | Smashing the Line | 117 |

| XIV | “Girls Are Queer” | 123 |

| XV | Phil Saves Wallops | 131 |

| XVI | Phil Is Nervous | 138 |

| XVII | The Sophomores Lose | 144 |

| XVIII | A Fire Alarm | 155 |

| XIX | The Freshmen Dance | 162 |

| XX | Phil Gets a Telegram | 172 |

| XXI | Strange Bedfellows | 179 |

| XXII | A Change in Signals | 187 |

| XXIII | Battering Boxer Hall | 195 |

| XXIV | Gerhart Has an Idea | 210 |

| XXV | Phil Gives Up | 217 |

| XXVI | Sid Is Bogged | 224 |

| XXVII | Woes of a Naturalist | 233 |

| XXVIII | Tom Is Jealous | 239 |

| XXIX | A Strange Discovery | 246 |

| XXX | A Bitter Enemy | 254 |

| XXXI | “It’s Too Late to Back Out!” | 260 |

| XXXII | Tom Gets a Tip | 265 |

| XXXIII | “Line Up!” | 273 |

| XXXIV | The Game | 280 |

| XXXV | Victory—Conclusion | 287 |

| “Smash and hammer; hammer and smash!” |

| “The pigskin struck him full in the back” |

| “Clarence McFadden, He Wanted to Waltz” |

| “There was a rush to where Phil lay” |

Phil Clinton looked critically at the rickety old sofa. Then he glanced at his chum, Tom Parsons. Next he lifted, very cautiously, one end of the antiquated piece of furniture. The sofa bent in the middle, much as does a ship with a broken keel.

“It—it looks like a mighty risky job to move it, Tom,” said Phil. “It’s broken right through the center.”

“I guess it is,” admitted Tom sorrowfully. Then he lifted the head of the sofa, and warned by an ominous creaking, he lowered it gently to the floor of the college room which he and his chum, Sid Henderson, were about to leave, with the assistance of Phil Clinton to help them move. “Poor old sofa,” went on Tom. “You’ve had a hard life. I’m afraid your days are numbered.”

“But you’re not going to leave it here, for some[2] measly freshman to lie on, are you, Tom?” asked Phil anxiously.

“Not much!” was the quick response.

“Nor the old chair?”

“Nope!”

“Nor the alarm clock?”

“Never! Even if it doesn’t keep time, and goes off in the middle of the night. No, Phil, we’ll take ’em along to our new room. But, for the life of me, I don’t see how we’re going to move that sofa. It will collapse if we lift both ends at once.”

“I suppose so, but we’ve got to take it, even if we move it in sections, Tom.”

“Of course, only I don’t see——”

“I have it!” cried Phil suddenly. “I know how to do it!”

“How?”

“Splice it.”

“Splice it? What do you think it is—a rope ladder? You must be in love, or getting over the measles.”

“No, I mean just what I say. We’ll splice it. You wait. I’ll go down cellar, and get some pieces of board from the janitor. Also a hammer and some nails. We’ll save the old sofa yet, Tom.”

“All right, go ahead. More power to ye, as Bricktop Molloy would say. I wonder if he’s coming back this term?”

“Yep. Post graduate course, I hear. He[3] wouldn’t miss the football team for anything. Well, you hold down things here until I come back. If the new freshmen who are to occupy this room come along, tell ’em we’ll be moved by noon.”

“I doubt it; but go ahead. I’ll try to be comfortable until your return, dearest,” and with a mocking smile Tom Parsons sank down into an easy chair that threatened to collapse under his substantial bulk. From the faded cushions a cloud of dust arose, and set Tom to sneezing so hard that the old chair creaked and rattled, as if it would fall apart.

“Easy! Easy there, old chap!” exclaimed the tall, good-looking lad, as he peered on either side of the seat. “Don’t go back on me now. You’ll soon have a change of climate, and maybe that will be good for your old bones.”

He settled back, stuck his feet out before him, and gazed about the room. It was a very much dismantled apartment. In the center was piled a collection of baseball bats, tennis racquets, boxing gloves, foils, catching gloves, a football, some running trousers, a couple of sweaters, and a nondescript collection of books. There were also a couple of trunks, while, flanking the pile, was the old sofa and the arm chair. On top of all the alarm clock was ticking comfortably away, as happy as though moving from one college dormitory to another was a most matter-of-fact proceeding. The[4] hands pointed to one o’clock, when it was, as Tom ascertained by looking at his watch, barely nine; but a little thing like that did not seem to give the clock any concern.

“I do hope Phil can rig up some scheme so we can move the sofa,” murmured the occupant of the easy chair. “That’s like part of ourselves now. It will make the new room seem more like home. I wonder where Sid can be? This is more of his moving than it is Phil’s, but Sid always manages to get out of hard work. Phil is anxious to room with us, I guess.”

Tom Parsons stretched his legs out a little farther, and let his gaze once more roam about the room. Suddenly he uttered an exclamation, as his eye caught sight of something on the wall.

“Came near forgetting that,” he said as he arose, amid another cloud of dust from the chair, and removed from a spot on the wall, behind the door, the picture of a pretty girl. “I never put that there,” he went on, as he wiped the dust from the photograph, and turned it over to look at the name written on the back—Madge Tyler. “Sid must have done that for a joke. He thought I’d forget it, and leave it for some freshy to make fun of. Not much! I got ahead of you that time, Sid, my boy. Queer how he doesn’t like girls,” added Tom, with the air of an expert. “Well, probably it’s[5] just as well he doesn’t take too much to Madge, for——”

But Tom’s musings, which were getting rather sentimental, were interrupted by the entrance of Phil Clinton. Phil had under one arm some boards, while in one hand he carried a hammer, and in the other some nails.

“Just the cheese,” he announced. “Now we’ll have this thing fixed up in jig time. Hasn’t Sid Henderson showed up?”

“No. I guess he’s over to the new room. He took his books and left some time ago. Maybe he’s studying.”

“Not much!” exclaimed Phil. “I wish he’d come and help move. Some of this stuff is his.”

“Most of it is. I’m glad you’re going to help, or I’d never have the courage to shift. Well, let’s get the sofa fixed. I doubt if we can make it hold together, though.”

“Yes, we can. I’ll show you.”

Phil went to work in earnest. He was an athletic-looking chap, of generous size, and one of the best runners at Randall College. He was one of Tom Parson’s particular chums, the other being Sidney Henderson. Tom and Sid, of whom more will be told presently, had roomed together during their freshman year at Randall, and Phil’s apartment was not far away. Toward the close of the term the three boys were much together, Phil[6] spending more time in the room of Tom and Sid than he did in his own. In this way he became very much attached to the old chair and sofa, which formed two of the choicest possessions of the lads.

With the opening of the new term, when the freshmen had become more or less dignified sophomores, Phil had proposed that he and his two chums shift to a large room in the west dormitory, where the majority of the sophomores and juniors lived. His plan was enthusiastically adopted by Sid and Tom, and, as soon as they had arrived at college, ready for the beginning of the term, moving day had been instituted. But Sid, after helping Tom get their possessions in a pile in the middle of the room they were about to leave, had disappeared, and Phil, enthusiastic about getting his two best friends into an apartment with him, had come over to aid Tom.

“Now, you see,” went on Phil, “I’ll nail this board along the front edge of the sofa—so.”

“But don’t you think, old chap—and I know you’ll excuse my mentioning it,” said Tom—“don’t you think that it rather spoils, well, we’ll say the artistic beauty of it?”

“Artistic fiddlesticks!” exclaimed Phil. “Of course it does! But it’s the only way to hold it together.”

“One could, I suppose, put a sort of drapery—flounce,[7] I believe, is the proper word—over it,” went on Tom. “That would hide the unsightly board.”

“I don’t care whether it’s hid or not!” exclaimed Phil. “But if you don’t get down here and help hold this end, while I nail the other, I know what’s going to happen.”

“What?” asked Tom, as he carefully put in his pocket the photograph of the pretty girl.

“Well, you’ll have a mob of howling freshmen in here, and there won’t be any sofa left.”

“Perish the thought!” cried Tom, and then he set to work in earnest helping Phil.

“Now a board on the back,” said the amateur carpenter, and for a few minutes he hammered vigorously.

“It’s a regular anvil chorus,” remarked Tom.

“Here, no knocking!” exclaimed his chum. “Now let’s see if it’s stiff enough.”

Anxiously he raised one end of the sofa. There was no sagging in the middle this time.

“It’s like putting a new keel on a ship!” cried the inventor of the scheme gaily. “A few more nails, and it will do. Do you think the chair will stand shifting?”

“Oh, yes. That’s like the ‘one-horse shay’—it’ll hold together until it flies apart by spontaneous combustion. You needn’t worry about that.”

Phil proceeded to drive a few more nails in the boards he had attached to the front and back of the sofa. Then he got up to admire his work.

“I call that pretty good, Tom; don’t you?” he asked.

The two chums drew back to the farther side of the room to get the effect.

“Yes, I guess with a ruffle or two, a little insertion, and a bit of old lace, it will hide the fractured places, Phil. It’s a pity——”

“Here, what are you scoundrels doing to my old sofa?” exclaimed a voice. “Vandals! How dare you spoil that antique?” and another lad entered the room. “Say, why didn’t you put new legs on it, insert new springs, and cover it over while you were about it?” he asked sarcastically.

“Because, you old fossil, we had to put those boards on,” said Tom. “Where have you been, Sid? Phil and I were getting ready to move without you.”

“Oh, I’ve been cleaning out the new room we’re going into. The juniors who were there last term must have tried to raise vegetables in it, judging by the amount of dirt I found. But it’s all right now.”

“Good! Now if you’ll catch hold here, we’ll move the old sofa first. The rest will be easy.”

Sid Henderson grasped the head of the couch,[9] while Tom took the foot. Phil acted as general manager, and steadied it on the side.

“Easy now, easy boys,” he cautioned, as they moved toward the door leading to the hall.

Out into the corridor went the three lads with the old sofa. It was no easy task, but they managed to get it out of the east dormitory, where they had roomed for a year, and then they began the journey across a stretch of grass to the west building.

The appearance of the three boys, carrying a dilapidated sofa, as tenderly as though it were some rare and fragile object, attracted the attention of a crowd of students. The lads swarmed over to surround the movers.

“Well, would you look at that!” exclaimed Holman, otherwise known as “Holly,” Cross. “Have you had a fire, Tom?”

“No; they’ve been to an auction sale of antiques, and this is the bed on which Louis XIV slept the night before he ate the Welsh rarebit,” declared Ed Kerr, the champion catcher on the ’varsity nine. “Why don’t you label it, Phil, so a fellow would know what it is?”

“You get out of the way!” exclaimed Tom good-naturedly.

“This side up, with care. Store in a cool, dry place, and water frequently,” quoted Billy Housenlager, who rejoiced in the title of Dutch. “Here, let me see if I can jump over it while it is in motion,” he added, for he was full of “horseplay,” and always anxious to try something new. He took a running start, and was about to leap full upon the sofa, when, at a signal from Phil, the three chums set the spliced piece of furniture on the grass.

“What’s the matter?” asked Dutch indignantly. “Can’t you give a fellow a chance to practice jumping? I can beat Grasshopper Backus, now.”

“You can not!” exclaimed the owner of the title. “I’m sure to make the track team this term, and then you’ll see what——”

“Say,” put in another student, “my uncle says that when he was here he used to jump——”

“Drown him!”

“Stuff grass in his mouth!”

“Make him eat the horsehair in the sofa!”

“Swallow it!”

“Chew it up!”

These were some of the cries of derision that greeted Ford Fenton’s mention of his uncle. The gentleman had once been a coach at Randall, and[12] a very good one, too, but his nephew was doing much to spoil his reputation.

For, at every chance he got, and at times when there was no opportunity but such as he made, Ford would quote his aforesaid uncle, upon any and all subjects, to the no small disapproval of his college mates. So they had gotten into the habit of “rigging” him every time he mentioned his relative.

“I don’t care,” Ford said, when the chorus of exclamations had ceased. “My uncle——”

But he got no further, for the students made a rush for him and buried him out of sight in a pile of wriggling arms and legs.

“First down; ten yards to gain!” yelled some one.

“Come on, now’s our chance,” said Tom. “First thing we know they’ll do that to our sofa, and then it will be all up with the poor old thing. Let’s move on.”

Once more the chums took up their burden, and walked toward the west dormitory. By this time the throng had done with punishing poor Fenton, and once more turned its attention to the movers.

“Going to split it up for firewood?” called Ed Kerr.

“No; it’s full of germs, and they’re going to dig ’em out and use ’em in the biology class,” suggested[13] Dan Woodhouse, who was more commonly called Kindlings.

“Maybe they’re going to make a folding bed of it,” came from Bricktop Molloy. “Come on, fellows, let’s investigate.”

The crowd of fun-loving students hurried after the three lads carrying the sofa.

“They’re coming!” exclaimed Tom.

“Let’s drop the sofa and cut for it?” proposed Sid. “They’ll make a rough house if they catch us.”

“I’m not going to desert the sofa!” exclaimed Tom.

“Nor I. I’ll stick by you—‘I will stand at thy right hand, and guard the bridge with thee,’” quoted Phil. “But if we put a little more speed on we can get to the dormitory, and that will be sanctuary, I guess. Come on; run, fellows!”

It was awkward work, running and carrying a clumsy sofa, but they managed it. Holly Cross caught up to them as they were at the door of the building.

“Ah, let’s have the old ark,” he pleaded. “We’ll make a bonfire of it, and circle about it to-night, after we haze some freshies. Give us the old relic, Tom.”

“Not on your life!” exclaimed the crack pitcher of the ’varsity nine. “This is our choicest possession, Holly. It goes wherever we go.”

“Well, it won’t go much longer,” observed Holly. “One of its legs is coming off.”

Almost as he spoke one of the sofa legs, probably jarred loose by the unaccustomed rapid rate of progress, fell to the dormitory steps.

“Oh, dear! Oh, dear!” exclaimed Phil. “It’s beginning to fall apart, Tom.”

“Never mind, you can nail it on. Sid, you carry the leg. The stairs are so narrow that only two of us can manage the sofa. Phil and I will do that, and you come in back to catch me, in case I fall.”

Seeing that there was no chance to get the sofa away from its owners, to make a college holiday with it, Holly Cross and his friends turned back to look for another source of sport. Sid picked up the leg, and then, with Phil mounting the stairs backward, carrying one end, and Tom advancing and holding the other, the task was begun. Up the stairs they went, and when they were half way there appeared at the head of the flight two lads. They were both well dressed in expensive clothes, and there was about them that indefinable air of “sportiness” which is so easily recognizable but hard to acquire.

“Hello, what’s this?” asked the foremost of the two, as he looked down on the approaching cavalcade and the sofa. “Here, what do you fellows mean by blocking up the stairway? Don’t you[15] know that no tradesmen are allowed in this entrance?”

“Who are you talking to?” demanded Phil, not seeing who was speaking.

“It’s Langridge,” explained Tom, as he looked up and saw his former enemy and rival.

“Oh, it’s Parsons, Henderson and Clinton,” went on Fred Langridge, as he recognized some fellow students. Then, without apologizing for his former words, he went on: “I say, you fellows will have to back down and let me and Gerhart past. We are in a hurry.”

“So are we,” said Tom shortly. “I guess you can wait until we come up.”

“No, I can’t!” exclaimed Langridge. “You back up! You have no right to block up the stairs this way!”

“Well, I guess we have,” put in Sid. “We’re moving some of our things to our new room.”

Langridge, followed by the other well-dressed lad, came down a few steps. He saw the old sofa, and exclaimed:

“What! Do you mean to say that you fellows are moving that fuzzy-wuzzy piece of architecture into this dormitory? I’ll not stand for it! I’ll complain to the proctor! Why, it’s full of disease germs!”

“Yes, and you’re full of prune juice!” cried[16] Phil Clinton, unable to stand the arrogant words and manner of Langridge.

“Don’t get gay with me!” exclaimed Tom’s former rival.

“I’ll lay you five to three that you can’t jump over their heads and clear the sofa,” put in the other student, whom Langridge had called Gerhart. “Do any of you fellows want to bet?” he asked rather sneeringly, as he looked down at Tom, Phil and Sid.

“I guess not,” answered Tom, good-naturedly enough.

“Ah, you’re not sports, I see,” rejoined Gerhart. “I thought you said this was a sporty college, Langridge?”

“So it is, when you strike the right crowd, and not a lot of greasy digs,” was the answer. “I say, are you chaps going to move back and let me and Gerhart pass?” he went on.

“No, we’re not,” replied Phil shortly. “You can wait until we get up. Go on back now, Langridge, and we’ll soon have this out of the way.”

“Burning it up would be the best method of getting it out of the way,” declared Langridge, still with that sneer in his voice. “I never saw such a disgraceful piece of furniture. What do you fellows want with it? Surely you’re not going to put it in your room.”

“That’s just what we are going to do,” declared[17] Sid. “We wouldn’t part with this for a good bit, would we, fellows?”

“Nope,” chorused Phil and Tom.

“Did it come over in the Mayflower?” asked Gerhart. “I’m willing to bet ten to one that if you think it’s an antique that you’re stuck. How about it?”

“You’re quite a sport, aren’t you, freshie?” asked Phil suddenly, for he knew that the new student must belong to the first-year class.

“Of course I’m a sport, but if you go to calling names I’ll show you that I’m something else!” exclaimed the other fiercely. “If you want to do a little something in the boxing line——”

“Dry up!” hastily advised Langridge in a whisper. “You’re a freshman, and you know it. They’re sophomores, and so am I. Don’t get gay.”

“Well, they needn’t insult a gentleman.”

“Tell us when one’s around, and we’ll be on our good behavior,” spoke Phil with a laugh.

“Come, now, are you fellows going to back down and let us pass?” asked Langridge hastily.

“Like the old guard, we die, but never surrender,” spoke Tom. “We’re not going to back down, Langridge. It’s easier for you to go back than for us.”

“Well, I’m not going to do it. You have no right to move your stuff in here, anyhow. The rooms are furnished.”

“We want our old chair and sofa,” explained Sid.

“I should think you’d be ashamed to bring such truck into a decent college,” expostulated Langridge. “It looks as if it had been through a fire in a second-hand store.”

“That’ll do you,” remarked Phil. “This is our sofa, and we’ll do as we please with it.”

“You won’t block up my way, that’s one thing you won’t do,” declared Langridge fiercely. “I’m going down. Look out! If I upset you fellows it won’t be my fault.”

He started down the stairs, and managed to squeeze past Phil, who, though he did not like Langridge, moved as far to one side as possible in the narrow passage. As Langridge passed the sofa he struck it with a little cane he carried. A cloud of dust arose.

“Whew!” exclaimed the sporty lad. “Smell the germs! Wow! Get me some disinfectant, Gerhart.”

Whether it was the action of Langridge in hitting the sofa that caused Tom to stagger, or whether Phil was unsteady on his feet and pushed on the sofa, did not develop. At any rate, just as Langridge came opposite to Tom on the stairs, the former pitcher was jostled against his rival. Langridge stumbled, tried to save himself by clutching[19] at Tom and then at the sofa. He missed both, and, with a loud exclamation, plunged down head first, bringing up with a resounding thud at the bottom.

For a moment after he struck the bottom of the stairs, Fred Langridge remained stretched out, making no move. Tom Parsons feared his former rival was badly hurt, and was about to call to Sid to go and investigate, when Langridge got up. His face showed the rage he felt, though it was characteristic of him that he first brushed the dust off his clothes. He was nothing if not neat about his person.

“What did you do that for?” he cried to Tom.

“Do what?”

“Shove me down like that. I might have broken my neck. As it is, I’ve wrenched my ankle.”

“I didn’t do it,” said Tom. “If you’d stayed up where you were, until we got past with the sofa, it wouldn’t have happened. You shouldn’t have tried to pass us.”

“I shouldn’t, eh? Well, I guess I’ve got as good a right on these stairs as you fellows have, with your musty old furniture. You oughtn’t be allowed to have it. You deliberately pushed[21] me down, Tom Parsons, and I’ll fix you for it!” and Langridge limped about, exaggerating the hurt to his ankle.

“I didn’t push you!” exclaimed Tom. “It was an accident that you jostled against me.”

“I didn’t jostle against you. You deliberately leaned against me to save yourself from falling.”

“I did not! And if you——”

“You brought it on yourself, Langridge,” interrupted Phil. “You got fresh and hit the sofa, and that made you lose your balance. It’s your own fault.”

“You mind your business! When I want you to speak I’ll address my remarks to you. I’m talking to Parsons now, and I tell him——”

“You needn’t take the trouble to tell me anything,” declared Tom. “I don’t want to hear you. I’ve told you it was an accident, and if you insist that it was done purposely I have only to say that you are intimating that I am not telling the truth. In that case there can be but one thing to do, and I’ll do it as soon as I’ve gotten this sofa into our room.”

There was an obvious meaning in Tom’s words, and Langridge had no trouble in fathoming it. He did not care to come to a personal encounter with Tom.

“Well, if you fellows hadn’t been moving that measly old sofa in, this would never have happened,”[22] growled Langridge as he limped away. “Come on, Gerhart. We’ll find more congenial company.”

“I guess I’ll wait until they get the sofa out of the way,” remarked the new chum Langridge appeared to have picked up.

Tom, Sid and Phil resumed their journey, and the old piece of furniture was carried to the upper hall. The stairs were clear, and Gerhart descended. As he passed Tom he looked at him with something of a sneer on his face, and remarked:

“I’ll lay you even money that Langridge can whip you in a fair fight.”

“Why, you little freshie,” exclaimed Phil, “fair fights are the only kind we have at Randall! We don’t have ’em very often, but every time we do Tom puts the kibosh all over your friend Langridge. Another thing—it isn’t healthy for freshies to bet too much. They might go broke,” and with these words of advice Phil caught up his end of the sofa and Tom the other. It was soon in the room the three sophomore chums had selected.

“Now for the chair and the rest of the truck,” called Phil.

“Oh, let’s rest a bit,” suggested Sid, as he stretched out on the sofa. No sooner had he reached a reclining position than he sat up suddenly.

“Wow!” he cried. “What in the name of the labors of Hercules is that?”

He drew from the back of his coat a long nail.

“Why, I must have left it on the sofa when I fixed it,” said Phil innocently. “I wondered what had become of it.”

“You needn’t wonder any longer,” spoke Sid ruefully. “Tom, take a look, that’s a good chap, and see if there’s a very big hole in my back. I think my lungs are punctured.”

“Not a bit of it, from the way you let out that yell,” said Phil. “That will teach you not to take a siesta during moving operations.”

“Not much damage done,” Tom reported with a laugh, as he inspected his chum’s coat. “Come on now, let’s get the rest of it done.”

“Do you think it will be safe to leave the sofa here?” asked Sid. “Perhaps I’d better stay and keep guard over it, while you fellows fetch the rest of the things in.”

“Well, listen to him!” burst out Phil. “What harm will come to it here?”

“Why, Langridge and that sporty new chum of his may slip in and damage it.”

“Say, if they can damage this sofa any more than it is now, I’d like to see them,” spoke Tom. “I defy even the fingers of Father Time himself to work further havoc. No, most noble Anthony, the sofa will be perfectly safe here.”

“I wouldn’t say as much for you, if Langridge gets a chance at you,” said Phil to Tom. “You know what tricks he played on you last term.”

“Yes; but I guess he’s had his lesson,” remarked Tom. “Now come on, and we’ll finish up.”

The three lads went back to the room formerly occupied by Sid and Tom during their freshman year. The chums were pretty much of a size, and they made an interesting picture as they strolled across the campus.

Tom Parsons had come to Randall College the term previous, from the town of Northville, where his parents lived. He did not care to follow his father’s occupation of farming, and so had decided on a college education, using part of his own money to pay his way.

As told in the first volume of this series, entitled “The Rival Pitchers,” Tom had no sooner reached Randall than he incurred the enmity of Fred Langridge, a rich youth from Chicago, who was manager of the ’varsity ball nine, and also its pitcher. Tom had ambitions to fill that position himself, and as soon as Langridge learned this, he was more than ever the enemy of the country lad.

Randall College was located near the town of Haddonfield, in one of our middle Western States, and was on the shore of Sunny River, not far from Lake Tonoka. Within a comparatively short distance from Randall were two other institutions of[25] learning. One was Boxer Hall, and the other Fairview Institute, a co-educational academy. These three colleges had formed the Tonoka Lake League in athletics, and the rivalry on the gridiron and diamond, as well as in milder forms of sport—rowing, tennis, basketball and hockey—ran high. When Tom arrived there was much talk of baseball, and Randall had a good nine in prospect. Her hopes ran toward winning the Lake League pennant in baseball, but as her nine had been at the bottom of the list for several seasons, the chances were dubious.

After many hardships, not a few of which Langridge was responsible for, Tom got a chance to play on the ’varsity nine. Langridge was a good pitcher, but he secretly drank and smoked, to say nothing of staying up late nights to gamble; and so he was not in good form. When it came to the crucial moment he could not “make good,” and Tom was put in his place, in the pitching box, and by phenomenal work won the deciding game. This made Randall champion of the baseball league, and Tom Parsons was hailed as a hero, Langridge being supplanted as pitcher and manager.

But if Langridge and some of the latter’s set were his enemies, Tom had many friends, not the least among whom were Phil Clinton and Sidney Henderson, to say nothing of Miss Madge Tyler. This young lady and Langridge were, at first, very[26] good friends, but when Madge found out what sort of a chap the rich city youth was, she broke friendship with him, and Tom had the pleasure of taking her to more than one college affair. This, of course, did not add to the good feeling between Tom and Langridge.

With the winning of the championship game, baseball came practically to an end at Randall, as well as at the other colleges in the Tonoka Lake League, and a sort of truce was patched up between Tom and Langridge. The summer vacation soon came, and the students scattered to their homes. Tom and his two chums agreed to room together during the term which opens with this story, and it may be mentioned incidentally that both Tom and Phil hoped to play on the football eleven. Phil was practically assured of a place, for he had played the game at a preparatory school, and had as good a reputation in regard to filling the position of quarter-back as Tom had in the pitching box.

It was due to a great catch which Phil made in the deciding championship game, almost as much as to Tom’s wonderful pitching, that Randall had the banner, and Captain Holly Cross, of the eleven, had marked Phil for one of his men during the season which was about to open on the gridiron.

“Now we’ll take the old armchair over,” proposed Tom, when he and his chums had reached the room they were vacating. “I guess I can manage[27] that alone. You fellows carry some of the other paraphernalia.”

Phil and Sid prepared to load themselves down with gloves, balls, bats, foils and various articles of sport. Before he left with the chair, Tom observed Sid looking behind the door as if for something.

“It’s not there, old man. I took it down,” said the pitcher, and he patted the pocket that held Madge Tyler’s photograph. “You thought you’d make me forget it, didn’t you?”

“Do you mean to say you’re going to stick girls’ pictures up in our new room?” asked Sid.

“Not girls’ pictures, in general,” replied Tom, “but one in particular.”

“You make me tired!” exclaimed Sid, who cared little for feminine society.

“You needn’t look at it if you don’t like,” responded his chum. “But I call her a pretty girl, don’t you, Phil?”

“She’s an all right looker,” answered the other with such enthusiasm that Tom glanced at him a trifle sharply.

“She’s no prettier than Phil’s sister,” declared Sid.

“Have you a sister?” demanded Tom.

Phil bowed in assent.

“Why didn’t you say so before?” asked Tom grumblingly.

“Because you never asked me.”

“Where is she?”

“Going to Fairview this term, I believe.”

“So is Madge—I mean Miss Tyler,” burst out Tom. “I’d like to meet her, Phil; your sister, I mean.”

“Say, you’re a regular Mormon!” expostulated Sid. “If we’re going to get this moving done, let’s do it, and not talk about girls. You fellows make me sick!”

“Wait until he gets bitten by the bug,” said Tom with a laugh, as he shouldered the easy chair.

It took the lads several trips to transfer all their possessions, but at last it was accomplished, and they sat in the new room in the midst of “confusion worse confounded,” as Holly Cross remarked when he looked in on them. Their goods were scattered all over, and the three beds in the room were piled high with them.

“It’s a much nicer place than the old room,” declared Tom.

“It will be when we get it fixed up,” added Phil.

“I s’pose that means sticking a lot of girls’ photos on the wall, some of those crazy banners they embroidered for you, a lot of ribbons, and such truck,” commented Sid disgustedly. “I tell you fellows one thing, though, and that is if you go to cluttering up this room too much, I’ll have something[29] to say. I’m not going to live in a cozy corner, nor yet a den. I want a decent room.”

“Oh, you can have one wall space to decorate in any style you like,” said Tom.

“Yes; he’ll probably adopt the early English or the late French style,” declared Phil, “and have nothing but a calendar on it. Well, every one to his notion. Hello, the alarm clock has stopped,” and he began to shake it vigorously.

“Easy with it!” cried Tom. “Do you want to jar the insides loose?”

“You can’t hurt this clock,” declared Phil, and, as if to prove his words, the fussy little timepiece began ticking away again, as loudly and insistingly as ever. “Well, let’s get the room into some decent kind of shape, and then I’m going out and see what the prospects are for football,” he went on. “I want to make that quarter-back position if I have to train nights and early mornings.”

“Oh, you’ll get it, all right,” declared Tom. “I wish I was as sure of a place as you are. I believe——”

He was interrupted by a knock at the door. Sid opened it. In the hall stood one of the college messengers.

“Hello, Wallops; what have you there?” asked Tom.

“Telegram for Mr. Phil Clinton.”

“Hand it over,” spoke Sid, taking the envelope[30] from the youth. “Probably it’s a proposition for him to manage one of the big college football teams.”

As Wallops, who, like nearly everything and every one else about the college had a nickname, departed down the corridor, Phil opened the missive. It was brief, but his face paled as he read it.

“Bad news?” asked Tom quickly.

“My mother is quite ill, and they will have to operate on her to save her life,” said Phil slowly.

There was a moment of silence in the room. No one cared to speak, for, though Tom and Sid felt their hearts filled with sympathy for Phil, they did not know what to say. It was curiously quiet—oppressively so. The fussy little alarm clock, on the table piled high with books, was ticking away, as if eager to call attention to itself. Indeed, it did succeed in a measure, for Tom remarked gently.

“Seems to me that sounds louder than it did in the other room.”

“There are more echoes here,” spoke Sid, also quietly. “It will be different when we get the things up.”

The spell had been broken. Each one breathed a sigh of relief. Phil, whose face had become strangely white, stared down at the telegram in his hand. The paper rustled loudly—almost as loudly as the clock ticked. Tom spoke again.

“Is it—is it something sudden?” he asked.[32] “Was she all right when you left home to come back to college?”

“Not exactly all right,” answered Phil, and he seemed to be carefully picking his words, so slowly did he speak. “She had been in poor health for some time, and we thought a change of air would do her good. So father took her to Florida—a place near Palm Beach. I came on here, and I hoped to hear good news. Now—now——” He could not proceed, and turned away.

Tom coughed unnecessarily loud, and Sid seemed to have suddenly developed a most tremendous cold. He had to go to the window to look out, probably to see if it was getting colder. In doing so he knocked from a chair a football, which bounded erratically about the room, as the spherical pigskin always does bounce. The movements of it attracted the attention of all, and mercifully came as a relief to their overwrought nerves.

“Well,” said Sid, as he blew his nose with seemingly needless violence, “I suppose you’ll have to give up football now; for you’ll go to Florida.”

“Yes,” said Phil simply, “of course I shall go. I think I’ll wire dad first, though, and tell him I’m going to start.”

“I’ll take the message to the telegraph office for you,” offered Tom eagerly.

“No, let me go,” begged Sid. “I can run faster than you, Tom.”

“That’s a nice thing to say, especially when I’m going to try for end on the ’varsity eleven,” said Tom a bit reproachfully. “Don’t let Holly Cross or Coach Lighton hear you say that, or I’ll be down and out. I’m none too good in my running, I know, but I’m going to practice.”

“Oh, I guess you’ll make out all right,” commented Phil. “I’m much obliged to you fellows. I guess I can take the message myself, though,” and he sat down at the littered table, pushing the things aside, to write the dispatch.

Tom and Sid said little when Phil went out to take the telegram to the office. The two chums, one on the old patched sofa and the other in the creaking chair, which at every movement sent up a cloud of dust from the ancient cushion, maintained a solemn silence. Tom did remark once:

“Tough luck, isn’t it?”

To which Sid made reply:

“That’s what it is.”

But, then, to be understood, you don’t need to talk much under such circumstances. In a little while footsteps were heard along the corridor.

“Here he comes!” exclaimed Tom, and he arose from the sofa with such haste that the new boards, which Phil had put on to strengthen it, seemed likely to snap off.

“Go easy on that, will you?” begged Sid. “Do you want to break it?”

“No,” answered Tom meekly, and he fell to arranging his books, a task which Sid supplemented by piling the sporting goods indiscriminately in a corner. They wanted to be busy when Phil came in.

“Whew! You fellows are raising a terrible dust!” exclaimed Phil. He seemed more at his ease now. In grief there is nothing so diverting as action, and now that he had sent his telegram, and hoped to be able to see his mother shortly, it made the bad news a little easier to bear.

“Yes,” spoke Tom; “it’s Sid. He raises a dust every time he gets into or out of that chair. I really think we ought to send it to the upholsterer’s and have it renovated.”

“There’d be nothing left of it,” declared Phil. “Better let well enough alone. It’ll last for some years yet—as long as we are in Randall.”

“Did you send the message?” blurted out Tom.

“Yes, and now I’ll wait for an answer.”

“Is it—will they have to—I mean—of course there’s some danger in an operation,” stammered Sid, blushing like a girl.

“Yes,” admitted Phil gravely. “It is very dangerous. I don’t exactly know what it is, but before she went away our family doctor said that if it came to an operation it would be a serious one. Now—now it seems that it’s time for it. Dear old mother—I—I hope——” He was struggling with[35] himself. “Oh, hang it all!” he suddenly burst out. “Let’s get this room to rights. If—if I go away I’ll have the nightmare thinking what shape it’s in. Let’s fix up a bit, and then go out and take a walk. Then it will be grub time. After that we’ll go out and see if any more fellows have arrived.”

It was good advice—just the thing needed to take their attention off Phil’s grief, and they fell to work with a will. In a short time the room began to look something like those they had left.

“Here, what are you sticking up over there?” called Sid to Tom, as he detected the latter in the act of tacking something on the wall.

“I’m putting up a photograph,” said Tom.

“A girl’s, I’ll bet you a new hat.”

“Yes,” said Tom simply. “Why, you old anchorite, haven’t I a right to? It’s a pity you wouldn’t get a girl yourself!”

“Humph! I’d like to see myself,” murmured Sid, as he carefully tacked up a calendar and a couple of football pictures.

“Oh, that’s Miss Tyler’s picture, isn’t it?” spoke Phil.

“Yes.”

Phil was sorting his books when from a volume of Pliny there dropped a photograph. Tom spied it.

“Ah, ha!” he exclaimed. “It seems that I’m[36] not the only one to have girls’ pictures. Say, but she’s a good-looker, all right!”

“She’s my sister Ruth,” said Phil quietly.

“Oh, I beg your pardon,” came quickly from Tom. “I—I didn’t know.”

“That’s all right,” spoke Phil genially. “I believe she is considered quite pretty. I was going to put her picture up on the wall, but since Sid objects to——”

“What’s that?” cried the amateur misogynist. “Say, you can put that picture up on my side of the room if you like, Phil. I—I don’t object to—to all girls’ pictures; it’s only—well—er—she’s your sister—put her picture where you like,” and he fairly glared at Tom.

“Wonders will never cease,” quoted the ’varsity pitcher. “Your sister has worked a miracle, Phil.”

“You dry up!” commanded Sid. “All I ask is, don’t make the room a photograph gallery. There’s reason in all things. Go ahead, Phil.”

“The next thing he’ll be wanting will be to have an introduction to your sister,” commented Tom.

“I’d like to have both you fellows meet her,” said Phil gravely. “You probably would have, only for this—this trouble of mother’s. Now I suppose sis will have to leave Fairview and go to Palm Beach with me. I must take a run over this evening, and see her. She’ll be all broken up.” It was not much of a journey to Fairview, a railroad[37] was well as a trolley line connecting the town of that name with Haddonfield.

The room was soon fitted up in fairly good shape, though the three chums promised that they would make a number of changes in time. They went to dinner together, meeting at the table many of their former classmates, and seeing an unusually large number of freshmen.

“There’ll be plenty of hazing this term,” commented Tom.

“Yes, I guess we’ll have our hands full,” added Sid.

Old and new students continued to arrive all that day. After reporting to the proper officials of the college there was nothing for them to do, save to stroll about, as lectures would not begin until the next morning, and then only preliminary classes would be formed.

“I think I’ll go down to the office and see if any telegram has arrived for me,” said Phil, as he and his chums were strolling across the campus.

“I hope you get good news,” spoke Tom. “We’ll wait for you in the room, and help you pack if you have to go.”

“Thanks,” was Phil’s answer as he walked away.

“Well, Tom, I suppose you’re going to be with us this fall?” asked Holly Cross, captain of the football eleven, as he spied Tom and Sid.

“I am if I can make it. What do you think?”

“Well, we’ve got plenty of good material for ends, and of course we want the best, and——”

“Oh, I understand,” said Tom with a laugh. “I’m not asking any favors. I had my honors this spring on the diamond. But I’m going to try, just the same.”

“I hope you make it,” said Holly fervently. “We’ll have some try-out practice the last of this week. Where’s Phil? I’ve about decided on him for quarter-back.”

“I don’t believe he can play,” remarked Sid.

“Not play!” cried Holly.

Then they told him, and the captain was quite broken up over the news.

“Well,” he said finally, “all we can hope is that his mother gets better in time for him to get into the game with us. We want to do the same thing to Boxer Hall and Fairview at football as we did in baseball. I do hope Phil can play.”

“So do we,” came from Tom, as he and Sid continued on to their room.

It was half an hour before Phil came in, and the time seemed three times as long to the two chums in their new apartment. When he entered the room both gazed apprehensively at him. There was a different look on Phil’s face than there had been.

“Well?” asked Tom, and his voice seemed very loud.

“Dad doesn’t want me to come,” was Phil’s answer.

“Not come—why? Is it too——”

“Well, they’ve decided to postpone the operation,” went on Phil. “It seems that she’s a little better, and there may be a chance. Anyhow, dad thinks if sis and I came down it would only worry mother, and make her think she was getting worse, and that would be bad. So I’ll not go to Florida.”

“Then it’s good news?” asked Sid.

“Yes, much better than I dared to hope. Maybe she’ll get well without an operation. I feel fine, now. I’m going over to Fairview and tell my sister. Dad asked me to let her know. I feel ten years younger, fellows!”

“So do we!” cried Tom, and he seized his chum’s hand.

“Let’s go out and haze a couple of dozen freshmen,” proposed Sid eagerly.

“You bloodthirsty old rascal!” commented Phil. “Let the poor freshies alone. They’ll get all that’s coming to them, all right. Well, I’m off. Hold down the room, you two.”

Tom and Sid spent the evening in their apartment, after Phil had received permission to go to Fairview, Tom having entrusted him with a message to Madge Tyler. The two chums had a number[40] of invitations to assist in hazing freshmen, but declined.

“We don’t want to do it without Phil,” said Tom, and this loyal view was shared by Sid.

Phil came back late that night, or, rather, early the next morning, for it was past midnight when he got to Randall College.

“Your friend Madge sends word that she hopes you’ll take her to the opening game of the football season,” said Phil to Tom, as he was undressing.

“Did you see her?” inquired Tom eagerly.

“Of course. Ruth sent for her. She’s all you said she was, Tom.”

“Oh!” spoke Tom in a curious voice, and then he was strangely silent. For Phil was a good-looking chap, and had plenty of money; and Tom remembered what friends Madge and Langridge had been. His sleep was not an untroubled one that night.

Two or three days more of general excitement ensued before matters were running smoothly at Randall. In that time most of the students had settled in their new rooms, the freshmen found their places, some were properly hazed, and that ordeal for others was postponed until a future date, much to the misery of the fledglings.

“Preliminary football practice to-morrow,” announced[41] Phil one afternoon, as he came in from the gymnasium and found Tom and Sid studying.

“That’s good!” cried Tom. “Are you going to try, Sid?”

“Not this year. I’ve got to buckle down to studies, I guess. Baseball is about all I can stand.”

“I hear Langridge is out of it, too,” said Phil. “His uncle has put a ban on it. He’s got to make good in lessons this term.”

“Well, I think the team will be better off without him,” commented Sid. “Not that he’s a poor player, but he won’t train properly, and that has a bad effect on the other fellows. It’s not fair to them, either. Look what he did in baseball. We’d have lost the championship if it hadn’t been for Tom.”

“Oh, I don’t know about that,” modestly spoke the hero of the pitching box.

“Well, turn out in football togs to-morrow,” went on Phil. “By the way, I hear that Langridge’s new freshman friend—Gerhart—is going to try for quarter-back against me.”

“What! that fellow who was with him when we were moving our sofa in?” asked Tom.

“That’s the one.”

“Humph! Doesn’t look as if he was heavy enough for football,” commented Sid.

“You can’t tell by the looks of a toad how much hay it can eat,” quoted Phil.

The following afternoon a crowd of sturdy lads, in their football suits, thronged out on the gridiron, which was the baseball field properly put in shape. The goal posts had been erected, and Coach Lighton and Captain Cross were on hand to greet the candidates.

“Now, fellows,” said the coach, “we’ll just have a little running, tackling, passing the ball, some simple formations and other exercises to test your wind and legs. I’ll pick out four teams, and you can play against each other.”

Ragged work, necessarily, marked the opening of the practice. The ball was dropped, fumbled, fallen upon, lost, regained, tossed and kicked. But it all served a purpose, and the coach and captain, with keen eyes, watched the different candidates. Now and then they gave a word of advice, cautioning some player about wrong movements, or suggesting a different method.

Phil had been put in as quarter-back on one scrub team, and Tom, as left-end, on the same. Phil found his opponent on the opposing eleven to be none other than Langridge’s friend, Gerhart. It did not need much of an eye to see that Gerhart did not know the game. He would have done well enough on a small eleven, but he had neither the ability nor the strength to last through a college contest.

Several times, when it was his rival’s turn to pass back the ball, Phil saw the inefficient work of Gerhart, but he said nothing. He felt that he was sure of his place on the ’varsity eleven, yet he[44] called to mind how Langridge had used his influence to keep Tom Parsons from pitching in the spring.

There was no denying that Langridge had influence with the sporting crowd, and it was possible that he might exert it in favor of his new chum and against Phil. But there was one comfort: Langridge was not as prominent in sports as he had been during the spring term, when he was manager of the baseball team. He had lost that position because of his failure to train and play properly, and, too, his uncle, who was his guardian, had insisted that he pay more attention to studies.

“After all, I don’t believe I have much to fear from him,” thought Phil. Then came a scrimmage, and he threw himself into the mass play to prevent the opposing eleven from gaining.

The practice lasted half an hour, and at the close Coach Lighton and Captain Cross walked off the field, talking earnestly.

“I wish I knew what they were saying,” spoke Phil, as he and Tom strolled toward the dressing-room.

“Oh, they’re saying you’re the best ever, Phil.”

“Nonsense! They’re probably discussing how they can induce you to play.”

“Well, how goes it?” called a voice, and they looked back to see Bricktop Molloy. He was[45] perspiring freely from the hard practice he had been through at tackle.

“Fine!” cried Tom. “We were just wondering if we would make the ’varsity.”

“Sure you will,” answered the genial Irish student, who was nothing if not encouraging. Perhaps it was because he was sure himself of playing on the first team that he was so confident.

“What did you think of Gerhart at quarter?” asked Tom, for the benefit of his chum.

“I didn’t notice him much,” answered Bricktop, as he ruffled his red hair. “Seemed to me to be a bit sloppy, though; and that won’t do.”

Phil did not say anything, but he looked relieved.

“Too bad you’re not going to play, Sid, old chap,” remarked Tom in the room that night, when the three chums were together. “You don’t know what you miss.”

“Oh, yes, I do,” was the answer, and Sid looked up from the depths of the chair, closing his Greek book. “The day has gone by when I want to have twenty-one husky lads trying to shove my backbone through my stomach. I don’t mind baseball, but I draw the line at posing as a candidate for a broken neck or a dislocated shoulder. Not any in mine, thank you.”

“You’re a namby-pamby milksop!” exclaimed Phil with a laugh and a pat on the back, that took[46] all the sting from the words. “Worse than that, you’re a——”

“Well, I don’t stick girls’ pictures, and banners worked in silk by the aforesaid damsels, all over the room,” and Sid looked with disapproval on an emblem which Tom had placed on the wall that day. It was a silk flag of Randall colors, which Madge Tyler had given to him.

“You’re a misguided, crusty, hard-shelled troglodytic specimen of a misogynist!” exclaimed Tom.

“Thanks, fair sir, for the compliment,” and Sid arose to bow elaborately.

Phil and Tom talked football until Sid begged them to cease, as he wanted to study, and, though it was hard work, they managed to do so. Soon they were poring over their books, and all that was heard in the room was the occasional rattle of paper, mingling with the ticking of the clock.

“Well, I’m done for to-night,” announced Sid, after an hour’s silence. “I’m going to get up early and bone away. Hand me that alarm clock, Tom, and I’ll set it for five.”

“Don’t!” begged Phil.

“Why not?”

“Because if you do it will go off about one o’clock in the morning. Set it at eleven, and by the law of averages it ought to go off at five. Try it and see. I never saw such a clock as that. It’s a most perverse specimen.”

Phil’s prediction proved, on trial, to be correct, so Sid set the clock at eleven, and went to bed, where, a little later, Tom and Phil followed.

There was more football practice the next afternoon, and also the following day. Tom was doing better than he expected, but his speed was not yet equal to the work that would be required of him.

“We need quick ends,” said the coach in talking to the candidates during a lull in practice. “You ends must get down the field like lightning on kicks, and we’re going to do a good deal of kicking this year.”

Tom felt that he would have to spend some extra time running, both on the gymnasium track and across country. His wind needed a little attention, and he was not a lad to favor himself. He wanted to be the best end on the team. He spoke to the coach about it, and was advised to run every chance he got.

“If you do, I can practically promise you a place on the eleven,” said Mr. Lighton.

“Who’s going to be quarter-back?” Tom could not help asking.

“I don’t know,” was the frank answer. “A few days ago I would have said Phil Clinton; but Gerhart, the new man, has been doing some excellent work recently. I’ll be able to tell in a few days.”

Somehow Tom felt a little apprehensive for Phil. He fancied he could see the hand of Langridge at work in favor of his freshman chum.

The matter was unexpectedly settled a few days later. There were two scrub teams lined up, Tom and Phil being on one, and Gerhart playing at quarter on the other. There had been some sharp practice, and a halt was called while the coach gave the men some instructions. As a signal was about to be given Phil went over to the coach, and, in a spirit of the utmost fairness, complained that the opposing center was continually offending in the matter of playing off side. Phil suggested that Mr. Lighton warn him quietly.

The coach nodded comprehendingly, and started to speak a word of caution. As he passed over to the opposing side, he saw Gerhart stooping to receive the ball.

“Gerhart,” he said, “I think you would improve if you would hold your arms a little closer to your body. Then the ball will come in contact with your hands and body at the same time, and there is less chance for a fumble. Here, I’ll show you.”

Now, when Mr. Lighton started he had no idea whatever of speaking to Gerhart. It was the center he had in mind, but he never missed a chance to coach a player. He came quite close to the quarter-back,[49] and was indicating the position he meant him to assume, when the coach suddenly started back.

“Gerhart, you’ve been smoking!” he exclaimed, and he sniffed the air suspiciously.

“I have not!” was the indignant answer.

“Don’t deny it,” was the retort of the coach. “I know the smell of cigarettes too well. You may go to the side lines. Shipman, you come in at quarter,” and he motioned to another player.

“Mr. Lighton,” began Gerhart, “I promise——”

“It’s too late to promise now,” was the answer the coach made. “At the beginning of practice I warned you all that if you broke training rules you couldn’t play. If you do it now, what will you do later on?”

“I assure you, I—er—I only took a few——”

“Shipman,” was all Mr. Lighton said, and then he spoke to the center.

Gerhart withdrew from the practice, and walked slowly from the gridiron. As he left the field he cast a black look at Phil, who, all unconscious of it, was waiting for the play to be resumed. But Tom saw it.

Fifteen minutes more marked the close of work for the day. As Tom and Phil were hurrying to the dressing-rooms, they were met by Langridge and Gerhart. The latter still had his football togs on.

“Clinton, why did you tell Lighton I had been smoking?” asked Gerhart in sharp tones.

“Tell him you had been smoking? Why, I didn’t know you had been.”

“Yes, you did. I saw you whispering to him, and then he came over and called me down.”

“You’re mistaken.”

“I am not! I saw you!”

Phil recollected that he had whispered to the coach. But he could not, in decency, tell what it was about.

“I never mentioned your name to the coach,” he said. “Nor did I speak of smoking.”

“I know better!” snapped Gerhart. “I saw you.”

“I can only repeat that I did not.”

“I say you did! You’re a——”

Phil’s face reddened. This insult, and from a freshman, was more than he could bear. He sprang at Gerhart with clenched fists, and would have knocked him down, only Tom clasped his friend’s arm.

“Not here! Not here!” he pleaded. “You can’t fight here, Phil!”

“Somewhere else, then!” exclaimed Phil. “He shan’t insult me like that!”

“Of course not,” spoke Tom soothingly, for he, too, resented the words and manner of the freshman. “Langridge, I’ll see you about this later if[51] you’re agreeable,” he added significantly, “and will act for your friend.”

“Of course,” said Tom’s former rival easily. “I guess my friend is willing,” and then the two cronies strolled off.

“Are you going to fight him?” asked Langridge of Gerhart, when they were beyond the hearing of Tom and Phil.

“Of course! I owe him something for being instrumental in getting me put out of the game.”

“Are you sure he did?”

“Certainly. Didn’t I see him sneak up to Lighton and put him wise to the fact that I’d taken a few whiffs? I only smoked half a cigarette in the dressing-room, but Clinton must have spied on me.”

“That’s what Parsons did on me, last term, and I got dumped for it. There isn’t much to this athletic business, anyway. I don’t see why you go in for it.”

“Well, I do, but I’m not going to stand for Clinton butting in the way he did. I wish he had come at me. You’d seen the prettiest fight you ever witnessed.”

“I don’t doubt it,” spoke Langridge dryly.

“What do you mean?” asked his crony, struck by some hidden meaning in the words.

“I mean that Clinton would just about have wiped up the field with you.”

“I’ll lay you ten to one he wouldn’t! I’ve taken boxing lessons from a professional,” and Gerhart seemed to swell up.

“Pooh! That’s nothing,” declared Langridge. “Phil Clinton has boxed with professionals, and beaten them, too. We had a little friendly mill here last term. It was on the quiet, so don’t say anything about it. Phil went up against a heavy hitter and knocked him out in four rounds.”

“He did?” and Gerhart spoke in a curiously quiet voice.

“Sure thing. I just mention this to show that you won’t have a very easy thing of it.”

There was silence between the two for several seconds. Then Gerhart asked:

“Do you think he wants me to apologize?”

“Would you?” asked his chum, and he looked sharply at him.

“Well, I’m not a fool. If he’s as good as you say he is, there’s no use in me having my face smashed just for fun. I think he gave me away, and nothing he can say will change it. Only I don’t mind saying to him that I was mistaken.”

“I think you’re sensible there,” was Langridge’s[54] comment. “It would be a one-sided fight. Shall I tell him you apologize?”

“Have you got to make it as bald as that? Can’t you say I was mistaken?”

“I don’t know. I’ll try. Clinton is one of those fellows who don’t believe in half-measures. You leave it to me. I’ll fix it up. I don’t want to see you knocked out so early in the term. Besides—well, never mind now.”

“What is it?” asked Gerhart quickly.

“Well, I was going to say we’d get square on him some other way.”

“That’s what we will!” came eagerly from the deposed quarter-back. “I counted on playing football this term, and he’s to blame if I can’t.”

“I wouldn’t be so sure about that,” came from Langridge. “I never knew Clinton to lie. Maybe what he says is true.”

“I don’t believe it. I think he informed on me, and I always will. Do you think there’s a chance for me to get back?”

“No. Lighton is too strict. It’s all up with you.”

“Then I’ll have my revenge on Phil Clinton, that’s all.”

“And I’ll help you,” added Langridge eagerly. “I haven’t any use for him and his crowd. He pushed me down stairs the other day, and I owe[55] him one for that. We’ll work together against him. What do you say?”

“It’s a go!” and they shook hands over the mean bargain.

“Then you’ll fix it up with him?” asked Gerhart after a pause.

“Yes, leave it to me.”

So that is how it was, that, a couple of hours later, Tom and Phil received a call from Langridge. He seemed quite at his ease, in spite of the feeling that existed between himself and the two chums.

“I suppose you know what I’ve come for,” he said easily.

“We can guess,” spoke Tom. “Take a seat,” and he motioned to the old sofa.

“No, thanks—not on that. It looks as if it would collapse. I don’t see why you fellows have such beastly furniture. It’s frowsy.”

“We value it for the associations,” said Phil simply. “If you don’t like it——”

“Oh, it’s all right, if you care for it. Every one to his notion, as the poet says. But I came on my friend Gerhart’s account. He says he was mistaken about you, Clinton.”

“Does that mean he apologizes?” asked Phil stiffly.

“Of course, you old fire-eater,” said Langridge, lighting a cigarette. “Is it satisfactory?”

“Yes; but tell him to be more careful in the future.”

“Oh, I guess he will be. He’s heard of your reputation,” and Langridge blew a ring of smoke toward the ceiling.

“I’ll take him on, if he thinks Phil is too much for him,” said Tom with a laugh.

“No, thanks; he’s satisfied, but it’s hard lines that he can’t play,” observed the bearer of the apology.

“That’s not my fault,” said Phil.

“No, I suppose not. Well, I’ll be going,” and, having filled the room with particularly pungent smoke, Langridge took his departure. If Tom and Phil could have seen him in the hall, a moment later, they would have observed him shaking his fist at the closed door.

“Whew!” cried Tom. “Open a window, Phil. It smells as if the place had been disinfected!”

“Worse! I wonder what sort of dope they put in those cigarettes? I like a good pipe or a cigar, but I’m blessed if I can go those coffin nails! Ah, that air smells good,” and he breathed in deep of the September air at the window.

Thus it was that there came about no fight between Phil and the “sporty freshman,” as he began to be called. There was some disappointment, among the students who liked a “mill,” but as[57] there were sure to be fights later in the term, they consoled themselves.

Meanwhile, the football practice went on. Candidates were being weeded out, and many were dropped. Gerhart made an unsuccessful attempt to regain his place at quarter, but the coach was firm; and though Langridge used all his influence, which was not small, it had no effect. Gerhart would not be allowed to play on the ’varsity (which was the goal of every candidate), though he was allowed to line up with the scrub.

“But I’ll get even with Clinton for this,” he said more than once to his crony, who eagerly assented.

Phil, meanwhile, was clinching his position at quarter, and was fast developing into a “rattling good player,” as Holly Cross said. Tom was not quite sure of his place at end, though he was improving, and ran mile after mile to better his wind and speed.

“You’re coming on,” said Coach Lighton enthusiastically. “I think you’ll do, Tom. Keep it up.”

There had been particularly hard practice one afternoon, and word went down the line for some kicking. The backs fell to it with vigor, and the pigskin was “booted” all over the field.

“Now for a good try at goal!” called the coach, as the ball was passed to Holly Cross, who was playing at full-back. He drew back his foot, and[58] his shoe made quite a dent in the side of the ball. But, as often occurs, the kick was not a success. The spheroid went to the side, sailing low, and out of bounds.

As it happened, Professor Emerson Tines, who had been dubbed “Pitchfork” the very first time the students heard his name, was crossing the field at that moment. He was looking at a book of Greek, and paying little attention to whither his steps led. The ball was coming with terrific speed directly at his back.

“Look out, professor!” yelled a score of voices.

Mr. Tines did look, but not in the right direction. He merely gazed ahead, and seeing nothing, and being totally oblivious to the football practice, he resumed his reading.

The next moment, with considerable speed, the pigskin struck him full in the back. It caught him just as he had lifted one foot to avoid a stone, and his balance was none too good. Down he went in a heap, his book flying off on a tangent.

“Wow!” exclaimed Holly Cross, who had been the innocent cause of the downfall. “I’ll be in for it now.”

“Keep mum, everybody, as to who did it,” proposed Phil. “The whole crowd will shoulder the blame.”

The players started on the run toward the professor, who still reclined in a sprawling attitude[59] on the ground. He was the least liked of all the faculty, yet the lads could do no less than go to his assistance.

“Maybe he’s hurt,” said Tom.

“He’s too tough for that,” was the opinion of Bricktop.

Before the crowd of players reached the prostrate teacher he had arisen. His face was first red and then pale by turns, so great was his rage. He looked at the dirt on his clothes, and then at his book, lying face downward some distance away.

“Young gentlemen!” he cried in his sternest voice. “Young gentlemen, I object to this! Most emphatically do I object! You have gone entirely too far! It is disgraceful! You shall hear further of this! You may all report to me in half an hour in my room! I most seriously object! It is disgraceful that such conduct should be allowed at any college! I shall speak to Dr. Churchill and enter a most strenuous objection! The idea!”

He replaced his glasses, which had fallen off, and accepted his book that Tom picked up.

“Don’t forget,” he added severely. “I shall expect you all to report to me in half an hour.”

At that moment Dr. Albertus Churchill, the aged and dignified head of the college, and Mr. Andrew Zane, a proctor, came strolling along.

“Ah! I shall report your disgraceful conduct to Dr. Churchill at once,” added Professor Tines,[60] as he walked toward the venerable, white-haired doctor. “I shall enter my strongest objection to the continuance of football here.”

There were blank looks on the faces of the players.

Evidently Dr. Churchill surmised that something unusual had occurred, for he changed his slow pace to a faster gait as he approached the football squad, in front of which stood Professor Tines, traces of anger still on his unpleasant face.

“Ah, young gentlemen, at football practice, I see,” remarked the doctor, smiling. “I trust there is the prospect of a good team, Mr. Lighton. I was very well pleased with the manner in which the baseball nine acquitted itself, and I trust that at the more strenuous sport the colors of Randall will not be trailed in the dust.”

“Not if I can help it, sir; nor the boys, either,” replied the coach.

“That’s right,” added Captain Holly Cross.

“I see you also take an interest in the sport,” went on Dr. Churchill to Professor Tines. “I am glad the members of the faculty lend their presence to sports. Nothing is so ennobling——”

“Sir,” cried Professor Tines, unable to contain himself any longer, “I have been grossly insulted[62] to-day. I wish to enter a most emphatic protest against the continuance of football at this college. But a moment ago, as I was crossing the field, reading this Greek volume, I was knocked over by the ball. I now formally demand that football be abolished.”

Dr. Churchill looked surprised.

“I want the guilty one punished,” went on Professor Tines. “Who kicked that ball at me?”

“Yes, young gentlemen, who did it?” repeated the proctor, for he thought it was time for him to take a hand. “I demand to know!”

“It wasn’t any one in particular, sir,” answered Coach Lighton, determined to defend his lads. “It was done on a new play we were trying, and it would be hard to say——”

“I think perhaps I had better investigate,” said Dr. Churchill. “Young gentlemen, kindly report at my study in half an hour.”

“If you please, sir,” spoke Phil Clinton, “Professor Tines asked us to call and see him.”

“Ah, I did not know that. Then I waive my right——”

“No, I waive mine,” interrupted the Latin teacher, and he smoothed out some of the pages in the Greek book.

“Perhaps we had better have them all up to my office,” proposed the proctor. “It is larger.”

“A good idea,” said the president of Randall.[63] “Gentlemen, you may report to the proctor in half an hour. I like to see the students indulge in sports, but when it comes to such rough play that the life of one of my teachers is endangered, it is time to call a halt.”

“His life wasn’t in any danger,” murmured Tom.

“Hush!” whispered the coach. “Leave it to me, and it will come out all right.”

“But if they abolish football!” exclaimed Phil. “That will be too much! We’ll revolt!”

“They’ll not abolish it. I’ll make some explanation.”

Dr. Churchill, Professor Tines, and the proctor moved away, leaving a very disconsolate group of football candidates on the gridiron.

“Do you suppose Pitchfork will prevail upon Moses to make us stop the game?” asked Jerry Jackson. “Moses,” as has been explained, being the students’ designation of Dr. Churchill.

“We’ll get up a counter protest to Pitchfork’s if they do,” added his brother, Joe Jackson.

“Hurrah for the Jersey twins!” exclaimed Tom. The two brothers, who looked so much alike that it was difficult to distinguish them, were from the “Garden State,” and thus had gained their nickname.

“Well, that sure was an unlucky kick of mine,” came from Holly Cross sorrowfully.

“Nonsense! You’re not to blame,” said Kindlings Woodhouse. “It might have happened to any of us. We’ll all hang together.”

“Or else we’ll hang separately, as one of the gifted signers of the Fourth of July proclamation put it,” added Ed Kerr. “Well, let’s go take our medicine like little soldiers.”

In somewhat dubious silence they filed up to the proctor’s office. It was an unusual sight to see the entire football squad thus in parade, and scores of students came from their rooms to look on.

Dr. Churchill and Professor Tines were on hand to conduct the investigation. The latter stated his case at some length, and reiterated his demand that football be abolished. In support of his contention he quoted statistics to show how dangerous the game was, how many had been killed at it, and how often innocent spectators, like himself, were sometimes hurt, though, he added, he would never willingly be a witness of such a brutal sport.

“Well, young gentlemen, what have you to say for yourselves?” asked Dr. Churchill, and Tom thought he could detect a twinkle in the president’s eye.

Then Coach Lighton, who was a wise young man, began a defense. He told what a fine game football was, how it brought out all that was best in a lad, and how sorry the entire squad was that any indignity had been put upon Professor Tines. He[65] was held in high esteem by all the students, Mr. Lighton said, which was true enough, though esteem and regard are very different.

Finally the coach, without having hinted in the least who had kicked the ball that knocked the professor down, offered, on behalf of the team, to present a written apology, signed by every member of the squad.

“I’m sure nothing can be more fair than that,” declared Dr. Churchill. “I admit that I should be sorry to see football abolished here, Professor Tines.”

Professor Tines had gained his point, however, and was satisfied. He had made himself very important, and had, as he supposed, vindicated his dignity. The apology was then and there drawn up by the proctor, and signed by the students.

“I must ask for one stipulation,” said the still indignant instructor. “I must insist that, hereafter, when I, or any other member of the faculty approaches, all indiscriminate knocking or kicking of balls cease until we have passed on. In this way all danger will be avoided.”

“We agree to that,” said Mr. Lighton quickly, and the incident was considered closed. But Professor Tines, if he had only known it, was the most disliked instructor in college from then on. He had been hated before, but now the venom was bitter against him.

“We’re well out of that,” remarked Tom to Phil, as they went to their room, having gotten rid of their football togs. “I wonder what fun Pitchfork has in life, anyhow?”

“Reading Latin and Greek, I guess. That reminds me, I must bone away a bit myself to-night. I guess Sid is in,” he added, as he heard some one moving about in the room.

They entered to find their chum standing on a chair, reaching up to one of the silken banners Tom had hung with such pride.

“Here, you old anchorite! What are you doing?” cried Phil.

“Why, I’m trying to make this room look decent,” said Sid. “You’ve got it so cluttered up that I can’t stand it! Isn’t it enough to have pictures stuck all over?”

“Here, you let that banner alone!” cried Tom, and he gave such a jerk to the chair on which Sid was standing that the objector to things artistic toppled to the floor with a resounding crash.

“I’ll punch your head!” he cried to Tom, who promptly ensconced himself behind the bed.

“Hurt yourself?” asked Phil innocently. “If you did it’s a judgment on you, misogynist that you are.”

“You dry up!” growled Sid, as he rubbed his shins.

Then, peace having finally been restored, they[67] all began studying, while waiting for the summons to supper. When the bell rang, Phil and Tom made a mad rush for the dining-room.

“Football practice gives you a fine appetite,” observed Phil.

“I didn’t know you fellows needed any inducement to make you eat,” spoke Sid.

“Neither we do,” said Tom. “But come on, Phil, if he gets there first there’ll be little left for us, in spite of his gentle words.”

“We’ll have harder work at practice to-morrow,” continued Phil as they sat down at the table. “It will be the first real line-up, and I’m anxious to see how I’ll do against Shipman.”

“He’s got Gerhart’s place for good, has he?” asked Tom.

“It looks so. Pass the butter, will you? Do you want it all?”

“Not in the least, bright-eyes. Here; have a prune.”

“Say, you fellows make me tired,” observed Sid.

“What’s the matter with you lately, old chap?” asked Tom. “You’re as grumpy as a bear with a sore nose. Has your girl gone back on you?”

“There you go again!” burst out Sid. “Always talking about girls! I declare, since those pictures and things are up in the room, you two have gone daffy! I’ll have ’em all down, first thing you know.”

“If you do, we’ll chuck you in the river,” promised Phil.

Thus, amid much good-natured banter, though to an outsider it might not sound so, the supper went on. There was more hazing that night, in which Phil and Tom had a share, but Sid would not come out, saying he had to study.

“Come on, Tom,” called Phil the next afternoon, “all out for the first real line-up of the season. I’m going to run the ’varsity against the scrub, and I want to see how I make out.”

“Has the ’varsity eleven all been picked out?” asked Tom anxiously.

“Practically so, though, of course, there will be changes.”

“I wonder if I——”

“You’re to go at left-end. Come on, and we’ll get our togs on.”

After a little preliminary practice the two teams were told to line-up for a short game of fifteen-minute halves. Coach Lighton named those who were to constitute a provisional ’varsity eleven, and, to his delight, Tom’s name was among the first named. Phil went to quarter, naturally, and several of Tom’s chums found themselves playing with him.

“Now try for quick, snappy work from the start,” was the advice of the coach. “Play as though you meant something, not as if you were[69] going on a fishing trip, and it didn’t matter when you got there.”

The ball was put into play. The ’varsity had it, and under the guidance of Phil Clinton, who gave his signals rapidly, the scrub was fairly pushed up the field, and a little later the ’varsity had scored a touchdown. Goal was kicked, and then the lads were ready for another tussle.

The scrub, by dint of extraordinary hard work, managed to keep the ball for a considerable time, making the necessary gains by rushes.

“We must hold ’em, fellows!” pleaded Phil, and Captain Holly Cross added his request to that end, in no uncertain words.

Shipman, the scrub quarter, passed the pigskin to his right half-back, and the latter hit the line hard. Phil Clinton, seeing an opening, dove in for a tackle. In some way there was a fumble, and Phil got the ball. The next instant Jerry Jackson, who was on the ’varsity, slipped and fell heavily on Phil’s right shoulder. The plucky quarter-back stifled a groan that came to his lips, and then, turning over on his back, stretched out white and still on the ground.