Title: Memoir of Rev. Joseph Badger

Author: E. G. Holland

Release date: August 29, 2012 [eBook #40609]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roberta Staehlin, Charlene Taylor, Josephine

Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

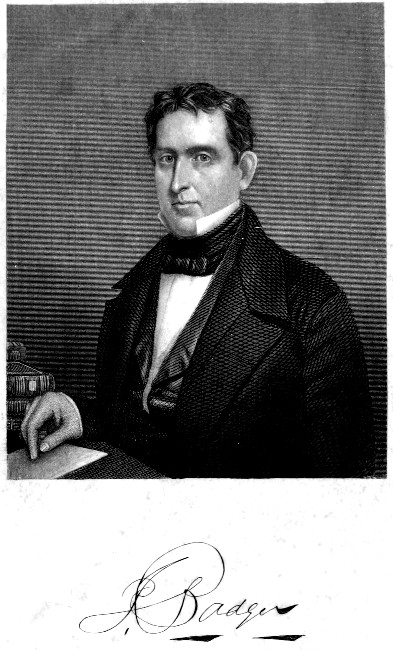

R. Badger

R. Badger

NEW YORK:

C. S. FRANCIS AND CO., 252 BROADWAY.

BOSTON: BENJAMIN H. GREENE, 124 WASHINGTON ST.

1854.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1853, by

MRS. ELIZA M. BADGER,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Western

District of New York.

DAMRELL & MOORE,

Printers,

16 Devonshire Street, Boston.

The present volume is the Memoir of a man and a minister whose character was strikingly individual, whose services to Religion in its more liberal and unsectarian form were large and successful; and in the denomination to which he belonged, no man was more generally known, and none, we believe, ever acted a more prominent and effective part. The writer of this has endeavored to set forth the life and sentiments of Mr. Badger, to a large extent in his own language. Much of his journal must be new even to old acquaintance, as it was written many years ago, and no part of it has ever been published. To those who would be pleased to read the outlines of the greatest theological reformation among the masses which the nineteenth century may justly claim, we trust this volume will be welcome; likewise to all those who may be liberal and evangelical Christians. Aged men, contemporaries with him, will rejoice in the revival of past scenes, and the young will be taught, encouraged, and warned by the paternal voices of the departed.

Two classes of great men figure effectively on the stage of the world. One class are strongest in writing.[Pg iv] Their written words embody the entire elegance and power of their minds. Such were Webster and Channing. The other class are strongest in speech. Their personal presence, their spontaneous eloquence in oral discourse, alone express their mind and heart. Such were Clay, Henry, and Whitfield. To the latter classification Mr. Badger unquestionably belongs. Though the marks of superiority are variously apparent in his papers, it was in the more natural medium of oral speech that his genius shone. Having now completed the task demanded by my duty to the family of Mr. Badger, I would, in the name of the self-sacrificing, trusting faith of which he was no common example, send forth this volume to the world, hoping that in an ease-loving age, the presentation of a Lutheran force in the example of a son of New Hampshire may serve to awaken in others a kindred energy.

Chapter I. Birth and Ancestry.

II. Childhood.

III. Youth and Education.

IV. Conversion.

V. Call to and Entrance upon the Ministry.

VI. Public Labors in the Province.

VII. Tour to New England, and Public Labors.

VIII. Ordination and Public Labors.

IX. Public Labors—Marriage—Travels.

X. Labors and Settlement in Western New York.

XI. Thoughts and Incidents of 1819 and 1820.

XII. Writings—Marriage—Travels.

XIII. Correspondence—Visits at Angelica with D. D. How, the Murderer—Sermon at the Gallows.

XIV. Journey at the South—Published Journal.

XV. Ministry at Boston.

XVII. Editorial Life.[Pg vi]

XVIII. General Views.

XIX. Ministry—Published Writings and Important Events from May, 1839, to March, 1848.

XX. Retired Life—Reading—Travels—Departure—1848 to 1852.

XXII. Addresses—Sermons—Reminiscences—Views of Contemporaries.[Pg 7]

XXIII. Reflections.

In so young a world as America, it has been held unsuitable for persons to spend much time in the tracing of pedigree, or to found important claims on family descent; nor can it accord less with the common sense of mankind than with the republican genius of the world, to say, that every genuine claim to human esteem is founded in character. In this is rooted every quality that can, of right, command the reverence of man. But, as character is not exactly isolated and independent of ancestral fountains, from which the innate impulses, capacity, and tendency to good and evil have flown, the subject of ancestry justly belongs to the history of every man's mind and life. Our ancestors flow in our veins. We retain them more or less in our characters always, so that the great stress which different countries have put upon this theme, rests on other than artificial and ostentatious reasons. In nature, below man, the various circuits and orders of[Pg 8] being do nothing more than to repeat ancestral forms and habits, to which the sweet rose, the eagle, and the strong-armed oak, are perpetual witnesses; and though man, by his God-like faculty of will is lifted out, in a great measure, from this necessity, he is so far a derivation from the past, that he ought to be seen in his connections with it. We therefore introduce the subject of Mr. Badger's ancestry as the chief part of the first chapter of this book.

Joseph Badger, the subject of this memoir, was a native of Gilmanton, Strafford county, New Hampshire, born August 16th, 1792. From an early manuscript of his I copy the following lines:—

"My father, Peaslee Badger, was born at Haverhill, Mass., 1756. He was the son of General Joseph Badger, who was a native of that place. When my father was nine years of age, his father removed to Gilmanton, N. H., where his family was settled, and where my grandsire, General Joseph, ended his days in peace, in the year of our Lord 1803. The good instruction I received from him, before my ninth year, will never be effaced from my memory. His name will long be held in remembrance as a peacemaker, and a great statesman. Every recollection of him is a fulfilment of the sacred passage—'The memory of the righteous is blessed.'

"In 1781, my father was married to Lydia Kelley, born in Lee, N. H., 1759. She was the daughter of Philip Kelley, who, in the triumphs of faith, departed this life the 11th of June, 1800, at New Hampton, N. H. For the space of thirty-six years my father resided at Gilmanton. In our family were nine children, five sons and four daughters. I was the fourth son, and the old[Pg 9] general, of whom I have already spoken, selected me as the one to bear up his name. I was accordingly named for him; but alas! I fear I have fallen greatly below his excellent examples."

Among his ancestors, there can be no doubt, that he most resembled, in mind and body, the venerable man whose name he bore. The personal form of Gen. Joseph Badger, as described in history, in which he is represented as nearly six feet in stature, somewhat corpulent, light and fair in complexion, and of dignified manners, answers most aptly to the subject of this memoir; nor is the correspondence less perfect, when his mental qualities of foresight, order, firmness, tact, and generosity are considered. "As a military man," says the faithful pen of history, "General Badger was commanding in his person, well skilled in the science of military tactics, expert as an officer, and courageous and faithful in the performance of every trust. With him order was law, rights were most sacred, and the discharge of duty was never to be neglected."

Hundreds, into whose hands this volume will fall, will never forget the promptness and the courageous efficiency with which Rev. Joseph Badger met every public duty, and every great emergency; and though his field was the ministry, and his soldierly skill that which referred to the Cross, none who ever knew him can cease to remember the ready, natural, and commanding generalship by which his entire action and influence in the world were distinguished. He did not float with the wave of circumstance, but carefully laid out his labors into system, always having a purpose and[Pg 10] a plan; and not unfrequently did his active energy and position in life, amidst many difficulties, remind one of a campaign. No mind, acting in the same sphere, was ever more productive in ways and means. Though a clergyman, he was a general, and one, we should say, of no common tact and skill.

His father, Major Peaslee Badger, with whom the writer of this memoir was acquainted, was a man of strong mental powers, quick perceptions, and of great vivacity. The quality last named, for which the subject of these biographical sketches was so generally distinguished, is readily traceable to his father; and the same remark in regard to quickness of perception might also apply, but for the fact that the mind of the son was more intuitive, and that he possessed both the qualities spoken of in a greater degree. Joseph Badger, though at heart deeply imbued with the solemnity and importance of all that belongs to the Gospel of human salvation, was no anchorite in spirit, no desponding meditator on man or his lot; he wore no formalities of a pretending sanctity. He had the good fortune never to have lost his naturalness; and I think I never saw one in whose nature was treasured a greater fulness of social life. It was apparent that Major Badger had a memory that was strong even in advanced years; that he was a general reader, and had reflected very independently; that, though capable of tender emotions and kindness of heart, the intellect had pretty full ascendency over his sympathetic nature; and that, in social feeling, in affection, in fineness of nature, and in general sympathy, his son possessed the richer inheritance.

His mother was a Christian, and judging from her letters, was an affectionate woman, of good plain sense, and rich in sympathy and maternal care. Father, mother and son are now in the spiritual world.[1]

As there are several public men wearing the family name of Badger, and as there are different branches of the same original family that in an early day exchanged their home in England for the then comparative wilderness of New Hampshire and Massachusetts, in obedience to the spirit of adventure that drew, in those times, the most earnest and enterprising persons to the New World, I have thought it proper briefly to present the lineage of Rev. Joseph Badger from the settlement of the first family of this name in Massachusetts; in doing which I shall not rely on uncertain tradition, but on the published history of Gilmanton, N. H., and on the Memoir of Hon. Joseph Badger, both of which are now before me. From these authorities it appears that the Badger family is of English origin, that its founder[Pg 12] was Giles Badger,[2] who settled at Newbury, Mass., previous to June 30, in 1643, only twenty-three years after the landing of the Pilgrims. His son, John Badger, a man of much respectability in his day, was by his first wife, the father of four children, only three of whom, John, Sarah and James, lived to arrive at years of responsibility, the first having died in infancy. His first wife, Elizabeth, died April 8th, 1669. By his second wife, Hannah Swett, to whom he was married February 23d, 1671, he had Stephen, Hannah, Nathaniel, Mary, Elizabeth, Ruth, Joseph, Daniel, Abigail and Lydia. Both of the parents died in 1691. John Badger, Jr., a merchant in Newbury, married Miss Rebecca Brown, October 5, 1691; their children were John, James, Elizabeth, Stephen, Joseph, Benjamin and Dorothy. Joseph was born in 1698.

Joseph Badger, son of John Badger, Jr., was a merchant, in Haverhill, Mass.,[3] and married Hannah, daughter of Col. Nathaniel Peaslee. Among his seven children was General Joseph Badger, whose usefulness and excellence of character are strongly expressed in the pages before me. He married Hannah Pearson, January 31st, 1740; their children were twelve in number, among whom was Major Peaslee Badger, the father of the subject of this memoir, and the Hon. Joseph Badger, Jr., the father of Hon. William Badger, late Governor of New Hampshire. Several of this name have been distinguished for ability, and have[Pg 13] held important positions of public duty. Some have been active in the defence of their country, some in the cause of education, the administration of justice, and the affairs of political life; and like the distinguished men of New Hampshire generally, they mostly seem to have had strong natures, with characters marked by native vigor and original force.

South of the White Mountains some fifty miles, and near the Lake and River Winnipiseogee, is the old town of Gilmanton. As the mind of Mr. Badger, during his childhood in this place, was lastingly impressed by the society and instruction of his uncle, I have thought best to copy the presentation of his character as found in the published history of Gilmanton.

"In the early settlement of Gilmanton," says Mr. Lancaster, "no individual was more distinguished than Gen. Joseph Badger. He was born in Haverhill, Mass., Jan. 11, 1722; and was the eldest child of Joseph Badger, a merchant in that place, who was one of the wealthiest and most influential men of that town. In the time of the Revolution, he was an active and efficient officer, was muster-master of the troops raised in this section of the State, and was employed in furnishing supplies for the army. He was a member of the Provincial Congress, and a member of the Convention that adopted the Constitution. He was appointed Brigadier General June 27th, 1780, and Judge of Probate for Strafford county, December 6th, 1784. He was also a member of the State Council in 1784, 1790, and 1791.

"He was a uniform friend and supporter of the institutions of learning and religion. He not only provided for the education of his own children by procuring private[Pg 14] teachers, but he also took a lively interest in the early establishment of common schools for the education of children generally. Not content with such efforts merely, he did much in founding and erecting the Academy in Gilmanton, which has been already a great blessing to the place and the vicinity. He was one of the most generous contributors to its funds, and was one of its Trustees, and the President of the Board of Trust until his death. Instructed in his childhood, by pious parents, in the principles of religion, he early appreciated the blessings of the Christian ministry. Having become the subject of divine grace, he publicly professed religion, and espoused the cause of Christ. As he was a generous supporter of the institutions of the Gospel, so to his hospitable mansion the ministers of religion always found a most hearty welcome. While the rich and great honored him, the poor held him in remembrance for his generous liberality. His whole life was marked by wisdom, prudence, integrity, firmness, and benevolence. Great consistency was manifested in all his deportment. He died April 4th, 1803, in the 82d year of his age—ripe in years, ripe in character and reputation, and ripe as a Christian. The text selected for his funeral sermon was strikingly characteristic of the man. 'And behold, there was a man named Joseph, a counsellor, and he was a good man and a just.'"

Rev. Joseph Badger had indeed a noble ancestry; and, in natural ability, in creative and executive intellect, in force of character and in general usefulness, he is probably unexcelled by the worthy examples that in past time may have shed honor upon the name. I[Pg 15] have dwelt thus long on the parentage and ancestry of Mr. B., not because I regard the tenacity of the Jewish race on the subject of lineage, nor the general excess of oriental homage to departed fathers, but because we appreciate the law of cause and effect, as it is manifested in the course of hereditary descent, which forbids that any man's written history shall begin like the priesthood of Melchizedek, successionless and without descent.

In approaching another chapter, the early life of Mr. Badger, perhaps nothing is more strikingly appropriate to the reader than the exclamation which stands as the first line of an old manuscript from his own pen, with which he begins his personal narrative, viz.: "What a mystery is Life!" Ah! who can wrestle with this wonder so as to exhaust it of its marvellousness? Who can explain the innate genius, and impulse, with the endless play of outward circumstance, that so constantly drive these human myriads on to their various destiny? Scribes can record what outwardly transpires; and even the reason can do nothing more than to look through the cluster of outward development we call man's history, to its centre in the inward life, where, though it may see the harmonious relationship of the facts to the soul whence they have flown; where, though it may perceive the combination of mental and moral qualities that make up the man, it is at last obliged to own the impenetrability of the veil that hides the genius that has taken individual form for some end of its own; and through the whole drama of man it owns that life is enacted in the temple of[Pg 16] mystery. Mr. Badger's written journal, among its opening paragraphs, has the following quotation:

The town of Gilmanton, which is only forty-five miles from Portsmouth, sixteen from Concord, and eighty from Boston, is, to a great extent, of rocky and hilly surface, having within its limits a chain of eminences that vary in height from three hundred to one thousand feet, called the Suncook Range, which commences at the northern extremity, near the Lake, and extending in a south-easterly direction through the town, divides the head-springs of the Suncook and the Soucook rivers. These fruitful highlands, covered in their early state with various kinds of hardwood, interspread with ever-welcome evergreens, have some commanding positions; especially the one called Peaked Hill, from whose summit the observer discovers within the area of his extended prospect the State House of[Pg 17] Concord, the Grand Monadnock,[4] in Jaffrey and Dublin, the Ascutney,[5] in Windsor, Vt., the Moosehillock, in Coventry,[6] Mount Major, the highest summit in the town of Gilmanton,[7] and Mount Washington,[8] which is the highest of the White Mountains. It was amidst scenery like this that the early unfolding of the mind of Joseph Badger occurred, where the spirit of beauty which everywhere finds mediums of influence and approach to man, found some romantic symbols of her presence, with which to impress the tender mind. Nature, which is everywhere the hundred-handed educator, is an agency not to be omitted even in speaking of childhood, for children see it from the heart and learn from it unconsciously. But entering the field of personal incident, let us listen to his own recorded memories.

"I cannot describe, as some have attempted to do, what transpired when only two or three years of age; but when four or five, I most distinctly remember going with my sisters on a visit to my grandsire's, Gen. Joseph Badger. It was but a few miles, and there being a school near, I consented through much persuasion to remain and attend it. The departure of my sisters was to me the severest trial I had known, one of whom however remained to comfort me. Here new and strange things, of which I had never before heard, presented themselves to my mind. At evening the family and servants were all called in. I was much surprised at the gathering, and inquired the cause. My sister told me that we were about to attend prayers. My young expectations were raised to see something new, as before this I had never[Pg 18] heard of anything of the kind. Whilst we were assembled, the old gentleman with the greatest solemnity leaning over his chair with his face to the wall prayed some time. I knew not what he said, nor to whom he spoke. His speaking with his eyes shut, and all the rest standing in profound silence, excited much anxiety in me for an explanation. As soon as this new scene had closed and we had retired, I remember having asked my sister to whom it was that my grandsire had been speaking. This to me was a mystery, as I saw no other standing by him. She told me that he spoke to God. I saw at once from her description that I was wholly ignorant of such a Being. She also told me that there was a place of happiness and misery, that all the good people went to heaven, and that the wicked must be burned up. I thought my sister Mary the happiest person in the world, because she knew so much about those great things; and young as I was, the story she told me filled my mind with solemnity; whilst the view she gave me of the certain doom of the wicked caused me to weep much, for I thought that I was one of that number. Impressions there made, and ideas there formed never wore off my mind.

"But another scene opened to my view, which also much surprised me. As there were several small children about the house, they were all called up at evening to say their prayers. They repeated the Lord's prayer, with some additions. This made my young heart tremble, as I thought they were all Christians, and I knew I never prayed in my life; and further, I knew not what to say. After all the rest had gone through their prayers, I was called up. My grandmother asked me if I ever prayed. I answered that I never did. She then told me to say the words after her, which I refused to do, from the feeling in my mind that the name of God was so holy and so[Pg 19] great that I could not speak that word. I wept aloud as she enjoined on me this practice, and was finally excused. I very much dreaded to have night come again. For several nights I was excused, and listened to the others; but finally she insisted on my praying, telling me plainly that I should be made to pray. That night she prepared a large whip and applied it to me severely several times before I would submit. At length I repeated the prayer, and from that time adopted the practice regularly. Through the influence of my sister, I was afterwards induced to thank my grandmother for the whipping, though I now think some milder measures had done as well."

In those stern Puritan days, the whip was far from being an idle instrument in teaching the rebellious young the fear of the Lord. Whatever was accepted as duty in religion, had no compromise with the diversity of taste and inclination in the families of the faithful. The reader, I think, will be unable to withhold his admiration from the naturalness of the question which the child asked in relation to whom it was that the praying man was speaking; and he will hardly fail to see the difference between his first religious devotions and the free appeal of ancient Scripture in saying, "Choose ye this day whom ye will serve," as the choice was made for him, and the rod was virtuous enough to see it enacted. He remained at this place about two years, making considerable proficiency in learning, and, as he thought, some in religion. Among these, his childhood's musings, was the wonder that he never heard his father pray, and why his brothers, who were older and of more understanding than himself, never talked about God. "It is still a great cause of[Pg 20] lamentation to me," said he in riper years, "that men of understanding dwell no more on the glories of the great Benefactor. In my opinion, a sense of religion should be early awakened, as first impressions are lasting, whether for good or for evil, and often appear in future years as the governing influence, as the foundation of future action. Ask the vilest man that whirls along in his career of evil, if he never thinks of the warnings, instructions and prayers of his fond parent in early days, and if he answers candidly he will say that they often arise to his condemnation. The destinies of different men are always teaching the worth of that holy wisdom which said, 'Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it.' In glancing back at the religion of my childhood, I find that I was unconsciously Pharisaical, and leaned on the virtue of my prayers and good works, although in the mixture there was a great degree of sincerity and of heartfelt repentance. Although I was wholly ignorant, probably, of the true love of God, I have always thought that, had I then departed this life, I should have been happy."

I have alluded to the fact that Major Peaslee Badger was not a pietist, and that in his family were no religious forms. At this time, and some years after, his mind, revolting from the ordinary theological teaching of the day, was inclined to a degree of general religious unbelief. The minds of the children were not softened and controlled by religious reverence, the absence of which is usually followed by a degree of rudeness in regard to all religious form. But, following the child Joseph to his own home, now that he[Pg 21] had learned to love the voice of prayer, we find him for a time determined in the way he had learned.

"On my return home," says he, "I missed my praying grandfather and his religious instructions, which had been frequent and impressive. I also missed my devoted grandmother, by whose side, as the silence of night came down, I had kneeled in prayer. Here I was lost, as our family had no form of religious worship, and their minds were on different subjects. For a long time I kept up my form of prayer, but at last, from two reasons, fell from my steadfastness, which were, that my school-mates none of them ever prayed, but made much fun of me for this practice; and my elder brothers, on knowing that I could pray, used to coax and hire me to do so, and then subject me to much laughter and derision for doing it. Here I left my religious exercise, which had served to keep my mind in a good moral state; and a reaction soon followed, that found me a noted swearer, using the most extravagant expressions that one of my age could easily command; a course in which I was encouraged by my father's hired men, who used to reward me with much praise and laughter. I well remember, when eight years old, of being in the company of several of Mr. Page's boys, who lived near my father's. Amidst my swearing, they, being very steady, began to rebuke me and to warn me of my danger. At first, I resisted their discourse, but the force of their arguments was such that I was compelled to yield. This restored me from my wicked habit, brought back my former feelings, and many a time did I think of it afterwards. It was also very remarkable that in 1815 I should preach in the same place and administer baptism to one of those young men. During this dark interval of which I have spoken, there were times in which I had solemn reflections; sickness[Pg 22] and death, when I heard of them, brought to my mind my former promise, and my thoughts always arose to my Creator whenever I heard the voice of thunder.

"When I was eight or nine years of age, I attended a singing-school, in which I made rapid progress in the art, sharing as I did, in common with our family, all of whom were natural singers, a passionate love of music. With this new employment I was greatly pleased. In the summer after I was nine, I remember going to the Friends' meeting. There was a small society in town, much despised by the popular. Their dress and manner were new to me. It was thought in those days a dreadful thing for a woman to speak in public; and this was the first time that I had ever listened to a female voice in meeting; and notwithstanding the prejudice through which education had taught me to view them, the persons who spake left on my mind the impression of their sincerity. Not far from this time, I went to the Congregational church to hear Mr. Smith. My father inquired, on my return, if I remembered the text, to which I replied in the negative. He then asked me if I could give him one word the minister had spoken, to which I responded that he said several times 'rambling wolves,' a part of the discourse that I could not have forgotten, as I had heard stories of wolves and was afraid of them. I inquired his meaning, when some of the family replied that he spoke of the Freewill Baptists, who he said went about like wolves, and much disturbed and deluded many good and honest people. The occasion of this assault, as I afterwards learned, was the great success which attended the preaching of Elder Kendall and other of Christ's ministers in Gilmanton and the adjoining town, where the happy effects of the Gospel were being seen and felt."

It is indeed an old story in history, that the powerful and established party in religion, medicine, science and politics becomes proscriptive toward the new and the weaker organizations, a fact which cannot be ascribed usually to the erroneousness of any one form of faith, so much as to the natural proclivity of human nature to lord it over the weak when put into possession of influence and power. Thus the persecuted parties turn persecutors as soon as they win the summit of command; and they who have tyrannized without a scruple, will at last plead for the sanctity of individual rights as soon as they are the subjects of the same oppression. But even these fierce winds of bigotry are able in some degree to purify. The young and proscribed sect gets humility and earnestness. A zeal and an enthusiasm also spring up that give them power over the hearts of men. They grow noble through their sacrifices and reliance on God.

"Not long after this several of the young people went to hear the Freewillers, as they were at that time styled. I accompanied them to the meeting, which was held in a private dwelling, in a retired neighborhood, and composed apparently of poor people. I thought they must be as bad as I had heard them represented. They prayed, they wept, they exhorted with much fervor and pathos, and notwithstanding I so much hated their manners, something reached my heart that robbed me for the time of all lightness and irreverence. Robinson Smith was the minister who spoke at this meeting, a strong, healthy man, of unusually clear and commanding voice. He spoke with power. Some of our company returned in solemnity of spirit, whilst others derided the scene we had witnessed.[Pg 24] Shortly after this, among my early reminiscences of Gilmanton, was a weekly conference, in which various persons spoke, offered prayers, and related their experience in things pertaining to religion—a meeting to which I was led sometimes from the examples of others, sometimes from curiosity, and sometimes from an inward desire to possess what Christians said they enjoyed. Thus was my early nature swayed by strong emotions, sometimes to good and sometimes to evil."

These pages, quoted from a private journal, written more than thirty years ago, nearly conclude all that pertains to his early life in Gilmanton. I have lingered thus long on these early years, because every man is indicated by his earliest development—certainly that part of him which may inhere in the natural character. It is true that man's latest period contains all his previous stages, somewhat as the earth we now inhabit contains the marks and proofs of all its previous states; yet, it is not given us to see the historical succession in man from a glance at the matured result. We follow the steps of nature, in whose procedure childhood and youth are not only illustrations of the substantial genius, temperament, and character, but are powerful causes in the performance of the remaining acts of life's drama. In these early years of Joseph Badger, a strong emotional nature is exhibited—a nature that could not be inactive—one that was easily reached by earnest moral and religious appeal, and one that overflowed in a wild excess of energy whenever the finer restraints of reverence were cast aside.

About this time, 1801, Major Peaslee Badger contemplated a change in his plans of life, the execution of which removed the subject of this memoir far away from the lovely waters and the romantic hills of his native town in New Hampshire. It also removed him from the various advantages of the better social influence and culture which belong to an older form of society; but it also rewarded him with the freedom, hardihood, and self-reliance of forest life.

Anxious to make farmers of his sons, Major Badger resolved to further this purpose by selling his farm in Gilmanton, and by making a more extensive purchase in a new country. At this early time, when emigration had not directed its course to the valley of the Mississippi, and when the attractions of Iowa and Minnesota lay sealed up for a future development, the mind of Mr. Badger was directed to the fertile woodland region of Lower Canada, which at that time was regarded as the best part of the world. To this region he accordingly made a journey, was much pleased with the country, and, after selling his farm in Gilmanton, which he sold for between four and five thousand dollars, he again visited this section of the king's dominions, in company with his eldest son, where he purchased eight hundred acres of the best [Pg 26]of land. Only a few families at this time resided in the town. Leaving his son and several hired men to wage the war of industrious labor on the primeval wilderness around them, he returned home, and recruiting himself with new forces, and taking with him all necessary farming utensils, with several yoke of oxen, hastened to join the company that were already at work in turning the wilderness into a fruitful field. When he had arrived within eighteen miles of his land, a wilderness of wide extent spread out before him. No road was visible. Sending some of his men forward as surveyors, and setting others to work in cutting a road through the woods, he continued slowly his progress; and, finally receiving some assistance from the inhabitants of the town of Stanstead, and augmenting his company with the addition of those who had been laboring on his farm, he went forward with the road with great courage and success, building several bridges across large streams, and conquering every obstacle in the way till an excellent road was completed through the whole distance to his farm. It has since become a highway of great travel, and is known by the name of the Badger Road to this day. This brave pioneer opened the way for the settlement of the town. Building a small cottage for temporary convenience, they prosecuted their work with zeal for several weeks, when they constructed a house for permanent residence, the best that had, at that time, been built in the town. These preparations being made, Major Badger returned to convey his family to their new abode, in the town of Compton, Lower Canada, for which place they set out in February, 1802, in eight sleighs, laden with provisions and furniture,[Pg 27] and after nineteen days of slow and expensive journeying, experiencing the alternations of good and evil fortune, they arrived on the 4th or 5th of March at their new home in the woods. Woman is ever the natural conservative, loving her established and long-tried home.

"My mother," says Mr. B., "was much opposed to the new arrangement, which caused her to leave her kind friends and neighbors; but such was her fortitude that none discovered her feelings. In taking leave of our native town and near relatives, the greatest solemnity filled my heart. Many wept at our departure, and I could scarcely bear up under the grief I felt in leaving the place of my birth. As we arrived at our new habitation, and my mother viewed her lonely palace, she could no longer suppress her feelings, but sat down and wept, whilst my sisters were also sad, and murmured somewhat at the new prospect before them. I wondered that my father should think of living in the midst of a forest, but thought that what others could accomplish, we could certainly do."

The contrast between the cheerful society and scenery of Gilmanton, and the solitude of this woodland region, which was swept by colder winds than the climate of the east had known; the isolation of the place, which required a journey of seventy miles to purchase the necessary grains for seed and family consumption, were calculated to awaken a deep feeling of loneliness, and at the same time to invigorate the spirit with new energy and promptings to personal efforts. But man's nature is flexible, and easily bends [Pg 28]to every variety of condition. As soon as the news of their arrival had spread, nearly all the inhabitants of the town came in to greet them in a friendly visit; and soon spring unfolded in all its gayety of woodland gem and costume, whilst all the company became laborers to the extent of their respective abilities. Joseph, now ten years of age, who had known nothing of work, learned his first lessons in the sugar groves of the new farm. Soon they became contented with their situation, and the woody solitudes gave cheering proofs of transition, as extended acres appeared to view, ready to bear the verdure of the meadow, or the harvests of golden grain. On each side of the Coatecook river lay four hundred acres; the eastern swell was called Mount Pleasant, the western, Mount Independence. Here, in a few years, they reaped a large prosperity from the productive earth. In the journal of Mr. B. I find a notice of the total eclipse in 1806, the effects that followed it on the agricultural prospects of that country, and the melancholy thoughtfulness which the day inspired in his own mind. The effect was great, according to his statement; so much so as to be sensibly felt through the seasons. Fourteen acres carefully planted with fruit-trees and grafted with the best of scions, yielded nothing to reward the toil of the laborer.

In the general picture here presented, the reader may see the theatre of action occupied by the young man who was destined in future years to impress great numbers with his own ideas and sentiments. Doubtless there are in the world some conventional minds, who, hastily deciding all things by local prejudice or capricious fashion, would hold it impossible for genius[Pg 29] and power to hail from any but certain favored localities; from college routine, and the aids of walls of books and of titled professors. But this is not the way in which the goddess of force and faculty distributes her gifts and makes her highest elections. She is by no means afraid of mountains and woodland solitudes; nor does she despair of winning her ends when professors and colleges do not wait upon her bidding. She exults rather in natural productions; being able to turn the night-stars, heaven's winds, earth's flowers, and even common events, into teachers; and the same of all experience and inward faculty. She brings a universal power from Stratford to London, from Ayreshire to Edinburgh, from Vosges and Domremi to Orleans and to Rheims. All great men are educated. The only variance resides in the modes and teachers. We like it that a prophet should, in early life, hail from the woodland world, and that the vastness and tranquillity of landscapes should reside in his public discourse; that his words and manners should savor, not of dry scholastic pretension and mannerism, but of songsters' voices, of colossal trees, wild rose and rushing brooks. Mr. B., however, for his time and day, was an educated man; we mean even in the more restricted sense in which the world understands this word; and certainly he was this, in its most important meanings.

"We soon had opportunity," says Mr. Badger, "for education in our new country. This was very pleasing to me, and I felt the necessity of improving every privilege of the kind." And I would say that those who knew him in after life could not but see in him the[Pg 30] rare faculty bestowed on some of our race, that of turning a few means to a great account.

Passing on to his fifteenth year, he speaks of a season of illness, occasioned by excessive ambition at manual labor, which kept him from school a part of the time during one summer. "My sickness," he says, "was of pleuritic nature, and at times my life was despaired of. A few Christian people had moved into the place, and during my sickness, some of them conversed with me on the subject of religion. At times I remember to have wept, and supposed that my condition was deplorable. The death of a Christian woman, who had often conversed with me, occurring at this time, made a deep impression on my mind. My reflections, when alone, were melancholy in the extreme. I often wished I had died when young; and frequently did I promise God that if my life was spared I would serve Him." Many paragraphs of this sort, whilst they may wear a tinge of the religious culture common to the age, show deep and unharmonized strivings of soul. To those who knew his great vivacity, the fact of melancholy, which he records in the journal of his youth, may seem strange; but it is natural. In susceptible and thoughtful natures, in natures of deep strivings, there is ever a stratum of seriousness, wearing at times the tinge of sadness. The soul, in such, will often say, "I am in Time an exile. The earth cannot feed me;" and especially will this feeling be active in the early experience, before the wisdom of years has given stability to life, to its aims and emotions.

But a young man like him could not be otherwise than fond of amusement. With young company of his age he frequently met, and was accustomed to spend considerable of the time when together in the favorite pastime of the young—the dance.

His elder brothers settling for themselves in life, threw an increased burden of care upon Joseph, whose health was so far restored as to act his part efficiently. His father about this time entered into the mercantile business, which turned out to his disadvantage; and soon after this, when seven miles from home, he had the misfortune to break his leg, suffering extremely for fifteen days, expecting constantly that amputation would have to take place. Recovering so far as to admit of removal home, after a long time he was restored to health. "After this," says his son, "he twice met the severe misfortune to break his leg, and on the 5th Sept., 1814, it was amputated six inches above the knee. This and several such misfortunes, in part, reduced him from the high station in which he was born and had formerly lived."

"The first preaching that we heard was by an old gentleman of the name of Huntington. He was a Universalist, a good man, I think, but not a great preacher. He addressed the people for the greater part of one summer generally at my father's house. I do not remember to have seen anything like reform among the people. The old gentleman died in a few years, and I trust has gone to rest. Also Elders[9] Robinson Smith and A. Moulton, of[Pg 32] Hatley, a neighboring town, favored us with their ministry. We called them Free-willers, but their preaching was life-awakening, and it was held in remembrance long after they were gone, although they saw no immediate fruits of their labors. I recollect of hearing Mr. Moulton once, the first time I think I ever saw him. His voice to me was like thunder. For several days after, it seemed as though I could hear the sound of it."

This indeed is the proof of God's presence in the mission, that the minister has that to say which the sinner cannot forget, that which lingers in his way like an invisible spell. The man who has God's word is not a mere lecturer or essayist in the holy temple. He has words of divine fire to speak, an undying love to utter, a warning of eternity to hold forth. He commands the giddy and the sinful to listen to a voice which, if he repent not, will tingle in his ears even to his dying day. Smooth, elegant composition may be patiently taught, and patiently learned, but God's living word out of heaven to unfaithful man, is another thing. This word has many organs, finds its way far and near, and reaches the heart of the ardent young man whose footsteps are on the classic ground, or in the larger path of nature's wild.

"When about sixteen or seventeen," continues the journal, "I heard that a young man about my age from Vermont would preach in our vicinity. There was a great move to hear him, and I resolved to go. The house was full. He was evidently one much engaged in God's work. He looked very pale and much worn out. Mr. Moulton was with him, prayed at the beginning of the meeting, after[Pg 33] which the young man, Benjamin Putnam, came forward, and in a manner and address that were engaging, and to me peculiarly pleasing, preached a sermon from Isaiah 22:22; a text which I shall never forget. 'And the key of the house of David will I lay upon his shoulder: so he shall open, and none shall shut; and he shall shut, and none shall open.' He described Christ as the Son of God, and the power as being laid upon his shoulder; he also dwelt on what he had opened both to and for man, which none could shut, and finally spoke of the closing of the same door, which none should be able to open. I thought this discourse more glorious than anything I had ever heard. I thought him the happiest young man I ever saw. As soon as meeting was closed he came forward through the assembly and spoke to my brother, which had a solemn effect on us both. Many of his expressions I have ever remembered.

"The Methodist ministers next made their way into our town, and I have always thought that they came in the name and spirit of the Highest. They were humble and earnest. As my father's family seldom attended their meetings, I perhaps did not become acquainted with the first that came. Hays and Briggs were the first I heard. While listening to the farewell sermon of the former I remember to have been deeply affected, and one evening, while listening to Mr. Briggs, I felt a strong conviction of my sin, and believed that I was undone without regeneration. They first formed a small class in town. Leaving the circuit the next year, Joseph Dennet and David Blanchard were their successors, under whose ministry many of the old and the young were turned to God, whilst even children were made happy in Christ. I think that the preaching of the latter was the first that ever brought [Pg 34]tears from my eyes. Also, in those days, we had frequent visits from the missionaries, but I do not remember that their preaching had much effect on my own mind or that of any other person.

"In the conflict of good and evil tendencies in the minds of young men who share largely of the passions and giddiness which characterize the period of one's youth, it is interesting to contemplate the skill with which these influences assail each other, each winning its temporary victory, and each wrestling at times with great might for the doubtful mastery. Notwithstanding these solemn emotions to good, I was quite wild and had several bad habits. In hearing Mr. H. preach the summer I was eighteen, I was much aroused to a sense of duty, and though seeing the way of my life to be death, my determinations as yet were not equal to the chain of habit that bound me. On the first of August I looked forward to the 16th, which was my birthday, as the day in which I should begin to walk in newness of life, and for several days this occupied my thoughts. But the time passed, and my resolution with it, whilst my feelings reacted more strongly than ever toward my former ways. The Spirit of God righteously strives with sinners; and many have I seen on languishing beds lamenting their early resistance to the holy influence, and that they had ever broken their promise to Him. I had a taste for reading, and spent much of my time in the perusal of novels and with vain young company. A young man by the name of Richardson was my most intimate friend. On the Sabbath and every other opportunity we were together; we spent the time mostly in reading; I thought I enjoyed happiness in his society. In our assemblies for diversion we ever had a good understanding. His friendship lasted until my conversion, when something far more glorious opened to my view. It appeared a great mystery to him, and it[Pg 35] caused me much sorrow to leave him, but the first lesson I learned from the cross taught me how to relinquish and how to renounce.

"In the autumn of 1810 we had many vain assemblies for dancing and other recreations. Never had I before gone so far in wickedness as at this time. But, in the midst of our gayety, events of Providence compelled our thoughts to serious objects, as death, through the agency of a fatal fever, spread over the town its sorrow and sadness, cutting off the old and the young indiscriminately. On the 10th of January, 1811, I commenced a journey to New Hampshire, to visit my friends, whom I had not seen since 1802. When I arrived at Stanstead, I passed several days with a cousin of mine who was engaged in teaching the art of dancing. He was an agreeable gentleman, and of great talents; but it was a grief to his friends that he had taken to this employment. I was much pleased with the instructions he gave me, as I was anxious to attain perfection in the art.

"With several young men I proceeded on my way to New Hampshire, and making the journey merry with rudeness and laughter, we prosecuted it till I arrived at Gilmanton. Here I found that my honored grandsire no longer occupied his place on earth. His companion, who had watched over my childhood for two years, and had made the voice of prayer familiar to my lips, still survived. Several other relatives had also gone to their long home, and though these things made little impression on my heart, owing to the state of my mind, I could not but solemnly reflect on the hand that had so long upheld me, when I visited my early home, the place of my birth, and recalled the many scenes of my childhood freshly to mind. We have in life but one childhood, and no hours of retrospect put us into such unison with nature as when we live it over in the revival of its scenes.

"I passed several weeks in Gilmanton, attending school a part of the time, and freely enjoyed the company of my young friends. My sister Mary, the wife of General Cogswell, occasionally rebuked me for my lightness, and though I made light of her admonitions at the time, they made much impression on my mind. But most of all I dreaded that my uncle, Mr. Smith, who had been the minister of the place for thirty years, should talk to me about religion. I was very loth to visit him at all, but I stayed with him the last night I remained in town, and to my happy disappointment escaped the drilling I had so much feared, as he did not once mention the subject. In company with my cousin, Joseph Smith, I set out the next day for home, and by evening arrived at Judge William Badger's, a cousin of mine, with whom we had an excellent visit. The next day, when passing through Meredith, we saw a young man standing in the door of a house with a multitude around him. The building appeared to be full of people, to whom he was preaching. We arrived that evening at Camptown, and though I was nearly sick and my spirits depressed by some influence I could not define, and my mind uninterested by surrounding objects, I yielded to the persuasion of my cousin to go on. Nothing was able to interest me. After some time we started for the place since so much celebrated, the Notch of the White Mountains.

"But nature, which to me was ever welcome, did not attract me as usual. A spirit, over which I had not control, seemed to work within me to the extreme of solemn conviction. People, road, trees, rivers—all seemed gloomy, and I appeared to myself as a monument spared to unite with them in mourning. We finally passed the gloomy Notch, and as I drank in its lonely influence, I felt, unavoidably, its likeness to the mood of my own spirit. At[Pg 37] Franconia, many new prospects and objects appeared to view. The manufactory of iron was at that time and there a great curiosity. At Littleton, further on in our journey, we rode on the river, as it was hardly frozen. I disguised my feelings, and as we were riding along, several in number, I fell in the rear that I might enjoy the meditations in which my mind was absorbed. At this time, an old gentleman, whose silver locks and grave appearance attracted my attention, appeared near me, coming from his house to the river to draw water. My eyes were fixed upon him. 'How far,' said he, 'is your company journeying?' To the province of Lower Canada, I answered. 'Do you live there?' said he. I answered that I did. Then in a solemn tone the old patriarch inquired, 'Is there any religion in that part of the world?' I was surprised to hear this subject introduced by a stranger. I told him there were some in our country who professed religion. He then burst into a flood of tears, and exhorted me with a warm-hearted pathos to seek salvation, and, though I disclosed none of my feelings to him, I was most deeply moved, and the image of the venerable old man was continually before my eyes through the day. I could scarcely refrain from weeping; and whatever others may think of such apparently accidental events, I am free to confess, that from that time until now, I have firmly believed that this old gentleman was a God-sent prophet unto me. The impressions he made continued till I enjoyed the sweet religion that inspired his look and his voice. I have often wished that I might see him and humble myself in thankfulness before him, a thing not to be expected in this life.

"When we arrived at Stewardstown, near the head of the Connecticut river, I parted with my cousin, whose destination was different from my own. Crossing the line,[Pg 38] I passed the night with Dr. Ladd, a friend of my father, who was a Christian and a man of extended knowledge. I treasured up many of his observations. I was then only twenty miles from home, and heard the sad news of the ravages sickness had made during my absence, which greatly disturbed me with the thought that I should never again see all my friends. On the 10th of March, however, I arrived, and though fearful to inquire for my relatives, found, to my joy, that they were all well. In company I sought to be cheerful, but in solitude the keenest sensations of sadness were active.

"Having business with my cousin at Stanstead, I made him a visit, where I heard a missionary preach and attended as a pall-bearer at a funeral, to which my feelings were much averse. On my return, when I had proceeded as far as Barnston, for some cause I returned a mile and a half, and taking a lantern started on foot through the woods, when suddenly a storm exhibited its signs of dark and angry violence. When about half through the forest, the winds, thunder and lightning were terrific. The rain fell in torrents, my light was soon extinguished, and nothing was left to guide me through the swamp except the lurid flashes of the lightning that made the gloom more terrible. Several trees were struck and fell near me across the road; some branches fell from the tree I had chosen for my shelter, as the tempest mingled with darkness, raged in madness; and never was I so deeply impressed with the might of Him who rules the world and sways the elements. Here I gained a fresh idea of the awful power and mercy of God. I was nearly induced to kneel upon the earth, and there, in the storm, make a covenant with my Maker.

"At length the storm ceased and I arrived in safety at the house of a friend. The next day I reached home, and[Pg 39] though met by cheerful faces, through the state of my mind, the music of their tones were as mournful sounds. The company in which I had found delight, could no longer entertain me; my home was dressed in mourning, my pillow wet with tears, and the bright prospects which had cheered me had vanished from my sky. I had no heart for business, no relish for pleasure. O how tiresome was every place! I read the Bible in private; often left my father's table in tears; often retired to the grove whose trees, more than those around me, seemed to know my heart, that I might relieve my soul in weeping. None knew the cause of this love of solitariness. Some said 'he suffers the influence of disappointment;' others, that 'he is plotting something for advantage:' none supposed that within me a deep striving was separating me from the world and leading me to the Fountain of Salvation. This period was a severe trial. Every power, it would seem, combined to test my spirit. Sometimes, from the conflict within, whilst darkness held its temporary victory, I was almost tempted to be angry with the Powers above, and with the whole creation; and once, I remember to have so far fallen under the evil power, as to swear at the existing order of things. It was continual trouble. I strove to labor what I could, and to fulfil my station in the family, using all the fortitude I could command. Here many things occurred that I shall not particularize; some things between my father and myself, which I once thought I should mention in every respect, but which the delicacy of the subject and the tenderness of our relation prevent. I can only say that my father was of deistical opinions, and at that time did not possess the degree of friendship and tenderness for the cause of religion which I could have wished him to, and which he indeed possessed some months after.

"At times, everything seemed to unite in tormenting me, in causing me trouble; again, all things in nature, when my clouds were partially dispersed, had a voice for the Creator's praise. I alone was untuned. The very winds, as they passed, spoke of His power. The stars, ever calm, looked down in love, seeming faithfully to perform the will of their Ordainer; and the flowers of the earth, which bloomed in beauty, sending forth their fragrance to His honor; and the songs of birds, whose notes were full of the primeval innocence, all combined to administer reproof. The following lines would then have spoken my feelings, as the full-blown spring-time lay unfolded around me:

"Leaving company almost entirely, and not going into society except on certain occasions, to please my friends or escape reproach, I gave myself up to solitary meditation and to the inward and undefined strivings of my being. In this state of spiritual disquietude, I felt no impulse to attend a church. I was most at home when alone. I heard divine voices where there was no man to act as medium or interpreter. At a funeral, I recollect having assisted in singing, and to have heard from Elder Moulton a sermon that impressed me, he being a man of considerable spiritual power, and one for whom I had particular respect. I heard him also a second time after this, when he most deeply affected my mind. I sometimes repaired to the forest for the express purpose of coming to God in prayer, but for some time was restrained from speaking aloud or kneeling on the earth. My heart was often eased in weeping; and though I had no form of prayer, I believe I prayed as really, as acceptably, as ever I did. Is it not a strange doctrine, so generally promulgated, that sinners, previous to conversion, ought not to pray? To me it is a dark doctrine. The Scriptures do not intimate it. My experience, the divine command, and common sense oppose the dogma. The fact that men are morally weak and sinful, is itself a sufficient occasion for prayer.

"One Sunday, without the knowledge of our family, I went about two miles to attend a Methodist meeting, in which several spoke, and spoke well. Mrs. John Gilson, a little, delicate woman, with much diffidence arose to[Pg 42] speak. Her wisdom and manner won my heart, and her message, which was particularly to me, seemed to carry the evidence that it was from God. I could never forget it. I knew she was my friend, and believed that she spoke for my good, and I would have rendered her my thanks at the close, but for the restraining power of a sentiment common to me, which was, an unwillingness to disclose to any one my deepest emotions. We had been taught by some, that before we could attain salvation, we should be willing to be damned and lost. I never had this willingness. But, in candor, I must say that my sense of guilt was so deep that I felt I had merited the sentence to be finally uttered against the impenitent."

The reader will perceive that the thread of this journal is drawn from such portions of Mr. Badger's early life as seem most directly to express its various moral phases. From other points of experience, it is natural to suppose, much was omitted, the main purpose being that of tracing the moral history of his mind through the years of his youth. I think I never opened a journal that contained throughout a plainer natural impress of truth and reality.

"Repent ye therefore and be converted, that your sins may be blotted out."—St. Peter.

To every work there is a crisis which openly exhibits success or failure. To every growth there are certain perceptible changes by which we note the progress from incipiency to the mature state. There is a symbolical new birth in nature when the rose-tree blooms, when leafless wintry trees are green with foliage and white with blossoms. Summer is a regeneration in the state of the earth, and it is none the less so because we cannot point out the moment, hour, or day, in which the actual summer assumed its effective reign. None fail to see the difference between June and January. If in July you meet the bending lilac, it silently tells you of all that March, April, May and June have done for it. So man's moral periods are marked. The soul in its struggles after divine life, through penitence and faith, reaches a crisis of victory and development of holy purpose, principle and power, which the church has generally agreed to call conversion, and for which we know no better name.

The journal of Mr. Badger, which refers to this epoch of his spiritual history, is headed with a poem on Christ, of which we have space for only a few lines:

In the religious experience of Joseph Badger, as intimated by this poem, Christ with him is always the central sun, the presiding power.

"I do not think," says Mr. B., "that persons can tell their religious experience, if their change is real and they have fully felt the effects of love divine. They are led to say with St. Peter, that it is 'joy unspeakable and full of glory.' Human language cannot describe the fulness and sweetness of the religion of Christ. Viewing the invisible depth of its wealth, how faint are our descriptions? How weak our best comparisons, and the metaphors by which we attempt to represent it! The soul which has become a partaker of the divine nature, of its love, is ever ready to exclaim—'The half had never been told me;' yet words, and other imperfect signs, will easily indicate the presence of the reality enjoyed.

"Eighteen hundred and eleven! that memorable year will never be forgotten by thousands now living, on account of the victorious spread of the Gospel in North America. Generations yet unborn will trace the pages[Pg 45] of ecclesiastical history with anxiety and delight, to learn what transpired among their ancestors during this year. But how soon, when a heavenly influence is in the ascendant, some counteracting power will enter the field with ruinous violence! The cruel war soon succeeded, and devastation spread her vermilion garb over our happy and enlightened land.

"As I have already alluded, in a former chapter, to the feelings of moral conviction that wrought in my breast, I will only say that they began with this year, and were of a kind neither to be drowned nor driven away. Not for Adam's sins, or the sins of our fathers, did I feel condemned; it was only for such as belonged to me. Light had come and I had chosen darkness. I therefore cast no reflections on any class of persons, as the Gospel, conscience, and the creation, seemed to unite in proclaiming—'Thou art the man;' and under a sense of my ingratitude to Jesus, the sinner's Friend, I felt to add my hearty Amen, and say, 'Father, I have sinned against heaven, and in thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called thy son.'"

In the pride of philosophical speculation, there are knowing ones who rob the rich idea of God of personality; also, in the attempts to deify the sacred parchments of Palestine, others unwittingly superannuate the Holy Ghost, driving us all to live solely upon ancient words—words that were undoubtedly its breathings when spoken. But one page from the journal of such an experience as that of Mr. Badger is better than all learned theory. Every page referring to his mind's exercise abounds in feeling—earnest, real feeling. He believes in the God of action, who converts the[Pg 46] repentant soul by his holy, actual agency; in Jesus he believes as the lone sinner's Friend and Saviour; in the Holy Spirit he confides, not doubting its real striving in his own heart; in the oracles of prophets, of Jesus, and of the apostles, he holds unwavering faith that they are God's real, eternal word; whilst his frequent and many tears in private attest his deep sincerity in seeking his soul's salvation. He recognizes the supernatural, the miraculous, in the conversion of the sinner; and whatever we may concede to the rationalistic statement on this subject in our severely philosophical moods, it is certain that the miraculous statement is the one which more than it concentrates the diviner charm and the more commanding energy. It has ever been so; the statement wearing the outward miraculous hue, is the strong one—the one that holds the element of triumph; and though we do not hold that any work of God with man violates the constitution and laws of the human mind, it would have struck us with diminished effect had St. Paul, before Agrippa, discoursed on the accordance of his conversion with some a priori argument for an abstract Christianity, or of its accordance with his own nature, and with all nature. This intellectualizing on great vital facts, whatever may be its philosophical merits, can never come up to the bold and picturesque sublimity of the words—"At mid-day, O king, I saw in the way a light from heaven, above the brightness of the sun, shining round about me; and I heard a voice speaking unto me and saying, Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?" Such passages reach the soul in every clime, as abstraction never could; and from the reverence we have been accustomed[Pg 47] to pay to universal convictions, and from the effect of such eloquence on our own feelings, we believe that mankind have not been fools in the cherishing of faith which brings Divinity into active and wonder-causing contact with humanity. If we have a God in our faith, let us have one who can do something, say something, and impart something to them who ask him, and not a tender abstraction who has no thunder for transgressors, and who is so lenient and plausible that no lawless spirit shall regard him as any essential obstruction in his way. Characters of most energy always grow up under the faith of God's omnipotence, of his awful majesty, beautified by justice and love.

The youth of this memoir looked around upon the dark world, and upward to the great God for his spirit's rest, and searched through the labyrinth of his own conflicting emotions to find a rock for his feet. Often his "eyes were rivers of waters;" and, "as I looked around for comfort, every place revealed some circumstance that gave to grief a keener edge." He is now so deeply touched by the Holy Spirit that nothing filled him with delight like the tender portraiture of the love of Christ; the profane word was now a loathed and jarring discord in his ear; the songs of the wicked deepened his sadness, and often did he repeat to himself, in tears, the well-known lines, "Alas! and did my Saviour bleed!" which he tells us had the power to penetrate his heart of hearts, whilst the most secret and hidden recesses of the wild witnessed his humble thank-offerings of praise and contrite confessions of sin. Without a minister to aid him, and without the sustaining sympathy of a single human creature, he continued[Pg 48] to wage his warfare with the powers of darkness. A young man, alone, with resolves and feelings unknown to man, longing for the clouds of his being to disperse, and for the influx of the immortal light to crown his life! This spectacle, however it may strike the mere formalist and the seeker of material good, is one which, to us, joins with myriads of heart-histories in different climes, to attest the derivation of the soul from God, to declare its yearnings and struggles against the obstacles of sin and sense, that it may regain the atmosphere and light of its native original heaven.

Contrary to the customs of his family, he went, once in a great while, to the Methodist meetings, a denomination whose power to reach the popular mind all over the world is known and honored. At one of these meetings, July, 1811, the persons present supposed, from his former reputation for rudeness, that he was there perhaps to criticise derisively their humble manner of worship. When Mrs. Tilden arose and said, "The eyes of the world are upon us, and if any came here to feast upon our failings, or to spy out our liberties, let us starve them to death, by living such lives that they can find no action of which to speak reproachfully"—after a few moments, he arose and said:

"I very much regret that any of my neighbors and friends should, for one moment, imagine me as an enemy, or suppose that I came here to ridicule what may pass before me. Far be it from my mind. I believe religion is what all men need to make them happy in time and eternity. With all my heart I wish you well and hope you will go on your way rejoicing."

This was the first time he had spoken in public, and though the object of his remark was merely to furnish a gentlemanly apology for being present, it caused the religious people much joy, as they saw him sit down in tears; and ever after his companions regarded him differently, all of whom were startled with surprise, and some wept as they heard his words.

"One of my young friends, a respectable young man, conversed with me on the subject. I stated to him all I had said, and in part I manifested my feelings to him with some degree of boldness. He expressed a fear that I would become deluded, though, by the way, he had never manifested a fear of the kind when we used to dance, play cards, and spend the Sabbath together in the reading of novels. 'About the things of religion,' said he, 'it is not well to be in haste. It is a subject which needs the greatest deliberation.' With this I agreed. He further remarked, 'If a person thinks of such things, it is not best to give expression to such thoughts, because people will talk about it, and you,' continued he, 'are already a subject of conversation. Many are concerned for you, and wish your society, and you know it is a disgrace for us to go among those foolish and ignorant Methodists.' By these remarks, coming from a particular friend, I was embarrassed, but soon learned that I must leave all, and part with my dearest companions for Christ; that two masters it was impossible to serve; and in my indecision I seemed to hear a voice as from heaven, saying, 'Choose ye this day whom ye will serve,' impressing my mind with the idea that then was the time for me to secure an interest in the Great Redeemer. Great things of eternity were continually resting on my mind; the saints, as they had opportunity, began to talk with me, of which I was glad,[Pg 50] though to them I did not say much, as I was resolved that others should not know my feelings; even if I were ever so happy as to feel my sins forgiven, I was determined not to say much about it to others, and certainly not to make such an ado over it as many did.

"I was in search for a great and sudden change. About August 1st, 1811, I felt impressed to retire and unbosom myself to the Eternal God, and cry once more for mercy. Walking through the woods to a large valley, I there, by a murmuring brook, fell on my knees and gave vent to my burdened heart in prayer. For a moment my soul felt delivered of all her griefs, and for a few moments I sung and praised God in that delightful place with all my heart; but doubts arose, and as I cast over the scene the eyes of reason, my little heaven vanished, and I remained in silence. I began to fear that I was walking by the light of imagination, and was warming myself by sparks of my own kindling.

"I began to be more familiar with the saints, sometimes revealing to them in part my determinations, and always gaining strength by so doing. I had not the same consciousness of sin as before. At times, before I was aware of it, my mind would be soaring above on heavenly things; the Scriptures would beautifully open to my mind, and glorious would seem the things of religion; yet I scarcely dared to rejoice. I derived much benefit and instruction from the conversation of the saints, and though I asked their prayers, I neither united with them in prayer, nor kneeled according to their custom. The narrated experience of others aided me some, and as all my Christian friends advised me to pray, I again kneeled in the solitude of nature to invoke divine aid, when the reflection that I was in the presence of an Omnipotent God sealed my lips in silence. Almost fearing that my performances were[Pg 51] but mockery, I felt inclined to despair. The next day gleams of hope entered my mind; and on Sunday, hearing many speak of the power of God, and of trials they had passed through, in a manner, some of them, that exactly expressed my feelings, I took courage, because there were others in whose Christianity I had confidence, who felt in some respects as I did. Moved, as I think, by the Spirit of God, and from a high state of mental resolve, I arose and told the assembly that I was determined to seek my happiness in religion, in which alone I believed it could be found. Many of the saints praised God aloud, and my soul was filled with joy and peace that were unspeakable. My love to the faithful was far superior to anything that ever before had dilated my heart. On my return home the very winds that waved the trees, and the streams that flowed through the quiet valley, seemed unitedly to speak my great Creator's praise. The fear of man now vanished, and a holy boldness moved me to speak to all around me of the beauties of my Lord. My soul overflowed with love to my greatest enemies, and my wonder was that the chief of sinners did not behold the glory of God, and unite to exalt his name. Through the night my soul was exceedingly happy, and the next morning I thought the sun was never before so richly laden with the glory of God. I had never known so happy, so pleasant a morning.

"Though I did not then suppose myself converted, I now think, from an analysis of my feelings, that I enjoyed something of the converting grace of God, for the following reasons:—1st. I had a witness in my own soul that God was my friend. 2d. I felt a vital union with all the saints, without respect to name, age, or color. I loved them, and could say, They are my people. Some who were poor and ignorant, whom I had formerly despised, I was able[Pg 52] to embrace as my best friends. 3d. I felt a particular regard for every creature and object God had made, and a tenderness even to the lowest animal forms—as nothing seemed unincluded in the bond of love that united me and all things to Him. 4th. For the chief of sinners I felt particular love, regarding such as brethren in nature, and I greatly wished them to share in the peaceful wealth of the Gospel. 5th. My former ways in which I had sought happiness, now seemed to me as worthless and vain. Indeed I abhorred them.

"My freedom from the former oppressive gloom, the fulness of the tide of joy that was rising in my breast, at times startled me with the apprehension that as I was not converted I ought not to feel so light and so free, and my embarrassment was increased by the circulation of the report among the people that I was converted. They began to call me brother, which also seemed quite too much for me; and as I could not feel that I had experienced the change as usually described, I began to fear that I was deceived, which caused me much trouble and induced me to be silent for some time, as I was unwilling to discourage or to deceive others. Although I never had so much confidence in dreams as some, yet at this time the glory of God was beautifully revealed to me in night visions, and through them my mind was relieved of many doubts and fears, and again partook of the inward peace which the world in its greatest ability is unable to give. For several weeks, however, I kept my joys to myself, saying nothing in meeting and little in private, as I was determined not to deceive others, as I might in case my joys should prove unreal. Employing myself constantly in reading the Scriptures, that I might walk understandingly, my mind for several weeks was swallowed up in the interest their pages revealed, which unfolded a glory and beauty I cannot[Pg 53] describe. In my retired moments, I held sweet communion with God, and, notwithstanding the shadows of doubt that crossed my mind in solitude, I was truly led from glory to glory.

"I heard others tell the day and the hour when the change was wrought in their hearts. Herein was my greatest trouble. My experience was not like others, nor indeed what I supposed it would be. I knew of several times when my mind was relieved of all its oppressions, but as I could single out no one of them and call it conversion, I concluded that the whole together was conversion. Though continually thirsting for new evidence, for which I was much drawn out in prayer, and selecting the most retired places for holy meditation, I pondered, like Mary, these things in my heart. Some conversations about this time, proved beneficial to me; especially was my soul refreshed by the dreams and night visions that came to me, making it seem ofttimes as though angels were hovering over my bed, and my apartment as filled with the divine glory. I was many times ready to say, I know that my Redeemer liveth."