Title: Paris Vistas

Author: Helen Davenport Gibbons

Illustrator: Lester G. Hornby

Release date: July 21, 2012 [eBook #40292]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

PARIS VISTAS

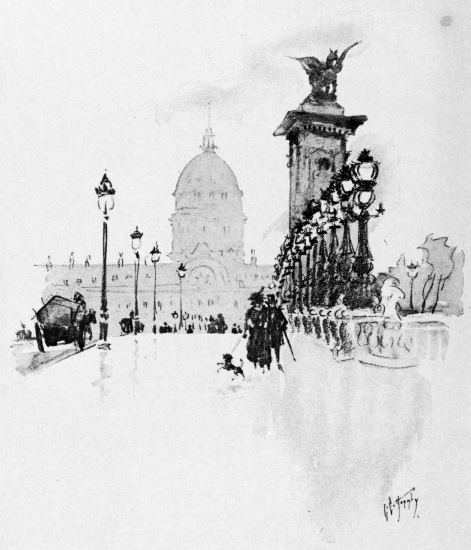

The Invalides from Pont Alexandre III

BY

HELEN DAVENPORT GIBBONS

Author of "A Little Gray Home in France,"

"Red Rugs of Tarsus," etc.

WITH SIXTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS

BY

LESTER GEORGE HORNBY

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1919

Copyright, 1919, by

THE CENTURY CO.

———

Published, December, 1919

TO

A CRITIC

WHO LIVED MOST

OF THESE DAYS

WITH ME

Webster defines a vista as "a view, especially a distant view, through or between intervening objects." If I were literal-minded, I suppose I should either abandon my title or make this book a series of descriptions of Sacré Coeur, crowning Montmartre, as you see the church from dark gray to ghostly white, according to the day, at the end of apartment-house-lined streets from the allée of the Observatoire, from the Avenue Montaigne, from the rue de Solférino, and from the Rue Taitbout. I ought to be writing about the vistas, than which no other city possesses a more beautiful and varied array, that feature the Arc de Triomphe, the Trocadéro, the Tour Eiffel, the Grande Roue, the Invalides, the Palais Bourbon, the Madeleine, the Opéra, Saint-Augustin, Val de Grâce and the Panthéon.

But may not one's vistas be memories, with the years acting as "intervening objects"? Has not distance as much to do with time as with space? Vistas in words can no more convey the impression of things seen than Lester Hornby's sketches. If you want a substitute for Baedeker, please do not read this book! If you want a substitute for photographs, you will be disappointed in Lester's sketches.

The monuments of Paris, ticketed by name and historical events to tourists whose eyes have had hardly more time than the camera, known by photographs to prospective tourists who dream of things as yet unseen, are interwoven into the canvas of my life. The Gare Saint-Lazaire, for instance, is the place where I was lost once as a kid, where I have had to say goodbye to my husband starting on a long and perilous journey, and over which I have seen a Zeppelin floating. Since Louis Philippe was long before my time, the obelisk always has been in the Place de la Concorde. And when you pass it, your eyes, meeting the Arc de Triomphe at the end of the Champs-Elysées, the Carrousel at the end of the Tuileries, the Madeleine at the end of the Rue Royale and the Palais Bourbon at the end of the bridge, record vistas as natural, as familiar as your mother's face in the doorway of the childhood home. Where else could the Arc de Triomphe be? Of course it looks like that!

I shall not attempt to apologize for the autobiography that comes to the front in my Paris vistas. Perhaps my own insignificance and unimportance and the lack of interest on the part of the public in what I do and think—impressed upon me by more than one critic of earlier volumes—should deter me from telling how I lived and brought up my family in Paris. But it is the only way I can tell how I feel about Paris. Whether the end justifies the means the reader must decide for himself.

H. D. G.

Paris, August, 1919.

| (1887-1888) | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Childhood Vistas | 3 |

| (1899) | ||

| II | At Sixteen | 15 |

| (1908) | ||

| III | A Honeymoon Promise | 31 |

| (1909-1910) | ||

| IV | The Promise Fulfilled | 41 |

| V | The Pension in the Rue Madame | 51 |

| VI | Lares and Penates in the Rue Servandoni | 63 |

| VII | Gold in the Chimney | 76 |

| VIII | At the Bibliothèque Nationale | 86 |

| IX | Emilie in Monologue | 97 |

| X | Hunting Apaches | 104 |

| XI | Driftwood | 112 |

| XII | Some of Our Guests | 119 |

| XIII | Walks at Nightfall | 132 |

| XIV | After-dinner Coffee | 142 |

| XV | Repos Hebdomadaire | 148 |

| XVI | "Many Waters Cannot Quench Love" | 154 |

| XVII | Real Paris Shows | 167 |

| XVIII | The Spell of June | 181 |

| (1913) | ||

| XIX | Childhood Vistas for a New Generation | 193 |

| XX | The Problem of Housing | 201 |

| (1914) | ||

| XXI | "Nach Paris!" | 211 |

| (1914-1915) | ||

| XXII | At Home in the Whirlwind | 223 |

| XXIII | Sauvons Les Bébés | 231 |

| XXIV | Uncomfortable Neutrality | 243 |

| (1917) | ||

| XXV | How We Kept Warm | 253 |

| XXVI | April Sixth | 262 |

| XXVII | The Vanguard of the A. E. F. | 269 |

| (1918) | ||

| XXVIII | The Darkest Days | 277 |

| XXIX | The Gothas and Big Bertha | 294 |

| XXX | The Bird Charmer of the Tuileries | 307 |

| XXXI | The Quatorze of Testing | 313 |

| XXXII | The Liberation of Lille | 321 |

| XXXIII | Armistice Night | 326 |

| XXXIV | Royal Visitors | 341 |

| XXXV | The First Peace Christmas | 348 |

| (1919) | ||

| XXXVI | Plotting Peace | 361 |

| XXXVII | La Vie Chère | 373 |

| XXXVIII | The Revenge of Versailles | 378 |

| XXXIX | The Quatorze of Victory | 385 |

| The Invalides from Pont Alexandre III | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| The Madeleine Flower Market | 16 |

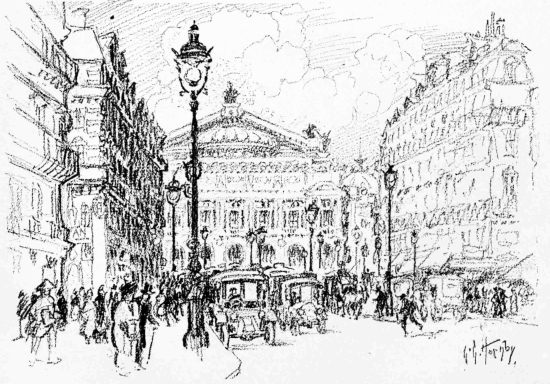

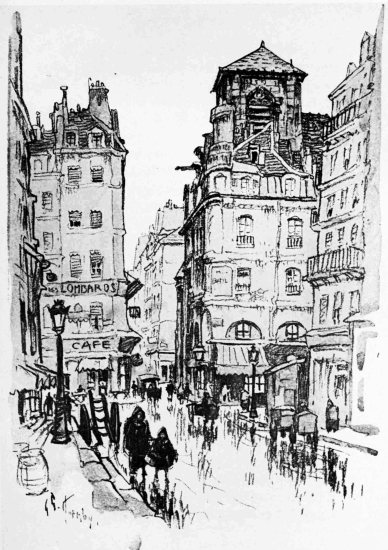

| Looking up the Avenue de l'Opéra | 32 |

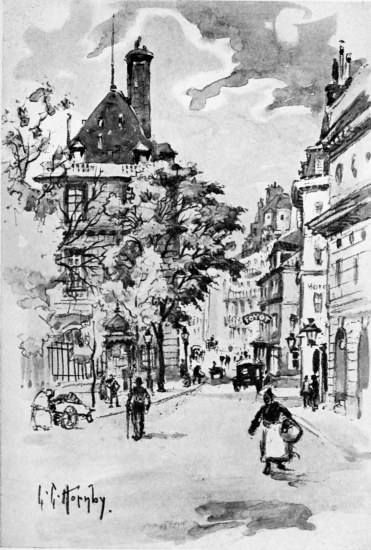

| The Rue de Vaugirard by the Luxembourg | 64 |

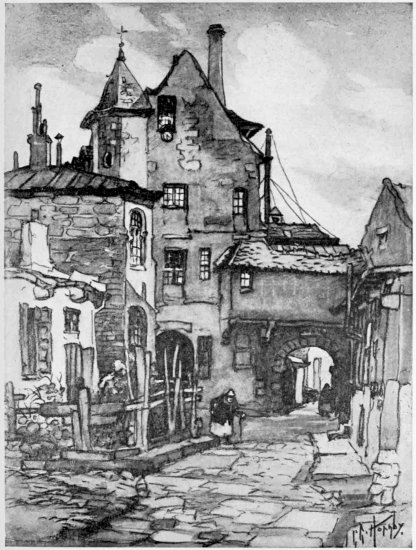

| Château de la Reine Blanche: Rue des Gobelins | 88 |

| Where stood the walls of old Lutetia | 120 |

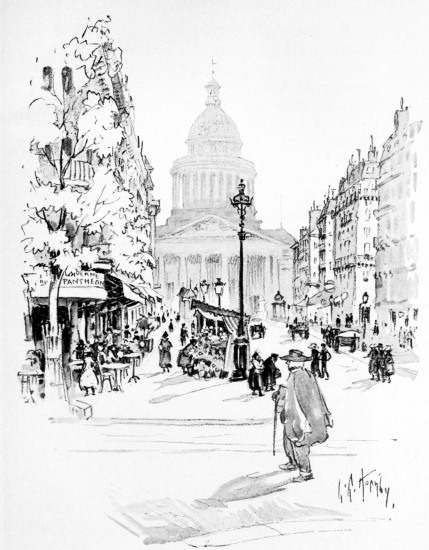

| The Panthéon from the Rue Soufflot | 144 |

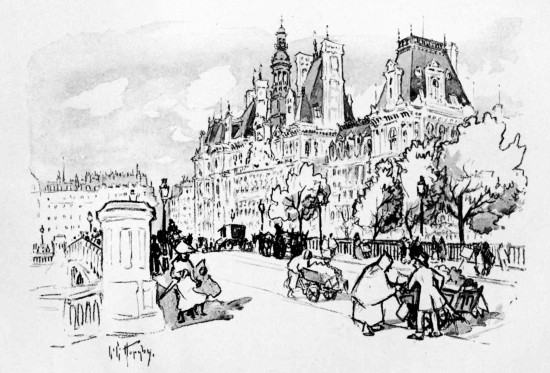

| Hôtel de Ville from the Pont d'Arcole | 168 |

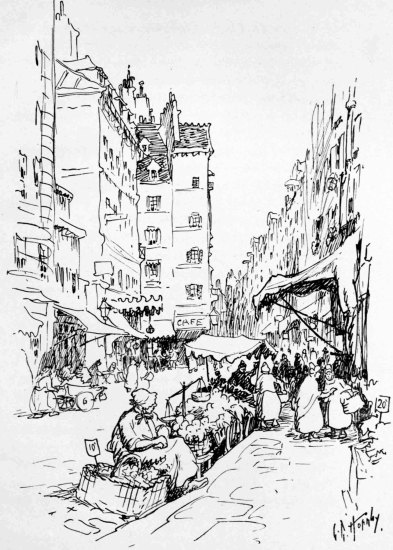

| Market day in the Rue de Seine | 184 |

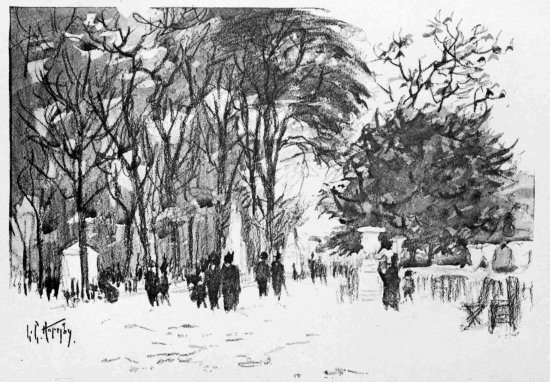

| The first snow in the Luxembourg | 224 |

| A passage through the Louvre | 256 |

| In an Old Quarter | 272 |

| Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois | 304 |

| Old Paris is disappearing | 320 |

| The Grand Palais | 336 |

| Spire of the Saint-Chapelle from the Place Saint-Michel | 368 |

MY Scotch-Irish grandfather was a Covenanter. He kept his whisky in a high cupboard under lock and key. If any of his children were around when he took his night-cap, he would admonish them against the use of alcohol. When he read in the Bible about Babylon, he thought of Paris. To Grandpa all "foreign places" were pretty bad. But Paris? His children would never go there. The Scotch-Irish are awful about wills. But life goes so by opposites that when my third baby, born in Paris a year before the war, was christened in the Avenue de l'Alma Church, Grandpa Brown's children and grandchildren and some of his great-grandchildren were present. My bachelor uncle had been living in Paris most of the time for thirty years. My mother, my brothers, and my sister were there. We Browns had become Babylonians. We were no longer Covenanters. And we had no high cupboard for the whisky.

After Grandpa's death, the Philadelphia house was sublet for a year. In the twilight we went through all the rooms to say good-by. Jocko, our monkey-doll, was on the sitting-room floor. Papa picked him up and began talking to him. Jocko tried to answer, but his voice was shaky, and he hadn't much to say. Papa took a piece of string out of his desk drawer, and tied it around Jocko's neck. He asked Jocko whether it was too tight. The monkey answered, "No, sir." Jocko never forgot to say "sir." We hung him on the shutter of a window in the west room where I learned to watch the sunset. There we left him. What a parting if we had known that the tenants' children were going to do for Jocko, and that we should never see him again! It was bad enough as it was. It is hard for me, even to-day, to believe that it was Papa and not Jocko who told us stories about the fairies in Ireland.

A carriage drove us to a place called Thelafayette-hotel. It was very dark outside and we seemed to have been traveling all night. Papa carried me upstairs to a room that had light green folding doors. My little sister Emily was sound asleep and had to be put right to bed. Papa sat me in a red arm-chair. Beside it were satchels and Papa's black valise. Wide awake, I looked around and asked, "Is this Paris?" I did not see why they had to laugh at me.

A steward of my very own on the Etruria told me that she was the biggest transatlantic liner. People gave me chocolates until I was sick. So Mama painted a picture of the poor little fishes that could get no candy in mid-ocean. She made me feel so sorry that when I got more chocolates I would slip to the railing and drop them overboard. Once, before I had heard about the fishes, I was lying in my berth. After a while I began to feel better and to wish that Papa and Mama had not left me alone. My feelings were hurt because I had to stay all by myself. I found my clothes and put on a good many of them. My steward came and was surprised that I was not on deck. He brought me a wide, thin glass of champagne. It was better than lemonade. The steward told me that by staying in my cabin I had missed the chance to see the ship's garden. He buttoned my dress and put on my coat. He found my bonnet. All the time he was telling me how the ship's garden was hitched to the deck. He carried me up those rubber-topped steps that smell so when your stomach feels funny. He hurried all he could and got terribly out of breath. But we did not reach the deck in time to see the garden. The steward said that you had to get there just at a certain time to catch it. I wondered how a ship could have a garden. He replied that he'd like to know where a ship's cook would find vegetables and fruit, and how there were so many freshly picked flowers on the dining-room table every day, if the ship hadn't a garden. To prove it he brought me a plate of cool white grapes—"picked before the garden went out of sight a few minutes ago," he assured me.

So the week at sea passed, and the next thing I remember is London. It was not a pretty city. Too much rain and smoke that dirtied your frock and pinafore. These funny names for my dress and apron, and calling a clock Big Ben, and a queer way of speaking English, form my earliest memories of London. No, I forgot sources of wonderment. The best orange marmalade was bitter, and the tooth-powder was in a round tin hard to open, that spilled and wasted a lot when you did succeed in prying the lid off.

And in Paris I found that my dress was a "robe" and my apron a "tab-lee-ay." This was worse than "pinafore," but not so astonishing, because one expected French words to be different.

Which is the greater joy and satisfaction—always to have had a thing, or, when you think of something in your life, to be able to remember how and when it came into your possession? Paris is my home city in the sense that I cannot remember first impressions of things in Paris. Of events, yes, and sometimes connected with things, but of things themselves, no. And I am glad of it. My husband did not see Paris until he was twenty, and he learned to speak French by hard work. I have always had a little feeling of superiority here, of belonging to Paris as my children belong to Paris. But Herbert contests this point of view. He claims that affection for what one adopts by an act of the will is as strong as, if not stronger than, affection for what is yours unwittingly. And he advances in refutation of what I say that he knew Paris before he knew me!

"Cinquante-deux Rue Galilée." I cannot remember learning to speak French. That just came. But standing on a trunk in the corner of a bedroom and repeating Cinquante-deux Rue Galilée after Marie is just as clear in my mind as if it were yesterday instead of thirty years ago. It is a blank to me how and when we came to Paris and how and when we got Marie Guyon for our nurse. I recall only learning the number and street of our pension, and the impressiveness of Marie telling me how little kids get lost in Paris and that in such a case I mustn't cry when the blue-coated agent came along, but simply say, "Cinquante-deux Rue Galilée."

Clear days were rare—days when it didn't look as if it were going to rain. Then I would have my long walk with Papa, who didn't stay like Marie on the Champs-Elysées or in the Tuileries, but who would take me (Emily was too little) where there were crowds. We would climb to the roof of the omnibus at the Madeleine and ride to the Place de la République. Then we would walk back along the Grands Boulevards. Down that way is a big clothing-store with sample suits on wooden models out on the side-walk. One day Papa bumped into a dummy wearing a dress-suit. Papa took off his hat, bowed, and said "Pardon." I thought Papa believed it was a real man. So I told him that he had made a mistake. But Papa replied that one never makes a mistake in being polite. I used to dance with glee when we came to the Porte Saint-Denis. For there, at the place the boulevard now cuts straight through a hill leaving the houses high above the pavement, the pastry and brioche and waffle stands were sure of my patronage. Papa may not have had regard for my digestion, but he always considered my feelings. I used to pity other little children who were dragged remorselessly past the potent appeal to eye and nose. The pastry places are still there on that corner. And a new generation of kiddies passes, tugging, remonstrating, sometimes crying. As for me, I beg the question. I walk my children on the other side of the street.

One afternoon Marie took us to buy Papa's newspaper. When we got to the front door, it was raining. So Marie left us in the bureau and told us to wait until she returned. But the valet de chambre came along with his wood-basket empty. He always boasted he could carry any basket of wood, no matter how high they piled it. So we asked if he could carry us. Immediately he made us jump in, and told us we must pretend to be good little kittens, and little kittens were never good unless they were quiet, and they were never quiet unless they were asleep. When we got to our room, we could look right in at Papa and Mama through the transom. We reached out and knocked. The sound came from so high up that Papa looked curiously at the door. When he opened it we ducked down into the basket, and were not seen until the valet dumped us out on the bed.

My first memory of a negro was in Paris. Probably they were common enough in Philadelphia not to have made an impression and I had forgotten that there were black men. I was paralyzed with fear, thinking I saw Croqueminot en chair et en os. Marie saved me by teaching me on the spot to stick out my index and little fingers, doubling over the two between. This charm against evil helped and comforted me greatly. I found it useful later when I saw suspicious-looking beggars in Rome. Only, although the gesture was the same, it was jettatura and not faire les cornes in Italy, and the charm was more efficacious if concealed. I was glad my dress had a pocket.

Mama and Marie took us to the Louvre. I was filled with anticipation. For had I not heard some one say at our pension that she had bought things there for a song? Why spend Papa's money if just a song would do? I could sing. Marie had taught me a pretty song about "La Fauvette." I was willing to sing if I could get a doll's trunk. I'd sing two or three songs for a pair of gloves with white fur on them. But when I sang "La Fauvette" they only smiled at me. I asked the saleslady to take me to the toy counter, as I could sing again for things I wanted. I had to explain a whole lot to Mama and Marie and the saleslady. I suppose I cried with disappointment. Then a man in black with a white tie came along and heard the story. He gave me a red balloon and Mama consoled me by buying me a blue velvet dress.

A few months before the war I was walking in the Rue Saint-Honoré with an old American friend who was doing Paris. He was brimming over with French history. Your part was to mention the name of the place you showed him. He would do the rest with enthusiasm and a wealth of detail.

"What is that church?" he asked.

"Saint-Roch," I answered.

"Saint-Roch! Saint-Roch! Saint-Roch!" he cried in crescendo. "Of course, OF COURSE, because this is the Rue Saint-Honoré. The Rue Saint-Honoré!" Beside himself with excitement, he rushed across the street, and up on the steps. I followed, mystified. My friend was waving his cane when I reached his side. "It was here," he announced, as if he had made a wonderful discovery, "right on this spot."

"In Heaven's name what?" I queried.

"The beginning of the most glorious epoch of French history, the birth of the Napoleonic era."

And then he told me the story of how young Bonaparte, called upon to prevent a mob from rushing the Tuileries, put his guns on the steps of Saint-Roch, swept the street in both directions, and demonstrated that he was the first man since '89 who could dominate a Parisian crowd. "You wouldn't have thought there was anything interesting about this old church, would you?" he ended triumphantly.

My eyes filled with tears, and my lips trembled. It was his turn to be mystified, and mine to lead. I took him inside the church, and back to the chapel of Saint Joseph. "Here," I said, "on Christmas Eve I came with my father when I was five years old. It was the first time I remember seeing the Nativity pictured. Good old Joseph looked down on the interior of the inn. The three wise men were there with the gifts. Le petit Jésus was in a real cradle, and I counted the jewels around the Mother's neck. My father tried to explain to me what Christmas means. He died when I was a little girl. I brought my firstborn here on Christmas Eve and the others as they came along. I never knew about Napoleon's connection with Saint-Roch before. And you asked me whether I would have thought there was anything interesting about this old church!"

The same place can mean so many different things to so many different people. Paris was Babylon to my grandfather who never went there. And to those who go there Paris gives what they seek, historical reminiscences, esthetic pleasure, intellectual profit, inspiration to paint or sing or play, a surfeit of the mundane, a diminution or an increase of the sense of nationality, pretty clothes and hats and perfumes, "rattling" good food and drink or a "howling" good time. You can be bored in Paris just as quickly and as completely as in any other place in the world. You can fill your life full of interesting and engrossing pursuits more quickly and completely than in any other place in the world. Best of all you make your home in Paris, with no sense of exile, and enjoy what Paris alone offers in material and spiritual values without being abnormal or living abnormally.

My childhood vistas seem fragmentary when I put them down on paper. But they have meant so much to me that I could choose for my children no greater blessing than to know Paris as home at the beginning of their lives.

THE family was abroad for the summer, one of those delightful May-first to October thirty-first summers when school is missed at both ends. The itinerary was supposed to be planned by letting each member drop into a hat slips of paper indicating preferences. Mother was astonishingly good about considering the wishes of all. But as the trip was undertaken for education as well as vacation, the head of the family did not intend to make it aimless rambling. Although, to get full benefit of the strawberry season, we took our cathedrals from south to north in England, none were omitted. By the time we reached Edinburg, Roman, Saxon, Early Norman and Gothic were as mixed up in the head of the sixteen-year-old member of the party as they were in the buildings inspected. "Inspected"—just the word for an educational tour! Later visits to East Coast cathedrals have not conquered the instinctive desire to avoid going inside. Impressions of places were vivid enough. But I fear Canterbury meant London the next stop; Ely a place near Cambridge; Peterborough the view from the top of the tower; Lincoln tea-cakes that crumbled in one's mouth; York a mean photographer who never sent me films I left to be developed; and Durham a batch of long-delayed letters from boys at home.

At sixteen strawberries do not satisfy hunger: cathedrals do not feed the soul.

No, cathedrals and history and the origin of the political institutions under which I lived interested me very mildly. At sixteen one is too young to have love affairs that interfere with the appetite, and too sophisticated to cling to the dream of a cloistered convent life that followed giving up the hope of being a chorus-girl. The mental effort of preparing for college (which the tour abroad was to stimulate) could not claim me to the exclusion of clothes and an engrossing interest in the doings of the group of boys and girls who formed my "crowd." The trip abroad was going to give me something to talk about at dinner-parties and the advantage of wearing clothes bought in Paris. One never looks forward to the coming winter with as keen anticipation as during the sixteen-year-old summer. Hair would be put up, and dances and dinners were a certainty for every Friday and Saturday evening.

If you believe in the value of first impressions and are in a mood to love Paris, plan your introduction to the queen of the world for an evening in June. Do not worry about your baggage. Send a porter from the hotel afterwards for your trunks. Find a fiacre if you can. An auto-taxi is second-best, but be sure that the top is off. Baisser la capote is a simple matter, done in the twinkling of an eye. Of course the chauffeur will scold. But handling cochers and chauffeurs in Paris requires the instinct of a lion-tamer. If you let the animal get the better of you, you are gone. You will never enjoy Paris. Mastery of Parisian drivers, hippomobile and automobile, does not require a knowledge of French. Your man will understand "put down the top" accompanied by the proper gesture. Whether he puts it down depends upon your iron will and not upon your French!

Best of all stations for the first entry to Paris is the Gare de Lyon. But that good fortune is yours only if you are coming from Italy or Spain or if you have landed at Marseilles. The Dover and Boulogne routes bring you to the Gare du Nord and the Dieppe and Havre and Cherbourg routes to the Gare Saint-Lazare. In any case, ask to be driven first to the Pont-Neuf, then along the quais of the Rive Gauche to the Pont-Alexandre Trois, then to the Avenue des Champs-Elysées. Only when you have gone over this itinerary and have passed between the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais are you ready to be driven to your hotel. It is the difference between seeing a girl first at a dance or a garden-party or running into her by accident in her mother's kitchen when the cook is on a strike.

How often, in the decades that have passed since June, 1899, have I wished that the return to Paris had included this program, not only initially but for every June and July evening of our weeks there. But it did not. The passionate love of Paris, my home city, that was born in me as a child, that was re-awakened and deepened in maturity, did not manifest itself when I was a school-girl as it should have done. The change from regular lessons to the governess-controlled days of sightseeing was not as amusing at the time as it seems in retrospect. Madame Raymond and I were not made for each other. It wasn't incorrigibility on my part or severity in a nasty way on hers. We just pulled in different directions, and shocked each other. It began on the first day. She found that I spoke French well enough not to call for the usual effort she had to make with American girls and that I did not need to be told the names of monuments and jardins and avenues. The memories of infancy had been carefully kept alive by word and picture. Mother had seen to that. Paris meant to me my father. Consequently, I suppose Madame Raymond's conscience stimulated her to lay stress upon history and art. She wanted to earn her money.

Mutual lack of comprehension began immediately. My first reading under Madame Raymond's direction was a volume of Guy de Maupassant's stories, with markers to show which could be read and which were forbidden. Next day Madame was horrified to see the markers gone and to learn that I had sat up late reading without censorship. She told me that a well-bred jeune fille ought to be ashamed of reading certain things, and refused to argue about it when I asked her why a jeune fille should be ashamed of reading the stories she had indicated to be skipped.

"To-day," said Madame Raymond, "I intend to take you to the Cluny Museum, and then we shall begin the Louvre."

"But," I protested, "I want to go first to Morgan Harjes."

"What for? Madame your mother gave me fifty francs this morning."

"She gave me a hundred and fifty. It isn't for money. I want my letters."

"If there are any letters for you, Madame your mother will give them to you if it is good for you to have them!" snapped Madame Raymond.

"Fiddlesticks! My mother doesn't read my letters."

"Letters written to a jeune fille of sixteen years can easily wait. They are not important. Your education is. Anyway, who would write to you over here?"

"Well, there is Bill. I'm crazy to know if he passed his examinations for Yale and how he liked going to the dance at the Country Club with Margaret when he asked me first. Joe and Charlie went off on a fishing trip to Canada before I sailed, and I've been waiting a month to know if they caught anything. Then Harold. He's an older man. You can talk to him about serious things and his advice is pretty good. Naturally, it would be—Harold is a member of the bar and knows lots."

"But," said Madame, "you mean to say you write to men and men write to you?"

"Certainly. Just ask mother. Here, I know how to fix it. You seem to be in a hurry to go to the Museum. If it interests you, go right along. I'll take a cab to the bank and follow you later. Meet you at the Cluny in an hour."

"Alone!" cried Madame; "my conscience would not allow it. Your mother trusts me."

Madame Raymond hailed a cabby.

"To the Cluny Museum," said she, with finality.

In its setting, the Cluny Museum is one of the most delightful spots in Paris. On the Boulevard Saint-Michel and the Boulevard Saint-Germain one has the life of Paris of to-day. Looking out from the little park with its remains of Roman baths and archæological treasures of old Lutetia scattered around in the shrubbery, one sees a fascinating carrefour of the Latin Quarter, noisy, bustling, ever-changing. It is a contrast more striking than any that Rome affords. On the other side, where one enters the Museum, you have the atmosphere of the middle ages, with the old well and the court yard and the fifteenth-century façade. Across the street, the great buildings of the Sorbonne and Collège de France seem to be carrying on the traditions of the past. But if you had to go inside with a governess who insisted on showing you everything in every room, you would rebel as I did.

Madame Raymond did not have it all in her head. She peered down over the glass cases and read the descriptions in a high voice, adding pages out of a guide book from time to time. She was near-sighted. As she droned along, I plotted a scheme for kidnapping her spectacles. When we left, I had seen embroideries and laces and carriages and cradles and slippers of famous people and stolen stained-glass windows to her heart's content.

We went to Foyot's, opposite the Luxembourg Palace, for lunch. After the meal was ordered, the waiter brought the carte de vins.

"A bottle of Medoc," said Madame. "I prefer red wine, don't you, my dear?"

"Plain water for me. No mineral water. Eau fraîche out of a carafe," said I.

"Extraordinary!" cried Madame.

"I think it is dreadful to drink wine," I protested, half in earnest and half in joke. "The Bible says strong drink is a mockery. The first thing I remember about Sunday school is that text."

"Ridiculous," said Madame, "table wine is not alcohol."

"Yes," I continued, "but it is the first steps toward strong drink. You are going to order a fine champagne with your coffee. You cannot tell me that brandy is not strong drink."

"Here in France," said Madame, "everybody takes a drink and nobody gets drunk. You must understand, my dear child, that we have a different point of view."

"Maybe you don't get drunk," said I, "but how about what one sees in Brittany?"

"You lack respect," answered Madame. She ignored Brittany. In France, one is not accustomed to argue with a sixteen-year-old girl. Questioning the judgment of one's elders is impertinent. Since I have brought up my own children in France, I am more than half won over to French ideas. The strong individualism of the American child shocks me now in somewhat the same way as my "freshness" must have shocked Madame Raymond. I was ready to contest her belief that American girls had no manners. I have not taught my children to courtesy—for the simple reason that it is no longer the fashion in France. But I am far from believing now, as I told Madame Raymond, that courtesying is affectation. And I fear that my children have had the example of French children in regard to wine. I am trying to put down here how I was at sixteen. When, after years in America, I returned to France, my point of view was different.

But about some things maturity has not changed the opinion of a pert young American miss. French ideas of sex relationship between adolescents seem to me now as they did then, absurd and false. Nor have I revised my opinion about high heels and tight corsets, powder and paint.

It was Madame's duty to take me to the dressmaker's. Before my dress appeared in the fitting room, I was put into my first pair of corsets. When they were laced up, I rebelled, took a long breath, and stretched them out again. Madame Raymond and the fitting woman shook their heads and assured me that my dress would not fit. My governess sided with the girl, when she remonstrated against my stretching the lacings. I showed little interest, too, in Madame Raymond's suggestion concerning the purchase of a box and a pretty puff with a silk rose-bud for a handle, which was to contain pink powder.

"I never make up," I declared. "If you put powder and other stuff on your face when you are young, you are not far-sighted. Ugh! I loathe pink powder."

One day we went to a foire, one of those delightful open-air second-hand markets that never cease to fascinate Parisians. A man darted out from a booth and offered to sell me a wedding gown.

"How much is that dress?" I inquired.

"Two hundred francs, Mademoiselle."

"Let me see. I wonder if it is big enough for me. I'm getting married next week. This would save me the bother of having one made, n'est-ce pas?"

"Certainly, Mademoiselle," cried the merchant delighted.

He pulled out his tape-line and was preparing to measure me when Madame dragged me away.

"It is not convenable, what you are doing," she exclaimed heatedly. "You must not speak lightly of marriage."

"Oh, it comes to us all like death or whooping-cough."

I must not give the impression that my mind at sixteen was absolutely insensible to historical sight-seeing and the art treasures of Paris. I always have loved some of the things in the Louvre, and after the Great War broke out, I discovered what a privation it was not to be able to drop in when I passed to look at something in the Luxembourg or the Louvre. But I did not like overdoses. And I have never gotten accustomed to crowds of pictures all at once in the field of vision or cabinets and glass-covered cases filled with a bewildering variety of bibelots. How I came to enjoy the Musée du Louvre will be told in a later chapter of the decade after Madame Raymond. Why should I not confess frankly that at sixteen I was more interested in the Magazin du Louvre, even though I knew I could no longer hope to purchase what I wanted there "for a song"? The best thing I took away from Paris in 1899 was an evening-dress with a low neck—my first to go with hair put up. It was in the middle tray of my trunk, packed with tissue paper and sachet. I can see now the different colored flowers woven into the soft cream of its background in such a way that, according to the girdle you chose to put on, your color effect in night light could be lavender, blue or rose.

Ten years before my father had taught me to love to ride on the top of an omnibus, on the impériale, as the French called it. Alas that I should have to use the past tense here. Impériales, still the fashion on Fifth Avenue and Riverside Drive, disappeared from Paris before the war. I shall tell later of the last horse-driven omnibus. The auto-buses started out with impériales, but banished the upstairs in 1912 and 1913. They were still the vogue in 1908. Madame Raymond objected to the impériale. She hated climbing up and down the little stairs, especially when carrying an umbrella prevented proper circumspection in regard to gathering in skirts. And by riding inside one avoided a courant d'air.

On a sunshiny day with a long ride ahead of us, I could not bear the thought of submitting to my governess's whim. I forgot my manners and jumped on first. With this advantage I was able to climb quickly to the top. There was nothing else for Madame Raymond to do but slip the guide-book hastily into her black silk bag and climb up after me. A man in uniform came along and stopped in front of me. I was reading, and did not look up when I offered him the necessary coppers. He took my money and sat down beside me. Then he laughed and handed it back to me. He was a sous-lieutenant of the French army. I was not confused by my mistake, for he gallantly took it as an opening. We chatted in English. Madame Raymond plucked at my sleeve, whispering admonitions. I was deaf on that side. Finally she told me that we had reached our destination, got up and started down. Naturally I followed. I found that we were still several blocks away from where we were going. We both held our tempers until we got off. Then the fur began to fly. That night my adventure was retailed to Mother at the hotel in the Rue de la Tremoille. Mother sided with the governess.

But the next week, when we were at the Opéra one night, I met my officer on the Grand Escalier. He came right up to me, and I didn't have it in my heart to turn my back or treat him coolly. When my governess turned around, she recognized him. I did not bat an eyelash. I introduced him to Mother and to her and he managed to get an invitation from Mother to call on us. This is the only time I was ever glad about the long intermission—the interminable intermission—between acts at the Paris Opéra. Afterwards, nothing I could say would convince Madame Raymond that the second meeting was pure hazard. She told me that she knew he had slipped me his address and I had written to him to arrange the rendez-vous. This did not make me mad. What did make me furious was her condemnation of the supposed intrigue solely on the ground of my age and my unmarried state. When does a girl cease being too young to talk to men in France? And why should it not be worse for a married woman than for an unmarried woman to encourage a little attention?

These questions interested me later as much as they did then. Was the Old World so different from the New World or was I taking for granted both a latitude and an attitude at home different from what I was going to meet? Little did I realize that I was destined to live in Paris as a bride and to bring up my children there to the age when I should have these problems to face from the standpoint of a mother of three girls.

WE left Oxford very suddenly. Six weeks in the Bodleian Library, in spite of canoeing every afternoon, sufficed to go through a collection of contemporary pamphlets about the Guises. And then we were getting hungry. Since he never changes the menu, roast beef and roast lamb alternating night after night, and accompanied by naked potatoes and cabbage, must content the Englishman. But all who have not a British birthright either lose their appetites or go wild after a time. We thought that we could not stand another day of seeing that awful two-compartment vegetable dish. It never contained a surprise. You could swear with safety to your soul that when the lid was lifted a definite combination of white and green would meet your eye.

So, when in the early days of July nineteen hundred and eight the London newspapers published telegrams from Constantinople that foreshadowed startling changes in Turkey, we were ready to flit. We had planned to spend our honeymoon winter in Asia Minor, anyway, and thought we might as well get out there as soon as possible. The spirit of adventure is strong in the blood of the twenties and decisions are made without reflection. It is great to be young enough to have a sudden change of plans matter to none, least of all to oneself. On Monday afternoon we were canoeing on the Cherwell, with no other thought than the very pleasant one of doing the same thing on the morrow. The next afternoon we were in a train speeding from Calais to Paris, trying to recuperate from the Channel passage.

Herbert and I both knew Paris. But we did not know Paris together, and that made all the difference in the world. When we reached the Gare du Nord, we were as filled with the joy of the unknown as if we had been entering Timbuktoo. On the train we discussed hotels. A slim pocketbook was the only bank in the world to draw upon for a long journey. On the other side was the less commonsense but more convincing argument, that this was once in our lives, and that if it ever was excusable to do things up right, now was the time. The pocketbook was so slim, however, that until we stepped out into the dazzling lights, we were not altogether sure that it would not be a modest little hotel. We compounded with prudence by hailing a fiacre instead of one of the new auto-taxis, and directed the cocher to take us where we wanted to go.

Looking up the Avenue de l'Opéra

It was the thought of being in the heart of things, right at the Place de l'Opéra, that prompted us to choose the Grand Hotel. The price of rooms was preposterous. We took the cheapest they had on the top floor. The economical choice is sometimes the lucky one. Next time you are in the Place de l'Opéra, look up to the attic of the Grand Hotel, and you will see little balconies between the windows. Each window represents a room. So does each balcony. We drew a balcony. It was just wide enough for two honeymoon chairs; and it was summer time.

When I was waiting in the vestibule of a New York church for the first strains of the wedding march, my brother pressed a five-dollar gold piece inside my white glove. "For a bang-up dinner when you get to London," he whispered. In London we had been entertained by friends. This was the time to spend it. The initiated would open his eyes wide at the thought of the "bang-up" dinner for two for twenty-five francs in Paris today—or anywhere else in the world. But remember I am writing about nineteen hundred and eight. Six years before the war, twenty-five francs would do the trick, and do it well, on the Grands Boulevards. We had fried chicken with peas, salad and fruits rafraîchis at Pousset's, and there was some change after a liberal (ante-bellum!) tip.

After dinner we strolled along the Boulevards des Italiens. We came to a big white place, with a wealth of electric lamps, that spelled PATHE—PALACE. A barker walked up and down in front, wearing a gold-braided cap and a green redingote. We paused as at the circus. It was a cinema. Herbert wanted to go in, but I wasn't sure. I had never seen moving pictures and had heard that they hurt one's eyes. To be a good sport I yielded. It was a revelation to me, and I felt as I did a year or two later when I first saw an aeroplane. My censor and literary critic, who has not the imagination of an Irishman, wants to eliminate this paragraph. But I have refused. It is true that I had never been to the cinema before I married him, and I am not sure that it was not his first time, too. The wonders of one decade are the commonplace of the next, and in retrospect we should not forget this. "Nineteen-eight" was to be the wonder year. Is there not an old Princeton song, still in the book, which was sung with expectation by our fathers? It went something like this:

And then the chorus, as they used to sing it—that older generation—on the steps of Nassau Hall:

After the movies we went back to the Hotel, and sat out on our balcony with the brilliant vistas of the Avenue de l'Opéra and the Boulevard des Italiens before us. We could hear the music of the opera orchestra, faintly to be sure, but it was there. The spell of six and sixteen came back. Nearly another decade had passed, but Paris was home to me, and I had a twinge of regret that we were going farther afield. Had it not been for the news of Niazi Bey and Enver taking to the mountains in a revolt against the Sultan, I might have suggested giving up Turkey.

I was glad that we would have to stay long enough to get our passports. The passport, now the indispensable vade mecum of travelers everywhere, was needed only for Rumania and Turkey and Russia ten years ago. To make up for the extravagance of the Grand Hotel we found our way to the American Embassy and the Turkish Embassy afoot. Every corner of the Champs-Elysées had brought back memories to me and I was able to point out to Herbert the guignol to which Marie had often taken my little sister and me nearly twenty years before. We stopped to listen. Some of the jokes were just the same. Judy had lost the stove-lid, and Punch told her to sit on the hole herself. And a useful and indispensable nursery household article (whose name I shall not mention) was suddenly clapped by Punch over the policeman's head in the same old way. The children laughed and clapped their hands in glee. Herbert, on his side, showed me the walk he used to take every morning from his room on the Rue d'Amsterdam by the Rue de la Boëtie and the Avenue d'Antin[A] to the Exposition of 1900, when he was writing feature stories for the Sunday edition of the New York World.

[A] The Avenue d'Antin has become since the victory in the recent war Avenue Victor Emmanuel III., in honor of Italy's intervention.

With passports obtained and visaed, tickets bought and baggage registered, we were having our last meal in Paris before taking the train for Rome. It was a late breakfast on the terrasse of the Café de la Paix. The waiter was not surprised when we ordered eggs with our coffee: but we were when we found they cost a franc apiece. As we sat there, at the most interesting vantage point in Paris for seeing the passing crowd, my childhood instinct came back with force. I cried, "O! I do want to come here to live when we return from Turkey!"

Herbert had a fellowship from Princeton for foreign study. It had been postponed a year so that he could teach for a winter at an American college in Asia Minor. Then and there we made a decision that was prophetic. All the other men were going to Germany. The German universities were a powerful attraction for American university men. The German Ph.D. was almost a sine qua non in our educational system. You could not get a Ph.D. in England or in France. Herbert gallantly sacrificed his on the spot. It was not a revolt against Kultur. Nor was it clairvoyance.

"On one's honeymoon," Herbert said, "the wife's wish should be law. The man who starts endeavoring to get the woman he has married to realize that the things to do are the things he thinks should be done gets into trouble, and stays in trouble."

The last thing we were looking for on that perfect July morning was trouble.

"All right," said he, "we'll come back and study in Paris, and if you want to live here afterwards, I guess we can find some way to do it."

"IT was alcohol! He was right, that old buck. It was alcohol!"

We were sitting in the restaurant of the Hotel Terminus in Marseilles. Our month-old baby was lying on the cushioned seat between us. The maître d'hôtel told us she was the youngest lady that had ever come to his establishment. Bowls of coffee were before us on the table, and we were enjoying our French breakfast when Herbert burst out with the remark I have just recorded.

"What is the matter with you?" I asked.

Shaking with laughter, he told me the story.

"You know the basket with breakables in it? And those two champagne bottles Major Doughty-Wylie gave us?"

"One of them had boracic acid in it. Well?"

"Yes, yes, that is just it. The customshouse officer spied the bottles and it did not take him long to uncork one and smell it. He wanted to stick me for duty."

"What did you do?"

"Protested against paying duty on boracic acid solution. I pointed you out to him sitting over there with the baby. He yielded finally—observing that Americans are queer, tough customers, and that their babies must be husky if their eyes can stand such stuff. But he got the wrong bottle. Don't you remember that in the second one is pure grape alcohol, and that is what he sniffed."

Traveling with a baby, when tickets do not allow one to take the rapide sleeping-cars, has its good points. People do not care to spend the night in a compartment with a baby. We got to the train early—very early. We put Christine's wicker basket (her bed) by the door, and found it to be the best kind of a "reserved" sign. Half a hundred travelers poked their heads in—and passed on. The sight of Christine acted like magic to our advantage. The baby started to cry. "Don't feed her yet," ordered her dad. "Until this train starts, the louder she cries the better for her later comfort." As the wheels began to move, a man came in, put his bag on the rack and sat down. Laughing, he closed the door and pulled down the curtain.

"I have been watching you," said he. "Yours is a clever game. I have three little cabbages myself, and I know babies don't disturb people as much as those who have none think. No," he added, "I must correct myself, thinking of my mother and my mother-in-law. Even those who have had many babies forget in the course of time how they were once used to them. We'll have a comfortable night. Have a cigar, monsieur!"

We did have a splendid sleep. Christine has always been one of those wonder babies. So we were ready to see Paris cheerfully. Heaven knows we needed every possible help to being cheerful! For we were embarked upon a venture that looked more serious than it had the year before. A pair of youngsters can knock around happily without worrying about uncertainties. A baby means a home—and certain unavoidable expenses. Where your progeny is concerned, you can't just do without. We had two hundred and fifty francs in cash, and the prospect of a six hundred dollar fellowship, payable in quarterly installments. That was all we could count upon. Our only other asset was some correspondence sent to the New York Herald that had not been ordered, but for which we hoped to be paid.

The Marseilles express used to arrive at Paris at an outlandish hour. It was not yet six when we were ready to leave the Gare de Lyon. Two porters, laden down with hand-luggage, asked where we wanted to go. We did not know. The Paris hotels that had been our habitats in days past were no longer possible, even temporarily. There was no mother to foot my bills, and Herbert wasn't a bachelor with only his own room and food to pay for. I suggested the possibility of a small hotel by the station. The porters took us out on the Boulevard Diderot. Across the street was a hotel (whose gilt letters, however, did not omit the invariable adjective "grand") that looked within our means.

Once settled and breakfasted, the family council tackled the first problem—Scrappie, gurgling on the big bed. Ever since she was born we had been traveling, and she naturally had to be with us all the time. Only now, after five weeks of parenthood, did the novel and amazing fact dawn upon us that no longer could we "just go out." Scrappie was to be considered. Without Scrappie, we could have set forth immediately upon our search for a place to live. With Scrappie—?

There always is a deus ex machina. In our case it was a dea. Marie still lived in Paris. The contact had never been lost, and when we went through Paris on our honeymoon the year before, I had taken my husband to show him off to Marie. It was decided that I should go out immediately and find her. A month before we had written that we were coming to Paris in June, and she would be expecting us. Marie, and Marie alone, meant freedom of movement. I could not think of trusting my baby to anyone else.

The address was at the tip of my tongue—22 Rue de Wattignies. A few people know vaguely of the battle, but how many life-long Parisians know the street? Not the boulevardiers or the faubouriens of Saint-Germain, or the Americans, North and South, of the Etoile Quarter. And yet the Rue de Wattignies is an artery of importance, copiously inhabited. We had gone in a cab last year, and remembered that it was somewhere beyond the Bastille. At the corner of the street beyond our hotel, just opposite the great clock tower of the Gare de Lyon, I saw the Bastille column not far away. Why waste money on cabs? To the right of the Bastille lay the Rue de Wattignies, and not very far to the right. I remembered perfectly, and started out unhesitatingly.

Oh, the Paris vistas! No other city in the world has every hill top, every great open space, marked by a building or monument that beckons to you at the end of boulevard or avenue. No other city in the world has familiar dome or tower or steeple popping up over housetops in the distance to reassure you wherever you may have wandered, that you are not far from, and that you can always find your way to, a familiar spot. The Eiffel Tower, the Great Wheel, the Arc de Triomphe, Sacré Coeur, the Panthéon, Val-de-Grâce, the Invalides, the Tour St. Jacques, give you your direction. But when you dip into Paris streets, on your way to the goal, you are lost. Even constant reference to a map and long experience do not save you from the deceptive encouragement of Paris vistas. You can walk in circles almost interminably.

I had done this so often in the old days when I escaped from my governess. I did so again when I tried to find the Rue de Wattignies. Perhaps I did not try very hard: for one never minds wandering in Paris. The life of the streets is a witchery that makes one forgot time and distance and goal. When I lost sight of the Bastille column, the labyrinth of St. Antoine streets led me on until I had crossed the canal and found myself by the Hôpital St. Louis. After the year in the East, and years before that in America, old houses and street markets held me in a new world. It was a glorious June day to boot, and after steamer and train, walking was a keen pleasure. Marital and parental responsibilities were forgotten. The Hôpital St. Louis brought me back to the realities of life. I knew that it was north of the Bastille, and not in the direction of the Rue de Wattignies. Suddenly there came uneasily into my mind the picture of a husband, a prisoner, patiently waiting in a very small room in a very small hotel, and a baby demanding lunch. Conscience insisted upon a cab: for nearly two hours had passed since I started forth to find Marie. I had left the hotel early enough to catch her before she might have gone out. What if Marie should not be at home? "Hurry, cocher!"

My panic was unjustified. Marie was at home. Delighted to hear of our arrival, and eager to see her petite Hélène's baby, she put on her funny little black hat, and went right down to the waiting cab.

When we got to the hotel, Herbert was eating a second mid-morning petit déjeuner. He had a copy of the Paris edition of the New York Herald, and showed me, well played up in a prominent place, the last of the Adana massacre stories he had forwarded by mail from Turkey. This was the first time he realized that his "stuff" had been exclusive. There was a pleasant prospect of drawing a little money. So my long absence brought forth no remark, specially as Scrappie had slept like an angel.

"We played a wise game," said Herbert, "when we sent the stories smuggled through Cyprus to the Herald. We shall not have to correspond with New York on a slim chance of a newspaper's gratitude. We can get at James Gordon Bennet right here in Paris." Then he showed me some advertisements picked out in the column of pensions as promising and within our means. We had decided to consider nothing outside of the Latin Quarter.

Marie had not changed a bit. She could not say the same for me although she fussed over me as if I were five going on six. She forgot that twenty years had gone since the last time she combed my hair. She communicated to me the old sense of security. She bathed the baby. She brought me food and sat beside me, observing that long ago she had to coax me to take one more mouthful to please her.

"You always were fussy about your food. Ma chère petite Hélène, you don't eat enough to keep a sparrow alive. You are a naughty one."

She insisted upon my drinking a cup of camomile tea, and took me straight back to my sixth year by calling it pipi du chat. Knowing that name for camomile tea is one of the tests of whether one really knows French.

"Marie," I begged, "show me how English people speak French—the way you used to do!"

But Herbert, who had gone out to get the Daily Mail for its pension list, was coming in the door, and Marie would not show off before Monsieur. Never did she call me chère petite Hélène when he or any other person was present. It was always Madame before company. The Mail had many advertisements of pensions in streets near the Luxembourg. Marie helped us pick them out. The Luxembourg Garden was an integral part of the Latin Quarter, and we had to think of Scrappie's outing.

After lunch we turned Christine over thankfully to Marie and went out pension-hunting together.

"You were lucky in finding Marie," was all Herbert said.

"Yes," I answered, "I really couldn't have left the baby with anyone else."

"But is Marie the only person in the world? Without her, would you be a slave for ever and ever? There must be plenty of people that we could get to look after Scrappie."

"You don't know what it means to have a child!" said Scrappie's mother.

"I guess I look pretty healthy for a fellow who has just landed in Paris with a wife and a baby and 250 francs!" said my husband.

"Can't make us mad," said I; "we're in Paris."

You pile up on one side of the scale heaps of things that ought to worry you, but if you put on the other side the fact that you are in Paris, down goes the Paris side with a sure and cheerful bang, up goes the other side, and the worries tumble off every which way into nowhere.

The main threads of the world's spider web start very far from Paris in all directions and the heaviest urge of traffic is towards the centre. Paris was the centre of the spider web long before Peace Delegates came here to discover the fact. Students, diplomats, travel-agencies, theatrical troupes knew it and whole shelves of books have been written, down the years, to prove it. If Paris is your birth-place, you learn that you are in the capital of the world long before you know how to read the books. If you are an expert on ancient coins, if you are a wood-carver, if you are a singer wanting a voice that will make your fortune because it was trained in France, if you are a baker, if you are a burglar, if you are a silk merchant, if you are a professor from Aberdeen hunting for manuscripts that will prove your thesis concerning Pelagius, if you are an apache, if you are an English nursemaid,—you'll never be lonely in Paris. No matter how isolated or queer or misunderstood you were where you came from, in Paris you'll find inspiration, competition, companionship, opportunity and pals. The papers tell us every week that the birth rate is going down. But the population of Paris is increasing. So in peace, in war and in peace again, there was one constant quantity underpinning existence—Paris, the centre of the spider web. The spider that lures is liberty to work out one's ideas in one's own way in a friendly country. It is a wonder the men who make maps in France can draw lines latitudinally and longitudinally. What difference did it make then if we had only two hundred and fifty francs?

WE started our search for a temporary home at the Observatoire, and good fortune took our footsteps down the Rue d'Assas rather than down the Boulevard Saint-Michel. Had we turned to the right instead of to the left, we should probably have found a pension that satisfied our requirements on the Rue Gay-Lussac, the Rue Claude Bernard, the Rue Soufflot, or behind the Panthéon. But a short distance down the Rue d'Assas, we turned into the Rue Madame, which held two possibilities on our list. The first place advertised proved to be a private apartment, whose mistress was looking for boarders for one room who would not only pay her rent but her food and her old father's as well. We got out quickly, and kept our hopes up for the second place. It was a small private hotel just below the Rue de Vaugirard, with a modest sign: Pension de Famille.

A beaming young woman, who told us that she was Mademoiselle Guyénot, propriétaire et directrice de la maison, answered our first question in a way that won our hearts forever. "Do I mind a baby!" she exclaimed. "I love them. No trouble in the world. Wish the bon dieu would allow me to have one myself. If any boarder complains about babies crying in my house, I ask them how they expect the world to keep on going. Parfait! Bring the little rabbit right along. Of course there is no charge. Is it I who will feed her? Think of it, then!" And Mademoiselle Guyénot opened wide her arms and lifted them Heavenward. Her eyes shone, and she laughed.

We engaged a room on the court, two flights up, for seventy francs a week tout compris, lodging, food, boots, wine. Lights would not amount to more than a franc a week. We could give what we wanted for attendance. The arrangement with Marie was perfect. She would stay at home and come for the days we wanted her. That meant only her noonday meal on our pension bill—one franc-fifty.

We got out of the Boulevard Diderot hotel none too soon. The charges were fully as much as at a first-class hotel (I have frequently since found this to be the case in trying to economize in travel) and made a serious dent in our nest-egg. When we reached the pension with our baby and baggage, we felt that it was only the square thing to acquaint the new friend who loved babies with our financial situation.

"Oh! la, la," cried Mademoiselle Guyénot, "you may pay me when you like!"

"You must understand," said my husband, "that we have just come out of Turkey and have very little money. Of course, as soon as we get settled, things will be all right again."

Mademoiselle received us in the bureau of her pension with open arms and lightning French. I could not get it all, but we knew she was glad to see us. She turned around on her chair and faced us as we sat on an old stuffed sofa surrounded by our suitcases.

"You must not worry," she exclaimed, "you must not worry du tout, du tout, du tout, du tout.... If you don't pay me I'll keep the baby, pauvre chou."

Mademoiselle's voice went up the scale and down again, dying away only when she opened her mouth wider to laugh.

Mademoiselle ran the pension single-handed in those days. Now she is Madame and the mother of two little girls. Monsieur is a mechanical genius and has himself installed many conveniences. He can paper a room, rig up a table lamp at the head of a bed, carry in the coal, forage for provisions with a hand-cart and a cheerful jusqu'au boutisme that stops at nothing. He is also able to make a quick change in clothes and bobs up serenely within fifteen minutes after unloading the potatoes, quite ready to make you a cocktail.

Mademoiselle handled her clients with cheerful firmness. She used to marshal the forces of her house with a strong and capable hand. You could not put one over on her then any more than you can now, as some transients discovered to their confusion. The regulars knew better than to try. On the other hand if your case was good and your complaint justified, she defended you with energy. Liberté, égalité, fraternité were realities in the Rue Madame.

The clientele was French for the most part: elderly people who had got tired of keeping house. Folks from the provinces who had come to town to spend the winter after Monsieur retired from business. Young people, mostly men, some of them long haired who were studying at the Sorbonne or elsewhere. And a sprinkling of transients whose chief effect upon the regulars was allowing them to shift about until they had possession of the rooms they wanted to keep at a monthly rate. When we went to the pension we were the only Americans. We paid five francs a day for room and board like everybody else excepting the old lady who had come to the house years ago when the rate was four francs fifty. German Hausfraus may be marvels in management, but I defy any lady Boche to beat Mademoiselle's efficiency. She got all the work of kitchen and dining-room done, and well done too, by Victorine the tireless, Louis the juggler and François the obsequious. Guillaume and Yvonne, a working menage, looked after the rooms until they got a swell job at the Ritz Hotel, where tips would count. The other three were fixtures.

In spirit the Rue Madame pension has not changed. The atmosphere to-day is as it was in nineteen hundred and nine. The table is good, plentiful, appetizing—and, oh, what a variety of meats and vegetables! The potatoes are never served in the same way twice in a week, and Madame Primel, as Mademoiselle is now called, cooks as many different plats de jour as her number in the street, which is forty-four. There the reader has my secret! But five francs a day no longer holds. In nineteen hundred and nineteen five francs will barely pay for a single meal. Not only has the price of food more than doubled, but the traveler is beginning to demand comforts that cost. We used to have buckets of coal brought up, and make a cheerful fire. We used to grope in the dark when we came home, strike a match, and look for our candle on the hall table. We used to have a lamp—the best light in the world—in our room. But now the pension in the Rue Madame has yielded to the demands of a discontented world. Steam heat, electric lights—these have had their part in making five francs a day disappear forever. The five franc pension exists only in the memory of Paris lovers, or in story books like mine.

At our table were Mrs. Reilly, a sprightly Irish woman called by the pensionnaires Madame Reely; Monsieur Mazeron, a law student with an ascetic blond face and hair like a duckling; an elderly couple from Normandy who had adopted Madame Reely, swallowed her at one gulp of perfection, only to discover afterwards that they did not understand her; a Polish doctor and his wife from Warsaw; and others. Madame Reely made a pretty speech the first night at dinner, proposing that our table volunteer to help us take care of the baby.

"To-morrow is the Fête Dieu," said she. "I'll go to the early mass so that I can come back and stay with the baby while you two go to the later mass. You will see the priests in their robes of ceremony, the Holy Relics, and a thousand children in the procession. It is too lovely,—all those little things with their baskets of flowers, throwing petals in the path of the priests. Who can tell," she went on in a whispered aside to her neighbor, "it may impress them. One never knows when new converts are to be added to the blessed Church!"

"And I shall look at the baby," said the Doctor from Warsaw. "Children are my specialty. That is why I am here, observing in the clinics of Paris, you see. I shall come to your room to-morrow after breakfast. Being an American mother, I suppose you give your baby orange juice?"

"Certainly I give her orange juice," said I; "it is good for her."

"Au contraire! au contraire!" cried the Doctor, waving his hands. The Doctor was always "au contraire" no matter what was said and who said it. Polish character.

In a corner was a tiny table for one. It was for the starboarder, a young Roumanian, who wore a purple tie held together by a large amethyst ring. Possibly he wore it because he believed in the ancient legend about amethysts being good to prevent intoxication. When we entered upon the scene he was still in high favor. His downfall came later and had to do with a wide-awake concierge and a luckless kiss at the front door.

The food we had was the kind we used to have in Paris when many visitors came here with no better excuse than to enjoy the cuisine. Mademoiselle gave us two meat dishes for each meal. If you did not like calves' liver, Louis would do a trick that landed a steaming plate of crisp fried eggs (fried in butter, you remember) before you. And that without being told. Behind the scenes was Victorine.

Victorine invited me into her kitchen to learn how to make sauce piquante.

"Are you married, Victorine?" I queried.

"My cookstove is my husband," she laughed; "his heart is good and warm and he never leaves me."

During meals Mademoiselle was to be found in the kitchen. She did the carving herself and tasted everything before it was passed through a window to Louis.

There was no felt covering under the table-cloth. The serving of the meal competed with piping, high-pitched, excited voices. Perhaps I oughtn't to say excited, but the Frenchman in his most ordinary matter of fact conversation sounds excited to the Anglo-Saxon. He asks you to pass the bread in the same tone you would use in announcing an event of moment. At each place was a glass knife-and-fork rest. In France, unless the first dish happens to be fish, you keep the same knife and fork. This is the custom in the best of homes. We are prodigal of cutlery where the French are prodigal of plates. The same knife and fork didn't matter, because the food was so good. Nor does it matter to-day, because now there is only one meat dish. Times have changed.

If fruit or pudding ran out, Mademoiselle opened a section of the wall, finding the key on a bunch that was suspended from her belt on a piece of faded black tape. From the cupboard she took tiny glasses filled with confiture or perhaps a paste made of mashed chestnuts and flour slightly sweetened. The glasses, to the touch, were cylindrical, but when you had broken the paper pasted across the top and had eaten half way down, the space was no wider than the fat part of your tea spoon. If your glass was a cylinder outside, on the inside it was an inverted cone.

The quantities of bread consumed in that house would be appalling to anybody but a Frenchman. A Turk can live on bread and olives. But a Frenchman can live on bread alone. If he had to choose between bread and wine he would forget the wine. When the basket was passed around, the pensionnaires, with a delightful absence of self-consciousness, would cast their eye over it in order to select the biggest piece. There was always one person who would look around the room furtively, take the biggest piece on the plate, slip the second biggest piece into the lap under the serviette, and then, gazing far away in ostrich fashion, glide the bread into pocket or reticule. If the dessert happened to be fruit, an orange or an apple would follow the bread for private consumption later in the day. Perhaps these people came in for luncheon only and the bread and fruit was devoured at twilight at some little café where it is permitted to customers to bring their own supplies, if they buy a drink. This stretching of luncheon procured the evening meal. If necessity is the mother of invention, the students of Paris are necessity's grandmother.

Louis, the arch-juggler, was forced by public opinion to alternate day by day his point of departure when passing the steaming plat du jour. Egalité, you remember, is one-third of French philosophy. It would never do for the same end of the dining-room to enjoy for two days running the little privilege of having the first pick at the best piece of meat in the plate.

François helped in the dining-room. But he was everywhere else too. He was useful for Louis to swear at and to blame. He was bell-hop, scullery-boy, errand-man, who needed all of his amazing reserves of cheerfulness. I wondered when François slept. He was on hand with his grin and his oui, madame, early and late. Once when we slid out of the house at five in the morning to go on an excursion, we found him in the lower hall surrounded by the boots of the house. Back of his ear was a piece of chalk used for marking the number of the room on the soles of the boots. He was polishing away, moving his arm back and forth with a diminutive imitation of the swing his legs had to accomplish when his brush-clad feet were polishing the waxed floors. As a concession to the early hour, he was whistling softly instead of singing. The whistling of François fascinated everyone because it came through a tongue folded funnel-wise and placed in the aperture where a front tooth was missing. And we would often find him up and about when we came home late at night. It was a pleasant surprise, when, after calling out your name, you made ready to walk back to the candlestick table, hands stretched out before you, to have François suddenly appear with a light. He would hold out over the table his little hand lamp with the flourish a Gascon alone can make. You picked out your candlestick by the number of your room cut in its shining surface. The number had an old-fashioned swing to its curve, suggesting that the solid bit of brass might have been dug up from the garden of some moss-grown hostelry after a passage of the Huns.

Mademoiselle Guyénot insisted that the flagged pavement be washed every day. François used to fill with water a tin can in the bottom of which he had punched half a dozen holes. He swung it about the court until figure eight shaped sprinkle-tracks lay all over the twelve-by-twenty garden. Afterwards he would take a short-handled broom, bend himself over like a hairpin, and sweep up the flag-stones. The dirt he accumulated was made into a neat newspaper package and set aside to wait until early to-morrow morning when it was put out on the street in the garbage-pail. François' thin high voice sang incessantly and sounded for all the world like the piping of a Kurdish shepherd above the timber line in the Taurus Mountains. In those days woe betide you if you put trash or garbage on a Paris street later than 8 A. M. It was as unseemly an act as shaking carpets out of your window after the regulation hour. Now, even if you are a late and leisurely bank clerk or fashionable milliner and you don't have to show up at work before 10 o'clock, you will see garbage-pails along curb-stones and likely as not get a dust shower furious enough to make you wish you hadn't left your umbrella at home. The old days—will they come back?

When the band plays soft Eliza-crossing-the-ice music, my mind flies to several Home-Sweet-Homes. I think of Tarsus, Constantinople, Oxford and Princeton. But there is no twinge of homesickness. Paris and my present home there satisfy every want and longing. Among the homes of the past, however, I think of others in Paris as well as of those of other places. I never forget the pension in the Rue Madame. Thankfully it is still a reality. During the past decade it has housed our mothers and sisters and cousins and friends. We have gone there to see them. And we go there to see our first warm friend in Paris and her husband and children. From time to time we have a meal in the old dining-room. We hope the pension will not disappear or will not be converted into too grand a hotel. For us it is a Paris landmark.

WE spent the first anniversary of our wedding in Egypt. A week later we arrived in Paris. For prospective residents as well as for tourists, June is the best time of the year to reach Paris. You have good weather and long days, both essentials of successful home-hunting. It is an invariable rule in Paris to divide the year in quarters, beginning with the fifteenth of January, April, July and October. Whether you are looking for a modest logement on a three months' lease or a grand appartement-confort moderne—on a three years' lease, the dates of entry are the same. One rarely breaks in between terms. If you have passed one period, you must wait for the next trimestre. The person who is leaving the apartment you rent might be perfectly willing to accommodate you, but he has to wait to get into his new place. So when we went to the pension, we had before us the best home-hunting weeks of the year, with the expectation of being able to get settled somewhere on July 15th.

At the pension, our room faced on the court, and the personnel, from Mademoiselle Guyénot down to Victorine and François, assured us that we need not feel bound to stay at home on the days Marie could not come to us. Marie for years had been sewing four different days of the week for old patrons, and we did not feel certain enough of our own plans and purse to accept the responsibility of her giving up a sure thing.

"Go out all you want to," urged our friends. "You only have to think about meal times for the baby. Someone is always in the court sewing or sorting the laundry or preparing vegetables. Your window is open. We cannot fail to hear the baby."

But a chorus of bien sûr and parfaitement and soyez tranquille did not reassure what was as new born as Christine herself—the maternal instinct. A letter from Herbert's father solved the problem. He inclosed the money for a baby carriage. We carried Scrappie down the Boulevard Raspail to the little square in front of the Bon Marché. I kept her on a bench while Herbert went in to follow my directions as well as he could. In a few minutes he came out and said he would rather take care of the baby. It was the first time I had seen him stumped. So I had the joy I had hoped would be mine all along but of which I did not want to deprive my husband, seeing that we could not share it. The reader may ask why we didn't take the baby inside. But it will not be a young mother who puts that question! With one's firstborn, one sees contagion stalking in every place where crowds gather indoors.[B]

[B] The critic would have me insert a modification here. Why confine the fear of the young mother to indoors? The critic insists that I used to be afraid of taking Scrappie into any sort of a crowd, and that my supersensitive ear translated the bark of every kiddie with a cold into whooping cough, while I saw measles in mosquito bites on children's faces.

The Rue de Vaugirard by the Luxembourg

We did not intend to consider a home that was not within baby-carriage distance of the Rue Madame. In fact, after a few days in the Luxembourg Quarter, we were determined to live as near the Garden as possible. There we were within walking distance of the Bibliothèque Nationale and the Sorbonne and the Ecole Libre des Sciences Politiques. Marie, whom the fact that I was my Mother's daughter did not blind to the extent of the Gibbons family resources, urged the Bois de Vincennes. But we would not hear of it.

It is strange how rich and poor rub elbows with each other in their homes. Paris is no different from American cities in this respect. The kind of an apartment we wanted would cost more than our total income, as rents around the Luxembourg for places equipped with electric lights and bathtubs and central heating seemed to be as expensive as around the Etoile. Then in the same street—sometimes next door—you had the other extreme. Our finances pointed to a logement in a workingmen's tenement. Care for Scrappie's health made our hearts sink every time we were shown a place that seemed within our means.

Of course there were reasonable places: for many others who demanded cleanliness had no more money than we. But the Latin and Montparnasse Quarters are the Mecca of slim-pursed foreigners. People foolish enough to study or sing or paint are almost invariably poor. Perhaps that is the reason! We had lots of exercise, and came to know every street between the Luxembourg and the Seine. Our good fortune arrived unexpectedly as good fortune always arrives to those who will not be side-tracked.

Between the Rue Vaugirard and Saint-Sulpice are three tiny streets, the houses on the opposite sides of which almost rub cornices. The Rue Férou is opposite the Musée de Luxembourg. On the Rue de Vaugirard is the home of Massenet. We used to get a glimpse of him occasionally on his terrasse—a sort of roof-garden with a vine-covered lattice on top of the low Rue Férou wing of his house. The other two streets paralleling the Rue Férou from the Palais du Luxembourg to the Eglise Saint-Sulpice are the Rue Servandoni and the Rue Garancière.

On the morning of the Fourth of July we had been diving in and out the side streets of the Rue Bonaparte and the Boulevard Saint-Germain. At Scrappie's meal time, we came to a bench in the Square in front of Saint-Sulpice. It wasn't a bit like a holiday. It was sultry and looked like rain. We were wondering whether we had better not hurry back to the pension for fear of getting the baby wet. Just then people began to stop and look up. A huge balloon was above us. And it carried the American flag.

"You can't beat it," said my husband. "And we are Americans. Ergo, you can't beat us!"