|

Transcriber’s note:

|

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version.

Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will

be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online.

|

THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

A DICTIONARY OF ARTS, SCIENCES, LITERATURE AND GENERAL INFORMATION

ELEVENTH EDITION

VOLUME XIV SLICE IV

Independence, Declaration of to Indo-European Languages

Articles in This Slice

372

INDEPENDENCE, DECLARATION OF, in United States

history, the act (or document) by which the thirteen original

states of the Union broke their colonial allegiance to Great Britain

in 1776. The controversy preceding the war (see American

Independence, War of) gradually shifted from one primarily

upon economic policy to one upon issues of pure politics and

sovereignty, and the acts of Congress, as viewed to-day, seem

to have been carrying it, from the beginning, inevitably into

revolution; but there was apparently no general and conscious

drift toward independence until near the close of 1775. The

first colony to give official countenance to separation as a solution

of colonial grievances was North Carolina, which, on the 12th of

April 1776, authorized its delegates in Congress to join with

others in a declaration to that end. The first colony to instruct

its delegates to take the actual initiative was Virginia, in accordance

with whose instructions—voted on the 15th of May—Richard

Henry Lee, on the 7th of June, moved a resolution

“that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be,

free and independent States.rdquo; John Adams of Massachusetts

seconded the motion. The conservatives could only plead the

unpreparedness of public opinion, and the radicals conceded

delay on condition that a committee be meanwhile at work on

a declaration “to the effect of the said ... resolution,” to

serve as a preamble thereto when adopted. This committee

consisted of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin,

Roger Sherman and Robert R. Livingston. To Jefferson the

committee entrusted the actual preparation of the paper. On

the 2nd of July, by a vote of 12 states—10 voting unanimously,

New York not voting, and Pennsylvania and Delaware casting

divided ballots (3 votes in the negative)—Congress adopted the

resolution of independence; and on the 4th, Jefferson’s “Declaration.”

The 4th has always been the day celebrated;1 the

decisive act of the 2nd being quite forgotten in the memory of

the day on which that act was published to the world. It should

also be noted that as Congress had already, on the 6th of

December 1775, formally disavowed allegiance to parliament,

the Declaration recites its array of grievances against the crown,

and breaks allegiance to the crown. Moreover, on the 10th of

May 1776, Congress had recommended to the people of the

colonies that they form such new governments as their representatives

should deem desirable; and in the accompanying

statement of causes, formulated on the 15th of May, had declared

it to be “absolutely irreconcilable to reason and good conscience

for the people of these colonies now to take the oaths and affirmations

necessary for the support of any government under the

crown of Great Britain,” whose authority ought to be “totally

suppressed” and taken over by the people—a determination

which, as John Adams said, inevitably involved a struggle for

absolute independence, involving as it did the extinguishment

of all authority, whether of crown, parliament or nation.

Though the Declaration reads as “In Congress, July 4, 1776.

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of

America,” New York’s adhesion was in fact not voted until the

9th, nor announced to Congress until the 15th—the Declaration

being unanimous, however, when it was ordered, on the 19th, to

be engrossed and signed under the above title.2 Contrary to the

inference naturally to be drawn from the form of the document,

no signatures were attached on the 4th. As adopted by Congress,

the Declaration differs only in details from the draft

prepared by Jefferson; censures of the British people and a noble

denunciation of slavery were omitted, appeals to Providence

were inserted, and verbal improvements made in the interest of

terseness and measured statement. The document is full of

Jefferson’s fervent spirit and personality, and its ideals were

those to which his life was consecrated. It is the best known

and the noblest of American state papers. Though open to

controversy on some issues of historical fact, not flawless in

logic, necessarily partisan in tone and purpose, it is a justificatory

preamble, a party manifesto and appeal, reasoned enough to

carry conviction, fervent enough to inspire enthusiasm. It

mingles—as in all the controversy of the time, but with a literary

skill and political address elsewhere unrivalled—stale disputation

with philosophy. The rights of man lend dignity to the rights

of Englishmen, and the broad outlook of a world-wide appeal,

and the elevation of noble principles, relieve minute criticisms

of an administrative system.

Jefferson’s political theory was that of Locke, whose words the

Declaration echoes. Uncritical critics have repeated John Adams’s

assertion that its arguments were hackneyed: so they undoubtedly

were—in Congress, and probably little less so without,—but

that is certainly pre-eminent among its great merits.

As Madison said, “The object was to assert, not to discover

truths.” Others have echoed Rufus Choate’s phrase, that the

Declaration is made up of “glittering and sounding generalities

of natural right.” In truth, its long array of “facts ...

submitted to a candid world” had its basis in the whole development

of the relations between England and the colonies; every

charge had point in a definite reference to historical events,

and appealed primarily to men’s reason; but the history is

to-day forgotten, while the fanciful basis of the “compact”

theory does not appeal to a later age. It should be judged,

however, by its purpose and success in its own time. The

“compact” theory was always primarily a theory of political

ethics, a revolutionary theory, and from the early middle ages

to the French Revolution it worked with revolutionary power.

It held up an ideal. Its ideal of “equality” was not realized

in America in 1776—nor in England in 1688—but no man

knew this better than Jefferson. Locke disclaimed for him in

16903 the shallower misunderstandings still daily put upon his

words. Both Locke and Jefferson wrote simply of political

equality, political freedom. Even within this limitation, the

idealistic formulas of both were at variance with the actual

conditions of their time. The variance would have been greater

had their phrases been applied as humanitarian formulas to

industrial and social conditions. The Lockian theory fitted

beautifully the question of colonial dependence, and was applied

to that by America with inexorable logic; it fitted the question

of individual political rights, and was applied to them in 1776,

but not in 1690; it did not apply to non-political conditions of

individual liberty, a fact realized by many at the time—and it

is true that such an application would have been more inconsistent

in America in 1776 as regards the negroes than in England

in 1690 as regarded freemen. Beyond this, there is no pertinence

in the stricture that the Declaration is made up of glittering

generalities of natural right. Its influence upon American legal

and constitutional development has been profound. Locke, says

Leslie Stephen, popularized “a convenient formula for enforcing

the responsibility of governors”—but his theories were those of

an individual philosopher—while by the Declaration a state,

for the first time in history, founded its life on democratic

idealism, pronouncing governments to exist for securing the

happiness of the people, and to derive their just powers from

the consent of the governed. It was a democratic instrument,

and the revolution a democratic movement; in South Carolina

and the Middle Colonies particularly, the cause of independence

was bound up with popular movements against aristocratic

elements. Congress was fond of appealing to “the purest

maxims of representation”; it sedulously measured public

opinion; took no great step without an explanatory address

to the country; cast its influence with the people in local

struggles as far as it could; appealed to them directly over the

heads of conservative assemblies; and in general stirred up

democracy. The Declaration gave the people recognition

equivalent to promises, which, as fast as new governments were

instituted, were converted by written constitutions into rights,

which have since then steadily extended.

373

The original parchment of the Declaration, preserved in the

Department of State (from 1841 to 1877 in the Patent Office, once

a part of the Department of State), was injured—the injury was

almost wholly to the signatures—in 1823 by the preparation of a

facsimile copper-plate, and since 1894, when it was already

partly illegible, it has been jealously guarded from light and air.

The signers were as follows: John Hancock (1737-1792), of

Massachusetts, president; Button Gwinnett (c. 1732-1777),

Lyman Hall (1725-1790), George Walton (1740-1804), of

Georgia; William Hooper (1742-1790), Joseph Hewes (1730-1779),

John Penn (1741-1788), of North Carolina; Edward

Rutledge (1749-1800), Thomas Heyward, Jr. (1746-1809),

Thomas Lynch, Jr. (1749-1779), Arthur Middleton (1742-1787),

of South Carolina; Samuel Chase (1741-1811), William Paca

(1740-1799), Thomas Stone (1743-1787), Charles Carroll (1737-1832)

of Carrollton, of Maryland; George Wythe (1726-1806),

Richard Henry Lee (1732-1794), Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826),

Benjamin Harrison (1740-1791), Thomas Nelson, Jr.(1738-1789),

Francis Lightfoot Lee (1734-1797), Carter Braxton (1736-1797),

of Virginia; Robert Morris (1734-1806), Benjamin Rush (1745-1813),

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), John Morton (1724-1777),

George Clymer (1739-1813), James Smith (c. 1719-1806), George

Taylor (1716-1781), James Wilson (1742-1798), George Ross

(1730-1779), of Pennsylvania; Caesar Rodney (1728-1784),

George Read (1733-1798), Thomas McKean (1734-1817), of

Delaware; William Floyd (1734-1821), Philip Livingston

(1716-1778), Francis Lewis (1713-1803), Lewis Morris (1726-1798),

of New York; Richard Stockton (1730-1781), John

Witherspoon (1722-1794), Francis Hopkinson (1737-1791), John

Hart (1708-1780), Abraham Clark (1726-1794), of New Jersey;

Josiah Bartlett (1729-1795), William Whipple (1730-1785),

Matthew Thornton (1714-1803), of New Hampshire; Samuel

Adams (1722-1803), John Adams (1735-1826), Robert Treat

Paine (1731-1814), Elbridge Gerry (1744-1814), of Massachusetts;

Stephen Hopkins (1707-1785), William Ellery (1727-1820),

of Rhode Island; Roger Sherman (1721-1793), Samuel

Huntington (1732-1796), William Williams (1731-1811), Oliver

Wolcott (1726-1797), of Connecticut. Not all the men who

rendered the greatest services to independence were in Congress

in July 1776; not all who voted for the Declaration ever signed

it; not all who signed it were members when it was adopted.

The greater part of the signatures were certainly attached on the

2nd of August; but at least six were attached later. With one

exception—that of Thomas McKean, present on the 4th of

July but not on the 2nd of August, and permitted to sign in

1781—all were added before printed copies with names attached

were first authorized by Congress for public circulation in

January 1777.

See H. Friedenwald, The Declaration of Independence, An Interpretation

and an Analysis (New York, 1904); J. H. Hazleton, The

Declaration of Independence: its History (New York, 1906); M.

Chamberlain, John Adams ... with other Essays and Addresses

(Boston, 1898), containing, “The Authentication of the Declaration

of Independence” (same in Massachusetts Historical Society,

Proceedings, Nov. 1884); M. C. Tyler, Literary History of the American

Revolution, vol. i. (New York, 1897), or same material in North

American Review, vol. 163, 1896, p. 1; W. F. Dana in Harvard

Law Review, vol. 13, 1900, p. 319; G. E. Ellis in J. Winsor,

Narrative and Critical History of America, vol. vi. (Boston, 1888);

R. Frothingham, Rise of the Republic, ch. ii. (Boston, 1872). There

are various collected editions of biographies of the signers; probably

the best are John Sanderson’s Biography of the Signers of the Declaration

of Independence (7 vols., Philadelphia, 1823-1827), and William

Brotherhead’s Book of the Signers (Philadelphia, 1860, new ed.,

1875). The Declaration itself is available in the Revised Statutes of

the United States (1878), and many other places. A facsimile of

the original parchment in uninjured condition is inserted in P.

Force’s American Archives, 5th series, vol. i. at p. 1595 (Washington,

1848). The reader will find it interesting to compare a study of the

French Declaration: G. Jellinek, The Declaration of the Rights

of Man and of Citizens (New York, 1901; German edition, Leipzig,

1895; French translation preferable because of preface of Professor

Larnande).

(F. S. P.)

1 “Independence Day” is a holiday in all the states and territories

of the United States.

2 As read before the army meanwhile, it was headed “In Congress,

July 4, 1776. A Declaration by the representatives of the United

States of America in General Congress assembled.”

3 Two Treatises of Government, No. ii. § 54, as to age, abilities,

virtue, &c.

INDEPENDENTS, in religion, a name used in the 17th century

for those holding to the autonomy of each several church or

congregation, hence otherwise known as Congregationalists.

Down to the end of the 18th century the former title prevailed

in England, though not in America; while since then “Congregationalist”

has obtained generally in both. (See Congregationalism.)

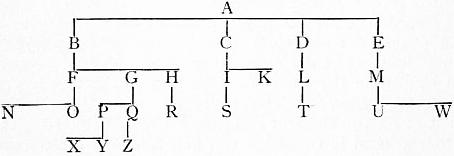

INDEX, a word that may be understood either specially as

a table of references to a book or, more generally, as an indicator

of the position of required information on any given subject.

According to classical usage, the Latin word index denoted a

discoverer, discloser or informer; a catalogue or list; an

inscription; the title of a book; and the fore or index-finger.

Cicero also used the word to express the table of contents to a

book, and explained his meaning by the Greek form syllabus.

Shakespeare uses the word with the general meaning of a table

of contents or preface—thus Nestor says (Troilus and Cressida,

i. 3):—

“And in such indexes, although small pricks;

To their subsequent volumes, there is seen;

The baby figure of the giant mass.”

|

Table was the usual English word, and index was not thoroughly

naturalized until the beginning of the 17th century, and even

then it was usual to explain it as “index or table.” By the

present English usage, according to which the word “table”

is reserved for the summary of the contents as they occur in a

book, and the word “index” for the arranged analysis of the

contents for the purpose of detailed reference, we obtain an

advantage not enjoyed in other languages; for the French table

is used for both kinds, as is indice in Italian and Spanish. There

is a group of words each of which has its distinct meaning but

finds its respective place under the general heading of index

work; these are calendar, catalogue, digest, inventory, register,

summary, syllabus and table.1 The value of indexes was

recognized in the earliest times, and many old books have full

and admirably constructed ones. A good index has sometimes

kept a dull book alive by reason of the value or amusing character

of its contents. Carlyle referred to Prynne’s Histrio-Mastix

as “a book still extant, but never more to be read by mortal”;

but the index must have given amusement to many from the

curious character of its entries, and Attorney-General Noy

particularly alluded to it in his speech at Prynne’s trial. Indexes

have sometimes been used as vehicles of satire, and the witty

Dr William King was the first to use them as a weapon of attack.

His earliest essay in this field was the index added to the second

edition of the Hon. Charles Boyle’s attack upon Bentley’s

Dissertation on the Epistles of Phalaris (1698).

To serve its purpose well, an index to a book must be compiled

with care, the references being placed under the heading that

the reader is most likely to seek. An index should be one and

indivisible, and not broken up into several alphabets; thus

every work, whether in one or more volumes, ought to have its

complete index. The mode of arrangement calls for special

attention; this may be either chronological, alphabetical or

according to classes, but great confusion will be caused by uniting

the three systems. The alphabetical arrangement is so simple,

convenient and easily understood that it has naturally superseded

the other forms, save in some exceptional cases. Much

of the value of an index depends upon the mode in which it is

printed, and every endeavour should be made to set it out with

clearness. In old indexes the indexed word was not brought to

the front, but was left in its place in the sentence, so that the

alphabetical order was not made perceptible to the eye. There

are few points in which the printer is more likely to go wrong

than in the use of marks of repetition, and many otherwise good

indexes are full of the most perplexing cases of misapplication

in this respect. The oft-quoted instance,

Mill on Liberty

——on the Floss

|

actually occurred in a catalogue. But in modern times there

374

has been a great advance in the art of indexing, especially since

the foundation in 1877 in England of the Index Society; and

the growth of great libraries has given a stimulus to this method

of making it easy for readers and researchers to find a ready

reference to the facts or discussions they require. Not only has

it become almost a sine qua non that any good book must have

its own index, but the art of indexing has been applied to those

books which are really collections of books (such as the Encyclopaedia

Britannica), to a great newspaper like the London Times,

and to the cataloguing of great libraries themselves. The work

in these more elaborate cases has been enormously facilitated by

the modern devices by means of which separate cards are used,

arranged in drawers and cases, American enterprise in this

direction having led the way. And the value of the work done

in this respect by the Congressional Library at Washington,

the British Museum and the London Library (notably by its

Subject Index published in 1909) cannot well be exaggerated.

(See also Bibliography).

There are numerous books on Indexing, but the best for any one

who wants to get a general idea is H. B. Wheatley’s How to make an

Index (1902).

1 Another old word occasionally used in the sense of an index is

“pye.” Sir T. Duffus Hardy, in some observations on the derivation

of the word “Pye-Book” (which most probably comes from the Latin

pica), remarks that the earliest use he had noted of pye in this sense

is dated 1547—“a Pye of all the names of such Balives as been to

accompte pro anno regni regis Edwardi Sexti primo.”

INDEX LIBRORUM PROHIBITORUM, the title of the official

list of those books which on doctrinal or moral grounds the

Roman Catholic Church authoritatively forbids the members of

her communion to read or to possess, irrespective of works

forbidden by the general rules on the subject. Most governments,

whether civil or ecclesiastical, have at all times in one

way or another acted on the general principle that some control

may and ought to be exercised over the literature circulated

among those under their jurisdiction. If we set aside the

heretical books condemned by the early councils, the earliest

known instance of a list of proscribed books being issued with

the authority of a bishop of Rome is the Notitia librorum apocryphorum

qui non recipiuntur, the first redaction of which, by

Pope Gelasius (494), was subsequently amplified on several

occasions. The document is for the most part an enumeration

of such apocryphal works as by their titles might be supposed

to be part of Holy Scripture (the “Acts” of Philip, Thomas

and Peter, and the Gospels of Thaddaeus, Matthias, Peter,

James the Less and others).1 Subsequent pontiffs continued to

exhort the episcopate and the whole body of the faithful to be

on their guard against heretical writings, whether old or new;

and one of the functions of the Inquisition when it was established

was to exercise a rigid censorship over books put in circulation.

The majority of the condemnations were at that time of a

specially theological character. With the discovery of the art

of printing, and the wide and cheap diffusion of all sorts of books

which ensued, the need for new precautions against heresy and

immorality in literature made itself felt, and more than one

pope (Sixtus IV. in 1479 and Alexander VI. in 1501) gave

special directions to the archbishops of Cologne, Mainz, Trier

and Magdeburg regarding the growing abuses of the printing

press; in 1515 the Lateran council formulated the decree De

Impressione Librorum, which required that no work should be

printed without previous examination by the proper ecclesiastical

authority, the penalty of unlicensed printing being excommunication

of the culprit, and confiscation and destruction of the books.

The council of Trent in its fourth session, 8th April 1546, forbade

the sale or possession of any anonymous religious book which

had not previously been seen and approved by the ordinary;

in the same year the university of Louvain, at the command

of Charles V., prepared an “Index” of pernicious and forbidden

books, a second edition of which appeared in 1550. In 1557,

and again in 1559, Pope Paul IV., through the Inquisition at

Rome, published what may be regarded as the first Roman

Index in the modern ecclesiastical use of that term (Index

auctorum et librorum qui tanquam haeretici aut suspecti aut

perversi ab Officio S. R. Inquisitionis reprobantur et in universa

Christiana republica interdicuntur). In this we find the three

classes which were to be maintained in the Trent Index:

authors condemned with all their writings; prohibited books,

the authors of which are known; pernicious books by anonymous

authors. An excessively severe general condemnation was

applied to all anonymous books published since 1519; and a

list of sixty-two printers of heretical books was appended.

This excessive rigour was mitigated in 1561. At the 18th session

of the council of Trent (26th February 1562), in consideration

of the great increase in the number of suspect and pernicious

books, and also of the inefficacy of the many previous “censures”

which had proceeded from the provinces and from Rome itself,

eighteen fathers with a certain number of theologians were

appointed to inquire into these “censures,” and to consider

what ought to be done in the circumstances. At the 25th session

(4th December 1563) this committee of the council was reported

to have completed its work, but as the subject did not seem

(on account of the great number and variety of the books) to

admit of being properly discussed by the council, the result

of its labours was handed over to the pope (Pius IV.) to deal with

as he should think proper. In the following March accordingly

were published, with papal approval, the Index librorum prohibitorum,

which continued to be reprinted and brought down to

date, and the “Ten Rules” which, supplemented and explained

by Clement VIII., Sixtus V., Alexander VII., and finally by

Benedict XIV. (10th July 1753), regulated the matter until the

pontificate of Leo XIII. The business of condemning pernicious

books and of correcting the Index to date has been since the

time of Pope Sixtus V. in the hands of the “Congregation of

the Index,” which consists of several cardinals, one of whom

is the prefect, and more or less numerous “consultors”

and “examiners of books.” An attempt has been made to

publish separately the Index Librorum Expurgandorum or Expurgatorius,

a catalogue of the works which may be read after the

deletion or amending of specified passages; but this was soon

abandoned.

With the alteration of social conditions, however, the Rules

of Trent ceased to be entirely applicable. Their application

to publications which had no concern with morals or religion

was no longer conceivable; and, finally, the penalties called for

modification. Already, at the Vatican Council, several bishops

had submitted requests for a reform of the Index, but the Council

was not able to deal with the question. The reform was accomplished

by Leo XIII., who, on the 25th of January 1897, published

the constitution Officiorum, in 49 articles. In this constitution,

although the writings of heretics in support of heresy are condemned

as before (No. 1), those of their books which contain

nothing against Catholic doctrine or which treat other subjects

are permitted (Nos. 2-3). Editions of the text of the Scriptures

are permitted for purposes of study; translations of the Bible

into the vulgar tongue have to be approved, while those published

by non-Catholics are permitted for the use of scholars (Nos. 5-8).

Obscene books are forbidden; the classics, however, are authorized

for educational purposes (Nos. 9-10). Articles 11-14 forbid

books which outrage God and sacred things, books which

propagate magic and superstition, and books which are pernicious

to society. The ecclesiastical laws relating to sacred images,

to indulgences, and to liturgical books and books of devotion are

maintained (Nos. 15-20). Articles 21-22 condemn immoral

and irreligious newspapers, and forbid writers to contribute to

them. Articles 23-26 deal with permissions to read prohibited

books; these are given by the bishop in particular cases, and

in the ordinary course by the Congregation of the Index. In

the second part of the constitution the pope deals with the

censorship of books. After indicating the official publications

for which the authorization of the divers Roman congregations

is required, he goes on to say that the others are amenable to the

ordinary of the editor and, in the case of regulars, to their

superior (Nos. 30-37). The examination of the books is entrusted

to censors, who have to study them without prejudice; if their

report is favourable, the bishop gives the imprimatur (Nos.

38-40). All books concerned with the religious sciences and

with ethics are submitted to preliminary censorship, and in

375

addition to this ecclesiastics have to obtain a personal authorization

for all their books and for the acceptance of the editorship

of a periodical (Nos. 41-42). The penalty of excommunication

ipso facto is only maintained for reading books written by

heretics or apostates in defence of heresy, or books condemned

by name under pain of excommunication by pontifical letters

(not by decrees of the Index). By the same constitution

Leo XIII. ordered the revision of the catalogue of the Index.

The new Index, which omits works anterior to 1600 as well as a

great number of others included in the old catalogue, appeared

in 1900. The encyclical Pascendi of Pius X. (8th September

1907) made it obligatory for periodicals amenable to the

ecclesiastical authority to be submitted to a censor, who subsequently

makes useful observations. The legislation of Leo

XIII. resulted in the better observance of the rules for the publication

of books, but apparently did not modify the practice as regards

the reading of prohibited books. It is to be regretted

that the catalogue does not discriminate among the prohibited

works according to the motive of their condemnation and the

danger ascribed to reading them. The tendency of the practice

among Catholics at large is to reduce these condemnations to

the proportions of the moral law.

See H. Reusch, Der Index der verbotenen Bücher (Bonn, 1883);

A. Arndt, De Libris prohibitis commentarii (Ratisbon, 1895); A.

Boudinhon, La Nouvelle Législation de l’index (Paris, 1899); J.

Hilgers, Der Index der verbotenen Bücher (Freiburg in B., 1904);

A. Vermeersch, De prohibitione et censura librorum (Tournai, 1907);

T. Hurley, Commentary on the Present Index Legislation (Dublin,

1908).

(A. Bo.*)

1 Hardouin, Conc. ii. 940; Labbé, Conc. ii. 938-941. The whole

document has also been reprinted in Smith’s Dict. of Chr. Antiq.,

art. “Prohibited Books.”

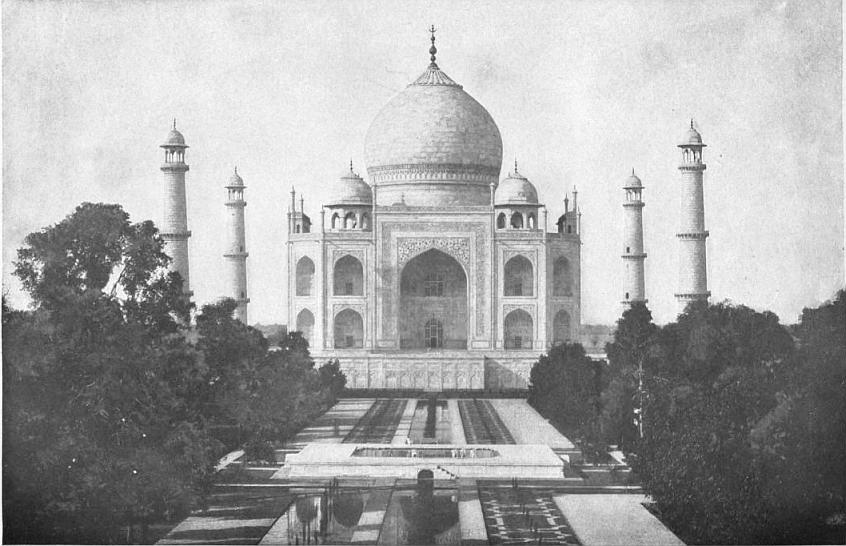

INDIA,1 a great country and empire of Asia under British

rule, inhabited by a congeries of different races, speaking upwards

of fifty different languages. The whole Indian empire, including

Burma, has an area of 1,766,000 sq. m., and a population

of 294 million inhabitants, being about equal to the area

and population of the whole of Europe without Russia. The

population more than doubles Gibbon’s estimate of 120

millions for all the races and nations which obeyed imperial

Rome.

The natives of India can scarcely be said to have a word of

their own by which to express their common country. In

Sanskrit, it would be called “Bharata-varsha,” from Bharata,

a legendary monarch of the Lunar line; but Sanskrit is no

more the vernacular of India than Latin is of Europe. The

name “Hindustan,” which was at one time adopted by European

geographers, is of Persian origin, meaning “the land of the

Hindus,” as Afghanistan means “the land of the Afghans.”

According to native usage, however, “Hindustan” is limited

either to that portion of the peninsula lying north of the Vindhya

mountains, or yet more strictly to the upper basin of the Ganges

where Hindi is the spoken language. The “East Indies,” as

opposed to the “West Indies,” is an old-fashioned and inaccurate

phrase, dating from the dawn of maritime discovery,

and still lingering in certain parliamentary papers. “India,”

the abstract form of a word derived through the Greeks from

the Persicized form of the Sanskrit sindhu, a “river,” pre-eminently

the Indus, has become familiar since the British

acquired the country, and is now officially recognized in the

imperial title of the sovereign.

The Country

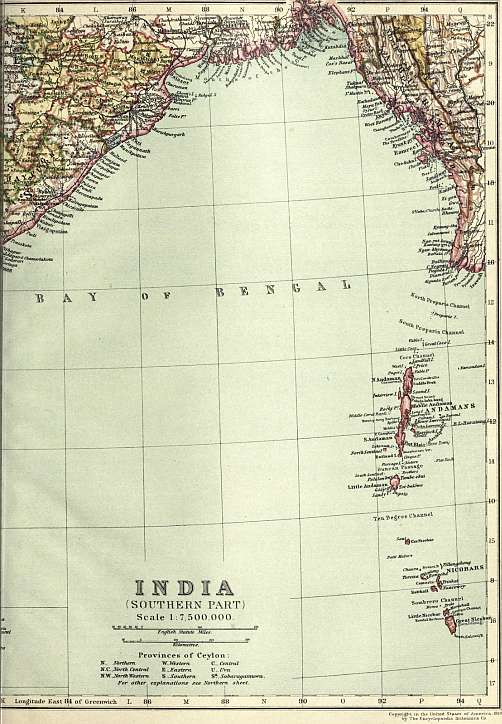

India, as thus defined, is the middle of the three irregularly

shaped peninsulas which jut out southwards from the mainland

of Asia, thus corresponding roughly to the peninsula

of Italy in the map of Europe. Its form is that of a

Position and shape.

great triangle, with its base resting upon the Himalayan

range and its apex running far into the ocean. The

chief part of its western side is washed by the Arabian Sea, and

the chief part of its eastern side by the Bay of Bengal. It extends

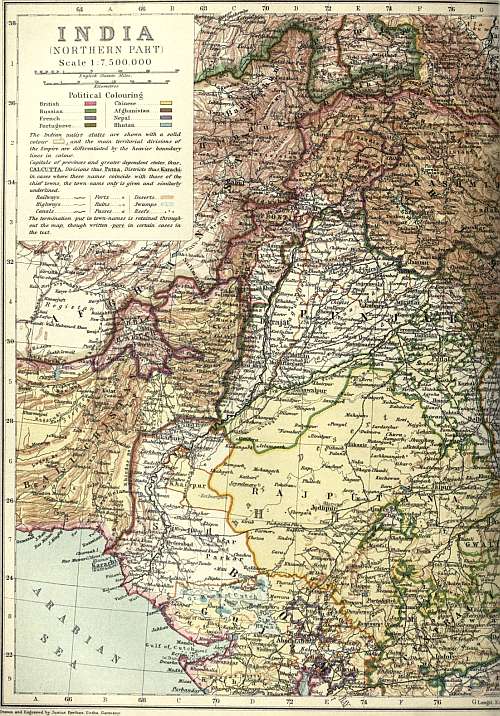

from the 8th to the 37th degree of north latitude, that is to say,

from the hottest regions of the equator to far within the temperate

zone. The capital, Calcutta, lies in 88° E., so that when the sun

sets at six o’clock there, it is just past mid-day in England and

early morning in New York. The length of India from north to

south, and its greatest breadth from east to west, are both about

1900 m.; but the triangle tapers with a pear-shaped curve to a

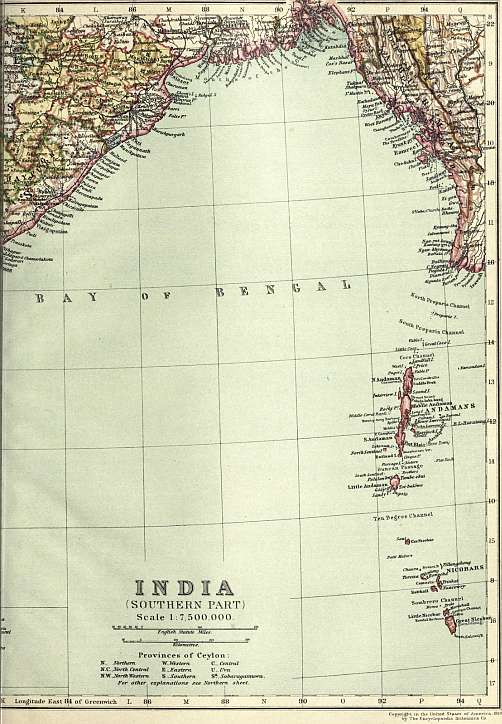

point at Cape Comorin, its southern extremity. To this compact

dominion the British have added Burma, the strip of country

on the eastern shores of the Bay of Bengal. But on the other

hand the adjacent island of Ceylon has been administratively

severed and placed under the Colonial Office. Two groups of

islands in the Bay of Bengal, the Andamans and the Nicobars;

one group in the Arabian Sea, the Laccadives; and the outlying

station of Aden at the mouth of the Red Sea, with Perim, and

protectorates over the island of Sokotra, along the southern

coast of Arabia and in the Persian Gulf, are all politically included

within the Indian empire; while on the coast of the peninsula

itself, Portuguese and French settlements break at intervals

the continuous line of British territory.

India is shut off from the rest of Asia on the north by a vast

mountainous region, known in the aggregate as the Himalayas, amid

which lie the independent states of Nepal and Bhutan,

with the great table-land of Tibet behind. The native

Boundaries.

principality of Kashmir occupies the north-western angle of

India. At this north-western angle (in 35° N., 74° E.) the mountains

curve southwards, and India is separated by the well-marked ranges

of the Safed Koh and Suliman from Afghanistan; and by a southern

continuation of lower hills from Baluchistan. Still farther southwards,

India is bounded along the W. and S.W. by the Arabian Sea

and Indian Ocean. Turning northwards from the southern extremity

at Cape Comorin (8° 4′ 20″ N., 77° 35′ 35″ E.), the long

sea-line of the Bay of Bengal forms the main part of its eastern

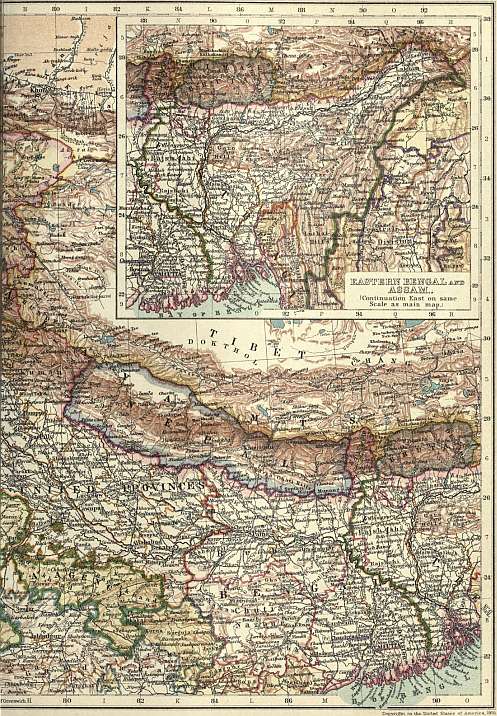

boundary. But on the north-east, as on the north-west, India has

again a land frontier. The Himalayan ranges at the north-eastern

angle (in about 28° N., 97° E.) throw off spurs and chains to the

south-east, which separate Eastern Bengal from Assam and Burma.

Stretching south-eastwards from the delta of the Irrawaddy, a confused

succession of little explored ranges separates the Burmese

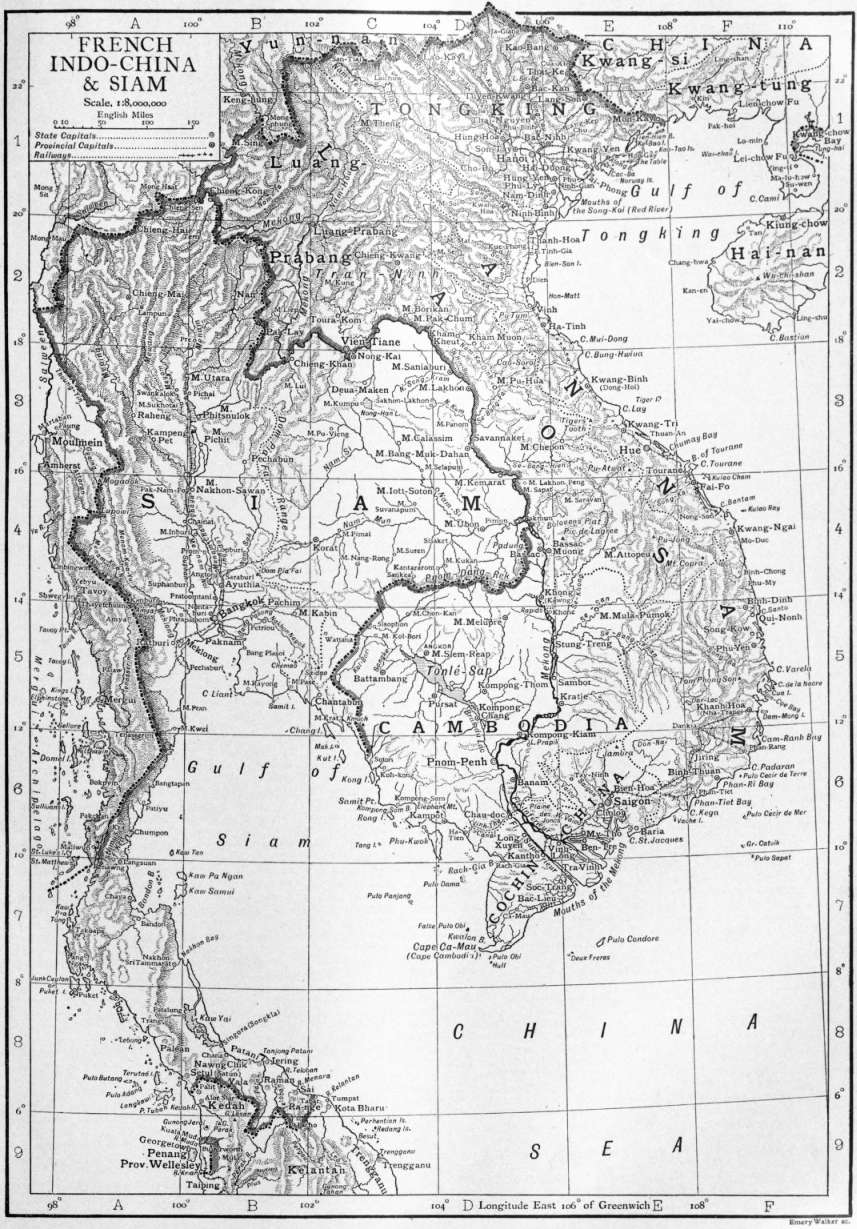

division of Tenasserim from the native kingdom of Siam. The

boundary line runs down to Point Victoria at the extremity of

Tenasserim (9° 59′ N., 98° 32′ E.), following in a somewhat rough

manner the watershed between the rivers of the British territory on

the west and of Siam on the east.

The empire included within these boundaries is rich in varieties

of scenery and climate, from the highest mountains in the world to

Three regions.

vast river deltas raised only a few inches above the level

of the sea. It practically forms a continent rather than

a country. But if we could look down on the whole from

a balloon, we should find that India (apart from Burma, for which

see the separate article) consists of three separate and well-defined

tracts.

The first of the three regions is the Himalaya (q.v.) mountains and

their offshoots to the southward, comprising a system of stupendous

ranges, the loftiest in the world. They are the Emodus

of Ptolemy (among other names), and extend in the shape

Himalayas.

of a scimitar, with its edge facing southwards, for a distance

of 1500 m. along the northern frontier of India. At the north-eastern

angle of that frontier, the Dihang river, the connecting link

between the Tsanpo of Tibet and the Brahmaputra of Assam,

bursts through the main axis of the range. At the opposite or north-western

angle, the Indus in like manner pierces the Himalayas, and

turns southwards on its course through the Punjab. This wild

region is in many parts impenetrable to man, and nowhere yields a

passage for a modern army. Ancient and well-known trade routes

exist, by means of which merchandise from the Punjab finds its way

over heights of 18,000 ft. into Eastern Turkestan and Tibet. The

Muztagh (Snowy Mountain), the Karakoram (Black Mountain), and

the Changchenmo are the most famous of these passes.

The Himalayas not only form a double wall along the north of

India, but at both their eastern and western extremities send out

ranges to the south, which protect its north-eastern and north-western

frontiers. On the north-east, those offshoots, under the

name of the Naga and Patkoi mountains, &c., form a barrier between

the civilized districts of Assam and the wild tribes of Upper Burma.

On the opposite or north-western frontier of India, the mountainous

offshoots run down the entire length of the British boundaries from

the Himalayas to the sea. As they proceed southwards, their best

marked ranges are in turn known as the Safed Koh, the Suliman

and the Hala mountains. These massive barriers have peaks of

great height, culminating in the Takht-i-Suliman or Throne of

Solomon, 11,317 ft. above the level of the sea. But the mountain

wall is pierced at the corner where it strikes southwards from the

Himalayas by an opening through which the Kabul river flows into

India. An adjacent opening, the Khyber Pass, the Kurram Pass

to the south of it, the Gomal Pass near Dera Ismail Khan, the Tochi

Pass between the two last-named, and the famous Bolan Pass

376

still farther south, furnish the gateways between India and Afghanistan.

The Hala, Brahui and Pab mountains, forming the southern

hilly offshoots between India and Baluchistan, have a much less

elevation.

The wide plains watered by the Himalayan rivers form the second

of the three regions into which we have divided India. They extend

from the Bay of Bengal on the east to the Afghan frontier

and the Arabian Sea on the west, and contain the richest

River plains.

and most densely crowded provinces of the empire. One

set of invaders after another has from prehistoric times entered

by the passes at their eastern and north-western frontiers. They

followed the courses of the rivers, and pushed the earlier comers

southwards before them towards the sea. About 167 millions of

people now live on and around these river plains, in the provinces

known as the lieutenant-governorship of Bengal, Eastern Bengal and

Assam, the United Provinces, the Punjab, Sind, Rajputana and

other native states.

The vast level tract which thus covers northern India is watered

by three distinct river systems. One of these systems takes its rise

in the hollow trough beyond the Himalayas, and issues

through their western ranges upon the Punjab as the

River systems.

Sutlej and Indus. The second of the three river systems

also takes its rise beyond the double wall of the Himalayas, not very

far from the sources of the Indus and the Sutlej. It turns, however,

almost due east instead of west, enters India at the eastern extremity

of the Himalayas, and becomes the Brahmaputra of Eastern Bengal

and Assam. These rivers collect the drainage of the northern slopes

of the Himalayas, and convey it, by long and tortuous although

opposite routes, into India. Indeed, the special feature of the

Himalayas is that they send down the rainfall from their northern as

well as from their southern slopes to the Indian plains. The third

river system of northern India receives the drainage of their southern

slopes, and eventually unites into the mighty stream of the Ganges.

In this way the rainfall, alike from the northern and southern slopes

of the Himalayas, pours down into the river plains of Bengal.

The third division of India comprises the three-sided table-land

which covers the southern half or more strictly peninsular portion

of India. This tract, known in ancient times as the

Northern table-land.

Deccan (Dakshin), literally “the right hand or south,”

comprises the Central Provinces and Berar, the presidencies

of Madras and Bombay, and the territories of Hyderabad,

Mysore and other feudatory states. It had in 1901 an aggregate

population of about 100 millions.

The northern side rests on confused ranges, running with a general

direction of east to west, and known in the aggregate as the Vindhya

mountains. The Vindhyas, however, are made up of several distinct

hill systems. Two sacred peaks guard the flanks in the extreme east

and west, with a succession of ranges stretching 800 m. between.

At the western extremity, Mount Abu, famous for its exquisite Jain

temples, rises, as a solitary outpost of the Aravalli hills 5650 ft. above

the Rajputana plain, like an island out of the sea. On the extreme

east, Mount Parasnath—like Mount Abu on the extreme west,

sacred to Jain rites—rises to 4400 ft. above the level of the Gangetic

plains. The various ranges of the Vindhyas, from 1500 to over

4000 ft. high, form, as it were, the northern wall and buttresses

which support the central table-land. Though now pierced by road

and railway, they stood in former times as a barrier of mountain and

jungle between northern and southern India, and formed one of the

main obstructions to welding the whole into an empire. They

consist of vast masses of forests, ridges and peaks, broken by

cultivated valleys and broad high-lying plains.

The other two sides of the elevated southern triangle are known

as the Eastern and Western Ghats. These start southwards from

the eastern and western extremities of the Vindhya

system, and run along the eastern and western coasts of

Ghats.

India. The Eastern Ghats stretch in fragmentary spurs and ranges

down the Madras presidency, here and there receding inland and

leaving broad level tracts between their base and the coast. The

Western Ghats form the great sea-wall of the Bombay presidency,

with only a narrow strip between them and the shore. In many

parts they rise in magnificent precipices and headlands out of the

ocean, and truly look like colossal “passes or landing-stairs” (gháts)

from the sea. The Eastern Ghats have an average elevation of

1500 ft. The Western Ghats ascend more abruptly from the sea to an

average height of about 3000 ft. with peaks up to 4700, along the

Bombay coast, rising to 7000 and even 8760 in the upheaved angle

which they unite to form with the Eastern Ghats, towards their

southern extremity.

The inner triangular plateau thus enclosed lies from 1000 to 3000

ft. above the level of the sea. But it is dotted with peaks and

seamed with ranges exceeding 4000 ft. in height. Its best known

hills are the Nilgiris, with the summer capital of Madras, Ootacamund,

7000 ft. above the sea. The highest point is Dodabetta Peak

(8760 ft.), at the upheaved southern angle.

On the eastern side of India, the Ghats form a series of spurs and

buttresses for the elevated inner plateau, rather than a continuous

mountain wall. They are traversed by a number of

broad and easy passages from the Madras coast. Through

Eastern Ghats.

these openings the rainfall of the southern half of the inner

plateau reaches the sea. The drainage from the northern or Vindhyan

edge of the three-sided table-land falls into the Ganges. The

Nerbudda and Tapti carry the rainfall of the southern slopes of the

Vindhyas and of the Satpura hills, in almost parallel lines, into the

Gulf of Cambay. But from Surat, in 21° 9′, to Cape Comorin, in

8° 4′, no large river succeeds in reaching the western coast from the

interior table-land. The Western Ghats form, in fact, a lofty unbroken

barrier between the waters of the central plateau and the

Indian Ocean. The drainage has therefore to make its way across

India to the eastwards, now turning sharply round projecting ranges,

now tumbling down ravines, or rushing along the valleys, until the

rain which the Bombay sea-breeze has dropped upon the Western

Ghats finally falls into the Bay of Bengal. In this way the three great

rivers of the Madras Presidency, viz., the Godavari, the Kistna and

the Cauvery, rise in the mountains overhanging the western coast,

and traverse the whole breadth of the central table-land before they

reach the sea on the eastern shores of India.

Of the three regions of India thus briefly surveyed, the first, or

the Himalayas, lies for the most part beyond the British frontier,

but a knowledge of it supplies the key to the ethnology and history of

India. The second region, or the great river plains in the north,

formed the theatre of the ancient race-movements which shaped the

civilization and the political destinies of the whole Indian peninsula.

The third region, or the triangular table-land in the south, has a

character quite distinct from either of the other two divisions, and

a population which is now working out a separate development of

its own. Broadly speaking, the Himalayas are peopled by Mongoloid

tribes; the great river plains of Hindustan are still the home of the

Aryan race; the triangular table-land has formed an arena for a

long struggle between that gifted race from the north and what is

known as the Dravidian stock in the south.

Geology.

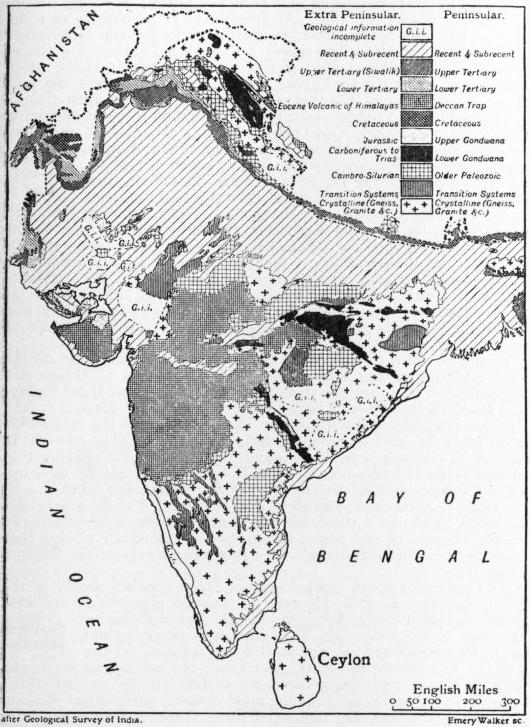

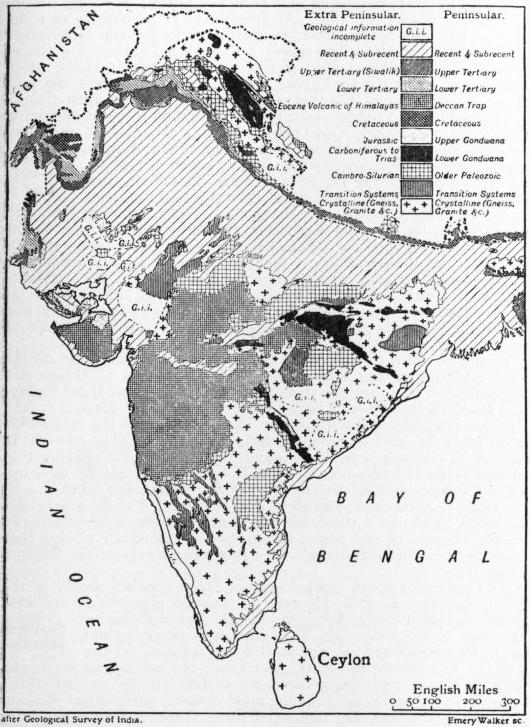

Geologically, as well as physically, India consists of three distinct

regions, the Himalayas, the Peninsula, and—between these two—the

Indo-Gangetic plain with its covering of alluvium and wind-blown

sands. The contrast between the Himalayas and the

Peninsula is one of fundamental importance. The former, from the

Tertiary period even to the present day, has been a region of compression;

the latter, since the Carboniferous period at least, has

been a region of equilibrium or of tension. In the former even the

Pliocene beds are crumpled and folded, overfolded and overthrust

in the most violent fashion; in the latter none but the oldest beds,

certainly none so late as the Permian, have been crumpled or crushed—occasionally

they are bent and frequently they are faulted, but

the faults, though sometimes of considerable magnitude, are simple

dislocations, unaccompanied by any serious disturbance of the

strata. The greater part of the Himalayan region lay beneath the

sea from early Palaeozoic times to the Eocene period, and the

deposits are accordingly marine; the Peninsula, on the other hand,

has been land since the Permian period at least—there is, indeed,

no evidence that it was ever beneath the sea—only on its margins

are any marine deposits to be found. It should, however, be mentioned

that in the eastern part of the Himalayas some of the beds

resemble those of the Peninsula, and it appears that a part of the old

Indian continent has here been involved in the folds of the mountain

chain.

The geology of the Himalayas being described elsewhere (see

Himalayas), the following account deals only with the Indo-Gangetic

plain and the Peninsula.

The Indo-Gangetic Plain covers an area of about 300,000 sq. m.,

and varies in width from 90 to nearly 300 m. It rises very gradually

from the sea at either end; the lowest point of the watershed

between the Punjab rivers and the Ganges is about 924 ft. above the

sea. This point, by a line measured down the valley, but not following

the winding of the river, is about 1050 m. from the mouth of the

Ganges and 850 m. from the mouth of the Indus, so that the average

inclination of the plain, from the central watershed to the sea, is

only about 1 ft. per mile. It is less near the sea, where for long

distances there is no fall at all. Near the watershed it is generally

more; but there is here no ridge of high ground between the Indus

and the Ganges, and a very trifling change of level would often turn

the upper waters of one river into the other. It is not unlikely that

such changes have in past time occurred; and if so an explanation

is afforded of the occurrence of allied forms of freshwater dolphins

(Platanista) and of many other animals in the two rivers and in the

Brahmaputra.

The alluvial deposits of the plain, as made known by the boring

at Calcutta, prove a gradual depression of the area in recent times.

There are peat and forest beds, which must have grown quietly at

the surface, alternating with deposits of gravel, sand and clay. The

thickness of the delta deposit is unknown; 481 ft. was proved at

the bore hole, but probably this represents only a small part of the

deposit. Outside the delta, in the Bay of Bengal, is a deep depression

known as the “swatch of no ground”; all around it the soundings

are only of 5 to 10 fathoms, but they very rapidly deepen to over

300 fathoms. Mr J. Ferguson has shown that the sediment is

carried away from this area by the set of the currents; probably

then it has remained free from sediment whilst the neighbouring

sea bottom has gradually been filled up. If so, the thickness of the

alluvium is at least 1800 ft., and may be much more. At Lucknow

377

a boring was driven through the Gangetic alluvium to a depth of

1336 ft. from the surface, or nearly 1000 ft. below sea-level. Even

at this depth there was no indication of an approach to the base of

the alluvial deposits.

|

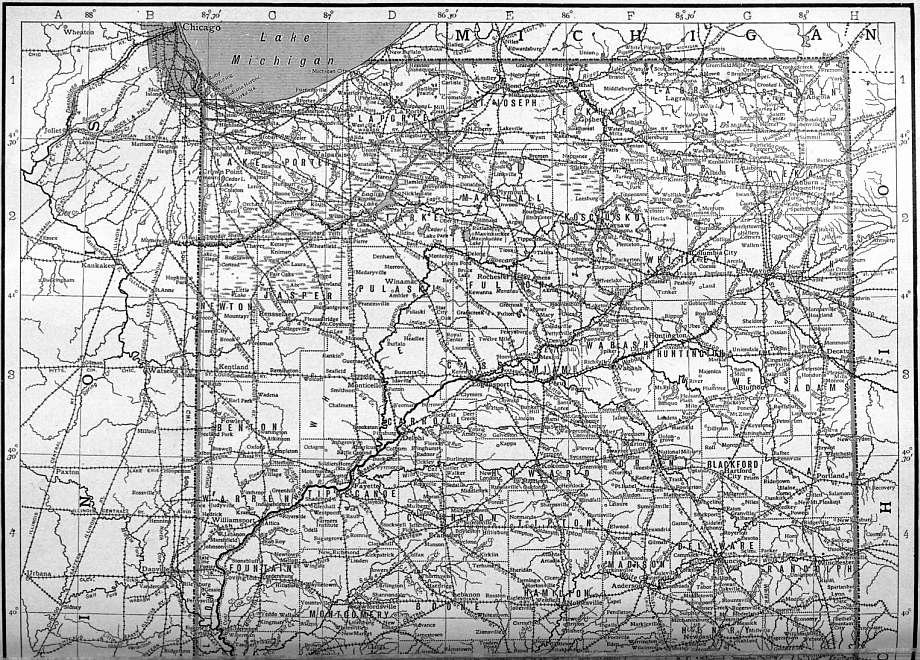

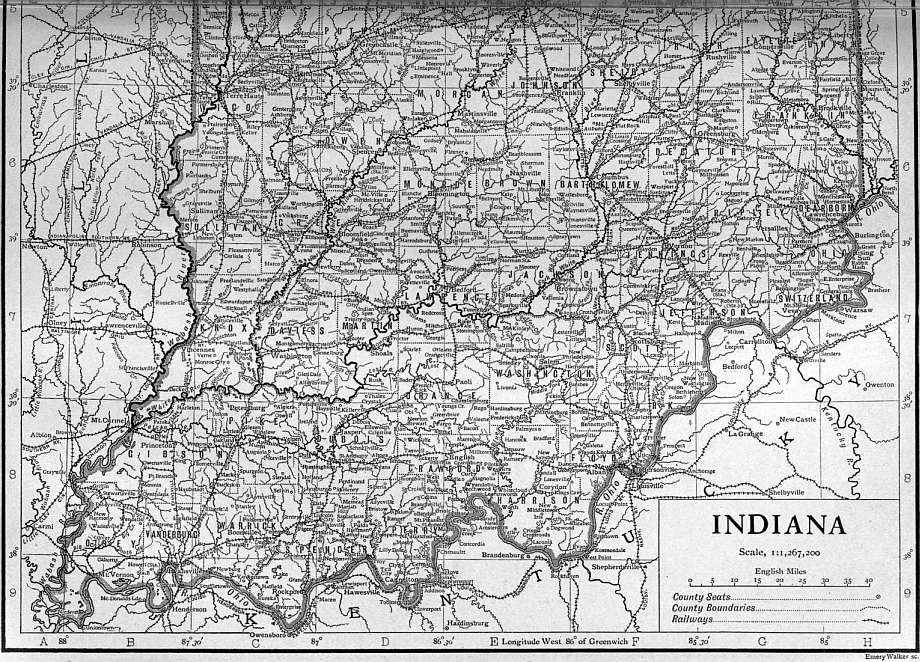

|

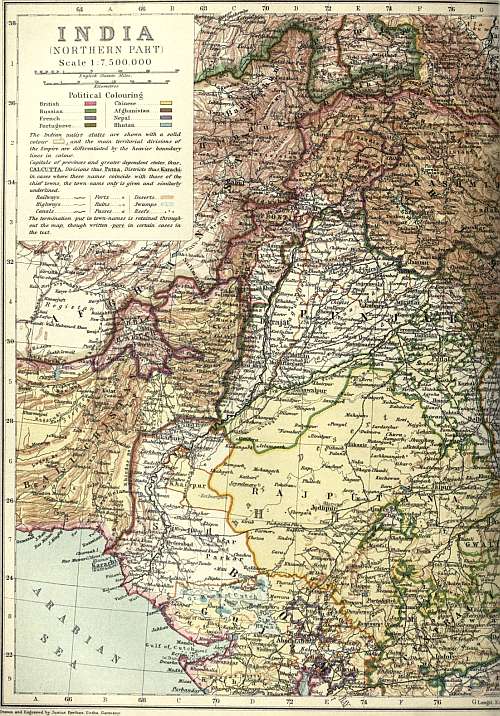

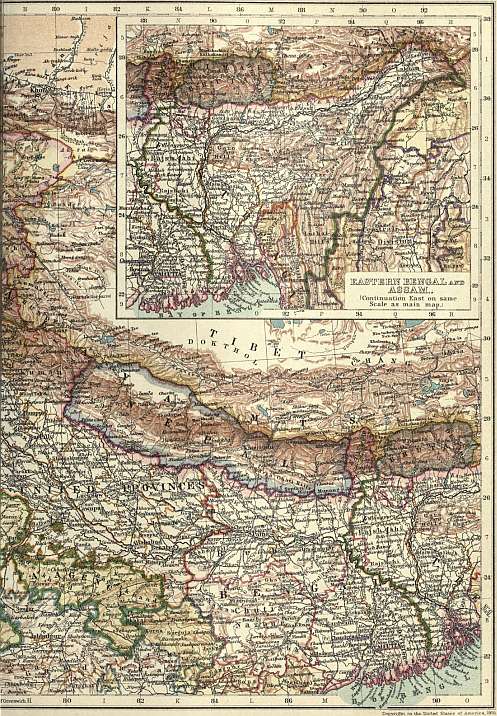

(Click to enlarge left side.)

(Click to enlarge right side.)

The deposits of the Indo-Gangetic plain are of modern date and

the formation of the depression which they fill is almost certainly

connected with the elevation of the Himalayas. Both movements

are probably still going on. The alluvial deposits prove depression

in quite recent geological times; and within the Himalayan region

earthquakes are still common, whilst in Peninsular India they are

rare.

Peninsular India.—The oldest rocks of this region consist of

gneiss, granite and other crystalline rocks. They cover a large area

in Bengal and Madras and extend into Ceylon; and they are found

also in Bundelkhand and in Gujarat. Upon them rest the unfossiliferous

strata known to Indian geologists as the Transition and

Vindhyan series. The Transition rocks are often violently folded

and are frequently converted into schists. In the south, where they

are known as the Dharwar series, they form long and narrow bands

running from north-north-west to south-south-east across the

ancient gneiss; and it is interesting to note that all the quartz-reefs

which contain gold in paying quantities occur in the Dharwar series.

The Transition rocks are of great but unknown age. The Vindhyan

rocks which succeed them are also of ancient date. But long before

the earliest Vindhyan rocks were laid down the Transition rocks

had been altered and contorted. Occasionally the Vindhyan beds

themselves are strongly folded, as in the east of the Cuddapah

basin; but this was the last folding of any violence which has

occurred in the Peninsula. In more recent times there have been

local disturbances, and large faults have in places been formed;

but the greater part of the Peninsula rocks are only slightly disturbed.

The Vindhyan series is generally sharply marked off from older

rocks; but in the Godavari valley there is no well-defined line

between them and the Transition rocks. The Vindhyan beds are

divided into two groups. The lower, with an estimated thickness

of only 2000 ft., or slightly more, cover a large area—extending,

with but little change of character, from the Sone valley in one

direction to Cuddapah, and in a diverging line to near Bijapur—in

each case a distance of over 700 m. The upper Vindhyans cover a

much smaller area, but attain a thickness of about 12,000 ft. The

Vindhyans are well-stratified beds of sandstone and shale, with some

limestones. As yet they have yielded no trace of fossils, and their

exact age is consequently unknown. They are however certainly

Pre-Permian, and it is most probable that they belong to the early

part of the Palaeozoic era. The total absence of fossils is a remarkable

fact, and one for which it is difficult to account, as the beds are

for the most part quite unaltered. Even if they are entirely of

freshwater origin, we should expect that some traces of life from the

waters or neighbouring land would be found.

The Gondwana series is in many respects the most interesting and

important series of the Indian Peninsula. The beds are almost

entirely of freshwater origin. Many subdivisions have been made,

but here we need only note the main division into two great groups:

Lower Gondwanas, 13,000 ft. thick; Upper Gondwanas, 11,000 ft.

thick. The series is mainly confined to the area of country between

the Nerbudda and the Sone on the north, and the Kistna on the

south; but the western part of this region is in great part covered

by newer beds. The lowest Gondwanas are very constant in character,

wherever they are found; the upper members of the lower

division show more variation, and this divergence of character in

different districts becomes more marked in the Upper Gondwana

series. Disturbances have occurred in the lower series before the

formation of the upper.

The Gondwana beds contain fossils which are of very great interest.

In large part these consist of plants which grew near the margins of

the old rivers, and which were carried down by floods, and deposited

in the alluvial plains, deltas and estuarine areas of the old Gondwana

period. The plants of the Lower Gondwanas consist chiefly of

acrogens (Equisetaceae and ferns) and gymnogens (cycads and conifers),

the former being the more abundant. The same classes of plants

occur in the Upper Gondwanas; but there the proportions are

reversed, the conifers, and still more the cycads, being more numerous

than the ferns, whilst the Equisetaceae are but sparingly found.

But even within the limits of the Lower Gondwana series there are

great diversities of vegetation, three distinct floras occurring in the

three great divisions of that formation. In many respects the flora

of the highest of these three divisions (the Panchet group) is more

nearly related to that of the Upper Gondwanas than it is to the other

Lower Gondwana floras. Although during the Gondwana period

the flora of India differed greatly from that of Europe, it was strikingly

similar to the contemporaneous floras of South America, South

Africa and Australia. It is somewhat remarkable that this characteristically

southern flora, known as the Glossopteris Flora (from

the name of one of the most characteristic genera), has also been

found in the north of Russia.

One of the most interesting facts in the history of the Gondwana

series is the occurrence near the base (in the Talchir group) of large

striated boulders in a fine mud or silt, the boulders in one place

resting upon rock (of Vindhyan age) which is also striated. These

beds are the result of ice-action, and it is interesting to note

that a similar boulder bed is associated with the Glossopteris-bearing

deposits of Australia, South Africa and probably South

America.

The Damuda series, the middle division of the Lower Gondwanas,

is the chief source of coal in Peninsular India, yielding more of that

mineral than all other formations taken together. The Karharbari

group is the only other coal-bearing formation of any value. The

Damudas are 8400 ft. thick in the Raniganj coal-field, and about

10,000 ft. thick in the Satpura basin. They consist of three divisions;

coal occurs in the upper and lower, ironstone (without coal) in the

middle division. The Raniganj coal-field is the most important in

India. It covers an area of about 500 sq. m. and is traversed by

the Damuda river, along which run the road from Calcutta to

Benares and the East Indian railway. From its situation and

importance this coal-field is better known than any other in India.

The upper or Raniganj series (stated by the Geological Survey to

be 5000 ft. thick) contains eleven seams, having a total thickness

of 120 ft., in the eastern district, and thirteen seams, 100 ft. thick,

in the western district. The average thickness of the seams worked

is from 12 to 18 ft., but occasionally a seam attains a great thickness—20

to 80 ft. The lower or Barakar series (2000 ft. thick) contains

four seams, of a total thickness of 69 ft. Compared with English

coals those of this coal-field are of but poor quality; they contain

much ash, and are generally non-coking. The seams of the lower

series are the best, and some of these at Sanktoria, near the Barakar

river, are fairly good for coke and gas. The best coal in India is in

the small coal-field at Karharbari. The beds there are lower in the

series than those of the Raniganj field; they belong to the upper

part of the Talchir group, the lowest of the Gondwana series. The

coal-bearing beds cover an area of only about 11 sq. m.; there are

three seams, varying from 9 to 33 ft. thick. The lowest seam is the

best, and this is as good as English steam coal. This coal-field, now

largely worked, is the property of the East Indian railway, which

is thus supplied with fuel at a cheaper rate than any other railway

in the world. Indian coal usually contains phosphoric acid, which

greatly lessens its value for iron-smelting.

The Damuda series, which, as we have seen, is the chief source of

coal in India, is also one of the most important sources of iron. The

ore occurs in the middle division, coal in the highest and lowest.

The ore is partly a clay ironstone, like that occurring in the Coal-measures

of England, partly an oxide of iron or haematite, and it

generally contains phosphorus. Excellent iron-ore occurs in the

crystalline rocks south of the Damuda river as also in many other

parts of India. Laterite (see below) is sometimes used as ore. It

378

is very earthy and of a low percentage; but it contains only a

comparatively small proportion of phosphorus.

The want of limestone for flux, within easy reach, is generally a

great drawback as regards iron-smelting in India. Kankar or ghutin

(concretionary carbonate of lime) is collected for this purpose from

the river-beds and alluvial deposits. It sometimes contains as much

as 70% of carbonate of lime; but generally the amount is much

less and the fluxing value proportionally diminished. The real

difficulty in India is to find the ore, the fuel, and the flux in sufficiently

close proximity to yield a profit.

Contemporaneously with the formation of the upper part of the

Gondwana series marine deposits of Jurassic age were laid down in

Cutch. Cretaceous beds of marine origin are also found in Cutch,

Kathiawar and the Nerbudda valley on the northern margin of the

Peninsula, and near Pondicherry and Trichinopoly on its south-eastern

margin. There is a striking difference between the Cretaceous

faunas of the two areas, the fossils from the north being closely

allied to those of Europe, while those of the south (Pondicherry and

Trichinopoly) are very different and are much more nearly related

to those from the Cretaceous of Natal. It is now very generally

believed that in Jurassic and Cretaceous times a great land-mass

stretched from South Africa through Madagascar to India, and that

the Cretaceous deposits of Cutch, &c., were laid down upon its

northern shore, and those of Pondicherry and Trichinopoly upon its

southern shore. The land probably extended as far as Assam, for

the Cretaceous fossils of Assam are similar to those of the south.

The enormous mass of basaltic rock known as the Deccan Trap

is of great importance in the geological structure of the Indian

Peninsula. It now covers about 200,000 sq. m., and formerly

extended over a much wider area. Where thickest, the traps are at

least 6000 ft. thick. They form some of the most striking physical

features of the Peninsula, many of the most prominent hill ranges

having been carved out of the basaltic flows. The great volcanic

outbursts which produced this trap commenced in the Cretaceous

period and lasted on into the Eocene period.

Laterite is a ferruginous and argillaceous rock, varying from 30 to

200 ft. thick, which often occurs over the trap area and also over

the gneiss. As a rule it makes rather barren land; it is highly

porous, and the rain rapidly sinks into it. Laterite may be roughly

divided into two kinds, high-level and low-level laterites. It has

usually been formed by the decomposition in situ of the rock on which

it rests, but it is often broken up and re-deposited elsewhere.

Meteorology.

The great peninsula of India, with its lofty mountain ranges

behind and its extensive seaboard exposed to the first violence of

the winds of two oceans, forms an exceptionally valuable and interesting

field for the study of meteorological phenomena.

From the gorge of the Indus to that of the Brahmaputra, a distance

of 1400 m., the Himalayas form an unbroken watershed, the northern

flank of which is drained by the upper valleys of these

two rivers; while the Sutlej, starting from the southern

Himalayas.

foot of the Kailas Peak, breaks through the watershed, dividing it

into two very unequal portions, that to the north-west being the

smaller. The average elevation of the Himalaya crest may be

taken at not less than 19,000 ft., and therefore equal to the height

of the lower half of the atmosphere; and indeed few of the passes

are under 16,000 or 17,000 ft. Across this mountain barrier there

appears to be a constant flow of air, more active in the day-time

than at night, northwards to the arid plateau of Tibet. There is

no reason to believe that any transfer of air takes place across the

Himalayas in a southerly direction, unless indeed in those most

elevated regions of the atmosphere which lie beyond the range of

observation; but a nocturnal flow of cooled air, from the southern

slopes, is felt as a strong wind where the rivers debouch on the plains,

more especially in the early morning hours; and this probably

contributes in some degree to lower the mean temperature of that

belt of the plains which fringes the mountain zone.

At the foot of the great mountain barrier, and separating it from

the more ancient land which now forms the highlands of the peninsula,

a broad plain, for the most part alluvial, stretches from

sea to sea. On the west, in the dry region, this is occupied

Indus plain.

partly by the alluvial deposits of the Indus and its tributaries

and the saline swamps of Cutch, partly by the rolling sands

and rocky surface of the desert of Jaisalmer and Bikaner, and the

more fertile tracts to the eastward watered by the Luni. Over the

greater part of this region rain is of rare occurrence; and not infrequently

more than a year passes without a drop falling on the

parched surface. On its eastern margin, however, in the neighbourhood

of the Aravalli hills, and again in the northern Punjab, rain is

more frequent, occurring both in the south-west monsoon and also

at the opposite season in the cold weather. As far south as Sirsa and

Multan the average rainfall does not much exceed 7 in.

The alluvial plain of the Punjab passes into that of the Gangetic

valley without visible interruption. Up or down this plain, at

opposite seasons, sweep the monsoon winds, in a direction

at right angles to that of their nominal course; and thus

Gangetic plain.

vapour which has been brought by winds from the Bay of

Bengal is discharged as snow and rain on the peaks and hillsides of

the Western Himalayas. Nearly the whole surface is under cultivation,

and it ranks among the most productive as well as the most

densely populated regions of the world. The rainfall diminishes

from 100 in. in the south-east corner of the Gangetic delta to less

than 30 in. at Agra and Delhi, and there is an average difference of

from 15 to 25 in. between the northern and southern borders of the

plain.

Eastward from the Bengal delta, two alluvial plains stretch up

between the hills which connect the Himalayan system with that of

the Burmese peninsula. The first, or the valley of Assam

and the Brahmaputra, is long and narrow, bordered on

Eastern Bengal.

the north by the Himalayas, on the south by the lower

plateau of the Garo, Khasi and Naga hills. The other, short and

broad, and in great part occupied by swamps and jhils, separates

the Garo, Khasi and Naga hills from those of Tippera and the

Lushai country. The climate of these plains is damp and equable,

and the rainfall is prolonged and generally heavy, especially on the

southern slopes of the hills. A meteorological peculiarity of some

interest has been noticed, more especially at the stations of Sibsagar

and Silchar, viz. the great range of the diurnal variation of barometric

pressure during the afternoon hours,—which is the more

striking, since at Rurki, Lahore, and other stations near the foot

of the Western Himalayas this range is less than in the open plains.

The highlands of the peninsula, which are cut off from the encircling

ranges by the broad Indo-Gangetic plain, are divided into two

unequal parts by an almost continuous chain of hills

running across the country from west by south to east by

Central table-land.

north, just south of the Tropic of Cancer. This chain may

be regarded as a single geographical feature, forming one

of the principal watersheds of the peninsula, the waters to the north

draining chiefly into the Nerbudda and the Ganges, those to the

south into the Tapti, the Mahanadi, the Godavari and some smaller

streams. In a meteorological point of view it is of considerable

importance. Together with the two parallel valleys of the Nerbudda

and Tapti, which drain the flanks of its western half, it gives, at

opposite seasons of the year, a decided easterly and westerly direction

to the winds of this part of India, and condenses a tolerably copious

rainfall during the south-west monsoon.

Separated from this chain by the valley of the Nerbudda on the

west, and that of the Sone on the east, the plateau of Malwa and

Baghelkhand occupies the space intervening between these valleys

and the Gangetic plain. On the western edge of the plateau are the

Aravalli hills, which run from near Ahmedabad up to the neighbourhood

of Delhi, and include one hill, Mount Abu, over 5000 ft. in

height. This range exerts an important influence on the direction

of the wind, and also on the rainfall. At Ajmer, an old meteorological

station at the eastern foot of the range, the wind is predominantly

south-west, and there and at Mount Abu the south-west

monsoon rains are a regularly recurrent phenomenon,—which can

hardly be said of the region of scanty and uncertain rainfall that

extends from the western foot of the range and merges in the Bikaner

desert.

The peninsula south of the Satpura range consists chiefly of the

triangular plateau of the Deccan, terminating abruptly on the west

in the Sahyadri range (Western Ghats), and shelving to

the east (Eastern Ghats). This plateau is swept by the

Southern plateau.

south-west monsoon, but not until it has surmounted the

western barrier of the Ghats; and hence the rainfall is, as a rule,

light at Poona and places similarly situated under the lee of the

range, and but moderate over the more easterly parts of the plateau.

The rains, however, are prolonged some three or four weeks later

than in tracts to the north of the Satpuras, since they are also

brought by the easterly winds which blow from the Bay of Bengal in

October and the early part of November, when the recurved southerly

wind ceases to blow up the Gangetic valley, and sets towards the

south-east coast.

At the junction of the Eastern and Western Ghats rises the bold

triangular plateau of the Nilgiris, and to the south of them come

the Anamalais, the Palnis, and the hills of Travancore.

These ranges are separated from the Nilgiris by a broad

Southern India.

depression or pass known as the Palghat Gap, some 25 m.

wide, the highest point of which is only 1500 ft. above the sea. This

gap affords a passage to the winds which elsewhere are barred by the

hills of the Ghat chain. The country to the east of the gap receives

the rainfall of the south-west monsoon; and during the north-east

monsoon ships passing Beypur meet with a stronger wind from the

land than is felt elsewhere on the Malabar coast. In the strip of low

country that fringes the peninsula below the Ghats the rainfall is

heavy and the climate warm and damp, the vegetation being dense

and characteristically tropical, and the steep slopes of the Ghats,

where they have not been artificially cleared, thickly clothed with

forest.

In Lower Burma the western face of the Arakan Yoma hills, like

that of the Western Ghats in India, is exposed to the full force of

the south-western monsoon, and receives a very heavy

Burma.

rainfall. At Sandoway this amounts to an annual mean

of 212 in. It diminishes to the northwards, but even at Chittagong

it is over 104 in. annually.

The country around Mandalay, as well as the hill country to the

north, has suffered from severe earthquakes, one of which destroyed

Ava in 1839. The general meridional direction of the ranges and

379

valleys determines the direction of the prevailing surface winds, this

being, however, subject to many local modifications. But it would

appear that throughout the year there is, with but slight interruption,

a steady upper current from the south-west, such as has been

already noticed over the Himalayas. The rainfall in the lower part

of the Irrawaddy valley, viz. the delta and the neighbouring part of

the province of Pegu, is very heavy; and the climate is mild and

equable at all seasons. But higher up the valley, and especially

north of Pegu, the country is drier, and is characterized by a less

luxuriant vegetation and a retarded and more scanty rainfall.

Within the boundaries of India almost any extreme of climate

that is known to the tropics or the temperate zone can be found. It

is influenced from outside by two adjoining areas. On

the north, the Himalaya range and the plateau of Afghanistan

Climate.

shut it off from the climate of central Asia, and give it a continental

climate, the characteristics of which are the prevalence of

land winds, great dryness of the air, large diurnal range of temperature,

and little or no precipitation. On the south the ocean

gives it an oceanic climate, the chief features of which are great

uniformity of temperature, small diurnal range of temperature,

great dampness of the air, and more or less frequent rain. The

continental type of weather prevails over almost the whole of India

from December to May, and the oceanic type from June to November,

thus giving rise to the two great divisions of the year, the dry season

or north-east monsoon, and the rainy season or south-west monsoon.

India thus becomes the type of a tropical monsoon climate. For

the origin of the monsoon currents and their distribution see

Monsoon.

The two monsoon periods are divided by the change of temperature,

due to solar action upon the earth’s surface, into two separate

seasons; and thus the Indian year may be divided into four

seasons: the cold season, including the months of January and

February; the hot season, comprising the months of March, April

and May; the south-west monsoon period, including the months of

June, July, August, September and October; and the retreating

monsoon period, including the months of November and December.

The temperature is nearly constant in southern India the whole year

round, but in northern India, where the extremes of both heat and

cold are greatest, the variation is very large.

In the cold season the mean temperature averages about 30°

lower in the Punjab than in southern India. In the Punjab, the

United Provinces, and northern India generally the climate

resembles that of the Riviera with a brilliant cloudless

The cold weather.

sky and cool dry weather. This is the time for the tourist

to visit India. In south India it is warmer on the west coast than on

the east, and the maximum temperature is found round the headwaters

of the Kistna. Calcutta, Bombay and Madras all possess

the equable climate that is induced by proximity to the sea, but

Calcutta enjoys a cold season which is not to be found in the other

presidency towns, while the hot season is more unendurable there.

The hot season begins officially in the Punjab on the 15th of March,

and from that date there is a steady rise in the temperature, induced

by the fiery rays of the sun upon the baking earth, until

the break of the rains in June. During this season the

The hot weather.

interior of the peninsula and northern India is greatly

heated; and the contrast of temperature is not between northern

and southern India, but between the interior of India and the coast

districts and adjacent seas. The greater part of the Deccan and the

Central Provinces are included within the hottest area, though in

May the highest temperatures are found in Upper Sind, north-west

Rajputana, and south-west Punjab. At Jacobabad the thermometer

sometimes rises to 125° in the shade.

The south-west monsoon currents usually set in during the first

fortnight of June on the Bombay and Bengal coasts, and give more

or less general rain in every part of India during the next

three months. But the distribution of the rainfall is

The monsoon period.

very uneven. On the face of the Western Ghats, and on

the Khasi hills, overlooking the Bay of Bengal, where the

mountains catch the masses of vapour as it rises off the sea, the

rainfall is enormous. At Cherrapunji in the Khasi hills it averages

upwards of 500 in. a year. The Bombay monsoon, after surmounting

the Ghats, blows across the peninsula as a west and sometimes in

places a north-west wind; but it leaves with very little rain a strip

100 to 200 m. in width in the western Deccan parallel with the Ghats,

and it is this part of the Deccan, together with the Mysore table-land

and the Carnatic, that is most subject to drought. Similarly the

Bengal monsoon passes by the Coromandel coast and the Carnatic

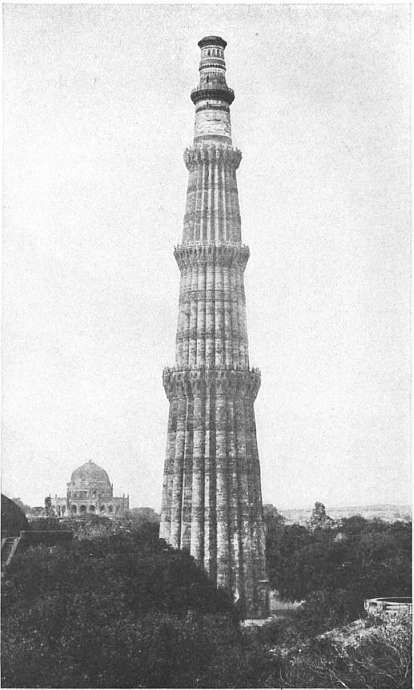

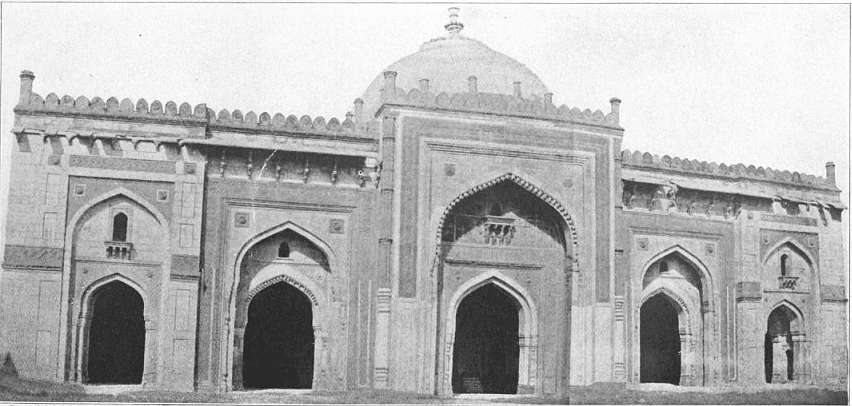

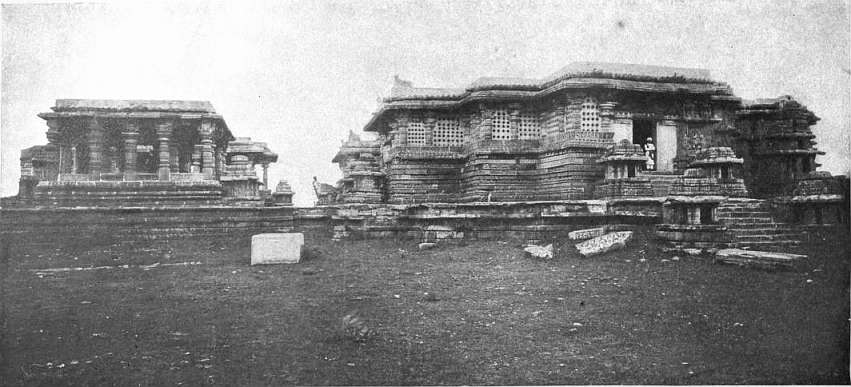

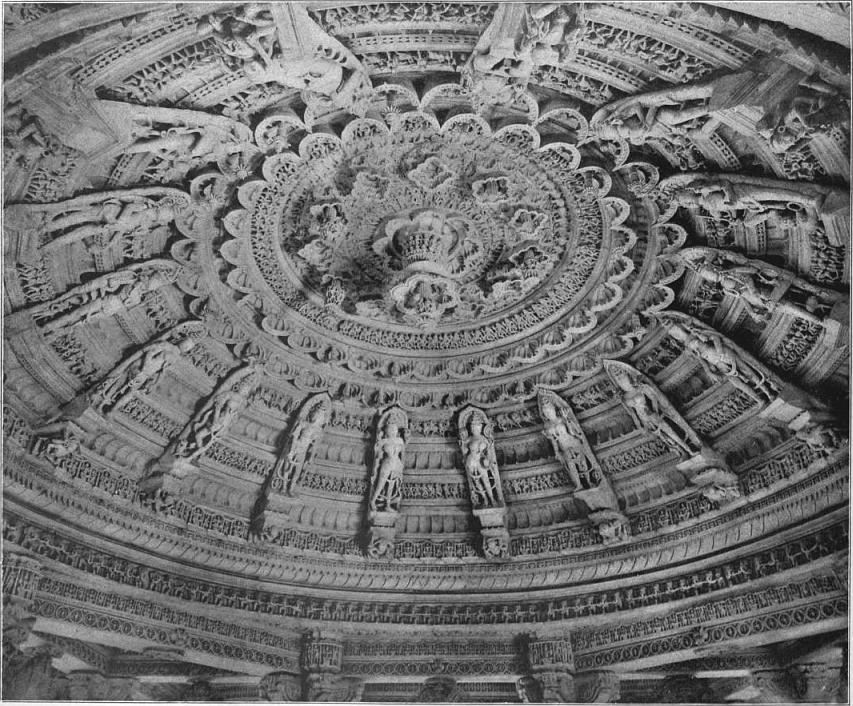

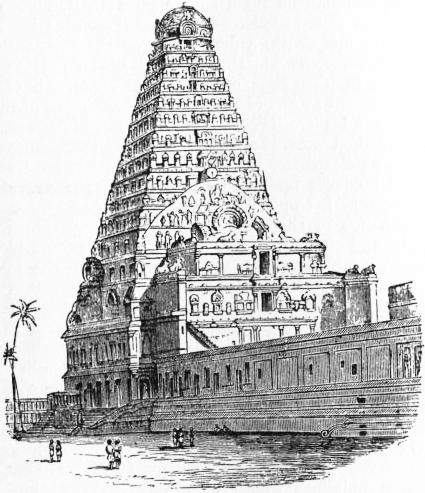

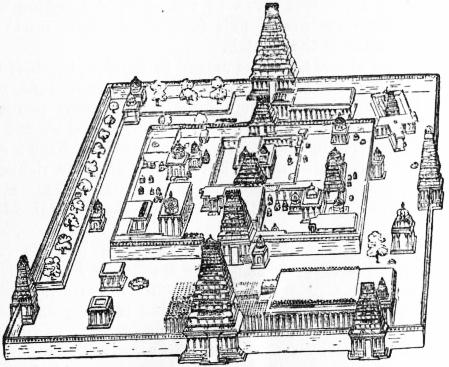

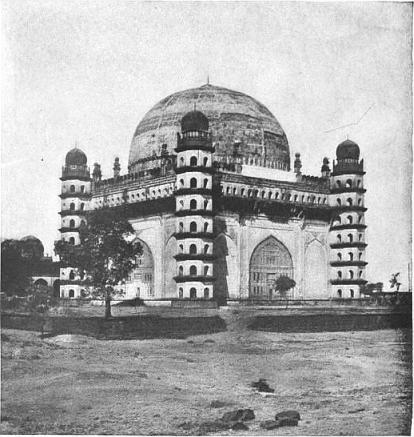

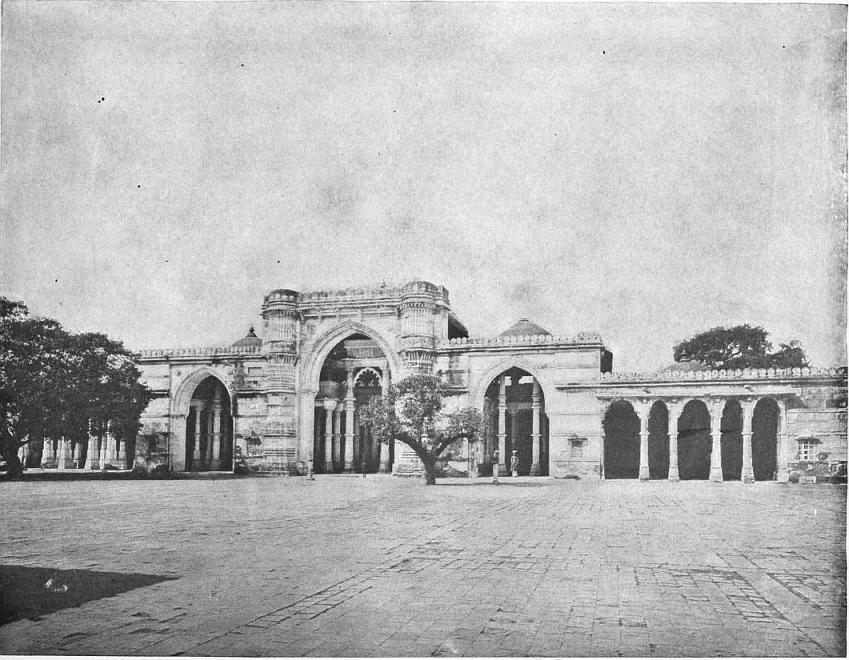

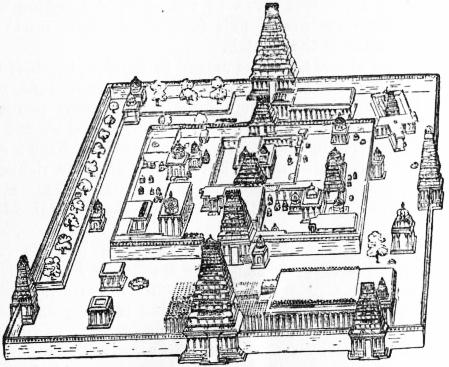

with an occasional shower, taking a larger volume to Masulipatam