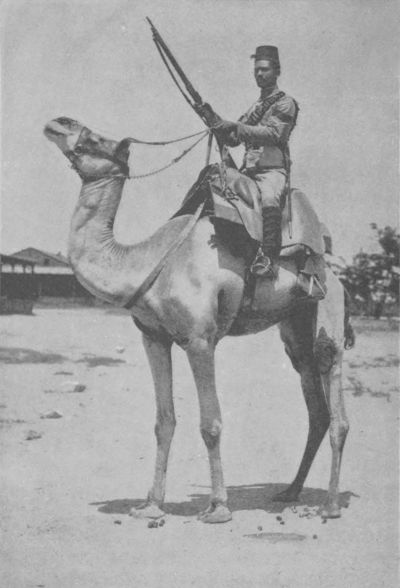

ONE OF THE CAMEL CORPS OF EGYPT

ONE OF THE CAMEL CORPS OF EGYPT

Title: The Rulers of the Mediterranean

Author: Richard Harding Davis

Release date: April 23, 2012 [eBook #39522]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mark C. Orton, Linda McKeown, Julia Neufeld

(illustrations were generously made available by The

Internet Archive) and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net

AUTHOR OF

"THE WEST FROM A CAR-WINDOW" "GALLEGHER"

"VAN BIBBER AND OTHERS" ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

1894

Copyright, 1893, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

TO

HON. EDWARD C. LITTLE

EX-DIPLOMATIC-AGENT AND CONSUL-GENERAL

OF

THE UNITED STATES TO EGYPT

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I | THE ROCK OF GIBRALTAR | 1 |

| II | TANGIER | 37 |

| III | FROM GIBRALTAR TO CAIRO | 72 |

| IV | CAIRO AS A SHOW-PLACE | 102 |

| V | THE ENGLISHMEN IN EGYPT | 139 |

| VI | MODERN ATHENS | 178 |

| VII | CONSTANTINOPLE | 198 |

If you have always crossed the Atlantic in the spring-time or in the summer months, as do most tourists, you will find that leaving New York in the winter is more like a relief expedition to the north pole than the setting forth on a pleasure tour to the summer shores of the Mediterranean.

There is no green grass on the hills of Staten Island, but there is, instead, a long field of ice stretching far up the Hudson River, and a wind that cuts into the face, and dashes the spray up over the tugboats in frozen layers, leaving it there like the icing on a cake. The Atlantic Highlands are black with bare branches and white with snow, and you observe for the first time that men who go down to the sea in ships know nothing[2] of open fireplaces. An icy wind keeps the deck as clear as a master-at-arms could do it; and sudden storms of snow, which you had always before associated with streets or fields, and not at all with the decks of ships, burst over the side, and leave the wood-work wet and slippery, and cold to the touch.

And then on the third or fourth day out the sea grows calm, and your overcoat seems to have taken on an extra lining; and strange people, who apparently have come on board during the night, venture out on the sunlit deck and inquire for steamer chairs and mislaid rugs.

These smaller vessels which run from New York to Genoa are as different from the big North Atlantic boats, with their twin screws and five hundred cabin passengers, as a family boarding-house is from a Broadway hotel. This is so chiefly because you are sailing under a German instead of an English flag. There is no one so important as an English captain—he is like a bishop in gold lace; but a German captain considers his passengers as one large happy family, and treats them as such, whether they like their new relatives or not. The discipline on board the Fulda was like that of a ship of war, where the officers and crew were concerned, but the passengers might have believed they were on their own private yacht.

There was music for breakfast, dinner, and tea; music when the fingers of the trombonist were frozen and when the snow fell upon the taut surface[3] of the big drum; and music at dawn to tell us it was Sunday, so that you awoke imagining yourself at church. There was also a ball, and the captain led an opening march, and the stewards stood at every point to see that the passengers kept in line, and "rounded up" those who tried to slip away from the procession. There were speeches, too, at all times, and lectures and religious services, and on the last night out a grand triumph of the chef, who built wonderful candy goddesses of Liberty smiling upon the other symbolic lady who keeps watch on the Rhine, and the band played "Dixie," which it had been told was the national anthem, and the portrait of the German Emperor smiled down upon us over his autograph. All this was interesting, because it was characteristic of the Germans; it showed their childish delight in little things, and the same simplicity of character which makes the German soldiers who would not move out of the way of the French bullets dance around a Christmas-tree. The American or the Englishman will not do these things, because he has too keen a sense of the ridiculous, and is afraid of being laughed at. So when he goes to sea he plays poker and holds auctions on the run.

There was only one passenger on board who objected to the music. He was from Detroit, and for the first three days remained lashed to his steamer chair like a mummy, with nothing showing but a blue nose and closed eyelids. The[4] band played at his end of the deck, and owing to the fingers of the players being frozen, and to the sudden lurches of the ship, the harmony was sometimes destroyed. Those who had an ear for music picked up their steamer chairs and moved to windward; but this young man, being half dead and firmly lashed to his place, was unable to save himself.

On the morning of the fourth day, when the concert was over and the band had gone to thaw out, the young man suddenly sat upright and pointed his forefinger at the startled passengers. We had generally decided that he was dead. "The Lord knows I'm a sick man," he said, blinking his eyes feebly; "but if I live till midnight I'll find out where they hide those horns, and I'll drop 'em into the Gulf Stream, if it takes my dying breath." He then fell over backwards, and did not speak again until we reached Gibraltar.

There is something about the sight of land after one has been a week without it which supplies a want that nothing else can fill; and it is interesting to note how careless one is as to its name, or whether it is pink or pale blue on the maps, or whether it is ruled by a king or a colonial secretary. It is quite sufficient that it is land. This was impressed upon me once, on entering New York Harbor, by a young man who emerged from his deck cabin to discover, what all the other passengers already knew, that we were in the upper bay. He gave a shout of ecstatic relief and pleasure. "That," he cried, pointing to the west,[5] "is Staten Island, but that," pointing to the right, "is Land."

The first land you see on going to Gibraltar is the Azores Islands. They are volcanic and mountainous, and accompany the boat for a day and a half; but they could be improved if they were moved farther south about two hundred miles, as one has to get up at dawn to see the best of them. It is quite warm by this time, and the clothes you wore in New York seem to belong to a barbarous period and past fashion, and have become heavy and cumbersome, and take up an unnecessary amount of room in your trunk.

And then people tell you that there is land in[6] sight again, and you find how really far you are from home when you learn that it is Portugal, and so a part of Europe, and not an island thrown up by a volcano, or stolen or strayed from its moorings at the mainland. Portugal is apparently a high red hill, with a round white tower on the top of it flying signal flags. Its chief industry is the arranging of these flags by a man. It is, on the whole, a disappointing country. After this, everybody begins to pack and to exchange visiting-cards; and those who are to get off at Gibraltar are pursued by stewards and bandmasters and young men with testimonials that they want signed, and by the weak in spirit, who, at the eleventh hour, think they will not go on to Genoa, but will get off here and go on to Tangier, and who want you to decide for them. And which do you think would pay best, and what is there to see in Tangier, anyway? And as that is exactly what you are going to find out, you cannot tell.

When I left the deck the last night out the stars were all over the heavens; and the foremast, as it swept slowly from side to side, looked like a black pendulum upside down marking out the sky and portioning off the stars. And when I woke there was a great creaking of chains, and I could see out of my port-hole hundreds of fixed lights and rows and double rows of lamps, so that you might have thought the ship during the night had run aground in the heart of a city.

The first sight of Gibraltar is, I think, disappointing.[7] It means so much, and so many lives have been given for it, and so many ships have been sunk by its batteries, and such great powers have warred for twelve hundred years for its few miles of stone, that its black outline against the sky, with nothing to measure it with but the fading stars, is dwarfed and spoiled. It is only after the sun begins to turn the lights out, and you are able to compare it with the great ships at its base, and you see the battlements and the mouths of cannon, and the clouds resting on its top, that you understand it; and then when the outline of the crouching lion, that faces all Europe, comes into relief, you remember it is, as they say, the lock to the Mediterranean, of which England holds the key. And even while you feel this, and are greedily following the course of each rampart and terrace with eyes that are tired of blank stretches of water, some one points to a low line of mountains lying like blue clouds before the red sky of the sunrise, dim, forbidding, and mysterious—and you know that it is Africa.

Spain, lying to the right, all green and amethyst, and flippant and gay with white houses and red roofs, and Gibraltar's grim show of battlements and war, become somehow of little moment. You feel that you have known them always, and that they are as you fancied they would be. But this other land across the water looks as inscrutable, as dark, and as silent as the Sphinx that typifies it, and you feel that its Pillar[8] of Hercules still marks the entrance to the "unknown world."

Nine out of every ten of those who visit Gibraltar for the first time expect to find an island. It ought to be, and it would be one but for a strip of level turf half a mile wide and half a mile long which joins it to the sunny green hills of Spain. But for this bit of land, which they call "the Neutral Ground," Gibraltar would be an island, for it has the Mediterranean to the east, a bay, and beyond that the hills of Spain to the west, and Africa dimly showing fourteen miles across the sea to the south.

Gibraltar has been besieged thirteen times; by Moors and by Spaniards, and again by Moors, and again by Spaniards against Spaniards. It was during one of these wars between two factions in Spain, in 1704, that the English, who were helping one of the factions, took the Rock, and were so well pleased with it that they settled there, and have remained there ever since. If possession is nine points of the law, there was never a place in the history of the world held with nine as obvious points. There were three more sieges after the English took Gibraltar, one of them, the last, continuing for four years. The English were fighting America at the time, and rowing in the Nile, and so did not do much towards helping General George Elliot, who was Governor of the Rock at that time. It would appear to be, as well as one can judge from this distance, a case of neglect on the part of the[11] mother-country for her little colony and her six thousand men, very much like her forgetfulness of Gordon, only Elliot succeeded where Gordon failed (if you can associate that word with that name), and so no one blamed the home government for risking what would have been a more serious loss than the loss of Calais, had Elliot surrendered, and "Gib" gone back to its rightful owners, that is, the owners who have the one point. The history of this siege is one of the most interesting of war stories; it is interesting whether you ever expect to visit Gibraltar or not; it is doubly interesting when you walk the pretty streets of the Rock to-day, with its floating population of twenty thousand, and try to imagine the place held by six thousand half-starved, sick, and wounded soldiers, living at times on grass and herbs and handfuls of rice, and yet carrying on an apparently forlorn fight for four years against the entire army and navy of Spain, and, at the last, against the arms of France as well.

We are apt to consider the Gibraltar of to-day as occupying the same position to the Mediterranean as Queenstown does to the Atlantic, a place where passengers go ashore while the mails are being taken on board, and not so much for their interest in the place itself as to again feel solid earth under their feet. There are passengers who will tell you on the way out that you can see all there is to be seen there in three hours. As a matter of fact, one can live in Gibraltar for many weeks and see something new every day.[12] It struck me as being more different kinds of a place than any other spot of land I had ever visited, and one that changed its aspect with every shifting of the wind, and with each rising and setting of the sun. It is the clearing-house for three most picturesque peoples—the Moors, in their yellow slippers and bare legs and voluminous robes and snowy turbans; the Spaniards, with romantic black capes and cloaks and red sashes, the women with the lace mantilla and brilliant kerchiefs and pretty faces; and, mixed with these, the pride and glory of the British army and navy, in all the bravery of red coats and white helmets, or blue jackets, or Highland kilts. It is a fortress as imposing as the Tower of London, a winter resort as pretty as St. Augustine, and a seaport town of free entry, into which come on every tide people of many nations, and ships flying every flag.

A TYPE

A TYPE

Around its base are the ramparts, like a band of stone and steel; above them the town, rising like a staircase, with houses for steps—yellow houses, with light green blinds sticking out at different angles, and with sloping red roofs meeting other lines of red roofs, and broken by a carpeting of green where the parks and gardens make an opening in the yellow front of the town, and from which rise tall palms and palmettoes, and rows of sea-pines, and fluttering union-jacks which mark the barracks of a regiment. Above the town is the Rock, covered with a green growth of scrub and of little trees below, and[13] naked and bare above, stretching for several miles from north to south, and rearing its great bulk up into the sky until it loses its summit in the clouds. It is never twice the same. To-day it may be smiling and resplendent under a warm, brilliant sun that spreads out each shade of green, and shows each terrace and rampart as clearly as though one saw it through a glass; the sky becomes as blue as the sea and the bay, and the white villages of Spain seem as near to one as the red soldier smoking his pipe on the mountings half-way up the Rock. And to-morrow the whole top of the Rock may be lost in a thick curtain of gray clouds, and the waters of the bay will be tossing and covered with white-caps, and the lands about disappear from sight as though they had sunk into the sea during the night and had left you alone on an island. At times a sunset paints the Rock a martial red, or the moonlight softens it, and you see only the tall palms and the graceful balconies and the gardens of plants, and each rampart becomes a terrace and each casemate a balcony. Or at night, when[14] the lamps are lit, you might imagine yourself on the stage of a theatre, walking in a scene set for Fra Diavolo.

There are no such streets or houses outside of stage-land. It is only in stage cities that the pavements and streets are so conspicuously clean, or that the hanging lamps of beaten iron-work throw such deep shadows, or that there are such high, heavily carved Moorish doorways and mysterious twisting stairways in the solid rock, or shops with such queer signs, or walls plastered with such odd-colored placards—streets where every footfall echoes, and where dark figures suddenly appear from narrow alleyways and cry "Halt, there!" at you, and then "All's well" as you pass by.

Gibraltar has one main street running up and clinging to the side of the hill from the principal quay to the most southern point of the Rock. Houses reach up to it from the first level of the ramparts, and continue on up the hill from its other side. On this street are the bazars of the Moors, and the English shops and the Spanish cafés, and the cathedral, and the hotels, and the Governor's house, and every one in Gibraltar is sure to appear on it at least once in the twenty-four hours. But the color and tone of the street are military. There are soldiers at every step—soldiers carrying the mail or bearing reports, or soldiers in bulk with a band ahead, or soldiers going out to guard the North Front, where lies the Neutral Ground, or to target practice, or to[17] play football; soldiers in two or threes, with their sticks under their arms, and their caps very much cocked, and pipes in their mouths. But these make slow progress, for there is always an officer in sight—either a boy officer just out from England riding to the polo field near the Neutral Ground, or a commanding officer in a black tunic and a lot of ribbons across his breast, or an officer of the day with his sash and sword; and each of these has to be saluted. This is an interesting spectacle, and one that is always new. You see three soldiers coming at you with a quick step, talking and grinning, alert and jaunty, and suddenly the upper part of their three bodies becomes rigid, though their legs continue as before, apparently of their own volition, and their hands go up and their pipes and grins disappear, and they pass you with eyes set like dead men's eyes, and palms facing you as though they were trying to learn which way the wind was blowing. This is due, you discover, to the passing of a stout gentleman in knickerbockers, who switches his rattan stick in the air in reply. Sometimes when he salutes the soldier stops altogether, and so his walks abroad are punctuated at every twenty yards. It takes an ordinary soldier in Gibraltar one hour to walk ten minutes.

Everybody walks in the middle of the main street in Gibraltar, because the sidewalks are only two feet wide, and because all the streets are as clean as the deck of a yacht. Cabs of yellow wood and diligences with jangling bells and red[18] worsted harness gallop through this street and sweep the people up against the wall, and long lines of goats who leave milk in a natural manner at various shops tangle themselves up with long lines of little donkeys and longer lines of geese, with which the local police struggle valiantly. All of these things, troops and goats and yellow cabs and polo ponies and dog-carts, and priests with curly-brimmed hats, and baggy-breeched Moors, and huntsmen in pink coats and Tommies in red, and sailors rolling along in blue, make the main street of Gibraltar as full of variety as a mask ball.

Of the Gibraltar militant, the fortress and the key to the Mediterranean, you can see but the little that lies open to you and to every one along the ramparts. Of the real defensive works of the place you are not allowed to have even a guess. The ramparts stretch all along the western side of the rock, presenting to the bay a high shelving wall which twists and changes its front at every hundred yards, and in such an unfriendly way that whoever tried to scale its slippery surface at one point would have a hundred yards of ramparts on either side of him, from which two sides gunners and infantry could observe his efforts with comfort and safety to themselves; and from which, when tired of watching him slip and scramble, they could and undoubtedly would blow him into bits. But they would probably save him the trouble of coming so far by doing that before he left his vessel in the bay. The[19] northern face of the Rock—that end which faces Spain, and which makes the head of the crouching lion—shows two long rows of teeth cut in its surface by convicts of long ago. You are allowed to walk through these dungeons, and to look down upon the Neutral Ground and the little Spanish town at the end of its half-mile over the butts of great guns. And you will marvel not so much at the engineering skill of whoever it was who planned this defence as at the weariness and the toil of the criminals who gave up the greater part of their lives to hewing and blasting out these great galleries and gloomy passages, through which your footsteps echo like the report of cannon.

Lower down, on the outside of this mask of rock, are more ramparts, built there by man, from which infantry could sweep the front of the enemy were they to approach from the only[20] point from which a land attack is possible. The other side of the Rock, that which faces the Mediterranean, is unfortified, except by the big guns on the very summit, for no man could scale it, and no ball yet made could shatter its front. To further protect the north from a land attack there is at the base of the Rock and below the ramparts a great moat, bridged by an apparently solid piece of masonry. This roadway, which leads to the north gate of the fortress—the one which is closed at six each night—is undermined, and at a word could be blown into pebbles, turning the moat into a great lake of water, and virtually changing the Rock of Gibraltar into an island. I never crossed this roadway without wondering whether the sentry underneath might not be lighting his pipe near the powder-magazine, and I generally reached the end of it at a gallop.

There is still another protection to the North Front. It is only the protection which a watch-dog gives at night; but a watch-dog is most important. He gives you time to sound your burglar-alarm and to get a pistol from under your pillow. A line of sentries pace the Neutral Ground, and have paced it for nearly two hundred years. Their sentry-boxes dot the half-mile of turf, and their red coats move backward and forward night and day, and any one who leaves the straight and narrow road crossing the Neutral Ground, and who comes too near, passes a dead-line and is shot. Facing them, a half-mile off, are the white[21] adobe sentry-boxes of Spain and another row of sentries, wearing long blue coats and queer little shakos, and smoking cigarettes. And so the two great powers watch each other unceasingly across the half-mile of turf, and say, "So far shall you go, and no farther; this belongs to me." There is nothing more significant than these two rows of sentries; you notice it whenever you cross the Neutral Ground for a ride in Spain. First you see the English sentry, rather short and very young, but very clean and rigid, and scowling fiercely over the chin strap of his big white helmet. His shoulder-straps shine with pipe-clay and his boots with blacking, and his arms are burnished and oily. Taken alone, he is a little atom, a molecule; but he is complete in himself, with his food and lodging on his back, and his arms ready to his hand. He is one of a great system that obtains from India to Nova Scotia, and from Bermuda to Africa and Australia; and he shows that he knows this in the way in which he holds up his chin and kicks out his legs as he tramps back and forward guarding the big rock at his back. And facing him,[22] half a mile away, you will see a tall handsome man seated on a stone, with the tails of his long coat wrapped warmly around his legs, and with his gun leaning against another rock while he rolls a cigarette; and then, with his hands in his pockets, he gazes through the smoke at the sky above and the sea on either side, and wonders when he will be paid his peseta a day for fighting and bleeding for his country. This helps to make you understand how six thousand half-starved Englishmen held Gibraltar for four years against the army of Spain.

This is about all that you can see of Gibraltar as a fortress. You hear, of course, of much more, and you can guess at a great deal. Up above, where the Signal Station is, and where no one, not even an officer in uniform not engaged on the works, is allowed to go, are the real fortifications. What looks like a rock is a monster gun painted gray, or a tree hides the mouth of another. And in this forbidden territory are great cannon which are worked from the lowest ramparts. These are the present triumphs of Gibraltar. Before they came, the clouds which shut out the sight of the Rock as well as the rest of the world from its summit rendered the great pieces of artillery there as useless in bad weather as they are harmless in times of peace. The very elements threatened to war against the English, and a shower of rain or a veering wind might have altered the fortunes of a battle. But a clever man named Watkins has invented a position-finder,[23] by means of which those on the lowest ramparts, well out of the clouds, can aim the great guns on the summit at a vessel unseen by the gunners lost in the mist above, and by electricity fire a shot from a gun a half-mile above them so that it will strike an object many miles off at sea. It will be a very strange sensation to the captain of such a vessel when he finds her bombarded by shells that belch forth from a drifting cloud.

No stranger has really any idea of the real strength of this fortress, or in what part of it its real strength lies. Not one out of ten of its officers knows it. Gibraltar is a grand and grim practical joke; it is an armed foe like the army in Macbeth, who came in the semblance of a wood, or like the wooden horse of Troy that held the pick of the enemy's fighting-men. What looks like a solid face of rock is a hanging curtain that masks a battery; the blue waters of the bay are treacherous with torpedoes; and every little smiling village of Spain has been marked down for destruction, and has had its measurements taken as accurately as though the English batteries had been playing on it already for many years. The Rock is undermined and tunnelled throughout, and food and provisions are stored away in it to last a siege of seven years. Telephones and telegraphs, signal stations for flagging, search-lights, and other such devilish inventions, have been planted on every point, and only the Governor himself knows what other modern improvements have been introduced[24] into the bowels of this mountain or distributed behind bits of landscape gardening on its surface.

On the 25th of February, at half-past ten in the morning, three guns were fired in rapid succession from the top of the Rock, and the windows shook. Three guns mean that Gibraltar is about to be attacked by a fleet of war-ships, and that "England expects every man to do his duty." So I went out to see him do it. Men were running through the streets trailing their guns, and officers were galloping about pulling at their gloves, and bodies of troops were swinging along at a double-quick, which always makes them look as though they were walking in tight boots, and bugles were calling, and groups of men, black and clearly cut against the sky, were excitedly switching the air with flags from every jutting rock and every rampart of the garrison.

Behind the ramparts, quite out of sight of the vessels in the bay, were many hundreds of infantrymen with rifles in hand, and only waiting for a signal to appear above the coping of the wall to empty their guns into the boats of the enemy. The enlisted men, who enjoy this sort of play, were pleased and interested; the officers were almost as calm as they would be before a real enemy, and very much bored at being called out and experimented with. The real object of the preparation for defence that morning was to learn whether the officers at different points could[27] communicate with the governor as he rode rapidly from one spot to another. This was done by means of flags, and although the officer who did the flagging for the Governor's party had about as much as he could do to keep his horse on four legs, the experiment was most successful. It was a very pretty and curious sight to see men talking a mile away to a party of horsemen going at full gallop.

The life of a subaltern of the British army, who belongs to a smart regiment, and who is stationed at such a post as Gibraltar, impresses you as being as easy and satisfactory a state of existence as a young and unmarried man could ask. He has always the hope that some day—any day, in fact—he will have a chance to see active service, and so serve his country and distinguish his name. And while waiting for this chance he enjoys the good things the world brings him with a clear conscience. He has duties, it is true, but they did not strike me as being wearing ones, or as threatening nervous prostration. As far as I could see, his most trying duty was the number of times a day he had to change his clothes, and this had its ameliorating circumstance in that he each time changed into a more gorgeous costume. There was one youth whom I saw in four different suits in two hours. When I first noticed him he was coming back from polo, in boots and breeches; then he was directing the firing of a gun, with a pill-box hat on the side of his head, a large pair of field-glasses[28] in his hand, and covered by a black and red uniform that fitted him like a jersey. A little later he turned up at a tennis party at the Governor's in flannels; and after that he came back there to dine in the garb of every evening. When the subaltern dines at mess he wears a uniform which turns that of the First City Troop into what looks in comparison like a second-hand and ready-made garment. The officers of the 13th Somerset Light Infantry wore scarlet jackets at dinner, with high black silk waistcoats bordered with two inches of gold lace. The jackets have gold buttons sewed along every edge that presents itself, and offer glorious chances for determining one's future by counting "poor man, rich man, beggar-man, thief." When eighteen of these jackets are placed around a table, the chance civilian feels and looks like an undertaker.

Dining at mess is a very serious function in a British regiment. At other times her Majesty's officers have a reticent air; but at dinner, when you are a guest, or whether you are a guest or not, there is an intent to please and to be pleased which is rather refreshing.

We have no regimental headquarters in America, and owing to our officers seeking promotion all over the country, the regimental esprit de corps is lacking. But in the English army regimental feeling is very strong; father and son follow on in the same regiment, and now that they are naming them for the counties from which[29] they are recruited, they are becoming very close corporations indeed. At mess the traditions of the regiment come into play, and you can learn then of the actions in which it has been engaged from the engravings and paintings around the walls, and from the silver plate on the table and the flags stacked in the corner.

When a man gets his company he presents the regiment with a piece of plate, or a silver inkstand, or a picture, or something which commemorates a battle or a man, and so the regimental headquarters are always telling a story of what has been in the past and inspiring fine deeds for the future. Each regiment has its peculiarity of uniform or its custom at mess, which is distinctive to it, and which means more the longer it is observed. Those in authority are trying to do away with these signs and differences[30] in equipment, and are writing themselves down asses as they do so.

You will notice, for instance, if you are up in such things, that the sergeants of the 13th Light Infantry wear their sashes from the left shoulder to the right hip, as officers do, and not from the right shoulder, as sergeants should. This means that once in a great battle every officer of the 13th was killed, and the sergeants, finding this out, and that they were now in command, changed their sashes to the other shoulder. And the officers ever after allowed them to do this, as a tribute to their brothers in command who had so conspicuously obliterated themselves and distinguished their regiment. There are other traditions, such as that no one must mention a woman's name at mess, except the title of one woman, to which they rise and drink at the end of the dinner, when the sergeant gives the signal to the band-master outside, and his men play the national anthem, while the bandmaster comes in, as Mr. Kipling describes him in "The Drums of the Fore and Aft," and "takes his glass of port-wine with the orfficers." The Sixtieth, or the Royal Rifles, for instance, wear no marks of rank at the mess, in order to express the idea that there they are all equal. This regiment had once for its name the King's American Rifles, and under that name it took Quebec and Montreal, and I had placed in front of me at mess one night a little silver statuette in the equipment of a Continental soldier, except[31] that his coat, if it had been colored, would have been red, and not blue. He was dated 1768. In the mess-room are pictures of the regiment swarming over the heights of Quebec, storming the walls of Delhi, and running the gauntlet up the Nile as they pressed forward to save Gordon. All of this goes to make a subaltern feel things that are good for him to feel.

Every day at Gibraltar there is tennis, and bands playing in the Alameda, and parades, or riding-parties across the Neutral Ground into Spain, and teas and dinners, at which the young ladies of the place dance Spanish dances, and twice a week the members of the Calpe Hunt meet in Spain, and chase foxes across the worst country that any Englishman ever rode over in pink. There are no fences, but there are ravines and cañons and precipices, down and up and over which the horses scramble and jump, and over which they will, if the rider leaves them alone, bring him safely.

And if you lose the rest of the field, you can go to an old Spanish inn like that which Don Quixote visited, with drunken muleteers in the court-yard, and the dining-room over the stable, and with beautiful dark-eyed young women to give you omelet and native wine and black bread. Or, what is as amusing, you can stop in at the officer's guard-room at the North Front, and cheer that gentleman's loneliness by taking tea with him, and drying your things before his fire while he cuts the cake, and the women of the party[32] straighten their hats in front of his glass, and two Tommies go off for hot water.

There was a very entertaining officer guarding the North Front one night, and he proved so entertaining that neither of us heard the sunset gun, and so when I reached the gate I found it locked, and the bugler of the guard who take the keys to the Governor each night was sounding his bugle half-way up the town. There was a dark object on a wall to which I addressed all my arguments and explanations, which the object met with repeated requests to "move on, now," in the tone of expostulation with which a London policeman addresses a very drunken man.

I knew that if I tried to cross the Neutral Ground I would be shot at for a smuggler; for, owing to Gibraltar's being a free port of entry, these gentlemen buy tobacco there, and carry it home each night, or run it across the half-mile of Neutral Ground strapped to the backs of dogs. So I wandered back again to the entertaining officer, and he was filled with remorse, and sent off a note of entreaty to his Excellency's representative, to whom he referred as a D. A. A. G., and whose name, he said, was Jones. We then went to the mess of the officers guarding the different approaches, and these gentlemen kindly offered me their own beds, proposing that they themselves should sleep on three chairs and a pile of overcoats; all except one subaltern, who excused his silence by saying diffidently that he fancied I would not care to sleep in the fever[35] officer of the keys pass every night, and the guards turn out to salute the keys, and I had rather imagined that it was more or less of a form, and that the pomp and circumstance were all there was of it. I did not believe that the Rock was really closed up at night like a safe with a combination lock. But I know now that it is. A note came back from the mysterious D. A. A. G. saying I could be admitted at eleven; but it said nothing at all about sentries, nor did the entertaining officer. Subalterns always say "Officer" when challenged, and the sentry always murmurs, "Pass, officer, and all's well," in an apologetic growl. But I suppose I did not say "Officer" as I had been told to do, with any show of confidence, for every sentry who appeared that night—and there seemed to be a regiment of them—would not have it at all, and wanted further data, and wanted it quick. Even if you have an order from a D. A. A. G. named Jones, it is very difficult to explain about it when you don't know whether to speak of him as the D. A. A. G. or as General Jones, and especially when a young and inexperienced shadow is twisting his gun about so that the moonlight plays up and down the very longest bayonet ever issued by a civilized nation. They were not nice sentries, either, like those on the Rock, who stand where you can see them, and who challenge you drowsily, like cabmen, and make the empty streets less lonely than otherwise.

[36]They were, on the contrary, fierce and in a terrible hurry, and had a way of jumping out of the shadow with a rattle of the gun and a shout that brought nerve-storms in successive shocks. To make it worse, I had gone over the post, while waiting for word from the D. A. A. G., to hear the sentries recite their instructions to the entertaining officer. They did this rather badly, I thought, the only portion of the rules, indeed, which they seemed to have by heart being those which bade them not to allow cows to trespass "without a permit," which must have impressed them by its humor, and the fact that when approached within fifty yards they were "to fire low." I found when challenged that night that this was the only part of their instructions that I also could remember.

This was the only trying experience of my stay in Gibraltar, and it is brought in here as a compliment to the force that guards the North Front. For of them, and the rest of the inhabitants and officers of the garrison, any one who visits there can only think well; and I hope when the Rock is attacked, as it never will be, that they will all cover themselves with glory. It never will be attacked, for the reason that the American people are the only people clever enough to invent a way of taking it, and they are far too clever to attempt an impossible thing.

A great many thousand years ago Hercules built the mountain of Abyla and its twin mountain which we call Gibraltar. It was supposed to mark the limits of the unknown world, and it would seem from casual inspection, as I suggested in the last chapter, that it serves the same purpose to this day. Men have crept into Africa and crept out again, like flies over a ceiling, and they have gained much renown at Africa's expense for having done so. They have built little towns along its coasts, and run little rocking, bumping railroads into its forests, and dragged launches over its cataracts, and partitioned it off among emperors and powers and trading companies, without having ventured into the countries they pretend to have subdued. But from Paul du Chaillu to W. A. Chanler, "the Last Explorer," as he has been called, just how much more do we know of Africa than did the Romans whose bridges still stand in Tangier?

The "Last Explorer" sounds well, and is distinctly[38] a mot, but there will be other explorers to go, and perhaps to return. There are still a few things for us to learn. The Spaniards and the Pilgrim fathers touched the unknown world of America only four hundred years ago, and to-day any commercial traveller can tell you, with the aid of an A B C railroad guide, the name of every town in any part of it. But Turks and Romans and Spaniards, and, of late, English and Germans and French, have been pecking and nibbling at Africa like little mice around a cheese, and they are still nibbling at the rind, and know as little of the people they "protect," and of the countries they have annexed and colonized, as did Hannibal and Scipio. The American forests have been turned into railroad ties and telegraph poles, and the American Indian has been "exterminated" or taught to plough and to wear a high hat. The cowboy rides freely over the prairies; the Indian agent cheats the Indian—the Indian does not cheat him; the Germans own Milwaukee and Cincinnati; the Irish rule everywhere; even the much-abused Chinaman hangs out his red sign in every corner of the country. There is not a nation of the globe that has not its hold upon and does not make fortunes out of the continent of America; but the continent of Africa remains just as it was, holding back its secret, and still content to be the unknown world.

You need not travel far into Africa to learn this; you can find out how little we know of it[39] at its very shore. This city of Tangier, lying but three hours off from Gibraltar's civilization, on the nearest coast of Africa, can teach you how little we or our civilized contemporaries understand of these barbarians and of their barbarous ways.

A few months since England sent her ambassador to treat with the Sultan of Morocco; it was an untaught blackamoor opposed to a diplomat and a gentleman, and a representative of the most civilized and powerful of empires; and we have Stephen Bonsal's picture of this ambassador and his suite riding back along the hot, sandy trail from Fez, baffled and ridiculed and beaten. So that when I was in Tangier, half-naked Moors, taking every white stranger for an Englishman, would point a finger at me and cry, "Your Sultana a fool; the Sultan only wise." Which shows what a superior people we are when we get away from home, and how well the English understand the people they like to protect.

Tangier lies like a mass of drifted snow on the green hills below, and over the point of rock on which stands its fortress, and from which waves the square red flag of Morocco. It is a fine place spoiled by civilization. And not a nice quality of civilization either. Back of it, in Tetuan or Fez, you can understand what Tangier once was and see the Moor at his best. There he lives in the exclusiveness which his religion teaches him is right—an exclusiveness to[40] which the hauteur of an Englishman, and his fear that some one is going to speak to him on purpose, become a gracious manner and suggest undue familiarity. You see the Moor at his best in Tangier too, but he is never in his complete setting as he is in the inland cities, for when you walk abroad in Tangier you are constantly brought back to the new world by the presence and abodes of the foreign element; a French shop window touches a bazar, and a Moor in his finest robes is followed by a Spaniard in his black cape or an Englishman in a tweed suit, for the Englishman learns nothing and forgets nothing. He may live in Tangier for years, but he never learns to wear a burnoose, or forgets to put on the coat his tailor has sent him from home as the latest in fashion. The first thing which meets your eye on entering the harbor at Tangier is an immense blue-and-white enamel sign asking you to patronize the English store for groceries and provisions. It strikes you as much more barbarous than the Moors who come scrambling over the vessel's side.

They come with a rush and with wild yells before the little steamer has stopped moving, and remind you of their piratical ancestors. They look quite as fierce, and as they throw their brown bare legs over the bulwarks and leap and scramble, pushing and shouting in apparently the keenest stage of excitement and rage, they only need long knives between their teeth and a cutlass to convince you that you are at the[43] mercy of the Barbary pirates, and not merely of hotel porters and guides.

My guide was a Moor named Mahamed. I had him about a week, or rather, to speak quite correctly, he had me. I do not know how he effected my capture, but he went with me, I think, because no one else would have him, and he accordingly imposed on my good-nature. As we say a man is "good-natured" when there is absolutely nothing else to be said for him, I hope when I say this that I shall not be accused of trying to pay myself a compliment. Mahamed was a tall Moor, with a fine array of different-colored robes and coats and undercoats, and a large white turban around his fez, which marked the fact that he was either married or that he had made a pilgrimage to Mecca. He followed me from morning until night, with the fidelity of a lamb, and with its sheeplike stupidity. No amount of argument or money or abuse could make him leave my side. Mahamed was not even picturesque, for he wore a large pair of blue spectacles and Congress gaiters. This hurt my sense of the fitness of things very much. His idea of serving me was to rush on ahead and shove all the little donkeys and blind beggars and children out of my way, at which the latter would weep, and I would have to go back and bribe them into cheerfulness again. In this way he made me most unpopular with the masses, and cost me a great deal in trying to buy their favor. I was never so completely at the[44] mercy of any one before, and I hope he found me "intelligent, courteous, and a good linguist."

As a matter of fact, there is very little need of a guide in Tangier. It has but few show places, for the place itself is the show. You can find your best entertainment in picking your way through its winding, narrow streets, and in wandering about the open market-places. The highways of Tangier are all very crooked and very steep. They are also very uneven and dirty, and one walks sometimes for hundreds of yards in a maze of dark alleys and little passageways walled in by whitewashed walls, and sheltered from the sun by archways and living-rooms hanging from one side of the street to the other. Green and blue doorways, through which one must stoop to enter, open in from the street, and you are constantly hearing them shut as you pass, as some of the women of the household recognize the presence of a foreigner. You are never quite sure as to what you will meet in the streets or what may be displayed at your elbow before the doors of the bazars. The odors of frying meat and of fresh fruit and of herbs, and of soap in great baskets, and of black coffee and hasheesh, come to you from cafés and tiny shops hardly as big as a packing-box. These are shut up at night by two half-doors, of which the upper one serves as a shield from the sun by day and the lower as a pair of steps. In the wider streets are the bazars, magnificent with color and with the glitter of gold lace and of brass plaques and[45] silver daggers; handsome, comfortable-looking Moors sit crossed-legged in the middle of their small extent like soldiers in a sentry-box, and speak leisurely with their next-door neighbor without gesture, unless they grow excited over a bargain, and with a haughty contempt for the passing Christian. There is always something beneficial in feeling that you are thoroughly despised; and when a whole community combines to despise you, and looks over your head gravely as you pass, you begin to feel that those Moors who do not apparently hold you in contempt are a very poor and middle-class sort of people, and you would much prefer to be overlooked by a proud Moor than shaken hands with by a perverted one. But the pride of the rich Moorish gentlemen is nothing compared to the fanatic intolerance of the poor farmers from the country of the tribes who come in on market-day, and who hate the Christian properly as the Koran tells them they should. They stalk through the narrow street with both eyes fixed on a point far ahead of them, with head and shoulders erect and arms swinging. They brush against you as though you were a camel or a horse, and had four legs on which to stand instead of two. Sometimes a foreigner forgets that these men from the desert, where the foreign element has not come, are following out the religious training of a lifetime, and strikes at one of them with his riding-whip, and then takes refuge in a consulate and leaves on the next boat.

[46]I find it very hard not to sympathize with the Moors. The Englishman is always preaching that an Englishman's house is his castle, and yet he invades this country, he and his French and Spanish and American cousins, and demands that not only he shall be treated well, but that any native of the country, any subject of the Sultan, who chooses to call himself an American or an Englishman shall be protected too. Of course he knows that he is not wanted there; he knows he is forcing himself on the barbarian, and that all the barbarian has ever asked of him is to be let alone. But he comes, and he rides around in his baggy breeches and varnished boots, and he gets up polo games and cricket matches, and gallops about in a pink coat after foxes, and asks for bitter ale, and complains because he cannot get his bath, and all the rest of it, quite as if he had been begged to come and to stop as long as he liked. Sometimes you find a foreigner who tries to learn something of these people, a man like the late Mr. Leared or "Bébé" Carleton, who can speak all their dialects, and who has more power with the Sultan than has any foreign minister, and who, if the Sultan will not pay you for the last shipment of guns you sent him, or for the grand-piano for the harem, is the man to get you your money. But the average foreign resident, as far as I can see, neither adopts the best that the Moor has found good, nor introduces what the Moor most needs, and what he does not know or care[47] enough about to introduce for himself. Tangier, for instance, is excellently adapted by nature for the purposes of good sanitation, but the arrangements are as bad and primitive as they were before a foreigner came into the place. They consist in dumping the refuse of the streets, into which everything is thrown, over the sea-wall out on the rocks below, where the pigs gather up what they want, and the waves wash the remainder back on the coast.

If some of the foreign ministers would use their undoubted influence with the Bashaw to amend this, instead of introducing point-to-point pony races, they might in time show some reason for their invasion of Morocco other than the curious and obvious one that they all grow rich there while doing nothing. The foreign resident has a very great contempt for the Moor. He[48] says the Moor is a great liar and a rogue. When people used to ask Walter Scott if it was he who wrote the Waverley Novels he used to tell them it was not, and he excused this afterwards by saying that if you are asked an impertinent or impossible question you have the right not to answer it or to tell an untruth. The very presence of the foreigner is an impertinence in the eyes of the Moor, and so he naturally does not feel severe remorse when he baffles the foreign invader, and does it whenever he can.

As a matter of fact, the foreign invader at Tangier is not, in a number of cases, in a position in which he can gracefully throw down gauntlets. There is something about these hot, raw countries, hidden out of the way of public opinion and police courts and the respectability which drives a gig, that makes people forget the rules and axioms laid down in the temperate zone for the guidance of tax-payers and all reputable citizens. As the sailors say, "There is no Sunday south of the equator." It is hard to tell just what it is, but the sun, or the example of the barbarians, or the fact that the world is so far away, breeds queer ideas, and one hears stories one would not care to print as long as the law of libel obtains in the land. You have often read in novels, especially French novels, or have heard men on the stage say: "Come, let us leave this place, with its unjust laws and cruel bigotry. We will go to some unknown corner of the earth, where we will make a new home.[49] And there, under a new flag and a new name, we will forget the sad past, and enter into a new world of happiness and content."

When you hear a man on the stage say that, you can make up your mind that he is going to Tangier. It may be that he goes there with somebody else's money, or somebody else's wife, or that he has had trouble with a check; or, as in the case of one young man who was fêted and dined there, had robbed a diamond store in Brooklyn, and is now in Sing Sing; or, as in the case of a recent American consul, had sold his protection for two hundred dollars to any one who wanted it, and was recalled under several clouds. And you hear stories of ministers who retire after receiving an income of a few hundred pounds a year with two hundred thousand dollars they have saved out of it, and of cruelty and bursts of sudden passion that would undoubtedly cause a lynching in the chivalric and civilized states of Alabama or Tennessee. And so when I heard why several of the people of Tangier had come there, and why they did not go away again, I began to feel that the barbarian, whose forefathers swept Spain and terrorized the whole of Catholic Europe, had more reason than he knew for despising the Christian who is waiting to give to his country the benefits of civilization.

Tangier's beauty lies in so many different things—in the monk-like garb of the men and in the white muffled figures of the women; in the brilliancy of its sky, and of the sea dashing upon[50] the rocks and tossing the feluccas with their three-cornered sails from side to side; and in the green towers of the mosques, and the listless leaves of the royal palms rising from the centre of a mass of white roofs; and, above all, in the color and movement of the bazars and streets. The streets represent absolute equality. They are at the widest but three yards across, and every one pushes, and apparently every one has something to sell, or at least something to say, for they all talk and shout at once, and cry at their donkeys or abuse whoever touches them. A water-carrier, with his goat-skin bag on his back and his finger on the tube through which the water comes, jostles you on one side, and a slave as black and shiny as a patent-leather boot shoves you on the other as he makes way for his master on a fine white Arabian horse with brilliant trappings and a huge contempt for the donkeys in his way. It is worth going to Tangier if for no other reason than to see a slave, and to grasp the fact that he costs anywhere from a hundred to five hundred dollars. To the older generation this may not seem worth while, but to the present generation—those of it who were born after Richmond was taken—it is a new and momentous sensation to look at a man as fine and stalwart and human as one of your own people, and feel that he cannot strike for higher wages, or even serve as a parlor-car porter or own a barbershop, but must work out for life the two hundred dollars his owner paid for him at Fez.

[51]There is more movement in Tangier than I have ever noticed in a place of its size. Every one is either looking on cross-legged from the bazars and coffee-shops, or rushing, pushing, and screaming in the street. It is most bewildering; if you turn to look after a particularly magnificent Moor, or a half-naked holy man from the desert with wild eyes and hair as long as a horse's mane, you are trodden upon by a string of donkeys carrying kegs of water, or pushed to one side by a soldier with a gun eight feet long.

There is something continually interesting in the muffled figures of the women. They make you almost ashamed of the uncovered faces of the American women in the town; and, in the lack of any evidence to the contrary, you begin to believe every Moorish woman or girl you meet is as beautiful as her eyes would make it appear that she is. Those of the Moorish girls whose faces I saw were distinctly handsome; they were the women Benjamin Constant paints in his pictures of Algiers, and about whom Pierre Loti goes into ecstasies in his book on Tangier. Their robe or cloak, or whatever the thing is that they affect, covers the head like a hood, and with one hand they hold one of its folds in front of the face as high as their eyes, or keep it in place by biting it between their teeth.

The only time that I ever saw the face of any of them was when I occasionally eluded Mahamed and ran off with a little guide called Isaac, the especial protector of two American[52] women, who farmed him out to me when they preferred to remain in the hotel. He is a particularly beautiful youth, and I noticed that whenever he was with me the cloaks of the women had a fashion of coming undone, and they would lower them for an instant and look at Isaac, and then replace them severely upon the bridge of the nose. Then Isaac would turn towards me with a shy conscious smile and blush violently. Isaac says that the young men of Tangier can tell whether or not a girl is pretty by looking at her feet. It is true that their feet are bare, but it struck me as being a somewhat reckless test for selecting a bride. I will recommend Isaac to whoever thinks of going to Tangier. He speaks eight languages, is eighteen years old, wears beautiful and barbarous garments, and is always happy. He is especially good at making bargains, and he entertained me for many half-hours while I sat and watched him fighting over two dollars more or less with the proprietors of the bazars. He was an antagonist worthy of the oldest and proudest Moor in Tangier. He had no respect for their rage or their contempt or their proffered bribes or their long white beards. Sometimes he would laugh them to scorn—them and their prices; and again he would talk to them sadly and plaintively; and again he would stamp and rage and slap his hands at them and rush off with a great show of disgust, until they called him back again, when he and they would go over the performance once more with unabated interest.[53] Mahamed always paid them what they asked, and got his commission from them later, as a guide should; but Isaac would storm and finally beat them down one-half. Isaac can be found at the Calpe Hotel, and is welcome to whatever this notice may be worth to him.

I had read in books on Morocco and had been given to understand that when you were told that the price of anything in a bazar was worth three dollars, you should offer one, and that then the Moor would cry aloud to Allah to take note of the insult, and would ask you to sit down and have a cup of coffee, and that he would then beat you up and you would beat him down, and that at the end of two or three hours you would get what you wanted for two dollars. It struck me[54] that this, if one had several months to spare and wanted anything badly enough, might be rather amusing. The first thing I saw that I wanted badly was a long gun, for which the Moor asked me twelve dollars. I offered him eight. I then waited to see him tear his beard and unwrap his turban and cry aloud to Allah; but he did none of these things. He merely put the gun back in its place and continued the conversation, which I had so flippantly interrupted, with a long-bearded friend. And no further remarks on my part affected him in the least, and I was forced to go away feeling very much ashamed and very mean. The next day a man at the hotel brought in the gun, having paid fourteen dollars for it, and said he would not sell it for fifty. We would pay much more than that for it at home, which shows that you cannot always follow guide-books.

There are only five things the guides take you to see in Tangier—the café chantant, the governor's palace, the prisons, and the harem, to which men are not admitted. They also take you to see the markets, but you can see them for yourself. The markets are bare, open places covered with stones and lined with bazars, and on market-days peopled with thousands of muffled figures selling or trying to sell herbs and eggs and everything else that is eatable, from dates to haunches of mutton. It is a wonderfully picturesque sight, with the sun trickling through the palm-leaf mats overhead on the piles of yellow melons at your feet, and with strings of camels dislocating their[55] countenances over their grain, and dancing-men and snake-charmers and story-tellers, as eloquent as actors, clamoring on every side.

The café chantant is a long room lined with mats, and with rugs scattered over the floor, on which sit musicians and the regular customers of the place, who play cards and smoke long pipes, with which they rap continually on the tin ash-holders. The music is very strange, to say the least, and the singing very startling, full of sudden pauses, and beginning again after one of these when you think the song is over. It is not a particularly exciting place to visit, but there is no choice between that and the hotel smoking-room. Tangier is not a town where one can move about much at night. There is also a place where the guests tell you that you can see Moorish women dance the dance which so startled Paris in the Algerian exhibit at the exposition. As I had no desire to be startled in that way again, I did not go to see them, and so cannot say what they are like. But it is quite safe to say that any visitor to Tangier who thinks he is seeing anything that is real and native to the home life of the people, and that is not a show gotten up by the guides, is going to be greatly taken in. The harem to which they lead women is not a harem at all, but the home of the widow of an ex-governor, who sits with her daughters for strange women to look at. It is a most undignified proceeding on the part of the widow of a dead Bashaw, and no one but the guides know what she is doing. I[56] came to find out about it through some American women who went there with Isaac in the morning, and were taken to call at the same place by an English lady resident in the afternoon. The English woman laughed at them for thinking they had seen the interior of a harem, and they did not tell her that they had already visited her friends and paid their franc for admittance to their society.

The other show places are the governor's palace and the prisons. The palace is a very handsome Moorish building, and the prisons are very dirty. All that the tourist can see of them is the little he can discern through a hole cut in the stout wooden door of each, which is the only exit and entrance. You cannot see much even then, for the prisoners, as soon as they discover a face at the opening, stick it full of the palm-leaf baskets that they make and sell in order to buy food. The government gives them neither water, which is expensive in Tangier, nor bread, unless they are dying for want of it, but expects the family or friends of each criminal to see that he is kept alive until he has served out his term of imprisonment.

A great deal has been written about these prisons of the Sultan, and of the cruelty shown to the inmates, notably of late by a Mr. Mackenzie in the London Times. You are told that in Tangier, within the four square walls of the prison, there are madmen and half-starved murderers and rebels, loaded with chains, dying of disease[59] and want, who are tortured and starved until they die. For this reason no one in Morocco is sentenced for more than ten or twelve years, so you are told, because he is sure to die before that time has expired. It seemed to me that if this were true it would be worth while to visit the prison and to tell what one saw there. When I was informed that, with the exception of two residents of Tangier, no one has been allowed to enter the Sultan's prison for the last ten years, I suspected that there must be something there which the Sultan did not want seen: it was not a difficult deduction to make. So I set about getting into the prison. It is not at all necessary to go into the details of my endeavors, or to tell what proposals I made; it is quite sufficient to say that in every way I was eminently unsuccessful. It was interesting, however, to find a people to whom the arguments and inducements which had proved effective with one's own countrymen were foolish and incomprehensible. For two days I haunted the outer walls of the prison, and was smiled upon contemptuously by the Bashaw's counsellors, who sat calmly in the cool hallway of the palace, and watched me kicking impatiently at the stones in the court-yard and broiling in the sun, while the governor or Bashaw returned me polite expressions of his regret. I finally dragged the Consul-General into it, and brought things to such a pass that I could see no way out of it but my admittance to the prison or a declaration of war from the United States.

[60]Either event seemed to promise exciting and sensational developments. Colonel Mathews, the Consul-General, did not, however, share my views, but arranged that I should have an audience with the Bashaw, during the course of which he promised he would bring up the question of my admittance to the prison.

On board the Fulda, I had had the pleasure of sitting at table next to the Rev. Dr. Henry M. Field, the editor of the Evangelist, and a distinguished traveller in many lands. While on the steamer I had twitted the doctor with not having seen certain phases of life with which, it seemed to me, he should be more familiar, and I offered, on finding we were making the same tour for the same purpose, to introduce him to bull-fights and pig-sticking and cafés chantants, and other incidents of foreign travel, of which he seemed to be ignorant. He refused my offer with dignity, but I think with some regret. I was, nevertheless, glad to find that he was in Tangier, and that he was to be one of the party to call at the governor's palace. On learning of my desire to visit the prison Dr. Field added his petition to mine, and I am quite sure that Colonel Mathews wished we were both in the United States.

We first called upon the Sultan's Minister of Foreign Affairs, who received us in a little room leading from a pretty portico near the street entrance. It was furnished, I was pained to note, not with divans and rugs, but with a set of red plush and walnut sofas and chairs, such as you[61] would find in the salon of a third-rate French hotel. The Minister of Foreign Affairs was a dear, kindly old gentleman, with a fine white beard down to his waist, but he had a cold in his head, and this kept him dabbing at his nose with a red bandanna handkerchief rolled up in a ball, which was not in keeping with the rest of his costume, nor with the dignity of his appearance. He and Dr. Field got on very well; they found out that they were both seventy years of age, and both highly esteemed in their different churches. Indeed, the Minister of Foreign Affairs was good enough to say, through Colonel Mathews, that Dr. Field had a good face, and one that showed he had led a religious life. He rather neglected me, and I was out of it, especially when both the doctor and the cabinet minister began hoping that Allah would bless them both. I thought it most unorthodox language for Dr. Field to use.

We then walked up the hill upon which stand the fort, the prisons, the treasury, and the governor's palace, and were received at the entrance to the latter by the same gentlemen who had for the last two days been enjoying my discomfiture. They were now most gracious in their manner, and bowed proudly and respectfully to Colonel Mathews as we passed between two rows of them and entered the hall of the palace. We went through three halls covered with colored tiles and topped with arches of ornamental scrollwork of intricate designs. At the extreme end[62] of these rooms the Bashaw stood waiting for us. He was the finest-looking Moor I had seen; and I think the Moorish gentleman, though it seems a strange thing to say, is the most perfect type of a gentleman that I have seen in any country. He is seldom less than six feet tall, and he carries his six feet with the erectness of a soldier and with the grace of a woman. The bones of his face are strong and well-placed, and he looks kind and properly self-respecting, and is always courteous. When you add to this clothing as brilliant and robes as clean and soft and white as a bride's, you have a very worthy-looking man. The Bashaw towered above all of us. He wore brown and dark-blue cloaks, with a long under-waistcoat of light-blue silk, yellow shoes, and a white turban as big as a bucket, and his baggy trousers were as voluminous as Letty Lind's divided skirts. He could not speak English, but he shook hands with us, which Moors do not do to one another, and walked on ahead through court-yards and halls and up stairways to a little room filled with divans and decorated with a carved ceiling and tiled walls. There we all sat down, and a soldier in a long red cloak and with numerous swords sticking out of his person gave us tea, and sweet cakes made entirely of sugar. As soon as we had finished one cup he brought in another, and, noticing this, I indulged sparingly; but the doctor finished his first, and then refused the rest, until the Consul-General told him he must drink or be guilty of a breach of etiquette.

[63]The Bashaw and Colonel Mathews talked together, and we paid the governor long and laborious compliments, at which he smiled indulgently. He did not strike me as being at all overcome by them; he had, on the contrary, very much the air of a man of the world, and seemed rather to be bored, but too polite to say so. He looked exactly like Salvini as Othello. While the tea-drinking was going on we were making asides to Colonel Mathews, and urging him to propose our going into the prison, which he said he would do, but that it must be done diplomatically. We told him we would give all the prisoners bread and water, or a lump sum to the guards, or whatever he thought would please the Bashaw best. He and the Bashaw then began to talk about it, and the doctor and I looked consciously at the ceiling. The Bashaw said that never since he had been governor of Tangier had he allowed either a native or a foreigner to enter the prison; and that if a European did so, he would be torn to[64] pieces by the fanatics imprisoned there, who would think they were pleasing Allah by abusing an unbeliever. Colonel Mathews also added, on his own account, that we would probably catch some horrible disease. The more they did not want us to go, the more we wanted to go, the doctor rising to the occasion with a keenness and readiness of resource worthy of a New York reporter after a beat. I can pay him no higher compliment. After a long, loud, and excited debate the Bashaw submitted, and the Consul-General won.

The first prison they showed us was the county jail, in which men are placed for a month or more. It was dirty and uninteresting, and we protested that it was not the one which the Bashaw had described, and asked to be shown the one where the enemies of the government were incarcerated. Colonel Mathews called back the Bashaw's soldiers, and we went on to the larger prison immediately adjoining. Some time ago the inmates of this made a break for liberty, and forced open the one door which bars those inside from the outer world. The guards fired into the mass of them, and the place shows where the bullets struck. To prevent a repetition of this, three heavy bars were driven into the masonry around the door, so close together that it is impossible for more than one man to leave or enter the prison at one time even when the door is open. And the opening is so small that to do this he must either crawl in on his hands and knees, or[65] lift himself up by the crossbar and swing himself in feet foremost. It impressed me as a particularly embarrassing way to make an entrance among a lot of people who meditated tearing you to pieces. I pointed this out to the doctor, but he was determined, though pale. So the guards swung the door in, and the first glimpse of a Christian gentleman the prisoners had in ten years was a pair of yellow riding-boots which shot into space, followed by a young man, and a moment later by an elderly gentleman with a white tie. We made a combined movement to the middle of the prison, which was lighted from above by a square opening in the roof, protected by iron bars. This was the only light in the place. All around the four sides of the patio or court were rows of pillars supporting a portico, and back of these was a second and outer corridor opening into the porticos, and so into the patio. The whole place—patio, porticos, and outer corridor—was about as big as the stage of a New York theatre. It was paved with dirt and broken slabs, and littered with straw. There was no furniture of any sort. With the exception of the sink upon which we stood, directly under the opening in the roof, the place was in almost complete darkness, although the sun was shining brilliantly outside.

I think there must have been about fifty or sixty men in the prison, and for a short time not one of them moved. They were apparently, to judge by the way they looked at us, as much[66] startled as though we had ascended from a trap like goblins in a pantomime, and then half of them, with one accord, came scrambling towards us on their hands and knees. They were half naked, and their hair hung down over their eyes; and this, and their crawling towards us instead of walking, made them look more or less like animals. As they came forward there was a clanking of chains, and I saw that it was because their legs were fettered that they came as they did, and not standing erect like human beings. The guard who followed us in was over two minutes in getting the door fastened behind him, and my mind was more occupied with this fact than with what I saw before me; for it seemed to me that if there was any tearing to pieces to be gone through with, I should hate to have to wait that long while the door was being opened again. This thought, with the shock of seeing thirty wild men moving upon us out of complete darkness on their hands and knees, was the only sensation of any interest that I received while visiting the prison.

The inmates looked exactly like the poorer of the Moors outside, except that their hair was longer and their clothing was not so white. There was one man, however, quite as well dressed as any of the Sultan's counsellors, and he seemed to be the only one who objected to our presence. The rest did nothing except to gratify their curiosity by staring at us; they did not even hold out their hands for money. They were very dirty[69] and poorly clothed, and their long imprisonment had made them haggard and pale, and the iron bars around their legs gave them a certain interest. The atmosphere of the place was horribly foul, but not worse than the atmosphere of either the men's or women's ward at night in a precinct station-house in New York city. Indeed, I was not so much impressed with the horrors of the Sultan's prison as with the fact that our own are so little better, considering our advanced civilization. I do not mean our large prisons, but the cells and the vagrants' rooms in the police stations. There the vagrant is given a sloping board and no ventilation. In Tangier he is given straw and an opening in the roof. To be fair, you must compare a prisoner's condition in jail with that which he is accustomed to in his own home, and the homes of the Moors of the lower class are as much like stables as their stables are like pigsties. The poor of Tangier are allowed, through the kindness of the Sultan, to sleep on the bare stones around the entrance to one of the mosques. For the poor sick there has been built a portico, about as large as a Fifth Avenue omnibus, opposite this same mosque. This is called the hospital of Tangier. It is considered quite good enough for sick people and for those who have no homes. And every night you will see bundles of rags lying in the open street or under the narrow roof of the portico, exposed to the rain and to the bitter cold. If this, in the minds of the Moors, is fair treatment of the sick and the poor, one cannot expect them[70] to give their criminals and murderers white bread and a freshly rolled turban every morning.

If I had seen horrible things in the Sultan's prison—men starving, or too sick to rise, or chained to the walls, or half mad, or loathsome with disease—I should certainly have been glad to call the attention of other people to it, not from any philanthropic motives perhaps, but as a matter of news interest. I did not, however, see any of these things. Dr. Field, I believe, was differently impressed, and is of the opinion that the outer corridor contained many things much too horrible to believe possible. He compared this to Dante's ninth circle of hell, and made a point of the fact that the guard had called me back when I walked towards it. I, however, went into it while the doctor and the guard were getting the door open for us to return, and saw nothing there but straw. It seemed to me to be the place where the men slept when the rain, coming through the opening in the roof, made it unpleasant for them to remain in the court.

It may seem that my persistence in visiting the prison is inconsistent with what I have said of foreigners forcing themselves into places in Morocco where they are not wanted, but I am quite sure that, had any one heard the stories told me of the horror of these jails, he would have considered himself justified in learning the truth about them; and I cannot understand why, if the members of the legations who tell these stories believe them, they have not used their influence[71] to try and better the condition of the prisoners, rather than to introduce game-laws for the protection of partridges and wild-boars. It is, perhaps, gratifying to note that the two gentlemen of whom I spoke as having visited the prison in the last ten years were the American Consul-General and another resident American. Both of these contributed food to the prisoners, and reported what they had seen to our government.

On the whole, Tangier impresses one as a fine thing spoiled by civilization. Barbarism with electric lights at night is not attractive. Tangier to every traveller should be chiefly interesting as a stepping-stone towards Tetuan or Fez. Tetuan can be reached in a day's journey, and there the Moor is to be seen pure and simple, barbarous and beautiful.