Title: The First Seven Divisions

Author: Lord Ernest Hamilton

Release date: March 15, 2012 [eBook #39158]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Charlene Taylor, Sigal Alon and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

THE FIRST SEVEN DIVISIONS

McCLELLAND, GOODCHILD & STEWART, Ltd.

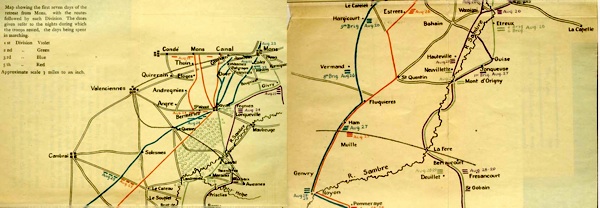

Map showing the first seven days of the retreat from Mons, with the routes followed by each Division. The dates given refer to the nights during which the troops rested, the days being spent in marching.

Approximate scale 7 miles to an inch.

PREFACE

The 1st Expeditionary Force to leave England consisted of the 1st A.C. (1st and 2nd Divisions) and the 2nd A.C. (3rd and 5th Divisions).

The 4th Division arrived in time to prolong the battle-front at Le Cateau, but it missed the terrible stress of the first few days, and can therefore hardly claim to rank as part of the 1st Expeditionary Force in the strict sense. The 6th Division did not join till the battle of the Aisne. These two divisions then formed the 3rd A.C.

In the following pages the doings of the 3rd A.C. are only very lightly touched upon, not because they are less worthy of record than those of the 1st and 2nd A.C., but simply because they do not happen to have come within the field of vision of the narrator.

The 7th Division's doings are dealt with because these were inextricably mixed up with the operations of the 1st A.C. east of Ypres. The 3rd A.C., on the other hand, acted throughout as an independent unit, and had no part in the Ypres and La Bassée fighting with which these pages are attempting to deal.

The main point aimed at is accuracy; no attempt is made to magnify achievements, or to minimise failures.

It must, however, be clearly understood that the mention from time to time of certain battalions as having been driven from their trenches does not in the smallest degree suggest inefficiency on the part of such battalions. It is probable that every battalion in the British Force has at some time or another during the past twelve months been forced to abandon its trenches. A battalion is driven from its trenches as often as not owing to insupportable shell-fire concentrated on a particular area. Such trenches may be afterwards retaken by another battalion under entirely different circumstances, and in any case in the absence of shell-fire. That goes without saying. It may, therefore, quite easily happen that lost trenches may be retaken by a battalion which is inferior in all military essentials to the battalion which was driven out of the same trenches the day before, or earlier in the same day, as the case may be.

I wish to take this opportunity of expressing the great obligations under which I lie to the many officers who have so kindly assisted me in the compilation of this work.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | v |

| BEFORE MONS | 1 |

| THE BATTLE OF MONS | 12 |

| THE RETREAT FROM MONS (LANDRECIES AND MAROILLES) | 33 |

| THE LE CATEAU PROBLEM | 50 |

| LE CATEAU | 55 |

| THE RETREAT FROM LE CATEAU (VILLERS-COTTERÊTS AND NÉRY) | 66 |

| THE ADVANCE TO THE AISNE | 84 |

| THE PASSAGE OF THE AISNE | 96 |

| TROYON (VERNEUIL AND SOUPIR) | 103 |

| THE AISNE | 120 |

| MANŒUVRING WESTWARD | 141 |

| FROM ATTACK TO DEFENCE | 159 |

| THE BIRTH OF THE YPRES SALIENT | 162 |

| THE STAND OF THE FIFTH DIVISION | 180 |

| NEUVE CHAPELLE | 192 |

| PILKEM | 203 |

| THE SECOND ADVANCE | 209 |

| THE FIGHTING AT KRUISEIK | 218 |

| THE LAST OF KRUISEIK | 230 |

| ZANDVOORDE | 249 |

| GHELUVELT | 257 |

| MESSINES AND WYTSCHATE | 265 |

| KLEIN ZILLEBEKE | 278 |

| THE RELIEF OF THE SEVENTH DIVISION | 285 |

| ZWARTELEN | 294 |

| THE PRUSSIAN GUARD ATTACK | 303 |

| EPITAPH | 310 |

The following abbreviations are used:—

| The C. in C. | = | Field Marshal Sir John French |

| A.C. | = | Army Corps |

| C.B. | = | Cavalry Brigade |

| K.O.S.B. | = | King's Own Scottish Borderers |

| K.O.Y.L.I. | = | King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry |

| K.R.R. | = | King's Royal Rifles (60th) |

LIST OF MAPS

| Showing the first seven days of the retreat from Mons, with the routes followed by each division. | Facing Title Page |

| Showing disposition of troops at the battle of Mons. | Facing page 12 |

| Showing line occupied by British troops after the battle of the Aisne. | 102 |

| Ypres and district | 162 |

THE FIRST SEVEN DIVISIONS

BEFORE MONS

When an entire continent has for eighteen months been convulsed by military operations on so vast a scale as almost to baffle imagination, the individual achievements of this division or of that division are apt to fade quickly out of recognition. Fresh scenes peopled by fresh actors hold the public eye, and, in the quick passage of events, the lustre of bygone deeds soon gets blurred. People forget. But when the deeds are such as to bring a thrill of national pride; when they set up an all but unique standard of valour for future generations to live up to, it is best not to forget.

On the outbreak of war with Germany on August 3rd, 1914, the British Army was so small as to be a mere drop in the ocean of armed men who were hurrying to confront one another on the plains of Belgium. It was derisively described as "contemptible." And yet, in the first three months of the war, this little army, varying in numbers from 80,000 to 130,000, may justly claim to have in some part moulded the history of Europe. It was the deciding factor in a struggle where the sides—at first—were none too equally matched. For this alone its deeds are worthy of record, and they are worthy of record too for another reason. They represent the supreme sacrifice in the interests of the national honour of what was familiarly known as our "regular army." Since the outbreak of the war, fresh armies have arisen, of new and unprecedented proportions. The members of these new armies are as familiar now to the public eye as the representatives of the old regular army are scarce. With the doings of these new armies the present pages have no concern. They are, it is true, the expression of a spirit of patriotism and duty so remarkable that their voluntary growth must for ever stand out as one of the grandest monuments in the history of Britain. But they form no part of the subject matter of these pages, which deal solely with the way in which the old regular army, led by the best in the land, saved the national honour in the acutest crisis in history, and practically ceased to exist in the doing of it.

The regular army, small as it was, did not lie under the hands of those who would use it. Much of it was far away across the seas, guarding the outposts of the Empire. A certain proportion, however, was at hand, and with a smoothness and expedition which silenced, no less than it amazed, the critics of our military administration, 50,000 infantry, with its artillery and five brigades of cavalry, were shipped off to France almost before the public had realized that we were at war. From Havre or Boulogne, as the case might be, these troops either marched or were trained northwards; shook themselves into shape; gradually assumed the form of two army corps of two divisions each, of which the 1st Division was on the right and the 5th on the left (the 4th Division having not yet arrived), and in this formation faced the Belgian frontier to meet and check the invaders.

The two advancing forces met at Mons, or, to be more accurate, the British force took up a defensive position at Mons—in conformity with the pre-arranged plan of extending the French line westwards—and there waited.

From this time on, the doings of the Expeditionary Force become historically interesting, and its movements are worthy of study in detail. In the first instance, however, in order to arrive at a proper understanding of the circumstances which governed the position of the British troops on the occasion of their first stand, and which afterwards dictated the line of retreat and the roads to be followed in that retreat, and the successive points at which the retreating army faced about and fought, it is desirable to get a general grasp of the geographical side of things. The Germans were advancing from the north-east on Paris; that was their avowed intention; there was no secret about it; the leaders openly proclaimed their intentions; the soldiers advertised the fact in chalk legends scribbled on the doors of the houses; and—as the fashion is with Germans in arms—they were taking the most direct route to their objective, their artillery and transport following the great main roads that shoot out north-eastward from Paris towards Brussels, with their infantry swarming in endless thousands along the smaller collateral roads. Here and there, at intervals of from twenty to thirty miles, this system of parallel roads running north-east from Paris is crossed by other main roads running at right angles and forming, as it were, a skeleton check with the point of the diamond to the north. These main cross-roads had, in anticipation, been selected for the lines of defence along which our troops should turn and fight if necessary, for though it is laid down in the text-books of the wise that a line of defence must not run along a main road, such a road has obvious value for purposes of correct alignment. As the German advance was from the north-east, it is self-evident that the line of resistance or defence had to extend from north-west to south-east.

When our troops, by forced marches, reached Mons on August 22nd, 1914, the primary business of the British Force was to prolong the French line of resistance in a north-westerly direction. The natural country feature which was geographically indicated for this purpose was the high road which runs from Charleroi through Binche to Mons, and this was the line for which our troops were originally destined. In effect, however, this line proved to be impracticable, for the simple reason that, when we reached it, the Germans were already in possession of Charleroi, and the French on our right had fallen back beyond the point of prolongation of this line. For the British Force in these circumstances to have occupied the Mons—Charleroi road would have laid it open to the very great risk—if not certainty—of being cut off and completely isolated. In these circumstances there was no alternative but to range our 1st A.C. along the Mons—Beaumont road, in rear of the original position contemplated, while the 2nd A.C. lined the canal between Mons and Condé. The position was not ideal, the formation being that of a broad arrow, with the two Army Corps practically at right angles to one another. However, it was the best that offered in the peculiar circumstances of the case. As it turned out in the end, the entire attack at Mons fell on the 2nd A.C., which lay back at an angle of forty-five degrees from the general line of defence. The battle of Mons may, therefore, in a sense be looked upon as an attempt at a flanking or enveloping movement on the part of the enemy, which was frustrated by the interposition of our troops.

In view of the fact that the scene of the first shock with the enemy was fixed by necessity and not by choice, the Mons canal may be considered as a fortunate feature in the landscape. It ran sufficiently true to the required line to offer an obvious line of defence, and an ideal one, except for the flagrant defect that, after running from Condé to Mons in a mathematically straight line, on reaching the town it flings off to the north in a loop some two miles long by one and a half miles across. This loop, as well as the straight reach to Condé, was occupied by our troops. The formation of the British army, then, was not only that of a broad arrow, but of a broad arrow with a loop two miles long by a mile and a half across projecting from the point. Such a position could obviously not be held for long, and Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, recognizing this, had prepared in advance a second and more defensible line running through Frameries, Paturages, Wasmes and Boussu. To this second line the troops were to fall back as soon as the salient became untenable. A glance at the map will serve to show that the effect of swinging back the right of the 2nd A.C. to this new position would be to at once bring the whole British Army into line, with a frontage facing the advance of the enemy from the north-east. In view, however, of the preparedness of the Germans and the comparative unpreparedness of the Allies, time was a factor in the case of the very first importance, and therefore the passage of the canal had to be opposed, if only for purposes of delay. It is important, however, to keep in mind that the real line which it was intended to defend at Mons was this second line. The intention was never carried out, because it was anticipated by an unexpected and most unwelcome order to retire in conformity with French movements on the right, which upset all plans.

In the meanwhile, the enemy's entry into Mons itself had to be delayed as long as possible, which meant that the canal salient, bad as it was, had perforce to be defended. This dangerous but most responsible duty was entrusted to Sir Hubert Hamilton with his 3rd Division, and, as a matter of fact, the battle of Mons in the end proved to be practically confined to the three brigades of this division.

The disposition of the division was as follows:

General Shaw, with the 9th Brigade, was posted along the western face of the canal loop, his right-hand battalion being the 4th R. Fusiliers, who held the line from the Nimy bridge, at Lock 6, to the Ghlin bridge. To the left of the R. Fusiliers, were the R. Scots Fusiliers, and beyond them again half the Northumberland Fusiliers reaching as far as Jemappes. The Lincolns and the rest of the Northumberland Fusiliers formed the reserve to the brigade and were at Cuesmes in rear of the canal.

On the right of the 9th Brigade was the 8th Brigade, occupying the north-east face of the canal salient. Of this brigade the 4th Middlesex on the left took up the line from the R. Fusiliers east of the Nimy bridge, and carried it on as far as the bridge and railway station at Obourg. Between Obourg and St. Symphorien were the 1st Gordon Highlanders, and on their right, thrown back so as to link up with the left of the 1st A.C., were the 2nd Royal Scots. The Royal Irish Regiment formed the brigade reserve at Hyon, and the 7th Brigade the divisional reserve at Cipley. So much then for the salient itself on which, as it turned out, the enemy's attack was mainly focussed. On the left of the 3rd Division, along the straight reach of the canal which runs to Condé, was Sir Charles Fergusson's 5th Division. Of this division we need only concern ourselves with the 13th Brigade, which continued the line of defence on the left of the 9th Brigade, the R. West Kents holding the ground from Mariette to Lock 5 at St. Ghislain, with the K.O.S.B. extended beyond them as far as Lock 4 at Les Herbières. The K.O.Y.L.I. and Duke of Wellington's Regiment were in reserve. On the left of the K.O.S.B. was the E. Surrey Regiment and beyond again the 14th and 15th Brigades. Later on the line was still further extended to the west by the 19th Brigade, which arrived during the afternoon of the 23rd.

Such then was the disposition of the 2nd A.C. The 1st A.C. lay back, as has been explained, almost at right angles to the line of the canal, along the two roads that branch off from Mons to Beaumont and Maubeuge respectively. On the first-named road was the 1st Division reaching as far as Grand Reng. This division, however, as events turned out, was merely a spectator of the operations of August 23rd. The 2nd Division was very much scattered, the 6th Brigade being at Givry, and the 5th at Bougnies, while of the 4th Brigade the two Coldstream Battalions were at Harveng and the rest of the brigade at Quévy.

The gap between the 1st and 2nd A.C. was patrolled by the 2nd C.B., an operation which brought about the first actual collision between British and German troops. This was on the 22nd near Villers St. Ghislain, when Captain Hornby with a squadron of the 4th Dragoon Guards fell in with a column of Uhlans, which he promptly charged and very completely routed, capturing a number of prisoners.

The rest of our cavalry was spread along the Binche road as a covering screen for the 1st A.C., with the exception of the 4th C.B. which was at Haulchin cross-roads, guarding the approach to that place from the direction of Binche, and at the same time keeping up a communication between the 1st and 2nd Divisions.

Such then was, generally speaking, the position on August 22nd. During that night, however, all the cavalry was withdrawn from the Binche road and moved across to the left of our line, where they took up a position guarding that flank along the two roads running north and south through Thulin and Eloges to Andregnies. The 4th C.B., having the shortest journey to make, went four miles further west again to Quiverain. This change of position meant a twenty mile night march for the cavalry on the top of a hard day's patrol work, and the journey took them from six o'clock in the evening till two o'clock the following morning.

THE BATTLE OF MONS

The morning of the 23rd opened sunny and bright. The weather was set fair with a breeze from the east, a cloudless sky, and the promise of great heat at midday. A pale blue haze rounded off the distance, and softened the outlines of the tall, gaunt chimney stacks with which the entire country is dotted.

With the first streak of dawn came the first German shell. It was evident from the outset that the canal loop had been singled out as the object of the enemy's special attentions. Its weakness from the defensive point of view was clearly as well known to them as it was to our own Generals. It was also fairly obvious to both sides that, if the enemy succeeded in crossing the canal in the neighbourhood of the salient, the line of defence along the straight reach to Condé would have to be abandoned. The straight reach of the canal was therefore, for the time being, neglected, and all efforts confined to the salient. The bombardment increased in volume as the morning advanced and as fresh German batteries arrived on the scene, and at 8 a.m. came the first infantry attack.

Map showing disposition of troops at the battle of Mons. Approximate scale 2 miles to an inch.

This first attack was launched against the north-west corner of the canal loop, the focus-point being—as had been anticipated—the Nimy bridge, on which the two main roads from Lens and Soignies converge. The attack, however, soon became more general and the pressure quickly extended for a good mile and a half to either side of the Nimy bridge, embracing the railway bridge and the Ghlin bridge to the left of it, and the long reach to the Obourg bridge on the right.

The northern side of the canal is here dotted, throughout the entire length of the attacked position, with a number of small fir plantations which proved of inestimable value to the enemy for the purpose of masking their machine-gun fire, as well as for massing their infantry preparatory to an attack.

About nine o'clock the German infantry attack, which had been threatening for some time past, took definite shape and four battalions were suddenly launched upon the head of the Nimy bridge. The bridge was defended by a single company of the R. Fusiliers under Captain Ashburner and a machine-gun in charge of Lieut. Dease.

The Germans attacked in close column, an experiment which, in this case proved a conspicuous failure, the leading sections going down as one man before the concentrated machine-gun and rifle fire from the bridge. The survivors retreated with some haste behind the shelter of one of the plantations, where they remained for half an hour. Then the attack was renewed, this time in extended order. The alteration in the formation at once made itself felt on the defenders. This time the attack was checked but not stopped. Captain Ashburner's company on the Nimy bridge began to be hard pressed and 2nd Lieut. Mead was sent up with a platoon to its support. Mead was at once wounded—badly wounded in the head. He had it dressed in rear and returned to the firing line, to be again almost immediately shot through the head and killed. Captain Bowdon-Smith and Lieut. Smith then went up to the bridge with another platoon. Within ten minutes both had fallen badly wounded. Lieut. Dease who was working the machine-gun had already been hit three times. Captain Ashburner was wounded in the head, and Captain Forster, in the trench to the right of him, had been shot through the right arm and stomach. The position on the Nimy bridge was growing very desperate, and it was equally bad further to the left, where Captain Byng's company on the Ghlin bridge was going through a very similar experience. Here again the pressure was tremendous and the Germans made considerable headway, but could not gain the bridges, Pte. Godley with his machine-gun sticking to his post to the very end, and doing tremendous execution. The defenders too had most effective support from the 107th Battery R.F.A. entrenched behind them, the Artillery Observer in the firing line communicating the enemy's range with great accuracy.

To the right of the Nimy bridge the 4th Middlesex were in the meanwhile putting up a no less stubborn defence, and against equally desperate odds. Major Davey, whose company was on the left, in touch with the right of the R. Fusiliers, had fallen wounded early in the day, and the position at that point finally became so serious that Major Abell's company was rushed up from reserve to its support. During this advance Major Abell himself, Captain Knowles and 2nd Lieut. Henstock were killed, and a third of the rank and file fell, but the balance succeeded in reaching the firing line trenches and—with this stiffening added—the position was successfully held for the time being.

Captain Oliver's company, in the centre of the Middlesex line, was also very hard pressed, and Col. Cox sent up two companies of the R. Irish Regiment (who were in reserve at Hyon) to its support, another half company of the same regiment being at the same time sent to strengthen the right of the Middlesex line at the Obourg bridge, where Captain Roy had already been killed and Captain Glass wounded. The Gordons, on the right of the Middlesex, also suffered severely, but the Royal Scots beyond them were just outside of the zone of pressure, and their casualties were few.

The attack along the straight reach of the canal towards Condé was less violent, and was not pressed till much later in the day. Here, lining the canal towards the west, was the 5th Division (13th, 14th and 15th Brigades). On the right of this division and in touch with the Northumberland Fusiliers, who were the left-hand battalion of the 9th Brigade (in the 3rd Division) were the 1st R. West Kents. This battalion had on the previous day, in its capacity as advance guard to the brigade, been thrown forward as a screen some distance to the north of the canal, where it sustained some fifty casualties, Lieuts. Anderson and Lister being killed and 2nd Lieut. Chitty wounded. Eventually, as the enemy advanced, the battalion was withdrawn to the south side of the canal, and on the 23rd it occupied the reach from Mariette on the east to the Pommeroeul—St. Ghislain road on the west, where two companies held the bridge at the lock. This position, however, was not seriously pressed, and the battalion had few further casualties during the day, though Captain Buchanon-Dunlop had the misfortune to be wounded by a shell at the outset of the attack.

Towards midday the attack against the straight reach of the canal became general. The whole line was shelled, and the German infantry, taking advantage of the cover afforded by the numerous fir plantations—which here, as at Nimy, dotted the north side of the canal—worked up to within a few hundred yards of the water, and from the cover of the trees maintained a constant rifle and machine-gun fire on the defenders.

About 3 o'clock in the afternoon the 19th Brigade under General Drummond arrived from Valenciennes and took up a position on the extreme left of our front, extending the line of the 5th Division as far as Condé itself, on the outskirts of which town were the 1st Cameronians, with the 2nd Middlesex on their right, and the 2nd R. Welsh Fusiliers again beyond.

They were hardly in position before the action became general all along the line of the canal.

The most serious attack in this quarter was on the bridge at Les Herbières, held by the 2nd K.O.S.B. This regiment had thrown one company forward on the north side, along the Pommeroeul road, with the remaining companies lining the south bank of the canal, and the machine-guns dominating the situation on the north side of the canal from the top storey of the highest house on the south side. The dispositions for defence were good, but on the other hand the K.O.S.B. were throughout the action a good deal harassed by a thick wood running up close to the north bank, in which the Germans were able to concentrate without coming under observation. Several times their infantry were seen massing on the edge of this wood with a view to a charge, but on each occasion the attack died away under the rifle fire from the Pommeroeul road and canal bank, and the machine-gun fire from the tall house beyond.

In the meanwhile, though undoubtedly inflicting very heavy losses on the enemy, the K.O.S.B. were losing men all the time, Captain Spencer, Captain Kennedy and Major Chandos-Leigh being early among the casualties. Curiously enough, the machine-gun position, though sufficiently conspicuous, was not located by the enemy for some considerable time, but eventually it became the object of much attention. In the end, however, it was luckily able to withdraw without loss, being more fortunate in this respect than the machine-gun section of the K.O.Y.L.I. on the right under Lieut. Pepys, that officer being the first man killed in action in the battalion, if not in the whole division.

The Germans, in spite of all efforts, were able to make no material headway along the straight canal, nor was the advantage of the fighting in that quarter by any means on their side, but with the abandonment of the Nimy salient the withdrawal of the troops to the left of it became imperative, for reasons already explained, and in the evening the 5th Division received the order to retire. This was not till long after the 3rd Division had abandoned the Nimy salient. The three brigades of this latter division, after putting up a heroic defence and suffering very severe casualties, got the order to retire at 3 p.m., whereupon the R. Fusiliers fell slowly back through Mons to Hyon, and the R. Scots Fusiliers, who had put up a great fight at Jemappes, through Flénu. The blowing up of the Jemappes bridge gave a lot of trouble. Corpl. Jarvis, R.E., worked at it for one and a half hours, continuously under fire, before he eventually managed to get it destroyed under the very noses of the Germans. He got a private of the R. Scots Fusiliers, named Heron, to help him, who got the D.C.M. Jarvis got the Victoria Cross.

The retirement of the R. Fusiliers from their dangerous position along the western boundary of the salient was not an easy matter. Before cover could be got they had to cross 250 yards of flat open ground swept at very close range by shrapnel and machine-gun fire. Dease had now been hit five times and was quite unable to move. Lieut. Steele, who was the only man in the whole section who had not been killed or wounded, caught him up in his arms and carried him across the fire zone to a place of safety beyond, where however he later on succumbed to his wounds. Dease was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, as also was Pte. Godley for his machine-gun work on the Ghlin bridge.

The 9th Brigade after abandoning the salient remained in the open fields near the Mons hospital till two o'clock in the morning, when it continued its retirement towards Frameries. The wounded were left in the Mons hospital. At Flénu the R. Scots Fusiliers lingered rather too long, and were caught near the railway junction by some very mobile machine-guns, which caused a number of casualties, Captain Rose being killed, and several other officers wounded.

By dusk the new line running through Montreuil, Boussu, Wasmes, Paturages and Frameries had been taken up by the greater part of the 2nd A.C., but the two extremities, i.e., the 14th, 15th and 19th Brigades on the left and the 8th Brigade on the right, remained in their original positions till the middle of the night. The latter brigade then retired through Nouvelles and Quévy to Amfroipret, just beyond Bavai, where it bivouacked. This brigade in common with the 9th Brigade had suffered very severely, the Middlesex alone having lost 15 officers and 353 rank and file.

By night the Germans had completed their pontoon bridges across the canal, and it became evident that they were advancing in great force in the direction of Frameries, Paturages and Wasmes. Sir Horace realized that the 3rd Division had been too severely knocked about during the day to hold the position unaided for long against the weight of troops known to be advancing. He accordingly motored over to the C. in C. to ask for the loan of the 5th Brigade which was at Bougnies, four miles off, and on the main road to Frameries. This was readily granted him, and without delay the 5th Brigade set out, half of it remaining in Frameries, and the other half passing on to Paturages.

In the meanwhile, however, came a most unwelcome change of programme. The first line in the Mons salient had been obviously untenable for long, and had been recognized as such by our commanders, but the line now held was a different matter altogether, and there was every reasonable expectation that it could be successfully defended, at any rate for a very considerable time. At 2 a.m., however, Sir Horace received the order to abandon it and retire without delay to the Valenciennes to Maubeuge road, as the French on our right were retreating. Not only was this unexpected order highly distasteful to the soldier-spirit of the corps, but it involved difficulties of a grave nature with regard to the clearance of the transport and impedimenta generally, and severe and costly rear-guard actions seemed inevitable. At Paturages the Oxfordshire L.I. from the newly-arrived 5th Brigade was detailed for this duty, and dug itself in in rear of the town, while the 3rd Division continued its retirement to Bermeries. The Germans, however, contented themselves with shelling and then occupying the town, and made no attempt to follow through on the far side—a matter for pronounced congratulation, the position of the 5th Brigade being very bad and its line of retreat worse. It is to be supposed that the attractions of the town were for the moment stronger than the lust of battle. There also can be no question but that the Germans lost very heavily in their advance on Frameries and Paturages, the British shrapnel being beautifully timed, and knocking the attacking columns to pieces.

At noon the 5th Brigade returned to its own division at Bavai, the 23rd Brigade R.F.A. remaining behind at Paturages to give all the exits from the town an hour's bombardment, in case the German pursuit might become too pressing.

In the cobbled streets of Bavai a fine confusion was found to reign—companies without regiments and officers without companies, and various units mixed up anyhow. The Staff officers had their hands very full.

In the meantime, while Frameries and Paturages were being occupied by the enemy with little or no infantry opposition, and with little attempt on the part of the enemy at further pursuit, the market square at Wasmes presented a very different scene. This town had been shelled from daybreak, the enemy's fire being replied to with magnificent courage and with the most conspicuous success by a single howitzer battery standing out by itself half a mile from the town. An officer, perched on the top of one of the huge slag heaps with which the country is dotted, was able to direct operations with the highest degree of accuracy, and rendered services to the retreating force which are beyond estimation.

At ten o'clock the German infantry attacked the town with the utmost confidence, advancing through the narrow streets in close column. A certain surprise, however, awaited them. In the town, lining the market square and the streets to either side, were the K.O.Y.L.I., the R. West Kents, the Bedfords and the Duke of Wellington's Regiment, these regiments having been detailed for rear-guard work and having successfully withstood the bombardment. The heads of the German columns, the moment they appeared in sight, were met by a concentrated rifle and machine-gun fire and were literally mown down like grass. Their losses were enormous. Time after time they were driven back, and time after time they advanced again with splendid but useless courage. After two hours' fighting in the streets, during which the enemy was able to make no headway, our troops, having fulfilled their duty as rear-guard, were able to withdraw in good order to St. Vaast, which was reached at dusk. The losses on our side were heavy. The R. West Kents alone had Major Pack-Beresford, Captain Philips, and Lieuts. Sewell and Broadwood killed, and several other officers wounded. The Duke of Wellington's also lost heavily. Sergt. Spence of that regiment distinguished himself very greatly. During one of the German advances he was badly wounded, but ignoring his wounds he charged with a platoon down one of the narrow streets to the right of the square, and drove the enemy clean out of the town with great loss. He was awarded the D.C.M. as was also Sergt. Hunt of the Bedfords.

Further west, at the extreme left of our line, the retirement was effected with even greater difficulty than at Wasmes. The second line of defence through Montreuil, Boussu, Wasmes, Paturages and Frameries—which in effect merely constituted a change of front with the right thrown half back—of necessity left the western end of our line in close proximity to the enemy's advance. In other words, the further west the greater the difficulty of retiring on account of the closer presence of the enemy. The 14th, 15th and 19th Brigades, with a view to conforming to the general direction of the second line of defence, had remained north of the Valenciennes—Mons road and railway throughout the night of the 23rd. In the morning, when the order to retire to the Valenciennes road came, the 15th and 19th Brigades crossed the railway at Quiverain, and the 14th at Thulin, but by this time the enemy was close upon their heels. The 1st Cavalry Division was able to help their retirement to a certain extent by dismounting and lining the railway embankment, from which position they got the advancing Germans in half flank, and did considerable execution. By 11.30, however, they too had been forced to retire to Andregnies. An urgent message now arrived from Sir Charles Fergusson, commanding the 5th Division, saying that he could not possibly extricate his division unless prompt and effective help was given by the cavalry. On receiving this message, General de Lisle, who was at Andregnies, sent off the 18th Hussars to the high ground along the Quiverain to Eloges road with orders to there dismount and make the most of the ground. The 119th Battery R.F.A. was at this time just south-west of Eloges, and L Battery R.H.A. just north-east of Andregnies, both being on the main road to Angre and about three miles apart. The 4th Dragoon Guards and 9th Lancers were in Andregnies itself.

No sooner were his dispositions made than the German columns were seen advancing from the direction of Quiverain towards Andregnies. De Lisle told the two regiments in the village that they had got to stop the advance at all costs, even if it entailed a charge. The very suggestion of a charge never fails to act as a tonic to any British cavalry regiment, and in great elation of spirits the two cavalry regiments debouched from the village, the 4th Dragoon Guards making their exit from the left, and the two squadrons of the 9th Lancers from the right.

The enemy were now seen some 2,000 yards away, the intervening ground being mainly stubble fields in which the corn stooks were still standing. The Germans no sooner saw the cavalry advancing with the evident intention of charging than they scattered in every direction, taking shelter behind the corn stooks and any other cover that presented itself, and opening fire from these positions. The cavalry advanced in the most perfect order, and was on the point of making a final charge when it became evident that this was impossible owing to a wire fence which divided two of the stubble fields.

With great coolness and presence of mind, the two C.O.'s, Col. Mullens of the 4th Dragoon Guards, and Col. Campbell of the 9th Lancers, without pausing, wheeled their troops to the right, and took cover behind some big slag heaps, where they dismounted under shelter. From this position the cavalry opened a galling fire on the advancing Germans, the two batteries on the Angre road joining in. The original scheme of charging the enemy having been frustrated, it now became necessary to get fresh orders from Head Quarters, and Col. Campbell accordingly galloped back across the open, in full view of the enemy and under a salute of bullets, to see the Brigadier, leaving Captain Lucas-Tooth in command of the two squadrons of the 9th Lancers.

For four hours the fight was kept up, the led horses being gradually withdrawn into safety, while the dismounted cavalry with their two attendant batteries held the enemy in check. During the whole of this period the Germans were quite unable to advance beyond the wire fence which had so suddenly changed a proposed charge into a dismounted attack. Captain Lucas-Tooth was awarded the D.S.O. for the gallantry with which he conducted this defence, and for the great coolness and skill with which he withdrew his men and horses.

General de Lisle's object having now been achieved, the dismounted men were gradually withdrawn. During the course of one of these withdrawals, Captain Francis Grenfell, 9th Lancers, noticed Major Alexander of the 119th Battery in difficulties with regard to the withdrawal of his guns. All his horses had been killed, and almost every man in the detachment was either killed or wounded. Captain Grenfell offered assistance which was gladly accepted, and presently he returned with eleven officers of his regiment and some forty men. The ground was very heavy and the guns had to be run back by hand under a ceaseless fire, but they were all saved, Major Alexander, Captain Grenfell and the rest of the officers working as hard as the men. Captain Grenfell was already wounded when he arrived, and was again hit while manhandling one of the guns, but he declined to retire till they were all saved. For this fine performance, Major Alexander and Captain Grenfell [1] were each awarded the Victoria Cross, Sergts. Turner and Davids getting the D.C.M. Others no doubt merited it too, but where so many were deserving it was hard to discriminate.

We may now consider the retirement of the 2nd A.C. to the Valenciennes to Maubeuge road to have been successfully effected; and the fall of night saw this corps dotted at intervals along this road between Jerlain and Bavai.

While they are there, enjoying their few hours' respite from marching and fighting, it may be well to cast a retrospective glance at the doings of the 1st A.C. This corps had so far had little serious fighting, but it had been very far from inactive, and in point of fact, it had probably covered more ground in the way of marching and counter-marching than its partner, owing to repeated scares of enemy attacks which did not materialize. At daybreak on the 24th, the 2nd Division was ordered to make a demonstration in the direction of Binche with a view to diverting attention from the retirement of the 2nd A.C. The 2nd Division now consisted of the 4th and 6th Brigades only, the 5th Brigade having, as we know, gone to Frameries and Paturages to help the 3rd Division. These two brigades, then, advanced at daybreak in the direction of Binche to the accompaniment of a tremendous cannonade, in which the artillery of the 1st Division joined from the neighbourhood of Pleissant. There was a great noise and a vigorous artillery response from the enemy, but not much else, and after an hour or so the 2nd Division returned to the Mons—Maubeuge road, where it entrenched. Here it remained for some four hours, when it retired to the Quévy road and again entrenched. Nothing, however, in the way of a serious attack occurred, and at five o'clock in the evening it fell back to its appointed place just east of Bavai. The 1st Division shortly afterwards arrived at Feignies and Longueville, and the whole British Army was once more in line between Jerlain and Maubeuge, with Bavai as the dividing point between the two A.C.'s.

THE RETREAT FROM MONS

In modern warfare the boundary line between the words "victory" and "defeat" is not easy to fix. It is perhaps particularly difficult to fix in relation to the part played by any arbitrarily selected group of regiments; the fact being that the value of results achieved can only be truly gauged from the standpoint of their conformity with the general scheme. So thoroughly is this now understood that the word "victory" or "defeat" is seldom used by either side in connection with individual actions, except in relation to the strategical bearing of such actions on the ultimate aims of the War Council.

The name of Mons will always be associated in the public mind with the idea of retreat, and retreat is the traditional companion of defeat. Incidentally, too, retreat is bitterly distasteful both to the soldier and the onlooking public. It must be borne in mind, however, that retreat is a more difficult operation than advance, and that when a retreat is achieved with practically intact forces, capable of an immediate advance when called upon, and capable of making considerable captures of guns and prisoners in the process of advance, a great deal of hesitation is needed before the word "defeat" can be definitely associated with such results.

During the first three months of the war the general idea on both sides was to stretch out seawards, and so overlap the western flank of the opposing army. At the moment of the arrival of the British Force on the Belgian frontier, Germany had outstripped France in this race to the west, and there was a very real danger of the French Army being outflanked; so much so, in fact, that in order to avoid any such calamity, a rearrangement of the French pieces seemed called for, to the necessary prejudice of the general scheme. However, at the psychological moment, the much-discussed British Force materialized and became a live obstacle in the path of the German outflanking movement. Its allotted task was to baulk this movement, while the French combination in rear was being smoothly unfolded.

It is now a matter of history that this was done. The German outflanking movement failed; Von Kluck's right wing was held in check; and the British Force fell back unbroken and fighting all the way, while the French dispositions further south and west were systematically and securely shaping for success.

Was Mons, then, a defeat? For forty-eight hours the British had held up the German forces north of the Maubeuge—Valenciennes road; the left of the French Army had been effectively protected, and—over and above all—the British Force had succeeded in retiring in perfect order and intact, except for the ordinary wear and tear of battle. It had "done its job;" it had accomplished the exact purpose for which it had been put in the field, and it had withdrawn thirty-five miles, or thereabouts, to face about and repeat the operation.

In attaching the label to such a performance, neither "victory" nor "defeat" is a word that quite fits. Such crude classifications are relics of primordial standards when scalps and loot were the only recognized marks of victory. To-day, generals commanding armies rather search for honour in the field of duty—duty accomplished, orders obeyed. These simple formulæ have always been the watchwords of the soldier-unit, whether that unit be a man, a platoon, a company or a regiment. Now, with the limitless increase in the size of armaments, a unit may well be an Army Corps, or even a combination of Army Corps, and the highest aim of the general officer commanding such a unit must be—as of old—fulfilment of duty, obedience to orders.

To the Briton, then, dwelling in mind on the battle of Mons, the reflection will always come with a certain pleasant flavour that the British Army was a unit which "did its job," and did it in a way worthy of the highest British traditions. More than this it is not open to man—whether military or civilian—to do.

The British Army continued its retreat from the Maubeuge road in the early morning of the 25th. The original intention of the C. in C. had been to make a stand along this road. That, however, was when the numbers opposed to him were supposed to be very much less than they ultimately turned out to be. Now it was known that there were three Army Corps on his heels, to say nothing of an additional flanking corps that was said to be working up from the direction of Tournai. This last was quite an ugly factor in the case, as it opened the possibility of the little British Force being hemmed in against Maubeuge and surrounded. The road system to the rear, too, was sketchy, and by no means well adapted to a hurried retreat—especially east of Bavai; nor was the country itself suitable for defence, the standing crops greatly limiting the field of fire. All things considered, it was decided not to fight here, but to get back to the Cambrai to Le Cateau road, and make that the next line of resistance.

Accordingly, about four o'clock on the morning of the 25th, the whole army turned its face southward once more. The 5th Division, which during the process of retirement had geographically changed places with the 3rd Division, travelled by the mathematically straight Roman road which runs to Le Cateau, along the western edge of the Forêt de Mormal, while the 3rd Division took the still more western route by Le Quesnoy and Solesme, their retreat being effectively covered by the 1st and 3rd C.B. At Le Quesnoy the cavalry, thinking that the enemy's attentions were becoming too pressing, dismounted and lined the railway embankment, which offered fine cover for men and horses. From here the Germans could be plainly seen advancing diagonally across the fields in innumerable short lines, which the cavalry fire was able to enfilade and materially check.

In the meanwhile the 1st A.C., which had throughout formed the eastern wing of the army, had perforce to put up with the eastern line of retreat on the far side of the Forêt de Mormal, a circumstance which—owing to the longer and more roundabout nature of the route followed—was not without its effect on the subsequent battle of Le Cateau. The six brigades belonging to the last named corps started at all hours of the morning between 4 and 8.30, at which latter hour the 2nd Brigade—the last to leave—quitted its billets at Feignies and marched to Marbaix. The 1st Brigade went to Taisnières, the 4th to Landrecies, the 6th to Maroilles, while the 5th got no farther than Leval, having had a scare and a consequent set-back at Pont-sur-Sambre.

Here then we may leave the 1st A.C. on the night of the 25th, considerably scattered, and separated by distances varying from ten to thirty miles from its partner, which was at the time making preparations to put up a fight along the Cambrai—Le Cateau road.

The original scheme agreed between the C. in C. and his two Army Corps commanders, had been that the 2nd Division should pass on westward across the river at Landrecies and link up with the 5th Division at Le Cateau, blowing up behind it the bridges at Landrecies and Catillon. This scheme was upset by the activity of the enemy on the east side of the Forêt de Mormal, rear-guard actions being forced upon each of the three divisional brigades at Pont-sur-Sambre, Landrecies and Maroilles respectively. These rear-guard actions, coupled with the longer and worse roads they had to follow, in the end so seriously delayed the retirement of the 2nd Division as to entirely put out of court any question of their co-operation with the 2nd A.C. at Le Cateau on the 26th.

The 4th Brigade got the nearest at Landrecies, but it got there dead beat and then had to fight all night. The 1st Division was a good thirty miles off at Marbaix and Taisnières, where it had its hands sufficiently full with its own affairs. This division may, therefore, for the moment, be put aside as a negligible quantity in the very critical situation which was developing west of the Sambre. The movements of the 2nd Division were not only more eventful in themselves, but were of far greater practical interest to the commander of the 2nd A.C. in his endeavour to successfully withdraw his harassed Mons army. We may, therefore, follow this division in rather closer detail during the day and night of the 25th.

In reckoning the miscarriage of the arrangements originally planned, it must not be lost sight of that the march from the Bavai road to the Le Cateau road was the longest to be accomplished during the retreat. From Bavai to Le Cateau is twenty-two miles as the crow flies. It is probable that the 5th Division, following the straight Roman road, did not greatly exceed this distance, but to the route of the 3rd Division it is certainly necessary to add another five miles, and to that of the 2nd Division, ten. In reflecting that the pursuing Germans had to cover the same distance, the following facts must be borne in mind. The training of our military schools has always been based to a very great extent on the experience of the previous war. The equipment of our military ménage is also largely designed to meet the exigencies of a war on somewhat similar lines to that of the last. Our wars for sixty years past have been "little wars" fought in far-off countries more or less uncivilized; and the probability of our armies fighting on European soil has always been considered as remote. Germany, on the other hand, has had few "little wars," but has, on the other hand, for many years been preparing for the contingency of a war amidst European surroundings. As a consequence, her army equipment at the outbreak of war was constructed primarily with a view to rapid movements on paved and macadamized roads; certainly ours was not. The German advance was therefore assisted by every known device for facilitating the rapid movement of troops along the roads of modern civilization. Later on, by requisitioning the motor-lorries and vans of trading firms, we placed ourselves on more or less of an equal footing in this respect, but that was not when the necessity for rapid movement was most keenly felt. The Germans reaped a double advantage, for not only were they capable of quicker movement, but they were also able to overtake our rear-guards with troops that were not jaded with interminable marching.

It must also be borne in mind that a pursuing force marches straight to its objective with a minimum of exhaustion in relation to the work accomplished, an advantage which certainly cannot be claimed for a retreating force which has to turn and fight.

We may now return to the 2nd Division, setting out from La Longueville on its stupendous undertaking. At first the whole division followed the one road by the eastern edge of the Forêt de Mormal, the impedimenta in front, the troops plodding behind. This road was choked from end to end with refugees and their belongings, chiefly from Maubeuge and district, and the average pace of the procession was about two miles an hour. An order came to hurry up so that the bridges over the Sambre could be blown up before the Germans came; but it was waste of breath. The troops were dead beat. Though they had so far had no fighting, they had done a terrible amount of marching, counter-marching and digging during the past four days, and they were dead beat. The reservists' boots were all too small, and their feet swelled horribly. Hundreds fell out from absolute exhaustion. The worst cases were taken along in the transport wagons; the rest became stragglers, following along behind as best they were able. Some of the cavalry that saw them pass said that their eyes were fixed in a ghastly stare, and they stumbled along like blind men. At Leval the division split up, the 4th Brigade taking the road to Landrecies, and the 6th that to Maroilles. The 5th Brigade, which was doing rear-guard to the division, got no farther than Leval, where it prepared to put up a fight along the railway line; for there was a scare that the Germans were very close behind. The Oxfordshire Light Infantry were even sent back along the road they had already travelled to Pont-sur-Sambre, where they entrenched. The Germans, however, did not come.

The Fight at Landrecies

The 4th (Guards') Brigade reached Landrecies at 1 p.m. This brigade had made the furthest progress towards the contemplated junction with the 2nd A.C., and they were very tired. They went into billets at once, some in the barracks, some in the town. They had about four hours' rest; then there came an alarm that the Germans were advancing on the town, and the brigade got to its feet. The four battalions were split up into companies—one to each of the exits from the town. The Grenadiers were on the western side; the 2nd Coldstream on the south and east; and the 3rd Coldstream to the north and north-west. The Irish Guards saw to the barricading of the streets with transport wagons and such-like obstacles. They also loop-holed the end houses of the streets facing the country.

As a matter of fact the attack did not take place till 8.30 p.m., and then it was entirely borne by two companies of the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards. At the north-west angle of the town there is a narrow street, known as the Faubourg Soyère. Two hundred yards from the town this branches out into two roads, each leading into the Forêt de Mormal. Here, at the junction of the roads, the Hon. A. Monck's company had been stationed. The sky was very overcast, and the darkness fell early. Shortly after 8.30 p.m. infantry was heard advancing from the direction of the forest; they were singing French songs, and a flashlight turned upon the head of the column showed up French uniforms. It was not till they were practically at arms' length that a second flashlight detected the German uniforms in rear of the leading sections. The machine-gun had no time to speak before the man in charge was bayoneted and the gun itself captured. A hand-to-hand fight in the dark followed, in which revolvers and bayonets played the principal part, the Coldstream being gradually forced back by weight of numbers towards the entrance to the town. Here Captain Longueville's company was in reserve in the Faubourg Soyère itself, and through a heavy fire he rushed up his men to the support of Captain Monck.

The arrival of the reserve company made things rather more level as regards numbers, though—as it afterwards transpired—the Germans were throughout in a majority of at least two to one. Col. Feilding and Major Matheson now arrived on the spot, and took over control. Inspired by their presence and example, the two Coldstream companies now attacked their assailants with great vigour and drove them back with considerable loss into the shadows of the forest. From here the Germans trained a light field-gun on to the mouth of the Faubourg Soyère, and, firing shrapnel and star-shell at point-blank range, made things very unpleasant for the defenders. Flames began to shoot up from a wooden barn at the end of the street, but were quickly got under, with much promptitude and courage, by a private of the name of Wyatt, who twice extinguished them under a heavy fire. A blaze of light at this point would have been fatal to the safety of the defenders, and Wyatt, whose act was one involving great personal danger, was subsequently awarded the Victoria Cross for this act, and for the conspicuous bravery which he displayed a week later when wounded at Villers-Cotteret.

In the meanwhile Col. Feilding had sent off for a howitzer, which duly arrived and was aimed at the flash of the German gun. By an extraordinary piece of marksmanship, or of luck, as the case may be, the third shot got it full and the field-gun ceased from troubling. The German infantry thereupon renewed their attack, but failed to make any further headway during the night, and in the end went off in their motor-lorries, taking their wounded with them.

It turned out that the attacking force, consisting of a battalion of 1,200 men, with one light field-piece, had been sent on in these lorries in advance of the general pursuit, with the idea of seizing Landrecies and its important bridge before the British could arrive and link up with the 2nd A.C. The attack quâ attack failed conspicuously, inasmuch as the enemy was driven back with very heavy loss; but it is possible that it accomplished its purpose in helping to prevent the junction of the two A.C.'s. This, however, is in a region of speculation, which it is profitless to pursue further.

The Landrecies fight lasted six hours and was a very brilliant little victory for the 3rd Coldstream; but it was expensive. Lord Hawarden and the Hon. A. Windsor-Clive were killed, and Captain Whitehead, Lieut. Keppel and Lieut. Rowley were wounded. The casualties among the rank and file amounted to 170, of whom 153 were left in the hospital at Landrecies. The two companies engaged fought under particularly trying conditions, and many of the rank and file showed great gallantry. Conspicuous amongst these were Sergt. Fox and Pte. Thomas, each of whom was awarded the D.C.M. The German losses were, of course, unascertainable, but they were undoubtedly very much higher than ours.

At 3.30 a.m. on the 26th, just as the 2nd A.C. in their trenches ten miles away to the west were beginning to look northward for the enemy, the 4th Brigade left Landrecies and continued its retirement down the beautiful valley of the Sambre.

Maroilles

On the same night the town of Maroilles further east was the scene of another little fight. About 10 p.m. a report arrived that the main German column was advancing on the bridge over the Petit Helpe and that the squadron of the 15th Hussars which had been left to guard the bridge was insufficient for the purpose. The obstruction of this bridge was a matter of the very first importance, as its passage would have opened up a short cut for the Germans, by which they might easily have cut off the 4th Brigade south of Landrecies. Accordingly the 1st Berks were ordered off back along the road they had already travelled to hold the position at all costs. The ground near the bridge here is very swampy, and the only two approaches are by means of raised causeways, one of which faces the bridge, while the other lies at right angles. Along this latter the Berks crept up, led by Col. Graham.

The night was intensely dark, and the causeway very narrow, and bounded on each side by a deep fosse, into which many of the men slipped. The Germans, as it turned out, had already forced the bridge, and were in the act of advancing along the causeway; and in the pitch blackness of the night the two forces suddenly bumped one into the other. Neither side had fixed bayonets, for fear of accidents in the dark, and in the scrimmage which followed it was chiefly a case of rifle-butts and fists. At this game the Germans proved no match for our men, and were gradually forced back to the bridge-head, where they were held for the remainder of the night.

In the small hours of the morning the Germans, who turned out not to be the main column, but only a strong detachment, threw up the sponge and withdrew westward towards the Sambre, following the right bank of the Petit Helpe. Whereupon the 1st Berks—having achieved their purpose—followed the rest of the 2nd Division along the road to Etreux.

THE LE CATEAU PROBLEM

It is necessary now to cast a momentary eye upon the general situation of the British forces on the night of August 25th. The 3rd and 5th Divisions, in spite of the severe fighting of the 23rd and 24th, and in spite of great exhaustion, had successfully accomplished the arduous march to the Le Cateau position. The 19th Brigade and the 4th Division, the latter fresh from England, were already there, extending the selected line towards the west. So far, so good. The 1st and 2nd Divisions, however, owing to causes which have already been explained, were not in a position to co-operate; and it was clear that, if battle was to be offered at Le Cateau, the already battered 2nd A.C. (supplemented by the newly-arrived troops) would have to stand the shock single-handed.

A consideration of these facts induced the C. in C. to change his original intention of making a stand behind the Le Cateau road, and he decided to continue his retirement to the single line of rail which runs from St. Quentin to Roisel, where his force would be once more in line. This change of plan he communicated to his two Army Corps commanders, Sir Douglas Haig and Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien. The former fell in with it gladly; the latter, however, was not to the same extent a free agent, and he returned word that, in view of the immense superiority in numbers of the German forces, which were practically treading on his heels, and of the necessarily slow progress made by his tired troops, it was impossible to continue his retirement, and that he had no alternative but to turn and fight. To which the C. in C. replied that he must do the best he could, but that he could give him no support from the 1st A.C., that corps being effectively cut off by natural obstacles from the scene of action. As a matter of fact the 1st Division was a good thirty miles away to the east at Marbaix and Taisnières. The 2nd Division was nearer, but very much scattered, the 5th Brigade—owing to rear-guard scares—being still twenty miles behind at Leval, and quite out of the reckoning, as far as the impending battle was concerned. The 4th Brigade, on the other hand, in spite of its all-night fight at Landrecies, might, by super-human efforts, have crossed the Sambre during the night at the little village of Ors, and reached the flank of the Le Cateau battlefield towards eight on the following morning; but the wisdom of such a move would have been more than questionable in view of the complete exhaustion of the troops, and, in point of fact, no such order reached the brigade. The orders were to fall back on St. Quentin, and by the time the first shot was fired at Le Cateau, the brigade was well on its way to Etreux.

Four miles further east, at Maroilles, the order to retire raised some doubts and a certain difference of opinion among the various commanders of the 6th Brigade as to the best route to be followed in order to arrive at the St. Quentin position. Local opinion was divided, and, in the end, the commanders assembled at midnight in the cemetery to decide the point, with the result that it was arranged that each C.O. should follow the road that seemed best to him.

It will be seen then that the disposition of the 1st A.C. was such that the C. in C. by no means overstated the case when he told Sir Horace that he could give him no help from that quarter. The position of the 2nd A.C. was now very nearly desperate, and it is to be doubted whether Sir Horace or the C. in C. himself saw the dawn break on August 26th with any real hope at heart that the three divisions west of the Sambre could be saved from capture or annihilation.

On paper the extrication of Sir Horace's force seemed in truth an impossibility. Three British divisions, very imperfectly entrenched, were awaiting the onset of seven German divisions, flushed with uninterrupted victory, and backed up by an overwhelming preponderance in artillery. Both flanks of the British force were practically in the air, the only protection on the right being the 1st and 3rd C.B. at Le Souplet, and on the left Allenby with another two Cavalry Brigades at Seranvillers. As a buffer against the German army corps which was threatening the British flank from Tournai, two Cavalry Brigades were clearly a negligible quantity. Desperate diseases call for desperate remedies, and the C. in C. had recourse to the only expedient in which lay a hope of salvation from the threatened flank attack, should it come.

General Sordet was at Avesnes with three divisions of French cavalry, and the C. in C.—with all the persuasion possible—put the urgency of the situation before him. The railways were no help; they ran all wrong; cavalry alone could save the situation; would he go? General Sordet—with the permission of his chief—went. It was a forty mile march, and cavalry horses were none too fresh in those days. Still he went, and in the end did great and gallant work; but not on the morning of the 26th. On that fateful day—or at least on the morning of that fateful day—his horses were ridden to a standstill, and he could do nothing.

LE CATEAU

The battle of August 26th is loosely spoken of as the Cambrai—Le Cateau battle, but, as a matter of fact, the British troops were never within half a dozen miles of Cambrai, nor, for that matter, were they actually at Le Cateau itself. The 5th Division on the right reached from a point halfway between Le Cateau and Reumont to Troisvilles, the 15th Brigade, which was its left-hand brigade, being just east of that place. Then came the three brigades of the 3rd Division, the 9th Brigade being north of Troisvilles, the 8th Brigade on the left of it north of Audencourt, with the 7th Brigade curled round the northern side of Caudry in the form of a horseshoe. Beyond was the 4th Division at Hautcourt. The whole frontage covered about eight miles, and for half that distance ran along north of the Cambrai to St. Quentin railway.

The 4th Division, under Gen. Snow, had just arrived from England; and these fresh troops were already in position when the Mons army straggled in on the night of the 25th and was told off to its various allotted posts by busy staff officers. The allotted posts did not turn out to be all that had been hoped for. Trenches, it is true, had been prepared (dug by French woman labour!), but many faced the wrong way, and all were too short. The short ones could be lengthened, but the others had to be redug. The men were dead beat: the ground baked hard, and there were no entrenching tools—these having long ago been thrown away. Picks were got from the farms and the men set to work as best they could, but of shovels there were practically none, and in the majority of cases the men scooped up the loosened earth with mess-tins and with their hands. The result was, trenches by courtesy, but poor things to stand between tired troops and the terrific artillery fire to which they were presently to be subjected.

The battle of Le Cateau was in the main an artillery duel, and a very unequal one at that. The afternoon infantry attack was only sustained by certain devoted regiments who failed to interpret with sufficient readiness the order to retire. Some of these regiments—as the price of their ignorance of how to turn their backs to the foe—were all but annihilated. But this is a later story. Up to midday the battle was a mere artillery duel. Our infantry lined their inadequate trenches and were bombarded for some half a dozen hours on end. Our artillery replied with inconceivable heroism, but they were outnumbered by at least five to one. They also—perhaps with wisdom—directed their fire more at the infantry than at the opposing batteries. The former could be plainly seen massing in great numbers on the crest of the ridge some two thousand yards away, and advancing in a succession of lines down the slope to the hidden ground below. They presented a tempting target, and their losses from our shrapnel must have been enormous. By the afternoon, however, many of our batteries had been silenced, and the German gunners had it more or less their own way. The sides were too unequal. Our infantry then became mere targets—Kanonen Futter. It was an ordeal of the most trying description conceivable, and one which can only arise where the artillery of one side is hopelessly outnumbered by that of the other; and it is to be doubted whether any other troops in the world would have stood it as long as did the 2nd A.C. at Le Cateau. The enemy's bombardment was kept up till midday. Then it slackened off so as to allow of the further advance of their infantry, who by this time had pushed forward into the concealment of the low ground, just north of the main road. By this time some of the 5th Division had begun to dribble away. That awful gun fire, to which our batteries were no longer able to reply, coupled with the insufficient trenches, was too much for human endurance. Sir Charles Fergusson, the Divisional General, with an absolute disregard of personal danger, galloped about among the bursting shells exhorting the division to stand fast. An eye-witness said that his survival through the day was nothing short of a miracle. It was a day indeed when the entire Staff from end to end of the line worked with an indefatigable heroism which could not be surpassed. In the 19th Brigade, for instance, Captain Jack, 1st Cameronians, was the sole survivor of the Brigade Staff at the end of the day, and this was through no fault of his. While supervising the retirement of the Argyll and Sutherlands, he coolly walked up and down the firing line without a vestige of protection, but by some curious law of chances was not hit. He was awarded a French decoration.

In spite of all, however, by 2.30 p.m., the right flank of the 5th Division had been turned, the enemy pressing forward into the gap between the two Army Corps, and Sir Charles sent word that the Division could hold its ground no longer. Sir Horace sent up all the available reserves he had, viz., the 1st Cameronians and 2nd R. Welsh Fusiliers from the 19th Brigade, together with a battery, and these helped matters to some extent, but the immense numerical superiority of the enemy made anything in the nature of a prolonged stand impossible, and at 3 p.m. he ordered a general retirement. This was carried out in fairly good order by the 3rd and 4th Divisions, which had been less heavily attacked. The withdrawal of the 5th Division was more irregular, and the regiments which stuck it to the end—becoming practically isolated by the withdrawal of other units to right and left—suffered very severely.

This irregularity in retirement was noticeable all along the battle-front, some battalions grasping the meaning of the general order to retire with more readiness than others. Among those in the 5th Division who were slow to interpret the signal were the K.O.S.B. and the K.O.Y.L.I.

These two 13th Brigade battalions were next one another just north of Reumont, with the Manchester Regiment on the right of the K.O.Y.L.I. It was common talk among the men of the 5th Division that the French were coming up in support, and that, therefore, there must be no giving way. The French in question were—and only could be—Gen. Sordet's cavalry, who, at the time, were plodding away in rear on their forty mile trek to the left flank of our army, and who could never under any circumstances have been of help to the 5th Division on the right of the Le Cateau battle-front. However, that was the rumour and they held on. Some of the K.O.S.B. in the first line trenches saw some men on their flank retiring, and, thinking it was a general order, followed suit. Col. Stephenson personally re-conducted them back to their trenches. He was himself almost immediately afterwards knocked out by a shell; but the force of example had its effect, and there was no more retiring till the general order to that effect was unmistakable. This was about three o'clock. The final retirement of those battalions which had held on till the enemy was on the top of them was very difficult, and very costly in casualties, as they were mowed down by shrapnel and machine-gun fire the moment they left their trenches. It was during this retirement that Corpl. Holmes, of the K.O.Y.L.I, won his Victoria Cross by picking up a wounded comrade and carrying him over a mile under heavy fire. Another Victoria Cross in the same battalion was won that day by Major Yate under very dramatic circumstances. His company had been in the second line of trenches during the bombardment, and had suffered terribly from the enemy's shell-fire directed at one of our batteries just behind. When the German infantry came swarming up in the afternoon, there were only nineteen sound men left in the company. These nineteen kept up their fire to the last moment and then left the trench and charged, headed by Major Yate. There could be but one result. Major Yate fell mortally wounded, and his gallant band of Yorkshiremen ceased to exist. It was the Thermopylae of B Company, 2nd K.O.Y.L.I. This battalion lost twenty officers and six hundred men during the battle, and was probably the heaviest sufferer in the 5th Division. It stuck it till the last moment and the enemy got round its right flank.

The 3rd Division line, further west, was also forced about three o'clock in the afternoon, when the enemy in great numbers broke through towards Troisvilles, to the right of the 9th Brigade, causing the whole division to retire. The actual order to retire in this case was passed down by word of mouth from right to left by galloping Staff officers, who—in the pandemonium that was reigning—were unable to get in touch with all the units of each battalion. As a result the retirement was necessarily irregular, and—as in the case of the 5th Division—the battalions that "stuck it" longest found themselves isolated and in time surrounded. This was the case with the 1st Gordon Highlanders, in the 8th Brigade, to whom the order to retire either never penetrated, or to whom it was too distasteful to be acted upon with promptitude. The exact circumstances of the annihilation of this historic battalion will never be known till the war is over, but the nett result was that it lost 80 per cent. of its strength in killed, wounded and missing. The same fate overtook one company of the 2nd R. Scots in the same brigade. This company was practically wiped out and the battalion as a whole had some 400 casualties in killed and wounded. The whole division, in fact, suffered very severely in carrying out the retirement, the ground to the rear being very open and exposed, and the enemy's rifle and machine-gun fire incessant. The village of Audencourt had been heavily shelled all day and was a mass of blazing ruins, effectually barring any retirement by the high road, and forcing the retreating troops to take to the open country. Once, however, behind the railway, the retreat became more organized, and a series of small rear-guard fights were put up from behind the shelter of the embankment.

The 23rd Brigade R.F.A., under Col. Butler, put in some most efficient work at this period, and materially assisted the retirement of the 8th Brigade. With remarkable coolness the gunners, entirely undisturbed by the general confusion reigning, continued to drop beautifully-timed shells among the advancing German infantry. The work of the artillery, in fact, all along the line was magnificent, and deeds of individual heroism were innumerable. The 37th Battery, for instance, kept up its shrapnel-fire on the advancing lines of Germans till these were within 300 yards of its position. Then Captain Reynolds, with some volunteer drivers, galloped up with two teams, and hitched them on to the two guns which had not been knocked out. Incredible as it may appear, in view of the hail of bullets directed at them, one of these guns was got safely away. The other was not. Captain Reynolds and Drivers Luke and Brain were given the Victoria Cross for this exploit. Sergt. Browne, of the same battery, got the D.C.M. The 80th Battery was another that distinguished itself by exceptional gallantry at Ligny during the retreat, and three of its N.C.O.'s won the D.C.M. Near the same place the 135th Battery also covered itself with glory. In fact, it is not too much to say that the situation on the afternoon of August 26th was very largely saved by the splendid heroism of our Field Artillery; and for the exploits of this branch of the service alone the battle of Le Cateau must always stand out as a bright spot in the annals of British arms.

The Germans did not pursue the 3rd Division beyond the line of the villages above named. In the case of the 5th Division there was no pursuit at all, in the strict sense of the term. That is to say, there were no rear-guard actions. The division made its way through Reumont, to the continuation of the straight Roman road by which it had reached Le Cateau, and down this road it continued its retreat unmolested. Rain began to fall heavily and numbers of the men, heedless alike of rain or of pursuing Germans, dropped like logs by the roadside and slept.

The extrication of the Le Cateau army from a position which, on paper, was all but hopeless, was undoubtedly a very fine piece of generalship on the part of Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien. The C. in C. in his despatch wrote: "I say without hesitation that the saving of the left wing of the army under my command, on the morning of August 26th, could never have been accomplished unless a commander of rare and unusual coolness, intrepidity and determination had been present to personally conduct the operation."

THE RETREAT FROM LE CATEAU

Le Cateau may without shame be accepted as a defeat. There was at no time, even in anticipation, the possibility of victory. It was an affair on altogether different lines to that of Mons. At Mons the British Army had been set a definite task, which it had cheerfully faced, and which it had carried through with credit to itself and with much advantage to its ally. Its ultimate retirement had only been in conformity with the movements of that ally. Everything worked according to book.