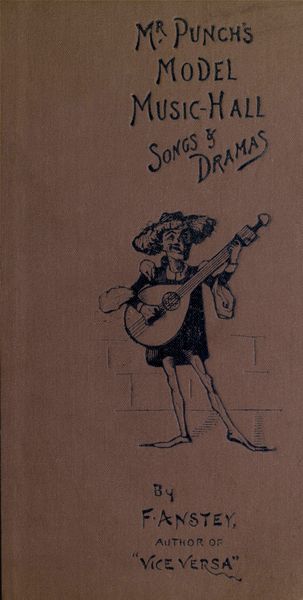

Title: Mr Punch's Model Music Hall Songs and Dramas

Author: F. Anstey

Release date: March 4, 2012 [eBook #39045]

Most recently updated: August 21, 2023

Language: English

Credits: David Clarke, Fulvia Hughes and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Illustrated.

Price 3s. 6d.

MR. PUNCH'S

Model Music-Hall

SONGS & DRAMAS.

Collected, Improved, and Re-Arranged

From "PUNCH."

AUTHOR OF "VICE VERSÂ," "MR. PUNCH'S YOUNG RECITER," &C

With Illustrations.

LONDON:

BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO. Ld., 9, BOUVERIE ST., E.C.

1892.

LONDON

BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO. LD., PRINTERS, WHITEFRIARS.

| Page | |

| Introduction | 3 |

| Illustrations. | |

| SONGS. | |

| I.—The Patriotic | 15 |

| Illustration. | |

| II.—The Topical-Political | 18 |

| Illustration. | |

| III.—A Democratic Ditty | 23 |

| Illustration. | |

| IV.—The Idyllic | 27 |

| Illustration. | |

| V.—The Amatory Episodic | 31 |

| Illustration. | |

| VI.—The Chivalrous | 37 |

| Illustration. | |

| VII.—The Frankly Canaille | 40 |

| Illustration.[vi] | |

| VIII.—The Dramatic Scena | 47 |

| Illustration. | |

| IX.—The Duettists | 53 |

| Illustration. | |

| X.—Disinterested Passion | 59 |

| Illustration. | |

| XI.—The Panegyric Patter | 63 |

| Illustration. | |

| XII.—The Plaintively Pathetic | 69 |

| Illustration. | |

| XIII.—The Military Impersonator | 73 |

| Illustration. | |

| DRAMAS. | |

| I.—The Little Crossing-Sweeper | 79 |

| Illustration. | |

| II.—Joe, the Jam-eater | 86 |

| Illustrations. | |

| III.—The Man-Trap | 93 |

| Illustration. | |

| IV.—The Fatal Pin | 99 |

| Illustration. | |

| V.—Brunette and Blanchidine | 106 |

| Illustration. | |

| VI.—Coming of Age | 113 |

| Illustration.[vii] | |

| VII.—Reclaimed! | 120 |

| Illustrations. | |

| VIII.—Jack Parker. | 132 |

| Illustration. | |

| IX.—Under the Harrow | 139 |

| Illustrations. | |

| X.—Tommy and his Sister Jane | 151 |

| Illustrations. | |

| XI.—The Rival Dolls | 158 |

| Illustration. | |

| XII.—Conrad; or, the Thumbsucker | 166 |

| Illustration. | |

[The Illustrations are by Edward T. Reed; with others from "Punch."]

MODEL MUSIC HALL.

The day is approaching, and may even now be within measurable distance, when the Music Halls of the Metropolis will find themselves under yet more stringent supervision than is already exercised by those active and intelligent guardians of middle-class morality, the London County Council. The moral microscope which detected latent indecency in the pursuit of a butterfly by a marionette is to be provided with larger powers, and a still more extended field. In other words, our far-sighted and vigilant County Councilmen, perceiving the futility of delaying the inspection of Variety Entertainments until such improprieties as are contained therein have been suffered to contaminate the public mind for a considerable period, are determined to nip these poison-flowers in the bud for the future; and, unless Mr. Punch is misinformed, will apply to Parliament at the earliest opportunity for clauses enabling them to require each item in every forthcoming performance[4] to be previously submitted to a special committee for sanction and approval.

The conscientious rigour with which they will discharge this new and congenial duty may perhaps be better understood after perusing the little prophetic sketch which follows; for Mr. Punch's Poet, when not employed in metrical composition, is a Seer of some pretensions in a small way, and several of his predictions have already been shamelessly plagiarised by the unscrupulous hand of Destiny. It is not improbable that this latest effort of his will receive a similar compliment, although this would be more gratifying if Destiny ever condescended to acknowledge such obligations. However, here is the forecast for what it is worth, a sum of incalculable amount:—

Scene—A Committee-room of the L. C. C.; Sub-Committee of Censors, (appointed, under new regulations, to report on all songs intended to be sung on the Music-hall Stage,) discovered in session.

Mr. Wheedler (retained for the Ballad-writers). The next licence I have to apply for is for—well, (with some hesitation)—a composition which certainly borders on the—er—amorous—but I think, Sir, you will allow that it is treated in a purely pastoral and Arcadian spirit.

The Chairman (gravely). There are arcades, Mr.[5] Wheedler, I may remind you, which are by no means pastoral. I cannot too often repeat that we are here to fulfil the mission entrusted to us by the Democracy, which will no longer tolerate in its entertainments anything that is either vulgar, silly, or offensive in the slightest degree. [Applause.

Mr. Wheedler. Quite so. With your permission, Sir, I will read you the Ballad. [Reads.

"Oh! the day shall be marked in red letter——"

The Chairman. One moment, Mr. Wheedler, (conferring with his colleagues). "Marked with red letter"—isn't that a little—eh? liable to——You don't think they'll have read Hawthorne's book? Very well, then. Go on, Mr. Wheedler, please.

Mr. W. "'Twas warm, with a heaven so blue."

First Censor. Can't pass those two epithets—you must tone them down, Mr. Wheedler—much too suggestive!

Mr. W. That shall be done.

The Chairman. And it ought to be "sky."

Mr. W. "When amid the lush meadows I met her,

My Molly, so modest and true!"

Second Censor. I object to the word "lush"—a direct incitement to intemperance!

Mr. W. I'll strike it out. (Reads.)

"Around us the little kids rollicked,

Lighthearted were all the young lambs——"

Second Censor. Surely "kids" is rather a vulgar expression, Mr. Wheedler? Make it "children," and I've no objection.

Mr. W. I have made it so. (Reads.)

"They kicked up their legs as they frolicked"—— [6]

Third Censor. If that is intended to be done on the stage, I protest most strongly—a highly indecorous exhibition! [Murmurs of approval.

Mr. W. But they're only lambs!

Third Censor. Lambs, indeed! We are determined to put down all kicking in Music-hall songs, no matter who does it! Strike that line out.

Mr. W. (reading). "And frisked by the side of their dams."

First Censor (severely). No profanity, Mr. Wheedler, if you please!

Mr. W. Er—I'll read you the Refrain. (Reads, limply.)

"Molly and I. With nobody nigh.

Hearts all a-throb with a rapturous bliss,

Molly was shy. And (at first) so was I,

Till I summoned up courage to ask for a kiss!"

The Chairman. "Nobody nigh," Mr. Wheedler? I don't quite like that. The Music Hall ought to set a good example to young persons. "Molly and I—with her chaperon by," is better.

Second Censor. And that last line—"asking for a kiss"—does the song state that they were formally engaged, Mr. Wheedler?

Mr. W. I—I believe it omits to mention the fact. But (ingeniously) it does not appear that the request was complied with.

Second Censor. No matter—it should never have been made. Have the goodness to alter that into—well, something of this kind. "And I always addressed her politely as "Miss." Then we may pass it.

Mr. W. (reading the next verse).

"She wore but a simple sun-bonnet."

[7]

First Censor (shocked). Now really, Mr. Wheedler, really, Sir!

Mr. W. "For Molly goes plainly attired."

First Censor (indignantly). I should think so—Scandalous!

Mr. W. "Malediction I muttered upon it,

One glimpse of her face I desired."

The Chairman. I think my colleague's exception is perhaps just a leetle far-fetched. At all events, if we substitute for the last couplet,

"Her dress is sufficient—though on it

She only spends what is strictly required."

Eh, Mr. Wheedler? Then we work in a moral as well, you see, and avoid malediction, which can only mean bad language.

Mr. W. (doubtfully). With all respect, I submit that it doesn't scan quite so well——

The Chairman (sharply). I venture to think scansion may be sacrificed to propriety, occasionally, Mr. Wheedler—but pray go on.

Mr. W. (continuing).

"To a streamlet we rambled together.

I carried her tenderly o'er.

In my arms—she's as light as a feather—

That sweetest of burdens I bore!"

First Censor. I really must protest. No properly conducted young woman would ever have permitted such a thing. You must alter that, Mr. Wheedler!

Second C. And I don't know—but I rather fancy there's a "double-intender" in that word "light"—(to colleague)—it strikes me—eh?—what do you think?——

The Chairman (in a conciliatory manner). I am inclined to agree to some extent—not that I consider the words particularly objectionable in themselves, but we are men of the world, Mr. Wheedler, and as such we cannot shut our eyes to the fact that a Music-hall audience is only too apt to find significance in many apparently innocent expressions and phrases.

Mr. W. But, Sir, I understood from your remarks recently[9] that the Democracy were strongly opposed to anything in the nature of suggestiveness!

The Ch. Exactly so; and therefore we cannot allow their susceptibilities to be shocked. (With a severe jocosity.) Molly and you, Mr. Wheedler, must either ford the stream like ordinary persons, or stay where you are.

Mr. W. (depressed). I may as well read the last verse, I suppose:

"Then under the flickering willow

I lay by the rivulet's brink,

With her lap for a sumptuous pillow——"

First Censor. We can't have that. It is really not respectable.

The Ch. (pleasantly). Can't we alter it slightly? "I'd brought a small portable pillow." No objection to that!

[The other Censors express dissent in undertones.

Mr. W. "Till I owned that I longed for a drink."

Third C. No, no! "A drink"! We all know what that means—alcoholic stimulant of some kind. At all events that's how the audience are certain to take it.

Mr. W. (feebly).

"So Molly her pretty hands hollowed

Into curves like an exquisite cup,

And draughts so delicious I swallowed,

That rivulet nearly dried up!"

Third C. Well, Mr. Wheedler, you're not going to defend that, I hope?

Mr. W. I'm not prepared to deny that it is silly—very silly—but hardly—er—vulgar, I should have thought?

Third C. That is a question of taste, which we won't dispute. I call it distinctly vulgar. Why can't he drink out of his own hands?

The Ch. (blandly). Allow me. How would this do for the[10] second line? "She had a collapsible cup." A good many people do carry them. I have one myself. Is that all of your Ballad, Mr. Wheedler?

Mr. W. (with great relief.) That is all, Sir.

[Censors withdraw, to consider the question.

The Ch. (after consultation with colleagues). We have carefully considered this song, and we are all reluctantly of opinion that we cannot, consistently with our duty, recommend the Council to license it—even with the alterations my colleagues and myself have gone somewhat out of our way to suggest. The whole subject is too dangerous for a hall in which young persons of both sexes are likely to be found assembled; and the absence of any distinct assertion that the young couple—Molly and—ah—the gentleman who narrates the experience—are betrothed, or that their attachment is, in any way, sanctioned by their parents or guardians, is quite fatal. If we have another Ballad of a similar character from the same quarter, Mr. Wheedler, I feel bound to warn you that we may possibly consider it necessary to advise that the poet's licence should be cancelled altogether.

Mr. W. I will take care to mention it to my client, Sir. I understand it is his intention to confine himself to writing Gaiety burlesques in future.

The Ch. A very laudable resolution! I hope he will keep it. [Scene closes in.

It is hardly possible that any Music-hall Manager or vocalist, irreproachable as he may hitherto have considered himself, can have taken this glimpse into a not very remote futurity without symptoms of uneasiness, if not of positive dismay. He will reflect that the ballad of "Molly and I," however repre[11]hensible it may appear in the fierce light of an L. C. C. Committee Room, is innocuous, and even moral, compared to the ditties in his own répertoire. How, then, can he hope, when his hour of trial strikes, to confront the ordeal with an unruffled shirt-front, or a collar that shall retain the inflexibility of conscious innocence? And he will wish then that he had confined himself to the effusions of a bard who could not be blamed by the most censorious moralist.

Here, if he will only accept the warning in time, is his best safeguard. He has only to buy this little volume, and inform his inquisitors that the songs and business with which he proposes to entertain an ingenuous public are derived from the immaculate pages of Mr. Punch. Whereupon censure will be instantly disarmed and criticism give place to congratulation. It is just possible, to be sure, that this somewhat confident prediction smacks rather of the Poet than the Seer, and that even the entertainment supplied by Mr. Punch's Music Hall may, to the Purist's eye, present features as suggestive as a horrid vulgar clown, or as shocking as a butterfly, an insect notorious for its frivolity. But then, so might the "songs and business" of the performing canary, or the innocent sprightliness of the educated flea, with its superfluity of legs, all[12] absolutely unclad. At all events, the compiler of this collection ventures to hope that, whether it is fortunate enough to find favour or not with Music-hall "artistes," literary critics, and London County Councilmen, it contains nothing particularly objectionable to the rest of the British Public. And very likely, even in this modest aspiration, he is over-sanguine, and his little joke will be taken seriously. Earnestness is so alarmingly on the increase in these days.

This stirring ditty—so thoroughly sound and practical under all its sentiment—has been specially designed to harmonise with the recently altered tone of Music-hall audiences, in which a spirit of enlightened Radicalism is at last happily discernible. It is hoped that, both in rhyme and metre, the verses will satisfy the requirements of this most elegant form of composition. The song is intended to be shouted through music in the usual manner by a singer in evening dress, who should carry a small Union Jack carelessly thrust inside his waistcoat. The title is short but taking:—

First Verse.

Of a Navy insufficient cowards croak, deah boys!

If our place among the nations we're to keep.

But with British beef, and beer, and hearts of oak, deah boys!—

(With enthusiasm.) We can make a shift to do it—On the Cheap!

Chorus.

(With a common-sense air.) Let us keep, deah boys! On the Cheap,

[16]While Britannia is the boss upon the deep,

She can wollop an invader, when he comes in his Armada,

If she's let alone to do it—On the Cheap!

Second Verse.

(Affectionately.) Johnny Bull is just as plucky as he was, deah boys!

(With a knowing wink.) And he's wide awake—no error!—not asleep;

But he won't stump up for ironclads—becos, deah boys!

He don't see his way to get 'em—On the Cheap!

Chorus.

So keep, deah boys! On the Cheap,

(Gallantly.) And we'll chance what may happen on the deep!

For we can't be the losers if we save the cost o' cruisers,

And contentedly continue—On the Cheap!

Third Verse.

The British Isles are not the Conti-nong, deah boys!

(Scornfully.) Where the Johnnies on defences spend a heap.

No! we're Britons, and we're game to jog along, deah boys!

(With pathos.) In the old time-honoured fashion—On the Cheap!

Chorus.

(Imploringly.) Ah! keep, deah boys! On the Cheap;

For the price we're asked to pay is pretty steep.

Let us all unite to dock it, keep the money in our pocket,

And we'll conquer or we'll perish—On the Cheap!

Fourth Verse.

If the Tories have the cheek to touch our purse, deah boys!

[17]Their reward at the elections let 'em reap!

They will find a big Conservative reverse, deah boys!

If they can't defend the country—On the Cheap!

Chorus.

They must keep, deah boys! On the Cheap,

Or the lot out of office we will sweep!

Bull gets rusty when you tax him, and his patriotic maxim

Is, "I'll trouble you to govern—On the Cheap!"

Fifth Verse (this to be sung shrewdly).

If the Gover'ment ain't mugs they'll take the tip, deah boys!

Just to look a bit ahead before they leap,

And instead of laying down an extry ship, deah boys!

They'll cut down the whole caboodle—On the Cheap!

Chorus (with spirit and fervour).

And keep, deah boys! On the Cheap!

For we ain't like a bloomin' lot o' sheep.

When we want to "parry bellum,"[A]

[Union Jack to be waved here.

You may bet yer boots we'll tell 'em!

But we'll have the "bellum" "parried"—On the Cheap!

This song, if sung with any spirit, should, Mr. Punch thinks, cause a positive furore in any truly patriotic gathering, and possibly go some way towards influencing the decision of the country, and consequently the fate of the Empire, in the next General Elections. In the meantime it is at the service of any Champion Music Hall Comique who is capable of appreciating it.

[A] Music-hall Latinity—"Para bellum."

In most respects, no doubt, the present example can boast no superiority to ditties in the same style now commanding the ear of the public. One merit, however, its author does claim for it. Though it deals with most of the burning questions of the hour, it can be sung anywhere with absolute security. This is due to a simple but ingenious method by which the political sentiment has been arranged on the reversible principle. A little alteration here and there will put the singer in close touch with an audience of almost any shade of politics. Should it happen that the title has been already anticipated, Mr. Punch begs to explain that the remainder of this sparkling composition is entirely original; any[19] similarity with previous works must be put down entirely to "literary coincidence." Whether the title is new or not, it is a very nice one, viz:—

(To be sung in a raucous voice, and with a confidential air.)

I've dropped in to whisper some secrets I've heard.

Between you and me and the Post!

Picked up on the wing by a 'cute little bird.

We are gentlemen 'ere—so the caution's absurd,

Still, you'll please to remember that every word

Is between you and me and the Post!

Chorus (to which the singer should dance).

Between you and me and the Post! An 'int is sufficient at most.

I'd very much rather this didn't go farther, than 'tween you and me and the Post!

At Lord Sorlsbury's table there's sech a to-do.

Between you and me and the Post!

When he first ketches sight of his dinner menoo,

And sees he's set down to good old Irish stoo—

Which he's sick of by this time—now, tell me, ain't you?

Between you and me and the Post!

(This happy and pointed allusion to the Irish Question is sure to provoke loud laughter from an audience of Radical sympathies. For Unionists, the words "Lord Sorlsbury's" can be altered by our patent reversible method into "the G. O. M.'s," without at all impairing the satire.) Chorus, as before.

The G. O. M.'s hiding a card up his sleeve.

Between you and me and the Post!

Any ground he has lost he is going to retrieve,

And what his little game is, he'll let us perceive,

And he'll pip the whole lot of 'em, so I believe,

Between you and me and the Post! (Chorus.)

(The hit will be made quite as palpably for the other side by substituting "Lord Sorlsbury's," &c., at the beginning of the first line, should the majority of the audience be found to hold Conservative views.)

Little Randolph won't long be left out in the cold.

Between you and me and the Post!

If they'll let him inside the Conservative fold,

He has promised no longer he'll swagger and scold,

But to be a good boy, and to do as he's told,

Between you and me and the Post! (Chorus.)

(The mere mention of Lord Randolph's name is sufficient to ensure the success of any song.)

Joey Chamberlain's orchid's a bit overblown,

Between you and me and the Post!

(This is rather subtle, perhaps, but an M.-H. audience will see a joke in it somewhere, and laugh.)

'Ow to square a round table I'm sure he has shown.

(Same observation applies here.)

But of late he's been leaving his old friends alone,

And I fancy he's grinding an axe of his own,

Between you and me and the Post! (Chorus.)

(We now pass on to Topics of the Day, which we treat in a light but trenchant fashion.)

On the noo County Councils they've too many nobs,

[21]Between you and me and the Post!

For the swells stick together, and sneer at the mobs;

And it's always the rich man the poor one who robs.

We shall 'ave the old business—all jabber and jobs!

Between you and me and the Post! (Chorus.)

(N.B.—This verse should not be read to the L. C. C. who might miss the fun of it.)

There's a new rule for ladies presented at Court,

Between you and me and the Post!

High necks are allowed, so no colds will be cort,

But I went to the droring-room lately, and thort

Some old wimmen had dressed quite as low as they ort!

Between you and me and the Post! (Chorus.)

By fussy alarmists we're too much annoyed,

Between you and me and the Post!

If we don't want our neighbours to think we're afroid,

[M.-H. rhyme.

Spending dibs on defence we had better avoid.

And give 'em instead to the poor unemployed.

[M.-H. political economy.

Between you and me and the Post! (Chorus.)

This style of perlitical singing ain't hard,

Between you and me and the Post!

As a "Mammoth Comique" on the bills I am starred,

And, so long as I'm called, and angcored, and hurrar'd,

I can rattle off rubbish like this by the yard,

Between you and me and the Post!

[Chorus, and dance off to sing the same song—with or without alterations—in another place.

The following example, although it gives a not wholly inadequate expression to what are understood to be the loftier aspirations of the most advanced and earnest section of the New Democracy, should not be attempted, as yet, before a West-End audience. In South or East London, the sentiment and philosophy of the song may possibly excite rapturous enthusiasm; in the West-End, though the tone is daily improving, they are not educated quite up to so exalted a level at present. Still, as an experiment in proselytism, it might be worth risking, even there. The title it bears is:—

Verse I.—(Introductory.)

Some Grocers have taken to keeping a stock

Of ornaments—such as a vase, or a clock—

With a ticket on each where the words you may see:

"To be given away—with a Pound of Tea!"

Chorus (in waltz time).

"Given away!"

That's what they say.

[24]Gratis—a present it's offered you free.

Given away.

With nothing to pay,

"Given away—[tenderly]—with a Pound of Tea!"

Verse II.—(Containing the moral reflection.)

Now, the sight of those tickets gave me an idear.

What it set me a-thinking you're going to 'ear:

I thought there were things that would possibly be

Better given away—with a Pound of Tea!

Chorus—"Given away." So much as to say, &c.

Verse III.—(This, as being rather personal than general in its application, may need some apology. It is really put in as a graceful concession to the taste of an average Music-hall audience, who like to be assured that the Artists who amuse them are as unfortunate as they are erratic in their domestic relations.)

Now, there's my old Missus who sits up at 'ome—

And when I sneak up-stairs my 'air she will comb,—

I don't think I'd call it bad business if she

Could be given away—with a Pound of Tea!

Chorus—"Given away!" That's what they say, &c. [Mutatis mutandis.

Verse IV.—(Flying at higher game. The social satire here is perhaps almost too good-natured, seeing what intolerable pests all Peers are to the truly Democratic mind. But we must walk before we can run. Good-humoured contempt will do very well, for the present.)

Fair Americans snap up the pick of our Lords.

It's a practice a sensible Briton applords.

[25]

[This will check any groaning at the mention of Aristocrats.

Far from grudging our Dooks to the pretty Yan-kee,—

(Magnanimously) Why, we'd give 'em away—with a Pound of Tea!

Chorus—Give 'em away! So we all say, &c.

Verse V.—(More frankly Democratic still.)

To-wards a Republic we're getting on fast;

Many old Institootions are things of the past.

(Philosophically) Soon the Crown 'll go, too, as an a-noma-lee,

And be given away—with a Pound of Tea!

Chorus—"Given away!" Some future day, &c.

Verse VI.—(Which expresses the peaceful proclivities of the populace with equal eloquence and wisdom. A welcome contrast to the era when Britons had a bellicose and immoral belief in the possibility of being called upon to defend themselves at some time!)

We've made up our minds—though the Jingoes may jor—

Under no provocation to drift into war!

So the best thing to do with our costly Na-vee

Is—Give each ship away, with a Pound of Tea!

Chorus—Give 'em away, &c.

Verse VII.—(We cannot well avoid some reference to the Irish Question in a Music-hall ditty, but observe the logical and statesmanlike method of treating it here. The argument—if crudely stated—is borrowed from some advanced by our foremost politicians.)

We've also discovered at last that it's crule

To deny the poor Irish their right to 'Ome Rule!

[26]

So to give 'em a Parlyment let us agree—

(Rationally) Or they may blow us up with a Pound of their "Tea"!

[A euphemism which may possibly be remembered and understood.

Chorus—Give it away, &c.

Verse VIII. (culminating in a glorious prophetic burst of the Coming Dawn).

Iniquitous burdens and rates we'll relax:

For each "h" that's pronounced we will clap on a tax!

[A very popular measure.

And a house in Belgraveyer, with furniture free,

Shall each Soshalist sit in, a taking his tea!

Chorus, and dance off.—Given away! Ippipooray! Gratis we'll get it for nothing and free!

Given away! Not a penny to pay! Given away!—with a Pound of Tea!

If this Democratic Dream does not appeal favourably to the imagination of the humblest citizen, the popular tone must have been misrepresented by many who claim to act as its chosen interpreters—a supposition Mr. Punch must decline to entertain for a single moment.

The following ballad will not be found above the heads of an average audience, while it is constructed to suit the capacities of almost any lady artiste.

The singer should, if possible, be of mature age, and incline to a comfortable embonpoint. As soon as the bell has given the signal for the orchestra to attack the prelude, she will step upon the stage with that air of being hung on wires, which seems to come from a consciousness of being a favourite of the public.

I'm a dynety little dysy of the dingle,

[Self-praise is a great recommendation—in Music-hall

songs.

So retiring and so timid and so coy.

If you ask me why so long I have lived single,

I will tell you—'tis because I am so shoy.

[Note the manner in which the rhyme is adapted to meet Arcadian peculiarities of pronunciation.

Spoken—Yes, I am—really, though you wouldn't think it to look at me, would you? But, for all that,—

Chorus—When I'm spoken to, I wriggle,

[28]Going off into a giggle,

And as red as any peony I blush;

Then turn paler than a lily,

For I'm such a little silly,

That I'm always in a flutter or a flush!

[After each chorus an elaborate step-dance, expressive of shrinking maidenly modesty.

I've a cottage far away from other houses,

Which the nybours hardly ever come anoigh;

When they do, I run and hoide among the rouses,

For I cannot cure myself of being shoy.

Spoken—A great girl like me, too! But there, it's no use trying, for—

Chorus—When I'm spoken to, I wriggle, &c.

Well, the other day I felt my fice was crimson,

Though I stood and fixed my gyze upon the skoy,

For at the gyte was sorcy Chorley Simpson,

And the sight of him's enough to turn me shoy.

Spoken—It's singular, but Chorley always 'as that effect on me.

Chorus—When he speaks to me, I wriggle, &c.

Then said Chorley: "My pursuit there's no evyding.

Now I've caught you, I insist on a reploy.

Do you love me? Tell me truly, little myding!"

But how is a girl to answer when she's shoy?

Spoken—For even if the conversation happens to be about nothing particular, it's just the same to me.

Chorus—When I'm spoken to, I wriggle, [29]&c.

There we stood among the loilac and syringas,

More sweet than any Ess. Bouquet you boy;

[Arcadian for "buy."

And Chorley kept on squeezing of my fingers,

And I couldn't tell him not to, being shoy.

Spoken—For, as I told you before,—

Chorus—When I'm spoken to, I wriggle, &c.

Soon my slender wyste he ventured on embrycing,

While I only heaved a gentle little soy;

Though a scream I would have liked to rise my vice in,

It's so difficult to scream when you are shoy!

Spoken—People have such different ways of listening to proposals. As for me,—

Chorus—When they talk of love, I wriggle, &c.

So very soon to Church we shall be gowing,

While the bells ring out a merry peal of jy.

If obedience you do not hear me vowing,

It will only be because I am so shy.

[We have brought the rhyme off legitimately at last, it will be observed.

Spoken—Yes, and when I'm passing down the oil, on Chorley's arm, with everybody looking at me,—

Chorus—I am certain I shall wriggle,

And go off into a giggle,

And as red as any peony I'll blush.

Going through the marriage service

Will be sure to mike me nervous,

[Note the freedom of the rhyme.

And to put me in a flutter and a flush!

The history of a singer's latest love—whether fortunate or otherwise—will always command the interest and attention of a Music-hall audience. Our example, which is founded upon the very best precedents, derives an additional piquancy from the social position of the beloved object. Cultivated readers are requested not to shudder at the rhymes. Mr. Punch's Poet does them deliberately and in cold blood, being convinced that without these somewhat daring concords, no ditty would have the slightest chance of satisfying the great ear of the Music-hall public.

The title of the song is:—

The singer should come on correctly and tastefully attired in a suit of loud dittoes, a startling tie, and a white hat—the orthodox costume (on the Music-hall stage) of a middle-class swain suffering from love-sickness. The air should be of the conventional jog-trot and jingle order, chastened by a sentimental melancholy.

I've lately gone and lost my 'art—and where you'll never guess—

[32]I'm regularly mashed upon a lovely Marchioness!

'Twas at a Fancy Fair we met, inside the Albert 'All;

So affable she smiled at me as I came near her stall!

Chorus—Don't tell me Belgravia is stiff in behaviour!

She'd an Uncle an Earl, and a Dook for her Pa—

Still there was no starchiness in that fair Marchioness,

As she stood at her stall in the Fancy Bazaar!

At titles and distinctions once I'd ignorantly scoff,

As if no bond could be betwixt the tradesman and the toff!

I held with those who'd do away with difference in ranks—

But that was all before I met the Marchioness of Manx!

Chorus—Don't tell me Belgravia, &c.

A home was being started by some kind aristo-cràts,

For orphan kittens, born of poor, but well-connected cats;

And of the swells who planned a Fête this object to assist,

The Marchioness of Manx's name stood foremost on the list.

Chorus—Don't tell me Belgravia, &c.

I never saw a smarter hand at serving in a shop,

For every likely customer she caught upon the 'op!

And from the form her ladyship displayed at that Bazaar,

(With enthusiasm)—You might have took your oath she'd been brought up behind a bar!

Chorus—Don't tell me Belgravia, &c.

In vain I tried to kid her that my purse had been forgot,

[33]She spotted me in 'alf a jiff, and chaffed me precious hot!

A sov. for one regaliar she gammoned me to spend.

"You really can't refuse," she said, "I've bitten off the end!"

[34] Chorus—Don't tell me Belgravia, &c.

"Do buy my crewel-work," she urged, "it goes across a chair,

You'll find it come in useful, as I see you 'ile your 'air!"

So I 'anded over thirty bob, though not a coiny bloke.

I couldn't tell a Marchioness how nearly I was broke!

Spoken—Though I did take the liberty of saying: "Make it fifteen bob, my lady!" But she said, with such a fascinating look—I can see it yet!—"Oh, I'm sure you're not a 'aggling kind of a man," she says, "you haven't the face for it. And think of all them pore fatherless kittings," she says; "think what thirty bob means to them!" says she, glancing up so pitiful and tender under her long eyelashes at me. Ah, the Radicals may talk as they like, but——

Chorus—Don't tell me Belgravia, &c.

A raffle was the next concern I put my rhino in:

The prize a talking parrot, which I didn't want to win.

Then her sister, Lady Tabby, shewed a painted milking stool,

And I bought it—though it's not a thing I sit on as a rule.

Spoken—Not but what it was a handsome article in its way, too,—had a snow-scene with a sunset done in oil on it. "It will look lovely in your chambers," says the Marchioness; "it was ever so much admired at Catterwall Castle!" It didn't look so bad in my three-pair back, I must say, though unfortunately the sunset came off on me the very first time I happened to set down on it. Still think of the condescension of painting such a thing at all!

Chorus—Don't tell me Belgravia, &c.

[35]

The Marquis kept a-fidgeting and frowning at his wife,

For she talked to me as free as if she'd known me all my life!

I felt that I was in the swim, so wasn't over-awed,

But 'ung about and spent my cash as lavish as a lord!

Spoken—It was worth all the money, I can tell you, to be chatting there across the counter with a real live Marchioness for as long as ever my funds would 'old out. They'd have held out much longer, only the Marchioness made it a rule never to give change—she couldn't break it, she said, not even for me. I wish I could give you an idea of how she smiled as she made that remark; for the fact is, when an aristocrat does unbend—well,——

Chorus—Don't tell me Belgravia, &c.

Next time I meet the Marchioness a-riding in the Row,

I'll ketch her eye and raise my 'at, and up to her I'll go,

(With sentiment)—And tell her next my 'art I keep the stump of that cigar

She sold me on the 'appy day we 'ad at her Bazaar!

Spoken—And she'll be pleased to see me again, I know! She's not one of your stuck-up sort; don't you make no mistake about it, the aristocracy ain't 'alf as bloated as people imagine who don't know 'em. Whenever I hear parties running 'em down, I always say:

Chorus—Don't tell me Belgravia is stiff in behaviour, &c.

The singer (who should be a large man, in evening dress, with a crumpled shirt-front) will come on the stage with a bearing intended to convey at first sight that he is a devoted admirer of the fair sex. After removing his crush-hat in an easy manner, and winking airily at the orchestra, he will begin:—

There's enthusiasm brimming in the breasts of all the women,

And they're calling for enfranchisement with clamour eloquent:

When some parties in a huff rage at the plea for Female Suffrage,

I invariably floor them with a simple argu-ment.

Chorus (to be rendered with a winning persuasiveness).

Why shouldn't the darlings have votes? de-ar things!

On politics each of 'em dotes, de-ar things!

(Pathetically.) Oh it does seem so hard

They should all be debarred,

'Cause they happen to wear petticoats, de-ar things!

Nature all the hens to crow meant, I could prove it in a moment,

[38]Though they've selfishly been silenced by the cockadoodle-doos.

But no man of sense afraid is of enfranchising the Ladies.

(Magnanimously.) Let 'em put their pretty fingers into any pie they choose!

Spoken—For——

Chorus—Why shouldn't the darlings, &c.

They would cease to care for dresses, if we made them elec-tresses,

No more time they'd spend on needlework, nor at pianos strum;

Every dainty little Dorcas would be sitting on a Caucus,

Busy wire-pulling to produce the New Millenni-um!

Spoken—Oh!——

Chorus—Why shouldn't the darlings, &c.

In the House we'll see them sitting soon, it will be only fitting

They should have an opportunity their country's laws to frame.

And the Ladies' legislation will be sure to cause sensation,

For they'll do away with everything that seems to them a shame!

Spoken—Then——

Chorus—Why shouldn't the darlings, &c.

They will promptly clap a stopper on whate'er they deem improper,

Put an end to vaccination, landed property, and pubs;

And they'll fine Tom, Dick, and Harry, if they don't look sharp and marry,

And for Kindergartens confiscate those nasty horrid Clubs!

Spoken—Ah!——

Chorus—Why shouldn't the darlings, [39]&c.

They'll declare it's quite immoral to engage in foreign quarrel,

And that Britons never never will be warriors any more!

When our forces are abolished, and defences all demolished,

They will turn upon the Jingo tack, and want to go to war!

Spoken—So——

Chorus—Why shouldn't the darlings, &c.

(With a grieved air.) Yet there's some who'd close such vistars to their poor down-trodden sistars,

And persuade 'em, if they're offered votes, politely to refuse!

Say they do not care about 'em, and would rather be without 'em—

Oh, I haven't common patience with such narrer-minded views!

Spoken—No!——

Chorus—Why shouldn't the darlings, &c.

And it's females—that's the puzzle!—who petition for the muzzle,

Which I call it poor and paltry, and I think you'll say so too.

They are not in any danger. Let 'em drop the dog-in-manger!

If they don't require the vote themselves, there's other Ladies do!

Spoken—And——

Chorus—Why shouldn't the darlings, &c.

[Here the singer will gradually retreat backwards to the rear of the stage, open his crush-hat, and extend it in an attitude of triumph as the curtain descends.

Any ditty which accurately reflects the habits and amusements of the people is a valuable human document—a fact that probably accounts for the welcome which songs in the following style invariably receive from Music-hall audiences generally. If—Mr. Punch presumes—they conceived such pictures of their manner of spending a holiday to be unjustly or incorrectly drawn in any way, they would protest strongly against being so grossly misrepresented. As they do nothing of the sort, no apology can be needed for the following effusion, which several ladies now adorning the Music-hall stage could be trusted to render with immense effect. The singer should be young and charming, and attired as simply as possible. Simplicity of attire imparts additional piquancy to the words:—

We 'ad a little outing larst Sunday arternoon;

And sech a jolly lark it was, I shan't forget it soon!

We borrered an excursion van to take us down to Kew,

And—oh, we did enjoy ourselves! I don't mind telling you.

[This to the Chef d'Orchestre, who will assume a polite interest.

[Here a little spoken interlude is customary. Mr. P. does not venture to do more than indicate this by a synopsis, the details can be filled in according to the taste and fancy of[41] the fair artiste:—"Yes, we did 'ave a time, I can assure yer." The party: "Me and Jimmy 'Opkins;" old "Pa Plapper." Asked because he lent the van. The meanness of his subsequent conduct. "Aunt Snapper;" her imposing appearance in her "cawfy-coloured front." Bill Blazer; his "girl," and his accordion. Mrs. Addick (of the fried-fish emporium round the corner); her gentility—"Never seen out of her mittens, and always the lady, no matter how much she may have taken." From this work round by an easy transition to—

The Chorus—For we 'ad to stop o' course,

Jest to bait the bloomin' 'orse,

So we'd pots of ale and porter

(Or a drop o' something shorter),

While he drunk his pail o' water,

He was sech a whale on water!

That more water than he oughter,

More water than he oughter,

'Ad the poor old 'orse!

Second Stanza.

That 'orse he was a rum 'un—a queer old quadru-pèd,

At every public-'ouse he passed he'd cock his artful 'ed!

Sez I: "If he goes on like this, we shan't see Kew to-night!"

Jim 'Opkins winks his eye, and sez—"We'll git along all right!"

Chorus—Though we 'ave to stop of course,—&c., &c.

[With slight textual modifications.

Third Stanza.

At Kinsington we 'alted, 'Ammersmith, and Turnham Green,

[42]The 'orse 'ad sech a thust on him, its like was never seen!

With every 'arf a mile or so, that animal got blown:

And we was far too well brought-up to let 'im drink alone!

Chorus—As we 'ad to stop, o' course, &c.

Fourth Stanza.

We stopped again at Chiswick, till at last we got to Kew,

But when we reached the Gardings—well, there was a fine to-do!

The Keeper, in his gold-laced tile, was shutting-to the gate,

Sez he: "There's no admittance now—you're just arrived too late!"

[Synopsis of spoken Interlude: Spirited passage-at-arms between Mr. Wm. Blazer and the Keeper; singular action of Pa Plapper; "I want to see yer Pagoder—bring out yer old Pagoder as you're so proud on!" Mrs. Addick's disappointment at not being able to see the "Intemperate Plants," and the "Pitcher Shrub," once more. Her subsidence in tears, on the floor of the van. Keeper concludes the dialogue by inquiring why the party did not arrive sooner. An' we sez, "Well, it was like this, ole cock robin—d'yer see?"

Chorus—We've 'ad to stop, o' course, &c.

Fifth Stanza.

"Don't fret," I sez, "about it, for they ain't got much to see

Inside their precious Gardings—so let's go and 'ave some tea!

A cup I seem to fancy now—I feel that faint and limp—

With a slice of bread-and-butter, and some creases, and a s'rimp!"

[Description of the tea:—"And the s'rimps—well, I don't want to say anything against the s'rimps—but it did strike me they were feelin' the 'eat a little—s'rimps are liable to it, and you can't prevent 'em." After tea. The only tune Mr. Blazer could play on his accordion. Tragic end of that instrument. How the party had a "little more lush." Scandalous behaviour of "Bill Blazer's girl." The company consume what will be elegantly referred to as "a bit o' booze." Aunt Snapper "gets the 'ump." The outrage to her front. The proposal to start—whereupon, "Mrs. Addick, who was a'-settin' on the geraniums in the winder, smilin' at her boots, which she'd just took off because she said they stopped her breathing," protested that there was no hurry, considering that—

Chorus, as before—We've got to stop, o' course, &c.

Sixth Stanza.

But when the van was ordered, we found—what do yer think?

[To the Chef d'Orchestre, who will affect complete ignorance.

That miserable 'orse 'ad been an' took too much to drink!

He kep' a reeling round us, like a circus worked by steam,

And, 'stead o' keeping singular, he'd turned into a team!

[Disgust of the party: Pa Plapper proposes to go back to the inn for more refreshment, urging—

Chorus—We must wait awhile o' course,

Till they've sobered down the 'orse.

Just another pot o' porter

Or a drop o' something shorter,

While our good landlady's daughter

[44]Takes him out some soda-warter.

For he's 'ad more than he oughter,

He's 'ad more than he oughter,

'As the poor old 'orse!

Seventh Stanza.

So, when they brought the 'orse round, we started on our way:

'Twas 'orful 'ow the animal from side to side would sway!

Young 'Opkins took the reins, but soon in slumber he was sunk—

(Indignantly.) When a interfering Copper ran us in for being drunk!

[Attitude of various members of the party. Unwarrantable proceeding on the part of the Constable. Remonstrance by Pa Plapper and the company generally in—

Chorus—Why, can't yer shee? o' coursh

Tishn't us—it ish the 'orsh!

He's a whale at swilling water,

We've 'ad only ale and porter,

Or a drop o' something shorter.

You le'mme go, you shnorter!

Don' you tush me till you oughter!

Jus' look 'ere—to cut it shorter—

Take the poor old 'orsh!

[General adjournment to the Police-station. Interview with the Magistrate on the following morning. Mr. Hopkins called upon to state his defence, replies in—

Chorus—Why, your wushup sees, o' course,

It was all the bloomin' 'orse!

He would 'ave a pail o' water

[45]Every 'arf a mile (or quarter),

Which is what he didn't oughter!

He shall stick to ale or porter,

With a drop o' something shorter,

I'm my family's supporter—

Fine the poor old 'orse!

[The Magistrate's view of the case. Concluding remark that, notwithstanding the success of the excursion, as a whole—it will be some time before the singer consents to go upon any excursion with a horse of such bibulous tendencies as those of the quadruped they drove to Kew.

This is always a popular form of entertainment, demanding, as it does, even more dramatic than vocal ability on the part of the artist. A song of this kind is nothing if not severely moral, an frequently depicts the downward career of an incipient drunkard with all the lurid logic of a Temperance Tract. Mr. Punch, however, is inclined to think that the lesson would be even more appreciated and taken to heart by the audience, if a slightly different line were adopted such as he has endeavoured to indicate in the following example:—

The singer should have a great command of facial expression, which he will find greatly facilitated by employing (as indeed is the usual custom) coloured limelight at the wings.

First Verse (to be sung under pure white light).

He (these awful examples are usually, and quite properly, anonymous) was once as nice a fellow as you could desire to meet,

Partial to a pint of porter, always took his spirits neat;

Long ago a careful mother's cautions trained her son to shrink

From the meretricious sparkle of an aërated drink.

[48]

Refrain (showing the virtuous youth resisting temptation. N.B. The refrain is intended to be spoken through music. Not sung.)

Here's a pub that's handy.

Liquor up with you?

Thimbleful of brandy?

Don't mind if I do.

Soda-water? No, Sir.

Never touch the stuff.

Promised mother—so, Sir.

(With an upward glance.)

'Tisn't good enough!

Second Verse. (Primrose light for this.)

Ah, how little we suspected, as we saw him in his bloom,

What a demon dogged his footsteps, luring to an awful doom!

Vain his mother's fond monitions; soon a friend, with fiendish laugh,

Tempts him to a quiet tea-garden, plies him there with shandy-gaff!

Refrain (illustrating the first false step).

Why, it's just the mixture

I so long have sought!

Here I'll be a fixture

Till I've drunk the quart!

Just the stuff to suit yer.

Waiter, do you hear?

Make it, for the future,

Three parts ginger-beer!

[49]

Third Verse (requiring violet-tinted slide).

By-and-by, the ale discarding, ginger-beer he craves alone.

Undiluted he procures it, buys it bottled up in stone.

(The earthenware bottles are said by connoisseurs to contain

liquor of superior strength and quality.)

From his lips the foam he brushes—crimson overspreads his brow.

To his brain the ginger's mounting! Could his mother see him now!

Refrain (depicting the horrors of a solitary debauch poisoned by remorse).

Shall I have another?

Only ginger-pop!

(Wildly.) Ah! I promised mother

Not to touch a drop!

Far too much I'm tempted.

(Recklessly.) Let me drink my fill!

That's the fifth I've emptied—

Oh, I feel so ill!

[Here the singer will stagger about the boards.

Fourth Verse. (Turn on lurid crimson ray for this.)

Next with drinks they style "teetotal" he his manhood must degrade;

Swilling effervescent syrups—"ice-cream-soda," "raspberry-ade,"

Koumiss tempts his jaded palate—payment he's obliged to bilk—

Then, reduced to destitution, finds forgetfulness in—milk!

[50]

Refrain (indicating rapid moral deterioration).

What's that on the railings?

[Point dramatically at imaginary area.

Milk—and in a can!

Though I have my failings,

I'm an honest man.

[Spark of expiring rectitude here.

I can not resist it. [Pantomime of opening can.

That celestial blue!

Has the milkman missed it? [Melodramatically.

I'll be missing too!

Fifth Verse (in pale blue light).

Milk begets a taste for water, so comparatively cheap,

Every casual pump supplies him, gratis, with potations deep;

He at every drinking-fountain pounces on the pewter cup,

Conscious of becoming bloated, powerless to give it up!

Refrain (illustrative of utter loss of self-respect).

"Find one straight before me?"

Bobby, you're a trump!

Faintness stealing o'er me—

Ha—at last—a pump!

If that little maid 'll

Just make room for one,

I could grab the ladle

After she has done.

The last verse is the culminating point of this moral drama:—The miserable wretch has reached the last stage. He shuts himself up in his cheerless abode, and there, in shameful secrecy, consumes the element for which he is powerless to pay—the inevitable Nemesis following.

Sixth Verse (All lights down in front. Ghastly green light at wings).

Up his sordid stairs in secret to the cistern now he steals,

Where, amidst organic matter, gambol microscopic eels;

Tremblingly he turns the tap on—not a trickle greets the trough!

For the stony-hearted turncock's gone and cut his water off!

Refrain (in which the profligate is supposed to demand an explanation from the turncock, with a terrible dénoûment).

"Rate a quarter owing,

Comp'ny stopped supply."

"Set the stream a-flowing,

Demon—or you die!"

"Mercy!—ah! you've choked me!"

[In hoarse, strangled voice as the turncock.

"Will you turn the plug?" [Savagely as the hero.

"No!" [Faintly, as turncock.

[Business of flinging a corpse on stage, and regarding it terror-stricken. A long pause; then, in a whisper,—

"The fool provoked me!

(With a maniac laugh.) Horror! I'm a Thug!"

[Here the artist will die, mad, in frightful agony, and rise to bow his acknowledgments.

The "Duet and Dance" form so important a feature in Music-hall entertainments, that they could hardly, with any propriety, be neglected in a model compilation such as Mr. Punch's, and it is possible that he may offer more than one example of this blameless diversion. For some reason or other, the habit of singing in pairs would seem to induce a pessimistic tone of mind in most Music-hall artistes, and—why, Mr. Punch does not pretend to say—this cynicism is always more marked when the performers are of the softer sex. Our present study is intended to fulfil the requirements of the most confirmed female sceptic, and, though the Message of the Music Halls may have been given worthier and fuller expression by pens more practised in such compositions, Mr. Punch is still modestly confident that this ditty, with all its shortcomings, can be sung in any Music Hall in the Metropolis without exciting any sentiment other than entire approval of the teaching it conveys. One drawback, indeed, it has, but that concerns the performers alone. For the sake of affording contrast and relief, it was thought expedient that one of the fair duettists should profess an optimism which may—perhaps must—tend to impair her popularity. A conscientious artiste may legitimately object, for the sake of her professional reputation, to present herself in so humiliating a character as that of an ingénue, and a female "Juggins";[54] and it does seem as if the Cynical Sister must inevitably monopolise the sympathies of an enlightened audience. However, this difficulty is less formidable than it appears; it should be easy for the Unsophisticated Sister to convey a subtle suggestion here and there, possibly in the incidental dance between the verses, that she is not really inferior to her partner in smartness and knowledge of the world. But perhaps it would be the fairest arrangement if the Sisters could agree to alternate so ungrateful a rôle.

First Verse.

First Sister (placing three of the fingers of her left hand on her heart, and extending her right arm in timid appeal).

Dear sister, of late I'm beginning to doubt

If the world is as black as they paint it.

It mayn't be as bad as some try to make out——

Second Sister (with an elaborate mock curtsy.) That is a discovery! Mayn't it?

First S. (abashed). I'm sure there are sev'ral who aren't a bad lot,

And some sort of principle seem to have got,

For they act on the square——

Second S. Don't you talk tommy-rot!

It's done for advertisement, ain't it?

Refrain.

Second S. Why, there's nobody at bottom any better than the rest!

First S. Are you sure of it?

[55]

Second S. I'm telling you, and I know,

The principle they act upon's whatever pays 'em best.

And the only real religion now is—Rhino!

[The last word must be rendered with full metallic effect. A step-dance, expressive of conviction on one part and incipient wavering on the other, should be performed between the verses.

Second Verse.

First S. (returning, shaken, to the charge). Some unmarried men lead respectable lives.

Second S. (decisively). Well, I've never happened to meet them!

First S. There are husbands who're always polite to their wives.

Second S. Of course—if their better halves beat them!

First S. Some tradesmen have consciences, so I've heard said;

Their provisions are never adulteratèd,

But they treat all their customers fairly instead.

Second S. 'Cause they don't find it answer to cheat them!

Refrain.

First S. What?

Second S. { No,—They're none of 'em at bottom any better than the rest.

Second S. I'm speaking from experience, and I know.

If you could put a window-pane in everybody's breast

You'd see on all the hearts was written—"Rhino!"

Third Verse.

First S. There are girls you can't tempt with a title or gold.

Second S. There may be—but I've never seen one.

First S. Some much prefer love in a cottage, I'm told.

[56]

Second S. (putting her arms a-kimbo). If you swallow that, you're a green one!

They'll stick to their lover so long as he's cash,

When it's gone, they look out for a wealthier mash.

A girl on the gush talks unpractical trash—

When it comes to the point, she's a keen one!

Refrain.

First S. Then, are none of us at bottom any better than the rest!

Second S. (cheerfully). Not a bit; I am a girl myself and I know.

First S. You'd surely never give your hand to someone you detest?

Second S. Why rather—if he's rolling in the Rhino!

Fourth Verse.

First S. Philanthropists give up their lives to the poor.

Second S. It's chiefly with tracts they present them.

First S. Still, some self-denial I'm sure they endure?

Second S. It's their hobby, and seems to content them.

First S. But don't they go into those horrible slums?

Second S. Sometimes—with a flourish of trumpets and drums.

First S. I've heard they've collected magnificent sums.

Second S. And nobody knows how they've spent them!

Refrain.

Second S. Oh, they're none of 'em at bottom any better than the rest!

[57]They are only bigger hypocrites, as I know;

They've famous opportunities for feathering their nest,

When so many fools are ready with the Rhino!

Fifth Verse.

First S. Our Statesmen are prompted by duty alone.

Second S. (compassionately). Whoever's been gammoning you so?

First S. They wouldn't seek office for ends of their own?

Second S. What else would induce 'em to do so?

First S. But Time, Health, and Money they all sacrifice.

Second S. I'd do it myself at a quarter the price.

There's pickings for all, and they needn't ask twice,

For they're able to put on the screw so!

Refrain (together).

No, they're none of 'em at bottom any better than the rest!

They may kid to their constituents—but I know;

Whatever lofty sentiments their speeches may suggest,

They regulate their actions by the Rhino!

[Here the pair will perform a final step-dance, indicative of enlightened scepticism, and skip off in an effusion of sisterly sympathy, amidst enthusiastic applause.

When a Music-hall singer does not treat of the tender passion in a rakish and knowing spirit, he is apt to exhibit an unworldliness truly ideal in its noble indifference to all social distinctions. So amiable a tendency deserves encouragement, and Mr. Punch has much pleasure in offering the following little idyl to the notice of any Mammoth Comique who may happen to be in a sentimental mood. It is supposed to be sung by a scion of the nobility, and the artiste will accordingly present himself in a brown "billy-cock" hat, a long grey frock-coat, fawn-coloured trousers, white "spats," and primrose, or green, gloves—the recognised attire of a Music-hall aristocrat. A powerful,—though not necessarily tuneful,—voice is desirable for the adequate rendering of this ditty; any words it is inconvenient to sing, can always be spoken.

First Verse.

When first I met my Mary Ann, she stood behind a barrow—

A bower of enchantment spread with many a dainty snack!

And, as I gazed, I felt my heart transfixed with Cupid's arrow,

For she opened all her oysters with so fairylike a knack.

[60]

Refrain (throaty, but tender).

She's only a little Plebeian!

And I'm a Patrician swell!

But she's as sweet as Aurora, and how I adore her,

No eloquence ever can tell!

Only a fried-fish vend-ar!

Selling her saucers of whilks,

[Almost defiant stress on the word "whilks."

But, for me, she's as slend-ar—far more true and tend-ar,

Than if she wore satins and silks!

[The grammar of the last two lines is shaky, but the Lion-Comique must try to put up with that, and, after all, does sincere emotion ever stop to think about grammar? If it does, Music-hall audiences don't—which is the main point.

Second Verse.

I longed before her little feet to grovel in the gutter:

I vowed, unless I won her as a wife, 'twould drive me mad!

Until at last a shy consent I coaxed her lips to utter,

For she dallied with her Anglo-Dutch, and whispered, "Speak to Dad!"

Refrain—For she's only a little Plebeian, &c.

Third Verse.

I called upon her sire, and found him lowly born, but brawny,

A noble type, when sober, of the British artisan;

[61]I grasped his honest hand, and didn't mind its being horny:

"Behold!" I cried, "a suitor for your daughter, Mary Ann!"

Refrain—Though she's only a little Plebeian, &c.

Fourth Verse.

"You ask me, gov'nor, to resign," said he, "my only treasure,

And so a toff her fickle heart away from me has won!"

He turned to mask his manly woe behind a pewter measure—

Then, breathing blessings through the beer, he said; "All right, my son!

Refrain—If she's only a little Plebeian,

And you're a Patrician swell,"—&c.

Fifth Verse.

(The author flatters himself that, in quiet sentiment and homely pathos he has seldom done anything finer than the two succeeding stanzas.)

Next I sought my noble father in his old ancestral castle,

And at his gouty foot my love's fond offering I laid—

A simple gift of shellfish, in a neat brown-paper parcel!

"Ah, Sir!" I cried, "if you could know, you'd love my little maid!"

Refrain—True, she's only a little Plebeian, &c.

Sixth Verse.

Beneath his shaggy eyebrows soon I saw a tear-drop twinkle;

[62]That artless present overcame his stubborn Norman pride!

And when I made him taste a whilk, and try a periwinkle,

His last objections vanished—so she's soon to be my bride!

Refrain—Ah! she's only a little Plebeian, &c.

Seventh Verse.

Now heraldry's a science that I haven't studied much in,

But I mean to ask the College—if it's not against their rules—

That three periwinkles proper may be quartered on our 'scutcheon,

With a whilk regardant, rampant, on an oyster-knife, all gules!

Refrain—As she's only a little Plebeian, &c.

This little ditty, which has the true, unmistakable ring about it, and will, Mr. Punch believes, touch the hearts of any Music-hall audience, is entirely at the service of any talented artiste who will undertake to fit it with an appropriate melody, and sing it in a spirit of becoming seriousness.

This ditty is designed to give some expression to the passionate enthusiasm for nature which is occasionally observable in the Music-hall songstress. The young lady who sings these verses will of course appear in appropriate costume; viz., a large white hat and feathers, a crimson sunshade, a pink frock, high-heeled sand-shoes, and a liberal extent of black silk stockings. A phonetic spelling has been adopted where necessary to bring out the rhyme, for the convenience of the reader only, as the singer will instinctively give the vowel-sounds the pronunciation intended by the author.

First Verse.

Oh, I love to sit a-gyzing on the boundless blue horizing,

When the scorching sun is blyzing down on sands, and ships, and sea!

And to watch the busy figgers of the happy little diggers,

Or to listen to the niggers, when they choose to come to me!

Chorus (to which the singer should sway in waltz-time).

For I'm offully fond of the Sea!-side!

[64]If I'd only my w'y I would de-cide

To dwell evermore,

By the murmuring shore,

With the billows a-blustering be-side!

Second Verse.

Then how pleasant of a morning, to be up before the dorning!

And to sally forth a-prorning—e'en if nothing back you bring!

Some young men who like fatigue 'll go and try to pot a sea-gull,

What's the odds if it's illegal, or the bird they only wing?

Chorus—For it's one of the sports of the Sea-side! &c.

Third Verse.

Then what j'y to go a bything—though you'll swim, if you're a sly thing,

Like a mermaid nimbly writhing, with a foot upon the sand!

When you're tired of old Poseidon, there's the pier to promenide on,

Strauss, and Sullivan, and Haydn form the programme of the band.

Chorus—For there's always a band at the Sea-side! &c.

Fourth Verse.

And, with boatmen so beguiling, sev'ral parties go out siling!

Sitting all together smiling, handing sandwiches about,

To the sound of concertiner,—till they're gradually greener,

And they wish the ham was leaner, as they sip their bottled stout.

[66] Chorus—And they cry, "Put us back on the Sea-side!" &c.

Fifth Verse.

There is pleasure unalloyed in hiring hacks and going roiding!

(If you stick on tight, avoiding any cropper or mishap,)

Or about the rocks you ramble; over boulders slip and scramble;

Or sit down and do a gamble, playing "Loo" or "Penny Nap."

Chorus—"Penny Nap" is the gyme for the Sea-side! &c.

Sixth Verse.

Then it's lovely to be spewning, all the glamour of the mewn in,

With your love his banjo tewning, ere flirtation can begin!

As along the sands you're strowling, till the hour of ten is towling,

And your Ma, severely scowling, asks "Wherever you have bin!"

Chorus—Then you answer "I've been by the Sea-side!" &c.

Seventh Verse.

Should the sky be dark and frowning, and the restless winds be mowning,

[67]With the breakers' thunder drowning all the laughter and the glee;

And the day should prove a drencher, out of doors you will not ventcher,

But you'll read the volumes lent yer by the Local Libraree!

Chorus—For there's sure to be one at the Sea-side! &c.

Eighth Verse.

If the weather gets no calmer, you can patronise the dramer,

Where the leading lady charmer is a chit of forty-four;

And a duty none would skirk is to attend the strolling circus,

For they'd all be in the workhouse, should their antics cease to dror!

Chorus—And they're part of the joys of the Sea-side! &c.

Encore Verse (to be used only in case of emergency).

Well, I reelly must be gowing—I've just time to make my bow in—

But I thank you for allowing me to patter on so long.

And if, like me, you're pining for the breezes there's some brine in,

Why, I'll trouble you to jine in with the chorus to my song!

Chorus (all together)—Oh, we're offully fond of the Sea-side! &c.

A Music-hall audience will always be exceedingly susceptible to pathos—so long as they clearly understand that the song is not intended to be of a comic nature. However, there is very little danger of any misapprehension in the case of our present example, which is as natural and affecting a little song as any that have been moving the Music Halls of late. The ultra-fastidious may possibly be repelled by what they would term the vulgarity of the title,—"The Night-light Ever Burning by the Bed"—but, although it is true that this humble luminary is now more generally called a "Fairy Lamp," persons of true taste and refinement will prefer the homely simplicity of its earlier name. The song only contains three verses, which is the regulation allowance for Music-hall pathos, the authors probably feeling that the audience could not stand any more. It should be explained that the "tum-tum" at the end of certain lines is not intended to be sung—it is merely an indication to the orchestra to pinch their violins in a pizzicato manner. The singer should either come on as a serious black man—for burnt cork is a marvellous provocative of pathos—or as his ordinary self. In either case he should wear evening dress, with a large brilliant on each hand.[70]

First Verse.

I've been thinking of the home where my early years were spent,

'Neath the care of a kind maiden aunt, (Tum-tum-tum!)

And to go there once again has been often my intent,

But the railway fare's expensive, so I can't! (Tum-tum!)

Still I never can forget that night when last we met:

"Oh, promise me—whate'er you do!" she said, (Tum-tum-tum!)

"Wear flannel next your chest, and, when you go to rest,

Keep a night-light always burning by your bed!" (Tum-tum!)

Refrain (pianissimo.)

And my eyes are dim and wet;

For I seem to hear them yet—

Those solemn words at parting that she said: (Tum-tum-tum!)

"Now, mind you burn a night-light,

—'Twill last until it's quite light—

In a saucerful of water by your bed!" (Tum-tum!)

Second Verse.

I promised as she wished, and her tears I gently dried,

As she gave me all the halfpence that she had: (Tum-tum-tum!)

And through the world e'er since I have wandered far and wide,

[71]And been gradually going to the bad! (Tum-tum!)

Many a folly, many a crime I've committed in my time,

For a lawless and a chequered life I've led! (Tum-tum-tum.)

Still I've kept the promise sworn—flannel next my skin I've worn,

And I've always burnt a night-light by my bed! (Tum-tum!)

Refrain.

All unhallowed my pursuits,

(Oft to bed I've been in boots!)

Still o'er my uneasy slumber has been shed (Tum-tum-tum!)

The moderately bright light

Afforded by a night-light,

In a saucerful of water by my bed! (Tum-tum!)

Third Verse. (To be sung with increasing solemnity.)

A little while ago, in a dream my aunt I saw;

In her frill-surrounded night-cap there she stood! (Tum-tum-tum!)

And I sought to hide my head 'neath the counterpane in awe,

And I trembled—for my conscience isn't good! (Tum-tum!)

But her countenance was mild—so indulgently she smiled

That I knew there was no further need for dread! (Tum-tum-tum!)

She had seen the flannel vest enveloping my chest,

And the night-light in its saucer by my bed! (Tum-tum!)

Refrain (more pianissimo still.)

But ere a word she spoke,

I unhappily awoke!

And away, alas! the beauteous vision fled! (Tum-tum-tum!)

(In mournful recitation)—There was nothing but the slight light

Of the melancholy night-light

That was burning in a saucer by my bed! (Tum-tum!)

To be a successful Military Impersonator, the principal requisite is a uniform, which may be purchased for a moderate sum, second-hand, in the neighbourhood of almost any barracks. Some slight acquaintance with the sword exercise and elementary drill is useful, though not absolutely essential. Furnished with these, together with a few commanding attitudes, and a song possessing a spirited, martial refrain, the Military Impersonator may be certain of an instant and striking success upon the Music-hall stage,—especially if he will condescend to avail himself of the ballad provided by Mr. Punch, as a vehicle for his peculiar talent. And—though we say it ourselves—it is a very nice ballad, to which Mr. McDougall himself would find it difficult to take exception. It is in three verses, too—the limit understood to be formally approved by the London County Council for such productions. It may be, indeed, that (save so far as the last verse illustrates the heroism of our troops in action—a heroism too real and too splendid to be rendered ridiculous, even by Military Impersonators), the song does not convey a particularly accurate notion of the manner and pursuits of an officer in the Guards. But then no Music-hall ditty can ever be accepted as a quite infallible authority upon any social type it may undertake to depict—with the single exception,[74] perhaps, of the Common (or Howling) Cad. So that any lack of actuality here will be rather a merit than a blemish in the eyes of an indulgent audience. Having said so much, we will proceed to our ballad, which is called,—

First Verse.

I'm a Guardsman, and my manner is perhaps a bit "haw-haw;"

But when you're in the Guards you've got to show esprit de corps.

[Pronounce "a spreedy core."

We look such heavy swells, you see, we're all aristo-cràts,

When on parade we stand arrayed in our 'eavy bearskin 'ats.

Chorus (during which the Martial Star will march round the stage in military order.)

We're all "'Ughies," "Berties," "Archies,"

In the Guards! Doncher know?

Twisting silky long moustarches,

[Suit the action to the word here.

Bein' Guards! Doncher know?

While our band is playing Marches,

For the Guards! Doncher know?

And the ladies stop to gaze upon the Guards,

Bing-Bang!

[Here a member of the orchestra will oblige with the cymbals, while the Vocalist performs a military salute, as he passes to—

Second Verse.

With duchesses I'm 'and in glove, with countesses I'm thick;

From all the nobs I get invites—they say I am "so chic!"

[Pronounce "chick."

It often makes me laugh to read, whene'er I go off guard,

"Dear Bertie, come to my At Home!" on a coronetted card!

Chorus.

For we're "Berties," "'Ughies," "Archies,"

In the Guards! Doncher know?

With our silky long moustarches,

In the Guards! Doncher know?

Where's a regiment that marches

Like the Guards? Doncher know?

All the darlings—bless 'em!—dote upon the Guards,

Bing-Bang!

Third Verse.

[Here comes the Singer's great chance, and by merely taking a little pains, he may make a tremendously effective thing out of it. If he can manage to slip away between the verses, and change his bearskin and scarlet coat for a solar topee and kharkee tunic at the wings, it will produce an enormous amount of enthusiasm, only he must not take more than five minutes over this alteration, or the audience—so curiously are British audiences constituted—may grow impatient for his return.

But hark! the trumpet sounds!... (Here a member of the orchestra will oblige upon the trumpet.) What's this? ... (The Singer will take a folded paper from his breast and peruse it with attention.) We're ordered to the front! [This should be shouted.

We'll show the foe how "Carpet-Knights" can face the battle's brunt!

They laugh at us as "Brummels"—but we'll prove ourselves "Bay-yards!"

[Now the Martial Star will draw his sword and unfasten his revolver-case, taking up the exact pose in which he is represented upon the posters outside.

As you were!... Form Square!... Mark Time!... Slope Arms!... now—'Tention!... (These military evolutions should all be gone through by the Artist.) Forward, Guards! [To be yelled through music.

Chorus.

Onward every 'ero marches,

In the Guards! Doncher know?

All the "'Ughies," "Berties," "Archies,"

Of the Guards! Doncher know?

They may twist their long moustarches,

For they're Guards! Doncher know?

Dandies? yes,—but dandy lions are the Guards!

Bing-Bang!

[Red fire and smoke at wings, as curtain falls upon the Military Impersonator in the act of changing to a new attitude.

Dramatis Personæ.

| The Little Crossing-Sweeper | By the unrivalled Variety Artist | Miss Jenny Jinks. |

| The Duke of Dillwater | Mr. Henry Irving. | |

| ||

| A Policeman | Mr. Rutland Barrington. | |

| ||

| A Butler (his original part) | Mr. Arthur Cecil. | |

| Foot-passengers, Flunkeys, Burglars. | By the celebrated Knockabout Quick-change Troupe. | |

Scene I.—Exterior of the Duke's Mansion in Euston Square by night. On the right, a realistic Moon (by kind permission of Professor Herkomer) is rising slowly behind a lamp-post. On left centre, a practicable pillar-box, and crossing, with real mud. Slow Music, as Miss Jenny Jinks enters, in rags, with broom. Various Characters cross the street, post letters, &c.; Miss Jinks follows them, begging piteously for a copper, which is invariably refused, whereupon she assails them with choice specimens of street sarcasm—which the Lady may be safely trusted to improvise for herself.

Miss Jenny Jinks (leaning despondently against pillar-box, on which a ray of limelight falls in the opposite direction to the Moon).

Ah, this cruel London, so marble-'arted and vast,

Where all who try to act honest are condemned to fast!

Enter two Burglars, cautiously.

First B. (to Miss J. J.) We can put you up to a fake as will be worth your while,

For you seem a sharp, 'andy lad, and just our style!

[They proceed to unfold a scheme to break into the Ducal abode, and offer Miss J. a share of the spoil, if she will allow herself to be put through the pantry window.

Miss J. J. (proudly). I tell yer I won't 'ave nothink to do with it, fur I ain't been used

To sneak into the house of a Dook to whom I 'aven't been introdooced!

Second Burglar (coarsely). Stow that snivel, yer young himp, we don't want none of that bosh!

Miss J. J. (with spirit). You hold your jaw—for, when you opens yer mouth, there ain't much o' yer face left to wash!

[The Burglars retire, baffled, and muttering. Miss J. leans against pillar-box again—but more irresolutely.

I've arf a mind to run after 'em, I 'ave, and tell 'em I'm game to stand in!...

But, ah,—didn't my poor mother say as Burglary was a Sin!

[Duke crosses stage in a hurry; as he pulls out his latchkey, a threepenny-bit falls unregarded, except by the little Sweeper, who pounces eagerly upon it.

What's this? A bit o' good luck at last for a starvin' orfin boy!

What shall I buy? I know—I'll have a cup of cawfy, and a prime saveloy!

Ah,—but it ain't mine—and 'ark ... that music up in the air!

[A harp is heard in the flies.

Can it be mother a-playin' on the 'arp to warn her boy to beware?

(Awestruck.) There's a angel voice that is sayin' plain (solemnly) "Him as prigs what isn't his'n,

Is sure to be copped some day—and then—his time he will do in prison!"

[Goes resolutely to the door, and knocks—The Duke throws open the portals.

Miss J. J. If yer please, Sir, was you aware as you've dropped a thruppenny-bit?

The Duke (after examining the coin.) 'Tis the very piece I have searched for everywhere! You rascal, you've stolen it!

Miss J. J. (bitterly). And that's 'ow a Dook rewards honesty in this world!