Title: Famous American Statesmen

Author: Sarah Knowles Bolton

Release date: February 29, 2012 [eBook #39012]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Darleen Dove, Julia Neufeld, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://www.archive.org/details/famousamericanst00bolt2 |

AUTHOR OF "POOR BOYS WHO BECAME FAMOUS," "GIRLS WHO

BECAME FAMOUS," "FAMOUS AMERICAN AUTHORS,"

"STORIES FROM LIFE," "FROM HEART,

AND NATURE," ETC.

"A nation has no possessions so valuable as its great men,

living or dead."—Hon. John Bigelow.

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL & CO.

No. 13 Astor Place

Copyright, 1888, by

Thomas Y. Crowell & Co.

Electrotyped

By C. J. Peters and Son, Boston.

Presswork by Berwick & Smith, Boston.

To

THOMAS Y. CROWELL.

Respected as a Publisher

and

Esteemed as a Friend.

"With the great, one's thoughts and manners easily become great; ... what this country longs for is personalities, grand persons, to counteract its materialities," says Emerson. Such lives as are sketched in this book are a constant inspiration, both to young and old. They teach Garfield's oft-repeated maxim, that "the genius of success is still the genius of labor." They teach patriotism—a deeper love for and devotion to America. They teach that life, with some definite and noble purpose, is worth living.

I have written of Abraham Lincoln, one of our greatest and best statesmen, in "Poor Boys Who Became Famous," which will explain its omission from this volume.

| Page | |

| George Washington | 1 |

| Benjamin Franklin | 38 |

| Thomas Jefferson | 67 |

| Alexander Hamilton | 99 |

| Andrew Jackson | 133 |

| Daniel Webster | 177 |

| Henry Clay | 230 |

| Charles Sumner | 268 |

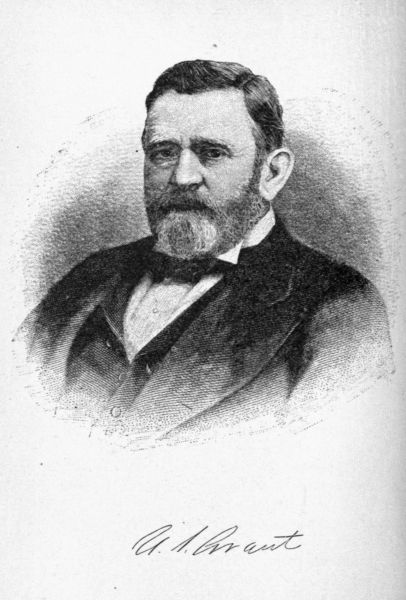

| Ulysses S. Grant | 307 |

| James A. Garfield | 361 |

The "purest figure in history," wrote William E. Gladstone of George Washington.

When Frederick the Great sent his portrait to Washington, he sent with it these remarkable words: "From the oldest general in Europe to the greatest general in the world."

Lord Brougham said: "It will be the duty of the historian, and the sage of all nations, to let no occasion pass of commemorating this illustrious man; and until time shall be no more will a test of the progress which our race has made in wisdom and virtue be derived from the veneration paid to the immortal name of Washington."

At Bridge's Creek, Maryland, in a substantial home, overlooking the Potomac, George Washington was born, February 22, 1732. His father, Augustine, was descended from a distinguished family in England—William de Hertburn, a knight who owned the village of Wessyngton (Washington). He married, at the age of twenty-one, Jane Butler, who died thirteen years afterward. Two years after her death he married[2] Mary Ball, a beautiful girl, of decided character and sterling common-sense. She became a good mother to his two motherless children; two having died in early childhood.

Six children were born to them, George being the eldest. The opportunities for education in the new world, especially on a plantation, were limited. From one of his father's tenants, the sexton of the parish, George learned to read, write, and cipher. He was fond of military things, and organized among the scholars sham-fights and parades; taking the position usually of commander-in-chief, by common consent. This love of war might have come through the influence of his half-brother Lawrence, who had been in battles in the West Indies.

When George was twelve, his father died suddenly, leaving Mary Ball, at thirty-seven, to care for her own five children, one having died in infancy, and two boys by the first marriage. Fortunately, a large estate was left them, which she was to control till they became of age.

While she loved her children tenderly, she exacted the most complete obedience. She was dignified and firm, yet cheerful, and possessed an unusually sweet voice. To his mother's intelligence and moral training George attributed his success in life. She would gather her children about her daily, and read to them from Matthew Hale's "Contemplations, Divine and Moral." The book had been loved by the first wife, who wrote[3] in it, "Jane Washington." Under this George's mother wrote, "and Mary Washington." This book was always preserved with tender care at Mount Vernon, in later years. Such teaching the boy never forgot. When he was thirteen, he wrote "Rules of courtesy and decent behavior in company and conversation," one hundred and ten maxims, which seemed to have great influence over him.

At fourteen, he desired to enter the navy, and a midshipman's warrant was procured by his brother Lawrence. Now he could see the world, and was happy at the prospect. All winter long, the mother's heart ached as she thought of the separation, and finally, when his clothing had been taken on board of a British man-of-war, her affection triumphed, and the lad was kept in his Virginia home; kept for a great work. However disappointed he may have been, his mother's word was law. Those who learn to obey in youth learn also how to govern in later life. George went back to school to study arithmetic and land-surveying. He was thorough in his work, and his record books, still preserved, are neat and exact.

It is never strange that a boy who idolizes his mother should think other women lovable. At fifteen, the bashful, manly boy had given his heart to a girl about his own age, and it was long before he could conquer the affection. A year later he wrote to a friend, "I might, was my heart disengaged, pass my time very pleasantly, as there's[4] a very agreeable young lady lives in the same house; but as that's only adding fuel to fire, it makes me the more uneasy, for by often and unavoidably being in company with her revives my former passion for your Lowland Beauty; whereas, was I to live more retired from young women, I might in some measure alleviate my sorrows, by burying that chaste and troublesome passion in the grave of oblivion."

Years afterwards, the son of this "Lowland Beauty," General Henry Lee, became a favorite with Washington in the Revolutionary War; possibly all the more loved from tender recollections of the mother. General Lee was the father of General Robert E. Lee of the Confederate Army, in the Civil War.

At sixteen, the real work of Washington's life began. Lord Fairfax of Virginia desired his large estates beyond the Blue Ridge to be surveyed, and he knew that the youth had the courage to meet the Indians in the wilderness, and would do his work well.

Washington and a friend set out on horseback for the valley called by the Indians Shenandoah, "the daughter of the stars." He made a record daily of the beauty of the trees—every refined soul loves trees almost as though they were human—and the richness of the soil, and selected the best sites for townships. In his diary he says, "A blowing, rainy night, our straw upon which we were lying took fire, but I was luckily preserved by[5] one of our men awaking when it was in a flame." For three years he lived this exposed life, sleeping out-of-doors, gaining self-reliance, and a knowledge of the Indians, which knowledge he was soon to need.

Trouble had begun already in the Ohio valley, between the French and English, in their claims to the territory. No wonder a sachem asked, "The French claim all the land on one side of the Ohio, the English claim all the land on the other side—now, where does the Indians' land lie?"

Virginia began to make herself ready for a war which seemed inevitable. She divided her province into military districts, and placed one in charge of the young surveyor, only nineteen, who was made adjutant general with the rank of major. Thus early did the sincere, self-poised young man take upon himself great responsibilities. Washington at once began to make himself ready for his duties, by studying military tactics; taking lessons in field-work from his brother Lawrence, and sword exercise from a soldier. This drill was broken in upon for a time by the illness and death of Lawrence, of whom he was very fond, and whom he accompanied to the Barbadoes. Here George took small-pox, from which he was slightly marked through life. The only child of Lawrence soon died, and Mount Vernon came to George by will. He was now a person of wealth, but riches did not spoil him. He did not seek ease; he sought work and honor.

[6]Matters were growing worse in the Ohio valley. The Virginians had erected forts at what is now Pittsburg; and the French, about fifteen miles south of Lake Erie. Governor Dinwiddie determined to make a last remonstrance with the French who should thus presume to come upon English territory. The way to their forts lay through an unsettled wilderness, a distance of from five hundred to six hundred miles. Some Indian tribes favored one nation; some the other. The governor offered this dangerous commission—a visit to the French—to several persons, who hastened to decline with thanks the proffered honor.

Young Washington, with his brave heart, was willing to undertake the journey, and started September 30, 1753, with horses, tents, and other necessary equipments. They found the rivers swollen, so that the horses had to swim. The swamps, in the snow and rain, were almost impassable. At last they arrived at the forts, early in December. Washington delivered his letter to the French, and an answer was written to the governor.

On December 25, Washington and his little party started homeward. The horses were well-nigh exhausted, and the men dismounted, put on Indian hunting-dress, and toiled on through the deepening snow. Washington, in haste to reach the governor, strapped his pack on his shoulders, and, gun in hand, with one companion, Mr. Gist, struck through the woods, hoping thus to reach the Alleghany River sooner, and cross on the ice. At[7] night they lit their camp-fire, but at two in the morning they pursued their journey, guided by the north star.

Some Indians now approached, and offered their services as guides. One was chosen, but Washington soon suspected that they were being guided in the wrong direction. They halted, and said they would camp for the night, but the Indian demurred, and offered to carry Washington's gun, as he was fatigued. This was declined, when the Indian grew sullen, hurried forward, and, when fifteen paces ahead, levelled his gun and fired at Washington. Gist at once seized the savage, took his gun from him, and would have killed him on the spot had not the humane Washington prevented. He was sent home to his cabin with a loaf of bread, and told to come to them in the morning with meat. Probably he expected to return before morning, and, with some other braves, scalp the two Americans; but Washington and Gist travelled all night, and reached the Alleghany River opposite the site of Pittsburg.

Unfortunately, the river was not frozen as they had hoped, but was full of broken ice. All day long they worked to construct a raft, with but one hatchet between them. After reaching the middle of the river the men on the raft were hurled into ten feet of water by the floating ice, and Washington was saved from drowning only by clinging to a log. They lay till morning on an island in the river, their clothes stiff with frost, and the hands[8] and feet of poor Gist frozen by the intense cold. The agony of that night Washington never forgot, even in the horrors of Valley Forge.

Happily, the river had grown passable in the night, and they were able to cross to a place of safety. He came home as speedily as possible and delivered the letter to Governor Dinwiddie. His journal was sent to London and published, because of the knowledge it gave of the position of the French. The young soldier of twenty-one had escaped death from the burning straw in surveying, from the Indian's gun, and from drowning. He had shown prudence, self-devotion, and heroism. "From that moment," says Irving, in his delightful life of Washington, "he was the rising hope of Virginia." And he was the rising hope of the new world as well.

The polite letter brought by Washington to the governor had declared that no Englishmen should remain in the Ohio valley! Dinwiddie at once determined to send three hundred troops against the French, and offered the command to Washington. He shrunk from the charge, and it was given to Colonel Fry, while he was made second in command. Fry soon died, and Washington was obliged to assume control. He was equal to the occasion. He said, "I have a constitution hardy enough to encounter and undergo the most severe trials, and, I flatter myself, resolution enough to face what any man dares, as shall be proved when it comes to the test."

[9]The test soon came. In the conflict which followed he was in the thickest of the fight, one man being killed at his side. He wrote to his brother, "I heard the bullets whistle, and, believe me, there is something charming in the sound." Years afterward, he said, when he had long known the sorrows of war, "If I said that, it was when I was young."

At Great Meadows, below Pittsburg, he was defeated by superior numbers, and obliged to evacuate the fort, but the Virginia House of Burgesses thanked him for his bravery.

The next year, England sent out General Braddock, who had been over forty years in the service, a fearless but self-willed officer, to take command of the American forces. Washington gladly joined him as an aide-de-camp. They set out with two thousand soldiers, toward Fort du Quesne (Pittsburg). The amount of baggage astonished Washington, who well knew the swamps and mountains that must be crossed, but Braddock could not be influenced. He remarked to Benjamin Franklin, "These savages may indeed be a formidable enemy to raw militia, but upon the king's regular and disciplined troops, sir, it is impossible they should make an impression." How great an "impression" savages could make upon the "king's regular and disciplined troops" was soon to be shown.

The march was exceedingly difficult. Sometimes a whole day was spent in cutting a passage of two miles over the mountains. Washington urged that[10] the Virginia Rangers be put to the front, as they understood Indian warfare. The general haughtily opposed it, and the regulars in brilliant uniforms, bayonets fixed, colors flying, and drums beating, swept over the open plain to battle, July 9, 1755.

Suddenly there was a cry, "The French and Indians!" The Indian yell struck terror to the hearts of the regulars. They fired in all directions, killing their own men. A panic ensued. Braddock tried to rally his men; even striking them with the flat of his sword. Five horses were killed under him. At last a bullet entered his lungs, and he fell, mortally wounded. Then the men fled precipitately, falling over their dead comrades. Out of eighty-six officers, twenty-six were killed and thirty-six wounded. Nearly half of the whole army were dead or disabled. The Virginia Rangers covered the retreat of the flying regulars, and thus saved a remnant. Braddock, bequeathing his horse and servant, Bishop, to Washington, died broken-hearted, moaning, "Who would have thought it!... We shall better know how to deal with them another time." Washington tenderly read the funeral service, and Braddock was buried in the new and wild country he had come to save.

Washington escaped as by a miracle. He wrote his brother, "By the all-powerful dispensations of Providence, I have been protected beyond all human probability or expectation; for I had four bullets through my coat, and two horses shot[11] under me, yet escaped unhurt, though death was levelling my companions on every side of me." Through life, this man, great in all that mankind prize, loved and believed in the Christian religion. Agnosticism had no charms for him.

Washington returned to Mount Vernon temporarily broken in health, and his fond mother, who was living at the old homestead, wrote begging that he would not again enter the service. In reply he said, "Honored Madam," for thus he always addressed her, "if it is in my power to avoid going to the Ohio again, I shall; but if the command is pressed upon me by the general voice of the country, and offered upon such terms as cannot be objected against, it would reflect dishonor on me to refuse it; and that, I am sure, must and ought to give you greater uneasiness than my going in an honorable command."

Braddock's defeat electrified the colonies. Governor Dinwiddie at once called for troops, and Washington was made "commander-in-chief of all the forces raised or to be raised in Virginia." For two years he protected the people in the attacks of the Indians; his heart so full of pity that he wrote the governor, "I solemnly declare, if I know my own mind, I could offer myself a willing sacrifice to the butchering enemy, provided that would contribute to the people's ease." No wonder that such self-sacrifice and unselfishness won the homage of the State, and later of the nation.

In May, 1758, the condition of the army was[12] such, the men so poorly clad and paid, that the young commander decided to go to Williamsburg to lay the matter before the council. In crossing the Pamunkey, a branch of the York River, he met a Mr. Chamberlayne, who pressed him to dine, more especially as a charming lady was visiting at his house. He accepted the invitation, and there met Martha Custis, a widow of twenty-six, two months younger than himself; a bright, frank, agreeable woman, with dark eyes and hair, below the middle size, a contrast indeed to his striking physique, six feet two inches tall, blue eyes, and grave demeanor.

Martha Dandridge, with amiable disposition and winning manners, had been married at seventeen to Daniel Parke Custis, thirty-eight, a kind-hearted and wealthy land-owner. For seven years they lived at "The White House," on the Pamunkey River, where he died, leaving two children, John Parke and Martha Parke Custis. Mrs. Custis had come to visit the Chamberlaynes, and now was to meet the most popular officer in Virginia.

The dinner passed pleasantly, and then Bishop, the servant, brought Colonel Washington's horse and his own to the gate at the appointed hour. But Colonel Washington did not appear. The afternoon seemed like a dream, for love takes no account of time. The sun was setting when he rose to go, but Major Chamberlayne urged his guest to pass the night. Probably he did not need to be urged, for the most sublime and beautiful[13] force in all the world now controlled the fearless Washington. The next morning he hastened to Williamsburg, transacted his business, returned to the home of Martha Custis, where he spent a day and a night, and left her his betrothed.

The commander went back to camp with a new joy in living. The army was now ordered against Fort du Quesne, under Brigadier-General Forbes of Great Britain; Washington leading the Virginia troops. He seized a moment before leaving to write to Mrs. Custis, which letter Lossing gives in his interesting lives of Mary and Martha Washington:—

"A courier is starting for Williamsburg, and I embrace the opportunity to send a few words to one whose life is now inseparable from mine. Since that happy hour when we made our pledges to each other, my thoughts have been continually going to you as to another self. That an all-powerful Providence may keep us both in safety is the prayer of your ever faithful and

"Ever affectionate friend,"

G. Washington."

The army marched again over the field where the bones of Braddock's men were bleaching in the sun, and approached the fort, only to find that the French had deserted it after setting it on fire, and retreated down the river. Washington, who led the advance, planted the British flag over the smoking ruin of what is now Pittsburg, so called from the illustrious William Pitt. With the French driven out of the Ohio valley, Washington, having[14] served five years in the army, resigned, and married Martha Custis, January 6, 1759. Every inch a soldier he must have looked in his suit of blue cloth lined with red silk, and ornamented with silver trimmings; while his bride wore white satin, with pearl necklace and ear-rings, and pearls in her hair. She rode home in a coach drawn by six horses, while Colonel Washington, on a fine chestnut horse, attended by a brilliant cortége, rode beside her carriage.

The year previous, 1758, Washington had been elected a member of the Virginia Assembly. When he took his seat, the House gave him an address of welcome. He rose to reply, trembled, and could not say a word. "Sit down, Mr. Washington," said the speaker; "your modesty equals your valor, and that surpasses the power of any language I possess." Beautiful attributes of character, not always found in conjunction; valor and modesty!

For three months Washington remained at the home of his wife, to attend to the business of the colony; becoming also guardian of her two pretty children, four and six years of age, whom he seemed to love as his own. When he took his bride to Mount Vernon to live, he wrote to a relative, "I am now, I believe, fixed in this spot with an agreeable partner for life; and I hope to find more happiness in retirement than I ever experienced in the wide and bustling world."

For seventeen years he lived on his estate of eight thousand acres, delighting in agriculture, and[15] enjoying the development of the two children. The years passed quickly, for affection, the holiest thing on earth, brought rest and contentment. He or she is rich who possesses it. To have millions, and yet live in a home where there is no affection, is to be poor indeed.

He was an early riser; in winter often lighting his own fire, and reading by candle-light; retiring always at nine o'clock. He was vestryman in the Episcopal Church, and judge of the county court, as well as a member of the House of Burgesses. So honest was he that a barrel of flour marked with his name was exempted from the usual inspection in West India ports.

Into this busy and happy life came sorrow, as it comes into other lives. Martha Parke Custis, a gentle and lovely girl, died of consumption at seventeen, Washington kneeling by her bedside in prayer as her life went out. The love of both parents now centred in the boy of nineteen, John Parke Custis, who, the following year, left Columbia College to marry a girl of sixteen, Eleanor Calvert. While Washington attended the wedding, Mrs. Washington could not go, in her mourning robes, but sent an affectionate letter to her new daughter.

The quiet life at Mount Vernon was now to be wholly changed. The Stamp Act and the oppressive taxes had stirred America. When the taxes were repealed, save that on tea, and Lord North was urged to include tea also, he said: "To temporize[16] is to yield; and the authority of the mother country, if it is not now supported, will be relinquished forever; a total repeal cannot be thought of till America is prostrate at our feet." Mrs. Washington, like other lovers of liberty, at once ceased to use tea at her table.

When the First Continental Congress met at Philadelphia, September 5, 1774, Washington was among the delegates chosen by Virginia. He rode thither on horseback, with his brilliant friends Patrick Henry and Edmund Pendleton. When they departed from Mount Vernon, the patriotic Martha Washington said: "I hope you will all stand firm. I know George will.... God be with you, gentlemen."

To a relative, who wrote deprecating Colonel Washington's "folly," his wife answered: "Yes; I foresee consequences—dark days, and darker nights; domestic happiness suspended; social enjoyments abandoned; property of every kind put in jeopardy by war, perhaps; neighbors and friends at variance, and eternal separations on earth possible. But what are all these evils when compared with the fate of which the Port Bill may be only a threat? My mind is made up, my heart is in the cause. George is right; he is always right. God has promised to protect the righteous, and I will trust him." Blessings on the woman who, in the darkest hour, knows how to be as the sunlight in her hope and trust, and to be well-nigh a divine embodiment of courage and fortitude![17] Truly said Schiller: "Honor to women! they twine and weave the roses of heaven into the life of man."

Congress remained in session fifty-one days. When the results of its labors were put before the House of Lords, the great Chatham said: "When your lordships look at the papers transmitted to us from America; when you consider their decency, firmness, and wisdom, you cannot but respect their cause, and wish to make it your own. For myself, I must declare and avow that, in the master states of the world, I know not the people, or senate, who, in such a complication of difficult circumstances, can stand in preference to the delegates of America assembled in General Congress at Philadelphia."

When Patrick Henry was asked, on his return home, who was the greatest man in Congress, he replied: "If you speak of eloquence, Mr. Rutledge of South Carolina is by far the greatest orator; but if you speak of solid information and sound judgment, Colonel Washington is unquestionably the greatest man on that floor." Wise reading in all these years had given Washington "solid information," and "sound judgment" was partly an inheritance from noble Mary Washington.

People all through New England were arming themselves. General Gage, who had been sent to Boston with British troops, said: "It is surprising that so many of the other provinces interest themselves so much in this. They have some warm friends in New York, and I learn that the people[18] of Charleston, South Carolina, are as mad as they are here." He was soon to possess a more thorough knowledge of the American character.

The Boston troops, under Gage, numbered about four thousand. He determined to destroy the military stores at Concord, on the night of April 18, 1775. It was to be done secretly, but as soon as the British regiment started, under Colonel Smith and Major Pitcairn, for Concord, the bells of Boston rang out, cannon were fired, and Paul Revere, with Prescott and Davis, rode at full speed in the bright moonlight to Lexington, to alarm the neighboring country. When cautioned against making so much noise, Revere replied: "You'll have noise enough here before long—the regulars are coming out."

Long before morning, nearly two-score of the villagers, under Captain Parker, gathered on the green, near the church, waiting for the red-coats, who came at double-quick, Major Pitcairn exclaiming, "Disperse, ye villains! Lay down your arms, ye rebels, and disperse!" Unmoved, Captain Parker said to his men, "Don't fire unless you are fired on; but if they want a war, let it begin here." The Revolutionary War began there, to end only when America should be free. Seven Americans were killed, nine wounded, and the rest were put to flight; but the blood shed on Lexington Green made liberty dear to every heart.

The British now marched to Concord, where, in the early morning, they found four hundred and[19] fifty men gathered to receive them. Captain Isaac Davis, who said, when his company led the force, "I haven't a man that is afraid to go," was killed at the first shot, at the North Bridge.

The British troops destroyed all the stores they could find, though most had been removed, and then started toward Boston. All along the road the indignant Americans fired upon them from behind stone fences and clumps of bushes. Tired by their night march, having lost three hundred in killed and wounded, over three times as many as the Americans, they were glad to meet Lord Percy coming to their rescue with one thousand men. He formed a hollow square, and, faint and exhausted, the soldiers threw themselves on the ground within it, and rested.

The whole country seemed to rise to arms. Men came pouring into Boston with such weapons as they could find. Noble Israel Putnam of Connecticut left his plough in the field and hastened to the war.

May 10, Congress again met at Philadelphia. They sent a second petition to King George, which John Adams called an "imbecile measure." They made plans for the support of the army already gathered at Cambridge from the different States. Who should be the commander of this growing army? Then John Adams spoke of the gentleman from Virginia, "whose skill and experience as an officer, whose independent fortune, great talents, and excellent universal character, would command[20] the approbation of all America, and unite the cordial exertions of all the colonies better than any other person in the Union." June 5, Washington was unanimously elected commander-in-chief.

Rising in his seat, and thanking Congress, he modestly said: "I beg it may be remembered by every gentleman in the room that I this day declare, with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with. As to pay, I beg leave to assure the Congress that, as no pecuniary consideration could have tempted me to accept this arduous employment, at the expense of my domestic ease and happiness, I do not wish to make any profit of it. I will keep an exact account of my expenses. Those, I doubt not, they will discharge, and that is all I desire." He wrote to his wife: "I should enjoy more real happiness in one month with you at home than I have the most distant prospect of finding abroad if my stay were to be seven times seven years. But as it has been a kind of destiny that has thrown me upon this service, I shall hope that my undertaking it is designed to answer some good purpose.... I shall feel no pain from the toil or danger of the campaign; my unhappiness will flow from the uneasiness I know you will feel from being left alone." No wonder Martha Washington loved him; so brave that he could meet any danger without fear, yet so tender that the thought of leaving her brought intense pain.

He was now forty-three; the ideal of manly[21] dignity. He at once started for Boston. Soon a courier met him, telling him of the battle of Bunker Hill—how for two hours raw militia had withstood British regulars, killing and wounding twice as many as they lost, and retreating only when their ammunition was exhausted. When Washington heard how bravely they had fought, he exclaimed: "The liberties of the country are safe." Under the great elm (still standing) at Cambridge, Washington took command of the army, July 3, 1775, amid the shouts of the multitude and the roar of artillery. His headquarters were established at Craigie House, afterward the home of the poet Longfellow. Here Mrs. Washington came later, and helped to lessen his cares by her cheerful presence.

The soldiers were brave but undisciplined; the terms of enlistment were short, thus preventing the best work. To provide powder was well-nigh an impossibility. For months Washington drilled his army, and waited for the right moment to rescue Boston from the hands of the British. Generals Howe, Clinton, and Burgoyne had been sent over from England. Howe had strengthened Bunker Hill, and, with little respect for the feelings of the Americans, had removed the pulpit and pews from the Old South Church, covered the floor with earth, and converted it into a riding-school for Burgoyne's light dragoons. They did not consider the place sacred, because it was a "meeting-house where sedition had often been preached."

[22]The "right moment" came at last. In a single night the soldiers fortified Dorchester Heights, cannonading the enemy's batteries in the opposite direction, so that their attention was diverted from the real work. When the morning dawned of March 5, 1776, General Howe saw, through the lifting fog, the new fortress, with the guns turned upon Boston. "I know not what to do," he said. "The rebels have done more work in one night than my whole army would have done in one month."

He resolved to attack the "rebels" by night, and for this attack twenty-five hundred men were embarked in boats. But a violent storm set in, and they could not land. The next day the rain poured in torrents, and when the second night came Dorchester Heights were too strong to be attacked. The proud General Howe was compelled to evacuate Boston with all possible dispatch, March 17, the navy going to Halifax and the army to New York. The Americans at once occupied the city, and planted the flag above the forts. Congress moved a vote of thanks to Washington, and ordered a gold medal, bearing his face, as the deliverer of Boston from British rule.

The English considered this a humiliating defeat. The Duke of Manchester, in the House of Lords, said: "British generals, whose name never met with a blot of dishonor, are forced to quit that town, which was the first object of the war, the immediate cause of hostilities, the place of arms,[23] which has cost this nation more than a million to defend."

The Continental Army soon repaired to New York. Washington spared no pains to keep a high moral standard among his men. He said, in one of his orders: "The general is sorry to be informed that the foolish and wicked practice of profane cursing and swearing—a vice heretofore little known in an American army—is growing into fashion. He hopes the officers will, by example as well as influence, endeavor to check it, and that both they and the men will reflect that we can have little hope of the blessing of Heaven on our arms if we insult it by our impiety and folly. Added to this, it is a vice so mean and low, without any temptation, that every man of sense and character detests and despises it." Noble words!

Great Britain now realized that the fight must be in earnest, and hired twenty thousand Hessians to help subjugate the colonies. When Admiral Howe came over from England, he tried to talk about peace with "Mr." Washington, or "George Washington, Esq.," as it was deemed beneath his dignity to acknowledge that the "rebels" had a general. The Americans could not talk about peace, with such treatment.

Soon the first desperate battle was fought, on Long Island, August 27, 1776, partly on the ground now occupied by Greenwood Cemetery, between eight thousand Americans and more than twice their number of trained Hessians. Washington,[24] from an eminence, watched the terrible conflict, wringing his hands, and exclaiming, "What brave fellows I must this day lose!"

The Americans were defeated, with great loss. Washington could no longer hold New York with his inadequate forces. With great energy and promptness he gathered all the boats possible, and then, so secretly that even his aides did not know his intention, nine thousand men, horses, and provisions, were ferried over the East River. A heavy fog hung over the Brooklyn side, as though provided by Providence, while it was clear on the New York side, so that the men could form in line. Washington crossed in the last boat, having been for forty-eight hours without sleep.

In the morning, the astonished Englishmen learned that the prize had escaped. A Tory woman, the night before, seeing that the Americans were crossing the river, sent her colored servant to notify the British. A Hessian sentinel, not understanding the servant, locked him up till morning, when, upon the arrival of an officer, his errand was known; but the knowledge came too late!

On October 28, the Americans were again defeated, at White Plains, Howe beginning the engagement. The condition of the Continental Army was disheartening. They were half-fed and half-clothed; the "ragged rebels," the British called them. There was sickness in the camp, and many were deserting. Washington said, "Men just dragged from the tender scenes of domestic life,[25] unaccustomed to the din of arms, totally unacquainted with every kind of military skill, are timid, and ready to fly from their own shadows. Besides, the sudden change in their manner of living brings on an unconquerable desire to return to their homes." So great-hearted was the commander-in-chief, though on the field of battle he had no leniency toward cowards.

Washington retreated across New Jersey to Trenton. When he reached the Delaware River, filled with floating ice, he collected all the boats within seventy miles, and transported the troops, crossing last himself. Lord Cornwallis, of Howe's army, came in full pursuit, reached the river just as the last boat crossed, and looked in vain for means of transportation. There was nothing to be done but to wait till the river was frozen, so that the troops could cross on the ice.

Washington, December 20, 1776, told John Hancock, President of Congress, "Ten days more will put an end to the existence of our army." Yet, on the night of December 25, Christmas, with almost superhuman courage, he determined to recross the Delaware, and attack the Hessians at Trenton. The weather was intensely cold. The boats, in crossing, were forced out of their course by the drifting ice. Two men were frozen to death. At four in the morning, the heroic troops took up the line of march, the snow and sleet beating in their faces. Many of the muskets were wet and useless. "What is to be done?" asked[26] the men. "Push on, and use the bayonet," was the answer.

At eight in the morning, the Americans rushed into the town. "The enemy! the enemy!" cried the Hessians. Their leader, Colonel Rahl, fell, mortally wounded. A thousand men laid down their arms and begged for quarter. Washington recrossed the Delaware with his whole body of captives, and the American nation took heart once more. That fearful crossing of the Delaware, in the blinding storm, and the sudden yet marvellous victory which followed, will always live among the most pathetic and stirring scenes of the Revolution. A few days later, January 3, 1777, with five thousand men, Washington defeated Cornwallis at Princeton, exposing himself so constantly to danger that his officers begged him to seek a place of safety.

The third year of the Revolutionary War had opened. France, hating England, sympathizing with America in her struggle for liberty, and being encouraged in this sympathy by the honored Benjamin Franklin, loaned us money, supplied muskets and powder, and many troops under such brave leaders as Lafayette and De Kalb. The year 1777, although our forces were defeated at Brandywine and Germantown, witnessed the defeat of a part of Burgoyne's army at Bennington, Vermont, and, on the 17th of October, the remaining part at Saratoga; over five thousand men, seven thousand muskets, and a great quantity[27] of military stores. Two months later, France made a treaty of alliance with the United States, to the joy of the whole country.

On December 11, Washington went into winter-quarters at Valley Forge, on the west side of the Schuylkill, about twenty miles from Philadelphia. Trees were felled to build huts, the men toiling with scanty food, often barefoot, the snow showing the marks of their bleeding feet. Continental money had so depreciated that forty dollars were scarcely equal in value to one silver dollar. Sickness was decreasing the forces. Washington wrote to Congress: "No less than two thousand eight hundred and ninety-eight men are now in camp unfit for duty, because they are barefoot and otherwise naked." From lack of blankets, he said, "numbers have been obliged, and still are, to sit up all night by fires, instead of taking comfortable rest in a natural and common way." A man less great would have been discouraged, but he trusted in a power higher than himself, and waited in sublime dignity and patience for the progress of events. Martha Washington had come to Valley Forge to share in its privations, and to minister to the sick and the dying.

The years 1778 and 1779 dragged on with their victories and defeats. The next year, 1780, the country was shocked by the treason of Benedict Arnold, who, having obtained command at West Point, had agreed to surrender it to the British for fifty thousand dollars in money and the position[28] of brigadier-general in their army. On September 21, Sir Henry Clinton sent Major John André, an adjutant-general, to meet Arnold. He went ashore from the ship Vulture, met Arnold in a wood, and completed the plan. When he went back to the boat, he found that a battery had driven her down the river, and he must return by land. At Tarrytown, on the Hudson, he was met by three militiamen, John Paulding, David Williams, and Isaac Van Wart, who at once arrested him, and found the treasonable papers in his boots. He offered to buy his release, but Paulding assured him that fifty thousand dollars would be no temptation.

André was at once taken to prison. While there he won all hearts by his intelligence and his cheerful, manly nature. He had entered the British army by reason of a disappointment in love. The father of the young lady had interfered, and she had become the second wife of the father of Maria Edgeworth. André always wore above his heart a miniature of Honora Sneyd, painted by herself. Just before his execution as a spy, he wrote to Washington, asking to be shot. When he was led to the gallows, October 2, 1780, and saw that he was to be hanged, for a moment he seemed startled, and exclaimed, "How hard is my fate!" but added, "It will soon be over." He put the noose about his own neck, tied the handkerchief over his eyes, and, when asked if he wished to speak, said only: "I pray you to bear witness[29] that I meet my fate like a brave man." His death was universally lamented. In 1821, his body was removed to London by the British consul, and buried in Westminster Abbey.

Every effort was made to capture Arnold, but without success. He once asked an American, who had been taken prisoner by the British, what his countrymen would have done with him had he been captured. The immediate reply was: "They would cut off the leg wounded in the service of your country, and bury it with the honors of war. The rest of you they would hang."

In 1781, the condition of affairs was still gloomy. Some troops mutinied for lack of pay, but when approached by Sir Henry Clinton, through two agents, offering them food and money if they would desert the American cause, the agents were promptly hanged as spies. Such was the patriotism of the half-starved and half-clothed soldiers.

In May of this year, Cornwallis took command of the English forces in Virginia, destroying about fifteen million dollars worth of property. Early in October, Washington with his troops, and Lafayette and De Rochambeau with their French troops, gathered at Yorktown, on the south bank of the York River. For ten days the siege was carried on. The French troops rendered heroic service. Washington was so in earnest that one of his aids, seeing that he was in danger, ventured to suggest that their situation was much exposed. "If you think so, you are at liberty to step back,"[30] was the grave response of the general. Shortly afterwards a musket-ball fell at Washington's feet. One of his generals grasped his arm, exclaiming, "We can't spare you yet." When the victory was finally won, Washington drew a long breath and said, "The work is done and well done." Cornwallis surrendered his whole army, over seven thousand soldiers, October 19, 1781.

The American nation was thrilled with joy and gratitude. Washington ordered divine service to be performed in the several divisions, saying, "The commander-in-chief earnestly recommends that the troops not on duty should universally attend, with that seriousness of deportment and gratitude of heart which the recognition of such reiterated and astonishing interpositions of Providence demands of us." Congress appointed a day of thanksgiving and prayer, and voted two stands of colors to Washington and two pieces of field-ordnance to the brave French commanders. When Lord North, Prime Minister of England, heard of the defeat of the British, he exclaimed, "Oh, God! it is all over!"

The nearly seven long years of war were ended, and America had become a free nation.

The articles of peace between Great Britain and the United States were not signed till September 3, 1783. On November 4 the army was disbanded, with a touching address from their idolized commander. On December 4, in the city of New York, in a building on the corner of Pearl and Broad[31] Streets, Washington said good-bye to his officers, losing for a time his wonderful self-command. "I cannot come to each of you to take my leave," he said, "but shall be obliged if each of you will come and take me by the hand." Tears filled the eyes of all, as, silently, one by one, they clasped his hand in farewell, and passed out of his sight.

Then Washington repaired to Annapolis, where Congress was assembled, and at twelve o'clock on the 23d of December, before a crowded house, offered his resignation. "Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of action; and bidding an affectionate farewell to this august body, under whose orders I have long acted, I here offer my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life." "Few tragedies ever drew so many tears from so many beautiful eyes," said one who was present.

The beloved general returned to Mount Vernon, to enjoy the peace and rest which he needed, and the honor of his country which he so well deserved. John Parke Custis, Mrs. Washington's only remaining child, had died, leaving four children, two of whom—Eleanor, two years old, and George Washington, six months old—the general adopted as his own. These brought additional "sweetness and light" into the beautiful home.

The following year the Marquis de Lafayette was a guest at Mount Vernon, and went to Fredericksburg to bid adieu to Washington's mother. When he spoke in high praise of the man whom he[32] so loved and honored, Mary Washington replied quietly, "I am not surprised at what George has done, for he was always a good boy." Blessed mother-heart, that, in training her child, could look into the future, and know, for a certainty, the result of her love and progress! She died August 25, 1789.

Three years later—May 25, 1787—a convention met at Philadelphia to form a more perfect union of the States, and frame a Constitution. Washington was made President of this convention. He had long been reading carefully the history and principles of ancient and modern confederacies, and he was intelligently prepared for the honor accorded him. When the Constitution was finished, and ready for his signature, he said: "Should the United States reject this excellent Constitution, the probability is that an opportunity will never again be offered to cancel another in peace; the next will be drawn in blood."

When the various States, after long debate, had accepted the Constitution, a President must be chosen, and that man very naturally was the man who had saved the country in the perils of war. On the way to New York, then the seat of government, Washington received a perfect ovation. The bells were rung, cannon fired, and men, women, and children thronged the way. Over the bridge crossing the Delaware the women of Trenton had erected an arch of evergreen and laurel, with the words, "The defender of the mothers will be the[33] protector of the daughters." As he passed, young girls scattered flowers before him, singing grateful songs. How different from that crossing years before, with his worn and foot-sore army, amid the floating ice!

The streets of New York were thronged with eager, thankful people, who wept as they cheered the hero, now fifty-seven, who had given nearly his whole life to his country's service. On April 30, 1789, the inauguration took place. At nine o'clock in the morning, religious services were held in all the churches. At twelve, in the old City Hall, in Wall Street, Chancellor Livingston administered the oath of office, Washington stooping down and kissing the open Bible, on which he laid his hand; "the man," says T. W. Higginson, "whose generalship, whose patience, whose self-denial, had achieved and then preserved the liberties of the nation; the man who, greater than Cæsar, had held a kingly crown within reach, and had refused it." Washington had previously been addressed by some who believed that the Colonies needed a monarchy for strong government. Astonished and indignant, he replied: "I am much at a loss to conceive what part of my conduct could have given encouragement to an address which to me seems big with the greatest mischiefs that can befall my country." After taking the oath, all proceeded on foot to St. Paul's Church, where prayers were read.

The next four years were years of perplexity and care in the building of the nation. The great war[34] debt, of nearly one hundred millions, must be provided for by an impoverished nation; commerce and manufactures must be developed; literature and education encouraged, and Indian outbreaks quelled. With a love of country that was above party-spirit, with a magnanimity that knew no self-aggrandizement, he led the States out of their difficulties. When his term of office expired, he would have retired gladly to Mount Vernon for life, but he could not be spared. Thomas Jefferson wrote him: "The confidence of the whole Union is centred in you.... North and South will hang together, if they have you to hang on."

Again he accepted the office of President. Affairs called more than ever for wisdom. He continually counselled "mutual forbearances and temporizing yieldings on all sides." France, who had helped us so nobly, was passing through the horrors of the Revolution. The blood of kings and people was flowing. The French Republic having sent M. Genet as her minister to the United States, he attempted to fit out privateers against Great Britain. Washington knew that America could not be again plunged into a war with England without probable self-destruction; therefore he held to neutrality, and demanded the recall of Genet. The people earnestly sympathized with France, and, but for the strong man at the head of the nation, would have been led into untold calamities. The country finally came to the verge of war with France, but when Napoleon overthrew the Directory, and made[35] himself First Consul, he wisely made peace with the United States.

Washington declined a third term of office, and sent his beautiful farewell address to Congress, containing the never-to-be-forgotten words: "Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.... Observe good faith and justice towards all nations. Cultivate peace and harmony with all."

He now returned to Mount Vernon to enjoy the rest he had so long desired. Three years later the great man lay dying, after a day's illness, from affection of the throat. From difficulty of breathing, his position was often changed. With his usual consideration for others, he said to his secretary, "I am afraid I fatigue you too much." "I feel I am going," he said to his physicians. "I thank you for your attentions, but I pray you to take no more trouble about me." The man who could face death on the battle-field had no fears in the quiet home by the Potomac. In the midst of his agony, he could remember to thank those who aided him, and regret that he was a source of care or anxiety. Great indeed is that soul which has learned that nothing in God's universe is a little thing.

At ten in the evening he gave a few directions about burial. "Do you understand me?" he asked. Upon being answered in the affirmative, he replied, "'Tis well!" when he expired without[36] a struggle, December 14, 1799. Mrs. Washington, who was seated at the foot of the bed, said: "'Tis well. All is now over. I shall soon follow him. I have no more trials to pass through."

On December 18, 1799, the funeral procession took its way to the vault on the Mount Vernon estate. The general's horse, with his saddle and pistols, led by his groom in black, preceded the body of his dead master. A deep sorrow settled upon the nation. The British ships lowered their flags to half-mast. The French draped their standards with crape.

Martha Washington died three years later, May 22, 1802, and was buried beside her husband. In 1837, the caskets were enclosed in white marble coffins, now seen by visitors to Mount Vernon. In 1885 a grand marble monument, five hundred and fifty-five feet high, was completed on the banks of the Potomac, at the capital, to the immortal Washington.

Truly wrote Jefferson: "His integrity was most pure; his justice the most inflexible I have ever known; no motives of interest or consanguinity, of friendship or hatred, being able to bias his decision. He was, indeed, in every sense of the word, a wise, a good, and a great man."

The life of George Washington will ever be an example to young men. He had the earnest heart and manner—never trivial—which women love, and men respect. He had the courage which the world honors, and the gentleness which made little[37] children cling to him. He controlled an army and a nation, because he understood the secret of power—self-control. Well does Mr. Gladstone call him the "purest figure in history;" unselfish, fair, patient, heroic, true.

"To say that his life is the most interesting, the most uniformly successful, yet lived by any American, is bold. But it is, nevertheless, strictly true." Thus writes John Bach McMaster, in his life of the great statesman.

In the year 1706, January 6 (old style), in the small house of a tallow-chandler and soap-boiler, on Milk Street, opposite the Old South Church, Boston, was born Benjamin Franklin. Already fourteen children had come into the home of Josiah Franklin, the father, by his two wives, and now this youngest son was added to the struggling family circle. Two daughters were born later.

The home was a busy one, and a merry one withal; for the father, after the day's work, would sing to his large flock the songs he had learned in his boyhood in England, accompanying the words on his violin.

From the mother, the daughter of Peter Folger of Nantucket, "a learned and godly Englishman," Benjamin inherited an attractive face, and much of his hunger for books, which never lessened through his long and eventful life. At eight years of age,[39] he was placed in the Boston Latin School, and in less than a year rose to the head of his class. The father had hoped to educate the boy for the ministry, but probably money was lacking, for at ten his school-life was ended, and he was in his father's shop filling candle-moulds and running on errands.

For two years he worked there, but how he hated it! not all labor, for he was always industrious, but soap and candle-making were utterly distasteful to him. So strongly was he inclined to run away to sea, as an older brother had done, that his father obtained a situation for him with a maker of knives, and later he was apprenticed to his brother James as a printer.

Now every spare moment was used in reading. The first book which he owned was Bunyan's "Pilgrim's Progress," and after reading this over and over, he sold it, and bought Burton's "Historical Collections," forty tiny books of travel, history, biography, and adventure. In his father's small library, there was nothing very soul-stirring to be found. Defoe's "Essays upon Projects," containing hints on banking, friendly societies for the relief of members, colleges for girls, and asylums for idiots, would not be very interesting to most boys of twelve, but Benjamin read every essay, and, strange to say, carried out nearly every "project" in later life. Cotton Mather's "Essays to do Good," with several leaves torn out, was so eagerly read, and so productive of good, that Franklin wrote, when he was eighty, that this volume "gave[40] me such a turn of thinking as to have an influence on my conduct through life; for I have always set a greater value on the character of a doer of good than on any other kind of reputation; and, if I have been a useful citizen, the public owe the advantage of it to that book."

As the boy rarely had any money to buy books, he would often borrow from the booksellers' clerks, and read in his little bedroom nearly all night, being obliged to return the books before the shop was opened in the morning. Finally, a Boston merchant, who came to the printing-office, noticed the lad's thirst for knowledge, took him home to see his library, and loaned him some volumes. Blessings on those people who are willing to lend knowledge to help the world upward, despite the fact that book-borrowers proverbially have short memories, and do not always take the most tender care of what they borrow.

When Benjamin was fifteen, he wrote a few ballads, and his brother James sent him about the streets to sell them. This the father wisely checked by telling his son that poets usually are beggars, a statement not literally true, but sufficiently near the truth to produce a wholesome effect upon the young verse-maker.

The boy now devised a novel way to earn money to buy books. He had read somewhere that vegetable food was sufficient for health, and persuaded James, who paid the board of his apprentice, that for half the amount paid he could board himself.

[41]Benjamin therefore attempted living on potatoes, hasty pudding, and rice; doing his own cooking,—not the life most boys of sixteen would choose. His dinner at the printing-office usually consisted of a biscuit, a handful of raisins, and a glass of water; a meal quickly eaten, and then, O precious thought! there was nearly a whole hour for books.

He now read Locke on "Human Understanding," and Xenophon's "Memorable Things of Socrates." In this, as he said in later years, he learned one of the great secrets of success; "never using, when I advanced anything that may possibly be disputed, the words certainly, undoubtedly, or any others that give the air of positiveness to an opinion; but rather say, I conceive or apprehend a thing to be so and so; it appears to me, or I should think it so or so, for such and such reasons; or, it is so, if I am not mistaken.... I wish well-meaning, sensible men would not lessen their power of doing good by a positive, assuming manner, that seldom fails to disgust, tends to create opposition, and to defeat every one of those purposes for which speech was given to us, to wit, giving or receiving information or pleasure.... To this habit I think it principally owing that I had early so much weight with my fellow-citizens, when I proposed new institutions or alterations in the old, and so much influence in public councils when I became a member; for I was but a bad speaker, never eloquent, subject to much hesitation in my choice of words, and yet[42] I generally carried my points." A most valuable lesson to be learned early in life.

Coming across an odd volume of the "Spectator," Benjamin was captivated by the style, and resolved to become master of the production, by rewriting the essays from memory, and increasing his fulness of expression by turning them into verse, and then back again into prose.

James Franklin was now printing the fifth newspaper in America. It was intended to issue the first—Publick Occurrences—monthly, or oftener, "if any glut of occurrences happens." When the first number appeared, September 25, 1690, a very important "occurrence happened," which was the immediate suspension of the paper for expressions concerning those in official position. The next newspaper,—the Boston News-Letter,—a weekly, was published April 24, 1704; the third was the Boston Gazette, which James was engaged to print, but, being disappointed, started one of his own, August 17, 1721, called the New England Courant. The American Weekly Mercury was printed in Philadelphia six months before the Courant.

Benjamin's work was hard and constant. He not only set type, but distributed the paper to customers. "Why," thought he, "can I not write something for the new sheet?" Accordingly, he prepared a manuscript, slipped it under the door of the office, and the next week saw it in print before his eyes. This was joy indeed, and he wrote again and again.

[43]The Courant at last gave offence by its plain speaking, and it ostensibly passed into Benjamin's hands, to save his brother from punishment. The position, however, soon became irksome, for the passionate brother often beat Benjamin, till at last he determined to run away. As soon as this became known, James went to every office, told his side of the story, and thus prevented Benjamin from obtaining work. Not discouraged, the boy sold a portion of his precious books, said good-bye to his beloved Boston, and went out into the world to more poverty and struggle.

Three days after this, he stood in New York, asking for work at the only printing-office in the city, owned by William Bradford. Alas! there was no work to be had, and he was advised to go to Philadelphia, nearly one hundred miles away, where Andrew Bradford, a son of the former, had established a paper. The boy could not have been very light-hearted as he started on the journey. After thirty hours by boat, he reached Amboy, and then travelled fifty miles on foot across New Jersey. It rained hard all day, but he plodded on, tired and hungry, buying some gingerbread of a poor woman, and wishing that he had never left Boston. His money was fast disappearing.

Finally he reached Philadelphia.

"I was," he says in his autobiography, "in my working dress, my best clothes being to come round by sea. I was dirty from my journey; my pockets were stuffed out with shirts and stockings, and I[44] knew no soul nor where to look for lodging. I was fatigued with travelling, rowing, and want of rest. I was very hungry, and my whole stock of cash consisted of a Dutch dollar and about a shilling in copper. The latter I gave the people of the boat for my passage, who at first refused it, on account of my rowing, but I insisted on their taking it; a man being sometimes more generous when he has but a little money than when he has plenty, perhaps through fear of being thought to have but little.

"Then I walked up the street, gazing about, till near the Market-house I met a boy with bread. I had made many a meal on bread, and, inquiring where he got it, I went immediately to the baker's he directed me to, in Second Street, and asked for biscuit, intending such as we had in Boston; but they, it seems, were not made in Philadelphia. Then I asked for a threepenny loaf, and was told they had none such. So, not considering or knowing the difference of money, and the greater cheapness, nor the names of bread, I bade him give me threepenny-worth of any sort. He gave me, accordingly, three great puffy rolls. I was surprised at the quantity, but took it, and, having no room in my pockets, walked off with a roll under each arm, and eating the other.

"Thus I went up Market Street as far as Fourth Street, passing by the door of Mr. Read, my future wife's father; when she, standing at the door, saw me, and thought I made, as I certainly did, a most[45] awkward, ridiculous figure. Then I turned and went down Chestnut Street and part of Walnut Street, eating my roll all the way, and, coming round, found myself again at Market Street wharf, near the boat I came in, to which I went for a draught of the river water; and, being filled with one of my rolls, gave the other two to a woman and her child that came down the river in the boat with us, and were waiting to go farther."

After this, he joined some Quakers who were on their way to the meeting-house, which he too entered, and, tired and homeless, soon fell asleep. And this was the penniless, runaway lad who was eventually to stand before five kings, to become one of the greatest philosophers, scientists, and statesmen of his time, the admiration of Europe and the idol of America. Surely, truth is stranger than fiction.

The youth hastened to the office of Andrew Bradford, but there was no opening for him. However, Bradford kindly offered him a home till he could find work. This was obtained with Keimer, a printer, who happened to find lodging for the young man in the house of Mr. Read. As the months went by, and the hopeful and earnest lad of eighteen had visions of becoming a master printer, he confided to Mrs. Read that he was in love with, and wished to marry, the pretty daughter, who had first seen him as he walked up Market Street, eating his roll. Mr. Read had died, and the prudent mother advised that these children, both[46] under nineteen, should wait till the printer proved his ability to support a wife.

And now a strange thing happened. Sir William Keith, governor of the province, who knew young Franklin's brother-in-law, offered to establish him in the printing business in Philadelphia, and, better still, to send him to England with a letter of credit with which to buy the necessary outfit.

A mine of gold seemed to open before him. He made ready for the journey, and set sail, disappointed, however, that the letter of credit did not come before he left. When he reached England, he ascertained that Sir William Keith was without credit, a vain man and devoid of principle. Franklin found himself alone in a strange country, doubly unhappy because he had used for himself and some impecunious friends one hundred and seventy-five dollars, collected from a business man. This he paid years afterward, ever considering the use of it one of the serious mistakes of his life.

He and a boy companion found lodgings at eighty-seven cents per week; very inferior lodgings they must have been. There was of course no money to buy type, no money to take passage back to America. He wrote a letter to Miss Read, telling her that he was not likely to return, dropped the correspondence, and found work in a printing-office.

After a year or two, a merchant offered him a position as clerk in America, at five dollars a week. He accepted, and, after a three-months voyage,[47] reached Philadelphia, "the cords of love," he said, drawing him back. Alas! Deborah Read, persuaded by her mother and other relatives; had married, but was far from happy. The merchant for whom Franklin had engaged to work soon died, and the printer was again looking for a situation, which he found with Keimer. He was now twenty-one, and life had been anything but cheerful or encouraging.

Still, he determined to keep his mind cheerful and active, and so organized a club of eleven young men, the "Junto," composed mostly of mechanics. They came together once a month to discuss questions of morals, politics, and science. As most of these were unable to buy books—a book in those days often costing several dollars—Franklin conceived the idea of a subscription library, raised the funds, and became the librarian. Every day he set apart an hour or two for study, and for twenty years, in the midst of poverty and hard work, the habit was maintained. If Franklin himself did not know that such a young man would succeed, the world around him must have guessed it. Out of this collection of books—the mother of all the subscription libraries of this country—has grown a great library in the city of Philadelphia.

Keimer proved a business failure; but kindness to a fellow-workman, Meredith, a youth of intemperate habits, led Franklin to another open door. The father of Meredith, hoping to save his son, started the young men in business by loaning them[48] five hundred dollars. It was a modest beginning, in a building whose rent was but one hundred and twenty dollars a year. Their first job of printing brought them one dollar and twenty-five cents. As Meredith was seldom in a condition for labor, Franklin did most of the work, he having started a paper—the Pennsylvania Gazette. Some prophesied failure for the new firm, but one prominent man remarked: "The industry of that Franklin is superior to anything I ever saw of the kind. I see him still at work when I go home from the club, and he is at work again before his neighbors are out of bed."

But starting in business had cost five hundred more than the five hundred loaned them. The young men were sued for debt, and ruin stared them in the face. Was Franklin discouraged? If so at heart, he wisely kept a cheerful face and manner, knowing what poor policy it is to tell our troubles, and made all the friends he could. Several members of the Assembly, who came to have printing done, became fast friends of the intelligent and courteous printer.

In this pecuniary distress, two men offered to loan the necessary funds, and two hundred and fifty dollars were gratefully accepted from each. These two persons Franklin remembered to his dying day. Meredith was finally bought out by his own wish, and Franklin combined with his printing a small stationer's shop, with ink, paper, and a few books. Often he wheeled his paper on a barrow along the[49] streets. Who supposed then that he would some day be President of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania?

Franklin was twenty-four. Deborah Read's husband had proved worthless, had run away from his creditors, and was said to have died in the West Indies. She was lonely and desolate, and Franklin rightly felt that he could brighten her heart. They were married September 1, 1730, and for forty years they lived a happy life. He wrote, long afterward, "We are grown old together, and if she has any faults, I am so used to them that I don't perceive them." Beautiful testimony! He used to say to young married people, in later years, "Treat your wife always with respect; it will procure respect to you, not only from her, but from all that observe it."

The young wife attended the little shop, folded newspapers, and made Franklin's home a resting-place from toil. He says: "Our table was plain and simple, our furniture of the cheapest. My breakfast was, for a long time, bread and milk (no tea), and I ate it out of a twopenny earthen porringer, with a pewter spoon: but mark how luxury will enter families, and make a progress in spite of principle. Being called one morning to breakfast, I found it in a china bowl, with a spoon of silver. They had been bought for me without my knowledge by my wife, and had cost her the enormous sum of three and twenty shillings! for which she had no other excuse or apology to make, but that[50] she thought her husband deserved a silver spoon and china bowl as well as any of his neighbors."

The years went by swiftly, with their hard work and slow but sure accumulation of property. At twenty-seven, having read much and written considerable, he determined to bring out an almanac, after the fashion of the day, "for conveying instruction among the common people, who bought scarcely any other book." "Poor Richard" appeared in December, 1732; price, ten cents. It was full of wit and wisdom, gathered from every source. Three editions were sold in a month. The average annual sale for twenty-five years was ten thousand copies. Who can ever forget the maxims which have become a part of our every-day speech?—"Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise."—"He that hath a trade, hath an estate."—"One to-day is worth two to-morrows."—"Never leave that till to-morrow which you can do to-day."—"Employ thy time well if thou meanest to gain leisure; and since thou art not sure of a minute, throw not away an hour."—"Three removes are as bad as a fire."—"What maintains one vice would bring up two children."—"Many a little makes a mickle."—"Beware of little expenses; a small leak will sink a great ship."—"If you would know the value of money, go and try to borrow some; for he that goes a-borrowing goes a-sorrowing."—"Rather go to bed supperless than rise in debt."—"Experience keeps a dear school, but fools will learn in no other."

[51]An interesting story is told concerning the proverb, "If you would have your business done, go; if not, send." John Paul Jones, one of the bravest men in the Revolutionary War, had become the terror of Britain, by the great number of vessels he had captured. In one cruise he is said to have taken sixteen prizes; burned eight and sent home eight. With the Ranger, on the coast of Scotland, he captured the Drake, a large sloop-of-war, and two hundred prisoners. At one time, Captain Jones waited for many months for a vessel which had been promised him. Eager for action, he chanced to see "Poor Richard's Almanac," and read, "If you would have your business done, go; if not, send." He went at once to Paris, sought the ministers, and was given command of a vessel, which, in honor of Franklin, he called Bon Homme Richard.

The battle between this ship and the Serapis, when, for three hours and a half, they were lashed together by Jones' own hand, and fought one of the most terrific naval battles ever seen, is well known to all who read history. The Bon Homme Richard sunk after her victory, while her captain received a gold medal from Congress and an appreciative letter from General Washington.

So bravely did Captain Pearson, the opponent, fight, that the King of England made him a knight. "He deserved it," said Jones, "and, should I have the good-fortune to fall in with him again, I will make a lord of him."

[52]No wonder that Franklin's proverbs were copied all over the continent, and translated into French, German, Spanish, Italian, Russian, Bohemian, Greek, and Portuguese. In all these very busy years, Franklin did not forget to study. When he was twenty-seven, he began French, then Italian, then Spanish, and then to review the Latin of his boyhood. He learned also to play on the harp, guitar, violin, and violoncello.

Into the home of the printer had come two sons, William and Francis. The second was an uncommonly beautiful child, the idol of his father. Small-pox was raging in the city, but Franklin could not bear to put his precious one in the slightest peril by inoculation. The dread disease came into the home, and Francis Folger, named for his grandmother—at the age of four years—went suddenly out of it. "I long regretted him bitterly," Franklin wrote years afterwards to his sister Jane. "My grandson often brings afresh to my mind the idea of my son Franky, though now dead thirty-six years; whom I have seldom since seen equalled in every respect, and whom to this day I cannot think of without a sigh." On a little stone in Christ Church burying-ground, Philadelphia, are the boy's name and age, with the words, "The delight of all that knew him."

This same year, when Franklin was thirty, he was chosen clerk of the General Assembly, his first promotion. If, as Disraeli said, "the secret of success in life is for a man to be ready for his[53] opportunity when it comes," Franklin had prepared himself, by study, for his opportunity.

The year later, he was made deputy postmaster, and soon became especially helpful in city affairs. He obtained better watch or police regulations, organized the first fire-company, and invented the Franklin stove, which was used far and wide.

At thirty-seven, so interested was he in education that he set on foot a subscription for an academy, which resulted in the noble University of Pennsylvania, of which Franklin was a trustee for over forty years. The following year his only daughter, Sarah, was born, who helped to fill the vacant chair of the lovely boy. The father, Josiah, now died at eighty-seven, already proud of his son Benjamin, for whom in his poverty he had done the best he could.

About this time, the Leyden jar was discovered in Europe by Musschenbroeck, and became the talk of the scientific world. Franklin, always eager for knowledge, began to study electricity, with all the books at his command. Dr. Spence, a gentleman from Great Britain, having come to America to lecture on the subject, Franklin bought all his instruments. So much did he desire to give his entire time to this fascinating subject that he sold his printing-house, paper, and almanac, for ninety thousand dollars, and retired from business. This at forty-two; and at fifteen selling ballads about the streets! Industry, temperance, and economy had paid good wages. He used to say[54] that these virtues, with "sincerity and justice," had won for him "the confidence of his country." And yet Franklin, with all his saving, was generous. The great preacher Whitefield came to Philadelphia to obtain money for an orphan-house in Georgia. Franklin thought the scheme unwise, and silently resolved not to give when the collection should be taken. Then, as his heart warmed under the preaching, he concluded to give the copper coins in his pocket; then all the silver, several dollars; and finally all his five gold pistoles, so that he emptied his pocket into the collector's plate.

Franklin now constructed electrical batteries, introduced the terms "positive" and "negative" electricity, and published articles on the subject, which his friend in London, Peter Collinson, laid before the Royal Society. When he declared his belief that lightning and electricity were identical, and gave his reasons, and that points would draw off electricity, and therefore lightning-rods be of benefit, learned people ridiculed the ideas. Still, his pamphlets were eagerly read, and Count de Buffon had them translated into French. They soon appeared in German, Latin, and Italian. Louis XV. was so deeply interested that he ordered all Franklin's experiments to be performed in his presence, and caused a letter to be written to the Royal Society of London, expressing his admiration of Franklin's learning and skill. Strange indeed that such a scientist should arise[55] in the new world, be a man self-taught, and one so busy in public life.

In 1752, when he was forty-six, he determined to test for himself whether lightning and electricity were one. He made a kite from a large silk handkerchief, attached a hempen cord to it, with a silk string in his hand, and, with his son, hastened to an old shed in the fields, as the thunder-storm approached.

As the kite flew upward, and a cloud passed over, there was no manifestation of electricity. When he was almost despairing, lo! the fibres of the cord began to loosen; then he applied his knuckle to a key on the cord, and a strong spark passed. How his heart must have throbbed as he realized his immortal discovery!