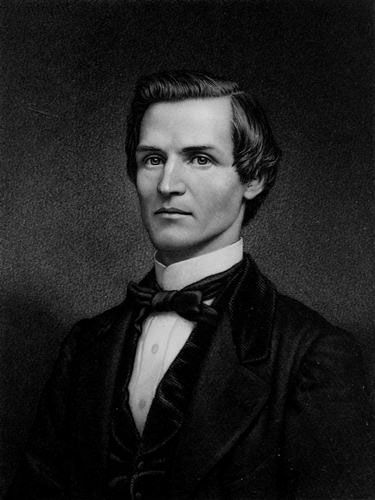

Engraved by Samuel Sartain, Phila.

Title: The Iron Furnace; or, Slavery and Secession

Author: John H. Aughey

Release date: February 13, 2012 [eBook #38855]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive.)

THE IRON FURNACE:

OR,

SLAVERY AND SECESSION.

BY

REV. JOHN H. AUGHEY,

A REFUGEE FROM MISSISSIPPI.

| Cursed be the men that obeyeth not the words of this covenant, which I commanded your fathers in the day that I brought them forth out of the land of Egypt, from the Iron Furnace.—Jer. xi. 3, 4. See also, 1 Kings viii. 51. |

PHILADELPHIA:

WILLIAM S. & ALFRED MARTIEN.

606 CHESTNUT STREET.

1863.

Entered, according to the Act of Congress, in the year 1863,

By WILLIAM S. & ALFRED MARTIEN,

In the office of the Clerk of the District Court for the

Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

TO MY PERSONAL FRIENDS

REV. CHARLES C. BEATTY, D.D., LL.D.,

OF STEUBENVILLE, OHIO,

Moderator of the General Assembly of the (O.S.) Presbyterian

Church in the United States of America,

and long Pastor of the Church in which

my parents were members, and

our family worshippers;

REV. WILLIAM PRATT BREED,

Pastor of the West Spruce Street Presbyterian Church, of

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania;

GEORGE HAY STUART, Esq.,

OF PHILADELPHIA, PA.,

The Philanthropist, whose virtues are known and

appreciated in both hemispheres,

THIS VOLUME IS AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED.

A celebrated author thus writes: “Posterity is under no obligations to a man who is not a parent, who has never planted a tree, built a house, nor written a book.” Having fulfilled all these requisites to insure the remembrance of posterity, it remains to be seen whether the author’s name shall escape oblivion.

It may be that a few years will obliterate the name affixed to this Preface from the memory of man. This thought is the cause of no concern. I shall have accomplished my purpose if I can in some degree be humbly instrumental in serving my country and my generation, by promoting the well-being of my fellow-men, and advancing the declarative glory of Almighty God.

This work was written while suffering intensely from maladies induced by the rigours of the Iron Furnace of Secession, whose sevenfold heat is reserved for the loyal citizens of[Pg 6] the South. Let this fact be a palliation for whatever imperfections the reader may meet with in its perusal.

There are many loyal men in the southern States, who to avoid martyrdom, conceal their opinions. They are to be pitied—not severely censured. All those southern ministers and professors of religion who were eminent for piety, opposed secession till the States passed the secession ordinance. They then advocated reconstruction as long as it comported with their safety. They then, in the face of danger and death, became quiescent—not acquiescent, by any means—and they now “bide their time,” in prayerful trust that God will, in his own good time, subvert rebellion, and overthrow anarchy, by a restoration of the supremacy of constitutional law. By these, and their name is legion, my book will be warmly approved. My fellow-prisoners in the dungeon at Tupelo, who may have survived its horrors, and my fellow-sufferers in the Union cause throughout the South, will read in my narrative a transcript of their own sufferings. The loyal citizens of the whole country will be interested in learning the views of one who has been conversant with the rise and progress of secession, from its incipiency to its culmination in rebellion[Pg 7] and treason. It will also doubtless be of general interest to learn something of the workings of the “peculiar institution,” and the various phases which it assumes in different sections of the slave States.

Compelled to leave Dixie in haste, I had no time to collect materials for my work. I was therefore under the necessity of writing without those aids which would have secured greater accuracy. I have done the best that I could under the circumstances; and any errors that may have crept into my statements of facts, or reports of addresses, will be cheerfully rectified as soon as ascertained.

That I might not compromise the safety of my Union friends who rendered me assistance, and who are still within the rebel lines, I was compelled to omit their names, and for the same reason to describe rather indefinitely some localities, especially the portions of Ittawamba, Chickasaw, Pontotoc, Tippah, and Tishomingo counties, through which I travelled while escaping to the Federal lines. This I hope to be able to correct in future editions.

Narratives require a liberal use of the first personal pronoun, which I would have gladly avoided, had it been possible without tedious[Pg 8] circumlocution, as its frequent repetition has the appearance of egotism.

I return sincere thanks to my fellow-prisoners who imperilled their own lives to save mine, and also to those Mississippi Unionists who so generously aided a panting fugitive on his way from chains and death to life and liberty. My thanks are also due to Rev. William P. Breed, for assistance in preparing my work for the press.

I am also under obligations to Rev. Francis J. Collier, of Philadelphia; to Rev. A. D. Smith, D. D., and Rev. J. R. W. Sloane, of New York, and to Rev. F. B. Wheeler, of Poughkeepsie, New York.

May the Triune God bless our country, and preserve its integrity!

JOHN HILL AUGHEY.

February 1, 1863.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| SECESSION. | |

| Speech of Colonel Drane—Submission Denounced—Northern Aggression—No more Slave States—Northern isms—Yankees’ Servants—Yankee inferiority—Breckinridge, or immediate, complete, and eternal Separation—A Day of Rejoicing—Abraham Lincoln, President elect—A Union Speech—A Southerner’s Reasons for opposing Secession—Address by a Radical Secessionist—Cursing and Bitterness—A Prayer—Sermon against Secession—List of Grievances—Causes which led to Secession | 13—49 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| VIGILANCE COMMITTEE AND COURT-MARTIAL. | |

| The election of Delegates to determine the status of Mississippi—The Vigilance Committee—Description of its members—Charges—Phonography—No formal verdict—Danger of Assassination—Passports—Escape to Rienzi—Union sentiment—The Conscript Law—Summons to attend Court-Martial—Evacuation of Corinth—Destruction of Cotton—Suffering poor—Relieved by General Halleck | 50—69 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| ARREST, ESCAPE, AND RECAPTURE. | |

| High price of Provisions—Holland Lindsay’s Family—The arrest—Captain Hill—Appearance before Colonel Bradfute at Fulton—Arrest of Benjamin Clarke—Bradfute’s [Pg 10]Insolence—General Chalmers—The clerical Spy—General Pfeifer—Under guard—Priceville—General Gordon—Bound for Tupelo—The Prisoners entering the Dungeon—Captain Bruce—Lieutenant Richard Malone—Prison Fare and Treatment—Menial Service—Resolve to escape—Plan of escape—Federal Prisoners—Co-operation of the Prisoners—Declaration of Independence—The Escape—The Separation—Concealment—Travel on the Underground Railroad—Pursuit by Cavalry and Bloodhounds—The Arrest—Dan Barnes, the Mail-robber—Perfidy—Heavily ironed—Return to Tupelo | 70—112 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| LIFE IN A DUNGEON. | |

| Parson Aughey as Chaplain—Description of the Prisoners—Colonel Walter, the Judge Advocate—Charges and Specifications against Parson Aughey, a Citizen of the Confederate States—Execution of two Tennesseeans—Enlistment of Union Prisoners—Colonel Walter’s second visit—Day of Execution specified—Farewell Letter to my Wife—Parson Aughey’s Obituary penned by himself—Address to his Soul—The Soul’s Reply—Farewell Letter to his Parents—The Union Prisoners’ Petition to Hon. W. H. Seward—The two Prisoners and the Oath of Allegiance—Irish Stories | 113—142 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| EXECUTION OF UNION PRISONERS. | |

| Resolved to Escape—Mode of Executing Prisoners—Removal of Chain—Addition to our Numbers—Two Prisoners become Insane—Plan of Escape—Proves a Failure—Fetters Inspected—Additional Fetters—Handcuffs—A Spy in the Disguise of a Prisoner—Special Police Guard on Duty—A Prisoner’s Discovery—Divine Services—The General Judgment—The Judge—The Laws—The Witnesses—The [Pg 11]Concourse—The Sentence | 143—167 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| SUCCESSFUL ESCAPE. | |

| The Second Plan of Escape—Under the Jail—Egress—Among the Guards—In the Swamp—Travelling on the Underground Railroad—The Fare—Green Corn eaten Raw—Blackberries and Stagnant Water—The Bloodhounds—Tantalizing Dreams—The Pickets—The Cows—Become Sick—Fons Beatus—Find Friends—Union Friend No. Two—The night in the Barn—Death of Newman by Scalding—Union Friend No. Three—Bound for the Union Lines—Rebel Soldiers—Black Ox—Pied Ox—Reach Headquarters in Safety—Emotions on again beholding the Old Flag—Kindness while Sick—Meeting with his Family—Richard Malone again—The Serenade—Leave Dixie—Northward bound | 168—211 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| SOUTHERN CLASSES—CRUELTY TO SLAVES. | |

| Sandhillers—Dirt-eating—Dipping—Their Mode of Living—Patois—Rain-book—Wife-trade—Coming in to see the Cars—Superstition—Marriage of Kinsfolks—Hardshell Sermon—Causes which lead to the Degradation of this Class—Efforts to Reconcile the Poor Whites to the Peculiar Institution—The Slaveholding Class—The Middle Class—Northern isms—Incident at a Methodist Minister’s House—Question asked a Candidate for Licensure—Reason of Southern Hatred toward the North—Letter to Mr. Jackman—Barbarities and Cruelties of Slavery—Mulattoes—Old Cole—Child Born at Whipping-post—Advertisement of a Keeper of Bloodhounds—Getting Rid of Free Blacks—The Doom of Slavery—Methodist Church South | 212—248 |

| [Pg 12] | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| NOTORIOUS REBELS.—UNION OFFICERS. | |

| Colonel Jefferson Davis—His Speech at Holly Springs, Mississippi—His Opposition to Yankee Teachers and Ministers—A bid for the Presidency—His Ambition—Burr, Arnold, Davis—General Beauregard—Headquarters at Rienzi—Colonel Elliott’s Raid—Beauregard’s Consternation—Personal description—His illness—Popularity waning.—Rev. Dr. Palmer of New Orleans—His influence—The Cincinnati Letter—His Personal Appearance—His Denunciations of General Butler—His Radicalism.—Rev. Dr. Waddell of La Grange, Tennessee—His Prejudices against the North—President of Memphis Synodical College—His Talents prostituted.—Union Officers—General Nelson—General Sherman | 249—263 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| CONDITION OF THE SOUTH. | |

| Cause of the Rebellion—Prevalence of Union Sentiment in the South—Why not Developed—Stevenson’s Views—Why Incorrect—Cavalry Raids upon Union Citizens—How the Rebels employ Slaves—Slaves Whipped and sent out of the Federal Lines—Resisting the Conscript Law—Kansas Jayhawkers—Guarding Rebel Property—Perfidy of Secessionists—Plea for Emancipation—The South Exhausted—Failure of Crops—Southern Merchants Ruined—Bragg Prohibits the Manufacture and Vending of Intoxicating Liquors—Its Salutary Effect | 264—281 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| BATTLES OF LEESBURG, BELMONT, AND SHILOH. | |

| Rebel Cruelty to Prisoners—The Fratricide—Grant Defeated—Saved by Gunboats—Buell’s Advance—Railroad Disaster—The South Despondent—General Rosecrans—Secession will become Odious even in the South—Poem | 282—296 |

THE IRON FURNACE;

OR

SLAVERY AND SECESSION.

SECESSION.

Speech of Colonel Drane.—Submission Denounced.—Northern Aggression.—No more Slave States.—Northern isms.—Yankees’ Servants.—Yankee inferiority.—Breckinridge, or immediate, complete, and eternal Separation.—A Day of Rejoicing.—Abraham Lincoln President elect.—A Union Speech.—A Southerner’s Reasons for opposing Secession.—Address by a Radical Secessionist.—Cursing and Bitterness.—A Prayer.—Sermon against Secession.—List of Grievances.—Causes which led to Secession.

At the breaking out of the present rebellion, I was engaged in the work of an Evangelist in the counties of Choctaw and Attala in Central Mississippi. My congregations were large, and my duties onerous. Being constantly employed in ministerial labours, I had no time to intermeddle with politics, leaving all such questions[Pg 14] to statesmen, giving the complex issues of the day only sufficient attention to enable me to vote intelligently. Thus was I engaged when the great political campaign of 1860 commenced—a campaign conducted with greater virulence and asperity than any I have ever witnessed. During my casual detention at a store, Colonel Drane arrived, according to appointment, to address the people of Choctaw. He was a member of one of my congregations, and as he had been long a leading statesman in Mississippi, having for many years presided over the State Senate, I expected to hear a speech of marked ability, unfolding the true issues before the people, with all the dignity, suavity, and earnestness of a gentleman and patriot; but I found his whole speech to be a tirade of abuse against the North, commingled with the bold avowal of treasonable sentiments. The Colonel thus addressed the people:

My Fellow-Citizens—I appear before you to urge anew resistance against the encroachments and aggressions of the Yankees. If the[Pg 15] Black Republicans carry their ticket, and Old Abe is elected, our right to carry our slaves into the territories will be denied us; and who dare say that he would be a base, craven submissionist, when our God-given and constitutional right to carry slavery into the common domain is wickedly taken from the South. The Yankees cheated us out of Kansas by their infernal Emigrant Aid Societies. They cheated us out of California, which our blood-treasure purchased, for the South sent ten men to one that was sent by the North to the Mexican war, and thus we have no foothold on the Pacific coast; and even now we pay five dollars for the support of the general Government where the North pays one. We help to pay bounties to the Yankee fishermen in New England; indeed we are always paying, paying, paying, and yet the North is always crying, Give, give, give. The South has made the North rich, and what thanks do we receive? Our rights are trampled on, our slaves are spirited by thousands over their underground railroad to Canada, our citizens are insulted while travelling in the[Pg 16] North, and their servants are tampered with, and by false representations, and often by mob violence, forced from them. Douglas, knowing the power of the Emigrant Aid Societies, proposes squatter sovereignty, with the positive certainty that the scum of Europe and the mudsills of Yankeedom can be shipped in in numbers sufficient to control the destiny of the embryo State. Since the admission of Texas in 1845, there has not been a single foot of slave territory secured to the South, while the North has added to their list the extensive States of California, Minnesota, and Oregon, and Kansas is as good as theirs; while, if Lincoln is elected, the Wilmot proviso will be extended over all the common territories, debarring the South for ever from her right to share the public domain.

The hypocrites of the North tell us that slaveholding is sinful. Well, suppose it is. Upon us and our children let the guilt of this sin rest; we are willing to bear it, and it is none of their business. We are a more moral people than they are. Who originated [Pg 17]Mormonism, Millerism, Spirit-rappings, Abolitionism, Free-loveism, and all the other abominable isms which curse the world? The reply is, the North. Their puritanical fanaticism and hypocrisy is patent to all. Talk to us of the sin of slavery, when the only difference between us is that our slaves are black and theirs white. They treat their white slaves, the Irish and Dutch, in a cruel manner, giving them during health just enough to purchase coarse clothing, and when they become sick, they are turned off to starve, as they do by hundreds every year. A female servant in the North must have a testimonial of good character before she will be employed; those with whom she is labouring will not give her this so long as they desire her services; she therefore cannot leave them, whatever may be her treatment, so that she is as much compelled to remain with her employer as the slave with his master.

Their servants hate them; our’s love us. My niggers would fight for me and my family. They have been treated well, and they know it. [Pg 18]And I don’t treat my slaves any better than my neighbours. If ever there comes a war between the North and the South, let us do as Abraham did—arm our trained servants, and go forth with them to the battle. They hate the Yankees as intensely as we do, and nothing could please our slaves better than to fight them. Ah, the perfidious Yankees! I cordially hate a Yankee. We have all suffered much at their hands; they will not keep faith with us. Have they complied with the provisions of the Fugitive Slave Law? The thousands and tens of thousands of slaves aided in their escape to Canada, is a sufficient answer. We have lost millions, and are losing millions every year, by the operations of the underground railroad. How deep the perfidy of a people, thus to violate every article of compromise we have made with them! The Yankees are an inferior race, descended from the old Puritan stock, who enacted the Blue Laws. They are desirous of compelling us to submit to laws more iniquitous than ever were the Blue Laws. I have travelled in the North, and have seen the depth [Pg 19]of their depravity. Now, my fellow-citizens, what shall we do to resist Northern aggression? Why simply this: if Lincoln or Douglas are elected, (as to the Bell-Everett ticket, it stands no sort of chance,) let us secede. This remedy will be effectual. I am in favour of no more compromises. Let us have Breckinridge, or immediate, complete, and eternal separation.

The speaker then retired amid the cheers of his audience.

Soon after this there came a day of rejoicing to many in Mississippi. The booming of cannon, the joyous greeting, the soul-stirring music, indicated that no ordinary intelligence had been received. The lightnings had brought the tidings that Abraham Lincoln was President elect of the United States, and the South was wild with excitement. Those who had been long desirous of a pretext for secession, now boldly advocated their sentiments, and joyfully hailed the election of Mr. Lincoln as affording that pretext. The conservative men were filled with gloom. They regarded the[Pg 20] election of Mr. Lincoln, by the majority of the people of the United States, in a constitutional way, as affording no cause for secession. Secession they regarded as fraught with all the evils of Pandora’s box, and that war, famine, pestilence, and moral and physical desolation would follow in its train. A call was made by Governor Pettus for a convention to assemble early in January, at Jackson, to determine what course Mississippi should pursue, whether her policy should be submission or secession.

Candidates, Union and Secession, were nominated for the convention in every county. The speeches of two, whom I heard, will serve as a specimen of the arguments used pro and con. Captain Love, of Choctaw, thus addressed the people.

My Fellow-Citizens—I appear before you to advocate the Union—the Union of the States under whose favoring auspices we have long prospered. No nation so great, so prosperous, so happy, or so much respected by earth’s thousand kingdoms, as the Great Republic, by [Pg 21]which name the United States is known from the rivers to the ends of the earth. Our flag, the star-spangled banner, is respected on every sea, and affords protection to the citizens of every State, whether amid the pyramids of Egypt, the jungles of Asia, or the mighty cities of Europe. Our Republican Constitution, framed by the wisdom of our Revolutionary fathers, is as free from imperfection as any document drawn up by uninspired men. God presided over the councils of that convention which framed our glorious Constitution. They asked wisdom from on high, and their prayers were answered. Free speech, a free press, and freedom to worship God as our conscience dictates, under our own vine and fig-tree, none daring to molest or make us afraid, are some of the blessings which our Constitution guarantees; and these prerogatives, which we enjoy, are features which bless and distinguish us from the other nations of the earth. Freedom of speech is unknown amongst them; among them a censorship of the press and a national church are established.

[Pg 22]Our country, by its physical features, seems fitted for but one nation. What ceaseless trouble would be caused by having the source of our rivers in one country and the mouth in another. There are no natural boundaries to divide us into separate nations. We are all descended from the same common parentage, we all speak the same language, and we have really no conflicting interests, the statements of our opponents to the contrary notwithstanding. Our opponents advocate separate State secession. Would not Mississippi cut a sorry figure among the nations of the earth? With no harbour, she would be dependent on a foreign nation for an outlet. Custom-house duties would be ruinous, and the republic of Mississippi would find herself compelled to return to the Union. Mississippi, you remember, repudiated a large foreign debt some years ago; if she became an independent nation, her creditors would influence their government to demand payment, which could not be refused by the weak, defenceless, navyless, armyless, moneyless, repudiating republic of Mississippi.[Pg 23] To pay this debt, with the accumulated interest, would ruin the new republic, and bankruptcy would stare us in the face.

It is true, Abraham Lincoln is elected President of the United States. My plan is to wait till Mr. Lincoln does something unconstitutional. Then let the South unanimously seek redress in a constitutional manner. The conservatives of the North will join us. If no redress is made, let us present our ultimatum. If this, too, is rejected, I for one will not advocate submission; and by the coöperation of all the slave States, we will, in the event of the perpetration of wrong, and a refusal to redress our grievances, be much abler to secure our rights, or to defend them at the cannon’s mouth and the point of the bayonet. The Supreme Court favours the South. In the Dred Scott case, the Supreme Court decided that the negro was not a citizen, and that the slave was a chattel, as we regard him. The majority of Congress on joint ballot is still with the South. Although we have something to[Pg 24] fear from the views of the President elect and the Chicago platform, let us wait till some overt act, trespassing upon our rights, is committed, and all redress denied; then, and not till then, will I advocate extreme measures.

Let our opponents remember that secession and civil war are synonymous. Who ever heard of a government breaking to pieces without an arduous struggle for its preservation? I admit the right of revolution, when a people’s rights cannot otherwise be maintained, but deny the right of secession. We are told that it is a reserved right. The constitution declares that all rights not specified in it are reserved to the people of the respective States; but who ever heard of the right of total destruction of the government being a reserved right in any constitution? The fallacy is evident at a glance. Nine millions of people can afford to wait for some overt act. Let us not follow the precipitate course which the ultra politicians indicate. Let W. L. Yancey urge his treasonable policy of firing the Southern heart and precipitating a[Pg 25] revolution; but let us follow no such wicked advice. Let us follow the things which make for peace.

We are often told that the North will not return fugitive slaves. Will secession remedy this grievance? Will secession give us any more slave territory? No free government ever makes a treaty for the rendition of fugitive slaves—thus recognising the rights of the citizens of a foreign nation to a species of property which it denies to its own citizens. Even little Mexico will not do it. Mexico and Canada return no fugitives. In the event of secession, the United States would return no fugitives, and our peculiar institution would, along our vast border, become very insecure; we would hold our slaves by a very slight tenure. Instead of extending the great Southern institution, it would be contracting daily. Our slaves would be held to service at their own option, throughout the whole border, and our gulf States would soon become border States; and the great insecurity of this species of property would work, before twenty years,[Pg 26] the extinction of slavery, and, in consequence, the ruin of the South. Are we prepared for such a result? Are we prepared for civil war? Are we prepared for all the evils attendant upon a fratricidal contest—for bloodshed, famine, and political and moral desolation? I reply, we are not; therefore let us look before we leap, and avoiding the heresy of secession—

“Rather bear the ills we have,

Than fly to others that we know not of.”

A secession speaker was introduced, and thus addressed the people:

Ladies and Gentlemen—Fellow-Citizens—I am a secessionist out and out; voted for Jeff Davis for Governor in 1850, when the same issue was before the people; and I have always felt a grudge against the free state of Tishomingo for giving H. S. Foote, the Union candidate, a majority so great as to elect him, and thus retain the State in this accursed Union ten years longer. Who would be a craven-hearted, cowardly, villanous [Pg 27]submissionist? Lincoln, the abominable, white-livered abolitionist, is President elect of the United States; shall he be permitted to take his seat on Southern soil? No, never! I will volunteer as one of thirty thousand, to butcher the villain if ever he sets foot on slave territory. Secession or submission! What patriot would hesitate for a moment which to choose? No true son of Mississippi would brook the idea of submission to the rule of the baboon Abe Lincoln—a fifth-rate lawyer, a broken-down hack of a politician, a fanatic, an abolitionist. I, for one, would prefer an hour of virtuous liberty to a whole eternity of bondage under northern, Yankee, wooden-nutmeg rule. The halter is the only argument that should be used against the submissionists, and I predict that it will soon, very soon, be in force.

We have glorious news from Tallahatchie. Seven tory-submissionists were hanged there in one day, and the so-called Union candidates, having the wholesome dread of hemp before their eyes, are not canvassing the county; therefore the heretical dogma of submission,[Pg 28] under any circumstances, disgraces not their county. Compromise! let us have no such word in our vocabulary. Compromise with the Yankees, after the election of Lincoln, is treason against the South; and still its syren voice is listened to by the demagogue submissionists. We should never have made any compromise, for in every case we surrendered rights for the sake of peace. No concession of the scared Yankees will now prevent secession. They now understand that the South is in earnest, and in their alarm they are proposing to yield us much; but the die is cast, the Rubicon is crossed, and our determination shall ever be, No union with the flat-headed, nigger-stealing, fanatical Yankees.

We are now threatened with internecine war. The Yankees are an inferior race; they are cowardly in the extreme. They are descended from the Puritan stock, who never bore rule in any nation. We, the descendants of the Cavaliers, are the Patricians, they the Plebeians. The Cavaliers have always been the rulers, the Puritans the ruled. The dastardly[Pg 29] Yankees will never fight us; but if they, in their presumption and audacity, venture to attack us, let the war come—I repeat it—let it come! The conflagration of their burning cities, the desolation of their country, and the slaughter of their inhabitants, will strike the nations of the earth dumb with astonishment, and serve as a warning to future ages, that the slaveholding Cavaliers of the sunny South are terrible in their vengeance. I am in favour of immediate, independent, and eternal separation from the vile Union which has so long oppressed us. After separation, I am in favour of non-intercourse with the United States so long as time endures. We will raise the tariff, to the point of prohibition, on all Yankee manufactures, including wooden-nutmegs, wooden clocks, quack nostrums, &c. We will drive back to their own inhospitable clime every Yankee who dares to pollute our shores with his cloven feet. Go he must, and if necessary, with the bloodhounds on his track. The scum of Europe and the mudsills of Yankeedom shall never be permitted to advance a step[Pg 30] south of 36° 30′. South of that latitude is ours—westward to the Pacific. With my heart of hearts I hate a Yankee, and I will make my children swear eternal hatred to the whole Yankee race. A mongrel breed—Irish, Dutch, Puritans, Jews, free niggers, &c.—they scarce deserve the notice of the descendants of the Huguenots, the old Castilians, and the Cavaliers. Cursed be the day when the South consented to this iniquitous league—the Federal Union—which has long dimmed her nascent glory.

In battle, one southron is equivalent to ten northern hirelings; but I regard it a waste of time to speak of Yankees—they deserve not our attention. It matters not to us what they think of secession, and we would not trespass upon your time and patience, were it not for the tame, tory submissionists with which our country is cursed. A fearful retribution is in waiting for the whole crew, if the war which they predict, should come. Were they then to advocate the same views, I would not give a fourpence for their lives. We would[Pg 31] hang them quicker than old Heath would hang a tory. Our Revolutionary fathers set us a good example in their dealings with the tories. They sent them to the shades infernal from the branches of the nearest tree. The North has sent teachers and preachers amongst us, who have insidiously infused the leaven of Abolitionism into the minds of their students and parishioners; and this submissionist policy is a lower development of the doctrine of Wendell Philips, Gerritt Smith, Horace Greely, and others of that ilk. We have a genial clime, a soil of uncommon fertility. We have free institutions, freedom for the white man, bondage for the black man, as nature and nature’s God designed. We have fair women and brave men. The lines have truly fallen to us in pleasant places. We have indeed a goodly heritage. The only evil we can complain of is our bondage to the Yankees through the Federal Union. Let us burst these shackles from our limbs, and we will be free indeed.

Let all who desire complete and eternal emancipation from Yankee thraldom, come to[Pg 32] the polls on the —— day of December, prepared not to vote the cowardly submissionist ticket, but to vote the secession ticket; and their children, and their children’s children, will owe them a debt of gratitude which they can never repay. The day of our separation and vindication of States’ rights, will be the happiest day of our lives. Yankee domination will have ceased for ever, and the haughty southron will spurn them from all association, both governmental and social. So mote it be!

This address was received with great eclat.

On the next Sabbath after this meeting, I preached in the Poplar Creek Presbyterian church, in Choctaw county, from Romans xiii. 1: “Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers. For there is no power but of God: the powers that be, are ordained of God.”

Previous to the sermon a prayer was offered, of which the following is the conclusion:

Almighty God—We would present our country, the United States of America, before[Pg 33] thee. When our political horizon is overcast with clouds and darkness, when the strong-hearted are becoming fearful for the permanence of our free institutions, and the prosperity, yea, the very existence of our great Republic, we pray thee, O God, when flesh and heart fail, when no human arm is able to save us from the fearful vortex of disunion and revolution, that thou wouldst interpose and save us. We confess our national sins, for we have, as a nation, sinned grievously. We have been highly favoured, we have been greatly prospered, and have taken our place amongst the leading powers of the earth. A gospel-enlightened nation, our sins are therefore more heinous in thy sight. They are sins of deep ingratitude and presumption. We confess that drunkenness has abounded amongst all classes of our citizens. Rulers and ruled have been alike guilty; and because of its wide-spreading prevalence, and because our legislators have enacted no sufficient laws for its suppression, it is a national sin. Profanity abounds amongst us; Sabbath-breaking is rife; and we have [Pg 34]elevated unworthy men to high positions of honour and trust. We are not, as a people, free from the crime of tyranny and oppression. For these great and aggravated offences, we pray thee to give us repentance and godly sorrow, and then, O God, avert the threatened and imminent judgments which impend over our beloved country. Teach our Senators wisdom. Grant them that wisdom which is able to make them wise unto salvation; and grant also that wisdom which is profitable to direct, so that they may steer the ship of State safely through the troubled waters which seem ready to engulf it on every side. Lord, hear us, and answer in mercy, for the sake of Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen and Amen!

The following is a synopsis of my sermon:

Israel had been greatly favoured as a nation. No weapon formed against them prospered, so long as they loved and served the Lord their God. They were blessed in their basket and their store. They were set on high above all the nations of the earth. * * * * [Pg 35]When all Israel assembled, ostensibly to make Rehoboam king, they were ripe for rebellion. Jeroboam and other wicked men had fomented and cherished the sparks of treason, till, on this occasion, it broke out into the flame of open rebellion. The severity of Solomon’s rule was the pretext, but it was only a pretext, for during his reign the nation prospered, grew rich and powerful. Jeroboam wished a disruption of the kingdom, that he might bear rule; and although God permitted it as a punishment for Israel’s idolatry, yet he frowned upon the wicked men who were instrumental in bringing this great evil upon his chosen people.

The loyal division took the name of Judah, though composed of the two tribes, Judah and Benjamin. The revolted ten tribes took the name of their leading tribe, Ephraim. Ephraim continued to wax weaker and weaker. Filled with envy against Judah, they often warred against that loyal kingdom, until they themselves were greatly reduced. At last, after various vicissitudes, the ten tribes were carried away, and scattered and lost. We often hear[Pg 36] of the lost ten tribes. What became of them is a mystery. Their secession ended in their being blotted out of existence, or lost amidst the heathen. God alone knows what did become of them. They resisted the powers that be—the ordinance of God—and received to themselves damnation and annihilation.

As God dealt with Israel, so will he deal with us. If we are exalted by righteousness, we will prosper; if we, as the ten tribes, resist the ordinance of God, we will perish. At this time, many are advocating the course of the ten tribes. Secession is a word of frequent occurrence. It is openly advocated by many. Nullification and rebellion, secession and treason, are convertible terms, and no good citizen will mention them with approval. Secession is resisting the powers that be, and therefore it is a violation of God’s command. Where do we obtain the right of secession? Clearly not from the word of God, which enjoins obedience to all that are in authority, to whom we must be subject, not only for wrath, but also for conscience’ sake. The following scriptural [Pg 37]argument for secession is often used, 1 Tim. vi. 1—5. In these verses Paul was addressing believing servants, and commanding them to absent themselves from the teaching of those who taught not the doctrine which is according to godliness. In a former epistle he had commanded Christians not to keep company with the incestuous person who had his father’s wife. He directed that they should not keep company with any man who was called a brother, if he were a fornicator, or covetous, or an idolator, or a railer, or a drunkard, or an extortioner; with such a one no not to eat; but he expressly declares that he does not allude to those who belong to the above classes that have made no profession of religion. He does not judge them that are without, for them that are without, God judgeth. He afterwards exhorts that the church confirm their love toward the incestuous person as he had repented of his wickedness. This direction of the Apostle to believers to withdraw from a brother who walked disorderly, till he had manifested proper repentance; and his exhortation[Pg 38] to believing servants to absent themselves from the teachings of errorists, cannot logically be construed as a scriptural argument in favour of secession. Were the President of the United States an unbeliever, a profane swearer, a Sabbath-breaker, or a drunkard, this fact would not, per se, give us the right to secede or rebel against the government.

There is no provision made in the Constitution of the United States for secession. The wisest statesmen, who made politics their study, regarded secession as a political heresy, dangerous in its tendencies, and destructive of all government in its practical application. Mississippi, purchased from France with United States gold, fostered by the nurturing care, and made prosperous by the wise administration of the general government, proposes to secede. Her political status would then be anomalous. Would her territory revert to France? Does she propose to refund the purchase-money? Would she become a territory under the jurisdiction of the United States Congress?

Henry Clay, the great statesman, Daniel [Pg 39]Webster, the expounder of the Constitution, General Jackson, George Washington, and a mighty host, whose names would fill a volume, regarded secession as treason. One of our smallest States, which swarmed with tories in the Revolution, whose descendants still live, invented the doctrine of nullification, the first treasonable step, which soon culminated in the advocacy of secession. Why should we secede, and thus destroy the best, the freest, and most prosperous government on the face of the earth? the government which our patriot fathers fought and bled to secure. What has Mississippi lost by the Union? I have resided seven years in this State, and have an extensive personal acquaintance, and yet I know not a single individual who has lost a slave through northern influence. I have, it is true, known of some ten slaves who have run away, and have not been found. They may have been aided in their escape to Canada by northern and southern citizens, for there are many in the South who have given aid and comfort to the fugitive; but the probability is that they[Pg 40] perished in the swamps, or were destroyed by the bloodhounds.

The complaint is made that the North regards slavery as a moral, social, and political evil, and that many of them denounce, in no measured terms, both slavery and slaveholders. To be thus denounced is regarded as a great grievance. Secession would not remedy this evil. In order to cure it effectually, we must seize and gag all who thus denounce our peculiar institution. We must also muzzle their press. As this is impracticable, it would be well to come to this conclusion:—If we are verily guilty of the evils charged upon us, let us set about rectifying those evils; if not, the denunciations of slanderers should not affect us so deeply. If our northern brethren are honest in their convictions of the sin of slavery, as no doubt many of them are, let us listen to their arguments without the dire hostility so frequently manifested. They take the position that slavery is opposed to the inalienable rights of the human race; that it originated in piracy and robbery; that manifold cruelties and [Pg 41]barbarities are inflicted upon the defenceless slaves; that they are debarred from intellectual culture by State laws, which send to the penitentiary those who are guilty of instructing them; that they are put upon the block and sold; parent and child, husband and wife being separated, so that they never again see each other’s face in the flesh; that the law of chastity cannot be observed, as there are no laws punishing rape on the person of a female slave; that when they escape from the threatened cat-o’-nine-tails, or overseer’s whip, they are hunted down by bloodhounds, and bloodier men; that often they are half-starved and half-clad, and are furnished with mere hovels to live in; that they are often murdered by cruel overseers, who whip them to death, or overtask them, until disease is induced, which results in death; that masters practically ignore the marriage relation among slaves, inasmuch as they frequently separate husband and wife, by sale or removal; that they discourage the formation of that relation, preferring that the offspring of[Pg 42] their female slaves should be illegitimate, from the mistaken notion that it would be more numerous. They charge, also, that slavery induces in the masters, pride, arrogance, tyranny, laziness, profligacy, and every form of vice.

The South takes the position, that if slavery is sinful, the North is not responsible for that sin; that it is a State institution, and that to interfere with slavery in the States in any way, even by censure, is a violation of the rights of the States. The language of our politicians is, Upon us and our children rest the evil! We are willing to take the responsibility, and to risk the penalty! You will find evil and misery enough in the North to excite your philanthropy, and employ your beneficence. You have purchased our cotton; you have used our sugar; you have eaten our rice; you have smoked and chewed our tobacco—all of which are the products of slave-labour. You have grown rich by traffic in these articles; you have monopolized the carrying trade, and borne our slave-produced[Pg 43] products to your shores. Your northern ships, manned by northern men, brought from Africa the greater part of the slaves which came to our continent, and they are still smuggling them in. When, finding slavery unprofitable, the northern States passed laws for gradual emancipation, but few obtained their freedom, the majority of them being shipped South and sold, so that but few, comparatively, were manumitted. If the slave trade and slavery are great sins, the North is particeps criminis, and has been from the beginning.

These bitter accusations are hurled back and forth through the newspapers; and in Congress, crimination and recrimination occur every day of the session. Instead of endeavouring to calm the troubled waters, politicians are striving to render them turbid and boisterous. Sectional bitterness and animosity prevail to a fearful extent; but secession is not the proper remedy. To cure one evil by perpetrating a greater, renders a double cure necessary. In order to cure a disease, the cause should be known, that we may treat it intelligently, and[Pg 44] apply a proper remedy. Having observed, during the last eleven years, that sectional strife and bitterness were increasing with fearful rapidity, I have endeavoured to stem the torrent, so far as it was possible for individual effort to do so. I deem it the imperative duty of all patriots, of all Christians, to throw oil upon the troubled waters, and thus save the ship of State from wreck among the vertiginous billows.

Most of our politicians are demagogues. They care not for the people, so that they accomplish their own selfish and ambitious schemes. Give them power, give them money, and they are satisfied. Deprive them of these, and they are ready to sacrifice the best interests of the nation to secure them. They excite sectional animosity and party strife, and are willing to kindle the flames of civil war to accomplish their unhallowed purposes. They tell us that there is a conflict of interest between the free and slave States, and endeavour to precipitate a revolution, that they may be leaders, and obtain positions of trust and[Pg 45] profit in the new government which they hope to establish. The people would be dupes indeed to abet these wicked demagogues in their nefarious designs. Let us not break God’s command, by resisting the ordinance of God—the powers that be. I am not discussing the right of revolution, which I deem a sacred right. When human rights are invaded, when life is endangered, when liberty is taken away, when we are not left free to pursue our own happiness in our own chosen way—so far as we do not trespass upon the rights of others—we have a right, and it becomes our imperative duty to resist to the bitter end, the tyranny which would deprive us and our children of our inalienable rights. Our lives are secure; we have freedom to worship God. Our liberty is sacred; we may pursue happiness to our hearts’ content. We do not even charge upon the general Government that it has infringed these rights. Whose life has been endangered, or who has lost his liberty by the action of the Government? If that man lives, in all this fair domain of ours, he has the right to complain.[Pg 46] But neither you nor I have ever heard of or seen the individual who has thus suffered. We have therefore clearly no right of revolution.

Treason is no light offence. God, who rules the nations, and who has established governments, will punish severely those who attempt to overthrow them. Damnation is stated to be the punishment which those who resist the powers that be, will suffer. Who wishes to endure it? I hope none of my charge will incur this penalty by the perpetration of treason. You yourselves can bear me witness that I have not heretofore introduced political issues into the pulpit, but at this time I could not acquit my conscience were I not to warn you against the great sin some of you, I fear, are ready to commit.

Were I to discuss the policy of a high or low tariff, or descant upon the various merits attached to one or another form of banking, I should be justly obnoxious to censure. Politics and religion, however, are not always separate. When the political issue is made, shall we, or shall we not, grant license to sell[Pg 47] intoxicating liquors as a beverage? the minister’s duty is plain; he must urge his people to use their influence against granting any such license. The minister must enforce every moral and religious obligation, and point out the path of truth and duty, even though the principles he advocates are by statesmen introduced into the arena of political strife, and made issues by the great parties of the day. I see the sword coming, and would be derelict in duty not to give you faithful warning. I must reveal the whole counsel of God. I have a message from God unto you, which I must deliver, whether you will hear, or whether you will forbear. If the sword come, and you perish, I shall then be guiltless of your blood. As to the great question at issue, my honest conviction is (and I think I have the Spirit of God,) that you should with your whole heart, and soul, and mind, and strength, oppose secession. You should talk against it, you should write against it, you should vote against it, and, if need be, you should fight against it.

I have now declared what I believe to be your[Pg 48] high duty in this emergency. Do not destroy the government which has so long protected you, and which has never in a single instance oppressed you. Pull not down the fair fabric which our patriot fathers reared at vast expense of blood and treasure. Do not, like the blind Samson, pull down the pillars of our glorious edifice, and cause death, desolation, and ruin. Perish the hand that would thus destroy the source of all our political prosperity and happiness. Let the parricide who attempts it receive the just retribution which a loyal people demand, even his execution on a gallows, high as Haman’s. Let us also set about rectifying the causes which threaten the overthrow of our government. As we are proud, let us pray for the grace of humility. As a State, and as individuals, we too lightly regard its most solemn obligations; let us, therefore, pray for the grace of repentance and godly sorrow, and hereafter in this respect sin no more. As many transgressions have been committed by us, let the time past of our lives suffice us to have wrought the will of the flesh,[Pg 49] and now let us break off our sins by righteousness, and our transgressions by turning unto the Lord, and he will avert his threatened judgments, and save us from dissolution, anarchy, and desolation.

If our souls are filled with hatred against the people of any section of our common country, let us ask from the Great Giver the grace of charity, which suffereth long and is kind, which envieth not, which vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, does not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil; rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth; beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things, and which never faileth; then shall we be in a suitable frame for an amicable adjustment of every difficulty; oil will soon be thrown upon the troubled waters, and peace, harmony, and prosperity would ever attend us; and our children, and our children’s children will rejoice in the possession of a beneficent and stable government, securing to them all the natural and inalienable rights of man.

VIGILANCE COMMITTEE AND COURT-MARTIAL.

The election of Delegates to determine the status of Mississippi—The Vigilance Committee—Description of its members—Charges—Phonography—No formal verdict—Danger of Assassination—Passports—Escape to Rienzi—Union sentiment—The Conscript Law—Summons to attend Court-Martial—Evacuation of Corinth—Destruction of Cotton—Suffering poor—Relieved by General Halleck.

Soon after this sermon was preached, the election was held. Approaching the polls, I asked for a Union ticket, and was informed that none had been printed, and that it would be advisable to vote the secession ticket. I thought otherwise, and going to a desk, wrote out a Union ticket, and voted it amidst the frowns and suppressed murmurs of the judges and bystanders, and, as the result proved, I had the honour of depositing the only vote in favour of the Union which was polled in that precinct. I knew of many who were in favour of the Union, who were intimidated by threats, and[Pg 51] by the odium attending it from voting at all. A majority of secession candidates were elected. The convention assembled, and on the 9th of January, 1861, Mississippi had the unenviable reputation of being the first to follow her twin sister, South Carolina, into the maelstrom of secession and treason. Being the only States in which the slaves were more numerous than the whites, it became them to lead the van in the slave-holders’ rebellion. Before the 4th of March, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas had followed in the wake, and were engulfed in the whirlpool of secession.

It was now dangerous to utter a word in favour of the Union. Many suspected of Union sentiments were lynched. An old gentleman in Winston county was arrested for an act committed twenty years before, which was construed as a proof of his abolition proclivities. The old gentleman had several daughters, and his mother-in-law had given him a negro girl. Observing that his daughters were becoming lazy, and were imposing all the labour upon the slave, he sent her back to the donor,[Pg 52] with a statement of the cause for returning her. This was now the ground of his arrest, but escaping from their clutches, a precipitate flight alone saved his life.

Self-constituted vigilance committees sprang up all over the country, and a reign of terror began; all who had been Union men, and who had not given in their adhesion to the new order of things by some public proclamation, were supposed to be disaffected. The so-called Confederate States, the new power, organized for the avowed purpose of extending and perpetuating African slavery, was now in full blast. These soi-disant vigilance committees professed to carry out the will of Jeff. Davis. All who were considered disaffected were regarded as being tinctured with abolitionism. My opposition to the disruption of the Union being notorious, I was summoned to appear before one of these august tribunals to answer the charge of being an abolitionist. My wife was very much alarmed, knowing that were I found guilty of the charge, there was no hope for mercy. Flight was impossible, and I deemed[Pg 53] it the safest plan to appear before the committee. I found it to consist of twelve persons, five of whom I knew, viz., Parson Locke, Armstrong, Cartledge, Simpson, and Wilbanks. Parson Locke, the chief speaker, or rather the inquisitor-general, was a Methodist minister, though he had fallen into disrepute among his brethren, and was engaged in a tedious strife with the church which he left in Holmes county. The parson was a real Nimrod. He boasted that in five months he had killed forty-eight raccoons, two hundred squirrels, and ten deer; he had followed the bloodhounds, and assisted in the capture of twelve runaway negroes. W. H. Simpson was a ruling elder in my church. Wilbanks was a clever sort of old gentleman, who had little to say in the matter. Armstrong was a monocular Hard-shell-Baptist. Cartledge was an illiterate, conceited individual. The rest were a motley crew, not one of whom, I feel confident, knew a letter in the alphabet. The committee assembled in an old carriage-shop. Parson Locke acted, as chairman, and conducted the trial, as follows.

[Pg 54]“Parson Aughey, you have been reported to us as holding abolition sentiments, and as being disloyal to the Confederate States.”

“Who reported me, and where are your witnesses?”

“Any one has a right to report, and it is optional whether he confronts the accused or not. The proceedings of vigilance committees are somewhat informal.”

“Proceed, then, with the trial, in your own way.”

“We propose to ask you a few questions, and in your answers you may defend yourself, or admit your guilt. In the first place, did you ever say that you did not believe that God ordained the institution of slavery?”

“I believe that God did not ordain the institution of slavery.”

“Did not God command the Israelites to buy slaves from the Canaanitish nations, and to hold them as their property for ever?”

“The Canaanites had filled their cup of iniquity to overflowing, and God commanded the Israelites to exterminate them; this, in[Pg 55] violation of God’s command, they failed to do. God afterwards permitted the Hebrews to reduce them to a state of servitude; but the punishment visited upon those seven wicked nations by the command of God, does not justify war or the slave-trade.”

“Did you say that you were opposed to the slavery which existed in the time of Christ?”

“I did, because the system of slavery prevailing in Christ’s day was cruel in the extreme; it conferred the power of life and death upon the master, and was attended with innumerable evils. The slave had the same complexion as his master; and by changing his servile garb for the citizen dress, he could not be recognised as a slave. You yourself profess to be opposed to white slavery.”

“Did you state that you believed Paul, when he sent Onesimus back to Philemon, had no idea that he would be regarded as a slave, and treated as such after his return?”

“I did. My proof is in Philemon, verses 15 and 16, where the apostle asks that Onesimus[Pg 56] be received, not as a servant, but as a brother beloved?”

“Did you tell Mr. Creath that you knew some negroes who were better, in every respect, than some white men?”

“I said that I knew some negroes who were better classical scholars than any white men I had as yet met with in Choctaw county, and that I had known some who were pre-eminent for virtue and holiness. As to natural rights, I made no comparison; nor did I say anything about superiority or inferiority of race; I also stated my belief in the unity of the races.”

“Have you any abolition works in your library, and a poem in your scrap-book, entitled ‘The Fugitive Slave,’ with this couplet as a refrain,

‘The hounds are baying on my track;

Christian, will you send me back?’”

“I have not Mrs. Stowe’s nor Helper’s work; they are contraband in this region, and I could not get them if I wished. I have many works in my library containing sentiments adverse to[Pg 57] the institution of slavery. All the works in common use amongst us, on law, physic, and divinity, all the text-books in our schools—in a word, all the works on every subject read and studied by us, were, almost without exception, written by men opposed to the peculiar institution. I am not alone in this matter.”

“Parson, I saw Cowper’s works in your library, and Cowper says:

‘I would not have a slave to fan me when I sleep,

And tremble when I wake, for all the wealth

That sinews bought and sold have ever earned.’”

“You have Wesley’s writings, and Wesley says that ‘Human slavery is the sum of all villany.’ You have a work which has this couplet:

‘Two deep, dark stains, mar all our country’s bliss:

Foul slavery one, and one, loathed drunkenness.’

You have the work of an English writer of high repute, who says, ‘Forty years ago, some in England doubted whether slavery were a sin, and regarded adultery as a venial offence; but behold the progress of truth! Who now[Pg 58] doubts that he who enslaves his fellow-man is guilty of a fearful crime, and that he who violates the seventh commandment is a great sinner in the sight of God?’”

“You are known to be an adept in Phonography, and you are reported to be a correspondent of an abolition Phonographic journal.”

“I understand the science of Phonography, and I am a correspondent of a Phonographic journal, but the journal eschews politics.”

Another member of the committee then interrogated me.

“Parson Aughey, what is Funnyography?”

“Phonography, sir, is a system of writing by means of a philosophic alphabet, composed of the simplest geometrical signs, in which one mark is used to represent one and invariably the same sound.”

“Kin you talk Funnyography? and where does them folks live what talks it?”

“Yes, sir, I converse fluently in Phonography, and those who speak the language live in Columbia.”

“In the Destrict?”

[Pg 59]“No, sir, in the poetical Columbia.”

I was next interrogated by another member of the committee.

“Parson Aughey, is Phonography a Abolition fixin?”

“No, sir; Phonography, abstractly considered, has no political complexion; it may be used to promote either side of any question, sacred or profane, mental, moral, physical, or political.”

“Well, you ought to write and talk plain English, what common folks can understand, or we’ll have to say of you, what Agrippa said of Paul, ‘Much learning hath made thee mad.’ Suppose you was to preach in Phonography, who’d understand it?—who’d know what was piped or harped? I’ll bet high some Yankee invented it to spread his abolition notions underhandedly. I, for one, would be in favour of makin’ the parson promise to write and talk no more in Phonography. I’ll bet Phonography is agin slavery, tho’ I never hearn tell of it before. I’m agin all secret societies. I’m agin the Odd-fellers, Free-masons,[Pg 60] Sons of Temperance, Good Templars and Phonography. I want to know what’s writ and what’s talked. You can’t throw dust in my eyes. Phonography, from what I’ve found out about it to-day, is agin the Confederate States, and we ought to be agin it.”

Parson Locke then resumed:

“I must stop this digression. Parson Aughey, are you in favour of the South?”

“I am in favour of the South, and have always endeavoured to promote the best interests of the South. However, I never deemed it for the best interests of the South to secede. I talked against secession, and voted against secession, because I thought that the best interests of the South would be put in jeopardy by the secession of the Southern States. I was honest in my convictions, and acted accordingly. Could the sacrifice of my life have stayed the swelling tide of secession, it would gladly have been made.”

“It is said that you have never prayed for the Southern Confederacy.”

[Pg 61]“I have prayed for the whole world, though it is true that I have never named the Confederate States in prayer.”

“You may retire.”

After I had retired, the committee held a long consultation. My answers were not satisfactory. I never learned all that transpired. They brought in no formal verdict. The majority considered me a dangerous man, but feared to take my life, as they were, with one exception, adherents of other denominations, and they knew that my people were devotedly attached to me before the secession movement. Some of the secessionists swore that they would go to my house and murder me, when they learned that the committee had not hanged me. My friends provided me secretly with arms, and I determined to defend myself to the last. I slept with a double-barrelled shot-gun at my head, and was prepared to defend myself against a dozen at least.

Learning that I was not acceptable to many of the members of my church, whilst my life[Pg 62] was in continual jeopardy, and my family in a state of constant alarm, I abandoned my field of labour, and sought for safety in a more congenial clime. I intended to go North. Jeff. Davis and his Congress had granted permission to all who so desired, to leave the South. Several Union men of my acquaintance applied for passports, but were refused. The proclamation to grant permits was an act of perfidy; all those, so far as I am informed, who made application for them, were refused. The design in thus acting was to get Union men to declare themselves as such, and afterwards to punish them for their sentiments by forcing them into the army, confining them in prison, shooting them, or lynching them by mob violence. Finding that were I to demand a passport to go north, I would be placed on the proscribed list, and my life endangered still more, I declared my intention of going back to Tishomingo county, in which I owned property, and which was the home of many of my relatives. I knew that I would be safer there, for this county had elected[Pg 63] Union delegates by a majority of over fourteen hundred, and a strong Union sentiment had always prevailed.

On my arrival in Tishomingo, I found that the great heart of the county still beat true to the music of the Union. Being thrown out of employment I deemed it my duty, in every possible way, to sustain the Union cause and the enforcement of the laws. It was impossible to go north. Union sentiments could be expressed with safety in many localities. Corinth, Iuka, and Rienzi had, from the commencement of the war, been camps of instruction for the training of Confederate soldiers. These three towns in the county being thus occupied, Union men found it necessary to be more cautious, as the cavalry frequently made raids through the county, arresting and maltreating those suspected of disaffection. After the reduction of Forts Henry and Donelson, and the surrender of Nashville, the Confederates made the Memphis and Charleston railroad the base of their operations, their armies extending from Memphis to Chattanooga. Soon, however, they were all[Pg 64] concentrated at Corinth, a town in Tishomingo county, at the junction of the Memphis and Charleston railroad with the Mobile and Ohio. After the battle of Shiloh, which was fought on the 6th and 7th of April, the Federal troops held their advance at Farmington, four miles from Corinth, while the Confederates occupied Corinth, their rear guard holding Rienzi, twelve miles south, on the Mobile and Ohio railroad.

Thus there were two vast armies encamped in Tishomingo county. Being within the Confederate lines, I, in common with many others, found it difficult to evade the conscript law. Knowing that in a multitude of counsellors there is wisdom, we held secret meetings, in order to devise the best method of resisting the law. We met at night, and had our countersigns to prevent detection. Often our wives, sisters, and daughters met with us. Our meeting-place was some ravine, or secluded glen, as far as possible from the haunts of the secessionists; all were armed; even the ladies had revolvers, and could use them too. The crime of treason we were resolved not to commit. Our[Pg 65] counsels were somewhat divided, some advocating, as a matter of policy, the propriety of attending the militia musters, others opposing it for conscience’ sake, and for the purpose of avoiding every appearance of evil. Many who would not muster as conscripts, resolved to escape to the Federal lines; and making the attempt two or three at a time, succeeded in crossing the Tennessee river, and reaching the Union army, enlisted under the old flag, and have since done good service as patriot warriors. Some who were willing to muster as conscripts, were impressed into the Confederate service, and I know not whether they ever found an opportunity to desert. Others, myself among the number, were saved by the timely arrival of the Federal troops, and the occupation of the county by them, after Beauregard’s evacuation of Corinth. I had received three citations to attend muster, but disregarding them, I was summoned to attend a court-martial on the first day of June, at the house of Mr. Jim Mock. The following is a copy of the citation.

[Pg 66] Ma the 22d. 1862

Parson Awhay, You havent tended nun of our mustters as a konskrip. Now you is her bi sumenzd to attend a kort marshal on Jun the fust at Jim Mock.

When I received the summons, I resolved to attempt reaching the Union lines at Farmington. Two of my friends, who had received a similar summons, expected to accompany me. On the 29th of May, I left for Rienzi, where my two friends were to meet me. I had not been many hours in Rienzi when it became evident that the Confederates were evacuating Corinth. On the 1st of June, (the day the court-martial was to convene,) I had the pleasure of once more beholding the star-spangled banner as it was borne in front of General Granger’s command, which led the van of the pursuing army. Had I remained and attended the court-martial, I would have been forced into the army. Were I then to declare that I would not take up arms against the United States, I would have been shot, as many[Pg 67] have been, for their refusal thus to act. General Rosecrans, on his arrival, made his head-quarters at my brother’s house, where I had the pleasure of forming his acquaintance, together with that of Generals Smith, Granger, and Pope. As this county was now occupied by the Federal army, I returned to my father-in-law’s, within five miles of which place the court-martial had been ordered to convene, considering myself comparatively safe. I learned that the court-martial never met, as Colonel Elliott, in his successful raid upon Boonville, had passed Jim Mock’s, scaring him to such a degree, that he did not venture to sleep in his house for two weeks. The Union cavalry scoured the country in all directions, daily, and we were rejoicing at the prospect of continuous safety, and freedom from outrage.

The Rebels, during their retreat, had burned all the cotton which was accessible to their cavalry, on their route. At night, the flames of the burning cotton lighted up the horizon for miles around. These baleful pyres, with[Pg 68] their lurid glare, bore sad testimony to the horrors of war. In this wanton destruction of the great southern staple, many poor families lost their whole staff of bread, and starvation stared them in the face. Many would have perished, had it not been for the liberal contributions of the North; for, learning the sufferings of the poor of the South, whose whole labour had been destroyed by pretended friends, they sent provisions and money, and thus many who were left in utter destitution, were saved by this timely succor. I have heard the rejoicings of the poor, who, abandoned by their supposed friends, were saved, with their children, from death, by the beneficence of those whom they had been taught to regard as enemies the most bitter, implacable, unmerciful, and persistent. Their prayer may well be, Save us from our friends, whose tender mercies are cruel! I have never known a man to burn his own cotton, but I have heard their bitter anathemas hurled against those who thus robbed them, and their denunciations were loud and deep against the government which[Pg 69] authorized such cruelty. It is true that those who thus lose their cotton, if secessionists, receive a “promise to pay,” which all regard as not worth the paper on which it is written. Ere pay-day, those who are dependent on their cotton for the necessaries of life, would have passed the bourne whence no traveller returns. ’Tis like the Confederate bonds—at first they were made payable two years after date, and printed upon paper which would be worn out entirely in six months, and would have become illegible in half that time. The succeeding issues were made payable six months after the ratification of a treaty of peace between the United States and the Confederate States. Though not a prophet, nor a prophet’s son, I venture the prediction that those bonds will never be due. The war of elements, the wreck of matter, and the crush of worlds, announcing the end of all things, will be heard sooner.

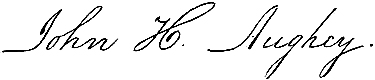

ARREST, ESCAPE, AND RECAPTURE.

High price of Provisions—Holland Lindsay’s Family—The arrest—Captain Hill—Appearance before Colonel Bradfute at Fulton—Arrest of Benjamin Clarke—Bradfute’s Insolence—General Chalmers—The clerical Spy—General Pfeifer—Under guard—Priceville—General Gordon—Bound for Tupelo—The Prisoners entering the Dungeon—Captain Bruce—Lieutenant Richard Malone—Prison Fare and Treatment—Menial Service—Resolve to escape—Plan of escape—Federal Prisoners—Co-operation of the Prisoners—Declaration of Independence—The Escape—The Separation—Concealment—Travel on the Underground Railroad—Pursuit by Cavalry and Bloodhounds—The Arrest—Dan Barnes, the Mail-robber—Perfidy—Heavily ironed—Return to Tupelo.

At this time—May and June, 1862—all marketable commodities were commanding fabulous prices; as a lady declared, it would soon be necessary, on going to a store, to carry two baskets, one to hold the money, and the other the goods purchased. Flour was thirty dollars per barrel, bacon forty cents per pound, and[Pg 71] coffee one dollar per pound. Salt was nominally one hundred dollars per sack of one hundred pounds, or one dollar per pound, but there was none to be obtained even at that price. Ladies were compelled to dispense with salt in their culinary operations; even the butter was unsalted. Cotton-cards, an article used in every house at the South, the ordinary price of which is fifty cents per pair, were selling at twenty-five dollars per pair, and wool-cards at fifteen dollars per pair, the usual price being thirty-eight cents. All the cotton used in the manufacture of home-made cloth, is carded into rolls upon these cotton-cards, which are brought from the North, there being not a single manufactory of them in the South. When the supply on hand becomes exhausted, the southern home manufacture of cloth must cease, no one as yet having been able to suggest a substitute for the cotton-card. There are only three factories in Mississippi, which must cease running as soon as their machinery wears out, as the most important parts of the machinery in those factories are supplied from the North. The people[Pg 72] are fully aware of these difficulties, but they can devise no remedy, hence the high price of all articles used in the manufacture of all kinds of cloths. All manufactured goods were commanding fabulous prices. On the occupation of the county by Federal troops, goods could be obtained at reasonable prices, but our money was all gone, except Confederate bonds, which were worthless. Planters who were beyond the lines of the retreating army had cotton, but many of them feared to sell it, as the Rebels professed to regard it treason to trade with the invaders, and threatened to execute the penalty in every case. As there was no penalty attached to the selling of cotton by one citizen of Mississippi to another, some of my friends offered to sell me their cotton for a reasonable price.

I was solicited also to act as their agent in the purchase of commodities. I agreed to this risk, because of the urgent need of my friends, many of whom were suffering greatly for the indispensable necessaries of life. I thought it was better that one should suffer, than that the[Pg 73] whole people should perish. By this arrangement my Union friends would escape the punishment meted out to those who were found guilty of trading with the Yankees; if discovered, I alone would be amenable to their unjust and cruel law, and they would thus save their cotton, which was liable to be destroyed at any moment by a dash of rebel cavalry. I now hired a large number of wagons to haul cotton into Eastport and Iuka, that I might ship it to the loyal States. On the 2d of June the wagons were to rendezvous at a certain point; there were a sufficient number to haul one hundred bales per trip. I hoped to keep them running for some time.

On the first of June I rode to Mr. Holland Lindsay’s on business. I had learned that he was a rabid secessionist, but supposed that no rebel cavalry had come so far north as his house since the evacuation of Corinth. Mr. Lindsay had gone to a neighbour’s. His wife was weaving; she was a coarse, masculine woman, and withal possessed of strong prejudice against all whom she did not like, but especially the[Pg 74] Yankees. I sat down to await the arrival of her husband, and it was not long before Mrs. Lindsay broached the exciting topic of the day, the war. She thus vented her spleen against the Yankees.

“There was some Yankee calvary passed here last week—they asked me if there wos ony rebels scoutin round here lately. I jest told em it want none of ther bizness. Them nasty, good for nothin scamps callen our men rebels. Them nigger-stealin, triflin scoundrels. They runs off our niggers, and wont let us take em to Mexico and the other territories.”

I ventured to remark, “The Yankees are mean, indeed, not to let us take our negroes to the Territories, and not to help catch them for us when they run off.”

The emphatic us and our nettled her, as none of the Lindsays ever owned a negro, being classed by the southern nabobs as among the poor white trash; nor did I ever own a slave. Her husband, however, had once been sent to the Legislature, which led the family to ape the manners, and studiously copy the ultraism of[Pg 75] the classes above them. Mrs. Lindsay became morose. I concluded to ride over and see her husband.

On my way I met a member of Hill’s cavalry. He halted me, inquired my name and business, which I gave. He said that, years ago, he had heard me preach, and that he was well acquainted with my brothers-in-law, who were officers in the Rebel army. He informed me that his uncle, Mr. Lindsay, had gone across the field home, and that he himself was on his way there. I returned with him, but fearing arrest, my business was hastily attended to, and I at once started for my horse. By this time one or two other cavalry-men rode up. I heard Mrs. Lindsay informing her nephew that I was a Union man, and advising my arrest. When I had reached my horse, Mr. Davis, Lindsay’s nephew arrested me, and sent my horse to the stable. After supper, my horse was brought, and I was taken to camp. Four men were detached to guard me during the night. They ordered me to lie down on the ground and sleep. As it had rained during the day, and I[Pg 76] had no blanket, I insisted upon going to a Mr. Spigener’s, about fifty yards distant, to secure a bed. After some discussion they consented, the guards remaining in the room, and guarding me by turns during the night. The next morning I sought Captain Hill, and asked permission to return home, when the following colloquy ensued.

“Are you a Union man?”

“I voted the Union ticket, sir.”

“That is not a fair answer. I voted the Union ticket myself, and am now warring against the Union.”

“I have seen no good reason for changing my sentiments.”

“You confess, then, that you are a Union man?”

“I do; I regard the union of these States as of paramount importance to the welfare of the people inhabiting them.”

“You must go to head-quarters, where you will be dealt with as we are accustomed to deal with all the abettors of an Abolition government.”

[Pg 77]A heavy guard was then detached to take charge of me, and the company set off for Fulton, the county seat of Ittawamba county, Mississippi, distant thirty miles. After going about ten miles, we halted, and two men were detached to go forward with the prisoners, a Mr. Benjamin Clarke and myself. Our guards were Dr. Crossland, of Burnsville, Tishomingo county, Mississippi, and Ferdinand Woodruff. They were under the influence of liquor, and talked incessantly, cursing and insulting us, on every occasion, by abusive language. They detailed to each other a history of their licentious amours. We halted for dinner at one o’clock, and being out of money, they asked me to pay their bill, which I did, they promising to refund the amount when they reached Fulton. This they forgot to do.