Title: The Little Princess of Tower Hill

Author: L. T. Meade

Release date: February 5, 2012 [eBook #38771]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Josephine Paolucci and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net.

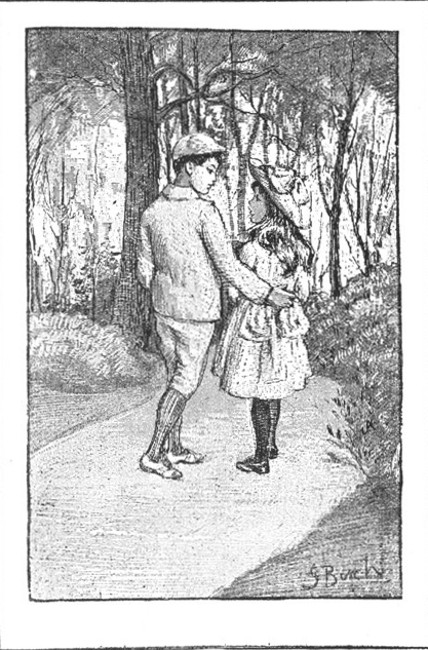

"I WILL KNOCK. YOU ARE TO SAY, 'PLEASE IS MRS. ROBBINS

IN?'"—Page 171.

"I WILL KNOCK. YOU ARE TO SAY, 'PLEASE IS MRS. ROBBINS

IN?'"—Page 171.

SIX PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS.

NEW YORK

A. L. BURT, PUBLISHER.

[Transcriber's note: This book contains the following stories as well: "Tom, Pepper, and Trusty", "Billy Anderson and his Troubles", "The Old Organ-Man". The table of contents in the book was only for The Little Princess of Tower Hill. I have created the table of contents for the other stories.]

THE LITTLE PRINCESS OF TOWER HILL

PAGE

CHAPTER I.

Her Very Young Days 1

CHAPTER II.

Father's Short Visitor 12

CHAPTER III.

Snubbed 23

CHAPTER IV.

The Stable Clock 35

CHAPTER V.

The Empty Hutch 49

CHAPTER VI.

Jo's Room 63

CHAPTER VII.

In Violet 77

CHAPTER VIII.

Choosing Her Colors 103

CHAPTER IX.

A Jolly Plan 113

CHAPTER X.

A Great Fear 127

CHAPTER XI.

Going Home 142

CHAPTER XII.

In the Wood 151

CHAPTER XIII.

Thank God for All 165

TOM, PEPPER, AND TRUSTY.

CHAPTER I. 173

CHAPTER II. 177

CHAPTER III. 190

CHAPTER IV. 200

CHAPTER V. 204

CHAPTER VI. 214

BILLY ANDERSEN AND HIS TROUBLES.

CHAPTER I. 216

CHAPTER II. 220

CHAPTER III. 228

CHAPTER IV. 237

CHAPTER V. 240

CHAPTER VI. 243

THE OLD ORGAN-MAN.

CHAPTER I. 252

CHAPTER II. 258

CHAPTER III. 268

CHAPTER IV. 273

All the other children who knew her thought Maggie a wonderfully fortunate little girl. She was sometimes spoken about as the "Little Princess of Tower Hill," for Tower Hill was the name of her father's place, and Maggie was his only child. The children in the village close by spoke of her with great respect, and looked at her with a good deal of longing and also no slight degree of envy, for while they had to run about in darned and shabby frocks, Maggie could wear the gayest and daintiest little dresses, and while they had[Pg 2] to trudge sometimes even on little bare feet, Maggie could sit by her mother's side and be carried rapidly over the ground in a most delicious and luxurious carriage, or, better still, she might ride on her white pony Snowball, followed by a groom. The poor children envied Maggie, and admired her vastly, and the children of those people who, compared to Sir John Ascot, Maggie's father, might be considered neither rich nor poor, also thought her one of the most fortunate little girls in existence. Maggie was nearly eight years old, and from her very earliest days there had been a great fuss made about her. At the time of her birth bonfires had been lit, and oxen killed and roasted whole to be given away to the poor people, and Sir John and Lady Ascot did not seem at all disappointed at their baby being a girl instead of a son and heir to the old title and the fine old place. There was a most extraordinary fuss made over Maggie while she was a baby; her mother was never tired of visiting her grand nurseries and watching her as she lay asleep, or smiling at[Pg 3] her and kissing her when she opened her big, bright blue eyes. The eyes in question were very pretty, so also was the little face, and the father and mother quite thought that there never was such a baby as their little Maggie. They had christened her Margarita Henrietta Villiers; these were all old family names, and very suitable to the child of proud old county folk. At least so Sir John thought, and his pretty young wife agreed with him, and she gave the servants strict directions that the baby was to be called Miss Margarita, and that the name was on no account whatever to be abridged or altered. This was very fine as long as the baby could only coo or make little inarticulate sounds, but that will of her own, which from the earliest minutes of her existence Maggie had manifested, came fully into play as soon as she found the full use of her tongue. She would call herself Mag-Mag, and would not answer to Margarita, or pay the smallest heed to any summons which came to her in this guise, and so, simply because they could not help themselves, Sir John and Lady[Pg 4] Ascot had almost virtually to rechristen their little daughter, and before she was two years old Maggie was the only name by which she was known.

Years passed, and no other baby came to Tower Hill, and every year Maggie became of a little more importance, and was made a little more fuss about, and as a natural consequence was a little more spoiled. She was a very pretty child; her hair was wavy and curly, and exquisitely fine; in its darkest parts it was nut-brown, but round her temples, and wherever the light fell on it, it was shaded off to the brightest gold; her eyes were large, and blue, and well open; her cheeks were pink, her lips rosy, and she had a saucy, never-me-care look, which her father and mother and the visitors who saw her thought wonderfully charming, but which now and then her nurse and her patient governess, Miss Grey, objected to. All things that money could buy, and all things that love could devise, were lavished at Maggie's feet. Her smallest wishes were instantly granted; the most expensive toys were purchased for[Pg 5] her; the most valuable presents were given to her day by day. "Surely," said the village children, "there can be no happier little girl in all the wide, wide world than our little princess. If there is a child who lives always, every day, in a fairy-land, it is Miss Maggie Ascot."

Maggie had two large nurseries to play in, and two nurses to wait upon her, and when she was seven years old a certain gentle-faced, kind-hearted Miss Grey arrived at Tower Hill to superintend the little girl's education. Then a schoolroom was added to her suit of apartments, and then also the troubles of her small life began. Hitherto everything had gone for Maggie Ascot with such smoothness and regularity, with such an eager desire on the part of every one around her not only to grant her wishes, but almost to anticipate them, that although nurse, and especially Grace, the under-nurse, strongly suspected that Miss Maggie had a temper of her own, yet certainly Sir John and Lady Ascot only considered her a somewhat daring, slightly self-willed, but altogether charming little girl.[Pg 6]

With the advent, however, of Miss Grey things were different. Maggie had taken the greatest delight in the furnishing and arranging of her schoolroom; she had laughed and clapped her hands with glee when she saw the pretty book-shelves being put up, and the gayly bound books arranged on them; and when Miss Grey herself arrived, Maggie had fallen quite in love with her, and had sat on her knee, and listened to her charming stories, and in fact for the first day or two would scarcely leave her new friend's side; but when lessons commenced, Maggie began to alter her mind about Miss Grey. That young lady was as firm as she was gentle, and she insisted not only on her little pupil obeying her, but also on her staying still and applying herself to her new duties for at least two hours out of every day. Long before a quarter of the first two hours had expired, Maggie had expressed herself tired of learning to read, and had announced, with her usual charming frankness, that she now intended to run into the garden and pick some roses.

"I WANT TO PICK THOSE WHITE ROSES."—Page 6.

"I WANT TO PICK THOSE WHITE ROSES."—Page 6.

"I want to pick a great quantity of those nice white roses, and some of the prettiest of the buds, and when they are picked, I'll give them all to you, Miss Grey, darling," she continued, raising her fearless and saucy eyes to her governess' face. "Here you go, you tiresome old book," and the new reading-book was flung to the other side of the room, and Maggie had almost reached the door before Miss Grey had time to say:

"Pick up your book and return to your seat, Maggie dear. You forget that these are lesson hours."

"But I'm tired of lessons," said Maggie, "and I don't wish to do any more. I don't mean to learn to read—I don't like reading—I like being read to. I shan't ever read, I have quite made up my mind. How many roses would you like, Miss Grey?"

"Not any, Maggie; you forget, dear, that Thompson, the gardener, told you last night you were not to pick any more roses at present, for they are very scarce just now."

"Well, what are they there for except for[Pg 8] me to pick?" answered the spoiled child, and from that moment Miss Grey's difficulties began. Maggie's hitherto sunshiny little life became to her full of troubles—she could not take pleasure in her lessons, and she failed to see any reason for her small crosses. Miss Grey was kind, and conscientious, and painstaking, but she certainly did not understand the spoiled but warm-hearted little girl she was engaged to teach, and the two did not pull well together. Nurse petted her darling and sympathized with her, and remarked in a somewhat injudicious way to Grace that Miss Maggie's cheeks were getting quite pale, and that she was certain, positive sure, that her brain was being forced into over-ripeness.

"What's over-ripeness?" inquired Maggie as she submitted to her hair being brushed and curled for dinner, and to nurse turning her about with many jerks as she tied her pink sash into the most becoming bow—"what's over-ripeness, nursey, and what has it to say to my brain? That's the part of me what thinks, isn't it?"[Pg 9]

"Yes, Miss Maggie dear, and when it's forced unnatural it gets what I call over-ripe. I had a nephew once whose brain went like that—he died eventual of the same cause, for it filled with water."

Maggie's round blue eyes regarded her nurse with a certain gleam of horror and satisfaction. Miss Grey had now been in the house for three months, and certainly the progress Maggie had made in her studies was not sufficiently remarkable to induce any one to dread evil consequences to her little brain. She trotted down to dinner, and took her usual place opposite her governess. In one of the pauses of the meal, her clear voice was heard addressing Sir John Ascot.

"Father dear, did you ever hear nurse talk of her nephew?"

"No, Mag-Mag, I can't say I have. Nurse does not favor me with much news about her domestic concerns, and she has doubtless many nephews."

"Oh, but this is the one who was over-ripe," answered Maggie, "so you'd be sure to remember about him father."[Pg 10]

"What an unpleasant description, little woman!" answered Sir John; "an over-ripe nephew! Don't let's think of him. Have a peach, little one. Here is one which I can promise you is not in that state of incipient decay."

Maggie received her peach with a little nod of thanks, but she was presently heard to murmur to herself:

"I'm over-ripe, too. I quite 'spect I'll soon fill with water."

"What is the child muttering?" asked Sir John of his wife; but Lady Ascot nodded to her husband to take no notice of Maggie, and presently she and her governess left the room.

"My dear," said Lady Ascot to Sir John, when they were alone, "Miss Grey says that our little girl is determined to grow up a dunce—she simply won't learn, and she won't obey her; and I often see Maggie crying now, and nurse is not at all happy about her."

"Miss Grey can't manage her; send her away," pronounced the baronet shortly.

"But, my dear, she seems a very nice, good[Pg 11] girl. I have really no reason for giving her notice to leave us—and—and—John, even though Maggie is our only little darling, I don't think we ought to spoil her."

"Spoil her! Bless me, I never saw a better child."

"Yes, my dear, she is all that is good and sweet to us, but she ought to be taught to obey her governess; indeed, I think we must not allow her to have the victory in this matter. If we sent Miss Grey away, Maggie would feel she had won the victory, and she would behave still more badly with the next governess."

"Tut! tut!" said Sir John. "What a worry the world is, to be sure! Of course the little maid must be taught discipline; we'd none of us be anywhere without it; eh, wife? I'll tell you what, Maggie is all alone; she needs a companion. I'll send for Ralph."

"That is a good idea," replied Lady Ascot.

"Well, say nothing about it until I see if my sister can spare him. I'll go up to town to-morrow, and call and see her. Ralph will mold Maggie into shape better than twenty Miss Greys."

Ralph's mother was a widow. She had traveled on the Continent for a long time, but had at last taken a small house in London. Sir John intended week after week to go and see his sister, and week after week put off doing so, until it suddenly dawned upon him that Ralph's society might do his own little princess good. Sir John told his wife to say nothing to Maggie about her cousin's visit, as it was quite uncertain whether his mother would spare him, and he did not wish the little maid to be disappointed. Maggie, however, was a very sharp child, and she was much interested in sundry mysterious preparations which were taking place in a certain very pretty bedroom not far from her own nurseries. A little brass bedstead, quite new and bright,[Pg 13] was being covered with snowy draperies; and sundry articles which girls were not supposed to care about, but which, nevertheless, Maggie looked at with eyes of the deepest veneration and curiosity, were being placed in the room; among these articles might have been seen some cricket-bats, a pair of boxing-gloves, a couple of racket-balls, and even a little miniature gun. The little gun was harmless enough in its way; it had belonged to Sir John when a lad, but why was it placed in this room, and what did all these preparations mean? Maggie eagerly questioned Rosalie, the under-housemaid, but Rosalie could tell her nothing, beyond the fact that she was bid to make certain preparations in the room, and she supposed one of master's visitors was expected.

"He must be a very short man," said Maggie, laying herself down at full length on the little white bed, and measuring the distance between her feet and the bright brass bars at the bottom; "he'll be about half a foot bigger than me," and then she scampered off to Miss Grey.

"Father's visitor's room is all ready," she[Pg 14] said. "How tall should you think he'd be, Miss Grey?"

"Dear me, Maggie, how can I tell? If the visitor is a man, he'll be sure to be somewhere between five feet and six feet; I can't tell you the exact number of inches."

"No, you're as wrong as possible," answered Maggie, clapping her hands. "There's a visitor coming to father, and of course he's a man, or he wouldn't be father's visitor, and he's only about one head bigger than me. He's very manly, too; he likes cricket, and racket, and boxing, and firing guns. His room is full of all those 'licious things. Oh, I wish I was a man too. Miss Grey, darling, how soon shall I be growed up?"

"Not for a long, long time yet. Now do sit straight, dear, and don't cross your legs. Sit upright on your chair, Maggie, like a little lady. Here is your hemming, love; I have turned down a nice piece for you. Now be sure you put in small stitches, and don't prick your finger."

These remarks and these little injunctions[Pg 15] always drew a deep frown between Maggie's arched brows.

"Sewing isn't meant for rich little girls like me," she said. "I'm not going to sew when I grow up; I know what I'll do then. I know quite well; when I'm tired I'll sit in an easy-chair and eat lollipops, and when I'm not tired I'll ride on all the wildest horses I can find, and I'll play cricket, and fire guns, and fish, and—and—oh, I wish I was grown up."

Miss Grey, who was by this time quite accustomed to Maggie's erratic speeches, thought it best to take no notice whatever of her present remarks. Maggie would have liked her to argue with her and remonstrate; she would have preferred anything to the calm and perfect stillness of the governess. She was allowed to talk a little while she was at her hemming, and she now turned her conversation into a different channel.

"Miss Grey," she said, "which do you think are the best off, very rich little only children girls, or very poor little many children girls?"

"Maggie dear," replied her governess, "you[Pg 16] are asking me, as usual, a silly question. The fact of a little girl being rich and an only child, or the fact of a little girl being poor and having a great many brothers and sisters, has really much less to do with happiness than people think. Happiness is a very precious possession, and sometimes it is given to people who look very pale and suffering, and sometimes it is denied to those who look as if they wanted for nothing."

"That's me," said Maggie, uttering a profound sigh. "I'm rich and I want for nothing, and I'm the mis'rable one, and Jim, the cripple in our village, is poor, and he hasn't got no nice things, and he's the happy one. Oh, how I wish I was Jim the cripple."

"Why, Maggie, you would not surely like to give up your dear father and mother to be somebody else's child."

"No, of course not. They'd have to be poor too. Mother would have to take in washing and father—I'm afraid father would have to put on ragged clothes, and go about begging from place to place. I don't think Jim, the[Pg 17] cripple, has any father, but I couldn't do without mine, so he'd have to be a beggar and go about from place to place to get pennies for mother and me. We'd be darling and poor, and we couldn't afford to keep you, Miss Grey, and I wouldn't mind that at all, 'cause then I need never do reading and hemming, and I'd be as ignoram as possible all my days."

Just at this moment somebody called Maggie, and she was told to put on her out-door things, and to go for a drive with her mother in the carriage.

Maggie was a very sharp little girl, and she could not help noticing a certain air of expectancy on Lady Ascot's face, and a certain brightening of her eyes, particularly when Maggie, in her usual impetuous fashion, asked eager questions about the very short gentleman visitor who was coming to stay with father.

"He's not four feet high," said Maggie. "I am sure I shall like him greatly; he'll be a sort of companion to me, and I know he must be very brave."

"Why do you know that, little woman?" asked Lady Ascot in an amused voice[Pg 18] "Oh, 'cause, 'cause—his gun, and his fishing-tackle, and his boxing-gloves have been sent on already. Of course he must be brave and manly, or father would have nothing to say to him. But as he's only three inches taller than me, I'm thinking perhaps he'll be tired keeping up with father's long steps, when they go out shooting together; and so perhaps he will really like to make a companion of me."

"I should not be surprised, Maggie—I should not be the least surprised, and now I'm going to tell you a secret. We are going at this very moment to drive to Ashburnham station to meet father and his gentleman visitor."

"Oh, mother!" exclaimed Maggie, "and do you know the visitor? Have you seen him before? What is his name?"

"His name is Ralph, and though I have heard a great deal about him, it so happens I have never seen him."

"Mr. Ralph," repeated Maggie, softly; "it's a nice short name, and easy to remember. I think Mr. Ralph is a very good name indeed for father's little tiny gentleman visitor."[Pg 19]

All during their drive to Ashburnham Maggie chattered, and laughed, and wondered. Her bright little face looked its brightest, and her merry blue eyes quite danced with fun and happiness. No wonder her mother thought her a most charming little girl, and no wonder the village children looked at the pretty and beautifully dressed child with eyes of envy and admiration!

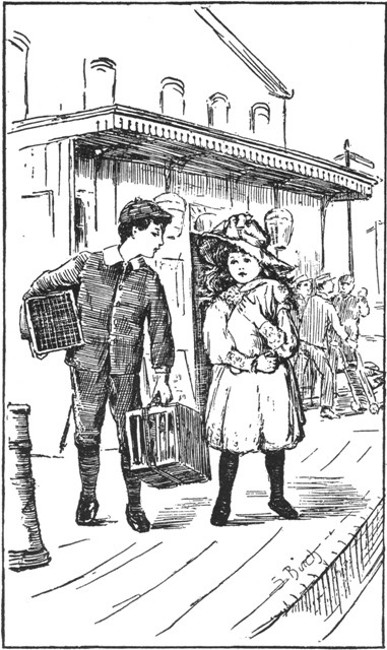

When they reached Ashburnham station, Lady Ascot got out of the carriage, and taking Maggie's hand in hers, went on the platform. They had scarcely arrived there before the train from London puffed into the station, and Sir John Ascot was seen to jump out of a first-class smoking carriage, accompanied by a brown-faced, slender-looking boy, whose hands were full of parcels, and who began to help Sir John vigorously, and to indignantly disdain the services of the porter, and of Sir John's own groom, who came up at that moment.

"No, thank you; I wish to hold these rabbits myself," he exclaimed, "and my[Pg 20] pigeons. Uncle John, will you please hand me down that cage? Oh, aren't my fantails beauties!"

"Mother," exclaimed Maggie in a low, breathless voice, "is that the gentleman visitor?"

"Yes, darling, your cousin Ralph Grenville. Ralph is your visitor, Maggie, not your father's. Come up and let me introduce you. Ralph, my dear boy, how do you do? I am your aunt. I am very glad to see you. Welcome to Tower Hill!"

"Are you Aunt Beatrice?" answered the brown-faced boy. "How do you do, Aunt Beatrice? Oh, I do hope my fishing-tackle is safe."

"And this is your Cousin Maggie," proceeded Lady Ascot. "You and Maggie must be great friends."

"Do you like fantails?" asked Ralph, looking full at his little cousin.

"Do you mean those darling white birds in the cage?" answered Maggie, her cheeks crimsoning.

"I CAUGHT HIM MY OWN SELF."—Page 21.

"I CAUGHT HIM MY OWN SELF."—Page 21.

"Yes; I've got some pouters at home, but I only brought the fantails here. I hope you've got a nice pigeon-cote at Tower Hill. Oh, my rabbits, my bunnies! Help me, Maggie; one of them has got loose; help me, Maggie, to catch him."

Before either Sir John or Lady Ascot could interfere, the two children had disappeared into a crowd of porters, passengers, and luggage. Lady Ascot uttered a scream of dismay, but Sir John said coolly:

"Let them be. The little lad has got his head screwed on the right way; and if I don't mistake, my pretty maid can hold her own with anybody. Don't agitate yourself, Bee; they'll be back all right in a moment."

So they were, Maggie holding a huge white rabbit clasped against her beautiful embroidered frock. The rabbit scratched and struggled, but Maggie held him without flinching, although her face was very red.

"I caught him my own self," she screamed. "Ralph couldn't, 'cause his hands were too full."[Pg 22]

"Pop him into this cage now," exclaimed the boy. "Uncle John, has a separate trap come for all the luggage? and if so, may I go home in it? I must watch my bunnies, and I should like to keep the fantails on my lap."

"Well, yes, Ralph," replied Sir John Ascot in an amused voice. "I have no doubt the dog-cart has turned up by now. Do you think you can manage to stick on, my boy? The mare is very fresh."

"I stick on? Rather!" answered Ralph. "You may hold the cage with the bunnies, if you like, while I step up, Jo—Maggie, I mean."

"I'd like to go up there, too, father," whispered little Miss Ascot's full round tones.

"No, no, bairnie," answered the baronet. "I don't want your pretty little neck to be broken. There, hop into the carriage beside mother, and I'll get in the dog-cart to keep this young scamp out of mischief. Now then, off we go. We'll all be at home in a twinkling."

When the children met next it was at tea-time. There was a very nice and tempting tea prepared in Maggie's schoolroom, and Miss Grey presided, and took good care to attend to the wants of the hungry little traveler. Ralph looked a very different boy sitting at the tea-table munching bread-and-butter, and disposing of large plates of strawberries and cream, from what he did when Maggie met him at Ashburnham station. He was no longer in the least excited; he was neatly dressed, with his hair well brushed, and his hands extremely clean and gentlemanly. He was polite and attentive to Miss Grey, and thanked her in quite a sweet voice for the little attentions which she lavished upon him. Maggie was far too excited to feel hungry.[Pg 24] She could scarcely take her round blue eyes off Ralph, who, for his part, did not pay her the smallest attention. He was conversing in quite a proper and grown-up tone with the governess.

"Do you really like flat countries best?" he said. "Ah! I suppose, then, you must suffer from palpitation. Mother does very much—she finds sal volatile does her good; did you ever try that? When I next write to mother, I'll ask her to send me a little bottle, and when you feel an attack coming on, I'll measure some drops for you. If you take ten drops in a little water, and then lie down, you don't know how much better you'll get. Thank you, yes, I'll have another cup of tea. I like a good deal of cream, please, and four or five lumps of sugar; if the lumps are small, I don't mind having six. Well, what were we talking about? Oh, scenery! I like hilly scenery. I like to get on the top of a hill, and race down as fast as ever I can to the bottom. Sometimes I shout as I go—it's awfully nice shouting out loud as you're racing through the air.[Pg 25] Did you ever try that? Oh, I forgot; you couldn't if you suffer from palpitation."

"I like steep mountains, and flying over big precipices," here burst from Maggie. "I hate flat countries, and I don't think much of running down little hills. Give me the mountains and the precipices, and you'll see how I'll scamper."

Ralph raised his eyebrows a tiny bit, smiled at Maggie with a gentle pity in his face, and then, without vouchsafing any comment to her audacious observations, resumed his placid conversation with the governess.

"Mother and I have been a good deal in Switzerland, you know," he continued, "so of course we can really judge what scenery is like. I got tired of those great mountains after a bit. I'm very fond indeed of England, particularly since I have spent so much of my time with Jo. Do you know my little friend Jo, Miss Grey?"

"No, Mr. Ralph, I cannot say I do. Is he a nice little boy? Is he about your age?"

Ralph laughed, but in a very moderate[Pg 26] "I beg your pardon," he exclaimed. "I hope you were not hurt when I laughed. Mother says it's very rude to laugh at a grown-up lady, but it seemed so funny to hear you speak of Jo as a boy. She's a girl, quite the very nicest girl in the world; her real name is Joanna, but I call her Jo."

Here Maggie, who, after Ralph's ignoring of her last audacious observation, had been getting through her tea in a subdued manner, brightened up considerably, shook back her shining curls, and said in a much more gentle voice than she had hitherto used:

"I should like to see her."

"You!" said Ralph. "She's not the least in your style. Well, I've done my tea. Have you done your tea, Miss Grey? And may I leave the table, please? I should like to have a run around the place before it gets dark."

"And may I come with you?" asked Maggie.

"Oh, yes, Mag! Come along."

Ralph held out his hand, which Maggie took with a great deal of gratitude in her heart, and the two children went out together into the sweet summer air.[Pg 27]

Ralph first of all inspected his pigeons, and then his rabbits. He grumbled a good deal over the arrangements made for the reception of his pets, and informed Maggie that the hutch for the rabbits was but small and close, and that the dove-cote must be altered immediately, and that he would take care to speak to his Uncle John about it in the morning.

Maggie agreed with every word Ralph said. She, too, pronounced the hutch small and dirty, and said the dove-cote must be altered, and while she echoed her cousin's sentiments, she felt herself quite big and important, and turned away from the rather smiling eyes of Jim, the stable-boy, who was in attendance on the pair.

The children then proceeded to the stable, where Maggie's pretty snow-white pony was kept.

"Ah!" said Ralph, "I wish you could see my horse. My horse is black, and rather bigger than this, and he has an eye of fire and such a beautiful glossy, arched neck. I can tell you it is worth something to see Raven. Yes,[Pg 28] Maggie, Snowball is rather a nice little pony, and very well suited for you, I should imagine."

"I don't like him much," said Maggie, who until this moment had adored her pet. "I like flashy, frisky horses. I like them fresh, don't you, Ralph?"

"Don't talk nonsense!" said Ralph rather pertly. "Now where shall we go?"

"Oh, Ralph, I should like to show you my garden. I dare say father will give you a little garden near mine if we ask him. I'm building a rockery. I don't work in my garden very often, 'cause it's rather tiresome, but I like building my rockery, and when we go to the seaside, I shall gather lots of shells for it. Come, Ralph, this is the way."

"Never mind to-night," said Ralph. "Here is a nice seat on this little mossy bank. If you like to sit by me, Maggie, we can talk."

Maggie was only too pleased. Ralph stretched himself on the soft velvety grass, put his hands under his head, and gazed up at the sky; Maggie took care to imitate his position in all particulars. She also put her hands under[Pg 29] her head, and gazed through her shady hat up at the tall trees where the rooks were going to sleep.

That night the rather spoiled little princess of Tower Hill lay awake for some time. It was very unusual for Maggie to remain for an instant out of the land of dreams. The moment she laid her curly head on the pillow she entered that pleasant country, and, as a rule, she stayed there and enjoyed delightful times with other dream-children until the morning. On the present occasion, however, sleep did not visit her so quickly; she was disturbed by the events of the day. Ralph was a very new experience in her little life; she thought of all he had said to her, of how he had looked, of his extreme manliness, his fearlessness, and his great politeness to Miss Grey. Maggie owned with a half-sigh that there was nothing at all particularly gracious in Ralph's manners to her.

"But I like him all the better for that," she thought. "He treats me as an equal; most likely half the time he forgets that I'm a girl,[Pg 30] and believes that I'm a boy like himself. I wish I were a boy! Wouldn't it be jolly to climb trees, and fish, and go out shooting with father! I'd be a great comfort to Ralph if I were a boy, but I'm not; that's the worst of it. How I do wish my pony was black, and was called Raven! I think I'll ask father to sell Snowball; he's rather a fat, stupid little horse. Ralph's horse has an eye of fire. How splendid he must be! I wonder if Jo has got a horse too, and if it is black, and if its eyes flash. Jo must be a splendid girl. How Ralph did look when he spoke of her! I wish I knew her! Ralph talks of her as if she were as good as a boy. I dare say she climbs trees, and fishes, and shoots. I should like Ralph to talk of me as he talks of Jo."

At this stage of Maggie's meditations her bright eyes closed very gently, and she remembered nothing more until the morning.

The sun shone brightly into her room when she awoke; she had been dreaming about Jo. She sprang up instantly, and began to dress herself. This feat she had never accomplished[Pg 31] before in her life. Two servants, as a rule, waited on the little princess when she made her toilet, but now, with a vivid dream of the manly Jo in her mind, and with some vague ideas that she would please Ralph if she were up very bright and early, she proceeded to tumble into her cold bath, and then, after an untidy fashion, to scramble into her clothes. At last her dressing was completed, she knelt down for a moment by her bedside to utter a very hasty little childish prayer, and then ran softly out of her bedroom. She certainly did not know how early it was, but as there was no one stirring in the house, and as she did not wish nurse to find her and to call her back, and perhaps pop her once more into bed, she went on tiptoe along the passages until she reached her Cousin Ralph's bedroom door. She opened the door and went in. The large window of Ralph's bedroom exactly faced his little white bed; the blind of the window was up to the top, and the full light of the morning sun shone directly on the little sleeper's face. Oh, how delightful! thought Maggie. Ralph was still[Pg 32] sound, sound asleep; she was the good one now, for Ralph was decidedly lazy. She went softly to the bedside and gazed at her cousin. His arms were thrown up over his head; he was lying on his back, and breathing softly and easily. Ralph had a handsome little face, and it looked gentle and sweet in his slumbers. The dauntless expression of his dark eyes, and the somewhat scornful and hard way in which he looked when he addressed himself to Maggie, were no longer perceptible. Maggie had a loving little heart, and it went out to her stranger cousin now.

"I hope some day he'll like me as well as he does Jo," she murmured, and then she bent down and printed the lightest of light kisses on his forehead.

"Bother those flies," muttered Ralph, raising his hand to brush the offending kiss away. This remark caused Maggie to burst into a peal of laughter, and of course her laugh aroused the young sleeper.

"Yes, I'm up," said Maggie, dancing softly up and down. "I'm up, and I'm dressed, and[Pg 33] I'm ready to go into the garden. Don't you think it's very good of me to get up so early? Don't you think I'm about as good as that Jo of yours?"

Ralph had recovered from his first surprise, and now he gazed tranquilly at his little cousin.

"What's the hour?" he asked.

Maggie said, "I don't know."

"Well, you'd better find out," responded Ralph; "it feels very early. My watch is on the dressing-table. Do you know the time by a watch yet? If you can read it, you may, and tell me the hour. How untidily you have dressed yourself!"

Maggie felt herself growing very red when Ralph asked her if she could tell the hour by a watch. The fact was, she could not; she had always been too lazy to learn. She went in a faltering way to the dressing-table, feeling quite sure in her little heart that Jo knew all about watches, and that if she revealed her ignorance to Ralph, he would despise her for the rest of her life. Just at this moment, however,[Pg 34] relief came, for the stable clock was heard to strike very distinctly. It struck four times.

"It's four o'clock," said Maggie.

"Yes, and what a muff you are!" answered Ralph. "Four o'clock! Why, it's the middle of the night. Good-night, Maggie. Please go away, and shut the door after you."

"Then you're not getting up?" questioned the little cousin wistfully.

"Getting up? No, thank you, not for many an hour to come. Good-night, Maggie. I don't want to be rude, but you really are a little worry coming in and waking me in this fashion."

It was rather desolate standing at the other side of Ralph's door in the passage. There was plenty of light in the passage, but no sunshine, and Maggie felt her excitement cooling down and her heart beating tranquilly again. All that delightful energy and zest which she had shown when dressing herself, which she had felt when she had danced into her cousin's room, had forsaken her. She walked slowly back to her own little chamber, wondering what she had better do now, and thinking how very disagreeable it was to be spoken of as "a muff." Was it really only the middle of the night, and had she better just ignominiously undress herself and go back to bed?

No; she would not do that. It was horrid to think of Ralph sound and happily asleep,[Pg 36] and of nurse asleep, and father and mother also in the land of dreams. Maggie felt quite forlorn, and as if she were alone in the world. But at this moment a thrush perched itself on a bough of clematis just outside the window, and sang a delicious morning song. The little princess clapped her hands.

"The birdies are up!" she exclaimed. "I expect lots of delightful creatures are up in the garden. I'll go into the garden. Perhaps, after all, Ralph is more of a muff than me."

She swung her garden hat on her head, and ran softly and quickly downstairs. All the doors were barred and locked; the place felt intensely still and strange; but Maggie found egress through a small side window, which she easily opened; and, once in the garden, her loneliness and sadness vanished like magic. She laughed aloud, and ran gayly hither and thither. The butterflies were out, the birds were having a splendid morning concert, and the flowers were opening their petals and taking their morning breakfast from the sunshine.[Pg 37]

"Oh, dear! Ralph is the muff, and I am the good one, after all!" exclaimed Maggie aloud. She ran until she was tired, then went into an arbor at one end of a long grass walk, and sat down to rest herself. In a moment the most likely thing happened—she fell asleep. She slept in the arbor, with her head resting on the rustic table, until the stable clock struck six; that sound awoke her. She rubbed her drowsy eyes and looked around. Jim, the boy who had smiled the night before when he saw Maggie and Ralph talking together, passed the entrance to the little arbor at this moment with a bag of tools slung over his shoulder. Maggie called to him:

"Jim, come here; aren't you surprised? I'm up, you see."

"Why, Miss Maggie!" exclaimed the astonished stable-boy, "you a sitting in the arbor at this hour, miss! Oh, dear! oh, dear! ain't you very cold, missie? And was you overtook with sleep, and did you spend the night here? Why, I 'spect your poor pa and ma were in a fine fright about you, Miss Maggie."[Pg 38]

"Oh, do, they are not," answered Maggie, shaking herself, and running up to Jim, and taking hold of one of his hands. "They know nothing at all about it, Jim. They are all in their beds, every one of them, sound, fast asleep. Even my new Cousin Ralph is asleep. He said I was a muff, but I 'spect he is. Isn't it 'licious being up so bright and early, Jim?"

"Well, no, missie, I don't think it is. I likes to lie in bed uncommon myself, so I do. I 'ates getting up of a morning, Miss Maggie; and whenever I gets a holiday, don't I take it out in my bed, that's all!"

"Oh, you poor Jim!" said Maggie in a very compassionate tone. "I didn't know bed was thought such a treat; I don't find it so. Well, Jim, I'm glad, anyhow, you're obliged to be up this morning, 'cause you and me, we can be company to one another. I'm going with you into the stable-yard now."

"Oh! but, missie, I has to clean out Snowball's stable, and get another stable ready for Master Ralph's pony Raven, and that's all work[Pg 39] that a little lady could have no call to mix with. I think, missie, if I was you, I'd go straight back to my bed, and have another hour or two before Sir John and her ladyship are up."

But Maggie shook her head very decidedly over this proposition.

"No," she said, "I'm going to the stable-yard; I'm going to look at Snowball. I don't think very much of Snowball; I think he'll have to be sold."

Jim opened his eyes and raised his eyebrows a trifle at this proof of inconstancy on Maggie's part, but he thought fit to offer no verbal objection, and the two walked together in the direction of the stables. Here the large stable clock attracted the erratic little maid's attention; she suddenly remembered the dreadful feeling of shame which had swept over her when Ralph had asked her to tell him the hour. She had earnestly wished at that moment that she had been a good child, and had learned how to tell the time when Miss Grey offered to teach her. It would never do for[Pg 40] Ralph to discover her deficiency in this matter. Perhaps Jim could teach her. She turned to him eagerly.

"Jim, do you know what o'clock it is?"

"Yes, missie, of course; it's a quarter-past six."

"Oh! how clever of you, Jim, to know that. Did you find it out by looking up at the stable clock?"

"Why, of course, Miss Maggie; there it is in front of us. You can see for yourself."

Maggie's face became very grave, and her eyes assumed quite a sad expression.

"I want to whisper something to you, Jim," she said. "Stoop down; I want to say it very, very low. I don't know the clock time."

Jim received this solemn secret in a grave manner. He was silent for a moment; then he said slowly:

"You can learn it, I suppose, Miss Maggie?"

"Oh, yes, dear Jim; and you can teach me."

Jim began to rumple up his hair and to look perplexed.[Pg 41]

"I—oh! that's another thing," he said.

"Yes, you can, Jim; and you must begin right away. There's a big, round white thing, and there are little figures marked on it; and there are two hands that move, 'cause I've watched them; and there's a funny thing at the bottom that goes tick-tick all the time."

"That's the pend'lum, Miss Maggie."

"Yes, the pend'lum," repeated Maggie glibly. "I'll remember that word; I won't forget. Now, go on, Jim. What's the next thing?"

"Well, there's the two 'ands, miss; the little 'and points to the hours, and the big 'un to the minutes."

"It sounds very puzzling," said Maggie.

"So it is, miss; so it is. You couldn't learn the clock not for a score of days. I took a week of Sundays over it myself, and I'm not to say dull. The clock's a puzzler, Miss Maggie, and can't be learned off in a jiffy, anyhow."

"Well, but, Jim, Ralph mustn't find out; he mustn't ever find out that I don't know it. It would be quite dreadful what Ralph would think of me then; he wouldn't ever, ever believe[Pg 42] that I could turn out as well as Jo. You don't think Jo such a wonderful girl, do you, Jim?"

"Oh, no, Miss Maggie; I don't think nothing at all about her. I'd better get to my work now, miss."

"Yes, but you must teach me something about the old clock, just to make Ralph s'pose I know about the hour."

"Well, miss, you can talk a little bit about the pend'lum, and the big 'and and the little 'un, and you can say that you think the stable clock is fast; it is that same, miss, and that will sound very 'cute. Now I must go to my sweeping. William will be round almost immediately, and he'll be ever so angry if I have nothing done, so you'll please to excuse me, miss."

Maggie left the stable-yard rather discontentedly.

It was not yet half-past six, and breakfast would not be on the table for two long hours. What should she do? After all, perhaps she was a muff to get up in the middle of the night;[Pg 43] perhaps she was the silly one, and Ralph, so snug and rosy and comfortable in his little bed, was the wise and good one. Some things very like tears came to Maggie's bright blue eyes as she turned back again to the garden, for she was beginning to feel a little tired, and oh! very, very hungry. She wondered if Jo ever got up at four o'clock in the morning, and if Ralph had ever called Jo a muff; but of course he had not. Jo was doubtless one of those unpleasant model little girls about whom nurse sometimes spoke to her on Sunday: little girls who always did at once what their old nurses told them, who never rumpled their pinafores, nor made their hair untidy, nor soiled their clean hands, but walked instead of running, and smiled instead of laughing. Nurse had spoken over and over of these dear little lady-like misses. These little girls delighted in doing plain needlework, and were intensely happy when they conquered a fresh word in their reading, and they always adored their governesses, and were rather sorry when holiday time came. When nurse spoke about these[Pg 44] children, Maggie usually interrupted her vehemently with the exclamation. "I hate that proper good little girl!" and then nurse's small twinkling brown eyes would grow full of suppressed fun, and she would passionately kiss her spoiled darling.

Maggie, as she walked through the garden, where the dew was still sparkling, quite made up her mind that Jo belonged to this unpleasant order of little maids, and she determined to dislike her very much. As she was sauntering slowly along she passed a small narrow path which led into a shrubbery; directly through the shrubbery was another path, which branched out in the direction of Maggie's neglected garden; suppose she went and did a little weeding in her garden; or no, suppose she did what would be much more enchanting, suppose she paid a visit to Ralph's rabbits! Ralph had complained the night before of the hutch where his pets had been put; he had grumbled at its not being bright enough, and large enough, and clean enough. Suppose Maggie went and furbished it up a little, and[Pg 45] looked at Ralph's pets, and gave them some lettuce leaves to eat.

In a moment she had flown through the shrubbery, had passed the little neglected garden and the half-finished rockery, and was kneeling down by the hutch where Ralph's rabbits had made for themselves a new home.

There they were, two beautiful snow-white creatures, with long silky hair, and funny bright red eyes, and pink noses. They had not a black hair on either of their glossy coats. Ralph had said they were very valuable rabbits, and because of the extreme purity of their coats he had called them Lily and Bianco. Maggie, too, thought them lovely; she bent close to the bars of the hutch and called them to her, and tried to stroke their noses through the little round holes. Bianco was very tame, but Lily was a little shy, and kept in the background, and did not allow her nose to be rubbed. Maggie showered endearing names on her; no pet she had ever possessed herself seemed equal to Ralph's snow-white rabbits. After playing with them for a little she ran[Pg 46] into the kitchen garden to fetch some lettuce leaves, and with a good bundle in her arms returned to the rabbit-hutch. At so tempting a sight even Lily lost her shyness, and pressed her nose against the bars of her cage, and struggled to get at the tempting green food.

"They shall come out and eat their breakfasts in peace and comfort, the darlings!" exclaimed Maggie. "Here, I'll make a nice pile of it just by this tree, and I'll open the door, and out they'll both come. While they are eating I can be cleaning the hutch. What a nice useful girl I am, after all! I expect Ralph will think I'm quite as good as that stupid old Jo of his. Come along, Bianco pet; here's your dear little breakfast ready for you. Oh, you darling, precious Lily! you need not be afraid of me. I would not hurt a hair of your lovely coat."

Open went the door of the hutch, and out scampered the two white rabbits. They bounded in rabbit fashion toward the green lettuces, and when Maggie saw them happily feeding, she turned her attention to the hutch.[Pg 47]

"No, this is not a proper hutch," she said to herself. "It's not large enough, nor roomy enough, nor handsome enough. I don't wonder at poor Ralph being put out—he felt he was treated shabby. I must speak to father about it. There must be a new hutch made as quick as possible. Well, I had better clean this one while the dear bunnies are at their breakfast. I'll see if I can get some fresh straw. I'll run round to the yard and try if I can pull some straw out of one of the ricks. I really am most useful. Good-by, Bianco and Lily; I'll be back with you in a moment, dear little pets."

The rabbits did not pay the slightest heed to Maggie's loving words. It is to be feared that, beautiful as they were in person, they possessed but small and selfish natures; they liked fresh lettuces very much, and when they had eaten enough they looked around somewhat shyly, after the manner of timid little creatures. The whole place represented a strange world to them, but as there was not a soul in sight, they thought they might explore[Pg 48] this new land a little. Bianco bounded on in front, and looked back at Lily; Lily scampered after her companion. In a short time they found themselves on the boundary of a green and shady and pleasant-looking wood. In this wood doubtless abounded those many good and tempting things to which rabbits as a race are partial. They went a little further, and lost themselves in the soft green herbage. When Maggie returned to the rabbit-hutch, with her arms full of straw and her rosy cheeks much flushed, Bianco and Lily were nowhere to be seen.

At breakfast that morning Lady Ascot noticed how tired Maggie looked—her blue eyes were swollen as if she had been crying, her pretty cheeks were very red, and she did not come to table with at all her usual appetite. Maggie always breakfasted with her father and mother. She also had her early dinner at their lunch, but her own lunch and tea she took in the schoolroom with Miss Grey. Miss Grey was now present at the breakfast-table, and so also was Ralph. Ralph was a very slight and thin boy, with a dark face and bright eyes. He looked uncommonly well this morning, remarkably neat in his person, and altogether a striking contrast to poor disheveled little Maggie. Maggie felt afraid to raise her eyes from her plate. When her mother noticed her[Pg 50] fatigue and languor, she knew that Ralph's quizzical and laughing gaze was upon her, and that his lips were softly moving to the inaudible words:

"Little muff, she got up in the middle of the night! She got up in the middle of the night!"

Maggie would have been quite saucy enough, and independent enough, to be indifferent to these remarks of Ralph's, and perhaps even to pay him back in his own coin, but for the loss of the rabbits. Bianco and Lily were gone, however; the hutch was empty; it was all the little princess' fault, and, in consequence, her versatile spirits had gone down to zero. With all her faults—and she had plenty—Maggie was far too honest a child to think of concealing what she had done from her cousin. She meant to tell him, but she had dreaded very much going through her revelation, and she felt that his contempt and anger would be very bitter and hard to bear. Maggie always sat next her father at breakfast, and he now patted her on her hot cheeks, looked tenderly at her, and piled the choicest morsels on her plate.[Pg 51]

"The little maid does not look quite the thing," Sir John called across the table to his wife. "I think we must give her a holiday. Miss Grey, you won't object to a holiday, I am sure, and Ralph and Maggie will have plenty to do with one another."

"If you please, sir," here burst from Ralph, "do you mind coming round with me after breakfast and seeing to the accommodation of the rabbits and pigeons? I think my rabbits want a larger and better hutch, if you please, Uncle John."

"All right, my boy, we'll see about them," replied the good-natured uncle. "Hullo, little maid, what is up with you—where are you off to?"

"I—I don't want any breakfast. I'm tired," said Maggie, and before her father could again interrupt her she ran out of the room.

Her heart was full, there was a limit to her endurance; she could not go with Sir John and her Cousin Ralph to look at the empty hutch. She wondered what she should do; she wished with all her heart at this moment[Pg 52] that Ralph had never come, that he had never brought those tiresome and beautiful rabbits to tempt her to open the door of their prison, and so unwittingly set them free. She ran once more into the garden, and went in a forlorn manner into the shrubbery; she had a kind of wild vain hope that Bianco and Lily might be tired of having run away, and might have returned to their new home. She approached the rabbit-hutch; alas! the truants were nowhere in sight; she stooped down and looked into the empty home; and just at this moment voices were heard approaching, the clear high voice of her boy cousin, accompanied by Sir John's deeper tones. Maggie had nothing for it but to hide, and the nearest and safest way for her to accomplish this feat was to climb into a large tree which partly over-shaded the rabbit-hutch. Maggie could climb like any little squirrel, and Sir John and Ralph took no notice of a rustling in the boughs as they approached. Her heart beat fast; she crouched down in the green leafy foliage, and hoped and trusted they would not look up.[Pg 53] There was certainly no chance of their doing that. When Ralph discovered that his pets were gone, he gave vent to something between a howl and a cry of agony, and then, dragging his uncle by the arm, they both set off in a vain search for the missing pets—Bianco and Lily. No one knew better than poor Maggie did how slight was their chance of finding them. She wondered if she might leave her leafy prison, if she would have time to rush in to nurse or mother before Ralph came back. She thought she might try. It would be such a comfort to put her head on mother's breast and tell the story to this sympathizing friend. She had just made the first rustling in the old tree, preparatory to her descent, when Sir John's portly form was seen returning. He was coming back alone, and, after a fashion he had, was saying aloud:

"Very strange occurrence. 'Pon my word, quite mysterious. Whoever did open the door of the hutch? Surely Jim would not be so mischievous! I must question him, and if I think the young rascal is telling me a lie, he[Pg 54] shall go—yes, he shall go. I won't be humbugged. And Ralph, poor lad! It's a disgrace to have my sister's son annoyed in this way on the very first morning of his visit. Why, hullo, Maggie, little woman! What are you doing up there?"

"I'm coming down if you'll just wait a minute, father," called down Maggie. "Oh, please, father, stand close under the tree, and don't let Ralph see us. I'm coming down as hard as ever I can. There, please stretch up your hand, father; when I catch it I'll jump."

"Into my arms," said Sir John, folding her tight in a loving embrace. "My darling, you are not well. You are all trembling. What is the matter, little woman?"

"Nothing, father; only I wanted to speak to you so badly, and I didn't want Ralph to hear. I heard you say that perhaps Jim did it, and you'd send him away. 'Twasn't Jim, 'twas me. I'm miserable about it—'twas all me, father."

"All you? Mag-Mag, what do you mean?"

"I let them out, father. I gave poor Bianco[Pg 55] and Lily some nice lettuce leaves just here under the tree. See, they have not quite finished what I gave them. While they were feeding I thought I'd clean the hutch to please Ralph, and I ran round to the hay-rick for some fresh hay, and when I came back Bianco and Lily were gone. I spent all the time before breakfast looking for them, but I couldn't see them anywhere. Poor Jim had nothing to do with it, father. I did see Jim this morning. I think he's an awfully good boy. Father, Jim had nothing to do with opening the door of the hutch—it was all me."

"Yes, Maggie, so it seems. Ah! here comes Ralph himself. Now, my dear little maid, you really need not be frightened. I'll undertake to break the tidings to Master Ralph. You were a good child to tell me the truth, Maggie."

"I can't find them anywhere, uncle," called back Ralph, in his high voice. "Who could have been the mischievous person? Don't you think it was very wicked, Uncle John, for any one to open my hutch door? I expect some[Pg 56] thief came and stole them. I suppose you are a magistrate, Uncle John; I hope you are, and that you'll have a warrant issued immediately, so that the person who stole my Bianco and Lily may find themselves locked up in prison. Why, if that is not Maggie standing behind you. How very, very queer you look, Maggie!"

Sir John laid his hand on Ralph's shoulder.

"The fact is, my lad," he said, "this poor dear little maid of mine has come to me with a sad confession. It seems that she is the guilty person. She gave your rabbits something to eat, and let them out in order that they might enjoy their meal the better. Then it occurred to her to get some fresh hay for the hutch, and while she was away Bianco and Lily took it into their heads to play truants. You must forgive Maggie, Ralph; she meant no harm. If the rabbits are not found I can only promise to get you another pair as handsome as money can buy."

While his uncle was speaking Ralph's face had grown very white.[Pg 57]

"I don't want any other rabbits, thank you, Uncle John," he said. "It was poor little Jo gave me Bianco and Lily, and I was fond of them; other rabbits would not be the same."

"I only hope, Ralph, your pets will be found. I shall send a couple of men to search for them directly. In the mean time, you must promise me not to be angry with my poor little girl; she meant no harm."

"Oh, I'm not angry," said Ralph; "most girls are muffs; Jo isn't, but then she's not like other people." He turned on his heel and sauntered slowly away.

It is difficult to say how the affair of the rabbits would have terminated, and how soon Maggie would have been taken back into Ralph's favor, but just then, on the afternoon of that very day in fact, an event occurred which turned every one's thoughts into a fresh channel.

Lady Ascot received a telegram announcing the dangerous illness of her favorite and only sister—it was necessary that she and Sir John should start that very night for the North to[Pg 58] see her. The question then arose. What was to become of the two children?

"Send us to mother, of course," promptly said Ralph.

"Hullo!" exclaimed Sir John; "why, I declare if it isn't a good thought. Violet wouldn't mind having you both on a visit for a fortnight or so, and Miss Grey could go with you, so that your mother need have no extra trouble. Remember, Ralph, you are bound to us for the summer, my boy, and we only lend you to your mother for a few days. You quite understand?"

"Lend me to mother; no, I'm sure I don't understand that," said Ralph. "Oh! Maggie," he exclaimed suddenly, in all his old brightest manner, "if we go to London, you'll see Jo!"

"I'll go off this very moment and telegraph to my sister," said Sir John; "the children and Miss Grey can start to-morrow morning. It's all arranged. It is a splendid plan."

In five minutes the plan was made which was to exercise so large an influence over little[Pg 59] Maggie, which was, in short, completely to alter her life. Sir John sent off his telegram, and in the course of the afternoon his sister, Mrs. Grenville, replied to it. She would be ready to receive Ralph and Maggie the next day, and would be pleased also to have Miss Grey, Maggie's governess, accompany the children. Maggie had never seen London; and Ralph became eloquent with regard to its charms.

"It will be delightful for you," he said; "of course I am rather tired of it, for I have been everywhere and seen all the sights, but it will really be very nice for you. You are young, you know, Maggie, and you'll have to go to the places where quite the little children are seen; Madame Tussaud's is one, and the Zoological Gardens is another. Oh, won't it be fun to see you jumping when the lions roar!"

At these words of Ralph's Maggie turned rather pale, and perceiving that he had made an impression, he proceeded still further to work on her feelings, describing graphically the scene at the Zoo when the lions are fed, the[Pg 60] cruel glitter in the eyes of the hungry beasts, and the awful sound which they make when they crush the great bones of meat provided for them.

"You mustn't go too near their cages," said Ralph; "nobody knows how strong a lion is; and though the cages are made with very large bars of iron, yet still——" Here Ralph made an expressive pause.

Maggie opened her blue eyes, remained quite silent for a moment, for she did not wish Ralph to suppose that she was really afraid of the lions, and then she said softly:

"I'm not going to the Zoo—at least not at first. I'm going to do my lessons with Miss Grey in the hours when the lions are fed. I know it's very good of me, but I'm going to be good, 'cause I am so sorry about your rabbits, Ralph."

"So you ought to be," said Ralph, turning red; "but weeks and weeks of being sorry won't bring them back. When people do very careless and thoughtless things, being sorry doesn't mend matters. You ask mother, and[Pg 61] she'll explain to you. But please don't say anything more about Bianco and Lily. I want to know what you mean by saying that you'll do your lessons at the hour the lions are fed. You do your lessons at the hour that most suits Miss Grey, don't you?"

Maggie nodded.

"Yes," she said, "I'm going to please poor Miss Grey too; I'm going to be very good."

"Well, Miss Grey won't like to be kept at home in the afternoons teaching you your lessons—she'll like to be out amusing herself in the afternoon. I call that more thoughtlessness. You'll have to do your lessons in the morning, and the lions are fed at three o'clock, so that excuse won't serve."

"I'm not going to the Zoo," continued Maggie, who began to feel decidedly worried. "If Miss Grey wants to be out in the afternoon, I'll go to Madame Tussaud's then. I don't like that Zoo, and I'm not fond of lions; but I expect Madame Tussaud's must be a nice sort of place."

"Oh—oh—oh," said Ralph, beginning to[Pg 62] jump about on one leg; "you see the chamber of horrors before you make up your mind whether it's a nice sort of place or not. Why, at Madame Tussaud's you always have your heart in your mouth because you don't know whether the wax figures are alive or not; and you are always saying, 'I beg your pardon;' and you are always knocking up against people whom you think are alive and want to speak to you, when they are only big wax dolls; and whenever you give a little start and show by your face that you have made a mistake, the real live people laugh. I can tell you, Maggie, you have to mind your p's and q's at Madame Tussaud's."

"I won't go," said Maggie; "I need not go unless I like;" and then she walked out of the room, beginning seriously to debate in her poor little mind on the joys of having a playmate, for Ralph contrived at every turn to make her feel so very small.

It was well for Maggie that Ralph was a very different boy when with his mother and when without her. When the children arrived in London and found themselves in Mrs. Grenville's pretty bright house in Bayswater, Ralph flew to the sweet-looking young mother who came up to meet them, clasped his arms round her neck, laid his head on her shoulder, and instantly a softened and sweet expression came over his dark and somewhat hard little face. Mrs. Grenville was very much like her brother, so that prevented Maggie being shy with her. She also petted the little girl a great deal, and, as a matter of course, took more notice of her than of Ralph. Mrs. Grenville also spoke about the Zoo and Madame Tussaud's, but she contrived to make these two places of entertainment[Pg 64] sound quite delightful to her little visitor. Instead of dwelling on their horrors she spoke of their manifold and varied charms, until Maggie's eyes sparkled, and she said in her quick, excitable way:

"I'll go there with you, Aunt Violet; I'd like to go to both of those places with you."

Aunt Violet read between the lines here, and gave Ralph a quick little glance which he pretended not to see.

The next morning Mrs. Grenville asked Miss Grey to allow Maggie to have a holiday.

"To-morrow she will begin her lessons regularly," continued the lady. "Of course by this time such a tall girl can read and write nicely, and I shall like to inclose a little letter from her to her mother; but to-day the children and I mean to be very busy together. Ralph, as you are older, and as you know most about London, you shall choose what our amusement shall be."

Maggie felt herself turning first red and then[Pg 65] white when Mrs. Grenville spoke of her reading and writing accomplishments, but Miss Grey was merciful and made no comment, and as Ralph had not yet been made acquainted with the poor little princess' profound ignorance, she trusted that her secret was safe.

"Mother," here eagerly burst in Ralph, "of course the very first thing we must do is to go and see Jo. Shall I go round to see Jo this morning, mother, and may I take Maggie with me? I think it would do Maggie lots of good to see a girl like Jo."

"Jo would do any one good," responded Mrs. Grenville. "It is a kind thought, Ralph, and you may carry it out. If you and Maggie like to run upstairs and get ready now, I will send Waters round with you, and I will call for you myself at Philmer's Buildings at twelve o'clock. After all, I should like to take Maggie myself to the Zoo—I want her to see the monkeys and the birds, and she shall have a ride on one of the elephants if she likes. As to the lions, dear," continued Mrs. Grenville, looking kindly at the little girl, "you shall not see them feed unless you like."[Pg 66]

"I don't mind seeing them feed if you are with me," whispered back Maggie; but just then Ralph called to her imperiously, and she had to hurry out of the room.

"Aren't you glad that you are going at last to see my dear little Jo?" exclaimed the boy. "Now do hurry, Mag; get yourself up nice and smart, for Jo does so admire pretty things."

Maggie made no response, but went slowly into her little bedroom.

In her heart of hearts she was becoming intensely jealous of this wonderful Jo. She was putting her in the same category with those unpleasant little girls who liked needlework, and were exceedingly proper and good, and belonged to that tiresome class of little models of whom nurse was so fond of speaking. Maggie had borne patiently all Ralph's rhapsodies over this perfect little Jo, but quite a pang went through her heart when she heard Mrs. Grenville also praise her.

"I don't want to go," she said as Miss Grey helped her to put on her boots, and took out[Pg 67] her neat little jacket and pretty shady hat from their drawers.

"Not want to go?" said the governess. "Oh, surely you will like the walk with Ralph this lovely morning, Maggie?"

"No, I won't," said Maggie. "I don't want to see Jo; I'm sure she's a horrid good little girl; she's like nurse's Sunday go-to-meeting girls, and I never could bear them."

Miss Grey could not help smiling slightly at Maggie's eager words.

"I remember," she said after a pause as she helped to put the little girl's sash straight, "when I was a child about your age, Maggie, I often amused myself making up pictures of people before I had seen them. I generally found that the pictures were wrong, and that the people were not at all like what I had fancied them to be."

Maggie pondered over this statement; then she said solemnly:

"But I know about Jo—I'm quite sure that my picture of Jo isn't wrong. She wears a white pinafore, and there are no spots on it, and[Pg 68] her hair is so shiny—I 'spect there is vaseline on her hair—and her nails are neat, and her shoes are always buttoned, and—and—and—she's a horrid good little girl—and I don't like her—and I never will like her."

"Maggie! Maggie!" shouted Ralph from below, and Maggie, with a nod at Miss Grey, and the parting words, "I know all about her," rushed out of the room, danced down the stairs, and holding her cousin's hand, and accompanied by the sedate Waters, set out on their morning walk.

It was Maggie's first walk in London, and the children and maid soon found themselves crossing Hyde Park, coming out at one of the gates at the opposite side from Mrs. Grenville's pretty house, and then entering a crowded thoroughfare. Here Waters stepped resolutely between the little pair, took a hand of each, and hurried them along. Ralph carried a small closed basket in his hand, and Maggie wondered what it contained, and why Ralph looked so grave and thoughtful, and why he so often questioned Waters as to the contents of a square box which she also carried.[Pg 69]

"You took great care of that box while I was away, Waters?"

"Well, yes, Master Ralph; it always stood on the mantelpiece in my mistress' room, and I dusted it myself most regularly."

"And do you really think it's getting heavy, Waters?"

"Well, sir, you were away exactly two nights and two days, and that means, by the allowance of one penny a day given to you, two pennies more in the money-box. It's two pennies heavier than it was, sir, when you left us, and that's all."

Ralph sighed profoundly.

"Time goes very slowly," he said. "How I wish I had more money, and that when I had it I didn't spend it so fast. Well, perhaps Jo has managed about the tambourine after all. If there is a good manager, Jo is one. Oh, here we are at last!"

The children and Waters had turned into a shabby-looking street, and were now standing before a block of buildings which looked new and tolerably clean. Unlike any ordinary[Pg 70] house Maggie had ever seen, this one appeared to possess no hall door, but was entered at once by a flight of stone stairs. The children and the servant began to ascend the stairs, and Maggie wondered how many they would have to go up before they reached the rooms where the little girl in the spotless pinafore with the white hands and the smoothly vaselined hair resided. Maggie was rather puzzled and disconcerted by the bare look of the stone stairs, and also by the somewhat anxious and grave expression on Ralph's face. She was unacquainted with that kind of look, and it puzzled her, and she began dimly to wonder if Miss Grey was right, and her picture of Jo was untrue.

At last they stopped at a door, which was shut, and which contained some writing in large black letters on its yellow paint. Maggie could not read, but Ralph pointed to the letters, and said joyfully:

"Here we are at last!"

The words on the door where these: "Mrs. Aylmer, Laundress and Charwoman," but Maggie,[Pg 71] of course, was not enlightened by what she could not understand.

Waters knocked at the door; a quick, eager little voice said, "Come in." There was the pattering of some small feet, the door was flung wide open, and Maggie, Ralph, and Waters found themselves inside Jo's room.

That was the first impression the room gave; it seemed to belong to Jo; Jo's spirit seemed to pervade it all over. Mrs. Aylmer, laundress and charwoman, might own the room and pay the rent for it, but that made no difference—it was Jo's.

Who was Jo? Maggie asked herself this question; then she turned red; then she felt her lips trembling; then she became silent, absorbed, fascinated. The picture she had conjured up faded never to return, and the real Jo took its place.

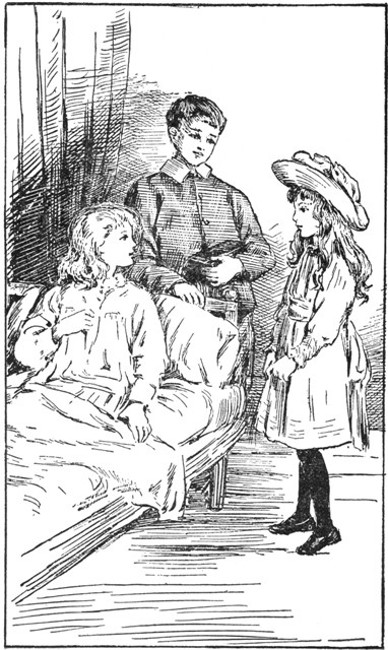

Jo was the most beautiful little girl Maggie had ever seen—she had fluffy, shining, tangled hair; her pale face was not thin, but round and smooth; each little feature was delicate and chiseled; the lips were little rosebuds; the[Pg 72] eyes had that serene light which you never see except in the faces of those children who have been taught patience through suffering. Jo was a sadly crippled little girl lying on a low bed. Maggie, of course, had seen poor children in the village at home; but those children had not been ill; they were rosy and hearty and strong. This child looked fragile, and yet there was nothing absolutely weak about her. At the moment when Ralph and Maggie entered Jo was keeping school; two twin boys were standing by her bedside, and listening eagerly to her instructions.

"No, no, Bob," she was saying, "you mustn't do it that way; you must do it more carefully, Bob, and slower. Now, shall we begin again?"

Bob tried to drone something in a monotonous sing-song, but just then the visitors' faces appeared, and all semblance of school vanished on the spot. Ralph poured out a whole string of remarks. The contents of the money-box were emptied on Jo's bed, and the exciting question of Susy's tambourine came under[Pg 73] earnest discussion. If Susy had a proper tambourine she could use her rather sweet voice to advantage, and earn money by singing and dancing in the streets. Susy was ten years old—a thick-set little girl with none of Jo's transparent beauty. Sixpence had been already collected for the coveted musical instrument; Ralph's box contained eightpence, but, alas! the tambourine on which Susy had set her heart could not be obtained for a smaller sum than half a crown.

"They are not worth nothing for less than that," she exclaimed; "they makes no sound, and when you sings or dances with them, your voice don't seem to carry nohow. No, I'd a sight rayther wait and have a good one. Them cheap 'uns cracks, too, when they gets wet. Here's sixpence and here's eightpence; that makes one shilling and two pennies. Oh! but it do seem as if it were a long way off afore we see our way to 'arf a crown."

Here Susy, whose face had been radiant, became suddenly depressed, and Maggie felt a lump in her throat, and an earnest, almost passionate,[Pg 74] wish to get hold of her father's purse-strings.

"Now come and talk to Jo," said Ralph, drawing his little cousin forward. "We need not say any more about the tambourine to-day; I'm saving up all my money; I earn a penny every day that I'm good, and I'll give my penny to Susy for the present, so she'll really have the half-crown by and by. Now, Jo, this is my Cousin Maggie; I've told her about you. She lives down in the country; she doesn't know much, but then that's not to be wondered at. She was very naughty and careless too about my rabbits; she has asked me to forgive her, and of course I haven't said much; it wouldn't be at all manly to scold a girl; but you are really the one to forgive her, Jo, for the rabbits were yours before they were mine."

"What, Bianco and Lily?" answered Jo, the pink color coming into her little face. "Oh, missie, wasn't they beautiful and white?"

"NOW, JO, THIS IS MY COUSIN MAGGIE."—Page 74.

"NOW, JO, THIS IS MY COUSIN MAGGIE."—Page 74.

"Yes, and they're lost," said Maggie; "'twas I did it. I opened the door of their little house, and they ran out, and went into a wood, and none of us could find them since. Ralph said it was you gave them to him, and he doesn't really and truly forgive me, though he pretends he does. I was sorry, but I won't go on being sorry if he doesn't really and truly forgive me."

To this rather defiant little speech of Maggie's Jo made a very eager reply. She looked into the pretty little country lady's face, right straight up into her eyes, and then she said ecstatically:

"Oh, ain't I happy to think as my beautiful darling white Bianco and Lily has got safe away into a real country wood! Oh, missie, are there real trees there, and grass? and I hopes, oh, I hopes there's a little stream."

"Yes, there is," said Maggie, "a sweet little stream, and it tinkles away all day and all night, and of course there are trees, and there's grass. It's just like any other country wood."

"I'm so glad," said Jo; "I can picter it. In course I has never seen it, but I can picter it. Trees, grass, and the little stream a-tinkling, and the white bunnies ever and ever so happy.[Pg 76] Yes, missie, thank you, missie; it's real beautiful, and when I shuts my eyes I can see it all."

Jo had said nothing about forgiving Maggie; on the contrary, she seemed to think her careless deed something rather heroic, Ralph raised his dark brows, fidgeted a little, and began to look at his cousin with a new respect. At this moment Mrs. Grenville's footman came up to say that the carriage was waiting for the children; so Maggie's first visit to Jo was over.

Maggie and Ralph spent a very happy afternoon at the Zoo. The best of Ralph always came to the surface when he was with his mother, and he was also impressed by Jo's remarks about her rabbits. Was it really true that Maggie had done a beautiful deed by giving his white and pretty darlings their liberty in a country wood? How Jo's eyes shone when she spoke, and how ecstatically she looked at the little princess! Ralph was a great deal too much of a boy, and a great deal too proud to make any set speech of forgiveness to Maggie, but he determined on the spot to restore her to his favor. He ceased to be condescending, and greeted her more as a little hail-fellow-well-met. Maggie rejoiced in the change. Mrs. Grenville was her brightest and most agreeable[Pg 78] self; the lions on near acquaintance proved more fascinating than dreadful, and on their way home Maggie pronounced in favor of the Zoo, said she would certainly like to go there again, and thought that on the whole it must be a nicer place than Madame Tussaud's, where, according to Ralph's account, unless you visited the chamber of horrors there were only large and overgrown dolls to be seen.

"I wonder," said Maggie to her cousin as they sat in the most amiable manner side by side at their tea that evening, "I wonder why Susy cares to go out into the streets and sing and play a funny little tambourine. She can't be at all shy to sing before a lot of people; can she, Ralph?"

Ralph stared hard at Maggie.

"Don't you really know what she does it for?" he asked.

"I suppose for a kind of play," said Maggie, opening her eyes a little.

Ralph stamped his foot impatiently. "A kind of play!" he repeated. "I was beginning to respect you. I forgot how ignorant you are,[Pg 79] Poor Susy goes out and plays the tambourine and dances and sings because she wants pennies—pennies to buy bread for Jo and for herself, and for Ben and Bob. No, of course you can't know! Susy wants the tambourine not to play with, but because she's hungry."

Ralph spoke with great energy; Maggie's little round sweet face became quite pale; she dropped the delicious bread-and-butter and marmalade which she was putting to her lips, and remained absolutely silent.

"Must the tambourine cost half a crown?" she asked presently.

"Yes," replied Ralph; "didn't you hear her say so? She knows best what it ought to cost."

Maggie wished she were not such a dunce, that she could read a little and write a little, and that she had some slight knowledge of figures. Hitherto she had been shy of revealing any of her great ignorance to Ralph, but now her intense longing to know how many pennies were in half a crown made her ask her cousin the question.[Pg 80]

Ralph assured her carelessly that there were thirty pennies in that very substantial piece of money.