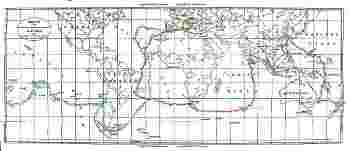

CHART OF THE TRACK OF THE AUSTRIAN IMPERIAL FRIGATE NOVARA

ON HER VOYAGE ROUND THE GLOBE

CHART OF THE TRACK OF THE AUSTRIAN IMPERIAL FRIGATE NOVARA

ON HER VOYAGE ROUND THE GLOBEIn The Years 1857, 1858 & 1859.

Larger.

Title: Narrative of the Circumnavigation of the Globe by the Austrian Frigate Novara, Volume I

Author: Ritter von Karl Scherzer

Commentator: Alexander von Humboldt

Release date: December 31, 2011 [eBook #38456]

Most recently updated: December 15, 2023

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Thorsten Kontowski, Henry Gardiner and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

(This file made from scans of public domain material at

Austrian Literature Online.)

CHART OF THE TRACK OF THE AUSTRIAN IMPERIAL FRIGATE NOVARA

ON HER VOYAGE ROUND THE GLOBE

CHART OF THE TRACK OF THE AUSTRIAN IMPERIAL FRIGATE NOVARA

ON HER VOYAGE ROUND THE GLOBEA member of the scientific corps attached to the Expedition, which, under the auspices of that enlightened friend of science and liberty, the Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian, was despatched on a voyage round the globe, the high honour has been conferred upon me of having entrusted to my care the publication of the Narrative of our Cruise.

In this not more difficult than enviable task, I have been most liberally assisted by my eminent fellow-labourers—the whole literary material collected during the voyage having been kindly placed at my disposal. The comprehensive journals and reports of the venerable Commander-in-Chief of the Expedition, Commodore Wullerstorff-Urbair, as well as the various memoranda of the other members of the Scientific Commission, contributed materially to the elucidation of my own general notes, as well as my observations upon special subjects, which latter chiefly referred to the Geography, Ethnography, and general Statistics of the various countries visited.vi

While preparing the details of our voyage for publication in my own language, the idea perpetually presented itself that a translation of this narrative into English might prove not unacceptable to the British public. And although fully aware that a voyage round the globe, in the course of which little more than the coasts were visited of the various countries we touched at, could not pretend to offer much new information to the greatest of maritime nations, it seemed, nevertheless, that it might interest a people so eager in the pursuit of knowledge as the English, to know the impression which has been made upon travellers of education by the Colonies and Settlements of Britain throughout the world.

The English language, moreover, being spoken more or less over the greater part of the earth's surface, geographically speaking, the author who addresses his readers in that tongue is sustained by the flattering conviction that he will be understood by the majority of the nations of the globe! For it is not alone the educated classes of all countries that seek to master a language which possesses such a grand—all but unrivalled literature! The political and commercial development which Great Britain enjoys under the benign influence of liberal institutions, has made English the medium of intercourse among almost all sea-faring nations; nay, even barbarous tribes find it their obvious interest to get a slight inkling at least of the language of a people whose civilizing and elevating energiesvii they may not, it is true, understand, far less appreciate, but whose imposing power inspires them with awe, while they are more closely attached by the tie of material advantage.

The following narrative describes the most important occurrences and most lasting impressions of a voyage during which we traversed 51,686 miles, visited twenty-five different places, and spent 551 days at sea, and 298 at anchor or on shore.

As the purely scientific results of the Expedition will be published separately under the supervision of Commodore Wullerstorf and the other members of the scientific corps, I shall, in this place, only attempt to place before the reader a general outline of the countries and races visited during our cruise in different regions of the world.

In relating simply and concisely what was seen and experienced, I have endeavoured to avoid incurring the reproach, so frequently launched by English critics against German works of travel, of dryness and minute detail, such as render them distasteful to the English reader, and make it almost impossible to enlist his attention or evoke his sympathy.

If, as is specially the case with respect to natural science, many a doubtful point still remains undecided—if the ingenious "Suggestions" of the immortal Alexander von Humboldt (for the translation of which I feel particularly indebted to that profound scholar, my learned and esteemed friend Mr. Haidinger, whose name will be familiar to theviii scientific world in Great Britain), could not be acted upon to the extent and in the effectual manner each of us could have wished, the reason for such deficiencies will be found in the peculiar mission of the Expedition, and in the arrangement of our route, which was specially laid out with reference to the numerous and widely different objects, which it was specially intended to keep in view throughout the voyage.

Among the more prominent of these, may be specified the opportunity thus afforded for the practical instruction of our young and rapidly-increasing navy; the unfurling of the Imperial flag of Austria in those distant climes, where it had never before floated; the promulgation of commercial treaties; the aid afforded to science in exploration and investigation, as well as by the collection of those objects of Natural History, the acquisition of which is all but impossible to the solitary naturalist, owing to the expense and difficulty of transport,[1] and the establishment everywhere of friendlyix correspondence between our own scientific institutions and those in remote regions, I have considered it necessary to invite the attention of the British reading public to these circumstances, in order to make them more intimately cognisant of our various and manifold tasks, and thus make them the more readily disposed to overlook the deficiencies and discrepancies of this book, which I now respectfully commit to their perusal.

[1] Notwithstanding the short period at our disposal at each port, which concomitant necessity militates so much against the practical utility of a circumnavigation of the globe as compared with an expedition solely directed to one single centre of scientific observation, the collection of objects of Natural History made during the cruise are very extensive, and unusually rich in new or rare species. The zoological department alone embraces above 23,700 individuals of different kinds of animals: viz. 440 mammalia, 300 reptiles, 1500 birds, 1400 Amphibiæ, 1330 fish, 9000 insects, 8900 Molluscs and Crustaceæ, 300 birds' eggs and nests, besides numerous skeletons. The botanical collection consists of Herbaria, seeds of useful plants, special regard being had to those best adapted for the various climates of the respective Austrian provinces, drugs, specimens of dye-woods, and timber, fruits preserved in alcohol, &c. The Geological and Palæontological Museums of our country have likewise been enriched with various rare and valuable specimens, particularly in consequence of Dr. Hochstetter, the geologist of the Expedition, having prolonged his stay in New Zealand, where, at the special request of the Colonial Government, he explored the province of Auckland. The Ethnographical and Anthropological collection consists of above 550 objects, among which are 100 skulls, representing the craniology of almost all the races of the globe.

Before concluding, I beg leave to express my hearty thanks to all those who have contributed in such various ways to aid my humble efforts—to specify some were invidious, as in so doing I must wrong others. To each and all I return the most heartfelt gratitude.

May the indulgent reader peruse the following pages with an approving eye—may they afford him as much satisfaction and as much interest as I experienced in committing to paper the descriptions and impressions therein set forth, since in so doing, I, so to speak, made the delightful voyage for the second time, and in thought visited once more the different localities, from every one of which I, and my fellow-travellers, brought away none but the most friendly and agreeable recollections.

It inspires a German traveller with a peculiar and loftyx feeling of pride and delight that he can look upon himself as belonging to a race, to whom seems to have been reserved the diffusion of a New Life over the earth—whose special mission it appears to be to make even the most primitive tribes in the remotest corner of the world acquainted with the blessings of Christian civilization, of political liberty, of intellectual culture, and, standing triumphant on the ruins of slavery and despotism, to proclaim to the great family of universal mankind, the advent of a new, a vernal era of Faith, Freedom, and Happiness!

Trieste, 18th March, 1861.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PREPARATIONS FOR THE VOYAGE. | |

| PAGE | |

| Approval of the Plan to fit out an Austrian Man-of-War for a Voyage round the World.—Object of the Expedition.—Appointment of a Scientific Commission.—Preparations.—Fitting out the Frigate Novara at Pola.—Departure for Trieste.—Visit of the Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian on board. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| FROM TRIESTE TO GIBRALTAR. | |

| Departure.—Fair Voyage down the Adriatic.—A Man lost and found again.—Passage through the Straits of Messina.—The Steamer Sta. Lucia returns to Trieste.—Regulations and Instructions for further Proceedings.—A Day on Board the Novara.—Sunrise.—Cleaning the Ship.—Mental and Physical Occupation.—Moonlight at Sea. | 11 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| GIBRALTAR. | |

| Political Significance of the Rock.—Courtesy of the British Authorities.—Fortifications.—Signal Stations.—The only Place in Europe frequented by Monkeys.—Calcareous Caves.—Chief Entrances into the Town.—Shutting the Town Gates.—Public Establishments.—Inhabitants.—Elliott's Gardens.—The Isthmus, or Neutral Ground.—Algeziras.—Ceuta.—Commerce and Navigation.—Excellent Regulation in the English Navy relative to Officers' Outfit.—Small-pox appears on board the Caroline.—Departure from Gibraltar.—A Fata Morgana.—The Novara passes the Straits.—Takes leave of Europe.—Voyage to Madeira.—Floating Bottles to ascertain the Currents.—Arrival in the Roads of Funchal. | 29 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| MADEIRA. | |

| First Impressions.—Difficulty in Landing.—Description of the Island.—History.—Unfavourable Political Circumstances connected with the Cultivation of the Ground.—Aqueducts.—First Planting of the Sugar-cane.—Culture of the Vine.—Its Disease and Decay.—Cochineal as a Compensation for its Loss.—Prospects of Success.—Climate.—A favourable Winter Residence for the Consumptive.—Strangers.—First Appearance of the Cholera.—Observations with the Ozonometer.—Great Distress among the Lower Classes.—Liberal Assistance from England.—Decline of Commerce.—Inhabitants and their Mode of Life.—Decrease of the Population, and its Causes.—Benevolent Institutions.—Public Libraries.—The Cathedral.—Barracks.—Prison.—Environs of Funchal.—Excursion to St. Anna.—Ascent of the Pico Ruivo.—Singular Sledge Party.—Return to Funchal.—Departure. | 58 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| RIO DE JANEIRO. | |

| Brazil the Land of Contrasts.—Appearance of the City of Rio and its Environs.—Excursion to the Peak of Corcovado, and the Tejuca Waterfalls.—Germans in Rio.—Brazilian Literary Men.—Assacú (Hura Brasiliensis.)—Snake-bite as an Antidote against Leprosy.—Public Institutions.—Negroes of the Mozambique Coast.—The House of Misericordia.—Lunatic Asylum.—Botanical Garden.—Public Instruction.—Historico-Geographical Institution.—Palæstra Scientifica.—Military Academy.—Library.—Conservatory of Music.—Sanitary Police.—Yellow Fever and Cholera.—Water Party on the Bay.—Chamber of Deputies.—Petropolis.—Condition of the Slave Population.—Prospects of German Emigration.—Suitability of Brazil as a Market for German Commerce.—Natural Products, and Exchange of Manufactures.—Audience of the Emperor and Empress.—Extravagant Waste of Powder for Salvoes.—Songs of the Sailors.—Departure from Rio.—Retrospect.—South-east Trades.—Cape Pigeons.—Albatrosses—Cape Tormentoso.—A Storm at the Cape.—Various Methods of Measuring the Height of Waves.—Arrival in Simon's Bay. | 121 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| CAPE OF GOOD HOPE. | |

| Contrasts of Scenery and Seasons at Cape Colony.—Ramble through Simon's Town.—Malay Population.—The Toad-fish, or Sea-devil.—Rondebosch and its delightful Scenery.—Cape Town.—Influence of the English Element.—Scientific and other Institutions.—Botanical Gardens.—Useful Plants.—Foreign Emigration.—A Caffre Prophet and the Consequences of his Prophecies.—Caffre Prisoners in the Armstrong Battery.—Five young Caffres take Service as Sailors on Board the Novara.—Trip into the Interior.—Stellenbosch.—Paarl.—Worcester.—Brand Vley.—The Mission of Moravian Brethren at Genaadendal.—Masticatories and intoxicating Substances used by the Hottentots.—Caledon.—Somerset West.—Zandvliet.—Tomb of a Malay Prophet.—Horse Sickness.—Tsetse-fly.—Vineyards of Constantia.—Fête Champétre in Honour of the Novara.—Excursion to the actual Cape of Good Hope.—Departure.—A Life saved.—Experiments with Brook's Deep-sea Sounding Apparatus.—Arrival at the Island of St. Paul in the South Indian Ocean. | 196 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE ISLANDS OF ST. PAUL AND AMSTERDAM, IN THE SOUTH INDIAN OCEAN. | |

| Former History.—Importance of the Situation of St. Paul.—Present Inhabitants.—Preliminary Observations.—To whom do the Islands belong?—Fisheries.—Hot springs.—Singular Experiment.—Penguins.—Disembarkation.—Inclement Weather.—Remarks on the Climate of the Island.—Cultivation of European Vegetables.—Animal Life.—Library in a Fisherman's Hut.—Narrative of old Viot.—Re-embarkation.—An official Document left behind.—Some Results obtained during the Stay of the Expedition.—Visit to the Island of Amsterdam.—Whalers.—Search for a Landing-place.—Remarks on the Natural History of the Islands.—A Conflagration.—Comparison of the Two Islands.—A Rencontre at Sea.—Trade-wind.—Christmas at Sea.—"A man overboard!"—Cingalese Canoe.—Arrival at Point de Galle, in Ceylon. | 267 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| CEYLON. | |

| Neglect of the Island hitherto by the English Government.—Better Prospects for the Future.—The Cingalese, their Language and Customs.—Buddhism and its Ordinances.—Visit to a Buddhist Temple in the Vicinity of Galle.—The sacred Bo-tree.—Other Aborigines of Ceylon.—The Weddàhs.—Traditions as to their Origin.—Galle as a City and Harbour.—Snake-charmers.—Departure for Colombo.—Cultivation of the Cocoa-nut Palm a benevolent, Buddha-pleasing work.—Polyandria; or, Community of Husbands—Supposed Origin.—Annual Exportation of Cocoa-nuts.—Rest-houses for Travellers.—Curry the national Dish.—A Misfortune and its Consequences.—The Catholic Mission of St. Sebastian de Makùn, and Father Miliani.—Annoying Delays with restive Horses.—Colombo.—A Stroll through the "Pettah," or Black Town.—Ice Trade of the Americans with Tropical Countries.—Cinnamon Gardens and Cinnamon Cultivation.—Consequences of the Monopoly of Cinnamon.—Rise and Expansion of the Coffee Culture in Ceylon.—Pearl-fishery.—Latest Examination of the Ceylon Banks of Pearl Oysters, by Dr. Kelaart, and its Results.—Aripo at the Season of Pearl-fishing.—The Divers.—Pearl-lime, a chewing Substance of wealthy Malays.—Annual Profit of the Pearl-fishery.—Origin of the Pearl.—Poetry and Natural Science.—Artificial Production of the Pearl.—The Chank-shell.—The Wealth of Ceylon in Precious Stones.—Visit to a Cocoa-nut Oil Manufactory.—The Cowry-shell, a Promoter of the Slave Trade.—Discovery of valuable Cingalese MSS. on Palm-leaves.—The heroic Poem of "Mahawanso," and Turnour's English Translation of it.—Hospitality of English Officials in Colombo.—A second Visit to Father Miliani.—Agreeable Reception.—The Antidote-oil against Bites of Poisonous Snakes.—Adventures on the Journey back to Galle.—Ascent of Adam's Peak by two Members of the Expedition.—The Sacred Footprint.—Descent.—The "Bullock-bandy," or Native Waggon.—Departure from Galle for Madras.—The Bassos (Shallows).—A Berlin Rope-dancer among the Passengers.—Nyctalopia; or, Night Blindness.—Fire on Board.—Arrival in Madras Roads. | 345 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| MADRAS. | |

| "Catamarans" and "Masuli" Boats.—Difficulty of Disembarkation, and Plans for remedying it.—History.—Brahminism.—Festival in Honour of Vishnù.—Employment of Heathens under a Christian Government.—Politics and Religion.—Laws of Brahminic Faith.—The Observatory.—Museum of Natural History and Zoological Garden.—Academy of Fine Arts.—Medical School.—Infirmary.—Orphan Asylum.—Dr. Bell.—Lancastrian Method of Teaching Children first Applied in Madras.—Colonel Mackenzie's Collection of Indian Inscriptions and MSS.—The Palace of the former Nabob of the Coromandel Coast.—Journey by Rail to Vellore.—Féte given by the Governor in Guindy Park.—Visit to the Monolithic Monuments of Mahamalaipuram.—Excursion to Pulicat Lake.—Madras Club.—Féte in Honour of the Members of the Novara Expedition.—"Tiffin" and Dance on Board.—Departure from Madras.—Zodiacal Light.—Shrove Tuesday in the Tropics.—Arrival at the Island of Kar-Nicobar. | 424 |

Transcriber's Note: The text of the letter above, along with supplemental address information, are in the first volume of the German edition:

In compliance with the gracious invitation which H.I.H. the Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian was pleased to address to me from Trieste (December 12th, 1856), and as yet barely recovered from an indisposition, I jot down these hasty notes, without presuming to give definite instructions, such as those I drew up, conjointly with M. Arago, for the guidance of the French expeditions, or for Lord Minto, then First Lord of the Admiralty, on the occasion of the Antarctic Voyage of Discovery of Sir James Ross (1840-43). The following pages consist simply of hints which may possibly prove serviceable to the distinguished and highly informed gentlemen, who have the good fortune to sail on board the Imperial Frigate, Novara, under the command of Commodore von Wüllerstorf. With two of these savans, Dr. Ferdinand Hochstetter and Dr. Karl Scherzer, I have had the pleasure, here in Berlin, to agree verbally on various subjects.xviii

As I do not exactly know what course it is intended the Novara shall follow in navigating the Atlantic, nor in what meridian it is proposed to cross the Equator, (in conformity with the sound and useful directions of my friend Lieut. Maury, of Washington), on her voyage to Rio de Janeiro, nor how near she shall keep to Cape San Roque and Fernando de Noronha, I must content myself with inviting the attention of the voyagers in a general way to the temperature of the sea, as also to the variations and aberrations of the magnetic curves, and their currents.

A lower degree of temperature is usually observed W. of the Canaries, and Cape Verde Islands, commencing with the Salvages, the thermometer indicating as low as 72°·7 Fahr. This has been already ascertained by Mr. Charles Deville, in his chart of temperature on the voyage "aux Antilles, à Ténériffe et à Fogo." I consider this diminution of temperature results from the North Guinea current, bringing with it cold water from the north southwards as far as the Bight of Biafra and the River Gaboon, at which point it is encountered by an opposite current flowing northwards along the south-western coast of Africa from Loando and Congo.

In 1825, Captain Duperrey had accurately laid down the point of intersection of the magnetic, with the terrestrial equator. In 1837, we learned from Sabine's investigations of magnetic inclination near the Island of St. Thomas (on the Equator, adjoining the above portion of the coast of Africa),xix that this point of intersection had already shifted four degrees to the westward. A period of twenty years having elapsed since Sabine's expedition for determining observations with the pendulum, it would be most desirable that fresh investigations should be made in that neighbourhood, for the purpose of verifying the secular changes of all magnetic curves, especially with regard to their variation. In 1840, the line of no declination in America began 9° 30′ E. of South Georgia, whence it ran to the S.E. coast of Brazil, near Cape Frio, thus traversing the mainland of South America only between the latter point and the parallel of 0° 36′ S., when it leaves the continent a little to the east of Gran Parà, near Cape Tigioca, cutting the terrestrial equator again, but in 50° 6′ W. According to Bache's Map of Equal Magnetic Declination, it reaches the coast of North America near Cape Fear, to the south-west of Cape Lookout. This line, along which the magnetic declination is nil, extends to a point in Lake Erie, 2° 40′ W. of Toronto, where the declination is already 1° 27′ W.[2]

[2] Wherever, in this paper, it is not precisely expressed to the contrary, the scale of the Centigrade Thermometer, the longitude from the Meridian of Paris, the French foot (pied du roi=12·79 inches English), and the geographical mile, 15 to a degree of the Equator, measuring 3807 "toises," are meant.

It is evident from the observations of Captains Beechey and Findley, and still more particularly from those of the French Captain Kerhallet, that the remarkable subdivision of the main equinoctial current, flowing from east to west into two branches, one directed to the N.W., the other to the S.S.W.,xx commences at a considerable distance from the Capes of St. Roque and St. Augustin. This bifurcation has always, and with good reason, been ascribed to the protruding convexity of the South American continent at these two promontories. It would be an important step gained in verifying the theory of currents, could the precise distance be ascertained by chronometer. It is apparently like an "actio in distans," probably a phenomenon of what is known as "packing." As the frigate, on leaving Rio de Janeiro is to make for the Cape of Good Hope, the opportunity will present, should she steer sufficiently southerly, for many interesting observations with respect to the connecting current W.N.W. and E.S.E. which encounters that from Madagascar and Mozambique, close to the Cape, more especially with regard to the temperature of the sea.

If the frigate is intended to approach the small cluster of islands of Fernando de Noronha, E. of Pernambuco (Lat. 3° 50′ S.), I would recommend to that excellent geognostic, Dr. Hochstetter, the hornblendic phonolithe rock found there, far from a volcanic crater, but with trachytic dykes and basaltic amygdaloid. The flat little island of St. Paul (Peñedo de San Pedro), 1° N. Lat., singular to say, is not volcanic at all, containing, like the Malouin or Falkland Islands, slaty green-stone passing into serpentine.

Should the frigate alter her course and cross the Equator more to the eastward, without touching at Rio de Janeiro, she might possibly fall in with the Marine Volcanic region,xxi (Lat. 0° 20′ S., Long. 22° W.), which has quite lately become famous again by the U. S. Expedition of the Brig Dolphin (1854), commanded by Lieutenant Lee. On 19th May, 1806, columns of black smoke were seen issuing from the sea by Krusenstern, and volcanic ashes were gathered, after a singular bubbling of the sea from 1748 to 1836, according to careful investigations by Daussy.

As the frigate is commissioned to visit Ceylon and the Nicobar Islands, she cannot sail direct from the Cape to Australia; and the hope must therefore be abandoned of her visiting the small basaltic islands, known as Prince Edward's (47° 2′ S., 38° E.), and Possession (46° 28′ S., 47° 30′ E.), belonging to the Crozet's Group, or the two islands, long confounded with each other, of Amsterdam (Lat. 37° 48′ S.) and St. Paul (Lat. 38° 38′ S.) The latter island, the more southerly of the two, (a very characteristic drawing of which was given by Willem de Vlaming so far back as 1696), is supposed to be volcanic, not only by its form, which will at once remind the geologist of Santorin, Barren Island, and Deception Island, (one of the New Shetland group), but also in consequence of the eruption of steam, and the flames occasionally observed there.

As for Amsterdam, which consists of a single densely-wooded mountain, the puzzle remains for solution as to how, during the expedition of D'Entrecasteaux in 1792, the whole island seemed, during two entire days, enveloped in smoke; whereas, on landing there, the naturalists of that expeditionxxii were satisfied that the mountain was not an active volcano, and that the columns of steam issued out of the ground near the shore! As yet, the phenomenon remains entirely unexplained.

If we examine any map of the Indian Ocean, we may trace the continuation of the Sunda group from Sumatra, N.W., through the Nicobar, and Great and Little Andaman Islands, and thence through the volcanoes of Barren Island, Narcondam and Cheduba, nearly parallel with the coasts of Malacca and Tenasserim, all on the eastern part of the Bay of Bengal. The minor volcanoes just enumerated will present valuable opportunities of geological enquiry.

Along the coasts of Orissa and Coromandel, the western portion of the Bay of Bengal is quite free of islands, Ceylon, like Madagascar presenting rather the type of a continent.

Off the W. coast of the peninsula of India, (that is opposite the Neilgherrie hills, and the coast of Canara and Malabar), there is a series of three archipelagoes, extending from 14° N. to 8° S., viz., the Laccadives, the Maldives, and the Chagos, which appears, as it were, continued through the banks of Sahia di Malha, and Cargados Carajos, to the volcanic group of the Mascarenhas and Madagascar. As the first-named archipelagoes, so far as is yet known, consist solely of coral, and are, consequently, true "atolls," or reef-lagoons, the bottom of the ocean should be examined over a large extent, adopting the ingenious hypothesis of Darwin, that it is to be considered as an area of subsidence, rather than an elevated region.xxiii

It would also be a matter of great importance to get observations respecting terrestrial magnetism, particularly so as to define the position of a given segment of the magnetic equator. Capt. Elliott, as the result of his comprehensive studies, (1846-49), ascertained that the magnetic equator passes through the north end of Borneo, and thence nearly due W. to the northern extremity of Ceylon. In this region the curve of minimum intensity is nearly parallel to the magnetic equator, which intersects the Continent of Africa near Cape Guardafui—according to Rochet d'Héricourt, in lat. 10° 7′ N., long. 38° 5′. E. Between this point and the Bight of Biafra nothing is known.

The South Asiatic islands comprise Formosa, the Philippines, the Sunda group, and the Moluccas. The great and little Sunda Islands and the Moluccas embrace 109 volcanoes, with fiery eruptions, and 10 what are called mud-volcanoes. This is not a mere estimate, but is the result of an enumeration by Junghuhn, who, within the last year (1856), has returned to Java, and thoroughly equipped by M. Pahud, Governor-General of the Indian Netherlands, will be of great assistance to the Imperial Expedition.

An exact mineralogical determination of the volcanic rocks (trachytes) is unfortunately wanting everywhere.

The most active volcano of Sumatra is the Gunung Merapi (8980 feet), which must not be confounded with a volcano in Java, of the same name. That of Sumatra was ascended by Dr. L. Horner, and Dr. Korthals in 1834. We mayxxiv pronounce Indrapura (11,500 feet, but this measurement is very uncertain), and Gunung Pasoman (9010 feet), the Ophir of our maps, to be utterly unknown geologically. The highest of the Java volcanoes is Gunung Semeru (11,480 feet), ascended by Junghuhn in 1844, 1220 feet higher than the Etna. The largest craters of the 45 which are disposed in a line along the shores of Java, are Gunung Tengger, and Gunung Raou. Dr. Junghuhn has recently given the outlines of each separate volcano in his splendid topographical and geological map of Java, in four sheets, published in 1856, which does great credit to the Dutch Government.

The following subjects are worthy of special attention while the frigate is at Java.

1. The curious phenomenon of the ribbed surface. (Vide Junghuhn, Java, Part II., p. 608.)

2. The disposition, as yet unaccounted for, of a series of regularly-shaped hills, formed by the mud-streams ejected in the year 1822 by the volcano of Gunung Galungung. (Vide ut suprà, pp. 127-731.)

3. The ejection of water by the Gunung Idjen, on 21st January, 1817, (pp. 707, and 717-121).

4. The erroneousness of the assertion that the volcanoes of the Island of Java do not emit streams of real lava.

It must be admitted that the mighty Javanese volcano, Gunung Merapi, already alluded to, has not, within the historic period, presented any coherent compact streams of lava, but mere fragments and boulders; although in 1837,xxv lines of fire were seen running uninterruptedly from the top down the sides of the cones in eruption. But each of the three volcanoes, Tengger, Idjen, and Slamat, present examples of black lava currents, descending as far as the tertiary strata.

Streams of stone-boulders, red-hot, similar to those of the Cotopaxi, but scarcely touching each other, flowed from Gunung Lamorgan on 6th July, 1838.

No active volcano is known in the island of Borneo. The highest mountain of the whole island, perhaps of the whole insular world of Southern Asia, is the Hina Baïlu (12,850 feet?) on the northern point of Borneo. It is as yet unexplored. According to Dr. Lewis Horner, son of the astronomer of the Krusenstern expedition, there occur among the syenite and serpentine mountain range of Rathus, on the S.E. of the island, deposits yielding gold (which has even been worked by diggings), diamonds, platinum, iridium, and osmium,—presenting, in fact, a similar association to those of the Ural mountains. No mention is made of palladium. Rajah (now Sir James) Brooke describes in the province of Sarawak in Borneo, a low hill, Gunung Api ("hill of fire" in Malay), the slags of which attest former volcanic activity. A visit to Borneo would be of very great service.

There are eleven volcanoes in Celebes, and six in Flores, all active.

It is still uncertain whether the conical mountain Wawari,xxvi or Atiti, which is more generally known as the volcano of the island of Amboyna, ever poured out anything except hot mud (1674), or whether it should be merely classed as a solfatara. The main group of the South Asiatic Islands is connected through the Moluccas and the Philippines with the Papua and Pellew islands, and the Caroline Archipelago of the South Sea.

The most important geological fact to be remarked with reference to the island of Formosa, abounding in mineral coals, is the break in the line of direction of the open vents, when, instead of N.E. to S.W., the central line follows the meridian line, which it pursues nearly as far as 6° S., passing through Formosa and the Philippine Islands (Luzon and Mindanao), respecting which deviation nothing certain is known, and in which region every mountain of conical shape, or outline is invariably set down as a volcano, even though there should be no indications of a crater. The Sooloo Archipelago forms the connecting link between the islands of Borneo and Mindanao, the long, narrow island of Palawan, constituting that between Borneo and Mindoro.

The Island of Yesso, separated from that of Niphon by the Straits of Sangar, or Tsugar, and from the islands of Krafto (Saghalien) and Tschoka, or Tarakai, by the Straits of La Pérouse, connects, through its North Eastern Cape, with the archipelago of the Kuriles. From Broughton's Southern Vulcan Bay up to its northernmost point, Yesso is traversed by an uninterrupted range of volcanoes—a fact the more worthyxxvii of being recorded, as in the expedition of La Pérouse there were found red porous lavas, as well as wide areas, covered with slags, in the Baie des Castries, in the narrow island of Krafto (Saghalien), which is, as it were, merely a continuation of Yesso. In our own day these regions command a higher interest, from a political point of view, more especially since Russia, dissatisfied with the situation of Okhotsk, at the sanded mouth of the Amoor, was anxious, after the destruction of Petropaulowski, on the coast of Kamtschatka, to obtain, on the S.E. coast, a harbour suitable for a military station.

Among the three islands which form the main portion of the Japanese Empire, six volcanoes are known to have had eruptions in the historic period. The volcano, Fusi Jama, in Niphon, province of Suruga (Lat. 35° 18′ N., Long. 136° 15′ E., altitude 11,675 feet), is said to have risen out of the plain 286 years before the Christian era. Its last eruption was in 1707. The volcano, Asama Jama, in the district of Saku, between the meridians of the two capitals, Miaco and Jeddo, was last in eruption in 1783. On the island of Kiusiu, adjoining the peninsula of Corea, four volcanoes are situated, from one of which, called Wanzen, there was a most destructive eruption in 1793.

The beautiful work of Commodore Perry, U.S.N., detailing his mission to Japan, on the part of the United States Government, in 1852, containing excellent photographs of races, as also drawings by the Berlin artist, Wilhelm Heine,xxviii does not, as yet, comprise the scientific results of that expedition.

Proceeding northwards, the volcanoes are more densely crowded, and are found arranged in series. Of the fifty-four which I enumerated as still in activity among the islands of Eastern Asia, there are thirty-four on the Aleutian, and ten on the Kurile Islands. The Peninsula of Kamtschatka contains nine volcanoes, which have been in activity within the historic period. Lying under the 54th and 60th degrees of northern latitude, we see a long strip of sea-bottom between two continents undergoing a perpetual process of destruction and re-arrangement.

The South Sea, the superficial extent of which is one-sixth greater than that of the entire solid crust of our planet, actually presents a smaller number of active volcanoes, less vents for communication between the centre of the earth and its atmospheric envelope, than the single Island of Java! Out of 40 volcanic cones, including those which are extinct, only 26 have been seen in eruption during the historic period. They are not scattered at random, but, on the contrary, as was pointed out by Mr. James Dana, the ingenious geologist of the great United States Exploring Expedition, under the command of Capt. Wilkes (1838-42), they have been thrown up, at widely extending clefts, communicating by submarine mountain systems. They are arranged in groups and distinct regions, analogous to the mountain chains of Central Asia andxxix Armenia (in the district of the Caucasus), and belong to two quite distinct systems, one running S.E. to N.W., the other S.S.W. to N.N.E.

In the Hawaiian Archipelago (or Sandwich Island group), we find Mauna Loa, according to Wilkes, 12,900 feet in height, which does not present any cone of volcanic scoriæ (resembling, in this particular, the volcanoes of the Eifel), but has emitted streams of lava. The lava basin of Killauea, 13,000 feet in its greatest, by 4800 in its smallest diameter, is not a solfatara, but a true lateral vent on the flank of the powerful Mauna Loa itself, exactly resembling the less elevated sheet of lava of Arak. Mauna Kea is 180 feet higher than Mauna Loa, but is extinct. Tafoa and Amangura, in the Tonga group, are still in eruption, the last discharge of lava having occurred in July, 1847. The volcano of Tanna was in full eruption during Capt. Cook's Voyage of Discovery in 1774, as was also the volcano of Ambrym, west of Malicollo in the archipelago of the New Hebrides. At the south point of New Caledonia, lies Matthew's Rock, a small smoking rocky island. The volcano of Santa Cruz, N.N.W. of Tina Kora, with periodical eruptions occasionally occurring at intervals of 10 minutes, had been already noticed as a volcano by Mendana, so far back as 1595. In the Salomon Archipelago, there is found the volcano of Sesarga, while others are said to be in full activity in the Marianas or Ladrones, just like those of Guguan, Pagon, and El Volcan Grande dexxx Asuncion, which appear to have broken forth along a line that follows the meridian. In New Britannia, three conical mountains were observed vomiting streams of lava, by Tasman, Carteret, and Labillardière. There are two volcanoes in full activity on the north-east coast of New Guinea, opposite Admiralty Islands, which themselves are so rich in obsidian. In New Zealand, numerous regions abound in basaltic and trachytic rocks. Of active volcanoes there are Puhia-i-Wakati (the volcano of White Island), and the lofty cone of Tongariro (5816 feet). To the absence of centres of volcanic agency in New Caledonia, where sedimentary formations and seams of coal have recently been discovered, is ascribed the vast development of coral reefs. Dana was the first to ascend the Peak of Tafua, in the Island of Upolu, one of the Samoa group, not to be confounded with the still active volcano of Tafoa, south of Amangura, in the Tonga Archipelago. Dana found in it a crater overgrown with thick forest. So, too, on the isolated Vaihu or Easter Island group, there is found a range of conical mountains with craters, but inactive.

Of the volcanic groups of the South Sea, the most violent is the farthest east, adjoining the shores of the New World, viz., the archipelago of the Gallipagos, which consists of five considerable islands, very admirably described by Darwin. There are streams of lava down to the very shore of the sea, but no pumice. Some of the trachytic lavas are said to abound with crystals of albite. It is important to examinexxxi whether or not this is oligoclase, as on Teneriffe, Popocatepetl, and Chimborazo; or labradorite, as on Etna and Stromboli. Palagonite, exactly similar to that of Iceland or in Italy, was discovered by Bunsen in the specimens of tufa from Chatham Island, one of the Gallipagos.

New Holland does not show any signs of recent volcanic activity, except at its most southern point (Australia Felix), at the foot of the Grampian Mountains. N.W. from Port Philip, as also towards the Murray River, there are numbers of volcanic cones and sheets or flows of lava.

It would be of great interest and utility to observe the relative inclinations of the Magnetic and the Geographical Equators, by means of the dip of the magnetic needle, though this will be rendered more difficult, from the fact of the ship's course being easterly, that is, contrary, to the Equinoctial current. As regards the low temperature of the current, which I discovered in 1802, running up from 40° S. to the Gallipagos along the coast of South America, and then turning westward, it would be highly important to investigate whether in the eastern part of the South Sea in 7° N. and between 117° and 140° W., there really exists in every season a counter current from west to east. But I need not enlarge upon this topic to such attentive navigators.

The line of no inclination was crossed six times by Duperrey between 1822 and 1825. When I first discovered, near Truxillo, the low temperature of the cold Peruvian current,xxxii it was 12°·8 Réaumur (60°·8 Fahr.). The temperature observed in the course of twenty years by Mr. Dirckinck von Holmfeld, in the neighbourhood of Callao, expressed in degrees of Réaumur, were as follows:—

| September 1802 | 12°·8 | (Fahr. | 60°·8) | Thermometer in the air. 13°·3 Réaumur. (61°·92 Fahr.) |

| November 1802 | 12°·4 | " | 59°·9 | |

| December, end of | 16°·8 | " | 69°·8 | |

| January 1825 | 12°·7 | " | 60°·57 | |

| February 1825 | 15°·3 | " | 66°·42 | |

| March 1825 | 15°·7 | " | 67°·32 | |

| April 1825 | 14°·5 | " | 64°·62 |

The temperature of the sea I found to be 22° Réaumur (81°·5 Fah.) north of Cape Blanco, when on my way from Callao de Lima, at which point the cold current diverged towards the Gallipagos.

Between the Gulfs of Guayaquil and Panama, north-east of the cold current, the temperature of the sea during the month of April rose as high as 24°·5, (87°·12 Fahr.). Within the range of the current, Mr. Dirckinck had carried on his observations in compliance with my instructions, by means of thermometers that had been compared by Arago. Everywhere in the current, in December 1824, he found from 16° to 18° (68° to 72°·5 Fahr.); between Quilca and Callao, in January, 1825, from 18° to 19° (72°·5 to 74°·75 Fahr.); between Chorillos, near Lima (Lat. 12° 39′ S.) and Valparaiso, in August, 1825, from 13°·8 to 10°·5 (63°·05 to 55°·62 Fahr.); between Chorillos and San Carlos de Chiloe, in June, 1825, from 18°·8 to 9°·2 (74°·3 to 52°·7).xxxiii

In sailing from the Sandwich Islands to the west coast of America, the Imperial Expedition will have to choose between the Ports of San Francisco or Acapulco. The first choice would be of great mineralogical advantage for those regions of the United States, lying North of the river Gila.[3] Parallel with the chain of the Rocky Mountains, which, according to Marcou, contains up to the present day several volcanoes in full activity in its northern part (Lat. 46° 12′ N.), run single, and at certain points double ranges of coast chains from San Diego to Monterey, from 32° 15′ N. to 46° 45′ N. They begin with the coast range specially so-called, which is a continuation of the high ridge of the Peninsula of Lower or Old California; after which, farther to the North, there follow in succession, first the Sierra Nevada di Alta California, between 36° and 38° N. the lofty Shasty mountains, and the Cascade Range, nearly twenty six miles distant from the littoral, including many high and active volcanoes, and extending far beyond Fuca Straits. The following are still in eruption:—Mount St. Elias (46° 2′ N.); Mount Regnier, or Rainier, (46° 46′); and Mount Baker, (48° 48′.) These three active cones would be most conveniently visited by the geologist of the expedition from San Francisco, as would likewise the whole Cascade Range. We have as yet no certain intelligence as to the geology of the entire longitudinal auriferous valley of thexxxiv Sacramento River, (where a trachytic crater, in a state of disintegration, is known as the Butt of Sacramento). Does the auriferous quartz occur in veins, and are these still in situ, or are they broken up? What description of rock is traversed by these veins? Does the wash-gold here contain occasionally, as in the Ural Mountains, fragments of vein-stones with isolated cavities, in which are found impressions of leaves and membranes, clearly proving that they have not been rolled, or transported by water, any great distance to the spot they now occupy? Have these been found, alongside of gold, diamonds, platinum, osmium, iridium, or mercury?

[3] The Gila falls into the Colorado about forty miles above the embouchure of the latter into the head of the Gulf of California.

Should the frigate steer for Acapulco, it may be assumed that there exists an intention to cross the Continent to Mexico and Vera Cruz, from the volcano of Colima (1877 toises) as it were, along the parallel of the range of volcanoes, and greatest heights rising in detached groups between the two seas, about the parallel of 19° N. New astronomical observations are greatly needed for determining the position of the volcanoes of Colima and Jorullo (667 toises). The volcano of Colima, with its twin peaks de fuego and de nieve, should be carefully examined, as also the volcano of Jorullo, with the fragments of granite enclosed in its lava; the Nevado de Toluca (2372 toises), Popocatepetl (2772 toises), Itztaccihuatl (2456 toises), Cofre de Perote (2098 toises), and the volcano of Tuxtla (18° 28′ N.), on the eastern slope of the Sierra St. Martin, from which a column of flame shot up with great violence on 2nd March, 1793, a fair specimen ofxxxv what the Spaniards term Malpays, the Sicilians Sciarra viva. The face of the country is covered over with boulders of lava, at San Nicolas de los Ranchos, at the foot of Popocatepetl, adjoining the city of Puebla de los Angeles, after which, on the road from Puebla to Vera Cruz, will be observed two narrow strips of boulders of cooled basaltic lava, rich in olivine. Similar examples will be found at Parage de Carros, near Tochtilacuaja and Loma de Tablas, between Cancas and the Casas de la Hoja. The mere ascension of volcanic cones is geologically of far less importance, than the bringing away numerous specimens, carefully selected, of various trachytic rocks, which, by their oryctognostical composition, are characteristic of each volcano. I would nevertheless recommend that the Pico del Fraile of the Toluca volcano (2372 toises) should be ascended, proper caution being used. From this very sharp peak, I brought away thin plates of trachyte perforated by lightning, and within the holes of a melted glassy surface, resembling those brought from Little Ararat. Both for the miner and geologist, an interesting and useful visit might be paid to the rich mines of Guanaxuato and the Mines de la Biscaina and Regla, on the road from Mexico to Real del Monte, so as to observe the close connection subsisting between the richer silver ores, occurring in trachytic porphyry without quartz, but with felspar, (glassy felspar?), and the thoroughly volcanic Cerro del Jakal, abounding in obsidian, and the Cerro de las Navajas (Razor Range), which remind one of the environs ofxxxvi Schemnitz, with the sole exception, that the trachytes "porphyres meulières" of Beudant, are wanting here.

As it is highly desirable that considerable time should be devoted to the volcanoes of Quito, Peru, and Chili, it appears uncertain whether the course of the frigate, on leaving Acalpulco, will be shaped direct for Guayaquil, thus reversing the route taken by myself, or whether she will not touch at some of the central American ports—Realejo or Sonsonate. The crowded series of volcanoes in Central America, of which no less than eighteen, conical or dome-shaped, may be considered as still in active eruption, would yield a rich harvest of facts of all kinds in elucidation of the theory of volcanic action, such as have never hitherto been sufficiently taken advantage of. We are still in need of the mineralogical determination of the rocks, while the form and situation of the mountain masses have been well described by Squier, Oersted, and other modern travellers. The greater number, indeed, of the eruptions of scoriæ and slag were unaccompanied by streams of lava, as, for example, those of Mount Isalco, abounding in ammonia. But recently eye-witnesses have furnished us with quite different accounts regarding these eruptions, in the case of several volcanoes—as the Nindiri (a twin volcano with that called Massaya), on which Dr. Scherzer has lately shed much light; the Volcano el Nuevo, erroneously called Volcano de las Pilas, that of Coseguina, situated on the Great Bay of Fonseca, and that of San Miguel de Bosotlan, from whichxxxvii there flowed an extensive stream of lava in July 1844. It would be most tempting to pass by land from Mexico southwards to Oaxaca, and thence to the Isthmus of Guasacualco or Tehuantepec, and Chiapas, so as to rejoin the frigate at Realejo or Sonsonate. Facts might be obtained, in such a journey, of great value in determining the dependence of geological phenomena on each other; but it is to be feared it would be attended with too much fatigue and loss of time. For similar reasons, it cannot be proposed that the scientific gentlemen attached to the Expedition, should leave the frigate for three or four months, when they reach Central America, in order to cross by rail the Isthmus of Panama, with the object of examining the Volcancitos of Turbaco and Gabra Zamba, both active, and thence ascend the Rio Magdalena from Carthagena de las Indias, as far as Honda, whence they could proceed by Bogotà and Popayan to Quitó.

It will be also unavoidable to forego the examination of the sedimentary rocks, rich in fossils, between Honda, Bogotà and Ibagues, the Mastodon fields (Campos del Gigante), and the Salto de Tegumidama on the plateau of Bogotà, the wax palm (Ceroxylon Andicola), and the Azufrales of the Passo de Quindiu, the volcanoes of Tolima, measured by myself and ascended by Boussingault, and of Paramo de Ruiz (4° 15′ N.), as also the two volcanoes of Popayan, the Puracé and the much more interesting but now extinct Sotará. As a middle course, I may suggest a disembarkation, not exactly at Guayaquil, but on the goldxxxviii and platinum coast of the Choco, near San Buenaventura, so as to proceed thence to Popayan, and afterwards return to the volcanoes of the province of Pasto, which are highly important, and so on to Quitó, by way of Guachucal, Tulcan, and Villa de Ibarra, rejoining the frigate only at Guayaquil.

I believe, however, it would be more advisable to select Quitó as the starting-point, whence to examine the important elevated volcanic region De los Pastos (between 2° 20′ and 0° 56′ N.), containing the volcano of the town of Pasto, the volcanoes of Tuguerres, Chiles and Cumbal, and the Azufral de Pasto, and not to land at any port of the Choco coast, not even from the Bahia de Cupica, which for half a century I have recommended in vain on account of its vicinity to the Rio Naipi, one of the tributaries of the Atrato. In drawing up a list of names of the volcanoes of the renowned lofty plateau of Quitó, I may include, Imbaburu, Cotocachi, Rucu, Pichincha, Antisana, the much-disputed question of the stony walls like streams of lava, on the east slope of Tana Volcan, and Reventazon de Ansango; Cotopaxi, with its strange inexplicable quarries of pumice, of Guapecho and Zumbalica, in the neighbourhood of Llactacunga and San Felipe, the pumice containing oligoclase, not glassy felspar, deposited in strata, like any rock in situ for a considerable distance on all sides of Cotopaxi; Tunguragua (mica slate), studded with garnets, and beds of granite, which dip under the former, and have themselves been pierced by the trachytes of Tungurahua at Rio Puela and the Hacienda de Ganace;xxxix the hills of Moya, near the village of Pelilco, cast up in the celebrated earthquake of 7th February, 1797, and still in a state of activity; the Chimborazo, which M. Jules Rémy, accompanied by an Englishman named Princkley, was in the belief they had ascended, on the 3rd of November, 1856, to the very summit, "mais sans s'en douter." Poggendorff, (Vol. X. p. 480), has clearly demonstrated that the boiling point given by Rémy for the summit, would not give 6544 mètres (little different from my own trigonometrical admeasurement of 6530 mètres), but fully 7328 mètres. As I distrust my own half-barometical measurements, I have vainly implored travellers, these fifty years past, to have a new series of trigonometrical observations made of the summit of Chimborazo. The merit, then, of settling this moot point, it also remains for the members of the Novara Expedition to obtain.

It would be important to examine the Sangay (16,068 feet)—which, like Stromboli, is in constant activity, yet without any traces of lava-streams—on account of the grains of quartz discovered by Wisse in the trachytic boulders ejected by the volcano, which is of such rare occurrence in the trachytes out of Hungary; and also on account of the close vicinity of beds of granite and gneiss, which are broken through by the Sangay trachyte, forming an island, as it were, of not hardly two miles in breadth. Still more deserving of attention is the extinct volcano El Altar de los Collanes (Capac Urcù) a sketch ofxl which I presented in the atlas published in my "Kleine Schriften" (Plate V. p. 461), formerly higher than Chimborazo, and still (?) 16,380 feet. Not a single specimen of its trachyte has ever been deposited in a European museum. The Altar itself is readily accessible from Riobamba Nuevo. In its vicinity may also be seen mica slate and gneiss, cropping out at the Paramo del Hatillo near Guamote, and Teocaxas, which are so seldom fallen in with in the highlands of Quitó. Tradition relates that gold-mines were worked here during the days of the Incas, in the neighbourhood of volcanic trachytes. From the Altar the geologist might proceed, by way of San Luis, (Query, whether the primitive clay-slate found here be of the Silurian formation?) and Guamote, to Paramo del Assuay (2428 toises), and Cuenca, as far as Atausca (2° 13′ S.), where an immense mass of sulphur, lying in a quartz seam is worked, forming a bed in the mica slate. Of what rock does the easily accessible Cayambe Urcù (18,170 feet) consist, crossing the Equator, S.E. of Otavalo? En route from Quitó to Cayambe, the rich deposits of obsidian near Quinche should also be inspected, which furnished the large mirrors to the Incas, and farther to the north of which are the volcanoes of Los Pastos, which form a separate system by themselves.

For examining the rocks and exploring the volcanoes of Southern Peru and Bolivia—respecting which see the last edition of Pentland's Maps, not those published between 1830 and 1848, in which the height of Sorata was indicated atxli 3949 toises (25,257 feet), and Illimani at 3753 toises (24,004), and accordingly both as much more lofty than Chimborazo, which is 3350 toises (21,426 feet)—the best starting-point would be the port of Arica, which may be reached, sailing the whole distance against the cold current, from Guayaquil, after a short stay at Callao de Lima. Of the volcanoes of Peru and Bolivia only three are now active.

(a.) The volcano of Arequipa, three miles N.E. of the town of the same name, which, according to Pentland and Rivero, is situated about 7366 feet above the level of the sea. The measurements of M. Dolley, of the French navy, which were published under my superintendence, give the summit of the volcano as 10,348 feet above the town of Arequipa, so that its total elevation above the sea would be 17,714 feet. In the table of heights for Mrs. Somerville's "Physical Geography," Mr. Pentland speaks of the summit as being 20,320 English feet in height, or 19,065 Paris feet, closely approximating to the old trigonometrical measurement (19,080 feet) given by Thaddeus Haenke, a Bohemian, who accompanied the expedition of Malaspina, in 1769. What a deplorable state for the science of hypsometry to be in! which the Novara ought to put an end to. Samuel Anzon, a North American, in 1811, and Dr. Weddell, in 1847, have ascended the volcano of Arequipa.

(b.) Sahama (18° 7' S.), according to Pentland's new map of 1848, is 871 feet higher than Chimborazo (which he gives as 20,970 feet), and is still active. The true heights of Illimanixlii and Sorata, ascertained since 1848, are, instead of 3949 and 3753 respectively, only 3329 toises (21,266 English feet), and 3307 toises (21,145 English feet).

(c.) Volcano Gualatieri, in the Bolivian province of Carangas (18° 25′ S.), height 20,604 feet.

The southern group of South American volcanoes, that, of Chili, presents the largest number of active fire-mountains—only second, indeed, to that of Central America, there being from eleven to thirteen. In order to increase the geological exploration of this region which has been so well prepared by the memorable expedition under Captain Fitzroy, in the ships Adventure and Beagle, the excellent generalizing theories of Mr. Darwin, and the naval astronomical expedition of Mr. Gilliss, for 1849-51, the Novara will probably land at Valparaiso. A great desideratum between Coquimbo and Valparaiso is an exact measurement of—

A. The volcano of Aconcagua (32° 39′ S.). Its height has been stated, in 1835, by Captain Fitzroy, as 21,767 feet, Pentland's correction assigning 22,431 feet; while Captain Kellet, of the frigate Herald, gives it as 21,584 feet. Miers and Darwin are both of opinion that the Aconcagua is still in activity, which is denied by Pentland and Gilliss. The most recent measurement of Aconcagua—that by Pissis in 1854 (see Gilliss, Vol. I. p. 63)—makes the height 20,924 feet. M. Pissis has published, in the "Anales de la Universidad de Chili," for 1852, the geodetical elements of his survey, which is based upon eight triangles. Aconcagua being probablyxliii the highest mountain in the New World, a new measurement is eminently desirable. Neither Dhawalagiri, with his 4930 toises, nor Kintsinjunga, measured by Colonel Waugh, with his 4406 toises, are any longer considered the highest mountains in the Himalaya range, but the Deodunga (Mount Everest), which is 29,003 English feet, equal to 27,212 Paris feet, or 4535 toises.

B. The volcano Maipu (34° 17′ S., height 16,572 feet), ascended by Meyen. The trachytic rock on the summit has broken through the Jurassic strata, in which Leopold von Buch has ascertained, from heights of 9000 feet, the existence of Exogyra couloni, Trigonia costata, and Ammonites biplex. This volcano has no streams of lava, but only eruptions of volcanic slags. It would be most desirable that Dr. Hochstetter should examine this remarkable protrusion of dislocated strata.

C. The volcano Antuco (37° 7′ S.), the geology of which was described by Pöppig, is a lofty basaltic crater, having a trachytic cone rising up in its centre to an elevation of 8672 feet. It was observed in full activity by Domeyko in 1845. Gilliss gives an account of an eruption in 1853. According to Domeyko, a fresh-burning cone was thrown up on the 25th of November, 1847, which remained in activity for a whole year. Molina considers the Nevada Descabezado (35° 1′ S.), ascended by Domeyko, to be the highest mountain in Chili; but its height is estimated by Gilliss at only 12,300 feet. The most southerly volcanoes are the still active Corcovadoxliv (43° 12′ S.), 7046 feet; Yanteles (43° 29′ S.), 7534 feet; and the Volcan de San Clemente, opposite the granite formation on the peninsula of Tres Montes. Still further south, in 51° 41′ S., another, the Volcan de los Gigantes, is laid down on the old maps of South America, by La Cruz Olmedella, as opposite the archipelago of La Madre de Dios.

Should the Novara return to Europe through the Straits of Maghellanes, it would be very desirable the members of the Expedition should visit the locality from which Prince Paul of Würtemberg, after long zoological travels through North America, has, within the last year, brought back to Germany a very large collection of specimens.

Altogether, I calculate the number of active volcanoes on the surface of the earth to be upwards of 225—one-third of which, or 75, are upon the various continents, and the remainder upon the insular world. The Western Continent has 53 active volcanoes—of which, North-Western America, north of the river Gila, has 5; Mexico, 4; Central America, 18; South America about 26. Viewing the globe as a whole, there presents itself an extensive oblique region in which volcanoes most abound, stretching from S.E. to N.W. in the more westerly part of the Pacific, between 75° W. and 125° E. of Paris, and between 47° S. and 66° N. In this region, the fused elements of the interior of our earth may be said to be most permanently in communication with the atmosphere.

The greatest attention should be paid, with the view ofxlv improving them, to the sections and maps of Chili, contained in the work, "Buenos Ayres and the Provinces of Rio de la Plata," published in 1852 by Sir Woodbine Parish, and still more so, to that entitled "Map of the Republic of Chili, compiled from the Surveys of Gilliss, Pissis, Allen, Campbell, and Claude Gay, between 23° and 44° S., as contained in Gilliss' 'United States Astronomical Expedition, 1847-52 Washington, 1855.'"

The chief object to be aimed at by the Novara, with respect to scientific enquiry, seems to me to be the formation of a collection in the Geological Institute of Vienna, in comparison to which all the collections which at present aspire to be considered rich in volcanic specimens, (such as those of Berlin, Paris and London), should appear to be insignificant. In all periods of history, travellers are only the representatives of the state of knowledge of their own time, and consequently, collections always present the readiest means of promulgating new discoveries by oryctognostical examination or chemical analysis. In order to set on foot a grand Volcanic Museum, it would be necessary to bring home from every one of the volcanoes visited, not less than 10 or 12, but still better 15 or 18, specimens of the porphyritic trachytes, all carefully selected, well-shaped, containing crystals not disintegrated, and of sufficient size to admit of a fresh fracture being made. For such quantities, however, there cannot be provided on board ship, even with the kindest patronage of the commanding officer, sufficient space forxlvi the accumulations of two years' arduous efforts in forming a collection. The greatest part, therefore, should be sent by other conveyance to Trieste, the most secure channel being through the consuls of the Austrian Empire, or those of allied powers, or through the medium of British, Dutch or American mercantile establishments, or by the regular packets.

Duplicates, say four or five specimens, from each volcano, should be taken on board the Novara in boxes of about 3 feet long. It would be too disheartening to have any misgivings of the success of this glorious scheme for getting together a Museum of Volcanic Rocks in Vienna, of all the regions of the globe, arranged upon a regular geographical system, each labelled with its own name, so as to promote a general acquaintance with these branches of knowledge:

Much of this work might be done on board the Novara. As to Nos. 3 and 4, Kamtschatka, the Kurile and Aleutian Islands, the Red Sea, and the West Indies, it will not be difficult to procure specimens at some future period.

Our piping times of peace are favourable to the execution of this project, which should be zealously kept in view throughout the Expedition. Travelling as I was, during the great wars, I did not dare shrink from the difficulty of having to carry along with me 44 large boxes, as I did on the road through Mexico from Acapulco to Vera Cruz, whence they were sent to Cuba, Philadelphia, and so to Bordeaux. The mechanical labour of having the collections carefully packed, keeping duplicates distinct, and sending away geological, botanical, zoological and ethnographical collections, is itself quite as important as the purely scientific work.

The exhibition of comprehensive volcanic collections brings to light the strong analogy subsisting between the trachytes belonging to volcanoes, far distant from one another, while it indicates the existence of great differences in the mineralogical composition of volcanoes situated very near each other. My most excellent friend and fellow-traveller in Siberia, Professor Gustavus Rose, recently subjected the trachytes of the Berlin Museum, the greater number of which were collected by myself, to careful crystallographical and chemical investigation. He found oligoclase and pyroxene on the trachytes of Chimborazo, Popocatepetl,xlviii Colima, Tunguragua, Puracé, Paramo de Ruiz, and the Peak of Teneriffe, which has recently been accurately examined by Mr. Charles Deville. The trachytes of Toluca, Orizaba, Gunung Barang, and Burung Agung, on the Island of Java, Argæus, in Asia Minor, Cuneguilla, south of Sta. Fé de Nuevo-Mexico, the Sièrra de San Francisco, west of the Rocky Mountains and Pueblo Zuni, consist of hornblende, oligoclase, and brown mica. The trachytes of Stromboli and Etna, those of the Siebengebirge (Drachenfels), and of Kara Hissar in Phrygia, consist of large crystals of glassy felspar, with numerous smaller crystals of oligoclase, some hornblende and mica. Oligoclase, having been mistaken for albite, led to the fantastic idea of a peculiar rock, the Andesite, prevailing in the Andes, and even led our great master, Leopold von Buch, to make some curious distinctions, (Déscription des Iles Canaries, 1836, pp. 186-87.)

To ascertain the average height above the level of the sea, I propose that furrows should be cut in the rocks of the different regions along with inscriptions, which might carry information to unborn ages, as has been done, on my suggestion, now some 25 years ago, by the Academy of Science at St. Petersburg, on the Caspian Sea, while Sir James Ross, in his "Voyage of Discovery in the Southern and Antarctic Regions," 1839-43, Vol. II. p. 23, regrets not having done so, or, at least, of having only once adopted this plan.

I would also, with all deference, suggest observations regarding the daily atmospheric variations or tides, so as toxlix obtain tables of maxima and minima. In order to obtain these, whenever the frigate is at anchor near any coast, but particularly within the tropics, hourly observations with the barometer and thermometer (the latter affixed to the barometer, and also freely suspended in the open air), should be made through several consecutive days and nights. During the occurrence of an Aurora Borealis (or Australis), attention should be paid to the perturbations of the magnetic variation, and the magnetic intensity of the horizontal needle. Boreal Auroras have been seen in the southern latitudes of the Peruvian Pacific, as low down as 12° 13′ S.; but the occurrence of such phenomena there is of much less frequent occurrence than that of Austral Auroras in Scotland. It is important to keep an exact register of the intensity of blackness in the "coalbags," when the smallest stars surrounding them are still visible to the naked eye. The daily meteorological observations, as also those on the temperature of the sea, will probably be made on board ship, in conformity with the views of Lieutenant Maury, and the method agreed upon at the last nautical congress.

As I shall have long ceased to be numbered with the living, when the Novara returns to Trieste, richly freighted with scientific treasures of all kinds, with fresh information relating to organic and inorganic nature, to the races of man, their habits and languages, I now pray to Almighty God that His blessing may rest upon this great and noble enterprise,l to the honour of our common German Fatherland! And concluding, in this night, these oblique, illegible lines, I remember, not without emotion, and with very mingled feelings, that joyous period of my life when, fifty-eight years ago, in the beautiful gardens of Schönbrunn, preparing myself for a long journey, I was enjoying with grateful mind the friendly kindness of the venerable Jacquin and Peter Frank.

Berlin, in the night of 7th April, 1857.

In the autumn of 1856, His Majesty the Emperor was graciously pleased to approve of the proposal for a voyage round the world, as projected by his Imperial Highness the Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian, the head of the2 Austrian navy, and to commission the sailing frigate Novara for that purpose, a vessel qualified to meet every requisite condition.

The chief object of the Expedition—a circumstance which must not be lost sight of—was to afford the officers and cadets of the ship an opportunity of acquiring that practical acquaintance with naval affairs which, added to the theoretical knowledge previously attained, would render them thoroughly familiar with nautical routine, and thus materially contribute to the further development of the Austrian navy.

This branch of the public service, placed since 1848 on an entirely new basis, has with difficulty worked its way through all those embarrassing circumstances inseparable from the organization of a new system; but the honest zeal and energy of the board appointed, supported by favour from the highest quarters, have succeeded in introducing many improvements, and in increasing by degrees the numerical strength of the men, thereby laying a secure foundation for the rising naval force, the importance of which, at this moment, every reflecting patriot will acknowledge.

The intended Expedition offered, besides the advantages for the service, another not less important for the State, namely, the recognition of the Austrian flag in remote quarters of the globe, to which it had never hitherto penetrated; and by thus opening new channels for the outlet of our natural products and manufactured goods, to promote the industrial, commercial, and maritime interests of the empire.3

In order to satisfy the scientific requirements of the age, the illustrious head of the navy issued orders, that the officers on board should in every way assist in the researches to be made, connected with navigation and geography; and was, moreover, pleased to invite the Imperial Academy of Sciences to nominate two members, he himself naming a third, to accompany the Expedition for the purpose of observing and investigating phenomena pertaining to the different branches of physical science, as well as collecting rare specimens and interesting objects of natural history. To this commission were ultimately attached a botanist, a practical zoologist, an artist, and a flower-gardener.

The Academy had, for the guidance of these gentlemen, drawn up instructions which, with a multitude of other papers containing useful hints and interesting queries, received from the Imp. Geographical, Geological, and Medical Societies, as well as from numerous foreign and native scientific men, formed a most valuable collection of materials for the purposes of the Expedition.[4]

[4] Of these instructions, "The physical and geognostical remarks," with which the Nestor of natural science honoured the voyagers of the Novara, being of a more general interest, are published at the end of this volume, together with the facsimile of an autograph letter of Baron von Humboldt to the commander of the Expedition.

Foremost amongst these savans stood Alexander von Humboldt, that illustrious man, who up to the last moment of his existence was alive with youthful enthusiasm for every scientific enterprise. In England great interest in the success of the Expedition was evinced by Sir Roderic Murchison, Sir W.4 Hooker, Sir Charles Lyell, General Sabine, Admiral Smyth, Admiral Fitzroy, Professor Robert Owen, Professor Philips, Professor Bell, Professor W. A. Ramsay, Professor Goodsir, of Edinburgh, W. J. Hamilton, Esq., Charles Darwin, Esq., L. Horner, Esq., James Yates, Esq., B. Davis, Esq., &c., &c. From the United States of North America, we received most valuable communications from Commander M. F. Maury, National Observatory, Washington, D. C.—Captain Rodgers, and others.

Letters of introduction were received from Germany, and particularly from England, to influential parties and societies in a variety of places abroad, amongst which were many warm and friendly recommendations from the English Government and Admiralty, as well as the Directors of the then East India Company, to various administrative authorities in the British Colonies.

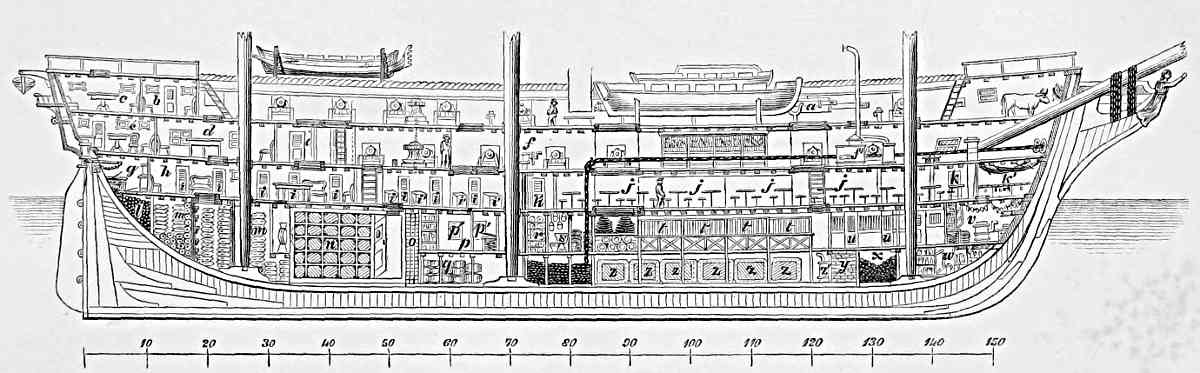

The frigate Novara was laid up in the arsenal of Pola, where all requisite steps were taken to complete her outfit, and5 prepare her thoroughly for the voyage. The ventilation of the lower deck was improved, and the number of cabins increased in proportion to the number of individuals for whom accommodation was to be provided.

The gun-room was, by command of the Archduke, converted into a reading-room, and provided with a well-selected library as well as with all the charts and maps necessary for the information of the officers, who here made their calculations and executed their drawings.

The store-rooms for the sails and tackle were enlarged, so as to hold a double quantity.

A distilling apparatus, the same as patented by M. Rocher, of Nantes, was fixed on the gun-deck, and being placed in connection with the ship's coppers, it was found that, during the few hours each day that the latter were used for cooking, enough sea-water was distilled to supply the entire ship's company with excellent water to drink. This distilled water, after having been kept in iron tanks for a month, was found pleasant to the taste, and agreed very well with the health. The excellent health enjoyed by all the crew throughout the voyage must, in a great measure, be ascribed to the circumstance, that scarcely any other but this distilled sea-water was used, so that the men were enabled entirely to forego drinking river or spring-water, which in the tropics are frequently found injurious.

The use of such an apparatus permits a great diminution in the store of water usually carried by a vessel. The space6 gained by this diminished bulk of water, enabled us to take on board a larger cargo of coal and provisions, such as preserved beef and compressed vegetables. The sailors were not, however, particularly fond of the preserved beef, because in cooking it loses a great part of its flavour (though the broth is strong and good); nor does it seem as an article of diet to have had a particularly beneficial influence on the health, for the sanitary condition of the crew was equally satisfactory, and the number of scorbutic patients not materially increased when, towards the end of the voyage, the fresh stores were exhausted, and only salt and pickled rations were issued.

Compressed dried vegetables were of great benefit to the health of our men, and cannot be sufficiently recommended. The so-called melange d'équipage of Chollet, as well as sauer kraut, potatoes, and other vegetables, have an excellent taste, improve the soups when mixed with them, and are easily preserved, provided they be protected from the effect of damp. Hence it might be advisable to keep them enclosed in well-soldered tin boxes. The price of these vegetables is so moderate, that it is surprising they are not more generally employed.

The long-continued satisfactory state of health of the crew must also partly be sought for in the constant use of shower-baths. For this purpose, apertures, three-quarters of an inch in diameter, were bored in the planks of both the deck and forecastle, under which a perforated disc could be screwed, and7 above which a pail of water was placed. By these simple means every one was enabled to enjoy the luxury of a bath; when, however, the desire for that refreshment became general, so that the arrangement above-mentioned was insufficient, a hand fire-engine was made use of, so as to accommodate as many at once as might present themselves—a process which found great favour with the jolly tars, as affording abundant opportunities for fun and merriment.

The frigate Novara had been placed on the stocks in the arsenal of Venice in the month of February, 1845, and was launched in April, 1850. She was pierced for 42 guns, but during the voyage carried only thirty 30-pounders,[5] and four of smaller calibre.

[5] The 30-pounder marine guns answer very nearly to the English 32-pounders.

The principal dimensions of the frigate (Vienna measurement) are:—

| Length between perpendiculars | 165 | feet | 5½ | inches.[6] |

| Length of water line | 156 | " | 5 | " |

| Greatest breadth | 44 | " | 11½ | " |

| Greatest breadth on water line | 43 | " | 2 | " |

| Depth of hold | 19 | " | ¾ | " |

| Draught of water aft | 18 | " | 9 | " |

| Draught of water fore | 17 | " | 5 2⁄3 | " |

[6] 96 423⁄1000 Austrian feet = 100 English.

The superficial area of the ship, or the load-water line, amounted to 5685.35 square feet; quantity of water displaced 2107 Austrian, or 2630 English tons. The superficial area of the principal sails amounted to 18,291 square feet.8

The frigate proved herself to be an excellent sailer, as, of the various vessels which, throughout the voyage, sailed in company with us, only three clippers outstripped her.

The question may here be asked, why, in the present state of navigation, a sailing-vessel was preferred to a steamer for this voyage? The principal consideration which decided this selection was the greater disposable area which a sailing-vessel offers in comparison with a steamer of the same dimensions, in which coal and machinery occupy so large a space. On the present occasion, it will be perceived that what was specially wanted was room for as great a number of officers, cadets, and men as possible, who were, as has been stated, to make this voyage for improvement in nautical affairs. Plenty of space was also required for the numerous instruments and bulky collections of objects of natural history; while in most parts of the ocean which we were to traverse, the winds blow so regularly, that, with very rare exceptions, sails form the best motive power. The expense of fuel requisite for a steamer, and the trouble of replacing it during the voyage, are thus saved; whilst, finally, the space occupied by the men employed in the management of the machinery, and that required for the stowage of special stores, would be withdrawn from more important objects.

After the frigate had been properly fitted up in the arsenal of Pola, she sailed on the 15th March, 1857, for Trieste, where she cast anchor on the 17th in the Bay of Muggia. H.I.M.'s corvette Caroline, likewise fitted out at Pola for a voyage9 to the coast of South America and Western Africa, followed in her wake, and it was now seen that the frigate was a better sailer than the corvette, a circumstance so much the more satisfactory, that the latter had hitherto been considered the swiftest ship in our navy.

The unfavourable state of the weather interfered so much with the works which were to be finished at Trieste, that the embarkation of provisions, swinging the compasses, &c., &c., could only be proceeded with very slowly.

At last, the members of the Commission arrived, and the vessel only waited for sailing orders.

Before leaving on so interesting an enterprise, with which the most pleasing recollections of our lives will ever be associated, we had the gratification of being honoured by a visit on board from the Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian. The commander of the Expedition introduced the officers and scientific gentlemen to his Imperial Highness, who addressed them in affecting terms, and concluded his remarks by expressing a hope that the frigate Novara would, with God's help, return happily from her mission to her own honour and that of the country.