Title: A Journal of Two Campaigns of the Fourth Regiment of U.S. Infantry

Adapter: Adam Walker

Release date: December 26, 2011 [eBook #38369]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note: Printer's inconsistencies in punctuation and hyphenation have been retained. Variant and alternative spellings have been preserved, except for obvious misspellings.

PREFACE.

When the Author of the succeeding pages had determined on recording the events and operations of the Regiment to which he belonged, it was far from his intention to give them publicity.—They were noted down for the amusement of his leisure hours and the perusal of his Friends, when he should return from the toils of the Camp and the fatigues of war;—to portray to the view of those Friends the various vicissitudes of fate attendant on the life of a Soldier.—But since his return, many who have perused the manuscript, have expressed their ardent desire to see it published, and to gratify their wishes, he has been induced to submit it to the press.—He indulges the hope that his simple narrative will fall into the hands of none but the candid and liberal, who affect not to despise the humble and unvarnished tale of the Private Soldier.

THE AUTHOR.

JOURNAL.

The 4th Regiment of U.S. Infantry was raised principally in the year 1808—from the five N. England States, viz. Vermont, New-Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode-Island and Connecticut, and consisted of between 8 & 900 men—under the command of Colonel John P. Boyd.—The regiment was not embodied until—

Ap. 29, 1811—When we received orders from Government to rendezvous at the Lazaretto Barracks on the Schuylkill, 5 miles below Philadelphia—Capt. Whitney's Company of U.S. Riflemen, then stationed at Newport, R.I. was also ordered to join the 4th regiment at this place.

May 24th—The whole regiment (except one Company under Capt. Rannie, which were detained at Marblehead) had arrived, and were immediately formed, consisting of about 600 of as noble fellows as ever trod the tented field; all in good health and fine spirits, and their discipline unrivaled;—nothing worthy of note took place while we remained here, which was but a few days, except the degrading situation in which Capt. Whitney of the Riflemen, had placed himself, while Commanding Officer, by descending to the level of a Musician, and with his own hands bestowing corporeal punishment upon the bare posteriors of two privates of his Company, in the face of the whole regiment on parade. Such conduct in a commander, merited and received the pointed scorn of every officer of the regiment.—The two men, who had heretofore been good soldiers, deserted within two hours after receiving their punishment—and a few days afterwards Capt. Whitney resigned a command he was totally unworthy of, and returned home.—Lieut. A. Hawkins, a fine officer, was afterwards appointed to the command of this Company.—We received our tents, camp, equipage, &c. and Col. Boyd and Lieut. Col. Miller, having arrived to take the command.—On the

3d. June—1811, we commenced our march for Pittsburgh;—Crowds of spectators from the city of Philadelphia came to witness our departure;—the day was extremely warm, and we were almost suffocated with heat and dust.—We marched five miles from the city, and encamped about 4 o'clock,—Many respectable citizens from Philadelphia accompanied us to our encampment.

I omit the particulars of our march through the State of Pennsylvania, as no event transpired, except what falls to the lot of all soldiers on long marches.—The country being extremely rough and mountainous, our shoulders pressed beneath the weight of our cumbrous knapsacks, our feet swollen and blistered, and performing toilsome marches beneath a burning sun, amid clouds of dust, in the warmest season of the year, rendered our situation painful in the extreme, and at times almost insupportable.—A number of desertions took place on this march, in consequence of its having been whispered among the troops, that they were to be sent to New-Orleans,—and it is believed, had not Col. Miller given them to understand that no such thing was intended, one third at least, of the regiment would never have reached Pittsburgh;—however, placing unbounded confidence in the word and honor of Col. Miller, order was restored, and the fears of the men were calmed.

On the 10th June, we arrived at Carlisle, a handsome little town about 120 miles from Philadelphia, where we halted one day, to refresh and rest our wearied limbs.

June 12, we again proceeded on our march, and arrived at the beautiful town of Pittsburgh on the 28th June, 1811.—At Pittsburgh we found excellent quarters, necessaries of all kinds, cheap and plenty;—the inhabitants were kind, generous and hospitable,—they knew how to commiserate, and were happy in relieving the sufferings of the soldier;—while we on our part were grateful for their favors, which we endeavored to merit by treating them with the respect due to good citizens. Our time here passed very agreeably for two or three weeks, at the expiration of which, we received orders to descend the Ohio river to Newport, (Ken.)

GEN. W. H. HARRISON

July 29th. The regiment embarked on board ten long keel boats; each boat being sufficiently large to contain one Company of men.—With our colors flying and drums beating, we left the shore in regular order, and commenced our passage while the band, attached to the regiment, were chaunting our favorite ditty of Yankee Doodle, amidst the cheers and acclamations of the generous citizens of Pittsburgh, assembled at the place of our embarkation.—After a passage of 4 days, without accident, we arrived at the little town of Marietta, where we had the pleasure of meeting with many of our hardy yankee brethren from N. England.—We tarried here over night, and early next morning we continued on our passage, and on the 8th of August we all safely arrived at Newport, a small village, situated at the mouth of the Licking, which empties into the Ohio, and directly opposite to the town of Cincinnati in the state of Ohio. Here we were to remain until further orders; while Lieut. Hawkins was dispatched to Indiana to inform Governor Harrison of our arrival at Newport and to receive his commands.

The troops at this time were perfectly ignorant of their destination, or the real object our government had in view, in sending us at such a distance to the westward. Many were still fearful that we were to be sent to New-Orleans, and knowing the fate of former troops, that had been stationed there, who had been swept off by sickness, it created much uneasiness in the minds of New-England troops; and some few desertions took place.—We experienced some very warm sultry weather, and considerable fear was entertained by Col. Boyd for the health of the troops.—Capt. Welsh, an amiable officer, died and was buried with Masonic and Military honors.

Aug. 28th. Lieut. Hawkins returned with orders from Governor Harrison for the regiment to proceed with all possible dispatch to Vincennes, in the Indiana Territory, where the conduct of the Indians on the Wabash had become very alarming. The Governor had previously been authorised to employ the 4th regiment in his service, should circumstances make it necessary.

On the 31st. August we left Newport, and proceeded down the Ohio, without difficulty, until we arrived at the falls or rapids, when we were obliged to disembark and have the baggage taken from the boats and conveyed round by land to the foot of the rapids, while skilful pilots navigated our boats through this difficult passage.

Governor Harrison was at this place, and accompanied by Col. Boyd, proceeded across the country to Vincennes, leaving the command of the regiment to Lt. Col. Miller, to continue their passage by water.

Sept. 4th. Early in the morning we left the Rapids, and on the 9th, without any occurrence worthy of note, we arrived at the mouth of the Wabash, a distance of 1022 miles from Pittsburgh; but the most disagreeable and difficult task in our navigation was yet to be performed. We had now 160 miles to ascend the Wabash, the current of which is very rapid, and at this season of the year, was quite low and much interrupted by rocks and sand-bars. We were daily obliged to wade the river, and haul the boats after us over the rapids, which occasioned many of our men, on our arrival at Vincennes, to be disordered with that painful disease, the fever and ague. Every precaution possible was taken by the humane and generous Col. Miller to preserve the health of the regiment; himself waded the river, as well as every other officer; in many instances performing the duties of the common soldier, and assisting them to haul up the boats. At the close of each day we brought the boats to a convenient landing; placed our guard for the night, while those who had obtained an evening's respite from the toils of this tedious and laborious passage, were suffered to regale their spirits over an extra glass of whiskey, bestowed by the liberality of our Commander. The utmost harmony and good humor prevailed—no contention—no murmuring—all cheerfully performed their duty.

Sept. 19, 1811. After a fatiguing passage of ten days through an unsettled country, which presented nothing to the view but a wild and dreary wilderness, our hearts were cheered by a prospect of the town of Vincennes. It was dark before we landed, and by the noise and confusion about us, we concluded the town to be overrun with troops. A rabble soon gathered about the boats and assisted in hauling them ashore;—their whooping and yells, and their appearance caused us to doubt whether we had not actually landed among the savages themselves. Many of these militia spoke the French language;—their dress was a short frock of Deer-skin, a belt around their bodies, with a tomahawk and scalping knife attached to it, and were nearly as destitute of discipline as the savages themselves. The militia from Kentucky, and a few companies of Indiana were decent soldiers; yet the large knife and hatchet which constituted a part of their equipment, with their dress, gave them rather a savage appearance. The hatchet, however, was found to be a very useful article on the march—they had no tents; but with their hatchets would in a short time form themselves a secure shelter from the weather, on encamping at night.

The Dragoons, commanded by Major Daviess, consisting of about 120 men, were well mounted and handsomely equipped, and composed of some of the most respectable citizens from Kentucky and Indiana.

The Indians who had been lurking about the town for a number of days suddenly disappeared, and on the

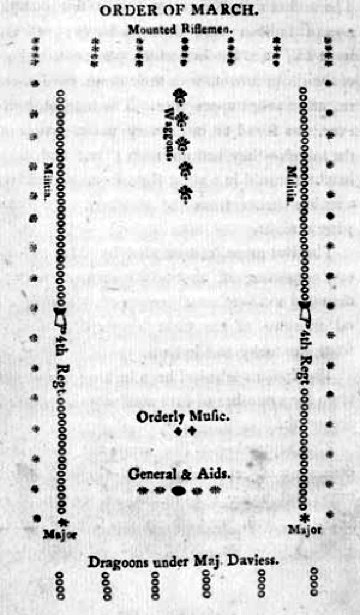

27th September.—The army was embodied, consisting of between ten and twelve hundred men; and under the immediate command of Gov. Harrison, we took up our line of march from Vincennes, being well furnished with arms, ammunition and provision, advancing with but little variation in the following

ORDER OF MARCH.

In this manner we proceeded on our march by the taps of the drums at the head of each column, to prevent the lines distancing each other too far. It was customary each morning, an hour before day-break, to rouse the troops from their slumbers, with three solitary taps of the drums of each line, when they turned out and formed in front of their tents, which was the line of battle in case of an attack; in this manner they stood to their arms until the beating of the Reveille.—This precaution was deemed a very necessary one, knowing it to be the time that the Indians generally choose to make their attacks, as the troops sleep more sound, and the sentinels become wearied and sleepy, and consequently less vigilant.

Oct. 3. After a march of six days, through an uninhabited country, we arrived at a place on the banks of the Wabash, called Battelle des Illinois. Here we formed our encampment with the intention of tarrying a few weeks, to ascertain more correctly the disposition of the Prophet and his warriors. A Fort and Block-Houses were ordered to be built at this place, which gave sufficient employment to the militia.—

Some murmuring took place among them, being heartily sick of the camp, and desirous of returning to their homes. Many, indeed, threatened to leave us at all hazards, which caused the Governor much anxiety and trouble. He appeared not disposed to detain any man against his inclination; being endowed by nature with a heart as humane as brave; in his frequent addresses to the militia, his eloquence was formed to persuade; appeals were made to reason as well as feeling—and never were they made in vain—when the militia, unused to military restriction, threatened a desertion, his eloquence calmed their passions, and hushed their discontented murmurings—and in a short time all became tranquil, and unanimity reigned throughout the army.

About this time many Indians came peaceably into camp, and held frequent Council, with the Governor; but all endeavors to effect an accommodation with the Prophet were vain—they still continued stubborn and refractory,—and would not listen to any terms of peace made them by the Governor. Their lurking Indians were nightly prowling about our encampment, and alarming the sentinels on their posts.—On the 20th Oct. in the evening, an Indian crept cautiously through the bushes, opposite one of the sentinels in the main guard and shot him through both thighs—the sentinel nearest to him, saw the flash of the rifle, and immediately presented his piece,—snapped it twice—both times it missed fire!—The Indian made his escape,—the camp was alarmed, and the troops called to arms. The Dragoons were instantly formed, and under the command of that gallant and spirited officer, Major Daviess, sallied out, and scoured the woods in the vicinity of the encampment; but no Indians could be found. The Dragoons in passing the line of sentinels, were fired upon by mistake, the sentinels supposing them to be the enemy (it being very dark) but fortunately no one was injured.—We stood to our arms the whole of this night, while the Gov. and Col. Boyd were riding down the lines animating the troops to do their duty in case we were attacked.

Thus after a tedious course of negotiations, and fruitless endeavors to effect by fair means, a redress of our wrongs, and the patience of the Governor and of the army being nearly exhausted, it was determined to give them some weightier reasons than had been heretofore offered, why peace should be concluded. Orders were therefore given for the army to be in readiness to march to the Prophet's town.

October 21.—We commenced our march from Fort Harrison, so called, in honor of our worthy Commander; Col. Miller, the officer so highly esteemed by the troops of our regiment was unfortunately detained at this place by sickness. After a few days of tedious marching, and having crossed the Wabash, we arrived at Vermillion river—Capt. Baen, who had been long absent from the command of his company, had a day or two previous, joined us on the march, and being the oldest Captain in Commission, was appointed, to act as Major, and headed the left column of the army. Having a number of sick who were unable to proceed farther, a small block-house was erected, for their accommodation, and a Sergeant's guard was left for their protection.

Nov. 1. We crossed the Vermillion river into the Indian possessions, at which time the weather became rainy and cold. Many Indians were discovered by our spies, lurking in the woods about us; supposed to be the scouts of the Prophet, watching our movements.—After marching about fourteen miles, we crossed a small creek, and encamped on a high open piece of land: still rainy and cold. An alarm was here given by one of the sentinels, who fired on a Horse, which had strayed out of Camp.

November 3, Continued on our march—came to an extensive level prairie, which took up the whole of this day in crossing—started up many deer, two of which we killed—also an animal called a prairie wolf. Nothing of importance transpired until—

November 6.—When our spies, who had ventured near the Indian village, returned, and informed the Governor we were within a few miles of the Prophet's town—We were ordered to throw off our knapsacks, and be in preparation for an attack. We advanced about 4 miles to the edge of a piece of woods, when we were ordered to break off by companies, and advance in single lines; keeping a convenient distance from each other to enable us to form a line of battle, should necessity require it;—this was frequently done in the course of our advance toward the town, in consequence of the unevenness of the land, and the appearance of many favorable places for the enemy to attack us. In this manner we advanced very cautiously, until we came in sight of the Indian village, when we halted. The Indians appeared much surprized and terrified at our sudden appearance before their town; we perceived them running in every direction about the village, apparently in great confusion; their object however, was to regain in season their different positions behind a breastwork of logs which encircled the town from the bank of the Wabash. A chief came out to the Governor, begging of him not to proceed to open hostilities; but to encamp with the troops for that night, and in the morning they solemnly promised to come into camp and hold a council, and they would agree to almost any terms the Governor might propose; expressing their earnest desire for peace without bloodshed—but the treacherous villains merely made this promise to gain sufficient time to put their infernal scheme in execution. The Governor enquired of the chief where a situation suitable for encamping might be found; being informed, he dispatched three or four officers to examine the ground, who returned with a favorable report of the place—which was a piece of narrow rising ground, covered with heavy timber, running some length into a marshy prairie, and about three quarters of a mile north-west of the town. Here we encamped for the night, as near the form of a hollow square as the nature of the ground would admit. Being cool, cloudy weather, we built large fires in front of our tents, to dry our clothing, cook our provisions &c. The signal for the field officers to collect at the Governors marque was given; we were soon after ordered to lay with our cartridge boxes on, and our guns at our sides;—and in case of an attack, (as was always the order, while on the march,) each man stepped 5 paces in front of his tent, which formed the line of battle.

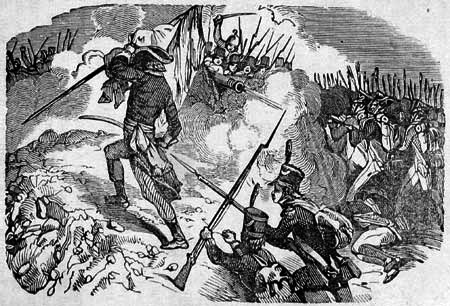

On the morning of the 7th Nov. a few minutes before 4 o'clock, while we were enjoying the sleep so necessary to the repose of our wearied limbs,—the attack commenced—when only a single gun was fired by the guard, and instantly we were aroused by the horrid yells of the savages close upon our lines.

The dreadful attack was first received by a Company of regulars, under the command of Capt. Barton, and a Company of Militia, commanded by Capt. Geiger,—their men had not the least notice of the approach of the Indians, until they were aroused by a horrid yell and a discharge of rifles at the very door of their tents; considerable confusion ensued in these two companies, before they could be formed in any regular order; but notwithstanding the disorder this sudden attack created, the men were not wanting in their duty—they sprang from their tents and discharged their pieces upon the enemy, with great execution, and kept their ground good until relief could be brought them. The attack soon extended round to the right line, where the troops were formed in complete order, and the assaults of the savages were returned in full measure. One company of Indiana militia fell back in great disorder, but after some arduous exertions of their officers, they were again rallied and fought with a spirit that evinced a determination to escape the odium of cowardice.—The battle had now become general, every musket and rifle contributed its share to the work of carnage. A few Indians had placed themselves in an advantageous situation on the left of the front line, and being screened from our fire by some large oak trees, did great execution in our ranks, The small company of U.S. Riflemen, commanded by Lieut. Hawkins, were stationed within two rods of these trees, and received the heaviest of their fire, but maintained the position in a most gallant manner, altho' the company of militia on their left were giving way in great disorder. Major Daviess, with a small detachment of dragoons attempted to dislodge them; but failed in the attempt, and was himself mortally wounded. Capt. Snelling, of the regulars, soon after made a desperate charge at the head of his company, with success, losing one man, who was tomahawked by a wounded Indian. The Indians fell back, and for a short time, continued the action at a distance—here was some sharp shooting, as they had greatly the advantage, by the light afforded them from our fires, which could not be entirely extinguished. We were well supplied with buck shot cartridges, which were admirably calculated for an engagement of this nature. The savages were severely galled by the steady and well directed fire of the troops. When near day-break, they made their last desperate effort to break our lines, when three cheers were given, and charge made by the 4th Regt. and a detachment of dragoons—they were completely routed and the whole put to a precipitate flight. They fled in all directions, leaving us masters of the field which was strewed with the bodies of the killed and wounded. Some sharp-shooters of the militia, harassed them greatly in their retreat, across the marshy prairie. The day was appropriated to the mournful duties of dressing the wounds of our unfortunate comrades, and burying the dead. To attempt a full and detailed account of this action, or portray to the imagination of the reader the horrors attendant on this sanguinary conflict, far exceeds my powers of description.—The awful yell of the savages, seeming rather the shrieks of despair, than the shouts of triumph—the tremendous roar of musquetry—the agonizing screams of the wounded and dying, added to the shouts of the victors, mingling in tumultuous uproar, formed a scene that can better be imagined than described.

The following statements are from Sergeant Montgomery Orr, of Capt. Barton's Company, (one of the Companies first attacked) and that of William Brigham, a private of the late Captain Whitney's Company of Riflemen, who was on his post, in front of Barton's Company, at the time of the attack; the latter of whom was mortally wounded, and died of his wounds a few weeks afterwards at Vincennes. Their veracity is unquestionable, and as I had the recital from their own lips, I do not hesitate to declare my belief of them.

Statement of Sergeant Orr.

"About 20 minutes, before the attack, I got up and went to the door of my tent, (No. 1.) and overheard the sentinels talking in front—listened, but could not distinctly hear what was said—it was rainy and very dark.—I laid down and was partly asleep, when some person rushed by and touched the corner of the tent—I sprang partly up—all was still. I jogged Corpl. Thomas, (who slept in the same tent) and asked, "if he did not hear somebody run by the tent?"—He said, "no—I've been asleep." I then laid down again, when something struck the top of the tent—Corpl. Thomas rose up, took his gun; in a moment three or four rifles were discharged at the very door of the tent, and an awful yell ensued—Thomas fell back on to me—I said, "Corpl. Thomas, for God's sake don't give back"—he made me no answer,—for he was a dead man.—I got out of the tent as soon as possible—the men were in confusion, some in front and some in the rear of the tents firing—the Indians within a rod of us.—Capt. Barton ordered the men to form instantly—they were too much broken, and no regular line could be formed; but they kept up a steady fire on the Indians, who fell back. Capt. Griger's company of militia, stationed near us, were in great confusion—they could hardly be distinguished from the Indians—I received a wound and was obliged to retire."

Statement of William Brigham.

"On the night of the battle, I was warned for Guard, and took post a little after sunset—Wm. Brown, (a regular) was the sentinel on my left, and a militia man on my right. These three posts were directly in front of Capt. Barton's Company of U.S. Infantry.

"I examined the ground adjacent to my post very particularly. There was a small thicket of willows, on a stream of water, about two rods in front of my post, and high grass between me and the willows—I observed it to be a favorable place for the approach of Indians and determined to be on the alert. Capt. Barton's Company were a few feet higher, and between us there were logs and some small bushes. I was relieved off post about 10 o'clock—At 3 o'clock I again took post; very dark, and rainy. I had resumed my station about half an hour, when I heard a faint whistle, not far from Wm. Brown's post, as I supposed—he called to me; but I did not think it prudent to answer—however, after he had called several times, I answered "holloa"—says he, "look sharp"—[the usual word of caution between sentinels]—I kneeled down, with my gun on a charge. It was so very dark that no object could be discerned within three feet of me, and I could hear nothing except the rustling noise occasioned by the falling rain among the bushes. At this time, Brown, (being much alarmed) very imprudently left his post, and came towards me. I heard light footsteps—presented my gun, and should have fired upon him had he not that moment spoke, much agitated—"Brigham, let us fire and run in—you may depend on it there are Indians in the bushes." I told him not to fire yet for fear we should give a false alarm.—While we were standing together, something struck in the brush near us, (I suppose an arrow)—we were both frightened and run in without firing—the Indians close upon our heels—we passed swiftly by Capt. Bartons's tents—I soon afterwards fell into Capt. Wilson's Company of militia, where I received a wound which broke my right arm."

Had this attack been delayed but ten minutes longer, the troops would have been formed in line of battle, and in readiness to receive it.—The General had arisen but a few moments previous to its commencement, and in four minutes more would have ordered the usual signal (three taps of the drum) to be given for the troops to rise and stand to their arms. The orderly Musician at the same time stood in readiness for that purpose, awaiting the orders of the General.—Some of the troops were up, and sitting by the fires; many of which had been furnished with fresh fuel, and the light arising from them, must have afforded the Indians a pretty correct view of our situation, and of the most proper place to make their assault. Every exertion was made to extinguish these fires the moment the attack commenced, which could not be but imperfectly accomplished, as the Indian marksmen were sure to pick off whoever approached them.

It was truly unfortunate that these fires were not extinguished the moment the troops retired to rest; for it is certain that the Indians derived a great advantage from this circumstance in the course of the action.

The hasty charge made by Major Daviess to dislodge the Indians from behind the trees on the left of the front line, was made with only 20 of his dragoons, dismounted; and its fatal consequence to the Major, was in a great measure owing to his having on a white blanket surstuot. He was easily distinguished by the Indians, and received three balls in his body; he immediately fell, exclaiming, "I am a dead man;" he was taken up and lived, however, till the close of the action. The fall of this brave and amiable officer was greatly lamented by the army, as well as the citizens of the state of Kentucky, where he held the office of Attorney General. He volunteered his services in the expedition under Gen. Harrison, who, knowing his worth, appointed him to the command of the volunteer dragoons.

Col. Owen, another brave officer, considerably advanced in years, and acting as aid-de-camp was shot from his horse by the side of the General, and immediately expired. Judge Taylor, the other aid, had his horse shot under him; in their fall the horse came on top of the Judge, where he lay confined for some time, unable to extricate himself; he was relieved from this disagreeable situation by a soldier, who happened to pass near him.

Capt. Baen, who had been with us but a few days, was shockingly mangled with the tomahawk;—he was taken up in a delirious state, and died a short time afterwards.—There was but one other instance of any person being tomahawked in this engagement; which was a private soldier of Capt. Snelling's company, upon a charge in the midst of the Indians.

Gen. Harrison received a shot through the rim of his hat. In the heat of the action, his voice was frequently heard and easily distinguished, giving his orders in the same calm, cool, and collected manner with which we had been used to receive them on a drill or parade.—The confidence of the troops in the General was unlimited, and his measures were well calculated to gain the particular esteem of the 4th Regt. All kinds of petty punishments, inflicted without authority, for the most trifling errors of the private soldier, by the pompous sergeant, or the insignificant corporal, [1] were at once prohibited.—A prohibition of other grievances which had too long existed, in this Regiment, at once fixed in the breast of every soldier, an affectionate and lasting regard for their General. The benefit of which was fully realized in the conduct of the troops in the engagement, as well as throughout the campaign.

After the action, a soldier of the Kentucky militia, discovered an Indian at some distance above the encampment, leading a horse out of the woods, into some high grass in the prairie; he caught his rifle and made after him. The Indian had loaded his horse with two others wounded, and was returning, when the Kentuckian gave a whoop, discharged his rifle, brought the Indian down, and returned in triumph to the camp, leading in his horse.

One Indian only broke through the lines into the encampment, and he was immediately afterwards dispatched by Capt. Adams, the pay-master of the regiment.

The force of the enemy in the engagement could never be correctly ascertained; but from the best information that could be obtained, it was calculated to amount to between ten and twelve hundred warriors, headed by Winnemac, a Kickapoo Chief,—and that they lost about four hundred in killed and wounded. Our loss amounted to forty-one killed, and one hundred forty-seven wounded. The names of those of the 4th regt are given in the latter part of this Journal.

A Potawatimie Chief was found severely wounded on the field, sometime after the action. He was brought before the General, and expressed the greatest sorrow at what had happened—and accused the Prophet of deceiving them. His wounds were dressed by the surgeon, and the best care taken of him while he remained with us on the ground. The Gen. left with him a speech to be delivered to the Indians, if they should return to the battle ground.

Nov. 8.—A small detachment of mounted men were ordered to advance to the Prophet's town, and see what had become of the Indians. They entered the town and found an aged squaw only, who informed them that the Indians had left it in great haste, immediately after the action, and had crossed the Wabash.—It was a handsome little Indian village of between one and two hundred huts or cabins, and a large store house, containing about 3,000 bushels of corn and beans. In their hasty retreat they left many articles of value to themselves, which except a few were destroyed in the conflagration of the town.

Nov. 9. After destroying considerable of our baggage, in order to make room in the waggons for the conveyance of the wounded, we began our march on the return to Vincennes expecting the Indians would follow and attack us. Such an event was greatly to be dreaded; as we were nearly out of provisions, and had upwards of a hundred and thirty wounded men to be attended to, who were painfully situated in the waggons, especially those who had broken limbs, by their continual jolting, on an unbeaten road through the wilderness.

Having suffered severely in consequence of the light afforded the Indians from our fires in the late attack, we adopted another method on our return, by building large fires some distance beyond the line of sentinels, while those in the encampment were extinguished on our retiring to rest; which in case of an attack, would have been of much service by placing the enemy between us and the fires. The sentinels on post at night having been frequently alarmed by lurking Indians, would place a stake in the ground about the height of a man, and hang their blanket and cap upon it, and retire a few paces behind some log or tree; as it had become hazardous for sentinels to walk their posts while the Indians were continually hovering about them. It was said that arrows had been found in some of the blankets put up in this manner, which is very probable, as they would approach within a few feet of a sentinel in the stillest night, without being discovered, as was the case at Fort Harrison, where a sentinel was shot down by an Indian, who had made his way through a thicket of bushes directly in front, and within twelve feet of the man on post.

On the 14th we arrived at the small block-house on the Vermillion river, where we left our sick, who had looked with painful anxiety for our safe return. The vigilance of Sergeant Reed, who commanded at this place was highly applauded in the arrest of two militia men, who deserted us the moment the action commenced, and fled with such precipitancy that they reached the block-house the night following, informing Sergeant Reed that the army was defeated, and nearly all were destroyed,—advising him to leave the place and hasten back to Fort Harrison. Their advice was disregarded by the sergeant, who put them under arrest. The express on his way to Vincennes a few hours afterwards passed the block-house, and informed them of the success of our engagement.

We suffered much for the want of provisions during our march to this place. Many of the troops had made use of horse meat to satisfy their craving appetites for the last 5 days. Col. Miller, then at Fort Harrison, being apprized of our destitute situation, immediately dispatched a boat with fresh provisions to our relief, which fortunately arrived at the block-house nearly at the same time with the army.

Nov. 15.—The wounded were placed in boats, and arrived at Fort Harrison on the morning of the ensuing day. Capt. Snelling with his company were left to garrison the Fort, and the army proceeded on their march.

The author being one of the wounded, was put on board a boat with other disabled men and sent down the river to Vincennes.—About 12 o'clock at night the boat we were in struck on a sand bank; which obliged us to lay by until the next morning. The night, as may be supposed, was passed in a very uncomfortable manner—the weather was freezing cold, and our wounds which had not been dressed for two days past, became stiff and extremely painful.

Nov. 19.—Arrived at Vincennes nearly at the same time the army did by land, and immediately after were placed in excellent quarters, and every possible attention paid to the sick and wounded, by Gov. Harrison and Col. Boyd, who always evinced the most anxious solicitude for the welfare of their soldiers.

Nothing more was heard from the Indians until the latter part of Dec. when a Kickapoo Chief, bearing a white flag, with a few others, who were desirous of concluding a peace with the United States, came to Vincennes with the intention of holding a council for that purpose. The Governor informed them that he did not consider them as qualified for making a treaty which would be binding on their leader the Prophet; and therefore no treaty would be made unless the Prophet was present at the council, with his principal chiefs.

They informed the Governor that the warriors of the Prophet had all left him; reproaching him with being the instigator of all their misfortunes, and threatened to put him to death.—They were impressed with a belief that they could defeat us with ease; and intended to have attacked us in our camp at Fort Harrison, had we remained there a week longer.

The Potawatimie chief who was taken prisoner by us and left on the battle ground, they said, had since died of his wounds; but that he faithfully delivered the speech of the Governor, to the different tribes, and urged them to abandon the Prophet, and agree to the terms offered them by the Governor.

March 10, 1812.—We experienced some heavy shocks of an Earthquake about this time, which occasioned considerable alarm; but did no other damage than throwing down a few chimnies in the town.—On the Mississippi the shocks were more severe, where considerable damage was done, especially to buildings. It is said the motion of the earth in that quarter was from six to eight inches to and fro; but at Vincennes, 250 miles to the north, it did not exceed three inches in the heaviest shocks, as was ascertained with a lead ball suspended by a thread from the ceiling in the house.—The duration of the longest shock was about 3 minutes—they continued at intervals throughout the month.

March 29.—About 150 Indians who were said to have remained neutral in the late contest, came to Vincennes, and encamped about two miles north of the town. They were requested to deliver up their arms, and a guard of soldiers should be placed over them for their protection, and tents supplied them while they tarried with us: this they complied with, and desired an audience of the Governor on the ensuing day, which was granted.

In Council, they declared their detestation of the Prophet and his adherents, expressing their wishes to remain in peace and friendship with their father, the President of the U. States.—The Governor, in a short reply, warned them against entering into any alliance with the Prophet and his warriors—telling them, if he should again be disturbed, and obliged to come among them, it would be out of his power to restrain his young warriors from destroying them all. A treaty was signed, and the Indians received their annual presents of blankets, broadcloths, calicoes, &c. and left the town for their encampment.

April 2.—The Indians again came in, habited in their new dresses, performing their dances through the town, to the great diversion of the Regiment, who were unacquainted with their peculiarities, except their propensity to deception and treachery; the ill consequences of which we had been taught at the battle of Tippecanoe.—Towards evening they retired in good order, and soon after received their arms, and returned to their villages up the Wabash.

There were still remaining many refractory Indians on the Wabash, who would agree to no terms of peace with the U. States. They had even opened the graves of our unfortunate comrades who fell in the late action—stripped and scalped them, and left their bodies above ground. Col. Miller was preparing to send a detachment of troops to the battle ground to have them again interred; but some friendly Indians undertook this office, and the bodies were again replaced.

April 4.—Information was received of the murder of a family of seven persons on White river, and others in Indiana, besides many depredations on the Mississippi. The settlers were alarmed, and fled to the forts and the most populous towns for protection, leaving their property to the mercy of the savages.

April 9.—A family on the Embaras river, only seven miles from Vincennes, consisting of a man, his wife and three small children, were massacred while in the act of leaving their home for the purpose of finding protection at Vincennes. A young man who had resided with the family escaped and fled to Vincennes, where he arrived about 12 o'clock at night, and gave the alarm; the troops were immediately called to arms, expecting an attack upon the town. The next day Col. Miller, with a small detachment from the regiment, proceeded to the river Embaras, where they found the bodies of the murdered family, shockingly cut up with the tomahawk and scalping knife. The man had his breast opened, his entrails torn out and strewed about the ground. They were all scalped except an infant child in the mother's arms, which was knocked on the head.—The bodies were decently interred and the party returned to Vincennes without being able to discover the perpetrators of this horrid massacre.

We received information soon after the above transaction, that the famous Indian Chief, Tecumseh, brother to the Prophet, had collected a considerable force on the Wabash with the intention of attacking the town of Vincennes,—saying to the Governor—"You have destroyed my town in my absence; I shall, when the corn is two inches high destroy yours before your face." Tecumseh was not an enemy to be despised; and the information of his approach towards Vincennes, created considerable alarm among the inhabitants. The town was filled with families who came to avoid the fury of the savages. Many of the principal dwelling-houses were piqueted in, and the militia were called upon to be at their posts at a moment's warning;—thus were we kept in fearful apprehension of an attack being made upon us by the Indians, whenever we should retire to rest; add to this the frequent shocks of earthquakes, and the reader may imagine the unhappy situation in which we were placed.

A serious misunderstanding had for some time existed between Gov. Harrison and Col. Boyd, the grounds of which, the author could never correctly ascertain; yet was supposed to originate from some hasty remark of Col. Boyd upon the conduct of the militia of Indiana, during the campaign; and perhaps he had laid claim to a greater share of the laurels won in the late engagement, than the people of Indiana were willing to allow him; however, it is admitted by all, that the bravery, good order and discipline of 4th Regiment secured to the army the victory at Tippecanoe;—for this Col. Boyd deserves the highest praise.

April 17.—Col. Boyd left Vincennes for the city of Washington, and Col. Miller assumed the command of the Regiment, when we soon after received orders from Government to march to Dayton, in the State of Ohio, there to join the army under Brigadier Gen. Hull.—The citizens of Vincennes, sincerely lamented our departure, as there would be but a small force left for their protection against the savages, who had now assumed a formidable aspect, and threatened destruction to the place.—Capt. Snelling, and his Company arrived from Fort Harrison, where they had been stationed during the winter.

May 3d.—We swung our knapsacks and commenced our march for the falls of the Ohio;—The road was so very bad that we were obliged to keep pioneers in advance to clear it, which greatly retarded our march. We observed on our rout through Indiana, several houses piquetted in, where a number of families had collected, and formed little garrisons, to defend themselves against the Indians, who daily committed the most flagrant depredations upon the defenceless emigrant; we frequently saw men armed going to their fields to work, leaving their women and children to garrison their dwellings until their return in the evening.

May 11.—We arrived on the banks of the Ohio, and immediately crossed the river to Louisville, (Ken.) where great respect was manifested towards us.—Many of the citizens of this place had fought by our sides at the battle of Tippecanoe.

May 12—We proceeded on our march, and on the 16th reached the arsenal at Newport, and halted one day.

May 18—We crossed the Ohio river again at Newport to Cincinnati, where we were highly honored by the patriotic citizens of this beautiful and flourishing town.—A grand salute was fired from two field pieces while we were crossing the river.—We landed and formed on its bank and were escorted through the town by a fine looking Company of Artillery.—In one of the principal streets through which we passed, a triumphal arch was erected, ornamented with wreaths of evergreen, and the words "Heroes of Tippecanoe" were displayed in large characters over the arch. We marched a few miles from the town and encamped, where we were bountifully regaled by the generous inhabitants of the place.

May 19th—Proceeded on our march to Dayton, where we arrived about the first of June—Gen. Hull had left this place and gone on to Urbana with the army, forty miles further.

June 3d—Arrived at Urbana, and joined Gen. Hull's army composed of three Regiments of Ohio militia volunteers, commanded by Colonels M'Arthur, Cass and Findley. Here we were received with a repetition of the honors shewn us at Cincinnati, and obtained a short respite from our long and fatiguing march from Indiana; having come the distance of nearly four hundred miles, with but one day's rest.

June 13th.—Col. M'Arthur's regiment of militia left the encampment and proceeded on the march for Detroit, with orders to build block-houses at the distance of every twenty miles, and to cut a road for the march of the army.

June 15th.—The army followed on the route of Col. M'Arthur;—the weather was extremely wet, and the new road had become a perfect slough nearly the whole distance to the River Scioto, which contributed greatly to retard our progress,—having many waggons attached to the army, we were frequently obliged to halt and relieve them from the mire—We came up with M'Arthur's regiment at the Scioto, where they were just completing a large block-house. A militia sentinel was shot through the body while peaceably walking his post, by one of his comrades in the regiment, without any previous provocation being given by the deceased. His punishment was as singular as his crime. A Court Martial found him guilty of murder, and he was sentenced to have both ears cropped, and both cheeks branded with the letter M. which was immediately put in execution.

June 17th.—Col. M'Arthur's regiment again went forward;—on the 20th the army followed. An extensive swamp we had to pass through, called the Black Swamp, rendered it impossible to carry our baggage on waggons; it was therefore found necessary to transfer the flour to pack-horses, which was put up in bags for the purpose. Much rain having previously fallen, we had to wade for whole days through mud and water, tormented in the extreme both night and day by the stings of the innumerable musquetos and knats. The water we drank could only be obtained from holes made by the pioneers in advance, or from places where trees had been torn up by the roots.

It was thought that the Indians might cause us some trouble on our march through this forest, and a temporary breast-work of felled trees was erected each day on encamping—however, we received no annoyance from any enemy, during our march to the Miami rapids, where we arrived on the 29th, and found Col. M'Arthur encamped on a beautiful plain on the bank of the river. On the opposite shore, we were told, was the famous spot where, on the 20th Aug. 1794, Gen. Wayne gained an important victory over a body of about 2000 Indians.

July 1—We crossed the river, and the 4th Regt. were mustered, when we marched a few miles through a small village and encamped. Here the General chartered a small schooner to take the sick and baggage, and hospital stores of the army to Detroit, with Lieut. Gooding of the 4th regiment, and lady, and the ladies of Lieuts. Bacon and Fuller, and two Sergeants, Jennison and Forbush, and about thirty privates.—These were all taken by the British brig Hunter, at the mouth of Detroit river, and which was the first notice these people had of the declaration of war.—The capture of this vessel was truly unfortunate in its consequences to the American army, as many papers of great importance, relative to our future operations, fell into the hands of the enemy, besides the private baggage of some of the officers of the army.

ANTHONY WAYNE

Mrs. Bacon and Mrs. Fuller were sent to Detroit by a flag of truce immediately after the schooner was taken.—Mrs. Gooding preferred remaining at Malden, with her husband, who was then seriously indisposed.

July 2d—Proceeded on our march, and without any occurrence worthy of notice, arrived at the river Huron on the 4th, and threw a bridge of logs across for the passage of the waggons. The Indians from Brownstown came to the river in considerable numbers, appearing very friendly—seeing many waggons cross the bridge; while the main body of the army were screened from their view by a piece of woods, they expressed their surprize that Gen. Hull should think of taking the Canadas, "with so many waggons and so few men!" and were very curious to examine some of the waggons, to ascertain if the army was not packed up within them. The army crossed the bridge and encamped. This day being the anniversary of American Independence, an extra glass of whiskey was issued to the troops on the occasion!

A little past sunset a rumor was spread in the camp, that an attack was intended on our army by a large force of British and Indians. In consequence we were called to arms, to which we stood by turns until day-break. No attack was made. We received our first information here of the declaration of War between the United States and Great-Britain.

July 5th—At sunrise we proceeded on our march without interruption, and passed through a small Indian village called Brownstown. The Indians appeared very friendly; some of their Chiefs came out and saluted the General with great cordiality. About 5 o'clock, P.M. we arrived within 3 miles of Detroit, at a place called Spring-Wells.

July 6th—Marched into the town of Detroit, and encamped. We continued here 5 or 6 days, making preparations to cross the river into Upper Canada. The troops were in much better health and spirits than was to be expected after the performance of so long and laborious a march; and all appeared anxious immediately to commence active operations against the enemy.

July 12—A little before day the troops were turned out with great silence and marched by detachments to the river, where we immediately embarked on board of boats prepared for the purpose, with muffled oars, and a few minutes after day-break we all safely landed in Upper Canada.—We then marched a short distance down the river and formed our encampment directly opposite to Detroit,—when the American standard was hoisted, and the following Proclamation issued by Gen. Hull:—

Inhabitants of Canada!

After thirty years of peace and prosperity, the United States have been driven to arms. The injuries and aggressions, the insults and indignities of Great Britain have once more left them no alternative but manly resistance or unconditional submission. The army under my command has invaded your country; the standard of the Union now waves upon the territory of Canada. To the peaceable unoffending inhabitants it brings neither danger nor difficulty. I come to find enemies, not to make them, I come to protect, not to injure you.

Separated by an extensive wilderness from Great Britain, you have no participation in her councils, no interest in her conduct. You have felt her tyranny, you have seen her injustice. But I do not ask you to avenge the one or to redress the other. The United States are sufficiently powerful to afford every security consistent with their rights and your expectations. I tender you the invaluable blessing of civil, political and religious liberty, and their necessary result, individual and general prosperity; that liberty which gave decision to our councils, and energy to our conduct in a struggle for independence,—which conducted us safely and triumphantly through the stormy period of the revolution—that liberty which has raised us to an elevated rank among the nations of the world; and which offered us a greater measure of peace and security, of wealth and improvement, than ever fell to the lot of any people. In the name of my country, and the authority of government, I promise you protection to your persons, property and rights; remain at your homes; pursue your peaceful and customary avocations; raise not your hands against your brethren. Many of your fathers fought for the freedom and independence we now enjoy. Being children therefore of the same family with us and heirs to the same heritage, the arrival of an army of friends must be hailed by you with a cordial welcome. You will be emancipated from tyranny and oppression, and restored to the dignified station of freedom. Had I any doubt of eventual success, I might ask your assistance, but I do not, I come prepared for every contingency. I have a force which will look down all opposition, and that force is but the vanguard of a much greater—If, contrary to your own interest and the just expectation of my country, you should take part in the approaching contest, you will be considered as enemies, and the horrors and calamities of war will stalk before you.

If the barbarous and savage policy of Great Britain be pursued, and the savages are let loose to murder our citizens and butcher even women and children, this war will be a war of extermination. The first stroke of a tomahawk—the first attempt with the scalping knife, will be the signal of an indiscriminate scene of desolation. No white man found fighting by the side of an Indian will be taken prisoner—instant death will be his lot. If the dictates of reason, duty, justice and humanity cannot prevent the employment of a force which respects no rights, and knows no wrong, it will be prevented by a severe and relentless system of retaliation. I doubt not your courage and firmness—I will not doubt your attachment to liberty. If you tender your services voluntarily, they will be accepted readily. The United States offer you peace, liberty and security. Your choice lies between these and war, slavery and destruction. Choose then, but choose wisely; and may He who knows the justice of our cause, and who holds in His hands the fate of nations, guide you to a result the most compatible with your rights and interests, your peace and happiness.

The troops considered this Proclamation as highly indicative of energetic measures; although the "exterminating" avowal was disapproved of by the advocates of humanity and generosity to a fallen enemy. The Canadians, who had fled from their homes on our entering Canada, or were doing duty in the service of the Crown at Fort Malden, returned to their dwellings, and sought protection from the American army; such was their confidence in the ability of Gen. Hull to afford them protection, that many of them had expressed their willingness to join our army whenever it should be ready to march against the enemy's post at Malden.

The Indians also seemed willing to remain neutral rather than to take up the tomahawk against a force which to them appeared so formidable as that of the American army. The troops were in high spirits, and loudly expressed their anxious wish to be immediately led on against the enemy—instead of which, or taking any advantage of the favorable moment offered to strike the important blow, the services of all the carpenters, blacksmiths, and artificers of every kind were put in requisition; building gun carriages, scaling-ladders, and gundolas for the transportation of our heavy ordnance.—In short, the preparations which were making seemed to bespeak some grand and brilliant achievement, unparallelled in the annals of martial prowess.

July 14—Col. M'Arthur was detached with 150 men to the river Thames, where he captured a considerable quantity of provisions, blankets, arms and ammunition, while another party secured several hundred merino sheep at Belle Donne, the property of the Earl of Selkirk.

July 15—Col. Cass with a detachment of about 300 men, left the encampment to reconnoitre the enemy's advanced posts. They were found in possession of the bridge over Aux Canard river, five miles from Malden. A detachment of regular troops passed the river to the south side at a ford about 5 miles above the bridge, thence down to the enemy, whom they attacked and drove from their position. The militia behaved in this affair with the greatest gallantry;—three times the British formed, and as often were compelled to retreat. The loss on our part was trifling. One prisoner was taken, and Col. Cass encamped during the night on the scene of action without molestation.

Frequent skirmishing took place between other detachments which were sent to reconnoitre the enemy. In one of these rencontres we lost seven killed and eleven wounded. Such skirmishing, marching and countermarching by detachments from the army, without obtaining any advantage over the enemy had become irksome to the troops and loud murmuring took place.

Sergeant Forbush, one of the prisoners confined at Malden, found means to have a letter conveyed to his Captain, (Burton) informing of the weak state of that post; it is even said the prisoners might at one time have taken it with ease, as all the force of the enemy had crossed the river to the American side, and left but a sergeant's guard at the fort.—It was further stated, at the time Col. Cass drove the British from their position at the river aux Canard, an immediate attack was expected upon the town and fort, and that preparations were made to secure the public property, and to make good their retreat in the event of an assault by our army.

July 21—A large schooner was taken possession of at Sandwich and towed up the river to Detroit, and men employed to fit her up for the service. A cartel arrived from Fort Michillimacinac with American prisoners, who had surrendered that post to the enemy without resistance.—They were ignorant of the declaration of war until they were made prisoners. Nothing further of consequence took place for eight or ten days. The vast preparations for an attack on Malden were still progressing with great industry. The militia from that place were daily coming in to join our standard, and it was expected an immediate attack upon that fort would now be made.

August 4—Major Van Horn, of Col. Findley's regiment was detached with 200 men to the river Raisin, for the purpose of escorting a quantity of provisions to the army, which were at that place under the charge of Capt. Brush. He was attacked in the woods of Brownstown by a large body of Indians while his men were partaking of a little refreshment. So sudden and unexpected was the attack that it was impossible to form the men in line of battle, although every exertion was made by the officers for that purpose. In this defeat seven officers and ten privates were killed, and many more wounded—They retreated in great disorder, leaving part of their killed on the field.

Aug. 5.—Orders are at last issued by Gen. Hull for the army to be in readiness to take the field against the enemy; the first step for this purpose, was to abandon our position in Upper Canada, and return to Detroit; which was accomplished on the night of the 6th, leaving a detachment, however, to garrison a small fort we had built during our stay at Sandwich: this also was shortly after set fire to and abandoned.

Aug. 8.—In consequence of the failure of the expedition under Major Van Horn, the 4th Regt. with a detachment from the militia, all under the command of Col. Miller, left Detroit about 3 o'clock P.M. and proceeded on our march to open the communication with Capt. Brush, who had fortified himself on the banks of the river Raisin. A little past sunset we arrived at the river De Coss, which we crossed, and encamped without tents.—Early next morning continued our march and about 12 o'clock our Cavalry were fired upon by some Indian scouts, who had stationed themselves behind an old log hut, and killed one and wounded another of the dragoons. The line of battle was instantly formed, and we advanced rapidly forward, for a considerable distance, but no enemy could be discovered.—We halted to refresh on an open field, where we tarried a short time, and again proceeded on our march.—At 3 o'clock, P.M. the vanguard, commanded by Capt. Snelling, was fired upon by an extensive line of British troops. Capt. Snelling maintained his position in a most gallant manner until the main body could be formed in line of battle, and advance to his relief; when the whole, excepting the rear guard was brought into action in a masterly style by our brave Commander.—The enemy were formed in an advantageous position behind a breast-work of felled trees; we had advanced but a few rods towards their works before a large body of Indians arose upon each flank of the British and poured a tremendous fire of rifles into our ranks; and in a moment dropped down behind their logs. We still continued on the advance, and could discover nothing but the smoke from their discharge until nearly upon them with the bayonet, which they perceived, before they had time to reload, and retreated to a second breast-work; but they, as well as the British, were driven from every place wherever they attempted to make a stand. The rout became general, and the pursuit continued for about two miles, to the village of Brownstown, where the British took to their boats, and the Indians to the woods.—Col. Miller had directed a charge to be made by the Cavalry, while the enemy were in full rout; which was not done, although Capt. Snelling offered himself to lead them on in person. This cowardice of the Cavalry alone saved the enemy from destruction. In the action an Indian had climbed into the top of a large tree, from which he discharged many arrows into our ranks, but was discovered by the soldiers, and brought down very suddenly. Another Indian who had been wounded, and lay in the woods unable to move from his place, had loaded his rifle and shot down a militia soldier, who was in search of some of his fallen comrades; a party near by heard the report of the rifle, came up and dispatched the Indian while in the act of reloading, for another victim who might pass in his way.—Our killed and wounded were collected before dark and brought to the camp; consisting of 18 killed and 58 wounded. The loss of the British and Indians were 100 killed, and nearly twice that number wounded. Many of them were picked up and brought into camp the same evening, and their wounds carefully attended to. The British were commanded in this action by Major Muir, and the Indians by Tecumseh, Marpot and Walk-in-the-water. Their force consisted of three hundred Regulars and five hundred Indians, nearly one third greater than the American force under Col. Miller.

The only Officers of the 4th Regt. wounded, were Lieut. Larabee, a brave officer who lost an arm—and Lieut. George P. Peters, who commanded the late Capt. Wentworth's company.

Aug. 10.—Boats from Detroit arrived to take up the wounded. On their return they were fired upon by the British brig Hunter, and even after the wounded were transferred from the boats to waggons, this vessel took several positions to harass them on their return to Detroit.

Col. Miller had determined to push on to the river Raisin; for which purpose the troops were paraded in readiness to march; but the Col. was suddenly attacked by a fit of the fever and ague, with which he had been partially afflicted from the time of his severe illness at Fort Harrison in Indiana. We therefore continued on the ground this day, expecting provisions from Detroit, but none arrived. We observed the British to be busy in crossing over troops from Malden a few miles below us, and concluded they intended an attack upon our encampment the following night. About sunset an express arrived in Camp from the General at Detroit, with a peremptory order for the troops to return that evening to the river De Coss. We were immediately formed and proceeded on our return. It having rained the whole of the day, and the night being extremely dark, it was with great difficulty we reached the river; being without tents we were wet to the skin; many lost their shoes in the mud and came on barefoot. About 2 o'clock the next morning we arrived at the river, and after partaking of some refreshment, which had been sent to this place, we spread our blankets, which were wet as well as the ground we lay upon; and notwithstanding our uncomfortable situation we slept soundly until day light.

Aug. 11.—Continued on our march, re-crossed the river De Coss, and arrived at Detroit about 12 o'clock.

Aug. 12.—The British had taken possession of the ground we had abandoned at Sandwich, and commenced throwing up their works; at which they continued without interruption until the 15th, working in open day. Our troops were also employed in erecting batteries on the bank of the river, opposite to those of the British.

Aug. 14.—A detachment of three hundred and fifty troops from M'Arthur's and Cass' regiments were ordered to the river Raisin to escort up the provisions which had so long remained there under the protection of Captain Brush. This was the third detachment which had been sent on that service.

Aug. 15.—The enemy had completed their batteries, and about 10 o'clock, P.M. Gen. Brock, the British commander, sent over a flag of truce from Sandwich, with a summons for the surrender of the town and fort; stating that he could no longer restrain the fury of the savages, and should at 3 o'clock, commence a cannonade upon the place unless the summons was complied with. A prompt and spirited refusal was returned. At 4 o'clock their batteries were opened upon the town, from two 18 pounders and a howitzer. Their fire was briskly returned from our two batteries of three 24 pounders, and continued without interruption until dark. In the evening they commenced throwing shells, and did not cease until 9 o'clock. No person was hurt, or but little damage done, except to a few buildings in the town.

Aug. 16.—At day light the firing recommenced upon the fort, where was stationed the 4th regiment. Not a gun was fired from this place in return. Five men were killed and wounded in the fort, where the Gen. and some citizens from the town had repaired. At sunrise the Indians appeared in the woods back of the town, while the British were seen landing from the Queen Charlotte at Spring Wells, three miles below us. About 8 o'clock they began to move towards us in close column. It was now that we every moment expected the orders of the Gen. to march out and commence the battle which was to decide the fate of this army.—The long wished for moment had now arrived; the eyes of the soldiers of the 4th regiment were turned towards their brave Commander, Col. Miller, and seemed to express the ardent wishes of the men for him to give the word and lead the way.

The militia were posted outside of the fort, behind a line of pickets. Two 24 pounders loaded with grape shot were placed in a situation to sweep the advancing column of the enemy.

The British troops advanced with a regular step, and in fine order. All was silent in the fort—"Not a discontent broke upon the ear—Not a look of cowardice met the eye." We listened in eager expectation, that each moment our ears would be saluted from the discharge of the 24 pounders. What was our surprise when we beheld the militia retreating towards the fort, and at the same time an American Officer on horseback riding towards the British column bearing a white flag, while another was placed on the parapet of the fort. A soldier attempted to knock it down with his musquet—an officer stepped up and commanded him to desist—"There sir," says the soldier, pointing to the American colors, then waving on the flag-staff—"There is the flag I choose to fight under!"—Such was the spirit which animated the whole body of the troops. A British officer rode up to the fort, and in thirty minutes afterwards a capitulation was signed. The Adjutant soon after came in and informed the troops that we must consider ourselves prisoners of war to His Britannic Majesty's forces under Gen. Brock.

Such curses and imprecations as were now uttered by the soldiers upon the head of our General, were perhaps never before made use in any army.—"Treachery"—"We are sold"—was the cry throughout.

We were ordered to pack up our effects as soon as possible. Some officers entered the loft of the store house, where they found a few articles of clothing, which was distributed among us. The militia had been crowded into the fort which now was nearly filled with troops, in great disorder.

At 12 o'clock the British marched in and took possession of the fort. We were then ordered to shoulder arms and march out in sections.—Passing near the British, we observed the greater part of their troops to be Militia, having "Canadian Militia," stamped on the buttons of their coats, which were red, and gave them the appearance of regulars.—Of the red coats there were 29 platoons, with 12 men to each, (348) and about the same number without uniforms.—We were marched into a field adjoining the fort, and stacked our arms—a British guard was immediately placed over them.

The colors of the 4th regiment were next brought out by the Adjutant and delivered into the hands of a British officer. On observing this the soldiers could not suppress their tears. These colors were a present to the regiment by some ladies in Boston, and had been borne victoriously on the banks of the Wabash, and the shores of Erie, and at last are obliged to be shamefully surrendered to Canadian Militia, in consequence of the cowardly, (if not treacherous) conduct of our General.

The absence of Cols. M'Arthur and Cass was greatly lamented—had they been present, doubtless an engagement would have taken place; but some how or other the plans of the Gen. seemed to be more wisely arranged for a surrender than a manly defence.

There were surrendered with the fort, 29 pieces of cannon, 2500 stands of arms and a considerable quantity of military stores and provisions.

At 2 o'clock we were sent on board a schooner, (the same we had taken possession of while at Sandwich) where wounded and sick men, women and children were stowed away without discrimination. We received no provisions from the British for two days; but fortunately some of the men had brought a small quantity on board with them, which was shared among us while it lasted.

Aug. 18.—We were transferred to another schooner and sent to Malden, where we met with our former comrades who were taken prisoners on the 2nd July, confined on board an old vessel in the river. They said they had been well treated by the British, but were frequently insulted by the Indians who passed along the shore. Sergt. Jennison has favored the author with the following minutes of the conduct of the Indians while he remained a prisoner at Malden:

"On the 18th July we were informed that an engagement took place at the river aux Canard between our troops and the British, and that the former were driven back. A British soldier was killed in the action, and buried near the river; the Indians afterwards dug up the body, (supposing him to be an American) and took off the scalp. Towards evening they came into the town with the scalp fixed to a pole, which they shook at us, saying "one yankee gone home.""

July 19.—A number of Indians came in from a skirmish with our troops, having one of their number badly wounded; when they came opposite to us, they suddenly halted and pointed their rifles towards us as we were walking the deck, in order to frighten us, as we supposed; but not taking any particular notice of them, they discharged several pieces at us; some of their shot came very close, but they did no injury.

July 21.—The Indians received new blankets and guns from the King's store. An American prisoner was brought to the fort by the name of Burns—he was shot through the thigh, and had been awfully beat by the squaws: an officer found means to purchase him, and thereby saved his life.

Aug. 4.—The Indians at Brownstown agreed in council to take up the tomahawk against the Americans, and a number of boats passed across the river to assist them over with their effects.—Gen. Brock soon after arrived with troops from York. Nothing more of consequence took place here until the arrival of our troops from Detroit.

On our arrival at Malden we were put on board of different vessels in the river: The private property taken in the schooner the 2d of July was restored to its right owners.

Aug. 19.—The regular troops were put on board the Queen Charlotte and another small vessel in the river. Provisions were dealt out to us, consisting of pork and flour; but we had no convenience allowed us to cook it, and were obliged to eat our pork raw. The flour, we contrived to mix into small cakes, and when the greasy cook to the vessel saw fit to grant us permission, we threw them into his kettle, where they were boiled.

The Militia prisoners departed in two vessels for Cleveland where they were to receive their paroles.

Aug. 20.—We set sail from Malden for fort Erie in the Queen Charlotte and a schooner.—Our situation on board the schooner was truly deplorable: being 150 of us in number, there was hardly room sufficient for us to stand together in the hold. Only a few were allowed to remain on deck at a time, and at night all were turned below, where we were obliged to huddle together and each one rest the best way he could. The hold became so foul before morning that the men would gather at the hatchway, greatly distressed for fresh air.

After a passage of three days we arrived at Fort Erie, half famished with hunger; although we had a plenty of provisions on board such as it was;—raw pork and dough may answer two or three meals for a soldier, but a continuance of such food would starve even him.

Aug. 23d.—We were landed, and informed that an armistice had been concluded between the two governments.—We tarried here but a short time—drew provisions for the day, and at ten o'clock we were formed, and under a guard proceeded on our march for Fort George. As we passed Black Rock, the American fort on the opposite shore, we beheld many of our country soldiers viewing us from the ramparts. At sunset we arrived at Chippewa and were confined in a large building where we remained for that night. Two or three of our men escaped from the British and crossed the river to the American side on a gate which they had taken from the fence near the building where we were confined.

Aug. 24.—A quantity of cooked provision was dealt out to us; and at 8 o'clock we again commenced our march; passed through Queenstown, and arrived at Fort George, about two o'clock, P.M.—We were paraded and a strict examination made for British deserters; but none were found among us.

One of our men by the name of Barker, an American by birth, had been previously claimed, and was taken from us as a British deserter—he had been in the British service at Quebec several years before, and from which he deserted, and enlisted at Fort Independence in Boston, in 1809.

Aug. 27.—We embarked on board two gun brigs, the Royal George and Prince Regent, and in two days arrived at Kingston, where we were well treated and had plenty of provisions allowed us. One of our men was prevailed upon to enter the British service, on board the Royal George.

Aug. 28.—Two hundred British troops arrived from Montreal in Batteaux; and at the same time we received orders to be in readiness to embark the next morning and proceed on our passage.

A Corporal and Musician of Captain Brown's Company made their escape by swimming to a small island a short distance from where we were confined.

Sept. 1.—We drew provisions for 4 days, and embarked on board the batteaux, and ordered to Montreal. A strong guard of soldiers, in boats carrying a small swivel in the bow, loaded with grape shot, escorted us on our passage;—we were compelled to row ourselves in the boats, which much fatigued us in our weakly situation; but complaints were of no other consequence here than an addition of abuse: he who complained least fared best.—Each night the boats were brought ashore, and a guard lined the beach to prevent us from leaving them.

We were not allowed to go three rods from the boats, and if in that compass we could procure fuel sufficient to cook our provision, it was well, otherwise our next day's fare must be on raw pork, as usual. At dark we were all driven to the boats, where we remained till morning, in a very uncomfortable situation, there being from twelve to fifteen men in each it was impossible to lay in any convenient position for resting or sleep.

Sept. 7.—We arrived at a small village, seventeen miles from Montreal—crowds of people had collected at this place, to have a peep as they said, at Gen. Hull's "exterminating yankees,"—Our guard was strengthened by a fine looking company of volunteers, and about three o'clock we were paraded in sections, and commenced our march for the city, where we arrived about 8 o'clock in the evening. The streets through which we passed, and the houses were filled with spectators, holding lights from their windows. A band of music joined the escort, and struck up our much admired ditty, "yankee doodle," in which they were joined by all of us who could whistle the tune; and like merry yankee soldiers we jogged on, and when they ceased to play, yankee doodle was loudly called for by the regiment. At last somewhat mortified at our conduct, they began "Rule Britannia," which was cheered by the multitude; but we still continued our favorite song, some singing and others whistling till we reached the barracks.

Sept. 7.—Many people crowded about the barrack yard, but none were permitted to converse with us. In the afternoon we were paraded by companies, and a list descriptive of each individual of the regiment was taken by the British officers.