Title: By Right of Sword

Author: Arthur W. Marchmont

Illustrator: Powell Chase

Release date: December 20, 2011 [eBook #38357]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

I raised my sword and struck him with the flat side of it

across the face.—Frontispiece, Page 42.

BY

ARTHUR W. MARCHMONT

AUTHOR OF

"Sir Jaffray's Wife," "Parson Thring's Secret,"

Etc., Etc.

NEW AMSTERDAM BOOK COMPANY

156 : FIFTH : AVENUE : NEW : YORK

HUTCHINSON & COMPANY, LONDON

Copyright 1897

BY

ARTHUR W. MARCHMONT

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

I Raised My Sword and Struck Him with the Flat Side of it across the Face . . . Frontispiece

"I Know that You are My Brother, Alexis"

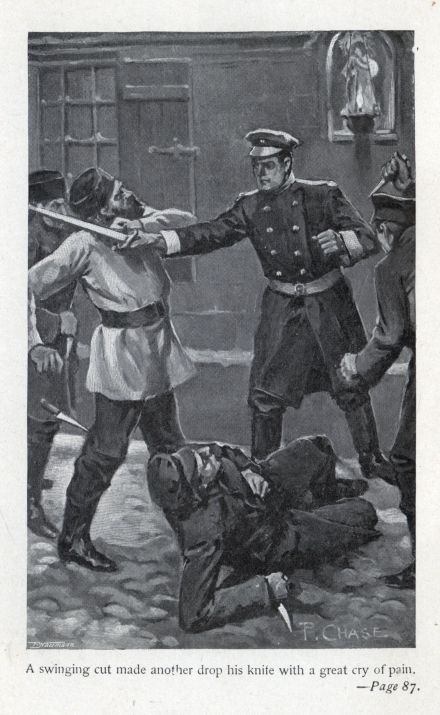

A Swinging Cut Made Another Drop His Knife with a Great Cry of Pain

"Alexis, Did You Bring That Proposal to Me Deliberately?"

"Take Another Two Grains, Mouse"

I Darted Forward into the Doorway

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | THE MEETING |

| II. | I AM A NIHILIST |

| III. | MY SECONDS |

| IV. | THE DUEL |

| V. | GETTING DEEPER |

| VI. | A LEGACY OF LOVE |

| VII. | A LESSON IN NIHILISM |

| VIII. | THE RIVERSIDE MEETING |

| IX. | DEVINSKY AGAIN |

| X. | "THAT BUTCHER, DURESCQ" |

| XI. | DANGER FROM A FRESH SOURCE |

| XII. | CHRISTIAN TUESKI |

| XIII. | OLGA IN A NEW LIGHT |

| XIV. | THE DEED WHICH RANG THROUGH RUSSIA |

| XV. | A SHE DEVIL |

| XVI. | THE NEXT NIHILIST PLOT |

| XVII. | AN EXTRAORDINARY ADVENTURE |

| XVIII. | THE REASON OF THE INTRIGUE |

| XIX. | OLGA'S ABDUCTION |

| XX. | THE RESCUE |

| XXI. | THREE TO ONE |

| XXII. | THE BEGINNING OF THE END |

| XXIII. | CHECKMATE! |

| XXIV. | CRISIS |

| XXV. | COILS THAT NO MAN COULD BREAK |

| XXVI. | MY DECISION |

| XXVII. | THE FOUR ALDER TREES |

| XXVIII. | THE ATTACK ON THE CZAR |

| XXIX. | THE TRUTH OUT AT LAST |

| XXX. | AFTERWARDS |

BY RIGHT OF SWORD.

Moscow.

"MY DEAR RUPERT.

"Don't worry your head about me. I shall be all right. I did not see you before leaving because of the scene with your sister and Cargill, which they may perhaps tell you about. I have done with England: and as the auspices are all for war, I mean to have a shy in. I went to Vienna, thinking to offer myself to the Turks: but my sixteen years in Russia have made too much of a Russ of me to let me tolerate those lazy cruel beggars. So I turned this way. I'm going on to St Petersburg to-day, for I find all the people I knew here as a lad have gone north. I have made such a mess of things that I shall never set foot in England again. If Russia will have me, I shall volunteer, and I hope with all my soul that a Turkish bullet will find its billet in my body. It shan't be my fault if it doesn't. If I hadn't been afraid of being thought afraid, I'd have taken a shorter way half a score of times. My life is an inexpressible burden, and I only wish to God someone would think it worth while to take it. I don't want to be hard on your sister, but whatever was left in my heart or life, she has emptied, and I only wish she'd ended it at the same time. You'll know I'm pretty bad when not even the thought of our old friendship gives me a moment's pleasure. Good-bye. Don't come out after me. You won't find me if you do.

Your friend,

HAMYLTON TREGETHNER."

The letter was wretchedly inconsequential. When I sat down to write I hadn't meant to tell Rupert Balestier that his sister's treatment had made such a mess of things for me; but my pen ran away with me as it always does, and I wasn't inclined to write the letter all over again. I hate letter writing. I was to leave Moscow, moreover, in an hour or two, and when I had had my things sent to the railway station and followed them, I dropped the letter into the box without altering a word.

It had made me thoughtful, however; and I stood on the platform looking moodily about me, wondering whether I should find the end I wished most speedily by joining the army or the Nihilists; and which course would bring me the most exciting and quickest death.

I had three or four hours to wait before my train left, and I walked up and down the platform trying to force myself to feel an interest in what was going on about me.

Presently I noticed that I was the object of the close vigilance of a small group of soldiers such as will generally be seen hanging about the big stations in Russia. They looked at me very intently; I noticed them whisper one to another evidently about me; and as I passed they drew themselves up to attention and saluted me. I returned the salute, amused at their mistake, and entered one of the large waiting saloons.

It was empty save for one occupant, who was standing by the big stove looking out of a window near. This was a girl, and a glimpse I caught of her face shewed me she was pretty, while her attitude seemed to suggest grief.

As I entered and went to another part of the room, she started and glanced at me and then looked away. A few seconds later, however, she looked round furtively, and then to my abundant surprise, came across and said in a low, confidential tone:

"It is not enough, Alexis. I knew you in a minute. But you acted the stranger to perfection."

She was not only pretty, but very pretty, I thought, as she stood with her face raised toward mine, a light of some kind of emotion shining in her eyes where I saw traces of tears. But my recent experiences of Edith Balestier had toughened me a lot, and I was suspicious of this young woman.

"Pardon me, Madam, you have made a mistake."

Then she smiled, rather sadly; and her teeth shone salt white between her full curved lips.

"Your voice would betray you, even if your dear handsome eyes did not. Do you think the mere shaving of your beard and moustache can hide your eyes. Just look into mine and see if the shade is not exact?"

I did look into them: and very beautiful eyes hers were. Little shining blue heavens all radiant with the light of infinite capacity to feel. Fascinating eyes, very. But I had not lived the first sixteen years of my life in Russia without getting to know that in that big land all is not snow that looks white; and that a very awkward intrigue may lurk beneath a very fair seeming surface.

"Madam, I am charmed, but I have not the honour of knowing you."

A passing cloud of irritation shewed and a little gesture of impatience, sufficient to remind me that the gloved hands were very small.

"Ah, why keep this up now? There is no need, and no time. Is not the train starting in less than an hour—and by the way, what madness is it that makes you loiter about here in this public way, out of uniform and as if there were no danger and you were merely taking a week's holiday, instead of flying for...."

"Madam," I broke in again. "I must repeat, I am a stranger. You must not tell me these things. My name is Hamylton Tregethner, an Englishman, and...."

"Yes, yes, I know you are: or at least I know you are going to call yourself English, though you haven't told me what your name is to be. But I know that you are my brother Alexis, going to leave me perhaps for ever, and that when I want to scold you for running this risk—for you know there are police, and soldiers, and spies in plenty to identify you—you...." here she made as if to throw herself into my arms. But suspecting some trick, I stepped back.

"I know that you are my brother, Alexis."

"Madam, I must ask you to be good enough not to play this comedy any farther." I spoke rather sternly.

"If your disguise were only as good as your acting, Alexis, not a soul in Russia would suspect you. Oh, I see what you mean," she cried, a look of intelligence breaking over her features. "I forgot. Of course, I am compromising your disguise by thus speaking to you. I am sorry. It was my love for you made me thoughtless, when I should have been thoughtful. I will go away." She turned on me such a look of genuine grief that it melted my scepticism.

"There is really some strange mistake," I said, speaking much more gently. "At first I thought you were intentionally mistaking me for someone else; for what object I knew not. But I see now the error was involuntary. I give you my honour, Madam, that you are under a complete mistake if you take me for any relative of your own. I am an Englishman, as I say, and I arrived in Moscow only last night, and am leaving for St Petersburg by the next express train. I am afraid, if you persist in your mistake, it may have unpleasant consequences for you. Hence my plain speech. But I am what I say."

As I finished, I raised my hat and stood that she might convince herself of her blunder.

She looked at me with the most careful scrutiny, even walking round to get a view of my figure. Then she came back and looked into my face again; and I could see that she was still unconvinced.

"It is impossible," she said, under her breath. "If I allow for the difference your beard and moustache would make, you are my brother."

"I am Hamylton Tregethner," I said, and I took out my pocket-book and shewed her my passport to Paris, Vienna, Moscow, "and travelling on the Continent."

"These things can be bought—or made," she said. Then she seemed to understand how she had committed herself with me, if I were really a stranger, and I saw her look at me with fear, doubt, and speculation on her pretty expressive face.

She sighed and lifted her hands as if in half despair.

"Madam, you have my word as an Englishman that not a syllable of what you have said shall pass my lips." The bright glance of gratitude she threw me inspired me to add:—"If I can be of any help in this matter, you may command me absolutely."

She gave me a little stiff look, and I thought I had offended her: but the next moment a light of eagerness took its place.

"When are you leaving?" she asked with an indifference I could see was assumed.

"By the St Petersburg express at 6 o'clock."

"That is two hours after the Smolensk train." She paused to think and glanced at me once, as if weighing whether she dare ask me something. Then she said quickly:—"Will you give me a couple of hours of your company on this platform and in the station this afternoon?"

It was a strange sort of request and when I saw how anxiously she awaited my reply I could perceive she had a strong motive: and one that had certainly nothing to do with any desire for my company.

Then suddenly I guessed her motive. The cunning little woman! Her brother was obviously going to fly from Moscow. She saw that inasmuch as she herself had mistaken me for him, others would certainly do so; and thus, if she and I were together, the brother would get away unsuspected and would be flying from Moscow while he would be thought to be still walking about the station with his sister. I liked the idea, and the girl's pluck on behalf of her brother.

"I will give you not only two hours," I said, "but two days, or two weeks, if you like—if you will tell me candidly what your reason is."

She started at this and saw by my expression that I had guessed her very open secret.

"If you will walk with me outside, I will do that," she said. "I am a very poor diplomatist." With that we went out on to the platform and commenced a conversation that had momentous results for us all.

She told me quite frankly that she wished me to act as a cover for her brother's flight.

"No harm can come to you. You will only have to prove your identity—otherwise I should not have asked this," she said, apologetically. And then to excuse herself, she added, "And I should have told you, even if you had not asked me."

I believed in her sincerity now, and I told her so in a roundabout way. Then I said:—"I am in earnest in saying that I will stay on in Moscow for a day or two if you wish. I have nothing whatever to do, and if the affair should bring me in conflict with anyone, I should like it. I can't tell you all my reasons, as that would mean telling you a biggish slice of my life; but feel assured that if there's likely to be any adventure in it from which some men might shrink, it would rather attract me than otherwise. But if you care to tell me the reasons of your brother's flight, I will breathe no word of them to a soul, and I may be of help." I began to scent an adventure in it, and the perfume pleased me.

My words set her thinking deeply, and we took two or three turns up and down before she answered.

"No, you mustn't stop over to-day," she said, slowly. Then she added thoughtfully:—"I don't know what Alexis would say to my confiding in you; but I should dearly like to." She turned her face to me and looked long and searchingly into my eyes. Then smiled slightly—a smile of confidence. "I feel I can trust you. I will risk it and tell you. My brother is flying because a man in his regiment"—here her eyes shone and her cheeks coloured to a deep red—"has fastened a quarrel on him. He has—has tried to—well, he has worried me and I don't like him"—the blush was of indignation now—"and because of this he has picked a quarrel with Alexis; and to-morrow—means to kill him in that form of barbarous assassination you men call duelling. He knows he is infinitely more skilful than poor Alexis, and that my dear brother is no match for him with either sword or pistol; and he will drag him out to-morrow, and either shoot or stab him."

The tears overflowed here, and made the eyes look more bright and beautiful than ever.

"Why didn't your brother refuse to fight?"

"How could he?" she asked despairingly. "He would have been a marked man—a coward. And this wretch would have triumphed over him. And he knows this, because he offered to let Alexis off, if I—if I—Oh, would that I were a man!" she cried, changing the note of indignant grief for anger.

"Do you mean he has made such an offer as this since the challenge passed?"

"Yes, my brother came and told me. But I could not do it. And now this has come."

I didn't think very highly of the brother, but he had evidently talked his sister round. What I thought of most was the chance of a real adventure which the thing promised.

The man must be a bully and a scoundrel, and it would serve him right to give him a lesson. If this girl had not recognised me, perhaps he would not. I felt that I should like to try. There was no reason why I should not. I could easily spare a couple of days for the little drama, and go on to St Petersburg afterwards.

"You are very anxious for your brother's safety?" I asked.

"He is my only protector in the world. If he gets away now to Berlin or Paris, I shall follow and go to him."

"But is he likely to get away when he will be missed in a few hours. A single telegram from Moscow will close every frontier barrier in Russia upon him."

"We know that;" and she wrung her hands.

"If he could have two clear days he could reach the frontier and pass unquestioned," I said, significantly.

She was a quick-witted little thing and saw my point with all a woman's sharpness.

"Your life is not ours to give away. This man is noted for his great skill."

"Would everyone be likely to make the same mistake about me that you have made this afternoon?" I asked in reply.

She looked at me again. She was trembling a little in her earnestness.

"Now that I know, I can see differences—especially in your expression; but in all Moscow there is not a man or woman who would not take you for my brother."

"Then I decide for the two days here. And if it will make you more comfortable, I can assure you I am quite as able to take care of myself with either sword or pistol as this bully you speak of. But it is for you to decide."

There came a pause, at the end of which she said, her face wearing a more frightened look:—

"No, it must not be. There are other reasons. My brother is mixed up with..."

"Excuse me, can you tell me which is the train for Smolensk?" asked a man who came up and interrupted us, speaking in a mixture of Russian, English and German.

The girl started violently, and I guessed the man was her brother. A glance at his eyes confirmed this. They were a weak rendering of the glorious blue eyes that had been inspiring me to all sorts of impulses for the last hour.

"That disguise is too palpable," I said, quietly. He had shaved and was wearing false hair that could deceive no one. In a few minutes the whole situation was explained to him by his quick sister.

"I've only consented to go in order that Olga here may not be robbed of her only protector," he said, thinking apparently to explain away his cowardice. "She has no one in the world to look after her but me, you know. If you'll help her in this matter, she will be very much obliged; and so shall I. You needn't go out to-morrow and fight Devinsky—that's the major's name: Loris Devinsky. My regiment's the Moscow Infantry Regiment, you know. If you'll go to my rooms and sham ill, no one will know you, and as soon as I'm over the frontier I'll wire Olga, and you can get away." He was cunning enough as well as a coward, evidently.

"Very well," said I. "But you'll get over no frontier if you wear a beard which everyone with eyes can see is false, and talk in a language that no one ever spoke on this earth. Pull off the beard: the little black moustache may stay. Speak English, or your own tongue, and play my part to the frontier; and here take my passport; but post it back to your sister to be given to me as soon as you're safe over. And for Heaven's sake don't walk as if you were a thief looking out for arrest. No one suspects; so carry yourself as if no one had cause to."

It was a good thing for him I had seen his sister first. He would never have got me to personate him even for a couple of hours.

But we got him off all right, and his sister was so pleased that I could not help feeling pleased also. First in his assumed character he made such arrangements for my luggage as I wished, and then we hurried up to the train just before it started. As we reached the barrier where the papers had to be examined, he turned and bade his sister good-bye, and then said to me aloud in Russian, hiding his voice a little:—

"Well, good-bye, Alexis;" and he shook hands with me.

"Good-bye," I answered with a laugh: and he waved an adieu to us from the other side of the barrier.

As we turned away together, Olga was a little pale.

Three soldiers saluted me, and I acknowledged the salute gravely, glancing at them as I passed.

Then I noticed a couple of men who had been standing together and watching the girl and myself for some time, leave their places and follow us. I told my companion and presently I saw her turn and look at them, and then start and shiver.

"Do you know them?" I asked.

"Alas, yes. They are Nihilist spies, watching us."

"Ah, then there is a little more in this than I have understood so far," I said.

"You shall know everything," she replied as we left the station together.

"I think if you don't mind we will go back to the station," said my companion, stopping after we had gone a little way without speaking. "It is very convenient for talking. Besides, you have to decide whether this thing shall be carried any farther."

"I have already decided," I replied, quietly. "I am going through with it, if it is at all possible. But I have thought of many difficulties."

"You must know all that I can tell you, please, before you decide, or I shall be very uncomfortable." She said this very firmly.

"Certainly you must tell me everything that will help me to know what manner of man I am now." I smiled as I said this to reassure her; but she was very earnest and a little pale.

She waited a while until there was no one near us, and then said in a low tone:—

"My brother is mixed up with the Nihilists in some way. I don't know how, quite: but I believe they suspect him of having played them false, and I think his life is threatened. Those two men you saw at the station were spies, sent either to stop him, or, if he got away, to follow him."

"But they didn't attempt to stop him."

"No, they mistook you for him, thinking they could see through the disguise of a clean shaven face. Had you entered the train, they would very likely have told you openly not to go, or have warned you of the consequences."

"And what would be the consequences?"

"Surely you know what it means for a Nihilist to disobey orders? It is death." She was white now and agitated. "I am so ashamed at not having told you before you took the first step."

"It would have made no difference in my decision," I replied promptly. I thought more of clearing her clouded face than of any possible consequences to me. "But tell me, are you also mixed up with them in any way?"

"I am putting my liberty and perhaps my life into your hands," she said, in the same very earnest tone and manner. "My brother has drawn me in with him to a certain extent. You know they like to have many women in the ranks."

"I am sorry for you. I have rarely known a Nihilist who was capable of getting much pleasure out of life." A cold touch of fear seemed to contract her features, as she glanced at me and shrank a little from me.

"You! What—how come you to know anything of this? You said you were—an Englishman?"

"I am an Englishman: but I lived the first sixteen years of my life in Russia: the last six of them in Moscow here; and I know much of Russian life. I have made only one visit to Russia since I left; and this time I arrived only last night, and intended to go on to St Petersburg as I told you to-day. It will save time in this matter if you can make up your mind to believe absolutely in my good faith."

I looked into her face as I said this, and I held out my hand. She laid hers in it, and we clasped hands in a strong firm grip as a token of mutual faith and friendship. I believed in the little soul, and meant to stand by her.

"I will trust you now," she said, simply, after a pause.

"As for what you have told me, it can make no difference to me," I declared. "If I go out and meet this fellow Devinsky to-morrow, and he beats me, it will be all the same to me whether I am a Nihilist or an Englishman. There is only one soul in all the world who will care; and I shall give you a letter to be posted to him—if things go wrong."

I stopped to give her an opportunity of promising to do this; but she remained silent, and walked with her head bent low. I felt rather a clumsy fool. She was such a sensitive little body, that the thought of my being killed, as the result of her having got me to help her brother away, naturally upset her. She couldn't know how gladly I should welcome the other man's sword-point between my ribs.

After a pause of considerable constraint she said:—

"There is no need whatever for you to go out and meet Major Devinsky. You can do as Alexis said; be ill in bed until the passport comes back, and then leave."

"Oh, I'm not one to play the coward in that way," said I, lightly, when a look of reproach from those most expressive eyes of hers made me curse myself for a clumsy fool for this reflection on her brother's want of pluck. "I mean this. If I take up a part in anything I must play it my own way; but there's more than that behind. I don't want to look like bragging before you; but I have come out here to Russia to volunteer for the war which everyone says must come with Turkey. I've done it because—well, you may guess that a man has a pretty strong reason when he wants to volunteer to fight another country's battles. It's the sort of thing in which he can expect plenty of the kicks, while others get all the ha'pence. I've not been a success in England and I've had a stroke lately that's made me sick of things. I can't explain all this in detail: but the long and short of it is that if anything were to happen to me to-morrow morning, it would be the most welcome thing imaginable for me. Now, you'll understand what I mean when I tell you that nothing you can say as to the danger of the business can do anything but attract me. If I could only feel my blood tingling again in a rush of excitement, I'd give anything."

My companion listened carefully to this, and her tell-tale face was all sympathy when I finished. Obviously she was deeply interested.

"Have you no mother or sister?" she asked.

"No—fortunately for them."

"Have you never had anyone to lean on you and trust to you for guidance and protection? That helps a good man."

"No. But I've had those who've taken good care to break my trust in them—and everything else." This with a bitter little reminiscent sneer and a shrug of the shoulders. "Still, it has its advantages. Any new part I might wish to play could not be more barren than the old."

My companion shot a glance up in my face as I said this, but made no answer. It was I who broke the silence.

"Time is flying," I said, in a lighter tone: "and I have much to learn if I am to be your brother for the next two or three days. I want to know where I live, where you live, all that you can tell me about my brother officers and my duties—everything. Indeed that is necessary to prevent my being at once discovered."

After some further expostulation she told me that she and her brother were orphans; that they had come about a year or so before to Moscow on her brother being transferred to this regiment; and that the brother had private quarters in the Square of St. Mark, while she lived with an aunt, their only relative, in a suite of rooms close to the Cathedral. They were of a very old family, neither rich nor poor, but having enough to live comfortably and mix in some amount of society.

I gathered, however, that Alexis had been the source of much trouble. He had embarrassed his money affairs; lived a fast life, become involved with the Nihilists; dragged in his sister; and had ended by compromising himself in many quarters. She told me the story, so much as she knew of it, very deftly, intending no doubt to screen her brother; but I could read enough between the lines to understand that his life had been anything but saintly. Moreover, I was very much mistaken if he were not as arrant a coward as ever crowed on a dung-hill and ran away when the time came for fighting.

All this gave me plenty of food for thought—some of it disagreeable enough. It was no pleasant thing to take up the part of a coward and a scape-grace. Scapegrace I had been all my life in a way: but no man ever thought me a coward.

I take no credit to myself for not being a coward; and I am quite ready to believe that there are sound physiological reasons for it. Nature may have forgotten to give me those nerves by which men feel fear; but it is the case that never in my life have I experienced even a passing sensation of fear. I would just as soon die as go to sleep. I have seen men—much better men than I, and quite as truly brave—shudder at the idea of death and shrink with dread from the thought of pain. But at no time in my life have I cared for either; and I have come to regard this as due to Nature's considerate omissions in my creation. Certain other omissions of hers have not been so considerate.

This will explain, however, why the thought of the danger which troubled my new "sister" so much did not cause me even a passing uneasiness, especially at such a time. What I was anxious to do was to get hold of as much detail as possible of my new character; and I was sufficiently interested by it to wish to play it successfully.

To this end I questioned my companion very closely indeed about the names and appearance of the brother's friends and fellow officers, about the habits of military life, and in short about everything I deemed likely to help me not to stumble.

At the close of the examination I said:——

"At any rate we two must begin to rehearse. You must call me Alexis and must allow me to call you Olga; and we must do it always to avoid slips."

She saw the need but blushed a bit when I added:—-"And now, Olga, we'll make our first practical experiment. We'll go together to my rooms and you must shew me what sailors call my bearings."

"Shall we walk—Alexis?" she asked, her eyes bright and her cheeks ruddy with pretty confusion.

"By all means—Olga," I answered, returning her smile, and imitating her emphasis on the Christian name. "Do you know that my sister's name has a very quaint sound in my ears, and comes very trippingly to a brother's tongue?"

"But you don't like it and you think it common," she returned.

"I?"

"Yes, you have often said so, Alexis. Surely you remember. Why, only this morning you said how silly you had always thought it," she replied, demurely.

"Oh, I see," I laughed. "Ah, I've changed that opinion. A good many other things have changed too, since this morning," I added drily; and we both laughed then, and, considering the circumstances, were in extremely good spirits.

"Alexis," she cried, with a sudden warning, as we turned a corner into the Square of St. Gregory. "Don't you see who is coming toward us? Major Devinsky and Lieutenants Trackso and Weisswich. The major will pass next you. What will you do?" She asked this in a quick hurried voice.

"Cut him as dead as a door nail," said I, instantly, drawing myself up. "And the other fellows too; are they friends of mine, by the way?"

"No, they are his toadies," she whispered.

Olga bent her face down and would not see them; but I squared my shoulders and held my head aloft, fixing my eyes steadily on the three men as they approached. At first they did not recognise me. Then I saw one of them start, and making a rapid motion of his hand across his chin, he whispered to his companion, both of whom started in their turn and laughed.

As we passed the major made an effusive bow to my "sister" which the other two copied, while all three sneered with an air of insolent braggadocio and simultaneously put their hands to their chins as their eyes fell on me.

My blood seethed with anger at the insult. Nothing could have fired my eagerness more effectively to begin the drama of my new life. If I didn't punish each of those three for that insult, it should be because death stepped in to stop me.

"I am glad we met them," said I, smiling. "I shall know now which is my adversary to-morrow, and shan't pink the wrong man by mistake. But you look a bit scared, Olga."—I saw she was very pale.

"I am afraid of that man," she answered. "He is a man of good family and great wealth, and has a lot of influence in certain circles. He is an ugly enemy."

"Ugly, he certainly is," said I, lightly, speaking of his face.

"I mean dangerous," replied the girl seriously.

"I know you do, child," I answered, as naturally as if she were really my sister. "But we'll wait till we talk this over after to-morrow morning. I tell you what I'll promise you as a treat. You shall breakfast with me, or rather I'll breakfast with you to-morrow, and tell you at first hand all about the meeting. You have been a little too anxious about me."

"I am afraid that might occasion remark," she replied with the demure look I had noticed once or twice before. "You know that you have not always been an attentive brother, Alexis: and it is not good acting to overdo the part:" and she threw me a little smile and a glance.

I laughed and answered:—"That may be: but I've changed since the morning, as I told you before."

"Very well, then. You remember of course that aunt never gets up early enough to have breakfast with me—but you shall come if"—and here the light died right out of her face and her underlip trembled so that she had to bite it to keep it steady—"if all goes well, as I pray it may."

"You are a good sister, and need have no fear. I am not made of the stuff to go down before that bully's sword. So get ready my favourite dish—whatever that may be—and I'll promise to do justice to it."

"Here are your rooms," she said, a moment later, as she stopped before a large wide house. "They are on the ground floor with those windows. But before we go in, remember your manservant's name is Vosk, and he is a very sharp fellow. And please let me give you a word of warning. Alexis has not only not been attentive to me, but his manner has often been very brusque and—oh, if you had had sisters you would know how brothers behave. They don't mind turning their backs on one; they contradict, and interrupt and laugh at one; treat one as a convenience, and are rude. They don't in the least mind hiding their affection under the garb of indifference and contempt, and all that."

"Am I to treat you with contempt, then?" I asked with a grin.

"I think you should be a little more brusque," she replied, laughing and blushing. She was really a very jolly little sister.

"I shall get into it all in a day or two, perhaps."

"You had better try. Vosk is very sharp indeed."

"All right, I'll find means somehow to dull his wits."

We went in and I then tried to put a little more bluntness into my manner and to play the brother.

The man was in his room when I entered and started when he saw the change in my appearance. I caught his vigilant eye glance sharply at the pattern and cut of my clothes.

"Does your face hurt you now, Alexis?" asked Olga.

I understood her and answered in a somewhat surly tone, putting my hand to my left cheek. "No, not so much now; but it was an infernally silly joke to play. It's cost me my beard and a suit of clothes. A good thing it wasn't a uniform. Put out something for me to wear, Vosk," I said sharply to the man.

He looked at me again very keenly, but went at once to do what I ordered. Olga and I went into the chief sitting room—there were two leading one out of the other—and sat down. The man's manner had reminded me of several things. Very soon I made an excuse and sent him out.

"You must tell me all about the clothes I have to wear at different functions," I said. "Vosk saw that these were not out of my wardrobe proper, and while he's out, I'll hurry and change them, and we'll see how the uniforms fit me. A mistake may spoil everything at the last moment."

I ran into the bedroom and slipped into the undress uniform the man had laid ready. To my supreme satisfaction I found that they fitted me fairly well; and though they required some touches here and there, they would pass muster as my own. I tried on also some of the other uniforms I saw in the room; and wearing one of them, I went back to my "sister."

She cried out in her astonishment:—"My brother Alexis to the life."

"Your brother Alexis to the death," I answered so earnestly that she coloured as I took her hand and kissed it. Then in a lighter tone I added, "Uniforms make all men of anything like the same figure look alike. It's fortunate that your brother's an army man." Then we chatted for some minutes until I thought it prudent to change back again into the undress uniform that Vosk had put out.

Then I took a lesson in uniforms and questioned Olga until she had told me all that she herself knew about them.

I walked with my sister to her home, and then returned to my rooms and sat down to think out seriously and in detail the extraordinary position into which I had fallen.

The more I considered it the more I liked it, and I am bound to add the more dangerous it seemed. Obviously it was one thing to be mistaken for a man and to pass for him for a few minutes or hours: but it was quite another to take up his life where he had dropped it and play the part day by day and week after week. There must be a thousand threads of the existence of which no one but himself could know, yet each would have to be laid correctly in continuation of the due pattern of his life; or discovery would follow.

Here lay my difficulty, and for a time I did not see a way round it or through it or under it. So far as I could judge by all that my sister had told me, the resemblance between the real Alexis and myself was strictly limited to physical qualities. A freak of nature had made us counterparts of one another in size, look, complexion, voice, and certain gestures. But it stopped there. My other self was a subtle, cunning, intriguing, traitorous conspirator, and very much of a coward: while I—well, I was not that.

I come of a very old Cornish family with many of the Celtic characteristics most strongly developed. I believe that I have a certain amount of mother wit or shrewdness, but no process that was ever known or tried with me was sufficient to drive into me even sufficient learning to enable me to scrape through a career. I was the despair first of the Russian schoolmasters for over ten years, and next of all the English tutors who took me in hand during the next ten. I went to a large English school, and was expelled, after a hundred scrapes, because I learnt nothing. I tried to cram for Oxford, but never could get through Smalls; and the good old Master, who loved a strong man, almost cried when, after two years of ploughs, he had to send me down, when I was the best oar in the eight, the smartest field and hardest hitter in the eleven, the fastest mile and half-mile in the Varsity, and one of the three strongest men in all Oxford.

But I had to go, and I went to an army crammer to try and be stuffed for the service. I never had a chance with the books; but I carried all before me in every possible form of sport. It was there I picked up my fencing and revolver shooting. It became a sort of passion with me. I could use the revolver like a trickster and shoot to a hair's breadth; while with either broadsword or rapier I could beat the fencing master all over the school. However, I was beaten by the examiners and my couple of years' work succeeded only in giving my muscles the hardness of steel and flexibility of whipcord. I am not a big man, nearly two inches under 6ft, but at that time I had never met anyone who could beat me in any trial where strength, endurance, or agility was needed. But these would not satisfy the examiners, so I gave up all thought of getting into the army that way.

I tried the ranks, therefore, and joined a regiment in which a couple of brainless family men had enlisted, as a step toward a commission. But I was only in for six months: and my surprise is that I stopped so long. There was a beast of a sergeant—a strong fellow in his way who had been cock of the dunghill until I came—and after I'd thrashed him first with the single-sticks, and then with the gloves, and in a wrestling bout had given him a taste of our Cornish methods, he marked me out for special petty illtreatment. It came to a climax one day when a couple of dozen of us were sent off on a train journey. I left on the platform some bit of the gear. He noticed it and bringing it to the carriage window, flung it in at me and, with a sneer and a big coarse oath, cried:—"D'ye think I'm here to wet-nurse you, you damnation great baby?" And he waited a moment with the sneer still on his face: and he didn't wait in vain, either. Forgetting all about discipline and thinking only of his insult, I flung out my left and hit him fair on the mouth, sending him down like a ninepin. Then I picked up my things and went straight away to report myself to the officer in charge of us. There was a big row, with the result that the sergeant was reduced to the ranks, and I was allowed to buy myself out, being given plainly to understand that if I stayed in, my chance of a commission was as good as lost. This closed my army career.

For a few years I was at a loose end altogether—a man of action without a sphere. Then the natural result followed. I fell madly in love with my best friend's sister, Edith Balestier. I cursed my folly in having wasted my life, and filled the air with vows that I would set to work to increase my income of £250 a year to an amount such as would let me give her a home worthy of her. She loved me. I know that. But her mother didn't; and in the end, the mother won. Edith tossed me over ruthlessly, while I was away for a couple of months; and all in a hurry she married another man for his title and money.

It was only the old tale. I knew that well enough; but it seemed to break my last hope. Everything I'd ever really wanted, I'd always failed to get. I was like a lunatic; and vowed I'd kill myself after I'd punished the woman who'd done worse than kill me.

I thought out a scheme and played it shrewdly enough. I shut the resolve out of sight, and laughed and jibed as though I felt no wound. And I waited. The chance came surely enough. I went down to a dance at a place a bit out of town and took my revolver with me. After a waltz I led my Lady Cargill out into the shrubbery and when she least suspected what I was about, whipped out the weapon and told her what I was going to do. She knew me well enough to feel I was in deadly earnest; but she made no scene, such as another woman might. Her white beauty held my hand an instant, and in that time her husband, Sir Philip, came up. Then I had a flash of genius. I knew he was as jealous as a man could be and as he had known nothing of my relations with Edith, like many another self-sufficient idiot, he imagined she had loved him and no one else. I opened his eyes that night. Keeping him in control with the pistol, I made him hear the whole passionful story of her love for me from her own lips; and I shall never forget how the white of his craven fear changed to the dull grey of a sickened heart as he heard. At a stroke it killed my desire to kill. I had had a revenge a thousand times more powerful. I had made the wife see the husband's craven poltroonery, and the husband the wife's heart infidelity; and I let them live for their mutual distrust and punishment.

A month later I stood on the Moscow platform, my back turned on England for ever, my face turned war-wards, and my heart ready for any devilment that might offer, when my fate was tossed topsy-turvy into a cauldron of welcome dangers, promising death and certainly calculated to give me that distraction from my own troubles which I desired so keenly.

I was thus ready enough to take up my new character in earnest and play it to the end. If I were discovered, it could not mean more than death; while there were possibilities in it which might have very different results. War with Turkey was a certainty, and at such a time I should be able to find my sphere, and might be able to carve for myself a position.

It was clear that Alexis had so far been known as a very different man from the kind that produces good soldiers: but men sometimes reform suddenly, and the new Alexis would be cast in a quite different mould. The difficulty was to invent a pretext for the sudden change; and in regard to this a good idea occurred to me.

I resolved to say that I had had an ugly accident and a great fright, and to connect this with the shaving of my beard and moustache. To pretend that the mishap had effected as complete a change in my nature as in my appearance: as if my brain had been in some way affected. I mapped out a very boldly defined course of eccentric conduct which would be not altogether inconsistent with some such mental disturbance. I would be moody, silent, reserved, and yet subject to gusts and fits of uncontrollable passion and anger: desperate in all matters touching courage, and contemptuously intolerant of any kind of interference. I knew that my skill with the sword and pistol would soon win me respect and a reputation, while any mistakes I made would be set down to eccentricity. I was drawing from life—a French officer whom I had known stationed at Rouen: evidently a man with a past which no one even dared to question. I calculated that in this way I should make time to choose my permanent course.

I soon had an opportunity of setting to work.

The officer who, as Olga had told me, was to be my chief second in the morning, Lieutenant Essaieff, came to see me. He was immensely surprised at the change in my appearance, scanned me very curiously and indeed suspiciously, and asked the cause.

"Drink or madness?" he put it laconically, in that tone of contempt with which one speaks to a distrusted servant or a disliked acquaintance.

Even my friends held me cheap, it seemed.

"Neither drink nor madness, if you please," said I, very sternly, eyeing him closely. "But a miracle."

"And which of the devils is it this time, Petrovitch?" he asked, laughing lightly. "Gad, he must have been hard put to it. Or is it one of the she-devils, eh? You know plenty of those. Let's have the tale." He laughed again; but the mirth was not so genuine that time, and I could see that the effect of the fixed stare with which I regarded him began to tell.

"I'm in no mood for this folly," said I, very curtly. "Save for a miracle, I should now be a dead man. That's all. And I'll thank you not to jest about it."

He was serious now and asked:—"How did it happen?"

I made no answer, but sat staring moodily out in front of me, and yet contriving to watch him as he eyed me furtively now and again, in surprise at the change in me.

"Are you ill, Petrovitch?" he asked at length.

"Hell!" I burst out with the utmost violence, springing to my feet. "What is it to you?" And then with complete inconsequence I added:—"I was praying, and in answer a light flashed on me and would have consumed me wholly, but for a miracle. Half my clothes and my face-hair were consumed—and I was changed."

"Ah, prayer's a dangerous thing when you've a lot of arrears to make up," he said with a sneer.

I turned and looked at him coldly and threateningly.

"Lieutenant Essaieff, you have been good enough to lend me your services for this business to-morrow morning, but that gives you no title to insult me. After to-morrow you will be good enough to give me an explanation of your words."

He had risen and stood looking at me so earnestly that I half thought he suspected the change. But he did not.

"You will not be alive to demand it," he said, at length, contemptuously, clipping the words short in a manner that shewed me how angry he was and how much he despised me. "I'm only sorry I was fool enough to be persuaded to act for you," he added as he swung out of the room.

I laughed to myself when he had gone, for I saw that I had imposed on him. He thought I was half beside myself with fear. Evidently I had an evil-smelling reputation. But I would soon change all that, I thought, as I set to work to examine all the papers and possessions in the rooms. I was engaged in this work when my other second arrived. He was named Ugo Gradinsk, and was a very different kind of man, and had been a much more intimate friend. He had heard of my accident and had come for news.

A glance at him filled me with instinctive disgust.

"What's up, Alexis?" was his greeting. "That prig Essaieff, has just told me you're in a devil of a funny mood, and thinks you're about out of your mind with fear. What the devil have you done to yourself?" He touched his chin as he spoke.

"Can't I be shaved without setting you all cackling with curiosity? I had half my hair burnt off and shaved the other half." He started at my surly tone and I saw in his eyes a reflection of the other man's thoughts.

"D'ye think you'll be a smaller mark for Devinsky's sword? It's made a devil of a difference in your looks, I must say. And in your manners too." I heard him mutter this last sentence into his moustache.

"Do you think I mean for an instant to allow that bully's sword to touch me?" I asked scowling angrily.

"Well, you thought so last night when I was giving you that wrinkle with the foils—and that was certainly why you got this infernal duel put off for a day."

"Ah, well, I've been fooling you, that's all," said I, shortly. "I've played the fool long enough too, and I mean business. I've taken out a patent." I laughed grimly.

"What the devil d'ye mean? What patent?"

"A new sword stroke. The sabre stroke, I call it. Every first-rank swordsman has one," I cried boastfully.

"First-rank swordsman be hanged. Why, you can't hold a candle to me. And I would not stand before Devinsky's weapon for the promise of a colonelcy. Don't be an ass."

"My cut's with the flat of the sword across the face directly I've disarmed my man."

"And a devilish effective cut too no doubt—when you have disarmed him. But you'd better be making your will and putting your things in order, instead of talking this sort of swaggering rubbish to keep your courage up. You know jolly well that Devinsky means mischief; and what always happens when he does. I don't want to frighten you, but hang it all, you know what he is."

"I'm going to pass the night in prayer," said I: and my visitor laughed boisterously at this.

"If you confess all we've done together, old man, you'll want a full night," he said.

"The prayers are for him, not for me," and at that he laughed more boisterously than before: and he began to talk of a hundred dissipated experiences we had had together. I let him talk freely as it was part of my education, and he rattled on about such a number of shameful things that I was disgusted alike with him and with the beast I was supposed to be. At length to my relief he stopped and asked me to go across to the club for the last night.

I resolved to go, thinking that if I were in his company it would seem appropriate, and I wished to paint in more of the garish colours of my new character among my fellow-officers. I made myself very offensive the moment I was inside the place. I swaggered about the rooms with an assumption of insufferable insolence. Whenever I found a man looking askance at me—and this was frequent enough—I picked him out for some special insult. I spoke freely of the "miracle" that had happened to me, and the change that had been effected. I repeated my coarse silly jest about praying all night for my antagonist: and I so behaved that before I had been in the place an hour, I had laid the foundations of enough quarrels to last me a month if I wished to have a meeting every morning.

"Ah, he knows well enough he's going to die to-morrow morning," said one man in my hearing. "It's no good challenging a man under sentence of death," said another; while a number of others held to Essaieff's view—that I was beside myself with fear, or drink, or both combined. I placed myself at the disposal of every man who had a word to say; but the main answer I received was an expression of thanks that after that night I should trouble them no more.

I left the place, hugely pleased with the result of the night's work. I had created at a stroke a new part for Alexis Petrovitch: and prepared everyone to expect and think nothing of any fresh eccentricities or further change they might observe in me in the future.

I reached my rooms in high spirits, and sat down to overhaul the place for papers, and to learn something more of myself than I at present knew.

The discoveries I made were more varied and interesting than agreeable: and I found plenty of evidence to more than justify my first ill impressions of Olga's real brother.

It was time indeed that there should be a change.

The man must have gone off without even waiting to sort his papers.

Rummaging in some locked drawers, the keys of which I found in a little cabinet that I broke open, I came across a diary with a number of entries with long gaps between them, which seemed to throw a good deal of light on my past.

There were indications of three separate intrigues which I was apparently carrying on at that very time; the initials of the women being "P.T.," "A.P.," and "B.G." The last-named, I may say at once, I never heard of or discovered: though in some correspondence I read afterwards, I came across some undated letters signed with the initials, making and accepting and declining certain appointments. But both "P.T." and "A.P." were the cause of trouble afterwards.

I found that a number of appointments of all kinds were fixed for the following afternoon. The initials of the persons only were given, but enough particulars were added to shew the nature of the business. Thus someone was coming for a bet of 1,000 roubles; a money lender was due who had seemingly declared that he would wait no longer; and quite a number of tradesmen for their bills.

I soon saw the reason for all this. I was evidently a fellow with a turn for a certain kind of humour; and I had obviously made the appointments in the full assurance either that Devinsky's sword would have squared all earthly accounts in full for me, or that I should be safe across the frontier and out of my creditors' way.

I recalled with a chuckle my words to Olga—that if I were to play the part I must play it thoroughly. This meant that not only must I fight the beggar's duel for him, but if I were not killed, fence with his creditors also or pay their claims.

I swept everything at length into one of the biggest and strongest drawers, locked them up, and sat down to think for a few minutes before going to bed.

If I fell in the morning I wished Rupert Balestier to hear of it; and the only means by which that could be done would be for me to write a note and get Olga to post it. Half a dozen words would be enough:

"MY DEAR RUPERT,

"The end has come much sooner than I hoped when writing you this afternoon. A queer adventure has landed me in a duel for to-morrow morning with a man who is known as a good swordsman. He may prove too much for me. If so, good-bye old friend, and so much the better. It will save an awful lot of trouble; and the world and I are quite ready to be quit of one another. The receipt of this letter posted by a friendly hand will be a sign to you that I have fallen. Again, good-bye, old fellow. H.T."

I did not put my name in full, to lessen the chance of complication should the letter go astray. I addressed it, and then put it under a separate cover. Next I wrote a short note to my sister; and this had to be ambiguously worded, lest it also should get into the wrong hands.

"MY DEAR SISTER,

"You know of my duel with Major Devinsky and that it is in honour unavoidable. Should I fall, I have one or two last words. I have many debts; but had arranged to pay them to-morrow; and I have more than enough money in English bank notes for the purpose. Pay everything and keep for yourself the balance, or do with it what you think best. My money could be used in no better way than to clear up entirely this part of my life. I ask you to post the enclosed letter to England; and please do so, without even reading the address. This is my one request.

"God bless you, Olga, and find you a better protector than I have been able to be.

Your brother,

"ALEXIS."

This I sealed up and then enclosed the whole in an envelope together with about £2,000 in bank notes which I had brought with me from England. The envelope I addressed to my "sister" and determined to ask my chief second, Lieutenant Essaieff, to give it to Olga, should I fall.

One other little task I had. I went through my clothes and my own few papers and carefully destroyed every trace of connection with Hamylton Tregethner, so that there should be nothing to complicate the matter of identity in the event of my death.

So far so good—if Devinsky killed me. But what if I could beat him?

The quarrel was none of mine. I had no right to go out and even fight a man in an assumed character, to say nothing of killing him. Look at the thing as I would I could make nothing else than murder of it; and very treacherous murder, to boot.

The man was doubtless a bully, and he seemed willing to use his superior skill to fix a quarrel on Olga's brother and kill him, in order to leave the girl without protection. But his blackguardism was no excuse for my killing him. I had no right to interfere. I had never seen her or him until the last few hours; and however much Major Devinsky deserved punishment, I had no authority to administer it.

Probably if the man knew how I could use the sword he would never have dreamt of challenging me; and I could not substitute my exceptional skill for Olga's brother's lack of it and so kill the man, without being in fact, whatever I might seem in appearance, an assassin.

If I were to warn him before the duel that a great mistake had been made as to my skill, I shouldn't be believed. He and others would only think I was keeping up the braggart conduct of that evening at the club. At the same time I liked the idea of the warning. It would at any rate be original, especially if I succeeded in beating the major. But it was clear that I could not kill him.

All roads led round to that decision: and as I had come to the end of my cigar and there was plenty of reason why I should have as much sleep as possible, I went to bed and slept like a top till my man, Vosk, called me early in the morning and told me that Lieutenant Gradinsk was already waiting for me.

"That beggar, Essaieff, has gone on to the Common"—this was where we were to fight—"Told me to tell you. Suppose he doesn't care to be seen in our company. I hate the snob," he said when I joined him.

"So long as he's there when I want him, it's enough for me," said I, so curtly, that my companion looked at me in some astonishment.

"Umph, don't seem over cheerful this morning, Alexis. Must perk up a bit and shew a bold front. It's an ugly business this, but you won't help yourself now by...."

"Silence," I cried sternly. "When I'm afraid, you may find courage to tell me so openly. At present it's dangerous."

Then I completed my few preparations in absolute silence, both Gradinsk and the servant watching me in astonishment. When I was ready, I turned to Vosk.

"What wages are due to you?" I asked sharply. He told me, and I paid him, adding the amount for three months' further. "You leave my service at once. I have no further need of you." I was in truth anxious to get rid of him.

"My things are here. I...." he began, obviously making excuses.

"I give you five minutes to take what is absolutely necessary. The rest you can have another time. You will not return here."

"Do you suspect..." he began again.

"I only discharge you," I returned curtly. "Half of one of your minutes is gone." He looked at me a moment, fear mingled with his utter astonishment, and then went out of the room.

Five minutes later I locked the doors behind us and put the keys in my pocket.

"What has he done, Alexis? Isn't it rather risky? You've been so intimate...." said Gradinsk, as soon as we were in the droschky.

"It is I who have done this, not he," I answered, sharply. "It is my private affair if you please."

"D—— your private affairs," he cried in a burst of temper. "Even if you are going to die, you needn't behave like a sullen hog."

I stared round at him coldly.

"After the meeting I shall ask you to withdraw that, Lieutenant Gradinsk," and we did not exchange another word till the place of meeting was reached.

We were the last to arrive: and there appeared to have been some doubt as to whether I should dare to turn up, I think; for I caught a significant gesture pass between my opponent's seconds.

How I looked I know not; but I felt very dangerous, and I tried to be perfectly calm and self-possessed and natural in my manner.

"Lieutenant Essaieff," I said, drawing my chief second on one side after I had saluted the others. "There are two matters to be mentioned. If I should fall, will you give this letter with your own hands immediately to my sister?"

"You have my word on that," he said, bowing gravely.

"One thing more. I have an explanation to make to my opponent, Major Devinsky, which I think should be made in the hearing of all."

"An apology?" he asked, with a slight curl of the lip.

"No, but an explanation without which this duel cannot take place. Will you arrange it?"

He went to Devinsky's seconds, and then returning fetched me and Gradinsk, who was very nervous. I went up to the other group and spoke very quietly but firmly.

"Before the duel takes place, Major Devinsky, I must make such an explanation as will prevent its being fought under a mistake. I am a much more expert swordsman than is currently known. I have purposely concealed my skill during the months I have been in Moscow; but I cannot engage with you now, without making the fact known. I have indeed rather drawn you into this affair and I now desire you to join with me in declining to carry the dispute further. After this explanation, and at any future time I shall of course be at your disposal."

The effect of this short speech was pretty much what might have been expected. All the men thought I was trying to get out of the fight by impudent bragging, and Devinsky's seconds laughed sneeringly.

I turned away as I finished speaking, but a minute later, Essaieff brought me a message—and the contempt rang in his tone as he delivered it.

"Major Devinsky's reply to your extraordinary request is this: The only terms on which he will let you off the fight are an unconditional compliance with the condition he has already named to you. What is your answer?"

"We will fight," I replied shortly: and forthwith threw off my coat and vest and made ready.

I eyed my antagonist with the keenest vigilance during the minute or two the seconds took in placing us, and I saw a certain boastful confidence in his looks and a swagger in his manner, which were eloquent of the cheap contempt in which he held me—a sentiment that was shared by all present.

My second, Essaieff, manifestly did not like his task; but he did everything in a workmanlike way which shewed me he knew well what he was about, and in a very short time our swords were crossed and we had the word to engage.

An ugly glint in the major's eyes told me he had come out to kill if he could; and the manner in which he pressed the fight from the outset shewed me that he thought he could finish it off straight away.

He was a good swordsman: I could tell that the instant our blades touched: and he had one or two pretty tricks which wanted watching and would be sure to have very ugly consequences for anyone whose eye and wrist were less quick than his own. As he fought I could readily see how he had gained his big reputation and had so often left the field victorious after only a few minutes' fighting.

But he was not to be compared with me. In two minutes I knew precisely his tactics and at every point I could outfight him. I had no need even to exert myself. After a few passes, all my old love of the art came back to me and all my old skill; and when he made his deadliest and trickiest lunges I parried them without an effort, and could have countered with fatal effect.

I wished to get the fullest measure of his skill, however, and for this reason did not attempt to touch him for some minutes. Then an idea occurred to me. I would prove to the men with us that I had no real wish to avoid the fight. Intentionally I let my adversary touch my left arm, drawing a little blood.

They stopped us instantly; and then came the question whether enough had been done to satisfy the demands of honour. Had I chosen, I could without actual cowardice have declared the thing finished: but I intended them all to understand that I had to the full as keen an appetite as my opponent for the business. I was peremptory therefore in my demand to go on.

In the pause I made my plan. I would cover my adversary with ridicule by outfencing him at all points: play with him, in fact; and give him a hundred little skin wounds to shew him and the rest how completely he had been at my mercy.

I did it with consummate ease. My sword point played round him as an electric spark will dart about a magnet, and he was like a child in his feeble efforts to follow its dazzling swiftness. Scarcely had we engaged before I had flicked a piece of skin from his cheek. The next time it was from his sword arm. Then from his neck, and after that from his other cheek; until there was no part of his flesh in view which had not a drop of blood to mark that my sword point had been there. The man was mad with baffled and impotent rage.

Then I put an end to it. After the last rest I put the whole of my energy and skill into my play, and pressed him so hard that any one of the onlookers could see I could have run him through the heart half a dozen times: and at the end of it I disarmed him with a wrench that was like to break his wrist.

To do the man justice, he had pluck. He made sure I meant to kill him, but he faced me resolutely enough when I raised my sword and put the point right at his heart.

"One word," said I, sternly. "I have put this indignity on you because of the insolent message you sent to me by Lieutenant Essaieff. But for that I would simply have disarmed you at once and made an end of the thing. Now, remember me by this...." I raised my sword and struck him with the flat side of it across the face, leaving an ugly red trail.

Then I turned on my heel and went to where my seconds stood, lost in staring amazement at what I had done. I put on my clothes in silence; and as I glanced about me I saw that the scene had created a powerful impression upon everybody present.

All men are irresistibly influenced by skill such as I had shewn under circumstances of the kind; and the utter humbling of a bully who had ridden rough-shod over the whole regiment was agreeable enough now that it had been accomplished. My own evil character was forgotten in the fact that I had beaten the man who had beaten everybody else and traded on his deadly reputation.

Lieutenant Essaieff came to me as I was turning to leave the place alone. He gave me back the letter I had entrusted to him, and after a momentary hesitation, said:—

"Petrovitch, I did you an injustice, and I am sorry for it. I thought you were afraid, and I had no idea that you had anything like such pluck and skill. I believed you were blustering; and I apologise to you for the way in which I brought Devinsky's message. But for what happened last night in your rooms"—and he drew himself up as he spoke—"I am at your service if you desire it."

"I'd much rather breakfast than fight with you to-morrow morning, Essaieff, if you won't think me a coward for crying off the encounter."

"After this morning no one will ever call you a coward;" said he; and I think he was a good deal relieved at not having to stand in front of a sword which could do what mine had just done. "Shall we drive back together?"

We saluted the others ceremoniously, my late antagonist scowling very angrily as he made an abrupt and formal gesture. Then I snubbed Gradinsk, who looked very white, remembering what I had said to him when driving to the ground; and Lieutenant Essaieff and I left together.

"How is it we have all been so mistaken in you, Petrovitch?" asked my companion when we had lighted our cigarettes.

"How is it that I have been so mistaken in you?" I retorted. "I chose to take my own way, that's all. I wished to know the relish of the reputation for cowardice, if you like. I have never been out before in Moscow, as you know; and have never had to shew what I could do with either sword or pistol. Nor did I seek this quarrel. But because I have never fought till I was compelled, that does not mean that I can't fight when I am compelled. But the truth's out now, and it may as well all be known. Come to my rooms for five minutes before breakfast—I am going to my sister's to breakfast—and I'll shew you what I can do with the pistols. It may prevent anyone making the mistake of choosing those should there be any more of this morning's work to do."

"I hope you can keep your head," he said, after a pause. "You'll be about the most popular man in the whole regiment after to-day's business. I don't believe there's a more hated man in the whole city than Devinsky; and everyone's sure to love you for making him bite the dust. I suppose you're coming to the ball at the Zemliczka Palace to-night. You'll be the lion."

There was a touch of envy in his voice, I think, and he smiled when I answered indifferently that I had not decided. As a fact I didn't know whether I had any invitation or not, so that my indifference was by no means feigned.

When we reached my rooms I took him in and as I wished to noise abroad so far as possible the fact of my skill with weapons, I shewed him some of the trick shots I had learnt. Pistol shooting had been with me, as I have said, quite a passion at one time and I had practised until I could hit anything within range, either stationary or moving. More than that, I was an expert in the reflection shot—shooting over my shoulder at a mark I could see reflected in a mirror held in front of me. Indeed there was scarcely a trick with the pistol which I did not know and had not practised.

The lieutenant had not words enough to express his amazement and admiration; and when I sent him away after about a quarter of an hour's shooting such as he had never seen, he was reduced to a condition of speechless wonder.

Then I dressed carefully, having bathed and attended to the light wound on my arm, and set out to relieve my "sister's" suspense and keep my appointment for breakfast. I found myself thinking pleasantly of the pretty, kindly little face of the girl, and when I saw a light of infinite relief and gladness sparkle in her eyes at sight of me safe and sound and punctual, I experienced a much more gratifying sensation than I had expected.

Her face was somewhat white and drawn and her eyes hollow, telling of a sleepless, anxious night; and she grasped my hand so warmly and was so moved, that I could not fail to see that she had been worrying lest trouble had come to me through her action of the previous day.

"You haven't had so much sleep as I have, Olga," I said, lightly.

"Are you really safe, quite safe, and unhurt? And have you really been mad enough to go out and fight that man? Oh, I could not sleep a wink all night for thinking of you and of the cruel gleam I have seen in his eyes." And she covered her face with her hands and shivered.

"Getting up early in the morning always gives me an unconscionable appetite, Olga. I thought you knew that," said I lightly and with a laugh. "But I see no breakfast; and that's hardly sisterly, you know."

"It's all in the next room ready," she answered, leading the way. "But tell me the news:" and her face was all aglow with eager inquiry.

"I had no difficulty with Major Devinsky. As I anticipated he was no sort of a match for me at that business. I'm not bragging, but I've been trained in a totally different school, and—well, the beggar never had a chance."

She smiled then, and her eyes danced in gladness, but as suddenly grew grave again. Wonderfully tell-tale eyes they were!

"What about—I mean—is he hurt?"

"No, not much. Nothing serious. His quarrel wasn't with me, you see, so I couldn't kill him or wound him seriously. But you'll hear probably from others what happened."

"I want to hear from you, please. You promised the news at first hand remember."

"Well, I played rather a melodrama, I fear. I managed to snick him in a number of places till he's pitted a good deal. I gave him a lesson for having treated you in that way and also for his insolence to me. Besides I wished to make a bit of an impression on the other men there. He won't trouble us again, I fancy."

"He's dangerous, Alexis: mind that. Very dangerous. But oh, I'm so glad it's all over and you're safe and sound—And here's your favourite dish—though you don't know what it is."

"I don't care what it is. I'll take whatever you give me on trust." At that she glanced at me and coloured, and hung her head.

She was very pretty indeed when the colour glowed in her cheeks, and as a rather long silence followed I had plenty of time to observe her. She made a most captivating little hostess, too; and I began to feel that if I had had a sister of my own like her, I should have been remarkably fond of her, and perhaps—who can tell?—a very different man myself.

"By the way, there's one thing you must be careful to say," I said, breaking a long pause that was getting embarrassing. "You will probably be asked whether you knew that I was an expert with the sword and pistol and was purposely concealing my skill from the men here in Moscow. That's what I've said, and it may be as well that you should seem to have known it. A brother and sister should have no secrets from each other, you know."

She shook her head at me and, with a smile and in a tone of mock reproach, said:

"You haven't always thought that, Alexis."

"It's never too late to mend," returned I. "And I'll promise for the future, if you like—so long as the relationship lasts, that is."

To that she made no answer, and when she spoke again she had changed the subject.

We chatted very pleasantly during breakfast, and I asked her presently about the dance at the Zemliczka Palace. She was going to it, she said, and told me that I had also accepted.

"Can a brother and sister dance together, Olga," I asked.

"I don't know," she replied, playing with the point as though it were some grave matter of diplomacy. "I have never had to consider the question practically because you have never asked me, Alexis. But I think they might sit out together," and with the laugh that accompanied that sentence ringing in my ears, like the refrain of a sweet song, we parted to meet again at the ball.

The news that I had beaten Devinsky, had played with him like a cat with a bird, spread like a forest fire. Essaieff was right enough in his forecast that everyone would be delighted at the major's overthrow. But the notoriety which the achievement brought me was not at all unlikely to prove a source of embarrassment.

I should be a marked man, and everything I did would be sure to be closely observed. Any gross blunder made in my new character would be the more certainly seen, and would thus be all the more likely to lead to my discovery.

There were of course a thousand things I ought to know; hundreds of acts that I had no doubt been in the habit of doing regularly—and thus any number of pitfalls lay gaping right under my feet.

My difficulties began at once with my regimental duties. I did not know even my brother officers by sight, to say nothing of the men. The fact that the real Alexis had not been very long with the regiment would of course help me somewhat in regard to this; as it was quite conceivable that having been very indifferent to my duties and anything but a zealous officer, I might not have got to know the men. But I was just as ignorant of the regimental routine which ought to be a matter of course. I had questioned Olga on every detail and drawn from her all that she knew—and she was surprisingly quickwitted and well informed on the subject—and I had of course my own limited military experience to back me; but I lacked completely that familiarity which only actual practice could give. This difficulty gave me much thought and I am bound to say amused me immensely. The way out that I chose was a mixture of impudence and eccentricity; and I relied on the reputation I had suddenly made for myself as a swordsman being sufficient to silence criticism.

I went back to my rooms, and while there a manservant whom Essaieff had promised to send to me, arrived. I would not have one from the ranks, but chose a civilian that had been a soldier; and under the guise of questioning his present knowledge of military matters, dress, etc., I drew out of him particulars of the uniforms I ought to wear on different occasions, the places and times of all regimental duties, and—what was of even more importance—a rough idea of the actual duties which fell to the share of Lieutenant Alexis Petrovitch.

That was enough for me. I dressed and went to head-quarters, resolved to see the Colonel, and on the plea of indisposition ask to be excused from duty on that and the following day. To my surprise—for I had heard from Olga that I stood very low down in Colonel Kapriste's estimation—I was received with especial cordiality and favour. His greeting was indeed effusive. He granted my request at once, said I could take a week if I liked, after my hard work, and declared that I must take great care of myself for the sake of the regiment. Then he pressed me to wait until he had finished his regimental work as he wished to talk to me.

What he wanted was an account of the duel, and a very few minutes shewed me that if he was no friend of mine, he was a strong enemy of the man I had fought. He questioned me also as to the change in my appearance, why I had shaved my beard and moustache, what excuse I had to give for having been out without my uniform on the previous day; and my blunt reply that I had had an accident and hoped I was master of my own features, and that if my uniform was burnt it was more becoming for an officer to be in mufti than naked, drew from him nothing more than the significant retort that he hoped I had changed as much in other respects. Then he turned curious to know where I had learnt to use the sword, and who was the fencing master that had taught me; and I turned the point with a laugh—that Major Devinsky's evil genie conferred the gift on me, as they were not ready yet below to take charge of the major's soul.

He was so delighted with my success over the man whom he evidently hated, that he let my impertinence pass; but I could see that the two aides who were present, were as much astonished at my conduct as at the Colonel's reception of it.

But it was of great service to me. It emphasized the complete change in me; and I left with a feeling of intense satisfaction that the difficulties of the position were proving much less formidable when faced than they had seemed in anticipation.