Title: The Fight for Constantinople: A Story of the Gallipoli Peninsula

Author: Percy F. Westerman

Illustrator: W. Edward Wigfull

Release date: October 2, 2011 [eBook #37600]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2015

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

The Fight for Constantinople

A Story of the Gallipoli Peninsula

BY

PERCY F. WESTERMAN

Author of "The Dispatch-Riders" "The Sea-girt Fortress"

"When East Meets West" "Captured at Tripoli" &c. &c.

Illustrated by W. E. Wigfull

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW AND BOMBAY

Contents

| CHAP. | |

| I. | Under Sealed Orders |

| II. | Cleared for Action |

| III. | The Demolition Party |

| IV. | Trapped in The Magazine |

| V. | A Dash up The Narrows |

| VI. | To The Rescue |

| VII. | The "Hammerer's" Whaler |

| VIII. | A Prisoner of War |

| IX. | In Captivity |

| X. | A Bid for Freedom |

| XI. | A Modern Odyssey |

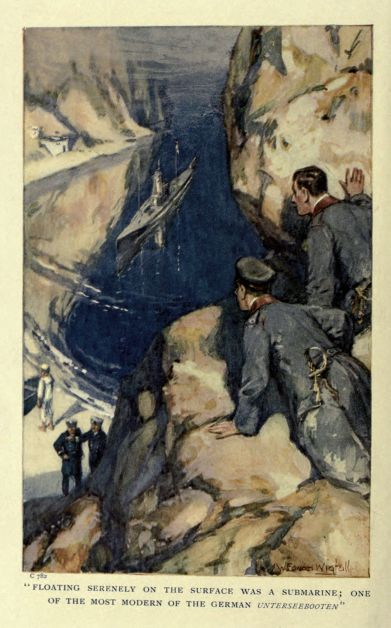

| XII. | The German Submarine |

| XIII. | Torpedoed |

| XIV. | Through Unseen Perils |

| XV. | Disabled |

| XVI. | A Daring Stroke |

| XVII. | Within Sight of Constantinople |

| XVIII. | A Midnight Encounter |

| XIX. | The Sub to the Rescue |

| XX. | Saving the Old "Hammerer" |

Illustrations

"Dick, my boy, here are your marching orders," announced Colonel Crosthwaite, holding up a telegram for his son's inspection.

"Marching orders, eh?" queried Sub-lieutenant Richard Crosthwaite with a breezy laugh. "Hope it's something good."

"Can't get out of the old routine, Dick. I suppose I ought to call it your appointment. It's to the Hammerer. Why, my boy, you don't look very happy about it: what's up?"

"Nothing much, pater," replied the Sub, as he strove to conceal the shade of disappointment that flitted over his features. "I must take whatever is given me without demur——"

"Of course," promptly interposed his parent. "That's duty all the world over."

"But at the same time I had hoped to get something, well—something not altogether approaching the scrap-iron stage."

"Yes, the Hammerer is a fairly old craft, I'll admit," said Colonel Crosthwaite. "I've just looked her up in Brassey's——"

"Launched in 1895, completed during the following year; of 14,900 tons; has a principal armament of four 12-inch guns, and a secondary battery of twelve 6-inch," added Dick, who had the details of most vessels of H.M. Navy and many foreign Powers at his fingers' ends. "She's a weatherly old craft, but it isn't likely she'll take part in an action with the German High Seas Fleet, when it does come out of the Kiel Canal. Things are fairly quiet in the North Sea, except for a few isolated destroyer actions, and, of course, the Blücher business. Aboard the Hammerer—one of the last line of defence—the chance of smelling powder will be a rotten one."

"In the opinion of those in authority, Dick, these ships are wanted, and officers and men must be found to man them. Everyone cannot be in the firing-line."

"I'm not grumbling exactly," explained Dick. "Only——"

"Grumbling just a little," added his father. "Well, my boy, you may get your chance yet. War was ever a strange thing for placing unknowns in the limelight, and this war in particular. Now buck up and get your kit together. It will mean an all-night railway journey, since you've to join your ship at Portsmouth at 9 a.m. to-morrow."

Dick Crosthwaite was on ten days' leave, after "paying off" the old Seasprite. The outbreak of war had been responsible for his fairly rapid promotion, and having put in seven months as a midshipman on board the light cruiser Seasprite—which had been engaged in patrol work in the North Sea—he found himself promoted to Acting Sub-lieutenant.

His work on the cruiser was, in spite of the dreary and bleak climatic conditions, interesting and not devoid of incident. He had not taken part in any action; his ship had escaped the attentions of hostile submarines and drifting mines. There was a spice of risk about the business that appealed to him—a possibility that before long the Seasprite would have a chance of using her guns in real earnest.

Then came orders for the light cruiser to proceed to Greenock and "pay off". Her ship's company were given leave, which after months of strenuous watch and ward they thoroughly deserved, and Sub-lieutenant Crosthwaite found himself once more in his home in a secluded part of Shropshire.

Although he fully appreciated the brief spell of leisure, his active mind was dwelling upon the prospects in store for him. With the certificates he had gained he considered, with all due respect for My Lords' discretion, that nothing short of an appointment on one of the super-Dreadnoughts or battle-cruisers would be a fitting reward for his zeal and activity. Hence it came as a decided set-back when he found himself appointed to the old Hammerer.

He knew the obsolescent battleship both by observation and repute. He had seen her lying in one of the basins of the dockyard extensions at Portsmouth, looking the picture of neglect in her garb of grey mottled with the stains of rusty iron.

He had also seen a painting of her when she was in her prime. That painting was an object of value to his uncle, Captain John Crosthwaite, R.N., for he had hoisted his pennant on the Hammerer when she was the pride of the then Channel Fleet. With her black hull, white upper works, and buff-coloured masts and funnels, she looked a totally different vessel from the grey monster that was on the point of being sent to the scrap-heap. For twenty years she had existed without having fired a shot in anger; now on the eve of her career she was to be given a chance—a very faint chance, Dick thought—of doing her part against the enemies of King and country.

That same evening Sub-lieutenant Crosthwaite bade his mother and sisters good-bye, and, accompanied by the Colonel and Dick's two young brothers, drove to the station.

"Au revoir, Dick!" exclaimed his brother George, with all the dignity of a public-school boy of fourteen.

"And don't forget to bring us home some war trophies," added twelve-year-old Peter.

Dick laughingly assented, then grasped his father's hand.

"Good-bye, Dad," he said.

"Good-bye, my lad; and don't forget to do your level best and keep our end up. It's no use mincing matters: we've a tough, uphill job. Good-bye, my lad; and may God bless you!"

Conscious that several pairs of eyes were upon them, father and son drew themselves up and saluted. Dick entered the train and was whirled away, while Colonel Crosthwaite returned home for a brief twelve hours before he, too, would be on his way to his regiment—a promising unit of Kitchener's Army.

At half-past eight on the following morning Dick passed through the main gate of Portsmouth Dockyard. Seamen and dockyard "maties" were everywhere, working with the utmost activity—for here at least there was no slacking.

Wagon-loads of stores came bounding along over the hard granite setts, drawn by stalwart bluejackets in working kit; no longer, as in the old piping times of peace, did the dockyard workmen amble quietly with their work. Everything was done at the double. It was a sign of the times, when the stress and strain of naval warfare requires promptness and activity.

Under the ruined buildings that formerly were surmounted by the semaphore tower—ruins that suggested the scene of a German raid—the Sub made his way to the South Railway Jetty, alongside of which was moored H.M.S. Hammerer, almost ready to proceed to sea.

In her new garb of neutral-grey the old ship looked smart and business-like. In each of her two barbettes a pair of re-lined 12-inch guns grinned menacingly. Her brasswork no longer glittered in the sunlight: it had been daubed over with the same hue of neutral paint. The only dashes of colour about her were the blue-and-gold uniforms of the officers, for she showed no flag. It was yet too soon for the time-honoured custom of hoisting the white ensign with full naval honours.

Having duly reported himself, Dick was informed that he was to be in charge of the gun-room—the cradle of budding Nelsons, for the Hammerer carried twelve midshipmen in addition to a clerk and two assistant clerks.

For the next three days the Sub had hardly a minute to call his own. It was a hasty, yet complete, commissioning, nothing being overlooked in the matter of detail; and during those three days the ship's company did a normal week's work. Meals had to be hurriedly snatched. Even the usual formal dinner had to be scrambled through, with grave danger to the digestions of the youthful officers. What with coaling, shipping ammunition and stores, and generally "shaking down", Dick was glad to tumble into his bunk and sleep the sleep of healthy exhaustion, until aroused by his servant announcing that it was time to begin another day's arduous duty.

At length the Hammerer was ready to sail to her unknown destination; for it was an understood thing that she was to proceed under sealed orders.

The Captain and most of the officers on duty were on the fore-bridge. Aft mustered the marine guard and the band, while the stanchion rails and gun-ports were packed with seamen in their white working-rig.

On the jetty were the dockyard Staff-captain's men, ready at the word of command to slip "springs" and hawsers; but the usual setting of the picture of a departing man-of-war was absent. No throng of relatives and friends of the crew gathered on the farewell jetty. The time of departure was a secret. In war-time the great silent navy is shown to perfection; and no crowd of civilians is permitted to see what may prove to be the last of a leviathan going forth to do her duty in the North Sea.

A signalman, holding the halyard in his hand, awaited a glance from the Captain. It came at last. Up fluttered a hoist of bunting—the formal asking for permission to proceed.

"Permission, sir!" reported the signalman, as an answering string of colour announced that the Commander-in-Chief of the port had graciously condescended to order the Hammerer to do what had been previously ordered.

"Stand clear!"

To the accompaniment of the shrill trill of the bos'n's mates' pipes, the working parties surged hither and thither in apparently utter confusion; then almost imperceptibly, as the powerful tug in attendance began to pull the ship's bows clear of the jetty, the Hammerer started on her voyage into the great unknown.

A bugle-call—and every officer and man stood to attention, the marines presenting arms as the battleship glided past the old Victory. Another call, and the men relaxed their attitude of rigidity. The last compliment had been paid to the authorities of the home port—the Hammerer was outward bound.

"Any idea of the rendezvous?" asked Jack Sefton, one of the midshipmen, as the lads forgathered in the gun-room to "stand easy", almost for the first time since commissioning.

"Rather," announced another, Trevor Maynebrace, who, having an uncle an admiral, professed somewhat loftily to be "in the know". "Rather—Rosyth: that's where we are bound, my dear Sefton; there to swing at moorings till the ship's bottom is smothered in barnacles. They'll keep us in reserve to fill up gaps caused by casualties, and, judging by recent events, we'll have to cool our heels a thundering long time."

"You're quite sure, Maynebrace?" asked the Sub.

"Quite—well, nearly so," admitted the midshipman.

"Then what do you make of that?" continued Dick, pointing through the open scuttle.

Broad on the starboard beam rose the frowning cliffs of Dunnose. The land was that of the Isle of Wight, so that the Hammerer's course was approximately south-west.

She was not alone. On either side, at ten cables' distance, were two long, lean destroyers of the River class, their mission being to safeguard the ship from the attack of a lurking German submarine.

"H'm!" muttered the discomfited middy. "P'r'aps there's been an alteration of plans. Looks as if we're bound for Plymouth."

"Or the Mediterranean, perhaps," remarked Jolly, the clerk, who looked anything but his name.

He was a weedy-limbed youth, narrow-chested and knock-kneed. He was as short-sighted as a bat, and wore spectacles with lenses of terrific power. To those not in the know, it seemed astonishing how he managed to pass the doctor; but Jolly's father was a post-captain, and that made all the difference. Unable owing to physical disabilities to enter the executive branch and follow in his father's footsteps, the lad had taken the only alternative career open to him that the Admiralty provides for short-sighted youths, and had entered the service as an assistant clerk.

Maynebrace gave the representative of the accountant branch a look of scorn.

"I don't think!" he said with a sneer. "Our Mediterranean Fleet is quite large enough for all emergencies. We'd be of no use for the Egyptian business. Our draught of water is too much for the Canal; besides, the Swiftsure and Triumph will attend to that little affair. No; I reckon it's Plymouth, and then the North Sea via Cape Wrath."

Just then the muffled sound of a tremendous roar of cheering, issuing from four hundred lusty throats, was faintly borne to the ears of the members of the gun-room. Again and again it was repeated.

"Scoot," ordered Crosthwaite, addressing Farnworth, one of the junior midshipmen. "Scoot as hard as you can, and see what the rumpus is about."

In two minutes the youngster, his face glowing with excitement, dashed into the gun-room.

"Glorious news!" he exclaimed. "The owner's opened the sealed orders. We're off to the Dardanelles. We'll have the time of our lives."

With admirable and well-kept secrecy the Admiralty had made all preparations for a strong attack to be delivered at the supposedly impregnable Dardanelles. In addition to the ships of the Mediterranean Fleet, battleships and cruisers were ordered to proceed to the Near East, until a fleet deemed sufficiently strong for the work in hand had collected in the Ægean Sea.

The Hammerer was one of the first to leave England for that purpose, while it was hinted amongst the officers that there was a big surprise up the sleeve of the Admiralty when the final depositions of the attacking fleet were completed.

Sub-lieutenant Dick Crosthwaite hailed the news with as much enthusiasm as the rest of the gun-room, which is saying much; for the youngsters let off a cheer that, if it did not equal the volume of sound emitted by the men, had the dire effect of arousing the chaplain and naval instructor from their afternoon nap.

It was a chance of a lifetime. Little Tommy Farnworth's announcement was a true one. While the Grand Fleet waited and watched in tireless energy for the German High Seas Fleet, this powerful squadron, detached without risk of disturbing the superiority of power in home waters, was silently and rapidly concentrating to match its strength against the vaunted Ottoman batteries on both sides of the Dardanelles. For this purpose the older type of war-ships with their 12-inch guns could be usefully and profitably employed, since speed—one of the greatest factors of modern naval warfare—was not so imperative when dealing with immobile batteries the position of which is already known.

When Ushant was astern and the Hammerer well into the Bay, the battleship's escort of destroyers turned and parted company. They had seen the ship through the waters within the radius of action of the German submarines. They were now free to return and take another battleship clear of the Channel. No doubt several huge grey-painted war-ships had been observed through the periscopes of these hostile under-water craft, but the presence of the swift, alert destroyers was sufficient to cause even the most reckless German lieutenant-commander to hesitate to attack. But for the destroyers more than one of the Mediterranean-bound war-ships would have fallen an easy prey to the lurking peril of the deep.

From the Atlantic, the Pacific, and the Indian Oceans came ships proudly displaying the white ensign. Under cover of complete secrecy, battleships and battle-cruisers gained the rendezvous without an inkling of their presence to the outside world.

The Canopus, which had been expected to join Admiral Cradock's ill-starred squadron in the Pacific, and had last been heard of in the Falkland Islands fight, suddenly turned up in the Ægean. The battle-cruisers that enabled Admiral Sturdee to avenge the Monmouth and Good Hope swiftly covered the 6500 miles between the Falkland Islands and the Piræus; the Triumph, after doing yeoman service at Kiao-Chau, and stopping in the Suez Canal to help put the fear of the British Empire into the Turkish invaders of Egypt, steamed into the Archipelago, ready to continue the good work she had so worthily begun.

Not only was the white ensign displayed at the southern gate of the Sea of Marmora; for a powerful French squadron, without weakening the force that held the Austrians under the guns at Pola and Trieste, had arrived to join hands with the former traditional enemy and now close ally of France; while in the Black Sea the Russians were making their presence felt upon the Turkish littoral of that inland sea.

The Ottoman Empire, tottering after the last disastrous Balkan War, was on the point of committing national suicide under the patronage of its bombastic German tutors.

On the ninth day after leaving Portsmouth the Hammerer was in the vicinity of Cape Matapan. She was bowling along at a modest sixteen knots, a rate that, considering the condition of her engines, reflected great credit upon the "black squad" and the engine-room staff.

It was two bells in the first dog watch. Dick Crosthwaite, who was on duty on the fore-bridge, was talking with the officer of the watch when a sail was reported astern.

Bringing the glasses to bear upon the vessel, both officers found that only her masts and funnels showed above the horizon. There was something unfamiliar about the appearance of the masts, for one was a tripod, the other one of the ordinary pre-Dreadnought type. The only battleships that sported this combination were the Lord Nelson and Agamemnon—and their position was known to an almost absolute certainty—and the newly-completed Queen Elizabeth.

"Strange," remarked Bourne, the officer of the watch. "I'd almost bet my bottom dollar that's the Queen Bess but for two reasons: first, she's not ready for sea; secondly, she's too powerful a ship to send out here while there's an impending job for her in the North Sea."

"She's coming on at a tremendous rate," observed Dick.

For several minutes the identity of the overtaking craft remained unknown; for, acting upon definite instructions, owing to the "tapping" of important messages by the enemy, the use of wireless had been almost entirely dispensed with during the voyage.

"Telephone to the fire-control platform, Mr. Crosthwaite," ordered Bourne. "Ask them what they make of yonder craft. Stay! Send one of the midshipmen—Maynebrace; he looks as if a little exercise would do him good."

Midshipman Maynebrace needed no spur. In a very few moments he had made his way to the foremast and was climbing the dizzy height by means of the iron rungs that, riveted to the lofty steel cylinder, formed the only means of personal communication with the fire-control platform. The interior of the Hammerer's hollow masts, which were originally fitted with lifts to convey the ammunition to the now discarded quick-firing guns in the fighting-tops, were now utilized for the numerous wires and voice-tubes communicating with the various parts of the ship.

Up through the lower top and upwards again the midshipman climbed with the dexterity acquired by long practice, never halting till he disappeared from view inside the elongated steel-plated box known as the fire-control platform.

Down again, seemingly at the imminent risk of breaking his neck, young Maynebrace made his way; then, cool and collected in spite of his exercise, he saluted the officer of the watch.

"It's the Lizzie, sir," he reported, using the abbreviated name by which the British seamen already knew the wonder ship of the year—the super-Dreadnought, Queen Elisabeth.

"By all the powers!" ejaculated Bourne. "This takes the proverbial biscuit. That's a nasty slight upon poor old Tirpitz: sending our last word in battleships to the Dardanelles."

"I pity the Turks, sir, when the Lizzie begins to tickle them up with her fifteen-inchers," said Maynebrace. "There'll be a few people surprised, not only out here but at home."

So well had the Admiralty plans been kept a secret that, until the Hammerer's ship's company saw the super-Dreadnought almost within the limits of the Ægean Sea, the Queen Elizabeth's presence was totally unexpected. The mere fact of her being sent out to the Near East indicated the gigantic task before the Allies: the forcing at all costs the hitherto supposedly impregnable defences of the Dardanelles.

Majestic in her business-like garb of grey, and with her eight monster 15-inch guns showing conspicuously against the skyline, the Queen Elizabeth overhauled and passed her older consort as easily as an express overtakes a suburban train.

For five minutes the "bunting tossers" on both ships were busily engaged; then, amid the outspoken and admiring criticism of the Hammerer's crew, the super-Dreadnought slipped easily ahead and was soon hull down.

Twelve hours later the Hammerer dropped anchor at the rendezvous off Tenedos. She was but one among many, for the Anglo-French fleet numbered nearly a hundred of various sizes—from the Queen Elizabeth of 27,500 tons down to the long, lean destroyers. In addition there were numerous trawlers—vessels that a few weeks previously had been at work off the coasts of Great Britain. Now, under conditions of absolute secrecy, these small but weatherly craft had risked the danger of a passage across the Bay in the early spring, had braved the "levanters" of the Mediterranean, and had assembled to do their important but frequently underrated work of clearing the mines to allow the advance of the battleships to within effective range of the hostile batteries.

Next morning, according to time-honoured custom, the Hammerer's crew assembled on the quarter-deck for prayers. It was a fitting prelude to the work in hand, for orders had been issued from the flagship for the fleet to go into action.

A bell tolled. To the signal yard-arm rose the "Church pennant": red, white, and blue, with a St. George's Cross on the "fly" or outer half. As the crew trooped aft, each man decorously saluted the quarter-deck and fell in; seamen, stokers, and marines forming three sides of a square, with the officers in the centre, while the "defaulters", few in number, were mustered separately under the eagle eye of the ship's police.

In ten minutes the solemn function was over. The Chaplain disappeared down the companion; the Captain gave the stereotyped order "Carry on"; the Commander, taking his cue, gave the word "pipe down", and the scene of devotion gave place to the grim preparation for "Action".

Stanchions, rails, ventilators, anchor-davits disappeared as if by magic. Hatches and skylights were battened down and secured by steel coverings, and everything liable to interfere with the training of the guns was either ruthlessly thrown overboard or stowed out of sight. Hoses were coupled up, ready to combat the dreaded result of any shell that might "get home" and cause fire on board. All superfluous gear aloft was sent below; shrouds were frapped to resist shell-fire, and the fore-top-mast was housed. The main-topmast, since it supported the wireless aerials, had perforce to remain. In less than an hour the crew, each man working with a set purpose, had transformed the Hammerer into a gaunt [Transcriber's note: giant?] floating battery.

Dick Crosthwaite's action station was in the for'ard port 6-inch casemate, an armoured box containing one of the secondary battery guns, capable of being trained nearly right ahead, and through an arc of 135 degrees to a point well abaft the beam.

The major portion of the casemate was taken up by the gun and its mountings, while a little to the rear of the weapon, and protected by a canvas screen, was the ammunition hoist, by which projectiles weighing 100 pounds each were sent up from the fore magazine. Around the walls were the voice tubes communicating with the conning-tower, the magazine, and other portions of the ship, while in addition was a bewildering array of switches and cased wires in connection with the lighting of the casemate and the firing mechanism of the gun. Buckets of water, for use in case of a conflagration, stood on the floor in close company with a tub full of barley water, at which the parched men could slake their thirst. What little space remained was fully occupied by the gun's crew, who, stripped to their singlets, were coolly speculating as to the chances of "losing the number of their mess".

Strangely enough, no one imagined that he was to be one of the unlucky ones; it is always his pal or some of his shipmates. It is an optimism that is shared equally alike by the Tommies in the trenches and the Jack Tars at their battle-stations.

Craning his neck, the Sub looked through the gun-port. It was an operation that required no small amount of manoeuvring, for the aperture was barely sufficient to allow the chase of the gun to protrude, while the armoured mounting left very little space between its face and the curved wall of the casemate.

The Hammerer was third ship of the port column, for the older battleships were steering in double column, line ahead. Preceding the squadron were the mine-sweepers, covered on either flank by strong patrols of destroyers.

Ten or twelve miles to the north could be discerned a mountainous and rocky coast terminating abruptly to the west'ard. Part of the highland was in Europe, part in Asia, but where the line of demarcation existed the Sub was unable to determine. Somewhere in that wall of rock lay the entrance to the Dardanelles, but distance rendered the position of the hostile straits invisible.

Away on the port hand lay the island of Imbros. Under its lee could be seen the misty outlines of the Queen Elisabeth, Agamemnon, Irresistible, and the French battleship Gaulois, ready to open a long-range bombardment of the Turkish batteries.

"Think the beggars will fight when they see this little lot?" asked Midshipman Sefton.

"Why not?" asked the Sub.

"I hope they will," continued the midshipman. "Especially after all this trouble. The Turk is a funny chap. See how he crumpled up against the rest of the Balkan States in 1912."

"On the other hand, the Turkish infantryman in '78 was reckoned one of the best 'stickers' in Europe," said Dick. "Under European officers these fellows will fight pretty gamely, and from all accounts there's a good leavening of German officers and artillerymen in these forts. Anyhow, we've got to get through. We've done it before, you know."

"Yes," admitted Sefton; "in the early nineteenth century, with a fleet of wooden walls. Duckworth did a grand thing then. In '78, when Hornby went through, the case was different. The Turks didn't open fire. Perhaps they funked it, and that's what makes me think they'll hesitate at the last moment."

Even as the midshipman spoke there came a peculiar screech that sounded almost above the armoured roof of the casemate.

The two young officers exchanged glances.

It was the first shell from the battery of Sedd-ul-Bahr.

A double crash announced that the leading battleship of the British squadron had opened fire with her foremost 12-inch guns. In two minutes the action had become general, the whole of the British and French pre-Dreadnoughts engaging with their principal armament, for as yet the range was too great for the 6-inch guns and smaller weapons to be trained upon the distant defences.

Ahead, the mine-sweepers, "straddled" by the hail of projectiles from Sedd-ul-Bahr and Kum Kale, as well as from mobile batteries cunningly concealed in difficult ground, proceeded with slow and grim determination. All across them the sea was churned by the ricochetting shells, while ever and anon a terrific waterspout accompanied by a dull roar showed that they were making good work in clearing away the hostile mines.

The Turks, in spite of the huge 12-inch projectiles that hailed incessantly upon the forts, stood to their guns with fanatical bravery. Tons of brickwork and masonry would be hurled high in the air, after taking with them the mangled remains of the Ottoman gunners and up-ending the Turkish weapon as easily as if it were a mere drain-pipe. Yet a few minutes later the defenders would bring up a field-piece and blaze away across the ruins at the nearest of the British mine-sweepers.

"Port 6-inch battery to fire," came the order.

Almost simultaneously the six secondary armament guns added their quota of death and destruction to the slower crash of the heavier weapons in the barbettes.

The Hammerer and her consorts were rapidly closing the shore, taking advantage of the already seriously damaged forts.

It was by no means a one-sided engagement. Shells from the Turkish defences were ricochetting all around the British warships or expending themselves harmlessly against the armoured plating. Other projectiles tore through the unprotected sides and upper works. Well it was that orders had been given out not to man the 12-pounder quick-firers on the upper deck. Had these weapons been used the casualties here must have been very heavy, for the light battery resembled a scrap-iron store.

Suddenly the men serving the gun in the casemate stopped their rapid yet deliberate work. A hostile shell had penetrated the 6-inch side armour almost under the casemate and had burst close to the lower part of the foremast. The shock well-nigh capsized the Sub, and almost caused the man at the ammunition hoist to drop the hundred-pound shell that he was in the act of transferring to the breech of the weapon. Suffocating fumes eddied through the ammunition hoist into the confined space. In the dim light men were gasping for breath, expecting every moment to find the magazine beneath their feet blown up.

"Hoist out of action, sir," reported one of the men, as he threw the contents of a bucket of water down the choked tube. Although everything of a supposedly inflammable nature had been got rid of, the heat generated by the explosion had been sufficient to start a fire, and the seat of the conflagration was between the armoured floor of the casemate and the magazine below the water-line.

"That's done it," ejaculated Dick dejectedly. It was not on account of the danger, for the men remained calmly within the casemate, trusting to the fire-party to extinguish the flames that were perilously close to the magazine. He was deploring the fact that the jamming of the ammunition hoist had deprived his gun of its supply of shells. The weapon was as much out of action as if the entire gun's crew had been annihilated. It seemed so humiliating to be inactive.

"Number one 6-inch, why are you not firing?" inquired an officer in the conning-tower through one of the voice tubes. There was a tinge of anxiety in his voice. He had noticed the sudden cessation of fire from that particular weapon, and it looked ominous.

"Ammunition hoist damaged, sir," replied the Sub.

"Any casualties?"

"No, sir."

"Then stand by."

Dick heard the whistle replaced in the tube as the officer completed his enquiries. Then hard-a-port the Hammerer described a semicircle, in order to bring her as yet unengaged starboard battery into action.

By this time the Turkish reply was but a feeble one. Pounded by the direct fire from the pre-Dreadnoughts; shattered by the long-range high-angle fire of the Queen Elizabeth and the Invincible, the forts were little better than mounds of rubbish.

Already the British warships had penetrated more than two miles up the formidable Straits, the mine-sweepers performing their difficult task with the utmost coolness and bravery. Night was coming on. All that could be done was to make sure of the complete reduction of the southernmost forts, and continue the sweeping operations as a prelude to a farther advance on the morrow.

Two British seaplanes, hovering at a height of nearly a thousand feet above the hostile positions, reported by wireless that the Turks were abandoning their shattered forts. The opportunity had arrived to consummate the day's work. A signal was made from the flagship to land armed parties. Joyfully the order was received, for the British seaman is not content with doing a lot of damage from afar; he must needs see for himself the result of his efforts.

Still maintaining a steady fire with their secondary batteries, the ships proceeded to hoist out their boats. Into these dropped seamen and marines, armed with rifles and bayonets, Maxims were passed into the boats, and charges of gun-cotton carefully stowed away for future use in completing the destruction of the Turkish guns.

"At this rate we'll be through in less than a week," remarked Midshipman Sefton to Dick, as they sat in the stern-sheets of a launch packed with armed seamen. The launch was in tow of a steam pinnace, while astern of her were two more boats, equally crowded.

"Seems like it," answered Crosthwaite, as he looked towards the rapidly nearing shore—a wild, precipitous line of rocks, surmounted by a pile of masonry that a few hours before was one of the strongest points of defence of the Dardanelles. "The Commander told me that the mine-sweepers ought to clear away all the mines as far as the Narrows within the next twenty-four hours. It's in the Narrows we're going to have a tough job."

Without a shot being fired—for the moral of the Turks seemed crushed—the boats grounded on the shore, and rapidly but in perfect order the demolition party landed, formed up, and began the difficult climb to the already sorely battered fort.

"What are you doing here, Sefton?" asked the Sub, observing that the midshipman was following him. "Your place is in your boat, you know."

"I asked the Commander's permission," replied Sefton. "It's not every day that I get a chance of examining a demolished position."

If the truth be told, Sefton was somewhat disappointed. He expected a "bit of a scrap" and a chance to use the heavy Service revolver that he wore in a large, buff-leather holster. At present it was of no use; it was an encumbrance.

"Steady, men," cautioned Crosthwaite, as those of the section under his orders were pressing forward somewhat recklessly. "There may be an ambush."

The warning was justifiable, for the strange silence which brooded over the hillside was somewhat ominous. The Hammerer's men had landed in three parties, two being each under the command of a lieutenant, while Crosthwaite had the third. Between these bodies of men there a keen rivalry as to who should first reach the demolished fort; and as each was advancing by a separate route and was almost entirely hidden from the others, the Sub's party had no means of judging the pace of their friendly competitors.

"'Ware barbed wire."

The men brought up suddenly. They were approaching the nearmost limit of the shell-torn ground. Deep cavities had been made in the rocky soil by the explosions of the heavy projectiles, yet the outer line of barbed wire was almost intact. The posts supporting the obstruction had been blown to atoms, but the wires were twisted and fused into a long, single, and almost inflexible coil impervious to the attacks of the seamen provided with wire-cutters.

A ripping sound, followed by a yell, announced the failure of a burly bluejacket to wriggle under the obstruction. Pinned down by the barbed wire, he was unable to move until his comrades, with a roar of laughter at his hapless plight, succeeded in extricating him.

"We'll prise it up, sir," exclaimed a petty officer. "The men can then wriggle underneath."

"Won't do," objected the Sub firmly. "It will have to be removed."

Two men advanced with slabs of gun-cotton, but again Dick demurred.

"No explosives to be used in the demolition of obstructions," he ordered. "They must be kept for the enemy's guns. We don't want to alarm the rest of the landing-party. Bend a rope there, and half a dozen of you clap on for all you're worth."

A rope was speedily forthcoming. The stalwart bluejackets, digging their heels into the sloping ground, tugged heroically. The stout wire sagged, quivered, and resisted their efforts.

The Sub realized that the obstruction must be removed. Although it was possible to crawl underneath, as the petty officer had suggested, it would never do to leave a trap like that between the fort and the shore. In the event of an ambuscade and a retirement to the boats, delay in negotiating the entanglements might spell disaster.

Another half a dozen men assisted their comrades. Still the wire, now at a terrific tension, showed no signs of being wrenched from its hold.

"All together—heave!"

With a burly "Heave-ho" the dozen bluejackets made a fresh effort. Balked, they gave a tremendous jerk. Something had to go, but it was not the wire. The rope parted with a crack, and twelve seamen were struggling in a confused heap on the steep hillside, while little Sefton, caught by the human avalanche, found himself head over heels in a particularly aggressive thorn-bush.

"Work round to the right there, and see what the infernal wire is made fast to!" ordered the Sub impatiently. "Look alive there, or the others will be at the top before us."

Four or five men hastened to carry out his commands. The work was of a difficult nature, for on either side of the rugged path by which the party had ascended thus far the ground was precipitous and thickly dotted with bushes.

Figuratively hanging on by their eyebrows the seamen worked along, following the course of the aggressive wire, till they were lost to sight beyond a fantastically shaped boulder.

Suddenly one of the men reappeared.

"Here's a blessed 12-pounder, sir," he announced. "What are we to do with it?"

Followed by Midshipman Sefton, who in the excitement caused by this latest discovery had lost all interest in the painful operation of extracting thorns from various remote portions of his anatomy, Crosthwaite hastened to the spot with as much haste as the nature of the ground would permit. The rest of the men, with the exception of those detailed to carry the explosives, also scrambled over the intervening ground.

A ghastly sight met their gaze. Beyond the boulder, and screened from seaward by a partly-burnt cluster of brushwood, was a field-piece. One wheel of the carriage had been smashed. The other was held only by a few spokes, while the muzzle of the weapon was buried deep in the ground. Coiled round the chase and jammed between the trunnion and the carriage was the end of the barbed wire. The gun was splattered with the yellow deposit from the explosion of a British lyddite shell, while all around lay the mangled bodies of the Turkish artillerymen. Five yards to the rear of the damaged weapon were the scanty remains of a limber. The same shell that had wrought the destruction of the gun and the men who served it, had completely exploded the ammunition.

"Smash the breech mechanism!" ordered Dick.

Two of the armourer's crew sprang to the gun for the purpose of breaking the interrupted screw-thread that locks the breech-block in the gun. Their efforts were in vain, for the explosion of the shell had rendered the breech-block incapable of being moved.

A fresh rope was speedily forthcoming. Its bight was placed under the heel of the 12-pounder, and by the united efforts of the seamen the heavy weapon was up-ended and toppled over the slope. Crashing through the brushwood, it rolled and bounded for quite a hundred feet, then with a resounding splash disappeared underneath the waters of the Dardanelles. The remains of the carriage were then hurled over, but, held up by the barbed wire that had caused so much fruitless effort, the mass of shattered steel effected a twofold purpose in its fall. It swept the cliff path clear of brushwood and brought the barbed wire into a position that it no longer formed an obstruction.

"This way up, men!" exclaimed Dick, pointing to a fairly broad and easy path in the rear of the gun emplacement. The Turks had conducted their defence with considerable cunning, for midway between the fort and the shore they had, by great exertion and ingenuity, placed several field-guns in well-sheltered spots, hoping that while the fire of the Allies was directed upon the visible batteries, their light pieces could with comparative impunity deliver a galling fire upon the mine-sweepers and the covering torpedo-boat destroyers. Unfortunately for the enemy the far-reaching effect of the heavy shells had resulted in the silencing of the concealed weapons, the men serving them being for the most part slain at their posts. A few had attempted to escape, but before they got beyond the danger zone they too were wiped out by the death-dealing lyddite.

The path Dick had indicated was the one by which the field-pieces had been lowered from the higher ground. It was obstructed in several places by craters torn by the explosion of the British shells, but these afforded no difficulty to the bluejackets.

Wellnigh breathless with their exertions, they reached the fort only to find, to their chagrin, that they had been forestalled by their friendly rivals, for the British flag floated proudly on the captured position.

So devastating had been the fire from the ships that the fort was little better than a shattered heap of brickwork and masonry. Armour-plated shields had been rent like paper, guns of immense size been dismounted and hurled aside like straws. Bodies of the devoted Ottoman garrison lay in heaps. Everything was smothered with a yellowish hue from the deadly lyddite and melanite. Yet several of the huge 80-ton guns were seemingly serviceable. These had to be rendered totally useless by means of slabs of gun-cotton placed well within the muzzle and fired electrically.

Sub-lieutenant Crosthwaite was studiously engaged in making a rough plan of the fort when Sefton, his soot-grimed face red with excitement, approached him.

"I believe I've found a magazine or something, sir," he exclaimed. "It's a funny sort of shop—like a tunnel. There are half a dozen Turks there——"

"Eh?" ejaculated Dick incredulously.

"Dead as door-nails," Sefton hastened to explain. "They look as if they had been suffocated. But the air's pure enough down there now."

Placing his notebook in his pocket, the Sub walked with Sefton across the littered open space in the centre of the fort till they came to a salient angle that faced the northern or landward side. Here the rubble rose to a height of about twenty feet. In places the wall, composed of armour-plate and concrete, had been riven from top to bottom, huge slabs of masonry being held up only by mutual support. On the top of the debris were half a dozen bluejackets, taking advantage of the daylight that still remained in flag-wagging a message to one of the destroyers.

"Here's the show," announced Sefton, pointing to a narrow passage between two immense artificial boulders.

At one time the opening had been much wider, and had been provided with stone steps, but the irresistible shock had contracted the passage, and had buried most of the steps under a heap of rubble.

"We want a lantern for the job," observed Dick. "How did you manage to see? You ought not to have gone on an exploring expedition without someone accompanying you."

"I've brought my electric torch," said the midshipman, studiously ignoring the latter portion of the Sub's remarks.

Unnoticed by the signalling party, the two young officers descended. For twenty yards they had to exercise considerable effort in order to negotiate the bulging sides, but beyond this the passage opened to a width of nearly six feet.

"Mind where you tread," cautioned Sefton, flashing his lamp on the ground. "They are not dangerous, but it isn't pleasant."

Either lying on the stone floor or propped up in a sitting position against the wall were the bodies of several Turkish infantrymen. Most of them were tunicless, while half a dozen 100-pounder shells lying on the ground showed that these men were engaged in bringing ammunition from the magazine when death in the form of lyddite fumes overtook them. There were no visible marks of wounds, so it was fairly safe to conclude that no shell had burst within the tunnel. Further, it showed that somewhere underneath the ruined fort was a still intact store of projectiles which would have to be rendered useless to the Turks before the demolition party returned to their ship.

"Didn't those fellows give you a turn?" enquired Dick.

"A bit at first," admitted the midshipman. "Then when I realized that if they had meant mischief they would have plugged me long before I saw them, I began to think something was wrong with them—and there was."

For nearly a hundred feet the passage zigzagged. With the exception of the dip near the main entrance the floor was almost level. At intervals were niches covered with steel slabs. The place had been electrically lighted, but owing to the destruction of the power-house the lamps were extinguished. Sefton's surmise was correct. It was a magazine, for the peculiar pattern of the electric bulbs in their double glass coverings told Dick the reason for the precaution.

"This is as far as I have been," announced Sefton, pointing to a heavy canvas screen.

"Then we had better both go carefully," added Dick, drawing his revolver, an example that the midshipman eagerly hastened to follow. "Don't go letting rip, mind, without you want to blow the whole crowd of us to pieces. Use your revolver as a moral persuader if there should be any of the enemy skulking here."

Telling the midshipman to keep close to the wall, and to hold the torch at arm's-length with the rays directed into the unexplored part of the tunnel, Dick pulled aside the curtain, half-expecting to find himself confronted by a dozen more or less intimidated ammunition-bearers.

The place was deserted.

"We'll carry on," said the Sub. "By Jove, what a big show! Absolutely shell-proof, I should imagine."

"I can only just hear the row outside," added the midshipman, as the muffled reports of the guncotton explosions showed that the demolition party were doing their work thoroughly.

The magazine was a vault hewn out of the solid rock. It had evidently been in existence for some years, certainly before the modernizing of the fortifications. The ammunition stowed here consisted of shells for the smaller quick-firers, as the absence of tram-lines for conveying the projectiles that were too heavy to man-handle proved.

"Krupp ammunition," reported Sefton, flashing his torch upon the base of one of the brass cylinders. "My word, when our fellows bust that lot up, won't the Turks feel a bit sick!"

"We'll get the men to bring the firing-charges as soon as possible," said Dick. "If we had known of this before, it would have saved no end of work. There would have been no need to have destroyed every gun singly."

"Can't say I envy the fellow who has to fire the stuff," added Sefton. "Hello, what's that?"

The noise of the detonating charges had ceased. Instead came the unmistakable crackle of rifle-firing.

"Look alive!" ordered the Sub. "Our fellows are being attacked."

Brushing aside the canvas screen the two officers made their way along the tunnel as swiftly as the dancing beams of the midshipman's torch permitted.

Before they reached the rise leading to the open air there was a terrific concussion. A waft of hot, pungent fumes bore down upon Dick and his companion. They were compelled to stop, almost choking in the stifling atmosphere. The rays from the torch failed to penetrate the dense brownish cloud of smoke and dust.

"Carry on," spluttered Dick; then noticing that the midshipman seemed on the point of asphyxiation, he seized the torch and, dragging his companion, made for the open air.

Suddenly he came to an abrupt halt. The gap between the crumbling walls no longer existed. They were trapped.

For some moments Crosthwaite stood stock-still. His senses were temporarily disorganized by the appalling discovery and by the acrid fumes. It was not until he felt Sefton's shoulder sink under his grasp that he realized the lad had collapsed.

Holding the torch in his left hand, Dick seized the midshipman by the strap of his field-glasses. Luckily the leather stood the strain well.

Keeping his lips tightly compressed, the Sub, bending as he made his way through the fumes, dragged his companion back along the passage. He felt like a man who has dived too deeply. He wanted to fill his lungs with air, yet he knew that to attempt to do so might certainly end in disaster. The midshipman's inert body, which at first seemed hardly any weight to drag, now began to feel as heavy as lead. Once or twice the Sub stumbled, the effort causing his lungs to strain almost to bursting-point. It required all his self-control to prevent himself relinquishing his burden and jumping to refill his lungs with air which was so heavily charged with noxious fumes.

At length he reached the canvas screen, that, having been soaked in water by the Turkish ammunition party, was still moist. With a final effort he thrust the curtain aside and took in a deep draught of air. It was comparatively fresh. The poisonous gases had failed to penetrate the close-grained fabric. Then, overcome by the reaction, Dick stumbled and fell across the body of his companion.

How long he lay unconscious he knew not, but at length he was aroused by Sefton vigorously working away at the exercises for restoring to life those apparently drowned. Half-stupefied, the Sub resented. He was under the vague impression that he was in the gun-room of the Hammerer and that the midshipmen were playing some practical joke. Then he began to realize his surroundings.

The torch was still alight, but already the charge showed signs of "running down". The air, although close, was not heavily impregnated with fumes. No sound penetrated the rock-hewn vault.

"Buck up, sir!" exclaimed Sefton with a familiarity engendered by the sense of danger. "We'll have to get out of this hole as soon as we can. Are you feeling fit to make a move?"

Dick sat up. His head was swimming. His limbs felt numbed. He wondered why he had been in an unconscious state longer than his companion, until he remembered that throughout that terrible journey along the gas-charged passage Sefton had been dragged with his head close to the ground. Consequently, owing to the fumes being lighter than the air, he was not so badly affected. For another reason: when Dick collapsed, his weight falling across Sefton's body had acted very efficiently in expelling the bad air from the midshipman's lungs, and as the Sub rolled over the subsequent release of pressure had allowed a reflux of comparatively pure air to take the place of that pumped out of Sefton's chest.

"Can't hear any firing," remarked Sefton. "I suppose our fellows have beaten them off."

Dick did not reply. He did not want to raise false hopes. He remembered the strict orders issued to the officers of the demolition party, that in the event of a counter-attack by the Turks they were to fall back immediately upon the boats, and allow the guns of the fleet to deal with the enemy. Yet it seemed strange that there were no sounds of firing, unless some time had elapsed and during that interval the Hammerer and her consorts had completely dispersed the Turkish infantry.

"Light won't last much longer," declared Sefton laconically. "What's the move, sir?"

Dick moved aside the curtain. The air in the passage was now almost normal. There was no longer any danger of asphyxiation.

Retracing their way along the passage, the two young officers made the disconcerting discovery that the tunnel was completely blocked for the last twenty feet towards the entrance. They stood in silence, till Dick flashed the light upon his companion's face. The midshipman's features were perfectly calm.

"A pretty mess up!" he exclaimed, and the two laughed; not that there was cause for mirth, but merely to show each other that they were not going to accept their misfortunes in fear and trembling. "Let's try shouting."

They shouted, but beyond the mocking echo of the voices no reassuring call came to them in return.

"Our fellows have been over-zealous with the gun-cotton," observed Sefton. "They'll miss us presently, and then they'll have a job to dig us out."

But Crosthwaite had other views on the situation, and these were much nearer the mark.

The rifle-firing he had heard that of the demolition party, who in the course of their operations had been attacked by overwhelming numbers of Ottoman troops.

Acting upon instructions the Lieutenant-Commander in charge ordered a retirement. Leaving a section in reserve to cover the retrograde movement, the bluejackets with very little loss descended the steep side of the hill and re-embarked. Then, covered by the guns of the fleet, the rear-guard successfully retired, in spite of a galling fire from a battery of field-pieces that the Turks, under German officers, had brought up.

One of the shells from these guns had resulted in the subsidence of the already tottering masonry, and had effectively imprisoned Sub-lieutenant Crosthwaite and Midshipman Sefton in the magazine.

It not until the Hammerer's men fell in on the beach that the two officers were missed. Someone suggested that they might be with the rearguard, now descending from the demolition fort, but inquiries proved that this was not so.

As one man the landing-party of the Hammerer's crew volunteered to return and search for their missing officers. Reluctantly the Lieutenant in charge had to refuse their request. Orders had to be carried out to the letter. Grave consequences might ensue if the devoted bluejackets returned to the scene of action. Not only would they risk their lives in an attempt that might be futile, but the fire of the fleet might be seriously interfered with.

So the boats returned to their respective ships, and Sub-lieutenant Richard Crosthwaite and Mr. Midshipman Sefton were duly reported as missing.

"Let's explore," suggested Dick. "It's no use sitting down and killing time. Let's make ourselves useful and explore while the torch lasts. I suppose you haven't another refill?"

"Half a dozen in my chest, but that's not here," replied the midshipman. "By Jove, I do feel stiff! Why, my jacket's torn, and I've grazed my knee."

"I'm afraid I must plead guilty to that, Sefton," replied Dick. "I had to get you along somehow, and there wasn't time for gentle usage."

"I wondered how I got there," declared the midshipman. "Everything seemed a blank. By Jove, sir, you saved my life!"

"I may have had a hand in it," admitted Dick modestly. "Now, suppose we bear away to the left?"

They had regained the central portion of the subterranean works, and were confronted by two small passages, one leading to the left and the other to the right, both diverging slightly. The one the officers followed was not zigzagged, showing that it did not communicate with the open air. Dick proposed that they should abandon their efforts in this direction and explore the right-hand passage.

"I'm game," assented Sefton. "Yes, this looks promising; it twists and turns as if it were intended to stop the splinter of any shell that happened to burst at its mouth."

"No go here!" exclaimed the Sub after traversing about twenty yards. "This has been bashed in. We must thank our 12-inch guns for that. The magazine evidently served the quickfirers both of the north and south bastions. The question is, what is the third passage for?"

"We'll see," replied the midshipman, regarding the rapidly failing light with considerable apprehension.

The tunnel ran in an almost horizontal direction for fifty paces, then gradually descended in a long, stepless incline.

"Steady!" whispered Crosthwaite, laying his hand on Sefton's shoulder and at the same time switching off the torch. "I hear voices."

The officers listened intently. At some considerable distance away men were talking volubly in an unknown tongue. More, there was a cool current of refreshing air wafting slowly up the incline.

"Stand by to scoot," continued Dick. "Gently now; we'll get a little closer. It's quite evident those chaps are Turks."

"Why?" asked Sefton.

"By a process of elimination. They're not speaking English; they're not French. The lingo is too soft for German, so only Turkish remains. Got your revolver ready?"

"Yes," said the midshipman, his nerves a-tingle.

"Then don't use it unless I give the word. Slip the safety-catch and be on the safe side. We don't want an accidental discharge."

Softly the Sub groped his way, Sefton following at arm's-length behind him. After traversing another fifty paces Dick stopped. Ahead he could see a mound of rubble reaching almost to the roof of the tunnel. It was night: not a star was to be seen. A driving rain was falling, while across the murky patch formed by the partly obstructed mouth of the tunnel the search-lights of the British fleet travelled slowly to and fro as they aided the mine-sweepers in their long, arduous task. Not a shot was being fired. The Turkish batteries silenced, at least temporarily, required no attention at present from the deadly British guns.

The sound of the voices still continued. The speakers were chattering volubly, yet there was no sign of them.

Gaining confidence, Crosthwaite advanced till farther progress was arrested by the barrier of rubble.

Feeling for a foothold, and cautiously making sure that the projecting stones would bear his weight, the Sub climbed to the summit of the barrier, then, lying at full length, peered over the edge.

A heavy shell had accounted for the damage done to this exit from the magazine, for a huge crater, twenty feet in diameter, yawned ten feet beneath him. Not only had the pit been torn up, but masses of rock had been wrenched from the of the cliff, as well as from the top and sides of the tunnel.

On the irregular platform thus formed were nearly a score of Turkish troops—artillerymen in greatcoats and helmets somewhat similar to those worn by the British during the last Sudan campaign. With them were two officers in long grey cloaks and fezes. All seemed to be talking at the same time, irrespective of disparity in rank. Some of the men were piling sand-bags on the seaward front of the crater, others were looking upwards as if expecting something from above.

Presently the expected object appeared, lowered by a powerful tackle. It was the carriage of a large field-piece.

"Those fellows show pluck, anyhow," thought Dick. "After the gruelling they've had, and seeing their forts knocked about their ears, they set about to place fresh guns in position. These field-pieces, well concealed, will take a lot of finding, unless we can stop the little game."

Meanwhile Sefton had climbed the barrier and lay by the side of his companion. Silently the two watched the development of the Turks' operations. They had not long to watt.

A pair of wheels followed the carriage, and then after a brief interval the huge gun, "parbuckled" from the edge of the cliff, was lowered into position. In less than half an hour the piece was reassembled; ammunition was brought down, and finally brushwood placed in front on the sand-bags and over the gun; while to show how complete had been the Germanizing of Turkey, a field-telephone had been laid between the emplacement and those on either side, which, of course, was invisible to the two British officers.

For some time the Turkish officers kept the trawlers and attendant destroyers under observation with the field-glasses. The men were obviously impatient to open fire, yet for some inexplicable reason they were restrained. Possibly it was to lure the mine-sweepers into a sense of security, or else the Turks thought fit to ignore the small craft and await the chance of a surprise attack upon the covering British battleships and cruisers.

Being well within the mouth of the tunnel, Dick and the midshipman were not exposed to the driving rain. But on the other hand the Turkish artillerymen were without any means of protection from the downpour, and, since they could not show their zeal by opening fire, they did not hesitate to show their resentment at being kept out in the open.

At length one of the Turkish officers gave an order. The men formed up with a certain show of smartness, broke into a quick march, and disappeared beyond a projection of the cliff. Only one man was left as sentry, and he hastened to get to leeward of a friendly rock. From where the two Englishmen lay, the point of his bayonet could just be discerned above the top of the boulder.

Then Dick directed his attention seaward. He mentally gauging the distance between the shore and the nearest of the mine-sweepers. These vessels were steaming slowly ahead, with sufficient way to stem the ever-running current from the Sea of Marmora to the Ægean. Certainly for the whole time Dick and his companion had been on the lookout there had been no explosion of a caught mine. Apparently the sweepers had almost completed their work up this particular area, and were making a final test to make certain that no hidden peril had escaped them.

The Sub nudged his companion, and the pair retraced their steps until they had put a safe distance between them and the sentry.

"Look here," said Crosthwaite. "We've two things to do. First, to warn our people of the formation of a new Turkish battery, and secondly, to rejoin our ship. The question is: how are we to set about it?"

"Flash a message with the torch," suggested Sefton.

"I thought of that, but dismissed it," remarked the Sub. "For one thing the light's pretty feeble, and our people mayn't spot it. If they did they might think it was a false message sent by the enemy. And another thing: the Turks might notice the glare in the mouth of the tunnel."

"And we would get collared," added the midshipman.

"That's hardly the point. Our liberty is a small matter, but being made prisoners we should have no chance of letting our trawlers know that there is a masked battery being placed in position. No; I think the best thing we can do is to swim for it."

"I'm game," declared Sefton.

"It's quite possible that we'll pull it off all right," continued Dick. "You see there's a steady current always setting down the Dardanelles. That means that if we miss the nearest destroyer or trawler, we'll get swept across the bows of one farther down. Take off your gaiters and see that your bootlaces are ready to be undone easily. We won't discard any more of our gear till we're ready to plunge into the water. That's right; now follow me."

Returning to the barrier at the entrance of the tunnel, the Sub wriggled cautiously over the obstruction until he could command a fairly extensive view of the gun emplacement and its surroundings. The rest of the artillerymen had not returned, while apparently the sentry, having been left to his own devices, had sought shelter from the rain and was enjoying a cigarette.

Softly Dick dropped down, alighting on a pile of cut brushwood. He waited till Sefton had rejoined him, and the pair crept slowly and deliberately towards a gap left between the rock and the end of the semicircular rampart of sand-bags.

Suddenly the Sub came to a dead stop almost within a handbreadth of the levelled bayonet of the Turkish sentry.

The Turk challenged. In the dim light he was not able to discern the uniform of the young officer. Perhaps he took him for one of the German taskmasters. At all events he merely held his rifle at the ready and made no attempt to fire.

The slight delay gave Dick his chance. Dropping on one knee he gripped the sentry by his ankle, at the same time delivering a terrific left-hander that caught the fellow fairly in that portion of his body commonly known as "the wind".

The Turk fell like a log. His rifle dropped from his nerveless grasp, fortunately without exploding. The back of his head came in violent contact with a lump of rock and rendered him insensible.

"You've killed him," whispered Sefton.

"Not much," replied Crosthwaite coolly. "He's got a skull as thick as a log of wood. At any rate we'll be spared the trouble of having to gag and truss him up. You might remove the bolt from his rifle and throw it away. It may save us a lot of bother if the fellow does pull himself together sooner than I expect."

It was hazardous work descending the almost sheer cliff, for the spot where the officers had emerged was midway between the fort and the beach, and, being in a totally different part to the place where they had landed, they were unfamiliar with the locality.

Once Sefton slipped, and rolled twenty feet through the brushwood, finally landing in a cavity caused by the explosion of a shell. On two occasions the Sub almost came to grief through the rock giving way beneath his feet, but by dint of hanging on like grim death he succeeded in regaining a firm foothold. The drizzling rain, too, made the ground slippery, and added to the difficulties; but after ten minutes' arduous exertions they found themselves on the stone-strewn beach.

"Now stop," ordered Dick. "Sling your revolver and ammunition into the sea. We want to travel light on the job. Ready? I'll set the course if you'll keep as close as you can. Thank goodness we're not in the Tropics, and that there are no sharks about!"

He might have added that amongst those rocks cuttle-fish were frequently to be found; but fearing there might be a limit to his young companion's pluck, he refrained from cautioning him on that point. It was a case of "ignorance is bliss" as far as Sefton was concerned.

The water was cold—much colder than that of the adjacent Mediterranean—yet it would be possible for the active swimmers to endure half an hour's swimming without risk of exhaustion. Long before that, they fervently hoped they would be safe on board a British vessel.

"Breast stroke—and don't splash," cautioned Dick, as the midshipman started off with powerful overhand stroke. Any suspicious movement in the water might bring a heavy rifle-fire upon the two swimmers from the numerous Turkish infantry who had reoccupied the position after the retirement of the demolition party. The Sub could hear them distinctly as they vigorously plied mattock and shovel in throwing up entrenchments on either side of the demolished fort.

Ahead, and less than half a mile from the shore, was a destroyer, moving slowly against the current and sweeping the shore with her search-lights. At first the Sub imagined she was stationary, but before the swimmers had covered fifty yards they were caught by the current, and swept southwards so rapidly that Dick realized that there was no chance of making for her. Their best plan was to swim at right angles to the shore, and let the drift help them to shape an oblique course that would bring them in the track of the mine-sweepers.

"How goes it?" enquired Crosthwaite laconically, after ten minutes of silence.

"All correct, sir," replied the middy confidently.

"We'll make that chap all right," continued Dick, pointing to a black shape "broad on his starboard bow" as he expressed its position.

Two minutes later he was not so certain. The vessel seemed to be changing course. Just then a search-light played full upon the heads of the swimmers. There it hung with irritating persistency.

"Hope they don't think we're a couple of drifting mines, sir," remarked Sefton. "Perhaps they'll give us a few rounds."

That possibility had entered Dick's mind. Raising his arm out of the water he waved it frantically. In so doing he completely forgot the other side of the question, and a crackle of musketry from the shore announced the disconcerting fact that the alert Turks had noticed the commotion in the water.

The bullets ricochetted all around the swimmers. The Sub turned and gave a swift glance at his companion. He was still "going strong", unperturbed by the leaden missiles that sung like angry bees.

A lurid flash burst from the fo'c'sle gun of the destroyer.

For a brief instant the Sub was in a state of suspense; then he gave a gasp of relief, for the projectile was not aimed at the two dark objects in the ray of the search-light. With a crash it landed on the hillside, and the rifle-firing ceased with commendable promptness.

The destroyer turned and, still maintaining a high speed, made straight for the two swimmers.

"Way enough!" exclaimed Dick cheerfully. "They're going to pick us up."

Suddenly, as the vessel's engines were reversed, the destroyer lost way. The creaking of tackle announced that her crew were lowering one of the Berthon boats—and within four hundred yards of the Turkish batteries.

Yet for some reason the field-pieces did not open fire until Dick and the midshipman were picked up and were in the act of being transferred from the boat to the destroyer Calder. Then, with a vivid and a sharp detonation, a shell burst a couple of hundred feet short of the British craft, quickly followed by another that missed by similar distance beyond.

Having revealed their identity, Dick and his companion were taken below and furnished with dry clothing. Quickly the Sub returned on deck and approached the Lieutenant-Commander on the bridge.

"Field-pieces lowered over the cliff, eh?" ejaculated that officer. "Jolly plucky of those fellows. We're engaged in trying to draw their fire. Sorry I can't put you on board the Hammerer. The battleships and cruisers have withdrawn until the mine-field is cleared a little higher up. They're going to tackle Chanak and Kilid Bahr to-morrow. We're just off to reconnoitre. The Calder's taking the European and the Irwell is trying her luck on the Asiatic side."

"Can I be of any service, sir?"

"I'm afraid not—as far as I can see at present. We'll find room for you in the conning-tower."

The Calder's search-lights had now been switched off. She was steaming slowly in a northerly direction, and had already passed the innermost of the mine-sweepers and their attendant destroyers.

Dick entered the limited expanse of the conning-tower, in which was a Naval Reserve sub-lieutenant and two seamen. The Lieutenant-Commander, called by courtesy the Captain, stood without on the bridge, in company with the mate and a yeoman of signals.

Presently the Lieutenant-Commander glanced at the luminous dial of his watch.

"Time!" he exclaimed decisively, in the tone of a referee at a boxing tournament. "Full speed ahead."

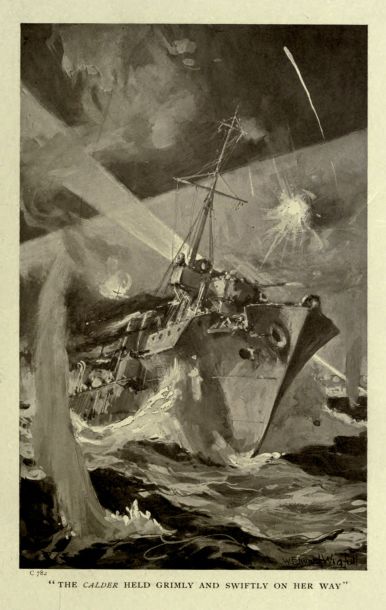

The engine-room telegraph-bell clanged. Black smoke tinged with lurid red flames belched from the four squat funnels, and, like a hound released from leash, the Calder raced on her perilous mission, her whole fabric quivering under the rapid pulsations of her engines.

The Calder was not one of the latest type of destroyers. Her tonnage was a little over 550, her speed supposed to be 24 knots, but by dint of terrific exertion on the part of her "black squad" that rate was considerably exceeded.

Almost everything depended on her pace. She had to draw the fire from the hostile batteries. If she were hit and sunk the British navy would be the poorer by the loss of a useful destroyer and a crew of seventy gallant men—and nothing would be gained except the glory of having died for their country. If on the other hand the Calder returned in safety, the British Admiral would be in possession of important information with reference to the position of new batteries that the Turks had thrown up to supplement those which were already known to be in existence. Moreover, there had been a report that The Narrows had been obstructed by a boom in addition to rows of mines, and a verification of the information or otherwise was urgently required before further extensive operations could be conducted.

On and on the Calder tore. Now she was abreast of the powerful batteries of Tekeh and Escali. Almost ahead, owing to the sinuosity of The Narrows, lay the huge fortress of Chanak. Each of these positions mounted guns heavy enough to blow the frail destroyer clean out of the water, while there was known to be rows of deadly mines which might be anchored sufficiently far beneath the surface to allow a craft of the Calder's draught to pass unscathed—but they might not. It was facing death at every revolution of the propellers.

Yet for some unknown reason the Turks made no attempt to open fire. It might be that they relied upon their mines, and were loath to disclose their positions by opening fire upon an insignificant destroyer. If such were the case, it showed that the Ottoman had learned a new virtue—forbearance under provocation.

It was useless to suppose that the enemy had not spotted the swiftly-moving destroyer. The flame-tinged smoke was enough. Besides, she had already crossed the path of three powerful fixed search-lights that swept the entire width of the Dardanelles.

"The beggars are going to spoof us," remarked the Naval Reserve officer to Dick. "We'll have our run for nothing. I wish they'd do something."

Before Crosthwaite could reply, the whole of the European shore between Tekeh and Kilid Bahr seemed to be one blaze of vivid flashes. Then, to the accompaniment of a continuous roar that would outvoice the clap of thunder, a hundred projectiles sped towards the daring British destroyer, some falling short, others bursting ahead and astern, while many flew harmlessly overhead. Yet in all that tornado of shell the Calder survived. Although her funnels were riddled with fragments of the bursting missiles and a shell penetrated her wardroom, she sustained no vital damage.

Zigzagging like an eel, in order to baffle the Turkish gun-layers, she held grimly on her way, her skipper, standing coolly on the bridge, sweeping the shore with powerful night-glasses.

Fragments of metal rattled against the thin armour of the conning-tower. Wafts of cordite drifted aft as the crew of the 4-inch on the foc'sle blazed away against the powerful shore batteries. A dozen streams of smoke from the perforated funnels eddied aft in the strong breeze caused by the destroyer's speed, and rendered it impossible for the after 4-inch gun to be worked.

Making a complete circle the Calder entered the belt of dense smoke previously thrown out by the funnels. A lot depended upon this manoeuvre, for she was lost sight of by the Turkish gunners. While they were congratulating themselves upon having sunk another of the Giaour's ships, the destroyer emerged from the bank of vapour, and in a position that necessitated an alteration in the sighting of the hostile guns.

It was grimly exciting, this game of dodging the fire of a hundred guns. Without giving a thought to the fact that the conning-tower afforded little or no protection, Dick revelled in the situation, now that the first salvo had been fired. Possibly the sight of the Lieutenant-Commander scorning to take shelter helped to steady Dick's nerves. He felt as much at home on that frail craft, the plating of which was a little thicker than cardboard, as he did behind a heavy-armoured casemate of the Hammerer.

From both sides of the Dardanelles shells, large and small, hurtled through the air. It seemed as if nothing could prevent the projectiles from Kilid Bahr and the adjacent batteries ricochetting into Chanak and the forts on the Asiatic shore. Yet, hit many times, the Calder held grimly and swiftly on her course till she came abreast of Nagara.

She had traversed the whole extent of The Narrows. Mines she missed, possibly by a few feet. More than once torpedoes, launched from the tubes mounted on the shore, tore past her, the trail of foam looming with a peculiar phosphorescence, showing how near they had been to getting home; while the shells that struck her, although inflicting considerable damage, failed to strike in any vital part.

Satisfied that no boom existed at Nagara, and that the Turkish cruisers and destroyers which were thought to have left the Sea of Marmora and had taken shelter beyond Nagara were not in their expected anchorage, the Lieutenant-Commander of the Calder ordered the helm to be put hard over.

Listing outwardly as she turned till her normal water-line showed three feet above the water, the destroyer began her return journey. Before she recovered her normal trim a 4-inch shell penetrated her thin plating, and, fortunately without exploding, missed one of the boilers by a fraction of an inch and disappeared out of the starboard side.

Then, as the destroyer steadied on her helm, the aperture a few seconds previously clear of the water was now eighteen inches beneath the surface. It poured a regular cascade that threatened to flood the engine-room.

In an instant one of the artificers saw the danger and acted promptly. Seizing a bundle of oily waste he thrust it into the irregular-shaped hole, and coolly sat with his broad shoulders hard against the impromptu plug and kept it in position.

"There's the Irwell," suddenly exclaimed the Royal Naval Reserve officer, who was looking through one of the slits in the conning-tower on the port side.

Dick also looked. At two cables' length from them was their consort, which, having circled to starboard, had closed in upon the Calder. Both were now running on parallel courses and at approximately the same speed.

The Calder's skipper also saw the other destroyer. He realized the danger of the formation, for both craft were in a direct line of fire from the forts.

"Hard-a-port!" he shouted.