Title: Puppets at Large: Scenes and Subjects from Mr Punch's Show

Author: F. Anstey

Illustrator: Bernard Partridge

Release date: September 17, 2011 [eBook #37449]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Clarke, Katie Hernandez and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO. LD., PRINTERS,

LONDON AND TONBRIDGE.

| PAGE | |

| Doing a Cathedral | 1 |

| The Instantaneous Process | 13 |

| In the Cause of Charity | 27 |

| The Classical Scholar in Reduced Circumstances | 43 |

| Rus in Urbe | 51 |

| Catching the Early Boat | 61 |

| Society's Next Craze | 71 |

| An Ideal Interviewer | 83 |

| Saturday Night in the Edgware Road | 91 |

| The "Model Husband" Contest | 101 |

| The Courier of the Hague | 109 |

| Feeling their Way | 119 |

| [ vi]A Testimonial Manque | 131 |

| The Model Democracy | 145 |

| By Parliamentary | 159 |

| The Farming of the Future | 167 |

| A Dialogue on Art | 177 |

| The Old Love and the New | 189 |

| A Doll's Diary | 201 |

| Elevating the Masses | 219 |

| Bookmakers on the Beach | 231 |

| 'Igher Up! | 243 |

| At a Highland Cattle Auction | 257 |

| The Country of Cockaigne | 265 |

| PAGE | |

| "What did 'e want to go and git the fair 'ump about?" | 11 |

| "What's she got hold of now?" | 21 |

| "You have lofty ambitions and the artistic temperament" | 37 |

| "They ain't on'y a lot o' sheep! I thought it was reciters, or somethink o' that" | 55 |

| "Mokestrians" | 75 |

| "Dear, dear! not a county family!" | 125 |

| "Well, he's had a sharp lesson,—there's no denying that". | 135 |

| "None of your humour here, mind!" | 155 |

| "I cann't get nothen done to 'en till the weather's a bit more hopen like" | 171 |

| "They haven't the patiensh for it" | 183 |

| "It must be a sort of animal, I suppose" | 193 |

| "I see him standing on the very brink of the precipice" | 209 |

| "To-night is ours!" | 225 |

| "Why the blazes don't ye take it?" | 239 |

| "Thash where 'tis, yer come on me too late!" | 251 |

| "'Ere, Florrie, you ain't croying, are yer?" | 271 |

The interior of Dulchester Cathedral. Time—About 12.30. The March sunshine slants in pale shafts through the clerestory windows, leaving the aisles in shadow. From without, the cawing of rooks and shouts of children at play are faintly audible. By the West Door, a party of Intending Sightseers have collected, and the several groups, feeling that it would be a waste of time to observe anything in the building until officially instructed to do so, are engaged in eyeing one another with all the genial antipathy and suspicion of true-born Britons.

A Stodgy Sightseer (to his friend). Disgraceful, keeping us standing about like this! If I'd only known, I'd have told the head-waiter at the "Mitre" to keep back those chops till——

[He breaks off abruptly, finding that the chops are

reverberating from column to column with

disproportionate solemnity; a white-haired and

apple-faced verger rustles down from the choir

[ 4]

and beckons the party forward benignantly,

whereupon they advance with a secret satisfaction

at the prospect of "getting the cathedral

'done' and having the rest of the day to themselves;"

they are conducted to a desk and

requested, as a preliminary, to put sixpence

apiece in the Restoration Fund box and inscribe

their names in a book.

Confused Murmurs. Would you put "Portico Lodge, Camden Road, or only London?"... Here, I'd better sign for the lot of you, eh?... They might provide a better pen—in a cathedral, I do think!... He might have given all our names in full instead of just "And party!"... Oh, I've been and made a blot—will it matter, should you think?... I never can write my name with people looking on, can you?... I'm sure you've done it beautifully, dear!... Just hold my umbrella while I take off my glove, Maria.... Oh, why don't they make haste? &c., &c.

[The Stodgy Sightseer fumes, feeling that, while they are fiddling, his chops are burning.

The Verger. Now, ladies and gentlemen, if you will please to follow me, the portion of the building where we now are is part of the original hedifice [ 5] founded by Ealfrytha, wife of Earl Baldric, in the year height 'undred heighty-height, though we 'ave reason to believe that an even hearlier church was in existence 'ere so far back as the Roman occupation, as is proved by a hancient stone receptacle recently discovered under the crypt and hevidently used for baptismal purposes.

A Spectacled S. (who feels it due to herself to put an intelligent question at intervals.) What was the method of baptism among the Early Christians?

The Verger. We believe it to 'ave been by total immersion, Ma'am.

The Spect. S. Oh? Baptists!

[She sets down the Early Christians as Dissenters, and takes no further interest in them.

The Verger. At the back of the choir, and immediately in front of you, is the shrine, formerly containing the bones of St. Chasuble, with relics of St. Alb. (An Evangelical Sightseer snorts in disapproval.) The 'ollow depressions in the steps leading up to the shrine, which are still visible, were worn away, as you see, by the pilgrims ascending on their knees. (The party verify the depressions conscientiously, and click their tongues to express indulgent contempt.) The spaces between the harches of the shrine were originally enriched by valuable gems and mosaics,[ 6] all of which 'ave now long since disappeared, 'aving been removed by the more devout parties who came 'ere on pilgrimages. In the chapel to your left a monument with recumbent heffigies of Bishop Buttress and Dean Gurgoyle, represented laying side by side with clasped 'ands, in token of the lifelong affection between them. The late Bishop used to make a rather facetious remark about this tomb. He was in the 'abit of observing that it was the honly instance in his experience of a Bishop being on friendly terms with his Dean. (He glances round for appreciation of this instance of episcopal humour, but is pained to find that it has produced a general gloom; the Evangelical Sightseer, indeed, conveys by another and a louder snort, his sense that a Bishop ought to set a better example.) In the harched recess to your right, a monument in painted halibarster to Sir Ralph Ringdove and his lady, erected immediately after her decease by the disconsolate widower, with a touching inscription in Latin, stating that their ashes would shortly be commingled in the tomb. (He pauses, to allow the ladies of the party to express a becoming sympathy—which they do, by clicks.) Sir Ralph himself, however, is interred in Ficklebury Parish Church, forty mile from this spot, along with his third wife, who survived him.

[The ladies regard the image of Sir Ralph with indignation, and pass on; the Verger chuckles faintly at having produced his effect.

The Evangelical S. (snuffing the air suspiciously). I'm sorry to perceive that you are in the habit of burning incense here!

[He looks sternly at the Verger, as though to imply that it is useless to impose upon him.

The Verger. No, Sir, what you smell ain't incense—on'y the vaults after the damp weather we've bin 'aving.

[The Evangelical Sightseer drops behind, divided between relief and disappointment.

A Plastic S. (to the Verger). What a perfectly exquisite rose-window that is! For all the world like a kaleidoscope. I suppose it dates from the Norman period, at least?

The Verger (coldly). No, Ma'am, it was only put up about thirty year ago. We consider it the poorest glass we 'ave.

The Plast. S. Oh, the glass, yes; that's hideous, certainly. I meant the—the other part.

The Verger. The tracery, Ma'am? That was restored at the same time by a local man—and a shocking job he made of it, too!

The Plast. S. Yes, it quite spoils the Cathedral, doesn't it? Couldn't it be taken down?[ 8]

The Verger (in answer to another Inquirer). Crowborough Cathedral finer than this, Sir? Oh, dear me, no. I went over a-purpose to 'ave a look at it the last 'oliday I took, and I was quite surprised to find 'ow very inferior it was. The spire? I don't say that mayn't be 'igher as a mere matter of feet, but our lantern-tower is so 'appily proportioned as to give the effect of being by far the 'ighest in existence.

A Travelled S. Ah, you should see the continental cathedrals. Why, our towers would hardly come up to the top of the naves of some of them!

The Verger (loftily). I don't take no notice of foreign cathedrals, Ma'am. If foreigners like to build so ostentatious, all I can say is, I'm sorry for them.

A Lady (who has provided herself with a "Manual of Architecture" and an unsympathetic Companion). Do notice the excessive use of the ball-flower as a decoration, dear. Parker says it is especially characteristic of this cathedral.

Unsympathetic Companion. I don't see any flowers myself. And if they like to decorate for festivals and that, where's the harm?

[The Lady with the Manual perceives that it is hopeless to explain.

The Verger. The dog-tooth mouldings round the[ 9] triforium harches is considered to belong to the best period of Norman work——

The Lady with the Manual. Surely not Norman? Dog-tooth is Saxon, I always understood.

The Verger (indulgently). You'll excuse me, Ma'am, but I fancy it's 'erringbone as is running in your 'ed.

The Lady with the M. (after consulting "Parker" for corroboration, in vain). Well, I'm sure dog-tooth is quite Early English, anyway. (To her Companion.) Did you know it was the interlacing of the round arches that gave the first idea of the pointed arch, dear?

Her Comp. No. But I shouldn't have thought there was so very much in the idea.

The Lady with the M. I do wish you took more interest, dear. Look at those two young men who have just come in. They don't look as if they'd care for carving; but they've been studying every one of the Miserere seats in the choir-stalls. That's what I like to see!

The Verger. That concludes my dooties, ladies and gentlemen. You can go out by the South Transept door, and that'll take you through the Cloisters. (The Party go out, with the exception of the two 'Arries, who linger, expectantly, and cough in[ 10] embarrassment.) Was there anything you wished to know?

First 'Arry. Well, Mister, it's on'y—er—'aven't you got some old carving or other 'ere of a rather—well, funny kind—sorter thing you on'y show to gentlemen, if you know what I mean?

The Verger (austerely). There's nothing in this Cathedral for gentlemen o' your sort, and I'm surprised at your expecting of it.

[He turns on his heel.

First 'Arry (to Second). I spoke civil enough to 'im, didn't I? What did 'e want to go and git the fair 'ump about?

Second 'Arry. Oh, I dunno. But you don't ketch me comin' over to no more cathedrils, and wastin' time and money all for nuthink—that's all.

[They tramp out, feeling that their confidence has been imposed upon.

"What did 'e want to go and git the fair 'ump about?"

"What did 'e want to go and git the fair 'ump about?"

A Photographer's Studio on the Seventh Floor. It is a warm afternoon. Mr. Stippler, Photographic Artist, is discovered alone.

Mr. Stippler (to himself). No appointments while this weather lasts, thank goodness! I shall be able to get ahead with those negatives now. (Sharp whistle from speaking-tube, to which he goes.) Well?

Voice of Lady Assistant (in shop below). Lady just brought her dog in; wants to know if she can have it taken now.

Mr. Stip. (to himself). Oh, dash the dog and the lady too!

The Voice. No, only the dog, the lady says.

Mr. Stip. (confused). Eh? Oh, exactly. Ask the lady to have the goodness to—ah—step up. (He opens the studio door, and awaits the arrival of his client; interval, at the end of which sounds as of a female in[ 16] distress about halfway down are distinctly audible.) She's stepping up. (Another interval. The head of a breathless Elderly Lady emerges from the gloom.) This way, Madam.

Elderly Lady (entering and sinking into the first plush chair). Oh, dear me, I thought I should never get to the top! Now why can't you photographers have your studios on the ground floor? So much more convenient!

Mr. Stip. No doubt, Madam, no doubt. But there is—ah—a prejudice in the profession in favah of the roof; possibly the light is considered somewhat superiah. I thought I understood there was—ah—a dog?

The E. L. Oh, he'll be here presently. I think he saw something in one of the rooms on the way up that took his fancy, or very likely he's resting on one of the landing mats,—such an intelligent dog! I'll call him. Fluffy, Fluffy, come along, my pet, nearly up now! Mustn't keep his missis waiting for him. (A very long pause: presently a small rough-haired terrier lounges into the studio with an air of proprietorship.) That's the dog; he's so small, he can't take very long to do, can he?

Mr. Stip. The—ah—precise size of the animal[ 17] does not signify, Madam; we do it by an instantaneous process. The only question is the precise pose you would prefer. I presume the dog is a good—ah—rattah?

The E. L. Really, I've no idea. But he's very clever at killing bluebottles; he will smash them on the window-panes.

Mr. Stip. (without interest). I see, Madam. We have a speciality for our combination backgrounds, and you might like to have him represented on a country common, in the act of watching a hole in a bank.

The E. L. (impressed). For bluebottles?

Mr. Stip. For—ah—rats. (By way of concession.) Or bluebottles, of course, if you prefer it.

The E. L. I think I would rather have something more characteristic. He has such a pretty way of lying on his back with all his paws sticking straight up in the air. I never saw any other dog do it.

Mr. Stip. Precisely. But I doubt whether that particulah pose would be effective—in a photograph.

The E. L. You think not? Where has he got to, now? Oh, do just look at him going round, examining everything! He quite understands what he's wanted to do; you've no idea what a clever dog he is![ 18]

Mr. Stip. Ray-ally? How would it do to have him on a rock in the middle of a salmon stream?

The E. L. It would make me so uncomfortable to see it; he has a perfect horror of wetting his little feet!

Mr. Stip. In that case, no doubt—— Then what do you say to posing him on an ornamental pedestal? We could introduce a Yorkshire moor, or a view of Canterbury Cathedral, as a background.

The E. L. A pedestal seems so suggestive of a cemetery, doesn't it?

Mr. Stip. Then we must try some other position. (He resigns himself to the commonplace.) Can the dog—ah—sit up?

The E. L. Bee-yutifully! Fluffy, come and show how nicely you can sit up!

Fluff (to himself). Show off for this fellow? Who pretends he's got rats—and hasn't! Not if I know it!

[He rolls over on his back with a well-assumed air of idiotcy.

The E. L. (delighted). There, that's the attitude I told you of. But perhaps it would come out rather too leggy?

Mr. Stip. It is—ah—open to that objection, certainly, Madam. Perhaps we had better take him[ 19] on a chair sitting up. (Fluff is, with infinite trouble, prevailed upon to mount an arm-chair, from which he growls savagely whenever Mr. Stippler approaches.) You will probably be more successful with him than I, Madam.

The E. L. I could make him sit up in a moment, if I had any of his biscuits with me. But I forgot to bring them.

Mr. Stip. There is a confectionah next door. We could send out a lad for some biscuits. About how much would you requiah—a quartah of a pound? He goes to the speaking tube.

The E. L. He won't eat all those; he's a most abstemious dog. But they must be sweet, tell them. (Delay. Arrival of the biscuits. The Elderly Lady holds one up, and Fluff leaps, barking frantically, until he succeeds in snatching it; a man[oe]uvre which he repeats with each successive biscuit.) Do you know, I'm afraid he really mustn't have any more—biscuits always excite him so. Suppose you take him lying on the chair, much as he is now? (Mr. Stippler attempts to place the dog's paws, and is snapped at.) Oh, do be careful!

Mr. Stip. (heroically). Oh, it's of no consequence, Madam. I am—ah—accustomed to it.

The E. L. Oh, yes; but he isn't, you know;[ 20] so please be very gentle with him! And could you get him a little water first? I'm sure he's thirsty. (Mr. Stippler brings water in a developing dish, which Fluff empties promptly.) Now he'll be as good——!

Mr. Stip. (after wiping Fluff's chin and arranging his legs). If we can only keep him like that for one second.

The E. L. But he ought to have his ears pricked. (Mr. Stippler makes weird noises behind the camera, resembling demon cats in torture; Fluff regards him with calm contempt.) Oh, and his hair is all in his eyes, and they're his best feature!

[Mr. Stippler attempts to part Fluff's fringe; snarls.

Mr. Stip. I have not discovered his eyes at present, Madam; but he appears to have excellent—ah—teeth.

The E. L. Hasn't he! Now, couldn't you catch him like that?

Mr. Stip. (to himself). He's more likely to catch me like that! (Aloud; as he retreats under a hanging canopy.) I think we shall get a good one of him as he is. (Focussing.) Yes, that will do very nicely. (He puts in the plate, and prepares to release the shutter, whereupon Fluff deliberately rises and presents his tail[ 21] to the camera.) I presume you do not desiah a back view of the dog, Madam!

"What's she got hold of now."

"What's she got hold of now."

The E. L. Certainly not! Oh, Fluffy, naughty—naughty! Now lie down again, like a good dog. Oh, I'm afraid he's going to sleep!

Mr. Stip. If you would kindly take this—ah—toy in your hand, Madam, it might rouse him a little.

The E. L. (exhibiting a gutta-percha rat). Here, Fluffy, Fluffy, here's a pitty sing! What is it, eh!

Fluff (after opening one eye). The old fool fancies she's got a rat! Well, she may keep it!

[He curls himself up again.

Mr. Stip. We must try to obtain more—ah—animation than that.

[He hands the Elderly Lady a jingling toy.

The E. L. (shaking it vigorously). Fluffy, see what Missis has got!

Fluff (by a yawn of much eloquence). At her age, too! Wonderful how she can do it!

[He closes his eyes wearily.

Mr. Stip. Perhaps you may produce a better effect with this. [He hands her a stuffed stoat.

Fluff (to himself). What's she got hold of now? Hul-lo! (He rises, and inspects the stoat with interest.) I'd no idea the old girl was so "varmint"!

Mr. Stip. Capital! Now, if he'll stay like that[ 24] another——(Fluff jumps down, and wags his tail with conscious merit.) Oh, dear me. I never saw such a dog!

The E. L. He's tired out, poor doggie, and no wonder. But he'll be all the quieter for it, won't he? (After restoring Fluff to the chair.) Now, couldn't you take him panting, like that?

Mr. Stip. I must wait till he's got a little less tongue out, Madam.

The E. L. Must you? Why? I should have thought it was a capital opportunity.

Mr. Stip. For a physician, Madam, not a photographer. If I were to take him now the result would be an—ah—enormous tongue, with a dog in the remote distance.

The E. L. And he's putting out more and more of it! Perhaps he's thirsty again. Here, Fluffy, water—water! [She produces the developing dish.

Fluff (in barks of unmistakable significance). Look here, I've had about enough of this tomfoolery. Let's go. Come on!

Mr. Stip. (seconding the motion with relief). I'm afraid we're not likely to do better with him to-day. Perhaps if you could look in some othah afternoon?

The E. L. Why, we've only been an hour and[ 25] twenty minutes as yet! But what would be the best time to bring him?

Mr. Stip. I should say the light and the temperatuah would probably be more favourable by the week aftah next—(to himself) when I shall be taking my holiday!

The E. L. Very well, I'll come then. Oh, Fluffy, Fluffy, what a silly little dog you are to give all this trouble!

Fluff (to himself, as he makes a triumphant exit). Not half so silly as some people think! I must tell the cat about this; she'll go into fits! I will say she has a considerable sense of humour—for a cat.[ 26]

Mona House, the Town Mansion of the Marquis of Manx, which has been lent for a Sale of Work in aid of the "Fund for Super-annuated Skirt-dancers," under the patronage of Royalty and other distinguished personages.

In the Entrance Hall.

Mrs. Wylie Dedhead (attempting to insinuate herself between the barriers). Excuse me; I only wanted to pop in for a moment, just to see if a lady friend of mine is in there, that's all!

The Lady Money-taker (blandly). If you will let me know your friend's name—?

Mrs. W. D. (splendide mendax). She's assisting the dear Duchess. Now, perhaps, you will allow me to pass!

The L. M. Afraid I can't, really. But if you mean Lady Honor Hyndlegges—she is the only lady at the Duchess's stall—I could send in for her. Or of course, if you like to pay half-a-crown—[ 30]—

Mrs. W. D. (hastily). Thank you, I—I won't disturb her ladyship. I had no idea there was any charge for admission, and—(bristling)—allow me to say I consider such regulations most absurd.

The L. M. (sweetly, with a half glance at the bowl of coins on the table). Quite too ridiculous, ain't they? Good afternoon!

Mrs. W. D. (audibly, as she flounces out). If they suppose I'm going to pay half-a-crown for the privilege of being fleeced——!

Footman (on steps, sotto voce, to confrère). "Fleeced"! that's a good 'un, eh? She ain't brought much wool in with her!

His Confrère. On'y what's stuffed inside of her ear. [They resume their former impassive dignity.

In the Venetian Gallery—where the Bazaar is being held.

A Loyal Old Lady (at the top of her voice—to Stall-keeper). Which of 'em's the Princess, my dear, eh? It's her I paid my money to see.

The Stall-keeper (in a dismayed whisper). Ssh! Not quite so loud! There—just opposite—petunia bow in her bonnet—selling kittens.

The L. O. L. (planting herself on a chair). So that's her! Well, she is dressed plain—for a Royalty—but looks pleasant enough. I wouldn't mind taking one[ 31] o' them kittens off her Royal 'Ighness myself, if they was going at all reasonable. But there, I expect, the cats 'ere is meat for my masters, so to speak; and you see, my dear, 'aving the promise of a tortoise-shell Tom from the lady as keeps the Dairy next door, whenever——

[She finds, with surprise, that her confidences are not encouraged.

Miss St. Leger de Mayne (persuasively to Mrs. Nibbler). Do let me show you some of this exquisite work, all embroidered entirely by hand, you see!

Mrs. Nibbler (edging away). Lovely—quite lovely; but I think—a—I'll just take a look round before I——

Miss de M. If there is any particular thing you were looking for, perhaps I could——

Mrs. N. (becoming confidential). Well, I did think if I could come across a nice sideboard-cloth——

Miss de M. (to herself). What on earth's a sideboard-cloth? (Aloud.) Why, I've the very thing! See—all worked in Russian stitch!

Mrs. N. (dubiously). I thought they were always quite plain. And what's that queer sort of flap-thing for?

Miss de M. Oh, that? That's—a—to cover up the[ 32] spoons, and forks, and things; quite the latest fashion, now, you know.

Mrs. N. (with self-assertion). I have noticed it at several dinner parties I've been to in society lately, certainly. Still I am not sure that——

Miss de M. I always have them on my own sideboard now—my husband won't hear of any others.... Then, I may put this one in paper for you? fifteen-and-sixpence—thanks so much! (To her colleague, as Mrs. N. departs). Connie, I've got rid of that awful nightgown case at last!

Mrs. Maycup. A—you don't happen to have a small bag to hold a powder-puff, and so on, you know?

Miss de M. I had some very pretty ones; but I'm afraid they're all—oh, no, there's just one left—crimson velvet and real passementerie. (She produces a bag). Too trotty for words, isn't it?

Mrs. Maycup (tacitly admitting its trottiness). But then—that sort of purse shape——Could I get a small pair of folding curling-irons into it, should you think, at a pinch?

Miss de M. You could get anything into it—at a pinch. I've one myself which will hold—well, I can't tell you what it won't hold! Half-a-guinea—so many thanks! (To herself, as Mrs. Maycup carries off her[ 33] bag.) What would the vicar's wife say if she knew I'd sold her church collection bag for that! But it's all in a good cause! (An Elderly Lady comes up.) May I show you some of these——?

The Elderly Lady. Well, I was wondering if you had such a thing as a good warm pair of sleeping socks; because, these bitter nights, I do find I suffer so from cold in my feet.

Miss de M. (with effusion). Ah, then I can feel for you—so do I! At least, I used to before I tried—(To herself.) Where is that pair of thick woollen driving-gloves? Ah, I know. (Aloud.)—these. I've found them such a comfort!

The E. L. (suspiciously). They have rather a queer——And then they are divided at the ends, too.

Miss de M. Oh, haven't you seen those before? Doctors consider them so much healthier, don't you know.

The E. L. I daresay they are, my dear. But aren't the—(with delicate embarrassment)—the separated parts rather long?

Miss de M. Do you think so? They allow so much more freedom, you see; and then, of course, they'll shrink.

The E. L. That's true, my dear. Well, I'll take a pair, as you recommend them so strongly.[ 34]

Miss de M. I'm quite sure you'll never regret it! (To herself, as the E. L. retires, charmed.) I'd give anything to see the poor old thing trying to put them on!

Miss Mimosa Tendrill (to herself). I do so hate hawking this horrid old thing about! (Forlornly, to Mrs. Allbutt-Innett.) I—I beg your pardon; but will you give me ten-and-sixpence for this lovely work-basket?

Mrs. Allbutt-Innett. My good girl, let me tell you I've been pestered to buy that identical basket at every bazaar I've set foot in for the last twelve-month, and how you can have the face to ask ten-and-six for it—you must think I've more money than wit!

Miss Tendr. (abashed). Well—eighteenpence then? (To herself, as Mrs. A. I. closes promptly.) There, I've sold something, anyhow!

The Hon. Diana D'Autenbas (to herself). It's rather fun selling at a Bazaar; one can let oneself go so much more! (To the first man she meets.) I'm sure you'll buy one of my buttonholes—now won't you? If I fasten it in for you myself?

Mr. Cadney Rowser. A button'ole, eh? Think I'm not classy enough as I am?

Miss D'Aut. I don't think anyone could accuse[ 35] you of not being "classy;" still a flower would just give the finishing-touch.

Mr. C. R. (modestly). Rats!—if you'll pass the reedom. But you've such a way with you that—there—'ow much.

Miss D'Aut. Only five shillings. Nothing to you!

Mr. C. R. Five bob? You're a artful girl, you are! "Fang de Seakale," and no error! But I'm on it; it's worth the money to 'ave a flower fastened in by such fair 'ands. I won't 'owl—not even if you do run a pin into me.... What? You ain't done a'ready! No 'urry, yer know.... 'Ere, won't you come along to the refreshment-stall, and 'ave a little something at my expense. Do!

Miss D'Aut. I think you must imagine you are talking to a barmaid!

Mr. C. R. (with gallantry). I on'y wish barmaids was 'alf as pleasant and sociable as you, Miss. But they're a precious stuck-up lot, I can assure you!

Miss D'Aut. (to herself as she escapes). I suppose one ought to put up with this sort of thing—for a charity!

Mrs. Babbicombe (at the Toy Stall, to the Belle of the Bazaar, aged three-and-a-half). You perfect duck! You're simply too sweet! I must find you something. (She tempers generosity with discretion by presenting[ 36] her with a small pair of knitted doll's socks.) There, darling!

The Belle's Mother. What do you say to the kind lady now, Marjory?

Marjory (a practical young person, to the donor). Now div me a dolly to put ve socks on.

[Mrs. B. finds herself obliged to repair this omission.

A Young Lady Raffler (to a Young Man). Do take a ticket for this charmin' sachet. Only half-a-crown!

The Young Man. Delighted! If you'll put in for this splendid cigar cabinet. Two shillin's!

[The Young Lady realises that she has encountered an Augur, and passes on.

Miss de. M. (to Mr. Isthmian Gatwick). Can't I tempt you with this tea-cosy? It's so absurdly cheap!

Mr. Isthmian Gatwick (with dignity). A-thanks; I think not. Never take tea, don't you know.

Miss de M. (with her characteristic adaptability). Really? No more do I. But you could use it as a smoking-cap, you know. I always——

[Recollects herself, and breaks off in confusion.

"You have lofty ambitions and the artistic temperament."

"You have lofty ambitions and the artistic temperament."

Miss Ophelia Palmer (in the "Wizard's Cave"—to Mr. Cadney Rowser). Yes, your hand indicates an intensely refined and spiritual nature; you are perhaps a little too indifferent to your personal comfort where that of others is concerned; sensitive—too much so for your own happiness, perhaps—you feel things keenly when you do feel them. You have lofty ambitions and the artistic temperament—seven-and-sixpence, please.

Mr. C. R. (impressed). Well, Miss, if you can read all that for seven-and-six on the palm of my 'and, I wonder what you wouldn't see for 'alf a quid on the sole o' my boot!

[Miss P.'s belief in Chiromancy sustains a severe shock.

Bobbie Patterson (outside tent, as Showman). This way to the Marvellous Jumping Bean from Mexico! Threepence!

Voice from Tent. Bobbie! Stop! The Bean's lost! Lady Honor's horrid Thought-reading Poodle has just stepped in and swallowed it.

Bobbie. Ladies and Gentlemen, owing to sudden domestic calamity, the Bean has been unavoidably compelled to retire, and will be unable to appear till further notice.

Miss Smylie (to Mr. Otis Barleywater, who—in his own set—is considered "almost equal to Corney Grain"). I thought you were giving your entertainment in the library? Why aren't you?[ 40] Mr. Otis Barleywater (in a tone of injury). Why? Because I can't give my imitations of Arthur Roberts and Yvette Guilbert with anything like the requisite "go," unless I get a better audience than three programme-sellers, all under ten, and the cloak-room maid—that's why!

Mrs. Allbutt-Innett (as she leaves, for the benefit of bystanders). I must say, the house is most disappointing—not at all what I should expect a Marquis to live in. Why, my own reception-rooms are very nearly as large, and decorated in a much more modern style!

Bobbie Patterson (to a "Doosid Good-natured Fellow, who doesn't care what he does," and whom he has just discovered inside a case got up to represent an automatic sweetmeat machine). Why, my dear old chap! No idea it was you inside that thing! Enjoying yourself in there, eh?

The Doosid Good-natured Fellow (fluffily, from the interior). Enjoying myself! With the beastly pennies droppin' down into my boots, and the kids howlin' because all the confounded chocolates have worked up between my shoulder-blades, and I can't shake 'em out of the slit in my arm? I'd like to see you tryin' it!

The L. O. L. (to a stranger, who is approaching the[ 41] Princess's stall). 'Ere, Mister, where are your manners? 'Ats off in the presence o' Royalty!

[She pokes him in the back with her umbrella; the stranger turns, smiles slightly, and passes on.

A Well-informed Bystander. You are evidently unaware, Madam, that the gentleman you have just addressed is His Serene Highness the Prince of Potsdam!

The L. O. L. (aghast). Her 'usban'! And me a jobbin' of 'im with my umbrella! 'Ere, let me get out!

[She staggers out, in deadly terror of being sent to the Tower on the spot.[ 42]

George. My dear, I bow to your superior knowledge of natural history. Now you mention it, I believe it is unusual. But I merely meant to suggest a general resemblance.

"They ain't on'y a lot o' sheep! I thought it was Reciters,

or somethink o' that."

"They ain't on'y a lot o' sheep! I thought it was Reciters,

or somethink o' that."

Lucilla (reprovingly). I know. And you've got into such a silly habit of seeing resemblances in things that are perfectly different. I'm sure I'm always telling you of it.

George. You are, my dear. But I'm not nearly so bad as I was. Think of all the things I used to compare you to before we were married!

Sarah Jane (to her Trooper). I could stand an' look at 'em hours, I could. I was born and bred in the country, and it do seem to bring back my old 'ome that plain.

Her Trooper. I'm country bred too, though yer mightn't think it. But there ain't much in sheep shearin' to my mind. If it was pig killin', now!

Sarah Jane. Ah, that's along o' your bein' in the milingtary, I expect.

Her Trooper. No, it ain't that. It's the reckerlections it 'ud call up. I 'ad a 'ole uncle a pork-butcher, d'ye see, and (with sentiment) many and many a 'appy hour I've spent as a boy—— [He indulges in tender reminiscences.

A Young Clerk (who belongs to a Literary Society, to his Fiancée). It has a wonderfully rural look—quite like a scene in 'Ardy, isn't it?[ 58]

His Fiancée (who has "no time for reading rubbish"). I daresay; though I've never been there myself.

The Clerk. Never been? Oh, I see. You thought I said Arden—the Forest of Arden, in Shakspeare, didn't you?

His Fiancée. Isn't that where Mr. Gladstone lives, and goes cutting down the trees in?

The Clerk. No; At least it's spelt different. But it was 'Ardy I meant. Far from the Madding Crowd, you know.

His Fiancée (with a vague view to the next Bank Holiday). What do you call "far"—farther than Margate?

[Her companion has a sense of discouragement.

An Artisan (to a neighbour in broadcloth and a white choker). It's wonderful 'ow they can go so close without 'urtin' of 'em, ain't it?

His Neighbour (with unction). Ah, my friend, it on'y shows 'ow true it is that 'eving tempers the shears for the shorn lambs!

A Governess (instructively, to her charge). Don't you think you ought to be very grateful to that poor sheep, Ethel, for giving up her nice warm fleece on purpose to make a frock for you?[ 59]

Ethel (doubtfully). Y—yes, Miss Mavor. But (with a fear that some reciprocity may be expected of her) she's too big for any of my best frocks, isn't she?

First Urchin (perched on the railings). Ain't that 'un a-kicking? 'E don't like 'aving 'is 'air cut, 'e don't, no more shouldn't I if it was me.... 'E's bin an' upset 'is bloke on the grorss, now! Look at the bloke layin' there larfin'.... 'E's ketched 'im agin now. See 'im landin' 'im a smack on the 'ed; that'll learn 'im to stay quiet, eh? 'E's strong, ain't 'e?

Second Urchin. Rams is the wust, though, 'cause they got 'orns, rams 'ave.

First Urch. What, same as goats?

Second Urch. (emphatically). Yuss! Big crooked 'uns. And runs at yer, they do.

First Urch. I wish they was rams in 'ere. See all them sheep waitin' to be done. I wonder what they're finkin' of.

Second Urch. Ga-arn! They don't fink, sheep don't.

First Urch. Not o' anyfink?

Second Urch. Na-ow! They ain't got nuffink to fink about, sheep ain't.

First Urch. I lay they do fink, 'orf and on.[ 60]

Second Urch. Well, I lay you never see 'em doin' of it!

[And so on. The first Shepherd disrobes his sheep, and dismisses it with a disrespectful spank. After which he proceeds to refresh himself from a brown jar, and hands it to his comrades. The spectators look on with deeper interest, and discuss the chances of the liquid being beer, cider, or cold tea, as the scene closes.

In Bed; At the Highland Hotel, Oban.

What an extraordinary thing is the mechanism of the human mind! Went to sleep last night impressed with vital importance of waking at six, to catch early steamer to Gairloch. And here I am—broad awake—at exactly 5.55! Is it automatic action, or what? Like setting clockwork for explosive machine. When the time comes, I blow up—I mean, get up. Think out this simile—rather a good one.... Need not have been so particular in telling Boots to call me, after all. Shall I get up before he comes? He'll be rather surprised when he knocks at the door, and hears me singing inside like a lark. But, on reflection, isn't it rather petty to wish to astonish an hotel Boots? And why on earth should I get up myself, when I've tipped another fellow to get me up? But suppose he forgets to call me. I've no right, as yet, to assume that[ 64] he will. To get up now would argue want of confidence in him—might hurt his feelings. I will give him another five minutes, poor fellow....

Getting up.—No actual necessity to get up yet, but, to make assurance doubly—something or other, forget what—I will ... I do. Portmanteau rather refractory; retreats under bed—quite ten minutes before I can coax it out.... When I have, it won't let me pack it. That's the worst of this breed of brown portmanteaus—they're always nasty-tempered. However, I am getting a few things into it now, by degrees. Very annoying—as fast as I put them in, this confounded portmanteau shoots them out again! If I've put in that pair of red and white striped pyjamas once, I've done it twenty times—and they always come twisting and rolling out of the back, somehow. Fortunate I left myself ample time.

Man next door to me is running it rather fine. He has to catch the boat, too, and he's not up yet! Hear the Boots hammering away at his door. How can a fellow, just for the sake of a few more minutes in bed—which he won't even know he's had!—go and risk losing his steamer in that way? I'll do him a good turn—knock at the wall myself. "Hi! get up, you lazy beggar. Look sharp—you'll be late!"[ 65] He thanks me, in a muffled tone, through the wall. He is a remarkably quick dresser, he tells me—it won't take him thirty-five seconds to pack, dress, pay his bill, and get on board. If that's the case, I don't see why I should hurry. I've got much more than that already.

At the Quay.—People in Oban stare a good deal. Can't quite make out reason, unless they're surprised to find me up so early. Explain that I got up without having even been called. Oban populace mildly surprised, and offer me neckties—Why?

Fine steamer this; has a paddle-wheel at both ends—"because," the Captain explains, "she has not only to go to Gairloch—but come back as well."

First-rate navigator, the Captain; he has written my weight, the date of my last birthday, and the number of the house I live in, down in a sort of ledger he keeps. He does this with all his passengers, he tells me, reduces the figures to logarithms, and works out the ship's course in decimals. No idea there was so much science in modern seamanship.

On Board.—Great advantage of being so early is that you can breakfast quietly on deck before starting. Have mine on bridge of steamer, under awning; everything very good—ham-méringues[ 66] excellent. No coffee, but, instead, a capital brand of dry, sparkling marmalade, served, sailor-fashion, in small pomatum-pots.

What a small world we live in! Of all people in the world, who should be sitting next to me but my Aunt Maria! I was always under the impression that she had died in my infancy. Don't like to mention this, because if I am wrong, she might be offended. But if she did die when I was a child, she ought to be a much older woman than she looks. I do tell her this—because it is really a compliment.

My Aunt, evidently an experienced traveller, never travels, she informs me, without a pair of globes and a lawn-mower. She offers, very kindly, to lend me the Celestial globe, if the weather is at all windy. This is behaving like an Aunt!

We are taking in live-stock; curious-looking creatures, like spotted pug-dogs (only bigger and woollier, of course) and without horns. Somebody leaning over the rail next to me (I think he is the Public Prosecutor, but am not quite sure), tells me they are "Scotch Shortbreads." Agreeable man, but rather given to staring.

Didn't observe it before, but my Aunt is really amazingly like Mr. Gladstone. Ask her to explain this. She is much distressed that I have noticed it;[ 67] says she has felt it coming on for some time; it is not, as she justly complains, as if she took any interest in politics either. She has consulted every doctor in London, and they all tell her it is simply weakness, and she will outgrow it with care. Singular case—must find out (delicately) whether it's catching.

We ought to be starting soon; feel quite fresh and lively, in spite of having got up so early. Mention this to Captain. Wish he and the Public Prosecutor wouldn't stare at me so. Just as if there was something singular in my appearance!

They're embarking my portmanteau now. Knew they would have a lively time of it! It takes at least four sailors, in kilts, to manage it. Ought I to step ashore and quiet it down? Stay where I am. Don't know why, but feel a little afraid of it when it's like this. Shall exchange it for a quiet hand-bag when I get home.

Captain busy hammering at a hole in the funnel—dangerous place to spring a leak in—hope he is making it water-tight. The hammering reminds me of that poor devil in the bedroom next to mine at the hotel. He won't catch the boat now—he can't! My Aunt (who has left off looking like Mr. Gladstone) asks me why I am laughing. I tell her about[ 68] that unfortunate man and his "thirty-five seconds." She screams with laughter. Very humorous woman, my Aunt.

Deck crowded with passengers now: all pointing and staring ... at whom? Ask Aunt Maria. She declines to tell me: says, severely, that "If I don't know, I ought to."

Great Heavens! It's at me they're staring! And no wonder—in the hurry I was in, I must have packed everything up!... I've come away just as I was! Now I understand why someone offered me a necktie. Where shall I go and hide myself? Shall I ever persuade that beast of a portmanteau to give me out one or two things to put on—because I really can't go about like this! Captain still hammering at funnel—but he can't wake that sleepy-headed idiot in the next room. "Louder—knock louder, or the boat will go without him! Tell him there isn't another for two days. He's said good-bye to everybody he knows at Oban—he will look such an ass if he doesn't go, after all!"... Not the least use! Wonder what his name is. My Aunt says she knows, only she won't tell me—she'll whisper it, as a great secret. She is just about to disclose the name, which, somehow, I am extremely curious to know—when ...[ 69]

Where am I? Haven't they got that unhappy fellow up yet? Why the dickens are they knocking at my door? I've been on board the steamer for hours, I tell you? Eh? what? Five minutes to eight! And the Gairloch boat? "Sailed at usual time—seven. Tried to make you hear—but couldn't."... Confound it all! Good mind not to get up all day—now![ 70]

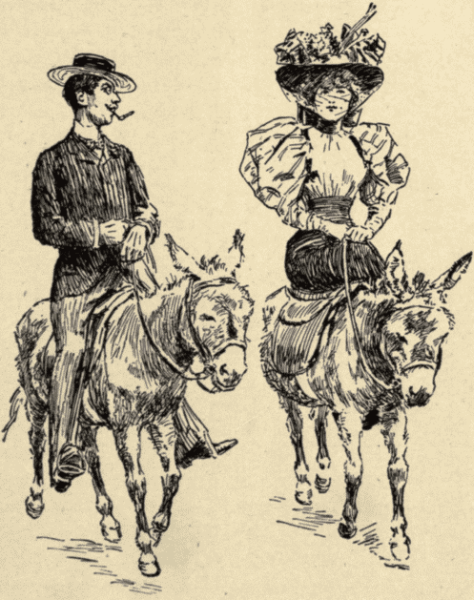

It is the summer of 189-. The scene is a road skirting Victoria Park, Bethnal Green, which Society's leaders have recently discovered and appointed as the rendez-vous for the Season, and where it is now the correct thing for all really smart people to indulge, between certain prescribed hours, in sports and pastimes that have hitherto been more characteristic of the masses than the classes. The only permissible mount now is the donkey, which must be ridden close to the tail, and referred to as a "moke." A crowd of well-turned-out spectators arrives from the West End every morning about eleven to watch the brilliant parade of "Mokestrians" (as the Society journalist will already have decided to call them). Some drive slowly up and down on coster-barrows, attended by cockaded and disgusted grooms. About twelve, they break up into light luncheon parties; after which they play democratic games for half an hour or so, and drive home on drags.

Mr. Woodby-Innett (to the Donkey Proprietor). Kept a moke for me? I told you I should be wantin' one every mornin' now.[ 74]

The Donkey Proprietor (after consulting engagement book). I've not got it down on my list, Sir. Very sorry, but the Countess of Cumberback has just booked the last for the 'ole of this week. Might let you 'ave one by-and-by, if Sir Hascot Goodwood brings his in punctual, but I can't promise it.

Mr. Woodby-Inn. That's no good; no point in ridin' after the right time. (To himself, as he turns away.) Nuisance! Not that I'm so keen about a moke. Not a patch on a bike!—though it don't do to say so. Only if I'd known this, I'd have turned up in a tall hat and frock coat; and then I could have taken a turn on the steam-circus. Wonder if it would be any sort of form shyin' at cocoa-nuts in tweeds and a straw hat. Must ask some chap who knows. More puzzlin' what to put on this year than ever!

Lady Ranela Hurlingham (breathlessly to Donkey Proprietor). That's mine, isn't it? Will you please put me up, and promise me you'll keep close behind and make him run. (Suppliantly.) You will, won't you?

The Donkey Proprietor (with a due sense of his own value). Well, I dessay I can come along presently, Lady 'Urlingham, and fetch 'im a whack or two; jest now I can't, having engaged to come and 'old the Marshiness of 'Ammercloth on 'er moke;[ 75] but there, you orter be able to git along well enough by yourself now—you ought!

"Mokestrians."

"Mokestrians."

Captain Sonbyrne (just home on leave from India—to Mrs. Chesham-Lowndes). Rather an odd sort of idea this—I mean, coming all the way out here to ride a lot of donkeys, eh?

Mrs. Chesham-Lowndes. It used to be rather amusing a month ago, before they all got used to riding so near the tail; but now they're all so good at it, don't you know.

Capt. Sonb. I went down to Battersea Park yesterday to see the bicyclists. Not a soul there, give you my word!

Mrs. C.-L. No; there wouldn't be this season. You see, all sorts and conditions of people began to take it up, and it got too fearfully common. And now moke-riding has quite cut it out.

Capt. Sonb. But why ride donkeys when you can get gees?

Mrs. C.-L. Oh, well, they're democratic, and cheap, and all that, don't you know. And one really can't be seen on a horse this year—in town, at least. In the country it don't matter so much.

First Mokestrian (to second ditto). Hullo, old chap, so you've taken to a moke at last, eh? How are you gettin' on?[ 78]

Second Mokestrian. Pretty well. I can sit on his tail all right now, but I can't get into the way of keepin' my heels off the ground yet, it's so beastly difficult.

Fragments from Spectators. That's rather a smart barrow Lady Barinrayne's drivin' to-day.... Who's the fellow with her, with the paper feather in his pot-hat? Bad style, I call it.... That's Lord Freddy Fugleman—best dressed man in London. You'll see everybody turnin' up in a paper feather in a day or two.... Lot of men seem to be using a short clay as a cigarette-holder now, don't they?... Yes, Roddie Rippingill introduced the idea last week, and it seems to have caught on. [&c., &c.]

After Luncheon; at the Steam-Circus and other Sports.

Scraps of Small-talk. No end sorry, Lady Gwendolen; been tryin' to get you a scent-squirt everywhere; but they're all gone; such a run on 'em for Ascot, don't you know.... Thanks; it doesn't matter; only dear Lady Buckram has just thrown some red ochre down the back of my neck, and Algy Vere came and shot out a coloured paper thing right in my face, and I shouldn't like to seem uncivil.... Suppose I shall see you at Lady Brabazon's "Kiss[ 79] in the Ring" at Bethnal Green to-morrow afternoon?... I believe she did send us cards, but we promised to look in at a friendly lead the Duchess of Dillwater is giving at such a dear little public she's discovered in Whitechapel, so we may be rather late.... You'll keep a handkerchief-throw for me if you do come on, won't you?... It will have to be an extra, then, I'm afraid.... Are you goin' to Lord Balmisyde's eight o'clock breakfast to-morrow? So glad; I hear he's engaged five coffee-stalls, and we're all to stand up and eat saveloys and trotters and thick bread and butter.... Oh, I wanted to ask you, my girls have got an invitation to a hoky-poky party the Vavasours are giving after the moke-ridin' next Thursday, and I'm told it's quite wrong to eat hoky-poky with a spoon—do you know how that is?... The only correct way, Caroline, is to lick it out of the glass, which requires practice before it can be attempted in public. But I hear there's quite a pleasant boy-professor somewhere in the Mile End Road who teaches it in a single lesson; he's very moderate; his terms are only half a guinea, which includes the hoky-poky. I'll send you his address if I can find it.... Thanks so much; the dear girls will be so grateful to you.... I do think it's quite too bad of Lady Geraldine Grabber, she goes[ 80] and sticks her card on the only decent wooden horse in the steam-circus and says she's engaged it for the whole time, though she hardly ever takes a round! And so many girls standing out who can ride without getting in the least giddy!... Rathah a boundah, that fellow, if you ask me; I've seen him pullin' a swing boat in brown boots and ridin'-breeches!... How wonderfully well your daughter throws the rings, dear Lady Cornelia, I hear she's won three walking-sticks and five clasp knives.... You're very kind. She is quite clever at it; but then she's had some private coaching from a gipsy, don't you know.... What are you going to do with yourself this afternoon?... Oh, I'm going to the People's Palace to see the finals played off for the Skittles Championship; bound to be a closish thing; rather excitin', don't you know.... Ah, Duchess, you've been in form to-day, I see, five cocoa-nuts! Can I relieve you of some of them?... Thanks, they are rather tiresome to carry; if you could find my carriage and tell the footman to keep his eye on them. [&c., &c.]

Lady Rosehugh (to Mr. Luke Walmer, on the way home). You know I do think it's such a cheering sign of the times, Society getting simpler in its tastes, and sharing the pleasures of the Dear People, and all[ 81] that; it must tend to bring all classes more together, don't you know!

Mr. Luke Walmer. Perhaps. Only I was thinking, I don't remember seeing any of the Dear People about.

Lady Rosehugh. No; somebody was telling me they had taken to playing Polo on bicycles in Hyde Park. So extraordinary of them—such a pity they haven't some higher form of amusement, you know![ 82]

Den of Latest Lion.

Latest Lion (perusing card with no visible signs of gratification). Confound it! don't remember telling the Editor of Park Lane I'd let myself be interviewed. Suppose I must have, though. (Aloud to Servant, who is waiting.) You can show the Gentleman up.

Servant (returning). Mr. Walsingham Jermyn!

[A youthful Gentleman is shown in; he wears a pink-striped shirt-front, an enormous buttonhole, and a woolly frock-coat, and is altogether most expensively and fashionably attired, which, however, does not prevent him from appearing somewhat out of countenance after taking a seat.

The L. L. (encouragingly). I presume, Mr. Jermyn, you're here to ask me some questions about the future of the British East African Company, and the duty of the Government in the matter?[ 86]

Mr. Jermyn (gratefully). Er—yes, that's what I've come about, don't you know—that sort of thing. Fact is (with a burst of confidence), this isn't exactly my line—I've been rather let in for this. You see, I've not been by way of doin' this long—but what's a fellow to do when he's stony-broke? Got to do somethin', don't you know. So I thought I'd go in for journalism—I don't mean the drudgery of it, leader-writin' and that—but the light part of it, Society, you know. But the other day, man who does the interviews for Park Lane (that's the paper I'm on) jacked up all of a sudden, and my Editor said I'd better take on his work for a bit, and see what I made of it. I wasn't particular. You see, I've always been rather a dead hand at drawin' fellows out, leadin' them on, you know, and all that, so I knew it would come easy enough to me, for all you've got to do is to sit tight and let the other chap—I mean to say, the man you're interviewin'—do all the talking, while you—I mean to say, myself—keep, keeps—hullo, I'm getting my grammar a bit mixed; however, it don't signify—I keep quiet and use my eyes and ears like blazes. Talking of grammar, I thought when I first started that I should get in a regular hat over the grammar, and the spellin', and that—you write, don't you, when you're not[ 87] travellin'? So you know what a grind it is to spell right. But I soon found they kept a Johnny at the office with nothing to do but put all your mistakes right for you, so, soon as I knew that, I went ahead gaily.

The L. L. Exactly, and now, perhaps, you will let me know what particular information you require?

Mr. J. Oh, you know the sort of thing the public likes—they'll want to know what sort of diggings you've got, how you dress when you're at home, and all that, how you write your books, now—you do write books, don't you? Thought so. Well, that's what the public likes. You see, your name's a good deal up just now—no humbug, it is though! Between ourselves, you know, I think the whole business is the balliest kind of rot, but they've got to have it, so there you are, don't you see. I don't pretend to be a well-read sort of fellow, never was particularly fond of readin' and that; no time for it, and besides, I've always said Books don't teach you knowledge of the world. I know the world fairly well—but I didn't learn it from books—ah, you agree with me there—you know what skittles all that talk is about education and that. Well, as I was sayin', I don't read much, I see the Field every week, and a clinkin' good paper[ 88] it is, tells you everythin' worth knowin', and I read the Pink Un, too. Do you know any of the fellows on it? Man I know is a great friend of one of them, he's going to introduce me some day, I like knowin' literary chaps, don't you? You've been about a good deal, haven't you? I expect you must have seen a lot, travellin' as you do. I've done a little travellin' myself, been to Monte Carlo, you know, and the Channel Islands—you ever been to the Channel Islands? Oh, you ought to go, it's a very cheery place. Talkin' of Monte Carlo, I had a rattlin' good time at the tables there; took out a hundred quid, determined I would have a downright good flutter, and Jove! I made that hundred last me over five days, and came away in nothing but my lawn-tennis flannels. That's what I call a flutter, don't you know! Er—beastly weather we're havin'! You have pretty good weather where you've been? A young brother of mine has been out for a year in Texas—he said he'd very good weather—of course that's some way off where you've come from—Central Africa, isn't it? Talkin' of my brother, what do you think the young ass did?—went out there with a thousand pounds, and paid it all down to some sportsmen who took him to see some stock they said belonged to them—of course he found out after[ 89] they'd off'd it that they didn't own a white mouse among 'em! But then, Dick's one of those chaps, you know, that think themselves so uncommon knowing, they can't be had. I always told him he'd be taken in some day if he let his tongue wag so much—too fond of hearing himself talk, don't you know, great mistake for a young fellow; sure to say somethin' you'd better have let alone. I suppose you're getting rather sick of all these banquets, receptions, and that? They do you very well, certainly. I went to one of these Company dinners some time ago, and they did me as well as I've ever been done in my life, but when you've got to sit still afterwards and listen to some chap who's been somewhere and done somethin' jawin' about it by the hour together without a check, why, it's not good enough, I'm hanged if it is! Well, I'm afraid I can't stay any longer—my time's valuable now, don't you know. I daresay yours is, too. I'm awfully glad to have had a chat with you, and all that. I expect you could tell me a lot more interestin' things, only of course you've got to keep the best of 'em to put in your book—you are writin' a book or somethin', ain't you? Such heaps of fellows are writin' books nowadays, the wonder is how any of 'em get read. I shall try and get a look at yours, though, if I come across it[ 90] anywhere; hope you'll put some amusin' things in,—nigger stories and that, don't make it too bally scientific, you know. Directly I get back, I shall sit down, slick off, and write off all you've told me. I shan't want any notes, I can carry it all in my head, and of course I shan't put in anything you'd rather I didn't, don't you know.

The L. L. (solemnly). Mr. Jermyn, I place implicit confidence in your discretion. I have no doubt whatever that your head, Sir, is more than capable of containing such remarks as I have found it necessary to make in the course of our interview. I like your system of extracting information, Sir, very much. Good morning.

Mr. J. (outside). Nice pleasant-spoken fellow—trifle long-winded, though! Gad, I was so busy listenin' I forgot to notice what his rooms were like or anythin'! How would it do to go back? No, too much of a grind. Daresay I can manage to fox up somethin'. I shall tell the Chief what he said about my system. Chief don't quite know what I can do yet—this will open his eyes a bit.

[And it does.

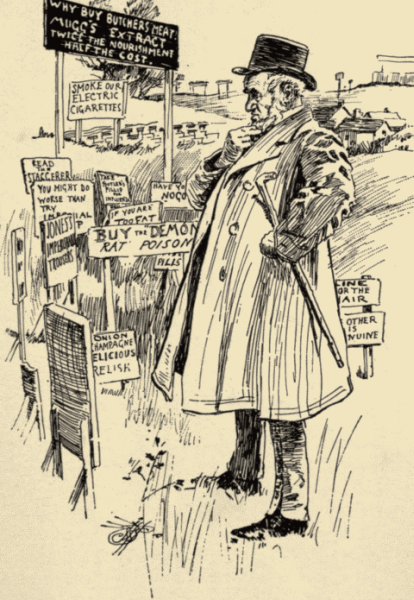

For over half-a-mile the pavement on the East side of the road is thronged with promenaders, and the curbstone lined with stalls and barrows, and hawkers of various wares. Marketing housewives with covered baskets oscillate undecidedly from stalls to shops, and put off purchasing to the last possible moment. Maids-of-all-work perambulate arm-in-arm, exchanging airy badinage with youths of their acquaintance, though the latter seem to prefer the society of their own sex. A man with a switchback skittle-board plays gloomy games by himself to an unspeculative group of small boys. The tradesmen stand outside their shops and conduct their business with a happy blend of the methods of a travelling showman and a clown.

[He executes a double shuffle, and knocks over several boxes of bloaters in the gaiety of his heart.

A Hawker of Penny Memorandum Books (to an audience of small boys). Those among you 'oo are not mechanics, decidedly you 'ave mechanical hideers!

[He enlarges upon the convenience of having a notebook in which to jot down any inspirations of this kind; but his hearers do not appear to agree with him.

A Lugubrious Vendor. One penny for six comic pypers. Hevery one different!

A Rude Boy. You ain't bin readin' o' any on 'em, 'ave yer, guv'nor?[ 95]

A Crockery Merchant (as he unpacks a variety of vases of appalling hideousness). I don't care—it's self-sacrifice to give away! Understand, you ain't buyin' common things, you're buyin' suthin' good! It 'appens to be my buthday to-night, so I'm goin' to let you people 'ave the benefit of the doubt. Come on 'ere. I don't ask you to b'lieve me—on'y to jedge fur yerselves. I'm not 'ere to tell you no fairy tales; and the reason why I'm in a position to orfer up these vawses—all richly gilt, and decorated in three colours, the most expensive ever made—the reason I'm able to sell them so cheap as I'm doin' is this—(he lowers his voice mysteriously)—'arf the stuff I 'ave 'ere we git in very funny ways!

[This ingeniously suggestive hint enhances the natural charm of his ware to such a degree that the vases are bought up briskly, as calculated to brighten the humblest home.

A Sanctimonious Young Man (with a tongue too large for his mouth, who has just succeeded in collecting a circle round him). I am only 'ere to-night, my friends, as a paid servant—for the purpose of deciding a wager. Some o' you may have noticed an advertisement lately in the Daily Telegrawf, asking for men to stand on Southwark Bridge and orfer arf-suverings for a penny apiece. You are equally well aware that[ 96] it is illegal to orfer the Queen's coinage for money: and that is not my intention this evening. But I 'ave 'ere several pieces of gold, guaranteed to be of the exact weight of arf a suvering, and 'all-marked, which, in order to decide the wager I 'ave spoken of, I shall now perceed to charge you the sum of one penny for, and no more. I am not allowed to sell more than one to each person——

[Here a constable comes up, and the decision of the wager is postponed until a more favourable opportunity.

First "General" (looking into a draper's window). Look at them coloured felt 'ats—all shades, and on'y sixpence three-fardens!

Second "G." They are reasonable; but I've 'eard as felt 'ats is gone out of fashion now.

First "G." Don't you believe it, Sarah. Why, my married sister bought one on'y last week!

Coster (to an old lady who has repudiated a bunch of onions after a prolonged scrutiny). Frorsty? So would you be if your onion 'ad bin layin' out in the fields all night as long as these 'ave!

First Itinerant Physician (as he screws up fragments of candy in pieces of newspaper). That is Frog in your Froat what I'm doin' up now. I arsk you to try it. It's given to me to give away, and[ 97] I'm goin' to give it away—you understand?—that's all. And now I'm going to tork to you about suthink else. You see this small bottle what I 'old up. I tell you there's 'undreds layin' in bed at this present moment as 'ud give a shillin' fur one of these—and I offer it to you at one penny! It corrects all nerve-pains connected with the 'ed, cures earache, toothache, neuralgy, noomonia, 'art-complaint, fits, an' syhatica. Each bottle is charged with helectricity, forming a complete galvanic-battery. Hall you 'ave to do is to place the bottle to one o' your nawstrils, first closing the other with your finger. You will find it compels you to sniff. The moment you tyke that sniff, you'll find the worter comin' into your heyes—and that's the helectricity. You'll say, "I always 'eard helectricity was a fluid." (With withering scorn.) Very likely! You 'ave? An' why? Be-cawse o' the hignirant notions prevailin' about scientific affairs! Hevery one o' these bottles contains a battery, and to each purchaser I myke 'im a present—a present, mind yer—of Frog in 'is Froat!

Susan Jane (to Lizerann, before a stall where "Novelettes, three a penny," are to be procured by the literary). Shall we 'ave a penn'orth, an' you go 'alves along o' me?[ 98]

Lizerann. Not me. I ain't got no time to go improvin' o' my mind, whatever you 'ave!

A Vendor of "'Ore'ound Tablets" (he is a voluble young man, with considerable lung-power, and a tendency to regard his cough lozenges as not only physical but moral specifics). I'm on'y a young feller, as you see, and yet 'ere I am, with my four burnin' lamps, and a lassoo-soot as belonged to my Uncle Bill, doin' wunnerful well. Why, I've took over two pound in coppers a'ready! Mind you, I don't deceive you; you may all on you do as well as me; on'y you'll 'ave to get two good ref'rences fust, and belong to a temp'rance society, like I do. This is the badge as I've got on me at this minnit. I ain't always bin like I am now. I started business four year ago, and was doin' wunnerful well, too, till I got among 'orse-copers an' dealers and went on the booze, and lost the lot. Then I turned up the drink and got a berth sellin' these 'ere Wangoo Tablets—and now I've got a neat little missus, and a nice 'ome, goin' on wunnerful comfortable. Never a week passes but what I buy myself something. Last week it was a pair o' noo socks. Soon as the sun peeps out and the doo dries up, I'm orf to Yarmouth. And what's the reason? I've enjoyed myself there. My Uncle Bill, as lives at Lowestoft,[ 99] and keeps six fine 'orses and a light waggon, he's doin' wunnerful well, and he'd take me into partnership to-morrow, he would. But no—I'm 'appier as I am. What's the reason I kin go on torkin' to you like this night after night, without injury to my voice? Shall I tell yer? Because, every night o' my life, afore I go to bed, I take four o' these Wangoo Tablets—compounded o' the purest 'erbs. You take them to the nearest doctor's and arsk 'im to analyse an' test them as he will, and you 'ear what he says of them! Take one o' them tablets—after your pipe; after your cigaw; after your cigarette. You won't want no more drink, you'll find them make you come 'ome reglar every evening, and be able to buy a noo 'at every week. You've ony to persevere for a bit with these 'ere lawzengers to be like I am myself, doin' wunnerful well! You see this young feller 'ere? (Indicating a sheepish head in a pot-hat, which is visible over the back of his stall.) Born and bred in Kenada, 'e was. And quite right! Bin over 'ere six year, so, o' course he speaks the lengwidge. And quite right. Now I'm no Amerikin myself, but they're a wunnerful clever people, the Amerikins are, allays inventin' or suthink o' that there. And you're at liberty to go and arsk 'im for yourselves whether this is a real[ 100] Amerikin invention or not—as he'll tell yer it is—and quite right, too! An' it stands to reason as he orter know, seein' he introdooced it 'imself and doin' wunnerful well with it ever since. I ain't come 'ere to rob yer. Lady come and give me a two-shillin' piece just now. I give it her back. She didn't know—thort it was a penny, till I told her. Well, that just shows you what these 'ere Wangoo 'Ore'ound Tablets are!

[After this practical illustration of their efficacy, he pauses for oratorical effect, and a hard-worked-looking matron purchases three packets, in the apparent hope that a similar halo of the best horehound will shortly irradiate the head of her household.

Lizerann (to Susan Jane, as they walk homewards). On'y fancy—the other evenin', as I was walkin' along this very pavement, a cab-'orse come up beyind me, unbeknown like, and put 'is 'ed over my shoulder and breathed right in my ear!

Susan Jane (awestruck). You must ha' bin a bad gell!

[Lizerann is clearly disquieted by so mystical an interpretation, even while she denies having done anything deserving of a supernatural rebuke.

Scene the First—At the Galahad-Green's.

Mrs. G.-G. Galahad!

Mr. G.-G. (meekly). My love?

Mrs. G.-G. I see that the proprietors of All Sorts are going to follow the American example, and offer a prize of £20 to the wife who makes out the best case for her husband as a Model. It's just as well, perhaps, that you should know that I've made up my mind to enter you!

Mr. G.-G. (gratified). My dear Cornelia! really, I'd no idea you had such a——

Mrs. G.-G. Nonsense! The drawing-room carpet is a perfect disgrace, and, as you can't, or won't, provide the money in any other way, why——Would you like to hear what I've said about you?

Mr. G.-G. Well, if you're sure it wouldn't be troubling you too much, I should, my dear.[ 104]

Mrs. G.-G. Then sit where I can see you, and listen. (She reads.) "Irreproachable in all that pertains to morality"—(and it would be a bad day indeed for you, Galahad, if I ever had cause to think otherwise!)—"morality; scrupulously dainty and neat in his person"—(ah, you may well blush, Galahad, but fortunately, they won't want me to produce you!)—"he imports into our happy home the delicate refinement of a preux chevalier of the olden time." (Will you kindly take your dirty boots off the steel fender!) "We rule our little kingdom with a joint and equal sway, to which jealousy and friction are alike unknown; he, considerate and indulgent to my womanly weakness"—(You need not stare at me in that perfectly idiotic fashion!)—"I, looking to him for the wise and tender support which has never yet been denied. The close and daily scrutiny of many years has discovered"—(What are you shaking like that for?)—"discovered no single weakness; no taint or flaw of character; no irritating trick of speech or habit." (How often have I told you that I will not have the handle of that paper-knife sucked? Put it down; do!) "His conversation—sparkling but ever spiritual—renders our modest meals veritable feasts of fancy and flows of soul.... Well, Galahad?"[ 105]

Mr. G.-G. Nothing, my dear; nothing. It struck me as, well,—a trifle flowery, that last passage, that's all!

Mrs. G.-G. (severely). If I cannot expect to win the prize without descending to floweriness, whose fault is that, I should like to know? If you can't make sensible observations, you had better not speak at all. (Continuing.) "Over and over again, gathering me in his strong, loving arms, and pressing fervent kisses upon my forehead, he has cried, 'Why am I not a Monarch that so I could place a diadem upon that brow? With such a Consort am I not doubly crowned?'" Have you anything to say to that, Galahad?

Mr. G.-G. Only, my love, that I—I don't seem to remember having made that particular remark.

Mrs. G.-G. Then make it now. I'm sure I wish to be as accurate as I can.

[Mr. G.-G. makes the remark—but without fervour.

Scene the Second—At the Monarch-Jones'.

Mr. M.-J. Twenty quid would come in precious handy just now, after all I've dropped lately, and I mean to pouch that prize if I can—so just you sit down, Grizzle, and write out what I tell you; do you hear?[ 106]

Mrs. M.-J. (timidly). But, Monarch, dear, would that be quite fair? No, don't be angry, I didn't mean that—I'll write whatever you please!

Mr. M.-J. You'd better, that's all! Are you ready? I must screw myself up another peg before I begin. (He screws.) Now, then. (Stands over her and dictates.) "To the polished urbanity of a perfect gentleman he unites the kindly charity of a true Christian." (Why the devil don't you learn to write decently, eh?) "Liberal, and even lavish, in all his dealings, he is yet a stern foe to every kind of excess"—(Hold on a bit, I must have another nip after that)—"every kind of excess. Our married life is one long dream of blissful contentment, in which each contends with the other in loving self-sacrifice." (Haven't you corked all that down yet!) "Such cares and anxieties as he has he conceals from me with scrupulous consideration as long as possible"—(Gad, I should be a fool if I didn't!)—"while I am ever sure of finding in him a patient and sympathetic listener to all my trifling worries and difficulties."—(Two f's in difficulties, you little fool—can't you even spell?) "Many a time, falling on his knees at my feet, he has rapturously exclaimed, his accents broken by manly emotion, 'Oh, that I were more worthy of such a[ 107] pearl among women! With such a helpmate, I am indeed to be envied!'" That ought to do the trick. If I don't romp in after that!—--(Observing that Mrs. M.-J.'s shoulders are convulsed.) What the dooce are you giggling at now?

Mrs. M.-J. I—I wasn't giggling, Monarch dear, only——

Mr. M.-J. Only what?

Mrs. M.-J. Only crying!

The Sequel.

"The judges appointed by the spirited proprietors of All Sorts to decide the 'Model Husband Contest'—which was established on lines similar to one recently inaugurated by one of our New York contemporaries—have now issued their award. Two competitors have sent in certificates which have been found equally deserving of the prize; viz., Mrs. Cornelia Galahad-Green, Graemair Villa, Peckham, and Mrs. Griselda Monarch-Jones, Aspen Lodge, Lordship Lane. The sum of twenty pounds will consequently be divided between these two ladies, to whom, with their respective spouses, we beg to tender our cordial felicitations."—(Extract from Daily Paper, some six months hence.)[ 108]

He is an elderly amiable little Dutchman in a soft felt hat; his name is Bosch, and he is taking me about. Why I engaged him I don't quite know—unless from a general sense of helplessness in Holland, and a craving for any kind of companionship. Now I have got him, I feel rather more helpless than ever—a sort of composite of Sandford and Merton, with a didactic, but frequently incomprehensible Dutch Barlow. My Sandford half would like to exhibit an intelligent curiosity, but is generally suppressed by Merton, who has a morbid horror of useful information. Not that Bosch is remarkably erudite, but nevertheless he contrives to reduce me to a state of imbecility, which I catch myself noting with a pained surprise. There is a statue in the Plein, and the Sandford element in me finds a satisfaction in recognising it aloud as William the Silent.[ 112] It is—but, as my Merton part thinks, a fellow would be a fool if he didn't recognise William after a few hours in Holland—his images, in one form or another, are tolerably numerous. Still Bosch is gratified. "Yass, dot is ole Volliam," he says, approvingly, as to a precocious infant just beginning to take notice. "Lokeer," he says, "you see dot Apoteek?" He indicates a chemist's shop opposite, with nothing remarkable about it externally, except a Turk's head with his tongue out over the door.

"Yes, I (speaking for Sandford and Merton) see it—has it some historical interest—did Volliam get medicine there, or what?"

"Woll, dis mornin dare vas two sairvans dere, and de von cot two blaces out of de odder's haid, and afderwarts he go opstairs and vas hang himself mit a pedbost."

Bosch evidently rather proud of this as illustrating the liveliness of The Hague.

"Was he mad?"

"Yass, he vas mard, mit a vife and seeks childrens."

"No, but was he out of his senses?"

"I tink it was oud of Omsterdam he vas com," says Bosch.

"But how did it happen?"[ 113] "Wol-sare, de broprietor vas die, and leaf de successor de pusiness, and he dells him in von mons he will go, begause he nod egsamin to be a Chimigal—so he do it, and dey dake him to de hosbital, and I tink he vas die too by now!" adds BOSCH, cheerfully.

Very sad affair evidently—but a little complicated. Sandford would like to get to the bottom of it, but Merton convinced there is no bottom. So, between us, subject allowed to drop.

Sandford (now in the ascendant again) notices, as the clever boy, inscription on house-front, "Hier woonden Groen Van Prinsterer, 1838-76."

"I suppose that means Van Prinsterer lived here, Bosch?"

"Yass, dot vas it."

"And who was he?"

"He vas—wol, he vos a Member of de Barliaments."

"Was he celebrated?"

"Celebrated? oh, yaas!"

"What did he do?" (I think Merton gets this in.)

"Do?" says Bosch, quite indignantly, "he nefer do nodings!"

Bosch takes me into the Fishmarket, when he[ 114] directs my attention to a couple of very sooty live storks, who are pecking about at the refuse.

"Dose pirts are shtorks; hier dey vas oblige to keep alvays two shtorks for de arms of de Haag. Vhen de yong shtorks porn, de old vons vas kill."

Sandford shocked—Merton sceptical.

"Keel dem? Oh, yaas, do anytings mit dem ven dey vas old," says Bosch, and adds:—"Ve haf de breference mit de shtorks, eh?"

What is he driving at?

"Yaas—ven ve vas old ve vas nod kill."

This reminds Bosch—Barlow-like—of an anecdote.

"Dere vas a vrent to me," he begins, "he com and say to me, 'Bosch, I am god so shtout and my bark is so dick, I can go no more on my lacks—vat vas I do?' To him I say, 'Wol, I dell you vat I do mit you—I dake you at de booshair to be cot op; I tink you vas make vary goot shdeak-meat!"

Wonder whether this is a typical sample of Bosch's badinage.

"What did he say to that, Bosch?"

"Oh, he vas vair moch loff, a-course!" says Bosch, with the natural complacency of a successful humorist.

We go into the Old Prison, and see some horrible[ 115] implements of torture, which seem to exhilarate Bosch.

"Lokeer!" he says, "Dis vas a pinition" (Bosch for "punishment") "mit a can. Dey lie de man down and vasten his foots, and efery dime he vas shdrook mit de can, he jomp op and hit his vorehaid.... Hier dey lie down de beoples on de back, and pull dis shdring queeck, and all dese tings go roundt, and preak deir bones. Ven de pinition was feenish you vas det." He shows where the Water-torture was practised. "Nottice 'ow de vater vas vork a 'ole in de tile," he chuckles, "I tink de tile vas vary hardt det, eh?" Then he points out a pole with a spiked prong. "Tief-catcher—put 'em in de tief's nack—and get 'im!" Before a grim-looking cauldron he halts appreciatively. "You know vat dat vas for?" he says. "Dat vas for de blode-foots; put 'em in dere, yaas, and light de vire onderneat."

No idea what "blode-foots" may be, but from the relish in Bosch's tone, evidently something very unpleasant, so don't press him for explanations. We go upstairs, and see some dark and very mouldy dungeons, which Bosch is very anxious that I should enter. Make him go in first, for the surroundings seem to have excited his sense of[ 116] the humorous to such a degree, that he might be unable to resist locking me in, and leaving me, if I gave him a chance.

Outside at last, thank goodness! The Groote Kerk, according to Bosch, "is not vort de see," so we don't see it. Sandford has a sneaking impression that I ought to go in, but Merton glad to be let off. We go to see the pictures at the Mauritshuis instead. Bosch exchanges greetings with the attendants in Dutch. "Got another of 'em in tow, you see—and collar-work, I can tell you!" would be a free translation, I suspect, of his remarks. Must say that, in a Picture-gallery, Bosch is a superfluous luxury. He does take my ignorance just a trifle too much for granted. He might give me credit for knowing the story of Adam and Eve, at all events! "De Sairpan gif Eva de opple, an' Eva gif him to Adam," Bosch carefully informs me, before a "Paradise," by Rubens and Brueghel.

This rouses my Merton half to inquire what Adam did with it.

"Oh, he ead him too!" says Bosch in perfect good faith.