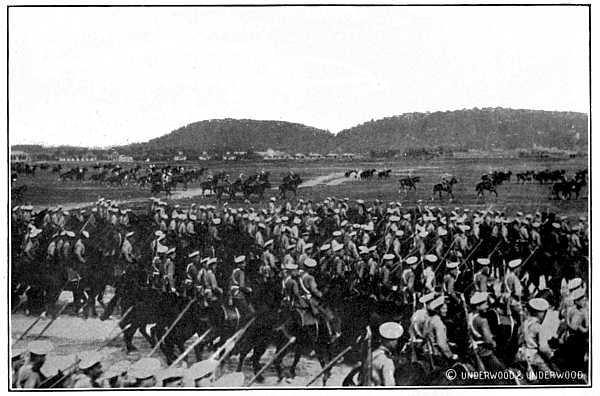

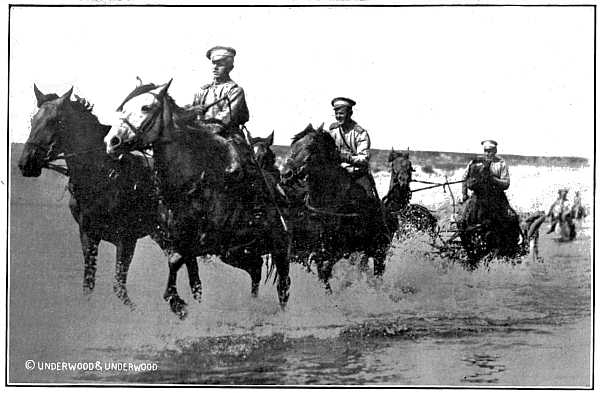

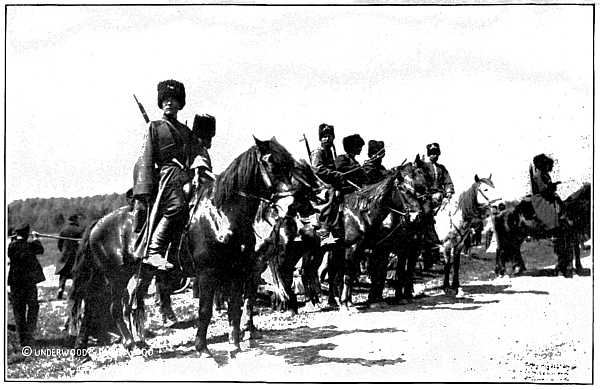

RUSSIA'S RENOWNED CALVARY ON THE MARCH

RUSSIA'S RENOWNED CALVARY ON THE MARCH

IN THE RUSSIAN RANKS

A Soldier's Account of

the Fighting in Poland

BY

JOHN MORSE

Englishman

ILLUSTRATED WITH

REPRODUCTIONS OF PHOTOGRAPHS

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

[1]

AN ENGLISHMAN IN THE RUSSIAN RANKS

CHAPTER I

THE OUTBREAK OF THE GREAT WAR

On the 1st July, 1914, if I could have seen one step ahead in my life's course, this book would not have been written. On the day named I crossed the German frontier west of Metz; and, for the first time, beheld the territory of the Hun.

Always a student of military matters, at this hour I loved war, and all that pertained to war; now I loathe it with an ineradicable hate and disgust, and hope never again to see ground crimsoned with blood.

But at this time I had heard no hint of war in the centre of Europe and of civilization, and no thoughts were farther from my mind than those of martial contention.

My object in going to Germany was business; but also to spend a holiday in a country I had heard friends praise for its beauty and hospitality; and particularly I wished to visit places renowned in history, art and romance. Little I dreamed that I was to see a horrible blight, a foul leprosy, settle on much that had a hallowed past for every cultivated intellect.[2]

I arrived at Metz from Paris via Chalons and Verdun; and, as my time and means were both limited, I went on, after only two days' delay, to Mayence and Frankfort, and thence to Leipzig, where I had some business to transact. On the 16th July I was at Dresden; on the 20th at Breslau; and on the 22nd I arrived at Ostrovo, a small German town barely ten miles from the Russian frontier, and not more than twelve, English measurement, from Kalisz, which is the capital of a Polish province of the same name.

At Ostrovo I went, by previous invitation, to the house of a German friend, from whom I received the most kindly treatment, and to whom I owe my liberty and possibly my life. It will be obvious that I cannot reveal the name of this person, nor the nature of my business with him. It was my intention to remain a month at Ostrovo, which was a convenient place from whence to make excursions to some of the most interesting Prussian towns.

I loved the sight of armed men; and during my journey, as opportunities occurred, I watched the soldiers I saw in the various cities I passed through. I could not fail to notice the great difference in the military forces of the two countries—France and Germany. On the Continent one expects to see a more prominent display of soldiers than is usually the case in our own quiet island home; but there was no great parade of the military element in any of the French garrisons I passed through. In all the large towns a force of some kind was stationed; but in so important a place as Verdun there did not appear to[3] be a stronger military garrison than one would see at such stations in England as Plymouth or Chatham. In the French fortress I saw a battalion marching to the music of bugles. The men did not exceed 600 in number. In another part of the town about 150 infantry were drilling; and many artillerymen were walking about; yet the numbers showed plainly that France was not mobilizing at this time.

As soon as the frontier was passed I saw that quite a different state of things existed. As I left the railway-station at Metz three battalions marched by—two of a line regiment, and a battalion of riflemen, or jagers, distinguished by wearing shakos instead of the nearly universal Pickelhaube, or spiked helmet. These battalions were quite a thousand strong in each case. In other words, they had their full war complement of men. A regiment of hussars was 600 strong; and field-artillery, with fifty-six guns, besides machine-guns, extended about a mile and a half along one of the country roads. Everywhere in Germany the towns, large and small, were crowded with soldiers. Cavalry and artillery and long lines of waggons lined the country highways and byways. I remarked on this to a fellow-passenger who spoke English. His reply was that the troops were assembling for the autumn manœuvres. I was sufficiently surprised to exclaim:—

"What! Already?"

"It is rather early, but they are probably going to have preliminary exercises in the forest-lands," was the reply.[4]

After this I perceived the passenger was regarding me with a peculiar air; and, recollecting certain cautions I had received concerning the danger of making inquiries about the movements of troops on the Continent, I did not recur to the subject.

At Dresden a large number of troops, infantry and cavalry, were departing northward by rail and road. At Breslau at least 20,000 men of all arms were concentrated. These circumstances had no particular significance to my mind at the time, but a very great one a few days later.

Even when I arrived at Ostrovo and found the country-side crowded with troops, impending war did not occur to my thoughts, though I did ponder on the extraordinary precautions Germany seemed to be taking to insure the inviolability of her powerful domain. Now I know, of course, that the mendacious Hun, with the low cunning of a murderous maniac, was preparing for a blood-feast, before a taint of it was floating in the surrounding air; and if it is thought that I am putting the case strongly, I shall have that to relate shortly which would make it remarkable if I were not to use forcible language. Blood and lust: lust and blood—this is the awful and disgusting story I have to tell—a story set in military surroundings which, for skill and magnitude, have never previously been approached; but military ability and the hugeness of the operations have only intensified the hellish misery of this the vastest struggle the world has seen. And that it may[5] never again see such must be the universal prayer to God.

In Germany it is the custom to billet soldiers on the people, and most of the houses at Ostrovo were full of men whose behaviour, even to their own countrymen, was sickening in its utter lack of decency. Complaints against soldiers have to be very strongly corroborated before their officers or the magistracy of the land take serious note of them.

In my friend's house some officers of the —th regiment were lodged. With these I speedily became on friendly terms, and, through them, with officers of other German corps, particularly with those of a Pomeranian artillery regiment, one of whom was a quiet and affable little gentleman. With him I thought I might venture to discuss military matters, and on the 28th July the following conversation took place between us. I should premise that I cannot read or speak German and that I had not seen an English newspaper for more than a week previously. Certain information had been communicated to me by my friend, but I had not been given to understand that war was imminent between Germany and Russia, or any other nation.

"All your units are very strong," I remarked. "Is it usual for you to embody your reserves for the manœuvres?"

"Our troops are not on manœuvre. We are going to fight," was the officer's reply.

"Fight!" I exclaimed, much astonished. "Whom are you going to fight?"[6]

"The Russians and the French."

"The two most powerful nations in the world! Are you strong enough to do that?" I said, amazed, and hardly able to believe that I had heard aright.

"The Austrians are going to join with us, and we shall be in Paris in a month."

I laughed—rather scornfully, I think.

"Are you joking? Is not what you say absurd?" I asked.

"Not in the least. You will see that what I say is correct."

"But is war declared? Has the matter been discussed in the Press?"

"In this country we do not permit the Press to make the announcement of such things. War is not declared yet, but it will be on Sunday next."

"Against Russia, you mean?" said I, astonished beyond degree of expression.

"Yes, and against France too," replied the officer.

"But why? I have not heard that France has given cause of offence to your country."

"She has been a standing menace to us for years, and will continue to be so until she is completely crushed."

This is how I heard that the Great War was about to begin. I hardly believed it, but my friend read me certain passages from German newspapers, and the following day I received a batch of journals from my own country, which, together, showed that the political situation of Europe was rapidly becoming serious.[7]

On the 30th I noticed a change of countenance on the part of most of the officers who had been friendly with me. The young artillery officer I have mentioned and a Colonel Swartz, who was, I believe, a Landwehr officer of the 99th regiment, continued their friendly behaviour towards me. Swartz was shortly afterwards killed near Turek, where his battalion was destroyed.

Early in the evening of the 31st, a lady came to my friend's house and strongly advised me to quit the country without delay. She gave as a reason that she had received a letter from her brother, an officer in the foot-guards at Berlin, in which he declared that it was well known that the Kaiser intended to send an ultimatum to England, and that a rupture with this country was the almost inevitable consequence. My friend backed the lady's advice, and my own opinion was that it would be wise of me to return home at once.

But later that night Swartz and the young officer came and declared that it was almost impossible for me to get out of Germany by any of the usual channels before war was declared, as nearly all the lines were required for the movements of troops and material. Swartz said that it would take at least four days for a civilian to reach France by railway. I suggested a motor-car, but he thought that all motors would immediately be confiscated—at any rate, those driven by foreigners.

The above circumstances and the date, of the correctness of which I am quite sure, show that the[8] German Sovereign had preconceived war, not only with France and Russia, but also with England, before the actual declaration of hostilities.

Down to this time, and until several days later, I did not hear Belgium mentioned in connection with the war, and for several reasons, not the least of which was my ignorance of the German and Russian languages, many facts relating to the operations of the Allies on the Western line of hostilities did not become known to me until some time after they had taken place. It must not be forgotten that this book is in no sense a history of the Great War, but simply a narrative of my experiences with the Russian Army in certain areas of the Eastern line of operations. These experiences I purpose to give in diary form, and with little or no reference to the fighting in other parts of the war area, of which I knew almost nothing—or at any rate, nothing that was very reliable.

All day on the 31st July it was persistently declared at Ostrovo that war had been declared against Russia and against France, and that it would be declared against England on the morrow, which was Saturday, the 1st August. The persons who were responsible for these assertions were the Army officers with whom I came in contact, and the people generally of all classes. Not a word was said about Belgium.

On the afternoon of the 1st August the Kaiser is said to have ordered the mobilization of the German Army. The German Army was already mobilized so far as the Russian frontier was concerned, and[9] had been so for eight or nine days. On the line between Neustadt-Baranow, a distance of about eighty English miles, there were concentrated five army corps, with three cavalry divisions, about 250,000 men. These were supported by two corps between Breslau and Glogau, two more at Posen, a large force at Oppeln, and other troops at Oels, Tarnowitz, and places which I need not name here. My calculation was that about 1,000,000 men were ready to act on the line Neustadt-Tchenstochow. There was another 2,000,000 on the line of frontier running northward through Thorn and East Prussia to the Baltic, and probably a fourth million in reserve to support any portion of the line indicated; and what was worth at least another 2,000,000 men to Germany was the fact that she could move any portion of these troops ten times more quickly than Russia could move her forces. It is officially stated that only 1,500,000 Germans were in line in August. I think that my estimate is correct.

Meanwhile, conscious that I had not permitted myself to be over-cautious in acquiring a dangerous knowledge, I was particularly anxious to leave Germany as speedily as possible. Chance had brought me to what was to become one of the most important points of the operations between Prussia and Russia, and chance greatly favoured my escape from what I began to fear was an awkward trap. Had I known what a nation of fiends the Germans were going to prove themselves, my anxiety would have been greatly increased. Thank God there is no race on earth in[10] which all are bad, all devoid of the attributes of humanity.

Late on the night of the 1st August (after I was in bed, indeed) the young artillery officer I have several times mentioned came to my friend's house. I do not think it would be wise or kind on my part to mention his name, as he may still be alive. He was accompanied by Swartz and a servant, with two horses, and recommended that I should cross the Russian frontier immediately, as all Englishmen in Germany were in danger of being interned. War with England was assumed by everybody to be inevitable, insomuch that, being ignorant of the true state of affairs, I assumed that an ultimatum had been sent to Germany by the British Government. I was told that many leading German papers asserted that it had been so sent.

I consented to leave at once, with the object of trying to reach Kalisz, and from there taking train to Riga, where, it was thought, I should find no difficulty in getting a steamboat passage to England. It is only twelve miles by railway from Ostrovo to Kalisz, but the line was already occupied by troops, "and," said the officers, "our forces will occupy the Russian town before daybreak to-morrow."[11]

CHAPTER II

THE SCENE AT KALISZ ON THE 2ND AUGUST, 1914

Had I not been under military escort I could not possibly have got along any of the roads in the neighbourhood of Ostrovo—all were crowded by Prussian infantry. I did not see any other branches of the service, but I understood that the engineers were mining the railway-line, and about half an hour after we started my friends declared that it would be hopeless to try to reach Kalisz from the German side. They said they must leave me, as it was imperative that they should rejoin their regiments before the hour of parade. A road was pointed out to me as one that led straight to the frontier, and that frontier I was recommended to endeavour to cross. The horse was taken away, and, after shaking hands with the officers and receiving their wishes of good-luck, I proceeded across the fields on foot.

Pickets of cavalry and infantry were moving about the country, but I avoided them, and after a two-hours' walk reached the low bank which I knew marked the frontier-line. It was then after three o'clock, and daylight was beginning to break. As far as I could see, nobody was about. Some cows were in the field, and they followed me a short distance[12]—a worry at the time, as I feared they would attract attention to my movements.

I jumped over the boundary, and walked in the direction of Kalisz, the dome and spire and taller buildings of which were now visible some miles to the northward. The country is very flat here—typical Polish ground, without trees or bushes or hedges, the fields being generally separated by ditches. It is a wild and lonely district, and very thinly peopled. And I do not think there were any Russian troops in the town. If there were, it must have been a very slender detachment, which fell back at once; for if any firing had occurred, I must have seen and heard it. Not a sound of this description reached my ears, but when I reached Kalisz at 5.30 a.m. it was full of German soldiers, infantry and Uhlans—the first definite information I had that war was actually declared between the two countries, and the first intimation I received of how this war was likely to be conducted, for many of the Germans were mad drunk, and many more acting like wild beasts.

I passed through crowds of soldiers without being interfered with—a wonderful circumstance. None of the shops were opened at that early hour, but the Germans had smashed into some of them, and were helping themselves to eatables and other things. I saw one unter-officer cramming watches, rings, and other jewellery into his pockets. He was quickly joined by other wretches, who cleared the shop in a very few minutes.

Hardly knowing what to do, but realizing the danger[13] of lurking about without an apparent object in view, I continued to walk through the streets in search of the railway-station, or a place where I could rest. A provost and a party of military policemen were closing the public-houses by nailing up the doors, and I saw a man only partly dressed, the proprietor of one of these houses, I supposed, murdered. He made an excited protest, and a soldier drove his bayonet into the poor man's chest. He uttered a terrible scream, and was instantly transfixed by a dozen bayonets. A woman, attracted by the fearful cry, came rushing out of the house screaming and crying. She had nothing on except a chemise, and the soldiers treated her with brutal indecency. I was impelled to interfere for her protection. At that moment an officer came up, and restored some order amongst the men, striking and pricking several of them with his sword. He said something to me which I did not understand, and, receiving no reply, struck me with his fist, and then arrogantly waved his hand for me to be gone. I had no alternative. I suppressed my wrath and moved away, but the horrible sight of the bleeding man and the weeping woman haunted me until I became used to such sights—and worse.

As I walked through the streets I heard the screams of women and children on all sides, mingled with the coarse laughter and shouts of men, which told plainly enough what was taking place, though I could not understand a word of what was said. I was struck by drunken or excited soldiers more than once, and kicked, but to retaliate or use the weapon with which[14] I was armed would, I could perceive, result in my instant destruction; so I smothered my wrath for the time.

Many women rushed into the streets dressed in their night-clothes only, some of them stained with blood, as evidence of the ill-usage they had suffered; and I passed the dead bodies of two men lying in the road, one of which was that of a youth. These, there can be no doubt, were the first acts of war on the part of Germany against Russia—the slaughter of unarmed and defenceless people.

In one of the principal streets I found two hotels or large public-houses open. They were both full of German officers, some of whom were drunk. At an upper window one man was being held out by his legs, while a comrade playfully spanked him, and a wild orgy was going on in the room behind. Bottles and glasses were thrown into the street, and a party of German prostitutes vied in bestiality with the men. I saw the hellish scene. Had I read an account of it, I should at once have stamped the writer in my heart as a liar. I am not going to dwell on the filthy horrors of that day. I do little more than hint at what took place, and only remark that at this hour no act of war, no fair fight or military operation, had taken place on any of Germany's borders. She showed the bestiality of the cowardly hyena before a fang had been bared against her. This was the information I afterwards obtained from Russian sources. On the morning Kalisz was sacked, not a shot had been fired by the Russian soldiers.[15]

My needs compelled me to take risks. All the belongings I had with me were contained in a small bag which I carried in my hand. I had some German money in my pocket, and a number of English sovereigns. The remainder of my luggage I had been compelled to leave behind at Ostrovo. Entering the quietest of the two hotels, I found the proprietor and several of his servants or members of his family trembling in the basement. I was stopped at the door by a sentry, but he was a quiet sort of youth, accepted a few marks, and while he was putting them in his pouch permitted me to slip into the house.

I have already intimated that I am no linguist. I could not muster a dozen words of German, and not one of Russian; so, holding the proprietor to insure his attention (the poor man was almost in a state of collapse), I made motions that I wished to eat and drink. No doubt they took me for a German. One of the maids literally rushed to the cellar, and returned with two large bottles of champagne of the size which our great-grandfathers, I believe, called "magnums," containing about two quarts apiece.

But champagne was not what I wanted, so I looked round till I found a huge teapot. The face of the maid was expressionless, but she was not lacking in intelligence. The Russians are great tea-drinkers, and I soon had a good breakfast before me, with plenty of the refreshing beverage. A Russian breakfast differs much from an English early morning meal, but on this occasion I contrived to obtain bacon and eggs, which, in spite of all doctors and economists[16] say to the contrary, is one of the best foods in existence for travelling or fighting on.

Before I had well finished this meal one of the riotous officers came downstairs. He made a sudden stop when he saw me, and blinked and winked like an owl in sunlight, for he had had plenty of liquor. He asked some question, and as I could not very well sit like a speechless booby, I replied in my own language.

"Good-morning," rather dryly, I am afraid.

"An English pig!" he exclaimed.

"An Englishman," I corrected.

[At least 50 per cent. of German officers speak English quite fluently, and an even greater number French, learned in the native countries of these languages.]

"Bah-a-a-a!" he exclaimed, prolonging the interjection grotesquely. "Do you know that we have wrecked London, blown your wonderful Tower and Tower Bridge and your St. Paul's to dust, killed your King, and our Zeppelins are now wrecking Manchester and Liverpool and your other fine manufacturing towns?"

"Nonsense!" I said.

"It is true, I assure you," he replied.

The news sent a terrible thrill through my nerves, for I did not yet know what liars Germans could be, and I did not think a Prussian officer could stoop to be so mendacious a scoundrel as this fellow proved to be.

"Then there is war between England and Germany?"[17] I asked, wondering at its sudden outbreak. "When was it declared?"

"It is not declared. We have taken time by the forelock, as you British say—as we mean to take it with all who dare to oppose us. You are a stinking Englishman, and I'll have you shot!" he concluded furiously.

Going to the foot of the stairs, he began to call to his companions, reviling the English, and declaring that there was a spy below. As his drunken comrades did not hear him or immediately respond, he ascended the stairs, and I took the opportunity to put down some money for my breakfast, catch up my bag, and escape from the house.

At the top of the street the road broadened out into a kind of square or open space, and as I reached this spot a large number of soldiers brought eight prisoners into the centre of it. Three of them were dressed in what I took to be the uniforms of Russian officers, three others were gendarmes or policemen. The other two wore the dress of civilians. All were very pale and serious-looking, but all were firm except one of the civilians, who I could see was trembling, while his knees were shaking so that he could scarcely stand. A German officer of rank—I believe a Major-General—stood in front of them and interrogated one of the Russian officers, who looked at him sternly and did not reply. The German also read something from a paper he held in his hand, while six men were ranged before each one of the prisoners. I saw what was about to take place, but[18] before I was prepared for it the German stood aside and waved his hand. Instantly the firing-parties raised their rifles and shot down the eight prisoners. They were not all killed outright. One man rolled about in dreadful agony, two others tried to rise after falling, and a fourth attempted to run away. A sickening fusillade ensued; at least a hundred shots were fired before all the victims lay stark and quiet. Nor were they the only victims. The officer in charge of the firing-party took no precautions, uttered no warnings, and several of the spectators were struck by the bullets, while there was a wild stampede of civilians from the square.

Let it be noted that these ferocious murders took place before a shot had been fired, so far as I know, between the armed forces of the two nations.

I never heard who the slain men were, or why they were put to death; but from what I afterwards read in English newspapers I suppose that the Mayor of Kalisz was one of them.[19]

CHAPTER III

THE EVENTS PRECEDING ACTUAL HOSTILITIES

Why were there no Russian soldiers in the neighbourhood of Kalisz in the beginning of August, 1914? The answer is simple.

Kalisz is an open town, with a single line running to Warsaw, 140 miles, via Lodz and Lowicz. The nearest branch lines are the Warsaw-Tchenstochow on the south, with nearest point to Kalisz about ninety English miles away; and the Warsaw-Plock line to Thorn, with nearest point to Kalisz, also about ninety miles. So far as transport was concerned, the Russians were not in it at all.

For on the German side of the frontier there is a complete and very elaborate network of railways, so that the Teuton could mass 1,000,000 men on Kalisz long before the Muscovite could transport 100,000 there. This is what harassed the last-named Power—want of railways. Wherever they tried to concentrate, the Germans were before them, and in overwhelming numbers. It is her elaborate railway system that has enabled Germany to get the utmost from her armies—to get the work of two or three corps, and in some cases even more, out of one. Her railways have practically doubled her armed force—this at least.[20]

The Germans are masters of the art of war, and have been so for fifty years; the Russians are hard fighters, but they are not scientific soldiers. The Germans have consolidated and perfected everything that relates to armed science; the Russians have trusted too much to their weight of numbers. Yet the Bear, though a slow and dull animal, has devilish long and strong claws; and, like another animal engaged in this contest for the existence of the world, has the habit so provoking to his enemies, of never knowing when he is beaten.

The reason, then, that there was no sufficient force, if any force at all, near Kalisz when the treacherous Teuton suddenly sprung hostilities upon her on the 1st August, 1914, was that the Muscovite, through apathy inherited from his Asiatic ancestors, combined with a paucity of money, had no railways, while his opponent had one of the most complete systems of locomotive transport for men and material that is to be found in the whole world.

It was its isolated situation and great distance from a base that made Kalisz the weak point on the Russian frontier, and the German Eagle saw this and swooped on it as a bird of prey on a damless lamb.

But the Russian base, if distant, was strong, and the force and material at Warsaw was powerful and great, and was in ponderous motion long before the Vulture had picked clean the bones of her first victim. Russia has no great fortress on the German frontier. This is another serious fault of defence.[21] Railways and fortresses are the need of the Northern Power to enable her to control effectually the bird of ill omen which has so long hovered over Central Europe, unless that bird is to die for all time, which is what should be, and which is what will be, unless the folly of the nations is incurable.

After witnessing the terrible scene described in the last chapter my feelings of insecurity and uncertainty were greatly increased. By means of a plan in my possession I found my way to the railway-station. It was in the hands of the German troops, thousands of whom crowded the building and its vicinity, and a glance was sufficient to show that I could not leave Kalisz by means of the railway. According to my plan, there were stations further up the line in an easterly direction, some of them at no great distance from Kalisz; but I felt sure these would be occupied by the Germans before I could reach them.

Personal safety required that I should make an immediate effort to escape. More than once I had noticed Teutonic eyes regarding me with suspicious glances—at least, so I thought—and I quite realized that delay would be dangerous.

Re-entering the town, which is a place of about 25,000 inhabitants, I reached the open country to the north through back streets, resolved to endeavour to reach Lodz by making a wide détour from the line, which was sure to be occupied by the hostile troops. What reception I should meet with from the hands of the Russian soldiers I could not tell,[22] but I felt sure that it would not be worse than that I might expect from their foes.

By this time it was past midday, and the streets of Kalisz were nearly deserted. I saw only one or two male fugitives hurrying along, apparently bent, like myself, on escape. As soon as I reached a retired spot I tore my maps and plans to shreds and threw them away. I had no doubt what it would mean to be caught with such things on me.

Patrols of cavalry, Uhlans and hussars, were scouring the country in all directions. Peasants in the fields were running together, and the hussars beat many of them with their sabres, but I do not think they killed any at this time. The Uhlans wounded some by tearing them down with the hooks with which the staves of their lances are furnished, and I saw a party of them amusing themselves by rending the clothes off a poor old woman who was working in one of the fields.

Perceiving that it would be impossible to avoid these cavalrymen, I looked about for a hiding-place. There was a range of low buildings about a quarter of a mile from the ditch in which I was crouching. The place seemed to be a farm, with a number of barns or sheds on one side of it, some of which were scattered about irregularly. I reached the nearest of these without attracting notice, and found there a weeping woman and two men, one of whom was bleeding badly from wounds on the head and face. They looked at me, and the unhurt man said something[23] which I did not understand. A party of hussars was riding towards the shed. As a forlorn chance of escape, I lay down on the floor and pulled some straw over me as well as I could. Apparently the men and woman ran away, and by so doing diverted the attention of the hussars from the shed. I lay there till dusk, when the unhurt man and the woman came back carrying a bowl of milk and some coarse bread, which they gave to me. I was very glad of it, having tasted nothing since the morning. They spoke, but chiefly together, as they perceived that I could not understand them.

Soon afterwards, expressing my thanks as well as I could, I left the shed and proceeded on my way towards Lodz. There was sufficient light to enable me to preserve a general direction and to avoid the numerous parties of German cavalry which were patrolling the country, but long before the night was over I had got beyond these. I do not think they extended more than ten or twelve miles beyond the points at which they had invaded Poland.

During the night I met with no adventures more serious than floundering into several water-courses and falling into a couple of ditches in endeavouring to jump them, for the ditches are very wide and deep in this country. To avoid such accidents, I afterwards kept to the roads. These are not bounded by hedges or fences of any kind, and there was nearly an entire absence of bridges. Arriving at a brook, the traveller might or might not find stepping-stones.[24] In the absence of these, one had to wade through the water, which in one case I experienced at this time came nearly up to the knees.

I could not know, of course, if the people knew that a state of war existed, but I saw no watchmen or police about the few hamlets and the villages I passed through. Once I was attacked by a couple of very fierce dogs, and was compelled to kill one of them to get free; but until after four o'clock the next morning no men appeared. A few of those who saluted me seemed surprised that I did not make a reply, but I could only raise my hat, and by doing so I perhaps occasioned greater astonishment than I would have done by entirely ignoring them.

There were hardly any trees in this country. The farms and isolated houses were usually marked by a poplar or two and a clump of willows, and there were some willows along the courses of the streams. The buildings, except the churches, were generally very low-pitched, and there was a singular paucity of chimneys, since stoves were the nearly universal means of warming the rooms; indeed, I saw stoves in this country which were almost rooms in themselves, with sleeping-places above the flues. Turf was the chief fuel used, and the dried droppings of horses and cattle.

There was a shower of rain during the night, but the morning broke clear and bright, and it was daylight long before I was as far beyond the reach of the Huns as I could have wished to be. The country seemed to be very sparsely peopled. The peasantry[25] were early risers, and most of them seemed to be in the fields before five o'clock. The crops were to a great extent cut, and some were in process of cartage in heavy waggons. It was a very hot day.

About ten o'clock I stopped at the door of a farm and made signs that I wanted food and drink. I was afraid to offer German money, though this would probably have been better understood than the tender of an English sovereign. The man took the coin, looked at it, bit it, and rubbed it, and handed it to a group of women and girls—his mother, wife and daughters, I thought. The image of His Majesty King George was evidently taken to be that of the Czar; but the denomination of the coin puzzled the farmer and excited great curiosity amongst the women. However, my wants were understood, and I obtained butter, bread, tea and cheese of a kind I had never previously eaten, and also some excellent honeycomb, but no kind of meat. The farmer wanted me to take back the sovereign, but it was so evidently coveted by his wife that I pressed it upon her until she pocketed it. In return I brought away as much provision as I could carry.

Before midday I thought I had walked about thirty miles, though not in a direct line. By this time I had arrived at a river which I knew must be the Warta. It was not very wide, but the banks where I struck it were deep, and crumbling away; and the stream was unfordable. Not knowing what else to do I turned southwards along its banks towards Sieradz, hoping to reach a village where I[26] might be ferried across; but just as I was about to enter a small hamlet, I was confronted by two policemen. They jabbered at me and I jabbered at them; but if ever "No nonsense" were seen in a human countenance I saw it in that of policeman No. 1. I produced my passports. One of these gave me permission to cross the Russian frontier; but as it was obtained in Germany I would, under the circumstances, have gladly suppressed it. Unfortunately it was folded up with the English-German document, and I was not sharp enough to separate them before No. 1 sighted the document, and demanded it with an impatient gesture. This he could read, but the other puzzled him; not that this circumstance interfered with the promptitude of his action. I saw with half an eye that I had to go somewhere with this Russian policeman: and the "somewhere" proved to be the lock-up in a tiny hamlet the name of which I never learned.

This wretched hole was three-parts under ground, about seven feet long, and scarcely four wide—a den evidently designed for torture: for one could not turn round in it without difficulty; and how to sleep in such a place puzzled me, though I was spared the ordeal of having to do so. For a few hours after I was incarcerated I was fetched out and handed over to the charge of five mounted cossacks, the leader seeming to be a corporal. I was handcuffed to the stirrups of this gentleman and one of his comrades, an arrangement which gave me the option of walking or being dragged along. All the party carried villainous-looking[27] whips in addition to rifles, sabres and lances. But they did not force the pace, and when we had gone about five miles we overtook a light cart, which the corporal stopped, and placed me therein. We then travelled at the rate of eight or nine miles an hour, halting at a roadside inn for drink, which I paid for with another English sovereign. Again the coin excited much curiosity, but the corporal saw that I obtained a fair amount of change in Russian money and I was civilly treated on the whole.

In less than two hours we arrived at the small town of Szadek, though I did not know the name of the place at the time. It is only twenty English miles (twenty-seven versts) from Lodz, and here for the first time since crossing the German frontier I saw Russian troops in force. I did not have the opportunity of seeing the strength of these troops; but Szadek was full of infantry, and we passed a great many tents before entering the town. It was nightfall when we arrived; but I was immediately taken to an hotel and questioned by an officer of General rank. Finding that I could not speak Russian, he tried German, and I said, in the best French I could muster, that I was an Englishman. I am not sufficient master of the polite language of Europe to carry on a conversation in it, so the officer sent for a Russian Major, Polchow, who spoke English fluently, and he acted as interpreter.

My story was listened to with great interest, especially those parts of it which related to the movements[28] and conduct of the German troops and the murder of citizens at Kalisz. I underwent a lengthened cross-examination, and, I suppose, the nature of my communications becoming known, the room was speedily crowded by officers, most of them evidently of high rank. It was after midnight before I was dismissed, having, I could see, made a favourable impression on all those who were present. It was then I learned, to my great relief, that the German accounts of the destruction of London, etc., were falsehoods. "As yet there is no war between Germany and England; but there will be in a few days," said the General.

Speaking through Major Polchow, the General further said, "You have come to Russia for help and protection: you shall have them. What do you wish?" In reply I said that I desired to return to my own country as speedily as possible, but that if the Germans, being near at hand, came up before arrangements could be made for my departure, I should be glad to use a rifle against them.

It was then explained to me that all the inn accommodation in Szadek being taken up I could be offered only a tent lodging, but that every endeavour would be made to render me comfortable. Then Major Polchow offered to look after me, and I accompanied him to a private house where he was billeted.

I much regret that I have forgotten the name of this obliging officer before whom I was examined, which name, a very unpronounceable one, was only[29] casually mentioned, and was forgotten in the excitement of the events which immediately followed.

Polchow was an artillery officer, attached to a South Russian regiment, but afterwards to an East Russian regiment, which lost all its officers—with one or two exceptions at any rate. I was entertained by him most royally.

On the following day I underwent another long examination before an Adjutant of the Grand Duke Nicholas and a large number of Staff officers, and was much complimented on my adventures and the value of the information I was able to give. These matters I must ask to be excused for passing over with bare mention. I expected to have had an interview with the Grand Duke himself; but he departed that evening without my having seen him.

The offer was made to send me on to Riga or Libau, or any port I might choose; and to facilitate my departure to my own country; but I am an Englishman, thank God, and I was not inclined to turn my back on my country's foes until I had seen the whites of their eyes and let them see mine. For by this time we were beginning to learn something of German dirt, and German cruelty.[30]

CHAPTER IV

THE FIRST FIGHT

It became necessary to know what the Germans were doing, or appeared to be going to do. Fugitives from Kalisz and the country eastward of it reported that thousands of Germans were pouring over the border, and it was known to Headquarters that they were gradually pressing onwards to Lodz.

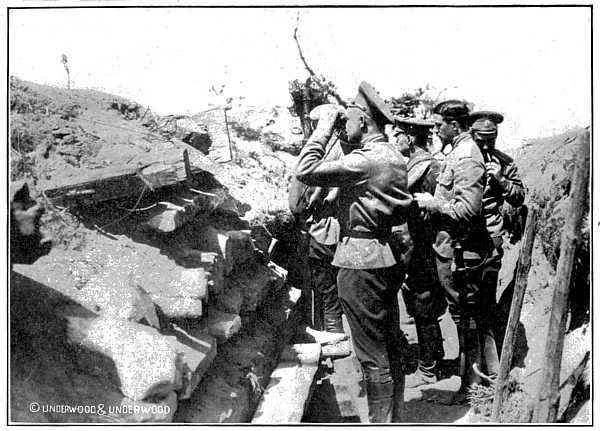

On the 6th, 7th, and 8th August, the 4th Cossacks of the Don, and five other cavalry regiments, with some light guns, were engaged in reconnaissance, and the result was to ascertain that the Germans were entrenching themselves on a line from Kalisz to Sieradz, covering the railway; and also extending their earthworks right and left along the banks of the Warta, thus forming a strong point, on Russian soil, for an advance on Warsaw. I was riding in the ranks of the 4th, and can say, from personal observation, that the works mentioned were of a formidable description, and armed with heavy guns.

On the 8th the Zeithen Hussars charged the 4th, which fell back; and the hussars were taken in hand by the 12th Russian Dragoons and very roughly handled. I counted forty dead bodies; but the Germans advanced some infantry and guns, and saved their wounded. Their total loss could not have been[31] less than 140 men. The dragoons had two men killed and about a dozen wounded, mostly by the fire of infantry. The general idea that the Germans are good swordsmen is erroneous. They are very poor broadswordsmen; and the Russians are inferior to the French in the use of this weapon.

I expected that the affair would develop into a general action, but it did not. The force of German cavalry was much inferior to that of the Russian, and they soon fell back, trying to lure our men under infantry and artillery fire. In this they did not succeed; but I believe that on our extreme right they did some execution with long-range shell fire. Why the Russians did not bring up infantry and artillery I am unable to conjecture. It is my opinion that there was something behind which did not appear to a spectator in my position. The Germans had certainly prepared something resembling a trap; and possibly the Russian commander saw, or suspected, more than was perceptible to the ordinary eye. At any rate he held his men back at a moment when I expected to see them advance and outflank the enemy. The fighting which followed was decidedly desultory and without important results. There was much artillery firing from guns which were, I think, four or five English miles from that part of the Russian position where I was. It did so very little execution that I considered it was a mere waste of ammunition.

In this combat the Russians seemed to be superior in strength of all three arms, which was the reason, I suppose, that the enemy did not make a decided[32] advance. He was probably waiting for reinforcements, which did not arrive until late in the day, if they came up at all. On the other hand, there was a force of German infantry lying in wait, and this body of troops may have been stronger than appeared.

I can only be responsible for what I saw, though I feel at liberty to repeat what I heard where probability of its truth may be inferred. I have also looked through files of English newspapers; and I cannot attempt to veil the fact that I must often be, or appear to be, in contradiction to accounts that were published about the time the narrated incidents were recorded to have taken place. Naturally, first records were imperfect, or needed explanations; but some things appeared in English papers which it is difficult to understand. For instance, it is said to be "officially reported from Petrograd" that the frontier was not crossed by the Germans in the neighbourhood of Kalisz, and that no fighting took place until the 14th or 15th August. (I am not sure which date is meant; or whether the old or new system is intended.) Both these assertions are incorrect, and could not have emanated from an "official" source. The Russians are our allies, and personally I received great kindness from the hands of many of them; but the only value of a narrative of the kind I am writing is its correctness, and I intend to record the truth without fear and without favour. I cannot perceive that it would be any advantage to them to make a misstatement. The assertion is probably an error. At any rate I can state, and do positively state, that[33] the frontier was crossed by the Germans at Kalisz; and that fighting took place at several points before the 14th August. Possibly the accounts were published before correction.

At this time I learned that there was a line of strong posts from Dabie to Petrikau, a distance of, roughly, eighty versts. These, probably, outflanked the Germans; and reinforcements were daily arriving in vast numbers, prolonging the line in the direction of the Vistula some seventy versts north of Dabie. The country between Dabie and the named river was patrolled by an enormous horde of cavalry—at least 20,000—and infantry and artillery were coming up by march route, there being no railway except the Kutno-Warsaw narrow-gauge line, which was used chiefly for the transport of ammunition and stores. This line runs direct to Thorn, one of Germany's strong frontier fortresses; and the Russians tried to push along it as far as possible; but the Germans sent flying parties into Russia as far as Wroclawick, fifty versts from Thorn, and completely destroyed the line. In doing this they suffered some losses, for a Russian force crossed the Vistula near Nieszawa and attacked one of the working-parties. They claimed to have killed and wounded 300 of the enemy, and they brought in ninety prisoners, four of whom were officers.

The only fighting I saw during these operations was between two cavalry pickets. There were thirty Cossacks on our side. I do not know how many Germans there were, but they were reinforced continually[34] during the fight until they compelled us to fall back. They held the verge of a pine-wood, while the Cossacks sheltered themselves behind some scattered trees, fighting, of course, dismounted with their horses picketed a mile behind them and left in charge of a trumpeter.

So far as I could see, the fight was a completely useless one. It resulted in the death of two men on our side, and six wounded. The firing lasted nearly three hours and would probably have gone on much longer had not our men run out of cartridges. In this little skirmish I shot off a hundred rounds myself, with what result must be left to the imagination; for, as the distance was 900 yards, I had not even the satisfaction of seeing the branches of the trees flying about. The German bullets cut off many twigs from our trees, and the trumpeter afterwards reported that several of their shots fell amongst the horses without doing any damage. It showed the great range of the German weapons, and also the very bad shooting of the men.

We drew off, and some of the hussars came out of the wood, mounted their horses, and looked after us; but they did not attempt to follow us. Enterprise was not a prominent attribute of the German cavalry, nor, indeed, of the mounted force of our own side, though the Cossacks sometimes showed considerable boldness. Often I longed for the presence of a few regiments of British or French cavalry, for some splendid opportunities were let slip by the Russian troopers; not from want of bravery, but simply from[35] the lack of that daring dash which is a distinguishing feature of all good horsemanship.

Yet, notwithstanding the want of energy on the part of the Russian mounted men, they were continually on the move, and, as I soon discovered for myself, were gradually moving to the north, apparently covering the advance of an ever-increasing mass of infantry and artillery. Polchow's battery was attached to the brigade of Cossacks of which the 4th was one of the units. The reason that I connected myself with this particular corps was because one of its officers spoke a little English; but it was so little that we frequently had much difficulty in understanding each other. I soon learned the Russian words of command and the names of common things and objects, and I often acted as officer of a squadron (or "sotnia," as the men call it); but I felt that I would rather be with Polchow, and I soon became attached to his battery as a "cadet," though I was the oldest man in the unit.

It was a "horse" battery; but the horse artillery in the Russian service is not a separately organized body as it is in the British Army. The guns are simply well-horsed, and the limbers, waggons, etc., rendered as light and mobile as possible. The batteries have not the dash and go of English horse-artillery; and I should be very sorry to see a Russian battery attempt to gallop over a ditch or other troublesome obstacle, as I can foresee what the result would be. The Russian horse-artillery is a sort of advanced-guard of the gunnery arm and has no special training[36] for its duties. In several important particulars its equipment and organization differs from ours.

At this time there were said to be several Englishmen, two Frenchmen, and Swedes, Norwegians and Dutch, in the Russian service. I never met any of them, but I know there was a German, born and bred in Brandenburg, an officer in the 178th line, who was permitted to remain in the Muscovite Army; and who fought with invincible bravery and determination against his countrymen. There was a mystery about him, the actual nature of which I never learned; but it was said that he had received some injury which had implanted in his breast a fierce hatred of the land of his birth.

For two days after I had joined the artillery we were making forced marches to the north, and on the 16th we crossed the Vistula at Plock. The next day we were in front of the enemy between Biezun and Przasnysz, with our left flank resting on a marshy lake near the first-named place. Beyond the lake this flank was supported by a very large body of cavalry—twenty-four regiments I think, or not less than 14,000 men. This large force effectually kept off the much inferior German cavalry. It suffered a good deal from shell-fire, but our artillery prevented the Prussian infantry from inflicting any losses on it.

The country had been raided by the Germans before our arrival, and they had committed many atrocities. The young women had been abused, and the older ones cruelly ill-treated. The hamlets and isolated[37] farms had been burnt down; in some cases the ruins were still smouldering; and what had become of the inhabitants did not appear. Some at least had been slain: for we found the body of one woman lying, head downwards, in a filthy gutter which drained a farmyard; and on the other side of the building, two men hanging from the same tree. The woman had been killed by a blow on the head which had smashed the skull, and her body had been treated with shameful irreverence. The gunners of the battery buried these three poor creatures in the same grave while we were waiting for orders to go into action.

Afterwards, while searching the ruined house, the men found the body of a bed-ridden cripple who had been murdered by bayonet-thrusts; and, under the bed, were three young children half dead with fright and starvation. There was also a baby of a few months old, lying in its cot, dead from want of food and attention, we supposed, as there were no marks of grosser violence on the little mite.

These sights and others seen in the neighbourhood had a terrible effect on the usually phlegmatic Russian soldiers, and afterwards cost many Germans their lives: for I know that wounded men and prisoners were slain in retaliation, and civilians too, when portions of the frontier were crossed, as will be found recorded later on.

We were puzzled what to do with the children, for it would have been inhuman to leave them in a plundered and wrecked home; the oldest appearing to be[38] not more than six years old. It was remembered that we had seen a woman at a cottage two miles to the rear, and so, accompanied by an orderly, I rode back with them. We found several women taking refuge in the house, and, though we could not understand one another, it was evident that we were leaving the poor little creatures amongst friends, as I could see by the attitude of the orderly.

When we got back to the farm we found that the battery had been advanced, and we had some difficulty in finding it. I had to leave that work to the orderly, an old non-commissioned officer named Chouraski, who afterwards acted as my servant.

The battery, with the rest of the regiment, and several others, about 200 guns in all, was massed behind a sandbank—not a wise arrangement. Other batteries were bringing a cross-fire to bear from distances which I computed to be two and three miles from our position. The Germans were evidently suffering severely, and so were we. One of our batteries had all its guns dismounted or put out of action, and many other guns were destroyed, though in some cases the gunners got them on fresh wheels, or even limbers. All the men were cool and brave beyond praise, though the effects of the fire were very terrible. One shell burst as it hit the body of a gunner, who was literally blown to pieces. Another shot smashed away the head of a man standing close to me. He threw up his hands, and stood rigid so long that I thought he was not going to fall. The sight of the headless trunk standing there with blood[39] streaming over the shoulders was so horrible that it was quite a relief to the nerves when he dropped. The gunners, who had stood still paralyzed by the sight, resumed their work; but they had not fired more than a round or two, when a shell smashed the gun-shield and wiped out the whole detachment. A piece of this shell entered the forehead of my horse and it fell like a pole-axed ox, dying with scarcely a quiver of the muscles.

Although the shield was destroyed the gun was not put out of action, and I got a couple of men from another gun, and we continued to fire it. This went on hour after hour, until all the shells (shrapnel and common) were expended. Twice a fresh supply was brought up by the reserve ammunition column men, and altogether about 500 rounds per gun were shot off in this part of the field, or about 100,000 in all. As there were at least 600 guns in action it is probable that 500,000 shells were thrown against the enemy; an enormous number; and nobody will be surprised to learn that the slaughter was terrible. Many of our guns were cleared of men over and over again, reserve gunners being sent up from the rear as they were required, the men running up quite eager to be engaged, and, generally speaking, taking no notice of the casualties which were constantly occurring close to them.

I strove hard to draw the attention of every officer within reach to the faulty position of the guns; but all were very excited, and my unfortunate ignorance of their language prevented me from making myself[40] understood. I did not know what had become of Major Polchow, but late in the afternoon he came up with a staff officer, and I pointed out to him the unnecessary slaughter which was taking place owing to the exposed position of the guns. He said that the error had been observed long before, but that it was considered to be unwise to retire them. Now, however, so many of the artillerymen had fallen that dozens of the guns were silenced, so an attempt was made to draw back the most exposed of the batteries. The horses had been sheltered in a hollow a hundred yards in the rear, yet even in their comparatively protected position so many of them had been killed and mangled that it was only possible to move back three guns at a time.

The Germans observed the movement, with the result that men, guns, waggons, and horses, were smashed to pieces in a horrible and very nerve-trying confusion. Many of the incidents were almost too horrible to be described. The leg of one man was blown off by a bursting shell. He saved himself from falling by clutching a gun-carriage; but this was on the move and dragged him down. The bleeding was stopped by a roughly improvised tourniquet; he was laid on the ground with his coat under his head and left to his fate.

When the guns were drawn back to the new position very few casualties occurred; but at this time the Germans made a determined onset with huge masses of infantry in close columns of companies—an amazing formation, but one which I was prepared[41] to see executed, knowing their general tactics as practised on peace manœuvres.

At this moment we had only twelve shells per gun left. These twelve cut great lanes deep into the advancing masses, but did not stop them, and orders were given to retire. Two of our guns were drawn away by the prolonge (that is, by means of ropes manned by men on foot), and two were abandoned. We should certainly have been overtaken and destroyed; but about a thousand yards to the rear we found three regiments of infantry halted in a slight hollow of the ground. These 12,000 men suddenly rushed forward and opened a tremendous fusillade on the advancing masses, bringing them down so fast that the appearance of falling men was continuous and had a very extraordinary effect. But they were not stopped, and our infantry was compelled to fall back with the guns, losing heavily from the fire which the Germans kept up as they advanced.

Our infantry, like that of the Germans, kept much too close a formation, and the losses were therefore appalling. Thus, early in the war, all the Russian units were at full strength; infantry four battalions per regiment—fully 4,000 men. The three regiments behind us lost half their strength, equal to 6,000 men, in twenty minutes; and the remnant was saved only by reaching a pine-wood about a mile in length and some 300 yards in depth. This enabled them to check the Germans; and two batteries of artillery coming up, evidently sent from another division to support us, they were compelled to halt, lying[42] down on the ground for such shelter as it afforded, to wait for their own artillery. This did not come up until it was nearly dusk. Before it opened fire we began to retreat and we were not pursued.

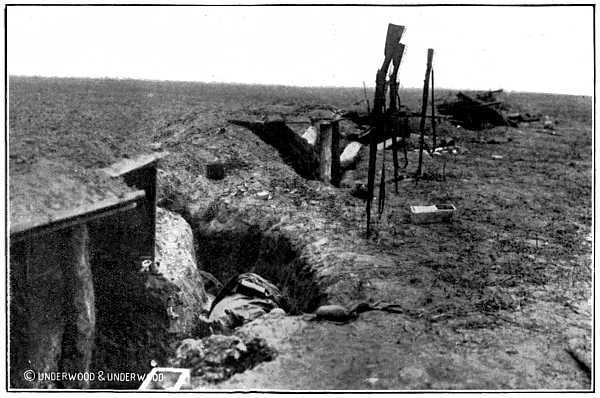

We fell back on two small hamlets with a farm between them, and here we entrenched ourselves, putting the buildings into a state of defence. Distant firing was heard all night, and we received a fresh supply of ammunition, and heard that 150 of the guns were saved. As we had thirty with us it was estimated that about twenty had fallen into the hands of the enemy besides twenty or thirty machine-guns.

Outposts reporting that the German division which had pursued us had retired northwards, I proposed, as soon as it was light enough for us to see our way, that a party should go out to look for the wounded men of our battery. These brave fellows had done their duty as only heroes do it—without a moment's hesitation, or the least flinching at the most trying moments; and with scarcely a groan from the horribly wounded, whose sufferings must have been excruciating.

Although unable to understand a word I uttered, all who stood by, when informed by Polchow of what was proposed, volunteered to accompany me. I took about thirty men with stretchers, which were mostly made of hurdles obtained at the farm.

It was about three English miles to the spot where the batteries had been first posted and the whole distance was thickly littered with dead bodies of Germans [43]and Russians intermingled. All the wounded except those desperately hurt had been removed, but none of the enemy were about. They appeared to be kept off by strong patrols of our cavalry, which could be seen in the distance; and, doubtless, the German horsemen were in view, as desultory shots were fired from time to time.

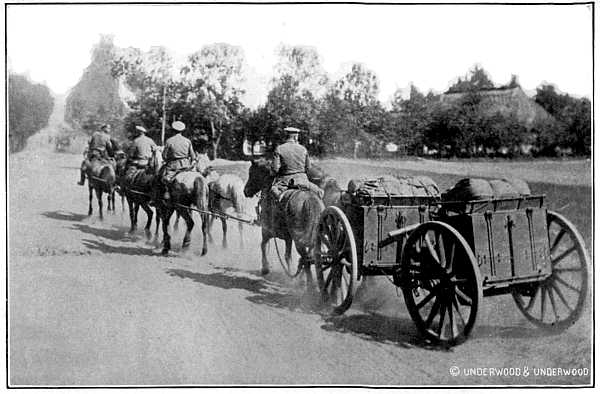

RUSSIAN ARTILLERY GOING INTO ACTION

RUSSIAN ARTILLERY GOING INTO ACTION

Dying men made piteous appeals for drink. One poor fellow expired while we were in the act of attending to him. The horribly inhuman nature of the Germans was evinced by the circumstance that they had made prisoners of all the wounded who would probably recover, and count in their lists of capture; but had left the mortal cases (even their own) unattended, to linger out a dreadful and agonized end. Their lack of feeling was fiendish. They had not even endeavoured to alleviate the sufferings of the men thus abandoned: for we found one German groaning, and seemingly praying for succour, pinned down under a dead horse. He was not even dangerously hurt, and would, I think, recover under the treatment he would receive from the Russians. For though these northern men were often barbarous enough on the field of battle, they were never cruel to their prisoners, or to injured men, unless these were known to have been guilty of atrocities.

The sights of that battlefield, and others which I afterwards witnessed, will be a nightmare to the end of life. I had often read of rivers "running red with blood," and thought this simply poetic exaggeration; but when we went to a brook to obtain[44] water for some gasping men, I noticed that it was horribly tinged with dark red streaks, which seemed to be partly coagulated blood. Some light fragments which floated by were undoubtedly human brains; yet at their urgent entreaty we gave of this water to poor creatures to drink, for no other was available.

This horror was not comparable to what we witnessed when we arrived at the spot where the artillery slaughter had taken place. The ground was covered with dark patches—blood blotches. Fragments of flesh, arms, legs, limbs of horses, and scattered intestines, lay everywhere about that horrible "first position." On the ground lay a human eye and within an inch or two of it, a cluster of teeth; all that remained of some poor head that had been dashed away. Where the body was that had owned these relics did not appear. The force of impact had probably driven them yards and yards; and it was a mere chance that they met my view. Close to one of our guns, too badly broken to be worth carrying away by the enemy, were two brawny hands, tightly clasping the handle of the sponge with which their owner had been cleaning the piece when they had been riven from his body. The man was close by, a mere mass of smashed flesh and bones, with thousands of beastly flies battening on his gore, as they were on that of all the corpses. The sight was unbearable. Sick and nearly fainting, I had to lean against a broken waggon to recover myself.

Our wounded had been murdered. There could[45] be no question of that. For we had not left any behind who were capable of fighting, yet a dozen had been finished off by bayonet wounds—and German bayonets make awful jagged wounds because their weapons have saw-backs.

One bayoneted gunner was not quite dead. At long intervals—about a minute it seemed to me—he made desperate efforts to breathe; and every time he did so bubbles of blood welled from the wound in his breast, and a horrible gurgling sound came from both throat and breast. There were two doctors in our party, but they looked at each other, and shook their heads when they examined this miserable man. Nothing could be done for him except to place him in a more comfortable position. War is hellish.

We found another of our men alive. His plight was so terrible that it was hardly worth while to increase his suffering by carrying him away. We did so: but he died before we had gone two versts. On that part of the field which the Germans had been compelled to cross without waiting to carry out their fell work, we found more survivors, and took back a dozen, of whom three were Germans. There happened to be no Red Cross men with our division just then; but we sent them to the rear in empty provision waggons.

This is what I saw of the battle of Biezum, if this is its correct designation. According to Polchow the Russian centre was at Radnazovo, a town, or large village, eleven versts further east; and the whole front extended more than thirty versts, though the[46] hottest fighting was near Biezum. It was afterwards reported that 10,000 Russians were killed in this engagement, and 40,000 wounded. The Germans must have lost heavily too. I saw thousands of their dead lying on the ground near Biezum alone. The fight was not a victory for the Russians, and scarcely could be claimed as such by the Germans. The two forces remained in contact, and fighting continued with more or less intensity until it developed into what modern battles seem destined to be, a prolonged series of uninterrupted operations.[47]

CHAPTER V

THE FIGHTING UP TO THE 26TH AUGUST

There appeared to be nearly 300 men in Polchow's battery when we went into action: only fifty-nine remained with the four guns we saved at the close of the day, and not one of these escaped a more or less serious hurt, though some were merely scratched by small fragments of shell or bruised by shrapnel bullets. At least twenty of the men would have been justified in going to hospital; several ultimately had to do so, and one died. Even British soldiers could not have shown greater heroism. Chouraski, the non-commissioned officer who had attached himself to me, had a bullet through the fleshy part of the left arm, yet he brought me some hot soup and black bread after dark; whence obtained, or how prepared, I have no idea. I was much touched by the man's kindness. All the soldiers with whom I came in contact were equally kind: and I have noticed that the men of other armies with whom I have come in contact in the course of my life, even the Germans, seemed to see something in my personality which attracted them, and to desire to be friendly. Perhaps they instinctively realized that I am an admirer of the military man; or perhaps it was the bonhomie which is universal amongst soldiers. Certainly I[48] got on well with them all, though some time elapsed before we could understand a simple sentence spoken on either side.

For two days I was not fit for much: then I went to the front with a detachment of sixty gunners which had arrived from Petrograd via Warsaw. I found the battery and the rest of the regiment encamped to the westward of Przasnysz.

Heavy fighting was going on somewhere in front; but the contending troops were not in sight. The whole country was full of smoke, and the smell of burning wood and straw was nearly suffocating. The Germans had set fire to everything that would burn, including the woods. During the night heavy showers of rain fell, and these extinguished most of the fires and saved a vast quantity of timber.

I could see that the Germans had been driven back a considerable distance; and the Russians claimed to have won great victories in the neighbourhood of Stshutchen and Graevo, and to have already passed 500,000 men across the German border. That they were making progress was obvious; and on the 20th August I witnessed some desperate infantry fighting.

The Germans came on, as they always did, in immense columns, literally jammed together, so that their men were held under fire an unnecessarily long time. The usual newspaper phrase, "Falling in heaps," was quite justifiable in this case. Thousands fell in ten minutes; and the remainder broke and fled in spite of the efforts of their officers to stop them. I was well in front and saw what took place. The[49] German officers struck their men with their swords and in several cases cut them down; and I saw one of them fire his revolver into the crowd. I did not actually see men fall, but he must have shot several.

The Russians, too, adopted a much closer formation than was wise, and suffered severely in consequence, but they never wavered. The Germans came on again and again, nine times in all, and proved themselves wonderful troops. Four out of the nine charges they drove home, and there was some desperate bayonet fighting in which the Teutons proved to be no match for the Muscovites. The last named used the "weapon of victory" with terrible effect, disproving all the modern theories about the impossibility of opposing bodies being able to close, or to come into repeated action on the same day.

On the contrary, it may be taken as certainly proved that men's nerves are more steeled than ever they were, and that the same body of men can make repeated and successive attacks within very short periods of time. In the above attacks fresh bodies of troops were brought up each time, but the remnants of the battalions previously used were always driven on in front. I noticed this: on three occasions the 84th regiment (probably Landwehr) formed part of the attacking force.

"Driven on" is the correct term. The German officers invariably drove their men in front of them. Arriving in contact with their foes, the soldiers fought with fury. It was the preliminary advance that seemed to discompose them: and, indeed, their[50] losses were dreadful. They certainly left at least 30,000 dead and wounded on the ground on the 20th. The greater number were dead, because those who lay helpless received a great part of the fire intended for their retreating comrades, and thus were riddled through and through.

The Russian artillery played on the masses both when they advanced and retreated; but the fight was chiefly an infantry one. The full effect of the guns could not be brought into play without danger of injury to our own men. In the end the Russians chased the enemy back and the artillery was advanced to support them. Considerable ground was gained; but four or five versts to the rear of their first position the Germans were found to be strongly entrenched. The day's fight was finished by a charge of a large body of Cossacks and Russian light cavalry. They swept away the force of German horsemen who ventured to oppose them, and also drove back several battalions of infantry. That part of the Russian Army which had been engaged bivouacked on the ground they had fought over.

The cries of the wounded during the night were terrible to hear, and came from many different points and distances. Hundreds must have died from want of attention, and hundreds more, on both sides, were murdered. The Germans, who were hovering about in small parties, persistently fired on the Red Cross men, so little could be done for the dying; and the cruelties which were perpetrated, and which were revealed (so I was told) by the shouts, entreaties and[51] imprecations of the sufferers, aroused a nasty spirit in the Russians, and particularly in the Cossacks, and led to fearful reprisals, so that in one part of the field I know that not a German was left alive. I am bound to add that after I had seen two Russians brought in with their eyes gouged out, and another with his nose and ears cropped, and his lacerated tongue lolling from his mouth, I had not a word of protest to utter against these reprisals. The Germans were finished fiends, and deserved all they got from a body of men notorious for their fierceness; and they did get it. I will say this, though: that throughout the campaign no instance of a Russian injuring a woman or a child came under my notice; nor did I hear of any such cases. But I was told that three Prussian girls, who were seen to be on friendly terms with some Russian soldiers, were nearly flogged to death by their own people; and the horrible treatment the Polish women received from the hands of the Germans has already been mentioned, and was ever recurring during the whole of the time I spent with the Russian Army.

I would here make mention of the quality of the Russian and German soldiery. Conscription sweeps into the ranks of an army numbers of men who are totally unfit for a military life and a still further number who abhor it. In the present war, hatred and vindictive feeling generally has run very high on the northern side of the fighting area; and this circumstance seems to have greatly increased the war-like instinct of the masses, and consequently decreased[52] the number of what I may term the natural non-combatants. In the Russian ranks, and I believe in the German also, this class is weeded out as far as possible, and relegated to the organizations which have least to do with the fighting line—that is, the administrative services, and troops organized to maintain the lines of communication. But these fellows—the natural non-combatants, or haters of the soldier's life, I mean—are, when found in the fighting ranks, the most detestable scoundrels imaginable; and I believe the greater part of the atrocities committed may be laid to their charge. They lose no opportunity of indulging in lust and murder; and as in civil life they are mostly wastrels, thieves and would-be murderers, they find in war an opportunity to indulge in those vices which, practised in time of peace, would bring them to the prison and the noose. In other words, the scum of the big cities is brought into the army, and often proves as great a curse to its own administrative, as it does to that of the enemy. Not all the Germans were fiends—not all the Russians saints.

Early in the war many of the German regiments were composed of exceedingly fine-looking men. There was a decided deterioration later on, but this was more in appearance than quality: they still fought with determined, or desperate, courage; I am inclined to think, often the last-named. They were taught that the only way to escape the brutality of their officers was to face the courage of their foes. They chose the latter. Often hundreds—whole[53] companies together—rushed over to the Russians, threw down their arms, and surrendered themselves prisoners of war. No such instance ever occurred in the Russian ranks. The Russian soldier is a very pious man, and, like the North Aryan stock from which he has sprung, is a great worshipper of ancestry and his superiors. His commanding officer, like his Czar, is a Father, or a Little Father—a sacred being—his priest as well as his temporal master. The consequence is that officer and soldier are one, a conjunction that is of great value from the military standpoint.

This is never the case in the German Army. The Teutonic officer is a brute and a slave-driver, and his soldiers fear him if they do not hate him. I doubt if any German soldier ever gets through his training without being repeatedly struck by all his superiors from the unter-officer upwards. Feathers show how the wind sets. A Prussian regiment (the Pomeranian Grenadiers) was route-marching. One of the musicians blew a false note: the bandmaster immediately turned and struck the man a stinging blow on the face. I believe the German Army is the only one in the world where such an incident could occur. Like master, like man. One brute breeds another.

Taken on the whole the old adage that "one volunteer is worth two pressed men" is true; but an army of ten or twelve millions could not be successfully met by one of a million or two. Numbers must count when they are excessive; though things militate[54] against this rule sometimes. If an army has not its heart in a contest very inferior numbers may win. In the present case it soon became clear to me that both the great nations had their hearts in the war: the surprising thing is that Russia with her huge hordes has so far done so little—Germany hard pressed on all sides effected so much.

These words will reveal that I do not take the general view that Russia is progressing as fast and as well as she might reasonably be expected to do.[1] Yet I am unable to point out very clearly where her principal defect lies. She brought up troops very rapidly; and by the 20th August she had an enormous army in the field on the East Prussian frontier. At this time, and later on, I learned that her lines extended throughout the German border and far along that of Austria to the Bug; and she was said to have at least 5,000,000 men massed in these lines. The Germans had not nearly so many—probably not more than 2,500,000 or 3,000,000; but they had the power, by means of their railways, to concentrate on a given point very rapidly, and so equal, or more than equal, the Russians, who, being without adequate railway communication, could not take advantage of their superior numbers. If the last-named saw a weakness in any part of the German defensive and attempted to take advantage of it, before they could bring up an adequate number of troops the Germans had discovered their intentions and rushed up a sufficient force to secure the threatened point: [55]and this they did by bringing men from positions so numerous, and so distant, that they nowhere materially weakened their line; or, if they did so, they were enabled to conceal the fact.

[1] This paragraph was written four or five months ago.

Europe, Austria and Germany, is surrounded by a ring of armed men, extending, roughly, a distance of 1,500 miles, and defended by a force of about 14,000,000 men, or some five men to the linear yard. This is, in modern war, a sufficient number for effective attack or defence, on ordinary ground; but it is not too many, and in prolonged operation may prove to be too few on some descriptions of terre-plein. Yet, after ten months of the fiercest and most destructive fighting the world has ever seen, this ring of armed men has not been broken, though persistently attacked by three of the most powerful military nations on earth.

My estimate of the number of German and Austrian troops actually in the fighting-line at the beginning of the war is much in excess of the numbers stated in English newspapers. I note this; but do not think that 14,000,000 is an exaggeration. I have information, and am not merely guessing. Nor are the losses of the enemy overstated by me.