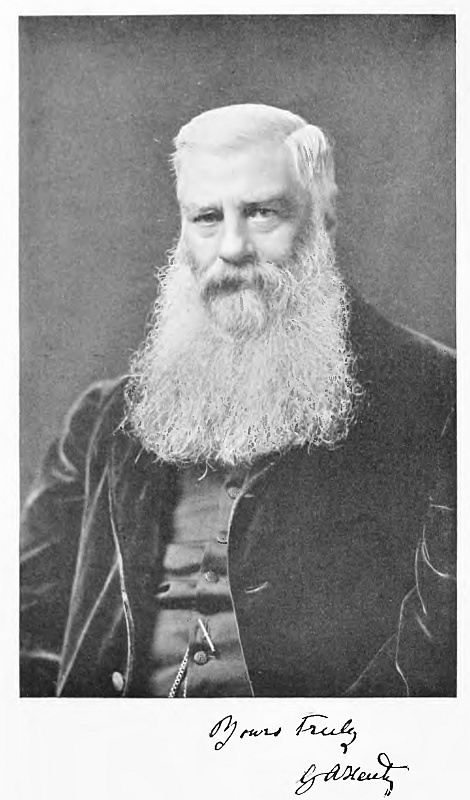

George Manville Fenn

"George Alfred Henty"

"The Story of an Active Life"

Preface.

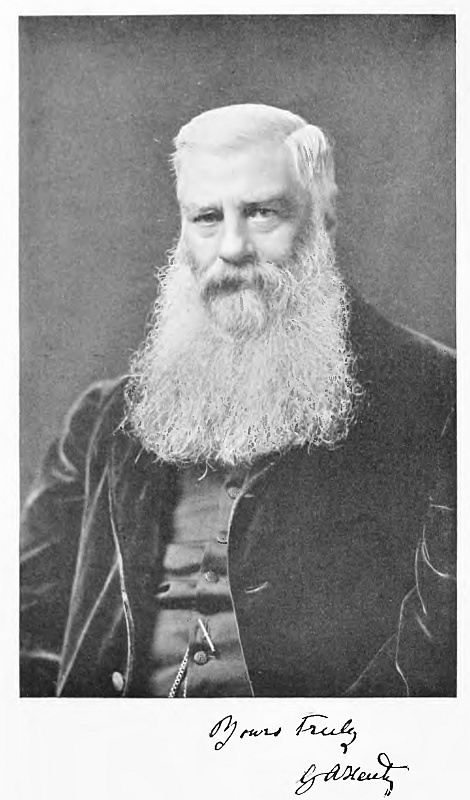

G.A. Henty occupied so large a place in the hearts of boys that, when his active life all too soon came to a close, it seemed desirable that those readers whom he had entertained for so many years should have an opportunity of knowing something more of the man himself than was contained in his books. Every writer, consciously or unconsciously, reveals himself in his work, but nevertheless it cannot fail to be interesting to boys to read of the actual experiences of the sturdy war correspondent—those experiences which furnished him with many a vivid background for his romances. It was at once the fascination and the value of his tales that, while nominally fiction, they were built up on a solid substratum of fact. When the present writer, however, was asked to undertake this memoir of his old and valued friend, he was confronted with a grave difficulty. Of few men of George Henty’s eminence is less known about their private lives. A staunch and loyal friend, he yet strongly believed, to use the old Cockney phrase, in “keeping himself to himself.” His letters were never autobiographical, and about himself he was never very communicative. Little more than his vivid letters from foreign countries exist to give an insight into the man and his character.

In his many absences from England during his career as a war correspondent, Henty contented himself with the briefest of home communications, and these told little more than where he was and what was the state of his health. He always said that those he loved could refer to the newspaper he represented for the rest.

To the courtesy of Mr C. Arthur Pearson, the present proprietor of The Standard, who placed the whole of the files of that paper unreservedly at his disposal, the writer is very greatly indebted, while for much valuable information he would like to thank the editors of The Captain, Chums, The Boy’s Own Paper, Great Thoughts, Young England, and Table Talk.

G.M.F.

Chapter One.

Early Days.

We might know very little of the life of the late George Alfred Henty—writer for and teacher of boys, novelist, and one of the most virile of our war correspondents—but for one fortunate fact. His busy pen soon made him popular, and in course of time this popularity was sufficient to make editors of journals for the young realise that their readers would gladly learn something of the early life of the man whose vivid tales of adventure were being read with avidity wherever the English language had spread. In these days few are content to know a man only by his work, and even boys like to know something about the personality and experiences of the writers who have given them keen pleasure. As a result the inevitable came to pass, and the modern chronicler of personal details sought out the author. To his interviewers Henty told fragments of his past life, and these reminiscences were taken down in short or long hand, and built up into articles, and have remained, to bring before us vividly what would otherwise never have been known save perhaps by tradition.

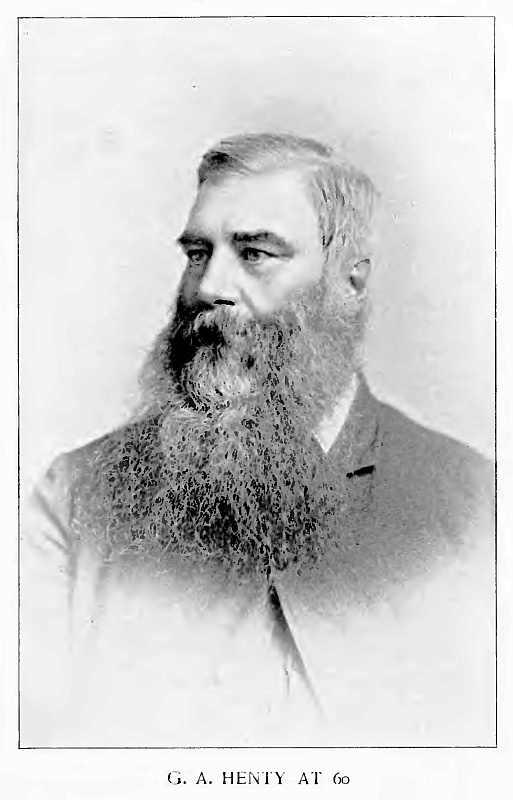

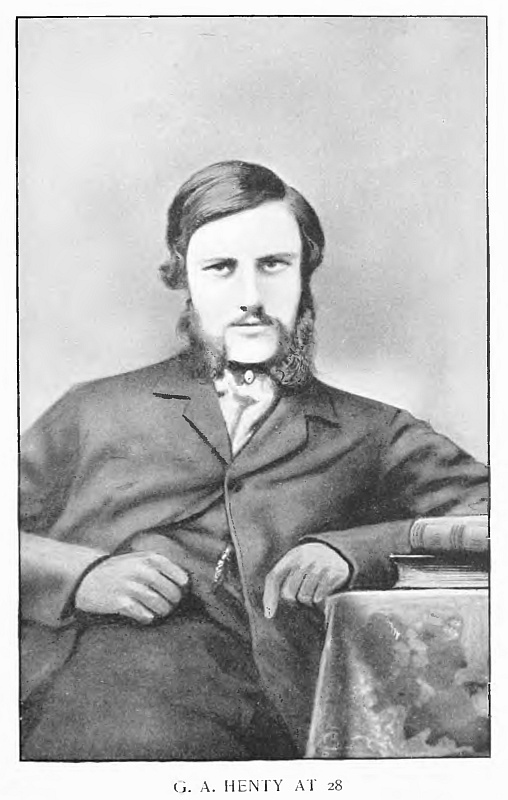

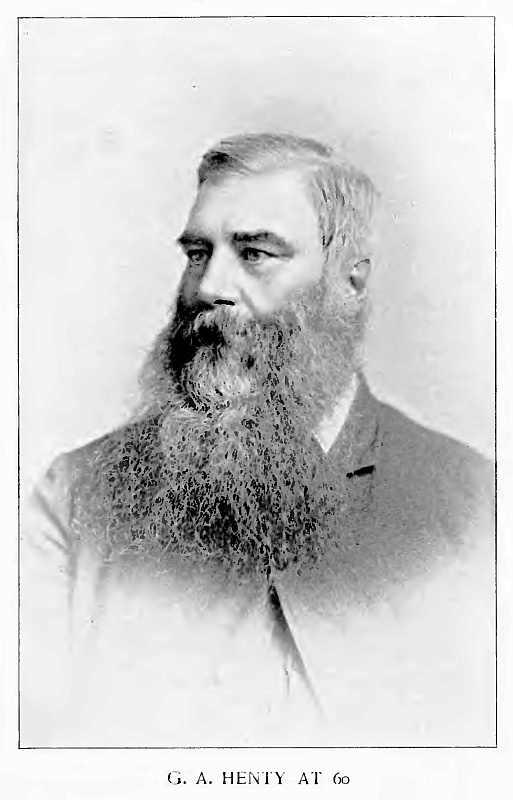

It is strange now to reflect that the big, robust, heavy, manly-looking Englishman of whom these lines are written, was once a puny, sickly boy who was looked upon by his relatives as one who could never by any possibility attain to man’s estate; but so it was. Here are his own words: “I spent my boyhood, to the best of my recollection, in bed.”

Descended from an old Sussex family, George Alfred Henty was born at Trumpington, near Cambridge, on December 8, 1832, and it would appear that he was a confirmed invalid. This ill-health was the more unfortunate because it was in the days when doctors were inclined to be narrow-minded, and parents and guardians in almost every household had intense belief in the virtues of physic. Most mothers then were given to doctoring, and at spring-time and fall considered it to be their duty to administer filthy infusions, decoctions, and very often concoctions, to unhappy boyhood; and a powder at night, to be followed by a nightmare of the draught that was to be taken in the morning, is a painful recollection to some of us.

Happy boys of the present generation! Why, who among them now know the meaning of words which must almost seem like cabalistic characters? Jalap, rhubarb, magnesia, salts and senna, gamboge, James’s powder—these were all in constant request, without taking into consideration the secrets promulgated by the wicked writers of books on domestic medicine.

It was in those days that George Henty was born. He tells of an early removal at the age of five to Canterbury, to a fine old house whose garden ran down to the River Stour. Here for the next five years his mind became stored with those most wholesome of recollections connected with boy life. It was the bird, bee, and butterfly time, brightened by the presence of a grand trout stream, to whose banks he would creep, so as not to send the spotted beauties darting off in a flash of ruddy gold to seek some hiding-place from the gigantic shadow that had suddenly been cast athwart the stream. He tells, too, in many a page of his later life, how the influences of this good old garden were a solace and delight to him during many a weary tramp or journey in the saddle far away; in the course of his journeys through Europe, the wilds of Asia, and the savage mountains and dense tropic forests and swamps of Africa.

The boy was fortunate, too, in his leanings towards natural history, for he speaks of a grandfather who was always ready to play the part of instructor to the young enquiring mind in regard to scientific matters, and explain the why and the wherefore of such objects as he collected.

When not confined to his bed, Henty attended a Dame school, where the love of reading was started, and grew and grew so that the sick boy’s lot was softened to the extent that the weariness and suffering of confinement to his bed became almost pleasant in the forgetfulness begotten by books. That which was wanting in the way of education was made up in these long hours by reading. To use his own words, he “read ravenously”—romance, adventure, everything—perfectly unconscious, of course, of the fact that he was laying in a mighty store for the future, preparing himself, in fact, for the great work of his life, the broad and wide education of the boys of a generation to come.

In those days, though the classics hardly had place (there was little of Latin or Greek), he was piling up general knowledge such as comes to the lot of few lads now, in spite of the boasted advance in educational matters and all the elaborate apparatus and routine. And yet it must not be supposed that the boy’s regular education was neglected. When ten years old there was an end to his simple country life, for though far from well he was sent to London to begin life in a private boarding-school, a life sadly interfered with by sickness and relapses into ailments more or less severe, among them being that terrible disease whose sequelae have shattered many lives—rheumatic fever. One of his ailments seems to have been near akin to that of the late Prince Leopold, namely, a tendency to profuse bleeding. For this he was attended by a well-known specialist of the time, whose great remedy for the boy’s complaint was camphine, this being the popular term in those days for one of the refinements of the so-called rock oils, nowadays known as petrol or paraffin.

Henty recorded to one of his interviewers that he was so thoroughly dosed with this peculiar medicine that the specialist warned the nurse in these words: “I don’t say that if you put a light to the boy he will catch fire, but I advise you not to risk it.” This was accompanied with further counsel that the future chronicler of boys’ adventures should not be allowed to handle sharp instruments, lest a cut or puncture should result in his bleeding to death.

Much reading in these early days had so influenced the boy that he had already become a story-teller, and, as is often the case with first attempts at writing, pleased with the jingle and flow of words, he had dropped into poetry. Now a young poet, as soon as he has satisfied himself with his lines and has carefully copied them in his best penmanship, burns to see himself in print. He then imagines, or is flattered into the belief, that numbers of people are as anxious as he to see his work become public; and it appears to have been so here, for owing to the well-meant kindness of a friend, certain of his early verse was printed, and it would appear to have been extremely sentimental and remarkably mild.

It was soon after this, when Henty was fourteen, that he went to Westminster School. Liddell was head-master then, and the boy became a half-boarder, and in a very little while, in his boyish and very natural vanity, he let his tongue run a little too fast. He had written verse, and consequently esteemed himself something of a poet, so it was not long before he mentioned the fact of his having his work in print. He quickly began to wish he had held his tongue. He had not counted upon the mischievous delight a pack of schoolboys would take in their special poet. If he had written Latin verses it would have been a different thing; but a love-tale with threatened difficulties to a lady was too much for them, and a long and continuous “roasting” ensued. Chaff flew, indirect and covert allusions were made, and then came bullying. Henty says: “It seemed as if the whole school bore a personal animosity towards poets, and as if they looked upon my publishing the unlucky book as a bit of ‘side’ unworthy of a Westminster scholar.”

This particular poem was unfortunately lost, and the same fate befell another attempt written later, for the school banter did not crush out the rhyming faculties. The later work was written upon a more serious occasion, and, devoted to his future wife, it was cared for and preserved for long years as a valued treasure; indeed, only about ten years before his death, Henty was taking it up to town and accidentally left it in the railway carriage. Attempts to recover it proved vain, and though he offered a large sum of money as a reward, he never heard of it again.

As the lad’s education progressed at Westminster it was not long before he began to realise that the curriculum was not complete, and that no boy’s studies were perfect without a thorough knowledge of the noble science of self-defence. Indeed, he had not been long at the great school before he came in contact with one of the regular school bullies, who began to tyrannise until young Henty awoke to the fact that he possessed a high spirit and an absence of that weak pusillanimity which makes men slaves. He was no mute inglorious Milton, though he aimed at being a poet.

The boy was father to the man he became, and he bore little before he turned in defiance and challenged his tyrant. The natural result was that he was thrashed out of hand and sent smarting with pain and mortification to where he could ponder over his defeat. But he was not of the mettle to sit down painfully under humiliation, and, to use his own words, “I soon changed all that.”

It was something to learn, something to study; how to acquire the power, the science, which makes a comparatively weak man the equal of one far stronger, and, judging the boy by what he was as a man, it was from no desire to become bully in his turn that he took lessons in boxing, but from a genuine ambition to hold his own in the matter of self-defence and to be able to protect those who looked to him for help. It was with this desire that, later, when he left Westminster for Cambridge, at a time when the so-called noble art was at its highest tide, and when professors of the science had quite a standing at the universities, he continued its study, and one of the first professors to whom he applied for lessons (out of college) was the once celebrated Nat Langham, who, by the way, was the only man who ever vanquished Tom Sayers. Not contented with this, but being then in the full burst of his growing youth and strength—a sort of young athlete thirsting for power like a boyish Hercules—he took to wrestling, perfectly unconscious then of the good stead in which it might stand him in the future. In this sport he chose as his instructor a Newcastle man, one Jamieson, famed in his way as being champion of the Cumberland style as opposed to the Cornish. It must be borne in mind that all this was prior to the days of the Great Exhibition, when pugilism was considered no disgrace, and before young men had begun to foster athleticism in other forms.

It was a strange reaction in the youth who had passed the greater part of his early life upon a sickbed, and it seemed as if the brave nature within him was exerting itself to throw off his natural weakness.

That thrashing he received in his early days at Westminster seemed to have roused him, spurred him on to gain strength, and he was encouraged too by the stirring times in which he found himself. Boating and cricket were all-important at Westminster. The studies were hard, but the masters, wisely enough, encouraged all sports; for the Westminster boys, as our chronicles have shown us, learned there to hold their own the wide world round. One need not here point to the long roll of famous names. These pages are devoted to one alone.

Henty takes a very modest view of his own prowess, and says of his life at Westminster: “Boating or cricket—you had your choice; but once made, you had to be perfect in one or the other. Fellows rowed then and played cricket then. They had to.”

The Thames was their course. There was no Saint Thomas’s Hospital then, and the boat-houses were on the banks. The river was pretty handy to the great school, and at the sight of the Westminster crews the boatmen used to come across to fetch the boys. These were the days before the Thames Embankment, when the river sprawled, so to speak, at low water over long acres of deep mud, swarming with blood-worms, and though the river tides ran swirling to and fro the current was greatly quickened. Later the number of steamers increased and cut up the Westminster rowing, so that it went all to pieces. It was so greatly affected that the Old Westminsters’ Club tried to move the sport to Putney; but it never regained its old standing. Westminster, however, though known best as a boating school, was a great cricketing one as well. At one time five Westminster men played in the All England Eleven; but Henty was not a cricketer. As a young athlete, he selected rowing. Both sports could not be managed; the standard was too high.

Henty describes himself in his growing days and at Cambridge as a sort of walking skeleton; but he was big-boned, and the life he led as manhood approached made him fill out and grow fast into the big, muscular, burly man that he was to the end of his life. In fact, he has said that in later days, when he went down to the Caius College Annual Dinners, while he knew most of the men of his own standing, not one recognised him. And this can easily be grasped when it is understood that in his college days at nineteen he weighed nine and a half stone, while as a man in vigorous health he was as much as seventeen.

He does not forget to credit his school with the education his Alma Mater afforded him. He says: “She did give me a good drilling in Latin. Perhaps not elegant classical Latin, but good, everyday, useful, colloquial stuff.” In his time the masters were great upon the old dramatic author whom so many of our modern dramatists have tapped right through Elizabethan, Restoration, and more modern times, down to the present. In Henty’s early days, just as is annually the custom now, one or other of Terence’s comedies was chosen for a performance by the Queen’s Scholars, while every other boy as a matter of course had to get up one play as the lesson of the year as well, and doubtless, as has been the case with many a schoolboy in turn, would fall a-wondering how it was that the great Latin poet possessed an Irish name.

Latin verses and Latin colloquial phrases were hard enough to pile up, while parents and guardians, ready enough to complain, found fault at so much time being devoted to the dead languages to the exclusion of those which are spoken now. Hear, ye grumblers, what George Henty says thereon to an interviewer:—

“When I went out to the Crimea, and later, to Italy, I found that everyday Latin invaluable. It was the key to modern Italian, and a very good key too. But more than that, it meant that wherever I could come across a priest I had a friend and an interpreter. Without my recollections of Terence I don’t know where I should have been when I first tackled life as a war correspondent.”

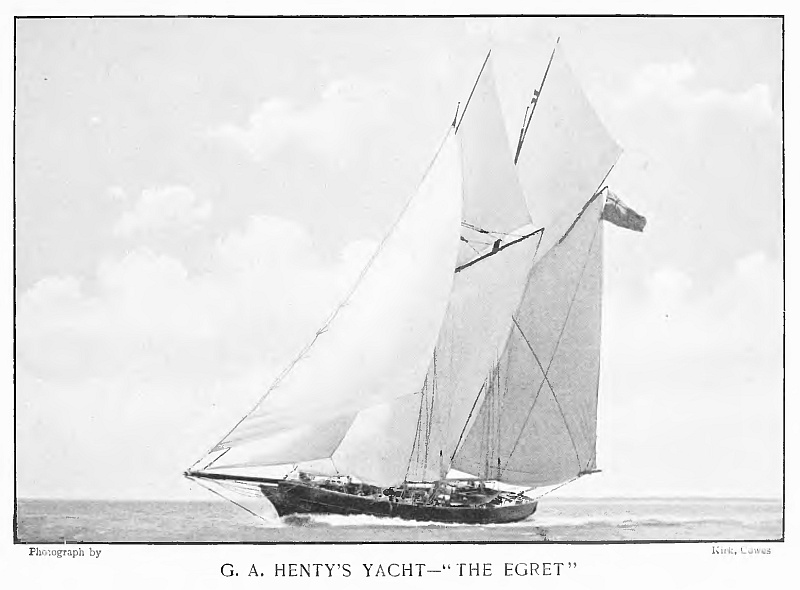

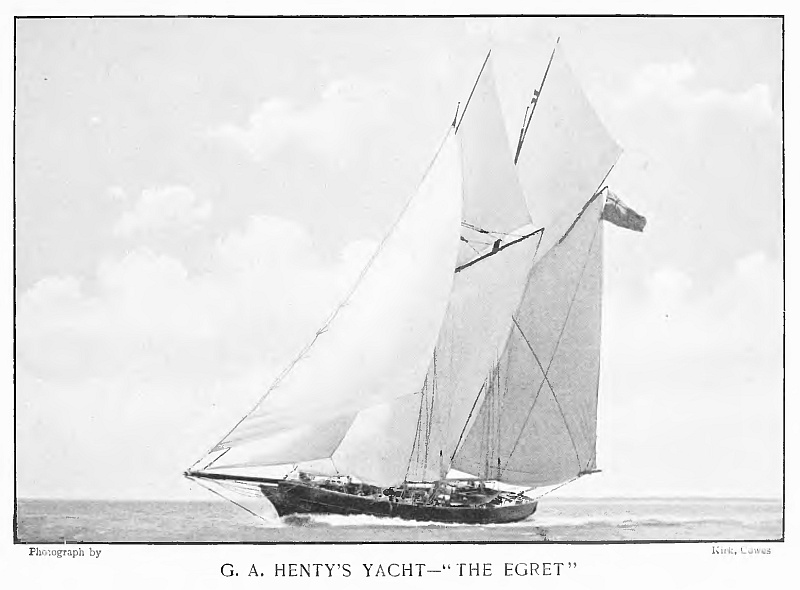

He speaks of Westminster as giving him his first introduction to boating, not merely rowing, but boating with the use of the sail. There was a man on the Surrey side in those days, named Roberts, from whom the boys used to hire their four-oared and eight-oared cutters, wager boats, and the occasional randan for three, two oars and sculls. This man had a small half-decked boat which Henty first learned to handle. In it he learned also the stern necessity of always being on the alert after hoisting sail—a necessity which doubtless gave rise to the good old proverbial warning, “Look out for squalls.” Yet, in spite of everyone knowing and often using this warning phrase, it is too often neglected by careless boating people, who will not realise what a duty it is never to make fast the sheet.

Here at Westminster and in the little half-decked boat commenced the healthy passion of Henty’s life, and he acquired something of the skill which enabled him through manhood to go to sea and feel no fear even in rough weather, strengthened as he was by the calm confidence that accompanied, in the broad sense of the term, “knowing the ropes.”

The days of a public-schoolboy came to an end, and with their conclusion arrived the feeling that he was a man. But after all it was the schoolboy feeling of manhood, though it was very manly in one thing, for it brought with it the knowledge that he had spent too much time in play, and with it too the feeling that he must make up for the past. Hence it was that he went in for what he termed a burst of hard reading as soon as he reached Cambridge and entered at Caius College. In the full realisation of his failings he proved that he was still a boy, for he set to and began reading night and day for about three weeks, so as to acquire as much as should have taken him about six months’ work. As a result nature said nay, and gave him a severe lesson in the shape of an illness which knocked him over, so that he had to go down for a year’s rest, as it was termed, but it was in reality a good spell of health-giving instructive work which greatly influenced his future career. In fact, he now began to pick up the information which he so largely utilised afterwards in his books. Here was his first study for Facing Death, one of his most widely read boys’ stories—boys’, though it was as much read by men. For he went down into Wales, where his father possessed a coal-mine and iron works, and at the latter he acquired such knowledge and insight into engineering as to enable him at a critical time in his career as a war correspondent to call himself an engineer. Reporting himself as an English engineer desirous of studying the practical effect of great gun fire, he had no difficulty in getting permission to accompany the Italian Fleet in what was virtually the first battle between iron-clad men-of-war.

Henty’s subsequent military training, together with his physique and stern decision of manner, made him naturally an excellent leader of men. In ordinary civilised life he was one who, at a gathering, would be pretty well sure to be selected as chairman, for upon occasion he could abandon his quiet soft-spoken manner, fill out his chest, and, if slightly roused by opposition, speak out with a decision and a firmness that would lay antagonism low; while, if it happened to be in a lower stratum of not to say savage but uncivilised life, his training had made him a picked disciplinarian, one who had his own particular way of maintaining order and gaining the affections as well as the obedience of those whom he had to command.

This was simple enough in the army with disciplined men, but there were occasions when his services were selected to guide and govern the undisciplined and those of the roughest and most obstreperous nature.

Upon one occasion fate placed him, the cultivated scholar and Westminster boy, as foreman, or as it was termed amongst the men, “ganger”, over a strong body of men engaged upon the construction of some small military railway. His men were a very lively party, extremely insubordinate at first, and ready if matters did not go exactly as they pleased—if the work seemed too rough, or the supply of available strong drink too handy—to throw down their tools, or reply with insolence to their foreman, whose calm, quiet ways and speech seemed to invite resistance. It was in ignorance that the fellow who offended did this thing, and he did not offend a second time, for Henty was leader with plenary powers, and he had but one way of dealing with a rough. It was to order him at once to the place which he used as his business office, and with quiet firmness and decision, and in the presence of his following, to pay the man off there and then, to the great delight of the rest of the gang, who knew what was to follow. The offender was paid in full and told to be off from the line. He, of course, retaliated with an outburst of flowery language, noting the while the gathering together of his mates. Henty meantime was quietly taking off his coat and rolling up his sleeves preparatory to showing the unbelieving ruffian how a muscular athletic English gentleman, a late pupil of a great professor of boxing, could scientifically handle his fists and give the scoundrel, to the intense delight of the lookers-on, a thoroughly solid and manly thrashing. This invariably ended in the offender crying, “Hold! Enough!” and accepting his punishment without bearing malice; and in almost every case the gang was not only not weakened by the loss of a man, but it maintained a more willing worker than it had possessed before.

As may be readily supposed, the gentleman ganger lost no prestige amongst his men by such an exhibition of his prowess, for he knew most accurately with whom he had to deal, that is to say, so many big stalwart men of thews and muscle, such as our contractors have utilised for linking land to land with road and bridge, men of untiring energy and endurance, but with the mental capacity of stupid children. These formed Henty’s gang, and to his credit be it recorded that his treatment proved as efficacious as it was firm, the punishment being given calmly and in cold blood, to the astonishment of the man who received it.

Chapter Two.

From Cambridge to the Crimea.

Soon after his return to Cambridge troubles with Russia were “on the tapis”, and as it to show the preparedness for war which did not exist, Punch, as is usually the case, began to take notice of our army and navy. It signalised the latter by referring to an event of the day, to wit, the sham-fight at Spithead, and represented a theatrical combat of the melodramatic Surrey or Victoria Theatre type between two British sailors, one being down and his comrade resting over him, hands on knees and cutlass in suspense, with the lines beneath: “Ah, it’s all werry well, Bill, but my, if you’d been a Rooshian!”

Then sham-fights and assumed preparation for war died into thin air. Matters came to a head, and our unpreparedness was awfully written in disease, starvation, and death for those who studied the columns of news from the Crimea.

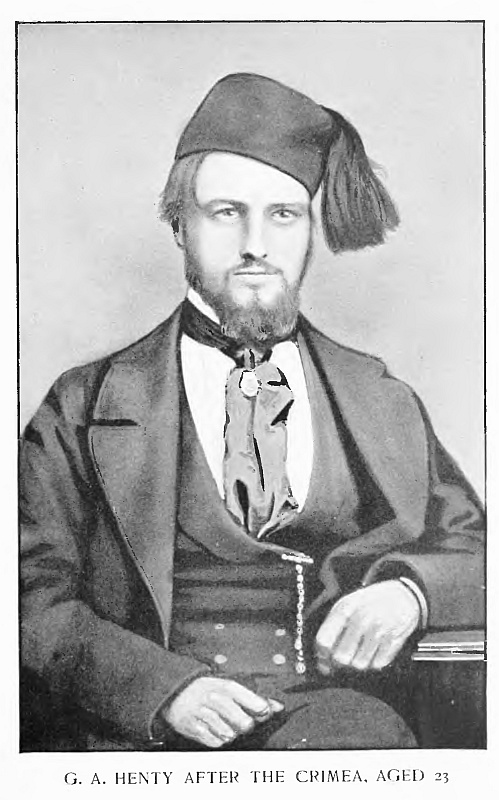

All young England was in a state of excitement. The Crimean War was upon every lip, and every hot-blooded young man burned to get to the front. Among these was George Henty. The quiet student life at the university became painful; the days passed in Caius College seemed to be prison-like. He too, strung up by that natural instinct that has made “Englishman” a name famous in the world’s history, grew more and more restless. In the nick of time he was offered an appointment in the Commissariat Department of the army, and the first steps were taken which enabled him to claim the rank of lieutenant in the British army, though it was to be in the utility more than in the fighting ranks.

One of our distributors of Attic salt once wrote, in the plain and pungent witticism of his time, that an army crawled upon its stomach in its progress to conquest; and by a strange irony of circumstances the young lieutenant—for, as said above, that was the rank Henty bore during the few years he served in the British army—found himself providing and superintending the supplies of that army in order to enable it to progress on that portion of its anatomy which keeps it alive, that is to say, when he was not busily engaged in superintending hospital wards and organising arrangements, sanitary and otherwise, in those depressing asylums for the wounded and the sick. The work was arduous enough, but Henty was the man to do it, in spite of the fragile promise of his youth, and the head-shaking as to his future of those who knew him. He must have been a very disappointing man to his social prophets, seeing that he grew above the ordinary height, and came to be big-boned and stalwart, his powerful frame well clothed with sinew and muscle. He was endowed with everything in fact suited to the making of what would be called a good all-round man, while his education, fostered by his natural pluck and determination, rendered him one who in his early manhood was a thorough athlete. Enough indeed has been said to show that in addition to being a powerful and skilful wrestler, and a formidable competitor in a friendly contest with the gloves, he was a dangerous adversary when necessity compelled him to make full use of what was veritably the noble art of self-defence against the brutal scum of European life with which he was brought into contact.

In the full vigour of his manly youth he was a splendid walker, thinking nothing of doing fifty miles in a day, and this not at the expense of exhaustion, for after a brief period of rest he could repeat the walk with comparative ease. Muscular to a degree, he was a steady and dependable comrade in a boat. In addition, aided by the possession and the capacity of a broad deep chest, whose buoyancy was a tremendous asset, he could swim with ease and untiring skill.

Then, too, he made himself a good wielder of the foils, and the usual training of a military man enabled him to handle the service sword with as much ability as he displayed in pistol practice or with the rifle. Following up the ordinary education of a youth and young man with the acquiring and strengthening of such accomplishments as these, his appearance was such as would render him in competition one who would be chosen on any emergency as a leader of men, one who would be obeyed, and whose word would be law to those over whom he was placed.

Excitement was raging in England after the failures and disappointments that were being canvassed during the Crimean War; all England was wroth as William Howard Russell’s letters were read, telling the terrible tales of disease, starvation, and neglect suffered by our brave soldiers. Accusations against the authorities were rife, accusations which stirred the Government to action and to making more systematic provision for our troops. It will be readily understood, therefore, that the offer made by a man, so full of energy as Henty, to become a recruit in the Purveyors’ Department in the Crimea, that is to say, the Hospital Commissariat, was accepted at once, though his place would more naturally have been in the fighting line.

However, fate ordained that he was to do good work in connection with the provisioning of the unfortunate soldiers who had suffered so cruelly during the previous winter. Attacking his task with his customary energy, as soon as he reached Balaclava in the early spring of 1855 he was found busy among the stores which were to be distributed, or arranging the contents of the huts which were filled with wine and the more medicinal stimulants which were to be reserved for the sick or the wounded that were brought into the temporary hospital.

Here he was brought into touch with the officers of the medical and surgical department, and in connection with the transport service, for order was now springing up fast where chaos and despair had reigned so long.

Henty writes home about the preparation of food and comforts for the sick, and the provision of mules and their drivers for the transport of the sick and wounded. And now his fighting times commence—not with the sword and revolver with which he was armed; his encounters were with the shadow of death, as an adjunct to the strong body of surgical and medical men who were struggling so hard to make up for the want of preparation in the past.

With regard to the mule service there is a grim touch in one of Henty’s letters home concerning the duties of these useful, hard-working but stubborn brutes. Where he found himself this portion of the transport service was kept in readiness, some fifty strong, to take ammunition down to the trenches, and on their return journey to bring the wounded back.

A strange life this, superintending and aiding in such matters, for a young man fresh from Cambridge University. It must have been a curious disillusionising to be hurried out to the Crimea, nerve and brain throbbing with warlike aspirations connected with the honour and glory of war, and then to find himself in the sordid atmosphere of the wet tents and rough huts, where the winter was still holding its own, while the constant booming of the great guns added to the general misery and wretchedness. The possibility of an explosion was another cause of anxiety, for there was ever the prospect of a shell falling in one or other of the magazines which supplied the batteries, and a resulting disaster unless the fire could be extinguished in time. These alarms generally occurred in the night, when, following upon the lurid display of flames from some hut or workshop set on fire by Russian shot, there would be the roar of orders, the shouting of men, and the dread of the fire being communicated to the crowd of shipping in the little sheltered harbour.

It was a wondrous change from the calm and quiet of the university city to the roar and turmoil of the besieging camp with the thunder of our batteries, the return fire from Sebastopol, and the constant shells dropping in from the enemy’s forts.

Very shortly after he reached Balaclava he seized an opportunity to ride over the held of Inkermann, the scene of the surprise attack made by the Russians nearly six months before, and he says that at the top of the hill where the principal struggle took place the ground was still covered with the remains of the contest—ammunition pouches, Russian caps, broken weapons and other grim relics—while, rather ironically, in allusion to the way in which the allies were surprised, he says that this spot is now commanded by heavy batteries recently erected, and alludes to the old adage about locking the stable door after the horse is stolen. Even then, so many months after the fight, many bodies of the Russians were still unburied, and lay there as though to demonstrate the horrors of war, the while the hill slope and a valley were so exquisite that the writer fell into raptures about the beauty of the place. The steep cliffs were honeycombed with caverns, a ruined castle stood on an eminence, and the place was beautifully wooded, a stream that trickled through the valley amidst the exquisitely fresh and green grass adding to the wonder and the beauty of the scene. But his day-dream was given a rude awakening by a hint thrown out, of the risks to which a war correspondent is exposed in the pursuit of his duty, for there was the sharp crack of a rifle and the dull thud of a bullet burying itself in a tree, having missed him narrowly, for luckily the Russian who had fired at him had not been quite correct in his aim.

Hurrying back, he forgets the danger that he has escaped, and to his mind it is April once more, and he begins to describe the beauty of the wild flowers with which the slopes are clothed—irises varying in tint from pale yellow to orange, others alternating from light blue to purple, the early spring crocus of pure white, and wild hyacinths in abundance.

On his way, as everything is fraternal among the besiegers, he and his companions pass through the French camp and taste the hospitality of their allies, receiving proof that in this camp, too, matters have been mended after the horrors of the past winter, for the English visitors are welcomed with what Henty declares to be first-rate provisions. But he is dreadfully matter-of-fact and businesslike directly after, as behoves an officer of the Purveyors’ Department, for he falls a-wondering why it is that the French bread is far superior to that made by the bakers in Balaclava, the latter having a sour taste that is unpleasant and, he thinks, unwholesome. For his part he prefers the biscuit, but feels that on their return to England he and his comrades will be entitled to a handsome compensation for wear and tear of teeth in the service of their country. Then, as if by way of comparison with the alarms that had suggested a fresh attack, he states that the night was less noisy than usual. “In the early part our sharpshooters and the Russians’ were cracking away, but about eleven the Russian works opened upon the parties engaged in the new parallel.” The next night he announces that a colonel of a French regiment of infantry was struck down while talking in the trenches to a subaltern—“a sixty-eight pound shot shattered him frightfully.”

At this time England was in the throes of expectation. The long-delayed assault upon Sebastopol was expected at any moment, and the main subject of conversation out in the camp was what day would be appointed. But Henty says, “What day that will be no one but Lord Raglan knows—even if he does himself.” However, at last the long-expected bombardment did begin. From a complete circle of batteries round the town, jets of smoke were bursting, while a perfect shower of shot and shell was poured into the town and was as incessantly answered. The wonder was that buildings did not crumble into dust before such a tremendous fire, for from our great crescent of mortars a shell was sent every ten minutes during the night, and the mules that bore the ammunition to the trenches came back sadly laden with wounded.

Day after day the assault went on, and Henty devoted his spare moments to recording the various proceedings of the historic siege—the continuous fire of the English and their French allies, which, in spite of their vigour, only silenced the Russian batteries for fresh ones to be opened again after a few hours’ hard work; the occasional skirmishes where attack was made by the Russians to carry a battery and be repelled; the destruction of rifle pits; the surprises caused by the Cossacks beginning to show themselves out upon the plain; attacks when prisoners were taken; replies and rescues. Then his interest was taken by the allies who now appeared upon the field in the shape of the Turks commanded by Omar Pasha in person. He describes them as a fine body of men who spend most of their time in drilling; for they display a great want of military discipline, and their movements are little better than a shuffle. But Henty compliments them with the remark that they are getting into order. Then he describes their arms and the excellence of their French rifles, and goes on to display the keenness of his observation as he seems to bring to bear old recollections of the Arabian Nights and the peculiarity of the immense number of hunchbacks among the Turks, nearly all of whom have high round shoulders, which in a great many amounts to actual deformity. It is hard to understand, though, why this should be attributed to their sitting cross-legged. However, he says the Turkish cavalry and artillery are good, the horses small but strongly made and in good condition. Altogether he thinks the Turkish army a most welcome reinforcement. All the time the siege goes on vigorously, with the English men-of-war and gunboats rendering all the help they can by checking the fire of the forts.

Something of the weird state of affairs around the young Commissariat officer and correspondent is seen in his description of a leisurely walk he took to one of our marine batteries. “The air,” he says, “was so still that I could hear not only the explosion but the whiz of every shell most distinctly, though distant seven miles as the crow flies.”

The delicious spring weather that lasted for a time was followed by a gale with sleet, and then by forty hours of rain. The change was mournfully depressing, the streets of Balaclava were a perfect sea of mud, everything was forlorn, miserable, and deserted, the officers in their waterproofs were dejected, and everyone was despondent. However, the purveyor officer remarked that the Guards were by this time all provided with waterproof coats, which kept them dry as they stood at their posts. But a thick mist hung over everything; the rain was soaking through all the tents; the ground had become so soft that the horses sank in over their fetlocks, while their heads were drooping, and they appeared the picture of discomfort. The soldiers going down into the trenches carried a perfect load of clay upon their shoes, while those returning came back wet, knocked up, and soaked to the skin.

In another letter, written just after this dreary time, Henty writes that the night closed in dark and lowering with every promise of wet, a horror for those dwelling in tents; just the sort of night, he says, which the Russians delight in for making a sortie from the besieged city, besides which, he says, they had been unusually quiet, a sign that mischief was afloat; but as the attacking force was growing pretty well accustomed to the habits of the enemy, a very strong body of men was sent down into the trenches. In proof that this was wise, about ten o’clock there came somewhere out of the darkness in front the sound of men using picks and shovels, as if the Russians were raising a breastwork prior to an attack. Then an order rang out, and from our own trenches a sharp fire was opened upon the attacking party; but owing to the darkness and want of aim it was probable that little damage was done, and the defenders crowded together in utter silence, listening and waiting for the attack that all felt was bound to come.

At last, about one o’clock, there was a dull, heavy roar from out of the foggy night. It was the signal gun, and instantly the enemy made a rush at the advanced trenches, to be met with a tremendous volley and stagger back, but only to come on again bravely out of the darkness, thousands strong, while the musketry firing was fiercer than anything that had taken place since the commencement of the siege. This went on for two hours, during which time the whole of the Russians, according to custom, supplemented their fire with the most demoniacal yells, which were responded to by their friends in the town and answered in defiance by the cheers of our men in the other batteries at each repulse which the Russians sustained, for never once, in spite of the bravery of the attack, did they succeed in entering our advanced trenches. The next morning, after they had retired, in spite of the number of wounded and the dead, whom it was their practice to carry off with them, the ground was covered with the fallen.

What an experience for the young war correspondent who was making his first essay in that which was to become his profession for years, and who in this instance proved how thoroughly adequate he was for his task!

Undaunted by their failure and their immense losses, but a short time elapsed before the besieged made another sortie, which proved as unsuccessful as the last; and though the Russian losses must have been immense, in our bayonet-bristling trenches but few men suffered. Henty goes on to say it is quite impossible to describe these night sorties accurately, for those engaged in them know next to nothing in the darkness and confusion. If asked in the morning, they would reply that the Russians came out strong and that our men loaded and fired in their direction as fast as they could, that the Russians yelled awfully, and the shot whizzed about like hail! This was the invariable account of a sortie by those engaged in repelling it, unless there was a surprise and the Russians got inside our trenches, when in the darkness and confusion all were so mixed up that it was hard to know enemy from friend. “Can anything wilder be conceived?” Henty asks in a description of an attempt made by the Russians to seize one of our batteries and spike the guns. The confusion was tremendous. Imagine an attack on a dark night, the rain pouring, the men up to their knees in mud, fighting away all mixed up together, the constant flashes and reports of guns and pistols—the revolver being a most useful weapon on these occasions—the cheers of our men and the yells of the Russians. At the commencement of one of these attacks one of our men saw someone crouching over one of the guns. He asked him what he was doing. The only answer was a cut of the sword, which took off luckily only the tip of his nose. He immediately pinned the man to the gun with his bayonet. He turned out to be a Russian artilleryman who had managed to get in to spike the gun.

These were strange surroundings for a young literary man, for a rough hut was often the study of one who was to grow by degrees one of the widest known of English writers. Not only the pen, but the pencil had become familiar to his fingers, and, possibly to fill up dull moments, he began to make sketches of such objects as took his attention; and the idea striking him that such subjects might prove attractive to one of the editors of an illustrated paper at home, he from time to time tried his hand at some little scene or some quaint-looking character which had caught his eye.

These supplemented his long letters to a relative, and the idea growing upon him, he elaborated his writing, making these letters, evidently with latent hopes for the future, the germs of those which later grew to be so familiar to the British public. Everything is said to have a beginning. Certainly this was the commencement of George Henty’s life as a war correspondent, but these efforts were not entirely successful. The sketches were duly taken by their recipient to the different London illustrated papers, but whether from not being up to the editorial artistic mark, or from the fact that each paper was already fully represented, no success attended their presentation. The letters, however, fared better in one case, for upon their being offered to the editor of the Morning Advertiser, with a statement as to who and what the writer was, and where he was engaged, the editor promised to read them. He kept his word, and proved his acumen by writing out to the young lieutenant with an invitation to him to represent the paper and send him from time to time a series of letters containing the most interesting occurrences of the campaign that came under his notice.

The opening was eagerly seized upon, and proved highly advantageous to both parties. The young officer was a privileged person at head-quarters, and his letters show that he had a keen power of observation and a great faculty for selecting subjects that were of interest to English readers. As a consequence, he continued to represent the Morning Advertiser until he was invalided home.

Chapter Three.

Invalided Home.

Henty’s Crimean experiences were to be but short, but they enabled him to give us many admirable and vivid pictures of those stirring days. Although a non-combatant, he was in the thick of the fight before Sebastopol, and he seems to have missed nothing, from the most sordid features to the brightest and best. He paints the horrors, and takes note of the pathetic, the good, and true.

He gives us straightforward, telling lines regarding the Turks, and he records how our comparatively pitiful strength for the gigantic task upon which we had embarked, and in which our meagre forces had to be supplemented by the gallant sailors landed from the fleet, now grew into immense strength, the last ally being Sardinia with her little army of eighteen thousand men.

He has something to say about Soyer and his culinary campaign and model kitchen, so urgently needed for the sick and suffering, and of the great aid it was to the doctors, whose hands were more than full of the sick and wounded when their battle began with the dire cholera. He has sympathetic words, too, for the heroine of Scutari, where she seems to have led a charmed life, saving the sinking and suffering by her calm sweet presence, and encouraging in their continuous struggle the nurses who would have given up in despair. No wonder that the name of Florence Nightingale was at the time on every lip, and that even now, from the far West and the antipodean South, the English-speaking race pay a pilgrim-like visit to the peaceful home in Derwent Dale where the illustrious lady is spending the evening of her life.

Henty paints, too, his own existence in camp during those spring days when the rain was upon them. He says to his readers: “Let them plant a small tent in the centre of an Irish bog, for to nothing else can I compare this place (before Sebastopol) when it is wet; the mud is everywhere knee-deep, while the wet weather has had another bad effect, in that it has accelerated the attacks of cholera, which is of a most malignant type, and a very large proportion of cases are fatal.” He begins one paragraph, too, with a short sentence which is terribly suggestive of a peril that had passed: “Miss Nightingale is better.”

But all through his narrative, so full of the observations of a young, clear-minded, energetic man, there stands out plainly the fact that he was there upon a particular duty—that connected with the department of which he was an officer. At one time he is writing about the water, the excellency and purity of the supply; then he is condemning the arrangements, and no doubt pointing out the need of a better system, so that this bounteous supply should not be wasted by allowing the horses and mules to trample it into a swamp of mud. And the need for these precautions was soon shown, even during his stay, for as the weeks passed, even where the produce of the springs was plentiful, the men had to go farther and farther afield for a fresh supply.

At another time he is falling foul of the bread which is served out to the officers and men. He denounces it as quite unfit for human food. It was by no means first-rate at the time of its leaving the ovens at Constantinople, but by the time it arrived it was “one mass of blue mould;” yet it was served out regardless of its condition and at a very great risk to the health of the soldiers. In fact, he notes that it was so bad that even animals refused it. No wonder he made comparisons between this and the admirable supply served out to the French army.

Thoughtful and wise too in these early days, Henty has much to say regarding sanitary matters, the necessity for care, and above all—no doubt this was forced upon him by their propinquity—he is eloquent about the hospitals; again, and this would scarcely have been expected from one so young, he points out the way in which the air is tainted by the dead animals which are allowed to lie unburied.

He began his duties at Balaclava in April, and at the beginning of June he writes, as might have been expected, that he is sorry that his letter this time will have to be a short one, as he has for the last two days suffered from a severe attack of the prevailing epidemic, which has prevented him from going out at all. Three days later he sends word that the great bombardment of Sebastopol has recommenced. He too is better—well enough to show his interest in the great general hospital kept especially for the reception of the wounded, and to record that it is filling fast. He has sympathetic words for the sufferers and their ghastly wounds from shot and shell splinter. He talks from personal observation of the firmness and patience of the poor fellows over their wounds, and of the extraordinary coolness and sang-froid with which they suffer the dressing, even to the amputation of an arm above the elbow, both bones below being broken by a minié-ball. The conduct of these humble heroes brings to mind the old naval story of the past, of the Jack whose leg had been taken off in action, and who resented the idea of being tied up while amputation was performed. “No,” he said; “only give me my pipe;” and he sat up and smoked till the surgeon had operated. This in the days, too, when anaesthetics were not in use, and haemorrhage was checked by means of a bucket of tar. Poor Jack sat up consciously and looked on!

Henty’s record is that when one soldier’s operation was performed and he was about to be carried into the hospital ward, he exclaimed, “I’m all right,” rose up and walked to his ward, lighted his pipe, and got into bed. This is given as a single instance taken at random from among numbers of cases.

In his last letter from the Crimea, dated June 18, 1855, he records that there had been a serious reverse to the allied arms. He had by this time somewhat recovered from his severe fit of illness, but he had long been over-exerting himself. The doctors delivered their ultimatum, and he became one of the many who, weakened by the terrible exposure, were invalided home.

Unfortunately a harder fate attended his only brother, Fred, who left England with him when he obtained his appointment to the Purveyors’ Department, for he was seized by the prevailing epidemic, cholera, and died at Scutari.

Chapter Four.

The First Glimpse of Italy.

The department which invalided George Henty and sent him home to recoup did not lose sight of the man who had earned such a good name in the Crimea, and as soon as he was reported convalescent it began to look about for a position in which his services would prove valuable.

Here was a man who, in connection with his duties in the Purveying Department during the late war, had more or less distinguished himself by the acumen he had displayed and the reports he had sent in concerning the state of the temporary hospitals and the treatment of the sick and wounded. There is not much favour shown over such work as his. The fact was patent that in Henty the authorities had a man of keen observation who grasped at once what was wanted in time of war in connection with the movements of an army, one whose mission it was not to direct movements and utilise the forces who were, so to speak, being used in warfare, but who knew how to make himself a valuable aid to supplement doctor and surgeon, and to carry on their work of saving life—in short, the right man in the right place.

So he was selected and sent out to Italy charged with the task of organising the hospitals of the Italian Legion. The very wording of such an appointment as this is enough to take an ordinary person’s breath away. It might have been supposed that the department would have selected as organiser some mature professional man and M.D., with the greatest experience in such matters, ripened in the work and well known as a great authority; but to their credit they grasped the fact that Henty’s experience was proved and real. Book-lore and the passing of examinations were as nothing in comparison with what this young man of twenty-seven had learned in roughly extemporised hospital, tent, and hut amidst the inclemency of a foreign clime, in the face of the horrible scourge of an Eastern epidemic, where the wounded died off like flies, not from the wounds, which under healthy environment would rapidly have healed, but from that deadly enemy, pyaemia, or hospital gangrene. It was this which proved so fatal after the otherwise healing touch of the skilful surgeon’s knife—for these were the days prior to the discoveries made by Lister, which completely revolutionised the surgical art.

While in Italy in 1859 in connection with the hospital work, Henty stored his mind with the results of his observations. They were stirring times. War was on the way; Sardinia’s army, fresh from fleshing its sword in the Crimea, was eager for the fight that was partially to free Italy, and the name of Garibaldi was on every lip, for he and his Red Shirts were burning to attack the hated Austrian. While finding an opportunity to be present at some of the engagements, Henty was busy preparing himself for writing history, and his brain was actively acquiring the language and habits of the people in a way that was an unconscious preparation for a future visit to the country in connection with the duties of a war correspondent.

It was during this visit to Italy in 1859, and while performing his duties of inspector and organiser of the Italian hospitals, that Henty made his first acquaintance with Garibaldi and his enthusiastic army so bent upon freeing Italy from the yoke of Austria. In a number of most interesting letters, picturesque and full of the observation and training that he was gathering for the construction of the series of adventurous stories now standing to his name, he details his meetings with the Red Shirts. Bright, high-spirited boys they were in many cases, ever with the cry of liberty upon their lips, and only too ready to welcome and to fraternise with the daring, manly young fellow who thought as little as they of the personal risks which had to be faced, and who was subsequently to chronicle this portion of their history and the warlike deeds of their chief.

After his return from the organising expedition with the Italian Legion, Henty was placed in charge of the Commissariat Departments at Belfast and Portsmouth, and now held the rank of captain. A plodding life this for a military man with all the making in him of a strong, thoughtful soldier, one who would have become the strongest link in the vertebrae of a regiment, so to speak, the one nearest the brain.

Fate, however did not guide him in that direction, but, as we know now, led him towards becoming the critic of armies instead of an actor in their ranks.

Judging from Henty’s nature and the steadiness and constancy of his life in the pursuit of the career which he chose, it could not have been lightly that he came to the decision that from the way in which he had entered the army there did not seem to be any future for him worthy of his attention, for the British army has always been marked by the way in which birth and money have been the stepping-stones to promotion. Of course there have been exceptions, but the British soldier has never been famed for carrying a field-marshal’s baton in his knapsack, and it is only of comparatively late years that the famous old anomaly of promotion by purchase has died out.

Certainly Henty entered the army as a university man and a gentleman, but he must have begun to feel, taught by experience, that he had gone in by the wrong door, the one which led in an administrative direction and not to the executive with a future of command.

During Henty’s stay in Ireland he had a very unpleasant experience with a rough in Dublin, or rather, to be accurate, a rough in Dublin had a very unpleasant experience with Henty. Somehow or other, while out walking with his young wife, for he was now married, a brutal fellow offered some insult to Mrs Henty, in the purest ignorance of the kind of man whose anger he had roused. One says roused, for in ordinary life Henty was one of the calmest and quietest of men; but he had plenty of chivalry in his composition, and moreover, as has been shown, he had had the education and training of an athlete, leavened with the instructions of the North-country trainer who taught him the jiu-jitsu of his day as practised by a Newcastle man. What followed was very brief, for there was a quick, short struggle, and the Dublin Pat—a city blackguard, and no carrier of a stick—was sent flying over Henty’s head, hors de combat, much surprised at the strength and skill of such a man as he had possibly never encountered before in his life.

Chapter Five.

The Italian War.

Henty proved early the excellence of his capabilities, and that he was a man who would be all that was required for the preservation of men’s lives; but such as he meet with scant encouragement, and at last, as said above, he made up his mind to try in a fresh direction, and resigned his commission.

Led no doubt by his leanings, and taught by old experience in connection with his father’s enterprises in coal-mining, he made a fresh start in life in mining engineering, and was for some time in Wales, where his knowledge of mining, and natural firmness and aptitude as a leader and trained controller of bodies of men, made him a valuable agent for the adventurous companies who are ready to open up new ground. His operations were so successful that after a time he entered into engagements which resulted in his proceeding to the Island of Sardinia. Here there was much untried ground to invite the speculation of the enterprising and adventurous; for it is a country rich in minerals, several of them being so-called precious stones, and there seemed excellent promise of profit. A good deal of speculative research was at one time on the way, and here, following his work in Wales, Henty spent some busy years, not, though, without finding the value of his early athletic education, for the lower orders were not too well disposed to the young English manager under whom they worked.

Returning to England early in the sixties, he once more turned his attention to his pen, having proved, while in the Crimea, his ability for writing quick and observant descriptive copy, specimens of which were extant in the columns of the Morning Advertiser, and of which he had examples pasted up and preserved. Moreover, when he began to make application for work, he had the satisfaction of finding that his articles had already excited notice in the literary world. This helped him to obtain an engagement, somewhere in 1865, as special correspondent of the Standard, and he carried out his duties so successfully that he became a standard of the Standard, and was sent out in 1866 as one of the special correspondents of that paper to Italy, to report upon the proceedings of the Italian armies which had then united in the operations against the Austrian forces.

Italy was to some extent familiar hunting-ground for Henty, inasmuch as at the time when he went to undertake the task of reorganising the hospitals of the Italian Legion he had seen a good deal of the country, picked up much of the language, and had become acquainted with Garibaldi and his followers when, as said before, they were engaged in the encounters which resulted in partially freeing Italy from the Austrian yoke.

It was now that his early experience of the country and the mastery he had obtained over the Italian language stood him in good stead, while, as a matter of course, his experience and general knowledge of the country made him an ideal chronicler of the movements of the campaign.

Plunged, as it were, right in the midst of the troubles, he seems to have been here, there, and everywhere, and by some means or another he was always on the spot whenever anything exciting was on the way. Now he was at sea, now with the Garibaldians scouting on the flanks of the Austrian army, now making journeys by Vetturinos across the mountains, to turn up somewhere along with the forces of the king, and always ready to bring a critical eye to bear—the eye of a soldier—in comparing the three forces, the volunteer Garibaldians, the Italian regulars, and the Austrians. The last mentioned seemed to him to be, in their drill, unquestionably superior to the Italians, displaying a strong esprit de corps, rigid obedience to their officers, and an amount of German impassibility far more adapted to make them bear unmoved the hardships and discouragements of long struggles and reverses than the enthusiasm of the Italians—an enthusiasm which was manifested in a perfect furore of delight throughout Italy on the news of the declaration of war, tidings reaching Henty from every city, of illuminations, of draping with flags, and other celebrations.

“Even Naples,” he says, “which has been far behind the rest of Italy in her ardour for the cause, began to rejoice at the termination of the long delay;” but he declares there was no doubt that the reactionary party had been very hard at work there, with the result that a number of turbulent spirits had been sent away from among the volunteers, the excesses which they had committed threatening to bring the Garibaldians into disrepute.

He now fully proved his ability for the task he had undertaken. Writing home as soon as he had crossed Switzerland early in June a long series of most interesting letters, he commenced with his first meeting with Garibaldi and his followers at Como, and continued throughout the war until victory crowned the efforts of the united armies of Italy and the patriots, and ended (as in a culminating outburst of pyrotechnic display) with the triumphant spectacles at Venice after the Austrians were finally expelled.

Later, Henty gave permanency to his ephemeral contributions to the journal upon which he was engaged; but in these early days he was a comparatively unknown man, with nothing to commend him to the notice of an enterprising publisher, and the makings of a most interesting descriptive work sparkled for a few hours in the pages of the big contemporary newspaper and then died out, with the ashes only left, hidden, save to searchers in the files preserved at the newspaper office and in the British Museum. For Henty, wanting time and opportunity, never reproduced these letters in their entirety, though they remained in the journalistic print and in petto, ready for use, as in a kind of brain mine when, as time rolled on, his adventures in story-land began to achieve success and excite demand. Then they doubtless supplied pabulum for such tales as Jack Archer, The Cat of Bubastes, and The Lion of Saint Mark, stories quite remarkable for the truth of their local colour. The last named so influenced a young American lad on a visit to England, that he prevailed upon his father to take him to see Henty, while afterwards, on being taken to Venice, he wrote a clever, naïve letter, which is quoted elsewhere, to the author of his choice, telling him of his delight in coming to Europe and seeing for himself the Venice of to-day, where he recognised the very places that Henty had so truthfully described.

It is a pity that these letters were not reprinted in book form; but long before an opportunity could have served, the brave struggles of the Italians to free themselves from the Austrian yoke, and the fame of Garibaldi, had grown stale as popular subjects for the general reader, and the question with the publisher, “would a book upon this subject sell?” being only answerable in the negative, nothing was done. In fact, in those days, save in one instance, there was no demand for the reprinting of a journalist’s contributions to a daily paper. This particular instance seemed to stand out at once as the prerogative of one man alone, he who has only just gone to his well-earned and honoured rest, and whose contributions to the Times, My Diary in India, that vivid narrative of the suppression of the Indian Mutiny, became a classic.

It was like old times to Henty, after crossing Switzerland, to find himself at Como awaiting the arrival of Garibaldi, who was reported to be on his way. A portion of the Garibaldian army was already there, and in a short time, to his great satisfaction, Henty found that their chief was hourly expected to take command of the volunteers.

His information proved to be true, and in the midst of tremendous enthusiasm he found the volunteers drawn up in double line reaching through the town, flags waving, the people shouting, and everyone working himself into a fever of heat.

As the chief approached, the people seemed to have gone out of their minds. Caps were thrown up recklessly, at the risk of never being recovered, and the people literally roared as the general, looking in good health, though older and greyer than when Henty last saw him in 1859, rode along the ranks of the seven thousand or so of volunteers that he was about to review and passed on, waving his hand in reply to the cheering, as if thoroughly appreciating the greeting, much as he did during his reception in London.

The town seemed afterwards to be swarming with his soldiers. It appeared as if two out of every three persons in the streets upon close examination proved to be Garibaldians—close examination was necessary, for it needed research to make sure that they were volunteers, consequent upon the fact that in many cases anything in the shape of uniforms was wanting.

As a rule their uniform, he points out, should have been the familiar red shirt, belt, and dark-grey trousers with red stripe, surmounted by red caps, with green bands and straight peaks. In one of his early letters at this stage Henty describes the incongruous nature of the men’s dress. Perhaps one-fourth would have the caps; another fourth would look like the ancient Phrygians or the French fishermen. Perhaps one-third would have the red shirts; possibly nearly half, the regulation trousers; and where uniform was wanting they made up their dress with articles of their usual wear—wide-awakes, hats, caps of every shape, jackets, coats black and coloured. Some were dressed like gentlemen, some like members of the extreme lower order, altogether looking such an unsatisfactory motley group as that which old Sir John Falstaff declared he would not march with through Coventry.

But in spite of this there seemed to be the material for a dashing army amongst these men. They promised to make the finest of recruits, though certainly the observant eyes of Henty told him that many of them were far too young to stand the fatigue that they would be called upon to suffer during the war, a number of them being mere boys, not looking above fifteen. But Garibaldi was said to be partial to youngsters, and he liked the activity of the boys, who, he declared, fought as well as men.

On the whole, according to Henty’s showing, Garibaldi’s volunteer troops were very much the same as flocked to our best volunteer regiments in London during the early days. In short, the enthusiasm of the Garibaldians was contagious, and Henty wrote of them with a running pen; but his enthusiasm was leavened with the common sense and coolness of the well-drilled organising young soldier, who made no scruple while admiring the Garibaldians’ pluck, self-denial, and determination to oust the hated Austrian, to point out their shortcomings as an army and their inability to prove themselves much more than a guerrilla band.

They were an army of irregulars, of course, but with a strong adhesion based upon enthusiastic patriotism. With such an army as this it may be supposed that the followers of their camp sent order and discipline to the winds, and the war correspondent had to thank once more that portion of his athletic education that had made him what he was. To use his own words, out there in Italy he “thanked his stars” that his youthful experience had made him a pretty good man with his hands. He found himself in his avocations amongst a scum of Italian roughs ready to play the European Ishmaelite, with their hands against every man—hands that in any encounter grasped the knife-like stiletto, ready, the moment there was any resistance to their marauding, to stab mercilessly Italian patriot or believer in the Austrian yoke, friend or foe, or merely an English spectator if he stood in their way. But to their cost in different encounters these gentry learned that the young correspondent was no common man, for Henty, in recording his experience with the pugnacious Garibaldian camp-followers, says calmly and in the most naïve manner, and moreover so simply that there is not even a suggestion of boastfulness or brag: “I learned from experiment that if necessary I could deal with about four of them at once; and they were the sort of gentry who would make no bones about getting one down and stabbing one if they got the chance.” It was no Falstaff who spoke these words, for they were the utterances of a perfectly sincere, modest Englishman, albeit rather proud, after such a childhood, of his robust physique and of the way in which he could use his fists or prove how skilfully he could deal with an attacking foe and hurl him headlong, much in the same sort of way as a North-country wrestler might dispose of some malicious monkey or any wasp-like enemy of pitiful physique—comparatively helpless unless he could use his sting.

Henty took all such matters as these quite as a matter of course. He felt, as he wrote, that a war correspondent to do his duty must accept all kinds of risks in his search for interesting material to form the basis of his letters to his journal. But incidentally we learn about semi-starvation, the scarcity of shelter, the rumours of the old dire enemy, cholera, whose name was so strongly associated with past adventures in the Crimea, risks from shell and shot, and ugly dangers too from those who should have been friends.

For there is one word—spy—that always stands out as a terror, and it was during this campaign that in his eagerness to obtain information he approached so closely to the lines that he was arrested as such by one of the sentries and passed on from pillar to post among the ignorant soldiery.

In this case he had started with a friend for an investigating drive in the neighbourhood of Peschiera, at a time when encounters had been taking place between the Italian army and the Austrians. Upon reaching a spot where a good view of the frowning earth-works with their tiers of cannon could be obtained, they left the carriage, and climbed a hill or two, when they were attracted by the sound of firing, and hurrying on they came to a spot where some of the peasants were watching what was going on across a river. Upon reaching the little group they found out that it was not a skirmish, but that the Austrians were engaged in a sort of review on the ground where there had been a battle a few days before.

Henty felt that he was in luck, for he found that the peasants had been witnesses of the battle from that very position and were eager to point out what had taken place, the men giving a vivid description of the horrors they had witnessed and the slaughter that had taken place.

Having obtained sufficient from one of the speakers to form an interesting letter, he and his friend returned to their carriage and told the driver to go back. Henty had picked up a good deal of Italian, but not sufficient to make himself thoroughly understood by the driver, and, as is often the case, a foreigner of the lower orders failed to grasp that which a cultivated person would comprehend at once. The consequence was that the man drove on instead of returning, and his fares did not find out the mistake till they caught sight of a couple of pickets belonging to the Guides, the finest body of cavalry in the Italian service. Seeing that they were on the wrong track, Henty stopped the driver, questioned him, and then, fully understanding the mistake, told him to drive back at once. But the pickets had seen them, and came cantering up. Explanations were made, but the Guides were not satisfied. They had noticed the coming of the carriage, and had become aware of what to them was a very suspicious act. The occupants were strangers, and had been making use of a telescope, which from their point of view was a spyglass—that is to say, an instrument that was used by a spy—while they might have come from the Austrian side before ascending the hill. This was exceedingly condemnatory in the eyes of a couple of fairly intelligent men, but they treated them politely enough when they explained matters and produced their passports.

A very unpleasant contretemps, however, began to develop when the pickets said the passports might be quite correct, but they did not feel justified in releasing the two foreign strangers, who might be, as they said, Englishmen, but who were in all probability Austrians. So they must be taken to their officer, who was about a mile farther on.

It was a case of only two to two, and Henty’s blood began to grow hot at the opposition. He was on the point of showing his resentment, but wiser counsels prevailed; after all, it was two well-mounted and well-armed soldiers of the flower of the Italian cavalry against a couple of civilians, and, feeling that this was one of the occasions when discretion is the better part of valour, especially as a seat in a carriage was a post of disadvantage when opposed to a swordsman in a saddle, he swallowed his wrath and told the driver to go in the direction indicated by his captors. For the first time in his life he realised what it was to be a prisoner with a mounted guard.

The officer, who proved to be a sergeant, received them with Italian politeness, listened to their explanations, and at the end pointed out that the movements of the carriage, which might have come from an entirely different direction from that which they asserted, and the use of the telescope, looked so suspicious in the face of the nearness of the enemy, that he must make them accompany him to his captain about a couple of miles away.

Matters were beginning to grow dramatic, and the feeling of uneasiness increased, for as a war correspondent no one could have realised more readily than Henty that he was undoubtedly looked upon as a spy, and one whom the sergeant felt he must in no wise suffer to escape, for he and his companion were now being escorted by a guard of four of the Guides.

There was nothing for it, however, but to put a good face upon the matter and keep perfectly cool, though, to say the least of it, affairs were growing very unpleasant. It was an accident the consequences of which might be very ugly indeed, and this appealed very strongly to his active imagination. When he set off from the offices of the Standard upon his letter-writing mission, no thought of ever being arrested and possibly sentenced as a spy had ever entered into his calculations.

Henty gives the merest skeleton of his adventure, but as a man who was in the habit of writing adventures and who possessed the active imaginative brain previously alluded to, it stands to reason that in the circumstances he must have thought out what he would have set down if he had been writing an account of the treatment likely to be meted out to an enemy’s spy, especially to a hated Austrian, by the hot-blooded patriotic Italians.

Some distance farther on in the warlike district, Henty and his companion were escorted to a small village occupied by about a hundred of the Guides and about twice as many Bersaglieri. Here they were in the presence of superior officers, before whom they were brought, and to whom they again explained and produced their passports, and in addition Henty brought out a letter of recommendation to the officers of the Italian army, with which he had been furnished before starting on his journey by the kindness of the Italian ambassador in London.

Here there was another example of the refined Italian politeness, and Henty must have felt a strange resentment against this extreme civility, so suggestive of the treatment that was being meted out to a man who was being adjudged before an ultimate condemnation, for the officers declared that the explanations were no doubt perfectly correct, but that in the circumstances it was their duty to forward the two prisoners to their general. The general was about half a dozen miles away, while, as unfortunately one of their men had been wounded, they must ask the strangers to put their carriage at the service of the poor fellow, who was suffering terribly from the jolting of the bullock-cart in which he lay with five other wounded men, lesser sufferers.

Accordingly Henty and his friend had to take their places on the bullock-cart with five wounded Austrian prisoners, and the procession started. A circumstance that was extremely ominous was that they were preceded by another cart in which was another prisoner. This man was a spy about whom there was not the slightest doubt, for he had been caught in the reprehensible act, and his fate would most probably be to have an extremely short shrift and be shot in the morning. These were facts that impressed themselves very painfully upon the imagination of the young war correspondent, who must have felt that going before the general in such extremely bad company was almost enough to seal his fate, and he felt the more bitter from the simple and natural fact that it would be most likely impossible for him to send a final letter to the Standard to record that his unfortunate engagement was at an end.

The decision having been made as well as the change, matters looked worse and worse, for the procession was now guarded by a line of about thirty cavalry. In front and rear marched a company of the Italian foot, while the officers proceeded cautiously, as the road on their side ran close to the Mincio, across which the Austrians might at any moment make a sortie.

Then the proceedings grew still more dramatic and depressing, for several military camps were passed, out of which the men came running to look at the prisoners, and on hearing from the escort that one of the party was a spy, they began to make remarks that were the reverse of pleasant. All the same the young captain in command of the Guides was particularly civil to Henty, and did all he could to make his position as little unpleasant as possible, chatting freely about the last engagement and the part his squadron had taken in the fight. But he was much taken up in looking after his troops, and his English prisoners had plenty of time for meditation as to their future prospects, and the outlook was not reassuring.

At last head-quarters were reached, and after a short detention the prisoners were taken before the General, Henty preserving all the time the calm, firm appearance that he had maintained from the first; and in all probability it was his quiet confidence that saved his life.