Title: Dr. John McLoughlin, the Father of Oregon

Author: Frederick V. Holman

Release date: May 18, 2011 [eBook #36146]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David E. Brown, Bryan Ness and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

DR. JOHN McLOUGHLIN[1]

Dr. John McLoughlin

Taken from a daguerreotype of Dr. John McLoughlin made in 1856, about a year before his death. The original daguerreotype belongs to Mrs. Josiah Myrick of Portland, Oregon, a granddaughter of Dr. McLoughlin.

DR. JOHN McLOUGHLIN

the Father of Oregon

BY

FREDERICK V. HOLMAN

Director of the Oregon Pioneer Association and of the Oregon Historical Society

With Portraits

Cleveland, Ohio

The Arthur H. Clark Company

1907

COPYRIGHT, 1907, BY[6]

FREDERICK V. HOLMAN

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

To the true, good, brave Oregon Pioneers of 1843, 1844, 1845, and 1846, whose coming in the time of joint-occupancy did so much to help save Oregon and assisted in making it what it is today; whose affections and regards for Dr. John McLoughlin and whose remembrances and heartfelt appreciations of his humanity and kindness to them and theirs can and could end only with their deaths, this volume is most respectfully dedicated.

CONTENTS

| PREFACE | 15 |

| TEXT | 19 |

| Early Settlements and Joint-occupancy of the Oregon Country | 20 |

| The Hudson's Bay Company and the Northwest Company | 21 |

| Genealogy and Family of Dr. John McLoughlin | 22 |

| McLoughlin and the Oregon Country | 25 |

| Fort Vancouver | 27 |

| Punishment of Indians | 35 |

| Early French Canadian Settlers | 41 |

| Early American Traders and Travellers | 45 |

| Presbyterian Missionaries | 52 |

| Methodist Missions and Missionaries | 54 |

| Provisional Government | 64 |

| Immigration of 1842 | 69 |

| Immigration of 1843 | 70 |

| Immigration of 1844 | 78 |

| Immigration of 1845 | 81 |

| The Quality of the Early Immigrants | 83 |

| The Resignation of Dr. John McLoughlin | 90 |

| Dr. McLoughlin's Religion | 98 |

| Dr. McLoughlin's Land Claim | 101 |

| Abernethy Island | 114 |

| The Shortess Petition | 116 |

| Land Laws of the Provisional Government | 119 |

| Dr. McLoughlin's Naturalization | 120 |

| Conspiracy against Dr. McLoughlin[10] | 122 |

| Thurston's Letter to Congress | 123 |

| Protests against Thurston's Actions | 137 |

| The Oregon Donation Land Law | 140 |

| The Conspiracy Effective | 143 |

| Career and Death of Thurston | 144 |

| The Methodist Episcopal Church | 146 |

| Dr. McLoughlin's Memorial To Congress | 149 |

| The Persecution Continued | 152 |

| The End of Dr. McLoughlin's Life | 154 |

| Justice To Dr. McLoughlin's Memory | 159 |

| Opinions by Dr. McLoughlin's Contemporaries | 162 |

| Eulogy upon Dr. McLoughlin | 169 |

ILLUSTRATIVE DOCUMENTS REFERRED TO IN THE TEXT:

| A: Article 3 of Convention of October 20, 1818, between the United States and Great Britain | 175 |

| B: Convention of August 6, 1827, between the United States and Great Britain | 175 |

| C: Statement concerning merger of Hudson's Bay Company and Northwest Company; and grant to Hudson's Bay Company of 1821 and 1838 to trade in the Oregon Country | 176 |

| D: Excerpts from Manuscript Journal of Rev. Jason Lee | 180 |

| E: Rev. Jason Lee's visit to Eastern States in 1838; and his report to the Missionary Board at New York in 1844 | 185 |

| F: Excerpts from Narrative of Commodore Charles Wilkes, U.S.N., published in Philadelphia in 1845 | 190 |

| G: Letter from Henry Brallier to Frederick V. Holman of October 27, 1905 | 196 |

| H: Shortess Petition; excerpts from Gray's "History[11] of Oregon" relating to Shortess Petition; and excerpt from speech of Samuel R. Thurston in Congress, December 26, 1850, as to author of Shortess Petition | 198 |

| I: Ricord's Proclamation; letters of A. Lawrence Lovejoy and Rev. A. F. Waller of March 20, 1844; Ricord's Caveat; invalidity of Waller's claim to Dr. McLoughlin's land; and excerpts from letters of Rev. Jason Lee to Rev. A. F. Waller and Rev. Gustavus Hines, written in 1844 | 212 |

| J: Agreement between Dr. John McLoughlin, Rev. A. F. Waller, and Rev. David Leslie, of April 4, 1844; statement of cause and manner of making said agreement | 224 |

| K: Statement of career in Oregon of Judge W. P. Bryant | 228 |

| L: Letter of Dr. John McLoughlin, published in the "Oregon Spectator" Thursday, September 12, 1850 | 229 |

| M: Letter by William J. Berry, published in the "Oregon Spectator," December 26, 1850 | 243 |

| N: Excerpts from speech of Samuel R. Thurston in Congress, December 26, 1850 | 246 |

| O: Correspondence of S. R. Thurston, Nathaniel J. Wyeth, Robert C. Winthrop and Dr. John McLoughlin, published in the "Oregon Spectator," April 3, 1851 | 256 |

| P: Letter from Rev. Vincent Snelling to Dr. John McLoughlin of March 9, 1852 | 262 |

| Q: Excerpts from "The Hudson's Bay Company and Vancouver's Island" by James Edward Fitzgerald, published in London in 1849; and excerpt from "Ten Years in Oregon," by Rev. Daniel Lee and Rev. J. H. Frost, published in New York in 1844 | 264 |

| [12]R: Note on Authorship of "History of Oregon" in Bancroft's Works; and sources of information for this monograph | 270 |

| S: Excerpts from opinions of contemporaries of Dr. McLoughlin | 272 |

| INDEX | 287 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| Portrait of Dr. John McLoughlin, taken from daguerreotype of 1856; from original belonging to Mrs. Josiah Myrick, Portland, Oregon | Frontispiece |

| Portrait of Dr. John McLoughlin, taken from miniature painted on ivory, 1838 or 1839; from original belonging to Mrs. James W. McL. Harvey, Mirabel, California. | facing p. 62 |

PREFACE

This is a plain and simple narrative of the life of Dr. John McLoughlin, and of his noble career in the early history of Oregon. The writing of it is a labor of love on my part, for I am Oregon-born. A number of my near relatives came to Oregon overland in the immigrations of 1843, 1845, and 1846. My father and mother came overland in 1846. The one great theme of the Oregon pioneers was and still is Dr. McLoughlin and his humanity. I came so to know of him that I could almost believe I had known him personally.

He, the father of Oregon, died September third, 1857, yet his memory is as much respected as though his death were of recent occurrence. In Oregon he will never be forgotten. He is known in Oregon by tradition as well as by history. His deeds are a part of the folk-lore of Oregon. His life is an essential part of the early, the heroic days of early Oregon. I know of him from the conversations of pioneers, who loved him, and from the numerous heart-felt expressions at the annual meetings of the Oregon pioneers, beginning with their first meeting. For years I have been collecting and reading books on early Oregon and the Pacific Northwest Coast. I am familiar with[16] many letters and rare documents in the possession of the Oregon Historical Society relating to events in the time of the settlement of Oregon, and containing frequent references to Dr. McLoughlin.

October sixth, 1905, was set apart as McLoughlin Day by the Lewis and Clark Exposition, at Portland, Oregon. I had the honor to be selected to deliver the address on that occasion. In writing that address I was obliged to familiarize myself with exact knowledge of dates and other important circumstances connected with the life and times of Dr. McLoughlin. In writing it, although I endeavored to be concise, the story grew until it went beyond the proper length for an address, and so I condensed it for oral delivery on McLoughlin Day.

Since that time I have largely rewritten it, and, while not changing the style essentially, I have added to it so that it has become a short history. For the benefit of those interested in Dr. John McLoughlin and the history of early Oregon, I have added notes and many documents. The latter show some of the sources from which I have drawn, but only some of them. They are necessary to a thorough understanding, particularly, as to the causes of his tribulations, and of what is due to him as a great humanitarian, and of his great services in the upbuilding of Oregon.

I have been kindly assisted by men and women still living who knew him personally, by those who gladly bear witness to what he was and what he did, and by those who have studied his life and times as a matter of historical interest.

[17]The full history of the life of Dr. John McLoughlin will be written in the future. Such a history will have all the interest of a great romance. It begins in happiness and ends in martyrdom. It is so remarkable that one unacquainted with the facts might doubt if some of these matters I have set forth could be true. Unfortunately they are true.

Frederick V. Holman

Portland, Oregon, January, 1907.

DR. JOHN McLOUGHLIN

The story of the life of Dr. John McLoughlin comprises largely the history of Oregon beginning in the time of joint-occupancy of the Oregon Country, and continuing until after the boundary treaty dividing the Oregon Country between the United States and Great Britain, the establishment of the Oregon Territorial Government, and the passage of the Oregon Donation Law. It relates directly to events in Oregon from 1824 until the death of Dr. McLoughlin in 1857, and incidentally to what occurred in Oregon as far back as the founding of Astoria in 1811.

Prior to the Treaty of 1846 between the United States and England fixing the present northern boundary line of the United States west of the Rocky Mountains, what was known as the "Oregon Country" was bounded on the south by north latitude forty-two degrees, the present northern boundary of the states of California and Nevada; on the north by latitude fifty-four degrees and forty minutes, the present southern boundary of Alaska; on the east by the Rocky Mountains; and on the west by the Pacific Ocean. It included all of the states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, and parts of the states of Montana[20] and Wyoming, and all of the present Dominion of Canada between latitudes forty-nine degrees and fifty-four degrees forty minutes, and west of the Rocky Mountains. Its area was approximately four hundred thousand square miles, an area about twenty-five per cent. greater than that of the original thirteen colonies at the time of the American Revolution.

Early Settlements and Joint-occupancy of the Oregon Country.

The first permanent settlement on the Columbia River was made by the Pacific Fur Company, which was organized and controlled by John Jacob Astor. It founded Astoria March 22, 1811. October 16, 1813, during the war of 1812, the establishments of the Pacific Fur Company in the Oregon Country, and all its furs and supplies, were sold, at less than one-third of their value, to the Northwest Company, of Montreal, by the treachery of Duncan McDougal, a partner of Astor in the Pacific Fur Company. December 1, 1813, the British sloop-of-war Raccoon arrived at Astoria and took formal possession of it in the name of the King of Great Britain. The captain of the Raccoon changed the name of Astoria to that of Fort George. Its name is now Astoria. The Northwest Company continued to carry on its business at Fort George and at other points in the Oregon Country until its coalition with the Hudson's Bay Company in 1821.

The treaty of peace between the United States and England at the conclusion of the war of 1812 was signed at Ghent, December 24, 1814. It is[21] known as the "Treaty of Ghent." Under this treaty Great Britain, on October 6, 1818, formally restored to the United States "the settlement of Fort George on the Columbia River." A Convention between the United States and Great Britain was signed October 20, 1818. That Convention provided that the Oregon Country should be free and open, for the period of ten years, to the citizens and subjects of the two countries, being what is called for convenience joint-occupancy by the two countries.[1] Another Convention between the two countries was made in 1827, by which this joint-occupancy was continued indefinitely, subject to termination after October 20, 1828, by either the United States or Great Britain giving to the other twelve months' notice.[2] In April, 1846, Congress passed a joint resolution giving the President authority, at his discretion, to give such notice to the British Government. Under the authority of this resolution President Polk signed a notice, dated April 28, 1846, which by its terms was to go into effect from and after its delivery to the British Government at London. June 6, 1846, the British Government proposed the present boundary. This was accepted by the American Government. The treaty was signed at Washington, June 15, 1846.

The Hudson's Bay Company and the Northwest Company.

The Hudson's Bay Company was established in 1670 under a charter granted by King Charles II.[22] The Northwest Company was formed in Montreal in 1783-4. It became the great rival of the Hudson's Bay Company. Warfare occurred between the two companies, beginning in 1815. A compromise was finally effected and in 1821 the Northwest Company coalesced with the Hudson's Bay Company[3]. Dr. McLoughlin was a partner of the Northwest Company and opposed the coalition in a most determined manner. He would not sign the final agreement, as he considered it unfair to himself and to his associates in the Northwest Company. But the Hudson's Bay Company knew of Dr. McLoughlin, his resolution, his power, and his capacity, and it employed him as Chief Factor to manage and to build up the Company's business in the Oregon Country. He was given plenary powers. He was the man for the place and the time.

Genealogy and Family of Dr. John McLoughlin.

Dr. John McLoughlin was born October 19, 1784, in Parish La Rivière du Loup, Canada, about one hundred and twenty miles below Quebec, on the south side of the St. Lawrence River. He was baptized November 3, 1784, at the Parish of Kamouraska, Canada, there being no Roman Catholic priest at La Rivière du Loup. Both of his parents were Roman Catholics. His father was John McLoughlin, a native of Ireland. Of him little is now known, excepting that he was a man of high character. He was accidentally drowned in the St. Lawrence River. The date I[23] have been unable to ascertain. It was probably while his son John was quite young. For convenience I shall hereinafter speak of John McLoughlin, the younger, as Dr. John McLoughlin, or Dr. McLoughlin. His mother's maiden name was Angelique Fraser. She was a very fine woman. She was born in the Parish of Beaumont, Canada, and died in Canada, July 3, 1842, aged 83 years. Her father was Malcolm Fraser, a native of Scotland. At the time of his retirement from the army and settlement in Canada, in 1763, he was a captain in the 84th regiment of the British regular army. He was at one time a lieutenant in the 78th regiment, known as the Fraser Highlanders. He spelled his name with two "f's"—Ffraser. His daughter was also related to Gen. Fraser, one of Burgoyne's principal officers, who was killed at the battle of Saratoga, October 7, 1777.

Dr. John McLoughlin's father and mother had seven children, of which five were daughters; the youngest daughter died while young. He was the second child, the eldest son, his only brother, David, being the third child. It is probable that Dr. John McLoughlin and his brother David were brought up in the home of their maternal grandfather. Their only maternal uncle was Samuel Fraser, M.D. He was a lieutenant in the Royal Highland Regiment (the famous "Black Watch" regiment). He took part in all the engagements fought by that regiment from 1795 to 1803, in the Napoleonic wars. Their maternal relatives seem to have exercised a strong influence on[24] both young John and David McLoughlin. They both became physicians. David served in the British army, and, after the Battle of Waterloo, practiced medicine in Paris, France. Dr. John McLoughlin was educated in Canada and Scotland. He joined the Northwest Company, which was composed and controlled by very active, practical, and forceful men. In 1821 he was in charge of Fort William, the chief depot and factory of the Northwest Company, when that Company coalesced with the Hudson's Bay Company. Fort William is situated on the north shore of Lake Superior, at the mouth of the Kaministiquia River. It was at Fort William, where he was stationed for a long time, that he became acquainted with the widow of Alexander McKay. Dr. McLoughlin married her, the exact date I have been unable to ascertain. Alexander McKay was a partner of John Jacob Astor in the Pacific Fur Company. He was killed in the capture, by Indians, of the ship Tonquin in June, 1811, at Clayoquot Sound, on the west coast of Vancouver's Island.

Dr. John McLoughlin and wife had four children, whose names in order of birth were as follows: Eliza, John, Eloisa, and David. They are all dead. Eliza McLoughlin married Captain Epps, an officer in the English army. John McLoughlin, Jr., was murdered in April, 1842, at Fort Stikeen, where he was in charge. Eloisa McLoughlin was Dr. McLoughlin's favorite child. She was married to William Glen Rae at Fort Vancouver in 1838. Rae was appointed, after his marriage, a Chief Trader of the Hudson's[25] Bay Company. In 1841 he was sent to California to take charge of the Company's business at Yerba Buena, now San Francisco. He continued in charge there until his death in 1844. All of their children are dead, excepting two—Mrs. Theodore Wygant and Mrs. Josiah Myrick, both now living in Portland. In October, 1850, Mrs. Rae was married to Daniel Harvey. There were three children by this second marriage, all of whom are now dead. Daniel Harvey died prior to his wife. She died at Portland in October, 1884. In Portland and its vicinity there are now living several children of Mrs. Wygant and Mrs. Myrick, and also several grandchildren of Mrs. Wygant. At Mirabel, Sonoma County, California, there are now living a son, a daughter, and also the widow of James W. McL. Harvey, a son of Daniel and Eloisa Harvey. A son of Mrs. Myrick is living at Los Angeles, California. David McLoughlin, the youngest child of Dr. McLoughlin, was educated in England. He returned to Oregon, and later made his home in Idaho, where he died at an advanced age.

Dr. McLoughlin and the Oregon Country.

Physically Dr. John McLoughlin was a superb specimen of man. His height was not less than six feet four inches. He carried himself as a master, which gave him an appearance of being more than six feet and a half high. He was almost perfectly proportioned. Mentally he was endowed to match his magnificent physical proportions. He was brave and fearless; he was true and just; he was[26] truthful and scorned to lie. The Indians, as well as his subordinates, soon came to know that if he threatened punishment for an offense, it was as certain as that the offense occurred. He was absolute master of himself and of those under him. He allowed none of his subordinates to question or to disobey. This was necessary to conduct the business of his Company, and to preserve peace in the vast Oregon Country. He was facile princeps. And, yet, with all these dominant qualities, he had the greatest kindness, sympathy, and humanity. He needed all his stern and manlike characteristics to govern the officers, employées, servants, and dependents of his Company, and to conduct its business, in the Oregon Country. Here was a great empire in physical extent, intersected by great rivers and chains of mountains. There was no one on whom he could depend, except his under-officers and the Company's servants. To him were given no bands of trained soldiers to govern a country half again larger than the Empire of Germany, and occupied by treacherous, hostile, crafty, and cruel savages; and to so govern as not to be to the prejudice, nor to the exclusion, of citizens of the United States, nor to encourage them, nor to help them.

When he first came to Oregon, it was not safe for the Company's parties to travel except in large numbers and heavily armed. In a few years there was practically no danger. A single boat loaded with goods or furs was as safe as a great flotilla had been when he arrived on the Columbia River in 1824. It was Dr. John McLoughlin who did this,[27] by his personality, by his example, and by his influence. He had accomplished all this when the Indian population of the Oregon Country is estimated to have been in excess of 100,000, including about 30,000 on the Columbia River below its junction with Snake River, and on the tributaries of that part of the Columbia River. This was before the great epidemics of the years 1829 to 1832, inclusive, which caused the deaths of great numbers of the Indians, especially those living on and near the lower Columbia River. There were no Indian wars in the Oregon Country during all the time Dr. McLoughlin was in charge at Fort Vancouver, from 1824 to 1846. All the Indian wars in the Oregon Country occurred after he resigned from the Hudson's Bay Company. The first of these wars began with the Whitman massacre in 1847.

When he came to Oregon, he was nearly forty years old. His hair was then almost white, and was worn long, falling almost to his shoulders. It did not take long for the Indians to know him and to give him a name. To some of the Indians he was the "White-Headed Eagle," and to others, the "Great White Chief."

Fort Vancouver.

Dr. McLoughlin came overland to Fort George (Astoria), arriving there in 1824. He soon saw that the place for a great trading and supply post should be further up the Columbia River. After careful surveys in small boats, he founded Fort Vancouver, on the north side of the Columbia[28] River, about seven miles above the mouth of the Willamette River, and several miles below the point named Point Vancouver by Lieut. Broughtan, in 1792, the latter point being near the present town of Washougal, Washington. In 1825 Fort Vancouver was constructed, in part, and the goods and effects at Fort George were moved to Fort Vancouver. The final completion of the latter fort was not until a later period, although the work was carried on as rapidly as possible. A few years after, about 1830, a new fort was erected about a mile westerly from the original fort. Here is now located the present United States' Military post, commonly known as Vancouver Barracks.

With characteristic energy and foresight Dr. McLoughlin soon established at and near Fort Vancouver a large farm on which were grown quantities of grain and vegetables. It was afterwards stocked with cattle, horses, sheep, goats, and hogs. In 1836 this farm consisted of 3,000 acres, fenced into fields, with here and there dairy houses and herdsmen's and shepherd's cottages. In 1836 the products of this farm were, in bushels: 8,000 of wheat; 5,500 of barley; 6,000 of oats; 9,000 of peas; 14,000 of potatoes; besides large quantities of turnips (rutabaga), pumpkins, etc.[4] There were about ten acres in apple, pear, and quince trees, which bore in profusion. He established two saw mills and two flour mills near the fort. For many years there were shipped, from Fort Vancouver, lumber to the Hawaiian Islands (then[29] called the Sandwich Islands) and flour to Sitka. It was not many years after Dr. McLoughlin came to the Oregon Country until it was one of the most profitable parts of North America to the Hudson's Bay Company. For many years the London value of the yearly gathering of furs, in the Oregon Country, varied from $500,000 to $1,000,000, sums of money representing then a value several fold more than such sums represent today.

Fort Vancouver was a parallelogram about seven hundred and fifty feet long and four hundred and fifty broad, enclosed by an upright picket wall of large and closely fitted beams, over twenty feet in height, secured by buttresses on the inside. Originally there was a bastion at each angle of the fort. In the earlier times there were two twelve pounders mounted in these bastions. In the center of the fort there were some eighteen pounders; all these cannon, from disuse, became merely ornamental early in the thirties.[5] In 1841, when Commodore Wilkes was at Fort Vancouver, there were between the steps of Dr. McLoughlin's residence, inside the fort, two old cannon on sea-carriages, with a few shot. There were no other warlike instruments.[6] It was a very peaceful fort.

The interior of the fort was divided into two courts, having about forty buildings, all of wood except the powder magazine, which was constructed of brick and stone. In the center, facing the main entrance, stood the Hall in which were the dining-room, smoking-room, and public sitting-room,[30] or bachelor's hall. Single men, clerks, strangers, and others made the bachelor's hall their place of resort. To these rooms artisans and servants were not admitted. The Hall was the only two-story house in the fort. The residence of Dr. McLoughlin was built after the model of a French Canadian dwelling-house. It was one story, weather-boarded, and painted white. It had a piazza with vines growing on it. There were flower-beds in front of the house. The other buildings consisted of dwellings for officers and their families, a school-house, a retail store, warehouses and shops.

A short distance from the fort, on the bank of the river, was a village of more than fifty houses, for the mechanics and servants, and their families, built in rows so as to form streets. Here were also the hospital, boat-house, and salmon-house, and near by were barns, threshing-mills, granaries, and dairy buildings. The whole number of persons, having their homes at Fort Vancouver and its vicinity, men, women, and children, was about eight hundred. The Hall was an oasis in the vast social desert of Oregon. Fort Vancouver was a fairy-land to the early travellers, after their long, hard journeys across the continent. Thomas J. Farnham was a traveller who came to Oregon in 1839. He was entertained by Dr. McLoughlin at Fort Vancouver. In his account of his travels, which he subsequently published, he gives the following description of the usual dinner at Fort Vancouver:

"The bell rings for dinner; we will now pay a[31] visit to the 'Hall' and its convivialities.... At the end of a table twenty feet in length stands Governor McLoughlin, directing guests and gentlemen from neighboring posts to their places; and chief-traders, traders, the physician, clerks, and the farmer slide respectfully to their places, at distances from the Governor corresponding to the dignity of their rank in the service. Thanks are given to God, and all are seated. Roast beef and pork, boiled mutton, baked salmon, boiled ham; beets, carrots, turnips, cabbage, and potatoes, and wheaten bread, are tastefully distributed over the table among a dinner-set of elegant queen's ware, burnished with glittering glasses and decanters of various-coloured Italian wines. Course after course goes round, ... and each gentleman in turn vies with him in diffusing around the board a most generous allowance of viands, wines, and warm fellow-feeling. The cloth and wines are removed together, cigars are lighted, and a strolling smoke about the premises, enlivened by a courteous discussion of some mooted point of natural history or politics, closes the ceremonies of the dinner hour at Fort Vancouver."

At Fort Vancouver Dr. John McLoughlin lived and ruled in a manner befitting that of an old English Baron in feudal times, but with a graciousness and courtesy, which, I fear, were not always the rule with the ancient Barons. Dr. McLoughlin was a very temperate man. He rarely drank any alcoholic beverages, not even wines. There was an exception one time, each year, when the festivities began at Fort Vancouver on the return of the[32] brigade, with the year's furs. He then drank a glass of wine to open the festivities. Soon after he came to Oregon, from morality and policy he stopped the sale of liquor to Indians. To do this effectually he had to stop the sale of liquor to all whites. In 1834, when Wyeth began his competition with the Hudson's Bay Company, he began selling liquor to Indians, but at the request of Dr. McLoughlin, Wyeth stopped the sale of liquors to Indians as well as to the whites. In 1841 the American trading vessel Thomas Perkins, commanded by Captain Varney, came to the Columbia River to trade, having a large quantity of liquors. To prevent the sale to the Indians, Dr. McLoughlin bought all these liquors and stored them at Fort Vancouver. They were still there when Dr. McLoughlin left the Hudson's Bay Company in 1846.

Dr. McLoughlin soon established numerous forts and posts in the Oregon Country, all of which were tributary to Fort Vancouver. In 1839 there were twenty of these forts besides Vancouver. The policy of the Hudson's Bay Company was to crush out all rivals in trade. It had an absolute monopoly of the fur trade of British America, except the British Provinces, under acts of Parliament, and under royal grants. But in the Oregon Territory its right to trade therein was limited by the Conventions of 1818 and 1827 and by the act of Parliament of July 2, 1821, to the extent that the Oregon Country (until one year's notice was given) should remain free and open to the citizens of the United States and to the subjects of Great[33] Britain, and the trade of the Hudson's Bay Company should not "be used to the prejudice or exclusion of citizens of the United States engaged in such trade."[7] Therefore, as there could be no legal exclusion of American citizens, it could be done only by occupying the country, building forts, establishing trade and friendly relations with the Indians, and preventing rivalry by the laws of trade, including ruinous competition. As the Hudson's Bay Company bought its goods in large quantities in England, shipped by sea, and paid no import duties, it could sell at a profit at comparatively low prices. In addition, its goods were of extra good quality, usually much better than those of the American traders. It also desired to prevent the settling of the Oregon Country. The latter purpose was for two reasons: to preserve the fur trade; and to prevent the Oregon Country from being settled by Americans to the prejudice of Great Britain's claim to the Oregon Country.

For more than ten years after Dr. McLoughlin came to Oregon, there was no serious competition to the Hudson's Bay Company in the Oregon Country west of the Blue Mountains. An occasional ship would come into the Columbia River and depart. At times, American fur traders entered into serious competition with the Hudson's Bay Company, east of the Blue Mountains. Such traders were Bonneville, Sublette, Smith, Jackson, and others. They could be successful, only partially, against the competition of the Hudson's Bay Company. Goods were often sold by it at prices[34] which could not be met by the American traders, except at a loss. Sometimes more was paid to the Indians for furs than they were worth.

Dr. McLoughlin was the autocrat of the Oregon Country. His allegiance was to his Country and to his Company. He knew the Americans had the legal right to occupy any part of the Oregon Country, and he knew from the directors of his Company, as early as 1825, that Great Britain did not intend to claim any part of the Oregon Country south of the Columbia River. The only fort he established south of the Columbia River was on the Umpqua River. I do not wish to place Dr. McLoughlin on a pedestal, nor to represent him as more than a grand and noble man, ever true, as far as possible, to his Company's interests and to himself. To be faithless to his Company was to be a weakling and contemptible. But he was not a servant, nor was he untrue to his manhood. As Chief Factor he was "Ay, every inch a King," but he was also ay, every inch a man. He was a very human, as well as a very humane man. He had a quick and violent temper. His position as Chief Factor and his continued use of power often made him dictatorial. And yet he was polite, courteous, gentle, and kind, and a gentleman. He was an autocrat, but not an aristocrat. In 1838 Rev. Herbert Beaver, who was chaplain at Fort Vancouver, was impertinent to Dr. McLoughlin in the fort-yard. Immediately Dr. McLoughlin struck Beaver with a cane. The next day Dr. McLoughlin publicly apologized for this indignity.

Punishment of Indians.

The policy of the Company, as well as that of Dr. McLoughlin, was to keep Americans, especially traders, out of all the Oregon Country. The difference was that he believed that they should be kept out only so far as it could be done lawfully. But he did not allow them to be harmed by the Indians, and, if the Americans were so harmed, he punished the offending Indians, and he let all Indians know that he would punish for offenses against the Americans as he would for offenses against the British and the Hudson's Bay Company. Personally he treated these rival traders with hospitality. In his early years in Oregon on two occasions he caused an Indian to be hanged for murder of a white man. In 1829, when the Hudson's Bay Company's vessel, William and Ann, was wrecked on Sand Island, at the mouth of the Columbia River, and a part of her crew supposed to have been murdered and the wreck looted, he sent a well armed and manned schooner and a hundred voyageurs to punish the Indians.

Jedediah S. Smith was a rival trader to the Hudson's Bay Company. In 1828 all his party of eighteen men, excepting four, one of which was Smith, were murdered by the Indians, near the mouth of the Umpqua River. All their goods and furs were stolen. These four survivors arrived at Fort Vancouver, but not all together. They were all at the point of perishing from exhaustion and were nearly naked. All their wants were at once supplied, and they received the kindest treatment. When the first one arrived Dr. McLoughlin sent[36] Indian runners to the Willamette chiefs to tell them to send their people in search of Smith and his two men, and if found to bring them to Fort Vancouver, and Dr. McLoughlin would pay the Indians; and also to tell these chiefs that if Smith, or his men, was hurt by the Indians, that Dr. McLoughlin would punish them. Dr. McLoughlin sent a strong party to the Umpqua River, which recovered these furs. They were of large value. Smith at his own instance sold these furs to the Hudson's Bay Company, receiving the fair value for the furs, without deduction. Dr. McLoughlin later said of this event that it "was done from a principle of Christian duty, and as a lesson to the Indians to show them they could not wrong the whites with impunity." The effect of this Smith matter was far-reaching and long-continued. The Indians understood, even if they did not appreciate, that the opposition of Dr. McLoughlin to Americans as traders did not apply to them personally.

Dunn, in his History of the Oregon Territory, narrates the following incident:[8] "On one occasion an American vessel, Captain Thompson, was in the Columbia, trading furs and salmon. The vessel had got aground, in the upper part of the river, and the Indians, from various quarters, mustered with the intent of cutting the Americans off, thinking that they had an opportunity of revenge, and would thus escape the censure of the[37] company. Dr. McLoughlin, the governor of Fort Vancouver, hearing of their intention, immediately despatched a party to their rendezvous; and informed them that if they injured one American, it would be just the same offence as if they had injured one of his servants, and they would be treated equally as enemies. This stunned them; and they relinquished their purpose; and all retired to their respective homes. Had not this come to the governor's ears the Americans must have perished."

In 1842 the Indians in the Eastern Oregon Country became alarmed for the reason that they believed the Americans intended to take away their lands. The Indians knew that the Hudson's Bay Company and its employées were traders and did not care for lands, except as incidental to trading. At this time some of the Indians desired to raise a war party and surprise and massacre the American settlements in the Willamette Valley. This could have been done easily at that time. Through the influence of Dr. McLoughlin with Peopeomoxmox (Yellow Serpent), a chief of the Cayuses, this trouble was averted. In 1845 a party of Indians went to California to buy cattle. An American there killed Elijah, the son of Peopeomoxmox. The Indians of Eastern Oregon threatened to take two thousand warriors to California and exterminate the whites there. Largely through the actions of Dr. McLoughlin the Indians were persuaded to abandon their project.

John Minto, a pioneer of 1844, in an address February 6, 1889, narrated the following incident.[38] In 1843 two Indians, for the purpose of robbery, at Pillar Rock, in the lower Columbia, killed a servant of the Hudson's Bay Company. One of the Indians was killed in the pursuit. The other was taken, after great trouble. There was no doubt as to his guilt. In order to make the lesson of his execution salutary and impressive to the Indians, Dr. McLoughlin invited the leading Indians of the various tribes, as well as all classes of settlers and missionaries, to be present. He made the arrangements for the execution in a way best calculated to strike terror to the Indian mind. When all was ready, and immediately prior to the execution, with his white head bared, he made a short and earnest address to the Indians, showing them that the white men of all classes, Englishmen, Americans, and Frenchmen, were as one man to punish such crimes. In a technical sense Dr. McLoughlin had no authority to cause Indians to be executed or to compel them to restore stolen goods, as in the William and Ann matter and the Jedediah S. Smith case.

Under the act of Parliament of July, 1821, the courts of judicature of Upper Canada were given jurisdiction of civil and criminal matters within the Indian territories and other parts of America not within the Provinces of Lower or Upper Canada, or of any civil government of the United States. Provisions were made for the appointment of justices of the peace in such territories, having jurisdiction of suits or actions not exceeding two hundred pounds, and having jurisdiction of ordinary criminal offenses. But it was expressly[39] provided that such justices of the peace should not have the right to try offenders on any charge of felony made the subject of capital punishment, or to pass sentence affecting the life of any offender, or his transportation; and that in case of any offense, subjecting the person committing the same to capital punishment or to transportation, to cause such offender to be sent, in safe custody, for trial in the court of the Province of Upper Canada. As to how far this law applied to Indians or to others than British subjects or to residents of the Oregon Country under joint-occupancy, it is not necessary here to discuss. It certainly did not apply to citizens of the United States. So far as I can learn, Dr. McLoughlin was never appointed such a justice of the peace, but he caused his assistant James Douglas to be so appointed, at Fort Vancouver.

As under joint-occupancy it was doubtful if either the laws of the United States or of Great Britain were in force in the Oregon Country, it was necessary for some one to assume supreme power and authority over the Indians, in the Willamette Valley, until the Oregon Provisional Government was established, and over the remainder of the Oregon Country, at least, until the boundary-line treaty was made. It was characteristic of Dr. McLoughlin that he assumed and exercised such power and authority, until he ceased to be an officer of the Hudson's Bay Company. He did so without question. It is true that this might have been an odious tyranny under a different kind of a man. Under Dr. McLoughlin it was a kind of despotism, but a just and beneficent despotism,[40] under the circumstances. It was a despotism tempered by his sense of justice, his mercy, his humanity, and his common-sense. No man in the Oregon Country ever knew the Indian character, or knew how to control and to manage Indians as well as Dr. McLoughlin did. The few severe and extreme measures he took with them as individuals and as tribes were always fully justified by the circumstances. To have been more lenient might have been fatal to his Company, its employées, and the early white settlers in the Oregon Country. They were of the few cases where the end justifies the means. The unusual conditions justified the unusual methods.

The Oregon Provisional Government was not a government in the true meaning of the word, it was a local organization, for the benefit of those consenting. It had no true sovereignty. And yet it punished offenders. It waged the Cayuse Indian war of 1847-8, caused by the Whitman massacre. It would have executed the murderers if it had caught them, although the scenes of the massacre and of the war were several hundred miles beyond the asserted jurisdiction of the Oregon Provisional Government. And it would have been justified in case of such executions. The war was a necessity, law or no law. Every act of punitive or vindicatory justice to the Indians by Dr. McLoughlin is greatly to his credit. These acts caused peace in the Oregon Country and were beneficial to the Indians as well as to the whites, both British and American, and, in the end, probably saved numerous massacres and hundreds of[41] lives. Dr. McLoughlin was a very just and far-seeing man. I shall presently tell how Dr. McLoughlin saved the immigrants of 1843 from great trouble and probable massacre by the Indians.

Early French Canadian Settlers.

After the death of Dr. McLoughlin there was found among his private papers a document in his own handwriting. This was probably written shortly prior to his death. It gives many interesting facts, some of which I shall presently set forth. This document was given to Col. J. W. Nesmith by a descendant of Dr. McLoughlin. It was presented to the Oregon Pioneer Association by Col. Nesmith in 1880. It was printed at length in the Transactions of that Association for that year, pages 46-55. I shall hereinafter refer to this document as "the McLoughlin Document." In the McLoughlin Document he says: "In 1825, from what I had seen of the country, I formed the conclusion, from the mildness and salubrity of the climate, that this was the finest portion of North America that I had seen for the residence of civilized man." The farm at Fort Vancouver showed that the wheat was of exceptionally fine quality. Dr. McLoughlin knew that where wheat grew well and there was a large enough area, that it would become a civilized country, especially where there was easy access to the ocean. Thus early he saw that what is now called Western Oregon was bound to be a populous country. It was merely a question of time. It was evidently with[42] this view that he located his land claim at Oregon City in 1829. If settlers came he could endeavor to have them locate in the Willamette Valley, and thus preserve, to a great extent, the fur animals in other parts of the Oregon Country, and especially north of the Columbia River.

The Hudson's Bay Company was bound, under heavy penalties, not to discharge any of its servants in the Indian country, and was bound to return them to the places where they were originally hired. As early as 1828 several French Canadian servants, or employées, whose times of service were about ended, did not desire to return to Canada, but to settle in Oregon. They disliked to settle in the Willamette Valley, notwithstanding its fertility and advantages, because they thought that ultimately it would be American territory, but Dr. McLoughlin told them that he knew "that the American Government and people knew only two classes of persons, rogues and honest men. That they punished the first and protected the last, and it depended only upon themselves to what class they would belong." Dr. McLoughlin later found out, to his own sorrow and loss, that he was in error in this statement. These French Canadians followed his advice. To allow these French Canadians to become settlers, he kept them nominally on the books of the Hudson's Bay Company as its servants. He made it a rule to allow none of these servants to become settlers unless he possessed fifty pounds sterling to start with. He loaned each of them seed and wheat to plant, to be returned from the produce of his farm, and sold him implements[43] and supplies at fifty per cent. advance on prime London cost. The regular selling price at Fort Vancouver was eighty per cent. advance on prime London cost. Dr. McLoughlin also loaned each of these settlers two cows, the increase to belong to the Hudson's Bay Company, as it then had only a small herd, and he wished to increase the herd. If any of the cows died, he did not make the settler pay for the animal. If he had sold the cattle the Company could not supply other settlers, and the price would be prohibitive, if owned by settlers who could afford to buy, as some settlers offered him as high as two hundred dollars for a cow. Therefore, to protect the poor settlers against the rich, and to make a herd of cattle for the benefit of the whole country, he refused to sell to any one.

In 1825 Dr. McLoughlin had at Fort Vancouver only twenty-seven head of cattle, large and small. He determined that no cattle should be killed, except one bull-calf every year for rennet to make cheese, until he had an ample stock to meet all demands of his Company, and to assist settlers, a resolution to which he strictly adhered. The first animal killed for beef was in 1838. Until that time the Company's officers and employées had lived on fresh and salt venison and salmon and wild fowl.

In August 1839, the expedition of Sir Edward Belcher was at Fort Vancouver. Dr. McLoughlin was not then at Fort Vancouver. He probably had not returned from his trip to England in 1838-9. James Douglas was in charge. Although[44] the latter supplied Sir Edward Belcher and his officers with fresh beef, Douglas declined to furnish a supply of fresh beef for the crew, because he did not deem it prudent to kill so many cattle. Sir Edward Belcher complained of this to the British government.[9] Dr. McLoughlin gave the American settlers, prior to 1842, the same terms as he gave to the French Canadian settlers. But some of these early American settlers were much incensed at the refusal of Dr. McLoughlin to sell the cattle, although they accepted the loan of the cows. It has been asserted that Dr. McLoughlin intended to maintain a monopoly in cattle. But if that was his intention, as he refused to sell, where was to be the profit? The Hudson's Bay Company was a fur-trading Company. It was not a cattle-dealing Company. If Dr. McLoughlin intended to create a monopoly, he himself assisted to break it. That such was not his intention is shown by his helping the settlers to procure cattle from California in 1836.

In 1836 a company was formed to go to California to buy cattle and drive them to Oregon overland. About twenty-five hundred dollars was raised for this purpose, of which amount Dr. McLoughlin, for the Hudson's Bay Company, subscribed about half. The number of cattle which were thus brought to Oregon was six hundred and thirty, at a cost of about eight dollars a head. In the McLoughlin Document he says: "In the Willamette the settlers kept the tame and broken-in oxen they had, belonging to the Hudson's[45] Bay Company, and gave their California wild cattle in the place, so that they found themselves stocked with tame cattle which cost them only eight dollars a head, and the Hudson's Bay Company, to favor the settlers, took calves in place of grown up cattle, because the Hudson's Bay Company wanted them for beef. These calves would grow up before they were required."

Early American Traders and Travellers.

In 1832 Nathaniel J. Wyeth of Cambridge, Massachusetts, came overland with a small party, expecting to meet in the Columbia River, a vessel with supplies, to compete with the Hudson's Bay Company. The vessel was wrecked in the South Pacific Ocean. She and the cargo were a total loss. This party arrived at Fort Vancouver in a destitute condition. Although Dr. McLoughlin knew they came as competing traders, he welcomed them cordially, supplied their necessities on their credit, and gave Wyeth a seat at his own table. In Wyeth's Journal of this expedition he says, under date of October 29, 1832: "Arrived at the fort of Vancouver.... Here I was received with the utmost kindness and hospitality by Dr. McLoughlin, the acting Governor of the place.... Our people were supplied with food and shelter.... I find Dr. McLoughlin a fine old gentleman, truly philanthropic in his ideas.... The gentlemen of this Company do much credit to their country by their education, deportment, and talents.... The Company seem disposed to render me all the assistance they can." Wyeth[46] was most hospitably entertained by Dr. McLoughlin until February 3, 1833, when Wyeth left Vancouver for his home overland. He was accompanied by three of his men, the others staying at Fort Vancouver. In his Journal under date February 3, 1833, he says: "I parted with feelings of sorrow from the gentlemen of Fort Vancouver. Their unremitting kindness to me while there much endeared them to me, more so than would seem possible during so short a time. Dr. McLoughlin, the Governor of the place, is a man distinguished as much for his kindness and humanity as his good sense and information; and to whom I am so much indebted as that he will never be forgotten by me." Dr. McLoughlin assisted the men of Wyeth's expedition who stayed, to join the Willamette settlement. He furnished them seed and supplies and agreed that they would be paid the same price for their wheat as was paid to the French Canadian settlers, i.e., three shillings, sterling, per bushel, and that they could purchase their supplies from the Hudson's Bay Company at fifty per cent. advance on prime London cost. This is said to have been equivalent to paying one dollar and twenty-five cents a bushel for wheat, with supplies at customary prices.

In 1834 Wyeth again came overland to the Columbia River with a large party. On the way he established Fort Hall (now in Idaho) in direct opposition to the Hudson's Bay Company, as he had a perfect right to do. He and his party arrived at Fort Vancouver September 14, 1834, and were hospitably received by Dr. McLoughlin and the[47] other gentlemen of the Hudson's Bay Company. In Wyeth's Journal of his second expedition he says, under date of September 14, 1834: "Arrived at Vancouver, where I found Dr. McLoughlin in charge, who received us in his usual manner. He has here power, and uses it as a man should, to make those about him, and those who come in contact with him, comfortable and happy." The brig May Dacre, with Wyeth's supplies, was then in the Columbia River. Immediately on his arrival, Wyeth started in active competition with the Hudson's Bay Company. He established a post, which he named Fort William, on Wappatoo Island (now Sauvie's Island). He forwarded supplies and men to Fort Hall. It was the beginning of a commercial war between the two companies, but it was a warfare on honorable lines. In the end Wyeth was beaten by Dr. McLoughlin, and sold out his entire establishment to the Hudson's Bay Company. While Dr. McLoughlin was personally courteous to Wyeth and his employées, he did not and would not be false or untrue to the business interests of the Hudson's Bay Company. For Dr. McLoughlin to have acted otherwise than he did, would have shown him to be unfit to hold his position as Chief Factor. Wyeth was too big, and too capable a man not to understand this. In his Journal, under date of September 31, 1834, (he evidently forgot that September has but thirty days) he says: "From this time until the 13th Oct. making preparations for a campaign into the Snake country and arrived on the 13th at Vancouver and was received with great attention by all there."[48] And under date of February 12, 1835, he says: "In the morning made to Vancouver and found there a polite reception."[10] Wyeth was a man of great ability, enterprise, and courage. His expeditions deserved better fates. He was a high-minded gentleman. Although his two expeditions were failures, he showed his countrymen the way to Oregon, which many shortly followed.

In the McLoughlin Document he says: "In justice to Mr. Wyeth I have great pleasure to be able to state that as a rival in trade, I found him open, manly, frank, and fair. And, in short, in all his contracts, a perfect gentleman and an honest man, doing all he could to support morality and encouraging industry in the settlement." It is pleasing to know that after all his hardships and misfortunes Wyeth established a business for the exportation of ice from Boston to Calcutta, which was a great financial success.

Rev. H. K. Hines, D.D., was a Methodist minister who came to Oregon in 1853. He was a brother of Rev. Gustavus Hines, the Methodist missionary, who came to Oregon in 1840, on the ship Lausanne. December 10, 1897, at Pendleton, Oregon, Rev. Dr. Hines delivered one of the finest tributes to Dr. McLoughlin that I know of. He was fully capable to do it, for he was a profound and scholarly student of Oregon history, and personally knew Dr. McLoughlin. His address should be read by everyone. In his address Rev. Dr. Hines said, speaking in regard to the failure[49] of the enterprises of Wyeth, Bonneville, and other fur traders in opposition to the Hudson's Bay Company: "My own conclusion, after a lengthy and laborious investigation, the result I have given here in bare outlines, is that Dr. McLoughlin acted the part only of an honorable, high-minded, and loyal man in his relation with the American traders who ventured to dispute with him the commercial dominion of Oregon up to 1835 or 1837." When Wyeth left Oregon in 1835, he left on the Columbia River a number of men. These, too, were assisted by Dr. McLoughlin to join the Willamette River settlements. They were given the same terms as to prices of wheat and on supplies as he had given to the French Canadian, and to the other American settlers. In assisting these men whom Wyeth left on his two expeditions, Dr. McLoughlin was actuated by two motives. The first was humanitarian; the second was the desirability, if not necessity, of not having men, little accustomed to think or to plan for themselves, roaming the country, and possibly, some of them, becoming vagabonds. It was liable to be dangerous for white men to join Indian tribes and become leaders. With great wisdom and humanity he made them settlers, which gave them every inducement to be industrious and to be law abiding.

John K. Townsend, the naturalist, accompanied by Nuttall, the botanist, crossed the plains in 1834 with Captain Wyeth. In 1839 Townsend published a book entitled, "Narrative of a Journey across the Rocky Mountains," etc. On page 169 he says: "On the beach in front of the fort, we[50] were met by Mr. Lee, the missionary, and Dr. John McLoughlin, the Chief Factor, and Governor of the Hudson's Bay posts in this vicinity. The Dr. is a large, dignified and very noble looking man, with a fine expressive countenance, and remarkably bland and pleasing manners. The Missionary introduced Mr. N. [Nuttall] and myself in due form, and we were greeted and received with a frank and unassuming politeness which was most peculiarly grateful to our feelings. He requested us to consider his house our home, provided a separate room for our use, a servant to wait upon us, and furnished us with every convenience which we could possibly wish for. I shall never cease to feel grateful to him for his disinterested kindness to the poor, houseless, and travel-worn strangers." And on page 263 he said: "I took leave of Doctor McLoughlin with feelings akin to those with which I should bid adieu to an affectionate parent; and to his fervent, 'God bless you, sir, and may you have a happy meeting with your friends,' I could only reply by a look of the sincerest gratitude. Words are inadequate to express my deep sense of the obligations which I feel under to this truly generous and excellent man, and I fear I can only repay them by the sincerity with which I shall always cherish the recollection of his kindness, and the ardent prayers I shall breathe for his prosperity and happiness."

The only persons who were not cordially received by Dr. McLoughlin were Ewing Young and Hall J. Kelley, who came to Fort Vancouver in October, 1834, from California. Gov. Figueroa,[51] the Governor of California, had written Dr. McLoughlin that Young and Kelley had stolen horses from settlers in California. Dr. McLoughlin told them of the charges, and that he would have nothing to do with them until the information was shown to be false. This was not done until long afterwards, when it was shown that neither Young nor Kelley was guilty, but that some of their party, with which they started to Oregon, were guilty, and were disreputable characters, which Young and Kelley knew. The stand taken by Dr. McLoughlin was the only proper one. He had official information from California. Fort Vancouver was not an asylum for horse thieves. Nevertheless, as Kelley was sick, Dr. McLoughlin provided Kelley with a house, such as was occupied by the servants of the Company, outside the fort, furnished him with an attendant, and supplied him with medical aid and all necessary comforts until March, 1835, when Dr. McLoughlin gave Kelley free passage to the Hawaiian Islands on the Hudson's Bay Company's vessel, the Dryad, and also presented Kelley with a draft for seven pounds sterling, payable at the Hawaiian Islands. On his return home, Kelley, instead of being grateful, most vigorously attacked the Hudson's Bay Company for its alleged abuses of American citizens, and abused Dr. McLoughlin and falsely stated that Dr. McLoughlin had been so alarmed with the dread that Kelley would destroy the Hudson's Bay Company's trade that Dr. McLoughlin had kept a constant watch over Kelley.

[52]Kelley was a Boston school teacher who became an Oregon enthusiast. From the year 1815, when he was twenty-six years of age, for many years, he wrote and published pamphlets and also a few books on Oregon and its advantages as a country to live in. He originated a scheme to send a colony to Oregon; to build a city on the east side of the Willamette River, at its junction with the Columbia River; and to build another city on the north side of the Columbia River, nearly opposite Tongue Point. His efforts resulted in immediate failures. He died a disappointed man. Young was a type of a man who was often successful in the Far West. He was forceful and self-reliant, but often reckless, and sometimes careless of appearances. He was so accustomed to meet emergencies successfully that he did not always consider what others might think of him and of the methods he sometimes felt compelled to adopt. He had been robbed in California of a large amount of furs and had not been fairly treated by the representatives of the Mexican Government in California. While Young was an adventurer, he was a man of ability and became a leading resident of early Oregon. The relations of Dr. McLoughlin and Ewing Young finally became quite amicable, for Dr. McLoughlin learned of and respected Young's good and manly qualities.

Presbyterian Missionaries.

For convenience I shall first mention the Presbyterian missionaries, although they came two years later than the first Methodist missionaries.[53] Rev. Samuel Parker was the first Presbyterian minister to arrive in Oregon. He came in 1835. He started to Oregon with Doctor Marcus Whitman, but Whitman returned East from Green River to obtain more associates for the Mission. These came out with Dr. Whitman in 1836. Parker returned home by sea, reaching his home in 1837. Parker published a book called, "Journal of an Exploring Tour beyond the Rocky Mountains." The first edition was published in Ithaca, New York, in 1838. On page 138 of his book he says: "At two in the afternoon, arrived at Fort Vancouver, and never did I feel more joyful to set my feet on shore, where I expected to find a hospitable people and the comforts of life. Doct. J. McLoughlin, a chief factor and superintendent of this fort and of the business of the Company west of the Rocky Mountains, received me with many expressions of kindness, and invited me to make his residence my home for the Winter, and as long as it would suit my convenience. Never could such an invitation be more thankfully received." On page 158 he says: "Here, [Fort Vancouver] by the kind invitation of Dr. McLoughlin, and welcomed by the other gentlemen of the Hudson Bay Company, I took up my residence for the winter." And on page 263 he says: "Monday, 11th April [1836]. Having made arrangements to leave this place on the 14th, I called upon the chief clerk for my bill. He said the Company had made no bill against me, but felt a pleasure in gratuitously conferring all they have done for the benefit of the object in which I am engaged. In justice to my own feelings,[54] and in gratitude to the Honorable Company, I would bear testimony to their consistent politeness and generosity; and while I do this, I would express my anxiety for their salvation, and that they may be rewarded in spiritual blessings. In addition to the civilities I had received as a guest, I had drawn upon their store for clothing, for goods to pay my Indians, whom I had employed to convey me in canoes, in my various journeyings, hundreds of miles; to pay my guides and interpreters; and have drawn upon their provision store for the support of these men while in my employ."

In 1836 Dr. Marcus Whitman came to Oregon. With him came his wife, Rev. Henry H. Spalding and wife, and W. H. Gray, a layman. They arrived at Fort Vancouver September 1, 1836. Here they were most hospitably entertained by Dr. McLoughlin and the other gentlemen of the Hudson's Bay Company, and all necessary and convenient assistance to these missionaries was freely given. When these missionaries arrived at Vancouver, they had hardly more than the clothes they had on. They concluded to locate one mission near Waiilatpu, near the present city of Walla Walla, Washington; and another at Lapwai, near the present city of Lewiston, Idaho. Mrs. Whitman and Mrs. Spalding remained at Fort Vancouver for several months, while their husbands and Gray were erecting the necessary houses at the Missions.

Methodist Missions and Missionaries.

With Wyeth's second expedition, in 1834, came the first Methodist missionaries: Rev. Jason Lee,[55] Rev. Daniel Lee, his nephew, and the following laymen: Cyrus Shepard, a teacher; P. L. Edwards, a teacher; and a man named Walker. They arrived at Fort Vancouver September 17, 1834. They were also hospitably received by Dr. McLoughlin, and treated with every consideration and kindness. On Dr. McLoughlin's invitation Jason Lee preached at Fort Vancouver. Boats and men were furnished by Dr. McLoughlin to the missionaries to explore the country and select a proper place for the establishment of their Mission. In the McLoughlin Document, he says: "In 1834, Messrs. Jason and Daniel Lee, and Messrs. Walker and P. L. Edwards came with Mr. Wyeth to establish a Mission in the Flat-head country. I observed to them that it was too dangerous for them to establish a Mission [there]; that to do good to the Indians, they must establish themselves where they could collect them around them; teach them first to cultivate the ground and live more comfortably than they do by hunting, and as they do this, teach them religion; that the Willamette afforded them a fine field, and that they ought to go there, and they would get the same assistance as the settlers. They followed my advice and went to the Willamette."

Rev. Dr. H. K. Hines published a book in 1899 entitled, "Missionary History of the Pacific Northwest." While, as is to be expected, Dr. Hines' book is biased in favor of the Methodist missionaries, and Jason Lee is his hero, nevertheless, he has endeavored to be fair and just to all. In this "Missionary History," page 92, Dr. Hines[56] says: "It was no accident, nor, yet, was it any influence that Dr. McLoughlin or any other man or men had over him [Jason Lee] that determined his choice [of a site for the Mission]. It was his own clear and comprehensive statesmanship. Mr. Lee was not a man of hasty impulse.... This nature did not play him false in the selection of the site of his Mission." And on pages 452, 453, he says: "Some writers have believed, or affected to believe, that the advice of Dr. McLoughlin both to Mr. Lee in 1834, and to the missionaries of the American Board in 1836, was for the purpose of pushing them to one side, and putting them out of the way of the Hudson's Bay Company, so that they could not interfere with its purposes, nor put any obstacle in the way of the ultimate British occupancy of Oregon. Such writers give little credit to the astuteness of Dr. McLoughlin, or to the intelligence and independence of the missionaries of the American Board. Had such been the purpose of Dr. McLoughlin, or had he been a man capable of devising a course of action so adverse to the purposes for which his guests were in the country, he certainly would not have advised them to establish their work in the very centers of the great region open to their choice. This he did, as we believe, honestly and honorably."

Jason Lee selected, as the original site of the Methodist Mission, a place on French Prairie, about ten miles north of the present city of Salem. When he and his party were ready to leave for their new home, Dr. McLoughlin placed at their disposal a boat and crew to transport the mission[57] goods from the May Dacre, Wyeth's vessel, on which their goods had come, to the new Mission. He loaned them seven oxen, one bull, and seven cows with their calves. The moving of these goods and cattle to the Mission required several days. He also provided and manned a boat to convey the missionaries, personally. In his diary, Jason Lee says: "After dinner embarked in one of the Company's boats, kindly manned for us by Dr. McLoughlin, who has treated us with the utmost attention, politeness and liberality."[11]

March 1, 1836, Dr. McLoughlin and the other officers of the Hudson's Bay Company, all British subjects, sent to Jason Lee, for the benefit of the Methodist Mission, a voluntary gift of one hundred and thirty dollars, accompanied by the following letter:

"Fort Vancouver, 1st March, 1836.

"The Rev. Jason Lee,

"Dear Sir:

"I do myself the pleasure to hand you the enclosed subscription, which the gentlemen who have signed it request you will do them the favor to accept for the use of the Mission; and they pray our Heavenly Father, without whose assistance we can do nothing, that of his infinite mercy he will vouchsafe to bless and prosper your pious endeavors, and believe me to be, with esteem and regard, your sincere well-wisher and humble servant.

"John McLoughlin."[12]

[58]From its beginning, and for several years after, the successful maintenance of the Methodist Mission in Oregon was due to the friendly attitude and assistance of Dr. McLoughlin and of the other officers of the Hudson's Bay Company in Oregon. Without these the Mission must have ceased to exist. This applies also to the successful maintenance of all other missions in the Oregon Country in the same period of time.[13]

In May, 1837, an addition to the Methodist Mission arrived at Vancouver. It consisted of eight adults and three children. Of these three were men, one of whom was Dr. Elijah White, the Mission physician; five were women, one of whom was Anna Maria Pittman, whom Jason Lee soon married. In September, 1837, the ship Sumatra arrived at Fort Vancouver loaded with goods for the Methodist Mission. The Sumatra also brought four more missionaries, two men, two women, and three children. Rev. David Leslie and wife were two of these missionaries. All these missionaries were entertained by Dr. McLoughlin, and provided with comfortable quarters at Fort Vancouver.

In March, 1838, Rev. Jason Lee left for the Eastern States, overland, on business for the Mission. His wife died June 26, 1838, three weeks after the birth and death of their son. Immediately on her death Dr. McLoughlin sent an express to overtake and tell Jason Lee of these sad events. The express reached Jason Lee about September 1, 1838, at Pawnee Mission, near Westport, Missouri.[14] From this act alone could anyone[59] doubt that Dr. McLoughlin was a sympathetic, kind, thoughtful, and considerate man? Or think that Jason Lee would ever forget? Later, in 1838 Dr. McLoughlin made a trip to London, returning to Fort Vancouver in 1839.

While Jason Lee was on this trip to the Eastern States, the Missionary Board was induced to raise $42,000 to provide for sending thirty-six adults, and sixteen children, and a cargo of goods and supplies, on the ship Lausanne, to Oregon for the Methodist Mission. Among these new missionaries were Rev. Alvan F. Waller, Rev. Gustavus Hines, and George Abernethy, a lay member, who was to be steward of the Mission and to have charge of all its secular affairs. This party of missionaries, who came on the Lausanne, are often referred to as "The great re-inforcement." The Lausanne, with its precious and valuable cargoes, arrived at Fort Vancouver June 1, 1840. As soon as Dr. McLoughlin knew of her arrival in the Columbia River, he sent fresh bread, butter, milk, and vegetables for the passengers and crew. At Fort Vancouver he supplied rooms and provisions for the whole missionary party, about fifty-three people. This party remained as his guests, accepting his hospitality, for about two weeks.[15] Shortly after some of this missionary party were endeavoring to take for themselves Dr. McLoughlin's land claim at Oregon City. The Lausanne was the last missionary vessel to come to Oregon.

Why this large addition to the Oregon Mission,[60] and these quantities of supplies, were sent, and this great expense incurred, has never been satisfactorily explained. It seems to have been the result of unusual, but ill-directed, religious fervor and zeal. The Methodist Oregon Mission was then, so far as converting the Indians, a failure. It was not the fault of the early missionaries. Until 1840 they labored hard and zealously. The Indians would not be converted, or, if converted, stay converted. Their numbers had been greatly reduced by the epidemics of 1829-32, and the numbers were still being rapidly reduced. And why the necessity of such secular business as a part of a mission to convert Indians to Christianity?[16] The failure to convert the Indians was because they were Indians. Their language was simple and related almost wholly to material things. They had no ethical, no spiritual words. They had no need for such. They had no religion of their own, worthy of the name, to be substituted for a better or a higher one. They had no religious instincts, no religious tendencies, no religious traditions. The male Indians would not perform manual labor—that was for women and slaves. The religion of Christ and the religion of Work go hand in hand.

Rev. Dr. H. K. Hines, in his Missionary History, after setting forth certain traits of the Indians and the failures of the Methodist missionaries to convert them, says (p. 402): "So on the Northwest Coast. The course and growth of a history whose beginnings cannot be discovered had[61] ended only in the production of the degraded tribes among whom the most consecrated and ablest missionary apostleship the Church of Christ had sent out for centuries made almost superhuman efforts to plant the seed of the 'eternal life.' As a people they gave no fruitful response." And, on page 476, he says: "Indeed, after Dr. Whitman rehabilitated his mission in the autumn of 1843, the work of that station lost much of its character as an Indian mission. It became rather a resting place and trading post, where the successive immigrations of 1844-'45-'46 and '47 halted for a little recuperation after their long and weary journey, before they passed forward to the Willamette. This was inevitable." And on page 478 Dr. Hines says that Dr. McLoughlin "advised Dr. Whitman to remove from among the Cayuses, as he believed not only that he could no longer be useful to them, but that his life was in danger if he remained among them."

J. Quinn Thornton in his "History of the Provisional Government of Oregon,"[17] says: "In the autumn of 1840 there were in Oregon thirty-six American male settlers, twenty-five of whom had taken native women for their wives. There were also thirty-three American women, thirty-two children, thirteen lay members of the Protestant Missions, thirteen Methodist ministers, six Congregational ministers, three Jesuit priests, and sixty Canadian-French, making an aggregate of one hundred and thirty-six Americans, and sixty-three Canadian-French [including the priests in the latter[62] class] having no connection as employées of the Hudson's Bay Company. [This estimate includes the missionaries who arrived on the Lausanne.] I have said that the population outside of the Hudson's Bay Company increased slowly. How much so, will be seen by the fact that up to the beginning of the year 1842, there were in Oregon no more than twenty-one Protestant ministers, three Jesuit priests, fifteen lay members of Protestant churches, thirty-four white women, thirty-two white children, thirty-four American settlers, twenty-five of whom had native wives. The total American population will thus be seen to have been no more than one hundred and thirty-nine." (This was prior to the arrival of the immigration of 1842.)

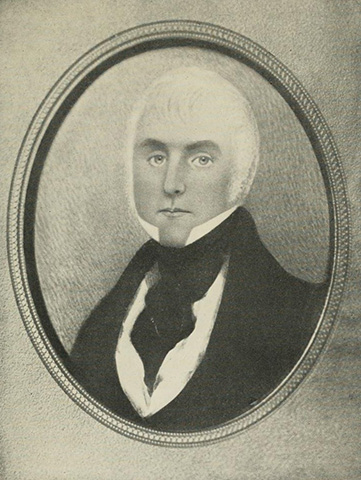

Dr. John McLoughlin

Taken from a miniature of Dr. John McLoughlin painted on ivory. This miniature was probably painted in 1838 or 1839, when he was in London. The original miniature belongs to the widow of James W. McL. Harvey, now living at Mirabel, California. Her husband was a grandson of Dr. McLoughlin.

In his Missionary History Rev. Dr. Hines says (page 249) that in 1841 and 1842, prior to the arrival of the immigration of 1842, the Oregon Methodist Mission "comprised nearly all the American citizens of the country." And on page 239 he says: "Up to 1840 it [the Methodist Mission] had been entirely an Indian Mission. After that date it began to take on the character of an American colony, though it did not lay aside its missionary character or purpose." He also says that in 1840 there were only nine Methodist ministers in the Oregon mission. Some of the lay members, of which J. L. Parrish was one, became ministers, which probably accounts for the difference in the estimates of Thornton and of Dr. Hines. In the summer of 1843 Rev. Jason Lee was removed, summarily, as Superintendent of the Oregon Methodist Mission by the Missionary[63] Board in New York, and Rev. George Gary was appointed in his place, with plenary powers to close the Mission, if he should so elect. He closed the Mission in 1844.

When the Lausanne arrived June 1, 1840, Dr. McLoughlin's power and fortunes were almost at their highest point. During his residence of sixteen years in the Oregon Country he had established the business of his Company beyond all question, and to the entire satisfaction of its board of directors. The Indians were peaceable and were friendly and obedient to him and to his Company. He was respected and liked by all its officers, servants, and employées. With them he was supreme in every way, without jealousy and without insubordination. He had become, for those days, a rich man, his salary was twelve thousand dollars a year, and his expenses were comparatively small. He was then fifty-six years old. He had prepared to end his days in Oregon on his land claim. His children had reached the age of manhood and womanhood. Few men at his age have a pleasanter, or more reasonable expectation of future happiness than he then had.

The half-tone portrait of Dr. McLoughlin, shown facing page 62, was taken from a miniature, painted on ivory, in London, probably when he was in London in 1838-9. It portrays Dr. McLoughlin as he was in his happy days. This miniature now belongs to the widow of James W. McL. Harvey, who was a grandson of Dr. McLoughlin. It was kindly loaned by her so that the half-tone could be made for use in this address.

Provisional Government.

For convenience I shall tell of the Provisional Government of Oregon before I speak concerning Dr. McLoughlin's land claim.

About 1841, owing to the death of Ewing Young, intestate, leaving a valuable estate and no heirs, the residents of the Oregon Country in the Willamette Valley saw the necessity of some form of government until the Oregon Question should be finally settled. As under the Conventions of 1818 and 1827 there was joint-occupancy between the United States and Great Britain, the Oregon Country was without any laws in force. It was commonly understood, at that time, that most of the Americans in Oregon favored a provisional organization—one which would exist until the laws of the United States should be extended over the Oregon Country. It was also commonly understood that the British residents in Oregon opposed a provisional government, as it might interfere with their allegiance to Great Britain. As there was a joint-occupancy, and the British were legally on an equality with the Americans, each had equal rights in the matter. February 17 and 18, 1841, a meeting of the inhabitants was held at the Methodist Mission. Although attempts were then made to form a government, several officers were appointed, and a committee appointed for framing a constitution and a code of laws, the movement failed. The matter lay dormant until the spring of 1843. The immigration of 1842, although small, and although about half of them went to California in the spring of 1843, materially increased the strength of the Americans in Oregon.