The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Great Captain: A Story of the Days of Sir Walter Raleigh

Title: The Great Captain: A Story of the Days of Sir Walter Raleigh

Author: Katharine Tynan

Release date: April 17, 2011 [eBook #35896]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Katherine Ward and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

CONTENTS.

- I.—Of Myself, that Great Captain Sir Walter Raleigh, and how I became his Leal Man 7

- II.—The Apparition of the Monk 21

- III.—Of My Secret, the Lord Boyle, and Other Matters 37

- IV.—The Dead Hand 52

- V.—Of a Strait Place and a Quiet Time 67

- VI.—The Treasure-ship 83

- VII.—Our Last Years Together 99

- VIII.—An Unravelled Thread 113

CHAPTER I.—OF MYSELF, THAT GREAT CAPTAIN SIR WALTER RALEIGH, AND OF HOW I BECAME HIS LEAL MAN.

I never knew my father and mother, having been born into a time like that of the great desolation foretold by the Scriptures. They were the days of what I have heard called the Rebellion of the Desmonds, when that great league was made against the power of Eliza, the English Queen, by the Irish princes, which went down in a red sunset of death and blood. Indeed I myself had starved, like other innocents, on the breasts of their dead mothers, had it not been for the pity of him I must ever regard as the greatest of Englishmen, albeit no friend, but rather the spoiler, of those of my blood and faith.

It was indeed while the end was not yet quite determined, for although Sir James Desmond, the wisest and most skilled of their generals in the art of war, was dead, there was yet the Seneschal of Imokilly and other Geraldine lords fighting for their inheritance and their country. It was on a day when Sir Walter Raleigh with a handful of troopers was returning from a visit to the Lord Deputy at Dublin that he found me. He had expected no ambush, and rode slowly, being fatigued by his journey, through the great woods to the Ford of the Kine. Now the woods covered many dead and dying, and as the Captain rode at the head of his men I came running from the undergrowth, a lusty and fearless lad of three, and held up my hands to the foremost rider. I had as like as not been spitted on a trooper’s sword but that the Captain himself, leaning from his horse, swung me to his saddle-bow.

He had perhaps a thought of his own little Wat, by his mother’s knee in an English pleasaunce, for, as I have heard since, he talked with me and provoked me to confidence. Nor was I slow to answer all he asked, being a bright and bold child, which perhaps was the saving of me, since I flung an arm round the great Captain’s steel-clad neck, and perched by him as bold as any robin that is housed in the frost.

But as we rode along in the summer evening, fearing no danger, though danger there was, for my lord the Seneschal of Imokilly had word of our coming, and as we forded the river was upon us from the further bank with his kerns, three times our number. But the Captain rode at them with his sword drawn, slashing hither and thither, and sorely I must have hampered him, and much marvel it was that he did not loose me into the stream. But that he held me shows what manner of man he was, that being fierce and violent in battle he yet was of so rare magnanimity. Little lad as I was then, I remember to this day the cold of his steel and silver breastplate against my cheek.

And when he had hewed his way through them and was on the further bank in safety, he looked back and saw one of his men, Jan Kneebone by name, dismounted in the stream and in peril. Then, setting me down gently, he rode back into deep water to his man’s deliverance, and having slain two kerns who had him in jeopardy he flung him upon his saddle-bow and rode with him again up the steep bank. It was a great feat of arms, and might well have cost the English this most splendid soldier; yet I have heard Sir Walter say that the Desmond Lord of Imokilly might have slain him had he willed it. “And think not, little Wat,” he said to me years after, speaking upon that day, “that chivalry departed from the world with the glorious pagan, Saladin; for in many places I have found it, nor least in this wild country of thine; and it is an exceeding good thing,” he added, “that men will forget their passions amid the heat of battle, and will remember only that the enemy they fight against is brave.”

Wat, he called me from himself, because he loved me, and after his little son. Indeed, he seemed in time to love me as fondly as any father; and while I was yet a little one and learning from him swordplay and fence, horsemanship, and other manly arts, I began to understand that amid all his splendor he carried sadness beneath it, and was a banished man. He had lost the Queen’s favor—not because he had enemies at court, for Eliza was not one to be misled by rumors or cunning, but because he had clasped around the white neck of Mistress Throckmorton, a dame of honor, the milky carcanet of pearls the Queen’s vanity desired to adorn her leanness, which in time the Queen might have forgiven, if he had not privily married the same Mistress Throckmorton; for she would have but one moon in the sky, and she liked not the gallantest man of her kingdom to be her dame’s satellite. So he was become a soldier of fortune, and since he might not have his lady or his little son with him in these wild times, they abode in his quiet English Manor-house, while his sword slashed a way to fortune for them through the inheritance of the great, unhappy Desmonds.

In later years, when I had become well acquainted with the character of my lord, it hath seemed to me that he was not one for marriage; for danger was his love, and he was homesick away from her smile. And yet no more tender lord than he to the Lady Elizabeth might be found, and he loved his little Walter greatly.

But presently, the war being ended and the last Desmond Earl slain by a traitor in a cabin in the mountains, my lord sailed away from the harbor of Youghall to London, to the end that he might win permission for another expedition in search of treasure, and so regain the Queen’s favor. By this time I was a tall lad, and was fain to go with my lord, but this he would by no manner of means permit. I hated so to live my life without him, even for a time, that I had thought of hiding myself aboard his ship, the Bon Aventure, but the fear which I had of him besides my love held me back. I had never seen him angry with me, and I prayed that I never should, so I heard him in silence when he bade me stay. Taking me aside then, he said to me, lovingly:

“I wrong you not, Wat, because I go without you, for Queen’s favor is vain, and it may be I go to Traitor’s Gate. You are no meat for the Tower, lad.”

Then I cried out that if he went to the Tower I should go with him; at which he seemed pleased, patting my shoulder with great gentleness.

“It may be,” he said, “that I return again to this Irish exile I weary of. Or, in the greatest event of all, I shall fit out a fleet for the Spanish Main, and make the Dons stand and deliver. That would be happiest for us, boy, for indeed I make but a bad port-sailor.”

“You sail in the Bon Aventure,” I said; “it is of good omen.”

“It is indeed,” he replied, “and I thank you for reminding me of it.”

He looked out to sea, where the English leopards flapped at the wind’s will on the mast of his ship, and I think I never saw such a longing in a man’s eyes: so great was it that my heart bled for him. I had thought perhaps that he longed so much to see the Lady Elizabeth and his boy. But he spoke, and I knew he was thinking of the free life of the rovers of the sea, not of that lady whom he so tenderly loved.

“If we prosper,” he said, “we shall sail for Guiana, and found there, who knows, another Virginia. The spoil of half a dozen fat galleons and a new country. These are things that even Gloriana need not disdain. Yet Essex hath all her ear, and Essex is mine enemy.”

“If you succeed, my lord—” I began.

“If I succeed I shall send for you. If I am sent to the Tower there are certain matters concerning you to which Master Richard Boyle is privy, and which he will impart to you. But it may be I shall be sent back to rot here; if so, there is nothing more to be said.”

So on a certain day of lusty summer my lord sailed away in the Bon Aventure, with Master Edmund Spenser, whose company had so greatly lightened his exile. The same carried with him two books of his poem, The Faëry Queen, which he designed to have printed in London. He was bound to return, whether my lord came or not, for he had left at his Castle of Kilcohnour his lady whom he had married at Cork, and his young son. The same lady he made famous forever by the most beautiful of marriage-songs, which thing I had come to know, young as I was, for my lord would have me a scholar as well as a soldier, and I was become a very excellent scribe, so that the fair copying of Master Spenser’s poems came to me.

I remember my last glimpse of them ere the Bon Aventure sunk over the rim of ocean, and evening seemed all at once to settle on the world. My lord was wearing a suit of black velvet over white, very finely embroidered with seed-pearls. The plume of his hat was held in its place by a clasp of diamonds. Beside him Master Spenser, in his black, looked over-grave. But when did Sir Walter—whom I call here “my lord” out of the love and loyalty I bore him—fail to shine before all the world by the splendor of his apparel as well as by his manly beauty and the greatness of his deeds?

After they had gone, set in the endless dusk of summer evening, I grew tired of wandering about the gardens, so strange and sad without their master. So I went within doors, where some one had set a starveling rushlight in the chamber that was my lord’s dining-hall, and there I sat me down with my Latin grammar and the Virgil my lord had given me. At this time I sat daily on the wooden benches of the College School at Youghall, and had my learning of an old clerk Sir Walter had summoned here from Devonshire to take the place of the doctors and singing-men who had gone with the Desmonds. But my heart was heavy, and my head, and I had pushed away from me untasted the supper a serving-wench had carried to me.

Now all was very still in the house, so that the tap-tapping of a twig by the window-pane seemed to me a little frightful, although I was a boy of spirit. Outside was the black of an early summer night before the moon has risen, and going to the window upon the tapping I could see no star for the myrtle boughs. Yet sure I was that were I outside the purple would be pierced by innumerable eyes of light, and I was greatly tempted to return to the garden. Indeed, out in the night there would be companionship, although every bird slept well within the boughs. It is the houses men build that breed these phantoms of the brain, and not the free air. But disregarding the temptation I went back to my book, knowing full well the pleasure it would give my lord to learn that I had been diligent in his absence. Wonderful it was that he was hardly less in love with learning than with adventure. Indeed a man of such parts was this knight and master of mine that there seemed to be nothing admirable in which he did not excel. And if I am blind to his faults, even to this day when I repent me of certain share of mine in his adventures, let that be forgiven me, for surely I owed him all love and loyalty.

As the night went I heard the scullions who had been disporting themselves in the town return one by one, and the bolting and barring of doors. The songs of the sailors which came up from the shipping in the bay fell off and ceased. Silence fell on the town, a silence as unbroken as that of the sleepers yon in St. Mary’s yard, and presently drowsiness overcoming me I too slept.

CHAPTER II.—THE APPARITION OF THE MONK.

The room in which I had studied and now slept was that to the right hand as you entered the door of the Manor-house. It was lined stoutly with oak, and it was dark because, though it had two fair windows, they were much obscured by the myrtles my lord had planted, which had thriven exceedingly in this mild air.

This room, as I have said, my lord used for a dining-hall. Else when he was within doors he sat in the oriel of the pleasant room overhead; and it was there that he and Master Spenser would sit and smoke or be silent; and there, which is not to be forgotten, Sir Walter listened to The Faëry Queen.

For some reason or another this dining-hall, despite its purpose, seemed a place of little cheer. The Manor-house had belonged to the warden of the college, and owed its construction to him; and it was built after the English manner, which need not be surprising, since the progenitors of those church and abbey builders, the Munster Geraldines, were of English blood and race. Not only was the dining-hall in itself low and somewhat forbidding of aspect, but it smelt of earth and new graves, for all the generous wine and meats that had been consumed within it. The cause of the same my lord had never been able to determine, and it stayed, although the chimney roared with logs of ships’ timber, and the brightness, the good cheer, the wit and gayety that met there were enough to scare away any thought of death or the earth that shall receive us.

I slept, I have said, and while I slept the moon had arisen. The low light of it filled the chamber when I awoke with a start, smelling the graves, and feeling very cold. On the myrtle tree without an owl hooted. The rushlight had gone out, but this I hardly knew, only that an earthy wind, smelling of damp and mildews, blew about my face, and I was stiff from lying asleep upon my book.

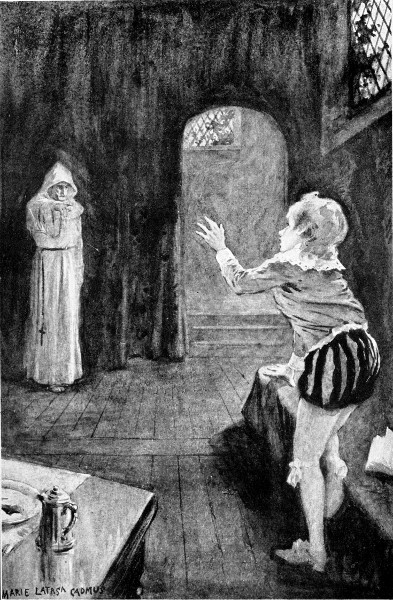

But this I noticed vaguely, for as soon as my eyes were well open a strange appearance in the room drew my gaze upon it. I was by this time a stout lad of some sixteen years, and accustomed to fear nothing, yet I will confess that the hair of my head stood up. The figure of a monk was in the further corner from me. I knew it to be a monk, because of the effigies, images, and portraits in St. Mary’s Church and the library of the college. Further, I knew the apparition to be of a white friar. The cowl was over the face; the head was bent; a fold of white cloth hid the hands. The stature of the monk was exceedingly tall, and of a great leanness, as I could see where the belt of brown leather clasped the white gown about the middle.

All this I saw clearly by the light of the moon, or was it by some unearthly light of which the figure stood the centre? I know not, only that I saw everything clear: and still the odor of graves was in my nostrils.

While I stood stammering and staring a lean finger was pointed at me, so lean that I know not if flesh covered it, or if it were the fleshless finger of a skeleton. A voice, hollow and strange, came forth of the cowl.

“Son of the Geraldines,” it said, “why art thou here among their murderers and despoilers?”

The voice constrained me to answer.

“Alas,” I said, “I know not what you mean. I am a nameless boy, a dead leaf drifted in the forests. Why do you call me a son of the Geraldines, unless it be that I come of the humblest of the clan?”

“You are no kern’s son, Walter Fitzmaurice, but of a noble house. How is it that you eat the bread and run at the stirrups of the Sassenach who is the destroyer of your race?”

I stretched my hands imploringly to the cowled figure.

“He rescued me from death,” I cried; “he warmed me with his love. He has taught me all a noble youth should know.”

“You love him?”

“I love him.”

“Listen, boy. They think they have destroyed the Desmonds, root and branch, as a man might tread out under his heel a nest of vipers. Yet hope is not dead. The line of the Geraldines is not destroyed. Return to your own people and leave this evil knight.”

“Alas, I cannot,” I said, “for I love him.”

“The blood of your kin is red on his hands.”

“And yet I love him.”

“He and his freebooters have wasted the country that was the portion of your fathers. Whom he spared to slay famine and pestilence have slain.”

“I should have died of the hunger,” said I, “had he not delivered me.”

“And you will follow him?”

“I will follow him.”

“Wherever he goes?”

“To death.”

“To death and evil. Very well, Walter Fitzmaurice, of the race of Desmond, then your kindred’s blood be on your hands, as they are on those for which you have held basin and ewer that they might wash. Water will not wash them clean, nor yours that share in the stain. He shall die by violence as he has slain many another—and as for you, what penance, what fast and prayer shall suffice to wipe out your sin? You have chosen, Walter Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald. Take care that you have not chosen forever.”

The voice rose in a shriek of menace, and I caught sight of burning eyes under the cowl. Suddenly through the hooting of the owl in the myrtles there rang, shrilly as a trumpet, the crowing of a cock. The wind from the grave rose in my nostrils and filled me with a great terror. I turned giddy and swayed hither and thither, and the room went up and down under my feet.

The next thing I knew was that the sun was in the room, and I was lying with my cheek on the open page of the Virgil. Nothing was changed in the room since last night, except only that the rushlight had dwindled to a pool of cold fat; but how long it had been out I could not gauge.

Slowly the happenings of the night came back to me; but now in the warm daylight who thought on ghosts and goblins, or was afraid of them if they came? Where the owl had hooted over night a blackbird was singing, bold and bright. The lawn of the Manor-house was under dew. As I looked a peacock spread his tail in the sun, and his more sober mate stood to admire him.

Sitting there I rubbed my eyes. Why, I had awakened just as I had fallen asleep, worn out with the sorrow of loneliness, and the trial to fix my discontented thoughts upon my book. I stood up and caught sight of myself in a mirror. Then I realized that it is ill to sleep full-dressed. I was pale, and my hair strayed in disorder. My doublet looked as if I had had the habit to sleep in it, and my cloak was awry. I had been no sight to please my lord, who loved daintiness, and observed it himself in the strangest circumstances.

I would down to the Port-side and bathe in the morning waters. But ere I did that, remembering the dream or vision of the night, I went towards that place where I had seen the monk and carefully examined the same. But nothing there was to give me clue. The room was stoutly panelled with oak, every panel as like to his brother as two peas. Yet in that corner of the room there was one thing that made me linger, for the smell of earth, it seemed to me, was there stronger than elsewhere.

I sniffed and smelt like a terrier after a mouse; but sniff and smell as I might found nothing. I was no stranger to sliding panels and the like, at least by hearsay, but press and push as I might nothing came of it, so that at last I was fain to desist.

As I made my way to the water-side in the glorious morning my thoughts were full of the night’s encounter. If it had been no dream but a true happening I did not doubt now, with the sun risen, that the monk was no ghost but a living man, albeit a spare one, for I recalled his lean finger, and the burning eyes set in the hollow cheeks. His words had been verily human, not ghostly at all: and had I been minded to leave my great lord whom I loved, had he not been ready to bear me away with him? Either the thing was a fantasy of a dream, every part of it exceedingly sensible, and one part following another as I have not known it in dreams, or else it were true, and he a living man who had stood before me last night.

One thought made my heart leap up with a sharp throb of pleasure. The monk had said I was noble—I, who had come from none knew where, a nameless youth and treated courteously only because I was dear to my lord, and myself very sharp in a quarrel and adroit in the practice of arms.

After I had bathed and lain to dry in the sun I returned back hungry as a hawk. In the blessed sun all was different from last night. My lord would return, and would bear me away to court, and presently we should have letters of marque, and should go sailing on the Spanish Main in search of good fighting, salted with doubloons and pieces of eight; and presently should make for the Treasure Islands, and find there, as I imagined, jewels as large as plums, and gold and silver in great portions. For I had read Maundeville and other travellers, and had magnified in my credulity even the marvels they had told. I knew, too, that my lord had brought home to the Queen’s Majesty a necklace of pearls whereof each stone was larger than a cherry. And we had heard of Guiana that the very sands of the seashore sparkled with gold and silver, and that in the workings the old inhabitants thereof had made, that they might build their heathen temples, the walls were of gold, while the idols were crusted with jewels so that no man might look on them without winking.

So much in the sunlight. And yet again I had a cause for joy and pride because the monk had declared me noble. How to prove it I knew not, but resolved that when my lord was come hither again I would tell him all, and he would somehow unriddle me the secret and I should be no longer nameless.

My breakfast I had beneath the shade of Sir Walter’s myrtles, where he had made his favorite seat. It was brought thither by that good Sukey who had nearly drowned my lord the first time she beheld him smoking that weed called tobacco, which he had brought from his settlement in Virginia. For she conceived him to be on fire, and half-drowned him that she might put him out. I had my white manchet and roast beef and flagon of ale, and had a fine hunger for it after my morning swim.

But when it had all vanished I strolled away to the stable-yard, where Gregory Dabchick rubbed down one of my lord’s horses, and hissed between his teeth as is the manner of ostlers in the doing. He was a shock-headed fellow, of slow wits, but honest, and loved my lord.

“It be lonely, Master Wat,” he said, “since the master be gone.”

“Gregory Dabchick,” said I, “you were of Sir Walter’s following the day the Seneschal of Imokilly set upon him at the Ford of the Kine.”

“Ay,” he said, grinning, “and Jan was spilt in the water. He got up dripping like a fish, and when the Captain haled him to dry land, and he would mount his beast he overleapt him and a good horse galloped into the forest and so became the goods of the Irishry. I wish,” he added, “that Margery May, at home in pleasant Devon, might have looked on Jan then.”

“I have nothing to do with your jealousies,” I said, as haughty as though I were my lord’s son. “But tell me, Gregory, do you remember me that day?”

“A brown babby, as fat as ever I see,” Gregory answered, still rubbing down his horse. “And as near being spitted by Dan’l Drewe as ever I wish to see. I never liked that work myself, killing o’ babes and sucklings, and fair women, or leaving the babe to die on its mother’s breast. ’Twere lucky for you, Master Wat, them that starved in the forest did not eat you, ere ever you came the way o’ Dan’l’s mercy. Eh, what a fat one you were!”

“But a comely, Gregory?” I asked anxiously. “A noble child? Was I that? And clad in silk and fine woollen, as became my condition?”

“Why, no, Master Walter, but a fat, brown babe; eh, so fat! And nought but rabbit-skins to cover you. You had been good eating for them in the forest.”

“You are rude and dull, Gregory,” said I, leaving him in dudgeon. As I looked back I saw that he had come to the stable door and stood watching me with a gaping mouth. Plainly there was nothing to be learned from Gregory Dabchick.

CHAPTER III.—OF MY SECRET, THE LORD BOYLE, AND OTHER MATTERS.

In the autumn of that year my lord came back, and in my joy at seeing him again I hardly felt that he was sad. The Lord Essex had prevailed against him with the Queen and he was returned to exile, although one of his ships had brought in a Spanish galleon worth fifty thousand pounds. It must be remembered of him that his passion for discovering the unknown worlds swallowed up all the treasure he was able to discover; so that the sea was never without his ships, and one expedition but led to another.

Had he been differently framed this season at Youghall had been happy enough. For now there was no fighting to be done he led that quiet and pastoral life which might have won him Master Spenser’s title for him, The Shepherd of the Ocean. He delighted himself by planting the strange seeds and roots he had brought from the ends of the earth and seeing them thrive. All his garden ventures were fortunate. The kindly Irish soil suited well with the tobacco, the myrtle, and the fuchsia. At Affane, a little way up the Blackwater, he had his orchards, where already the cherry grew abundantly. There, also, on sunny banks, he sowed in long rows a strange fruit called the potato, whereof the fruit is in the earth, and the leaves above it, and a very pleasant fruit to eat when well boiled, being of a sweet flouriness within.

Another fruit from the Indies which he planted at Affane was called the tomato—a great, smooth-skinned, scarlet fruit, over-heavy for its branches, and of a strange half-sour flavor, which yet grew on one in the eating. Another seed brought him by his captains was that of the clove-gilly-flower, or wall-flower, a most sweet-smelling plant; and the cedar also he planted.

He was as much set upon gardens as upon adventure and the search for new countries. Those of his captains who had returned had brought with them charts of the lands in which they had sailed, together with long reports concerning the inhabitants, their manner of living, their food and pursuits, the beasts and birds, the plants and ore, and all such matters; over which my lord would sit and pore in the long winter evenings, by the fire of driftwood, and smoking his long pipe. And sometimes he would talk with Master Spenser concerning them; but more often their talk ran on poetry and the arts. Master Spenser was working at the later books of The Faëry Queen, and had written also a very pretty pastoral entitled Colin Clout’s Come Home Again. Nor was my lord’s admirable pen silent. I went to and fro almost as a son; and I can see my lord now in some gallant apparel, for he knew not what it was to be slovenly, leaning back in his great chair, and reading from the manuscript in his hand that lament he made for the death of the stainless knight, Sir Philip Sidney, slain then at the battle of Zutphen:

England does hold thy limbs that bred the same;Flanders thy valour where it last was tried;The camp thy sorrow where thy body died;Thy friends thy want; the world thy virtue’s fame.

Alas, if but Sir Walter had been content to be poet and gardener; but whereas the one part of him was content the other tugged at his heart-strings so that he was not happy. In gardening he had no rivals except the Dutch, that great little republic of the water, since as famous as England herself for great battles and adventures by sea.

Now, quiet as the time was, and I was often alone with my lord, it was long before I found courage to speak to him of my birth. I know not why I was so wary in approaching it, but somewhere in my heart I had a warning that it would be unwelcome matter to him; so that often the words rose to my lips and fell silent before I could say them. It was indeed close upon a year from the time I had seen the monk that at last I dared to touch upon the subject. It was one evening when we had been gardening together, and tired after that pleasant toil we sat beneath the myrtle trees. My lord’s brow for a little while was unfurrowed with care, and his eagle eyes looked at me softened through the mists of his smoke.

“My lord—” I began, and then could go no further.

“What is it, Wat?” he asked kindly.

“My lord, I am troubled about the question of my birth. To be nameless where every one hath a name is no light matter to bear.”

“Hath any one reproached you?” he asked, and his eyes flashed.

“If any hath I should not have come even to you for redress,” I said, fingering my sword.

“Ah,” he said, and he looked well pleased. “There spoke no nameless boy!”

I breathed hard at the thought of what his speech meant. I was in act indeed to ask him if I were truly a Fitzmaurice and of noble birth when his next words held me, and, as it proved, the silence between us was to last to the edge of the grave for one of us.

“Be content, boy, for a little while,” he said, and his voice was of great sweetness. “You are no nameless child; but let it be my secret for a time. In time I shall reveal it. If I told you now it might mean that we should part company.”

“Never that,” I said.

“Never that, I pray,” he rejoined, adding—“because I love you, Wat.”

Then after a few minutes of silence he went on:

“Your secret is left to no such blind chance as may befall such an one as I. If aught happen to me, Master Boyle holds it safe, and will reveal it in proper time.”

“You will not tell me?” I broke out.

“To have it known would bring me some steps nearer the Tower,” he said, “and I wend that way already.”

“Then keep it silent forever,” I cried out.

“Nay; that would be hardly fair to you. Besides, you forget that Master Boyle hath it.”

“I like not Master Boyle.”

“Nor do I, overmuch, Wat. He is one of your still, secret men, with the lawyer’s craft and cunning. What should there be between us?”

“I hate his peaked face and his yellow eyes, and the way he hath of watching you and peering like a cat that sees in the dark.”

“You are hard on Master Boyle, Wat. There is too much of the lawyer in him, and he treads soft as a cat. Yet there is a man behind his greed and his cunning. He is better framed for times like these than such an one as I. I could never walk warily.”

“He has your secret and can use it against you.”

“He would do me no more harm than beggar me if he might so enrich himself. My head would be no use to him, little Wat.”

“’Tis a poor warranty for holding a secret,” said I, bitterly.

“I am well-disposed to Master Boyle,” my lord went on. “He is a man of substance, Wat, and a useful friend for one like myself, who can keep nothing. We shall not pluck the jewels from the gold-trees of Guiana without money and ships. I am nearly sucked dry, and the Queen hath lost faith in me.”

Then I knew that my lord was not so contented as he had seemed of late, and that further voyages were afoot. In the joy and excitement of the prospect I forgot to fret about my namelessness. Besides, my lord knew that I was noble; and Master Boyle knew it, and treated me with a consideration which should have won my regard if it were not that I distrusted his dealings with my lord.

And as the autumn of that year came on I noticed that my lord ceased to care for his gardens and orchards and plantations, and would be forever poring over maps and charts, and had long conversations with the master of the Bon Aventure, which good ship lay yet in Youghall Harbor, and the master did seem nigh as weary of idleness as Sir Walter himself. And sometimes he had Master Boyle privily. Indeed, though I speak of him as Master Boyle, ’tis from old habit; for about this time he had been created my Lord Boyle for his services to the Queen’s Majesty in the better governance of Ireland.

At last the word came that we were to sail; and it was as if the quiet, sleeping town of Youghall had started awake. Such a burnishing of arms and armor; such a getting out of old materials of war; such a polishing of decks and making of sails and mounting of guns on the good ship Bon Aventure as never was known. All day long the singing of the sailors in the harbor floated to us through the still air. And my lord’s swarthy face smiled once again as I had known it when I was a little lad, before he was like a led eagle that is chained beyond hopping a little way.

My Lord Boyle had found us the funds; so much I knew, but liked him no better. The evening before we were to sail there was a great banquet, and many gentlemen came even from so far off as Dublin to wish the Great Captain Godspeed. We were to sail at blink of the morning star, and there was to be no sleeping for us till we were on shipboard. Never have I seen my lord but once so magnificently clad. His doublet was of white silk, so sewn with diamonds that the silk was hardly to be seen. His hose were of white silk, his trunk-hose of silk with slashings of gold. Over one shoulder he wore a short cloak of yellow velvet clasped with diamonds; and the rosettes of his shoes were a blaze of diamonds. Seeing his face in the midst of such splendor I marvelled how the Queen could harden her heart against him—for never have I seen him in any assemblage, however honorable, that he did not make the other gentlemen seem mean and dull beside him.

When the gayety was at its highest and he feared not to be missed, I saw him slip from the table with my Lord Boyle, and retire with him into the oriel. The banquet had been set in the oriel-chamber because it was lighter and more spacious.

When my lord had left the table I too went away. Looking at the horologe my lord had given me, I saw that it lacked yet two hours of the time when we should be aboard.

I went down stairs to the lower chamber, which was dark and silent. Once more I thought I should endeavor to find the secret way through which the death-damp came, and my midnight visitor of more than a year ago. If he had sought me since he had not found me, for I had avoided being alone there since that night.

There was neither moonlight nor rushlight in the room, so that I could only grope with my fingers for the secret the panel must contain. For some time I groped in vain. Then my nails seemed to have found a crack in the wood, a mere notch in which they fitted. It gave me no promise, for the oak had warped here and there, and had left a few furrows. I was sure I had been over all the place before, yet now as I drew a little way the whole panel began to move. I did not know then, nor could I see, the cunning by which that door was devised so that none should discover it. I have said that the chamber was quite dark.

Feeling now before me with my hands, I found a vacant square wide enough for one to creep through. Through it the wind blew strongly, and it was a cold, earthy, evil-smelling wind, such as I knew full well. Where might it lead? There was a report amongst us that the house had secret ways to the harbor; but it was no honest sea-wind, however confined and far from its source, that blew my way, but something far more villanous.

I know not how it was that I seemed to forget that in less than two hours we must embark. The present adventure held me to the exclusion of all else. I stepped within the narrow passageway—crept within it, for I had to go on hands and knees. I had no light nor aught else to guide me; but if I thought at all it was that if the monk could come this way in safety, I could go as he had come. But to leave a gaping panel was not in my thoughts. Having entered I drew the panel to. Then feeling with my hands I came upon a lock. Had I moved it by my touch, or had it been left unlocked of design? There was no time for answering of riddles, and having pushed the panel to I turned to pursue the adventure.

CHAPTER IV.—THE DEAD HAND.

After a little I found that I could stand upright in the passage. Stretching up my hands I could feel a solid roof above my head. The walls on either side of me were of earth, held back by stout balks of timber. If one were to give way the passage had been a grave indeed; but so far as I could feel with my feet the clay had not fallen at all. Else indeed there could not have been so much air in the passage as to give me breath; and I breathed freely enough, albeit with a certain oppression, and a loathing of the dank smells.

For a time the passage went down into the bowels of the earth as it seemed to me. I guessed by the direction it took from the dining-hall that it must grope under the graveyard—and thinking on this I realized how that indeed the wind that blew from it was a wind of death. And at that time I was too ignorant and too vain to rebuke myself by the thought that this was a burying-place of saints.

Presently my foot stumbled against a step, and much relieved I was to find on ascending it that there was another step and yet another; for I liked not this burrowing among graves like the mole; and the steps seemed to promise a speedy end to my journey. Taking them in the dark there seemed to me a prodigious number of them; yet I was not gone very far when I perceived agreeably a lightening and sweetening of the air. I could have taken but a little while in coming, for I had met with no obstacles; yet it seemed long since the time I had plunged into that pit of blackness ere I came up against a stout door, with a grating in it, designed no doubt to give air to the passage.

To my great joy it was held only by a latch, and even before I had made this happy discovery I felt the sweet air of heaven blow into my face; and I think I never before knew how sweet it tasted.

Undoing the latch and drawing the door to me I stepped within a stone tower. The moon had arisen on the eastward side of the tower, and looking through the crumbling lancet window I saw below me, serene and beautiful, the quiet, terraced graveyard of St. Mary’s.

I could have laughed aloud to think that the journey had seemed to me so long. In truth it had occupied some five minutes, as I discovered, holding my horologe to the moon, and had not occupied so long if it were not for my groping and pausing.

But the floor was solid under my feet. I had to think a minute before I knew where I was. I was in that blind tower of St. Mary’s to the eastward corner, in the basement whereof were deposited the brooms and pails for cleaning of the church.

Playing hide and seek therein with a boy’s irreverence I had marvelled why, since the tower was blind—nothing but a roof of stone above the chamber—that they should have troubled to pierce it with lancets like any honest belfry. The upper portion of the tower was in ruins, as you could see from the graveyard without. Ah, and so the blind tower had its uses; as a hiding-place it might be for some one who had lived in the Manor-house in old wild days. For, as to any manner of egress from the tower, that I could not see at all.

The chamber where I stood was full of the drifted leaves and the nests of birds. Except for the shaft of light from the lancet it was in blackness, and I began to wonder if the tower went no further.

I groped about the walls, however, till I came upon a staircase, which went up, not in the middle, as is usual in towers, but at one corner, so that each story formed a room.

’Twas three stories’ climb to the upper room. Here it was that the ruin had befallen the tower; for where the lancet had been there was a great gap, and somewhat of the roof had fallen away.

I was now clear of the low trees, and the half-veiled moon looked within the chamber. Then I saw to my amazement that at the side of it, yet roofed over, there was a bed, a chair, a table, all of the rudest. But little of this I saw till afterwards, for on the bed lay the figure of that monk who had spoken with me, now nearly fifteen months ago.

His face was in shadow, yet I never thought for a moment that he slept. One lean hand dangled from his great sleeve over the side of the bed; it hung helplessly; and young as I was I had looked on death often enough to know that this was the hand of the dead. The habit was composed decently about the figure. Either the monk had so composed himself for death or he had had some companion who had fled away leaving him to the eye of heaven.

Standing there, a great awe and compassion fell upon me. Something of yearning and tenderness afflicted me as though the dead man had been of my blood: the tears rushed from my eyes, and I trembled so that I was forced to my knees; yea, as though invisible hands had bent me. I knew little of praying, but something of wordless petition to the Great Father of us all stirred in my dull and proud spirit. In that moment I had indeed the heart of a child.

When I had arisen from my knees I went to the side of the pallet and looked upon the sleeper’s face. In the shadow it gleamed like polished ivory, and as I looked the moon, climbing higher, touched the still mouth with a sweet and sanctified light, making it as though it smiled. I touched the hand that swung by the side of the pallet. It was scarcely cold. I knew not how I thought of such a thing, except that I was familiar with the knights and ladies who sleep in stone in St. Mary’s Church, but I composed the sleeper’s hands in the manner of Christ’s cross upon his breast; and afterwards turned away from the patient, smiling mouth like one who hath sinned and been forgiven.

Then I did what I believed he would have me do: I made a search for any letters and papers he might have left; for I could not think he had left me ignorant of what he would have me know. I searched busily; and there were not many places wherein to look. There was nothing anywhere. But my search was not yet over till I had examined the monk’s person. I went back to his side, and with a prayer to him for forgiveness, I groped gently in his habit for anything in the nature of papers, and doing so I felt his body to be by wasting scarcely greater than a child’s. Yet ’twas not starvation, I knew, for a loaf of bread and a pitcher of water stood on the table.

I had not far to seek. The papers were within the folds of his habit, where they met upon his breast, and were confined with the claspings of his leathern belt.

I drew them forth and went to the full flood of the moonlight. By it I read the superscription:

“To Walter Devereux Fitz-Hugo Fitz-Theobald Fitz-Maurice”—

As I read it my heart leaped up. What a proud name it was, and telling of a glorious ancestry!

“—commonly known as Walter Munster, the ward and page of Sir Walter Raleigh.”

When I had deciphered so far the tower seemed suddenly to rock. It was the great clock in the neighboring tower striking of midnight; and I had yet to ford the passageway between the graves! Already I might have been missed. I read no more, but thrust the papers within my breast. Then I bent and kissed the hands of the monk, feeling again that rush of softness, and as I kissed the hands I noticed the great string of beads which fell from the girdle, and that too I kissed, and the crucifix dependent from it; and these things I did blindly, having then a hard and ignorant heart, but being compelled I knew not how.

Then I stole from the tower-room and again down the winding staircase; but first I had drawn the cowl over the face and hid the hands and feet in the folds of the habit; and so left him to quietness and the night.

I made the return passage without any mishap; and though a fear assailed me on the way lest I had locked myself within by closing the door, there was no ground for it, for the panel opened simply enough, and was indeed secured by a bolt on the passage side; which no doubt had prevented my finding the opening before. For either the monk had left it undone now by design, or being surprised by his last sickness, or else a companion or companions of his had fled the house-way while we slept, leaving the door unbarred. Yet I had seen no sign of any other inmate of the tower save one; that is of visible folk, for I doubt not there were others, ministering and invisible.

So I returned as I had come and went hastily to the banquet-hall. As I entered my lord and the Lord Boyle were returning slowly to their places. I caught a word of their speech. “You will remember the trust,” said my dear lord; and I knew not it was of me they were talking. “Yea,” said my Lord Boyle, and showed his yellow teeth; “let it be in my hands, or else when Jamie succeeds some Scot will have it.” And then he laughed, rubbing his lean hands together.

Then my lord observed me, and calling me to him he put his hand upon my shoulder and looked at me with surprise.

“Why, Wat,” he said, “what spider’s nest hath caught you?”

I looked down then at my brave apparel, and was confused to find that it was gray with dust and cobwebs from my journey.

“He hath been ratting,” said my Lord Boyle, “and hath pursued the quarry even within their holes.”

“It matters less,” said my lord, “since it is the hour to put on soberer attire. Be in good time, Wat,”—and so saying he released me. Then I hurried to my chamber in the roof, and was right pleased that I had not been questioned more closely. And when I had laid away my fine apparel and all was ready for our journey, I took my paper to the candle-light that I might decipher it.

It had been written for my hand and none other, and the writer thereof was mine own father’s brother. I was indeed of the illustrious Desmond house, though of a younger branch; and yet in the havoc that had come upon it I might well now be all that was living of the race. I had, it seemed, my father being slain, been hidden with my mother in the forest by a faithful clansman, who had provided us with what food he might; who being out one day snaring rabbits in the forest had been caught by a party of the enemy and borne away by them strapped to one of their horses. He had escaped them by the mercy of God, and returned to the place where he had left us, to find his lady dead of starvation and myself gone. Doubtless that sweet mother of mine had starved through giving all she had to her child. The man knew not if I had met an enemy and been hacked or speared to death, or if the wolves had had me, or the fierce eagles that yet infest the forest in search of tender prey. He grieved to death not knowing. But the friar, Brother Ambrose, the last of the White Monks of Youghall, and mine uncle, known to men as Roderick Fitzmaurice, rested not till he had found if I were of this life, and at last discovered me. Having written this history for mine eyes, he wrestled with me further that I should come out from among the enemies of my people. But to what end? I asked, having so much worldly wisdom, since the Desmond clan was gone down in blood, and its inheritance with strangers. Indeed, when I had come to the dead man’s prayers, I folded up the paper as one that will not listen and fears to be persuaded. Even then there came from the harbor a ringing of bells and the shouts of the sailors as they drew up the anchor of the Bon Aventure from its bed in the sands. I therefore thrust my fine garments into my sea-chest and shot the bolt; but mine uncle’s message to me I put within my doublet. As the ship swung round, and we headed her for eastward I turned my thoughts away from the quiet sleeper in the church tower, and looked rather to my lord’s dark figure as he leant over the vessel’s side, gazing not the way she was going, but rather to westward. For though he was the enemy of my race and my country, yet I loved him with such a love that nothing could dissever my heart from him. And for his sake I was not sorry even that I had not sooner discovered that poor kinsman of mine—the very last it well might be—in his hiding-place. For no doubt he had come many times to the room in which he had first found me, but never found me again. And now he was dead and past caring any more.

CHAPTER V.—OF A STRAIT PLACE AND A QUIET TIME.

A few days later the Bon Aventure was lying in the river Thames, and we had no more than cast anchor when my lord put on his richest clothes, and bidding me to attend him, went by water to the steps leading to the Queen’s palace of Westminster. I remember that the way took us past Traitor’s Gate, the low and threatening portals by which prisoners are brought within the Tower. As we passed my lord looked at me with a sad smile. “I shall go that way yet, Wat,” he said. And when I burst into a passionate protest, he said to me: “Why, Wat, if you could look upon the company which hath passed by way of that gate, you would see it to be of the finest. I shall not blush to tread in their footsteps.” But I could not believe it, looking upon him in his garb of peach-bloom velvet laced with silver, and the jewels of a king’s ransom; and yet alas! he spoke too truly.

I remember when we were come to those stairs of Westminster how the people pressed to look upon him, and shouted for him, and flung their caps in the air. If he was not in favor at the court, certainly he lacked not favor outside it.

Even within the palace the pages and the maids of honor peeped at him, and many courtiers thronged to welcome him, and the scullions and grooms of the chambers looked through windows and down staircases to see him pass, so that to me it was as though the tapestry wavered with whispers and eyes. As we waited for an audience we saw many great men pass, but not one fit to stand beside my lord. Then came the Queen, a shrunk, tall, high-boned woman, in a blaze of diamonds, the ruff standing about her spare, pale head like a setting sun, so thick it was with jewels, and her farthingale and petticoat making a prodigious circle about her. She had green eyes, and they were cold, and coldly she gave her hand to my lord to kiss.

She had called him back because Spain threatened; but now he was come she could not forget her anger. That was for the old affair of Mistress Throckmorton. I heard the pages whispering that day that she had not forgiven him; and one, a pert, bright lad, who won my heart because he was so eager to see and hear of the Great Captain, told me how my Lord Essex had in likewise nearly forfeited the Queen’s favor. For he had admired upon the person of the Lady Mary Howard a farthingale of cloth of gold, sewn with seed-pearls, the which coming to the Queen’s ears she had demanded the garment for herself, saying that no subject should go finer than the Queen’s Majesty. But having acquired it she discovered herself to be too tall and too broad for it, so that it misbecame her mightily. Whereupon she cast it aside so that none should wear it since she could not.

Of the same palace I grew sick to death. How long were we kept waiting about its corridors till the Queen’s favor should veer towards us again. It suited not with a country lad like myself; and as for my lord, his face grew lined and he seldom smiled: so that often, often, I longed that the old gardening days in Youghall were come again. Nor had he yet seen his wife and son. At last he grew restive, and declared that Devonshire air consorted better with his humor than the dank fogs that spread at evening about Westminster. But ere he could be gone he was committed to the Tower on the Queen’s warrant. So, sooner than we dreamt were we come to Traitor’s Gate.

I went thither with him, and together we passed the low arch. There I was permitted to be in attendance on him, and listened often to his cries and groans, for he could not endure the imprisonment while there were so many glorious things in the world to be done. Sometimes he would solace himself with philosophy and poetry. But at times his fury would break forth so that the governor of the Tower feared for him lest he should go mad. He well described his own sufferings.

“I am become like a fish cast on dry land,” he wrote, “gasping for breath, with lame legs and lamer lungs.”

Indeed there were times when it seemed as if he would die from being so imprisoned and confined. Trust in the Queen’s pity he had not.

“There is no chance for me now, Wat,” he said once, “unless it be that one of my captains should bring home a treasure-ship to pour into her lap, which might buy my freedom if she conceived that by that means I might find her more. For she loves gold as other women love love, wherefore is her face become yellower than a guinea.”

It was for some such saying, doubtless, the Queen had had him cast in the Tower. He was not one to learn guile; and, like his rival, Essex, he was over-brave in speech as in other things.

However, that happened that one of his captains did bring home a treasure-ship. He had been in the Tower two months, and had worn the stone floors with his pacing of them, more restless than the lion. The folk came to stare at him in the courtyard without. Then word came to us that his ships were in from the Azores and had brought with them the Spanish plate-ship, the Madre di Dios, which they had captured from the Dons. Half a million, a million, there was no end to the guineas she was worth. She was lined with glowing, woven carpets, sarcenet quilts, and lengths of white silks and cyprus. She carried, in chests of sandalwood and ebony, such stores of rubies and pearls, such porcelain and ivory and crystal, such planks of cinnamon, and such marvellous treasures as had never before been seen. Her hold seemed like a garden of spices, so laden was it with cloves, cinnamon, ambergris, and frankincense.

But even then the Queen was not minded to deliver him. His chief captain came from the mouth of the Dart, where the ship lay, to bring him his reports; but no message came from the Queen. However, his freeing was taken out of her hands and came not a whit too soon, for he had aged ten years in those two months. It seemed that the usurers and dealers in precious metals in London had flocked to the Dart upon the news of the treasure. And vagrants from all the winds flocked thither. And between those vultures and my lord’s own seamen and men of Devon there was soon riot and bloodshed. Then, since all means of restoring the peace seemed to have failed, at last they took my lord from the Tower that he might make peace.

It seemed that half the world was about the treasure-ship, and my lord’s ships. There came to greet us at our journey’s end that Lord Cecil of whom I had heard so much. I trusted him not, and I was rejoiced that he should see the passion of welcome which awaited my lord from his men of Devon. It was well that it was so, for my Lord Cecil reported upon it to the Queen.

“I assure you,” he wrote, “all his servants and his mariners came to him with such shouts of joy as I never saw a man more troubled to quiet them in all my life. But his heart is broken, and whenever he is saluted with congratulation for liberty he doth answer, ‘No, I am still the Queen of England’s poor captive.’ But I vow to you his credit among the mariners is greater than I could have thought it.”

My Lord Cecil was well disposed to my lord, albeit his cunning eyes and old, wise face made my youth feel of a sudden cold. The Queen harkened to him, and we were returned no more to the Tower; yet those two months of impatient fretting had set their mark upon my lord.

After this we sailed up the Dart to that Manor-house where the Lady Raleigh dwelt with her son. And again there was a very sweet interval of peace. I have now but to close my eyes and see again the red-brick ivied house, with its chimney-stack dark against the sky. The swallows are wheeling overhead, shouting and playing with one another. The rooks are coming homeward across the evening sky. On the green and velvety bowling green young Walter and I are playing at bowls. There are roses on the terrace and a peacock spreading his tail. Below these is the garden with its box borders, its roses and pinks and pansies; its fountain where the goldfish swim round and round, and its mossy dial. Further yet is the orchard, and beyond it the deer feeding amid the trees, and further still the river, and apple-orchards, with maids and men a-gathering apples for the cider brew. But I look not so far. My eye rests with my heart upon my lord, when he goeth between the box-borders in sweet converse with his lady-wife; and I watch him till young Walter rallies me as a poor comrade and player at the game.

Often my lady would take me apart, and bid me tell her of my lord when he was in Ireland. Of those years she was never tired of hearing; and when my tongue or my thoughts would grow slack she would grow impatient with me. Yet I think my love for her lord pleased her. She was a little lady, and the brightest ever I saw, with cream-pale cheeks and the liveliest of black eyes. I could not wonder that for a time she lulled to sleep my lord’s desires for America. Very pitiful she was towards the havoc their long parting and the trouble and the imprisonment had wrought in him, and would stand a-tiptoes to smooth the wrinkles out with her dainty finger.

The Lord Cecil was now my lord’s friend at court, and to him she writ beseeching that there might be no more voyages, at least for the time.

“I hope for my sake,” she writ, “that you wilt rather draw Walter toward the East than help him forward toward the sunset, if any respect to me or love to him be not forgotten.”

So we remained in peace, and young Walter and I flew our hawks and played at the ball, and fished and swam to our hearts’ content. And dearly as I loved my lord, I came to love his son hardly less. He was a brave lad of Devon, this Walter Raleigh, tall as his father, and nigh as comely, yet innocent and quiet, with the country innocence and quietude, because by reason of the Queen’s displeasure he had abode all his years in those sequestered ways; yet skilled in all such manly and courtly arts as became the son of his father; so that he was as good with a sonnet as at swordplay, and could dance the pavane as prettily as he could loose his goshawk. And for all his innocence was not unfit to face a rough world; and for all his quiet kindliness was as brave and as quick to fight as any gallant ever I saw.

My lord looked on at our comradeship well pleased. I heard him ask my Lady Raleigh one day if we did not make a gallant couple, at which my lady pouted, and said he was loving me in Ireland when she and her Wat were forgotten. “Nay,” said he, “that never was, Sweetlips; but he comforted me something in my loneliness without wife and son.” Then my lady called me to her, and kissed me like a mother, and vowed that she loved me for what I had been to her lord in those Irish years. She changed quickly in her pretty humors; but there was no change in her constancy and kindness towards me any more than in her lord’s love.

After that we went eastward for a season to the village of Bath, to drink at its springs, which had been discovered to be sovereign remedy for many ills. It was my Lady Raleigh’s will to make her lord well again. “As though, Bess,” he said, “you could turn backward the years we have been parted.”

And I left the Manor-house with grief and pain, for never again, I feared, should we have a season of such peace. My lord was not one to abide long in peace; and certainly the Bath waters as they restored his strength restored also his passion for adventure and turmoil, so that my Lady Raleigh in healing him but defeated her desire of keeping him with her. For after a time he seemed no longer quiet and well-content. And he had yet not only his share of the treasure-ship, though I doubt not the greater part was poured in the Queen’s lap, but he had also my Lord Boyle’s purse to draw upon.

Then as he was becoming restive, yea, straining as a hound strains at the leash, and declaring that he would sail before the mast if he might none other way, one of his captains, Popham by name, and a stout old sea-dog from the harbor town of Plymouth, brought him letters writ by a Spanish captain to the King of Spain, and captured by the English ship. Reading them my lord seemed as he would choke with fury. I knew how my lord’s heart turned to Guiana, the golden country. And these letters reported that the Governor of Trinidad had annexed this same wondrous land in the name of King Philip. Then, even my Lady Raleigh saw that it was no use seeking to hold her lord any longer; and she bade him go, with so sweet a grace and so high a spirit that she proved herself even a worthy mate for the Great Captain.

CHAPTER VI.—THE TREASURE-SHIP.

We left my Lady Raleigh alone in the spring of the year. It was February the sixth, and the snowdrop and crocus were up in the garden-beds of the Manor-house, and the blackbirds and thrushes singing nigh as sweet as they sing in Ireland, when we put out from Plymouth with five ships and a motley company. It was a stolen expedition in a manner of speaking; for we hoisted our flag for Virginia, yet I think the meanest scullion aboard knew that Guiana was our port. For it was not politic to flout too openly Philip of Spain; though we might fly the Jolly Roger and overhaul his treasure-ships on the high seas. For the Queen of England, as she grew older grew craftier; and would have any cat’s-paw to draw her chestnuts out of the fire, and bear the brunt of it as well, while she went free.

We two Wats sailed with Sir Walter. ’Twas time, he said, his son should see the world; and indeed it would have gone hard with us to be left behind.

It is wonderful to me now to recall how I had learnt—yea, as though I had been English-born—to hate the Spaniard, as though he had been a rat or some such thing, and no evil but merit in the slaying and despoiling of him. And therein was shown the folly and vanity of my youth; for not only was the Spaniard a grave and majestic foe, but he was of the faith my fathers had died to defend. Yet of this I thought not at all at the time, being indeed little better than a heathen; for my lord, albeit he was religious at heart, yet showed little of it in his life, and troubled not at all about it in others. Indeed, it is a strange thing to me now to reflect that all who led that wild life had yet some measure of religion; for then the days of the cold-heart and the mocker had not yet begun.

I remember as we made the voyage how Wat and I used to gather at night about the mast to hear the sailors tell stories and sing songs. There was one, Jonas Tittlebat, of Devizes, who was our favorite story-teller of them all, and I doubt not our favorite stories were of the slaying of Spaniards and sacking of their ships. It was as though one should inure a tender child to the shambles. For we grew to love the talk of blood, and to desire to see and smell and taste it; and I remember how at the end of the recitals Wat and I used to sit and pant, facing each other like a pair of tiger-cats, with the lust of blood in our hearts. For though we had been brought up simply and innocently the evil was there, only awaiting the breath that should fan it to a flame, and the fostering hands that would not let it go out.

Many weeks, even months, were we sailing till we came in sight of land, and for some days before this the southwesterly wind had brought us many an earnest of the beautiful country, brilliant and strange leaves, and plumes, and shells, and flowers, drifting to us over the phosphorescent water which at night made the sea a dance of silver.

Of my lord we saw little during the voyage. He was ever busy with his maps and charts in the cabin, observing the motion of his compasses, and studying the stars by night. Or else he was writing; and often it made me wonder to see how he, so greatly in love with action and energy, could yet content himself so many hours with the pen.

As we sailed up the river the beauty of it struck us dumb. I saw my lord stand in the bows of the vessel and drink in hungrily the beauty of that land. Exceedingly fertile it seemed, nor can I describe it better than in his own words.

“I never imagined a more beautiful country nor more lively prospects,” he wrote; “hills so raised here and there over the valleys; the river winding into divers branches; the plains adjoining without bush or stubble, but all fair, green grass; the deer crossing in every path; the birds towards the evening singing on every tree with a thousand several tunes, cranes and herons of white, crimson, and carnation, perching on the river’s side; the air fresh with a gentle easterly wind, and every stone that we stooped to take up promised either gold or silver by his complexion.”

We sailed even into the golden city of Manoa, and there saw the houses with their strange carvings, and their cups and drinking-vessels of precious metal; and the marvellous temple with its hundred images of beaten gold, the eyes of diamonds, and with necklets of rubies large as pigeon’s eggs, and garments sewn with pearls and emeralds.

The poor Indians who possessed these treasures were a mild and gentle race, ignorant of how greatly men’s passions were inflamed by gold and gems, which to them were common matters. They were no savages, but a nation with a certain knowledge of the arts and a civilization after their own manner; and it was touching to see how kindly and sweetly they welcomed the white man among them, although indeed in the ships were to be found some of the worst rascals that ever sailed out of Plymouth. However, fear of my lord kept this rascaldom in check; for he loved the Indians, and made it a matter with the Queen that in any expedition to the Guianas there should be no ill-treatment of the gentle race. Indeed he believed honestly that he were better their master than Spain, and so had less compunction in seeking their treasures.

But now a larger expedition was needed, and one that would have the Queen’s sanction; and so having feasted our eyes on the delights of this enchanting country we turned our ships for home, bearing with us gifts of gems and gold with which the Indians had loaded us, and also great stores of roots and plants and many strange matters.

We were not bent on any adventure, for my lord thought only of gaining the Queen’s ear, displaying to her the earnest he brought of the treasures of Guiana, and returning thither as fast as might be after fitting out a large fleet of ships; and then of taking possession in the Queen’s name. For greater even than his passion for adventure were his love of England and hatred of Spain; and the new policy of pleasing King Philip he loathed with all his heart.

The homeward voyage therefore he spent in writing for the Queen’s eye an account of Guiana, which afterwards he magnified into his book “On the Discovery of the large, rich, and beautiful Empire of Guiana, with a relation of the great and Golden City of Manoa, which the Spaniards call El Dorado, and the Provinces of Emeria, Arromaia, Amapaia, and other Countries, with their Rivers adjoining.”

So we were left again to the story-telling about the mast; and this grew more violent and rank with blood, as though the sight of so much treasure as we had left behind us had inflamed the minds of the tellers. Yea, we ate and drank blood, it seems to me, now looking back on those recitals; and were thus prepared for what followed.

For lo, one evening we saw far off upon the waters the shape of a great ship. Her poop was high out of the water, and apart from her size she was easy to be seen, for as the night gathered she blazed with candles so that she was like a fiery thing upon the waters.

Then there was such a confusion and excitement on the ships as never have I seen surpassed. My lord had left his books, and standing by the prow of the Bon Aventure gazed through his telescope upon that far-away vision that hung like a great golden bird against the purple of the after-sunset. There was no doubt in any mind that she was a Spanish galleon by her high poop and her great decks above the water. She was indeed none other than the famous treasure-ship, Nuestra Señora del Pilar, and she was riding without any escort.

We extinguished every light we had aboard the ships, and in cover of the darkness we crept upon her. She was big as a little town, it seemed to me; and for all she was so gayly lit she slept well, for we crept up under her stern, and there was no cry from her lookout. At last we were so near that I could see the image of the Holy Virgin at her masthead, and the lamp burning before it. But the image said nothing to me then.

The great ship was almost motionless on the dark water. Indeed I wondered if she had cast anchor, so still she was; yet how cast anchor in so many fathoms of water?

With much care and muffling of our oars we now took to the boats, and as fast as the boats filled they rowed towards the ship. The boat in which I was came up by the poop. I looked above me in wonder at all the rows of carven saints and angels, as it were the hierarchy of heaven. Over the side a rope swung noiselessly, as though it had been left there for our purpose. We clambered up it one after another and stood on deck, where was not a living soul, and this puzzled us not a little. But the bulwarks were set round with carven images in little niches, and each had its lamp, and the like on every deck; and that was how the illumination had come.

I looked round on the shipmen in the light of the many shrines. Some had the brown and wholesome faces of seamen, and though they looked fierce and blood-thirsty enough, were yet no worse than any fighting man. But others were no better than Algerine pirates, and carried a knife in their teeth and their pistols at full cock, and were as ready to slay and murder as any evil beast. For my lord had sailed with but a handful of his own men amid the scum of Plymouth rascaldom.

Yet even these did the silence of the great ship somewhat appal. And for myself, though I was as ready for murder and rapine as any, yet was I given pause; and hearing my lord’s whisper at my elbow, I turned and looked at him. “What do you make of it, Wat?” he asked. “Do you think it is a trap?”

But ere I could answer him a figure came up the stairway from the cabin. It was an old man, very tall, and in the garb of a white friar, just such another as I had left sleeping in St. Mary’s Tower. The likeness sent a thrill of terror through me. The old man saw us not. He carried a taper in his hand; he was going round doubtless to replenish the lamps if they had gone out. The light from the taper showed a face of much benignancy—an old, kind face. The cowl had fallen back, and the silver tonsure gleamed in the light.

Suddenly some one stirred in our midst, and all at once he knew that we were there. He opened his lips as though to speak. Then some of those pirates were upon him. I saw him lift the great crucifix that hung by his side between them and him. Then he was down, and the knives were hewing him. I thought no more on it, though it turned me sick an instant.

The ship now swarmed with our men rushing hither and thither in search of treasure. Some were seizing the silver lamps before the shrines, others were tearing down the images. A rush of men swept me from my feet and down the cabin stairs, and I grasped my sword tighter. But here was no enemy. Only rich garments flung hither and thither in the silk-hung rooms, and many signs of the ship having been deserted in haste.

I would have gone further, leaving the place to those who were tearing it to pieces, dragging down the hangings, kicking open the cedar-wood lockers, and pouring the precious wine they found there down their throats; I would have gone further had not my lord prevented me.

“Come up on deck, Wat,” he said; “there is a scent of death here that sickens me. I am glad I left my boy on the Bon Aventure.”

He dragged me with him. We were hardly up in the pure air before there was a scream from the mad herd below that turned one cold to hear; and as though the devil pursued them they came clambering up the hatches and staircases white as death, and sobered, and began flinging themselves off the sides of the vessel into their boats.

“They would leave us here, Wat, to the terror, whatever it may be,” said my lord, “if I had not had with me by good fortune a handful of mine own shipmates. Ah, Gregory Dabchick”—seizing one—“what white devil hast thou seen below-stairs?”

“If you please, none, Captain,” cried Dabchick, his breath sobbing; “but a worse thing. There are half a dozen corpses below there, dead of the smallpox. ’Tis a floating pest-house, my lord, and the place reeks with death.”

“Ah,” said Sir Walter, as we stood waiting for the mob to get off the ship, “the monk would have told us so if those dogs had not murdered him. Doubtless he remained behind when the others fled away, to nurse the living and bury the dead, and solaced himself, poor soul, by setting candles to his saints.”

Ere we were put into Plymouth town again there were eighty of our hundred dead of the smallpox; and I was carried ashore more dead than alive, to be nursed back to health by the Lady Raleigh’s ministering hands.

CHAPTER VII.—OUR LAST YEARS TOGETHER.

I came out of that illness no longer the youth I had been; for God used the things that had happened me to make a change in my heart. I went very near to death, and I came back to life very grievously disfigured, yea, as though I had been slashed criss-cross with swords, and the sight of one of mine eyes gone. Nevermore should I ruffle it with gallants; and indeed it seemed a bitter and cruel thing to the boy, this ruin of comeliness, so that for long the bitterness was greater than death, yet since then the man has learned to thank the Hand that wielded that most merciful rod.

I was yet but a moping thing, creeping up heavily from death to life, when my lord sailed on that expedition to Cadiz with the Lord Admiral Thomas Howard and his old-time enemy the Lord Essex, which brought such glory to the English name. I think there was but one part of my old self remained alive in me, and that was my love for Sir Walter, which is wrought so inextricably within the chords of my being that nothing shall disentangle it.

I had been sick to death during that time when Sir Walter had wrestled vainly with the Queen for an expedition to Guiana, and been discomfited. For truly her will was brass and iron; nothing for man, however great, to prevail against, and for long her face had been turned away from him, and seemed like to remain so.

I was getting well, with no heart to recover, when the reports came of the Cadiz expedition. It was glorious summer weather, and my Lady Raleigh, whose patience was more than human with me, would have me carried to the lawn under shade of trees; and there laid on my pillows I would listen to her proud recitals of her lord’s heroic deeds.

It was on the 21st of June that the fleet entered Cadiz Harbor. My lord was on board the Water Sprite; and he had no sooner entered than he received the fire of seventeen great galleons. But as though she had been indeed spirit and not body, the Sprite went unharmed. Raleigh blew his trumpets upon them in a great blare of defiance. Near at hand lay the St. Philip and the St. Andrew, the two ships foremost in that attack on the Revenge in which the brave Sir Richard Greville had fallen. “These,” wrote he, “were the marks I shot at, being resolved to be revenged for the Revenge, or to second her with my own life.... Having no hope of my fly-boats to board, and the Earl and my Lord Thomas having both promised to second me, I laid out a way by the side of the Philip to shake hands with her, for with the wind we could not get aboard; which when she and the rest perceived they all let slip and ran aground, tumbling into the sea heaps of soldiers as thick as if coals had been poured out of a sack in many parts at once, some drowned and some sticking in the mud. The Philip burned itself, the St. Andrew and the St. Matthew were recovered by our boats ere they could get out to fire them. The spectacle was very lamentable, for many drowned themselves; many, half-burned, leaped into the water; very many hanging by the rope’s end by the ship’s side, under the water even to the lips; many swimming with grievous wounds, and withal so huge a fire and so great a tearing of ordnance in the great Philip and the rest, when the fire came to them, as if a man had a desire to see Hell itself it was there most lively figured. Ourselves spared the lives of all after the victory, but the Flemings, who did little or nothing in the fight, used merciless slaughter, till they were by myself, and afterwards by the Lord Admiral, beaten off.”

“The poor Spaniards!” cried my Lady Raleigh with tears, even while she was proudest; but as for me, I had no heart to rejoice or to be sorry, being so marred myself, and scarce anything alive in me except my love for her lord, and even that pulsed faintly.

He came home to be hailed with such cheers and shouts by the common people as pleased the Queen but little, for she liked not to be eclipsed by a subject. Besides, the victory gave her little treasure; and she grew more and more miserly. Though my lord was glorious with wounds, she even refused to look upon him, which led me to say, as I have said often since, that the greatness of those Tudors lay chiefly in their hard usage of those who made them great. However, there was to gauge a deeper depth when the Stuart came to England’s throne.

I had feared my lord’s face when he came to look on me in my disfigurement, for he loved beauty, so that I scarcely dared to lift my one sound eye to his. Yet when I had found courage to do so I found nothing but love in his regard, and he embraced me as a father might, kissing my seamed cheek and calling me his dear lad. And young Walter likewise; for in the years that followed, during which we continued the tender friendship that had sprung up between us at the first, I have never once seen in his manner that pity which I could not have borne.

But the end of our misfortunes was not yet. Elizabeth died, and the son of Mary of Scotland succeeded; and now my lord anticipated no more ill than came, for the Stuart truckled to King Philip as never a Tudor had done, and ’twas like the Spaniard’s first demand would be that the most glorious of his enemies should be laid away beyond power of annoying him more. So it was that presently my lord was accused of being joined with the Lord Cobham in a plot to bring the Lady Arabella Stuart to the throne, and was cast into the Tower.

Then began that long martyrdom which is the everlasting disgrace of the meanest of Kings. He had made friends with his mother’s slayer. What was to be looked for from him? But to shut an eagle in a cage, to clip a sea-bird’s wings, to confine in a little space the noblest, freest spirit that lived, and the loyalist to England! This remained for Mary Stuart’s son to do.