Title: John Patrick, Third Marquess of Bute, K.T. (1847-1900), a Memoir

Author: Sir David Oswald Hunter Blair

Release date: April 16, 2011 [eBook #35884]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

JOHN PATRICK

THIRD MARQUESS OF

BUTE, K.T.

(1847-1900)

A MEMOIR

BY

THE RIGHT REV. SIR DAVID HUNTER BLAIR

BT., O.S.B.

AUTHOR OF "A MEDLEY Of MEMORIES," ETC.

WITH PORTRAITS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1921

All rights reserved

TO THE MEMORY

OF MY FRIEND

Just twenty years have passed away since the death, at the age of little more than fifty, of the subject of this memoir—a period of time not indeed inconsiderable, yet not so long as to render unreasonable the hope that others besides the members of his family (who have long desired that there should be some printed record of his life), and the sadly diminished numbers of his intimate friends, may be interested in learning something of the personality and the career of a man who may justly be regarded as one of the not least remarkable, if one of the least known, figures of the closing years of the nineteenth century.

Disraeli, when he published fifty years ago his most popular romance, thought fit to place on the title-page a motto from old Terence: "Nosse omnia haec salus est adulescentulis."[1] Was he really of opinion—it is difficult to credit it—that the welfare of the youth of his generation depended on their familiarising themselves with the wholly imaginary life-story of "Lothair"? the romantic, sentimental, and somewhat invertebrate youth who owed such {viii} fame as he achieved to the fact that he was popularly supposed to be modelled on the young Lord Bute—though never, in truth, did any hero of fiction bear less resemblance to his fancied prototype.

The present biographer ventures to think that the motto of Lothair might with greater propriety figure on the title-page of this volume. For there is at least one feature in the life of John third Marquess of Bute which teaches a salutary lesson and points an undoubted moral to a pleasure-loving generation, such a lesson and moral as it would be vain to look for in the puppet of Disraeli's Oriental fancy. If there is any characteristic which stands out in that life more saliently than another, it is surely the strong and compelling sense of duty—a sense, it is to be noticed, acquired rather than congenital, for Bute was by nature and constitution, as an acute observer early remarked,[2] inclined to indolence—which runs all through it like a silver thread. Other traits, and marked ones, he no doubt possessed—among them a penetrating sense of religion, a curious tenderness of heart, a singular tenacity of purpose, and a deep veneration for all that is good and beautiful in the natural and supernatural world; but these were for the most part below the surface, though the pages of this record are not without evidence of them all. But in the whole external conduct of his life it may be said that the desire of doing his duty was paramount with him—his duty to God and to man; his duty, above all, to the innumerable human beings {ix} whose happiness and welfare his great position and manifold responsibilities rendered to some extent dependent on him; and, finally, his duty in such public offices as he was called on to fill, and from which his diffidence of character and aversion from anything like personal display would have naturally inclined him to shrink. If the writer has succeeded in presenting in these pages something of this aspect of the life and character of his departed friend with anything like the vividness with which, at the end of twenty years, they still remain impressed on his own memory, he will be well content.

"The true life of a man," wrote John Henry Newman nearly sixty years ago,[3] "is in his letters"; and no apology is needed for the inclusion in this volume of some, at least, of the large number of Lord Bute's letters which have been placed at the disposal of his biographer, and for the use of which he takes this opportunity of thanking the several owners. Bute possessed in a high degree the essential qualities of a good letter-writer—a remarkable command of language, the power of clear and forcible expression, and (not least) a salutary sense of humour; and his voluminous correspondence, especially in connection with his literary work, was always and thoroughly characteristic of himself.

The writer desires, in conclusion, to express his gratitude not only for the loan of Lord Bute's letters, but for the kind help he has received from many quarters in the elucidation (especially) of details regarding his childhood and youth. In this connection his thanks are particularly due to the late Earl of Galloway and his sisters for their interesting reminiscences of Bute's boyhood at Galloway House; and also to the family of the late Mr. Charles Scott Murray for some particulars of his life during the critical years of his early manhood.

+ DAVID OSWALD HUNTER BLAIR, O.S.B.

CHRISTMAS, 1920.

[1] "It is for the profit of young men to have known all these things." Terence, Eunuchus, v. 4, 18.

[2] Mgr. Capel. Post, p. 75. See also p. 111.

[3] "It has ever been a hobby of mine, though perhaps it is a truism, not a hobby, that the true life of a man is in his letters.... Not only for the interest of a biography, but for the arriving at the insides of things, the publication of letters is the true method. Biographers varnish, they conjecture feelings, they assign motives, they interpret Lord Burleigh's nods; but contemporary letters are facts." (Newman to his sister, Mrs. John Mozley, May 18, 1863.)

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE

I. EARLY LIFE. (1847-1861) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

II. HARROW AND CHRIST CHURCH. (1862-1866) . . . . . . . . . 18

III. RELIGIOUS INQUIRIES--RECEPTION POSTPONED--COMING

OF AGE. (1867, 1868) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

IV. DANESFIELD--RECEPTION INTO CATHOLIC CHURCH. (1867-1869) 60

V. THE WESTERN MAIL--ROME AND THE COUNCIL--RETURN

TO SCOTLAND. (1869-1871) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

VI. MARRIAGE--HOME AND FAMILY LIFE--VISIT TO

MAJORCA. (1871-1874) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

VII. LITERARY WORK--THE SCOTTISH REVIEW. (1875-1886) . . . . 117

VIII. LITERARY WORK--continued. (1886, 1887) . . . . . . . . 137

IX. FOREIGN TRAVEL--ST. JOHN'S LODGE--MAYOR OF

CARDIFF. (1888-1891) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156

X. FREEDOM OF GLASGOW--WELSH BENEFACTIONS--ST. ANDREWS.

(1891-1894) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 179

XI. NOTES AND ANECDOTES--ST. ANDREWS (2)--PROVOST

OF ROTHESAY. (1894-1897) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 198

XII. ARCHITECTURAL WORK--PSYCHICAL RESEARCH--CONCLUSION.

(1898-1900) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 215

APPENDICES

I. PRIZE POEM (HARROW SCHOOL) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231

II. HYMN ON ST. MAGNUS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 236

III. HYMN: "OUR LADY OF THE SNOWS" . . . . . . . . . . . . . 238

IV. A PROVOST'S PRAYER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240

V. RECOLLECTIONS. BY SIR R. ROWAND ANDERSON . . . . . . . 241

VI. OBITUARY. BY F. W. H. MYERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . 245

VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247

INDEX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

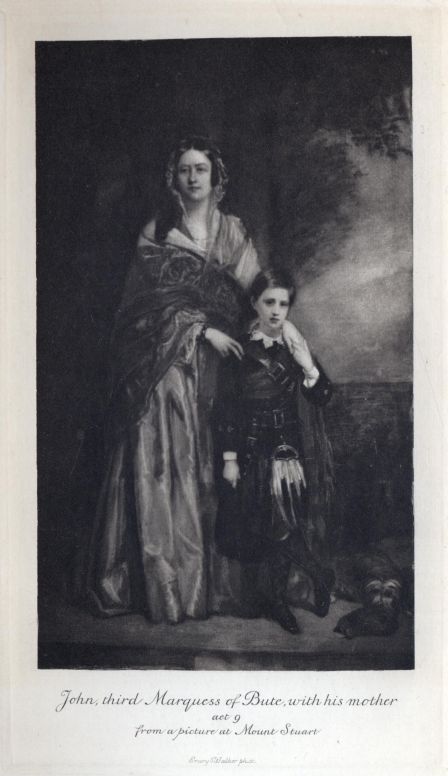

JOHN, THIRD MARQUESS OF BUTE ÆT 9, WITH HIS MOTHER Frontispiece

From a Painting by Mountstuart. Photo by F. C. Inglis, Edinburgh.

FACING PAGE

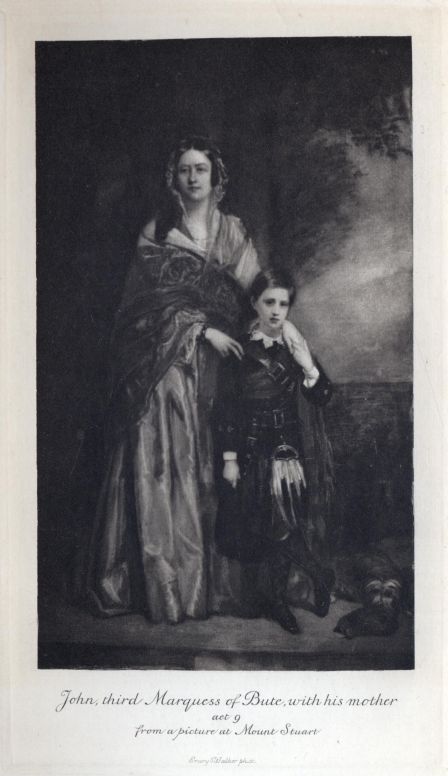

THE MARQUESS OF BUTE, ÆT 2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

From a Pencil Drawing by Ross at Cardiff Castle. This

Drawing, executed for Lord Bute's great-grand-aunt (then

aged 92), daughter of the third Earl, George III's Prime

Minister, was left by her to her niece. Lady Ann Damson,

whose great-niece, Mrs. Clark of Tal-y-Garn, gave it in

1906 to Augusta, wife of John, fourth Marquess of Bute.

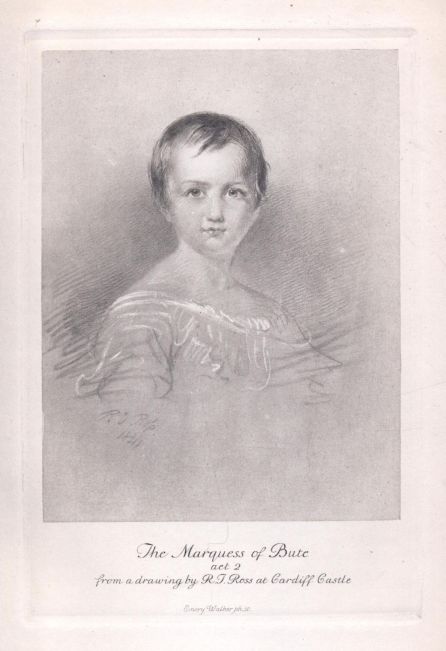

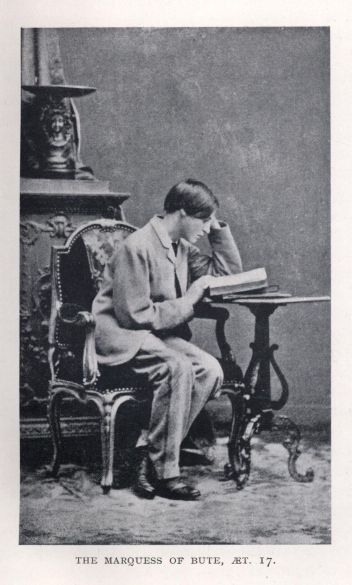

THE MARQUESS OF BUTE, ÆT 17 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

THE COMMUNION OF ST. MARGARET, QUEEN OF SCOTLAND . . . . . . . 48

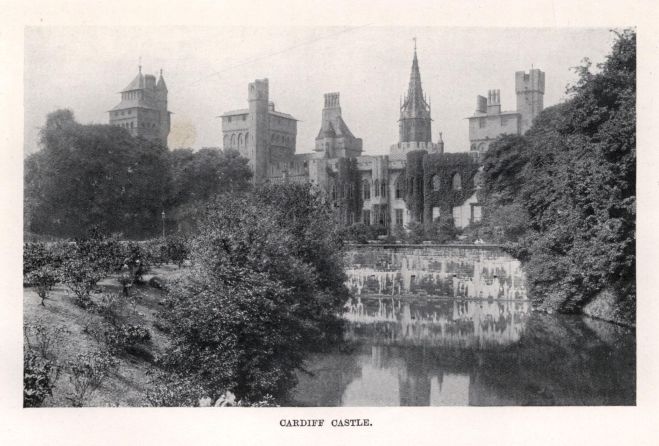

CARDIFF CASTLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

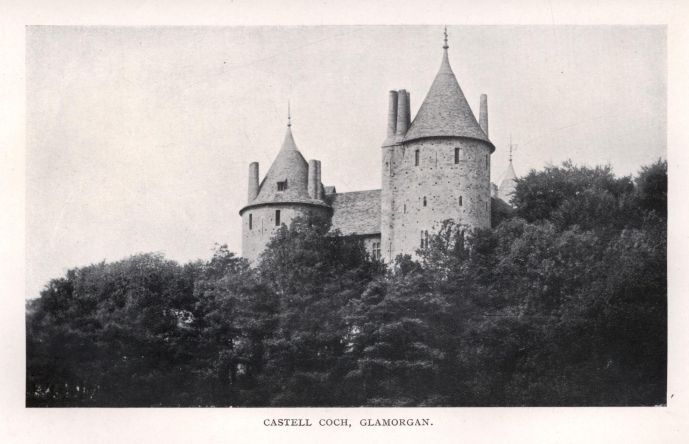

CASTELL COCH, GLAMORGAN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118

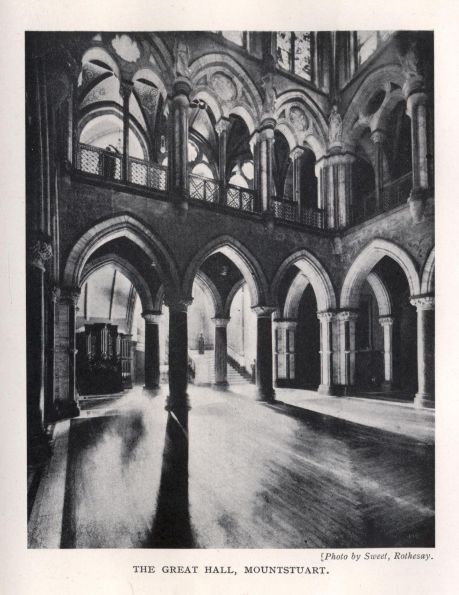

THE GREAT HALL, MOUNTSTUART . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

Photo by Sweet, Rothesay.

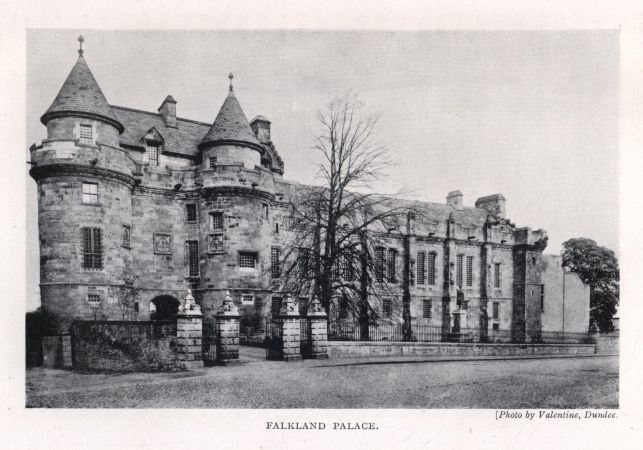

FALKLAND PALACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 152

Photo by Valentine, Dundee.

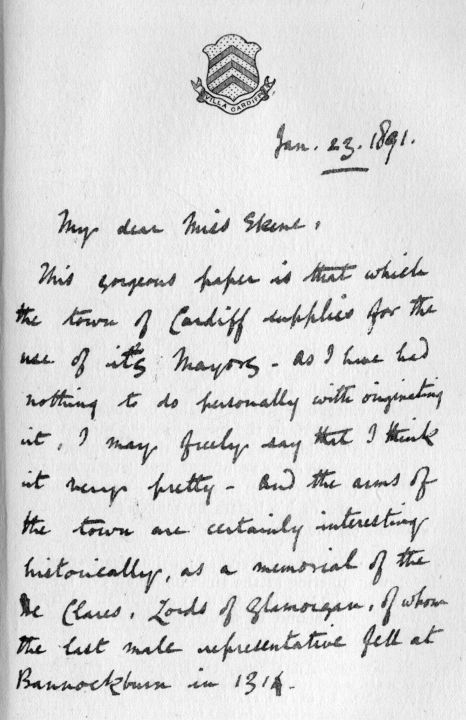

FACSIMILE LETTER FROM THE MARQUESS OF BUTE TO MISS SKENE . . . 174

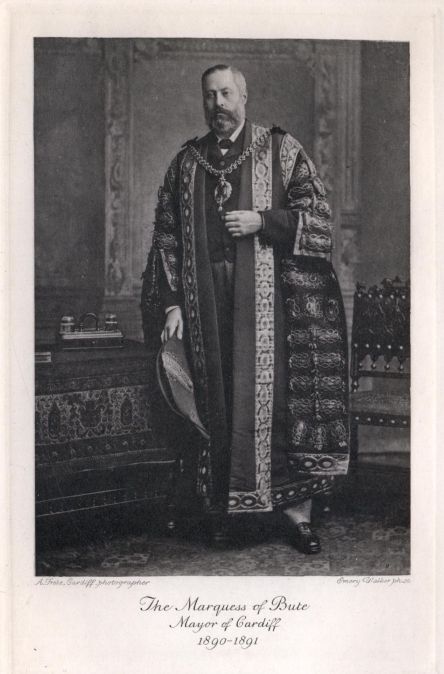

THE MARQUESS OF BUTE AS MAYOR OF CARDIFF . . . . . . . . . . . 176

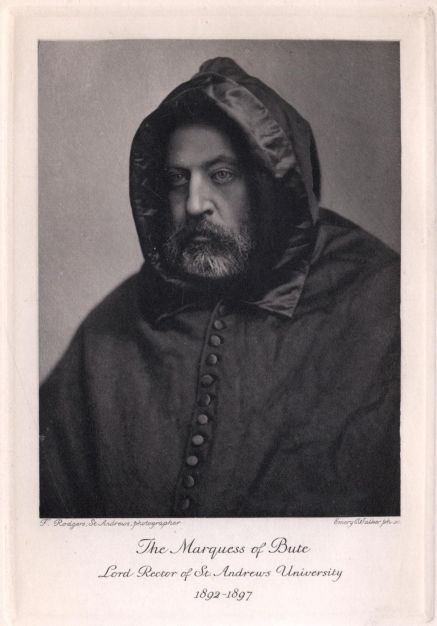

THE MARQUESS OF BUTE AS LORD RECTOR OF ST. ANDREWS

UNIVERSITY. (1892-1897) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 202

Photo by Rodger, St. Andrews.

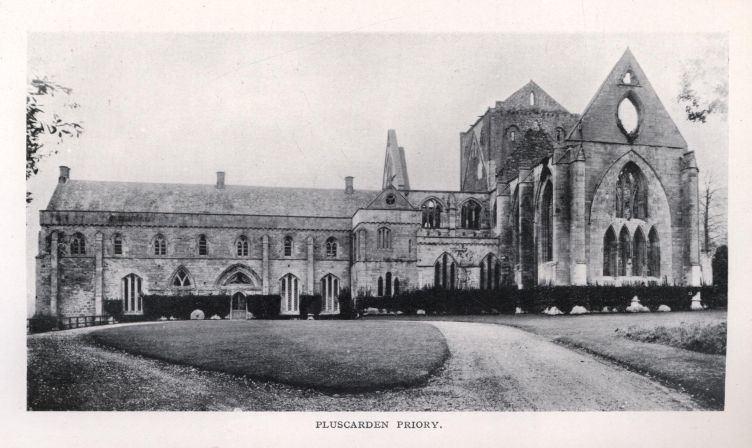

PLUSCARDEN PRIORY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 216

John Patrick, third Marquess of Bute, Earl of Windsor, Mountjoy and Dumfries, holder of nine other titles in the peerages of Great Britain and of Scotland, and a baronet of Nova Scotia, was fifteenth in descent from Robert II., King of Scotland, who, towards the end of the fourteenth century, created his son John Stuart, or Steuart, hereditary sheriff of the newly-erected county of Bute, Arran and Cumbrae, making to him at the same time a grant of land in those islands. His lineal descendant, the sixth sheriff of Bute, who adhered faithfully to the monarchy in the Civil Wars, and suffered considerably in the royal cause, was created a baronet in 1627; and his grandson, a stalwart opponent of the union of Scotland with England, was raised to the peerage of Scotland as Earl of Bute, with several subsidiary titles, in 1702. Lord Bute's grandson, the third earl, was the well-known Tory minister and favourite of the young king, George III., and his mother—a faithful servant of his sovereign, a man of culture and refinement, admirable as husband, father, and friend, and withal, by the irony of fate, unquestionably the most unpopular prime minister {2} who ever held office in England. His heir and successor made a great match, marrying in 1766 the eldest daughter and co-heiress of the second and last Viscount Windsor; and thirty years later he was created Marquess of Bute, Earl of Windsor, and Viscount Mount joy. Lord Mountstuart, his heir, who predeceased his father, married Penelope, only surviving child and heiress of the fifth Earl of Dumfries and Stair; and the former of those titles devolved on his son, together with valuable estates in Ayrshire. The second marquess, who succeeded to the family honours the year before Waterloo, when he was just of age (he had already travelled extensively, and had paid a visit to Napoleon at Elba), earned the reputation of being one of the most enlightened and public-spirited noblemen of his generation. During the thirty-four years that he owned and controlled the vast family estates in Wales and Scotland, he devoted his whole energies to their improvement, and to promoting the welfare of his tenantry and dependents. His practical interest in agriculture was evinced by the fact that the arable land on his Buteshire property was trebled during his tenure of it; and foreseeing with remarkable prescience the great future in store for the port and docks of Cardiff, he spared neither labour nor means in their development. He was Lord-Lieutenant both of Glamorgan and of Bute, and discharged with tact and success the office of Lord High Commissioner to the Church of Scotland in 1842, on the eve of the ecclesiastical crisis which ended in the secession of more than 400 ministers of the Establishment. His political opinions were in the best sense liberal, and he was a consistent advocate of Catholic Emancipation, even when that {3} measure was opposed by the Duke of Wellington, whom he generally supported. A few hours before his death, which occurred at Cardiff Castle with startling suddenness in March, 1848, he had expressed the confident hope that his successor, if not he himself, would live to see Cardiff rival Liverpool as a great commercial seaport.

1847, Birth at Mountstuart

Lord Bute was twice married—first to Lady Maria North, of the Guilford family, by whom he had no issue; and secondly, three years before his death, to Lady Sophia Hastings, second daughter of the first Marquess of Hastings. By this lady, who survived him eleven years, he had one child, John Patrick, the subject of this memoir, who was born on September 12, 1847, at Mountstuart House, the older mansion of that name in the Isle of Bute, which was burnt down in 1877 and replaced by the great Gothic pile designed by Sir Robert Rowand Anderson. Old Mountstuart was an unpretending eighteenth-century house, built by James, second Earl of Bute (1690-1723), a few years before his early death. It was the favourite residence of his son the third earl, George III.'s prime minister, who is commemorated by an obelisk in the grounds not far from the house. The wings at the two extremities escaped the fire, and are incorporated in the modern mansion.

Here, then, on the fair green island which had been the home of his race for nearly five centuries, opened the life of this child of many hopes, who within a year was by a cruel stroke of fate to be deprived of the guardianship and guidance of his amiable and excellent father. The second marquess died, as has been said, deeply regretted, in the spring following the birth of his heir; and the manifold {4} honours and possessions of the family devolved upon a baby six months old. Up to his thirteenth year the fatherless boy was under the constant and unremitting care of a devoted mother, whose memory he cherished with veneration to the end of his life. Sophia Lady Bute was a woman of warm heart and deep personal piety, tinged, however, with an uncompromising Protestantism commoner in that day than in ours. One of her fondest hopes or dreams was the conversion to her own faith of the numerous Irish Catholics whom the development of the port of Cardiff, and the rapid growth of the mining industry, had attracted to South Wales; and the venerable Benedictine bishop who had at that time the spiritual charge of the district, and for whom Lord Bute had a sincere regard and respect, used to tell of the band of "colporteurs" (peripatetic purveyors of bibles and polemical tracts) whom the marchioness engaged to hawk their wares about the mining villages of Glamorgan.

Lord Bute's upbringing as a child was, by the force of circumstances, under entirely feminine influences and surroundings; and to this fact was probably to some extent due the strain of shyness and sensitive diffidence which were among his life-long characteristics. He seems to have been inclined sometimes to resent, even in his early boyhood, the strictness of the surveillance under which he lived. His mother once took him from Dumfries House to call at Blairquhan Castle, driving thither in a carriage and four, as her custom was. While the ladies were conversing in the drawing-room, a young married daughter of the house took the little boy out to see the gardens, ending with a call at the head gamekeeper's. A day or two afterwards {5} the châtelaine of Blairquhan received a letter from Lady Bute, expressing her dismay, indignation, and distress at learning that her precious boy had actually been taken to the kennels, and exposed to the risk of contact with half a dozen pointers and setters. When reminded many years later of this incident (which he had quite forgotten), Lord Bute said, in his quiet way: "Yes, I was kept wrapped in cotton wool in those days, and I did not always like it. The dogs would not have hurt me, and I am sure that I made friends with them."

1859, Death of Lady Bute

Lady Bute died in 1859, leaving behind her, both in Scotland and in Wales, the memory of many deeds of kindness and benevolence. Her husband had made no provision whatever in his will for the guardianship of his only son, who had been constituted a ward in Chancery two months after his father's death, his mother being nominated by the Lord Chancellor his sole guardian. Lady Bute's will recommended the appointment as her son's guardian of Colonel (afterwards Major-General) Charles Stuart, Sir Francis Hastings Gilbert, and Lady Elizabeth Moore, who was distantly related to the Bute family through the Hastings', and had been one of Lady Bute's dearest friends. Sir Francis Gilbert being at this time absent from England in the consular service, the Court of Chancery appointed as guardians the two other persons named by Lady Bute.

It seems unnecessary to describe in detail the prolonged friction and regrettable litigation which were the result of this dual guardianship of the orphaned boy; yet they must be here referred to, for it is beyond question that they were not only detrimental to his happiness and welfare during his {6} early boyhood, but could not fail seriously to affect the development of his character in later years. The child was deeply attached to Lady Elizabeth Moore, who had assumed the entire charge of him after his mother's death; and his letters written at this period give evidence not only of this attachment, but of his very strong reluctance to leave her for the care of General Stuart, who insisted that it was time that a boy of nearly thirteen should be removed from the exclusively female custody in which he had been kept from babyhood. Lady Elizabeth, yielding partly to her own feelings, and partly to the earnest and repeated solicitations of her young ward, was ill-advised enough, instead of committing him as desired to the care of her co-guardian, to carry him off surreptitiously to Scotland, and to keep him concealed for some time in an obscure hotel in the suburbs of Edinburgh. Here is the boy's own account of the affair, written from this hotel to a relation in India[1] (he was between twelve and thirteen years of age):—

I prayed, I entreated, I agonised, I abused the general; I adjured her not to give me up to him. She was shaken but not convinced. So we went to Newcastle, to York, and to London, where I got a bad cold, my two teeth were pulled, etc., etc. We were delayed some time there, and meanwhile my prayers and adjurations were trebled: Lady E. was convinced, and promised not to let me go. She got one of the solicitors to the Bank of England in the City to write a letter to Genl. S. for her, as civil as possible, but declining to give me up; to which the general returned a furious answer, conveying his determination to appeal to the Vice-Chancellor about {7} the matter. After a month we became convinced that the Vice-Chancellor would decide against us; and on the night of April 16th Lady E. left the hotel secretly, and with her maid and me shot the moon to Edinburgh, where we arrived at 7 next morning.[2]

1859, Rival guardians

For a boy of twelve this is a sufficiently remarkable letter; but an even more precocious document is a draft letter dated a fortnight before the flight to Edinburgh, and composed entirely by young Bute, who recommended Lady Elizabeth to copy it and send it to her co-guardian as from herself!

DEAR GENERAL STUART,

You will, I am afraid, be much surprised upon the reception of this letter, but I trust that your love for Bute will make you accede to the request which I am about to make. B. has lately had much sorrow, and he has formed an attachment to me only to have it broken by separation, and in order to go among entire strangers to him—for in that light, I am sorry to say, I must regard you and Mrs. Stuart. With your consent, then, dear Genl. Stuart, I shall be happy to keep him with me until he is 14, when he will of course choose for himself. We could live with good Mr. Stacey very nicely at Dumfries House or Mountstuart, and I could occasionally bring him to England—or indeed you could come to see him at Mountstuart. I trust, dear Gen. Stuart, you will be the more inclined to accede to my request when I tell you that he has {8} expressed to me the greatest reluctance at parting from me and going to you—a repugnance which I can only regard as very natural, for I was much grieved to see that you did not follow my advice in walking with him and consulting him (and believe me without so doing you will never gain his affections), while I have always done so, as was his poor mother's invariable custom.[3]

It does not appear whether this letter, which is dated from 23 Dover Street, and is entirely in the boy's own handwriting, exactly as given above, was actually sent by Lady Elizabeth. In any case General Stuart was not the man to submit to the compulsory separation from his ward which resulted from what the House of Lords afterwards characterised as the "clandestine, furtive, and fraudulent action" of Lady Elizabeth Moore. He at once laid the case before the Court of Chancery, which directed that the boy was to be immediately handed over to his care, and sent without delay to an approved private school, and in due time to Eton or Harrow, and then to one of the English universities. Lady Elizabeth absolutely refused to comply with the order of the Court, and was consequently removed in July, 1860, from the office of guardian. Meanwhile the case was complicated by the intervention of the Scottish tutor-at-law, Colonel {9} James Crichton Stuart, who had been since the death of Lord Bute's father manager and administrator of the family estates in Scotland. Colonel Stuart obtained from the Scottish Courts an order that the boy should be sent to Loretto, a well-known school near Edinburgh, and that the Earl of Galloway should be the "custodier" of his person. The Court of Chancery promptly issued an injunction forbidding the tutor-at-law to interfere in any way with the boy's education, whereupon both Colonel Stuart and the English guardian appealed to the House of Lords. That tribunal gave its judgment on May 17, 1861, censuring the Court of Session for its delay in dealing with this important matter, confirming General Stuart as sole guardian, and sanctioning his scheme for the boy's education.

1861, Lords' decision

The House of Lords, in giving the decision which brought this long litigation to a close, had raised no objection to the continued residence of the young peer with the Earl of Galloway, an arrangement which had already been approved by the Court of Chancery. Bute had, in fact, at the time the judgment was pronounced, been living for some months with Lord and Lady Galloway at their beautiful place on the Wigtownshire coast; and this was certainly, as it turned out, the most favourable and beneficial solution of the difficult question of providing a suitable and congenial home for one who, whilst the possessor of three or four splendid seats in England and Scotland, had yet, by a pathetic anomaly, never known what home life was since his mother's death in 1859. At Galloway House he found himself for the first time the inmate of a large and cheerful family circle, including several young people of about his own age. "I {10} am comfortably established here," he wrote to Lady Elizabeth Moore soon after his arrival in December, 1860. "This house is like Dumfries House, but much prettier. I have a charming room, not at all lonely. Lord and Lady G. are so kind to me, and the little girls treat me like a brother." "They are all very very kind to me," he wrote a week or two later, adding in the same letter that he had on the previous day attended two services in Lord Galloway's private chapel. "It is very plain," was the comment of the thirteen-year-old critic; "but the chaplain's sermons were all about the saints and the Church. Do you know what he called the Communion? a 'commemorative sacrifice!' In a subsequent letter he says, "Mr. Wildman (the chaplain) says that Mary should be called the 'Holy Mother of God.'"

1861, At Galloway House

These new religious impressions, contrasting sharply as they must have done with the narrow Evangelical teaching of his early days, are of interest in connection with his first schoolmaster's report of him some six months later, which will be mentioned in its proper place. "He was very fond," writes one of his former playfellows at Galloway House in those far-off days, "of sketching with pen and pencil religious processions and ceremonies, and his thoughts seemed to be constantly turned on religion. He liked having religious discussions with our family chaplain, who was a clever and well-read man." "Our dear father and mother," writes another member of the same large family, "told us that we must be very kind to him, as he had lost both his parents and was almost alone in the world. I remember seeing him in the library on the night of his arrival—a tall, dark, good-looking boy, {11} looking so shy and lonely, but with very nice manners." "I recollect him," says the son of a neighbouring laird, who was about two years his senior, and was often at Galloway House, "rather a pathetic figure among the swarm of joyous young things there, distinct among them from never seeming joyous himself." This was doubtless the impression which his extreme diffidence generally made on strangers; and it is the pleasanter to read the further testimony of the playfellow already quoted: "His shyness soon wore off when he got away from the elders to play with us, and he entered with zest into all our amusements. He was intensely earnest about everything he took up, whether serious things or games. He was greatly attached to our brother Walter,[4] whose bright, cheery nature appealed to him. Walter was always full of fun and spirits and mischief; and Bute was delighted at this, and soon joined in it all. I remember our old housekeeper, after some great escapade, saying, "Yes, and the young marquis was as bad as any of you!" One of his hobbies was collecting from the seashore the skulls and skeletons of rabbits, birds, etc. I spent much time on the cliffs and rocks looking for these things, of which we collected boxes full. With his curious psychic turn of mind he liked to conduct some kind of ceremonies over these remains after dark, inviting us children to take part, sometimes dressed in white sheets. He loved legends of all kinds, and used often to tell them to us: I was very fond of hearing him, he told them so well. History, too, especially Scottish history, {12} he liked very much. He wrote a delightful little history of Scotland for my youngest brother,[5] of whom he was very fond—a tiny boy then. It was all written in capital letters, with delightful and clever pen-and-ink sketches, one on every page."

These recollections of happy home life in a Scottish country house, nearly sixty years ago, call up a pretty picture of the orphan boy, whose childhood had been so strangely lonely and isolated, contented and at home in this charming family circle. That he was truly so is further testified by letters that passed about this time between him and his tutor-at-law, Colonel Crichton Stuart. In reply to a letter from Colonel Stuart, expressing a desire to hear from Bute himself whether he was comfortably settled at Galloway House, the boy wrote: "In answer to your request, I write to confirm Mr. A.'s statement regarding my happiness here. Lord and Lady Galloway did indeed receive me as a child of their own, which I felt deeply."

That these words were a sincere expression of the young writer's sentiments there is no reason to doubt; but thoughtful and advanced as he was in some ways for his years, he was too young to realise then—-possibly he did later on, though he very seldom spoke of his boyhood's days—how much more he owed to the Galloway family than mere kindness. It seemed, indeed, a special providence which had brought the orphaned marquis at this critical moment under influence so salutary and so much needed as that of the admirable and excellent family which had welcomed him to their beautiful home as one of themselves. The numerous letters {13} written by Bute at this period, of which many have been preserved, are marked indeed by propriety of expression and a command of language remarkable in a boy of his age; but they also reveal very clearly a self-centred view of life even more extraordinary in so young a boy, and due, it cannot be doubted, to the singularity of his upbringing. Surrounded from babyhood by a circle of adoring females, in whose eyes the fatherless infant was the most precious and priceless thing on earth, he had grown up to boyhood penetrated, no doubt almost unconsciously, with an exaggerated and overweening sense of his own importance in the scale of creation, to which the wholesome influence of Galloway House provided the best possible corrective. Distinguished, high-principled, exemplary in every relation of life, Lord and Lady Galloway held up to their children, by precept and example, a constant ideal of duty, unselfishness and simplicity of life; and the young stranger within their gates was fortunate in being able to profit by that teaching. If his future life was to be marked by generous impulses and noble ambitions—if one of his most notable characteristics was to be a personal simplicity of taste and an utter antipathy to that ostentation which is not always dissociated from high rank and almost unbounded wealth—if he was to realise something of the supreme joy and satisfaction of working for others rather than for oneself; for all this he owed a debt of gratitude (can it be doubted?) to the kindly and gracious influences which were brought to bear on his sensitive nature during these years of his boyhood. He was received at Galloway House as a child of the family; and his companions spoke their minds to him with fraternal freedom. "You {14} will never find your level, Bute," the eldest son of the house (whom he greatly liked and respected) once said to him, "until you get to a public school." He did not resent the remark, for his good sense told him that it was true. Harrow was the public school of the Galloway family; but it was not so much for that reason that Harrow was chosen for him rather than Eton, as because his wise and kind guardians believed, rightly or wrongly, that a boy in his peculiar position would be less exposed to adulation and flattery at the more democratic school on the Hill than at its great rival on Thames-side.

Meanwhile a preparatory school had to be selected; and the choice fell on May Place, the well-known school conducted by Mr. Thomas Essex at Malvern Wells, where one of Lord Galloway's sons was just finishing his course. It was locally known as the "House of Lords" from its connection with the peerage; and the pupils included members of the ducal houses of Sutherland, Argyll, Manchester, and Leinster, as well as of many other well-known families. One who well remembers the first arrival at May Place of the young Scottish peer, then aged thirteen and a half, has described him as a slight tall lad, reserved and gentle in manner, and particularly courteous to every one. The shyness and also the reverence for sacred things which always distinguished him as a man were equally noticeable in him as a boy; and it is remembered that when he revisited the school three or four years later, during the Harrow holidays, and was asked where he would like to drive to, he chose to go and inspect an interesting old church in the neighbourhood. A school contemporary with whom he occasionally squabbled was William Sinclair, the future Archdeacon of London; and there was {15} once nearly a pitched battle between them, in consequence of some caricatures which Sinclair drew, purporting to represent Bute's near relatives, but for which he afterwards handsomely apologised.

1861, First school report

Towards the end of Bute's first term at Malvern Wells, his master wrote to Lord Galloway the following account of his young pupil. The concluding sentence is of curious interest in view of what the future held in store. It seems to show that the reaction in his mind—a mind already thoughtful beyond his years—against the one-sided view of religion and religious history which had been impressed upon him from childhood had already begun.

May Place,

Malvern Wells,

July 14, 1861.

Lord Bute is going on more comfortably than I could have expected. He is on excellent terms with his schoolfellows; and though he prefers "romps" to cricket or gymnastics, yet I am glad to see him making himself happy with the others. More manly tastes will, I think, come in time. His obedience and his desire to please are very pleasing; while his strong religious principles and gentlemanly tone are everything one could desire. His opinions on things in general are rather an inexplicable mixture. I was not surprised to find in him an admiration of the Covenanters and a hatred of Archbishop Sharpe; but I was certainly startled to discover, on the other hand, a liking for the Romish priesthood and ceremonial. I shall, of course, do my best to bring him to sounder views.

1861, At May Place

We have no evidence as to what methods were employed, or what arguments adduced, by the excellent preceptor in order to carry out the purpose {16} indicated in the concluding lines of his letter. Bute himself never referred to the matter afterwards, but the result was in all probability nugatory. It is not within the recollection of the present writer, who was an inmate of May Place a year or two later, that any serious effort was ever made there to impress religious truths on the minds of the pupils, or indeed to impart to them any definite religious teaching at all. The views and opinions of the young Scot, although only in his fourteenth year, were probably already a great deal more formed on these and kindred subjects than those of his worthy schoolmaster. In any case the time available for detaching his sympathies from the "Romish" priesthood and ritual was short. The boy had come to school very poorly equipped in the matter of general education, as the term was then understood. In the correspondence between his rival guardians, when he was just entering his 'teens, allusion is made to the boy's "precocious intellect," also to the fact that he knew little Latin, no Greek, and (what was considered worse) hardly any French. Mathematics he always cordially disliked; and it is on record that all the counting he did in those early years was invariably on his fingers. His natural intelligence, however, and his aptitude for study soon enabled him to make up for much that had been lost owing to the haphazard and interrupted education of his childhood; and it was not long before he was pronounced intellectually equal to the not very exacting standard of the entrance examination at Harrow. A final reminiscence of his connection with May Place may here be recorded. He revisited his old school not long after his momentous change of creed; and being left alone awhile in {17} the study took up a blank report that lay on the table, and filled it up as follows[6]:—

MONTHLY REPORT OF THE MARQUESS OF BUTE.

LATIN CONSTRUING . . . . . . Partially preserved.

LATIN WRITING . . . . . . . Ditto.

GREEK CONSTRUING . . . . . . Getting very bad from disuse.

GREEK WRITING . . . . . . . Ditto.

ARITHMETIC . . . . . . . . . Entirely abandoned.

HISTORY . . . . . . . . . . So-so.

GEOGRAPHY . . . . . . . . . Improved by foreign travel.

DICTATION . . . . . . . . . Ditto by business letters.

FRENCH . . . . . . . . . . . Ditto by travelling.

DRAWING . . . . . . . . . . Grown rather rusty.

RELIGION . . . . . . . . . . Unhappily not to the taste

of the British public.

CONDUCT . . . . . . . . . . Not so bad as it is painted.

[1] Charles MacLean, to whom he referred more than thirty years later, in his Rectorial address at St. Andrews (p. 188).

[2] During Bute's travels with Lady Elizabeth Moore, in the course of her efforts to retain the custody of her little ward, his most trusted retainer was one Jack Wilson. The pertinacity with which the child was pursued, and the extent of Wilson's devotion, are attested by the known fact that on one occasion he knocked a writ-server down the stairs of a Rothesay hotel where Bute was staying with Lady Elizabeth. Wilson was accustomed always to sleep outside his young master's door. He rose later to be head-keeper at Mountstuart, and died there on May 23, 1912.

[3] It seems right to mention that Bute had another reason, apart from his attachment to Lady Elizabeth Moore, for his apparently unreasonable hostility to his other guardian. One of his strongest feelings at this time was his almost passionate devotion to the memory of his mother; and he never forgot what he called General Stuart's "gross disrespect" in not accompanying her remains from Edinburgh, where she died, to Bute, where she was buried. "He left her body," wrote Bute to an intimate friend from Christ Church, Oxford, "to be attended on that long and troublesome journey, in the depth of winter, only by women, servants, and myself, a child of twelve."

[4] Hon. Walter Stewart, afterwards colonel commanding 12th Lancers (died 1908). He was about eighteen months younger than Bute.

[5] Hon. Fitzroy Stewart (died 1914). He was at this time just five years old.

[6] This anecdote was communicated to a weekly journal (M.A.P.) soon after Lord Bute's death, by the son of the master of his old school.

In September, 1861, Lord Bute completed his fourteenth year, attaining the age of "minority" (as it is called in Scots law), which put him in possession of certain important rights as regarded his property in the northern kingdom. The young peer had from his childhood, as is shown by his early correspondence with Lady Elizabeth Moore, been aware that he would be entitled at the age of fourteen to exercise certain powers of nomination in respect to the management of his Scottish estates. Most of the members of the Lords' tribunal which had adjudicated on his position in May, 1861, had evinced a curious ignorance of the nature, if not of the very existence, of these prospective rights, and even when informed of them had been inclined to question the expediency of their being acted upon. Bute himself, however, was not only perfectly aware of these rights, but resolved to exercise them; and we accordingly find him, a few weeks after his fourteenth birthday, writing as follows, from his private school, to his guardian, General Stuart:—

May Place,

November 25, 1861.

DEAR GEN. STUART,

I wish the necessary steps to be taken in the Court of Session for the appointment of Curators {19} of my property in Scotland. The Curators whom I wish to appoint are Sir James Fergusson, Sir Hastings Gilbert, Lt.-Col. William Stuart, Mr. David Mure, Mr. Archibald Boyle, and yourself.

I wish the Solicitor-General of Scotland to be employed as my legal adviser in this buisness (sic).

I remain,

Your affectionate cousin,

BUTE AND DUMFRIES.

Bute was now entitled to choose from the number of these curators any one to whose personal guardianship he was willing to be entrusted during the seven years of his minority. His choice fell on Sir James Fergusson of Kilkerran, M.P. for Ayrshire, who had recently married the daughter of Lord Dalhousie, Governor-General of India; but he did not immediately take up his residence with Sir James, as it was thought best that he should continue, at any rate during the earlier part of his public school life, to spend his holidays at Galloway House, where he had become thoroughly at home. Lord Galloway's younger son Walter was destined for Harrow School; and thither Bute preceded him after spending two terms at May Place.

1862, Entrance at Harrow

It was in the first term of 1862 that Bute entered the school at Harrow, then under the headmastership of Montagu Butler. His position was at first that of a "home boarder," and he was under the charge of one of the masters, Mr. John Smith, known to and beloved by several generations of Harrovians.

There was a rather well-known and self-important Mr. Winkley, quite a figure among Harrow tradesmen (writes a school contemporary of Bute's, son of a famous Harrow master, and himself afterwards {20} headmaster of Charterhouse), a mutton-chop-whiskered individual who collected rates, acted as estate agent, published (I think) the Bill Book, sold books to the School, &c. He occupied the house beyond Westcott's, on the same side of High Street, between Westcott's and the Park. There John Smith resided with the Marquess of Bute.

Mr. Smith, whose mother lived at Pinner, used to visit her there every Saturday, and to take over with him on these occasions one or two of his pupils, who enjoyed what was then a pretty rural walk of three miles, as well as the quaint racy talk of their master, and the excellent tea provided by his kind old mother.

Another of his schoolfellows, Sir Henry Bellingham, writes:

I remember first meeting Bute on one of these little excursions. Mr. Smith had told me that the tall, shy, quiet boy (he was a year younger than me, but much bigger) had neither father, mother, brother nor sister, and was therefore much to be pitied. I wondered why he did not come more forward, and said so little either to Smith himself or to Mrs. Smith; for Smith was a man who had great capabilities for drawing people out, and was a general favourite with every one. The impression I had of Bute during all our time at Harrow was always the same—that of his very shy and quiet manner.

1862, A real palm branch

Undemonstrative as he was by nature, Bute never forgot those who had shown him any kindness, and he always preserved a grateful affection for John Smith, who accompanied him more than once during the summer holidays to Glentrool, Lord Galloway's lodge among the Wigtownshire hills, and enjoyed some capital fishing there. Bute wrote to him in {21} later years from time to time, and during the sadly clouded closing period of the old man's life, when he was an inmate of St. Luke's Hospital, he gave him much pleasure by sending him annually a palm branch which had been blessed in his private chapel. More than twenty years after Bute's Harrow days, he received this appreciative letter from his former master:

St. Luke's Hospital,

Old Street, E.C.,

Easter Tuesday, 1887.

DEAR LORD BUTE,

I must try and write a few lines, asking you to pardon all defects.

The real Palm Branch was most welcome, with its special blessing: it is behind me as I write, and many happy thoughts and messages does it bring. God bless you for your most kind thought. I intend to forward it in due time to Gerald Rendall (late head of Harrow, then Fellow of Trin. Coll., Cambridge, now Principal of University College, Liverpool), as my share in furnishing his new home: he was married this vacation. The students, male and female, will be glad to see what a real Palm Branch is like. Your gift of last year is now in the valued keeping of Mrs. Edward Bradby, whose husband was a master of Harrow in your day, and, after fifteen years of hard and successful work at Haileybury, has taken up his abode at St. Katherine's Dock House, Tower Hill, with wife and children, to live among the poor and brighten their dull existence with music and pictures and dancing; besides inviting them, in times of real necessity, to dine with himself and his wife, in batches of eight and ten.

I look forward to the Review[1] with great interest. {22} I show it to the Medical Gentlemen here, read what I can, and then forward it to my sister at Harrow for friends there.

I try to realise the old chapel on the beach, in which the branches were consecrated,[2] but fail utterly to do so. Whereabouts is it? I suppose you have a chapel in the house also, for invalids, &c., in bad weather.

God bless you all: Lady Bute and the children, especially the maiden who is working at Greek.[3]

Ever your grateful

J. S.

From John Smith's quasi-parental care, Bute passed in due time into the house of Mr. Westcott (afterwards Bishop of Durham), who occupied "Moretons," on the top of West Hill (now in the possession of Mr. M. C. Kemp). The future bishop, with all his attainments, had not the reputation of a very successful teacher in class, nor of a good disciplinarian; but as a house-master he had many admirable qualities, and was greatly beloved by his pupils. For him also Bute preserved a warm and lifelong sentiment of regard and gratitude; and to him, as to John Smith, he was accustomed to send every Easter a blessed palm from his private chapel, which Dr. Westcott preserved carefully in his own chapel at Auckland Castle. "See that the Bishop of Durham gets his palm," were Lord Bute's whispered words as he was lying stricken by his last illness in the Holy Week of 1900. The tribute of affectionate {23} remembrance had been an annual one for more than thirty years.

1863, School friendships

Of all Bute's contemporaries at the great school, there were perhaps only two with whom he struck up a real and close friendship. One was Adam Hay Gordon of Avochie (a cadet of the Tweeddale family), who was with him afterwards at Christ Church, and was one of his few intimate associates there. The intimacy was not continued into later years, but the memory of it remained. "I heard with sorrow," Bute recorded in his diary on July 12, 1894, "of the death of one of my dearest friends, Addle Hay Gordon. Though at Harrow together, and very intimate at college, we had not met for many years. In my Oxford days I several times stayed in Edinburgh with him and his parents, in Rutland Square. We were as brothers."[4]

An even more intimate, and more lasting, friendship was that with George E. Sneyd, who was at Westcott's house with Bute, and who afterwards became his private secretary, married his cousin, Miss Elizabeth Stuart (granddaughter of Admiral Lord George Stuart) in 1880, and died in the same year as Adam Hay Gordon. "It is difficult to say," wrote Bute in January, 1894, "what this loss is to me. He had been an intimate friend ever since we were at Westcott's big house at Harrow—one of my few at all, the most intimate (unless Addle Hay Gordon) and the most trusted I ever had. He had a very important place in my will. For these two I had prayed by name regularly at every Mass I have heard for many, many years."

A school contemporary, who records Bute's close friendship with George Sneyd, mentions (as do others) his fancy for keeping Ligurian bees in his tiny study-bedroom. "My only recollection of his room at Harrow, where I once visited him," writes Sir Herbert Maxwell, "is of an arrangement whereby bees entered from without into a hive within the room, where their proceedings could be watched." A brother of Sir Redvers Buller, who boarded in the adjoining house, has recorded that "Bute's bees" were a perfect nuisance to him, as they had a way of flying in at his window instead of their own, and disturbing him at his studies or other employments.

1863, Harrow school prizes

"At Harrow," said one of Bute's obituary notices, "the young Scottish peer was as poetical as Byron." This rather absurd remark is perhaps to some extent justified by one episode in Bute's school career. "I have a general recollection of him," writes a correspondent already quoted, "as a very amiable, though reserved, boy, not given to games, who astonished us all by securing the English Prize Poem. He won this distinction (the assigned subject was 'Edward the Black Prince') in the summer of 1863, when only fifteen years of age." "His winning this prize in 1863, when quite young," writes the Archbishop of Canterbury, who was in the same form as Bute at Harrow and knew him well, "was his most notable exploit. There is a special passage about ocean waves and their 'decuman,' which has often been quoted as a remarkable effort on the part of a young boy.[5] {25} He was very quiet and unassuming in all his ways."

A further honour gained by Bute in the same year (1863) was one of the headmaster's Fifth Form prizes for Latin Verse; but the text of this composition (it was a translation from English verse) has not been preserved. The fact of his winning these two important prizes is a sufficient proof that, if not "as poetical as Byron," he had a distinct feeling for poetry, and that generally his industry and ability had enabled him to make up much, if not all, of the leeway caused by the imperfect and desultory character of his early education. In other words he passed through his school course with credit and even distinction; and that he preserved a kindly memory of his Harrow days is sufficiently shown by the fact that he took the unusual step—unusual, that is, in the case of the head of a great Roman Catholic family—of sending all his three sons to be educated at the famous school on the Hill.

Bute's career at Harrow, like his private school course, was an unusually short one, extending over only three years. He left the school in the first term of 1865, presenting to the Vaughan Library at his departure a small collection of books, which it may be of some interest to enumerate. They were Pierotti's Jerusalem Explained, 2 vols. folio; {26} Digby's Broadstone of Honour, 3 vols.; Victor Hugo's Les Miserables, 3 vols.; Miss Proctor's Legends and Lyrics; Gil Blas, 2 vols. (illustrated); Don Quixote; Napier's Memoirs of Montrose, 3 vols.; and Memoirs of Dundee, 2 vols.

He further evinced his interest in his old school by presenting to it, five years after leaving, a portrait of John first Marquess of Bute (then Lord Mountstuart), wearing the dress of the school Archery Corps of that day (1759). This portrait (which is a copy of a well-known painting by Allan Ramsay) now hangs in the Vaughan Library.

1865, Pilgrimage to Palestine

It was characteristic of the young Harrovian that, his school-days over, he took the very first opportunity to turn his steps towards the East, in which from his earliest boyhood he had always been curiously interested. It was not the first occasion of his leaving England, for he had visited Brussels and other cities several times with his mother during his childhood, and used in later years to note in his diary the half-forgotten recollections of places which he had seen in those early and happy days. But his visit to Palestine in the spring of 1865—the first of many journeys to the Holy Land—was an entirely new experience; and to this youth of seventeen, thoughtful and religious-minded beyond his years, it was no mere pleasure trip, but a veritable pilgrimage. "I am sending you a copy," he wrote to a friend at Oxford in the autumn of this year, "of a document which I value more than anything I have ever received in my life: the certificate of my visit to the Holy Places of Jerusalem given to me by the Father Guardian of the Franciscan convent on Mount Sion. Here it is:

In Dei Nomine. Amen. Omnibus et singulis praesentes literas inspecturis, lecturis, vel legi audituris, fidem notumque facimus Nos Terrae Sanctæ Custos, devotum Peregrinum Illustrissimum Dominum Dominum Joannem, Marchionem de Bute in Scotia, Jerusalem feliciter pervenisse die 10 Mensis Maii anni 1865; inde subsequentibus diebus præcipua Sanctuaria in quibus Mundi Salvator dilectum populum Suum, immo et totius generis humani perditam congeriem ab inferi servitute misericorditer liberavit, utpote Calvarium ... SS. Sepulchrum ... ac tandem ea omnia sacra Palestinæ loca gressibus Domini ac Beatissimæ ejus Matris Mariæ consecrata, à Religiosis nostris et Peregrinis visitari solita, visitasse.

In quorum fidem has scripturas Officii Nostri sigillo munitas per Secretarium expediri mandavimus.

Datis apud S. Civitatem Jerusalem, ex venerabili Nostro Conventu SS. Salvatoris, die 29 Maii, 1865.

L.S. De mandato Reverendiss. in Christo Patris

F. REMIGIUS BUSELLI, S.T.L., secret.

+ Sigillum Guardiani Montis Sion.

(There is an image of the Descent of the H. Spirit, and of the Mandatum.)

"It touched and interested me extremely," Bute said many years later, "to find myself described in this document as 'devotus Peregrinus,' and this for more than one reason. The phrase, in the first place, seemed to link me, a mere schoolboy, with the myriads of devout and holy men, saints and warriors, who had made the pilgrimage before me. 'Illuc enim ascenderunt tribus, tribus Domini.' And then I remembered that I descended lineally through my mother's family, the Hastings', from a very famous pilgrim, the 'Pilgrim of Treves,' the Hebrew who went to Rome during the great Papal Schism, sat himself down on one of the Seven Hills, and dubbed himself Pope. When Martin V. (Colonna) was recognised as lawful Pope, {28} my ancestor returned to Rome and, I believe, reverted to the Judaism from which he had temporarily lapsed. But this celebrated journey earned him the title, par excellence, of the Pilgrim of Treves; and the name of Peregrine has been borne since, all through the centuries, by many of his descendants, of whom I am one." All this is so curiously characteristic of Lord Bute's half serious, half whimsical (and always original) manner of regarding out-of-the-way corners of history and genealogy, that it seems worth reproducing in this place.

1866, Steeplechasing at Oxford

Soon after his return from his Palestine journey, Bute was duly matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford, and he went into residence in the October term. He was one of the last batch of peers who entered the university on the technical footing of "noblemen," with the privilege of wearing a distinctive dress, sitting at a special table in hall, and paying double for everything. Among his contemporaries at the House were the Duke of Hamilton, Lord Rosebery, the seventh Duke of Northumberland, and Lords Cawdor, Doune, and Willoughby de Broke. His cousin, the fourth and last Marquess of Hastings, who was five years his senior, had not long before gone down from the university, had been married for a year, and was at the height of the meteoric career which came to a premature and inglorious end just when Bute attained his majority. The latter had that strong sense of family attachment which is so marked a characteristic of Scotsmen; and noblesse oblige was a maxim which for him had a very real and serious meaning. It is certain that the contemplation of his cousin's wasted life not only distressed him deeply, but tended to confirm in him an almost exaggerated {29} antipathy to the extravagant craze for racing, gambling and betting, which was the form of "sport" most prevalent among the young men of family and fashion who were his contemporaries at Oxford. Bute's entire want of sympathy with such pursuits and such ideals thus inevitably cut him off from anything like intimate intercourse with the predominant members of the undergraduate society of his college. He would not be persuaded to frequent their clubs or share in their amusements, which to him would have been no amusements at all; although he was elected a member of "Loders," to which the noblemen and gentlemen-commoners of the House as a matter of course belonged. He was, however, induced, on the representations of one of his friends (probably Hay Gordon) to own and nominate a horse in the university steeplechases (or "grinds," as they were called). "Some one, I do not know who," writes one of his contemporaries, "had informed him that I was the proper person to ride his horse. When I interviewed him on the subject (which I did with some trepidation, as he was exceedingly shy and stiff with strangers), he evinced not the slightest interest either in his horse or the contest in which it was to take part. The animal came in only third, but Bute showed neither disappointment nor pleasure in anything it did or failed to do either on this or on subsequent occasions." Another anecdote in connection with this episode of "Bute's steeplechaser" is related by one of his fellow-undergraduates, who was charged, or had charged himself, with the duty of informing the owner of this unprofitable horse (for which, by the way, he had paid a good round sum) that it was among the "Also Rans" in the Christ Church {30} grinds. "Ah! indeed?" was his only comment; "but now I want to know," he continued eagerly, "if you can help me to solve a much more important question. What real claim had the [Greek: kremastoí kêpoi] (the hanging gardens) of Semiramis at Babylon, to be classified, as they were in ancient times, among the Seven Wonders of the World?"

Whilst on the subject of Bute's diversions at Christ Church (though steeplechasing, even vicariously, can hardly be said to have been one of them), reference may appropriately be made to a rather remarkable entertainment which he gave by way of repaying the hospitalities extended to him by his companions, including some of his former school-fellows at Harrow. It took the form of a fancy-dress ball, which came off in the fine suite of rooms which he occupied in the north-west corner of Tom Quad (since subdivided). Here is the invitation card, surmounted with the emblazoned arms of the House, which was sent out:

MARQUESS OF BUTE

AT HOME

La Morgue Bal Masqué

IV. I. Tom. R.S.V.P.

"La Morgue" was the room, adjacent to his own, which was, as a matter of fact, used as a mortuary when any death occurred within the college. The young host received his guests at the entrance to this apartment in the character of his Satanic Majesty, attired in a close-fitting garment of scarlet and black, with wings, horn, and tail; and most of the guests figured as dons, eminent churchmen, and other well-known personages in the university, the stately dean being, of course, represented, as well as {31} Mrs. Liddell, who afterwards expressed regret that she had not been present in person. A fracas in the refreshment room resulted in a jockey (the Hon. H. Needham) being arrested by a policeman, who conducted him to the police-office before the culprit discovered that the supposed constable was one of his fellow-revellers. The affair was altogether so successful that Bute designed to repeat it a year later; but the authorities of the House, who had given no permission for the original entertainment, peremptorily forbade its repetition.[6]

1865, Oxford friends

Bute had come into residence at Oxford a few weeks after his eighteenth birthday; and the above reminiscences show that with all his serious-mindedness he possessed, as indeed might have been expected, something also, at that period, of what Disraeli called "the irresponsible frivolity of immature manhood." His amiability of character and remarkable personal courtesy prevented him from being in any degree unpopular; but his intimate friends at Oxford were undoubtedly very few; and it is curious that the most intimate of them all was not an undergraduate, or an Oxford man at all, but a lady much his senior, Miss Felicia Skene, daughter of a well-known man of letters and friend of Walter Scott, long resident in Oxford. Miss Skene was herself a person of remarkable attainments and qualities, one of them being a rare gift of sympathy, which seems to have won the heart of the solitary young Scotsman from the first {32} day of their acquaintance. Bute corresponded with her constantly and regularly, not only during his undergraduate days, but for many years subsequently; and his letters show to how large a degree he gave her his confidence in matters of the most intimate interest to himself. One of the earliest of these is dated from Dumfries House, Ayrshire, in the Christmas vacation following his first term at Oxford.

Dumfries House,

Cumnock,

Christmas Day [1865].

MY DEAR MISS SKENE,

A happy Xmas to you. Mine is comfortable, if not merry nor ideal. Let me say in black and white that I mean to pay for the meat and wine ordered by the doctor for the poor woman you mention.... Money I cannot send. I have little more than £100 to spend myself. My allowance is £2000, and I have overdrawn £1630, with a draft for £1000 coming due. I am trying to raise the wind here: it seems absurd that I should be "hard up," but it is a long story. I am only sorry that the offerings I should make at this time to the "Little Child of Bethlehem" are not procurable.

Ever yours most truly,

BUTE.

1865, At Dumfries House

Bute had now finally left Galloway House, which had been his holiday residence during his Harrow days; and his home when not at Oxford was at Dumfries House, his Ayrshire seat, then in the occupation of Sir James and Lady Edith Fergusson. "I saw a good deal of him when he was living at Dumfries House under the tutelage of Sir James Fergusson," writes one who had known him from {33} childhood. "He used to come down to the smoking-room at night arrayed in a gorgeous garment of pale blue and gold: I think he said he had had it made on the pattern of a saintly bishop's vestment in a stained glass window of the Harrow Chapel. Sir James was anxious to make a sportsman of Bute, and bought a hunter or two for him. I remember his coming out one day with Lord Eglinton's hounds, but I never saw him take the field again." The tyro, as a matter of fact, got a toss in essaying to jump a hedge; and so mortified was he by this public discomfiture that he not only never again appeared in the hunting-field, but he never quite forgave Sir James for being the indirect cause of the misadventure.

Miss Skene not only acted to some extent as Bute's almoner during his Oxford days (it is fair to say that the "hard-up" condition alluded to in the above letter was due at least as much to his lavish almsgiving as to any personal extravagance), but was his adviser in regard to other matters. "Mrs. Leighton [wife of the Warden of All Souls] has invited me," runs one of his notes, "to come and meet a Scottish bishop (St. Andrews) at dinner, and asks me in the same letter to give 'out of my abundance' a cheque to enlarge the Penitentiary chapel. Now I dislike Scots Episcopalian bishops (not individually but officially), their genesis having been unblushingly Erastian, and their present status in Scotland being schismatic and dissenting; and my 'abundance' at present consists of a heavy overdraft at the bank. Read and forward the enclosed reply, unless you think the lady will take offence, which can hardly be."

He often copied for his friend extracts which {34} struck him from books he was reading. "I have transcribed for you," he wrote a few weeks after his nineteenth birthday, "the account of the death of Krishna from the Vishnu Purána. A hunter by accident shot him in the foot with an arrow. When he saw what he had done he prostrated himself and implored pardon. Krishna granted it and translated him at once to heaven. 'Then the illustrious Krishna, having united himself with his own pure, spiritual, inexhaustible, inconceivable, unborn, undecaying, imperishable and universal spirit, which is one with Vásundera, abandoned his mortal body and the condition of the threefold qualities.' To my mind this description of the great Saviour becoming one with universal spirit approaches the sublime."

At the end of his first summer term (June, 1866) Bute made his second tour in the East—a more extended one this time, visiting not only Constantinople and Palestine, but Kurdistan and Armenia. His tutor, the Rev. S. Williams, accompanied him, as well as one or two friends, including Harman Grisewood, one of his associates at the House, and one of the few with whom he maintained an intimacy after their Oxford days. A diary kept by Bute of the first portion of this tour has been preserved: it describes his doings with great minuteness, and is a remarkable record for a youth of eighteen to have written. In Paris nothing seems to have much interested him except the churches, and long antiquarian conversations with the Vicomte de Vogüé and others. "I again visited the Comte de V.,"[7] {35} runs one entry. "We got into the Cities of Bashan, and stayed there three or four hours." Many pages are devoted to a detailed description of Avignon, and later of St. John's Church at Malta, of Syracuse, Catania, and Messina. At Malta he visited the tomb of his grandfather (the first Marquess of Hastings, who died when governor of Malta in 1826), and "was much pleased with it." Describing the high mass in the Benedictine Church at Catania, he says, "At the end, during the Gospel of St. John, the organist (the organ is one of the finest in the world) played a military march so well that I, at least, could hardly be persuaded that the loud clear clash, the roll of the drums, the ring of the triangle, and the roar of the brass instruments were false. It seemed to me that this passage, which was admirably executed, harmonised wonderfully well with the awful words of the part of the Mass which it accompanied."

1866, Ascent of Mount Etna

The young diarist's vivid descriptive powers are well shown in his narrative of the ascent of Etna, and the impression it made on him:

We dined [at Nicolosi] on omelet, bread, and figs, and the nastiest wine, and at about 7 p.m. started on mules. These beasts had saddles more uncomfortable than words can describe. Their pace was about 2-½ miles per hour, which it was too easy to reduce, but quite impossible to accelerate. Mine had for bridle a cord three feet long, tied to one of several large rings on one side of its head. The journey lasted till 1.30 a.m. or later.... About {36} 1 in the morning, Mr. W. and one guide having long dropped far behind, where their shrieks and yells (now growing hoarse from despair) could be faintly heard in the darkness far down the mountain, we emerged upon the summit between the peaks; and at the same time the full moon, silver, intense, rose from behind the lower summit, and shed a flood of light over the tremendous scene of desolation. As far as the eye could reach, there was nothing visible but cinders and sky. At every step we sank eighteen inches into the black dust as we stumbled on in single file in perfect silence. A couple of miles ahead rose the great crater peak, with patches of snow at its foot and the eternal white cloud emanating and writhing from the summit. After an hour's rest at the Casa Inglese, a miserable hovel at the foot of the Cone, we started, wrapped in plaids, the cold being intense. Mr. W. had now rejoined us. The Cone is a hill about the size of Arthur's Seat, covered with rolling friable cinders, from which rise clouds of white sulphureous dust. The ascent took rather more than an hour. Mr. W. gave out half-way up, declaring he should faint. The pungent sulphur-smoke came sweeping down the hill-side, choking and blinding one. Eyes were smarting, lungs loaded, throat burnt, mouth dry and nostrils choked. On we struggled till the very ground gave forth curling clouds of smoke from every cranny. A few more steps and we were on the summit, at the very edge of the crater, which yawned into perdition within a few inches of one's foot. It is an immense glen, surrounded by a chain of heights, with tremendously precipitous sides, bright yellow in the depths, whence rises continually the cloud of smoke. The whole scene is exactly like Doré's illustrations of the Inferno.... The sun rose over Italy as we sat with our heads wrapped up and handkerchiefs in our mouths; but there was no view at all, the height is too stupendous. The {37} horror of the whole place cannot be depicted. We were delighted to get back to the Casa Inglese, where we remounted our mules and crept away.

1866, Impressions of Eastern travel

From Sicily the travellers visited Smyrna and Chios on their way to Constantinople. Pages of the diary are taken up with descriptions of churches, and functions attended in them, and it is of interest to note that, profoundly interested as Bute was in the Greek churches and the Greek liturgy, his religious sympathies were entirely with the Latin communion. The "spiritual deadness," as he calls it, of the schismatic churches of the East, repelled and dismayed him. "It strikes me as essentially dreadful," he writes of a visit to the Church of the Transfiguration at Syra, "that the Photian Tabernacle everywhere enshrines a deserted Saviour. The daily sacrifice is not offered; the churches are closed and cold, save for a few hours on Sunday and festivals; visits to the B. Sacrament are unknown. Pictures are exposed to receive an exaggerated homage, unknown and undreamt of in the West. But it is absolutely true to say that the Perpetual Presence (to which no reverence at all is offered, by genuflection or otherwise) receives less respect than one ordinarily pays to any place of worship whatever, even a meeting-house or synagogue." Later, recording a visit to the Greek cathedral at Pera, he describes the service there as "the most disagreeable function I ever attended: the church crammed with people in a state of restlessness and irreverence characteristic of Photian schismatics; and the whole service as much spoiled as slurring, drawling, utter irreverence, bad music, and bad taste could spoil it. After breakfast I {38} attended the High Mass at the Church of the Franciscans—a different thing indeed from the Photian Cathedral; and I went back there in the afternoon for Vespers and Benediction."

It has been sometimes said that Bute, during the period immediately preceding his reception into the Catholic Church, was even more drawn towards the "Orthodox" form of belief than he was to the prevailing religion of Western Christendom. The above extracts show that the very reverse was the case. Genuine and earnest worship stirred and impressed him everywhere: thus he writes, after witnessing an elaborate ceremonial (including the dance of the dervishes) in a mosque at Constantinople: "I left the mosque very much wrought up and excited. There are those who are not impressed by this. There are those also who laugh at a service in a language they do not know: there are those who see nothing august or awful even in the Holy Mass." Slovenliness, irreverence, tepidity in religion were what pained and repelled him; and finding those characteristics everywhere in the liturgical services of those whom he called the Photians, he was so far from being attracted towards any idea of joining their communion, that he returned to England, and to Oxford, after this Eastern journey, with the whole bent of his religious aspirations set more and more in the direction of the Catholic and Roman Church. His conversion was, in fact, accomplished before the end of this year, although circumstances, as will be seen, compelled the postponement for a considerable time of the public and formal profession of his faith.

[1] The Scottish Review, which Lord Bute controlled at this time, and to which he contributed many articles.

[2] This was the chapel on the edge of the sea, among the Mountstuart woods, which had been built for the convenience of the people living and working near the house. Lord Bute used it as a domestic chapel until the new chapel at Mountstuart was opened. He was buried there in 1900.

[3] Lord Bute's only daughter, Lady Margaret Crichton-Stuart, then in her twelfth year, and under the tutelage of a Greek governess.

[4] Adam Hay Gordon married in 1873 the beautiful granddaughter of Sir Robert Dalrymple Horn Elphinstone, and died without issue, as above recorded, in July, 1894.

[5] "'Tis said that when upon a rocky shore

The salt sea billows break with muffled roar,

And, launched in mad career, the thundering wave

Leaps booming through the weedy ocean cave;

Each tenth is grander than the nine before.

And breaks with tenfold thunder on the shore.

Alas! it is so on the sounding sea;

But so, O England, it is not with thee!

Thy decuman is broken on the shore:

A peer to him shall lave thee never more!"

The text of the whole poem is given in Appendix I.

[6] The particulars of this whimsical incident in Bute's university career have been kindly furnished by Mr. Algernon Turnor, C.B., who was his contemporary at Christ Church. It was he who rode—though not to victory—the steeplechaser mentioned in the text. Mr. Turner married in 1880 Lady Henrietta Stewart, one of Bute's early playmates and companions at Galloway House.

[7] Eugene Vicomte de Vogüé, whom Bute wrongly styles "Comte" in his diary, was a few months his junior. One of the most brilliant and charming men of his generation, he was in turn soldier, diplomatist, politician, and littérateur. He became a member of the Academy in 1888 and died in 1910. He published books and articles on a great variety of subjects, all marked with the profoundly religious feeling which characterised him.

A well-meaning person thought well to compile and publish, some years ago, a volume in which a few distinguished Roman Catholics, and a great number of mediocrities, were invited to describe the process and motives which led them "to abandon" (as some cynic once expressed it) "the errors of the Church of England for those of the Church of Rome." Lord Bute, who was among the many more or less eminent people who received and declined invitations to contribute to this symposium, was certainly the last man likely to consent to recount his own religious experiences for the benefit of a curious public. It is, therefore, all the more interesting that in a copy of the book above referred to, belonging to one of his most intimate friends,[1] was preserved a memorandum in Bute's writing, which throws an interesting light on some, at least, of the causes which were contributory to his own submission to the Roman Church.

I came to see very clearly indeed that the Reformation was in England and Scotland—I had not studied it elsewhere—the work neither of God nor of the people, its real authors being, in the former country, {40} a lustful and tyrannical King, and in the latter a pack of greedy, time-serving and unpatriotic nobles. (Almost the only real patriots in Scotland at that period were bishops like Elphinstone, Reid, and Dunbar.)

I also convinced myself (1) that while the disorders rampant in the Church during the sixteenth century clamoured loudly for reform, they in no way justified apostacy and schism; and (2) that were I personally to continue, under that or any other pretext, to remain outside the Catholic and Roman Church, I should be making myself an accomplice after the fact in a great national crime and the most indefensible act in history. And I refused to accept any such responsibility.

1860, Attraction to Roman Church

The late Jesuit historian, Father Joseph Stevenson, who spent a great number of years in laborious study (for his work in the Record Office) of the original documents and papers of the Reformation period, frankly avowed that it was what he learned in these researches, and no other considerations whatever, which convinced him—an elderly Anglican clergyman of the old school—that the Catholic Church was the Church of God, and the so-called Reformation the work of His enemies. It was one of his colleagues in the Society of Jesus[2] who quoted this to Lord Bute, and his emphatic comment was, "That is a point of view which I thoroughly appreciate." As to Bute himself, there were undoubtedly many sides of his character to which the appeal of the ancient Church would be strong and insistent. Her august and venerable ritual, the ordered splendour of her ceremonial, the deep significance of her liturgy and worship, {41} could not fail to attract one who had learned to see in them far more than the mere outward pomp and beauty which are but symbols of their inward meaning. The love and tenderness and compassion with which she is ever ready to minister to the least of her children would touch the heart of one who beneath a somewhat cold exterior had himself a very tender feeling for the stricken and the sorrowful. The marvellous roll of her saints, the story of their lives, the record of their miracles, would stir the imagination and kindle the enthusiasm of one who loved to remember, as we have seen, that the blood of pilgrims flowed in his veins, and found one of his greatest joys in visiting the shrines, following in the footsteps, venerating the remains, and verifying the acts of the saints of God in many lands, even in the remotest corners of Christendom. His mind and heart and soul found satisfaction in all these things; but most of all it was the historic sense which he possessed in so peculiar a degree, the craving for an exact and accurate presentment of the facts of history, which was one of his most marked characteristics—it was these which, during his many hours of painful and laborious searching into the records of the past, were the most direct and immediate factors in convincing his intellect, as his heart was already convinced, that the Catholic and Roman Church, and no other, was the Church founded by Christ on earth, and that to remain outside it was, for him, to incur the danger of spiritual shipwreck.