POSITION OF P. ERECTUS.

POSITION OF P. ERECTUS.(Manouvrier, Bul. Soc. d'Anthrop. 1896, p. 438.)

Title: Man, Past and Present

Author: A. H. Keane

Editor: Alfred C. Haddon

A. Hingston Quiggin

Release date: March 26, 2011 [eBook #35685]

Most recently updated: January 29, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Adrian Mastronardi and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

| NEW YORK: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS | ||

| BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS | } | MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. |

| TORONTO: J. M. DENT AND SONS, Ltd. | ||

| TOKYO: MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA | ||

Those who are familiar with the vast amount of ethnological literature published since the close of last century will realize that to revise and bring up to date a work whose range in space and time covers the whole world from prehistoric ages down to the present day, is a task impossible of accomplishment within the compass of a single volume. Recent discoveries have revolutionized our conception of primeval man, while still providing abundant material for controversy, and the rapidly increasing pile of ethnographical matter, although a vast amount of spade work remains to be done, is but one sign of the remarkable interest in ethnology which is so conspicuous a feature of the present decade. Even to keep abreast of the periodical literature devoted to his subject provides ample occupation for the ethnologist and few are those who can now lay claim to such an omniscient title.

Under such circumstances the faults of omission and compression could not be avoided in revising Professor Keane's work, but it is hoped that the copious references which form a prominent feature of the present edition will compensate in some measure for these obvious defects. The main object of the revisers has been to retain as much as possible of the original text wherever it fairly represents current opinion at the present time, but so different is our outlook from that of 1899 that certain sections have had to be entirely rewritten and in many places pages have been suppressed to make room for more important information. In every case where new matter has been inserted references are given to the responsible authorities and the fullest use has been made of direct quotation from the authors cited.

Mrs Hingston Quiggin is responsible for the whole work of revision with the exception of Chapter XI, revised by Miss Lilian Whitehouse, while Dr A. C. Haddon has criticized, corrected and supervised the work throughout.

A. H. Q.

A. C. H.

10 October, 1919.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS | 1 |

| II. | THE METAL AGES—HISTORIC TIMES AND PEOPLES | 20 |

| III. | THE AFRICAN NEGRO: I. SUDANESE | 40 |

| IV. | THE AFRICAN NEGRO: II. BANTUS—NEGRILLOES—BUSHMEN—HOTTENTOTS | 84 |

| V. | THE OCEANIC NEGROES: PAPUASIANS (PAPUANS AND MELANESIANS)—NEGRITOES—TASMANIANS | 132 |

| VI. | THE SOUTHERN MONGOLS | 163 |

| VII. | THE OCEANIC MONGOLS | 219 |

| VIII. | THE NORTHERN MONGOLS | 254 |

| IX. | THE NORTHERN MONGOLS (continued) | 300 |

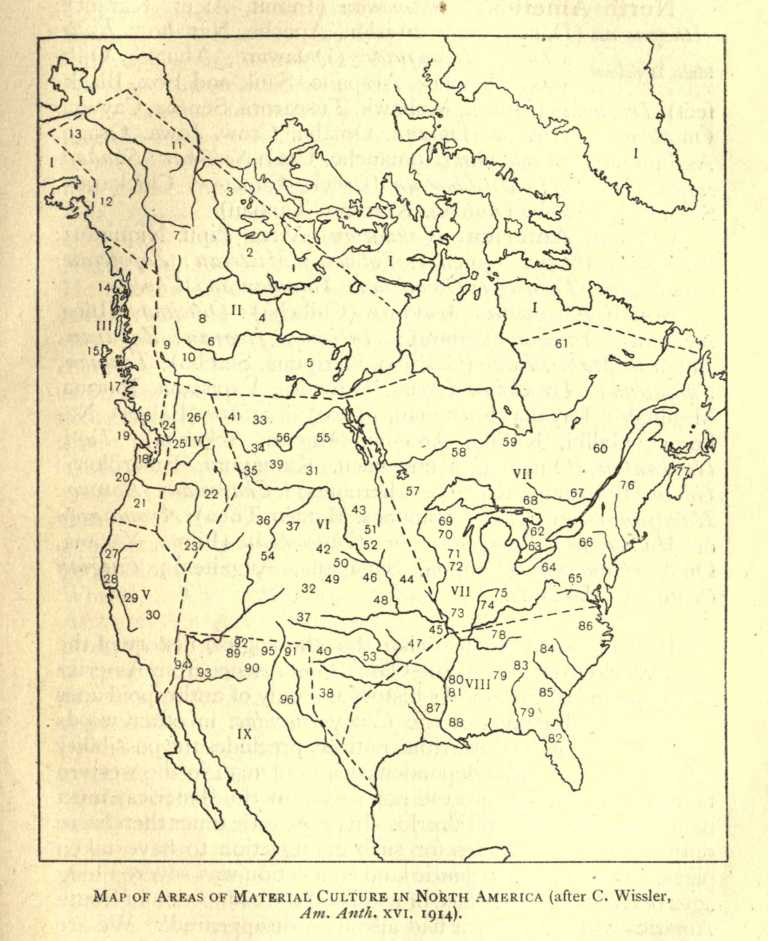

| X. | THE AMERICAN ABORIGINES | 332 |

| XI. | THE AMERICAN ABORIGINES (continued) | 388 |

| XII. | THE PRE-DRAVIDIANS: JUNGLE TRIBES OF THE DECCAN, SAKAI, AUSTRALIANS | 422 |

| XIII. | THE CAUCASIC PEOPLES | 438 |

| XIV. | THE CAUCASIC PEOPLES (continued) | 488 |

| XV. | THE CAUCASIC PEOPLES (continued) | 501 |

| APPENDIX | 556 | |

| INDEX | 562 |

| PLATE I. | |

| 1. | Hausa slave of Tunis (Western Sudanese Negro). |

| 2. | Zulu girl, South Africa (Bantu Negroid). |

| 3, 4. | Abraham Lucas, Age 32, South Africa (Koranna Hottentot). |

| 5, 6. | Swaartbooi, Age 20, South Africa (Bushman). |

| PLATE II. | |

| 1. | Andamanese (Negrito). |

| 2. | Semang, Malay Peninsula (Negrito). |

| 3. | Aeta, Philippines (Negrito). |

| 4. | Central African Pygmy (Negrillo). |

| 5-7. | Tapiro, Netherlands New Guinea (Negrito). |

| PLATE III. | |

| 1, 2. | Jemmy, native of Hampshire Hills, Tasmania (Tasmanian). |

| 3, 4. | Native of Oromosapua, Kiwai, British New Guinea (Papuan). |

| 5, 6. | Native of Hula, British New Guinea (Papuo-Melanesian). |

| PLATE IV. | |

| 1. | Chinese man (Mixed Southern Mongol). |

| 2. | Chinese woman of Kulja (mixed Southern Mongol). |

| 3, 4. | Kara-Kirghiz of Semirechinsk. |

| 5. | Kara-Kirghiz woman of Semirechinsk. |

| 6. | Solon of Kulja (Manchu-Tungus). |

| PLATE V. | |

| 1. | Jelai, an Iban (Sea-Dayak) of the Rejang river, Sarawak, Borneo (mixed Proto-Malay). |

| 2. | Buginese, Celebes (Malayan). |

| 3. | Bontoc Igorot, Luzon, Philippines (Malayan). |

| 4. | Bagobo, Mindanao, Philippines (Malayan). |

| 5, 6. | Kenyah girls, Sarawak, Borneo (mixed Proto-Malay). |

| PLATE VI. | |

| 1. | Samoyed, Tavji. |

| 2. | Tungus. |

| 3. | Ostiak of the Yenesei (Palaeo-Siberian). |

| 4. | Kalmuk woman (Western Mongol). |

| 5. | Gold of Amur river (Tungus). |

| 6. | Gilyak woman (N.E. Mongol). |

| PLATE VII. | |

| 1. | Ainu woman, Yezo, Japan (Palaeo-Siberian). |

| 2. | Ainu man, Yezo, Japan (Palaeo-Siberian). |

| 3, 4. | Fine and coarse types of Japanese men (mixed Manchu-Korean and Southern Mongol.) |

| 5. | Korean (mixed Tungus-Eastern Mongoloid). |

| 6. | Lapp (Finnish). |

| PLATE VIII. | |

| 1. | Eskimo, Port Clarence, West Alaska. |

| 2. | Indian of the north-west coast of North America. ?Kwakiutl (Wakashan stock). |

| 3. | Cocopa, Lower California (Yuman stock). |

| 4. | Navaho, Arizona (Athapascan linguistic stock). |

| 5, 6. | Buffalo Bull Ghost, Dakota of Crow Creek (Siouan stock). |

| PLATE IX. | |

| 1. | Carib, British Guiana. |

| 2. | Guatuso, Costa Rica. |

| 3. | Native of Otovalo, Ecuador. |

| 4. | Native of Zámbisa, Ecuador. |

| 5. | Tehuel-che man, Patagonia. |

| 6. | Tehuel-che woman, Patagonia. |

| PLATE X. | |

| 1. | Sita Wanniya, a Henebedda Vedda, Ceylon (Pre-Dravidian). |

| 2. | Sakai, Perak, Malay Peninsula (Pre-Dravidian). |

| 3. | Irula of Chingleput, Nilgiri Hills, South India (Pre-Dravidian). |

| 4. | Paniyan woman, Malabar, South India (Pre-Dravidian). |

| 5. | Kaitish, Central Australia (Australian). |

| 6. | Mulgrave woman (Australian). |

| PLATE XI. | |

| 1, 2. | Dane (Nordic). |

| 3. | Dane (mixed Alpine). |

| 4. | Breton woman of Guingamp (mixed Alpine). |

| 5. | Swiss woman (Nordic). |

| 6. | Swiss woman (Alpine). |

| PLATE XII. | |

| 1. | Catalan man, Spain (Iberian). |

| 2. | Irishman, Co. Roscommon (Mediterranean). |

| 3, 4. | Kababish, Egyptian Sudan (mixed Semite). |

| 5. | Egyptian Bedouin (mixed Semite). |

| 6. | Afghan of Zerafshán (Iranian). |

| PLATE XIII. | |

| 1, 2. | Bisharin, Egyptian Sudan (Hamite). |

| 3. | Beni Amer, Egyptian Sudan (Hamite). |

| 4. | Masai, British East Africa (mixed Nilote and Hamite). |

| 5. | Shilluk, Egyptian Sudan (Nilote, showing approach to Hamitic type). |

| 6. | Shilluk, Egyptian Sudan (Nilote). |

| PLATE XIV. | |

| 1, 2. | Kurd, Nimrud-Dagh, lake Van, Kurdistan, Asia Minor (Nordic). |

| 3, 4. | Armenian, Kessab, Djebel Akrah, Kurdistan (Armenoid Alpine). |

| 5. | Tajik woman of E. Turkestan (Alpine). |

| 6. | Tajik of Tashkend (mixed Alpine and Turki). |

| PLATE XV. | |

| 1, 2. | Sinhalese, Ceylon (mixed "Aryan"). |

| 3. | Hindu merchant, Western India (mixed "Aryan"). |

| 4. | Kling woman, Eastern India (Dravidian). |

| 5. | Linga Banajiga, South India (Dravidian). |

| 6. | Vakkaliga, Canarese, South India (mixed Alpine). |

| PLATE XVI. | |

| 1, 2. | Ruatoka and his wife, Raiatea (Polynesian). |

| 3. | Tiawhiao, Maori, New Zealand (Polynesian). |

| 4. | Maori woman, New Zealand (Polynesian). |

| 5, 6. | Girls of the Caroline Islands (Micronesian). |

We offer our sincere thanks for the use of the following photographs:

A. H. Keane, Ethnology (1896), IV. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; IX. 3, 4; XII. 6; XIV. 5, 6.

A. H. Keane, Man, Past and Present (1899), I. 2; II. 3; V. 2; VI. 4, 5, 6; VII. 5; IX. 1, 2; X. 4, 6; XII. 5.

A. R. Brown, II. 1.

Prof. R. B. Yapp, II. 2.

Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, II. 4; V. 4; VII. 1, 2; VIII. 1, 2, 3, 4; IX. 5, 6; XV. 1, 2.

Dr Wollaston, cf. Pygmies and Papuans, p. 212; II. 5, 6, 7.

Dr G. Landtman, III. 3, 4.

Anthony Wilkin, III. 5, 6.

Prof. C. G. Seligman, V. 1; (The Veddas, pl. V) X. 1; XII. 3, 4; XIII. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6.

L. F. Taylor, V. 3.

A. C. Haddon, I. 3, 4, 5, 6; III. 1, 2; IV. 1; V. 5, 6; VII. 6; XI. 1, 2, 3; XII. 1, 2; XIII. 4; XVI. 1, 2, 3, 4.

Miss M. A. Czaplicka, VI. 1, 2, 3.

Dr W. Crooke (cf. Northern India, pl. III), XV. 3.

Baelz, VII. 3, 4.

Bureau of American Ethnology, VIII. 5, 6.

E. Thurston (Castes and Tribes of Southern India, II. p. 387), X. 3; (ibid. IV. pp. 236, 240), XV. 5; XV. 6.

Sir Baldwin Spencer and F. J. Gillen and Messrs Macmillan & Co. (Across Australia, II. fig. 169), X. 5.

Prof. J. Kollmann, XI. 5, 6.

P. W. Luton, XII. 2.

Prof. F. von Luschan and the Council of the Royal Anthropological Institute (Journ. Roy. Anth. Inst., XLI., pl. XXIV, 1, 2, pl. XXX, 1, 2), XIV. 1, 2, 3, 4.

Dr W. H. Furness, XVI. 5, 6.

The World peopled by Migration from one Centre by Pleistocene Man—The Primary Groups evolved each in its special Habitat—Pleistocene Man: Pithecanthropus erectus; The Mauer jaw, Homo Heidelbergensis; The Piltdown skull, Eoanthropus Dawsoni—General View of Pleistocene Man—The first Migrations—Early Man and his Works—Classification of Human Types: H. primigenius, Neandertal or Mousterian Man; H. recens, Galley Hill or Aurignacian Man—Physical Types—Human Culture: Reutelian, Mafflian, Mesvinian, Strepyan, Chellean, Acheulean, Mousterian, Aurignacian, Solutrian, Magdalenian, Azilian—Chronology—The early History of Man a Geological Problem—The Human Varieties the Outcome of their several Environments—Correspondence of Geographical with Racial and Cultural Zones.

In order to a clear understanding of the many difficult questions connected with the natural history of the human family, two cardinal points have to be steadily borne in mind—the specific unity of all existing varieties, and the dispersal of their generalised precursors over the whole world in pleistocene times. As both points have elsewhere been dealt with by me somewhat fully[1], it will here suffice to show their direct bearing on the general evolution of the human species from that remote epoch to the present day.

It must be obvious that, if man is specifically one, though not necessarily sprung of a single pair, he must have had, in homely language, a single cradle-land, from which the peopling of the earth was brought about by migration, not by independent developments from different species in so many independent geographical areas.

It follows further, and this point is all-important, that, since the world was peopled by pleistocene man, it was [Pg 2] peopled by a generalised proto-human form, prior to all later racial differences. The existing groups, according to this hypothesis, have developed in different areas independently and divergently by continuous adaptation to their several environments. If they still constitute mere varieties, and not distinct species, the reason is because all come of like pleistocene ancestry, while the divergences have been confined to relatively narrow limits, that is, not wide enough to be regarded zoologically as specific differences.

The battle between monogenists and polygenists cannot be decided until more facts are at our disposal, and much will doubtless be said on both sides for some time to come[2]. Among the views of human origins brought forward in recent years should be mentioned the daring theory of Klaatsch[3]. Recognising two distinct human types, Neandertal and Aurignac (see pp. 8, 9 below), and two distinct anthropoid types, gorilla and orang-utan, he derives Neandertal man and African gorilla from one common ancestor, and Aurignac man and Asiatic orang-utan from another. Though anatomists, especially those conversant with anthropoid structure[4], are not able to accept this view, they admit that many difficulties may be solved by the recognition of more than one primordial stock of human ancestors[5]. The questions of adaptation to climate and environment[6], the possibilities of degeneracy, the varying degrees of physiological activity, of successful mutations, the effects of crossing and all the complicated problems of heredity are involved in the discussion, and it must be acknowledged that our information concerning all of these is entirely inadequate.

Nevertheless all speculations on the subject are not based merely on hypotheses, and three discoveries of late years have provided solid facts for the working out of the problem.

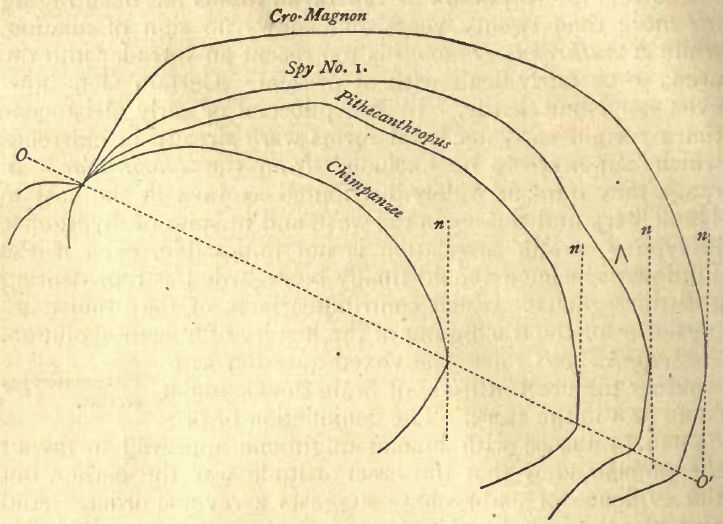

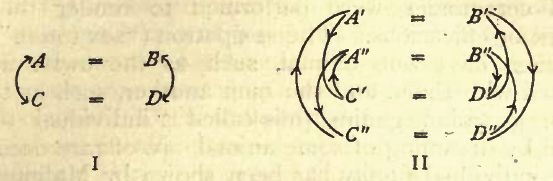

These discoveries were the remains of Pithecanthropus erectus[7] in Java, in 1892, of the Mauer jaw[8], near Heidelberg, in 1907, and of the Piltdown skull[9] in Sussex in 1912. Although the Mauer jaw was accepted without hesitation, the controversy concerning the correct interpretation of the Javan fossils has been raging for more than twenty years and shows no sign of abating, while Eoanthropus Dawsoni is too recent an intruder into the arena to be fairly dealt with at present. Certain facts however stand out clearly. In late pliocene or early pleistocene times certain early ancestral forms were already in existence which can scarcely be excluded from the Hominidae. In range they were as widely distributed as Java in the east to Heidelberg and Sussex in the west, and in spite of divergence in type a certain correlation is not impossible, even if the Piltdown specimen should finally be regarded as representing a distinct genus[10]. Each contributes facts of the utmost importance for the tracing out of the history of human evolution. Pithecanthropus raises the vexed question as to whether the erect attitude or brain development came first in the story. The conjunction of pre-human braincase with human thighbone appeared to favour the popular view that the erect attitude was the earlier, but the evidence of embryology suggests a reverse order. And although at first the thighbone was recognised as distinctly human it seems that of late doubts have been cast on this interpretation[11], and even the claim to the title erectus is called in question. The characters of straightness and slenderness on which much stress was laid are found in exaggerated form in gibbons and lemurs. The intermediate position in respect of mental endowment (in so far as brain can be estimated by cranial capacity) is shown in the accompanying diagram in which the cranial measurements of Pithecanthropus are compared with those of a chimpanzee and prehistoric man. The[Pg 4] teeth strengthen the evidence, for they are described as too large for a man and too small for an ape. Thus Pithecanthropus has been confidently assigned to a place in a branch of the human family tree.

POSITION OF P. ERECTUS.

POSITION OF P. ERECTUS.The Mauer jaw, the geological age of which is undisputed, also represents intermediate characters. The extraordinary strength and thickness of bone, the wide ascending ramus with shallow sigmoid notch (distinctly simian features) and the total absence of chin[12] would deny it a place among human jaws, but the teeth, which are all fortunately preserved in their sockets, are not only definitely human, but show in certain peculiarities less simian features than are to be found in the dentition of modern man[13].[Pg 5]

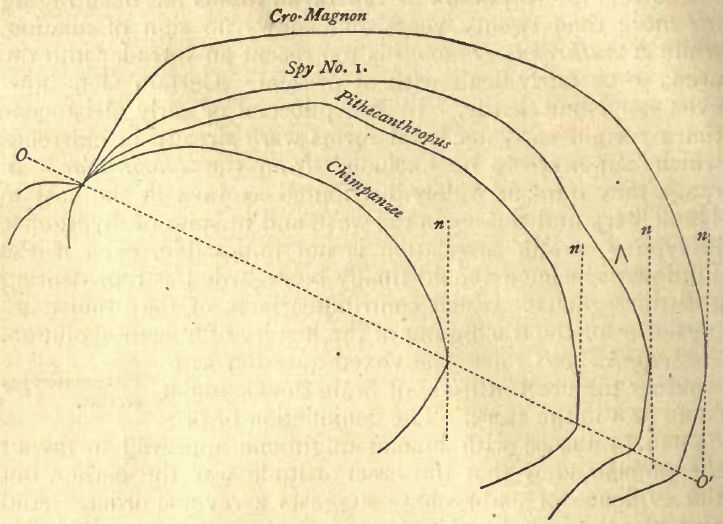

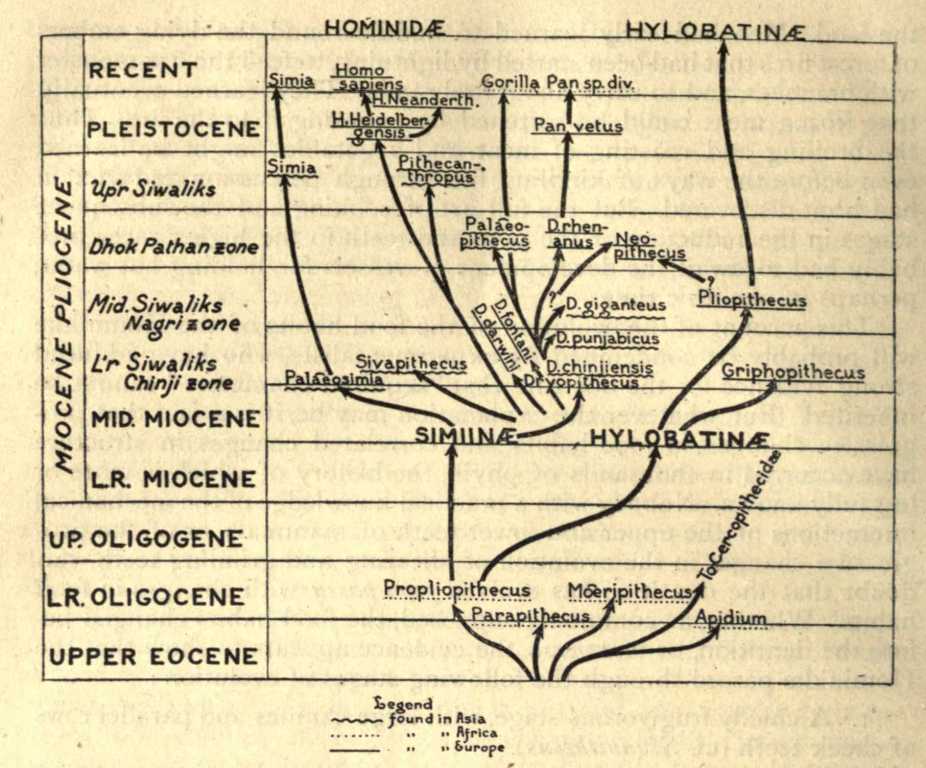

GENEALOGICAL TREE OF MAN'S ANCESTRY.

GENEALOGICAL TREE OF MAN'S ANCESTRY.The cranial capacity of the Piltdown skull, though variously estimated[14], is certainly greater than that of Pithecanthropus, the general outlines with steeply rounded forehead resemble that of modern man, and the bones are almost without exception typically human. The jaw, however, though usually attributed to the same individual[15], recalls the primitive features of the[Pg 6] Mauer specimen in its thick ascending portion and shallow notch, while in certain characters it differs from any known jaw, ancient or modern[16]. The evidence afforded by the teeth is even more striking. The teeth of Pithecanthropus and of Homo Heidelbergensis were recognised as remarkably human, and although primitive in type, are far more advanced in the line of human evolution than the lowly features with which they are associated would lead one to expect. The Piltdown teeth are more primitive in certain characters than those of either the Javan or the Heidelberg remains. The first molar has been compared to that of Taubach, the most ape-like of human or pre-human teeth hitherto recorded, but the canine tooth (found by P. Teilhard in the same stratum in 1913[17]) finds no parallel in any known human jaw; it resembles the milk canine of the chimpanzee more than that of the adult dentition.

It cannot be said that any clear view of pleistocene man can be obtained from these imperfect scraps of evidence, valuable though they are. Rather may we agree with Keith that the problem grows more instead of less complex. "In our first youthful burst of Darwinianism we pictured our evolution as a simple procession of forms leading from ape to man. Each age, as it passed, transformed the men of the time one stage nearer to us—one more distant from the ape. The true picture is very different. We have to conceive an ancient world in which the family of mankind was broken up into narrow groups or genera, each genus again divided into a number of species—much as we see in the monkey or ape world of to-day. Then out of that great welter of forms one species became the dominant form, and ultimately the sole surviving one—the species represented by the modern races of mankind[18]."

We may assume therefore that the earth was mainly peopled by the generalised pleistocene precursors, who moved about, like the other migrating faunas, unconsciously, everywhere following the lines of least resistance, advancing or receding, and acting generally on blind impulse rather than of any set purpose.[Pg 7]

That such must have been the nature of the first migratory movements will appear evident when we consider that they were carried on by rude hordes, all very much alike, and differing not greatly from other zoological groups, and further that these migrations took place prior to the development of all cultural appliances beyond the ability to wield a broken branch or a sapling, or else chip or flake primitive stone implements[19].

Herein lies the explanation of the curious phenomenon, which was a stumbling-block to premature systematists, that all the works of early man everywhere present the most startling resemblances, affording absolutely no elements for classification, for instance, during the times corresponding with the Chellean or first period of the Old Stone Age. The implements of palaeolithic type so common in parts of South India, South Africa, the Sudan, Egypt, etc., present a remarkable resemblance to one another. This, while affording a prima facies case for, is not conclusive of, the migrations of a definite type of humanity.

After referring to the identity of certain objects from the Hastings kitchen-middens and a barrow near Sevenoaks, W. J. L. Abbot proceeds: "The first thing that would strike one in looking over a few trays of these implements is the remarkable likeness which they bear to those of Dordogne. Indeed many of the figures in the magnificent 'Reliquiae Aquitanicae' might almost have been produced from these specimens[20]." And Sir J. Evans, extending his glance over a wider horizon, discovers implements in other distant lands "so identical in form and character with British specimens that they might have been manufactured by the same hands.... On the banks of the Nile, many hundreds of feet above its present level, implements of the European types have been discovered, while in Somaliland, in an ancient river valley, at a great elevation above the sea, Seton-Karr has collected a large number of implements formed of flint and quartzite, which, judging from their form and character, might have been dug out of the drift-deposits of the Somme and the Seine, the Thames or the ancient Solent[21]."[Pg 8]

It was formerly held that man himself showed a similar uniformity, and all palaeolithic skulls were referred to one long-headed type, called, from the most famous example, the Neandertal, which was regarded as having close affinities with the present Australians. But this resemblance is shown by Boule[22] and others to be purely superficial, and recent archaeological finds indicate that more than one racial type was in existence in the Palaeolithic Age.

W. L. H. Duckworth on anatomical evidence constructs the following table[23].

| Group I. | Early ancestral forms. | |

| Ex. gr. H. heidelbergensis. | ||

| Group II. | Subdivision A. H. primigenius. | |

| Ex. gr. La Chapelle. | ||

| Subdivision B. H. recens; with varieties | ||

| { | H. fossilis. Ex. gr. Galley Hill. H. sapiens. |

H. Obermaier[24] argues as follows: Homo primigenius is neither the representative of an intermediate species between ape and man, nor a lower or distinct type than Homo sapiens, but an older primitive variety (race) of the latter, which survives in exceptional cases down to the present day[25]. Clearly then, according to the rules of zoological classification, we must term the two, Homo sapiens var. primigenius, as compared with Homo sapiens var. recens.

Whatever classification or nomenclature may be adopted the dual division in palaeolithic times is now generally recognised. The more primitive type is commonly called Neandertal man, from the famous cranium found in the Neandertal cave in 1857, or Mousterian man, from the culture associations. To this group belong the Gibraltar skull[26], and the skeletons from Spy[27], and Krapina, Croatia[28], together with[Pg 9] the later discoveries (1908-11) at La Chapelle[29] (Corrèze), Le Moustier[30], La Ferassie[31] (Dordogne) and many others.

Palaeolithic examples of the modern human type have been found at Brüx (Bohemia)[32], Brünn (Moravia)[33] and Galley Hill in Kent[34], but the most complete find was that at Combe Capelle in 1909[35]. The numerous skeletons found at Cro-Magnon[36] and at the Grottes de Grimaldi at Mentone[37] though showing certain skeletal differences may be included in this group, the earliest examples of which are associated with Aurignacian culture[38].

From the evidence contributed by these examples the main characteristics of the two groups may be indicated, although, owing to the imperfection of the records, any generalisations must necessarily be tentative and subject to criticism.

The La Chapelle skull recalls many of the primitive features of the "ancestral types." The low receding forehead, the overhanging brow-ridges, forming continuous horizontal bars of bone overshadowing the orbits, the inflated circumnasal region, the enormous jaws, with massive ascending ramus, shallow sigmoid notch, "negative" chin and other "simian" characters seem reminiscent of Pithecanthropus and Homo Heidelbergensis. The cranial capacity however is estimated at over 1600 c.c., thus exceeding that of the average modern European, and this development, even though associated, as M. Boule has pointed out, with a comparatively lowly brain, is of striking significance. The low stature, probably about 1600 mm. (under 5½ feet) makes the size of the skull and cranial capacity all the more remarkable. "A survey of the[Pg 10] characters of Neanderthal man—as manifested by his skeleton, brain cast, and teeth—have convinced anthropologists of two things: first, that we are dealing with a form of man totally different from any form now living; and secondly, that the kind of difference far exceeds that which separates the most divergent of modern human races[39]."

The earliest complete and authentic example of "Aurignacian man" was the skeleton discovered near Combe Capelle (Dordogne) in 1909[40]. The stature is low, not exceeding that of the Neandertal type, but the limb bones are slighter and the build is altogether lighter and more slender. The greatest contrast lies in the skull. The forehead is vertical instead of receding, and the strongly projecting brow-ridges are diminished, the jaw is less massive and less simian with regard to all the features mentioned above. Especially is this difference noticeable in the projection of the chin, which now for the first time shows the modern human outline. In short there are no salient features which cannot be matched among the living races of the present day.

On the cultural side no less than on the physical, the thousands of years which the lowest estimate attributes to the Early Stone Age were marked by slow but continuous changes.

The Reutelian (at the junction of the Pliocene and Pleistocene), Mafflian and Mesvinian industries, recognised by M. Rutot in Belgium, belong to the doubtful Eolithic Period, not yet generally accepted[41].

The lowest palaeolithic deposit is the Strepyan, so called from Strépy, near Charleroi, typically represented at St Acheul, Amiens, and recognised also in the Thames Valley[42]. The tools exhibit deliberate flaking, and mark the transition between eolithic and palaeolithic work. The associated fauna includes two species of elephant,[Pg 11] E. meridionalis and E. antiquus, two species of rhinoceros, R. Etruscus and R. Merckii, and the hippopotamus. It is possible that the Mauer jaw and the Piltdown skull belong to this stage.

The Chellean industry[43], with the typical coarsely flaked almond-shaped implements, occurs abundantly in the South of England and in France, less commonly in Belgium, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia, while examples have been recognised in Palestine, Egypt, Somaliland, Cape Colony, Madras and other localities, though outside Europe the date is not always ascertainable and the form is not an absolute criterion[44].

Acheulean types succeed apparently in direct descent but the implements are altogether lighter, sharper, more efficient, and are characterised by finer workmanship and carefully retouched edges. A small finely finished lanceolate implement is typical of the sub-industry or local development at La Micoque (Dordogne).

The Chellean industry is associated with a warm climate and the remains of Elephas antiquus, Rhinoceros Merckii and hippopotamus. Lower Acheulean shows little variation, but with Upper Acheulean certain animals indicating a colder climate make their appearance, including the mammoth, Elephas primigenius, and the woolly rhinoceros, R. tichorhinus, but no reindeer.

The Mousterian industry is entirely distinct from its predecessors. The warm fauna has disappeared, the reindeer first occurs together with the musk ox, arctic fox, the marmot and other cold-loving animals. Man appears to have sought refuge in the caves, and from complete skeletons found in cave deposits of this stage we gain the first clear ideas concerning the physical type of man of the early palaeolithic period. Typical Mousterian implements consist of leaf-like or triangular points made from flakes struck from the nodule instead of from the dressed nodule itself, as in the earlier stages. The Levallois flakes, occurring at the base of the Mousterian (sometimes included in the Acheulean stage), initiate this new style of workmanship, but the Mousterian point shows an improvement in[Pg 12] shape and a greater mastery in technique, producing a more efficient tool for piercing and cutting. Scrapers, carefully retouched, with a curved edge are also characteristic, besides many other forms. The complete skeletons from Le Moustier itself, La Chapelle, La Ferassie, and Krapina all belong to this stage, which marks the end of the lower palaeolithic period, the Age of the Mammoth.

The upper palaeolithic or Reindeer Age is divided into Aurignacian, Solutrian, and Magdalenian[45] culture stages, with the Azilian[46] separating the Magdalenian from the neolithic period. Each stage is distinguished by its implements and its art. The Aurignacian fauna, though closely resembling the Mousterian, indicates an amelioration of climate, the most abundant animals being the bison, horse, cave lion, and cave hyena, and human settlements are again found in the open. Among the typical implements are finely worked knife-like blades (Châtelperron point, Gravette point), keeled scrapers (Tarté type), burins or gravers, and various tools and ornaments of bone. Art is represented by engravings and wall paintings, and to this stage belong statuettes representing nude female figures such as those of Brassempouy, Mentone, Pont-à-Lesse (Belgium), Predmost and Willendorf, near Krems. The Neandertal type appears to have died out and Aurignacian man belongs to the modern type represented at Combe Capelle. If the evidence of the figurines is to be accepted, a steatopygous race was at this time in existence, which Sollas is inclined to connect with the Bushmen[47].

The Solutrian stage is characterised by the abundance of the horse, replaced in the succeeding period by the reindeer. The Solutrians seem to have been a warlike steppe people who came from the east into western Europe. Their subsequent fate has not been elucidated. The culture appears to have had a limited range, only a few stations being found outside Dordogne and the neighbouring departments. The technique, as shown in the laurel-leaf and willow-leaf points, exhibits a perfection of workmanship unequalled in the Palaeolithic Age, and only excelled by late prehistoric knives of Egypt.[Pg 13]

The rock shelter at La Madeleine has given its name to the closing epoch of the Palaeolithic Age. The flint industry shows distinct decadence, but the working in bone and horn was at its zenith; indeed, so marked is the contrast between this and the preceding stage that Breuil is convinced that "the first Magdalenians were not evolved from the Solutrians; they were new-comers in our region[48]." The typical implements are barbed harpoons in reindeer antler (later that of the stag), often decorated with engravings. Sculpture and engravings of animals in life-like attitudes are among the most remarkable records of the age, and the polychrome pictures in the caves of Altamira, "the Sistine chapel of Quaternary Art," are the admiration of the world[49].

In the cave of Mas-d'Azil, between the Magdalenian and Neolithic deposits occurs a stratum, termed Azilian, which, to some extent, bridges over the obscure transition between the Palaeolithic and Neolithic Ages. The reindeer has disappeared, and its place is taken by the stag. The realistic art of the Magdalenians is succeeded by a more geometric style. In flint working a return is made to Aurignacian methods, and a particular development of pygmy flints has received the name Tardenoisian[50].

The characteristic implement is still the harpoon, but it differs in shape from the Magdalenian implement, owing to the different structure of the material. Painted pebbles, marked with red and black lines, in some cases suggesting a script, have given rise to much controversy. Their meaning at present remains obscure[51].

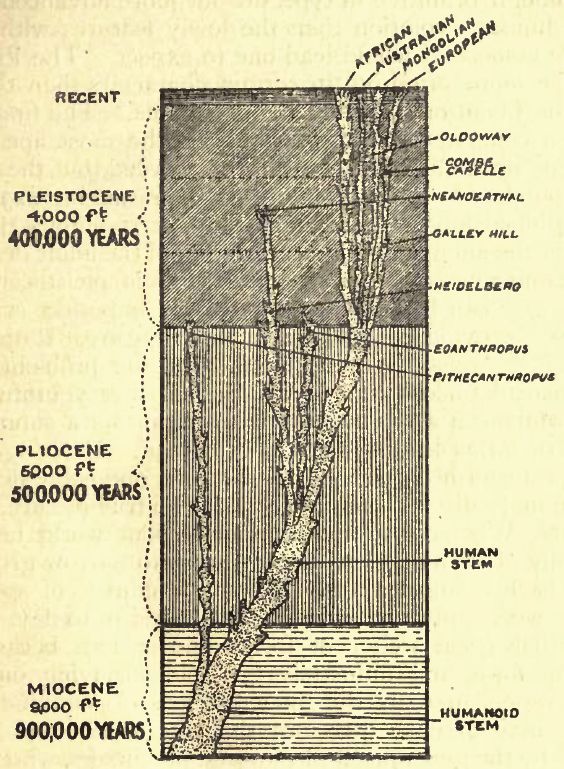

The question of prehistoric chronology is a difficult one, and the more cautious authorities do not commit themselves to dates. Of late years, however, such researches as those of A. Penck and E. Brückner[Pg 14] in the Alps[52] and of Baron de Geer and W. C. Brøgger in Sweden[53], have provided a sound basis for calculations. Penck recognises four periods of glaciation during the pleistocene period, which he has named after typical areas, the Günz, Mindel, Riss and Würm. He dates the Würm maximum at between 30,000 and 50,000 years ago and estimates the duration of the Riss-Würm interglacial period at about 100,000 years. According to his calculations the Chellean industry occurs in the Mindel-Riss, or even in the Günz-Mindel interval, but it is more commonly placed in the mild phase intervening before the last (Würm) glaciation, this latter corresponding with the cold Mousterian stage. At least four subsequent oscillations of climate have been recognised by Penck, the Achen, Bühl, Gschnitz and Daun, and the correspondence of these with palaeolithic culture stages may be seen in the following table[54].

James Geikie[55], under the heading, "Reliable and Unreliable estimates of geological time," points out that the absolute duration of the Pleistocene cannot be determined, but such investigations as those of Penck "enable us to form[Pg 15] some conception of the time involved." He accepts as a rough approximation Penck's opinion that "the Glacial period with all its climatic changes may have extended over half a million years, and as the Chellean stage dates back to at least the middle of the period, this would give somewhere between 250,000 and 500,000 years for the antiquity of man in Europe. But if, as recent discoveries would seem to indicate, man was an occupant of our Continent during the First Interglacial epoch, if not in still earlier times, we may be compelled greatly to increase our estimate of his antiquity" (p. 303).

W. J. Sollas, on the other hand, is content with a far more contracted measure. Basing his calculations mainly on the investigations of de Geer, he concludes that the interval that separates our time from the beginning of the end of the last glacial episode is 17,000 years. He places the Azilian age at 5500 B.C., the middle of the Magdalenian age somewhere about 8000 B.C., Mousterian 15,000 B.C., and the close of the Chellean 25,000 B.C.[56]

But when all the changes in climate are taken into consideration, the periods of elevation and depression of the land, the transformations of the animals, the evolution of man, the gradual stages of advance in human culture, the development of the races of mankind, and their distribution over the surface of the globe, this estimate is regarded by many as insufficient. Allen Sturge claims "scores of thousands of years" for the neolithic period alone[57], and Sir W. Turner points out the very remote times to which the appearance of neolithic man must be assigned in Scotland. After showing that there is undoubted evidence of the presence of man in North Britain during the formation of the Carse clays, this careful observer explains that the Carse cliffs, now in places 45 to 50 feet above the present sea-level, formed the bed of an estuary or arm of the sea, which in post-glacial times extended almost, if not quite across the land from east to west, thus separating the region south of the Forth from North Britain. He even suggests, after the separation of Britain from the Continent in earlier times, another land connection, a "Neolithic land-bridge" by which the men of the New Stone Age may have reached Scotland when the[Pg 16] upheaved 100-foot terrace was still clothed with the great forest growths that have since disappeared[58].

One begins to ask, Are even 100,000 years sufficient for such oscillations of the surface, upheaval of marine beds, appearance of great estuaries, renewed connection of Britain with the Continent by a "Neolithic land-bridge"? In the Falkirk district neolithic kitchen-middens occur on, or at the base of, the bluffs which overlook the Carse lands, that is, the old sea-coast. In the Carse of Gowrie also a dug-out canoe was found at the very base of the deposits, and immediately above the buried forest-bed of the Tay Valley[59].

That the neolithic period was also of long duration even in Scandinavia has been made evident by Carl Wibling, who calculates that the geological changes on the south-east coast of Sweden (Province of Bleking), since its first occupation by the men of the New Stone Age, must have required a period of "at least 10,000 years[60]."

Still more startling are the results of the protracted researches carried on by J. Nüesch at the now famous station of Schweizersbild, near Schaffhausen in Switzerland[61]. This station was apparently in the continuous occupation of man during both Stone Ages, and here have been collected as many as 14,000 objects belonging to the first, and over 6000 referred to the second period. Although the early settlement was only post-glacial, a point about which there is no room for doubt, L. Laloy[62] has estimated "the absolute duration of both epochs together at from 24,000 to 29,000 years." We may, therefore, ask, If a comparatively recent post-glacial station in Switzerland is about 29,000 years old, how old may a pre- or inter-glacial station be in Gaul or Britain?

From all this we see how fully justified is J. W. Powell's remark that the natural history of early man becomes more and more a geological, and not merely an ethnological problem[63]. We also begin to understand how it is that, after an existence of some five score millenniums, the first specialised human[Pg 17] varieties have diverged greatly from the original types, which have thus become almost "ideal quantities," the subjects rather of palaeontological than of strictly anthropological studies.

And here another consideration of great moment presents itself. During these long ages some of the groups—most African negroes south of the equator, most Oceanic negroes (Negritoes and Papuans), and Australian and American aborigines—have remained in their original habitats ever since what may be called the first settlement of the earth by man. Others again, the more restless or enterprising peoples, such as the Mongols, Manchus, Turks, Ugro-Finns, Arabs, and most Europeans, have no doubt moved about somewhat freely; but these later migrations, whether hostile or peaceable, have for the most part been confined to regions presenting the same or like physical and climatic conditions. Wherever different climatic zones have been invaded, the intruders have failed to secure a permanent footing, either perishing outright, or disappearing by absorption or more or less complete assimilation to the aboriginal elements. Such are some "black Arabs" in Egyptian Sudan, other Semites and Hamites in Abyssinia and West Sudan (Himyarites, Fulahs and others), Finns and Turks in Hungary and the Balkan Peninsula (Magyars, Bulgars, Osmanli), Portuguese and Netherlanders in Malaysia, English in tropical or sub-tropical lands, such as India, where Eurasian half-breeds alone are capable of founding family groups.

The human varieties are thus seen to be, like all other zoological species, the outcome of their several environments. They are what climate, soil, diet, pursuits and inherited characters have made them, so that all sudden transitions are usually followed by disastrous results[64]. "To urge the emigration of women and children, or of any save those of the most robust health, to the tropics, may not be to murder in the first degree, but it should be classed, to put it mildly, as incitement to it[65]." Acclimatisation may not be impossible[Pg 18] but in all extreme cases it can be effected only at great sacrifice of life, and by slow processes, the most effective of which is perhaps Natural Selection. By this means we may indeed suppose the world to have been first peopled.

At the same time it should be remembered that we know little of the climatic conditions at the time of the first migrations, though it has been assumed that it was everywhere much milder than at present. Consequently the different zones of temperature were less marked, and the passage from one region to another more easily effected than in later times. In a word the pleistocene precursors had far less difficulty in adapting themselves to their new surroundings than modern peoples have when they emigrate, for instance, from Southern Europe to Brazil and Paraguay, or from the British Isles to Rhodesia and Nyassaland.

What is true of man must be no less true of his works; from which it follows that racial and cultural zones correspond in the main with zones of temperature, except so far as the latter may be modified by altitude, marine influences, or other local conditions. A glance at past and existing relations the world over will show that such harmonies have at all times prevailed. No doubt the overflow of the leading European peoples during the last 400 years has brought about divers dislocations, blurrings, and in places even total effacements of the old landmarks.

But, putting aside these disturbances, it will be found that in the Eastern hemisphere the inter-tropical regions, hot, moist and more favourable to vegetable than to animal vitality, are usually occupied by savage, cultureless populations. Within the same sphere are also comprised most of the extra-tropical southern lands, all tapering towards the antarctic waters, isolated, and otherwise unsuitable for areas of higher specialisation.

Similarly the sub-tropical Asiatic peninsulas, the bleak Tibetan tableland, the Pamir, and arid Mongolian steppes are found mainly in possession of somewhat stationary communities, which present every stage between sheer savagery and civilisation.

In the same way the higher races and cultures are confined to the more favoured north temperate zone, so that between the parallels of 24° and 50° (but owing to local conditions[Pg 19] falling in the far East to 40° and under, and in the extreme West rising to 55°) are situated nearly all the great centres, past and present, of human activities—the Egyptian, Babylonian, Minoan (Aegean), Hellenic, Etruscan, Roman, and modern European. Almost the only exceptions are the early civilisations (Himyaritic) of Yemen (Arabia Felix) and Abyssinia, where the low latitude is neutralised by altitude and a copious rainfall.

Thanks also to altitude, to marine influences, and the contraction of the equatorial lands, the relations are almost completely reversed in the New World. Here all the higher developments took place, not in the temperate but in the tropical zone, within which lay the seats of the Peruvian, Chimu, Chibcha and Maya-Quiché cultures; the Aztec sphere alone ranged northwards a little beyond the Tropic of Cancer.

Thus in both hemispheres the iso-cultural bands follow the isothermal lines in all their deflections, and the human varieties everywhere faithfully reflect the conditions of their several environments.

[1] Ethnology, Chaps. V. and VII.

[2] See A. H. Keane, Ethnology, 1909, Chap. VII.

[3] H. Klaatsch, "Die Aurignac-Rasse und ihre Stellung im Stammbaum des Menschen," Ztschr. f. Eth. LII. 1910. See also Prähistorische Zeitschrift, Vol. I. 1909.

[4] Cf. A. Keith's criticisms in Nature, Vol. LXXXV. 1911, p. 508.

[5] W. L. H. Duckworth, Prehistoric Man, 1912, p. 146.

[6] W. Ridgeway, "The Influence of Environment on Man," Journ. Roy. Anthr. Inst., Vol. XL. 1910, p. 10.

[7] E. Dubois, "Pithecanthropus erectus, transitional form between Man and the Apes," Sci. Trans. R. Dublin Soc. 1898.

[8] O. Schoetensack, Der Unterkiefer des Homo Heidelbergensis, etc., 1908.

[9] C. Dawson and A. Smith Woodward, "On the Discovery of a Palaeolithic Skull and Mandible," etc., Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc. 1913.

[10] This was the view of A. Smith Woodward when the skull was first exhibited (loc. cit.), but in his paper, "Missing Links among Extinct Animals," Brit. Ass. Birmingham, 1913, he is inclined to regard "Piltdown man, or some close relative" as "on the direct line of descent with ourselves." For A. Keith's criticism see The Antiquity of Man, 1915, p. 503.

[11] W. L. H. Duckworth, Prehistoric Man, 1912, p. 8.

[12] For the relation between chin formation and power of speech, see E. Walkhoff, "Der Unterkiefer der Anthropomorphen und des Menschen in seiner funktionellen Entwicklung und Gestalt," E. Selenka, Menschenaffen, 1902; H. Obermaier, Der Mensch der Vorzeit, 1912, p. 362; and W. Wright, "The Mandible of Man from the Morphological and Anthropological points of view," Essays and Studies presented to W. Ridgeway, 1913.

[13] Cf. W. L. H. Duckworth, Prehistoric Man, 1912, p. 10, and A. Keith, The Antiquity of Man, 1915, p. 237.

[14] A. Smith Woodward, 1070 c.c.; A. Keith, 1400 c.c.

[15] G. G. MacCurdy, following G. S. Miller, Smithsonian Misc. Colls. Vol. 65, No. 12 (1915), is convinced that "in place of Eoanthropus dawsoni we have two individuals belonging to different genera," a human cranium and the jaw of a chimpanzee. Science, N.S. Vol. XLIII. 1916, p. 231. See also Appendix A.

[16] For a full description see Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc. March, 1913. Also A. Keith, The Antiquity of Man, 1915, p. 320, and pp. 430-452.

[17] C. Dawson and A. Smith Woodward, "Supplementary Note on the Discovery of a Palaeolithic Human Skull and Mandible at Piltdown (Sussex)," Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc. April, 1914.

[18] The Antiquity of Man, 1915, p. 209.

[19] Thus Lucretius:

"Arma antiqua manus, ungues, dentesque fuerunt,

Et lapides, et item silvarum fragmina rami."

[20] Jour. Anthrop. Inst. 1896, p. 133.

[21] Inaugural Address, Brit. Ass. Meeting, Toronto, 1897.

[22] M. Boule, "L'homme fossile de la Chapelle-aux-Saints," Annales de Paléontologie, 1911 (1913). Cf. also H. Obermaier, Der Mensch der Vorzeit, 1912, p. 364.

[23] Prehistoric Man, 1912, p. 60.

[24] Der Mensch der Vorzeit, 1912, p. 365.

[25] This is not generally accepted. See A. Keith's diagram, p. 5 and pp. 9-10.

[26] W. J. Sollas, "On the Cranial and Facial Characters of the Neandertal Race," Phil. Trans. 1907, CXCIV.

[27] J. Fraipont and M. Lohest, "Recherches Ethnographiques sur les Ossements Humains," etc., Arch. de Biologie, 1887.

[28] Gorjanovič-Kramberger, Der diluviale Mensch von Krapina in Kroatia, 1906.

[29] M. Boule, "L'homme fossile de la Chapelle-aux-Saints," L'Anthr. XIX. 1908, and Annales de Paléontologie, 1911 (1913).

[30] H. Klaatsch, Prähistorische Zeitschrift, Vol. I. 1909.

[31] Peyrony and Capitan, Rev. de l'Ecole d'Anthrop. 1909; Bull. Soc. d'Anthr. de Paris, 1910.

[32] G. Schwalbe, "Der Schädel von Brüx," Zeitschr. f. Morph. u. Anthr. 1906.

[33] Makowsky, "Der diluviale Mensch in Löss von Brünn," Mitt. Anthrop. Gesell. in Wien, 1892.

[34] See A. Keith, The Antiquity of Man, 1915, Chap. X.

[35] H. Klaatsch, "Die Aurignac-Rasse," etc., Zeitschr. f. Ethn. LII. 1910.

[36] L. Lartet, "Une sépulture des troglodytes du Périgord," and Broca, "Sur les crânes et ossements des Eyzies," Bull. Soc. d'Anthr. de Paris, 1868.

[37] R. Verneau, Les Grottes de Grimaldi, 1906-11.

[38] For a complete list with bibliographical references, see H. Obermaier, "Les restes humains Quaternaires dans l'Europe centrale," Anthr. 1905, p. 385, 1906, p. 55.

[39] A. Keith, The Antiquity of Man, 1915, p. 158. See also W. J. Sollas, Ancient Hunters, 1915, p. 186 ff.

[40] H. Klaatsch, "Die Aurignac-Rasse," Zeitschr. f. Eth. 1910, LII. p. 513.

[41] The Mesvinian implements are now accepted as artefacts and placed by H. Obermaier immediately below the Chellean, though M. Commont interprets them as Acheulean or even later. See W. J. Sollas, Ancient Hunters, 1915, p. 132 ff.

[42] R. Smith and H. Dewey, "Stratification at Swanscombe," Archaeologia, LXIV. 1912.

[43] So called from Chelles-sur-Marne, near Paris.

[44] Cf. J. Déchelette, Manuel d'Archéologie préhistorique, I. 1908, p. 89.

[45] From Aurignac (Haute-Garonne), Solutré (Saône-et-Loire), and La Madeleine (Dordogne).

[46] Mas-d'Azil, Ariège.

[47] W. J. Sollas, Ancient Hunters, 1915, pp. 378-9.

[48] "Les Subdivisions de paléolithique supérieur," Congrès Internat. d'Anth. 1912, XIV. pp. 190-3.

[49] H. Breuil and E. Cartailhac, La Caverne d'Altamira, 1906. For a list of decorated caves, with the names of their discoverers, see J. Déchelette, Manuel d'Archéologie préhistorique, I. 1908, p. 241. A complete Répertoire de l'Art Quaternaire is given by S. Reinach, 1913; and for chronology see E. Piette, "Classifications des Sédiments formés dans les cavernes pendant l'Age du Renne," Anthr. 1904.

[50] From La Fère-en-Tardenois, Aisne.

[51] Cf. W. J. Sollas, Ancient Hunters, 1915, pp. 95, 534 f.

[52] Die Alpen in Eiszeitalter, 1901-9. See also "Alter des Menschengeschlechts," Zeit. f. Eth. XL. 1908.

[53] See W. J. Sollas, Ancient Hunters, 1915, p. 561.

[54] H. Obermaier, Der Mensch der Vorzeit, 1911-2, p. 332.

[55] The Antiquity of Man in Europe, 1914, p. 301.

[56] Ancient Hunters, 1915, p. 567.

[57] Proc. Prehist. Soc. E. Anglia, 1. 1911, p. 60.

[58] Discourse at the R. Institute, London, Nature, Jan. 6 and 13, 1898.

[59] Nature, 1898, p. 235.

[60] Tiden för Blekings första bebyggande, Karlskrona, 1895, p. 5.

[61] "Das Schweizersbild, eine Niederlassung aus palaeolithischer und neolithischer Zeit," in Nouveaux Mémoires Soc. Helvétique des Sciences Naturelles, Vol. XXXV. Zurich, 1896. This is described by James Geikie, The Antiquity of Man in Europe, 1914, pp. 85-99.

[62] L'Anthropologie, 1897, p. 350.

[63] Forum, Feb. 1898.

[64] The party of Eskimo men and women brought back by Lieut. Peary from his Arctic expedition in 1897 were unable to endure our temperate climate. Many died of pneumonia, and the survivors were so enfeebled that all had to be restored to their icy homes to save their lives. Even for the Algonquians of Labrador a journey to the coast is a journey to the grave.

[65] W. Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe, 1900, p. 586.

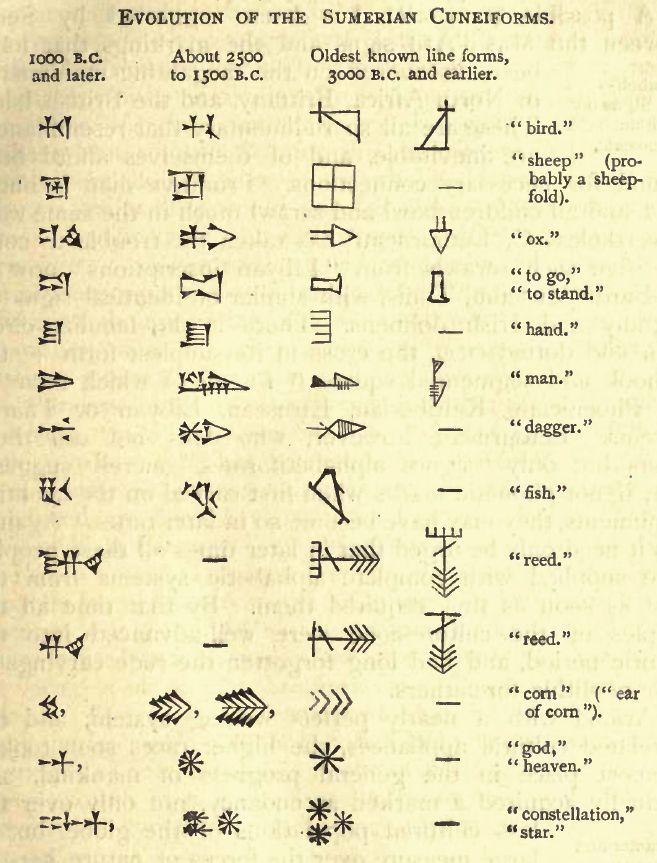

Progress of Archaeological Studies—Sequence of the Metal Ages—The Copper Age—Egypt, Elam, Babylonia, Europe—The Bronze Age—Egypt and Babylonia, Western Europe, the Aegean, Ireland—Chronology of the Copper and Bronze Ages—The Iron Age—Hallstatt, La Tène—Man and his Works in the Metal Ages—The Prehistoric Age in the West, and in China—Historic Times—Evolution of Writing Systems—Hieroglyphs and Cuneiforms—The Alphabet—The Persian and other Cuneiform Scripts—The Mas-d'Azil Markings—Alphabetiform Signs on Neolithic Monuments—Character and Consequences of the later historic Migrations—The Race merges in the People—The distinguishing Characters of Peoples—Scheme of Classification.

If, as above seen, the study of human origins is largely a geological problem, the investigation of the later developments, during the Metal Ages and prehistoric times, belongs mainly to the field of Archaeology. Hence it is that for the light which has in recent years been thrown upon the obscure interval between the Stone Ages and the strictly historic epoch, that is to say, the period when in his continuous upward development man gradually exchanged stone for the more serviceable metals, we are indebted chiefly to the pioneer labours of such men as Worsaae, Steenstrup, Forchhammer, Schliemann, Sayce, Layard, Lepsius, Mariette, Maspero, Montelius, Brugsch, Petrie, Peters, Haynes, Sir J. Evans, Sir A. J. Evans and many others, all archaeologists first, and anthropologists only in the second instance.

From the researches of these investigators it is now clear that copper, bronze, and iron were successively in use in Europe in the order named, so that the current expressions, "Copper," "Bronze," and "Iron" Ages remain still justified. But it also appears that overlappings, already beginning in late Neolithic times, were everywhere so frequent that in many localities it is quite impossible to draw any well-marked dividing lines between the successive metal periods.[Pg 21]

That iron came last, a fact already known by vague tradition to the ancients[66], is beyond doubt, and it is no less certain that bronze of various types intervened between copper and iron. But much obscurity still surrounds the question of copper, which occurs in so many graves of Neolithic and Bronze times, that this metal has even been denied an independent position in the sequence.

But we shall not be surprised that confusion should prevail on this point, if we reflect that the metals, unlike stone, came to remain. Once introduced they were soon found to be indispensable to civilised man, so that in a sense the "Metal Ages" still survive, and must last to the end of time. Hence it was natural that copper should be found in prehistoric graves associated, first with polished stone implements, and then with bronze and iron, just as, since the arrival of the English in Australia, spoons, clay pipes, penknives, pannikins, and the like, are now found mingled with stone objects in the graves of the aborigines.

But that there was a true Copper Age[67] prior to that of Bronze, though possibly of not very long duration, except of course in the New World[68], has been placed beyond reasonable doubt by recent investigations. Considerable attention was devoted to the subject by J. H. Gladstone, who finds that copper was worked by the Egyptians in the Sinaitic Peninsula, that is, in the famous mines of the Wadi Maghára, from the fourth to the eighteenth dynasty, perhaps from 3000 to 1580 B.C.[69] During that epoch tools were made of pure copper in Egypt and Syria, and by the Amorites in Palestine, often on the model of their stone prototypes[70].

Elliot Smith[71] claims that "the full story of the coming of [Pg 22]copper, complete in every detail and circumstance, written in a simple and convincing fashion that he who runs may read," has been displayed in Egypt ever since the year 1894, though the full significance of the evidence was not recognised until Reisner called attention to the record of pre-dynastic graves in Upper Egypt when superintending the excavations at Naga-ed-dêr in 1908[72]. These excavations revealed the indigenous civilisation of the ancient Egyptians and, according to Elliot Smith, dispose of the idea hitherto held by most archaeologists that Egypt owed her knowledge of metals to Babylonia or some other Asiatic source, where copper, and possibly also bronze, may be traced back to the fourth millennium B.C. There was doubtless intercourse between the civilisations of Egypt and Babylonia but "Reisner has revealed the complete absence of any evidence to show or even to suggest that the language, the mode of writing, the knowledge of copper ... were imported" (p. 34). Elliot Smith justly claims (p. 6) that in no other country has a similarly complete history of the discovery and the evolution of the working of copper been revealed, but until equally exhaustive excavations have been undertaken on contemporary or earlier sites in Sumer and Elam, the question cannot be regarded as settled.

The work of J. de Morgan at Susa[73] (1907-8) shows the extreme antiquity of the Copper Age in ancient Elam, even if his estimate of 5000 B.C. is regarded as a millennium too early[74]. At the base of the mound on the natural soil, beneath 24 meters of archaeological layers, were the remains of a town and a necropolis consisting of about 1000 tombs. Those of the men contained copper axes of primitive type; those of the women, little vases of paint, together with discs of polished copper to serve as mirrors. At Fara, excavations by Koldewey in 1902, and by Andrae and Nöldeke in 1903 on the site of Shuruppak (the home of the Babylonian Noah) in the valley of the Lower Euphrates, revealed graves attributed[Pg 23] to the prehistoric Sumerians, containing copper spear heads, axes and drinking vessels[75].

In Europe, North Italy, Hungary and Ireland[76] may lay claim to a Copper Age, but there is very little evidence of such a stage in Britain. To this period also may be attributed the nest or cache of pure copper ingots found at Tourc'h, west of the Aven Valley, Finisterre, described by M. de Villiers du Terrage, and comprising 23 pieces, with a total weight of nearly 50 lbs.[77] These objects, which belong to "the transitional period when copper was used at first concurrently with polished stone, and then disappeared as bronze came into more general use[78]," came probably from Hungary, at that time apparently the chief source of this metal for most parts of Europe. Of over 200 copper objects described by Mathaeus Much[79] nearly all were of Hungarian or South German provenance, five only being accredited to Britain and eight to France.

The study of this subject has been greatly advanced by J. Hampel, who holds on solid grounds that in some regions, especially Hungary, copper played a dominant part for many centuries, and is undoubtedly the characteristic metal of a distinct culture. His conclusions are based on the study of about 500 copper objects found in Hungary and preserved in the Buda Pesth collections. Reviewing all the facts attesting a Copper Age in Central Europe, Egypt, Italy, Cyprus, Troy, Scandinavia, North Asia, and other lands, he concludes that a Copper Age may have sprung up independently wherever the ore was found, as in the Ural and Altai Mountains, Italy, Spain, Britain, Cyprus, Sinai; such culture being generally indigenous, and giving evidence of more or less characteristic local features[80]. In fact we know for certain that such an independent Copper Age was developed not only in the region of the Great Lakes of North America, but also amongst the Bantu peoples of Katanga and other parts of Central Africa. Copper is not an alloy like bronze, but a[Pg 24] soft, easily-worked metal occurring in large quantities and in a tolerably pure state near the surface in many parts of the world. The wonder is, not that it should have been found and worked at a somewhat remote epoch in several different centres, but that its use should have been so soon superseded in so many places by the bronze alloys.

From copper to bronze, however, the passage was slow and progressive, the proper proportion of tin, which was probably preceded in some places by an alloy of antimony, having been apparently arrived at by repeated experiments often carried out with no little skill by those prehistoric metallurgists.

As suggested by Bibra in 1869, the ores of different metals would appear to have been at first smelted together empirically, and the process continued until satisfactory results were obtained. Hence the extraordinary number of metals, of which percentages are found in some of the earlier specimens, such as those of the Elbing Museum, which on analysis yielded tin, lead, silver, iron, antimony, arsenic, sulphur, nickel, cobalt, and zinc in varying quantities[81].

Some bronzes from the pyramid of Medum analysed by J. H. Gladstone[82] yielded the high percentage of 9.1 of tin, from which we must infer, not only that bronze, but bronze of the finest quality, was already known to the Egyptians of the fourth dynasty, i.e. 2840 B.C. The statuette of Gudea of Lagash (2500 B.C.) claimed as the earliest example of bronze in Babylonia is now known to be pure copper, and though objects from Tello (Lagash) of earlier date contain a mixture of tin, zinc, arsenic and other alloys, the proportion is insignificant. The question of priority must, however, be left open until the relative chronology of Egypt and Babylonia is finally settled, and this is still a much disputed point[83]. Neither would all the difficulties with regard to the origin of bronze be cleared up should Egypt or Babylonia establish her claim to possess the earliest example of the metal, for neither country appears[Pg 25] to possess any tin. The nearest deposit known in ancient times would seem to be that of Drangiana, mentioned by Strabo, identified with modern Khorassan[84].

Strabo and other classical writers also mention the occurrence of tin in the west, in Spain, Portugal and the Cassiterides or tin islands, whose identity has given rise to so much speculation[85], but "though in after times Egypt drew her tin from Europe it would be bold indeed to suppose that she did so [in 3000 B.C.] and still bolder to maintain that she learned from northern people how to make the alloy called bronze[86]." Apart from the indigenous Egyptian origin maintained by Elliot Smith (above) the hypothesis offering fewest difficulties is that the earliest bronze is to be traced to the region of Elam, and that the knowledge spread from S. Chaldaea (Elam-Sumer) to S. Egypt in the third millennium B.C.[87]

There seems to be little doubt that the Aegean was the centre of dispersal for the new metals throughout the Mediterranean area, and copper ingots have been found at various points of the Mediterranean, marked with Cretan signs[88]. Bronze was known in Crete before 2000 B.C. for a bronze dagger and spear head were found at Hagios Onuphrios, near Phaistos, with seals resembling those of the sixth to eleventh dynasties[89].

From the eastern Mediterranean the knowledge spread during the second millennium along the ordinary trade routes which had long been in use. The mineral ores of Spain were exploited in pre-Mycenean times and probably contributed in no small measure to the industrial development of southern Europe. From tribe to tribe, along the Atlantic coasts the traffic in minerals reached the British Isles, where the rich ores were discovered which, in their turn, supplied the markets of the north, the west and the south.

Even Ireland was not left untouched by Aegean influence, [Pg 26] which reached it, according to G. Coffey[90], by way of the Danube and the Elbe, and thence by way of Scandinavia, though this is a matter on which there is much difference of opinion. Ireland's richness in gold during the Bronze Age made her "a kind of El Dorado of the western world," and the discovery of a gold torc found by Schliemann in the royal treasury in the second city of Troy raises the question as to whether the model of the torc was imported into Ireland from the south[90], or whether (which J. Déchelette[91] regards as less probable) there was already an exportation of Irish gold to the eastern Mediterranean in pre-Mycenean times.

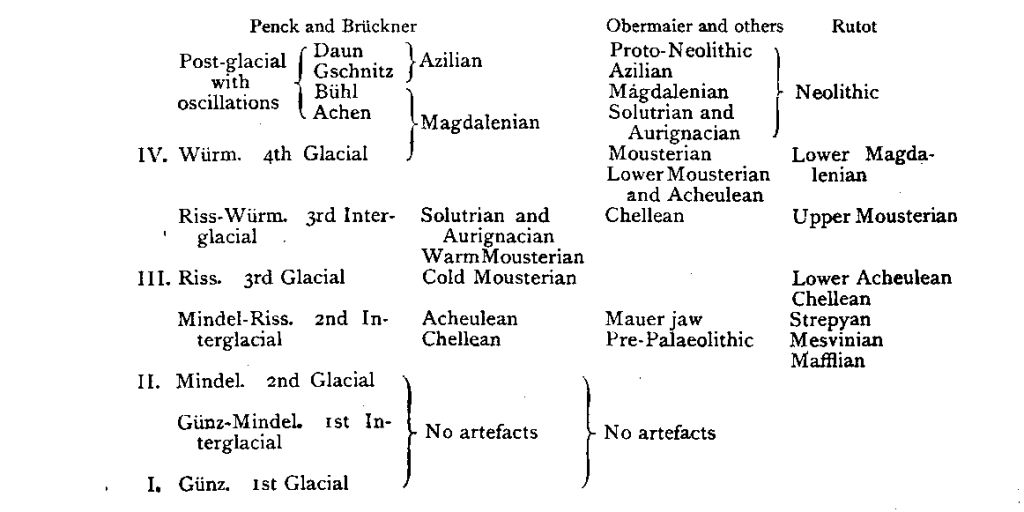

Of recent years great strides have been made towards the establishment of a definite chronology linking the historic with the prehistoric periods in the Aegean, in Egypt and in Babylonia, and as the estimates of various authorities differ sometimes by a thousand years or so, the subjoined table will be of use to indicate the chronological schemes most commonly followed; the dates are in all cases merely approximate.

It has often been pointed out that there is no reason why iron should not have been the earliest metal to be used by man. Its ores are more abundant and more easily reduced than any others, and are worked by peoples in a low grade of culture at the present day[92]. Iron may have been known in Egypt almost as early as bronze, for a piece in the British Museum is attributed to the fourth dynasty, and some beads of manufactured iron were found in a pre-dynastic grave at El Gerzeh[93]. But these and other less well authenticated occurrences of iron are rare, and the metal was not common in Egypt before the middle of the second millennium. By the end of the second millennium the knowledge had spread throughout the eastern Mediterranean[94], and towards 900 at latest iron was in common use in Italy and Central Europe.[Pg 27]

| Egypt[95] | Babylonia[96] | Aegean[97] | Greece[98] | Bronze Age in Europe[99] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3300 | Dynasty I | ||||

| 3200 | |||||

| 3100 | |||||

| 3000 | Dynasty of Opis | ?Early Minoan I | ?Pre-Mycenean | ||

| 2900 | Dyn. of Kish | ||||

| 2800 | Dyn. III, IV | Dyn. of Erech Dyn. of Akkad[100] | |||

| 2700 | |||||

| 2600 | Dyn. V | 2nd Dyn. of Erech | |||

| 2500 | Dyn. VI | Gutian Domination | Early Minoan II | Period I. Eneolithic | |

| 2400 | Dyn. of Ur | (implements of stone, copper | |||

| 2300 | Dyn. IX | and bronze, poor in tin) | |||

| 2200 | Dyn. of Isin | Middle Minoan I | |||

| 2100 | Dyn. XI | Mid. Minoan II | |||

| 2000 | Dyn. XII | 1st Dyn. Babylon | Mycenean I | ||

| 1900 | 2nd Dyn. | Mid. Minoan III | Period II | ||

| 1800 | |||||

| 1700 | Dyn. XIII | 3rd Dyn. | Late Minoan I | ||

| 1600 | Dyn. XV | Period III | |||

| 1500 | Dyn. XVIII | Late Minoan II | Mycenean II | ||

| 1400 | Late Minoan III | ||||

| 1300 | Dyn. XIX | Period IV | |||

| 1200 | Dyn. XX | Homeric Age | |||

| 1100 | 4th Dyn. | ||||

| 1000 | Dyn. XXI | 5th to 7th Dyn. | Close of Bronze Age[101] | ||

| 900 | Dyn. XXII | 8th Dyn. | Hallstatt | ||

The introduction of iron into Italy has often been attributed to the Etruscans, who were thought to have brought the knowledge from Lydia. But the most abundant remains of the Early Iron Age are found not in Tuscany, but along the coasts of the Adriatic[102], showing that iron followed the well-known route of the amber trade, thus reaching Central Europe and Hallstatt (which has given its name to the Early Iron Age), where alone in Europe the gradual transition from the use of bronze to that of iron has been clearly traced. W. Ridgeway[103] believes that the use of iron was first discovered in the Hallstatt area and that thence it spread to Switzerland, France, Spain, Italy, Greece, the Aegean area, and Egypt rather than that the culture drift was in the opposite direction. There is no difference of opinion however as to the importance of this Central European area which contained the most famous iron mines of antiquity. Hallstatt culture extended from the Iberian peninsula in the west to Hungary in the east, but scarcely reached Scandinavia, North Germany, Armorica or the British Isles where the Bronze Age may be said to have lasted down to about 500 B.C. Over such a vast domain the culture was not everywhere of a uniform type and Hoernes[104] recognises four geographical divisions distinguished mainly by pottery and fibulae, and provisionally classified as Illyrian in the South West, or Adriatic region, in touch with Greece and Italy; Celtic in the Central or Danubian area; with an off-shoot in Western Germany, Northern Switzerland and Eastern France; and Germanic in parts of Germany, Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and Posen.

The Hallstatt period ends, roughly, at 500 B.C., and the Later Iron Age takes its name from the settlement of La Tène, in a bay of the Lake of Neuchâtel in Switzerland. This culture, while owing much to that of Hallstatt, and much also to foreign sources, possesses a distinct individuality, and though soon overpowered on the Continent by Roman influence, attained a remarkable brilliance in the Late Celtic period in the British Isles.[Pg 29]

That the peoples of the Metal Ages were physically well developed, and in a great part of Europe and Asia already of Aryan speech, there can be no reasonable doubt. A skull of the early Hallstatt period, from a grave near Wildenroth, Upper Bavaria, is described by Virchow as long-headed, with a cranial capacity of no less than 1585 c.c., strongly developed occiput, very high and narrow face and nose, and in every respect a superb specimen of the regular-featured, long-headed North European[105]. But owing to the prevalence of cremation the evidence of race is inadequate. The Hallstatt population was undoubtedly mixed, and at Glasinatz in Bosnia, another site of Hallstatt civilisation, about a quarter of the skulls examined were brachycephalic[106].

Their works, found in great abundance in the graves, especially of the Bronze and Iron periods, but a detailed account of which belongs to the province of archaeology, interest us in many ways. The painted earthenware vases and incised metal-ware of all kinds enable the student to follow the progress of the arts of design and ornamentation in their upward development from the first tentative efforts of the prehistoric artist at pleasing effects. Human and animal figures, though rarely depicted, occasionally afford a curious insight into the customs and fashions of the times. On a clay vessel, found in 1896 at Lahse in Posen, is figured a regular hunting scene, where we see men mounted on horseback, or else on foot, armed with bow and arrow, pursuing the quarry (nobly-antlered stags), and returning to the penthouse after the chase[107]. The drawing is extremely primitive, but on that account all the more instructive, showing in connection with analogous representations on contemporary objects, how in prehistoric art such figures tend to become conventionalised and purely ornamental, as in similar designs on the vases and textiles from the Ancon Necropolis, Peru. "Most ornaments of primitive peoples, although to our eye they may seem merely geometrical and freely-invented designs, are in reality nothing more than degraded animal and human figures[108]."[Pg 30]

This may perhaps be the reason why so many of the drawings of the metal period appear so inferior to those of the cave-dwellers and of the present Bushmen. They are often mere conventionalised reductions of pictorial prototypes, comparable, for instance, to the characters of our alphabets, which are known to be degraded forms of earlier pictographs.

Of the so-called "Prehistoric Age" it is obvious that no strict definition can be given. It comprises in a general way that vague period prior to all written records, dim memories of which—popular myths, folklore, demi-gods[109], eponymous heroes[110], traditions of real events[111]—lingered on far into historic times, and supplied ready to hand the copious materials afterwards worked up by the early poets, founders of new religions, and later legislators.

That letters themselves, although not brought into general use, had already been invented, is evident from the mere fact that all memory of their introduction beyond the vaguest traditions had died out before the dawn of history. The works of man, while in themselves necessarily continuous, stretched back to such an inconceivably remote past, that even the great landmarks in the evolution of human progress had long been forgotten by later generations.

And so it was everywhere, in the New World as in the Old, amongst Eastern as amongst Western Peoples. In the Chinese records the "Age of the Five Emperors"—five, though nine are named—answers somewhat to our prehistoric epoch. It had its eponymous hero, Fu Hi, reputed founder of the empire, who invented nets and snares for fishing and hunting, and taught his people how to rear domestic animals. To him also is ascribed the institution of marriage, and in his time Tsong Chi is supposed to have invented the Chinese characters, symbols, not of sounds, but of objects and ideas.[Pg 31]

Then came other benevolent rulers, who taught the people agriculture, established markets for the sale of farm produce, discovered the medicinal properties of plants, wrote treatises on diseases and their remedies, studied astrology and astronomy, and appointed "the Five Observers of the heavenly bodies."

But this epoch had been preceded by the "Age of the Three [six] Rulers," when people lived in caves, ate wild fruits and uncooked food, drank the blood of animals and wore the skins of wild beasts (our Old Stone Age). Later they grew less rude, learned to obtain fire by friction, and built themselves habitations of wood or foliage (our Early Neolithic Age). Thus is everywhere revealed the background of sheer savagery, which lies behind all human culture, while the "Golden Age" of the poets fades with the "Hesperides" and Plato's "Atlantis" into the region of the fabulous.

Little need here be said of strictly historic times, the most characteristic feature of which is perhaps the general use of letters. By means of this most fruitful of human inventions, everything worth preserving was perpetuated, and thus all useful knowledge tended to become accumulative. It is no longer possible to say when or where the miracle was wrought by which the apparently multifarious sounds of fully-developed languages were exhaustively analysed and effectively expressed by a score or so of arbitrary signs. But a comparative study of the various writing-systems in use in different parts of the world has revealed the process by which the transition was gradually brought about from rude pictorial representations of objects to purely phonetical symbols.

As is clearly shown by the "winter counts" of the North American aborigines, and by the prehistoric rock carvings in Upper Egypt, the first step was a pictograph, the actual figure, say, of a man, standing for a given man, and then for any man or human being. Then this figure, more or less reduced or conventionalised, served to indicate not only the term man, but the full sound man, as in the word manifest, and in the modern rebus. At this stage it becomes a phonogram, or phonoglyph, which, when further reduced beyond all recognition of its original form, may stand for the syllable ma as in ma-ny,[Pg 32] without any further reference either to the idea or the sound man. The phonogram has now become the symbol of a monosyllable, which is normally made up of two elements, a consonant and a vowel, as in the Devanágari, and other syllabic systems.

Lastly, by dropping the second or vowel element the same symbol, further modified or not, becomes a letter representing the sound m, that is, one of the few ultimate elements of articulate speech. A more or less complete set of such characters, thus worn down in form and meaning, will then be available for indicating more or less completely all the phonetic elements of any given language. It will be a true alphabet, the wonderful nature of which may be inferred from the fact that only two, or possibly three, such alphabetic systems are known with absolute certainty to have ever been independently evolved by human ingenuity[112]. From the above exposition we see how inevitably the Phoenician parent of nearly all late alphabets expressed at first the consonantal sounds only, so that the vowels or vowel marks are in all cases later developments, as in Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic, Greek, the Italic group, and the Runes.

In primitive systems, such as the Egyptian, Sumerian, Chinese, Maya-Quiché and Mexican, one or more of the various transitional steps may be developed and used simultaneously, with a constant tendency to advance on the lines above indicated, by gradual substitution of the later for the earlier stages. A comparison of the Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphic systems brings out some curious results. Thus at an extremely remote epoch, some millenniums ago, the Sumerians had already got rid of the pictorial, and to a great extent of the ideographic, but had barely reached the alphabetic phase. Consequently their cuneiform groups, although possessing phonetic value, mainly express full syllables, scarcely ever letters, and rarely complete words. Ideographs had given place first to phonograms and then to mere syllables,[Pg 33] "complex syllables in which several consonants may be distinguished, or simple syllables composed of only one consonant and one vowel or vice versa[113]."

The Egyptians, on the other hand, carried the system

right through the whole gamut from pictures to letters, but

retained all the intermediate phases, the initial tending to fall

away, the final to expand, while the bulk of the hieroglyphs

represented in various degrees the several transitional states.

In many cases they "had kept only one part of the syllable,

namely a mute consonant; they detached, for instance, the

final u from bu and pu, and gave only the values b and p to

the human leg

![]() and to the mat

and to the mat

![]() .

The peoples of the

Euphrates stopped half way, and admitted actual letters for

the vowel sounds a, i and u only[114]."

.

The peoples of the

Euphrates stopped half way, and admitted actual letters for

the vowel sounds a, i and u only[114]."

In the process of evolution, metaphor and analogy of

course played a large part, as in the evolution of language

itself. Thus a lion might stand both for the animal and for

courage, and so on. The first essays in phonetics took somewhat

the form of a modern rebus, thus:

![]() = khau = sieve,

= khau = sieve,

![]() = pu = mat;

= pu = mat;

![]() = ru = mouth, whence

= ru = mouth, whence

= kho-pi-ru = to be,

where the sounds and not the meaning of the several

components are alone attended to[115].

= kho-pi-ru = to be,

where the sounds and not the meaning of the several

components are alone attended to[115].

By analogous processes was formed a true alphabet, in which, however, each of the phonetic elements was represented at first by several different characters derived from several different words having the same initial syllable. Here was, therefore, an embarras de richesses, which could be got rid of only by a judicious process of elimination, that is, by discarding all like-sounding symbols but one for the same sound. When this final process of reduction was completed by the scribes, in other words, when all the phonetic signs were rejected except 23, i.e. one for each of the 23 phonetic elements, the Phoenician alphabet as we now have it was completed. Such may be taken as the real origin of this system, whether the scribes in question were Babylonians, Egyptians, Minaeans, or Europeans, that is, whether the Phoenician alphabet had a cuneiform, a hieroglyphic, a South Arabian, a Cretan (Aegean), Ligurian or Iberian origin, for all these and perhaps other peoples have[Pg 34] been credited with the invention. The time is not yet ripe for deciding between these rival claimants[116].