Title: Fine Books

Author: Alfred W. Pollard

Release date: March 6, 2011 [eBook #35494]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Chris Curnow and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

THE CONNOISSEUR’S LIBRARY

GENERAL EDITOR: CYRIL DAVENPORT

|

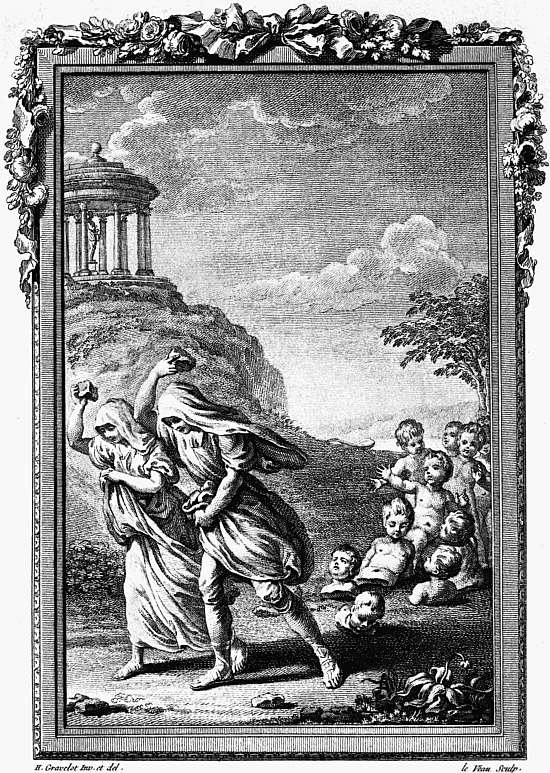

| Deucalion et Pyrrha repeuplant la Terre, Suivant l’Oracle de Themis. |

FINE BOOKS

BY

ALFRED W. POLLARD

NEW YORK: G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

LONDON: METHUEN & CO. LTD.

1912

TO

SIR EDWARD MAUNDE THOMPSON, G.C.B.

DIRECTOR AND PRINCIPAL LIBRARIAN OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

1888-1909

PREFACE

If the mere taking of trouble ensured good work, this contribution to the Connoisseur’s Library should be entitled to the modest praise of being “superior to the rest” of its author’s book-makings, since it has been ten years on the stocks and much of it has been written two or three times over, either because the writer’s own information had increased or to take account of the successful researches of others. Yet in the end defeat in one main point has to be acknowledged. The book was begun with a confident determination to cover the whole ground, from the beginnings of printing and printed book-illustration down to our own day, and in the case of printing the survey has been carried through, however sketchily. But the corresponding survey of book-illustration ends, with rather obvious marks of compression and fatigue, about 1780, leaving the story of a hundred and thirty years of very interesting picture-work untold. Pioneering is always so exciting that recognition of the impossibility of carrying out the full plan of the book within the limits either of the present volume or of the author’s working life was not made without sincere regret. The subject, however, of the abandoned chapter was not only very large, but very miscellaneous, and the survey for it would have had to include at least three other countries (France, Germany, and the United States) besides our own. To one section, moreover, that of illustrations in colour, a separate volume of this series has already been devoted. The author would, therefore, fain console himself with the hope that in one or more other volumes a competent account may be given by some other hand of the wood-engravings, etchings, steel-engravings, and lithographs, with which books have been decorated since 1780. The poorness of paper and print with which these modern illustrated books have too often been handicapped has caused collectors to take little interest in them—it even suggested the unworthy excuse for the failure to write the missing chapter that these are not really Fine Books, but only books with fine pictures in them, and so are outside our subject. But both students and collectors have their duties as well as their delights, and in view of the high artistic value of quite a large proportion of these modern illustrations, the preservation of clean and uncropped copies of the books in which they occur and the tribute of careful cataloguing and description are certainly their due.

While the desired completeness has not been attained the ground here covered is still very wide, and for the book as a whole no more can be claimed than that it is a compilation from the best sources—a list of these will be found in the Bibliography—controlled by some personal knowledge, the amount of which naturally varies very much from chapter to chapter. The obligations incurred in writing it have thus been great, and a sad number of these are to fellow-workers and friends—Proctor, John Macfarlane, W. H. Allnutt, Konrad Burger, Dr. Lippmann, Anatole Claudin, and the Prince d’Essling—who have died while the book has been in progress. Among those still happily alive acknowledgment must specially be made to Sir Sidney Colvin for help received from his masterly introduction to the great monograph on Early Engravers and Engraving in England published by the Trustees of the British Museum; to Mr. A. M. Hind for use made of the list of engravers and their works in the same book; to Mr. Campbell Dodgson for dippings into the wealth of information in his Catalogue of German and Flemish Woodcuts in the Print Room of the British Museum (Vols. I and II); to Mr. Gordon Duff for help derived from his three series of Sandars Lectures on English Printing, and to Mr. Evans for information obtained from his American Bibliography. Among other obligations the chief is to the writers (notably Mr. H. R. Plomer) of numerous papers contributed to the Transactions of the Bibliographical Society and to The Library, and these are acknowledged with special pleasure.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |||

| Chapter | I. | Collectors and Collecting | 1 |

| ” | II. | Block-Books | 19 |

| ” | III. | The Invention of Printing—Holland | 32 |

| ” | IV. | The Invention of Printing—Mainz | 44 |

| ” | V. | Other Incunabula | 59 |

| ” | VI. | The Development of Printing | 83 |

| ” | VII. | Early German and Dutch Illustrated Books | 100 |

| ” | VIII. | Early Italian Illustrated Books | 123 |

| ” | IX. | Early French and Spanish Illustrated Books | 143 |

| ” | X. | Later Foreign Books | 165 |

| ” | XI. | Foreign Illustrated Books of the 16th Century | 180 |

| ” | XII. | Printing in England (1476-1580) | 204 |

| ” | XIII. | English Books Printed Elsewhere than at London | 224 |

| ” | XIV. | English Woodcut Illustrations | 250 |

| ” | XV. | Engraved Illustrations | 267 |

| ” | XVI. | Modern Fine Printing | 297 |

| Bibliography | 309 | ||

| Index | 319 | ||

LIST OF PLATES

| I. | Deucalion and Pyrrha repeopling the world. From Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Paris, 1767 | Frontispiece |

| TO FACE PAGE | ||

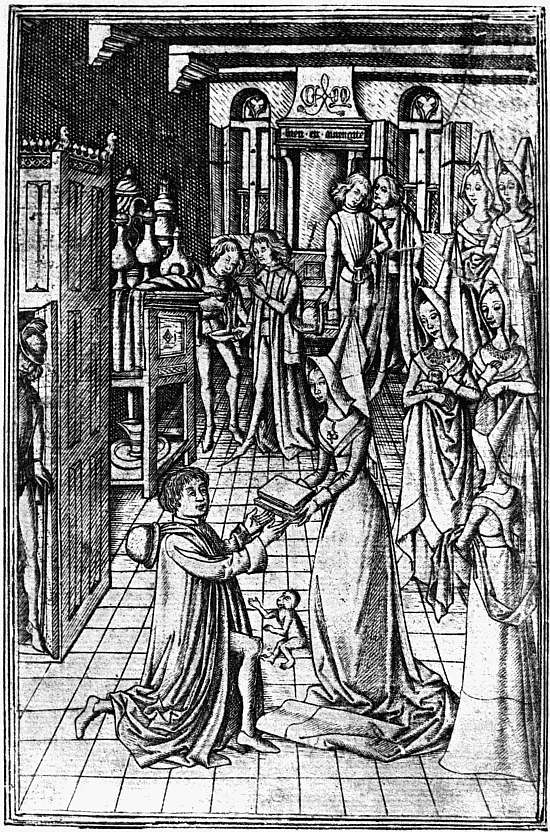

| II. | An author (Caxton?) presenting a book to Margaret of Burgundy. Fifteenth century engraving inserted in the Chatsworth copy of the Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye | 1 |

| (From the plate made for the Bibliographical Society’s edition of Mr. Seymour De Ricci’s Census of Caxtons.) | ||

| III. | The “Bona Inspiratio angeli contra vanam gloriam.” From a smaller version of the Ars Moriendi. Block-book from the Lower Rhine, c. 1465 | 26 |

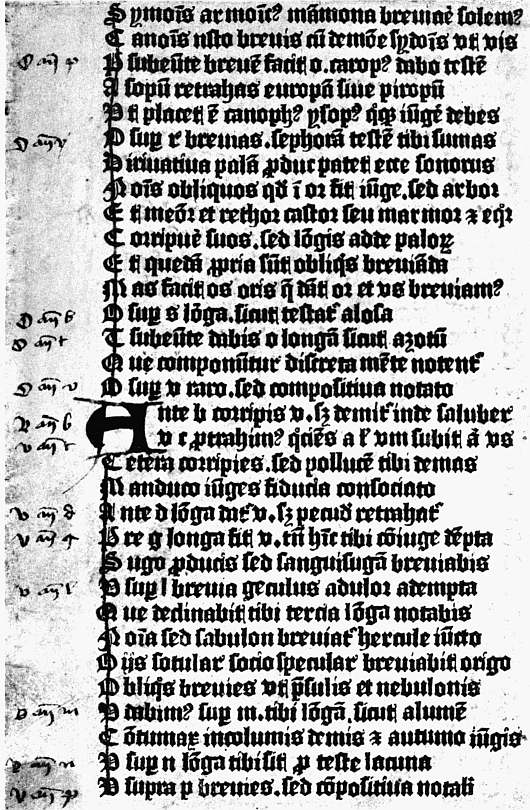

| IV. | Leaf 3a of a fragment of the Doctrinale of Alexander Gallus. One of the so-called “Costeriana” | 32 |

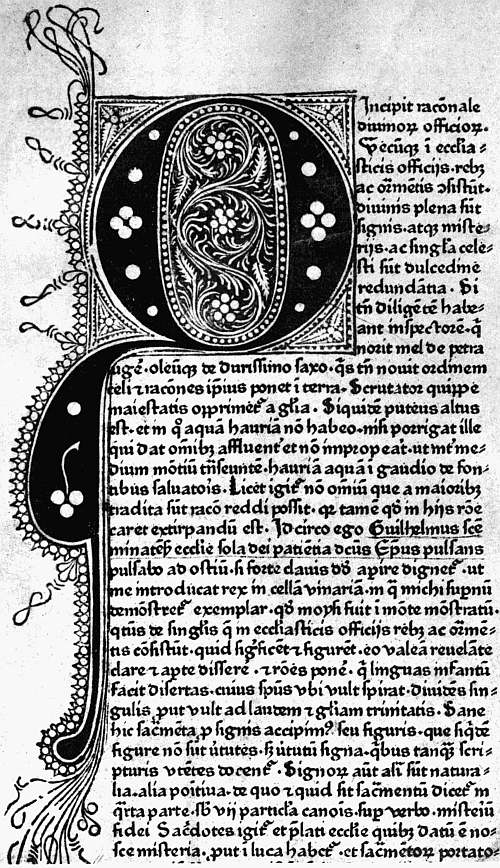

| V. | Beginning, with printed capital, of the Rationale Diuinorum Officiorum of Gulielmus Duranti. Mainz, Fust and Schoeffer, 1459 | 44 |

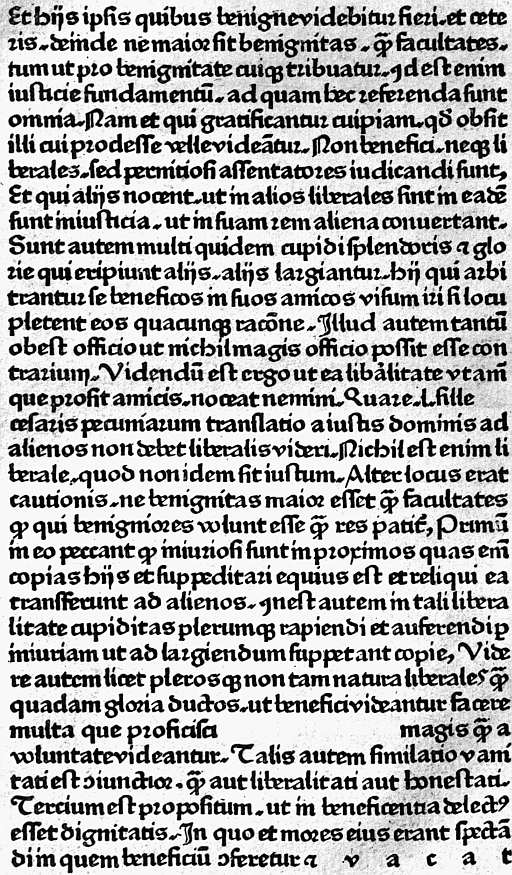

| VI. | Leaf 7b of the first book printed at Cologne, Cicero, De Officiis, Ulrich Zel, not later than 1466 | 60 |

| The space left in the sixth line from the foot stands for the words ab ostentatione, which the printer apparently could not read in his manuscript. The word vacat at the end was inserted to show that the space in the last line was accidental and that nothing had been omitted. | ||

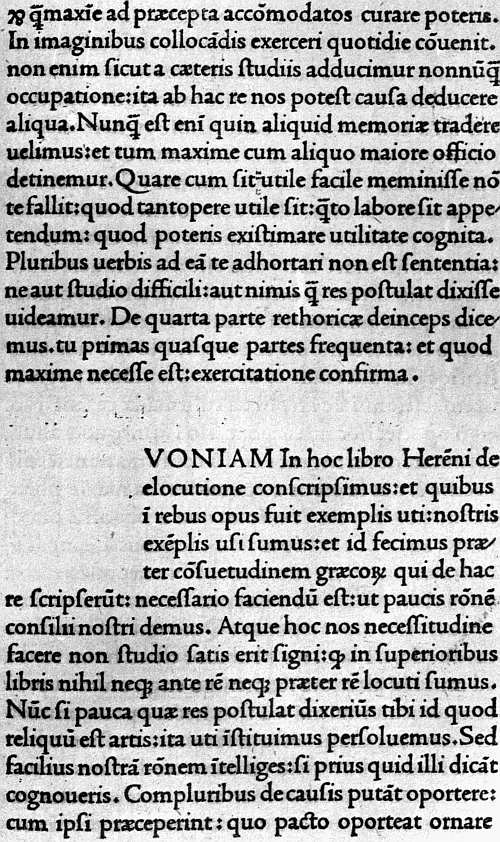

| VII. | Leaf 41a of Cicero’s Rhetorica, Venice, Nicolas Jenson, 1470, showing spaces left for a chapter heading and capital | 84 |

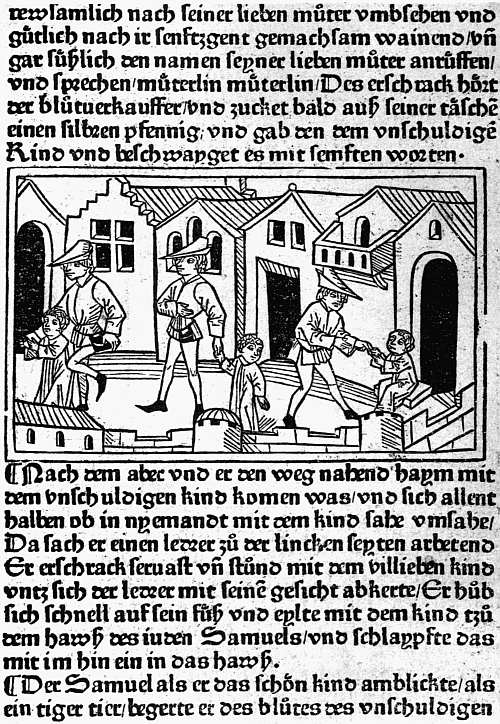

| VIII. | Part of leaf 4a, with woodcut, from the Geschicht von dem seligen Kind Symon of Tuberinus. Augsburg, Günther Zainer, about 1475 | 100 |

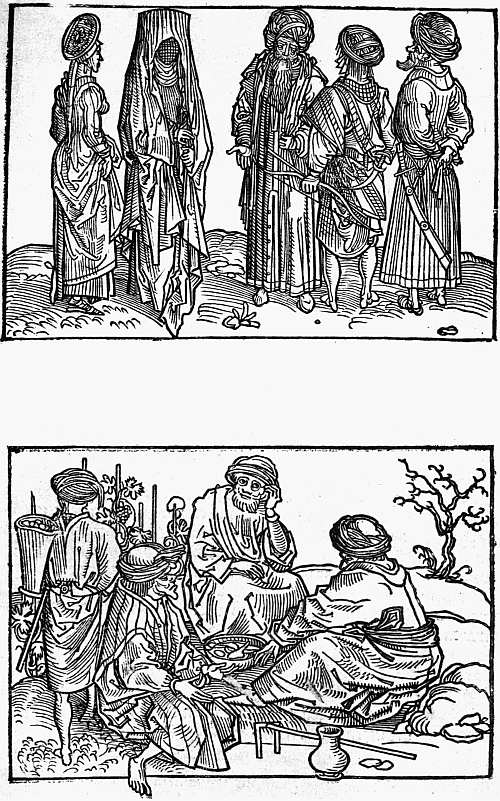

| IX. | Woodcuts of Saracens and Syrians from Breidenbach’s Sanctae Peregrinationis in montem Syon atque in montem Sinai descriptio. Mainz, Erhard Reuwich, 1486 | 114 |

| X. | Woodcut on leaf 1b of the Egloga Theoduli. Leipzig, Conrad Kachelofen, 1489 | 116 |

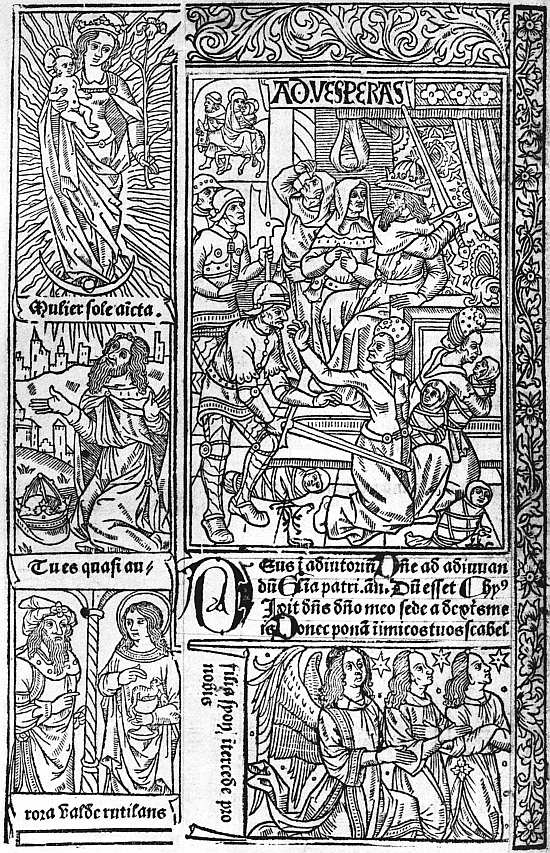

| XI. | Page (sig. H 8 verso) from the Psalterium Beatae Mariae Virginis of Nitschewitz, showing the Emperor Frederick and his son Maximilian. From a press at the Cistercian Monastery at Zinna, c. 1493 | 118 |

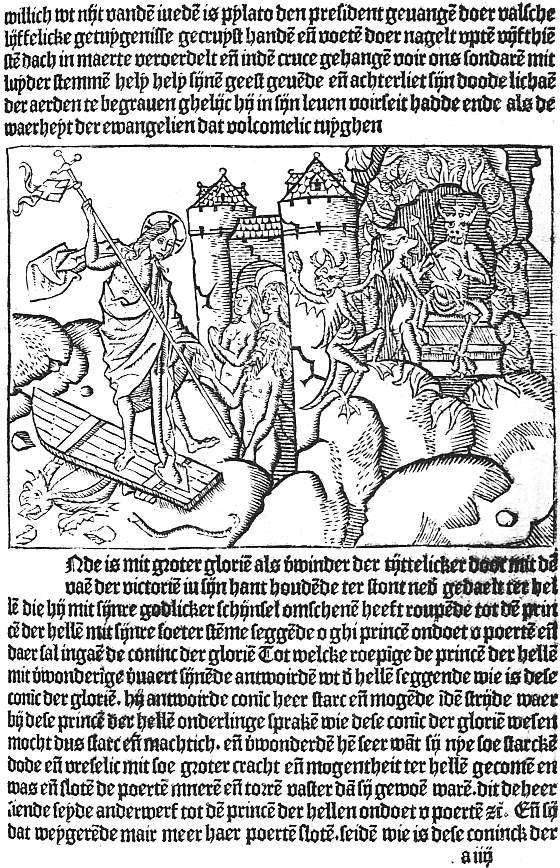

| XII. | The Harrowing of Hell, with text, from leaf 4a of the Belial of Jacobus de Theramo. Haarlem, Bellaert, 1484. (Size of the original, 7¼″ × 5″) | 120 |

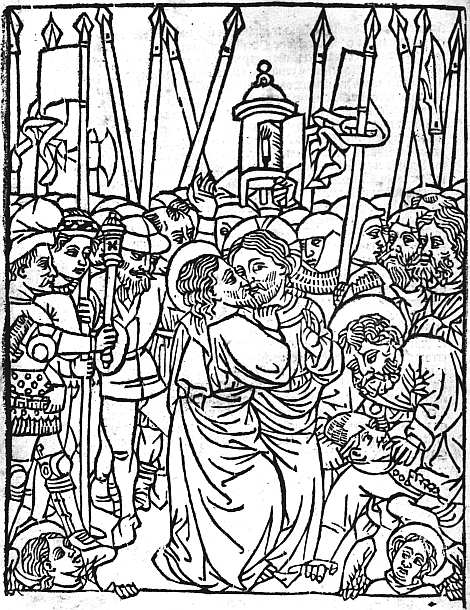

| XIII. | Woodcut of the Betrayal. From leaf 14b of the Meditatione sopra la Passione del Nostro Signore attributed to S. Bonaventura. Venice, Geronimo di Sancti, 1487. (Size of original, 6¾″ × 5¼″) | 124 |

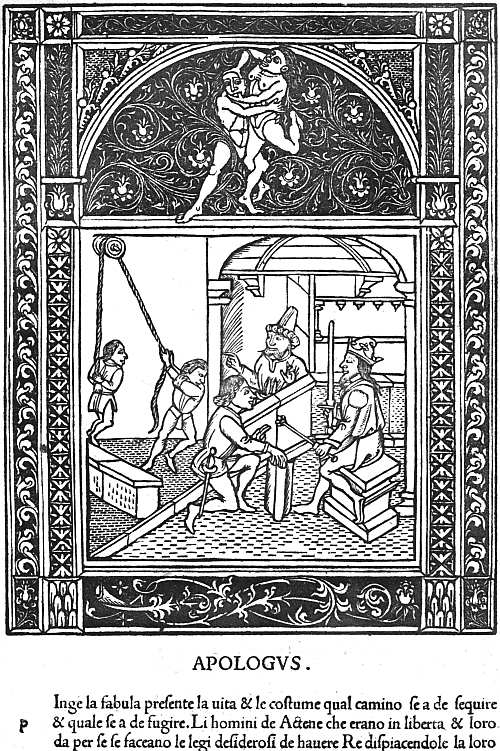

| XIV. | Woodcut, De Atheniensibus petentibus regem, illustrating Fable xxii. in the Aesop printed at Naples, by Francesco Tuppo, 1485 | 126 |

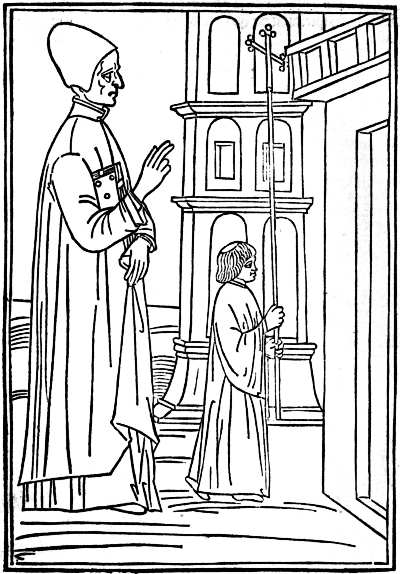

| XV. | Woodcut of Lorenzo Giustiniano preceded by a crucifer, from his Della vita religiosa. Venice, 1494 | 130 |

| XVI. | Page with woodcut of the Procession to Calvary, from the Meditatione sopra la Passione del Nostro Signore attributed to S. Bonaventura. Florence, Ant. Miscomini, c. 1495 | 138 |

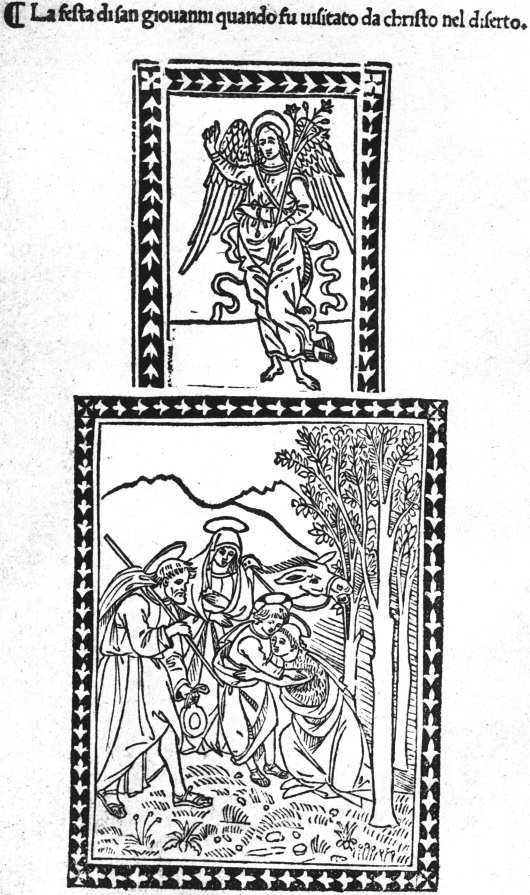

| XVII. | Titlepage of La Festa di San Giovanni. Florence, Bart. di Libri, c. 1495 | 140 |

| XVIII. | Leaf 5a, with woodcut of Death seizing an Archbishop and a Chevalier, from the Danse Macabre. Paris, Gui Marchant, 1491. (Size of original 8¾″ × 6¼″) | 144 |

| XIX. | Leaf 2a, with woodcut of Adam and Eve, from a Bible en Francoys. Paris, Antoine Vérard, about 1505. (Size of original, 9¾″ × 7″) | 150 |

| XX. | Page (sig. C 6 verso), with woodcut of the Massacre of the Innocents, from the Grandes Heures. Paris, Antoine Vérard, about 1490. (Size of original, 77⁄8″ × 5¼″) | 152 |

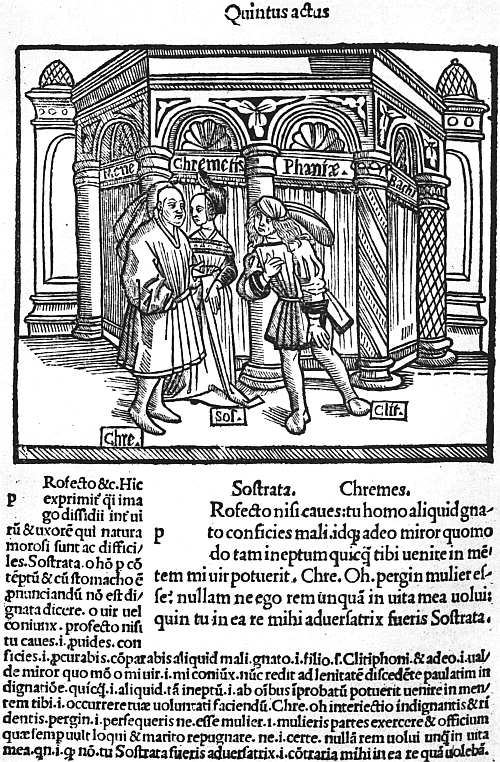

| XXI. | Page (sig. U 7 verso) from the edition of Terence, printed by J. Trechsel at Lyon, 1493 | 160 |

| XXII. | Titlepage from the Improbratio Alcorani of Ricoldus. Seville, Stanislaus Polonus, 1500 | 162 |

| XXIII. | Hroswitha presenting her plays to the Emperor Otto I, leaf 4b of the Opera Hrosvite. Nuremberg, Sodalitas Celtica, 1501 | 180 |

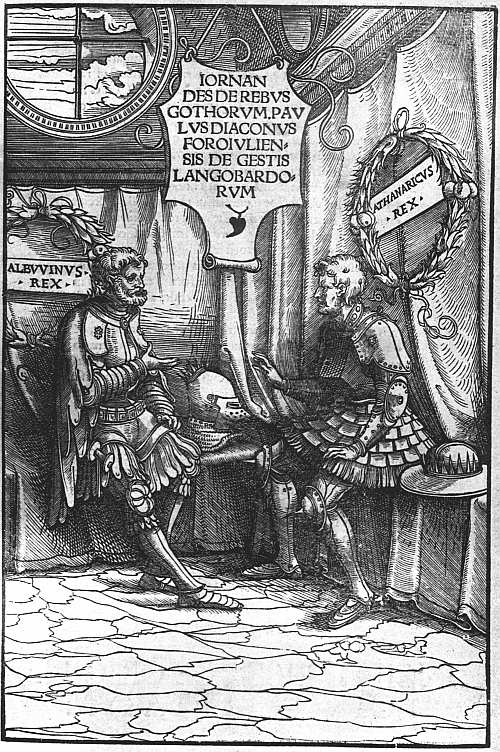

| XXIV. | Titlepage of Jornandes De rebus Gothorum. Augsburg, 1515 | 186 |

| XXV. | Page (leaf 246b) of a Missale Romanum, printed at Venice by Gregorius de Gregoriis, 1518 | 194 |

| XXVI. | Title-cut from Les dix premiers livres de l’Iliade d’Homère, Prince des poètes, traduictz en vers François, par M. Hugues Salel. Paris, Jehan Loys for Vincent Sertenas, 1545 | 200 |

| XXVII. | Page from the Fifteen Oes. Westminster, Caxton, about 1490 | 204 |

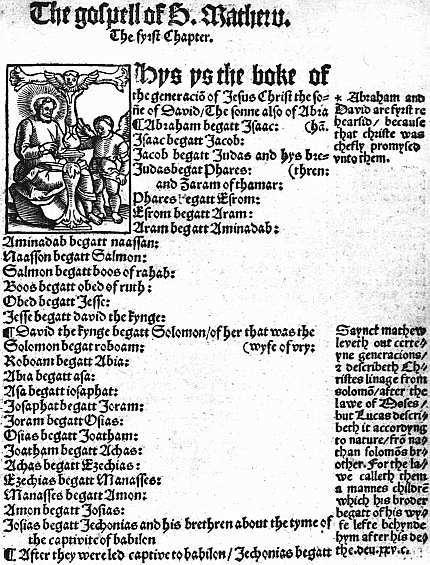

| XXVIII. | First page of text from the first edition (left incomplete) of Tyndale’s New Testament. Cologne, 1525 | 224 |

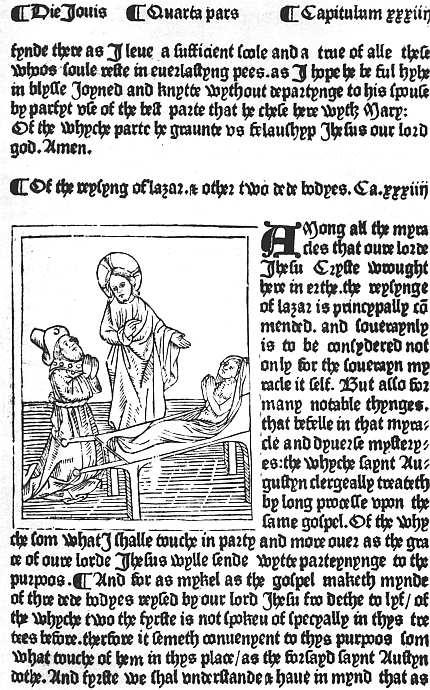

| XXIX. | Part of sig. K 5 recto, with woodcut of Christ raising the Centurion’s Daughter, from the Speculum Vitae Christi of S. Bonaventura. Westminster, W. Caxton, about 1488 | 250 |

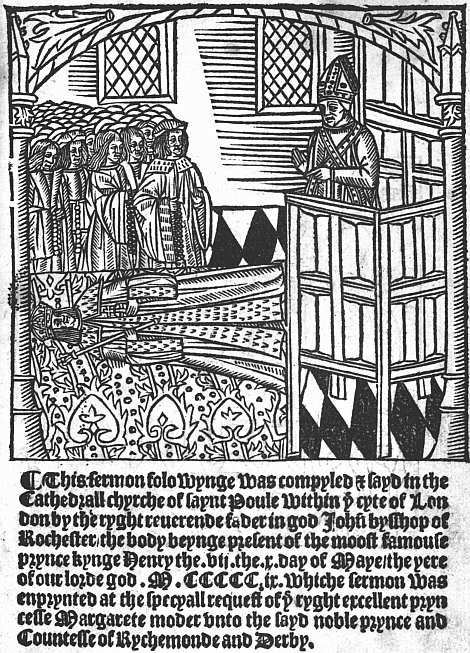

| XXX. | Titlepage of Bishop Fisher’s Funeral Sermon on Henry VII. London, W. de Worde, 1509 | 254 |

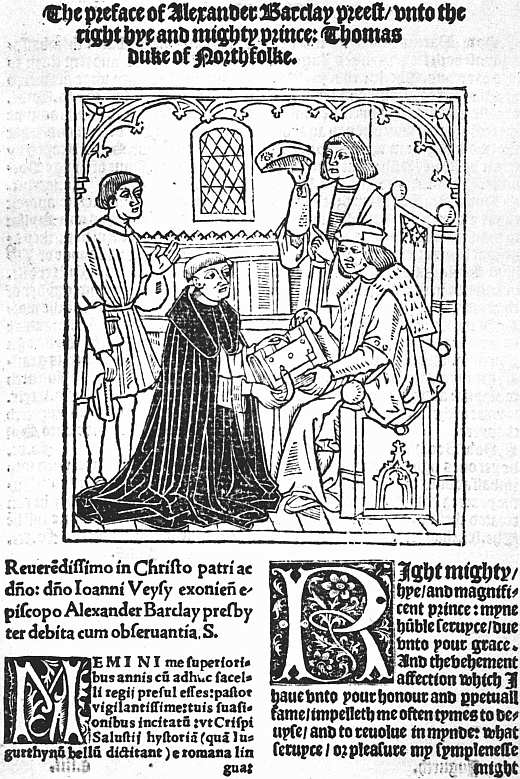

| XXXI. | Woodcut of the translator presenting his book to the Duke of Norfolk, from Alexander Barclay’s version of Sallust’s Jugurtha. London, R. Pynson, about 1520 | 256 |

| XXXII. | Portrait of the Author, from John Heywood’s The Spider and the Flie. London, T. Powell, 1556 | 260 |

| XXXIII. | Woodcut of Queen Elizabeth hawking, from Turberville’s The Booke of Faulconrie, 1575 | 264 |

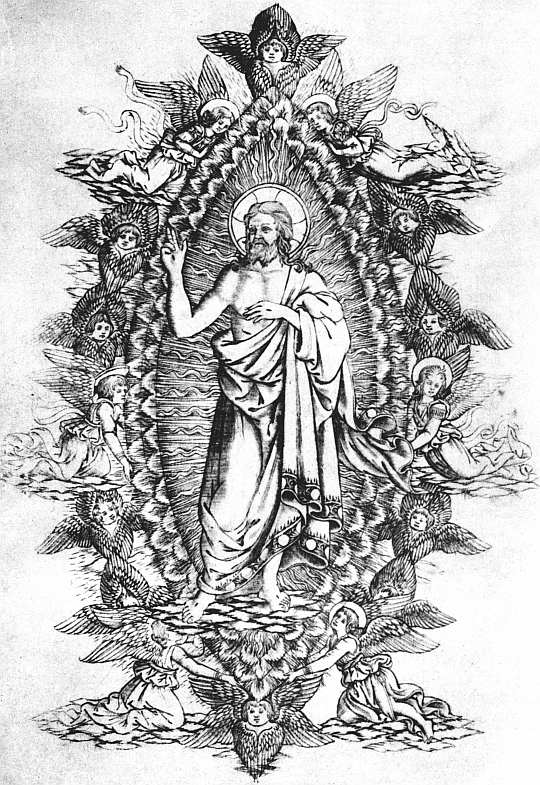

| XXXIV. | Engraving of Christ in a mandorla from Bettini’s Monte Santo di Dio. Florence, Nicolaus Laurentii, 477. (Size of original, 10″ × 7″) | 268 |

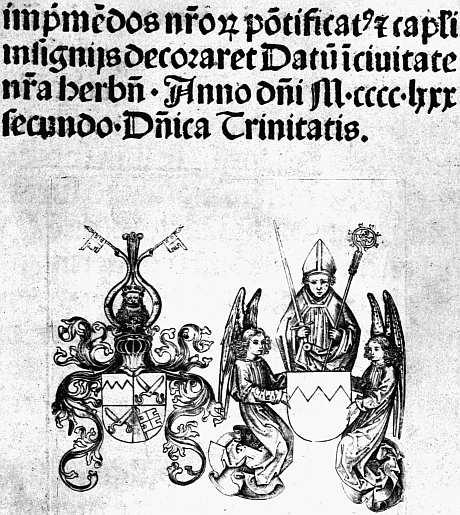

| XXXV. | Last page of preface, giving the arms of the Bishop of Würzburg, from the Würzburg Agenda. Würzburg, G. Reyser, 1482 | 270 |

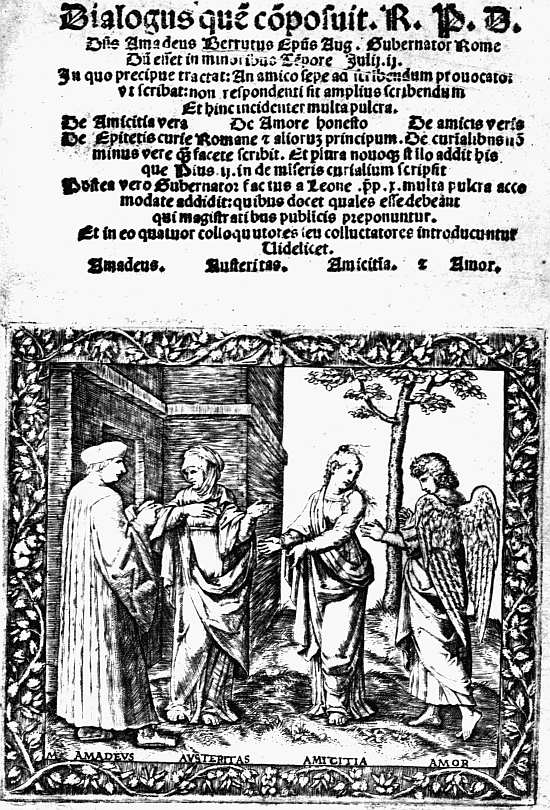

| XXXVI. | Titlepage of the Dialogus of Amadeus Berrutus. Rome, Gabriel of Bologna, 1517 | 274 |

| XXXVII. | Engraved portrait of the Author by Theodore de Bry after J. J. Boissard, from the Emblemata of Denis Le Bey. Frankfort, De Bry, 1596 | 280 |

| XXXVIII. | Page 22 from the Hieroglyphikes of the Life of Man by Quarles, the engraving by W. Marshall, London, 1638 | 286 |

| XXXIX. | Page, with engraving after Eisen, from Dorat’s Les Baisers, La Haye et se vend à Paris, Lambert, 1770 | 292 |

| XL. | Engraving by W. W. Rylands after Samuel Wale, from Walton’s Compleat Angler. London, T. Hope, 1760 | 296 |

|

| Engraving of an Author, possibly CAXTON Presenting a Book to Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy, prefixed to the Chatsworth copy of the ‘Recuyell.’ |

FINE BOOKS

CHAPTER I

COLLECTORS AND COLLECTING

From the stray notes which have come down to us about the bibliophiles of the later Roman Empire it is evident that book-collecting in those days had at least some modern features. Owing to the abundance of educated slave-labour books were very cheap, almost as cheap as they are now, and book-collectors could busy themselves about refinements not unlike those in which their successors are now interested. But in the Middle Ages books were by no means cheap, and until quite the close of the fourteenth century there were few libraries in which they could be read. Princes and other very wealthy book-buyers took pleasure in possessing finely written and illuminated manuscripts, but the ruling ideals were mainly literary and scholastic, the aim (the quite right and excellent aim) being to have the best books in as many subjects as possible. After printing had been invented the same ideals continued in force, the only difference being that they could now be carried out on a larger scale. Libraries like those formed in the sixteenth century by Archbishop Cranmer and Lords Arundel and Lumley, or that gathered in France by the historian De Thou, were essentially students’ libraries, and the books themselves and the catalogues of them were often classified so as to show what books had been acquired in all the different departments of human knowledge. Even in the sixteenth century, when these literary ideals were dominant, we find 2 some examples of another kind. In Jean Grolier, for instance, we find the book-lover playing the part, too seldom assumed, of the discriminating patron of contemporary printing and bookbinding. Instead of collecting more old books than he could find time to read, Grolier bought the best of his own day, but of these sometimes as many as four or five copies of the same work that he might have no difficulty in finding one for a friend; and whatever book he bought he had bound and decorated with simple good taste in Venice or at home in France. It would be an excellent thing if more of our modern collectors, instead of taking up antiquarian hobbies, were content to follow Grolier’s example. Books always look best when clad in jackets of their own time, and this in the future will apply to the books of the twentieth century as much as to any others. Moreover, there is more actual binding talent available in England just now than at any previous time, and it is much to be desired that modern Groliers would give it scope, not in pulling about old books, but in binding beautifully those of our own day.

Grolier found a modest imitator in England in the person of Thomas Wotton, but with some at least of the Elizabethan book-lovers the havoc wrought in the old libraries by the commissioners of Henry VIII and Edward VI provoked an antiquarian reaction which led them to devote all their energies to collecting, from the unworthy hands into which they had fallen, such treasures of English literary and bookish art as still remained. Putting aside John Leland who worked (to what extent and with what success is not quite clear) for Henry VIII, Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury, was the earliest of these antiquaries, to the great benefit of the libraries of Lambeth Palace and of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, though as to how he came by his books perhaps the less said the better. Parker was soon followed by Sir Robert Cotton, whose success in gathering books and documents illustrating English history was so great that his library was sequestered and very nearly altogether 3 taken from him, on the plea that it contained state papers which no subject had a right to possess. Owing to the carelessness and brutality of the previous generation, Cotton’s opportunities were as great as his zeal in making use of them, and at the cost of his fortune he laid the foundations of a national library. Humbler men imitated him without being able to secure the same permanence for their collections, more especially Humphrey Dyson, a notary, who seems to have acquired early printed books and proclamations, with the same zeal which Cotton devoted to manuscripts. Many of his treasures passed into the hands of Richard Smith, the Secondary of the Poultry Compter, but at his sale they were scattered beyond recall, and the unity of one of the most interesting of English collections was thus unkindly destroyed. Both these men, and some others of whom even less is known, worked with a public aim, and already Sir Thomas Bodley had gone a step further by founding anew the University Library at Oxford on lines which at once gave it a national importance. This it preserved and developed for over a century and a half, and has never since lost, though no national help, unfortunately, has ever been given it, save the right already conceded by the Stationers’ Company, of claiming a copy of any new English book offered for sale.

Bodley’s munificent donation marked an epoch in the history of English book-collecting because its tendency was to make private book-collecting of the kind which was then admired incongruous and even absurd. When there were no public libraries open to scholars, for a great man to maintain a splendid library in his own house and allow students to read in it was worthy of Aristotle’s μεγαλόψυχος, the man who does everything on a scale that befits his dignity. But in proportion as public collections of books and facilities for obtaining access to them are increased, the preservation of a library on a large scale in a private house, where none of the inmates have any desire to use it, becomes an easy and justifiable object of 4 satire. A man without literary instincts who inherits a fine library is indeed in a parlous state, for if he keeps it he is as a dog in the manger, and if he sells it he is held up to opprobrium.

That considerations of this kind were beginning to have weight is shown by the rapidity with which during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries one private collection after another drifted into public ownership. In some cases there were intermediate stages. Thus Archbishop Usher’s books were not bequeathed to Trinity College, Dublin, but were purchased for it by the subscriptions of the soldiers of Cromwell’s army in Ireland. The manuscripts of Sir Simeon d’Ewes remained in the possession of his family for nearly a century, were then purchased by Harley, and came to the British Museum with Harley’s collection. Stillingfleet’s manuscripts were in the same temporary ownership; his printed books came to Dublin through the public spirit of Archbishop Marsh. So again Bishop Moore’s books were purchased for the University Library at Cambridge by George I. Thus even when a collector was not inspired by, or could not afford to indulge, public motives, respect for his memory or desire to benefit an institution often brought his books to a safe haven. But more often the munificence was personal and direct. For some cause not quite easy to see the flow of benefactions to English libraries has dwindled sadly of late years,1 so that journalists with short memories write of gifts and bequests to American libraries as if they were unprecedented. Even of late years, however, the foundation of the John Rylands Library, Chancellor Christie’s gifts and bequest to the Victoria University, the Sandars legacy to the University Library, Cambridge, and Mr. Alfred Huth’s bequest to the British Museum of any fifty books it might choose to select from his fine collection, show that the stream is not quite dried up, while for nearly two centuries 5 and a half from the foundation of the Bodleian it ran with splendid freedom. Thus Archbishop Williams gave noble gifts of books to S. John’s College, Cambridge, and to the Chapter House Library at Westminster Abbey; Selden’s books enriched the Bodleian; Laud was a generous benefactor alike to the Bodleian, to S. John’s College, Oxford, and to the library of Lambeth Palace; Sir Kenelm Digby gave both to Bodley and to Harvard; Ralph Sheldon benefited the Heralds’ College; Pepys (through his nephew) bequeathed his collection to Magdalene College, Cambridge; Archbishop Marsh founded a library at Dublin; Richard Rawlinson gave his manuscripts to the Bodleian, and Harley arranged that his should be offered to the nation.

The example of the men who bought under the influence of an intention to bestow their books on some public institution naturally affected others, and was responsible for a good deal of rather haphazard collecting in the eighteenth century. The private modern library was often confused with the antiquarian collection, and the antiquarian collection itself was seldom dominated by any central idea. Yet collectors who devoted themselves to one subject and knew thoroughly well what they were aiming at were already coming into existence, and these also, when their work was done, were inspired by an honourable ambition to preserve it intact, and so the libraries were once more enriched. Thus Garrick, guided by his professional interest, devoted himself to early plays, and bequeathed his collection to the British Museum. Malone bought the books which were useful to him as a student of Elizabethan literature, more especially of Shakespeare, and bequeathed them to the Bodleian, while Capell left his similar collection to Trinity College, Cambridge. The library of Natural History books brought together by Sir Joseph Banks and bequeathed by him to the British Museum is another example of well-defined collecting, though of a different sort. Among men who were not themselves specialists the vogue lay in 6 the direction of first editions of the Greek and Latin classics and of a few Italian and English authors of special merit, together with books illustrating the history of printing down to about the year 1480 or 1485. The early classics seem to have been the indispensable element in any collection of the first rank, and they appear with monotonous regularity in the libraries of George III, of the Rev. Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode, and of Thomas Grenville, which all three passed to the British Museum; in the Spencer Collection, now in the John Rylands Library, Manchester; and in the Sunderland Library, sold at auction in 1881-3. When these prizes were secured the collector seems to have felt himself free to follow his individual taste in supplementary purchases, and the Grenville Library is a fine proof of the broader interests of its possessor. Two notable collectors, Heber, the last of the great book-gluttons, and William Henry Miller, founder of the famous Christie-Miller Library at Britwell, cut themselves free from the cult of the editio princeps, the latter (despite a taste for modern Latin verse) devoting himself to English poetry, while Heber added to this the literatures of France, Italy, and Spain.

Despite the exceptions we have mentioned, in almost all of the collections of the early years of the nineteenth century two different ideals were combined: the student’s ideal of the best books in the best editions, and the antiquary’s ideal of the books by which the history of printing and its kindred arts could be most vividly illustrated. The combination is still common, for one of à Beckett’s comic histories (though I am not prepared to assert that this is a “best book”) still figures as the first entry in many sale catalogues which contain also incunabula assuredly not bought for their literary interest. It is more easy to defend such a medley on the ground of sentiment than of logic. Whoever uses books has reason to be grateful to the men who invented or diffused the art of printing, and may be interested in learning something about them. Yet it can hardly be denied that to collect 7 various kinds of books from an antiquarian, æsthetic, or any other well-defined point of view, not directly literary, is an independent pursuit in its own right, just as to collect old or beautiful china or silver is an independent pursuit, whether or no the china or silver be used for eating or drinking from. It will be said, of course, that on this view books are no better than china (or postage stamps), and there are indeed some strange instances of men who have fallen below their possibilities and have collected books, and not without success, despite a most amazing indifference to their contents. This reduces the joy they can get from their hobby to the bare pleasure of collecting for the sake of collecting, an ignoble delight in indulging acquisitiveness, redeemed to some extent by the higher pleasure of overcoming difficulties and observing the rules of the game. But the ignorant book-collector, until he has educated himself, is like a rose-fancier who cannot distinguish one odour from another. By the time they attract the collector books have become, or are on the road to becoming, so precious that their primary usefulness has to be left dormant. To use them constantly for our daily reading would approach the fault which the Greeks called ὔβρις, the arrogance which makes a man esteem himself so highly that he thinks nothing too good for his own use. But even when this limitation is recognized, for those who can appreciate them they preserve all the associations of their primary use, and it is because these associations are so delightful and so various that the bookman claims that his form of collecting is the best of all.

What then are the associations and qualities which give books value in the eyes of a collector? We may answer the question negatively in the first instance by reducing to their proper importance the two qualities which are popularly supposed to be the most attractive to the book-hunter—rarity and age. If a book is otherwise uninteresting, what is it the better for being rare? In passing it may be noted that unless a book is interesting for other reasons its rarity is necessarily an unknown 8 quantity. Sir Sidney Lee’s Census of the extant copies of the First Folio Shakespeare, a comparatively common book, but of supreme interest for its associations, is a striking example of the zeal with which every discoverable copy of a valuable book is now hunted down. Those whose business it is to gather such information can tell in the case of dozens of books of much less importance exactly how many copies have been discovered and in whose possession they remain. But in the case of a book of little interest the most that can be said is that it is “undescribed,” and it may be “undescribed” not in the least because it is really rare, but because no bibliographer has troubled himself to make a note of it. Were some real point of interest discovered in it the chances are that the attention thus attracted would speedily bring to light other copies, as in the case of the school magazine to which Mr. Kipling was found to have contributed. Of this the first set catalogued sold for over £100, with the result that so many others were unearthed that the price speedily sank to less than as many shillings.

Granted, however, that it could be proved that a dull book is not merely undescribed, but absolutely, what so few works are, unique, in what way does this make it of interest to the collector? A great library might buy it for a trifle out of compassion, or under the idea that its registration in a catalogue might help to piece out a genealogy, or that it might count as another unit in statistics (a poor reason), or justify its purchase in some other haphazard way. But considerations of this kind, such as they are, cannot affect private collectors. A really dull book is merely a nuisance, and whether only one copy of it, or many, can be proved to exist, nobody wants it. If this be so we are justified in saying that, although as soon as a book is found desirable for any other reason its rarity becomes of paramount importance in determining its price, Rarity by itself is of no interest to collectors.

The attractiveness bestowed by Age cannot be treated quite so summarily, because although the same line of 9 argument can be followed, it has to be helped out by an explanation arising from a particular case. No collector would value a dull sermon printed in 1800 any higher than a dull sermon printed in 1900, and if we go back two centuries instead of one, in the case of a book printed in London its value is none the greater for the extra hundred years. If, however, the sermon chanced to have been printed in 1700 in some provincial town, its age would distinctly be an element of value. Down to 1693 printing was only permitted in London, Oxford, Cambridge, and (after the outbreak of the Civil War2) at York. When the restraining Act was dropped in 1693 printing made its way, not very rapidly, into one provincial town after another. Hence a dull sermon with a provincial imprint may be dear to the heart of some local antiquary as the first-fruit of the press in his neighbourhood.

If we go back another sixty years from 1700 we reach another typographic zone, as we may call it, within which some slight interest attaches to all examples of English printing, for the end of the year 1640 is the limit of the special catalogues of early books published by the British Museum, the Cambridge University Library, and the John Rylands Library, Manchester. The first and last of these have indexes of printers; in the second the primary arrangement is typographical. Thus all books which are old enough to have been printed before the end of 1640 are thereby invested with some slight interest solely as products of English presses. When we get back to before 1600 we are in the period covered by the different editions of the Typographical Antiquities of Joseph Ames. When we go back another hundred years we are within the fifteenth century; printing has been introduced into England for less than twenty-five years, and the smallest fragment of a book from one of the early presses at work at Westminster, Oxford, St. Albans, or the City of London, is esteemed as of interest and importance.

Thus if we go far enough back Age does add to the interest of a book, but only by bringing it under another influence, that the interest of an English fifteenth century book is due to its importance in the history of printing and not to its antiquity being easily demonstrated by the fact that a contemporary unadorned manuscript of the same work will probably have only a fraction of the value of the printed edition. There are, of course, other cases in which age may be said to have some secondary influence, as in the case of books dealing with social customs, ballads and the like. But here it is still more evident that the social or literary interest is the primary consideration, and that this cannot be created, though it is greatly enhanced, by Age.

Having thus to the best of our ability abated the pride both of Age and Rarity, we come back to our original question as to what are the qualities and associations which give books value in the eyes of a collector.

The only good qualities which a book can possess in its own right are those of strength and beauty of form. Everything else about it is inherent in no single edition, though association of ideas may give greater dignity to one edition than to another. Type, paper, ink, presswork, the arrangement of the page, and also (though not quite in the same way or to the same extent) the illustrations, are all part and parcel of the book itself, and may be combined, at least so bookmen believe, in a really beautiful unity. No doubt as to this students run some risk of losing their sense of proportion. I myself am conscious, for instance, that I have looked at so many fifteenth century woodcuts, as compared with other works of art, that I distinctly overrate them. Mr. Robert Proctor, who knew more about fifteenth century books than any other man has ever known, or is ever likely to know, once said to me in all seriousness, that he did not think he had ever seen an ugly one. Allowing, however, for this very human tendency to set up our own esoteric standard, there yet remains a more generally recognizable beauty of form 11 which some books possess in a higher degree than others, and to collect such beautiful books independently of any other kind of attraction would be no unworthy pursuit. As a matter of fact, bookmen are more inclined to make beauty of form a secondary consideration to which, as to age and rarity, they pay attention, but without adopting it as the basis of their collection.

As a secondary consideration the attention collectors pay to beauty can hardly be exaggerated in respect to the condition of copies, the ratio of an unusually good to an unusually bad copy of the same book, even if the bad copy have no leaves actually wanting, being often as ten to one. The unusually bad copy, indeed, would often have no selling value at all were it not that it may be useful to students and so win a purchaser at a small price. The collector should leave it severely alone, partly because such “working copies” are the rightful perquisite of poor scholars, partly because, as he presumably buys books for his pleasure, he defeats his own object if, except in the case of the very rarest, he buys copies at which he cannot look without regretting that their headlines are cut off or the paper rotten through bad cleaning. Mr. Frederick Locker recorded in his catalogue that his copy of Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience had been cut down by a previous owner to the dimensions of the old covers of a washing-book. I think it was his chivalry, his piety toward Blake’s memory, that induced him to rescue it from this dishonour. Had he bought such a poor copy simply because it was cheap, he would have fallen far below his standard as a collector.

Putting on one side beauty of form, the interest of books in the eyes of a collector lies in their associations, historical, personal, or purely literary. For reasons touched on already but which we may now consider more fully, among historical associations those connected with the history of printing fill a very large place. As we have said before, the invention of an art by which books were so greatly cheapened and multiplied was an 12 event of almost unique importance in the social history of Europe, and everything which throws light on the first discovery, on the manner in which it was carried from one country and city to another, and on the methods and lives of the early printers, is of interest, and in its degree and measure, of importance. Moreover, just as foxes are hunted because they show such good sport, so these early books are collected because the study of them combines in a singular degree the charms of scientific and historical discovery, with all sorts of literary, social, and human side-interests. The claim which Henry Bradshaw put forward that antiquarian bibliography must be studied scientifically has been perverted by the unwise into the assertion that bibliography is a Science, or as they are sometimes pleased to put it, an Exact Science, till sensible people are wearied of the silly phrase. But the claim itself is absolutely true, and the gifts which enabled Mr. Proctor to classify, exactly or approximately, any fragment of early printing according to its country, place, printer, and date, if employed on any other field of scientific inquiry would easily have gained him a Fellowship of the Royal Society, besides the European recognition which, in his own small field, was already his before he died.

A large proportion of early printed books are without any indication whatever of their place of origin, printer, or date. The dates are obscured by the quickness or slowness of individual printers in adopting various improvements—sheet-numbering, leaf-numbering, printed capitals, titlepages, methods of imposition, etc.—which thus become uncertain and delusive landmarks. The place of origin is obscured by the existence of almost identical types in different cities and even in different countries. A fortiori the identity of the individual printer may baffle research from types being transferred or copied in all but one or two letters of the fount, which thus become the sole means of differentiating them. As helps the bibliographer has, in the first place, such a classification of 13 the two or three thousand fifteenth century types as he is able to carry in his head. This, in proportion to its completeness, enables him to narrow down the field to be investigated. Some small typographical peculiarity, the way in which the illuminator or rubricator has filled the blank spaces, the note which by good fortune he may have appended in this or some other known copy saying when he finished his work, similar notes by early purchasers which occasionally give the date of their bargain, these and other points may all help forward the happy moment of final identification. Such a hunt as this may sound alarmingly difficult, as if it were all over five-barred gates and inconveniently hedged ditches. But facsimiles and other aids have been greatly multiplied of late years; many a book can be run down and the identification verified in a few minutes, and the possibility of hunting successfully in one’s own library presupposes the purchase of many books giving full information as to their origin. These, while offering the means of identifying other books, will themselves raise no questions, so that the collector’s life need not be unceasingly strenuous.

The side-interests of these old books are very varied. Many of them, at least to eyes trained to perceive it, are of great beauty. Others, although the half century during which printing was in its infancy produced few masterpieces of literature, have real literary interest. More than any other single event the invention of printing hurried on the transition from the medieval world to the modern, but while many printers in Italy nearly ruined themselves by the zeal with which they helped forward the classical renaissance, all over Europe the medieval books which were still read were seized on for the press, so that in the books printed between 1470 and 1490 we are presented with a conspectus or summary of medieval literature. Caxton printed the works of Chaucer and Gower and prose renderings of the old romances. The Italian presses were busy with Boccaccio, Petrarch, and Dante. The enormous size of the great Speculum or Encyclopædia of 14 Vincent de Beauvais did not deter the printers of France and Germany, and the ponderous tomes of medieval theology and law seem to have found a ready market. Above all, the highest skill available in the best equipped workshops was employed almost ceaselessly in the production of beautiful and often magnificent editions of the service-books of the Church for the use both of priests and laity, and it is hardly possible to dabble much in old books without acquiring an interest in liturgiology.

Owing to this fact, that the early presses were so largely occupied with printing the works of the previous three centuries, there is comparatively little human interest in incunabula on their literary side. Instead of authors we have mostly to deal with editors, an assertive and depreciatory race, always vaunting their own accuracy and zeal and insisting on the incredible blunders by which previous editions had been deformed past recognition. We receive, however, no small compensation in the personal details which many of the early printers give us about themselves. Titlepages, though they occur at haphazard in a few books of the early seventies (and there is one still earlier example), did not become common till about 1490, and even twenty years later we find many books still without them. The information which we now expect to find on a titlepage was given in a paragraph, mostly at the end of the book, to which bibliographers have agreed to give the name “colophon,” from κολοφών, the Greek for a “finishing stroke.” As we have already noted, in many books no information of this kind is given, but when printers, or their proof readers or editors, took the trouble to write a colophon at all, they had no reason to confine themselves to the severe brevity and simplicity of statement which marks the modern titlepage. It was in colophons that editors cast stones at their predecessors, or demanded sympathy for the severity of their own labours, and it is in colophons that we find the expressions of the printer’s piety and pride, his complaints of his troubles with his workmen and rivals, his pleas for encouragement, and 15 occasionally, penned by another hand, the record of how he was struck down by death in the midst of his work. I have never heard of any one making a representative collection of books with interesting colophons, but collecting has taken many worse forms.

To lend grace to their colophons, or sometimes as a substitute for them, the early printers and publishers often used a woodcut containing their mark, sign, or device. Like the colophon itself, this was printed as a token of the master’s pride in his work and his desire that it might be recognized as his, and many printers’ marks are very decorative and even beautiful. Comparatively neglected until recently, within the last few years the devices used in various countries have been almost exhaustively reproduced in facsimile, thus leaving few chances of fresh discovery.

The mention of devices brings us to a very interesting section of early printed books, and one which has attracted only too much attention of recent years, those decorated with the primitive cuts on wood or metal with which fifteenth century printers endeavoured to imitate the glories of illuminated manuscripts, or to increase the popularity of their books with not too critical readers. Occasionally, as in the metal cuts in the best editions of the French Horae, in the Florentine and Venetian woodcuts of the last ten years of the century, and in the best work of other countries, these early pictures possess real beauty. Often they are badly spoilt by the incompetence of the cutters, who were working without the aid of modern gravers or modern methods of preparing the wood. The early German wood-cutters, whilst their outlines are often less graceful than those of their French and Italian competitors, had a special gift for characterization, and the quality of their work is much more uniform, perhaps because even before the invention of printing with movable types they were an organized craft. But in almost all fifteenth century cuts there is a certain naive simplicity which captivates those who allow themselves to study it, until they are apt, as the present writer has confessed is 16 probably true of himself, to rate it too highly. As is the case with the more ambitious artists in oils of the same periods, wherever there was any demand for book-illustrators a local school with strongly marked characteristics at once appears. The work of the Augsburg cutters can be told at a glance from that executed at Strassburg, and the styles predominant at Venice and Florence, at Milan and Naples are all absolutely distinct. With one or two exceptions we know nothing, until after 1500, of the men who designed or cut these illustrations, and (except in the case of those of the Low Countries) hardly any attempt has been made, or seems possible, to subdivide the work done in any given locality so as to group it under individual masters. Otherwise the problems of fifteenth century book-illustrations are much like the problems of the types with which they harmonize so well, and the collector can either devote himself to representing as fully as possible the work done in any single district, or range at large over the Continent (as regards fifteenth century illustrations England may almost be left out of account) and collect a few good specimens of each school.

It has been made a cause of complaint recently against bibliographers that they know more of the work done at any insignificant fifteenth century press than of the history of printing at any subsequent time. It is not easy to coerce men into taking up any sections of a subject beyond those in which they are interested, and the supposed culprits have at least this much justification for their neglect of the later work that very little of it repays examination. Until 1465, save for some possible Dutch experiments, Germany enjoyed the monopoly of printing. From 1465 to about 1530 she shared the primacy in it with Italy, though during most of this period Italy was slightly ahead; from 1530 to about 1570 France was far in advance of the rest of Europe; after 1570 there was a higher technical level in the Low Countries than elsewhere, and Plantin and the Elzevirs gained individual reputations. But there was very little good taste even in 17 the Low Countries, and from a typographical standpoint the seventeenth century is a Sahara with hardly any oases. From this wilderness the eighteenth century, under the guidance of France and England, timidly felt its way back to a kind of trim neatness, but the positive experiments of Baskerville and the Didots, and in Italy of Bodoni, were not very exciting, and at present are quite out of fashion. In the nineteenth century the work of the Whittinghams in England deserves more attention from collectors than it has received, and throughout the whole period any one working on historical lines, with the desire to illustrate the vicissitudes of the art of printing and not merely its successes, has an ample field. But for positive excellence, after the period of “origins,” the French books of the middle of the sixteenth century offer almost the only hunting ground in which the fastidious collector is likely to find an attractive quarry, and it is no use to try to tell any other tale.

Of the later book illustrations a somewhat better account may be given. Owing to the steady deterioration of paper and presswork, which was the real cause of the typographical decline, woodcuts by the end of the sixteenth century had gone quite out of fashion, the old simple style having been lost and no printer being able to do justice to the finer work on which designers insisted. But copper engravings throve in Germany and the Low Countries, and when the fashion of engraved frontispieces and titles took root in England in the last years of the century it was pursued with considerable success for a couple of generations, while in the eighteenth century the French livres à vignettes attained an extraordinary brilliancy and elegance, and Gravelot and other French engravers bestowed some of their skill on English books.

The use of wood, now worked with the graver and no longer with the knife, was revived in England by Bewick about 1784, and was pursued with varying success for over a century, great technical skill and, at least in the 18 “sixties,” very fine design being marred by the poverty and often the tawdriness of its typographical setting. Despite these drawbacks, the collectors who are bestowing attention on all this wood-engraved work of the nineteenth century will probably reap their reward.

When wood engraving was killed a few years ago by the extraordinary perfection attained, at a much smaller cost, by the process block, its fate was shared by the line-engraved illustrations which had appeared fitfully throughout the century, and had lingered on in the beautiful work of C. H. Jeens, who died in 1879, and in the use of old plates. As the wood engraving was killed by the half-tone block, so the line engraving disappeared before the photogravure, and the colour processes now being rapidly perfected threaten to reduce all black and white illustrations to unimportance. In so far, however, as the new processes necessitate the use of heavily loaded papers as a condition of their being even tolerably well printed, the least antiquarian of collectors may be forgiven for neglecting the books illustrated by them. Some of them can only be preserved by every plate being backed with sound paper, and a hundred years hence of all this illustrated work, much of it really beautiful, which is now being produced in such quantities, very little will remain. The modern Groliers whom we tried to call forth at the beginning of this chapter will need to be experts both in paper and in leather if they are to leave behind them any permanent record of their good taste. But this is only a crowning proof of how urgently they are needed.

It would be pleasant to glance briefly at some of the more literary considerations which bring books within the collector’s scope. But the scheme of this series restricts the subject of the present volume to books which are prized either for their typographical beauty, their place in the history of printing, or the charm of their illustrations. This is in itself so large a field that no more pages must be wasted on introducing it.

1 Even Mr. Carnegie will only help to found new libraries, not to make old ones more efficient.

2 During the Civil War itself presses were also set up temporarily at Newcastle-on-Tyne, at Shrewsbury, and perhaps elsewhere.

CHAPTER II

BLOCK-BOOKS

The collector of the time of George III, whose heart was set on Typographical Antiquities, and who was ambitious enough to wish to begin at the beginning, must have hungered after a block-book. Even in the days of Bagford, at the very outset of the eighteenth century, interest had been aroused in the block-printed editions of the Speculum Humanae Saluationis, so that Bagford himself travelled from Amsterdam to Haarlem on purpose to see a copy of one of the Dutch editions, and set an English wood-cutter to work, with very poor success, to manufacture a bogus specimen of it, wherewith “to oblige the curious.” This, with a similar imitation of a page in the Biblia Pauperum, was intended to illustrate the History of Printing which Bagford had the temerity to plan, although such of his smaller dissertations as have been preserved show conclusively that he was quite incapable of carrying it out.

The interest thus early shown in block-books sprang from an entirely reasonable, but probably incorrect, view of the part which they had played in the development of printing with movable type. It was known that woodcuts without letterpress were printed in Germany quite early in the fifteenth century, the cut of S. Christopher, formerly in the Spencer Collection, now in the John Rylands Library, bearing the date 1423.3 On the other hand, printing with movable type was practised at Mainz in the fifties, and about 1461 Albrecht Pfister published at Bamberg several books with woodcut illustrations 20 and printed letterpress. In the logical order of development nothing could be more reasonable than the sequence:

| i. | Woodcut pictures. |

| ii. | Woodcut pictures and woodcut text. |

| iii. | Woodcut pictures and text printed from movable type. |

Facts, however, do not always arrange themselves with the neatness which commends itself to an a priori historian, and the most recent students of block-books are unable to discover sufficient justification for the early dates which their predecessors assigned to them. On the old theory, in order to put it in front of the invention of printing with movable types, the Biblia Pauperum, which appears to be the oldest of the block-books, was placed about 1430 or 1440, and the Ars Moriendi and the other chief specimens of block-printing were all supposed to have been produced before 1460, the main period of block-printing thus coinciding with the interval between the S. Christopher of 1423 and Pfister’s activity at Bamberg about 1461. Positive evidence in favour of this chronology there was none. It rested solely on the idea, at which bibliographers had jumped, that the block-books were necessary “steps towards the invention of printing,” as they have often been called, and on what seemed the improbability that any one, when the art of printing with movable type had once been invented, would have troubled himself laboriously to cut letterpress on wood.

So far from block-printing being unable to co-exist with printing from movable type, it was not till nearly a century after printing had been invented that block-books finally ceased to be produced. The example generally quoted as the latest4 is the Opera nova contemplativa per ogni fedel christiano laquale tratta de le figure del testamento vecchio: le quale figure sonno verificate nel testamento 21 nuovo. As its title implies, this, curiously enough, is an adaptation of the Biblia Pauperum, which was thus the last, as it may have been the first, of the block-books. It is undated, but has the name of its publisher, Giovanni Andrea Vavassore, who worked at Venice about 1530.

The Opera nova contemplativa was from one point of view a mere survival, but Vavassore is not likely to have produced it solely to cause twentieth century antiquaries surprise. He must have had a business reason for having recourse to block-printing, nor is that reason very hard to find. From the frequency with which the early printers changed and recast their types, and the short intervals at which popular books printed with types were set up afresh, it is clear (1) that the type-metal5 employed was much softer and less durable than that now in use, and that only small impressions6 could be taken from the same setting up; (2) that only a small amount of type was cast at a time, and that type was quickly distributed and used again, never kept standing on the chance that another edition would be wanted. Now when we come to the illustrations in printed books, we find the same woodblocks used for five or six successive editions, and then, in many cases, enjoying a second lease of life as job-blocks, used at haphazard by inferior printers. It is clear, therefore, that while it was a much more difficult and laborious business to cut the letterpress of a book on blocks of wood than to set it up with movable types, when the blocks were once made much more work could be got out of them. In a word, in the case of a small book for which there was a steady demand, a printer might be tempted to have it cut as a 22 block-book for the same reasons as might cause a modern publisher to have it stereotyped. The labour of cutting the letterpress on wood was much greater than that now involved in stereotyping, and the result clumsier. Hence it was only to short books intended for unexacting purchasers that the process was applied and with two or three exceptions it was used only for illustrated books with a small amount of text. But within this restricted field it had its own commercial possibilities, and there is thus nothing surprising in its coexistence with printing from movable type.

When the theory that block-books were “Steps towards the Invention of Printing” is thus opposed by the rival theory that they were forerunners of stereotyped plates, we are left free to consider, uncoerced by supposed necessities, such evidence as exists as to the dates of the specimens of block-printing still extant. Putting aside the late Italian block-book as a mere survival, we find two7 broadly distinguished groups, one earlier, the dates of members of which can only be conjectured, the other later, several of which can only be definitely connected with the years 1470 to 1473. The characteristics of the earlier group are that they are printed (1) with a watery brown ink; (2) always on one side of the paper only; (3) without mechanical pressure;8 (4) two consecutive pages at a time, so that they cannot be arranged in quires, but must be folded and stitched separately, and the book thus formed9 begins and ends with a blank 23 page and has a pair of blank pages between each pair of printed ones. This arrangement in some extant copies has been altered by modern binders, who have divided the sheets, mounted each leaf on a guard, and then gathered them, at their own will, into quires. The inconvenient intervention of the blank pages has also sometimes been wrestled with (at an early date) by gluing the leaves together, so that all the leaves, except the first and last, are double, and the printed pages follow each other without interruption. These expedients, however, are easily detected, and the original principle of arrangement is free from doubt.

In the later block-books, on the other hand, we note one or more of the following characteristics: (1) the use of the thick black ink (really a kind of paint) employed in ordinary printing; (2) printing on both sides of the paper; (3) marks of pressure, showing that the paper has been passed through a printing-press; (4) the arrangement of the blocks in such a way as to permit the sheets to be gathered into quires.

In the case of the more popular block-books which went through many issues and editions10 we can trace the gradual substitution of later characteristics for earlier ones. At what intervals of time these changes were made we have bibliographically no adequate grounds even for guessing. Analogies from books printed with movable types may be quoted on both sides. On the one hand, we find the blocks for book-illustrations enjoying an amazingly long life. Thus blocks cut at Venice and Florence between 1490 and 1500 continued in use for fifteen or twenty years, were then laid aside, and reappear between 1550 and 1560, certainly the worse for wear, but yet capable by a lucky chance of yielding 24 quite a fair impression. The fact that one issue of a block-book can be positively assigned to 1470 or 1473, thus does not of itself forbid an earlier issue being placed as far back in the fifteenth century as any one may please to propose. On the other hand, when a printed book was a popular success editions succeeded each other with great rapidity, and one centre of printing vied with another in producing copies of it. The chief reason for the current disinclination to assume a date earlier than 1450 or 1460 for any extant block-book is the total absence of any evidence demanding it. If such evidence were forthcoming, there would be no inherent impossibility to set against it. But in the absence of such evidence twenty years seems an ample time to allow for the vogue of the block-books, and (despite the neatness of the a priori theory of development mentioned at the beginning of this chapter) this fits in better with the history both of printing and of book-illustration than any longer period.

The first attempt to describe the extant block-books was made by Carl Heinrich von Heinecken in 1771, in his Idée générale d’une collection d’estampes. This held the field until the publication in 1858 of Samuel Legh Sotheby’s Principia Typographica: the block-books issued in Holland, Flanders and Germany, during the fifteenth century, a painstaking and well-illustrated work in three folio volumes. The most recent and probably the final treatment of the subject is that by Dr. W. L. Schreiber, in Vol. IV of his Manuel de l’Amateur de la Gravure sur bois et sur métal au xve siècle, published in 1902 (facsimiles in Vols. VII and VIII, 1895-1900). Dr. Schreiber enumerates no fewer than thirty-three works as existing in the form of block-books, the number of extant issues and editions of them amounting to over one hundred. Here it must suffice to offer brief notes on some of the more important.

BIBLIA PAUPERUM

A series of forty composite pictures, the central compartment in each representing a scene from the life of Christ, while on each side of it is an Old Testament type, and above and below are in each case two half-figures of prophets. The explanatory letterpress is given in the two upper corners and also on scrolls. Schreiber distinguishes ten issues and editions, in addition to an earlier German one of a less elaborate design and with manuscript text, which belongs to a different tradition. The earlier of these ten editions appear to have been made in the Netherlands. An edition with German text was published with the colophon, “Friederich walther Mauler zu Nördlingen vnd Hans Hurning habent dis buch mitt einender gemacht,” and a second issue of this (without the colophon) is dated 1470. In the following year another edition, with copied cuts, was printed with the device of Hans Spoerer.

ARS MORIENDI

Twenty-four leaves, two containing a preface, and the remaining twenty-two eleven pictures and eleven pages of explanatory letterpress facing them, showing the temptations to which the dying are exposed, and the good inspirations by which they may be resisted, and, lastly, the final agony. The early editions are ascribed to the Netherlands or district of the Rhine; the later to Germany. There are also editions with German text, one of them signed “hanns Sporer,” and dated 1473. A set of engravings on copper by the Master E. S. (copied by the Master of S. Erasmus) may be either imitations or the originals of the earliest of these Ars Moriendi designs. (See Lionel Cust’s The Master E. S. and the Ars Moriendi.) The designs were imitated in numerous printed editions in various countries. In addition to a copy of the edition usually regarded as the 26 earliest extant, the British Museum possesses one with the same characteristics, but of a much smaller size (the blocks measuring 137 by 100 mm. instead of 226 by 162), and from this, as much less known, a page is here given as an illustration.

CANTICA CANTICORUM

Sixteen leaves, each containing two woodcuts, illustrating the Song of Songs as a parable of the Blessed Virgin. Produced in the Netherlands.

APOCALYPSIS SANCTI JOHANNIS

Fifty leaves, or in some editions forty-eight, showing scenes from the life of S. John and illustrations of the Apocalypse, mostly with two pictures on each leaf. The early editions are assigned to the Netherlands, the later to Germany. A copy of the edition regarded as the fourth, lately sold by Herr Ludwig Rosenthal, bears a manuscript note, most probably as to the writer, just possibly as to the book, entering the household of the Landgrave Heinrich of Hesse in 1463.

|

| III. ARS MORIENDI, BLOCKBOOK, C. 1465 INSPIRATIO CONTRA VANAM GLORIAM |

SPECULUM HUMANAE SALUATIONIS

Scenes from Bible history, arranged in pairs, within architectural borders, with explanatory text beneath. No complete xylographic, or block-printed, edition is known, but twenty leaves printed from blocks are found in conjunction with forty-four leaves printed from type, and have not unreasonably been held to prove the previous production of a complete block-printed edition now lost. In like manner, the fact that two different types are used in different parts of a Dutch printed edition has encouraged Dr. Hessels to believe that this “mixed edition” should be regarded as proving the production of two complete editions, one in each type. On this theory we have (1) a hypothetical Latin block-printed edition; 27 (2-4) three Dutch editions, each printed in a different type; (5) a Latin edition, entirely printed from type; (6) a Latin edition, printed partly from type, partly from some of the blocks of No. 1. The copy of this “mixed Latin edition,” as it is called, in the University Library at Munich, is dated in manuscript 1471, and the hypothetical complete block-printed edition may be as much earlier than this as any one pleases to imagine. But other bibliographers recognize only four editions and arrange them differently.

ANTICHRISTUS

Thirty-eight leaves, with two pictures on each leaf, illustrating the Legends relating to the Coming of Antichrist, and the Fifteen Signs which were to precede the Last Judgment. The text is in German, and the block-book was executed in Germany, probably about 1470.

FRANCISCUS DE RETZA. DEFENSORIUM INVIOLATAE CASTITATIS VIRGINIS MARIAE

Sixteen leaves, mostly with four pictures and four pieces of explanatory letterpress on each leaf, concerning marvels in the natural world which were supposed to be equally wonderful with that of the Virgin Birth, and therefore to render faith in this easier. Unfortunately the marvels are so very marvellous that they do not inspire belief, e.g. one story relates how the sun one day drew up the moisture from the earth with such rapidity that an ox was drawn up with it and subsequently deposited out of a cloud in another field. One edition was issued by a certain F. W. in 1470, another at Ratisbon by Johann Eysenhut the following year.

JOHANN MÜLLER (JOHANNES REGIOMONTANUS). KALENDER

Thirty-two leaves, containing lunar tables, tables of the eclipses for fifty-six years (1475-1530), other astronomical 28 information, and a figure of the human body with notes of the signs of the zodiac by which it was influenced. Composed by the famous astronomer, Johann Müller, and sold by Hans Briefftruck, probably Hans Spoerer, about 1474-5, at Nuremberg and elsewhere.

JOHANN HARTLIEB. DIE KUNST CHIROMANTIA

Forty-four figures of hands, with a titlepage and page of text and a printed wrapper. Early issues are printed on one side of the paper only, later on both. The printer appears to have been Jorg Schaff, of Augsburg, and the date of issue about 1475. The date 1448 found in the book is that of composition, and it probably circulated in manuscript for many years before being printed.

MIRABILIA ROMAE

A German guide-book for visitors to Rome. Ninety-two leaves, printed with black ink on both sides of the leaf, with only a few illustrations. It was perhaps first published to meet the rush of German pilgrims to Rome at the Jubilee of Pope Sixtus IV, 1475. The blocks were probably cut in Germany, and the printing done at Rome. Some of the ornaments are said to have been used in type-printed editions by Stephan Plannck. This suggests that the book may have been published by his predecessor, Ulrich Han.

In addition to these block-books of Low Country and German origin, mention must also be made of a very curious Italian one, a Passio domini nostri Jesu Christi, fully described by the Prince d’Essling. The copy of this at Berlin contains eighteen leaves, and was probably executed at Venice about the middle of the fifteenth century. Some of the blocks were subsequently used (after a scroll at the foot had been cut off) for an edition of the Devote Meditatione sopra la Passione del Nostro 29 Signore (attributed to S. Bonaventura), published at Venice in 1487 by Jeronimo di Sancti e Cornelio suo Compagno, and a page from this is reproduced as a frontispiece to our chapter on Italian Illustrated Books.

Mention has already been made of the Opera nova contemplativa, an adaptation of the Biblia Pauperum, printed as a block-book at Venice about 1530.

The only extant French block-book, if it can be called one, is that of the “Nine Worthies” (Les Neuf Preux). This consists of three sheets, the first showing three heathen worthies—Hector, Alexander, and Julius Cæsar; the second, three from the Old Testament—Joshua, David, and Judas Maccabæus; the third, three from medieval romance—Arthur, Charlemagne, and Godfrey of Boulogne. Under each picture are six lines of verse. These three triple woodcuts, with the woodcut text, are assigned to about 1455.

No English block-book has yet been discovered, nor is it in the least likely that one ever existed, though there are a few single woodcuts.

Block-books possess two permanent attractions in addition to their supposed historical importance in the development of the invention of printing on which doubt is now cast—the attraction of popular literature and the attraction of the illustrated book. As we have seen, it would not have been worth any one’s while to cause a block-book to be laboriously engraved, or cut, unless a large and speedy sale could be expected for it. The most famous block-books are nearly all of a religious character, and they prove a widespread desire for simple instruction as to the incidents of the life of Christ and the events in the Old Testament history which were regarded as prefigurements of them, as to the dignity of the Blessed Virgin and the doctrine of the Virgin Birth, as to the end of the world and the coming of Antichrist, and as to the spiritual dangers and temptations of the dying and the means by which they might be resisted. 30 As early specimens of book-illustration the value of the block-books varies very greatly. The majority of them are more curious than beautiful, but the pictures of the Cantica Canticorum, the Speculum Humanae Saluationis, and the Ars Moriendi have all very great merit. The tall, slender figures in the Song of Songs have a charm as great as any Dutch book-illustrations of the fifteenth century; the cuts of the Speculum are full of vigour, while the serene dignity of the scenes in the Ars Moriendi illustrating the Inspirations of the Good Angel is as impressive as the grotesque force used in depicting the diabolic suggestions. If we must grant, as the weight of authority now bids us, that these woodcuts are copies from the copper engravings of the Master E. S., it can hardly be disputed that the wood-cutter was the better artist of the two.

The block-books are a striking example of the difficulty of gleaning where the earlier collectors have reaped, a difficulty to which we shall often have to call attention. They vary greatly in positive rarity. Of the Biblia Pauperum and Ars Moriendi, which in their different issues and editions enjoyed the longest life and early attracted attention, Dr. Schreiber (if I have counted rightly) was able to enumerate in the one case as many as eighty-three copies—many of them, it is true, mere fragments—in the other sixty-one. Of the Apocalypse fifty-seven copies were known to him, of the Speculum twenty-nine, of the Antichrist thirteen, of the Defensorium twelve, and of the Mirabilia Romae six. But of these 261 copies and fragments no fewer than 223 are recorded as being locked up in public libraries and museums, the ownership of thirteen was doubtful, and only twenty-five are definitely registered as being in the hands of private collectors, viz. of the Apocalypse, eight copies or fragments; of the Biblia Pauperum, six; of the Speculum and Ars Moriendi, four each; of the Defensorium, two; and of the Cantica Canticorum, one. The chief owners known to Dr. Schreiber were the Earl of 31 Pembroke, Baron Edmond de Rothschild, and Major Holford, to whom must now be added Mr. Pierpont Morgan and Mr. Perrins. No doubt the copies in public institutions are much more easily enumerated than those in private hands, and probably most of the untraced copies are owned by collectors. But when allowance has been made for this, it remains obvious that this is no field where an easy harvest can be reaped, and that the average collector may think himself lucky if he obtains one or two single leaves. The last great opportunity of acquiring such treasures was at the sale in 1872 of the wonderful collection formed by T. O. Weigel,11 at which the British Museum bought a very fine copy of the first edition of the Ars Moriendi, the first edition, dated 1470, of the Biblia Pauperum, in German, a block-book illustrating the virtues of the hymn Salve Regina, and the compassion of the Blessed Virgin, printed at Regensburg about 1470, besides fragments and woodcut single sheets. The foundation of the Museum collection of block-books had been laid by George III, added to by Mr. Grenville, and completed by a series of purchases from 1838 to this final haul of 1872, since when there have been few opportunities for new acquisitions. It is now quite adequate for purposes of study, though not so rich as that of the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris.

3 The authenticity of a still earlier date, 1418, on a cut of the Blessed Virgin at Brussels is disputed.

4 The Libro di M. Giovanbattista Palatino, printed at Rome in 1548, is spoken of by Mr. Campbell Dodgson as a “belated specimen” of a block-book. But this was a writing-book, and hardly counts.

5 Numerous references in colophons show that the metal mostly used was brass, e.g. “Primus in Adriaca formis impressit aenis Vrbe libros Spira genitus de stirpe Johannes,” and the use of Chalcographi as a name for printers. But there are one or two references to printing “stanneis typis,” with types of tin.

6 Of the first book printed at Venice only 100 copies were struck off, but the number was trebled in the case of its immediate successors. At Rome Sweynheym and Pannartz mostly printed 275 copies, only in a few instances as many as 300. But at the end of the century Pynson was printing at least 600 copies of large books and as many as 1000 of small ones.

7 A very small third group, earlier than either of these, consists of woodcuts with manuscript text. The most important of these is a German Biblia Pauperum quite distinct from those started in the Netherlands.

8 Some early woodcuts were printed by pressing the block down on the paper by hand; for the early block-books, however, the usual method seems to have been to press the paper on to the face of the block by rubbing it on the back with a burnisher. The paper was thus quite as strongly indented as if passed through a press, but the impression is usually less even. The friction on the back of the paper often gives it a polished appearance. As long as this method continued in use it was, of course, impossible to print on both sides of the paper.

9 It is possible that the earliest specimens of block-printing were intended not to be bound in books but to be pasted on walls. In the case of the Biblia Pauperum, for instance, the space between the two woodcuts placed on each sheet is so small in some issues that the sheets cannot be bound without concealing part of the pictures.

10 Different issues are distinguished by the signs of wear in the blocks, or occasionally by their being differently arranged, or with changes made in the blocks. In a different edition we have to deal with a new set of blocks.

11 Since this was written the interesting collection formed by Dr. Schreiber himself has been dispersed.

CHAPTER III

THE INVENTION OF PRINTING—HOLLAND

Up to the year 1465 only one firm of printers evinced any appreciation of the uses of advertisement. In 1457 Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer, of Mainz, set their names at the end of the liturgical Psalter which they were issuing from their press, and stated also the date of its completion, “In vigilia Assumpcionis,” on the vigil of the feast of the Assumption, i.e. August 14th. Save in the case of a few unimportant books this preference for publicity remained the settled practice of the firm until Peter Schoeffer’s death early in the sixteenth century, and later still when it was in the hands of his son Johann. With other printers at first the tendency was all the other way. Albrecht Pfister placed his name in one or two of the handful of popular illustrated books which he printed at Bamberg about 1461. No other book before 1465 contains its printer’s name, and both at Strassburg and at Basel the practice of publishing anonymously continued in fashion throughout the ’seventies—in Strassburg, indeed, for the best part of another decade.

|

| IV. EARLY DUTCH PRESS ALEXANDER GALLES, DOCTRINALE (3a) |

While printing continued mainly anonymous chroniclers took no note of it, but in the ten years which began in 1465 the progress of the art was rapid and triumphant. Printers, mostly Germans, invaded the chief cities of Europe, and boasted in their books of having been the first to practise it in this place or that. Curiosity as to the beginnings of the invention was thus aroused, and from 1470 onwards we meet with numerous attempts, not always accurate, to satisfy it. The earliest of these attempts is in a letter from Guillaume 33 Fichet, a Professor at the Sorbonne, who was mainly responsible for bringing the first printers to Paris, to his friend Robert Gaguin. This is contained in one copy of the second Paris book, the Orthographia of Gasparinus Barzizius, printed in 1470, Fichet having a fondness for giving individuality to special copies by additions of this kind. In this letter he speaks of the great light which he thinks learning will receive from the new kind of bookmen whom Germany, like another Trojan Horse, has poured forth.

Ferunt enim illic, haut procul a ciuitate Maguncia, Ioannem quendam fuisse cui cognomen bonemontano, qui primus omnium impressoriam artem excogitauerit, qua non calamo (ut prisci quidem illi) neque penna (ut nos fingimus) sed æreis litteris libri finguntur, et quidem expedite, polite et pulchre. Dignus sane hic uir fuit quem omnes musæ, omnes artes, omnesque eorum linguæ qui libris delectantur, diuinis laudibus ornent, eoque magis dis deabusque anteponant, quo propius ac presentius litteris ipsis ac studiosis hominibus suffragium tulit. Si quidem deificantur Liber et alma Ceres, ille quippe dona Liei inuenit poculaque inuentis acheloia miscuit uuis, hæc chaoniam pingui glandem mutauit arista. Atque (ut poeta utamur altero) prima Ceres unco glebam dimouit aratro, prima dedit fruges alimenta mitia terris. At bonemontanus ille, longe gratiora diuinioraque inuenit, quippe qui litteras eiusmodi exculpsit, quibus quidquid dici, aut cogitari potest, propediem scribi ac transcribi & posteritatis mandari memoriæ possit.

The good Fichet is absurdly rhetorical, but here in 1470 is a quite clear statement that, according to report, there (i.e. in Germany), not far from12 the city of Mainz, a certain John, surnamed Gutenberg, first of all men thought out the printing art, by which books are fashioned not with a reed or pen, but with letters of brass, and thus deserved better of mankind than either 34 Bacchus or Ceres, since by his invention whatever can be said or thought can forthwith be written and transcribed and handed down to posterity.

Four years later in his continuation of the Chronica Summorum Pontificum, begun by Riccobaldus, Joannes Philippi de Lignamine, the physician of Pope Sixtus IV, who had set up a press of his own at Rome, wrote as one of the events of the pontificate of Pius II (1458-64), how “Jakob Gutenberg, a native of Strassburg, and a certain other whose name was Fust, being skilled in printing letters on parchment with metal forms, are known each of them to be turning out three hundred sheets a day at Mainz, a city of Germany, and Johann Mentelin also, at Strassburg, a city of the same province, being skilled in the same craft, is known to be printing daily the same number of sheets.”13 A little later De Lignamine records the arrival at Rome of Sweynheym and Pannartz, and also of Ulrich Han, and credits them also with printing three hundred sheets a day. Other references follow in later books without adding to our knowledge, save by proving the widespread recognition in the fifteenth century that printing was invented at Mainz; but there is nothing specially to detain us until the publication by Johann Koelhoff in 1499 of the Cologne Chronicle—Die Cronica van der hilliger Stat Coellen—in which occurs a famous passage about printing, which may be translated or paraphrased as follows:—