Sir William Cornwallis Harris

"The Highlands of Ethiopia"

Introduction

In putting forward a second edition of my “Highlands of Ethiopia,” I have two very different duties to perform: first, to thank the press for the extremely liberal and generous manner in which it has received my work; secondly, to reply to certain objections which have been made by one or two periodicals, happily not of the first eminence, against both me and my travels. So numerous, however, are the publications that have evinced a favourable, I might almost say a friendly, disposition towards me, that I am unable to specify them. They will, therefore, I trust, accept in general terms my thanks to them one and all.

Their very flattering testimonies have induced me to revise carefully what I have written, in order, if possible, to render it worthy of their warm praise, and to justify their predilection in my behalf. On the other hand, fas est et ab hoste doceri. I have consequently turned to account even the animadversions of my enemies—for enemies unhappily I have, and those, too, of the most implacable and malignant character—mean persons to whom I have shown kindness, which they have apparently no means of repaying but by inveterate aversion. This circumstance I ought not perhaps to regret, except on their account. The parts we play are suitable to our respective characters; and I should even now abstain from prejudicing them in the estimation of the public, if I did not apprehend that my forbearance might be misconstrued.

The points of attack selected by my adversaries are not many in number. Ultimately, indeed, they resolve themselves into three: first, my style of composition, which they say is gorgeous and inflated, and therefore obscure; second, the inaccuracy of several of my details; and third, the absence of much new information, which it seems the public had a right to expect from me. On the subject of the first accusation it will not perhaps be requisite that I should say much. To any one who cannot understand what I write I must necessarily appear obscure; but it may sometimes, I think, be a question with which of us the fault lies. That my composition is generally intelligible may not unfairly, I think, be inferred from the number of persons who have understood and praised it; since it can scarcely be imagined that the majority of reviewers would warmly recommend to the public that in which they could discern no meaning. Besides, on the subject of style there is a great diversity of opinion, some thinking that very extraordinary scenes and objects should be delineated in forcible language, while others advocate a tame and formal phraseology which they would see employed on all occasions whatsoever. I may observe, moreover, that “style,” as Gibbon remarks, “is the image of character,” and it is quite possible that my fancy may have a natural aptitude to take fire at the prospect of unusual scenes and strange manners. Still I am far from defending obstinately my own idiosyncracies, and yet farther from setting them up as a rule to others. In describing what I saw, and endeavouring to explain what I felt, I may very possibly have used expressions too poetical and ornate; but the public will, I am convinced, do me the justice to believe that, in acting thus, my object was exactly to delineate, and not to delude. I called in to my aid the language which seemed to me best calculated to reflect upon the minds of others, those grand and stupendous objects of nature which had made so deep and lasting an impression on my own. At all events, I am not conscious of having had in this any sinister purpose to serve.

It is a far more serious charge, that I have presented the public with a false account of the Embassy to Shoa; that I have altered or suppressed facts; that I have been unjust to my predecessors and companions; and that I have at once misrepresented the country and its inhabitants. It has been already observed, that my accusers are few in number. Probably they do not exceed three individuals, two who affect to speak from their own knowledge, and one whom they have taken under their patronage as their cat’s-paw. It may seem somewhat humiliating to answer such persons at all. I feel that it is so. But if dirt be cast at me, I must endeavour to shield myself from it, without enquiring whether the hands of the throwers be naturally filthy or not. That is their own affair. Mine is to avoid the pollution aimed at me. This must be my apology for entering into the explanations I am about to give.

When I undertook to lay before the public an account of my travels in Abyssinia, I had to choose between the inartificial and somewhat tedious form of a journal, and that of a more elaborate history, in which the exact order of dates should not be observed. I preferred the latter; whether wisely or unwisely remains to be seen, though hitherto public opinion seems to declare itself in favour of my choice. Having come to this determination, it was necessary that I should act in all things consistently with it. As I had abandoned the journal, it was no way incumbent on me to observe the laws which govern that form of composition. My business, as it appeared to me, was to produce a work with some pretensions to a literary character; that is, one in which the order of time is not regarded as a primary element, the principal object being the grouping of events and circumstances so as to produce a complete picture. I perfectly understood that I was to add nothing and to invent nothing, but that I was at liberty to throw aside all trivial details, and dwell only on such points as seemed calculated to place in their proper light the labours of the mission, with the institutions, customs, and type of civilisation found among the people to whom we had been sent. In conformity with this theory I wrote. One of the first consequences, however, of the view I had taken of my subject, was the sacrifice of all minute personal adventures, which scarcely appeared in any way compatible with my plan. I abandoned likewise the use of the first personal pronoun, and always spoke of myself and my companions collectively, thereby perhaps doing some little injustice to my own exertions, but certainly not arrogating to myself any credit properly due to others. Among my friends there are those who object to this manner of writing, and I submit my judgment to theirs. In this Second Edition, therefore, I have reconstructed the narrative so far as was necessary in order to convert the third person into the first. To the charge that I have not observed the strict chronology of a journal, I have already pleaded guilty. It seemed to me far better to arrange together under one head whatever belonged properly to one topic. For example, when recording the medical services rendered to the people of Shoa, high or low, I have not inserted in my work each individual instance as it occurred, but have placed the whole before the reader in a separate chapter. So likewise in other cases, that which appeared to elucidate the matter in hand, was introduced into what I thought its proper place, because there it might both receive and reflect light, whereas in any other part, perhaps, of the work, it might have been without significance, if not altogether absurd. Not being infallible, I may possibly have misinterpreted the laws of rhetoric which I adopted as my guide: of this let the public be judge. I have aimed, at all events, at drawing a correct outline of Shoa and the surrounding countries, as far as my materials would permit, and should I have sometimes fallen into error, I claim that indulgence which is always readily extended to authors similarly circumstanced. While in Abyssinia, my official position very greatly interfered with my predilections as a traveller. I could not move hither and thither freely. To enlarge the circle of science was not the principal object of my mission; but at the same time it must not be forgotten that I enjoyed some advantages which a traveller visiting the country under other auspices would scarcely have commanded. In drawing up my work, however, the character in which I travelled was of considerable disservice to me. Much of the information that I collected, it was not permitted me to impart, which I say, not by way of complaint against the regulations of the service in which I have the honour to be engaged,—on the contrary, I think it most just and proper that such should be the case—but that the reader, when he feels a deficiency in political or commercial information, may know that it has not been withheld through any negligence or disrespect of the public on my part.

I now come to consider more in detail the objections which have been urged against my travels. Some of these, it will at once be perceived, are so loose and indefinite as to be wholly incapable of being answered. For example, it is said, I have made no addition to the information already existing respecting the southern provinces of Abyssinia. How can I reply to this? Must I reprint all the works which had been previously published, and point out the additions I have made? The process, it will be acknowledged, is an unusual one. Besides, the scientific world has not hitherto been averse to look at several views of the same country, to compare them for itself, and to derive from the very comparison both pleasure and information. Some additions, moreover, to geographical science I undoubtedly have made, and there are those who have not been ashamed to borrow them. I have ascertained, for example, that the Gochob does not flow into the Nile, as it is made to do in a map which I have seen, constructed by one of the reviewer’s greatest authorities. The inquiries I instituted render it probable that the Gochob is the same river with the Juba. And, above all, the longitude of Ankóber was, under my directions, and by a laborious series of operations, correctly determined. The importance of this to travellers who may not possess the ability or the means of resolving it themselves, I need scarcely point out. Previously, every position in the maps of Southern Abyssinia was calculated from a false position, and therefore of necessity wrong. But I shall not here enter upon an inventory of my humble services to science. I could wish they were more numerous, but such as they are I trust they will be found not wholly without their value.

In “ethnography,” or rather perhaps “ethnology,” the critic discovers my ideas to be all wrong; and he accounts for the circumstance by supposing in me some innate aversion to the “savage.” I certainly dislike that particular variety of our species whether at home or abroad, but it does not necessarily follow that I have been therefore guilty of misrepresentation. These things, nevertheless, I leave to be determined by public opinion, which, so far as I can perceive, is little, if at all, influenced by the bitter and self-interested censures of my enemies.

When I determined on making some reply to the “slashing” Aristarchus who has assailed my work—I would say publicly, but that the thing is so obscure that few persons have even heard of it—my design was to attempt something like order, that I might not by a multiplicity of disjointed remarks confound the memory of my readers. But the impossibility of following any rational plan soon became apparent. The reviewer with whom I have to deal is a man who scorns all order and regularity. His only rule is that of hysteron proteron, or putting the cart before the horse. Not possibly that he considers such a method of writing best in itself, but that by introducing perfect anarchy into his critique, and returning a dozen times to each objection urged, my faults might in appearance be so multiplied that they would suffice to fill a whole encyclopaedia. Now if in my reply I followed any other than his fragmentary system, I might perhaps seem to many not to answer all his objections, whereas my intention is to demolish every one of them. I resolved therefore to begin ab ovo, and giving quarter to no impertinence or absurdity by the way, to clear the ground completely, and leave a perfect rase campagne behind me. That in so doing I shall not prove tedious, is more than I can hope. My adversary is insipidity personified. But if the controversy be unamusing, it shall, at least as far as I can render it so, be brief.

The critic whose vagaries I have undertaken to expose, though affecting not to be hypercritical, first dwells with a puerile pertinacity on the title of my book, which he pronounces to be a misnomer, because, forsooth, the territories of Shoa are not high lands, but a high land! Possibly he figures to himself the whole of Abyssinia as one single vast plateau, whose surface presents neither elevation nor depression, otherwise the reader will see no reason why it should be spoken of in the singular.

In describing the contents of the second volume, my reviewer speaks of “a slaving expedition among the Galla, in which the Embassy,” he affirms, “took part.” The assertion, however, is incorrect, not to apply to it a harsher epithet; for the spectator who looks on a play can with no propriety be said to take part in the acting of it. The mission was sent to Sáhela Selássie, not to the city of Ankóber. It was consequently my business to attend the king, to watch his movements, and study his character, just as the Embassy under Sir John McNeil attended the Shah of Persia to Herát, though instead of taking part in the siege, he laboured earnestly to put a stop to it.

The contents of the third volume are next wilfully misrepresented, the critic desiring to make it appear that a very small portion indeed has reference to the country or people of Abyssinia, though at least two-thirds treat expressly of those subjects, whilst the remainder is strictly connected with them.

But it is not merely in the third volume that the critic is unable to discover any information respecting Shoa. He takes courage as he proceeds, advances from particulars to generals, and contends that the book contains no information at all in any part of it, that no account is given of the geography of the country, no sketch of its history, in short no account of it in any way whatsoever. Afterwards, indeed, an exception is made in favour of religion. Taking no interest in this, however, he treats it as a twice-told tale with which he was previously familiar. Considering the modes of thinking prevalent in the quarter, it may, without much uncharitableness, be permitted one to doubt this. Not to insist, however, on a point which may be disagreeable to the reviewer, I hasten to compliment him on his sagacity, which, through the table of contents, has made the discovery, that the political history of Abyssinia for the last thirty years is not given. I acknowledge the omission, and may perhaps have been to blame for suffering any consideration connected with the size of the volumes to weigh with me in such a matter. The historical sketch in question, however, was actually written, though the critic would probably not have derived from it any more satisfaction than from the rest of the book. He objected to its absence because it was not there. Had I introduced it, he would have said it was a twice-told tale, and absolutely good for nothing.

My adversary now and then qualifies, as he proceeds, his absolute affirmations. Having again and again maintained that there is no account, “historical or otherwise,” given of the country, he afterwards admits his error, but says the account is “confused and unintelligible.” I think it was Mr Coleridge who made the remark, when persons complained that they could not understand his work, that it was their fault, since all he had to do was to bring the book, and that it was their duty to bring the understanding. I make the same reply to the critic. Other people understand my account of Abyssinia; and if he really does not, I am sorry for him, but can offer him no assistance. However, there is an old proverb, I believe, which says, “There are none so blind as those who won’t see.”

The argument by which I am proved to have read Mr Salt, though I make no allusion to him, is curious; but I either profited by my reading, or I did not. If I profited, the consequences must be visible in my work; if I derived nothing from Mr Salt, then my work can contain no proof that I did. But it does, according to the critic, contain such proof; ergo, I have profited by Mr Salt’s labours. It would have been well, however, if the critic had pointed out where and how much; for until he does so, my word will probably be thought as good as his, especially as he is anonymous, and I am not. One proof of my careless reading of Mr Salt is, I own, very remarkable. It seems, had I been well versed in his production, I should have known that Oubié is “still alive and ruler of Tigré;” Mr Salt having, of course, been careful to relate that circumstance. It so happens, however, that at the period I was engaged in writing my work, Oubié was a prisoner, and another prince seated on his throne—a fact, I believe, not preserved in Salt.

Next comes on the tapis the orthography of Ethiopia; apropos of which, the critic takes occasion to call in question my classical acquirements. I was not, however, aware that, by preferring one orthography to another, I was laying claim to profound erudition, or setting myself up for “an authority among scholars.” On the contrary, I followed those who appeared to me very sufficient guides. Gibbon and Dr Johnson,—authors who may perhaps, even by the reviewer himself, be permitted to claim a humble niche among our classics. But they wrote, it may be said, in the last century. I therefore refer to a perfectly new publication, on a classical subject, if not the work of a classic,—I mean Mr Saint John’s “History of the Manners and Customs of Ancient Greece,” in which the orthography I have adopted is likewise made use of. If then I have been affected, I have at all events indulged my affectation in very good company. But the reviewer does not stop here. He thinks the orthography involves a mystery, and he goes about the unveiling of it in a very mysterious way. It is a proof he thinks that I am indebted to Mr Krapf for what little proficiency I may have made in the art of spelling; nay more, that I have derived from that gentleman all my knowledge of Abyssinia of every kind!

Before I make any other remark on this part of the subject, I will take occasion to compliment myself on my simplicity; for if I had desired to conceal my obligations to Dr Krapf, and have been conscious of any which I have not frankly stated, I should have been careful to spell Ethiopia classically, that is, as the reviewer does, in order to conceal the source from which I had drawn. I should thus clearly have put him on a very wrong scent, since a single letter suffices to lead him by the nose. But the most curious view of this question remains yet to be taken. Dr Krapf, he says, possesses the most complete knowledge of Abyssinia, its geography, language, and literature. He then goes on to maintain that Dr Krapf imparted his knowledge to me, and I that same knowledge to the public. But, no! the reviewer stops short here, and affirms that I envied the public the possession of Dr Krapf’s knowledge, and withheld it all; since he everywhere asserts that there is no information whatever in my book. Verily, I have been taking a lesson from that ancient Briton who is represented as having plundered a naked Scotchman:

“A painted vest Prince Vortigern had on,

Which from a naked Pict his grandsire won!”

Because, if I tell nothing new, and owe all I do tell to Dr Krapf, who also imparted to me all he knew, his knowledge must clearly have been very limited. I have acknowledged, however, and I repeat the acknowledgment, that Dr Krapf was of essential service to me in various ways; that he freely imparted to me the valuable information he possessed, and gave me to understand that I was at liberty to make use of it. I did make use of it, having previously however been careful to publish my obligations to him. In fact, there is no man who would be more ready than Dr Krapf, were he now in England, to express his perfect satisfaction with what I have done. He has, indeed, expressed it publicly in his “Journal,” where he acknowledges himself to be under obligations to me; and the Church Missionary Society, in its preface, makes the same admission.

I am next blamed for not giving a connected history of the mission; the proper answer to which is, that I never undertook to give it. I have not entitled my book “the History of an Eighteen Months’ Residence in Shoa,” but have said that my observations were collected during an eighteen months’ residence there. They are not all my observations, nor have I arranged them chronologically; therefore, though the reviewer feels disappointed, he has no right to quarrel with me. He expected one thing—I published another; simply because I did not write for him, or such as he, but for the public. As it is, however, I am not sorry that he is “tantalised,” which he would not be if he possessed one-tenth of the knowledge to which he obliquely lays claim. On most points he is profoundly ignorant, and it suits my purpose to leave him so. Any information that I can impart, without prejudice to the public service, it is doubtless my duty to give; and accordingly, in this second edition, I have stated some facts not recorded in the first. In most cases, indeed, men publish a first edition as an experiment, to ascertain how far their views of what information the public needs are correct, that they may afterwards diligently, and to the best of their power, supply it.

The Mission, it is said, has been “a complete failure.” But how is this proved? By a scrap extracted from some anonymous correspondent to a newspaper, who writes, not from Angollála or Ankóber, but from Caïro, which is nearly as though a person residing in Saint Petersburgh were to write authoritatively to China respecting what is going on in Lisbon. But it does not follow that the Mission has been a failure, because some Cairo gossip chooses to say so, or because all the fruits of it have not yet been reaped. A treaty has been concluded, friendly relations have been established, and upon this basis commerce will proceed, slowly perhaps, but surely, to erect its structure. It will be for the next generation to determine whether or not the mission was “a complete failure.” A reviewer residing in the purlieus of High Holborn is not competent to do it.

On the subject of “German crowns,” the critic may, for aught I know, be a great authority; or, as he says on another matter, may know somebody that is. But the quarrel which he seeks to pick with me is so utterly puerile, that I will not engage in it. His positiveness, however, is as usual proportioned to his ignorance, for even on so infinitesimal a point as this he contrives to be wrong, since the marks are not three, as he supposes, but seventeen, on the coronet and shoulder-clasp. However, supposing I had here been wrong, would it therefore have been fair to infer that on every other point I must be wrong also? An usurer would be a better authority on the aspect of a gold coin than the Chancellor of the Exchequer, yet in finance the Jew might not be a match for the Chancellor. Let it not, however, be supposed that I desire to compare myself with Mr Goulburn, or the critic to a Jew; I merely mention these things by way of illustration. At any rate, my censor’s blunder must be obvious to every one who has seen a German dollar, and to adopt his own phrase, “Ex pede Herculem.”

On the practice observed by the Mohammadans in slaughtering animals, the reviewer displays a vast deal of erudition, and quotes the treatise of Mr Lane, on the “Manners of the Modern Egyptians.” It happens, however, that there are variations in the practices of the Moslems; and he might as well have argued, that because there are pyramids in Egypt, there must also be pyramids in Abyssinia, as that because the Egyptians do not make use of certain words on particular occasions, therefore, the Danákil and the Somauli cannot possibly employ them. My narrative does not touch on the customs of Egypt, on which Mr Lane writes but on those of a different part of Africa, in which, so far as I can discover, that author has never been. What I relate, however, is matter of fact, and the critic only exhibits his profound ignorance of human nature by supposing that Mohammadanism is stereotyped in any part of the world, since there are as many differences in the customs of the Mohammadan nations, as in those of Christendom. For example,—the practice of “bundling,” so common in Wales, does not, I believe, prevail in Egypt; but if our critic were to infer that it is, therefore, altogether anti-Islamite, he would be as completely wrong as he is in the present instance; for that which the Egyptian Mussulman detests, is the established custom in certain parts of Afghanistan. So, likewise, is the invocation of the name of God during the slaughter of animals. The Egyptians, it seems, invoke the sacred name without coupling with it “the Compassionate, the Merciful,” which they think would sound like mockery; but what proof is the reviewer prepared to advance in his wisdom, that this rule is observed in India and every other part of the East?

The Mohammadans, again, he says, never drink blood; and why? because it is forbidden them by the Korán. But stealing is no less peremptorily prohibited. Will he, therefore, argue, that there is no such thing as a Mohammadan thief? The question is not as to what is forbidden or ordained, but as to a simple matter of fact. I state what I saw with my own eyes. The critic, who was never in the country, who cannot possibly know what I saw or did not see, contradicts me. I leave it to the public to judge between us; asserting, however, that he is fully as ignorant of the people whose customs he so glibly writes about, as he is of the rules of common decency.

For verbal criticism I entertain no contempt, though I think that a strict application of its rules to a book of travels, is scarcely called for. However, let us see how the critic succeeds in his task. I relate that the Arabs call the cove Mirsa good Ali, the “source of the sea;” from which he immediately infers my utter ignorance of Arabic. The only thing, however, that is really clear from the remark he has made is, that he does not understand English when it happens to be in the slightest degree inverted. A Biblical critic. Dr Parr, if I remember rightly, objected to a passage in the English version of the Bible upon much the same grounds. “Thus,” says the Scripture, “he giveth his beloved sleep.” Now the doctor maintains “beloved” to be an epithet bestowed on sleep, although the real sense is, that sleep is given to the “beloved.” Still, in my opinion, the meaning is so obvious, that it required some ingenuity to mistake it. In my own case, the meaning I think is equally obvious; at least, what I intended to say was, that the Adaïel bestow on Mirsa good Ali cove, the additional name of “the source of the sea.”

Upon the remarks on “mafeesh,” I scarcely know what to say; but if he were to ask me,—is there any point or sense in them? I should reply “mafeesh, there is none”—an idiom well understood in English. Let the critic try again at Richardson’s dictionary, and if he really can make out the Arabic characters, I think he will be able to discover a meaning which would come in very properly where I have placed it. “It is of no consequence,” exclaimed the young assassin, “none,” which is precisely the answer sometimes given to the insatiate “beggars” that we are told “surround the traveller” in certain countries, “there is no money in my pocket—none.” Nevertheless, as I have passed public examinations, and obtained certificates of superior proficiency in no more than four oriental tongues, I cannot be deemed so competent to offer an opinion on this subject as the reviewer and his accomplices.

With regard to the critiques on the Amháric expressions found in my work, it may be sufficient to say, that by his own confession “the reviewer does not understand one syllable of the language,” but hazards his remarks on the strength of knowing somebody who does. This appears to me a very poor qualification. It is as though I should set up as a critic in Sanscrit because I have shaken hands with Professor Wilson. However, let us examine the notions of this man who is so learned by proxy. One of the greatest triumphs of his erudition is his explanation of the Amháric word “Shoolada,” which, strengthened by Salt, and others, he determines to signify exclusively a “rump-steak.” That it has this signification there can be no doubt, but if the critic be disposed to defer on this, as on other occasions, to Dr Krapf’s Amháric scholarship, he may yet, as he expresses it, “live and learn.” In a copy of manuscript notes in Dr Krapf’s handwriting, still in my possession, occurs the following passage, which I quote verbatim et literatim:—“In one point the Abyssinian practices agree remarkably with those of the Jews, we mean the practice mentioned in Genesis chapter xxxii, where we find that the Israelites did not eat the nerve, since Jacob had been lamed in consequence of his earnest supplication to the Almighty, before he met his brother Esau. This nerve is called in Amháric ‘Shoolada.’ I cannot determine how far the abstinence from this kind of meat is kept in the other parts of Abyssinia, but it is a fact in Shoa, that many people, particularly those of royal blood (called Negassian), do not eat it, as they believe that by eating it they would lose their teeth, the Shoolada being prohibited and unlawful food. Therefore, if anybody has lost his teeth, he is abused with the reproach of having eaten prohibited meat, as that of vultures, dogs, mules, donkeys, horses, and particularly of man, the meat of whom is said to prove particularly destructive for the teeth.”

From the above passage, if the reviewer be disposed to accept Dr Krapf for his teacher, he may clearly learn one or two particulars not hitherto comprehended within the wide circle of his knowledge. For example, he will perceive that the idea of eating man’s flesh is not yet entirely exploded from that part of Africa. On the contrary, the forbidden luxury would appear sometimes to be indulged in even by those who are one step at least, advanced before the polite Danákil, whom, at the sacrifice of my reputation for charity, I have denominated “vagabonds and savages.”

The critic’s observations on the pronunciation of Amháric and Galla words are so elaborate a specie men of trifling, that it would be wholly lost labour to wade through them. Of the Galla language he knows nothing, and had the case been different, still I might be permitted to judge by my own ear in the case of a tongue absolutely unwritten. Those acquainted with the works of travellers in the East are aware that almost every one has adopted a peculiar system of orthography. All, therefore, but one, might, by a disingenuous critic, be accused of ignorance. But the reviewer goes on to inform the public that “the vulgar mistakes of English pronunciation—which are not participated in by Germans—are the wrong insertion or omission of the aspirate.” This is designed as a death-blow to me for writing Etagainya without an initial A, which highly culpable omission he presently afterwards takes occasion to rectify. Under this charge of vulgarity it is some consolation to me to quote as my authority Isenberg’s Amháric Dictionary, more especially since that gentleman is a German; but had he even been otherwise, I think his views on this subject of the aspirate might perhaps be preferred to those of any cockney.

The elaborate disquisition on larva and boudak (For boudak read boudah. It ought to have been translated sorcerer, but all artisans, blacksmiths especially, are regarded as boudahs. Vide Isenberg’s Amháric Dictionary. For larva read lava.) proves the critic to be qualified for the reading of proof-sheets, which appears to be the highest praise he can justly lay claim to. He can detect a misprint in other men’s works, and when his passions are unexcited, may possibly be able to correct it. But in the matters of ear or style, I would just as soon defer to the judgment of the great “Arqueem Nobba,” whoever that may be, (Vide Anti-Slavery Reporter, November 29th, 1843, page 222. For the information of my readers, it may be proper to explain that “Arqueem nobba” is believed to be doing duty for “Hakim nabaroo,” “You were the doctor”) from whom he seems to have obtained so much of his Oriental learning. He well knows to whom I allude, if no one else does. I shall turn his weapons against himself, and take occasion to question the classical attainments of a reviewer who translates “suum cuique”—“be it for good or ill;” and shall direct the public indignation to the fact of his having aroused curiosity “without gratifying it,” by the statement that I “studiously laboured to keep out of sight a very special service performed by the members of the Embassy.” What was it? He must surely be thinking of his reporters, not of my assistants. Be this as it may, he will not attempt to screen himself behind the printer’s devil, it being clear that no typical errors can be admissible in his forty pages of letter-press, if two are to be held inexcusable in my twelve hundred!

It will by this time, I think, be apparent that an extremely peculiar system of criticism has been adopted in reviewing my book. Here the diction is attacked, there the want of information; now we have complaints that information is given, but that it was obtained through the instrumentality of Dr Krapf; then the reviewer wanders into political and other considerations, and attacks my conduct as leader of the Mission. Occasionally he appears to be overwhelmed by a painful sympathy, an intense philanthropy, extreme sorrow for the dead, which betrays him into persevering rancour towards the living. In discussing, for example, the melancholy catastrophe at Goongoonteh, which, if credit be given me for the smallest particle of human feeling, I must be supposed to have regretted as much as any man, especially since Sergeant Walpole and Corporal Wilson were under my command, and both highly useful to me as soldiers and artisans, the critic suffers his compassion so powerfully to disturb his intellect, that he literally knows not what he says. He may, therefore, if such be his object, be thought extremely amiable by some people, but, upon the whole, I apprehend, he will appear to be infinitely more absurd: because, to obtain credit for a generous and expansive humanity, it is necessary, at least, to bear the semblance of an unwillingness to wound men’s reputations, living or dead. A genuine sympathy is always most active in proportion to the capacity of feeling possessed by the object of it. Thus we sympathise with our contemporaries more than with generations passed away; with Christians more than with Turks and Pagans; with Englishmen more than with Chinese; with our relations and friends more than with persons whom we never saw. But my critic reverses this order of things. His benevolence clings to individuals whose names he never heard, and urges him to inflict injury at all events, and pain if he can, upon persons whose sensibilities, he supposes, lay them open to his attacks. In one publication it seems to be intimated that I killed the men myself, whilst in the other I am conjectured to have been standing sentry, and to have dropped asleep at my post. The former charge I shall leave the Government of my country to answer; for if I be guilty and still at large. Government has made itself my accomplice. Shall I on the second point enlighten the critic, or shall I not? The fact is, I was not asleep, though with the greatest propriety I might have been, but at the very moment of the perpetration of the murder, I was leaning in bed upon my elbow, conversing with Captain Graham. Nevertheless, from the form of the wady, I could not command a view of every part of the encampment, or discern in the dark the approach of the assassins, at the distant point which they selected for their noiseless attack.

As to the manner in which I have related the circumstance, that is another affair, and the critic is at liberty to judge of it as he pleases. I claim, however, the same liberty for myself, and will venture to observe, that this part of his review is more lumbering, heavy, and absurd than ordinary; that in attempting to display feeling, he is only betrayed into lugubrious affectation; and that however I may be able to wield our mother tongue, he manages it so unskilfully that he wounds no one but himself.

The next charge is based, like the former, on the critic’s sympathy. I relate that at the village of Fárri the gentleman entrusted with the command of the watch, “worn out by incessant vigils,” fell asleep. The apology, it will be perceived, precedes the statement of the fact. But this new knight of La Mancha is not satisfied. Putting his redoubtable quill in rest, he tilts most chivalrously at my narrative; and, the operation over, chuckles with delight at my supposed discomfiture. He may, perhaps, have learned from some prying visitor to what particular officer I allude in the above passage. But most assuredly the public has not, and therefore no evil consequence can arise from what I say. All our critic’s ideas, however, are peculiar. He considers it criminal to hint indistinctly in a published work at a “breach of discipline,” but thinks I might with propriety have reported the circumstance officially to Government! My theory of propriety is different. I made no report to Government; but when there were so many broad shoulders to share the blame between them, I thought it quite safe to touch upon it in my volumes.

Having waded through the above tedious list of charges, we arrive, so the reader may be tempted to imagine, at something new. But that is not the critic’s plan. On the contrary, we find Monsieur Tonson on the stage again. Well might Dr Krapf exclaim, “Deliver me from my friends!” if the reviewer in question be really one among the number. Secretly, however, it is not the Missionary that is aggrieved, but another individual whose name I will not be provoked to print in my pages. This person, we are told, came down to Dinómali, in company with Mr Krapf, “to welcome the Embassy.” What he came down to do is not, however, the question. Come he certainly did; and I should have made honourable mention of him had I, during my stay in Shoa, found no reason to be dissatisfied with his conduct. The reverse was the case; and as I did not choose to be at the trouble of writing in his dispraise, I thought it better to say nothing. Let the reviewer be satisfied with that, for, if I should say anything further, I am sure his satisfaction would not be augmented. He is perfectly right in supposing, that I have not imparted to the public all the knowledge I acquired in Shoa, and that I have not related all the piquant comic anecdotes which were often at my pen’s point, struggling to see the light. But who knows? The time for telling them with effect is not yet passed, and it is quite possible that, under certain combinations of circumstances, I may yet return to this part of my subject, especially if the anonymous system be persevered in, and attempts be made to wound me from behind the friendly figure of the Missionary.

I may here, however, mention by the way, that, besides the learned Theban alluded to, the critic has two other authorities. Dr Krapf and M. Rochet D’Héricourt. Upon them he relies with equal and entire confidence. But I would beg to suggest, that there exist some slight discrepancies between the statements of those two writers, and that weight can be laid on the testimony of the one only in proportion as you mistrust the other. Yet the critic appears to discover nothing of this, never perceives that their testimonies are inter-destructive, but is perfectly satisfied to play off each in his turn against me. These authorities, in fact, are the legs on which his whole accusation appears to stand, though there be in reality an anonymous authority, which, like the third leg in the riddle, helps to support the tottering figure. To Mr Krapf, it is said, the Embassy owed whatever influence it possessed in Shoa. The officers of the Mission were nothing; the presents were nothing; the expectation of assistance and support from the Indian Government, in which Sáhela Selássie indulged, were nothing:—the reverend missionary was the “life and soul of the Embassy.” I know not whether, as Dr Krapf is a minister of the Gospel, this be meant as a compliment or as a sneer; but so it is. I am said to have had no influence with the king, save through him who was literally all-powerful at court. This being borne in mind, turn we now to the critic’s other authority, M. Rochet D’Héricourt, who is said to have been equally influential. But here comes the difficulty, which the critic either perceived or did not perceive. In the latter case he is criminally ignorant of what he ought to have known before he ventured to attack me; and if he did perceive it, then he is still more criminal for having suppressed the truth, and made that suppression serve the purpose of its contrary. It will be seen that I abstain from harsh language, and rather extenuate than otherwise the unworthiness of my adversary. The circumstance, however, to which I allude, is this: the critic maintains that Dr Krapf was all-powerful with Sáhela Selássie; M. Rochet D’Héricourt, on the other hand, asserts that Dr Krapf possessed so little influence, that it was only through his special interference, and at his earnest entreaty, that the king suffered him to proceed towards the Galla frontier with the army. Nay, not only had the missionary, according to this traveller, (Rochet D’Héricourt, Voyage dans le Pays D’Adel, et le Royaume de Choa, pages 224-233.) no influence, but the king displayed the strongest possible repugnance for him, and made him feel the effects of his dislike throughout the whole campaign. Consult the “Journal” (Journal of the Rev. Messrs Isenberg and Krapf, page 187) of the worthy missionary himself; and we find that both he and M. Rochet D’Héricourt were, without solicitation or entreaty, on his part at least, “ordered to accompany the king.” I am not pretending to dictate to the public as to which of these authorities it shall prefer. I only state facts, and leave others to draw the proper inference. The authority of Dr Krapf, however, at the court of Shoa to me seems to be strangely and wilfully exaggerated. It was a reflected authority, if I may so speak, that he exercised during the residence of the Mission in the country; an authority based upon the influence of the British Government, represented there for the time by me. The amount of his personal influence was such that the slightest accident sufficed to overthrow it. Had it been greater, his application to return would have been listened to. It may no doubt be observed in reply, that neither could my influence, which was fully exerted in his behalf, have been very considerable. But the caprices of despotism are not always to be accounted for, and they will serve to explain both the missionary’s want of success, and my own.

This subject has been artfully connected with the return of the Mission from Shoa. It is said, that had we not retired, we should have been forcibly expelled. I can certainly offer no proof that we should not; but the probability is, that the king of Shoa would have been in no hurry to dry up a constant source of profit to himself. It may, in fact, be laid down as a general rule, that no Oriental despot ever expels the giver of presents. It is the receiver of presents that he regards as an eyesore, the man who is dependent on him for his daily bread. The critic, however, has been “assured,” that had we not retired, we should “probably ere long” have been expelled. But to this I reply, that probably we should not; and I call on him to state his proofs of the “disrepute” into which he asserts we had fallen. I have been “assured,” that “probably” he has none to give, and “probably” this assurance is correct; otherwise, I think he would have been too glad to offer them. Be this as it may, the fact is, that we were not expelled, but recalled by our own government, when it considered that the duties for which I had been deputed, were fully accomplished.

The next attack upon me is based on certain “strange stories,” which the critic says he has heard. For myself, considering the strange people with whom he associates, I entertain not the slightest doubt in the world that he has been crammed with “strange stories,” and that he firmly believes them. In fact, he reminds me strongly of an anecdote related by Vossius, who, as Charles the Second observed, would believe anything but the Gospel. So this critic, who has no appetite whatever for plain truth, will swallow “strange stories” by the bushel. For example, with an earnestness which does great credit to his simplicity, he believes that the British officers in Shoa, with the few rank and file under their command, assisted the king in making prisoners among the Gallas. He believes, too, of course, that the field-piece, which had been presented to the king, and was therefore no longer under the control of the embassy, was employed to batter down villages, and, in one word, to effect the triumph of Sáhela Selássie over his refractory subjects and heathen neighbours. I feel for the distress his humanity must have suffered, and all through the “strange stories” to which he lends so greedy an ear! But let him be re-assured. The slaughter was not perpetrated by means of the galloper gun, which went not on the expedition at all, but was left by the king at his palace newly erected near Yeolo, the place of rendezvous. (N.B. This is not meant as a translation.) There were no “rounds of artillery” in the case, and the escort of British soldiers was taken with us, not to join in the foray, but to protect our own tents. Neither is this “memorable circumstance.” “omitted in my volumes,” as asserted by the veracious critic. It is distinctly stated for the information of those who are able to read, and the conduct of one of the privates stands specially recorded, who was urged by the Amhára to destroy a Galla.

(As a military man, and an Engineer officer to boot, I may perhaps be permitted to suggest, although with the utmost deference to the reviewer and his anonymous authorities, that the term “ammunition” might here have been employed with advantage. But perhaps he may consider “rounds of artillery” to be a more classical expression!)

The critic’s persevering patronage of Dr Krapf is so chivalrous, that I almost regret to show that it has been exerted in vain. Truth, however, requires that I should do so. Perhaps, indeed, the reviewer’s purpose may be less benevolent than it appears at first sight. His object may not be so much to exalt the clergyman, as to depress me, by creating, as far as he is able, in the public mind, the belief of what he asserts so positively, namely, that the Embassy fell into utter “disrepute” after the departure of the missionary, that so far from being able to exercise any influence, it would have been forcibly expelled, had it not beaten a hasty retreat. My opponent is a man of dates, and parades them in a manner truly pathetic. But how on these points did he happen to remain so much in the dark? Had he not all the great Abyssinian authorities at his elbow? Was he not acquainted with those who knew everything about the country—Arabic and Amháric scholars, who, by the help of Isenberg’s Dictionary, could translate boudah, and with the aid of Richardson, plunge into the mysteries of mafeesh? Where was the erudite individual who weighed my classical attainments in the balance, and found them wanting? Where was his fidus Achates, the “Arqueem Nobba?” How happens it that his oracles grew suddenly dumb when he consulted them on the subject of dates? The reader will scarcely credit the reason of all this when it is stated; but the fact is, that the reviewer had no other object in view than to misrepresent and injure me, though of course aware that it was in my power fully to refute him. I shall do so now, and, as I think, so satisfactorily, that he will not return to the charge.

I state in my travels, that through the interference of the British Embassy, four thousand seven hundred persons, reduced by an arbitrary edict of the king to bondage, were liberated; upon which the critic, full of the “strange stories” which his strange associates had related to him, immediately concludes that Dr Krapf might have had some hand in that transaction. At all events he must contrive to make it appear so, otherwise what would become of his primary thesis, that the Embassy “fell into such disrepute?” Montaigne, the reader will doubtless remember, observes somewhere in his essays, that in order to catch his critics napping, he often put forth the opinions of the greatest writers of antiquity, without making the least allusion to the author, in order that, if these should be turned into ridicule, as was not unlikely, he might show that it was not himself that they had attacked, but Seneca, or Cicero, or Plato. Without having any such intention, I have caught my critic in a similar trap. Believing he could attribute the honour to Dr Krapf, he does not call in question the issuing of the edict or the liberation of the slaves, but inquires knowingly, “had he, the missionary, nothing to do with their deliverance?” Next, with a skill which does him much credit, he connects the liberation of the princes with this other transaction, so that if the reader believes his unfounded assertion that it was Dr Krapf, not the Embassy, whose influence prevailed with the king in the one case, he may be led to suppose that it was so in the other. This, it must be acknowledged, is a very ingenious piece of workmanship, and has, I doubt not, earned its author much credit. Nevertheless, it will not bear the touch of examination. The simplest statement of facts in the world will suffice to destroy it, together with the critic’s main theory on the subject of my loss of influence at the court of Shoa. Dr Krapf quitted Angollála on the 12th of March, 1842, and during May of the same year, left Massowah for Aden. His active influence, it may fairly be inferred, terminated at this date. The forlorn Embassy was now abandoned to its own resources. There was no one to interest the king in its behalf; no one to perform great and benevolent actions, in order that I might obtain the credit of them. While we were in this state of torpor, the proclamation in question was published by the herald. Before Dr Krapf quitted Massowah? Alas! no. For that event took place in May, whereas the royal edict was only promulgated on the 3rd of August. It was by me, therefore, and not by Dr Krapf, that the remonstrance was forwarded to Sáhela Selássie, which produced the liberation of the slaves. This fact is known to every member of the Mission, and it ought to have been within the recollection of some of those infallible authorities who at once supplied the critic with facts and with learning, who remembered for him, understood languages for him, and when need was, invented for him.

The statement that the parents of the four thousand seven hundred individuals liberated, were slaves, is not true. I have said that their fathers were bondsmen, and their mothers free women, and this position I maintain. To the question who delivered the petition, I reply, “my dragoman of course.” Upon his boasted maxim of “giving honour to whom honour is due,” the conscientious reviewer will doubtless award the sole credit of the success attending this remonstrance, not to myself, but to the party who presented it, and his doing so will be quite as reasonable as the decision that I collected no geographical information, because my assistant. Dr Kirk, was entrusted by me with the department of survey. In equity he ought surely to have taken the case of Dollond into consideration, since he made the satellite glass and the sextant used in determining the longitude of Ankóber, upon which every recent addition to the geography of southern Abyssinia is indebted for whatever value it does possess.

Next comes the deliverance of the princes, which took place little more than three months before my return to India. These facts, known to every person in Abyssinia, the correctness of which will be vouched for by every member of the Mission, and the whole particulars of which were laid at the time before the Indian and British governments, may, perhaps, suffice to show in what spirit I have been criticised, and how totally unscrupulous my assailants have been. The gross misstatements disseminated anonymously through some of the public journals, and repeated by the candid reviewer, I have already publicly contradicted with my name. I here also contradict the assertion, that the king remained silent during my sojourn on the frontier. What object the sage reviewer would propose by my going back to take a second leave of His Majesty, when such is the etiquette of no country in the whole world, and my public duties imperatively required my presence at Fárri, the reader will be, as I am, at some loss to comprehend.

The treaty concluded with the king of Shoa having now been placed by Parliament before the country, I should have thought it unnecessary to notice the remarks which have been made on that subject, but for one or two considerations connected with it. First, it is said, that the ancient practice of detaining strangers had in usage been previously abolished, and it seems that, notwithstanding the treaty, it was afterwards, in one particular case, revived. Clearly the critic does not perceive the force of his own statements; for if, in spite of the most solemn engagements that a prince can enter into, Sáhela Selássie denied a British subject ingress to his country, does it not follow that distinct stipulations on this point were necessary? What does it signify, that practically Sáhela Selássie had in many instances permitted Europeans to enter his country? Were they not all, whilst there, legally subject to his caprice, and was it not prudent to endeavour to emancipate them from that caprice? But Sáhela Selássie, it is said, shortly violated the treaty, and his act is made the subject of accusation against me. Had I broken it myself, the circumstance would have been somewhat more germane to the matter. At present, all that can be said is, that Sáhela Selássie is a novice in European diplomacy.

The case of hardship alluded to, is that of Dr Krapf, who, having quitted Shoa on urgent private business, was denied re-admission. On this subject I might enter into a long explanation, which, because of the peculiarity of my position, could never be complete. I therefore judge it more satisfactory to refer to the testimony of the Church Missionary Society, which, as well as Dr Krapf himself, has put on record its entire satisfaction with my proceedings. If, therefore, the parties most deeply concerned be content because they understand the whole state of the case, I may safely despise the reproaches of a critic who neither knows nor cares any thing about the matter, further than as it may enable him to prejudice me in public opinion.

In every page of the criticism the sophisms and fallacies of which I have undertaken to expose, there is some fresh proof that the reviewer does not see his own way, and that he is perpetually at contradiction with himself. For example, he insists on nothing more incessantly than the all-powerful influence of Dr Krapf over the king of Shoa, to which, he says, the Embassy owed whatever success it met with. No sooner, however, does the missionary quit the precincts of the court, than he is arrested and plundered, evidently, the reviewer insinuates, with the knowledge and connivance of his fast friend Sáhela Selássie. What then becomes of his prodigious influence, since it did not suffice for his own protection? But if Dr Krapf was powerless, so likewise, argues the critic, was the Embassy; “for we read of no remonstrances, no applications made to the king on behalf of the missionary, and surely there are no political considerations to restrain communicativeness upon a subject like this.” He is perfectly mistaken. For although it may, without compromising any one, be stated that remonstrances were made, there are reasons, and those public ones too, which forbid me to explain why those remonstrances were ineffectual. Had the critic, or his Amháric philosopher, possessed one atom of sagacity, they would have divined those reasons; but as the case is otherwise, I leave them in the darkness which encompasses the whole coterie.

As to my having no right to use information expressly collected for me by the Political Agent at Aden, and by Lieutenant Christopher, in reference to the Eastern Coast, that is really a point upon which the reviewer can hardly be reckoned a competent judge. Lieutenant Barker, like Dr Kirk and the rest of my assistants, was under my orders, and sent with me for the express purpose of taking share, as I might see fit, in the duties allotted to me. The authorities quoted by the reviewer, as having been first in the field with every particular respecting slavery and the slave-trade in Shoa, do not bear out his assertion. Not to go any farther, where does he find the fact, which is rather an important one, that the king claims one out of every ten slaves that pass through his dominions? Like most other points which bear materially upon the subject, this is omitted in the “reports” which are so confidently advanced, in order to throw dust in the eyes of those who will take the Reviewer’s word for whatever he has the effrontery to assert.

Next comes the question of the royal arms of Shoa, which I have stated to be the Holy Trinity. Here the critic, as he thinks, has me clearly at disadvantage. He denounces me, accordingly, to be in the wrong, by showing, not what the arms of Shoa are, but what are the arms of the Ethiopic empire; which is exactly the same as if a traveller in Flanders, having described the royal arms of that country, were to be taken to task because the arms of the Austrian Emperor were different. I make a statement on one subject, and he refutes me by making a different statement on a different subject, which is somewhat comic, to say the least of it. But the arms of Abyssinia are, it seems, the “Lion of the Tribe of Judah,” to which the Catholic missionaries have added a cross. M. le Grand, in speaking of Abyssinian coronations, says: “The escutcheon is a lion holding a cross, with this motto: Vicit leo de tribu Judah.” But all this has nothing to do with the king of Shoa, who employs a device of his own, and that device is exactly what I have represented.

The ignorance of the reviewer and his anonymous authorities is again conspicuous in the remarks offered relative to the signet. Why has he not followed the rule he has laid down for my guidance, and “said openly,” who these mysterious informants are, in order that, by their calibre, the public might have been enabled to judge whether on any, and on what subject, their opinion or their assertion is likely to be better than my own? As it is, the reader might really be tempted to believe that there existed a penny post in the kingdom of Shoa, and that every subject was in the daily habit of corresponding through it with all his acquaintance. But with exception of a few letters indited by His Majesty, or by the Queen, there are, perhaps, not half a dozen penned during the year, and those are upon scraps of parchment the size of a visiting card, and have neither signature nor superscription, much less device to adorn them. More than ignorance is displayed in the sneers cast upon my ability to use the pencil and the rifle. These qualifications, however incompatible their exercise may be with the dignity to which the critic has been pleased to elevate me, are far from being lightly estimated in Abyssinia; and that foreigner who can neither draw portraits, nor ride, nor slay wild beasts, is not likely to hold a very high place in the estimation of Sáhela Selássie, whatever may be thought of him by a learned reviewer.

The speculations indulged in as to the success or failure of my Embassy, are artfully spread over the whole article, a little here and a little there; so that the reader, should a reader be found, must always of necessity have doubts unanswered in his mind. There is some skill in this, and I give the writer credit for it; but though he manages his matter well, the matter itself is good for nothing. He puts himself in the place of the public, and demands certain explanations which I am not permitted to give. Parliament alone has it in its power to satisfy my critic, and to Parliament I refer him. Everybody else will feel that an imperfect explanation would be worse than none at all; a complete one I cannot furnish, though it may hereafter be permitted me to clear up the whole matter, which I am fully able to do.

It appears to me that I have now answered every objection worthy of notice that has been made against my work on Shoa. Not improbably, I shall be thought by some to have been too minute and circumstantial in my reply—to have exposed too seriously misrepresentations originating in ignorance or wanton malice—to have expended argument on that which deserved only contempt. But, respecting the public as I do, I judged it to be incumbent on me completely to disprove the assertion that I had imposed upon it. I trust I have established my own veracity, which I have been far more solicitous to do than to defend the plan adopted in the composition of my narrative. Much more might have been said, to show that the truth is neither in the reviewer, nor his “private informants,” but it is not worth my while to trouble myself further with such people. The public, I am convinced, will agree with me in thinking that I have left no just cause for cavil, and if, therefore, the system of abuse should be persevered in, it can only be because I happen to have enemies who will make a point of pursuing me as long as I am above ground, and perhaps much longer. I wish they could discover some better and more profitable employment, and with that wish I leave them.

W.C. Harris.

London, March 31, 1844.

Extract of Instructions Addressed by the Secretary to the Government of Bombay to Captain W.C. Harris.

Bombay Castle, 24th April, 1841.

Sir,

I am directed to inform you, that the Honourable the Governor in Council having formed a very high estimate of your talents and acquirements, and of the spirit of enterprise and decision, united with prudence and discretion, exhibited in your recently published Travels “through the territories of the chief Moselekatse to the tropic of Capricorn,” has been pleased to select you to conduct a Mission which the British Government has resolved to send to Sáhela Selássie, the King of Shoa in Southern Abyssinia, whose capital, Ankóber, is computed to be about four hundred miles inland from the port of Tajúra on the African coast.

The Mission will be conveyed to Aden in the Honourable Company’s steam frigate Auckland, now under orders to leave Bombay on the 27th instant; and it has been arranged that one of the Honourable Company’s vessels of war, at present in the Red Sea, shall be in readiness to convey the Mission thence to Tajúra, at which latter place it should immediately disembark, and commence its journey to Ankóber.

(Signed) J.P. Willoughby, Secretary to Government.

To Captain W.C. Harris, Corps of Engineers.

The Embassy was thus Composed:

Captain W.C. Harris, Bombay Engineers.

Captain Douglas Graham, Bombay Army. Principal Assistant.

Assistant-Surgeon Rupert Kirk, Bombay Medical Service.

Dr J.R. Roth, Natural Historian.

Lieutenant Sydney Horton, H.M. 49th Foot,—as a Volunteer.

Lieutenant W.C. Barker, Indian Navy.

Assistant-Surgeon Impey, Bombay Medical Service.

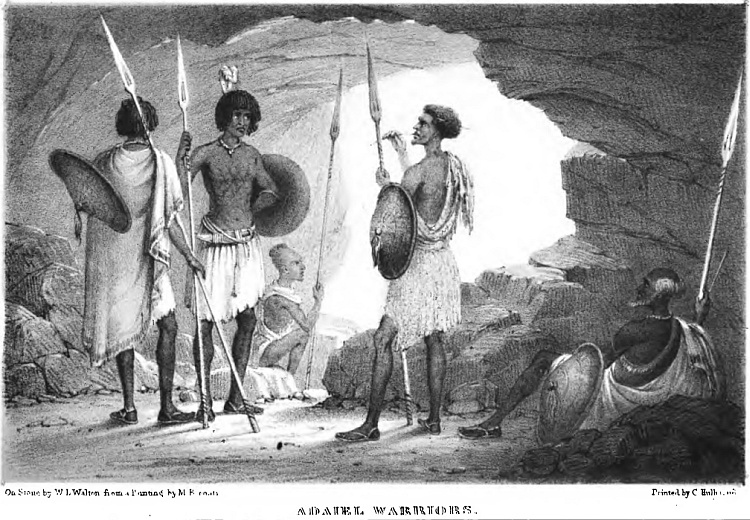

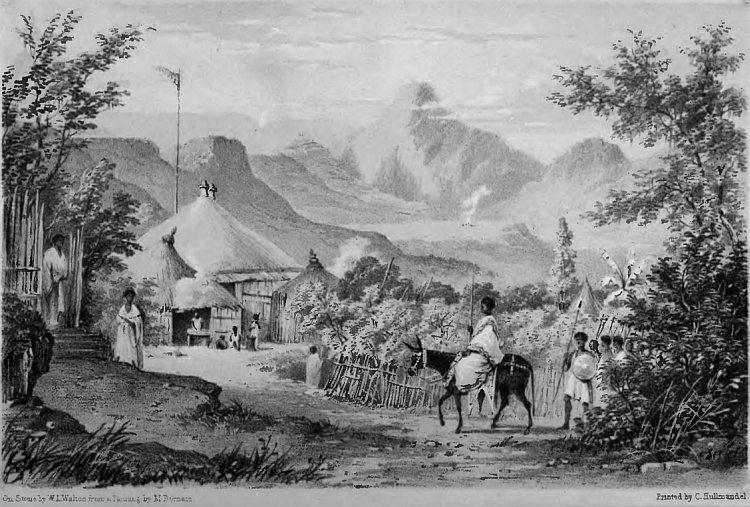

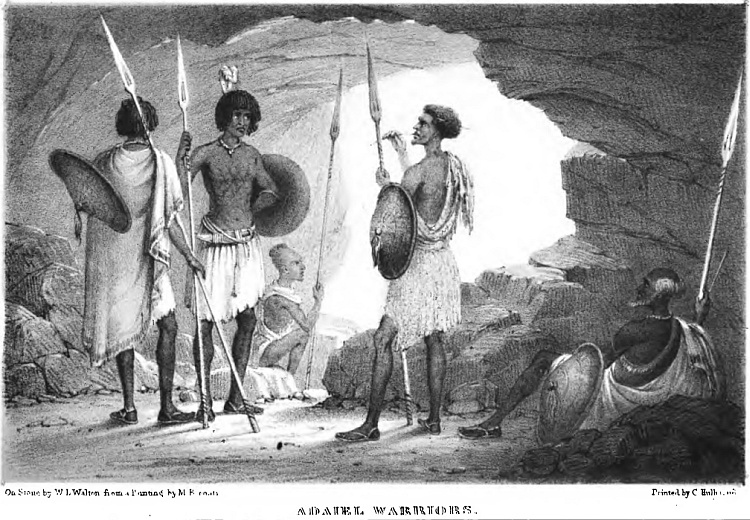

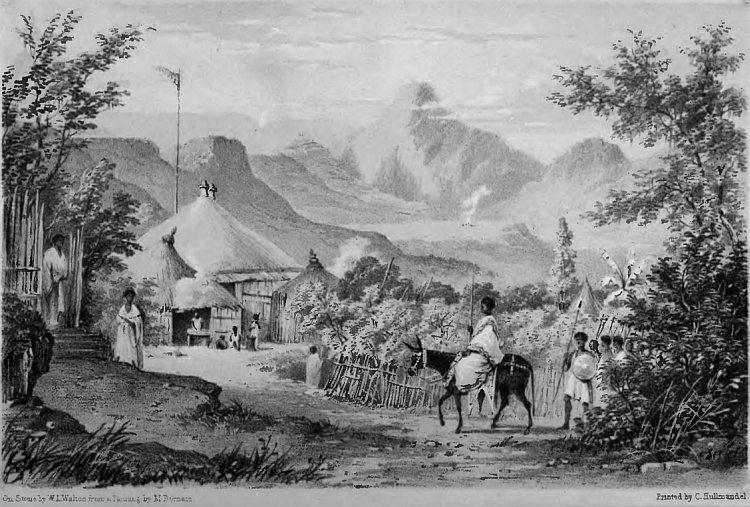

Mr Martin Bernatz, Artist.

Mr Robert Scott, Surveyor and Draftsman.

Mr J. Hatchatoor, British Agent at Tajúra.

Escort and Establishment:—

Two sergeants and fifteen rank and file; volunteers from H.M. 6th Foot, and from the Bombay Artillery.

An Assistant Apothecary.

Carpenter.

Smith.

Two Tent Lascars.

Introduction.

Written in the heart of Abyssinia, amidst manifold interruptions and disadvantages, the following pages will, in many respects, be found imperfect. Their chief recommendation must be sought in the fact of their embodying a detail of efforts zealously directed, under the auspices of a liberal Government, towards the establishment of a more intimate connexion with a Christian people, who know even less of the world than the world knows of them,—towards the extension of the bounds of geographical and scientific knowledge, the advancement of the best interests of commerce, and the amelioration of the lot of some of the least favoured portions of the human race.

An obvious necessity for the introduction of the foregoing extract from his instructions will exonerate the Author from an intention to appropriate as his due the very gratifying encomium passed upon his previous exertions in Southern Africa. As a public servant, the freedom of his pen has now in some measure been curtailed; but his official position and resources, added to the able assistance placed at his command, have, on the other hand, extended more than commensurate advantages.

To Captain Douglas Graham, his accomplished and early friend, and principal assistant, he acknowledges himself most especially indebted, for the aid of a head and of a pen, such as are not often to be found united.

The exertions of Assistant-Surgeon Kirk alleviated incalculable human suffering; and his perseverance, although long opposed by an unfavourable climate, carried through a series of magnetic and astronomical observations of the highest importance to Abyssinian geography.

An indefatigable devotion to the cause of science, added to the experience gained during previous wanderings in Palestine, eminently adapted the learned Dr Roth to discharge the arduous functions of natural historian to the Mission; and the splendid collection realised, together with the researches embodied in the various appendices to these volumes, will afford the fullest evidence of his industry and success.

To all who were associated with himself, in view to the better attainment of the objects contemplated, the Author here offers his warm acknowledgments for the cheerfulness displayed under trials and privations. Of the able assistance of some he was unavoidably deprived during an early period of the service. The disappointment thus involved in his own person has been fully equal to that experienced by themselves; but they must be sensible that their hardships have not been undergone in vain, and that they too have accomplished their share in the undertaking, so far as fortune permitted.

To the Reverend Dr Krapf the thanks of Government have already been conveyed, for the valuable co-operation derived from his extended acquaintance with the languages of Abyssinia. But the Author gladly avails himself of this opportunity publicly to record his personal sense of obligation to the active and pious Missionary of the Church of England, whose kindness from the first arrival of the Embassy on the frontiers of Shoa, to the date of his own departure for Cairo, was unremitting.

By no tribute of his own could the writer of these volumes extend the well-deserved reputation of McQueen’s Geographical Survey. It will nevertheless be satisfactory to one who takes rank among the foremost benefactors of the oppressed “children of the sun,” to receive the additional testimony which is due to the undeviating accuracy of theories and conclusions founded upon years of patient and honest investigation; and this the Author unhesitatingly records, in so far as the north-eastern portions of Africa have come within the observation of the Embassy which he has the honour to conduct.

Ankóber, 1st January, 1843.

Postscriptum.

The length of time that has unavoidably elapsed between the preparation and the appearance of these volumes, needs no apology, neither is it proposed to offer any for their termination in the country of which they treat, and wherein they were written. But the work must not now be suffered to go forth without the expression of the Author’s gratitude for the assistance derived during its progress through the press, from the talents and literary taste of his friend Major Franklin Lushington, C.B.

Volume One—Chapter One.

Departure of the British Embassy from the Shores of india.

It was late on the afternoon of a sultry day in April, which had been passed amid active preparations, when a dark column of smoke, streaming over the tall shipping in the crowded harbour of Bombay, proclaimed the necessity of a hurried adieu to a concourse of friends who still thronged the deck; and scarcely was the last wish for success expressed to the parties that had embarked, before the paddles performed their first revolution, and the Honourable East India Company’s steam frigate “Auckland,” bound upon her maiden voyage, shot through the still blue water.

A turbaned multitude of manifold religions had lined the pier and the ramparts of the saluting battery, to pay a parting tribute of respect to their late governor. Sir James Rivett Carnac, who, with his lady and family, was now returning to his native land. On board also were the officers and gentlemen composing an Embassy organised under instructions by the government of India. More than a fortnight had been diligently passed in the equipment of this mission; but its objects, no less than the destination of its innumerable bales and boxes, still served as puzzles to public curiosity; and many a sapient conjecture on the subject was doubtless launched after the bounding frigate as she disappeared amid the haze of the closing day.

Immortal Watt! sordid is the man who places his foot behind the Titanic engines which owe their birth to thee, and who would withhold, as an offering to the altar of thy memory, a mite, according to his worldly means, wherewith to erect a fabric colossal as the power enthralled by thy transcendent genius! Strange are the revolutions undergone in affairs nautical since the introduction of the marine steam-engine upon the Indian seas. The creaking of yards has given place to the coughing and sobbing of machinery, as it heaves in convulsive throes. Tacking and wearing have become terms obsolete, and through the clang of the fire-doors, and the ceaseless stroke of paddle-wheels, the voice of the pilot is rarely heard, save in conjunction with “Stop her,” or “Turn a-head.”

Marked by a broad ploughed wake, the undeviating course pursued through the trackless main was demonstrated midway of the voyage by a tall pillar of smoke from the funnel of the “Cleopatra,” rising against the clear hot horizon, like a genie liberated from his sealed bottle, to proclaim the advent of the English mails. The deep blue sea was glassy smooth. Each passing zephyr set from Araby’s shores; but, heedless alike of wind and opposing current, the good ship steadily pursued her arrow-like flight,—passed the bold outline of Socotra, redolent of spicy odours,—and before sunset of the ninth day was within sight of her destined haven, one thousand six hundred and eighty miles from the port she had left.

Cape Aden was the bold promontory in view, and it had borrowed an aspect even more sombre and dismal from a canopy of heavy clouds which stole across the naked and shattered peaks, to invest the castle-capped mountain with a funereal shroud. Crossed by horizontal ledges, and seamed with gaps and fissures, Jebel Shemshán rears its turreted crags nearly eighteen hundred feet above the ocean, into which dip numerous bare and rugged buttresses, of width only sufficient to afford footing to a cony, and each terminating in a bluff inaccessible scarp. Sand and shingle strew the cheerless valleys by which these spurs are divided, and save where a stunted balsam, or a sallow clump of senna, has struggled through the gaping fissure, hollow as well as hill is destitute of even the semblance of vegetation.

“How hideously

Its shapes are heap’d around, rude, bare, and high.

Ghastly, and scarr’d, and riven! Is this the scene

Where the old earthquake’s demon taught her young

Ruin? Were these their toys? - or did a sea

Of fire envelope once this dismal cape?”

Rounding the stern peninsula, within stone’s cast of the frowning headlands, the magnificent western bay developed its broad expanse as the evening closed. Here, with colliers and merchantmen, were riding the vessels of war composing the Red Sea squadron. Among the isolated denizens of British Arabia, the unexpected arrival of a steam frigate created no small sensation. Exiles on a barren and dreary soil, which is precluded from all intercourse with the fruitful, but barbarous interior, there is nothing to alleviate a positive imprisonment, save the periodical flying visits of the packets that pass and repass betwixt Suez and Bombay. In the dead of night the sudden glare of a blue light in the offing is answered by the illumination of the blockship, heretofore veiled behind a curtain of darkness. The double thunder of artillery next peals from her decks; and as the labouring of paddle-wheels, at first faint and distant, and heard only at broken intervals, comes booming more heavily over the still waters, the spectral lantern at the mast-head is followed by a red glow under the stem, as the witch, buffeting a cascade of snowy spray, vibrates to every stroke of the engine, and leaving a phosphoric train to mark her even course, glides, hissing and boiling, towards her anchorage. Warped alongside the blockship, the dingy hulls lean over like affectionate sisters that have been long parted; and, flinging their arms together, remain fast locked in each other’s embrace.

And who are these swart children of the sun, that, like a May-day band of chimney-sweeps, are springing with wild whoops and yells over the bulwarks of the new arrival? ’tis a gang of brawny Seedies, enfranchised negroes from the coast of Zanzibar, whose pleasure consists in the transhipment of yonder mountain of coal, lying heaped in tons upon the groaning deck. To the dissonant tones of a rude tambourine, thumped with the thighbone of a calf, their labour has already commenced. Increasing the vehemence of their savage dance, they heave the ponderous sacks like giants busied at pitch and toss, and begrimed from head to foot, roll at intervals upon the blackened planks, to stanch the streaming perspiration. Thus stamping and howling with increased fury, while the harsh notes of the drum peal louder and louder to the deafening vehemence of the frantic musician, they pursue their task, night as well as day, amid clamour and fiendish vociferations, such as might suggest the idea of furies engaged in unearthly orgies. In the first burst of their revelry, the spectator is happy to escape from the suffocating atmosphere of impalpable coal-dust; and rarely does it happen that for every hundred tons of fuel received, fewer than one life is forfeited by the actors in the wild scene described—some doomed victim, swollen with copious draughts, and exhausted by the frenzy of excitement, invariably casting himself down when his Herculean task is done, to rally and rise up no more.

Volume One—Chapter Two.

Disembarkation at Cape Aden.

Quitting the boisterous deck of the steamer, and pulling towards the shores of Arabia, a cluster of barren rocks, which might fitly be likened to heaps of fused coal out of a glass furnace, present an appearance very far from inviting or prepossessing. They are little relieved by a few straggling cadjan buildings, temporarily occupied by those whose avocations enable them, during the summer months, to fly the intolerable heat of the oven-like town. But under the roof of Captain Stafford Haines, who fills the honourable and responsible post of Political Agent, there awaited the embassy, on its landing, a hospitality of no ordinary stamp. It literally knew no bounds, and could not fail to obliterate at once any unfavourable first impression arising out of the desolate aspect bestowed by Dame Nature upon “Steamer Point.”

A volunteer escort of European artillerymen was yet to be obtained from the garrison of Aden; horses, too, were to be purchased, and sundry other indispensable preparations made for the coming journey into the interior of Africa. During a full week there seemed no termination to the influx of bags containing dates, rice, and juwarree, and scarcely a shorter period was occupied in the selection from the government treasury of many thousand star-dollars of the reign of Maria Theresa, displaying, each in its turn, all the multifarious marks and tokens most esteemed by the capricious savage. Neither was the bustle one whit diminished by the remote position of the town, which, unless through the kindness of friends, is only to be attained on the back of one of the many diminutive donkeys stationed along the beach for the convenience of the stranger. Encumbered with a straw-stuffed pack-saddle far exceeding its own dimensions, the wretched quadruped is zealously bastinadoed into a painful amble by the heavy club of some juvenile Israelite with flowing auburn ringlets, whose chubby freckled cheeks, influenced by the sultry sun no less than by the incessant manual labour employed, are wont to assume a strangely excited appearance ere the journey be at an end.

Along the entire coast of Southern Arabia, there is not a more remarkable feature than the lofty promontory of Aden, which has been flung up from the bed of the ocean, and in its formation is altogether volcanic. The Arab historian (Masudi) of the tenth century, after speaking of the volcanoes of Sicily and in the kingdom of the Maha Raj, alludes to it as existing in the desert of Barhut, adjacent to the province of Nasafan and Hadramaut, in the country of Shaher. “Its sound, like the rumbling of thunder, might then be heard many miles, and from its entrails were vomited forth red-hot stones with a flood of liquid fire.” The skeleton of the long-exhausted crater, once, in all probability, a nearly perfect circle, now exhibits a horse-shoe-shaped crescent, hemmed in by splintered crags, which, viewed from the turreted summit of Jebel Shemshán especially, whence the eye ranges over the entire peninsula, presents the wildest chaos of rock, ruin, and desolation.