Title: Mr Punch's Pocket Ibsen - A Collection of Some of the Master's Best Known Dramas

Author: F. Anstey

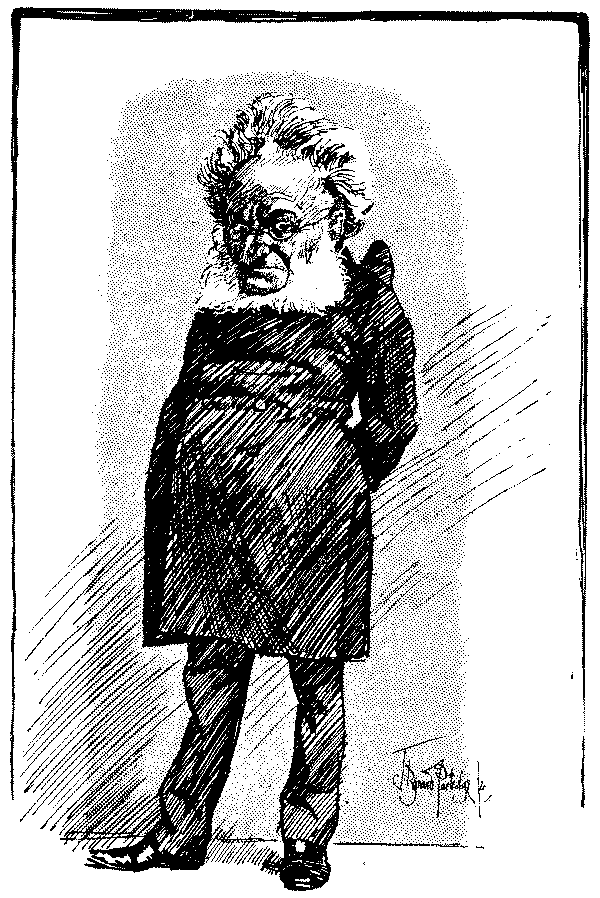

Illustrator: Bernard Partridge

Release date: February 17, 2011 [eBook #35305]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Neville Allen, David Clarke and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

CONDENSED, REVISED, AND SLIGHTLY RE-ARRANGED FOR THE BENEFIT OF THE EARNEST STUDENT

The concluding piece, "Pill-Doctor Herdal," is, as the observant reader will instantly perceive, rather a reverent attempt to tread in the footprints of the Norwegian dramatist, than a version of any actually existing masterpiece. The author is conscious that his imitation is painfully lacking in the mysterious obscurity of the original, that the vein of allegorical symbolism is thinner throughout than it should be, and that the characters are not nearly so mad as persons invariably are in real life—but these are the faults inevitable to a prentice hand, and he trusts that due allowances may be made for them by the critical.

In conclusion he wishes to express his acknowledgments to Messrs. Bradbury and Agnew for their permission to reprint the present volume, the contents of which made their original appearance in the pages of "Punch"

| ROSMERSHOLM | |

| ACT FIRST | |

| ACT SECOND | |

| ACT THIRD | |

| ACT FOUR | |

| NORA; OR, THE BIRD-CAGE | |

| ACT FIRST | |

| ACT SECOND | |

| ACT THIRD | |

| HEDDA GABLER | |

| ACT FIRST | |

| ACT SECOND | |

| ACT THIRD | |

| THE WILD DUCK | |

| ACT FIRST | |

| ACT SECOND | |

| ACT THIRD | |

| ACT FOURTH | |

| PILL-DOCTOR HERDAL | |

| ACT FIRST | |

| ACT SECOND | |

| ACT THIRD |

Sitting-room at Rosmershölm, with a stove, flower-stand, windows, ancient and modern ancestors, doors, and everything handsome about it. Rebecca West is sitting knitting a large antimacassar which is nearly finished. Now and then she looks out of a window, and smiles and nods expectantly to someone outside. Madam Helseth is laying the table for supper.

[Folding up her work slowly.] But tell me precisely, what about this white horse?

[Smiling quietly.

Lord forgive you, Miss!—[fetching cruet-stand, and placing it on table]—but you're making fun of me!

[Gravely.] No, indeed. Nobody makes fun at Rosmershölm. Mr. Rosmer would not understand it. [Shutting window.] Ah, here is Rector Kroll. [Opening door.] You will stay to supper, will you not, Rector, and I will tell them to give us some little extra dish.

[Hanging up his hat in the hall.] Many thanks. [Wipes his boots.] May I come in? [Comes in, puts down his stick, sits down, and looks about him.] And how do you and Rosmer get on together, eh?

Ever since your sister, Beata, went mad and jumped into the mill-race, we have been as happy as two little birds together. [After a pause, sitting down in arm-chair.] So you don't really mind my living here all alone with Rosmer? We were afraid you might, perhaps.

Why, how on earth—on the contrary, I shouldn't object at all if you—[looks at her meaningly]—h'm!

[Interrupting, gravely.] For shame, Rector; how can you make such jokes?

[As if surprised.] Jokes! We do not joke in these parts—but here is Rosmer.

[Enter Rosmer, gently and softly.

So, my dear old friend, you have come again, after a year's absence. [Sits down.] We almost thought that——

[Nods.] So Miss West was saying—but you are quite mistaken. I merely thought I might remind you, if I came, of our poor Beata's suicide, so I kept away. We Norwegians are not without our simple tact.

It was considerate—but unnecessary. Reb—I mean, Miss West—and I often allude to the incident, do we not?

[Strikes Tändstickor.] Oh yes, indeed. [Lighting lamp.] Whenever we feel a little more cheerful than usual.

You dear good people! [Wanders up the room.] I came because the Spirit of Revolt has crept into my School. A Secret Society has existed for weeks in the Lower Third! To-day it has come to my knowledge that a booby trap was prepared for me by the hand of my own son, Laurits, and I then discovered that a hair had been inserted in my cane by my daughter Hilda! The only way in which a right-minded Schoolmaster can combat this anarchic and subversive spirit is to start a newspaper, and I thought that you, as a weak, credulous, inexperienced and impressionable kind of man, were the very person to be the Editor.

[Rebecca laughs softly, as if to herself.

Rosmer jumps up and sits down again.

[With a look at Rosmer.] Tell him now!

[Returning the look.] I can't—Some other evening. Well, perhaps—— [To Kroll.] I can't be your Editor—because [in a low voice] I—I am on the side of Laurits and Hilda!

[Looks from one to the other, gloomily.] H'm!

Yes. Since we last met, I have changed my views. I am going to create a new democracy, and awaken it to its true task of making all the people of this country noblemen, by freeing their wills, and purifying their minds!

What do you mean!

[Takes up his hat.

[Bowing his head.] I don't quite know, my dear friend; it was Reb—— I should say Miss West's scheme.

H'm! [A suspicion appears in his face.] Now I begin to believe that what Beata said about schemes—— no matter. But under the circumstances, I will not stay to supper.

[Takes up his stick, and walks out.

I told you he would be annoyed. I shall go to bed now. I don't want any supper. [He lights a candle, and goes out; presently his footsteps are heard overhead, as he undresses. Rebecca pulls a bell-rope.

[To Madam Helseth, who enters with dishes.] No, Mr. Rosmer will not have supper to-night. [In a lighter tone.] Perhaps he is afraid of the nightmare. There are so many sorts of White Horses in this world!

[Shaking.] Lord! lord! that Miss West—the things she does say!

[Rebecca goes out through door, knitting antimacassar thoughtfully, as Curtain falls.

Rosmer's study. Doors and windows, bookshelves, a writing-table. Door, with curtain, leading to Rosmer's bedroom. Rosmer discovered in a smoking jacket cutting a pamphlet with a paper-knife. There is a knock at the door. Rosmer says "Come in." Rebecca enters in a morning wrapper and curl-papers. She sits on a chair close to Rosmer, and looks over his shoulder as he cuts the leaves. Rector Kroll is shown up.

[Lays his hat on the table and looks at Rebecca from head to foot.] I am really afraid that I am in the way.

[Surprised.] Because I am in my morning wrapper and curl-papers? You forget that I am emancipated, Rector Kroll.

[She leaves them and listens behind curtain in Rosmer's bedroom.

Yes, Miss West and I have worked our way forward in faithful comradeship.

[Shakes his head at him slowly.] So I perceive. Miss West is naturally inclined to be forward. But, I say, really you know—— However, I came to tell you that poor Beata was not so mad as she looked, though flowers did bewilder her so. [Taking off his gloves meaningly.] She jumped into the mill-race because she had an idea that you ought to marry Miss West!

[Jumps half up from his chair.] I? Marry—Miss West! My good gracious, Kroll! I don't understand, it is most incomprehensible. [Looks fixedly before him.] How can people?—— [Looks at him for a moment, then rises.] Will you get out? [Still quiet and self-restrained.] But first tell me why you never mentioned this before?

Why? Because I thought you were both orthodox, which made all the difference. Now I know that you side with Laurits and Hilda, and mean to make the democracy into noblemen, and accordingly I intend to make it hot for you in my paper. Good morning!

[He slams the door with spite as Rebecca enters from bedroom.

[As if surprised..] You—in my bedroom! You have been listening, dear? But you are so emancipated. Ah, well! so our pure and beautiful friendship has been misinterpreted, bespattered! Just because you wear a morning wrapper, and have lived here alone for a year, people with coarse souls and ignoble eyes make unpleasant remarks! But what really did drive Beata mad? Why did she jump into the mill-race? I'm sure we did everything we could to spare her! I made it the business of my life to keep her in ignorance of all our interests—didn't I, now?

You did. But why brood over it? What does it matter? Get on with your great beautiful task, dear—[approaching him cautiously from behind]—winning over minds and wills, and creating noblemen, you know—joyful noblemen!

[Walking about restlessly, as if in thought.] Yes, I know. I have never laughed in the whole course of my life—we Rosmers don't—and so I felt that spreading gladness and light, and making the democracy joyful, was properly my mission. But now—I feel too upset to go on, Rebecca, unless—— [Shakes his head heavily.] Yes, an idea has just occurred to me—— [Looks at her, and then runs his hands through his hair]—Oh, my goodness! No—I can't.

[He leans his elbows on table.

Be a free man to the full, Rosmer—tell me your idea.

[Gloomily.] I don't know what you'll say to it. It's this: Our platonic comradeship was all very well while I was peaceful and happy. Now that I am bothered and badgered, I feel—why, I can't exactly explain, but I do feel that I must oppose a new and living reality to the gnawing memories of the past. I should perhaps, explain that this is equivalent to an Ibsenian proposal.

[Catches at the chair-back with joy.] How? at last—a rise at last! [Recollects herself.] But what am I about? Am I not an emancipated enigma? [Puts her hands over her ears as if in terror.] What are you saying? You mustn't. I can't think what you mean. Go away, do!

[Softly.] Be the new and living reality. It is the only way to put Beata out of the Saga. Shall we try it?

Never! Do not—do not ask me why—for I haven't a notion—but never! [Nods slowly to him and rises.] White Horses would not induce me! [With her hand on door-handle.] Now you know!

[She goes out.

[Sits up, stares, thunderstruck, at the stove, and says to himself.] Well—I—am——

Quick Curtain.

Sitting-room at Rosmershölm. Sun shining outside in the Garden. Inside Rebecca West is watering a geranium with a small watering-pot. Her crochet antimacassar lies in the arm-chair. Madame Helseth is rubbing the chairs with furniture-polish from a large bottle. Enter Rosmer, with his hat and stick in his hand. Madame Helseth corks the bottle and goes out to the right.

Good morning, dear. [A moment after—crocheting.] Have you seen Rector Kroll's paper this morning? There's something about you in it.

Oh, indeed? [Puts down hat and stick, and takes up paper.] H'm! [Reads—then walks about the room.] Kroll has made it hot for me. [Reads some more.] Oh, this is too bad! Rebecca, they do say such nasty spiteful things! they actually call me a renegade—and I can't think why! They mustn't go on like this. All that is good in human nature will go to ruin if they're allowed to attack an excellent man like me! Only think, if I can make them see how unkind they have been!

Yes, dear, in that you have a great and glorious object to attain—and I wish you may get it!

Thanks. I think I shall. [Happens to look through window and jumps.] Ah, no, I shan't—never now, I have just seen——

Not the White Horse, dear? We must really not overdo that White Horse!

No—the mill-race, where Beata—— [Puts on his hat—takes it off again.] I'm beginning to be haunted by—no, I don't mean the Horse—by a terrible suspicion that Beata may have been right after all! Yes, I do believe, now I come to think of it, that I must really have been in love with you from the first. Tell me your opinion.

[Struggling with herself, and still crocheting.] Oh—I can't exactly say—such an odd question to ask me!

[Shakes his head.] Perhaps; I have no sense of humour—no respectable Norwegian has—and I do want to know—because, you see, if I was in love with you, it was a sin, and if I once convinced myself of that——

[Wanders across the room.

[Breaking out.] Oh, these old ancestral prejudices! Here is your hat, and your stick, too; go and take a walk.

[Rosmer takes hat and stick, first, then goes out and takes a walk; presently Madam Helseth appears, and tells Rebecca something. Rebecca tells her something. They whisper together. Madam Helseth nods, and shows in Rector Kroll, who keeps his hat in his hand, and sits on a chair.

I merely called for the purpose of informing you that I consider you an artful and designing person, but that, on the whole, considering your birth and moral antecedents, you know—[nods at her]—it is not surprising. [Rebecca walks about wringing her hands.] Why, what is the matter? Did you really not know that you had no right to your father's name? I'd no idea you would mind my mentioning such a trifle!

[Breaking out.] I do mind. I am an emancipated enigma, but I retain a few little prejudices still. I don't like owning to my real age, and I do prefer to be legitimate. And, after your information—of which I was quite ignorant, as my mother, the late Mrs. Gamvik, never once alluded to it—I feel I must confess everything. Strong-minded advanced women are like that. Here is Rosmer. [Rosmer enters with his hat and stick.] Rosmer, I want to tell you and Rector Kroll a little story. Let us sit down, dear, all three of us. [They sit down, mechanically, on chairs.] A long time ago, before the play began—[in a voice scarcely audible]—in Ibsenite dramas, all the interesting things somehow do happen before the play begins—;

But, Rebecca, I know all this.

[Looks hard at her.] Perhaps I had better go?

No—I will be short. This was it. I wanted to take my share in the life of the New Era, and march onward with Rosmer. There was one dismal, insurmountable barrier—[to Rosmer, who nods gravely]—Beata! I understood where your deliverance lay—and I acted. I drove Beata into the mill-race.... There!

[After a short silence.] H'm! Well, Kroll—[takes up his hat]—if you're thinking of walking home, I'll go too. I'm going to be orthodox once more—after this!

[Severely and impressively, to Rebecca.] A nice sort of young woman you are! [Both go out hastily, without looking at Rebecca.

[Speaks to herself, under her breath.] Now I have done it. I wonder why. [Pulls bell-rope.] Madam Helseth, I have just had a glimpse of two rushing White Horses. Bring down my hair-trunk.

[Enter Madam Helseth, with large hair-trunk, as Curtain falls.

Late evening. Rebecca West stands by a lighted lamp, with a shade over it, packing sandwiches, &c., in a reticule, with a faint smile. The antimacassar is on the sofa. Enter Rosmer.

[Seeing the sandwiches, &c.] Sandwiches? Then you are going! Why, on earth—I can't understand!

Dear, you never can. Rosmershölm is too much for me. But how did you get on with Kroll?

We have made it up. He has convinced me that the work of ennobling men was several sizes too large for me—so I am going to let it alone——

[With her faint smile.] There I almost think, dear, that you are wise.

[As if annoyed.] What, so you don't believe in me either, Rebecca—you never did!

[Sits listlessly on chair.

Not much, dear, when you are left to yourself—but I've another confession to make.

What, another? I really can't stand any more confessions just now!

[Sitting close to him.] It is only a little one. I bullied Beata into the mill-race—because of a wild uncontrollable—— [Rosmer moves uneasily.] Sit still, dear—uncontrollable fancy—for you!

[Goes and sits on sofa.] Oh, my goodness, Rebecca—you mustn't, you know!

[He jumps up and down as if embarrassed.

Don't be alarmed, dear, it is all over now. After living alone with you in solitude, when you showed me all your thoughts without reserve—little by little, somehow the fancy passed off. I caught the Rosmer view of life badly, and dulness descended on my soul as an extinguisher upon one of our Northern dips. The Rosmer view of life is ennobling, very—but hardly lively. And I've more yet to tell you.

[Turning it off.] Isn't that enough for one evening?

[Almost voiceless.] No, dear. I have a Past—behind me!

Behind you? How strange. I had an idea of that sort already. [Starts, as if in fear.] A joke! [Sadly.] Ah, no—no, I must not give way to that! Never mind the Past, Rebecca; I once thought that I had made the grand discovery that, if one is only virtuous, one will be happy. I see now it was too daring, too original—an immature dream. What bothers me is that I can't—somehow I can't—believe entirely in you—I am not even sure that I have ennobled you so very much—isn't it terrible?

[Wringing her hands.] Oh, this killing doubt! [Looks darkly at him.] Is there anything I can do to convince you?

[As if impelled to speak against his will.] Yes, one thing—only I'm afraid you wouldn't see it in the same light. And yet I must mention it. It is like this. I want to recover faith in my mission, in my power to ennoble human souls. And, as a logical thinker, this I cannot do now, unless—well, unless you jump into the mill-race, too, like Beata!

[Takes up her antimacassar, with composure, and puts it on her head.] Anything to oblige you.

[Springs up.] What? You really will! You are sure you don't mind? Then, Rebecca, I will go further. I will even go—yes—as far as you go yourself!

Rebecca.

[Bows her head towards his breast.] You will see me off? Thanks. Now you are indeed an Ibsenite.

[Smiles almost imperceptibly.

[Cautiously.] I said as far as you go. I don't commit myself further than that. Shall we go?

Rebecca.

First tell me this. Are you going with me, or am I going with you?

A subtle psychological point—but we have not time to think it out here. We will discuss it as we go along. Come!

[Rosmer takes his hat and stick, Rebecca her reticule, with sandwiches. They go out hand-in-hand through the door, which they leave open. The room (as is not uncommon with rooms in Norway) is left empty. Then Madam Helseth enters through another door.

The cab, Miss—not here! [Looks out.] Out together—at this time of night—upon my—not on the garden seat? [Looks out of window.] My goodness! what is that white thing on the bridge—the Horse at last! [Shrieks aloud.] And those two sinful creatures running home!

Enter Rosmer and Rebecca, out of breath.

[Scarcely able to get the words out.] It's no use, Rebecca—we must put it off till another evening. We can't be expected to jump off a footbridge which already has a White Horse on it. And if it comes to that, why should we jump at all? I know now that I really have ennobled you, which was all I wanted. What would be the good of recovering faith in my mission at the bottom of a mill-pond? No, Rebecca—[Lays his hand on her head]—there is no judge over us, and therefore——

[Interrupting gravely.] We will bind ourselves over in our own recognisances to come up for judgment when called upon.

[Madam Helseth holds on to a chair-back. Rebecca finishes the antimacassar calmly as Curtain falls.

A room tastefully filled with cheap Art-furniture. Gimcracks in an étagère: a festoon of chenille monkeys hanging from the gaselier. Japanese fans, skeletons, cotton-wool spiders, frogs and lizards, scattered everywhere about. Drain-pipes with tall dyed grasses. A porcelain stove decorated with transferable pictures. Showily-bound books in book-case. Window. The Visitor's bell rings in the hall outside. The hall-door is heard to open, and then to shut. Presently Nora walks in with parcels; a porter carries a large Christmas-tree after her—which he puts down. Nora gives him a shilling—and he goes out grumbling.

Nora hums contentedly, and eats macaroons. Then Helmer puts his head out of his Manager's room, and Nora hides macaroons cautiously.

[Playfully.] Is that my little squirrel twittering—that my lark frisking in here?

Ess! [To herself.] I have only been married eight years, so these marital amenities have not yet had time to pall!

[Threatening with his finger.] I hope the little bird has surely not been digging its beak into any macaroons, eh?

[Bolting one, and wiping her mouth.] No, most certainly not. [To herself] The worst of being so babyish is—one does have to tell such a lot of taradiddles! [To Helmer.] See what I've bought—it's been such fun! [Hums.

[Inspecting parcels.] H'm—rather an expensive little lark!

[Takes her playfully by the ear.

Little birds like to have a flutter occasionally. Which reminds me—— [Plays with his coat-buttons.] I'm such a simple ickle sing—but if you are thinking of giving me a Christmas present, make it cash!

Just like your poor father, he always asked me to make it cash—he never made any himself! It's heredity, I suppose. Well—well!

[Goes back to his Bank. Nora goes on humming.

[Enter Mrs. Linden, doubtfully.

What, Christina—why, how old you look! But then you are poor. I'm not. Torvald has just been made a Bank Manager. [Tidies the room.] Isn't it really wonderfully delicious to be well off? But of course, you wouldn't know. We were poor once, and, do you know, when Torvald was ill, I—[tossing her head]—though I am such a frivolous little squirrel, and all that, I actually borrowed £300 for him to go abroad. Wasn't that clever? Tra-la-la! I shan't tell you who lent it. I didn't even tell Torvald. I am such a mere baby I don't tell him everything. I tell Dr. Rank, though. Oh, I'm so awfully happy I should like to shout, "Dash it all!"

[Stroking her hair.] Do—it is a natural and innocent outburst—you are such a child! But I am a widow, and want employment. Do you think your husband could find me a place as clerk in his Bank? [Proudly.] I am an excellent knitter!

That would really be awfully funny. [To Helmer, who enters.] Torvald, this is Christina; she wants to be a clerk in your Bank—do let her! She thinks such a lot of you. [To herself.] Another taradiddle!

She is a sensible woman, and deserves encouragement. Come along, Mrs. Linden, and we'll see what we can do for you.

[He goes out through the hall with Mrs. Linden, and the front-door is heard to slam after them.

[Opens door, and calls.] Now, Emmy, Ivar, and Bob, come in and have a romp with Mamma—we will play hide-and-seek. [She gets under the table, smiling in quiet satisfaction; Krogstad enters—Nora pounces out upon him.] Boo!... Oh, I beg your pardon. I don't do this kind of thing generally—though I may be a little silly.

[Politely.] Don't mention it. I called because I happened to see your husband go out with Mrs. Linden—from which, being a person of considerable penetration, I infer that he is about to give her my post at the Bank. Now, as you owe me the balance of £300, for which I hold your acknowledgment, you will see the propriety of putting a stop to this little game at once.

But I don't at all—not a little wee bit! I'm so childish, you know—why should I?

[Sitting upright on carpet.

I will try to make it plain to the meanest capacity. When you came to me for the loan, I naturally required some additional security. Your father, being a shady Government official, without a penny—for, if he had possessed one, he would presumably have left it to you—without a penny, then—I, as a cautious man of business, insisted upon having his signature as a surety. Oh, we Norwegians are sharp fellows!

Well, you got papa's signature, didn't you?

Oh, I got it right enough. Unfortunately, it was dated three days after his decease—now, how do you account for that?

How? Why, as poor Papa was dead, and couldn't sign, I signed for him, that's all! Only somehow I forgot to put the date back. That's how. Didn't I tell you I was a silly, unbusiness like little thing? It's very simple.

Very—but what you did amounts to forgery, notwithstanding. I happen to know, because I'm a lawyer, and have done a little in the forging way myself. So, to come to the point—if I get kicked out, I shall not go alone!

[He bows, and goes out.

It can't be wrong! Why, no one but Krogstad would have been taken in by it! If the Law says it's wrong, the Law's a goose—a bigger goose than poor little me even! [To Helmer, who enters.] Oh, Torvald, how you made me jump!

Has anybody called? [Nora shakes her head.] Oh, my little squirrel mustn't tell naughty whoppers. Why, I just met that fellow Krogstad in the hall. He's been asking you to get me to take him back—now, hasn't he?

[Walking about.] Do just see how pretty the Christmas-tree looks!

Never mind the tree—I want to have this out about Krogstad. I can't take him back, because many years ago he forged a name. As a lawyer, a close observer of human nature, and a Bank Manager, I have remarked that people who forge names seldom or never confide the fact to their children—which inevitably brings moral contagion into the entire family. From which it follows, logically, that Krogstad has been poisoning his children for years by acting a part, and is morally lost. [Stretches out his hands to her.] I can't bear a morally lost Bank-cashier about me!

But you never thought of dismissing him till Christina came!

H'm! I've got some business to attend to—so good-bye, little lark!

[Goes into office and shuts door.

[Pale with terror.] If Krogstad poisons his children because he once forged a name, I must be poisoning Emmy, and Bob, and Ivar, because I forged papa's signature! [Short pause; she raises her head proudly.] After all, if I am a doll, I can still draw a logical inference! I mustn't play with the children any more—[hotly]—I don't care—I shall, though! Who cares for Krogstad?

[She makes a face, choking with suppressed tears, as Curtain falls.

The room, with the cheap Art-furniture as before—except that the candles on the Christmas tree have guttered down and appear to have been lately blown out. The cotton-wool frogs and the chenille monkeys are disarranged, and there are walking things on the sofa. Nora alone.

[Putting on a cloak and taking it off again.]

Bother Krogstad! There, I won't think of him. I'll only think of the costume ball at Consul Stenborg's, overhead, to-night, where I am to dance the Tarantella all alone, dressed as a Capri fisher-girl. It struck Torvald that, as I am a matron with three children, my performance might amuse the Consul's guests, and, at the same time, increase his connection at the Bank. Torvald is so practical. [To Mrs. Linden, who comes in with a large cardboard box.] Ah, Christina, so you have brought in my old costume? Would you mind, as my husband's new Cashier, just doing up the trimming for me?

Not at all—is it not part of my regular duties? [Sewing.] Don't you think, Nora, that you see a little too much of Dr. Rank?

Oh, I couldn't see too much of Dr. Rank! He is so amusing—always talking about his complaints, and heredity, and all sorts of indescribably funny things. Go away now, dear; I hear Torvald.

[Mrs. Linden goes. Enter Torvald from the Manager's room. Nora runs trippingly to him.

[Coaxing.] Oh, Torvald, if only you won't dismiss Krogstad, you can't think how your little lark would jump about and twitter.

The inducement would be stronger but for the fact that, as it is, the little lark is generally engaged in that particular occupation. And I really must get rid of Krogstad. If I didn't, people would say I was under the thumb of my little squirrel here, and then Krogstad and I knew each other in early youth; and when two people knew each other in early youth—[a short pause]—h'm! Besides, he will address me as, "I say, Torvald"—which causes me most painful emotion! He is tactless, dishonest, familiar, and morally ruined—altogether not at all the kind of person to be a Cashier in a Bank like mine.

But he writes in scurrilous papers—he is on the staff of the Norwegian Punch. If you dismiss him, he may write nasty things about you, as wicked people did about poor dear papa!

Your poor dear papa was not impeccable—far from it. I am—which makes all the difference. I have here a letter giving Krogstad the sack. One of the conveniences of living close to the Bank is, that I can use the housemaids as Bank-messengers. [Goes to door and calls.] Ellen! [Enter parlourmaid.] Take that letter—there is no answer. [Ellen takes it and goes.] That's settled—and now, Nora, as I am going to my private room, it will be a capital opportunity for you to practise the tambourine—thump away, little lark, the doors are double!

[Nods to her and goes in, shutting door.

[Stroking her face.] How am I to get out of this mess? [A ring at the visitors' bell.] Dr. Rank's ring! He shall help me out of it! [Dr. Rank appears in doorway, hanging up his great-coat.] Dear Dr. Rank, how are you?

[Takes both his hands.

[Sitting down near the stove.] I am a miserable, hypochondriacal wretch—that's what I am. And why am I doomed to be dismal? Why? Because my father died of a fit of the blues! Is that fair—I put it to you?

Do try to be funnier than that! See, I will show you the flesh-coloured silk tights that I am to wear to-night—it will cheer you up. But you must only look at the feet—well, you may look at the rest if you're good. Aren't they lovely? Will they fit me, do you think?

[Gloomily.] A poor fellow with both feet in the grave is not the best authority on the fit of silk stockings. I shall be food for worms before long—I know I shall!

You mustn't really be so frivolous! Take that! [She hits him lightly on the ear with the stockings; then hums a little.] I want you to do me a great service, Dr. Rank. [Rolling up stockings.] I always liked you. I love Torvald most, of course—but, somehow, I'd rather spend my time with you—you are so amusing!

If I am, can't you guess why? [A short silence.] Because I love you! You can't pretend you didn't know it!

Perhaps not—but it was really too clumsy of you to mention it just as I was about to ask a favour of you! It was in the worst taste! [With dignity.] You must not imagine because I joke with you about silk stockings, and tell you things I never tell Torvald, that I am therefore without the most delicate and scrupulous self-respect! I am really quite a good little doll, Dr. Rank, and now—[sits in rocking chair and smiles]—now I shan't ask you what I was going to!

[Ellen comes in with a card.

[Terrified.] Oh, my goodness!

[Puts it in her pocket.

Excuse my easy Norwegian pleasantry—but—h'm—anything disagreeable up?

[To herself.] Krogstad's card! I must tell another whopper! [To Rank.] No, nothing—only—only my new costume. I want to try it on here. I always do try on my dresses in the drawing-room—it's cosier, you know. So go in to Torvald and amuse him till I'm ready.

[Rank goes into Helmer's room, and Nora bolts the door upon him, as Krogstad enters from hall in a fur cap.

Well, I've got the sack, and so I came to see how you are getting on. I mayn't be a nice man, but—[with feeling]—I have a heart! And, as I don't intend to give up the forged I.O.U.. unless I'm taken back, I was afraid you might be contemplating suicide, or something of that kind; and so I called to tell you that, if I were you, I wouldn't. Bad thing for the complexion, suicide—and silly, too, because it wouldn't mend matters in the least. [Kindly.] You must not take this affair too seriously, Mrs. Helmer. Get your husband to settle it amicably by taking me back as Cashier; then I shall soon get the whip-hand of him, and we shall all be as pleasant and comfortable as possible together!

Not even that prospect can tempt me! Besides, Torvald wouldn't have you back at any price now!

All right, then. I have here a letter, telling your husband all. I will take the liberty of dropping it in the letter-box at your hall-door as I go out. I'll wish you good evening!

[He goes out; presently the dull sound of a thick letter dropping into a wire box is heard.

[Softly, and hoarsely.] He's done it! How am I to prevent Torvald from seeing it?

[Inside the door, rattling.] Hasn't my lark changed its dress yet? [Nora unbolts door.] What—so you are not in fancy costume, after all? [Enters with Rank.] Are there any letters for me in the box there?

[Voicelessly.] None—not even a postcard! Oh, Torvald, don't, please, go and look—promise me you won't! I do assure you there isn't a letter! And I've forgotten the Tarantella you taught me—do let's run over it. I'm so afraid of breaking down—promise me not to look at the letter-box. I can't dance unless you do.

[Standing still, on his way to the letter-box.] I am a man of strict business habits, and some powers of observation; my little squirrel's assurances that there is nothing in the box, combined with her obvious anxiety that I should not go and see for myself, satisfy me that it is indeed empty, in spite of the fact that I have not invariably found her a strictly truthful little dicky-bird. There—there. [Sits down to piano.] Bang away on your tambourine, little squirrel—dance away, my own lark!

[Dancing, with a long gay shawl.] Just won't the little squirrel! Faster—faster! Oh, I do feel so gay! We will have some champagne for dinner, won't we, Torvald?

[Dances with more and more abandonment.

[After addressing frequent remarks in correction.] Come, come—not this awful wildness! I don't like to see quite such a larky little lark as this.... Really it is time you stopped!

[Her hair coming down as she dances more wildly still, and swings the tambourine.] I can't....I can't! [To herself, as she dances.] I've only thirty-one hours left to be a bird in; and after that—[shuddering]—after that, Krogstad will let the cat out of the bag!

Curtain.

The same room—except that the sofa has been slightly moved, and one of the Japanese cotton-wool frogs has fallen into the fire-place. Mrs. Linden sits and reads a book—but without understanding a single line.

[Laying down her book, as a light tread is heard outside.] Here he is at last! [Krogstad comes in, and stands in the doorway.] Mr. Krogstad, I have given you a secret rendezvous in this room, because it belongs to my employer, Mr. Helmer, who has lately discharged you. The etiquette of Norway permits these slight freedoms on the part of a female cashier.

It does. Are we alone? [Nora is heard overhead dancing the Tarantella.] Yes, I hear Mrs. Helmer's fairy footfall above. She dances the Tarantella now—by-and-by she will dance to another tune! [Changing his tone.] I don't exactly know why you should wish to have this interview—after jilting me as you did, long ago, though?

Don't you? I do. I am a widow—a Norwegian widow. And it has occurred to me that there may be a nobler side to your nature somewhere—though you have not precisely the best of reputations.

Right. I am a forger, and a money-lender; I am on the staff of the Norwegian Punch—a most scurrilous paper. More, I have been blackmailing Mrs. Helmer by trading on her fears, like a low cowardly cur. But, in spite of all that—[clasping his hands]—there are the makings of a fine man about me yet, Christina!

I believe you—at least, I'll chance it. I want some one to care for, and I'll marry you.

[Suspiciously.] On condition, I suppose, that I suppress the letter denouncing Mrs. Helmer?

How can you think so? I am her dearest friend; but I can still see her faults, and it is my firm opinion that a sharp lesson will do her all the good in the world. She is much too comfortable. So leave the letter in the box, and come home with me.

I am wildly happy! Engaged to the female cashier of the manager who has discharged me, our future is bright and secure!

[He goes out; and Mrs. Linden sets the furniture straight; presently a noise is heard outside, and Helmer enters, dragging Nora in. She is in fancy dress, and he in an open black domino.

I shan't! It's too early to come away from such a nice party. I won't go to bed!

[She whimpers.

[Tenderly.] There'sh a naughty lil' larkie for you, Mrs. Linen! Poshtively had to drag her 'way! She'sh a capricious lil' girl—from Capri. 'Scuse me!—'fraid I've been and made a pun. Shan' 'cur again! Shplendid champagne the Consul gave us—'counts for it! [Sits down smiling.] Do you knit, Mrs. Cotton?... You shouldn't. Never knit. 'Broider. [Nodding to her, solemnly.] 'Member that. Alwaysh 'broider. More—[hiccoughing]—Oriental! Gobblesh you!—goo'ni!

I only came in to—to see Nora's costume. Now I've seen it, I'll go.

[Goes out.

Awful bore that woman—hate boresh! [Looks at Nora, then comes nearer.] Oh, you prillil squillikins, I do love you so! Shomehow, I feel sho lively thishevenin'!

[Goes to other side of table.] I won't have all that, Torvald!

Why? ain't you my lil' lark—ain't thish our lil' cage? Ver-well, then. [A ring.] Rank! confound it all! [Enter DR. Rank.] Rank, dear old boy, you've been [hiccoughs] going it upstairs. Cap'tal champagne, eh? 'Shamed of you, Rank!

[He sits down on sofa, and closes his eyes gently.

Did you notice it? [With pride.] It was almost incredible the amount I contrived to put away. But I shall suffer for it to-morrow. [Gloomily.] Heredity again! I wish I was dead! I do.

Don't apologise. Torvald was just as bad; but he is always so good-tempered after champagne.

Ah, well, I just looked in to say that I haven't long to live. Don't weep for me, Mrs. Helmer, it's chronic—and hereditary too. Here are my P.P.C. cards. I'm a fading flower. Can you oblige me with a cigar?

[With a suppressed smile.] Certainly. Let me give you a light?

[Doctor Rank lights his cigar, after several ineffectual attempts, and goes out.

[Compassionately.] Poo' old Rank—he'sh very bad to-ni'! [Pulls himself together.] But I forgot—Bishness—I mean, bu-si-ness—mush be 'tended to. I'll go and see if there are any letters. [Goes to box.] Hallo! some one's been at the lock with a hairpin—it's one of your hairpins!

[Holding it out to her.

[Quickly.] Not mine—one of Bob's, or Ivar's—they both wear hairpins!

[Turning over letters absently.] You must break them of it—bad habit! What a lot o' lettersh! double usual quantity. [Opens Krogstad's.] By Jove! [Reads it and falls back completely sobered.] What have you got to say to this?

[Crying aloud.] You shan't save me—let me go! I won't be saved!

Save you, indeed! Who's going to save Me? You miserable little criminal. [Annoyed.] Ugh—ugh!

[With hardening expression.] Indeed, Torvald, your singing-bird acted for the best!

Singing-bird! Your father was a rook—and you take after him. Heredity again! You have utterly destroyed my happiness. [Walks round several times.] Just as I was beginning to get on, too!

I have—but I will go away and jump into the water.

What good will that do me? People will say I had a hand in this business. [Bitterly.] If you must forge, you might at least put your dates in correctly! But you never had any principle! [A ring.] The front-door bell! [A fat letter is seen to fall into the box; Helmer takes it, opens it, sees enclosure, and embraces Nora.] Krogstad won't split. See, he returns the forged I.O.U.! Oh, my poor little lark, what you must have gone through! Come under my wing, my little scared song-bird.... Eh? you won't! Why, what's the matter now?

[With cold calm.] I have wings of my own, thank you, Torvald, and I mean to use them!

What—leave your pretty cage, and [pathetically] the old cock bird, and the poor little innocent eggs!

Exactly. Sit down, and we will talk it over first. [Slowly.] Has it ever struck you that this is the first time you and I have ever talked seriously together about serious things?

Come, I do like that! How on earth could we talk about serious things when your mouth was always full of macaroons?

[Shakes her head.] Ah, Torvald, the mouth of a mother of a family should have more solemn things in it than macaroons! I see that now, too late. No, you have wronged me. So did papa. Both of you called me a doll, and a squirrel, and a lark! You might have made something of me—and instead of that, you went and made too much of me—oh, you did!

Well, you didn't seem to object to it, and really I don't exactly see what it is you do want!

No more do I—that is what I have got to find out. If I had been properly educated, I should have known better than to date poor papa's signature three days after he died. Now I must educate myself. I have to gain experience, and get clear about religion, and law, and things, and whether Society is right or I am—and I must go away and never come back any more till I am educated!

Then you may be away some little time? And what's to become of me and the eggs meanwhile?

That, Torvald, is entirely your own affair. I have a higher duty than that towards you and the eggs. [Looking solemnly upward.] I mean my duty towards Myself!

And all this because—in a momentary annoyance at finding myself in the power of a discharged cashier who calls me "I say, Torvald," I expressed myself with ultra-Gilbertian frankness! You talk like a silly child!

Because my eyes are opened, and I see my position with the eyes of Ibsen. I must go away at once, and begin to educate myself.

May I ask how you are going to set about it?

Certainly. I shall begin—yes, I shall begin with a course of the Norwegian theatres. If that doesn't take the frivolity out of me, I don't really know what will!

[She gets her bonnet and ties it tightly.

Then you are really going? And you'll never think about me and the eggs any more! Oh, Nora!

Indeed, I shall—occasionally—as strangers. [She puts on a shawl sadly, and fetches her dressing-bag.] If I ever do come back, the greatest miracle of all will have to happen. Good-bye!

[She goes out through the hall; the front door is heard to bang loudly.

[Sinking on a chair.] The room empty? Then she must be gone! Yes, my little lark has flown! [The dull sound of an unskilled latchkey is heard trying the lock; presently the door opens, and Nora, with a somewhat foolish expression, reappears.] What? back already! Then you are educated?

[Puts down dressing-bag.] No, Torvald, not yet. Only, you see, I found I had only threepence-halfpenny in my purse, and the Norwegian theatres are all closed at this hour—and so I thought I wouldn't leave the cage till to-morrow—after breakfast.

[As if to himself.] The greatest miracle of all has happened. My little bird is not in the bush just yet!

[Nora takes down a showily-bound dictionary from the shelf and begins her education; Helmer fetches a bag of macaroons, sits near her, and tenders one humbly. A pause. Nora repulses it, proudly. He offers it again. She snatches at it suddenly, still without looking at him, and nibbles it thoughtfully as Curtain falls.

Scene—A sitting-room cheerfully decorated in dark colours. Broad doorway, hung with black crape, in the wall at back, leading to a back drawing-room, in which, above a sofa in black horsehair, hangs a posthumous portrait of the late General Gabler. On the piano is a handsome pall. Through the glass panes of the back drawing-room window are seen a dead wall and a cemetery. Settees, sofas, chairs, &c., handsomely upholstered in black bombazine, and studded with small round nails. Bouquets of immortelles and dead grasses are lying everywhere about.

Enter Aunt Julie (a good-natured-looking lady in a smart hat.)

Well, I declare, if I believe George or Hedda are up yet! [Enter George Tesman, humming, stout, careless, spectacled.] Ah, my dear boy, I have called before breakfast to inquire how you and Hedda are after returning late last night from your long honeymoon. Oh, dear me, yes; am I not your old aunt, and are not these attentions usual in Norway?

Good Lord, yes! My six months' honeymoon has been quite a little travelling scholarship, eh? I have been examining archives. Think of that! Look here, I'm going to write a book all about the domestic interests of the Cave-dwellers during the Deluge. I'm a clever young Norwegian man of letters, eh?

Fancy your knowing about that too! Now, dear me, thank Heaven!

Let me, as a dutiful Norwegian nephew, untie that smart, showy hat of yours. [Unties it, and pats her under the chin.] Well, to be sure, you have got yourself really up—fancy that!

[He puts hat on chair close to table.

[Giggling.] It was for Hedda's sake—to go out walking with her in. [Hedda approaches from the back-room; she is pallid, with cold, open, steel-grey eyes; her hair is not very thick, but what there is of it is an agreeable medium brown.] Ah, dear Hedda!

[She attempts to cuddle her.

[Shrinking back.] Ugh, let me go, do! [Looking at Aunt Julie's hat.] Tesman, you must really tell the housemaid not to leave her old hat about on the drawing-room chairs. Oh, is it your hat? Sorry I spoke, I'm sure!

[Annoyed.] Good gracious, little Mrs. Hedda; my nice new hat that I bought to go out walking with you in!

[Patting her on the back.] Yes, Hedda, she did, and the parasol too! Fancy, Aunt Julie always positively thinks of everything, eh?

[Coldly.] You hold your tongue. Catch me going out walking with your aunt! One doesn't do such things.

[Beaming.] Isn't she a charming woman? Such fascinating manners! My goodness, eh? Fancy that!

Ah, dear George, you ought indeed to be happy—but [brings out a flat package wrapped in newspaper] look here, my dear boy!

[Opens it.] What? my dear old morning shoes! my slippers! [Breaks down.] This is positively too touching, Hedda, eh? Do you remember how badly I wanted them all the honeymoon? Come and just have a look at them—you may!

Bother your old slippers and your old aunt too! [aunt Julie goes out annoyed, followed by George, still thanking her warmly for the slippers; Hedda yawns; George comes back and places his old slippers reverently on the table.] Why, here comes Mrs. Elvsted—another early caller! She had irritating hair, and went about making a sensation with it—an old flame of yours, I've heard.

Enter Mrs. Elvsted; she is pretty and gentle, with copious wavy white-gold hair and round prominent eyes, and the manner of a frightened rabbit.

[Nervous.] Oh, please, I'm so perfectly in despair. Ejlert Lövborg, you know, who was our tutor; he's written such a large new book. I inspired him. Oh, I know I don't look like it—but I did—he told me so. And, good gracious! now he's in this dangerous wicked town all alone, and he's a reformed character, and I'm so frightened about him; so, as the wife of a sheriff twenty years older than me, I came up to look after Mr. Lövborg. Do ask him here—then I can meet him. You will? How perfectly lovely of you! My husband's so fond of him!

George, go and write an invitation at once; do you hear? [George looks around for his slippers, takes them up and goes out.] Now we can talk, my little Thea. Do you remember how I used to pull your hair when we met on the stairs, and say I would scorch it off? Seeing people with copious hair always does irritate me.

Goodness, yes, you were always so playful and friendly, and I was so afraid of you. I am still. And please, I've run away from my husband. Everything around him was distasteful to me. And Mr. Lövborg and I were comrades—he was dissipated, and I got a sort of power over him, and he made a real person out of me—which I wasn't before, you know; but, oh, I do hope I'm real now. He talked to me and taught me to think—chiefly of him. So, when Mr. Lövborg came here, naturally I came too. There was nothing else to do! And fancy, there is another woman whose shadow still stands between him and me! She wanted to shoot him once, and so, of course, he can never forget her. I wish I knew her name—perhaps it was that red-haired opera-singer?

[With cold self-command.] Very likely—but nobody does that sort of thing here. Hush! Run away now. Here comes Tesman with Judge Brack. [Mrs. Elvsted goes out; George comes in with Judge Brack, who is a short and elastic gentleman, with a round face, carefully brushed hair, and distinguished profile.] How awfully funny you do look by daylight, Judge!

[Holding his hat and dropping his eye-glass.] Sincerest thanks. Still the same graceful manners, dear little Mrs. Hed—Tesman! I came to invite dear Tesman to a little bachelor-party to celebrate his return from his long honeymoon. It is customary in Scandinavian society. It will be a lively affair, for I am a gay Norwegian dog.

Asked out—without my wife! Think of that! Eh? Oh, dear me, yes, I'll come!

By the way, Lövborg is here; he has written a wonderful book, which has made a quite extraordinary sensation. Bless me, yes!

Lövborg—fancy! Well, I am—glad. Such marvellous gifts! And I was so painfully certain he had gone to the bad. Fancy that, eh? But what will become of him now, poor fellow, eh? I am so anxious to know!

Well, he may possibly put up for the Professorship against you, and, though you are an uncommonly clever man of letters—for a Norwegian—it's not wholly improbable that he may cut you out!

But, look here, good Lord, Judge Brack!—[gesticulating]—that would show an incredible want of consideration for me! I married on my chance of getting that professorship. A man like Lövborg, too, who hasn't even been respectable, eh? One doesn't do such things as that!

Really? You forget we are all realistic and unconventional persons here, and do all kinds of odd things. But don't worry yourself!

[He goes out.

[To Hedda.] Oh, I say, Hedda, what's to become of our fairyland now, eh? We can't have a liveried servant, or give dinner parties, or have a horse for riding. Fancy that!

[Slowly, and wearily.] No, we shall really have to set up as fairies in reduced circumstances, now.

[Cheering up.] Still, we shall see Aunt Julie every day, and that will be something, and I've got back my old slippers. We shan't be altogether without some amusements, eh?

[Crosses the floor.] Not while I have one thing to amuse myself with, at all events.

[Beaming with joy.] Oh, Heaven be praised and thanked for that! My goodness, so you have! And what may that be, Hedda, eh?

[At the doorway, with suppressed scorn.] Yes, George you have the old slippers of the attentive aunt, and I have the horse-pistols of the deceased general!

[In an agony.] The pistols! Oh, my goodness! what pistols?

[With cold eyes.] General Gabler's pistols—same which I shot—[recollecting herself]—no, that's Thackeray, not Ibsen—a very different person.

[She goes through the back drawing-room.

[At doorway, shouting after her.] Dearest Hedda, not those dangerous things, eh? Why, they have never once been known to shoot straight yet! Don't! Have a catapult. For my sake, have a catapult!

[Curtain.

Scene—The cheerful dark drawing-room. It is afternoon. Hedda stands loading a revolver in the back drawing-room.

[Looking out and shouting.] How do you do, Judge? [Aims at him.] Mind yourself!

[She fires.

[Entering.] What the devil! Do you usually take pot-shots at casual visitors?

[Annoyed.

Invariably, when they come by the back-garden. It is my unconventional way of intimating that I am at home. One does do these things in realistic dramas, you know. And I was only aiming at the blue sky.

Which accounts for the condition of my hat. [Exhibiting it.] Look here—riddled!

Couldn't help myself. I am so horribly bored with Tesman. Everlastingly to be with a professional person!

[Sympathetically.] Our excellent Tesman is certainly a bit of a bore. [Looks searchingly at her.] What on earth made you marry him?

Tired of dancing, my dear, that's all. And then I used Tesman to take me home from parties; and we saw this villa; and I said I liked it, and so did he; and so we found some common ground, and here we are, do you see! And I loathe Tesman, and I don't even like the villa now; and I do feel the want of an entertaining companion so!

Try me. Just the kind of three-cornered arrangement that I like. Let me be the third person in the compartment—[confidentially]—the tried friend, and, generally speaking, cock of the walk!

[Audibly drawing in her breath.] I cannot resist your polished way of putting things. We will conclude a triple alliance. But hush!—here comes Tesman.

[Enter George with a number of books under his arm.

Puff! I am hot, Hedda. I've been looking into Lövborg's new book. Wonderfully thoughtful—confound him! But I must go and dress for your party, Judge.

[He goes out.

I wish I could get Tesman to take to politics, Judge. Couldn't he be a Cabinet Minister, or something?

H'm!

[A short pause; both look at one another, without speaking. Enter George, in evening dress with gloves.

It is afternoon, and your party is at half-past seven—but I like to dress early. Fancy that! And I am expecting Lövborg.

Ejlert Lövborg comes in from the hall; he is worn and pale, with red patches on his cheek-bones, and wears an elegant perfectly new visiting-suit and black gloves.

Welcome! [Introduces him to Brack.] Listen—I have got your new book, but I haven't read it through yet.

You needn't—it's rubbish. [Takes a packet of MSS. out.] This isn't. It's in three parts; the first about the civilising forces of the future, the second about the future of the civilising forces, and the third about the forces of the future civilisation. I thought I'd read you a little of it this evening?

[Hastily.] Awfully nice of you—but there's a little party this evening—so sorry we can't stop! Won't you come too?

No, he must stop and read it to me and Mrs. Elvsted instead.

It would never have occurred to me to think of such clever things! Are you going to oppose me for the professorship, eh?

[Modestly.] No; I shall only triumph over you in the popular judgment—that's all!

Oh, is that all? Fancy! Let us go into the back drawing-room and drink cold punch.

Thanks—but I am a reformed character, and have renounced cold punch—it is poison.

[George and Brack go into the back-room and drink punch, whilst Hedda shows Lövborg a photograph album in the front.

[Slowly, in a low tone.] Hedda Gabler! how could you throw yourself away like this!—Oh, is that the Ortler Group? Beautiful!—— Have you forgotten how we used to sit on the settee together behind an illustrated paper, and—yes, very picturesque peaks—I told you all about how I had been on the loose?

Now, none of that here! These are the Dolomites.—Yes, I remember; it was a beautiful fascinating Norwegian intimacy—but it's over now. See, we spent a night in that little mountain village, Tesman and I.

Did you, indeed? Do you remember that delicious moment when you threatened to shoot me down? [Tenderly.] I do!

[Carelessly.] Did I! I have done that to so many people. But now all that is past, and you have found the loveliest consolation in dear, good, little Mrs. Elvsted—ah, here she is! [Enter Mrs. Elvsted.] Now, Thea, sit down and drink up a good glass of cold punch. Mr. Lövborg is going to have some. If you don't, Mr. Lövborg, George and the Judge will think you are afraid of taking too much if you once begin.

Oh, please, Hedda! When I've inspired Mr. Lövborg so—good gracious! don't make him drink cold punch!

You see, Mr. Lövborg, our dear little friend can't trust you!

So that is my comrade's faith in me! [Gloomily.] I'll show her if I am to be trusted or not. [He drinks a glass of punch.] Now I'll go to the Judge's party. I'll have another glass first. Your health, Thea! So you came up to spy on me, eh? I'll drink the Sheriff's health—everybody's health!

[He tries to get more punch.

[Stopping him.] No more now. You are going to a party, remember.

[George and Tesman come in from back-room.

Don't be angry, Thea. I was fallen for a moment. Now I'm up again! [Mrs. Elvsted beams with delight.] Judge, I'll come to your party, as you are so pressing, and I'll read George my manuscript all the evening. I'll do all in my power to make that party go!

No? fancy! that will be amusing!

There, go away, you wild rollicking creatures! But Mr. Lövborg must be back at ten, to take dear Thea home!

Oh, goodness, yes! [In concealed agony.] Mr. Lövborg, I shan't go away till you do!

[The three men go out laughing merrily; the Act-drop is lowered for a minute; when it is raised, it is 7 A.M., and Mrs. Elvsted and Hedda are discovered sitting up, with rugs around them.

[Wearily.] Seven in the morning, and Mr. Lövborg not here to take me home yet! what can he be doing?

[Yawning.] Reading to Tesman, with vine-leaves in his hair, I suppose. Perhaps he has got to the third part.

Oh, do you really think so, Hedda. Oh, if I could but hope he was doing that!

You silly little ninny! I should like to scorch your hair off. Go to bed!

[Mrs. Elvsted goes. Enter George.

I'm a little late, eh? But we made such a night of it. Fancy! It was most amusing. Ejlert read his book to me—think of that! Astonishing book! Oh, we really had great fun! I wish I'd written it. Pity he's so irreclaimable.

I suppose you mean he has more of the courage of life than most people?

Good Lord! He had the courage to get more drunk than most people. But, altogether, it was what you might almost call a Bacchanalian orgy. We finished up by going to have early coffee with some of these jolly chaps, and poor old Lövborg dropped his precious manuscript in the mud, and I picked it up—and here it is! Fancy if anything were to happen to it! He never could write it again. Wouldn't it be sad, eh? Don't tell any one about it.

[He leaves the packet of MSS. on a chair, and rushes out; Hedda hides the packet as Brack enters.

Another early call, you see! My party was such a singularly animated soirée that I haven't undressed all night. Oh, it was the liveliest affair conceivable! And, like a true Norwegian host, I tracked Lövborg home; and it is only my duty, as a friend of the house, and cock of the walk, to take the first opportunity of telling you that he finished up the evening by coming to mere loggerheads with a red-haired opera-singer, and being taken off to the police-station! You mustn't have him here any more. Remember our little triple alliance!

[Her smile fading away.] You are certainly a dangerous person—but you must not get a hold over me!

[Ambiguously.] What an idea! But I might—I am an insinuating dog. Good morning!

[Goes out.

[Bursting in, confused and excited.] I suppose you've heard where I've been?

[Evasively.] I heard you had a very jolly party at Judge Brack's.

[Mrs. Elvsted comes in.

It's all over. I don't mean to do any more work. I've no use for a companion now, Thea. Go home to your sheriff!

[Agitated.] Never! I want to be with you when your book comes out!

It won't come out—I've torn it up! [Mrs. Elvsted rushes out, wringing her hands.] Mrs. Tesman, I told her a lie—but no matter. I haven't torn my book up—I've done worse! I've taken it about to several parties, and it's been through a police-row with me—now I've lost it. Even if I found it again, it wouldn't be the same—not to me! I am a Norwegian literary man, and peculiar. So I must make an end of it altogether!

Quite so—but look here, you must do it beautifully. I don't insist on your putting vine-leaves in your hair—but do it beautifully. [Fetches pistol.] See, here is one of General Gabler's pistols—do it with that!

Thanks!

[He takes the pistol, and goes out through the hall-door; as soon as he has gone, Hedda brings out the manuscript, and puts it on the fire, whispering to herself, as Curtain falls.

Scene.—The same room, but—it being evening—darker than ever. The crape curtains are drawn. A servant, with black ribbons in her cap, and red eyes, comes in and lights the gas quietly and carefully. Chords are heard on the piano in the back drawing-room. Presently Hedda comes in and looks out into the darkness. A short pause. Enter George Tesman.

I am so uneasy about poor Lövborg. Fancy! he is not at home. Mrs. Elvsted told me he has been here early this morning, so I suppose you gave him back his manuscript, eh?

[Cold and immovable, supported by arm-chair.] No, I put it on the fire instead.

On the fire! Lövborg's wonderful new book that he read to me at Brack's party, when we had that wild revelry last night! Fancy that! But, I say, Hedda—isn't that rather—eh? Too bad, you know—really. A great work like that. How on earth did you come to think of it?

[Suppressing an almost imperceptible smile.] Well, dear George, you gave me a tolerably strong hint.

Me? Well, to be sure—that is a joke! Why, I only said that I envied him for writing such a book, and it would put me entirely in the shade if it came out, and if anything was to happen to it, I should never forgive myself, as poor Lövborg couldn't write it all over again, and so we must take the greatest care of it! And then I left it on a chair and went away—that was all! And you went and burnt the book all up! Bless me, who would have expected it?

Nobody, you dear simple old soul! But I did it for your sake—it was love, George!

[In an outburst between doubt and joy.] Hedda, you don't mean that! Your love takes such queer forms sometimes. Yes, but yes——[laughing in excess of joy] why, you must be fond of me! Just think of that now! Well, you are fun, Hedda! Look here, I must just run and tell the housemaid that—she will enjoy the joke so, eh?

[Coldly, in self-command.] It is surely not necessary even for a clever Norwegian man of letters in a realistic social drama, to make quite such a fool of himself as all that.

No, that's true too. Perhaps we'd better keep it quiet—though I must tell Aunt Julie—it will make her so happy to hear that you burnt a manuscript on my account! And, besides, I should like to ask her whether that's a usual thing with young wives. [Looks uneasy and pensive again.] But poor old Ejlert's manuscript! Oh Lor', you know! Well, well!

[Mrs. Elvsted comes in.

Oh, please, I'm so uneasy about dear Mr. Lövborg. Something has happened to him, I'm sure!

[Judge Brack comes in from the hall, with a new hat in his hand.

You have guessed it, first time. Something has!

Oh, dear, good gracious! What is it? Something distressing, I'm certain of it!

[Shrieks aloud.

[Pleasantly.] That depends on how one takes it. He has shot himself, and is in a hospital now, that's all!

[Sympathetically.] That's sad, eh? poor old Lövborg! Well, I am cut up to hear that. Fancy, though, eh?

Was it through the temple, or through the breast? The breast? Well, one can do it beautifully through the breast, too. Do you know, as an advanced woman, I like an act of that sort—it's so positive to have the courage to settle the account with himself—it's beautiful, really!

Oh, Hedda, what an odd way to look at it! But never mind poor dear Mr. Lövborg now. What we've got to do is to see if we can't put his wonderful manuscript, that he said he had torn to pieces, together again. [Takes a bundle of small pages out of the pocket of her mantle.] There are the loose scraps he dictated it to me from. I hid them on the chance of some such emergency. And if dear Mr. Tesman and I were to put our heads together, I do think something might come of it.

Fancy! I will dedicate my life—or all I can spare of it—to the task. I seem to feel I owe him some slight amends, perhaps. No use crying over spilt milk, eh, Mrs. Elvsted? We'll sit down—just you and I—in the back drawing-room, and see if you can't inspire me as you did him, eh?

Oh, goodness, yes! I should like it—if it only might be possible!

[George and Mrs. Elvsted go into the back drawing-room and become absorbed in eager conversation; Hedda sits in a chair in the front room, and a little later Brack crosses over to her

[In a low tone.] Oh, Judge, what a relief to know that everything—including Lövborg's pistol—went off so well! In the breast! Isn't there a veil of unintentional beauty in that? Such an act of voluntary courage, too!

[Smiles.] H'm!—perhaps, dear Mrs. Hedda——

[Enthusiastically.] But wasn't it sweet of him! To have the courage to live his own life after his own fashion—to break away from the banquet of life—so early and so drunk! A beautiful act like that does appeal to a superior woman's imagination!

Sorry to shatter your poetical illusions, little Mrs. Hedda, but, as a matter of fact, our lamented friend met his end under other circumstances. The shot did not strike him in the breast—but——

[Pauses.

[Excitedly.] General Gabler's pistols! I might have known it! Did they ever shoot straight? Where was he hit, then?

[In a discreet undertone.] A little lower down!

Oh, how disgusting!—how vulgar!—how ridiculous!—like everything else about me!

Yes, we're realistic types of human nature, and all that—but a trifle squalid, perhaps. And why did you give Lövborg your pistol, when it was certain to be traced by the police? For a charming cold-blooded woman with a clear head and no scruples, wasn't it just a leetle foolish!

Perhaps; but I wanted him to do it beautifully, and he didn't! Oh, I've just admitted that I did give him the pistol—how annoyingly unwise of me! Now I'm in your power, I suppose?

Precisely—for some reason it's not easy to understand. But it's inevitable, and you know how you dread anything approaching scandal. All your past proceedings show that. [To George and Mrs. Elvsted who come in together from the back-room.] Well, how are you getting on with the reconstruction of poor Lövborg's great work, eh?

Capitally; we've made out the first two parts already. And really, Hedda, I do believe Mrs. Elvsted is inspiring me; I begin to feel it coming on. Fancy that!

Yes, goodness! Hedda, won't it be lovely if I can. I mean to try so hard!

Do, you dear little silly rabbit; and while you are trying I will go into the back drawing-room and lie down.

[She goes into the back room and draws the curtains. Short pause. Suddenly she is heard playing "The Bogie Man" within on the piano.

But, dearest Hedda, don't play "The Bogie Man" this evening. As one of my aunts is dead, and poor old Lövborg has shot himself, it seems just a little pointed, eh?

[Puts her head out between the curtains.] All right. I'll be quiet after this. I'm going to practise with the late General Gabler's pistol!

[Closes the curtains again; George gets behind the stove, Judge Brack under the table, and Mrs. Elvsted under the sofa. A shot is heard within.

[Behind the stove.] Eh, look here, I tell you what—she's hit me! Think of that!

[His legs are visibly agitated for a short time. Another shot is heard.

[Under the sofa.] Oh, please, not me! Oh, goodness, now I can't inspire anybody any more. Oh!

[Her feet, which can be seen under the valance, quiver a little and then are suddenly still.

[Vivaciously, from under the table.] I say, Mrs. Hedda, I'm coming in every evening—we will have great fun here togeth—— [Another shot is heard.] Bless me! to bring down the poor old cock-of-the-walk—it's unsportsmanlike!—people don't do such things as that!

[The table-cloth is violently agitated for a minute, and presently the curtains open, and Hedda appears.

[Clearly and firmly.] I've been trying in there to shoot myself beautifully—but with General Gabler's pistol—[She lifts the table-cloth, then looks behind the stove and under the sofa.] What! the accounts of all those everlasting bores settled? Then my suicide becomes unnecessary. Yes, I feel the courage of life once more!

[She goes into the back-room and plays "The Funeral March of a Marionette" as the Curtain falls.

At Werle's house. In front a richly-upholstered study. (R.) A green baize door leading to Werle's office. At back, open folding doors, revealing an elegant dining-room, in which a brilliant Norwegian dinner-party is going on. Hired Waiters in profusion. A glass is tapped with a knife. Shouts of "Bravo!" Old Mr. Werle is heard making a long speech, proposing—according to the custom of Norwegian society on such occasions—the health of his House-keeper, Mrs. Sörby. Presently several short-sighted, flabby, and thin-haired Chamberlains enter from the dining-room with Hialmar Ekdal, who writhes shyly under their remarks.

As we are the sole surviving specimens of Norwegian nobility, suppose we sustain our reputation as aristocratic sparklers by enlarging upon the enormous amount we have eaten, and chaffing Hialmar Ekdal, the friend of our host's son, for being a professional photographer?

Bravo! We will.

[They do; delight of Hialmar. Old Werle comes in, leaning on his Housekeeper's arm, followed by his son, Gregers Werle.

[Dejectedly.] Thirteen at table! [To Gregers, with a meaning glance at Hialmar.] This is the result of inviting an old college friend who has turned photographer! Wasting vintage wines on him, indeed.

[He passes on gloomily.

[To Gregers.] I am almost sorry I came. Your old man is not friendly. Yet he set me up as a photographer fifteen years ago. Now he takes me down! But for him, I should never have married Gina, who, you may remember, was a servant in your family once.

What? my old college friend married fifteen years ago—and to our Gina, of all people! If I had not been up at the works all these years, I suppose I should have heard something of such an event. But my father never mentioned it. Odd!

[He ponders; Old Ekdal comes out through the green baize-door, bowing, and begging pardon, carrying copying work. Old Werle says "Ugh" and "Pah" involuntarily. Hialmar shrinks back, and looks another way. A Chamberlain asks him pleasantly if he knows that old man.

I—oh no. Not in the least. No relation!

[Shocked.] What, Hialmar, you, with your great soul, deny your own father!

[Vehemently.] Of course—what else can a photographer do with a disreputable old parent, who has been in a penitentiary for making a fraudulent map? I shall leave this splendid banquet. The Chamberlains are not kind to me, and I feel the crushing hand of fate on my head!

[Goes out hastily, feeling it.

[Archly.] Any nobleman here say "Cold Punch"?

[Every nobleman says "Cold Punch" and follows her out in search of it with enthusiasm. Gregers approaches his father, who wishes he would go.

Father, a word with you in private. I loathe you. I am nothing if not candid. Old Ekdal was your partner once, and it's my firm belief you deserved a prison quite as much as he did. However, you surely need not have married our Gina to my old friend Hialmar. You know very well she was no better than she should have been!

True—but then no more is Mrs. Sörby. And I am going to marry her—if you have no objection, that is.

None in the world! How can I object to a step-mother who is playing Blind Man's Buff at the present moment with the Norwegian nobility? I am not so overstrained as all that. But really I cannot allow my old friend Hialmar, with his great, confiding, childlike mind, to remain in contented ignorance of Gina's past. No, I see my mission in life at last! I shall take my hat, and inform him that his home is built upon a lie. He will be so much obliged to me!

[Takes his hat, and goes out.

Ha!—I am a wealthy merchant, of dubious morals, and I am about to marry my house-keeper, who is on intimate terms with the Norwegian aristocracy. I have a son who loathes me, and who is either an Ibsenian satire on the Master's own ideals, or else an utterly impossible prig—I don't know or care which. Altogether, I flatter myself my household affords an accurate and realistic picture of Scandinavian Society!

[Curtain.

Hialmar Ekdal's Photographic Studio. Cameras, neck-rests, and other instruments of torture lying about. Gina Ekdal and Hedvig, her daughter, aged 14, and wearing spectacles, discovered sitting up for Hialmar.

Grandpapa is in his room with a bottle of brandy and a jug of hot water, doing some fresh copying work. Father is in society, dining out. He promised he would bring me home something nice!

[Coming in, in evening dress.] And he has not forgotten his promise, my child. Behold! [He presents her with the menu card; Hedvig gulps down her tears; Hialmar notices her disappointment, with annoyance.] And this all the gratitude I get! After dining out and coming home in a dress-coat and boots, which are disgracefully tight! Well well, just to show you how hurt I am, I won't have any beer now! What a selfish brute I am! [Relenting.] You may bring me just a little drop. [He bursts into tears.] I will play you a plaintive Bohemian dance on my flute. [He does.] No beer at such a sacred moment as this! [He drinks.] Ha, this is real domestic bliss!

[Gregers Werle comes in, in a countrified suit.

I have left my father's home—dinner-party and all—for ever. I am coming to lodge with you.

[Still melancholy.] Have some bread and butter. You won't?—then I will. I want it, after your father's lavish hospitality. [Hedvig goes to fetch bread and butter.] My daughter—a poor short-sighted little thing—but mine own.

My father has had to take to strong glasses, too—he can hardly see after dinner. [To Old Ekdal, who stumbles in very drunk.] How can you, Lieutenant Ekdal, who were such a keen sportsman once, live in this poky little hole?

I am a sportsman still. The only difference is that once I shot bears in a forest, and now I pot tame rabbits in a garret. Quite as amusing—and safer.

[He goes to sleep on a sofa.

[With pride.] It is quite true. You shall see.

[He pushes back sliding doors, and reveals a garret full of rabbits and poultry—moonlight effect. Hedvig returns with bread and butter.

[To Gregers.] If you stand just there, you get the best view of our Wild Duck. We are very proud of her, because she gives the play its title, you know, and has to be brought into the dialogue a good deal. Your father peppered her out shooting, and we saved her life.

Yes, Gregers, our estate is not large—but still we preserve, you see. And my poor old father and I sometimes get a day's gunning in the garret. He shoots with a pistol, which my illiterate wife here will call a "pigstol." He once, when he got into trouble, pointed it at himself. But the descendant of two lieutenant-colonels who had never quailed before living rabbit yet, faltered then. He didn't shoot. Then I put it to my own head. But at the decisive moment, I won the victory over myself. I remained in life. Now we only shoot rabbits and fowls with it. After all I am very happy and contented as I am.

[He eats some bread and butter.

But you ought not to be. You have a good deal of the Wild Duck about you. So have your wife and daughter. You are living in marsh vapours. Tomorrow I will take you out for a walk and explain what I mean. It is my mission in life. Good night!

[He goes out.

What was the gentleman talking about, father?

[Eating bread and butter.] He has been dining, you know. No matter—what we have to do now, is to put my disreputable old whitehaired pariah of a parent to bed.

[He and Gina lift Old Eccles—we mean Old Ekdal—up by the legs and arms, and take him off to bed as the Curtain falls.

Hialmar's Studio. A photograph has just been taken. Gina and Hedvig are tidying up.

[Apologetically.] There should have been a luncheon-party in this act, with Dr. Relling and Mölvik, who would have been in a state of comic "chippiness," after his excesses overnight. But, as it hadn't much to do with such plot as there is, we cut it out. It came cheaper. Here comes your father back from his walk with that lunatic, young Werle—you had better go and play with the Wild Duck.

[Hedvig goes.

[Coming in.] I have been for a walk with Gregers; he meant well—but it was tiring. Gina, he has told me that, fifteen years ago, before I married you, you were rather a Wild Duck, so to speak. [Severely.] Why haven't you been writhing in penitence and remorse all these years, eh?

[Sensibly.] Why? Because I have had other things to do. You wouldn't take any photographs, so I had to.

All the same—it was a swamp of deceit. And where am I to find elasticity of spirit to bring out my grand invention now? I used to shut myself up in the parlour, and ponder and cry, when I thought that the effort of inventing anything would sap my vitality. [Pathetically.] I did want to leave you an inventor's widow; but I never shall now, particularly as I haven't made up my mind what to invent yet. Yes, it's all over. Rabbits are trash, and even poultry palls. And I'll wring that cursed Wild Duck's neck!

[Coming in beaming.] Well, so you've got it over. Wasn't it soothing and ennobling, eh? and ain't you both obliged to me?

No; it's my opinion you'd better have minded your own business.

[Weeps.

[In great surprise.] Bless me! Pardon my Norwegian naïveté, but this ought really to be quite a new starting-point. Why, I confidently expected to have found you both beaming!—Mrs. Ekdal, being so illiterate, may take some little time to see it—but you, Hialmar, with your deep mind, surely you feel a new consecration, eh?

[Dubiously.] Oh—er—yes. I suppose so—in a sort of way.

[Hedvig runs in, overjoyed.

Father, only see what Mrs. Sörby has given me for a birthday present—a beautiful deed of gift!

[Shows it.

[Eluding her.] Ha! Mrs. Sörby, the family house-keeper. My father's sight failing! Hedvig in goggles! What vistas of heredity these astonishing coincidences open up! I am not short-sighted, at all events, and I see it all—all! This is my answer. [He takes the deed, and tears it across.] Now I have nothing more to do in this house. [Puts on overcoat.] My home has fallen in ruins about me. [Bursts into tears.] My hat!

Oh, but you mustn't go. You must be all three together, to attain the true frame of mind for self-sacrificing forgiveness, you know!

Self-sacrificing forgiveness be blowed!

[He tears himself away, and goes out.

[With despairing eyes.] Oh, he said it might be blowed! Now he'll never come home any more!

Shall I tell you how to regain your father's confidence, and bring him home surely? Sacrifice the Wild Duck.

Do you think that will do any good?

You just try it!

[Curtain.