Title: Red Hunters and the Animal People

Author: Charles A. Eastman

Release date: November 27, 2010 [eBook #34461]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by K Nordquist, Christine Aldridge and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

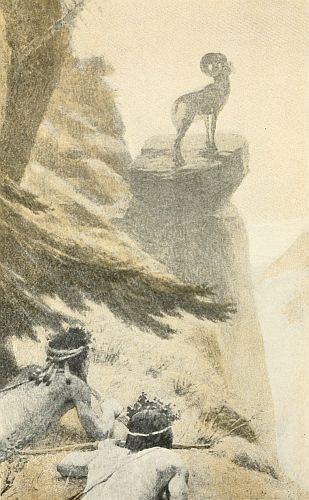

[See p. 149

[See p. 149(Ohiyesa)

AUTHOR OF "INDIAN BOYHOOD"

New York and London

Harper & Brothers

Publishers, 1904

Copyright, 1904, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

Published November, 1904.

| PAGE | |

| The Great Cat's Nursery | 3 |

| On Wolf Mountain | 24 |

| The Dance of the Little People | 46 |

| Wechah the Provider | 66 |

| The Mustering of the Herds | 89 |

| The Sky Warrior | 106 |

| A Founder of Ten Towns | 123 |

| The Gray Chieftain | 143 |

| Hootay of the Little Rosebud | 159 |

| The River People | 177 |

| The Challenge | 200 |

| Wild Animals from the Indian Stand-point | 224 |

| Glossary of Indian Words and Phrases | 247 |

"And who is the grandfather of these silent people? Is it not the Great Mystery? For they know the laws of their life so well! They must have for their Maker our Maker. Then they are our brothers!"

Thus spoke one of the philosophers and orators of the Red men.

It is no wonder that the Indian held the animals to be his brothers. In his simple mind he regards the killing of certain of them for his sustenance to be an institution of the "Great Mystery." Therefore he kills them only as necessity and the exigencies of life demand, and not wantonly. He regards the spirit of the animal as a mystery belonging to the "Great Mystery," and very often after taking its life he pays due homage to its spirit. In many of the Dakota legends it appeared that such and such an animal[vi] came and offered itself as a sacrifice to save the Red man from starvation.

It was formerly held by him that the spirits of animals may communicate important messages to man. The wild hunter often refused during the remainder of his life to kill certain animals, after he had once become acquainted with their spirit or inner life. Many a hunter has absented himself for days and nights from his camp in pursuit of this knowledge. He considered it sacrilege to learn the secrets of an animal and then use this knowledge against him. If you wish to know his secrets you must show him that you are sincere, your spirit and his spirit must meet on common ground, and that is impossible until you have abandoned for the time being your habitation, your weapons, and all thoughts of the chase, and entered into perfect accord with the wild creatures. Such were some of the most sacred beliefs of the Red man, which led him to follow the trails of the animal people into seclusion and the wildest recesses of the woods and mountains.

Observations made for the purposes of the hunt are entirely distinct from this, the[vii] "spirit hunt," and include only the outward habits and noticeable actions of the game.

The stories contained in this book are based upon the common experiences and observations of the Red hunter. The main incidents in all of them, even those which are unusual and might appear incredible to the white man, are actually current among the Sioux and deemed by them worthy of belief.

When the life-story of an animal is given, the experiences described are typical and characteristic of its kind. Here and there the fables, songs, and superstitious fancies of the Indian are brought in to suggest his habit of mind and manner of regarding the four-footed tribes.

The scene of the stories is laid in the great Northwest, the ancient home of the Dakota or Sioux nation, my people. The Great Pipestone Quarry, Eagle's Nest Butte, the Little Rosebud River, and all the other places described under their real names are real and familiar features of that country, which now lies mainly within the States of Minnesota and the Dakotas. The time is[viii] before 1870, when the buffalo and other large game still roamed the wilderness and the Red men lived the life I knew as a boy.

Ohiyesa (Charles A. Eastman)

Amerst, Mass.

A harsh and hateful cry of a sudden broke the peace of a midsummer night upon the creek called Bear-runs-in-the-Lodge. It told many things to the Red hunter, who, though the hour was late, still sat beside the dying camp-fire, pulling away at his long-stemmed pipe.

"Ugh!" he muttered, as he turned his head in the direction of the deep woods and listened attentively. The great cat's scream was not repeated. The hunter resumed his former attitude and continued to smoke.

The night was sultry and threatened storm, and all creatures, especially the fiercer wild animals, become nervous and irritable when thunder is in the air. Yet this fact did not fully explain to his mind Igmutanka's woman-like, almost hysterical complaint.[4]

Having finished his smoke, he emptied the ashes out of the bowl of the pipe and laid it against the teepee-pole at his back. "Ugh!" the hunter once more muttered to himself, this time with a certain complacency. "I will find your little ones to-morrow! That is what you fear."

The Bear-runs-in-the-Lodge is a deep and winding stream, a tributary of the Smoking Earth River, away up at the southern end of the Bad Lands. It is, or was then, an ideal home of wild game, and a resort for the wild hunters, both four-footed and human. Just here the stream, dammed of many beaver, widens its timbered bottoms, while its high banks and the rough country beyond are studded with dwarf pines and gullied here and there with cañon-like dry creeks.

Here the silvertip held supreme sway over all animals, barring an occasional contest with the mountain lion and with the buffalo bull upon the adjoining plains. It is true that these two were as often victorious as he of the big claws and sharp incisors, yet he remained the terror of that region, for he alone takes every opportunity[5] to fight and is reckless in his courage, while other chiefs of the Wild Land prefer to avoid unnecessary trouble.

Igmutanka, the puma mother, had taken her leave of her two little tawny babes about the middle of the afternoon. The last bone of the buffalo calf which she had brought home from her last hunt had been served for dinner. Polished clean by her sharp teeth, it lay in the den for the kittens to play with. Her mate had left her early on that former hunt, and had not returned. She was very nervous about it, for already she feared the worst.

Since she came to Bear-runs they had been together, and their chance acquaintance had become a love affair, and finally they had chosen and made a home for themselves. That was a home indeed! Wildness, mystery, and beauty combined in its outlook and satisfied every craving of the savage pair. They could scarcely say that it was quiet; for while they were unassuming enough and willing to mind their own affairs, Wild Land is always noisy, and the hubbub of the wild people quite as great in its way as that of the city of man.[6]

The stream was dammed so often that Igmu did not have to jump it. The water-worn cliffs, arching and overhanging every turn of the creek, were dark with pines and cedars. Since her babies came she had not ventured upon any long hunts, although ordinarily she was the more successful of the two.

Now Igtin was gone and she was very hungry. She must go out to get meat. So, after admonishing her babies to be still during her absence, and not to come out of their den when Shunktokecha, the wolf, should invite them to do so, she went away.

As the great cat slunk down the valley of the Bear-runs she stopped and glanced nervously at every tree-root and grinning ledge of rock. On the way to Blacktail Creek she had to cross the divide, and when she had attained the Porcupine Butte she paused a moment for a survey, and saw a large herd of buffalo lying down. But their position was not convenient for an attack. There was no meat for her there.

She entered the upper end of the Blacktail and began to hunt down to its mouth. At the first gulch there was a fresh trail. On[7] that very morning three black-tail deer had watered there.

Igmu withdrew and re-entered the valley lower down. She took her stand upon a projection of the bank almost overhanging the stream, a group of buffalo-berry bushes partly concealing her position. Here they will pass, she thought, in returning to the main stream. Her calculation proved correct. Soon she saw a doe with two yearlings coming towards her, leisurely grazing on the choice grass.

The three were wholly unconscious of their danger. Igmu flattened her long, lanky body against the ground—her long, snaky tail slowly moved to and fro as the animals approached. In another moment she had sprung upon the nearest fawn! A shrill scream of agony and the cracking of tender bones mingled with the gladness of satisfying the pangs of hunger. The mother doe and the remaining fawn fled for their lives over the hills to the next creek, knowing well that she would not expose herself in an open chase.

She stood over the lifeless body for a moment, then grabbed it by the neck and[8] dragged it into the dry bed of a small creek, where she was not likely to be disturbed at her feast. The venison tasted deliciously, especially as the poor nursing mother was almost famished. Having eaten all she wanted, she put her claim-mark on the deer and covered it partly up. It was her practice to cover her game to season, and also to make it plain to all that know the laws of Wild Land that it is her game—Igmutanka's! If any one disturbs it, he is running great risk of a pitched battle, for nothing exasperates her family like the theft of their game.

She could not carry any of it home with her, for even while she feasted she had seen an enemy pass by on the other side of the creek. He rode a long-tailed elk (pony) and carried a bagful of those dreadful winged willows, and the crooked stick which makes the winged willows fly. Igmu stopped eating at once and crouched lower. "Don't you dare come near me," was the thought apparent through her large, round eyes. The man passed without discovering her retreat.

"My babies!" thought Igmu. "They are[9] all alone!" The mother-anxiety seized her. It was dangerous now to cross the open, but her desire to get back to her babies was stronger than fear. She ran up the ravine as far as it went; then, seeing no one, ran like a streak over the divide to the Porcupine Butte, where there were large rocks piled one upon another. Here she watched again under cover. "Aw-yaw-yaw!" burst from her in spite of herself. There were many cone-shaped teepees, which had sprung up since the day before upon the wide plain.

"There are the homes of those dreadful wild men! They always have with them many dogs, and these will surely find my home and babies," she thought. Although her anxiety was now very great, and the desire to reach home almost desperate, she yet kept her animal coolness and caution. She took a winding ravine which brought her nearer to Bear-runs, and now and then she had to run swiftly across the openings to gain less-exposed points.

At last she came to the old stream, and the crossing where the Bobtail Beaver had lived for as long as she knew anything about that country. Her dam was always in[10] perfect order, and afforded an excellent bridge. To be sure, they had never been exactly on calling terms, but they had become accustomed to one another as neighbors, and especially whenever danger threatened upon the Bear-runs there was a certain sense of security and satisfaction to each in the presence of the other.

As she passed hurriedly over the dam she observed a trap. Igmu shivered as she recognized the article, and on a closer examination she detected the hated odor of man. She caught the string attached to it and jerked it out upon dry land, thus doing a good turn to her neighbor Sinteksa.

This discovery fully convinced her of the danger to her home and children. She picked her way through the deep woods, occasionally pausing to listen. At that time of the day no people talk except the winged people, and they were joyous as she passed through the timber. She heard the rushing of a water-fall over the cliff, now vibrating louder, now fainter as she listened. Far beyond, towards the wild men's camp, she heard the barking of a dog, which gave her a peculiar shiver of disgust.[11]

A secret path led along the face of the cliff, and there was one open spot which she must cross to get to her den. "Phur-r-r!" she breathed, and dropped to the ground. There stood one of the dreaded wild men!

No sooner had she put her head out of the woods than his quick eye caught her. "Igmutanka!" he exclaimed, and pulled one of the winged sticks out of his little bag.

Igmu was surprised for once, and fear almost overcame her. The danger to her children and the possible fate of her mate came into her mind in a flash. She hesitated for one instant, and in that instant she felt the sting of the swift arrow. She now ran for her life, and in another moment was out of sight among the gray ledges. "Ugh! I got her," muttered the Indian, as he examined the spot where she had stood.

Igmu never stopped until she reached her den. Her wild eyes gleamed as she paused at the entrance to ascertain whether any one had been there since she went away. When she saw and smelled that her home had not been visited, she forgot for the moment all her fright and pain. Her heart beat fast with[12] joy—the mother-joy. Hastily she crawled into the dark cave.

"Yaw-aw-aw!" was the mother's greeting to her tawny babes. "Yaw-aw-aw!" they replied in chorus. She immediately laid herself down in the farthest corner of the den facing the entrance and invited her babies to come and partake of their food. Doubtless she was considering what she should do when the little ones had appeased their hunger.

Presently the bigger baby finished his meal and began to claw the eyes of his brother. The latter pulled away, smacking his lips and blindly showing fight.

"Hush!" said the mother Igmu. "You must be good. Lie down and I will come back soon."

She came out of her den, still carrying the winged stick in her back. It was only a skin wound. She got hold of the end between her teeth and with one jerk she pulled it out. The blood flowed freely. She first rolled upon some loose earth and licked the wound thoroughly. After this she went and rubbed against pine pitch. Again she licked the pitch off from her fur; and having applied[13] all the remedies known to her family, she re-entered the cave.

Igmu had decided to carry her helpless babes to a den she knew of upon Cedar Creek, near the old Eagle's Nest—a rough and remote spot where she felt sure that the wild men would not follow. But it was a long way to travel, and she could carry only one at a time. Meanwhile the hunters and their dogs would certainly track her to her den.

In her own mind she had considered the problem and hit upon an expedient. She took the smaller kitten by the skin of the back and hurried with it to her neighbor Sinteksa's place, down on the creek. There were some old, tumble-down beaver houses which had long been deserted. Without ceremony she entered one of these and made a temporary bed for her babe. Then she went back to her old home for the last time, took the other kitten in her mouth, and set out on her night journey to Cedar Creek.

It was now dark. Her shortest road led her near the camp of the red people; and as she knew that men and dogs seldom hunt by night, she ventured upon this way. Fires[14] were blazing in the camp and the Red men were dancing the "coyote dance." It was a horrible din! Igmu trembled with fear and disgust as the odor of man came to her sensitive nostrils. It seemed to her at this moment that Igtin had certainly met his death at the hands of these dreadful people.

She trotted on as fast as she could with her load, only stopping now and then to put it down and lick the kitten's back. She laid her course straight over the divide, down to the creek, and then up towards its source. Here, in a wild and broken land, she knew of a cavern among piled-up rocks that she intended to make her own. She stopped at the concealed threshold, and, after satisfying herself that it was just as she had left it several months before, she prepared a bed within for her baby, and, having fed him, she admonished him to be quiet and left him alone. She must return at once for the other little cat.

But Igmu had gone through a great deal since the day before. It was now almost morning, and she was in need of food. She remembered the cached deer on the Blacktail Creek, and set out at once in that direction.[15] As usual, there were many fresh deer-tracks, which, with the instinct of a hunter, she paused to examine, half inclined to follow them, but a second thought apparently impelled her to hurry on to her cache.

The day had now dawned and things appeared plain. She followed the creek-bed all the way to the spot where she had killed her deer on the day before. As she neared it her hunger became more and more irresistible; yet, instead of rushing upon her own, when she came within a few paces of it she stopped and laid herself prone upon the earth, according to the custom of her people. She could not see it, for it was hidden in a deep gully, the old bed of a dry stream. As she lay there she switched her tail slowly to and fro, and her eyes shot yellow fire.

Suddenly Igmu flattened out like a sunfish and began to whine nervously. Her eyes became two flaming globes of wrath and consternation. She gradually drew her whole body into a tense lump of muscles, ready to spring. Her lips unconsciously contracted, showing a set of fine teeth—her weapons—while the very ground upon which she lay was deeply scarred by those other[16] weapons, the claws. Eagerly she listened once more—she could hear the cracking of bones under strong teeth.

Her blood now surged beyond all discretion and control. She thought of nothing but that the thief, whoever he might be, must feel the punishment due to his trespass. Two long springs, and she was on top of a wicked and huge grizzly, who was feasting on Igmutanka's cached deer! He had finished most of the tender meat, and had begun to clean his teeth by chewing some of the cartilaginous bones when the attack came.

"Waw-waw-waw-waaw!" yelled the old root-digger, and threw his immense left arm over his shoulder in an effort to seize his assailant. At the same time her weight and the force of her attack knocked him completely over and rolled him upon the sandy ground.

Igmu saw her chance and did not forget the usage of her people in a fight with his. She quickly sprang aside when she found that she could not hold her position, and there was danger of Mato slashing her side with either paw. She purposely threw herself upon her back, which position must have[17] been pleasing to Mato, for he rushed upon her with all the confidence in the world, being ignorant of the trick.

It was not long before the old bear was forced to growl and howl unmercifully. He found that he could neither get in his best fight for himself nor get away from such a deadly and wily foe. He had hoped to chew her up in two winks, but this was a fatal mistake. She had sprung from the ground under him and had hugged him tight by burying the immense claws of her fore-paws in his hump, while her hind claws tore his loins and entrails. Thus he was left only his teeth to fight with; but even this was impossible, for she had pulled herself up close to his neck.

When Mato discovered his error he struggled desperately to get away, but his assailant would not let go her vantage-hold.

"Waw-waw-waw!" yelled the great boastful Mato once more, but this time the tone was that of weakness and defeat. It was a cry of "Murder! murder! Help! help!"

At last Igmutanka sprang aside, apparently to see how near dead the thief might be,[18] and stood lashing her long, snaky tail indignantly.

"Waw-waw, yaw-waw!" moaned and groaned the grizzly, as he dragged himself away from the scene of the encounter. His wounds were deadly and ugly. He lay down within sight of the spot, for he could go no farther. He moaned and groaned more and more faintly; then he was silent. The great fighter and victor in many battles is dead!

Five paces from the remains of the cached deer the victor, lying in the shade of an immense pine, rested and licked her blood-soaked hair. She had received many ugly gashes, but none of them necessarily mortal. Again she applied her soil and pitch-pine remedy and stopped the hemorrhage. Having done this, she realized that she was still very hungry; but Igmu could not under any circumstances eat of the meat left and polluted by the thief. She could not break the custom of her people.

So she went across from Blacktail to the nearest point upon Bear-runs-in-the-Lodge, her former home, hoping to find some game on the way. As she followed the ravine[19] leading from the creek of her fight she came upon a doe and fawn. She crouched down and crawled up close to them, then jumped upon the fawn. The luscious meat—she had all she wanted!

The day was now well advanced, and the harassed mother was growing impatient to reach the babe which she had left in one of the abandoned homes of Mrs. Bobtail Beaver. The trip over the divide between Blacktail and Bear-runs was quickly made. Fear, loneliness, and anxiety preyed upon her mind, and her body was weakened by loss of blood and severe exertion. She dwelt continually on her two babes, so far apart, and her dread lest the wild men should get one or both of them.

If Igmu had only known it, but one kitten was left to her at that moment! She had not left the cave on Cedar Creek more than a few minutes when her own cousin, whom she had never seen and who lived near the Eagle's Nest upon the same creek, came out for a hunt. She intercepted her track and followed it.

When she got to the den it was clear to Nakpaksa (Torn Ear) that this was not a[20] regular home, so that she had a right to enter and investigate. To her surprise she found a little Igmutanka baby, and he cried when he saw her and seemed to be hungry. He was the age of her own baby which she had left not long before, and upon second thought she was not sure but that he was her own and that he had been stolen. He had evidently not been there long, and there was no one near to claim him. So she took him home with her. There she found her own kitten safe and glad to have a playmate, and Nakpaksa decided, untroubled by any pangs of conscience, to keep him and bring him up as her own.

It is clear that had Igmu returned and missed her baby there would have been trouble in the family. But, as the event proved, the cousin had really done a good deed.

It was sad but unavoidable that Igmu should pass near her old home in returning for the other kitten. When she crawled along the rocky ledge, in full view of the den, she wanted to stop. Yet she could not re-enter the home from which she had been forced to flee. It was not the custom of her[21] people to do so. The home which they vacate by chance they may re-enter and even re-occupy, but never the home which they are forced to leave. There are evil spirits there!

Hurt and wearied, yet with courage unshaken, the poor savage mother glided along the stream. She saw Mrs. Bobtail and her old man cutting wood dangerously far from the water, but she could not stop and warn them because she had borrowed one of their deserted houses without their permission.

"Mur-r-r-r!" What is this she hears? It is the voice of the wild men's coyotes! It comes from the direction of the kitten's hiding-place. Off she went, only pausing once or twice to listen; but it became more and more clear that there was yelling of the wild men as well.

She now ran along the high ledges, concealing herself behind trees and rocks, until she came to a point from which she could overlook the scene. Quickly and stealthily she climbed a large pine. Behold, the little Igmu was up a small willow-tree! Three Indians were trying to shake him down, and their dogs were hilarious over the fun.[22]

Her eyes flamed once more with wrath and rebellion against injustice. Could neither man nor beast respect her rights? It was horrible! Down she came, and with swift and cautious step advanced within a very few paces of the tree before man or beast suspected her approach.

Just then they shook the tree vigorously, while the poor little Igmu, clinging to the bough, yelled out pitifully, "Waw, waw, waw!"

Mother-love and madness now raged in her bosom. She could not be quiet any longer! One or two long springs brought her to the tree. The black coyotes and the wild men were surprised and fled for their lives.

Igmu seized and tore the side of one of the men, and threw a dog against the rocks with a broken leg. Then in lightning fashion she ran up the tree to rescue her kitten, and sprang to the ground, carrying it in her teeth. As the terrified hunters scattered from the tree, she chose the path along the creek bottom for her flight.

Just as she thought she had cleared the danger-point a wild man appeared upon the bank overhead and, quick as a flash, sent one[23] of those winged willows. She felt a sharp pang in her side—a faintness—she could not run! The little Igmu for whom she had made such a noble fight dropped from her mouth. She staggered towards the bank, but her strength refused her, so she lay down beside a large rock. The baby came to her immediately, for he had not had any milk since the day before. She gave one gentle lick to his woolly head before she dropped her own and died.

"Woo, woo! Igmutanka ye lo! Woo, woo!" the shout of triumph resounded from the cliffs of Bear-runs-in-the-Lodge. The successful hunter took home with him the last of the Igmu family, the little orphaned kitten.

On the eastern slope of the Big Horn Mountains, the Mayala clan of gray wolves, they of the Steep Places, were following on the trail of a herd of elk. It was a day in late autumn. The sun had appeared for an instant, and then passed behind a bank of cold cloud. Big flakes of snow were coming down, as the lean, gray hunters threaded a long ravine, cautiously stopping at every knoll or divide to survey the outlook before continuing their uncertain pursuit.

The large Mayala wolf with his mate and their five full-grown pups had been driven away from their den on account of their depredations upon the only paleface in the Big Horn valley. It is true that, from their stand-point, he had no right to encroach upon their hunting-grounds.

For three days they had been trailing over[25] the Big Horn Mountains, moving southeast towards Tongue River, where they believed that no man would come to disturb them. They had passed through a country full of game, but, being conscious of the pursuit of the sheepman and his party on their trail, they had not ventured to make an open hunt, nor were they stopping anywhere long enough to seek big game with success. Only an occasional rabbit or grouse had furnished them with a scanty meal.

From the Black Cañon, the outlet of the Big Horn River, there unfolds a beautiful valley. Here the wild man's ponies were scattered all along the river-bottoms. In a sheltered spot his egg-shaped teepees were ranged in circular form. The Mayala family deliberately sat upon their haunches at the head of the cañon and watched the people moving, antlike, among the lodges.

Manitoo, the largest of the five pups, was a famous runner and hunter already. He whimpered at sight of the frail homes of the wild man, and would fain have gotten to the gulches again.

The old wolf rebuked his timidity with a low growl. He had hunted many a time[26] with one of these Red hunters as guide and companion. More than this, he knew that they often kill many buffalo and elk in one hunting, and leave much meat upon the plains for the wolf people. They respect his medicine and he respects theirs. It is quite another kind of man who is their enemy.

Plainly there was an unusual commotion in the Sioux village. Ponies were brought in, and presently all the men rode out in a southerly direction.

"Woo-o-o!" was the long howl of the old wolf. It sounded almost like a cry of joy.

"It is the buffalo-hunt! We must run to the south and watch until the hunt is ended."

Away they went, travelling in pairs and at some distance apart, for the sake of better precaution. On the south side of the mountain they stood in a row, watching hungrily the hunt of the Red men.

There was, indeed, a great herd of buffalo grazing upon the river plain surrounded by foot-hills. The hunters showed their heads on three sides of the herd, the fourth side rising abruptly to the sheer ascent of the mountain.

Now there arose in the distance a hoarse[27] shout from hundreds of throats in unison. The trained ponies of the Indians charged upon the herd, just as the wolves themselves had sometimes banded together for the attack in better days of their people. It was not greatly different from the first onset upon the enemy in battle. Yelling and brandishing their weapons, the Sioux converged upon the unsuspecting buffalo, who fled blindly in the only direction open to them—straight toward the inaccessible steep!

In a breath, men and shaggy beasts were mixed in struggling confusion. Many arrows sped to their mark and dead buffalo lay scattered over the plain like big, black mounds, while the panic-stricken survivors fled down the valley of the Big Horn. In a little while the successful hunters departed with as much meat as their ponies could carry.

No sooner were they out of sight than the old wolf gave a feast-call. "Woo-o-o! woo, woo, woo!" He was sure that they had left enough meat for all the wolf people within hearing distance. Then away they all went for the hunting-ground—not in regular order,[28] as before, but each one running at his best speed. They had not gone far down the slope before they saw others coming from other hills—their gray tribesmen of the rocks and plains.

The Mayala family came first to two large cows killed near together. There is no doubt that they were hungry, but the smell of man offends all of the animal kind. They had to pause at a distance of a few paces, as if to make sure that there would be no trick played on them. The old Mayala chief knew that the man with hair on his face has many tricks. He has a black, iron ring that is hidden under earth or snow to entrap the wolf people, and sometimes he puts medicine on the meat that tortures and kills them. Although they had seen these buffalo fall before their brothers, the wild Red men, they instinctively hesitated before taking the meat. But in the mean time there were others who came very hungry and who were, apparently, less scrupulous, for they immediately took hold of it, so that the Mayala people had to hurry to get their share.

In a short time all the meat left from the wild men's hunt had disappeared, and the[29] wolves began grinding the soft and spongy portions of the bones. The old ones were satisfied and lay down, while the young ones, like young folks of any race, sat up pertly and gossipped or squabbled until it was time to go home.

Suddenly they all heard a distant call—a gathering call. "Woo-oo-oo!" After a few minutes it came again. Every gray wolf within hearing obeyed the summons without hesitation.

Away up in the secret recesses of the Big Horn Mountains they all came by tens and hundreds to the war-meeting of the wolves. The Mayala chief and his young warriors arrived at the spot in good season. Manitoo was eager to know the reason of this great council. He was young, and had never before seen such a gathering of his people.

A gaunt old wolf, with only one eye and an immensely long nose, occupied the place of honor. No human ear heard the speech of the chieftain, but we can guess what he had to say. Doubtless he spoke in defence of his country, the home of his race and that of the Red man, whom he regarded with toleration. It was altogether different with[30] that hairy-faced man who had lately come among them to lay waste the forests and tear up the very earth about his dwelling, while his creatures devoured the herbage of the plain. It would not be strange if war were declared upon the intruder.

"Woo! woo! woo!" The word of assent came forth from the throats of all who heard the command at that wild council among the piled-up rocks, in the shivering dusk of a November evening.

The northeast wind came with a vengeance—every gust swayed and bent even the mighty pines of the mountains. Soon the land became white with snow. The air was full of biting cold, and there was an awfulness about the night.

The sheepman at his lonely ranch had little warning of the storm, and he did not get half of his cows in the corral. As for the sheep, he had already rounded them up before the blizzard set in.

"My steers, I reckon, 'll find plenty of warm places for shelter," he remarked to his man. "I kinder expect that some of my cows'll suffer; but the worst of it is the wolves—confound[31] them! The brutes been howling last night and again this evenin' from pretty nigh every hill-top. They do say, too, as that's a sure sign of storm!"

The long log-cabin creaked dismally under the blast, and the windward windows were soon coated with snow.

"What's that, Jake? Sounds like a lamb bleating," the worried rancher continued.

Jake forcibly pushed open the rude door and listened attentively.

"There is some trouble at the sheep-sheds, but I can't tell just what 'tis. May be only the wind rattling the loose boards," he suggested, uncertainly.

"I expect a grizzly has got in among the sheep, but I'll show him that he is at the wrong door," exclaimed Hank Simmons, with grim determination. "Get your rifle, Jake, and we'll teach whoever or whatever it may be that we are able to take care of our stock in night and storm as well as in fair weather!"

He pushed the door open and gazed out into the darkness in his turn, but he could not see a foot over the threshold. A terrific gust of wind carried a pall of snow into the[32] farthest corner of the cabin. But Hank was a determined fellow, and not afraid of hardship. He would spend a night in the sod stable to watch the coming of a calf, rather than run even a small chance of losing it.

Both men got into their cowhide overcoats and pulled their caps well down over their ears. Rifle in hand, they proceeded towards the sheep-corral in single file, Jake carrying the lantern. The lambs were bleating frantically, and as they approached the premises they discovered that most of the sheep were outside.

"Keep your finger on the trigger, Jake! All the wolves in the Big Horn Mountains are here!" exclaimed Hank, who was a few paces in advance.

Had they been inexperienced men—but they were not. They were both men of nerve. "Bang! bang!" came from two rifles, through the frosty air and blinding snow.

But the voice of the guns did not have the demoralizing effect upon which they had counted. Their assailants scarcely heard the reports for the roar of the storm. Undaunted[33] by the dim glow of the lantern, they banded together for a fresh attack. The growling, snarling, and gnashing of teeth of hundreds of great gray wolves at close quarters were enough to dismay even Hank Simmons, who had seen more than one Indian fight and hair-breadth adventure.

"Bang! bang!" they kept on firing off their pieces, now and then swinging the guns in front of them to stay the mad rush of the wild army. The lantern-light revealed the glitter of a hundred pairs of fierce eyes and shining rows of pointed teeth.

Hank noticed a lean, gray wolf with one eye and an immense head who was foremost in the attack. Almost abreast of him was a young wolf, whose great size and bristling hair gave him an air of ferocity.

"Hold hard, Jake, or they'll pick our bones yet!" Hank exclaimed, and the pair began to retreat. They found it all they could do to keep off the wolves, and the faithful collie who had fought beside them was caught and dragged into darkness. At last Hank pushed the door open and both men tumbled backward into the cabin.[34]

"Shoot! shoot! They have got me!" yelled Jake. The other snatched a blazing ember from the mud chimney and struck the leading wolf dead partly within the hut.

"Gol darn them!" ejaculated Jake, as he scrambled to his feet. "That young wolf is a good one for fighting—he almost jerked my right leg off!"

"Well, I'll be darned, Jake, if they haven't taken one of your boots for a trophy," Hank remarked, as he wiped the sweat from his brows, after kicking out the dead wolf and securely barring the door. "This is the closest call I've had yet! I calculate to stand off the Injuns most any time, but these here wolves have no respect for my good rifle!"

Wazeyah, the god of storm, and the wild mob reigned outside the cabin, while the two pioneer stockmen barricaded themselves within, and with many curses left the sheep to their fate.

The attack had stampeded the flock so that they broke through the corral. What the assailants did not kill the storm destroyed. On the plateau in front of Mayaska the wolves gathered, bringing lambs,[35] and here Manitoo put down Jake's heavy cowhide boot, for it was he who fought side by side with the one-eyed leader.

He was immediately surrounded by the others, who examined what he had brought. It was clear that Manitoo had distinguished himself, for he had stood by the leader until he fell, and secured, besides, the only trophy of the fight.

Now they all gave the last war-cry together. It was the greatest wolf-cry that had been heard for many years upon those mountains. Before daybreak, according to custom, the clans separated, believing that they had effectually destroyed the business of the hairy-faced intruder, and expecting by instant flight to elude his vengeance.

On the day before the attack upon the ranch, an Indian from the camp in the valley had been appointed to scout the mountains for game. He was a daring scout, and was already far up the side of the peak which overhung the Black Cañon when he noticed the air growing heavy and turned his pony's head towards camp. He urged him on, but the pony was tired, and, suddenly, a blinding[36] storm came sweeping over the mountainside.

The Indian did not attempt to guide his intelligent beast. He merely fastened the lariat securely to his saddle and followed behind on foot, holding to the animal's tail. He could not see, but soon he felt the pony lead him down a hill. At the bottom it was warm, and the wind did not blow much there. The Indian took the saddle off and placed it in a wash-out which was almost dry. He wrapped himself in his blanket and lay down. For a long time he could feel and hear the foot-falls of his pony just above him, but at last he fell asleep.

In the morning the sun shone and the wind had subsided. The scout started for camp, knowing only the general direction, but in his windings he came by accident upon the secret place, a sort of natural cave, where the wolves had held their war meeting. The signs of such a meeting were clear to him, and explained the unusual number of wolf-tracks which he had noticed in this region on the day before. Farther down was the plateau, or wopata, where he found the carcasses of many sheep, and there lay[37] Jake's boot upon the bloody and trampled snow!

When he reached the camp and reported these signs to his people, they received the news with satisfaction.

"The paleface," said they, "has no rights in this region. It is against our interest to allow him to come here, and our brother of the wandering foot well knows it for a menace to his race. He has declared war upon the sheepman, and it is good. Let us sing war-songs for the success of our brother!" The Sioux immediately despatched runners to learn the exact state of affairs upon Hank Simmons's ranch.

In the mean time the ruined sheepman had made his way to the nearest army post, which stood upon a level plateau in front of Hog's Back Mountain.

"Hello, Hank, what's the matter now?" quoth the sutler. "You look uncommonly serious this morning. Are the Injuns on your trail again?"

"No, but it's worse this time. The gray wolves of the Big Horn Mountains attacked my place last night and pretty near wiped us out! Every sheep is dead. They even carried[38] off Jake Hansen's boot, and he came within one of being eaten alive. We used up every cartridge in our belts, and the bloody brutes never noticed them no more than if they were pebbles! I'm afraid the post can't help me this time," he concluded, with a deep sigh.

"Oh, the devil! You don't mean it," exclaimed the other. "Well, I told you before to take out all the strychnine you could get hold of. We have got to rid the country of the Injuns and gray wolves before civilization will stick in this region!"

Manitoo had lost one of his brothers in the great fight, and another was badly hurt. When the war-party broke up, Manitoo lingered behind to look for his wounded brother. For the first day or two he would occasionally meet one of his relations, but as the clan started southeast towards Wolf Mountain, he was left far behind.

When he had found his brother lying helpless a little way from the last gathering of the wolf people, he licked much of the blood from his coat and urged him to rise and seek a safer place. The wounded gray with difficulty[39] got upon his feet and followed at some distance, so that in case of danger the other could give the signal in time.

Manitoo ran nimbly along the side gulches until he found a small cave. "Here you may stay. I will go hunting," he said, as plain as signs can speak.

It was not difficult to find meat, and a part of Hank's mutton was brought to the cave. In the morning Manitoo got up early and stretched himself. His brother did not offer to move. At last he made a feeble motion with his head, opened his eyes and looked directly at him for a moment, then closed them for the last time. A tremor passed through the body of the warrior gray, and he was still. Manitoo touched his nose gently, but there was no breath there. It was time for him to go.

When he came out of the death-cave on Plum Creek, Manitoo struck out at once for the Wolf Mountain region. His instinct told him to seek a refuge as far as possible from the place of death. As he made his way over the divide he saw no recent sign of man or of his own kinsfolk. Nevertheless, he had lingered too long for safety. The[40] soldiers at the post had come to the aid of the sheepman, and they were hot on his trail. Perhaps his senses were less alert than usual that morning, for when he discovered the truth it was almost too late.

A long line of hairy-faced men, riding big horses and armed with rifles, galloped down the valley.

"There goes one of the gray devils!" shouted a corporal.

In another breath the awful weapons talked over his head, and Manitoo was running at top speed through a hail of bullets. It was a chase to kill, and for him a run for his life. His only chance lay in reaching the bad places. He had but two hundred paces' start. Men and dogs were gaining on him when at last he struck a deep gulch. He dodged the men around the banks, and their dogs were not experts in that kind of country.

The Sioux runners in the mean time had appeared upon a neighboring butte, and the soldiers, taking them for a war-party, had given up the chase and returned to the post. So, perhaps, after all, his brothers, the wild hunters, had saved Manitoo's life.[41]

During the next few days the young wolf proceeded with caution, and had finally crossed the divide without meeting either friend or foe. He was now, in truth, an outcast and a wanderer. He hunted as best he could with very little success, and grew leaner and hungrier than he had ever been before in his life. Winter was closing in with all its savage rigor, and again night and storm shut down over Wolf Mountain.

The tall pines on the hill-side sighed and moaned as a new gust of wind swept over them. The snow came faster and faster. Manitoo had now and again to change his position, where he stood huddled up under an overarching cliff. He shook and shook to free himself from the snow and icicles that clung to his long hair.

He had been following several black-tail deer into a gulch when the storm overtook him, and he sought out a spot which was somewhat protected from the wind. It was a steep place facing southward, well up on the side of Wolf Mountain.

Buffalo were plenty then, but as Manitoo was alone he had been unable to get meat.[42]

These great beasts are dangerous fighters when wounded, and unless he had some help it would be risking too much to tackle one openly. A band of wolves will attack a herd when very hungry, but as the buffalo then make a fence of themselves, the bulls facing outward, and keep the little ones inside, it is only by tiring them out and stampeding the herd that it is possible to secure one.

Still the wind blew and the snow fell fast. The pine-trees looked like wild men wrapped in their robes, and the larger ones might have passed for their cone-shaped lodges. Manitoo did not feel cold, but he was soon covered so completely that no eye of any of the wild tribes of that region could have distinguished him from a snow-clad rock or mound.

It is true that no good hunter of his tribe would willingly remain idle on such a day as that, for the prey is weakest and most easily conquered on a stormy day. But the long journey from his old home had somewhat disheartened Manitoo; he was weak from lack of food, and, more than all, depressed by a sense of his loneliness. He is as keen for the companionship of his kind as his brother the[43] Indian, and now he longed with a great longing for a sight of the other members of the Mayala clan. Still he stood there motionless, only now and then sniffing the unsteady air, with the hope of discovering some passer-by.

Suddenly out of the gray fog and frost something emerged. Manitoo was hidden perfectly, but at that moment he detected with joy the smell of one of his own people. He sat up on his haunches awaiting the new-comer, and even gave a playful growl by way of friendly greeting.

The stranger stopped short as if frozen in her tracks, and Manitoo perceived a lovely maid of his tribe, robed in beautiful white snow over her gray coat. She understood the sign language of the handsome young man, with as nice a pair of eyes as she had ever seen in one of the wolf kind. She gave a yelp of glad surprise and sprang aside a pace or two.

Manitoo forgot his hunger and loneliness. He forgot even the hairy-faced men with the talking weapons. He lifted his splendid, bushy tail in a rollicking manner and stepped up to her. She raised her beautiful tail coquettishly[44] and again leaped sidewise with affected timidity.

Manitoo now threw his head back to sniff the wind, and all the hair of his back rose up in a perpendicular brush. Under other circumstances this would be construed as a sign of great irritation, but this time it indicated the height of joy.

The wild courtship was brief. Soon both were satisfied and stood face to face, both with plumy tail erect and cocked head. Manitoo teasingly raised one of his fore-paws. They did not know how long they stood there, and no one else can tell. The storm troubled them not at all, and all at once they discovered that the sun was shining!

If any had chanced to be near the Antelope's Leap at that moment, he would have seen a beautiful sight. The cliff formed by the abrupt ending of a little gulch was laced with stately pines, all clad in a heavy garment of snow. They stood like shapes of beauty robed in white and jewels, all fired by the sudden bursting forth of the afternoon sun.

The wolf maiden was beautiful! Her robe[45] was fringed with icicles which shone brilliantly as she stood there a bride. The last gust of wind was like the distant dying away of the wedding march, and the murmuring pines said Amen.

It was not heard by human ear, but according to the customs of the gray wolf clan it was then and there Manitoo promised to protect and hunt for his mate during their lifetime.

In full view of Wetaota, upon an open terrace half-way up the side of the hill in the midst of virgin Big Woods, there were grouped in an irregular circle thirty teepees of the Sioux. The yellowish-white skin cones contrasted quite naturally with the variegated foliage of September, yet all of the woodland people knew well that they had not been there on the day before.

Wetaota, the Lake of Many Islands, lies at the heart of Haya Tanka, the Big Mountain. It is the chosen home of many wild tribes. Here the crane, the Canadian goose, the loon, and other water-fowl come annually to breed undisturbed. The moose are indeed the great folk of the woods, and yet there are many more who are happily paired here, and who with equal right may claim it as their domicile. Among them are some insignificant[47] and obscure, perhaps only because they have little or nothing to contribute to the necessities of the wild man.

Such are the Little People of the Meadow, who dwell under a thatched roof of coarse grasses. Their hidden highways and cities are found near the lake and along the courses of the streams. Here they have toiled and played and brought forth countless generations, and few can tell their life-story.

"Ho, ho, kola!" was the shout of a sturdy Indian boy, apparently about ten years old, from his post in front of the camp and overlooking the lake. A second boy was coming towards him through the woods, chanting aloud a hunting song after the fashion of their fathers. The men had long since departed on the hunt, and Teola, who loved to explore new country, had already made the circuit of Wetaota. He had walked for miles along its tortuous sandy shores, and examined the signs of most of the inhabitants.

There were footprints of bears, moose, deer, wolves, mink, otter, and others. The sight of them had rejoiced the young hunter's heart, but he knew that they were for[48] his elders. The woods were also full of squirrels, rabbits, and the smaller winged tribes, and the waters alive with the finny folk, all of which are boys' game. Yet it was the delicate sign-language of the Hetunkala, the Little People of the Meadow, which had aroused the enthusiasm of Teola, and in spite of himself he began to sing the game scout's song, when Shungela heard and gave him greeting.

"What is the prospect for our hunt to-day?" called Shungela, as soon as his friend was near enough to speak.

"Good!" Teola replied, simply. "It is a land of fatness. I have looked over the shores of Wetaota, and I think this is the finest country I have ever seen. I am tired enough of prairie-dog hunts and catching young prairie-chickens, but there is everything here that we can chase, kill, or eat."

Shungela at once circulated the good game news among the boys, and in less time than it takes an old man to tell a story all the boys of the camp had gathered around a bonfire in the woods.

"You, Teola, tell us again what you have seen," they exclaimed, in chorus.[49]

"I saw the footprint of every creature that the Great Mystery has made! We can fish, we can hunt the young crane, and snare the rabbit. We can fool the owl for a night-play," he replied, proudly.

"Ho, kola, washtay! Good news! good news!" one urchin shouted. Another ran up a tree like a squirrel in the exuberance of his delight. "Heye, heye, he-e-e-e!" sang another, joyously.

"Most of all in number are the Little People of the Meadow! Countless are their tiny footprints on the sandy shores of Wetaota! Very many are their nests and furrows under the heavy grass of the marshes! Let Shungela be the leader to-day in our attack upon the villages of the Little People," suggested Teola, in whose mischievous black eyes and shaggy mane one beheld the very picture of a wild rogue.

"Ho, ho, hechetu!" they all replied, in chorus.

"This is our first mouse-hunt this season, and you all know the custom. We must first make our tiny bows and arrows," he said, again.

"Tosh, tosh! Of course!" said they all.[50]

In the late afternoon the sun shone warmly and everything was still in the woods, but upon the lake the occasional cry of the loon was heard. At some distance from the camp thirty or more little redskins met together to organize their mimic deer-hunt. They imitated closely the customs and manners of their elders while hunting the deer. Shungela gave the command, and all the boys advanced abreast, singing their hunting song, until they reached the meadow-land.

Here the leader divided them into two parties, of which one went twenty paces in advance, and with light switches raked aside the dead grass, exposing a net-work of trails. The homes of the Little People were underground, and the doors were concealed by last year's rank vegetation. While they kneeled ready to shoot with the miniature bow and arrows the first fugitives that might pass, the second party advanced in turn, giving an imitation of the fox-call to scare the timorous Little People. These soon became bewildered, missed their holes, and were shot down with unerring aim as they fled along their furrow-like paths.

There was a close rivalry among the boys[51] to see who could bring down the largest number of the tiny fugitives, but it was forbidden to open the homes or kill any who were in hiding.

In a few minutes the mice were panic-stricken, running blindly to and fro, and the excitement became general.

"Yehe, yehe! There goes their chief! A white mouse!" exclaimed one of the boys.

"Stop shooting!" came the imperative command from the shaggy-haired boy.

"It is a good sign to see their chief, but it is a very bad sign if we kill any after we have seen him," he explained.

"I have never heard that this is so," demurred Shungela, unwilling to yield his authority.

"You can ask your grandmother or your grandfather to-night, and you will find that I am right," retorted the shaggy-haired one.

"Woo, woo!" they called, and all the others came running.

"How many of you saw the white mouse?" Teola asked.

"I saw it!" "I too!" "I too!" replied several.[52]

"And how many have heard that to see the chief of the mouse people brings good luck if the mice are spared after his appearance, but that whoever continues to kill them invites misfortune?"

"I have heard it!" "And I!" "And I!" The replies were so many that all the boys were willing to concede the authenticity of the story, and the hunt was stopped.

"Let us hear the mouse legends again this evening. My grandfather will tell them to us," Teola suggested, and not a boy there but was ready to accept the invitation.

Padanee was an ordinary looking old Indian, except that he had a really extraordinary pair of eyes, whose searching vision it seemed that nothing could escape. These eyes of his were well supported by an uncommonly good memory. His dusky and furrowed countenance was lighted as by an inner flame when once he had wound the buffalo-robe about his lean, brown limbs and entered upon the account of his day's experience in the chase, or prepared to relate to an attentive circle some oft-repeated tradition of his people.[53]

"Hun, hun, hay!" The old savage cleared his throat. A crowd of bright-eyed little urchins had slipped quietly into his lodge. "Teola tells me that you had all set out to hunt down and destroy the Little People of the Meadow, and were only stopped by seeing their chief go by. I want to tell you something about the lives of these little creatures. We know that they are food for foxes and other animals, and that is as far as most of us think upon the matter. Yet the Great Mystery must have had some purpose in mind when He made them, and doubtless that is good for us to know."

Padanee was considered a very good savage school-teacher, and he easily held his audience.

"When you make mud animals," he continued, "you are apt to vary them a little, perhaps for fun and perhaps only by accident. It is so with the Great Mystery. He seems to get tired of making all the animals alike, for in every tribe there are differences.

"Among the Hetunkala, the Little People, there are several different bands. Some live in one place and build towns and cities like the white man. Some wander much over[54] forest and prairie, like our own people. These are very small, with long tails, and they are great jumpers. They are the thieves of their nation. They never put up any food of their own, but rob the store-houses of other tribes.

"Then there is the bobtailed mouse with white breast. He is very much like the paleface—always at work. He cannot pass by a field of the wild purple beans without stopping to dig up a few and tasting to see if they are of the right sort. These make their home upon the low-lying prairies, and fill their holes with great store of wild beans and edible roots, only to be robbed by the gopher, the skunk, the badger, who not only steal from them but often kill and eat the owner as well. Our old women, too, sometimes rob them of their wild beans.

"This fellow is always fat and well-fed, like the white man. He is a harvester, and his full store-houses are found all through the bottom lands."

"Ho, ho! Washtay lo!" the boys shouted. "Keep on, grandfather!"

"Perhaps you have heard, perhaps not," resumed the old man. "But it is the truth.[55] These little folk have their own ways. They have their plays and dances, like any other nation."

"We never heard it; or, if we have, we can remember it better if you will tell it to us again!" declared the shaggy-haired boy, with enthusiasm.

"Ho, ho, ho!" they all exclaimed, in chorus.

"Each full moon, the smallest of the mouse tribe, he of the very sharp nose and long tail, holds a great dance in an open field, or on a sandy shore, or upon the crusty snow. The dance is in honor of those who are to be cast down from the sky when the nibbling of the moon begins; for these Hetunkala are the Moon-Nibblers."

As this new idea dawned upon Padanee's listeners, all tightened their robes around them and sat up eagerly.

At this point a few powerful notes of a wild, melodious music burst spontaneously from the throat of the old teacher, for he was wont to strike up a song as a sort of interlude. He threw his massive head back, and his naked chest heaved up and down like a bellows.[56]

"One of you must dance to this part, for the story is of a dance and feast!" he exclaimed, as he began the second stanza.

Teola instantly slipped out of his buffalo-robe and stepped into the centre of the circle, where he danced crouchingly in the firelight, keeping time with his lithe brown body to the rhythm of the legend-teller's song.

"O-o-o-o!" they all hooted at the finish.

"This is the legend of the Little People of the Meadow. Hear ye! hear ye!" said Padanee.

"Ho-o-o!" was the instant response from the throats of the little Red men.

"A long time ago, the bear made a medicine feast, and invited the medicine-men (or priests) of all the tribes. Of each he asked one question, 'What is the best medicine (or magic) of your tribe?'

"All told except the little mouse. He was pressed for an answer, but replied, 'That is my secret.'

"Thereupon the bear was angry and jumped upon the mouse, who disappeared instantly. The big medicine-man blindly grabbed a handful of grass, hoping to squeeze[57] him to death. But all the others present laughed and said, 'He is on your back!'

"Then the bear rolled upon the ground, but the mouse remained uppermost.

"'Ha, ha, ha!' laughed all the other medicine-men. 'You cannot get rid of him.'

"Then he begged them to knock him off, for he feared the mouse might run into his ear. But they all refused to interfere.

"'Try your magic on him,' said they, 'for he is only using the charm that was given him by the Great Mystery.'

"So the bear tried all his magic, but without effect. He had to promise the little mouse that, if he would only jump off from his body, neither he nor any of his tribe would ever again eat any of the Little People.

"Upon this the mouse jumped off.

"But now Hinhan, the owl, caught him between his awful talons, and said:

"'You must tell your charm to these people, or I will put my charm on you!'

"The little medicine-man trembled, and promised that he would if the owl would let him go. He was all alone and in their power, so at last he told it.

"'None of our medicine-men,' he began,[58] 'dared to come to this lodge. I alone believed that you would treat me with the respect due to my profession, and I am here.' Upon this they all looked away, for they were ashamed.

"'I am one of the least of the Little People of the Meadow,' said the mouse. 'We were once a favored people, for we were born in the sky. We were able to ride the round moon as it rolls along. We were commissioned at every full moon to nibble off the bright surface little by little, until all was dark. After a time it was again silvered over by the Great Mystery, as a sign to the Earth People.

"'It happened that some of us were careless. We nibbled deeper than we ought, and made holes in the moon. For this we were hurled down to the earth. Many of us were killed; others fell upon soft ground and lived. We do not know how to work. We can only nibble other people's things and carry them away to our hiding-places. For this we are hated by all creatures, even by the working mice of our own nation. But we still retain our power to stay upon moving bodies, and that is our magic.'[59]

"'Ho, ho, ho!' was the response of all present. They were obliged to respond thus, but they were angry with the little mouse, because he had shamed them.

"It was therefore decreed in that medicine-lodge that all the animals may kill the Hetunkala wherever they meet them, on the pretext that they do not belong upon earth. All do so to this day except the bear, who is obliged to keep his word."

"O-o-o-o!" shouted the shaggy-haired boy, who was rather a careless sort in his manners, for one should never interrupt a story-teller.

"It is almost full moon now, grandfather," he continued, "and there are nice, open, sandy places on the shore near the mouse villages. Do you think we might see them dancing if we should watch to-night?"

"Ho, takoja! Yes, my grandson," simply replied the old man.

The sand-bar in front of the Indian camp was at some little distance, out of hearing of the occasional loud laughter and singing of the people. Wetaota was studded with myriads of jewel-like sparkles. On the shadowy[60] borders of the lake, tall trees bodied forth mysterious forms of darkness. There was something weird in all this beauty and silence.

The boys were scattered along in the tall grass near the sand-bar, which sloped down to the water's edge as smooth as a floor. All lay flat on their faces, rolled up in their warm buffalo-robes, and still further concealed by the shadows of the trees. The shaggy-haired boy had a bow and some of his best arrows hidden under his robe. No two boys were together, for they knew by experience the temptation to whisper under such circumstances. Every redskin was absorbed in watching for the Little People to appear upon their playground, and at the same time he must be upon the alert for an intruder, such as Red Fox, or the Hooting-owl of the woods.

"It seems strange," thought Teola, as he lay there motionless, facing the far-off silvery moon, "that these little folk should have been appointed to do a great work," for he had perfect faith in his grandfather's legend of the Moon-Nibblers.

"Ah-h-h!" he breathed, for now he heard[61] a faint squeaking in the thick grass and rushes. Soon several tiny bodies appeared upon the open, sandy beach. They were so round and so tiny that one could scarcely detect the motion of their little feet. They ran to the edge of the water and others followed them, until there was a great mass of the Little People upon the clean, level sand.

"Oh, if Hinhan, the owl, should come now, he could carry away both claws full!" Teola fancied.

Presently there was a commotion among the Hetunkala, and many of them leaped high into the air, squeaking as if for a signal. Teola saw hundreds of mice coming from every direction. Some of them went close by his hiding-place, and they scrutinized his motionless body apparently with much care. But the young hunter instinctively held his breath, so that they could not smell him strongly, and at last all had gone by.

The big, brown mice did not attend this monthly carnival. They were too wise to expose themselves upon the open shore to the watchful eyes of their enemies. But upon the moonlit beach the small people, the Moon-Nibblers, had wholly given themselves[62] up to enjoyment, and seemed to be forgetful of their danger. Here on Wetaota was the greatest gathering that Teola had ever seen in all his life.

Occasionally he thought he noticed the white mouse whom he supposed to be their chief, for no reason except that he was different from the others, and that was the superstition.

As he watched, circles were formed upon the sand, in which the mice ran round and round. At times they would all stand still, facing inward, while two or three leaped in and out of the ring with wonderful rapidity. There were many changes in the dance, and now and then one or two would remain motionless in the centre, apparently in performance of some ceremony which was not clear to Teola.

All at once the entire gathering became, in appearance, a heap of little round stones. There was neither sound nor motion.

"Ho, ho, ho!" Teola shouted, as he half raised himself from his hiding-place and flourished part of his robe in the clear moonlight. A big bird went up softly among the shadowy trees. All of the boys had been[63] so fascinated by the dance that they had forgotten to watch for the coming of Hinhan, the owl, and now this sudden transformation of the Little People! Each one of them had rolled himself into the shape of a pebble, and sat motionless close to the sand to elude the big-eyed one.

They remained so until the owl had left his former perch and flown away to more auspicious hunting-grounds. Then the play and dance became more general and livelier than ever. The Moon-Nibblers were entirely given over to the spirit and gayety of the occasion. They ran in new circles, sometimes each biting the tail of his next neighbor. Again, after a great deal of squeaking, they all sprang high in the air, towards the calm, silvery orb of the moon. Apparently they also beheld it in front of them, reflected in the placid waters of Wetaota, for they advanced in columns to the water's edge, and there wheeled into circles and whirled in yet wilder dance.

At the height of the strange festival, another alarm came from the shaggy-haired boy. This time all the boys spied Red Fox coming as fast as his legs could carry him[64] along the beach. He, too, had heard the fairy laughter and singing of the Moon-Nibblers, and never in his whole wild career is he better pleased than when he can catch a few of them for breakfast or supper.

No people know the secret of the dance except a few old Indians and Red Fox. He is so clever that he is always on the watch for it just before the full moon. At the first sound that came to his sharp ears he knew well what was going on, and the excitement was now so great that he was assured of a good supper.

"Hay-ahay! Hay-ahay!" shouted the shaggy-haired boy, and he sent a swift arrow on a dangerous mission for Red Fox. In a moment there came another war-whoop, and then another, and it was wisdom for the hungry one to take to the thick woods.

"Woo, woo! Eyaya lo! Woo, woo!" the boys shouted after him, but he was already lost in the shadows.

The boys came together. Not a single mouse was to be seen anywhere, nor would any one suspect that they had been there in such numbers a few moments earlier, except[65] for the finest of tracery, like delicate handwriting, upon the moonlit sand.

"We have learned something to-night," said Teola. "It is good. As for me, I shall never again go out to hunt the Little People."

"Come, Wechah, come away! the dogs will tease you dreadfully if they find you up a tree. Enakanee (hurry)!" Wasula urged, but the mischievous Wechah still chose to remain upon the projecting limb of an oak which made him a comfortable seat. It was apparently a great temptation to him to climb every large, spreading tree that came in his way, and Wasula had had some thrilling experiences with her pet when he had been attacked by the dogs of the camp and even by wild animals, so it was no wonder that she felt some anxiety for him.

Wasula was the daughter of a well-known warrior of the Rock Cliff villagers of the Minnesota River. Her father had no son living, therefore she was an only child, and the most-sought-after of any maiden in that band. No other girl could boast of Wasula's[67] skill in paddling the birch canoe or running upon snow-shoes, nor could any gather the wild rice faster than she. She could pitch the prettiest teepees, and her nimble, small fingers worked very skilfully with the needle. She had made many embroidered tobacco-pouches and quivers which the young men were eager to get.

More than all this, Wasula loved to roam alone in the woods. She was passionately fond of animals, so it was not strange that, when her father found and brought home a baby raccoon, the maiden took it for her own, kept it in an upright Indian cradle and played mother to it.

Wasula was as pretty and free as a teal-duck, or a mink with its slender, graceful body and small face. She had black, glossy hair, hanging in two plaits on each side of her head, and a calm, childlike face, with a delicate aquiline nose. Wechah, when he was first put into her hands, was nothing more than a tiny ball of striped fur, not unlike a little kitten. His bright eyes already shone with some suggestion of the mischief and cunning of his people. Wasula made a perfect baby of him. She even carved all[68] sorts of playthings out of hoof and bone, and tied them to the bow of the cradle, and he loved to play with them. He apparently understood much that she said to him, but he never made any attempt to speak. He preferred to use what there is of his own language, but that, too, he kept from her as well as he could, for it is a secret belonging only to his tribe.

Wechah had now grown large and handsome, for he was fat and sleek. They had been constantly together for over a year, and his foster-mother had grown very much attached to him. The young men who courted Wasula had conspired at different times against his life, but upon second thought they realized that if Wasula should suspect the guilt of one of them his chance of winning her would be lost forever.

It is true he tried their patience severely, but he could not help this, for he loved his mistress, and his ambition was to be first in her regard. He was very jealous, and, if any one appeared to divide her attention, he would immediately do something to break up the company. Sometimes he would resort to hiding the young man's quiver, bow,[69] or tomahawk, if perchance he put it down. Again he would pull his long hair, but they could never catch him at this. He was quick and sly. Once he tripped a proud warrior so that he fell sprawling at the feet of Wasula. This was embarrassing, and he would never again lay himself open to such a mishap. At another time he pulled the loose blanket off the suitor, and left him naked. Sometimes he would pull the eagle feather from the head of one and run up a tree with it, where he would remain, and no coaxing could induce him to come down until Wasula said:

"Wechah, give him his feather! He desires to go home."

Wechah truly thought this was bright and cunning, and Wasula thought so too. While she always reprimanded him, she was inwardly grateful to him for breaking the monotony of courtship or rebuking the presumption of some unwelcome suitor.

"Come down, Wechah!" she called, again and again. He came part way at last, only to take his seat upon another limb, where he formed himself into a veritable muff or nest upon the bough in a most unconcerned[70] way. Any one else would have been so exasperated that all the dogs within hearing would have been called into service to bay him down, but Wasula's love for Wechah was truly strong, and her patience with him was extraordinary. At last she struck the tree a sharp blow with her hatchet. The little fellow picked himself up and hastily descended, for he knew that his mistress was in earnest, and she had a way of punishing him for disobedience. It was simple, but it was sufficient for Wechah.

Wasula had the skin of a buffalo calf's head for a work-bag, beautifully embroidered with porcupine quills about the open mouth, nose, eyes, and ears. She would slip this over Wechah's head and tie his fore-paws together so that he could not pull it off. Then she would take him to the spring under the shadow of the trees and let him look at himself. This was enough punishment for him. Sometimes even the mention of the calf's head was enough to make him submit.

Of course, the little Striped Face could take his leave at any time that he became dissatisfied with his life among the Red people.[71] Wasula had made it plain to him that he was free. He could go or stay; but, apparently, he loved her too well to think of leaving. He would curl himself up into a ball and lie by the hour upon some convenient branch while the girl was cutting wood or sitting under a tree doing her needle-work. He would study her every movement, and very often divine her intentions.

Wasula was a friend to all the little people of the woods, and especially sympathized with the birds in their love-making and home-building. Wechah must learn to respect her wishes. He had once stolen and devoured some young robins. The parent birds were frantic about their loss, which attracted the girl's attention. The wicked animal was in the midst of his feast.

"Glechu! glechu (Come down)!" she called, excitedly. He fully understood from the tone that all was not right, but he would not jump from the tree and run for the deep woods, thereby avoiding punishment and gaining his freedom. The rogue came down with all the outward appearance of one who pleads guilty to the charge and throws himself upon the judge's mercy. She at once[72] put him in the calf's head and bound his legs, and he had nothing to eat for a day and a night.

It was a great trial to both of them. Wadetaka, the dog, for whom he had no special love, was made to stand guard over the prisoner so that he could not get away and no other dog could take advantage of his helplessness. Wasula was very sorry for him, but she felt that he must learn his lesson. That night she lay awake for a long time. To be sure, Wechah had been good and quiet all day, but his tricks were many, and she had discovered that his people have danger-calls and calls for help quite different from their hunting and love calls.

After everybody was asleep, even Wadetaka apparently snoring, and the camp-fire was burning low, there was a gentle movement from the calf's-head bag. Wasula uncovered her head and listened. Wechah called softly for help.

"Poor Wechah! I don't want him to be angry with me, but he must let the little birds' homes alone."

Again Wechah gave his doleful call. In a little while she heard a stealthy footfall,[73] and at the same time Wadetaka awoke and rushed upon something.

It was a large raccoon! He ran up a near-by tree to save himself, for Wadetaka had started all the dogs of the camp. Next the hunters came out. Wasula hurriedly put on her moccasins and ran to keep the men from shooting the rescuer.

Wechah's friend took up his position upon one of the upper limbs of a large oak, from which he looked down with blazing eyes upon a motley crew. Near the root of the tree Wechah lay curled up in a helpless ball. The new-comer scarcely understood how this unfortunate member of his tribe came into such a predicament, for when some one brought a torch he was seen to rise, but immediately fell over again.

"Please do not kill him," pleaded Wasula. "It is a visitor of my pet, whom I am punishing for his misconduct. As you know, he called for help according to the custom of his tribe."

They all laughed heartily, and each Indian tied up his dog for the rest of the night, so that the visitor might get away in safety, while the girl brought her pet to her own bed.[74]

It was the Moon of Falling Leaves, and the band to which Wasula's father belonged were hunting in the deep woods in Minnesota, the Land of Sky-colored Water. The band had divided itself into many small parties for the fall and winter hunt. When this particular party reached Minnetonka, the Big Lake, they found the hunting excellent. Deer were plenty, and the many wooded islands afforded them good feeding-places. The men hunted daily, and the women were busy preparing the skins and curing the meat. Wechah wandered much alone, as Wasula was busy helping her mother.

All went well for many weeks; and even when the snow fell continuously for many a day and the wind began to blow, so that no hunter dared emerge from his teepee, there was dried venison still and all were cheerful. At last the sun appeared.

"Hoye! hoye!" was the cheerful cry of the hunting bonfire-builder, very early in the morning. As it rang musically on the clear, frosty air, each hunter set out, carrying his snow-shoes upon his back, in the pleasant anticipation of a good hunt. After the customary smoke, they all disappeared in[75] the woods on the north shore of Minnetonka.

Alas! it was a day of evil fortune. There was no warning. In the late afternoon one came back bleeding, singing a death-dirge. "We were attacked by the Ojibways! All are dead save myself!"

Thus was the little camp suddenly plunged into deep sorrow and mourning. Doleful wails came forth from every lodge, and the echoes from the many coves answered them with a double sadness.