Chicago Historical Society's Collection.—Vol. V.

The Settlement of Illinois

1778-1830

by Arthur Clinton Boggess, Ph.D.

Professor of History and political Science in Pacific University; a Director of the Oregon Historical Society; sometime Harrison Scholar in American History in the University of Pennsylvania; sometime Fellow in American History in the University of Wisconsin.

Chicago

Published by the society

1908

Contents

- Preface.

- Chapter I. The County of Illinois.

- Chapter II. The Period of Anarchy in Illinois.

- Chapter III.

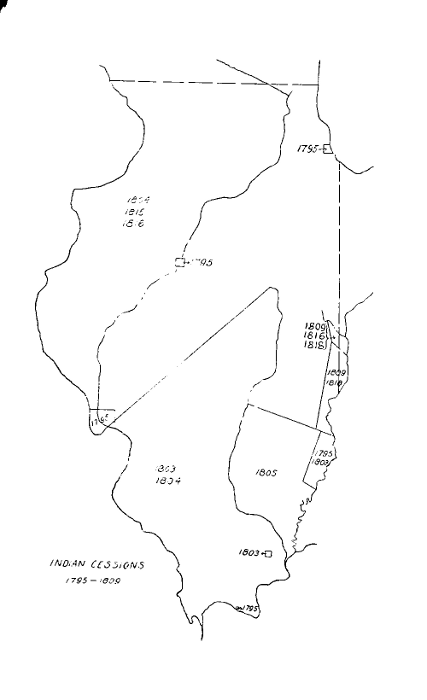

- I. The Land and Indian Questions. 1790 to 1809.

- II. Government Succeeding the Period of Anarchy, 1790 to 1809.

- III. Obstacles to Immigration. 1790 to 1809.

- Chapter IV. Illinois During Its Territorial Period. 1809 to 1818.

- I. The Land and Indian Questions.

- II. Territorial Government of Illinois. 1809 to 1818.

- IV. Transportation and Settlement, 1809 to 1818.

- IV. Life of the Settlers.

- Chapter V. The First Years of Statehood, 1818 to 1830.

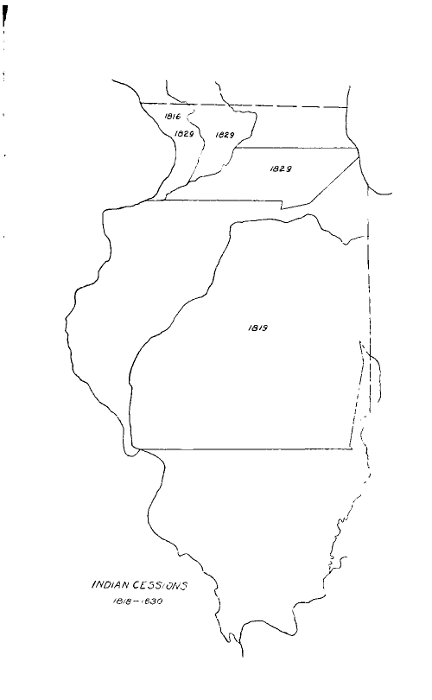

- The Indian and Land Questions.

- The Government and Its Representatives, 1818 to 1830.

- Transportation.

- Life of the People.

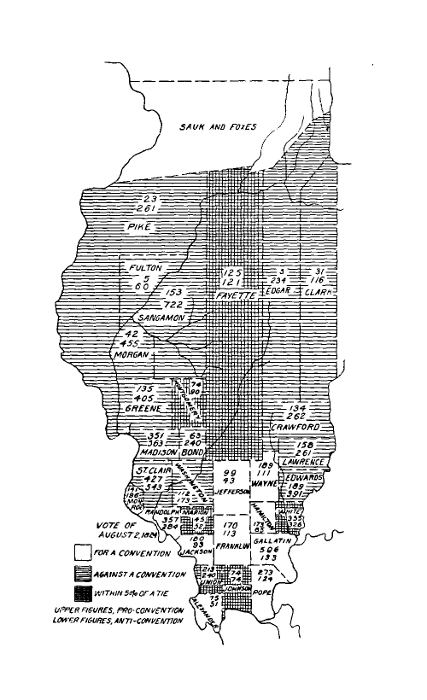

- Chapter VI. Slavery in Illinois As Affecting Settlement.

- Chapter VII. Successful Frontiersmen.

- Works Consulted.

- Index.

- Footnotes

Preface.

In the work here presented, an attempt has been made to apply in the field of history, the study of types so long in use in biological science. If the settlement of Illinois had been an isolated historical fact, its narration would have been too provincial to be seriously considered, but in many respects, the history of this settlement is typical of that of other regions. The Indian question, the land question, the transportation problem, the problem of local government; these are a few of the classes of questions wherein the experience of Illinois was not unique.

This work was prepared while the writer was a student in the University of Wisconsin. The first draft was critically and carefully read by Prof. Frederick Jackson Turner, of that University, and the second draft was read by Prof. John Bach McMaster, of the University of Pennsylvania. In addition to suggestions received from my teachers, valuable aid has been rendered by Miss Caroline M. McIlvaine, the librarian of the Chicago Historical Society, who placed at my disposal her wide knowledge of the sources of Illinois history.

The omission of any reference in this work to the French manuscripts, found by Clarence W. Alvord, is due to the fact that at the time they were found, my work was so nearly completed that it was loaned to Mr. Alvord to use in the preparation of his article on the County of Illinois, while the press of professional duties has been such that a subsequent use of the manuscripts has been impracticable.

Arthur C. Boggess.

Chapter I. The County of Illinois.

An Act for establishing the County of Illinois, and for the more effectual protection and defence thereof, passed both houses of the Virginia legislature on December 9, 1778.1 The new county was to include the inhabitants [pg 010] of Virginia, north of the Ohio River, but its location was not more definitely prescribed.2

The words “for the more effectual protection and defence thereof” in the title of the Act were thoroughly appropriate. The Indians were in almost undisputed possession of the land in Illinois, save the inconsiderable holdings of the French. Some grants and sales of large tracts of land had been made. In 1769, John Wilkins, British commandant in Illinois, granted to the trading-firm of Baynton, Wharton and Morgan, a great tract of land lying between the Kaskaskia and the Mississippi rivers. The claim to the land descended to John Edgar, who shared it with John Murray St. Clair, son of Gov. Arthur St. Clair. The claim was filed for 13,986 acres, but was found on survey to contain 23,000 acres, and was confirmed by Gov. St. Clair. At a later examination of titles, this claim was rejected because the grant was made in the first instance counter to the king's proclamation of 1763, and because the confirmation by Gov. St. Clair was made after his authority ceased and was not signed by the Secretary of the Northwest Territory.3 In 1773, William Murray and others, subsequently known as the Illinois Land Company, bought two large tracts of land in Illinois from the Illinois Indians. In 1775, a great tract lying on both sides of the Wabash was similarly purchased by what later became the Wabash Land Company. The purchase of the Illinois Company was made in the presence, but without the sanction, of the British officers, and Gen. Thomas Gage had the Indians re-convened and the validity of the purchase expressly denied. These large grants were illegal, and the Indians [pg 011] were not in consequence disposessed of them.4 Thus far, the Indians of the region had been undisturbed by white occupation. British landholders were few and the French clearings were too small to affect the hunting-grounds. French and British alike were interested in the fur trade. A French town was more suited to be the center of an Indian community than to become a point on its periphery, for here the Indians came for religious instruction, provisions, fire-arms, and fire-water. The Illinois Indian of 1778 had been degraded rather than elevated by his contact with the whites. The observation made by an acute French woman of large experience, although made at another time and place, was applicable here. She said that it was much easier for a Frenchman to learn to live like an Indian than for an Indian to learn to live like a Frenchman.5

[pg 012]In point of numbers and of occupied territory, the French population was trifling in comparison with the Indian. In 1766-67, the white inhabitants of the region were estimated at about two thousand.6 Some five years later,7 Kaskaskia was reported as having about five hundred white and between four and five hundred black inhabitants; Prairie du Rocher, one hundred whites and eighty negroes; Fort Chartres, a very few inhabitants; St. Philips, two or three families; and Cahokia, three hundred whites and eighty negroes. At the same time, there was a village of the Kaskaskia tribe with about two hundred and ten persons, including sixty warriors, three miles north of Kaskaskia, and a village of one hundred and seventy warriors of the Peoria and Mitchigamia Indians, one mile northwest of Fort Chartres. It is said of these Indians: “They were formerly brave and warlike, but are degenerated into a drunken and debauched tribe, and so indolent, as scarcely to procure a sufficiency of Skins and Furrs to barter for clothing,” and a pastoral letter of August 7, 1767, from the Bishop of Quebec to the inhabitants of Kaskaskia shows the character of the French. The French are told that if they will not acknowledge the authority of the vicar-general—Father Meurin, pastor of Cahokia—cease to marry without the intervention of the priest, and cease to absent themselves from church services, they will be abandoned by the bishop as unworthy of his care.8 Two years earlier, [pg 013] George Croghan had visited Vincennes, of which he wrote: “I found a village of about eighty or ninety French families settled on the east side of this river [Wabash], being one of the finest situations that can be found.... The French inhabitants, hereabouts, are an idle, lazy people, a parcel of renegadoes from Canada, and are much worse than the Indians.”9 Although slave-holders, a large proportion of the French were almost abjectly poor. Illiteracy was very common as is shown by the large proportion who signed legal documents by their marks.10 The people had been accustomed to a paternal rule and had not become acquainted with English methods during the few years of British rule. Such deeds as were given during the French period were usually written upon scraps of paper, described the location of the land deeded either inaccurately or not at all, and were frequently lost.11 Land holdings were in long narrow strips along the rivers.12

The country was physically in a state of almost primeval simplicity. The chief highways were the winding rivers, although roads, likewise winding, connected the various settlements. These roads were impassable in times of much rain. All settlements were near the water, living on a prairie being regarded as impossible and living far from a river as at least impracticable.13 The difficulties of [pg 014] George Rogers Clark in finding his way, overland, from the Ohio River to Kaskaskia and Vincennes on his awful winter march, are such as must manifestly have confronted anyone who wished to go over the same routes at the same season of the year.

Wild animals were abundant. A quarter of a century after the Revolution, two hunters killed twenty-five deer before nine in the morning near the Illinois settlements.14 In 1787, the country between Vincennes and Kaskaskia abounded in buffalo, deer, and bear.15 For years, the chase furnished a large part of the provisions. The raising of hogs was rendered difficult by the presence of wolves. Game-birds were plentiful, and birds were sometimes a pest because of their destruction of corn and smaller grains and even of mast.

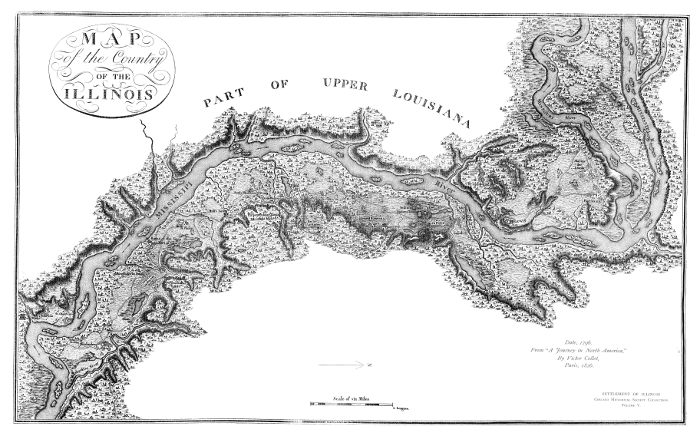

An early traveler wrote in 1796: “The province of the Illinois is, perhaps, the only spot respecting which travelers have given no exaggerated accounts; it is superior to any description which has been made, for local beauty, fertility, climate, and the means of every kind which nature has lavished upon it for the facility of commerce.”16 The wide-spreading prairies added to the beauty of the country. Land which now produces one hundred bushels of corn to the acre must have been capable of producing wonderful crops at the beginning of its cultivation. Coal was not known to exist in great quantities in the region nor was its use as a fuel yet known.

[pg 015]Such was the country and such the people now organized into the County of Illinois.17 The Act establishing the county provided that the governor and council should appoint a county-lieutenant or commandant-in-chief, who should appoint and commission as many deputy-commandants, militia officers, and commissaries as were needed. The religion, civil rights, property and law of the inhabitants should be respected. The people of the county should pay the salaries of such officers as they had been accustomed to, but officers with new duties, including the county-lieutenant, were to be paid by Virginia. The governor and council might send five hundred troops, paid by Virginia, to defend Illinois. Courts were to be established with judges elected by the people, although the judges of other county-courts of Virginia were appointed by the governor and council.18

While Gov. Patrick Henry was writing instructions concerning the organization of government in Illinois, the British general, Hamilton, was marching to take Vincennes. Henry did not know this particular fact, but he had a keen perception of the difficulties, both civil and military, which awaited the county. On December 12, 1778, without waiting for the formal signing of the act creating the county, he wrote instructions to George Rogers Clark, to Col. John Todd, jr., and to Lieut.-Col. John Montgomery. Clark was instructed to retain the command of the troops then in the Illinois country, and to assume command of five other companies, soon to be sent out.19 Col. Todd was appointed county-lieutenant or [pg 016] commandant. His instructions contained much wise direction. He was to take care to cultivate and conciliate the affections of the French and Indians, to coöperate with Clark and give the military department all the aid possible, to use the French against the British, if the French were willing, but otherwise to remain on the defensive, to inculcate in the people an appreciation of the value of liberty, to see that the inhabitants had justice done them for any injuries from the troops. A neglect of this last instruction, it was pointed out, might be fatal. “Consider yourself as at the head of the civil department, and as such having the command of the militia, who are not to be under the command of the military, until ordered out by the civil authority and act in conjunction with them.” An express was to be sent to Virginia every three months with a report. A letter to the Spanish commandant at Ste. Genevieve was inclosed, and Todd was told to be very friendly to him.20 Col. Montgomery, then in Virginia, was ordered to recruit men to reënforce Clark. “As soon as the state of affairs in the recruiting business will permit, you are to go to the Illinois country & join Col. Clarke, I need not tell you how necessary [pg 017] the greatest possible Dispatch is to the good of the service in which you are engaged. Our party at Illinois may be lost, together with the present favorable Disposition of the French and Indians there, unless every moment is improved for their preservation, & no future opportunity, if the present is lost, can ever be expected so favorable to the Interest of the commonwealth.” Montgomery was urged not to be daunted by the inclement season, the great distance to Illinois, the “want of many necessaries,” or opposition from enemies.21 Gov. Henry deserves much credit for his prompt and aggressive action at a time when Virginia was in the very midst of the Revolution.

Col. Clark was much pleased with the appointment of Col. Todd, both because civil duties were irksome to the conqueror and because of his confidence in Todd's ability.22 Upon the arrival of the new county-lieutenant, Clark called a meeting of the citizens of Kaskaskia to meet the new officer and to elect judges. He introduced Col. Todd as governor and said that he was the only person in the state whom he had desired for the place. The people were told that the government, Virginia, was going to send a regiment of regular troops for their defense, that the new governor would arrange and settle their affairs, and that they would soon become accustomed to the American system of government. In regard to the election of judges, Clark said: “I pray you to consider the importance of this choice; to make it without partiality, and to choose the persons most worthy of such posts.”23 The nine members of the court of Kaskaskia, the seven members of the court of Cahokia, and the nine members of the court of Vincennes, as also the respective clerks were French. Of the three sheriffs, Richard Winston, sheriff [pg 018] of Kaskaskia, was the only one who was not French.24

Military commissions were promptly made out, those of the districts of Kaskaskia and Cahokia being dated May 14, 1779. So many of the persons elected judges were also given military commissions that it seems probable that the supply of suitable men was small. No fewer than fourteen such cases occur. Of the militia officers appointed at Vincennes, P. Legras, appointed lieutenant-colonel, had been a major in the British service, and F. Bosseron, appointed major, had been a captain in the British service.25

The position of Illinois among the counties of Virginia was necessarily anomalous. All counties, except the County of Illinois, were asked to furnish one twenty-fifth of their militia to defend the state. Illinois county was omitted from the western counties enumerated in “An act for adjusting and settling the titles of claimers to unpatented lands under the present and former government, previous to the establishment of the commonwealth's land office.” Settlers northwest of the Ohio were warned to remove. No settlement would be permitted there, and if attempted, the intruder might be removed by force—“Provided, That nothing herein contained shall be construed in any manner to injure or affect any French, [pg 019] Canadian, or other families, or persons heretofore actually settled in or about the villages near or adjacent to the posts reduced by the forces of this state.” These exceptions were made at the May session of 1779. At this session, there was passed an act for raising one troop of cavalry, consisting of one captain, one lieutenant, one cornet, and thirty-two privates to defend the inhabitants of Illinois county. All officers were to be appointed by the governor and council. The men were to receive the same pay as Continentals. Any soldier who would serve in Illinois during the war should receive a bounty of seven hundred and fifty dollars and a grant of one hundred acres of land.26

Acting upon the policy that caused Virginia to warn all intruders not to settle northwest of the Ohio, Todd issued a proclamation warning all persons against such settlement, “unless in manner and form as heretofore made by the French inhabitants.” All inhabitants were ordered to file a description of lands held by them, together with a deed or deposition, in order to be ready for the press of adventurers that was expected.27

Some of the incidents of the summer of 1779 indicate difficulties of the new government. When the governor was to be absent for a short time, he wrote to Winston, who as commander of Kaskaskia would be acting governor, telling him not to impress property, and by all means to keep up a good understanding with Col. Clark and the officers. The judges of the court at Kaskaskia were ordered to hold court “at the usual place of holding court ... any adjournment to the contrary notwithstanding.” Richard McCarty, of Cahokia, wrote to the county-lieutenant complaining that the writer's stock had been [pg 020] killed by the French inhabitants. McCarty had allowed his stock to run at large and they had destroyed uninclosed crops, which crops, he contended, were not in their proper place. Two months later, McCarty wrote from Cahokia: “Col. Todd residence hear will spoil the people intirely. I think it would be a happy thing could we get Colol Todd out of the country for he will possitively sett the Inhabitants and us by the Ears. I have wrote him a pritty sharp Letter on his signing a Death warrant against my poor hog's for runing in the Oppen fields ... on some complaints by the Inhabitants the other day he wished that there was not a Soldier in the country.”28 McCarty's hogs were not his only trouble. A fellow-officer wrote: “I received a line from Capt. McCarty [captain of troops at Cahokia] yesterday. He is well. He writes to me that he has lost most of his French soldiers, and that the inhabitants are so saucy that they threaten to drive him and his soldiers away, telling him that he has no business there—nobody sent for him. They are very discontented. The civil law has ruined them.”29

Col. Todd's position was difficult because of the discontent prevailing among both the French and the Americans in Illinois. His salary was so small that he feared that he must sell his property in Kentucky to support himself [pg 021] while in public service. He regarded Kentucky as a much better place than Illinois for the ambitious man, the retired farmer, or the young merchant.30 He had been scarcely more than three months in office when he wrote to the governor of Virginia: “I expected to have been prepared to present to your excellency some amendments upon the form of Government for Illinois, but the present will be attended with no great inconveniences till the Spring Session, when I beg your permission to attend and get a Discharge from an Office, which an unwholesome air, a distance from my connexions, a Language not familiar to me, and an impossibility of procuring many of the conveniences of Life suitable; all tend to render uncomfortable.”31 This letter was intercepted by the British and did not reach the governor.

Great difficulty was experienced in securing supplies for the soldiers. At times, both troops and people suffered from lack of clothing. The Spanish refused to allow the Americans to navigate the Mississippi, Virginia money entirely lost its credit, hard money was scarce, and peltry was difficult for the military commissaries to obtain. Col. Todd, in desperation, refused to allow the commander at Kaskaskia to pay the people peltry for provisions as had been promised, and calling the inhabitants in council, he told them that if they would not sell on the credit of the state they would be subject to military discipline.32 The [pg 022] fall of 1779 saw the garrison at Vincennes without salt, and starving; while at Kaskaskia the money was worthless, troops were without clothes and deserting daily.33 This great lack of supplies resulted in the impressment of supplies, in disagreement among the officers, and was a prominent factor in a resolution to withdraw the troops from their several situations and concentrate them at a single point on the Ohio River. The discontent of the French was extreme, and it was increased by the departure of Col. Todd for Virginia. The officers who were left in command ruled with a rod of iron and took cattle, flour, wood, and other necessaries, without payment.34 Capt. [pg 023] Dodge, of Kaskaskia, refused to honor a draft presented, apparently, by the government of Virginia, and when sued in the civil court, he declared that he had nothing but his body and that could not be levied upon; besides, he was an officer and as such was not amenable to civil law.35

In the very midst of starvation, the French, unaccustomed to English ways, were wishing to increase the expense of government. An unsigned official letter says, in speaking of affairs in Illinois: “I find that justices of the peace, appointed among them, expect to be paid, this not being the practice under our laws, there is no provision for it. Would it not be expedient to restrain these appointments to a very small number, and for these (if it be necessary) to require small contributions either from the litigants or the people at large, as you find would be most agreeable. In time, I suppose even this might be discontinued. The Clerks & Sheriffs perhaps may be paid, as with us, only converting Tobacco fees into their worth in peltry. As to the rules of decision & modes of proceding, I suppose ours can be only gradually introduced. It would be well to get their militia disciplined by calling them regularly together according to our usage; however, all this can only be recommended to your Discretion.”36 Some eight years later the exaction of exorbitant fees was one of the chief reasons which caused the reform of the French court at Vincennes.37

[pg 024]The plan for concentrating most of the Illinois troops at a single point was carried out in the spring of 1780. The chief objects sought were to procure supplies and to prevent the advance of the Spaniards. At first, it was thought advisable to locate the new fort on the north side of the Ohio near the Mississippi, and Col. Todd made some grants of land to such persons as were willing to settle in the vicinity and assist in raising provisions, but the fact that Virginia currency, although refused in Illinois, was accepted in Kentucky caused the fort to be built south of the Ohio, and it is probable that Todd's grants of land at the site first proposed lapsed.38 As the troops had a great need for settlers to raise crops, Capt. Dodge suggested to the governor of Virginia that immigrants to Illinois should receive aid from Virginia. This would aid the troops and would stop emigration to the Spanish possessions west of the Mississippi.39

As the French could neither support the soldiers nor do without them, commissions in blank were sent to Maj. Bosseron, district commandant at Vincennes, with power to raise a company there, and to assure the company that pay would be allowed by the government. It was feared that the settlers at Vincennes would consider themselves abandoned upon the withdrawal of troops. It was proposed to leave enough troops among the French to satisfy them, but scarcely had the new fort been established when the people of Cahokia sent a special messenger to Clark at Fort Jefferson, the new fort, asking that troops be sent [pg 025] to protect them. The Indians so surround the place, say the petitioners, that the fields can not be cultivated. If troops are sent the people can not feed them, but if they are not sent the people can not long feed themselves.40 French creditors of the government were unpaid and some of them must have been in sore need.41

The act establishing the County of Illinois would terminate by limitation at the end of the May session of 1780, unless renewed. At that session, the act was renewed “for one year after the passing of this act, and from thence to the end of the next session of assembly.”42

The condition of the people in the county during the latter half of 1780 was one of misery. Contemporary accounts have a melancholy interest. An attack by Indians upon Fort Jefferson being imminent, the few troops in the outlying districts were ordered to come to the aid of the garrison. The order reached Cahokia when its few defenders were sick and starving. Corn, without grease or salt, was their only food. Deaths were of frequent occurrence. The people of the village had petitioned Col. Montgomery to ease their burden by quartering some of the troops in other villages, but he refused the request of other officers for a council and threatened to abandon the country entirely. In such a condition of affairs, Capt. McCarty proceeded to obey the orders from Fort Jefferson. The only boats at the disposal of the garrison were unseaworthy, so five small boats were pressed for use. On the [pg 026] way, several of the famished soldiers became so sick that they had to be left along the route. Even military discipline was bad in the country. Capt. McCarty, upon being arrested for having quarreled with Dodge, because the latter would not buy food for the starving troops, was left for months without trial because Col. Montgomery had left the country and a military court could not be convened.43 In October, McCarty wrote: “In short, we are become the hated beasts of a whole people by pressing horses, boats, &c., &c., &c., killing cattle, &c., &c., for which no valuable consideration is given; even many not a certificate, which is here looked upon as next to nothing.”44

Of the same tenor as McCarty's testimony to Illinois conditions is that of Winston. A remonstrance of the civil authorities against the extravagance of the military officers was treated as insolent and impertinent. The military power refused the civil department the use of the military prison, even when pay was offered, and made strenuous efforts to establish military rule. Col. Montgomery and Capt. Brashears had departed for New Orleans without settling the account for the peltry which Todd had committed to the joint care of Montgomery and Winston. Montgomery was openly accused of having taken a large amount of public property away with him. Capt. Dodge was a notorious disturber of the peace, and Capt. Bentley, a more recent arrival, was equally undesirable. In the closing paragraph of a long letter is the significant statement: “It Being so long a time since we [pg 027] had any news from you, we conclude therefrom that the Government has given us up to do for Ourselves the Best we can, untill such time as it pleases Some other State or Power to take us under their Protection—a few lines from you would give Some of us great satisfaction, yett the Generality of the People are of Opinion that this Country will be given up to France....”45

At the close of October, the troops, with the exception of a very few, were collected at Fort Jefferson. There the garrison was sick and starving,46 clothes were much needed, desertion was rife, and the abandonment of the post seemed imminent.47 Among the few troops that were not called to Fort Jefferson were those of Capt. Rogers, at Kaskaskia. This company “had to impress supplies, giving certificates for the value—thus would kill cattle when they wanted them, hogs, & take flour from the horse-mills—& thus lived very comfortably.”48

Mutual recrimination was common among the officers. Todd, in a letter to Gov. Jefferson, in which he inclosed letters from the Illinois officers, said: “Winston is commandant at Kaskaskia; McCarty, a captain in the Illinois regiment, who has long since rendered himself disagreeable by endeavoring to enforce military law upon the civil department at Kohos.

[pg 028]“The peltry, mentioned by Winston as purloined or embezzled by Montgomery, was committed to their joint care by me in Novr, 1779; and from the circumstance of Montgomery's taking up with an infamous girl, leaving his wife, & flying down the river, I am inclined to believe the worst that can be said of him. Being so far out of the road of business, I can not do the State that justice I wish by sending down his case immediately to the Spanish commandants on the Mississippi.”49 From January 28, 1779, to October 18, 1780, Montgomery drew drafts upon Virginia to the amount of thirty-nine thousand three hundred twenty dollars.50 Winston and McCarty accused Capt. Rogers, who succeeded Col. Montgomery in command at Kaskaskia, of shooting down the stock of the inhabitants without warrant. In a dignified defence, Capt. Rogers declared that he took only so much food as was absolutely required to save his starving sick, and that Mr. Bentley, who endeavored to secure supplies from the people, offering his personal credit, was persistently opposed by Winston and McCarty. “I can not conclude without informing you that 'tis my positive opinion the people of the Illinois & Post Vincennes have been in an absolute state of rebellion for these several months past, & ought to have no further indulgence shown them; and such is the nature of those people, the more they are indulged, the more turbulant they grow. I look upon it that Winston and McCarty have been principal instruments to bring them to the pitch they are now at.”51 Capt. Dodge, against whom complaints had become general, and Capt. McCarty, [pg 029] whose quarrel has been narrated, were ordered to appear before a court of inquiry at Fort Jefferson.52 Clark was very angry at Montgomery's conduct. He sent a message to New Orleans ordering him to return for trial; he warned all persons against trusting the offender on the credit of the State, and he requested the governor of Virginia to arrest the fugitive if he should come to Richmond.53 How low public morals had sunk is shown by the fact that Montgomery had the effrontery to return to Fort Jefferson, where he arrived on May 1, 1781, and resumed his command. In February, 1783, he made his defense and asked for his pay.54 In April, 1781, Todd wrote: “I still receive complaints from the Illinois. That Department suffers, I fear, through the avarice and prodigality of our officers; they all vent complaints against each other. I believe our French friends have the justest grounds of dissatisfaction.”55

On June 2, 1781, Capt. McCarty was killed in a fight between the Illinois troops and some Indians on the one side and a party of Ouia Indians, who favored the British, on the other. The engagement took place near the Wabash. McCarty's papers were sent to the British, who laconically reported: “They give no information other than that himself and all the Inhabitants of the Illenoise were heartily tired of the Virginians.”56 There is slight [pg 030] reason to doubt the truth of the statement. It is enforced by the fact that in 1781, a letter written in French to the governor of Virginia and said to be signed in the name of the inhabitants of Vincennes and to give the views of the people of Vincennes, Kaskaskia, Vermilion, Ouia, etc., declared that the French had decided to receive no troops except those sent by the king of France to aid in defeating the enemies of the country. The Indians who are friendly to the French, said the writer, would regard the coming of Virginia troops as a hostile act. A copy of the memoir sent by the French settlers to the French minister Luzerne was inclosed.57

On June 8, 1781, the garrison of Fort Jefferson, being without food, without credit, and for more than two years without pay, evacuated the place and withdrew to the Falls of Ohio, only to find themselves without credit in even the adjoining counties of Virginia. The troops were billeted in small parties.58 Once again there comes a despairing plea from the feeble garrison at Vincennes, in the County of Illinois. The commander wrote: “Sir, I must inform you once more that I can not keep garrison any longer, without some speedy relief from you. My men have been 15 days upon half-allowance; there is plenty of provisions here but no credit—I can not press, being the weakest party—Some of the Gentlemen would help us, but their credit is as bad as ours, therefore, if you have not provisions send us Whisky which will answer as good an end.”59

[pg 031]In the Virginia House of Delegates, a committee for courts of justice reported that the laws which would expire at the end of the session had been examined, together with certain other laws, and that a series of resolutions had been agreed upon by the committee. Among these resolutions was the following: “Resolved, That it is the opinion of this committee, That the act of assembly, passed in the year 1778, entitled ‘an act, for establishing the county of Illinois, and for the more effectual protection and defence thereof;’ which was continued and amended by a subsequent act, and will expire at the end of this present session of assembly, ought to be further continued.” This report was presented and the resolutions agreed to by the House on November 22, 1781. Three days later, a bill in accordance with the resolution was presented. The consideration of the bill in a committee of the whole House was postponed from day to day until December 14, when it was considered and the question being upon engrossment and advancement to a third reading, it passed in the negative.60 On January 5, 1782, the General Assembly adjourned, and the County of Illinois ceased to exist.61 So far as instituting a civil government was concerned, the county was a failure. Its military history shows a mixture of American, British, French, and Spanish efforts at mastery.

The first important military operation in which the County of Illinois was concerned, after the well-known [pg 032] movements of Clark and Hamilton, was organized by the British at Detroit in compliance with a circular letter from Lord George Germain. The plan was to attack St. Louis, the French settlements near it on the east side of the Mississippi, Vincennes, Fort Nelson at the falls of the Ohio, and Kentucky. Large use was to be made of Indians, and British emissaries were busy among the tribes early in 1780. An expedition was to be led against Kentucky, while diversions should be made at outlying posts. It was thought that the reduction of St. Louis would present little difficulty, because it was known to be unfortified, and was reported to be garrisoned by but twenty men. In addition to this, it was regarded as an easy matter to use Indians against the place from the circumstance that many Indians frequented it. Less assurance was felt as to holding the place after it should have been captured, and to make this easier, it was proposed to appeal to the cupidity of the British fur traders. By the middle of February, a war-party had been sent out from Michilimackinac to arouse and act with the Sioux Indians, and early the next month another party was sent out to engage Indians to attack St. Louis and the Illinois towns. Seven hundred and fifty traders, servants, and Indians having been collected, on the 2d of May they started down the Mississippi, and at the lead mines, near the present Galena, seventeen Spanish and American prisoners were taken. In conjunction with this expedition, another, with a chosen band of Indians and French, was to advance by way of Chicago and the Illinois River; a third was to guard the prairies between the Wabash and the Illinois; and the chief of the Sioux was to attack St. Genevieve and Kaskaskia.62

[pg 033]The expedition against St. Louis and the Illinois towns, as well as in its larger aspect, was not successful. It was impossible to keep it secret and as early as March, an attack was expected. Spanish and Americans joined in repulsing the intruders. Another potent element in the failure was the treachery of some of the traders who acted as leaders for the British, notably that of Ducharme and Calvé, who had a lucrative trade and regarded the prospect of increasing it by the proposed attack as doubtful. In the last week of May, 1780, the attack on St. Louis was made. Several persons were killed, but the place was not taken. Cahokia was beleaguered for three days, but it was so well defended by George Rogers Clark that on the third night the enemy withdrew, when Clark hastened to intercept the expedition against Kentucky, while the Illinois and Spanish troops pursued the retreating enemy and burned the towns of the Sauk and Fox Indians. The British were much chagrined at the result of the expedition, yet they resolved to continue their plan of using Indians and sending out several parties at once.63

An expedition which gains much interest from the character of its leader was that of Col. Augustin Mottin de la Balme. This man had been commissioned quartermaster of gendarmerie, by the authorities of Versailles, in 1766; [pg 034] had come to America and been recommended by Silas Deane and Benjamin Franklin to the president of Congress, John Hancock, as a man who would be of service in training cavalry; had been breveted lieutenant-colonel of cavalry, in May, 1777; made inspector of cavalry, with the rank of colonel, in July following; and had resigned in October of the same year. The next year, a public notice, in French with English and German translations, announced that carpenters, bakers, and some other classes of laborers could find shelter and employment at a workshop established by La Balme, twenty-eight miles from Philadelphia.64 In the summer of 1780, La Balme went from Fort Pitt to the Illinois country.

A contemporary who writes from Vincennes speaks of La Balme as a French colonel. He was regarded by the Americans with much suspicion. Capt. Dalton, the American commander at Vincennes, whose character was later much questioned, allowed him to go among the Indians,65 whereupon La Balme advised them to send word to the tribes which Clark was preparing to attack and to warn them of their danger. La Balme also ingratiated himself with the discontented French, asking why they did not drive “these vagabonds,” the American soldiers, away, and saying that to refuse to furnish provisions was the most efficient method. “Everything he advances tends to advance the French interest and depreciate the American. The people here are easily misled; buoy'd up with the flattering hopes of being again subject to the king of France, he could easily prevail on them to drive every American out of the Place and this appears to me to be [pg 035] his Plan.” After thoroughly stirring up the people at Vincennes, the adventurer left, with an escort of thirty French and Indians, to visit Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and St. Louis. He and Col. Montgomery, then the superior officer in Illinois, did not meet, and he received not the slightest countenance from the Spanish commandant at St. Louis. By the French inhabitants, La Balme “was received ... just as the Jews would receive the Messiah—was conducted from the post here [at Kaskaskia] by a large detachment of the inhabitants as well as different tribes of Indians.” The French in the towns near the Mississippi were so enthusiastic that La Balme had little difficulty in raising forty or fifty troops for an expedition against Detroit. Some of the American soldiers at Cahokia deserted to him, and when placed under arrest by the military authorities were rescued by a mob. On October 5, 1780, after telling the Indians to be quiet because they would see the French in Illinois in the spring, the French troops set out from Cahokia.66

The troops from Illinois were to be joined by a body from Vincennes, but without waiting for them La Balme pushed on to the Miami towns, where he hoped to capture a British Indian trader who was especially hated by the French. The trader was not found, but his store of goods to the amount of one hundred horse-loads was seized. The expected reinforcements not arriving, La Balme felt too weak to attack Detroit and started to return. He was attacked by the Indians on the river Aboite, eleven miles southwest of the present Fort Wayne, and he and some [pg 036] thirty of his men were killed and at least one hundred horses, richly laden with plunder, were taken by the Indians. It was reported that disaffected inhabitants of Detroit had concealed five hundred stands of arms with which to assist the forces of La Balme in taking the place. Among La Balme's papers, which fell into the hands of the British and are now in the Canadian archives, were addresses, in French, by M. Mottin de la Balme, French colonel, etc., to the French settled on the Mississippi, dated St. Louis, September 17, 1780; a declaration, in French, in the name of the inhabitants of the village of Cahokia, addressed to La Balme: “We unanimously request you to listen with a favorable ear to the declaration which we venture to present to you, touching all the bad treatment we have suffered patiently since the Virginian troops unfortunately arrived amongst us till now,” dated Cahokia, September 21, 1780; a note from F. Trottier, a member of the court of Cahokia, elected under the Virginia government, to La Balme, saying that no meeting can be held until Sunday next, when he hopes the young men will show themselves worthy the high idea La Balme has of them, but that at present there are only twelve entirely determined to follow him wherever he goes, although others may follow their example, and asking La Balme to receive depositions against the Virginians, dated Cahokia, September 27, 1780; a petition, in French, addressed to the Chevalier de la Luzerne, minister plenipotentiary from France to the United States, by inhabitants of Post Vincennes, dated Vincennes, August 22, 1780; and a commission to Augustin Mottin de la Balme as quartermaster of gendarmèrie, dated Versailles, February 23, 1766.67 The British promptly set about promoting the [pg 037] Indian trader whom La Balme and the French had sought to kill, believing that he would be serviceable as a spy.68

In the autumn of 1780, a party of seventeen men from Cahokia went on an expedition against St. Josephs. The party was commanded by “a half Indian,” and seems to have included but one American. The attack was so timed as to come when the Indians in the vicinity of St. Josephs were out hunting. The place was taken without difficulty, the traders of the place were captured and plundered, and the party, laden with booty, set out on the route to Chicago. A pursuing party was quickly organized and at the Rivière du Chemin, a small stream in Indiana, emptying into the southeastern part of Lake Michigan, the returning victors were summoned to surrender, on December 5, 1780. Upon their refusal, four were killed, two wounded, seven made prisoners, while three escaped.69 [pg 038] The one American, Brady, was among the prisoners. He told the British that the party was sent by the creoles to plunder St. Josephs, and that there was not a Virginian in all the Illinois country, including Vincennes.70

In the very midst of winter, on January 2, 1781, an expedition commanded by Eugenio Pierre, a Spanish captain of militia, set out from St. Louis against St. Josephs. According to a Spanish account, the party consisted of sixty-five militia men and sixty Indians, while an American account declares it to have contained thirty Spaniards, twenty men from Cahokia, and two hundred Indians.

The purpose of the expedition was to retaliate upon the British for the attack on St. Louis and for the defeat of La Balme. On the march, severe difficulties incident to the season were encountered. The post was easily taken, the Indians were conciliated by a liberal proportion of the booty, the Spanish flag was raised and the Illinois country with St. Josephs and its dependencies was claimed for the crown of Spain. The British flag was given to Commandant Cruzat, of St. Louis. These proceedings made some prominent Americans fear that Spain would advance claims to the region at the close of the Revolution.71

[pg 039]In the summer of 1781, a party of seven men was sent out by the commandant at Michilimackinac with a letter to the inhabitants of Cahokia and Kaskaskia asking them to furnish troops to be paid by the king of England, and to assume the defensive against the Spaniards. The men reached St. Louis before visiting Cahokia or Kaskaskia, and were arrested by the Spanish commandant, who sent a copy of the letter to Major Williams, knowing no officer in Illinois superior to him. This created jealousy at Cahokia and Kaskaskia, each of several officers claiming superiority. Charles Gratiot, a man of some ability, who had removed from Cahokia to St. Louis because unable to endure the lawlessness at the former place, wrote that he did not know what course the Illinois people might have taken if Cruzat had not intercepted the British agents. Illinois was a country without a head where everyone expected to do as he pleased.72

In noting the operations of the medley of military forces in the County of Illinois, it is easy to conceive how the result might have been different, but the fact is that as the county ceased to exist, no nation had established a better title to the region than that of the Americans.

Chapter II. The Period of Anarchy in Illinois.73

Illinois was practically in a state of anarchy during the time that it was a county of Virginia, and when that county ceased to be, anarchy became technically as well as practically its condition, and remained so until government under the Ordinance of 1787 was inaugurated in 1790.

Virginia's legacy from her ephemeral county was one of unpaid bills. Scarcely had the general assembly adjourned, in January, 1782, when Benjamin Harrison wrote: “We know of no power given to any person to draw bills on the State but to Colo Clarke and yet we find them drawn to an immense amount by Colo Montgomery, and Captn Robt. George and some others; we have but too much reason to suppose a collusion and fraud betwixt the drawers and those they are made payable to; most of them are for specie when they well knew we had none amongst us, and from the largeness of the sums, proves the transactions must have been in paper and the depreciation taken into account, when the bargains were made; indeed George confesses this to have been the case when he gave Philip Barbour a bill for two hundred and thirty two thousand, three hundred and twenty Dollars and uses the plea of ignorance.” The transactions of Oliver Pollock, purchasing agent at New Orleans, should be carefully examined from the time he began to act with [pg 041] Montgomery.74 Thimothé Demunbrunt, as he signed his name, asked pay for his services as lieutenant, in order that he might not be a charge to his friends—a thing which would be shameful to one of noble descent. He wished to be able to support his family and to go with Clark on a proposed expedition. His petition was supported by a certificate from Col. Montgomery, testifying that Demunbrunt had been active in his military duty, had gone against the savages in the spring of 1780, had gone on the “Expedition up the Wabash,” and had gone to the relief of Fort Jefferson when Montgomery could raise only twelve men.75

The military troubles continued. The commander at Vincennes reported his troops as destitute and unpaid. Richard Winston, of Kaskaskia, who had succeeded Todd as head of the civil government in Illinois, was arrested by military force and put in jail. The prisoner claimed that the proceedings were wholly irregular and that he was unacquainted with the nature of the charge against [pg 042] him.76 The next year, he was accused of treason, the accuser declaring that Winston had proposed to turn Illinois over to Spain, but that his proposal had been despised by the Spanish commandant.77 Upon Winston was also laid the chief blame for the discontent of the French, he being charged with having told Montgomery that the French were strangers to liberty and must be ruled with a rod of iron or the bayonet, and that if he wanted anything he must send his guards and take it by force; while, at the same time, he told the French that the military was a band of robbers and came to Illinois for plunder.78 However, numerous and well-founded as the accusations might be, both accused and accuser laid their claims for salary before the Virginia Board of Commissioners for the Settlement of Western Accounts.79 Even the notorious Col. Montgomery presented before this board his defence, which consisted of a recital of his meritorious deeds, others being omitted.80

Another visitor to the Board of Commissioners was Francis Carbonneaux, prothonotary and notary public for the Illinois country. Although he came to get some private affairs settled, his chief mission was to lay before the Board the confusion in Illinois, and the Board correctly surmised that if Virginia did not afford relief the messenger [pg 043] would proceed to Congress.81 It was but natural that at this time, the people of Illinois should be in doubt as to whom to present their petition, because Virginia had offered to cede her western lands to Congress, although the terms of cession were not yet agreed upon. Carbonneaux complained that Illinois was wholly without law or government; that the magistrates, from indolence or sinister views, had for some time been lax in the execution of their duties, and were now altogether without authority; that crimes of the greatest enormity might be committed with impunity, and a man be murdered in his own house and no one regard it; that there was neither sheriff nor prison; and to crown the general confusion, that many persons had made large purchases of three and four hundred leagues, and were endeavoring to have themselves established lords of the soil, as some had done in Canada, and to have settlements made on these purchases, composed of a set of men wholly subservient to their views. The Spanish traded freely in Illinois, but strictly prohibited Illinois from trading in Spanish dominions. Complaint was also made that the Board of Commissioners had not settled the Illinois accounts in peltry according to the known rule and practice, namely: that fifty pounds of peltry should represent one hundred livres in money.

The petitioners prayed that a president of judicature be sent to them, with executive powers to a certain extent, and that subordinate civil officers be appointed, to reside in each village or station, with power to hear and decide all causes upon obligations not exceeding three hundred dollars, higher amounts to be determined by a court to be held at Kaskaskia and to be composed of the president and a majority of the magistrates. It was [pg 044] desired that the grant in which the Kaskaskia settlements lay should be considered as one district. It contained five villages, of which Kaskaskia and Cahokia were the largest. The grant extended to the headwaters of the Illinois River on the north. The land had been granted to the settlers by the Indians, and the Indians, having given their consent by solemn treaties, had never denied the sale. The tract referred to was probably the two purchases of the Illinois Company. Maps give but one of these and, in fact, the other was said to be so described as to comprise a line only. Naturally, this fact was not known at the time of purchase.

It was frankly acknowledged that Illinois had no man fitted for the office of president. It was hoped that Virginia would furnish one, and would send with him a company of regulars to act under his direction and enforce laws and authority. The president should be empowered to grant land in small tracts to immigrants. The privilege of trading in Spanish waters, especially on the Missouri, was much desired. It was said that Carbonneaux “appears to have been instructed as to the ground of his message by the better disposed part of the inhabitants of the country whose complaints he represents.”82

At the time of Carbonneaux's petition, there was no legal way by which newcomers to Illinois could acquire public land. Virginia had prepared to open a land-office, soon after the conquest of the Illinois country, but she seems to have heeded the recommendation of Congress that no unappropriated land be sold during the war.83 Some grants had been made by Todd, Demunbrunt, the Indians, and others with less show of right, but they were made without [pg 045] governmental authority. The Indians had presented a tract of land to Clark, but the view consistently held was that individuals could not receive Indian land merely upon their own initiative.84 One of the grants made at Vincennes, which seems to have been a typical one, was signed by Le Grand, “Colonel commandant and President of the Court,” and was made by the authority granted to the magistrates of the court of Vincennes by John Todd, “Colonel and Grand civil Judge for the United States.” The purpose of the grant, which comprised four hundred arpents “in circumference,” was to induce immigration.85 The grants made by the court of Vincennes became notorious from the fact that thousands of acres were granted by the court to its own members.86

On March 1, 1784, Virginia ceded her western lands to the United States, thus transferring to the general government the question of land titles. The country had been in a state of unconcealed anarchy for more than two years, all semblance of Virginia authority having ceased, and the cession is quite as much a tribute to Virginia's shrewdness as to her generosity. Never was so large a present made with less sacrifice. The cession was made with the following conditions, some of which were to have a direct and potent influence upon the settlement of the ceded region:

1. The territory should be formed into states of not less than one hundred nor more than one hundred and fifty square miles each;

2. Virginia's expenses in subduing and governing the territory should be reimbursed by the United States;

[pg 046]3. Settlers should have their “possessions and titles confirmed;”

4. One hundred and fifty thousand acres, or less, should be granted to George Rogers Clark and his soldiers;

5. The Virginia military bounty lands should be located north of the Ohio River, unless there should prove to be enough land for the purpose south of that river;

6. The proceeds from the sale of the lands should be for the United States, severally.87

In the year of the Virginia cession, Congress passed the Ordinance for the Government of the Western Territory, but as it never went into effect, its importance is slight except as indicative of the trend of public feeling on the subjects which it involved. Should Jefferson's plan, proposed at this time, have been carried out, Illinois would have been parts of the states of Polypotamia, Illinois, Assenisipia, and Saratoga.88

Carbonneaux, the messenger from Illinois to Virginia, carried his petition to Congress. Congress paid the messenger, referred the petition to a committee, and upon the report of the committee voted to choose one or more commissioners to go to Illinois and investigate conditions there.89 No record of the appointment of such commissioners has been found. Congress considered Carbonneaux's petition early in 1785. In November of the same year comes a record of the anarchy in Illinois. This was addressed to George Rogers Clark, who was the hope of the people of that neglected country. The commandant at St. Louis is afraid of an attack from the Royalists at Michilimackinac, or he has given orders for all the people [pg 047] in that place to be in readiness when called on, with their arms.

“The Indians are very troublesome on the rivers, and declare an open war with the Americans, which I am sure is nothing lessened by the advice of our neighbors, the French in this place, and the people from Michilimackinac, who openly say they will oppose all the Americans that come into this country. For my part, it is impossible to live here, if we have not regular justice very soon. They are worse than the Indians, and ought to be ruled with a rod of iron.”90

During the year 1786, George Rogers Clark was the chief factor in Illinois affairs. He was regarded by the people as their advocate before Congress. In March, seven of the leading men of Vincennes, at the request of the French and American inhabitants, sent a petition to him asking him to persuade Congress to send troops to defend them from the Indians, and also saying: “We have unanimously agreed to present a petition to Congress for relief, apprehensive that the Deed we received from an office, established or rather continued by Colo Todd for lands, may possibly be a slender foundation; so that after we have passed through a scene of suffering in forming settlements in a remote and dangerous part may have the mortification to be totally deprived of our improvements.”91 In June, seventy-one American subscribers from Vincennes, “in the County of Illinois,” asked Congress to settle their land-titles and give them a government. They held land from grants from an office established by Col. Todd, whose validity they questioned. The commandant [pg 048] and magistracy had resigned because of the disobedience of the people. There was no executive, no law, no government, and the Indians were very hostile.92

Clark was not unmindful of the needs of the people. He wrote to the president of Congress: “The inhabitants of the different towns in the Illinois are worthy the attention of Congress. They have it in their power to be of infinite service to us, and might act as a great barrier to the frontier, if under proper regulation; but having no law or government among them, they are in great confusion, and without the authority of Congress is extended to them, they must, in all probability, fall a sacrifice to the savages, who may take advantage of the disorder and want of proper authority in that country. I have recommended it to them, to re-assume their former customs, and appoint temporary officers until the pleasure of Congress is known, which I have flattered them would be in a short time. How far the recommendation will answer the desired purpose is not yet known.”93

Clark's fears of the Indians were only too well grounded. During the summer, the American settlers were compelled to retire to a fort at Bellefontaine, and four of their number were killed. At the same time, about twenty Americans were killed about Vincennes. The French were still safe from Indian attacks and were very angry because the Americans complained of existing conditions.94 The strife between the French and the Americans at Vincennes, over the proper relations of the whites to the Indians, became intense. The French contended that the Indians should [pg 049] be allowed to come and go freely, while the Americans held that it was unsafe to grant such freedom. At last, upon the occasion of the killing of an Indian by the Americans, after they had been attacked by the Indians, the French citizens ordered all persons, who had not permission to settle from the government under which they last resided, to leave at once and at their own risk. The French told the Americans plainly that they were not wanted, and that they, the French, did not know whether the place belonged to the United States or to Great Britain.95 This last assertion was probably true. The British Michilimackinac Company had a large trading-house at Cahokia for supplying the Indians, they held Detroit, and their machinations among the Indians were constant. The feeling of all intelligent Americans in Illinois must have been expressed by John Edgar when he wrote that the Illinois country was totally lost unless a government should soon be established.96 Clark wrote a vigorous letter to the people at Vincennes, telling them that unless they stopped quarreling military rule would be established; that the government established under Virginia was still in force, having been confirmed by Congress upon the acceptance of the Virginia deed of cession, and that the court, if depleted, should be filled by election.97

In one respect, even during this trying period, the western country gave promise of its future growth. There was a large crop. Flour and pork, quoted, strangely enough, together, sold at the Falls of Ohio at [pg 050] twelve shillings per hundred pounds, while Indian corn sold at nine pence per bushel.98

On August 24, 1786, Congress ordered its secretary to inform the inhabitants of Kaskaskia that a government was being prepared for them.99 In 1787, conditions in the Illinois country became too serious to be ignored. The Indian troubles were grave and persistent, but graver still was the danger of the rebellion or secession of the Western Country or else of a war with Spain. The closure of the Mississippi by Spain made the West desperate. Discontent, anarchy, and petitions might drag a weary length, but when troops raised without authority were quartered at Vincennes, when these troops seized Spanish goods, and impressed the property of the inhabitants of Vincennes, and proposed to treat with the Indians, the time for action was at hand. In April, Gen. Josiah Harmar, then at Falls of Ohio, was ordered to move the greater part of his troops to Vincennes to restore order among the distracted people at that place. Intruders upon the public lands were to be removed, and the lawless and illegally levied troops were to be dispersed.100

Arrived at Vincennes, Gen. Harmar proceeded with vigor. The resolution of Congress against intruders on the public lands was published in English and in French. The inhabitants, especially the Americans whose hold on their lands was the more insecure, were dismayed, and French and Americans each prepared a petition to Congress, [pg 051] and appointed Bartholomew Tardiveau, who was to go to Congress within a month, as their agent. Tardiveau was especially fitted for this task by his intimate acquaintance with the land grants of the region. Each party at Vincennes also prepared an address to Gen. Harmar, the Americans declaring that they were settled on French lands and feared that their lands would be taken from them without payment and asking aid from Congress, and the French expressing their joy at being freed from their former bad government. Many of Clark's militia had made tomahawk-rights, and this added to the confusion of titles.101

From August 9 to 16, Gen. Harmar, with an officer and thirty men, some Indian hunters, and Tardiveau, journeyed overland from Vincennes to Kaskaskia, where conditions were to be investigated. The August sun poured down its rays upon the parched prairies and dwindling streams. Water was bad and scarce, but buffalo, deer, bear, and smaller game were abundant.

Harmar found life in the settlements he visited as crude as the path he traveled. Kaskaskia was a French village of one hundred and ninety-one men, old and young, with an accompaniment of women and children of various mixtures of white and red blood. Cahokia, then the metropolis, had two hundred and thirty-nine Frenchmen, old and young, with an accompaniment similarly mixed. Between these settlements was Bellefontaine, a small stockade, inhabited altogether by Americans, who had settled without authority. The situation was a beautiful one; the land was fertile; there [pg 052] was no taxation, and the people had an abundance to live upon. They were much alarmed when told of their precarious state respecting a title to their lands, and they gave Tardiveau a petition to carry to Congress. On the route to Cahokia, another stockade, Grand Ruisseau, similarly inhabited by Americans, was passed. There were about thirty other American intruders in the fertile valleys near the Mississippi, and they, too, gave Tardiveau a petition to Congress.

The Kaskaskia, Peoria, Cahokia, and Mitcha tribes of Indians numbered only about forty or fifty members, of whom but ten or eleven individuals composed the Kaskaskia tribe; but this does not mean that danger from the Indians was not great, because other and more hostile tribes came in great numbers to hunt in the Illinois country. The significance of the diminished numbers of these particular tribes lies in the fact that they had the strongest claim to that part of Illinois which would be first needed for settlement. At Kaskaskia and Cahokia, the French were advised to obey their magistrates until Congress had a government ready for them, and Cahokia was advised to put its militia into better shape, and to put any turbulent or refractory persons under guard until a government could be instituted.102

Having finished his work in the settlements near the Mississippi, Harmar returned to Vincennes, where he held councils with the Indians, and on October 1, set out on his return to Fort Harmar. Although without authority to give permanent redress, he had persuaded the French at Vincennes to relinquish their charter and to throw themselves upon the generosity of Congress. “As it would have been impolitic, after the parade we had made, to [pg 053] entirely abandon the country,” he left Maj. John F. Hamtramck, with ninety-five men, at Vincennes.103 Harmar's visit was doubtless of some value, but he had not been gone five weeks when Hamtramck wrote to him: “Our civil administration has been, and is, in a great confusion. Many people are displeased with the Magistrates; how it will go at the election, which is to be the 2d of Decr, I know not. But it is to be hoped that Congress will soon establish some mode of government, for I never saw so injudicious administration. Application has repeatedly been made to me for redress. I have avoided to give answer, not knowing how far my powers extended. In my opinion, the Minister of War should have that matter determined, and sincerely beg you would push it. I confess to you, that I have been very much at a loss how to act on many occasions.”104

Not earlier than the 24th of November, Tardiveau set out for Congress with his petitions from the Illinois country. Harmar was much pleased to have so able a messenger, and spoke of him as sensible, well-informed, and able to give a minute and particular description of the western country, particularly the Illinois. He had been preceded to Congress by Joseph Parker, of Kaskaskia. Harmar seems to have regarded Tardiveau as a sort of antidote to Parker, for he closes his recommendation of the former by saying: “There have been some imposters before Congress, particularly one Parker, a whining, canting Methodist, a kind of would-be governor. He is extremely unpopular at Kaskaskia, and despised by the inhabitants.”105

[pg 054]This detracts from the value of Parker's representations, which had been made in a letter to St. Clair, the President of Congress. After explaining that when he left Kaskaskia, on June 5, 1787, the people did not have an intended petition ready, Parker complained of the lack of government in Illinois, the presence of British traders, the depopulation of the country by the inducements of the Spaniards, and the high rate at which it was proposed to sell lands. His complaints were true, although he may have failed to give them in their proper proportion.106

On July 13, 1787, the Ordinance of 1787 had been passed by Congress. The Illinois country was at that time ready for war against the Spanish, who persisted in closing the Mississippi. The troops, irregularly levied by George Rogers Clark at Vincennes, had seized some Spanish goods on the theory that if the Spanish would not allow the United States to navigate the lower Mississippi, the Spanish should not be allowed to navigate the upper Mississippi. John Rice Jones, later the first lawyer in Illinois, was Clark's commissary.107

The Ordinance of 1787 was the only oil then at hand for these troubled waters. The situation in Illinois was a complicated one, and probably the numerical weakness of the population alone saved the country from disastrous results. The few Americans in Illinois desired governmental protection from the Spanish, the Indians, the British, and any Americans who might seek to jump the claims of the first squatters; the few French desired protection from the Spanish, the Americans, the British, and soon from the Indians; the numerous Indians, permanent or transient, desired protection from the Spanish, the Americans, and in rare cases from an Americanized [pg 055] Frenchman. Americans, French, Spanish, British, and Indians made an opportunity for many combinations.

For the French inhabitants, the somewhat paternal character of the government provided for by the Ordinance was a matter of no concern. The great rock of offense for them was the prohibition of slavery. An exodus to the Spanish side of the Mississippi resulted and St. Louis profited by what the older villages of Illinois lost.108 In addition to a justifiable feeling of uncertainty as to whether they would be allowed to retain their slaves, the credulous French had their fears wrought upon by persons interested in the sale of Spanish lands. These persons took pains to inculcate the belief that all slaves would be released upon American occupancy. The Spanish officials were also active. The commandant at St. Louis wrote to the French at Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes, respectively, inviting them to settle west of the Mississippi and offering free lands.109 Mr. Tardiveau, the agent for the Illinois settlers to Congress, tried to induce Congress to repeal the anti-slavery clause of the Ordinance. He said that it threatened to be the ruin of Illinois. Designing persons had told the French that the moment Gen. St. Clair arrived all their slaves would be free. Failing in his efforts to secure a repeal, he wrote to Gen. St. Clair, asking him to secure from Congress a resolution giving the true intent of the act.110 In this letter, Tardiveau advanced the doctrine, later so much used, that the evils of slavery would be mitigated by its diffusion.111 The first panic of [pg 056] the French only gradually subsided and the question of slavery was a persistent one.

One of the most industrious of those interested in the sale of Spanish lands was George Morgan, of New Jersey.112 In 1788, he tried to secure land in Illinois also. He and his associates petitioned Congress to sell them a tract of land on the Mississippi. A congressional committee found upon investigation that the proposed purchase [pg 057] comprised all of the French settlements in Illinois.113 Thereupon was passed the Act of June 20, 1788. According to its provisions, the French inhabitants of Illinois were to be confirmed in their possessions and each family which was living in the district before the year 1783 was to be given a bounty of four hundred acres. These bounty-lands were to be laid off in three parallelograms, at Kaskaskia, Prairie du Rocher, and Cahokia, respectively. They were to be bounded on the east by the ridge of rocks—a natural formation trending from north to south, a short distance to the east of the French settlements. Morgan was to be sold a large described tract for not less than sixty-six and two-thirds cents per acre. Indian titles were to be extinguished if necessary.114

The Act of June 20, 1788, is an important landmark in the settlement of Illinois. The grant of bounty-lands was made for the purpose of giving the French settlers a means of support when the fur-trade and hunting should have become unprofitable from the advance of American settlement. This was a clear acknowledgment that the Indians were right in believing, as they did, that the American settlement would be fatal to Indian hunting-grounds. The Indians were soon bitterly hostile. Then, too, the claims of the settlers to land, founded upon French, British, or Virginia grants, were to be investigated. This investigation dragged on year after year, even for decades, and as it was the policy of the United States not to sell public land in Illinois until these claims were [pg 058] settled, the country became a great squatters'115 camp. The length of the investigation was doubtless due in part to the utter carelessness of the French in giving and in keeping their evidences of title.

By a congressional resolution of August 28, 1788, it was provided that the lands donated to Illinois settlers should be located east, instead of west, of the ridge of rocks. As this would throw the land too far from the settlements to be available, petitions followed for the restoration of the provisions of June 20, and in 1791 the original location was decreed. By a resolution of August 29, 1788, the governor of the Northwest Territory was ordered to carry out the provisions of the acts of June 20 and August 28, 1788, respectively.116

The beginning of operations, in accordance with the acts just cited, was delayed by the fact that the governor and judges, appointed under the Ordinance of 1787, and who alone could institute government under it, did not reach the Illinois country until 1790. In the meantime, anarchy continued. Contemporary accounts give a good idea of the attempts at government during the time, and the fact of their great interest, combined with the fact that most of them are yet unpublished, seems to warrant treatment of the subject at some length.

The court at Kaskaskia met more than a score of times during 1787 and 1788. Its record consists in large part of mere meetings and adjournments. All members of the court were French, while litigants and the single jury recorded were Americans. Jurors from Bellefontaine received forty-five livres each, and those from Prairie du [pg 059] Rocher, twenty-five livres each. This court seems to have been utterly worthless.117 At Vincennes, matters were at least as bad. “It was the most unjust court that could have been invented. If anybody called for a court, the president had 20 livers in peltry; 14 magistrates, each 10 livers; for a room, 10 livers; other small expenses, 10 livers; total in peltry, 180 livers—which is 360 in money. So that a man who had twenty or thirty dollars due, was obliged to pay, if he wanted a court, 180 livers in peltry: This court also never granted an execution, but only took care to have the fees of the court paid. The government of this country has been in the Le Gras and Gamelin family for a long time, to the great dissatisfaction of the people, who presented me a Petition some days ago, wherein they complained of the injustice of their court—in consequence of which, I have dissolved the old court, ordered new magistrates to be elected, and established new regulations for them to go by.”118 Upon the dissolution of the court, Maj. Hamtramck issued the following:

“REGULATIONS FOR THE COURT OF POST VINCENNES.

“In consequence of a Petition presented to me by the people of Post Vincennes, wherein they complain of the [pg 060] great expence to which each individual is exposed in the recovery of his property by the present court, and as they express a wish to have another mode established for the administration of justice—I do, therefore, by these presents, dissolve the said court, and direct that five magistrates be elected by the suffrages of the people who, when chosen, will meet and settle their seniority.

“One magistrate will have power to try causes, not exceeding fifty livers in peltry. Two magistrates will determine all causes not exceeding one hundred livers in peltry,—from their decision any person aggrieved may (on paying the cost of the suit) appeal to the District Court, which will consist of three magistrates; the senior one will preside. They will meet the third Tuesday in every month and set two days, unless the business before them be completed within that time. All causes in this court shall be determined by a jury of twelve inhabitants. Any person summoned by the sheriff as a juryman who refuses or neglects to attend, shall be fined the price of a day's labour. In case of indisposition, he will, previous to the sitting of the court, inform the clerk, Mr. Antoine Gamelin, who will order such vacancies to be filled.

“The fees of the court shall be as follows: A magistrate, for every cause of fifty livers or upwards in peltry, shall receive one pistole in peltry, and in proportion for a lesser sum. The sheriff for serving a writ or a warrant shall receive three livers in peltry; for levying an execution, 5 per cent, including the fees of the clerk of the court.

“The clerk for issuing a writ shall receive three livers in peltry, and all other fees as heretofore. The jury being an office which will be reciprocal, are not to receive pay. All expenses of the court are to be paid by the person that is cast. This last part may appear to you to be an extraordinary charge—but my reason for mentioning it is, that [pg 061] formerly the court made the one who was most able pay the fees of the court, whether he lost or no.

“The magistrates, before they enter into the execution of their office, will take the following oath before the commandant: I, A., do swear that I will administer justice impartially, and to the best of my knowledge and understanding, so help me God.

“Given under my hand this 5th day of April, 1788.”

A little later, Hamtramck wrote: “Our new government has taken place; five magistrates have been elected by the suffrage of the people, but not one of the Ottoman families remains in. One Mr. Miliet, Mr. Henry, Mr. Bagargon, Capt. Johnson, and Capt. Dalton, have been elected. You will be surprised to see Dalton in office; but I found that he had too many friends to refuse him. I keep a watch-side eye over him, and find that he conducts himself with great propriety.”120