Title: Harper's Round Table, July 30, 1895

Author: Various

Release date: July 4, 2010 [eBook #33078]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire

Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| PUBLISHED WEEKLY. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, JULY 30, 1895. | FIVE CENTS A COPY. |

| VOL. XVI.—NO. 822. | TWO DOLLARS A YEAR. |

The sharp crackling of the gravel, and the sound of a horse's hoofs coming up the driveway which led to the Thompsons' house, told Joe that Ned was going to be as prompt as he always was when the two boys had made any appointment, so he dropped his book, and ran to the door just as a neat little buckboard pulled up at the doorstep.

"Hello, Ned!" said Joe; "just on time. I knew that was you the moment I heard the rig turn in the gate. Wait till I get my hat and I'll drive to the stable with you. Say, will you stay to lunch? Jerry'll take care of him," he nodded toward the little roan, and disappeared in the doorway. In a moment he was back again, and jumping in with Ned they spun off to the stable, where Jerry, the coachman, promised to see that Tot should get his full measure of feed at noon.

"Now, to work," said Joe, "and after lunch we'll start off for the lake. Just you wait till you've heard my scheme, and you'll think it a dandy; see if you don't."

"Well, what is it?" said Ned. "There's no use keeping it to yourself forever."

"Come up in the workshop, for we've got to spend the rest of the morning there, and I'll tell you all about it."

The boys on leaving the stable turned down towards the farm barns, where in one of the vacant rooms Mr. Thompson had fitted up a neat little carpenter shop for his son. In one corner was a first-class lathe for all kinds of wood-turning, and across the room was a long carpenter's bench with all the appliances complete, while over in one of the other corners was what remained of Joe's first scroll-saw, rather dilapidated and cheap-looking now, but still of some service. Joe would not have parted with it even if[Pg 762] he did not use it, for with it he developed his first love for carpentry, which had finally led to the present shop.

"Now look here," said Joe; "my scheme is the simplest in the world; it's a plan to catch those bass in Laurel Lake which we can't get any way we've tried so far. It isn't the bait. Jingo! we've tried everything, from grasshoppers, dobsons, and live bait down to worms; they just look at it, and then look up at the boat over their heads, and scoot. Remember that monster we saw off Sea Lion last Tuesday? What would you give to get him, eh?"

"What would I give? Why, Joe, he's the biggest bass in that lake. I'd give—now, let me see," said Ned, scratching his head as he turned it from one side to the other; "I'd be willing to throw my new rod in the lake and stop fishing the rest of the summer."

"So would I," said Joe. "But look here, just get that cross-cut saw and help me get this plank so that we can get at it, and I'll explain as we go along." Joe measured off on the board ten divisions of eight inches each, and started sawing across the first line. "Now, you see," said he, "what I propose is that we take each of these ten pieces, cut up that old line of mine into lengths of about eight or nine feet, and then—see? Isn't that easy? The beauty of it is that we have a chance in ten different places; just string them along the shore, leave them, and while we wait jump in and play fish ourselves off Baldwin's Cliff; we can easily watch the floats from there. Catch?"

Ned had been listening eagerly, and approved the scheme heartily, only wondering why it had not occurred to them before. When Joe finished, Ned raised the question of bait, but was put off by Joe's saying there would be time enough to get all the grasshoppers and crickets they wanted, and maybe a few frogs, so they went to work, coats off, and sleeves rolled up in a businesslike manner. In the course of an hour or more they had that part of the work all done, and a short time afterwards they started up to the stable with their arms full of their invention, and deposited it complete in the box under the seat of Ned's buckboard.

"Now for bait," said Joe; "you take this box and keep along by that old stone wall and look sharp for crickets. There are lots of old boards and stones there; turn them all over and you'll get enough. I'll stick to this field and get the 'hoppers."

They separated, and were soon hard at work, both using their hands to catch the wily bait; Ned said he never had any luck with 'hoppers or crickets that were caught with a butterfly net. After an hour they decided they had enough, and turned down toward a small stream which ran through the meadow, and got a dozen or more frogs, and so complete in all the details of their plan they came into the house and sat down to lunch. It seemed to both the boys entirely too long, and Joe fidgeted so much that his father noticed it, and tried to find out what the cause was.

"No, nothing's the matter, only we want to hurry up and get to the lake. We've got a scheme, and later we're going to have a swim."

"What is it, Joe?" said Mr. Thompson. "What's up? You're not going to catch that Jonah's whale you told me about with dynamite or anything like that, are you? You had better try putting salt on his tail," he added, jokingly, and he quietly passed the salt-cellar to Joe. "Come, fill your pockets; you'll need it."

Now it might as well be said right here that Mr. Thompson owned many a fine split bamboo rod, and two or three beautiful guns, and that there were pictures of partridges and woodcock in his den. Two fishing pictures in particular, which had always been Joe's delight, hung near the door, one of a great trout rolling up to take a fly as it skimmed the surface of the water, while the other, its mate, was of a fine small-mouthed bass clearing the water, and shaking himself in the air in his efforts to break away from the hook which had tempted him. In fact, Mr. Thompson was a sportsman of the truest kind. Little did Ned and Joe know how near he came to adding set lines to dynamite when talking seriously before he mentioned the salt. If he had been told "the scheme" this story would never have been written, but the boys went off unaware of what Mr. Thompson's views were on the method they had devised to try the bass in Laurel Lake. They took their rods and bait, of course, but kept mum about what was rattling under the seat as Jerry drove Tot up to the door.

A mile and a half and they turned in at old Farmer Sayre's, hitched and blanketed the pony, and with their variety of equipment went down to the shore of the lake, where their boat was made last.

"Go ahead, Ned, you row," said Joe; "we'll get there quicker, and I'm most crazy to see how she works; aren't you?"

"You bet," replied Ned. "Shove off. Let fall," he added, giving himself part of the orders he had picked up but a week before, while on a visit to a friend on the Sound. "Give way; how's that for nautical, Joe?"

"Never mind nautical," said Joe; "git there is what we want. One, two—now, now!" He grunted out each word to help Ned, who was pulling with all his might, and the light little boat jumped ahead at each stroke.

Around the point, which formed the bay in which the boat was kept, on the shore, but partly hidden by the trees, was an old, rather dilapidated ice-house; it was called that by courtesy, for it was no house at all; it had no roof—it never had one—but it was used once to store ice in, and the fishing-ground along the shore in front of it had always been designated by the boys as "off the ice-house." Ned and Joe claimed to themselves that they alone knew of the existence of a certain ledge which ran for some distance parallel to the shore, but much farther out than the average fisherman would think of dropping anchor.

As they approached the place, in order to get the right spot to leave the first float, which had a choice fat frog wriggling at the end of the line, Ned slowed down and began to row quietly. He got a certain stump on a point of land in line with the roof of a barn way back on the hill-side, and was watching for the cross-line, a clump of bright willows with a scraggly dead tree some distance behind them.

"Whoa, slowly," said Joe, who was also watching. "There! hold her, and I'll let him go. There, my fine friend," he added, addressing the frog; "good-by to you and good luck to us. Now, a stroke or two: there, let her slide! And to you, Mr. Hoppergrass, good-by, and good-luck." He gently dropped the line over the side, and, so with the others, all had a farewell given them as they were dropped over at intervals. Then the boys rowed on towards Baldwin's Cliff, keeping their eyes on the small floats as they left them bobbing under and over the tiny waves.

About four o'clock Ned and Joe had had enough swimming and diving, and fetching white stones from the bottom; they had been in, as was usually the case, too long, yet both wanted to stay in longer. Nothing had happened, as far as they could see, to their floats, and they felt keenly disappointed. They had hardly noticed that the clouds were gathering over the hills, and that the wind had risen so that little white caps had sprung up, and were dancing in towards shore. But a low mutter of thunder startled them, and they saw now no way but to adopt a means for shelter which they had followed before to keep dry.

"Hurry up, Ned," said Joe; "make for the boat; that storm's a dandy, and coming like thunder, too. It's pouring at the end of the lake already."

The boys put for the boat as hard as they could, and a moment later had her beached and rolled over, and their clothes snugly tucked away under perfect shelter.

"Here she is!" they both cried at the same moment, as the rain started to come down in large noisy drops, and the wind caught the spray from the water and whirled it along in sudden gusts.

"Let her rain," said Joe; "but doesn't that sting your back, it does mine; and that wind's cold, too. I'm going to swim out a way, the water's warmer than here."

So Joe plunged in and swam out from the shore.

Ned watched him as he paddled around in the deep water; he did not exactly like the idea. The whole scene, with the dark lowering clouds, broken now and then by the jagged streaks of lightning, each one followed by a sharp and startling smash and roar, made him shiver, and the large drops and an occasional hailstone made him skip[Pg 763] around on the beach. The situation was exciting, though, and Joe, now quite a way out, felt the tingles creep through him. Finally, as Ned was still watching Joe, he saw him start forward with the overhand Indian stroke, making straight for the middle of the lake. He put his hands to his mouth and shouted:

"Say, Joe! come back here! Don't be a fool; come back!"

Joe paid no attention; he did not hear the call, which was carried back into the woods by the gusts of wind; he kept on straight ahead, swimming as though in a race.

Ned turned and looked at the boat and then at Joe. "I know what's the matter," he said, aloud; "he's seen one of the floats way out there, and he's after it; but he can't stand it, I know he can't; he'll be all tired out when he gets there, and then when he has to tread water and play that fish—" Here he stopped, and gave a long low whistle. "By jingo! he must be a monster! why, he's towed that float nearly a hundred yards dead against this sea. No, sir! Joe can't do it, and here goes for wet clothes to get home in."

Ned had hardly finished speaking, and inwardly calling Joe some hard names for his foolishness, when he heard a cry from the water:

"Ned, oh, Ned! he's a whale! Hurry with the boat; I'm tuckered! Hurry!"

The last call to hurry was rather faint, and sounded almost as bad to Ned as if it had been "help" that Joe had cried; it made his heart leap in his throat.

"Let go the line," Ned cried back, "and keep your head, and I'll be there in a moment."

Again the words were lost in the wind, and Joe continued his struggle. In his excitement he felt that letting go that line would be like cutting it, and he hung on, now thrashing and splashing as the fish started to twine the line around his legs, and the sharp points of his fins pricked him. It was a case of the fish playing Joe, a pretty even struggle, but Joe was game and bound to have him. He did not appreciate that his strokes and kicks to keep his head up over the choppy surface of the lake were leaving him weaker and weaker.

As Joe turned his head a moment towards shore he saw Ned pulling towards him with all his strength; a moment later a wave struck him full in the face and caught him with his mouth open; he gulped and choked, and again started thrashing and struggling to gain his breath, but all he could do was to give a feeble cry of "help," then he sank out of sight, holding fast to the line.

Ned heard the faint cry, and turned as he rowed against the storm, which was now luckily falling as quickly as it had come up. The only thing he saw was the small piece of board tip up on its side and disappear. "Thank goodness he had hold of that line!" murmured Ned. "Now brace yourself," he added, aloud, "and keep cool, keep cool, keep cool."

It seemed to Ned that he said those words a thousand times; he was right on the spot, and was standing and waiting. The strain was something awful. He knew a good deal about swimming and about its dangers, and knew that a person had to come up twice, and that the third time down was down for good. He thought that Joe had not called before, yet he could not tell; but there was only one thing to do—wait, and, as he had said, "keep cool."

Ages and ages seemed to pass as Ned, shivering and pale, strained his eyes to see the block of wood appear again. Suddenly he caught a glimpse of the bit of wood slowly rising close by the side of the boat, and below it, as it came up zigzagging to the surface, he saw the white body following. It was a lucky thing that a stout trolling-line had been used in the scheme, for Ned reached far over the gunwale and firmly seized the line, then gently and steadily pulled the heavy weight to the surface. There were no signs of life in Joe's limp body; his cramped hand held the line twisted about his fingers, his eyes were closed, and his mouth half open.

Ned grasped the wrist which appeared first, and drew Joe along towards the bow of the boat, so that there would be no chance of capsizing. He lay out flat over the bow and held Joe under the arms, keeping his head well out of water, and waited. There was nothing to be done now but wait; no one was in sight, and shouting would have done no good, so he held on in his cramped position and watched the boat get a little headway in drifting towards shore, driven by the light wind. The sun had come out again, and blue patches of sky were appearing through the fast-flying clouds.

As the boat reached the shallow water, Ned leaped out up to his waist, still clinging to Joe's wrist; a moment more and he had him safe on shore, and, strange to say, there, too, was the cause of the trouble, the huge bass, still fast to the hook, which was far out of sight down his throat. The fight had been too much for him, and as Ned half carried Joe up the beach to a mossy bank, he also hauled the monster bass, that showed not a quiver of the gills or a movement of fin or tail. Ned placed Joe softly down, with his feet up on the bank and his head, face downward, over a soft rotten log, and then began the work which meant life or death. He had kept cool up to this time in a wonderful way, but now he began to get excited. He rolled Joe over and over, and kneaded him with his hands. Occasionally he stopped to listen to Joe's heart and feel for the chance of a single breath. It was a strange sight but a most impressive one—a young boy working for the life of his friend with all the fervor and love that a close friendship could call forth. Finally Ned's efforts began to have effect; there was a slight movement, a slow turning of the limp body, and Ned felt that Joe was safe, and he uttered a sigh that meant everything.

Gradually Joe's eyes opened, and finally, after more rubbing, he slowly sat up, and for the first time let go the line which he had held stronger than a vise up to this time.

"Ned," he said, feebly, "where am I? Where have I been? I can't remember anything. I am awful cold," he continued, and a shiver ran over him. "I must have swallowed half the lake. But I'll be all right in a moment. There! now I'm more comfortable," he added, as Ned propped him up against an old stump. "Is that the fish? Oh! Now I remember it all. He is a whale; I told you so; and I got him too!"

The excitement of seeing the fish changed his thoughts from himself, and the blood began to flow through his veins. The wind had died out, and the sun was warm and cheering. The spirits of the boys rose, and they began to forget a little of their narrow escape.

"Joe," said Ned, "is my hair gray? It ought to be; you scared me half to death."

"I'm sorry, Ned," replied Joe, "but I didn't do it on purpose; but I'm feeling rather queer. Let's get home."

They put on their clothes, wet as they were, and Joe staggered to the boat and fell into the stern seat and lifted the bass into his lap, where he could look at him and feel him.

As Ned, tired out and pale, took the oars and rowed slowly over the now glassy water towards the bay, Joe listlessly took a small pair of scales from his pocket and weighed the fish, and when he found that he weighed over six pounds, just a little, he gave a long sigh.

"That's the biggest bass on record for this lake, don't you think so?"

Ned did not reply; he was too tired to even speak.

The other floats had been washed ashore or had disappeared somewhere; the boys did not look for them, or even think of them.

Tot seemed to know that he was pulling two very tired boys, and went along gently, and turned in of his own accord at the gate of the Thompsons' place.

Joe tottered as he got out of the buckboard, and held the bass up by the gills, to the astonishment of his father and mother, who were at the door to meet them. They had seen the storm come up, and had anxiously awaited the boys' return. As he stepped forward, the set line and block fell on the steps.

The long story was being told in a slow and labored way by Joe after Ned had gone, when it was interrupted by Mr. Thompson, who saw that his son was growing pale and faint.[Pg 764]

"That'll do for the present," he said. "Now come with me, old man," and putting his arm around Joe's waist, he gently helped him into the house and up to his own room, where he was undressed and carefully tucked into bed.

"So you caught him on a set line, did you?" said Mr. Thompson, as he sat by the bed-side, holding Joe's hand. "Now listen to a word of advice. Don't ever use set lines again. Fish with your rod and reel if you want to be called a true sportsman."

There have been a great many Kings, since Kings first began to rule; but perhaps the little boy who to-day wears the Spanish crown is the only one among them all who was born a King; his father, Alfonso XII., having died more than five months before his birth, the throne remaining vacant during that time.

For the young people of America Alfonso XIII. possesses an interest apart from and superior to that which attaches to his exalted position as the ruler of a great nation, in being a descendant of the noble-minded and great-hearted Queen, the illustrious Isabella, who, by her encouragement and assistance, enabled Columbus to undertake the voyage across unknown seas which resulted in the discovery of a new world.

He is descended also from Henry of Navarre—the famous Henry of Navarre whose white plume so often led his soldiers on to victory—through Philip, Duke of Anjou, Henry's great-grandson, who succeeded to the Spanish crown, under the title of Philip V., on the death of his uncle Charles II. of Spain. Philip was the first of the Bourbon family who reigned in Spain, as Henry of Navarre was the first of that family who reigned in France.

THE KING OF SPAIN.

THE KING OF SPAIN.

To the Spanish people, who sincerely mourned the death of Alfonso XII., who had endeared himself to them by his frank and amiable disposition and by his many good qualities, the birth of the young King, which took place in the royal palace in Madrid on the 17th of May, 1886, was a joyful event. It was announced to all Spain by the firing of twenty-one cannon in every city throughout the kingdom. On the same day the infant was proclaimed King, his mother, Queen Maria Cristina, who had acted as Regent from the time of the late King's death, continued to fill the same office during the young King's minority.

A few weeks afterward, Queen Maria Cristina went with the royal infant, in accordance with the Spanish custom, to the church of Atocha. She drove to the church in a magnificent state carriage drawn by six horses covered with plumes and glittering with gold, and followed by many other splendid carriages. The Queen was dressed in deep mourning, and from time to time she held up the little Alfonso, who wore neither cap nor other head-covering, to the view of the people, who cheered and crowded forward to obtain a sight of the infant King, while the band played the Royal March.

The little Alfonso grew and thrived, more or less like other babies, until he was two years old, when he was taken in state to several of the provinces to show him to his people. Then he first experienced the uneasiness to which the head that wears a crown is said by Shakespeare to be subject, for the incessant cheering of the people and the ear-piercing strains of the martial music, wherever he was taken, disturbed him so greatly at last that he would cry out in his baby accents, "Stop, stop, no more!" Very soon, however, he began to grow accustomed to the honors paid him, and when he was taken out walking by the Queen, whose greatest pleasure it was, after he had learned to walk, to go out walking unattended with her children, Alfonso holding her by the hand while his two sisters walked in front, he would wave his hand to every one who passed. Sometimes he would forget to return a bow or a wave of a handkerchief, and then the Queen would say to him, "Bow, Alfonso."

At this time the little King had to take care of him and to attend upon him a Spanish nurse and an English nurse and an Austrian and a Spanish lady, besides his own special cook. The Spanish nurse of the royal children is always brought from one particular part of Spain, the valley of Paz, in the province of Santander, where one of the court physicians goes to select the healthiest and most robust among the various candidates for the position. As the young King is of a delicate constitution, thought to have been inherited from his father, the greatest care has been lavished upon him ever since his birth, the Queen herself exercising a watchful supervision over every detail of his daily life.

About four years ago Alfonso had a very serious illness, which everybody feared would terminate fatally, and which was probably due to a cause that has made many another little boy ill. Being in the apartments of his aunt, the Infanta Isabel, the elder sister of the Princess Eulalia, whose visit to us at the time of the opening of the exposition at Chicago made so pleasant an impression upon everybody, the Infanta gave the little boy a box of bonbons of a particularly delicious kind, which, seeing that he was observed by no one, he went on eating until he had finished the box. During his illness he would often inquire after a little lame girl to whom he used to give money in his drives to the country, wonder what she was doing, and ask that bonbons should be sent to her. All Spain followed the course of his illness with profound anxiety, and there was no one who did not sympathize with the widowed mother in her affliction, and rejoice with her when the dangerous symptoms passed away and the sick boy began to recover.

In October, 1892, Alfonso had another serious illness, the[Pg 765] result of a cold, contracted probably at the celebration of the fourth centenary of the discovery of America at Huelva, where he presided at the inauguration of the monument erected to Columbus on the hill of La Rabida. This sickness also caused for a time the greatest uneasiness.

The young King begins the day by saluting the national flag from his windows in the palace that look out upon the Plaza de Armas, where the relieving of the guard takes place every morning at ten o'clock, a ceremony which he loves to witness. He is passionately fond of everything military. He takes a great interest in the soldiers, in what they eat, and in other details of their life, and he often expresses pity for the cold which the sentinels on guard at the palace must feel. In the park at Miramar, when the troops are returning to their barracks after drill, he may often be seen delightedly watching the soldiers forming in line, and he returns their salute with a military salute. He is very fond of horses, and the bigger they are the better he likes them, as he himself says. He delights in military music and military evolutions, and a review of the troops is one of his great pleasures. On his seventh birthday he held a grand review of the troops, riding then for the first time in public. On that occasion 40,000 troops were reviewed.

Since that time his education has been directed less exclusively by women than before. His chief companions are his tutor, and the General who is the Captain of the King's guard, with whom he loves to talk about military matters. He still has his little playmates, however, and toys in abundance. He is fond of riding and driving, and he has a little carriage of his own, with two small Moorish donkeys to draw it, which looks very odd among all the large carriages in the royal stables in Madrid.

When the weather is fine he spends almost the whole of the day at the royal villa, called the Quinta del Pardo, situated a little outside Madrid. He is driven there in a carriage generally drawn by four mules, and is accompanied by his royal escort wearing their splendid uniforms and long white plumes. He knows personally all the soldiers who form his escort, and the moment he sees the Captain, as soon as the carriage leaves the palace gate, he speaks to him, and continues chatting with him all the way to the villa, the Captain riding beside the carriage door. He is accompanied by his tutor, his governess, and generally one other person.

In the villa he is instructed in the studies suitable to his age, particular attention being paid, however, to military science. The venerable priest, who is his religious instructor, teaches him also the Basque language, which is altogether different from the Spanish. In the afternoon his two sisters, Isabel Teresa Cristina Alfonsa Jacinta, the Princess of Asturias, who is now about fourteen years of age, and Maria Teresa Isabel Eugenia Patrocinio Diega, the Infanta of Spain, who is about twelve, often go out to take afternoon tea with him. In the gardens of the villa he runs about and plays, after lessons are over, just like other boys of his age, playing as familiarly with the children of the gardener as if they were the sons of princes. Whatever money he happens to have with him he gives to the children of the guard and to such poor people as he may chance to meet on the way, for he is extremely charitable and generous, both by nature and education, the Queen, his mother, instilling into his mind the best and noblest sentiments.

In appearance Alfonso is interesting and attractive. His complexion is very fair, his hair light and curly, his expression rather serious. His usual dress is a sailor jacket and knickerbockers, sometimes sent from Vienna by his grandmother, the Archduchess Isabel, sometimes ordered from London by the Infanta Isabel, his aunt.

He is a very intelligent child, is very vivacious, and his manners, notwithstanding the high honors that have been paid to him since his birth as the chief of a great nation, are entirely free from arrogance and self-conceit. When the Queen Regent is holding audience in her apartments in the palace, which are directly below his, he will often go down and salute those who are waiting in the antechamber, giving them his hand, even though he may never have seen them before, this frankness of manner being a trait of the Spanish people, who are of all people the most democratic.

ALFONSO XIII., WITH HIS MOTHER AND SISTERS.

ALFONSO XIII., WITH HIS MOTHER AND SISTERS.

He is very affectionate in his disposition, although he has a very firm will; and he tenderly loves his mother, whom he also greatly respects, and his sisters, who are his favorite playmates.

He seems, as he grows older, however, to be perfectly conscious of his exalted position. He knows that he is the King, and in the official receptions and ceremonies at which he has to be present he rarely becomes impatient however long and solemn they may be. One of these rare occasions was during a royal reception in the throne-room. He was sitting at the right hand of the Queen, and all the high functionaries and courtiers were defiling past him, when he began to play with the white wand of office of the Duke of Medina-Sidonia, a great officer of the palace. Suddenly leaving his seat and the wand of the Duke he ran down the steps of the throne, and mounted astride one of the bronze lions that stand on either side of it. The act was so entirely childlike and spontaneous, and was performed with so much grace, that it gave every one present a sensation of real pleasure. Even the Queen herself, while she regretted that the young King should have failed in the etiquette of the occasion, could not help smiling.

On another occasion of a similar kind he amused himself greatly watching the Chinese diplomats, looking with wonder and delight at their silk dresses, which he would touch from time to time with his little hands.

What most attracted his attention, however, was the Chinese minister's pigtail. He waited a long time in vain for a chance to look at it from behind, for the Chinese are a very polite people, and the minister would never think of turning his back upon the King. At last it occurred to Alfonso to run and hide himself in a corner of the vast apartment, and wait for his opportunity, which he did. After a while the President of the Cabinet, seeing him in the corner, went over to him, and said, "What is your Majesty doing here?" "Let me alone," answered the boy; "I am waiting for the Chinese minister to turn round, so that I may steal up behind him, and look at his pigtail."[Pg 766]

The boy King, like most other boys, is very fond of boats, as may be gathered from the following anecdote. About three years ago the Queen gave a musical at San Sebastian, a sea-port where the royal family spend some months every summer for the sea-bathing, at which the Commandant of the Port was present. The little Alfonso was very fond of the Commandant, and had asked him for a boat, which the Commandant had promised to give the boy. He had not yet done so, however, and seeing him at the concert, the young King ran from one end of the room to the other, when the concert was at its best, and, stopping in front of him, said, "Commandant, when are you going to bring me the boat?"

In San Sebastian the royal family have a magnificent palace called the palace of Ayete, where, however, they live very simply. Alfonso plays all day on the beach with his sisters and other children, running about or making holes in the sand with his little shovel, in view of everybody. He takes long drives also among the mountains and through the valleys. Sometimes there is a children's party in the gardens of the palace, when he mingles freely with his young guests. Indeed, it is not always necessary that he should know who his playmates are. Not long since he was getting out of the carriage with his mother at the door of the palace in Madrid, when two little boys who were passing stopped to look at the boy King. "Mamma, may I ask those two boys to come upstairs to play with me?" Alfonso asked the Queen. "If you like," was the answer. He accordingly went over to the two boys, and asked them upstairs to play with him, and all three ran together up the palace stairs to the King's apartments.

The young King's birthday is always observed as a festival in the palace, and on his Saint's day, also, which is the 23d of January, there is always a grand reception. On this day it is the custom to confer decorations on such public functionaries as have merited them.

As a descendant of Queen Isabella there is something appropriate in Alfonso having sent an exhibit—a small brass cannon—to the great Fair in Chicago, at which he was the youngest exhibitor.

It is fortunate for the young King and for the country over which he is to rule that the important work of forming his character and educating his heart has fallen to a woman so admirably qualified for the task as the Queen Regent.

Born on the 21st of July, 1858, Maria Cristina is now in the early prime of life. Her appearance is distinguished and majestic; her manners are simple and amiable. She has a sound understanding and a cultivated mind, well stored with varied information. She is of a serious disposition, and is religious without bigotry, and good without affectation. During the lifetime of King Alfonso, her husband, she took no part whatever in politics, so that when she was called upon to assume the important responsibilities of the regency she was able to place herself above political parties, and to be the Queen of the nation. She has had the good fortune, in the midst of her personal grief—for the death of her husband, whom she loved devotedly, was a terrible blow to her—to win the good-will of the greater part of the Spanish people, and the respect of all by the wisdom and discretion with which, through her ministers and according to the constitution, she has governed the country. She is exceedingly charitable, and delights especially in relieving the wants of children; she gives large sums to children's aid societies. She educates at her own expense the children of public functionaries who have been left in poverty; she is constantly taking upon herself the care of orphaned children, and no mother ever asks her help in vain.

"Tail-piece." This title Hogarth, the celebrated English painter, gave to his last work. It is said that the idea for it was first started when, in the company of his friends, they sat around the table at his home. His guests had consumed all of the eatables and et cætera, and nothing remained but the empty plates and glasses. Hogarth, glancing over the table, sadly remarked, "My next undertaking shall be the end of all things." "If that is the case," replied one of his friends, "your business will be finished, for there will be an end of the painter." "There will be," answered Hogarth, sighing heavily.

The next day he started the picture, and he pushed ahead rapidly, seemingly in fear of being unable to complete it. Grouped in an ingenious manner, he painted the following list to represent the end of all things: a broken bottle; the but-end of an old musket; an old broom worn to the stump; a bow unstrung; a crown tumbled to pieces; towers in ruins; a cracked bell; the sign-post of an inn, called the "World's End," falling down; the moon in her wane; a gibbet falling, the body gone, and the chains which held it dropping down; the map of the globe burning; Phœbus and his horses lying dead in the clouds; a vessel wrecked; Time with his hour-glass and scythe broken; a tobacco-pipe with the last whiff of smoke going out; a play-book opened, with the exeunt omnes stamped in the corner; a statute of bankruptcy taken out against nature; and an empty purse.

Hogarth reviewed this work with a sad and troubled countenance. Alas! something lacks. Nothing is wanted but this, and taking up his palette, he broke it and the brushes, and then with his pencil sketched the remains. "Finis, 'tis done!" he cried. It is said that he never took up the palette again, and a month later died.

Miles Standish was a fellow

Who understood quite well, oh,

In fighting with the redskins how to plan, plan, plan.

But I think him very silly

When he wished to woo Priscilla

To send another man, man, man.

For she said unto this other,

Whom she loved more than a brother,

"Why don't you speak, John Alden, for yourself, self, self?"

So of course John Alden tarried,

And the fair Priscilla married,

And they laid poor Captain Standish on the shelf, shelf, shelf.

When morning came, old Wallace's face had grown a year older. Up to midnight he had hoped that better counsels might prevail, and that the meetings called by the leaders of kindred associations, such as the Trainmen's Union, would result in refusal to sustain the striking switchmen; but when midnight came, and no Jim, things looked ominous. A sturdy, honest, hard-working fellow was Jim, devoted to his mother and sisters, and proud of the little home built and paid for by their united efforts. Content, happy, and hopeful, too, he seemed to be for several years; but of late he had spent much time attending the meetings at Harmonie Hall and listening to the addresses of certain semi-citizens, whose names and accent alike declared their foreign descent, and whose mission was the preaching of a gospel of discord. Their grievance was not that their hearers were hungry or in rags, down-trodden or oppressed, but that the higher officials of the road owned handsome homes and equipages, and lived in a style and luxury beyond the means of the honest toilers in the lower ranks. Jim used to come home with a smile of content[Pg 767] as he looked upon the happy healthful faces of his mother and sisters, but for months past his talk had been of the way the Williams people lived, how they rode in their parlor car and went to the sea-shore every summer and to the theatre or opera every night, drove to the Park in carriages, and hobnobbed with the swells in town. "Why, I knew Joe Williams when he was yard-master and no bigger a man on the road than I am to-day," said Jim, "and now look at him." His mother laughingly bade him take comfort, then, from the contemplation of Williams's success. If he could rise to such affluence, why shouldn't Jim? Besides, Mr. Williams had married a wealthy woman. "Yes, the daughter of another bloated bondholder," said Jim. A year or two before they regarded it, one and all of them, as no bad thing that there were men eager to buy the bonds and meet the expense of extending the road; but since the advent of Messrs. Steinman and Frenzel, the orators of the Socialist propaganda, Jim had begun to develop a feeling of antipathy towards all persons vaguely grouped in the "capitalistic class."

He had long since joined the Brotherhood of Trainmen, having confidence in its benevolent and protective features. There was no actual coercion, yet all seemed to find it to their best interest to belong to the union, even though they merely paid the small dues and rarely attended its meetings. These latter were usually conducted by a class of men prevalent in all circles of society, fellows of some gift for speech-making or debate. The quiet, thoughtful, and conservative rarely spoke, and more frequently differed than agreed with the speakers, but all through the year the meetings had become more turbulent and excited, and little by little men who had been content and willing wage-workers became infected with the theories so glibly expounded by the speakers. They were the bone and sinew of the great corporation; why should not they be rolling in wealth they won rather than seeing it lavished on the favored few, their employers? The only way for workingmen to get their fair percentage of the profits, said these leaders, was to strike and stick together, for the men of one union to "back" those of another, and then success was sure. Called from his home to a meeting of the trainmen, Jim Wallace was one of the five hundred of his brethren to decide whether or no they too should strike in support of their fellows, the switchmen, demanding not only the restoration of the discharged freight-handlers, but now also that of Stoltz. Old Wallace had firmly told him No; they had no case. But by midnight the trainmen had said Yes.

An hour after midnight, anxious and unable to sleep, the father had stolen quietly up into the boys' room. Jim's bed was unoccupied; but over on the other side lay Corporal Fred, his duties early completed, sleeping placidly and well. With two exceptions, all the companies of his regiment were made up of men who lived in the heart of the city. The two junior companies, "L" and "M," had been raised in the western suburb, and as many as a dozen young fellows living almost as far west as the great freight-yards were members of these. According to the system adopted in some of the Eastern States, each company was divided into squads, so that in the event of sudden need for their services the summons could be quickly made. Every man's residence and place of work or business were duly recorded. Each Lieutenant had two sergeants to aid him, each sergeant, two corporals; and immediately on receipt of notification, it was the business of each corporal to bustle around and convey the order to the seven men comprising his squad. By ten o'clock on the previous evening Fred Wallace had seen and notified every one of his party, and then, returning home, had gone straightway to bed. "There won't be much sleep after we're called out," said he, "so now is my time."

It would have been well for all his comrades had they followed his example, but one or two of the weak-headed among them could not resist the temptation of going to the freight-yards to see how matters were progressing, and there, boy like, telling their acquaintances among the silent, gloomy knots of striking railway men, that they too, "the Guards," were ordered out. It was not strictly true, but young men and many old ones rejoice in making a statement as sensational as possible. It would not surprise or excite a striker to say "we've received orders to be in readiness." It did excite them not a little when Billy Foster told them in so many words, "Say, we've got our orders, and you fellows'll have to look out."

"There need be no resort to violence," said the leaders. "We can win at a walk. The managers have simply got to come down as soon as they see we're in earnest." And at ten o'clock at night the striking switchmen, many of them ill at ease, had been waiting to see the prophesied "come down" which was to be the immediate result of the tie-up. What the leaders failed to mention to their followers as worthy of consideration was that superintendents, yard-masters, conductors, engineers, brakemen, and firemen, one and all had risen from the bottom, and could throw switches just as well as those employed for no other purpose. It was inconvenient, of course. It meant slow work at the start, but so far from being paralyzed, as the leaders predicted, the officials went to work with a vim. Silk-hatted managers, kid-gloved superintendents, and "dude-collated" clerks were down in the train-shed swinging lanterns and handling switches, and so it had resulted that all the night express trains of the five companies using the Great Western tracks, one after another, slowly, cautiously, but surely had threaded the maze of green and red lights, and safely steamed over the four miles of shining steel rails between the Union depot in the heart of the city and these outlying freight-yards, and, only an hour or so behind time, had haunted their long rows of brilliantly lighted plate-glass windows in the sullen faces of the striking operatives, and then gone whistling merrily away to their several destinations over the dim, starlit prairies. The managers were only spurred, not paralyzed.

"We'll win yet," said Stoltz, in a furious harangue to a thousand hearers, one-tenth of them, only railway employés, the others being recruited from the tramps, the ne'er-do-wells, the unemployed and the criminal classes, ever lurking about a great city. "The managers cannot play switchmen more than one night, and no men they hire dare attempt to work in your places—if you're the men I take you to be. Now I'm going to the trainmen's meeting to demand their aid." And go he did, with the result already indicated.

Half an hour after midnight, despite the protests of the old and experienced men, the resolution to strike went through with a yell, and when the dawn came, faint and pallid in the eastern sky, and the myriad switch-lights in the dark, silent yards began to grow blear and dim, there stood the long rows of freight cars doubly fettered now, for not only were there no switchmen to make up the trains, there were no crews to man them and take them to their destination. Jim Wallace had struck with the rest.

It was two o'clock when at last the father heard the heavy footfalls of his first-born on the wooden walk without. There he seemed to pause for some few words in low tone with a companion who had walked home with him from the yards. Old Wallace, going to the door to meet his son, heard these words as the other turned away. "And you tell Fred what I say. I'm a friend of yours, and always have been, but the boys won't stand any nonsense. It'll be the worst for him if he don't quit that militia business at once, and if he don't, he won't be the only one to suffer."

"WHO THREATENS MY SON AND MY PEOPLE?" DEMANDED OLD WALLACE.

"WHO THREATENS MY SON AND MY PEOPLE?" DEMANDED OLD WALLACE.

"Who is that?" demanded old Wallace, stepping promptly out from his front door. "Who threatens my son or my people?"

The stranger had stepped away into the shade of an ailantus-tree before he answered. Jim Wallace stood in moody silence, confused by his father's sudden appearance, and ashamed that such menace as this against him and his should have been spoken without instant rebuke. "What I said was meant in all friendship to you and yours, Mr. Wallace. You don't know me, but I know you," said the stranger; with marked foreign accent, but in civil tone. "I want to avert trouble from your roof if I can, and therefore told Jim to get Fred out of that tin-soldier connection. No son of yours ought to be used in the intimidation of honest[Pg 768] workingmen who only seek their rights, and if he is wise he'll quit it now and at once."

"No son of mine shall be intimidated from doing a sworn duty by any such threats as yours," said Wallace, with rising wrath; "and if that's the game you play I'm ashamed to think that son of mine has had anything to do with you. Who are you, anyway? What do you mean by coming round 'intimidating honest workingmen,' as you say, at this hour of the night? You're no trainman. Man and boy I've known the hands on this road nearly forty years, and I never thought to see the day when rank outsiders could come in and turn them against one another as you have. Who are you, I say?"

"Never mind who I am, Mr. Wallace. I speak what I know, and my voice is that of ten thousand working—or more than working—thinking men. If you're wise you'll see to it that this is the last time your boy carries orders to his fellows to turn out against us, for that's what he has done. If you don't, somebody may have to do it for you."

"That isn't all!" shouted the old Scotchman, as the other turned away, "and you hear this here and now. My voice is that of ten million law-abiding people, high and low, rich and poor, and it says my boys shall stand by their duty, the one to his employers, the other to his regiment, you and your threats to the contrary notwithstanding. You haven't struck, have you, Jim?" he asked, turning in deep anxiety to his silent, crestfallen son.

And for all answer Jim simply shrugged his broad shoulders and made a deprecatory gesture with his brown, hairy hand, then turned slowly into the little hallway, and went heavily to his room. At breakfast-time he was gone.

Fred came bounding in at half past six, alert and eager, yet with grave concern on his keen young face. "I've been the length of the yards," he said, "and I'm hungry as a wolf, mother. They say they're going to block the incoming trains, and prevent others going out. Big crowds are gathering already, and I shouldn't be surprised if we were ordered on duty this very day. Where's Jim?"

"He got up and dressed after you went out, Fred," was the reply. "He said he wanted no breakfast. Father has gone early to the shops. He thought he might meet you."

"Well, I'll stop there to see him on my way to the office. I've got to see Mr. Manners first thing about getting off if the call comes."

"I hope he'll say no," said Jessie Wallace, promptly. She was the younger, prettier sister, and the more impulsive.

"You thought the regiment beautiful on Memorial day, Jess, and were glad enough to go and see the parade," said Fred, with a mouth nearly full of porridge.

"That's different. I like the band, and the plumes and uniforms, and parading and drilling, but I don't want you to be shot or stoned or abused the way the other regiment was at the mines last spring."

"Well, there's where you and Manners don't agree. He objects to my belonging because of the parades and drills and summer camp, says it's all vanity, foolishness, and that only popinjays want to wear uniforms. I guess he'd be glad enough to have us in line if a mob should make a break for the works, but I own I'm worried about what he'll say to-day."

And Fred might well be worried. Dense throngs of excited men were gathered along the yards as he wended his way to the works after a few words with his father at the gloomy shop. An engine with some flat cars had come out with newly employed men to man the switches. Engineer, firemen, and the newly employed had to flee for their lives, and the assistant-superintendent was being carried to the emergency hospital in a police patrol wagon. Nobody was being carried to the police station. "There'll be worse for the next load that comes," shouted Stoltz from the sidewalk, and a storm of jeers and yells was the applauding answer. These sounds were still ringing in young Wallace's ears when he came before the manager. Mr. Manners turned round in his chair when Fred told him of his orders of the night before.

"Wallace," said he, "I told you last month that no man could serve two masters. We can't afford to employ young men who at any time may be called out to go parading with a lot of tin soldiers."

"This isn't parade, sir; It's business. It's protecting life and property."

"Fudge!" said Manners; "let the police attend to that—or the regulars. It's their business. If you leave your desk on any such ridiculous orders you leave it for good."

And at four o'clock that afternoon, towards the close of a day filled with wild rumors of riot, bloodshed, and destruction, a young man in the neat service dress of a sergeant of infantry—blue blouse and trousers, and tan-colored felt hat and leggings—walked in to Corporal Fred's office with a written slip in his hand, and Corporal Fred walked out.

Jack and Neal entered into partnership in the poultry business.

"You see, I sha'n't have a cent of my own until I am twenty-five," explained Neal, "and my old grandmother left most of the cash to Hessie. She had some crazy old-fashioned notions about men being able to work for their living, but women couldn't. It's all a mistake. Nowadays women can work just as well as men, if not better. Besides, they marry, and their husbands ought to support them. Now, what am I going to do when I marry?"

Cynthia, who was present at this discussion, gave a little laugh. "Are you thinking of taking this important step very soon? Perhaps you will have time to earn a little first. Chickens may help you. Or you might choose a wife who will work—you say women do it better than men—and she will be pleased to support you, I have no doubt."

They were on the river, tied up under an overhanging tree. Cynthia, who had been paddling, sat in the stern of the canoe; the boys were stretched in the bottom. It was a warm, lazy-feeling day for all but Cynthia. The boys had been taking their ease and allowing her to do the work, which she was always quite willing to do.

"I'll tell you how it is," continued Neal, ignoring Cynthia's sarcasm. "I'll have a tidy little sum when I am twenty-five, and until then Hessie is to make me an allowance and pay my school and college expenses. She's pretty good about it—about giving me extras now and then, I mean—but you sort of hate to be always nagging at a girl for money. It was a rum way of doing the thing, anyhow, making me dependent on her. I wish my grandmother hadn't been such a hoot-owl."

Cynthia looked at him reprovingly. "You are terribly disrespectful," she said, "and I think you needn't make such a fuss. You're pretty lucky to have such a sister as mamma."

"Oh, Hessie might be worse, I don't deny. It's immense to hear you great girls call her 'mamma,' though. I never thought to see Hessie marry a widower with a lot of children. What was she thinking of, anyway?"

"Well, you are polite! She was probably thinking what a very nice man my father is," returned Cynthia, loftily.

"He is a pretty good fellow. So far I haven't found him a bad sort of brother-in-law. I don't know how it will be when I put in my demand for a bigger allowance in the fall. I have an idea he could be pretty stiff on those occasions. But that's why I want to go into the poultry business."

"And I don't mind having you," said Jack. "Sharing the profits is sharing the expense, and so far I've seen more expense than profit. However, when they begin to lay and we send the eggs to market, then the money will pour in. I say we don't do anything but sell eggs. It would be an awful bore to get broilers ready for market. By-the-way, I think we had better go back now and finish up that brooder we were making."

"Oh, no hurry," said Neal. "It won't take three minutes to do that, and it's jolly out here. It's the coolest place I've been in to-day. Let's talk some more about the poultry business. We'll call ourselves 'Franklin & Gordon, Oakleigh Poultry Farm.' That will look dandy on the bill-heads. And we'll make a specialty of those pure white eggs. I say, Cynthia, what are you grinning at?"

"I am not grinning. I am not a Cheshire cat."

"I don't know. I've already felt your claws once or twice. But you've got something funny in your head. The corners of your mouth are twitching, and your eyes are dancing like—like the river."

Cynthia cast up her blue eyes in mock admiration.[Pg 770] "Hear! hear! He grows poetical. But as you are so very anxious to know what I am 'grinning' at," she added, demurely, "I'll tell you. I was only thinking of a little proverb I have heard. It had something to do with counting chickens before they are hatched."

"Oh, come off!" exclaimed Jack, while Neal laughed good-naturedly.

"And I've also a suggestion to make," went on Cynthia. "From what I have gathered during our short acquaintance, I think Mr. Neal Gordon isn't over-fond of exerting himself. I think it would be a good idea, Jack, when you sign your partnership papers, or whatever they are, to put in something about dividing the work as well as the expense and the profits."

"There go your claws again," said Neal. "Let's change the subject by trying to catch a 'lucky-bug.'" And he made a grab towards the myriads of insects that were darting hither and thither on the surface of the water. "I'll give a prize—this fine new silver quarter to the one who catches a 'lucky-bug.'"

He laid the money on the thwart of the boat and made another dash.

"When you have lived on the river as long as I have you'll know that 'lucky-bugs' can't be caught," said Cynthia. "Now see what you have done, you silly boy!"

For with Neal's last effort the quarter had flown from the canoe and sunk with a splash in the river.

"Good-by, quarter!" sang Neal. "I might find you if I thought it would pay to get wet for the likes of you."

"If that is the way you treat quarters, I don't wonder you think your allowance isn't big enough," said Cynthia, severely; "and may I ask you a question?"

"You may ask a dozen; but the thing is, will I answer them?"

"You will if I ask them. Were you ever in a canoe before?"

"A desire to crush you tempts me to say 'yea,' but a stern regard for truth compels me to answer 'nay.'"

"You couldn't crush me if you tried for a week, and you couldn't make me believe you had ever been in a canoe before, for your actions show you haven't. People that have spent their time on yachts and sail-boats think they can go prancing about in a canoe and catch all the lucky-bugs they want. When you have upset us all you will stop prancing, I suppose."

"Claws again," groaned Neal, in exaggerated despair.

"I say, Cynth, let's go back and put him to work on that brooder," said Jack, who had been enjoying this sparring-match. "We'll see what work we can get out of him."

And, notwithstanding his remonstrances, Neal was paddled home and put to work. Cynthia's "claws" did take effect, and for the first time in his life he began to feel a little ashamed of being so lazy.

Jack was one of the plodding kind. His mind was not as brilliant as Neal's, nor his tongue as ready, but at the end of the year he would have more to show than Neal Gordon.

Mrs. Franklin carried out her plan of inviting their friends to the "hatching bee," and Thursday was the day on which the chicks were expected to come out. As the morning wore on Cynthia's excitement grew more and more intense, and all the family shared it.

"What shall we do if they don't come out?" she exclaimed a dozen times.

At one o'clock a crack was discovered in one of the eggs in the "thermometer row." At three it was a decided break, and several others could be seen. Cynthia declared that she heard a chirping, but it was very faint.

Mrs. Franklin remained upstairs to receive the guests, who came down as soon as they arrived. There were about a dozen girls and boys. Fortunately the cellar was large and airy, and the coolest place to be found on this warm summer day.

And presently the fun began. Pop! pop! went one egg after another, and out came a little struggling chick, which in due time floundered across the other eggs or the deserted egg-shells, and flopped down to the gravel beneath on the lower floor of the machine. It was funny to see them, and, as they gradually recovered from their efforts, and their feathers dried off, the little downy balls crowded at the front, and, chirping loudly, pecked at the glass.

Mrs. Franklin joined them now and then, and at last, when about seventy chicks had been hatched, she insisted upon all coming upstairs for a breath of fresh air before supper.

Here a surprise awaited them. Unknown to her daughters Mrs. Franklin had given orders that the supper-table should be arranged upon the lawn in the shade of the house, and when Edith stepped out on the piazza she paused in astonishment.

What terrible innovation into the manners and customs of Oakleigh was this? Last year, for a little party the children gave, she had wanted tea on the lawn, but it could not be accomplished. How had the new-comer managed to do it?

"Isn't this too lovely!" cried Gertrude Morgan, enthusiastically, turning to Edith. "My dear, I think you are the luckiest girl I ever knew, to have any one give you such a surprise. Didn't you really know a thing about it?"

"I have been consulted about nothing," returned Edith, stiffly. She would have liked to run upstairs and hide, out of sight of the whole affair.

"I hope you like the effect, Edith," said Mrs. Franklin, coming up to her as she stood on the piazza step. "I thought it would be great fun to surprise you."

"I detest surprises of all kinds," replied Edith, turning away, "and it seems to me I have had nothing else lately."

Much disappointed and greatly hurt, Mrs. Franklin was about to speak again, but at this moment Cynthia, enchanted with the success of the hatch, and with the pretty sight on the lawn, rushed up to her step-mother and squeezed her arm.

"YOU ARE A PERFECT DEAR!" SHE WHISPERED. "EVERYTHING IS NICER SINCE YOU CAME."

"YOU ARE A PERFECT DEAR!" SHE WHISPERED. "EVERYTHING IS NICER SINCE YOU CAME."

"You are a perfect dear!" she whispered. "Everything is nicer since you came. Even the chickens came out for you, and last time it was so dreadful." And Mrs. Franklin smiled again and felt comforted.

The table was decorated with roses and lovely ferns, strewn here and there with apparent carelessness, but really after much earnest study of effects. Bowls of great unhulled strawberries added their touch of color, as did the generous slices of golden sponge-cake. The dainty china and glass gleamed in the afternoon light, and the artistic arrangement added not a little to the already good appetites of the boys and girls.

Fortunately Oakleigh was equal to any emergency in the eating line, and as rapidly as the piles of three-cornered sandwiches, fairylike rolls, and other goodies disappeared the dishes were replenished as if by magic.

After supper the piano was rolled over to the front window in the long parlor.

"Put it close to the window," said Mrs. Franklin, "and I will sit outside, like the eldest daughter in The Peterkins, to play. That will give me the air, and you can hear the music better."

They danced on the lawn and played games to the music; then they gathered on the porch and sang college songs, while the sun sank at the end of the long summer day, and the stars came twinkling out, and by-and-by the full moon rose over the tree-tops and flooded them with her light.

Altogether, Jack's second "hatching bee" was a success. A good time, a good supper, and, best of all, one hundred and forty chickens. Yes, it really seemed as if poultry were going to pay, and "Franklin & Gordon," of the Oakleigh Poultry Farm, went to bed quite elated with prosperity.

The next morning at breakfast they were discussing the matter, and Mr. Franklin expressed his unqualified approval of the scheme.

"If you succeed in raising your chickens, now that they are hatched, Jack, my boy, I think you are all right. You owe Aunt Betsey a debt of thanks. By-the-way, where is Aunt Betsey? Have you heard from her lately?"

There was no answer. Jack exploded into a laugh[Pg 771] which he quickly repressed, Edith looked very solemn, while Cynthia had the appearance of being on the verge of tears.

"I want to see Aunt Betsey," said Mrs. Franklin, as she buttered a roll for Willy. "I think she must be a very interesting character."

"It is very extraordinary that we have heard nothing from her," went on Mr. Franklin. "What can be the meaning of it? When was she last here, Edith?"

"In June."

"Was it when I was at home? Hasn't she been here since the time she gave Jack the money for the incubator?"

"That was in May. You were in Albany when she was here the last time."

"It is very strange that she has never written nor come to see you, Hester. It can't be that she is offended with something, can it? I must take you up to Wayborough to see the dear old lady. I am very fond of Aunt Betsey, and I would not hurt her feelings for the world."

There was a pause, and then into the silence came Janet's shrill tones:

"I know why Aunt Betsey's feelings are hurted. They was turribly hurted. Edith an' Cynthia an' Jack all knows too."

"Janet, hush!" interposed Edith.

"Not at all; let the child speak," said her father. "What do you know, Janet?"

"Aunt Betsey came, an' she went to see Mrs. Parker, an' Mrs. Parker said she'd been there before an' Aunt Betsey said she hadn't, an' it wasn't Aunt Betsey at all, it was Cynthia dressed up like her, an' Aunt Betsey said we was all naughty 'cause we didn't want the bride to come, an' the bride was mamma, and we didn't want her, it was the trufe, an' Aunt Betsey went off mad 'cause Cynthia dressed up like her. She wouldn't stay all night, she just went off slam-bang hopping mad."

"What does the child mean?" exclaimed her father. "Will some one explain? Edith, what was the trouble?"

"I would rather not say," said Edith, her eyes fastened on her plate.

"That is no way to speak to your father. Answer me."

"Papa, I cannot. It is not my affair."

"It is your affair. I insist."

"Wait, John," interposed Mrs. Franklin.

"Not at all; I can't wait. Edith was here in charge of the family. Something happened to offend Aunt Betsey. Now she must explain what it was. I hold her responsible."

"Indeed she's not, papa," said Cynthia, at last finding her voice. "Edith is not to blame; I am the one. I found Aunt Betsey's false front, and I dressed up and looked exactly like her, and Jack drove me to see Mrs. Parker. Edith didn't want me to go, but I would do it. Really, papa, Edith isn't a bit to blame. And then when Aunt Betsey came soon afterwards she went to see Mrs. Parker, and she didn't like it because she said she had been there two weeks ago and told her—I mean, Mrs. Parker told me about—"

Cynthia stopped abruptly.

"Well, go on," said her father, impatiently.

Still Cynthia said nothing.

"Cynthia, will you continue? If not—"

"Oh yes, papa; though—but—well, Mrs. Parker told me that you were going to marry again. And then when Aunt Betsey really went, Mrs. Parker said, 'I told you so.' Aunt Betsey didn't like that, and when she asked us if she had been here, of course we had to say no, and she was going right back to tell Mrs. Parker what we said; so I had to confess, and, of course, Aunt Betsey didn't like it, and she went right home that day."

Mr. Franklin pushed back his chair from the table, and began to walk up and down.

"I am perfectly astonished at your doing such a thing, and more astonished still that Edith—"

"Papa, please don't say another word about Edith. She didn't want me to go, and I would do it."

"Why have you not told me all this before?"

"Because, you see, I couldn't. I had heard that you were going to be married, and I didn't believe it until you told me; at least—"

Cynthia paused and grew uncomfortably red.

"Poor child!" said Mrs. Franklin, smiling at her sympathetically. "It must have been very hard for you."

"It was," said Cynthia, simply; "only you know, mamma, I don't feel a bit so now. And then when you came home, papa, it was all so exciting I forgot about it, and I have only thought of it once in a while, and—well, I've been afraid to tell you," she added, honestly.

"I should think so! I am glad you have the grace to be ashamed of yourself, Cynthia. Has no apology gone to Aunt Betsey?"

"No, papa."

"It is outrageous. The only thing to do is to go there at once. Jack, get the Pathfinder."

The Pathfinder, boon of New England households, was brought, and Mr. Franklin studied the trains for Wayborough.

"Hester, you had better come too. It is only proper that I should take you to call on Aunt Betsey. Get ready now, and we will go for the day."

The Franklins were quite accustomed to these sudden decisions on the part of their father, and Mrs. Franklin did not demur. She and Cynthia hurried off to make ready, and the carriage was ordered to take them to the station.

Cynthia's preparations did not take long. Her sailor-hat perched sadly on one side, her hair tied with a faded blue ribbon, one of the cuffs of her shirt-waist fastened with a pin. All this Edith took in at a glance.

"Cynthia, you look like a guy."

"I guess I am one."

"Don't be so terribly Yankee as to say 'guess.'"

"I am a Yankee, so why shouldn't I talk like one? Oh, Edith, what do I care about ribbons and sleeve-buttons when I have to go and apologize to Aunt Betsey."

Edith was supplying the deficiencies in her sister's toilet.

"It is too bad. Janet ought not to have told. But it is just like everything else—all Mrs. Franklin's fault."

"Edith, what do you mean? Mamma did not make Janet tell; she tried to stop papa."

"I know she appeared to. But if papa had not married again would this ever have happened? You would not have heard at Mrs. Parker's that he was going to, Mrs. Parker wouldn't have said 'I told you so' to Aunt Betsey, Aunt Betsey wouldn't have found out you were there—"

"Edith, what a goose you are! Any other time you would scold me for having done it, and I know I deserve it. Now you are putting all the blame on mamma. You are terribly unjust."

"There, now, you have turned against me, all because of Mrs. Franklin. I declare it is too bad!"

"Oh, Edith, I do wonder when you will find out what a lovely woman mamma is! Of course you will have to some day; you can't help it. There, they are calling, and I must run! Good-by."

Hastily kissing her sister, Cynthia ran off.

Neal had much enjoyed the scene at the breakfast-table. He only wished that he had been present when Cynthia impersonated her aunt. It must have been immense. He wished that he could go also to Wayborough, but he was not invited to join the party. He was to be left alone for the day with Edith, for Mr. Franklin had decided that Jack should accompany them, to thank Aunt Betsey once more, and to tell her himself of the success of the hatch.

"I'll have to step round pretty lively, then," said Jack. "Those birds must get to the brooders before I go. Come along, Neal. It's an awful bore having to go to Wayborough the very first day. You'll have to look after the chicks, and don't you forget it."

The chickens safely housed, and the family gone, Neal prepared to enjoy the day. He had made up his mind to see something of Edith, and he had no idea of working by himself, especially as there was no absolute necessity for it.

"The day is too hot for work, anyhow," he said to himself.

The executive business of the national government is divided into eight departments, and the heads of these eight departments are known as Cabinet officers, and form the President's Cabinet.

It often happens that we use the same name that is used in England for an officer or an institution, which is not, however, quite the same, and is sometimes widely different, and we must always be on our guard not to be confused by such seeming similarity. This is true in our political life, just as it is true in our sports. For instance, we could not get an international match between Harvard, Yale, or Princeton, and Oxford or Cambridge on the football field, because, although football is played at all of them, yet the game in the American colleges is so different from that played in the English universities that it would be impossible to have American and English teams meet on the same ground, any more than we could put a baseball nine against a cricket eleven. It is just the same way in our politics. The Senate is sometimes spoken of as corresponding to the House of Lords; but they really have few points of resemblance, save that they are both second chambers. So the Speaker of the House of Representatives is sometimes spoken of as if his position corresponded to that of Speaker of the House of Commons. This is not true at all. The Speaker of the House of Commons is, properly, merely a moderator, like the moderator of a New England town meeting, and his duty is to preside and keep order, but not to be a Speaker, in our sense of the word, at all, not to give any utterance to party policy. In the American House, on the contrary, the Speaker is the great party leader, who is second in power and influence only to the President himself. The functions of the two officers have nothing in common, save in the mere presiding over the deliberations of the body itself.

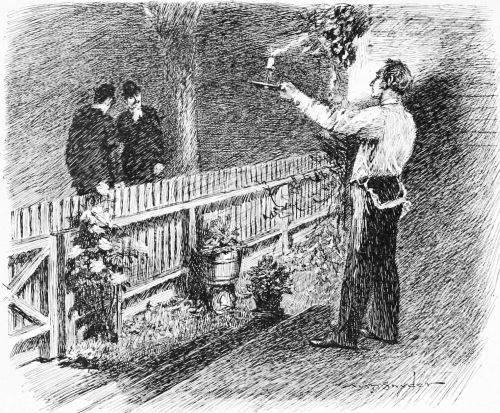

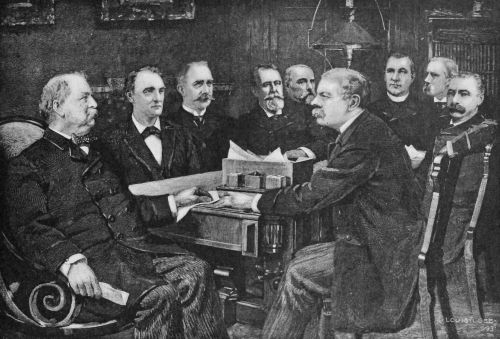

THE CABINET-ROOM.

THE CABINET-ROOM.

So in England the cabinet officers are all legislators, exactly as the Prime Minister, their chief, and they are elected by separate constituencies just as he is. In America the cabinet officers are not legislators at all, and have no voice in legislation. Instead of being elected by their own constituencies, they are appointed by the President, and he is directly responsible for them. It is upon his Cabinet officers that the President has to rely for information as to what action to take, in ordinary cases, and he has to trust to them to see the actual executive business of the government well performed.

The chief of them all is the Secretary of State. At the Cabinet meetings he sits on the right hand of the President. He would take the President's place should both the President and the Vice-President die. It is he who shapes or advises the shaping of our foreign policy, and who has to deal with our ministers and consuls abroad. He does not have nearly as much work to do, under ordinary circumstances, as several other Cabinet officers; but whereas if they blunder it is only a question of internal affairs, and is a blunder that we ourselves can remedy, if the Secretary of State blunders it may involve the whole nation in war, or may involve the surrender of rights which ought never to be given up save through war. Questions of grave difficulty with foreign powers continually arise: now about fisheries or sealing rights with Great Britain, now about an island in the Pacific with Germany, now about some Cuban filibustering expedition with Spain, and again with some South-American or Asiatic power over insults offered to our flag, or outrages committed on our citizens. All of these questions come before the Secretary of State, and it is his duty to digest them thoroughly, and advise the President of the proper course to take in the matter. The Secretary of State very largely holds in his hands the national honor.

Next in importance to the Secretary of State comes the Secretary of the Treasury. The great economic questions which the country always has to face are those connected with the currency and the tariff, and the Secretary of the Treasury has to deal with both. On his policy it largely depends whether the business of our merchants is to shrink or grow, whether the workingmen in our factories shall see their wages increase or lessen, whether our debts shall be paid in money that is worth more or less than when they were contracted, or in money that is worth practically the same. I do not mean by this to say for a moment that the Secretary of the Treasury, or any other official, can do anything like as much for the prosperity of any class or of any individual as that class or individual can do for itself or himself. In the end it is each man's individual capacity and efforts which count for most. No legislation can make any man permanently prosperous; and the worst evil we can do is to persuade a man to trust to anything save his own powers and dogged perseverance. Nevertheless, the Secretary of the Treasury can shape a policy which will do great good or great harm to our industries; and, moreover, he has to work out the financial and tariff policies which he thinks the President and the party leaders demand. The position is therefore one of the utmost importance.

The Postmaster-General has to deal with more offices than any other official, for he has to control all the post-offices of the United States. He is the great administrative officer of the country. Unfortunately, under our stupid spoils system, postmasters are appointed merely for political reasons, and are changed with every change of party, no matter what their services to the community have been. This is a very silly and very brutal practice, and all friends of honest government are striving to overthrow it by bringing in the policy of civil service reform. Under this all these postmasters will be appointed purely because they will make good postmasters, and will render[Pg 773] faithful service to the people of their districts, and they will be kept so long as they do render it, and no longer.

J. Harmon, Attorney-General. J. D. Morton, Agriculture. H. Smith, Interior. W. L. Wilson, Post. Gen.

J. Harmon, Attorney-General. J. D. Morton, Agriculture. H. Smith, Interior. W. L. Wilson, Post. Gen.The Secretary of the Interior has to deal with the disposal and management of the great masses of lands we have in the West, and also he has to deal with the management of the Indians, and with the administration of the pension laws. All three are most difficult problems, and their solution demands the utmost care, patriotism, and intelligence.

The Attorney-General is the law officer of the government. He sees to the execution of the Federal laws throughout the country, and appoints his agents to do this work in every district of every State, and he also advises the President and heads of departments on all legal matters.

The Secretary of Agriculture is a man of mixed duties. A good many bureaus of one kind and another are under his supervision, and most of the scientific work of the government is done under him. Some of the scientific bureaus, however, are under other departments. The work done by these scientific bureaus, as by the coast survey and the geological survey, and by the zoologists in the department, has been of the very highest value, and has won cordial recognition from all European countries. Much of the work of the early scientific explorers in the West reads like a veritable romance; and this governmental work has added enormously to our knowledge in all branches of science, from the natural history of mammals and birds, to the geological formation of mountains, and the contour of the coasts.

The remaining two officers are the Secretary of the Navy and the Secretary of War. The Secretary of the Navy, again, occupies a most important position, for upon the navy depends to a very great extent the nation's power of protecting its citizens abroad, and of enforcing the respect to which it is entitled. Most fortunately for the last ten or twelve years the secretaries of the navy have done admirable work. Each has built on the good work of his predecessor, so that we are gradually getting our navy to a pitch where it can worthily uphold the honor and dignity of the American flag.