Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Coquelin, Benoît Constant" to "Costume"

Author: Various

Release date: April 29, 2010 [eBook #32182]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz, Juliet Sutherland and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

COQUELIN, BENOÎT CONSTANT (1841-1909), French actor, known as Coquelin aîné, was born at Boulogne on the 23rd of January 1841. He was originally intended to follow his father’s trade of baker (he was once called un boulanger manqué by a hostile critic), but his love of acting led him to the Conservatoire, where he entered Regnier’s class in 1859. He won the first prize for comedy within a year, and made his début on the 7th of December 1860 at the Comédie Française as the comic valet, Gros-René, in Molière’s Dépit amoureux, but his first great success was as Figaro, in the following year. He was made sociétaire in 1864, and during the next twenty-two years he created at the Français the leading parts in forty-four new plays, including Théodore de Banville’s Gringoire (1867), Paul Ferrier’s Tabarin (1871), Émile Augier’s Paul Forestier (1871), L’Étrangère (1876) by the younger Dumas, Charles Lomon’s Jean Dacier (1877), Edward Pailleron’s Le Monde où l’on s’ennuie (1881), Erckmann and Chatrian’s Les Rantzau (1884). In consequence of a dispute with the authorities over the question of his right to make provincial tours in France he resigned in 1886. Three years later, however, the breach was healed; and after a successful series of tours in Europe and the United States he rejoined the Comédie Française as pensionnaire in 1890. It was during this period that he took the part of Labussière, in the production of Sardou’s’ Thermidor, which was interdicted by the government after three performances. In 1892 he broke definitely with the Comédie Française, and toured for some time through the capitals of Europe with a company of his own. In 1895 he joined the Renaissance theatre in Paris, and played there until he became director of the Porte Saint Martin in 1897. Here he won successes in Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac (1897), Émile Bergerat’s Plus que reine (1899), Catulle Mendès’ Scarron (1905), and Alfred Capus and Lucien Descaves’ L’Attentat (1906). In 1900 he toured in America with Sarah Bernhardt, and on their return continued with his old colleague to appear in L’Aiglon, at the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt. He was rehearsing for the creation of the leading part in Rostand’s Chantecler, which he was to produce, when he died suddenly in Paris, on the 27th of January 1909. Coquelin was an Officier de l’Instruction Publique and of the Legion of Honour. He published L’Art et le comédien (1880), Molière et le misanthrope (1881), essays on Eugène Manuel (1881) and Sully-Prudhomme (1882), L’Arnolphe de Molière (1882), Les Comédiens (1882), L’Art de dire le monologue (with his brother, 1884), Tartuffe (1884), L’Art du comédien (1894).

His brother, Ernest Alexandre Honoré Coquelin (1848-1909), called Coquelin cadet, was born on the 16th of May 1848 at Boulogne, and entered the Conservatoire in 1864. He graduated with the first prize in comedy and made his début in 1867 at the Odéon. The next year he appeared with his brother at the Théâtre Francais and became a sociétaire in 1879. He played a great many parts, in both the classic and the modern répertoire, and also had much success in reciting monologues of his own composition. He wrote Le Livre des convalescents (1880), Le Monologue moderne (1881), Fairiboles (1882), Le Rire (1887), Pirouettes (1888). He died on the 8th of February 1909.

Jean Coquelin (1865- ), son of Coquelin aîné, was also an actor, first at the Théâtre Francais (début, 1890), later at the Renaissance, and then at the Porte Saint Martin, where he created the part of Raigoné in Cyrano de Bergerac.

COQUEREL, ATHANASE JOSUÉ (1820-1875), French Protestant divine, son of A. L. C. Coquerel (q.v.), was born at Amsterdam on the 16th of June 1820. He studied theology at Geneva and at Strassburg, and at an early age succeeded his uncle, C. A. Coquerel, as editor of Le Lien, a post which he held till 1870. In 1852 he took part in establishing the Nouvelle Revue de théologie, the first periodical of scientific theology published in France, and in the same year helped to found the “Historical Society of French Protestantism.” Meanwhile he had gained a high reputation as a preacher, and especially as the advocate of religious freedom; but his teaching became more and more offensive to the orthodox party, and on the appearance (1864) of his article on Renan’s Vie de Jésus in the Nouvelle Revue de théologie he was forbidden by the Paris consistory to continue his ministerial functions. He received an address of sympathy from the consistory of Anduze, and a provision was voted for him by the Union Protestante Libérale, to enable him to continue his preaching. He received the cross of the Legion of Honour in 1862. He died at Fismes (Marne), on the 24th of July 1875. His chief works were Jean Calas et sa famille (1858); Des Beaux-Arts en Italie (Eng. trans. 1859); La Saint Barthélemy (1860); Précis de l’église réformée (1862); 130 Le Catholicisme et le protestantisme considérés dans leur origine et leur développement (1864); Libres études, and La Conscience et la foi (1867).

COQUEREL, ATHANASE LAURENT CHARLES (1795-1868), French Protestant divine, was born in Paris on the 17th of August 1795. He received his early education from his aunt, Helen Maria Williams, an Englishwoman, who at the close of the 18th century gained a reputation by various translations and by her Letters from France. He completed his theological studies at the Protestant seminary of Montauban, and in 1816 was ordained minister. In 1817 he was invited to become pastor of the chapel of St Paul at Jersey, but he declined, being unwilling to subscribe to the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England. During the following twelve years he resided in Holland, and preached before Calvinistic congregations at Amsterdam, Leiden and Utrecht. In 1830, at the suggestion of Baron Georges de Cuvier, then minister of Protestant worship, Coquerel was called to Paris as pastor of the Reformed Church. In the course of 1833 he was chosen a member of the consistory, and rapidly acquired the reputation of a great pulpit orator, but his liberal views brought him into antagonism with the rigid Calvinists. He took a warm interest in all matters of education, and distinguished himself so much by his defence of the university of Paris against a sharp attack, that in 1835 he was chosen a member of the consistory of the Legion of Honour. In 1841 appeared his Réponse to the Leben Jesu of Strauss. After the revolution of February 1848, Coquerel was elected a member of the National Assembly, where he sat as a moderate republican, subsequently becoming a member of the Legislative Assembly. He supported the first ministry of Louis Napoleon, and gave his vote in favour of the expedition to Rome and the restoration of the temporal power of the pope. After the coup d’état of the 2nd of December 1851, he confined himself to the duties of his pastorate. He was a prolific writer, as well as a popular and eloquent speaker. He died at Paris on the 10th of January 1868. A large collection of his sermons was published in 8 vols. between 1819 and 1852. Other works were Biographie sacrée (1825-1826); Histoire sainte et analyse de la Bible (1839); Orthodoxie moderne (1842); Christologie (1858), &c.

His brother, Charles Augustin Coquerel (1797-1851), was the author of a work on English literature (1828), an Essai sur l’histoire générale du christianisme (1828) and a Histoire des églises du désert, depuis la revocation de l’édit de Nantes (1841). A liberal in his views, he was the founder and editor of the Annales protestantes, Le Lien, and the Revue protestante.

COQUES (or Cocx), GONZALEZ (1614-1684), Flemish painter, son of Pieter Willemsen Cocx, a respectable Flemish citizen, and not, as his name might imply, a Spaniard, was born at Antwerp. At the age of twelve he entered the house of Pieter, the son of “Hell” Breughel, an obscure portrait painter, and at the expiration of his time as an apprentice became a journeyman in the workshop of David Ryckaert the second, under whom he made accurate studies of still life. At twenty-six he matriculated in the gild of St Luke; he then married Ryckaert’s daughter, and in 1653 joined the literary and dramatic club known as the “Retorijkerkamer.” After having been made president of his gild in 1665, and in 1671 painter in ordinary to Count Monterey, governor-general of the Low Countries, he married again in 1674, and died full of honours in his native place. One of his canvases in the gallery at the Hague represents a suite of rooms hung with pictures, in which the artist himself may be seen at a table with his wife and two children, surrounded by masterpieces composed and signed by several contemporaries. Partnership in painting was common amongst the small masters of the Antwerp school; and it has been truly said of Coques that he employed Jacob von Arthois for landscapes, Ghering and van Ehrenberg for architectural backgrounds, Steenwijck the younger for rooms, and Pieter Gysels for still life and flowers; but the model upon which Coques formed himself was Van Dyck, whose sparkling touch and refined manner he imitated with great success. He never ventured beyond the “cabinet,” but in this limited field the family groups of his middle time are full of life, brilliant from the sheen of costly dress and sparkling play of light and shade, combined with finished execution and enamelled surface.

COQUET (pronounced Cócket), a river of Northumberland, draining a beautiful valley about 40 m. in length. It rises in the Cheviot Hills. Following a course generally easterly, but greatly winding, it passes Harbottle, near which relics of the Stone Age are seen, and Holystone, where it is recorded that Bishop Paulinus baptized a great body of Northumbrians in the year 627. Several earthworks crown hills above this part of the valley, and at Cartington, Fosson and Whitton are relics of medieval border fortifications. The small town of Rothbury is beautifully situated beneath the ragged Simonside Hills. The river dashes through a narrow gully called the Thrum, and then passes Brinkburn priory, of which the fine Transitional Norman church was restored to use in 1858, while there are fragments of the monastic buildings. This was an Augustinian foundation of the time of Henry I. The dale continues well wooded and very beautiful until Warkworth is reached, with its fine castle and remarkable hermitage. A short distance below this the Coquet has its mouth in Alnwick Bay (North Sea), with the small port of Amble on the south bank, and Coquet Island a mile out to sea. The river is frequented by sportsmen for salmon and trout fishing. No important tributary is received, and the drainage area does not exceed 240 sq. m.

COQUET (pronounced co-kétte), to simulate the arts of love-making, generally from motives of personal vanity, to flirt; in a figurative sense, to trifle or dilly-dally with anything. The word is derived from the French coqueter, which originally means, “to strut about like a cock-bird,” i.e. when it desires to attract the hens. The French substantive coquet, in the sense of “beau” or “lady-killer,” was formerly commonly used in English; but the feminine form, coquette, now practically alone survives, in the sense of a woman who gratifies her vanity by using her powers of attraction in a frivolous or inconstant fashion. Hence “to coquet,” the original and more correct form, has come frequently to be written “to coquette.” Coquetry (Fr. coquetterie), primarily the art of the coquette, is used figuratively of any dilly-dallying or “coquetting” and, by transference of idea, of any superficial qualities of attraction in persons or things. “Coquet” is still also occasionally used adjectivally, but the more usual form is “coquettish”; e.g. we speak of a “coquettish manner,” or a “coquettish hat.” The crested humming-birds of the genus Lophornis are known as coquettes (Fr. coquets).

COQUIMBO, an important city and port of the province and department of Coquimbo, Chile, in 29° 57′ 4″ S., 71° 21′ 12″ W. Pop. (1895) 7322. The railway connexions are with Ovalle to the S., and Vicuña (or Elqui) to the E., but the proposed extension northward of Chile’s longitudinal system would bring Coquimbo into direct communication with Santiago. The city has a good well-sheltered harbour, reputed the best in northern Chile, and is the port of La Serena, the provincial capital, 9 m. distant, with which it is connected by rail. There are large copper-smelting establishments in the city, which exports a very large amount of copper, some gold and silver, and cattle and hay to the more northern provinces.

The province of Coquimbo, which lies between those of Aconcagua and Atacama and extends from the Pacific inland to the Argentine frontier, has an area of 13,461 sq. m. (official estimate) and a population (1895) of 160,898. It is less arid than the province of Atacama, the surface near the coast being broken by well-watered river valleys, which produce alfalfa, and pasture cattle for export. Near the mountains grapes are grown, from which wine of a good quality is made. The mineral resources include extensive deposits of copper, and some less important mines of gold and silver. The climate is dry and healthy, and there are occasional rains. Several rivers, the largest of which is the Coquimbo (or Elqui) with a length of 125 m., cross the province from the mountains. The capital is La Serena, and the principal cities are Coquimbo, Ovalle (pop. 5565), and Illapel (3170).

CORACLE (Welsh corwg-l, from corwg, cf. Irish and mod. Gaelic curach, boat), a species of ancient British fishing-boat which is still extensively used on the Severn and other rivers of Wales, notably on the Towy and Teifi. It is a light boat, oval in shape, and formed of canvas stretched on a framework of split and interwoven rods, and well-coated with tar and pitch to render it water-tight. According to early writers the framework was covered with horse or bullock hide (corium). So light and portable are these boats that they can easily be carried on the fisherman’s shoulders when proceeding to and from his work. Coracle-fishing is performed by two men, each seated in his coracle and with one hand holding the net while with the other he plies his paddle. When a fish is caught, each hauls up his end of the net until the two coracles are brought to touch and the fish is then secured. The coracle forms a unique link between the modern life of Wales and its remote past; for this primitive type of boat was in existence amongst the Britons at the time of the invasion of Julius Caesar, who has left a description of it, and even employed it in his Spanish campaign.

CORAËS (Koraïs), ADAMANTIOS [in French, Diamant Coray] (1748-1833), Greek scholar and patriot, was born at Smyrna, the son of a merchant. As a schoolboy he distinguished himself in the study of ancient Greek, but from 1772 to 1779 he was occupied with the management of his father’s business affairs in Amsterdam. In 1782, on the collapse of his father’s business, he went to Montpellier, where for six years he studied medicine, supporting himself by translating German and English medical works into French. He then settled in Paris, where he lived until his death on the 10th of April 1833. Inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution, he devoted himself to furthering the cause of Greek independence both among the Greeks themselves and by awakening the interest of the chief European Powers against the Turkish rule. His great object was to rouse the enthusiasm of the Greeks for the idea that they were the true descendants of the ancient Hellenes by teaching them to regard as their own inheritance the great works of antiquity. He sought to purify the ordinary written language by eliminating the more obvious barbarisms, and by enriching it with classical words and others invented in strict accordance with classical tradition (see further Greek Language: modern). Under his influence, though the common patois was practically untouched, the language of literature and intellectual intercourse was made to approximate to the pure Attic of the 5th and 4th centuries B.C. His chief works are his editions of Greek authors contained in his Έλληνικὴ Βιβλιοθήκη and his Πάρεργα; his editions of the Characters of Theophrastus, of the De aëre, aquis, et locis of Hippocrates, and of the Aethiopica of Heliodorus, elaborately annotated.

His literary remains have been edited by Mamoukas and Damalas (1881-1887); collections of letters written from Paris at the time of the French Revolution have been published (in English, by P. Ralli, 1898; in French, by the Marquis de Queux de Saint-Hilaire, 1880). His autobiography appeared at Paris (1829; Athens, 1891), and his life has been written by D. Thereianos (1889-1890); see also A. R. Rhangabé, Histoire littéraire de la Grèce moderne (1877).

CORAL, the hard skeletons of various marine organisms. It is chiefly carbonate of lime, and is secreted from sea-water and deposited in the tissues of Anthozoan polyps, the principal source of the coral-reefs of the world (see Anthozoa), of Hydroids (see Hydromedusae), less important in modern reef-building, but extremely abundant in Palaeozoic times, and of certain Algae. The skeletons of many other organisms, such as Polyzoa and Mollusca, contribute to coral masses but cannot be included in the term “coral.” The structure of coral animals (sometimes erroneously termed “coral insects”) is dealt within the articles cited above; for the distribution and formation of reefs see Coral-reefs.

Beyond their general utility and value as sources of lime, few of the corals present any special feature of industrial importance, excepting the red or precious coral (Corallium rubrum) of the Mediterranean Sea. It, however, is and has been from remote times very highly prized for jewelry, personal ornamentation and decorative purposes generally. About the beginning of the Christian era a great trade was carried on in coral between the Mediterranean and India, where it was highly esteemed as a substance endowed with mysterious sacred properties. It is remarked by Pliny that, previous to the existence of the Indian demand, the Gauls were in the habit of using it for the ornamentation of their weapons of war and helmets; but in his day, so great was the Eastern demand, that it was very rarely seen even in the regions which produced it. Among the Romans branches of coral were hung around children’s necks to preserve them from danger, and the substance had many medicinal virtues attributed to it. A belief in its potency as a charm continued to be entertained throughout medieval times; and even to the present day in Italy it is worn as a preservative from the evil eye, and by females as a cure for sterility.

The precious coral is found widespread on the borders and around the islands of the Mediterranean Sea. It ranges in depth from shallow water (25 to 50 ft.) to water over 1000 ft., but the most abundant beds are in the shallower areas. The most important fisheries extend along the coasts of Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco; but red coral is also obtained in the vicinity of Naples, near Leghorn and Genoa, and on the coasts of Sardinia, Corsica, Catalonia and Provence. It occurs also in the Atlantic off the north-west of Africa, and recently it has been dredged in deep water off the west of Ireland. Allied species of small commercial value have been obtained off Mauritius and near Japan. The black coral (Antipathes abies), formerly abundant in the Persian Gulf, and for which India is the chief market, has a wide distribution and grows to a considerable height and thickness in the tropical waters of the Great Barrier Reef of Australia.

From the middle ages downwards the securing of the right to the coral fisheries on the African coasts was an object of considerable rivalry among the Mediterranean communities of Europe. Previous to the 16th century they were controlled by the Italian republics. For a short period the Tunisian fisheries were secured by Charles V. to Spain; but the monopoly soon fell into the hands of the French, who held the right till the Revolutionary government in 1793 threw the trade open. For a short period (about 1806) the British government controlled the fisheries, and now they are again in the hands of the French authorities. Previous to the French Revolution much of the coral trade centred in Marseilles; but since that period, both the procuring of the raw material and the working of it up into the various forms in which it is used have become peculiarly Italian industries, centring largely in Naples, Rome and Genoa. On the Algerian coast, however, boats not flying the French flag have to pay heavy dues for the right to fish, and in the early years of the 20th century the once flourishing fisheries at La Calle were almost entirely neglected. Two classes of boats engage in the pursuit—a large size of from 12 to 14 tons, manned by ten or twelve hands, and a small size of 3 or 4 tons, with a crew of five or six. The large boats, dredging from March to October, collect from 650 to 850 ℔ of coral, and the small, working throughout the year, collect from 390 to 500 ℔. The Algerian reefs are divided into ten portions, of which only one is fished annually—ten years being considered sufficient for the proper growth of the coral.

The range of value of the various qualities of coral, according to colour and size, is exceedingly wide, and notwithstanding the steady Oriental demand its price is considerably affected by the fluctuations of fashion. While the price of the finest tints of rose pink may range from £80 to £120 per oz., ordinary red-coloured small pieces sell for about £2 per oz., and the small fragments called collette, used for children’s necklaces, cost about 5s. per oz. In China large spheres of good coloured coral command high prices, being in great requisition for the button of office worn by the mandarins. It also finds a ready market throughout India and in Central Asia; and with the negroes of Central Africa and of America it is a favourite ornamental substance.

CORALLIAN (Fr. Corallien), in geology, the name of one of the divisions of the Jurassic rocks. The rocks forming this division 132 are mainly calcareous grits with oolites, and rubbly coral rock—often called “Coral Rag”; ferruginous beds are fairly common, and occasionally there are beds of clay. In England the Corallian strata are usually divided into an upper series, characterized by the ammonite Perisphinctes plicatilis, and a lower series with Aspidoceras perarmatus as the zonal fossil. When well developed these beds are seen to lie above the Oxford Clay and below the Kimeridge Clay; but it will save a good deal of confusion if it is recognized that the Corallian rocks of England are nothing more than a variable, local lithological phase of the two clays which come respectively above and below them. This caution is particularly necessary when any attempt is being made to co-ordinate the English with the continental Corallian.

The Corallian rocks are nowhere better displayed than in the cliffs at Weymouth. Here Messrs Blake and Huddleston recognized the following beds:—

| Upper Corallian | { |

Upper Coral Rag and Abbotsbury Iron Ore. Sandsfoot Grits. Sandsfoot Clay. Sandsfoot Clay. Trigonia Beds. Osmington Oolite (quarried at Marnhull and Todbere). |

| Lower Corallian | { |

Bencliff Grits. Nothe Clay. Nothe Clay. Nothe Grit. |

In Dorsetshire the Corallian rocks are 200 ft. thick, in Wiltshire 100 ft., but N.E. of Oxford they are represented mainly by clays, and the series is much thinner. (At Upware, the “Upware limestone” is the only known occurrence of beds that correspond in character with the Coralline oolite between Wiltshire and Yorkshire). In Yorkshire, however, the hard rocky beds come on again in full force. They appear once more at Brora in Sutherlandshire. Corallian strata have been proved by boring in Sussex (241 ft.). In Huntingdon, Bedfordshire, parts of Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire and Lincolnshire the Corallian series is represented by the “Ampthill Clay,” which has also been called “Bluntesham” or “Tetworth” Clay. Here and there in this district hard calcareous inconstant beds appear, such as the Elsworth rock, St Ives rock and Boxworth rock.

In Yorkshire the Corallian rocks differ in many respects from their southern equivalents. They are subdivided as follows:—

| Kimeridge Clay |

Corallian Rock |

{ | “Coralline Oolite” |

{ | Upper Calcareous Grit Coral Rag and Upper Limestone Middle Calcareous Grit |

} | A. plicatilis. |

| Oxford Clay |

Lower Limestone Passage Beds Lower Calcareous Grit |

} | A. perarmatus. |

These rocks play an important part in the formation of the Vale of Pickering, and the Hambleton and Howardian Hills; they are well exposed in Gristhorpe Bay.

The passage beds, highly siliceous, flaggy limestones, are known locally as “Greystone” or “Wall stones”; some portions of these beds have resisted the weathering agencies and stand up prominently on the moors—such are the “Bridestones.” Cement stone beds occur in the upper calcareous grit at North Grimstone; and in the middle and lower calcareous grits good building stones are found.

Among the fossils in the English Corallian rocks corals play an important part, frequently forming large calcareous masses or “doggers”; Thamnastrea, Thecosmilia and Isastrea are prominent genera. Ammonites and belemnites are abundant and gasteropods are very common (Nerinea, Chemnitzia, Bourgetia, &c.). Trigonias are very numerous in certain beds (T. perlata and T. mariani). Astarte ovata, Lucina aliena and other pelecypods are also abundant. The echinoderms Echinobrissus scutatus and Cidaris florigemma are characteristic of these beds.

Rocks of the same age as the English Corallian are widely spread over Europe, but owing to the absence of clearly-marked stratigraphical and palaeontological boundaries, the nomenclature has become greatly involved, and there is now a tendency amongst continental geologists to omit the term Corallian altogether. According to A. de Lapparent’s classification the English Corallian rocks are represented by the Séquanien stage, with two substages, an upper Astartien and lower Rauracien; but this does not include the whole Corallian stage as defined above, the lower part being placed by the French author in his Oxfordien stage. For the table showing the relative position of these stages see the article Jurassic.

See also “The Jurassic Rocks of Great Britain,” vol. i. (1892) and vol. v. (1895) (Memoirs of the Geological Survey); Blake and Huddleston, “On the Corallian Rocks of England,” Q.J.G.S. vol. xxxiii. (1877).

CORAL-REEFS. Many species of coral (q.v.) are widely distributed, and are found at all depths both in warmer and colder seas. Lophohelia prolifera and Dendrophyllia ramea form dense beds at a depth of from 100 to 200 fathoms off the coasts of Norway, Scotland and Portugal, and the “Challenger” and other deep-sea dredging expeditions have brought up corals from great depths in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. But the larger number of species, particularly the more massive kinds, occur only in tropical seas in shallow waters, whose mean temperature does not fall below 68° Fahr., and they do not flourish unless the temperature is considerably higher. These conditions of temperature are found in a belt of ocean which may roughly be indicated as lying between the 28th N. and S. parallels. Within these limits there are numerous reefs and islands formed of coral intermixed with the calcareous skeletons of other animals, and their formation has long been a matter of dispute among naturalists and geologists.

Coral formations may be classed as fringing or shore reefs, barrier reefs and atolls. Fringing reefs are platforms of coral rock extending no great distance from the shores of a continent or island. The seaward edge of the platform is usually somewhat higher than the inner part, and is often awash at low water. It is intersected by numerous creeks and channels, especially opposite those places where streams of fresh water flow down from the land, and there is usually a channel deep enough to be navigable by small boats between the edge of the reef and the land. The outer wall of the reef is rather steep, but descends into a comparatively shallow sea. Since corals are killed by fresh water or by deposition of mud or sand, it is obvious that the outer edge of the reef is the region of most active coral growth, and the boat channel and the passages leading into it from the open sea have been formed by the suppression of coral growth by one of the above-mentioned causes, assisted by the scour of the tides and the solvent action of sea-water. Barrier reefs may be regarded as fringing reefs on a large scale. The great Australian barrier reef extends for no less a distance than 1250 m. from Torres Strait in 9.5° S. lat. to Lady Elliot island in 24° S. lat. The outer edge of a barrier reef is much farther from the shore than that of a fringing reef, and the channel between it and the land is much deeper. Opposite Cape York the seaward edge of the great Australian barrier reef is nearly 90 m. distant from the coast, and the maximum depth of the channel at this point is nearly 20 fathoms. As is the case in a fringing reef, the outer edge of a barrier reef is in many places awash at low tides, and masses of dead coral and sand may be piled up on it by the action of the waves, so that islets are formed which in time are covered with vegetation. These islets may coalesce and form a strip of dry land lying some hundred yards or less from the extreme outer edge of the reef, and separated by a wide channel from the mainland. Where the barrier reef is not far from the land there are always gaps in it opposite the mouths of rivers or considerable streams. The outer wall of a barrier reef is steep, and frequently, though not always, descends abruptly into great depths. In many cases in the Pacific Ocean a barrier reef surrounds one or more island peaks, and the strips of land on the edge of the reef may encircle the peaks with a nearly complete ring. An atoll is a ring-shaped reef, either awash at low tide or surmounted by several islets, or more rarely by a complete strip of dry land surrounding a central lagoon. The outer wall of an atoll generally descends with a very steep but irregular slope to a depth of 500 fathoms or more, but the lagoon is seldom more than 20 fathoms deep, and may be much less. Frequently, especially to the 133 leeward side of an atoll, there may be one or more navigable passages leading from the lagoon to the open sea.

Though corals flourish everywhere under suitable conditions in tropical seas, coral reefs and atolls are by no means universal in the torrid zone. The Atlantic Ocean is remarkably free from coral formations, though there are numerous reefs in the West Indian islands, off the south coast of Florida, and on the coast of Brazil. The Bermudas also are coral formations, their high land being formed by sand accumulated by the wind and cemented into rock, and are remarkable for being the farthest removed from the equator of any recent reefs, being situated in 32° N. lat. In the Pacific Ocean there is a vast area thickly dotted with coral formations, extending from 5° N. lat. to 25° S. lat., and from 130° E. long, to 145° W. long. There are also extensive reefs in the westernmost islands of the Hawaiian group in about 25° N. lat. In the Indian Ocean, the Laccadive and Maldive islands are large groups of atolls off the west and south-west of India. Still farther south is the Chagos group of atolls, and there are numerous reefs off the north coast of Madagascar, at Mauritius, Bourbon and the Seychelles. The Cocos-Keeling Islands, in 12° S. lat. and 96° E. long., are typical atolls in the eastern part of the Indian Ocean.

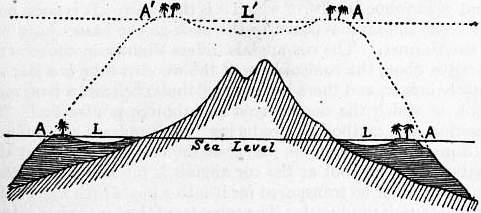

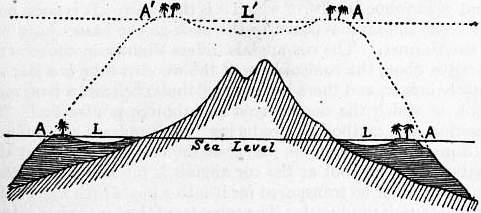

Diagram showing the formation of an atoll during subsidence. (After C. Darwin.) The lower part of the figure represents a barrier reef surrounding a central peak.

A, A, outer edges of the barrier reef at the sea-level; the coco-nut trees indicate dry land formed on the edges of the reef.

L, L, lagoon channel.

A’, A’, outer edges of the atoll formed by upgrowth of the coral during the subsidence of the peak.

L’, lagoon of the atoll.

The vertical scale is considerably exaggerated as compared with the horizontal scale.

The remarkable characters of barrier reefs and atolls, their isolated position in the midst of the great oceans the seemingly unfathomable depths from which they rise their peaceful and shallow lagoons and inner channels, their narrow strips of land covered with coco-nut palms and other vegetation, and rising but a few feet above the level of the ocean, naturally attracted the attention of the earlier navigators, who formed sundry speculations as to their origin. The poet-naturalist, A. von Chamisso, was the first to propound a definite theory of the origin of atolls and encircling reefs, attributing their peculiar features to the natural growth of corals and the action of the waves. He pointed out that the larger and more massive species of corals flourish best on the outer sides of a reef, whilst the more interior corals are killed or stunted in growth by the accumulation of coral and other debris. Thus the outer edge of a submerged reef is the first to reach the surface, and a ring of land being formed by materials piled up by the waves, an atoll with a central lagoon is produced. Chamisso’s theory necessarily assumed the existence of a great number of submerged banks reaching nearly, but not quite, to the surface of the sea in the Pacific and Indian oceans, and the difficulty of accounting for the existence of so many of these led C. Darwin to reject his views and bring forward an explanation which may be called the theory of subsidence. Starting from the well-known premise that reef-building species of corals do not flourish in a greater depth of water than 20 fathoms, Darwin argued that all coral islands must have a rocky base, and that it was inconceivable that, in such large tracts of sea as occur in the Pacific and Indian oceans, there should be a vast number of submarine peaks or banks all rising to within 20 or 30 fathoms of the surface and none emerging above it. But on the supposition that the atolls and encircling reefs were formed round land which was undergoing a slow movement of subsidence, their structure could easily be explained. Take the case of an island consisting of a single high peak. At first the coral growth would form a fringing reef clinging to its shores. As the island slowly subsided into the ocean the upward growth of coral would keep the outer rim of the reef level with or within a few fathoms of the surface, so that, as subsidence proceeded, the distance between the outer rim of the reef and the sinking land would continually increase, with the result that a barrier-reef would be formed separated by a wide channel from the central peak. As corals and other organisms with calcareous skeletons live in the channel, their remains, as well as the accumulation of coral and other debris thrown over the outer edge of the reef, would maintain the channel at a shallower depth than that of the ocean outside. Finally, if the subsidence continued, the central peak would disappear beneath the surface, and an atoll would be left consisting of a raised margin of reef surrounding a central lagoon, and any pause during the movement of subsidence would result in the formation of raised islets or a strip of dry land along the margin of the reef. Darwin’s theory was published in 1842, and found almost universal acceptance, both because of its simplicity and its applicability to every known type of coral-reef formation, including such difficult cases as the Great Chagos Bank, a huge submerged atoll in the Indian Ocean.

Darwin’s theory was adopted and strengthened by J. D. Dana, who had made extensive observations among the Pacific coral reefs between 1838 and 1842, but it was not long before it was attacked by other observers. In 1851 Louis Agassiz produced evidence to show that the reefs off the south coast of Florida were not formed during subsidence, and in 1863 Karl Semper showed that in the Pelew islands there is abundant evidence of recent upheaval in a region where both atolls and barrier-reefs exist. Latterly, many instances of recently upraised coral formations have been described by H. B. Guppy, J. S. Gardiner and others, and Alexander Agassiz and Sir J. Murray have brought forward a mass of evidence tending to shake the subsidence theory to its foundations. Murray has pointed out that the deep-sea soundings of the “Tuscarora” and “Challenger” have proved the existence of a large number of submarine elevations rising out of a depth of 2000 fathoms or more to within a few hundred fathoms of the surface. The existence of such banks was unknown to Darwin, and removes his objections to Chamisso’s theory. For although they may at first be too far below the surface for reef-building corals, they afford a habitat for numerous echinoderms, molluscs, crustacea and deep-sea corals, whose skeletons accumulate on their summits, and they further receive a constant rain of the calcareous and silicious skeletons of minute organisms which teem in the waters above. By these agencies the banks are gradually raised to the lowest depth at which reef-building corals can flourish, and once these establish themselves they will grow more rapidly on the periphery of the bank, because they are more favourably situated as regards food-supply. Thus the reef will rise to the surface as an atoll, and the nearer it approaches the surface the more will the corals on the exterior faces be favoured, and the more will those in the centre of the reef decrease, for experiment has shown that the minute pelagic organisms on which corals feed are far less abundant in a lagoon than in the sea outside. Eventually, as the margin of the reef rises to the surface and material is accumulated upon it to form islets or continuous land, the coral growth in the lagoon will be feeble, and the solvent action of sea-water and the scour of the tide will tend to deepen the lagoon. Thus the considerable depth of some lagoons, amounting to 40 or 50 fathoms, may be accounted for. The observations of Guppy in the Solomon islands have gone far to confirm Murray’s conclusions, since he found in the islands of Ugi, Santa Anna and Treasury and Stirling islands unmistakable evidences of a nucleus of volcanic rock, covered with soft earthy bedded deposits several hundred feet thick. These deposits are highly fossiliferous in parts, and contain the remains of pteropods, lamellibranchs and echinoderms, embedded in a foraminiferous deposit mixed with volcanic debris, like the deep-sea muds brought up by 134 the “Challenger.” The flanks of these elevated beds are covered with coralline limestone rocks varying from 100 to 16 ft. in thickness. One of the islands, Santa Anna, has the form of an upraised atoll, with a mass of coral limestone 80 ft. in vertical thickness, resting on a friable and sparingly argillaceous rock resembling a deep-sea deposit. A. Agassiz, in a number of important researches on the Florida reefs, the Bahamas, the Bermudas, the Fiji islands and the Great Barrier Reef of Australia, has further shown that many of the peculiar features of these coral formations cannot be explained on the theory of subsidence, but are rather attributable to the natural growth of corals on banks formed by prevailing currents, or on extensive shore platforms or submarine flats formed by the erosion of pre-existing land surfaces.

In face of this accumulated evidence, it must be admitted that the subsidence theory of Darwin is inapplicable to a large number of coral reefs and islands, but it is hardly possible to assert, as Murray does, that no atolls or barrier reefs have ever been developed after the manner indicated by Darwin. The most recent research on the structure of coral reefs has also been the most thorough and most convincing. It is obvious that, if Murray’s theory were correct, a bore hole sunk deep into an atoll would pass through some 100 ft. of coral rock, then through a greater or less thickness of argillaceous rock, and finally would penetrate the volcanic rock on which the other materials were deposited. If Darwin’s theory is correct, the boring would pass through a great thickness of coral rock, and finally, if it went deep enough, would pass into the original rock which subsided below the waters. An expedition sent out by the Royal Society of London started in 1896 for the island of Funafuti, a typical atoll of the Ellice group in the Pacific Ocean, with the purpose of making a deep boring to test this question. The first attempt was not successful, for at a depth of 105 ft. the refractory nature of the rock stopped further progress. But a second attempt, under the management of Professor Edgeworth David of Sydney, proved a complete success. With improved apparatus, the boring was carried down to a depth of 697 ft. (116 fathoms), and a third attempt carried it down to 1114 ft. (185 fathoms). The boring proves the existence of a mass of pure limestone of organic origin to the depth of 1114 ft., and there is no trace of any other rock. The organic remains found in the core brought up by the drill consist of corals, foraminifera, calcareous algae and other organisms. A boring was also made from the deck of a ship into the floor of the lagoon, which shows that under 100 ft. of water there exists at the bottom of the lagoon a deposit more than 100 ft. thick, consisting of the remains of a calcareous alga, Halimeda opuntia, mixed with abundant foraminifera. At greater depths, down to 245 ft., the same materials, mixed with the remains of branching madrepores, were met with, and further progress was stopped by the existence of solid masses of coral, fragments of porites, madrepora and heliopora having been brought up in the core. These are shallow-water corals, and their existence at a depth of nearly 46 fathoms, buried beneath a mass of Halimeda and foraminifera, is clear evidence of recent subsidence. Halimeda grows abundantly over the floor of the lagoon of Funafuti, and has been observed in many other lagoons. The writer collected a quantity of it in the lagoon of Diego Garcia in the Chagos group. The boring demonstrates that the lagoon of Funafuti has been filled up to an extent of at least 245 ft. (nearly 41 fathoms), and this fact accords well with Darwin’s theory, but is incompatible with that of Murray. In the present state of our knowledge it seems reasonable to conclude that coral reefs are formed wherever the conditions suitable for growth exist, whether in areas of subsidence, elevation or rest. A considerable number of reefs, at all events, have not been formed in areas of subsidence, and of these the Florida reefs, the Bermudas, the Solomon islands, and possibly the Great Barrier Reef of Australia are examples. Funafuti would appear to have been formed in an area of subsidence, and it is quite probable that the large groups of low-lying islands in the Pacific and Indian oceans have been formed under the same conditions. At the same time, it must be remembered that the atoll or barrier reef shape is not necessarily evidence of formation during subsidence, for the observations of Karl Semper, A. Agassiz, and Guppy are sufficient to prove that these forms of reefs may be produced by the natural growth of coral, modified by the action of waves and currents in regions in which subsidence has certainly not taken place.

See A. Agassiz, many publications in the Mem. Amer. Acad. (1883) and Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool. (Harvard, 1889-1899); J. D. Dana, Corals and Coral Islands (1853; 2nd ed., 1872; 3rd ed., 1890); C. Darwin, The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs (3rd ed., 1889); H. B. Guppy, “The Recent Calcareous Formations of the Solomon Group,” Trans. Roy. Soc. Edinb. xxxii. (1885); R. Langenbeck, “Die neueren Forschungen über die Korallenriffe,” Hettner geogr. Zeitsch. iii. (1897); J. Murray, “On the Structure and Origin of Coral Reefs and Islands,” Proc. Roy. Soc. Edinb. x. (1879-1880); J. Murray and Irvine, “On Coral Reefs and other Carbonate of Lime Formations in Modern Seas,” Proc. Roy. Soc. Edinb. (1889); W. Savile Kent, The Great Barrier Reef of Australia (London, W. H. Allen & Co., 1893); Karl Semper, Animal Life, “Internat. Sci. Series,” vol. xxxi. (1881); J. S. Gardiner, Nature, lxix. 371.

CORAM, THOMAS (1668-1751), English philanthropist, was born at Lyme Regis, Dorset. He began life as a seaman, and rose to the position of merchant captain. He settled at Taunton, Massachusetts, for several years engaging there in farming and boat-building, and in 1703 returned to England. His acquaintance with the destitute East End of London, and the miserable condition of the children there, inspired him with the idea of providing a refuge for such of them as had no legal protector; and after seventeen years of unwearied exertion, he obtained in 1739 a royal charter authorizing the establishment of his hospital for foundling infants (see Foundling Hospitals). It was opened in Hatton Garden, on the 17th of October 1740, with twenty inmates. For fifteen years it was supported by voluntary contributions; but in 1756 it was endowed with a parliamentary grant of £10,000 for the support of all that might be sent to it. Children were brought, however, in such numbers, and so few (not one-third, it is said) survived infancy, that the grant was stopped, and the charity, which had been removed to Guilford Street, was from that time only administered under careful restrictions. Coram’s later years were spent in watching over the interests of the hospital; he was also one of the promoters of the settlement of Georgia and Nova Scotia; and his name is honourably connected with various other charities. In carrying out his philanthropic schemes he spent nearly all his private means; and an annuity of £170 was raised for him by public subscription. He died on the 29th of March 1751.

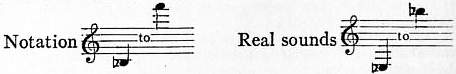

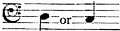

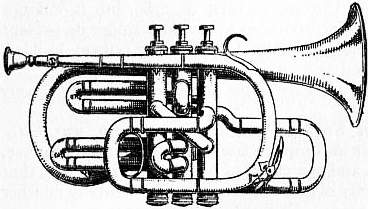

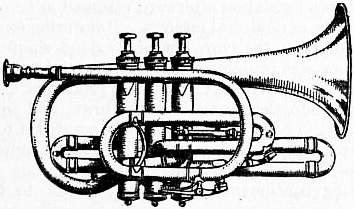

COR ANGLAIS, or English Horn (Ger. englisches Horn or alt Hoboe; Ital. corno inglese), a wood-wind double-reed instrument of the oboe family, of which it is the tenor. It is not a horn, but bears the same relation to the oboe as the basset horn does to the clarinet. The cor anglais differs slightly in construction from the oboe; the conical bore of the wooden tube is wider and slightly longer, and there is a larger globular bell and a bent metal crook to which the double reed mouthpiece is attached. The fingering and method of producing the sound are so similar in both instruments that the player of the one can in a short time master the other, but as the cor anglais is pitched a fifth lower, the music must be transposed for it into a key a fifth higher than the real sounds produced. The compass of the cor anglais extends over two octaves and a fifth:

The true quality of the cor anglais is penetrating like that of the oboe, but mellower and more melancholy.

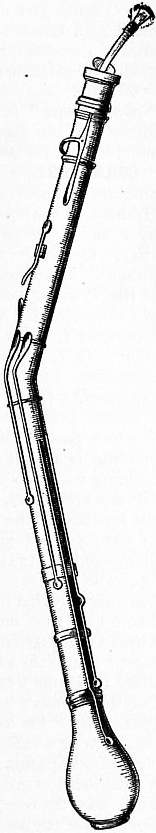

The cor anglais is the alto Pommer (q.v.) or haute-contre de hautbois (see Oboe), gradually developed, improved and provided with key-work. It is not known exactly when the change took place, but it was probably during the 17th century, after the Schalmey or Shawm had been transformed into the oboe. In a 17th century MS. (Add. 30,342, f. 145) in the British Museum, written in French, giving pen and ink sketches of many instruments, is an “accord de hautbois” which comprises a pédalle 135 (bass oboe or Pommer), a sacquebute (sackbut) as basse-contre, a taille (tenor) with a note that the haute-contre (the cor anglais) est de mesme sinon plus petite. The tubes of all the members of the hautbois family are straight in this drawing. Before 1688 the French hoboy, made in four parts and having two keys, was known in England.1 It is probable that in France, where the hautbois played such an important part in court music, the cor anglais, under the name of haute-contre de hautbois, was also provided with keys. At the end of the 17th century there were two players of the haute-contre de hautbois among the musicians of the Grande Écurie du Roi.2

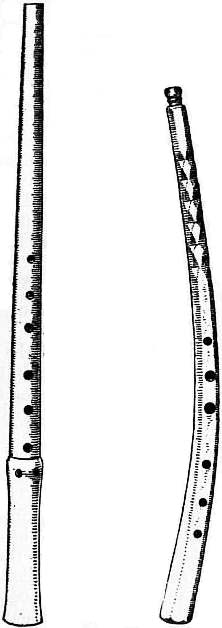

|

| Fig. 1.—Modern Cor anglais. (Besson & Co.) |

|

| From Richard Hofmann’s Katechismus der Musikinstrumente.

Fig. 2.—Cor anglé, 18th century. |

The origin of the name of the instrument is also a matter of conjecture. Two theories exist—one that cor anglais is a corruption of cor anglé, a name given on account of the angular bend of the early specimens. In that case the name, but not necessarily the instrument, probably originated in France early in the 18th century, for Gluck scored for two cors anglais in his Italian version of Alceste played in Vienna in 1767. When a French version of this opera was given in Paris two years later, the cor anglais, not being known or available there, was replaced by oboes. It was not until 1808 that the cor anglais was heard at the Paris Opera, when it was played by the oboist Vogt in Catel’s Alexandre chez Apelle. This, however, proves only that the name was not familiar in France, where the oboe of the same pitch was called haute-contre de hautbois. The bending of the tube and the development of the cor anglais as solo instrument originated in Germany, unless the oboe da caccia was identical with the cor anglais, in which case Italy would be the country of origin. Thomas Stanesby, junior, made an oboe da caccia in 1740 of straight pattern in four pieces, having a bent metal crook for the insertion of the reed and two saddle keys; but the bell was like the bell of the oboe, not globular like that of the cor anglais, a form to which the veiled quality of its timbre is due. It is interesting in this connexion to recall some experiments in bending the cor anglais, which do not appear to have led to any practical result. A French broadside (c. 1650), “La Musique,” preserved in the British Museum, contains drawings of many musical instruments in use in the 17th century; among them are an oboe with keys in a perforated case, and two other wood wind instruments of the same family, which may be taken to represent attempts to dispose of the inconvenient length of the haute-contre (1) by bending the tube at right angles for about one quarter of its length from the mouthpiece, which contains a large double reed, (2) by bending the tube in the elongated “S” shape of the corno torto or bass Zinke, for which the drawing in question might be mistaken but for the bent crook inserted in the end for the reception of the reed, which, however, is missing. The other hypothesis is that when the cor anglais was given a bend in order to facilitate the handling, the name was adopted to mark its resemblance to a kind of hunting-horn said to be in use in England at the time. This suggestion does not seem to be a happy one; for if the reference be to the crescent-shaped horn, that instrument was in use in all countries at various periods before the 17th century, while if it be to the angular form, then a reproduction of such a horn should be forthcoming to support the statement.

The idea of bending the instrument is attributed to Giovanni or Giuseppe Ferlendis of Bergamo,3 brothers and virtuosi on the oboe. One of these had settled in Salzburg, and both were equally renowned as performers on the English horn. They visited Venice, Brescia, Trieste, Vienna, London (in 1795) and Lisbon, where Giuseppe died. In this case we might expect the name to have been given in Italian, corno inglese; yet Gluck in his Italian edition used the French name already in 1767, when Giuseppe was but twelve years old. We must await some more conclusive explanation, but we may suppose that the new name was bestowed when the instrument assumed a form entirely new to the family of hautbois or oboes. The cor anglais was well known in England before 1774, for in a quaint book of travels through England, published in that year, we read that Signor Sougelder,4 “an eminent surgeon of Bristol,” was a performer “on the English horn.”

The experiment of bending the cor anglais did not prove satisfactory, for the tube instead of being bored had to be cut out of two pieces of wood which were then glued together and covered with leather. Even the most skilful craftsman did not succeed in making the inside of the tube quite smooth; the roughness of the wood was detrimental to the tone and gave the cor anglais a veiled, somewhat hoarse quality, and makers before long reverted to the direct or vertical form.

1 See Harleian MS. 2034, f. 207b, British Museum, in the third part of Randle Holme’s Academy of Armoury, written before 1688, where an outline sketch in ink is also given.

2 See J. Écorcheville, “Quelques documents sur la musique de la Grande Écurie du Roi,” Sammelband intern. Musikges. ii. 4, pp. 609 and 625. Deeds exist creating charges for four hautbois and musettes de Poitou in the hand of King John, middle of 14th century, see p. 633.

3 See Henri Lavoix, Histoire de l’instrumentation, p. 111; Gerber, Lexikon, “Giuseppe Ferlendis”; Robert Eitner, Quellen-Lexikon der Tonkünstler, “Gioseffo Ferlendis.” Fétis and Pohl also refer to him.

4 See Musical Travels thro’ England (London, 1774), p. 56.

CORATO, a city of Apulia, Italy, in the province of Bari, 26 m. W. of Bari by steam tramway. Pop. (1901) 41,573. It is situated in the centre of an agricultural district. It contains no buildings of great interest, but is a clean and well-kept town.

CORBAN (ןברק), an Aramaic word meaning “a consecrated gift.” Josephus uses the word of Nazirites and of the temple treasure of Jerusalem. Such a votive offering lay under a curse if it were diverted to ordinary purposes, like the spoil of Jericho which Achan appropriated (Josh. vii.), or the temple treasure of Delphi which was seized by the Phocians, 356 B.C. The word is found in Mark vii. 11, the usual interpretation of which is that Jesus refers to an abuse—a man might declare that any part of his property which came into his parents’ hands was corban, consecrated, i.e. that a curse rested on any benefit they might get from it. The Jewish scribes thus fenced the law of vows with a traditional interpretation which made men break the most binding injunctions of the Mosaic Law, in this case the fifth commandment. A totally different explanation of the passage is put forward by J. H. A. Hart in The Jewish Quarterly Review for July 1907, the gist of which is that Jesus commends the Pharisees for insisting that when a man has vowed a vow to God he should pay it even though his parents should suffer.

CORBEIL, WILLIAM OF (d. 1136), archbishop of Canterbury, was born probably at Corbeil on the Seine, and was educated at Laon. He was soon in the service of Ranulf Flambard, bishop of Durham; then, having entered the order of St Augustine, he became prior of the Augustinian foundation at St Osyth in Essex. At the beginning of 1123 he was chosen from among several candidates to be archbishop of Canterbury, and as he refused to admit that Thurstan, archbishop of York, was independent of the see of Canterbury, this prelate refused to consecrate him, and the ceremony was performed by his own suffragan bishops. Proceeding to Rome the new archbishop found that Thurstan had anticipated his arrival in that city and had made out a strong case against him to Pope Calixtus II.; however, the exertions of the English king Henry I. and of the emperor Henry V. prevailed, and the pope gave William the pallium. The archbishop’s next dispute was with the papal 136 legate. Cardinal John of Crema, who had arrived in England and was acting in an autocratic manner. Again travelling to Rome, William gained another victory, and was himself appointed papal legate (legatus natus) in England and Scotland, a precedent of considerable importance in the history of the English Church. The archbishop had sworn to Henry I. that he would support the claim of his daughter Matilda to the English crown, but nevertheless he crowned Stephen in December 1135. He died at Canterbury on the 21st of November 1136. William built the keep of Rochester Castle, and finished the building of the cathedral at Canterbury, which was dedicated with great pomp in May 1130.

See W. F. Hook, Lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury (1860-1884); and W. R. W. Stephens, History of the English Church (1901).

CORBEIL, a town of northern France, capital of an arrondissement in the department of Seine-et-Oise, at the confluence of the Essonne with the Seine, 21 m. S. by E. of Paris on the Orléans railway to Nevers. Pop. (1906) 9756. A bridge across the Seine unites the main part of the town on the left bank with a suburb on the other side; handsome boulevards lead to the village of Essonnes (pop. 7255), about a mile to the south-west. St Spire, the only survivor of the formerly numerous churches of Corbeil, dates from the 12th to the 15th centuries. Behind the church there is a Gothic gateway. A monument has been erected to the brothers Galignani, publishers of Paris, who gave a hospital and orphanage to the town. Corbeil is the seat of a sub-prefect, and has tribunals of first instance and commerce and a chamber of commerce. It has important flour-mills, tallow-works, printing-works, large paper-works at Essonnes, and carries on boat and carriage-building, and the manufacture of plaster. The Decauville engineering works are in the vicinity. There is trade in grain and flour.

From the 10th to the 12th century Corbeil was the chief town of a powerful countship, but it was united to the crown by Louis VI.; it continued for a long time to be an important military post in connexion with the commissariat of Paris. In 1258 St Louis concluded a treaty here with James I. of Aragon. Of the numerous sieges to which it has been exposed the most important were those by the Huguenots in 1562, and by Alexander Farnese, prince of Parma, in 1590.

CORBEL (Lat. corbellus, a diminutive of corvus, a raven, on account of the beak-like appearance; Ital. mensola, Fr. corbeau, cul-de-lampe, Ger. Kragstein), the name in medieval architecture for a piece of stone jutting out of a wall to carry any super-incumbent weight. A piece of timber projecting in the same way was called a tassel or a bragger. Thus the carved ornaments from which the vaulting shafts spring at Lincoln are corbels. Norman corbels are generally plain. In the Early English period they are sometimes elaborately carved, as at Lincoln above cited, and sometimes more simply so, as at Stone. They sometimes end with a point apparently growing into the wall, or forming a knot, as at Winchester, and often are supported by angels and other figures. In the later periods the foliage or ornaments resemble those in the capitals. The corbels carrying the arches of the corbel tables in Italy and France were often elaborately moulded, and sometimes in two or three courses projecting over one another; those carrying the machicolations of English and French castles had four courses. The corbels carrying balconies in Italy and France were sometimes of great size and richly carved, and some of the finest examples of the Italian Cinquecento style are found in them. Throughout England, in half-timber work, wood corbels abound, carrying window-sills or oriels in wood, which also are often carved. A “corbel table” is a projecting moulded string course supported by a range of corbels. Sometimes these corbels carry a small arcade under the string course, the arches of which are pointed and trefoiled. As a rule the corbel table carries the gutter, but in Lombard work the arcaded corbel table was utilized as a decoration to subdivide the storeys and break up the wall surface. In Italy sometimes over the corbels will be a moulding, and above a plain piece of projecting wall forming a parapet (see also Masonry).

CORBET, RICHARD (1582-1635), English bishop and poet, was born in 1582, the son of a nurseryman at Ewell, Surrey. At Oxford, to which he proceeded from Westminster school in 1597, he was noted as a wit. On taking orders he continued to display this talent from the pulpit, and James I., in consideration of his “fine fancy and preaching,” made him one of the royal chaplains. In 1620 he became vicar of Stewkley, Berkshire, and in the same year was made dean of Christchurch, Oxford. In 1628 he was made bishop of Oxford, and in 1632 translated thence to the see of Norwich. Corbet was the author of many poems, for the most part of a lively, satirical order, his most serious production being the Fairies’ Farewell. His verses were first collected and published in 1647. His conviviality was famous, and many stories are told of his youthful merrymaking in London taverns in company with Ben Jonson, who always remained his close friend, and other dramatists. He died at Norwich on the 28th of July 1635.

CORBIE (Lat. corvus), a crow or raven. In architecture, “corbie steps” is a Scottish term (cf. Corbel) for the steps formed up the sides of the gable by breaking the coping into short horizontal beds.

CORBRIDGE, a small market town in the Hexham parliamentary division of Northumberland, England; 3½ m. E. of Hexham, on the north bank of the river Tyne, which is here crossed by a fine seven-arched bridge dating from 1674. Pop. (1901) 1647. Corbridge was formerly of greater importance than at present. Its name, derived from the small river Cor, a tributary of the Tyne, is said to be associated with the Brigantian tribe of Corionototai. About 760 it became the capital of Northumbria; later it was a borough and was long represented in parliament. In 1138 David of Scotland made it a centre of military operations, and it was ravaged by Wallace in 1296, by Bruce in 1312, and by David II. in 1346. Its chief remains of antiquity are a square peel-tower and the cruciform church of St Andrew, of which part of the fabric is of pre-Conquest date, though the building is mainly Early English. Extensive use is made of building materials from the Roman station of Corstopitum (also called Corchester), which lay half a mile west of Corbridge at the junction of the Cor with the Tyne. This site has from time to time yielded many valuable relics, notably a silver dish, discovered in 1734, 148 oz. in weight and ornamented with figures of deities; but the first-rate importance of the station was only revealed by careful excavations undertaken in 1907 seq. There were then unearthed remains of several buildings fronting a broad thoroughfare, one of which is the largest Roman building, except the baths at Bath, yet discovered in England. Two of these buildings were granaries, and indicate the importance of Corstopitum as a base of the northward operations of Antoninus Pius. After his conquests had been lost, and Corstopitum ceased to be a military centre, its military buildings passed into civilian occupation, of which many evidences have been found. A fine hoard of gold coins, wrapped in lead-foil and hidden in a wall, was discovered in 1908. Corstopitum ceased to exist early in the 5th century, and the site was never again occupied.

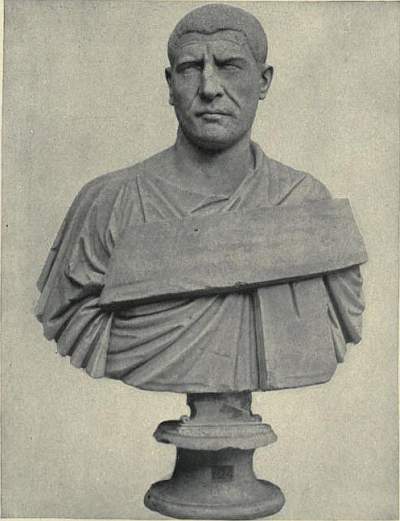

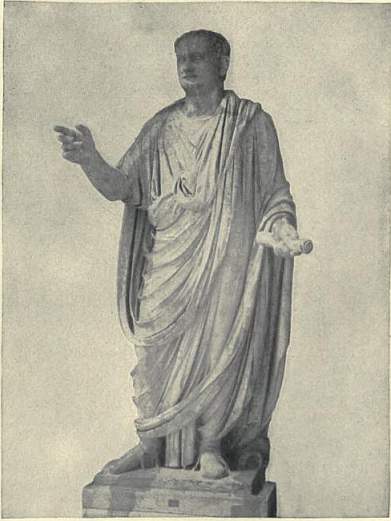

CORBULO, GNAEUS DOMITIUS (1st century A.D.), Roman general, was the half-brother of Caesonia, one of the wives of the emperor Caligula. In the reign of Tiberius he held the office of praetor, and was appointed to the superintendence of the roads and bridges. Under Claudius he was governor of lower Germany (A.D. 47). He punished the Frisii who refused to pay the tribute, and was on the point of advancing against the Chauci, but was recalled by the emperor and ordered to withdraw behind the Rhine. In order to provide employment for his soldiers, Corbulo made them cut a canal from the Mosa (Meuse) to the northern branch of the Rhine, which still forms one of the chief drains between Leiden and Sluys, and before the introduction of railways was the ordinary traffic road between Leiden and Rotterdam. Soon after the accession of Nero, Vologaeses (Vologasus), king of Parthia, overran Armenia, drove out Rhadamistus, who was under the protection of the Romans, and set his own brother Tiridates on the throne. Corbulo was thereupon sent out to the East with full military powers. After some delay, he took 137 the offensive in 58, and, reinforced by troops from Germany, attacked Tiridates. Artaxata and Tigranocerta were captured, and Tigranes, who had been brought up in Rome and was the obedient servant of the government, was installed king of Armenia. In 61 Tigranes invaded Adiabene, an integral portion of the Parthian kingdom, and a conflict between Rome and Parthia seemed unavoidable. Vologaeses, however, thought it better to come to terms. It was agreed that both the Roman and Parthian troops should evacuate Armenia, that Tigranes should be dethroned, and the position of Tiridates recognized. The Roman government declined to accede to these arrangements, and L. Caesennius Paetus, governor of Cappadocia, was ordered to settle the question by bringing Armenia under direct Roman administration. The protection of Syria in the meantime claimed all Corbulo’s attention. Paetus, a weak and incapable man, suffered a severe defeat at Rhandea (62), where he was surrounded and forced to capitulate and to evacuate Armenia. The command of the troops was again entrusted to Corbulo. In 63, with a strong army, he crossed the Euphrates, but Tiridates declined to give battle and concluded peace. At Rhandea he laid down his diadem at the foot of the emperor’s statue, promising not to resume it until he received it from the hand of Nero himself in Rome. In 67 disturbances broke out in Judaea, but Nero, jealous of Corbulo’s success and popularity, ordered Vespasian to take command of the forces and summoned Corbulo to Greece. On his arrival at Cenchreae, the port of Corinth, messengers from Nero met Corbulo, and ordered him to commit suicide. Without hesitation he obeyed, exclaiming, “I have deserved it.” Whether he had really given any grounds for suspicion is unknown; but there is no doubt, so great was his popularity with the soldiers and such the hatred felt for Nero, that he could easily have seized the throne. Corbulo wrote an account of his Asiatic experiences, which is lost.

See Tacitus, Annals, xii.-xv.; Dio Cassius lix. 15, lx. 30, lxii. 19-23, lxiii. 6, 17, lxvi. 3; H. Schiller, Geschichte des römischen Kaiserreichs unter der Regierung des Nero (1872); E. Egli, “Feldzüge in Armenien von 41-63,” in M. Büdinger’s Untersuchungen zur römischen Kaisergeschichte, i. (1868); Mommsen, Hist. of the Roman Provinces, ii. (1886); for the Armenian campaigns see B. W. Henderson in Classical Review (April, May, June, 1901); in general D. T. Schoonover, A Study of Cn. Domitius Corbulo (Chicago, 1909).

CORD (derived through the Fr. corde, from the Lat. chorda, Gr. χορδή, the string of a musical instrument), a length of twisted or woven strands, in thickness coming between a rope and a string, a smaller kind of rope (q.v.). From the use of such a cord for measuring, the word is applied to a quantity of cut wood, differing according to locality. The variant “chord,” which, in spelling, reverts to the original Latin, is used in particular senses, as, in physiology, for such cord-like structures as the vocal chords; in the case of the “umbilical cord,” the other spelling is usually retained. In mathematics a “chord” is a straight line joining any two points on the same curve, and, in music, the word is used of several musical notes sounded simultaneously and in harmony (q.v.). In this last sense, “chord” is properly a shortened form of “accord,” agreement, from Late Lat. accordare, and the spelling with h is due to a confusion.

CORDAY D’ARMONT, MARIE ANNE CHARLOTTE (1768-1793), French revolutionary heroine, the murderess of Marat, born at St Saturnin des Lignerets, near Séez in Normandy, was descended from a noble but poor family, and numbered among her ancestors the dramatist Corneille. Charlotte Corday was educated in the convent of the Holy Trinity at Caen, and then sent to live with an aunt. Here she saw hardly any one but her relative, and passed her lonely hours in reading the works of the philosophes, especially Voltaire and the Abbé Raynal. Another of her favourite authors was Plutarch, from whose pages she doubtless imbibed the idea of classic heroism and civic virtue which prompted the act that has made her name famous. On the outbreak of the Revolution she began to study current politics, chiefly in the papers issued by the party afterwards known as the Girondins. On the downfall of this party, on May 31, 1793, many of the leaders took refuge in Normandy, and proposed to make Caen the headquarters of an army of volunteers, at the head of whom Félix de Wimpffen, who commanded the army assembled for the defence of the coasts at Cherbourg, was to have marched upon Paris. Charlotte attended their meetings, and heard them speak; but we have no reason to believe that she saw any of them privately, till the day when she went to ask for introductions to friends of theirs in Paris. She saw that their efforts in Normandy were doomed to fail. She had heard of Marat as a tyrant and the chief agent in their overthrow, and she had conceived the idea of going alone to Paris and assassinating him,—doubtless thinking that this would break up the party of the Terrorists and be the signal of a counter-revolution, and ignorant of the fact that Marat was ill almost to the point of death, and that others were more influential than he.

Apparently she had thought of going to Paris in April, before the fall of the Girondins, for she had then procured a passport which she used in July. It contained the usual description of the bearer, and ran thus: Laissez passer la citoyenne Marie, &c., Corday, âgée de 24 ans, taille de 5 pieds 1 pouce, cheveux et sourcils châtains, yeux gris, front élevé, nez long, bouche moyenne, menton rond fourchu, visage ovale. Arrived in Paris she first attended to some business for a friend at Caen, and then she wrote to Marat: “Citizen, I have just arrived from Caen. Your love for your native place doubtless makes you desirous of learning the events which have occurred in that part of the republic. I shall call at your residence in about an hour; have the goodness to receive me and to give me a brief interview. I will put you in a condition to render great service to France.” On calling she was refused admittance, and wrote again, promising to reveal important secrets, and appealing to Marat’s sympathy on the ground that she herself was persecuted by the enemies of the republic. She was again refused an audience, and it was only when she called a third time (July 13) that Marat, hearing her voice in the antechamber, consented to see her. He lay in a bathing tub, wrapped in towels, for he was suffering from a horrible disease which had almost reduced him to a state of putrefaction. Our only source of information as to what followed is Charlotte’s own confession. She spoke to Marat of what was passing at Caen, and his only comment on her narrative was that all the men she had mentioned should be guillotined in a few days. As he spoke she drew from her bosom a dinner-knife (which she had bought the day before for two francs) and plunged it into his left side. It pierced the lung and the aorta. He cried out, “À moi, ma chère amie!” and expired. Two women rushed in, and prevented Charlotte from escaping. A crowd collected round the house, and it was with difficulty that she was escorted to the prison of the Abbaye. On being brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal she gloried in her act, and when the indictment against her was read, and the president asked her what she had to say in reply, her answer was, “Nothing, except that I have succeeded.” Her advocate, Claude François Chauveau Lagarde, put forward in vain the plea of insanity. She was sentenced to death, and calmly thanked her counsel for his efforts on her behalf, adding that the only defence worthy of her was an avowal of the act. She was then conducted to the Conciergerie, where at her own desire her portrait (now in the museum of Versailles) was painted by the artist Jean Jacques Hauer. She preserved her perfect calmness to the last. When she saw the guillotine, she placed herself in position under the fatal blade without assistance from any one. The knife fell, and one of the executioners held up her head by the hair, and had the brutality to strike it with his fist. Many believed they saw the dead face blush,—probably an effect of the red stormy sunset. It was the 17th of July 1793. It is difficult to analyse the character of Charlotte Corday; but there was in it much that was noble and exalted. Her mind had been formed by her studies on a pagan type. To C. J. M. Barbaroux and the Girondins of Caen she wrote from her prison, anticipating happiness “with Brutus in the Elysian Fields” after her death, and with this letter she sent a simple loving farewell to her father, revealing a tender side to her character that otherwise we would hardly have looked for in such a woman. Lamartine called her 138 l’ange de l’assassinat, and Vergniaud said, “Elle nous perd, mais elle nous apprend à mourir.”

See Œuvres politiques de Charlotte Corday (Caen, 1863; some letters and an Adresse aux Français amis des lois el de la paix), with a supplement printed in the same year; Louvet de Couvrai, Mémoires (ed. Aulard, Paris, 1889); Alphonse Esquiros, Charlotte Corday (2nd ed., 2 vols., Paris, 1841); Cheron de Villiers, Marie Anne Charlotte Corday (Paris, 1865); Casimir Périer, “La Jeunesse de Charlotte Corday” (Revue des deux mondes, 1862); C. Vatel, Dossiers du procès criminel de Charlotte de Corday ... extraits des archives impériales (Paris, 1861), and Dossier historique de Charlotte Corday (Paris, 1872); Austin Dobson, Four Frenchwomen (London, 1890); A. Ducos, Les Trois Girondines, Mme Roland, Charlotte Corday ... (Paris, 1896); Dr Cabanès, “La vraie Charlotte Corday,” in Le Cabinet secret de l’histoire (4 vols., 1897-1900). Her tragic history was the subject of two anonymous tragedies, Charlotte Corday (1795), said to be by the Conventional F. J. Gamon, and Charlotte Corday (Caen, 1797), neither of which have any merit; another by J. B. Salles is published by C. Vatel in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins (1864-1872). See further bibliographical articles in M. Tourneux, Bibl. de l’hist. de Paris ... (vol. iv., 1906), and in the Bibliographie des femmes célèbres (3 vols., Turin and Rome, 1892-1905); and also E. Defrance, Charlotte Corday et la mort de Marat (1909).

CORDELIERS, CLUB OF THE, or Society of the Friends of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a popular society of the French Revolution. It was formed by the members of the district of the Cordeliers, when the Constituent Assembly suppressed the 60 districts of Paris to replace them with 48 sections (21st of May 1790). It held its meetings at first in the church of the monastery of the Cordeliers,—the name given in France to the Franciscan Observantists,—now the Dupuytren museum of anatomy in connexion with the school of medicine. From 1791, however, the Cordeliers met in a hall in the rue Dauphine. The aim of the society was to keep an eye on the government; its emblem on its papers was simply an open eye. It sought as well to encourage revolutionary measures against the monarchy and the old régime, and it was it especially which popularized the motto “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” It took an active part in the movement against the monarchy of the 20th of June and the 10th of August 1792; but after that date the more moderate leaders of the club, Danton, Fabre d’Eglantine, Camille Desmoulins, seem to have ceased attending, and the “enragés” obtained control, such as J. R. Hébert, F. N. Vincent, C. P. H. Ronsin and A. F. Momoro. Its influence was especially seen in the creation of the revolutionary army destined to assure provisions for Paris, and in the establishment of the worship of Reason. The Cordeliers were combated by those revolutionists who wished to end the Terror, especially by Danton, and by Camille Desmoulins in his journal Le Vieux Cordelier. The club disowned Danton and Desmoulins and attacked Robespierre for his “moderation,” but the new insurrection which it attempted failed, and its leaders were guillotined on the 24th of March 1794, from which date nothing is known of the club. We know little of its composition.

The papers emanating from the Cordeliers are enumerated in M. Tourneux, Bibliographie de l’histoire de Paris pendant la Révolution (1894), i. (on the trial of the Hebertists) Nos. 4204-4210, ii. Nos. 9795-9834 and 11,813. See also A. Bougeart, Les Cordeliers, documents pour servir à l’histoire de la Révolution (Caen, 1891); G. Lenotre, Paris révolutionnaire (Paris, 1895); G. Tridon, Les Hébertists, plainte contre une calomnie de l’histoire (Paris, 1864). The last-named author was condemned to four months’ prison; his work was reprinted in 1871. The inventory of the pictures found in 1790 in the monastery of the Cordeliers was published by J. Guiffrey in Nouvelles archives de l’art français, viii., 2nd series, iii. (1880).

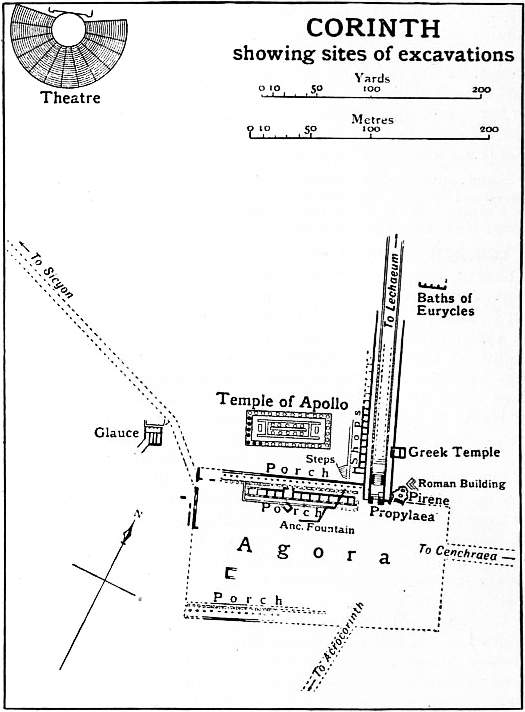

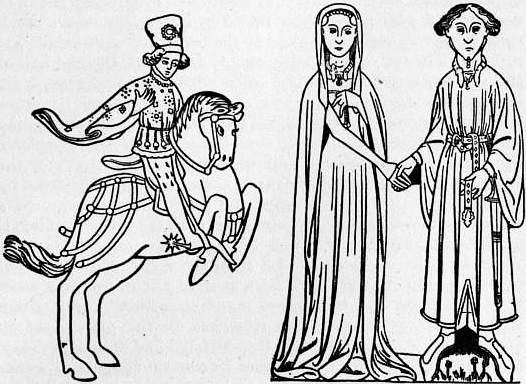

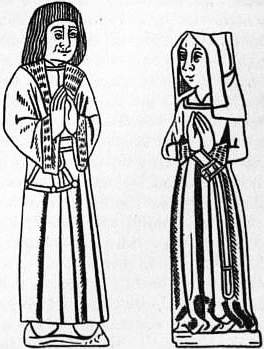

CORDERIUS, the Latinized form of name used by Mathurin Cordier (c. 1480-1564), French schoolmaster, a native of Normandy or Perche. He possessed special tact and liking for teaching children, and taught first at Paris, where Calvin was among his pupils, and, after a number of changes, finally at Geneva, where he died on the 8th of September 1564. He wrote several books for children; the most famous is his Colloquia (Colloquiorum scholasticorum libri quatuor), which has passed through innumerable editions, and was used in schools for three centuries after his time. He also wrote: Principia Latine loquendi scribendique, sive selecta quaedam ex Epistolis Ciceronis; De corrupti sermonis apud Gallos emendatione et Latine loquendi Ratione; De syllabarum quantitate; Conciones sacrae viginti sex Galliae; Catonis disticha de moribus (with Latin and French translation); Remontrances et exhortations au roi et aux grands de son royaume.