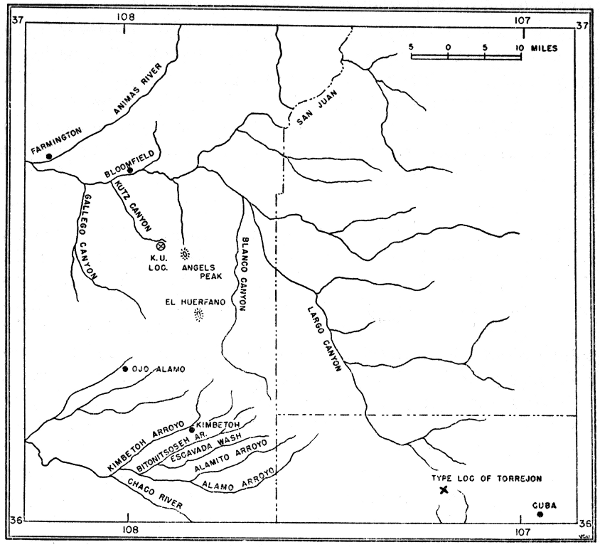

Figure 1. Map of a part of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico, showing

location of University of Kansas fossil locality west of Angels Peak.

Figure 1. Map of a part of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico, showing

location of University of Kansas fossil locality west of Angels Peak.

Title: Preliminary Survey of a Paleocene Faunule from the Angels Peak Area, New Mexico

Author: Robert W. Wilson

Release date: April 29, 2010 [eBook #32175]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Diane Monico, and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

BY

ROBERT W. WILSON

University of Kansas Publications

Museum of Natural History

Volume 5, No. 1, pp. 1-11, 1 figure in text

February 24, 1951

University of Kansas

LAWRENCE

1951

University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History

Editors: E. Raymond Hall, Chairman, A. Byron Leonard,

Edward H. Taylor, Robert W. Wilson

Volume 5, No. 1, pp. 1-11, 1 figure in text

February 24, 1951

University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas

PRINTED BY

FERD VOILAND, JR., STATE PRINTER

TOPEKA, KANSAS

1951

23-4458

By

ROBERT W. WILSON

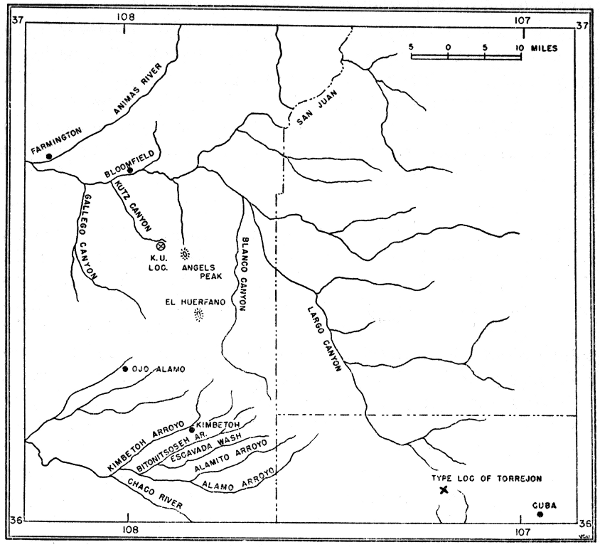

Angels Peak stands on the eastern rim of a large area of badlands carved by a tributary of the San Juan River from Paleocene strata of the Nacimiento formation, and presumably also from Wasatchian strata of the San José (Simpson, 1948). This area of badlands lies some twelve miles south of Bloomfield, New Mexico in the Kutz Canyon drainage. Angels Peak (Angel Peak of Granger, 1917) and Kutz Canyon (Coots Cañon of Granger, and of Matthew, 1937) are names that have been applied to the location (figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of a part of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico, showing

location of University of Kansas fossil locality west of Angels Peak.

Figure 1. Map of a part of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico, showing

location of University of Kansas fossil locality west of Angels Peak.

E. D. Cope's collector, David Baldwin, possibly worked in this area in the Eighties. The first published record, however, of mammalian fossils from the Angels Peak badlands was made by Walter Granger in 1917 as a result of his field work in the preceding summer. Granger obtained specimens, usually poorly preserved, but occasionally rather abundant locally, from various levels up to within 150 feet of the western rim of the badlands basin. This collection was obviously of Torrejonian or middle Paleocene age. In the 1917 report, Granger gave as a faunal list the following species:

Tetraclaenodon

Mioclaenus turgidus

Periptychus rhabdodon

Anisonchus sectorius

Protogonodon sp. nov.

Tricentes

Deltatherium

Psittacotherium

To this list should be added Triisodon antiquus, a specimen of which is stated by Matthew to come from Kutz Canyon in his monograph (1937:80) on the Paleocene faunas of the San Juan Basin.

In the summer of 1948, a field party from the University of Kansas was fortunate in finding a local concentration of rather well preserved material at the western edge of the badlands at Angels Peak. Because it probably will be some time before a full account of this faunule can be prepared, it is thought advisable, preliminarily, to give a general statement as to occurrence, and tentatively to list the species.

The mammalian fossils, numbering approximately 150 specimens, were all obtained within a small area located in the NW 1/4 of sec. 14, T. 27 N, R. 11 W, San Juan County, New Mexico. The specimens were collected from a zone of reddish silt three to four feet in thickness. The actual bone layer, not as yet located, may prove to be thinner than this. Almost all the material was recovered from approximately 100 linear yards of outcrop. A few specimens, however, were obtained at varying distances away from this central area, as far distant perhaps as one-half mile. Of these, nineteen were at the same level stratigraphically, and only one was lower (by 70 feet) in the section. This latter specimen, representing a new genus and species of Primates, is not certainly duplicated by material at the main concentration. Seemingly, the others are.

The red zone at the "bone pocket" carries many concretionary masses which frequently contain the fossil specimens. Not all specimens, however, are from such lumps.[Pg 5]

Even within the area of greatest concentration, specimens are of sporadic occurrence. A low ridge, a few feet high, may have abundant material weathering from the rock on one slope, but have the opposite side barren. Occasionally, a small rill three or four feet in length and six inches or so across may carry fragments of five or six individuals representing several genera. For example, in one such rill were found Didymictis, n. sp. b; Goniacodon levisanus; Tricentes cf. T. subtrigonus; and Protoselene opisthacus. No specimens were found in place in unweathered rock, but the quarry possibilities of the bone pocket have still to be tested.

The stratigraphic position of the bone concentration in relation to the total Nacimiento section exposed in Kutz Canyon has not been determined. It is approximately 160 feet below the western rim at a point nearest the "pocket". The upper 100 feet of strata consists of sandstone believed by Granger (1917:822) to represent either: (1) equivalent of the "Wasatch" (San José) of the Ojo Alamo section, or (2) "Torrejon" (upper Nacimiento). Granger perhaps favored the first interpretation, but the writer, at present, thinks the second probable.[Pg 6]

The following mammalian species have been identified as present in the Angels Peak "pocket".

Order Multituberculata

Family Ptilodontidae

Mimetodon? cf. M. trovessartianus

Order Insectivora

Family Palaeoryctidae

Palaeoryctes cf. P. puercensis

Family Leptictidae

Prodiacodon? sp.

Family Pantolestidae

Pentacodon n. sp.

Family Mixodectidae

Indrodon malaris

Order Primates

Family Anaptomorphidae

anaptomorphid? new gen. and sp.

(70 feet stratigraphically below level of Angels Peak pocket).

? Primates, gen. and sp. indet.

Order Taeniodonta

Family Stylinodontidae

Psittacotherium? sp.

Order Carnivora

Family Arctocyonidae

Tricentes cf. T. subtrigonus

Chriacus truncatus

Chriacus nr. C. baldwini

Deltatherium fundaminus?

Claenodon n. sp.

Triisodon? sp.

Goniacodon levisanus

Family Miacidae

Didymictis n. sp. a

Didymictis n. sp. b

Order Condylarthra

Family Hyopsodontidae

Mioclaenus turgidus

Ellipsodon cf. E. inaequidens

Ellipsodon acolytus

Protoselene opisthacus

Family Phenacodontidae

Tetraclaenodon nr. T. puercensis

Family Periptychidae

Coriphagus encinensis

Anisonchus sectorius

Periptychus nr. P. carinidens

The total number of specimens for each member (species or genus) of the faunule is tabulated in the list on the page facing, page 7. For the purposes of this list, census, a few of the isolated teeth have been counted as jaws. They were so counted whenever they seemed to be representative of separate, individual animals.

The census-count includes all of the specimens that were identified. The numbers in parentheses, on page 7, refer to those individuals that were found outside of the 100 linear yards or so of outcrop comprising the principal area of concentration of specimens.[Pg 7]

| upper jaws (isolated) | lower jaws (isolated) | upper and lower jaws (associated) | |

| Mimetodon? cf. M. trovessartianus | 1 | ||

| Palaeoryctes cf. P. puercensis | 1 | ||

| Prodiacodon? sp. | 1 | ||

| Pentacodon n. sp. | 2 (1) | ||

| Indrodon malaris | 4 | ||

| Primates n. gen. and sp. | 1 (1) | ||

| ? Primates | 2 | ||

| Psittacotherium? sp. | 1 | ||

| Tricentes cf. T. subtrigonus | 7 | 15 | 4 |

| Chriacus truncatus | 1 | 6 | 5 (2) |

| Chriacus nr. C. baldwini | 1 | ||

| Deltatherium fundaminus? | 3 | 1 | |

| Claenodon n. sp. | 1 | 1 | |

| Triisodon? sp. | 1 | ||

| Goniacodon levisanus | 2 | ||

| Didymictis n. sp. a | 1 | 1 | |

| Didymictis n. sp. b | 1 | 3 | |

| Mioclaenus turgidus | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ellipsodon cf. E. inaequidens | 3 (1) | ||

| Ellipsodon acolytus | 3 | 11 | 1 |

| Protoselene opisthacus | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 |

| Tetraclaenodon nr. T. puercensis | 5 (2) | 18 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Coriphagus encinensis | 2 | ||

| Anisonchus sectorius | 4 (2) | 8 (2) | |

| Periptychus nr. P. carinidens | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 2 |

| Totals | 36 | 90 | 22 148 |

The faunal list is rather long for one obtained from such a restricted area. It is not exceptional in this regard, however, for even longer lists have been made from single quarry sites in the Paleocene (Simpson, 1937:33-34). The exact number of genera and species represented is still uncertain. It seems that twenty-one genera and twenty-four species are present and that they are distributed among eleven to twelve families and five to six orders. A greater number of genera and species may be recorded eventually.

The ferungulate cohort constitutes most of the fauna (91 percent), and this fact indicates a floodplain facies as the most probable depositional environment. The small representation of multituberculates, insectivores, and insectivore derivatives, however, may be attributed in part to the difficulties inherent in surface collecting of minute specimens.

Some resemblance in percentage composition is shown to the faunules of the Fort Union Group if those forms too small to be seen readily in collecting of surface material are omitted from the Montanan lists, but differences exist not entirely the result of either geographic or stratigraphic separation. Thus, the phenacodontids of the Angels Peak are relatively abundant, matching figures obtained for surface collecting in the Fort Union of Montana (Simpson, 1937:61).

That the faunule is not completely of floodplain type is seen in the absence or rarity of such relatively large carnivores as Claenodon ferox, the larger species of Chriacus, Triisodon, and the entire absence of the Mesonychidae. The absence of the mesonychids might, but probably should not, be explained as a result of stratigraphic differences. There seems to be no reason for thinking that the Angels Peak faunule antedates the appearance of the Mesonychidae. They are absent from the Dragon and earlier levels, but are also extremely rare in the Lebo of the Fort Union Group. In the ungulate population, the absence of species of Ellipsodon other than E. acolytus (E. inaequidens is so rare everywhere that it hardly seems an exception to this statement), and the complete absence of Haploconus likewise suggest some, presumably local, peculiarity of environment. The latter genus is absent from the Lebo, but is recorded from the Dragon (Gazin, 1941:3), a fact which prevents attaching any age significance to its absence from the Angels Peak faunule. It should be mentioned, however, that no remains of Haploconus were reported as a result of the more extensive collecting[Pg 9] by Granger in the Angels Peak area. Incidentally, the type of Haploconus angustus is said to come from near Huerfano Peak (Matthew, 1937:156).

The high ratio of carnivores to ungulates is a peculiarity shared with, but far exceeded by, the Lebo fauna if figures obtained from surface collections of the latter are used. It seems unlikely that this ratio is the result of selective trapping in the accumulating sediments. Perhaps, this high ratio reflects the imperfectly carnivorous habits of the Paleocene creodonts as a group. One obvious explanation, regardless of probability or merit, is that some of these do not belong to the Carnivora.

The percentage composition of the Angels Peak faunule based on 148 identifiable mammalian specimens, is as follows:

| Percent | |||

| Insectivora: | 5 | ||

| Carnivora: | |||

| Arctocyonidae: | 32 | ||

| Miacidae: | 4 | ||

| —— | 36 | ||

| Condylarthra: | |||

| Hyopsodontidae: | 22 | ||

| Phenacodontidae: | 18 | ||

| Periptychidae: | |||

| Anisonchinae: | 10 | ||

| Periptychinae: | 5 | ||

| —— | 15 | ||

| —— | 55 | ||

| Others: | 4 | ||

| —— | |||

| 100 |

The most common forms in the Angels Peak faunule are: Tricentes cf. T. subtrigonus, Chriacus truncatus, Ellipsodon acolytus, Tetraclaenodon nr. T. puercensis, and Anisonchus sectorius.

Post-cranial skeletal elements are of relatively rare occurrence in the pocket. The presence of several more or less complete skulls, and the relatively frequent association of upper and lower dentitions, however, seem to be points against ascribing the accumulation to the activities of predators and scavengers, otherwise perhaps indicated by the large amount of resistant tooth material.

The Angels Peak faunule, as Granger stated, is of Torrejonian age. This fact is clearly evident for the genera are all, with the exception of the forms referred to the Primates, represented in beds of that age elsewhere in the Nacimiento. Further, approximately two-thirds of the known "Torrejon" genera are recorded by specimens from the Angels Peak pocket. The primate remains present no evidence[Pg 10] for suspecting a difference in age, because the order is otherwise unrecorded in the Torrejonian of New Mexico. The species are in most instances identical or closely allied with those hitherto recognized. It is evident from this that the Angels Peak faunule is more closely correlated in time with the San Juan Torrejonian fauna as a whole than with either the Dragon fauna or the Tiffanian. In respect to the San Juan Torrejonian, closest resemblance is to the Deltatherium zone fauna rather than to the Pantolambda zone fauna (Osborn, 1929:62). The difference in the faunas of these two zones is largely, if not entirely, facial in character.

It is not clearly evident, however, that we are dealing with exactly contemporaneous assemblages when comparison is made between the Angels Peak faunule and the rest of the San Juan fauna which serves collectively to define the typical Torrejonian. It may be: (1) that the Angels Peak faunule is of slightly different age than the latter, or (2) that the latter is susceptible of stratigraphic subdivision, and the Angels Peak faunule marks one stage of a sequence in time. This problem will not be easily solved, and perhaps may never be, for concentrations similar to that of the Angels Peak faunule are of infrequent occurrence. It is beyond the scope of the present paper, and of the present stage of our knowledge of the "Torrejon" fauna, to discuss at length the possible difference in age, but the following remarks summarize the matter for the Angels Peak material.

Many of the Angels Peak specimens differ in minor ways from those previously described from the Torrejonian of the San Juan Basin. Some of these differences are sufficiently great for the recognition of new species. Other differences at present are not clearly valid on a specific level, and it may become necessary to restudy the entire fauna if satisfactory conclusions ever are reached.

A direct comparison can be made between the Angels Peak faunule, and a numerically smaller and less well preserved one obtained by the University of Kansas from a bone concentration near the head of Kimbetoh Arroyo. The latter faunule presumably is from the "Deltatherium zone," and hence does not occupy a demonstrably high position in the "Torrejon," rather, one seemingly down toward the first known appearance of the fauna. Closely related or identical species of nine genera occur at both localities. Of these, the specimens of one species seem to be indistinguishable; the specimens of another Angels Peak member are perhaps slightly more advanced; and seven include specimens, distinguishable in greater or lesser degree, which suggest, principally in smaller size, a less advanced stage for the Angels Peak faunule.[Pg 11]

In general, the non-ferungulate part of the Angels Peak faunule seems to depart more widely from what is typical of the "Torrejon" fauna than do the Carnivora and Condylarthra. Because the former is very poorly represented in the faunule, and not too well known elsewhere in the San Juan Basin, it may be argued that the apparent differences would disappear with the acquisition of more material. This may be so, but at present the point can not be demonstrated.

It is not justified at present to maintain that the Angels Peak species occupy an earlier position in the Torrejonian than do those obtained from outcrops between Kimbetoh and the heads of the two forks of Arroyo Torrejon. Indeed, the stratigraphic position of the Angels Peak pocket with a considerable thickness of Torrejonian strata beneath it, tends to argue against such a view. Nevertheless, it is possible, if not probable, that such is the case, or at least that detailed work would reveal a series of faunules of slightly different ages in the Torrejonian stage of the Nacimiento formation. Of course, chance in collecting, as well as geographic and ecologic differences, play their part in giving such a local faunule as that at Angels Peak its somewhat different aspect, but these factors may not account altogether for the observed differences.

Gazin, C. L.

1941. The mammalian faunas of the Paleocene of central Utah, with notes

on the geology. Proc. U. S. Nat. Mus., 91, no. 3121: 1-53, 3 pls., 29

figs. in text.

Granger, Walter.

1917. Notes on Paleocene and lower Eocene mammal horizons of northern

New Mexico and southern Colorado. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist., art.

32: 821-830, 2 pls., 1 fig.

Matthew, W. D.

1937. Paleocene faunas of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Trans. Amer.

Philos. Soc., n. s., 30: i-viii, 1-510, 65 pls., 85 figs. in text.

Osborn, H. F.

1929. The titanotheres of ancient Wyoming, Dakota, and Nebraska. U. S.

Geol. Surv., Monog. 55 (2 vols.): i-xxiv, i-xi, 1-953, 236 pls., 797 figs.

in text.

Simpson, G. G.

1937. The Fort Union of the Crazy Mountain Field, Montana, and its

mammalian faunas. U. S. Nat. Mus., Bull. 169: i-x, 1-287, 10 pls., 80

figs. in text, 62 tbls.

1948. The Eocene of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Amer. Jour. Sci.,

246: 257-282, 363-385, 5 figs. in text.

University of Kansas, Museum of Natural History, Lawrence, Kansas. Transmitted July 1, 1950.

Page 4: Changed preceeding to preceding

(field work in the preceding summer).