Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Columbus" to "Condottiere"

Author: Various

Release date: April 11, 2010 [eBook #31950]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz, Juliet Sutherland and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

COLUMBUS, a city and the county-seat of Muscogee county, Georgia, U.S.A., on the E. bank and at the head of navigation of the Chattahoochee river, about 100 m. S.S.W. of Atlanta. Pop. (1890) 17,303; (1900) 17,614, of whom 7267 were negroes; (1910, census) 20,554. There is also a considerable suburban population. Columbus is served by the Southern, the Central of Georgia, and the Seaboard Air Line railways, and three steamboat lines afford communication with Apalachicola, Florida. The city has a public library. A fall in the river of 115 ft. within a mile of the city furnishes a valuable water-power, which has been utilized for public and private enterprises. The most important industry is the manufacture of cotton goods; there are also cotton compresses, iron works, flour and woollen mills, wood-working establishments, &c. The value of the city’s factory products increased from $5,061,485 in 1900 to $7,079,702 in 1905, or 39.9%; of the total value in 1905, $2,759,081, or 39%, was the value of the cotton goods manufactured. There are many large factories just outside the city limits. Columbus was one of the first cities in the United States to maintain, at public expense, a system of trade schools. It has a large wholesale and retail trade. The city was founded in 1827 and was incorporated in 1828. In the latter year Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar (1798-1859) established here the Columbus Independent, a State’s-Rights newspaper. For the first twenty years the city’s leading industry was trade in cotton. As this trade was diverted by the railways to Savannah, the water-power was developed and manufactories were established. During the Civil War the city ranked next to Richmond in the manufacture of supplies for the Confederate army. On the 16th of April 1865 it was captured by a Union force under General James Harrison Wilson (b. 1837); 1200 Confederates were taken prisoners; large quantities of arms and stores were seized, and the principal manufactories and much other property were destroyed.

COLUMBUS, a city and the county-seat of Bartholomew county, Indiana, U.S.A., situated on the E. fork of White river, a little S. of the centre of the state. Pop. (1890) 6719; (1900) 8130, of whom 313 were foreign-born and 224 were of negro descent (1910 census) 8813. In 1900 the centre of population of the United States was 5 m. S.E. of Columbus. The city is served by the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St Louis, and the Pittsburg, Cincinnati, Chicago & St Louis railways, and is connected with Indianapolis and with Louisville, Ky., by an electric interurban line. Columbus is situated in a fine farming region, and has extensive tanneries, threshing-machine and traction and automobile engine works, structural iron works, tool and machine shops, canneries and furniture factories. In 1905 the value of the city’s factory product was $2,983,160, being 28.4% more than in 1900. The water-supply system and electric-lighting plant are owned and operated by the city.

COLUMBUS, a city and the county-seat of Lowndes county, Mississippi, U.S.A., on the E. bank of the Tombigbee river, at the head of steam navigation, 150. m. S.E. of Memphis, Tennessee. Pop. (1890) 4559; (1900) 6484 (3366 negroes); (1910) 8988. It is served by the Mobile & Ohio and the Southern railways, and by passenger and freight steamboat lines. It has cotton and knitting mills, cotton-seed oil factories, machine shops, and wagon, stove, plough and fertilizer factories; and is a market and jobbing centre for a fertile agricultural region. It has a public library, and is the seat of the Mississippi Industrial Institute and College (1885) for women, the first state college for women—the successor of the Columbus Female Institute (1848)—of Franklin Academy (1821), and of the Union Academy (1873) for negroes. The site was first settled about 1818; the city was incorporated in 1821, and in 1830 it became the county-seat of the newly formed Lowndes county. During the Civil War the legislature met here in 1863 and 1865, and in the former year Governor Charles Clark (1810-1877) was inaugurated here.

COLUMBUS, a city, a port of entry, the capital of Ohio, U.S.A., and the county-seat of Franklin county, at the confluence of the Scioto and Olentangy rivers, near the geographical centre of the state, 120 m. N.E. of Cincinnati, and 138 m. S.S.W. of Cleveland. Pop. (1890) 88,150; (1900) 125,560, of whom 12,328 were foreign-born and 8201 were negroes; (1910) 181,511. Columbus is an important railway centre and is served by the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis, the Pittsburg, Cincinnati, Chicago & St Louis (Pennsylvania system), the Baltimore & Ohio, the Ohio Central, the Norfolk & Western, the Hocking Valley, and the Cleveland, Akron & Columbus (Pennsylvania system) railways, and by nine interurban electric lines. It occupies a land area of about 17 sq. m., the principal portion being along the east side of the Scioto in the midst of an extensive plain. High Street, the principal business thoroughfare, is 100 ft. wide, and Broad Street, on which are many of the finest residences, is 120 ft. wide, has four rows of trees, a roadway for heavy vehicles in the middle, and a driveway for carriages on either side.

The principal building is the state capitol (completed in 1857) in a square of ten acres at the intersection of High and Broad streets. It is built in the simple Doric style, of grey limestone taken from a quarry owned by the state, near the city; is 304 ft. long and 184 ft. wide, and has a rotunda 158 ft. high, on the walls of which are the original painting, by William Henry Powell (1823-1879), of O. H. Perry’s victory on Lake Erie, and portraits of most of the governors of Ohio. Other prominent structures are the U.S. government and the judiciary buildings, the latter connected with the capitol by a stone terrace, the city hall, the county court house, the union station, the board of trade, the soldiers’ memorial hall (with a seating capacity of about 4500), and several office buildings. The city is a favourite meeting-place for conventions. Among the state institutions in Columbus are the university (see below), the penitentiary, a state hospital for the insane, the state school for the blind, and the state institutions for the education of the deaf and dumb and for feeble-minded youth. In the capitol grounds are monuments to the memory of Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, William T. Sherman, Philip H. Sheridan, Salmon P. Chase, and Edwin M. Stanton, and a beautiful memorial arch (with sculpture by H. A. M‘Neil) to William McKinley.

The city has several parks, including the Franklin of 90 acres, the Goodale of 44 acres, and the Schiller of 24 acres, besides the Olentangy, a well-equipped amusement resort on the banks of the river from which it is named, the Indianola, another amusement resort, and the United States military post and recruiting station, which occupies 80 acres laid out like a park. The state fair grounds of 115 acres adjoin the city, and there is also a beautiful cemetery of 220 acres.

The Ohio State University (non-sectarian and co-educational), opened as the Ohio Agricultural and Mechanical College in 1873, and reorganized under its present name in 1878, is 3 m. north of the capitol. It includes colleges of arts, philosophy and science, of education (for teachers), of engineering, of law, of pharmacy, of agriculture and domestic science, and of veterinary medicine. It occupies a campus of 110 acres, has an adjoining farm of 325 acres, and 18 buildings devoted to instruction, 2 dormitories, and a library containing (1906) 67,709 volumes, besides excellent museums of geology, zoology, botany and archaeology and history, the last being owned jointly by the university and by 747 the state archaeological and historical society. In 1908 the faculty numbered 175, and the students 2277. The institution owed its origin to federal land grants; it is maintained by the state, the United States, and by small fees paid by the students; tuition is free in all colleges except the college of law. The government of the university is vested in a board of trustees appointed by the governor of the state for a term of seven years. The first president of the institution (from 1873 to 1881) was the distinguished geologist, Edward Orton (1829-1899), who was professor of geology from 1873 to 1899.

Other institutions of learning are the Capital University and Evangelical Lutheran Theological Seminary (Theological Seminary opened in 1830; college opened as an academy in 1850), with buildings just east of the city limits; Starling Ohio Medical College, a law school, a dental school and an art institute. Besides the university library, there is the Ohio state library occupying a room in the capitol and containing in 1908 126,000 volumes, including a “travelling library” of about 36,000 volumes, from which various organizations in different parts of the state may borrow books; the law library of the supreme court of Ohio, containing complete sets of English, Scottish, Irish, Canadian, United States and state reports, statutes and digests; the public school library of about 68,000 volumes, and the public library (of about 55,000), which is housed in a marble and granite building completed in 1906.

Columbus is near the Ohio coal and iron-fields, and has an extensive trade in coal, but its largest industrial interests are in manufactures, among which the more important are foundry and machine-shop products (1905 value, $6,259,579); boots and shoes (1905 value, $5,425,087, being more than one-sixtieth of the total product value of the boot and shoe industry in the United States, and being an increase from $359,000 in 1890); patent medicines and compounds (1905 value, $3,214,096); carriages and wagons (1905 value, $2,197,960); malt liquors (1905 value, $2,133,955); iron and steel; regalia and society emblems; steam-railway cars, construction and repairing; and oleo-margarine. In 1905 the city’s factory products were valued at $40,435,531, an increase of 16.4% in five years. Immediately outside the city limits in 1905 were various large and important manufactories, including railway shops, foundries, slaughter-houses, ice factories and brick-yards. In Columbus there is a large market for imported horses. Several large quarries also are adjacent to the city.

The waterworks are owned by the municipality. In 1904-1905 the city built on the Scioto river a concrete storage dam, having a capacity of 5,000,000,000 gallons, and in 1908 it completed the construction of enormous works for filtering and softening the water-supply, and of works for purifying the flow of sewage—the two costing nearly $5,000,000. The filtering works include 6 lime saturators, 2 mixing or softening tanks, 6 settling basins, 10 mechanical filters and 2 clear-water reservoirs. A large municipal electric-lighting plant was completed in 1908.

The first permanent settlement within the present limits of the city was established in 1797 on the west bank of the Scioto, was named Franklinton, and in 1803 was made the county-seat. In 1810 four citizens of Franklinton formed an association to secure the location of the capital on the higher ground of the east bank; in 1812 they were successful and the place was laid out while still a forest. Four years later, when the legislature held its first session here, the settlement was incorporated as the Borough of Columbus. In 1824 the county-seat was removed here from Franklinton; in 1831 the Columbus branch of the Ohio Canal was completed; in 1834 the borough was made a city; by the close of the same decade the National Road extending from Wheeling to Indianapolis and passing through Columbus was completed; in 1871 most of Franklinton, which was never incorporated, was annexed, and several other annexations followed.

See J. H. Studer, Columbus, Ohio; its History and Resources (Columbus, 1873); A. E. Lee, History of the City of Columbus, Ohio (New York, 1892).

COLUMELLA, LUCIUS JUNIUS MODERATUS, of Gades, writer on agriculture, contemporary of Seneca the philosopher, flourished about the middle of the 1st century A.D. His extant works treat, with great fulness and in a diffuse but not inelegant style which well represents the silver age, of the cultivation of all kinds of corn and garden vegetables, trees, flowers, the vine, the olive and other fruits, and of the rearing of cattle, birds, fishes and bees. They consist of the twelve books of the De re rustica (the tenth, which treats of gardening, being in dactylic hexameters in imitation of Virgil), and of a book De arboribus, the second book of an earlier and less elaborate work on the same subject.

The best complete edition is by J. G. Schneider (1794). Of a new edition by K. J. Lundström, the tenth book appeared in 1902 and De arboribus in 1897. There are English translations by R. Bradley (1725), and anonymous (1745); and treatises, De Columellae vita et scriptis, by V. Barberet (1887), and G. R. Becher (1897), a compact dissertation with notes and references to authorities.

COLUMN (Lat. columna), in architecture, a vertical support consisting of capital, shaft and base, used to carry a horizontal beam or an arch. The earliest example in wood (2684 B.C.) was that found at Kahun in Egypt by Professor Flinders Petrie, which was fluted and stood on a raised base, and in stone the octagonal shafts of the early temple at Deir-el-Bahri (c. 2850). In the tombs at Beni Hasan (2723 B.C.) are columns of two kinds, the octagonal or polygonal shaft, and the reed or lotus column, the horizontal section of which is a quatrefoil. This became later the favourite type, but it was made circular on plan. In all these examples the column rests on a stone base. (See also Capital and Order.)

The column was employed in Assyria in small structures only, such as pavilions or porticoes. In Persia the column, employed to carry timber superstructures only, was very lofty, being sometimes 12 diameters high; the shaft was fluted, the number of flutes varying from 30 to 52.

The earliest example of the Greek column is that represented in the temple fresco at Cnossus (c. 1600 B.C.), of which portions have been found. The columns were in cypress wood raised on a stone base and tapered downwards.1 The same, though to a less degree, is found in the stone semi-detached columns which flank the doorway of the Tomb of Agamemnon at Mycenae; the shafts of these columns were carved with the chevron design.

The earliest Greek columns in stone as isolated features are those of the Temple of Apollo at Syracuse (early 7th century B.C.) the shafts of which were monoliths, but as a rule the Greek columns were all built of drums, sometimes as many as ten or twelve. There was no base to the Doric column, but the shafts were fluted, 20 flutes being the usual number. In the Archaic Temple of Diana at Ephesus there were 52 flutes. In the later examples of the Ionic order the shaft had 24 flutes. In the Roman temples the shafts were very often monoliths.

Columns were occasionally used as supports for figures or other features. The Naxian column at Delphi of the Ionic order carried a sphinx. The Romans employed columns in various ways: the Trajan and the Antonine columns carried figures of the two emperors; the columna rostrata (260 B.C.) in the Forum was decorated with the beaks of ships and was a votive column, the miliaria column marked the centre of Rome from which all distances were measured. In the same way the column in the Place Vendôme in Paris carries a statue of Napoleon I.; the monument of the Fire of London, a finial with flames sculptured on it; the duke of York’s column (London), a statue of the duke of York.

With the exception of the Cretan and Mycenaean, all the shafts of the classic orders tapered from the bottom upwards, and about one-third up the column had an increment, known as the entasis, to correct an optical illusion which makes tapering shafts look concave; the proportions of diameter to height varied with the order employed. Thus, broadly speaking, a Roman Doric column will be eight, a Roman Ionic nine, a Corinthian 748 ten diameters in height. Except in rare cases, the columns of the Romanesque and Gothic styles were of equal diameter at top and bottom, and had no definite dimensions as regards diameter and height. They were also grouped together round piers which are known as clustered piers. When of exceptional size, as in Gloucester and Durham cathedrals, Waltham Abbey and Tewkesbury, they are generally called “pillars,” which was apparently the medieval term for column. The word columna, employed by Vitruvius, was introduced into England by the Italian writers of the Revival.

In the Renaissance period columns were frequently banded, the bands being concentric with the column as in France, and occasionally richly carved as in Philibert De L’Orme’s work at the Tuileries. In England Inigo Jones introduced similar features, but with square blocks sometimes rusticated, a custom lately revived in England, but of which there are few examples either in Italy or Spain.

The word “column” is used, by analogy with architecture, for any upright body or mass, in chemistry, anatomy, typography, &c.

1 The tree-trunk used as a column was inverted to retain the sap; hence the shape.

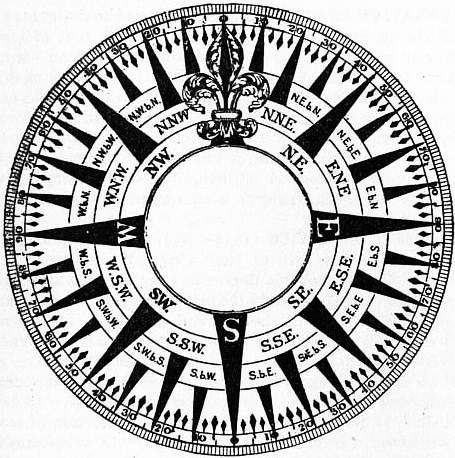

COLURE (from Gr. κόλος, shortened, and οὐρά, tail), in astronomy, either of the two principal meridians of the celestial sphere, one of which passes through the poles and the two solstices, the other through the poles and the two equinoxes; hence designated as solstitial colure and equinoxial colure, respectively.

COLUTHUS, or Colluthus, of Lycopolis in the Egyptian Thebaid, Greek epic poet, flourished during the reign of Anastasius I. (491-518). According to Suidas, he was the author of Calydoniaca (probably an account of the Calydonian boar hunt), Persica (an account of the Persian wars), and Encomia (laudatory poems). These are all lost, but his poem in some 400 hexameters on The Rape of Helen (Άρπαγὴ Έλένης) is still extant, having been discovered by Cardinal Bessarion in Calabria. The poem is dull and tasteless, devoid of imagination, a poor imitation of Homer, and has little to recommend it except its harmonious versification, based upon the technical rules of Nonnus. It related the history of Paris and Helen from the wedding of Peleus and Thetis down to the elopement and arrival at Troy.

The best editions are by Van Lennep (1747), G. F. Schäfer (1825), E. Abel (1880).

COLVILLE, JOHN (c. 1540-1605), Scottish divine and author, was the son of Robert Colville of Cleish, in the county of Kinross. Educated at St Andrews University, he became a Presbyterian minister, but occupied himself chiefly with political intrigue, sending secret information to the English government concerning Scottish affairs. He joined the party of the earl of Gowrie, and took part in the Raid of Ruthven in 1582. In 1587 he for a short time occupied a seat on the judicial bench, and was commissioner for Stirling in the Scottish parliament. In December 1591 he was implicated in the earl of Bothwell’s attack on Holyrood Palace, and was outlawed with the earl. He retired abroad, and is said to have joined the Roman Church. He died in Paris in 1605. Colville was the author of several works, including an Oratio Funebris on Queen Elizabeth, and some political and religious controversial essays. He is said to be the author also of The Historie and Life of King James the Sext (edited by T. Thompson for the Bannatyne Club, Edinburgh, 1825).

Colville’s Original Letters, 1582-1603, published by the Bannatyne Club in 1858, contains a biographical memoir by the editor, David Laing.

COLVIN, JOHN RUSSELL (1807-1857), lieutenant-governor of the North-West Provinces of India during the mutiny of 1857, belonged to an Anglo-Indian family of Scottish descent, and was born in Calcutta on the 29th of May 1807. Passing through Haileybury he entered the service of the East India Company in 1826. In 1836 he became private secretary to Lord Auckland, and his influence over the viceroy has been held partly responsible for the first Afghan war of 1837; but it has since been shown that Lord Auckland’s policy was dictated by the secret committee of the company at home. In 1853 Mr Colvin was appointed lieutenant-governor of the North-West Provinces by Lord Dalhousie. On the outbreak of the mutiny in 1857 he had with him at Agra only a weak British regiment and a native battery, too small a force to make head against the mutineers; and a proclamation which he issued to the natives was censured at the time for its clemency, but it followed the same lines as those adopted by Sir Henry Lawrence and subsequently followed by Lord Canning. Exhausted by anxiety and misrepresentation he died on the 9th of September, his death shortly preceding the fall of Delhi.

His son, Sir Auckland Colvin (1838-1908), followed him in a distinguished career in the same service, from 1858 to 1879. He was comptroller-general in Egypt (1880 to 1882), and financial adviser to the khedive (1883 to 1887), and from 1883 till 1892 was back again in India, first as financial member of council, and then, from 1887, as lieutenant-governor of the North-West Provinces and Oudh. He was created K.C.M.G. in 1881, and K.C.S.I. in 1892, when he retired. He published The Making of Modern Egypt in 1906, and a biography of his father, in the “Rulers of India” series, in 1895. He died at Surbiton on the 24th of March 1908.

COLVIN, SIDNEY (1845- ), English literary and art critic, was born at Norwood, London, on the 18th of June 1845. A scholar of Trinity College, Cambridge, he became a fellow of his college in 1868. In 1873 he was Slade professor of fine art, and was appointed in the next year to the directorship of the Fitzwilliam Museum. In 1884 he removed to London on his appointment as keeper of prints and drawings in the British Museum. His chief publications are lives of Landor (1881) and Keats (1887), in the English Men of Letters series; the Edinburgh edition of R. L. Stevenson’s works (1894-1897); editions of the letters of Keats (1887), and of the Vailima Letters (1899), which R. L. Stevenson chiefly addressed to him; A Florentine Picture-Chronicle (1898), and Early History of Engraving in England (1905). But in the field both of art and of literature, Mr Colvin’s fine taste, wide knowledge and high ideals made his authority and influence extend far beyond his published work.

COLWYN BAY, a watering-place of Denbighshire, N. Wales, on the Irish Sea, 40½ m. from Chester by the London & North-Western railway. Pop. of urban district of Colwyn Bay and Colwyn (1901) 8689. Colwyn Bay has become a favourite bathing-place, being near to, and cheaper than, the fashionable Llandudno, and being a centre for picturesque excursions. Near it is Llaneilian village, famous for its “cursing well” (St Eilian’s, perhaps Aelianus’). The stream Colwyn joins the Gwynnant. The name Colwyn is that of lords of Ardudwy; a Lord Colwyn of Ardudwy, in the 10th century, is believed to have repaired Harlech castle, and is considered the founder of one of the fifteen tribes of North Wales. Nant Colwyn is on the road from Carnarvon to Beddgelert, beyond Llyn y gader (gadair), “chair pool,” and what tourists have fancifully called Pitt’s head, a roadside rock resembling, or thought to resemble, the great statesman’s profile. Near this is Llyn y dywarchen (sod pool), with a floating island.

COLZA OIL, a non-drying oil obtained from the seeds of Brassica campestris, var. oleifera, a variety of the plant which produces Swedish turnips. Colza is extensively cultivated in France, Belgium, Holland and Germany; and, especially in the first-named country, the expression of the oil is an important industry. In commerce colza is classed with rape oil, to which both in source and properties it is very closely allied. It is a comparatively inodorous oil of a yellow colour, having a specific gravity varying from 0.912 to 0.920. The cake left after expression of the oil is a valuable feeding substance for cattle. Colza oil is extensively used as a lubricant for machinery, and for burning in lamps.

COMA (Gr. κῶμα, from κοιμᾶν, to put to sleep), a deep sleep; the term is, however, used in medicine to imply something more than its Greek origin denotes, namely, a complete and prolonged loss of consciousness from which a patient cannot be roused. There are various degrees of coma: in the slighter 749 forms the patient can be partially roused only to relapse again into a state of insensibility; in the deeper states, the patient cannot be roused at all, and such are met with in apoplexy, already described. Coma may arise abruptly in a patient who has presented no pre-existent indication of such a state occurring. Such a condition is called primary coma, and may result from the following causes:—(1) concussion, compression or laceration of the brain from head injuries, especially fracture of the skull; (2) from alcoholic and narcotic poisoning; (3) from cerebral haemorrhage, embolism and thrombosis, such being the causes of apoplexy. Secondary coma may arise as a complication in the following diseases:—diabetes, uraemia, general paralysis, meningitis, cerebral tumour and acute yellow atrophy of the liver; in such diseases it is anticipated, for it is a frequent cause of the fatal termination. The depth of insensibility to stimulus is a measure of the gravity of the symptom; thus the conjunctival reflex and even the spinal reflexes may be abolished, the only sign of life being the respiration and heart-beat, the muscles of the limbs being sometimes perfectly flaccid. A characteristic change in the respiration, known as Cheyne-Stokes breathing occurs prior to death in some cases; it indicates that the respiratory centre in the medulla is becoming exhausted, and is stimulated to action only when the venosity of the blood has increased sufficiently to excite it. The breathing consequently loses its natural rhythm, and each successive breath becomes deeper until a maximum is reached; it then diminishes in depth by successive steps until it dies away completely. The condition of apnoea, or cessation of breathing, follows, and as soon as the venosity of the blood again affords sufficient stimulus, the signs of air-hunger commence; this altered rhythm continues until the respiratory centre becomes exhausted and death ensues.

Coma Vigil is a state of unconsciousness met with in the algide stage of cholera and some other exhausting diseases. The patient’s eyes remain open, and he may be in a state of low muttering delirium; he is entirely insensible to his surroundings, and neither knows nor can indicate his wants.

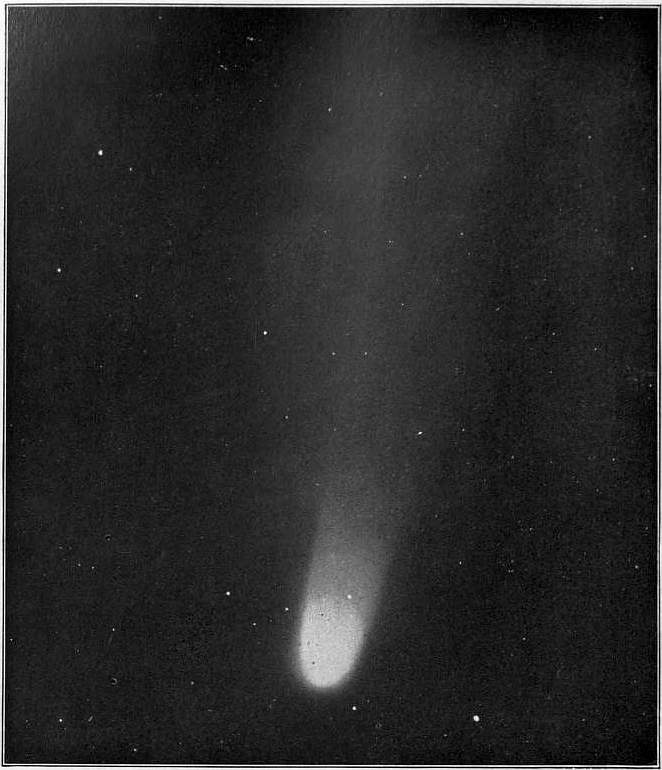

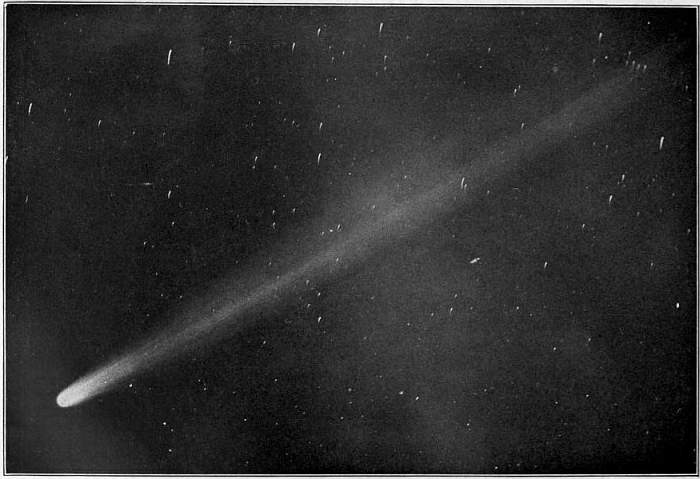

There is a distinct word “coma” (Gr. κόμη, hair), which is used in astronomy for the envelope of a comet, and in botany for a tuft.

COMA BERENICES (“Berenice’s Hair”), in astronomy, a constellation of the northern hemisphere; it was first mentioned by Callimachus, and Eratosthenes (3rd century B.C.), but is not included in the 48 asterisms of Ptolemy. It is said to have been named by Conon, in order to console Berenice, queen of Ptolemy Euergetes, for the loss of a lock of her hair, which had been stolen from a temple to Venus. This constellation is sometimes, but wrongly, attributed to Tycho Brahe. The most interesting member of this group is 24 Comae, a fine, wide double star, consisting of an orange star of magnitude 5½, and a blue star, magnitude 7.

COMACCHIO, a town of Emilia, Italy, in the province of Ferrara, 30 m. E.S.E. by road from the town of Ferrara, on the level of the sea, in the centre of the lagoon of Valli di Comacchio, just N. of the present mouth of the Reno. Pop. (1901) 7944 (town), 10,745 (commune). It is built on no less than thirteen different islets, joined by bridges, and its industries are the fishery, which belongs to the commune, and the salt-works. The seaport of Magnavacca lies 4 m. to the east. Comacchio appears as a city in the 6th century, and, owing to its position in the centre of the lagoons, was an important fortress. It was included in the “donation of Pippin”; it was taken by the Venetians in 854, but afterwards came under the government of the archbishops of Ravenna; in 1299 it came under the dominion of the house of Este. In 1508 it became Venetian, but in 1597 was claimed by Clement VIII. as a vacant fief.

COMANA, a city of Cappadocia [frequently called Chryse or Aurea, i.e. the golden, to distinguish it from Comana in Pontus; mod. Shahr], celebrated in ancient times as the place where the rites of Mā-Enyo, a variety of the great west Asian Nature-goddess, were celebrated with much solemnity. The service was carried on in a sumptuous temple with great magnificence by many thousands of hieroduli (temple-servants). To defray expenses, large estates had been set apart, which yielded a more than royal revenue. The city, a mere apanage of the temple, was governed immediately by the chief priest, who was always a member of the reigning Cappadocian family, and took rank next to the king. The number of persons engaged in the service of the temple, even in Strabo’s time, was upwards of 6000, and among these, to judge by the names common on local tombstones, were many of Persian race. Under Caracalla, Comana became a Roman colony, and it received honours from later emperors down to the official recognition of Christianity. The site lies at Shahr, a village in the Anti-Taurus on the upper course of the Sarus (Sihun), mainly Armenian, but surrounded by new settlements of Avshar Turkomans and Circassians. The place has derived importance both in antiquity and now from its position at the eastern end of the main pass of the western Anti-Taurus range, the Kuru Chai, through which passed the road from Caesarea-Mazaca (mod. Kaisarieh) to Melitene (Malatia), converted by Septimius Severus into the chief military road to the eastern frontier of the empire. The extant remains at Shahr include a theatre on the left bank of the river, a fine Roman doorway and many inscriptions; but the exact site of the great temple has not been satisfactorily identified. There are many traces of Severus’ road, including a bridge at Kemer, and an immense number of milestones, some in their original positions, others in cemeteries.

See P. H. H. Massy in Geog. Journ. (Sept. 1905); E. Chantre, Mission en Cappadocie (1898).

COMANA (mod. Gumenek), an ancient city of Pontus, said to have been colonized from Comana in Cappadocia. It stood on the river Iris (Tozanli Su or Yeshil Irmak), and from its central position was a favourite emporium of Armenian and other merchants. The moon-goddess was worshipped in the city with a pomp and ceremony in all respects analogous to those employed in the Cappadocian city. The slaves attached to the temple alone numbered not less than 6000. St John Chrysostom died there on the way to Constantinople from his exile at Cocysus in the Anti-Taurus. Remains of Comana are still to be seen near a village called Gumenek on the Tozanli Su, 7 m. from Tokat, but they are of the slightest description. There is a mound; and a few inscriptions are built into a bridge, which here spans the river, carrying the road from Niksar to Tokat.

COMANCHES, a tribe of North American Indians of Shoshonean stock, so called by the Spaniards, but known to the French as Padoucas, an adaptation of their Sioux name, and among themselves nimenim (people). They number some 1400, attached to the Kiowa agency, Oklahoma. When first met by Europeans, they occupied the regions between the upper waters of the Brazos and Colorado on the one hand, and the Arkansas and Missouri on the other. Until their final surrender in 1875 the Comanches were the terror of the Mexican and Texan frontiers, and were always famed for their bravery. They were brought to nominal submission in 1783 by the Spanish general Anza, who killed thirty of their chiefs. During the 19th century they were always raiding and fighting, but in 1867, to the number of 2500, they agreed to go on a reservation. In 1872 a portion of the tribe, the Quanhada or Staked Plain Comanches, had again to be reduced by military measures.

COMAYAGUA, the capital of the department of Comayagua in central Honduras, on the right bank of the river Ulua, and on the interoceanic railway from Puerto Cortes to Fonseca Bay. Pop. (1900) about 8000. Comayagua occupies part of a fertile valley, enclosed by mountain ranges. Under Spanish rule it was a city of considerable size and beauty, and in 1827 its inhabitants numbered more than 18,000. A fine cathedral, dating from 1715, is the chief monument of its former prosperity, for most of the handsome public buildings erected in the colonial period have fallen into disrepair. The present city chiefly consists of low adobe houses and cane huts, tenanted by Indians. The university founded in 1678 has ceased to exist, but there is a school of jurisprudence. In the neighbourhood are many ancient Indian ruins (see Central America: Archaeology).

Founded in 1540 by Alonzo Caceres, who had been instructed 750 by the Spanish government to find a site for a city midway between the two oceans, Valladolid la Nueva, as the town was first named, soon became the capital of Honduras. It received the privileges of a city in 1557, and was made an episcopal see in 1561. Its decline dates from 1827, when it was burned by revolutionaries; and in 1854 its population had dwindled to 2000. It afterwards suffered through war and rebellion, notably in 1872 and 1873, when it was besieged by the Guatemalans. In 1880 Tegucigalpa (q.v.), a city 37 m. east-south-east, superseded it as the capital of Honduras.

COMB (a word common in various forms to Teut. languages, cf. Ger. Kamm, the Indo-Europ. origin of which is seen in γόμφος, a peg or pin, and Sanskrit, gambhas, a tooth), a toothed article of the toilet used for cleaning and arranging the hair, and also for holding it in place after it has been arranged; the word is also applied, from resemblance in form or in use, to various appliances employed for dressing wool and other fibrous substances, to the indented fleshy crest of a cock, and to the ridged series of cells of wax filled with honey in a beehive. Hair combs are of great antiquity, and specimens made of wood, bone and horn have been found in Swiss lake-dwellings. Among the Greeks and Romans they were made of boxwood, and in Egypt also of ivory. For modern combs the same materials are used, together with others such as tortoise-shell, metal, india-rubber and celluloid. There are two chief methods of manufacture. A plate of the selected material is taken of the size and thickness required for the comb, and on one side of it, occasionally on both sides, a series of fine slits are cut with a circular saw. This method involves the loss of the material cut out between the teeth. The second method, known as “twinning” or “parting,” avoids this loss and is also more rapid. The plate of material is rather wider than before, and is formed into two combs simultaneously, by the aid of a twinning machine. Two pairs of chisels, the cutting edges of which are as long as the teeth are required to be and are set at an angle converging towards the sides of the plate, are brought down alternately in such a way that the wedges removed from one comb form the teeth of the other, and that when the cutting is complete the plate presents the appearance of two combs with their teeth exactly inosculating or dovetailing into each other. In india-rubber combs the teeth are moulded to shape and the whole hardened by vulcanization.

COMBACONUM, or Kumbakonam, a city of British India, in the Tanjore district of Madras, in the delta of the Cauvery, on the South Indian railway, 194 m. from Madras. Pop. (1901) 59,623, showing an increase of 10% in the decade. It is a large town with wide and airy streets, and is adorned with pagodas, gateways and other buildings of considerable pretension. The great gopuram, or gate-pyramid, is one of the most imposing buildings of the kind, rising in twelve stories to a height of upwards of 100 ft., and ornamented with a profusion of figures of men and animals formed in stucco. One of the water-tanks in the town is popularly reputed to be filled with water admitted from the Ganges every twelve years by a subterranean passage 1200 m. long; and it consequently forms a centre of attraction for large numbers of devotees. The city is historically interesting as the capital of the Chola race, one of the oldest Hindu dynasties of which any traces remain, and from which the whole coast of Coromandel, or more properly Cholamandal, derives its name. It contains a government college. Brass and other metal wares, silk and cotton cloth and sugar are among the manufactures.

COMBE, ANDREW (1797-1847), Scottish physiologist, was born in Edinburgh on the 27th of October 1797, and was a younger brother of George Combe. He served an apprenticeship in a surgery, and in 1817 passed at Surgeons’ Hall. He proceeded to Paris to complete his medical studies, and whilst there he investigated phrenology on anatomical principles. He became convinced of the truth of the new science, and, as he acquired much skill in the dissection of the brain, he subsequently gave additional interest to the lectures of his brother George, by his practical demonstrations of the convolutions. He returned to Edinburgh in 1819 with the intention of beginning practice; but being attacked by the first symptoms of pulmonary disease, he was obliged to seek health in the south of France and in Italy during the two following winters. He began to practise in 1823, and by careful adherence to the laws of health he was enabled to fulfil the duties of his profession for nine years. During that period he assisted in editing the Phrenological Journal and contributed a number of articles to it, defended phrenology before the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh, published his Observations on Mental Derangement (1831), and prepared the greater portion of his Principles of Physiology Applied to Health and Education, which was issued in 1834, and immediately obtained extensive public favour. In 1836 he was appointed physician to Leopold I., king of the Belgians, and removed to Brussels, but he speedily found the climate unsuitable and returned to Edinburgh, where he resumed his practice. In 1836 he published his Physiology of Digestion, and in 1838 he was appointed one of the physicians extraordinary to the queen in Scotland. Two years later he completed his Physiological and Moral Management of Infancy, which he believed to be his best work and it was his last. His latter years were mostly occupied in seeking at various health resorts some alleviation of his disease; he spent two winters in Madeira, and tried a voyage to the United States, but was compelled to return within a few weeks of the date of his landing at New York. He died at Gorgie, near Edinburgh, on the 9th of August 1847.

His biography, written by George Combe, was published in 1850.

COMBE, GEORGE (1788-1858), Scottish phrenologist, elder brother of the above, was born in Edinburgh on the 21st of October 1788. After attending Edinburgh high school and university he entered a lawyer’s office in 1804, and in 1812 began to practise on his own account. In 1815 the Edinburgh Review contained an article on the system of “craniology” of F. J. Gall and K. Spurzheim, which was denounced as “a piece of thorough quackery from beginning to end.” Combe laughed like others at the absurdities of this so-called new theory of the brain, and thought that it must be finally exploded after such an exposure; and when Spurzheim delivered lectures in Edinburgh, in refutation of the statements of his critic, Combe considered the subject unworthy of serious attention. He was, however, invited to a friend’s house where he saw Spurzheim dissect the brain, and he was so far impressed by the demonstration that he attended the second course of lectures. Investigating the subject for himself, he became satisfied that the fundamental principles of phrenology were true—namely “that the brain is the organ of mind; that the brain is an aggregate of several parts, each subserving a distinct mental faculty; and that the size of the cerebral organ is, caeteris paribus, an index of power or energy of function.” In 1817 his first essay on phrenology was published in the Scots Magazine; and a series of papers on the same subject appeared soon afterwards in the Literary and Statistical Magazine; these were collected and published in 1819 in book form as Essays on Phrenology, which in later editions became A System of Phrenology. In 1820 he helped to found the Phrenological Society, which in 1823 began to publish a Phrenological Journal. By his lectures and writings he attracted public attention to the subject on the continent of Europe and in America, as well as at home; and a long discussion with Sir William Hamilton in 1827-1828 excited general interest.

His most popular work, The Constitution of Man, was published in 1828, and in some quarters brought upon him denunciations as a materialist and atheist. From that time he saw everything by the light of phrenology. He gave time, labour and money to help forward the education of the poorer classes; he established the first infant school in Edinburgh; and he originated a series of evening lectures on chemistry, physiology, history and moral philosophy. He studied the criminal classes, and tried to solve the problem how to reform as well as to punish them; and he strove to introduce into lunatic asylums a humane system of treatment. In 1836 he offered himself as a candidate for the chair of logic at Edinburgh, but was rejected in favour of Sir William Hamilton. In 1838 he visited America and spent about two years lecturing on phrenology, education and the 751 treatment of the criminal classes. On his return in 1840 he published his Moral Philosophy, and in the following year his Notes on the United States of North America. In 1842 he delivered, in German, a course of twenty-two lectures on phrenology in the university of Heidelberg, and he travelled much in Europe, inquiring into the management of schools, prisons and asylums. The commercial crisis of 1855 elicited his remarkable pamphlet on The Currency Question (1858). The culmination of the religious thought and experience of his life is contained in his work On the Relation between Science and Religion, first publicly issued in 1857. He was engaged in revising the ninth edition of the Constitution of Man when he died at Moor Park, Farnham, on the 14th of August 1858. He married in 1833 Cecilia Siddons, a daughter of the great actress.

COMBE, WILLIAM (1741-1823), English writer, the creator of “Dr Syntax,” was born at Bristol in 1741. The circumstances of his birth and parentage are somewhat doubtful, and it is questioned whether his father was a rich Bristol merchant, or a certain William Alexander, a London alderman, who died in 1762. He was educated at Eton, where he was contemporary with Charles James Fox, the 2nd Baron Lyttelton and William Beckford. Alexander bequeathed him some £2000—a little fortune that soon disappeared in a course of splendid extravagance, which gained him the nickname of Count Combe; and after a chequered career as private soldier, cook and waiter, he finally settled in London (about 1771), as a law student and bookseller’s hack. In 1776 he made his first success in London with The Diaboliad, a satire full of bitter personalities. Four years afterwards (1780) his debts brought him into the King’s Bench; and much of his subsequent life was spent in prison. His spurious Letters of the Late Lord Lyttelton1 (1780) imposed on many of his contemporaries, and a writer in the Quarterly Review, so late as 1851, regarded these letters as authentic, basing upon them a claim that Lyttelton was “Junius.” An early acquaintance with Lawrence Sterne resulted in his Letters supposed to have been written by Yorick and Eliza (1779). Periodical literature of all sorts—pamphlets, satires, burlesques, “two thousand columns for the papers,” “two hundred biographies”—filled up the next years, and about 1789 Combe was receiving £200 yearly from Pitt, as a pamphleteer. Six volumes of a Devil on Two Sticks in England won for him the title of “the English le Sage”; in 1794-1796 he wrote the text for Boydell’s History of the River Thames; in 1803 he began to write for The Times. In 1809-1811 he wrote for Ackermann’s Political Magazine the famous Tour of Dr Syntax in search of the Picturesque (descriptive and moralizing verse of a somewhat doggerel type), which, owing greatly to Thomas Rowlandson’s designs, had an immense success. It was published separately in 1812 and was followed by two similar Tours, “in search of Consolation,” and “in search of a Wife,” the first Mrs Syntax having died at the end of the first Tour. Then came Six Poems in illustration of drawings by Princess Elizabeth (1813), The English Dance of Death (1815-1816), The Dance of Life (1816-1817), The Adventures of Johnny Quae Genus (1822)—all written for Rowlandson’s caricatures; together with Histories of Oxford and Cambridge, and of Westminster Abbey for Ackermann; Picturesque Tours along the Rhine and other rivers, Histories of Madeira, Antiquities of York, texts for Turner’s Southern Coast Views, and contributions innumerable to the Literary Repository. In his later years, notwithstanding a by no means unsullied character, Combe was courted for the sake of his charming conversation and inexhaustible stock of anecdote. He died in London on the 19th of June 1823.

Brief obituary memoirs of Combe appeared in Ackermann’s Literary Repository and in the Gentleman’s Magazine for August 1823; and in May 1859 a list of his works, drawn up by his own hand, was printed in the latter periodical. See also Diary of H. Crabb Robinson, Notes and Queries for 1869.

1 Thomas, 2nd Baron Lyttelton (1744-1779), commonly known as the “wicked Lord Lyttelton,” was famous for his abilities and his libertinism, also for the mystery attached to his death, of which it was alleged he was warned in a dream three days before the event.

COMBE, or Coomb, a term particularly in use in south-western England for a short closed-in valley, either on the side of a down or running up from the sea. It appears in place-names as a termination, e.g. Wiveliscombe, Ilfracombe, and as a prefix, e.g. Combemartin. The etymology of the word is obscure, but “hollow” seems a common meaning to similar forms in many languages. In English “combe” or “cumb” is an obsolete word for a “hollow vessel,” and the like meaning attached to Teutonic forms kumm and kumme. The Welsh cwm, in place-names, means hollow or valley, with which may be compared cum in many Scots place-names. The Greek κύμβη also means a hollow vessel, and there is a French dialect word combe meaning a little valley.

COMBERMERE, STAPLETON COTTON, 1st Viscount (1773-1865), British field-marshal and colonel of the 1st Life Guards, was the second son of Sir Robert Salusbury Cotton of Combermere Abbey, Cheshire, and was born on the 14th of November 1773, at Llewenny Hall in Denbighshire. He was educated at Westminster School, and when only sixteen obtained a second lieutenancy in the 23rd regiment (Royal Welsh Fusiliers). A few years afterwards (1793) he became by purchase captain in the 6th Dragoon Guards, and he served in this regiment during the campaigns of the duke of York in Flanders. While yet in his twentieth year, he joined the 25th Light Dragoons (subsequently 22nd) as lieutenant-colonel, and, while in attendance with his regiment on George III. at Weymouth, he became a great favourite of the king. In 1796 he went with his regiment to India, taking part en route in the operations in Cape Colony (July-August 1796), and in 1799 served in the war with Tippoo Sahib, and at the storming of Seringapatam. Soon after this, having become heir to the family baronetcy, he was, at his father’s desire, exchanged into a regiment at home, the 16th Light Dragoons. He was stationed in Ireland during Emmett’s insurrection, became colonel in 1800, and major-general five years later. From 1806 to 1814 he was M.P. for Newark. In 1808 he was sent to the seat of war in Portugal, where he shortly rose to the position of commander of Wellington’s cavalry, and it was here that he most displayed that courage and judgment which won for him his fame as a cavalry officer. He succeeded to the baronetcy in 1809, but continued his military career. His share in the battle of Salamanca (22nd of July 1812) was especially marked, and he received the personal thanks of Wellington. The day after, he was accidentally wounded. He was now a lieutenant-general in the British army and a K.B., and on the conclusion of peace (1814) was raised to the peerage under the style of Baron Combermere. He was not present at Waterloo, the command, which he expected, and bitterly regretted not receiving, having been given to Lord Uxbridge. When the latter was wounded Cotton was sent for to take over his command, and he remained in France until the reduction of the allied army of occupation. In 1817 he was appointed governor of Barbadoes and commander of the West Indian forces. From 1822 to 1825 he commanded in Ireland. His career of active service was concluded in India (1826), where he besieged and took Bhurtpore—a fort which twenty-two years previously had defied the genius of Lake and was deemed impregnable. For this service he was created Viscount Combermere. A long period of peace and honour still remained to him at home. In 1834 he was sworn a privy councillor, and in 1852 he succeeded Wellington as constable of the Tower and lord lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets. In 1855 he was made a field-marshal and G.C.B. He died at Clifton on the 21st of February 1865. An equestrian statue in bronze, the work of Baron Marochetti, was raised in his honour at Chester by the inhabitants of Cheshire. Combermere was succeeded by his only son, Wellington Henry (1818-1891), and the viscountcy is still held by his descendants.

See Viscountess Combermere and Captain W. W. Knollys, The Combermere Correspondence (London, 1866).

COMBES, [JUSTIN LOUIS] ÉMILE (1835- ), French statesman, was born at Roquecourbe in the department of the Tarn. He studied for the priesthood, but abandoned the idea before ordination, and took the diploma of doctor of letters (1860), 752 then he studied medicine, taking his degree in 1867, and setting up in practice at Pons in Charente-Inférieure. In 1881 he presented himself as a political candidate for Saintes, but was defeated. In 1885 he was elected to the senate by the department of Charente-Inférieure. He sat in the Democratic left, and was elected vice-president in 1893 and 1894. The reports which he drew up upon educational questions drew attention to him, and on the 3rd of November 1895 he entered the Bourgeois cabinet as minister of public instruction, resigning with his colleagues on the 21st of April following. He actively supported the Waldeck-Rousseau ministry, and upon its retirement in 1903 he was himself charged with the formation of a cabinet. In this he took the portfolio of the Interior, and the main energy of the government was devoted to the struggle with clericalism. The parties of the Left in the chamber, united upon this question in the Bloc republicain, supported Combes in his application of the law of 1901 on the religious associations, and voted the new bill on the congregations (1904), and under his guidance France took the first definite steps toward the separation of church and state. He was opposed with extreme violence by all the Conservative parties, who regarded the secularization of the schools as a persecution of religion. But his stubborn enforcement of the law won him the applause of the people, who called him familiarly le petit père. Finally the defection of the Radical and Socialist groups induced him to resign on the 17th of January 1905, although he had not met an adverse vote in the Chamber. His policy was still carried on; and when the law of the separation of church and state was passed, all the leaders of the Radical parties entertained him at a noteworthy banquet in which they openly recognized him as the real originator of the movement.

COMBINATION (Lat. combinare, to combine), a term meaning an association or union of persons for the furtherance of a common object, historically associated with agreements amongst workmen for the purpose of raising their wages. Such a combination was for a long time expressly prohibited by statute. See Trade Unions; also Conspiracy and Strikes and Lock Outs.

COMBINATORIAL ANALYSIS. The Combinatorial Analysis, as it was understood up to the end of the 18th century, was of limited scope and restricted application. P. Nicholson, in his Essays on the Combinatorial Analysis, published Historical Introduction. in 1818, states that “the Combinatorial Analysis is a branch of mathematics which teaches us to ascertain and exhibit all the possible ways in which a given number of things may be associated and mixed together; so that we may be certain that we have not missed any collection or arrangement of these things that has not been enumerated.” Writers on the subject seemed to recognize fully that it was in need of cultivation, that it was of much service in facilitating algebraical operations of all kinds, and that it was the fundamental method of investigation in the theory of Probabilities. Some idea of its scope may be gathered from a statement of the parts of algebra to which it was commonly applied, viz., the expansion of a multinomial, the product of two or more multinomials, the quotient of one multinomial by another, the reversion and conversion of series, the theory of indeterminate equations, &c. Some of the elementary theorems and various particular problems appear in the works of the earliest algebraists, but the true pioneer of modern researches seems to have been Abraham Demoivre, who first published in Phil. Trans. (1697) the law of the general coefficient in the expansion of the series a + bx + cx² + dx³ + ... raised to any power. (See also Miscellanea Analytica, bk. iv. chap. ii. prob. iv.) His work on Probabilities would naturally lead him to consider questions of this nature. An important work at the time it was published was the De Partitione Numerorum of Leonhard Euler, in which the consideration of the reciprocal of the product (1 - xz) (1 - x²z) (1 - x³z) ... establishes a fundamental connexion between arithmetic and algebra, arithmetical addition being made to depend upon algebraical multiplication, and a close bond is secured between the theories of discontinuous and continuous quantities. (Cf. Numbers, Partition of.) The multiplication of the two powers xa, xb, viz. xa + xb = xa+b, showed Euler that he could convert arithmetical addition into algebraical multiplication, and in the paper referred to he gives the complete formal solution of the main problems of the partition of numbers. He did not obtain general expressions for the coefficients which arose in the expansion of his generating functions, but he gave the actual values to a high order of the coefficients which arise from the generating functions corresponding to various conditions of partitionment. Other writers who have contributed to the solution of special problems are James Bernoulli, Ruggiero Guiseppe Boscovich, Karl Friedrich Hindenburg (1741-1808), William Emerson (1701-1782), Robert Woodhouse (1773-1827), Thomas Simpson and Peter Barlow. Problems of combination were generally undertaken as they became necessary for the advancement of some particular part of mathematical science: it was not recognized that the theory of combinations is in reality a science by itself, well worth studying for its own sake irrespective of applications to other parts of analysis. There was a total absence of orderly development, and until the first third of the 19th century had passed, Euler’s classical paper remained alike the chief result and the only scientific method of combinatorial analysis.

In 1846 Karl G. J. Jacobi studied the partitions of numbers by means of certain identities involving infinite series that are met with in the theory of elliptic functions. The method employed is essentially that of Euler. Interest in England was aroused, in the first instance, by Augustus De Morgan in 1846, who, in a letter to Henry Warburton, suggested that combinatorial analysis stood in great need of development, and alluded to the theory of partitions. Warburton, to some extent under the guidance of De Morgan, prosecuted researches by the aid of a new instrument, viz. the theory of finite differences. This was a distinct advance, and he was able to obtain expressions for the coefficients in partition series in some of the simplest cases (Trans. Camb. Phil. Soc., 1849). This paper inspired a valuable paper by Sir John Herschel (Phil. Trans. 1850), who, by introducing the idea and notation of the circulating function, was able to present results in advance of those of Warburton. The new idea involved a calculus of the imaginary roots of unity. Shortly afterwards, in 1855, the subject was attacked simultaneously by Arthur Cayley and James Joseph Sylvester, and their combined efforts resulted in the practical solution of the problem that we have to-day. The former added the idea of the prime circulator, and the latter applied Cauchy’s theory of residues to the subject, and invented the arithmetical entity termed a denumerant. The next distinct advance was made by Sylvester, Fabian Franklin, William Pitt Durfee and others, about the year 1882 (Amer. Journ. Math. vol. v.) by the employment of a graphical method. The results obtained were not only valuable in themselves, but also threw considerable light upon the theory of algebraic series. So far it will be seen that researches had for their object the discussion of the partition of numbers. Other branches of combinatorial analysis were, from any general point of view, absolutely neglected. In 1888 P. A. MacMahon investigated the general problem of distribution, of which the partition of a number is a particular case. He introduced the method of symmetric functions and the method of differential operators, applying both methods to the two important subdivisions, the theory of composition and the theory of partition. He introduced the notion of the separation of a partition, and extended all the results so as to include multipartite as well as unipartite numbers. He showed how to introduce zero and negative numbers, unipartite and multipartite, into the general theory; he extended Sylvester’s graphical method to three dimensions; and finally, 1898, he invented the “Partition Analysis” and applied it to the solution of novel questions in arithmetic and algebra. An important paper by G. B. Mathews, which reduces the problem of compound partition to that of simple partition, should also be noticed. This is the problem which was known to Euler and his contemporaries as “The Problem of the Virgins,” or “the Rule of Ceres”; it is only now, nearly 200 years later, that it has been solved.

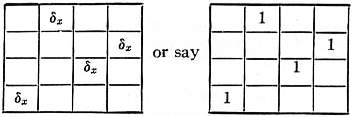

The most important problem of combinatorial analysis is connected with the distribution of objects into classes. A number n may be regarded as enumerating n similar objects; it is then said to be unipartite. On the other hand, if the Fundamental problem. objects be not all similar they cannot be effectively enumerated by a single integer; we require a succession of integers. If the objects be p in number of one kind, q of a second kind, r of a third, &c., the enumeration is given by the succession pqr... which is termed a multipartite number, and written,

pqr...,

where p + q + r + ... = n. If the order of magnitude of the numbers p, q, r, ... is immaterial, it is usual to write them in descending order of magnitude, and the succession may then be termed a partition of the number n, and is written (pqr...). The succession of integers thus has a twofold signification: (i.) as a multipartite number it may enumerate objects of different kinds; (ii.) it may be viewed as a partitionment into separate parts of a unipartite number. We may say either that the objects are represented by the multipartite number pqr..., or that they are defined by the partition (pqr...) of the unipartite number n. Similarly the classes into which they are distributed may be m in number all similar; or they may be p1 of one kind, q1 of a second, r1 of a third, &c., where p1 + q1 + r1 + ... = m. We may thus denote the classes either by the multipartite numbers p1q1r1..., or by the partition (p1q1r1...) of the unipartite number m. The distributions to be considered are such that any number of objects may be in any one class subject to the restriction that no class is empty. Two cases arise. If the order of the objects in a particular class is immaterial, the class is termed a parcel; if the order is material, the class is termed a group. The distribution into parcels is alone considered here, and the main problem is the enumeration of the distributions of objects defined by the partition (pqr...) of the number n into parcels defined by the partition (p1q1r1...) of the number m. (See “Symmetric Functions and the Theory of Distributions,” Proc. London Mathematical Society, vol. xix.) Three particular cases are of great importance. Case I. is the “one-to-one distribution,” in which the number of parcels is equal to the number of objects, and one object is distributed in each parcel. Case II. is that in which the parcels are all different, being defined by the partition (1111...), conveniently written (1m); this is the theory of the compositions of unipartite and multipartite numbers. Case III. is that in which the parcels are all similar, being defined by the partition (m); this is the theory of the partitions of unipartite and multipartite numbers. Previous to discussing these in detail, it is necessary to describe the method of symmetric functions which will be largely utilized.

Let α, β, γ, ... be the roots of the equation

xn - a1xn-1 + a2xn-2 - ... = 0

The symmetric function Σαpβqγr..., where p + q + r + ... = n is, in the partition notation, written (pqr...). Let A(pqr...), (p1q1r1...) denote the number of ways of distributing The distribution function. the n objects defined by the partition (pqr...) into the m parcels defined by the partition (p1q1r1...). The expression

ΣA(pqr...), (p1q1r1...) · (pqr...),

where the numbers p1, q1, r1 ... are fixed and assumed to be in descending order of magnitude, the summation being for every partition (pqr...) of the number n, is defined to be the distribution function of the objects defined by (pqr...) into the parcels defined by (p1q1r1...). It gives a complete enumeration of n objects of whatever species into parcels of the given species.

1. One-to-One Distribution. Parcels m in number (i.e. m = n).—Let hs be the homogeneous product-sum of degree s of Case I. the quantities α, β, γ, ... so that

(1 - αx. 1 - βx. 1 - γx. ...)-1 = 1 + h1x + h2x² + h3x³ + ...

| h1 = Σα = (1) h2 = Σα² + Σαβ = (2) + (1²) h3 = Σα³ + Σα²β + Σαβγ = (3) + (21) + (1³). |

Form the product hp1hq1hr1...

Any term in hp1 may be regarded as derived from p1 objects distributed into p1 similar parcels, one object in each parcel, since the order of occurrence of the letters α, β, γ, ... in any term is immaterial. Moreover, every selection of p1 letters from the letters in αpβqγr ... will occur in some term of hp1, every further selection of q1 letters will occur in some term of hq1, and so on. Therefore in the product hp1hq1hr1 ... the term αpβqγr ..., and therefore also the symmetric function (pqr ...), will occur as many times as it is possible to distribute objects defined by (pqr ...) into parcels defined by (p1q1r1 ...) one object in each parcel. Hence

ΣA(pqr...), (p1q1r1...) · (pqr...) = hp1hq1hr1....

This theorem is of algebraic importance; for consider the simple particular case of the distribution of objects (43) into parcels (52), and represent objects and parcels by small and capital letters respectively. One distribution is shown by the scheme

| A | A | A | A | A | B | B |

| a | a | a | a | b | b | b |

wherein an object denoted by a small letter is placed in a parcel denoted by the capital letter immediately above it. We may interchange small and capital letters and derive from it a distribution of objects (52) into parcels (43); viz.:—

| A | A | A | A | B | B | B |

| a | a | a | a | a | b | b. |

The process is clearly of general application, and establishes a one-to-one correspondence between the distribution of objects (pqr ...) into parcels (p1q1r1 ...) and the distribution of objects (p1q1r1 ...) into parcels (pqr ...). It is in fact, in Case I., an intuitive observation that we may either consider an object placed in or attached to a parcel, or a parcel placed in or attached to an object. Analytically we have

Theorem.—“The coefficient of symmetric function (pqr ...) in the development of the product hp1hq1hr1 ... is equal to the coefficient of symmetric function (p1q1r1 ...) in the development of the product hphqhr ....”

The problem of Case I. may be considered when the distributions are subject to various restrictions. If the restriction be to the effect that an aggregate of similar parcels is not to contain more than one object of a kind, we have clearly to deal with the elementary symmetric functions a1, a2, a3, ... or (1), (1²), (1³), ... in lieu of the quantities h1, h2, h3, ... The distribution function has then the value ap1aq1ar1 ... or (1p1) (1q1) (1r1) ..., and by interchange of object and parcel we arrive at the well-known theorem of symmetry in symmetric functions, which states that the coefficient of symmetric function (pqr ...) in the development of the product ap1aq1ar1 ... in a series of monomial symmetric functions, is equal to the coefficient of the function (p1q1r1 ...) in the similar development of the product apaqar....

The general result of Case I. may be further analysed with important consequences.

Write

| X1 = (1)x1, X2 = (2)x2 + (1²)x1², X3 = (3)x3 + (21)x2x1 + (1³)x1³ |

.......

and generally

Xs = Σ(λμν ...) xλ xμ xν ...

the summation being in regard to every partition of s. Consider the result of the multiplication—

Xp1Xq1Xr1 ... = ΣP xσ1s1 xσ2s2 xσ3s3 ...

To determine the nature of the symmetric function P a few definitions are necessary.

Definition I.—Of a number n take any partition (λ1λ2λ3 ... λs) and separate it into component partitions thus:—

(λ1λ2) (λ3λ4λ5) (λ6) ...

in any manner. This may be termed a separation of the partition, the numbers occurring in the separation being identical with those which occur in the partition. In the theory of symmetric functions the separation denotes the product of symmetric functions—

Σ αλ1 βλ2 Σ αλ3 βλ4 γλ5 Σ αλ6 ...

The portions (λ1λ2), (λ3λ4λ5), (λ6), ... are termed separates, and if λ1 + λ2 = p1, λ3 + λ4 + λ5 = q1, λ6 = r1... be in descending order of magnitude, the usual arrangement, the separation is said to have a species denoted by the partition (p1q1r1 ...) of the number n.

Definition II.—If in any distribution of n objects into n parcels (one object in each parcel), we write down a number ξ, whenever we observe ξ similar objects in similar parcels we will obtain a succession of numbers ξ1, ξ2, ξ3, ..., where (ξ1, ξ2, ξ3 ...) is some partition of n. The distribution is then said to have a specification denoted by the partition (ξ1ξ2ξ3 ...).

Now it is clear that P consists of an aggregate of terms, each of which, to a numerical factor près, is a separation of the partition (sσ11 sσ32 sσ33 ...) of species (p1q1r1 ...). Further, P is the distribution function of objects into parcels denoted by (p1q1r1 ...), subject to the restriction that the distributions have each of them the specification 754 denoted by the partition (sσ11 sσ32 sσ33 ...) Employing a more general notation we may write

Xπ1p1 Xπ2p2 Xπ3p3 ... = ΣP xσ1s1 xσ2s2 xσ3s3 ...

and then P is the distribution function of objects into parcels (pπ11 pπ22 pπ33 ...), the distributions being such as to have the specification (sσ11 sσ22 sσ33 ...). Multiplying out P so as to exhibit it as a sum of monomials, we get a result—

Xπ1p1 Xπ2p2 Xπ3p3 ... = ΣΣθ (λl11 λl22 λl33 ...) xσ1s1 xσ2s2 xσ3s3 ...

indicating that for distributions of specification (sσ11 sσ32 sσ33 ...) there are θ ways of distributing n objects denoted by (λl11 λl22 λl33 ...) amongst n parcels denoted by (pπ11 pπ22 pπ33 ...), one object in each parcel. Now observe that as before we may interchange parcel and object, and that this operation leaves the specification of the distribution unchanged. Hence the number of distributions must be the same, and if

Xπ1p1 Xπ2p2 Xπ3p3 ... = ... + θ (λl11 λl22 λl33 ...) xσ1s1 xσ2s2 xσ3s3 ... + ...

then also

Xl1λ1 Xl2λ2 Xl3λ3 ... = ... + θ (pπ11 pπ22 pπ33 ...) xσ1s1 xσ2s2 xσ3s3 ... + ...

This extensive theorem of algebraic reciprocity includes many known theorems of symmetry in the theory of Symmetric Functions.

The whole of the theory has been extended to include symmetric functions symbolized by partitions which contain as well zero and negative parts.

2. The Compositions of Multipartite Numbers. Parcels denoted by (Im).—There are here no similarities between the parcels. Case II.

Let (π1 π2 π3) be a partition of m.

(pπ11 pπ22 pπ33 ...) a partition of n.

Of the whole number of distributions of the n objects, there will be a certain number such that n1 parcels each contain p1 objects, and in general πs parcels each contain ps objects, where s = 1, 2, 3, ... Consider the product hπ1p1 hπ2p2 hπ3p3 ... which can be permuted in m! / π1!π2!π3! ... ways. For each of these ways hπ1p1 hπ2p2 hπ3p3 ... will be a distribution function for distributions of the specified type. Hence, regarding all the permutations, the distribution function is

| m! | hπ1p1 hπ2p2 hπ3p3 ... |

| π1!π2!π3! ... |

and regarding, as well, all the partitions of n into exactly m parts, the desired distribution function is

| Σ | m! | hπ1p1 hπ2p2 hπ3p3 ... [Σπ = m, Σπ p = n], |

| π1!π2!π3! ... |

that is, it is the coefficient of xn in (h1x + h2x² + h3x³ + ... )m. The value of A (pπ11 pπ22 pπ33 ...) is the coefficient of (pπ11 pπ22 pπ33 ...)xn in the development of the above expression, and is easily shown to have the value

| ( | p1 + m - 1 | ) | π1 | ( | p2 + m - 1 | ) | π2 | ( | p3 + m - 1 | ) | π3 | ... | ||||

| p1 | p2 | p3 | ||||||||||||||

| - | ( | m | ) | ( | p1 + m - 2 | ) | π1 | ( | p2 + m - 2 | ) | π2 | ( | p3 + m - 2 | ) | π3 | ... |

| 1 | p1 | p2 | p3 | |||||||||||||

| + | ( | m | ) | ( | p1 + m - 3 | ) | π1 | ( | p2 + m - 3 | ) | π2 | ( | p3 + m - 3 | ) | π3 | ... |

| 2 | p1 | p2 | p3 | |||||||||||||

| - ... to m terms. | ||||||||||||||||

Observe that when p1 = p2 = p3 = ... = π1 = π2 = π3 ... = 1 this expression reduces to the mth divided differences of 0n. The expression gives the compositions of the multipartite number pπ11 pπ22 pπ33 ... into m parts. Summing the distribution function from m = 1 to m = ∞ and putting x = 1, as we may without detriment, we find that the totality of the compositions is given by (h1 + h2 + h3 + ...) / (1 - h1 - h2 - h3 + ...) which may be given the form (a1 - a2 + a3 - ...) / [1 - 2(a1 - a2 + a3 - ...)] Adding ½ we bring this to the still more convenient form

| ½ | 1 | . |

| 1 - 2(a1 - a2 + a3 - ...) |

Let F (pπ11 pπ22 pπ33 ... ) denote the total number of compositions of the multipartite pπ11 pπ22 pπ33 .... Then ½ · (1 / 1 - 2a) = ½ + Σ F(p)αp, and thence F(p) = 2p - 1. Again ½ · [1 / 1 - 2(α + β - αβ)] = Σ F(p1p2) αp1βp2, and expanding the left-hand side we easily find

| F(p1p2) = 2p1 + p2 - 1 | (p1 + p2)! | - 2p1 + p2 - 2 | (p1 + p2 - 1)! | + 2p1 + p2 - 3 | (p1 + p2 - 2)! | - ... |

| 0! p1! p2! | 1! (p1 - 1)! (p2 - 1)! | 2! (p1 - 2)! (p2 - 2)! |

We have found that the number of compositions of the multipartite p1p2p3 ... ps is equal to the coefficient of symmetric function (p1p2p3 ... ps) or of the single term αp11 αp22 αp22 ... αpss in the development according to ascending powers of the algebraic fraction

| ½ · | 1 | . |

| 1 - 2 (Σα1 - Σα1α2 + Σα1α2α3 - ... + (-)S + 1 α1α2α3 ... αs |

This result can be thrown into another suggestive form, for it can be proved that this portion of the expanded fraction

| ½ · | 1 | , |

| {1 - t1 (2α1 + α2 + ... + αs)} {1 - t2 (2α1 + 2α2 + ... + αs)} ... {1 - ts (2α1 + 2α2 + ... + 2αs)} |

which is composed entirely of powers of

t1α1, t2α2, t3α3, ... tsαs

has the expression

| ½ · | 1 | , |

| 1 - 2 (Σt1α1 - Σt1t2α1α2 + Σt1t2t3α1α2α3 - ... + (-)s + 1t1t2 ... tsα1α2 ... αs) |

and therefore the coefficient of αp11 αp22 ... αpss in the latter fraction, when t1, t2, &c., are put equal to unity, is equal to the coefficient of the same term in the product

½ (2α1 + α2 + ... + αs)p1 (2α1 + 2α2 + ... + αs)p2 ... (2α1 + 2α2 + ... + 2αs)ps.

This result gives a direct connexion between the number of compositions and the permutations of the letters in the product αp11 αp22 ... αpss. Selecting any permutation, suppose that the letter ar occurs qr times in the last pr + pr+1 + ... + ps places of the permutation; the coefficient in question may be represented by ½ Σ2q1+q2+ ... +qs, the summation being for every permutation, and since q1 = p1 this may be written

2p1-1 Σ2q1+q2+ ... +qs.

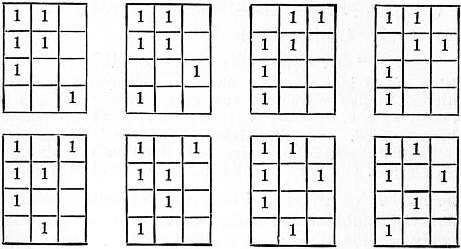

Ex. Gr.—For the bipartite 22, p1 = p2 = 2, and we have the following scheme:—

| α1 | α1 | α2 | α2 | q2 = 2 |

| α1 | α2 | α1 | α2 | = 1 |

| α1 | α2 | α2 | α1 | = 1 |

| α2 | α1 | α1 | α2 | = 1 |

| α2 | α1 | α2 | α1 | = 1 |

| α2 | α2 | α1 | α1 | = 0 |

Hence

F(22) = 2 (2² + 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 2°) = 26.

We may regard the fraction

| ½ · | 1 | , |

| {1 - t1 (2α1 + α2 + ... + αs)} {1 - t2 (2α1 + 2α2 + ... + αs)} ... {1 - ts (2α1 + 2α2 + ... + 2αs)} |

as a redundant generating function, the enumeration of the compositions being given by the coefficient of

(t1α1)p1 (t2α2)p2 ... (tsαs)ps.

The transformation of the pure generating function into a factorized redundant form supplies the key to the solution of a large number of questions in the theory of ordinary permutations, as will be seen later.

[The transformation of the last section involves The theory of permutations. a comprehensive theory of Permutations, which it is convenient to discuss shortly here.

If X1, X2, X3, ... Xn be linear functions given by the matricular relation

| (X1, X2, X3, ... Xn) = | (a11 | a12 | ... | a1n) | (x1, x2, ... xn) |

| a21 | a22 | ... | a2n | ||

| . | . | ... | . | ||

| . | . | ... | . | ||

| an1 | an2 | ... | ann |

that portion of the algebraic fraction,

| 1 | , |

| (1 - s1X1) (1 - s2X2) ... (1 - snXn) |

which is a function of the products s1x1, s2x2, s3x3, ... snxn only is

| 1 |

| |(1 - a11s1x1) (1 - a22s2x2) (1 - a33s3x3) ... (1 - annsnxn)| |

where the denominator is in a symbolic form and denotes on expansion

1 - Σ |a11|s1x1 + Σ |a11a22|s1s2x1x2 - ... + (-)n |a11a22a33 ... ann| s1s2 ... snx1x2 ... xn,

where |a11|, |a11a22|, ... |a11a22, ... ann| denote the several co-axial minors of the determinant

|a11a22 ... ann|

of the matrix. (For the proof of this theorem see MacMahon, “A certain Class of Generating Functions in the Theory of Numbers,” Phil. Trans. R. S. vol. clxxxv. A, 1894). It follows that the coefficient of

xξ11 xξ22 ... xξnn

in the product

(a11x1 + a12x2 + ... + a1nxn)ξ1 (a21x1 + a22x2 + ... + a2nxn)ξ2 ... (an1x1 + an2x2 + ... + annxn)ξn

is equal to the coefficient of the same term in the expansion ascending-wise of the fraction

| 1 | . |

| 1 - Σ |a11|x1 + Σ |a11a22|x1x2 + (-)n |a11a22 ... | x1x2 ... xn |

If the elements of the determinant be all of them equal to unity, we obtain the functions which enumerate the unrestricted permutations of the letters in

xξ11 xξ22 ... xξnn,

viz.

(x1 + x2 + ... - xn)ξ1+ξ2+ ... +ξn

and

| 1 | . |

| 1 - (x1 + x2 + ... + xn) |

Suppose that we wish to find the generating function for the enumeration of those permutations of the letters in xξ11 xξ22 ... xξnn which are such that no letter xs is in a position originally occupied by an x3 for all values of s. This is a generalization of the “Problème des rencontres” or of “derangements.” We have merely to put

a11 = a22 = a33 = ... = ann = 0

and the remaining elements equal to unity. The generating product is

(x2 + x2 + ... + xn)ξ1 (x1 + x3 + ... + xn)ξ2 ... (x1 + x2 + ... + xn-1)ξn,

and to obtain the condensed form we have to evaluate the co-axial minors of the invertebrate determinant—

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ... | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | ... | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | ... | 1 |

| . | . | . | ... | . |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | ... | 0 |

The minors of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd ... nth orders have respectively the values

0

-1

+2

.

.

.

(-)n-1 (n - 1),

therefore the generating function is

| 1 | ; |

| 1 - Σ x1x2 - 2Σ x1x2x3 - ... - sΣ x1x2 ... xs+1 - ... - (n - 1) x1x2 ... xn |

or writing

(x - x1) (x - x2) ... (x - xn) = xn - a1xn-1 + a2xn-2 - ...,

this is

| 1 |

| 1 - a2 - 2a3 - 3a4 - ... - (n - 1) an |

Again, consider the general problem of “derangements.” We have to find the number of permutations such that exactly m of the letters are in places they originally occupied. We have the particular redundant product

(ax1 + x2 + ... + xn)ξ1 (x1 + ax2 + ... + xn)ξ2 ... (x1 + x2 + ... + axn)ξn

in which the sought number is the coefficient of am xξ11 xξ22 ... xξnn. The true generating function is derived from the determinant

| a | 1 | 1 | 1 | . | . | . |

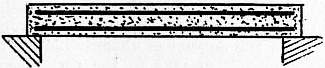

| 1 | a | 1 | 1 | . | . | . |