SPECIAL EDITION

WITH THE WORLD’S

GREAT TRAVELLERS

EDITED BY CHARLES MORRIS

AND OLIVER H. G. LEIGH

Vol. I

Title: With the World's Great Travellers, Volume 1

Editor: Charles Morris

Oliver Herbrand Gordon Leigh

Release date: April 7, 2010 [eBook #31908]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D Alexander and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Copyright 1896 and 1897

BY

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

Copyright 1901

E. R. DuMONT

THE PRODIGAL’S RETURN

THE PRODIGAL’S RETURN

Painting by Spada

| SUBJECT | AUTHOR | PAGE |

| New Dependencies of the United States | Oliver H. G. Leigh | 9 |

| Winter and Summer in New England | Harriet Martineau | 22 |

| Niagara Falls and the Thousand Islands | Charles Morris | 31 |

| From New York to Washington in 1866 | Henry Latham | 39 |

| The Natural Bridge and Tunnel of Virginia | Edward A. Pollard | 49 |

| Plantation Life in War Times | William Howard Russell | 62 |

| Among Florida Alligators | S. C. Clarke | 74 |

| In the Mammoth Cave | Thérèse Yelverton | 83 |

| Down the Ohio and Mississippi | Thomas L. Nichols | 94 |

| From New Orleans to Red River | Frederick Law Olmsted | 104 |

| Winter on the Prairies | G. W. Featherstonhaugh | 114 |

| A Hunter’s Christmas Dinner | J. S. Campion | 124 |

| A Colorado “Round-Up” | Alfred Terry Bacon | 133 |

| Among the Cow-boys | Louis C. Bradford | 141 |

| Hunting the Buffalo | Washington Irving | 147 |

| In the Country of the Sioux | Meriwether Lewis | 157 |

| The Great Falls of the Missouri | William Clarke | 168 |

| Hunting Scenes in Canadian Woods | B. A. Watson | 178 |

| The Grand Falls of Labrador | Henry G. Bryant | 189 |

| Life Among the Esquimaux | William Edward Parry | 200 |

| Fugitives from the Arctic Seas | Elisha Kent Kane | 210 |

| Rescued from Death | W. S. Schley | 220 |

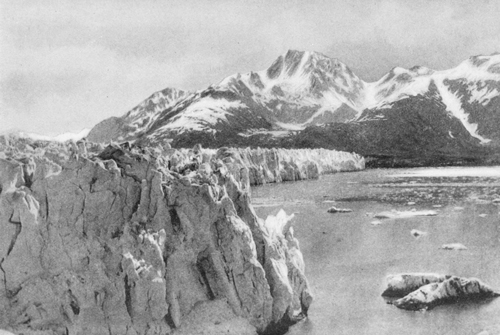

| The Muir Glacier | Septima M. Collis | 230 |

| A Summer Trip to Alaska | James A. Harrison | 239 |

| The Fort William Henry Massacre | Jonathan Carver | 249 |

| The Gaucho and His Horse | Thomas J. Hutchinson | 257 |

| Valparaiso and Its Vicinity | Charles Darwin | 265 |

| An Escape from Captivity | Benjamin F. Bourne | 274 |

VOLUME I

| The Prodigal’s Return | Frontispiece |

| Morro Castle, Havana | 14 |

| Washington Elm, Cambridge | 28 |

| New York and the Brooklyn Bridge | 42 |

| On the Coast of Florida | 78 |

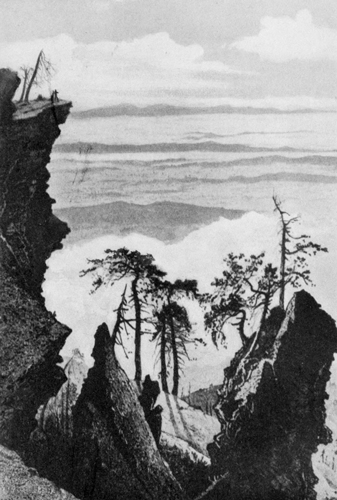

| Sunrise From the Summit of Pike’s Peak | 134 |

| A Kansas Cyclone | 144 |

| The Catskills—Sunrise From South Mountain | 180 |

| Parliament Houses, Ottawa | 198 |

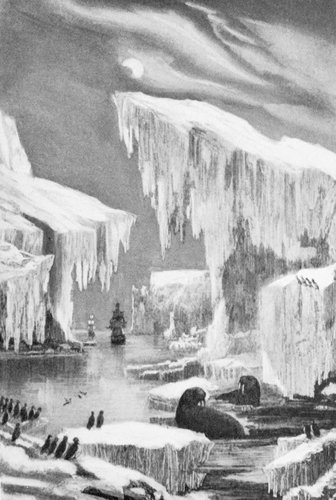

| Winter in the Far North | 214 |

| Muir Glacier, Alaska | 236 |

Next to actual travel, the reading of first-class travel stories by men and women of genius is the finest aid to the broadening of views and enlargement of useful knowledge of men and the world’s ways. It is the highest form of intellectual recreation, with the advantage over fiction-reading of satisfying the wholesome desire for facts. With all our modern enthusiasm for long journeys and foreign travel, now so easy of accomplishment, we see but very little of the great world. The fact that ocean voyages are now called mere “trips” has not made us over-familiar with even our own kinsfolk in our new dependencies. Foreign peoples and lands are still strange to us. Tropic and Arctic lands are as far apart in condition as ever; Europe differs from Asia, America from Africa, as markedly as ever. Man still presents every grade of development, from the lowest savagery to the highest civilization, and our interest in the marvels of nature and art, the variety of plant and animal life, and the widely varied habits and conditions, modes of thought and action, of mankind, is in no danger of losing its zest.

These considerations have guided us in our endeavor to tell the story of the world, alike of its familiar and unfamiliar localities, as displayed in the narratives of those who have seen its every part. Special interest attaches to the stories of those travellers who first gazed upon the wonders and observed the inhabitants of previously unknown lands, and whose descriptions are therefore those of discoverers.

One indisputable advantage belongs to this work over the average record of travel: the reader is not tied down to the perusal of a one-man book. He has the privilege of calling at pleasure upon any one of these eminent travellers to recount his or her exploit, with the certainty of finding they are all in their happiest vein and tell their best stories.

The adventures and discoveries here described are gathered from the four quarters of the globe, and include the famous stories of men no longer living, as well as those of present activity. Many of the articles were formerly published in the exhaustive work entitled, “The World’s Library of Literature, History and Travel” [The J. B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia].

For the rich variety and quality of our material we are indebted to many travellers of note, and to the courtesy of numerous publishers and authors. Among these it is desired to acknowledge particularly indebtedness to the following publishers and works: To Harper and Brothers, for selections from Stanley’s “Through the Dark Continent,” Du Chaillu’s “Equatorial Africa,” Prime’s “Tent-Life in the Holy Land,” Orton’s “The Andes and the Amazon,” and Browne’s “An American Family in Germany.” To Charles Scribner’s Sons: Stanley’s “In Darkest Africa,” Field’s “The Greek Islands,” and Schley’s “The Rescue of Greely.” To G. P. Putnam’s Sons: De Amicis’s “Holland and its People,” Taylor’s “Lands of the Saracens,” and Brace’s “The New West.” To Houghton, Mifflin and Co.: Melville’s “In the Lena Delta,” and Hawthorne’s “Our Old Home.” To Roberts Brothers: Hunt’s “Bits of Travel at Home.” To H. C. Coates and Co.: Leonowen’s “Life and Travel in India.” Equal tribute is offered to the authors who have courteously permitted the use of their material, and in these acknowledgments we include Charles Morris, editor of the above work, and Oliver H. G. Leigh, whose pen has won honors in various fields, for their special contributions to this edition.

[The trend of events makes it certain that our geographical knowledge is going to be enlarged by personal investigation. The boom of Dewey’s big guns sent us to our school-books with mixed feelings as to the practical value of much of our alleged learning. The world suddenly broadened as we gazed in surprise. Hawaii invited itself into the circle of new relations. The near West Indies and the remote Philippines craved peculiar attentions. Whether moved by commercial zeal, official duty or the profitable curiosity of pleasure or scientific investigation, he is in the highest sense a patriotic benefactor of his own country and the land he visits, who devotes his energies to making Americans more intimately acquainted with the communities now linked with the most powerful of nations.]

The scope of holiday travel, or tours of profitable investigation, has been widely extended by the new relationship between the United States and Hawaii, now included in its possessions, and the former Spanish islands over which it exercises a kindly protectorate. Through the usual channels public sentiment is being formed upon the resources and responsibilities of the new dependencies. Many will be attracted to Cuba, Porto Rico, Hawaii, and even to the remote Philippines, by considerations of a practical kind. No truer patriotic motive can inspire the American traveller than the desire to develop the natural resources, and, by consequence, the social welfare of a dependent community [Pg 10]Whether bent on business, pleasure, or official duty in the service of the United States the prospective voyager, and the friends he leaves behind him, will profit by these gatherings from the impressions and experiences of former travellers.

The approach to Havana at daybreak overwhelms the senses with the gorgeous beauties of the sky and landscape. Foul as the harbor may be with city drainage it seems a silvery lake encircled with the charms of Paradise and over-arched with indescribable glories of celestial forms and hues and ever-changing witcheries wrought by the frolicsome sun in his ecstasy of morning release. Strange that where nature most lavishes her wealth of charms and favors, the listlessness of perverse man responds in ungrateful contrasts rather than in harmonies. Havana has the interest of age, with the drawbacks incident to hereditary indifference to progressive change. As in all important cities there are sharp contrasts in its quarters. With long avenues of stately mansions, marble-like and colonnaded, and exquisitely designed courtyards, there are unpaved thoroughfares with an open sewer in the mid-roadway, flanked by tenement houses with a family in each room. Most of Havana’s two hundred thousand citizens live in one-story buildings, lacking conveniences which the poorest American considers necessities. The older streets are mere alleys, about twenty feet wide, of which the sidewalks take up seven. Light and ample ventilation are obtained by grated window-openings without frames or glass. The dwellings and public buildings throughout Cuba are planned to give free passage to every zephyr that wafts relief from the oppressive heat. This is not because the thermometer mounts much higher than it does in the United States, for it never touches the records of our great cities, where a hundred in the shade is not [Pg 11]unknown. From 80 to 50 degrees is the year’s average, and it is this steady continuance of warmth that tries strength and temper.

In the better districts of Havana the driveways are twenty-three feet and the sidewalks about ten feet wide. Politeness keeps native and foreign men hopping up and down the foot deep curb to allow ladies a fair share of elbow-room on the pavements. Your guest-chamber in a well-to-do family residence has probably a window twenty by eight feet, sashless, but with several lace curtains and shutters to suit the weather. The walls are tinted with the Spaniard’s eye for rich color display, the massive furniture is solid carved old mahogany, and the graceful mosquito curtains suggest experiences better left untold. House-rent is high, owing to the heavy taxation, which will doubtless be modified after American administration has put the city in a sanitary condition. Flour used to cost the poorer classes from two to three times its price in the United States.

Before we leave the capital for the interior we must note two or three of the time-mellowed edifices, which give the flavor of old-world mediævalism to the island. The gloomy Morro Castle is familiar in the chronicles of the war. It stands guard at the water-gate of the city, a grim-visaged dungeon that echoes with the despairing groans of more victims of cruel oppression than can ever be counted. A more cheerful landmark is the old Cathedral, looking as if it dates further back than 1724, cooped up in its crowded quarter. Here rest the ashes of Columbus, say the faithful, and they are probably right. He died in Spain May 20, 1506. In 1856, his bones were brought to San Domingo and from there were transferred in January, 1796, to this Cathedral, where they rest in the wall behind the bust and tablet to his memory. The [Pg 12]elaborate monument under the dome is a splendid work of art. Four life-size sculptured ecclesiastics bear a sarcophagus on their shoulders. There is also a supposed portrait bust on a mural tablet.

The Spanish element in the city is popularly said to be an exaggeration of the old country quality. The Tacon theatre holds three thousand people. Cafés and restaurants abound, and never lack customers. Some day Havana may be transformed into a nearer Paris, with a larger American colony than haunts the dearer city across the sea. Cuba has nearly the same area as England. The Province of Havana has a population of 452,000, of whom 107,500 are black. Large tracts of the island have not yet been explored. The long years of intermittent battling between the Cubans and Spaniards have grievously hindered progress in all directions. Nature is bountiful beyond belief, yet her overtures have been scorned, partly because of native inertia, but mainly through dread of loss. Both sides have been guilty of laying waste vast areas of cultivated land, ruining its husbandmen, capitalists and laborers alike. The millennium bids fair to come before long. Peace is restoring confidence. The reign of justice will bring capital and labor back to the soil and tempt American migration to the cities and towns, where life can be lived so enjoyably by those who bring modern methods and ideas to bear in the task of converting a man-made wilderness into an alluring paradise. Not long ago an American bought seventy acres of ground in Trinidad valley, which he cleared and planted at a cost of $3,070 for the first year. The second year’s cultivation cost $1,120. He made it a banana orchard. At the end of the second year he had realized $30,680 net profit by the sale of his crop of 54,000 bunches.

[Pg 13]Havana has the cosmopolitan air. Clubs, cafés, and entertainments abound and flourish. Its suburbs and nearby towns afford all the allurements the modern city-man seeks in country life. The rural charms of Marianao are unsurpassed in any land. Ornately simple architecture marks the columned houses of its best street. Around it are the cosy cottages in their luxuriant gardens, and beyond these the open country, a veritable Eden of foliage, flowers and fruit. In one spot a famous old banyan tree has thrown out its limbs, thrusting them deep into the soil till they have sprouted and spread over a five-acre field.

As we traverse the garden landscape in any settled part of the island, and in Porto Rico, we note the habits of the rustic native in his interesting simplicity. Poor enough in all conscience, but wonderfully contented with his crust of bread, his cigarette, the family pig, bananas for the pickaninnies’ staple fare, and the frequent sips of rum which are to the West Indian laborer what beefsteak is to the American toiler. He is by no means a drunkard, and if he lacks book-learning he excels in some civic virtues of the homelier kind, and is not extravagant in his tailor-bills. The children’s costume is usually that of Eve before the fall, and the apparel of a goodly family might be bought for the price of a dude’s red vest.

Cock-fighting is the favorite native sport. It is encountered at any hour, anywhere. There are other sports, such as boar hunts, spearing fish, not to mention that of killing tarantulas, sand-flies, land-crabs, and the gentle crocodile. The thousand miles of steam railway in Cuba are unevenly distributed. From Havana the trip through Pinar del Rio gives an astounding revelation of the wealth of forest and soil and mines. Devastated as so much of this country was during the long years of dragging war, [Pg 14]its charms of scenery and possibilities of development will work its speedy salvation. A single acre of choice land has produced $3,000 worth of tobacco.

Two crops of corn and two of strawberries grow each year, vegetables and many fruits are superabundant, yet wheat and flour are imported, and cotton, besides other important staples, can be successfully cultivated.

Journeying to the charming Isle of Pines, and then south and east through Matanzas, Santa Clara, and Puerto Principe to Santiago, there is the same invitation of Nature to come and enjoy all that makes earth lovely. The island is dotted with towns large and small having much the same characteristics as Havana. Her virgin forests have some of the richest woods known to commerce. Her hills hold stores of iron, copper, coal and other minerals. Her soil is ready to yield many-fold to the courageous cultivator. When the swords have been turned into plough-shares and the spears to pruning-hooks, there will come a new day for the native Cuban. He will feel himself liberated from the hindering rancors and jealousies, inevitable in the light of recent history, which alone now stand between his beautiful island and the prosperity that hovers, waiting his encouragement to alight. Then the traveller will return with reports of Havana rejuvenated, her harbor dredged and purified, her highways paved, homes made healthy and the whole island lifted to the higher and happier plane that will give the Pearl of the Antilles its rightful setting among the other gems of God’s earth.

MORRO CASTLE, HAVANA

MORRO CASTLE, HAVANA

Porto Rico, the “rich port,” so named by Columbus, came gladly under the American flag. Its population of about 900,000 has had a sorry time for three hundred years. They have been steeped in spiritless poverty from first to last, so used to the oppressor’s yoke that ambition seems to have been crushed. Yet their island is an earthly paradise,[Pg 15] save for its rain-storms and occasional droughts. It is rich in undeveloped mineral deposits and splendid forests. Nature has helped to discourage native effort by providing the means of sustenance over-lavishly, in one sense. The people scattered through the interior find everything ready grown to hand. The bulk of the population throng the shore areas and are as listlessly happy with the minimum of life’s necessaries as are the animals.

Spain has left its mark upon the island, a mark representing a civilization not to be sneered at, though not of the modern stamp. Range through the island’s lovely valleys, struggle up its mountain slopes to isolated hamlets where primitive life lingers in all its bewildering unloveliness; thread the rude thoroughfare of its picturesque towns, and you will come upon replicas of the familiar Spanish church, the symbol and centre of an ever potent influence for good. With all its faults, this local haven of peace and good cheer has tempered the lot of generations that never fully realized the hopelessness of their fate. A venerable church peeping out of a leafy glade gives a touch of poetic grace to the landscape. It is something, perhaps, though not very much, that sectarian animosities do not embitter the easy minds of these peasants, who dwell together in enviable fraternity.

Porto Rico is only one of some thirteen hundred islands in the West Indies that are now in the American fold. It has several large towns that will intensely interest the traveller. San Juan, with twenty-five thousand inhabitants, is the principal city. A fine old military road runs from it across the mountains to Ponce, on the south shore. It is twenty feet wide, hard and dustless, winds along through eighty miles of scenery unsurpassed in any country, though the island is only forty miles directly across.

[Pg 16]Every considerable town has its cathedral. That at Sabana Grande was built in 1610. Some of them have gorgeous altars and precious paintings. In one little church the figure of the Blessed Virgin is of pure gold. Another has an altar of silver.

The retail stores in the cities make little or no front display. The store is virtually a sample room, with extensive warehouses in the rear. Town life is, in its way, Parisian. The cathedral stands in a square or park, the promenade and gossiping ground for both sexes. The midday siesta is the rule, a two hours’ cessation from the round of toil. The evenings are given to music and dancing, or the merry chatter of groups as they enjoy the strains of the band. The lacy mantilla adds grace to the generally captivating beauty of the women, as they cunningly drape it over their heads to take the place of hats. The palms and cocoa-nut trees, the clusters of coffee-trees, the sugar-cane, the groves of oranges, lemons, bananas, and other fruits lend great beauty to the landscape. Tobacco is largely cultivated, with plenty of inducements for a more systematic treatment of a commodity which ought greatly to increase the wealth of the island.

Since it has come under American influence many improvements have been effected. The cities are treated to the modern system of drainage, and roads have been constructed which will make traffic between the towns easier and thus encourage trade.

Exceptionally fierce hurricanes and floods wrought havoc with many plantations soon after the war. Other misfortunes plunged the always poor laboring class into absolute starvation, many of the well-to-do were ruined, and business has been severely hampered by questions of tariff arising out of the change in political status. The United [Pg 17]States government has done much and will continue its kindly endeavors to ameliorate the condition of these people. With the speedy return of good times there ought to be a growing stream of pleasure as well as business traffic to an island so exceptionally rich in the natural features which give fresh delight to the travelled eye and unfold a new world of charm to the fortunate ones who go abroad for the first time.

Honolulu, the capital of the Hawaiian group, has long been an American city in all but name. The geographical position of the islands destined them to come within the pale of our civilization. Within a century the natives have been transformed from a state of animalism into a self-respecting, progressive people. While the aborigines have been rapidly dying out there has been a steady influx of new blood from various sources. The population is about 120,000, immigrants from Japan and Portugal forming a considerable proportion of the laboring class. Chinese immigration has been restricted.

The traveller might almost imagine himself in some New England or Pennsylvania town as he drives through the streets of Honolulu. The capital is laid out on the American plan, the churches and houses might have been transplanted by a cyclone, and the very attire of the people in general keeps up the illusion of being at home from home. The palace of the last king and queen bears as little relation to the hut of their great predecessor, Kamehameha the First, as do the New York tailor-made suits and dresses of the citizens of Honolulu to the scanty loin-cloth which their grandparents considered the height of Sandwich Islands fashion.

More and more will these lovely isles become the pleasure-grounds for our people and for all world-tourists. The [Pg 18]important practical value of their annexation will be better understood if it ever becomes necessary to back up the essential principle of the Monroe Doctrine against foreign foes. As a growing metropolis Honolulu has charms of its own independent of the ideal climate and luxuriant flora of the twelve islands.

The narratives of the first travellers to Owhyee, as they styled it, glowed with descriptions of the voluptuous charms of the natives, whose life was a round of pleasure, untempered by the wholesome necessity for hard toil. It was a lotos land for all who sojourned there. The harmful consequences of unwholesome ease are not yet eradicated. Christianity has achieved almost miraculous triumphs, and the conditions of modern life in crowded communities are helping to harden the native temperament. The leper colony in Molokai is one of several sad sights which are, perhaps, better left unseen. Also the clandestine Saturnalia still kept up on the old lines, with some winking or dozing on the part of natives in authority.

Trips can be made to the surrounding islands, famous for their volcanic mountains and tropical verdure. The largest active crater in the world is that of Kilauea, being nine miles in circumference, with vertical sides about one thousand feet deep and at the bottom a lake of molten lava, boiling furiously in some parts and throwing off fibres like spun silk which float in the air. These craters are apt to break into activity without warning.

City life in Honolulu, as already remarked, can almost delude a Southerner into fancying himself at home. It is quite cosmopolitan in its degree. There are well-equipped hotels, an English library, street railways, electric lights, telephones, insurance offices, colonies and clubs of American and British lawyers, business men, physicians and journalists. Modern progress is strikingly impressed [Pg 19]on the visitor who draws his own picture of the primitive semi-savages he expects to see, when he hears the familiar hum of mills and factories, the roar and pounding noises of foundries, and the imposing array of wharves and vessels. Hawaii is a natural hub of the wheel of world-traffic. From its ports there is a large and fast-growing steamship trade with the principal commercial centres all over the globe. We shall pass from Honolulu round to the Philippines in the easiest fashion. One is surprised at the number of Chinese and Japanese laborers in Hawaii, some of whom have prospered and own large business establishments. The foreign element in the labor field has been a source of mild trouble but is now in a fair way to solve itself. A gratifying feature is the public school system. Everywhere are centres of light and learning, promising a grand future for the island population. The abundant yield of rice, sugar, coffee, bananas, and other foodstuffs is mostly bought for the American people.

The pleasures and pains of the voyage to the Philippines have been the subject of too many public letters since the war to need re-telling. The two thousand islands which form the little-known archipelago are the homes of a number of mixed tribes, with whom the traveller will not crave intimate acquaintance for some time. In Luzon, the chief island, we may feel fairly at home, now that its all but pathless wilds, as well as its long-settled towns and hamlets, are sprinkled with American soldiers. In time, doubtless, scientific exploration will approximately fix the value of the mineral and arable fields of the archipelago. Until knowledge increases in this direction there will not be much inducement to roam among peoples with questionable manners, strange religions and outlandish dialects. The Tagal folk has reached, as regards the more [Pg 20]favored class, a high degree of civilization. The Malay blood has peculiarities of its own. Under long-continued Spanish rule the Luzon native has developed intellectually and nurtured an ambition for self-government. This half-amicable, half-hostile relationship between the Spanish friars, who have been the spiritual, and perhaps still more the civic, trainers and masters of the natives, is a most interesting study for the newly arrived visitor.

Landing at Manila, the commercial centre and capital of the islands, we find ourselves in a city blending the characteristics of an old-fashioned Spanish town with the mild business air of a third-rate western port. The buildings speak of the tropical perils to be encountered. Dewey’s bombardment was more generous than the earthquakes and gales that smote the Cathedral. These visitations come oftener than those of angels. Houses are built low and massively on the ground floor, to insure that a one-story home shall remain when the upstairs section flies away. Terrific gales come unannounced and life is temporarily suspended until it is possible to swim into the streets and rake in the flotsam and jetsam that once lodged within your walls. Periodical rains lend variety to the novice’s experience. They descend in Niagaras, giving free and wholesome baths to the many who need them and to those who need them not, and give the mud lanes that serve for streets a timely cleaning up. The rainfall record has shown as much as 114 inches in a year.

Your hotel will be the perfection of cleanliness, but the window openings are vast and glass-panes are unknown. The mahogany bedstead is bedless, a mat of woven cane strips, bare of everything that can encourage warmth or harbor little neighbors, but winged visitors float in to remind the sleeper he is not in the Waldorf-Astoria, and then depart, perhaps. By day life can be very enjoyable. [Pg 21]Churches, which are largely art-galleries also, fine squares and promenades, fashionable drives, town clubs and country clubs, shared by the American, English, and German business men, these and other aids to happiness flourish in Manila and suburbs.

The general aspect of Philippine scenery to the untutored eye of a stranger resembles the tropical views already described, allowance being made for differing conditions. When the fortunes of war brought the islands within our ken the principal trade was divided between Spain and outside countries. The treaty of 1898 brought the archipelago into closer trade relations, with mutual advantages. When Aguinaldo, the Tagal leader, declared his allegiance to the United States, the fact assured the establishment of a friendly arrangement which in time will bring high prosperity to the islands and civilization to their people. The two hundred thousand who live in and around Manila are mainly Christians.

Generally the natives with whom we are in closest contact are a civil and good-tempered people. Picturesque in costume, or the lack of it, they share with the scenery around the characteristic freedom from commonplace. Prolonged familiarity with modern methods of culture will take much of the charm out of life in the Philippines, replacing it, no doubt, with the practical methods which conduce to progress. A voyage to these distant islands affords a rare opportunity to trace the process of evolution from the simple and natural to the complex machinery which is grinding organized society into drab-tinted duplications of a rather uninteresting original.

[The “Society in America” and the “Retrospect of Western Travel,” by Harriet Martineau, contain many interesting pictures of life and scenery in the United States. Of the descriptive passages of the latter work we select that detailing her experience of winter weather in Boston, which she seems to have looked upon with true English eyes, and not with the vision of one “to the manner born.”]

I believe no one attempts to praise the climate of New England. The very low average of health there, the prevalence of consumption and of decay of the teeth, are evidences of an unwholesome climate which I believe are universally received as such. The mortality among children throughout the whole country is a dark feature of life in the United States.... Wherever we went in the North we heard of the “lung fever” as a common complaint, and children seemed to be as liable to it as grown persons.

The climate is doubtless chiefly to blame for all this, and I do not see how any degree of care could obviate much of the evil. The children must be kept warm within-doors; and the only way of affording them the range of the house is by warming the whole, from the cellar to the garret, by means of a furnace in the hall. This makes all comfortable within; but, then, the risk of going out is very great. There is far less fog and damp than in England, and the perfectly calm, sunny days of midwinter are endurable; but the least breath of wind seems to chill one’s very life. I had no idea what the suffering from extreme cold amounted to till one day, in Boston, I walked the [Pg 23]length of the city and back again in a wind, with the thermometer seven degrees and a half below zero. I had been warned of the cold, but was anxious to keep an appointment to attend a meeting. We put on all the merinoes and furs we could muster, but we were insensible of them from the moment the wind reached us. My muff seemed to be made of ice; I almost fancied I should have been warmer without it. We managed getting to the meeting pretty well, the stock of warmth we had brought out with us lasting till then. But we set out cold on our return, and by the time I got home I did not very well know where I was and what I was about. The stupefaction from cold is particularly disagreeable, the sense of pain remaining through it, and I determined not to expose myself to it again. All this must be dangerous to children; and if, to avoid it, they are shut up through the winter, there remains the danger of encountering the ungenial spring....

Every season, however, has its peculiar pleasures, and in the retrospect these shine out brightly, while the evils disappear.

On a December morning you are awakened by the domestic scraping at your hearth. Your anthracite fire has been in all night; and now the ashes are carried away, more coal is put on, and the blower hides the kindly red from you for a time. In half an hour the fire is intense, though, at the other end of the room, everything you touch seems to blister your fingers with cold. If you happen to turn up a corner of the carpet with your foot, it gives out a flash, and your hair crackles as you brush it. Breakfast is always hot, be the weather what it may. The coffee is scalding, and the buckwheat cakes steam when the cover is taken off. Your host’s little boy asks whether he may go coasting to-day, and his sisters tell you what days the schools will all go sleighing. You may see boys coasting on [Pg 24]Boston Common all the winter day through, and too many in the streets, where it is not so safe.

To coast is to ride on a board down a frozen slope, and many children do this in the steep streets which lead down to the Common, as well as on the snowy slopes within the enclosure where no carriages go. Some sit on their heels on the board, some on their crossed legs. Some strike their legs out, put their arms akimbo, and so assume an air of defiance amid their velocity. Others prefer lying on their stomachs, and so going headforemost, an attitude whose comfort I could never enter into. Coasting is a wholesome exercise for hardy boys. Of course, they have to walk up the ascent, carrying their boards between every feat of coasting; and this affords them more exercise than they are at all aware of taking.

As for the sleighing, I heard much more than I experienced of its charms. No doubt early association has something to do with the American fondness for this mode of locomotion, and much of the affection which is borne to music, dancing, supping, and all kinds of frolic is transferred to the vehicle in which the frolicking parties are transported. It must be so, I think, or no one would be found to prefer a carriage on runners to a carriage on wheels, except on an untrodden expanse of snow. On a perfectly level and crisp surface I can fancy the smooth, rapid motion to be exceedingly pleasant; but such surfaces are rare in the neighborhood of populous cities. The uncertain, rough motion in streets hillocky with snow, or on roads consisting for the season of a ridge of snow with holes in it, is disagreeable and provocative of headache. I am no rule for others as to liking the bells; but to me their incessant jangle was a great annoyance. Add to this the sitting, without exercise, in a wind caused by the rapidity of the motion, and the list of désagrémens is complete. [Pg 25]I do not know the author of a description of sleighing which was quoted to me, but I admire it for its fidelity. “Do you want to know what sleighing is like? You can soon try. Set your chair on a spring-board out on the porch on Christmas-day; put your feet in a pailful of powdered ice; have somebody to jingle a bell in one ear, and somebody else to blow into the other with the bellows, and you will have an exact idea of sleighing.”

[This quotation would appear to be a variant of Dr. Franklin’s recipe for sleighing. As for Miss Martineau’s experience “behind the bells,” it seems to have been very unfortunate.]

If the morning be fine, you have calls to make, or shopping to do, or some meeting to attend. If the streets be coated with ice, you put on your India-rubber shoes—unsoled—to guard you from slipping. If not, you are pretty sure to measure your length on the pavement before your own door. Some of the handsomest houses in Boston, those which boast the finest flights of steps, have planks laid on the steps during the season of frost, the wood being less slippery than stone. If, as sometimes happens, a warm wind should be suddenly breathing over the snow, you go back to change your shoes, India-rubbers being as slippery in wet as leather soles are on ice. [It must be borne in mind that the writer is speaking of the rubber shoes of sixty years ago.] Nothing is seen in England like the streets of Boston and New York at the end of the season, while the thaw is proceeding. The area of the street had been so raised that passengers could look over the blinds of your ground-floor rooms; when the sidewalks become full of holes and puddles they are cleared, and the passengers are reduced to their proper level; but the middle of the street remains exalted, and the carriages drive along a ridge. Of course, this soon becomes too dangerous, and [Pg 26]for a season ladies and gentlemen walk; carts tumble, slip, and slide, and get on as they can; while the mass, now dirty, not only with thaw, but with quantities of refuse vegetables, sweepings of the poor people’s houses, and other rubbish which it was difficult to know what to do with while every place was frozen up, daily sinks and dissolves into a composite mud. It was in New York and some of the inferior streets of Boston that I saw this process in its completeness.

If the morning drives are extended beyond the city there is much to delight the eye. The trees are cased in ice; and when the sun shines out suddenly the whole scene looks like one diffused rainbow, dressed in a brilliancy which can hardly be conceived of in England. On days less bright, the blue harbor spreads in strong contrast with the sheeted snow which extends to its very brink....

The skysights of the colder regions of the United States are resplendent in winter. I saw more of the aurora borealis, more falling stars and other meteors, during my stay in New England than in the whole course of my life before. Every one knows that splendid and mysterious exhibitions have taken place in all the Novembers of the last four years, furnishing interest and business to the astronomical world. The most remarkable exhibitions were in the Novembers of 1833 and 1835, the last of which I saw....

On the 17th of November in question, that of 1835, I was staying in the house of one of the professors of Harvard University at Cambridge. The professor and his son John came in from a lecture at nine o’clock, and told us that it was nearly as light as day, though there was no moon. The sky presented as yet no remarkable appearance, but the fact set us telling stories of skysights. A venerable professor told us of a blood-red heaven which [Pg 27]shone down on a night of the year 1789, when an old lady interpreted the whole French Revolution from what she saw. None of us had any call to prophesying this night. John looked out from time to time while we were about the piano, but our singing had come to a conclusion before he brought us news of a very strange sky. It was now near eleven. We put cloaks and shawls over our heads, and hurried into the garden. It was a mild night, and about as light as with half a moon. There was a beautiful rose-colored flush across the entire heavens, from southeast to northwest. This was every moment brightening, contracting in length, and dilating in breadth.

My host ran off without his hat to call the Natural History professor. On the way he passed a gentleman who was trudging along, pondering the ground. “A remarkable night, sir,” cried my host. “Sir! how, sir?” replied the pedestrian. “Why, look above your head!” The startled walker ran back to the house he had left to make everybody gaze. There was some debate about ringing the college-bell, but it was agreed that it would cause too much alarm.

The Natural Philosophy professor came forth in curious trim, and his household and ours joined in the road. One lady was in her nightcap, another with a handkerchief tied over her head, while we were cowled in cloaks. The sky was now resplendent. It was like a blood-red dome, a good deal pointed. Streams of a greenish-white light radiated from the centre in all directions. The colors were so deep, especially the red, as to give an opaque appearance to the canopy, and as Orion and the Pleiades and many more stars could be distinctly seen, the whole looked like a vast dome inlaid with constellations. These skysights make one shiver, so new are they, so splendid, so mysterious. We saw the heavens grow pale, and before midnight [Pg 28]believed that the mighty show was over; but we had the mortification of hearing afterwards that at one o’clock it was brighter than ever, and as light as day.

Such are some of the wintry characteristics of New England.

If I lived in Massachusetts, my residence during the hot months should be beside one of its ponds. These ponds are a peculiarity in New England scenery very striking to the traveller. Geologists tell us of the time when the valleys were chains of lakes; and in many parts the eye of the observer would detect this without the aid of science. There are many fields and clusters of fields of remarkable fertility, lying in basins, the sides of which have much the appearance of the greener and smoother of the dykes of Holland. These suggest the idea of their having been ponds at the first glance. Many remain filled with clear water, the prettiest meres in the world. A cottage on Jamaica Pond, for instance, within an easy ride of Boston, is a luxurious summer abode. I know of one unequalled in its attractions, with its flower-garden, its lawn, with banks shelving down to the mere,—banks dark with nestling pines, from under whose shade the bright track of the moon may be seen, lying cool on the rippling waters. A boat is moored in the cove at hand. The cottage itself is built for coolness, and the broad piazza is draperied with vines, which keep out the sun from the shaded parlor.

WASHINGTON ELM, CAMBRIDGE

WASHINGTON ELM, CAMBRIDGE

The way to make the most of a summer’s day in a place like this is to rise at four, mount your horse and ride through the lanes for two hours, finding breakfast ready on your return. If you do not ride, you slip down to the bathing-house on the creek; and, once having closed the door, have the shallow water completely to yourself, carefully avoiding going beyond the deep-water mark, where no one knows how deep the mere may be. After breakfast [Pg 29]you should dress your flowers, before those you gather have quite lost the morning dew. The business of the day, be it what it may, housekeeping, study, teaching, authorship, or charity, will occupy you till dinner at two. You have your dessert carried into the piazza, where, catching glimpses of the mere through the wood on the banks, your watermelon tastes cooler than within, and you have a better chance of a visit from a pair of humming-birds.

You retire to your room, all shaded with green blinds, lie down with a book in your hands, and sleep soundly for two hours at least. When you wake and look out, the shadows are lengthening on the lawn, and the hot haze has melted away. You hear a carriage behind the fence, and conclude that friends from the city are coming to spend the evening with you. They sit within till after tea, telling you that you are living in the sweetest place in the world. When the sun sets you all walk out, dispersing in the shrubbery or on the banks. When the moon shows herself above the opposite woods, the merry voices of the young people are heard from the cove, where the boys are getting out the boat. You stand, with a companion or two, under the pines, watching the progress of the skiff and the receding splash of the oars. If you have any one, as I had, to sing German popular songs to you, the enchantment is all the greater. You are capriciously lighted home by fireflies, and there is your table covered with fruit and iced lemonade. When your friends have left you you would fain forget it is time to rest, and your last act before you sleep is to look out once more from your balcony upon the silvery mere and moonlit lawn.

The only times when I felt disposed to quarrel with the inexhaustible American mirth was on the hottest days of summer. I liked it as well as ever; but European strength [Pg 30]will not stand more than an hour or two of laughter in such seasons. I remember one day when the American part of the company was as much exhausted as the English. We had gone, a party of six, to spend a long day with a merry household in a country village, and, to avoid the heat, had performed the journey of sixteen miles before ten o’clock. For three hours after our arrival the wit was in full flow; by which time we were all begging for mercy, for we could laugh no longer with any safety. Still, a little more fun was dropped all round, till we found that the only way was to separate, and we all turned out of doors. I cannot conceive how it is that so little has been heard in England of the mirth of the Americans; for certainly nothing in their manner struck and pleased me more. One of the rarest characters among them, and a great treasure to all his sportive neighbors, is a man who cannot take a joke.

The prettiest playthings of summer are the humming-birds. I call them playthings because they are easily tamed, and are not very difficult to take care of for a time. It is impossible to attend to book, work, or conversation while there is a humming-bird in sight, its exercises and vagaries are so rapid and beautiful. Its prettiest attitude is vibrating before a blossom which is tossed in the wind. Its long beak is inserted in the flower, and the bird rises and falls with it, quivering its burnished wings with dazzling rapidity. My friend E—— told me how she had succeeded in taming a pair. One flew into the parlor where she was sitting, and perched. E——’s sister stepped out for a branch of honeysuckle, which she stuck up over the mirror. The other bird followed, and the pair alighted on the branch, flew off, and returned to it. E—— procured another branch, and held it on the top of her head; and thither also the little creatures came without fear. She next held it in her [Pg 31]hand, and still they hovered and settled. They bore being shut in for the night, a nest of cotton-wool being provided. Of course, it was impossible to furnish them with honeysuckles enough for food; and sugar-and-water was tried, which they seemed to relish very well.

One day, however, when E—— was out of the room, one of the little creatures was too greedy in the saucer; and, when E—— returned, she found it lying on its side, with its wings stuck to its body and its whole little person clammy with sugar. E—— tried a sponge and warm water: it was too harsh; she tried old linen, but it was not soft enough; it then occurred to her that the softest of all substances is the human tongue. In her love for her little companion she thus cleansed it, and succeeded perfectly, so far as the outward bird was concerned. But though it attempted to fly a little, it never recovered, but soon died of its surfeit. Its mate was, of course, allowed to fly away.

[Among travellers’ descriptions of the natural marvels of this continent, much has been written of perhaps the greatest of them all, the celebrated cataract of the Niagara River. The Thousand Islands have also excited much admiration. Fortunately, these two scenic wonders are sufficiently contiguous to be dealt with in one record, and the compiler of the present work ventures to give his own impressions of them, from a printed statement made some twenty-five years ago.]

Who has not read in story and seen in picture, countless times, how the water goes over at Niagara? I came here expecting to find every curve and plunge of the river appealing like a household thing to my memory. So in [Pg 32]great measure it proved, yet travellers never succeed in exhausting a situation in their narratives; something of the unexpected always remains to freshen the sated appetite of new-comers.

Tourists are apt to be disappointed at first sight of the cataract. Their expectations have been overwhetted; and, moreover, the first glance is usually obtained from the American shore, an edgewise view that gives but an inkling of the full majesty of the scene. Yet even from this point of view we behold the river, almost at our feet, rushing with concentrated energy to the brink of the precipice, and pouring headlong, in an agony of froth and foam, into a fearful void, from which forever rises a rainbow-crowned mist. To stand on the brink and gaze into this terrible abyss, with the foaming waters plunging in a white wall downward, is apt to rouse an undefined desire to cast one’s self after the torrent, while minute by minute the mind grows into a realization of the sublimity of Niagara.

But to behold the cataract in the fulness of its might and glory one must cross to the Canadian shore, and make his way on foot from the bridge westward. Carriages will be found in abundance, manned by drivers more importunate than mellifluous; but if the tourist would see the Falls at leisure and from every point of view, he must be obdurate, and resolutely foot his way along the river’s precipitous bank.

First, arriving opposite the American Fall, we seat ourselves under a tree, and gaze with admiration on this magnificent water front, spread before us in one broad, straight sheet of milk-white foam, swooping ever downward with graceful undulations, until beaten into mist on the rocks below.

Passing onward, we approach that grand curved reach of falling water, whose sublime aspect has been a fruitful [Pg 33]theme for poet and artist since America has had poetry and art. The Horseshoe Fall is the paragon of cataracts. Sitting on what remains of Table-Rock, and gazing on the tumbling, heaving, foaming world of waters, which seem to fill the whole horizon of vision, the mind becomes oppressed with a feeling of awe, and realizes to its full extent nature’s grandest vision.

With one vast leap the broad river shoots headlong into an abyss whose real depth we are left to imagine, since the feet of the cataract are forever hidden in a white cloud of mist, shrouded in a dense veil which no eye can penetrate. At the centre of the curve, where the water is deepest, the creamy whiteness of the remainder of the cataract is replaced by a hue of deep green. It seems one vast sheet of liquid emerald, curving gracefully over the edge of the precipice, and swooping downward with endless change yet endless stability, its green tinge relieved with countless flecks of white foam.

The mind cannot long maintain its high level of appreciation of so grand a scene. The mighty monotony of the view soon loses its absorbing hold on the senses, and from sheer reaction one perforce passes to prosaic conceptions of the situation. For our part, we found ourselves purchasing popped corn from a peripatetic merchant who ludicrously misplaced the h’s in his conversation, and, taking a seat above the Falls, where the edge of the rapids swerved in and broke in mimic billows at our feet, we enjoyed mental and creature comforts together.

One need but return to the American side, and cross to the islands which partly fill the river above the Falls, to obtain rest for his overstrained brain among quieter aspects of nature. Goat Island one cannot appreciate without a visit. Travellers, absorbed in the wilder scenery, rarely do justice to its peculiar charm. Instead of the contracted [Pg 34]space one is apt to expect, he finds himself in an area of many acres in extent, probably a mile in circumference, its whole surface to the water’s edge covered with dense forest. Passing inward from its shore, scarce twenty steps are taken before every vestige of the river is lost to sight, and on reaching its centre we find ourselves, to all appearance, in the heart of a primeval forest,—only the subdued roar of the rapids reminding us of the grand scene surrounding. On all sides rise huge trunks of oaks and beeches, straight, magnificent trees, many of the beeches seemingly from six to eight feet in circumference, their once smooth bark covered inch by inch with a directory of the names of notoriety-loving visitors. At our feet wild flowers bloom, the twittering of birds is heard overhead, nimble ground-squirrels fearlessly cross our path, soft mosses and thick grass form a verdant carpet, and on all sides nature presents us one of her most charming phases, a picture from Arcadia framed in the heart of a scene of hurry and turmoil undescribable.

Near the edge of the Falls a rickety bridge leads to a small island on which stands Terrapin Tower, which yields a fine outlook upon the Horseshoe Fall, with its mists and rainbows. From the opposite side of Goat Island we pass to the charming little Luna Island, from whose brink one may lave his hand in the edge of the American Fall. From the upper end of Goat Island bridges lead to the Three Sisters. These are small, thickly-timbered islands, standing in the stream far back from the edge of the precipice, but in the very foam and fume of the rapids, the contracted stream dashing under their graceful suspension bridges with frightful speed and roar.

From the bridge joining the two outer islands one may see the rapids in their wildest aspect. Here the river, dashing fiercely onward, plunges over a shelf of rock six [Pg 35]or eight feet deep, and is tossed upward in so tumultuous a turmoil of foam that the heart involuntarily stops beating and the teeth set hard, as if one were preparing for a desperate conflict with the fierce power beneath him. From every point on the shore of the outer island the rapids are seen heaving and tossing as far as the sight can reach, like the waves of a sea fretted by contrary winds, here tossed many feet into the air, there sweeping fiercely over a long ledge of rocks, and ever hurrying forward with eager speed to where in the distance we see a long, curved, liquid edge, with a light mist floating upward and hovering in the air beyond it. Here one hears only the roar of the rapids. Indeed, anywhere in the nearer vicinity, the sound of the rapids is chiefly heard, the voice of the cataract itself predominating only on the Canadian side near the Horseshoe Fall.

Here, on this outreaching island, I sat for hours on the gnarled trunk of a fallen tree that overhung the water, drinking in the grandeur and glory of Niagara with a mental thirst that seemed unquenchable, and feeling in my soul that I could willingly stretch the hours into days and the days into weeks, and still descend with regret from the poetry of life into its prose.

Leaving Niagara, I took car for Lewistown, the railroad running for its whole length in full view of the river, whose lofty and rigidly-erect walls, stretching in unbroken lines for miles below the cataract, give striking evidence of the vast work performed by the stream in cutting its way, century after century, through the ridge of solid limestone that separates the lakes. Far down below the level of the railroad the water is seen, placidly winding through the deep gorge, or speeding onward in rapids, its hue intensely green, its banks as lofty and precipitous as the Palisades of the Hudson.

[Pg 36]Before Lewistown is reached the ridge sinks to the river level. At this point the cataract began its long career, inch by inch eating its way backward through the former rapids, until they were converted into one mighty vertical downfall. At Lewistown boat is taken for Toronto,—of which city only a lake view of warehouses and church steeples is seen as we change boats for the lake journey.

For the rest of the day and evening we steamed along in full view of the Canadian shore, an ever-changing panorama of farm lands, sandy bluffs, occasional hamlets, and several towns of some pretensions to size and beauty. Kingston, a city at the head of the lake, is reached at four o’clock in the morning. Immediately after leaving this thriving town the state-rooms begin to disgorge their occupants, for we now enter the broad throat of the St. Lawrence River, and here the Thousand Islands begin. Who that has a soul beyond cakes and ale would let the desire to indulge in his own dreams cheat him from enjoying one of nature’s loveliest visions?

For some four hours thereafter the boat runs through an uninterrupted succession of the most beautiful island scenery. These islands number, in fact, more than eighteen hundred, and are of every conceivable size and shape; some so minute that they seem but rock pediments to the single tree that is rooted upon their surface, while the rocky shores of others stretch for a mile or more along the channel. They are all heavily wooded, with here and there a light-house, or a rude hovel, as the only indication of man’s contest with primitive nature.

[This description, it may be said, does not apply to the present time, when mansions and hotels have taken possession of many of these islands, and evidences of man’s occupancy are somewhat too numerous.]

[Pg 37]Every few turns of the wheel reveal some new feature of the scene, unexpected channels cutting through the centre of a long, wooded reach, broad open spaces studded with islets, narrow creek-like channels between rocky island shores, in which the whole river seems contracted to a slender stream, while farther on the channel expands to a mile in width, and glimpses of other channels open behind distant islands. Quick turns in our course plunge us into archipelagoes, through which a dozen channels run and wind in every direction. Sudden openings in the wooded shore along which we are swiftly gliding yield glimpses of charming islands, here closing the view, there cut by narrow channels which reveal more distant wooded shores, and lead the imagination suggestively onward till we fancy that scenes of fairy-like beauty lie hidden beyond those leafy coverts, enviously torn from our sight by the remorseless onward flight of the boat. For hours we sit in rapt delight, drinking in new beauty at every turn, and heedless of the fact that the breakfast gong has long since sounded, and the more prosaic of the passengers have allowed their physical to overcome their mental hunger.

One tall, long-whiskered old devotee of “cakes and ale,” hailing from somewhere in Ohio, shaped somewhat like a note of interrogation, and sustaining his character by asking everybody all sorts of questions, did not, I am positive, digest his breakfast well, for I took a wicked pleasure in assuring him that we had passed far the most beautiful portions of the scenery while he was engaged in absorbing creature comforts, and that the world beside had nothing to compare with the fairy visions he had lost. Old Buckeye, as I had irreverently christened him, wished his breakfast was in Hades, and at once set out on a tour of interrogation to learn if he could not return by the same route and pick up the lost threads of beauty he had so idly dropped.

[Pg 38]Another of our fellow-passengers was an English gentleman of perfect Lord Dundreary pattern, his every movement being so suggestive of those of his stage counterpart as to furnish us an unfailing source of amusement. At Prescott, Canada, a New England college boat-club came on board with their boat, and highly amused the passengers during the remainder of the journey with a long succession of comical songs. Three of them were sons of one of our venerable New England professors, one an unvenerable professor himself, yet their tanned faces, worn habiliments, and wild songs bore so strong a flavor of the backwoods that it was hard mentally to locate them within college walls.

We were roused from dinner by the announcement that the Long Sault Rapid was at hand, and gladly deserted one of the meanest tables we had ever encountered to partake of one of nature’s rarest banquets.

The boat was entering what seemed a heaving sea, the waters lifting into dangerous billows, and tossing our craft with unmitigated rudeness, until it became almost impossible to retain a level footing. But the appearance of these rapids was different from what we had been led to expect. The frightful aspect of danger, the rapid down-hill plunge of the boat, and all the fear-inspiring adornments of the guide-books, while they might be visible from the shore, did not appear to those on the deck. Apparently the boat was fixed in the heart of a watery turmoil, her onward motion lost in her various upward and sidelong movements, while as for fear, its only evidence lay in little shrieks full of laughter, as the equilibrium of the craft was suddenly destroyed.

Five minutes or so of this experience carried us through the perilous portion of the great rapid, and brought us into safe waters again. The St. Lawrence has various [Pg 39]other rapids between the Long Sault and Montreal, differing in appearance, some of them being, as far as the eye can reach, a succession of crossing and tumbling waves, which give the boat unexpected little heaves, and appear like the waves of a tossing sea. Here the water plunges rapidly down a narrow throat between two islands, there it curves round a rocky shore, on which it breaks in ocean-like billows. But the only point where danger becomes apparent to untrained eyes is at the La Chine Rapids, near Montreal, where the river runs through a narrow foaming channel between two long ridges of rock, over which the water tumbles with a terrible suggestion of peril.

The peak of Montreal mountain has been long visible, and now we rapidly approach the long line of Victoria bridge, the great pride of Canadian engineering. Under this we glide with a gymnast at the mast-head, whose erected feet seem nearly to touch the bridge; and in a short time we round in to the wharf and are ashore in the largest city of Canada.

[It is not our purpose to enter into descriptions of the cities of the United States. They are sufficiently familiar already to our readers. But Mr. Latham has given so graphic a picture of the outward aspect of the two leading coast cities and the capital of this country during a past generation that we have been tempted to quote it. It need scarcely be said that this account represents only in embryo these cities as they appear to-day.]

Safe arrived last night, after spending twelve days of my life at sea. I say last night, as it took us so long to [Pg 40]land and get through the custom-house that it was dark before we reached the Fifth Avenue Hotel. But it was bright daylight and sunshine as we steamed up the splendid harbor of New York, a view which I should have been sorry to have missed. As far as our personal experiences go, the custom-house officers of New York are not half so troublesome as they are said to be. We had nothing to smuggle, but there was a vast amount of smuggling done by some of our fellow-passengers. One man landed with his pocket full of French watches, and another with a splendid Cashmere shawl round his neck. The custom-house officer, searching the next luggage to mine, unearthed two boxes of cigars; of course these were contraband. He spoke as follows: “Which are the best?” Opens box. “Have you a light? I forgot; we must not smoke here. Well, I will take a few to smoke after my supper.” Takes twenty cigars, and passes the rest.

December 14, 1866.—I have been on my feet all day, delivering letters of introduction. These are plants that require to be put in early, or they are apt to flower after the sower has quitted the country. The stores of the Broadway are the most wonderfully glorified shops ever seen. Something between a Manchester warehouse and a London club-house.

I have spent all my day in going to and fro in Broadway, the wonderful street of New York; in ten years’ time the finest street in the world. At present there are still so many small old houses standing in line with the enormous stores, that the effect is somewhat spoiled, by reason of the ranks not being well dressed. Broadway is now much in the condition of a child’s mouth when cutting its second set of teeth,—slightly gappy. The enormous stores look even larger now than they will do when the intervals are filled up. The external splendor of the [Pg 41]shops is chiefly architectural; they make no great display of goods in the windows; but the large size of the rooms within enables them to set out and exhibit many times the amount of goods that an English shop-keeper shows.

The city of New York is on the southern point of Manhattan Island, having the East River running along one side, and the North River or Hudson along the other. Some day far in the future, when the present municipality is purged or swept away, and the splendor of the Thames Embankment scheme has been realized, New York will probably have two lines of quays, planted with trees and edged with warehouses, which will make it one of the finest cities in the world. The business quarter is at the point of the peninsula. The fashionable quarter is to the north, reaching every year farther inland. As the city increases, the stores keep moving northward, taking possession of the houses, and driving the residents farther back. The land is not yet built over up to Central Park, said to be called so because it will be the future centre of the city that is to be.

The concentrated crowd that passes along Broadway in the morning “down-town” to its business, and back in the evening “up-town” to its homes, is enormous; but the pavements are bad for men and abominable for horses: to-day I saw five horses down, and two lying dead. At the same time, allowance must be made for the fact that it has been snowing and thawing and freezing again; but as this is no uncommon state of things in this climate, why pave the streets with flat stones that give no foothold? The “street-cars” are the universal means of conveyance. These are omnibuses running on tramways, but the name of omnibus is unknown: if you speak of a “bus” you are stared at. A young New Yorker, recently returned from London, was escorting his cousin home one evening; as [Pg 42]the way was long, he stopped and said, “Hold on, Mary, and let’s take a bus.” “No, George, not here in the street,” the coy damsel replied....

We went to-day to the top of Trinity Church tower; a beautiful panorama, with the bay of New York to the south, the city stretching away northward, and a great river on either side. But it was bitterly cold at the top, as we had heavy snow yesterday, and the wind was blowing keenly. We went also to the Gold Exchange, and gold happened to be “very sensitive” this morning, in consequence of some rumors from Mexico which made it possible that the time for United States interference was nearer than had been supposed. The noise was deafening; neither the Stock Exchange nor the ring at Epsom at all approach it. All the men engaged in a business which one would suppose required more experience than any other, the buying and selling of gold, seemed to be under twenty-five years of age; most of them much younger, some quite boys. The reason given me was that older heads could not stand the tumult, all gesticulating, all vociferating, every man with a note-book and pencil, crowded round a ring in the centre of the hall like a little cock-pit, to which you descend by steps. Every now and then a man rushes out of the telegraph corner with some news, which oozes out and makes the crowd howl and seethe again. The hands of a big dial on the wall are moved on from time to time, marking the hour of the day and the price of gold. This is the dial of the barometer of national prosperity, marked by gold instead of mercury....

NEW YORK AND THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE

NEW YORK AND THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE

A huge sum of money has been laid out on Central Park, the Bois de Boulogne of New York. When the timber has grown larger it will be very pretty. The ground is rocky, with little depth of soil in it; this makes it difficult to get the trees to grow, but, on the other hand, gives the place a [Pg 43]feature not to be found in our parks or at the Bois, in the large masses of brown sandstone cropping up through the turf here and there, and in the rocky shores of the little lakes.

In the evening we went, by invitation of our courteous banker, to the Assembly at Delmonico’s rooms. In this we consider ourselves highly honored and introduced to the best society of New York. The toilets and the diamonds were resplendent, and one figure of the “German” (cotillon), in which the ladies formed two groups in the centre, facing inward with their bright trains spread out behind them, was a splendid piece of color and costume. Prince Doria was there, and most of the magnates of the city looked in. Some of the wealthiest people in the room were pointed out to me as the present representatives of the families of the old Dutch settlers; those are the pedigrees respected here.

December 20, 1866.—We left New York, having stayed exactly a week, and meaning to return again. By rail to Philadelphia, ninety-two miles, through a flat, snow-covered country, which, under the circumstances, looked as dismal as might be. The latter part of our journey lay along the left bank of the Delaware, which we crossed by a long wooden bridge, and arrived at the Continental Hotel just at dusk. It is evident we are moving South. The waiters at this hotel are all darkies.

December 21, 1866.—Philadelphia is a most difficult town just now for pedestrians, the door-steps being all of white marble glazed with ice, and sliding on the pavement may be had in perfection. Spent the best part of the day in slipping about, trying to deliver letters of introduction. The system of naming the streets of Philadelphia and of numbering the houses is extremely ingenious, and answers perfectly when you have made yourself acquainted with [Pg 44]it; but as it takes an ordinary mind a week to find it out, the stranger who stops four or five days is apt to execrate it. All the streets run at right angles to one another, so that a short cut, the joy of the accomplished Londoner, is impossible. It is a chess-board on which the bishop’s move is unknown. Nothing diagonal can be done. The city is ruled like the page of a ledger, from top to bottom with streets, from side to side with avenues. It is all divided into squares. When you are first told this, a vision arises of the possibility of cutting across these squares from corner to corner. Not a bit of it: a square at Philadelphia means a solid block of houses, not an open space enclosed by buildings. When you have wandered about for some time, the idea suggests itself that every house is exactly like the house next to it; although the inhabitants have given up the old uniformity of costume, the houses have not; and without this elaborate system of numbering, the inhabitants of Philadelphia would never be able to find their way home.

Nevertheless, if that is the finest town in which its inhabitants are best lodged, Philadelphia is the finest town in the world. It lodges a much smaller population than that of New York in more houses. In no other large town are rents comparatively so cheap. Every decent workingman can afford to have his separate house, with gas and water laid on, and fitted with a bath.

We have been making a study of the negro waiters. Perhaps cold weather affects them; but the first thing about them that strikes you is the apathetic infantine feeble-mindedness of the “colored persons” lately called niggers. I say nothing of the seven colored persons, of various shades, who always sit in a row on a bench in the hall, each with a little clothes-brush in his hand, and never attempt to do anything; I allude to those who minister to [Pg 45]my wants in the coffee-room with utterly unknown dishes. I breakfasted yesterday off dun-fish and cream, Indian pudding, and dipped toast; for dinner I had a baked black-fish with soho sauce, and stewed venison with port wine; for vegetables, marrow, squash, and stewed tomatoes; and for pudding, “floating island.”

You see there is something exciting about dinner. After you have ordered four courses of the unknown, and your colored person has gone in the direction of the kitchen, you sit with the mouth of expectation wide open. Sometimes you get grossly deceived. Yesterday F—— ordered “jole,” and was sitting in a state of placid doubt, when his colored person returned with a plate of pickled pork. At present I am quite of the opinion of the wise man who discovered that colored persons are born and grow in exactly the same way as uncolored persons up to the age of thirteen, and that they then cease to develop their skulls and their intelligence. All the waiters in this hotel appear to be just about the age of thirteen. There are two who in wisdom are nearly twelve, and one gray-headed old fellow who is just over fourteen.

[Our traveller contented himself in the way of sight-seeing by following Charles Dickens’s path to the Penitentiary, and afterwards visited Girard College. He concludes as follows:]

Even in this city of Penn the distinctive marks of Quakerism are dying out. The Quaker dress does not seem much more common in Philadelphia than in any other city, nor do they use the “thee” and “thou” in the streets; but at their own firesides, where the old people sit, they still speak the old language. A Quaker in the streets is not to be distinguished from other Philadelphians. I was talking to Mr. C—— about this, and he said, “Let me introduce you to a Quaker; I am a member of the church [Pg 46]myself.” L—— was not quite clear whether he was a Quaker or not. His parents had been; his sons certainly were not. Some of the best of the Southern soldiers came from the city of the Quakers. There is a story of a Quaker girl, who was exchanging rings with her lover as he set off to join the army; when they parted she said, “Thee must not wear it on thy trigger-finger, George.”

Dined with Mr. L——, the publisher. He showed us over his enormous store, which seemed to be a model of discipline and organization, and described the book-market of America as being, like the Union, one and indivisible, and opened his ledger, in which were the names of customers in every State in the Union. He told us that he had about five thousand open accounts with different American booksellers. His policy is to keep in stock everything that a country bookseller requires, from a Bible to a stick of sealing-wax, so that when their stores get low they are able to write to him for everything they want. He contends, as other Philadelphians do, that New York is not the capital of America, but only its chief port of import, and that Philadelphia is the chief centre for distribution. Mr. Hepworth Dixon had been here not long before, and, as was right and fitting in the city of Quakers, a high banquet had been held in honor of the vindicator of William Penn.

[Thence Mr. Latham went to Baltimore, of which he describes the following old-time experience: “When an American train reaches a town it does not dream of pulling up short in a suburb, but advances slowly through the streets; the driver on the engine rings a large bell, and a man on horseback rides in front to clear the way. Thus we entered Baltimore, arrived at the terminus and uncoupled the engine; and then, still sitting in the railway-car, were drawn by a team of horses along the street-rails to the terminus of the Baltimore and Ohio Railway on the other side of the town.” He is talking of antediluvian days. We have reformed all that. After some experience in duck [Pg 47]and partridge shooting, and a taste of terrapin soup, he proceeded to Washington. Of his varied experience there we can give but a single out-door example.]

We went this morning over the Capitol, an enormous edifice still in progress; parts of it are continually built on to, and rebuilt, to meet the wants of the legislature. The two new white marble wings are very beautiful and nearly complete, and the dome is on the same scale with them, and of the same material. The centre is now out of proportion since the wings were built, and is of stone, painted white to match the rest in color and preserve it from the frost. If the South had succeeded in seceding it might have sufficed; but now it is bound to grow, and Congress are going to vote the amount of dollars necessary to make the Capitol complete. When completed it will be magnificent.

We are very unlucky in seeing these great marble palaces (for several of the public buildings of Washington are of this material) with the snow upon the ground. Against the pure white snow they appear dingy; under a summer sun they must show to far greater advantage. What ancient Athens appeared like, surrounding its marble temples, I can hardly realize; but the effect of the splendid public buildings in Washington is very much detracted from by the sheds and shanties which are near them. The builders of Washington determined that it should be a great city, and staked out its streets accordingly twice the width and length of any other streets: rightly is it named the city of magnificent distances. But although the Potomac is certainly wide enough, and apparently deep enough, to justify a certain amount of trade, and its situation is more central than that of Philadelphia, the town has never grown to fill the outlines traced for it.

To make a Washington street, take one marble temple or [Pg 48]public office, a dozen good houses of brick, and a dozen of wood, and fill in with sheds and fields. Some blight seems to have fallen upon the city. It is the only place we have seen which is not full of growth and vitality. I have even heard its inhabitants tell stories of nightly pig-hunts in the streets, and of the danger of tumbling over a cow on the pavement on a dark night; but this must refer to by-gone times.

One of the most curious and characteristic of the great public buildings of Washington is the Patent Office, in which a working model is deposited of every patent taken out in the United States for the improvement of machinery.

This assemblage of specimens is an exhibition of which all Americans are proud, as a proof of the activity of American ingenuity working in every direction. Capacity to take out a patent is a quality necessary to make up the character of the perfect citizen. Labor is honorable, but the man who can invent a labor-saving machine is more honorable; he has gained a step in the great struggle with the powers of nature. An American who has utilized a water-power feels, I take it, two distinct and separate pleasures: first, in that dollars and cents drip off his water-wheel, and, secondly, in that he has inveigled the water-sprites into doing his work. If you tell an American that you are going to Washington, his first remark is not, “Then you will see Congress sitting,” but, “Mind you go and see the Patent Office.”