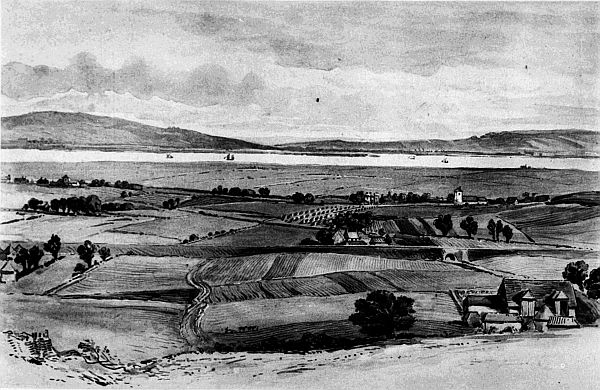

The Marshes, Cooling.

The Marshes, Cooling.

Title: A Week's Tramp in Dickens-Land

Author: William R. Hughes

Illustrator: Frederic George Kitton

Release date: February 25, 2010 [eBook #31394]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The Marshes, Cooling.

The Marshes, Cooling.

"'I should like to show you a series of eight articles, Sir, that have appeared in the Eatanswill Gazette. I think I may venture to say that you would not be long in establishing your opinions on a firm and solid basis, Sir.'

"'I dare say I should turn very blue long before I got to the end of them,' responded Bob.

"Mr. Pott looked dubiously at Bob Sawyer for some seconds, and turning to Mr. Pickwick said:—

"'You have seen the literary articles which have appeared at intervals in the Eatanswill Gazette in the course of the last three months, and which have excited such general—I may say such universal—attention and admiration?'

"'Why,' replied Mr. Pickwick, slightly embarrassed by the question, 'the fact is, I have been so much engaged in other ways, that I really have not had an opportunity of perusing them.'

"'You should do so, Sir,' said Pott with a severe countenance.

"'I will,' said Mr. Pickwick.[viii]

"'They appeared in the form of a copious review of a work on Chinese metaphysics, Sir,' said Pott.

"'Oh,' observed Mr. Pickwick—'from your pen I hope?'

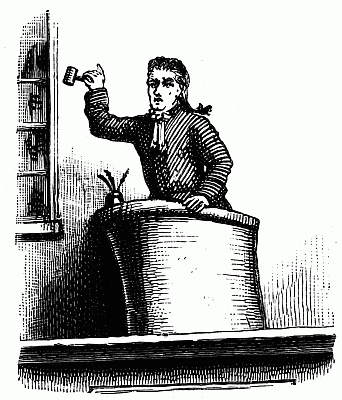

"'From the pen of my critic, Sir,' rejoined Pott with dignity.

"'An abstruse subject I should conceive,' said Mr. Pickwick.

"'Very, Sir,' responded Pott, looking intensely sage. 'He crammed for it, to use a technical but expressive term; he read up for the subject, at my desire, in the Encyclopædia Britannica.'

"'Indeed!' said Mr. Pickwick; 'I was not aware that that valuable work contained any information respecting Chinese metaphysics.'

"'He read, Sir,' rejoined Mr. Pott, laying his hand on Mr. Pickwick's knee, and looking round with a smile of intellectual superiority, 'he read for metaphysics under the letter M, and for China under the letter C; and combined his information, Sir!'

"Mr. Pott's features assumed so much additional grandeur at the recollection of the power and research displayed in the learned effusions in question, that some minutes elapsed before Mr. Pickwick felt emboldened to renew the conversation."

The above perennial extract from the immortal Pickwick Papers suggests to some extent the nature of the contents of this Volume. It is the record of a pilgrimage made by two enthusiastic Dickensians during the late summer of 1888, together with "combined[ix] information,"—not indeed "crammed" from the ninth edition just completed of the valuable work above referred to, but gathered mostly from original sources,—respecting the places visited, the characters alluded to in some of the novels, personal reminiscences of their Author, appropriate passages from his works (for which acknowledgments are due to Messrs. Chapman and Hall), and some little mention of the thoughts developed by the associations of "Dickens-Land."

Although the pilgrimage only extended to a week, and every spot referred to (save one) was actually visited during that time, it is but right to state that on three subsequent occasions the author has gone over the greater part of the same ground—once in the early winter, when the blue clematis and the aster had given place to the yellow jasmine and the chrysanthemum; once in the early spring, when those had been succeeded by the almond-blossom and the crocus; and again in the following year, when the beautiful county of Kent was rehabilitated in summer clothing, thus enabling him to verify observations, to correct possible errors arising from first impressions, and to gain new experiences.

As our head-quarters were at Rochester, and most of the city and other parts were taken at odd times, it has not been found practicable to preserve in consecutive chapters a perfect sequence of the records of each day's tramp, although they appear in fairly chronological order throughout the work. "A preliminary tramp in London" will possibly be dull to[x] those familiar with the great Metropolis, but it may be useful to foreign tramps in "Dickens-Land."

Availing myself of the privilege adopted by most travellers at home and abroad, I have made occasional references to the weather. This is perhaps excusable when it is remembered that the year 1888 was a very remarkable one in that respect, so much so indeed, that the writer of a leading article in The Times of January 18th, 1889, in commenting on Mr. G. J. Symons' report of the British rainfall of the previous year, remarked that "seldom within living memory had there been a twelve-month with more unpleasantness in it and less of genial sunshine." We were specially favoured, however, in getting more "sunshine" than "unpleasantness," thus adding to the enjoyment of our never-to-be-forgotten tramp.

Upwards of three years have elapsed since this book was commenced, and the limited holiday leisure of a hard-working official life has necessarily prevented its completion for such a lengthened period, that it has come to be pleasantly referred to by my many Dickensian friends as the "Dictionary," in allusion to the important work of that nature contemplated by Dr. Strong, respecting which (says David Copperfield) "Adams, our head-boy, who had a turn for mathematics, had made a calculation, I was informed, of the time this Dictionary would take in completing, on the Doctor's plan, and at the Doctor's rate of going. He considered that it might be done in one thousand six hundred and forty-nine years, counting from the Doctor's last, or sixty-second, birthday."[xi]

My hearty and sincere acknowledgments are due to the publishers, Messrs. Chapman and Hall, not only for the very handsome manner in which they have allowed my book to be got up as regards print, paper, and execution (to follow the model of their Victoria Edition of Pickwick is indeed an honour to me), but especially for their great liberality in the matter of the Illustrations, which number more than a hundred. These were selected in conference by Mr. Fred Chapman, Mr. Kitton, and myself, and include about fifty original drawings by Mr. Kitton, from sketches specially made by him for this work. Of the remainder, six are from Forster's Life of Dickens, fifteen from Langton's Childhood and Youth of Charles Dickens, seven from Charles Dickens by Pen and Pencil, ten from the Jubilee Edition of Pickwick, and five from Rimmer's About England with Dickens. A few interesting fac-similes of handwriting, etc., have also been introduced. Surely such an eclectic series of Dickens Illustrations has never before been presented in one volume.

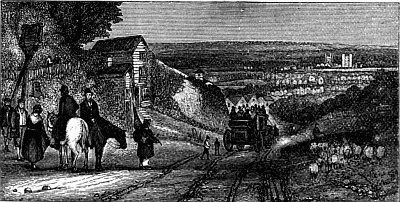

To Messrs. Chapman and Hall, Mr. Robert Langton, F.R.H.S., Messrs. Frank T. Sabin and John F. Dexter, Messrs. Macmillan and Co., and Messrs. Chatto and Windus (the proprietors of the above-mentioned works), the author's acknowledgments are also due, and are hereby tendered. Mr. Stephen T. Aveling has kindly supplied an illustration of Restoration House as it appeared in Dickens's time, and Mr. William Ball, J.P., generously commissioned a local artist to make a sketch of the Marshes, which[xii] forms the frontispiece to the book, and gives a good idea of the "long stretches of flat lands" on the Kent and Essex coasts.

To those friends whom we then met for the first time, and from whom we subsequently received help, the author's most cordial acknowledgments are due, and are also tendered, for kind information and assistance. They are a goodly number, and include Mr. A. A. Arnold, Mr. Stephen T. Aveling, Mr. William Ball, J.P., Mr. James Baird, Mr. Charles Bird, F.G.S., Major and Mrs. Budden, Mr. W. J. Budden, Mr. R. L. Cobb, Mr. J. Couchman, The Misses Drage, Mrs. Easedown, Mr. Franklin Homan, Mr. James Hulkes, J.P., and Mrs. Hulkes, Mr. Apsley Kennette, Mrs. Latter, Mr. J. Lawrence, Mr. C. D. Levy, Mr. B. Lillie, Mr. J. E. Littlewood, Mr. J. N. Malleson, Rev. J. J. Marsham, M.A., Mrs. Masters, Mr. Miles, Mr. W. Millen, Mr. Geo. Payne, F.S.A., Mr. William Pearce, Mr. George Robinson, Mr. T. B. Rosseter, F.R.M.S., Dr. Sheppard, Mr. Henry Smetham, Dr. Steele, M.R.C.S., Mr. William Syms, Mrs. Taylor, Miss Taylor, Mr. W. S. Trood, Major Trousdell, Rev. Robert Whiston, M.A., Mr. W. T. Wildish, Mr. Humphrey Wood, Mr. C. K. Worsfold, and Mrs. Henry Wright. The late Mr. Roach Smith, F.S.A., took much interest in my work and gave valuable assistance. Mr. Luke Fildes, R.A., and Mrs. Lynn Linton generously contributed very interesting information. The Right Honourable the Earl of Darnley, Mr. Henry Fielding Dickens, Mr. W. P. Frith, R.A., and Lady Head, also kindly answered enquiries.[xiii]

Miss Hogarth has at my request very kindly consented to the publication of the original letters of the Novelist—about a dozen—now printed for the first time.

My sincere thanks are due to Mr. E. W. Badger, F.R.H.S., the friend of many years, for valuable help.

To my old friend and fellow-tramp, Mr. F. G. Kitton, with whose memory this delightful excursion will ever be pleasantly connected, my warmest thanks are due for reading proofs and for much kind help in many ways. "He wos werry good to me, he wos." As Pip wrote to another "Jo," "woT larX" we did have.

Last, but not least, my cordial thanks are due to Mr. Charles Dickens for much kind information and valuable criticism.

So long as readers continue to be, so long will our great English trilogy of cognate authors, Shakespeare, Scott, and Dickens, continue to be read. Indeed as regards Dickens, a writer in Blackwood, June, 1871 (and Blackwood was not always a sympathetic critic), said:—"We may apply to him, without doubt, the surest test to which the maker can be subject: were all his books swept by some intellectual catastrophe out of the world, there would still exist in the world some score at least of people, with all whose ways and sayings we are more intimately acquainted than with those of our brothers and sisters, who would owe to him their being. While we live Sam Weller and Dick Swiveller, Mr. Pecksniff and Mrs. Gamp, the Micawbers and the Squeerses, can never die. . . . They are more real than we are[xiv] ourselves, and will outlive and outlast us, as they have outlived their creator. This is the one proof of genius which no critic, not the most carping or dissatisfied, can gainsay."

So long also, the author ventures to think, will pilgrimages continue to be made to the shrines of Stratford-on-Avon, Abbotsford, and Gad's Hill Place, and to their vicinities. The modest aim of this Volume is, that it may add a humble unit in helping to keep his memory green, and that it may be a useful and acceptable companion to pilgrims, not only of our own country, but also from that still "Greater Britain," where "All the Year Round" the name of Charles Dickens is almost a dearer "Household Word" than it is with us.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| Preface | vii | |

| I. | Introductory | 1 |

| II. | A Preliminary Tramp in London | 7 |

| III. | Rochester City | 51 |

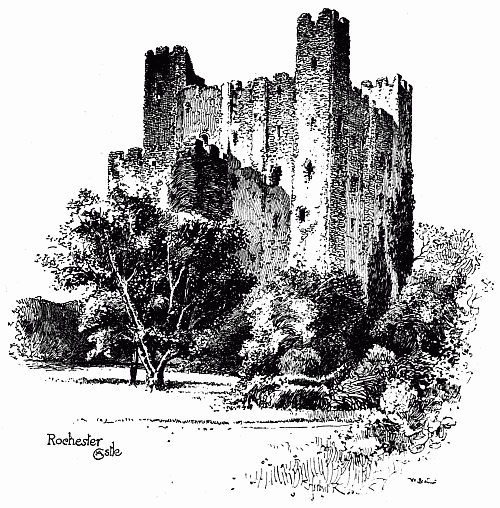

| IV. | Rochester Castle | 98 |

| V. | Rochester Cathedral | 111 |

| VI. | Richard Watts's Charity, Rochester | 142 |

| VII. | An Afternoon at Gad's Hill Place | 161 |

| VIII. | Charles Dickens and Strood | 211 |

| IX. | Chatham:—St. Mary's Church, Ordnance Terrace, The House on the Brook, The Mitre Hotel, and Fort Pitt. Landport:—Portsea, Hants | 251 |

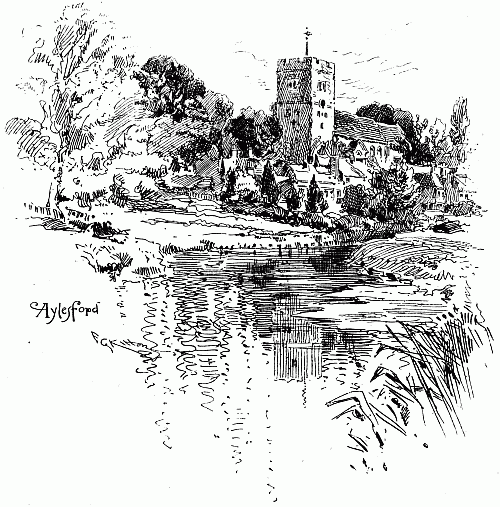

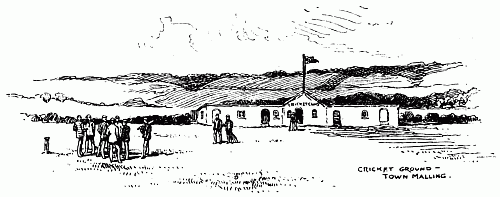

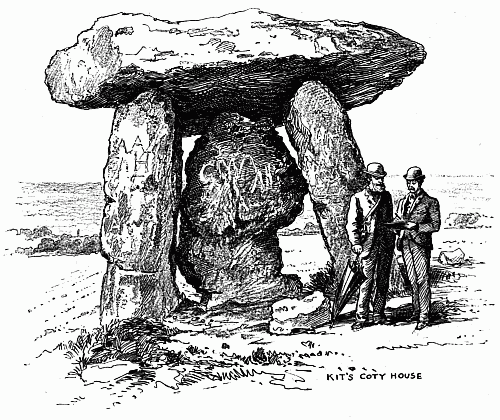

| X. | Aylesford, Town Malling, and Maidstone | 288 |

| XI. | Broadstairs, Margate, and Canterbury | 317 |

| XII. | Cooling, Cliffe, and Higham | 349 |

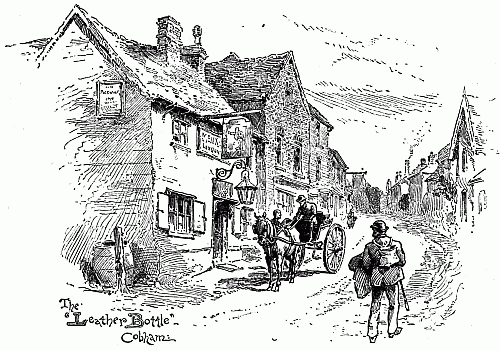

| XIII. | Cobham Park and Hall, The Leather Bottle, Shorne, Chalk, and the Dover Road | 376 |

| XIV. | A Final Tramp in Rochester and London | 405 |

| Index | 427 | |

| LISTOFILLUSTRATIONS |

|

| PAGE | ||

The Marshes, Cooling | F. G. Kitton (from a Sketch by E. L. Meadows) | Frontispiece |

Headpiece, "Humour" (From two Statuettes of "Mr. Pickwick" and "Sam Weller" in Crown Derby Ware) | Engraved by R. Langton | xvii |

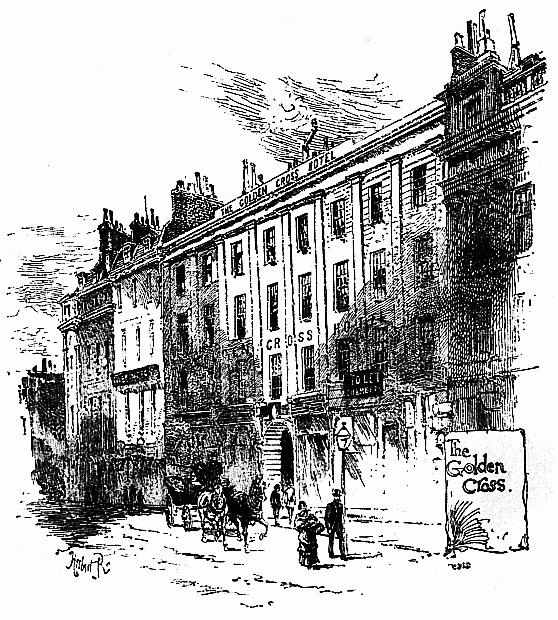

The Golden Cross | Herbert Railton | 10 |

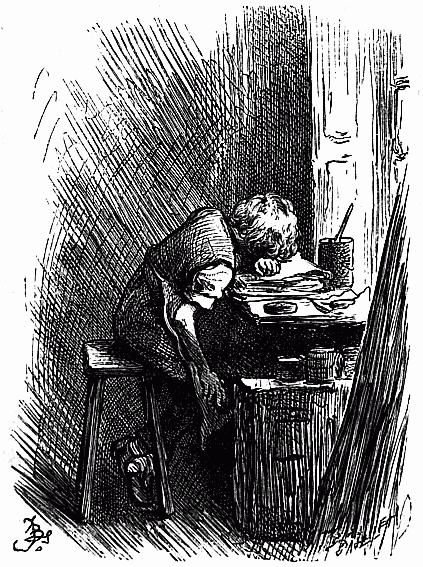

Young Dickens at the Blacking Warehouse | F. Barnard | 12 |

Fountain Court, Temple | C. A. Vanderhoof | 16 |

Staple Inn, Holborn | " " | 21 |

Barnard's Inn | Herbert Railton | 23 |

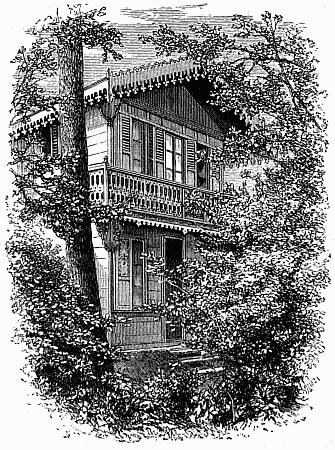

Dickens's House, Furnival's Inn | " " | 25 |

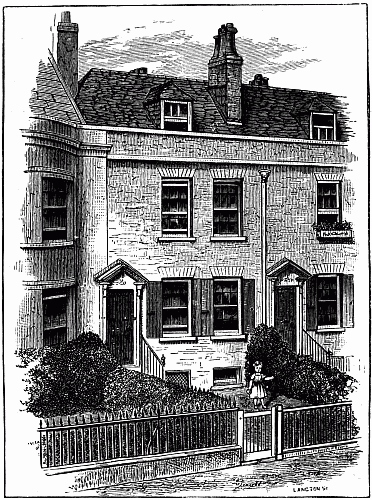

No. 48, Doughty Street | J. Grego | 28 |

Tavistock House, Tavistock Square | J. Liddell | 30 |

No. 141, Bayham Street | F. G. Kitton | 37 |

No. 1, Devonshire Terrace | D. Maclise, R.A. | 40 |

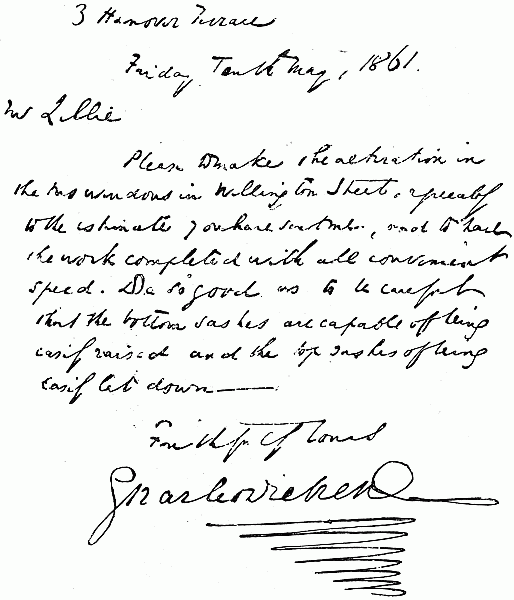

Fac-simile of Letter, Charles Dickens | 43 | |

Apotheosis of "Grip" the Raven | D. Maclise, R.A. | 45 |

"My magnificent order at the Public House" | Phiz | 49 |

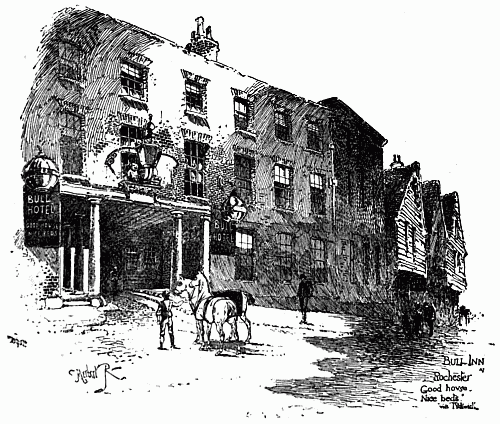

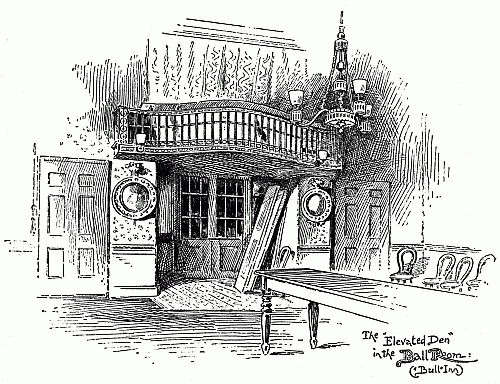

Bull Inn, Rochester—"good house, nice beds" | Herbert Railton | 56 |

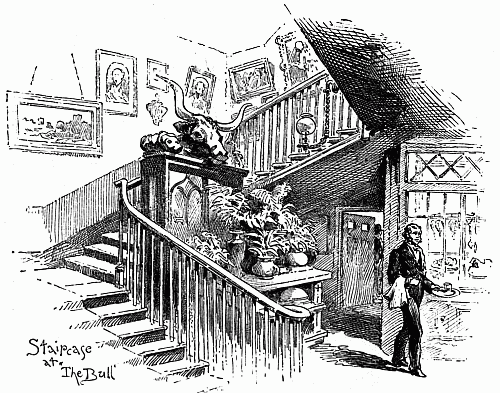

Staircase at "the Bull" | F. G. Kitton | 58 |

The "Elevated Den" in the Ball-room, "Bull Inn" | F. G. Kitton | 61 |

Old Rochester Bridge | Herbert Railton | 68 |

The Guildhall, Rochester | F. G. Kitton | 71 |

The "Moon-faced" Clock in High Street | " " | 72 |

| [xviii] In High Street, Rochester | " " | 73 |

Eastgate House, Rochester | F. G. Kitton | 74 |

Mr. Sapsea's House, Rochester | " " | 76 |

Mr. Sapsea's Father | (After sketch by H. Wickham) | 77 |

Restoration House, Rochester | F. G. Kitton | 79 |

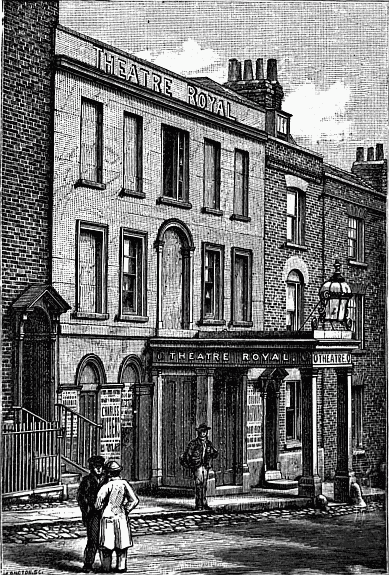

Old Rochester Theatre, Star Hill | W. Hull | 84 |

The Castle from Rochester Bridge | F. G. Kitton | 99 |

The Keep of Rochester Castle | Herbert Railton | 101 |

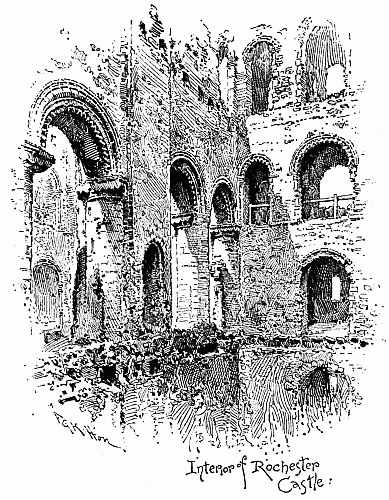

Interior of Rochester Castle | F. G. Kitton | 105 |

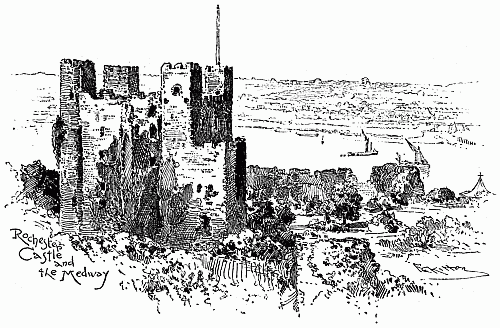

Rochester Castle and the Medway | " " | 109 |

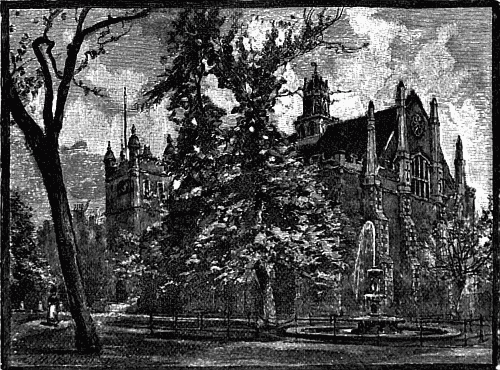

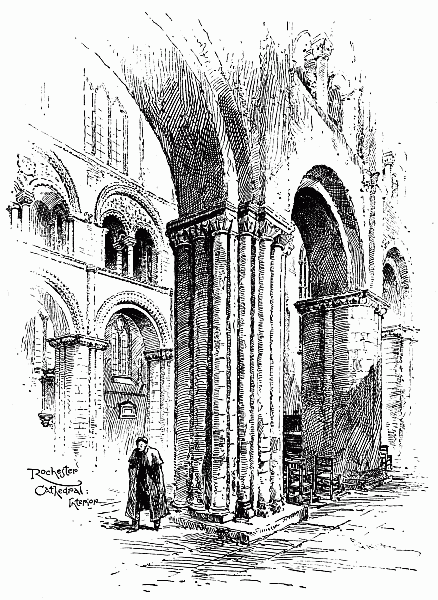

Rochester Cathedral | " " | 112 |

Rochester Cathedral, Interior | " " | 115 |

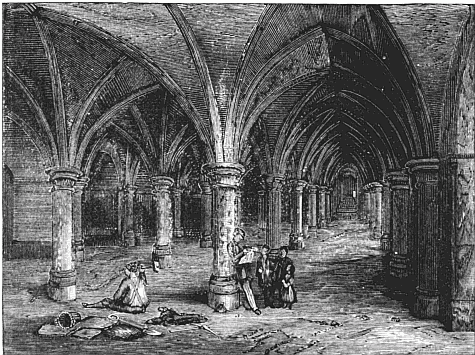

The Crypt, Rochester Cathedral | Phiz | 118 |

Minor Canon Row, Rochester | F. G. Kitton | 123 |

College Gate (or "Chertsey's" Gate), Rochester | F. G. Kitton | 125 |

Prior's Gate, Rochester | " " | 126 |

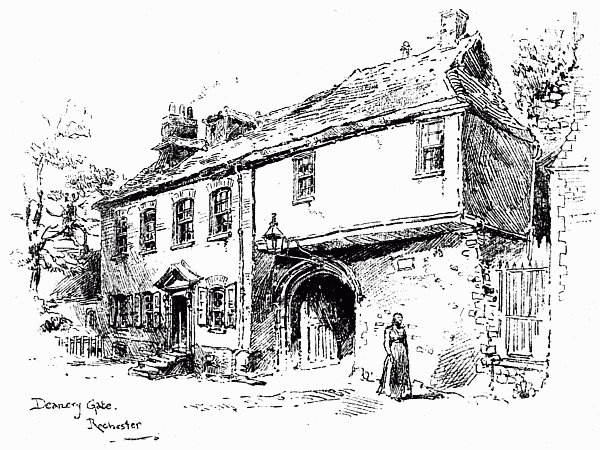

Deanery Gate, Rochester | " " | 128 |

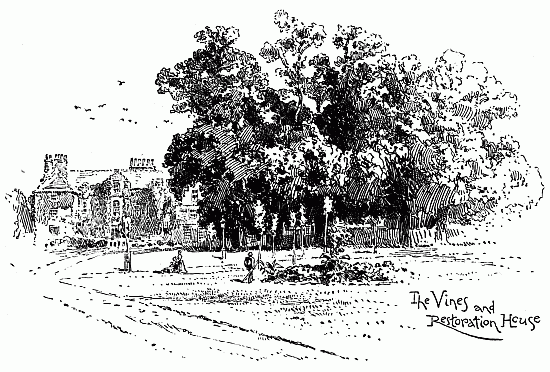

The Vines and Restoration House, Rochester | " " | 131 |

Restoration House, as it appeared in Dickens's time | (Engraved from a Drawing by an Amateur) | 133 |

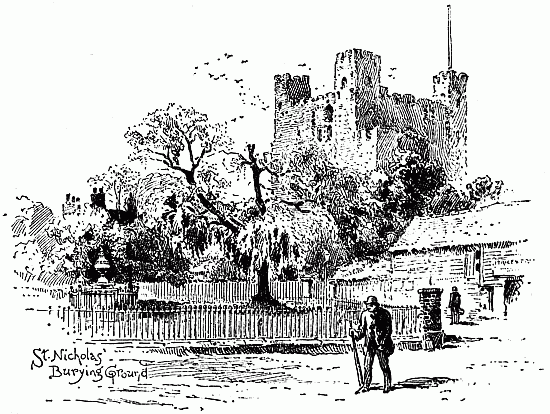

St. Nicholas' Burying-ground | F. G. Kitton | 136 |

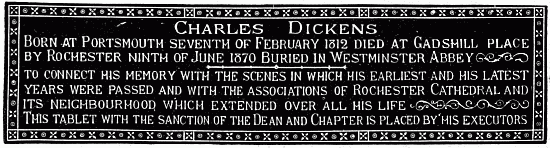

Memorial Brass in Rochester Cathedral | 138 | |

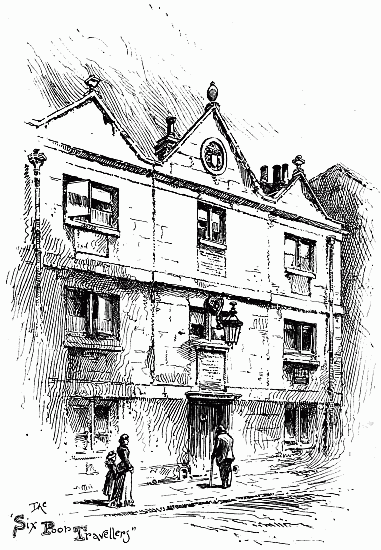

The "Six Poor Travellers" | F. G. Kitton | 143 |

Richard Watts's Almshouses, Rochester | " " | 149 |

Fac-similes of Signatures of Charles Dickens and Mark Lemon | 151 | |

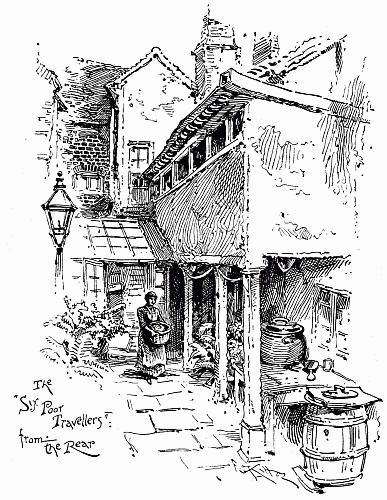

The "Six Poor Travellers" from the Rear | F. G. Kitton | 153 |

A Dormitory in the "Six Poor Travellers": Gallery leading to the Dormitories | F. G. Kitton | 154 |

Satis House | (From a Photograph) | 156 |

Watts's Monument in Rochester Cathedral | R. Langton | 157 |

Rochester from Strood Hill | C. Marshall | 162 |

The "Sir John Falstaff" Inn, Gad's Hill | F. G. Kitton | 164 |

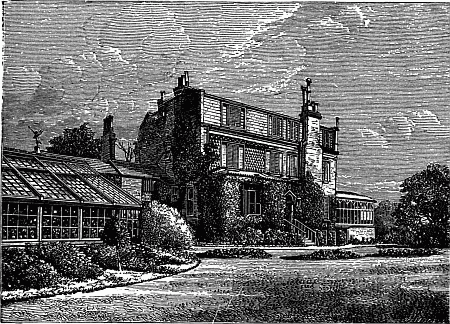

Gad's Hill Place | " " | 166 |

"The Empty Chair." Gad's Hill, Ninth of June, 1870 | F. G. Kitton (from the Drawing by S. L. Fildes, R.A.) | 170 |

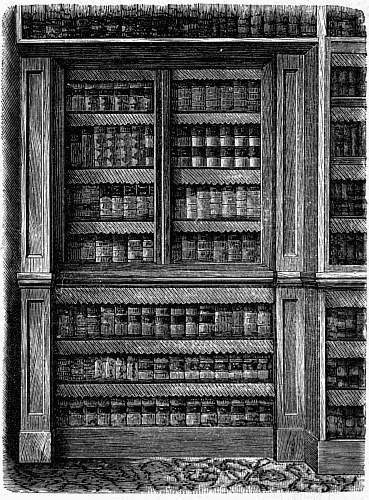

Counterfeit Book-backs on Study Door | R. Langton | 172 |

| [xix] Gad's Hill Place from the Rear | J. Liddell | 177 |

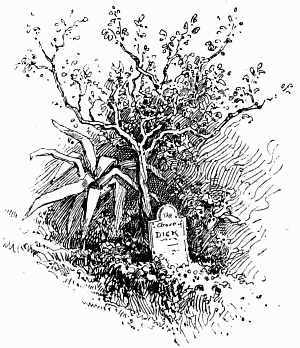

"The Grave of Dick, the best of Birds" | F. G. Kitton | 178 |

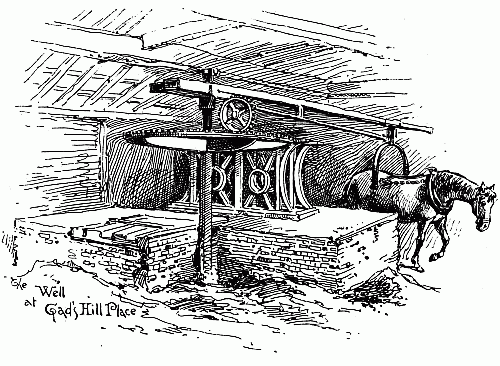

The Well at Gad's Hill Place | " " | 181 |

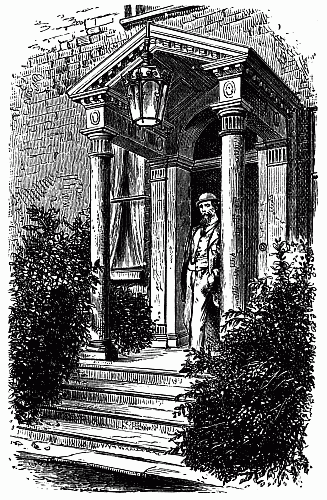

The Porch, Gad's Hill Place | J. Liddell | 183 |

The Cedars, Gad's Hill | E. Hull | 185 |

View from the Roof of Dickens's House, Gad's Hill | F. G. Kitton | 189 |

Fac-similes of Gad's Hill Gazette and Final Notice | 199-203 | |

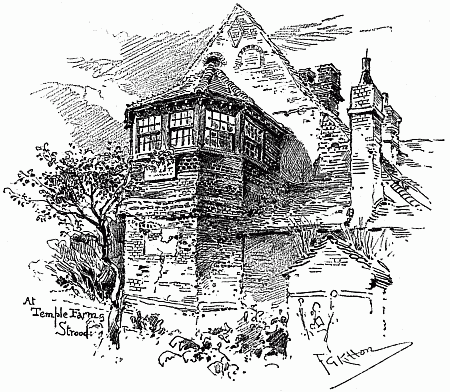

Temple Farm, Strood | F. G. Kitton | 213 |

At Temple Farm, Strood | " " | 214 |

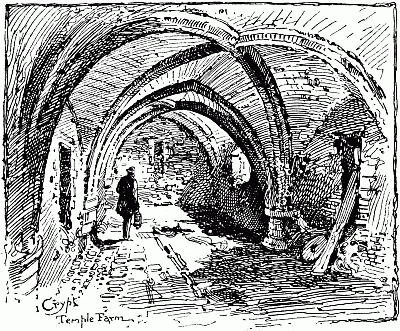

Crypt, Temple Farm | " " | 215 |

The "Crispin and Crispianus," Strood | " " | 218 |

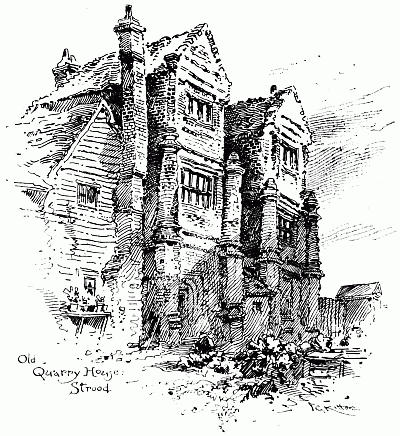

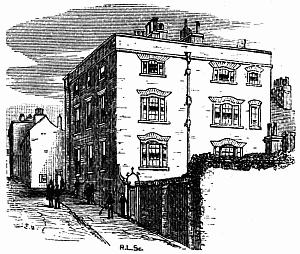

Old Quarry House, Strood | " " | 236 |

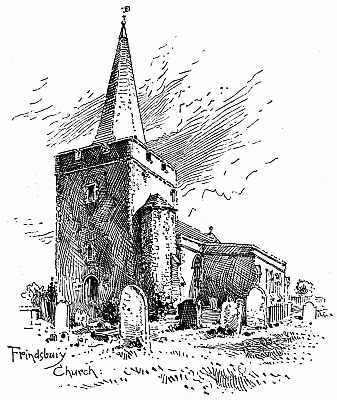

Frindsbury Church | " " | 239 |

Rochester from Strood Pier | " " | 245 |

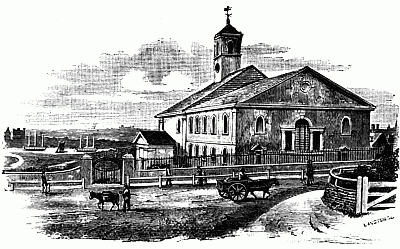

St. Mary's Church, Chatham | W. Dadson | 256 |

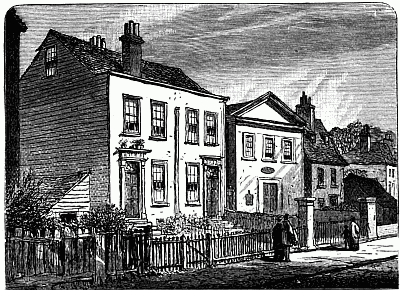

No. 11, Ordnance Terrace, Chatham | E. Hull | 259 |

The House on the Brook, Chatham | " | 260 |

Giles's School, Chatham | " | 261 |

Mitre Inn, Chatham | " | 263 |

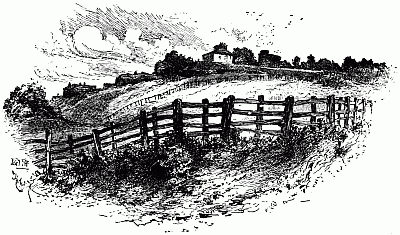

Navy-Pay Office, Chatham | " | 275 |

Fort Pitt, Chatham | Herbert Railton | 277 |

Birthplace of Charles Dickens, Portsea | (From a Photograph) | 281 |

St. Mary's Church, Portsea | R. Langton | 285 |

Aylesford | F. G. Kitton | 289 |

Aylesford Bridge | " " | 291 |

The High Street, Town Malling | Herbert Railton | 293 |

Cob Tree Hall | F. G. Kitton | 297 |

Cricket Ground, Town Malling | " " | 302 |

The Medway at Maidstone | " " | 307 |

Chillington Manor House, Maidstone | " " | 310 |

Kit's Coty House | " " | 312 |

Kit's Coty House and "Blue Bell" | " " | |

| (From the Painting by Gegan) | 315 | |

Hop-picking in Kent | F. G. Kitton | 319 |

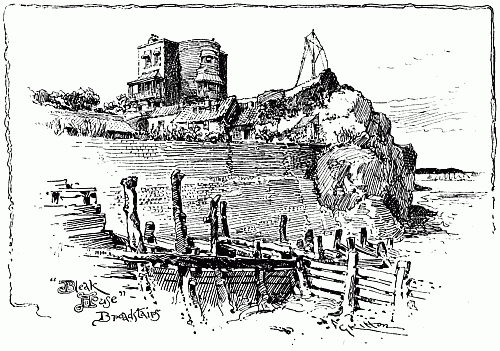

"Bleak House," Broadstairs | " " | 328 |

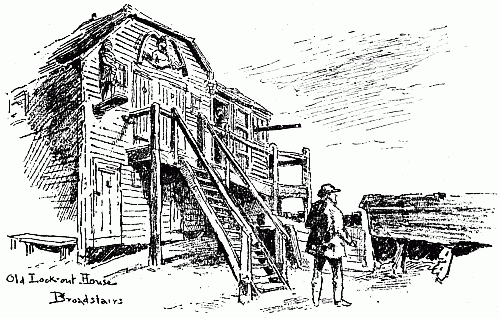

Old Look-out House, Broadstairs | " " | 332 |

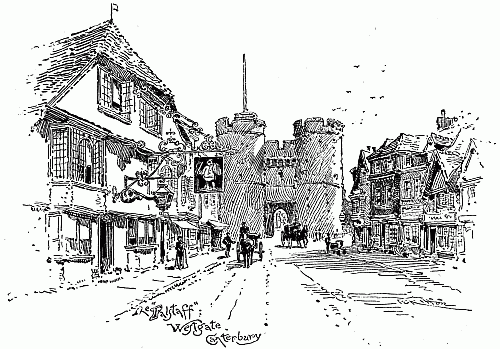

| [xx] The "Falstaff," Westgate, Canterbury | " " | 335 |

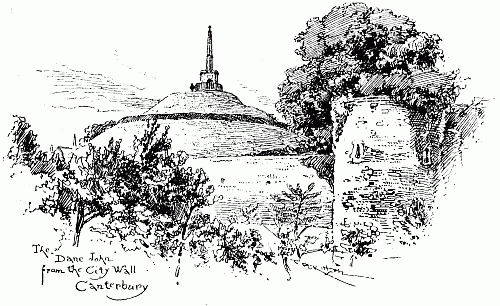

The "Dane John" from the City Wall, Canterbury | F. G. Kitton | 337 |

Bell Harry Tower, Canterbury Cathedral | " " | 339 |

Scene of the Martyrdom, Canterbury Cathedral | F. G. Kitton | 341 |

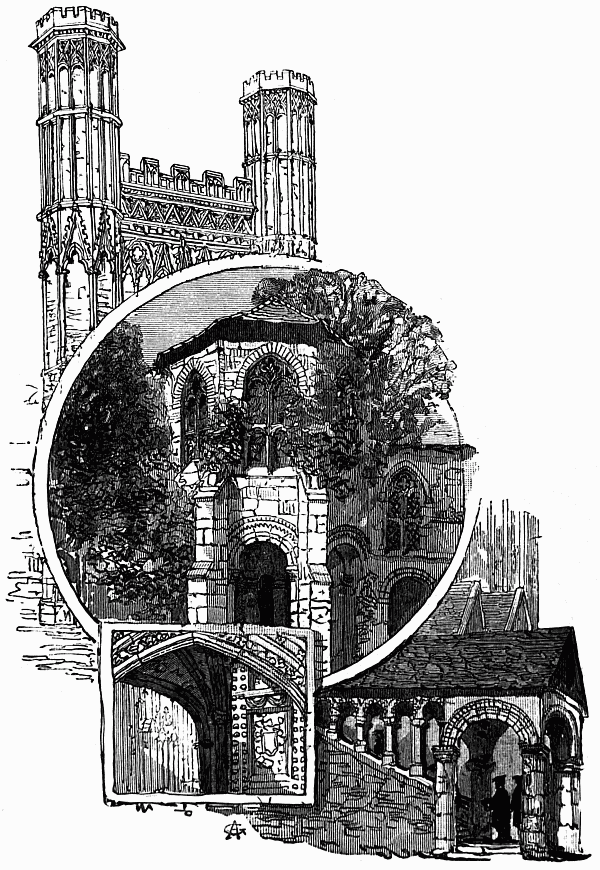

"Bits" of Old Canterbury | C. A. Vanderhoof | 342 |

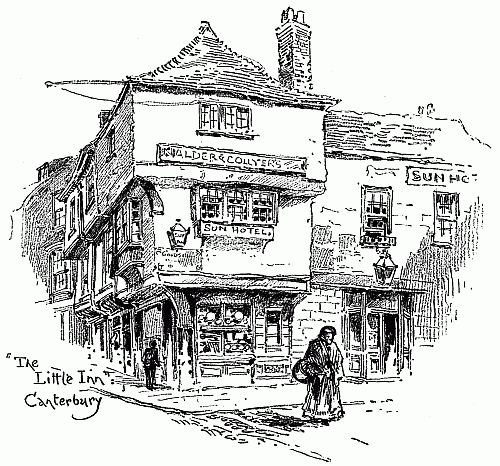

"The Little Inn," Canterbury | F. G. Kitton | 345 |

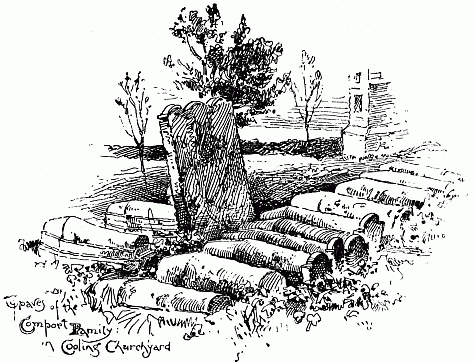

Graves of the Comport Family, Cooling Churchyard | F. G. Kitton | 353 |

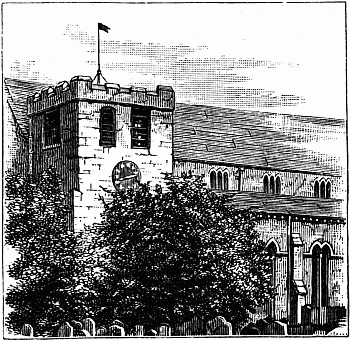

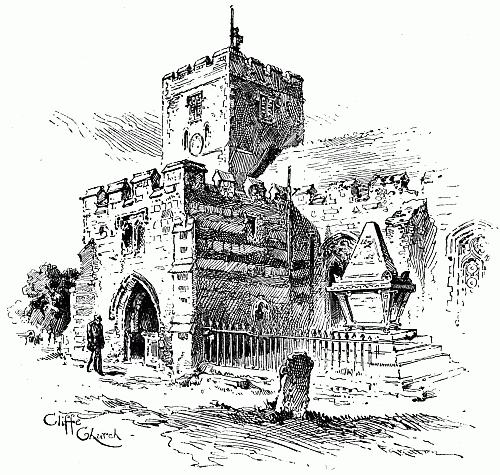

Cooling Church | C. A. Vanderhoof | 355 |

Gateway, Cooling Castle | F. G. Kitton | 359 |

Cliffe Church | " " | 361 |

Cobham Hall | Herbert Railton | 381 |

Dickens's Châlet, now in Cobham Park | J. Liddell | 384 |

The "Leather Bottle," Cobham | F. G. Kitton | 387 |

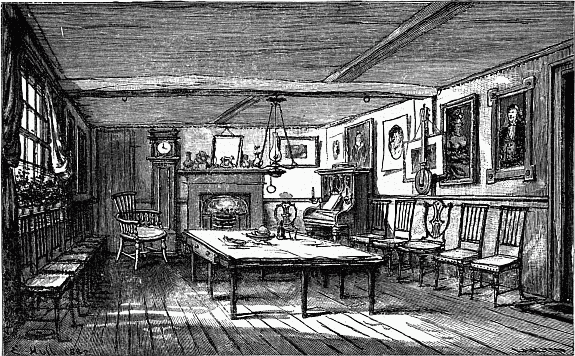

The Old Parlour of the "Leather Bottle" | E. Hull | 389 |

Cobham Church | Herbert Railton | 390 |

Shorne Church | F. G. Kitton | 392 |

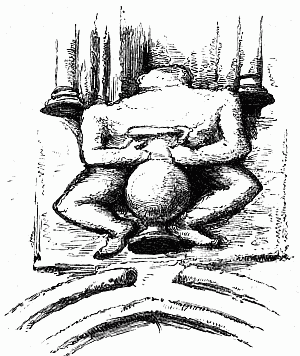

Curious Old Figure over the Porch, Chalk Church | F. G. Kitton | 394 |

"There's Milestones on the Dover Road" | " " | 400 |

Doorway, Rochester Cathedral | " " | 407 |

Fac-similes of Charles Dickens's Handwriting 1837, 1850, 1854, 1870 | 418-20 | |

The Grave in Westminster Abbey | F. G. Kitton | 425 |

Tailpiece, "Pathos" | (From two Plaques of the "Old Man" and "Little Nell" in Wedgwood Ware) | |

| Engraved by R. Langton | xx | |

|

|

Probably the pioneer in this class of literature was that comprehensive work, Dickens's London, or London in the Works of Charles Dickens, by my friend, that thorough Dickensian, Mr. T. Edgar Pemberton, 1876; this was followed by a very readable volume, In Kent with Charles Dickens, by Thomas Frost, 1880; then came a dainty tome from Boston, U.S.A., entitled, A Pickwickian Pilgrimage, by John R. G.[2] Hassard, 1881. Afterwards appeared The Childhood and Youth of Charles Dickens, by Robert Langton, 1883, beautifully illustrated by the late William Hull of Manchester, the author, and others—a work developed from the brochure by the same author, Charles Dickens and Rochester, 1880, which has passed through five editions. Next to Forster's Life of Dickens, Mr. Robert Langton's larger work undoubtedly ranks—especially from the richness of the illustrations—as a very valuable original contribution to the biography of the great novelist. Another handsome volume, containing the illustrations to a series of papers in Scribner's Monthly—written by B. E. Martin—entitled About England with Dickens, came from the pen of Mr. Alfred Rimmer, 1883, and included additional illustrations drawn by the author, C. A. Vanderhoof, and others. Yet another little brochure recently appeared, called London Rambles en zigzag with Charles Dickens, by Robert Allbut, 1886. Lastly, there was published in the Christmas Number of Scribner's Magazine, 1887, an article, "In Dickens-Land," by Edward Percy Whipple, in which this veteran and appreciative critic of the eminent English writer's works points out that, "In addition to the practical life that men and women lead, constantly vexed as it is by obstructive facts, there is an interior life which they imagine, in which facts smoothly give way to sentiments, ideas, and aspirations. Dickens has, in short, discovered and colonized one of the waste districts of 'Imagination,' which we may call 'Dickens-Land,' or 'Dickens-Ville,' . . . better known than such geographical countries as Canada and Australia, . . . and confirming us in the belief of the reality of a population which has no actual existence."[3]

It must not be assumed that the above list exhausts the literature on the subject of "Dickens-Land," many references to which are made in such high-class works as Augustus J. C. Hare's Walks in London, and Lawrence Hutton's Literary Landmarks of London.

Since the above was written, a very interesting and prettily illustrated article has appeared in the English Illustrated Magazine for October, 1888, entitled "Charles Dickens and Southwark," by Mr. J. Ashby-Sterry, who is second to none as an enthusiastic admirer and loyal student of Dickens. There is also a paper in Longman's Magazine for the same month, by the delightful essayist A. K. H. B., called "That Longest Day," in which there are several allusions to Dickens and "Dickens-Land." It, however, lacks the freshness of his earlier writings. Surely he must have lost his old love for Dickens, or things must have gone wrong at the Ecclesiastical Conference which took place at Gravesend on "That Longest Day." Altogether it is pitched in a minor key.

None of these contributions (with the exception of Mr. Langton's book), interesting as they are, and indispensable to the collector, attempt in any way to give personal reminiscences of Charles Dickens from friends or others, nor do they in any way help to throw light on his everyday life at home, beyond what was known before.

The circumstances narrated in this work do not concern the imaginary "Dickens-Land" of Mr. Whipple, but refer to the actual country in which the imaginary characters played their parts, and to that still more interesting actual country in which Dickens lived long and loved most—the county of Kent.

On Friday, 24th August, 1888, two friends met in London—one of them, the writer of these lines, a Dickens collector of[4] some years' experience; the other, Mr. F. G. Kitton, author of that sumptuous work, Charles Dickens by Pen and Pencil; both ardent admirers of "the inimitable 'Boz,'" and lovers of nature and art.

We were a sort of self-constituted roving commission, to carry into effect a long-projected intention to make a week's tramp in "Dickens-Land," for purposes of health and recreation; to visit Gad's Hill, Rochester, Chatham, and neighbouring classical ground; to go over and verify some of the most important localities rendered famous in the novels; to identify, if possible, doubtful spots; and to glean, under whatever circumstances naturally developed in the progress of our tramp, additions in any form to the many interesting memorials already published, and still ever growing, relating to the renowned novelist. The idea of recording our reminiscences was not a primary consideration. It grew out of our experiences, generating a desire for others to become acquainted with the results of our enjoyable peregrinations; and the labour therein involved has been somewhat of the kind described by Lewis Morris:—

We mixed with representatives of the classes of domestics, labourers, artizans, traders, professional men, and scientists. Many of those whom we met were advanced in years,—several were octogenarians,—and there is no doubt that we have been the means of placing on record here and there an interesting item from the past generation (mostly told in the exact words of the narrators) that might otherwise have perished. This is a special feature of this work, which makes it different from all[5] the preceding. In every instance we were received with very great kindness, courtesy, and attention. The replies to our questions were frank and generous, and in several cases permission was accorded us to make copies of original documents not hitherto made public.

Considering that almost every inch of ground connected with Dickens has been so thoroughly explored, we were, on the whole, quite satisfied with our excursion: "the results were equal to the appliances."

By a coincidence, the month which we selected (August) was Dickens's favourite month, if we may judge from the opening sentences of the sixteenth chapter of Pickwick:—

"There is no month in the whole year, in which nature wears a more beautiful appearance than in the month of August. Spring has many beauties, and May is a fresh and blooming month, but the charms of this time of year are enhanced by their contrast with the winter season. August has no such advantage. It comes when we remember nothing but clear skies, green fields, and sweet-smelling flowers—when the recollection of snow, and ice, and bleak winds, has faded from our minds as completely as they have disappeared from the earth,—and yet what a pleasant time it is. Orchards and cornfields ring with the hum of labour; trees bend beneath the thick clusters of rich fruit which bow their branches to the ground; and the corn, piled in graceful sheaves, or waving in every light breath that sweeps above it, as if it wooed the sickle, tinges the landscape with a golden hue. A mellow softness appears to hang over the whole earth; the influence of the season seems to extend itself to the very wagon, whose slow motion across the well-reaped field, is perceptible only to the eye, but strikes with no harsh sound upon the ear."

By another coincidence, the day which we selected to commence our tramp was Friday—the day upon which most of the important incidents of Dickens's life happened, as[6] appears from frequent references in Forster's Life to the subject.

Provided with a selection of books inseparably connected with the subject of our tour, including, of course, copies of Pickwick, Great Expectations, Edwin Drood, The Uncommercial Traveller, Bevan's Tourist's Guide to Kent, one or two local Handbooks, one of Bacon's useful cycling maps, with a sketch map of the geology of the district (which greatly helped us to understand many of its picturesque effects, and was kindly furnished by Professor Lapworth, LL.D., F.R.S., of the Mason College, Birmingham), and with a pocket aneroid barometer, which every traveller should possess himself with if he wishes to make convenient arrangements as regards weather, we make a preliminary tramp in London.

"There seemed," says this biographer, "to be not much to add to our knowledge of London until his books came upon us, but each in this respect outstripped the other in its marvels. In Nickleby, the old city reappears under every aspect; and whether warmth and light are playing over what is good and cheerful in it, or the veil is uplifted from its darker scenes, it is at all times our privilege to see and feel it as it absolutely is. Its interior hidden life becomes familiar as its commonest outward forms, and we discover that we hardly knew anything of the places we supposed that we knew the best."

What Scott did for Edinburgh and the Trossachs, Dickens did for London and the county of Kent. His fascination for the London streets has been dwelt on by many an author. Mr. Frank T. Marzials says in his interesting Life of Charles Dickens:—

"London remained the walking-ground of his heart. As he liked best to walk in London, so he liked best to walk at night. The darkness of the great city had a strange fascination for him. He never grew tired of it."[9]

Mr. Sala records that he had been encountered "in the oddest places and in the most inclement weather: in Ratcliff Highway, on Haverstock Hill, on Camberwell Green, in Gray's Inn Lane, in the Wandsworth Road, at Hammersmith Broadway, in Norton Folgate, and at Kensal New Town. A hansom whirled you by the 'Bell and Horns' at Brompton, and there was Charles Dickens striding as with seven-leagued boots, seemingly in the direction of North End, Fulham. The Metropolitan Railway disgorged you at Lisson Grove, and you met Charles Dickens plodding sturdily towards the 'Yorkshire Stingo.' He was to be met rapidly skirting the grim brick wall of the prison in Coldbath Fields, or trudging along the Seven Sisters' Road at Holloway, or bearing under a steady press of sail through Highgate Archway, or pursuing the even tenor of his way up the Vauxhall Bridge Road."

That his feelings were intensely sympathetic with all classes of humanity there is amply evidenced in the following lines, written so far back as 1841, which Master Humphrey, "from his clock side in the chimney corner," speaks in the last page before the opening of Barnaby Rudge:—

"Heart of London, there is a moral in thy every stroke! as I look on at thy indomitable working, which neither death, nor press of life, nor grief, nor gladness out of doors will influence one jot, I seem to hear a voice within thee which sinks into my heart, bidding me, as I elbow my way among the crowd, have some thought for the meanest wretch that passes, and, being a man, to turn away with scorn and pride from none that bear the human shape."

On a sultry day, such as this of Friday, the 24th August, 1888, with the thermometer at nearly 80 degrees in the shade, one needs some enthusiasm to undertake a tramp for a few hours over the hot and dusty streets of London, that we may[10] glance at a few of the memorable spots that we have visited over and over again before. This preliminary tramp is therefore necessarily limited to visiting the houses where Dickens lived, from the year 1836 until he finally left it in 1860, on disposing of Tavistock House, and took up his residence at Gad's Hill Place. In our way we shall take a few of the places rendered famous in the novels, but it would require a "knowledge of London" as "extensive and peculiar" as that of Mr. Weller, and would occupy a week at least, to exhaust the interest of all these associations.

Our temporary quarters are at our favourite "Morley's," in[11] Trafalgar Square, one of those old-fashioned, comfortable hotels of the last generation, where the guest is still known as "Mr. H.," and not as "Number 497." And what is very relevant to our present purpose, Morley's revives associations of the hotels, or "Inns," as they were more generally called in Charles Dickens's early days. Strolling from Morley's eastward along the Strand, to which busy thoroughfare there are numerous references in the works of Dickens, we pass on our left the Golden Cross Hotel, a great coaching-house half a century ago, from whence the Pickwickians and Mr. Jingle started, on the 13th of May, 1827, by the "Commodore" coach for Rochester. "The low archway," against which Mr. Jingle thus prudently cautioned the passengers,—"Heads! Heads! Take care of your heads!" with the addition of a very tragic reference to the head of a family, was removed in 1851, and the hotel has the same appearance now that it presented after that alteration. The house was a favourite with David Copperfield, who stayed there with his friend Steerforth on his arrival "outside the Canterbury coach;" and it was in one of the public rooms here, approached by "a side entrance to the stable-yard," that the affecting interview took place with his humble friend Mr. Peggotty, as touchingly recorded in the fortieth chapter of David Copperfield. The two famous "pudding shops" in the Strand, so minutely described in connection with David's early days, have of course long been removed:—

"One was in a court close to St. Martin's Church—at the back of the Church,—which is now removed altogether. The pudding at that shop was made of currants, and was rather a special pudding, but was dear, two pennyworth not being larger than a pennyworth of more ordinary pudding. A good shop for the latter was in the[12] Strand,—somewhere in that part which has been rebuilt since. It was a stout pale pudding, heavy and flabby, and with great flat raisins in it, stuck in whole at wide distances apart. It came up hot at about my time every day, and many a day did I dine off it."

Young Dickens at the Blacking Warehouse.

Young Dickens at the Blacking Warehouse.

Nearly opposite the Golden Cross Hotel is Craven Street, where (says Mr. Allbut), at No. 39, Mr. Brownlow in Oliver Twist resided after removing from Pentonville, and where the villain Monks was confronted, and made a full confession of his guilt.

"Ruminating on the strange mutability of human affairs," after the manner of Mr. Pickwick, we call to mind, on the same side of the way, Hungerford Stairs, Market, and Bridge,[13] all well remembered in the days of our youth, but now swept away to make room for the commodious railway terminus at Charing Cross. Here poor David Copperfield "served as a labouring hind," and acquired his grim experience with poverty in Murdstone and Grinby's (alias Lamert's) Blacking Warehouse. Hungerford Suspension Bridge many years ago was removed to Clifton, and we never pass by it on the Great Western line without recalling recollections of poor David's sorrows.

Next in order comes Buckingham Street, at the end house of which, on the east side (No. 15), lived Mrs. Crupp, who let apartments to David Copperfield in happier days. Here he had his "first dissipation," and entertained Steerforth and his two friends, Mrs. Crupp imposing on him frightfully as regards the dinner; "the handy young man" and the "young gal" being equally troublesome as regards the waiting. The description of "my set of chambers" in David Copperfield seems to point to the possibility of Dickens having resided here, but there is no evidence to prove it. At Osborn's Hotel, now the Adelphi, in John Street, Mr. Wardle and his daughter Emily stayed on their visit to London, after Mr. Pickwick was released from the Fleet Prison.

Durham Street, a little further to the right, leads to the "dark arches," which had attractions for David Copperfield, who "was fond of wandering about the Adelphi, because it was a mysterious place with those dark arches." He says:—"I see myself emerging one evening from out of these arches, on a little public-house, close to the river, with a space before it, where some coal-heavers were dancing." Nearly opposite is the Adelphi Theatre, notable as having been the stage[14] whereon most of the dramas founded on Dickens's works were first produced, from Nicholas Nickleby in 1838, in which Mrs. Keeley, John Webster, and O. Smith took part, down to 1867, when No Thoroughfare was performed, "the only story," says Mr. Forster, "Dickens himself ever helped to dramatize," and which was rendered with such fine effect by Fechter, Benjamin Webster, Mrs. Alfred Mellon, and other important actors. He certainly assisted in Madame Celeste's production of A Tale of Two Cities, even if he had no actual part in the writing of the piece.

Mr. Allbut thinks that the residence of Miss La Creevy, the good-natured miniature painter (whose prototype was Miss Barrow, Dickens's aunt on his mother's side) in Nicholas Nickleby, was probably at No. 111, Strand. It was "a private door about half-way down that crowded thoroughfare."

We proceed onwards, passing Wellington Street North, where at No. 16, the office of the famous Household Words formerly stood; All the Year Round, its successor, conducted by Mr. Charles Dickens, the novelist's eldest son, now being at No. 26 in the same street.

A little further on, on the same side of the way, and almost facing Somerset House, at No. 332, was the office of the once celebrated Morning Chronicle, on the staff of which Dickens in early life worked as a reporter. The Chronicle was a great power in its day, when Mr. John Black ("Dear old Black!" Dickens calls him, "my first hearty out-and-out appreciator, . . . with never-forgotten compliments . . . coming in the broadest of Scotch from the broadest of hearts I ever knew,") was editor, and Mr. J. Campbell, afterwards Lord Chief-Justice Campbell, its chief literary critic. The Chronicle died in 1862.

The west corner of Arundel Street (No. 186, Strand, where[15] now stand the extensive premises of Messrs. W. H. Smith and Son) was formerly the office of Messrs. Chapman and Hall, the publishers of almost all the original works of Charles Dickens. After 1850 the firm removed to 193, Piccadilly, their present house being at 11, Henrietta Street, Covent Garden. They own the copyright, and publish all Dickens's works; and they estimate that two million copies of Pickwick[1] have been sold in England alone, exclusive of the almost innumerable popular editions, from one penny upwards, published by other firms, the copyright of this work having expired. The penny edition was sold by hundreds of thousands in the streets of London some years ago.

This statement will probably be surprising to the remarkable class of readers thus described by that staunch admirer of Dickens, Mr. Andrew Lang, in "Phiz," one of his charming Lost Leaders. He says:—

"It is a singular and gloomy feature in the character of young ladies and gentlemen of a particular type, that they have ceased to care for Dickens, as they have ceased to care for Scott. They say they cannot read Dickens. When Mr. Pickwick's adventures are presented to the modern maid, she behaves like the Cambridge freshman. 'Euclide viso, cohorruit et evasit.' When he was shown Euclid he evinced dismay, and sneaked off. Even so do most young people act when they are expected to read Nicholas Nickleby and Martin Chuzzlewit. They call these master-pieces[16] 'too gutterly gutter'; they cannot sympathize with this honest humour and conscious pathos. Consequently the innumerable references to Sam Weller, and Mrs. Gamp, and Mr. Pecksniff, and Mr. Winkle, which fill our ephemeral literature, are written for these persons in an unknown tongue. The number of people who could take a good pass in Mr. Calverley's Pickwick Examination Paper is said to be diminishing. Pathetic questions are sometimes put. Are we not too much cultivated? Can this fastidiousness be anything but a casual passing phase of taste? Are all people over thirty who cling to their Dickens and their Scott old fogies? Are we wrong in preferring them to Bootles' Baby, and The Quick or the Dead, and the novels of M. Paul Bourget?"

Fountain Court, Temple.

Fountain Court, Temple.

But this by the way. Turning down Essex Street, we visit the Temple, celebrated in several of Dickens's novels—Barnaby Rudge, A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations, and Our Mutual Friend,—but in none more graphically than in Martin Chuzzlewit, in which is described the fountain in Fountain Court, where Ruth Pinch goes to meet her lover, "coming briskly up, with the best little laugh upon her face that ever played in opposition to the fountain; and beat it all to nothing." And when John Westlock came at last, "merrily the fountain leaped and danced, and merrily the smiling dimples twinkled and expanded more and more, until they broke into a laugh against the basin's rim, and vanished." As we saw the fountain on the bright August morning of our tramp, the few shrubs, flowers, and ferns planted round it gave it quite a rural effect, and we wished long life to the solitary specimen of eucalyptus, whose glaucous-green leaves and tender shoots seemed ill-fitted to bear the nipping frosts of our variable climate.

Coming out of the Temple by Middle Temple Lane, we pass on our left Child's Bank, the "Tellson's Bank" of A Tale of Two Cities, "which was an old-fashioned place even in the year 1780," but was replaced in 1878 by the handsome building suitable to its imposing neighbours, the Law Courts. Temple Bar, which adjoined the Old Bank, and was one of the relics of Dickens's London, has passed away, having since been re-erected on "Theobalds," near Waltham Cross.

"A walk down Fleet Street"—one of Dr. Johnson's enjoyments—leads us to Whitefriars Street, on the east side of which, at No. 67, is the office of The Daily News, edited by Dickens from 21 Jany. to 9 Feby., 1846, and for which he wrote the original prospectus, and subsequently, in a series of[18] letters descriptive of his Italian travel, his delightful Pictures from Italy. St. Dunstan's Church in Fleet Street is supposed to have been that immortalized in The Chimes.

It was in this street many years before (in the year 1833, when he was only twenty-one), as recorded in Forster's Life, that Dickens describes himself as dropping his first literary sketch, Mrs. Joseph Porter over the Way, "stealthily one evening at twilight, with fear and trembling, into a dark letter-box in a dark office up a dark court in Fleet Street; and he has told his agitation when it appeared in all the glory of print:—'On which occasion I walked down to Westminster Hall, and turned into it for half an hour, because my eyes were so dimmed with joy and pride, that they could not bear the street, and were not fit to be seen there.'" The "dark court" referred to was no doubt Johnson's Court, as the printers of the Monthly Magazine, Messrs. Baylis and Leighton, had their offices here. This contribution appeared in the January number 1834 of this magazine, published by Messrs. Cochrane and Macrone of 11 Waterloo Place.

Turning up Chancery Lane, also celebrated in many of Charles Dickens's novels, we leave on our left Bell Yard, where lodged the ruined suitor in Chancery, poor Gridley, "the man from Shropshire" in Bleak House, but the yard has, through part of it being required for the New Law Courts and other modern improvements, almost lost its identity.

On our right is Old Serjeant's Inn, which leads into Clifford's Inn, where the conference took place between John Rokesmith and Mr. Boffin, when the former, to the latter's amazement, said:—"If you would try me as your Secretary." The place is thus referred to in the eighth chapter of Our Mutual Friend:[19]—

"Not very well knowing how to get rid of this applicant, and feeling the more embarrassed because his manner and appearance claimed a delicacy in which the worthy Mr. Boffin feared he himself might be deficient, that gentleman glanced into the mouldy little plantation or cat preserve, of Clifford's Inn, as it was that day, in search of a suggestion. Sparrows were there, dry-rot and wet-rot were there, but it was not otherwise a suggestive spot."

Symond's Inn, described as "a little, pale, wall-eyed, woebegone inn, like a large dust-bin of two compartments and a sifter,"—where Mr. Vholes had his chambers, and where Ada Clare came to live after her marriage, there tending lovingly the blighted life of the suitor in Jarndyce and Jarndyce, poor Richard Carstone,—exists no more. It formerly stood on the site of Nos. 25, 26, and 27, now handsome suites of offices.

Lincoln's Inn, a little higher up on the opposite side of the way, claims our attention, in the Hall of which was formerly the Lord High Chancellor's Court, wherein the wire-drawn Chancery suit of Jarndyce and Jarndyce in Bleak House dragged its course wearily along. The offices of Messrs. Kenge and Carboy, of Old Square, Solicitors in the famous suit, were visited by Esther Summerson, who says:—"We passed into sudden quietude, under an old gallery, and drove on through a silent square, until we came to an old nook in a corner, where there was an entrance up a steep broad flight of stairs like an entrance to a church." Mr. Serjeant Snubbin, Mr. Pickwick's counsel in the notorious cause of Bardell v. Pickwick, also had his chambers in this square. We then enter Lincoln's Inn Fields, and pay a visit to No. 58, on the furthest or west side near Portsmouth Street. This ancient mansion was the residence of Dickens's friend and biographer, John Forster, before he went to live at Palace[20] Gate. It is minutely described in the tenth chapter of Bleak House as the residence of Mr. Tulkinghorn, "a large house, formerly a house of state, . . . let off in sets of chambers now; and in those shrunken fragments of its greatness lawyers lie like maggots in nuts." The "foreshortened allegory in the person of one impossible Roman upside down," who afterwards points to the "new meaning" (i. e. the murder of Mr. Tulkinghorn) has, it is to be regretted, since been whitewashed. On the 30th November, 1844, here Dickens read The Chimes to a few intimate friends, an event immortalized by Maclise's pencil, and, as appreciative of the feelings of the audience, Forster alludes "to the grave attention of Carlyle, the eager interest of Stanfield and Maclise, the keen look of poor Laman Blanchard, Fox's rapt solemnity, Jerrold's skyward gaze, and the tears of Harness and Dyce."

That celebrated tavern called the "Magpie and Stump," referred to in the twenty-first chapter of Pickwick,—where that hero spent an interesting evening on the invitation of Lowten (Mr. Perker's clerk), and heard "the old man's tale about the queer client,"—is supposed to have been "The old George the IVth" in Clare Market, close by. Retracing our steps through Bishop's Court (where lived Krook the marine-store dealer, and in whose house lodged poor Miss Flite and Captain Hawdon, alias Nemo) into Chancery Lane, we arrive at the point from whence we diverged, and turn into Cursitor Street. Like other places adjacent, this street has been subjected to "improvements," and it is scarcely possible to trace "Coavinses," so well known to Mr. Harold Skimpole, or indeed the place of business and residence of Mr. Snagsby, the good-natured law stationer, and his jealous "little woman." It will be remembered that it was here the Reverend Mr.[22] Chadband more than once "improved a tough subject":—"toe your advantage, toe your profit, toe your gain, toe your welfare, toe your enrichment,"—and refreshed his own. Thackeray was partial to this neighbourhood, and Rawdon Crawley had some painful experiences in Cursitor Street.

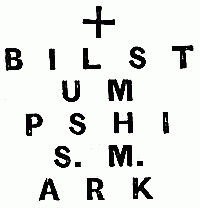

Bearing round by Southampton Buildings, we reach Staple Inn,—behind the most ancient part of Holborn,—originally a hostelry of the merchants of the Wool-staple, who were removed to Westminster by Richard II. in 1378. At No. 10 in the first court, opposite the pleasant little garden and picturesque hall, resided the "angular" but kindly Mr. Grewgious, attended by his "gloomy" clerk, Mr. Bazzard, and on the front of the house over the door still remains the tablet with the mysterious initials:—

Turning into Holborn through the Archway of Staple Inn, and stopping for a minute to admire the fine effect of the recently restored fourteenth-century old-timbered houses of the Inn which face that thoroughfare, a few steps lower down take us to Barnard's Inn, where Pip in Great Expectations lodged with his friend Herbert Pocket when he came to London. Dickens calls it, "the dingiest collection of shabby buildings ever squeezed together in a rank corner as a club for tom-cats." Simple-minded Joe Gargery, who visited Pip here, persisted for a time in calling it an "hotel," and after his visit thus recorded his impressions of the place:—

"The present may be a werry good inn, and I believe its character do stand i; but I wouldn't keep a pig in it myself—not in the case that I wished him to fatten wholesome and to eat with a meller flavour on him."

A few plane trees—the glory of all squares and open spaces in London, where they thrive so luxuriantly—give a rural appearance to this crowded place, while the sparrows tenanting them enjoy the sunbeams passing through the scanty branches.

Our next halting-place, Furnival's Inn, is one of profound interest to all pious pilgrims in "Dickens-Land," for there the genius of the young author was first recognized, not only by the novel-reading world, but also by his contemporaries in literature. Thackeray generously spoke of him as "the young man who came and took his place calmly at the head of the whole tribe, and who has kept it."

Furnival's Inn in Holborn, which stands midway between Barnard's Inn and Staple Inn on the opposite side of the way, is famous as having been the residence of Charles Dickens in his bachelor days, when a reporter for the Morning Chronicle.[25] He removed here from his father's lodgings at No. 18, Bentinck Street, and had chambers, first the "three pair back" (rather gloomy rooms) of No. 13 from Christmas 1834 until Christmas 1835, when he removed to the "three pair floor south" (bright little rooms) of No. 15, the house on the right-hand side of the square having Ionic ornamentations, which he occupied from 1835 until his removal to No. 48, Doughty Street, in March 1837. The brass-bound iron rail still remains, and the sixty stone steps which lead from the ground-floor to the top[26] of each house are no doubt the same over which the eager feet of the youthful "Boz" often trod. He was married from Furnival's Inn on 2nd April, 1836, to Catherine, eldest daughter of Mr. George Hogarth, his old colleague on the Morning Chronicle, the wedding taking place at St. Luke's Church, Chelsea, and doubtless lived here in his early matrimonial days much in the same way probably as Tommy Traddles did, as described in David Copperfield. Here the Sketches by Boz were written, and most of the numbers of the immortal Pickwick Papers, as also the lesser works: Sunday under Three Heads, The Strange Gentleman, and The Village Coquettes. The quietude of this retired spot in the midst of a busy thoroughfare, and its accessibility to the Chronicle offices in the Strand, must have been very attractive to the young author. His eldest son, the present Mr. Charles Dickens, was born here on the 6th January, 1837.

It was in Furnival's Inn, probably in the year 1836, that Thackeray paid a visit to Dickens, and thus described the meeting:—

"I can remember, when Mr. Dickens was a very young man, and had commenced delighting the world with some charming humorous works in covers which were coloured light green and came out once a month, that this young man wanted an artist to illustrate his writings; and I remember walking up to his chambers in Furnival's Inn, with two or three drawings in my hand, which, strange to say, he did not find suitable."

How wonderfully interesting these "two or three drawings" would be now if they could be discovered! Of the score or so of "Extra Illustrations" to Pickwick which have appeared, surely these (if they were such) which Dickens "did not find suitable," combining as they did the genius of[27] Dickens and Thackeray, whatever their merits or defects may have been, would be most highly prized.

John Westlock, in Martin Chuzzlewit, had apartments in Furnival's Inn, and was there visited by Tom Pinch. Wood's Hotel occupies a large portion of the square, and is mentioned in The Mystery of Edwin Drood as having been the Inn where Mr. Grewgious took rooms for his charming ward Rosa Bud, from whence he ordered for her refreshment, soon after her arrival at Staple Inn to escape Jasper's importunities, "a nice jumble of all meals," to which it is to be feared she did not do justice, and where "at the hotel door he afterwards confided her to the Unlimited head chamber-maid."

The Society of Arts have considerately put up on the house No. 15 one of their neat terra-cotta memorial tablets with the following inscription:—

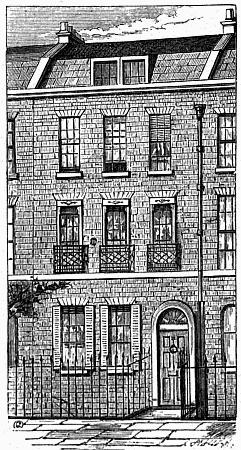

No. 48, Doughty Street, Mecklenburgh Square.

No. 48, Doughty Street, Mecklenburgh Square.We proceed along Holborn, and go up Kingsgate Street, where "Poll Sweedlepipe, Barber and Bird Fancier," lived, "next door but one to the celebrated mutton-pie shop, and directly opposite the original cats'-meat warehouse." The immortal Sairey Gamp lodged on the first floor, where doubtless she helped herself from the "chimley-piece" whenever she felt "dispoged." Here also the quarrel took place between that old lady and her friend Betsey Prig anent[28] that mythical personage, "Mrs. Harris." We pass through Red Lion Square and up Bedford Row, and after proceeding along Theobald's Road for a short distance, turn up John Street, which leads into Doughty Street, where, at No. 48, Charles Dickens lived from 1837 to 1839. The house, situated on the east side of the street, has twelve rooms, is single-fronted, three-storied, and not unlike No. 2, Ordnance Terrace, Chatham. A tiny little room on the ground-floor, with a bolt inside in addition to the usual fastening, is pointed[29] out as having been the novelist's study. It has an outlook into a garden, but of late years this has been much reduced in size. A bill in the front window announces "Apartments to let," and they look very comfortable. Doughty Street, now a somewhat noisy thoroughfare, must have been in Charles Dickens's time a quiet, retired spot. A large pair of iron gates reach across the street, guarded by a gate-keeper in livery. "It was," says Mr. Marzials in his Life of Dickens, "while living at Doughty Street that he seems, in great measure, to have formed those habits of work and relaxation which every artist fashions so as to suit his own special needs and idiosyncrasies. His favourite time for work was the morning between the hours of breakfast and lunch; . . . he was essentially a day worker and not a night worker. . . . And for relaxation and sedative when he had thoroughly worn himself with mental toil, he would have recourse to the hardest bodily exercise. . . . At first riding seems to have contented him, . . . but soon walking took the place of riding, and he became an indefatigable pedestrian. He would think nothing of a walk of twenty or thirty miles, and that not merely in the vigorous hey-day of youth, but afterwards to the very last. . . ."

It was at Doughty Street that he experienced a bereavement which darkened his life for many years, and to which Forster thus alludes:—

"His wife's next younger sister Mary, who lived with them, and by sweetness of nature even more than by graces of person had made herself the ideal of his life, died with a terrible suddenness that for a time completely bore him down. His grief and suffering were intense, and affected him . . . through many after years." Pickwick was temporarily[30] suspended, and he sought change of scene at Hampstead. Forster visited him there, and to him he opened his heart. He says:—"I left him as much his friend, and as entirely in his confidence, as if I had known him for years."

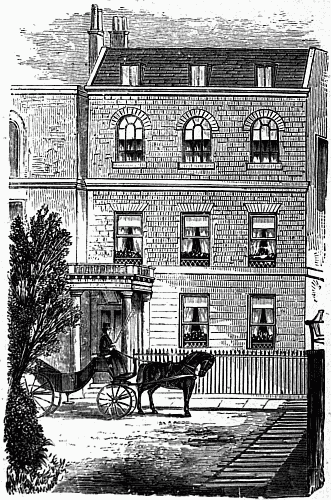

Tavistock House, Tavistock Square.

Tavistock House, Tavistock Square.Some time afterwards, we find him inviting Forster "to join him at 11 a.m. in a fifteen-mile ride out and ditto in, lunch on the road, with a six o'clock dinner in Doughty Street."

Charles Dickens's residence in Doughty Street was but of[31] short duration—from 1837 to 1840 only; but there he completed Pickwick, and wrote Oliver Twist, Memoirs of Grimaldi, Sketches of Young Gentlemen, Sketches of Young Couples, and The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. His eldest daughter Mary was born here.

In proper sequence we ought to proceed to Dickens's third London residence, No. 1, Devonshire Terrace, but it will be more convenient to take his fourth residence on our way. We therefore retrace our steps into Theobald's Road, pass through Red Lion and Bloomsbury Squares, and along Great Russell Street as far as the British Museum, where Dickens is still remembered as "a reader" (merely remarking that it of course contains a splendid collection of the original impressions of the novelist's works, and "Dickensiana," as is evidenced by the comprehensive Bibliography furnished by Mr. John P. Anderson, one of the librarians, to Mr. Marzials' Life of Dickens), which we leave on our left, and turn up Montague Street, go along Upper Montague Street, Woburn Square, Gordon Square, and reach Tavistock Square, at the upper end of which, on the east side, Gordon Place leads us into a retired spot cut off as it were from communication with the rest of this quiet neighbourhood. Three houses adjoin each other—handsome commodious houses, having stone porticos at entrance—and in the first of these, Tavistock House, Dickens lived from 1851 until 1860, with intervals at Gad's Hill Place. This beautiful house, which has eighteen rooms in it, is now the Jews' College. The drawing-room on the first floor still contains a dais at one end, and it is said that at a recent public meeting held here, three hundred and fifty people were accommodated in it, which serves to show what ample quarters Dickens had to entertain his friends.[32]

Hans Christian Andersen, who visited Dickens here in 1857, thus describes this fine mansion:—

"In Tavistock Square stands Tavistock House. This and the strip of garden in front are shut out from the thoroughfare by an iron railing. A large garden with a grass-plat and high trees stretches behind the house, and gives it a countrified look, in the midst of this coal and gas steaming London. In the passage from street to garden hung pictures and engravings. Here stood a marble bust of Dickens, so like him, so youthful and handsome; and over a bedroom door were inserted the bas-reliefs of Night and Day, after Thorwaldsen. On the first floor was a rich library, with a fireplace and a writing-table, looking out on the garden; and here it was that in winter Dickens and his friends acted plays to the satisfaction of all parties. The kitchen was underground, and at the top of the house were the bedrooms."

It appears that Andersen was wrong about the plays being acted in the "rich library," as I am informed by Mr. Charles Dickens that "the stage was in the school-room at the back of the ground-floor, with a platform built outside the window for scenic purposes."

With reference to the private theatricals (or "plays," as Andersen calls them, including The Frozen Deep, by Wilkie Collins, in which Dickens, the author, Mark Lemon, and others performed, and for which in the matter of the scenery "the priceless help of Stanfield had again been secured"), on a temporary difficulty arising as to the arrangements, Dickens applied to Mr. Cooke of Astley's, "who drove up in an open phaeton drawn by two white ponies with black spots all over them (evidently stencilled), who came in at the gate with a little jolt and a rattle exactly as they come into the ring when[33] they draw anything, and went round and round the centre bed (lilacs and evergreens) of the front court, apparently looking for the clown. A multitude of boys, who felt them to be no common ponies, rushed up in a breathless state—twined themselves like ivy about the railings, and were only deterred from storming the enclosure by the Inimitable's eye." Mr. Cooke was not, however, able to render any assistance.

Mrs. Arthur Ryland of The Linthurst, near Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, who was present at Tavistock House on the occasion of the performance of The Frozen Deep, informs me that when Dickens returned to the drawing-room after the play was over, the constrained expression of face which he had assumed in presenting the character of Richard Wardour remained for some time afterwards, so strongly did he seem to realize the presentment. The other plays performed were Tom Thumb, 1854, and The Lighthouse and Fortunus, 1855.

The following copy of a play-bill—in my collection—of one of these performances is certainly worth preserving in a permanent form, for the double reason that it is extremely rare, and contains one of Dickens's few poetical contributions, The Song of the Wreck, which was written specially for the occasion.

| Aaron Gurnock, the head Light-keeper | Mr. Crummles. |

| Martin Gurnock, his son; the second Light-keeper | Mr. Wilkie Collins. |

| Jacob Dale, the third Light-keeper | Mr. Mark Lemon. |

| Samuel Furley, a Pilot | Mr. Augustus Egg, A.R.A. |

| The Relief of Light-keepers, by | Mr. Charles Dickens, Junior, |

| Mr. Edward Hogarth, | |

| Mr. Alfred Ainger, and | |

| Mr. William Webster. | |

| The Shipwrecked Lady | Miss Hogarth. |

| Phœbe | Miss Dickens, |

| Mr. Nightingale | Mr. Frank Stone, A.R.A. | |

| Mr. Gabblewig, of the Middle Temple | ||

| Charley Bit, a Boots | ||

| Mr. Poulter, a Pedestrian and cold water drinker | Mr. Crummles. | |

| Captain Blower, an invalid | ||

| A Respectable Female | ||

| A Deaf Sexton | ||

| Tip, Mr. Gabblewig's Tiger | Mr Augustus Egg, A.R.A. | |

| Christopher, a Charity Boy | ||

| Slap, Professionally Mr. Flormiville, a country actors | ||

| Mr. Tickle, Inventor of the Celebrated Compounds | Mr. Mark Lemon. | |

| A Virtuous Young Person in the confidence of Maria | ||

| Lithers, Landlord of the Water-lily | Mr. Wilkie Collins. | |

| Rosina, Mr. Nightingale's niece | Miss Kate Dickens. | |

| Susan her Maid | Miss Hogarth. |

It was from Tavistock House that Dickens received this startling message from a confidential servant:—

"The gas-fitter says, sir, that he can't alter the fitting of your gas in your bedroom without taking up almost the ole of your bedroom floor, and pulling your room to pieces. He says of course you can have it done if you wish, and he'll do it for you and make a good job of it, but he would have to destroy your room first, and go entirely under the jistes."[37]

The same female, in allusion to Dickens's wardrobe, also said, "Well, sir, your clothes is all shabby, and your boots is all burst."

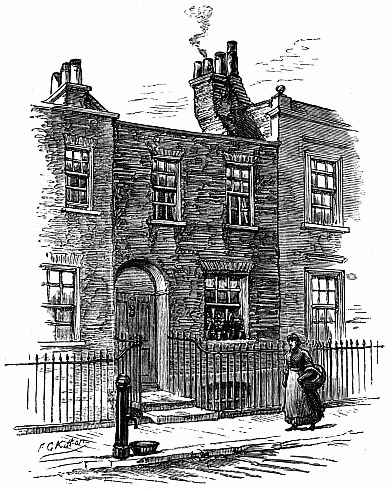

No. 141, Bayham Street, Camden Town,

No. 141, Bayham Street, Camden Town,Among the important works of Charles Dickens which were wholly or partly written at Tavistock House are:—Bleak House, A Child's History of England, Hard Times, Little Dorrit, A Tale of Two Cities, The Uncommercial Traveller, and Great Expectations. All the Year Round was also determined[38] upon while he lived here, and the first number was dated 30th April, 1859.

Tavistock House is the nearest point to Camden Town, interesting as being the place where, in 1823, at No. 16 (now No. 141) Bayham Street, the Dickens family resided for a short time[2] on leaving Chatham. There is an exquisite sketch of the humble little house by Mr. Kitton in his Charles Dickens by Pen and Pencil, and it is spoken of as being "in one of the then poorest parts of the London suburbs." We therefore proceed along Gordon Square, and reach Gower Street. At No. 147, Gower Street, formerly No. 4, Gower Street North, on the west side, was once the elder Mr. Dickens's establishment. The house, now occupied by Mr. Müller, an artificial human eye-maker ("human eyes warious," says Mr. Venus), has six rooms, with kitchens in basement. The rooms are rather small, each front room having two windows, which in the case of the first floor reach from floor to ceiling. It seems to be a comfortable house, but has no garden. There is an old-fashioned brass knocker on the front door, probably the original one, and there is a dancing academy next door. (Query, Mr. Turveydrop's?) The family of the novelist, which had removed from Bayham Street, were at this time (1823) in such indifferent circumstances that poor Mrs. Dickens had to[39] exert herself in adding to the finances by trying to teach, and a school was opened for young children at this house, which was decorated with a brass-plate on the door, lettered Mrs. Dickens's Establishment, a faint description of which occurs in the fourth chapter of Our Mutual Friend, and of its abrupt removal "for the interests of all parties." These facts, and also that of young Charles Dickens's own efforts to obtain pupils for his mother, are alluded to in a letter written by Dickens to Forster in later life:—

"I left, at a great many other doors, a great many circulars calling attention to the merits of the establishment. Yet nobody ever came to school, nor do I ever recollect that anybody ever proposed to come, or that the least preparation was made to receive anybody. But I know that we got on very badly with the butcher and baker; that very often we had not too much for dinner; and that at last my father was arrested."

This period, subsequently most graphically described in David Copperfield as the "blacking bottle period," was the darkest in young Charles's existence; but happier times and brighter prospects soon came to drown the recollections of that bitter experience.

Walking up Euston Road from Gower Street, we see St. Pancras Church (not the old church of "Saint Pancridge" in the Fields, by the bye, situated in the St. Pancras Road, where Mr. Jerry Cruncher and two friends went "fishing" on a memorable night, as recorded in A Tale of Two Cities, when their proceedings, and especially those of his "honoured parent," were watched by young Jerry), and proceed westward along the Marylebone Road, called the New Road in Dickens's time, past Park Crescent, Regent's Park, and do not stop until we[41] reach No. 1, Devonshire Terrace. This commodious double-fronted house, in which Dickens resided from 1839 to 1850, is entered at the side, and the front looks into the Marylebone Road. Maclise's beautiful sketch of the house (made in 1840), as given in Forster's Life, shows the windows of the lower and first floor rooms as largely bowed, while over the top flat of one of the former is a protective iron-work covering, thus allowing the children to come out of their nursery on the third floor freely to enjoy the air and watch the passers-by. In the sketch Maclise has characteristically put in a shuttlecock just over the wall, as though the little ones were playing in the garden. Forster calls it "a handsome house with a garden of considerable size, shut out from the New Road by a brick wall, facing the York Gate into Regent's Park;" and Dickens himself admitted it to be "a house of great promise (and great premium), undeniable situation, and excessive splendour." That he loved it well is shown by the passage in a letter which he addressed to Forster, "in full view of Genoa's perfect bay," when about to commence The Chimes (1844); he says:—"Never did I stagger so upon a threshold before. I seem as if I had plucked myself out of my proper soil when I left Devonshire Terrace, and could take root no more until I return to it. . . . Did I tell you how many fountains we have here? No matter. If they played nectar, they wouldn't please me half so well as the West Middlesex water-works at Devonshire Terrace."

Mr. Jonathan Clark, who resides here, kindly shows us over the house, which contains thirteen rooms. The polished mahogany doors in the hall, and the chaste Italian marble mantel-pieces in the principal rooms, are said to have been put up by the novelist. On the ground floor, the smaller[42] room to the eastward of the house, with window facing north and looking into the pleasant garden where the plane trees and turf are beautifully green, is pointed out as having been his study.

Mr. Benjamin Lillie, of 70, High Street, Marylebone, plumber and painter, remembers Mr. Dickens coming to Devonshire Terrace. He did a good deal of work for him while he lived there, and afterwards, when he removed to Tavistock House, including the fitting up of the library shelves and the curious counterfeit book-backs, made to conceal the backs of the doors. He also removed the furniture to Tavistock House, and subsequently to Gad's Hill Place. He spoke of the interest which Mr. Dickens used to take in the work generally, and said he would stand for hours with his back to the fire looking at the workmen. In the summer time he used to lie on the lawn with his pocket-handkerchief over his face, and when thoughts occurred to him, he would go into his study, and after making notes, would resume his position on the lawn. On the next page we give an illustration of the courteous and precise manner—not without a touch of humour—in which he issued his orders.

Here it was that Dickens's favourite ravens were kept, in a stable on the south side of the garden, one of which died in 1841, it was supposed from the effects of paint, or owing to "a malicious butcher," who had been heard to say that he "would do for him." His death is described by Dickens in a long passage which thus concludes:—

"On the clock striking twelve he appeared slightly agitated, but he soon recovered, walked twice or thrice along the coach-house, stopped to bark, staggered, exclaimed, 'Holloa, old girl!' (his favourite expression), and died."

In an interesting letter addressed to Mr. Angus Fletcher, recently in the possession of Mr. Arthur Hailstone of Manchester, Dickens further describes the event:—"Suspectful of a butcher who had been heard to threaten, I had the body opened. There were no traces of poison, and it appeared he[44] died of influenza. He has left considerable property, chiefly in cheese and halfpence, buried in different parts of the garden. The new raven (I have a new one, but he is comparatively of weak intellect) administered to his effects, and turns up something every day. The last piece of bijouterie was a hammer of considerable size, supposed to have been stolen from a vindictive carpenter, who had been heard to speak darkly of vengeance down the mews."

Maclise on hearing the news sent to Forster a letter, and a pen-and-ink sketch, being the famous "Apotheosis." The second raven died in 1845, probably from "having indulged the same illicit taste for putty and paint, which had been fatal to his predecessor." Dickens says:—

"Voracity killed him, as it did Scott's; he died unexpectedly by the kitchen fire. He kept his eye to the last upon the meat as it roasted, and suddenly turned over on his back with a sepulchral cry of 'Cuckoo!'"

These ravens were of course the two "great originals" of which Grip in Barnaby Rudge was the "compound." There was a third raven at Gad's Hill, but he "gave no evidence of ever cultivating his mind." The novelist's remarkable partiality for ravens called forth at the time the preposterous rumour that "Dickens had gone raving (raven) mad."

Here Longfellow visited Dickens in 1841, and thus referred to his visit:—"I write this from Dickens's study, the focus from which so many luminous things have radiated. The raven croaks in the garden, and the ceaseless roar of London fills my ears."

Dickens lived longer at Devonshire Terrace than he did at any other of his London homes, and a great deal of his[45] best work was done here, including Master Humphrey's Clock (I. The Old Curiosity Shop, II. Barnaby Rudge), American Notes, Martin Chuzzlewit, A Christmas Carol, The Cricket on the Hearth, Dombey and Son, The Haunted Man, and David Copperfield. The Battle of Life was written at Geneva in 1846. All these were published from his twenty-eighth to his thirty-eighth year; and Household Words, his[46] famous weekly popular serial of varied high-class literature, was determined upon here, the first number being issued on 30th March, 1850.

From Devonshire Terrace we pass along High Street, and turn into Devonshire Street, which leads into Harley Street, minutely described in Little Dorrit as the street wherein resided the great financier and "master-spirit" Mr. Merdle, who entertained "Bar, Bishop, and the Barnacle family" at the "Patriotic conference" recorded in the same work, in his noble mansion there, and he subsequently perishes "in the warm baths, in the neighbouring street"—as one may say—in the luxuriant style in which he had always lived.

Harley Street leads us into Oxford Street, and a pleasant ride outside an omnibus—which, as everybody knows, is the best way of seeing London—takes us to Hyde Park Place, a row of tall stately houses facing Hyde Park. Here at No. 5, (formerly Mr. Milner Gibson's town residence) Charles Dickens temporarily resided during the winter months of 1869, and occasionally until May 1870, during his readings at St. James's Hall, and while he was engaged on Edwin Drood, part of which was written here; this being illustrative of Dickens's power of concentrating his thoughts even near the rattle of a public thoroughfare. In a letter addressed to Mr. James T. Fields from this house, under date of 14th January, 1870, he says:—"We live here (opposite the Marble Arch) in a charming house until the 1st of June, and then return to Gad's. . . . I have a large room here with three fine windows over-looking the park—unsurpassable for airiness and cheerfulness."

A similar public conveyance takes us back to Morley's by way of Regent Street, about the middle of which, on the west[47] side, is New Burlington Street, containing, at No. 8, the well-known publishing office of Messrs. Richard Bentley and Son, whose once celebrated magazine, Bentley's Miscellany, Dickens edited for a period of two years and two months, terminating, 1838, on his resignation of the editorship to Mr. W. Harrison Ainsworth; and we also pass lower down, at the bottom of Waterloo Place, that most select of clubs, "The Athenæum," at the corner of Pall Mall, of which Dickens was elected a member in 1838, and from which, on the 20th May, 1870, he wrote his last letter to his son, Mr. Alfred Tennyson Dickens, in Australia; and a tenderly loving letter it is, indicating the harmonious relations between father and son. It expresses the hope that the two (Alfred and "Plorn") "may become proprietors," and "aspire to the first positions in the colony without casting off the old connection," and thus concludes:—"From Mr. Bear I had the best accounts of you. I told him that they did not surprise me, for I had unbounded faith in you. For which take my love and blessing." Sad to say, a note to this (the last in the series of published letters) states:—"This letter did not reach Australia until after these two sons of Charles Dickens had heard, by telegraph, the news of their father's death."[3]

At Morley's we refresh ourselves with Mr. Sam Weller's idea of a nice little dinner, consisting of "pair of fowls and a weal cutlet; French beans, taturs, tart and tidiness;" and then depart for Victoria Station, to take train by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway to Rochester.

The weather forecast issued by that most valuable institution, the Meteorological Office (established since Mr. Pickwick's days, in which doubtless as a scientist and traveller he would have taken great interest), was verified to the letter, and we had "thunder locally." On our way down Parliament Street, we pass Inigo Jones's once splendid Whitehall—now looking very insignificant as compared with its grand neighbours the Government Offices opposite—remembering Mr. Jingle's joke about Whitehall, which seems to have been Dickens's first thought of "King Charles's head":—"Looking at Whitehall, Sir—fine place—little window—somebody else's head off there, eh, Sir?—he didn't keep a sharp look out enough either—eh, Sir, eh?"

We also pass "The Red Lion," No. 48, Parliament Street, "at the corner of the very short street leading into Cannon Row," where David Copperfield ordered a glass of the very best ale—"The Genuine Stunning with a good head to it"—at twopence half-penny the glass, but the landlord hesitated to draw it, and gave him a glass of some which he suspected was not the "genuine stunning"; and the landlady coming into the bar returned his money, and gave him a "kiss that was half-admiring and half-compassionate, but all womanly and good [he says], I'm sure."[49]

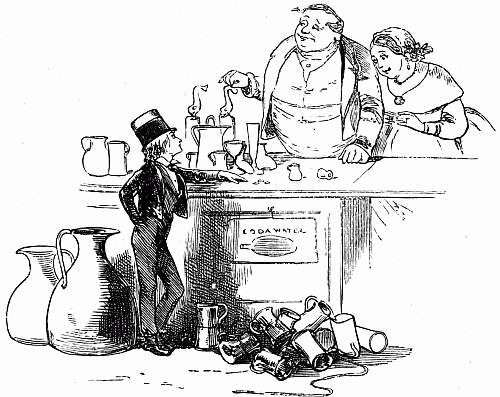

"My magnificent order at the Public House" (vide "David Copperfield").

"My magnificent order at the Public House" (vide "David Copperfield").

The Horse-Guards' clock is the last noteworthy object, and reminds us that Mark Tapley noticed the time there, on the occasion of his last meeting with Mary Graham in St. James's Park, before starting for America. It also reminds us of Mr. Micawber's maxim, "Procrastination is the thief of time—collar him;"—a few minutes afterwards we are comfortably seated in the train, and can defy the storm, which overtakes us precisely in the manner described in The Old Curiosity Shop:—

"It had been gradually getting overcast, and now the sky was dark and lowering, save where the glory of the departing sun piled up masses of gold and burning fire, decaying embers of which gleamed here and there through the black veil, and shone redly down upon the earth. The wind began to moan in hollow murmurs, as the sun went down, carrying glad day elsewhere; and a train of[50] dull clouds coming up against it menaced thunder and lightning. Large drops of rain soon began to fall, and, as the storm clouds came sailing onward, others supplied the void they left behind, and spread over all the sky. Then was heard the low rumbling of distant thunder, then the lightning quivered, and then the darkness of an hour seemed to have gathered in an instant."

We pass Dulwich,—where Mr. Snodgrass and Emily Wardle were married,—a fact that recalls kindly recollections of Mr. Pickwick and his retirement there, as recorded in the closing pages of the Pickwick Papers, where he is described as "employing his leisure hours in arranging the memoranda which he afterwards presented to the secretary of the once famous club, or in hearing Sam Weller read aloud, with such remarks as suggested themselves to his mind, which never failed to afford Mr. Pickwick great amusement." He is subsequently described as "somewhat infirm now, but he retains all his former juvenility of spirit, and may still be frequently seen contemplating the pictures in the Dulwich Gallery, or enjoying a walk about the pleasant neighbourhood on a fine day."

Although it is but a short distance—under thirty miles—to Rochester, the journey seems tedious, as the "iron-horse" does not keep pace with the pleasurable feelings of eager expectation afloat in our minds on this our first visit to "Dickens-Land"; it is therefore with joyful steps that we leave the train, and, the storm having passed away, find ourselves in the cool of the summer evening on the platform of Strood and Rochester Bridge Station.

It would occupy too much space in this narrative to adequately give even a brief historical sketch of the City of Rochester, which is twenty-nine miles from London, situated on the river Medway, and stands on the chalk on the margin of the London basin; but we think lovers of Dickens will not object to a recapitulation of a few of the most noteworthy circumstances which have happened here, and which are not touched upon in the chapters relating to the Castle and Cathedral.

According to the eminent local antiquary, Mr. Roach Smith, F.S.A., the name of the city has been thus evolved:—"The ceastre or chester is a Saxon affix to the Romano-British (DU)RO. The first two letters being dropped in sound, it became Duro or Dro, and then ROchester, and it was the Roman station Durobrovis." The ancient Britons called it "Dur-brif," and the Saxons "Hrofe-ceastre"—Horf's castle, of which appellation some people think Rochester is a corruption.