Title: The Golden House

Author: Charles Dudley Warner

Release date: October 10, 2004 [eBook #3104]

Most recently updated: January 27, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

It was near midnight: The company gathered in a famous city studio were under the impression, diligently diffused in the world, that the end of the century is a time of license if not of decadence. The situation had its own piquancy, partly in the surprise of some of those assembled at finding themselves in bohemia, partly in a flutter of expectation of seeing something on the border-line of propriety. The hour, the place, the anticipation of the lifting of the veil from an Oriental and ancient art, gave them a titillating feeling of adventure, of a moral hazard bravely incurred in the duty of knowing life, penetrating to its core. Opportunity for this sort of fruitful experience being rare outside the metropolis, students of good and evil had made the pilgrimage to this midnight occasion from less-favored cities. Recondite scholars in the physical beauty of the Greeks, from Boston, were there; fair women from Washington, whose charms make the reputation of many a newspaper correspondent; spirited stars of official and diplomatic life, who have moments of longing to shine in some more languorous material paradise, had made a hasty flitting to be present at the ceremony, sustained by a slight feeling of bravado in making this exceptional descent. But the favored hundred spectators were mainly from the city-groups of late diners, who fluttered in under that pleasurable glow which the red Jacqueminot always gets from contiguity with the pale yellow Clicquot; theatre parties, a little jaded, and quite ready for something real and stimulating; men from the clubs and men from studios—representatives of society and of art graciously mingled, since it is discovered that it is easier to make art fashionable than to make fashion artistic.

The vast, dimly lighted apartment was itself mysterious, a temple of luxury quite as much as of art. Shadows lurked in the corners, the ribs of the roof were faintly outlined; on the sombre walls gleams of color, faces of loveliness and faces of pain, studies all of a mood or a passion, bits of shining brass, reflections from lustred ware struggling out of obscurity; hangings from Fez or Tetuan, bits of embroidery, costumes in silk and in velvet, still having the aroma of balls a hundred years ago, the faint perfume of a scented society of ladies and gallants; a skeleton scarcely less fantastic than the draped wooden model near it; heavy rugs of Daghestan and Persia, making the footfalls soundless on the floor; a fountain tinkling in a thicket of japonicas and azaleas; the stems of palmettoes, with their branches waving in the obscurity overhead; points of light here and there where a shaded lamp shone on a single red rose in a blue Granada vase on a toppling stand, or on a mass of jonquils in a barbarous pot of Chanak-Kallessi; tacked here and there on walls and hangings, colored memoranda of Capri and of the North Woods, the armor of knights, trophies of small-arms, crossed swords of the Union and the Confederacy, easels, paints, and palettes, and rows of canvases leaning against the wall-the studied litter, in short, of a successful artist, whose surroundings contribute to the popular conception of his genius.

On the wall at one end of the apartment was stretched a white canvas; in front of it was left a small cleared space, on the edge of which, in the shadow, squatting on the floor, were four swarthy musicians in Oriental garments, with a mandolin, a guitar, a ney, and a darabooka drum. About this cleared space, in a crescent, knelt or sat upon the rugs a couple of rows of men in evening dress; behind them, seated in chairs, a group of ladies, whose white shoulders and arms and animated faces flashed out in the semi-obscurity; and in their rear stood a crowd of spectators—beautiful young gentlemen with vacant faces and the elevated Oxford shoulders, rosy youth already blase to all this world can offer, and gray-headed men young again in the prospect of a new sensation. So they kneel or stand, worshipers before the shrine, expecting the advent of the Goddess of AEsthetic Culture.

The moment has come. There is a tap on the drum, a tuning of the strings, a flash of light from the rear of the room inundates the white canvas, and suddenly a figure is poised in the space, her shadow cast upon the glowing background.

It is the Spanish dancer!

The apparition evokes a flutter of applause. It is a superb figure, clad in a high tight bodice and long skirts simply draped so as to show every motion of the athletic limbs. She seems, in this pose and light, supernaturally tall. Through her parted lips white teeth gleam, and she smiles. Is it a smile of anticipated, triumph, or of contempt? Is it the smile of the daughter of Herodias, or the invitation of a 'ghazeeyeh'? She pauses. Shall she surprise, or shock, or only please? What shall the art that is older than the pyramids do for these kneeling Christians? The drum taps, the ney pipes, the mandolin twangs, her arms are extended—the castanets clink, a foot is thrust out, the bosom heaves, the waist trembles. What shall it be—the old serpent dance of the Nile, or the posturing of decorous courtship when the olives are purple in the time of the grape harvest? Her head, wreathed with coils of black hair, a red rose behind the left ear, is thrown back. The eyes flash, there is a snakelike movement of the limbs, the music hastens slowly in unison with the quickening pulse, the body palpitates, seems to flash invitation like the eyes, it turns, it twists, the neck is thrust forward, it is drawn in, while the limbs move still slowly, tentatively; suddenly the body from the waist up seems to twist round, with the waist as a pivot, in a flash of athletic vigor, the music quickens, the arms move more rapidly to the click of the heated castenets, the steps are more pronounced, the whole woman is agitated, bounding, pulsing with physical excitement. It is a Maenad in an access of gymnastic energy. Yes, it is gymnastics; it is not grace; it is scarcely alluring. Yet it is a physical triumph. While the spectators are breathless, the fury ceases, the music dies, and the Spaniard sinks into a chair, panting with triumph, and inclines her dark head to the clapping of hands and the bravos. The kneelers rise; the spectators break into chattering groups; the ladies look at the dancer with curious eyes; a young gentleman with the elevated Oxford shoulders leans upon the arm of her chair and fans her. The pose is correct; it is the somewhat awkward tribute of culture to physical beauty.

To be on speaking terms with the phenomenon was for the moment a distinction. The young ladies wondered if it would be proper to go forward and talk with her.

“Why not?” said a wit. “The Duke of Donnycastle always shakes hands with the pugilists at a mill.”

“It is not so bad”—the speaker was a Washington beauty in an evening dress that she would have condemned as indecorous for the dancer it is not so bad as I—”

“Expected?” asked her companion, a sedate man of thirty-five, with the cynical air of a student of life.

“As I feared,” she added, quickly. “I have always had a curiosity to know what these Oriental dances mean.”

“Oh, nothing in particular, now. This was an exhibition dance. Of course its origin, like all dancing, was religious. The fault I find with it is that it lacks seriousness, like the modern exhibition of the dancing dervishes for money.”

“Do you think, Mr. Mavick, that the decay of dancing is the reason our religion lacks seriousness? We are in Lent now, you know. Does this seem to you a Lenten performance?”

“Why, yes, to a degree. Anything that keeps you up till three o'clock in the morning has some penitential quality.”

“You give me a new view, Mr. Mavick. I confess that I did not expect to assist at what New Englanders call an 'evening meeting.' I thought Eros was the deity of the dance.”

“That, Mrs. Lamon, is a vulgar error. It is an ancient form of worship. Virtue and beauty are the same thing—the two graces.”

“What a nice apothegm! It makes religion so easy and agreeable.”

“As easy as gravitation.”

“Dear me, Mr. Mavick, I thought this was a question of levitation. You are upsetting all my ideas. I shall not have the comfort of repenting of this episode in Lent.”

“Oh yes; you can be sorry that the dancing was not more alluring.”

Meantime there was heard the popping of corks. Venetian glasses filled with champagne were quaffed under the blessing of sparkling eyes, young girls, almond-eyed for the occasion, in the costume of Tokyo, handed round ices, and the hum of accelerated conversation filled the studio.

“And your wife didn't come?”

“Wouldn't,” replied Jack Delancy, with a little bow, before he raised his glass. And then added, “Her taste isn't for this sort of thing.”

The girl, already flushed with the wine, blushed a little—Jack thought he had never seen her look so dazzlingly handsome—as she said, “And you think mine is?”

“Bless me, no, I didn't mean that; that is, you know”—Jack didn't exactly see his way out of the dilemma—“Edith is a little old-fashioned; but what's the harm in this, anyway?”

“I did not say there was any,” she replied, with a smile at his embarrassment. “Only I think there are half a dozen women in the room who could do it better, with a little practice. It isn't as Oriental as I thought it would be.”

“I cannot say as to that. I know Edith thinks I've gone into the depths of the Orient. But, on the whole, I'm glad—” Jack stopped on the verge of speaking out of his better nature.

“Now don't be rude again. I quite understand that she is not here.”

The dialogue was cut short by a clapping of hands. The spectators took their places again, the lights were lowered, the illumination was turned on the white canvas, and the dancer, warmed with wine and adulation, took a bolder pose, and, as her limbs began to move, sang a wild Moorish melody in a shrill voice, action and words flowing together into the passion of the daughter of tents in a desert life. It was all vigorous, suggestive, more properly religious, Mavick would have said, and the applause was vociferous.

More wine went about. There was another dance, and then another, a slow languid movement, half melancholy and full of sorrow, if one might say that of a movement, for unrepented sin; a gypsy dance this, accompanied by the mournful song of Boabdil, “The Last Sigh of the Moor.” And suddenly, when the feelings of the spectators were melted to tender regret, a flash out of all this into a joyous defiance, a wooing of pleasure with smiling lips and swift feet, with the clash of cymbals and the quickened throb of the drum. And so an end with the dawn of a new day.

It was not yet dawn, however, for the clocks were only striking three as the assembly, in winter coats and soft wraps, fluttered out to its carriages, chattering and laughing, with endless good-nights in the languages of France, Germany, and Spain.

The streets were as nearly deserted as they ever are; here and there a lumbering market-wagon from Jersey, an occasional street-car with its tinkling bell, rarer still the rush of a trembling train on the elevated, the voice of a belated reveler, a flitting female figure at a street corner, the roll of a livery hack over the ragged pavement. But mainly the noise of the town was hushed, and in the sharp air the stars, far off and uncontaminated, glowed with a pure lustre.

Farther up town it was quite still, and in one of the noble houses in the neighborhood of the Park sat Edith Delancy, married not quite a year, listening for the roll of wheels and the click of a night-key.

Everybody liked John Corlear Delancy, and this in spite of himself, for no one ever knew him to make any effort to incur either love or hate. The handsome boy was a favorite without lifting his eyebrows, and he sauntered through the university, picking his easy way along an elective course, winning the affectionate regard of every one with whom he came in contact. And this was not because he lacked quality, or was merely easy-going and negative or effeminate, for the same thing happened to him when he went shooting in the summer in the Rockies. The cowboys and the severe moralists of the plains, whose sedate business in life is to get the drop on offensive persons, regarded him as a brother. It isn't a bad test of personal quality, this power to win the loyalty of men who have few or none of the conventional virtues. These non-moral enforcers of justice—as they understood it liked Jack exactly as his friends in the New York clubs liked him—and perhaps the moral standard of approval of the one was as good as the other.

Jack was a very good shot and a fair rider, and in the climate of England he might have taken first-rate rank in athletics. But he had never taken first-rate rank in anything, except good-fellowship. He had a great many expensive tastes, which he could not afford to indulge, except in imagination. The luxury of a racing-stable, or a yacht, or a library of scarce books bound by Paris craftsmen was denied him. Those who account for failures in life by a man's circumstances, and not by a lack in the man himself, which is always the secret of failure, said that Jack was unfortunate in coming into a certain income of twenty thousand a year. This was just enough to paralyze effort, and not enough to permit a man to expand in any direction. It is true that he was related to millions and moved in a millionaire atmosphere, but these millions might never flow into his bank account. They were not in hand to use, and they also helped to paralyze effort—like black clouds of an impending shower that may pass around, but meantime keeps the watcher indoors.

The best thing that Jack Delancy ever did, for himself, was to marry Edith Fletcher. The wedding, which took place some eight months before the advent of the Spanish dancer, was a surprise to many, for the girl had even less fortune than Jack, and though in and of his society entirely, was supposed to have ideals. Her family, indeed, was an old one on the island, and was prominent long before the building of the stone bridge on Canal Street over the outlet of Collect Pond. Those who knew Edith well detected in her that strain of moral earnestness which made the old Fletchers such stanch and trusty citizens. The wonder was not that Jack, with his easy susceptibility to refined beauty, should have been attracted to her, or have responded to a true instinct of what was best for him, but that Edith should have taken up with such a perfect type of the aimlessness of the society strata of modern life. The wonder, however, was based upon a shallow conception of the nature of woman. It would have been more wonderful if the qualities that endeared Jack to college friends and club men, to the mighty sportsmen who do not hesitate, in the clubs, to devastate Canada and the United States of big game, and to the border ruffians of Dakota, should not have gone straight to the tender heart of a woman of ideals. And when in all history was there a woman who did not believe, when her heart went with respect for certain manly traits, that she could inspire and lift a man into a noble life?

The silver clock in the breakfast-room was striking ten, and Edith was already seated at the coffee-urn, when Jack appeared. She was as fresh as a rose, and greeted him with a bright smile as he came behind her chair and bent over for the morning kiss—a ceremony of affection which, if omitted, would have left a cloud on the day for both of them, and which Jack always declared was simply a necessity, or the coffee would have no flavor. But when a man has picked a rose, it is always a sort of climax which is followed by an awkward moment, and Jack sat down with the air of a man who has another day to get through with.

“Were you amused with the dancing—this morning?”

“So, so,” said Jack, sipping his coffee. “It was a stunning place for it, that studio; you'd have liked that. The Lamons and Mavick and a lot of people from the provinces were there. The company was more fun than the dance, especially to a fellow who has seen how good it can be and how bad in its home.”

“You have a chance to see the Spanish dancer again, under proper auspices,” said Edith, without looking up.

“How's that?”

“We are invited by Mrs. Brown—”

“The mother of the Bible class at St. Philip's?”

“Yes—to attend a charity performance for the benefit of the Female Waifs' Refuge. She is to dance.”

“Who? Mrs. Brown?”

Edith paid no attention to this impertinence. “They are to make an artificial evening at eleven o'clock in the morning.”

“They must have got hold of Mavick's notion that this dance is religious in its origin. Do you, know if the exercises will open with prayer?”

“Nonsense, Jack. You know I don't intend to go. I shall send a small check.”

“Well, draw it mild. But isn't this what I'm accused of doing—shirking my duty of personal service by a contribution?”

“Perhaps. But you didn't have any of that shirking feeling last night, did you?”

Jack laughed, and ran round to give the only reply possible to such a gibe. These breakfast interludes had not lost piquancy in all these months. “I'm half a mind to go to this thing. I would, if it didn't break up my day so.”

“As for instance?”

“Well, this morning I have to go up to the riding-school to see a horse—Storm; I want to try him. And then I have to go down to Twist's and see a lot of Japanese drawings he's got over. Do you know that the birds and other animals those beggars have been drawing, which we thought were caricatures, are the real thing? They have eyes sharp enough to see things in motion—flying birds and moving horses which we never caught till we put the camera on them. Awfully curious. Then I shall step into the club a minute, and—”

“Be in at lunch? Bess is coming.”

“Don't wait lunch. I've a lot to do.”

Edith followed him with her eyes, a little wistfully; she heard the outer door close, and still sat at the table, turning over the pile of notes at her plate, and thinking of many things—things that it began to dawn upon her mind could not be done, and things of immediate urgency that must be done. Life did not seem quite such a simple problem to her as it had looked a year ago. That there is nothing like experiment to clear the vision is the general idea, but oftener it is experience that perplexes. Indeed, Edith was thinking that some things seemed much easier to her before she had tried them.

As she sat at the table with a faultless morning-gown, with a bunch of English violets in her bosom, an artist could have desired no better subject. Many people thought her eyes her best feature; they were large brown eyes, yet not always brown, green at times, liquid, but never uncertain, apt to have a smile in them, yet their chief appealing characteristic was trustfulness, a pure sort of steadfastness, that always conveyed the impression of a womanly personal interest in the person upon whom they were fixed. They were eyes that haunted one like a remembered strain of music. The lips were full, and the mouth was drawn in such exquisite lines that it needed the clear-cut and emphasized chin to give firmness to its beauty. The broad forehead, with arching eyebrows, gave an intellectual cast to a face the special stamp of which was purity. The nose, with thin open nostrils, a little too strong for beauty, together with the chin, gave the impression of firmness and courage; but the wonderful eyes, the inviting mouth, so modified this that the total impression was that of high spirit and great sweetness of character. It was the sort of face from which one might expect passionate love or unflinching martyrdom. Her voice had a quality the memory of which lingered longer even than the expression of her eyes; it was low, and, as one might say, a fruity voice, not quite clear, though sweet, as if veiled in femineity. This note of royal womanhood was also in her figure, a little more than medium in height, and full of natural grace. Somehow Edith, with all these good points, had not the reputation of a belle or a beauty—perhaps for want of some artificial splendor—but one could not be long in her company without feeling that she had great charm, without which beauty becomes insipid and even commonplace, and with which the plainest woman is attractive.

Edith's theory of life, if one may so dignify the longings of a young girl, had been very simple, and not at all such as would be selected by the heroine of a romance. She had no mission, nor was she afflicted by that modern form of altruism which is a yearning for notoriety by conspicuous devotion to causes and reforms quite outside her normal sphere of activity. A very sincere person, with strong sympathy for humanity tempered by a keen perception of the humorous side of things, she had a purpose, perhaps not exactly formulated, of making the most out of her own life, not in any outward and shining career, but by a development of herself in the most helpful and harmonious relations to her world. And it seemed to her, though she had never philosophized it, that a marriage such as she believed she had made was the woman's way to the greatest happiness and usefulness. In this she followed the dictates of a clear mind and a warm heart. If she had reasoned about it, considering how brief life is, and how small can be any single contribution to a better social condition, she might have felt more strongly the struggle against nature, and the false position involved in the new idea that marriage is only a kind of occupation, instead of an ordinance decreed in the very constitution of the human race. With the mere instinct of femineity she saw the falseness of the assumption that the higher life for man or woman lies in separate and solitary paths through the wilderness of this world. To an intelligent angel, seated on the arch of the heavens, the spectacle of the latter-day pseudo-philosophic and economic dribble about the doubtful expediency of having a wife, and the failure of marriage, must seem as ludicrous as would a convention of birds or of flowers reasoning that the processes of nature had continued long enough. Edith was simply a natural woman, who felt rather than reasoned that in a marriage such as her heart approved she should make the most of her life.

But as she sat here this morning this did not seem to be so simple a matter as it had appeared. It began to be suspected that in order to make the most of one's self it was necessary to make the most of many other persons and things. The stream in its own channel flowed along not without vexations, friction and foaming and dashings from bank to bank; but it became quite another and a more difficult movement when it was joined to another stream, with its own currents and eddies and impetuosities and sluggishness, constantly liable to be deflected if not put altogether on another course. Edith was not putting it in this form as she turned over her notes of invitation and appointments and engagements, but simply wondering where the time for her life was to come in, and for Jack's life, which occupied a much larger space than it seemed to occupy in the days before it was joined to hers. Very curious this discovery of what another's life really is. Of course the society life must go on, that had always gone on, for what purpose no one could tell, only it was the accepted way of disposing of time; and now there were the dozen ways in which she was solicited to show her interest in those supposed to be less fortunate in life than herself-the alleviation of the miseries of her own city. And with society, and charity, and sympathy with the working classes, and her own reading, and a little drawing and painting, for which she had some talent, what became of that comradeship with Jack, that union of interests and affections, which was to make her life altogether so high and sweet?

This reverie, which did not last many minutes, and was interrupted by the abrupt moving away of Edith to the writing-desk in her own room, was caused by a moment's vivid realization of what Jack's interests in life were. Could she possibly make them her own? And if she did, what would become of her own ideals?

It was indeed a busy day for Jack. Great injustice would be done him if it were supposed that he did not take himself and his occupations seriously. His mind was not disturbed by trifles. He knew that he had on the right sort of four-in-hand necktie, with the appropriate pin of pear-shaped pearl, and that he carried the cane of the season. These things come by a sort of social instinct, are in the air, as it were, and do not much tax the mind. He had to hasten a little to keep his half-past-eleven o'clock appointment at Stalker's stables, and when he arrived several men of his set were already waiting, who were also busy men, and had made a little effort to come round early and assist Jack in making up his mind about the horse.

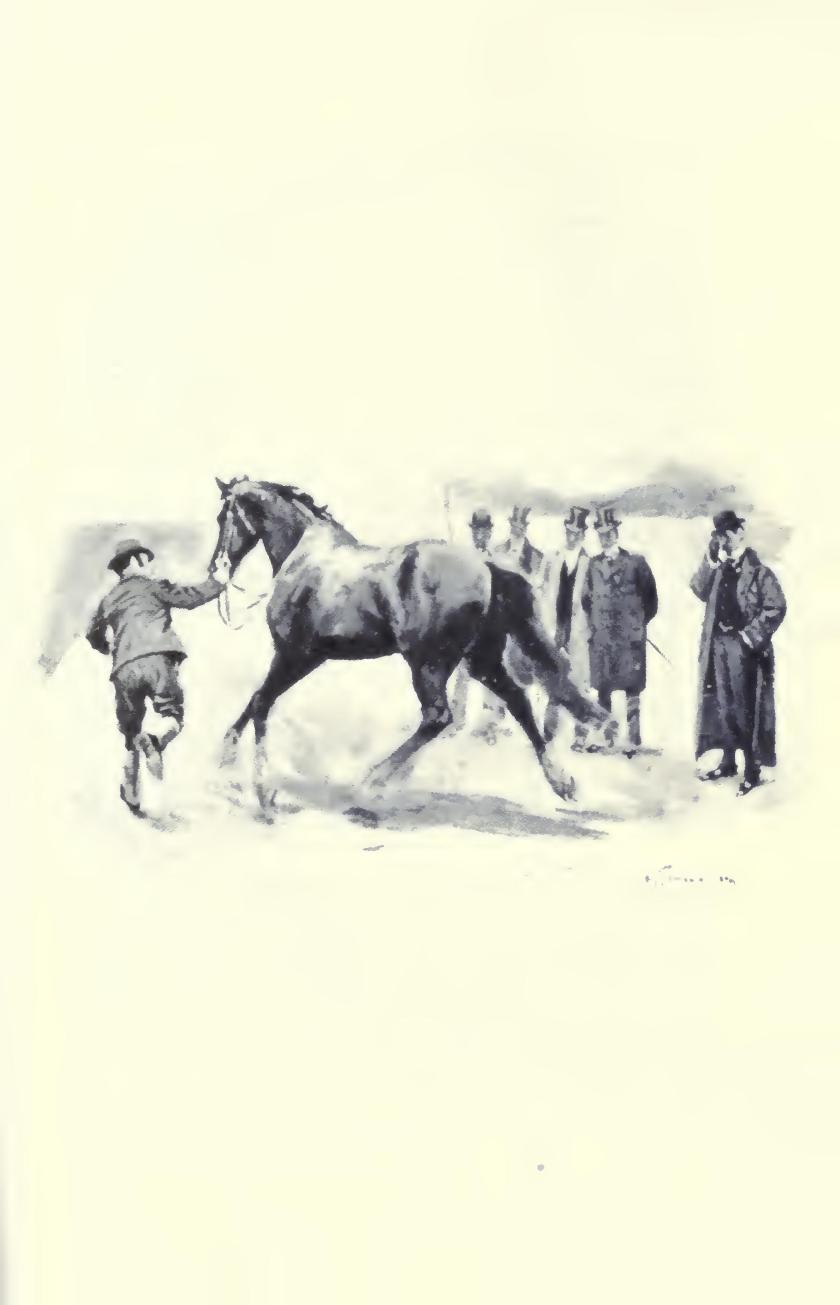

When Mr. Stalker brought out Storm, and led him around to show his action, the connoisseurs took on a critical attitude, an attitude of judgment, exhibited not less in the poise of the head and the serious face than in the holding of the cane and the planting of legs wide apart. And the attitude had a refined nonchalance which professional horsemen scarcely ever attain. Storm could not have received more critical and serious attention if he had been a cooked terrapin. He could afford to stand this scrutiny, and he seemed to move about with the consciousness that he knew more about being a horse than his judges.

Storm was, in fact, a splendid animal, instinct with life from his thin flaring nostril to his small hoof; black as a raven, his highly groomed skin took the polish of ebony, and showed the play of his powerful muscles, and, one might say, almost the nervous currents that thrilled his fine texture. His large, bold eyes, though not wicked, flamed now and then with an energy and excitement that gave ample notice that he would obey no master who had not stronger will and nerve than his own. It was a tribute to Jack's manliness that, when he mounted him for a turn in the ring, Storm seemed to recognize the fine quality of both seat and hand, and appeared willing to take him on probation.

“He's got good points,” said Mr. Herbert Albert Flick, “but I'd like a straighter back.”

“I'll be hanged, though, Jack,” was Mr. Mowbray Russell's comment, “if I'd ride him in the Park before he's docked. Say what you like about action, a horse has got to have style.”

“Moves easy, falls off a little too much to suit me in the quarter,” suggested Mr. Pennington Docstater, sucking the head of his cane. “How about his staying quality, Stalker?”

“That's just where he is, Mr. Docstater; take him on the road, he's a stayer for all day. Goes like a bird. He'll take you along at the rate of nine miles in forty-five minutes as long as you want to sit there.”

“Jump?” queried little Bobby Simerton, whose strong suit at the club was talking about meets and hunters.

“Never refused anything I put him at,” replied Stalker; “takes every fence as if it was the regular thing.”

Storm was in this way entirely taken to pieces, praised and disparaged, in a way to give Stalker, it might be inferred from his manner, a high opinion of the knowledge of these young gentlemen. “It takes a gentleman,” in fact, Stalker said, “to judge a hoss, for a good hoss is a gentleman himself.” It was much discussed whether Storm would do better for the Park or for the country, whether it would be better to put him in the field or keep him for a roadster. It might, indeed, be inferred that Jack had not made up his mind whether he should buy a horse for use in the Park or for country riding. Even more than this might be inferred from the long morning's work, and that was that while Jack's occupation was to buy a horse, if he should buy one his occupation would be gone. He was known at the club to be looking for the right sort of a horse, and that he knew what he wanted, and was not easily satisfied; and as long as he occupied this position he was an object of interest to sellers and to his companions.

Perhaps Mr. Stalker understood this, for when the buyers had gone he remarked to the stable-boy, “Mr. Delancy, he don't want to buy no hoss.”

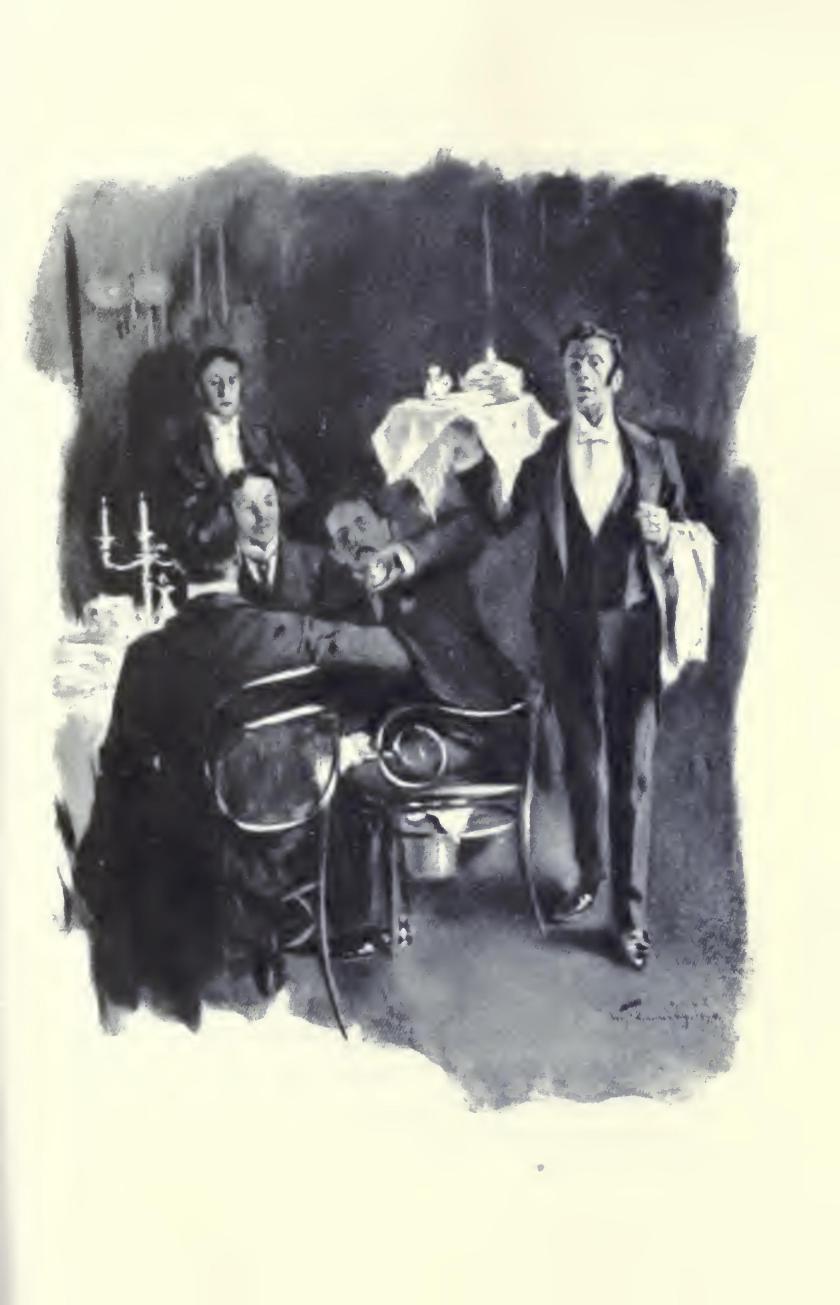

When the inspection of the horse was finished it was time for lunch, and the labors of the morning were felt to justify this indulgence, though each of the party had other engagements, and was too busy to waste the time. They went down to the Knickerbocker.

The lunch was slight, but its ordering took time and consideration, as it ought, for nothing is so destructive of health and mental tone as the snatching of a mid-day meal at a lunch counter from a bill of fare prepared by God knows whom. Mr. Russell said that if it took time to buy a horse, it ought to take at least equal time and care to select the fodder that was to make a human being wretched or happy. Indeed, a man who didn't give his mind to what he ate wouldn't have any mind by-and-by to give to anything. This sentiment had the assent of the table, and was illustrated by varied personal experience; and a deep feeling prevailed, a serious feeling, that in ordering and eating the right sort of lunch a chief duty of a useful day had been discharged.

It must not be imagined from this, however, that the conversation was about trifles. Business men and operators could have learned something about stocks and investments, and politicians about city politics. Mademoiselle Vivienne, the new skirt dancer, might have been surprised at the intimate tone in which she was alluded to, but she could have got some useful hints in effects, for her judges were cosmopolitans who had seen the most suggestive dancing in all parts of the world. It came out incidentally that every one at table had been “over” in the course of the season, not for any general purpose, not as a sightseer, but to look at somebody's stables, or to attend a wedding, or a sale of etchings, or to see his bootmaker, or for a little shooting in Scotland, just as one might run down to Bar Harbor or Tuxedo. It was only an incident in a busy season; and one of the fruits of it appeared to be as perfect a knowledge of the comparative merits of all the ocean racers and captains as of the English and American stables and the trainers. One not informed of the progress of American life might have been surprised to see that the fad is to be American, with a sort of patronage of things and ways foreign, especially of things British, a large continental kind of attitude, begotten of hearing much about Western roughing it, of Alaska, of horse-breeding and fruit-raising on the Pacific, of the Colorado River Canon. As for stuffs, well yes, London. As for style, you can't mistake a man who is dressed in New York.

The wine was a white Riesling from California. Docstater said his attention had been called to it by Tom Dillingham at the Union, who had a ranch somewhere out there. It was declared to be sound and palatable; you know what you are drinking. This led to a learned discussion of the future of American wines, and a patriotic impulse was given to the trade by repeated orders. It was declared that in American wines lay the solution of the temperance question. Bobby Simerton said that Burgundy was good enough for him, but Russell put him down, as he saw the light yellow through his glass, by the emphatic affirmation that plenty of cheap American well-made wine would knock the bottom out of all the sentimental temperance societies and shut up the saloons, dry up all those not limited to light wines and beer. It was agreed that the saloons would have to go.

This satisfactory conclusion was reached before the coffee came on and the cigarettes, and the sound quality of the Riesling was emphasized by a pony of cognac.

It is fortunate when the youth of a country have an ideal. No nation is truly great without a common ideal, capable of evoking enthusiasm and calling out its energies. And where are we to look for this if not in the youth, and especially in those to whom fortune and leisure give an opportunity of leadership? It is they who can inspire by their example, and by their pursuits attract others to a higher conception of the national life. It may take the form of patriotism, as in this country, pride in the great republic, jealousy of its honor and credit, eagerness for its commanding position among the nations, patriotism which will show itself, in all the ardor of believing youth, in the administration of law, in the purity of politics, in honest local government, and in a noble aspiration for the glory of the country. It may take the form of culture, of a desire that the republic-liable, like all self-made nations, to worship wealth-should be distinguished not so much by a vulgar national display as by an advance in the arts, the sciences, the education that adorns life, in the noble spirit of humanity, and in the nobler spirit of recognition of a higher life, which will be content with no civilization that does not tend to make the country for every citizen a better place to live in today than it was yesterday. Happy is the country, happy the metropolis of that country, whose fortunate young men have this high conception of citizenship!

What is the ideal of their country which these young men cherish? There was a moment—was there not for them?—in the late war for the Union, when the republic was visible to them in its beauty, in its peril, and in a passion of devotion they were eager—were they not?—to follow the flag and to give their brief lives to its imperishable glory. Nothing is impossible to a nation with an ideal like that. It was this flame that ran over Europe in the struggle of France against a world in arms. It was this national ideal that was incarnate in Napoleon, as every great idea that moves the world is sooner or later incarnated. What was it that we saw in Washington on his knees at Valley Forge, or blazing with wrath at the cowardice on Monmouth? in Lincoln entering Richmond with bowed head and infinite sorrow and yearning in his heart? An embodiment of a great national idea and destiny.

In France this ideal burns yet like a flame, and is still evoked by a name. It is the passion of glory, but the desire of a nation, and Napoleon was the incarnation of passion. They say that he is not dead as others are dead, but that he may come again and ride at the head of his legions, and strike down the enemies of France; that his bugle will call the youth from every hamlet, that the roll of his drum will transform France into a camp, and the grenadiers will live again and ride with him, amid hurrahs, and streaming tears, and shouts of “My Emperor! Oh, my Emperor!” Is it only a legend? But the spirit is there; not a boy but dreams of it, not a girl but knots the thought in with her holiday tricolor. That is to have an abiding ideal, and patiently to hold it, in isolation, in defeat, even in an overripe civilization.

We believe—do we not?—in other triumphs than those of the drum and the sword. Our aspirations for the republic are for a nobler example of human society than the world has yet seen. Happy is the country, and the metropolis of the country, whose youth, gilded only by their virtues, have these aspirations.

When the party broke up, the street lamps were beginning to twinkle here and there, and Jack discovered to his surprise that the Twiss business would have to go over to another day. It was such a hurrying life in New York. There was just time for a cup of tea at Mrs. Trafton's. Everybody dropped in there after five o'clock, when the duties of the day were over, with the latest news, and to catch breath before rushing into the program of the evening.

There were a dozen ladies in the drawing-room when Jack entered, and his first impression was that the scream of conversation would be harder to talk against than a Wagner opera; but he presently got his cup of tea, and found a snug seat in the chimney-corner by Miss Tavish; indeed, they moved to it together, and so got a little out of the babel. Jack thought the girl looked even prettier in her walking-dress than when he saw her at the studio; she had style, there was no doubt about that; and then, while there was no invitation in her manner, one felt that she was a woman to whom one could easily say things, and who was liable at any moment to say things interesting herself.

“Is this your first appearance since last night, Mr. Delancy?”

“Oh no; I've been racing about on errands all day. It is very restful to sit down by a calm person.”

“Well, I never shut my eyes till nine o'clock. I kept seeing that Spanish woman whirl around and contort, and—do you mind my telling you?—I couldn't just help it, I” (leaning forward to Jack) “got up and tried it before the glass. There! Are you shocked?”

“Not so much shocked as excluded,” Jack dared to say. “But do you think—“.

“Yes, I know. There isn't anything that an American girl cannot do. I've made up my mind to try it. You'll see.”

“Will I?”

“No, you won't. Don't flatter yourself. Only girls. I don't want men around.”

“Neither do I,” said Jack, honestly.

Miss Tavish laughed. “You are too forward, Mr. Delancy. Perhaps some time, when we have learned, we will let in a few of you, to look in at the door, fifty dollars a ticket, for some charity. I don't see why dancing isn't just as good an accomplishment as playing the harp in a Greek dress.”

“Nor do I; I'd rather see it. Besides, you've got Scripture warrant for dancing off the heads of people. And then it is such a sweet way of doing a charity. Dancing for the East Side is the best thing I have heard yet.”

“You needn't mock. You won't when you find out what it costs you.”

“What are you two plotting?” asked Mrs. Trafton, coming across to the fireplace.

“Charity,” said Jack, meekly.

“Your wife was here this morning to get me to go and see some of her friends in Hester Street.”

“You went?”

“Not today. It's awfully interesting, but I've been.”

“Edith seems to be devoted to that sort of thing,” remarked Miss Tavish.

“Yes,” said Jack, slowly, “she's got the idea that sympathy is better than money; she says she wants to try to understand other people's lives.”

“Goodness knows, I'd like to understand my own.”

“And were you trying, Mr. Delancy, to persuade Miss Tavish into that sort of charity?”

“Oh dear, no,” said Jack; “I was trying to interest the East End in something, for the benefit of Miss Tavish.”

“You'll find that's one of the most expensive remarks you ever made,” retorted Miss Tavish, rising to go.

“I wish Lily Tavish would marry,” said Mrs. Trafton, watching the girl's slender figure as it passed through the portiere; “she doesn't know what to do with herself.”

Jack shrugged his shoulders. “Yes, she'd be a lovely wife for somebody;” and then he added, as if reminiscently, “if he could afford it. Good-by.”

“That's just a fashion of talking. I never knew a time when so many people afforded to do what they wanted to do. But you men are all alike. Good-by.”

When Jack reached home it was only a little after six o'clock, and as they were not to go out to dine till eight, he had a good hour to rest from the fatigues of the day, and run over the evening papers and dip into the foreign periodicals to catch a topic or two for the dinner-table.

“Yes, sir,” said the maid, “Mrs. Delancy came in an hour ago.”

Edith's day had been as busy as Jack's, notwithstanding she had put aside several things that demanded her attention. She denied herself the morning attendance on the Literature Class that was raking over the eighteenth century. This week Swift was to be arraigned. The last time when Edith was present it was Steele. The judgment, on the whole, had been favorable, and there had been a little stir of tenderness among the bonnets over Thackeray's comments on the Christian soldier. It seemed to bring him near to them. “Poor Dick Steele!” said the essayist. Edith declared afterwards that the large woman who sat next to her, Mrs. Jerry Hollowell, whispered to her that she always thought his name was Bessemer; but this was, no doubt, a pleasantry. It was a beautiful essay, and so stimulating! And then there was bouillon, and time to look about at the toilets. Poor Steele, it would have cheered his life to know that a century after his death so many beautiful women, so exquisitely dressed, would have been concerning themselves about him. The function lasted two hours. Edith made a little calculation. In five minutes she could have got from the encyclopaedia all the facts in the essay, and while her maid was doing her hair she could have read five times as much of Steele as the essayist read. And, somehow, she was not stimulated, for the impression seemed to prevail that now Steele was disposed of. And she had her doubts whether literature would, after all, prove to be a permanent social distraction. But Edith may have been too severe in her judgment. There was probably not a woman in the class that day who did not go away with the knowledge that Steele was an author, and that he lived in the eighteenth century. The hope for the country is in the diffusion of knowledge.

Leaving the class to take care of Swift, Edith went to the managers' meeting at the Women's Hospital, where there was much to do of very practical work, pitiful cases of women and children suffering through no fault of their own, and money more difficult to raise than sympathy. The meeting took time and thought. Dismissing her carriage, and relying on elevated and surface cars, Edith then took a turn on the East Side, in company with a dispensary physician whose daily duty called her into the worst parts of the town. She had a habit of these tours before her marriage, and, though they were discouragingly small in direct results, she gained a knowledge of city life that was of immense service in her general charity work. Jack had suggested the danger of these excursions, but she had told him that a woman was less liable to insult in the East Side than in Fifth Avenue, especially at twilight, not because the East Side was a nice quarter of the city, but because it was accustomed to see women who minded their own business go about unattended, and the prowlers had not the habit of going there. She could even relate cases of chivalrous protection of “ladies” in some of the worst streets.

What Edith saw this day, open to be seen, was not so much sin as ignorance of how to live, squalor, filthy surroundings acquiesced in as the natural order, wonderful patience in suffering and deprivation, incapacity, ill-paid labor, the kindest spirit of sympathy and helpfulness of the poor for each other. Perhaps that which made the deepest impression on her was the fact that such conditions of living could seem natural to those in them, and that they could get so much enjoyment of life in situations that would have been simple misery to her.

The visitors were in a foreign city. The shop signs were in foreign tongues; in some streets all Hebrew. On chance news-stands were displayed newspapers in Russian, Bohemian, Arabic, Italian, Hebrew, Polish, German-none in English. The theatre bills were in Hebrew or other unreadable type. The sidewalks and the streets swarmed with noisy dealers in every sort of second-hand merchandise—vegetables that had seen a better day, fish in shoals. It was not easy to make one's way through the stands and push-carts and the noisy dickering buyers and sellers, who haggled over trifles and chaffed good-naturedly and were strictly intent on their own affairs. No part of the town is more crowded or more industrious. If youth is the hope of the country, the sight was encouraging, for children were in the gutters, on the house steps, at all the windows. The houses seemed bursting with humanity, and in nearly every room of the packed tenements, whether the inmates were sick or hungry, some sort of industry was carried on. In the damp basements were junk-dealers, rag-pickers, goose-pickers. In one noisome cellar, off an alley, among those sorting rags, was an old woman of eighty-two, who could reply to questions only in a jargon, too proud to beg, clinging to life, earning a few cents a day in this foul occupation. But life is sweet even with poverty and rheumatism and eighty years. Did her dull eyes, turning inward, see the Carpathian Hills, a free girlhood in village drudgery and village sports, then a romance of love, children, hard work, discontent, emigration to a New World of promise? And now a cellar by day, the occupation of cutting rags for carpets, and at night a corner in a close and crowded room on a flock bed not fit for a dog. And this was a woman's life.

Picturesque foreign women going about with shawls over their heads and usually a bit of bright color somewhere, children at their games, hawkers loudly crying their stale wares, the click of sewing-machines heard through a broken window, everywhere animation, life, exchange of rough or kindly banter. Was it altogether so melancholy as it might seem? Not everybody was hopelessly poor, for here were lawyers' signs and doctors' signs—doctors in whom the inhabitants had confidence because they charged all they could get for their services—and thriving pawnbrokers' shops. There were parish schools also—perhaps others; and off some dark alley, in a room on the ground-floor, could be heard the strident noise of education going on in high-voiced study and recitation. Nor were amusements lacking—notices of balls, dancing this evening, and ten-cent shows in palaces of legerdemain and deformity.

It was a relenting day in March; patches of blue sky overhead, and the sun had some quality in its shining. The children and the caged birds at the open windows felt it-and there were notes of music here and there above the traffic and the clamor. Turning down a narrow alley, with a gutter in the centre, attracted by festive sounds, the visitors came into a small stone-paved court with a hydrant in the centre surrounded by tall tenement-houses, in the windows of which were stuffed the garments that would no longer hold together to adorn the person. Here an Italian girl and boy, with a guitar and violin, were recalling la bella Napoli, and a couple of pretty girls from the court were footing it as merrily as if it were the grape harvest. A woman opened a lower room door and sharply called to one of the dancing girls to come in, when Edith and the doctor appeared at the bottom of the alley, but her tone changed when she recognized the doctor, and she said, by way of apology, that she didn't like her daughter to dance before strangers. So the music and the dance went on, even little dots of girls and boys shuffling about in a stiff-legged fashion, with applause from all the windows, and at last a largesse of pennies—as many as five altogether—for the musicians. And the sun fell lovingly upon the pretty scene.

But then there were the sweaters' dens, and the private rooms where half a dozen pale-faced tailors stitched and pressed fourteen and sometimes sixteen hours a day, stifling rooms, smelling of the hot goose and steaming cloth, rooms where they worked, where the cooking was done, where they ate, and late at night, when overpowered with weariness, lay down to sleep. Struggle for life everywhere, and perhaps no more discontent and heart-burning and certainly less ennui than in the palaces on the avenues.

The residence of Karl Mulhaus, one of the doctor's patients, was typical of the homes of the better class of poor. The apartment fronted on a small and not too cleanly court, and was in the third story. As Edith mounted the narrow and dark stairways she saw the plan of the house. Four apartments opened upon each landing, in which was the common hydrant and sink. The Mulhaus apartment consisted of a room large enough to contain a bed, a cook-stove, a bureau, a rocking-chair, and two other chairs, and it had two small windows, which would have more freely admitted the southern sun if they had been washed, and a room adjoining, dark, and nearly filled by a big bed. On the walls of the living room were hung highly colored advertising chromos of steamships and palaces of industry, and on the bureau Edith noticed two illustrated newspapers of the last year, a patent-medicine almanac, and a volume of Schiller. The bureau also held Mr. Mulhaus's bottles of medicine, a comb which needed a dentist, and a broken hair-brush. What gave the room, however, a cheerful aspect were some pots of plants on the window-ledges, and half a dozen canary-bird cages hung wherever there was room for them.

None of the family happened to be at home except Mr. Mulhaus, who occupied the rocking-chair, and two children, a girl of four years and a boy of eight, who were on the floor playing “store” with some blocks of wood, a few tacks, some lumps of coal, some scraps of paper, and a tangle of twine. In their prattle they spoke, the English they had learned from their brother who was in a store.

“I feel some better today,” said Mr. Mulhaus, brightening up as the visitors entered, “but the cough hangs on. It's three months since this weather that I haven't been out, but the birds are a good deal of company.” He spoke in German, and with effort. He was very thin and sallow, and his large feverish eyes added to the pitiful look of his refined face. The doctor explained to Edith that he had been getting fair wages in a type-foundry until he had become too weak to go any longer to the shop.

It was rather hard to have to sit there all day, he explained to the doctor, but they were getting along. Mrs. Mulhaus had got a job of cleaning that day; that would be fifty cents. Ally—she was twelve—was learning to sew. That was her afternoon to go to the College Settlement. Jimmy, fourteen, had got a place in a store, and earned two dollars a week.

“And Vicky?” asked the doctor.

“Oh, Vicky,” piped up the eight-year-old boy. “Vicky's up to the 'stution”—the hospital was probably the institution referred to—“ever so long now. I seen her there, me and Jim did. Such a bootifer place! 'Nd chicken!” he added. “Sis got hurt by a cart.”

Vicky was seventeen, and had been in a fancy store.

“Yes,” said Mulhaus, in reply to a question, “it pays pretty well raising canaries, when they turn out singers. I made fifteen dollars last year. I hain't sold much lately. Seems 's if people stopped wanting 'em such weather. I guess it 'll be better in the spring.”

“No doubt it will be better for the poor fellow himself before spring,” said the doctor as they made their way down the dirty stairways. “Now I'll show you one of my favorites.”

They turned into a broader street, one of the busy avenues, and passing under an archway between two tall buildings, entered a court of back buildings. In the third story back lived Aunt Margaret. The room was scarcely as big as a ship's cabin, and its one window gave little light, for it opened upon a narrow well of high brick walls. In the only chair Aunt Margaret was seated close to the window. In front of her was a small work-table, with a kerosene lamp on it, but the side of the room towards which she looked was quite occupied by a narrow couch—ridiculously narrow, for Aunt Margaret was very stout. There was a thin chest of drawers on the other side, and the small coal stove that stood in the centre so nearly filled the remaining space that the two visitors were one too many.

“Oh, come in, come in,” said the old lady, cheerfully, when the door opened. “I'm glad to see you.”

“And how goes it?” asked the doctor.

“First rate. I'm coming on, doctor. Work's been pretty slack for two weeks now, but yesterday I got work for two days. I guess it will be better now.”

The work was finishing pantaloons. It used to be a good business before there was so much cutting in.

“I used to get fifteen cents a pair, then ten; now they don't pay but five. Yes, the shop furnishes the thread.”

“And how many pairs can you finish in a day?” asked Edith.

“Three—three pairs, to do 'em nice—and they are very particular—if I work from six in the morning till twelve at night. I could do more, but my sight ain't what it used to be, and I've broken my specs.”

“So you earn fifteen cents a day?”

“When I've the luck to get work, my lady. Sometimes there isn't any. And things cost so much. The rent is the worst.”

It appeared that the rent was two dollars and a half a month. That must be paid, at any rate. Edith made a little calculation that on a flush average of ninety cents a week earned, and allowing so many cents for coal and so many cents for oil, the margin for bread and tea must be small for the month. She usually bought three cents' worth of tea at a time.

“It is kinder close,” said the old lady, with a smile. “The worst is, my feet hurt me so I can't stir out. But the neighbors is real kind. The little boy next room goes over to the shop and fetches my pantaloons and takes 'em back. I can get along if it don't come slack again.”

Sitting all day by that dim window, half the night stitching by a kerosene lamp; lying for six hours on that narrow couch! How to account for this old soul's Christian resignation and cheerfulness! “For,” said the doctor, “she has seen better days; she has moved in high society; her husband, who died twenty years ago, was a policeman. What the old lady is doing is fighting for her independence. She has only one fear—the almshouse.”

It was with such scenes as these in her eyes that Edith went to her dressing-room to make her toilet for the Henderson dinner.

It was the first time they had dined with the Hendersons. It was Jack's doings. “Certainly, if you wish it,” Edith had said when the invitation came. The unmentioned fact was that Jack had taken a little flier in Oshkosh, and a hint from Henderson one evening at the Union, when the venture looked squally, had let him out of a heavy loss into a small profit, and Jack felt grateful.

“I wonder how Henderson came to do it?” Jack was querying, as he and old Fairfax sipped their five-o'clock “Manhattan.”

“Oh, Henderson likes to do a good-natured thing still, now and then. Do you know his wife?”

“No. Who was she?”

“Why, old Eschelle's daughter, Carmen; of course you wouldn't know; that was ten years ago. There was a good deal of talk about it at the time.”

“How?”

“Some said they'd been good friends before Mrs. Henderson's death.”

“Then Carmen, as you call her, wasn't the first?”

“No, but she was an easy second. She's a social climber; bound to get there from the start.”

“Is she pretty?”

“Devilish. She's a little thing. I saw her once at Homburg, on the promenade with her mother.

“The kind of sweet blonde, I said to myself, that would mix a man up in a duel before he knew where he was.”

“She must be interesting.”

“She was always clever, and she knows enough to play a straight game and when to propitiate. I'll bet a five she tells Henderson whom to be good to when the chance offers.”

“Then her influence on him is good?”

“My dear sir, she gets what she wants, and Henderson is going to the... well, look at the lines in his face. I've known Henderson since he came fresh into the Street. He'd rarely knife a friend when his first wife was living. Now, when you see the old frank smile on his face, it's put on.”

It was half-past eight when Mr. Henderson with Mrs. Delancy on his arm led the way to the diningroom. The procession was closed by Mrs. Henderson and Mr. Delancy. The Van Dams were there, and Mrs. Chesney and the Chesney girls, and Miss Tavish, who sat on Jack's right, but the rest of the guests were unknown to Jack, except by name. There was a strong dash of the Street in the mixture, and although the Street was tabooed in the talk, there was such an emanation of aggressive prosperity at the table that Jack said afterwards that he felt as if he had been at a meeting of the board.

If Jack had known the house ten years ago, he would have noticed certain subtle changes in it, rather in the atmosphere than in many alterations. The newness and the glitter of cost had worn off. It might still be called a palace, but the city had now a dozen handsomer houses, and Carmen's idea, as she expressed it, was to make this more like a home. She had made it like herself. There were pictures on the walls that would not have hung there in the late Mrs. Henderson's time; and the prevailing air was that of refined sensuousness. Life, she said, was her idea, life in its utmost expression, untrammeled, and yes, a little Greek. Freedom was perhaps the word, and yet her latest notion was simplicity. The dinner was simple. Her dress was exceedingly simple, save that it had in it somewhere a touch of audacity, revealing in a flash of invitation the hidden nature of the woman. She knew herself better than any one knew her, except Henderson, and even he was forced to laugh when she travestied Browning in saying that she had one soul-side to face the world with, one to show the man she loved, and she declared he was downright coarse when on going out of the door he muttered, “But it needn't be the seamy side.” The reported remark of some one who had seen her at church that she looked like a nun made her smile, but she broke into a silvery laugh when she head Van Dam's comment on it, “Yes, a devil of a nun.”

The library was as cozy as ever, but did not appear to be used much as a library. Henderson, indeed, had no time to add to his collection or enjoy it. Most of the books strewn on the tables were French novels or such American tales as had the cachet of social riskiness. But Carmen liked the room above all others. She enjoyed her cigarette there, and had a fancy for pouring her five-o'clock tea in its shelter. Books which had all sorts of things in them gave somehow an unconventional atmosphere to the place, and one could say things there that one couldn't say in a drawing-room.

Henderson himself, it must be confessed, had grown stout in the ten years, and puffy under the eyes. There were lines of irritation in his face and lines of weariness. He had not kept the freshness of youth so well as Carmen, perhaps because of his New England conscience. To his guest he was courteous, seemed to be making an effort to be so, and listened with well-assumed interest to the story of her day's pilgrimage. At length he said, with a smile, “Life seems to interest you, Mrs. Delancy.”

“Yes, indeed,” said Edith, looking up brightly; “doesn't it you?”

“Why, yes; not life exactly, but things, doing things—conflict.”

“Yes, I can understand that. There is so much to be done for everybody.”

Henderson looked amused. “You know in the city the gospel is that everybody is to be done.”

“Well,” said Edith, not to be diverted, “but, Mr. Henderson, what is it all for—this conflict? Perhaps, however, you are fighting the devil?”

“Yes, that's it; the devil is usually the other fellow. But, Mrs. Delancy,” added Henderson, with an accent of seriousness, “I don't know what it's all for. I doubt if there is much in it.”

“And yet the world credits you with finding a great deal in it.”

“The world is generally wrong. Do you understand poker, Mrs. Delancy? No! Of course you do not. But the interest of the game isn't so much in the cards as in the men.”

“I thought it was the stakes.”

“Perhaps so. But you want to win for the sake of winning. If I gambled it would be a question of nerve. I suppose that which we all enjoy is the exercise of skill in winning.”

“And not for the sake of doing anything—just winning? Don't you get tired of that?” asked Edith, quite simply.

There was something in Edith's sincerity, in her fresh enthusiasm about life, that appeared to strike a reminiscent note in Henderson. Perhaps he remembered another face as sweet as hers, and ideals, faint and long ago, that were once mixed with his ideas of success. At any rate, it was with an accent of increased deference, and with a look she had not seen in his face before, that he said:

“People get tired of everything. I'm not sure but it would interest me to see for a minute how the world looks through your eyes.” And then he added, in a different tone, “As to your East Side, Mrs. Henderson tried that some years ago.”

“Wasn't she interested?”

“Oh, very much. For a time. But she said there was too much of it.” And Edith could detect no tone of sarcasm in the remark.

Down at the other end of the table, matters were going very smoothly. Jack was charmed with his hostess. That clever woman had felt her way along from the heresy trial, through Tuxedo and the Independent Theatre and the Horse Show, until they were launched in a perfectly free conversation, and Carmen knew that she hadn't to look out for thin ice.

“Were you thinking of going on to the Conventional Club tonight, Mr. Delancy?” she was saying.

“I don't belong,” said Jack. “Mrs. Delancy said she didn't care for it.”

“Oh, I don't care for it, for myself,” replied Carmen.

“I do,” struck in Miss Tavish. “It's awfully nice.”

“Yes, it does seem to fill a want. Why, what do you do with your evenings, Mr. Delancy?”

“Well, here's one of them.”

“Yes, I know, but I mean between twelve o'clock and bedtime.”

“Oh,” said Jack, laughing out loud, “I go to bed—sometimes.”

“Yes, 'there's always that. But you want some place to go to after the theatres and the dinners; after the other places are shut up you want to go somewhere and be amused.”

“Yes,” said Jack, falling in, “it is a fact that there are not many places of amusement for the rich; I understand. After the theatres you want to be amused. This Conventional Club is—”

“I tell you what it is. It's a sort of Midnight Mission for the rich. They never have had anything of the kind in the city.”

“And it's very nice,” said Miss Tavish, demurely.

“The performers are selected. You can see things there that you want to see at other places to which you can't go. And everybody you know is there.”

“Oh, I see,” said Jack. “It's what the Independent Theatre is trying to do, and what all the theatrical people say needs to be done, to elevate the character of the audiences, and then the managers can give better plays.”

“That's just it. We want to elevate the stage,” Carmen explained.

“But,” continued Jack, “it seems to me that now the audience is select and elevated, it wants to see the same sort of things it liked to see before it was elevated.”

“You may laugh, Mr. Delancy,” replied Carmen, throwing an earnest simplicity into her eyes, “but why shouldn't women know what is going on as well as men?”

“And why,” Miss Tavish asked, “will the serpentine dances and the London topical songs do any more harm to women than to men?”

“And besides, Mr. Delancy,” Carmen said, chiming in, “isn't it just as proper that women should see women dance and throw somersaults on the stage as that men should see them? And then, you know, women are such a restraining influence.”

“I hadn't thought of that,” said Jack. “I thought the Conventional was for the benefit of the audience, not for the salvation of the performers.”

“It's both. It's life. Don't you think women ought to know life? How are they to take their place in the world unless they know life as men know it?”

“I'm sure I don't know whose place they are to take, the serpentine dancer's or mine,” said Jack, as if he were studying a problem. “How does your experiment get on, Miss Tavish?”

Carmen looked up quickly.

“Oh, I haven't any experiment,” said Miss Tavish, shaking her head. “It's just Mr. Delancy's nonsense.”

“I wish I had an experiment. There is so little for women to do. I wish I knew what was right.” And Carmen looked mournfully demure, as if life, after all, were a serious thing with her.

“Whatever Mrs. Henderson does is sure to be right,” said Jack, gallantly.

Carmen shot at him a quick sympathetic glance, tempered by a grateful smile. “There are so many points of view.”

Jack felt the force of the remark as he did the revealing glance. And he had a swift vision of Miss Tavish leading him a serpentine dance, and of Carmen sweetly beckoning him to a pleasant point of view. After all it doesn't much matter. Everything is in the point of view.

After dinner and cigars and cigarettes in the library, the talk dragged a little in duets. The dinner had been charming, the house was lovely, the company was most agreeable. All said that. It had been so somewhere else the night before that, and would be the next night. And the ennui of it all! No one expressed it, but Henderson could not help looking it, and Carmen saw it. That charming hostess had been devoting herself to Edith since dinner. She was so full of sympathy with the East-Side work, asked a hundred questions about it, and declared that she must take it up again. She would order a cage of canaries from that poor German for her kitchen. It was such a beautiful idea. But Edith did not believe in her one bit. She told Jack afterwards that “Mrs. Henderson cares no more for the poor of New York than she does for—”

“Henderson?” suggested Jack.

“Oh, I don't know anything about that. Henderson has only one idea—to get the better of everybody, and be the money king of New York. But I should not wonder if he had once a soft spot in his heart. He is better than she is.”

It was still early, lacked half an hour of midnight, and the night was before them. Some one proposed the Conventional. “Yes,” said Carmen; “all come to our box.” The Van Dams would go, Miss Tavish, the Chesneys; the suggestion was a relief to everybody. Only Mr. Henderson pleaded important papers that must have his attention that night. Edith said that she was too tired, but that her desertion must not break up the party.

“Then you will excuse me also,” said Jack, a little shade of disappointment in his face.

“No, no,” said Edith, quickly; “you can drop me on the way. Go, by all means, Jack.”

“Do you really want me to go, dear?” said Jack, aside.

“Why of course; I want you to be happy.”

And Jack recalled the loving look that accompanied these words, later on, as he sat in the Henderson box at the Conventional, between Carmen and Miss Tavish, and saw, through the slight haze of smoke, beyond the orchestra, the praiseworthy efforts of the Montana Kicker, who had just returned with the imprimatur of Paris, to relieve the ennui of the modern world.

The complex affair we call the world requires a great variety of people to keep it going. At one o'clock in the morning Carmen and our friend Mr. Delancy and Miss Tavish were doing their part. Edith lay awake listening for Jack's return. And in an alley off Rivington Street a young girl, pretty once, unknown to fortune but not to fame, was about to render the last service she could to the world by leaving it.

The impartial historian scarcely knows how to distribute his pathos. By the electric light (and that is the modern light) gayety is almost as pathetic as suffering. Before the Montana girl hit upon the happy device that gave her notoriety, her feet, whose every twinkle now was worth a gold eagle, had trod a thorny path. There was a fortune now in the whirl of her illusory robes, but any day—such are the whims of fashion—she might be wandering again, sick at heart, about the great city, knocking at the side doors of variety shows for any engagement that would give her a pittance of a few dollars a week. How long had Carmen waited on the social outskirts; and now she had come into her kingdom, was she anything but a tinsel queen? Even Henderson, the great Henderson, did the friends of his youth respect him? had he public esteem? Carmen used to cut out the newspaper paragraphs that extolled Henderson's domestic virtue and his generosity to his family, and show them to her lord, with a queer smile on her face. Miss Tavish, in the nervous consciousness of fleeting years, was she not still waiting, dashing here and there like a bird in a net for the sort of freedom, audacious as she was, that seemed denied her? She was still beautiful, everybody said, and she was sought and flattered, because she was always merry and good-natured. Why should Van Dam, speaking of women, say that there were horses that had been set up, and checked up and trained, that held their heads in an aristocratic fashion, moved elegantly, and showed style, long after the spirit had gone out of them? And Jack himself, happily married, with a comfortable income, why was life getting flat to him? What sort of career was it that needed the aid of Carmen and the serpentine dancer? And why not, since it is absolutely necessary that the world should be amused?

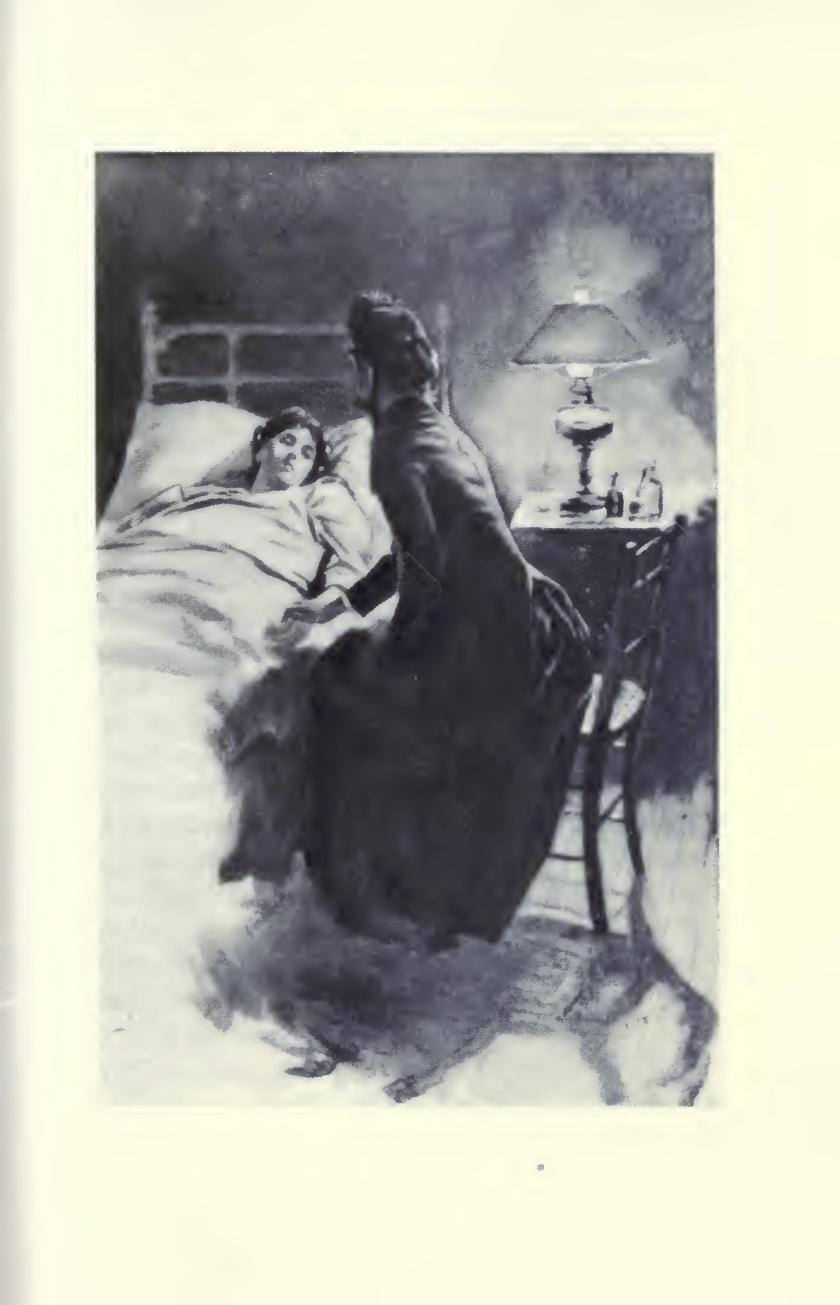

We are in no other world when we enter the mean tenement in the alley off Rivington Street. Here also is the life of the town. The room is small, but it contains a cook-stove, a chest of drawers, a small table, a couple of chairs, and two narrow beds. On the top of the chest are a looking-glass, some toilet articles, and bottles of medicine. The cracked walls are bare and not clean. In one of the beds are two children, sleeping soundly, and on the foot of it is a middle-aged woman, in a soiled woolen gown with a thin figured shawl drawn about her shoulders, a dirty cap half concealing her frowzy hair; she looks tired and worn and sleepy. On the other bed lies a girl of twenty years, a woman in experience. The kerosene lamp on the stand at the head of the bed casts a spectral light on her flushed face, and the thin arms that are restlessly thrown outside the cover. By the bedside sits the doctor, patient, silent, and watchful. The doctor puts her hand caressingly on that of the girl. It is hot and dry. The girl opens her eyes with a startled look, and says, feebly:

“Do you think he will come?”

“Yes, dear, presently. He never fails.”

The girl closed her eyes again, and there was silence. The dim rays of the lamp, falling upon the doctor, revealed the figure of a woman of less than medium size, perhaps of the age of thirty or more, a plain little body, you would have said, who paid the slightest possible attention to her dress, and when she went about the city was not to be distinguished from a working-woman. Her friends, indeed, said that she had not the least care for her personal appearance, and unless she was watched, she was sure to go out in her shabbiest gown and most battered hat. She wore tonight a brown ulster and a nondescript black bonnet drawn close down on her head and tied with black strings. In her lap lay her leathern bag, which she usually carried under her arm, that contained medicines, lint, bandages, smelling-salts, a vial of ammonia, and so on; to her patients it was a sort of conjurer's bag, out of which she could produce anything that an emergency called for.

Dr. Leigh was not in the least nervous or excited. Indeed, an artist would not have painted her as a rapt angelic visitant to this abode of poverty. This contact with poverty and coming death was quite in her ordinary experience. It would never have occurred to her that she was doing anything unusual, any more than it would have occurred to the objects of her ministrations to overwhelm her with thanks. They trusted her, that was all. They met her always with a pleasant recognition. She belonged perhaps to their world. Perhaps they would have said that “Dr. Leigh don't handsome much,” but their idea was that her face was good. That was what anybody would have said who saw her tonight, “She has such a good face;” the face of a woman who knew the world, and perhaps was not very sanguine about it, had few illusions and few antipathies, but accepted it, and tried in her humble way to alleviate its hardships, without any consciousness of having a mission or making a sacrifice.

Dr. Leigh—Miss Ruth Leigh—was Edith's friend. She had not come from the country with an exalted notion of being a worker among the poor about whom so much was written; she had not even descended from some high circle in the city into this world, moved by a restless enthusiasm for humanity. She was a woman of the people, to adopt a popular phrase. From her childhood she had known them, their wants, their sympathies, their discouragements; and in her heart—though you would not discover this till you had known her long and well—there was a burning sympathy with them, a sympathy born in her, and not assumed for the sake of having a career. It was this that had impelled her to get a medical education, which she obtained by hard labor and self-denial. To her this was not a means of livelihood, but simply that she might be of service to those all about her who needed help more than she did. She didn't believe in charity, this stout-hearted, clearheaded little woman; she meant to make everybody pay for her medical services who could pay; but somehow her practice was not lucrative, and the little salary she got as a dispensary doctor melted away with scarcely any perceptible improvement in her own wardrobe. Why, she needed nothing, going about as she did.

She sat—now waiting for the end; and the good face, so full of sympathy for the living, had no hope in it. Just another human being had come to the end of her path—the end literally. It was so everyday. Somebody came to the end, and there was nothing beyond. Only it was the end, and that was peace. One o'clock—half-past one. The door opened softly. The old woman rose from the foot of the bed with a start and a low “Herr! gross Gott.” It was Father Damon. The girl opened her eyes with a frightened look at first, and then an eager appeal. Dr. Leigh rose to make room for him at the bedside. They bowed as he came forward, and their eyes met. She shook her head. In her eyes was no expectation, no hope. In his was the glow of faith. But the eyes of the girl rested upon his face with a rapt expression. It was as if an angel had entered the room.

Father Damon was a young man, not yet past thirty, slender, erect. He had removed as he came in his broad-brimmed soft hat. The hair was close-cut, but not tonsured. He wore a brown cassock, falling in straight lines, and confined at the waist with a white cord. From his neck depended from a gold chain a large gold cross. His face was smooth-shaven, thin, intellectual, or rather spiritual; the nose long, the mouth straight, the eyes deep gray, sometimes dreamy and puzzling, again glowing with an inner fervor. A face of long vigils and the schooled calmness of repressed energy. You would say a fanatic of God, with a dash of self-consciousness. Dr. Leigh knew him well. They met often on their diverse errands, and she liked, when she could, to go to vespers in the little mission chapel of St. Anselm, where he ministered. It was not the confessional that attracted her, that was sure; perhaps not altogether the service, though that was soothing in certain moods; but it was the noble personality of Father Damon. He was devoted to the people as she was, he understood them; and for the moment their passion of humanity assumed the same aspect, though she knew that what he saw, or thought he saw, lay beyond her agnostic vision.

Father Damon was an Englishman, a member of a London Anglican order, who had taken the three vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, who had been for some years in New York, and had finally come to live on the East Side, where his work was. In a way he had identified himself with the people; he attended their clubs; he was a Christian socialist; he spoke on the inequalities of taxation; the strikers were pretty sure of his sympathy; he argued the injustice of the present ownership of land. Some said that he had joined a lodge of the Knights of Labor. Perhaps it was these things, quite as much as his singleness of purpose and his spiritual fervor, that drew Dr. Leigh to him with a feeling that verged on devotion. The ladies up-town, at whose tables Father Damon was an infrequent guest, were as fully in sympathy with this handsome and aristocratic young priest, and thought it beautiful that he should devote himself to the poor and the sinful; but they did not see why he should adopt their views.

It was at the mission that Father Damon had first seen the girl. She had ventured in not long ago at twilight, with her cough and her pale face, in a silk gown and flower-garden of a hat, and crept into one of the confessional boxes, and told him her story.

“Do you think, Father,” said the girl, looking up wistfully, “that I can—can be forgiven?”

Father Damon looked down sadly, pitifully. “Yes, my daughter, if you repent. It is all with our Father. He never refuses.”

He knelt down, with his cross in his hand, and in a low voice repeated the prayer for the dying. As the sweet, thrilling voice went on in supplication the girl's eyes closed again, and a sweet smile played about her mouth; it was the innocent smile of the little girl long ago, when she might have awakened in the morning and heard the singing of birds at her window.

When Father Damon arose she seemed to be sleeping. They all stood in silence for a moment.

“You will remain?” he asked the doctor.

“Yes,” she said, with the faintest wan smile on her face. “It is I, you know, who have care of the body.”

At the door he turned and said, quite low, “Peace be to this house!”