“FORWARD!” HE SHOUTED

Title: With Ethan Allen at Ticonderoga

Author: W. Bert Foster

Illustrator: F. A. Carter

Release date: January 13, 2010 [eBook #30952]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank, D Alexander and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

With

ETHAN ALLEN

at

TICONDEROGA

by

W. Bert Foster

Author of

“With Washington

at Valley Forge” etc.

Illustrated

by

F. A. Carter

THE PENN

PUBLISHING COMPANY

PHILADELPHIA

M C M IV

COPYRIGHT 1903 BY THE PENN PUBLISHING COMPANY

With Ethan Allen at Ticonderoga

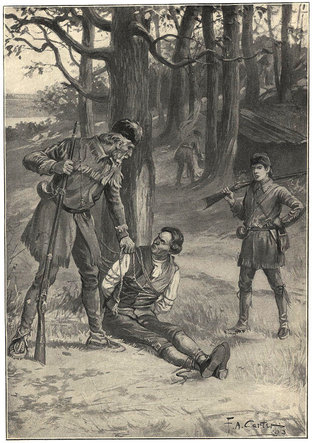

“FORWARD!” HE SHOUTED

| Contents | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I | A Boy of the Wilderness | 5 |

| II | Enoch Harding Feels Himself a Man | 19 |

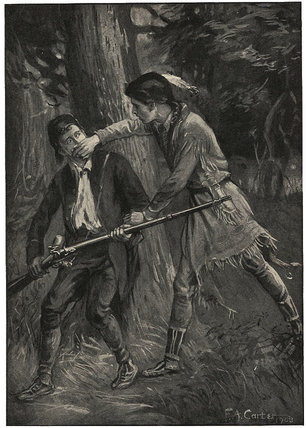

| III | The Ambush | 31 |

| IV | ’Siah Bolderwood’s Stratagem | 45 |

| V | The Pioneer Home | 60 |

| VI | The Stump Burning | 76 |

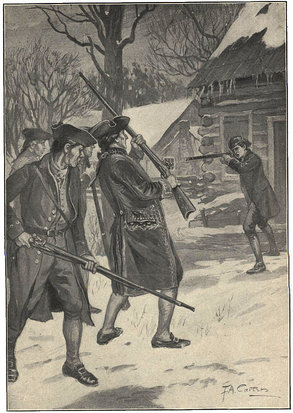

| VII | A Night Attack | 94 |

| VIII | The Traitor’s Way | 107 |

| IX | The Otter Creek Raid | 127 |

| X | The Warning | 139 |

| XI | An Unequal Battle | 160 |

| XII | Backwoods Justice | 174 |

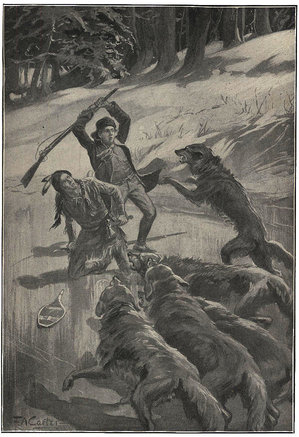

| XIII | The Wolf Pack | 191 |

| XIV | The Testimony of Crow Wing | 208 |

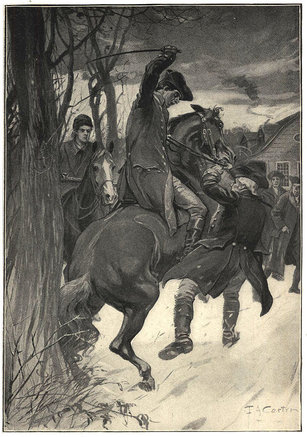

| XV | The Storm Cloud Gathers | 220 |

| XVI | The Westminster Massacre | 236 |

| XVII | The Cloven Hoof | 251 |

| XVIII | “The Cross of Fire” | 270 |

| XIX | The Rising of the Clans | 284 |

| XX | The Rival Commanders | 298 |

| XXI | The Escape of the Spy | 313 |

| XXII | The End of Simon Halpen | 330 |

| XXIII | The Dawn of the Tenth of May | 343 |

| XXIV | The Guns of Old Ti Speak | 355 |

The forest was still. A calm lay upon its vast extent, from the green-capped hills in the east to the noble river which, fed by the streams so quietly meandering through the pleasantly wooded country, found its way to the sea where the greatest city of the New World was destined to stand. The clear, bell-like note of a waking bird startled the morning hush. A doe and her fawn that had couched in a thicket seemed roused to activity by this early matin and suddenly showered the short turf with a dewy rain from the bushes which they disturbed as they leaped away toward the “lick.” The gentle creatures first slaked their thirst at the margin of the creek hard by and then stood a moment with outstretched nostrils, snuffing the wind before tasting the salt impregnated earth trampled as hard as adamant by a thousand hoofs. The fawn dropped its muzzle quickly; but the mother, not so well assured, snuffed again and yet again.

In the wilderness, before the white man came, there were to be found paths made by the wild folk going to and from their watering places and feeding grounds, and paths made by the red hunter and warrior. Although hundreds of deer traveled to this lick yearly, they had not originally made the trail. It was an ancient Indian runaway, for the creek was fordable near this point. The tribesmen had used it for generations until it was worn almost knee-deep in the forest mould, but wide enough only to be traveled in single file. Along this ancient trail, and approaching the lick with infinite caution, came a boy of thirteen, bearing a heavy rifle.

Although so young, Enoch Harding was well built, and the play of his hardened muscles was easily observed under his tight-fitting, homespun garments. The circumstances of border life in the eighteenth century molded hardy men and sturdy boys. His face was as brown as a berry and his eyes clear and frankly open. The brown hair curled tightly above his perspiring brow, from which his old otter-skin cap was thrust back. His coming to the bank of the wide stream was attended with all the care and silent observation of an Indian on the trail. He set his feet so firmly and with such precision that not even the rustle of a leaf or the crackling of a twig would have warned the sharpest ear of his approach. The wind was in his favor, too, blowing from the creek toward him. The doe, which he could not yet see but the patter of whose light hoofs he had heard as she trotted with her fawn to the drinking place, could not possibly have discovered his presence; yet she continued to raise her muzzle at intervals and snuff the wind suspiciously.

The dark aisles of the forest, as yet unillumined by the sun whose crimson banners would soon be flung above the mountain-tops, seemed deserted. In the distance the birds were beginning their morning song; but here the shadow of the mountains lay heavy upon wood and stream and the feathered choristers awoke more slowly. The two deer at the lick and the boy who now, from behind the massive bole of a tree, surveyed them, seemed the only living objects within view.

Enoch raised his heavy rifle, resting the barrel against the tree trunk, and drew bead at the doe’s side. He was chancing a long shot, rather than taking the risk of approaching any nearer to the animals. He had seen that the doe was suspicious and she might be off in a flash into the thicker forest beyond unless he fired at once. Had he been more experienced he would have wondered what had made the creature suspicious, his own approach to the lick being quite evidently undiscovered. But he thought only of getting a perfect sight and that the larder at home was empty. And this last fact was sufficient to make the boy’s aim certain, his principal care being to waste no powder and to bring down his game with as little loss of time as might be.

The next moment the heavy muzzle-loading gun roared and the buckshot sped on its mission. The mother deer gave a convulsive spring forward, thus warning the poor fawn, which disappeared in the brush like a flash of brown light. The doe dropped in a heap upon the sward and Enoch, flushed with success, ran forward to view his prize. In so doing, however, the boy forgot the first rule of the border ranger and hunter. He did not reload his weapon.

Stumbling over the widely spread roots of the great tree behind which he had hidden, he reached the opening in the forest where the tragedy had been enacted, and would have been on his knees beside the dead deer in another instant had not an appalling sound stayed him. A scream, the like of which once heard is never to be forgotten, thrilled him to the marrow. He started back, casting his glance upward. There was a rustling in the thick branches of the tree beneath which the doe had fallen. Again the maddened scream rang out and a tawny body flashed from concealment in the foliage.

“A catamount!” Enoch shouted, and seeing the creature fairly over his head in its flight through the air, he leaped away toward the creek, his feet winged with fear. Of all the wild creatures of the Northern wilderness this huge cat was most to be avoided. It would not hesitate to attack man when hungry, and maddened and disappointed as this one was, its charge could not be stayed. At the instant when the beast was prepared to leap upon either the doe or her fawn, Enoch’s shot had laid the one low and frightened the other away. His appearance upon the scene attracted the attention of the cat and had given it a new object of attack. Possibly the creature did not even notice the fall of the deer, being now bent upon vengeance for the loss of its prey, for which it had doubtless searched unsuccessfully all the night through.

The young hunter was in a desperate situation. His gun was empty and the prospect of an encounter with the catamount would have quenched the courage of the bravest. And to run from it was still more foolish, yet this was the first thought which inspired him. The creek was beyond and although the ford was some rods above the deer-lick, he thought to cast himself into the stream and thus escape his enemy. The beast, possessing that well-known trait of the feline tribe which causes it to shrink from water, might not follow him into the creek.

A long log, the end of which had caught upon the bank, swung its length into the stream, forming a boom against which light drift-stuff had gathered; the swift current foamed about the timber as though vexed at this delay to its progress. Upon the tree Enoch leaped and ran to the further extremity. His feet, shod in home-made moccasins of deer-hide, did not slip on this insecure footing; but his weight on the stranded log set it in motion. The timber began to swing off from the shore and one terrified glance about him assured the boy that he was at a most deep and dangerous part of the stream.

Although so shallow above at the ford, the bed of the creek directly below was of rock instead of gravel, and ragged boulders thrust themselves up from the depths, causing many whirlpools which dimpled the surface of the water. About the boulders the current tore, the brown froth from the angry jaws of rock dancing lightly away upon the waves. Although even with his clothing on he might have swum in a quiet pool, to do so here would be almost impossible. The boy was between two perils!

He turned about in horror to escape the flood, and was in time to see the huge cat gain the end of the log in a single bound as it was torn from the shore by the current. There the beast crouched, less than twenty feet away, lashing its tail and snarling menace at the victim of its wrath. The situation was paralyzing. As for loading his rifle now, the boy had not the strength to do it. The fascination of the beast’s blazing eyes held him motionless, like a bird charmed by the unwinking gaze of a black snake.

And Enoch Harding knew, if he knew anything, that the beast would not give him time to reload the clumsy gun. At his first movement it would spring. And if he leaped into the water, it might follow him, considering its present savage mood. He beheld its muscles, which slipped so easily under the tawny skin, knotting themselves for a spring. The forelegs were drawn up under the breast the curved, sabre-sharp claws scratching the bark on the floating timber. In another instant the fatal leap would be made.

Never had the boy been in such danger. He did not utterly lose his presence of mind; but he was helpless. What chance had he with an empty gun before the savage brute? He seized the barrel in both hands and raised the weapon above his head. It was too heavy for him to swing with any ease, and being so would fall but lightly on the creature, did he succeed in reaching it at all. He could not hope to stun the cat at a single blow. And beside, the tree, rocking now like a water-logged canoe, made his footing more and more insecure. In a moment it would be among the boulders and at the first collision be overturned.

But he could not drag his eyes from those of the catamount. With a fierce snarl which ended in a thrilling scream, the brute cast itself into the air! At the moment it rose, exposing its lighter colored breast to view, a gun-shot shattered the silence of river and forest. The spring of the cat was not stayed, but its yell again changed–this time to a note of agony.

“Jump, lad, jump!” shouted a voice and Enoch, as though awaking from a dream, obeyed the command. He leaped sideways, and landed upon a slippery rock, falling to his knees, yet securing a hand-hold upon a protuberance. Nor did he lose hold of his gun with the other hand.

The body of the catamount landed just where he had stood; but then rolled off the log and disappeared in the rushing stream, while the timber itself crashed instantly into one of the larger boulders. Enoch staggered to his feet, his hand bleeding and also his knee, where the stocking had been torn away by the rock. The log swung broadside to the current again, and seeing his chance, the boy ran along its length and leaped from its end into comparatively shallow water under the bank.

His rescuer was at hand and dragged him, panting and exhausted, to the shore, where he fell weakly on the turf, unable for a moment to utter a word. The man who leaned over him was lean, as dark as an Indian, and in a day when smoothly shaven features were the rule, his face was marked by a tangled growth of iron-gray beard. His hair hung to the fringed collar of his deerskin shirt, and straggled over his low brow in careless locks, instead of being tightly drawn back and fastened in a queue; and out of this wilderness of hair and beard looked two eyes as sharp as the hawk’s.

He was so tall that there was a slight stoop to his shoulders as though, when he walked, he feared to collide with the branches of the trees under which he passed. Erect, he must have lacked but a few inches of seven feet and, possessing not an ounce of superfluous flesh on his big bones, his appearance was not impressive. The deerskin hunting shirt, worked in a curious pattern on the breast with red and blue porcupine quills, fitted him tightly, as did his linsey-woolsey breeches; and his thin shanks were covered with gray hose darned clumsily in more than one place. He would have been selected at first sight as a wood-ranger and hunter, and carried his long rifle with more grace than he ever held plough or wielded reaping-hook.

Indeed, Josiah Bolderwood was one of that strange class of white men so frequently found during the pioneer era of our Eastern country. He seemed to have been born, as he often said himself, with a gun in his hands. His mother, lying on her couch behind the double wall of a blockhouse in the Maine wilderness, loaded spare guns for her husband and his comrades while they beat off the yelling redskins, when Josiah was but a few days old. He was a ranger and trapper from the beginning. He had slept under the canopy of the forest more often than in a bed and beneath a roof made by men’s hands. From early youth he had hunted all through the northern wilderness, and had been no more able to tie himself to a farm, and earn his bread by tilling the soil, than an Indian. Indeed, he was more of an Indian than a white man in habits, tastes, and feelings; he lacked only that marvelous appreciation of signs and sounds in the forest, in which the white can never hope to equal the red man.

“Lad, that was a near chance for you!” he said, when he saw that Enoch was practically unhurt. “The Almighty surely brought me to this lick jest right. I knowed you was here when I heard the shot; but as your marm said you’d gone for a deer, I didn’t s’pose you’d be huntin’ for catamounts, too! Howsomever, somethin’ tol’ me ter run when I heard your gun, an’ run I did.”

“I didn’t shoot at the wild-cat, ’Siah,” said the boy, getting upon his feet. “See yonder; there’s the doe I knocked over. But the critter was after her, too, and it madded him when I fired, I s’pose.”

“And ye didn’t git your gun loaded again!” exclaimed Bolderwood.

His young friend blushed with shame. “I–I didn’t think. I ran over to look at the doe, and the critter jumped at me outer the tree. Then I got on the log and he follered me―”

“Jonas Harding’s boy’d oughter known better than that,” declared the old ranger, with some vexation.

“I know it, ’Siah. Poor father told me ’nough times never to move outer my tracks till I had loaded again. An’ I reckon this’ll be a lesson for me. I–I ain’t got over it yet.”

“Wal,” said Bolderwood, “while you git yer breath, Nuck, I’ll flay that critter and hang her up. I’m in somethin’ of a hurry this mornin’; but as the widder’s needin’ the meat, we won’t leave the carcass to the varmints.”

“You’ve been to my house, ’Siah?” cried Enoch, following him across the little glade.

“Yes. Jest stopped there on my way down from Manchester. That’s how I knew you was over here hunting.”

“But if you’re in a hurry, leave me to do that,” said the boy. “I’m all right now.”

“You’re in as big a hurry as I be, Nuck,” returned the ranger, with a grim smile. “I’m going to take you with me over to Mr. James Breckenridge’s. Ev’ry gun we kin git may count to-day, lad.”

“Did mother say I could go, ’Siah?” cried the youngster, with undoubted satisfaction in his voice. “You’re the best man that I know to get her to say ‘yes’!”

Bolderwood looked up from his work with much gravity. “This ain’t no funnin’ we’re goin’ on, Nuck. It’s serious business. You kin shoot straight, an’ that’s why I begged for ye. This may be the most turrible day you ever seen, my lad, for the day on which a man or boy sees bloodshed for the fust time, is a mem’ry that he takes with him to the grave.”

Although Enoch Harding had not grasped the serious nature of the matter which the ranger’s words suggested, there was something he had realized, however, and this thought sent the blood coursing through his veins with more than wonted vigor and his eyes sparkled. He was a man. He was to play a man’s part on this day and the neighbors–even the old ranger who had stood his friend on so many occasions already–recognized him as the head of the family.

Bolderwood saw this thought expressed in his face and without desiring to “take him down” and humble his pride, wished to show him the serious side of the situation. To this end he spoke upon another subject, beginning: “D’ye remember where we be, Nuck? ’Member this place? Seems strange that you sh’d have such a caper here with that catamount after what happened only last spring, doesn’t it?” He glanced keenly at young Harding and saw that his words had at once the desired effect. Enoch stood up, the skinning-knife in his hand, and looked over the little glade. In a moment his brown eyes filled with tears, which rolled unchastened down his smooth cheeks.

“Aye, Nuck, a sorry day for you an’ yourn when Jonas Harding met his death here. And a sorry day was it for me, too, lad. I loved him like a brother. He an’ I, Nuck, trapped this neck of woods together before the settlement was started. We knew how rich the land was and naught but the wars with the redskins an’ them French kept us from comin’ here long before the Robinsons. Jonas wouldn’t come ’less it was safe to bring your mother an’ you–an’ he was right. There’s little good in a man’s roamin’ the world without a wife an’ fireside ter tie to. I was sayin’ the same to neighbor Allen last week, an’ he agreed–though he’s wuss off than me, for he has a family back in Litchfield an’ is under anxiety all the time to bring them here, if the Yorkers but leave us in peace. As for me–well, a tough old knot like me ain’t fit to marry an’ settle down. I’m wuss nor an Injin.”

It is doubtful if the boy heard half this monologue. He stood with thoughtful mien and his eyes were still wet when Bolderwood’s words finally aroused him. “Do you know, Nuck, there’s many a time I stop at this ford and think of your father’s death? There’s things about it I’ll never understand, I reckon.”

Enoch Harding started and flashed a quick glance at his friend. “What things?” he asked.

“Well, lad, mainly that Jonas Harding, who was as quick on the trail and as good a woodsman as myself, should be worsted by a mad buck; it seems downright impossible, Nuck.”

“I know. But there could be no mistake about it, ’Siah. There were the hoof-marks–and there was no bullet wound on the body, only those gashes made by the critter’s horns. Simon Halpen―”

Bolderwood raised his hand quickly. “Nay, lad! don’t utter evil even about that Yorker. We all know he was anigh here when your father died. He was seen at Bennington the night before, and later crossed James Breckenridge’s farm on his way to Albany. Black enemy as he is to you and yourn, there’s naught to be gained by accusing him of Jonas’ death. It would be impossible. There was not, as you say, a bullet wound upon your father’s body. There was not a mark of man’s footstep near the lick here but your father’s own. How else, then, could he have been killed but by the charge of the buck?”

“You say yourself that father was far too sharp to so be taken by surprise,” muttered the boy.

“Aye–that is so. But the facts are there, lad. I s’arched the ground over–I headed the band of scouts who found him–remember that! Nobody had been near the lick but Jonas. There wasn’t a footmark for rods around. Even an Injin couldn’t have got near enough to strike Jonas down with his gun-butt―”

“You believe that wound on his head, then, was made by no deer’s antler?” exclaimed Enoch, eagerly.

“Tut, tut! You jump too quick,” said Bolderwood, turning his face away. “That’s never well. Allus look b’fore ye leap, Nuck. My ’pinion be that your father struck his head on a stone in falling―”

“Where is there a stone here?” demanded the boy, with a speaking gesture of his disengaged hand. “I saw that deep wound in father’s skull. I never believed a buck did that.”

“And yet there was naught but the prints of the buck’s hoofs in the soil here–be sure of that. The ground was trampled all about as though the fight had been desp’rate–as indeed it must have been.”

“But that blow on the head?” reiterated Enoch.

“Ah, lad, I can’t understand that. The wound certainly was mainly like a blow from a gun-stock,” admitted Bolderwood.

“Then Simon Halpen compassed his death–I am sure of it!” cried the boy. “You well know how he hated father. Halpen would never forget the beech-sealing he got last fall. He threatened to be terribly revenged on us; and Bryce and I heard him threaten father, too, when he fought him upon the crick bank and father tossed the Yorker into the middle of the stream.”

Bolderwood chuckled. “Simon as well might tackle Ethan Allen himself as to have wrastled with Jonas,” he said.... “But we must hurry, lad. We have work–and perhaps serious work–before us this day. It may be the battle of our lives; we may l’arn to-day whether we are to be free people here in Bennington, or are to be driven out like sheep at the command of a flunkey under a royal person who lives so far across the sea that he knows naught of, nor cares naught for us.”

“You talk desp’rately against the King, Mr. Bolderwood!” exclaimed Enoch, looking askance at his companion.

“Nay–what is the King to me?” demanded the ranger, in disgust. “He would be lost in these woods, I warrant. We’re free people over here; why should we bother our heads about kings and parliament? They are no good to us.”

“You talk more boldly than Mr. Ethan Allen,” said the boy. “He was at our house once to talk with father. Father said he was a master bold man and feared neither the King nor the people.”

“And no man need fear either if he fear God,” declared the ranger, simply. “We are only seeing the beginnings of great trouble, Nuck. We may do battle to Yorkers now; perhaps we shall one day have to fight the King’s men for our farms and housel-stuff. The Governor of New York is a powerful man and is friendly to men high in the King’s councils, they say. This Sheriff Ten Eyck may bring real soldiers against us some day.”

“You don’t believe that, ’Siah?” cried the boy.

“Indeed and I do, lad,” returned the ranger, rising now with the carcass of the doe flayed and ready for hanging up.

“But we’ll fight for our lands!” cried Enoch. “My father fought Simon Halpen for our farm. I’ll fight him, too, if he comes here and tries to take it, now father is dead.”

“Mayhap this day’s work will settle it for all time, Nuck,” said the ranger, hopefully. “But do you shin up that sapling yonder, and bend it down. We wanter hang this carcass where no varmit–not even a catamount–can git it.”

The boy did as he was bade and soon the fruit of Enoch Harding’s early morning adventure was hanging from the top of a young tree, too small to be climbed by any wild-cat and far enough from the ground to be out of reach of the wolves and foxes. “Now we’ll git right out o’ here, lad,” Bolderwood said, picking up his rifle and starting for the ford. “We’ve got to hurry,” and Enoch, nothing loath, followed him across the creek and into the forest on the other bank.

“Do you r’ally think there’ll be fightin’, Master Bolderwood?” he asked.

“I hope God’ll forbid that,” responded the ranger, with due reverence. “But if the Yorkers expect ter walk in an’ take our farms the way this sheriff wants ter take Master Breckenridge’s, we’ll show ’em diff’rent!” He increased his stride and Enoch had such difficulty in keeping up with his long-legged companion that he had no breath for rejoinder and they went on in silence.

The controversy between the New York colony and the settlers of the Hampshire Grants who had bought their farms of Governor Benning Wentworth, of New Hampshire, was a very important incident of the pre-Revolutionary period. The not always bloodless battles over the Disputed Ground arose from the claim of New York that the old patent of King Charles to the Duke of York, giving to him all the territory lying between the Connecticut River on the east and Delaware Bay on the west, was still valid north of the Massachusetts line.

In 1740 King George II had declared “that the northern boundary of Massachusetts be a similar curved line, pursuing the course of the Merrimac River at three miles distant on the north side thereof, beginning at the Atlantic Ocean and ending at a point due north of a place called Pawtucket Falls, and by a straight line from thence due west till it meets with his Majesty’s other governments.” Nine years later Governor Wentworth made the claim that, because of this established boundary between Massachusetts and New Hampshire, the latter’s western boundary was the same as Massachusetts’–a line parallel with and twenty miles from the Hudson River–and he informed Governor Clinton, of New York, that he should grant lands to settlers as far west as this twenty-mile line. Therewith he granted to William Williams and sixty-one others the township of Bennington (named in his honor) and it was surveyed in October of that same year. But the outbreak of the French and Indian troubles made the occupation of this exposed territory impossible until 1761, when there came into the rich and fertile country lying about what is now the town of Bennington, several families of settlers from Hardwick, Mass., in all numbering about twenty souls.

But there had been an earlier survey of the territory along Walloomscoik Creek under the old Dutch patent and in 1765 Captain Campbell, under instructions from the New York colony, attempted to resurvey this old grant. He came to the land of Samuel Robinson who, with his neighbors, drove the Yorkers off. For this Robinson and two others were carried to Albany where they were confined in the jail for some weeks and afterward fined for “rioting.” At once the settlers, who had increased greatly since ’61, saw that they must present their case before the King if they would have justice rendered them; so Captain Robinson went to England to represent their side of the matter. Unfortunately he died there before completing his work.

On the part of the governors of New Hampshire and New York it was merely a land speculation, and both officials were after the fees accruing from granting the lands; whereas the settlers who had gone upon the farms, and established their families and risked their little all in the undertaking, bore the brunt of the fight. The speculators and the men they desired to place on the farms of the New Hampshire grantees, hovered along the Twenty-Mile Line, and occasionally made sorties upon the more unprotected farmers, despite the fact that the King had instructed the Governor of New York to make no further grants until the rights of the controversy should be plainly established. This settled determination of the New York authorities to drive them out convinced the men of the Grants that they must combine to defend their homes and when, early in July, 1771, news came from Albany that Sheriff Ten Eyck with a large party of armed men was intending to march to James Breckenridge’s farm and seize it in the name of the New York government, the people of Bennington in town-meeting assembled determined to defend their townsman’s rights.

Sheriff Ten Eyck started from Albany on the 18th of July with more than 300 men and at once the settlers began to gather near the threatened farmstead. ’Siah Bolderwood having no farm of his own, was sent through the country raising men and guns for the defense of the Breckenridge place. On his way back he had stopped for Enoch Harding and learning that the boy had gone hunting before daybreak, the ranger followed him, arriving at the deer-lick in time to render important assistance in the dramatic scene just pictured. After crossing the creek at the spot where the boy’s father had met his frightful and mysterious death a few months before, the two volunteers, while still the day was new, reached the place of the settlers’ gathering.

The house of James Breckenridge was built at the foot of a slight ridge of land running east and west, which ridge was heavily wooded. It was only a mile from the Twenty-Mile Line and therefore particularly open to attack by the New York authorities. Once before had an attempt been made by the grasping land speculators of the sister colony to oust its rightful owner, but at that time naught but a wordy controversy had ensued, whereas the present attack bade fair to be more serious. Breckenridge had sent his family to the settlement in expectation of this trouble, while he and his neighbors made ready to meet the sheriff and his army. Some of the Bennington men had arrived at the farm the evening before when news went forth that the invaders were only seven miles away, at Sancock. But the greater number of the defenders came, as did ’Siah Bolderwood and young Enoch Harding, soon after sun-up.

This gathering of Grants men was a memorable one. Heretofore, the clashes with the Yorkers had been little more than skirmishes in which half a dozen or a dozen men on both sides had taken part. Ethan Allen, Seth Warner, Remember Baker, and others of the more venturesome spirits, had seized some of the land-grabbers and their tools, and delivered upon their bared backs more strokes of “the twigs of the wilderness,” as Allen called the blue beech rods, than the unhappy Yorkers thus treated would forget in many a day.

Ethan Allen was not as long in the settlement as many of the other men about him; but he was a born leader, and entering heart and soul into the cause of the Grants was soon acknowledged the most fiery spirit among the settlers. He was born in Litchfield, Conn., January 10, 1737, and probably came to the Hampshire Grants some time in ’69. Although but thirty-four years old at this time he carried his point in most arguments regarding the well-being of the settlers, and the Green Mountain boys, as his followers came to be called, fairly worshipped him. He was singularly handsome, with ruddy face, a ready wit, bold, unpolished, brave and almost a giant in size, for though not so tall as Seth Warner he was a much heavier and broader man.

With this company of armed men, too, was Remember Baker and his flint-lock musket, which seldom left his side waking or sleeping. Baker was the best shot on the northern border and performed feats of marksmanship with this musket that could scarce be equaled by any of our famous marksmen to-day with their improved weapons. Like the stories told of Robin Hood and his cloth-yard shafts, Baker could split a wand with a bullet and always filed the flint on his musket to a sharp point.

Other men there were in this early morning assembly destined to be heard from later in the affairs of the struggling community, but none so filled young Enoch Harding’s eye as did these two. Remember Baker lived not far from the Harding farm and Enoch often went there to visit young Robert Baker, or had Robert to stay all night with him at his home. But Enoch’s closest boy friend was James Breckenridge’s nephew, Lot, who was two years young Harding’s senior and bore arms on this morning with the older youths and men. At once when the two spied each other they found opportunity to step aside and hold such confidences as boys are wont. Yet they were so excited by the prospect of the forthcoming battle with the Yorkers that even Nuck’s adventure with the catamount was lightly passed over.

Meanwhile the settlers were divided into several bands, each captained by an efficient officer who, as ’Siah Bolderwood expressed it, “had snuffed powder.” Bolderwood himself was given command of the larger number and arranged his men along the top of the ridge behind the house, where they would be concealed by the brush but could draw bead upon any person passing along the road or approaching the farmhouse. One hundred and twenty under a second leader were hidden beside the road while eighteen and an officer were stationed inside the house itself.

These arrangements had scarce been made when a figure was descried approaching at top speed. It was a messenger to warn the settlers of the coming of the enemy. “Run down to the house, Nuck,” commanded ’Siah, “and get the news for me. Keep your heads down, lads! Let them Yorkers when they come, think there ain’t nobody to home!”

Enoch crept through the brush and descended the slope, appearing before the house just as the runner reached it. Coming so suddenly from behind the dwelling Enoch startled the newcomer, who sprang back and placed his hand on the hunting knife at his belt. Then, with a contemptuous grunt, the messenger passed Enoch by and lifted the latch-string which had been left hanging out. Enoch followed him into the Breckenridge house.

The runner was a tall Indian lad with a keen face and coal-black eyes and hair. Enoch knew him, for his people had camped for several years near the Harding place. But Jonas Harding had had that contempt for the red race which characterized many of the pioneer people and was the foundation for more than half the trouble between the whites and reds; and he had often expressed this contempt before young Crow Wing, who was a chief’s son although his tribe was scattered and decimated by disease. Crow Wing had hated Enoch’s father for his taunts and unkind words, and now that the elder Harding was dead the young Indian considered his son cast in the same mould and worthy of the same hatred which he had borne Jonas. Naturally Enoch would have shared his parent’s contempt for the Indians; but ’Siah Bolderwood, although he had camped, hunted and fought with Enoch’s father for so many years, did not share the latter’s opinion of the Indian character, and from him Enoch had imbibed many ideas of late which changed his opinion of the red men. There was a time, however, when the white boy had ridiculed Crow Wing and the latter had not forgotten.

Enoch watched him now with admiration. The young brave had run for several miles, having been sent out toward Sancock by one of the settlers for whom he sometimes worked, but he breathed as easily as though he had walked instead of run. When one of the men in the Breckenridge kitchen spoke to him he answered in a perfectly even voice which showed no tremor of fatigue.

“Him sheriff march now,” he said. “Mebbe t’ink um t’ree mile off.”

“Where did you leave them?” asked the man in command of the house. The Indian youth told him. “And how many are there, Crow Wing?” asked another.

“Many–many!” cried the Indian, his eyes flashing. He held up both hands and spread all his ten fingers rapidly seven times. “Seventy!” cried one of the white men. “He means seven hundred,” declared the leader. “That so, Crow Wing, eh?”

The Indian nodded. “Many white men–many guns,” he said.

“It’s not true,” growled one man. “You can’t believe anything an Injin says. Where would the New York sheriff get seven hundred men?”

Crow Wing’s eyes flashed and he drew himself up proudly. “Me no lie–me speak true. Injin not two-tongue like white man!” he declared, with scorn, and turning his back on his traducer, stalked out of the house.

The settlers, however, paid little attention to his departure. Enoch scuttled back to the ridge where ’Siah was waiting to hear the news. There he lay down beside Lot Breckenridge and the two boys talked earnestly as the men about them smoked or chatted while waiting for the coming of the Yorkers. Seven hundred seemed a great number to oppose. The odds would be more than two to one. Despite the ambush which had been so carefully laid for them, the sheriff and his men might fight as desperately as the settlers themselves.

“Tell ye what!” whispered Lot to Enoch, “I ain’t fixin’ to git shot. Marm didn’t want Uncle Jim to let me come, but he said ev’ry gun’d count this mornin’, so she ’lowed I’d hafter. But she says if I git shot she’ll larrup me well.”

Enoch chuckled. Although Lot was his senior he was more of a child than young Harding. The experiences of the last few months had aged Enoch a good deal. “My mother won’t whip me if I git shot; but I mustn’t run into danger, for she wouldn’t know what to do without me,” he said, proudly. “Bryce ain’t much use yet, you know.”

“Zuckers!” exclaimed Lot, “I wisht my marm was like yourn. I ain’t got no father neither; but Uncle Jim don’t let me do nothin’, an’ marm’s allus wearin’ out a beech twig on me.”

“Guess you do somethin’ for it,” said Enoch, wisely.

“She’d do it jest th’ same if I didn’t,” declared Lot, yet with perfect good-nature, as though the Widow Breckenridge’s vigorous applications of the beech wand was a part of existence not to be escaped. “Gran’pap says I might’s well be hung for an ole sheep as a lamb, so in course I do somethin’ for it–mostly.”

“If the Yorkers fight we’ll hafter stay right here and shoot like the men,” said Nuck, reflectively. “It’ll be like the Injin fights my father and ’Siah were in. I s’pose we’ll take trees, an’ scatter out so’t the Yorkers can’t git up around us here―”

“An’ we’ll raise the warwhoop an’ shoot jest as fast as we kin!” exclaimed Lot, excitedly. “Crow Wing taught me the warwhoop last year. An’ I know how to scalp, too.”

“Oh, I wouldn’t do that!” exclaimed Enoch, in horror.

“Umph! Yorkers ain’t no better’n Injins, an’ I’d scalp an Injin,” declared Lot, blood-thirstily.

“I wouldn’t. My father never did that, an’ he was in the war. He said that was why the Injins warn’t no better’n brute-beasts, an’ didn’t have no souls–’cause they scalped their enemies.”

“Be still there, you youngsters!” growled ’Siah, coming down the line. “If you want to be men, l’arn to keep yer tongues quiet. Voices carry far on a day like this. What’d they say down ter the house, Nuck, ’bout the signal?”

“When they want help, or want us to sail into ’em, they’re goin’ to raise a red flag through the chimbley,” replied the boy.

“Wal, I’m hopin’ they won’t fight,” said the ranger, squinting along the road below the ridge.

“Oh, I wanter see a fight–zuckers, I do!” exclaimed Lot.

“Be still, you bloodthirsty young savage!” commanded ’Siah. “You wanter shoot down men of your own color, do ye? Beech-sealin’ an’ duckin’ is all right; but it’s an awful thing to draw bead on another white man, as ye’ll l’arn some day.”

“But you fought the Frenchmen with the Injins,” declared Lot.

“Huh! Them’s only half-bred. Frenchmen ain’t no more’n savages,” said ’Siah, gloomily.

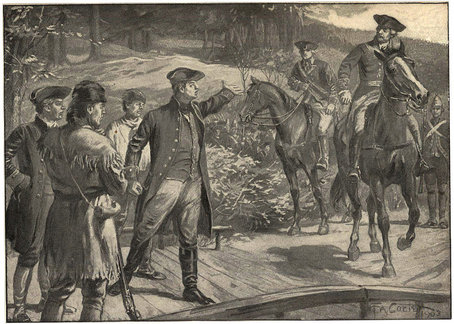

An hour passed–a long, long time to the excited boys. Then, far down the winding road quite a piece of which they could observe from the summit of the wooded ridge, was seen the sudden glint of sunlight on metal. “They’re coming!” the message went round and the settlers in ambush crouched more closely behind their screens and even the hearts of old Indian fighters beat faster at the nearing prospect of an engagement. James Breckenridge, Ethan Allen, and several others advanced slowly from the direction of the house to the bridge across which the Yorkers must pass. Sheriff Ten Eyck spurred forward with his personal staff to meet them. With him came the infamous John Munro who, as a justice of the peace under commission from New York, was such a thorn in the flesh of the settlers. The sheriff was a very pompous Dutchman who believed without question in the validity of New York’s jurisdiction over the Grants, and who, despite his bombastic manner, was personally no coward.

“Master Breckenridge,” he said to the man whom he had come to evict from his home, “we have heard that you and your neighbors are armed to oppose the authority vested in me by His Most Gracious Majesty’s colony of New York. If there be blood shed this day, it will be upon your head, for I here command you to leave this neighborhood and give over the possession of this land to its rightful owners.”

“I cannot do that, Master Sheriff,” said Breckenridge, quietly. “As for blood being upon my head for this day’s work, you can see that I am unarmed,” and he spread his hands widely. “Besides, I have nothing to do with this grant at the present time. The township of Bennington has taken the farm upon its own hands, and it will oppose your entrance with armed resistance. I have nothing to do with it.”

“I COMMAND YOU TO LEAVE THIS NEIGHBORHOOD”

“What is the township of Bennington?” demanded Ten Eyck. “This land belongs to the colony of New York under the crown. There is no town of Bennington. What legal rights have a parcel of squatters to this territory?”

Then Allen spoke. “The gods of the valleys are not the gods of the hills, Sir Sheriff. You on the other side of the Twenty-Mile Line may acknowledge the Governor of New York as your master; we on this side are a free people. We have bought our lands from the government to which they were granted by the King, and you shall not drive us from them!”

The colloquy ended and the settlers went back toward the house. After the main body of his army came up, and their numbers seemed quite as formidable as Crow Wing had reported, the sheriff pressed forward across the bridge and approached the Breckenridge dwelling. Every settler had disappeared by now and even those inside the house were still. Neither the sheriff nor his men suspected that quite three hundred guns were turned upon them and that, at the first fire, the carnage would be terrible.

“Open in the name of the law!” exclaimed Ten Eyck, thundering at the stout oak door of the house. “I demand admittance and that all within come peaceably forth. Open, or I shall break down the door!”

There was silence for a moment, and then a voice said clearly from within: “Attempt it and you are a dead man!”

The reply angered the doughty sheriff. He was being flouted and the majesty of the law scorned. That was more than he could quietly bear. “Come out and deliver up your arms in the name o’ the King!” he cried. “Ye rebels! I’ll take the last of ye to Albany jail if ye do not surrender!”

At this a chorus of derisive groans issued from behind the barred door and shutters, and these sounds were echoed by other groans from the men in ambush, until the very forest itself seemed deriding the Yorkers. The knowledge that he and his men had fallen into a trap did not balk the sheriff; his rage rose to white heat and calling for an axe he advanced to the attack. The moment was freighted with peril. If the Yorkers attacked the house a withering fire would spring from the guns in the bushes and on the ridge and blood would flow in plenty in that heretofore peaceful vale of the northern forest.

Sheriff Ten Eyck was a man of determination and although he had before tested the mettle of the Grants men, he felt a burden of confidence now with this army behind him. The ridicule of the party in ambush stung his pride, and although warned that a considerable number of settlers were hidden in the wood, he was not disposed to temporize. But the men who had accompanied him on his nefarious mission were far differently impressed by the situation. They had followed the doughty sheriff in the hope of plunder, it is true; if the settlers of the Hampshire Grants were to be driven incontinently from their homes as Ten Eyck and the Governor declared, somebody must benefit by the circumstance, and the sheriff’s men hoped to be of the benefited party. But this armed opposition was disheartening. When the chorus of groans rose from the surrounding forest, his men as well as himself, knew that they had fallen into ambush, and this thought troubled the Yorkers greatly.

From the top of the ridge ’Siah Bolderwood had heard much of the controversy at the door of the Breckenridge house and as the really serious moment approached the old ranger was blessed with a sudden inspiration. He sprang forward and seizing Enoch Harding by the collar dragged him to his knees and whispered a command in his ear. “Quick, you young snipe you!” he exclaimed, as Enoch prepared to obey. “Run like the wind–and don’t let ’em see you or you may get potted!”

Enoch was off in an instant, trailing his gun behind him and stooping low that the passage of his body through the brush might not be noted. He got the house between him and the sheriff’s column and soon reached the side of the road where the other settlers in ambush were stationed. He found their leader and whispered Bolderwood’s message to him. Instantly the man caught the idea and the word was passed down the straggling line. Enoch did not return but waited with these men, who were nearer the enemy, to see the matter out.

The sheriff was on the verge of giving the command to break down the door of the besieged house when suddenly a wild yell broke out upon the ridge above and was taken up by the settlers in the brush by the roadside. It was the warwhoop–the yell which originally incited the red warriors to action and was supposed to strike terror to the hearts of their enemies. The shrill cry echoed through the wood with startling significance. At the same instant every man’s cap was raised upon his gun barrel and thrust forward into view of the startled Yorkers, while the settlers themselves showed their heads, but nearer the ground. Only for a moment were they thus visible; then they dropped back into hiding again.

But the effect upon the sheriff’s unwilling army was paralyzing. The Yorkers thought that twice as many men were hidden in the forest as were really there, for the hats on the gun barrels had seemed like heads, too. They thought every man in Bennington–and indeed, as far east as Brattleboro and Westminster–must have come to defend James Breckenridge’s farm, and they clamored loudly to return to the Twenty-Mile Line and safety.

In vain the sheriff fumed and stormed, threatening all manner of punishment for his mutinous troops; the army was determined to a man to have no conflict with the settlers of the Disputed Ground. Like “the noble Duke of York” in the old catch-song familiar at that day, Sheriff Ten Eyck had marched his seven hundred or more men up to James Breckenridge’s door only “to march them down again!” ’Siah Bolderwood’s idea had taken all the desire for fight out of the Yorkers, and after some wrangling between the personal attendants of the sheriff and the volunteer army, the whole crew marched away, leaving the farm to the undisputed possession of its rightful owner.

When the Yorkers departed the little garrison of the house appeared and cheered lustily; but the men in the woods did not come out of hiding until the last of the enemy had disappeared, for they did not wish the invaders to know how badly they had been deceived regarding their numbers. By and by Bolderwood and his men marched down from the ridge and ’Siah was congratulated upon his happy thought in bringing about the confusion of the Yorkers.

“You’ve a long head on those narrow shoulders of yours, neighbor,” declared Ethan Allen, striking the old ranger heartily on the back. “That little wile finished them. And this is the boy I saw trailing through the bushes, is it?” and he seized Enoch and turned his face upward that he might the better view his features. “Why, holloa, my little man! I’ve seen you before surely?”

“It is poor Jonas Harding’s eldest lad, neighbor Allen,” Bolderwood said. “He’s the head of the family now, and bein’ sech, had to come along to fight the Yorkers.”

“I remember your father,” declared Allen, kindly. “A noble specimen of the Almighty’s workmanship. I stopped a night with him once at his cabin–do you remember me?”

As though Nuck could have forgotten it! His youthful mind had made Ethan Allen a veritable hero ever since, placing him upon a pedestal before which he worshipped. But he only nodded for bashfulness.

“You’ll make a big man, too,” said the giant. “And if you can shoot straight there’ll be plenty of chance for you later on. This is only the beginning, ’Siah,” he pursued, turning to Bolderwood and letting his huge hand drop from Enoch’s head. “There will be court-doings, now–writs, and ejectments, and enough red seals to run the King’s court itself. But while the Yorkers are red-sealing us, we’ll blue-seal them–if they come over here, eh?” and he went off with a great shout of laughter at his own punning.

The men were minded to scatter but slowly. All were rejoiced that the battle had been a bloodless one; yet none believed the matter ended. The fiasco of the New York sheriff might act as a wet blanket for the time upon the movements of the authorities across the line; but the land speculators were too numerous and active to allow the people of the Grants to remain in peace. Parties of marauders might swoop down at any time upon the more unprotected settlers, drive them out of their homes, destroy their property, and possibly do bodily injury to the helpless people. Methods must be devised to keep these Yorkers on their own side of the disputed line. Those settlers, such as the widow Harding, who were least able to protect themselves, must have the help of their neighbors. The present victory proved the benefit to be derived from concerted action. Now, in the flush of this triumph, the leaders went among the yeomanry who had gathered here and outlined a plan for permanent military organization. In all the colonies at that day, “training bands,” or militia, had become popular, made so in part by the interest aroused by the wars with the French and Indians. Many of the men who joined these military companies did not look deeply into the affairs of the colonies, nor were they much interested in politics; but their leaders looked ahead–just as did Ethan Allen and his conferees in the Grants–and realized that an armed yeomanry might some time be called upon to face hirelings of the King.

“Even a lad like you can bear a rifle, and your mother will spare you from the farm for drill,” Allen said, with his hand again on Enoch’s shoulder, before riding away. “I shall expect to see Jonas Harding’s boy at Bennington when word is sent round for the first drill.” And Enoch, his heart beating high with pride at this notice, promised to gain his mother’s permission if possible.

Bolderwood had already gone, and Lot Breckenridge detained Enoch until after the dinner hour. Lot would have kept him all night, but the latter knew his mother would be anxious to see him safe home, and he started an hour or two before sunset, on the trail which Bolderwood and he had followed early in the morning. Being one of the last to leave James Breckenridge’s house, he traveled the forest alone. But he had no feeling of fear. The trails and by-paths were as familiar to him as the streets of his hometown are to a boy of to-day. And the numberless sounds which reached his ears were distinguished and understood by the pioneer boy. The hoarse laugh of the jay as it winged its way home over the tree-tops, the chatter of the squirrel in the hollow oak, the sudden scurry of deer in the brake, the barking of a fox on the hillside, were all sounds with which Enoch Harding was well acquainted.

As he crossed a heavily shadowed creek, a splash in the water attracted his particular attention and he crept to the brink in time to see a pair of sleek dark heads moving swiftly down the stream. Soon the heads stopped, bobbed about near a narrow part of the stream, and finally came out upon the bank, one on either side. The trees stood thick together here, and both animals attacked a straight, smooth trunk standing near the creek, their sharp teeth making the chips fly as they worked. They were a pair of beavers beginning a dam for the next winter. Enoch marked the spot well. About January he would come over with Lot, or with Robbie Baker, stop up the mouth of the beaver’s tunnel, break in the dome of his house, and capture the family. Beaver pelts were a common article of barter in a country where real money was a curiosity.

But watching the beavers delayed Enoch and it was growing dark in the forest when he again turned his face homewards. He knew the path well enough–the runway he traveled was so deep that he could scarce miss it and might have followed it with his eyes blindfolded,–but he quickened his pace, not desiring to be too late in reaching his mother’s cabin. Unless some neighbor had passed and given them the news of the victory at James Breckenridge’s they might be worried for fear there had actually been a battle. Deep in the forest upon the mountainside there sounded the human-like scream of a catamount, and the memory of his adventure of the morning was still very vivid in his mind. He began to fear his mother’s censure for his delay, too, for Mistress Harding brought up her children to strict obedience and Enoch, man though he felt himself to be because of this day’s work, knew he had no business to loiter until after dark in the forest.

He stumbled on now in some haste and was approaching the ford in the wide stream near which he had shot the doe, when a flicker of light off at one side of the trail attracted his attention. It was a newly kindled campfire and the pungent smoke of it reached his nostrils at the instant the flame was apparent to his eyes. He leaped behind a tree and peered through the thickening darkness at the spot where the campfire was built. His heart beat rapidly, for despite the supposed peacefulness of the times there was always the possibility of enemies lurking in the forest. And the settlers had grown wary since the controversy with the Yorkers became so serious.

Enoch was nearing the boundaries of his father’s farm now and ever since Simon Halpen had endeavored to evict them and especially since Jonas Harding’s death, the possibility of the Yorkers’ return had been a nightmare to Enoch. Lying a moment almost breathless behind the tree, he began to recover his presence of mind and fortitude. First he freshened the priming of his gun and then, picking his way cautiously, approached the campfire. Like a shadow he flitted from tree to tree and from brush clump to stump, circling the camp, but ever drawing nearer. With the instinct of the born wood-ranger he took infinite pains in approaching the spot and from the moment he had observed the light he spent nearly an hour in circling about until he finally arrived at a point where he could view successfully the tiny clearing.

Now, at once, he descried a figure sitting before the blaze. The man had his back against a tree and that is why Enoch had found such difficulty at first in seeing him. He was nodding, half asleep, with his cap pulled down over his eyes, so that only the merest outline of his face was revealed. It was apparent that he had eaten his own supper, for there were the indications of the meal upon the ground; but it looked as though he expected some other person to join him. The wind began to moan in the tree-tops; far away the mournful scream of the catamount broke the silence again. The boy cast his gaze upward into the branches, feeling as though one of the terrible creatures, with which he had engaged in so desperate a struggle that very morning, was even then watching him from the foliage.

And he was indeed being watched, and by eyes well nigh as keen as those of the wild-cat. While he stood behind the tree, all of half a gun-shot from the camp, a figure stepped silently out of the shadows and stood at his elbow before the startled lad realized that he was not alone. A vice-like hand seized his arm so that he could not turn his rifle upon this unexpected enemy. Before he could cry out a second hand was pressed firmly over his parted lips. “No speak!” breathed a voice in Enoch Harding’s ear. “If speak, white boy die!”

A HAND WAS PRESSED OVER HIS LIPS

It was Crow Wing, the young Iroquois, and Enoch obeyed. He found himself forced rapidly away from the campfire and when they were out of ear-shot of the unconscious stranger, and not until then, did the grasp of the Indian relax. “What do you want with me?” Enoch demanded, in a whisper. The other did not reply. He only pushed the white boy on until they came to the ford of the creek where Enoch and ’Siah Bolderwood had crossed early in the day. There Crow Wing released him altogether and pointed sternly across the river. “Your house–that way!” he said. “Go!”

“Who is that man back yonder?” cried Enoch, angrily. “You can’t make me do what you say―”

Crow Wing tapped the handle of the long knife at his belt suggestively. “White boy go–go now!” he commanded again, and in spite of his being armed with a rifle while the Indian had no such weapon, Enoch felt convinced that it would be wiser for him to obey without parley. Although Crow Wing could not have been three years his senior, he was certainly the master on this occasion. With lagging step he descended the bank and began to ford the stream. He glanced back and saw the Indian, standing like a statue of bronze, on the bank above him. When he reached the middle of the stream, however, he felt the full ignominy of his retreat before a foe who was not armed equally with himself. What would Bolderwood say if he told him? What would his father have done?

He swung about quickly and raised the rifle to his shoulder. But the Indian lad had gone. Not an object moved upon the further shore of the creek and, after a minute or two of hesitation, the white boy stumbled on through the stream and reached the other bank. He was angry with himself for being afraid of Crow Wing, and he was also angry that he had not seen the face of the stranger at the campfire. It must have been somebody whom Crow Wing knew and did not wish the white boy to see. Enoch Harding continued his homeward way, his mind greatly disturbed by the adventure and with a feeling of deep resentment against the Indian youth.

Enoch arrived feeling not of half so much importance as he had on starting from the Breckenridge farm. His adventure with Crow Wing had mightily taken down his self-conceit. Like most of the settlers he had very little confidence in the Indian character; so, although Crow Wing had rendered the defenders of the Grants a signal service that very day, Enoch was not at all sure that the red youth was not helping the Yorkers, too.

But when he came out of the wood at the edge of the great corn-field which his father had cleared first of all, and saw the light of the candles shining through the doorway of the log house, he forgot his recent rage against Crow Wing and hurried on to greet those whom he loved. The children came running out to meet him and the light of the candles was shrouded as his mother’s tall form appeared in the doorway. Bryce, who was eleven years old, was almost as tall as Enoch, although he lacked his elder brother’s breadth of shoulders and gravity of manner. Enoch was deliberate in everything he did; Bryce was of a more nervous temperament and was apt to act upon impulse. He was a fair-haired boy and was forever smiling. Now he reached Nuck first and fairly hugged him around the neck, exclaiming:

“We thought you were shot! However came you to be so long comin’ back, Nuck? Mother’s quite worritted ’bout you, she says.”

Katie, the fly-away sister of ten, hurled herself next upon her elder brother and seized the heavy rifle from his hands. “Look out for it, Kate!” commanded Nuck. “It’s been freshly primed.” But Katie was not afraid of firearms. She shouldered the gun and marched bravely toward the house. Mary, demure and curly headed, and little Harry, remained nearer the door, and lifted their faces to be kissed in turn by Enoch when he arrived. Then the boy turned to his mother.

“Come in, my son,” she said. “I have saved your supper for you. I could not send the children to bed before you came. They were a-well nigh wild to see you and hear about the doings at farmer Breckenridge’s. You are late.”

This was all she said regarding his tardiness at the moment. She was a very pleasant featured woman of thirty-five, with kind eyes and a cheery, if grave, smile; but Enoch knew she could be stern enough if occasion required. Indeed, she was a far stricter disciplinarian than his father had been. They crowded into the house and Mrs. Harding went to the fire and hung the pot over the glowing coals to heat again the stewed venison which she had saved for Enoch’s supper.

“Tell us about it, Enoch, my son,” she said. “Did the Yorkers come as friend Bolderwood said they would–in such numbers?”

“In greater numbers,” declared the boy, and he went on to recount the incidents of the morning when Sheriff Ten Eyck had demanded the surrender of the Breckenridge house and farm. The incident had appealed strongly to the boy and he drew a faithful picture of the scene when the army of Yorkers marched up to the farmhouse door and demanded admission.

“And Mr. Allen was there and spoke to me–he did!” declared Enoch. “He’s a master big man–and so handsome. He asked me if I remembered his coming here once to see father, and he told me to be sure and go to Bennington when the train-band is mustered in. I can, can’t I, mother?”

“And me, too!” cried Bryce. “I can carry Nuck’s musket now’t he shoots with father’s gun. I can shoot, too–from a rest.”

“Huh!” exclaimed his elder brother, “you can’t carry the old musket even, and march.”

“Yes I can!”

“No you can’t!”

But the mother’s voice recalled the boys to their better behavior. “I will talk with ’Siah Bolderwood about your joining the train-band, Enoch. And if you go to Bennington with Enoch, Bryce, who will defend our home? You must stay here and guard mother and the other children, my boy.”

Bryce felt better at that suggestion and the argument between Enoch and himself was dropped. The widow soon sent all but Enoch to bed in the loft over the kitchen and living room of the cabin. There was a bedroom occupied by herself partitioned off from the living room, while Enoch slept on a “shakedown” near the door. This he had insisted upon doing ever since his father’s death.

“You were very late in returning, my son,” said the widow when the others had climbed the ladder to the loft.

“Yes, marm.”

“You did not come right home?”

“No, marm. I stayed to eat with Lot Breckenridge. And then I wanted to hear the men talk.”

“You should have started earlier for home, Enoch,” she said, sternly.

“Well, I’d got here pretty near sunset if it hadn’t been for somethin’ that happened just the other side of the crick,” Enoch declared, forgetting the fact that he had stopped to watch the beavers before ever he saw the campfire in the wood.

“What was it?” she asked.

“There’s somebody over there–a tall man, but I couldn’t see his face―”

“Where?”

“Beyond the crick; ’twarn’t half a mile from where father was killed at the deer-lick. I saw a light in the bushes. It was a campfire an’ I couldn’t go by without seein’ what it was for. So I crept up on it an’ bymeby I saw the man.”

“You don’t know who he was?” asked the widow, quickly.

“No, marm.”

“Did he have a dark face and was his nose hooked?”

“I couldn’t see his face. He was sittin’ down all the time. His face was shaded with his cap. He sat with his back up against a tree. I was a long while gittin’ near enough to see him, an’ then―”

“Well, what happened, my son?”

“Then that Crow Wing–you know him; the Injin boy that useter live down the crick with his folks–Crow Wing come out of the forest an’ grabbed me an’ told me not to holler or he’d kill me. I wasn’t ’zactly ’fraid of him,” added Enoch, thinking some explanation necessary, “but I saw if I fought him it would bring the man at the fire to help, and I couldn’t fight two of ’em, anyway. The pesky Injin made me walk to the crick with him an’ then he told me to go home and not come back. I wish ’Siah Bolderwood was here. We’d fix ’em!”

“The Indian threatened you!” cried the widow. “Have you done anything to anger him, Enoch? I know your father was very bitter toward them all; but I hoped―”

“I never done a thing to him!” declared the boy. “I don’t play with him much, though Lot does; but I let him alone. I useter make fun of him b’fore–b’fore ’Siah told me more about his folks. Crow Wing’s father is a good friend to the whites. He fought with our folks ag’in the French Injins.”

“But who could the man have been?” asked the widow, gravely. “The children saw a man lurking about the corn-field at the lower end to-day. And when I was milking, Mary came and told me that he was then across the river at the ox-bow, looking over at the house. If it should be Simon Halpen! He will not give up his hope of getting our rich pastures, I am afraid. We must watch carefully, Enoch.”

“I’ll shoot him if he comes again!” declared the boy, belligerently. Then he closed and barred the door and rapidly prepared for bed. His mother retired to her own room, but long after Enoch was soundly sleeping on his couch, the good woman was upon her knees beside her bed. Although she was proud to see Enoch so sturdy and helpful, she feared this controversy with the Yorkers would do him much harm; and it was for him, as well as for the safety of them all in troublous times, that she prayed to the God in whom she so implicitly trusted.

The next day ’Siah Bolderwood came striding up to the cabin with the carcass of the doe Enoch had shot across his shoulders, and found the widow at her loom, just within the door. She welcomed the lanky ranger warmly, for he had not only been her husband’s closest friend but had been of great assistance to her children and herself since Jonas’ death. “The children will be glad to see you, ’Siah,” she said. “I will call them up early and get supper for us all. I will have raised biscuit, too–it is not often you get anything but Johnny-cake, I warrant. The boys are working to clear the new lot to-day.”

“Aye, I saw them as I came along,” said Bolderwood, laughing. “There was Mistress Kate on top of a tall stump, her black hair flying in the wind, and Nuck’s old musket in her hands. She said she was on guard, and she hailed me before I got out of the wood. Her eyes are sharp.”

“She should have been a boy,” sighed the widow. “Indeed, this wilderness is no place for girls at all.”

“Bless their dear little souls!” exclaimed Bolderwood, with feeling. “What’d we do without Kate an’ Mary? They keep the boys sweet, mistress! And Kate’s as good as a boy any day when it comes to looking out for herself; while as I came through the stumpage Mary was working with the best of ’em to pull roots and fire-weed.”

“The boys want a stump-burning as soon as possible. Jonas got the new lot near cleared. There’s only the rubbish to burn.”

“Good idea. Nuck and Bryce are doing well.... But what was the sentinel for?”

“It isn’t all play,” said the widow, stopping her work and speaking seriously. “Yesterday the children saw a strange man hanging about the creek yonder. And last night on his way back from Master Breckenridge’s, Enoch saw a campfire in the forest and a man sitting by it. An Indian youth whom perhaps you have seen here–Crow Wing, he is called–was with the man. Crow Wing drove Enoch off before he could find out who the white man was.”

“Crow Wing, eh?” repeated ’Siah, shaking his head thoughtfully. “I know the red scamp. If he was treated right by the settlers, though, he’d be decent enough. But he got angry at Breckenridge’s yesterday, they tell me. Somebody spoke roughly to him. You can ruffle the feathers of them birds mighty easy.”

This was all the comment the ranger made upon the story; but later he wandered down to the new lot which the Hardings were clearing, and instead of lending a hand inquired particularly of Enoch where he had seen the campfire the night before. Learning the direction he plunged into the wood without further ado and went to the ford, crossing it with caution and going at once to the vicinity of the fire which Enoch had observed. But the ashes had been carefully covered and little trace of the occupation of the spot left. At one point, however, ’Siah found where two persons–a white man and a red one–had embarked in a canoe which had been hidden under the bank of the creek. Evidently Crow Wing had expected the place would be searched and had done all in his power to mystify the curious.

When ’Siah returned Mistress Harding had called up the children and supper–a holiday meal–was almost ready. A lamb had been killed the day before and was stuffed and baked in the Dutch oven. There were light white-flour biscuits, Enoch had ridden to Bennington with the wheat slung across his saddle to have it ground, and there was sweet butter and refined maple sap which every family in the Grants boiled down in the spring for its own use, although as yet there was little market for it. It was a jolly meal, for when ’Siah came the children were sure of something a bit extra, both to eat and to do. He taught the girls how to make doll babies with cornsilk hair, and begged powder and shot of their mother for Bryce and Enoch to use in shooting at a mark. Under his instructions Enoch had become a fairly good marksman, while Bryce, by resting his gun in the fork of a sapling set upright in the ground, did almost as well as his elder brother.

After supper Bolderwood talked with the widow while he smoked his pipe. “We need boys like Enoch, Mistress Harding,” he said. “While he’s young I don’t dispute, he’s big for his age and can handle that rifle pretty well. You must let him go up to Bennington next week and drill with the other young fellows. There will be no need of his going on any raids with the older men. We shall keep the boys out of it, and most of the beech-sealin’ will be done by the men who hain’t got no fam’blies here and are free in their movements. But the drill will be good for him and the time may come when all this drillin’ will pay.”

“You really look for serious trouble with the Yorkers, Master Bolderwood?” she asked.

“I reckon I do. With them or–or others. Things is purty tick’lish–you know that, widder. The King ain’t treatin’ us right, an’ his ministers and advisers don’t care anything about these colonies, ’ceptin’ if we don’t make ’em rich. Then they trouble us. And the governors are mostly all alike. I don’t think a bit better of Benning Wentworth than I do of these ’ere New York governors. They don’t re’lly care nothin’ for us poor folk.”

So the widow agreed to allow Enoch to go to Bennington; and when the day came for the gathering of those youths and men who could be spared from the farms, to meet there, he mounted the old claybank mare, his shoes and stockings slung before him over the saddle bow that his great toes might be the easier used as spurs, and with a bag of corn behind him to be left for grinding at the mill, trotted along the trail to the settlement. Before he had gone far on the road he saw other men and boys bound in the same direction. Remember Baker passed him, with Robbie, his boy, perched behind on the saddle, and clinging like a leech to his father’s coat-tails as the horse galloped over the rough road. Enoch saw Robbie later, however, and invited him to the stump burning which was to take place the following week. He saw Lot Breckenridge, too, at the Green Mountain Inn, and invited him to come, and sent word to other boys and girls in the Breckenridge neighborhood.

Lot’s mother would not let him carry a gun, but he had come to look on and see the “greenhorns” take their first lesson in the manual of arms. Stephen Fay, mine host of the “Catamount” Inn as the hostlery had come to be called–a large, jocund individual who was a Grants man to the core and earnest in the cause of the Green Mountain Boys–made all welcome and the old house was crowded from daylight till dark. In the gallery which ran along the face of the inn, even with the second story windows, the ladies of the town sat and viewed the maneuvres of the newly formed train-band. Before the door stood the twenty-five foot post that held the sign and was likewise capped by a stuffed catamount, in a very lifelike pose, its grinning teeth and extended claws turned toward the New York border in defiance of “Yorker rule.”

The leaders of the party which had suggested these drills–all staunch Whigs and active in their defiance of the Yorkers,–met together in the inn that day, too, and laid plans for a campaign against certain settlers from New York who had come into the Grants and taken up farms without having paid the New Hampshire authorities for the same. In not all cases had these New York settlers driven off people who had bought the land of New Hampshire or her agents; but if it was really the property of that colony the Yorkers had no right upon the eastern side of the Twenty-Mile Line, or on that side of the lake, at all. As far north as the opposite shore from Fort Ticonderoga, that key to the Canadian route which had been wrested from the French but a few years before, Yorkers had settled; and the Green Mountain Boys determined that these people must leave the Disputed Ground or suffer for their temerity.

After the failure of Ten Eyck to capture the Breckenridge farm, New York began a system of flattery and underhanded methods against the Grants men which was particularly effective. The Yorkers chose certain more or less influential individuals and offered them local offices, gifts of money, and even promised royal titles to some, if they would range themselves against the Green Mountain Boys. In some cases these offers were accepted; in this way John Munro had become a justice of the peace, and Benjamin Hough followed his example. Some foolish folk went so far as to accept commissions as New York officers, but hoped to hide the fact from their neighbors until a fitting season–when the Grants were not afflicted with the presence of the Green Mountain Boys. But in almost every case such cowardly sycophants were discovered and either made ridiculous before their neighbors by being tried and hoisted in a chair before the Catamount Inn, or were sealed with the twigs of the wilderness–and the Green Mountain Boys wielded the beech wands with no light hand.

Almost every week the military drills were held in Bennington and Enoch attended. But before the second one the “stump burning” came off at the Harding place and that was an occasion worthy of being chronicled.

Enoch and Lot Breckenridge, with Robbie Baker, had completed all the plans for the stump burning that first training day at Bennington. Lot, who lived so far from the Harding cabin, agreed to come over the night before if his mother would let him, and Robbie was to remain with Enoch the night after. The stumps and rubbish would be pretty well piled up and fired by afternoon, and then the boys could run races, and play games, and perhaps shoot at a mark, until supper-time. Mrs. Harding had already promised if the boys worked well to make a nice supper for them.

“An’ we’ll have the girls,” said Lot.

“Oh, what good’ll they be at a stump burnin’?” demanded young Baker, ungallantly.

“Lots o’ good. They allus want good times, too,” said Lot, standing up for his sisters manfully. “You have no sisters, an’ that’s why you don’t want ’em.”

“They’ll be in the way. Their frocks’ll git torn if they help us, an’ they’ll git afire–or–or somethin’!”

“Nuck’s sisters will be there. They’ll want other girls,” said the wise Lot. “An’ b’sides, Mis’ Harding’ll be lots better to us if the girls is there. She allus is–my marm is. Mothers like girls, but boys is only a nuisance, they says.” Lot had drawn these conclusions from the remarks of his own mother, who was troubled by many children and lacked that “faculty,” as New England folk used to term it, for bringing them up cheerfully.

“I guess we’ll get a better supper if the girls are there,” admitted Nuck, quietly.

“But what’ll they do?” demanded Robbie, the embryo woman-hater.

“I’ll get mother ter be layin’ out a quilt, or something, an’ the girls can help about that.”

“Zuckers!” cried Lot. “We’ll have the finest time ever was. I’ll be sure an’ tell ev’rybody down my way. An’ we’ll all bring powder an’ shot; it won’t matter so much about guns, for them that don’t have ’em can borry of them that has, when it comes to shootin’.”

“And I’ll get Master Bolderwood to come an’ be empire,” declared Nuck, no farther out in his pronunciation of the word than some boys are nowadays.

So the girls were allowed to come, and an hour or two after sun-up on the day in question the Harding place was fairly overrun with young folk of both sexes. Those boys who came from a goodly distance brought their sisters with them; but the greater number of the girls, living within a radius of a few miles of the Harding cabin, did not come until after dinner, having to remain at home to help their own mothers before attending the merrymaking.

And what a merrymaking it was! Truly, all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy, and in a country and at a time when all young people had to work almost as hard as their parents, the pioneer fathers and mothers encouraged the young folk to mix pleasure well with their tasks. Indeed, it was a system followed by the older folks as well on many occasions. Corn-shuckings, apple-parings, log-rollings, sugaring-off–all these tasks even down to “hog-killings”–were made the excuse for social gatherings. The idea of helping one another in the heavier tasks of their existence on the frontier was likewise combined in this. Many hands make light work, and a cabin which would have kept one family busy for a fortnight was often put up and the roof of drawn shingles laid in a day’s time, by the neighbors of the proprietor of the new structure all taking hold of the work.