Title: Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Author: Various

Editor: Harry Bates

Release date: November 23, 2009 [eBook #30532]

Most recently updated: September 10, 2015

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

W. M. CLAYTON, Publisher HARRY BATES, Editor DR. DOUGLAS M. DOLD, Consulting Editor

That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid, by leading writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the Authors' League of America;

That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS MONTHLY, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE, WESTERN ADVENTURES, and WESTERN LOVE STORIES.

More than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

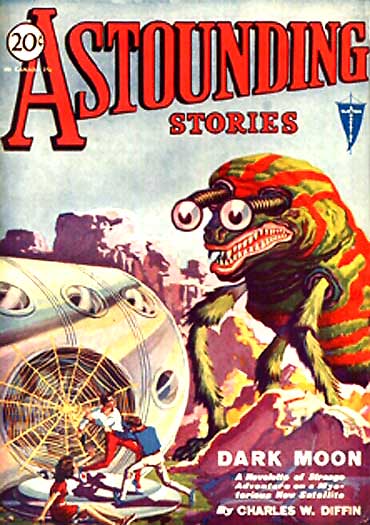

| COVER DESIGN | H. W. WESSO | ||

| Painted in Water-Colors from a Scene in "Dark Moon." | |||

| DARK MOON | CHARLES W. DIFFIN | 148 | |

| Mysterious, Dark, Out of the Unknown Deep Comes a New Satellite to Lure Three Courageous Earthlings on to Strange Adventure. (A Complete Novelette.) | |||

| WHEN CAVERNS YAWNED | CAPTAIN S. P. MEEK | 198 | |

| Only Dr. Bird's Super-Scientific Sleuthing Stands in the Way of Ivan Sarnoff's Latest Attempt at Wholesale Destruction. | |||

| THE EXILE OF TIME | RAY CUMMINGS | 216 | |

| Young Lovers of Three Eras Are Swept down the Torrent of the Sinister Cripple Tugh's Frightful Vengeance. (Part Two of a Four-Part Novel.) | |||

| WHEN THE MOON TURNED GREEN | HAL K. WELLS | 241 | |

| Outside His Laboratory Bruce Dixon Finds a World of Living Dead Men—and Above, in the Sky, Shines a Weird Green Moon. | |||

| THE DEATH-CLOUD | NAT SCHACHNER AND ARTHUR L. ZAGAT | 256 | |

| The Epic Exploit of One Who Worked in the Dark and Alone, Behind the Enemy Lines, in the Great Last War. | |||

| THE READERS' CORNER | ALL OF US | 276 | |

| A Meeting Place for Readers of Astounding Stories. | |||

Single Copies, 20 Cents (In Canada, 25 Cents) Yearly Subscription, $2.00

Issued monthly by Readers' Guild, Inc., 80 Lafayette Street, New York, N. Y. W. M. Clayton, President; Francis P. Pace, Secretary. Entered as second-class matter December 7, 1929, at the Post Office at New York, N. Y., under Act of March 3, 1879. Title registered as a Trade Mark in the U. S. Patent Office. Member Newsstand Group. For advertising rates address The Newsstand Group, Inc., 80 Lafayette St., New York or The Wrigley Bldg., Chicago.

Behind them a red ship was falling—falling free!

Behind them a red ship was falling—falling free!

he one hundred and fifty-ninth floor of the great Transportation Building allowed one standing at a window to look down upon the roofs of the countless buildings that were New York.

Flat-decked, all of them; busy places of hangars and machine shops and strange aircraft, large and small, that rose vertically under the lift of flashing helicopters.

The air was alive and vibrant with directed streams of stubby-winged shapes that drove swiftly on their way, with only a wisp of vapor from their funnel-shaped sterns to mark the continuous explosion that propelled them. Here and[149] there were those that entered a shaft of pale-blue light that somehow outshone the sun. It marked an ascending area, and there ships canted swiftly, swung their blunt noses upward, and vanished, to the upper levels.

A mile and more away, in a great shaft of green light from which all other craft kept clear, a tremendous shape was dropping. Her hull of silver was striped with a broad red band; her multiple helicopters were dazzling flashes in the sunlight. The[150] countless dots that were portholes and the larger observation ports must have held numberless eager faces, for the Oriental Express served a cosmopolitan passenger list.

But Walter Harkness, standing at the window, stared out from troubled, frowning eyes that saw nothing of the kaleidoscopic scene. His back was turned to the group of people in the room, and he had no thought of wonders that were prosaic, nor of passengers, eager or blase; his thoughts were only of freight and of the acres of flat roofs far in the distance where alternate flashes of color marked the descending area for fast freighters of the air. And in his mind he could see what his eyes could not discern—the markings on those roofs that were enormous landing fields: Harkness Terminals, New York.

nly twenty-four, Walt Harkness—owner now of Harkness, Incorporated. Dark hair that curled slightly as it left his forehead; eyes that were taking on the intent, straightforward look that had been his father's and that went straight to the heart of a business proposal with disconcerting directness. But the lips were not set in the hard lines that had marked Harkness Senior; they could still curve into boyish pleasure to mark the enthusiasm that was his.

He was not typically the man of business in his dress. His broad shoulders seemed slender in the loose blouse of blue silk; a narrow scarf of brilliant color was loosely tied; the close, full-length cream-colored trousers were supported by a belt of woven metal, while his shoes were of the coarse-mesh fabric that the latest mode demanded.

He turned now at the sound of Warrington's voice. E. B. Warrington, Counsellor at Law, was the name that glowed softly on the door of this spacious office, and Warrington's gray head was nodding as he dated and indexed a document.

"June twentieth, nineteen seventy-three," he repeated; "a lucky day for you, Walter. Inside of ten years this land will be worth double the fifty million you are paying—and it is worth more than that to you."

He turned and handed a document to a heavy-bodied man across from him. "Here is your copy, Herr Schwartzmann," he said. The man pocketed the paper with a smile of satisfaction thinly concealed on his dark face.

arkness did not reply. He found little pleasure in the look on Schwartzmann's face, and his glance passed on to a fourth man who sat quietly at one side of the room.

Young, his tanned face made bronze by contrast with his close-curling blond hair, there was no need of the emblem on his blouse to mark him as of the flying service. Beside the spread wings was the triple star of a master pilot of the world; it carried Chet Bullard past all earth's air patrols and gave him the freedom of every level.

Beside him a girl was seated. She rose quickly now and came toward Harkness with outstretched hand. And Harkness found time in the instant of her coming to admire her grace of movement, and the carriage that was almost stately.

The mannish attire of a woman of business seemed almost a discordant note; he did not realize that the hard simplicity of her costume had been saved by the soft warmth of its color, and by an indefinable, flowing line in the jacket above the rippling folds of an undergarment that gathered smoothly at her knees. He knew only that she made a lovely picture, surprisingly appealing, and that her smile was a compensation[151] for the less pleasing visage of her companion, Schwartzmann.

"Mademoiselle Vernier," Herr Schwartzmann had introduced her when they came. And he had used her given name as he added: "Mademoiselle Diane is somewhat interested in our projects."

She was echoing Warrington's words as she took Harkness' hand in a friendly grasp. "I hope, indeed, that it is the lucky day for you, Monsieur. Our modern transportation—it is so marvelous, and I know so little of it. But I am learning. I shall think of you as developing your so-splendid properties wonderfully."

nly when she and Schwartzmann were gone did Harkness answer his counsellor's remark. The steady Harkness eyes were again wrinkled about with puckering lines; the shoulders seemed not so square as usual.

"Lucky?" he said. "I hope you're right. You were Father's attorney for twenty years—your judgment ought to be good; and mine is not entirely worthless.

"Yes, it is a good deal we have made—of course it is!—it bears every analysis. We need that land if we are to expand as we must, and the banks will carry me for the twenty million I can't swing. But, confound it, Warrington, I've had a hunch—and I've gone against it. Schwartzmann has tied me up for ready cash, and he represents the biggest competitors we have. They're planning something—but we need the land.... Oh, well, I've signed up; the property is mine; but...."

The counsellor laughed. "You need a change," he said; "I never knew you to worry before. Why don't you jump on the China Mail this afternoon; it connects with a good line out of Shanghai. You can be tramping around the Himalayas to-morrow. A day or two there will fix you up."

"Too busy," said Harkness. "Our experimental ship is about ready, so I'll go and play with that. We'll be shooting at the moon one of these days."

"The moon!" the other snorted. "Crazy dreams! McInness tried it, and you know what happened. He came back out of control—couldn't check his speed against the repelling area—shot through and stripped his helicopters off against the heavy air. And that other fellow, Haldgren—"

"Yes," said Harkness quietly, "Haldgren—he didn't fall back. He went on into space."

mpossible!" the counsellor objected. "He must have fallen unobserved. No, no, Walter; be reasonable. I do not claim to know much about those things—I leave them to the Stratosphere Control Board—but I do know this much: that the lifting effect above the repelling area—what used to be known as the heaviside layer—counteracts gravity's pull. That's why our ships fly as they please when they have shot themselves through. But they have to fly close to it; its force is dissipated in another ten thousand feet, and the old earth's pull is still at work. It can't be done, my boy; the vast reaches of space—"

"Are the next to be conquered," Harkness broke in. "And Chet and I intend to be in on it." He glanced toward the young flyer, and they exchanged a quiet smile.

"Remember how my father was laughed at when he dared to vision the commerce of to-day? Crazy dreams, Warrington? That's what they said when Dad built the first unit of our plant, the landing stages for the big freighters, the docks for ocean ships while they lasted, the berths for the big submarines that he knew were coming. They jeered at him then. 'Harkness' Folly,' the[152] first plant was called. And now—well you know what we are doing."

He laughed softly. "Leave us our crazy dreams, Warrington," he protested; "sometimes those dreams come true.... And I'll try to forget my hunch. We've bought the property; now we'll make it earn money for us. I'll forget it now, and work on my new ship. Chet and I are about ready for a try-out."

he flyer had risen to join him, and the two turned together to the door where a private lift gave access to the roof. They were halfway to it when the first shock came to throw the two men on the floor.

The great framework of the Transportation Building was swaying wildly as they fell, and the groaning of its wrenched and straining members sounded through the echoing din as every movable object in the room came crashing down.

Dazed for the moment, Harkness lay prone, while his eyes saw the nitron illuminator, like a great chandelier, swing widely from the ceiling where it was placed. Its crushing weight started toward him, but a last swing shot it past to the desk of the counsellor.

Harkness got slowly to his feet. The flyer, too, was able to stand, though he felt tenderly of a bruised shoulder. But where Warrington had been was only the crumpled wreckage of a steeloid desk, the shattered bulk of the illuminator upon it, and, beneath, the mangled remains where flowing blood made a quick pool upon the polished floor.

Warrington was dead—no help could be rendered there—and Harkness was reaching for the door. The shock had passed, and the building was quiet, but he shouted to the flyer and sprang into the lift.

"The air is the place for us," he said; "there may be more coming." He jammed over the control lever, and the little lift moved.

"What was it?" gasped Bullard, "earthquake?—explosion? Lord, what a smash!"

Harkness made no reply. He was stepping out upon the broad surface of the Transportation Building. He paid no attention to the hurrying figures about him, nor did he hear the loud shouting of the newscasting cone that was already bringing reports of the disaster. He had thought only for the speedy little ship that he used for his daily travel.

he golden cylinder was still safe in the grip of its hold-down clutch, and its stubby wings and gleaming sextuple-bladed helicopter were intact. Harkness sprang for the control-board.

He, too, wore an emblem: a silver circle that marked him a pilot of the second class; he could take his ship around the world below the forty level, though at forty thousand and above he must give over control to the younger man.

The hiss of the releasing clutch came softly to him as the free-signal flashed, and he sank back with a great sigh of relief as the motors hummed and the blades above leaped into action. Then the stern blast roared, though its sound came faintly through the deadened walls, and he sent the little speedster for the pale blue light of an ascending area. Nor did he level off until the gauge before him said twenty thousand.

His first thought had been for their own safety in the air, but with it was a frantic desire to reach the great plant of the Harkness Terminals. What had happened there? Had there been any damage? Had they felt the shock? A few seconds in level twenty would tell him. He reached the place of alternate flashes where he could descend, and the little ship fell smoothly down.

Below him the great expanse of buildings took form, and they[153] seemed safe and intact. His intention was to land, till the slim hands of Chet Bullard thrust him roughly aside and reached for the controls.

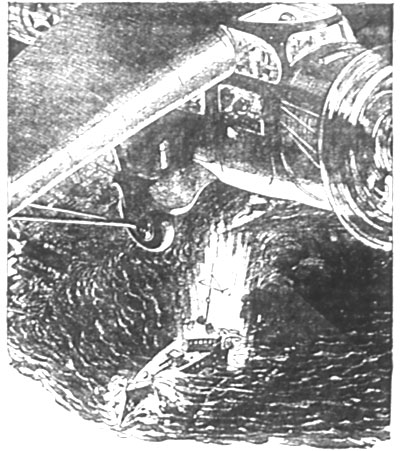

It was Bullard's right—a master pilot could take control at any time—but Harkness stared in amazement as the other lifted the ship, then swung it out over the expanse of ocean beyond—stared until his own eyes followed those of Chet Bullard to see the wall of water that was sweeping toward the land.

Chet, he knew, had held them in a free-space level, where they could maneuver as they pleased, but he knew, too, that the pilot's hands were touching levers that swung them at a quite unlawful speed past other ships, and that swept them down in a great curve above the ocean's broad expanse.

arkness did not at once grasp the meaning of the thing. There was the water, sparkling clear, and a monstrous wave that lifted itself up to mountainous heights. Behind it the ocean's blue became a sea of mud; and only when he glanced at their ground-speed detector did he sense that the watery mountain was hurling itself upon the shore with the swiftness of a great super-liner.

There were the out-thrusting capes that made a safe harbor for the commerce that came on and beneath the waters to the Harkness Terminals; the wave built itself up to still greater heights as it came between them. They were riding above it by a thousand feet, and Walter Harkness, in sudden knowledge of what this meant, stared with straining eyes at the wild thing that raced with them underneath.

He must do something—anything!—to check the monster, to flatten out the onrushing mountain! The red bottom-plates of a submarine freighter came rolling up behind the surge to show how futile was the might of man. And the next moment marked the impact of the wall of water upon a widespread area of landing roofs, where giant letters stared mockingly at him to spell the words: Harkness Terminals, New York.

He saw the silent crumbling of great buildings; he glimpsed in one wild second the whirling helicopters on giant freighters that took the air too late; he saw them vanish as the sea swept in and engulfed them. And then, after endless minutes, he knew that Chet had swung again above the site of his plant, and he saw the stumps of steel and twisted wreckage that remained....

he pilot hung the ship in air—a golden beetle, softly humming as it hovered above the desolate scene. Chet had switched on the steady buzz of the stationary-ship signal, and the wireless warning was swinging passing craft out and around their station. Within the quiet cabin a man stood to stare and stare, unspeaking, until his pilot laid a friendly hand upon the broad shoulders.

"You're cleaned," said Chet Bullard. "It's a washout! But you'll build it up again; they can't stop you—"

But the steady, appraising eyes of Walter Harkness had moved on and on to a rippling stretch of water where land had been before.

"Cleaned," he responded tonelessly; "and then some! And I could start again, but—" He paused to point to the stretch of new sea, and his lips moved that he might laugh long and harshly. "But right there is all I own—that is, the land I bought this morning. It is gone, and I owe twenty million to the hardest-hearted bunch of creditors in the world. That foreign crowd, who've been planning to invade our territory here. You know what chance I'll have with them...."[154]

The disaster was complete, and Walter Harkness was facing it—facing it with steady gray eyes and a mind that was casting a true balance of accounts. He was through, he told himself; his other holdings would be seized to pay for this waste of water that an hour before had been dry land; they would strip him of his last dollar. His lips curved into a sardonic smile.

"June twentieth, nineteen seventy-three," he repeated. "Poor old Warrington! He called this my lucky day!"

he pilot had respected the other man's need of silence, but his curiosity could not be longer restrained.

"What's back of it all?" he demanded. "What caused it? The shock was like no earthquake I've ever known. And this tidal wave—" He was reaching for a small switch. He turned a dial to the words: "News Service—General," and the instrument broke into hurried speech.

It told of earth shocks in many places—the whole world had felt it—some tremendous readjustment among the inner stresses of the earth—most serious on the Atlantic seaboard—the great Harkness Terminals destroyed—some older buildings in the business district shaken down—loss of life not yet computed....

"But what did it?" Chet Bullard was repeating in the cabin of their floating ship. "A tremendous shake-up like that!" Harkness silenced him with a quick gesture of his hand. Another voice had broken in to answer the pilot's question.

"The mystery is solved," said the new voice. "This is the Radio-News representative speaking from Calcutta. We are in communication with the Allied Observatories on Mount Everest. At eleven P. M., World Standard Time, Professor Boyle observed a dark body in transit across the moon. According to Boyle, a non-luminous and non-reflecting asteroid has crashed into the earth's gravitational field. A dark moon has joined this celestial grouping, and is now swinging in an orbit about the earth. It is this that has disturbed the balance of internal stresses within the earth—"

dark moon!" Chet Bullard broke in, but again a movement from Harkness silenced his exclamations. Whatever of dull apathy had gripped young Harkness was gone. No thought now of the devastation below them that spelled his financial ruin. Some greater, more gripping idea had now possessed him. The instrument was still speaking:

"—Without light of its own, nor does it reflect the sun's light as does our own moon. This phenomenon, as yet, is unexplained. It is nearer than our own moon and smaller, but of tremendous density." Harkness nodded his head quickly at that, and his eyes were alive with an inner enthusiasm not yet expressed in words. "It is believed that the worst is over. More minor shocks may follow, but the cause is known; the mystery is solved. Out from the velvet dark of space has come a small, new world to join us—"

The voice ceased. Walter Harkness had opened the switch.

"The mystery is solved," Chet Bullard repeated.

"Solved?" exclaimed the other from his place at the controls. "Man, it is only begun!" He depressed a lever, and a muffled roar marked their passage to a distant shaft of blue, where he turned the ship on end and shot like a giant shell for the higher air.

There was northbound travel at thirty-five, and northward Harkness would go, but he shot straight up. At forty thousand he motioned the[155] master-pilot to take over the helm.

"Clear through," he ordered; "up into the liner lanes; then north for our own shop." Nor did he satisfy the curiosity in Chet Bullard's eyes by so much as a word until some hours later when they floated down.

n icy waste was beneath them, where the sub-polar regions were wrapped in the mantle of their endless winter. Here ships never passed. Northward, toward the Pole, were liner lanes in the higher levels, but here was a deserted sector. And here Walter Harkness had elected to carry on his experiments.

A rise of land showed gaunt and black, and the pilot was guiding the ship in a long slant upon it. He landed softly beside a building in a sheltered, snow-filled valley.

Harkness shivered as he stepped from the warmth of their insulated cabin, and he fumbled with shaking fingers to touch the combination upon the locked door. It swung open, to close behind the men as they stood in the warm, brightly-lighted room.

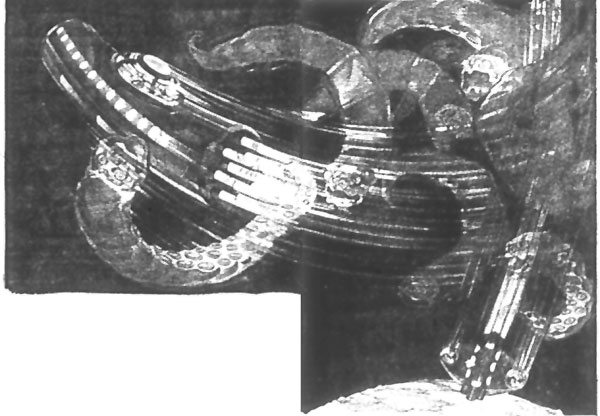

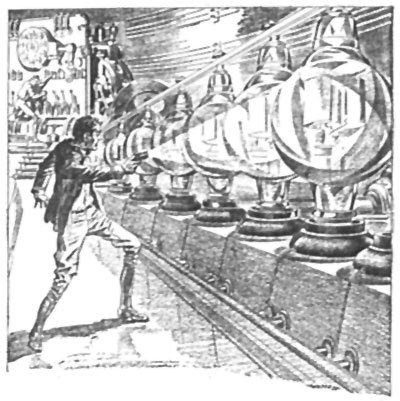

Nitro illuminators were hung from the ceiling, their diffused brilliance shining down to reflect in sparkling curves and ribbons of light from a silvery shape. It stood upon the floor, a metal cylinder a hundred feet in length, whose blunt ends showed dark openings of gaping ports. There were other open ports above and below and in regular spacing about the rounded sides. No helicopters swung their blades above; there were only the bulge of a conning tower and the heavy inset glasses of the lookouts. Nor were there wings of any kind. It might have been a projectile for some mammoth gun.

Harkness stood in silence before it, until he turned to smile at the still-wondering pilot.

"Chet," he said, "it's about finished and ready—just in time. We've built it, you and I; freighted in the parts ourselves and assembled every piece. We've even built the shop: lucky the big steeloid plates are so easily handled. And you and I are the only ones that know.

"Every ship in the airlanes of the world is driven by detonite—and we have evolved a super-detonite. We have proved that it will work. It will carry us beyond the pull of gravitation; it will give us the freedom of outer space. It is ours and ours alone."

"No," the other corrected slowly, "it is yours. You have paid the bills and you have paid me. Paid me well."

"I'm paying no more," Harkness told him. "I'm broke, right this minute. I haven't a dollar—and yet I say now that poor Warrington was right: this is my lucky day."

e laughed aloud at the bewilderment on the pilot's face.

"Chet," he said slowly, and his voice was pitched to a more serious tone, "out there is a new world, the Dark Moon. 'Tremendous density,' they said. That means it can hold an atmosphere of its own. It means new metals, new wealth. It means a new little world to explore, and it's out there waiting for us. Waiting for us; we will be the first. For here is the ship that will take us.

"It isn't mine, Chet; it's ours. And the adventure is ours; yours and mine, both. We only meant to go a few hundred miles at first, but here's something big. We may never come back—it's a long chance that we're taking—but you're in on it, if you want to go...."

He paused. The expression in the eyes of Chet Bullard, master-pilot of the world, was answer enough. But Chet amplified it with explosive words.

"Am I in on it?" he demanded. "Try to count me out—just try to do it! I was game for a trial flight out[156] beyond. And now, with a real objective to shoot at—a new world—"

His words failed him. Walt Harkness knew that the hand the other extended was thrust forth blindly; he gripped at it hard, while he turned to look at the shining ship.

But his inner gaze passed far beyond the gleaming thing of metal, off into a realm of perpetual night. Out there a new world was waiting—a Dark Moon!—and there they might find.... But his imagination failed him there; he could only thrill with the adventure that the unknown held.

wo days, while a cold sun peeped above an icy horizon! Two days of driving, eager work on the installation of massive motors—yet motors so light that one man could lift them—then Harkness prepared to leave.

"Wealth brings care when it comes," he told Chet, "but it leaves plenty of trouble behind it when it goes. I must get back to New York and throw what is left of my holdings to the wolves; they must be howling by this time to find out where I am. I'll drop back here in a week."

There were instruments to be installed, and Chet would look after that. He would test the motors where the continuous explosion of super-detonite would furnish the terrific force for their driving power. Then the exhaust from each port must be measured and thrusts equalized, where needed, by adjustment of great valves. All this Chet would finish. And then—a test flight. Harkness hoped to be back for the first try-out of the new ship.

"I'll be seeing you in a week," he repeated. "You'll be that long getting her tuned up."

But Chet Bullard grinned derisively. "Two days!" he replied. "You'll have to step some if you get in on the trial flight. But don't worry; I won't take off for the Dark Moon. I'll just go up and play around above the liner lanes and see how the old girl stunts."

Harkness nodded. "Watch for patrol ships," he warned. "There's no traffic directly over here—that's one reason why I chose this spot—but don't let anyone get too close. Our patents have not been applied for."

arkness spent a day in New York. Then a night trip by Highline Express took him to London where he busied himself for some hours. Next, a fast passenger plane for Vienna.

In other days Walter Harkness would have chartered a private ship to cut off a few precious hours, but he was traveling more economically now. And the representatives of his foreign competitors were not now coming to see him; he must go to them.

At the great terminal in Vienna a man approached him. "Herr Harkness?" he inquired, and saluted stiffly.

He was not in uniform. He was not of the Allied Patrol nor of any branch of the police force that encircled the world in its operations. Yet his military bearing was unmistakable. To Harkness it was reminiscent of old pictures of Prussian days—those curious pictures revived at times for the amusement of those who turned to their television sets for entertainment. He had to repress a smile as he followed where the other led him to a gray speedster in a distant corner of the open concourse.

He stepped within a luxurious cabin and would have gone on into the little control room, but his guide checked him. Harkness was mildly curious as to their course—Schwartzmann was to have seen him in[157] Vienna—but the way to the instrument board was barred. Another precise salute, and he was motioned to the cabin at the rear.

"It is orders that I follow," he was told. And Walter Harkness complied.

"It could happen only here," he told himself. And he found himself exasperated by a people who were slow to conform to the customs of a world whose closely-knit commerce had obliterated the narrow nationalism of the past.

hey landed in an open court surrounded by wide lawns. He glimpsed trees about them in the dusk, and looming before him was an old-time building of the chateau type set off in this private park. He would have followed his guide toward the entrance, but a flash of color checked him.

Like a streak of flame a ship shot in above them; hung poised near the one that had brought them and settled to rest beside it. A little red speedster, it made a splash of crimson against the green lawns beyond. And, "Nice flying," Harkness was telling himself.

The hold-down clamps had hardly gripped it when a figure sprang out from an opened door. A figure in cool gray that took warmth and color from the ship behind—a figure of a girl, tall and slender and graceful as she came impulsively toward him.

"Monsieur Harkness!" she exclaimed. "But this is a surprise. I thought that Herr Schwartzmann was to see you in Vienna!" For a brief moment Harkness saw a flicker of puzzled wonderment in her eyes.

"And I am sorry," she went on, "—so very sorry for your misfortune. But we will be generous."

She withdrew her hand which Harkness was holding. He was still phrasing a conventional greeting as she flung him a gay laugh and a look from brown eyes that smiled encouragement. She was gone before he found words for reply.

Walter Harkness had been brought up in a world of business, and knew little of the subtle message of a woman's eyes. But he felt within him a warm response to the friendly companionship that the glance implied.

Within the chateau, in a dark-paneled room, Herr Schwartzmann was waiting. He motioned Harkness to a chair and resumed his complacent contemplation of a picture that was flowing across a screen. Color photography gave every changing shade. It was coming by wireless, as Harkness knew, and he realized that the sending instrument must be in a ship that cruised slowly above a scene of wreckage and desolation.

He recognized the ruins of his great plant; he saw the tiny figures of men, and he knew that the salvage company he had placed in charge was on the job. Beyond was a stretch of rippling water where the great wave had boiled over miles of land and had sucked it back to the ocean's depths. And he realized that the beginning of his conference was not auspicious.

After the warmth of the girl's greeting, this other was like a plunge into the Arctic chill of his northern retreat.

have listed every dollar's worth of property that I own," he was saying an hour later, "and I have turned it over to a trustee who will protect your rights. What more do you want?"

"We have heard of some experimental work," said Herr Schwartzmann smoothly. "A new ship; some radical changes in design. We would like that also."

"Try and get it," Harkness invited.

The other passed that challenge by. "There is another alternative,"[158] he said. "My principals in France are unknown to you; perhaps, also, it is not known that they intend to extend their lines to New York and that they will erect great terminals to do the work that you have done.

"Your father was the pioneer; there is great value in the name of Harkness—the 'good-will' as you say in America. We would like to adopt that name, and carry on where you have left off. If you were to assign to us the worthless remains of your plant, and all right and title to the name of Harkness Terminals, it might be—" He paused deliberately while Harkness stiffened in his chair. "It might be that we would require no further settlement. The balance of your fortune—and your ship—will be yours."

Harkness' gray eyes, for a moment, betrayed the smouldering rage that was his.

"Put it in plain words," he demanded. "You would bribe me to sell you something you cannot create for yourselves. The name of Harkness has stood for fair-dealing, for honor, for scrupulous observance of our clients' rights. My father established it on that basis and I have continued in the same way. And you?—well, it occurs to me that the Schwartzmann interests have had a different reputation. Now you would buy my father's name to use it as a cloak for your dirty work!"

He rose abruptly. "It is not for sale. Every dollar that I own will be used to settle my debt. There will be enough—"

err Schwartzmann refused to be insulted. His voice was unruffled as he interrupted young Harkness' vehement statement.

"Perhaps you are right; perhaps not. Permit me to remind you that the value of your holdings may depreciate under certain influences that we are able to exert—also that you are in Austria, and that the laws of this country permit us to hold you imprisoned until the debt is paid. In the meantime we will find your ship and seize it, and whatever it has of value will be protected by patents in our name."

His unctuous voice became harsh. "Honor! Fair dealing!" He spat out the words in sudden hate. "You Americans who will not realize that business is business!"

Harkness was standing, drawn unconsciously to his full height. He looked down upon the other man. All anger had gone from his face; he seemed only appraising the individual before him.

"The trouble with you people," he said, "is that you are living in the past—way back about nineteen fourteen, when might made right—sometimes."

He continued to look squarely into the other's eyes, but his lips set firmly, and his voice was hard and decisive.

"But," he continued, "I am not here to educate you, nor to deal with you. Any further negotiations will be through my counsellors. And now I will trouble you to return me to the city. We are through with this."

err Schwartzmann's heavy face drew into lines of sardonic humor. "Not quite through," he said; "and you are not returning to the city." He drew a paper from his desk.

"I anticipated some such verdammpt foolishness from you. You see this? It is a contract; a release, a transfer of all your interests in Harkness, Incorporated. It needs only your signature, and that will be supplied. No one will question it when we are done: the very ink in the stylus you carry will be duplicated. For the last time, I repeat my offer; I am patient with you.[159] Sign this, and keep all else that you have. Refuse, and—"

"Yes?" Harkness inquired.

"And we will sign for you—a forgery that will never be detected. And as for you, your body will be found—a suicide! You will leave a letter: we will attend to all that. Herr Harkness will have found this misfortune unbearable.... We shall be very sad!" His heavy smile grew into derisive laughter.

"I am still patient, and kind," he added. "I give you twenty-four hours to think it over."

A touch of a button on his desk summoned the man who had brought Harkness there. "Herr Harkness is in your charge," were the instructions to the one who stood stiffly at attention. "He is not to leave this place. Is it understood?"

As he was ushered from the room, Walter Harkness also understood, and he knew that this was no idle threat. He had heard ugly rumors of Herr Schwartzmann and his methods. One man, he knew, had dared to oppose him—and that man had gone suddenly insane. A touch of a needle, it was whispered....

There had been other rumors; Schwartzmann got what he wanted; his financial backing was enormous. And now he would bring his ruthless methods to America. But there he needed the Harkness standing, the reputation for probity—and Walter Harkness was grimly resolved that they should never buy it from him. But the problem must be faced, and the answer found, if answer there was, in twenty-four hours.

n amazing state of affairs in a modern world! He stood meditating upon his situation in a great, high-ceilinged room. A bed stood in a corner, and other furniture marked the room as belonging to an earlier time. Even mechanical weather-control was wanting; one must open the windows, Harkness found, to get cooling air.

He stood at the open window and saw storm clouds blowing up swiftly. They blotted the stars from the night sky; they swept black and ominous overhead, and seemed to touch the giant trees that whipped their branches in the wind. But he was thinking not at all of the storm, and only of the fact that this room where he stood must be directly above the one where Schwartzmann was seated. Schwartzmann—who would put an end to his life as casually as he would bring down a squirrel from one of those trees!

And again he thought: "Twenty-four hours!... Why hours? Why not minutes?... Whatever must be done he must do now. And might made right: it was the only way to meet this unscrupulous foreign scoundrel."

A wind-tossed branch lashed at him. On the ground below he saw the man who had brought him, posting another as a guard. They glanced up at his window. There would be no escape there.

And yet the branch seemed beckoning. He caught it when again it whipped toward him, and, without any definite plan, he lashed it fast with a velvet cord from the window drapes.

But his thoughts came back to the room. He snatched suddenly at the covers of the bed. What were the sheets?—fabric as old-fashioned as the room, or were they cellulex? The touch of the soft fabric reassured him: it was as soft as though woven of spider's web, and strong as fibres of steel.

It took all of his strength to rip it into strips, but it was a matter of minutes, only, until he had a rope that would bear his weight. The storm had broken; the black clouds let loose a deluge of water that drove in at the window. If only the window below was still open![160]

He found the middle of his rope, looped it over a post of the bed, and, with both strands in his grasp, let himself out and over the dripping sill.

Would the guard see him, or had he taken to shelter? Harkness did not pause to look. He left the branch tied fast. "A squirrel in a tree," he thought: the branch would mislead them. His feet found the window-sill one story below. He drew himself into the room and let loose of one strand of his rope as he entered.

Schwartzmann was gone. Harkness, with the bundle of wet fabric in his hands, glanced quickly about. A door stood open—it was a closet—and the rain-drenched man was hidden there an instant later. But he stepped most carefully across the floor and touched his wet shoes only to the rugs where their print was lost. And he held himself breathlessly silent as he heard the volley of gutteral curses that marked the return of Herr Schwartzmann some minutes later.

"Imbecile!" Schwartzmann shouted above the crash of the closing window. "Dumkopff! You have let him escape.

"Give me your pistol!" Harkness glimpsed the figure of his recent guard. "Get another for yourself—find him!—shoot him down! A little lead and detonite will end this foolishness!"

From his hiding place Harkness saw the bulky figure of Schwartzmann, who made as if to follow where the other man had gone. The pistol was in his hand. Walt Harkness knew all too well what that meant. The tiny grain of detonite in the end of each leaden ball was the same terrible explosive that drove their ships: it would tear him to pieces. And he had to get this man.

He was tensed for a spring as Schwartzmann paused. From the wall beyond him a red light was flashing; a crystal flamed forth with the intense glare of a thousand fires. It checked the curses on the other's thick lips; it froze Harkness to a rigid statue in the darkness of his little room.

n emergency flash broadcast over the world! It meant that the News Service had been commandeered. This flashing signal was calling to the peoples of the earth!

What catastrophe did this herald? Had it to do with the Dark Moon? Not since the uprising of the Mole-men, those creatures who had spewed forth from the inner world, had the fiery crystal called!... It seemed to Harkness that Schwartzmann was hours in reaching the switch.... A voice came shouting into the room:

"By order of the Stratosphere Control Board," it commanded, "all traffic is forbidden above the forty level. Liners take warning. Descend at once."

Over and over it repeated the command—an order whose authority could not be disregarded. In his inner vision Harkness saw the tumult in the skies, the swift dropping of huge liners and great carriers of fast freight, the scurrying of other craft to give clearance to these monsters whose terrific speed must be slowly checked. But why? What had happened? What could warrant such disruption of the traffic of the world? His tensed muscles were aching unheeded; his sense of feeling seemed lost, so intently was he waiting for some further word.

"Emergency news report," said another voice, and Harkness strained every faculty to hear. "Highline ships attacked by unknown foe. Three passenger carriers of the Northpolar Short Line reported crashed. Incomplete warnings from their commanders indicate they were attacked. Patrol ship has spotted[161] one crash. They have landed beside it and are reporting....

"The report is in; it is almost beyond belief. They say the liner is empty, that no human body, alive or dead, is in the ship. She was stripped of crew and passengers in the air.

"We await confirmation. Danger apparently centered over arctic regions, but traffic has been ordered from all upper levels—"

The voice that had been held rigidly to the usual calm clarity of an official announcer became suddenly high-pitched and vibrant. "Stand by!" it shouted. "An S. O. S. is coming in. We will put it through our amplifiers; give it to you direct!"

he newscaster crackled and hissed: they were waiving all technical niceties at R. N. Headquarters, Harkness knew. The next voice came clearly, though a trifle faint.

"Air Patrol! Help! Position eighty-two—fourteen north, ninety-three—twenty east—Superliner Number 87-G, flying at R. A. plus seven. We are attacked!—Air Patrol!—Air Patrol!—Eighty-two—fourteen north, ninety-three—twenty—"

The voice that was repeating the position was lost in a pandemonium of cries. Then—

"Monsters!" the voice was shouting. "They have seized the ship! They are tearing at our ports—" A hissing crash ended in silence....

"Tearing at our ports!" Harkness was filled with a blinding nausea as he sensed what had come with the crash. The opening ports—the out-rush of air released to the thin atmosphere of those upper levels! Earth pressure within the cabins of the ship; then in an instant—none! Every man, every woman and child on the giant craft, had died instantly!

The announcer had resumed, but above the sound was a guttural voice that shouted hoarsely in accents of dismay. "Eighty-seven-G!" Schwartzmann was exclaiming, "—Mein Gott! It iss our own ship, the Alaskan! Our crack flyer!"

arkness heard him but an instant, for another thought was hammering at his brain. The position!—the ship's position!—it was almost above his experimental plant! And Chet was there, and the ship.... What had Chet said? He would fly it in two days—and this was the second day! Chet had no radio-news; no instrument had been installed in the shop; they had depended upon the one in Harkness' own ship. And now—

Walt Harkness' clear understanding had brought a vision that was sickening, so plainly had he glimpsed the scene of terror in that distant cabin. And now he saw with equal clarity another picture. There was Chet, smiling, unafraid, proud of their joint accomplishment and of the gleaming metal shape that he was lifting carefully from its bed. He was floating it out to the open air; he was taking off, and up—up where some horror awaited.

"Monsters!" that thin voice had cried in a tone that was vibrant with terror. What could it be?—great ships out of space?—an invasion? Or beasts?... But Harkness' vision failed him there. He knew only that a fast ship was moored just outside. He had planned vaguely to seize it; he had needed it for his own escape; but he needed it a thousand times more desperately now. Chet might have been delayed, and he must warn him.... The thoughts were flashing like hot sparks through his brain as he leaped.

e bore the heavier body of Schwartzmann to the floor. He rained smashing blows upon him with a furious frenzy that would not be curbed. The weapon with its[162] deadly detonite bullet came toward him. In the same burst of fury he tore the weapon from the hand that held it; then sprang to his feet to stand wild-eyed and panting is he aimed the pistol at the cursing man and dragged him to his feet.

"The ship!" he said between heavy breaths, "—the ship! Take me to it! You will tell anyone we meet it is all right. One word of alarm, one wrong look, and I'll blow you to hell and make a break for it!"

The pistol under Harkness' silken jacket was pressed firmly into Schwartzmann's side; it brought them safely past excited guards and out into the storm; it held steady until the men had fought their way through blasts of rain to the side of the anchored ship. Not till then did Schwartzmann speak.

"Wait," he said. "Are you crazy, Harkness? You can never take off; the trees are close; a straight ascent is needed. And the wind—!"

He struggled in the other's grasp as Harkness swung open the cabin door, his fear of what seemed a certain death overmastering his fear of the weapon. He was shouting for help as Harkness threw him roughly aside and leaped into the ship.

Outside Harkness saw running figures as he threw on the motors. A pistol's flash came sharply through the storm and dark. A window in the chateau flashed into brilliance to frame the figure of a girl. Tall and slender, she leaned forward with outstretched arms. She seemed calling to him.

arkness seized the controls, and knew as he did so that Schwartzmann was right: he could never lift the ship in straight ascent. Before her whirling fans could raise her they would be crashed among the trees.

But there were two helicopters—dual lift, one forward and one aft. And Walt Harkness, pilot of the second class, earned immediate disbarment or a much higher rating as he coolly fingered the controls. He cut the motor on the big fan at the stern, threw the forward one on full and set the blades for maximum lift, then released the hold-down grips that moored her.

The grips let go with a crashing of metal arms. The bow shot upward while a blast of wind tore at the stubby wings. The slim ship tried to stand erect. Another furious, beating wind lifted her bodily, as Harkness, clinging desperately within the narrow room, threw his full weight upon the lever that he held.

The full blast of a detonite motor, on even a small ship, is terrific, and the speedster of Herr Schwartzmann did not lack for power. Small wonder that the rules of the Board of Control prohibit the use of the stern blast under one thousand feet.

The roaring inferno from the stern must have torn the ground as if by a mammoth plow; the figures of men must have scattered like leaves in a gusty wind. The ship itself was racked and shuddering with the impact of the battering thrust, but it rose like a rocket, though canted on one wing, and the crashing branches of wind-torn trees marked its passage on a long, curving slant that bent upward into the dark. Within the control room Walter Harkness grinned happily as he drew his bruised body from the place where he had been thrown, and brought the ship to an even keel.

ice work! But there was other work ahead, and the smile of satisfaction soon passed. He held the nose up, and the wireless warning went out before as the wild climb kept on.

Forty thousand was passed; then fifty and more; a hundred thousand; and at length he was through the repelling area, that zone of mys[163]terious force, above which was a magnetic repulsion nearly neutralizing gravity. He could fly level now; every unit of force could be used for forward flight to hurl him onward faster and faster into the night.

Harkness was flying where his license was void; he was flying, too, where all aircraft were banned. But the rules of the Board of Control meant nothing to him this night. Nor did the voluble and sulphurous orders to halt that a patrol-ship flashed north. The patrol-ship was on station; she was lost far astern before she could gather speed for pursuit.

Walter Harkness had caught his position upon a small chart. It was a sphere, and he led a thin wire from the point that was Vienna to a dot that he marked on the sub-polar waste. He dropped a slender pointer upon the wire and engaged its grooved tip, and then the flying was out of his hands. The instrument before him, with its light bulbs and swift moving discs, would count their speed of passage; it would hold the ship steadily upon an unerring course and allow for drift of winds. The great-circle course was simple; the point he marked was drawing them as if it had been a magnet—drawing them as it drew the eyes of Walt Harkness, staring strainingly ahead as if to span the thousands of miles of dark.

he control room was glassed in on all sides. The thick triple lenses were free from clouding, and the glasses between them kept out the biting cold of the heights. The glass was strong, to hold the pressure of one atmosphere that was maintained within the ship. The lookouts gave free vision in all directions except directly below the hull, and a series of mirrors corrected this defect.

But Walt Harkness had eyes solely for the black void ahead. Only the brilliant stars shone now in the mantle of velvety night. No flashing lights denoted the passing of liners, for they were safe in the harbor of the lower levels. He moved the controls once to avoid the green glare of an ascending area, then he knew that there were no ships to fear, and let the automatic control put him back on his course.

Before him, under a hooded light, was a heavy lens. It showed in magnification a portion of the globe. There were countries and seas on a vari-colored map, and one pin-point of brilliance that marked his ever-changing position.

He watched the slow movement of the glowing point. The Central Federated States of Europe were behind him; the point was tracing a course over the vast reaches of the patchwork map that meant the many democracies of Russia. This cruiser of Schwartzmann's was doing five hundred miles an hour—and the watching man cursed under his breath at the slow progress of the tiny light.

But the light moved, and the slow hours passed, while Harkness tried to find consolation in surmises he told himself must be true.

Chet had been delayed, he insisted to himself; Chet could never have finished the work in two days; he had been bluffing good-naturedly when he threatened to fly the ship alone....

he Arctic Ocean was beneath. The tiny light had passed clear of the land on the moving chart.

He would be there soon.... Of course Chet had been fooling; he was always ready for a joke.... Great fellow, Chet! They had taken their training together, and Chet had gone on to win a master-pilot's[164] rating, the highest to be had....

Another hour, and a rising hum from a buzzer beside him gave warning of approach to the destination he had fixed. The automatic control was warning him to decelerate. Harkness well knew what was expected of the pilot when that humming sounded; yet, with total disregard for the safety of his helicopters, he dived at full speed for the denser air beneath.

He felt the weight that came suddenly upon him as he drove through and beneath the repelling area, and he flattened out and checked his terrific speed when the gauges quivered at forty thousand.

Then down and still down in a long, slanting dive, till a landmark was found. He was off his course a bit, but it was a matter of minutes until he circled, checked his wild flight, and sank slowly beneath the lift of the dual fans to set the ship down as softly as a snowflake beside a building that was dark and forbiddingly silent—a lonely outpost in a lonely waste.

No answer came to his hail. The building was empty; the ship was gone. And Chet! Chet Bullard!... Harkness' head was heavy on his shoulders; his feet took him with hopeless, lagging steps to his waiting ship. He was tired—and the long strain of the flight had been in vain. He was suddenly certain of disaster. And Chet—Chet was up there at some hitherto untouched height, battling with—what?

e broke into a stumbling run and drew himself within the little ship. He was helpless; the ship was unarmed, even if the weapons of his world were of use against this unknown terror; but he knew that he was going up. He would find Chet if he could get within reach of his ship; he would warn him.... He tried to tell himself that he might yet be in time.

The little cruiser rose slowly under the lift of the fans; then he opened the throttle and swept out in a parabolic curve that ended in a vertical line. Straight up, the ship roared. It shot through a stratum of clouds. The sun that was under the horizon shone redly now; it grew to a fiery ball; the earth contracted; the markings that were coastlines and mountains drew in upon themselves.

He passed the repelling area and felt the lift of its mysterious force—the "R. A. Effect" that permitted the high-level flying of the world. His speed increased. It would diminish again as the R. A. Effect grew less. Record flights had been made to another ten thousand.... He wondered what the ceiling would be for the ship beneath him. He would soon learn....

He set his broadcast call for the number of Chet's ship. They had been given an experimental license, and "E—L—29-X" the instrument was flashing, "E—L—29-X." Above the heaviside layer that had throttled the radio of earlier years, he knew that his call from so small an instrument as this would be carried for hundreds of miles.

He reached the limit of his climb and was suddenly weightless, floating aimlessly within the little room; the ship was falling, and he was falling with it. His speed of descent built up to appalling figures until his helicopters found air to take their thrust.

And still no answering word from Chet. The cruiser was climbing again to the heights. The hands of Harkness, trembling slightly now, held her to a vertical climb, while his eyes crept back to the unlit plate where Chet's answering call should flash. But his own call would be a guide to Chet; the directional finders on the new ship would trace the position of his own craft if the new ship were afloat—if it were not ly[165]ing crushed on the ice below, empty, like the liners, of any sign of life.

is despairing mind snapped sharply to attention. His startled jerk threw the ship widely from her course. A voice was speaking—Chet's voice! It was shouting in the little room!

"Go down, Walt," it told him. "For God's sake, go down! I'm right above you; I've been fighting them for an hour; but I'll make it!"

He heard the clash of levers thrown sharply over in that distant ship; his own hands were frozen to the controls. His ship roared on in its upward course, the futile "E—L—29-X" of his broadcast call still going out to a man who could not remove his hands to send an answer, but who had managed to switch on his sending set into which he could shout.

Harkness was staring into the black void whence the wireless voice had come—staring into the empty night. And then he saw them.

The thin air was crystal clear; his gaze penetrated for miles. And far up in the heights, where his own ship could never reach and where no clouds could be, were diaphanous wraiths. Like streamers of cloud in long serpentine forms, they writhed and shot through space with lightning speed. They grew luminous as they moved living streamers of moonlit clouds.... A whirling cluster was gathered into a falling mass. Out of it in a sharp right turn shot a projectile, tiny and glistening against the velvet black. The swarm closed in again.... There were other lashing shapes that came diving down. They were coming toward him.

And, in his ears, a voice was imploring: "Down! down! The R. A. tension may stop them!... Go down! I am coming—you can't help—I'll make it—they'll rip you to pieces—"

The wraith-like coils that had left the mass above had straightened to sharp spear-heads of speed. They were darting upon him, swelling to monstrous size in their descent. And Walt Harkness saw in an instant the folly of delay: he was not helping Chet, but only hindering.... His ship swung end for end under his clutching hands, and the thrust of his stern exhaust was added to the pull of Earth to throw him into a downward flight that tore even the thin air into screaming fragments.

ne glance through the lookouts behind him showed lashing serpent forms, translucent as pale fire; impossible beasts from space. His reason rejected them while his eyes told him the terrible truth. Despite the speed of his dive, they were gaining on him, coming up fast; one snout that ended in a cupped depression was plain. A mouth gaped beneath it; above was a row of discs that were eyes—eyes that shone more brightly than the luminous body behind—eyes that froze the mind and muscles of the watching man in utter terror.

He forced himself to look ahead, away from the spectral shapes that pursued. They were close, yet he thrilled with the realization that he had helped Chet in some small degree: he had drawn off this group of attackers.

He felt the upthrust of the R. A. Effect; he felt, too, the pull of a body that had coiled about his ship. No intangible, vaporous thing, this. The glass of his control room was obscured by a clinging, glowing mass while still the little cruiser tore on.

Before his eyes the glowing windows went dark, and he felt the clutching thing stripped from the hull as the ship shot through the invisible area of repulsion. A scant hundred yards away a huge cylinder drove crashingly past. Its metal[166] shone and glittered in the sun; he knew it for his own ship—his and Chet's. And what was within it? What of Chet? The loudspeaker was silent.

He eased the thundering craft that bore him into a slow-forming curve that did not end for fourscore miles before the wild flight was checked. He swung it back, to guide the ship with shaking hands where a range of mountains rose in icy blackness, and where a gleaming cylinder rested upon a bank of snow whose white expanse showed a figure that came staggering to meet him.

ome experiences and dangers that come to men must be talked over at once; thrills and excitement and narrow escapes must be told and compared. And then, at rare times, there are other happenings that strike too deeply for speech—terrors that rouse emotions beyond mere words.

It was so with Harkness and Chet. A gripping of hands; a perfunctory, "Good work, old man!"—and that was all. They housed the two ships, closing the great doors to keep out the arctic cold; and then Chet Bullard threw himself exhausted upon a cot, while he stared, still wordless, at the high roof overhead. But his hands that gripped and strained at whatever they touched told of the reaction to his wild flight.

Harkness was examining their ship, where shreds of filmy, fibrous material still clung, when Chet spoke.

"You knew they were there?" he asked, "—and you came up to warn me?"

"Sure," Harkness answered simply.

"Thanks," Chet told him with equal brevity.

Another silence. Then: "All right, tell me! What's the story?"

And Walt Harkness told him in brief sentences of the world-wide warning that had flashed, of the liners crashing to earth and their cabins empty of human life.

"They could do it," said Chet. "They could open the ports and ram those snaky heads inside to feed." He seemed to muse for a moment upon what might have come to him.

"My speed saved me," he told Harkness. "Man, how that ship can travel! I shook them off a hundred times—outmaneuvered them when I could—but they came right back for more.

"How do they propel themselves?" he demanded.

"No one knows," Harkness told him. "That luminosity in action means something—some conversion of energy, electrical, perhaps, to carry them on lines of force of which we know nothing as yet. That's a guess—but they do it. You and I can swear to that."

Chet was pondering deeply. "High-level lanes are closed," he said, "and we are blockaded like the rest of the world. It looks as if our space flights were off. And the Dark Moon trip! We could have made it, too."

f there was a questioning note in those last remarks it was answered promptly.

"No!" said Harkness with explosive emphasis. "They won't stop me." He struck one clenched fist upon the gleaming hull beside him.

"This is all I've got. And I won't have this if that gang of Schwartzmann's gets its hands upon it. The best I could expect would be a long-drawn fight in the courts, and I can't afford it. I am going up. We've got something good here; we know it's good. And we'll prove it to the world by reaching the Dark Moon."

Another filmy, fibrous mass that had been torn from one of the monsters of the heights slid from above to make a splotch of colorless matter upon the floor.[167]

Harkness stared at it. The firm line of his lips set more firmly still, but his eyes had another expression as he glanced at Chet. He would go alone if he must; no barricade of unearthly beasts could hold him from the great adventure. But Chet?—he must not lead Chet to his death.

"Of course," he said slowly, "you've had one run-in with the brutes." Again he paused. "We don't know where they come from, but my guess is from the Dark Moon. They may be too much for us.... If you don't feel like tackling them again—"

The figure of Chet Bullard sprang upright from the cot. His harsh voice told of the strain he had endured and his reaction from it.

"What are you trying to tell me?" he demanded. "Are you trying to leave me out?" Then at the look in the other's eyes he grinned sheepishly at his own outburst.

And Walter Harkness threw one arm across Chet's shoulder as he said; "I hoped you would feel that way about it. Now let's make some plans."

Provisions for one year! Even in concentrated form this made a prodigious supply. And, arms—pistols and rifles, with cases of cartridges whose every bullet was tipped with the deadly detonite—all this was brought from the nearest accessible points. They landed, though, in various cities, keeping Schwartzmann's ship as inconspicuous as possible, and made their purchases at different supply houses to avoid too-pointed questioning. For Harkness found that he and Bullard were marked men.

The newscaster in the Schwartzmann cabin brought the information. It brought, too, continued reports of the menace in the upper air. It told of patrol-ships sent down to destruction with no trace of commander or crew; and a cruiser of the International Peace Enforcement Service came back with a story of horror and helplessness.

Their armament was useless. No shells could be timed to match the swift flight of the incredible monsters, and impact charges failed to explode on contact; the filmy, fibrous masses offered little resistance to the shells that pierced them. Yet a wrecked after compartment and smashed port-lights and doors gave evidence of the strength of the brutes when their great sinuous bodies, lined with rows of suction discs, secured a hold.

"Speed!" was Chet Bullard's answer to this, when the newscaster ceased. "Speed!—until we find something better. I got clear of them when they caught me unprepared, but we can rip right through them now that we know what we're up against."

e had turned again to the packing of supplies, but Harkness was held by the sound of his own name.

Mr. Walter Harkness, late of New York, was very much in the day's news. When a young millionaire loses all his wealth beneath a tidal wave; when, further, he flies to Vienna and transfers all rights in the great firm of Harkness, Incorporated, to the Schwartzmann interests in part settlement of his obligations; and, still further, when he is driven to fury by his losses and attacks the great Herr Schwartzmann in a murderous frenzy, wounds him and escapes in Schwartzmann's own ship—that is an item that is worth broadcasting between announcements of greater importance.

It interested Harkness, beyond a doubt. He remembered the shot outside the cabin as he took off in his wild flight. Schwartzmann had been wounded, it seemed, and he was to be blamed for the assault. He smiled[168] grimly as he heard the warrant for his arrest broadcast. Every patrol-ship would be on the watch. And there would be a dozen witnesses to swear to the truth of Schwartzmann's lie.

The plan seemed plain to him. He saw himself in custody; taken to Vienna. And then, at the best, months of waiting in the psychopathic ward of a great institution where the influence of Herr Schwartzmann would not be slight. And, meanwhile, Schwartzmann would have his ship. Clever! But not clever enough. He would fool them, he and Chet.

And then he recalled the girl, Mademoiselle Diane, a slim figure outlined in a lighted window of the old chateau. Was there hope there? he wondered. Had her clear, smiling eyes seen what occurred?

"Nonsense," he told himself. "She saw nothing in that storm. And, besides, she is one of their crowd—tarred with the same stick. Forget her."

But he knew, as he framed the unspoken words, that the advice was vain. He would never forget her. There was a picture in his mind that could not be blotted out—a picture of a tall, slender girl, trim and straight in her mannish attire, who came toward him from her little red speedster. She held out her hand impulsively, and her eyes were smiling as she said; "We will be generous, Monsieur Harkness—"

"Generous!" His smile was bitter as he turned to help Chet in their final work.

ow often are the great things of life submerged beneath the trivial. The vast reaches of space that must be traversed; the unknown world that awaited them out there; its lands and seas and the life that was upon it: Walter Harkness was pondering all this deep within his mind. It must have been the same with Chet, yet few words of speculation were exchanged. Instead, the storage of supplies, a checking and rechecking of lists, additional careful testing of generators—such details absorbed them.

And the heavy, gray powder with its admixture of radium that transformed it to super-detonite—this must be carefully charged into the magazines of the generators. A thousand such responsibilities—and yet the moment finally came when all was done.

The midnight sun shone redly from a distant horizon. It cast strange lights across the icy waste. And it flashed back in crimson splendor from the gleaming hull that floated from the hangar and came to rest upon the snowy world.

The two men closed the great doors, and it was as if they were shutting themselves off from their last contact with the world. They stood for long moments, silent, in the utter silence of the frozen north.

Chet Bullard turned, and Harkness gripped his hand. He was suddenly aware of his thankfulness for the companionship of this tall, blond youngster. He tried to speak—but what words could express the tumult of emotions that arose within him? His throat was tight....

It was Chet who broke the tense silence; his happy grin flashed like sunshine across his lean face.

"You're right," he answered his companion's unspoken thoughts; "it's a great little old world we're leaving. I wonder what the new one will be like."

And Harkness smiled back. "Let's go!" he said, and turned toward the waiting ship.

he control room was lined with the instruments they had installed. A nitron illuminator flashed[169] brilliantly upon shining levers—emergency controls that they hoped they would not have to use. Harkness placed his hand upon a small metal ball as Chet reported all ports closed.

The ball hung free in space, supported by the magnetic attraction of the curved bars that made a cage about it. An adaptation of the electrol device that had appeared on the most modern ships, Harkness knew how to handle it. Each movement of the ball within its cage, where magnetic fields crossed and recrossed, would bring instant response. To lift the ball would be to lift the ship; a forward pressure would throw their stern exhaust into roaring life that would hurl them forward; a circular motion would roll them over and over. It was as if he held the ship itself within his hand.

Chet touched a button, and a white light flashed to confirm his report that all was clear. Harkness gently raised the metal ball.

Beneath them a soft thunder echoed from the field of snow, and came back faintly from icy peaks. The snow and ice fell softly away as they rose.

A forward pressure upon the ball, and a louder roaring answered from the stern. A needle quivered and swung over on a dial as their speed increased. Beneath them was a blur of whirling white; ahead was an upthrust mountain range upon which they were driving. And Harkness thrilled with the sense of power that his fingers held as he gently raised the ball and nosed the ship upward in meteor-flight.

The floor beneath them swung with their change of pace. Without it, they would have been thrown against the wall at their backs. The clouds that had been above them lay dead ahead; the ship was pointing straight upward. It flashed silently into the banks of gray, through them, and out into clear air above. And always the quivering needle crept up to new marks of speed, while their altimeter marked off the passing levels.

hey were through the repelling area when Harkness relinquished the controls to Chet. The metal ball hung unmoving; it would hold automatically to the direction and speed that had been established. The hand of the master-pilot found it quickly. They were in dangerous territory now—a vast void under a ceiling of black, star-specked space. No writhing, darting wraith-forms caught the rays of the distant sun. Their way seemed clear.

Harkness' eyes were straining ahead, searching for serpent forms, when the small cone beside him hummed a warning that they were not alone. Another ship in this zone of danger?—it seemed incredible. But more incredible was the scream that rang shrilly from the cone. "Help! Oh, help me!" a feminine voice implored.

Harkness sprang for the instrument where the voice was calling. "We aren't the only fools up here," he exclaimed; "and that's a woman's voice, too!" He pressed a button, and a needle swung instantly to point the direction whence the radio waves were coming.

"Hard a-port!" he ordered. "Ten degrees, and hold her level. No—two points down."

But Chet's steady hand had anticipated the order. He had seen the direction-finder, and he swung the metal ball with a single motion that swept them in a curve that seemed crushing them to the floor.

The ship levelled off; the ball was thrust forward, and the thunder from the stern was deafening despite their insulated walls. The shuddering structure beneath them was hurled forward till the needle of the speed-indicator jammed tight[170]ly against its farthest pin. And ahead of them was no emptiness of space.

he air was alive with darting forms. Harkness saw them plainly now—great trailing streamers of speed that shot downward from the heights. The sun caught them in their flight to make iridescent rainbow hues that would have been beautiful but for the hideous heads, the sucker-discs that lined the bodies and the one great disc that cupped on the end of each thrusting snout.

And beneath those that fell from on high was a cluster of the same sinister, writhing shapes which clung to a speeding ship that rolled and swung vainly in an effort to shake them off.

The coiling, slashing serpent-forms had fastened to the doomed ship. Their thrashing bodies streamed out behind it. They made a cluster of flashing color whose center point was a tiny airship, a speedster, a gay little craft. And her sides shone red as blood—red as they had shone on the grassy lawn of an old chateau near far-off Vienna.

"It's Diane!" Harkness was shouting. "Good Lord, Chet, it's Diane!"

This girl he had told himself he would forget. She was there in that ship, her hands were wrenching at the controls in a fight that was hopeless. He saw her so plainly—a pitiful, helpless figure, fighting vainly against this nightmare attack.

Only an instant of blurred wonderment at her presence up there—then a frenzy possessed him. He must save her! He leaped to the side of the crouching pilot, but his outstretched hands that clutched at the control stopped motionless in air.

het Bullard, master-pilot of the first rank, upon whose chest was the triple star that gave him authority to command all the air-levels of earth, was tense and crouching. His eyes were sighting along an instrument of his own devising as if he were aiming some super-gun of a great air cruiser.

But he was riding the projectile itself and guiding it as he rode. He threw the ship like a giant shell in a screaming, sweeping arc upon the red craft that drove across their bow.

They were crashing upon it; the red speedster swelled instantly before their eyes. Harkness winced involuntarily from the crash that never came.

Chet must have missed it by inches, Harkness knew; but he knew, too, that the impact he felt was no shattering of metal upon metal. The heavy windows of the control room went black with the masses of fibrous flesh that crashed upon them; then cleared in an instant as the ship swept through.

Behind them a red ship was falling—falling free! And vaporous masses, ripped to ribbons, were falling, too, while other wraith-like forms closed upon them in cannibalistic feasting.

Their terrific speed swept them on into space. When the pilot could check it, and turn, they found that the red ship was gone.

"After it!" Harkness was shouting. "She went down out of control, but they didn't get her. They've only sprung the door-ports a crack, releasing the internal pressure." He told himself this was true; he would not admit for an instant the possible truth of the vision that flashed through his mind—a ripping of doors—a thrusting snout that writhed in where a girl stood fighting.

"Get it!" he ordered; "get it! I'll stand by for rescue."

e sprang for the switch that controlled the great rescue magnets. Not often were they used,[171] but every ship must have them: it was so ordered by the Board of Control. And every ship had an inset of iron in its non-magnetic hull.

His hand was upon the switch in an agony of waiting. Outside were other beastly shapes, like no horror of earth, that came slantingly upon them, but even their speed was unequal to the chase of this new craft that left them far astern. Harkness saw the last ones vanish as Chet drove down through the repelling area. And he had eyes only for the first sight of the tiny ship that had fallen so helplessly.

Ahead and below them the sun marked a brilliant red dot. It was falling with terrific speed, and yet, so swift was their own pace, it took form too quickly: they would overshoot the mark.... Harkness felt the ship shudder in slackening speed as the blast from the bow roared out.

They were turning; aiming down. The red shape passed from view where Harkness stood. His hand was tight upon the heavy switch.

Chet's voice came sharp and clear: "Rescue switch—ready?" He appeared as cool and steady as if he were commanding on an experimental test instead of making his first rescue in the air. And Harkness answered: "Ready."

A pause. To the waiting man it was an eternity of suspense. Then, "Contact!" Chet shouted, and Harkness' tense muscles threw the current into crashing life.

e felt the smash and jar as the two ships came together. He knew that the great magnets in their lower hull had gripped the plates on the top of the other ship. He was certain that the light fans of the smaller craft must have been crushed; but they had the little red speedster in an unshakable grip; and they would land it gently. And then—then he would know!

The dreadful visions in his mind would not down.... Chet's voice broke in upon him.

"I can't maintain altitude," Chet was saying. "Our vertical blasts strike upon the other ship; they are almost neutralized." He pointed to a needle that was moving with slow certainty and deadly persistence across a graduated dial. It was their low-level altimeter, marking their fall. Harkness stared at it in stunned understanding.

"We can't hold on," the pilot was saying; "We'll crash sure as fate. But I'm darned if we'll ever let go!"

Harkness made no reply. He had dashed for an after-compartment to their storage place of tools, and returned with a blow-torch in his hand. He lit it and checked its blue flame to a needle of fire.

"Listen, Chet," he said, and the note of command in his voice told who was in charge, at the final analysis, in this emergency. "I will be down below. You call out when we are down to twenty thousand: I can stand the thin air there. I will open the emergency slot in the lower hull."

"You're going down?" Chet asked. He glanced at the torch and nodded his understanding. "Going to cut your way through and—"

"I'll get her if she's there to get," Harkness told him grimly. "At five hundred, if I'm not back, pull the switch."

he pilot's reply came with equal emphasis. "Make it snappy," he said: "this collision instrument has picked up the signals of five patrol-ships a hundred miles to the south."

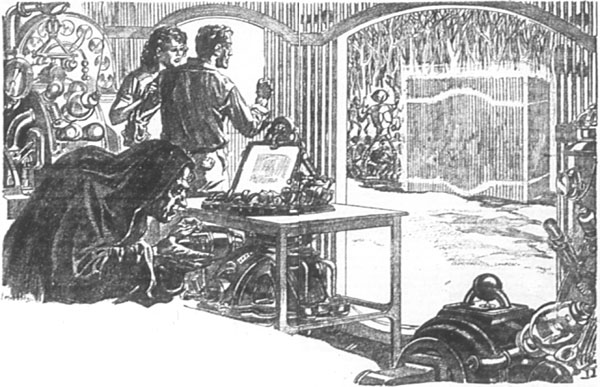

They dropped swiftly to the twenty level, and Harkness heard the deafening roar of their lower exhausts as he opened the slot in their ship's hull. He dropped to the red surface held close beneath, while the cold gripped him and the whirling blasts of air tore at him. But the[172] torch did its work, and he lowered himself into the cabin of the little craft that had been the plaything of Mademoiselle Diane.

The cabin was a splintered wreck, where a horrible head had smashed in search of food. One entrance port was torn open, and the head itself still hung where it had lodged. The mouth gaped flabbily open; above it was the suction cup that formed a snout; and above that, a row of staring, sightless eyes. Chet had slammed into the mass of serpents just in time, Harkness realized. Just in time, or just too late....

The door to the control room was sprung and jammed. He pried it open to see the unconscious body that lay huddled upon the floor. But he knew, with a wave of thankfulness that was suffocating, that the brute had not reached her; only the slow release of the air-pressure had rendered her unconscious. He was beside her in an instant.