"PEASANT GIRLS BRINGING THE MILK."

"PEASANT GIRLS BRINGING THE MILK."

Title: St. Nicholas Magazine for Boys and Girls, Vol. 5, No 10, August 1878

Author: Various

Editor: Mary Mapes Dodge

Release date: September 14, 2009 [eBook #29983]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Vol. V. | AUGUST, 1878. | No. 10. |

|---|

[Copyright, 1878, by Scribner & Co.]

(A Story of the Paris Exhibition of 1867.)

By J. T. Trowbridge.

"PEASANT GIRLS BRINGING THE MILK."

"PEASANT GIRLS BRINGING THE MILK."

"SO THEY MADE A GRAND PARADE."

"SO THEY MADE A GRAND PARADE."

"ENCIRCLED ALL DAY BY A WONDERING THRONG."

"ENCIRCLED ALL DAY BY A WONDERING THRONG."

"FIRST, ONE RAT."

"FIRST, ONE RAT."

"DOWN TUMBLES, DOWN CRUMBLES, THE KING OF THE

CHEESES."

"DOWN TUMBLES, DOWN CRUMBLES, THE KING OF THE

CHEESES."

By Sarah Winter Kellogg.

Not birch-rods; fishing-rods. They were going fishing, these five young people, of whom I shall treat "under four heads," as the ministers say,—1, names; 2, ages; 3, appearance; 4, their connection.

1. Their names were John and Elsie Singletree, Puss Leek, Luke Lord, and Jacob Isaac; the last had no surname.

2. John was fifteen and a few months past; Elsie was thirteen and many months past; Puss Leek was fourteen to a day; Luke Lord crowded John so closely, there was small room for superior age to claim precedence, or for the shelter which inferior age makes on certain occasions; Jacob Isaac was "thutteen, gwyne on fou'teen."

3. John Singletree was a dark-eyed, sharp-eyed, wiry, briery boy. Elsie, of the same name, was much like him, being a dark-eyed, sharp-eyed, wiry, briery girl. Her father used to call her Sweet-brier and Sweet-pickle, because, he said, she was sweet but sharp. Puss Leek had long, heavy, blonde hair, that hung almost to her knees when it was free, which it seldom was, for Puss braided it every morning, the first thing,—not loosely, to give it a fat look, hinting of its luxuriance, but just as hard as she could, quite to Elsie's annoyance, who used to say, resentfully, "You're so afraid that somebody'll think that you are vain of your hair." Puss's ears were over large for perfect beauty, and her eyes a trifle too deeply set; but I've half a mind to say that she was a beauty, in spite of these, for, after all, the ears had a generous look, in har[Pg 646]mony with the frank, open face, and the shadowed eye was the softest, sweetest blue eye I ever saw. She had been called Puss when a baby, because of her nestling, kitten-like way, and the odd name clung to her. Luke Lord was homely; but he didn't care a bit. He was so jolly and good-natured that everybody liked him, and he liked everybody, and so was happy. He had light hair, very light for fifteen years, and a peculiar teetering gait, which was not unmanly, however. It made people laugh at him, but he didn't care a bit. Jacob Isaac was a "cullud pusson," as he would have said, protesting against the word "negro." "Nigger," he used to say, "is de mos' untolerbulis word neber did year." It was the word he applied to whatever moved his anger or contempt. It was his descriptive epithet for the old hen that flew at him for abducting her traipsing chicken; for the spotted pig that led him that hour's chase; for the goat that butted, and the cow that hooked; and for gray Selim when he stood on his hind legs and let Jacob Isaac over the sleek haunches.

But to return to No. 4. John and Elsie Singletree were brother and sister. Puss Leek was Elsie's boarding-school friend, and her guest. Luke Lord was a neighboring boy invited to join the fishing-party, to honor Puss Leek's birthday, and to help John protect the girls. Jacob Isaac was hired to "g'long" as general waiter, to do things that none of the others wanted to do—to do the drudgery while they did the frolicking.

They were all on horseback,—John riding beside Puss Leek, protecting her; Luke riding beside Elsie, and protecting her; Jacob Isaac riding beside his shadow, and protecting the lunch-basket, carried on the pommel of his saddle.

"I keep thinking about the 'snack,'" said Puss Leek's protector, before they had made a mile of their journey.

"What do you think about it?" asked the protected.

"I keep thinking how good it'll taste. Aunt Calline makes mighty good pound-cake. I do love pound-cake!"

"Like it, you mean, John," said his sister Elsie, looking back over her shoulder.

"I don't mean like," said John. "If there is anything I love better than father and mother, brother and sister, it's pound-cake."

"But there isn't anything," said Puss.

"My kingdom for a slice!" said John, with a tragic air. "I don't believe I can stand it to wait till lunch-time."

"Why, it hasn't been a half-hour since you ate breakfast. Are you hungry?" Elsie said.

"No, I'm not hungry; I'm ha'nted." John pronounced the word with a flatness unwritable. "The pound-cake ha'nts me; the fried chicken ha'nts me; the citron ha'nts me. I see 'em!" John glared at the vacant air as though he saw an apparition. "I taste 'em! I smell 'em! I feel moved to call on him" (here Jacob Isaac was indicated by a backward glance and movement) "to yield the wittles or his life. Look here!" he added, suddenly reining-up his horse and speaking in dead earnest, "let's eat the snack now. Halt!" he cried to the advance couple, "we're going to eat."

"Going to eat?" cried Elsie. "You're not in earnest?"

"Yes, I am. I can't rest. The cake and things ha'nt me."

"Well, do for pity's sake eat something, and get done with it," Elsie said.

"But you must wait for me," John persisted. "I'll have to spread the things out on the grass. I keep thinking how good they'll taste eaten off the grass. There's where the ha'ntin' comes in."

"Did you ever hear anything so ridiculous?" said Elsie to the others. "But I suppose we had better humor him; he wont give us any rest till we do; he's so persistent. When he gets headed one way, he's like a pig." Elsie began to pull at the bridle to bring her horse alongside a stump. "Puss and I can get some flowers during the repast."

"I call this a most peculiar proceeding," said her protector, leaping from his horse, and hastening to help her to "'light."

Jacob Isaac gladly relinquished the lunch-basket, which had begun to make his arm ache, and soon John had the "ha'nting things" spread. Then he sat down Turk-like to eating; the others stood around, amused spectators, while chicken, beaten biscuits, strawberry tart, pound-cake disappeared as though they enjoyed being eaten.

"I believe I'm getting 'ha'nted,' too," said Luke Lord, whose mouth began to water,—the things seemed to taste so good to John.

"Good for you!" John said, cordially. "Come along! Help yourself to a chicken-wing."

"Why, Luke, you aint going to eating!" Elsie said.

"Yes, I am; John's made me hungry."

"Me, too," said Jacob Isaac.

"Of course, you're hungry," said John. "Come along! Hold your two hands."

"Let's go look for sweet-Williams and blue-flags," Puss proposed to Elsie.

"No; if we go away, the boys will eat everything up. Just look at them! Did ever you see such eatists? You boys, stop eating all the lunch."

"Aint you girls getting 'ha'nted?'" Luke asked. "If you don't come soon, there wont be left for you."

"I believe that's so," said Puss confidentially to Elsie. "I reckon we'll have to take our share now, or not at all. We've got to eat in self-defense."

And so it came about that those five ridiculous children sat there, less than a mile on their journey, and less than an hour from their breakfast, and ate, ate, ate, till there was nothing of their lunch left except a half biscuit and a chicken neck. John, fertile in invention, proposed that they should go back home and get something more for dinner; but Puss said everybody would laugh at them, and Elsie thought they wouldn't be able to eat anything more that day, and, if they should be hungry, they could have a fish-fry.

"Aint no use totin' this yere basekit 'long no mawr," Jacob Isaac suggested. "I'll leave it hang in this yere sass'fras saplin'." When it was intimated that it would be needed for the remainder of the lunch, he said there wasn't any "'mainder." "What's lef' needn't pester you-all; I'll jis eat it."

Arrived at the water, the boys baited the hooks, at which the girls gave little shrieks, and hid their eyes, demanding to know of the boys how they would like to be treated as they were treating the worms.

"The poor creatures!" said Puss.

"So helpless!" added Elsie, peeping through her fingers at the boys. "Aren't the hooks ready yet?"

"Yours is," and Luke delivered a rod into her hands.

"And here's yours, Puss," John said. "Drop it in."

Soon there were five rods extended over the water, and five corks were floating which might have told of robbed molasses-jugs and vinegar-jugs, and five young people were laughing, and talking nonsense by the—— How is nonsense estimated? Everybody kept asking everybody else if he had had a bite, and everybody was guilty of giving false alarms. As for Elsie, she shrieked out, "A bite!" at every provocation,—whenever the current bore unusually against her line, when the floating hook dragged bottom or encountered a twig.

"Jupiter!" said John, growing impatient at the idle drifting of his cork. "I can't stand this, Elsie. You girls stop talking. You chatter like magpies; you scare the fish. Girls oughtn't ever to go fishing."

Jacob Isaac snickered, and remarked sotto voce: "He talks hisse'f maw 'n the res' of the ladies."

Elsie did not heed John's attack. Her eye was riveted on her bobbing cork; her cheeks were glowing with excitement; her heart was beating wildly. There was a pulling at her line.[Pg 647]

"Keep quiet!" she called. "I've got a bite."

"You would have, if I could get at your arm," said John, who didn't believe she had a bite.

"I have, truly," she said, excitedly. "Look!"

All came tramping, crowding about her.

"I feel him pull," she said, eagerly.

"Well, get him out," said Luke.

"Shall I pull him or jerk him?" Elsie was nearly breathless.

"If I knew about his size, I could tell you," said Luke. "If he's big, give him a dignified pull; if he's a little chap, jerk him; no business to be little."

"Oh! I'm afraid it will hurt him," said Puss.

"Out with him!" said Luke.

"I'm afraid the line will break," said Elsie, all in a quiver.

"No, it wont," said John.

"The rod might snap," said Elsie.

"Here, let me take the rod," John proposed.

"No, no; I'm going to catch the fish myself," Elsie said, in vehement protest.

"Then jerk, sharp and strong," her brother said.

Elsie made ready; steadied her eager brain; planted her feet firmly; braced her muscles by her will; and then, with a shriek, threw up her rod, "as high as the sky," Puss said. There was a fleeting vision of a dripping white-bellied fish going skyward; and then a faint thud was heard.

"She's thrown it a half-mile, or less, in the bushes," said Luke.

"And there's her hook in the top of that tree," said John. "What gumps girls are when you take them out-of-doors!"

All went into the bushes to look for the astonished fish. They looked, and looked, and looked; listened for its beating and flopping against the ground.

After a while, Luke said he thought it must be one of the climbing fish described by Agassiz, and that it had gone up a tree.

"I mos' found it twice't; but it was a frog an' a lizar', 'stead uv the fish," said Jacob Isaac.

To this day, it remains a mystery where Elsie's fish went to.

Jacob Isaac climbed the tree to rescue Elsie's hook and line, while the other boys went down the stream to find a cat-fish hole that they had heard of.

"Don't pull at the line that way," Puss said to the thrasher in the tree-top; "you'll break it. There, the hook is caught on that twig. You must go out on the limb and unhitch it."

"Lim' hangs over the watto," Jacob Isaac said; but he crawled out on it, and reached for the hook.

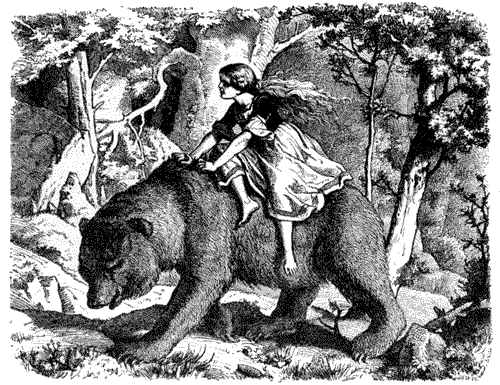

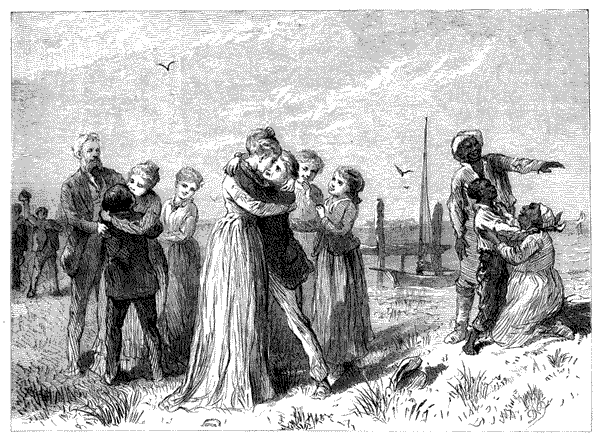

Then Elsie shrieked, for crashing through the branches came Jacob Isaac, and splashed back-foremost into the water. Then there was con[Pg 648]fusion. Jacob called to the girls to help him; they called to the boys to help; the boys, ignorant of the accident, shouted back that they were going on to where they could have quiet, and went tramping away. Then Elsie tried to tell Jacob Isaac how to swim, while Puss Leek darted off to where the horses were tethered. She mounted the one she had ridden—a gentle thing, aged eighteen. Then she came crashing through the bushes and brush, clucking and jerking the bridle, dashed down the bank, and plunged into the stream.

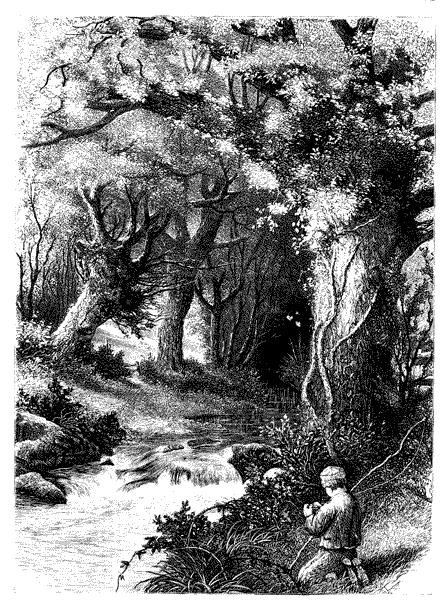

"HE KNELT ON THE BANK TO FIX HIS BAIT."

"HE KNELT ON THE BANK TO FIX HIS BAIT."

Elsie held her breath at the sight. The water rose to the flanks, but Puss kept her head steady, sat her saddle coolly, and, when Jacob Isaac appeared, put out a resolute hand, and got hold of his jacket,—speaking, meanwhile, a soothing word to the horse, which was now drinking. She got the boy's head above water.

"I'll hold on to you; and you must hold on to the stirrup and to the horse's mane," she said.

Jacob Isaac, without a word, got hold as directed. Puss held on with a good grip, as she had promised, and the careful old horse pawed through the water to the bank—only a few yards distant, by the way.

"Thankee, Miss Puss," is what Jacob Isaac said, as he stretched himself on a log to dry.

"Puss, you're a hero," is what Elsie said, adding immediately: "Those hateful boys! Great protectors they are!"

John had found up-stream a deep hole in the shade of some large trees. Just above it the creek tumbled and foamed over a rocky bed. John said to Luke: "It just empties the fish in here by the basketfuls. All we've got to do is to empty 'em out,"—and he knelt on the bank to fix his bait.

But Luke was not satisfied. "You'll never catch any fish there," said he. "The current's too swift." And off went he, to look for a likelier place.

Yet neither of the boys had better luck than when with the girls, and both soon went back to them. When Elsie's vivid account of the rescue had been given, the boys stared at Puss with a new interest, as though she had undergone some transformation in their brief absence.

Then somebody suggested that they must hurry up and catch something for dinner. So all five dropped hooks into the water, everybody pledged to silence, Fishing was now business; it meant dinner or no dinner.

For some moments, the fishers sat or stood in statuesque silence, eyes on the corks. Then Jacob Isaac showed signs of excitement.

"I's got a fish, show's yer bawn," he called, dancing about on the bank.

"Let me see it," John challenged.[Pg 649]

"Aint pulled it out yit," said Jacob Isaac, jumping and capering.

"What's the matter with you? What are you cavorting about in that style for?" John asked.

"Playin' 'im!" answered Jacob Isaac, running backward and forward, and every other way.

"Is that the way they play a fish?" Elsie said, gazing. "I never knew before how they did it."

She went over to where the jubilant fisherman was yet skipping about, and asked if she might play the fish a while.

"Law, Miss Elsie! he'd pull yo' overboa'd! Yo' couldn't hol' 'im no maw 'n nuffin. He's mighty strong; stronges' fish ever did see."

But Elsie teased till Jacob Isaac gave the rod into her hand, when she danced forward and back, chassé-ed, and executed other figures of a quadrille, till Puss Leek came up to play the fish. She wasn't so much like a katydid as Elsie, or so much like a wired jumping-jack as Jacob Isaac. She played the fish so awkwardly that John came up and took the rod from her hand. He had no sooner felt the pull at the line than he began to laugh and "pshaw! pshaw!" and said that all in that party were gumps and geese, except himself and Luke.

"You wouldn't except Luke," Elsie interrupted, "if he wasn't a big boy. You'd call him a gump and a goose, if he was a girl."

"If he was a girl, he would be a gump and a goose," said this saucy John. "This fish," he continued, "which you've been playing, is a piece of brush. Oh! how you did play it! This is the way that Jacob Isaac played it." John jumped and danced and hopped and strutted and plunged, till everybody was screaming with laughter. "And this is the way that Elsie played it." He got hold of his coat-skirts after the manner of an affected girl with her dress; then he hugged the rod to his bosom, and capered, flitted, pranced. Then, having reproduced Puss Leek's "playing," he said, grandly: "I shall now proceed to land this monster of the deep."

"He made a great show of getting ready, and then pulled, pulled, pulled, pulled,—when out and up there came, not the brush everybody was expecting, but a fine, beautiful fish.

You ought to have heard, then, the cheers of those surprised boys and girls! Jacob Isaac danced, turned somersaults, walked on his hands, and for one supreme half-second stood on his head.

"Looks like he was playing a whale or a sea-serpent," said Luke, between his bursts of laughter.

"You're all playing a fool that you've caught," said John, who had joined in the laugh against himself, "and you've a right to."[Pg 650]

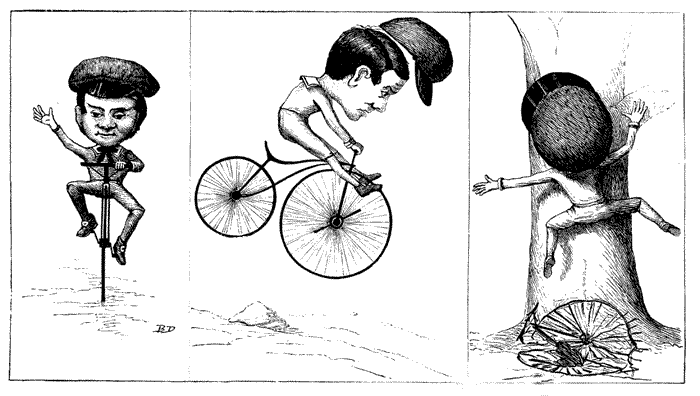

1.—HE GETS A GOOD START,

2.—HAS A FINE RUN DOWN-HILL,

3.—AND COMES TO A SUDDEN STOP.

1.—HE GETS A GOOD START,

2.—HAS A FINE RUN DOWN-HILL,

3.—AND COMES TO A SUDDEN STOP.

By Susan Anna Brown.

This article does not refer to the journey to Europe, toward which almost all young people are looking. When the opportunity for foreign travel comes, there are plenty of guide-books and letters from abroad which will tell you just what to take with you, and what you ought to do in every situation. This is for short, every-day trips, which people take without much thought; but as there is a right and a wrong way of doing even little things, young folks may as well take care that they receive and give the most pleasure possible in a short journey, and then, when the trip across the ocean comes, they will not be annoying themselves and others by continual mistakes.

As packing a trunk is usually the first preparation for a trip, we will begin with that.

It is a very good way to collect what is most important before you begin, so that you may not leave out any necessary article. Think over what you will be likely to need; for a little care before you start may save you a great deal of inconvenience in the end. Be sure, before you begin, that your trunk is in good order, and that you have the key. And when you shut it for the last time, do not leave the straps sticking out upon the outside. Put your heavy things at the bottom, packing them tightly, so that they will not rattle about when the trunk is reversed. Put the small articles in the tray. Anything which will be likely to be scratched or defaced by rubbing, should be wrapped in a handkerchief and laid among soft things. If you must carry anything breakable, do it up carefully, and put it in the center of the trunk, packing clothing closely about it. Bottles should have the corks tied in with strong twine. Put them near articles which cannot be injured by the contents, if a breakage occurs. Tack on your trunk a card with your permanent address. As this card is to be consulted only if the trunk is lost, it is not necessary to be constantly changing it. Take in the traveling-bag, pins and a needle and thread, so that, in case of any accident to your clothes, they can be repaired without troubling any one else. A postal-card and a pencil and paper take up but little room, and may be very convenient. The best way to carry your lunch is in a pasteboard box, which can be thrown away after you have disposed of the contents.

Put your money in an inner pocket, reserving in your purse only what you will be likely to need on the way, so that you may be able to press your way through a crowd without fear of pickpockets. Your purse should also contain your name and address.

Try to be ready, so that you will not be hurried at the last moment; and this does not mean that it is necessary to be at the station a long time before the train leaves. To be punctual does not mean to be too early, but to be just early enough.

Try to find out, before you start, what train and car you ought to take, and have your trunk properly checked. Put the check in some safe place, but first look at the number, so that you may identify the check if lost by you and found by others. Have your ticket where you can easily get it, and need not be obliged to appear, when the conductor comes, as if it was a perfect surprise to you that he should ask for it.

Of course, you have a right to the best seat which is vacant, and, if there is plenty of room, you can put your bundles beside or opposite you; but remember that you have only paid for one seat, and be ready at once to make room for another passenger, if necessary, without acting as though you were conferring a favor.

If you have several packages, and wish to put any of them in the rack over your head, you will be less likely to forget them, if you put all together, than you will if you keep a part in your hand.

If you must read in the cars, never in any circumstances take a book that has not fair, clear type; and stop reading at the earliest approach of twilight. If, as you read, you hold your ticket, or some other plain piece of paper, under the line you are reading, sliding it down as you proceed, you will find that you can read almost as rapidly, and with much less injury to your eyes. A newspaper is the worst reading you can have, as the print is usually indistinct, and it is impossible to hold it still.

You may not care to read in the cars when in motion, but it is convenient to have a book with you, in case the train should be delayed.

If your friends accompany you to the station, be careful that your last words are not too personal or too loud. Young people are apt to overlook this,[Pg 651] and thus sometimes make themselves ridiculous before the other passengers by joking and laughing in a way which might be perfectly proper at home, but which before a company of strangers is not in good taste.

If you meet acquaintances, do not call out their names so distinctly as to introduce them to the other passengers, as it is never pleasant for people to have the attention of strangers called to them in that way. If you are alone, do not be too ready to make acquaintances. Reply politely to any civil remark or offer of assistance, but do not allow yourself to be drawn into conversation, unless it is with some one of whose trustworthiness you are reasonably sure, and even then do not forget that you are talking to a perfect stranger.

If you cannot have everything just as you prefer, remember that you are in a public conveyance, and that the other passengers have as much right to their way as you have to yours. If you find that your open window annoys your neighbor, do not refuse to shut it; and if the case is reversed, do not complain, unless you are really afraid of taking cold, and cannot conveniently change your seat. Above all things, do not get into a dispute about it, like the two women, one of whom declared that she should die if the window was open, and the other responded that she should stifle if it was shut, until one of the passengers requested the conductor to open it a while and kill one, and then shut it and kill the other, that the rest might have peace.

There are few situations where the disposition is more thoroughly shown than it is in traveling. A long journey is considered by some people to be a perfect test of the temper. There are many ways in which an unselfish person will find an opportunity to be obliging. It is surprising to see how people who consider themselves kind and polite members of society can sometimes forget all their good manners in the cars, showing a perfect disregard of the comfort—and even the rights—of others, which would banish them from decent society if shown elsewhere.

To return to particular directions: Do not entertain those who are traveling with you by constant complaints of the dust or the heat or the cold. The others are probably as much annoyed by these things as you are, and fault-finding will only make them the more unpleasant to all. Be careful what you say about those near you, as a thoughtless remark to a friend in too loud a tone may cause a real heartache. Many a weary mother has been pained by hearing complaints of a fretful child, whose crying most probably distresses her more than any one else. Instead of saying, "Why will people travel with babies?" remember that it is sometimes unavoidable, and do not disfigure your face by a[Pg 652] frown at the disturbance, but try to do what you can to make the journey pleasant for those around you, at least by a serene and cheerful face. A person who really wishes to be helpful to others, will find plenty of opportunities to "lend a hand" without becoming conspicuous in any way.

Do not ask too many questions of other passengers. Keep your eyes and ears open, and you will know as much as the rest do. If you wish to inquire about anything, let it be of the conductor, whose business it is to answer you, and do not detain him unnecessarily. Remember what he tells you, that you may not be like the woman Gail Hamilton describes, who asked the conductor the same question every time he came around, as if she thought he had undergone a moral change during his absence, and might answer her more truthfully.

If you get out of the car at any station on your way, be sure to observe which car it was, and which train, so that you need not go about inquiring where you belong when you wish to return to your seat.

A large proportion of the accidents which happen every year are caused by carelessness. Young people are afraid of seeming timid and anxious, and will sometimes, in avoiding this, risk their lives very foolishly. They step from the train before it has fairly stopped, or put their heads out of the window when the car is in motion, or rest the elbow on the sill of an open window in such a way that a passing train may cause serious, if not fatal, injury. Sometimes they pass carelessly from one car to another when the train is still, forgetting that it may start at any moment and throw them off their balance. Many similar exposures can be avoided by a little care and thought.

These are very plain, simple rules, which it may be supposed are already known to every one; but a little observation will show that they are not always put in practice.

A great deal has been left unsaid here on the advantages and pleasures of travel; but, without a knowledge of the simple details we have given, one will be sure to miss much of the culture and enjoyment which might otherwise be gained by it.

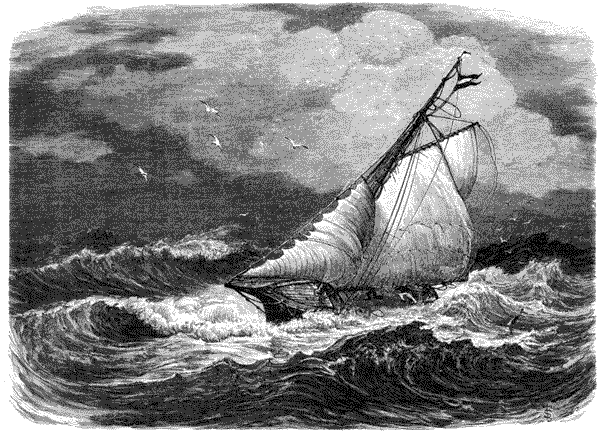

AN EXCITING RIDE.

AN EXCITING RIDE.

By Dora Read Goodale.

By Louisa M. Alcott.

If Sancho's abduction made a stir, one may easily imagine with what warmth and interest he was welcomed back when his wrongs and wanderings were known. For several days he held regular levees, that curious boys and sympathizing girls might see and pity the changed and curtailed dog. Sancho behaved with dignified affability, and sat upon his mat in the coach-house pensively eying his guests, and patiently submitting to their caresses; while Ben and Thorny took turns to tell the few tragical facts which were not shrouded in the deepest mystery. If the interesting sufferer could only have spoken, what thrilling adventures and hair-breadth escapes he might have related. But, alas! he was dumb, and the secrets of that memorable month never were revealed.

The lame paw soon healed, the dingy color slowly yielded to many washings, the woolly coat began to knot up into little curls, a new collar handsomely marked made him a respectable dog, and Sancho was himself again. But it was evident that his sufferings were not forgotten; his once sweet temper was a trifle soured, and, with a few exceptions, he had lost his faith in mankind. Before, he had been the most benevolent and hospitable of dogs; now, he eyed all strangers suspiciously, and the sight of a shabby man made him growl and bristle up, as if the memory of his wrongs still burned hotly within him.

Fortunately, his gratitude was stronger than his resentment, and he never seemed to forget that he owed his life to Betty,—running to meet her whenever she appeared, instantly obeying her commands, and suffering no one to molest her when he walked watchfully beside her, with her hand upon his neck,[Pg 654] as they had walked out of the almost fatal back-yard together, faithful friends forever.

Miss Celia called them little Una and her lion, and read the pretty story to the children when they wondered what she meant. Ben, with great pains, taught the dog to spell "Betty," and surprised her with a display of this new accomplishment, which gratified her so much that she was never tired of seeing Sanch paw the five red letters into place, then come and lay his nose in her hand, as if he added: "That's the name of my dear mistress."

Of course Bab was glad to have everything pleasant and friendly again, but in a little dark corner of her heart there was a drop of envy, and a desperate desire to do something which would make every one in her small world like and praise her as they did Betty. Trying to be as good and gentle did not satisfy her; she must do something brave or surprising, and no chance for distinguishing herself in that way seemed likely to appear. Betty was as fond as ever, and the boys were very kind to her; but she felt that they both liked "little Betcinda," as they called her, best, because she found Sanch, and never seemed to know that she had done anything brave in defending him against all odds. Bab did not tell any one how she felt, but endeavored to be amiable while waiting for her chance to come, and when it did arrive made the most of it, though there was nothing heroic to add a charm.

Miss Celia's arm had been doing very well, but it would, of course, be useless for some time longer. Finding that the afternoon readings amused herself as much as they did the children, she kept them up, and brought out all her old favorites, enjoying a double pleasure in seeing that her young audience relished them as much as she did when a child; for to all but Thorny they were brand new. Out of one of these stories came much amusement for all, and satisfaction for one of the party.

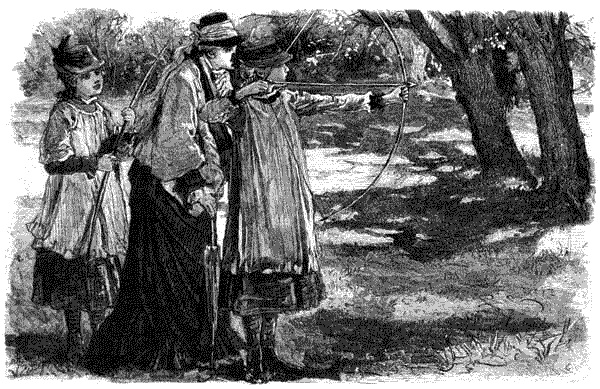

"Celia, did you bring our old bows?" asked her brother, eagerly, as she put down the book from which she had been reading Miss Edgeworth's capital story of "Waste not Want not; or, Two Strings to your Bow."

"Yes, I brought all the playthings we left stored away in uncle's garret when we went abroad. The bows are in the long box where you found the mallets, fishing-rods and bats. The old quivers and a few arrows are there also, I believe. What is the idea now?" asked Miss Celia in her turn, as Thorny bounced up in a great hurry.

"I'm going to teach Ben to shoot. Grand fun this hot weather, and by and by we'll have an archery meeting, and you can give us a prize. Come on, Ben. I've got plenty of whip-cord to rig up the bows, and then we'll show the ladies some first-class shooting."

"I can't; never had a decent bow in my life. The little gilt one I used to wave round when I was a Coopid wasn't worth a cent to go," answered Ben, feeling as if that painted "prodigy" must have been a very distant connection of the respectable young person now walking off arm-in-arm with the lord of the manor.

"Practice is all you want. I used to be a capital shot, but I don't believe I could hit anything but a barn-door now," answered Thorny, encouragingly.

As the boys vanished, with much tramping of boots and banging of doors, Bab observed, in the young-ladyish tone she was apt to use when she composed her active little mind and body to the feminine task of needlework:

"We used to make bows of whalebone when we were little girls, but we are too old to play so now."

"I'd like to, but Bab wont, 'cause she's most 'leven years old," said honest Betty, placidly rubbing her needle in the "ruster," as she called the family emery-bag.

"Grown people enjoy archery, as bow and arrow shooting is called, especially in England. I was reading about it the other day, and saw a picture of Queen Victoria with her bow, so you needn't be ashamed of it, Bab," said Miss Celia, rummaging among the books and papers in her sofa corner to find the magazine she wanted, thinking a new play would be as good for the girls as for the big boys.

"A queen, just think!" and Betty looked much impressed by the fact, as well as uplifted by the knowledge that her friend did not agree in thinking her silly because she preferred playing with a harmless home-made toy to firing stones or snapping a pop-gun.

"In old times, bows and arrows were used to fight great battles with, and we read how the English archers shot so well that the air was dark with arrows, and many men were killed."

"So did the Indians have 'em, and I've got some stone arrow-heads,—found 'em by the river, in the dirt!" cried Bab, waking up, for battles interested her more than queens.

"While you finish your stints I'll tell you a little story about the Indians," said Miss Celia, lying back on her cushions, while the needles began to go again, for the prospect of a story could not be resisted.

"A century or more ago, in a small settlement on the banks of the Connecticut,—which means the Long River of Pines,—there lived a little girl called Matty Kilburn. On a hill stood the fort where the people ran for protection in any danger, for the country was new and wild, and more than once the Indians had come down the river in their canoes and burned the houses, killed men, and carried away women and children. Matty lived alone with her father, but felt quite safe in the log-house, for he was never far away. One afternoon, as the farmers were all busy in their fields, the bell rang suddenly,—a sign that there was danger near,—and, dropping their rakes or axes, the men hurried to their houses to save wives and babies, and such few treasures as they could. Mr. Kilburn caught up his gun with one hand and his little girl with the other, and ran as fast as he could toward the fort. But before he could reach it he heard a yell, and saw the red men coming up from the river. Then he knew it would be in vain to try to get in, so he looked about for a safe place to hide Matty till he could come for her. He was a brave man, and could fight, so he had no thought of hiding while his neighbors needed help; but the dear little daughter must be cared for first.

In the corner of the lonely pasture which they dared not cross, stood a big hollow elm, and there the farmer hastily hid Matty, dropping her down into the dim nook, round the mouth of which young shoots had grown, so that no one would have suspected any hole was there.

'Lie still, child, till I come; say your prayers and wait for father,' said the man, as he parted the leaves for a last glance at the small, frightened face looking up at him.

'Come soon,' whispered Matty, and tried to smile bravely, as a stout settler's girl should.

"Mr. Kilburn went away, and was taken prisoner in the fight, carried off, and for years no one knew if he was alive or dead. People missed Matty, but supposed she was with her father, and never expected to see her again. A great while afterward the poor man came back, having escaped and made his way through the wilderness to his old home. His first question was for Matty, but no one had seen her; and when he told where he had left her, they shook their heads as if they thought he was crazy. But they went to look, that he might be satisfied; and he was; for there they found some little bones, some faded bits of cloth, and two rusty silver buckles marked with Matty's name in what had once been her shoes. An Indian arrow lay there, too, showing why she had never cried for help, but waited patiently so long for father to come and find her."

If Miss Celia expected to see the last bit of hem done when her story ended, she was disappointed; for not a dozen stitches had been taken. Betty was using her crash-towel for a handkerchief, and Bab's lay on the ground as she listened with snapping eyes to the little tragedy.

"Is it true?" asked Betty, hoping to find relief in being told that it was not.

"Yes; I have seen the tree, and the mound[Pg 655] where the fort was, and the rusty buckles in an old farm-house where other Kilburns live, near the spot where it all happened," answered Miss Celia, looking out the picture of Victoria to console her auditors.

"We'll play that in the old apple-tree. Betty can scrooch down, and I'll be the father, and put leaves on her, and then I'll be a great Injun and fire at her. I can make arrows, and it will be fun, wont it?" cried Bab, charmed with the new drama in which she could act the leading parts.

"No, it wont! I don't like to go in a cobwebby hole, and have you play kill me. I'll make a nice fort of hay, and be all safe, and you can put Dinah down there for Matty. I don't love her any more, now her last eye has tumbled out, and you may shoot her just as much as you like."

Before Bab could agree to this satisfactory arrangement, Thorny appeared, singing, as he aimed at a fat robin, whose red waistcoat looked rather warm and winterish that August day:

"But he didn't," chirped the robin, flying away, with a contemptuous flirt of his rusty-black tail.

"That is exactly what you must promise not to do, boys. Fire away at your targets as much as you like, but do not harm any living creature," said Miss Celia, as Ben followed armed and equipped with her own long-unused accouterments.

"Of course we wont if you say so; but, with a little practice, I could bring down a bird as well as that fellow you read to me about with his woodpeckers and larks and herons," answered Thorny, who had much enjoyed the article, while his sister lamented over the destruction of the innocent birds.

"You'd do well to borrow the Squire's old stuffed owl for a target; there would be some chance of your hitting him, he is so big," said his sister, who always made fun of the boy when he began to brag.

Thorny's only reply was to send his arrow straight up so far out of sight that it was a long while coming down again to stick quivering in the ground near by, whence Sancho brought it in his mouth, evidently highly approving of a game in which he could join.

"Not bad for a beginning. Now, Ben, fire away."

But Ben's experience with bows was small, and, in spite of his praiseworthy efforts to imitate his great exemplar, the arrow only turned a feeble sort of somersault, and descended perilously near Bab's uplifted nose.[Pg 656]

"If you endanger other people's life and liberty in your pursuit of happiness, I shall have to confiscate your arms, boys. Take the orchard for your archery ground; that is safe, and we can see you as we sit here. I wish I had two hands, so that I could paint you a fine, gay target," and Miss Celia looked regretfully at the injured arm, which as yet was of little use.

"I wish you could shoot, too; you used to beat all the girls, and I was proud of you," answered Thorny, with the air of a fond elder brother; though, at the time he alluded to, he was about twelve, and hardly up to his sister's shoulder.

"Thank you. I shall be happy to give my place to Bab and Betty if you will make them some bows and arrows; they could not use those long ones."

The young gentlemen did not take the hint as quickly as Miss Celia hoped they would; in fact, both looked rather blank at the suggestion, as boys generally do when it is proposed that girls—especially small ones—shall join in any game they are playing.

"P'r'aps it would be too much trouble," began Betty, in her winning little voice.

"I can make my own," declared Bab, with an independent toss of the head.

"Not a bit; I'll make you the jolliest small bow that ever was, Betcinda," Thorny hastened to say, softened by the appealing glance of the little maid.

"You can use mine, Bab; you've got such a strong fist, I guess you could pull it," added Ben, remembering that it would not be amiss to have a comrade who shot worse than he did, for he felt very inferior to Thorny in many ways, and, being used to praise, had missed it very much since he retired to private life.

"I will be umpire, and brighten up the silver arrow I sometimes pin my hair with, for a prize, unless we can find something better," proposed Miss Celia, glad to see that question settled, and every prospect of the new play being a pleasant amusement for the hot weather.

It was astonishing how soon archery became the fashion in that town, for the boys discussed it enthusiastically all that evening, formed the "William Tell Club" next day, with Bab and Betty as honorary members, and, before the week was out, nearly every lad was seen, like young Norval, "With bended bow and quiver full of arrows," shooting away, with a charming disregard of the safety of their fellow-citizens. Banished by the authorities to secluded spots, the members of the club set up their targets and practiced indefatigably, especially Ben, who soon discovered that his early gymnastics had given him a sinewy arm and a true eye; and, taking Sanch into partnership as picker-up, he got more shots out of an hour than those who had to run to and fro.

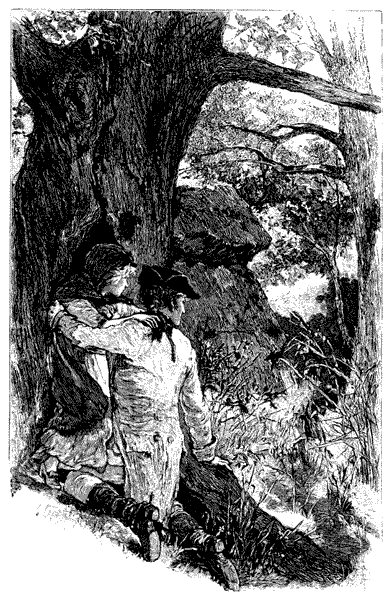

MATTY KILBURN AND HER FATHER AT THE TREE.

MATTY KILBURN AND HER FATHER AT THE TREE.

Thorny easily recovered much of his former skill, but his strength had not fully returned, and he soon[Pg 657] grew tired. Bab, on the contrary, threw herself into the contest heart and soul, and tugged away at the new bow Miss Celia gave her, for Ben's was too heavy. No other girls were admitted, so the outsiders got up a club of their own, and called it "The Victoria," the name being suggested by the magazine article, which went the rounds as general guide and reference-book. Bab and Betty belonged to this club also, and duly reported the doings of the boys, with whom they had a right to shoot if they chose, but soon waived the right, plainly seeing that their absence would be regarded in the light of a favor.

The archery fever raged as fiercely as the baseball epidemic had done before it, and not only did the magazine circulate freely, but Miss Edgeworth's story, which was eagerly read, and so much admired that the girls at once mounted green ribbons, and the boys kept yards of whip-cord in their pockets, like the provident Benjamin of the tale.

Every one enjoyed the new play very much, and something grew out of it which was a lasting pleasure to many, long after the bows and arrows were forgotten. Seeing how glad the children were to get a new story, Miss Celia was moved to send a box of books—old and new—to the town library, which was but scantily supplied, as country libraries are apt to be. This donation produced a good effect; for other people hunted up all the volumes they could spare for the same purpose, and the dusty shelves in the little room behind the post-office filled up amazingly. Coming in vacation time they were hailed with delight, and ancient books of travel, as well as modern tales, were feasted upon by happy young folks, with plenty of time to enjoy them in peace.

The success of her first attempt at being a public benefactor pleased Miss Celia very much, and suggested other ways in which she might serve the quiet town, where she seemed to feel that work was waiting for her to do. She said little to any one but the friend over the sea, yet various plans were made then that blossomed beautifully by and by.

The first of September came all too soon, and school began. Among the boys and girls who went trooping up to the "East Corner knowledge-box," as they called it, was our friend Ben, with a pile of neat books under his arm. He felt very strange, and decidedly shy; but put on a bold face, and let nobody guess that, though nearly thirteen, he had never been to school before. Miss Celia had told his story to Teacher, and she, being a kind little woman, with young brothers of her own, made things as easy for him as she could. In reading and writing he did very well, and proudly took his place among lads of his own age; but when it came to arithmetic and geography, he had to go down a long way, and begin almost at the beginning, in spite of Thorny's efforts to "tool him along fast." It mortified him sadly, but there was no help for it; and in some of the classes he had dear little Betty to condole with him when he failed, and smile contentedly when he got above her, as he soon began to do,—for she was not a quick child, and plodded through First Parts long after sister Bab was flourishing away among girls much older than herself.

Fortunately, Ben was a short boy and a clever one, so he did not look out of place among the ten and eleven year olders, and fell upon his lessons with the same resolution with which he used to take a new leap, or practice patiently till he could touch his heels with his head. That sort of exercise had given him a strong, elastic little body; this kind was to train his mind, and make its faculties as useful, quick and sure, as the obedient muscles, nerves and eye, which kept him safe where others would have broken their necks. He knew this, and found much consolation in the fact that, though mental arithmetic was a hopeless task, he could turn a dozen somersaults, and come up as steady as a judge. When the boys laughed at him for saying that China was in Africa, he routed them entirely by his superior knowledge of the animals belonging to that wild country; and when "First class in reading" was called, he marched up with the proud consciousness that the shortest boy in it did better than tall Moses Towne or fat Sam Kitteridge.

Teacher praised him all she honestly could, and corrected his many blunders so quietly that he soon ceased to be a deep, distressful red during recitation, and tugged away so manfully that no one could help respecting him for his efforts, and trying to make light of his failures. So the first hard week went by, and though the boy's heart had sunk many a time at the prospect of a protracted wrestle with his own ignorance, he made up his mind to win, and went at it again on the Monday with fresh zeal, all the better and braver for a good, cheery talk with Miss Celia in the Sunday evening twilight.

He did not tell her one of his greatest trials, however, because he thought she could not help him there. Some of the children rather looked down upon him, called him "tramp" and "beggar," twitted him with having been a circus boy, and lived in a tent like a gypsy. They did not mean to be cruel, but did it for the sake of teasing, never stopping to think how much such sport can make a fellow-creature suffer. Being a plucky fellow, Ben pretended not to mind; but he did feel it keenly,[Pg 658] because he wanted to start afresh, and be like other boys. He was not ashamed of the old life, but finding those around him disapproved of it, he was glad to let it be forgotten,—even by himself,—for his latest recollections were not happy ones, and present comforts made past hardships seem harder than before.

He said nothing of this to Miss Celia, but she found it out, and liked him all the better for keeping some of his small worries to himself. Bab and Betty came over on Monday afternoon full of indignation at some boyish insult Sam had put upon Ben, and finding them too full of it to enjoy the reading, Miss Celia asked what the matter was. Then both little girls burst out in a rapid succession of broken exclamations which did not give a very clear idea of the difficulty:

"Sam didn't like it because Ben jumped farther than he did——"

"And he said Ben ought to be in the poor-house."

"And Ben said he ought to be in a pig-pen."

"So he had!—such a greedy thing, bringing lovely big apples and not giving any one a single bite!"

"Then he was mad, and we all laughed, and he said, 'Want to fight?'"

"And Ben said, 'No, thanky, not much fun in pounding a feather-bed.'"

"Oh, he was awfully mad then and chased Ben up the big maple."

"He's there now, for Sam wont let him come down till he takes it all back."

"Ben wont, and I do believe he'll have to stay up all night," said Betty, distressfully.

"He wont care, and we'll have fun firing up his supper. Nut-cakes and cheese will go splendidly; and may be baked pears wouldn't get smashed, he's such a good catch," added Bab, decidedly relishing the prospect.

"If he does not come by tea-time we will go and look after him. It seems to me I have heard something about Sam's troubling him before, haven't I?" asked Miss Celia, ready to defend her protégé against all unfair persecution.

"Yes'm, Sam and Mose are always plaguing Ben. They are big boys and we can't make them stop. I wont let the girls do it, and the little boys don't dare to, since Teacher spoke to them," answered Bab.

"Why does not Teacher speak to the big ones?"

"Ben wont tell of them or let us. He says he'll fight his own battles and hates tell-tales. I guess his wont like to have us tell you, but I don't care, for it is too bad," and Betty looked ready to cry over her friend's tribulations.

"I'm glad you did, for I will attend to it and stop this sort of thing," said Miss Celia, after the children had told some of the tormenting speeches which had tried poor Ben.

Just then, Thorny appeared, looking much amused, and the little girls both called out in a breath: "Did you see Ben and get him down?"

"He got himself down in the neatest way you can imagine," and Thorny laughed at the recollection.

"Where is Sam?" asked Bab.

"Staring up at the sky to see where Ben has flown to."

"Oh, tell about it!" begged Betty.

"Well, I came along and found Ben treed, and Sam stoning him. I stopped that at once and told the 'fat boy' to be off. He said he wouldn't till Ben begged his pardon, and Ben said he wouldn't do it if he stayed up for a week. I was just preparing to give that rascal a scientific thrashing when a load of hay came along and Ben dropped on to it so quietly that Sam, who was trying to bully me, never saw him go. It tickled me so, I told Sam I guessed I'd let him off that time, and walked away, leaving him to hunt for Ben and wonder where the dickens he had vanished to."

The idea of Sam's bewilderment tickled the others as much as Thorny, and they all had a good laugh over it before Miss Celia asked:

"Where has Ben gone now?"

"Oh, he'll take a little ride and then slip down and race home full of the fun of it. But I've got to settle Sam. I wont have our Ben hectored by any one——"

"But yourself," put in his sister, with a sly smile, for Thorny was rather domineering at times.

"He doesn't mind my poking him up now and then, it's good for him, and I always take his part against other people. Sam is a bully and so is Mose, and I'll thrash them both if they don't stop."

Anxious to curb her brother's pugnacious propensities, Miss Celia proposed milder measures, promising to speak to the boys herself if there was any more trouble.

"I have been thinking that we should have some sort of merry-making for Ben on his birthday. My plan was a very simple one, but I will enlarge it and have all the young folks come, and Ben shall be king of the fun. He needs encouragement in well-doing, for he does try, and now the first hard part is nearly over I am sure he will get on bravely. If we treat him with respect and show our regard for him, others will follow our example, and that will be better than fighting about it."

"So it will! What shall we do to make our party tip-top?" asked Thorny, falling into the trap at once, for he dearly loved to get up theatricals, and had not had any for a long time.

"We will plan something splendid, a 'grand combination,' as you used to call your droll mixtures of tragedy, comedy, melodrama and farce," answered his sister, with her head already full of lively plots.

"We'll startle the natives. I don't believe they ever saw a play in all their lives, hey Bab?"

"I've seen a circus."

"We dress up and do 'Babes in the Wood,'" added Betty, with dignity.

"Pho! that's nothing. I'll show you acting that will make your hair stand on end, and you shall act too. Bab will be capital for the naughty girls," began Thorny, excited by the prospect of producing a sensation on the boards, and always ready to tease the girls.

Before Betty could protest that she did not want her hair to stand up, or Bab could indignantly decline the rôle offered her, a shrill whistle was heard, and Miss Celia whispered, with a warning look:

"Hush! Ben is coming, and he must not know anything about this yet."

The next day was Wednesday, and in the afternoon Miss Celia went to hear the children "speak pieces," though it was very seldom that any of the busy matrons and elder sisters found time or inclination for these displays of youthful oratory. Miss Celia and Mrs. Moss were all the audience on this occasion, but Teacher was both pleased and proud to see them, and a general rustle went through the school as they came in, all the girls turning from the visitors to nod at Bab and Betty, who smiled all over their round faces to see "Ma" sitting up "side of Teacher," and the boys grinned at Ben, whose heart began to beat fast at the thought of his dear mistress coming so far to hear him say his piece.

Thorny had recommended Marco Bozzaris, but Ben preferred John Gilpin, and ran the famous race with much spirit, making excellent time in some parts and having to be spurred a little in others, but came out all right, though quite breathless at the end, sitting down amid great applause, some of which, curiously enough, seemed to come from outside; which in fact it did, for Thorny was bound to hear but would not come in, lest his presence should abash one orator at least.

Other pieces followed, all more or less patriotic and warlike, among the boys; sentimental among the girls. Sam broke down in his attempt to give one of Webster's great speeches. Little Cy Fay boldly attacked

"Again to the battle, Achaians!"

and shrieked his way through it in a shrill, small voice, bound to do honor to the older brother who[Pg 659] had trained him, even if he broke a vessel in the attempt. Billy chose a well-worn piece, but gave it a new interest by his style of delivery; for his gestures were so spasmodic he looked as if going into a fit, and he did such astonishing things with his voice that one never knew whether a howl or a growl would come next. When

Billy's arms went round like the sails of a windmill; the "hymns of lofty cheer" not only "shook the depths of the desert gloom," but the small children on their little benches, and the schoolhouse literally rang "to the anthems of the free!" When "the ocean eagle soared," Billy appeared to be going bodily up, and the "pines of the forest roared" as if they had taken lessons of Van Amburgh's biggest lion. "Woman's fearless eye" was expressed by a wild glare; "manhood's brow, severely high," by a sudden clutch at the reddish locks falling over the orator's hot forehead, and a sounding thump on his blue checked bosom told where "the fiery heart of youth" was located. "What sought they thus afar?" he asked, in such a natural and inquiring tone, with his eye fixed on Mamie Peters, that the startled innocent replied, "Dunno," which caused the speaker to close in haste, devoutly pointing a stubby finger upward at the last line.

This was considered the gem of the collection, and Billy took his seat proudly conscious that his native town boasted an orator who, in time, would utterly eclipse Edward Everett and Wendell Phillips.

Sally Folsom led off with "The Coral Grove," chosen for the express purpose of making her friend Almira Mullet start and blush, when she recited the second line of that pleasing poem,

One of the older girls gave Wordsworth's "Lost Love" in a pensive tone, clasping her hands and bringing out the "O" as if a sudden twinge of toothache seized her when she ended.

Bab always chose a funny piece, and on this afternoon set them all laughing by the spirit with which she spoke the droll poem, "Pussy's Class," which some of my young readers may have read. The "meou" and the "sptzzs" were capital, and when the "fond mamma rubbed her nose," the children shouted, for Miss Bab made a paw of her hand and ended with an impromptu purr, which was considered the best imitation ever presented to an appreciative public. Betty bashfully murmured "Little[Pg 660] White Lilly," swaying to and fro as regularly as if in no other way could the rhymes be ground out of her memory.

"THE OCEAN EAGLE SOARED."

"THE OCEAN EAGLE SOARED."

"That is all, I believe. If either of the ladies would like to say a few words to the children, I should be pleased to have them," said Teacher, politely, pausing before she dismissed school with a song.

"Please'm, I'd like to speak my piece," answered Miss Celia, obeying a sudden impulse; and, stepping forward with her hat in her hand, she made a pretty courtesy before she recited Mary Howitt's sweet little ballad, "Mabel on Midsummer Day."

She looked so young and merry, used such simple but expressive gestures, and spoke in such a clear, soft voice that the children sat as if spellbound, learning several lessons from this new teacher, whose performance charmed them from beginning to end, and left a moral which all could understand and carry away in that last verse:

Of course there was an enthusiastic clapping when Miss Celia sat down, but even while hands applauded, consciences pricked, and undone tasks, complaining words and sour faces seemed to rise up reproachfully before many of the children, as well as their own faults of elocution.

"Now we will sing," said Teacher, and a great clearing of throats ensued, but before a note could be uttered, the half-open door swung wide, and Sancho, with Ben's hat on, walked in upon his hind legs, and stood with his paws meekly folded, while a voice from the entry sang rapidly:

Mischievous Thorny got no further, for a general explosion of laughter drowned the last words, and Ben's command "Out, you rascal!" sent Sanch to the right-about in double-quick time.

Miss Celia tried to apologize for her bad brother, and Teacher tried to assure her that it didn't matter in the least as this was always a merry time, and Mrs. Moss vainly shook her finger at her naughty daughters; they as well as the others would have[Pg 661] their laugh out, and only partially sobered down when the bell rang for "Attention." They thought they were to be dismissed, and repressed their giggles as well as they could in order to get a good start for a vociferous roar when they got out. But, to their great surprise, the pretty lady stood up again and said, in her friendly way:

"I just want to thank you for this pleasant little exhibition, and ask leave to come again, I also wish to invite you all to my boy's birthday party on Saturday week. The archery meeting is to be in the afternoon, and both clubs will be there, I believe. In the evening we are going to have some fun, when we can laugh as much as we please without breaking any of the rules. In Ben's name I invite you, and hope you will all come, for we mean to make this the happiest birthday he ever had."

There were twenty pupils in the room, but the eighty hands and feet made such a racket at this announcement that an outsider would have thought a hundred children, at least, must have been at it. Miss Celia was a general favorite because she nodded to all the girls, called the boys by their last names, even addressing some of the largest as "Mr.," which won their hearts at once, so that if she had invited them all to come and be whipped they would have gone, sure that it was some delightful joke. With what eagerness they accepted the present invitation one can easily imagine, though they never guessed why she gave it in that way, and Ben's face was a sight to see, he was so pleased and proud at the honor done him that he did not know where to look, and was glad to rush out with the other boys and vent his emotions in whoops of delight. He knew that some little plot was being concocted for his birthday, but never dreamed of anything so grand as asking the whole school, Teacher and all. The effect of the invitation was seen with comical rapidity, for the boys became overpowering in their friendly attentions to Ben. Even Sam, fearing he might be left out, promptly offered the peaceful olive-branch in the shape of a big apple, warm from his pocket, and Mose proposed a trade in jack-knives which would be greatly to Ben's advantage. But Thorny made the noblest sacrifice of all, for he said to his sister, as they walked home together:

"I'm not going to try for the prize at all. I shoot so much better than the rest, having had more practice, you know, that it is hardly fair. Ben and Billy are next best, and about even, for Ben's strong wrist makes up for Billy's true eye, and both want to win. If I am out of the way Ben stands a good chance, for the other fellows don't amount to much."

"Bab does; she shoots nearly as well as Ben, and wants to win even more than he or Billy. She must have her chance at any rate."

"So she may, but she wont do anything; girls can't, though it's good exercise and pleases them to try."

"If I had full use of both my arms I'd show you that girls can do a great deal when they like. Don't be too lofty, young man, for you may have to come down," laughed Miss Celia, amused by his airs.

"No fear," and Thorny calmly departed to set his targets for Ben's practice.

"We shall see," and from that moment Miss Celia made Bab her especial pupil, feeling that a little lesson would be good for Mr. Thorny, who rather lorded it over the other young people. There was a spice of mischief in it, for Miss Celia was very young at heart, in spite of her twenty-four years, and she was bound to see that her side had a fair chance, believing that girls can do whatever they are willing to strive patiently and wisely for.

So she kept Bab at work early and late, giving her all the hints and help she could with only one efficient hand, and Bab was delighted to think she did well enough to shoot with the club. Her arms ached and her fingers grew hard with twanging the bow, but she was indefatigable, and being a strong, tall child of her age, with a great love of all athletic sports, she got on fast and well, soon learning to send arrow after arrow with ever increasing accuracy nearer and nearer to the bull's-eye.

The boys took very little notice of her, being much absorbed in their own affairs, but Betty did for Bab what Sancho did for Ben, and trotted after arrows till her short legs were sadly tired, though her patience never gave out. She was so sure Bab would win that she cared nothing about her own success, practicing little and seldom hitting anything when she tried.

A superb display of flags flapped gayly in the breeze on the September morning when Ben proudly entered his teens. An irruption of bunting seemed to have broken out all over the old house, for banners of every shape and size, color and design flew from chimney-top and gable, porch and gate-way, making the quiet place look as lively as a circus tent, which was just what Ben most desired and delighted in.

The boys had been up very early to prepare the show, and when it was ready enjoyed it hugely, for the fresh wind made the pennons cut strange capers. The winged lion of Venice looked as if trying to fly away home; the Chinese dragon appeared to[Pg 662] brandish his forked tail as he clawed at the Burmese peacock; the double-headed eagle of Russia pecked at the Turkey crescent with one beak, while the other seemed to be screaming to the English royal beast, "Come on and lend a paw." In the hurry of hoisting, the Siamese elephant got turned upside down, and now danced gayly on his head, with the stars and stripes waving proudly over him. A green flag with a yellow harp and sprig of shamrock hung in sight of the kitchen window, and Katy, the cook, got breakfast to the tune of "St. Patrick's day in the morning." Sancho's kennel was half hidden under a rustling paper imitation of the gorgeous Spanish banner, and the scarlet sun-and-moon flag of Arabia snapped and flaunted from the pole over the coach-house, as a delicate compliment to Lita, Arabian horses being considered the finest in the world.

The little girls came out to see, and declared it was the loveliest sight they ever beheld, while Thorny played "Hail Columbia" on his fife, and Ben, mounting the gate-post, crowed long and loud like a happy cockerel who had just reached his majority. He had been surprised and delighted with the gifts he found in his room on awaking, and guessed why Miss Celia and Thorny gave him such pretty things, for among them was a match-box made like a mouse-trap. The doggy buttons and the horsey whip were treasures indeed, for Miss Celia had not given them when they first planned to do so, because Sancho's return seemed to be joy and reward enough for that occasion. But he did not forget to thank Mrs. Moss for the cake she sent him, nor the girls for the red mittens which they had secretly and painfully knit. Bab's was long and thin, with a very pointed thumb, Betty's short and wide, with a stubby thumb, and all their mother's pulling and pressing could not make them look alike, to the great affliction of the little knitters. Ben, however, assured them that he rather preferred odd ones, as then he could always tell which was right and which left. He put them on immediately and went about cracking the new whip with an expression of content which was droll to see, while the children followed after, full of admiration for the hero of the day.

They were very busy all the morning preparing for the festivities to come, and as soon as dinner was over every one scrambled into his or her best clothes as fast as possible, because, although invited to come at two, impatient boys and girls were seen hovering about the avenue as early as one.

The first to arrive, however, was an uninvited guest, for just as Bab and Betty sat down on the porch steps, in their stiff pink calico frocks and white ruffled aprons, to repose a moment before the party came in, a rustling was heard among the lilacs and out stepped Alfred Tennyson Barlow, looking like a small Robin Hood, in a green blouse with a silver buckle on his broad belt, a feather in his little cap and a bow in his hand.

"I have come to shoot. I heard about it. My papa told me what arching meant. Will there be any little cakes? I like them."

With these opening remarks the poet took a seat and calmly awaited a response. The young ladies, I regret to say, giggled, then remembering their manners, hastened to inform him that there would be heaps of cakes, also that Miss Celia would not mind his coming without an invitation, they were quite sure.

"She asked me to come that day. I have been very busy. I had measles. Do you have them here?" asked the guest, as if anxious to compare notes on the sad subject.

"We had ours ever so long ago. What have you been doing besides having measles?" said Betty, showing a polite interest.

"I had a fight with a bumble-bee."

"Who beat?" demanded Bab.

"I did. I ran away and he couldn't catch me."

"Can you shoot nicely?"

"I hit a cow. She did not mind at all. I guess she thought it was a fly."

"Did your mother know you were coming?" asked Bab, feeling an interest in runaways.

"No; she is gone to drive, so I could not ask her."

"It is very wrong to disobey. My Sunday-school book says that children who are naughty that way never go to heaven," observed virtuous Betty, in a warning tone.

"I do not wish to go," was the startling reply.

"Why not?" asked Betty, severely.

"They don't have any dirt there. My mamma says so. I am fond of dirt. I shall stay here where there is plenty of it," and the candid youth began to grub in the mold with the satisfaction of a genuine boy.

"I am afraid you're a very bad child."

"Oh yes, I am. My papa often says so and he knows all about it," replied Alfred with an involuntary wriggle suggestive of painful memories. Then, as if anxious to change the conversation from its somewhat personal channel, he asked, pointing to a row of grinning heads above the wall, "Do you shoot at those?"

Bab and Betty looked up quickly and recognized the familiar faces of their friends peering down at them, like a choice collection of trophies or targets.

"I should think you'd be ashamed to peek before the party was ready!" cried Bab, frowning darkly upon the merry young ladies.[Pg 663]

"Miss Celia told us to come before two, and be ready to receive folks, if she wasn't down," added Betty, importantly.

"It is striking two now. Come along, girls," and over scrambled Sally Folsom, followed by three or four kindred spirits, just as their hostess appeared.

"You look like Amazons storming a fort," she said, as the girls came up, each carrying her bow and arrows, while green ribbons flew in every direction. "How do you do, sir? I have been hoping you would call again," added Miss Celia, shaking hands with the pretty boy, who regarded with benign interest the giver of little cakes.

Here a rush of boys took place, and further remarks were cut short, for every one was in a hurry to begin. So the procession was formed at once, Miss Celia taking the lead, escorted by Ben in the post of honor, while the boys and girls paired off behind, arm in arm, bow on shoulder, in martial array. Thorny and Billy were the band, and marched before, fifing and drumming "Yankee Doodle" with a vigor which kept feet moving briskly, made eyes sparkle, and young hearts dance under the gay gowns and summer jackets. The interesting stranger was elected to bear the prize, laid out on a red pin-cushion, and did so with great dignity, as he went beside the standard-bearer, Cy Fay, who bore Ben's choicest flag, snow white, with a green wreath surrounding a painted bow and arrow, and with the letters W. T. C. done in red below.

Such a merry march all about the place, out at the Lodge gate, up and down the avenue, along the winding-paths till they halted in the orchard where the target stood and seats were placed for the archers, while they waited for their turns. Various rules and regulations were discussed, and then the fun began. Miss Celia had insisted that the girls should be invited to shoot with the boys, and the lads consented without much concern, whispering to one another with condescending shrugs—"Let 'em try, if they like, they can't do anything."

There were various trials of skill before the great match came off, and in these trials the young gentlemen discovered that two at least of the girls could do something, for Bab and Sally shot better than many of the boys, and were well rewarded for their exertions by the change which took place in the faces and conversation of their mates.

"Why, Bab, you do as well as if I'd taught you myself," said Thorny, much surprised and not altogether pleased at the little girl's skill.

"A lady taught me, and I mean to beat every one of you," answered Bab, saucily, while her sparkling eyes turned to Miss Celia with a mischievous twinkle in them.

"Not a bit of it," declared Thorny, stoutly; but he went to Ben and whispered, "Do your best, old fellow, for sister has taught Bab all the scientific points, and the little rascal is ahead of Billy."

"She wont get ahead of me," said Ben, picking out his best arrow, and trying the string of his bow with a confident air which re-assured Thorny, who found it impossible to believe that a girl ever could, would, or should excel a boy in anything he cared to try.

It really did look as if Bab would beat when the match for the prize came off, and the children got more and more excited as the six who were to try for it took turns at the bull's-eye. Thorny was umpire and kept account of each shot, for the arrow which went nearest the middle would win. Each had three shots, and very soon the lookers on saw that Ben and Bab were the best marksmen, and one of them would surely get the silver arrow.

Sam, who was too lazy to practice, soon gave up the contest, saying, as Thorny did, "It wouldn't be fair for such a big fellow to try with the little chaps," which made a laugh, as his want of skill was painfully evident. But Mose went at it gallantly, and if his eye had been as true as his arms were strong, the "little chaps" would have trembled. But his shots were none of them as near as Billy's, and he retired after the third failure, declaring that it was impossible to shoot against the wind, though scarcely a breath was stirring.

Sally Folsom was bound to beat Bab, and twanged away in great style; all in vain, however, as with tall Maria Newcome, the third girl who attempted the trial. Being a little near-sighted, she had borrowed her sister's eye-glasses, and thereby lessened her chance of success; for the pinch on her nose distracted her attention, and not one of her arrows went beyond the second ring, to her great disappointment. Billy did very well, but got nervous when his last shot came, and just missed the bull's-eye by being in a hurry.

Bab and Ben each had one turn more, and as they were about even, that last arrow would decide the victory. Both had sent a shot into the bull's-eye, but neither was exactly in the middle; so there was room to do better, even, and the children crowded round, crying eagerly, "Now, Ben!" "Now, Bab!" "Hit her up, Ben!" "Beat him, Bab!" while Thorny looked as anxious as if the fate of the country depended on the success of his man. Bab's turn came first, and as Miss Celia examined her bow to see that all was right, the little girl said, with her eyes on her rival's excited face:

"I want to beat, but Ben will feel so bad, I 'most hope I sha'n't."

"Losing a prize sometimes makes one happier than gaining it. You have proved that you could do better than most of them, so, if you do not beat, you may still feel proud," answered Miss Celia, giv[Pg 664]ing back the bow with a smile that said more than her words.

It seemed to give Bab a new idea, for in a minute all sorts of recollections, wishes and plans, rushed through her lively little mind, and she followed a sudden generous impulse as blindly as she often did a willful one.

"I guess he'll beat," she said, softly, with a quick sparkle of the eyes, as she stepped to her place and fired without taking her usual careful aim.

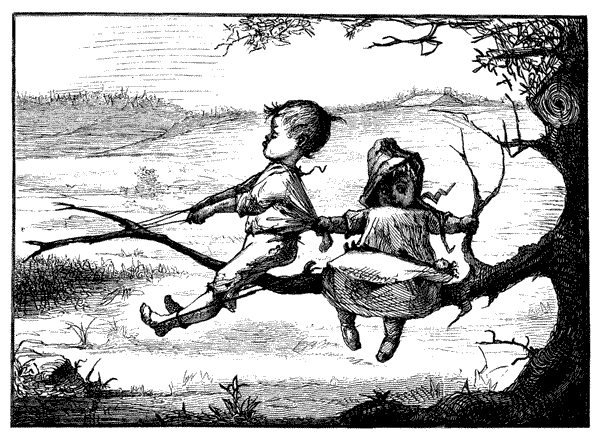

PRACTICING FOR THE MATCH.

PRACTICING FOR THE MATCH.

Her shot struck almost as near the center on the right as her last one had hit on the left, and there was a shout of delight from the girls as Thorny announced it before he hurried back to Ben, whispering anxiously:

"Steady, old man, steady; you must beat that, or we shall never hear the last of it."

Ben did not say, "She wont get ahead of me," as he had said at the first; he set his teeth, threw off his hat, and knitting his brows with a resolute expression, prepared to take steady aim, though his heart beat fast, and his thumb trembled as he pressed it on the bow-string.

"I hope you'll beat, I truly do," said Bab, at his elbow; and as if the breath that framed the generous wish helped it on its way, the arrow flew straight to the bull's-eye, hitting, apparently, the very spot where Bab's best shot had left a hole.

"A tie! a tie!" cried the girls, as a general rush took place toward the target.

"No; Ben's is nearest. Ben's beat! Hooray!" shouted the boys, throwing up their hats.

There was only a hair's-breadth difference, and Bab could honestly have disputed the decision; but she did not, though for an instant she could not help wishing that the cry had been, "Bab's beat! Hurrah!" it sounded so pleasant. Then she saw Ben's beaming face, Thorny's intense relief, and caught the look Miss Celia sent her over the heads of the boys, and decided, with a sudden warm glow all over her little face, that losing a prize did sometimes make one happier than winning it. Up went her best hat, and she burst out in a shrill, "Rah, rah, rah!" that sounded very funny coming all alone after the general clamor had subsided.

"Good for you, Bab! you are an honor to the club, and I'm proud of you," said Prince Thorny, with a hearty hand-shake; for, as his man had won, he could afford to praise the rival who had put him on his mettle though she was a girl.

Bab was much uplifted by the royal commendation, but a few minutes later felt pleased as well as proud when Ben, having received the prize, came to her, as she stood behind a tree sucking her blistered thumb, while Betty braided up her disheveled locks.

"I think it would be fairer to call it a tie, Bab,[Pg 665] for it nearly was, and I want you to wear this. I wanted the fun of beating, but I don't care a bit for this girl's thing, and I'd rather see it on you."

As he spoke, Ben offered the rosette of green ribbon which held the silver arrow, and Bab's eyes brightened as they fell upon the pretty ornament, for to her "the girl's thing" was almost as good as the victory.

"Oh no; you must wear it to show who won. Miss Celia wouldn't like it. I don't mind not getting it; I did better than all the rest, and I guess I shouldn't like to beat you," answered Bab, unconsciously putting into childish words the sweet generosity which makes so many sisters glad to see their brothers carry off the prizes of life, while they are content to know that they have earned them and can do without the praise.

But if Bab was generous, Ben was just; and though he could not explain the feeling, would not consent to take all the glory without giving his little friend a share.

"You must wear it; I shall feel real mean if you don't. You worked harder than I did, and it was only luck my getting this. Do, Bab, to please me," he persisted, awkwardly trying to fasten the ornament in the middle of Bab's white apron.